ゾンビ

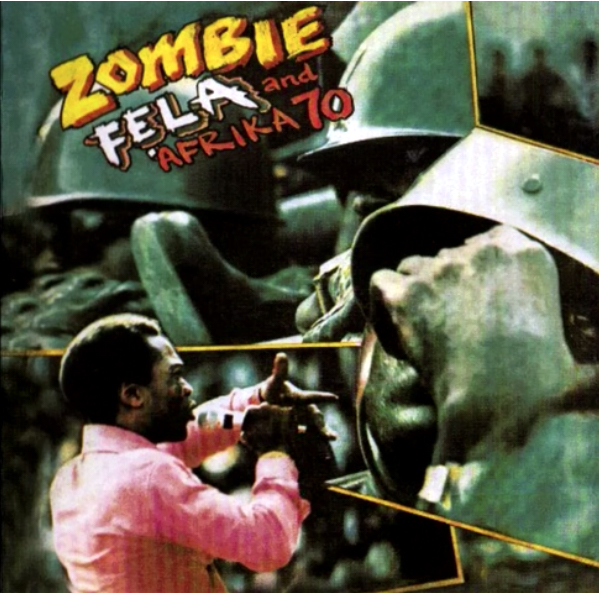

Fela Kuti's album, Zombie (1976)

☆ 『Zombie』 は、ナイジェリアのアフロビート・ミュージシャン、フェラ・クティのスタジオ・アルバムである。ナイジェリアでは1976年にココナッツ・レコードから、 イギリスでは1977年にクレオール・レコードからリリースされた[1]。 このアルバムはナイジェリア政府を批判しており、その結果、クティの母ファンミラヨ・ランソメ=クティが殺害され、彼のコミューンが軍によって破壊された と考えられている。

★

わたしはかつて、フンミラヨ・アニクラポ・クティと呼ばれていました。1978年4月13日、ラゴスで死にました。78歳でした。しかし、今となっては、

この日付、この名前になんの意味があるのでしょう?魂は肉、骨、内臓を離れて霊となり、屍は数時間のうちに蛆虫が食い尽くしてしまいました。これでやっ

と、私は自由の身になったのです。

Fela Kuti and

Afrika '70 - Zombie (1976) FULL ALBUM

Fela

Kuti and Afrika '70 - Zombie (1976) FULL ALBUM

| Zombie is

a studio

album by Nigerian Afrobeat musician Fela Kuti. It was

released in

Nigeria by Coconut Records in 1976, and in the United Kingdom by Creole

Records in 1977.[1] The album criticised the Nigerian government; and it is thought to have resulted in the murder of Kuti's mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, and the destruction of his commune by the military. |

『Zombie』は、ナイジェリアのアフロビート・ミュージシャン、

フェラ・クティのスタジオ・アルバムである。ナイジェリアでは1976年にココナッツ・レコードから、イギリスでは1977年にクレオール・レコードから

リリースされた[1]。 このアルバムはナイジェリア政府を批判しており、その結果、クティの母ファンミラヨ・ランソメ=クティが殺害され、彼のコミューンが軍によって破壊された と考えられている。 |

| Controversy and fallout This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (August 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The album was a scathing attack on Nigerian soldiers using the zombie metaphor to describe the methods of the Nigerian military. The album was a smash hit with the people and infuriated the government, setting off a vicious attack against the Kalakuta Republic (a commune that Kuti had established in Nigeria), during which one thousand soldiers attacked the commune.[2][3] Kuti was severely beaten, and his elderly mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was thrown from a window, causing fatal injuries. The Kalakuta Republic was burned, and Kuti's studio, instruments, and master tapes were destroyed. Kuti claimed that he would have been killed if it were not for the intervention of a commanding officer as he was being beaten. Kuti's response to the attack was to deliver his mother's coffin to the main army barrack in Lagos and write two songs, "Coffin for Head of State" and "Unknown Soldier", referencing the official inquiry that claimed the commune had been destroyed by an unknown soldier. Kuti and his band then took residence in Crossroads Hotel as the Shrine had been destroyed along with his commune. In 1978 Kuti married 27 women, many of whom were his dancers, composers, and singers to mark the anniversary of the attack on the Kalakuta Republic. Later, he was to adopt a rotation system of keeping only twelve simultaneous wives.[4] The year was also marked by two notorious concerts. The first was in Accra, where riots broke out during the song "Zombie," which led to Kuti being banned from entering Ghana. The second was at the Berlin Jazz Festival, after which most of Kuti's musicians deserted him, due to rumors that Kuti was planning to use the entirety of the proceeds to fund his presidential campaign. |

論争と放射性降下物 このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性がある。主張 を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してほしい。独自研究のみからなる記述は削除すべきである。(2013年8月)(このメッセージを削除する 方法とタイミングを学ぶ) このアルバムは、ナイジェリア軍のやり方をゾンビに喩えて表現し、ナイジェリア軍兵士を痛烈に攻撃したものだった。このアルバムは人々の間で大ヒットし、 政府を激怒させ、カラクタ共和国(クティがナイジェリアに設立したコミューン)に対する凶悪な攻撃を引き起こし、1000人の兵士がコミューンを襲撃した [2][3]。 クティはひどく殴打され、年老いた母親ファンミラヨ・ランソメ=クティは窓から投げ落とされ、致命傷を負った。カラクタ共和国は焼かれ、クティのスタジ オ、楽器、マスターテープは破壊された。クティは、殴られているときに指揮官の介入がなければ殺されていたと主張した。この襲撃に対するクティの反応は、 母親の棺をラゴスの陸軍本部に届け、「国家元首のための棺」と「未知の兵士」という2曲を書いたことだった。 その後、クティと彼のバンドはクロスロード・ホテルに居を構え、シュラインは彼のコミューンと共に破壊された。1978年、クティは27人の女性と結婚し たが、その多くは彼のダンサー、作曲家、歌手であった。後に彼は、同時に12人の妻を持つというローテーション・システムを採用することになる[4]。こ の年はまた、2つの悪名高いコンサートが行われた。ひとつはアクラでのコンサートで、「ゾンビ」の演奏中に暴動が起こり、クティはガーナへの入国を禁止さ れた。もうひとつはベルリン・ジャズ・フェスティバルで、クティが収益金の全額を大統領選の資金に充てるつもりだという噂が流れたため、クティのミュージ シャンのほとんどが彼を見捨てた。 |

| Critical reception Professional ratings Review scores Source Rating AllMusic [5] Christgau's Record Guide A−[6] The Rolling Stone Album Guide [7] Reviewing Zombie in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau said Kuti's English lyrics are "very political" and "associative" while the sound is "real fusion music — if James Brown's stuff is Afro-American, his is American-African."[6] AllMusic's Sam Samuelson called the album Kuti and Africa 70's "most popular and impacting record".[5] Pitchfork ranked it number 90 on their list of the 100 best albums of the 1970s.[8] It was ranked number 19 in Treble Magazine's top 150 albums of the '70s.[9] The album was included in Robert Dimery's 2005 book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[10] |

批評家の評価 プロの評価 レビュースコア ソース評価 オールミュージック [5] クリストガウのレコードガイド A-[6] ザ・ローリング・ストーン・アルバム・ガイド[7] Christgau's Record Guide』でZombieをレビューしている: ロバート・クリストガウは、『Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies』(1981年)でゾンビを評し、クティの英語の歌詞は「非常に政治的」で「連想的」であり、サウンドは「本物のフュージョン・ミュー ジックだ。 6]AllMusicのサム・サミュエルソンは、アルバム『Kuti and Africa 70's』を「最も人気があり、衝撃的なレコード」と評した[5]。 Pitchforkは、1970年代のベストアルバム100の90位にランクインさせた[8]。 このアルバムは、ロバート・ディメリーの2005年の著書『1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die』に収録されている[10]。 |

| Track listing All tracks are written by Fela Kuti Original LP No. Title Length 1. "Zombie" 12:26 2. "Mister Follow Follow" 12:58 Total length: 25:24 CD Reissue bonus tracks No. Title Length 3. "Observation Is No Crime" 13:26 4. "Mistake" (Live at the Berlin Jazz Festival, 1978) 14:47 Total length: 53:41 |

トラックリスト 全曲フェラ・クティ作詞作曲 オリジナルLP 番号 タイトル 長さ 1. 「ゾンビ」 12:26 2. 「ミスター・フォロー・フォロー」 12:58 全長:25分24秒 CDリイシュー・ボーナス・トラック 番号 タイトル 長さ 3. 「観察は犯罪ではない" 13:26 4. 「Mistake"(1978年ベルリン・ジャズ・フェスティバルでのライヴ) 14:47 全長:53分41秒 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zombie_(album) YoTube 音声:Fela Kuti and Afrika '70 - Zombie (1976) FULL ALBUM |

|

| Zombie 0, zombie (Zombie 0,

zombie) Zombie 0, zombie (Zombie 0, zombie) Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go (Zombie) Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop (Zombie) Zombie no go tum, unless you tell am to tum (Zombie) Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think (Zombie)Tell am to go straight A Joro, Jara, Joro No break, no job, no sense A Jora, Jara, Joro Tell am to go kill A Jora, Jara, Joro No break, no job, no sense A Joro, Jara, Joro Tell am to go quench A Jora, Jara, Joro No break, no job, no sense A Jora, Jara, Joro |

ゾンビ0、ゾンビ(ゾンビ0、ゾンビ) ゾンビ0、ゾンビ(ゾンビ0、ゾンビ) ゾンビは行かない、行けと言わない限り(ゾンビ) ゾンビは止まらない、止まれと言わない限り(ゾンビ) ゾンビは転ばない、転べと言わない限り(ゾンビ) ゾンビは考えない、あなたが考えるように言わない限り(ゾンビ)まっすぐ行くように言う ジョロ、ジャラ、ジョロ 休みなし、仕事なし、センスなし ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョロ 殺しに行けと言え ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョロ 休みなし、仕事なし、センスなし ジョロ、ジャラ、ジョロ 消えてしまえと言え ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョロ 休みなし、仕事なし、センスなし ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョロ |

| Go and kill! (Jora, Jara, Jora) Go and die! (Jora, jara, jora) Go and quench! (Jora, jara, Jora) Put am for reverse! (Jare, Jara, jora) |

殺しに行け!(ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョラ) 行って死ね!(ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョラ) 行って鎮めよ!(ジョラ、ジャラ、ジョラ) 逆転だ (ジャレ、ジャラ、ジョラ) |

| Jare, jara, jora, zombie way na

one way Jare, jara, JOrD, zombie wey na one way Jare, jara, Jore, zombie wey na one way Jare, jara, jare |

ジャレ、ジャラ、ジョラ、片道ゾンビ道 Jare, jara, JOrD, zombie wey na one way. Jare, jara, Jore, zombie wey on one way. ジャレ、ジャレ、ジャレ |

| Attention! (Zombie) Quick march! Slow march! (Zombie) Left turn! Right turn! (Zombie) About tum! Double up! (Zombie) Salute! Open your hatl (Zombie) Stand at ease! Fall in! (Zombie) Fallout! Fall down! (Zombie) Get ready! Hall! Order! Dismiss! |

注目 (ゾンビ) 急行だ ゆっくりと行進する!(ゾンビ) 左旋回! 右旋回だ (ゾンビ) 腫瘍について ダブルアップ!(ゾンビ) 敬礼 帽子を開けろ! 落ち着いて立つんだ 落ちろ!(ゾンビ) 落ちろ! 倒れろ!(ゾンビ) 準備しろ! ホールだ! 命令だ 解散だ! |

Family pic of her on 70th birthday from Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti And The Women’s Union of Abeokuta Comic strip Illustrations: Alaba Onajin Script and text: Obioma Ofoego - Published by UNESCO with share alike license

ファ ンミラヨ・ランソメ=クティとアベオクタ女性ユニオンの70歳の誕生日を祝う家族写真: アラバ・オナジン 台本・テキスト:オビオマ・オフォエゴ オビオマ・オフォエゴ - ユネスコ発行(Share alike license (→フンミラヨ・ランソメ=クティ, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, 1900-1978)

Fela

Kuti - Coffin For Head of State

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆