チリにおけるフェミニズム

Feminism

in Chile

Chilean women protest against the Pinochet regime.

☆ チリのフェミニズムは、チリの政治的、経済的、社会的システムによって形成された独自の解放言語と権利のための活動家戦略を持っている。19世紀に始ま り、チリの女性たちは政治的権利を主張するために組織化されてきた。 Círculo de Estudios de la Mujer(女性研究サークル)は、ピノチェト独裁政権時代(1973-1989)に女性の責任と権利を再定義し、「母親の権利」を女性の権利と女性の市 民的自由に結びつけた先駆的な女性組織の一例である。彼女たちは「チリの女性の状況を議論するため」に集まり、最初の会合には300人以上の参加者が集ま り、そこからサンティアゴの権威主義的な生活に異議を唱えた。彼女たちはチリの女性の権利の形成に貢献した。

| Feminism

in Chile has its own liberation language and activist strategies for

rights that is shaped by the political, economic, and social system of

Chile. Beginning in the 19th century, Chilean women have been

organizing with aspirations of asserting their political rights.[1]

These aspirations have had to work against the reality that Chile is

one of the most socially conservative countries in Latin America.[2]

The Círculo de Estudios de la Mujer (Women's Studies Circle) is one

example of a pioneering women's organization during the Pinochet

dictatorship (1973–1989) which redefined women's responsibilities and

rights, linking “mothers’ rights” to women's rights and women's civil

liberties.[3] The founding members of the Círculo de Estudios de La

Mujer consisted of a small group of Santiago feminists who were from

the Academia de Humanismo Cristiano. These women gathered "to discuss

the situation of women in Chile," their first meeting drew a crowd of

over 300 participants and from there challenged the authoritarian life

in Santiago. These women helped shape the rights for women in Chile.[4] |

チ

リのフェミニズムは、チリの政治的、経済的、社会的システムによって形成された独自の解放言語と権利のための活動家戦略を持っている。19世紀に始まり、

チリの女性たちは政治的権利を主張するために組織化されてきた。 [2] Círculo de Estudios de la

Mujer(女性研究サークル)は、ピノチェト独裁政権時代(1973-1989)に女性の責任と権利を再定義し、「母親の権利」を女性の権利と女性の市

民的自由に結びつけた先駆的な女性組織の一例である。彼女たちは「チリの女性の状況を議論するため」に集まり、最初の会合には300人以上の参加者が集ま

り、そこからサンティアゴの権威主義的な生活に異議を唱えた。彼女たちはチリの女性の権利の形成に貢献した。[4]1 |

| Early history of feminism in Chile With the strong influence of Catholicism in Chile, some of the first feminist movements ironically came from socially conservative women. In 1912, upper-class women began to advocate for working-class women in a way that was favorable to conservative groups of the time.[5] The first female organizations that came to be in Chile started around 1915, but unlike many other countries and their groups, these women were most likely to be in the upper middle class.[6] As such, they were largely able to put together these groups where exploration of the interest in feminism came to be by shedding particular light on the issues that middle to upper-class feminists found to be the most important. One of the earliest examples of this in Chilean history occurred on June 17, 1915, when a young university student, and later a diplomat and suffragist, named Amanda Labarca decided to start a group called the Círculo de Lectura, where she was able to promote Chilean culture towards women.[7] With this, she was able to bring together positivity and change within the women in her community because she strived to ensure that all women could be given a chance to have their voices heard, through education, regardless of their affiliations and social status.[8] Early feminism in Chile also took notes on the international feminist mobilizations, while catering to Chile's specific culture. For example, feminists such as Amanda Labarca promoted a domestic form of feminism which was sensitive to the socially and politically conservative governmental powers of the time.[9] Generally speaking, this was what was seen as the beginning of first-wave feminism amongst Chilean women.[10] |

チリにおけるフェミニズムの初期の歴史 チリではカトリックの影響が強く、最初のフェミニズム運動のいくつかは皮肉にも社会的に保守的な女性から生まれた。1912年、上流階級の女性たちが、当 時の保守的なグループにとって好都合な方法で労働者階級の女性たちを擁護し始めたのである[5]。チリで生まれた最初の女性団体は1915年頃に始まった が、他の多くの国やそのグループとは異なり、これらの女性たちは上流中産階級にいる可能性が最も高かった[6]。そのため、彼女たちは、中流階級から上流 階級のフェミニストたちが最も重要だと考える問題に特別な光を当てることによって、フェミニズムへの関心の探求が生まれたこれらのグループをまとめること ができた。1915年6月17日、アマンダ・ラバルカ(Amanda Labarca)という若い大学生(後に外交官兼参政権論者)がCírculo de Lecturaと呼ばれるグループを立ち上げ、そこで女性に対するチリの文化を広めることにした。 [7]彼女は、所属や社会的地位に関係なく、教育を通じてすべての女性が自分の声を聞く機会を与えられるように努めたため、この活動によって、コミュニ ティの女性たちに積極性と変化をもたらすことができた[8]。例えば、アマンダ・ラバルカのようなフェミニストたちは、当時の社会的・政治的に保守的な政 府権力に配慮した国内的なフェミニズムを推進した[9]。一般的に言えば、これがチリの女性たちの間で第一波フェミニズムの始まりと見られていたものであ る[10]。 |

| History The most compactly organized feminist movement in South America in the early 20th century was in Chile.[citation needed] There were three large organizations which represented three different classes of people: the Club de Señoras of Santiago represented the more prosperous women; the Consejo Nacional de Mujeres represented the working class, such as schoolteachers; other laboring women organized another active society for the improvement of general educational and social conditions.[11] The Circulo de Lectura de Señoras was founded in 1915 in Santiago Chile by Delia Matte de Izquierdo.[12] Only one month later, the Club de Señoras was created and founded by Amanda Labarca.[13] Women such as Amanda Labarca were particularly successful in their feminist efforts mainly due to some of their international contacts and experiences resulting from studying abroad.[9] While Chile was very conservative socially and ecclesiastically during this time, its educational institutions were opened to women since around the 1870s. When Sarmiento as an exile was living in Santiago, he recommended the liberal treatment of women and their entrance into the university. This latter privilege was granted while Miguel Luis Amunategui was minister of education. In 1859, when a former minister of education opened a contest for the best paper on popular education, Amunategui received the prize. Among the things which he advocated in that paper was the permitting of women to enter the university, an idea which he had received from Sarmiento. The development of women's education was greatly delayed by the war between Chile, Peru, and Bolivia. President Balmaceda was a great friend of popular education. Under him, the first national high school, or "liceo," for girls was opened, about 1890. This first wave of feminism began in about 1884.[14] Chile was one of the first Latin American countries to admit women to institutions of higher education as well as to send women abroad to study.[9] By the 1920s, there were 49 national "liceos" for girls, all directed by women. Besides these, there were two professional schools for young women in Santiago and one in each Province.[11] The Consejo Nacional de Mujeres maintained a home for girls attending the university in Santiago, and helped the women students in the capital city. There were nearly a 1,000 young women attending the University of Chile in the early 20th century. The conservative element of this club focused primarily on pursuing women's intellectual work, while later on, Consejo Nacional took more progressive ideas into account. Their members consisted of impressive middle class, aristocratic, woman who had a great deal of influence on their communities, including government and private sectors.[13] Labarca wrote several interesting volumes— such as, Actividades femeninas en Estados Unidos (1915), and ¿A dónde va la mujer? (1934). She was accompanied in her work by a circle of women, most, of whom were connected with educational work in Chile. Several women's periodicals were published in Chile during this period, one of note being El Pefleca, directed by Elvira Santa Cruz.[11] Labarca is perhaps considered one of Chile's most prominent feminist leaders. In a 1922 address given before the Club de Señoras of Santiago, Chilean publisher Ricardo Salas Edwards stated the following: "There have been manifested during the last 25 years phenomena of importance that have bettered woman's general culture and the development of her independence. Among them were the spread of establishments for the primary and secondary education of women; the occupations that they have found themselves as the teachers of the present generation, which can no longer entertain a doubt of feminine intellectual capacity; the establishment of great factories and commercial houses, which have already given her lucrative employment, independent of the home; the organization of societies and clubs; and, finally, artistic and literary activities, or the catholic social action of the highest classes of women, which has been developed as a stimulus to the entire sex during recent years."[11] Amanda Labarca initially thought that asking for suffrage in Chile was inappropriate. In 1914, she wrote, "I am not a militant feminist, nor am I a suffragist, for above all I am Chilean, and in Chile today the vote for women is out of order."[9] This sentiment began to change as the post-World War I economic crisis hit, and more and more women were pushed into the working class. In order to complement this new economic responsibility, women began to fight for political, legal, and economic rights. In 1919, Labarca transformed the Ladies Reading Circle into the National Women's Council, which was informed by international women's councils.[9] A new political body was formed in the early 1920s under the name of the Progressive Feminist Party with the purpose of gaining all the rights claimed by women. The platform was: The right to the municipal and parliamentary vote and to eligibility for office. The publishing of a list of women candidates of the party for public offices. The founding of a ministry of public welfare and education, headed by a woman executive, to protect women and children and to improve living conditions.[15] The founders of the party (middle-class women) carried on a quiet and cautious campaign throughout the country. No distinction was made between the social positions of party adherents, the cooperation of all branches of feminine activity being sought to further the ends of the party. The press investigated public opinion regarding the new movement. Congress had already received favorably a bill to yield civil and legal rights to women. The greatest pressure was brought to bear to obtain the concession of legal rights to women to dispose of certain property, especially the product of their own work, and the transference to the mother, in the father's absence, of the power to administer the property of the child and the income therefrom until the minor's majority. It was understood that concession of these rights would elevate the authority of the mother and bring more general consideration for women, as well as benefits to family life and social welfare.[15] One group that stands out in particular as a historical cornerstone of feminism in Chile[according to whom?] is the Movement for the Emancipation of Chilean Women (MEMCh). Founded in 1935 by influential feminists such as Marta Vergara, MEMCh fought for the legal, economic, and reproductive emancipation of women as well as their community involvement to improve social conditions.[9] MEMCh produced an inspiring monthly bulletin (La Mujer Nueva) that contextualized the work being done in Chile with international feminism. While feminism in Chile of a decade earlier had focused on more nationalistic and religious goals, MEMCh initiated a connectedness between South and North American women, in defense of democracy. In December 1948, the Chilean Congress had approved a bill granting full political rights to the women of Chile.[9] During Pinochet's dictatorship throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, coalitions and federations of women's groups—not all of which necessarily designated themselves in name as feminists—gathered in kitchens, living rooms, and other non-political arenas to devise strategies of bringing down the dictator's rule. During his presidency, the second wave of feminism was occurring.[14] Because political movements, mostly male-dominated, were oppressed nearly out of existence during the dictatorship, women gathered in a political manner outside of what was traditionally male. Through this they created grassroots organizations such as Moviemento pro emancipación de la Mujer that is credited with directly influencing the downfall of Pinochet.[16] Pinochet's rule also involved mass exile—an estimation of over 200,000 by 1980. While Chilean women were living in exile in Vancouver, Canada, a feminist magazine created by Latinas, called Aquelarre began to circulate widely.[17] There were a variety of reasons that women sought to gain more freedom. One of the reasons consisted on the fact that Chilean women were trying to mirror the independence that women had in North America during the Industrial era. Women were eager to work, and make money. However, there was a very large belief that if women worked, then households would fall apart. Some of the strategic preferences that allowed for women's rights was autonomy, double militancy, and integration. Even within the feminist community in Chile, there is an overall disagreement as to how feminism has been affected by democracy post dictatorship. Even though more feminist policies were put in place during the 1990s, feminists paradoxically largely lost their voices politically. This reconfiguration of the feminist movement post dictatorship has posed certain challenges to the advancement of feminist ideals. There has been a general trend towards disregarding this moment in the history of feminism in Chile even though there were significant organizations who continued to work towards liberation.[18] In the 1990s, there was often a dichotomy between groups that worked within institutions to instill change, and those who wanted to distance their motives as far away from the patriarchy as possible. While the privileged professors of newly established gender and women's studies programs in universities were given more of a say, the average citizens found that their voices were often muffled and restrained by institutionalized feminism.[19] Chile made marital rape illegal in 1999.[20] More recently, the Chilean women's movements continue to advocate for their rights and participation in all levels of the democratic society and through non-governmental organizations. Similarly, a large political barrier for women was broken when Michelle Bachelet became Chile's first female president. Laura Albornoz was also delegated as Minister of Women's Affairs during Bachelet's first term as president. This position's duties includes running the Servicio Nacional de la Mujer or the National Women's Service. Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERNAM) - protects women's legal rights in the public sector. In the beginning of its creation, some opinions were that SERNAM organization was said to have weakened the women's rights agenda due because it wasn't successful at policy influence. The organization was later found to be successful at creating programs and legislation that promoted the protection of women's rights at work, school and worked to criminalize domestic violence and protection.[21] The success of this organization is debated, but it has made substantial moves to publicize the issues women face across Chile. Motherhood has also been an important aspect of the feminist movement in Chile. Due to the vast influence of Catholicism in the country, the first (1940s) women's centers for mothering began with religious motives. Most of these centers, however, were catered to upper-class women, leaving the poorest women the least supported. The CEMA Chile [es] (Center for Mothers) was created in 1954, to "provide spiritual and material well-being to the Chilean women".[22] CEMA worked, more so than other women's centers, to provide services for underprivileged women in Chile.[23] Through motherhood, the Chilean woman has been politicized- not only is she ridiculed for overpopulating a country while given minimal means of reproductive support, but she is also taken as a passive object of governance.[24] The parity promoted by Bachelet did not survive her. Half of the ministries in her first government were occupied by women; in her successor's team, Sebastián Piñera, they barely reached 18%.[25] |

歴史 サンティアゴのクラブ・デ・セニョーラはより豊かな女性たちを代表し、コンセホ・ナシオナル・デ・ムヘーレスは学校の教師などの労働者階級を代表し、その 他の労働者女性たちは一般的な教育や社会条件の改善のために別の活動的な協会を組織していた。 [アマンダ・ラバルカのような女性たちがフェミニストとしての活動で特に成功を収めたのは、主に彼女たちの国際的な人脈や留学から得た経験によるもので あった[13]。 この時代、チリは社会的にも教会的にも非常に保守的であったが、教育機関は1870年代頃から女性に開放されていた。亡命者だったサルミエントがサンティ アゴに住んでいたとき、彼は女性の自由な扱いと大学への入学を勧めた。この後者の特権は、ミゲル・ルイス・アムナテギが教育大臣であった時に認められた。 1859年、前教育大臣が民衆教育に関する最優秀論文のコンテストを開いたとき、アムナテギはその賞を受賞した。その論文の中で彼が提唱したものの中に、 サルミエントから受けたアイデアである女性の大学入学の許可があった。女子教育の発展は、チリ、ペルー、ボリビア間の戦争によって大きく遅れた。バルマセ ダ大統領は、民衆教育の大いなる友であった。バルマセダ大統領のもとで、1890年頃、最初の国立女子高校(リセオ)が開校した。このフェミニズムの最初 の波は1884年頃に始まった[14]。チリは、高等教育機関に女性を入学させ、女性を海外に留学させた最初のラテンアメリカ諸国のひとつであった [9]。1920年代までに、49の国立の女子「リセオ」があり、すべて女性が監督していた。これに加えて、若い女性のための専門学校がサンティアゴに2 校、各州に1校あった[11]。 コンセホ・ナシオナル・デ・ムヘーレスはサンティアゴの大学に通う女子のための施設を維持し、首都の女子学生を援助した。20世紀初頭、チリ大学には 1,000人近くの若い女性が通っていた。このクラブの保守的な要素は、主に女性の知的活動の追求に重点を置いていたが、後にコンセホ・ナシオナルはより 進歩的な考えを取り入れた。ラバルカは、『Actividades femeninas en Estados Unidos』(1915年)、『¿A dónde va la mujer? 彼女の活動には、チリの教育関係者を中心とする女性サークルが同行していた。この時期、チリではいくつかの女性定期刊行物が発行され、そのうちのひとつが エルヴィラ・サンタ・クルスが編集長を務めた『エル・ペフレカ』であった[11]。ラバルカはおそらくチリで最も著名なフェミニスト指導者の一人と考えら れている。 1922年、チリの出版社リカルド・サラス・エドワーズは、サンティアゴのクラブ・デ・セニョーラの前で行った演説の中で、次のように述べている: 「過去25年間に、女性の一般的な教養と自立の発展を向上させる重要な現象が現れた。その中には、女性の初等・中等教育のための施設の普及、女性の知的能 力をもはや疑うことのできない現世代の教師としての職業、家庭から独立して女性に有利な雇用をすでに与えている大規模な工場や商業施設の設立、協会やクラ ブの組織化、そして最後に、芸術活動や文学活動、あるいは近年性全体に刺激を与えるものとして発展してきた女性の最高階級のカソリックな社会活動などがあ る」[11]。 アマンダ・ラバルカは当初、チリで参政権を求めるのは不適切だと考えていた。1914年、彼女は「私は戦闘的なフェミニストではなく、参政権論者でもあり ません。何よりも私はチリ人であり、今日のチリでは女性の参政権は論外だからです」[9]と書いている。この新しい経済的責任を補完するために、女性は政 治的、法的、経済的権利を求めて闘い始めた。1919年、ラバルカは婦人読書サークルを全国婦人評議会に改組し、国際婦人評議会から情報を得ていた [9]。1920年代初頭には、女性が主張するすべての権利を獲得することを目的に、進歩的フェミニスト党という名の新しい政治団体が結成された。その綱 領は次のようなものだった: 市政選挙権と議会選挙権、および公職に就く資格の獲得。 党の女性公職候補者名簿の発行。 女性と子供を保護し、生活条件を改善するために、女性幹部が率いる公共福祉・教育省を設立すること[15]。 党の創設者たち(中流階級の女性)は、全国で静かで慎重なキャンペーンを展開した。党員の社会的地位に区別はなく、党の目的を達成するために、あらゆる女 性的活動の協力が求められた。マスコミは新しい運動に関する世論を調査した。議会はすでに、女性に市民的・法的権利を与える法案を好意的に受け止めてい た。最大の圧力は、特定の財産、特に自分の仕事の生産物を処分する法的権利を女性に譲歩させ、父親が不在の場合には、未成年者が成人するまでの間、子供の 財産とその収入を管理する権限を母親に移譲させるようにすることであった。これらの権利の譲歩は、母親の権威を高め、女性に対するより一般的な配慮をもた らすだけでなく、家庭生活や社会福祉にも利益をもたらすと理解されていた[15]。 チリにおけるフェミニズムの歴史的礎石として特に際立っているグループは[誰によれば]、チリ女性解放運動(MEMCh)である。マルタ・ベルガラなどの 影響力のあるフェミニストによって1935年に設立されたMEMChは、女性の法的・経済的・生殖的解放と、社会状況を改善するための地域社会への参加の ために闘った。その10年前のチリのフェミニズムは、より民族主義的で宗教的な目標に焦点を当てていたが、MEMChは民主主義を守るために、南米と北米 の女性たちの結びつきを始めた。 1948年12月、チリ議会はチリの女性に完全な政治的権利を与える法案を承認した[9]。 1970年代後半から1980年代前半にかけてのピノチェト独裁政権の間、女性グループの連合や連合体は、必ずしもフェミニストと名乗るものばかりではな かったが、独裁者の支配を崩壊させるための戦略を練るために、台所や居間、その他の非政治的な場に集まっていた。独裁政権下では、ほとんどが男性主導で あった政治運動がほとんど存在しないほど弾圧されていたため、女性たちは伝統的に男性であったものから外れた政治的な方法で集まった。これを通じて、彼女 たちは、ピノチェトの失脚に直接影響を与えたとされるMovmento pro emancipación de la Mujerのような草の根組織を作り上げた[16]。チリの女性たちがカナダのバンクーバーで亡命生活を送っていた頃、ラティーナたちによって作られた フェミニスト雑誌『Aquelarre』が広く流通し始めた[17]。 女性たちがより自由を得ようとした理由はさまざまであった。その理由のひとつは、チリの女性たちが、工業化時代の北米で女性たちが持っていた自立を反映し ようとしていたことにあった。女性たちは働き、お金を稼ぐことを熱望していた。しかし、女性が働けば家庭が崩壊するという考え方が非常に強かった。女性の 権利を可能にした戦略的選好には、自律性、二重の戦闘性、統合性などがあった。 チリのフェミニスト・コミュニティ内でも、独裁政権後の民主主義によってフェミニズムがどのような影響を受けたかについては、全体的に意見が分かれてい る。1990年代により多くのフェミニズム政策が実施されたにもかかわらず、フェミニストたちは逆説的に政治的な発言力を大きく失ってしまった。独裁政権 後のフェミニズム運動のこの再構成は、フェミニズムの理想の前進にある種の課題を突きつけた。チリのフェミニズムの歴史において、解放に向 けて活動を続けた重要な団体があったにもかかわ らず、この瞬間を軽視する一般的な傾向があ った[18]。1990年代には、変化を浸透させるた めに組織内で活動するグループと、家父長制から 可能な限り距離を置こうとするグループとの 間で、しばしば二分化が見られた。大学に新しく設立されたジェンダー・女性学プログラムの特権的な教授たちにはより多くの発言権が与えられていたが、一般 市民は、制度化されたフェミニズムによって自分たちの声がしばしば消され、抑制されていることに気づいていた[19]。 チリは1999年に夫婦間のレイプを違法とした[20]。 最近では、チリの女性運動は、民主主義社会のあらゆるレベルにおいて、また非政府組織を通じて、女性の権利と参加を主張し続けている。同様に、ミシェル・ バチェレがチリ初の女性大統領となったとき、女性にとっての大きな政治的障壁が打ち破られた。ラウラ・アルボルノスもまた、バチェレの最初の大統領任期中 に女性問題大臣を委嘱された。この役職の任務には、Servicio Nacional de la Mujer(国立女性サービス)の運営が含まれる。Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERNAM) - 公共部門における女性の法的権利を保護する。設立当初は、SERNAMは政策に影響を与えることに成功しなかったため、女性の権利の課題を弱めたという意 見もあった。後に、この組織は、職場や学校における女性の権利保護を促進するプログラムや法律の作成に成功し、家庭内暴力の犯罪化と保護に取り組んだこと が判明した[21]。この組織の成功については議論があるが、チリ全土で女性が直面する問題を公表するために実質的な動きを見せた。 母性もまた、チリのフェミニズム運動の重要な側面であった。同国ではカトリックの影響が大きいため、最初の(1940年代の)女性母親センターは宗教的動 機から始まった。しかし、これらのセンターのほとんどは、上流階級の女性を対象としており、最も貧しい女性たちの支援は最も手薄であった。CEMAチリ [es](母親のためのセンター)は1954年に設立され、「チリの女性たちに精神的・物質的な幸福を提供する」ことを目的としていた[22]。CEMA は、他の女性センター以上に、チリの恵まれない女性たちにサービスを提供するために活動していた[23]。 母親であることを通して、チリの女性は政治化されてきた。最低限の生殖支援手段を与えられながら、国を過剰に人口増加させたと揶揄されるだけでなく、統治 の受動的な対象としても捉えられてきた[24]。 バチェレによって推進された平等は、彼女を存続させることはできなかった。彼女の最初の政権では省庁の半分を女性が占めたが、後任のセバスティアン・ピニェラ政権では、かろうじて18%にとどまった[25]。 |

| Women's access to voting in Chile Chile has been considered one of the most socially conservative countries in Latin America.[by whom?] This has been exemplified by women's struggle to gain freedom in terms of voting. The Chilean government esteems Catholicism, which puts women in a patriarchal, domesticated setting, and has been used as reasoning for restricting women's rights. Even though the first woman (Domitila Silva Y Lepe) voted in 1875, voting was still considered a barrier well into the 1900s to women's rights in Chile.[26] By 1922, Graciela Mandujano and other women founded the Partido Cívico Femenino (Women's Civic Party) which focused on women getting the right to vote.[citation needed] Women formally gained the right to vote in 1949.[27] During that time, women and men voted in separate polling stations due to an effort to provide women with less influence on their preferences.[27] Women also tended to vote more conservatively than men, demonstrating the influence of religion on voting preferences.[27] Although most organizations dissolved after suffrage was granted, Partido Femenino Chileno (Chilean Women's Party), founded by María de la Cruz in 1946, continued to grow and work for more women's rights throughout the years.[28] Chilean women's influence on politics has been demonstrated through multiple occasions during presidential elections - for example, had women not voted in the 1958 election, Salvador Allende would have won.[29] During Chile's dictatorship (1973-1990), developments in regards to women's rights stalled comparatively. This did not stop some feminist groups from speaking out, however, as exemplified by the women's march of 1971 against Salvador Allende. This march had long-lasting effects, particularly by establishing women's role in politics, and turning the day of the march into National Women's Day.[30] Post dictatorship, women paradoxically also seemed to lose their voice politically.[19] With a more recent surge in feminism in Chile, the first female leader, Michelle Bachelet, became the 34th president in 2006–2010. While not immediately re-electable for the next election, she was appointed the first executive director of United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). On March 11, 2014, she became the 36th president, beginning her second term. |

チリにおける女性の投票権 チリはラテンアメリカで最も社会的に保守的な国のひとつとみなされてきた。チリ政府は、女性を家父長的で家畜的な環境に置くカトリックを尊重しており、女 性の権利を制限する理由付けとして使われてきた。1875年に最初の女性(ドミティラ・シルバ・イ・レペ)が投票に行ったにもかかわらず、1900年代に 入っても、投票権はチリにおける女性の権利の障壁であると考えられていた[26]。1922年までに、グラシエラ・マンドゥハーノと他の女性たちは、女性 の選挙権獲得に焦点を当てたPartido Cívico Femenino(女性市民党)を設立した。 [1949年、女性は正式に選挙権を獲得した[27]。この間、女性の投票行動に影響を与えないようにするため、女性と男性は別々の投票所で投票した [27]。 [27]参政権が認められた後、ほとんどの団体は解散したが、1946年にマリア・デ・ラ・クルスによって設立されたチリ女性党(Partido Femenino Chileno)は成長し続け、長年にわたってより多くの女性の権利のために活動した[28]。チリの女性の政治への影響力は、大統領選挙で何度も実証さ れてきた。例えば、1958年の選挙で女性が投票しなければ、サルバドール・アジェンデが勝利していただろう。しかし、1971年のサルバドール・アジェ ンデに反対する女性の行進に代表されるように、一部のフェミニストグループの発言は止められなかった。このデモ行進は、特に政治における女性の役割を確立 し、デモ行進の日を全国女性デーにするなど、長期にわたって影響を及ぼした[30]。独裁政権後は、逆説的に、女性も政治的な発言力を失っていくように思 われた[19]。チリにおけるフェミニズムの最近の盛り上がりに伴い、2006年から2010年にかけて、初の女性指導者であるミシェル・バチェレが第 34代大統領に就任した。次の選挙ですぐに再選されることはなかったが、国連ジェンダー平等と女性の地位向上のための機関(UN Women)の初代事務局長に任命された。2014年3月11日、第36代大統領に就任し、2期目を開始した。 |

| Leaders of the feminist movement in Chile Main article: Women in Chile Julieta Kirkwood, born in 1937, was considered[by whom?] the founder of the feminist movement of the 1980s and an instigator of the organization of gender studies at universities in Chile. After studying at the University of Chile, she was influenced by the 1968 revolution in France. At the core of her ideologies was the mantra, ‘There is no democracy without feminism”.[31] Influenced by the ideologies of sociologist Enzo Faletto [es; pt], she contributed to FLACSO’s theoretical framework of rebellious practices in the name of feminism. Kirkwood not only theorized, but also practiced a life full of activism – being a part of MEMCh 83 as well as the Center for Women's Studies. She also wrote opinionated pieces in a magazine called Furia. Her book, Ser política en Chile, framed how academia has contributed to the social movements of the 1980s.[1] She argued for equal access to scientific knowledge for women, as well as advocating for a more just educational system. Amanda Labarca was one of the pioneering feminists in Chile and paved the way for what feminism is today.[citation needed] |

チリにおけるフェミニスト運動の指導者たち 主な記事 チリの女性たち ジュリエッタ・カークウッドは1937年生まれで、1980年代のフェミニスト運動の創始者であり、チリの大学でジェンダー研究を組織するきっかけを作っ た人物である。チリ大学で学んだ後、1968年のフランス革命に影響を受ける。社会学者エンツォ・ファレット[es; pt]の思想に影響を受け、フェミニズムの名の下に反抗的な実践を行うFLACSOの理論的枠組みに貢献した。カークウッドは理論化するだけでなく、 MEMCh83や女性研究センターの一員として、アクティビズムに満ちた生活を実践した。彼女はまた、Furiaという雑誌に意見を書いた。彼女の著書 『Ser política en Chile』は、1980年代の社会運動に学問がどのように貢献してきたかを枠にはめたものである。 アマンダ・ラバルカは、チリにおけるフェミニストの先駆者の一人であり、今日のフェミニズムへの道を開いた[要出典]。 |

| 2018 feminist wave The Ni una menos and Me Too movements generated Chilean marches in November 2016, March 2017 and October 2017 to protest violence against women. Following Sebastián Piñera's assumption of the Presidency in March 2018, women's marches and university occupations were expanded from April to June 2018 to protest against machismo, domestic violence and sexual harassment and sexist behaviour in universities and schools, and for abortion rights.[32][33] |

2018年フェミニストの波 Ni una menos運動とMe Too運動は、女性に対する暴力に抗議するため、2016年11月、2017年3月、2017年10月にチリのデモ行進を発生させた。2018年3月のセ バスティアン・ピニェラの大統領就任後、2018年4月から6月にかけて、大学や学校におけるマチズモ、家庭内暴力、セクシュアル・ハラスメントや性差別 的言動に抗議し、中絶の権利を求めて、女性のデモ行進や大学占拠が拡大した[32][33]。 |

| A Rapist in Your Path Feminism in Latin America Feminism in Argentina Feminism in Mexico Women in Chile |

あなたの行く手にレイプ犯がいる ラテンアメリカのフェミニズム アルゼンチンのフェミニズム メキシコのフェミニズム チリの女性たち |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism_in_Chile |

|

| The lives, roles, and rights of women in Chile

have gone through many changes over time. Chilean women's societal

roles have historically been impacted by traditional gender roles and a

patriarchal culture, but throughout the twentieth century, women

increasingly involved themselves in politics and protest, resulting in

provisions to the constitution to uphold equality between men and women

and prohibit sex discrimination. Women's educational attainment, workforce participation, and rights have improved, especially since Chile became a democracy again in 1990. Chile legalized divorce in 2004 and is also one of the few countries to have elected a female president.[4] However, Chilean women still face many economic and political challenges, including income disparity, high rates of domestic violence, and lingering patriarchal gender roles. |

チ

リにおける女性の生活、役割、権利は、時代とともに多くの変化を遂げてきた。チリ女性の社会的役割は、歴史的に伝統的な性別役割分担と家父長制文化の影響

を受けてきたが、20世紀を通じて、女性が政治や抗議活動に参加する機会が増え、その結果、憲法に男女平等を謳い、性差別を禁止する規定が設けられた。 特に1990年にチリが再び民主化して以来、女性の教育水準、労働参加、権利は向上してきた。チリは2004年に離婚を合法化し、女性大統領を選出した数 少ない国のひとつでもある[4]。しかし、チリの女性は、所得格差、家庭内暴力の高率、家父長的性別役割分担の残存など、依然として多くの経済的・政治的 課題に直面している。 |

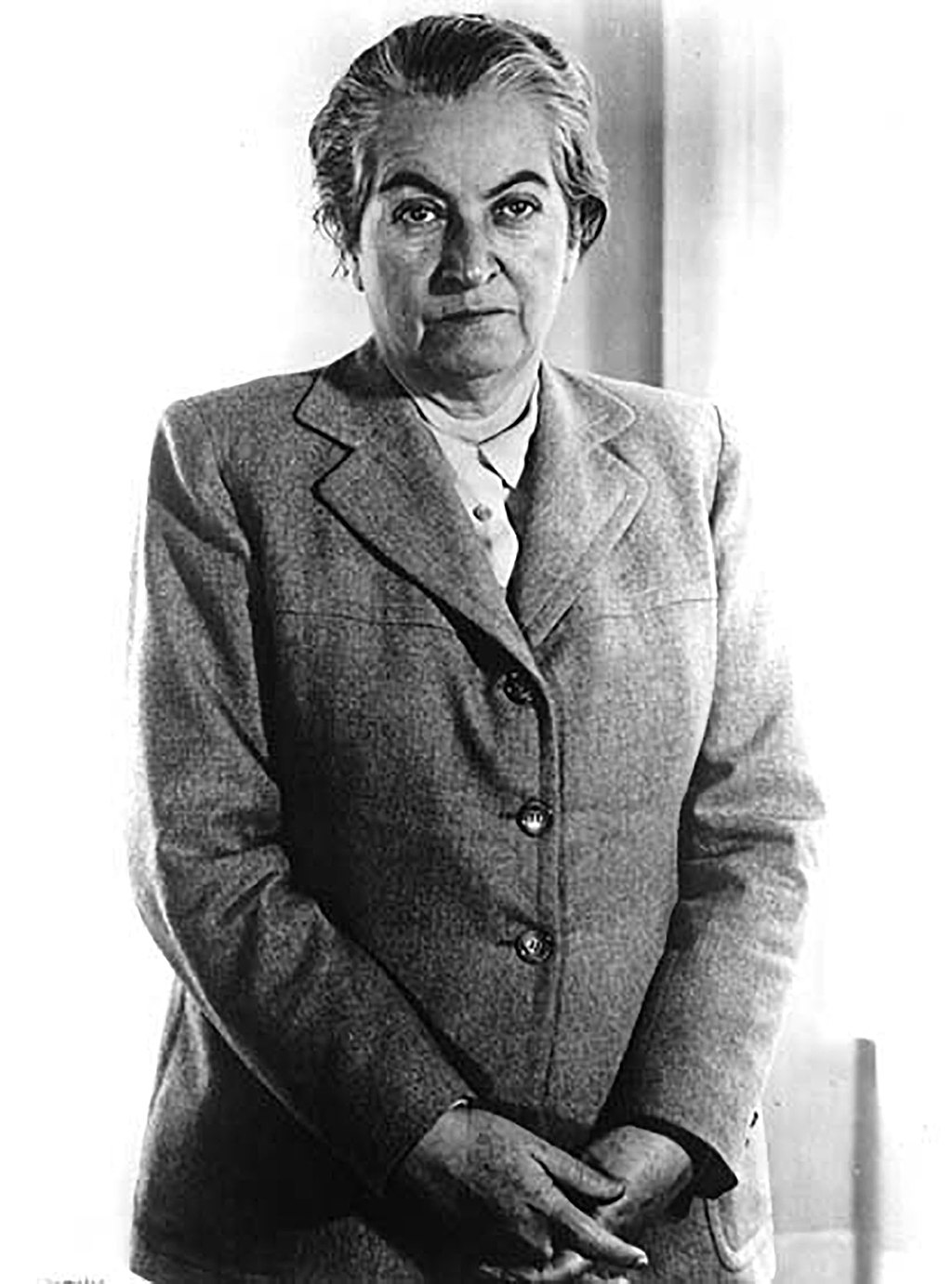

| History of Women Further information: History of Chile and Feminism in Chile  María de la Cruz, (1912–1995), Chilean political activist for women's suffrage, journalist, writer, and political commentator. In 1953, she became the first woman ever elected to the Chilean Senate Women were granted the right to vote in 1931 and 1949 during Chile's presidential era.[5][6] Also during the era, thousands of women protested against socialist president Salvador Allende in the March of the Empty Pots and Pans.[7] While under Augusto Pinochet's authoritarian regime, women also participated in las protestas, protests against Allende's plebiscite in which women voted "no."[5] During Chile's time under dictator Pinochet, the state of women's legal rights fell behind most of Latin America, even though Chile had one of the strongest economies in South America.[8] Chile returned to democracy in 1990, leading to changes in women's lives and roles within society.[9] Chile's government has committed more political and financial resources than ever before to enhancing social welfare programs since the country's return to democracy..[10] The Concertación political party has been in power since the end of Pinochet's dictatorship, and from 2006 to 2010, Michelle Bachelet of the party served as the first female President of Chile.[11][12] Women in society Chile has been described as one of the most socially conservative countries of Latin America.[13][14][15] In comparison to the United States, Chile did not have so many feminists among its evolution of women's intrusion to the political sphere. Chilean women esteemed Catholicism as their rites of passage, which initiated women's movements in opposition to the liberal political party's eruption in the Chilean government. The traditional domesticated setting that women were accustomed to was used as a patriarchal reasoning for women's restriction of women's votes. However, Chileans religious convictions as devout Catholics initiated their desire to vote against the adamant anticlerical liberal party. In 1875, Domitila Silva Y Lepe, the widow of a former provincial governor, read the requirements deeming "all adult Chileans the right to vote", and was the first woman to vote.[16] Other elitist Chilean women followed her bold lead, which resulted in the anticlerical liberal party of congress to pass a law denying women the right to vote. Despite this set back, Ms. Lepe and other elite women expressed their religious standings to the conservative party. The conservative party were favorable of the women because they knew their support would influence the conservative party's domination in politics. In 1912 Social Catholicism began to erupt.[16] Social Catholicism- upper-class women's organization of working-class women-was led by Amalia Errazuriz de Subercaseaux. She introduced the Liga de Damas Chilenas (League of Chilean Ladies) amongst 450 other upper-middle-class women with intentions to "uphold and defend the interests of those women who worked for a living without attacking the principles of order and authority". Following this organization, many other elite women began socially constructed women's institutions. Amanda Labarca was also an elitist, but disagreed with the privileged women's subjection of working-class women and founded the Círculo de Lectura (ladies reading club) in 1915.[16] She believed women should be educated, regardless of their socioeconomic status to have a more influentially productive role in society. Gender roles Traditional gender role beliefs are prevalent in Chilean society, specifically the ideas that women should focus on motherhood and be submissive to men.[17] A 2010 study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reported that 62 percent of Chileans are opposed to full gender equality. Many of those surveyed expressed the belief that women should limit themselves to the traditional roles of mother and wife.[18] However, the 2012 World Development Report states that male attitudes toward gender equality are that "men do not lose out when women's rights are promoted."[19] Motherhood Catholicism is embodied wholly among Chilean family identities. Virgin Mary is the idolized example of motherhood. Her pure and sacrificial acts are to be embodied by Chilean mothers.[20] Traditionally, women are supposed to be the picture of endurance like the Virgin Mary. The biblical significance is portrayed through the traditional government of Chile. In the early 1900s, the gendered examples among Catholicism were embodied by the patriarchal government and suffrage of women. Women were domesticated and confined to the home. In the late 1940s women's issues were embraced by First Lady Rosa Markmann de González Videla in acknowledgement of Mothers centers, women gaining access to resources to fulfill their role as housewives, encouraged women as consumers to fight against high living costs, and to raise their interest in partaking in other avenues of public life within the country, such as work and political participation.[21] The First Lady's efforts to advocate the evolution of women reform led to the modern techniques of the women reform. In the 1960s, campaigns for the Christian democrat, Frei, emphasized women and women's issues. Voting had just become mandatory for all Chileans and was the first time in history registration for female voters increased from thirty-five percent to seventy-five percent. The Christian democratic change of government opened women's access to birth control. However, the government's emphasis on the modernization of women institutions and underlying issues of gender hierarchy, women in poverty were neglected. Restrictions within the women's institutions, mother centers, restricted mothers under 18. To further structurally cripple Chilean women, first lady Maria Ruiz Tagle de Frei supervised "proper functioning" of feminist organizations.[21] The Central Organization for Mothers (CEMA) was created as a formal structure to advise the underprivileged Chilean mothers.[21] Carmen Gloria Aguayo revolutionized the mother's centers during the period of conflict between change and tradition during the Christian democrat campaign.[21] Ms. Aguayo also headed the party's women's departments amongst forty-eight men and reflected the political direction of the initiatives: policies to protect the family- defending women's rights to work, to maternity leave, to equitable pay and occupation, a new opportunities for training and learning in the promised department for female labor studies. Because familial welfare was deemed important within the Chilean society, mothers have served as a political representation to have a voice in amongst the government. |

女性の歴史 さらなる情報 チリの歴史、チリのフェミニズム  マリア・デ・ラ・クルス(1912-1995)、女性参政権を求めるチリの政治活動家、ジャーナリスト、作家、政治評論家。1953年、女性として初めてチリの上院議員に選出される。 チリの大統領時代の1931年と1949年に女性参政権が認められ、[5][6]またこの時代には、何千人もの女性が社会主義者のサルバドール・アジェン デ大統領に抗議する「空鍋の行進」を行った。 [7]アウグスト・ピノチェトの権威主義政権下でも、女性は「ノー」に投票したアジェンデの国民投票に対する抗議活動である「ラス・プロテスタス」に参加 した[5]。独裁者ピノチェト政権下のチリでは、チリが南米で最も強力な経済のひとつであったにもかかわらず、女性の法的権利の状況はラテンアメリカの大 半に遅れをとった。 [8]チリは1990年に民主主義に復帰し、女性の生活と社会における役割に変化をもたらした[9]。チリ政府は民主主義に復帰して以来、社会福祉プログ ラムの充実にこれまで以上に政治的・財政的資源を投入している[10]。ピノチェト独裁政権が終わってからはコンセルタシオン政党が政権を握っており、 2006年から2010年まで同党のミシェル・バチェレがチリ初の女性大統領を務めた[11][12]。 女性の社会進出 チリはラテンアメリカで最も社会的に保守的な国のひとつであると言われている[13][14][15]。 アメリカと比較すると、チリは女性の政治的進出が進む中でフェミニストがそれほど多くなかった。チリの女性は通過儀礼としてカトリシズムを尊重し、それが チリ政府における自由主義政党の台頭に反対する女性運動を引き起こした。女性が慣れ親しんだ伝統的な家庭的環境は、女性の投票権を制限する家父長的な理由 付けとして使われた。しかし、敬虔なカトリック教徒としてのチリ人の宗教的信念が、反宗教的な自由党に反対する投票への欲求を引き起こした。 1875年、元州知事の未亡人であったドミティラ・シルバ・イ・レペは、「すべての成人チリ人に選挙権がある」とする要件を読み上げ、女性として初めて選 挙権を獲得した[16]。他のエリート主義者のチリ人女性たちも彼女の大胆なリードに従ったため、議会の反宗教的自由党は女性の選挙権を否定する法律を可 決する結果となった。この挫折にもかかわらず、レペ女史や他のエリート女性たちは保守党に宗教的立場を表明した。保守党は、彼女たちの支持が保守党の政治 支配に影響を与えることを知っていたからだ。 1912年、社会的カトリシズムが勃発し始めた[16]。社会的カトリシズムとは、労働者階級の女性による上流階級の女性組織で、アマリア・エラズリズ・ デ・スベルカソーが主導した。彼女は、「秩序と権威の原則を攻撃することなく、生活のために働く女性たちの利益を支持し擁護する」ことを意図して、他の 450人の上流中産階級の女性たちの中に「チリ婦人連盟(Liga de Damas Chilenas)」を導入した。この組織に続いて、他の多くのエリート女性たちが、社会的に構築された女性組織を立ち上げた。アマンダ・ラバルカもエ リート主義者であったが、特権階級の女性が労働者階級の女性を服従させることに反対し、1915年にCírculo de Lectura(婦人読書クラブ)を設立した[16]。彼女は、女性が社会でより影響力のある生産的な役割を果たすためには、社会経済的地位に関係なく教 育を受けるべきだと考えていた。 ジェンダー役割 伝統的な性別役割分担の考え方はチリ社会に広く浸透しており、特に女性は母性に専念し、男性に従順であるべきだという考えがある[17]。国連開発計画 (UNDP)による2010年の調査では、チリ人の62%が完全な男女平等に反対していると報告されている。調査対象者の多くは、女性は母親と妻という伝 統的な役割に自らを限定すべきだという考えを表明している[18]。しかし、2012年の世界開発報告書は、ジェンダー平等に対する男性の態度は、「女性 の権利が促進されても、男性が損をすることはない」と述べている[19]。 母性 カトリックはチリの家族のアイデンティティの中で完全に具現化されている。聖母マリアは母性の偶像化された模範である。彼女の純粋で犠牲的な行為は、チリ の母親たちによって体現されるべきものである[20]。伝統的に、女性は聖母マリアのような忍耐を絵に描いたような存在であるとされている。聖書の意義 は、チリの伝統的な政府を通して描かれている。1900年代初頭、カトリシズムの中でジェンダー化された例は、家父長制政府と女性の参政権によって具現化 された。女性は家畜化され、家庭に閉じこもっていた。1940年代後半には、ロサ・マルクマン・デ・ゴンサレス・ビデラ大統領夫人によって、マザーズ・セ ンター、主婦としての役割を果たすために女性が資源を利用できるようにすること、消費者としての女性が高い生活費と闘うこと、仕事や政治参加など国内の他 の公共生活への参加への関心を高めることなどが認められ、女性問題が受け入れられた[21]。女性改革の進化を提唱する大統領夫人の努力は、女性改革の近 代的な手法へとつながった。1960年代、キリスト教民主党員フレイのキャンペーンでは、女性と女性の問題が強調された。投票がすべてのチリ国民に義務づ けられ、女性有権者の登録が史上初めて35%から75%に増加した。キリスト教民主主義による政権交代は、女性の避妊へのアクセスを開放した。しかし、政 府は女性制度の近代化を重視し、根本的な問題である男女のヒエラルキー、貧困にあえぐ女性は軽視された。女性施設であるマザーセンターでは、18歳未満の 母親を制限していた。さらに構造的にチリの女性を不自由にするために、マリア・ルイス・タグレ・デ・フレイ大統領夫人はフェミニスト組織の「適切な機能」 を監督した[21]。母親のための中央組織(CEMA)は、恵まれないチリの母親たちに助言するための正式な組織として創設された[21]。カルメン・グ ロリア・アグアヨは、キリスト教民主主義運動中の変化と伝統の対立の時期に母親センターに革命を起こした。 [21]アグアヨ女史はまた、48人の男性の中で党の女性部門を率い、家族を守る政策、すなわち女性の労働権、出産休暇、公平な給与と職業、約束された女 性労働研究部門における訓練と学習のための新たな機会などを擁護し、イニシアチブの政治的方向性を反映させた。チリ社会では家族の福祉が重要視されていた ため、母親たちは政府内で発言するための政治的代弁者としての役割を果たしてきた。 |

| Legal rights Currently, women have many of the same rights as men.[22] The National Women's Service (SERNAM) is charged with protecting women's legal rights in the public sector.[22][23] Marriage Until 2020, women lost their right to manage their own assets once they were married[24] and husbands received all of the wealth,[5] but that law has since changed and women can now administer their own assets.[24] A couple can also sign a legal agreement before marriage so that all assets continue to be owned by the one who brought them into the marriage.[24] The Chilean Civil Code previously mandated that wives had to live with and be faithful and obedient to their husbands, but it is no longer in the law.[5] A married woman cannot be head of the household or head of the family in the same way as a man; however, married women are not required by law to obey their husbands.[25] Divorce Chile legalized divorce in 2004, overturning an 1884 legal code.[26] The law that legalizes divorce is the New Civil Marriage Law which was first introduced as a bill in 1995. There had been previous divorce bills before, but this one managed to secure enough conservative and liberal support to pass.[8] With divorce now being legal, four marital statuses exist within Chile: married, separated, divorced, and widow (er). Only the divorced and widow (er) statuses allow a new marriage.[27] Before the legalization of divorce, the only way to leave a marriage was to obtain a civil annulment which would only be granted by telling the civil registrar that the spouse had lied in some way concerning the marriage license, thereby voiding the marriage contract.[8] Property In marriage, there are three types of assets: those of the husband, those of the wife, and the common assets that pertain to both. Land and houses in a marriage continue to be the property of the person who brought them to the marriage, but in order to sell them, both the husband and wife must sign.[24] In the case of divorce, both the man and woman are entitled to ownership of the marital home.[25] In the case of the death of a spouse, the surviving spouse, regardless of gender, has equal inheritance rights to the marital home.[25] If there is no will when the husband dies, the wife is given an equal category as the children for inheritance.[24] Before marriage, a couple can sign a legal document separating all assets so that the woman and man each administer her or his own; in this case, the husband cannot control his wife's assets.[24] If women work outside the home independent of their husbands, acquire personal assets, and can prove that they came by these assets through their independent work, then these working women can accumulate these assets as their own, unable to be touched by husbands.[24] Sons and daughters have equal inheritance rights to moveable and immovable property from their parents.[25] Unmarried men and women have equal ownership rights to moveable and immoveable property.[25] In rural Chile, inheritance is the principal way in which land is acquired by both men and women, whether the land has titles or not.[24] Sometimes women and men cannot claim their inheritance to land without titles because the cost of legal documents is too high.[24] Suffrage Women were granted the right to vote in municipal elections in 1931[5] and obtained the right to vote in national elections on January 8, 1949, resulting in their ability to vote under the same equal conditions as men and increasing women's participation in politics.[6] Family law Both Chilean men and women qualify for a family allowance if they have dependent children under the age of eighteen (or twenty-four if in school). There are differences in entitlement requirements for the spouse-related family allowance since a man qualifies for a family allowance if he has a dependent wife, but a woman only qualifies for a family allowance if her husband is disabled.[10] Until a reform of paternity laws in 1998, children born outside marriage had less right to parental financial support and inheritance than children born within marriage.[8] A bill was passed in 2007 to give mothers direct access to child support payments.[8] Working mothers of a certain low socioeconomic status and with proof of an employment contract and working hours receive subsidized child care through legislation passed in 1994. This system excludes: women whose household income is too high, unemployed women, women working in the informal sector, and women whose jobs are not by contract.[10] Chile offers paid maternity leave for women working in the formal sector, paying women 100 percent of their salary during the leave, and also allows women a one-hour feeding break each day until the child has reached the age of two.[10] Female workers unattached to the formal market and without an employment contract do not receive paid maternity leave.[10] Postnatal maternity leave is now six months instead of the previous three.[28] |

法的権利 現在、女性は男性と同じ多くの権利を有している[22]。国家女性サービス(SERNAM)は、公的部門における女性の法的権利を保護する任務を担っている[22][23]。 結婚 2020年までは、女性は結婚すると自分の資産を管理する権利を失い[24]、夫がすべての財産を受け取っていたが[5]、その後法律が改正され、女性は 自分の資産を管理できるようになった[24]。夫婦は結婚前に法的な合意に署名することで、すべての資産を結婚に持ち込んだ側が所有し続けることもできる [24]。 チリ民法は以前、妻は夫と同居し、夫に忠実で従順でなければならないと定めていたが、現在は法律上は定められていない[5]。既婚女性は男性と同じように世帯主や家族の長になることはできないが、既婚女性は夫に従うことを法律で義務付けられていない[25]。 離婚 離婚を合法化する法律は、1995年に法案として提出された「新民間婚姻法」である[26]。それ以前にも離婚法案はあったが、この法案は保守派とリベラル派の支持を十分に得て成立した[8]。 離婚が合法化されたことで、チリでは既婚、別居、離婚、未亡人の4つの婚姻ステータスが存在する。離婚が合法化される以前は、婚姻を解消する唯一の方法は 民事取消を得ることであったが、その民事取消は、配偶者が婚姻届に関して何らかの嘘をついたことを民事登記官に告げることによってのみ認められるものであ り、それによって婚姻契約は無効となる[8]。 財産 結婚には、夫の財産、妻の財産、両者に属する共有財産の3種類がある。婚姻中の土地や家屋は、婚姻に持ち込んだ人の財産であり続けるが、売却するためには 夫と妻の双方が署名する必要がある[24]。離婚の場合、婚姻中の家屋の所有権は男女双方にある[25]。配偶者が死亡した場合、性別に関係なく、生存配 偶者は婚姻中の家屋について平等な相続権を有する[25]。 [25]夫が死亡したときに遺言がない場合、妻は子供と同等の相続権が与えられる[24]。結婚前に、夫婦がすべての資産を分ける法的文書に署名すること で、女性と男性がそれぞれ自分の資産を管理することができる。この場合、夫は妻の資産を管理することはできない[24]。 女性が夫から独立して家庭外で働き、個人資産を取得し、独立した仕事を通じてこれらの資産を手に入れたことを証明できる場合、これらの働く女性は、夫が手出しできない自分の資産としてこれらの資産を蓄積することができる[24]。 未婚の男女は、動産と不動産を平等に所有する権利を有する[25]。 チリの農村部では、土地の所有権の有無にかかわらず、相続が男女ともに土地を取得する主な方法である[24]。法的文書にかかる費用が高すぎるため、女性も男性も所有権のない土地の相続を主張できないことがある[24]。 参政権 女性は、1931年に市町村選挙での選挙権が認められ[5]、1949年1月8日には国政選挙での選挙権を獲得し、その結果、男性と同じ平等な条件で投票できるようになり、女性の政治参加が増加した[6]。 家族法 チリの男女ともに、18歳(在学中の場合は24歳)未満の扶養家族がいる場合、家族手当を受ける資格がある。配偶者関連の家族手当については、男性は扶養 している妻がいる場合に家族手当を受ける資格があるが、女性は夫が障害者である場合にのみ家族手当を受ける資格があるため、受給要件に違いがある [10]。1998年に父子法が改正されるまでは、婚姻外で生まれた子どもは婚姻内で生まれた子どもよりも親の経済的支援や相続を受ける権利が少なかった [8]。2007年に、母親が児童扶養手当を直接利用できるようにする法案が可決された[8]。 社会経済的地位が一定程度低く、雇用契約と労働時間を証明できる働く母親は、1994年に成立した法律により、保育料の補助を受けることができる。この制 度は、世帯収入が高すぎる女性、失業中の女性、インフォーマル・セクターで働く女性、契約がない仕事を持つ女性を除外している[10]。チリは、正規部門 で働く女性に有給の出産休暇を提供しており、休暇中は給与の100%が支払われ、子どもが2歳になるまで毎日1時間の授乳休憩も認められている[10]。 正規市場に属さず、雇用契約を結んでいない女性労働者には、有給の出産休暇はない[10]。 産後産休は従来の3カ月から6カ月になった[28]。 |

Education School girls running in the playground Women's literacy rates almost match those of men, with 97.4 percent of women being able to read, versus 97.6 percent of men (in 2015).[29] Chilean law mandates compulsory primary and secondary education for children, boys and girls.[25] In 2007, the World Bank declared that enrollment levels for boys and girls in primary and secondary education were at a "virtual parity."[23] Women's education in Chile is generally higher than neighboring countries.[23] In higher education, as of 2002, women had similar attendance rates as men, with women at 47.5 percent attendance, versus men at 52.5 percent.[30] Employment Participation Chile has one of the lowest rate of female employment in all of Latin America, but women's workforce participation has steadily increased over the years.[31] As of 2016, the employment rate of women was 52%.[1] Despite the fact that 47.5% of students in college are women, many still choose to be homemakers rather than join the workforce.[9] A 2012 World Bank study showed that the expansion of public day care had no effect on female labor force participation.[19] The low number of women entering the labor force causes Chile to rank low amongst upper-middle class countries regarding women in the work force despite higher educational training.[23] In Chile, poorer women make up a smaller share of the workforce.[23] A 2004 study showed that 81.4 percent of women worked in the service sector.[30] Formal and informal work Women have increasingly moved out of unpaid domestic work and into the paid formal and informal labor markets.[10] Many female workers are in Chile's informal sector because national competition for jobs has increased the number of low-skill jobs.[10] In 1998, 44.8 percent of working-aged women in Chile worked in the informal sector while only 32.9 percent of men worked informally.[10] Income gap For jobs that do not require higher education, women make 20 percent less money on average than men. For jobs requiring a university degree, the gap in pay increases to 40 percent. Women without a university degree make 83 percent of the income men make without a university degree.[30] The quadrennial 2004 National Socio-Economic Survey and World Bank report in 2007 say that the overall gender income gap stands at 33 percent (since women make 67 percent of men's salaries).[23] |

教育 運動場で走る女子生徒 女性の識字率は男性の識字率にほぼ匹敵し、女性の97.4パーセントが文字を読むことができるのに対し、男性は97.6パーセントである(2015年) [29]。チリの法律では、少年少女に対する初等・中等教育の義務化が義務付けられている[25]。 [25]2007年、世界銀行は、初等・中等教育における男女の就学率は「事実上同等」であると宣言した[23]。 チリにおける女性の教育水準は、一般的に近隣諸国よりも高い[23]。高等教育においては、2002年時点で、女性の出席率は男性と同程度であり、女性が 47.5%であるのに対し、男性は52.5%であった[30]。 雇用 雇用 チリはラテンアメリカ全体で女性の就業率が最も低い国のひとつであるが、女性の労働力参加率は年々着実に増加している[31]。 2016年現在、女性の就業率は52%である[1]。 大学生の47.5%が女性であるにもかかわらず、多くの学生が労働力に加わるよりも主婦になることを選択している[9]。 2012年の世界銀行の調査では、公的保育所の拡大は女性の労働力参加に影響を及ぼさなかった。 [19]労働力に入る女性の数が少ないため、チリは、より高い教育訓練を受けているにもかかわらず、女性の労働力に関して上位中流階級の国の中で下位にラ ンクされている[23]。チリでは、より貧しい女性が労働力に占める割合が低い[23]。2004年の調査では、女性の81.4%がサービス部門で働いて いた[30]。 フォーマルな仕事とインフォーマルな仕事 1998年には、チリの労働年齢の女性の44.8%がインフォーマル・セクターで働いていたが、男性の32.9%だけがインフォーマル・セクターで働いていた[10]。 所得格差 高等教育を必要としない仕事では、女性の収入は男性より平均20%低い。大卒の学歴が必要な仕事の場合、賃金格差は40%に拡大する。大卒でない女性の収 入は、大卒でない男性の収入の83パーセントである[30]。4年に1度の2004年全国社会経済調査と2007年の世界銀行の報告書によると、男女の収 入格差は全体で33パーセントに達している(女性の収入は男性の67パーセントであるため)[23]。 |

| Politics Female participation in politics Women were not involved in politics until 1934, when they could first use their municipal vote.[7] The municipal, and later national, vote caused women to involve themselves in politics more than before, pressuring the government and political parties.[5] With women's increased political importance, many parties established women's sections for support and tried to pursue women's votes, though it would take years for political parties to truly view women as important to politics.[7]  Chilean feminists gather in Santiago during Pinochet's regime  Gladys Marín (1941–2005), Chilean activist and political figure. She was Secretary-General of the Communist Party of Chile (PCCh) (1994–2002) and then president of the PCCh until her death On December 1, 1971 thousands of women who were against the newly elected Salvador Allende marched through Santiago to protest government policies and Fidel Castro's visiting of Chile.[7] This march, known as the March of the Empty Pots and Pans, brought together many conservative and some liberal women as a force in Chilean politics,[7] and in 1977 Augusto Pinochet decreed the day of the march to be National Women's Day.[32] Women also made their voices heard in the late 1980s when 52 percent of the national electorate was female, and 51.2 percent of women voted "no" in Augusto Pinochet's plebiscite.[5] The women in these popular protests are considered to have played a central role in increasing national concern with the history of women's political activism.[33] As of 2006, Chile was lower than eight other Latin American countries in regards to women in political positions.[11] With only a few women legislators, sustaining attention to the topic of women's rights a difficult task, especially in the Senate, where there are fewer female representatives than in the Chamber of Deputies.[8] Unlike neighboring Argentina, where 41.6 percent of the Argentine Chamber of Deputies is made up of women, only 22,6 percent of Chile's lower house is made up of female representatives. Chile has no government mandate requiring that women must make up a certain percentage of party candidates.[9] Women's political representation is low but is on the rise in many political parties, and there is growing support for a quota law concerning women's representation.[8] The progressive parties of the Left have greater openness to the participation of women, evident in the Party for Democracy's and Socialist Party's quotas for women's representation as candidates for internal party office.[8] In 2009, activists demanded that presidential candidates develop reforms that would improve work conditions for women. Reforms included maternity leave, flexible work schedules and job training.[9] Aimed at improving women's work opportunities, former president Michelle Bachelet made it illegal to ask for a job applicants' gender on applications and for employers to demand pregnancy tests be taken by employees in the public sector.[11] Second Wave Feminism Following these Chilean women, the contemporary phase of feminism was constructed through the social conflict between socialism and feminism.[34] The democratically elected president, Allende, was ousted on September 11, 1973 when a military coup invaded his palace, brutally excising all Popular Unity Government officials and resulting in Allende's debated suicide.[34] This revolution "The Chilean Road to Socialism" abruptly came to an end, revitalizing the foundation of the government. However, the foundation was hastily corrupted by patriarchal values. Prominent feminist sociologist Maria Elena Valenzuela argued, the military state can be interpreted as the quintessential expression of patriarchy: "The Junta, with a very clear sense of its interests, has understood that it must reinforce the traditional family, and the dependent role of women, which is reduced to that of mother.[34] The dictatorship, which institutionalizes social inequality, is founded on inequality in the family."[34] These inequalities began to agitate Chilean women. Women began to formulate groups opposing the patriarchal domination of the political sphere. Michelle Bachelet's presidency Michelle Bachelet was the first female president of Chile, leading the country between 2006 and 2010.[23] During her presidency, Bachelet increased the budget of the National Women's Service (Servicio Nacional de la Mujer, SERNAM) and helped the institution gain funding from the United Nations Development Fund for Women.[8] Her administration had an active role in furthering opportunities and policies for and about women, creating or improving child care, pension reform and breastfeeding laws. During her presidency, Bachelet appointed a cabinet that was 50 percent female.[8] Bachelet served as the first executive director of United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women.[8] On March 11, 2014, she became president of Chile for the second time. Policy The National Women's Service (SERNAM) has noticed that it is easier to get politicians to support and pass poverty-alleviation programs aimed at poor women than proposals that challenge gender relations.[8] Much of Chile's legislation concerning women's rights has been pushed by SERNAM: Between 1992 and 2010, sixty-four legislative proposals to expand women's legal equality were introduced by SERNAM.[8] Historically the progressive parties of the Left have drawn more attention to women's rights.[8] Yet many political parties insincerely support women's agenda and the concept of gender equality, instead leaving any action to be taken by SERNAM or nongovernmental organizations.[5] Although SERNAM exists to aid women, there is no non-discrimination clause in the Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile.[25] |

政治 女性の政治参加 1934年に初めて地方選挙権を行使できるようになるまで、女性は政治に関与していなかった[7]。地方選挙権、後には全国選挙権によって、女性は以前よ りも政治に関与するようになり、政府や政党に圧力をかけるようになった[5]。女性の政治的重要性が増すにつれて、多くの政党が支援のために女性部を設立 し、女性票を追求しようとしたが、政党が女性を政治にとって本当に重要な存在とみなすようになるまでには何年もかかった[7]。  ピノチェト政権時代にサンティアゴに集まったチリのフェミニストたち  グラディス・マリーン(1941-2005)、チリの活動家、政治家。1994年から2002年までチリ共産党(PCCh)書記長を務め、その後亡くなるまでPCCh議長を務めた。 1971年12月1日、新たに選出されたサルバドール・アジェンデに反対する数千人の女性たちが、政府の政策とフィデル・カストロのチリ訪問に抗議するた め、サンティアゴ市内を行進した[7]。この行進は「空の鍋の行進」として知られ、多くの保守的な女性たちと一部のリベラルな女性たちをチリの政治におけ る勢力として結集させた[7]。 [1980年代後半には、全国有権者の52パーセントが女性であり、アウグスト・ピノチェトの国民投票では51.2パーセントの女性が「ノー」に投票した [5]。これらの民衆抗議の女性たちは、女性の政治活動の歴史に対する国民の関心を高める上で中心的な役割を果たしたと考えられている[33]。 2006年の時点で、チリは政治的地位に就いている女性に関して他のラテンアメリカの8カ国よりも低かった[11]。少数の女性議員しかいないため、女性 の権利というトピックへの関心を持続させることは困難な課題であり、特に上院では、女性議員の数は下院よりも少ない[8]。アルゼンチン下院の41.6 パーセントが女性で構成されている隣国アルゼンチンとは異なり、チリの下院の22.6パーセントのみが女性議員で構成されている。チリには、政党候補者の 一定割合を女性が占めなければならないとする政府の指令はない[9]。女性の政治的代表権は低いが、多くの政党で増加傾向にあり、女性の代表権に関する割 当法を求める支持が高まっている[8]。左派の進歩的な政党は女性の参加に対してよりオープンであり、民主主義党と社会党が党内役職の候補者として女性の 代表権を割当制にしていることからも明らかである[8]。 2009年、活動家たちは大統領候補者たちに、女性の労働条件を改善する改革を展開するよう要求した。ミシェル・バチェレ前大統領は、女性の就労機会を改 善することを目的として、応募時に求職者の性別を尋ねることを違法とし、雇用主が公的部門の従業員に妊娠検査を受けることを要求することを違法とした [11]。 第二波フェミニズム 民主的に選出された大統領アジェンデは、1973年9月11日、軍事クーデターによって宮殿に侵入され追放された。しかし、その基盤は家父長制的価値観に よって急遽腐敗した。著名なフェミニスト社会学者マリア・エレナ・ヴァレンスエラは、軍事国家は家父長制の典型的な表現と解釈できると主張した: 「軍事政権は、その利益について非常に明確な感覚を持ち、伝統的な家族と、母親という役割に縮小された女性の従属的な役割を強化しなければならないと理解 している。女性たちは家父長的な政治支配に反対するグループを結成し始めた。 ミシェル・バチェレの大統領就任 ミシェル・バチェレはチリ初の女性大統領で、2006年から2010年にかけて同国を率いた[23]。大統領在任中、バチェレは国家女性サービス (Servicio Nacional de la Mujer, SERNAM)の予算を増額し、同機関が国連女性開発基金から資金を得るのを支援した[8]。彼女の政権は、女性のための、また女性に関する機会や政策を 推進する上で積極的な役割を果たし、育児、年金改革、母乳育児法の制定や改善を行った。大統領在任中、バチェレは50パーセントが女性である内閣を任命し た[8]。 バチェレは、ジェンダー平等と女性のエンパワーメントのための国連機関の初代事務局長を務めた[8]。 2014年3月11日、2度目のチリ大統領に就任した。 政策 国家女性局(SERNAM)は、ジェンダー関係に挑戦する提案よりも、貧困層の女性を対象とした貧困緩和プログラムを政治家に支持させ、可決させる方が簡 単であることに気づいた[8]。1992年から2010年の間に、女性の法的平等を拡大するための64の立法案がSERNAMによって提出された[8]。 歴史的に、左派の進歩的な政党は女性の権利により多くの関心を寄せてきた[8]。しかし、多くの政党は、女性の議題と男女平等の概念を不誠実に支持しており、その代わりに、いかなる行動もSERNAMや非政府組織に委ねている[5]。 SERNAMは女性を支援するために存在するが、チリ共和国の政治憲法には差別禁止条項はない[25]。 |

| Organizations State The National Women's Service is the political institution created in 1991 that crafts executive bills concerning women's rights.[8] Its Spanish name is Servicio Nacional de la Mujer, or SERNAM; it has established a program to aid female heads of households, a program for prevention of violence against women, and a network of information centers that focus on the issues of women's rights.[8] Its presence in Chile is important because it was established by law and is a permanent part of Chile's state structure.[35] As an institution it tends to focus much of its attention on certain segments of women: low-income women heads of households, women seasonal workers, domestic violence prevention, and teen pregnancy prevention.[35] A common complaint that SERNAM has is that the top appointees are not women linked to the feminist community.[8] The institution also has restrictions when it comes to policy regarding women due to its state ties, as seen in 2000 when SERNAM favored but would not explicitly support the bill to legalize divorce because it was under the leadership of the Christian Democratic party. In 2002 it was finally allowed to support the bill.[8] Research and activism International Women's Day march in San Antonio, Chile Many of Chile's women's groups function outside the state sphere.[10] Centers for research began to emerge in the later part of the twentieth century, including the Centro de Estudios de la Mujer (The Women's Study Center) and La Morada.[33] The Women's Study Center is a nonprofit organization founded in 1984 and conducts research, trains women, has a consulting program, and tries to increase women's political participation.[36] La Morada is another nonprofit organization that works to expand the rights of women through political involvement, education, culture, and efforts to eradicate violence.[37] Chile’s feminist anthem “The rapist is you,” went viral in 2019. The chant became an anthem for women during the social unrest of 2019, which was sparked by deepening inequality in the country. International relations Chile ratified the United Nation's Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1988, internationally declaring support for women's human rights.[32] One of Chile's missions as part of the UN is commitment to democracy, human rights and gender perspective as foundations of multilateral action.[38] Crimes against women Domestic violence Main article: Domestic violence in Chile Domestic violence in Chile is a serious issue affecting a large percentage of the population, especially among lower income demographics.[22] The Intrafamily Violence Law passed in 1994 was the first political measure to address violence in the home, but because the law would not pass without being accepted by both sides, the law was weak in the way it addressed victim protection and punishment for abusers.[8] The law was later reformed in 2005.[39] A 2004 SERNAM study reported that 50 percent of married women in Chile had suffered spousal abuse, 34 percent reported having suffered physical violence, and 16 percent reported psychological abuse.[22] According to another study from 2004, 90 percent of low-income women in Chile experience some type of domestic violence.[40] Due to the high prevalence of domestic violence, many Chilean women accept it as normal.[40] The legalization of divorce in 2004 won the approval of women throughout the country, especially those concerned about domestic violence, as women were previously unable to escape abusive relationships due to the divorce laws.[9] From January to November 2005, 76,000 cases of family violence were reported to the Carabineros; 67,913 were reported by women, 6,404 by men, and approximately 1,000 by children.[22] Rape Rape, including spousal rape, is a criminal offense. Penalties for rape range from five to 15 years' imprisonment, and the government generally enforces the law.[22] In 2004 the Criminal Code was changed so that the age for statutory rape is 14; previously, the age was 12.[41] The law protects the privacy and safety of the person making the charge. In 2006 from January to November, police received reports of 1,926 cases of rape, compared with 2,451 cases in all of 2005; experts believed that most rape cases go unreported. The Ministry of Justice and the PICH have several offices specifically to provide counseling and assistance in rape cases.[22] A number of NGOs, such as La Morada Corporation for Women, provide counseling for rape victims.[33] Sexual harassment A 2005 law against sexual harassment provides protection and financial compensation to victims and penalizes harassment by employers or co-workers.[22] The law provides severance pay to anyone who resigns due to being a victim of sexual harassment if she/he has worked for the employer for at least one year.[42] During 2005 the Labor Directorate received 244 complaints of sexual harassment,[22] and in 2009 there were 82 complaints were received.[42] The majority of the complaints come from women.[43] Discrimination A 2005 study by Corporacion Humana and the University of Chile's Institute of Public Affairs revealed that 87 percent of women surveyed felt that women suffered discrimination. According to the survey, 95 percent believed women faced discrimination in the labor market, 67 percent believed they faced discrimination in politics, 61 percent felt that women were discriminated against by the media, and 54 percent within the family.[22] |

組織 国家 国立女性局は、女性の権利に関する行政法案を作成する1991年に設立された政治機関である[8]。そのスペイン語名はServicio Nacional de la Mujer(セルナム)であり、女性の世帯主を支援するプログラム、女性に対する暴力防止プログラム、女性の権利の問題に焦点を当てた情報センターのネッ トワークを確立している。 [低所得の女性世帯主、季節労働者の女性、家庭内暴力の防止、10代の妊娠防止などである[35]。 SERNAMが抱える一般的な不満は、トップの任命者がフェミニスト・コミュニティとつながりのある女性ではないことである[8]。2000年には、 SERNAMはキリスト教民主党の指導下にあったため、離婚合法化法案を支持したが、明確には支持しなかった。2002年にようやく法案を支持することが 認められた[8]。 研究と活動 チリのサンアントニオで行われた国際女性デーの行進 チリの女性団体の多くは、国家の領域外で機能している[10]。 女性研究センター(Centro de Estudios de la Mujer)やラ・モラーダ(La Morada)など、20世紀後半に研究のためのセンターが出現し始めた[33]。女性研究センターは1984年に設立された非営利団体で、研究を行い、 女性を訓練し、コンサルティング・プログラムを持ち、女性の政治参加を増やそうとしている[36]。ラ・モラーダも非営利団体で、政治参加、教育、文化、 暴力根絶の取り組みを通じて女性の権利拡大に取り組んでいる[37]。 チリのフェミニスト賛歌「レイプ犯はあなた」は2019年に流行した。この聖歌は、同国における不平等の深刻化に端を発した2019年の社会不安の中で、女性のための賛歌となった。 国際関係 チリは1988年に国連の女性差別撤廃条約を批准し、女性の人権を支持することを国際的に宣言した[32]。 国連の一員としてのチリの使命のひとつは、多国間行動の基盤としての民主主義、人権、ジェンダーの視点へのコミットメントである[38]。 女性に対する犯罪 家庭内暴力 主な記事 チリにおける家庭内暴力 1994年に可決された家族内暴力法は、家庭内での暴力に対処するための最初の政治的措置であったが、この法律は双方から受け入れられなければ可決されな いため、被害者の保護や加害者の処罰に対処する方法としては弱いものであった。 [2004年のSERNAMの調査では、チリの既婚女性の50%が配偶者からの虐待を受けたことがあり、34%が身体的暴力を受けたことがあると報告し、 16%が心理的虐待を受けたことがあると報告した[22]。 [22]2004年の別の調査によると、チリの低所得層の女性の90%が何らかのDVを経験している[40]。 DVの有病率が高いため、多くのチリ人女性はDVを普通のこととして受け入れている[40]。2004年に離婚が合法化されたことで、国中の女性、特に DVを懸念する女性たちの賛同を得た。それまで女性は離婚法のために虐待的な関係から逃れることができなかったからである[9]。 2005年1月から11月までに、76,000件の家庭内暴力がカラビネロに報告され、67,913件が女性から、6,404件が男性から、約1,000件が子どもから報告された[22]。 レイプ レイプは、配偶者によるレイプも含め、犯罪である。2004年に刑法が改正され、法定強姦罪の対象年齢は14歳となった[22]。2006年1月から11 月までに警察が受理した強姦事件の件数は1,926件で、2005年全体の2,451件と比較している。法務省とPICHは、特にレイプ事件のカウンセリ ングと援助を提供するためにいくつかの事務所を持っている[22]。 女性のためのラ・モラーダ・コーポレーションなど、多くのNGOがレイプ被害者のカウンセリングを行っている[33]。 セクシュアル・ハラスメント 2005年に制定されたセクシュアル・ハラスメント禁止法は、被害者の保護と金銭的補償を規定し、雇用主や同僚によるハラスメントを罰則化している [22]。同法は、セクシュアル・ハラスメントの被害者であることを理由に退職した者に対し、その雇用主の下で1年以上働いていた場合に退職金を支給して いる[42]。2005年に労働総局が受けたセクシュアル・ハラスメントの苦情は244件[22]、2009年には82件であった[42]。苦情の大半は 女性からのものである[43]。 差別 Corporacion Humanaとチリ大学公共問題研究所による2005年の調査では、調査対象となった女性の87%が女性が差別を受けていると感じていることが明らかに なった。調査によると、95パーセントが労働市場で、67パーセントが政治で、61パーセントがメディアで、54パーセントが家庭内で、女性が差別を受け ていると感じていた[22]。 |

| Other concerns Family Today, younger women are opting out of marriage and having fewer children than their predecessors.[9] The total fertility rate as of 2015 was 1.82 children born/woman.[44] This is below the replacement rate of 2.1, and also lower than in previous years. A 2002 study reported that urban women averaged 2.1 children per woman, with women living in rural areas having more children, at 2.9. As of the 1990s, both urban and rural women were averaging fewer children than previously. For those women who do have children, after former president Michelle Bachelet's childcare mandates, childcare centers that provide free services are four times more numerous. Nursing mothers also have the legal right to breastfeed during the workday.[9] Women are less likely to seek divorces and marriage annulments.[45] Health and sexuality Women in Chile have long life expectancy, living an average of 80.8 years, about six years longer than men.[9][45] Sex education is rarely taught in schools and is considered "taboo" by many Chilean families. Friends and family usually are the main source of sex education.[17] In 1994, Chile decriminalized adultery.[46] HIV/AIDS The HIV/AIDS rate in Chile was estimated in 2012 at 0.4% of adults aged 15–49.[47] While cases of HIV and AIDS in women have stabilized internationally, Chile has seen a rise in HIV/AIDS infection. Societal beliefs about traditional women's roles as mothers leads to women being less likely to use contraceptives, increasing the opportunity for disease. Chilean women also often feel subordinate to men due to these traditional belief systems, making women less likely to negotiate for the use of condoms. In 2007, 28 percent of people with HIV/AIDS in Chile were women. Numbers of women living with HIV is lower than those with AIDS. A study by Vivo Positivo showed that 85 percent of women living with HIV/AIDS reported that they had little to no education or information about HIV/AIDS until diagnosis.[17] A 2004 study found that Chilean women with HIV/AIDS were susceptible to coerced sterilization. Fifty-six percent of HIV-positive Chilean women reported being pressured by health-care workers to prevent pregnancy by being sterilized. Of the women who chose to be sterilized, half were forced or persuaded to do so. Women victims of domestic abuse face a higher risk of getting HIV, and in 2004, 56 percent of women who have HIV and 77 percent of women with HIV/AIDS were victims of domestic abuse, sexual abuse, or rape before their diagnosis.[17] Abortion Further information: Abortion in Chile Between 1989 and 2017, Chile had some of the strictest abortion laws in the world, banning the procedure completely.[48] The current law allows abortion if the mother's life in danger, in case of lethal malformations of the fetus, or in cases of rape.[49] |

その他の懸念事項 家族 2015年時点の合計特殊出生率は、1.82人/女性[44]であり、代替出生率である2.1を下回っている。2002年の調査では、都市部の女性は1人 当たり平均2.1人の子どもを産んでおり、農村部に住む女性は2.9人と、より多くの子どもを産んでいることが報告されている。1990年代の時点では、 都市部、農村部ともに、女性の平均子ども数は以前より少なくなっている。ミシェル・バチェレ前大統領の育児義務化以降、子どもを持つ女性にとって、無料 サービスを提供する保育所の数は4倍に増えた。授乳中の母親には、勤務中に授乳する法的権利もある[9]。女性は離婚や結婚の取り消しを求める傾向が低い [45]。 健康とセクシュアリティ チリの女性は平均寿命が長く、平均80.8歳で、男性より約6歳長い[9][45]。性教育は学校ではほとんど教えられておらず、多くのチリの家庭では「タブー」とされている。1994年、チリは不倫を非犯罪化した[46]。 HIV/エイズ 2012年のチリのHIV/AIDS感染率は、15~49歳の成人の0.4%と推定されている[47]。国際的に女性のHIV/AIDS感染者は安定して いるが、チリではHIV/AIDS感染者が増加している。母親としての伝統的な女性の役割に関する社会的信念が、女性が避妊具を使用しにくいことにつなが り、病気の機会を増やしている。また、チリの女性は、こうした伝統的な信念体系のために、しばしば男性に従属的だと感じており、コンドームの使用について 交渉しにくくなっている。2007年には、チリのHIV/AIDS患者の28%が女性であった。HIVとともに生きる女性の数は、エイズ患者よりも少な い。Vivo Positivoの調査によると、HIV/AIDSとともに生きる女性の85%が、診断されるまでHIV/AIDSに関する教育や情報がほとんどなかった と報告している[17]。 2004年の調査では、チリのHIV/AIDS女性は不妊手術の強要を受けやすいことがわかった。HIV陽性のチリ人女性の56%が、不妊手術によって妊 娠を防ぐよう医療従事者から圧力を受けたと報告している。不妊手術を選択した女性のうち、半数は不妊手術を強要されたり、説得されたりしている。家庭内虐 待の被害女性はHIVに感染するリスクが高く、2004年には、HIV感染女性の56%、HIV/AIDS感染女性の77%が、診断前に家庭内虐待、性的 虐待、レイプの被害者であった[17]。 中絶 さらに詳しい情報 チリにおける中絶 1989年から2017年にかけて、チリは世界で最も厳格な人工妊娠中絶法を制定し、人工妊娠中絶を完全に禁止していた[48]。現在の法律では、母体の生命が危険な場合、胎児に致死的な奇形がある場合、レイプの場合に人工妊娠中絶を認めている[49]。 |

Notable Chilean women Gabriela Mistral, the first Latin American woman to win a Nobel Prize for Literature.  Irene Morales, a soldier during the War of the Pacific who was recognized for her valor. Literature Chile has a rich literary history, being described as the "Land of the Poets." In 1945, Gabriela Mistral was the first Latin American, including men and women, to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.[6][50] Other notable female authors from Chile include Isabel Allende, Marta Brunet, María Luisa Bombal, Marcela Paz, and Mercedes Valdivieso. Politics This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (October 2017) In 1999, Gladys Marín was one of the first women to be a presidential candidate in Chile.[6] The year before, she was the first person in Chile to charge Augusto Pinochet for crimes committed during his dictatorship.[6] Sara Larraín was the other woman, along with Marín, to be one of the first female presidential candidates in Chile.[6] From 2006 until 2010, Michelle Bachelet served as the first woman president of Chile.[9] In the 2006 election, Soledad Alvear, a Christian Democrat, ran for the presidency against Bachelet.[51] She is also the woman responsible for organizing and structuring SERNAM.[6] The daughter of late President Salvador Allende, Isabel Allende, also second cousin to the author of the same name, is a prominent Chilean politician. Senator Carolina Tohá is the president of the Party for Democracy. Camila Vallejo has risen in national and international popularity as a leader of the Chilean student movement as well as a member of the Central Committee of Communist Youth of Chile. Other Chile's first canonized saint of the Roman Catholic Church is Teresa de los Andes, a Discalced Carmelite, canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1993. Javiera Carrera Verdugo was the first woman to have sewn a national flag of Chile.[6] Candelaria Pérez and Irene Morales were cantinières who fought in the War of the Confederation and War of the Pacific, respectively, and were recognized for their courage in battle.[52] Margot Duhalde was the first female war pilot from Chile, having flown for the Air Transport Auxiliary of the Royal Air Force in World War II.[6][53] |

著名なチリ人女性 ガブリエラ・ミストラル、ラテンアメリカの女性として初めてノーベル文学賞を受賞。  イレーネ・モラレス、太平洋戦争中の兵士で、その勇敢さが評価された。 文学 チリは豊かな文学の歴史を持ち、"詩人の国 "と称されている。 1945年、ガブリエラ・ミストラルは男女を含むラテンアメリカ人として初めてノーベル文学賞を受賞した[6][50]。 チリ出身のその他の著名な女性作家には、イサベル・アジェンデ、マルタ・ブルネット、マリア・ルイサ・ボンバル、マルセラ・パス、メルセデス・バルディビエソなどがいる。 政治 このセクションは更新が必要である。最近の出来事や新たに入手した情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力いただきたい。(2017年10月) 1999年、グラディス・マリンはチリで初めて大統領候補となった女性の一人である[6]。 その前年、彼女はアウグスト・ピノチェトの独裁政権時代に犯した罪を告発したチリ初の人物であった[6]。 サラ・ララインは、マリーンと並んでチリ初の女性大統領候補の一人であった[6]。 2006年から2010年まで、ミシェル・バチェレがチリ初の女性大統領を務めた[9]。 2006年の選挙では、キリスト教民主党員のソレダド・アルベアルがバチェレに対抗して大統領選に出馬した[51]。彼女はまた、SERNAMの組織化と構成を担当した女性でもある[6]。 故サルバドール・アジェンデ大統領の娘であるイサベル・アジェンデは、同名の作家の2番目のいとこでもあり、チリの著名な政治家である。 カロリナ・トハ上院議員は民主党の党首である。 カミラ・バジェホは、チリの学生運動の指導者として、またチリ共産主義青年中央委員会のメンバーとして、国内外での人気を高めている。 その他 ローマ・カトリック教会でチリ初の列聖者は、1993年に教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世によって列聖された跣足カルメル会のテレサ・デ・ロス・アンデスである。 ハヴィエラ・カレラ・ヴェルドゥゴは、チリの国旗を縫った最初の女性である[6]。 カンデラリア・ペレスとイレーネ・モラレスは、それぞれ盟約者団戦争と太平洋戦争で戦ったカンティニエールであり、戦場での勇気が評価された[52]。 マルゴット・デュハルデは、第二次世界大戦でイギリス空軍の航空輸送補助部隊のために飛行したチリ出身の最初の女性パイロットであった[6][53]。 |

| Prostitution in Chile Michelle Bachelet Gabriela Mistral Chilean Civil Code National Women's Service History of Chile Politics of Chile List of Chile-related topics |

チリの売春 ミシェル・バチェレ ガブリエラ・ミストラル チリ民法典 国家女性サービス チリの歴史 チリの政治 チリ関連トピックリスト |

| Asunción Lavrin Women, Feminism and Social Change: Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, 1890–1940. (Nebraska Press, 1995) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_Chile |

|

| "A Rapist in Your Path" (Spanish: Un violador en tu camino),

also known as "The Rapist Is You" (Spanish: El violador eres tú),[1] is

a Chilean feminist performance piece that originated in 2019 to protest

violence against women.[2][3] The performance has garnered

international attention and has been staged in various locations

including Latin America, the United States, and Europe.[4] Developed by

the Valparaíso feminist collective LasTesis,[5] the piece draws

inspiration from the work of Rita Segato.[6][7] Lyrics and choreography The performance takes its name from the slogan Un amigo en tu camino ("A Friend Along Your Path"), which was used by Carabineros de Chile in the 1990s.[6][8] The lyrics of the original Chilean version of "Un violador en tu camino" include a verse from the Chilean police anthem, Orden y Patria ("Order and Homeland"), which addresses a young girl and suggests that her Carabinero lover is watching over her.[9] These references serve as direct criticisms of the Chilean police for their history of claiming to protect women while perpetrating sexual violence against female demonstrators.[10][neutrality is disputed] In the English version of the song, adapted for performances in the United States and other English-speaking regions, this verse of the police anthem is omitted.[9] Additionally, the choreography includes a squatting motion that references a practice employed by the police against female detainees, where they are forced to strip naked and assume a squatting position.[11] Participants often dress in "party" clothes to protest victim-blaming practices that unfairly shift blame onto victims of sexual assault by focusing on their clothing choices. The lyrics "y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba, ni cómo vestía" ("and it was not my fault, nor where I was, nor how I dressed") convey the message that women have the right to dress however they choose and occupy public and private spaces without becoming victims of sexual assault or being held responsible for the actions of the perpetrator.[12][11][13] Moreover, the use of blindfolds in the performance references both the victims of eye injuries during the 2019-2020 Chilean protests and La Venda Sexy, a torture center from the Pinochet era where female political prisoners were blindfolded and subjected to sexual violence and other forms of torture.[11][14] |

"A Rapist in Your Path"(スペイン語:Un violador en tu camino)、

別名 "The Rapist Is You"(スペイン語:El violador eres

tú)[1]は、女性に対する暴力に抗議するために2019年に生まれたチリのフェミニスト・パフォーマンス作品である。

[2][3]このパフォーマンスは国際的な注目を集めており、ラテンアメリカ、アメリカ、ヨーロッパなど様々な場所で上演されている[4]。

バルパライソのフェミニスト集団LasTesisによって開発された[5]この作品は、リタ・セガトの作品からインスピレーションを得ている[6]

[7]。 歌詞と振付 このパフォーマンスは、1990年代にチリのカラビネロが使用していたスローガン「Un amigo en tu camino」(「あなたの道に沿う友」)に由来している[6][8]。オリジナルのチリ版「Un violador en tu camino」の歌詞には、チリの警察歌「Orden y Patria」(「秩序と祖国」)の一節が含まれており、少女に語りかけ、カラビネロの恋人が彼女を見守っていることを示唆している。 [9]これらの引用は、女性デモ参加者に性的暴力を振るう一方で、女性を守ると主張してきた歴史に対するチリ警察への直接的な批判となっている[10] [中立性が争われている]。 米国やその他の英語圏での公演用に翻案された英語版では、この警察賛歌の一節は省略されている[9]。さらに、振り付けにはスクワットの動作が含まれてい るが、これは警察が女性被拘禁者に対して採用している、全裸にさせられてスクワットの姿勢を取らされる慣習を参照したものである[11]。 歌詞の "y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba, ni cómo vestía"(「そしてそれは私のせいでも、私がいた場所のせいでも、私の服装のせいでもない」)は、女性には性的暴行の被害者になったり、加害者の行 動に責任を負わされたりすることなく、どのような服装を選び、公的・私的空間を占有する権利があるというメッセージを伝えている。 [12][11][13]さらに、パフォーマンスにおける目隠しの使用は、2019年から2020年にかけてのチリの抗議行動で目を負傷した犠牲者と、ピ ノチェト時代の拷問センターであり、女性の政治犯が目隠しをされ、性的暴力やその他の拷問を受けたラ・ベンダ・セクシーの両方を参照している[11] [14]。 |

Performance in Concepción, Chile at the 2020 International Women's Day. The girl has a Mapuche flag. |

2020年国際女性デーにおける チリのコンセプシオンでのパフォーマンス。少女はマプチェの旗を持っている。 |

Women performing "A Rapist in Your Path" in Alameda Central, Mexico |

メキシコ、アラメダ・セントラルで「A Rapist in Your Path」を上演する女性たち |

| Performance history Origins in Chile Although initially planned for October 2019, the debut of the piece was delayed due to nationwide protests.[15] Finally, on 20 November, "Un violador en tu camino" was performed for the first time in public at Plaza Aníbal Pinto in downtown Valparaíso.[16] On 25 November, in commemoration of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, various groups of women performed "Un violador en tu camino" in multiple locations in Santiago, the capital of Chile.[16] Encouraged by the success of these demonstrations, the creators urged women in other countries to perform their own renditions of the piece.[16] In Temuco, a city in southern Chile, indigenous Mapuche women performed a translated version of "Un violador en tu camino" in Mapudungun.[17] While the dance was originally conceived as a critique of rape culture and state violence in general, it resonated even more deeply with Chilean women following incidents of sexual violence against protesters during the October 2019 demonstrations.[18] In response to these events, the creators decided to adapt the piece specifically to address the actions of the police.[15] The Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (National Human Rights Institute) reported that between 17 October 2019 and 13 March 2020, they had initiated legal action on behalf of 282 victims of torture with sexual violence perpetrated by the police and other government agents during the protests.[19] It is worth noting that sexual violence was also used as a form of torture during the military dictatorship in Chile from 1973 to 1990.[20] Although the piece was not originally intended as a form of protest, the female demonstrators who began recreating the performance played a significant role in its rise to international fame.[21] Outside of Chile Videos of the performance quickly went viral, rapidly spreading across the world.[7] Similar performances soon emerged in various countries such as Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom.[7] A momentous gathering took place on 29 November 2019, when thousands of women performed the piece at the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square.[22] However, when the performance reached Istanbul, Turkey on December 8, 2019, the police intervened and apprehended several of the dancing protestors.[23] Undeterred, a few days later, female Turkish members of Parliament defiantly sang the song within the walls of the Turkish parliament. Republican People's Party MP, Saliha Sera Kadıgil Sütlü, directly addressed Minister of the Interior Süleyman Soylu, emphatically declaring that "Thanks to you, Turkey is the only country in which you must have (parliamentary) immunity to participate in this protest."[24] The impact of "Un violador en tu camino" resonated deeply in the United States, particularly in the aftermath of the MeToo Movement, serving as an anthem for ongoing activism against sexual abuse. In January 2020, during the high-profile trial of Harvey Weinstein in New York City, demonstrators performed the piece in response to allegations of sexual misconduct involving powerful figures like Weinstein and Donald Trump.[18] In Miami, the performers specifically named Brett Kavanaugh.[25] Meanwhile, in Bogotá, Colombia, journalists devised their own adaptation of the song, altering the lyrics to confront sexism within the press industry and prominently displaying signs in honor of femicide victims.[26] According to GeoChicas, an organization that tracks documented performances, "Un violador en tu camino" has been performed in more than 400 locations across over 50 countries as of 2021.[27] |

パフォーマンスの歴史 チリでの起源 当初は2019年10月に予定されていたが、全国的な抗議デモのために初演が延期された[15]。最終的に11月20日、バルパライソのダウンタウンにあ るアニバル・ピント広場で「Un violador en tu camino」が公の場で初演された[16]。11月25日、女性に対する暴力撤廃国際デーを記念して、さまざまな女性グループがチリの首都サンティアゴ の複数の場所で「Un violador en tu camino」を上演した。 [チリ南部の都市テムコでは、先住民のマプチェ族の女性たちがマプドゥングン語で「Un violador en tu camino」の翻訳版を踊った[17]。 このダンスはもともとレイプ文化や国家による暴力全般に対する批判として考案されたものだったが、2019年10月のデモでデモ参加者に対する性的暴力事 件が発生したことで、チリの女性たちの心にさらに深く響くことになった[18]。 [15] Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos(国立人権研究所)は、2019年10月17日から2020年3月13日の間に、抗議行動中に警察やその他の政府機関によって行われた性的 暴力による拷問の被害者282人に代わって法的措置を開始したと報告した[19]。 1973年から1990年までのチリの軍事独裁政権時代にも、性的暴力が拷問の一形態として用いられていたことは注目に値する[20]。 この作品はもともと抗議の形として意図されたものではなかったが、このパフォーマンスを再現し始めた女性デモ参加者たちは、この作品が国際的に有名になる上で重要な役割を果たした[21]。 チリ国外 パフォーマンスの動画は瞬く間に拡散し、世界中に広まった[7]。 同様のパフォーマンスはすぐにアルゼンチン、メキシコ、コロンビア、フランス、スペイン、イギリスなど様々な国で出現した[7]。 2019年11月29日には記念すべき集会が開催され、数千人の女性たちがメキシコシティの主要広場であるゾカロでこの作品を上演した。 [22] しかし、パフォーマンスが2019年12月8日にトルコのイスタンブールに到達したとき、警察が介入し、踊っていた抗議者の何人かを逮捕した[23] にもかかわらず、数日後、トルコの女性国会議員がトルコ国会の壁の中で反抗的にこの曲を歌った。共和人民党のサリハ・セラ・カドゥギル・スットリュ議員 は、スレイマン・ソユル内務大臣に直談判し、「あなたのおかげで、この抗議に参加するために(議会)免責が必要な国はトルコだけです」と力強く宣言した [24]。 Un violador en tu camino」のインパクトは、特にMeToo運動の余波を受けた米国で深く共鳴し、性的虐待に対する継続的な活動の賛歌として機能した。2020年1 月、ニューヨークで注目されたハーヴェイ・ワインスタインの裁判の最中、デモ隊はワインスタインやドナルド・トランプのような権力者の性的不品行疑惑に呼 応してこの曲を演奏した[18]。マイアミでは、演奏者たちは特にブレット・カバノーの名前を挙げた[25]。一方、コロンビアのボゴタでは、ジャーナリ ストがこの曲を独自に翻案し、歌詞を変えて報道業界内の性差別に立ち向かったり、女性殺人の犠牲者を称える看板を目立つように掲げたりした[26]。 文書化されたパフォーマンスを追跡する組織GeoChicasによると、「Un violador en tu camino」は2021年現在、50カ国以上の400以上の場所で演奏されている[27]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Rapist_in_Your_Path |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆