メキシコにおけるフェミニズム

Feminism in Mexico

Femicide Protest at Zocalo in 2019 in front of Palacio National / Members of the Women's Human Rights Centre in Ciudad Chihuahua, Mexico call for justice for the murders of Rubí Frayre (16-year-old daughter of Marisela) and Marisela Escobedo Ortiz.

☆ メキシコにおけるフェミニズム(Feminism in Mexico)とは、メキシコ女性の権利と機会における政治的、経済的、文化的、社会的平等を創造し、定義し、保護することを目的とした哲 学と活動である。自由主義思想に根ざしたフェミニズムという言葉は、19世紀後半のメキシコで使われるようになり、20世紀初頭にはエリートたちの間で一 般的に使われるようになった。征服時代と植民地時代については、現代において再評価され、メキシコにおけるフェミニズムの歴史の一部とみなすことができる 人物もいる。19世紀初頭の独立時には、女性を市民として定義する要求があった。19世紀後半には、イデオロギーとしてのフェミニズムが明確に発展した。 リベラリズムは近代化プロジェクトの一環として、女子と男子の両方に世俗教育を提唱し、女性は教師として労働力として参入した。これらの女性たちはフェミ ニズムの最前線に立ち、法的地位、教育へのアクセス、経済的・政治的権力の領域における女性の既存の扱いを批判するグループを形成した。より多くの学者が 革命期(1915年~1925年)に注目しているが、女性の市民権と法的平等は革命が戦われた明確な問題ではなかった。 [フェミニズムは男女平等を提唱してきたが、フェミニスト・グループの結成、フェミニズム思想を広めるための雑誌の創刊、その他の活動においては、中産階 級の女性が主導権を握っていた。現代の労働者階級の女性は、労働組合や政党の中で主張することができた。1985年の震災後、労働組合の中で自らを確立し た助言者たちは、組織労働の法的・政治的側面を理解する教育を受けた女性たちであった。彼女たちが気づいたのは、持続的な運動を形成し、大部分が中産階級 の運動であったものに労働者階級の女性を惹きつけるためには、労働者の専門知識や仕事に関する知識を活用して、実践的で実用的なシステムを融合させる必要 があるということであった。1990年代には、特にチアパスのサパティスタ蜂起において、先住民コミュニティにおける女性の権利が問題となった。特に 1991年以降、メキシコのカトリック教会が政治に関与することが憲法上制限されなくなったため、生殖に関する権利は現在も続いている問題である。

| Feminism

in Mexico is the philosophy and activity aimed at creating,

defining,

and protecting political, economic, cultural, and social equality in

women's rights and opportunities for Mexican women.[1][2] Rooted in

liberal thought, the term feminism came into use in late

nineteenth-century Mexico and in common parlance among elites in the

early twentieth century.[3] The history of feminism in Mexico can be

divided chronologically into a number of periods with issues. For the

conquest and colonial eras, some figures have been re-evaluated in the

modern era and can be considered part of the history of feminism in

Mexico. At the time of independence in the early nineteenth century,

there were demands that women be defined as citizens. The late

nineteenth century saw the explicit development of feminism as an

ideology. Liberalism advocated secular education for both girls and

boys as part of a modernizing project, and women entered the workforce

as teachers. Those women were at the forefront of feminism, forming

groups that critiqued existing treatment of women in the realms of

legal status, access to education, and economic and political power.[4]

More scholarly attention is focused on the Revolutionary period

(1915–1925), although women's citizenship and legal equality were not

explicitly issues for which the revolution was fought.[5] The Second

Wave (1968–1990, peaking in 1975–1985) and the post-1990 period have

also received considerable scholarly attention.[6] Feminism has

advocated for the equality of men and women, but middle-class women

took the lead in the formation of feminist groups, the founding of

journals to disseminate feminist thought, and other forms of activism.

Working-class women in the modern era could advocate within their

unions or political parties. The participants in the Mexico 68 clashes

who went on to form that generation's feminist movement were

predominantly students and educators.[7] The advisers who established

themselves within the unions after the 1985 earthquakes were educated

women who understood the legal and political aspects of organized

labor. What they realized was that to form a sustained movement and

attract working-class women to what was a largely middle-class

movement, they needed to utilize workers' expertise and knowledge of

their jobs to meld a practical, working system.[8] In the 1990s,

women's rights in indigenous communities became an issue, particularly

in the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas.[9] Reproductive rights remain an

ongoing issue, particularly since 1991, when the Catholic Church in

Mexico was no longer constitutionally restricted from being involved in

politics. |

メキシコにおけ

るフェミニズムとは、メキシコ女性の権利と機会における政治的、経済的、文化的、社会的平等を創造し、定義し、保護することを目的とした哲学と活動である

[1][2]。自由主義思想に根ざしたフェミニズムという言葉は、19世紀後半のメキシコで使われるようになり、20世紀初頭にはエリートたちの間で一般

的に使われるようになった[3]。征服時代と植民地時代については、現代において再評価され、メキシコにおけるフェミニズムの歴史の一部とみなすことがで

きる人物もいる。19世紀初頭の独立時には、女性を市民として定義する要求があった。19世紀後半には、イデオロギーとしてのフェミニズムが明確に発展し

た。リベラリズムは近代化プロジェクトの一環として、女子と男子の両方に世俗教育を提唱し、女性は教師として労働力として参入した。これらの女性たちは

フェミニズムの最前線に立ち、法的地位、教育へのアクセス、経済的・政治的権力の領域における女性の既存の扱いを批判するグループを形成した[4]。より

多くの学者が革命期(1915年~1925年)に注目しているが、女性の市民権と法的平等は革命が戦われた明確な問題ではなかった。

[フェミニズムは男女平等を提唱してきたが、フェミニスト・グループの結成、フェミニズム思想を広めるための雑誌の創刊、その他の活動においては、中産階

級の女性が主導権を握っていた。現代の労働者階級の女性は、労働組合や政党の中で主張することができた。1985年の震災後、労働組合の中で自らを確立し

た助言者たちは、組織労働の法的・政治的側面を理解する教育を受けた女性たちであった。彼女たちが気づいたのは、持続的な運動を形成し、大部分が中産階級

の運動であったものに労働者階級の女性を惹きつけるためには、労働者の専門知識や仕事に関する知識を活用して、実践的で実用的なシステムを融合させる必要

があるということであった[8]。1990年代には、特にチアパスのサパティスタ蜂起において、先住民コミュニティにおける女性の権利が問題となった

[9]。特に1991年以降、メキシコのカトリック教会が政治に関与することが憲法上制限されなくなったため、生殖に関する権利は現在も続いている問題で

ある。 |

| Feminist theory in Mexico Main article: Feminist theory Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical or philosophical fields. Traditional stereotypes  Our Lady of Guadalupe In Mexico, most of these theories stem from postcolonialism and social constructionist ideologies. A postmodern approach to feminism highlights "the existence of multiple truths (rather than simply men and women's standpoints)," which plays out in the Mexican social perception, where the paternalistic machismo culture is neither clearly juxtaposed against a marianismo nor a malinchismo counterpart.[10] In a particularly Mexican context, the traditional views of women have resided at polar opposite positions, wherein the pure, chaste, submissive, docile, giver-of-life marianistic woman,[11] in the guise of Our Lady of Guadalupe, is at one end of the spectrum and the sinful, scheming, traitorous, deceptive, mestizo-producing, La Malinche is at the other.[12] These stereotypes are further reinforced in popular culture via literature,[13][14] art,[15][16] theater,[17] dance,[18][19] film,[20] television[21] and commercials.[22] Regardless of whether these portrayals are accurate, historically based, or were manipulated to serve vested interests,[23] they have promoted three of the underlying themes of the female Mexican identity — Catholicism, Colonialism and Mestizo.[6] Until the latter part of the 19th century, the predominant images of women, whether in the arts or society as a whole, were those dictated by men and men's perceptions of women.[24][25] After the Revolution the state created a new image of who was Mexican. Largely through the efforts of President Álvaro Obregón the cultural symbol became an indigenous Indian, usually a mestizo female, who represented a break with colonialism and Western imperialism.[26] While men's definitions of women and their sphere remained the "official" and predominant cultural model,[27] beginning in the 1920s women demanded that they define their own sphere.[28] In Mexico, some demands for women's equality stem from women's struggle between household commitments and underpaid jobs. Upper and middle-class families employ domestic help, allowing some women of means to be more accepting of traditional gender roles.[29] Changing perceptions  Elena Poniatowska Women's depictions of themselves in art, novels, and photography were in opposition to their objectification and portrayal as subjects of art. By creating their own art, in the post-Revolutionary period, artists could claim their own identity and interpretation of femininity.[30] While the female artists of the immediate period following the revolution tried in their own ways to redefine their personal perceptions of body and its imagery in new ways,[31][32][33][34] they did not typically champion social change. It was the feminists who came after, looking back at their work, who began to characterize it as revolutionary in sparking social change.[35] In the 1950s, a group of Mexican writers called "Generation of '50" were influential in questioning the values of Mexican society.[36] Rosario Castellanos was one of the first to bring attention to the complicity of middle-class women in their own oppression and stated, "with the disappearance of the last servant will the first angry rebel appear".[37] Castellanos sought to question caste and privilege, oppression, racism, and sexism through her writing.[36] Her voice was joined by Elena Poniatowska, whose journalism, novels and short stories philosophically analyzed and evaluated the roles of women, those who had no empowerment, and the greater society.[38] Up until the 1980s, most discussion of feminism centered on the relationships between men and women, child-centric spheres, and wages. After that time period, bodies, personal needs, and sexuality emerged.[39] Some feminist scholars since the 1980s have evaluated the historic record on women and shown that they were participants in shaping in the history of the country. In 1987, Julia Tuñón Pablos wrote Mujeres en la historia de México (Women in the History of Mexico), which was the first comprehensive account of women's historical contributions to Mexico from prehistory through the Twentieth Century. Since that time, extensive studies have shown that women were involved all areas of Mexican life. From the 1990s, gender perspective has increasingly become a focus for academic study.[40] |

メキシコのフェミニズム理論 主な記事 フェミニズム理論 フェミニズム理論とは、フェミニズムを理論的または哲学的分野に拡張したものである。 伝統的なステレオタイプ  グアダルーペの聖母 メキシコでは、これらの理論のほとんどはポストコロニアリズムと社会構築主義のイデオロギーに由来する。フェミニズムに対するポストモダンのアプローチ は、「(単純な男女の立場ではなく)複数の真実の存在」を強調するもので、メキシコの社会認識では、父権主義的なマチズモ文化がマリアニスモやマリンチズ モと明確に並置されることはない。 [特にメキシコの文脈では、伝統的な女性観は正反対の位置にあり、グアダルーペの聖母[11]に扮した純粋で貞淑、従順で、命を与えるマリア的な女性がス ペクトルの一方の端にあり、罪深く、謀略的で、裏切り者で、欺瞞的で、メスティソを生み出すラ・マリンチェがもう一方の端にある。 [12]こうしたステレオタイプは、文学、[13][14]芸術、[15][16]演劇、[17]ダンス、[18][19]映画、[20]テレビ、コマー シャル[21]などを通じて大衆文化の中でさらに強化されている。[22]こうした描写が正確なものであるか、歴史に基づいたものであるか、あるいは既得 権益のために操作されたものであるかはともかく[23]、メキシコ人女性のアイデンティティの根底にある3つのテーマ、すなわちカトリック、植民地主義、 メスティーソを助長してきた[6]。 19世紀後半までは、芸術においても社会全体においても、女性のイメージは男性と男性の女性に対する認識によって決定されたものが主流であった[24] [25]。主にアルバロ・オブレゴン大統領の努力によって、文化的シンボルは植民地主義や西洋帝国主義との決別を象徴する先住民のインディアン、通常はメ スティーソの女性となった[26]。男性による女性とその領域の定義が「公式」かつ支配的な文化モデルであり続けた一方で[27]、1920年代から女性 は自らの領域を定義することを要求するようになった[28]。 メキシコでは、女性の平等を求めるいくつかの要求は、家事と低賃金の仕事の間で女性が葛藤していることから生じている。上流階級や中流階級の家庭は家事手 伝いを雇うため、一部の裕福な女性は伝統的な性別役割分担をより受け入れることができる[29]。 認識の変化  エレナ・ポニャトフスカ 美術、小説、写真における女性自身の描写は、芸術の対象として客観化され描かれることと対立していた。革命直後の女性芸術家たちは、身体とそのイメージに 対する個人的な認識を新たな方法で再定義することをそれぞれの方法で試みたが[31][32][33][34]、一般的に社会変革を支持することはなかっ た。1950年代、「50年世代」と呼ばれるメキシコ人作家のグループは、メキシコ社会の価値観に疑問を投げかける上で影響力を持った[36]。ロサリ オ・カステジャーノスは、中流階級の女性たちが自分たちの抑圧に加担していることに注意を向けた最初の人物の一人であり、「最後の使用人がいなくなれば、 最初の怒れる反逆者が現れる」と述べている。 [カステジャーノスは、その執筆活動を通じて、カーストと特権、抑圧、人種差別、性差別を問い直そうとした[36]。彼女の声にエレナ・ポニャトフスカが 加わり、彼女のジャーナリズム、小説、短編小説は、女性、エンパワーメントのない人々、そしてより大きな社会の役割を哲学的に分析し、評価した[38]。 1980年代まで、フェミニズムの議論のほとんどは、男女の関係、子ども中心の領域、賃金に集中していた。1980年代以降のフェミニズム研究者の中に は、女性に関する歴史的記録を評価し、女性がこの国の歴史の形成に参加していたことを示した者もいる。1987年、ジュリア・トゥニョン・パブロスは 『Mujeres en la historia de México(メキシコ史における女性たち)』を著し、先史時代から20世紀までのメキシコにおける女性の歴史的貢献について初めて包括的に記述した。そ れ以来、広範な研究により、女性がメキシコ生活のあらゆる分野に関与していたことが明らかになっている。1990年代からは、ジェンダーの視点がますます 学術研究の焦点となっている[40]。 |

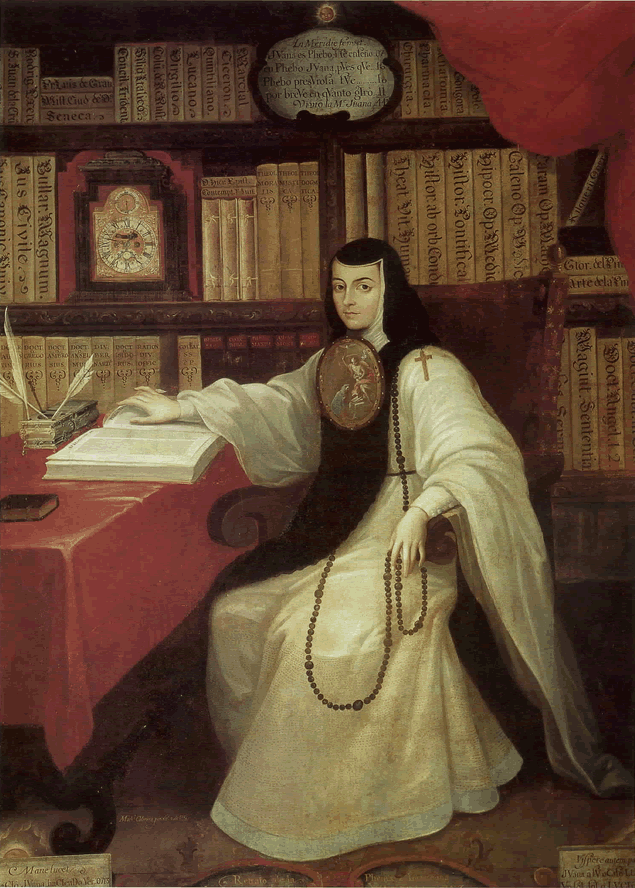

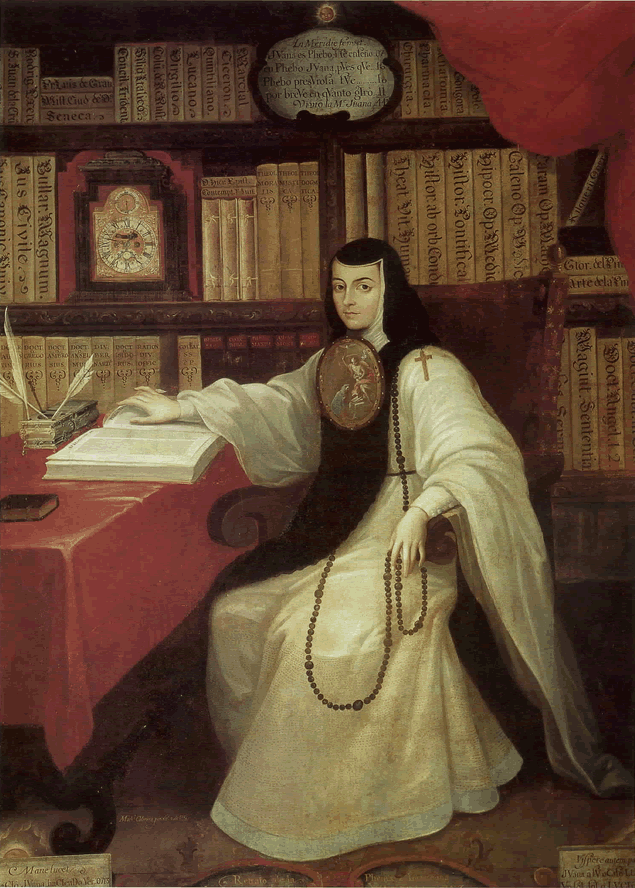

| History Women have played a pivotal role in Mexico's political struggles throughout its history,[41] yet their service to the country did not result in political rights until the middle of the twentieth century,[42] when women gained the right to vote.[43][44] Conquest era, 1519-21  Modern statue of Cortés,

Marina, and their son Martín Modern statue of Cortés,

Marina, and their son MartínThe most famous indigenous woman is Doña Marina, also known as La Malinche, whose role in the conquest of Mexico as cultural translator of Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés depicted her as a traitor to her race and to Mexico. There are many colonial-era depictions of Malinche in indigenous manuscripts, showing her as the central figure, often larger than Cortés. In recent years, feminist scholars and writers have re-evaluated her role, showing sympathy for the choices she faced.[45][46][47] However, the attempt to rescue her historical image from that as a traitor has not found popular support. President José López Portillo commissioned a sculpture of the first mixed-race family, Cortés, Doña Marina, and their mixed-race son Martín, which when he left office was removed from in front of Cortés house in Coyoacan, to an obscure location, the Jardín Xicoténcatl, Barrio de San Diego Churubusco, Mexico City.[48] Colonial era, 1521-1810  Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695), the "Tenth Muse" in her convent cell with her extensive library. Posthumous portrait by eighteenth-century painter Miguel Cabrera There were customary practices and legal structures that regulated society and women's roles in colonial Mexico. The Spanish crown divided the colonial population into two legal categories, the Republic of Indians (República de indios) and Republic of Spaniards (Republica de españoles), that comprised all non-indigenous individuals, including Afro-Mexicans and those of mixed-race. Racial status had a strong determinant on women's legal and social standing.[49][50] Women were under the authority of men: fathers over daughters, husbands over wives. Widows were able to have fuller control over their lives and property. Women from families of financial means were provided a dowry, which remained the property of the wife. A husband gave his wife at marriage funds (arras) that were under her control, protected from his bankruptcy or other financial difficulty. A widow received a specified share of her husband's estate. Wealthy women were expected to uphold their family's honor by chaste and modest behavior. Despite restrictions, women were active in the economy, buying, selling property, and bequeathing property. Women also participated in the workforce, often forced by circumstances such as poverty or widowhood to do so.[51] In colonial Mexico, the vast majority of population was illiterate and entirely unschooled, and there was no priority for the education of girls. A few girls in cities attended schools run by cloistered nuns. Some entered convent schools at around age eight, "to remain cloistered for the rest of their lives."[52] Private tutors educated girls from wealthy families, but generally only enough so that they could oversee a household. There were few opportunities for mixed-race boys or girls. "Education was, in short, highly selective as befits a stratified society, and the possibilities of self-realization were a lottery of birth rather than talent."[53] The one major exception to this picture of marginalization of women is Juana Inés de la Cruz, a Jeronymite nun known in her lifetime as the "Tenth Muse," for her literary output of plays and poems. She wrote a remarkable autobiography, in which she recounts her failed attempt to gain a formal education at the University of Mexico, and her decision to become a nun. In the twentieth century, her life and works have become widely known, and there is a vast literature on her life and works. She is celebrated by feminists. The Answer/La Respuesta by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was published by The Feminist Press.[54] Independence era, 1810-1821  Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, known as the Corregidora Some women distinguished themselves during the Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821),[55] and also were employed as spies, provocateurs, and seductresses. Newspapers in 1812 harangued women to take part in the independence effort as they owed their countrymen a debt for submitting to conquest and subordinating Mexico to Spanish rule.[56] The most prominent female hero of the independence movement is Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, known in Mexican history as La Corregidora. Her remains were moved to the Monument to Independence in Mexico City, there are statues of her in her honor, and her face has appeared on Mexican currency. Other distinguished women of the era are Gertrudis Bocanegra, María Luisa Martínez de García Rojas, Manuela Medina, Rita Pérez de Moreno, Maria Fermina Rivera, María Ignacia Rodríguez de Velasco y Osorio Barba, known as the Güera Rodríguez; and Leona Vicario. Early national period and the Porfiriato, 1821-1911  Laureana Wright de Kleinhans, considered the most brilliant and radical defender of women's emancipation. As early as 1824, some women in Zacatecas petitioned the state government, "Women also wish the title of citizen...to see themselves counted in the census as 'La ciudadana' (woman citizen)."[57] There were feminist gains between 1821 and 1910, but they were typically individual gains and not a formalized movement.[58] In the late nineteenth century, feminism as a term came into the language. Rooted in liberalism, feminism in Mexico saw secular education as a means to means to give dignity to the roles of women as wives and mothers in Mexican families and to expand the women's freedom as individuals. Equal rights for women was not the primary focus in this period;[3] however, some feminists began forming organizations for women's rights and founding journals to disseminate their ideas. Political and literary journals "were a central forum for the public debate of women's issues in Latin America."[59] A way to disseminate feminist thought was the founding of publications by and for women. In 1870, Rita Cetina Gutiérrez founded La Siempreviva (The Everlasting) in Yucatán, one of the first feminist societies in Mexico. The society founded a secondary school, which Cetina directed from 1886 to 1902, educating generations of young teaching women.[60] and inspired others to open schools for women.[61] In 1887, Laureana Wright de Kleinhans established a literary feminist group that published a magazine, "Violetas de Anáhuac" (Violets of Anáhuac), which demanded equality of the sexes and women's suffrage.[62] In this period, the question of women's roles and the need for emancipation was taken up by men as well, most notably Genero García, who wrote two works on the problem of women's inequality, Educación errónea de la mujer y medios prácticas para corregirla (The erroneous education of woman and the practical means to correct it) (1891) and La emancipación de la mujer por medio del estudio (The emancipation of woman by means of education) (1891), as well as a volume of notable Mexican women. García saw the problem of women's inequality as a legal one within marriage, since the 1884 legal code prevented married women from acting in civil society on their own without the permission of their husbands. His critical stance on the equality of the sexes did not translate into political action.[63] As opposition to the Porfirio Díaz regime increased after 1900, activist women were brought together in anti-reelectionist liberal clubs, including supporters of the radical Mexican Liberal Party (PLM) and supporters of the presidency candidacy of Francisco I. Madero. Women's rights including suffrage were not an integral part of the anti- Díaz movements.[63] In 1904, the Sociedad Protectora de la Mujer (The Society for the Protection of Women)[58] formed and began publishing a feminist magazine, "La Mujer Mexicana" (The Mexican Woman).[64] In 1910, the Club Femenil Antirreeleccionista Hijas de Cuauhtémoc (Anti-Reelectionist Women's Club of the Daughters of Cuauhtémoc) led a protest against election fraud and demanded women's right to political participation.[65] Revolutionary period: 1911–1925  María Arias Bernal, supporter of Francisco I. Madero, defender of Mexico City in the coup against him.  Elvia Carrillo Puerto Level of education has played a large part in Mexican feminism because schoolteachers were some of the first women to enter the work-force in Mexico.[42] Many of the early feminists who emerged from the Revolution were teachers either before or after the war,[66] as were the participants of the Primer Congreso Feminista, the first feminist congress in Mexico.[42] As they had in the War for Independence, many Mexican women served during the Mexican Revolution as soldiers and even troop leaders, as well as in more traditional camp-follower roles as cooks, laundresses, and nurses.[67] However, those who gained recognition as veterans of the war were typically educated women who acted as couriers of arms and letters, propagandists, and spies. In part, this was due to an order issued on March 18, 1916, which decommissioned all military appointments of women retroactively and declared them null and void.[68] Because of the nature of espionage, many of the women spies worked directly with the leadership of the revolution and thus had at least a semi-protected status as long as the leader they worked with was living. They formed anti-Huerta clubs,[69] like the Club Femenil Lealtad (Women's Loyalty Club) founded in 1913 by María Arias Bernal,[70] using their gender to disguise their activities.[69] The late nineteenth century had seen the emergence of educated women who pursued careers as novelists, journalists, and political activists. In Latin America generally and in Mexico in particular, a shared feminist consciousness was developing.[71] Some legal gains for women were made during the Revolution, with the right to divorce attained in 1914.[70] In 1915, Hermila Galindo founded a feminist publication, Mujer Moderna (The Modern Woman) which discussed both politics and feminist ideas,[72] including suffrage. Galindo became an important adviser to Venustiano Carranza, leader of the winning Constitutionalist faction of the Revolution.[70] Also in 1915, in October, the newly appointed governor of the Yucatán, Salvador Alvarado, who had studied both European and United States feminist theory and socialism, called for a feminist congress to be convened. In January 1916, the Primer Congreso Feminista (First Feminist Congress) was held in Mérida, Mexico, and discussed topics of education, including sexual education; the problem of religious fanaticism; legal rights and reforms; equal employment opportunity; and intellectual equality among others,[42] but without any real challenge to defining women in terms of motherhood.[73] The 1917 Constitution of Mexico created by the reformist movement contained many of the ideas discussed in the Feminist Congress — free, mandatory, state-sponsored secular education;[74] "equal pay for equal work" (though the delegates were not attempting to protect women, but rather protecting male workers from foreigners being paid higher wages);[42] the preliminary steps to land reform; and a social, as well as political structure.[74] While the Constitution did not prohibit women's enfranchisement, the 1918 National Election Law limited voting rights to males. Women continued to be outside the definition of "citizen."[75] Women did not attain the vote until 1953 in Mexico.[42] The Law of Family Relations of 1917 expanded the previous divorce provisions, giving women the right to alimony and child custody, as well as the ability to own property and take part in lawsuits.[61] In 1919, the Consejo Feminista Mexicano (Mexican Feminist Council)[76] was created with the goals of attaining the right to vote and social and economic liberty[77] and co-founded by Elena Torres Cuéllar; María "Cuca" del Refugio García, who was a proponent of indigenous women's rights, including protection of their lands and wages;[78] and Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza, who became the first president of the Council and was an advocate of miner's rights and education.[79] In 1922, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, governor of the Yucatán, proposed legislation giving women the right to vote and urged women to run for political offices. Heeding his call, Rosa Torre González became the first woman to be elected in any political capacity in Mexico, when she won a seat that same year on the Mérida Municipal Council. The following year, 1923, Carrillo Puerto's younger sister, Elvia Carrillo Puerto was one of three women delegates elected to the state legislature. The other two were Beatríz Peniche Barrera and Raquel Dzib Cicero.[80] In 1923 the First Feminist Congress of the Pan American League of Women was held in Mexico and demanded a wide range of political rights.[81] That same year the Primer Congreso Nacional de Mujeres (First National Women's Congress) in Mexico City was held from which two factions emerged. The radicals, who were part of workers unions and resistance leagues from Yucatán and were aligned with Elena Torres Cuéllar and María "Cuca" del Refugio García. The moderates, who were teachers and women from Christian societies in Mexico City and representatives from the Pan American League and US feminist associations, followed the lead of G. Sofía Villa de Buentello.[82] 1923 also saw the formation of the Frente Unico Pro Derechos de la Mujer (FUPDM) (United Front for Women‟s Rights). By 1925, women in two other Mexican states, Chiapas and San Luis Potosí had also gained the right to vote.[83] Villa de Buentello organized the League of Iberian and Latin American Women to promote civil code reform in 1925. The group adopted a series of resolutions, primarily dealing with gender relations and behavior, which also contained provisions on the right to vote and hold public office.[84] In 1925, the Liga de Mujeres Ibéricas e Hispanoamericanas (League of Spain and Spanish-American Women) with G. Sofía Villa de Buentello taking the lead organizing the Congreso de Mujeres de la Raza (Congress of Hispanic Women). Factional disputes emerged almost immediately, with Villa taking a moderate position and María del Refugio García and Elvia Carrillo Puerto taking a leftist position. Leftists saw the economic situation being at the root of women's oppression, including problems of working-class women, while Villa de Buentello was concerned with moral and judicial issues. Villa de Buentello supported the political equality of men and women, but condemned divorce. Such factional splits characterized later meetings of feminists.[85] Post-revolution: 1926–1967 Throughout the 1920s and 1930s a series of conferences, congresses and meetings were held, dealing with sexual education and prostitution.[86] Much of this attention was in response to the 1926 passage of the Reglamento para el Ejercicio de la Prostitución (Regulation for the Practice of Prostitution), an ordinance requiring prostitutes to register with authorities and submit to inspection and surveillance,[87] which may have been part of a normal phenomenon which occurs at the end of conflict. Often, at the end of armed conflict, citizens turn to reordering the social and moral codes, regulating sexuality and redefining social roles.[88] Near the end of the decade, political parties, like the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (the precursor to PRI) and Partido Nacional Antireeleccionista (National Anti-Reelectionist Party (PNA)) included a women's platform in their agendas,[61] but the most significant gains in this period were regarding practical matters[61] of economic and social concerns. In 1931, 1933 and 1934 the Congreso Nacional de Mujeres Obreras y Campesinas (National Congress of Women Workers and Peasants) sponsored the Congreso Contra la Prostitución (Congress Against Prostitution).[86] One important development that these groups secured in this time frame was the legalization of abortion in case of rape in 1931.[89] Throughout the 1930s FUPDM concentrated on social programs that would benefit lower-class women, advocating for rent reductions of market stalls, and lowered taxes and utility rates. These programs earned the group a large following and their pressure, with the support of President Lázaro Cárdenas, resulted in the ratification in 1939 by all 28 Mexican states of an amendment to Article 34 of the Constitution granting enfranchisement to women. The Mexican Congress refused to formally recognize the ratification or proclaim that the change was in effect.[90] The years from 1940 to 1968 were predominantly a period of inactivity for feminists as World War II shifted the focus to other concerns. There were scattered gains,[91] most specifically, women finally acquired the right to vote. In 1952, the FUPDM had organized the Alianza de Mujeres Mexicanas (Mexican Women's Alliance) and made a deal with candidate Adolfo Ruiz Cortines that they would support his presidential bid in exchange for suffrage. Ruiz consented to the arrangement if Alianza could secure 500,000 women's signatures on a petition asking for enfranchisement. When Ruiz was elected, Alianza delivered the signatures and as promised, women were granted the right to vote in federal elections in 1953.[92] The Second Wave: 1968–1974  Armored cars at protests at the "Zócalo" in Mexico City in 1968 Between July and October 1968, a group of women participants in the student protests that would become known as Mexico 68, began a fledgling feminist movement.[93] During the uprising, women used their perceived apolitical status and gender to bypass police barricades. Gaining access to places that men could not go raised women's awareness of their power.[7] Though the protests were suppressed by government forces before political change happened,[94] the dynamic of man-woman relationships changed, as activists realized platonic working relationships could exist without leading to romance.[95] The uprising mobilized students and mothers. Seeing their children slain brought some lower class and poor women en masse for the first time[citation needed] into the realm of activism with educated middle-class women. In the early 1970s, feminists were overwhelmingly middle-class, university-educated, Marxist-influenced women, who participated in left-wing politics. They did not have much larger influence at the time and were often the butt of jokes and derision in the mainstream press.[96] Some "Mother's Movements" developed in rural and urban areas and across socio-economic barriers, as mothers protested repeatedly for social ills and inequalities to be addressed by their governments. What began as a voice for their children, soon became demands for other kinds of change, like adequate food, sufficient water, and working utilities.[97] Voices also were raised questioning disappearances in various places in the country, but in this period, those questions met with little success.[98] The visibility of feminists increased in the 1970s. Rosario Castellanos presented her critique of the current situation of women at a government-sponsored gathering. "La abnegación, una virtud loca" (Submission, an insane virtue)[99] denounced women's lack of rights. Gabriela Cano calls Castellanos "the lucid voice of the new feminism."[100] In 1972, Alaíde Foppa created the radio program "Foro de la Mujer" (Women's Forum) which was broadcast on Radio Universidad, to discuss inequalities within Mexican society, violence and how violence should be treated as a public rather than a private concern, and to explore women's lives. In 1975, Foppa co-founded with Margarita García Flores the publication Fem, a magazine for scholarly analysis of issues from a feminist perspective.[101] In addition to the more practical Mother's Movements, Mexican feminism, called "New Feminism" in this era, became more intellectual and began questioning gender roles and inequalities. Between June and July 1975, the UN World Conference on Women was held in Mexico City. Mexico hosted delegates from 133 member states, who discussed equality, and governments were forced to evaluate how women fared in their societies.[97] Despite the fact that many Mexican feminists viewed the proceedings as a publicity stunt by the government and that some of the international feminists disparaged the Mexican feminist movement, the conference laid the groundwork for a future path, bringing new issues and concerns into the open and marking the point when frank discussions of sexuality emerged.[102] Spurred by the 1975 conferences, six of the Mexican women's organizations merged into the Coalicion de Mujeres Feministas (Coalition of Feminist Women), hoping to make headway on abortion, rape and violence in 1976. The Coalicion dominated women's efforts until 1979, when some of its more leftist members formed the Frente Nacional de Lucha por la Liberacion y los Derechos de las Mujeres, (National Front in the Struggle for Women's Liberation and Rights). Both groups had withered by the early 1980s.[103] In the 1970s during the presidency of Luis Echeverría (1970-1976), the Mexican government launched a program to encourage family planning in Mexico. With gains in the sphere of public health and the drop in child mortality, overpopulation was seen as national problem. The government initiated a campaign to lower the national birthrate by reaching women directly, though telenovelas, ("soap operas"). Story lines portrayed families with fewer families as being more prosperous. The Catholic Church was adamantly against family planning and the government's way of promoting it was innovative.[104] Second wave: 1975 to 1989 An economic crisis, which began in 1976, brought women together across class lines for the first time. Social issues gave women a new political voice as they demanded solutions to address problems created by the rural-to-urban migration which was taking place. Women formed neighborhood coalitions to deal with lack of housing, sanitation, transportation, utilities, and water. As more people moved into cities to find work, lack of investment in those areas, as well as education and health facilities, became challenges that united women's efforts.[105] Though these colonias populares (neighborhood movements) were making "demands for genuine representation and state accountability as well as social citizenship rights" they did not ask for systemic changes to improve women's societal positions.[106] As the debt crisis intensified and Mexico devalued its currency to gain international loans, wages decreased while the cost of living escalated, causing more and more women to enter the workforce. Companies began hiring women because they could pay them lower wages, male unemployment soared, and feminist activity came to a standstill.[107] Mobilization, popular demonstration, and social movements came together in a new way in response to the devastating 1985 earthquakes. The scope of the destruction invigorated the dormant women's movement to meet the immediate needs of families. There was a recognition during this time that a short-term disaster relief movement could be turned into an organization focused on implementing long-term political gain. Feminist groups, local grass-roots organizations, and NGOs (non-governmental organizations) stepped in to offer aid that the government or official political organizations were either unable or incapable of providing. Feminists were prominent in many NGOs, and were connected to networks beyond Mexico. In the wake of the fraudulent 1988 elections, women's groups became involved in movements for democratization and organization against the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which had been in power since 1929. One such organization was Mujeres en Lucha por the Democracia (Women's Struggle for Democracy).[9] Simultaneously, several worker's unions implemented female advisory boards, with the goals of educating, training and politically organizing garment workers. Feminists serving on advisory boards made workers aware that they could change the environment and attitude of their places of employment and demand changes in areas other than wages and hours. They expanded demands to include addressing sexual harassment, covering child and health care, improving job training and education, raising workers' awareness, and changing the actual work conditions.[108] Feminism and gender as fields of academic study emerged in the 1980s, with courses as Mexican universities offered for the first time. Under the editorship of Marta Lamas, a biannual publication, Debate feminista was launched in 1990. In Guadalajara, Cristina Palomar launched the gender studies publication La Ventana in 1995.[9] Post-1990  Members of the Women's Human Rights Centre in Ciudad Chihuahua, Mexico call for justice for the murders of Rubi and Marisela. The period beginning in 1990 marked a shift in the politics of Mexico which would open up Mexican democracy and see the presidency won in 2000 by the opposition National Action Party (PAN). State governorships were earlier taken by the PAN.[109] As a new electoral law went into effect in 1997 the PRI lost control of the lower house followed by the PRI's historic loss of the presidency in 2000.[110] The impact that end of the virtual one-party-rule would have on women in Mexico was an open question.[111] The year 1990 saw the launch of Debate Feminista (Feminist Debate), a publication founded by Marta Lamas, which aimed at connecting academic feminist theory with the practices of activists in the women's movement.[112][9] Debate has become one of the most important journals in Latin America, printing articles written by both women and men.[113] In 1991, there were a number of constitutional changes as Mexico sought to join the North American Free Trade Agreement with the U.S. and Canada. The 1917 Constitution had strong anticlerical measures that restricted the role of the Catholic Church in Mexico. A major reform established freedom of religious belief, granted open practice of all religions, and was an opening for the Catholic Church to participate in politics. For the first time in the 20th century, established diplomatic relations between Mexico and the Vatican.[114][115] Almost immediately, the Catholic church launched a campaign opposing family planning and a condom distribution program the Mexican government was sponsoring as part of an HIV/AIDS prevention program. In reaction, the feminist movement began studying pro-choice movements in France and the United States, to analyze how to direct the discourse in Mexico. In 1992 they formed the Grupo de Information en Reproduction Elegida (GIRE) (Information Group on Reproductive Choice).[116] Transforming the discussion from whether one was for or against abortion to focus on who should decide was a pivotal change in forward-progress of the abortion debate in Mexico.[113] In order the gauge the public perception, GIRE in conjunction with Gallup polling, completed national surveys in 1992, 1993 and 1994, which confirmed that over 75% of the population felt that the decision of family planning should belong to a woman and her partner.[116] After 1997, when PRI lost control of the legislature,[110] female activists and victims' relatives in Chihuahua convinced the state government to create special law enforcement divisions to address disappearances and deaths of women in Ciudad Juarez. Success in the state legislature led to a similar law at the national level, which also aimed at investigating and prosecution of Dirty War and narco-trafficking disappearances.[98] By 2004 the violence toward women had escalated to the point that María Marcela Lagarde y de los Ríos introduced the term femicide, originally coined in the United States,[117] to Latin American audiences to refer to abductions, death and disappearances of women and girls which is allowed by the state and happens with impunity.[118]  Femicide Protest at Zocalo in 2019 in front of Palacio National  Protest on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2019 in Mexico City 2019-Present Day In early August 2019, around 300 women in Mexico City gathered to protest two incidents of accused rape of a teenage girl by policemen, which had occurred within a few days of each other.[119] Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum, ally to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, "infuriated feminist protesters by branding their first mobilisation – which resulted in the glass entrance to the attorney general’s office being smashed – a provocation”, leading to thousands more gathering to protest.[120] Furthermore, President López Obrador himself was elected on a populist left-wing platform, but made alliance with evangelical Christian conservatives, and has also enacted significant budget cuts to programs like women's shelters, which has further contributed to feminist disappointment and dissent with López Obrador and his ally Sheinbaum.[120] Protesters and feminist activists called for an increase in police accountability, better media reporting and respect for the privacy of rape victims, and policy at the local and federal level for increased security and action against domestic violence and femicide.[121][122] Protesters and activists called attention to widespread harassment and murder, with nearly 70% of Mexican women being victims of sexual assault and around 9 women killed every day, as well as a very low rate of rape reporting due to a lack in trust of the police.[121][119] Since August 2019 there have been a number of marches and protests centered around stopping violence against women in Mexico in Mexico City with hundreds of participants, notably after The Day of the Dead celebrations (early November 2019) [123] and International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2019.[124] In 2020 a National Women’s Strike was held in Mexico on March 9, partly organized by Arussi Unda, to protest and raise awareness of the increasing violence faced by women across the country.[125][126][127] The COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico and accompanying lockdowns put a damper on the growing movement, and the March 8, 2021, International Women's Day demonstrations were smaller and generally more peaceful than those of previous years.[128] Much of the women′s ire was directed at AMLO personally and MORENA′s support of accused rapist Felix Salgado as a candidate for governor of Guerrero. AMLO insists he has been a strong supporter of women′s rights and of feminism.[129] Although the world was shutting down due to COVID-19, the number of women being murdered continued to increase. There was a 2.7% increase in killings from the year 2022 to 2023.[130] Flashing forwarding to 2024, the femicide in Mexico has steadily increased each year. However, this does not stop the crowds of women who show up each International Women's Day to support a change in women's rights in their country. |

歴史 女性はその歴史を通じてメキシコの政治闘争において極めて重要な役割を果たしてきた[41]が、20世紀半ば[42]に女性が選挙権を獲得するまで、彼女 たちの国への奉仕が政治的権利に結びつくことはなかった[43][44]。 征服時代、1519-21年  コルテス、マリーナ、マルティンの近代的な像 最も有名な先住民の女性は、ラ・マリンチェとしても知られるドーニャ・マリーナで、スペイン征服者エルナン・コルテスの文化通訳としてメキシコ征服に果た した役割は、彼女を種族とメキシコに対する裏切り者として描いた。植民地時代の先住民の写本には、マリンチェを中心人物として描いたものが数多くあり、し ばしばコルテスよりも大きく描かれている。近年、フェミニストの学者や作家が彼女の役割を再評価し、彼女が直面した選択に共感を示している[45] [46][47]。しかし、裏切り者としての歴史的イメージから彼女を救い出そうとする試みは、一般的な支持を得ていない。ホセ・ロペス・ポルティージョ 大統領は、最初の混血家族であるコルテス、ドニャ・マリーナ、混血の息子マルティンの彫刻を依頼したが、大統領退任時にコヨアカンのコルテス邸前からメキ シコシティ、バリオ・デ・サン・ディエゴ・チュルブスコのシコテンカトル庭園というわかりにくい場所に撤去された[48]。 植民地時代、1521年-1810年  ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス(1648-1695)、「10人目のミューズ」。18世紀の画家ミゲル・カブレラによる遺影。 植民地時代のメキシコには、社会と女性の役割を規制する慣習や法的構造があった。スペイン王室は植民地人口を2つの法的カテゴリー、インディオ共和国 (República de indios)とスペイン人共和国(Republica de españoles)に分けた。人種的地位は女性の法的・社会的地位を強く左右するものであった。未亡人は自分の生活と財産を完全に管理することができ た。経済的に余裕のある家庭の女性には持参金が支給されたが、それは妻の財産として残された。夫は結婚の際に妻に資金(アーラ)を与え、それは妻の管理下 に置かれ、夫の破産やその他の経済的困難から保護された。未亡人は、夫の財産の特定の分け前を受け取った。裕福な女性は、貞淑で慎み深い振る舞いによって 一族の名誉を守ることが期待された。制限にもかかわらず、女性は経済活動に積極的に参加し、財産の売買や遺贈を行った。女性は労働力にも参加し、貧困や未 亡人などの事情によってそうせざるを得ないことも多かった[51]。 植民地時代のメキシコでは、人口の大多数は読み書きができず、学校にも通っていなかった。都市部では、修道女が運営する学校に通う少女が少数いた。一部の 少女は8歳頃に修道院の学校に入り、「生涯、隠遁生活を送る」[52]。私立の家庭教師は裕福な家庭の少女を教育したが、一般的には家庭を監督できる程度 の教育しか受けられなかった。混血の少年少女が教育を受ける機会はほとんどなかった。「要するに、教育は階層社会にふさわしく非常に選別的なものであり、 自己実現の可能性は才能よりもむしろ生まれによるくじ引きだった」[53]。 このような女性の疎外という図式に対する一つの大きな例外は、フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスというジェロニム会の修道女で、その生涯において、戯曲や詩 の文学的業績から「10人目のミューズ」として知られていた。彼女は、メキシコ大学で正規の教育を受けようとして失敗し、修道女になる決心をしたことを語 る驚くべき自伝を書いている。20世紀になって、彼女の生涯と作品は広く知られるようになり、彼女の生涯と作品に関する膨大な文献が存在する。彼女はフェ ミニストたちから称賛されている。ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスの『答え/La Respuesta』がフェミニスト・プレスから出版された[54]。 独立時代、1810年~1821年  コレヒドラ(王室代理官の妻)として知られるホセファ・オルティス・デ・ドミンゲス メキシコ独立戦争(1810年~1821年)の間、何人かの女性たちは頭角を現し[55]、スパイ、挑発者、誘惑者として雇われた。1812年の新聞は、 征服に服従し、メキシコをスペインの支配に従属させた同胞に借りがあるとして、独立運動に参加するよう女性に呼びかけた[56]。独立運動の最も著名な女 性の英雄は、メキシコ史においてラ・コレヒドーラとして知られるホセファ・オルティス・デ・ドミンゲスである。彼女の遺骨はメキシコシティの独立記念塔に 移され、彼女を称える銅像があり、彼女の顔はメキシコの通貨に描かれている。この時代の他の著名な女性には、ゲルトルディス・ボカネグラ、マリア・ルイ サ・マルティネス・デ・ガルシア・ロハス、マヌエラ・メディナ、リタ・ペレス・デ・モレノ、マリア・フェルミナ・リベラ、マリア・イグナシア・ロドリゲ ス・デ・ベラスコ・イ・オソリオ・バルバ(グエラ・ロドリゲスとして知られる)、レオナ・ビカリオがいる。 初期国家時代とポルフィリアート、1821年~1911年  ラウレアナ・ライト・デ・クラインハンスは、女性解放の最も優秀で急進的な擁護者と考えられている。 早くも1824年には、サカテカスの一部の女性が州政府に「女性も市民の称号を望む...国勢調査で『ラ・シウダダーナ(女性市民)』として数えられるの を見たい」と請願した[57]。 1821年から1910年にかけて、フェミニストの利益はあったが、それは典型的には個人の利益であり、正式な運動ではなかった[58]。自由主義に根ざ したメキシコのフェミニズムは、メキシコの家庭における妻や母親としての女性の役割に尊厳を与え、女性の個人としての自由を拡大するための手段として世俗 教育を考えていた。しかし、一部のフェミニストは女性の権利のための組織を結成し、自分たちの考えを広めるために雑誌を創刊し始めた。政治雑誌と文学雑誌 は「ラテンアメリカにおける女性問題を公に議論する中心的な場であった」[59]。 フェミニスト思想を広める方法は、女性による、女性のための出版物の創刊であった。1870年、リタ・セティナ・グティエレスはユカタンにメキシコで最初 のフェミニスト協会の一つである「ラ・シエンプレヴィーバ(永遠のもの)」を設立した。この協会は中等学校を設立し、セティナは1886年から1902年 まで同校の監督を務め、何世代にもわたって若い教職に就く女性たちを教育した[60]。1887年、ラウレアナ・ライト・デ・クラインハンスは文学的な フェミニストグループを設立し、男女平等と女性参政権を要求する雑誌『アナワクのスミレ』(Violetas de Anáhuac)を発行した[62]。 この時代、女性の役割と解放の必要性の問題は男性にも取り上げられ、特にジェネロ・ガルシアは女性の不平等問題について2つの著作を書いた、 女性の誤った教育とそれを正す実践的手段』(1891年)と『教育による女性の解放』(1891年)である。ガルシアは、女性の不平等という問題を、結婚 生活における法的な問題として捉えていた。1884年に制定された法律では、既婚女性が夫の許可なしに市民社会で独自に行動することを禁じていたからであ る。男女平等に対する彼の批判的な姿勢は、政治的行動には結びつかなかった[63]。 1900年以降、ポルフィリオ・ディアス政権への反発が強まると、活動家の女性たちは、急進的なメキシコ自由党(PLM)の支持者やフランシスコ・I・マ デロの大統領候補の支持者など、反選挙主義の自由主義クラブに集められた。参政権を含む女性の権利は反ディアス運動には不可欠なものではなかった [63]。1904年、女性保護協会(Sociedad Protectora de la Mujer)[58]が結成され、フェミニスト雑誌『メキシコの女』(La Mujer Mexicana)の発行を開始した[64]。 1910年、Club Femenil Antirreeleccionista Hijas de Cuauhtémoc(クアウテモックの娘たちの反選挙主義女性クラブ)が不正選挙に対する抗議活動を主導し、女性の政治参加の権利を要求した[65]。 革命期: 1911-1925  マリア・アリアス・ベルナル、フランシスコ1世マデロの支持者、マデロに対するクーデターでメキシコシティを守る。  エルビア・カリージョ・プエルト 教育水準はメキシコのフェミニズムにおいて大きな役割を果たした。革命から生まれた初期のフェミニストの多くは、戦前または戦後に教師であった[66]。 独立戦争でもそうであったように、メキシコ革命でも多くのメキシコ人女性が兵士として、さらには部隊のリーダーとして、また料理人、洗濯係、看護婦といっ たより伝統的な野営の従者として従軍した[67]。しかし、戦争の帰還兵として認知されたのは、一般的に武器や手紙の運び屋、宣伝係、スパイとして活動し た教養ある女性たちであった。これは、1916年3月18日に発令された、女性のすべての軍人任命を遡及的に廃止し、その任命を無効とする命令のためでも あった[68]。スパイ活動の性質上、女性スパイの多くは革命の指導者と直接仕事をしていたため、一緒に働いていた指導者が生きている限り、少なくとも半 保護された地位にあった。彼女たちは、マリア・アリアス・ベルナルによって1913年に創設されたクラブ・フェメニル・レアルタッド(女性忠誠クラブ)の ような反ウエルタ・クラブ[69]を結成し[70]、性別を利用して活動を偽装していた[69]。 19世紀後半には、小説家、ジャーナリスト、政治活動家としてのキャリアを追求する教養ある女性たちが出現していた。1915年、エルミラ・ガリンドは政 治と参政権を含むフェミニズム思想の両方を論じるフェミニスト出版物『現代の女』(Mujer Moderna)を創刊した[72]。ガリンドは、革命で勝利した立憲主義派の指導者であるヴェヌスティアーノ・カランサの重要な助言者となった [70]。同じく1915年の10月、新たにユカタン州知事に任命されたサルバドール・アルバラードは、ヨーロッパとアメリカのフェミニズム理論と社会主 義の両方を研究しており、フェミニスト会議の開催を呼びかけた。1916年1月、メキシコのメリダで第1回フェミニスト会議(Primer Congreso Feminista)が開催され、性教育を含む教育、宗教的狂信の問題、法的権利と改革、雇用機会の均等、知的平等などのテーマについて議論されたが [42]、母性という観点から女性を定義することへの真の挑戦はなかった[73]。 改革派運動によってつくられた1917年のメキシコ憲法は、フェミニスト会議で議論されたアイデアの多くを含んでいた。無料で義務的な、国が後援する世俗 的な教育[74]、「同一労働同一賃金」(ただし、代表団は女性を保護しようとしたのではなく、むしろ外国人が高い賃金を支払われることから男性労働者を 保護しようとした)[42]、土地改革への予備的なステップ、政治的な構造だけでなく社会的な構造[74]。女性は引き続き「市民」の定義から外れていた [75]。1917年の家族関係法は、それまでの離婚規定を拡大し、女性に扶養料と子どもの親権を与えるとともに、財産を所有し、訴訟に参加する権利を与 えた[61]。 1919年には、選挙権と社会的・経済的自由[77]の獲得を目的としたメキシコ・フェミニスト協議会(Consejo Feminista Mexicano)[76]が設立され、エレナ・トーレス・クエラルが共同設立者となった; マリア・"クーカ"・デル・レフージョ・ガルシアは先住民女性の土地と賃金の保護を含む女性の権利の支持者であり[78]、フアナ・ベレン・グティエレ ス・デ・メンドーサは評議会の初代会長となり、鉱山労働者の権利と教育の擁護者であった。 [1922年、ユカタン州知事のフェリペ・カリージョ・プエルトは、女性に選挙権を与える法案を提出し、女性に政治家への立候補を促した。彼の呼びかけに 従ったロサ・トーレ・ゴンサレスは、同年メリダ市議会の議席を獲得し、メキシコ初の女性政治家となった。翌1923年、カリージョ・プエルトの妹エルビ ア・カリージョ・プエルトは、州議会議員に選出された3人の女性代議員のうちの1人となった。他の2人はベアトリス・ペニシェ・バレラとラケル・ジブ・シ セロであった[80]。 1923年、汎アメリカ女性同盟の第一回フェミニスト会議がメキシコで開催され、幅広い政治的権利を要求した[81]。同年、メキシコシティで第一回全国 女性会議(Primer Congreso Nacional de Mujeres)が開催され、そこから2つの派閥が生まれた。急進派はユカタン州の労働組合や抵抗組織に属し、エレナ・トーレス・クエジャールやマリア・ デル・レフージョ・ガルシアと同盟を結んでいた。穏健派は、メキシコシティのキリスト教団体の教師や女性、パンアメリカン連盟や米国のフェミニスト協会の 代表者であり、G.ソフィア・ビジャ・デ・ブエンテロの指導に従った[82]。1923年には、女性の権利のための統一戦線(Frente Unico Pro Derechos de la Mujer、FUPDM)が結成された。1925年までに、メキシコの他の2つの州、チアパス州とサンルイスポトシ州の女性も選挙権を獲得した[83]。 ビジャ・デ・ブエンテロは1925年に民法改正を促進するためにイベリア・ラテンアメリカ女性連盟を組織した。1925年、G.ソフィア・ビジャ・デ・ブ エンテロが中心となって、スペイン・スペイン系アメリカ人女性連盟(Liga de Mujeres Ibéricas e Hispanoamericanas)がヒスパニック系女性会議(Congreso de Mujeres de la Raza)を組織した。ビジャは穏健派の立場をとり、マリア・デル・レフージョ・ガルシアとエルビア・カリージョ・プエルトは左派の立場をとった。左派 は、労働者階級の女性の問題を含め、女性の抑圧の根底には経済状況があると考え、ビジャ・デ・ブエンテロは道徳と司法の問題に関心を持った。ヴィラ・デ・ ブエンテッロは男女の政治的平等を支持したが、離婚は非難した。このような派閥の分裂は、後のフェミニストたちの会合を特徴づけるものであった[85]。 革命後: 1926-1967 1920年代から1930年代にかけて、一連の会議、大会、会合が開催され、性教育と売春を扱っていた[86]。このような注目の多くは、1926年に Reglamento para el Ejercicio de la Prostitución(売春の実施に関する規則)が可決され、売春婦が当局に登録し、検査と監視を受けることを義務づける条例が制定されたことに対応 するものであった[87]。多くの場合、武力紛争が終結すると、市民は社会的・道徳的規範の再整理、セクシュアリティの規制、社会的役割の再定義に目を向 ける[88]。 この10年の終わり近くには、PRIの前身であるPartido Nacional Revolucionario(全国革命党)やPartido Nacional Antireeleccionista(全国反選挙党)のような政党が、そのアジェンダの中に女性の綱領を含んでいた[61]が、この時期における最も重 要な利益は、経済的・社会的関心事の実際的な問題[61]に関するものであった。1931年、1933年、1934年には、全国女性労働者・農民会議 (Congreso Nacional de Mujeres Obreras y Campesinas)が売春反対会議(Congreso Contra la Prostitución)を後援した[86]。この時期にこれらのグループが確保した重要な発展のひとつは、1931年にレイプの場合の中絶が合法化さ れたことであった[89]。 1930年代を通じて、FUPDMは下層階級の女性に利益をもたらす社会的プログラムに集中し、市場の屋台の家賃の引き下げ、税金や公共料金の引き下げを 提唱した。これらのプログラムは多くの支持者を獲得し、ラサロ・カルデナス大統領の支持を得た彼らの圧力は、1939年にメキシコの全28州によって、女 性に参政権を与える憲法第34条の改正が批准されるに至った。1940年から1968年までは、第二次世界大戦の影響でフェミニストの関心は他の関心事に 移っていたため、フェミニストにとっては活動休止の時期であった。散発的な利益はあったが[91]、最も具体的なものは、女性がついに選挙権を獲得したこ とであった。1952年、FUPDMはメキシコ女性同盟(Alianza de Mujeres Mexicanas)を組織し、大統領候補アドルフォ・ルイス・コルティネス(Adolfo Ruiz Cortines)と、参政権と引き換えに彼の大統領選を支援するという取引を行った。ルイズは、アリアンザが参政権獲得を求める請願書に50万人の女性 の署名を集めることができれば、この取り決めに同意した。ルイズが当選すると、アリアンサは署名を届け、約束通り、1953年に連邦選挙での女性の投票権 が認められた[92]。 第二の波:1968年~1974年  1968年、メキシコシティの「ゾカロ」での抗議行動での装甲車 1968年7月から10月にかけて、「メキシコ68」として知られるようになる学生抗議デモに参加した女性グループが、駆け出しのフェミニズム運動を始め た[93]。蜂起の間、女性たちは、自分たちが無政治的であると認識される地位と性別を利用して、警察のバリケードを迂回した。抗議活動は政治的変化が起 こる前に政府軍によって弾圧されたが[94]、活動家たちは恋愛に発展しなくてもプラトニックな労働関係が存在しうることに気づき、男女関係のダイナミズ ムが変化した[95]。 蜂起は学生や母親たちを動員した。自分たちの子どもが殺されるのを見て、下層階級や貧困層の女性たちが初めて[要出典]、教育を受けた中流階級の女性たち と一緒に活動するようになった。1970年代初頭、フェミニストたちは圧倒的に中流階級で、大学で教育を受け、マルクス主義の影響を受けた女性たちであ り、左翼政治に参加していた。当時、彼女たちはそれほど大きな影響力を持っておらず、しばしば主流派の報道機関ではジョークや嘲笑の的であった[96]。 農村部や都市部、社会経済的な障壁を越えて、母親たちが社会悪や不平等に政府が対処するよう繰り返し抗議する中で、いくつかの「母親運動」が発展した。子 どものための声として始まったものは、やがて、十分な食料、十分な水、公共事業など、他の種類の変化を求める要求となった[97]。国内のさまざまな場所 で失踪に疑問を呈する声も上がったが、この時期、こうした疑問はほとんど成功しなかった[98]。 1970年代には、フェミニストの知名度が高まった。ロサリオ・カステジャーノスは、政府主催の集会で女性の現状に対する批判を発表した。"La abnegación, una virtud loca"(服従、非常識な美徳)[99]は女性の権利の欠如を非難した。ガブリエラ・カノはカステジャーノスを「新しいフェミニズムの明晰な声」と呼ぶ [100]。1972年、アレイデ・フォッパはラジオ・ウニベルシダで放送されたラジオ番組「Foro de la Mujer」(女性フォーラム)を創り、メキシコ社会における不平等、暴力、そして暴力が私的な関心事ではなく公的な関心事としてどのように扱われるべき かを議論し、女性の生き方を探求した。1975年、フォッパはマルガリータ・ガルシア・フローレスと共同で、フェミニズムの視点から問題を学術的に分析す る雑誌『Fem』を創刊した[101]。 より実践的な母親運動に加え、この時代に「ニュー・フェミニズム」と呼ばれたメキシコのフェミニズムは、より知的なものとなり、ジェンダーの役割や不平等 を問い始めた。1975年6月から7月にかけて、国連女性世界会議がメキシコシティで開催された。メキシコは133の加盟国からの代表団を受け入れ、平等 について議論し、各国政府は自分たちの社会における女性の状況を評価することを余儀なくされた[97]。多くのメキシコのフェミニストたちはこの会議を政 府による売名行為とみなし、国際的なフェミニストたちの中にはメキシコのフェミニズム運動を軽蔑する者もいたにもかかわらず、この会議は将来の道への土台 を築き、新たな問題や懸念を公の場にもたらし、セクシュアリティについて率直な議論が生まれるきっかけとなった。 [102] 1975年の会議に刺激され、メキシコの6つの女性団体は、1976年に中絶、レイプ、暴力について前進することを期待して、フェミニスト女性連合 (Coalicion de Mujeres Feministas)に統合された。1979年、より左派的なメンバーの一部が「女性の解放と権利のための闘いにおける全国戦線」を結成するまで、「連 合」は女性たちの活動を支配していた。両グループは1980年代初頭には消滅していた[103]。 1970年代、ルイス・エチェベリアの大統領時代(1970-1976年)、メキシコ政府はメキシコで家族計画を奨励するプログラムを開始した。公衆衛生 の分野で成果が上がり、子どもの死亡率が低下したことで、人口過剰が国家的な問題と見なされるようになった。政府は、テレノベラ(「ソープオペラ」)を通 じて女性に直接働きかけ、国民の出生率を下げるキャンペーンを開始した。ストーリーは、家族の数が少ない家庭の方が豊かであるかのように描かれた。カト リック教会は断固として家族計画に反対しており、政府の推進方法は革新的だった[104]。 第二の波:1975年から1989年 1976年に始まった経済危機によって、女性たちは初めて階級の垣根を越えて集まった。社会問題は、農村から都市への移住が引き起こした問題に対処する解 決策を求め、女性に新たな政治的発言力を与えた。女性たちは、住宅、衛生、交通、公共事業、水の不足に対処するため、近隣連合を結成した。より多くの人々 が仕事を求めて都市に移動するにつれて、教育や保健施設だけでなく、それらの地域への投資の欠如が、女性たちの努力を結束させる課題となった[105]。 これらのコロニアス・ポピュラーレス(近隣住民運動)は、「社会的市民権だけでなく、真の代表権と国家の説明責任に対する要求」を行っていたけれども、女 性の社会的地位を改善するための制度的な変化を求めてはいなかった。 [106] 債務危機が激化し、メキシコは国際的な融資を得るために通貨を切り下げた。企業は低賃金を支払えるので女性を雇い始め、男性の失業率は急上昇し、フェミニ ストの活動は行き詰まった[107]。 1985年の壊滅的な地震に対応して、動員、民衆のデモ、社会運動が新たな形で結集した。破壊の規模は、家族の差し迫ったニーズを満たすために、休眠状態 にあった女性運動を活性化させた。この時期、短期的な災害救援運動が、長期的な政治的利益の実現に焦点を当てた組織に変わる可能性があることが認識され た。フェミニスト・グループ、地元の草の根組織、NGO(非政府組織)は、政府や公的な政治組織が提供できない、あるいは提供できない援助を提供するため に介入した。フェミニストたちは多くのNGOで頭角を現し、メキシコ国外とのネットワークにもつながっていた。1988年の不正選挙をきっかけに、女性グ ループは民主化を求める運動や、1929年以来政権を握っていた制度的革命党に対抗する組織に関わるようになった。同時に、いくつかの労働組合は、衣料品 労働者の教育、訓練、政治的組織化を目標に、女性諮問委員会を設置した。諮問委員会の委員を務めるフェミニストたちは、労働者たちに、自分たちが職場の環 境や態度を変えることができ、賃金や労働時間以外の分野でも変化を要求できることを認識させた。彼らは要求を、セクシャルハラスメントへの対処、育児や健 康管理のカバー、職業訓練や教育の改善、労働者の意識の向上、実際の労働条件の変更にまで広げた[108]。 学術研究の分野としてのフェミニズムとジェンダーは1980年代に台頭し、メキシコの大学で初めて講座が開かれた。マルタ・ラマス編集長のもと、1990 年に年2回発行の『Debate feminista』が創刊された。グアダラハラでは、クリスティーナ・パロマールが1995年にジェンダー研究出版『La Ventana』を創刊した[9]。 1990年以降  メキシコのシウダー・チワワにある女性人権センターのメンバーが、ルビとマリセラの殺害に対する正義を訴える。 1990年に始まるこの時期は、メキシコの民主主義を開放し、2000年に野党の国民行動党(PAN)が大統領の座を獲得することになるメキシコの政治の 変化を示していた。1997年に新しい選挙法が施行されると、PRIは下院の支配権を失い、2000年にはPRIが大統領職を歴史的に失った[110]。 事実上の一党支配の終焉がメキシコの女性に与える影響は未解決の問題であった。 [1990年には、マルタ・ラマスによって創刊されたDebate Feminista(フェミニスト・ディベート)が創刊され、学術的なフェミニズム理論と女性運動の活動家の実践を結びつけることを目的としていた。 1991年、メキシコはアメリカやカナダとの北米自由貿易協定への加盟を目指し、多くの憲法改正が行われた。1917年憲法には、メキシコにおけるカト リック教会の役割を制限する強力な反宗教的措置があった。大改革によって信教の自由が確立され、すべての宗教の自由な実践が認められ、カトリック教会が政 治に参加するきっかけとなった。20世紀で初めて、メキシコとバチカンの間に外交関係が樹立された[114][115]。ほぼ直ちに、カトリック教会は家 族計画やメキシコ政府がHIV/AIDS予防プログラムの一環として後援していたコンドーム配布プログラムに反対するキャンペーンを開始した。その反動と して、フェミニスト運動はフランスとアメリカのプロチョイス運動を研究し始め、メキシコでの言説をどのように方向づけるべきかを分析した。1992年、彼 らはGIRE(Grupo de Information en Reproduction Elegida)(生殖選択に関する情報グループ)を結成した[116]。中絶に賛成か反対かという議論から、誰が決めるべきかという焦点に議論を転換さ せることは、メキシコにおける中絶議論の前進において極めて重要な変化であった。 [113]国民の認識を測定するために、GIREはギャラップ社の世論調査と共同で1992年、1993年、1994年に全国調査を実施し、75%以上の 国民が家族計画の決定は女性とそのパートナーのものであるべきだと感じていることを確認した[116]。 1997年以降、PRIが議会を制することができなくなると[110]、チワワの女性活動家と被害者の親族は、シウダー・フアレスにおける女性の失踪と死 亡に対処するための特別な法執行部門を設置するよう州政府を説得した。州議会での成功は、ダーティー戦争と麻薬人身売買による失踪者の捜査と訴追を目的と した、国家レベルでの同様の法律へとつながった[98]。2004年までに、女性に対する暴力は、マリア・マルセラ・ラガルデ・イ・デ・ロス・リオスが、 国家によって許され、平然と行われている女性と女児の誘拐、死亡、失踪を指すために、もともとアメリカで作られたフェミサイドという言葉[117]をラテ ンアメリカの聴衆に紹介するまでにエスカレートしていた[118]。  2019年、パラシオ・ナショナル前のソカロでのフェミサイド抗議デモ  Protest on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2019 in Mexico City 2019年-現在 2019年8月上旬、メキシコシティでは約300人の女性が集まり、数日以内に発生した警官による10代の少女へのレイプとされる2つの事件に抗議した [119]。 アンドレス・マヌエル・ロペス・オブラドール大統領の盟友であるクラウディア・シャインバウム・メキシコシティ市長は、「彼らの最初の動員(司法長官事務 所のガラス張りの入り口が壊される結果となった)を挑発行為と決めつけ、フェミニストの抗議者たちを激怒させた」ため、さらに数千人が抗議に集まることと なった。 [120] さらに、ロペス・オブラドール大統領自身は、ポピュリスト的な左翼の綱領で当選したが、福音主義的なキリスト教保守派と同盟を結び、女性保護施設のような プログラムへの大幅な予算削減も実施したため、ロペス・オブラドールと彼の同盟者であるシェインバウムに対するフェミニストの失望と反対はさらに大きく なった。 [120]デモ参加者やフェミニスト活動家たちは、警察の説明責任の強化、メディア報道の改善、レイプ被害者のプライバシーの尊重、DVやフェミサイドに 対する警備や対策を強化するための地方や連邦レベルでの政策を求めた[121][122]。デモ参加者や活動家たちは、メキシコ人女性の70%近くが性的 暴行の被害者であり、毎日約9人の女性が殺されていることや、警察への信頼がないためにレイプの報告率が非常に低いことなど、広範なハラスメントや殺人に 注意を喚起した。 [121][119]2019年8月以降、メキシコ・シティでは、死者の日のお祝い(2019年11月初旬)の後[123]、女性に対する暴力撤廃国際 デー2019の後[124]を中心に、メキシコにおける女性に対する暴力の阻止を中心とした行進や抗議行動が数百人の参加者を集めて行われている。 2020年、3月9日にメキシコで全国女性ストライキが開催され、一部はアルッシ・ウンダが主催し、国中で女性が直面している暴力の増加に抗議し、意識を 高めるために行われた。 [125][126][127]メキシコにおけるCOVID-19の流行とそれに伴う封鎖は、拡大する運動に水を差すものであり、2021年3月8日の国 際女性デーのデモは、例年のものよりも規模が小さく、概して平和的なものであった。AMLOは、自分は女性の権利とフェミニズムの強力な支持者であると主 張している[129]。COVID-19のために世界は閉鎖されていたが、殺害される女性の数は増え続けていた。2022年から2023年にかけて、殺害 件数は2.7%増加した[130]。2024年に向けても、メキシコの女性殺人は毎年着実に増加している。しかし、国際女性デーのたびに、自国の女性の権 利の変化を支援するために集まる女性たちの群衆を止めることはできない。 |

| Issues As of 2023 in the Global Gender Gap Index measurement of countries by the World Economic Forum, Mexico, is ranked 33rd on gender equality; the United States is ranked 43rd. Reproductive rights  Women campaigning for the decriminalisation of abortion in 2011 In the middle of the Second Wave, there was hope by activists that gains would be made in the area of contraception and a woman's right to her own body choices. President Luis Echeverría had convened the Interdisciplinary Group for the Study of Abortion, which included anthropologists, attorneys, clergy (Catholic, Jewish and Protestant), demographers, economists, philosophers, physicians, and psychologists. Their findings, in a report issued in 1976, were that criminality of voluntary abortion should cease and that abortion services should be included in the government health package. The recommendations were neither published or implemented. In 1980, feminists convinced the Communist Party to table a bill for voluntary motherhood, but it never moved forward. In 1983, a proposal was made to modify the penal code, but the strong reactions from conservative factions dissuaded the government from action.[116] In 1989, a scandal broke when police raided a private abortion clinic, detaining doctors, nurses and patients. They were jailed without a court order in Tlaxcoaque, subjected to extortion demands, and some of the women reported they were tortured. After her release, one of the victims filed a lawsuit alleging police brutality and the media picked up the story. In a first for Mexico's feminist movement, feminists published a notice in response to the situation, and obtained 283 signatories with different political alliances and gained 427 endorsements. For the first time, feminists and political parties spoke in harmony.[116] The period marked slow, but steady gains for women in the country.[131] Within a month Vicente Fox's 2000 election, the PAN governor of Guanajuato attempted to ban abortion even in the case of rape. In a speech to commemorate International Women's Day Fox's Secretary of Labor, Carlos Abascal, angered many women by proclaiming feminism "as the source of many moral and social ills, such as 'so-called free love, homosexuality, prostitution, promiscuity, abortion, and the destruction of the family'."[132] In reaction, feminists staged protests and demanded political protection. In Guanajuato, Verónica Cruz Sánchez coordinated protests over numerous weeks which eventually defeated the measure.[133] Rosario Robles, feminist leader of the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) led efforts in Mexico City to expand abortion rights in cases when the health of the mother or child is jeopardized.[132] After 38 years of work by the feminist movement, in 2007 the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation decriminalized abortions in Mexico City which occur by 12 weeks of gestation. GIRE lawyers assisted in drafting legislation and in coordinating defense of the law when lawsuits alleged it was unconstitutional. Marta Lamas testified during the Supreme Court trial.[134] The fight for abortion rights in other states continues, since many state laws criminalize miscarriage in a crime characterized as "aggravated homicide of a family member" and activists have worked to have excessively harsh sentences of up to 30 years reduced.[135] In 2010, Veronica Cruz was successful in leading the effort to free seven women serving prison sentences for abortion or miscarriage in Guanajuato[136] and in 2011 secured a similar release in Guerrero.[137] In November 2014, the SCJN began hearings on a case from Veracruz, which is the first case in Mexico to ask the court to consider whether women have a constitutional right to abortion and whether criminalization should be eliminated across the nation.[138] In 2019, during a surge of feminist protests happening in the country, the “green tide” — an originally-Argentinian movement that seeks reproductive rights — was popularized by different feminist groups in Mexico. This movement uses mobilization (such as campaigns and protests) to demand bodily autonomy and protection for women in Latin America, and has continued to rise in popularity in Mexico during the early 2020s. [139][140] On September 7, 2021, the SCJN declared the federal decriminalization of abortion in Mexico. Before this, 28 states had restrictive abortion laws that only allowed people to terminate their pregnancy if they met certain criteria (such as rape, fetal malformations, and health risks for the pregnant person) and punished them otherwise. Now, given the SCJN’s decision, even if these states have penalties for abortion stipulated in their laws, they cannot legally enforce them.[141][142] Indigenous women's rights  Poster commemorating EZLN Comandanta Ramona In 1987 feminists from the organization Comaletzin A.C. began working with indigenous women in Chiapas, Morelos, Puebla, and Sonora for the first time. In 1989 the Center for Research and Action for Women and the Women's Group of San Cristóbal de las Casas initiated programs for indigenous women in Chiapas and the Guatemalan refugee community against sexual and domestic violence. In Oaxaca and Veracruz, Women for Dialogue and in Michoacán, Women in Solidarity Action (EMAS), who work with Purépecha women, also began helping indigenous women in their struggles for rights.[143] Indigenous women began demanding rights beginning in 1990. Because many indigenous women had been forced into the workplace, their concerns had similarities with urban workers, as were their concerns with violence, lack of political representation, education, family planning choices, and other issues typically addressed by feminists. However, indigenous women also faced an ethnic discrimination and cultural orientation that was different from feminists, and particularly those from urban areas. In some of their cultures, early marriage, as young as 13 or 14 prevailed;[143] in other cultures, derecho de pernada (right of the first night) allowed rape and abuse of women with impunity for their attackers,[144] while in others, organized violence against women had been used to both punish activism and send a message to their men that women's demands would not be tolerated.[143] Similar to other women of color and minorities in other feminist movements[145][146] indigenous women in Mexico have struggled with ethnocentrism from mainstream feminist groups.[143] With the 1994 formation of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) (Zapatista Army of National Liberation), indigenous women in Chiapas advocated for gender equality with the leaders of the uprising. On January 1, 1994, the Zapatistas announced the Ley Revolucionaria de Mujeres (Women's Revolutionary Law), which in a series of ten provisions recognized women's rights regarding children, education, health, marriage, military participation, political participation, protection from violence and work and wages.[9][143] While not recognized by official state or federal governments,[147] the laws were an important gain for these indigenous women within their native cultures. In 1997 a national meeting of indigenous women titled "Constructing our History" resulted in the formation of the Coordinadora Nacional de Mujeres Indígenas (CNMI) (National Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Women) among communities from Chiapas, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Mexico City, Michoacán, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, and Veracruz. The purpose of the organization is to strengthen from a gender perspective the leadership opportunities, networking potential and skills of indigenous women, within their communities and nationally, and sensitize indigenous peoples on indigenous women's human rights.[143] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism_in_Mexico |

課題 世界経済フォーラムによるグローバル・ジェンダー・ギャップ指数では、2023年現在、メキシコは男女平等で33位、米国は43位である。 リプロダクティブ・ライツ  2011年、中絶の非犯罪化を求めて運動する女性たち 第2次世界大戦のさなか、活動家たちは、避妊と女性が自分の体を選択する権利の分野で前進があると期待していた。ルイス・エチェベリア大統領は、人類学 者、弁護士、聖職者(カトリック、ユダヤ教、プロテスタント)、人口統計学者、経済学者、哲学者、医師、心理学者からなる「中絶研究学際グループ」を招集 した。1976年に発表された報告書の中で、彼らの発見は、自発的中絶の犯罪性をなくし、中絶サービスを政府の医療パッケージに含めるべきだというもの だった。この勧告は公表も実施もされなかった。1980年、フェミニストたちは共産党を説得し、自発的な母性保護のための法案を提出させたが、それは前進 しなかった。1983年には、刑法改正の提案がなされたが、保守派からの強い反発があり、政府は行動を起こさなかった[116]。 1989年、警察が民間の中絶クリニックを急襲し、医師、看護師、患者を拘束するというスキャンダルが起こった。彼らは裁判所命令なしにトラクスコアクに 収監され、恐喝を要求され、女性の中には拷問を受けたという者もいた。釈放後、被害者の一人が警察の蛮行を訴えて訴訟を起こし、メディアもこの話を取り上 げた。メキシコのフェミニズム運動にとって初めてのことだが、フェミニストたちはこの事態に呼応する通知を発表し、さまざまな政治同盟から283人の署名 を集め、427人の賛同を得た。初めて、フェミニストと政党が調和して発言したのである[116]。この時期は、メキシコの女性にとって、ゆっくりではあ るが着実な前進となった[131]。 ビセンテ・フォックスが2000年の選挙で当選して1ヵ月も経たないうちに、グアナファトのPAN州知事はレイプの場合でも中絶を禁止しようとした。 フォックスのカルロス・アバスカル労働長官は、国際女性デーを記念する演説で、フェミニズムを「『いわゆる自由恋愛、同性愛、売春、乱交、中絶、家族の破 壊』など、多くの道徳的・社会的悪の根源である」と宣言し、多くの女性を怒らせた[132]。グアナファトでは、ベロニカ・クルス・サンチェスが何週間に もわたって抗議行動を調整し、最終的にこの法案は否決された[133]。 左翼の民主革命党(PRD)のフェミニスト指導者であるロサリオ・ロブレスは、母子の健康が脅かされる場合に中絶の権利を拡大するためのメキシコシティで の取り組みを主導した[132]。フェミニスト運動による38年間の活動の後、2007年にメキシコシティの最高裁判所は妊娠12週までに発生した中絶を 非犯罪化した。GIREの弁護士は、法律の起草を支援し、法律が違憲であると主張された訴訟の弁護を調整した。マルタ・ラマスは最高裁の裁判で証言した [134]。 多くの州法が流産を「家族に対する加重殺人」と特徴づけられる犯罪として犯罪化しており、活動家たちは最高30年という過度に厳しい刑を減刑させるために 活動してきたため、他の州における中絶の権利のための闘いは続いている[135]。2010年、ベロニカ・クルスはグアナファトで中絶や流産で服役してい た7人の女性を釈放するための活動を主導することに成功し[136]、2011年にはゲレーロでも同様の釈放を確保した。 [137]2014年11月、SCJNはベラクルス州の裁判の審理を開始した。これは、女性が中絶する憲法上の権利を有するかどうか、また全国的に犯罪化 を撤廃すべきかどうかを検討するよう裁判所に求めるメキシコ初の裁判である[138]。 2019年、国内でフェミニストによる抗議が急増している最中、メキシコのさまざまなフェミニスト・グループによって「緑の潮流」(リプロダクティブ・ラ イツを求めるアルゼンチン発祥の運動)が広まった。この運動は、ラテンアメリカの女性の身体の自律と保護を要求するために動員(キャンペーンや抗議など) を用いており、2020年代前半にメキシコで人気が高まり続けている。[139][140] 2021年9月7日、司法省はメキシコにおける中絶の連邦非犯罪化を宣言した。それ以前は、28の州で、一定の基準(レイプ、胎児の奇形、妊娠者の健康リ スクなど)を満たした場合のみ妊娠中絶を認め、それ以外は罰するという制限的な中絶法があった。現在、SCJNの決定を踏まえると、これらの州が中絶に対 する罰則を法律に定めていたとしても、それを法的に執行することはできない[141][142]。 先住民女性の権利  EZLNコマンダンタ・ラモーナを記念するポスター 1987年、Comaletzin A.C.という組織のフェミニストたちが、初めてチアパス、モレロス、プエブラ、ソノラで先住民女性と活動を始めた。1989年、女性研究行動センターと サン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサス女性グループは、チアパスの先住民女性とグアテマラ難民コミュニティのために、性的暴力や家庭内暴力に対するプログ ラムを開始した。オアハカとベラクルスでは、「対話のための女性たち」(Women for Dialogue)が、ミチョアカンでは、プレペチャの女性たちと活動する「連帯行動の女性たち」(Women in Solidarity Action:EMAS)が、先住民女性の権利闘争を支援し始めた[143]。 先住民女性は1990年から権利を要求し始めた。多くの先住民女性は職場に追いやられたため、彼女たちの懸念は、暴力、政治的代表権の欠如、教育、家族計 画の選択、その他一般的にフェミニストが扱う問題への懸念と同様に、都市労働者と類似していた。しかし、先住民の女性たちは、フェミニスト、 特に都市部の女性たちとは異なる民族的差別や文 化的志向にも直面していた。先住民の文化のなかには、13歳や14歳という若さでの早期結婚が主流であるものもあり[143]、また他の文化では、初夜権 (derecho de pernada)によって、女性をレイプしたり虐待したりすることが許されており、その加害者は無罰であった[144]。 [143]他のフェミニズム運動における有色人種の女性やマイノリティと同様に[145][146]、メキシコの先住民女性も主流のフェミニスト・グルー プからのエスノセントリズムと闘ってきた[143]。 1994年のサパティスタ民族解放軍(Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional: EZLN)の結成により、チアパスの先住民女性は蜂起の指導者たちとともに男女平等を提唱した。1994年1月1日、サパティスタはLey Revolucionaria de Mujeres(女性革命法)を発表し、一連の10の条項で、子ども、教育、健康、結婚、軍事参加、政治参加、暴力からの保護、労働と賃金に関する女性の 権利を認めた[9][143]。正式な州政府や連邦政府には認められていなかったが[147]、この法律は先住民の女性たちにとって、固有の文化の中で重 要な利益を得た。1997年、「私たちの歴史を構築する」と題された先住民女性の全国会議の結果、チアパス、ゲレーロ、イダルゴ、ハリスコ、メキシコシ ティ、ミチョアカン、モレロス、オアハカ、プエブラ、ケレタロ、サンルイスポトシ、ソノラ、ベラクルスのコミュニティの間で、先住民女性の全国調整委員会 (CNMI)が結成された。この組織の目的は、先住民女性のリーダーシップの機会、ネットワーク形成の可能性、スキルをジェンダーの観点から強化し、コ ミュニティ内および全国的に、先住民女性の人権について先住民を啓発することである[143]。 |

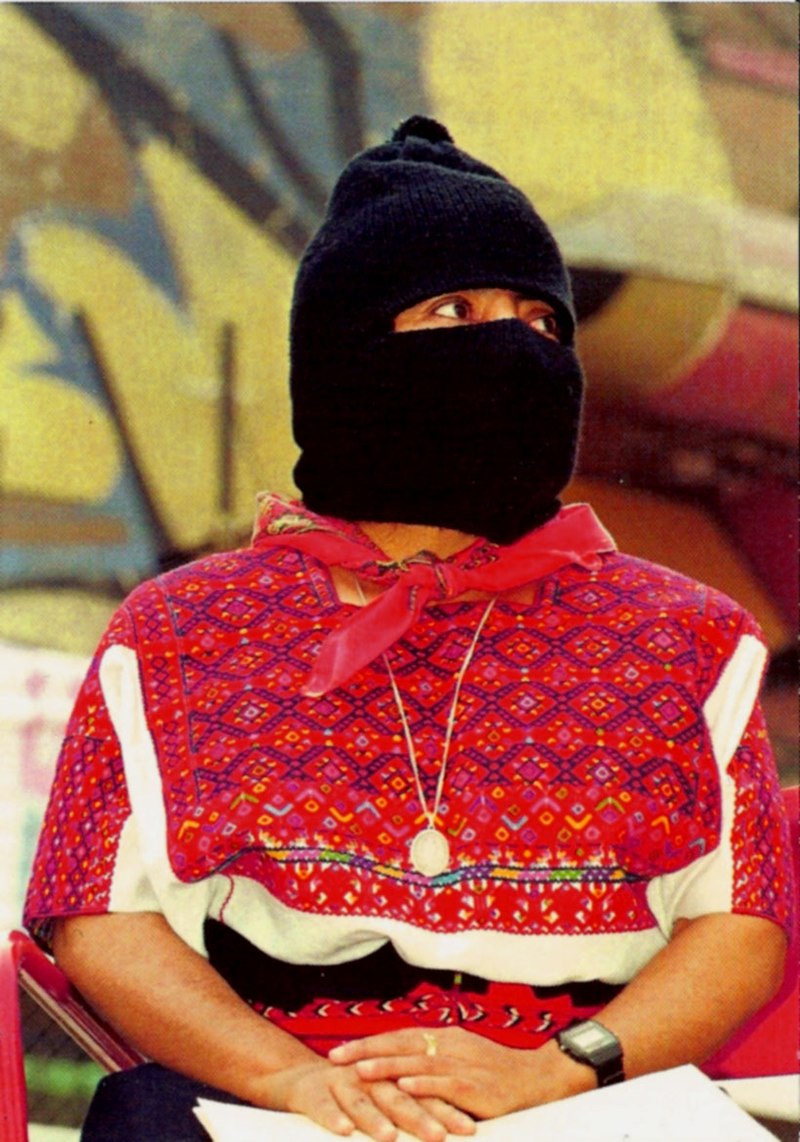

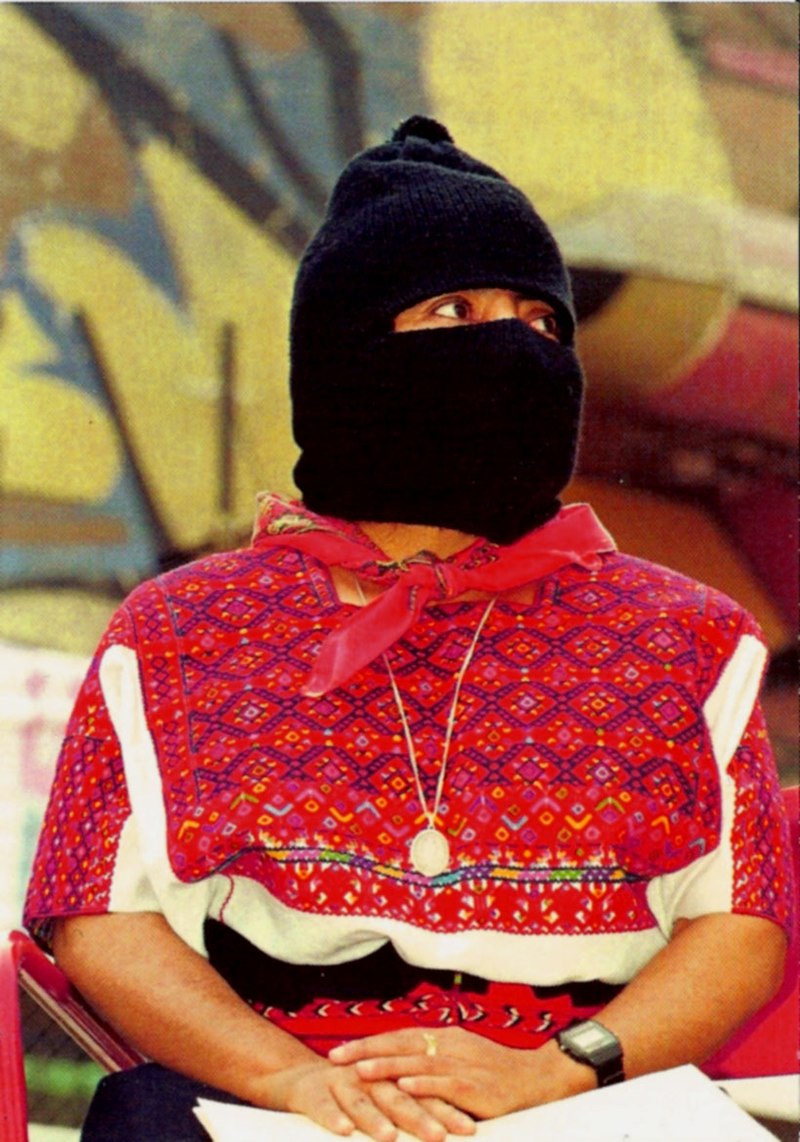

Comandanta

Ramona (1959 – 6 January 2006) was an officer of the Zapatista Army of

National Liberation (EZLN), a revolutionary indigenous autonomist

organization based in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. She led

the Zapatista Army into San Cristóbal de las Casas during the Zapatista

uprising of 1994, and was the first Zapatista to appear publicly in

Mexico City.[1][2][3] Comandanta

Ramona (1959 – 6 January 2006) was an officer of the Zapatista Army of

National Liberation (EZLN), a revolutionary indigenous autonomist

organization based in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. She led

the Zapatista Army into San Cristóbal de las Casas during the Zapatista

uprising of 1994, and was the first Zapatista to appear publicly in

Mexico City.[1][2][3]Biography Ramona was born in 1959 in a Tzotzil Maya community in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico.[4][5] Ramona used to sell handmade goods to make a poor living before she joined the EZLN.[6] By the 1990s, Ramona was a women's rights activist, and helped to draw up a 'Revolutionary Law on Women' through consulting with women in indigenous communities. This called for access to power in decision making, free choice of a spouse, an end to domestic abuse and access to health care.[1][2] Ramona took control of the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas, the former capital of Chiapas, on 1 January 1994 during the Zapatista uprising. She was one of the seven women comandantas of the Zapatistas, and around one-third of the Zapatista army were women.[6] After the rebellion ended, she remained in the Lacandon Jungle with Subcomandante Marcos to apply political pressure on the Mexican government.[2] In February 1994, Ramona was sent to the peace talks with the government in San Cristóbal's cathedral.[2] In 1996, she traveled to Mexico City to help found the National Indigenous Congress, despite a government ban. Zapatista sympathisers surrounded her to prevent her arrest. She also addressed a crowd of 100,000 in the central plaza, highlighting the lack of a hospital in San Andrés de Larrainzer and that this meant indigenous people had to travel for 12 hours to get treatment.[7][2][6] Health and death By 1996, Ramona was seriously ill with kidney failure, and was granted immunity to travel to receive a kidney transplant from her brother.[1][6] She died on 6 January 2006 of kidney failure.[2] Legacy Ramona was famous for being masked and wearing traditional Indigenous clothing. Vendors in her hometown created doll replicas of Ramona in her honor, wearing traditional costume, a mask and carrying a gun.[6][1] Ramona appeared in the 1996 film The Sixth Sun: Mayan Uprising in Chiapas.[8] Ramona had campaigned for access to medical treatment: a Zapatista health clinic in La Garrucha is now named the Comandanta Ramona after her.[9] See also Subcomandante Elisa https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comandanta_Ramona |

コ

マンダンタ・ラモーナ(Comandanta Ramona、1959年 -

2006年1月6日)は、メキシコ南部チアパス州を拠点とする革命的先住民自治組織サパティスタ民族解放軍(EZLN)の将校であった。1994年のサパ

ティスタ蜂起の際、サパティスタ軍を率いてサン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサスに入り、メキシコ・シティで公の場に姿を現した最初のサパティスタとなっ

た[1][2][3]。 コ

マンダンタ・ラモーナ(Comandanta Ramona、1959年 -

2006年1月6日)は、メキシコ南部チアパス州を拠点とする革命的先住民自治組織サパティスタ民族解放軍(EZLN)の将校であった。1994年のサパ

ティスタ蜂起の際、サパティスタ軍を率いてサン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサスに入り、メキシコ・シティで公の場に姿を現した最初のサパティスタとなっ

た[1][2][3]。経歴 ラモーナは1959年、メキシコ、チアパス州の高地にあるツォツィル・マヤのコミュニティで生まれた[4][5]。ラモーナはEZLNに参加する前は、貧 しい生活のために手作り品を売っていた。 1990年代までに、ラモーナは女性の権利活動家であり、先住民コミュニティの女性たちとの協議を通じて「女性に関する革命法」の作成に貢献した。これ は、意思決定における権力へのアクセス、配偶者の自由な選択、家庭内虐待の廃止、医療へのアクセスを求めたものであった[1][2]。 ラモーナは、サパティスタ蜂起中の1994年1月1日、チアパス州の旧首都サン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサス市を掌握した。彼女はサパティスタの7人 の女性コマンダンタの一人であり、サパティスタ軍の約3分の1は女性であった[6]。反乱終結後、彼女はメキシコ政府に政治的圧力をかけるため、サブコマ ンダンテ・マルコスとともにラカンドン密林に残った[2]。 1994年2月、ラモーナはサン・クリストバルの大聖堂で行われた政府との和平交渉に派遣された[2]。 1996年、彼女はメキシコシティに行き、政府の禁止にもかかわらず、全国先住民会議の設立を手伝った。サパティスタのシンパは彼女の逮捕を阻止するため に彼女を取り囲んだ。彼女はまた、中央広場で10万人の群衆を前に演説し、サン・アンドレス・デ・ラリンザーに病院がないこと、そのために先住民が治療を 受けるために12時間かけて移動しなければならないことを強調した[7][2][6]。 健康と死 1996年までにラモーナは腎不全を患い、兄から腎臓移植を受けるための渡航を免除された[1][6]。 2006年1月6日、腎不全のため死去した[2]。 遺産 ラモーナは仮面をかぶり、先住民の伝統的な服を着ていたことで有名だった。彼女の故郷の業者は、彼女に敬意を表して、伝統的な衣装を身に着け、マスクをつ け、銃を持っているラモーナの人形のレプリカを作った[6][1]。 ラモーナは1996年の映画『The Sixth Sun』に登場した: チアパスにおけるマヤの蜂起』[8]に出演した。 ラモーナは医療を受けられるように運動していた。ラ・ガルチャにあるサパティスタの診療所は現在、彼女にちなんでコマンダンタ・ラモーナと名付けられてい る[9]。 参照 サブコマンダンテ・エリサ |

| Gender rebels Mexico has a long history of "gender rebels" [148] which according to archaeological, ethno-linguistic and historical studies of pre-contact include tribes of Albardaos, Aztec, Cipacingo, Itzá, Jaguaces, Maya, Pánuco,[149] Sinaloa,[150] Sonora, Tabasco, Tahus, Tlasca, and Yucatec peoples.[149] During the colonial period, Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz wrote against patriarchy, the church's policy of denying education to women, and women's intellectual equality to men. She has been called one of Mexico's first feminists.[151][152] Several women came out of the Mexican Revolution and refused to return to gender "normalty".[61][153] These are typically isolated cases, and not indicative of a social or political movement. Artists and writers  Frida photographed in 1932 by her father, Guillermo The countercultural artists movement of the post-Revolutionary period, beginning in the 1920s, was clearly political and aimed at allowing other voices in the development of a modern Mexico.[154] In Guadalupe Marín's novel La Única (The Unique Woman) she speaks of violence against women, misogyny and lack of citizenship for women, but also feminine and homosexual desires. She presented publicly the understanding that sexuality has a political component.[34] Frida Kahlo's work, blending both masculine and feminine gender perceptions, challenged false perceptions,[31][155] as did Maria Izquierdo's insistence on her right to be independent of any state or cultural attempts to define her art.[33] Tina Modotti's move away from portraiture and toward images of social change through the lens of realism and revolutionary action[32] and Concha Michel's dedication to the rights and status of Mexican women, without challenging sexual inequality, represented a more humanist rather than feminist approach to their art.[35] Whereas Michel explored feminism and politics with Anita Brenner, Modotti did not. The women were bound by their questioning of women's place in Mexico and society with their art, but they did not formally join with the suffragettes or in feminist organizations.[156] In retrospect these artists have become feminist icons because their actions and work questioned gender restrictions, but in their time, they may not have seen themselves in that way.[35] Beginning in the 1970s, when Nancy Cárdenas declared her lesbianism on national television, activism increased, but mostly in small private gatherings.[157] She founded the first gay organization in Mexico, organized the first Pride Parade, and both lectured and participated in media events, seminars, and congresses on feminism and sexuality.[158] As early as 1975, at a seminar organized by Carla Stellweg to address feminist expression in Mexican art, psychologist and art historian Teresa del Conde was making arguments that biology did not dictate gender roles.[159] By the mid-90s, almost half of the membership in feminist organizations was lesbian.[29] Muxe  Lukas Avendano, a Zapotec muxe performance artist. The Zapotec cultures of the Isthmus of Oaxaca in Juchitán de Zaragoza and Teotitlán del Valle are home to a non-binary gender sometimes called a third gender, which has been accepted in their society since pre-conquest. The Muxe of Juchitán and biza'ah of Teotitlán del Valle are not considered homosexual but instead a separate category, with male physiology and, typically, the skills and aesthetics of women. According to Lynn Stephen in her study of Zapotec societies, muxe and biza'ah are sometimes disparaged by other men, but generally accepted by women in society.[160] The AIDs pandemic caused the coming together of the Muxe and feminist groups. Gunaxhi Guendanabani (Loves Life, in the Zapotec languages) was a small women's NGO operating in the area for 2-years when the muxe approached them and joined in the effort to promote safe sex and protect their community.[161] On November 4, 2014, Gunaxhi Guendanabani celebrated its 20-year anniversary and their efforts in decreasing HIV/AIDs and gender-based violence, as well as its campaigns against discrimination for people living with HIV and against homophobia.[162] Nuns In Mexico, where 6.34% of the female population has a child between the age of 15 and 19,[163] there are some who make a conscious choice against motherhood. For some, becoming a nun offers a way out domesticity, machismo, and a lack of educational opportunity toward a more socially responsible path.[164] Those in orders who see their work as allies of the poor and imbued with a mission for social justice[165] have increasingly been characterized as feminists, even from a secular perspective.[166] Mexico's nuns who work along the US/Mexico border with migrants experience difficulties trying to balance strict Catholic doctrine against suffering that they see and some believe the church needs to take a more humanitarian approach.[164] Those religious who work to bring visibility to femicide and halt violence against women see beyond religious beliefs and call attention to the human dignity of victims.[167] An organization called the Rede Latinoamericana de Católicas (Latin American Catholic Network) has gone so far as to send a letter to Pope Francis supporting feminism, women's rights to life and health, their quest for social justice and their rights to make their own choices regarding sexuality, reproduction and abortion.[168] |

ジェンダーの反逆者たち メキシコには「ジェンダーの反逆者」[148]の長い歴史があり、接触以前の考古学的、民族言語学的、歴史学的研究によれば、アルバルダオ族、アステカ 族、シパシンゴ族、イツァ族、ジャグアセス族、マヤ族、パヌコ族、[149]シナロア族、[150]ソノラ族、タバスコ族、タフス族、トラスカ族、ユカテ ク族が含まれる。 [149] 植民地時代、シスター、フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスは、家父長制、女性への教育を否定する教会の方針、女性の男性に対する知的平等に反対する著作を残 した。彼女はメキシコ最初のフェミニストの一人と呼ばれている[151][152]。メキシコ革命から何人かの女性が現れ、ジェンダーの「普通」に戻るこ とを拒否した[61][153]。 芸術家と作家  1932年、父ギジェルモによって撮影されたフリーダ 1920年代に始まった革命後のカウンターカルチャー芸術家たちの運動は、明らかに政治的であり、近代メキシコの発展において他の声を認めることを目的と していた[154]。グアダルーペ・マリーンの小説『La Única(唯一無二の女)』において、彼女は女性に対する暴力、女性嫌悪、女性に対する市民権の欠如だけでなく、女性的で同性愛的な欲望についても語っ ている。彼女はセクシュアリティが政治的な要素を持っているという理解を公に提示した[34]。フリーダ・カーロの作品は、男性性と女性性の両方のジェン ダー認識を融合させ、誤った認識に挑戦した[31][155]。マリア・イスキエルドは、彼女の芸術を定義しようとする国家や文化の試みから独立する権利 を主張した。 [33]ティナ・モドッティは肖像画から離れ、リアリズムと革命的行動というレンズを通して社会変革のイメージへと向かっていき[32]、コンチャ・ミッ シェルは性的不平等に挑戦することなくメキシコ女性の権利と地位に献身していたが、これは彼女たちの芸術に対するフェミニズムというよりもむしろヒューマ ニズム的なアプローチを表していた[35]。彼女たちは、メキシコと社会における女性の居場所に対する疑問によって芸術と結びついていたが、正式に参政権 運動やフェミニスト団体に参加することはなかった[156]。振り返ってみると、彼女たちの行動や作品がジェンダーの制約に疑問を投げかけるものであった ため、これらの芸術家たちはフェミニストのアイコンとなったが、当時、彼女たちは自分たちをそのようには見ていなかったかもしれない[35]。 ナンシー・カルデナスが国営テレビでレズビアンであることを宣言した1970年代から、活動は活発化したが、そのほとんどは小さな個人的な集まりの中で あった[157]。彼女はメキシコで最初のゲイ団体を設立し、最初のプライド・パレードを組織し、フェミニズムとセクシュアリティに関するメディアイベン ト、セミナー、会議において講演を行い、参加した。 [1975年には、メキシコ美術におけるフェミニズムの表現に取り組むためにカーラ・ステルウェグが主催したセミナーで、心理学者で美術史家のテレサ・デ ル・コンデが、生物学は性別の役割を規定するものではないと主張していた[159]。 90年代半ばまでには、フェミニスト団体のメンバーのほぼ半数がレズビアンであった[29]。 ムクセ  ルーカス・アベンダーノ、サポテカ族のムクセ・パフォーマンス・アーティスト。 オアハカ地峡のフチタン・デ・サラゴサとテオティトラン・デル・バジェのサポテカ文化圏には、征服以前から彼らの社会で受け入れられてきた、時に第3の性 と呼ばれる二元的でないジェンダーが存在する。フチタンのムクセとテオティトラン・デル・バジェのビサアは、同性愛者ではなく、男性の生理機能を持ち、一 般的には女性の技術と美的感覚を持つ、別のカテゴリーと考えられている。サポテカ社会の研究においてリン・スティーブンによれば、ムクセとビサアは他の男 性からは蔑視されることもあるが、社会では一般的に女性から受け入れられている[160]。 AIDsの流行は、ムクセとフェミニスト集団の結集を引き起こした。Gunaxhi Guendanabani(サポテカ語でLoves Life)は、2年間この地域で活動していた小さな女性NGOであったが、ムクセが彼らに接触し、安全なセックスを促進し、コミュニティを保護するための 取り組みに参加した[161]。 2014年11月4日、Gunaxhi Guendanabaniは20周年を迎え、HIV/AIDsとジェンダーに基づく暴力を減少させるための彼らの努力と、HIVとともに生きる人々の差別 に反対し、同性愛嫌悪に反対するキャンペーンを祝った[162]。 修道女 メキシコでは、女性人口の6.34%が15歳から19歳の間に子供をもうけている[163]。貧しい人々の味方であり、社会正義の使命を帯びていると考え る修道会の人々[165]は、世俗的な観点からでさえも、フェミニストとして特徴づけられることが多くなっている[166]。アメリカとメキシコの国境沿 いで移民とともに働くメキシコの修道女たちは、彼らが目にする苦しみに対して厳格なカトリックの教義を両立させようとする難しさを経験しており、教会がよ り人道的なアプローチをとる必要があると考える人々もいる。 [164] フェミサイドを可視化し、女性に対する暴力を止めるために活動している宗教者たちは、宗教的信条を越えて、犠牲者の人間的尊厳に注意を喚起している。 167] Rede Latinoamericana de Católicas(ラテンアメリカ・カトリック・ネットワーク)と呼ばれる組織は、フェミニズム、生命と健康に対する女性の権利、社会正義の探求、セク シュアリティ、生殖、中絶に関して自ら選択する権利を支持する書簡をフランシスコ法王に送るまでに至っている[168]。 |