フレッド・ウィルソン

Fred Wilson (artist),

b.1954

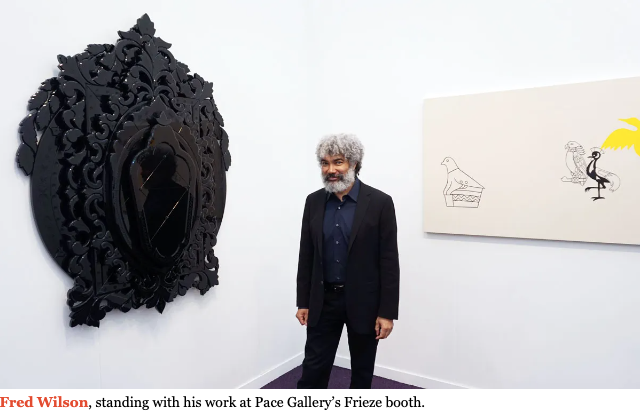

‘Being Here Is an Unusual Experience’: Finding Some Quiet Time With Fred Wilson at Frieze New York

☆フ

レッド・ウィルソン(1954年生まれ)は、アフリカ系アメリカ人とカリブ系の血を引くアメリカ人アーティスト。ニューヨーク州立大学パーチェス校で美術

学士号を取得。[1]

ウィルソンは、歴史、文化、人種に関する植民地時代の固定観念に疑問を投げかけ、西洋の規範を表す社会的、歴史的物語について観客に考えさせる。[2]

ウィルソンは、1999年にマッカーサー財団の「天才助成金」を、2003年にラリー・アルドリッチ財団賞を受賞した。ウィルソンは、1992年のカイ

ロ・ビエンナーレ、2003年のヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレで米国代表を務めた。[3]

2008年5月、ウィルソンがチャック・クローズの後任としてホイットニー美術館の理事に就任することが発表された。[4]

| Fred Wilson

(born 1954) is an American artist of African-American and Caribbean

heritage. He received a BFA from Purchase College, State University of

New York.[1] Wilson challenges colonial assumptions on history,

culture, and race – encouraging viewers to consider the social and

historical narratives that represent the western canon.[2] Wilson

received a MacArthur Foundation "genius grant" in 1999 and the Larry

Aldrich Foundation Award in 2003. Wilson represented the United States

at the Biennial Cairo in 1992 and the Venice Biennale in 2003.[3] In

May 2008, it was announced that Wilson would become a Whitney Museum

trustee replacing Chuck Close.[4] |

フ

レッド・ウィルソン(1954年生まれ)は、アフリカ系アメリカ人とカリブ系の血を引くアメリカ人アーティスト。ニューヨーク州立大学パーチェス校で美術

学士号を取得。[1]

ウィルソンは、歴史、文化、人種に関する植民地時代の固定観念に疑問を投げかけ、西洋の規範を表す社会的、歴史的物語について観客に考えさせる。[2]

ウィルソンは、1999年にマッカーサー財団の「天才助成金」を、2003年にラリー・アルドリッチ財団賞を受賞した。ウィルソンは、1992年のカイ

ロ・ビエンナーレ、2003年のヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレで米国代表を務めた。[3]

2008年5月、ウィルソンがチャック・クローズの後任としてホイットニー美術館の理事に就任することが発表された。[4] |

| Career An alumnus of Music & Art High School in New York, Wilson received a BFA from SUNY Purchase in 1976, where he was the only black student in his program.[5] While studying Wilson worked as a guard at the Neuberger Museum.[6] Between 1978 and 1980, he worked as an artist in East Harlem as part of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act's (CETA) employment of artists.[7] He says that he no longer has a strong desire to make things with his hands. "I get everything that satisfies my soul," he says, "from bringing together objects that are in the world, manipulating them, working with spatial arrangements, and having things presented in the way I want to see them."[8] An installation artist and political activist, Wilson's subject is social justice and his medium is museology. In the 1970s, he worked as a free-lance museum educator for the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Craft Museum. Beginning in the late 1980s, Wilson used his insider skills to create "Rooms with a View", a series of "mock museums" that address how museums consciously or unwittingly reinforce racist beliefs and behaviors.[9] This strategy, which Wilson refers to as "a trompe l'oeil of museum space,"[10] has increasingly become the focus of his life's work.[11] In 1987, as part of his outdoor "Platform" series, Wilson created No Noa Noa, Portrait of a History of Tahiti, designed to illustrate "how Western societies turn Third World peoples into exotic sideshow creatures to entertain and titillate but who are not to be taken seriously."[12] In his 1992 seminal work co-organized with the Contemporary Museum Baltimore, Mining the Museum, Wilson reshuffled the Maryland Historical Society's collection to highlight the history of Native and African Americans in Maryland. In 1994, Wilson continued in this vein with Insight: In Site: In Sight: Incite in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where, according to art historian Richard J. Powell, his "re-positioning of historical objects and manipulation of exhibition labels, lighting, and other display techniques helped reveal aspects of the site's tragic African-American past that (because of the conspiratorial forces of time, ignorance, and racism) had largely become invisible."[13] In 2001, Wilson was the subject of a retrospective, Fred Wilson: Objects and Installations, 1979–2000, organized by Maurice Berger for the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The show traveled to numerous venues, including the Santa Monica Museum of Art, Berkeley Museum of Art, Blaffer Gallery (University of Houston), Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery (Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY), The Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, Chicago Cultural Center, Studio Museum in Harlem. For the 2003 Venice Biennale, Wilson created a multi-media installation that borrowed its title from a line in Othello. His elaborate Venice work "Speak of Me as I Am" focused on representations of Africans in Venetian culture.[5] In 2007 Fred Wilson was invited to be a part of the Indianapolis, Indiana, Cultural trail. Wilson proposed to redo the sole African American depicted in the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in downtown Indianapolis. The African American represents a recently freed slave reaching up to lady liberty. Wilson planned on using a scan of the African American to make an entirely new work, which would give the African American a more proud and strong posture, holding a flag composed of all of the African countries' flags.[14] The proposed work was entitled, E Pluribus Unum, and was met with much controversy, eventually leading to the project's rejection. In 2009, Wilson was awarded the Cheek Medal[15] by William & Mary's Muscarelle Museum of Art. The Cheek Medal is a national arts award given by The College of William & Mary to those who have contributed significantly to the field of museum, performing or visual arts. 2011 saw the publication of Fred Wilson: A Critical Reader by Ridinghouse, edited by Doro Globus. An anthology of critical texts about and interviews with the artist, this publication focuses on the artist's pivotal exhibitions and projects, and includes a wide range of significant texts that mark the critical reception of Wilson's work over the last two decades.[16] |

経歴 ニューヨークのミュージック&アート高校を卒業後、1976年にニューヨーク州立大学パーチェス校で美術学士号を取得。同校では、同プログラムで唯一の黒 人学生だった。[5] 学生時代、ウィルソンはノイバーガー美術館で警備員として働いていた。[6] 1978年から1980年まで、包括的雇用訓練法(CETA)の芸術家雇用プログラムの一環として、イーストハーレムで芸術家として働いた。[7] 彼は、もはや自分の手で物を作りたいという強い願望は持っていないと語っている。「私の魂を満足させるものはすべて、この世界にある物体を組み合わせ、それを操作し、空間的な配置を考え、自分の見たいように表現することで得られる」と彼は言う。[8] インスタレーションアーティストであり、政治活動家でもあるウィルソンの主題は社会正義であり、その表現手段は博物館学だ。1970年代、彼はアメリカ自 然史博物館、メトロポリタン美術館、アメリカ工芸博物館でフリーランスの博物館教育者として働いた。1980年代後半から、ウィルソンは、そのインサイ ダーとしてのスキルを生かして、美術館が意識的または無意識的に人種差別的な信念や行動を強化している実態を批判する「Rooms with a View」という一連の「偽の美術館」を制作した[9]。ウィルソンが「美術館空間のトロンプ・ルイユ」と呼ぶこの手法は、彼の作品活動の焦点としてます ます重要になってきている。[11] 1987年、ウィルソンは、屋外シリーズ「Platform」の一環として、「西洋社会が、第三世界の人民を、楽しませ、刺激を与えるためのエキゾチック な見世物の生き物として、真剣に受け止めない存在に変えてしまう様子」を表現するために、「No Noa Noa, Portrait of a History of Tahiti」を制作した。 1992 年、ボルチモア現代美術館と共同で開催した画期的な展覧会「Mining the Museum」では、メリーランド歴史協会のコレクションを再構成し、メリーランド州におけるネイティブアメリカンとアフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史を強調し た。1994 年、ウィルソンは、この流れを継承した「Insight: ノースカロライナ州ウィンストン・セーラムで開催された「Site: In Sight: Incite」では、美術史家のリチャード・J・パウエルによると、「歴史的遺物の位置換え、展示ラベル、照明、その他の展示手法の操作により、この場所 の悲劇的なアフリカ系アメリカ人の過去(時間、無知、人種主義という陰謀的な力によって)が、ほとんど見えなくなっていた側面を明らかにした」[13]。 2001年、ウィルソンは、メリーランド大学ボルチモア郡の芸術・デザイン・視覚文化センターのためにモーリス・バーガーが企画した回顧展「フレッド・ ウィルソン:オブジェクトとインスタレーション、1979-2000」で取り上げられた。この展覧会は、サンタモニカ美術館、バークレー美術館、ブラッ ファー・ギャラリー(ヒューストン大学)、タン・ティーチング・ミュージアム・アンド・アート・ギャラリー(スキッドモア大学、ニューヨーク州サラトガス プリングス)、マサチューセッツ州アンドーバーのアディソン・ギャラリー・オブ・アメリカン・アート、シカゴ・カルチャー・センター、ハーレム・スタジ オ・ミュージアムなど、数多くの会場で開催された。2003年のヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレでは、オセロの台詞からタイトルを借りたマルチメディア・イン スタレーション作品を制作。ヴェネツィアの文化におけるアフリカ人の表現に焦点を当てた、精巧な作品「Speak of Me as I Am」を発表した。 2007年、フレッド・ウィルソンはインディアナ州インディアナポリスのカルチュラル・トレイルへの参加を招待された。ウィルソンは、インディアナポリス のダウンタウンにある「兵士と船員記念碑」に描かれている唯一のアフリカ系アメリカ人を再制作することを提案した。このアフリカ系アメリカ人は、自由の女 神に手を伸ばす、最近解放された奴隷を表している。ウィルソンは、このアフリカ系アメリカ人のスキャン画像を使用して、アフリカ諸国の国旗で構成された旗 を掲げた、より誇り高く力強い姿勢のアフリカ系アメリカ人を表現した、まったく新しい作品を作ることを計画した[14]。この作品のタイトルは「E Pluribus Unum」で、多くの論争を巻き起こし、結局、プロジェクトは却下された。 2009年、ウィルソンはウィリアム&メアリー・マスカレル美術館からチーク・メダル[15]を受賞した。チーク・メダルは、美術館、舞台芸術、視覚芸術の分野において顕著な功績を残した人物に、ウィリアム&メアリー大学が授与する全国的な芸術賞だ。 2011年には、ドロ・グローバスが編集した『Fred Wilson: A Critical Reader』がウィリアム&メアリー大学から出版された。この本は、アーティストに関する批評文やインタビューを収録したアンソロジーで、アーティスト の重要な展覧会やプロジェクトに焦点を当て、過去 20 年間のウィルソンの作品に対する批評的な評価を示す、幅広い重要な文章が掲載されている。[16] |

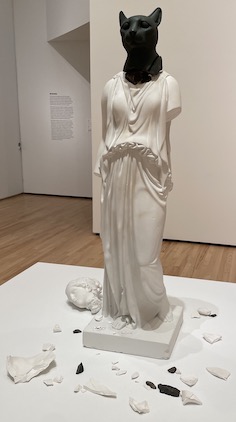

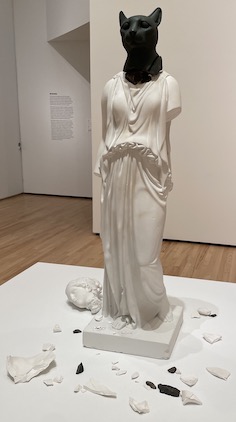

Major themes Artemis / Bast (1992) at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2022 Wilson's unique artist approach is to examine, question, and deconstruct the traditional display of art and artifacts in museums. With the use of new wall labels, sounds, lighting, and non-traditional pairings of objects, he leads viewers to recognize that changes in context create changes in meaning. Wilson's juxtaposition of evocative objects forces the viewer to question the biases and limitations of cultural institutions and how they have shaped the interpretation of historical truth, artistic value, and the language of display.[8] According to Wilson, "Museums ignore and often deny the other meanings [of objects]. In my experience it is because if an alternate meaning is not the subject of the exhibition or the focus of the museum, it is considered unimportant by the museum."[17] Wilson uses these objects to analyze the representation of race in museums and to examine the power and privileges of cultural institutions.[18] For example, for his installation at the 2003 Venice Biennale he employed a tourist to pretend to be an African street vendor selling fake designer bags — in fact his own designs. He also incorporated "blackamoors", sculptures of black people in the role of servants, into the show.[19] Such figures were often used as stands for lights. Wilson placed his wooden blackamoors carrying acetylene torches and fire extinguishers. He noted that such figures are so common in Venice that few people notice them, stating, "they are in hotels everywhere in Venice...which is great, because all of a sudden you see them everywhere. I wanted it to be visible, this whole world which sort of just blew up for me."[19] |

主なテーマ 2022年にボルチモア美術館で展示された「アルテミス/バスト」(1992年 ウィルソンのユニークな芸術的アプローチは、美術館における芸術作品や工芸品の伝統的な展示方法を検証、疑問視、そして分解することです。新しい壁面の説 明文、音、照明、そして従来とは異なる作品の組み合わせを用いて、彼は、文脈の変化が意味の変化をもたらすことを観客に認識させます。ウィルソンが刺激的 なオブジェクトを並置することで、観客は文化機関が持つ偏見や限界、そしてそれらが歴史的真実、芸術的価値、展示の言語の解釈にどのように影響してきたか を疑問視せざるを得なくなるのです。ウィルソンは、「美術館は(オブジェクトの)他の意味を無視し、しばしば否定する」と述べています。私の経験では、そ れは、別の意味が展覧会の主題や美術館の焦点ではない場合、美術館はそれを重要ではないとみなすからだ」[17] と述べている。ウィルソンは、これらのオブジェクトを用いて、美術館における人種の表現を分析し、文化機関の権力と特権を検証している[18]。 例えば、2003 年のヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレでのインスタレーションでは、観光客に、偽のデザイナーバッグ(実際には彼自身のデザイン)を売るアフリカの露天商のふり をさせた。また、使用人としての黒人を表現した彫刻「ブラックアモール」も展示に組み込んだ[19]。このような彫刻は、多くの場合、照明のスタンドとし て使われていた。ウィルソンは、アセチレンランプと消火器を持った木製のブラックアモールを配置した。彼は、このような人物像はヴェネツィアではごくあり ふれたもので、ほとんど誰も気にも留めないことを指摘し、「ヴェネツィアの至る所のホテルにある...それは素晴らしいことだ。なぜなら、突然、どこを見 てもそればかりが目に入るからだ。私にとって、この世界全体が突然爆発したかのように、それを目に見える形にしたかったのだ」と述べている[19]。 |

| Mining the Museum exhibition Mining the Museum was an exhibition created by Fred Wilson held from April 4, 1992, to February 28, 1993, at the Maryland Historical Society. Background The title of the exhibition refers to how Wilson extracted and unearthed objects from the Maryland Historical Society collections to create this exhibition.The purpose of the exhibition was to address the biases museums have, often omitting or under-representing oppressed peoples and focusing on "prominent white men".[20] Wilson took the existing museum's collection and reshuffled them to highlight the history of African-American and Native American Marylanders. This reassembly created a new viewpoint of colonization, slavery and abolition through the use of satire and irony. Artifacts Wilson juxtaposed historically important artifacts with each other to address the injustices in history and the injustices of not being properly exhibited. The entrance of the exhibition displayed three busts of important individuals: Napoleon, Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay displayed on pedestals. To the left of these busts were empty black pedestals with the names of three important, overlooked African American Marylanders: Frederick Douglass, Benjamin Banneker, and Harriet Tubman. Arranged in the center of these pedestals is a silver-plated copper globe with the word "Truth" inscribed on it in a case.[21] Wilson extracted paintings from the eighteenth century and nineteenth century featuring African Americans from the MHS collection. Within this collection Wilson renamed the paintings in order to shift the focus towards African Americans in them. One of the oil paintings titled "Country Life" was renamed "Frederick Serving Fruit" in order to emphasize and underline the young African American that was serving "well-dressed whites at a picnic".[21] Other paintings featuring slave children were paired with audiotape recordings that played on a loop in which visitors were able to hear these children in the paintings ask various poignant questions. Wilson used these paintings to force visitors to recognize how the depiction of African Americans and their invisibility in portrayals of American life is "paradoxical".[21] The installation titled "metalwork" arranged ornate silverware with slave shackles to address that the prosperity of one could not have been achieved without the other. Similarly, "Cabinet Making" addresses more subjugation by having antique chairs gathered around and facing an authentic whipping post, incorrectly reported by several publications to have been used on slaves. In fact, the post had been used to punish wife-beaters in the Baltimore City jail.[22] However, these false assumptions helped bolster Wilson's idea that the exhibit was "charged by what you bring to it."[22] Pieces such as "Cabinet Making" encouraged visitors to interpret the works however they saw it, to think critically and acquire a new perspective. Other works included cigar-store Indians turned away from visitors, a KKK mask in a baby carriage, a hunting rifle with runaway slave posters and a black chandelier hung in the museum's neoclassical pavilion made for the exhibition. Impact The exhibition was successful in that it made visitors more historically conscious of the racism that is an integral part of American history. ""Mining the Museum" worked because it was suggestive rather than didactic, provocative rather than moralizing" [20] More than 55,000 people viewed Wilson's exhibit and helped him create other similar exhibitions around the United States. Critics would coin this new type of work as "museumist art".[23] |

Mining the Museum 展 Mining the Museum は、1992年4月4日から1993年2月28日までメリーランド歴史協会で開催された、フレッド・ウィルソンによる展覧会。 背景 展覧会のタイトルは、ウィルソンがメリーランド歴史協会のコレクションから作品を抜き出し、発掘してこの展覧会を企画したことを表している。この展覧会の 目的は、抑圧された人々を省略したり、過小評価したり、「著名な白人男性」に焦点を当てたりする、博物館の偏見に対処することだった[20]。ウィルソン は、既存の博物館のコレクションを取り出し、それらを再構成して、アフリカ系アメリカ人やネイティブアメリカンであるメリーランド州民の歴史を強調した。 この再構成により、風刺や皮肉を用いて、植民地化、奴隷制度、奴隷制度廃止に関する新しい視点が生まれた。 展示品 ウィルソンは、歴史的に重要な展示品を並べて、歴史上の不正や、適切に展示されていないという不正を指摘した。展示室の入り口には、ナポレオン、アンド ルー・ジャクソン、ヘンリー・クレイの 3 人の重要人物の胸像が台座に置かれていた。これらの胸像の左側には、見過ごされてきた 3 人の重要なアフリカ系アメリカ人メリーランド州民、フレデリック・ダグラス、ベンジャミン・バンカー、ハリエット・タブマンの名前が刻まれた空の黒い台座 があった。これらの台座の中央には、「真実」という言葉が刻まれた銀メッキの銅製の地球儀がケースに入れて置かれていた。[21] ウィルソンは、MHS のコレクションの中から、18 世紀と 19 世紀のアフリカ系アメリカ人を題材にした絵画を厳選した。このコレクションの中で、ウィルソンは、アフリカ系アメリカ人に焦点を当てるために、絵画のタイ トルを変更した。油絵「Country Life(田舎の生活)」は、「Frederick Serving Fruit(果物を提供するフレデリック)」と改題され、「ピクニックで身なりの良い白人たちにサービスをする」アフリカ系アメリカ人の若者を強調、強調 した。[21] 奴隷の子供たちを描いた他の絵画には、その絵画に登場する子供たちがさまざまな切実な質問をする音声が録音されたオーディオテープが流され、訪問者はそれ を繰り返し聞くことができた。ウィルソンは、これらの絵画を用いて、アフリカ系アメリカ人の描写と、アメリカの生活描写における彼らの存在の不可視性が 「逆説的」であることを訪問者に認識させた。[21] 「金属細工」と題されたインスタレーションは、華麗な銀食器と奴隷の足かせを一緒に配置し、一方の繁栄は他方なしには達成できなかったことを表現してい る。同様に、「キャビネット作り」は、いくつかの出版物で奴隷に使用されたと誤って報じられた本物の鞭打ち台を囲んで、アンティークの椅子を配置すること で、より強い服従を表現している。実際、この柱はボルチモア市の刑務所で妻を虐待した者を罰するために使用されていた[22]。しかし、こうした誤った推 測は、この展示は「観客が持ち込むものによって意味が決まる」というウィルソンの考えを補強する結果となった[22]。「キャビネットメイキング」などの 作品は、観客が自分の見たままに作品を解釈し、批判的に考え、新しい視点を得ることを促した。その他の作品としては、訪問者から背を向けた葉巻店のイン ディアン、乳母車に乗せられた KKK のマスク、逃亡奴隷のポスターが貼られた狩猟用ライフル、そしてこの展覧会のために博物館の新古典主義のパビリオンに掛けられた黒いシャンデリアなどが あった。 影響 この展覧会は、アメリカの歴史に欠かせない人種主義について、訪問者の歴史意識を高めるという点で成功を収めた。「Mining the Museum」は、教訓的ではなく示唆的であり、道徳的ではなく挑発的であったため、成功を収めたのです」[20] 55,000 人以上の人々がウィルソンの展覧会を観覧し、彼が全米で同様の展覧会を開催するのを支援しました。批評家たちは、この新しいタイプの作品を「ミュージアム アート」と名付けました[23]。 |

| 50th Venice Biennale Wilson represented the United States at the 50th Venice Biennale, staging the solo exhibition Speak of Me as I Am (2003) in the American pavilion. A series of works was a reworking of Shakespeare's Othello that consisted of various objects such as mirrors and chandeliers that were used to comment on the text. These works have been extended on in the exhibition, Fred Wilson: Sculptures, Paintings, and Installations, 2004–2014. These objects are made of black Murano glass, which indicates how Wilson has transferred the context of Othello into a world where race is not ignored and is instead is a crucial central focus.[24] Afro Kismet, a mixed-media installation also included in the exhibition, focused on issues and representations of race in Venice, specifically the history of black people in Venice. The installation consisted of prints, paintings, and other artifacts from the Pera Museum collections and underlined the "discarded" or "hidden" history of African people in the Ottoman Empire.[25] |

第50回ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレ ウィルソンは、第50回ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレでアメリカ代表として、アメリカ館で個展「Speak of Me as I Am(2003)」を開催した。一連の作品は、シェイクスピアの「オセロ」を改作したもので、テキストを解説するために、鏡やシャンデリアなどのさまざま なオブジェが使用されていた。これらの作品は、2004年から2014年にかけて開催された展覧会「フレッド・ウィルソン:彫刻、絵画、インスタレーショ ン」でさらに発展した。これらのオブジェは、黒いムラーノガラスで制作されており、ウィルソンが「オセロ」の文脈を、人種が無視されるのではなく、むしろ 重要な中心的な焦点となる世界へと移し替えたことを表している。[24] 同展にも出展されたミクストメディアのインスタレーション「アフロ・キスメット」は、ヴェネツィアにおける人種問題と表現、特にヴェネツィアにおける黒人 の歴史に焦点を当てた作品だ。このインスタレーションは、ペラ美術館のコレクションから集められた版画、絵画、その他の工芸品で構成され、オスマン帝国に おけるアフリカ人の「捨てられた」あるいは「隠された」歴史を浮き彫りにしている。 |

| Other activities From 1988 to 1992, Wilson served on the board of directors at Artists Space in TriBeCa, New York.[26] He currently serves on the board of trustees of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Wilson co-chaired (with Naomi Beckwith) the jury that chose the winners of the Rome Prize for the 2023–24 cycle.[27] |

その他の活動 1988年から1992年まで、ウィルソンはニューヨークのトライベッカにあるアーティスト・スペースの理事会メンバーを務めた[26]。現在は、ニューヨークのホイットニー美術館の評議員会メンバーを務めている。 ウィルソンは、2023年から2024年のローマ賞の受賞者を決定する審査委員会を(ナオミ・ベックウィズとともに)共同委員長を務めた[27]。 |

| Exhibitions Wilson has staged a large number of solo shows and exhibitions in the United States and internationally. His notable solo shows include Primitivism: High & Low (1991), Metro Pictures Gallery, New York;[28] Mining the Museum (1992-1993), Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, and Contemporary Museum Baltimore;[29] Fred Wilson: Objects and Installations 1979-2000 (2001-2003), originating at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture, Baltimore;[30] Speak of Me as I Am (2003), American pavilion, 50th Venice Biennale;[31] and Fred Wilson: Works 2004-2011 (2012-2013), Cleveland Museum of Art[32] He has also participated in many group exhibitions, including the Whitney Biennial (1993);[33] Liverpool Biennial (1999);[34] Glasstress (2009, 2011);[35] and the NGV Triennial (2020).[36] |

展覧会 ウィルソンは、米国および海外で数多くの個展や展覧会を開催している。主な個展には、「Primitivism: High & Low」(1991年、メトロ・ピクチャーズ・ギャラリー、ニューヨーク)、「Mining the Museum」(1992年~1993年、メリーランド歴史協会、ボルチモア、およびボルチモア現代美術館)、「[29] 「フレッド・ウィルソン:オブジェとインスタレーション 1979-2000」(2001-2003)、ボルチモアの芸術・デザイン・視覚文化センターで初公開。[30] 「Speak of Me as I Am」(2003年、第50回ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレ、アメリカ館)、[31] 「Fred Wilson: Works 2004-2011」(2012-2013年、クリーブランド美術館)などがある。 また、ホイットニー・ビエンナーレ(1993年)、リバプール・ビエンナーレ(1999年)、グラスストレス(2009年、2011年)、NGVトリエンナーレ(2020年)など、数多くのグループ展にも参加している。 |

| Notable works in public collections Colonial Collection (1990), Nasher Museum of Art, Durham, North Carolina[37] Guarded View (1991), Whitney Museum, New York[38] Addiction Display (1991), Pérez Art Museum Miami, Florida[39] Queen Esther/Harriet Tubman (1992), Jewish Museum, New York[40] Untitled (1992), Baltimore Museum of Art[41] Untitled (1992), Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts[42] Grey Area (1993), Tate, London[43] Mine/Yours (1994), Whitney Museum, New York[44] Atlas (1995), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York[45] Me and It (1995), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[46] Speak of Me as I Am: Chandelier Mori (2003), High Museum of Art, Atlanta[47] Untitled (Venice Biennale) (2003), Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Evanston, Illinois;[48] and Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts[49] The Wanderer (2003), Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, California[50] Arise! (2004), British Museum, London;[51] Museum of Modern Art, New York;[52] National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.;[53] and Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio[54] Convocation (2004), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;[55] National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.;[56] and Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio[57] We Are All in the Gutter, But Some of Us are Looking at the Stars (2004), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.;[58] Studio Museum in Harlem, New York;[59] and Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio[60] X (2005), Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, California;[61] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;[62] and Whitney Museum, New York[63] Pssst! (2005), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[64] Dark Day, Dark Night (2006), Nasher Museum of Art, Durham, North Carolina[65] The Mete of the Muse (2006), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne;[66] and New Orleans Museum of Art[67] The Ominous Glut (2006), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri[68] Ota Benga (2008), Tate, London[69] Flag (2009), Tate, London[70] Iago's Mirror (2009), Des Moines Art Center, Iowa;[71] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston;[72] and Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio[73] To Die Upon a Kiss (2011), Cleveland Museum of Art;[74] Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York;[75] Museum of Fine Arts, Houston;[76] Museum of Modern Art, New York;[77] and National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne[78] LIBERATION (2012), Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio[79] I Saw Othello's Visage in His Mind (2013), Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York;[80] and Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[81] Iago's Desdemona (2013), Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire[82] Act V. Scene II—Exeunt Omnes (2014), Wichita Art Museum, Kansas[83] Grinding Souls (2016), Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio[84] The Way the Moon's in Love with the Dark (2017), Denver Art Museum[85] Mother (2022), LaGuardia Airport Terminal C, New York[86] |

公共コレクションに収蔵されている主な作品 コロニアル・コレクション(1990年)、ナッシャー美術館、ノースカロライナ州ダーラム[37] ガードド・ビュー(1991年)、ホイットニー美術館、ニューヨーク[38] 『Addiction Display』(1991年)、ペレス美術館、フロリダ州マイアミ[39] 『Queen Esther/Harriet Tubman』(1992年)、ユダヤ美術館、ニューヨーク[40] 『Untitled』(1992年)、ボルチモア美術館[41] 『Untitled』(1992年)、ハーバード美術館、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ[42] グレー・エリア(1993)、テート、ロンドン[43] マイン/ユアーズ(1994)、ホイットニー美術館、ニューヨーク[44] アトラス(1995)、ハーレム・スタジオ美術館、ニューヨーク[45] ミー・アンド・イット(1995)、サンフランシスコ近代美術館[46] 『私を私として語れ:シャンデリア・モリ』(2003年)、アトランタ・ハイ美術館[47] 無題(ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレ)(2003年)、メアリー・アンド・リー・ブロック美術館、イリノイ州エバンストン;[48]およびスミス・カレッジ美術館、マサチューセッツ州ノースampton[49] 「放浪者」(2003年)、バークレー美術館およびパシフィック・フィルム・アーカイブ、カリフォルニア州[50] 「立ち上がれ!」(2004年)、大英博物館、ロンドン[51]、ニューヨーク近代美術館[52]、ワシントンD.C.のナショナル・ギャラリー・オブ・アート[53]、オハイオ州トレド美術館[54] 「Convocation」(2004年)、メトロポリタン美術館、ニューヨーク、[55] ワシントン D.C. のナショナル・ギャラリー、[56] オハイオ州トレド美術館[57] 「We Are All in the Gutter, But Some of Us are Looking at the Stars」(2004年)、ワシントン D.C. のナショナル・ギャラリー、[58] ニューヨーク、ハーレム・スタジオミュージアム[59]、オハイオ州トレド美術館[60] X(2005)、カリフォルニア州バークレー美術館およびパシフィックフィルムアーカイブ[61]、ニューヨーク、メトロポリタン美術館[62]、ニューヨーク、ホイットニー美術館[63] Pssst!(2005)、ワシントン D.C.、ナショナル・ギャラリー・オブ・アート[64] Dark Day, Dark Night (2006)、ナッシャー美術館、ノースカロライナ州ダーラム[65] The Mete of the Muse (2006)、ビクトリア国立美術館、メルボルン[66]、およびニューオーリンズ美術館[67] The Ominous Glut (2006)、ネルソン・アトキンス美術館、ミズーリ州カンザスシティ[68] オタ・ベンガ(2008)、テート、ロンドン[69] フラッグ(2009)、テート、ロンドン[70] イアゴの鏡(2009)、デモイン・アート・センター、アイオワ州;[71] ボストン美術館;[72] トーレド美術館、オハイオ州[73] キスで死ぬ (2011年)、クリーブランド美術館[74]、コーニングガラス博物館、ニューヨーク州コーニング[75]、ヒューストン美術館[76]、ニューヨーク近代美術館[77]、ビクトリア国立美術館、メルボルン[78] 解放 (2012年)、アレン記念美術館、オハイオ州オーバーリン[79] 『オセロの姿を彼の心に見た』(2013年)、コーニングガラス美術館、ニューヨーク州コーニング[80]、スミソニアンアメリカンアート美術館、スミソニアン協会、ワシントンD.C.[81] イアゴのデズデモーナ(2013)、ニューハンプシャー州マンチェスター、カーリア美術館[82] 第5幕第2場—全員退場(2014)、カンザス州ウィチタ、ウィチタ美術館[83] 魂をすりつぶす(2016)、オハイオ州オベリン、アレン記念美術館[84] 月が闇を愛するように(2017年)、デンバー美術館[85] 母(2022年)、ラガーディア空港ターミナルC、ニューヨーク[86] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_Wilson_(artist) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099