脱植民地批判

Decolonial critique

Graffiti on the Israeli West Bank barrier wall. Graffiti can function as an open or public challenge to colonial and imperialist structures.

☆ 研究者、著者、クリエイター、理論家、その他の人々は、エッセイ、アートワーク、メディアを通じて脱植民地化に取り組んでいる。これらのクリエイターの多 くは脱植民地化批評に取り組んでいる。脱植民地化批評では、思想家は脱植民地化によって進められた理論的、政治的、認識論的、社会的枠組みを用いて、広く 受け入れられ賞賛されている概念を精査し、再定式化し、自然化を否定する。多くの脱植民地的批判は、植民地および人種的枠組みの中で位置づけられる近代性 の概念の再構築に焦点を当てている。脱植民地的批判は、西洋の階層構造の再生産から脱却する脱植民地的文化を鼓舞する可能性がある。脱植民地的批判は、脱 植民地的方法と実践を認識論、社会、政治的思考のあらゆる側面に適用する方法である。

★脱植民地性(スペイン語:decolonialidad)とは、地球上の他の存在形態を可能にするために、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識のヒエラルキーや世界におけるあり方から脱却することを目指す学派である。それは、西洋の知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優越性、そしてこれらの認識を強化する制度や機関を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義は資本主義的近代性と帝国主義の日常的な機能の基礎であると理解されている。 デコロニアリティは、南米の運動の一部として、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たし た役割を検証するものとして登場した。この用語と概念を定義したアニバル・キハーノによると、デコロニアリティ理論と実践は、最近、批判の対象となりつつ ある。例えば、オルフェミ・タイウォ(Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò)は、「脱植民地化」は分析上不適切であり、「植民地性」はしばしば「近代性」と混同され、「脱植民地化」は完全な解放という不可能なプロジェクトになる、と主張している。[6] ヨナタン・クルツウェリとMalin Wilckensは、植民地時代に人種差別理論を裏付け、植民地支配の正統性を与えるために収集された人骨の学術コレクションの脱植民地化を例に挙げ、現代の学術的手法と政治的実践の両方が、アイデンティティの物象化された本質主義的概念を永続させていることを示した。(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality)

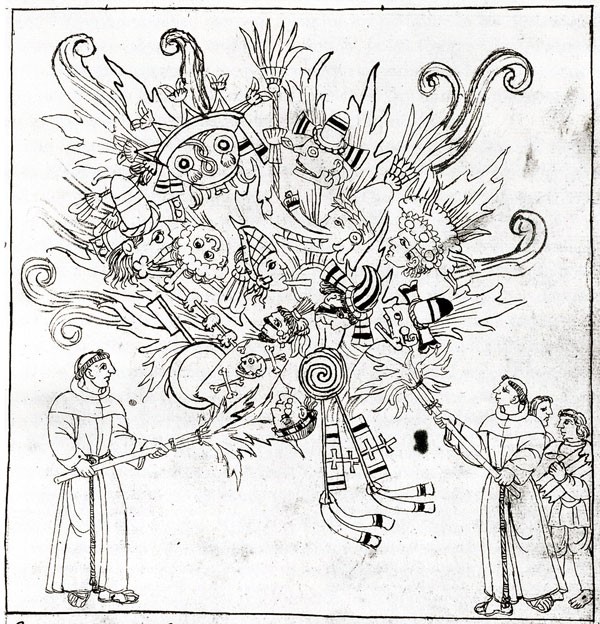

| Decolonial critique Researchers, authors, creators, theorists, and others engage in decoloniality through essays, artwork, and media. Many of these creators engage in decolonial critique. In decolonial critique, thinkers employ the theoretical, political, epistemic, and social frameworks advanced by decoloniality to scrutinize, reformulate, and denaturalize often widely accepted and celebrated concepts.[20][25] Many decolonial critiques focus on reformulating the concept of modernity as situated within colonial and racial frameworks.[26] Decolonial critique may inspire a decolonial culture that delinks from reproducing Western hierarchies.[27] Decolonial critique is a method of applying decolonial methods and practices to all facets of epistemic, social, and political thinking.[20] Decolonial art  Graffiti on the Israeli West Bank barrier wall. Graffiti can function as an open or public challenge to colonial and imperialist structures.[28]  Installation by Romuald Hazoumè using gas cans. Hazoumè has stated: “I send back to the West that which belongs to them, that is to say, the refuse of consumer society that invades us every day.”[1] Decolonial art critiques Western art for the way it is alienated from the surrounding world and its focus on pursuing aesthetic beauty.[29] Rather than feelings of sublime at the beauty of an art object, decolonial art seeks to evoke feelings of "sadness, indignation, repentance, hope, solidarity, resolution to change the world in the future, and, most importantly, with the restoration of human dignity."[30] Decolonial aesthetics "seek to recognize and open options for liberating the senses" beyond just visual senses[31] and challenge "the idea of art from Eurocentric forms of expression and philosophies of the beautiful."[32] Decolonial art may "re-inscribe indigeneity on the land" that has been obscured by colonialism and reveal alternatives or an "always elsewhere of colonialism."[31] Graffiti can function as an open or public challenge to colonial or imperialist structures and disrupt notions of a contented oppressed or colonized people. Notable artists include: Kwame Akoto-Bamfo (Ghana): Creates sculptures and installations that reflect on the history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and its impact on African communities. Maria Thereza Alves (Brazil): Focuses on Indigenous and environmental issues, shedding light on the impact of colonization on Indigenous communities. Wangechi Mutu (Kenya/United States): Explores African identities and the interplay between tradition and modernity in a postcolonial context through painting, collage, and sculpture. Tracey Moffatt (Australia): Examines identities, stories, and representations of Indigenous populations in Australia, focusing on colonial and postcolonial themes. Yinka Shonibare (United Kingdom/Nigeria): Utilizes African batik-printed fabrics and examines cultural identity, colonialism, and postcolonial issues through sculptures and installations. Decolonial feminism Decolonial feminism reformulates the coloniality of gender by critiquing the very formation of gender and its subsequent formations of patriarchy and the gender binary, not as universal constants across cultures, but as structures that have been instituted by and for the benefit of European colonialism.[5][33] Marìa Lugones proposes that decolonial feminism speaks to how "the colonial imposition of gender cuts across questions of ecology, economics, government, relations with the spirit world, and knowledge, as well as across everyday practices that either habituate us to take care of the world or to destroy it."[33] Decolonial feminists like Karla Jessen Williamson and Rauna Kuokkanen have examined colonialism as a force that has imposed gender hierarchies on Indigenous women that have disempowered and fractured Indigenous communities and ways of life.[5] Decolonial love  In Lak'ech has been referred to as a reflection of decolonial love.[34] Decolonial love is a love established on our relationality that is directed toward the emancipation of community from the coloniality of power, including human and non-human beings.[35] It was developed by Chicana feminist Chela Sandoval as a reformulation of love beyond individualist romantic notions of love.[35] Decolonial love "demands a deep recognition of our humanity and mutual implacability in undoing colonial relations of power and oppression that lead to indifference, contempt, and dehumanization."[34] It begins from within, as a love of one's humanity and for those who have resisted colonial violence in their pursuit of healing and liberation.[34] Thinkers who speak to the concept state that it is rooted in Indigenous cosmologies, including In Lak'ech ("you are my other me"), where love is a relational and resisting act toward the coloniality of power.[34] |

脱植民地批判(批評) 研究者、著者、クリエイター、理論家、その他の人々は、エッセイ、アートワーク、メディアを通じて脱植民地化に取り組んでいる。これらのクリエイ ターの多くは脱植民地化批評に取り組んでいる。脱植民地化批評では、思想家は脱植民地化によって進められた理論的、政治的、認識論的、社会的枠組みを用い て、広く受け入れられ賞賛されている概念を精査し、再定式化し、自然化を否定する。多くの脱植民地的批判は、植民地および人種的枠組みの中で位置づけられ る近代性の概念の再構築に焦点を当てている。脱植民地的批判は、西洋の階層構造の再生産から脱却する脱植民地的文化を鼓舞する可能性がある。脱植民地的批 判は、脱植民地的方法と実践を認識論、社会、政治的思考のあらゆる側面に適用する方法である。 脱植民地的なアート  イスラエル・ヨルダン川西岸地区の分離壁に描かれた落書き。落書きは、植民地主義や帝国主義の構造に対するオープンで公的な挑戦として機能しうる。  ロミュアルド・ハゾメによるガス缶を使ったインスタレーション。ハゾメは次のように述べている。「私は西洋に、西洋のものであるものを送り返す。つまり、私たちを日々襲う消費社会の廃棄物を。」[1] 脱植民地化された芸術は、西洋芸術が周囲の世界から疎外されているあり方や、美的な美の追求に焦点を当てていることを批判する。脱植民地化された芸術は、 芸術作品の美しさに対する崇高な感情よりも、「悲しみ、憤り、悔い改め、希望、連帯、将来の世界を変える決意 、そして最も重要なのは、人間の尊厳の回復である」という感情を呼び起こそうとする。脱植民地的美学は、視覚的な感覚を超えて「感覚を解放するための選択 肢を認識し、開放しよう」とするものであり[31]、「ヨーロッパ中心主義的な表現形式や、美しいという哲学から生み出された芸術の概念」に挑戦するもの である。 脱植民地化アートは、植民地主義によって覆い隠されてきた「土地の固有性を再び書き記す」ものであり、代替案や「常に植民地主義の他にあるもの」を明らか にする可能性がある。[31] グラフィティは、植民地主義や帝国主義の構造に対するオープンで公共的な挑戦として機能し、抑圧されたり植民地化されたりした人々が満足しているという概 念を覆すことができる。 著名なアーティストには以下のような人たちがいる。 クワメ・アコト=バムフォ(ガーナ):大西洋奴隷貿易の歴史とアフリカのコミュニティへの影響を反映した彫刻やインスタレーションを制作。 マリア・テレザ・アルベス(ブラジル):先住民問題や環境問題に焦点を当て、植民地化が先住民のコミュニティに与えた影響を明らかにする。 ワンゲチ・ムトゥ(ケニア/米国): 絵画、コラージュ、彫刻を通して、アフリカのアイデンティティと、ポストコロニアルの文脈における伝統と近代の相互作用を探求している。 トレイシー・モファット(オーストラリア):オーストラリアの先住民のアイデンティティ、物語、表現を、植民地時代とポストコロニアルのテーマに焦点を当てて検証している。 インカ・ショニバレ(英国/ナイジェリア):アフリカのバティックプリントの布地を使用し、彫刻やインスタレーションを通して、文化的アイデンティティ、植民地主義、ポストコロニアルの問題を検証している。 脱植民地化フェミニズム 脱植民地化フェミニズムは、ジェンダーの形成そのもの、およびその後の家父長制とジェンダー二元論の形成を批判することで、ジェンダーの植民地性を再定義 する。それは、文化を横断する普遍的な定数ではなく、ヨーロッパの植民地主義によって、またその利益のために制定された構造としてである。[5][33] マリア・ルゴネスは、脱植民地化フェミニズムが「ジェンダーの植民地化が、生態学、経済学、 精神世界との関係、知識、そして世界を大切にするか、それとも破壊するかを習慣づける日常的な実践を横断している」と述べている。[33] カルラ・ジェッセン・ウィリアムソンやラウナ・クオッカネンといった脱植民地フェミニストは、植民地主義を、ジェンダーのヒエラルキーを先住民の女性たち に押し付け、先住民のコミュニティや生活様式を弱体化させ、分断する力として検証している。[5] 脱植民地化された愛  In Lak'echは脱植民地化された愛の反映であると表現されている。[34] 脱植民地化の愛とは、人間と非人間を含む、権力の植民地性からの共同体の解放に向けられた、私たちの関係性の上に築かれた愛である。[35] それは、個人主義的なロマンチックな愛の概念を超えた愛の再定義として、チカーナのフェミニストであるチェラ・サンドヴァルによって発展した。脱植民地化 の愛は、「無関心、軽蔑、非人間化につながる、権力と抑圧の植民地関係を解消するために、私たちの人間性と相互の容赦のなさを深く認識することを求める」 [34]。無関心、軽蔑、非人間化につながる植民地主義的な権力と抑圧の関係を解消するために、私たちの人間性と相互の容赦のなさを深く認識することが必 要である」[34]。それは内側から始まるものであり、癒しと解放を追求する中で植民地主義の暴力に抵抗してきた人々に対する、そして自分自身の人間性に 対する愛である[34]。この概念について語る思想家たちは、この愛は「In Lak'ech(「あなたは私のもう一人の私」)」などの先住民の宇宙論に根ざしており、そこでは愛は権力の植民地主義に対する関係的かつ抵抗的な行為で あると述べている[34]。 |

| Critiquing Western liberal democracy Moving beyond the critiques of enlightenment philosophy and modernity, decolonial critiques of democracy uncover how practices in democratic governance root themselves in colonial and racial rhetoric. Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee seeks to counter "hegemonic models of democracy that cannot address issues of inequality and colonial difference."[25] Banerjee critiques western liberal democracy: "In liberal democracies colonial power becomes the epistemic basis of a privileged Eurocentric position that can explain culture and define the realities and identities of marginalized populations, while eliding power asymmetries inherent in the fixing of colonial difference.”[25] He also extends this analysis against deliberative democracy, arguing that this political theory fails to take into account colonized forms of deliberation often discounted and silenced—including oral history, music production, and more—as well as how asymmetries of power are reproduced within political arenas.[25] |

西洋のリベラル民主主義を批判する 啓蒙思想や近代性に対する批判を乗り越え、脱植民地的な民主主義批判は、民主的統治の実践が植民地主義的・人種主義的なレトリックにいかに根ざしているか を明らかにする。Subhabrata Bobby Banerjeeは、「不平等や植民地的差異の問題に対処できない民主主義のヘゲモニーモデル」に異議を唱えることを目指している。 バネルジーは西洋のリベラル民主主義を批判している。「リベラル民主主義においては、植民地支配の権力が、文化を説明し、疎外された人々の現実やアイデン ティティを定義する特権的なヨーロッパ中心主義の認識論的基礎となる。一方で、植民地的な差異の固定化に内在する権力の非対称性は無視される」[25]。 また、この分析を熟議民主主義にも適用し、この政治理論は、しばしば軽視され、沈黙させられてきた植民地化された形の熟議(オーラル・ヒストリー、音楽制 作など)や、政治の場における権力の非対称性がどのように再生産されるかについて考慮していないと主張している。[25] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality#Decolonial_feminism |

|

| Decoloniality

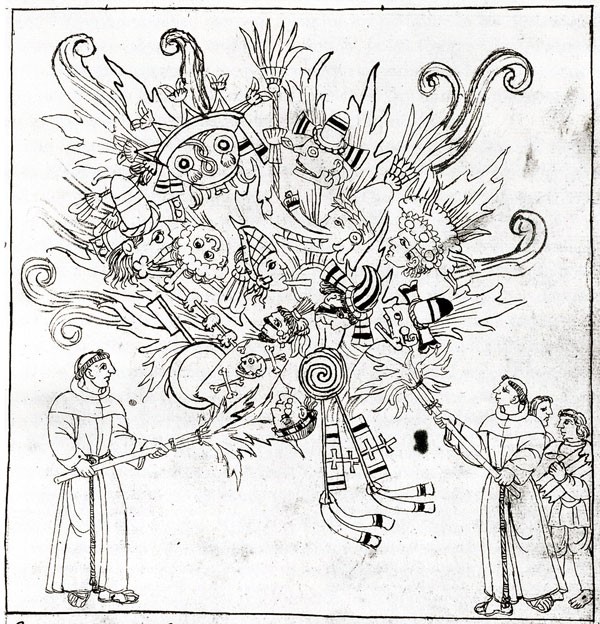

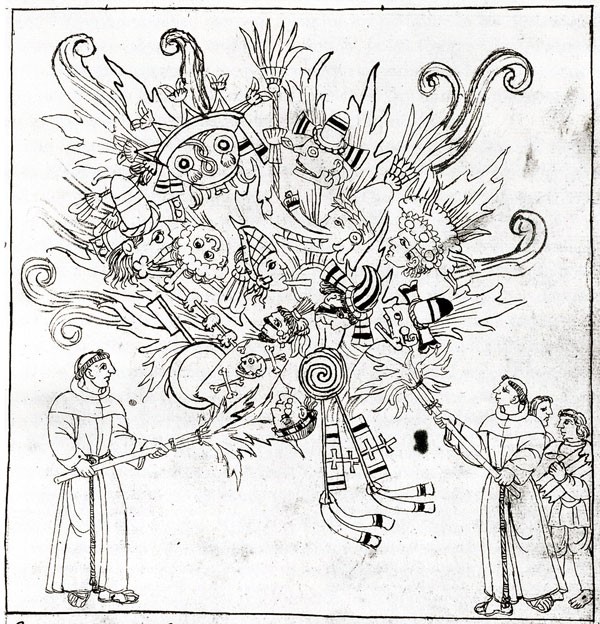

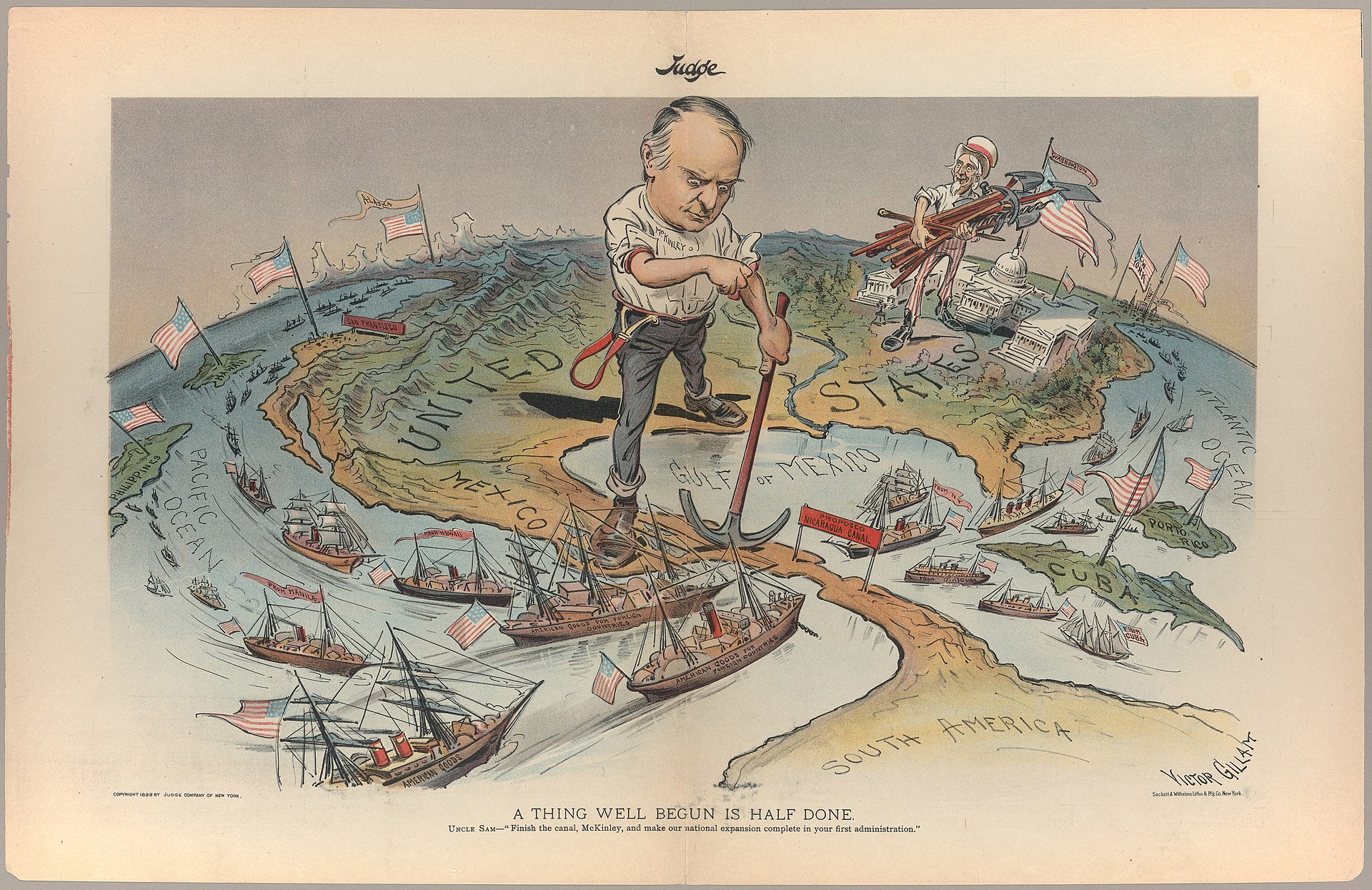

(Spanish: decolonialidad) is a school of thought that aims to delink

from Eurocentric knowledge hierarchies and ways of being in the world

in order to enable other forms of existence on Earth.[2] It critiques

the perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of

Western culture, including the systems and institutions that reinforce

these perceptions. Decolonial perspectives understand colonialism as

the basis for the everyday function of capitalist modernity and

imperialism.[3]: 168-174 Decoloniality emerged as part of a South America movement examining the role of the European colonization of the Americas in establishing Eurocentric modernity/coloniality according to Aníbal Quijano, who defined the term and reach.[2][4][5] Decolonial theory and practice have recently been subject to increasing critique. For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò argued that it is analytically unsound, that "coloniality" is often conflated with "modernity", and that "decolonisation" becomes an impossible project of total emancipation.[6] Jonatan Kurzwelly and Malin Wilckens used the example of decolonisation of academic collections of human remains, which were collected during colonial times to support racist theories and give legitimacy to colonial oppression, and showed how both contemporary scholarly methods and political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of identities.[7] Foundational principles Coloniality of knowledge This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of knowledge.[edit]  In his 1585 Descripción de Tlaxcala, Diego Muñoz Camargo illustrated the book burning of pre-Columbian codices by Franciscan friars.[8] Coloniality of knowledge is a concept that Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano developed and adapted to contemporary decolonial thinking. The concept critiques what proponents call the Eurocentric system of knowledge, arguing the legacy of colonialism survives within the domains of knowledge. For decolonial scholars, the coloniality of knowledge is central to the functioning of the coloniality of power and is responsible for turning colonial subjects into victims of the coloniality of being, a term that refers to the lived experiences of colonized peoples. Coloniality of power This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of power.[edit] The coloniality of power is a concept interrelating the practices and legacies of European colonialism in social orders and forms of knowledge, advanced in postcolonial studies, decoloniality, and Latin American subaltern studies, most prominently by Anibal Quijano. It identifies and describes the living legacy of colonialism in contemporary societies in the form of social discrimination that outlived formal colonialism and became integrated in succeeding social orders.[9] The concept identifies the racial, political and social hierarchical orders imposed by European colonialism in Latin America that prescribed value to certain peoples/societies while disenfranchising others. Colonialism as the root  Decoloniality is founded on the principle that European colonialism is at the root of how the modern world functions today.[10][11] The decolonial movement includes diverse forms of critical theory, articulated by pluriversal forms of liberatory thinking that arise out of distinct situations. In its academic forms, it analyzes class distinctions, ethnic studies, gender studies, and area studies. It has been described as consisting of analytic (in the sense of semiotics) and practical “options confronting and delinking from [...] the colonial matrix of power"[12]: xxvii or from a "matrix of modernity" rooted in colonialism.[10][11] It considers colonialism "the underlying logic of the foundation and unfolding of Western civilization from the Renaissance to today," although this foundational interconnectedness is often downplayed.[12]: 2 This logic is commonly referred to as the colonial matrix of power or coloniality of power. Some have built upon decolonial theory by proposing Critical Indigenous Methodologies for research.[13] Imperialism as the successor  Decoloniality sees imperialism as a perpetuation of inequalities initiated by Western colonialism.[3]: 168 Although formal and explicit colonization ended with the decolonization of the Americas during the eighteenth and nineteenth century and the decolonization of much of the Global South in the late twentieth century, its successors, Western imperialism and globalization perpetuate those inequalities. The colonial matrix of power produced social discrimination eventually variously codified as racial, ethnic, anthropological or national according to specific historic, social, and geographic contexts.[3]: 168 Decoloniality emerged as the colonial matrix of power was put into place during the 16th century.[citation needed][clarification needed] It is, in effect, a continuing confrontation of, and delinking from, Eurocentrism.[14]: 542 Coloniality of gender This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of gender.[edit]  March against femicide at UNAM in 2017. The coloniality of gender has been used to explain how modern femicide is tied to the European colonization of the Americas.[15] Coloniality of gender is a concept developed by Argentine philosopher Maria Lugones. Building off Aníbal Quijano's foundational concept of coloniality of power,[16] coloniality of gender explores how European colonialism influenced and imposed European gender structures on Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This concept challenges the notion that gender can be isolated from the impacts of colonialism. Scholars have also extended the concept of coloniality of gender to describe colonial experiences in Asian and African societies. The concept is notably employed in academic fields like decolonial feminism and the broader study of decoloniality.[17] Disobedience and de-linking Decoloniality has been called a form of "epistemic disobedience",[12]: 122-123 "epistemic de-linking",[18]: 450 and "epistemic reconstruction".[3]: 176 In this sense, decolonial thinking is the recognition and implementation of a border gnosis or subaltern,[19]: 88 a means of eliminating the provincial tendency to pretend that Western European modes of thinking are universal.[14]: 544 In less theoretical applications—such as movements for Indigenous autonomy—decoloniality is considered a program of de-linking from contemporary legacies of coloniality,[18]: 452 a response to needs unmet by the modern Rightist or Leftist governments,[12]: 217 or, most broadly, social movements in search of a “new humanity”[12]: 52 or the search for “social liberation from all power organized as inequality, discrimination, exploitation, and domination”.[3]: 178 Decoloniality Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire contributed to decolonial thinking, theory, and practice by identifying core principles of decoloniality. The first principle they identified is that colonialism must be confronted and treated as a discourse which fundamentally frames all aspects of thinking, organization, and existence. Framing colonialism as a "fundamental problem" empowers the colonized to center their experiences and thinking without seeking the recognition of the colonizer—a step towards the creation of decolonial thinking.[20] The second core principle is that decolonization goes beyond ending colonization. Nelson Maldonado-Torres explains, "For decolonial thinking decolonization is less the end of colonialism wherever it has occurred and more the project of undoing and unlearning the coloniality of power, knowledge, and being and of creating a new sense of humanity and forms of interrelationality."[20] This is the work of the decolonial project that has epistemic, political, and ethical dimensions.[21] Aníbal Quijano summarized the goals of decoloniality as a need to recognize that the instrumentation of reason by the colonial matrix of power produced distorted paradigms of knowledge and spoiled the liberating promises of modernity, and by that recognition, realize the destruction of the global coloniality of power.[18]: 452 Alanna Lockward explains that Europe has engaged in an intentional "politics of confusion" to conceal the relationship between modernity and coloniality.[22] Decoloniality is synonymous with decolonial "thinking and doing",[12]: xxiv and it questions or problematizes the histories of power emerging from Europe. These histories underlie the logic of Western civilization.[3]: 168 Thus, decoloniality refers to analytic approaches and socioeconomic and political practices opposed to pillars of Western civilization: coloniality and modernity. This makes decoloniality both a political and epistemic project.[12]: xxiv-xxiv Examples Examples of contemporary decolonial programmatics and analytics exist throughout the Americas. Decolonial movements include the contemporary Zapatista governments of Southern Mexico, Indigenous movements for autonomy throughout South America, ALBA,[23] CONFENIAE in Ecuador, ONIC in Colombia, the TIPNIS movement in Bolivia, and the Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil. These movements embody action oriented towards the goals expressed to seek ever-increasing freedoms by challenging the reasoning behind modernity, since modernity is in fact a facet of the colonial matrix of power.[citation needed] Examples of contemporary decolonial analytics include ethnic studies programs at various educational levels designed primarily to appeal to certain ethnic groups, including those at the K-12 level recently banned in Arizona, as well as long-established university programs. Scholars primarily with analytics who fail to recognize the connection between politics or decoloniality and the production of knowledge—between programmatics and analytics—are those claimed by decolonialists to most likely to reflect "an underlying acceptance of capitalist modernity, liberal democracy, and individualism" values which decoloniality seeks to challenge.[24]: 6 |

脱

植民地性(スペイン語:decolonialidad)とは、地球上の他の存在形態を可能にするために、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識のヒエラルキーや世界

におけるあり方から脱却することを目指す学派である。[2]

それは、西洋の知識の普遍性と西洋文化の優越性、そしてこれらの認識を強化するシステムや制度を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義を資本主義的

近代性と帝国主義の日常的な機能の基礎として理解している。[3]:168-174 脱植民地性は、南米の運動の一部として、欧州によるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、欧州中心主義的な近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たした役割を検証するものとして登場した。この用語を定義したアニバル・キハーノによると、[2][4][5] 脱植民地理論と実践は、最近、批判の対象となっている。例えば、オルフェミ・タイウォは、脱植民地理論は分析的に不適切であり、「植民地性」はしばしば 「近代性」と混同され、「脱植民地化」は完全な解放という不可能なプロジェクトになる、と主張している。[6] ジョナサン・カーツウェルとマリン・ウィルケンズは、 とマリン・ウィルケンズは、植民地時代に人種差別理論を裏付け、植民地支配の正統性を与えるために収集された人骨の学術コレクションの脱植民地化の例を挙 げ、現代の学術的手法と政治的実践の両方が、アイデンティティの物象化された本質主義的概念を永続させていることを示した。[7] 基礎原則 知識の植民地性(→ラテンアメリカにおけるポストコロニアリティの発見) このセクションは、知識の植民地性からの抜粋である。[編集]  1585年の『トラスカラの記述』の中で、ディエゴ・ムニョス・カマルゴは、コロンブス到来以前の時代にフランシスコ会の修道士たちによって行われたコデックスの焼却について描いている。[8] 知識の植民地性とは、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キハノが開発し、脱植民地的な思考に適応させた概念である。この概念は、知識の欧州中心主義システムと呼 ぶものを批判し、知識の領域内に植民地主義の遺産が生き残っていると主張する。脱植民地化を研究する学者にとって、知識の植民地性は権力の植民地性の機能 の中心であり、植民地化された人々の生活体験を指す「植民地化された存在」の犠牲者へと植民地化された主体を転換させる原因である。 権力の植民地性 このセクションは、 権力の植民地性(Coloniality of Power)からの抜粋である。 権力の植民地性とは、ポストコロニアル研究、脱植民地化、ラテンアメリカの下位研究(特にアニバル・キハーノによる)で発展した、社会秩序と知識の形態に おけるヨーロッパの植民地主義の実践と遺産を相互に関連付ける概念である。それは、現代社会における植民地主義の生き残った遺産を、形式的な植民地主義が 終焉を迎えた後も存続し、後続の社会秩序に統合された社会差別の形態として特定し、記述するものである。[9] この概念は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義がラテンアメリカに課した人種的、政治的、社会的階層秩序を特定し、特定の人々や社会に価値を規定する一方で、他の人 々を排除した。 植民地主義を根源とする  脱植民地化は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義が現代世界の機能の根底にあるという原則に基づいている。[10][11] 脱植民地化運動には、さまざまな状況から生じる解放的思考の多元的形態によって明確化された、多様な批判理論の形態が含まれる。学術的な形態では、階級区 分、民族研究、ジェンダー研究、地域研究を分析する。それは、分析的(記号論的な意味で)かつ実践的な「選択肢」であり、植民地主義の権力構造[12]、 あるいは植民地主義に根ざした「近代性の構造」[10][11]に立ち向かい、そこから脱却するものであると説明されている。 植民地主義は「ルネサンスから今日に至る西洋文明の基礎と展開の根底にある論理」であると考えるが、この基礎的な相互関連性はしばしば軽視されている。 [12]: 2 この論理は一般的に、植民地的な権力の基盤または権力の植民地性と呼ばれている。 研究のための批判的土着的方法論を提案することで、脱植民地理論を基盤とするものもある。[13] 帝国主義は後継者である  脱植民地化論は、帝国主義を西洋の植民地主義によって始まった不平等が永続しているものと見なしている。[3]: 168 公式かつ明白な植民地化は、18世紀から19世紀にかけてのアメリカ大陸の脱植民地化と、20世紀後半におけるグローバル・サウスの大部分の脱植民地化に よって終結したが、その継承者である西洋の帝国主義とグローバリゼーションは、それらの不平等を永続させている。植民地主義的な権力の構造は、特定の歴史 的、社会的、地理的文脈に応じて、最終的に人種的、民族的、人類学的、あるいは国家的としてさまざまな形で法制度化された社会差別を生み出した。[3]: 168 脱植民地性は、16世紀に植民地主義的な権力の構造が確立された際に登場した。[要出典][要説明] 実質的には、脱植民地性は、ユーロセントリズムとの継続的な対立であり、ユーロセントリズムからの脱却である。[14]: 542 ジェンダーの植民地性 このセクションは、ジェンダーの植民地性からの抜粋である。  2017年のUNAMにおけるフェミサイド反対デモ。ジェンダーの植民地性は、近代のフェミサイドがヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化とどのように結びついているかを説明するのに用いられてきた。 ジェンダーの植民地性は、アルゼンチンの哲学者マリア・ルゴネスが開発した概念である。アニバル・キハノの「権力の植民地性」の基礎概念を基に構築された ジェンダーの植民地性は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義がアメリカ大陸の先住民にヨーロッパのジェンダー構造をどのように影響させ、押し付けたかを探究する。こ の概念は、ジェンダーが植民地主義の影響から切り離されるという考えに異議を唱えるものである。 学者たちはジェンダーの植民地性という概念をさらに発展させ、アジアやアフリカの社会における植民地体験を説明している。この概念は、脱植民地フェミニズムや脱植民地主義のより広範な研究といった学術分野で特に用いられている。 不服従と脱連結 脱植民地性は、「認識的不服従」の一形態であると称され[12]:122-123、「認識的脱連結」[18]:450、「認識的再構築」[3]:176で ある。この意味において、脱植民地的な思考とは、 認識または従属者[19]: 88、西欧の思考様式が普遍的であるかのように装う地方的な傾向を排除する手段[14]: 544 である。先住民の自治を求める運動など、理論的な応用が少ない分野では、脱植民地性は、植民地主義の現代的な遺産からの脱リンクのプログラム[18]: 45 2 近代の右派または左派の政府が満たさなかったニーズへの対応[12]: 217、または最も広く言えば、「新しい人間性」[12]: 52、あるいは「不平等、差別、搾取、支配として組織化されたあらゆる権力からの社会的解放」[3]: 178の追求としての社会運動である。 脱植民地性 フランツ・ファノンとエメ・セゼールは、脱植民地性の核心となる原則を特定することで、脱植民地主義的な思考、理論、実践に貢献した。彼らが最初に特定し た原則は、植民地主義は思考、組織、存在のあらゆる側面を根本的に形作る言説として対峙し、扱われなければならないというものである。植民地主義を「根本 的な問題」として捉えることで、植民地化された人々は、植民地主義者の承認を求めずに、自らの経験や思考を重視することが可能になる。これは脱植民地主義 的な思考の創造に向けた一歩である。[20] 2つ目の主要原則は、脱植民地化は植民地主義の終結を越えるものであるというものである。ネルソン・マルドナド=トーレスは次のように説明している。「脱 植民地化とは、脱植民地化が起こった場所における植民地主義の終結というよりも、権力、知識、存在の植民地性を覆し、それを学ばないようにするプロジェク トであり、新たな人間性と相互関係性の形態を創造するプロジェクトである」[20] これは、認識論的、政治的、倫理的な側面を持つ脱植民地化プロジェクトの作業である。[21] アニバル・キハノは脱植民地化の目標を、植民地主義的な権力のマトリックスによる理性の道具化が歪んだ知識のパラダイムを生み出し、近代の解放的な約束を 台無しにしたことを認識する必要性であり、その認識によって、 グローバルな権力の植民地性を破壊することに気づく必要があると主張している。[18]: 452 アラーナ・ロックワードは、ヨーロッパが近代性と植民地性の関係を隠蔽するために意図的な「混乱の政治」を行ってきたと説明している。[22] 脱植民地性は脱植民地的な「思考と実践」と同義であり[12]: xxiv、ヨーロッパから生じた権力の歴史を問い質すものである。これらの歴史は西洋文明の論理の根底にある[3]: 168。したがって、脱植民地性とは西洋文明の柱である植民地性と近代性に対抗する分析的アプローチと社会経済的・政治的実践を指す。このため、脱植民地 化は政治的かつ認識論的なプロジェクトである。[12]: xxiv-xxiv 例 現代の脱植民地化のプログラムや分析の例は、南北アメリカ大陸全体に存在する。脱植民地化運動には、南メキシコのサパティスタ政府、南米全域の自治を求め る先住民運動、ベネズエラとコロンビアの南米諸国による同盟(ALBA)[23]、エクアドルのCONFENIAE、コロンビアのONIC、ボリビアの ティピサニ運動、ブラジルの土地なし労働者運動などがある。これらの運動は、近代性の背後にある論理に異議を唱えることで、増大し続ける自由を求めるとい う目標に向けられた行動を体現している。なぜなら、近代性は実際には権力の植民地的な基盤の側面であるからだ。 現代の脱植民地化分析の例としては、主に特定の民族グループに訴えることを目的とした、さまざまな教育レベルにおける民族研究プログラムがある。これに は、最近アリゾナ州で禁止された幼稚園から高校3年生までのレベルのプログラムや、長年にわたって確立された大学のプログラムも含まれる。主に分析学を専 門とする学者で、政治や脱植民地性と知識の生産との関係、すなわちプログラムと分析学との関係を認識していない者は、脱植民地主義者たちから、脱植民地性 が挑戦しようとしている「資本主義的近代、自由民主主義、個人主義」の価値観を根底から受け入れている可能性が高いと主張されている。[24]: 6 |

| Decolonial critique |

脱植民地批判(→冒頭の説明のセクション) |

| Distinction from related ideas Decoloniality is often conflated with postcolonialism, decolonization, and postmodernism. However, decolonial theorists draw clear distinctions. Postcolonialism Postcolonialism is often mainstreamed into general oppositional practices by "people of color", "Third World intellectuals", or ethnic groups.[19]: 87 Decoloniality—as both an analytic and a programmatic approach—is said to move "away and beyond the post-colonial" because "post-colonialism criticism and theory is a project of scholarly transformation within the academy".[18]: 452 This final point is debatable, as some postcolonial scholars consider postcolonial criticism and theory to be both an analytic (a scholarly, theoretical, and epistemic) project and a programmatic (a practical, political) stance.[36]: 8 This disagreement is an example of the ambiguity—"sometimes dangerous, sometimes confusing, and generally limited and unconsciously employed"—of the term "postcolonialism," which has been applied to analysis of colonial expansion and decolonization, in contexts such as Algeria, the 19th-century United States, and 19th-century Brazil.[37]: 93-94 Decolonial scholars consider the colonization of the Americas a precondition for postcolonial analysis. The seminal text of postcolonial studies, Orientalism by Edward Said, describes the nineteenth-century European invention of the Orient as a geographic region considered racially and culturally distinct from, and inferior to, Europe. However, without the European invention of the Americas in the sixteenth century, sometimes referred to as Occidentalism, the later invention of the Orient would have been impossible.[12]: 56 This means that postcolonialism becomes problematic when applied to post-nineteenth-century Latin America.[37]: 94 Political decolonization Decolonization is largely political and historical: the end of the period of territorial domination of lands primarily in the global south by European powers. Decolonial scholars contend that colonialism did not disappear with political decolonization. It is important to note the vast differences in the histories, socioeconomics, and geographies of colonization in its various global manifestations. However, coloniality— meaning racialized and gendered socioeconomic and political stratification according to an invented Eurocentric standard—was common to all forms of colonization. Similarly, decoloniality in the form of challenges to this Eurocentric stratification manifested previous to de jure decolonization. Gandhi and Jinnah in India, Fanon in Algeria, Mandela in South Africa, and the early 20th-century Zapatistas in Mexico are all examples of decolonial projects that existed before decolonization. Postmodernism "Modernity" as a concept is complementary to coloniality. Coloniality is called "the darker side of western modernity".[12] The problematic aspects of coloniality are often overlooked when describing the totality of Western society, whose advent is instead often framed as the introduction of modernity and rationality, a concept critiqued by post-modern thinkers. However, this critique is largely "limited and internal to European history and the history of European ideas".[18]: 451 Although postmodern thinkers recognize the problematic nature of the notions of modernity and rationality, these thinkers often overlook the fact that modernity as a concept emerged when Europe defined itself as the center of the world. In this sense, those seen as part of the periphery are themselves part of Europe's self-definition.[38]: 13 To summarize, like modernity, postmodernity often reproduces the "Eurocentric fallacy" foundational to modernity. Therefore, rather than criticizing the terrors of modernity, decolonialism criticizes Eurocentric modernity and rationality because of the "irrational myth" that these conceal.[18]: 453-454 Decolonial approaches thus seek to "politicise epistemology from the experiences of those on the 'border,' not to develop yet another epistemology of politics".[38]: 13 |

関連する概念との区別 脱植民地性は、ポストコロニアリズム、脱植民地化、ポストモダニズムと混同されることが多い。しかし、脱植民地性の理論家たちは明確な区別を設けている。 ポストコロニアリズム ポストコロニアリズムは、有色人種、第三世界の知識人、あるいは民族集団による一般的な反対運動の実践として主流化されることが多い。[19]: 87 脱植民地性は、分析的アプローチおよびプログラム的アプローチの両方として、「ポストコロニアリズムの批判と理論は学術界における学術的変革のプロジェク トである」ため、「ポストコロニアリズムから離れ、それを超える」ものであるとされる。[18]: 452 この最後の指摘については議論の余地がある。ポストコロニアル学派の一部の学者は、ポストコロニアル批判と理論を分析的(学術的、理論的、認識論的)プロ ジェクトとプログラム的(実際的、政治的)スタンスの両方であるとみなしているからだ。[36]: 8 この意見の相違は、「ポストコロニアル主義」という用語の曖昧さの例である。この用語は、アルジェリア、19世紀の米国、19世紀のブラジルなどの文脈に おいて、植民地拡大と脱植民地化の分析 、一般的に限定的で無意識的に用いられる」という「ポストコロニアリズム」という用語の曖昧さの例である。この用語は、アルジェリア、19世紀の米国、 19世紀のブラジルなどの文脈において、植民地拡大と脱植民地化の分析に適用されてきた。 脱植民地化の研究者は、アメリカ大陸の植民地化がポストコロニアリズム分析の前提条件であると考える。ポストコロニアリズム研究の重要なテキストであるエ ドワード・サイード著『オリエンタリズム』では、19世紀のヨーロッパによるオリエントの地理的地域としての発明が、人種的・文化的にヨーロッパとは異な り、劣っているものとみなされたと説明されている。しかし、16世紀のヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の発見(西洋中心主義と呼ばれることもある)がなけれ ば、その後のオリエントの発見は不可能であった。[12]: 56 つまり、ポストコロニアリズムは19世紀以降のラテンアメリカに適用されると問題が生じるのである。[37]: 94 政治的な脱植民地化 脱植民地化は、主に政治的・歴史的なものであり、主に南半球の土地がヨーロッパの列強によって領土支配されていた時代の終焉を意味する。脱植民地化の研究者は、植民地主義は政治的な脱植民地化によって消滅したわけではないと主張している。 植民地化の歴史、社会経済、地理には、世界中でさまざまな形で現れた植民地化の間に大きな違いがあることに注目することが重要である。しかし、人種や性別 による社会経済的・政治的階層化を意味するコロニアリティ(植民地主義)は、欧州中心主義の基準によって作り出されたものであり、あらゆる形態の植民地化 に共通するものであった。同様に、この欧州中心主義的階層化への挑戦という形のコロニアリティは、法的な脱植民地化に先立って現れていた。インドのガン ディーやジンナー、アルジェリアのファノン、南アフリカのマンデラ、そしてメキシコの20世紀初頭のサパティスタは、いずれも脱植民地化以前から存在して いた脱植民地化プロジェクトの例である。 ポストモダニズム 「近代」という概念は、植民地主義と表裏一体である。植民地主義は「西洋近代の負の側面」と呼ばれている。[12] 西洋社会の全体像を説明する際には、植民地主義の問題点がしばしば見落とされる。その代わりに、西洋社会の到来は近代性と合理性の導入として描かれること が多く、この概念はポストモダンの思想家たちによって批判されている。しかし、この批判は「ヨーロッパの歴史とヨーロッパの思想の歴史に限定されたもの」 である。[18]: 451 ポストモダンの思想家たちは、近代性や合理性の概念の問題点を認識しているが、近代性という概念がヨーロッパが世界の中心であると定義したときに生まれた という事実を見落としていることが多い。この意味で、周辺部と見なされているものは、ヨーロッパの自己定義の一部である。[38]: 13 要約すると、近代性と同様に、ポストモダニティは近代性の基礎をなす「ヨーロッパ中心主義の誤謬」をしばしば再生産する。したがって脱植民地主義は、近代 の恐怖を批判するのではなく、近代が隠蔽する「非合理的な神話」を理由に、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代と合理性を批判する。脱植民地主義的なアプローチ は、このように「『境界』に位置する人々の経験から認識論を政治化」することを目指すものであり、「政治に関する認識論をさらに発展させる」ことを目的と するものではない。 |

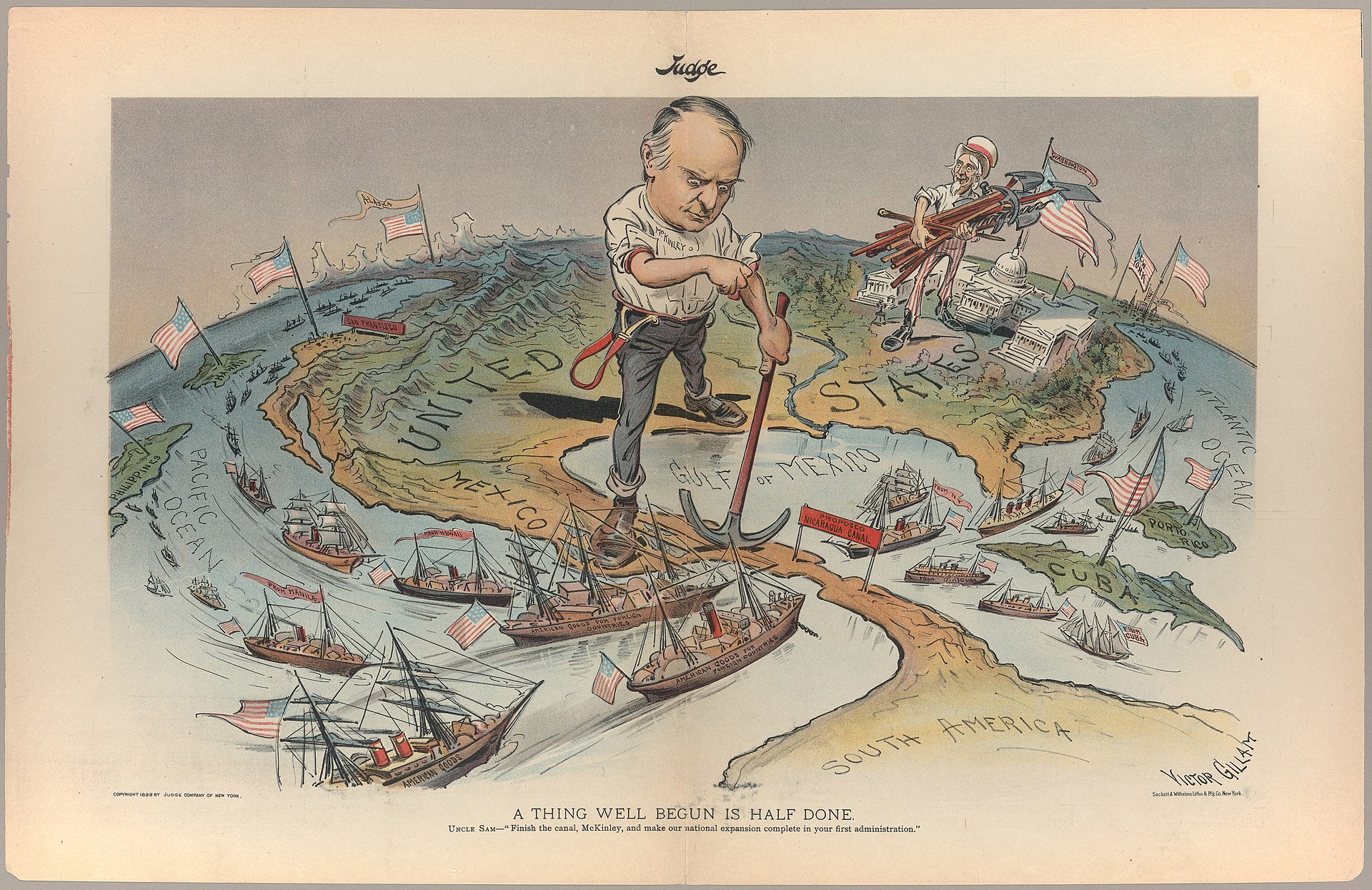

| Anti-imperialism |

反帝国主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality |

|

| Decoloniality

(Spanish: decolonialidad) is a school of thought that aims to delink

from Eurocentric knowledge hierarchies and ways of being in the world

in order to enable other forms of existence on Earth. It critiques the

perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of

Western culture, including the systems and institutions that reinforce

these perceptions. Decolonial perspectives understand colonialism as

the basis for the everyday function of capitalist modernity and

imperialism. Decoloniality emerged as part of a South America movement

examining the role of the European colonization of the Americas in

establishing Eurocentric modernity/coloniality according to Aníbal

Quijano, who defined the term and reach.Decolonial theory and practice

have recently been subject to increasing critique. For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò

argued that it is analytically unsound, that "coloniality" is often

conflated with "modernity", and that "decolonisation" becomes an

impossible project of total emancipation.[6] Jonatan Kurzwelly

and Malin Wilckens used the example of decolonisation of academic

collections of human remains, which were collected during colonial

times to support racist theories and give legitimacy to colonial

oppression, and showed how both contemporary scholarly methods and

political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of

identities. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality [*]Kurzwelly, Jonatan; Wilckens, Malin S (2023). "Calcified identities: Persisting essentialism in academic collections of human remains". Anthropological Theory. 23 (1): 100–122. doi:10.1177/14634996221133872 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality |

脱植民地性(スペイン語:decolonialidad)とは、地球上の他の存在形態を可能にするために、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識のヒエラルキーや世界におけるあり方から脱却することを目指す学派である。それは、西洋の知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優越性、そしてこれらの認識を強化する制度や機関を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義は資本主義的近代性と帝国主義の日常的な機能の基礎であると理解されている。

デコロニアリティは、南米の運動の一部として、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たし

た役割を検証するものとして登場した。この用語と概念を定義したアニバル・キハーノによると、デコロニアリティ理論と実践は、最近、批判の対象となりつつ

ある。例えば、オルフェミ・タイウォ(Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò)は、「脱植民地化」は分析上不適切であり、「植民地性」はしばしば「近代性」と混同され、「脱植民地化」は完全な解放という不可能なプロジェクトになる、と主張している。[6] ヨナタン・クルツウェリとMalin Wilckensは、植民地時代に人種差別理論を裏付け、植民地支配の正統性を与えるために収集された人骨の学術コレクションの脱植民地化を例に挙げ、現代の学術的手法と政治的実践の両方が、アイデンティティの物象化された本質主義的概念を永続させていることを示した。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆