ゲーム理論

Game theory

☆ ゲーム理論(Game theory)とは、戦略的相互作用の数学的モデルの研究である。[1] 社会科学の多くの分野に応用されており、経済学、論理学、システム科学、コンピュータサイエンスなどでも広く用いられている。[2] 当初、ゲーム理論は2人のプレイヤーによるゼロサムゲームを対象としていた。ゼロサムゲームとは、参加者の利益または損失が、もう一方の参加者の利益また は損失と完全に釣り合うゲームである。1950年代には非ゼロサムゲームの研究にまで拡大され、最終的には幅広い行動関係に適用されるようになった。現在 では、人間、動物、コンピュータにおける合理的な意思決定の科学を包括する用語となっている。 近代ゲーム理論は、2人によるゼロサムゲームにおける混合戦略均衡の概念と、ジョン・フォン・ノイマンによるその証明から始まった。フォン・ノイマンの当 初の証明では、コンパクト凸集合への連続写像に関するブラウワー固定点定理が用いられ、これはゲーム理論および数理経済学における標準的な手法となった。 彼の論文は、オスカー・モルゲンシュテルンとの共著『ゲームと経済行為の理論』(1944年)に引き継がれ、複数のプレイヤーによる協力ゲームについて考 察した。[3] 第2版では、期待効用の公理理論が提示され、これにより数学統計学者や経済学者が不確実性下での意思決定を扱うことが可能となった。[4] ゲーム理論は1950年代に広く発展し、1970年代には進化に明示的に応用されたが、同様の発展は少なくとも1930年代まで遡ることができる。ゲーム 理論は多くの分野において重要なツールとして広く認識されている。ジョン・メイナード・スミスは、進化ゲーム理論の応用により1999年にクラフォード賞 を受賞し、2020年までにゲーム理論学者15名がノーベル経済学賞を受賞している。その中には、ポール・ミルグラムとロバート・B・ウィルソンも含まれ ている。

| Game theory is the

study of mathematical models of strategic interactions.[1] It has

applications in many fields of social science, and is used extensively

in economics, logic, systems science and computer science.[2]

Initially, game theory addressed two-person zero-sum games, in which a

participant's gains or losses are exactly balanced by the losses and

gains of the other participant. In the 1950s, it was extended to the

study of non zero-sum games, and was eventually applied to a wide range

of behavioral relations. It is now an umbrella term for the science of

rational decision making in humans, animals, and computers. Modern game theory began with the idea of mixed-strategy equilibria in two-person zero-sum games and its proof by John von Neumann. Von Neumann's original proof used the Brouwer fixed-point theorem on continuous mappings into compact convex sets, which became a standard method in game theory and mathematical economics. His paper was followed by Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), co-written with Oskar Morgenstern, which considered cooperative games of several players.[3] The second edition provided an axiomatic theory of expected utility, which allowed mathematical statisticians and economists to treat decision-making under uncertainty.[4] Game theory was developed extensively in the 1950s, and was explicitly applied to evolution in the 1970s, although similar developments go back at least as far as the 1930s. Game theory has been widely recognized as an important tool in many fields. John Maynard Smith was awarded the Crafoord Prize for his application of evolutionary game theory in 1999, and fifteen game theorists have won the Nobel Prize in economics as of 2020, including most recently Paul Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson. |

ゲーム理論とは、戦略的相互作用の数学的モデルの研究である。[1]

社会科学の多くの分野に応用されており、経済学、論理学、システム科学、コンピュータサイエンスなどでも広く用いられている。[2]

当初、ゲーム理論は2人のプレイヤーによるゼロサムゲームを対象としていた。ゼロサムゲームとは、参加者の利益または損失が、もう一方の参加者の利益また

は損失と完全に釣り合うゲームである。1950年代には非ゼロサムゲームの研究にまで拡大され、最終的には幅広い行動関係に適用されるようになった。現在

では、人間、動物、コンピュータにおける合理的な意思決定の科学を包括する用語となっている。 近代ゲーム理論は、2人によるゼロサムゲームにおける混合戦略均衡の概念と、ジョン・フォン・ノイマンによるその証明から始まった。フォン・ノイマンの当 初の証明では、コンパクト凸集合への連続写像に関するブラウワー固定点定理が用いられ、これはゲーム理論および数理経済学における標準的な手法となった。 彼の論文は、オスカー・モルゲンシュテルンとの共著『ゲームと経済行為の理論』(1944年)に引き継がれ、複数のプレイヤーによる協力ゲームについて考 察した。[3] 第2版では、期待効用の公理理論が提示され、これにより数学統計学者や経済学者が不確実性下での意思決定を扱うことが可能となった。[4] ゲーム理論は1950年代に広く発展し、1970年代には進化に明示的に応用されたが、同様の発展は少なくとも1930年代まで遡ることができる。ゲーム 理論は多くの分野において重要なツールとして広く認識されている。ジョン・メイナード・スミスは、進化ゲーム理論の応用により1999年にクラフォード賞 を受賞し、2020年までにゲーム理論学者15名がノーベル経済学賞を受賞している。その中には、ポール・ミルグラムとロバート・B・ウィルソンも含まれ ている。 |

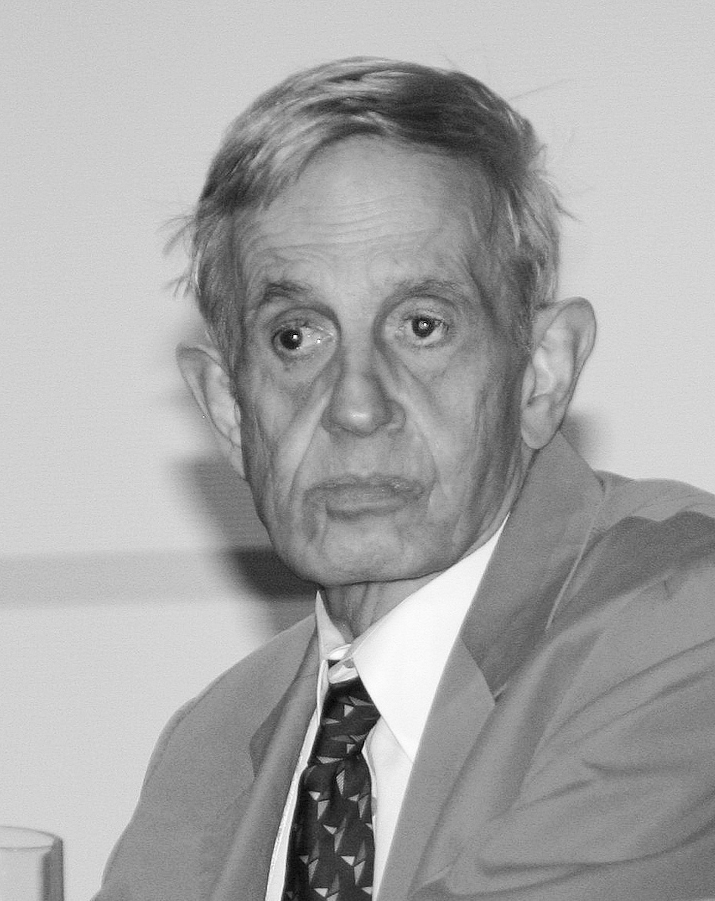

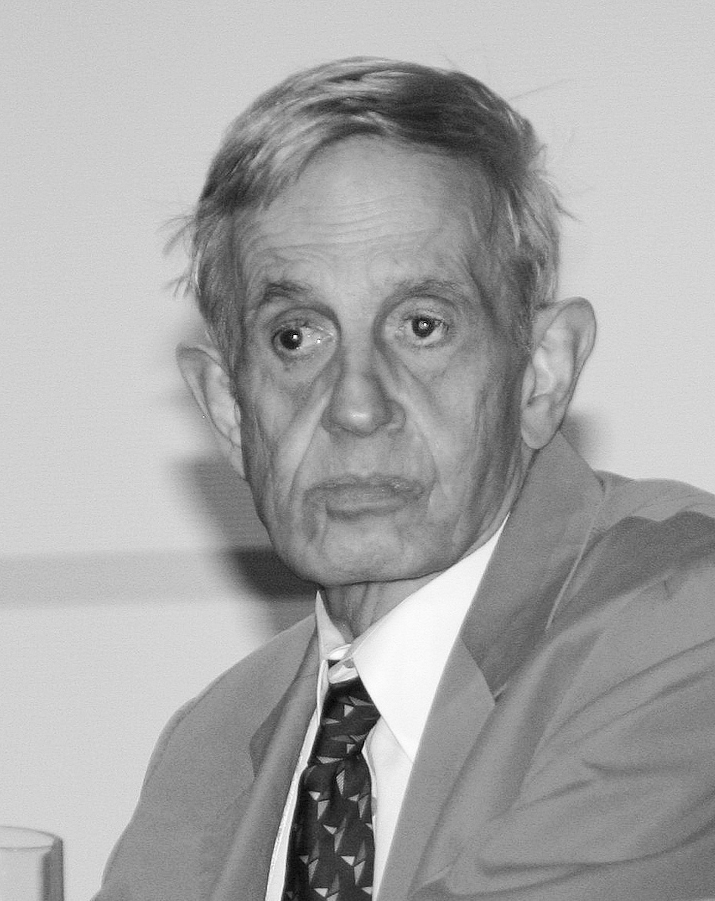

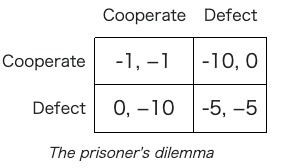

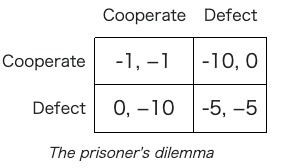

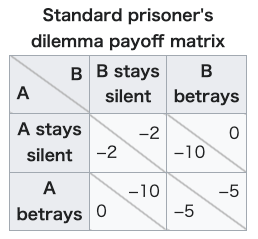

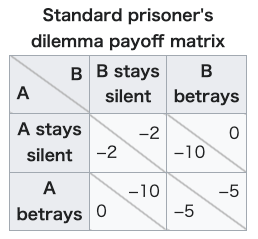

| History Game-theoretic thought Main article: The Art of War For broader coverage of this topic, see Military strategy. See also: International relations theory Game-theoretic strategy within recorded history dates back at least to Sun Tzu's guide on military strategy.[5][6] In The Art of War, he wrote Knowing the other and knowing oneself, In one hundred battles no danger, Not knowing the other and knowing oneself, One victory for one loss, Not knowing the other and not knowing oneself, In every battle certain defeat — Sun Tzu Mathematical origins Discussions on the mathematics of games began long before the rise of modern mathematical game theory. Cardano's work Liber de ludo aleae (Book on Games of Chance), which was written around 1564 but published posthumously in 1663, sketches some basic ideas on games of chance. In the 1650s, Pascal and Huygens developed the concept of expectation on reasoning about the structure of games of chance. Pascal argued for equal division when chances are equal while Huygens extended the argument by considering strategies for a player who can make any bet with any opponent so long as its terms are equal.[7] Huygens later published his gambling calculus as De ratiociniis in ludo aleæ (On Reasoning in Games of Chance) in 1657. In 1713, a letter attributed to Charles Waldegrave, an active Jacobite and uncle to British diplomat James Waldegrave, analyzed a game called "le her".[8][9] Waldegrave provided a minimax mixed strategy solution to a two-person version of the card game, and the problem is now known as Waldegrave problem. In 1838, Antoine Augustin Cournot considered a duopoly and presented a solution that is the Nash equilibrium of the game in his Recherches sur les principes mathématiques de la théorie des richesses (Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth). In 1913, Ernst Zermelo published Über eine Anwendung der Mengenlehre auf die Theorie des Schachspiels (On an Application of Set Theory to the Theory of the Game of Chess), which proved that the optimal chess strategy is strictly determined. This paved the way for more general theorems.[10] In 1938, the Danish mathematical economist Frederik Zeuthen proved that the mathematical model had a winning strategy by using Brouwer's fixed point theorem.[11] In his 1938 book Applications aux Jeux de Hasard and earlier notes, Émile Borel proved a minimax theorem for two-person zero-sum matrix games only when the pay-off matrix is symmetric and provided a solution to a non-trivial infinite game (known in English as Blotto game). Borel conjectured the non-existence of mixed-strategy equilibria in finite two-person zero-sum games, a conjecture that was proved false by von Neumann. Birth and early developments  John von Neumann Game theory emerged as a unique field when John von Neumann published the paper On the Theory of Games of Strategy in 1928.[12][13] Von Neumann's original proof used Brouwer's fixed-point theorem on continuous mappings into compact convex sets, which became a standard method in game theory and mathematical economics. Von Neumann's work in game theory culminated in his 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, co-authored with Oskar Morgenstern.[14] The second edition of this book provided an axiomatic theory of utility, which reincarnated Daniel Bernoulli's old theory of utility (of money) as an independent discipline. This foundational work contains the method for finding mutually consistent solutions for two-person zero-sum games. Subsequent work focused primarily on cooperative game theory, which analyzes optimal strategies for groups of individuals, presuming that they can enforce agreements between them about proper strategies.[15]  John Nash In 1950, the first mathematical discussion of the prisoner's dilemma appeared, and an experiment was undertaken by notable mathematicians Merrill M. Flood and Melvin Dresher, as part of the RAND Corporation's investigations into game theory. RAND pursued the studies because of possible applications to global nuclear strategy.[16] Around this same time, John Nash developed a criterion for mutual consistency of players' strategies known as the Nash equilibrium, applicable to a wider variety of games than the criterion proposed by von Neumann and Morgenstern. Nash proved that every finite n-player, non-zero-sum (not just two-player zero-sum) non-cooperative game has what is now known as a Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies. Game theory experienced a flurry of activity in the 1950s, during which the concepts of the core, the extensive form game, fictitious play, repeated games, and the Shapley value were developed. The 1950s also saw the first applications of game theory to philosophy and political science. Prize-winning achievements In 1965, Reinhard Selten introduced his solution concept of subgame perfect equilibria, which further refined the Nash equilibrium. Later he would introduce trembling hand perfection as well. In 1994 Nash, Selten and Harsanyi became Economics Nobel Laureates for their contributions to economic game theory. In the 1970s, game theory was extensively applied in biology, largely as a result of the work of John Maynard Smith and his evolutionarily stable strategy. In addition, the concepts of correlated equilibrium, trembling hand perfection and common knowledge[a] were introduced and analyzed. In 1994, John Nash was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in the Economic Sciences for his contribution to game theory. Nash's most famous contribution to game theory is the concept of the Nash equilibrium, which is a solution concept for non-cooperative games. A Nash equilibrium is a set of strategies, one for each player, such that no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their strategy. In 2005, game theorists Thomas Schelling and Robert Aumann followed Nash, Selten, and Harsanyi as Nobel Laureates. Schelling worked on dynamic models, early examples of evolutionary game theory. Aumann contributed more to the equilibrium school, introducing equilibrium coarsening and correlated equilibria, and developing an extensive formal analysis of the assumption of common knowledge and of its consequences. In 2007, Leonid Hurwicz, Eric Maskin, and Roger Myerson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics "for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory". Myerson's contributions include the notion of proper equilibrium, and an important graduate text: Game Theory, Analysis of Conflict.[1] Hurwicz introduced and formalized the concept of incentive compatibility. In 2012, Alvin E. Roth and Lloyd S. Shapley were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics "for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design". In 2014, the Nobel went to game theorist Jean Tirole. |

歴史 ゲーム理論的思考 詳細は「孫子」を参照 このトピックをより広くカバーするものについては、「軍事戦略」を参照のこと。 関連項目:国際関係論 記録に残る歴史におけるゲーム理論的戦略は、少なくとも孫子の兵法指南書にまで遡る。[5][6] 孫子は『孫子』において、 敵を知り、己を知れば百戦危うからず、 敵を知らず、己を知れば一勝一敗、 敵も己も知らざれば戦えば必ず敗北す —孫子 数学的起源 ゲームの数学に関する議論は、近代的な数学的ゲーム理論が台頭するはるか以前から始まっていた。カルダーノの著書『Liber de ludo aleae』(1564年頃に執筆され、1663年に死後出版された『賭博の書』)は、偶然性のゲームに関する基本的な考え方をいくつか概説している。 1650年代には、パスカルとホイヘンスが偶然性のゲームの構造に関する推論における期待値の概念を開発した。パスカルは、チャンスが等しい場合には等分 すべきだと主張し、ホイヘンスは、条件が等しければ、どのような相手とどのような賭けをすることもできるプレイヤーの戦略を考慮することで、その主張を拡 張した。[7] ホイヘンスは後に、1657年に『De ratiociniis in ludo aleæ(チャンスゲームにおける推論)』として、自身のギャンブルの計算方法を発表した。 1713年には、英国の外交官ジェームズ・ウォルデグレイヴの叔父で、ジャコバイト党の活動家であったチャールズ・ウォルデグレイヴに帰せられる書簡で、 「le her」と呼ばれるゲームが分析された。[8][9] ウォルデグレイヴは、2人用のカードゲームのミニマックス混合戦略による解法を提供し、この問題は現在ではウォルデグレイヴ問題として知られている。 1838年、アントワーヌ・オーギュスティン・クールノーは独占的競争を考察し、著書『富の理論の数学的諸原理についての研究』の中で、そのゲームのナッ シュ均衡となる解決策を提示した。 1913年にはエルンスト・ツェルメロが『集合論のチェス理論への応用』を発表し、最適なチェスの戦略は厳密に決定されることを証明した。これにより、より一般的な定理の道筋がつけられた。[10] 1938年、デンマークの数学経済学者フレデリック・ゼウテンはブラウワーの不動点定理を用いて、数学モデルに必勝法があることを証明した。[11] 1938年の著書『Applications aux Jeux de Hasard』 およびそれ以前のノートにおいて、エミール・ボレルは、ペイオフ行列が対称である場合の2人用ゼロサム行列ゲームにおけるミニマックス定理を証明し、非自 明な無限ゲーム(英語では「Blottoゲーム」として知られている)の解決策を提供した。ボレルは、有限の2人用ゼロサムゲームにおける混合戦略均衡の 非存在を推測したが、フォン・ノイマンによってその推測は誤りであることが証明された。 誕生と初期の発展  ジョン・フォン・ノイマン ゲーム理論は、1928年にジョン・フォン・ノイマンが「戦略ゲームの理論」という論文を発表したことにより、独自の分野として登場した。[12] [13] フォン・ノイマンの当初の証明では、コンパクト凸集合への連続写像に関するブラウワーの不動点定理が用いられており、これはゲーム理論および数理経済学に おける標準的な手法となった。フォン・ノイマンのゲーム理論に関する研究は、1944年にオスカー・モルゲンシュテルンとの共著『ゲームと経済行為の理 論』で頂点に達した。[14] この本の第2版では、ダニエル・ベルヌーイの古い効用理論(貨幣の効用)を独立した学問分野として復活させた公理的な効用理論が提示された。この基礎的な 研究には、2人によるゼロサムゲームの相互に矛盾しない解を見つける方法が含まれている。その後の研究は主に協力ゲーム理論に焦点を当て、個人のグループ が適切な戦略について合意を強制できると仮定し、そのグループにとっての最適戦略を分析するものである。[15]  ジョン・ナッシュ 1950年、囚人のジレンマに関する最初の数学的議論が発表され、著名な数学者であるMerrill M. FloodとMelvin Dresherが、ゲーム理論に関するRAND Corporationの調査の一環として実験を行った。RAND社が研究を続けたのは、世界的な核戦略への応用が考えられたためである。[16] ほぼ同時期に、ジョン・ナッシュは、フォン・ノイマンとモーゲンシュテルンが提案した基準よりも幅広い種類のゲームに適用できる、ナッシュ均衡として知ら れるプレイヤーの戦略の相互整合性の基準を開発した。ナッシュは、有限のn人プレイヤー、ゼロサムではない(2人プレイヤーのゼロサムに限らない)非協力 ゲームには、混合戦略におけるナッシュ均衡として知られるものがあることを証明した。 1950年代にはゲーム理論が活況を呈し、コア、エクステンシブ・フォーム・ゲーム、フィクスト・プレイ、繰り返しゲーム、シャプレー値などの概念が開発された。1950年代には、ゲーム理論が初めて哲学や政治学に応用された。 受賞に値する功績 1965年、ラインハルト・ゼルテンはナッシュ均衡をさらに洗練させた部分ゲーム完全均衡という解決概念を導入した。その後、彼は「震える手」完全均衡も導入した。1994年、ナッシュ、ゼルテン、ハーサンジーは経済ゲーム理論への貢献によりノーベル経済学賞を受賞した。 1970年代には、ジョン・メイナード・スミス(John Maynard Smith)の進化安定戦略(evolutionarily stable strategy)の研究を主な要因として、ゲーム理論が生物学に広く応用されるようになった。さらに、相関均衡(correlated equilibrium)、震える手完全(trembling hand perfection)、共通知識(common knowledge)[a]の概念が導入され、分析された。 1994年には、ゲーム理論への貢献によりジョン・ナッシュがノーベル経済学賞を受賞した。ナッシュのゲーム理論への最も有名な貢献は、非協力ゲームの解 概念であるナッシュ均衡の概念である。ナッシュ均衡とは、各プレイヤーが持つ戦略の集合であり、どのプレイヤーも一方的に戦略を変更しても利得を改善でき ないようなものである。 2005年には、ゲーム理論学者のトーマス・シェリングとロバート・アウマンが、ナッシュ、ゼルテン、ハルサニに続いてノーベル賞を受賞した。シェリング は動的モデル、すなわち進化ゲーム理論の初期の例に取り組んだ。アウマンは均衡学派により貢献し、均衡の粗視化と相関均衡を導入し、共通認識の仮定とその 帰結に関する広範な形式分析を開発した。 2007年には、「メカニズムデザイン理論の基礎を築いた」としてレオン・ヒルヴィッチ、エリック・マスキン、ロジャー・マイヤソンがノーベル経済学賞を 受賞した。マイヤソンの貢献には、適切な均衡の概念、および重要な大学院テキストである『ゲーム理論、対立の分析』がある。[1] ヒルヴィッチはインセンティブ・コンパティビリティの概念を導入し、それを形式化した。 2012年には、アルビン・E・ロスとロイド・S・シャプレーが「安定配分理論と市場設計の実践」によりノーベル経済学賞を受賞した。2014年には、ゲーム理論学者のジャン・ティロールがノーベル賞を受賞した。 |

| Different types of games See also: List of games in game theory Cooperative / non-cooperative Main articles: Cooperative game theory and Non-cooperative game A game is cooperative if the players are able to form binding commitments externally enforced (e.g. through contract law). A game is non-cooperative if players cannot form alliances or if all agreements need to be self-enforcing (e.g. through credible threats).[17] Cooperative games are often analyzed through the framework of cooperative game theory, which focuses on predicting which coalitions will form, the joint actions that groups take, and the resulting collective payoffs. It is different from non-cooperative game theory which focuses on predicting individual players' actions and payoffs by analyzing Nash equilibria.[18][19] Cooperative game theory provides a high-level approach as it describes only the structure and payoffs of coalitions, whereas non-cooperative game theory also looks at how strategic interaction will affect the distribution of payoffs. As non-cooperative game theory is more general, cooperative games can be analyzed through the approach of non-cooperative game theory (the converse does not hold) provided that sufficient assumptions are made to encompass all the possible strategies available to players due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperation. |

異なる種類のゲーム 関連項目:ゲーム理論におけるゲームの一覧 協力型/非協力型 主な記事:協力型ゲーム理論および非協力型ゲーム プレイヤーが外部から強制力のある拘束力のある約束を結ぶことができる場合、ゲームは協力型となる(例えば契約法を通じて)。プレイヤーが同盟を結ぶこと ができない場合、またはすべての合意が自己強制力を持つ必要がある場合(例えば信頼できる脅威を通じて)、ゲームは非協力型となる。[17] 協力ゲームは、協力ゲーム理論の枠組みで分析されることが多い。協力ゲーム理論は、どの連合が形成されるか、グループがとる共同行動、およびその結果とし ての集団の利益分配を予測することに焦点を当てている。これは、ナッシュ均衡を分析することで個々のプレイヤーの行動と利益分配を予測することに焦点を当 てている非協力ゲーム理論とは異なる。[18][19] 非協力ゲーム理論では、戦略的相互作用が成果の分配にどのような影響を与えるかも考慮するが、協力ゲーム理論では連合の構造と成果のみを記述するため、よ り高次なアプローチとなる。非協力ゲーム理論の方がより一般的であるため、協力ゲームは非協力ゲーム理論のアプローチによって分析することができる(その 逆は成立しない)。ただし、協力の外部強制の可能性を考慮し、プレーヤーが利用可能なすべての戦略を網羅する十分な仮定が立てられる場合に限る。 |

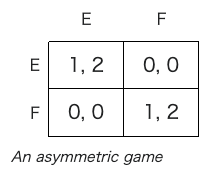

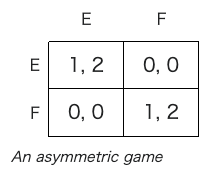

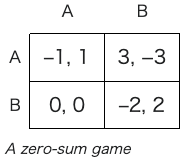

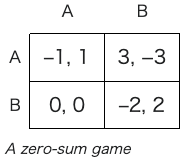

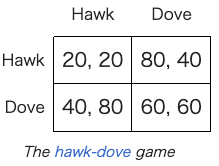

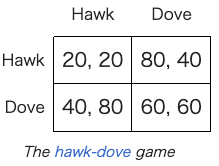

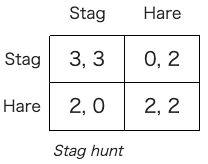

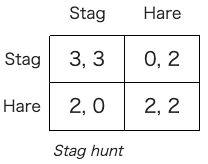

Symmetric game A symmetric game is a game where each player earns the same payoff when making the same choice. In other words, the identity of the player does not change the resulting game facing the other player.[20] Many of the commonly studied 2×2 games are symmetric. The standard representations of chicken, the prisoner's dilemma, and the stag hunt are all symmetric games. The most commonly studied asymmetric games are games where there are not identical strategy sets for both players. For instance, the ultimatum game and similarly the dictator game have different strategies for each player. It is possible, however, for a game to have identical strategies for both players, yet be asymmetric. For example, the game pictured in this section's graphic is asymmetric despite having identical strategy sets for both players. |

対称ゲーム 対称ゲームとは、各プレイヤーが同じ選択をした場合、同じ利益を得るゲームである。言い換えれば、プレイヤーの身元は、相手プレイヤーが直面するゲームの 結果を変えることはない。一般的に研究されている2×2ゲームの多くは対称ゲームである。チキン、囚人のジレンマ、雄鹿狩りの標準的な表現は、すべて対称 ゲームである。 非対称ゲームとして最もよく研究されているのは、両プレイヤーの戦略セットが同一ではないゲームである。例えば、最後通牒ゲームやそれに類似したディク タートゲームでは、各プレイヤーの戦略は異なる。しかし、両プレイヤーの戦略が同一であるにもかかわらず非対称であるゲームも存在する。例えば、このセク ションの図に示されているゲームは、両プレイヤーの戦略セットが同一であるにもかかわらず非対称である。 |

Zero-sum game Zero-sum games (more generally, constant-sum games) are games in which choices by players can neither increase nor decrease the available resources. In zero-sum games, the total benefit goes to all players in a game, for every combination of strategies, and always adds to zero (more informally, a player benefits only at the equal expense of others).[21] Poker exemplifies a zero-sum game (ignoring the possibility of the house's cut), because one wins exactly the amount one's opponents lose. Other zero-sum games include matching pennies and most classical board games including Go and chess. Many games studied by game theorists (including the famed prisoner's dilemma) are non-zero-sum games, because the outcome has net results greater or less than zero. Informally, in non-zero-sum games, a gain by one player does not necessarily correspond with a loss by another. Furthermore, constant-sum games correspond to activities like theft and gambling, but not to the fundamental economic situation in which there are potential gains from trade. It is possible to transform any constant-sum game into a (possibly asymmetric) zero-sum game by adding a dummy player (often called "the board") whose losses compensate the players' net winnings. |

対称ゲーム ゼロ和ゲーム ゼロサムゲーム(より一般的にはコンスタントサムゲーム)とは、プレイヤーの選択が利用可能な資源を増やすことも減らすこともできないゲームのことであ る。ゼロサムゲームでは、どのような戦略の組み合わせであっても、ゲームに参加するすべてのプレイヤーに利益の合計が行き渡り、常にゼロに加算される(よ り非公式には、プレイヤーは他のプレイヤーの平等な犠牲の上にのみ利益を得る)[21]。ポーカーはゼロサムゲーム(ハウスのカットの可能性を無視する) の例であり、対戦相手が失う金額と全く同じだけ勝つからである。他のゼロサムゲームには、ペニーのマッチングや、囲碁やチェスを含む古典的なボードゲーム のほとんどが含まれる。 ゲーム理論家によって研究されている多くのゲーム(有名な囚人のジレンマを含む)は、結果がゼロより大きいか小さい正味の結果を持つので、非ゼロサムゲー ムである。非公式には、非ゼロサムゲームでは、あるプレーヤーが利益を得ても、他のプレーヤーが損失を被るとは限らない。 さらに、コンスタントサムゲームは、窃盗やギャンブルのような活動には対応するが、貿易から利益が得られる可能性があるという基本的な経済状況には対応し ない。ダミーのプレーヤー(しばしば「ボード」と呼ばれる)を加えることで、定 和ゲームを(場合によっては非対称の)ゼロ和ゲームに変換することができる。 |

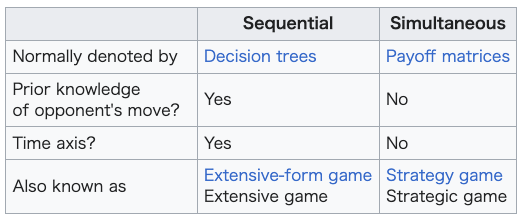

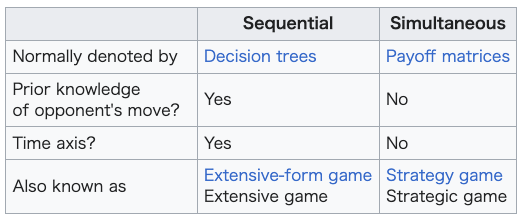

Simultaneous / sequential Main articles: Simultaneous game and Sequential game Simultaneous games are games where both players move simultaneously, or instead the later players are unaware of the earlier players' actions (making them effectively simultaneous). Sequential games (or dynamic games) are games where players do not make decisions simultaneously, and player's earlier actions affect the outcome and decisions of other players.[22] This need not be perfect information about every action of earlier players; it might be very little knowledge. For instance, a player may know that an earlier player did not perform one particular action, while they do not know which of the other available actions the first player actually performed. The difference between simultaneous and sequential games is captured in the different representations discussed above. Often, normal form is used to represent simultaneous games, while extensive form is used to represent sequential ones. The transformation of extensive to normal form is one way, meaning that multiple extensive form games correspond to the same normal form. Consequently, notions of equilibrium for simultaneous games are insufficient for reasoning about sequential games; see subgame perfection. In short, the differences between sequential and simultaneous games are as follows: |

同時/連続 主な記事 同時対局と連続対局 同時対局とは、両プレイヤーが同時に動くか、あるいは後のプレイヤーが前のプレイヤーの行動に気づかない(事実上同時対局となる)対局のことである。逐次 ゲーム(または動的ゲーム)とは、プレイヤーが同時に決定を下さず、プレイヤーの以前の行動が他のプレイヤーの結果と決定に影響を与えるゲームである [22]。例えば、あるプレイヤーは、先にプレイしたプレイヤーがある特定の 行動を取らなかったことを知っていても、先にプレイしたプレイヤーが実際に 取った行動が他のどの行動であったかは知らない。 同時対局と逐次対局の違いは、上述したさまざまな表現に現れている。多くの場合、同時対局の表現には正規形が使われ、逐次対局の表現には広範形が使われ る。広範形から正規形への変換は一方通行であり、複数の広範形ゲームが同じ正規形に対応することを意味する。したがって、同時ゲームの均衡の概念は、逐次 ゲームの推論には不十分である。 要するに、逐次ゲームと同時ゲームの違いは以下の通りである: |

| Perfect information and imperfect information Main article: Perfect information  A game of imperfect information. The dotted line represents ignorance on the part of player 2, formally called an information set. An important subset of sequential games consists of games of perfect information. A game with perfect information means that all players, at every move in the game, know the previous history of the game and the moves previously made by all other players. An imperfect information game is played when the players do not know all moves already made by the opponent such as a simultaneous move game.[23] Examples of perfect-information games include tic-tac-toe, checkers, chess, and Go.[24][25][26] Many card games are games of imperfect information, such as poker and bridge.[27] Perfect information is often confused with complete information, which is a similar concept pertaining to the common knowledge of each player's sequence, strategies, and payoffs throughout gameplay.[28] Complete information requires that every player know the strategies and payoffs available to the other players but not necessarily the actions taken, whereas perfect information is knowledge of all aspects of the game and players.[29] Games of incomplete information can be reduced, however, to games of imperfect information by introducing "moves by nature".[30] |

完全情報と不完全情報 主な記事 完全情報  不完全情報のゲーム。点線はプレイヤー2の無知を表し、正式には情報セットと呼ばれる。 逐次ゲームの重要な部分集合は、完全情報ゲームである。完全情報ゲームとは、すべてのプレーヤーが、ゲームの各手において、ゲームの前の履歴と、他のすべ てのプレーヤーが以前に打った手を知っていることを意味する。不完全情報ゲームとは、同時手ゲームのように、対戦相手が既に打ったすべての手をプレイヤー が知らない場合に行われるゲームである[23]。完全情報ゲームの例としては、三目並べ、チェッカー、チェス、囲碁などがある[24][25][26]。 完全情報はしばしば完全情報と混同されるが、これはゲームプレイを通じて各プレイヤーのシークエンス、戦略、ペイオフを共通に知っていることに関連する同 様の概念である[27]。 [28]完全情報は、すべてのプレイヤーが他のプレイヤーが利用可能な戦略とペイオフを知っている必要があるが、必ずしも取られた行動ではないのに対し、 完全情報はゲームとプレイヤーのすべての側面に関する知識である[29]。不完全情報のゲームは、しかし、「自然による動き」を導入することによって不完 全情報のゲームに縮小することができる[30]。 |

| Bayesian game Main article: Bayesian game One of the assumptions of the Nash equilibrium is that every player has correct beliefs about the actions of the other players. However, there are many situations in game theory where participants do not fully understand the characteristics of their opponents. Negotiators may be unaware of their opponent's valuation of the object of negotiation, companies may be unaware of their opponent's cost functions, combatants may be unaware of their opponent's strengths, and jurors may be unaware of their colleague's interpretation of the evidence at trial. In some cases, participants may know the character of their opponent well, but may not know how well their opponent knows his or her own character.[31] Bayesian game means a strategic game with incomplete information. For a strategic game, decision makers are players, and every player has a group of actions. A core part of the imperfect information specification is the set of states. Every state completely describes a collection of characteristics relevant to the player such as their preferences and details about them. There must be a state for every set of features that some player believes may exist.[32]  Example of a Bayesian game For example, where Player 1 is unsure whether Player 2 would rather date her or get away from her, while Player 2 understands Player 1's preferences as before. To be specific, supposing that Player 1 believes that Player 2 wants to date her under a probability of 1/2 and get away from her under a probability of 1/2 (this evaluation comes from Player 1's experience probably: she faces players who want to date her half of the time in such a case and players who want to avoid her half of the time). Due to the probability involved, the analysis of this situation requires to understand the player's preference for the draw, even though people are only interested in pure strategic equilibrium. |

ベイズゲーム 主な記事 ベイズゲーム ナッシュ均衡の仮定の一つは、すべてのプレイヤーが他のプレイヤーの行動に関して正しい信念を持っているということである。しかし、ゲーム理論では、参加 者が相手の特性を完全に理解していない状況が多く存在する。交渉者は相手の交渉対象の評価を知らないかもしれないし、企業は相手のコスト関数を知らないか もしれないし、戦闘員は相手の強さを知らないかもしれないし、陪審員は裁判での証拠の同僚の解釈を知らないかもしれない。場合によっては、参加者は相手の 性格をよく知っているかもしれないが、相手が自分の性格をどの程度知っているかは知らないかもしれない[31]。 ベイズゲームとは、情報が不完全な戦略的ゲームを意味する。戦略ゲームの場合、意思決定者はプレーヤーであり、各プレーヤーは行動グループを持っている。 不完全情報仕様の中核となるのは、状態の集合である。各状態は、プレーヤーの嗜好やその詳細など、プレーヤーに関連する特性の集合を完全に記述する。ある プレイヤーが存在すると考える特徴の集合ごとに状態が存在しなければならない[32]。  ベイズゲームの例 例えば、プレイヤー1が、プレイヤー2が彼女と付き合いたいのか、それとも彼女から逃げたいのか、迷っている一方で、プレイヤー2はプレイヤー1の嗜好を 従来通り理解しているとする。具体的には、プレイヤー1が、プレイヤー2は1/2の確率で自分と付き合い、1/2の確率で自分から離れたいと考えていると する(この評価は、おそらくプレイヤー1の経験に由来する:彼女は、このような場合、半分の確率で自分と付き合いたいプレイヤーに直面し、半分の確率で彼 女を避けたいプレイヤーに直面する)。このような確率が関係するため、この状況を分析するには、純粋な戦略的均衡にしか興味がないにもかかわらず、引き分 けに対するプレーヤーの選好を理解する必要がある。 |

| Combinatorial games Games in which the difficulty of finding an optimal strategy stems from the multiplicity of possible moves are called combinatorial games. Examples include chess and Go. Games that involve imperfect information may also have a strong combinatorial character, for instance backgammon. There is no unified theory addressing combinatorial elements in games. There are, however, mathematical tools that can solve some particular problems and answer some general questions.[33] Games of perfect information have been studied in combinatorial game theory, which has developed novel representations, e.g. surreal numbers, as well as combinatorial and algebraic (and sometimes non-constructive) proof methods to solve games of certain types, including "loopy" games that may result in infinitely long sequences of moves. These methods address games with higher combinatorial complexity than those usually considered in traditional (or "economic") game theory.[34][35] A typical game that has been solved this way is Hex. A related field of study, drawing from computational complexity theory, is game complexity, which is concerned with estimating the computational difficulty of finding optimal strategies.[36] Research in artificial intelligence has addressed both perfect and imperfect information games that have very complex combinatorial structures (like chess, go, or backgammon) for which no provable optimal strategies have been found. The practical solutions involve computational heuristics, like alpha–beta pruning or use of artificial neural networks trained by reinforcement learning, which make games more tractable in computing practice.[33][37] Discrete and continuous games Much of game theory is concerned with finite, discrete games that have a finite number of players, moves, events, outcomes, etc. Many concepts can be extended, however. Continuous games allow players to choose a strategy from a continuous strategy set. For instance, Cournot competition is typically modeled with players' strategies being any non-negative quantities, including fractional quantities. Differential games Main article: Differential game Differential games such as the continuous pursuit and evasion game are continuous games where the evolution of the players' state variables is governed by differential equations. The problem of finding an optimal strategy in a differential game is closely related to the optimal control theory. In particular, there are two types of strategies: the open-loop strategies are found using the Pontryagin maximum principle while the closed-loop strategies are found using Bellman's Dynamic Programming method. A particular case of differential games are the games with a random time horizon.[38] In such games, the terminal time is a random variable with a given probability distribution function. Therefore, the players maximize the mathematical expectation of the cost function. It was shown that the modified optimization problem can be reformulated as a discounted differential game over an infinite time interval. Evolutionary game theory Main article: Evolutionary game theory Evolutionary game theory studies players who adjust their strategies over time according to rules that are not necessarily rational or farsighted.[39] In general, the evolution of strategies over time according to such rules is modeled as a Markov chain with a state variable such as the current strategy profile or how the game has been played in the recent past. Such rules may feature imitation, optimization, or survival of the fittest. In biology, such models can represent evolution, in which offspring adopt their parents' strategies and parents who play more successful strategies (i.e. corresponding to higher payoffs) have a greater number of offspring. In the social sciences, such models typically represent strategic adjustment by players who play a game many times within their lifetime and, consciously or unconsciously, occasionally adjust their strategies.[40] Stochastic outcomes (and relation to other fields) Individual decision problems with stochastic outcomes are sometimes considered "one-player games". They may be modeled using similar tools within the related disciplines of decision theory, operations research, and areas of artificial intelligence, particularly AI planning (with uncertainty) and multi-agent system. Although these fields may have different motivators, the mathematics involved are substantially the same, e.g. using Markov decision processes (MDP).[41] Stochastic outcomes can also be modeled in terms of game theory by adding a randomly acting player who makes "chance moves" ("moves by nature").[42] This player is not typically considered a third player in what is otherwise a two-player game, but merely serves to provide a roll of the dice where required by the game. For some problems, different approaches to modeling stochastic outcomes may lead to different solutions. For example, the difference in approach between MDPs and the minimax solution is that the latter considers the worst-case over a set of adversarial moves, rather than reasoning in expectation about these moves given a fixed probability distribution. The minimax approach may be advantageous where stochastic models of uncertainty are not available, but may also be overestimating extremely unlikely (but costly) events, dramatically swaying the strategy in such scenarios if it is assumed that an adversary can force such an event to happen.[43] (See Black swan theory for more discussion on this kind of modeling issue, particularly as it relates to predicting and limiting losses in investment banking.) General models that include all elements of stochastic outcomes, adversaries, and partial or noisy observability (of moves by other players) have also been studied. The "gold standard" is considered to be partially observable stochastic game (POSG), but few realistic problems are computationally feasible in POSG representation.[43] Metagames These are games the play of which is the development of the rules for another game, the target or subject game. Metagames seek to maximize the utility value of the rule set developed. The theory of metagames is related to mechanism design theory. The term metagame analysis is also used to refer to a practical approach developed by Nigel Howard,[44] whereby a situation is framed as a strategic game in which stakeholders try to realize their objectives by means of the options available to them. Subsequent developments have led to the formulation of confrontation analysis. Mean field game theory Main article: Mean field game theory Mean field game theory is the study of strategic decision making in very large populations of small interacting agents. This class of problems was considered in the economics literature by Boyan Jovanovic and Robert W. Rosenthal, in the engineering literature by Peter E. Caines, and by mathematicians Pierre-Louis Lions and Jean-Michel Lasry. |

組み合わせゲーム 可能な手の数が多いために最適戦略を見つけるのが難しいゲームは、組み合わせゲームと呼ばれる。チェスや囲碁などがその例である。情報が不完全なゲーム も、バックギャモンなど、組み合わせ論的な性格が強い場合がある。ゲームにおける組み合わせ論的要素を扱う統一理論は存在しない。しかし、いくつかの特定 の問題を解き、いくつかの一般的な疑問に答えることができる数学的なツールは存在する[33]。 完全情報のゲームは組合せゲーム理論で研究されており、シュール数などの新しい表現や、無限に長い手番が続く可能性のある「ルーピー」ゲームなど、ある種 のゲームを解くための組合せ的・代数的な(時には非構成的な)証明方法が開発されている。これらの方法は、伝統的な(あるいは「経済的な」)ゲーム理論で 通常考慮されるゲームよりも、組合せ複雑度が高いゲームに対処するものである。関連する研究分野として、計算複雑性理論から導き出されたゲームの複雑性が あり、最適戦略を見つける計算難易度の推定に関係している[36]。 人工知能の研究では、証明可能な最適戦略が見つかっていない非常に複雑な組み合わせ構造を持つゲーム(チェス、囲碁、バックギャモンなど)を完全情報ゲー ムと不完全情報ゲームの両方で扱ってきた。実用的な解決策としては、アルファ・ベータ刈り込みや強化学習によって訓練された人工ニューラルネットワークの 使用などの計算ヒューリスティックがあり、計算実務においてゲームをより扱いやすくしている[33][37]。 離散ゲームと連続ゲーム ゲーム理論の多くは、プレイヤー、手、イベント、結果などの数が有限である、有限の離散ゲームに関係している。しかし、多くの概念は拡張可能である。連続 ゲームでは、プレイヤーは連続的な戦略セットから戦略を選択することができる。例えば、Cournot競争は通常、プレーヤーの戦略が分数を含む任意の非 負量であるものとしてモデル化される。 微分ゲーム 主な記事 微分ゲーム 連続追跡ゲームや回避ゲームなどの微分ゲームは、プレーヤーの状態変数の展開が微分方程式によって支配される連続ゲームである。微分ゲームにおける最適戦 略を求める問題は、最適制御理論と密接な関係がある。特に、開ループ戦略はポントリャギンの最大原理を用い、閉ループ戦略はベルマンの動的計画法を用いて 求める。 差分ゲームの特殊なケースは、ランダムな時間地平を持つゲームである[38]。このようなゲームでは、終局時間は与えられた確率分布関数を持つ確率変数で ある。したがって、プレイヤーはコスト関数の数学的期待値を最大化する。修正最適化問題は、無限の時間間隔にわたる割引微分ゲームとして再定式化できるこ とが示された。 進化ゲーム理論 主な記事 進化ゲーム理論 進化ゲーム理論では、必ずしも合理的でも先見の明があるわけでもないルールに従って経時的に戦略を調整するプレーヤーを研究する[39]。一般に、このよ うなルールに従って経時的に戦略が進化する様子は、現在の戦略プロファイルや最近の過去にゲームがどのようにプレイされたかというような状態変数を持つマ ルコフ連鎖としてモデル化される。このようなルールには、模倣、最適化、適者生存などがある。 生物学では、このようなモデルは進化を表現することができ、子孫は親の戦略を採用し、より成功した戦略(すなわち、より高いペイオフに対応する)をプレー する親は、より多くの子孫を持つ。社会科学では、このようなモデルは、生涯に何度もゲームをプレイし、意識的または無意識的に、時折戦略を調整するプレイ ヤーによる戦略調整を表すのが一般的である[40]。 確率的結果(および他の分野との関係) 確率的な結果を伴う個人の意思決定問題は、「ワンプレイヤーゲーム」とみなされることがある。これらの問題は、意思決定理論、オペレーションズ・リサー チ、人工知能の分野、特に(不確実性を伴う)AIプランニング、マルチエージェントシステムなどの関連分野で、同様のツールを使ってモデル化されることが ある。これらの分野は動機が異なるかもしれないが、マルコフ決定過程(MDP)を使用するなど、関係する数学は実質的に同じである[41]。 確率的な結果は、「偶然の動き」(「自然による動き」)をするランダムに行動するプレーヤーを追加することによって、ゲーム理論の観点からモデル化するこ ともできる[42]。このプレーヤーは、通常、そうでなければ2人用のゲームにおける第3のプレーヤーとはみなされず、ゲームによって要求されるサイコロ の目を提供する役割を果たすだけである。 問題によっては、確率的な結果をモデル化するための異なるアプローチが、異なる解を導くことがある。例えば、MDPとミニマックス解のアプローチの違い は、後者が、固定確率分布が与えられた場合の手について期待値で推論するのではなく、敵対する手の集合について最悪のケースを考慮することである。 minimaxのアプローチは、不確実性の確率モデルが利用できない場合に有利かもしれないが、非常に起こりにくい(しかしコストのかかる)事象を過大評 価する可能性もあり、敵対者がそのような事象を強制的に発生させることができると仮定した場合、そのようなシナリオでの戦略を劇的に揺るがすことになる [43](この種のモデル化の問題、特に投資銀行業務における損失の予測と制限に関する詳細な議論については、ブラック・スワン理論を参照のこと)。 確率的な結果、敵対者、(他のプレーヤーの手の)部分的またはノイズの多い観測可能性など、すべての要素を含む一般的なモデルも研究されている。ゴールド スタンダード」は部分的に観測可能な確率ゲーム(POSG)と考えられているが、POSG表現で計算可能な現実的な問題はほとんどない[43]。 メタゲーム メタゲーム(Metagames)とは、別のゲーム(ターゲット・ゲームまたはサブジェクト・ゲーム)のルールを開発するゲームである。メタゲームは、開 発されたルールセットの効用値を最大化しようとするものである。メタゲームの理論は、メカニズム設計理論と関連している。 メタゲーム分析という用語は、ナイジェル・ハワード(Nigel Howard)によって開発された実践的なアプローチ[44]を指す場合にも使用され、これによって状況は、利害関係者が利用可能な選択肢によって目的を 実現しようとする戦略的なゲームとして組み立てられる。その後の発展により、対立分析が定式化されるに至った。 平均場ゲーム理論 主な記事 平均場ゲーム理論 平均場ゲーム理論は、相互作用する小さなエージェントの非常に大きな集団における戦略的意思決定の研究である。この種の問題は、経済学ではBoyan JovanovicとRobert W. Rosenthalによって、工学ではPeter E. Cainesによって、数学ではPierre-Louis LionsとJean-Michel Lasryによって考察された。 |

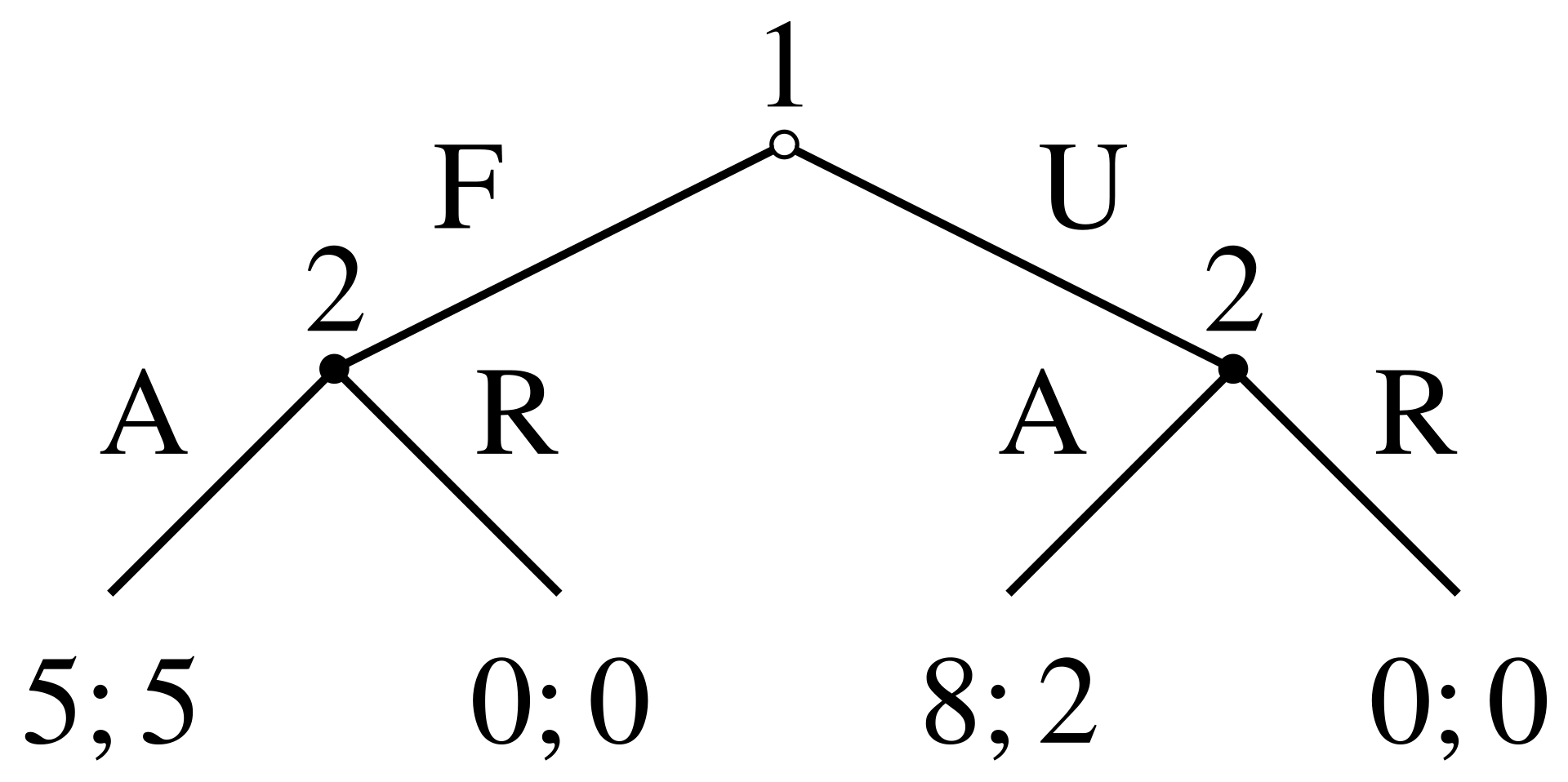

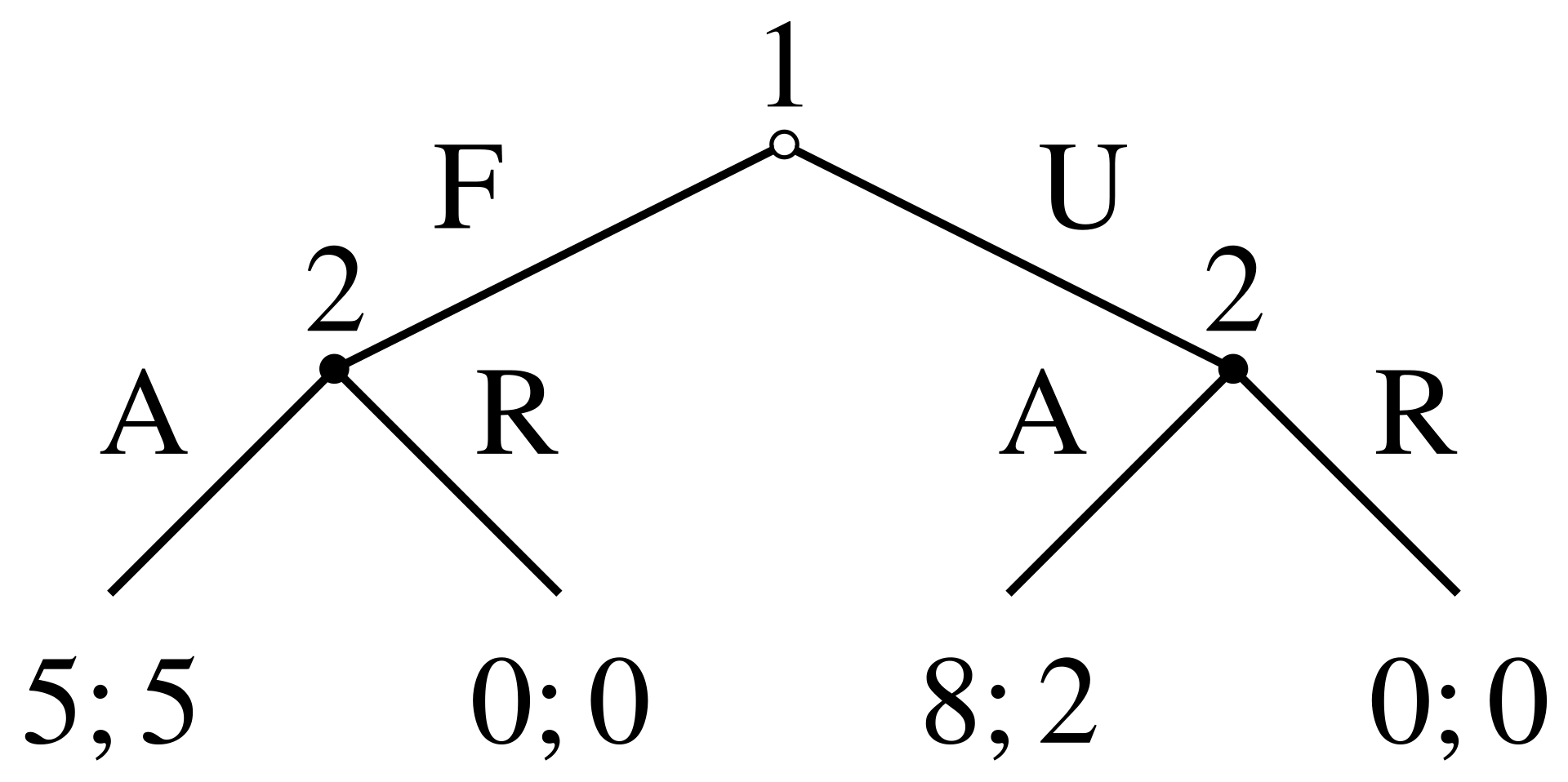

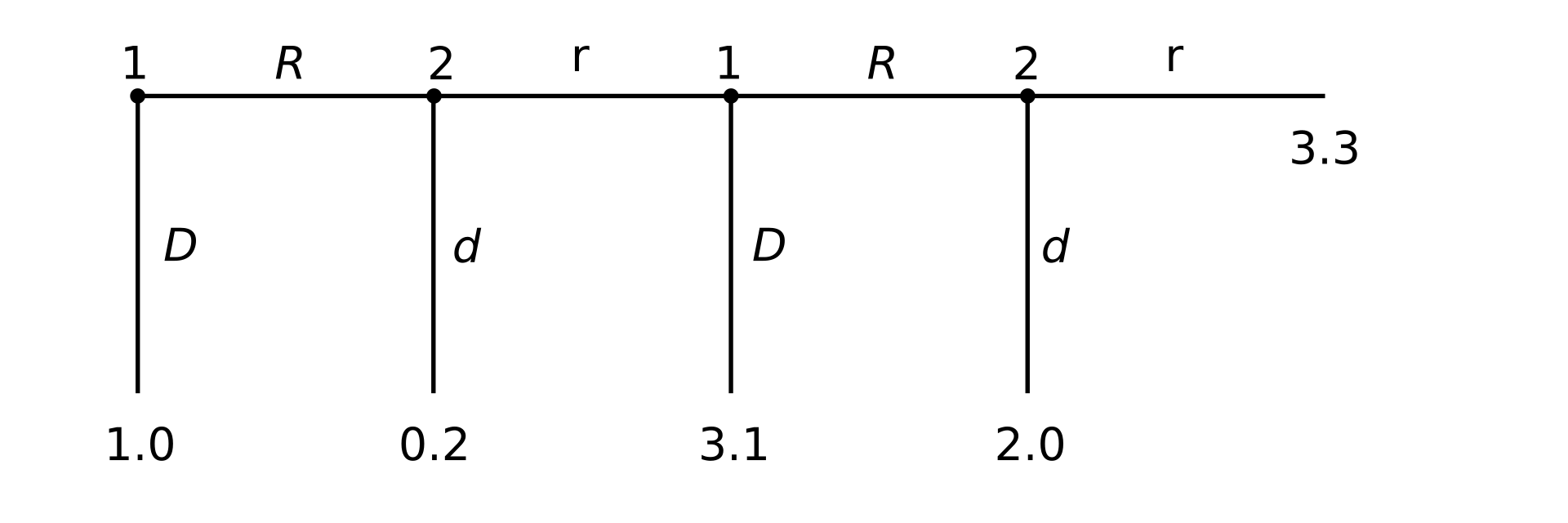

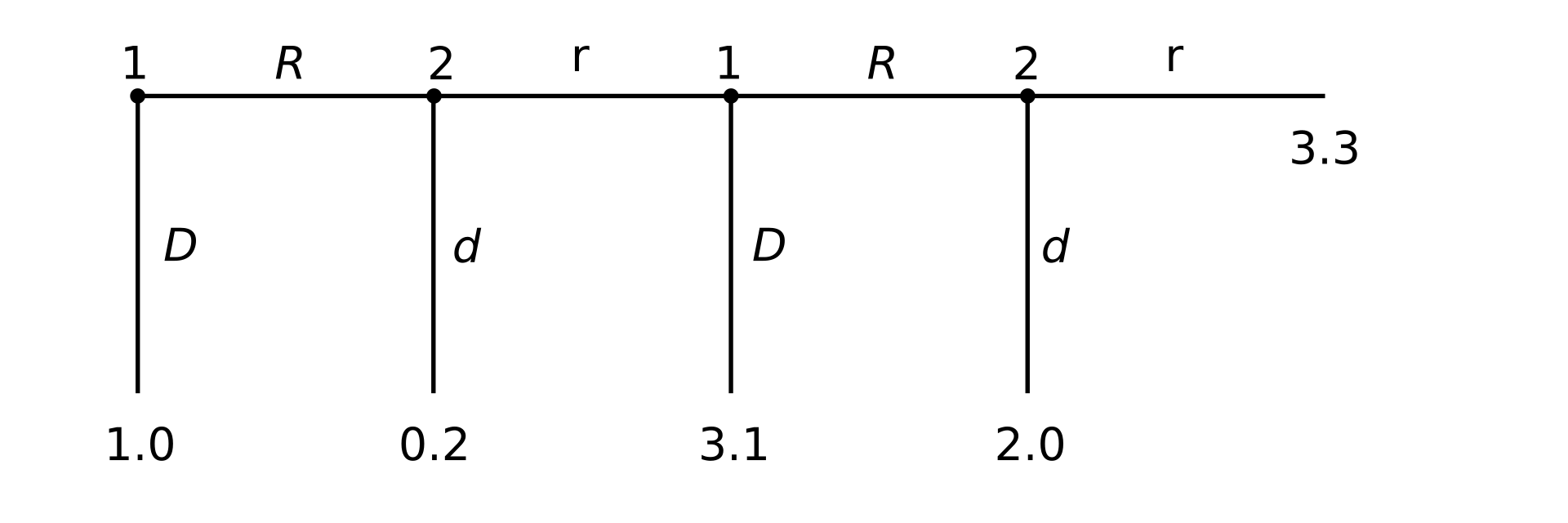

| Representation of games The games studied in game theory are well-defined mathematical objects. To be fully defined, a game must specify the following elements: the players of the game, the information and actions available to each player at each decision point, and the payoffs for each outcome. (Eric Rasmusen refers to these four "essential elements" by the acronym "PAPI".)[45][46][47][48] A game theorist typically uses these elements, along with a solution concept of their choosing, to deduce a set of equilibrium strategies for each player such that, when these strategies are employed, no player can profit by unilaterally deviating from their strategy. These equilibrium strategies determine an equilibrium to the game—a stable state in which either one outcome occurs or a set of outcomes occur with known probability. Most cooperative games are presented in the characteristic function form, while the extensive and the normal forms are used to define noncooperative games. Extensive form Main article: Extensive form game  An extensive form game The extensive form can be used to formalize games with a time sequencing of moves. Extensive form games can be visualised using game trees (as pictured here). Here each vertex (or node) represents a point of choice for a player. The player is specified by a number listed by the vertex. The lines out of the vertex represent a possible action for that player. The payoffs are specified at the bottom of the tree. The extensive form can be viewed as a multi-player generalization of a decision tree.[49] To solve any extensive form game, backward induction must be used. It involves working backward up the game tree to determine what a rational player would do at the last vertex of the tree, what the player with the previous move would do given that the player with the last move is rational, and so on until the first vertex of the tree is reached.[50] The game pictured consists of two players. The way this particular game is structured (i.e., with sequential decision making and perfect information), Player 1 "moves" first by choosing either F or U (fair or unfair). Next in the sequence, Player 2, who has now observed Player 1's move, can choose to play either A or R (accept or reject). Once Player 2 has made their choice, the game is considered finished and each player gets their respective payoff, represented in the image as two numbers, where the first number represents Player 1's payoff, and the second number represents Player 2's payoff. Suppose that Player 1 chooses U and then Player 2 chooses A: Player 1 then gets a payoff of "eight" (which in real-world terms can be interpreted in many ways, the simplest of which is in terms of money but could mean things such as eight days of vacation or eight countries conquered or even eight more opportunities to play the same game against other players) and Player 2 gets a payoff of "two". The extensive form can also capture simultaneous-move games and games with imperfect information. To represent it, either a dotted line connects different vertices to represent them as being part of the same information set (i.e. the players do not know at which point they are), or a closed line is drawn around them. (See example in the imperfect information section.) |

ゲームの表現 ゲーム理論で研究されるゲームは、よく定義された数学的対象である。ゲームが完全に定義されるためには、ゲームのプレイヤー、各決定ポイントで各プレイ ヤーが利用可能な情報と行動、各結果に対するペイオフという要素を特定する必要がある(Eric Rasmusenはこの4つの「必須要素」を頭文字をとって「PAPI」と呼んでいる)[45][46]。(エリック・ラスムセンは、この4つの「必須要 素」を頭文字をとって「PAPI」と呼んでいる)[45][46][47][48] ゲーム理論家は通常、これらの要素と、自分が選んだ解の概念を用いて、各プレイヤーの均衡戦略のセットを推論する。これらの均衡戦略は、ゲームの均衡を決 定する。均衡とは、1つの結果が発生するか、あるいは一連の結果が既知の確率で発生する安定状態のことである。 非協力ゲームの定義には広義形と正規形が用いられる。 広範形式 主な記事 広範形ゲーム  広範形式ゲーム 広範形は、手の時間的順序を持つゲームを公式化するのに用いることができる。広範形対局は、ゲーム木を用いて視覚化することができる(この写真のよう に)。ここで、各頂点(またはノード)は、プレーヤーの選択点を表す。対局者は、頂点に記載された番号で指定される。頂点から伸びる線は、そのプレイヤー が取りうる行動を表す。ペイオフは木の一番下で指定される。広範形は決定木のマルチプレイヤー一般化と見なすことができる[49]。広範形ゲームを解くに は、後方帰納法を用いなければならない。これは、ゲームツリーの最後の頂点で合理的なプレイヤーが何をするのか、最後の手を 持ったプレイヤーが合理的であるとすると前の手を持ったプレイヤーは何をするのか、などツリーの最初の頂点に到達するまで、ゲームツリーを逆向きに作業し て決定することを含む[50]。 描かれているゲームは2人のプレイヤーで構成されている。この特殊なゲームの構造では(つまり、逐次的な意思決定と完全な情報によって)、プレイヤー1が FかU(フェアかアンフェア)のどちらかを選んで最初に「動く」。次に、プレイヤー1の動きを観察したプレイヤー2が、AかR(受け入れるか拒否するか) のいずれかを選択することができる。プレイヤー2が選択した時点でゲームは終了し、各プレイヤーはそれぞれのペイオフを得る。プレイヤー1がUを選択し、 プレイヤー2がAを選択したとする。プレイヤー1は「8」のペイオフを得(これは現実世界ではさまざまな解釈が可能で、最も単純なのは金銭的な意味だが、 8日間の休暇や8カ国の征服、あるいは他のプレイヤーと同じゲームをプレイする機会が8回増えるといった意味もある)、プレイヤー2は「2」のペイオフを 得る。 広範形は同時手ゲームや不完全情報のゲームも捉えることができる。これを表現するには、異なる頂点を点線で結んで同じ情報集合の一部であることを表現する か(つまり、プレイヤーはどの地点にいるのかわからない)、頂点を囲むように閉じた線を引く。(不完全情報のセクションの例を参照)。 |

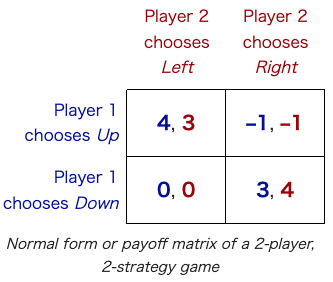

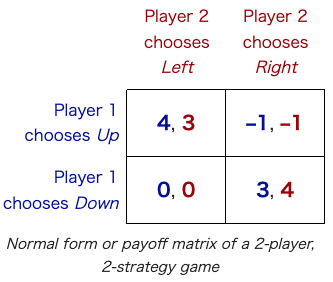

Normal-form game The normal (or strategic form) game is usually represented by a matrix which shows the players, strategies, and payoffs (see the example to the right). More generally it can be represented by any function that associates a payoff for each player with every possible combination of actions. In the accompanying example there are two players; one chooses the row and the other chooses the column. Each player has two strategies, which are specified by the number of rows and the number of columns. The payoffs are provided in the interior. The first number is the payoff received by the row player (Player 1 in our example); the second is the payoff for the column player (Player 2 in our example). Suppose that Player 1 plays Up and that Player 2 plays Left. Then Player 1 gets a payoff of 4, and Player 2 gets 3. When a game is presented in normal form, it is presumed that each player acts simultaneously or, at least, without knowing the actions of the other. If players have some information about the choices of other players, the game is usually presented in extensive form. Every extensive-form game has an equivalent normal-form game, however, the transformation to normal form may result in an exponential blowup in the size of the representation, making it computationally impractical.[51] |

正規形ゲーム 正規形(または戦略形)ゲームは通常、プレイヤー、戦略、ペイオフを示す行列で表される(右の例を参照)。より一般的には、各プレイヤーのペイオフをあら ゆる可能な行動の組み合わせに関連付ける任意の関数で表すことができる。右の例では2人のプレーヤーがおり、一方が行を選び、もう一方が列を選ぶ。各プ レーヤーは2つの戦略を持ち、それは行の数と列の数で指定される。ペイオフは内部で与えられる。最初の数字は行のプレイヤー(この例ではプレイヤー1)が 受け取るペイオフで、2番目の数字は列のプレイヤー(この例ではプレイヤー2)が受け取るペイオフである。プレイヤー1が「上」をプレイし、プレイヤー2 が「左」をプレイしたとする。するとプレイヤー1のペイオフは4で、プレイヤー2のペイオフは3となる。 ゲームが正規の形で提示される場合、各プレイヤーは同時に行動するか、少なくとも他のプレイヤーの行動を知らずに行動すると仮定される。プレーヤーが他のプレーヤーの選択について何らかの情報を持っている場合、そのゲームは通常、広範形式で示される。 すべての拡大形ゲームは等価な正規形ゲームを持つが、正規形への変換は表現サイズを指数関数的に増大させる可能性があり、計算上非実用的である[51]。 |

| General and applied uses As a method of applied mathematics, game theory has been used to study a wide variety of human and animal behaviors. It was initially developed in economics to understand a large collection of economic behaviors, including behaviors of firms, markets, and consumers. The first use of game-theoretic analysis was by Antoine Augustin Cournot in 1838 with his solution of the Cournot duopoly. The use of game theory in the social sciences has expanded, and game theory has been applied to political, sociological, and psychological behaviors as well.[68] Although pre-twentieth-century naturalists such as Charles Darwin made game-theoretic kinds of statements, the use of game-theoretic analysis in biology began with Ronald Fisher's studies of animal behavior during the 1930s. This work predates the name "game theory", but it shares many important features with this field. The developments in economics were later applied to biology largely by John Maynard Smith in his 1982 book Evolution and the Theory of Games.[69] In addition to being used to describe, predict, and explain behavior, game theory has also been used to develop theories of ethical or normative behavior and to prescribe such behavior.[70] In economics and philosophy, scholars have applied game theory to help in the understanding of good or proper behavior. Game-theoretic approaches have also been suggested in the philosophy of language and philosophy of science.[71] Game-theoretic arguments of this type can be found as far back as Plato.[72] An alternative version of game theory, called chemical game theory, represents the player's choices as metaphorical chemical reactant molecules called "knowlecules".[73] Chemical game theory then calculates the outcomes as equilibrium solutions to a system of chemical reactions. Description and modeling  A four-stage centipede game The primary use of game theory is to describe and model how human populations behave.[citation needed] Some[who?] scholars believe that by finding the equilibria of games they can predict how actual human populations will behave when confronted with situations analogous to the game being studied. This particular view of game theory has been criticized. It is argued that the assumptions made by game theorists are often violated when applied to real-world situations. Game theorists usually assume players act rationally, but in practice, human rationality and/or behavior often deviates from the model of rationality as used in game theory. Game theorists respond by comparing their assumptions to those used in physics. Thus while their assumptions do not always hold, they can treat game theory as a reasonable scientific ideal akin to the models used by physicists. However, empirical work has shown that in some classic games, such as the centipede game, guess 2/3 of the average game, and the dictator game, people regularly do not play Nash equilibria. There is an ongoing debate regarding the importance of these experiments and whether the analysis of the experiments fully captures all aspects of the relevant situation.[b] Some game theorists, following the work of John Maynard Smith and George R. Price, have turned to evolutionary game theory in order to resolve these issues. These models presume either no rationality or bounded rationality on the part of players. Despite the name, evolutionary game theory does not necessarily presume natural selection in the biological sense. Evolutionary game theory includes both biological as well as cultural evolution and also models of individual learning (for example, fictitious play dynamics). |

一般的・応用的な使い方 応用数学の一手法として、ゲーム理論は人間や動物のさまざまな行動を研究するために使われてきた。当初は経済学において、企業、市場、消費者の行動を含む 多くの経済行動を理解するために開発された。ゲーム理論的分析を最初に用いたのは、1838年、アントワーヌ・オーギュスタン・クルノによるクルノー・ デュオポリーの解法である。社会科学におけるゲーム理論の使用は拡大し、ゲーム理論は政治的、社会学的、心理学的行動にも適用されている[68]。 チャールズ・ダーウィンのような20世紀以前の博物学者はゲーム理論的な発言をしていたが、生物学におけるゲーム理論的分析の使用は、1930年代のロナ ルド・フィッシャーによる動物行動の研究から始まった。この研究は「ゲーム理論」と呼ばれる以前のものだが、この分野と多くの重要な特徴を共有している。 その後、経済学における発展が、ジョン・メイナード・スミスによって1982年に出版された著書『進化とゲームの理論』(Evolution and the Theory of Games)の中で生物学に大きく応用された[69]。 行動を記述、予測、説明するために使用されるだけでなく、ゲーム理論は倫理的行動や規範的行動の理論を発展させ、そのような行動を規定するためにも使用さ れてきた[70]。経済学や哲学において、学者は善良な行動や適切な行動の理解に役立てるためにゲーム理論を応用してきた。また、言語哲学や科学哲学にお いても、ゲーム理論的アプローチが提案されている[71]。この種のゲーム理論的議論は、プラトンにまで遡ることができる[72]。化学ゲーム理論と呼ば れるゲーム理論の代替バージョンでは、プレイヤーの選択を「ノウレキュール」と呼ばれる比喩的な化学反応分子として表現する[73]。 説明とモデル化  4段階のムカデゲーム ゲーム理論の主な用途は、人間の集団がどのように行動するかを記述し、モデル化することである[citation needed]。ゲームの均衡を見つけることで、研究対象のゲームに類似した状況に直面したときに、実際の人間の集団がどのように行動するかを予測できる と考える学者もいる[who?] ゲーム理論のこのような見方は批判されてきた。それは、ゲーム理論家が立てた仮定が、現実の状況に適用されたときにしばしば破られるというものである。 ゲーム理論家は通常プレイヤーが合理的に行動すると仮定しているが、実際には人間の合理性や行動はゲーム理論で使われる合理性のモデルから逸脱しているこ とが多い。ゲーム理論家は、自分たちの仮定を物理学で使われる仮定と比較することで対応している。したがって、彼らの仮定が常に成り立つとは限らないが、 彼らはゲーム理論を物理学者が使用するモデルに似た合理的な科学的理想として扱うことができる。しかし、ムカデゲーム、平均の2/3を当てるゲーム、独裁 者ゲームなど、いくつかの古典的なゲームでは、人々は定期的にナッシュ均衡をとらないことが、経験的な研究によって示されている。これらの実験の重要性 や、実験の分析が関連する状況のすべての側面を完全に捉えているかどうかについては、現在も議論が続いている[b]。 ゲーム理論家の中には、ジョン・メイナード・スミスとジョージ・R・プライスの研究に続いて、これらの問題を解決するために進化ゲーム理論に目を向けた者 もいる。これらのモデルは、プレーヤーの側に合理性がないか、あるいは境界合理性があると仮定している。名前に反して、進化ゲーム理論は必ずしも生物学的 な意味での自然淘汰を前提としているわけではない。進化ゲーム理論には、生物学的進化だけでなく文化的進化も含まれ、さらに個人の学習モデル(たとえば架 空のプレーの力学)も含まれる。 |

Prescriptive or normative analysis Some scholars see game theory not as a predictive tool for the behavior of human beings, but as a suggestion for how people ought to behave. Since a strategy, corresponding to a Nash equilibrium of a game constitutes one's best response to the actions of the other players – provided they are in (the same) Nash equilibrium – playing a strategy that is part of a Nash equilibrium seems appropriate. This normative use of game theory has also come under criticism.[75] Use of game theory in economics Game theory is a major method used in mathematical economics and business for modeling competing behaviors of interacting agents.[c][76][77][78] Applications include a wide array of economic phenomena and approaches, such as auctions, bargaining, mergers and acquisitions pricing,[79] fair division, duopolies, oligopolies, social network formation, agent-based computational economics,[80][81] general equilibrium, mechanism design,[82][83][84][85][86] and voting systems;[87] and across such broad areas as experimental economics,[88][89][90][91][92] behavioral economics,[93][94][95][96][97][98] information economics,[45][46][47][48] industrial organization,[99][100][101][102] and political economy.[103][104][105][106] This research usually focuses on particular sets of strategies known as "solution concepts" or "equilibria". A common assumption is that players act rationally. In non-cooperative games, the most famous of these is the Nash equilibrium. A set of strategies is a Nash equilibrium if each represents a best response to the other strategies. If all the players are playing the strategies in a Nash equilibrium, they have no unilateral incentive to deviate, since their strategy is the best they can do given what others are doing.[107][108] The payoffs of the game are generally taken to represent the utility of individual players. A prototypical paper on game theory in economics begins by presenting a game that is an abstraction of a particular economic situation. One or more solution concepts are chosen, and the author demonstrates which strategy sets in the presented game are equilibria of the appropriate type. Economists and business professors suggest two primary uses (noted above): descriptive and prescriptive.[70] Application in managerial economics Game theory also has an extensive use in a specific branch or stream of economics – Managerial Economics. One important usage of it in the field of managerial economics is in analyzing strategic interactions between firms.[109] For example, firms may be competing in a market with limited resources, and game theory can help managers understand how their decisions impact their competitors and the overall market outcomes. Game theory can also be used to analyze cooperation between firms, such as in forming strategic alliances or joint ventures. Another use of game theory in managerial economics is in analyzing pricing strategies. For example, firms may use game theory to determine the optimal pricing strategy based on how they expect their competitors to respond to their pricing decisions. Overall, game theory serves as a useful tool for analyzing strategic interactions and decision making in the context of managerial economics. Use of game theory in business The Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS) promotes knowledge and use of game theory within the context of business procurement.[110] CIPS and TWS Partners have conducted a series of surveys designed to explore the understanding, awareness and application of game theory among procurement professionals. Some of the main findings in their third annual survey (2019) include: application of game theory to procurement activity has increased – at the time it was at 19% across all survey respondents 65% of participants predict that use of game theory applications will grow 70% of respondents say that they have "only a basic or a below basic understanding" of game theory 20% of participants had undertaken on-the-job training in game theory 50% of respondents said that new or improved software solutions were desirable 90% of respondents said that they do not have the software they need for their work.[111] Use of game theory in project management Sensible decision-making is critical for the success of projects. In project management, game theory is used to model the decision-making process of players, such as investors, project managers, contractors, sub-contractors, governments and customers. Quite often, these players have competing interests, and sometimes their interests are directly detrimental to other players, making project management scenarios well-suited to be modeled by game theory. Piraveenan (2019)[112] in his review provides several examples where game theory is used to model project management scenarios. For instance, an investor typically has several investment options, and each option will likely result in a different project, and thus one of the investment options has to be chosen before the project charter can be produced. Similarly, any large project involving subcontractors, for instance, a construction project, has a complex interplay between the main contractor (the project manager) and subcontractors, or among the subcontractors themselves, which typically has several decision points. For example, if there is an ambiguity in the contract between the contractor and subcontractor, each must decide how hard to push their case without jeopardizing the whole project, and thus their own stake in it. Similarly, when projects from competing organizations are launched, the marketing personnel have to decide what is the best timing and strategy to market the project, or its resultant product or service, so that it can gain maximum traction in the face of competition. In each of these scenarios, the required decisions depend on the decisions of other players who, in some way, have competing interests to the interests of the decision-maker, and thus can ideally be modeled using game theory. Piraveenan[112] summarises that two-player games are predominantly used to model project management scenarios, and based on the identity of these players, five distinct types of games are used in project management. Government-sector–private-sector games (games that model public–private partnerships) Contractor–contractor games Contractor–subcontractor games Subcontractor–subcontractor games Games involving other players In terms of types of games, both cooperative as well as non-cooperative, normal-form as well as extensive-form, and zero-sum as well as non-zero-sum are used to model various project management scenarios. |

規範的分析 ゲーム理論を、人間の行動を予測する道具としてではなく、人間がどのように行動すべきかを示唆するものとして捉える学者もいる。ゲームのナッシュ均衡に対 応する戦略は、他のプレイヤーの行動に対する自分の最良の対応策を構成するので、(同じ)ナッシュ均衡にあるのであれば、ナッシュ均衡の一部である戦略を とることが適切であるように思われる。このようなゲーム理論の規範的な使用も批判にさらされている[75]。 経済学におけるゲーム理論の利用 ゲーム理論は、数理経済学やビジネスにおいて、相互作用するエージェントの競合行動をモデル化するために用いられる主要な手法である[c][76] [77]。 [オークション、交渉、M&Aのプライシング、[79]公正分割、二重競争、寡占、社会的ネットワーク形成、エージェントベースの計算経済学、 [80][81]一般均衡、メカニズム設計、[82][83][84][85][86]投票システムなど、幅広い経済現象やアプローチが応用されている; [87]、実験経済学、[88][89][90][91][92]行動経済学、[93][94][95][96][97][98]情報経済学、[45] [46][47][48]産業組織論、[99][100][101][102]政治経済学などの広範な分野にわたっている。 [103][104][105][106] この研究は通常、「解の概念」または「均衡」として知られる特定の戦略の集合に焦点を当てている。一般的な仮定は、プレイヤーは合理的に行動するというも のである。非協力ゲームでは、ナッシュ均衡が最も有名である。戦略の集合は、それぞれが他の戦略に対する最良の対応である場合、ナッシュ均衡となる。すべ てのプレイヤーがナッシュ均衡の戦略をとっている場合、プレイヤーは一方的に逸脱するインセンティブを持たない。 ゲームのペイオフは、一般に個々のプレイヤーの効用を表すとされる。 経済学におけるゲーム理論の典型的な論文は、特定の経済状況を抽象化したゲームを提示することから始まる。1つまたは複数の解の概念が選択され、著者は提 示されたゲームにおいてどの戦略セットが適切なタイプの均衡であるかを示す。経済学者やビジネス教授は、(上述の)記述的と処方的という2つの主な用途を 提案している[70]。 経営経済学への応用 ゲーム理論はまた、経済学の特定の分野や流れである経営経済学でも幅広く利用されている。例えば、企業は限られた資源しかない市場で競争している場合があ り、ゲーム理論は経営者が自らの意思決定が競争相手や市場全体の結果にどのような影響を与えるかを理解するのに役立つ。ゲーム理論はまた、戦略的提携や合 弁事業の形成など、企業間の協力関係を分析するためにも使用することができる。経営経済学におけるゲーム理論のもう一つの利用法は、価格戦略の分析であ る。例えば、企業はゲーム理論を用いて、競合他社が自社の価格決定に対してどのような反応を示すかを予想した上で、最適な価格戦略を決定することができ る。全体として、ゲーム理論は、経営経済学の文脈における戦略的相互作用や意思決定を分析するための有用なツールとして機能している。 ビジネスにおけるゲーム理論の活用 CIPSとTWSパートナーズは、調達プロフェッショナルのゲーム理論に対する理解、認識、適用を探ることを目的とした一連の調査を実施した[110]。彼らの第3回年次調査(2019年)における主な調査結果の一部は以下の通りである: 調達活動へのゲーム理論の適用は増加している-当時は全調査回答者の19%であった 参加者の65%が、ゲーム理論アプリケーションの利用は拡大すると予測している 回答者の70%が、ゲーム理論について「基本的な理解しかない」または「基本的な理解以下である」と回答している。 ゲーム理論に関するOJTを受けたことのある回答者は全体の20%であった。 回答者の50%が、新しい、あるいは改良されたソフトウェア・ソリューションが望ましいと答えている。 回答者の90%が、業務に必要なソフトウェアを持っていないと答えている[111]。 プロジェクト管理におけるゲーム理論の利用 プロジェクトの成功には、賢明な意思決定が不可欠である。プロジェクトマネジメントでは、投資家、プロジェクトマネジャー、請負業者、下請け業者、政府、 顧客などのプレーヤーの意思決定プロセスをモデル化するために、ゲーム理論が用いられる。多くの場合、これらのプレーヤーは競合する利害関係を持ち、時に はその利害関係が他のプレーヤーに直接不利益をもたらすこともあるため、プロジェクトマネジメントのシナリオはゲーム理論でモデル化するのに適している。 Piraveenan(2019)[112]のレビューでは、ゲーム理論がプロジェクトマネジメントのシナリオをモデル化するために用いられている例をい くつか挙げている。例えば、投資家には通常いくつかの投資オプションがあり、各オプションは異なるプロジェクトになる可能性が高いため、プロジェクト憲章 を作成する前に投資オプションの1つを選択しなければならない。同様に、下請け業者が関与する大規模プロジェクト、例えば建設プロジェクトでは、元請け業 者(プロジェクトマネージャー)と下請け業者、あるいは下請け業者自身の間に複雑な相互関係があり、通常、いくつかの意思決定ポイントがある。例えば、請 負業者と下請け業者の間の契約に曖昧な点がある場合、それぞれが、プロジェクト全体、ひいては自分たちの利害関係を危うくすることなく、自分たちの主張を どれだけ強く押し通すかを決めなければならない。同様に、競合する組織のプロジェクトが立ち上げられる場合、マーケティング担当者は、プロジェクトやその 結果の製品やサービスを売り込むための最良のタイミングと戦略を決めなければならない。これらのシナリオのそれぞれにおいて、必要な決定は、何らかの形で 意思決定者の利益と競合する利益を持つ他のプレーヤーの決定に依存するため、理想的にはゲーム理論を使ってモデル化することができる。 Piraveenan[112]は、プロジェクトマネジメントのシナリオをモデル化するために、2人用ゲームが主に使用され、これらのプレーヤーのアイデンティティに基づいて、プロジェクトマネジメントでは5つの異なるタイプのゲームが使用されると要約している。 官民ゲーム(官民パートナーシップをモデル化したゲーム) 請負業者対請負業者のゲーム 請負業者-下請け業者ゲーム 下請け-下請けゲーム 他のプレーヤーを巻き込んだゲーム ゲームの種類としては、協力型と非協力型、正規形と拡大形、ゼロサムと非ゼロサムの両方が、さまざまなプロジェクトマネジメントのシナリオをモデル化するために使われる。 |

| The application of game theory

to political science is focused in the overlapping areas of fair

division, political economy, public choice, war bargaining, positive

political theory, and social choice theory. In each of these areas,

researchers have developed game-theoretic models in which the players

are often voters, states, special interest groups, and politicians.[113] Early examples of game theory applied to political science are provided by Anthony Downs. In his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy,[114] he applies the Hotelling firm location model to the political process. In the Downsian model, political candidates commit to ideologies on a one-dimensional policy space. Downs first shows how the political candidates will converge to the ideology preferred by the median voter if voters are fully informed, but then argues that voters choose to remain rationally ignorant which allows for candidate divergence. Game theory was applied in 1962 to the Cuban Missile Crisis during the presidency of John F. Kennedy.[115] It has also been proposed that game theory explains the stability of any form of political government. Taking the simplest case of a monarchy, for example, the king, being only one person, does not and cannot maintain his authority by personally exercising physical control over all or even any significant number of his subjects. Sovereign control is instead explained by the recognition by each citizen that all other citizens expect each other to view the king (or other established government) as the person whose orders will be followed. Coordinating communication among citizens to replace the sovereign is effectively barred, since conspiracy to replace the sovereign is generally punishable as a crime.[116] Thus, in a process that can be modeled by variants of the prisoner's dilemma, during periods of stability no citizen will find it rational to move to replace the sovereign, even if all the citizens know they would be better off if they were all to act collectively.[citation needed] A game-theoretic explanation for democratic peace is that public and open debate in democracies sends clear and reliable information regarding their intentions to other states. In contrast, it is difficult to know the intentions of nondemocratic leaders, what effect concessions will have, and if promises will be kept. Thus there will be mistrust and unwillingness to make concessions if at least one of the parties in a dispute is a non-democracy.[117] However, game theory predicts that two countries may still go to war even if their leaders are cognizant of the costs of fighting. War may result from asymmetric information; two countries may have incentives to mis-represent the amount of military resources they have on hand, rendering them unable to settle disputes agreeably without resorting to fighting. Moreover, war may arise because of commitment problems: if two countries wish to settle a dispute via peaceful means, but each wishes to go back on the terms of that settlement, they may have no choice but to resort to warfare. Finally, war may result from issue indivisibilities.[118] Game theory could also help predict a nation's responses when there is a new rule or law to be applied to that nation. One example is Peter John Wood's (2013) research looking into what nations could do to help reduce climate change. Wood thought this could be accomplished by making treaties with other nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, he concluded that this idea could not work because it would create a prisoner's dilemma for the nations.[119] Use of game theory in defence science and technology Game theory has been used extensively to model decision-making scenarios relevant to defence applications.[120] Most studies that has applied game theory in defence settings are concerned with Command and Control Warfare, and can be further classified into studies dealing with (i) Resource Allocation Warfare (ii) Information Warfare (iii) Weapons Control Warfare, and (iv) Adversary Monitoring Warfare.[120] Many of the problems studied are concerned with sensing and tracking, for example a surface ship trying to track a hostile submarine and the submarine trying to evade being tracked, and the interdependent decision making that takes place with regards to bearing, speed, and the sensor technology activated by both vessels. Ho et al [120] provides a concise summary of the state-of-the-art with regards to the use of game theory in defence applications and highlights the benefits and limitations of game theory in the considered scenarios. |

政治科学へのゲーム理論の応用は、公正分割、政治経済学、公共選択、戦

争交渉、積極的政治理論、社会的選択理論といった重複する分野に集中している。これらの各分野において、研究者はゲーム理論的モデルを開発しており、その

プレイヤーは有権者、国家、特別利益団体、政治家であることが多い[113]。 ゲーム理論を政治学に応用した初期の例は、アンソニー・ダウンズによって提供されている。1957年の著書『An Economic Theory of Democracy』[114]において、彼はホテリング企業立地モデルを政治プロセスに適用している。ダウンズ・モデルでは、政治家候補者は一次元の政 策空間上のイデオロギーにコミットする。ダウンズはまず、有権者が十分な情報を持っていれば、政治家候補が中央有権者の好むイデオロギーに収束することを 示すが、その後、有権者は合理的に無知でいることを選択するため、候補者の発散が可能になると主張する。ゲーム理論は、1962年にジョン・F・ケネディ 大統領時代のキューバ危機に対して適用された[115]。 また、ゲーム理論があらゆる政治形態の安定性を説明することも提案されている。最も単純な君主制の場合を例にとると、国王はたった一人であるため、臣民の すべて、あるいはかなりの数を個人的に物理的に支配することによってその権威を維持することはないし、また維持することもできない。君主制は、その代わり に、他のすべての国民が、国王(または他の確立された政府)をその命令に従うべき人物としてみなすことを互いに期待しているという、各市民の認識によって 説明される。主権者に取って代わろうとする共謀は一般に犯罪として処罰されるため、主権者に取って代わろうとする市民間のコミュニケーションを調整するこ とは事実上禁じられている[116]。したがって、囚人のジレンマの変種によってモデル化することができるプロセスにおいて、安定期には、たとえすべての 市民が集団的に行動した方がより良い状況になると知っていたとしても、主権者に取って代わろうと動くことが合理的であると考える市民はいない[要出典]。 民主主義的平和に関するゲーム理論的な説明は、民主主義国家では公開されたオープンな議論が行われることで、他国に対して自国の意図に関する明確で信頼で きる情報が送られるというものである。対照的に、非民主主義的な指導者の意図や、譲歩がどのような効果をもたらすのか、約束が守られるのかを知ることは困 難である。したがって、紛争当事者の少なくとも一方が非民主主義国家である場合には、不信感が生じ、譲歩することに消極的になる[117]。 しかし、ゲーム理論は、2つの国の指導者が戦闘のコストを認識していたとしても、2つの国が戦争に突入する可能性があることを予測している。戦争は情報の 非対称性から生じる可能性があり、2つの国が手持ちの軍事資源の量を誤って伝えるインセンティブを持つことで、戦闘に頼らずに紛争を合意的に解決すること ができなくなる可能性がある。さらに、コミットメントの問題から戦争が起こることもある。2つの国が平和的手段で紛争を解決したいと考えているにもかかわ らず、それぞれがその解決条件を反故にしようとする場合、戦争に訴える以外に選択肢がなくなる可能性がある。最後に、問題の不可分性から戦争が生じること もある[118]。 ゲーム理論は、その国に新しいルールや法律が適用される場合のその国の対応を予測するのにも役立つ可能性がある。一例として、ピーター・ジョン・ウッド (Peter John Wood)の研究(2013年)がある。ウッド氏は、温室効果ガスの排出量を削減するために他国と条約を結ぶことで達成できると考えた。しかし彼は、この 考えは各国にとって囚人のジレンマを生み出すことになるため、うまくいかないと結論づけた[119]。 防衛科学技術におけるゲーム理論の利用 ゲーム理論は、防衛用途に関連する意思決定シナリオをモデル化するために広範に使用されてきた[120]。防衛環境においてゲーム理論を適用した研究のほ とんどは、指揮統制戦に関するものであり、さらに(i)資源配分戦、(ii)情報戦、(iii)兵器統制戦、(iv)敵国監視戦を扱う研究に分類すること ができる。 [研究された問題の多くは、例えば敵対的な潜水艦を追跡しようとする水上艦と、追跡されることを回避しようとする潜水艦のような、感知と追跡に関するもの であり、方位、速度、両艦によって起動されるセンサー技術に関して行われる相互依存的な意思決定に関するものである。Hoら[120]は、防衛アプリケー ションにおけるゲーム理論の使用に関して、最先端の簡潔な要約を提供し、考察されたシナリオにおけるゲーム理論の利点と限界を強調している。 |

Evolutionary game theory Unlike those in economics, the payoffs for games in biology are often interpreted as corresponding to fitness. In addition, the focus has been less on equilibria that correspond to a notion of rationality and more on ones that would be maintained by evolutionary forces. The best-known equilibrium in biology is known as the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), first introduced in (Maynard Smith & Price 1973). Although its initial motivation did not involve any of the mental requirements of the Nash equilibrium, every ESS is a Nash equilibrium. In biology, game theory has been used as a model to understand many different phenomena. It was first used to explain the evolution (and stability) of the approximate 1:1 sex ratios. (Fisher 1930) suggested that the 1:1 sex ratios are a result of evolutionary forces acting on individuals who could be seen as trying to maximize their number of grandchildren. Additionally, biologists have used evolutionary game theory and the ESS to explain the emergence of animal communication.[121] The analysis of signaling games and other communication games has provided insight into the evolution of communication among animals. For example, the mobbing behavior of many species, in which a large number of prey animals attack a larger predator, seems to be an example of spontaneous emergent organization. Ants have also been shown to exhibit feed-forward behavior akin to fashion (see Paul Ormerod's Butterfly Economics). Biologists have used the game of chicken to analyze fighting behavior and territoriality.[122] According to Maynard Smith, in the preface to Evolution and the Theory of Games, "paradoxically, it has turned out that game theory is more readily applied to biology than to the field of economic behaviour for which it was originally designed". Evolutionary game theory has been used to explain many seemingly incongruous phenomena in nature.[123] One such phenomenon is known as biological altruism. This is a situation in which an organism appears to act in a way that benefits other organisms and is detrimental to itself. This is distinct from traditional notions of altruism because such actions are not conscious, but appear to be evolutionary adaptations to increase overall fitness. Examples can be found in species ranging from vampire bats that regurgitate blood they have obtained from a night's hunting and give it to group members who have failed to feed, to worker bees that care for the queen bee for their entire lives and never mate, to vervet monkeys that warn group members of a predator's approach, even when it endangers that individual's chance of survival.[124] All of these actions increase the overall fitness of a group, but occur at a cost to the individual. Evolutionary game theory explains this altruism with the idea of kin selection. Altruists discriminate between the individuals they help and favor relatives. Hamilton's rule explains the evolutionary rationale behind this selection with the equation c < b × r, where the cost c to the altruist must be less than the benefit b to the recipient multiplied by the coefficient of relatedness r. The more closely related two organisms are causes the incidences of altruism to increase because they share many of the same alleles. This means that the altruistic individual, by ensuring that the alleles of its close relative are passed on through survival of its offspring, can forgo the option of having offspring itself because the same number of alleles are passed on. For example, helping a sibling (in diploid animals) has a coefficient of 1⁄2, because (on average) an individual shares half of the alleles in its sibling's offspring. Ensuring that enough of a sibling's offspring survive to adulthood precludes the necessity of the altruistic individual producing offspring.[124] The coefficient values depend heavily on the scope of the playing field; for example if the choice of whom to favor includes all genetic living things, not just all relatives, we assume the discrepancy between all humans only accounts for approximately 1% of the diversity in the playing field, a coefficient that was 1⁄2 in the smaller field becomes 0.995. Similarly if it is considered that information other than that of a genetic nature (e.g. epigenetics, religion, science, etc.) persisted through time the playing field becomes larger still, and the discrepancies smaller. |

進化ゲーム理論 経済学とは異なり、生物学におけるゲームのペイオフはしばしばフィットネスに対応すると解釈される。さらに、合理性の概念に対応する均衡よりも、進化の力 によって維持される均衡に焦点が当てられてきた。生物学で最もよく知られている均衡は進化的に安定な戦略(ESS)として知られ、(Maynard Smith & Price 1973)で初めて紹介された。ESSの最初の動機はナッシュ均衡のような精神的な要求を含んでいなかったが、すべてのESSはナッシュ均衡である。 生物学では、ゲーム理論はさまざまな現象を理解するためのモデルとして使われてきた。最初に使われたのは、ほぼ1対1の性比の進化(と安定性)を説明する ためであった。(フィッシャー1930)は、1対1の性比は、孫の数を最大化しようとする個体に進化的な力が作用した結果であると示唆した。 さらに、生物学者は進化ゲーム理論やESSを用いて、動物のコミュニケーションの出現を説明してきた[121]。シグナリングゲームやその他のコミュニ ケーションゲームの分析は、動物間のコミュニケーションの進化についての洞察を与えてきた。例えば、多くの種の群れ行動(多数の獲物動物がより大きな捕食 者を攻撃する)は、自然発生的な創発組織の一例であるように思われる。アリもまた、ファッションに似たフィードフォワード行動を示すことが示されている (ポール・オーメロッドの『バタフライ・エコノミクス』参照)。 生物学者はチキンゲームを使って、闘争行動や縄張り意識を分析している[122]。 メイナード・スミスは『進化とゲームの理論』の序文で、「逆説的ではあるが、ゲーム理論は、本来そのために設計された経済行動の分野よりも、生物学の分野 の方が適用しやすいことが判明した」と述べている。進化ゲーム理論は、自然界に存在する一見不自然な現象の多くを説明するために用いられてきた。 そのような現象のひとつに、生物学的利他主義がある。これは、ある生物が他の生物に利益をもたらし、自分自身には不利益となるような行動をとるように見え る状況である。このような行動は意識的ではなく、全体的なフィットネスを向上させるための進化的適応であると考えられるため、従来の利他主義の概念とは異 なる。一晩の狩りで得た血液を吐き出し、餌を食べられなかったグループのメンバーに与える吸血コウモリや、一生女王蜂の世話をしながら交尾をしない働き 蜂、捕食者の接近をグループのメンバーに警告するベルベットモンキーなど、様々な種にその例が見られる[124]。これらの行動はすべてグループ全体の フィットネスを高めるが、個体にとっては犠牲を伴う。 進化ゲーム理論では、この利他主義を血縁淘汰という考え方で説明する。利他主義者は助ける個体を差別し、親族を優遇する。ハミルトンの法則は、この淘汰の 背後にある進化論的根拠を、c<b×rという方程式で説明している。ここで、利他主義者のコストcは、被利他者の利益bに血縁係数rをかけたものより小さ くなければならない。つまり、利他的な個体は、近縁の対立遺伝子が子孫の生存を通じて受け継がれるようにすることで、同じ数の対立遺伝子が受け継がれるた め、子孫を残すという選択肢を見送ることができる。例えば、(2倍体動物の場合)兄弟を助けることの係数は1/2である。なぜなら、(平均して)個体はそ の兄弟の子孫の対立遺伝子の半分を共有しているからである。兄弟姉妹の子孫のうち十分な数が成人になるまで生き残るようにすれば、利他的な個体が子孫を残 す必要性がなくなるからである[124]。この係数の値は、競技場の範囲に大きく依存する。例えば、誰を優遇するかの選択に、すべての親族だけでなくすべ ての遺伝的生物が含まれる場合、すべての人間間の不一致が競技場の多様性の約1%しか占めないと仮定すると、小さい競技場では1/2だった係数は 0.995になる。同様に、遺伝的性質以外の情報(エピジェネティクス、宗教、科学など)が時間と共に持続したと考えれば、土俵はさらに大きくなり、不一 致は小さくなる。 |

| Computer science and logic Game theory has come to play an increasingly important role in logic and in computer science. Several logical theories have a basis in game semantics. In addition, computer scientists have used games to model interactive computations. Also, game theory provides a theoretical basis to the field of multi-agent systems.[125] Separately, game theory has played a role in online algorithms; in particular, the k-server problem, which has in the past been referred to as games with moving costs and request-answer games.[126] Yao's principle is a game-theoretic technique for proving lower bounds on the computational complexity of randomized algorithms, especially online algorithms. The emergence of the Internet has motivated the development of algorithms for finding equilibria in games, markets, computational auctions, peer-to-peer systems, and security and information markets. Algorithmic game theory[86] and within it algorithmic mechanism design[85] combine computational algorithm design and analysis of complex systems with economic theory.[127][128][129] |

計算機科学と論理学 ゲーム理論は、論理学やコンピュータサイエンスにおいてますます重要な役割を果たすようになってきた。いくつかの論理理論は、ゲームの意味論を基礎として いる。また、コンピュータ科学者はゲームを用いて対話型計算をモデル化してきた。また、ゲーム理論はマルチエージェントシステムの分野に理論的基礎を提供 している[125]。 これとは別に、ゲーム理論はオンラインアルゴリズムにおいても役割を果た してきた。特に、kサーバー問題は、過去に移動コストゲームや要求-回答ゲームと 呼ばれてきた[126]。 インターネットの出現は、ゲーム、市場、計算オークション、ピアツーピアシステム、セキュリティ市場や情報市場における均衡を見つけるためのアルゴリズム の開発を動機付けた。アルゴリズム・ゲーム理論[86]と、その中のアルゴリズム・メカニズム設計[85]は、複雑系の計算アルゴリズム設計と分析を経済 理論と組み合わせたものである[127][128][129]。 |

Game theory has been put to several uses in philosophy. Responding to two papers by W.V.O. Quine (1960, 1967), Lewis (1969) used game theory to develop a philosophical account of convention. In so doing, he provided the first analysis of common knowledge and employed it in analyzing play in coordination games. In addition, he first suggested that one can understand meaning in terms of signaling games. This later suggestion has been pursued by several philosophers since Lewis.[130][131] Following Lewis (1969) game-theoretic account of conventions, Edna Ullmann-Margalit (1977) and Bicchieri (2006) have developed theories of social norms that define them as Nash equilibria that result from transforming a mixed-motive game into a coordination game.[132][133] Game theory has also challenged philosophers to think in terms of interactive epistemology: what it means for a collective to have common beliefs or knowledge, and what are the consequences of this knowledge for the social outcomes resulting from the interactions of agents. Philosophers who have worked in this area include Bicchieri (1989, 1993),[134][135] Skyrms (1990),[136] and Stalnaker (1999).[137] The synthesis of game theory with ethics was championed by R. B. Braithwaite.[138] The hope was that rigorous mathematical analysis of game theory might help formalize the more imprecise philosophical discussions. However, this expectation was only materialized to a limited extent.[139] In ethics, some (most notably David Gauthier, Gregory Kavka, and Jean Hampton) [who?] authors have attempted to pursue Thomas Hobbes' project of deriving morality from self-interest. Since games like the prisoner's dilemma present an apparent conflict between morality and self-interest, explaining why cooperation is required by self-interest is an important component of this project. This general strategy is a component of the general social contract view in political philosophy (for examples, see Gauthier (1986) and Kavka (1986)).[d] Other authors have attempted to use evolutionary game theory in order to explain the emergence of human attitudes about morality and corresponding animal behaviors. These authors look at several games including the prisoner's dilemma, stag hunt, and the Nash bargaining game as providing an explanation for the emergence of attitudes about morality (see, e.g., Skyrms (1996, 2004) and Sober and Wilson (1998)). |

ゲーム理論は哲学の分野でもいくつか利用されている。ルイス(1969)は、W.V.O.クワインの2つの論文(1960、1967)に反論し、ゲーム理 論を用いて慣習の哲学的説明を展開した。そうすることで、彼は共通知識の最初の分析を提供し、協調ゲームにおけるプレーの分析にそれを用いた。さらに、彼 は初めて、意味をシグナリングゲームの観点から理解できることを示唆した。この後の示唆はルイス以降の哲学者たちによって追求されてきた[130] [131]。ルイス(1969年)のゲーム理論的な慣習の説明を受けて、エドナ・ウルマン=マルガリット(1977年)やビッキエリ(2006年)は社会 的規範の理論を展開しており、それは混合動機ゲームを調整ゲームに変換することによって生じるナッシュ均衡として定義されている[132][133]。 ゲーム理論はまた、集団が共通の信念や知識を持つことが何を意味するのか、そしてエージェントの相互作用から生じる社会的結果に対してこの知識がどのよう な結果をもたらすのか、という対話的認識論の観点から考えることを哲学者に課してきた。この領域で研究を行った哲学者には、ビッキエリ(1989、 1993)[134][135]、スカイレムス(1990)[136]、スタルネーカー(1999)[137]などがいる。 ゲーム理論と倫理学の統合はR.B.ブレイスウェイトによって提唱された[138]。ゲーム理論の厳密な数学的分析が、より不正確な哲学的議論を形式化するのに役立つかもしれないという期待があった。しかし、この期待は限定的な範囲でしか実現されなかった[139]。 倫理学においては、自己利益から道徳を導き出すというトマス・ホッブズのプロジェクトを追求しようとする者(特にデイヴィッド・ゴーティエ、グレゴリー・ カヴカ、ジャン・ハンプトン)がいる。囚人のジレンマのようなゲームでは、道徳と利己心の間に明らかな対立が見られるため、なぜ利己心によって協力が求め られるのかを説明することが、このプロジェクトの重要な要素となっている。この一般的な戦略は、政治哲学における一般的な社会契約観の構成要素である(例 としては、Gauthier(1986)やKavka(1986)を参照)[d]。 他の著者は、道徳に関する人間の態度やそれに対応する動物の行動の出現を説明するために、進化ゲーム理論を使おうとしている。これらの著者は、道徳に関す る態度の出現を説明するものとして、囚人のジレンマ、クワガタ狩り、ナッシュ交渉ゲームなどのいくつかのゲームに注目している(Skyrms (1996, 2004)やSober and Wilson (1998)などを参照)。 |

| Epidemiology Since the decision to take a vaccine for a particular disease is often made by individuals, who may consider a range of factors and parameters in making this decision (such as the incidence and prevalence of the disease, perceived and real risks associated with contracting the disease, mortality rate, perceived and real risks associated with vaccination, and financial cost of vaccination), game theory has been used to model and predict vaccination uptake in a society.[140][141] Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Game theory has multiple applications in the field of AI/ML. It is often used in developing autonomous systems that can make complex decisions in uncertain environment.[142] Some other areas of application of game theory in AI/ML context are as follows - multi-agent system formation, reinforcement learning,[143] mechanism design etc.[144] By using game theory to model the behavior of other agents and anticipate their actions, AI/ML systems can make better decisions and operate more effectively.[145] |

疫学 特定の病気に対するワクチンを接種するかどうかの決定は、多くの場合、個人によって行われ、その決定を行う際に、様々な要因やパラメータ(病気の発生率や 有病率、病気に感染することに関連する知覚されたリスクと実際のリスク、死亡率、ワクチン接種に関連する知覚されたリスクと実際のリスク、ワクチン接種に かかる金銭的コストなど)を考慮することができるため、ゲーム理論は、社会におけるワクチン接種率をモデル化し予測するために使用されている[140] [141]。 人工知能と機械学習 ゲーム理論は、AI/MLの分野において複数の応用がある。AI/MLの文脈におけるゲーム理論の他の応用分野としては、マルチエージェントシステムの形 成、強化学習、[143]メカニズム設計などがある[144]。ゲーム理論を用いて他のエージェントの行動をモデル化し、その行動を予測することで、 AI/MLシステムはより良い意思決定を行い、より効果的に動作することができる[145]。 |