バリにおける人間・時間・行為

文

化の分析に関する考察:"Person, time, and conduct in Bali: an essay in cultural

analysis", pp. 360-411

Person, time, and conduct in Bali: an essay in cultural analysis. New-Haven/Ct./USA 1966: Yale University Press: ed. by the Department of Southeast Asia Studies (distributor: Cellar Book Shop, Detroit/Mi./USA), (ISBN 0598551581; III, 85 pp.; caption title), in Clifford Geertz: The interpretation of cultures (1973)

| Person, Time, and

Conduct in Bali. The Social Nature of Thought Clifford Geertz Human thought is consummately social: social in its origins, social in its functions, social in its forms, social in its applications. At base, thinking is a public activity--its natural habitat is the houseyard, the marketplace, and the town square. The implications of this fact for the anthropological analysis of culture, my concern here, are enormous, subtle, and insufficiently appreciated. I want to draw out some of these implications by means of what might seem at first glance an excessively special, even a somewhat esotric inquiry: an examination of the cultural apparatus in terms of which the people of Bali define, perceive, and react to--that is, think about--individual persons. Such an investigation is, however, special and esoteric only in the descriptive sense. The facts, as facts, are of little immediate interest beyond the confines of ethnography, and I shall summarize them as briefly as I can. But when seen against the background of a general theoretical aim--to determine what follows for the analysis of culture from the proposition that human thinking is essentially a social activity--the Balinese data take on a peculiar importance. Not only are Balinese ideas in this area unusually well developed, but they are, from a Western perspective, odd enough to bring to light some general relationships between different orders of cultural conceptualization that are hidden from us when we look only at our own all-too-familiar framework for the identification, classification, and handling of human and quasi-human individuals. In particular, they point up some unobvious connections between the way in which a people perceive themselves and others, the way in which they experience time, and the affective tone of their collective life--connections that have an import not just for the understanding of Balinese society but human society generally. |

バリにおける人、時間、行動。 思考の社会的性質 クリフォード・ギアーツ 人間の思考は完全に社会的である。その起源において社会的であり、機能においても社会的であり、形態においても社会的であり、応用においても社会的であ る。根本的には、思考とは公共的な活動であり、その自然の生息地は家屋の庭、市場、広場である。この事実が文化の人類学的分析に与える影響は、膨大かつ微 妙であり、十分に評価されているとは言えない。 私は、一見すると過度に特殊で、やや難解な調査と思われるかもしれない方法によって、これらの含意のいくつかを引き出したい。すなわち、バリの人々が個人 を定義し、知覚し、反応する、つまり考える際の文化装置を検証することである。しかし、このような調査は、記述的な意味においてのみ特殊で難解である。事 実を事実として捉える場合、民族誌学の枠組みを超えて、即座に興味を引くことはほとんどない。私は、できるだけ簡潔に事実を要約するつもりである。しか し、一般的な理論的目標、すなわち「人間の思考は本質的に社会的活動である」という命題から文化の分析に何が導かれるかを明らかにするという目標を背景に 考えると、バリ人のデータは独特の重要性を持つ。 バリ人のこの分野における考え方は、非常に良く練られているだけでなく、西洋の観点から見ると、奇妙なほど、人間や人間に準ずる個体の識別、分類、処理に 関する、私たちにとってあまりにも見慣れた枠組みだけを見ていると見えなくなってしまう、異なる文化の概念化の秩序間の一般的な関係を明らかにしてくれ る。特に、人々が自分自身や他人をどう認識するか、時間をどう経験するか、集団生活の情緒的なトーンといったものとのあいだにある、明白ではないいくつか のつながりを浮き彫りにしている。それはバリ社会の理解にとどまらず、人間社会一般にとって重要な意味を持つつながりである。 |

| The Study of Culture A great deal of recent social scientific theorizing has turned upon an attempt to distinguish and specify two major analytical concepts: culture and social structure.1 The impetus for this effort has sprung from a desire to take account of ideational factors in social processes without succumbing to either the Hegelian or the Marxist forms of reductionism. In order to avoid having to regard ideas, concepts, values, and expressive forms either as shadows cast by the organization of society upon the hard surfaces of history or as the soul of history whose progress is but a working out of their internal dialectic, it has proved necessary to regard them as independent but not self-sufficient forces--as acting and having their impact only within specific social contexts to which they adapt, by which they are stimulated, but upon which they have, to a greater or lesser degree, a determining influence. "Do you really expect," Marc Bloch wrote in his little book on The Historian's Craft, "to know the great merchants of Renaissance Europe, vendors of cloth or spices, monopolists in copper, mercury or alum, bankers of Kings and the Emperor, by knowing their merchandise alone? Bear in mind that they were painted by Holbein, that they read Erasmus and Luther. To understand the attitude of the medieval vassal to his seigneur you must inform yourself about his attitude to his God as well." Both the organization of social activity, its institutional forms, and the systems of ideas which animate it must be understood, as must the nature of the relations obtaining between them. It is to this end that the attempt to clarify the concepts of social structure and of culture has been directed. There is little doubt, however, that within this two-sided development it has been the cultural side which has proved the more refractory and remains the more retarded. In the very nature of the case, ideas are more difficult to handle scientifically than the economic, political, and social relations among individuals and groups which those ideas inform. And this is all the more true when the ideas involved are not the explicit doctrines of a Luther or an Erasmus, or the articulate images of a Holbein, but the half-formed, taken-for-granted, indifferently systematized notions that guide the normal activities of ordinary men in everyday life. If the scientific study of culture has lagged, bogged down most often in mere descriptivism, it has been in large part because its very subject matter is elusive. The initial problem of any science--defining its object of study in such a manner as to render it susceptible of analysis--has here turned out to be unusually hard to solve. It is at this point that the conception of thinking as basically a social act, taking place in the same public world in which other social acts occur, can play its most constructive role. The view that thought does not consist of mysterious processes located in what Gilbert Ryle has called a secret grotto in the head but of a traffic in significant symbols --objects in experience (rituals and tools; graven idols and water holes; gestures, markings, images, and sounds) upon which men have impressed meaning--makes of the study of culture a positive science like any other.2 The meanings that symbols, the material vehicles of thought, embody are often elusive, vague, fluctuating, and convoluted, but they are, in principle, as capable of being discovered through systematic empirical investigation--especially if the people who perceive them will cooperate a little--as the atomic weight of hydrogen or the function of the adrenal glands. It is through culture patterns, ordered clusters of significant symbols, that man makes sense of the events through which he lives. The study of culture, the accumulated totality of such patterns, is thus the study of the machinery individuals and groups of individuals employ to orient themselves in a world otherwise opaque. In any particular society, the number of generally accepted and frequently used culture patterns is extremely large, so that sorting out even the most important ones and tracing whatever relationships they might have to one another is a staggering analytical task. The task is somewhat lightened, however, by the fact that certain sorts of patterns and certain sorts of relationships among patterns recur from society to society, for the simple reason that the orientational requirements they serve are generically human. The problems, being existential, are universal; their solutions, being human, are diverse. It is, however, through the circumstantial understanding of these unique solutions, and in my opinion only in that way, that the nature of the underlying problems to which they are a comparable response can be truly comprehended. Here, as in so many branches of knowledge, the road to the grand abstractions of science winds through a thicket of singular facts. One of these pervasive orientational necessities is surely the characterization of individual human beings. Peoples everywhere have developed symbolic structures in terms of which persons are perceived not baldly as such, as mere unadorned members of the human race, but as representatives of certain distinct categories of persons, specific sorts of individuals. In any given case, there are inevitably a plurality of such structures. Some, for example kinship terminologies, are ego-centered: that is, they define the status of an individual in terms of his relationship to a specific social actor. Others are centered on one or another subsystem or aspect of society and are invariant with respect to the perspectives of individual actors: noble ranks, age-group statuses, occupational categories. Some--personal names and sobriquets--are informal and particularizing; others--bureaucratic titles and caste designations--are formal and standardizing. The everyday world in which the members of any community move, their taken-for-granted field of social action, is populated not by anybodies, faceless men without qualities, but by somebodies, concrete classes of determinate persons positively characterized and appropriately labeled. And the symbol systems which define these classes are not given in the nature of things--they are historically constructed, socially maintained, and individually applied. Even a reduction of the task of cultural analysis to a concern only with those patterns having something to do with the characterization of individual persons renders it only slightly less formidable, however. This is because there does not yet exist a perfected theoretical framework within which to carry it out. What is called structural analysis in sociology and social anthropology can ferret out the functional implications for a society of a particular system of person-categories, and at times even predict how such a system might change under the impact of certain social processes; but only if the system--the categories, their meanings, and their logical relationships--can be taken as already known. Personality theory in social-psychology can uncover the motivational dynamics underlying the formation and the use of such systems and can assess their effect upon the character structures of individuals actually employing them; but also only if, in a sense, they are already given, if how the individuals in question see themselves and others has been somehow determined. What is needed is some systematic, rather than merely literary or impressionistic, way to discover what is given, what the conceptual structure embodied in the symbolic forms through which persons are perceived actually is. What we want and do not yet have is a developed method of describing and analyzing the meaningful structure of experience (here, the experience of persons) as it is apprehended by representative members of a particular society at a particular point in time--in a word, a scientific phenomenology of culture. |

文化の研究 最近の社会科学の理論の多くは、2つの主要な分析概念、すなわち「文化」と「社会構造」を区別し、特定しようとする試みに基づいている。1 この取り組みの原動力は、ヘーゲル主義やマルクス主義の還元主義に屈することなく、社会過程における観念的要因を考慮に入れようとする願望から生じてい る。思想、概念、価値、表現形式を、社会の組織が歴史の硬い表面に投げかける影として、あるいは歴史の魂として、その進歩は内部の弁証法の産物に過ぎない としてみなすことを避けるためには、 それらを独立した、しかし自己充足的なものではない力として捉えることが必要である。すなわち、それらは特定の社会的な文脈の中でのみ作用し、影響を及ぼ す。それらはその文脈に適応し、刺激されるが、その文脈に対しては、程度の差こそあれ、決定的な影響力を持つ。「あなたは本当に、ルネサンス期ヨーロッパ の偉大な商人たち、つまり布や香辛料の商人、銅や水銀やミョウバンの独占業者、王や皇帝の銀行家たちについて、彼らの商品だけを知ることで理解できると期 待しているのか?」とマーク・ブロックは著書『歴史家の技法』で書いている。彼らはホルバインによって描かれ、エラスムスやルターを読んでいたことを念頭 に置いてほしい。中世の臣下が領主に対して取る態度を理解するには、領主が神に対して取る態度についても知っておく必要がある。」社会活動の組織、その制 度形態、そしてそれを活性化する思想体系は、それらの間に存在する関係の性質と同様に理解されなければならない。社会構造と文化の概念を明確にしようとす る試みは、まさにこの目的のために行われてきた。 しかし、この二面性のある発展の中で、より難治性があり、より遅れたままであるのは文化的な側面であることは疑いの余地がない。本質的に、個々人や集団間 の経済、政治、社会関係よりも、思想の方が科学的に扱うのが難しい。そして、ルターやエラスムスの明白な教義、あるいはホルバインの明晰なイメージではな く、半ば形成され、当然視され、無関心に体系化された概念が、日常生活における一般人の通常の活動を導くものである場合、この傾向はさらに強まる。文化の 科学的調査が遅れ、単なる記述主義に陥りがちであるのは、その主題が捉えどころのないものだからである。あらゆる科学の初期の問題、すなわち、分析可能な 形で研究対象を定義するという問題は、ここでは解決が非常に難しいことが判明した。 この点において、思考は基本的に社会的行為であり、他の社会的行為が起こるのと同じ公共の世界で行われるという考え方が、最も建設的な役割を果たすことが できる。思考は、ギルバート・ライルが「頭の中の秘密の洞窟」と呼んだ場所にある神秘的なプロセスではなく、意味のあるシンボル(儀式や道具、偶像や水 場、ジェスチャー、印、イメージ、音など)のやりとりから成り立っているという見解は、文化研究を 。2 思考の物質的な媒体である象徴が体現する意味は、しばしば捉えどころがなく、曖昧で、変動し、複雑であるが、それらは、特にそれらを認識する人々が多少協 力すれば、水素の原子量や副腎の機能を発見するのと同様に、体系的な実証的調査によって発見できる可能性がある。人間は、重要なシンボルを秩序ある集合体 として体系化した文化パターンを通じて、自らが生きる出来事を理解する。文化の研究とは、このようなパターンの集積全体を研究することであり、したがっ て、個人や個人集団が、それ以外の点では不透明な世界で自己を方向づけるために用いる仕組みの研究である。 特定の社会において一般的に受け入れられ、頻繁に使用される文化パターンの数は極めて多いため、最も重要なものを整理し、それらの間に存在するであろう関 係性をすべて追跡することは、途方もない分析作業となる。しかし、特定の種類のパターンやパターン間の特定の種類の関係性が社会から社会へと繰り返される という事実によって、この作業はいくらか軽減される。その理由は単純で、それらのパターンや関係性が果たす方向付けの要件は、一般的に人間的なものだから である。問題は実存的なものであるため普遍的であり、その解決策は人間的なものであるため多様である。しかし、これらの独特な解決策を状況に応じて理解す ること、そして私の意見では、それによってのみ、それらに匹敵する対応である根本的な問題の本質を真に理解することができる。多くの知識分野と同様に、科 学の壮大な抽象概念への道は、特異な事実の茂みを通り抜ける。 こうした広範な方向性の必要性のひとつは、間違いなく個々の人間を特徴づけることである。世界中の人々は、人間を単に飾り気のない人類の一員としてではな く、特定のカテゴリーに属する個人、特定の種類の個体として認識する記号体系を発達させてきた。いずれの場合も、このような構造は必然的に複数存在する。 例えば、親族関係の用語は自己中心的なものである。つまり、特定の社会的行為者との関係性において個人の地位を定義する。一方、社会のサブシステムや側面 のいずれかに焦点を当て、個々の行為者の視点とは無関係に変化しないものもある。例えば、貴族の位階、年齢層別の地位、職業カテゴリーなどである。個人名 や通称は非公式で個別化されたものである。一方、官僚的な肩書きやカーストの呼称は公式で標準化されたものである。 あらゆるコミュニティのメンバーが日常的に活動する世界、すなわち、社会活動の当然視された領域には、無名で特徴のない「だれでもない人々」ではなく、 「だれか」が存在する。「だれか」とは、明確な特徴を持ち、適切にラベル付けされた特定の個人階級である。そして、これらのカテゴリーを定義する記号体系 は、物事の本質として与えられているわけではない。それは歴史的に構築され、社会的に維持され、個別的に適用されるものである。 文化分析の課題を、個人の性格付けに関係するパターンだけに絞っても、それは依然として非常に困難な課題であることに変わりはない。なぜなら、それを実行 するための完成された理論的枠組みがまだ存在しないからだ。社会学や社会人類学で構造分析と呼ばれるものは、ある特定の個人カテゴリーの体系が社会に及ぼ す機能的意味を明らかにし、時には、ある特定の社会過程の影響下でそのような体系がどのように変化するかを予測することさえできる。しかし、体系(カテゴ リー、その意味、およびそれらの論理的関係)がすでに既知のものとして扱える場合に限られる。社会心理学における性格理論は、このような体系の形成と使用 の根底にある動機づけの力学を明らかにし、実際にそれを使用している個人の性格構造に対するその影響を評価することができる。しかし、それはある意味で、 すでに与えられている場合に限られる。つまり、問題となっている個人が自分自身と他者をどのように見ているかが、何らかの方法で決定されている場合に限ら れる。必要なのは、単に文学的あるいは印象的なものではなく、体系的な方法で、人が何を前提としているのか、人がどのように認識されるかという象徴的な形 態に具体化された概念的構造が実際にはどのようなものなのかを発見することである。私たちが望んでいるが、まだ持っていないのは、特定の社会の代表的な構 成員が特定の時点で把握する経験(ここでは、人の経験)の意味構造を記述し分析する発展した方法である。つまり、一言で言えば、科学的な文化現象学であ る。 |

| Predecessors, Contemporaries,

Consociates, and Successors There have been, however, a few scattered and rather abstract ventures in cultural analysis thus conceived, from the results of which it is possible to draw some useful leads into our more focused inquiry. Among the more interesting of such forays are those which were carried out by the late philosopher-cum-sociologist Alfred Sch¸tz, whose work represents a somewhat heroic, yet not unsuccessful, attempt to fuse influences stemming from Scheler, Weber, and Husserl on the one side with ones stemming from James, Mead, and Dewey on the other.3 Sch¸tz covered a multitude of topics--almost none of them in terms of any extended or systematic consideration of specific social processes--seeking always to uncover the meaningful structure of what he regarded as "the paramount reality" in human experience: the world of daily life as men confront it, act in it, and live through it. For our own purposes, one of his exercises in speculative social phenomenology--the disaggregation of the blanket notion of "fellowmen" into "predecessors," "contemporaries," "consociates," and "successors" --provides an especially valuable starting point. Viewing the cluster of culture patterns Balinese use to characterize individuals in terms of this breakdown brings out, in a most suggestive way, the relationships between conceptions of personal identity, conceptions of temporal order, and conceptions of behavioral style which, as we shall see, are implicit in them. The distinctions themselves are not abstruse, but the fact that the classes they define overlap and interpenetrate makes it difficult to formulate them with the decisive sharpness analytical categories demand. "Consociates" are individuals who actually meet, persons who encounter one another somewhere in the course of daily life. They thus share, however briefly or superficially, not only a community of time but also of space. They are "involved in one another's biography" at least minimally; they "grow older together" at least momentarily, interacting directly and personally as egos, subjects, selves. Lovers, so long as love lasts, are consociates, as are spouses until they separate or friends until they fall out. So also are members of orchestras, players at games, strangers chatting on a train, hagglers in a market, or inhabitants of a village: any set of persons who have an immediate, face-to-face relationship. It is, however, persons having such relations more or less continuously and to some enduring purpose, rather than merely sporadically or incidentally, who form the heart of the category. The others shade over into being the second sort of fellowmen: "contemporaries." Contemporaries are persons who share a community of time but not of space: they live at (more or less) the same period of history and have, often very attenuated, social relationships with one another, but they do not--at least in the normal course of things--meet. They are linked not by direct social interaction but through a generalized set of symbolically formulated (that is, cultural) assumptions about each other's typical modes of behavior. Further, the level of generalization involved is a matter of degree, so that the graduation of personal involvement in consociate relations from lovers through chance acquaintances--relations also culturally governed, of course--here continues until social ties slip off into a thoroughgoing anonymity, standardization, and interchangeability: Thinking of my absent friend A., I form an ideal type of his personality and behavior based on my past experience of A. as my consociate. Putting a letter in a mailbox, I, expect that unknown people, called postmen, will act in a typical way, not quite intelligible to me, with the result that my letter will reach the addressee within typically reasonable time. Without ever having met a Frenchman or a German, I understand "Why France fears the rearmament of Germany." Complying with a rule of English grammar, I follow [in my writings] a socially-approved behavior pattern of contemporary English-speaking fellow-men to which I have to adjust to make myself understandable. And, finally, any artifact or utensil refers to the anonymous fellow-man who produced it to be used by other anonymous fellow-men for attaining typical goals by typical means. These are just a few of the examples but they are arranged according to the degree of increasing anonymity involved and therewith of the construct needed to grasp the Other and his behavior.4 Finally, "predecessors" and "successors" are individuals who do not share even a community of time and so, by definition, cannot interact; and, as such, they form something of a single class over against both consociates and contemporaries, who can and do. But from the point of view of any particular actor they do not have quite the same significance. Predecessors, having already lived, can be known or, more accurately, known about, and their accomplished acts can have an influence upon the lives of those for whom they are predecessors (that is, their successors), though the reverse is, in the nature of the case, not possible. Successors, on the other hand, cannot be known, or even known about, for they are the unborn occupants of an unarrived future; and though their lives can be influenced by the accomplished acts of those whose successors they are (that is, their predecessors), the reverse is again not possible.5 For empirical purposes, however, it is more useful to formulate these distinctions less strictly also, and to emphasize that, like those setting off consociates from contemporaries, they are relative and far from clear-cut in everyday experience. With some exceptions, our older consociates and contemporaries do not drop suddenly into the past, but fade more or less gradually into being our predecessors as they age and die, during which period of apprentice ancestorhood we may have some effect upon them, as children so often shape the closing phases of their parents' lives. And our younger consociates and contemporaries grow gradually into becoming our successors, so that those of us who live long enough often have the dubious privilege of knowing who is to replace us and even occasionally having some glancing influence upon the direction of his growth. "Consociates," "contemporaries," "predecessors," and "successors" are best seen not as pigeonholes into which individuals distribute one another for classificatory purposes, but as indicating certain general and not altogether distinct, matter-of-fact relationships which individuals conceive to obtain between themselves and others. But again, these relationships are not perceived purely as such; they are grasped only through the agency of cultural formulations of them. And, being culturally formulated, their precise character differs from society to society as the inventory of available culture patterns differs; from situation to situation within a single society as different patterns among the plurality of those which are available are deemed appropriate for application; and from actor to actor within similar situations as idiosyncratic habits, preferences, and interpretations come into play. There are, at least beyond infancy, no neat social experiences of any importance in human life. Everything is tinged with imposed significance, and fellowmen, like social groups, moral obligations, political institutions, or ecological conditions are apprehended only through a screen of significant symbols which are the vehicles of their objectification, a screen that is therefore very far from being neutral with respect to their "real" nature. Consociates, contemporaries, predecessors, and successors are as much made as born.6 |

先人、同時代人、協力者、後継者 しかし、このような文化分析はこれまでにも断片的に、またかなり抽象的に試みられてきた。その成果から、より焦点を絞った調査に役立ついくつかの手がかり を引き出すことができる。そうした試みの中でも特に興味深いものの一つは、哲学者であり社会学者でもあった故アルフレッド・シュッツ(Alfred Sch?tz)によるもので、彼の研究は、シェーラー(Scheler)、ウェーバー(Weber)、フッサール(Husserl)に由来する影響と、 ジェームズ(James)、ミード(Mead)、デューイ(Dewey)に由来する影響とを融合させるという、ある意味で英雄的な、しかし決して失敗では ない試みを表している 。3 シュッツは、数多くのテーマを扱ったが、そのほとんどは特定の社会的プロセスに関する拡張的または体系的な考察という観点からはほとんどなかった。彼は、 人間が直面し、その中で行動し、その中で生きる日常生活の世界という、人間経験における「最も重要な現実」とみなされるものの意味のある構造を明らかにし ようと常に努めていた。我々の目的のためには、彼の思索的社会現象学の研究のひとつである「同胞」という包括的な概念を「先人」、「同時代人」、「仲 間」、「後継者」に分解するという試みは、特に価値ある出発点となる。バリ人がこの分類を用いて個人の特徴を表現する文化パターンの集合を観察すると、個 人としてのアイデンティティの概念、時間的秩序の概念、行動様式の概念の関係が、非常に示唆的な形で浮かび上がる。 これらの分類自体は難解なものではないが、各分類が重なり合い、相互に浸透しているという事実により、分析カテゴリーが要求するような明確な鋭さをもって それらを定式化することが困難になっている。「コンソシエイト」とは、実際に顔を合わせる人々、日常生活のどこかで互いに遭遇する人々のことである。 したがって、彼らは、たとえそれが短時間であったり表面的なものであったとしても、時間だけでなく空間も共有している。 彼らは少なくとも最低限、「互いの伝記に関わっている」し、少なくとも瞬間的には「一緒に年を取っている」のである。自我、主体、自己として直接かつ個人 的に交流しているのだ。愛が続く限り、恋人たちは仲間であり、別れるまで夫婦であり、仲違いするまでは友人である。オーケストラの団員、ゲームの対戦相 手、電車の中で立ち話をしている見知らぬ人々、市場での値引き交渉者、村の住人など、即座に顔を合わせる関係にある人々の集まりも同様である。しかし、こ のカテゴリーの中心となるのは、単に散発的または偶発的にではなく、ある程度継続的に、そして何らかの持続的な目的を持ってそのような関係を持つ人々であ る。それ以外の人は、2番目の種類の同胞である「同時代人」に分類される。 同時代人とは、空間ではなく時間を共有する人々である。彼らは(多少の差こそあれ)ほぼ同じ時代に生き、お互いに非常に希薄な社会的関係を持っているが、 少なくとも通常の流れにおいては、出会うことはない。彼らは直接的な社会的交流によってではなく、お互いの典型的な行動様式に関する象徴的に定式化された (つまり文化的)前提条件の一般化された集合によって結びついている。さらに、この一般化の度合いには程度の問題があるため、恋人から偶然の知り合いま で、文化によっても支配されている共同関係における個人的関与の段階は、 不在の友人Aのことを考えると、私は共同者としてのAとの過去の経験に基づいて、Aの人格と行動の理想型を思い描く。郵便ポストに手紙を投函するとき、私 は、郵便配達人と呼ばれる見知らぬ人々が、私には理解できない典型的な行動を取ることを期待する。その結果、私の手紙は通常妥当な時間内に宛先に届く。フ ランス人やドイツ人に会ったことがないにもかかわらず、私は「なぜフランスはドイツの再軍備を恐れるのか」を理解している。英語の文法の規則に従い、私は (自分の文章において)現代の英語話者たちの間で社会的に承認された行動パターンに従っている。そして、最終的に、あらゆる人工物や道具は、それを生産し た匿名の人物を指し、他の匿名の人物が典型的な手段で典型的な目標を達成するために使用される。これらはほんの一例に過ぎないが、匿名性の度合いに従って 分類されており、それによって「他者」とその行動を把握するために必要な構造が示されている。 最後に、「前任者」と「後任者」は、時間的にも共通点を持たないため、定義上、相互作用を持つことはできない。しかし、特定の行為者の観点から見ると、彼 らはまったく同じ重要性を持っているわけではない。先人たちはすでに生きていたので、知られている、あるいはより正確に言えば、知られている可能性があ る。彼らの成し遂げた行為は、彼らにとっての先人(つまり、彼らの後継者)の人生に影響を与える可能性がある。しかし、その逆は、本質的に不可能である。 一方、後継者は、まだ生まれていない未来の住人であるため、知られることも、知られることもない。また、後継者の先人(すなわち、先人)の達成された行為 によって、後継者の生活が影響を受けることはあっても、その逆はありえない。5 しかし経験的な目的のためには、これらの区別もあまり厳密に定式化せず、共同体の構成員と同時代の人々を区別するのと同様に、日常的な経験においては相対 的で明確なものではないことを強調する方がより有益である。いくつかの例外はあるものの、私たちの年長のコソシエイトや同時代人は、突然過去に消え去るの ではなく、年齢を重ねて死を迎えるにつれ、徐々に先人へとフェードアウトしていく。その間、私たちは見習い先祖として、彼らに少なからず影響を与える可能 性がある。子供が親の晩年を形作るように、というように。そして、私たちの若い仲間や同世代の人々は、徐々に私たちの後継者へと成長していく。そのため、 長生きする人ほど、誰が自分の後を継ぐことになるのかを知るという疑わしい特権を持ち、時にはその成長の方向性にわずかながら影響を与えることもある。 「同輩」、「同時代人」、「前任者」、「後継者」は、分類目的で個人が互いを振り分けるための分類項目としてではなく、個人と他者との間に存在すると考え られる、一般的で、完全に区別できるものではない、ある種の事実上の関係を示すものとして捉えるのが最善である。 しかし、繰り返しになるが、これらの関係は純粋にそれ自体として認識されるものではない。それらは、文化的な定式化を通じてのみ把握される。そして、文化 的に形成されているため、利用可能な文化パターンの品揃えが異なるため、社会によってその正確な性質は異なる。また、ひとつの社会の中でも、適用に適して いるとみなされる利用可能なパターンのうちの異なるパターンが存在するため、状況によっても異なる。さらに、類似した状況の中でも、独特の習慣、好み、解 釈が関わってくるため、行為者によっても異なる。少なくとも乳幼児期を過ぎた後においては、人間の生活において重要な、きちんとした社会経験など存在しな い。すべてに意味が与えられ、同時代の人々、社会集団、道徳的義務、政治制度、あるいは生態学的条件は、客観化の手段である象徴のフィルターを通してのみ 理解される。したがって、その「本質」に関して中立であるとは程遠い。仲間、同時代の人々、先人、後輩は、生まれながらに存在するのと同様に、作られた存 在でもある。 |

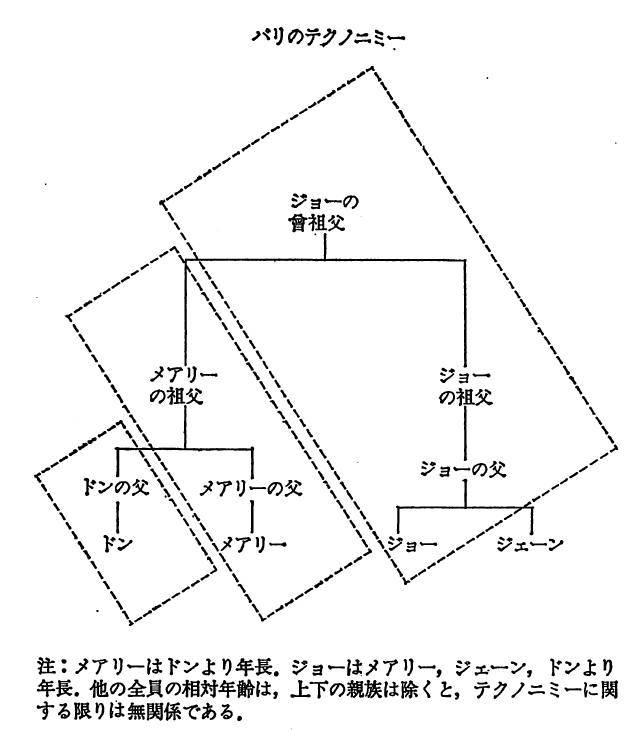

| Balinese Orders of

Person-Definition In Bali,7 there are six sorts of labels which one person can apply to another in order to identify him as a unique individual and which I want to consider against this general conceptual background: (1) personal names; (2) birth order names; (3) kinship terms; (4) teknonyms; (5) status titles (usually called "caste names" in the literature on Bali); and (6) public titles, by which I mean quasi-occupational titles borne by chiefs, rulers, priests, and gods. These various labels are not, in most cases, employed simultaneously, but alternatively, depending upon the situation and sometimes the individual. They are not, also, all the sorts of such labels ever used; but they are the only ones which are generally recognized and regularly applied. And as each sort consists not of a mere collection of useful tags but of a distinct and bounded terminological system, I shall refer to them as "symbolic orders of person-definition" and consider them first serially, only later as a more or less coherent cluster. PERSONAL NAMES The symbolic order defined by personal names is the simplest to describe because it is in formal terms the least complex and in social ones the least important. All Balinese have personal names, but they rarely use them, either to refer to themselves or others or in addressing anyone. (With respect to one's forebears, including one's parents, it is in fact sacrilegious to use them.) Children are more often referred to and on occasion even addressed by their personal names. Such names are therefore sometimes called "child" or "little" names, though once they are ritually bestowed 105 days after birth, they are maintained unchanged through the whole course of a man's life. In general, personal names are seldom heard and play very little public role. Yet, despite this social marginality, the personal-naming system has some characteristics which, in a rather left-handed way, are extremely significant for an understanding of Balinese ideas of personhood. First, personal names are, at least among the commoners (some 90 percent of the population), arbitrarily coined nonsense syllables. They are not drawn from any established pool of names which might lend to them any secondary significance as being "common" or "unusual," as reflecting someone's being named "after" someone--an ancestor, a friend of the parents, a famous personage--or as being propitious, suitable, characteristic of a group or region, indicating a kinship relation, and so forth.8 Second, the duplication of personal names within a single community--that is, a politically unified, nucleated settlement--is studiously avoided. Such a settlement (called a bandjar, or "hamlet") is the primary face-to-face group outside the purely domestic realm of the family, and in some respects is even more intimate. Usually highly endogamous and always highly corporate, the hamlet is the Balinese world of consociates par excellence; and, within it, every person possesses, however unstressed on the social level, at least the rudiments of a completely unique cultural identity. Third, personal names are monomials, and so do not indicate familial connections, or in fact membership in any sort of group whatsoever. And, finally, there are (a few rare, and in any case only partial, exceptions aside) no nicknames, no epithets of the "Richard-the-Lion-Hearted" or "Ivan-the-Terrible" sort among the nobility, not even any diminutives for children or pet names for lovers, spouses, and so on. Thus, whatever role the symbolic order of person-definition marked out by the personal-naming system plays in setting Balinese off from one another or in ordering Balinese social relations is essentially residual in nature. One's name is what remains to one when all the other socially much more salient cultural labels attached to one's person are removed. As the virtually religious avoidance of its direct use indicates, a personal name is an intensely private matter. Indeed, toward the end of a man's life, when he is but a step away from being the deity he will become after his death and cremation, only he (or he and a few equally aged friends) may any longer know what in fact it is; when he disappears it disappears with him. In the well-lit world of everyday life, the purely personal part of an individual's cultural definition, that which in the context of the immediate consociate community is most fully and completely his, and his alone, is highly muted. And with it are muted the more idiosyncratic, merely biographical, and, consequently, transient aspects of his existence as a human being (what, in our more egoistic framework, we call his "personality") in favor of some rather more typical, highly conventionalized, and, consequently, enduring ones. BIRTH ORDER NAMES The most elementary of such more standardized labels are those automatically bestowed upon a child, even a stillborn one, at the instant of its birth, according to whether it is the first, second, third, fourth, etc., member of a sibling set. There is some local and status-group variation in usage here, but the most common system is to use Wayan for the first child, Njoman for the second, Made (or Nengah) for the third, and Ktut for the fourth, beginning the cycle over again with Wayan for the fifth, Njoman for the sixth, and so on. These birth order names are the most frequently used terms of both address and reference within the hamlet for children and for young men and women who have not yet produced offspring. Vocatively, they are almost always used simply, that is, without the addition of the personal name: "Wayan, give me the hoe," and so forth. Referentially, they may be supplemented by the personal name, especially when no other way is convenient to get across which of the dozens of Wayans or Njomans in the hamlet is meant: "No, not Wayan Rugrug, Wayan Kepig," and so on. Parents address their own children and childless siblings address one another almost exclusively by these names, rather than by either personal names or kin terms. For persons who have had children, however, they are never used either inside the family or out, teknonyms being employed, as we shall see, instead, so that, in cultural terms, Balinese who grow to maturity without producing children (a small minority) remain themselves children--that is, are symbolically pictured as such--a fact commonly of great shame to them and embarrassment to their consociates, who often attempt to avoid having to use vocatives to them altogether.9 The birth order system of person-definition represents, therefore, a kind of plus Áa change approach to the denomination of individuals. It distinguishes them according to four completely contentless appellations, which neither define genuine classes (for there is no conceptual or social reality whatsoever to the class of all Wayans or all Ktuts in a community), nor express any concrete characteristics of the individuals to whom they are applied (for there is no notion that Wayans have any special psychological or spiritual traits in common against Njomans or Ktuts). These names, which have no literal meaning in themselves (they are not numerals or derivatives of numerals) do not, in fact, even indicate sibling position or rank in any realistic or reliable way.10 A Wayan may be a fifth (or ninth!) child as well as a first; and, given a traditional peasant demographic structure--great fertility plus a high rate of stillbirths and deaths in infancy and childhood--a Made or a Ktut may actually be the oldest of a long string of siblings and a Wayan the youngest. What they do suggest is that, for all procreating couples, births form a circular succession of Wayans, Njomans, Mades, Ktuts, and once again Wayans, an endless four-stage replication of an imperishable form. Physically men come and go as the ephemerae they are, but socially the dramatis personae remain eternally the same as new Wayans and Ktuts emerge from the timeless world of the gods (for infants, too, are but a step away from divinity) to replace those who dissolve once more into it. KINSHIP TERMS Formally, Balinese kinship terminology is quite simple in type, being of the variety known technically as "Hawaiian" or "Generational." In this sort of system, an individual classifies his relatives primarily according to the generation they occupy with respect to his own. That is to say, siblings, half-siblings, and cousins (and their spouses' siblings, and so forth) are grouped together under the same term; all uncles and aunts on either side are terminologically classed with mother and father; all children of brothers, sisters, cousins, and so on (that is, nephews of one sort or another) are identified with own children; and so on, downward through the grandchild, great-grandchild, etc., generations, and upward through the grandparent, great-grandparent, etc., ones. For any given actor, the general picture is a layer-cake arrangement of relatives, each layer consisting of a different generation of kin--that of actor's parents or his children, of his grandparents or his grandchildren, and so on, with his own layer, the one from which the calculations are made, located exactly halfway up the cake.11 Given the existence of this sort of system, the most significant (and rather unusual) fact about the way it operates in Bali is that the terms it contains are almost never used vocatively, but only referentially, and then not very frequently. With rare exceptions, one does not actually call one's father (or uncle) "father," one's child (or nephew/niece) "child," one's brother (or cousin) "brother," and so on. For relatives genealogically junior to oneself vocative forms do not even exist; for relatives senior they exist but, as with personal names, it is felt to demonstrate a lack of respect for one's elders to use them. In fact, even the referential forms are used only when specifically needed to convey some kinship information as such, almost never as general means of identifying people. Kinship terms appear in public discourse only in response to some question, or in describing some event which has taken place or is expected to take place, with respect to which the existence of the kin tie is felt to be a relevant piece of information. ("Are you going to Fatherof-Regreg's tooth-filing?" "Yes, he is my 'brother.'") Thus, too, modes of address and reference within the family are no more (or not much more) intimate or expressive of kin ties in quality than those within the hamlet generally. As soon as a child is old enough to be capable of doing so (say, six years, though this naturally varies) he calls his mother and father by the same term--a teknonym, status group title, or public title--that everyone else who is acquainted with them uses toward them, and is called in turn Wayan, Ktut, or whatever, by them. And, with even more certainty, he will refer to them, whether in their hearing or outside of it, by this popular, extradomestic term as well. In short, the Balinese system of kinship terminology defines individuals in a primarily taxonomic, not a face-to-face idiom, as occupants of regions in a social field, not partners in social interaction. It functions almost entirely as a cultural map upon which certain persons can be located and certain others, not features of the landscape mapped, cannot. Of course, some notions of appropriate interpersonal behavior follow once such determinations are made, once a person's place in the structure is ascertained. But the critical point is that, in concrete practice, kin terminology is employed virtually exclusively in service of ascertainment, not behavior, with respect to whose patterning other symbolic appliances are dominant.12 The social norms associated with kinship, though real enough, are habitually overridden, even within kinship-type groups themselves (families, households, lineages) by culturally better armed norms associated with religion, politics, and, most fundamentally of all, social stratification. Yet in spite of the rather secondary role it plays in shaping the moment-to-moment flow of social intercourse, the system of kinship terminology, like the personal-naming system, contributes importantly, if indirectly, to the Balinese notion of personhood. For, as a system of significant symbols, it too embodies a conceptual structure under whose agency individuals, one's self as well as others, are apprehended; a conceptual structure which is, moreover, in striking congruence with those embodied in the other, differently constructed and variantly oriented, orders of person-definition. Here, also, the leading motif is the immobilization of time through the iteration of form. This iteration is accomplished by a feature of Balinese kin terminology I have yet to mention: in the third generation above and below the actor's own, terms become completely reciprocal. That is to say, the term for "great-grandparent" and "great-grandchild" is the same: kumpi. The two generations, and the individuals who comprise them, are culturally identified. Symbolically, a man is equated upwardly with the most distant ascendant, downwardly with the most distant descendant, he is ever likely to interact with as a living person. Actually, this sort of reciprocal terminology proceeds on through the fourth generation, and even beyond. But as it is only extremely rarely that the lives of a man and his great-great-grandparent (or great-greatgrandchild) overlap, this continuation is of only theoretical interest, and most people don't even know the terms involved. It is the four-generation span (i.e., the actor's own, plus three ascending or descending) which is considered the attainable ideal, the image, like our threescore-and-ten, of a fully completed life, and around which the kumpikumpi terminology puts, as it were, an emphatic cultural parenthesis. This parenthesis is accentuated further by the rituals surrounding death. At a person's funeral, all his relatives who are generationally junior to him must make homage to his lingering spirit in the Hindu palms-to-forehead fashion, both before his bier and, later, at the graveside. But this virtually absolute obligation, the sacramental heart of the funeral ceremony, stops short with the third descending generation, that of his "grandchildren." His "great-grandchildren" are his kumpi, as he is theirs, and so, the Balinese say, they are not really junior to him at all but rather "the same age." As such, they are not only not required to show homage to his spirit, but they are expressly forbidden to do so. A man prays only to the gods and, what is the same thing, his seniors, not to his equals or juniors.13 Balinese kinship terminology thus not only divides human beings into generational layers with respect to a given actor, it bends these layers into a continuous surface which joins the "lowest" with the "highest" so that, rather than a layer-cake image, a cylinder marked off into six parallel bands called "own," "parent," "grandparent," "kumpi," "grandchild," and "child" is perhaps more exact. 14 What at first glance seems a very diachronic formulation, stressing the ceaseless progression of generations is, in fact, an assertion of the essential unreality--or anyway the unimportance--of such a progression. The sense of sequence, of sets of collaterals following one another through time, is an illusion generated by looking at the terminological system as though it were used to formulate the changing quality of face-to-face interactions between a man and his kinsmen as he ages and dies--as indeed many, if not most such systems are used. When one looks at it, as the Balinese primarily do, as a common-sense taxonomy of the possible types of familial relationships human beings may have, a classification of kinsmen into natural groups, it is clear that what the bands on the cylinder are used to represent is the genealogical order of seniority among living people and nothing more. They depict the spiritual (and what is the same thing, structural) relations among coexisting generations, not the location of successive generations in an unrepeating historical process. TEKNONYMS If personal names are treated as though they were military secrets, birth order names applied mainly to children and young adolescents, and kinship terms invoked at best sporadically, and then only for purposes of secondary specification, how, then, do most Balinese address and refer to one another? For the great mass of the peasantry, the answer is: by teknonyms.15 As soon as a couple's first child is named, people begin to address and refer to them as "Father-of" and "Mother-of" Regreg, Pula, or whatever the child's name happens to be. They will continue to be so called (and to call themselves) until their first grandchild is born, at which time they will begin to be addressed and referred to as "Grandfatherof" and "Grandmother-of" Suda, Lilir, or whomever; and a similar transition occurs if they live to see their first great-grandchild.16 Thus, over the "natural" four-generation kumpi-to-kumpi life span, the term by which an individual is known will change three times, as first he, then at least one of his children, and finally at least one of his grandchildren produce offspring. Of course, many if not most people neither live so long nor prove so fortunate in the fertility of their descendants. Also, a wide variety of other factors enter in to complicate this simplified picture. But, subtleties aside, the point is that we have here a culturally exceptionally well developed and socially exceptionally influential system of teknonymy. What impact does it have upon the individual Balinese's perceptions of himself and his acquaintances? Its first effect is to identify the husband and wife pair, rather as the bride's taking on of her husband's surname does in our society; except that here it is not the act of marriage which brings about the identification but of procreation. Symbolically, the link between husband and wife is expressed in terms of their common relation to their children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren, not in terms of the wife's incorporation into her husband's "family" (which, as marriage is highly endogamous, she usually belongs to anyway). This husband-wife--or, more accurately, father-mother--pair has very great economic, political, and spiritual importance. It is, in fact, the fundamental social building block. Single men cannot participate in the hamlet council, where seats are awarded by married couple; and, with rare exceptions, only men with children carry any weight there. (In fact, in some hamlets men are not even awarded seats until they have a child.) The same is true for descent groups, voluntary organizations, irrigation societies, temple congregations, and so on. In virtually all local activities, from the religious to the agricultural, the parental couple participates as a unit, the male performing certain tasks, the female certain complementary ones. By linking a man and a wife through an incorporation of the name of one of their direct descendants into their own, teknonymy underscores both the importance of the marital pair in local society and the enormous value which is placed upon procreation.17 This value also appears, in a more explicit way, in the second cultural consequence of the pervasive use of teknonyms: the classification of individuals into what, for want of a better term, may be called procreational strata. From the point of view of any actor, his hamletmates are divided into childless people, called Wayan, Made, and so on; people with children, called "Father (Mother)-of"; people with grandchildren, called "Grandfather (Grandmother)-of"; and people with greatgrandchildren, called "Great-grandparent-of." And to this ranking is attached a general image of the nature of social hierarchy: childless people are dependent minors; fathers-of are active citizens directing community life; grandfathers-of are respected elders giving sage advice from behind the scenes; and great-grandfathers-of are senior dependents, already half-returned to the world of the gods. In any given case, various mechanisms have to be employed to adjust this rather too-schematic formula to practical realities in such a way as to allow it to mark out a workable social ladder. But, with these adjustments, it does, indeed, mark one out, and as a result a man's "procreative status" is a major element in his social identity, both in his own eyes and those of everyone else. In Bali, the stages of human life are not conceived in terms of the processes of biological aging, to which little cultural attention is given, but of those of social regenesis. Thus, it is not sheer reproductive power as such, how many children one can oneself produce, that is critical. A couple with ten children is no more honored than a couple with five; and a couple with but a single child who has in turn but a single child outranks them both. What counts is reproductive continuity, the preservation of the community's ability to perpetuate itself just as it is, a fact which the third result of teknonymy, the designation of procreative chains, brings out most clearly. The way in which Balinese teknonymy outlines such chains can be seen from the model diagram (Figure 1 ). For simplicity, I have shown only the male teknonyms and have used English names for the referent generation. I have also arranged the model so as to stress the fact that teknonymous usage reflects the absolute age not the genealogical order (or the sex) of the eponymous descendants. FIGURE 1 Balinese Teknonymy (not available) NOTE: Mary is older than Don; Joe is older than Mary, Jane, and Don. The relative ages of all other people, save of course as they are ascendants and descendants, are irrelevant so far as teknonymy is concerned. As Figure 1 indicates, teknonymy outlines not only procreative statuses but specific sequences of such statuses, two, three, or four (very, very occasionally, five) generations deep. Which particular sequences are marked out is largely accidental: had Mary been born before Joe, or Don before Mary, the whole alignment would have been altered. But though the particular individuals who are taken as referents, and hence the particular sequences of filiation which receive symbolic recognition, is an arbitrary and not very consequential matter, the fact that such sequences are marked out stresses an important fact about personal identity among the Balinese: an individual is not perceived in the context of who his ancestors were (that, given the cultural veil which slips over the dead, is not even known), but rather in the context of whom he is ancestral to. One is not defined, as in so many societies of the world, in terms of who produced one, some more or less distant, more or less grand founder of one's line, but in terms of whom one has produced, a specific, in most cases still living, half-formed individual who is one's child, grandchild, or great-grandchild, and to whom one traces one's connection through a particular set of procreative links.18 What links "Great-grandfather-of-Joe," "Grandfather-of-Joe," and "Father-of-Joe" is the fact that, in a sense, they have cooperated to produce Joe--that is, to sustain the social metabolism of the Balinese people in general and their hamlet in particular. Again, what looks like a celebration of a temporal process is in fact a celebration of the maintenance of what, borrowing a term from physics, Gregory Bateson has aptly called a "steady state."19 In this sort of teknonymous regime, the entire population is classified in terms of its relation to and representation in that subclass of the population in whose hands social regenesis now most instantly lies--the oncoming cohort of prospective parents. Under its aspect even that most time-saturated of human conditions, great-grandparenthood, appears as but an ingredient in an unperishing present. STATUS TITLES In theory, everyone (or nearly everyone) in Bali bears one or another title--Ida Bagus, Gusti, Pasek, Dauh, and so forth--which places him on a particular rung in an all-Bali status ladder; each title represents a specific degree of cultural superiority or inferiority with respect to each and every other one, so that the whole population is sorted out into a set of uniformly graded castes. In fact, as those who have tried to analyze the system in such terms have discovered, the situation is much more complex. It is not simply that a few low-ranking villagers claim that they (or their parents) have somehow "forgotten" what their titles are; nor that there are marked inconsistencies in the ranking of titles from place to place, at times even from informant to informant; nor that, in spite of their hereditary basis, there are nevertheless ways to change titles. These are but (not uninteresting) details concerning the day-to-day working of the system. What is critical is that status titles are not attached to groups at all, but only to individuals.20 Status in Bali, or at least that sort determined by titles, is a personal characteristic; it is independent of any social structural factors whatsoever. It has, of course, important practical consequences, and those consequences are shaped by and expressed through a wide variety of social arrangements, from kinship groups to governmental institutions. But to be a Dewa, a Pulosari, a Pring, or a Maspadan is at base only to have inherited the right to bear that title and to demand the public tokens of deference associated with it. It is not to play any particular role, to belong to any particular group, or to occupy any particular economic, political, or sacerdotal position. The status title system is a pure prestige system. From a man's title you know, given your own title, exactly what demeanor you ought to display toward him and he toward you in practically every context of public life, irrespective of whatever other social ties obtain between you and whatever you may happen to think of him as a man. Balinese politesse is very highly developed and it rigorously controls the outer surface of social behavior over virtually the entire range of daily life. Speech style, posture, dress, eating, marriage, even house-construction, place of burial, and mode of cremation are patterned in terms of a precise code of manners which grows less out of a passion for social grace as such as out of some rather far-reaching metaphysical considerations. The sort of human inequality embodied in the status title system and the system of etiquette which expresses it is neither moral, nor economic, nor political--it is religious. It is the reflection in everyday interaction of the divine order upon which such interaction, from this point of view a form of ritual, is supposed to be modeled. A man's title does not signal his wealth, his power, or even his moral reputation, it signals his spiritual composition; and the incongruity between this and his secular position may be enormous. Some of the greatest movers and shakers in Bali are the most rudely approached, some of the most delicately handled the least respected. It would be difficult to conceive of anything further from the Balinese spirit than Machiavelli's comment that titles do not reflect honor upon men, but rather men upon their titles. In theory, Balinese theory, all titles come from the gods. Each has been passed along, not always without alteration, from father to child, like some sacred heirloom, the difference in prestige value of the different titles being an outcome of the varying degree to which the men who have had care of them have observed the spiritual stipulations embodied in them. To bear a title is to agree, implicitly at least, to meet divine standards of action, or at least approach them, and not all men have been able to do this to the same extent. The result is the existing discrepancy in the rank of titles and of those who bear them. Cultural status, as opposed to social position, is here once again a reflection of distance from divinity. Associated with virtually every title there are one or a series of legendary events, very concrete in nature, involving some spiritually significant misstep by one or another holder of the title. These offenses-one can hardly call them sins--are regarded as specifying the degree to which the title has declined in value, the distance which it has fallen from a fully transcendent status, and thus as fixing, in a general way at least, its position in the overall scale of prestige. Particular (if mythic) geographical migrations, cross--title marriages, military failures, breaches of mourning etiquette, ritual lapses, and the like are regarded as having debased the title to a greater or lesser extent: greater for the lower titles, lesser for the higher. Yet, despite appearances, this uneven deterioration is, in its essence, neither a moral nor an historical phenomenon. It is not moral because the incidents conceived to have occasioned it are not, for the most part, those against which negative ethical judgments would, in Bali any more than elsewhere, ordinarily be brought, while genuine moral faults (cruelty, treachery, dishonesty, profligacy) damage only reputations, which pass from the scene with their owners, not titles which remain. It is not historical because these incidents, disjunct occurrences in a once-upona-time, are not invoked as the causes of present realities but as statements of their nature. The important fact about title-debasing events is not that they happened in the past, or even that they happened at all, but that they are debasing. They are formulations not of the processes which have brought the existing state of affairs into being, nor yet of moral judgments upon it (in neither of which intellectual exercises the Balinese show much interest): they are images of the underlying relationship between the form of human society and the divine pattern of which it is, in the nature of things, an imperfect expression--more imperfect at some points than at others. But if, after all that has been said about the autonomy of the title system, such a relationship between cosmic patterns and social forms is conceived to exist, exactly how is it understood? How is the title system, based solely on religious conceptions, on theories of inherent differences in spiritual worth among individual men, connected up with what, looking at the society from the outside, we would call the "realities" of power, influence, wealth, reputation, and so on, implicit in the social division of labor? How, in short, is the actual order of social command fitted into a system of prestige ranking wholly independent of it so as to account for and, indeed, sustain the loose and general correlation between them which in fact obtains? The answer is: through performing, quite ingeniously, a kind of hat trick, a certain sleight of hand, with a famous cultural institution imported from India and adapted to local tastes--the Varna System. By means of the Varna System the Balinese inform a very disorderly collection of status pigeonholes with a simple shape which is represented as growing naturally out of it but which in fact is arbitrarily imposed upon it. As in India, the Varna System consists of four gross categories--Brahmana, Satria, Wesia, and Sudra--ranked in descending order of prestige, and with the first three (called in Bali, Triwangsa--"the three peoples") defining a spiritual patriciate over against the plebeian fourth. But in Bali the Varna System is not in itself a cultural device for making status discriminations but for correlating those already made by the title system. It summarizes the literally countless fine comparisons implicit in that system in a neat (from some points of view all-too-neat) separation of sheep from goats, and first-quality sheep from second, second from third.21 Men do not perceive one another as Satrias or Sudras but as, say, Dewas or Kebun Tubuhs, merely using the Satria-Sudra distinction to express generally, and for social organizational purposes, the order of contrast which is involved by identifying Dewa as a Satria title and Kebun Tubuh as a Sudra one. Varna categories are labels applied not to men, but to the titles they bear--they formulate the structure of the prestige system; titles, on the other hand, are labels applied to individual men--they place persons within that structure. To the degree that the Varna classification of titles is congruent with the actual distribution of power, wealth, and esteem in the society--that is, with the system of social stratification--the society is considered to be well ordered. The right sort of men are in the right sort of places: spiritual worth and social standing coincide. This difference in function between title and Varna is clear from the way in which the symbolic forms associated with them are actually used. Among the Triwangsa gentry, where, some exceptions aside, teknonymy is not employed, an individual's title is used as his or her main term of address and reference. One calls a man Ida Bagus, Njakan, or Gusi (not Brahmana, Satria, or Wesia) and refers to him by the same terms, sometimes adding a birth order name for more exact specification ( Ida Bagus Made, Njakan Njoman, and so forth). Among the Sudras, titles are used only referentially, never in address, and then mainly with respect to members of other hamlets than one's own, where the person's teknonym may not be known, or, if known, considered to be too familiar in tone to be used for someone not a hamletmate. Within the hamlet, the referential use of Sudra titles occurs only when prestige status information is considered relevant ("Father-of-Joe is a Kedisan, and thus 'lower' than we Pande," and so on), while address is, of course, in terms of teknonyms. Across hamlet lines, where, except between close friends, teknonyms fall aside, the most common term of address is Djero. Literally, this means "inside" or "insider," thus a member of the Triwangsa, who are considered to be "inside," as against the Sudras, who are "outside" (Djaba); but in this context it has the effect of saying, "In order to be polite, I am addressing you as though you were a Triwangsa, which you are not (if you were, I would call you by your proper title), and I expect the same pretense from you in return." As for Varna terms, they are used, by Triwangsa and Sudra alike, only in conceptualizing the overall prestige hierarchy in general terms, a need which usually appears in connection with transhamlet political, sacerdotal, or stratificatory matters: "The kings of Klungkung are Satrias, but those of Tabanan only Wesias," or "There are lots of rich Brahmanas in Sanur, which is why the Sudras there have so little to say about hamlet affairs," and so on. The Varna System thus does two things. It connects up a series of what appear to be ad hoc and arbitrary prestige distinctions, the titles, with Hinduism, or the Balinese version of Hinduism, thus rooting them in a general world view. And it interprets the implications of that world view, and therefore the titles, for social organization: the prestige gradients implicit in the title system ought to be reflected in the actual distribution of wealth, power, and esteem in society, and, in fact, be completely coincident with it. The degree to which this coincidence actually obtains is, of course, moderate at best. But, however many exceptions there may be to the rule--Sudras with enormous power, Satrias working as tenant farmers, Brahmanas neither esteemed nor estimable--it is the rule and not the exceptions that the Balinese regard as truly illuminating the human condition. The Varna System orders the title system in such a way as to make it possible to view social life under the aspect of a general set of cosmological notions: notions in which the diversity of human talent and the workings of historical process are regarded as superficial phenomena when compared with the location of persons in a system of standardized status categories, as blind to individual character as they are immortal. PUBLIC TITLES This final symbolic order of person-definition is, on the surface, the most reminiscent of one of the more prominent of our own ways of identifying and characterizing individuals.22 We, too, often (all too often, perhaps) see people through a screen of occupational categories --as not just practicing this vocation or that, but as almost physically infused with the quality of being a postman, teamster, politician, or salesman. Social function serves as the symbolic vehicle through which personal identity is perceived; men are what they do. The resemblance is only apparent, however. Set amid a different cluster of ideas about what selfhood consists in, placed against a different religio-philosophical conception of what the world consists in, and expressed in terms of a different set of cultural devices--public titles --for portraying it, the Balinese view of the relation between social role and personal identity gives a quite different slant to the ideographic significance of what we call occupation but the Balinese call linggih-"seat," "place," "berth." This notion of "seat" rests on the existence in Balinese thought and practice of an extremely sharp distinction between the civic and domestic sectors of society. The boundary between the public and private domains of life is very clearly drawn both conceptually and institutionally. At every level, from the hamlet to the royal palace, matters of general concern are sharply distinguished and carefully insulated from matters of individual or familial concern, rather than being allowed to interpenetrate as they do in so many other societies. The Balinese sense of the public as a corporate body, having interests and purposes of its own, is very highly developed. To be charged, at any level, with special responsibilities with respect to those interests and purposes is to be set aside from the run of one's fellowmen who are not so charged, and it is this special status that public titles express. At the same time, though the Balinese conceive the public sector of society as bounded and autonomous, they do not look upon it as forming a seamless whole, or even a whole at all. Rather they see it as consisting of a number of separate, discontinuous, and at times even competitive realms, each self-sufficient, self-contained, jealous of its rights, and based on its own principles of organization. The most salient of such realms include: the hamlet as a corporate political community; the local temple as a corporate religious body, a congregation; the irrigation society as a corporate agricultural body; and, above these, the structures of regional--that is, suprahamlet--government and worship, centering on the nobility and the high priesthood. A description of these various public realms or sectors would involve an extensive analysis of Balinese social structure inappropriate in the present context.23 The point to be made here is that, associated with each of them, there are responsible officers--stewards is perhaps a better term--who as a result bear particular titles: Klian, Perbekel, Pekaseh, Pemangku, Anak Agung, Tjakorda, Dewa Agung, Pedanda, and so on up to perhaps a half a hundred or more. And these men (a very small proportion of the total population) are addressed and referred to by these official titles--sometimes in combination with birth order names, status titles, or, in the case of Sudras, teknonyms for purposes of secondary specification.24 The various "village chiefs" and "folk priests" on the Sudra level, and, on the Triwangsa, the host of "kings," "princes," "lords," and "high priests" do not merely occupy a role. They become, in the eyes of themselves and those around them, absorbed into it. They are truly public men, men for whom other aspects of personhood--individual character, birth order, kinship relations, procreative status, and prestige rank take, symbolically at least, a secondary position. We, focusing upon psychological traits as the heart of personal identity, would say they have sacrificed their true selves to their role; they, focusing on social position, say that their role is of the essence of their true selves. Access to these public-title-bearing roles is closely connected with the system of status titles and its organization into Varna categories, a connection effected by what may be called "the doctrine of spiritual eligibility." This doctrine asserts that political and religious "seats" of translocal--regional or Bali-wide--significance are to be manned only by Triwangsas, while those of local significance ought properly to be in the hands of Sudras. At the upper levels the doctrine is strict: only Satrias--that is, men bearing titles deemed of Satria rank--may be kings or paramount princes, only Wesias or Satrias lords or lesser princes, only Brahmanas high priests, and so on. At the lower levels, it is less strict; but the sense that hamlet chiefs, irrigation society heads, and folk priests should be Sudras, that Triwangsas should keep their place, is quite strong. In either case, however, the overwhelming majority of persons bearing status titles of the Varna category or categories theoretically eligible for the stewardship roles to which the public titles are attached do not have such roles and are not likely to get them. On the Triwangsa level, access is largely hereditary, primogenitural even, and a sharp distinction is made between that handful of individuals who "own power" and the vast remainder of the gentry who do not. On the Sudra level, access to public office is more often elective, but the number of men who have the opportunity to serve is still fairly limited. Prestige status decides what sort of public role one can presume to occupy; whether or not one occupies such a role is another question altogether. Yet, because of the general correlation between prestige status and public office the doctrine of spiritual eligibility brings about, the order of political and ecclesiastical authority in the society is hooked in with the general notion that social order reflects dimly, and ought to reflect clearly, metaphysical order; and, beyond that, that personal identity is to be defined not in terms of such superficial, because merely human, matters as age, sex, talent, temperament, or achievement--that is, biographically, but in terms of location in a general spiritual hierarchy-that is, typologically. Like all the other symbolic orders of person-definition, that stemming from public titles consists of a formulation, with respect to different social contexts, of an underlying assumption: it is not what a man is as a man (as we would phrase it) that matters, but where he fits in a set of cultural categories which not only do not change but, being transhuman, cannot. And, here too, these categories ascend toward divinity (or with equal accuracy, descend from it), their power to submerge character and nullify time increasing as they go. Not only do the higher level public titles borne by human beings blend gradually into those borne by the gods, becoming at the apex identical with them, but at the level of the gods there is literally nothing left of identity but the title itself. All gods and goddesses are addressed and referred to either as Dewa (f. Dewi) or, for the higher ranking ones, Betara (f. Betari). In a few cases, these general appellations are followed by particularizing ones: Betara Guru, Dewi Sri, and so forth. But even such specifically named divinities are not conceived as possessing distinctive personalities: they are merely thought to be administratively responsible, so to speak, for regulating certain matters of cosmic significance: fertility, power, knowledge, death, and so on. In most cases, Balinese do not know, and do not want to know, which gods and goddesses are those worshipped in their various temples (there is always a pair, one male, one female), but merely call them " Dewa (Dewi) Pura Such-and-Such"--god (goddess) of temple such-and-such. Unlike the ancient Greeks and Romans, the average Balinese shows little interest in the detailed doings of particular gods, nor in their motivations, their personalities, or their individual histories. The same circumspection and propriety is maintained with respect to such matters as is maintained with respect to similar matters concerning elders and superiors generally.25 The world of the gods is, in short, but another public realm, transcending all the others and imbued with an ethos which those others seek, so far as they are able, to embody in themselves. The concerns of this realm lie on the cosmic level rather than the political, the economic, or the ceremonial (that is, the human) and its stewards are men without features, individuals with respect to whom the usual indices of perishing humanity have no significance. The nearly faceless, thoroughly conventionalized, never-changing icons by which nameless gods known only by their public titles are, year after year, represented in the thousands of temple festivals across the island comprise the purest expression of the Balinese concept of personhood. Genuflecting to them (or, more precisely, to the gods for the moment resident in them) the Balinese are not just acknowledging divine power. They are also confronting the image of what they consider themselves at bottom to be; an image which the biological, psychological, and sociological concomitants of being alive, the mere materialities of historical time, tend only to obscure from sight. |