アルファ世代 / α 世代

Generation Alpha

☆ジェネレーション・アルファ[Generation Alpha]

(略してGen

Alpha)とは、ジェネレーションZに続き、提案されているジェネレーション・ベータに先行する世代を指す。研究者や一般メディアは、おおむね2010

年代前半を出生開始年、2020年代を終了年と位置付けているが、これらの範囲は厳密に定義されておらず、情報源によって異なる場合がある(詳細は「日付

と年齢範囲の定義」の節を参照)。ギリシャ文字の最初の文字「アルファ」に因んで名付けられたジェネレーション・アルファは、21世紀および第三千年紀に

完全に生まれた最初の世代である。ジェネレーション・アルファの大半はミレニアル世代の子どもたちである[1][2][3][4][5]。

アルファ世代は、スマートフォンやソーシャルメディアのない世界を経験したことのない最初の世代である。[6]

彼らは世界的に出生率が低下している時期に生まれ[7][8]、幼少期にCOVID-19パンデミックの影響を経験した。2020年代において、子供向け

娯楽は携帯型デジタル技術、ソーシャルネットワーク、ストリーミングサービスによってますます支配され、従来のテレビへの関心は同時に低下している。教室

や生活における技術利用の変化は、この世代が初期教育を経験する方法を、過去の世代と比べて大きく変えた。研究によれば、スクリーン時間に関連する健康問

題、アレルギー、肥満は2010年代後半に増加傾向を示している。

| Generation Alpha,

often shortened to Gen Alpha, is the demographic cohort succeeding

Generation Z and preceding the proposed Generation Beta. While

researchers and popular media loosely identify the early 2010s as the

starting birth years and the 2020s as the ending birth years, these

ranges are not precisely defined and may vary depending on the source

(see § Date and age range definitions). Named after alpha, the first

letter of the Greek alphabet, Generation Alpha is the first to be born

entirely in the 21st century and the third millennium. The majority of

Generation Alpha are the children of Millennials.[1][2][3][4][5] Generation Alpha is the first full generation not to have known a world without smartphones and social media.[6] They were born at a time of falling fertility rates across much of the world,[7][8] and experienced the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as young children. In the 2020s, children's entertainment has been increasingly dominated by portable digital technology, social networks, and streaming services, with interest in traditional television concurrently falling. Changes in the use of technology in classrooms and other aspects of life have had a significant effect on how this generation has experienced early learning compared to previous generations. Studies have suggested that health problems related to screen time, allergies, and obesity became increasingly prevalent in the late 2010s. |

ジェネレーション・アルファ[Generation Alpha](略してGen

Alpha)とは、ジェネレーションZに続き、提案されているジェネレーション・ベータに先行する世代を指す。研究者や一般メディアは、おおむね2010

年代前半を出生開始年、2020年代を終了年と位置付けているが、これらの範囲は厳密に定義されておらず、情報源によって異なる場合がある(詳細は「日付

と年齢範囲の定義」の節を参照)。ギリシャ文字の最初の文字「アルファ」に因んで名付けられたジェネレーション・アルファは、21世紀および第三千年紀に

完全に生まれた最初の世代である。ジェネレーション・アルファの大半はミレニアル世代の子どもたちである[1][2][3][4][5]。 アルファ世代は、スマートフォンやソーシャルメディアのない世界を経験したことのない最初の世代である。[6] 彼らは世界的に出生率が低下している時期に生まれ[7][8]、幼少期にCOVID-19パンデミックの影響を経験した。2020年代において、子供向け 娯楽は携帯型デジタル技術、ソーシャルネットワーク、ストリーミングサービスによってますます支配され、従来のテレビへの関心は同時に低下している。教室 や生活における技術利用の変化は、この世代が初期教育を経験する方法を、過去の世代と比べて大きく変えた。研究によれば、スクリーン時間に関連する健康問 題、アレルギー、肥満は2010年代後半に増加傾向を示している。 |

| Terminology The name Generation Alpha originated from a 2008 survey conducted by the Australian consulting agency McCrindle Research, according to founder Mark McCrindle, who is generally credited with the term.[9][10] McCrindle describes how his team arrived at the name in a 2015 interview: When I was researching my book The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations (published in 2009) it became apparent that a new generation was about to commence and there was no name for them. So I conducted a survey (we're researchers after all) to find out what people think the generation after Z should be called and while many names emerged, and Generation A was the most mentioned, Generation Alpha got some mentions too and so I settled on that for the title of the chapter Beyond Z: Meet Generation Alpha. It just made sense as it is in keeping with scientific nomenclature of using the Greek alphabet in lieu of the Latin and it didn't make sense to go back to A, after all they are the first generation wholly born in the 21st Century and so they are the start of something new not a return to the old.[11] McCrindle Research also took inspiration from the naming of hurricanes, specifically the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season in which the names beginning with the letters of the Latin alphabet were exhausted, and the last six storms were named with the Greek letters alpha to zeta.[10] "Generation Alpha" is sometimes shortened to "Generation A".[12][13][14][15][16] In 2020 and 2021, some anticipated that the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic would become this generation's defining event, suggesting the name Generation C or "Coronials" for those either born during, or growing up during, the pandemic.[17][18][19][20] Psychologist Jean Twenge refers to this cohort as "Polars" in light of the growing political polarization of the United States during the 2010s and 2020s, as well as the melting of polar ice caps, a sign of (anthropogenic) climate change.[21] This demographic cohort has also been dubbed "Generation AI" in light of the increasing role of artificial intelligence (AI) in daily activities[22][23] and the "iPad kids" after a popular series of tablet computers.[24] |

用語 ジェネレーション・アルファという名称は、オーストラリアのコンサルティング会社マクリンドル・リサーチが2008年に実施した調査に由来する。この用語 の考案者として広く認められている創設者マーク・マクリンドルによれば、同社の調査でこの名称が生まれたのである[9][10]。マクリンドルは2015 年のインタビューで、自身のチームがこの名称にたどり着いた経緯を説明している: 『The ABC of XYZ: 『グローバル世代を理解する』(2009年刊行)を執筆中、新たな世代が始まろうとしているのに名称がないことに気づいた。そこで調査を実施した(我々は 研究者だからな)。Z世代の次に何と呼ぶべきか尋ねたところ、多くの名称が挙がったが、ジェネレーションAが最も多く言及された。ジェネレーション・アル ファもいくつか言及されたので、章のタイトルを『Zを超えて:ジェネレーション・アルファとの出会い』と決めたのだ。これは科学的な命名法に沿ったもの で、ラテン文字の代わりにギリシャ文字を使うという理にかなっていた。何しろ彼らは21世紀に完全に生まれた最初の世代であり、古いものへの回帰ではなく 新たな始まりを象徴するのだから、Aに戻るのは意味をなさない。[11] マックリンデル・リサーチはハリケーン命名法からも着想を得た。特に2005年の大西洋ハリケーンシーズンではラテン文字のアルファベットが尽き、最後の 6つの嵐はギリシャ文字のアルファからゼータで命名された[10]。「ジェネレーション・アルファ」は時に「ジェネレーションA」と略される[12] [13][14][15][16]。 2020年から2021年にかけて、COVID-19パンデミックの世界的影響がこの世代を定義する出来事になると予測する者も現れ、パンデミック期間中 に生まれた、あるいは成長した世代に対して「ジェネレーションC」または「コロナ世代(Coronials)」という名称が提案された。[17][18] [19][20] 心理学者ジーン・トゥウェンジは、2010年代から2020年代にかけて米国で進行した政治的分極化と、(人為的)気候変動の兆候である極地の氷冠融解を 踏まえ、この世代を「ポーラーズ」と呼んでいる。[21] この世代層はまた、日常生活における人工知能(AI)の役割拡大[22][23]を踏まえ「Generation AI」とも呼ばれ、人気タブレット端末シリーズにちなんで「iPadキッズ」とも称される[24]。 |

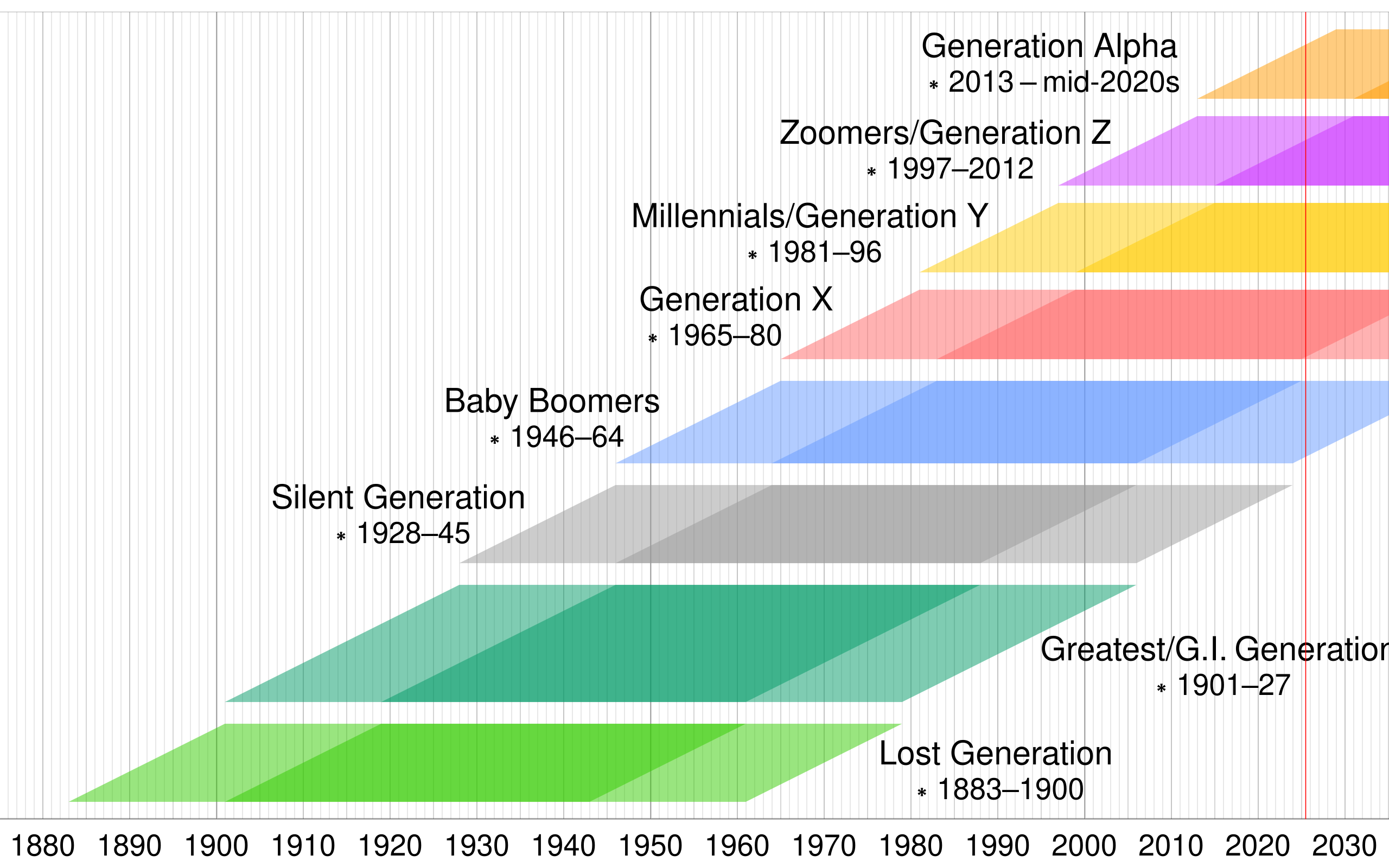

| Date and age range definitions There is no consensus yet on the birth years for Generation Alpha. McCrindle Research uses 2010–2024[25] with some news outlets citing them,[26][27][28] while others using shorter ranges, such as 2011–2021[29] or 2013–2021.[30] However other sources, while they have not specified a range for Generation Alpha, have specified end years for Generation Z of 2012[31][32][33] or 2013,[34] which suggests a later date range instead of McCrindle's for Generation Alpha. For example, psychologist Jean Twenge defines Generation Alpha as those born from 2013 to 2029.[35] The Cambridge Dictionary, which added Gen Alpha to its corpus in 2025, defines this cohort generally as people born during the 2010s and 2020s.[36] Despite the defined boundary between Generation Z and Generation Alpha not being universally agreed upon, individuals born in the cusp years between the two demographic cohort are sometimes assorted into a "micro-generation" known as Zalphas.[37] |

年代と年齢層の定義 アルファ世代の出生年についてはまだ合意が得られていない。マクリンドル・リサーチは2010年から2024年[25]を定義としており、一部の報道機関 もこれを引用している[26][27][28]。一方、2011年から2021年[29]や2013年から2021年[30]といったより短い範囲を用い る機関もある。しかし他の情報源は、アルファ世代の範囲を特定していないものの、Z世代の終了年を2012年[31][32][33]または2013年 [34]と明記しており、これはマックリンドルの定義よりもアルファ世代の開始年が後になることを示唆している。例えば心理学者ジーン・トゥウェンジは、 アルファ世代を2013年から2029年生まれと定義している[35]。ケンブリッジ辞書は2025年に「Gen Alpha」を収録し、この世代を概ね2010年代から2020年代に生まれた人々として定義している[36]。 Z世代とアルファ世代の境界線は普遍的に合意されていないが、両世代の境界年に生まれた個人は「Zアルファ」と呼ばれる「マイクロ世代」に分類されることがある[37]。 |

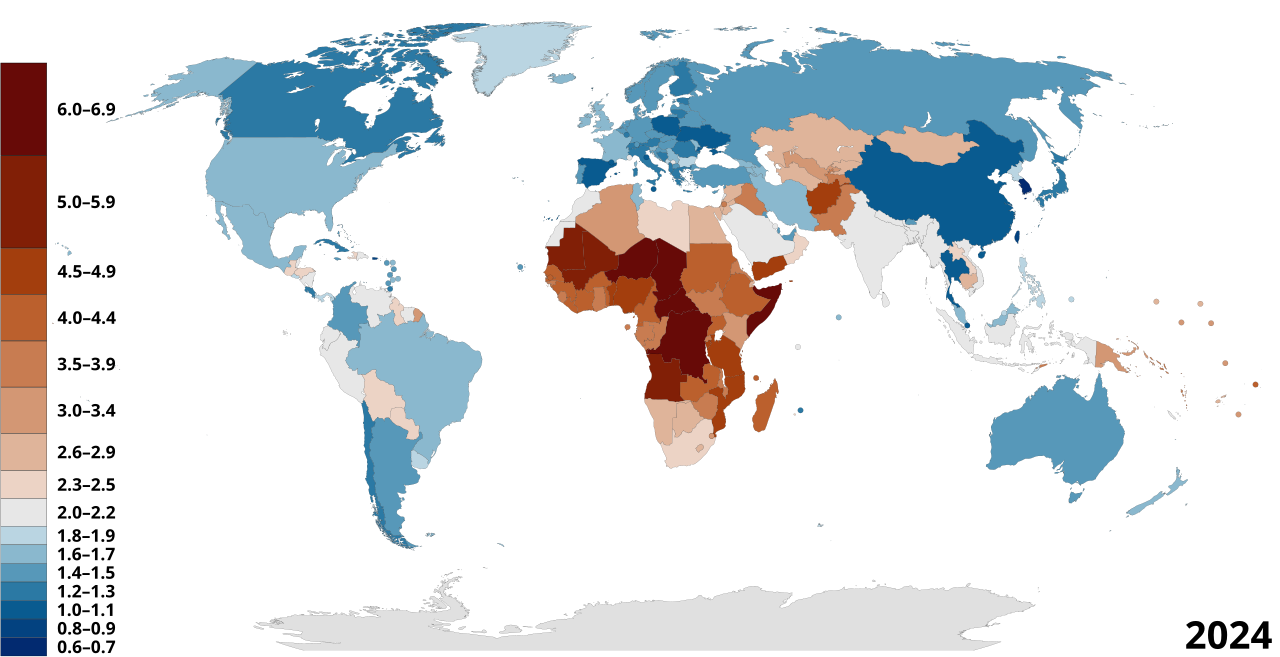

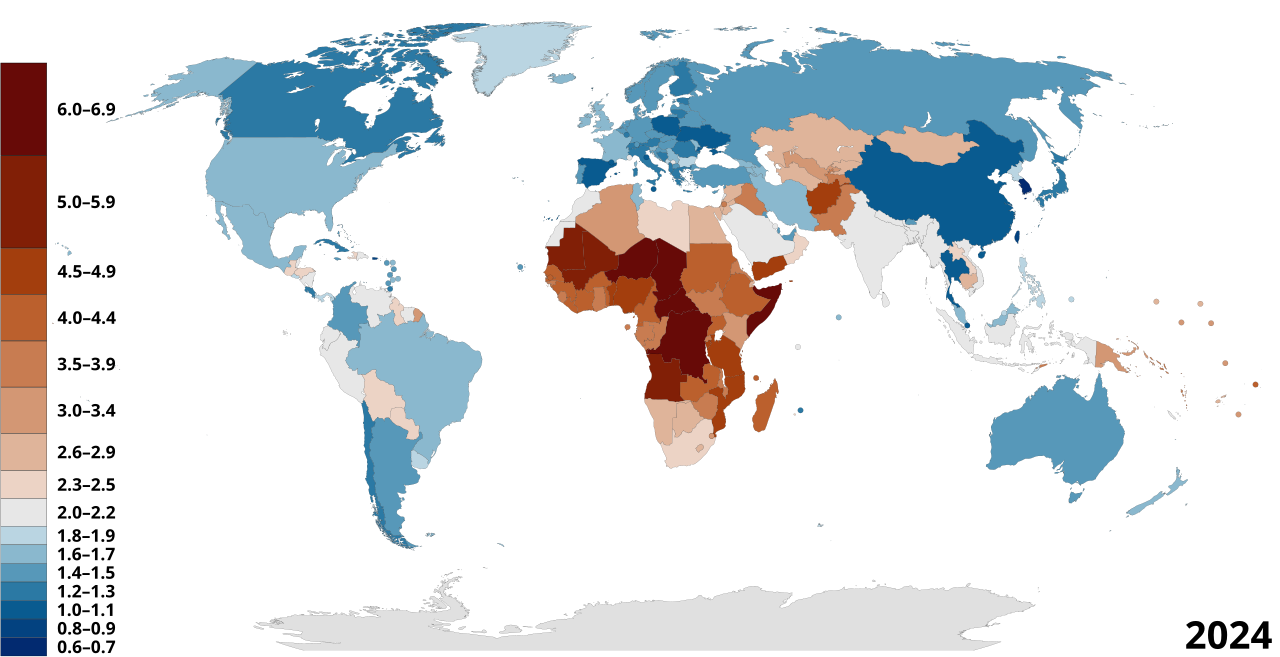

Map of countries by total fertility rate (2022–2023), referring to the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime, according to the Population Reference Bureau[38] |

合計特殊出生率による国別地図(2022–2023年)。これは人口参考局[38]によると、女性が一生の間に産む子供の平均数を示すものである。 |

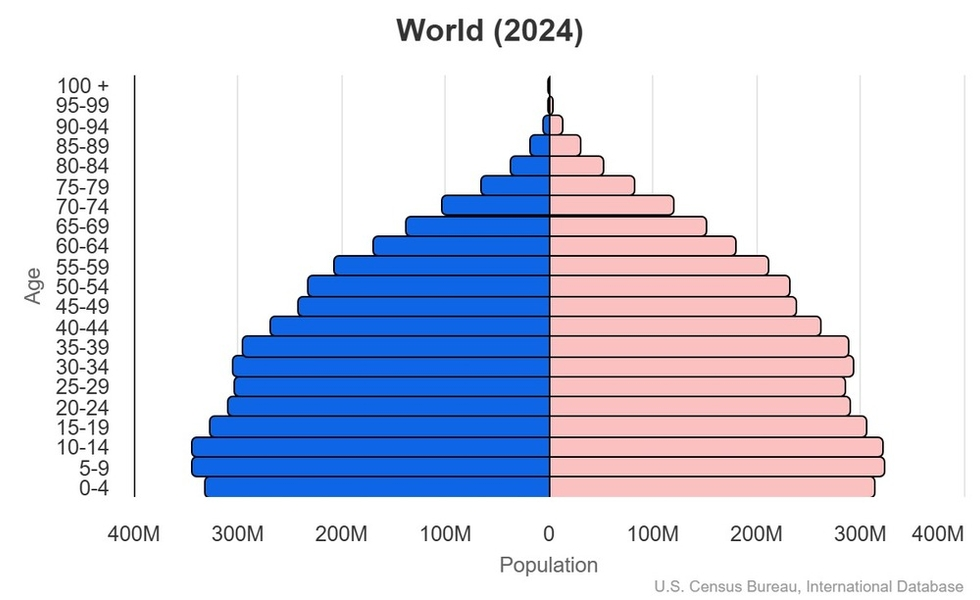

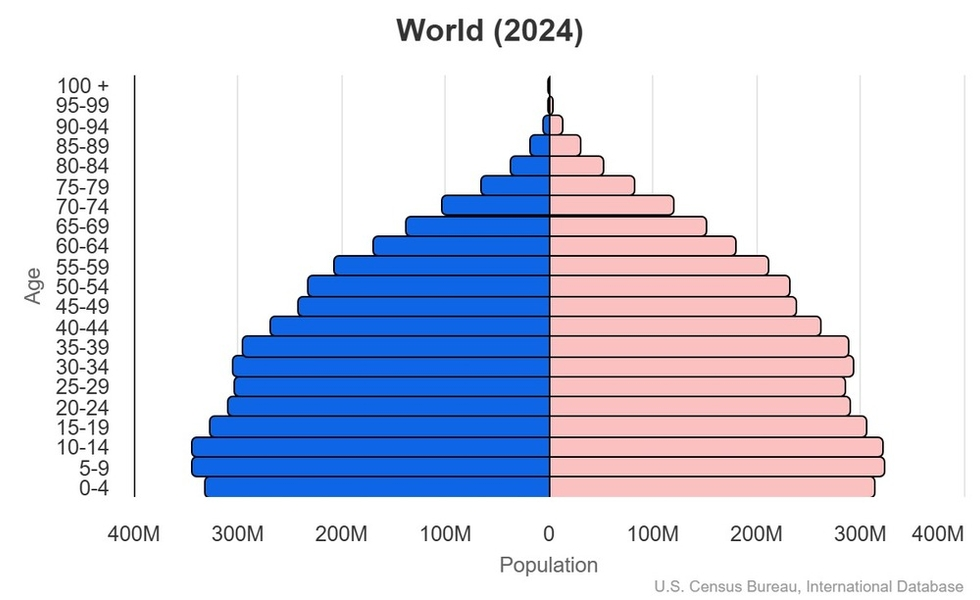

As

of 2015, there were some two and a half million people born every week

around the globe; Generation Alpha was expected to reach close to two

billion by 2025.[39] By 2024, Generation Alpha has exceeded 2 billion

members worldwide.[40] For comparison, the United Nations estimated

that the human population was about 7.8 billion in 2020, up from 2.5

billion in 1950. As of 2020, roughly three-quarters of all people

reside in Africa and Asia,[41] where most human population growth is

coming from, as nations in Europe and the Americas tend to have too few

children to replace themselves.[42] Population pyramid of the world in 2024 The number of people above 65 years of age (705 million) exceeded those between the ages of zero and four (680 million) for the first time in 2018. If current trends continue, the ratio between these two age groups will top two by 2050.[43] Birth rates have been falling around the world due to rising standards of living, higher access to contraceptives, and more educational and economic opportunities. In fact, about half of all countries had sub-replacement fertility in the mid-2010s. The global average reproduction rate in 1950 was 4.7 but dropped to 2.4 in 2017. However, this average masks the huge variation between countries. Niger has the world's highest fertility rate at 7.1, while South Korea has one of the lowest at 0.78 (2022). In general, the more developed countries, including much of Europe, the United States, South Korea, and Japan, tend to have lower reproduction rates,[44] with people statistically having fewer children, and at later ages.[43] Surveys conducted in developed economies suggest that women's desired family sizes tend to be higher than the one they end up building. Stagnant wages and eroding welfare programs are the contributing factors.[citation needed] While some countries like Sweden and Singapore have tried various incentives to raise their birth rates, such policies have not been particularly successful. Moreover, birth rates following the COVID-19 global pandemic might drop significantly due to economic recession.[45] Data from late 2020 and early 2021 suggests that in spite of expectations of a baby boom occurring due to COVID-19 lockdowns, the opposite ended up happening in developed nations, though developing countries were not heavily affected.[citation needed] Education is commonly cited as one of the most important determinants. The more educated a person is, the fewer children they have, and the later the age is in which they have children.[42] At the same time, global average life expectancy has risen from 52 in 1960 to 72 in 2017.[43] Higher interest in education brings about an environment in which mortality rates fall, which in turn increases population density.[46] Half of the human population lived in urban areas in 2007, and this figure became 55% in 2019. If the current trend continues, it will reach two thirds by the middle of the century. A direct consequence of urbanization is a falling birth rate. People in urban environments demand greater autonomy and exercise more control over their bodies.[47] In mid-2019, the United Nations estimated that the human population will reach about 9.7 billion by 2050, a downward revision from an older projection to account for faster falling fertility rates in the developing world. The global annual rate of growth has been declining steadily since the late twentieth century, dropping to about one percent in 2019.[48] By the late 2010s, 83 of the world's countries had sub-replacement fertility.[49] During the early to mid-2010s, more babies were born to Christian families than to those of any other religion in the world, while Muslims had a faster rate of growth. About 33% of the world's babies were born to Christians who made up 31% of the global population between 2010 and 2015, compared to 31% to Muslims, whose share of the human population was 24%. During the same period, the religiously unaffiliated (including atheists and agnostics) made up 16% of the population and gave birth to 10% of the world's children.[50] |

2015

年時点で、世界では毎週約250万人が生まれていた。アルファ世代は2025年までに約20億人に達すると予測されていた[39]。2024年までに、ア

ルファ世代は全世界で20億人を突破した。比較のため、国連の推計によれば、世界人口は1950年の25億人から2020年には約78億人に増加した。

2020年時点で、全人口の約4分の3がアフリカとアジアに居住している[41]。これら地域が人口増加の大部分を占めており、欧州や米州諸国では人口置

換水準に達しない低出生率が続いている。[42] 2024年の世界人口ピラミッド 65歳以上の人口(7億500万人)が、0歳から4歳までの人口(6億8000万人)を2018年に初めて上回った。現在の傾向が続けば、この二つの年齢層の比率は2050年までに2倍に達する見込みだ。[43] 生活水準の向上、避妊手段の普及、教育・経済機会の拡大により、世界的に出生率は低下している。実際、2010年代半ばには全国の約半数が人口置換水準を 下回る出生率となった。1950年の世界平均出生率は4.7人だったが、2017年には2.4人に低下した。ただしこの平均値は国ごとの大きな格差を隠し ている。ニジェールは7.1で世界最高、韓国は0.78(2022年)で最低水準だ。一般的に欧州諸国、米国、韓国、日本など先進国ほど出生率は低く [44]、統計上、子供の人数が少なく、出産年齢も遅い傾向にある[43]。 先進国で行われた調査によれば、女性の希望する家族規模は実際に築く家族規模よりも大きい傾向がある。賃金の停滞と福祉制度の縮小が要因だ[出典必要]。 スウェーデンやシンガポールなど一部の国は出生率向上のため様々な奨励策を試みたが、こうした政策は特に成功していない。さらに、COVID-19の世界 的パンデミック後の出生率は、経済不況により大幅に低下する可能性がある[45]。2020年末から2021年初頭のデータによれば、COVID-19に よるロックダウンでベビーブームが起きるとの予想に反し、先進国では逆の現象が起きた。ただし発展途上国では大きな影響はなかった。[出典が必要] 教育は最も重要な決定要因の一つとして広く指摘される。教育水準が高い人ほど、子供を持つ数が少なく、出産年齢も遅くなる。[42] 同時に、世界の平均寿命は1960年の52歳から2017年には72歳に伸びている。[43] 教育への関心の高まりは死亡率を低下させる環境を生み、それが人口密度を増加させる。[46] 2007年には人類の半数が都市部に居住し、この割合は2019年には55%となった。この傾向が続けば、21世紀半ばには3分の2に達する見込みだ。都 市化の直接的な結果として出生率は低下する。都市環境に住む人々はより大きな自律性を求め、自身の身体に対する支配力を強める。[47] 2019年半ば、国連は2050年までに世界人口が約97億人に達すると推計した。これは途上国における出生率の急激な低下を考慮し、従来の予測から下方 修正された数値である。世界の年間成長率は20世紀後半から着実に低下し、2019年には約1%まで落ち込んだ[48]。2010年代後半までに、世界の 83カ国で出生率が人口置換水準を下回った[49]。 2010年代前半から中盤にかけて、世界で最も多くの新生児が生まれたのはキリスト教徒の家庭であった。一方でイスラム教徒の人口増加率はより速かった。 2010年から2015年の間に、世界の新生児の約33%がキリスト教徒の家庭で生まれた。この期間、キリスト教徒は世界人口の31%を占めていた。一 方、イスラム教徒の新生児割合は31%であったが、その人口比率は24%であった。同じ期間に、無宗教(無神論者や不可知論者を含む)は人口の16%を占 め、世界の子供の10%を出産した。 |

| Economic trends and prospects Effects of intensifying wealth inequality in the early twenty-first century is expected to be seen in the next generation, as parental income and educational level are positively correlated with children's success.[51] In the United States, children from families in the highest income quintile are the most likely to live with married parents (94% in 2018), followed by children of the middle class (74%) and the bottom quintile (35%).[52] |

経済動向と展望 21世紀初頭の富の格差拡大の影響は、親の収入と教育水準が子供の成功と正の相関関係にあることから、次世代に現れると予想される。[51] 米国では、最高所得層の家庭の子どもが既婚の両親と同居する可能性が最も高く(2018年時点で94%)、次いで中産階級の子ども(74%)、最下位層の 子ども(35%)となっている。[52] |

| Education In many developing countries around the world, large numbers of children could not read a simple passage in their own national languages by the age of ten, according to the World Bank. In the Congo, the Philippines, and Ethiopia, over 80% of children were in this category. In India and Indonesia, the rates were at about 50%. In China and Vietnam, the corresponding numbers were under 20%.[53] Asia Addressing Japan's demographic crisis and low birthrate, in 2019, the government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe introduced a number of education reforms. Starting in October 2019, preschool education would be free for all children between the ages of three and five, and child care would be free for children under the age of two from low-income households. These programs would be funded by a consumption tax hike, from eight to ten percent. Starting April 2020, entrance and tuition fees for public as well as private universities would be waived or reduced. Students from low-income and tax-exempt families would be eligible for financial assistance to help them cover textbook, transportation, and living expenses. The whole program was projected to cost 776 billion yen (7.1 billion USD) per year.[54] In 2020, the government of Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc recommended a series of education reforms in order to raise the fertility rates of localities that found themselves below the replacement level, including the construction of daycare facilities and kindergartens in urban and industrial zones, housing subsidies for couples with two children in sub-replacement areas, and priority admission for children of said couples in public schools.[55] In early 2021, the government of China announced a plan to invest more in physical education (PE) in order to make young boys "more masculine". Due to a combination of the (now rescinded) one-child policy and the traditional preference for sons, young boys are perceived by many to be overly coddled by their parents, and looked at as effeminate, delicate, and timid. In order to calm public concerns, state-controlled media published pieces downplaying gender roles and gender differences.[56] In India, the population of Generation Alpha (those aged 0–14 years) was recorded as 346.9 million in the year 2011. By 2021, this figure slightly decreased to 336.9 million. As per the latest projections, it is estimated that the population of Generation Alpha will further decline to approximately 327 million by the year 2026.[citation needed] Europe In France, while year-long mandatory military service for men was abolished in 1996,[57] all citizens between 17 and 25 years of age must still participate in the Defense and Citizenship Day, when they are introduced to the French Armed Forces, and take language tests.[57] In 2019, President Emmanuel Macron introduced a similar mandatory service program for teenagers, as promised during his presidential campaign. Known as the Service National Universel or SNU, it is a compulsory civic service. Though it does not explicitly involve military training, it requires recruits to spend four weeks at a camp where they participate in a variety of activities designed to teach practical skills, personal discipline and a greater understanding of the French political system and society. The aim of this program is to promote national cohesion and patriotism, and to encourage interaction among young people of different backgrounds.[58] The SNU is due to become mandatory for all French 16 to 21 year olds by 2026.[58] In 2023, the French government announced a two-billion-euro plan to promote biking in the country. This includes an initiative to train all primary school children on how to ride a bicycle.[59] |

教育 世界銀行によれば、世界中の多くの発展途上国では、10歳になっても自国語で簡単な文章が読めない子供が大勢いる。コンゴ、フィリピン、エチオピアでは、80%以上の子供がこれに該当した。インドとインドネシアでは約50%、中国とベトナムでは20%未満だった。[53] アジア 日本の人口危機と少子化対策として、2019年に安倍晋三首相率いる政府は一連の教育改革を導入した。2019年10月より、3歳から5歳までの全児童を 対象に就学前教育を無償化し、低所得世帯の2歳未満児には保育料を無料化する。これらの施策は消費税率を8%から10%に引き上げることで財源を確保す る。2020年4月からは、公立・私立大学の入学金と授業料が免除または減額される。低所得世帯や非課税世帯の学生は、教科書代・交通費・生活費を補助す る給付金の対象となる。この制度全体の年間費用は7760億円(71億米ドル)と見込まれている。[54] 2020年、ベトナムのグエン・スアン・フック首相率いる政府は、人口置換水準を下回る地域の出生率向上を目的とした一連の教育改革を提言した。これには 都市部や工業地帯における保育施設・幼稚園の建設、人口置換水準未満地域における二人っ子世帯への住宅補助、同世帯の子女に対する公立学校優先入学権の付 与などが含まれる。[55] 2021年初頭、中国政府は少年を「より男らしく」するため体育教育への投資拡大計画を発表した。一人っ子政策(現在は廃止)と男子偏重の伝統的価値観が 相まって、少年は過保護に育てられ、女々しく繊細で臆病だと見なされる傾向がある。国民の懸念を和らげるため、国営メディアはジェンダー役割やジェンダー の違いを軽視する記事を掲載した。[56] インドでは、2011年にアルファ世代(0~14歳)の人口が3億4690万人と記録された。2021年までにこの数値はわずかに減少し、3億3690万 人となった。最新の予測によれば、アルファ世代の人口は2026年までにさらに減少して約3億2700万人になると推定されている。[出典が必要] ヨーロッパ フランスでは、1996年に男性の1年間の義務兵役が廃止されたが、17歳から25歳までの全ての市民は、依然として「防衛と市民権の日」に参加しなけれ ばならない。この日、彼らはフランス軍を紹介され、言語テストを受ける。[57] 2019年、エマニュエル・マクロン大統領は大統領選挙公約通り、10代向けの同様の義務サービスプログラムを導入した。「普遍的国民サービス (SNU)」と呼ばれるこの制度は、義務的な市民サービスである。軍事訓練を明示的に含むものではないが、新兵は4週間のキャンプに参加し、実践的技能、 個人的規律、フランス政治システムと社会への理解を深めるための様々な活動に従事する。このプログラムの目的は、国民的結束と愛国心を促進し、異なる背景 を持つ若者同士の交流を促すことにある。[58] SNUは2026年までに、フランスの16歳から21歳までの全若年層に義務化される予定だ。[58] 2023年、フランス政府は国内での自転車利用促進に向けた20億ユーロ規模の計画を発表した。これには、全小学生に自転車の乗り方を指導する取り組みも含まれている。[59] |

North America A playground in The Bronx, New York (2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents allow their children more time to play. In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement summarizing progress on developmental and neurological research on unstructured time spent by children, colloquially 'play', and noting the importance of playtime for social, cognitive, and language skills development. This is because to many educators and parents, play has come to be seen as outdated and irrelevant.[60] In fact, between 1981 and 1997, time spent by children on unstructured activities dropped by 25% due to increased amounts of time spent on structured activities. Unstructured time tended to be spent on screens at the expense of active play.[61] The statement encourages parents and children to spend more time on "playful learning", which reinforces the intrinsic motivation to learn and discover and strengthens the bond between children and their parents and other caregivers. It also helps children handle stress and prevents "toxic stress", something that hampers development. Dr. Michael Yogman, the lead author of the statement, noted that play does not necessarily have to involve fancy toys; common household items would do as well. Moreover, parents reading to children also counts as play, because it encourages children to use their imaginations.[60] In 2019, psychiatrists from Quebec launched a campaign advocating the creation of courses on mental health for primary schoolchildren in order to teach them how to handle a personal or social crisis, and to deal with the psychological impact of the digital world. According to the Association des médecins psychiatres du Québec (AMPQ), this campaign focuses on children born after 2010, that is, Generation Alpha. In addition to the AMPQ, this movement is backed by the Fédération des médecins spécialistes du Québec (FMSQ), the Quebec Pediatric Association (APQ), the Association des spécialistes en médecine préventive du Québec (ASMPQ) and the Fondation Jeunes en Tête.[62][63] Although the Common Core standards, an education initiative in the United States, eliminated the requirement that public elementary schools teach cursive writing in 2010, lawmakers from many states, including Illinois, Ohio, and Texas, have introduced legislation to teach it in theirs in 2019.[64] Some studies point to the benefits of handwriting – print or cursive – for the development of cognitive and motor skills as well as memory and comprehension. For example, one 2012 neuroscience study suggests that handwriting "may facilitate reading acquisition in young children."[65] Cursive writing has been used to help students with learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, a disorder that makes it difficult to interpret words, letters, and other symbols.[66] Unfortunately, lawmakers often cite these studies out of context, conflating handwriting in general with cursive handwriting.[64] In any case, some 80% of historical records and documents of the United States, such as the correspondence of Abraham Lincoln, were written by hand in cursive, and students today tend to be unable to read them.[67] Historically, cursive writing was regarded as a mandatory, almost military, exercise. But today, it is thought of as an art form by those who pursue it, both adults and children.[65] |

北アメリカ ニューヨーク市ブロンクス区の遊び場(2019年)。アメリカ小児科学会は、親が子供にもっと遊ぶ時間を与えるよう勧めた。 2018年、アメリカ小児科学会は政策声明を発表した。そこでは、子供たちが過ごす自由な時間(俗に言う「遊び」)に関する発達・神経学的研究の進捗をま とめ、社会的・認知的・言語能力の発達における遊び時間の重要性を指摘している。これは多くの教育者や保護者にとって、遊びが時代遅れで無関係なものと見 なされるようになったためだ[60]。実際、1981年から1997年の間に、構造化された活動に費やす時間が増えた結果、子どもが非構造化された活動に 費やす時間は25%減少した。自由時間は、活発な遊びを犠牲にしてスクリーン媒体に費やされる傾向があった[61]。声明は、親と子どもが「遊びを通じた 学び」に時間を割くよう促している。これは学習と発見への内発的動機付けを強化し、子どもと親や養育者との絆を深める。またストレス対処能力を高め、発達 を阻害する「有害なストレス」を防ぐ効果もある。声明の筆頭著者であるマイケル・ヨグマン博士は、遊びに必ずしも高級なおもちゃは必要なく、家庭にある普 通の品物でも十分だと指摘した。さらに、親が子供に本を読む行為も遊びに含まれる。それは子供の想像力を働かせるからである。[60] 2019年、ケベック州の精神科医たちは、小学生向けのメンタルヘルス講座創設を提唱する運動を開始した。個人的または社会的な危機への対処法、デジタル 世界の心理的影響への対応を教えるためである。ケベック州精神科医協会(AMPQ)によれば、この運動は2010年以降に生まれた子ども、すなわちアル ファ世代に焦点を当てている。この運動はAMPQに加え、ケベック専門医連盟(FMSQ)、ケベック小児科医協会(APQ)、ケベック予防医学専門家協会 (ASMPQ)、若者の頭脳財団(Fondation Jeunes en Tête)の支援を受けている。[62][63] 米国の教育イニシアチブであるコモンコア基準は2010年に公立小学校での筆記体指導義務を廃止したが、イリノイ州、オハイオ州、テキサス州を含む多くの 州の議員が2019年に州内での筆記体指導を義務付ける法案を提出した[64]。いくつかの研究は、認知能力や運動能力、記憶力、理解力の発達において、 印刷体であれ筆記体であれ手書きの利点を指摘している。例えば2012年の神経科学研究では、手書きが「幼児の読解力習得を促進する可能性がある」と示唆 している[65]。筆記体は、単語や文字、記号の解釈が困難な学習障害である失読症などの生徒支援に活用されてきた[66]。残念ながら、立法者はこうし た研究を文脈から切り離して引用し、手書き全般と筆記体を混同することが多い。[64] いずれにせよ、エイブラハム・リンカーンの書簡など、アメリカ合衆国の歴史的記録や文書の約80%は筆記体で手書きされており、現代の学生はそれらを読む ことができない傾向にある。[67] 歴史的に、筆記体は義務的な、ほぼ軍事的な訓練と見なされていた。しかし今日では、それを追求する大人も子供も、芸術形式として捉えている。[65] |

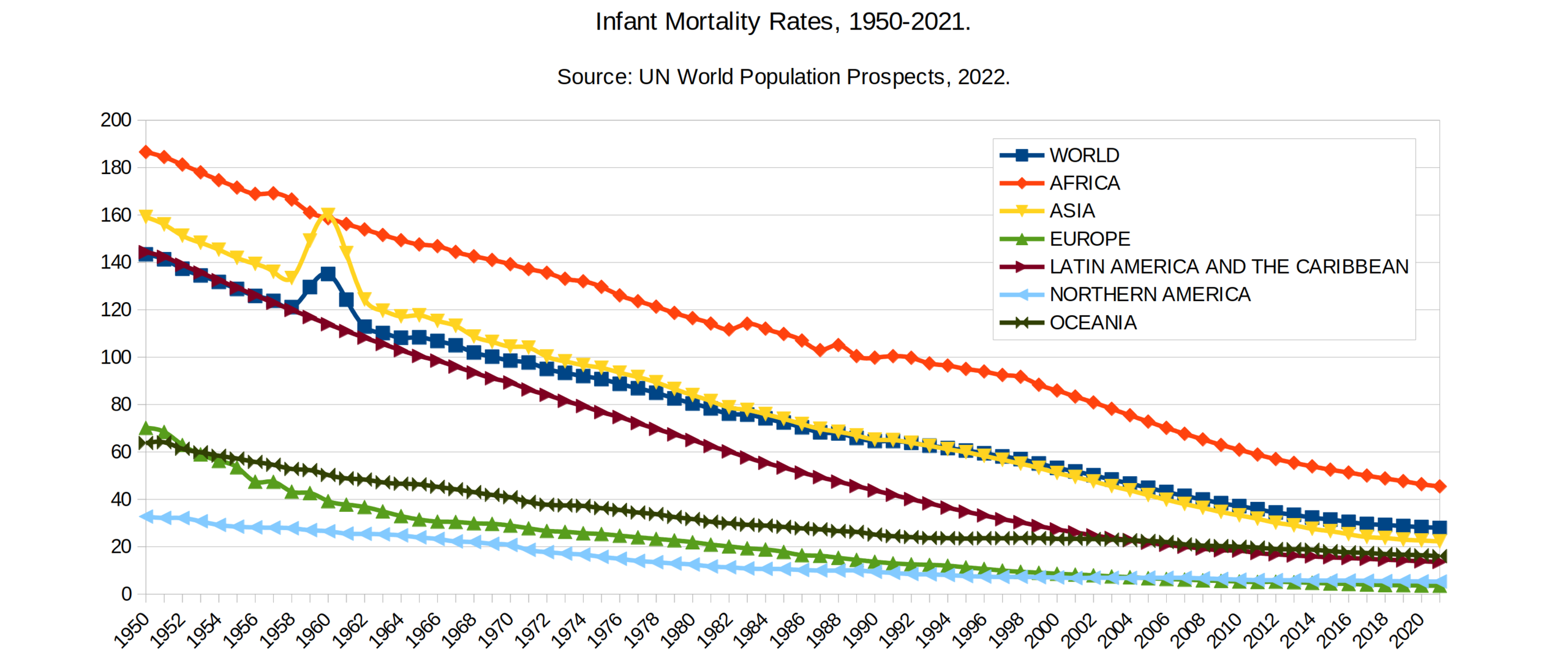

Schoolchildren learning geometry with a tablet computer in 2019  A child learns programming with Scratch in 2020. In 2013, less than a third of American public schools had access to broadband Internet service, according to the non-profit EducationSuperHighway. By 2019, however, that number reached 99%. This has increased the frequency of digital learning.[68] Since the early 2010s, a number of U.S. states have taken steps to strengthen teacher education. Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas had the top programs in 2014. Meanwhile, Rhode Island, which previously had the nation's lowest bar on who can train to become a school teacher, has been admitting education students with higher and higher average SAT, ACT, and GRE scores. As of 2014, the state aimed by 2020 to accept only those with standardized test scores in the top third of the national distribution, similar to Finland and Singapore.[69] According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 63% of American fourth graders could read at the basic level in 2022, which is lower than previous years of assessment, dating back to 2005.[70] Nevertheless, scores have been in decline even before the COVID-19 pandemic.[71] Taking advantage of the latest advances in the neuroscience of reading, some instructors have returned to the teaching of phonics to help rectify this problem,[71] with support from the parents and their state governments.[72][73] According to Jill Barshay of Heschinger Report, because U.S. fertility rates never recovered after the 2007–2008 Great Recession, those born in the late 2000s and onward will likely face less competition getting accepted to colleges and universities.[74]  This chart shows infant mortality rates by world regions from 1950 to 2021. |

2019年、タブレット端末で幾何学を学ぶ小学生たち  2020年、Scratchでプログラミングを学ぶ子供。 非営利団体EducationSuperHighwayによれば、2013年時点でアメリカの公立学校の3分の1未満しかブロードバンドインターネットを 利用できなかった。しかし2019年までにその割合は99%に達した。これによりデジタル学習の頻度が増加した。[68] 2010年代初頭以降、複数の米国州が教員養成の強化に乗り出した。2014年時点でオハイオ州、テネシー州、テキサス州が最上位プログラムを有してい た。一方、かつて教員養成の参入障壁が全米最低だったロードアイランド州では、教育学部の学生受け入れ基準としてSAT・ACT・GREの平均スコアが年 々引き上げられている。2014年時点で、同州は2020年までに全国分布の上位3分の1に入る標準テストスコア保持者のみを受け入れる方針を掲げた。こ れはフィンランドやシンガポールと同様の方針である。[69] 全米教育進捗度評価(NAEP)によれば、2022年の米国小学4年生のうち基礎レベルの読解力を有する者は63%であった。これは2005年まで遡る過 去の評価年次よりも低い数値である。[70] とはいえ、COVID-19パンデミック以前からスコアは低下傾向にあった。[71] 読解に関する神経科学の最新進歩を活用し、この問題の改善を図るため、一部の指導者はフォニックス教育に回帰している。[71] これは保護者や州政府の支援を得て行われている。[72][73] ヘシンガー・レポートのジル・バーシェイによれば、米国の出生率は2007-2008年の大不況以降回復していないため、2000年代後半以降に生まれた世代は大学進学における競争が緩和される可能性が高いという。[74]  この図は、1950年から2021年までの世界各地域の乳児死亡率を示している。 |

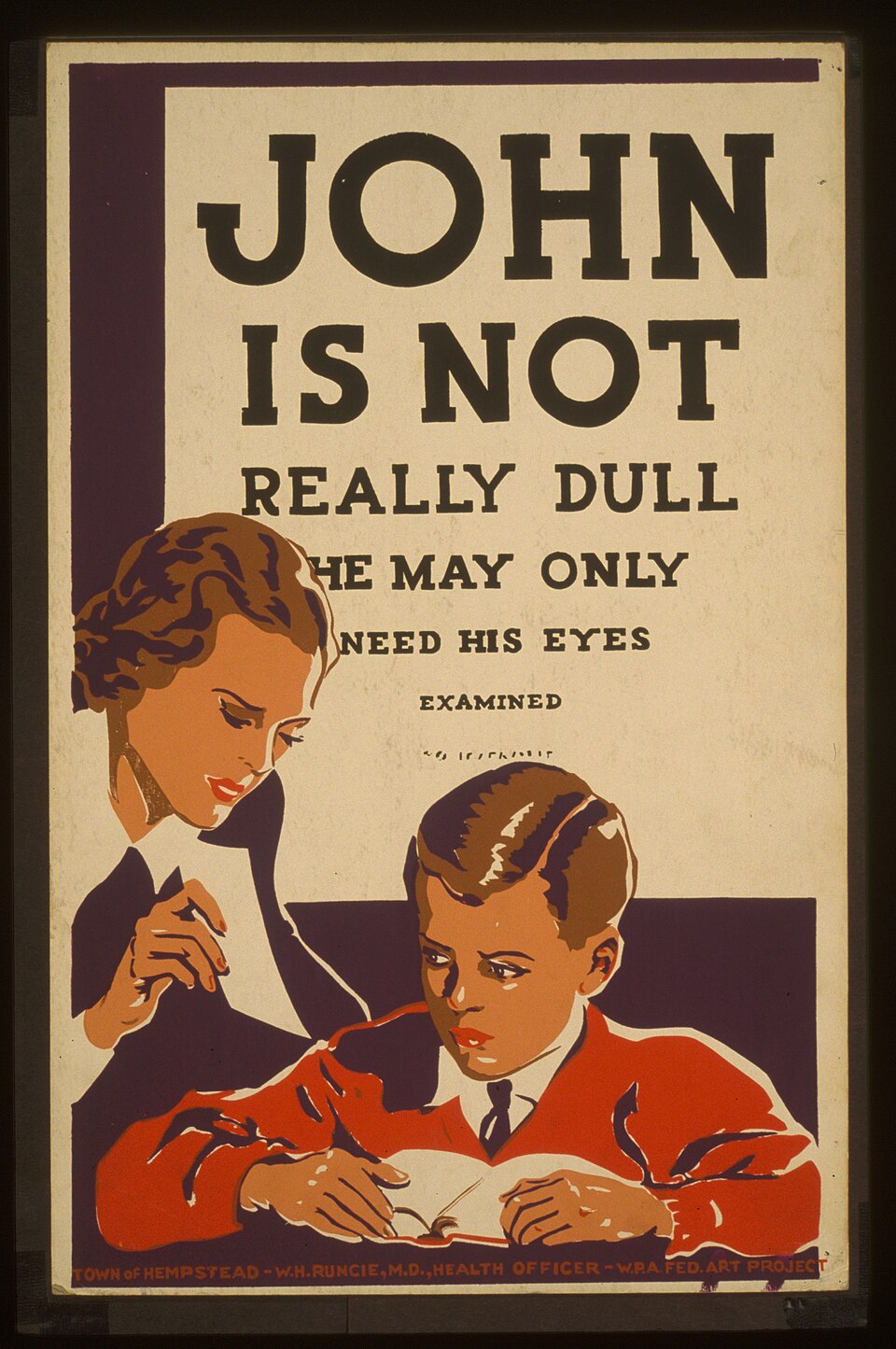

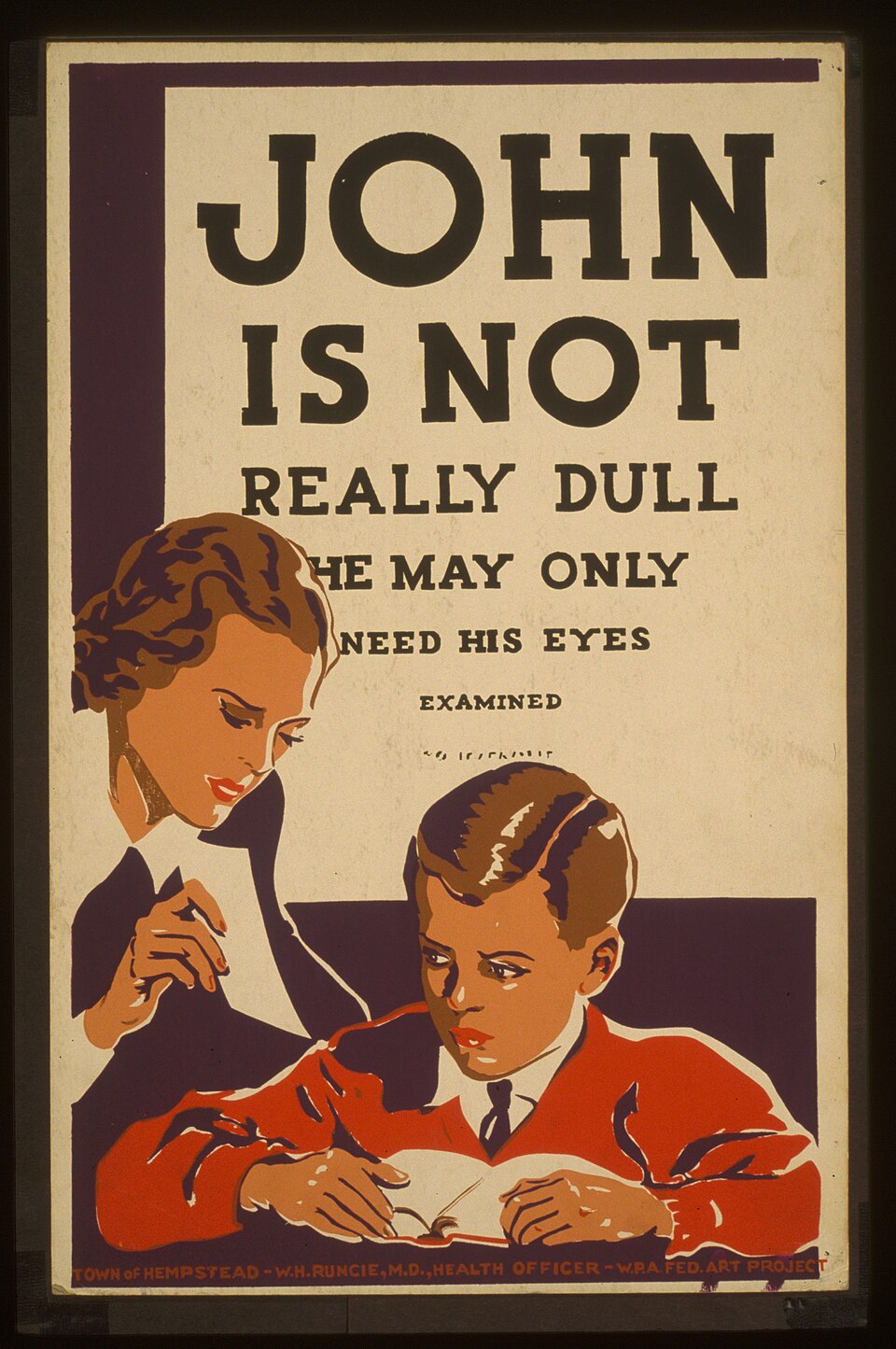

| Health and welfare Problems arising from screen time  Growing numbers of children now suffer from eye problems. W.P.A. Federal Art Project, [1936 or 1937]. A 2015 study found that the frequency of nearsightedness had doubled in the United Kingdom within the last 50 years. Ophthalmologist Steve Schallhorn, chairman of the Optical Express International Medical Advisory Board, noted that researchers had pointed to a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain. The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm in a similar vein.[75] According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome, is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, and headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage. In order to alleviate or prevent eyestrain, the Vision Council recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust the screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray, increase text sizes, and blink more often. The Council advises parents to limit their children's screen time as well as lead by example by reducing their own screen time in front of children.[76] In 2019, the WHO issued recommendations on the amount young children should spend in front of a screen every day. WHO said toddlers under the age of five should spend no more than an hour watching a screen and infants under the age of one should not be watching at all. Its guidelines are similar to those introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which recommended that children under 19 months old should not spend time watching anything other than video chats. Moreover, it said children under two years old should only watch "high-quality programming" under parental supervision. However, Andrew Przybylski, who directs research at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, told the Associated Press that "Not all screen time is created equal" and that screen time advice needs to take into account "the content and context of use." In addition, the United Kingdom's Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health said its available data was not strong enough to indicate the necessity of screen time limits. WHO said its recommendations were intended to address the problem of sedentary behavior leading to health issues such as obesity.[77] A 2019 study published in JAMA Pediatrics investigated how screen time affected the brain structure of children aged three to five (preschoolers) using MRI scans. The test subjects—27 girls and 20 boys—took cognitive tests before their brain scans while their parents answered a questionnaire on screen time developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The researchers found that the toddlers who spent more than an hour per day in front of a screen without parental involvement showed less development in the brain's white matter, the region responsible for cognitive and linguistic skills. Lead author Dr. John Hutton, a pediatrician and clinical researcher at Cincinnati Children's Hospital, told CNN that this finding was significant because the brain develops most rapidly during the first five years of a person's life. Previous studies revealed that excessive screen time is linked to sleep deprivation, impaired language development, behavioral problems, difficulty paying attention and thinking clearly, poor eating habits, and damaged executive functions.[78][79] |

健康と福祉 スクリーン時間から生じる問題  今や多くの子供たちが目の問題に苦悩している。W.P.A. 連邦美術事業、[1936年または1937年]。 2015年の研究によれば、英国では過去50年間で近視の頻度が倍増した。オプティカル・エクスプレス国際医療諮問委員会の委員長を務める眼科医スティー ブ・シャルホルンは、研究者たちが携帯電子機器の日常的な使用と眼精疲労の関連性を指摘していると述べた。米国検眼協会も同様の懸念を表明している [75]。広報担当者によれば、デジタル眼精疲労(コンピューター視覚症候群)は「特に小型デバイスへの移行や日常生活におけるデバイスの重要性が増すに つれ、蔓延している」という。症状には目の乾燥・刺激、疲労、眼精疲労、視界のぼやけ、焦点合わせの困難、頭痛などが含まれる。ただし、この症候群は視力 低下やその他の恒久的損傷を引き起こすものではない。眼精疲労を軽減・予防するため、ビジョン・カウンシルは画面使用時間の制限、頻繁な休憩、画面輝度の 調整、背景色を明るい色から灰色への変更、文字サイズの拡大、まばたきの増加を推奨している。同団体は保護者に対し、子供の画面使用時間を制限するととも に、子供の前で自身の画面使用時間を減らすことで模範を示すよう助言している。[76] 2019年、WHOは幼児が1日に画面を見るべき時間について勧告を発表した。WHOは、5歳未満の幼児は1日1時間以上画面を見るべきではなく、1歳未 満の乳児はまったく画面を見るべきではないと述べた。このガイドラインは、19ヶ月未満の子供はビデオチャット以外の画面を見るべきではないと勧告した米 国小児科学会が導入したものと同様である。さらに、2歳未満の子供は、保護者の監督下にある「質の高い番組」のみを見るべきだと述べた。しかし、オックス フォード大学オックスフォード・インターネット研究所の研究責任者であるアンドルー・プシェビルスキー氏は、AP通信に対し、「すべてのスクリーンタイム が同じように作られているわけではない」と述べ、スクリーンタイムに関するアドバイスは「コンテンツと使用状況」を考慮に入れる必要があると語った。さら に、英国王立小児科学会は、利用可能なデータではスクリーンタイムの制限の必要性を示すには不十分だと述べた。WHO は、その勧告は、肥満などの健康問題につながる座りがちな行動の問題に対処することを目的としていると述べた。[77] JAMA Pediatrics に掲載された 2019 年の研究では、MRI スキャンを用いて、スクリーンタイムが 3 歳から 5 歳の子供(就学前児童)の脳構造にどのような影響を与えるかを調査した。被験者(女児27名、男児20名)は脳スキャン前に認知テストを受け、保護者は米 国小児科学会が作成したスクリーンタイムに関する質問票に回答した。研究者らは、保護者の関与なしに1日1時間以上スクリーンを視聴した幼児において、認 知・言語機能を司る脳の白質の発達が遅れていることを発見した。筆頭著者であるシンシナティ小児病院の小児科医兼臨床研究者、ジョン・ハットン博士は CNNに対し、この発見が重要だと述べた。なぜなら、脳は人生の最初の5年間に最も急速に発達するからだ。過去の研究では、過度なスクリーンタイムが睡眠 不足、言語発達の阻害、行動問題、注意力や思考力の低下、食習慣の悪化、実行機能の損傷と関連していることが明らかになっている。[78][79] |

| Allergies While food allergies have been observed by doctors since ancient times and virtually all foods can be allergens, research by the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota found that they have become increasingly common since the early 2000s. By the late 2010s, one in twelve American children had a food allergy, with peanut allergy being the most prevalent type. Reasons for this remain poorly understood.[80] Nut allergies in general quadrupled and shellfish allergies increased 40% between 2004 and 2019. In all, about 36% of American children have some kind of allergy. By comparison, this number among the Amish in Indiana is 7%. Allergies have also risen ominously in other Western countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, the number of children hospitalized for allergic reactions increased by a factor of five between 1990 and the late 2010s, as did the number of British children allergic to peanuts. In general, the better developed the country, the higher the rates of allergies.[81] Reasons for this also remain poorly understood.[80] One possible explanation, supported by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is that parents keep their children "too clean for their own good." They recommend exposing newborn babies to a variety of potentially allergenic foods, such as peanut butter, before they reach the age of six months. According to this "hygiene hypothesis", such exposures give the infant's immune system some exercise, making it less likely to overreact. Evidence for this includes the fact that children living on a farm are consistently less likely to be allergic than their counterparts who are raised in the city, and that children born in a developed country to parents who immigrated from developing nations are more likely to be allergic than their parents are.[81] |

アレルギー 食物アレルギーは古代から医師によって観察されており、事実上全ての食品がアレルゲンとなり得る。しかしミネソタ州メイヨークリニックの研究によれば、 2000年代初頭以降、その発生率は増加傾向にある。2010年代後半には、アメリカの子供12人に1人が食物アレルギーを持ち、中でもピーナッツアレル ギーが最も多い。その原因は未だに解明されていない。[80] 2004年から2019年の間に、ナッツアレルギーは全体で4倍に増加し、甲殻類アレルギーは40%増加した。全体として、アメリカの子どもの約36%が 何らかのアレルギーを持っている。比較すると、インディアナ州のアミッシュコミュニティにおけるこの数値は7%だ。アレルギーは他の西欧諸国でも不気味な ほど増加している。例えばイギリスでは、アレルギー反応で入院する子どもの数が1990年から2010年代後半にかけて5倍に増加し、ピーナッツアレル ギーを持つ英国の子どもの数も同様に増加した。一般的に、国が発展すればするほどアレルギーの発生率は高くなる。[81] その理由も依然として十分に解明されていない。[80] 米国国立アレルギー感染症研究所が支持する一つの説明は、親が子供を「清潔にしすぎて害を及ぼしている」というものだ。同研究所は生後6ヶ月になる前に、 新生児にピーナッツバターなど様々な潜在的なアレルゲンを含む食品を摂取させることを推奨している。この「衛生仮説」によれば、こうした接触は乳児の免疫 系に一定の刺激を与え、過剰反応を起こしにくくする。その根拠として、農場で育った子供は都市で育った子供よりアレルギー発症率が常に低いこと、また先進 国で生まれた移民の子供は親よりアレルギーになりやすいことが挙げられる。[81] |

| Vaccinations In the United States, public health officials were raising the alarm in the 2010s when vaccination rates dropped. Many parents thought that they did not need to vaccinate their children against diseases such as polio and measles because they had become either extremely rare or eliminated. Officials warn that infectious diseases could return if not enough people get inoculated.[82] In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that mass vaccination campaigns be suspended in order to ensure social distancing. Dozens of countries followed this advice. However, some public health experts warned that the suspension of these programs can come with serious consequences, especially in poor countries with weak healthcare systems. For children from these places, such campaigns are the only way for them to get vaccinated against various communicable diseases such as polio, measles, cholera, human papillomavirus (HPV), and meningitis. Case numbers could surge afterwards. Moreover, because of the lockdown measures, namely, the restriction of international travels and transport, some countries might find themselves running short on not just medical equipment but also vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 can inflict more damage than the people it infects and kills.[83] In fact, SARS-CoV-2 is less dangerous for infants compared to influenza or the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).[84] |

予防接種 アメリカでは2010年代、予防接種率が低下したことで公衆衛生当局が警鐘を鳴らした。多くの親は、ポリオや麻疹といった病気は極めて稀になったか根絶さ れたため、子供に予防接種をする必要はないと考えていた。当局は、十分な人数が接種を受けなければ感染症が再流行する恐れがあると警告している。[82] COVID-19パンデミックを受けて、世界保健機関(WHO)は社会的距離の確保のため、集団予防接種キャンペーンの中止を勧告した。数十カ国がこの助 言に従った。しかし一部の公衆衛生専門家は、特に医療体制が脆弱な貧困国において、こうしたプログラムの中止が深刻な結果を招きかねないと警告した。これ らの地域の子供たちにとって、ポリオ、麻疹、コレラ、ヒトパピローマウイルス(HPV)、髄膜炎などの様々な伝染病に対する予防接種を受ける唯一の手段 が、こうしたキャンペーンだからだ。その後、症例数が急増する可能性がある。さらに、ロックダウン措置、すなわち国際的な移動や輸送の制限により、一部の 国では医療機器だけでなくワクチンも不足する事態に陥るかもしれない。SARS-CoV-2は、感染させたり死に至らせたりする人々以上に大きな損害をも たらしうる。[83] 実際、SARS-CoV-2は乳幼児にとって、インフルエンザや呼吸器合胞体ウイルス(RSV)に比べて危険性が低い。[84] |

| Obesity and malnutrition A report by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released October 2019 stated that some 700 million children under the age of five worldwide are either obese or undernourished. Although there was a 40% drop in malnourishment in developing countries between 1990 and 2015, some 149 million toddlers are too short for their age, which hampers body and brain development. UNICEF's nutrition program chief Victor Aguayo said, "A mother who is overweight or obese can have children who are stunted or wasted." About one in two youngsters suffer from deficiencies of vitamins and minerals. Although pediatricians and nutritionists recommend exclusive breastfeeding for infants below five months of age, only about 40% were. Meanwhile, the sale of formula milk jumped 40% globally. In advanced developing countries such as Brazil, China, and Turkey, that number is 75%. Even though obesity was virtually non-existent in poor countries three decades ago, today, at least ten percent of children in them suffer from this condition. The report recommends taxes on sugary drinks and beverages and enhanced regulatory oversight of breast milk substitutes and fast foods.[85] |

肥満と栄養失調 国連児童基金(ユニセフ)が2019年10月に発表した報告書によると、世界中で5歳未満の子供約7億人が肥満か栄養不良の状態にある。1990年から 2015年にかけて途上国における栄養不良は40%減少したものの、約1億4900万人の幼児が年齢に対して身長が低すぎる。これは身体と脳の発達を妨げ る。ユニセフ栄養プログラム責任者ビクター・アグアヨは「肥満の母親から低身長ややせすぎの子どもが生まれる可能性がある」と指摘した。約半数の若年層が ビタミンやミネラル不足に苦悩している。小児科医や栄養士は生後5か月未満の完全母乳育児を推奨しているが、実践率は約40%に留まる。一方、粉ミルクの 世界的な販売量は40%急増した。ブラジル、中国、トルコなどの先進途上国ではその割合は75%に達する。30年前には貧困国で肥満がほとんど存在しな かったにもかかわらず、今日では少なくとも10%の子どもがこの状態に陥っている。報告書は、糖分を含む飲料への課税と、母乳代替品及びファストフードに 対する規制監督の強化を推奨している。[85] |

| Diet In 2021, Illinois-based ingredient company FONA issued a survey about Generation Alpha that found "72% of Millennials with kids say their families are consuming plant-based meats more often." The survey also found that Generation Alpha likes international food from countries which include India, Peru, Vietnam and Morocco.[86] A 2019 research study from Linda McCartney Foods found close to 50% of Generation Alpha reducing meat consumption, with 70% reporting their schools did not offer many vegetarian or vegan school meals.[87] In 2022, newspaper columnist Avery Yale Kamila wrote that "knowing quite a few members of Gen Alpha, I predict these young people will look at Gen Z's love of vegan meals and say, 'Hold my soy milk', before showing us how veg-forward a generation can get."[88] In 2021, brand firm JDO issued a research report that found less structured mealtimes mean more snacking among Generation Alpha and that Generation Alpha prefers nutrient-dense snacks that engage the senses and are sustainable or more mindful.[89] |

食事 2021年、イリノイ州に本拠を置く原料メーカーFONAが実施したアルファ世代に関する調査では、「子供を持つミレニアル世代の72%が、家族が植物性 肉をより頻繁に消費している」と報告された。また調査では、アルファ世代がインド、ペルー、ベトナム、モロッコなど諸外国の料理を好むことも判明した [86]。リンダ・マッカートニー・フーズの2019年調査では、アルファ世代の約50%が肉消費を減らしており、70%が学校給食でベジタリアン・ ヴィーガン向けメニューが少ないと回答した。[87] 2022年、新聞コラムニストのアベリー・エール・カミラは「アルファ世代の若者を何人か知っているが、彼らはZ世代のヴィーガン食への愛着を見て『豆乳 を持ってて』と言い、いかに菜食志向の強い世代になるかを示すだろう」と記した。[88] 2021年、ブランドコンサルティング会社JDOは調査報告書を発表した。それによると、アルファ世代は食事時間が不規則なため間食が増え、五感を刺激す る栄養価の高いスナックを好む傾向がある。また持続可能で意識的な選択肢を重視する傾向も見られた。[89] |

| Climate change Further information: Climate justice and Intergenerational equity Generation Alpha will be significantly more affected by climate change than older generations. It is estimated that children born in 2020 will experience up to seven times as many extreme weather events over their lifetimes, particularly heat waves, compared to people born in 1960, under current climate policy pledges.[90][91] |

気候変動 詳細情報:気候正義と世代間公平性 アルファ世代は、それ以前の世代よりも気候変動の影響をはるかに大きく受けることになる。現在の気候政策の公約に基づけば、2020年に生まれた子供たち は、1960年に生まれた人々と比べて、生涯で最大7倍もの異常気象、特に熱波を経験すると推定されている。[90][91] |

| Use of media technologies Information and communications technologies (ICT)  A child uses a tablet at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. (2018).  Twins watching a video from a portable device (2020) Many members of Generation Alpha have grown up using smartphones and tablets as part of their childhood entertainment, with many being exposed to devices as a soothing distraction or educational aids.[92][39] Screen time among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers increased significantly during the 2010s. Some 90% of young children used a handheld electronic device by the age of one; in some cases, children started using them when they were only a few months old.[78] Using smartphones and tablets to access video streaming services such as YouTube Kids and free or reasonably low-budget mobile games became a popular form of entertainment for young children.[93] A report by Common Sense media suggested that the amount of time children under nine in the United States spent using mobile devices increased from 15 minutes a day in 2013 to 48 minutes in 2017.[94] Research by the children's charity Childwise suggested that a majority of British three- and four-year-olds owned an Internet-connected device by 2018.[95] Being born into an environment where the use of electronic devices is ubiquitous comes with its own challenges: cyber-bullying, screen addiction, and inappropriate content.[1] On the other hand, much of the research on the effects of screen time on children has been inconclusive or even suggested positive effects.[96] The writer and educator Jordan Shapiro has suggested that the increasingly technological nature of childhood should be embraced as a way to prepare children for life in an increasingly digital world as well as teaching them skills for offline life.[96] In recognition of the Internet culture of Generations Z and Alpha, Oxford English Dictionary chose brain rot as its word of the year in 2024.[97][98] Cambridge Dictionary added the word skibidi in 2025. That word was coined by the creator of the viral video series "Skibidi Toilet" on YouTube, which was popular among Generation Alpha.[36] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary added six seven as another nonsensical slang or interjection of vogue among Generation Alpha in 2025.[99] |

メディア技術の利用 情報通信技術(ICT)  ワシントンD.C.の国立航空宇宙博物館でタブレットを使う子供(2018年)。  携帯端末で動画を見る双子(2020年) アルファ世代の多くは、幼少期の娯楽としてスマートフォンやタブレットを使いながら成長してきた。多くの場合、これらの機器は気を紛らわせる手段や教育補 助として利用されている。[92] [39] 乳幼児や未就学児のスクリーンタイムは2010年代に大幅に増加した。1歳までに約90%の幼児が携帯電子機器を使用しており、生後数ヶ月の頃から使い始 めるケースもあった。[78] YouTube Kidsなどの動画配信サービスや無料・低価格モバイルゲームにスマートフォンやタブレットでアクセスすることが、幼児の娯楽として普及した。[93] コモンセンス・メディアの報告書によれば、米国における9歳未満の児童のモバイル端末使用時間は、2013年の1日15分から2017年には48分に増加 した。[94] 児童慈善団体チャイルドワイズの調査では、2018年までに英国の3~4歳児の大半がインターネット接続端末を所有していた。[95] 電子機器の使用が日常的な環境で生まれることは、ネットいじめ、スクリーン依存症、不適切なコンテンツといった独自の課題をもたらす。[1] 一方で、スクリーン時間が子供に与える影響に関する研究の多くは結論が出ておらず、むしろ良い効果を示唆するものさえある。[96] 作家で教育者のジョーダン・シャピロは、子供の時代がますます技術的になる性質は、デジタル化が進む世界での生活に備えさせる手段として、またオフライン 生活のためのスキルを教える方法として受け入れるべきだと提案している。[96] Z世代とアルファ世代のインターネット文化を反映し、オックスフォード英語辞典は2024年の年間単語に「脳の腐敗(brain rot)」を選んだ。[97][98] ケンブリッジ辞書は2025年に「スキビディ」という単語を追加した。この言葉はYouTubeで流行した動画シリーズ「スキビディ・トイレ」の制作者に よって造語されたもので、アルファ世代の間で人気を博した。[36] メリアム・ウェブスター辞書は2025年、アルファ世代の間で流行したもう一つの無意味なスラングまたは感嘆詞として「シックス・セブン」を追加した。 [99] |

| Parental internet use Generation Alpha have also been surrounded by adult Internet use from the beginning of their lives. Their parents, primarily Millennials, are heavy social media users. A 2014 report from cybersecurity firm AVG stated that 6% of parents created a social media account and 8% an email account for their baby or toddler. According to BabyCenter, an online company specializing in pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing, 79% of Millennial mothers used social media on a daily basis and 63% used their smartphones more frequently since becoming pregnant or giving birth. More specifically, 24% logged on to Facebook more frequently and 33% did the same to Instagram after becoming a mother. Non-profit advocacy group Common Sense Media warned that parents should take better care of their online privacy, lest their and their children's personal information and photographs fall into the wrong hands. This warning was issued after a Utah mother reportedly found a photograph of her children on a social media post with pornographic hashtags in May 2015.[100] Nevertheless, the Millennial generation's familiarity with the online world allows them to use their personal experience to help their children navigate it.[1] Members of Generation Z often use the term "iPad kid" when referring to Generation Alpha.[101][102] This term was coined due to the majority of Generation Alpha's early childhood being spent watching and interacting with tablets and other smart mobile devices with the assumption of them being addicted.[103] In 2017, a study suggested that at least 80 percent of young children had access to a smart mobile device and schoolchildren had an average screen time of around seven hours a day.[103][104] Apple's iPads are one of the most popular smart mobile devices, hence the name. |

親のインターネット利用 アルファ世代もまた、生まれてからずっと大人のインターネット利用に囲まれて育ってきた。彼らの親、主にミレニアル世代はソーシャルメディアを頻繁に利用 する。サイバーセキュリティ企業AVGの2014年報告書によると、6%の親が乳幼児のためにソーシャルメディアアカウントを作成し、8%がメールアカウ ントを作成したという。妊娠・出産・育児専門のオンライン企業BabyCenterによれば、ミレニアル世代の母親の79%が毎日ソーシャルメディアを利 用し、63%が妊娠または出産後、スマートフォンの使用頻度が増加した。具体的には、母親になった後、24%がFacebookへのログイン頻度を、 33%がInstagramの利用頻度をそれぞれ増やした。非営利団体コモン・センス・メディアは、親がオンライン上のプライバシー管理を強化すべきだと 警告した。さもなければ、自身や子供の個人的な情報や写真が悪意ある者の手に渡る恐れがあるからだ。この警告は、2015年5月にユタ州の母親が、ポルノ 関連のハッシュタグが付いたソーシャルメディア投稿に自身の子供の写真が掲載されているのを発見したとの報道を受けて発せられたものである。[100] とはいえ、ミレニアル世代はオンライン世界に精通しているため、個人的な経験を活かして子供たちがネットを安全に利用できるよう導ける。[1] ジェネレーションZの成員は、ジェネレーションアルファを指す際に「iPadキッズ」という用語をよく使う。[101][102] この用語は、ジェネレーションアルファの幼少期の大半がタブレットやその他のスマートモバイルデバイスを見て操作することに費やされ、依存症と見なされる ことから生まれた。[103] 2017年の研究によれば、幼児の少なくとも80%がスマートモバイル端末を利用可能であり、学童の平均スクリーンタイムは1日約7時間に達していた。 [103][104] アップル社のiPadは最も普及したスマートモバイル端末の一つであり、これが名称の由来である。 |

| Television and streaming services In part due to the surge in use of handheld devices,[39] broadcast television viewing among children has declined in the 2020s.[105] Ratings figures from the United States suggested that viewing of children's cable networks among American 2- to 11-year-olds were falling sharply in early 2020, and continued to do so (albeit by smaller amounts) even after COVID-19 restrictions forced many children to stay home.[105] Disney Channel in particular lost a third of their viewers in 2020, leading to closures in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Southeast Asia.[106] Research from the United Kingdom suggested that viewing of traditional broadcasting among British 4- to 15-year-olds fell from an average of 151 minutes in 2010 to 77 minutes in 2018.[107] However, accessing televised programming via streaming and catch-up services has become increasingly popular among children during the same time period.[105][106] In 2019, almost 60% of Netflix's 152 million global subscribers accessed content for children and families at least once a month.[108] In the United Kingdom, requests for children's programming on the BBC's catch up service iPlayer increased substantially during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.[109][110] In 2019, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's ABC iview service received more than half its views via children's content.[111] By 2025, YouTube, Netflix, and Disney+ have become the most popular substitutes for traditional children's programming on television among young viewers.[112] Animated programs Cocomelon (2018–2024) and Peppa Pig (2004–present) on Netflix, and Bluey (2018–present) on Disney+ are some of the most-watched shows for youngsters.[112] |

テレビとストリーミングサービス 携帯端末の利用急増も一因となり、[39] 2020年代には子どものテレビ視聴率が低下した。[105] アメリカの視聴率データによれば、2020年初頭には2歳から11歳のアメリカ人児童における子供向けケーブルネットワークの視聴率が急落し、COVID -19による制限で多くの子供が自宅待機を余儀なくされた後も(減少幅は小さくなったものの)下落傾向が続いた。[105] 特にディズニーチャンネルは2020年に視聴者の3分の1を失い、スカンジナビア、英国、オーストラリア、東南アジアでの放送終了につながった。 [106] 英国の調査によれば、4歳から15歳の英国人児童・青少年の従来型放送視聴時間は、2010年の平均151分から2018年には77分に減少した。 [107] しかし同時期に、ストリーミングや見逃し配信サービスを通じたテレビ番組へのアクセスは児童の間で急速に普及した。[105][106] 2019年には、Netflixの全世界1億5200万人の加入者のうち、ほぼ60%が月に少なくとも1回は子供向け・家族向けコンテンツを利用してい た。[108] イギリスでは、COVID-19パンデミック期間中、BBCのキャッチアップサービス「iPlayer」における子供向け番組の視聴要求が大幅に増加し た。[109][110] 2019年には、オーストラリア放送協会(ABC)のiviewサービスにおける視聴回数の半分以上が子供向けコンテンツによるものだった。[111] 2025年までに、YouTube、Netflix、Disney+は、若い視聴者層において、従来のテレビ子供番組に代わる最も人気のある選択肢となっ た。[112] Netflixのアニメ番組『Cocomelon』(2018年~2024年)と『Peppa Pig』(2004年~現在)、Disney+の『Bluey』(2018年~現在)は、子供たちにとって最も視聴されている番組の一部だ。[112] |

| Family and social life Upbringing Research from 2021 suggested that British children were allowed out to play without adult supervision almost two years later than their parents had been. The study of five- to eleven-year-olds suggested that the average age for a child to be first given that freedom was 10.7 years old whilst their parents recalled being let out noticeably earlier at an average of 8.9 years of age. Helen Dodd, a professor of child psychology at the University of Reading, who led the study commented "In the largest study of play in Britain, we can clearly see that there is a trend to be protective and to provide less freedom for our children now than in previous generations... The concerns we have from this report are twofold. First, we are seeing children getting towards the end of their primary school years without having had enough opportunities to develop their ability to assess and manage risk independently. Second, if children are getting less time to play outdoors in an adventurous way, this may have an impact on their mental health and overall wellbeing." The research also suggested that children were more likely to be allowed to play outside unsupervised at an earlier age if they were white, the second or later born, living in Scotland or had better educated parents.[113] In the United States, the share of children living with single parents (and no other adults) continued to grow during the 2010s, reaching 23% in 2019, higher than any other country studied by the Pew Research Center, including neighbouring Canada, at 15%.[114] This has raised concern over their welfare.[115][116] On the other hand, in Asia (including the Middle East), single-parent households are extremely rare.[114] But American children of the 2010s and 2020s are much safer than ever before, thanks to children's car seats, seat-belt laws, and swimming-pool safety reforms, among other things. At the same time, their parents tend to have fewer of them and to have them later in life, after achieving financial security, and as such are in a position to devote more resources to rearing them.[21] |

家族と社会生活 子育て 2021年の研究によると、英国の子供たちは、親が遊ばせてもらった時期よりほぼ2年遅く、大人の監督なしに外で遊ぶことを許されている。5歳から11歳 を対象としたこの研究では、子供が初めてその自由を与えられる平均年齢は10.7歳であった。一方、親たちは平均8.9歳という、明らかに早い時期に遊ば せてもらったと記憶していた。研究を主導したレディング大学の児童心理学教授ヘレン・ドッドは次のようにコメントしている。「英国で最大規模の遊びに関す る研究から、現代の親は保護的傾向が強く、以前の世代よりも子供に自由を与えていない傾向が明らかになった。この報告から懸念される点は二つある。第一 に、子供たちが小学校高学年になるまでに、リスクを独自に評価・管理する能力を十分に育む機会を得られていないことだ。次に、冒険的な屋外遊びの時間が減 少すれば、子どもの健康や総合的な幸福度に影響を及ぼす可能性がある」と指摘した。また本調査では、白人であること、第二子以降であること、スコットラン ド在住であること、親の学歴が高いことなどが、より早い年齢での無監督屋外遊びの許可率と相関することが示唆された[113]。 アメリカでは、2010年代を通じて単親家庭(他の大人がいない)で暮らす子供の割合が増え続け、2019年には23%に達した。これはピュー・リサー チ・センターが調査した他国(隣国カナダは15%)よりも高い数値だ。[114] この状況は彼らの福祉に対する懸念を引き起こしている。[115] [116] 一方、アジア(中東を含む)では、片親世帯は極めて稀だ。[114] しかし2010年代から2020年代のアメリカの子供たちは、チャイルドシートやシートベルト着用義務、プール安全対策などの改革により、かつてないほど 安全である。同時に、親は経済的安定を得た後で、より少ない子供を、より遅い年齢で持つ傾向にある。そのため、子育てにより多くの資源を割ける立場にある のだ。[21] |

| Major events COVID-19 pandemic A girl in a medical mask during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the beginning of the crisis, people around the world were expected to wear face masks in many settings, often including children at an early age. Much of Generation Alpha lived through the global COVID-19 pandemic as young children. Although they are at far less risk of becoming seriously ill with the disease than their elders,[84] this cohort is dramatically affected by the crisis in other ways.[117] Many are faced with extended periods out of school or daycare and much more time at home,[118] which raised concerns about potential harm to the development of small children and the academic attainment of those of school age[119][120][121] while putting some, especially the particularly vulnerable, at greater risk of abuse.[122] The crises also led to increased child malnutrition and increased mortality, especially in developing countries.[123] A study of the understanding of seven- to twelve-year-olds of the pandemic in the UK, Spain, Canada, Sweden, Brazil and Australia found that more than half of children knew a significant amount about COVID-19. They associated the topic with various negative emotions saying it made them feel "worried", "scared", "angry" and "confused". They tended to be aware of the types of people which were most vulnerable to the virus and the restrictions which were enforced in their communities. Many had learned new terms and phrases in relation to the pandemic such as social distancing. They were most commonly informed about COVID-19 by teachers and parents, but also learned about the subject from friends, television and the Internet.[124] A report by UNICEF in late 2021 described the COVID-19 pandemic as "the biggest threat to children in our 75-year history." It noted that amongst other effects, levels of child poverty and malnutrition had sharply increased. Education and the services designed to protect vulnerable children had been disrupted across the world. Child labour rates had increased, reversing a 20-year fall.[125] While children were at less direct risk in general from COVID-19, the disease was nevertheless a top-ten cause of death for children during the most acute phases of the pandemic. In the United States, it was the sixth leading cause of death for children in 2021[126] and the eighth in 2023.[127] The CDC reported that, globally, 10.5 million children had been orphaned by COVID-19.[128] |

主要な出来事 COVID-19パンデミック COVID-19パンデミック中に医療用マスクを着用した少女。危機の初期段階では、世界中の人々が多くの場面でマスクを着用することが求められ、幼い子供たちも例外ではなかった。 アルファ世代の多くは幼い子供として世界的なCOVID-19パンデミックを経験した。彼らは高齢者よりも重症化するリスクがはるかに低いものの [84]、この世代は他の形で危機の影響を劇的に受けている[117]。多くの子供が長期にわたり学校や保育所を離れ、自宅で過ごす時間が大幅に増加した [118]。これにより、幼児の発達や学齢期の学業達成度への潜在的な悪影響が懸念された[119][120]。[121] 同時に、特に脆弱な立場にある者を中心に、虐待リスクが高まる事態も生じている[122]。この危機はまた、特に発展途上国において、子どもの栄養不良と 死亡率の増加を招いた[123]。 英国、スペイン、カナダ、スウェーデン、ブラジル、オーストラリアにおける7歳から12歳の子どもたちのパンデミック理解度調査では、半数以上が COVID-19についてかなりの知識を有していることが判明した。彼らはこの話題を様々な否定的な感情と結びつけ、「心配」「怖い」「怒り」「混乱」を 感じると述べた。ウイルスに最も脆弱な人々のタイプや、地域社会で施行された制限について認識している傾向があった。多くの子供が「社会的距離」などパン デミック関連の新たな用語を習得していた。COVID-19に関する情報は主に教師や親から得ていたが、友人やテレビ、インターネットからも学んでいた。 [124] 2021年末のユニセフ報告書は、COVID-19パンデミックを「75年の歴史で最も深刻な子供への脅威」と位置付けた。特に指摘された影響として、子 どもの貧困率と栄養不良率が急激に増加したことが挙げられる。教育や脆弱な子どもを守るためのサービスは世界中で混乱した。児童労働率は20年間続いた減 少傾向を逆転させ、増加した。[125] 子どもは一般的にCOVID-19による直接的なリスクが低いものの、パンデミックの最も深刻な段階では、この疾患は子どもの死因トップ10に入ってい た。米国では、2021年に子どもの死因第6位[126]、2023年には第8位[127]となった。CDCの報告によれば、世界全体で1050万人の子 どもがCOVID-19によって孤児となった[128]。 |

| Projections of demographic changes See also: Projections of population growth and Growth of religion § Future change The first wave of Generation Alpha will reach adulthood by the 2030s. It was predicted in 2018 that, by that time, the world population is expected to be just under nine billion, and the world will have the highest ever proportion of people aged over 60,[129] meaning this demographic cohort will bear the burden of an aging population.[2] According to Mark McCrindle, a social researcher from Australia, Generation Alpha will most likely delay standard life markers such as marriage, childbirth, and retirement, as did the previous generations. McCrindle estimated that Generation Alpha will make up 11% of the global workforce by 2030.[2] He also predicted that they will live longer and have smaller families, and will be "the most formally educated generation ever, the most technology-supplied generation ever, and globally the wealthiest generation ever."[39] In 2018, the United Nations forecasted that while the global average life expectancy would rise from 70 in 2015 to 83 in 2100, the ratio of people of working age to senior citizens would shrink due to falling fertility rates worldwide. By 2050, many nations in Asia, Europe, and Latin America would have fewer than two workers per retiree. U.N. figures show that, leaving out migration, all of Europe, Japan, and the United States were shrinking in the 2010s, but by 2050, 48 countries and territories would experience a population decline.[130] As of 2020, the latest demographic projections from the United Nations predict that there would be 8.5 billion people by 2030, 9.7 billion by 2050, and 10.9 billion by 2100. U.N. calculations assume countries with especially low fertility rates will see them rise to an average of 1.8 per woman. However, a 2020 study by researchers from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, published in the Lancet projected there would only be about 8.8 billion people by 2100, two billion fewer than what the U.N. predicted. This was because their analysis suggested that as educational opportunities and family planning services become more and more accessible for women, they would choose to have no more than 1.5 children on average. A majority of the world's countries would continue to see their fertility rates decline, the researchers claimed. In particular, over 20 countries—including China, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Poland—would find their populations reduced by around half or more. Meanwhile, sub-Saharan Africa would continue to experience a population boom, with Nigeria reaching 800 million people by century's end. Lower-than-expected human population growth means less stress on the environment and on food supplies, but it also points to a bleak economic picture for the greying countries. For the sub-Saharan African countries, though, there would be considerable opportunity for growth. The researchers predicted that as the century unfolds, major but aging economies such as Brazil, Russia, Italy, and Spain would shrink while Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom would remain within the top ten. India would eventually claim the third spot. China would displace the United States as the largest economy in the world by mid-century, but would return to second place later on.[131] A 2017 projection by the Pew Research Center suggests that between 2015 and 2060, the human population would grow by about 32%. Among the major religious groups, only Muslims (70%) and Christians (34%) are above this threshold and as such would have a higher share of the global population than they do now, especially Muslims. Hindus (27%), Jews (15%), followers of traditional folk religions (5%), and the religiously unaffiliated (3%) would grow in absolute numbers, but would be in relative decline because their rates of growth are below the global average. On the other hand, Buddhists would find their numbers shrink by 7% during the same period. This is due to sub-replacement fertility and population aging in Buddhist-majority countries such as China, Japan, and Thailand. This projection has taken into account religious switching. Moreover, previous research suggests that switching plays only a minor role in the growth or decline of religion compared to fertility and mortality.[50] |

人口動態の変化に関する予測 関連項目:人口増加の予測、宗教の成長 § 将来の変化 アルファ世代の第一波は2030年代までに成人期を迎える。2018年の予測によれば、その時点で世界人口は90億人に迫り、60歳以上の人口比率が史上 最高となる見込みだ[129]。つまりこの世代が、高齢化社会の重荷を担うことになる。[2] オーストラリアの社会研究者マーク・マクリンドルによれば、アルファ世代は前世代と同様に、結婚・出産・退職といった標準的な人生の節目(ライフマー カー)を遅らせる可能性が高い。マクリンドルは2030年までにアルファ世代が世界の労働力の11%を占めると推定した。[2] 同氏はさらに、アルファ世代はより長生きし、家族規模は縮小すると予測。彼らは「史上最も高等教育を受けた世代、史上最も技術に恵まれた世代、そして世界 的に見て史上最も豊かな世代」となるだろうと述べた[39]。 2018年、国連は世界の平均寿命が2015年の70歳から2100年には83歳に伸びると予測した。しかし世界的な出生率低下により、労働年齢人口と高 齢者の比率は縮小する見込みだ。2050年までに、アジア、ヨーロッパ、ラテンアメリカの多くの国では、退職者1人あたりの労働者数が2人を下回る見込み だ。国連の統計によれば、移民を除くと、2010年代にはヨーロッパ全域、日本、アメリカ合衆国の人口が減少していたが、2050年までに48の国と地域 で人口減少が発生すると予測されている。[130] 2020年時点の国連最新人口推計によれば、2030年には85億人、2050年には97億人、2100年には109億人に達すると予測されている。国連 の試算では、特に出生率が低い国々でも平均1.8人まで上昇すると想定している。しかし、ワシントン大学健康指標評価研究所(IHME)の研究者らが 2020年に『ランセット』誌で発表した研究では、2100年の人口は88億人程度と予測され、国連の予測より20億人少ない数値となった。これは、女性 の教育機会や家族計画サービスがますます利用しやすくなるにつれ、平均して1.5人以上の子供を持たない選択をするという分析結果に基づくものだ。研究者 らは、世界の大半の国々で出生率の低下が続くと主張している。特に中国、日本、韓国、タイ、スペイン、イタリア、ポルトガル、ポーランドを含む20カ国以 上では、人口が約半分以下に減少すると予測される。一方、サハラ以南のアフリカでは人口急増が続き、ナイジェリアは世紀末までに8億人に達する見込みだ。 予想を下回る人口増加は環境や食糧供給への負担軽減につながるが、高齢化が進む国々にとっては暗い経済見通しを示している。しかしサハラ以南のアフリカ諸 国には、成長の大きな機会が訪れるだろう。研究者らは、世紀が進むにつれ、ブラジル、ロシア、イタリア、スペインといった主要だが高齢化した経済国は縮小 する一方、日本、ドイツ、フランス、英国は上位10カ国に留まると予測した。インドは最終的に第3位となる。中国は2050年までに米国を追い抜き世界最 大の経済大国となるが、その後再び第2位に後退する見込みだ。[131] ピュー・リサーチ・センターの2017年予測によれば、2015年から2060年にかけて世界人口は約32%増加する。主要宗教グループの中で、この増加 率を上回るのはイスラム教徒(70%)とキリスト教徒(34%)のみであり、特にイスラム教徒は現在より世界人口に占める割合が高まる。ヒンドゥー教徒 (27%)、ユダヤ教徒(15%)、伝統的民間信仰の信者(5%)、無宗教者(3%)は絶対数では増加するが、成長率が世界平均を下回るため相対的には減 少する。一方、仏教徒は同期間に7%減少する。これは中国、日本、タイなどの仏教徒多数国における出生率の低下と高齢化によるものである。この予測は宗教 の転換を考慮している。さらに、過去の研究によれば、転換は出生率や死亡率に比べ、宗教の増減に及ぼす影響は小さいとされる。[50] |

| List of generations |

世代の一覧 |