大東亜共栄圏

Dai Tōa Kyōeiken, the Greater East Asia

Co-Prosperity Sphere

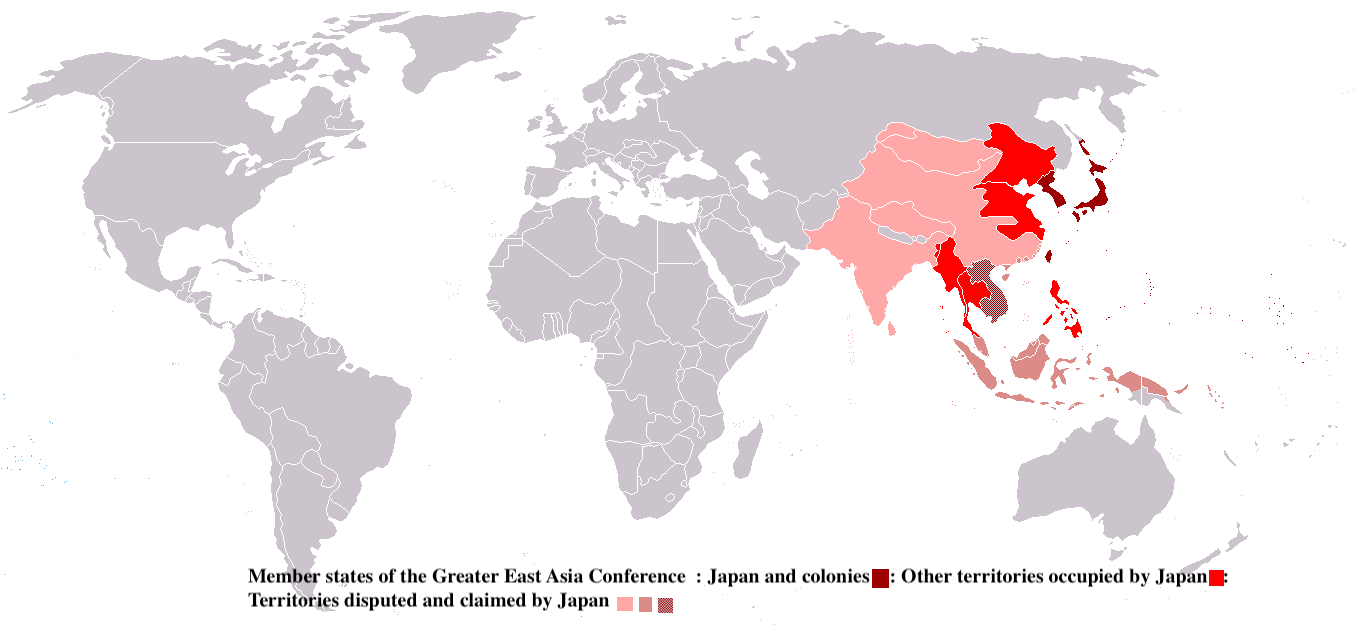

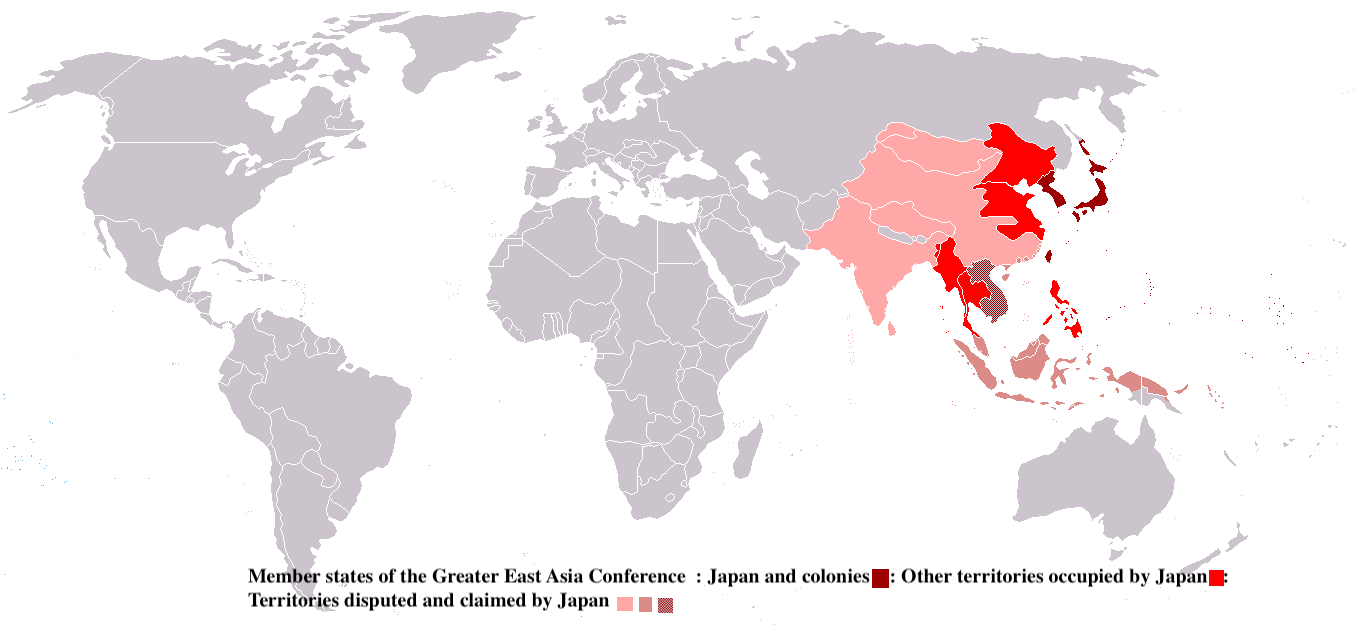

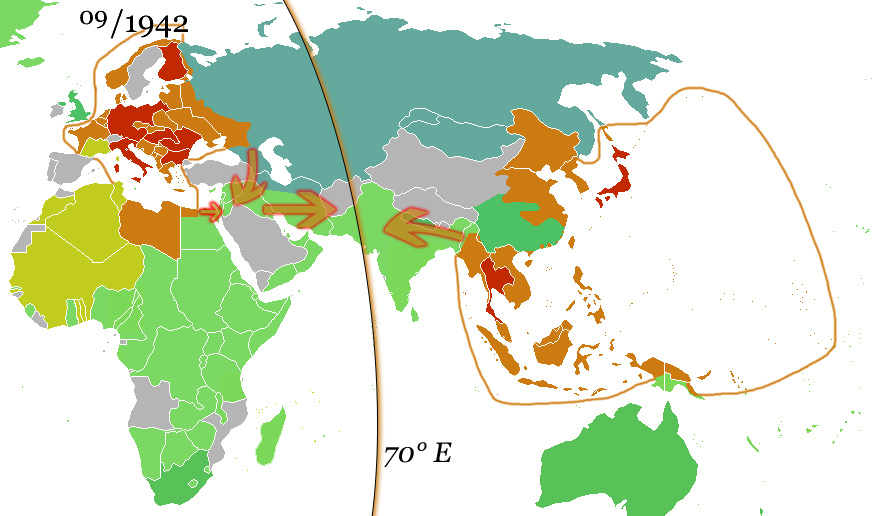

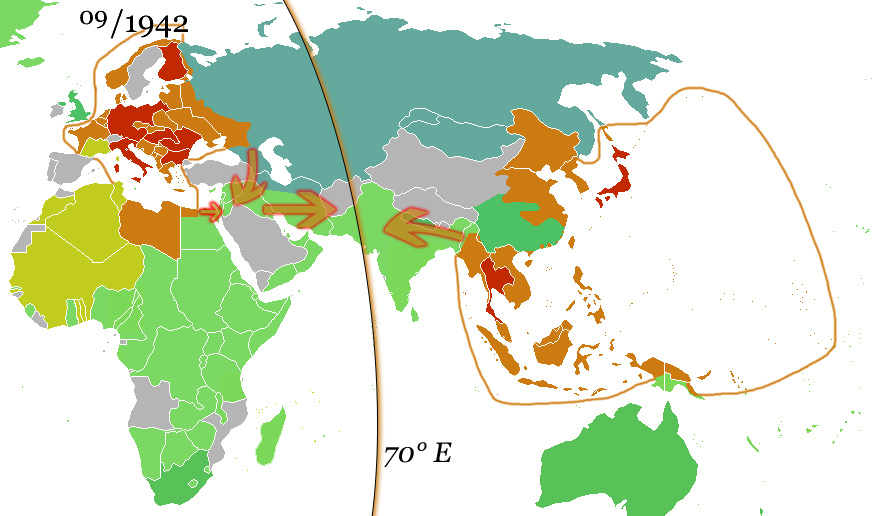

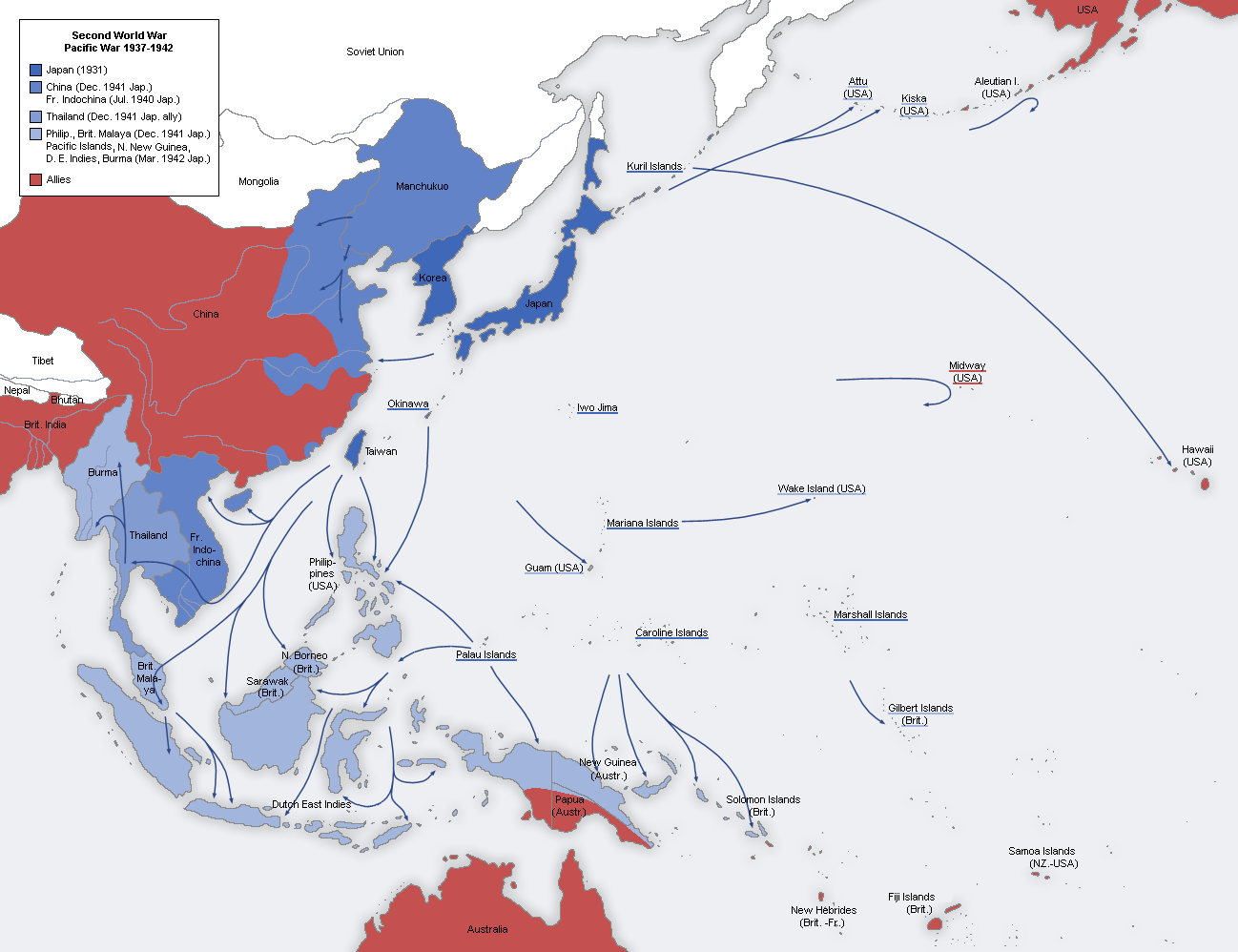

☆The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in 1942 The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphereとは大東亜共栄圏の英訳

大

東亜共栄圏

(だいとうあきょうえいけん、英: Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity

Sphere)は、GEACPSとも呼ばれ、大日本帝国が樹立しようとした汎アジア連合である。当初は日本、満州国、中国を対象としていたが、太平

洋戦争が進むにつれて東南アジアの領土も含まれるようになった。この言葉は1940年6月29日に有田八郎外務大臣によって初めて作られた。この同盟の目

的として提案されたのは、経済的自給自足と加盟国間の協力を確保するとともに、西洋帝国主義とソビエト共産主義の影響に抵抗することであった

。現実には、軍国主義者とナショナリストは、大きな抵抗を引き起こすことなく日本の優位性を強制するための効果的なプロパガンダの道具と考えた。

[後者のアプローチは、日本の厚生省が発表した「大和民族を核とする世界政策の検討」という文書に反映されており、連合における日本の覇権を推進していた

[5]。

日本のスポークスマンは、大東亜共栄圏を「日本民族の発展」のための装置であると公然と述べていた。第二次世界大戦が終わると、大東亜共栄圏は批判

と軽蔑の対象となった。

大

東亜共栄圏

(だいとうあきょうえいけん、英: Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity

Sphere)は、GEACPSとも呼ばれ、大日本帝国が樹立しようとした汎アジア連合である。当初は日本、満州国、中国を対象としていたが、太平

洋戦争が進むにつれて東南アジアの領土も含まれるようになった。この言葉は1940年6月29日に有田八郎外務大臣によって初めて作られた。この同盟の目

的として提案されたのは、経済的自給自足と加盟国間の協力を確保するとともに、西洋帝国主義とソビエト共産主義の影響に抵抗することであった

。現実には、軍国主義者とナショナリストは、大きな抵抗を引き起こすことなく日本の優位性を強制するための効果的なプロパガンダの道具と考えた。

[後者のアプローチは、日本の厚生省が発表した「大和民族を核とする世界政策の検討」という文書に反映されており、連合における日本の覇権を推進していた

[5]。

日本のスポークスマンは、大東亜共栄圏を「日本民族の発展」のための装置であると公然と述べていた。第二次世界大戦が終わると、大東亜共栄圏は批判

と軽蔑の対象となった。

★大東亜会議(だ

いとうあかいぎ、旧字体:大東亞會議)は、1943年(昭和18年)11月5日 -

11月6日に東京で開催されたアジア地域の首脳会議。同年5月31日に御前会議[1]で決定された大東亜政略指導大綱に基づき開催された。

当時の日本の同盟国や、日本が太平洋戦争(大東亜戦争)で旧宗主国を放逐したことにより独立されたアジア諸国の国政最高責任者を招請して行われた。そこで

は、大東亜共栄圏の綱領ともいうべき大東亜共同宣言が採択された。日本は第2回目の大東亜会議を開催する計画を持っていたが、戦局の悪化に伴って開催困難

となり、昭和20年(1945年)4月には代替として駐日特命全権大使や駐日代表による「大使会議」が開催された[2]。

| The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

(Japanese: 大東亜共栄圏, Hepburn: Dai Tōa Kyōeiken), also known as the

GEACPS,[1] was a pan-Asian union that the Empire of Japan tried to

establish. Initially, it covered Japan, Manchukuo, and China but as the

Pacific War progressed, it also included territories in Southeast

Asia.[2] The term was first coined by Minister for Foreign Affairs

Hachirō Arita on June 29 1940.[3] The proposed objectives of this union were to ensure economic self-sufficiency and cooperation among the member states, along with resisting the influence of Western imperialism and Soviet communism.[4] In reality, militarists and nationalists saw it as an effective propaganda tool to enforce Japanese supremacy without provoking significant resistance.[3] The latter approach was reflected in a document released by Japan's Ministry of Health and Welfare, An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus, which promoted Japanese hegemony in the union.[5] Japanese spokesmen openly described the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as a device for the "development of the Japanese race."[6] When World War II ended, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere became a source of criticism and scorn.[7] |

大東亜共栄圏

(だいとうあきょうえいけん、英: Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity

Sphere)は、GEACPSとも呼ばれ[1]、大日本帝国が樹立しようとした汎アジア連合である。当初は日本、満州国、中国を対象としていたが、太平

洋戦争が進むにつれて東南アジアの領土も含まれるようになった[2]。この言葉は1940年6月29日に有田八郎外務大臣によって初めて作られた[3]。 この同盟の目的として提案されたのは、経済的自給自足と加盟国間の協力を確保するとともに、西洋帝国主義とソビエト共産主義の影響に抵抗することであった [4]。現実には、軍国主義者とナショナリストは、大きな抵抗を引き起こすことなく日本の優位性を強制するための効果的なプロパガンダの道具と考えた。 [後者のアプローチは、日本の厚生省が発表した「大和民族を核とする世界政策の検討」という文書に反映されており、連合における日本の覇権を推進していた [5]。 日本のスポークスマンは、大東亜共栄圏を「日本民族の発展」のための装置であると公然と述べていた[6]。第二次世界大戦が終わると、大東亜共栄圏は批判 と軽蔑の対象となった[7]。 |

Development of the concept 1935 propaganda poster of Manchukuo promoting harmony between Japanese, Chinese, and Manchu. The caption from right to left says: "With the help of Japan, China, and Manchukuo, the world can be in peace." The flags shown are, right to left: the "Five Races Under One Union" flag of China, the flag of Japan, and the flag of Manchukuo. Main articles: Japanese nationalism and Propaganda in Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II The concept of a unified Asia under Japanese leadership had its roots dating back to the 16th century. For example, Toyotomi Hideyoshi proposed to make China, Korea, and Japan into "one". Modern conceptions emerged in 1917. During the proceedings of the Lansing-Ishii Agreement, Japan explained to Western observers that their expansionism in Asia was analogous to the United States' Monroe Doctrine.[3] This conception was influential in the development of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity concept, with the Japanese Army also comparing it to the Roosevelt Corollary.[2] One of the reasons why Japan tried to expand in other Asian territories was to resolve domestic issues such as overpopulation and resource scarcity. Another reason was to withstand Western imperialism. [3] On 3 November 1938, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe and Minister for Foreign Affairs Hachirō Arita proposed the development of the New Order in East Asia (東亜新秩序[8], Tōa Shin Chitsujo), which was limited to Japan, China, and the puppet state of Manchukuo.[9] They believed that the union had 6 purposes:[3] Permanent stability of Eastern Asia Neighborly amity and international justice Joint defense against Communism Creation of a new culture Economic cohesion and co-operation World peace The vagueness of the above points were effective in making people more agreeable to militarism and collaborationism.[3] On June 29 1940, Arita renamed the union the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which he announced by radio address. At Yōsuke Matsuoka's advice, Arita emphasised on the economic aspects more. On August 1, Konoe, who still used the original name, expanded the scope of the union to include the territories of Southeast Asia. [3]On November 5, Konoe reaffirmed that a Japan-Manchukuo-China yen bloc[10] would continue and be 'perfected'. [3] |

コンセプトの発展 1935年、日本、中国、満州の融和を訴える満州国の宣伝ポスター。キャプションは右から順に "日本、中国、満州国の協力で世界は平和になる"。描かれている旗は、右から中国の「五族協和」旗、日本の国旗、満州国の国旗。 主な記事 日本のナショナリズム、日中戦争と第二次世界大戦中の日本のプロパガンダ 日本主導のアジア統一というコンセプトのルーツは16世紀にさかのぼる。例えば、豊臣秀吉は中国、朝鮮、日本を「ひとつ」にすることを提案した。近代的な 構想は1917年に登場した。この概念は、大東亜共栄構想の展開に影響を与え、日本陸軍もルーズベルト・コラリーと比較した[2]。日本が他のアジア地域 で拡大を試みた理由のひとつは、人口過剰や資源不足などの国内問題を解決するためであった。もうひとつの理由は、西洋の帝国主義に対抗するためであった。 [3] 1938年11月3日、近衛文麿内閣総理大臣と有田八郎外務大臣は、日本、中国、満州国の傀儡国家に限定した東亜新秩序(東亜新秩序[8]、東亜新秩序) の発展を提案した[9]。 東アジアの恒久的な安定 近隣友好と国際正義 共産主義に対する共同防衛 新しい文化の創造 経済的結束と協力 世界平和 上記の諸点が曖昧であったことは、軍国主義や協調主義に賛同する人々を増やす上で効果的であった[3]。 1940年6月29日、有田は連合を大東亜共栄圏と改称し、ラジオ演説で発表した。松岡洋右の助言により、有田は経済面をより重視した。8月1日、近衛は 当初の名称のまま、大東亜共栄圏の範囲を東南アジア地域にまで拡大した[3]。[3]11月5日、近衛は日本・満州国・中国の円ブロック[10]が継続 し、「完成」されることを再確認した。[3] |

| History Main articles: Japanese colonial empire and Military history of Japan § Shōwa era and World War II (1926–1945) The outbreak of World War II in Europe gave the Japanese an opportunity to fulfill the objectives of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, without significant pushback from the Western powers or China.[11] This entailed the conquest of South East Asian territories to extract their natural resources. When certain territories were found to be unprofitable, the Japanese would encourage their subjects, including those in mainland Japan, to endure through "economic suffering" and make efforts to prevent outflow of material to the enemy. Nonetheless, they preached the moral superiority of creating a "spiritual essence" in Asian countries instead of prioritising material gain like Western powers.[4] After Japanese advancements into French Indochina in 1940, knowing that Japan was completely dependent on other countries for natural resources, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered a trade embargo on steel and oil, raw materials that were vital to Japan's war effort.[12] Without steel and oil imports, Japan's military could not fight for long.[12] As a result of the embargo, Japan decided to attack the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia in 7-19 December 1941, seizing the raw materials needed for the war effort.[12] These efforts were successful, with Japanese politician Nobusuke Kishi announcing via radio broadcast that vast resources were available for Japanese use in the newly conquered territories.[13] As part of its war drive in the Pacific, Japanese propaganda included phrases like "Asia for the Asiatics!" and talked about the need to "liberate" Asian colonies from the control of Western powers.[14] They also planned to change the Chinese hegemony in the agricultural market in Southeast Asia with Japanese immigrants to boost its economic value, with the former being despised by Southeast Asian natives.[4] The Japanese failure to bring the ongoing Second Sino-Japanese War to a swift conclusion was blamed in part on the lack of resources; Japanese propaganda claimed this was due to the refusal by Western powers to supply Japan's military.[15] Although invading Japanese forces sometimes received rapturous welcomes throughout recently captured Asian territories due to anti-Western and occasionally, anti-Chinese sentiment,[4] the subsequent brutality of the Japanese military led many of the inhabitants of those regions to regard Japan as being worse than their former colonial rulers.[14] The Japanese government directed that economies of occupied territories be managed strictly for the production of raw materials for the Japanese war effort; a cabinet member declared, "There are no restrictions. They are enemy possessions. We can take them, do anything we want".[16] For example, according to estimates, under Japanese occupation, about 100,000 Burmese and Malay Indian labourers died while constructing the Burma-Siam Railway.[17] Despite this, the Japanese would sometimes refrain from repressing certain ethnic groups, such as Chinese immigrants, as long as they supported the war effort, whether genuinely or as part of lip service.[4] An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus – a secret document completed in 1943 for high-ranking government use – laid out that Japan, as the originator and strongest military power within the region, would naturally take the superior position within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with the other nations under Japan's umbrella of protection.[18][5] The booklet Read This and the War is Won—for the Japanese Army—presented colonialism as an oppressive group of colonists living in luxury by burdening Asians. According to Japan, since racial ties of blood connected other Asians to the Japanese, and Asians had been weakened by colonialism, it was Japan's self-appointed role to "make men of them again" and liberate them from their Western oppressors.[19] According to Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō (in office 1941–1942 and 1945), should Japan be successful in creating this sphere, it would emerge as the leader of Eastern Asia, and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere would be synonymous with the Japanese Empire.[20] |

沿革 主な記事 日本の植民地帝国、日本の軍事史 § 正和年間と第二次世界大戦(1926年-1945年) ヨーロッパで第二次世界大戦が勃発したことで、日本は欧米列強や中国からの大きな反発を受けることなく、大東亜共栄圏の目標を達成する機会を得た [11]。ある領土が採算に合わないとわかったとき、日本は日本本土を含む臣民に「経済的苦難」を耐え忍ぶことを奨励し、敵国への物資流出を防ぐ努力をし た。それでも彼らは、欧米列強のように物質的利益を優先するのではなく、アジア諸国に「精神的本質」を創造することの道徳的優位性を説いた[4]。 1940年に日本がフランス領インドシナに進出した後、日本が天然資源を他国に完全に依存していることを知っていたアメリカ大統領フランクリン・D・ルー ズベルトは、日本の戦争努力に不可欠な原材料である鉄鋼と石油の貿易禁輸を命じた[12]。 [12]禁輸措置の結果、日本は1941年12月7日から19日にかけて東南アジアのイギリスとオランダの植民地を攻撃することを決定し、戦争努力に必要 な原材料を押収した[12]。これらの努力は成功し、日本の政治家岸信介はラジオ放送を通じて、新たに征服された領土で日本が使用するために膨大な資源が 利用可能であると発表した[13]。 太平洋における戦争推進の一環として、日本のプロパガンダには「アジアをアジア人のために!」といったフレーズが含まれ、アジアの植民地を欧米列強の支配 から「解放」する必要性が語られていた[14]。また、東南アジアの農業市場における中国人の覇権を、東南アジアの原住民から軽蔑されていた日本人移民に よって変えることで、その経済的価値を高めることも計画されていた。 日本のプロパガンダは、これは欧米列強が日本軍への補給を拒否したためだと主張した[15]。 [15]侵略してきた日本軍は、反欧米感情や時には反中国感情から、最近占領したアジア全域で歓呼の歓迎を受けることもあったが[4]、その後の日本軍の 残虐性によって、それらの地域の住民の多くは、日本をかつての植民地支配者よりも悪い存在とみなすようになった[14]。 日本政府は、占領地の経済を日本の戦争努力のための原材料生産のために厳密に管理するよう指示した。ある閣僚は、「何の制限もない。占領地は敵の領土だ。 例えば、日本の占領下では、ビルマ・シャム鉄道の建設中に約10万人のビルマ人とマレー系インド人の労働者が死亡したと推定されている[17]。にもかか わらず、日本人は、中国系移民など特定の民族集団が、純粋にであれリップサービスの一環であれ、戦争努力を支援する限り、弾圧を控えることもあった [4]。 1943年に完成した政府高官用の極秘文書である『大和民族を核とする世界政策の検討』は、日本がこの地域の創始者であり最強の軍事大国であるため、大東 亜共栄圏の中で当然優位な立場に立ち、他の国々は日本の傘の下で保護されるだろうと述べている[18][5]。 日本陸軍のための小冊子『これを読めば戦争は勝てる』は、植民地主義を、アジア人に負担をかけることによって贅沢な生活を送る植民地主義者の抑圧的な集団 として提示した。日本によれば、人種的な血のつながりが他のアジア人と日本人を結びつけており、アジア人は植民地主義によって弱体化していたため、「彼ら を再び男にする」ことが日本の自任する役割であり、彼らを西洋の抑圧者から解放することであった[19]。 外務大臣であった東郷茂徳(在任1941年~1942年、1945年)によれば、日本がこの圏域の創設に成功すれば、日本は東アジアのリーダーとして台頭 し、大東亜共栄圏は大日本帝国の代名詞となるであろう[20]。 |

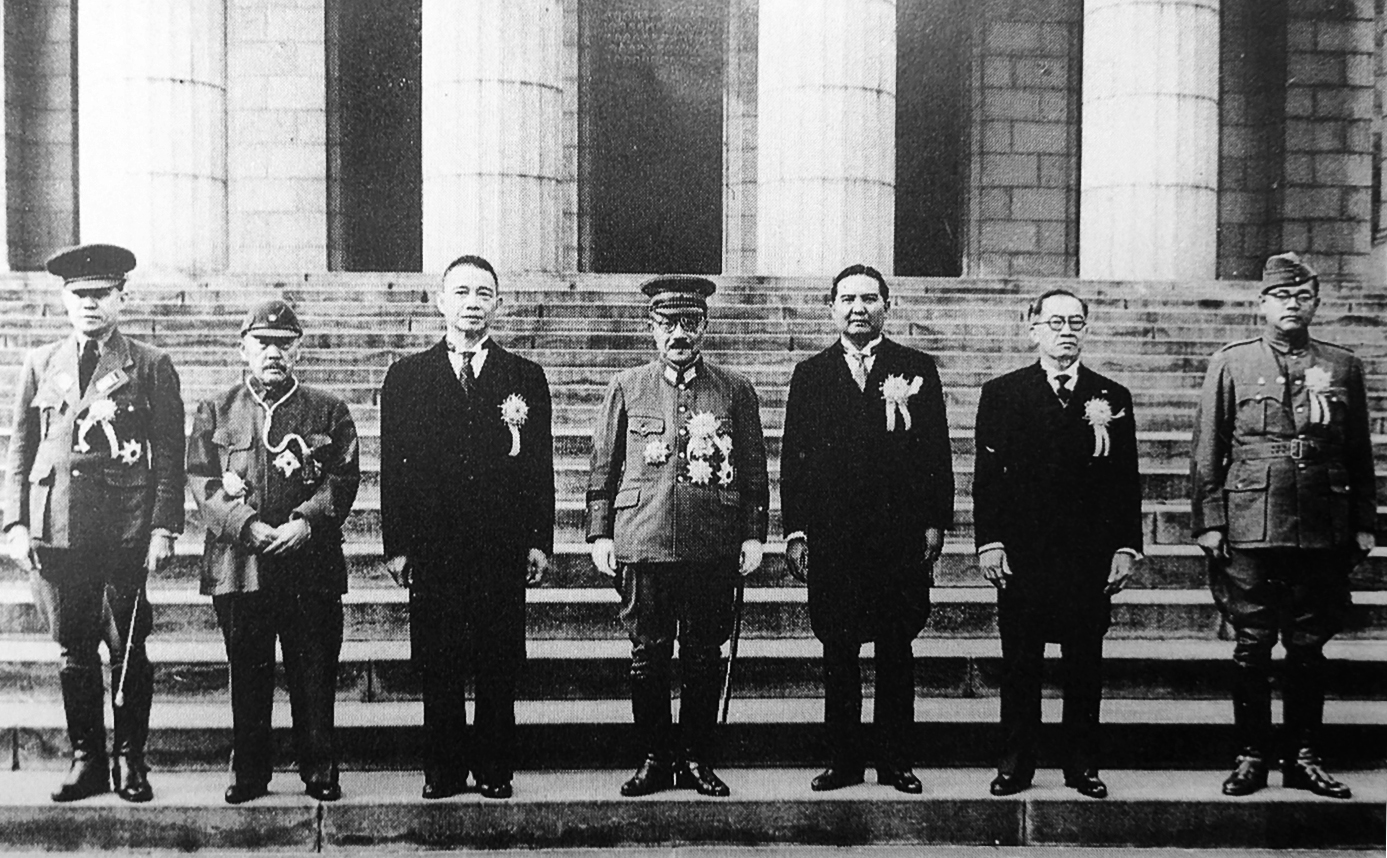

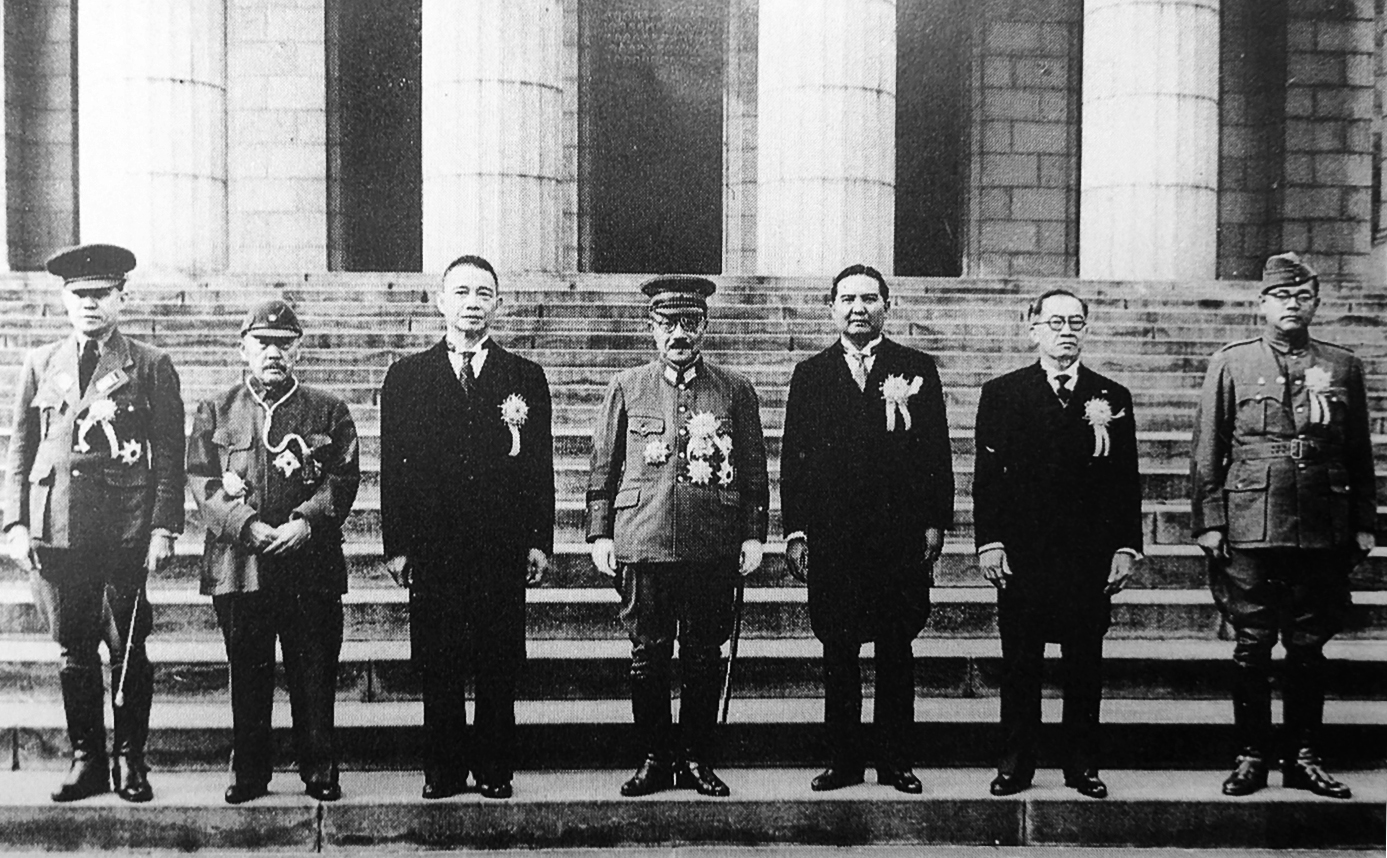

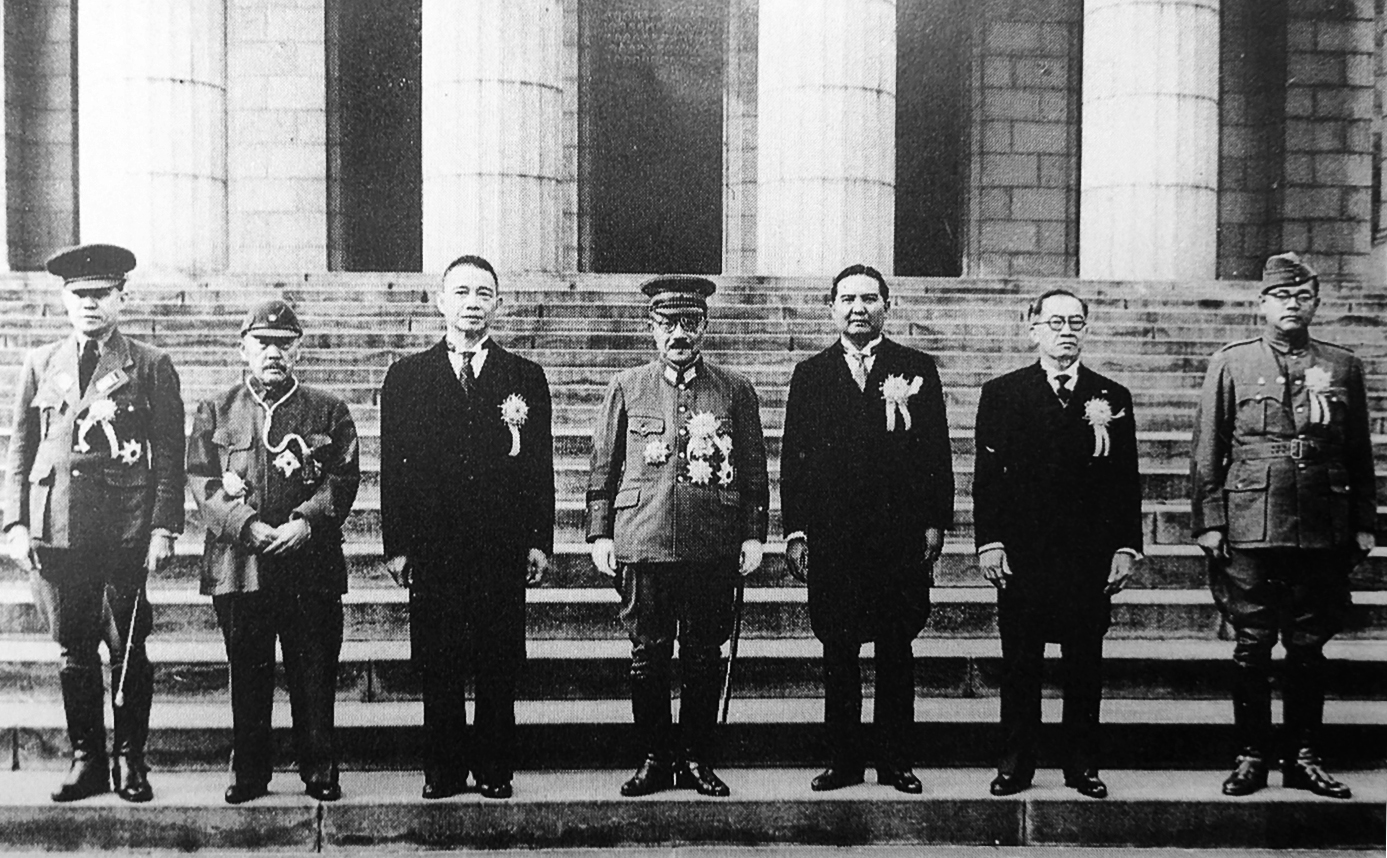

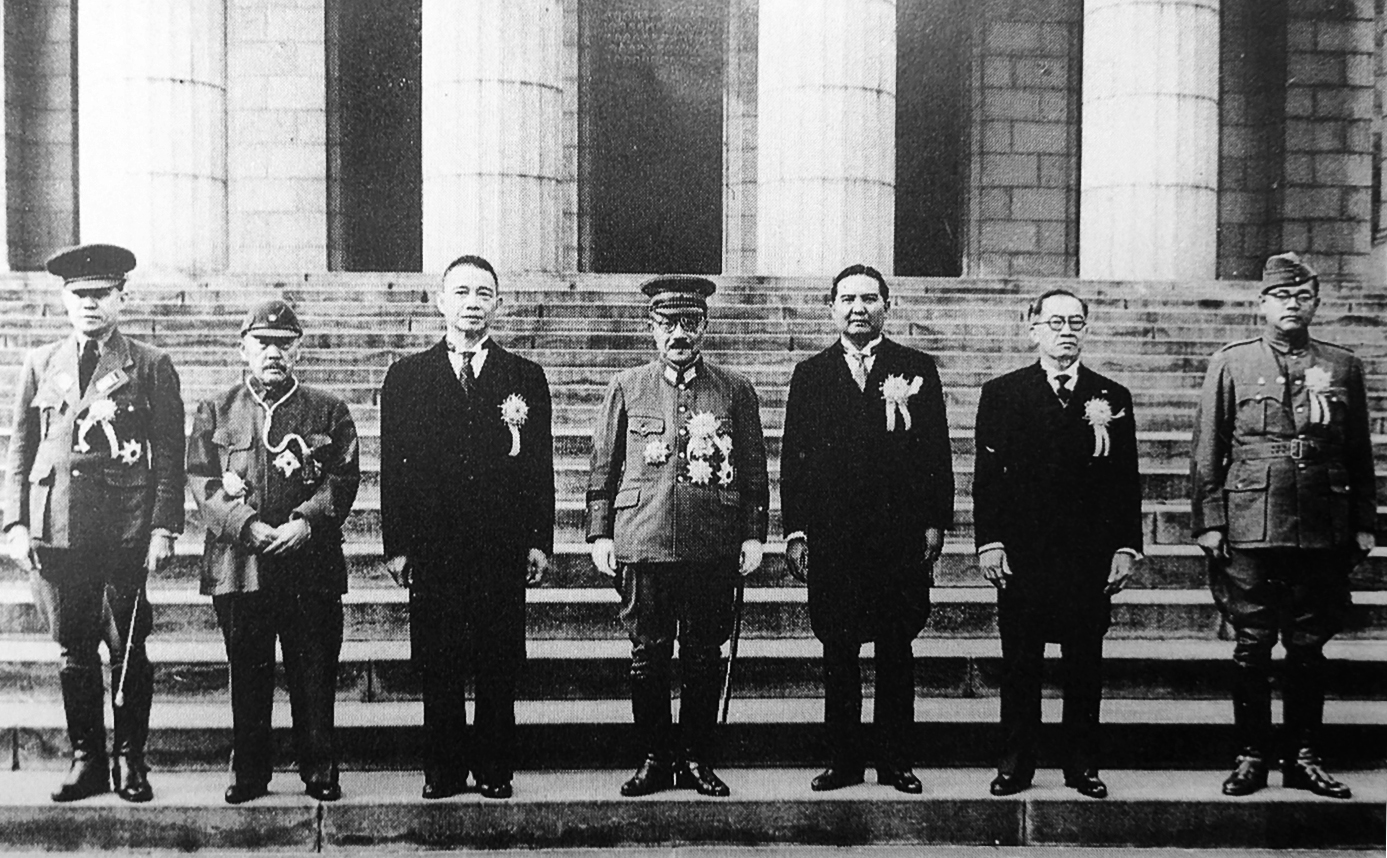

| Greater East Asia Conference Main article: Greater East Asia Conference Attendees of the Greater East Asia Conference : Japan and colonies : Thailand and other territories occupied by Japan : Territories disputed and claimed by Japan  The Greater East Asia Conference in November 1943. Participants left to right: Ba Maw, Zhang Jinghui, Wang Jingwei, Hideki Tojo, Wan Waithayakon, José P. Laurel, and Subhas Chandra Bose   大東亜会議の会場だった帝国議会議事堂(現在の国会議事堂) Fragment of a Japanese propaganda booklet published by the Tokyo Conference (1943), depicting scenes of situations in Greater East Asia, from the top, left to right: the Japanese occupation of Malaya, Thailand under Plaek Phibunsongkram gaining the territories of Saharat Thai Doem, the Republic of China under Wang Jingwei allied with Japan, Subhas Chandra Bose forming the Provisional Government of Free India, the State of Burma gaining independence under Ba Maw, the Declaration of the Second Philippine Republic, and people of Manchukuo. The Greater East Asia Conference (大東亞會議, Dai Tōa Kaigi) took place in Tokyo on 5–6 November 1943: Japan hosted the heads of state of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The conference was also referred to as the Tokyo Conference. The common language used by the delegates during the conference was English.[21] The conference was mainly used as propaganda.[22] At the conference, Tojo greeted them with a speech praising the "spiritual essence" of Asia instead of the "materialistic civilisation" of the West.[23] Their meeting was characterised by the praise of solidarity and condemnation of Western colonialism but without practical plans for either economic development or integration.[24] Because of a lack of military representatives at the conference, the conference served little military value.[22] With the simultaneous use of Wilsonian and Pan-Asian rhetoric, the goals of the conference were to solidify the commitment of certain Asian countries to Japan's war effort and to improve Japan's world image; however, the representatives of the other attending countries were in practice neither independent nor treated as equals by Japan.[25] The following dignitaries attended: Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan Zhang Jinghui, Prime Minister of the Empire of Manchuria Wang Jingwei, President of the Republic of China Ba Maw, Head of State of the State of Burma Subhas Chandra Bose, Head of State of the Provisional Government of Free India José P. Laurel, President of the Republic of the Philippines Prince Wan Waithayakon, envoy from the Kingdom of Thailand Imperial rule The ideology of the Japanese colonial empire, as it expanded dramatically during the war, contained two contradictory impulses. On the one hand, it preached the unity of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a coalition of Asian races directed by Japan against Western imperialism in Asia. This approach celebrated the spiritual values of the East in opposition to the "crass materialism" of the West.[26] In practice, however, the Japanese installed organisationally-minded bureaucrats and engineers to run their new empire, and they believed in ideals of efficiency, modernisation, and engineering solutions to social problems.[27] Japanese was the official language of the bureaucracy in all of the areas and was taught at schools as a national language.[28] Japan set up puppet regimes in Manchuria and China; they vanished at the war's end. The Imperial Army operated ruthless administrations in most conquered areas but paid more favourable attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to obtain oil but the Dutch colonial government destroyed the oil wells. However, the Japanese could repair and reopen them within a few months of their conquest. However, most tankers transporting oil to Japan were sunk by US Navy submarines, so Japan's oil shortage became increasingly acute. Japan also sponsored an Indonesian nationalist movement under Sukarno.[29] Sukarno finally came to power in the late 1940s after several years of fighting the Dutch.[30] Philippines To build up the economic base of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese Army envisioned using the Philippine islands as a source of agricultural products needed by its industry. For example, Japan had a surplus of sugar from Taiwan, and a severe shortage of cotton, so they tried to grow cotton on sugar lands with disastrous results; they lacked the seeds, pesticides, and technical skills to grow cotton. Jobless farm workers flocked to the cities, where there was minimal relief and few jobs. The Japanese Army also tried using cane sugar for fuel, castor beans and copra for oil, Derris for quinine, cotton for uniforms, and abacá for rope. The plans were difficult to implement due to limited skills, collapsed international markets, bad weather, and transportation shortages. The program failed, giving very little help to Japanese industry and diverting resources needed for food production.[31] As Karnow reports, Filipinos "rapidly learned as well that 'co-prosperity' meant servitude to Japan's economic requirements".[32] Living conditions were poor throughout the Philippines during the war. Transportation between the islands was difficult because of a lack of fuel. Food was in short supply, with sporadic famines and epidemic diseases that killed hundreds of thousands of people.[33][34] In October 1943, Japan declared the Philippines an independent republic. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic headed by President José P. Laurel proved to be ineffective and unpopular as Japan maintained very tight controls.[35] Failure The Co-Prosperity Sphere collapsed with Japan's surrender to the Allies in September 1945. Dr. Ba Maw, wartime President of Burma under the Japanese, blamed the Japanese military: The militarists saw everything only from a Japanese perspective and, even worse, they insisted that all others dealing with them should do the same. For them, there was only one way to do a thing, the Japanese way; only one goal and interest, the Japanese interest; only one destiny for the East Asian countries, to become so many Manchukuos or Koreas tied forever to Japan. This racial impositions ... made any real understanding between the Japanese militarists and the people of our region virtually impossible.[36] In other words, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere operated not for the betterment of all the Asian countries but for Japan's interests, and thus the Japanese failed to gather support in other Asian countries. Nationalist movements did appear in these Asian countries during this period, and these nationalists cooperated with the Japanese to some extent. However, Willard Elsbree, professor emeritus of political science at Ohio University, claims that the Japanese government and these nationalist leaders never developed "a real unity of interests between the two parties, [and] there was no overwhelming despair on the part of the Asians at Japan's defeat".[37]   The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere at its greatest extent  The failure of Japan to understand the goals and interests of the other countries involved in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere led to a weak association of countries bound to Japan only in theory and not in spirit. Dr. Ba Maw argues that Japan could have engineered a very different outcome if the Japanese had only managed to act according to the declared aims of "Asia for the Asiatics". He argues that if Japan had proclaimed this maxim at the beginning of the war and if the Japanese had acted on that idea, No military defeat could then have robbed her of the trust and gratitude of half of Asia or even more, and that would have mattered a great deal in finding for her a new, great, and abiding place in a postwar world in which Asia was coming into her own.[38] |

大東亜会議 主な記事 大東亜会議 大東亜会議出席者 : 日本と植民地 : タイと日本の占領地 : 日本が領有権を主張する紛争地域  1943年11月の大東亜会議。参加者左から右へ: バ・モウ、張景輝、王景偉、東条英機、ワン・ワイタヤコン、ホセ・P・ローレル、スバス・チャンドラ・ボース。   大東亜会議の会場だった帝国議会議事堂(現在の国会議事堂) 東京会議が発行した日本の宣伝用小冊子の断片(1943年)。大東亜の情勢を描いたもので、上段左から順に、日本のマレー占領、プラック・ピブンソンク ラーム率いるタイのサハラット・タイ・ドーム領獲得、日本と同盟を結んだ王景偉率いる中華民国、スバス・チャンドラ・ボースが自由インド臨時政府を樹立、 バ・マウ率いるビルマ国の独立、フィリピン第二共和国宣言、満州国の人々。 1943年11月5~6日、東京で大東亜会議が開催された: 日本は、大東亜共栄圏の各構成国の首脳を主催した。この会議は東京会議とも呼ばれた。会議中、代表団によって使用された共通語は英語であった[21]。 会議では、東條は西洋の「物質主義的文明」の代わりにアジアの「精神的本質」を賞賛する演説で彼らを迎えた[23]。 彼らの会議は、連帯の賞賛と西洋の植民地主義の非難によって特徴づけられたが、経済発展や統合のための実践的な計画はなかった[24]。 ウィルソン的なレトリックと汎アジア的なレトリックを同時に用いることで、会議の目的は、日本の戦争努力に対する特定のアジア諸国のコミットメントを強固 なものにし、日本の世界的イメージを向上させることであった。しかし、他の出席国の代表は、実際には、日本から独立していたわけでも、対等に扱われていた わけでもなかった[25]。 以下の要人が出席した: 東条英機、大日本帝国首相 張景輝、満州帝国首相 王景偉、中華民国国家主席 バ・モウ、ビルマ国家元首 スバス・チャンドラ・ボース、自由インド臨時政府元首 ホセ・P・ローレル、フィリピン共和国大統領 ワン・ワイタヤコン王子、タイ王国特使 帝国支配 戦時中に飛躍的に拡大した日本の植民地帝国のイデオロギーは、2つの矛盾した衝動を含んでいた。一方では、大東亜共栄圏の統一を説き、アジアにおける西洋 の帝国主義に対抗するため、日本がアジア諸民族の連合を指揮した。このアプローチは、西洋の「粗野な物質主義」に対抗して、東洋の精神的価値を称賛するも のであった[26]。しかし実際には、日本は新帝国を運営するために組織志向の官僚や技術者を任命し、効率性、近代化、社会問題に対する工学的解決策の理 想を信じた[27]。 日本は満州と中国に傀儡政権を樹立したが、終戦とともに消滅した。帝国陸軍はほとんどの征服地域で冷酷な統治を行ったが、オランダ領東インドに対してはよ り好意的な注意を払った。主な目的は石油を得ることだったが、オランダ植民地政府は油田を破壊した。しかし、日本軍は征服後数カ月で修復して再開すること ができた。しかし、日本に石油を運ぶタンカーのほとんどがアメリカ海軍の潜水艦に撃沈されたため、日本の石油不足はますます深刻になった。日本はまた、ス カルノの下でインドネシアの民族主義運動を後援した[29]。スカルノは数年にわたるオランダとの戦いの後、1940年代後半にようやく政権を握った [30]。 フィリピン 共栄圏の経済基盤を構築するために、日本陸軍はフィリピン諸島を自国の産業が必要とする農産物の供給源として利用することを構想していた。例えば、日本に は台湾産の砂糖が余っていたが、綿花が極端に不足していたため、砂糖の土地で綿花を栽培しようとしたが、綿花を栽培するための種子、農薬、技術的スキルが 不足していたため、悲惨な結果となった。種も農薬も綿花栽培の技術も不足していたのだ。職を失った農民は、救済措置も仕事もほとんどない都市に押し寄せ た。日本軍はまた、サトウキビ糖を燃料に、ヒマシ豆とコプラを油に、デリスをキニーネに、綿を軍服に、アバカをロープに使おうとした。この計画は、限られ た技術、国際市場の崩壊、悪天候、輸送手段の不足のために実行が困難だった。この計画は失敗に終わり、日本の産業にはほとんど役に立たず、食糧生産に必要 な資源は流用された[31]。 カーノーが報告しているように、フィリピン人は「『共栄』が日本の経済的要求に隷属することを意味することも、急速に学んだ」[32]。 戦争中、フィリピン全土の生活環境は劣悪だった。燃料が不足していたため、島々の間の輸送は困難だった。1943年10月、日本はフィリピンの独立を宣 言。日本が支援したホセ・P・ラウレル大統領率いるフィリピン第二共和国は、日本が非常に厳しい統制を維持したため、効果がなく不人気であることが判明し た[35]。 失敗 共栄圏は、1945年9月の日本の連合国への降伏とともに崩壊した。戦時中、日本統治下のビルマ大統領だったバ・モウ博士は、日本軍を非難した: 軍国主義者たちは、すべてを日本人の視点からしか見ておらず、さらに悪いことに、自分たちに関わるすべての相手も同じであるべきだと主張していた。彼らに とって、物事を行う方法はただ一つ、日本のやり方だけであり、目標と利益はただ一つ、日本の利益だけであり、東アジア諸国の運命はただ一つ、永遠に日本に 縛られた多くの満州国や朝鮮半島になることだった。この人種的な押しつけは、日本の軍国主義者とこの地域の人々との間の真の理解を事実上不可能にした [36]。 言い換えれば、大東亜共栄圏はアジア諸国を良くするためではなく、日本の利益のために運営されたのであり、そのため日本は他のアジア諸国の支持を集めるこ とができなかったのである。この時期、アジア諸国では民族主義運動が起こり、これらの民族主義者はある程度日本に協力した。しかし、オハイオ大学のウィ ラード・エルスブリー名誉教授(政治学)は、日本政府とこれらのナショナリストの指導者が「両者の間に真の利害の一致が生まれることはなく、日本の敗北に 対するアジア人の圧倒的な絶望はなかった」と主張している[37]。   最大領域の時代の大東亜共栄圏  日本が大東亜共栄圏に参加する他の国々の目標や利益を理解できなかったために、日本とは理論上だけで、精神的には結びつかない弱い国同士の連合になってし まった。バ・モウ博士は、もし日本が「アジア人のためのアジア」という宣言された目的に従って行動していれば、もっと違った結果をもたらすことができたは ずだと主張する。もし日本が開戦時にこの理念を宣言し、その理念に基づいて行動していれば、軍事的敗北はなかったはずだと、 そしてそれは、アジアが本領を発揮しつつある戦後世界において、日本が新たな、偉大な、そして変わらぬ居場所を見出す上で、非常に重要なことであっただろ う[38]。 |

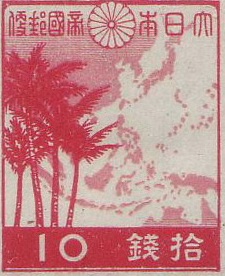

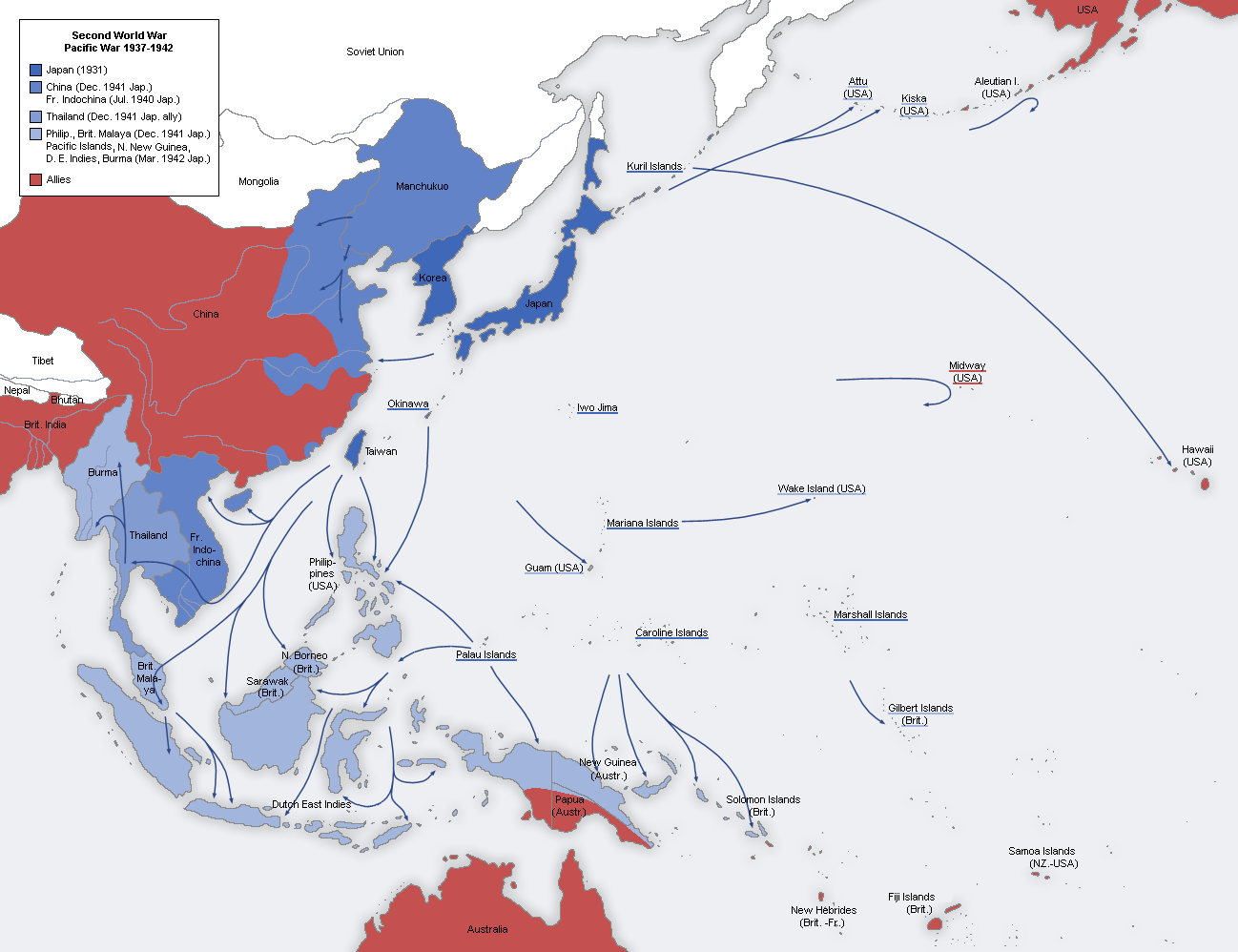

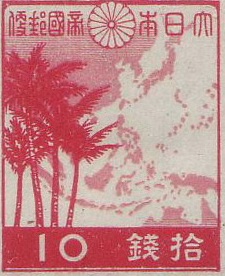

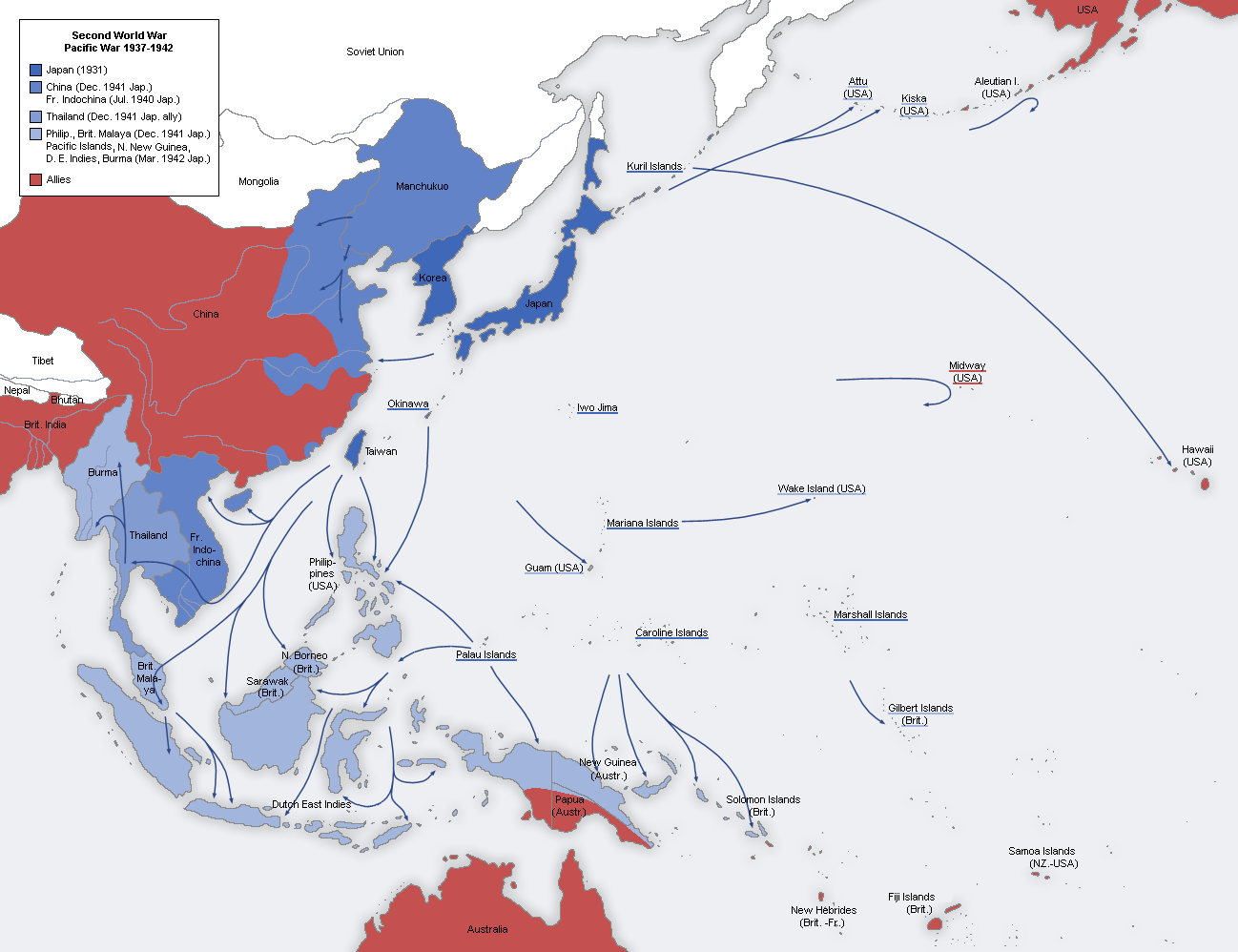

| Propaganda efforts Pamphlets were dropped by airplane on the Philippines, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore, and Indonesia, urging them to join the movement.[39] Mutual cultural societies were founded in all conquered lands to ingratiate with the natives and try to supplant English with Japanese as the commonly used language.[40] Multi-lingual pamphlets depicted many Asians marching or working together in happy unity, with the flags of all the states and a map depicting the intended sphere.[41] Others proclaimed that they had given independent governments to the countries they occupied, a claim undermined by the lack of power given to these puppet governments.[42] In Thailand, a street was built to demonstrate it, to be filled with modern buildings and shops, but 9⁄10 of it consisted of false fronts.[43] A network of Japanese-sponsored film production, distribution, and exhibition companies extended across the Japanese Empire and was collectively referred to as the Greater East Asian Film Sphere. These film centers mass-produced shorts, newsreels, and feature films to encourage Japanese language acquisition as well as cooperation with Japanese colonial authorities.[44] Projected territorial extent  A Japanese 10 sen stamp from 1942 depicting the approximate extension of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere  Japanese expansion in Asia and the Pacific, 1937–1942 Prior to the escalation of World War II to the Pacific and East Asia, Japanese planners regarded it as self-evident that the conquests secured in Japan's earlier wars with Russia (South Sakhalin and Kwantung), Germany (South Seas Mandate), and China (Manchuria) would be retained, as well as Korea (Chōsen), Taiwan (Formosa), the recently seized additional portions of China, and occupied French Indochina.[45] The Land Disposal Plan A reasonably accurate indication as to the geographic dimensions of the Co-Prosperity Sphere are elaborated on in a Japanese wartime document prepared in December 1941 by the Research Department of the Imperial Ministry of War.[45] Known as the "Land Disposal Plan in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" (大東亜共栄圏における土地処分案)[46] it was put together with the consent of and according to the directions of the Minister of War (later Prime Minister) Hideki Tōjō. It assumed that the already established puppet governments of Manchukuo, Mengjiang, and the Wang Jingwei regime in Japanese-occupied China would continue to function in these areas.[45] Beyond these contemporary parts of Japan's sphere of influence it also envisaged the conquest of a vast range of territories covering virtually all of East Asia, the Pacific Ocean, and even sizable portions of the Western Hemisphere, including in locations as far removed from Japan as South America and the eastern Caribbean.[45] Although the projected extension of the Co-Prosperity Sphere was extremely ambitious, the Japanese goal during the "Greater East Asia War" was not to acquire all the territory designated in the plan at once, but to prepare for a future decisive war some 20 years later by conquering the Asian colonies of the defeated European powers, as well as the Philippines from the United States.[47] When Tōjō spoke on the plan to the House of Peers he was vague about the long-term prospects, but insinuated that the Philippines and Burma might be allowed independence, although vital territories such as Hong Kong would remain under Japanese rule.[23] The Micronesian islands that had been seized from Germany in World War I and which were assigned to Japan as C-Class Mandates, namely the Marianas, Carolines, Marshall Islands, and several others do not figure in this project.[45] They were the subject of earlier negotiations with the Germans and were expected to be officially ceded to Japan in return for economic and monetary compensations.[45] The plan divided Japan's future empire into two different groups.[45] The first group of territories were expected to become either part of Japan or otherwise be under its direct administration. Second were those territories that would fall under the control of a number of tightly controlled pro-Japanese vassal states based on the model of Manchukuo, as nominally "independent" members of the Greater East Asian alliance.  German and Japanese direct spheres of influence at their greatest extents in fall 1942. Arrows show planned movements to the proposed demarcation line at 70° E, which was, however, never even approximated. Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the 70th meridian east longitude. This line, running southwards through the Ob River's Arctic estuary, southwards to just east of Khost in Afghanistan and heading into the Indian Ocean just west of Rajkot in India, would have split Germany's Lebensraum and Italy's spazio vitale territories to the west of it, and Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and its other areas to the east of it.[48] The plan of the Third Reich for fortifying its own Lebensraum territory's eastern limits, beyond which the Co-Prosperity Sphere's northwestern frontier areas would exist in East Asia, involved the creation of a "living wall" of Wehrbauer "soldier-peasant" communities defending it. However, it is unknown if the Axis powers ever formally negotiated a possible, complementary second demarcation line that would have divided the Western Hemisphere. Japanese-governed Government-General of Formosa Hong Kong, the Philippines, Portuguese Macau (to be purchased from Portugal), the Paracel Islands, and Hainan Island (to be purchased from the Chinese puppet regime). Contrary to its name it was not intended to include the island of Formosa (Taiwan)[45] South Seas Government Office Guam, Nauru, Ocean Island, the Gilbert Islands, and Wake Island[45] Melanesian Region Government-General or South Pacific Government-General British New Guinea, Australian New Guinea, the Admiralties, New Britain, New Ireland, the Solomon Islands, the Santa Cruz Archipelago, the Ellice Islands, the Fiji Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, the Loyalty Islands, and the Chesterfield Islands[45] Eastern Pacific Government-General Hawaii Territory, Howland Island, Baker Island, the Phoenix Islands, the Rain Islands, the Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands, the Society Islands, the Cook and Austral Islands, all of the Samoan Islands and Tonga.[45] The possibility of re-establishing the defunct Kingdom of Hawaii was also considered, based on the model of Manchukuo.[49] Those favoring annexation of Hawaii (on the model of Karafuto) intended to use the local Japanese community, which had constituted 43% (c. 160,000) of Hawaii's population in the 1920s, as a leverage.[49] Hawaii was to become self-sufficient in food production, while the Big Five corporations of sugar and pineapple processing were to be broken up.[50] No decision was ever reached regarding whether Hawaii would be annexed to Japan, become a puppet kingdom, or be used as a bargaining chip for leverage against the US.[49] Australian Government-General All of Australia including Tasmania.[45] Australia and New Zealand were to accommodate up to two million Japanese settlers.[49] However, there are indications that the Japanese were also looking for a separate peace with Australia, and a satellite state rather than colony status similar to that of Burma and the Philippines.[49] New Zealand Government-General The New Zealand North and South Islands, Macquarie Island, as well as the rest of the Southwest Pacific[45] Ceylon Government-General All of India below a line running approximately from Portuguese Goa to the coastline of the Bay of Bengal[45] Alaska Government-General The Alaska Territory, the Yukon Territory, the western portion of the Northwest Territories, Alberta, British Columbia, and Washington.[45] There were also plans to make the American West Coast (comprising California and Oregon) a semi-autonomous satellite state. This latter plan was not seriously considered as it depended upon a global victory of Axis forces.[49] Government-General of Central America Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, British Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, the Maracaibo (western) portion of Venezuela, Ecuador, Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and the Bahamas. In addition, if either Mexico, Peru or Chile were to enter the war against Japan, substantial parts of these states would also be ceded to Japan.[45] Events that transpired between May 22, 1942, when Mexico declared war on the Axis, through Peru's declaration of war on February 12, 1944, and concluding with Chile only declaring war on Japan by April 11, 1945 (as Nazi Germany was nearly defeated at that time), brought all three of these southeast Pacific Rim nations of the Western Hemisphere's Pacific coast into conflict with Japan by the war's end. The future of Trinidad, British and Dutch Guiana, and the British and French possessions in the Leeward Islands at the hands of Imperial Japan were meant to be left open for negotiations with Nazi Germany had the Axis forces been victorious.[45] Asian puppet states East Indies Kingdom Dutch East Indies, British Borneo, Christmas Islands, Cocos Islands, Andaman, Nicobar Islands, and Portuguese Timor (to be purchased from Portugal)[45] Kingdom of Burma Burma proper, Assam (a province of the British Raj), and a large part of Bengal.[45] Kingdom of Malaya Remainder of the Malay states[45] Kingdom of Annam Annam, Laos, and Tonkin[45] Kingdom of Cambodia Cambodia and French Cochinchina[45] Puppet states which already existed at the time, the Land Disposal Plan has been drafted, were: Empire of Manchuria Chinese Manchuria RNG Republic of China Other parts of China occupied by Japan Mengjiang Inner Mongolia territories west of Manchuria, since 1940 officially a part of the Republic of China. It was meant as a starting point for a regime which would cover all of Mongolia. Contrary to the plan Japan installed a puppet state on the Philippines instead of exerting direct control. In the former French Indochina, the Empire of Vietnam, Kingdom of Kampuchea, and Kingdom of Luang Phrabang were founded. The Empire of Vietnam, despite being pro-Japan, attempted to work for independence and made some progressive reforms.[51] The State of Burma did not become a kingdom. Political parties and movements with Japanese support Azad Hind (Indian nationalist movement) Indian Independence League (Indian nationalist movement) Indonesian National Party (Indonesian nationalist movement) Kapisanan ng Paglilingkod sa Bagong Pilipinas (Philippine nationalist ruling party of the Second Philippine Republic) Kesatuan Melayu Muda (Malayan nationalist movement) Khmer Issarak (Cambodian-Khmer nationalist group) Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association) (Burmese nationalist association) Đại Việt National Socialist Party (Vietnamese nationalist movement) |

宣伝活動 フィリピン、マラヤ、北ボルネオ、サラワク、シンガポール、インドネシアに飛行機でパンフレットが投下され、運動への参加を促した[39]。征服されたす べての土地で相互文化協会が設立され、原住民と友好を結び、英語を日本語に置き換えて一般的に使用される言語にしようとした[40]。 [40]多言語のパンフレットは、すべての国家の旗と意図された領域を描いた地図とともに、多くのアジア人が幸せな団結のうちに行進したり、一緒に働いた りする様子を描いていた[41]。他の人々は、占領した国々に独立政府を与えたと宣言したが、これらの傀儡政府に与えられた権力の欠如によって、その主張 は損なわれた[42]。 タイでは、それを実証するために、近代的なビルや商店で埋め尽くされた通りが建設されたが、そのうちの9/10は偽の前面で構成されていた[43]。日本 が後援した映画製作、配給、上映会社のネットワークは日本帝国全体に広がり、大東亜映画圏と総称された。これらの映画センターは、日本語の習得や日本の植 民地当局との協力を奨励するために、短編映画、ニュース映画、長編映画を大量生産した[44]。 予想された領土の範囲  大東亜共栄圏のおおよその範囲を描いた1942年の日本の10銭切手。  Japanese expansion in Asia and the Pacific, 1937–1942 第二次世界大戦が太平洋と東アジアに拡大する前に、日本の計画者たちは、ロシア(南樺太と関東軍)、ドイツ(南洋委任統治領)、中国(満州)との先の戦争 で確保した征服、朝鮮(長旋)、台湾(フォルモサ)、最近占領した中国の追加部分、占領したフランス領インドシナを保持することは自明であると考えていた [45]。 土地処分計画 共栄圏の地理的寸法に関する合理的に正確な示唆は、1941年12月に陸軍省調査局によって作成された日本の戦時文書に詳述されている[45]。 [大東亜共栄圏における土地処分案」(大東亜共栄圏における土地処分案)[46]として知られるこの文書は、陸軍大臣(後の内閣総理大臣)である東条英機 の同意を得て、その指示に従って作成された。それは、日本が占領した中国において、すでに確立されていた満州国、蒙江、および王敬威政権の傀儡政権がこれ らの地域で機能し続けることを前提としていた[45]。また、日本の勢力圏のこれらの現代的な部分を超えて、事実上すべての東アジア、太平洋、さらには南 米やカリブ海東部のように日本から遠く離れた場所を含む西半球のかなりの部分をカバーする広大な領土の征服を想定していた[45]。 共栄圏の拡大計画は極めて野心的なものであったが、「大東亜戦争」における日本の目標は、計画で指定されたすべての領土を一度に獲得することではなく、敗 戦したヨーロッパ列強のアジア植民地とアメリカからフィリピンを征服することによって、約20年後の将来の決戦に備えることであった[47]。 [47] 東条は貴族院でこの計画について語ったとき、長期的な見通しについては曖昧であったが、香港のような重要な領土は日本の統治下に置かれたままであるが、 フィリピンとビルマは独立を許されるかもしれないとほのめかしていた[23]。 第一次世界大戦でドイツから接収され、丙種委任統治領として日本に割り当てられたミクロネシアの島々、すなわちマリアナ諸島、カロリン諸島、マーシャル諸 島、その他いくつかの島々は、この計画には含まれていない[45]。これらの島々はドイツとの以前の交渉の対象であり、経済的・金銭的補償と引き換えに日 本に正式に割譲されることが期待されていた[45]。 この計画では、日本の将来の帝国を2つの異なるグループに分けていた[45]。第一のグループは、日本の一部となるか、さもなければ日本の直接統治下に置 かれることが期待されていた領土であった。第二は、大東亜同盟の名目上の「独立」加盟国として、満州国をモデルとしたいくつかの緊密な親日属国の支配下に 置かれる領土であった。  1942年秋、ドイツと日本の直接勢力圏が最も拡大した状態。矢印は、東経 70 度の分界線への移動計画を示すが、この分界線は概算すらされなかった。 この計画の一部は、ナチス・ドイツとの交渉が成功し、枢軸国が世界的な勝利を収めるかどうかにかかっていた。1941年12月11日にドイツとイタリアが 米国に宣戦布告した後、日本はドイツ側に、東経70度子午線に沿った分割線によってアジア大陸を具体的に画定する軍事条約案を提示した。この線は、オブ川 の北極圏河口を南下し、アフガニスタンのコーストのすぐ東まで南下し、インドのラジコットのすぐ西でインド洋に向かうもので、その西側でドイツのレーベン スラウムとイタリアのスパツィオ・ヴィターレの領土を、その東側で日本の大東亜共栄圏とそのほかの地域を分割するものであった。 [共栄圏の北西辺境地域が存在する東アジアを越えて、第三帝国が自国のレーベンスラウ ム領土の東限を要塞化する計画には、レーベンスラウムを防衛するヴェールバウアー「兵士と農民」 の共同体の「生きた壁」を作ることが含まれていた。しかし、枢軸国が西半球を分割する補完的な第二分水嶺の可能性について正式に交渉したかどうかは不明で ある。 日本統治 フォルモサ総督府 香港、フィリピン、ポルトガル領マカオ(ポルトガルから購入)、パラセル諸島、海南島(中国の傀儡政権から購入)。その名前に反して、フォルモサ島(台 湾)を含むことは意図されていなかった[45]。 南洋庁 グアム、ナウル、オーシャン島、ギルバート諸島、ウェーク島[45]。 メラネシア地域総督府または南太平洋総督府 英領ニューギニア、オーストラリア領ニューギニア、アドミラルティー諸島、ニューブリテン島、ニューアイルランド島、ソロモン諸島、サンタクルス群島、エ リス諸島、フィジー諸島、ニューヘブリディーズ諸島、ニューカレドニア、ロイヤリティ諸島、チェスターフィールド諸島[45]。 東太平洋総督府 ハワイ準州、ハウランド島、ベーカー島、フェニックス諸島、レイン諸島、マルケサス諸島とツアモツ諸島、ソサエティ諸島、クック諸島とオーストラル諸島、 サモア諸島のすべて、トンガ[45]。消滅したハワイ王国を再興する可能性も、満州国をモデルとして検討された[49]。ハワイ併合(樺太モデル)に賛成 する人々は、ハワイの43%(約16万人)を占めていた地元の日本人コミュニティを利用するつもりであった。ハワイは食料生産で自給自足する一方、砂糖と パイナップル加工のビッグファイブ企業は解体されることになっていた[50]。 ハワイが日本に併合されるのか、傀儡王国になるのか、対米交渉の切り札として利用されるのかについては、決定が下されることはなかった[49]。 オーストラリア政府 タスマニアを含むオーストラリア全土[45] オーストラリアとニュージーランドは、最大200万人の日本人入植者を受け入れることになっていた[49]。 しかし、日本側はオーストラリアとの単独講和や、ビルマやフィリピンのような植民地ではなく衛星国としての地位も求めていたとの指摘もある[49]。 ニュージーランド総督府 ニュージーランド北島、南島、マッコーリー島、およびその他の南西太平洋地域[45]。 セイロン総督府 ポルトガルのゴアからベンガル湾の海岸線までを結ぶ線より下のインド全土[45]。 アラスカ州政府-一般 アラスカ準州、ユーコン準州、ノースウェスト準州の西部、アルバータ州、ブリティッシュコロンビア州、ワシントン州[45]。アメリカ西海岸(カリフォル ニア州とオレゴン州を含む)を半自治衛星国とする計画もあった。この後者の計画は、枢軸国の世界的な勝利に依存していたため、真剣に検討されることはな かった[49]。 中央アメリカ総督府 グアテマラ、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラス、イギリス領ホンジュラス、ニカラグア、コスタリカ、パナマ、コロンビア、ベネズエラのマラカイボ(西部)、エ クアドル、キューバ、ハイチ、ドミニカ共和国、ジャマイカ、バハマ。加えて、メキシコ、ペルー、チリのいずれかが日本との戦争に参戦した場合、これらの国 のかなりの部分も日本に割譲されることになる。 [メキシコが枢軸国に対して宣戦布告した1942年5月22日から、ペルーが1944年2月12日に宣戦布告し、チリが1945年4月11日までに日本に 対して宣戦布告するまでの間に起こった出来事(このときナチス・ドイツはほぼ敗北していた)により、西半球太平洋沿岸の環太平洋南東部に位置するこれら3 国すべてが、戦争終結までに日本と対立することになった。大日本帝国の手によるトリニダード、イギリス領とオランダ領のギアナ、およびリーワード諸島のイ ギリス領とフランス領の将来は、枢軸軍が勝利していれば、ナチス・ドイツとの交渉の余地が残されていたことになっていた[45]。 アジアの傀儡国家 東インド王国 オランダ領東インド、イギリス領ボルネオ、クリスマス諸島、ココス諸島、アンダマン、ニコバル諸島、ポルトガル領ティモール(ポルトガルから購入予定) [45]。 ビルマ王国 ビルマ固有領土、アッサム(イギリス領ラージの州)、ベンガルの大部分[45]。 マラヤ王国 マレー諸州の残り[45]。 アンナム王国 アンナム、ラオス、トンキン[45]。 カンボジア王国 カンボジア、フランス領コーチシナ[45]。 国土廃棄計画が立案された当時、すでに存在していた傀儡国家は以下の通り: 満州帝国 中国満州国 中華民国 日本が占領した中国のその他の地域 蒙古 1940年から正式に中華民国の一部となった、満州の西に位置する内モンゴル自治区。モンゴル全土をカバーする体制の出発点として意図された。 日本は計画に反して、直接支配する代わりにフィリピンに傀儡国家を設置した。旧フランス領インドシナでは、ベトナム帝国、カンプチア王国、ルアン・プラバ ン王国が建国された。ベトナム帝国は親日的であったが、独立を目指し、いくつかの先進的な改革を行った[51]。 日本の支持を受けた政党や運動 アザド・ヒンド(インド民族主義運動) インド独立同盟(インド民族主義運動) インドネシア国民党(インドネシアの民族主義運動) Kapisanan ng Paglilingkod sa Bagong Pilipinas(フィリピン第二共和国のフィリピン民族主義与党) ケサトゥアン・ムラユ・ムダ(マレー民族主義運動) Khmer Issarak(カンボジア・クメール民族主義グループ) Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association) (ビルマの民族主義団体) ダヴィエット民族社会党(ベトナムの民族主義運動) |

| Administration Collaboration with Imperial Japan East Asia Development Board Imperial Rule Assistance Association List of East Asian leaders in the Japanese sphere of influence (1931–1945) Ministry of Greater East Asia People Hachirō Arita: an army thinker who thought up the Greater East Asian concept Ikki Kita: a Japanese nationalist who developed a similar pan-Asian concept Satō Nobuhiro: the alleged developer of the Greater East Asia concept Related topics Flying geese paradigm Japanese war crimes Kantokuen Political extremism in Japan Tanaka Memorial (Tanaka Jōsōbun) – an alleged Japanese strategic planning document from 1927 in which Prime Minister Baron Tanaka Giichi, who laid out a strategy to take over the world for Emperor Hirohito Others Civilizing mission Eurasianism Greater Germanic Reich Latin Bloc (proposed alliance) Monroe Doctrine New Order (Nazism) Russkiy mir Scramble for Africa White man's burden |

行政 帝国日本との協力 東アジア開発庁 大日本帝国統治援助協会 日本勢力圏の東アジア指導者リスト(1931~1945年) 大東亜省 人物 有田八郎:大東亜概念を提唱した陸軍の思想家 北一輝:同様の汎アジア構想を展開した日本のナショナリスト 佐藤信淵: 大東亜構想の立案者とされる人物 関連トピック 空飛ぶ雁のパラダイム 日本の戦争犯罪 関特演(関東軍特種演習) 日本の政治的過激主義 田中記念碑(田中上奏文) - 天皇裕仁のために世界征服戦略を打ち出した田中義一男爵首相が、1927年に作成したとされる日本の戦略立案文書。 その他 文明開化の使命 ユーラシア主義 大ゲルマン帝国 ラテン・ブロック(同盟案) モンロー・ドクトリン 新秩序(ナチズム) ロシア主義 アフリカのためのスクランブル 白人の重荷 |

Japanese expansion in Asia and the Pacific, 1937–1942 |

Subhas Chandra Bose speaking at the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo, November 1943 author:unknown Downloaded from the British Library Collection on Indian Independence 1943年11月、東京で開催された大東亜会議で演説するスバス・チャンドラ・ボース 著者:不明 インド独立に関する英国図書館コレクションよりダウンロード |

| https://x.gd/yEqKh |

Tokyo, 1943. Greater East Asia Conference. |

|

1941年時点での大日本帝国の版図 |

| ★大

東亜共栄圏の内部における原住民政策(姫本由美子, n,d. p.146) 1940年8月1日 基本国策要綱「大東亜新秩序の建設」 ・「東亜経済圏」に不足する資源の獲得 ・大東亜地域の諸民族を解放し、日本が指導して共存共栄の関係を構築 1941年11月20日「南方占領地行政実施要領」 ・国防資源の獲得 ・「原住民」の独立運動は過早に誘発することを避ける 1941年12月 開戦時の戦争目的の不統一 ・10日 大本営政府連絡会議「自存自衛」←(海軍省) ・12日 情報局発表「大東亜新秩序建設」←(陸軍省) 1942年3月14日「占領地軍政処理要綱」 ・「原住民」の風俗、習慣、宗教にさしあたり干渉しない ・欧式教育の是正 ・日本語、日本文化の普及に努める 1942年2月21日 大東亜建設審議会設置 1942年5月4日 基本答申「大東亜建設に関する基礎要件」 「大東亜建設に処する文教政策答申」 ・欧米優越観念の排除 ・圏域文化は、諸民族の文化の特殊性を尊重しつつ日本文化を中心に統一 ・現地の固有語は尊重するが、大東亜の共通語としての日本語の普及 ・日本文化を顕揚し、内地から派遣する研究者等と現地有識者と共に文化の向上 を促進し渾然たる「大東亜」文化を培う https://www.rikkyo.ac.jp/research/institute/caas/qo9edr000000ml88-att/ni_55.pdf |

|

| In

contrast the wartime Japanese imperialists had confronted with the

dilemma of multi-racial, muti-ethnic and pluri-cultural convivial

situation in occupied areas. On one hand they should maintain

ethnocentric pride themselves as “blood purity, one dominant race”

nation, on the other they had pretended to be good friend with the

colonized people in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Dai-Tōa

Kyōei Ken) (Dower 1986). |

|

| The

Greater East Asia Conference (大東亞會議, Dai Tōa Kaigi) was an

international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which

the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component

parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also

referred to as the Tokyo Conference. The conference addressed few issues of substance, but was intended from the start as a propaganda show piece, to convince members of Japan's commitments to the Pan-Asianism ideal, with an emphasis on their role as the "liberator" of Asia from Western imperialism.[1] |

大東亜会議(大東亞會議、Dai Tōa

Kaigi)は、1943年11月5日から6日にかけて東京で開催された国際会議であり、大東亜共栄圏を構成する各国の主要な政治家を日本帝国が招いた。

この会議は東京会議とも呼ばれた。 この会議では実質的な問題はほとんど議論されなかったが、当初からプロパガンダのショーケースとして意図されていた。日本の「解放者」としてアジアを西洋 の帝国主義から解放するという役割を強調し、日本の大アジア主義の理想への献身を確信させることを目的としていた。[1] |

| Background Since the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, people in the Asian nations ruled by the "white powers" such as India, Vietnam, etc. and those that had "unequal treaties" forced upon them like China had always looked to Japan as a role model, the first Asian nation that had modernised and defeated a European nation, Russia, in modern times.[2] Throughout the 1920s-30s, Japanese newspapers had always given extensive coverage to the racist laws meant to exclude Asian immigrants such as the "White Australia" policy; the anti-Asian immigrant laws by the U.S. Congress in 1882, 1917, and 1924; and the "White Canada" policy together with reports about how Asians suffered from prejudice in the United States, Canada, Australia, and European colonies in Asia.[3] Most Japanese at the time seemed to have sincerely believed that Japan was a uniquely virtuous nation ruled over by an emperor who was a living god, and thus the font of all goodness in the world.[4] Because the emperor was worshiped as a living god who was morally "pure" and "just", the self-perception in Japan was that the Japanese state could never do anything wrong as under the leadership of the divine Emperor, everything the Japanese state did was "just".[4] For this reason, Japanese people were predisposed to view any war as "just" and "moral" as the divine Emperor could never wage an "unjust" war.[4] Within this context, many Japanese believed it was the "mission" of Japan to end the domination of "white" nations in Asia, and free the other Asians suffering under the rule of the "white powers".[5] A pamphlet titled Read this Alone-and the War Can Be Won issued to all Japanese troops and sailors in December 1941 read: "These white people may expect, from the moment they issue from their mothers' wombs, to be allotted a score or so of natives as their personal slaves. Is this really God's will?".[6] Japanese propaganda stressed the theme of the mistreatment of Asians by whites to motivate their troops and sailors.[7] Starting in 1931, Japan had always sought to justify its imperialism under the grounds of Pan-Asianism. The war with China, which began in 1937, was portrayed as an effort to unite the Chinese and Japanese peoples together in Pan-Asian friendship, to bring the "imperial way" to China, which justified "compassionate killing" as the Japanese sought to kill the "few trouble-makers" in China who were alleged to be causing all the problems in Sino-Japanese relations.[4] As such, Japanese propaganda had proclaimed that the Imperial Army, guided by the "emperor's benevolence" had come to China to engage in "compassionate killing" for the good of the Chinese people.[4] In 1941, when Japan declared war on the United States and several European nations which possessed colonies in Asia, the Japanese portrayed themselves as engaging in a war of liberation on behalf of all the peoples of Asia. In particular, there was a marked racism to Japanese propaganda with the Japanese government issuing cartoons depicting the Western powers as "white devils" or "white demons", complete with claws, fangs, horns, and tails.[8] The Japanese government depicted the war as a race war between the benevolent Asians led by Japan, the most powerful Asian country against the Americans and Europeans, who were portrayed as sub-human "white devils".[8] At times, Japanese leaders spoke like they believed their own propaganda about whites being in a process of racial degeneration and were actually turning into the drooling, snarling demonical creatures depicted in their cartoons.[9] Thus, Japanese Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka had stated in a 1940 press conference that "the mission of the Yamato race is to prevent the human race from becoming devilish, to rescue it from destruction and lead it to the light of the world".[10] At least some people within the Asian colonies of the European powers had welcomed the Japanese as liberators from the Europeans. In the Dutch East Indies, the nationalist leader Sukarno in 1942 had created the formula of the "Three A's": Japan the Light of Asia, Japan the Protector of Asia, and Japan the Leader of Asia.[11] But for all their talk about creating a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere where all the Asian peoples would live together as brothers and sisters, in reality as shown by a July 1943 planning document titled An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus, the Japanese saw themselves as the racially superior "Great Yamato race", which was naturally destined to forever dominate the other racially inferior Asian peoples.[12] Prior to the Greater East Asia Conference, Japan had made vague promises of independence to various anti-colonial pro-independence organisations in the territories it had overrun, but aside from a number of obvious puppet states set up in China, these promises had not been fulfilled. Now, with the tide of the Pacific War turning against Japan, bureaucrats in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and supporters of the Pan-Asian philosophy within the government and military pushed forward a program to grant rapid "independence" to various parts of Asia in an effort to increase local resistance to the Allies and trigger the latter's return and to boost local support for the Japanese war effort. The Japanese military leadership agreed in principle, understanding the propaganda value of such a move, but the level of "independence" the military had in mind for the various territories was even less than that enjoyed by Manchukuo. Several components of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere were not represented. In early 1943, the Japanese established the Ministry of Greater East Asia to conduct relations with the supposedly independent states of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".[13] American historian Gerhard Weinberg writes about the establishment of the Greater East Asia Ministry: "This step itself showed that the periodic announcements from Tokyo that the peoples of Asia were to be liberated and allowed to determine their own fate were a sham and were so intended. If any of the territories nominally declared to be independent were in fact to be so, they could obviously be dealt with by the Foreign Ministry, which existed precisely for the purpose of handling relations with independent states".[13] Korea and Taiwan had long been annexed as external territories of the Empire of Japan, and there were no plans to extend any form of political autonomy or even nominal independence. Vietnamese and Cambodian delegates were not invited for fear of offending the Vichy French regime, which maintained a legal claim to French Indochina and to which Japan was still formally allied. The issue of Malaya and the Dutch East Indies was complex. Large portions were under occupation by the Imperial Japanese Army or Imperial Japanese Navy, and the organisers of the Greater East Asia Conference were dismayed by the unilateral decision of the Imperial General Headquarters to annex these territories to the Japanese Empire on May 31, 1943, rather than to grant nominal independence. This action considerably undermined efforts to portray Japan as the "liberator" of the Asian peoples. Indonesian independence leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta were invited to Tokyo shortly after the close of the conference for informal meetings, but were not allowed to participate in the conference itself.[14] In the end, seven countries (including Japan) participated. |

背景 1904年から1905年にかけての日露戦争以来、インドやベトナムなど「白人」の列強諸国に支配されていたアジア諸国の人々や、中国のように不平等条約 を押し付けられていた国々は、近代において初めて欧州の国家ロシアを打ち破り近代化を成し遂げたアジアの国として、常に日本を手本として見ていた。[2] 1920年代から30年代にかけて、日本の新聞は常に アジア系移民排斥を目的とした人種差別法、例えば「白豪主義」政策や、1882年、1917年、1924年の米国議会によるアジア系移民排斥法、そして 「白カナダ」政策などについて、また、米国、カナダ、オーストラリア、アジアのヨーロッパ植民地でアジア人が偏見に苦しめられているという報道を、日本の 新聞は常に大々的に取り上げていた。[3] 当時のほとんどの日本人は、日本が 唯一無二の徳の高い国民であり、天皇は現人神として世界におけるあらゆる善の源であると信じていたようである。[4] 天皇は道徳的に「純粋」で「公正」な現人神として崇められていたため、日本では、神聖な天皇の指導の下では、日本国が間違ったことを行うことはあり得ず、 日本国が行うことはすべて「正義」であるという自己認識があった。[4] このため、日本人は、 神聖な天皇が「不正な」戦争を仕掛けることはあり得ないため、どんな戦争も「正義」であり「道徳的」であると考える傾向があった。[4] この文脈において、多くの日本人は、アジアにおける「白人」諸国の支配を終わらせ、「白人」の支配下で苦しむ他のアジア諸国を解放することが日本の「使 命」であると信じていた。[5] 1941年12月に全軍の陸軍兵士と海軍兵士に配布されたパンフレット『これだけは独り占め―そして戦争に勝つ』には、次のように書かれていた。「これら の白人は、母親の胎内から出てきた瞬間から、10人ほどの原住民を自分の奴隷として割り当てられるものと期待しているかもしれない。これは本当に神の御心 なのだろうか?」[6] 日本のプロパガンダは、白人がアジア人を虐待しているというテーマを強調し、軍や海軍の士気を高めるよう動機づけた。[7] 1931年以降、日本は常に汎アジア主義を理由に帝国主義を正当化しようとしてきた。1937年に始まった中国との戦争は、日中両国民を大アジア主義の友 好で結びつけ、「帝国の道」を中国にもたらすための努力として描かれた。これは、日中関係におけるすべての問題の原因となっているとされる中国国内の「少 数のトラブルメーカー」を殺害しようとする日本人の「慈悲ある殺人」を正当化するものであった。[4] このように、日本の プロパガンダでは、日本帝国軍は「天皇の慈悲」に導かれ、中国の人々のために「慈悲の殺戮」を行うために中国にやってきたと宣言していた。[4] 1941年、日本が米国およびアジアに植民地を持っていたヨーロッパ諸国に宣戦布告した際、日本はアジアの全人民を代表して解放戦争を行っていると主張し た。特に、日本政府によるプロパガンダには顕著な人種差別主義が見られ、欧米諸国を「白い悪魔」あるいは「白い鬼」として描いた漫画を発行し、鉤爪、牙、 角、尻尾まで描き込んだ。[8] 日本政府は、この戦争を、アジア諸国の中で最も強力な国である日本が率いる慈悲深いアジア諸国と、アメリカ人およびヨーロッパ人との間の人種戦争として描 いた 、白人たちは人間以下の「白い悪魔」として描かれた。[8] 時には、日本の指導者たちは、白人は人種退化の過程にあり、彼らの漫画に描かれたよだれを垂らし、唸り声をあげる悪魔のような生き物に実際に変貌しつつあ ると信じているかのように語った。[9] そのため、日本の外務大臣であった松岡洋右は、 1940年の記者会見で「大和民族の使命は、人類が悪魔化するのを防ぎ、滅亡から救い、世界の光へと導くことである」と述べていた。[10] 少なくとも、ヨーロッパ諸国の植民地であったアジア諸国の中には、ヨーロッパからの解放者として日本を歓迎する人々もいた。オランダ領東インドでは、 1942年に民族主義者スカルノが「3つのA」という公式を打ち出した。すなわち、「アジアの光、アジアの保護者、アジアの指導者としての日本」である。 しかし、アジアのすべての人々が兄弟姉妹として共存する大東亜共栄圏の創設についてあれほど語っていたにもかかわらず、実際には、1943年7月の「大東 亜民族を核とする世界政策の考察」と題された計画文書が示すように、日本人は自分たちを人種的に優れた「大いなる大和民族」と見なし 、他の劣ったアジア諸民族を永遠に支配することが当然の運命であると信じていた。[12] 大東亜会議に先立ち、日本はその占領下にあった地域の植民地独立派組織に対して、曖昧な独立の約束をしていたが、中国にいくつかの明らかな傀儡国家を設立 した以外には、これらの約束は果たされていなかった。そして、太平洋戦争の戦況が日本に不利に傾くと、外務省の官僚や政府および軍部内の汎アジア主義の支 持者たちは、連合国に対するアジア各地の抵抗を強め、連合国が日本に復帰するきっかけを作り、日本の戦争努力に対する現地の支持を高めるために、アジア各 地に迅速に「独立」を与える計画を推進した。日本軍部は、そのような動きが宣伝効果を持つことを理解し、原則的には賛成したが、軍部が想定していた各領土 の「独立」のレベルは、満州国が享受していたものよりもさらに低いものであった。大東亜共栄圏のいくつかの構成要素は含まれていなかった。1943年初 頭、日本は「大東亜共栄圏」内の独立国と見なされていた国々との関係を管理するために大東亜省を設立した。[13] 米国の歴史家ゲアハルト・ワインバーグは、大東亜省の設立について次のように書いている。「この措置自体が、アジア諸国民が解放され、自らの運命を決定で きるようになるという東京からの定期的な発表が偽りであり、そのように意図されていたことを示していた。名目上独立を宣言された領土が実際に独立している 場合、それは独立国との関係を処理することを目的として存在する外務省が当然対処できるはずである」[13]。韓国と台湾は、長い間日本帝国の植民地とし て併合されていた。そして、いかなる形であれ政治的な自治や名目上の独立を拡大する計画はなかった。ベトナムとカンボジアの代表団は、フランス領インドシ ナに対する法的権利を主張し、日本と形式上は同盟関係にあったヴィシー政権のフランスを刺激するのを恐れて招待されなかった。マレーとオランダ領東インド の問題は複雑であった。その大部分は日本帝国陸軍または日本帝国海軍によって占領されていたが、大東亜会議の主催者は、名目的な独立を与えるのではなく、 1943年5月31日に大本営がこれらの地域を日本帝国に併合するという一方的な決定を下したことに落胆した。この行動は、日本をアジア諸国民の「解放 者」として描くという努力を著しく損なうものとなった。インドネシアの独立運動指導者であるスカルノとモハマッド・ハッタは、会議終了直後に東京に招かれ 非公式な会合を行ったが、会議自体には参加を許されなかった。[14] 最終的に、日本を含む7カ国が参加した。 |

| Participants There were six "independent" participants and one observer that attended the Greater East Asia Conference.[15] These were: Hideki Tōjō, Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan Zhang Jinghui, Prime Minister of the Empire of Manchuria Wang Jingwei, President of the Republic of China Ba Maw, Head of State and Prime Minister of the State of Burma Subhas Chandra Bose, Head of State of the Provisional Government of Free India Jose P. Laurel, President of the Republic of the Philippines Wan Waithayakon, envoy from the Kingdom of Thailand Strictly speaking, Subhas Chandra Bose was present only as an "observer", since India was a British colony. Furthermore, Thailand sent Prince Wan Waithayakon in place of Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram to emphasise that Thailand was not a country under Japanese domination. He was also worried that he might be ousted should he leave Bangkok.[16] Tōjō greeted them with a speech praising the "spiritual essence" of Asia, as opposed to the "materialistic civilisation" of the West.[17] Their meeting was characterised by praise of solidarity and condemnation of Western imperialism, but without practical plans for either economic development or integration.[18] As Korea had been annexed by Japan in 1910, there was no official Korean delegation to the conference, but a number of leading Korean intellectuals such as historian Choe Nam-seon, novelist Yi Gwangsu, and children's writer Ma Haesong attended the conference as part of the Japanese delegation to deliver speeches praising Japan and to express their thanks to the Japanese for colonising Korea.[19] The purpose of these speeches was to reassure other Asian peoples about their future in a Japanese-dominated Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The fact that Choe and Yi had once been Korean independence activists who had been bitterly opposed to Japanese rule made their presence at the conference a propaganda coup for the Japanese government, as it seemed to show that Japanese imperialism was so beneficial to the peoples subjected to Japan that even those who once been opposed to the Japanese had now seen the errors of their ways.[20] The Korean delegates also spoke passionately against the "Western devils", describing them as the "most deadly enemies of Asian civilisation that had ever existed", and praising Japan for its role in standing up to them.[19] |

参加者 大東亜会議には「独立」した立場の参加者6名とオブザーバー1名が出席した。[15] 出席者は以下の通りである。 東條英機、大日本帝国首相 張景恵、満州国国務総理 汪兆銘、中華民国国民政府主席 バ・マウ、ビルマ国家元首兼首相 スバス・チャンドラ・ボース、自由インド仮政府元首 ホセ・ラウレル、フィリピン共和国大統領 ワン・ワイタイコン、タイ王国からの特使 厳密に言えば、インドはイギリスの植民地であったため、スバス・チャンドラ・ボースは「オブザーバー」として出席したに過ぎなかった。さらに、タイは首相 プラキップ・フィブンソンクラームの代理としてワン・ワイタイコン王子を派遣し、タイが日本の支配下にある国ではないことを強調した。また、バンコクを離 れると追放されるのではないかと心配していた。[16] 東条は、西洋の「物質文明」とは対照的なアジアの「精神の本質」を称賛する演説で彼らを迎えた。[17] 彼らの会合は連帯の称賛と西洋の帝国主義の非難を特徴としたが、 経済発展や統合のための具体的な計画はなかった。[18] 1910年に韓国が日本に併合されていたため、公式の韓国代表団は存在しなかったが、歴史家の崔南善(チェ・ナムソン)、小説家の李光洙(イ・グァン ス)、児童文学者の 馬海城(Ma Haesong)などの韓国の主要な知識人たちが、日本を称賛し、韓国を植民地化した日本への感謝の意を表する演説を行うために、日本代表団の一員として 会議に参加した。[19] これらの演説の目的は、日本が支配する大東亜共栄圏におけるアジア諸国の将来について、他のアジアの人々を安心させることだった。崔と李がかつては日本の 支配に激しく抵抗した韓国独立運動家であったという事実が、この会議における彼らの存在を日本政府にとって宣伝上の成功に導いた。それは、日本帝国主義が 日本に支配された人々にとって非常に有益であり、かつては日本に抵抗していた者でさえも、今ではその誤りに気づいていることを示しているように思われたか らだ 。韓国代表団もまた、「西洋の悪魔」に対して熱烈に反対し、彼らを「これまでに存在した中で最も致命的なアジア文明の敵」と表現し、彼らに立ち向かう日本 の役割を賞賛した。[19] |

| Themes The major theme of the conference was for the need for all the Asian peoples to rally behind Japan and offer an inspiring example of Pan-Asian idealism against the evil "white devils".[21] American historian John W. Dower writes that the various delegates "...placed the war in the East-versus-the West, Oriental-versus-the Occidental, and ultimately a blood-versus-blood context."[21] Ba Maw of Burma stated: "My Asian blood has always called out to other Asians... This is not the time to think with other minds, this is the time to think with our blood, and this thinking has brought me from Burma to Japan."[21] Ba Maw later remembered: "We were Asians rediscovering Asia".[22] Hideki Tōjō of Japan stated in his speech: "It is an incontrovertible fact that the nations of Greater East Asia are bound in every respect by ties of an inseparable relationship".[23] Jose Laurel of the Philippines in his speech claimed that no-one in the world could "stop or delay the acquisition of one billion Asians of the free and untrammelled right and opportunity to shape their own destiny".[23] Subhas Chandra Bose of India declared: "If our Allies were to go down, there will be no hope for India to be free for at least 100 years".[13] A major irony of the conference was that despite all of the vehement talk condemning the "Anglo-Saxons", English was the language of the conference as it was the only common language of the various delegates from all over Asia.[13] Bose recalled that the atmosphere at the conference was like a "family gathering" as everybody was Asian, and he felt like they belonged together.[24] Many Indians supported Japan, and throughout the conference Indian university students studying in Japan mobbed Bose like an idol.[24] The Filipino ambassador, representing the Laurel government stated "the time has come for the Filipinos to disregard Anglo-Saxon civilisation and its enervating influence... and to recapture their charm and original virtues as an Oriental people."[24] As Japan had about two million soldiers fighting in China, making it by far the largest theatre of operations for Japan, by 1943 the Tōjō cabinet had decided to make peace with China to focus on fighting the Americans.[25] The idea of peace with China had first been raised in early 1943, but Tōjō had encountered fierce resistance with the Japanese elite to giving up any of the Japanese "rights and interests" in China, which were the only conceivable basis for making peace with China.[4] To square this circle about how to make peace with China without surrendering any of the Japanese "rights and interests" in China, it was believed in Tokyo that a major demonstration of Pan-Asianism would lead the Chinese to make peace with Japan, and join the Japanese against their common enemies, the "white devils".[25] Thus, a major theme of the conference was by being allied to the United States and the United Kingdom, Chiang Kai-shek was not a proper Asian as no Asian would ally himself with the "white devils" against other Asians. Weinberg noted that in regards to Japanese propaganda in China, "the Japanese had in effect written off any prospects for propaganda in China by their atrocious conduct in the country", but in the rest of Asia the slogan "Asia for Asians" had much "resonance" as many people in Southeast Asia had no love for the various Western powers who ruled over them.[26] Ba Maw maintained later on the Pan-Asian spirit of the 1943 conference lived after the war, becoming the basis of the 1955 Bandung Conference.[22] Indian historian Pankaj Mishra praised the Greater East Asia Conference as the part of the coming together process of the Asian peoples against the whites as "...the Japanese had revealed how deep the roots of anti-Westernism went and how quickly Asians could seize power from their European tormentors".[22] Mishra argued that the behaviour of the "white powers" towards their Asian colonies, which according to him had been led by marked amount of racism, meant that it was natural for Asians to look to Japan as a liberator from their colonial rulers.[27] |

テーマ 会議の主要テーマは、アジアのすべての人々が日本を支援し、悪の「白人」に対する汎アジア的理想主義の素晴らしい模範を示す必要があるというものであっ た。[21] アメリカの歴史家ジョン・W・ダワーは、さまざまな代表団が「...この戦争を東対西、東洋対西洋、そして究極的には血対血という文脈に位置づけた」と記 している。[21] ビルマのバ・マウは次のように述べた。「私のアジアの血は、常に他のアジア人に呼びかけている...。これは他者の心で考える時ではない。これは我々の血 で考える時なのだ。そして、この考えが私をビルマから日本へと導いたのだ」[21] バ・マウは後に、「我々はアジアを再発見したアジア人だった」と述べた。[22] 日本の東条英機は演説で次のように述べた。「大東亜諸国民が、あらゆる関係において切っても切れない関係で結ばれていることは、まぎれもない事実である」 と述べた。[23] フィリピンのホセ・ラウレルは演説で、10億のアジア人が自らの運命を切り開くための自由で妨げられない権利と機会を得ることを、世界中の誰もが「阻止し たり遅らせたりすることはできない」と主張した。[23] インドのスバス・チャンドラ・ボースは次のように宣言した。「連合国が敗北すれば、インドが自由になる望みは少なくとも100年間はなくなるだろう」と宣 言した。[13] 会議における大きな皮肉は、熱烈な「アングロサクソン」批判の声が飛び交っていたにもかかわらず、アジア各地から集まった代表者たちの共通言語は英語しか なかったため、会議では英語が使用されていたことである。[13] ボースは、会議の雰囲気は「 誰もがアジア人であったため、ボースは「家族の集まり」のような雰囲気であったと回想しており、自分たちもその一員であると感じたという。[24] 多くのインド人が日本を支持しており、会議中、日本に留学中のインド人大学生たちはボースをアイドルのように取り囲んだ。[24] ローレル政権を代表するフィリピン大使は、「フィリピン人がアングロサクソン文明とその弱体化させる影響を無視し、東洋民族としての魅力と本来の美徳を取 り戻す時が来た」と述べた。[24] 日本には中国で戦う兵士が約200万人おり、日本にとって中国は圧倒的に最大の作戦地域であったため、1943年までに東条内閣はアメリカとの戦いに集中 するために中国と講和を結ぶことを決定していた。[25] 中国との講和という考えは1943年初頭に初めて浮上したが、東条は 中国との和平交渉の唯一の根拠と考えられる、中国における日本の「権益」を放棄することに対して、日本のエリート層から激しい抵抗に遭ったのである。 [4] 中国における日本の「権益」を放棄することなく、中国と和平を結ぶというこの難題を解決するため、東京では、大アジア主義の明確な表明が 中国が日本と講和し、共通の敵である「白い悪魔」に対して日本と手を組むよう導くことになるだろうと考えられていた。[25] したがって、会議の主要テーマは、米国および英国と同盟関係にあることで、蒋介石はアジア人としてふさわしくないというものであった。なぜなら、アジア人 が「白い悪魔」と手を組んで他のアジア人と戦うことはありえないからだ。ワインバーグは、中国における日本のプロパガンダについて、「日本人は中国での残 虐な行為によって、中国でのプロパガンダの可能性を事実上断念していた」と指摘したが、その他のアジア地域では、「アジア人のためのアジア」というスロー ガンは、東南アジアの多くの人々が自分たちを支配するさまざまな西洋列強に対して愛着を持っていなかったため、大きな「共鳴」を生んだ。 バ・マウは、1943年の会議の汎アジア精神が戦後も生き続け、1955年のバンドン会議の基礎となったと主張した。[22] インドの歴史家パンカジ・ミシュラは、大東亜会議をアジア諸民族が白人に対して団結する過程の一部として賞賛し、「...日本人は反西洋主義の根がどれほ ど深く、アジア人がヨーロッパの加害者からいかに素早く権力を奪うことができるかを明らかにした」と述べた。反西洋主義の根がどれほど深く、アジア人が ヨーロッパの加害者からいかに素早く権力を奪うことができるかを、日本人は明らかにした」と述べた。[22] ミシュラは、「白人列強」がアジアの植民地に対して取った行動は、著しい人種差別主義によって導かれたものであり、アジア人が植民地支配者からの解放者と して日本に目を向けるのは自然なことだったと主張した。[27] |

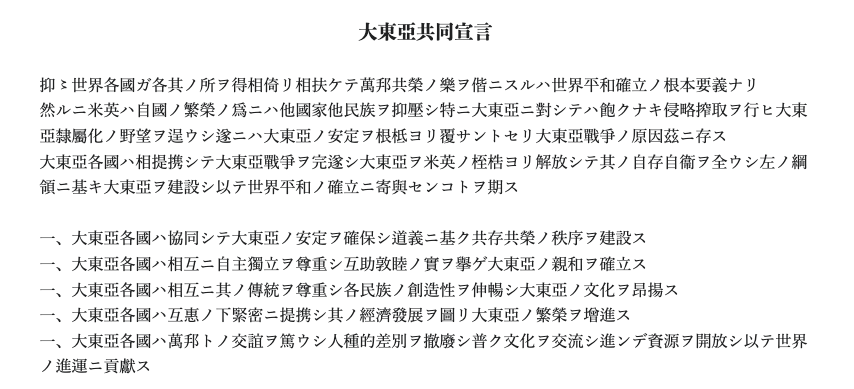

| Joint Declaration The Joint Declaration of the Greater East Asia Conference was published as follows: It is the basic principle for the establishment of world peace that the nations of the world have each its proper place, and enjoy prosperity in common through mutual aid and assistance. The United States of America and the British Empire have in seeking their own prosperity oppressed other nations and peoples. Especially in East Asia, they indulged in insatiable aggression and exploitation, and sought to satisfy their inordinate ambition of enslaving the entire region, and finally they came to menace seriously the stability of East Asia. Herein lies the cause of the recent war. The countries of Greater East Asia, with a view to contributing to the cause of world peace, undertake to cooperate toward prosecuting the War of Greater East Asia to a successful conclusion, liberating their region from the yoke of British-American domination, and ensuring their self-existence and self-defence, and in constructing a Greater East Asia in accordance with the following principles: The countries of Greater East Asia through mutual cooperation will ensure the stability of their region and construct an order of common prosperity and well-being based upon justice. The countries of Greater East Asia will ensure the fraternity of nations in their region, by respecting one another's sovereignty and independence and practicing mutual assistance and amity. The countries of Greater East Asia by respecting one another's traditions and developing the creative faculties of each race, will enhance the culture and civilisation of Greater East Asia. The countries of Greater East Asia will endeavour to accelerate their economic development through close cooperation upon a basis of reciprocity and to promote thereby the general prosperity of their region. The countries of Greater East Asia will cultivate friendly relations with all the countries of the world, and work for the abolition of racial discrimination, the promotion of cultural intercourse and the opening of resources throughout the world, and contribute thereby to the progress of mankind.[28] |

共同宣言 大東亜会議の共同宣言は以下の通り発表された。 世界の国民が、それぞれ正当な地位を占め、相互に援助し、扶助し合って繁栄を享楽することは世界平和確立の要義である。 アメリカ合衆国と大英帝国は、自国の繁栄を追求する中で、他の国民や民族を圧迫してきた。特に東アジアにおいては、彼らは際限のない侵略と搾取にふけり、 その地域全体を奴隷化するという途方もない野望を満たそうとし、ついには東アジアの安定を深刻に脅かすようになった。ここにこそ、先の戦争の原因がある。 大東亜諸国は、世界平和に貢献するとの大義のもとに、大東亜戦争を完勝に導き、英米の支配から地域を解放し、自らの生存と自衛を確保し、以下の原則に従っ て大東亜を建設するために協力することを誓う。 大東亜諸国は、相互に協力し、もって地域安定を確保し、正義に基づく共同繁栄の秩序を建設する。 大東亜諸国は、相互に主権を尊重し、自主性を尊重し、相互に援助し、親善を行うことにより、地域内における諸国民の兄弟関係を確保する。 大東亜諸国は、相互の伝統を尊重し、各民族の創造的才能を発揮することにより、大東亜の文化と文明を発展させる。 大東亜諸国は、互恵主義の原則に基いて緊密なる協同関係を確立し、以て経済発展の促進を期し、地域文化の進展に努める。 大東亜諸国は、世界の諸国と親善関係を樹立し、人種差別の撤廃、文化の交流、資源の開拓等に努め、もって人類の進歩に貢献する。[28] ++++++++++++++ 《原文》 大東亞共同宣言  大東亞共同宣言 抑〻世界各國ガ各其ノ所󠄁ヲ得相倚リ相扶ケテ萬邦󠄁共榮ノ樂ヲ偕ニスルハ世界平󠄁和確立ノ根本要󠄁義ナリ 然ルニ米英ハ自國ノ繁榮ノ爲ニハ他國家他民族ヲ抑壓シ特ニ大東亞ニ對シテハ飽󠄁クナキ侵󠄁略搾取ヲ行ヒ大東亞隸屬化󠄁ノ野望󠄁ヲ逞ウシ遂󠄂ニハ大東亞ノ安定ヲ根柢ヨリ覆󠄁サントセリ大東亞戰爭ノ原因茲ニ存ス 大東亞各國ハ相提携シテ大東亞戰爭ヲ完遂󠄂シ大東亞ヲ米英ノ桎梏ヨリ解放シテ其ノ自存自衞ヲ全󠄁ウシ左ノ綱領ニ基キ大東亞ヲ建󠄁設シ以テ世界平󠄁和ノ確立ニ寄與センコトヲ期ス 一、大東亞各國ハ協同シテ大東亞ノ安定ヲ確保シ道󠄁義ニ基ク共存共榮ノ秩序ヲ建󠄁設ス 一、大東亞各國ハ相互ニ自主獨立ヲ尊󠄁重シ互助敦睦ノ實ヲ擧ゲ大東亞ノ親和ヲ確立ス 一、大東亞各國ハ相互ニ其ノ傳統ヲ尊󠄁重シ各民族ノ創造󠄁性ヲ伸暢シ大東亞ノ文󠄁化󠄁ヲ昂揚ス 一、大東亞各國ハ互惠ノ下緊密ニ提携シ其ノ經濟發展ヲ圖リ大東亞ノ繁榮ヲ增進󠄁ス 一、大東亞各國ハ萬邦󠄁トノ交󠄁誼ヲ篤ウシ人種的󠄁差別ヲ撤廢シ普ク文󠄁化󠄁ヲ交󠄁流シ進󠄁ンデ資󠄁源ヲ開放シ以テ世界ノ進󠄁運󠄁ニ貢獻ス |

| Assessment The conference and the formal declaration adhered to on November 6 was little more than a propaganda gesture designed to rally regional support for the next stage of the war, outlining the ideals of which it was fought.[14] However, the conference marked a turning point in Japanese foreign policy and relations with other Asian nations. The defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal and an increasing awareness of the limitations to Japanese military strength led the Japanese civilian leadership to realise that a framework based on cooperation, rather than one of colonial domination, would enable a greater mobilisation of manpower and resources against the resurgent Allied forces. It was also the start of efforts to create a framework that would allow for some form of diplomatic compromise should the military solution fail altogether.[14] However these moves came too late to save the empire, which surrendered to the Allies less than two years after the conference. Embarrassed by the fact in October 1943, the United Kingdom and the United States had signed treaties giving up their extraterritorial concessions and rights in China, on 9 January 1944 Japan signed a treaty with the regime of Wang Jingwei giving up its extraterritorial rights in China.[25] Emperor Hirohito thought this treaty was so significant that he had his younger brother Prince Mikasa sign the treaty in Nanjing on his behalf.[29] Chinese public opinion was unimpressed with this attempt to put Sino-Japanese relations on a new footing, not the least because the treaty did not change the relationship between Wang and his Japanese masters.[29] Hirohito did not accept the idea of national self-determination, and never called for any changes to Japanese policies in Korea and Taiwan, where the Japanese state had a policy of imposing the Japanese language and culture on the Koreans and Taiwanese, which somewhat undercut the Pan-Asian rhetoric .[29] The emperor viewed Asia through the notion of "place", meaning that all of the Asian peoples were different races that had a proper "place" within a Japanese-dominated "co-prosperity sphere" in Asia, with the Japanese as the leading race.[29] The change to a more co-operative relationship between Japan and the other Asian peoples in 1943-45 were largely cosmetic and were made in response to a losing war as the Allied forces inflicted defeat after defeat on the Japanese on land, sea, and in the air.[29] Dower writes that Japan's Pan-Asian claims were just a "myth", and that the Japanese were as every bit as racist and exploitive towards other Asians as the "white powers" that they were fighting against, and even more brutal as the Japanese treated their supposed Asian brothers and sisters with an appalling ruthlessness.[30] In 1944–45, the Burmese welcomed Allied forces reentering Japanese-occupied Burma as liberators from the Japanese. Moreover, the reality of Japanese rule belied the idealistic statements made at the Greater East Asia Conference. Whenever they went, Japanese soldiers and sailors had a routine habit of publicly slapping the faces of other Asians as a way of showing who were the "Great Yamato race" and who were not.[31] During the war, 670,000 Koreans and 41,862 Chinese were taken to work as slave labour under the most degrading conditions in Japan; the majority did not survive the experience.[32] About 60,000 people from Burma, China, Thailand, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies together with some 15,000 British, Australian, American, Indian, and Dutch prisoners of war died while building the "Burma Death Railway".[33] The Japanese treatment of slaves was based upon an old Japanese proverb for the proper treatment of slaves: ikasazu korasazu (do not let them live, do not let them die).[34] In China between 1937 and 1945, the Japanese were responsible for the deaths of between 8 and 9 million Chinese.[35] |

評価 11月6日に開催された会議と正式宣言は、次段階の戦争に対する地域的な支持を結集させることを目的とした、戦いの理想を概説した宣伝的なジェスチャーに 過ぎなかった。[14] しかし、この会議は日本の外交政策とアジア諸国民との関係における転換点となった。ガダルカナルでの日本軍の敗北と、日本の軍事力の限界に対する認識の高 まりにより、日本の文民指導部は、植民地支配ではなく協力に基づく枠組みが、復活しつつある連合国軍に対抗するためのより大きな人的・物的資源の動員を可 能にすることを理解した。また、軍事的解決が完全に失敗した場合に備え、何らかの外交的妥協を可能にする枠組みを構築するための取り組みの始まりでもあっ た。[14] しかし、これらの動きは大日本帝国を救うには遅すぎた。帝国は、この会議から2年も経たないうちに連合国に降伏した。 この事実を恥じたイギリスとアメリカは、1943年10月に、中国における治外法権の権利を放棄する条約に調印していた。1944年1月9日、日本も汪兆 銘政権と条約を結び、中国における治外法権の権利を放棄した。[25] 昭和天皇は、この条約を非常に重要視し、 この条約を締結するにあたり、弟の三笠宮が南京で天皇に代わって署名した。[29] 中国国民の世論は、日中関係を新たな基盤に立てるためのこの試みに感銘を受けなかった。この条約は、汪と日本人の主君との関係を変えるものではなかったか らである。[29] 裕仁は国民の自己決定という考えを受け入れず、 朝鮮や台湾における日本の政策に変更を求めることは決してなかった。日本国家は朝鮮人や台湾人に日本語や日本文化を押し付ける政策をとっていたが、これは アジア主義的な大げさな表現をいくらか弱めるものであった。[29] 天皇はアジアを「場所」という概念で捉えていた。つまり、アジアのすべての民族は異なる人種であり、日本が主導するアジアの「 。1943年から45年にかけて、日本と他のアジア諸国との関係がより協調的なものへと変化したことは、主に表面的なものであり、連合軍が陸・海・空のあ らゆる面で日本に次々と敗北を強いた敗戦への対応策であった。 ダウアーは、日本の大東亜圏の主張は単なる「神話」であり、日本人は戦っていた「白人勢力」と同様に他のアジア人に対して人種差別的で搾取的であり、さら に日本人が自分たちのアジア人の兄弟姉妹を扱う際には、驚くほど冷酷な非情さで接していたと書いている。[30] 1944年から45年にかけて、ビルマ人は連合軍が日本占領下のビルマに再進駐した際には、日本からの解放者として彼らを歓迎した。さらに、日本による統 治の実態は、大東亜会議で発表された理想主義的な声明とはかけ離れたものであった。日本兵や水兵は、どこに行こうとも、他のアジア人の顔を平手打ちして、 誰が「偉大なる大和民族」で誰がそうでないかを示そうとする習慣があった。[31] 戦時中、670,000人の韓国人と41,862人の中国人が、最も屈辱的な環境下で奴隷労働に従事するために日本に連れて行かれた。 。その大半は生き延びることができなかった。[32] ビルマ、中国、タイ、マレー、オランダ領東インドから連れてこられた約6万人の人々と、1万5000人のイギリス、オーストラリア、アメリカ、インド、オ ランダの捕虜が、「ビルマ死の鉄道」の建設中に死亡した。[33] 日本軍による奴隷の扱いは、奴隷の適切な扱い方に関する古い日本のことわざ「生かさず殺さず(生かさず、殺さず)」に基づいている。[34] 1937年から1945年の間、中国では日本軍のせいで800万人から900万人の中国人が死亡した。[35] |

| Afro–Asian Conference East Asia Development Board Greater East Asia Railroad List of East Asian leaders in the Japanese sphere of influence (1931–1945) Ministry of Greater East Asia |

アフロ・アジア会議 東アジア開発委員会 大東亜鉄道 日本の勢力下にあった東アジアの指導者一覧(1931年~1945年) 大東亜省 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_East_Asia_Conference |

|

| The Tokyo

Conference was a conference held between March 28 and 30, 1942 at

Tokyo by South-East Asian Indian Nationalist groups including the

Indian Independence League, the Indian National Council, and smaller

local Indian associations and clubs.[1][2] This conference led to the

decision to establish an all-unifying Indian Independence League. The

conference was held at the invitation of Rash Behari Bose who was

instrumental in persuading the Japanese authorities to stand by the

Indian nationalists and ultimately to support actively the Indian

freedom struggle abroad. Bose was also elected the leader of the Indian

movement in South-East Asia during this conference. However, the Tokyo

conference failed to reach any definitive decisions due to the

differences between various regional factions, and also because of

differences both with Rash Behari especially given his long connection

with Japan and the current position of Japan as the occupying power in

South-east Asia, and also because many were wary of vested Japanese

interests.[1] The Tokyo conference however, did agree on the decision

to meet again in Bangkok to establish an all-unifying IIL at a future

date.[1] Rash Behari arrived in Singapore in April with the returning

Indian delegation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1942_Tokyo_Conference |

東京会議は、1942年3月28日から30日にかけて東京で開催された

会議で、インド独立連盟、インド国民協議会、および小規模な地元インド人協会やクラブを含む東南アジアのインド人民族主義団体によって開催された。[1]

[2]

この会議は、インド独立連盟を設立するという決定につながった。この会議は、日本当局にインド民族主義者たちを支援し、最終的には海外におけるインドの自

由闘争を積極的に支援するよう説得するのに尽力したラシュ・ビハリ・ボースの招きにより開催された。また、この会議でボースは東南アジアにおけるインド運

動の指導者に選出された。しかし、東京会議では、各地域の派閥間の相違や、特に日本とのつながりが長いラシュ・ベハリと日本が占領国として東南アジアに存

在しているという現状を踏まえた相違、また、 多くの者が日本の既得権益を警戒していたためである。[1]

しかし、東京会議では、将来、すべての国を統合するIILを設立するために、バンコクで再び会合を開くことで合意した。[1]

ラシュ・ベハリは、帰国するインド代表団とともに、4月にシンガポールに到着した。 |

★廣松渉と「東亜の新体制」問題

「日中を軸とした東亜の新体制を!これが今では、日本資本主義そのものの抜本的な問い直しを含むかたちで反体制左翼のスローガンになってよい時期であろう」(廣松渉 「朝日新聞」1994.3.16)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099