ジョセフ・コンラッド『闇の奥』関連年表

Joseph Conrad,

"Heart of Darkness," related timeline

ジョセ

フ・コンラッド『闇の奥』Heart of Darkness, より移転

『闇の奥』(Heart of Darkness、1899年)は、ポーランド系イギリス人の小説家ジョセフ・コンラッド(Joseph Conrad)による小説で、船乗りチャールズ・マーロウが、アフリカ内陸部でベルギー企業の汽船船長として赴任したときの話を聞き手に語る。この小説 は、アフリカにおけるヨーロッパの植民地支配に対する批評として広く評価されており、同時に権力力学と道徳のテーマについても考察している。コンラッドは 物語の舞台となる川の名前を挙げていないが、執筆当時、コンゴ自由国(大きくて経済的に重要なコンゴ川のある場所)はベルギー国王レオポルド2世の私的植 民地だった。マーロウは川のはるか上流の交易所で働く象牙商人カーツから文章を渡されるが、彼は「原住民化」しており、マーロウの探検の対象である。 コンラッドの作品の中心は、「文明人 」と 「未開人」の間にはほとんど差がないという考え方である。闇の奥』は、帝国主義と人種差別について暗にコメントしている。この小説の舞台は、象牙商人カー ツに魅せられたマーロウの物語のフレームを提供する。コンラッドはロンドン(「地上で最も偉大な町」)とアフリカを闇の場所として類似させている。 ブラックウッド誌の創刊1000号を記念して3部作の連作として発表された『闇の奥』は広く再刊され、多くの言語で翻訳されている。フランシス・フォー ド・コッポラ監督の1979年の映画『アポカリプス・ナウ(邦題:地獄の黙示録)』にイン スピレーションを与えた。1998年、モダン・ライブラリーは『闇の奥』を20世紀の英語小説ベスト100の67位にランクした。

****

1857 12月3日Joseph Conradは(父の流刑地であった)ロシア帝国キエフ県のベルディチフ(現ウクライナ・ジトーミル州)に、没落したシュラフタ(ポーランド貴 族)の小地 主であった父アポロ・コジェニョフスキと母エヴァの子として生まれる。

1868

母方のボブロフスキ家の尽力によって流刑を解かれ、

西ウクライナのルヴフ(リ

ヴィウ)に移ることを許可されたが、結核を患っていた父はその翌年クラクフに移った直後に死去。コンラッドは母方の伯父であるタデウシュ・ボブロフスキ

(Tadeusz Bobrowski, 1829-1894)に引き取られて、この地で祖母と暮らしながら家庭教師による教育を受けた。

1873 ルヴフのギムナジウムに通う。

1874 マルセイユへ渡って、フランス商船の船員となる。

「西インド諸島のマルチニックなどへ航海し、時にコ

ロンビアやベネズエラに密輸物質の運搬にも関わった。その後密貿易へのに投資話しに騙され、モンテカルロで賭博に手を出して一文無しになり、1878年に

マルセイユで拳銃自殺を図った。回顧録によれば、コンラッドの乗る船は武器密輸や国家間の政治的陰謀にも関わっていた。」ジョゼフ・コンラッド)

1877 L.H.モルガン『古代社会』岩波文庫

1878

20歳になると流刑囚の子に課されるロシアの兵役を

忌避したと見なされてフランス船には乗れなくなり、英国船に移り勤務し、以降英語を学びつつ、マルタ島、イスタンブール、アゾフ海などを経て、イギリス本

土のサフォーク州ロースロフトに着き、石炭運搬船に乗り込み、ついでシドニーなどへ航行したのち、ロンドンの訓練学校に通って二等航海士の資格を得て、イ

ンド、シンガポールなどに航行する

1880 フランス海軍士官ド・プラザ、コンゴ川西岸の首 長マココと条約締結

1882 Florian Witold Znaniecki(-1958)生まれる。

1884 Bronislaw Kasper Malinowski(-1942)生まれる。コンラッド、一等航海士の試験に合格。

1885-6 ベルリン植民地会議

1885 ベルギー・レオポルドII世「コンゴ自由国」独 立(→コンゴ国際協会)

1886 Ernest Watson

Burgess(-1966)生まれる。コンラッド、船長試験に合格し、またイギリス国籍を取得して、ジョゼフ・コンラッドと改名した。

1888 ボアズ、合衆国で就職

1888 American Anthropologist 創刊

1888 ボアズ、アメリカ民俗学会創設

1889 『オルメイヤーの阿房宮』の執筆開始。

1890

当時デイヴィッド・リヴィングストンやヘンリー・

モートン・スタンリーの探検によりアフリカへの注目が集まると、1890年にベルギーの象牙採取会社の船の船長となって、コンゴ川就航船に乗り[5]、さ

らに陸路でレオポルドヴィル(キンシャサ)まで行き、船を乗り換えてキサンガニに到達、その後病に倒れ、1891年にブリュッセル経由でロンドンに戻っ

た。またこの年には痛風、神経痛による右手の痛み、マラリアの再発のために数ヶ月入院し、また伯父のアドバイスに従ってスイスの温泉で療養した[6]。そ

の後はイギリスとオーストラリアを往復する旅客船に乗ったり、船員以外の仕事をしていた。

1890-1936J.G.フレーザー『金枝編』

1893 E.デュルケム『社会学的方法の規準』岩波文庫

1893 シカゴ大学創設

1895 Almayer's Folly, 1895

1896 ボアズ、自然史博物館に属しながら、コロンビア大学で教鞭。

1896年に16歳年下のイギリス人女性ジョシー・ ジョージと結婚し、ケント州に居住して作家活動を始め、ボリスとジョンの二人の息子をもうけた[6]。そしてこの2作によって、コンラッドはエキゾチック な舞台でのロマンチックな語り手と見なされるようになった。

An Outcast of the

Islands, 1896

1897 Tha Nigger of the Narcissus

(J.Conrad)

1899 『闇の奥』

1899年、『闇の奥』(Heart Of

Darkness)を発表した。西洋文化の暗い側面を描写したこの小説は、英国船時代にアフリカ・コンゴ川で得た経験を元に書かれたもので、T・S・エリ

オット『荒地』、ユージン・オニール『皇帝ジョーンズ』、F・スコット・フィッツジェラルド『グレート・ギャツビー』、ジョージ・オーウェル『1984

年』などにも影響を及ぼした。またこの作品は、オーソン・ウェルズが映画化の構想を持ったが実現せず、1979年にフランシス・フォード・コッポラによっ

て翻案され『地獄の黙示録』として映画化された。1900年、小説『ロード・ジム』(Lord

Jim)を発表した。この小説は、コンラッドの代表作の一つとされる。1925年(米、監督ヴィクター・フレミング)と1965年(米、監督リチャード・

ブルックス)に映画化されている。

1900 Load Jim(J.Conrad)

1900 ボアズ、アメリカ民族学会を復興

1902 The End of the Tether, 1902

1904 Nostromo (J.Conrad)

1905 ボアズ、コロンビア大学に正式に就職(-1937年)

1906

南米の架空の国を舞台にした政治小説の大作『ノスト

ローモ』執筆後に体調を崩し、1906年に南フランスのモンペリエに転地療養した。その間に1894年に起きたグリニッジ天文台爆破未遂事件に関心を持

ち、テロリストを題材にした『密偵』を執筆を始め、その後フォード・マドックス・フォード邸やゴールズワージー邸などを移りながら1907年に完成し、ア

メリカの週刊誌『リッジウェイズ』に連載された[8]。

1907 The Secret Agent, 1907

1908 コンゴ独立国(コンゴ自由国)ベルギー領となる

1909 A.ファン・ヘネップ『通過儀礼』思索社・弘文堂

1910 L.レヴィ=ブリュル『未開社会の思惟』岩波文庫

1910 9月ロジャー・ケイスメント(Roger Casement,

1864-1916)プトマヨ流域のアマゾンに到着。『西欧人の眼に』執筆後の1910年にも、心身の衰弱により数ヶ月間病床に伏した

1911

F.ボアズ『未開人の心』(出版1913)

Under Western Eyes, 1911

1912 E.デュルケム『宗教生活の原初形態』岩波文庫

1912 7月 ロジャー・ケイスメント(Roger Casement, 1864-1916)がペルー・アマゾン会社を 非難する報告書を公刊

(ペルー・アマゾン会社はプトマヨでゴム採集活動をおこなっていた)

1913

R・パーク、シカゴ大学のスタッフになる

Chance, 1913

1914 第一次大戦

1914年にコンラッド夫妻と二人の息子はポーラン

ドを訪問し、オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国下のクラクフに滞在した。しかし第一次世界大戦が始まったためにリゾート地のザコパネに移り、いとこの

Aniela

Zagórskaの経営するペンションに滞在し、ここには政治家のユゼフ・ピウスツキや、ピアニストのアルトゥール・ルービンシュタインなども出入りして

いた。またZagórskaは、ザコパネに疎開していた、作家のステファン・ジェロムスキ、Tadeusz

Nalepiński、人類学者のブロニスワフ・マリノフスキなどにコンラッドを紹介した[6]。コンラッドの一家は11月にイギリスに帰国。いとこの同

名の娘であるAniela Zagórska(コンラッドの姪)はその後1923-39年にコンラッドの作品をポーランド語への翻訳を行なっている。

1915 Victory, 1915

1916 ケイスメント、アイルランド義勇軍の蜂起のための武器調達にベルリンに渡り、帰国後、反逆罪で 処刑(8月3日)

1918-20 『ヨーロッパとアメリカにおけるポーランド農民』

1919-1924

1919年と1922年には、ヨーロッパの作家、批

評家の間で、コンラッドのノーベル文学賞受賞を望む声が上がっていた[6]。1919年には全集の刊行が決まり、また1870年代ののスペインの第三次カ

ルリスタ戦争下での王位継承権を巡る争いを舞台にしたロマンス『黄金の矢』を書くが、後世の評価は高くない。1923年にはアメリカへ宣伝旅行に出かける

[9]。1924年にラムゼイ・マクドナルド首相よりナイトの称号を打診されたが辞退した(これ以前にもコンラッドはケンブリッジ大学、ダラム大学、エ

ディンバラ大学、リヴァプール大学、イェール大学からの名誉学位を断っている)[6]。

1917 The Shadow Line, 1917

1919 The Arrow of Gold, 1919

1920

R.ローウィー『未開社会』(邦訳「原始社会」)未 来社

The Rescue, 1920

1922 B.K.マリノフスキー『西太平洋の遠洋航海者』中央公論社[抄訳]

1922 A.R.ラドクリフ=ブラウン『アンダマン島の人びと』

1923 N.ミクルホ=マクライ『ニューギニア紀行』平凡社[抄訳]

1923

The Nature of a Crime,

1923(フォード・マドックス・フォードと共著)、The Rover, 1923

1924 コンラッド死亡。W.シュミッ ト,W.コッパーズ『民衆と文化』

1924年、ケント州のビショップバーンで心臓発作

でこの世を去った。遺体は本名のユゼフ・コジェニョフスキの名前でカンタベリーの墓地に埋葬された。墓石には、コンラッドの最後の長編小説『The

Rover』で巻頭に掲げられた、エドマンド・スペンサー『妖精の女王』からの引用が刻まれている。

1925 Suspense: A Napoleonic Novel, 1925(未完、没後刊行)

1948

没後の1940年代から1950年代に再評価が広く

進められ、F・R・リーヴィスの『偉大なる伝統』(1948)により、従来の海洋小説作家としてに加えて政治小説の面にも注目され、ジェイン・オースティ

ン、ジョージ・エリオット、チャールズ・ディケンズ、ヘンリー・ジェイムズと並んでイギリス小説史の伝統を担う作家として評されるようになった[18]。

このリーヴィスの影響力は大きかったが、第二次世界大戦を経て、複雑な利害関係の絡む国際政治の実情や、ソビエト連邦の内情について知られるようになった

ことによって、繰り返す革命によって荒廃した架空の国家を描く『ノストローモ』、無政府主義者の跋扈するロンドンを描く『密偵』、ロシア人や亡命者たちの

複雑怪奇な社会を描く『西欧人の眼に』などの政治小説が、世界について先駆的な認識を示していたと理解されるようになったためでもあった[19]。

1954 ベトナムのジュネーブ協定調印、合州国の介入はじまる[→ベトナム戦争]

1958 『闇の奥』邦訳(中野好夫訳)

1960 コンゴ動乱

1965 チェ・ゲバラ、コンゴに入国、内戦を闘う

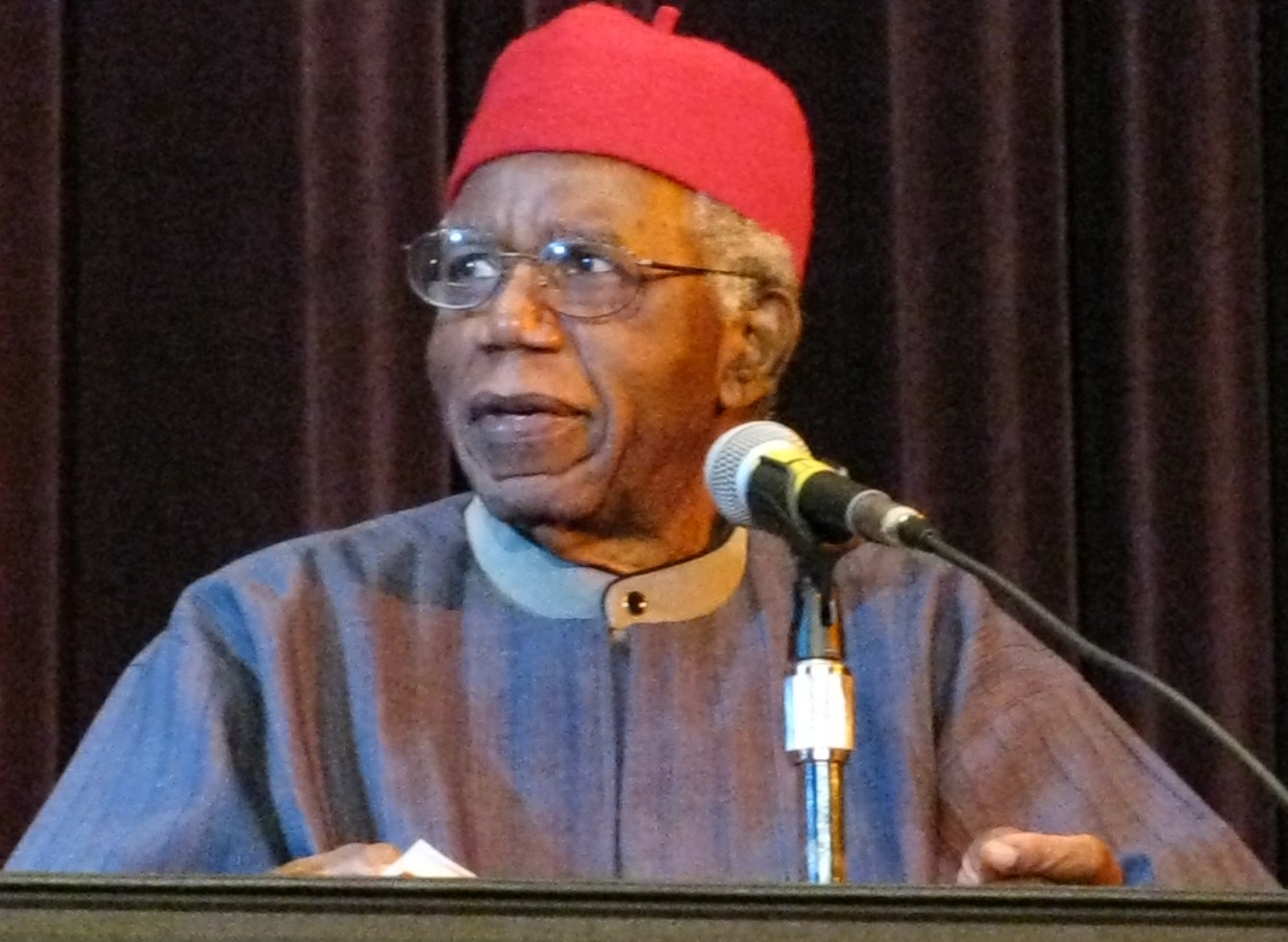

1978

1978年にナイジェリアの作家チヌア・アチェベ

は、『闇の奥』にアフリカ人の内面が描かれていないことにより、人種差別主義者と批判し、それまで19世紀末においてヨーロッパの植民地支配の本質を見抜

いていたと評価されていたコンラッドについて、西欧人としての限界がさまざまに論考されるようになった。

1998 南アフリカ共和国でコンラッド国際学会が開催。

2001 911事件以降には、テロリストを描いた『密偵』について言及されることが多く なっている。

2007

批評家のテリー・イーグルトンは『人生の意味』

(2007年)で、20世紀前半のモダニスト芸術家たちの一人として、コンラッドを意味がないことに矛盾を見出すモダニズム作家と位置づけ、また柴田元幸

は人生に意味がないことを承知の上で戯れるユーモアをコンラッドに認めて、ポストモダニズムを予見していたと評している[12]。

■ 年表:ポーランド・コネクション(出典)

1857 Joseph Conrad(-1924)生まれる。

1858 Frans Boas(-1942)生まれる。

1864 Robert Ezla Park生まれる。

1871 E.B.タイラー『原始文化』誠信書房

1871 ヘンリー・スタンレー、ディビッド・リビングス トンを「発見」

1874 スタンレーは、ザンジバル、コンゴ上流を通り大 西洋に抜ける

+++

| Heart of

Darkness (1899) Heart of Darkness (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel is widely regarded as a critique of European colonial rule in Africa, whilst also examining the themes of power dynamics and morality. Although Conrad does not name the river on which most of the narrative takes place, at the time of writing, the Congo Free State—the location of the large and economically important Congo River—was a private colony of Belgium's King Leopold II. Marlow is given a text by Kurtz, an ivory trader working on a trading station far up the river, who has "gone native" and is the object of Marlow's expedition. Central to Conrad's work is the idea that there is little difference between "civilised people" and "savages." Heart of Darkness implicitly comments on imperialism and racism.[1] The novella's setting provides the frame for Marlow's story of his fascination for the prolific ivory trader Kurtz. Conrad draws parallels between London ("the greatest town on earth") and Africa as places of darkness.[2] Originally issued as a three-part serial story in Blackwood's Magazine to celebrate the 1000th edition of the magazine,[3] Heart of Darkness has been widely republished and translated in many languages. It provided the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Heart of Darkness 67th on their list of the 100 best novels in English of the 20th century.[4] |

『闇の奥』(Heart of

Darkness、1899年) 『闇の奥』(Heart of Darkness、1899年)は、ポーランド系イギリス人の小説家ジョセフ・コンラッド(Joseph Conrad)による小説で、船乗りチャールズ・マーロウが、アフリカ内陸部でベルギー企業の汽船船長として赴任したときの話を聞き手に語る。この小説 は、アフリカにおけるヨーロッパの植民地支配に対する批評として広く評価されており、同時に権力力学と道徳のテーマについても考察している。コンラッドは 物語の舞台となる川の名前を挙げていないが、執筆当時、コンゴ自由国(大きくて経済的に重要なコンゴ川のある場所)はベルギー国王レオポルド2世の私的植 民地だった。マーロウは川のはるか上流の交易所で働く象牙商人カーツから文章を渡されるが、彼は「原住民化」しており、マーロウの探検の対象である。 コンラッドの作品の中心は、「文明人 」と 「未開人 」の間にはほとんど差がないという考え方である。闇の奥』は、帝国主義と人種差別について暗にコメントしている[1]。この小説の舞台は、象牙商人カーツ に魅せられたマーロウの物語のフレームを提供する。コンラッドはロンドン(「地上で最も偉大な町」)とアフリカを闇の場所として類似させている[2]。 ブラックウッド誌の創刊1000号を記念して3部作の連作として発表された『闇の奥』は広く再刊され、多くの言語で翻訳されている[3]。フランシス・ フォード・コッポラ監督の1979年の映画『アポカリプス・ナウ』にインスピレーションを与えた。1998年、モダン・ライブラリーは『闇の奥』を20世 紀の英語小説ベスト100の67位にランクした[4]。 |

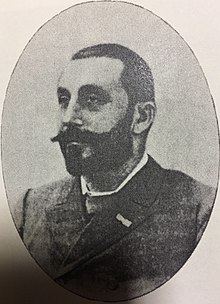

Composition and publication Joseph Conrad based Heart of Darkness on his own experiences in the Congo. In 1890, at the age of 32, Conrad was appointed by a Belgian trading company to serve on one of its steamers. While sailing up the Congo River from one station to another, the captain became ill and Conrad assumed command. He guided the ship up the tributary Lualaba River to the trading company's innermost station, Kindu, in Eastern Congo Free State; Marlow has similar experiences to the author.[5] When Conrad began to write the novella, eight years after returning from Africa, he drew inspiration from his travel journals.[5] He described Heart of Darkness as "a wild story" of a journalist who becomes manager of a station in the (African) interior and makes himself worshipped by a tribe of natives. The tale was first published as a three-part serial, in February, March, and April 1899, in Blackwood's Magazine (February 1899 was the magazine's 1000th issue: special edition). Heart of Darkness was later included in the book Youth: a Narrative, and Two Other Stories, published on 13 November 1902 by William Blackwood. The volume consisted of Youth: a Narrative, Heart of Darkness and The End of the Tether in that order. In 1917, for future editions of the book, Conrad wrote an "Author's Note" where he, after denying any "unity of artistic purpose" underlying the collection, discusses each of the three stories and makes light commentary on Marlow, the narrator of the tales within the first two stories. He said Marlow first appeared in Youth. On 31 May 1902, in a letter to William Blackwood, Conrad remarked, I call your own kind self to witness ... the last pages of Heart of Darkness where the interview of the man and the girl locks in—as it were—the whole 30000 words of narrative description into one suggestive view of a whole phase of life and makes of that story something quite on another plane than an anecdote of a man who went mad in the Centre of Africa.[6] There have been many proposed sources for the character of the antagonist, Kurtz. Georges-Antoine Klein, an agent who became ill and died aboard Conrad's steamer, is proposed by literary critics as a basis for Kurtz.[7] The principal figures involved in the disastrous "rear column" of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition have also been identified as likely sources, including column leader Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, slave trader Tippu Tip and the expedition leader, Welsh explorer Henry Morton Stanley.[8][9] Conrad's biographer Norman Sherry judged that Arthur Hodister (1847–1892), a Belgian solitary but successful trader, who spoke three Congolese languages and was venerated by Congolese to the point of deification, served as the main model, while later scholars have refuted this hypothesis.[10][11][12] Adam Hochschild, in King Leopold's Ghost, believes that the Belgian soldier Léon Rom influenced the character.[13] Peter Firchow mentions the possibility that Kurtz is a composite, modelled on various figures present in the Congo Free State at the time as well as on Conrad's imagining of what they might have had in common.[14] A corrective impulse to impose one's rule characterizes Kurtz's writings which were discovered by Marlow during his journey, where he rants on behalf of the so-called "International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" about his supposedly altruistic and sentimental reasons to civilise the "savages"; one document ends with a dark proclamation to "Exterminate all the brutes!".[15] The "International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" is interpreted as a sarcastic reference to one of the participants at the Berlin Conference, the International Association of the Congo (also called "International Congo Society").[16][17] The predecessor to this organisation was the "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa". |

構成と出版 ジョゼフ・コンラッドは、『闇の奥』をコンゴでの自身の体験に基づいて執筆した。 1890年、32歳だったコンラッドは、ベルギーの貿易会社からある蒸気船の乗組員に任命された。コンゴ川を上流から下流へと航行中、船長が病気になり、 コンラッドが指揮を執ることになった。彼は船を支流のルアラバ川を遡り、コンゴ自由州東部にある商社の最奥のステーション、キンドゥまで導いた。 コンラッドは、アフリカから帰国して8年後にこの小説を書き始めたとき、旅行記からインスピレーションを得た[5]。彼は『闇の奥』を、(アフリカの)奥 地にある基地の支配人となり、原住民の部族から崇拝されるようになるジャーナリストの「荒唐無稽な物語」と表現した。この物語は、1899年2月、3月、 4月に3部構成の連載としてブラックウッド誌に掲載された(1899年2月は同誌の1000号記念号:特別版)。ハート・オブ・ダークネス』はその後、 ウィリアム・ブラックウッドが1902年11月13日に出版した『青春:物語、そして他の2つの物語』に収録された。 この本は、『青春:物語』、『闇の奥』、『綱渡りの果て』の順で構成されていた。1917年、コンラッドはこの本の将来の版のために「著者ノート」を書 き、そこでは、この作品集の根底にある「芸術的目的の統一」を否定した後、3つの物語それぞれについて論じ、最初の2つの物語の語り手であるマーロウにつ いて軽く解説している。彼によれば、マーロウが最初に登場するのは『青春』である。 1902年5月31日、コンラッドはウィリアム・ブラックウッドへの手紙の中でこう述べている、 闇の奥』の最後のページで、男と少女のインタビューが、いわば30000語に及ぶ物語の記述全体を、人生の全局面についての示唆に富んだ一つの見解に閉じ 込め、その物語を、アフリカの中心で発狂した男の逸話とはまったく別の次元のものにしている。 敵役クルツの性格については、多くの出典が提案されている。また、エミンパシャ救援遠征の悲惨な「後列」に関与した主要人物も、隊長のエドモンド・マスグ レイブ・バートロット、奴隷商人のティップ・ティップ、遠征隊長のウェールズ人探検家ヘンリー・モートン・スタンリーなど、有力な情報源として特定されて いる[7]。 [8][9]コンラッドの伝記作家であるノーマン・シェリーは、3つのコンゴ語を話し、コンゴ人から神格化されるほど崇拝されていたベルギー人のアー サー・ホディスター(1847年-1892年)、孤独だが成功した貿易商が主なモデルであると判断したが、後の学者はこの仮説に反論している。 [10][11][12]アダム・ホーホシルトは『レオポルド王の亡霊』の中で、ベルギーの軍人レオン・ロムがこの人物に影響を与えたと考えている [13]。 ピーター・フィルチョーは、クルツが当時コンゴ自由国に存在した様々な人物や、彼らに共通するものがあったかもしれないというコンラッドの想像をモデルに した合成物である可能性に言及している[14]。 いわゆる「野蛮人の風習を抑制する国際協会」の代表として、「野蛮人」を文明化するという利他的で感傷的と思われる理由をわめき散らしている。 [15]「野蛮な風習を抑圧するための国際協会」は、ベルリン会議の参加者の1人であるコンゴ国際協会(「国際コンゴ協会」とも呼ばれる)への皮肉と解釈 されている[16][17]。この組織の前身は「中央アフリカの探検と文明のための国際協会」であった。 |

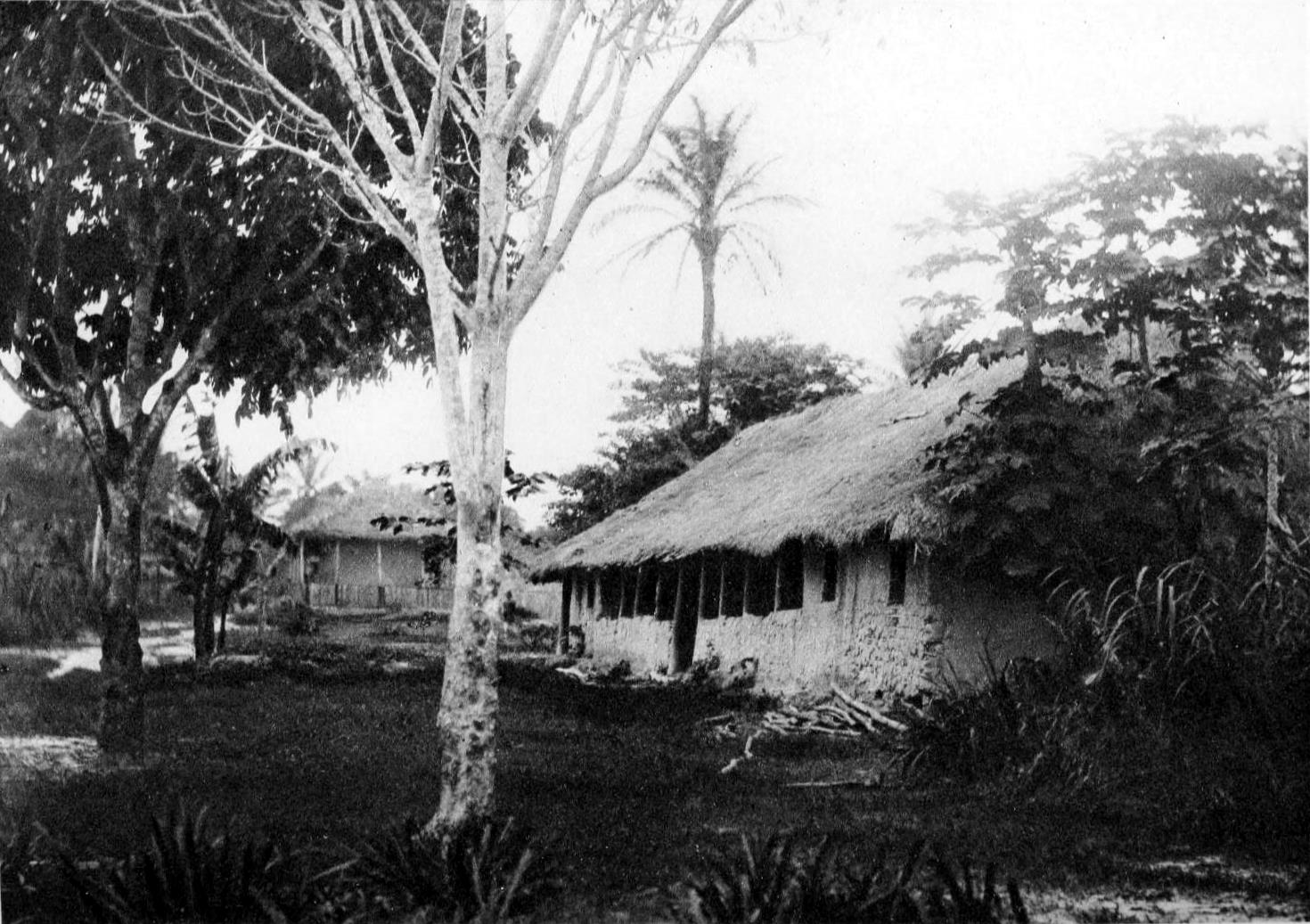

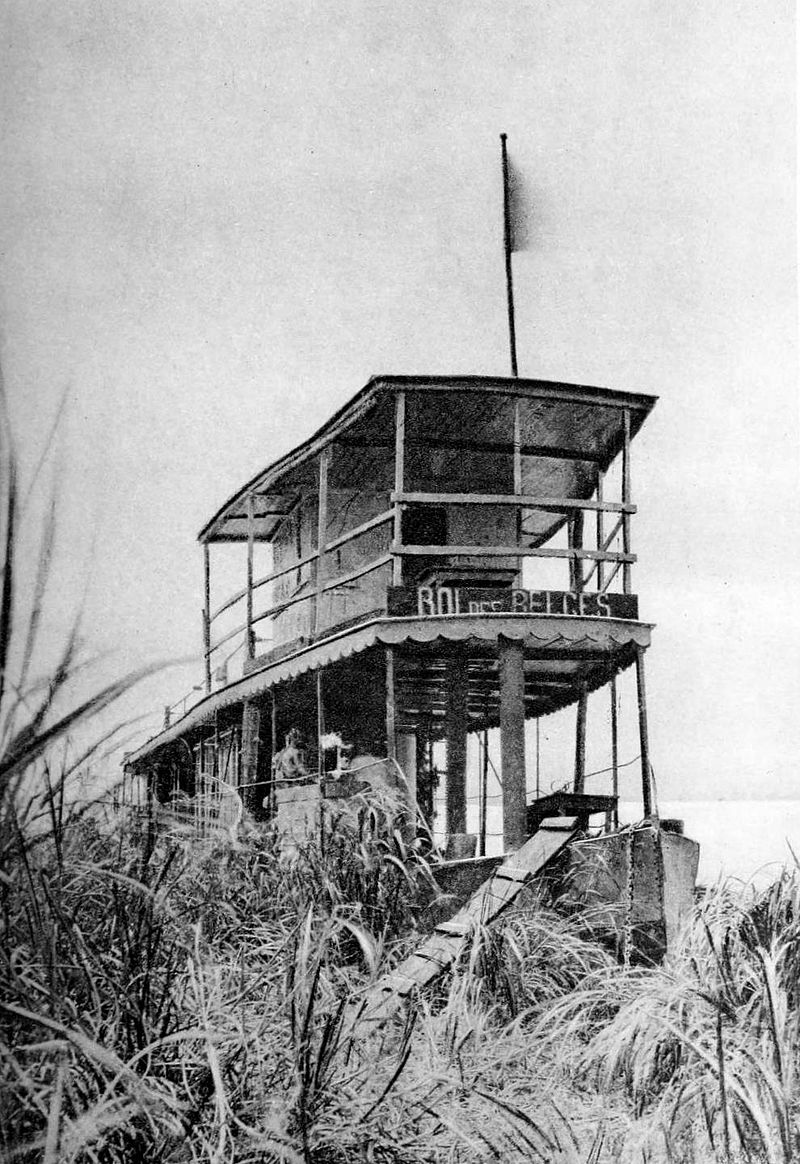

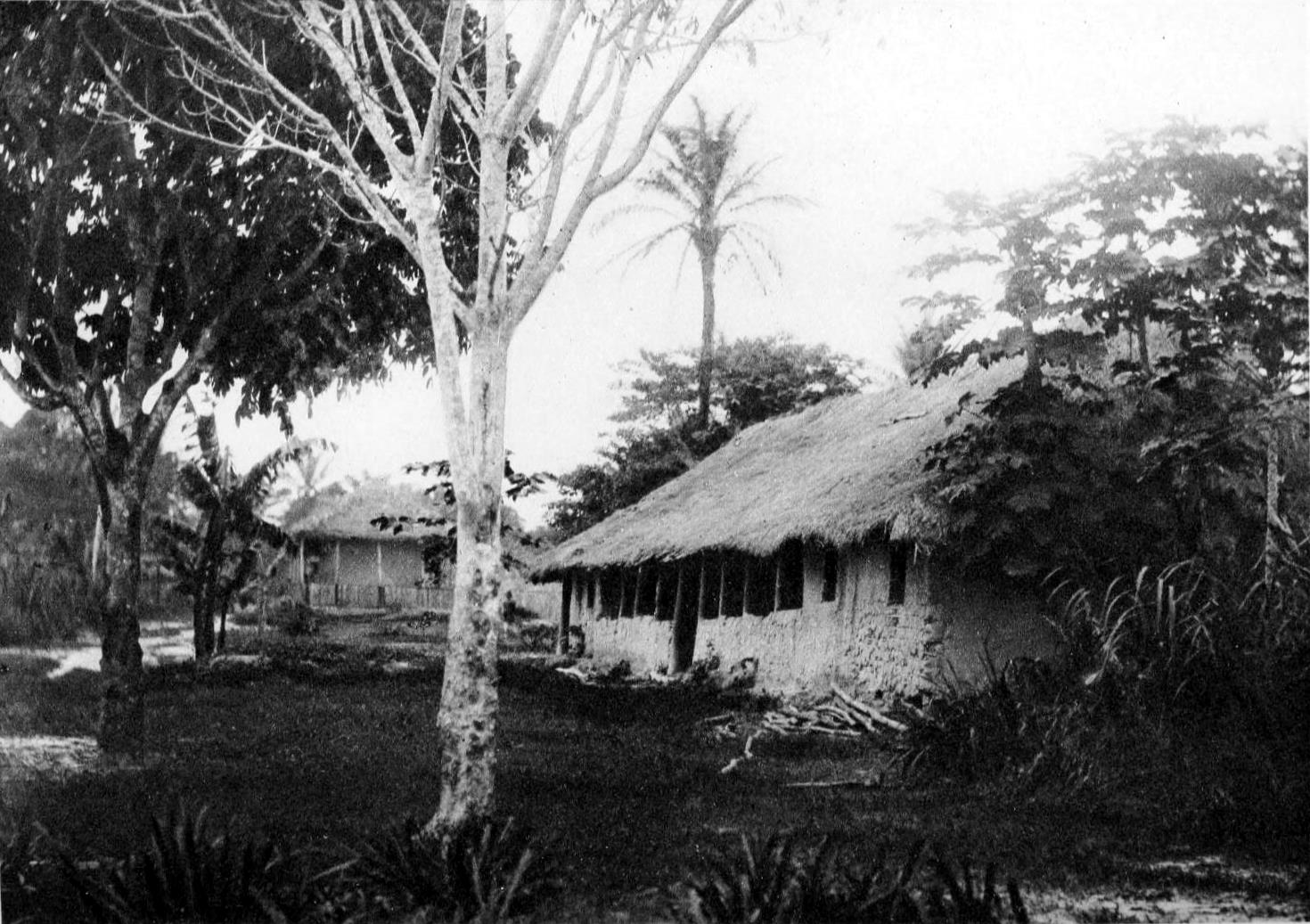

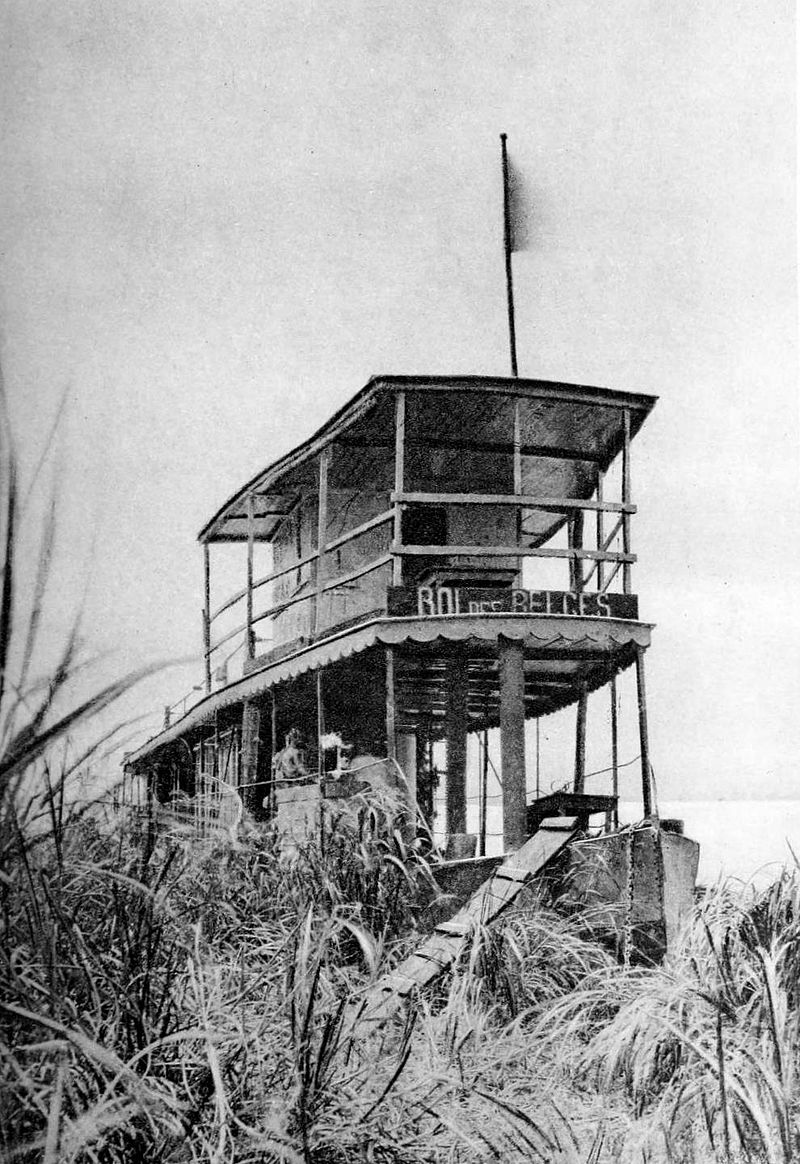

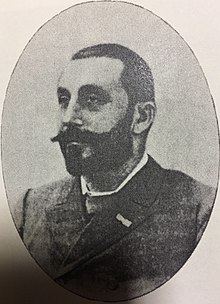

| Summary Charles Marlow tells his friends the story of how he became captain of a river steamboat for an ivory trading company. As a child, Marlow was fascinated by "the blank spaces" on maps, particularly Africa. The image of a river on the map particularly fascinated Marlow. In a flashback, Marlow makes his way to Africa, taking passage on a steamer. He travels 30 mi (50 km) up the river where his company's station is. Work on a railway is taking place. Marlow explores a narrow ravine, and is horrified to find himself in a place full of critically ill Africans who worked on the railroad and are now dying. Marlow must wait for ten days in the company's devastated Outer Station. Marlow meets the company's chief accountant, who tells him of a Mr. Kurtz, who is in charge of a very important trading post, and is described as a respected first-class agent. The accountant predicts that Kurtz will go far.  Belgian river station on the Congo River, 1889 Marlow departs with 60 men to travel to the Central Station, where the steamboat that he will command is based. At the station, he learns that his steamboat has been wrecked in an accident. The general manager informs Marlow that he could not wait for Marlow to arrive, and tells him of a rumour that Kurtz is ill. Marlow fishes his boat out of the river and spends months repairing it. Delayed by the lack of tools and replacement parts, Marlow is frustrated by the time it takes to perform the repairs. He learns that Kurtz is resented, not admired, by the manager. Once underway, the journey to Kurtz's station takes two months.  The Roi des Belges ("King of the Belgians"—French), the Belgian riverboat Conrad commanded on the upper Congo, 1889 The journey pauses for the night about 8 miles (13 km) below the Inner Station. In the morning the boat is enveloped by a thick fog. The steamboat is later attacked by a barrage of arrows, and the helmsman is killed. Marlow sounds the steam whistle repeatedly, frightening the attackers away. After landing at Kurtz's station, a man boards the steamboat: a Russian wanderer who strayed into Kurtz's camp. Marlow learns that the natives worship Kurtz and that he has been very ill. The Russian tells of how Kurtz opened his mind and admires Kurtz even for his power and his willingness to use it. Marlow suspects that Kurtz has gone mad. Marlow observes the station and sees a row of posts topped with the severed heads of natives. Around the corner of the house, Kurtz appears with supporters who carry him as a ghost-like figure on a stretcher. The area fills with natives ready for battle, but Kurtz shouts something and they retreat. His entourage carries Kurtz to the steamer and lays him in a cabin. The manager tells Marlow that Kurtz has harmed the company's business in the region because his methods are "unsound". The Russian reveals that Kurtz believes the company wants to kill him, and Marlow confirms that hangings were discussed.  Arthur Hodister (1847–1892), who Conrad's biographer Norman Sherry has argued served as one of the sources of inspiration for Kurtz After midnight, Kurtz returns to shore. Marlow finds Kurtz crawling back to the station house. Marlow threatens to harm Kurtz if he raises an alarm, but Kurtz only laments that he did not accomplish more. The next day they prepare to journey back down the river. Kurtz's health worsens during the trip. The steamboat breaks down, and while stopped for repairs, Kurtz gives Marlow a packet of papers, including his commissioned report and a photograph, telling him to keep them from the manager. When Marlow next speaks with him, Kurtz is near death; Marlow hears him weakly whisper, "The horror! The horror!" A short while later, the manager's boy announces to the crew that Kurtz has died (the famous line "Mistah Kurtz—he dead" would become the epigraph of T. S. Eliot's poem The Hollow Men). The next day Marlow pays little attention to Kurtz's pilgrims as they bury "something" in a muddy hole. Returning to Europe, Marlow is embittered and contemptuous of the "civilised" world. Several callers come to retrieve the papers Kurtz entrusted to him, but Marlow withholds them or offers papers he knows they have no interest in. He gives Kurtz's report to a journalist, for publication if he sees fit. Marlow is left with some personal letters and a photograph of Kurtz's fiancée. When Marlow visits her, she is deep in mourning although it has been more than a year since Kurtz's death. She presses Marlow for information, asking him to repeat Kurtz's final words. Marlow tells her that Kurtz's final word was her name. |

あらすじ チャールズ・マーロウは、象牙貿易会社の蒸気船の船長になったいきさつを友人たちに語る。子供の頃、マーロウは地図の「余白」、特にアフリカに魅了されて いた。地図に描かれた川のイメージは特にマーロウを魅了した。 フラッシュバックの中で、マーロウは汽船に乗ってアフリカに向かう。彼は会社の駅がある川を30マイル(50キロ)さかのぼる。鉄道の工事が行われてい る。マーロウは狭い渓谷を探検し、自分が鉄道で働き、今にも死にそうな重病のアフリカ人でいっぱいの場所にいることに気づき、愕然とする。マーロウは会社 の荒廃したアウター・ステーションで10日間待たなければならない。マーロウは会社の会計主任に会い、非常に重要な交易所の責任者であり、尊敬を集める一 流のエージェントと言われるカーツ氏のことを聞かされる。会計士はカーツが遠くまで行くだろうと予測する。  1889年、コンゴ川のベルギー河川事務所 マーロウは60人の部下とともに、彼が指揮を執る蒸気船の基地がある中央駅へと旅立つ。駅で、彼は自分の蒸気船が事故で難破したことを知る。総支配人は マーロウが到着するのを待てなかったと告げ、カーツが病気だという噂を伝える。マーロウはボートを川から引き上げ、数ヶ月かけて修理する。工具や交換部品 がないために修理が遅れ、マーロウは修理にかかる時間に苛立つ。彼は、カーツが支配人から賞賛されるどころか恨まれていることを知る。一旦動き出すと、 カーツのステーションまでの旅は2ヶ月かかる。  コンラッドがコンゴ上流で指揮していたベルギーの川船、ロワ・デ・ベルジュ号(フランス語)(1889年) コンラッドの船旅は、インナー・ステーションの約8マイル(13キロ)下で夜を明かす。朝、船は濃い霧に包まれた。その後、蒸気船は矢の嵐に襲われ、操舵 手は命を落とす。マーロウは何度も汽笛を鳴らし、襲撃者を追い払う。 クルツのステーションに上陸した後、蒸気船に一人の男が乗り込む。マーロウは原住民がカーツを崇拝していること、カーツが重い病気にかかっていることを知 る。そのロシア人はカーツがいかに自分の心を開いたかを語り、カーツの権力とそれを利用しようとする意欲さえ賞賛する。マーロウはカーツが狂ってしまった のではないかと疑う。 マーロウは駅を観察し、原住民の首を切断した柱が並んでいるのを見る。その角を曲がると、カーツが幽霊のように担架に乗せられた支援者たちとともに現れ る。辺りは戦闘態勢の原住民で埋め尽くされるが、カーツが何かを叫ぶと彼らは退却する。側近たちはカーツを汽船に運び、キャビンに寝かせる。支配人はマー ロウに、カーツのやり方は 「不健全 」であるため、この地域での会社の事業に損害を与えたと告げる。ロシア人は、カーツが会社に殺されたがっていると考えていることを明かし、マーロウは絞首 刑が検討されたことを確認する。  アーサー・ホディスター(1847-1892)は、コンラッドの伝記作家ノーマン・シェリーが、カーツのインスピレーションの源のひとつになったと主張し ている。 真夜中過ぎ、カーツは岸に戻る。マーロウはカーツが駅舎に這い戻っているのを見つける。マーロウは、もしカーツが警報を出したら危害を加えると脅すが、 カーツは自分がもっと多くのことを成し遂げられなかったことを嘆くだけだった。翌日、彼らは川を下る準備をする。 旅の途中でカーツの体調は悪化する。蒸気船が故障し、修理のために停泊している間に、カーツはマーロウに、依頼された報告書と写真を含む書類の包みを渡 し、支配人から隠しておくように言う。マーロウが次に彼と話したとき、カーツは瀕死の状態だった。マーロウは彼が弱々しくささやくのを聞く!マーロウは彼 が弱々しくささやくのを聞いた。しばらくして、支配人の少年が乗組員にカーツが死んだことを告げる(この有名な台詞 「Mistah Kurtz-he dead 」はT・S・エリオットの詩『The Hollow Men』のエピグラフとなる)。翌日、マーロウはカーツの巡礼者たちが 「何か 」を泥だらけの穴に埋めるのをほとんど気に留めなかった。 ヨーロッパに戻ったマーロウは憤慨し、「文明」世界を軽蔑する。カーツから預かった書類を取り戻そうと何人かの訪問者がやってくるが、マーロウは差し止め たり、興味がないとわかっている書類を差し出したりする。マーロウはカーツの報告書をジャーナリストに渡し、出版を依頼する。マーロウはいくつかの個人的 な手紙とカーツの婚約者の写真を手元に残す。マーロウが彼女を訪ねると、カーツの死から1年以上経っているにもかかわらず、彼女は喪に服していた。彼女は マーロウに情報を求め、カーツの最期の言葉を繰り返すように頼む。マーロウは彼女に、カーツの最後の言葉は彼女の名前だったと告げる。 |

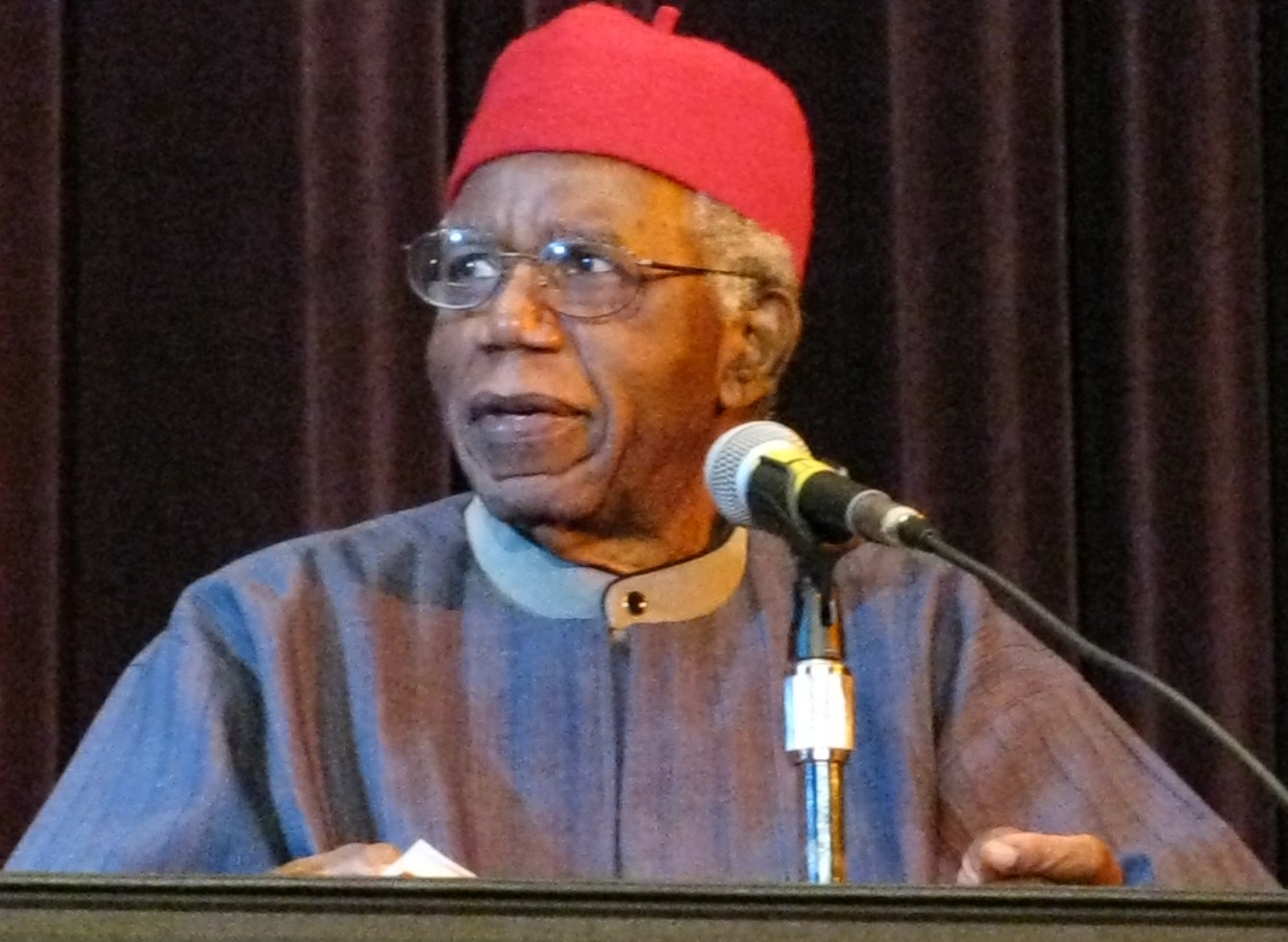

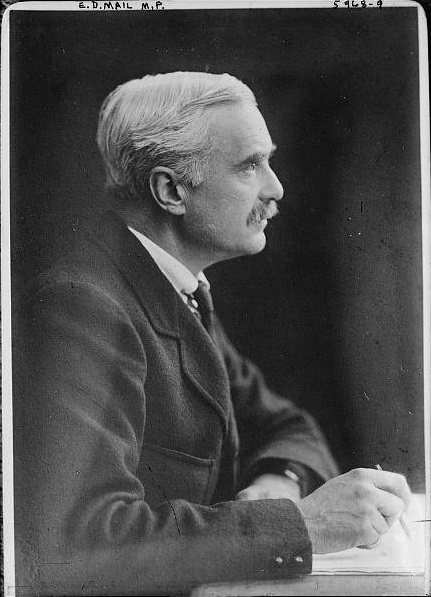

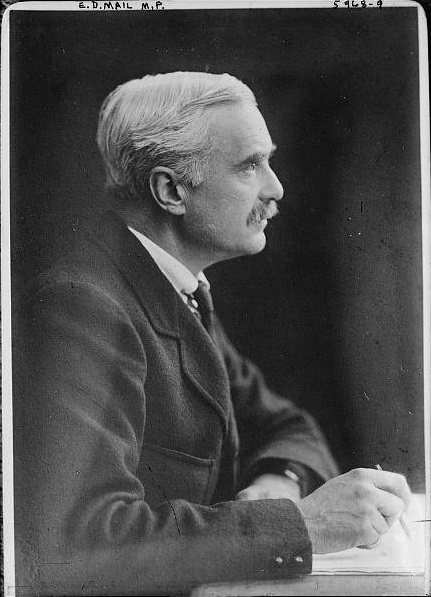

| Critical reception The novella was not a big success during Conrad's life.[18] When it was published as a single volume in 1902 with two novellas, "Youth" and "The End of the Tether", it received the least commentary from critics.[18] F. R. Leavis referred to Heart of Darkness as a "minor work" and criticised its "adjectival insistence upon inexpressible and incomprehensible mystery".[19] Conrad did not consider it to be particularly notable;[18] but by the 1960s it was a standard assignment in many college and high school English courses.[20] Literary critic Harold Bloom wrote that Heart of Darkness had been analysed more than any other work of literature that is studied in universities and colleges, which he attributed to Conrad's "unique propensity for ambiguity".[21] In King Leopold's Ghost (1998), Adam Hochschild wrote that literary scholars have made too much of the psychological aspects of Heart of Darkness, while paying scant attention to Conrad's accurate recounting of the horror arising from the methods and effects of colonialism in the Congo Free State. "Heart of Darkness is experience ... pushed a little (and only very little) beyond the actual facts of the case".[22] Other critiques include Hugh Curtler's Achebe on Conrad: Racism and Greatness in Heart of Darkness (1997).[23] The French philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe called Heart of Darkness "one of the greatest texts of Western literature" and used Conrad's tale for a reflection on "The Horror of the West".[24]  Chinua Achebe's 1975 lecture on the book sparked decades of debate. Heart of Darkness is criticised in postcolonial studies, particularly by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe.[25][26] In his 1975 public lecture "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness", Achebe described Conrad's novella as "an offensive and deplorable book" that de-humanised Africans.[27] Achebe argued that Conrad, "blinkered ... with xenophobia", incorrectly depicted Africa as the antithesis of Europe and civilisation, ignoring the artistic accomplishments of the Fang people who lived in the Congo River basin at the time of the book's publication. He argued that the book promoted and continues to promote a prejudiced image of Africa that "depersonalises a portion of the human race" and concluded that it should not be considered a great work of art.[25][28] Achebe's critics argue that he fails to distinguish Marlow's view from Conrad's, which results in very clumsy interpretations of the novella.[29] In their view, Conrad portrays Africans sympathetically and their plight tragically, and refers sarcastically to, and condemns outright, the supposedly noble aims of European colonists, thereby demonstrating his skepticism about the moral superiority of European men.[30] Ending a passage that describes the condition of chained, emaciated slaves, Marlow remarks: "After all, I also was a part of the great cause of these high and just proceedings." Some observers assert that Conrad, whose native country had been conquered by imperial powers, empathised by default with other subjugated peoples.[31] Jeffrey Meyers notes that Conrad, like his acquaintance Roger Casement, "was one of the first men to question the Western notion of progress, a dominant idea in Europe from the Renaissance to the Great War, to attack the hypocritical justification of colonialism and to reveal... the savage degradation of the white man in Africa."[32]: 100–01 Likewise, E.D. Morel, who led international opposition to King Leopold II's rule in the Congo, saw Conrad's Heart of Darkness as a condemnation of colonial brutality and referred to the novella as "the most powerful thing written on the subject."[33]  Author and anti-slavery pacifist E. D. Morel (1873–1924) considered the novella was "the most powerful thing written on the subject." Conrad scholar Peter Firchow writes that "nowhere in the novel does Conrad or any of his narrators, personified or otherwise, claim superiority on the part of Europeans on the grounds of alleged genetic or biological difference". If Conrad or his novel is racist, it is only in a weak sense, since Heart of Darkness acknowledges racial distinctions "but does not suggest an essential superiority" of any group.[34][35] Achebe's reading of Heart of Darkness can be (and has been) challenged by a reading of Conrad's other African story, "An Outpost of Progress", which has an omniscient narrator, rather than the embodied narrator, Marlow. Masood Ashraf Raja has suggested that Conrad's positive representation of Muslims in his Malay novels complicates these charges of racism.[36] In 2003, Motswana scholar Peter Mwikisa concluded the book was "the great lost opportunity to depict dialogue between Africa and Europe".[37] Zimbabwean scholar Rino Zhuwarara, however, broadly agreed with Achebe, though considered it important to be "sensitised to how peoples of other nations perceive Africa".[38] The novelist Caryl Phillips stated in 2003 that: "Achebe is right; to the African reader the price of Conrad's eloquent denunciation of colonisation is the recycling of racist notions of the 'dark' continent and her people. Those of us who are not from Africa may be prepared to pay this price, but this price is far too high for Achebe".[39] In his 1983 criticism, the British academic Cedric Watts criticizes the insinuation in Achebe's critique—the premise that only black people may accurately analyse and assess the novella, as well as mentioning that Achebe's critique falls into self-contradictory arguments regarding Conrad's writing style, both praising and denouncing it at times.[27] Stan Galloway writes, in a comparison of Heart of Darkness with Jungle Tales of Tarzan, "The inhabitants [of both works], whether antagonists or compatriots, were clearly imaginary and meant to represent a particular fictive cipher and not a particular African people".[40] More recent critics like Nidesh Lawtoo have stressed that the "continuities" between Conrad and Achebe are profound and that a form of "postcolonial mimesis" ties the two authors via productive mirroring inversions.[41] |

批判的受容 この小説はコンラッドの生前には大きな成功を収めたとは言えなかった[18]。1902年に「青春」と「綱渡りの果て」の2つの小説とともに単行本として 出版された際には、批評家たちから最も少ないコメントしか得られなかった[18]。リーヴィスは『闇の奥』を「マイナーな作品」と呼び、その「形容詞的な 表現不能で理解不能な謎への主張」を批判した[19]。コンラッドはこの作品が特に注目される作品だとは考えていなかったが[18]、1960年代までに は多くの大学や高校の英語コースの標準的な課題となっていた[20]。 文芸批評家のハロルド・ブルームは、『闇の奥』は大学やカレッジで研究される他のどの文学作品よりも多く分析されており、それはコンラッドの「曖昧さに対 する独特な傾向」によるものだと書いている[21]。 アダム・ホックチャイルドは『レオポルド王の亡霊』(1998年)の中で、文学者たちは『闇の奥』の心理学的側面を強調しすぎる一方で、コンラッドがコン ゴ自由国における植民地主義の方法と影響から生じる恐怖を正確に描写していることにはほとんど注意を払っていないと書いている。暗黒の心』は経験であ り......事件の実際の事実を少し(そしてほんの少し)超えている」[22] 他の批評には、ヒュー・カートラーの『アチェベ・オン・コンラッド:『暗黒の心』における人種差別と偉大さ』(1997年)がある[23]。 フランスの哲学者フィリップ・ラクー=ラバルテは『暗黒の心』を「西洋文学の最も偉大なテクストのひとつ」と呼び、コンラッドの物語を「西洋の恐怖」につ いての考察に用いた[24]。  チヌア・アチェベは1975年にこの本について講演し、数十年にわたる議論を巻き起こした。 闇の奥』はポストコロニアル研究、特にナイジェリアの小説家チヌア・アチェベによって批判されている[25][26]: コンラッドの『闇の奥』における人種差別」において、アチェベはコンラッドの小説をアフリカ人を非人間化した「不快で嘆かわしい書物」と評した[27]。 アチェベは、コンラッドが「外国人恐怖症で......まばゆいばかりに」アフリカをヨーロッパと文明の対極として誤って描き、この本の出版当時にコンゴ 川流域に住んでいたファング族の芸術的業績を無視していると主張した。彼は、この本が「人類の一部を非人格化する」アフリカに対する偏見に満ちたイメージ を助長し、現在も助長し続けていると主張し、この本は偉大な芸術作品とみなされるべきではないと結論づけた[25][28]。 アチェベの批評家たちは、コンラッドがマーローの見解とコンラッドの見解を区別しておらず、その結果、この小説を非常に不器用に解釈していると主張する [29]。彼らの見解では、コンラッドはアフリカ人を同情的に、彼らの苦境を悲劇的に描き、ヨーロッパの植民地主義者の崇高とされる目的に皮肉を込めて言 及し、それを真っ向から非難することで、ヨーロッパ人の道徳的優越性に対する懐疑を示している。 [30] 鎖につながれ、やせ細った奴隷の状態を描写した一節の終わりに、マーローはこう述べている。「結局のところ、私もまた、こうした高邁で公正な手続きの大義 の一部だったのだ」。コンラッドは、彼の知人であるロジャー・ケースマンと同様に、「ルネサンスから第一次世界大戦までヨーロッパで支配的だった進歩とい う西洋の概念に疑問を投げかけ、植民地主義の偽善的な正当化を攻撃し、アフリカにおける白人の野蛮な堕落を明らかにした最初の人物の一人である」とジェフ リー・マイヤーズは指摘している[32]: 100-01 同様に、コンゴにおけるレオポルド2世の支配に対する国際的な反対運動を率いたE.D.モレルは、コンラッドの『闇の奥』を植民地支配の残虐性を非難する ものと見なし、この小説を「このテーマについて書かれた最も力強いもの」と呼んだ[33]。  作家で反奴隷平和主義者のE.D.モレル(1873-1924)は、この小説を「このテーマについて書かれた最も力強いもの」だと考えていた。 コンラッド研究者のピーター・フィルチョーは、「この小説のどこにも、コンラッドやその語り手は、擬人化されていようがいまいが、遺伝的・生物学的差異を 理由にヨーロッパ人の優越性を主張していない」と書いている。コンラッドや彼の小説が人種差別的であるとすれば、それは弱い意味においてのみであり、『闇 の奥』は人種的区別を認めてはいるが、いかなる集団の「本質的な優越性を示唆しているわけではない」[34][35]。マスード・アシュラフ・ラジャは、 コンラッドがマレー小説においてイスラム教徒を肯定的に表現していることが、こうした人種差別の告発を複雑にしていると示唆している[36]。 2003年、モツワナの学者Peter Mwikisaは、この本は「アフリカとヨーロッパの対話を描く大きな失われた機会」であると結論づけた[37]。ジンバブエの学者Rino Zhuwararaは、「他国の人々がアフリカをどのように認識しているかに感応する」ことが重要であるとしながらも、アチェベに大筋で同意した [38]: アフリカの読者にとって、コンラッドの雄弁な植民地化糾弾の代償は、「暗い 」大陸とその人々に対する人種主義的観念の再利用である。アフリカ出身でない私たちはこの代償を払う覚悟があるかもしれないが、アチェベにとってはこの代 償は高すぎる」[39]。 イギリスの学者セドリック・ワッツは1983年の批評の中で、アチェベの批評における仄めかし-黒人だけがこの小説を正確に分析し評価することができると いう前提-を批判し、またアチェベの批評がコンラッドの文体に関して自己矛盾した議論に陥っており、時にそれを賞賛し、また非難していることにも言及して いる。 [27]スタン・ギャロウェイは『闇の奥』と『ターザンのジャングル物語』の比較において、「(両作品の)住人は敵対者であれ同胞であれ、明らかに想像上 のものであり、特定のアフリカの人々ではなく、特定の架空の暗号を表すことを意図していた」と書いている[40]。ニデシュ・ロートゥーのような最近の批 評家は、コンラッドとアチェベの間の「連続性」は深遠であり、「ポストコロニアル・ミメーシス」の一種が生産的な鏡映反転によって二人の作家を結びつけて いると強調している[41]。 |

| Adaptations and influences Radio and stage Orson Welles adapted and starred in Heart of Darkness in a CBS Radio broadcast on 6 November 1938 as part of his series, The Mercury Theatre on the Air. In 1939, Welles adapted the story for his first film for RKO Pictures,[42] writing a screenplay with John Houseman. The story was adapted to focus on the rise of a fascist dictator.[42] Welles intended to play Marlow and Kurtz[42] and it was to be entirely filmed as a POV from Marlow's eyes. Welles even filmed a short presentation film illustrating his intent. It is reportedly lost. The film's prologue to be read by Welles said "You aren't going to see this picture - this picture is going to happen to you."[42] The project was never realised; one reason given was the loss of European markets after the outbreak of World War II. Welles still hoped to produce the film when he presented another radio adaptation of the story as his first program as producer-star of the CBS radio series This Is My Best. Welles scholar Bret Wood called the broadcast of 13 March 1945, "the closest representation of the film Welles might have made, crippled, of course, by the absence of the story's visual elements (which were so meticulously designed) and the half-hour length of the broadcast."[43]: 95, 153–156, 136–137 In 1991, Australian author/playwright Larry Buttrose wrote and staged a theatrical adaptation titled Kurtz with the Crossroads Theatre Company, Sydney.[44] The play was announced to be broadcast as a radio play to Australian radio audiences in August 2011 by the Vision Australia Radio Network,[45] and also by the RPH – Radio Print Handicapped Network across Australia. In 2011, composer Tarik O'Regan and librettist Tom Phillips adapted an opera of the same name, which premiered at the Linbury Theatre of the Royal Opera House in London.[46] A suite for orchestra and narrator was subsequently extrapolated from it.[47] In 2015, an adaptation of Welles' screenplay by Jamie Lloyd and Laurence Bowen aired on BBC Radio 4.[48] The production starred James McAvoy as Marlow. Another BBC Radio 4 adaptation, first broadcast in 2021, transposes the action to the 21st century.[49] Film and television In 1958, the CBS television anthology Playhouse 90 (S3E7) aired a loose 90-minute television play adaptation. This version, written by Stewart Stern, uses the encounter between Marlow (Roddy McDowall) and Kurtz (Boris Karloff) as its final act, and adds a backstory in which Marlow had been Kurtz's adopted son. The cast includes Inga Swenson and Eartha Kitt.[50] Perhaps the best known adaptation is Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now, based on the screenplay by John Milius, which moves the story from the Congo to Vietnam and Cambodia during the Vietnam War.[51] In Apocalypse Now, Martin Sheen stars as Captain Benjamin L. Willard, a US Army Captain assigned to "terminate the command" of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando. A film documenting the production, titled Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, was released in 1991. It chronicles a series of difficulties and challenges that director Coppola encountered during the making of the film, several of which mirror some of the novella's themes. TNT aired a version of the story (1993), directed by Nicolas Roeg, starring Tim Roth as Marlow and John Malkovich as Kurtz.[52] James Gray's 2019 science fiction film Ad Astra is loosely inspired by the events of the novel. It features Brad Pitt as an astronaut travelling to the edge of the Solar System to confront and potentially kill his father (Tommy Lee Jones), who has gone rogue.[53] In 2020, African Apocalypse, a documentary film directed and produced by Rob Lemkin and featuring Femi Nylander portrays a journey from Oxford, England to Niger on the trail of a colonial killer called Captain Paul Voulet. Voulet's descent into barbarity mirrors that of Kurtz in Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Nylander discovers Voulet's massacres happened at exactly the same time that Conrad wrote his book in 1899. It was broadcast by the BBC in May 2021 as an episode of the Arena documentary series.[54] A British animated film adaption of the novella is planned, directed by Gerald Conn. It was written by Mark Jenkins and Mary Kate O Flanagan and is produced by Gritty Realism and Michael Sheen. Kurtz is voiced by Sheen and Harlequin by Andrew Scott.[55] The animation uses sand to better convey atmosphere of the book.[56] A Brazilian animated film (2023) also adapts the novella. It is directed by Rogério Nunes and Alois Di Leo and moves the story to a near future Rio de Janeiro.[57][58][59] Video games The video game Far Cry 2, released on 21 October 2008, is a loose modernised adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The player assumes the role of a mercenary operating in Africa whose task it is to kill an arms dealer, the elusive "Jackal". The last area of the game is called "The Heart of Darkness".[60][61][62] Spec Ops: The Line, released on 26 June 2012, is a direct modernised adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The player assumes the role of Delta Force operator Captain Martin Walker as he and his team search Dubai for survivors in the aftermath of catastrophic sandstorms that left the city without contact to the outside world. The character John Konrad, who replaces the character Kurtz, is a reference to Joseph Conrad.[63] Literature T. S. Eliot's 1925 poem The Hollow Men quotes, as its first epigraph, a line from Heart of Darkness: "Mistah Kurtz – he dead."[64] Eliot had planned to use a quotation from the climax of the tale as the epigraph for The Waste Land, but Ezra Pound advised against it.[65] Eliot said of the quote that "it is much the most appropriate I can find, and somewhat elucidative."[66] Biographer Peter Ackroyd suggested that the passage inspired or at least anticipated the central theme of the poem.[67] Chinua Achebe's 1958 novel Things Fall Apart is Achebe's response to what he saw as Conrad's portrayal of Africa and Africans as symbols-- "the antithesis of Europe and therefore civilization".[68] Achebe set out to write a novel about Africa and Africans by an African. In Things Fall Apart we see the effects of colonialism and Christian missionary endeavors on an Igbo community in West Africa through the eyes of that community's West African protagonists. Another literary work with an acknowledged debt to Heart of Darkness is Wilson Harris' 1960 postcolonial novel Palace of the Peacock.[69][70][71] J. G. Ballard's 1962 climate fiction novel The Drowned World includes many similarities to Conrad's novella. However, Ballard said he had read nothing by Conrad before writing the novel, prompting literary critic Robert S. Lehman to remark that "the novel's allusion to Conrad works nicely, even if it is not really an allusion to Conrad".[72][73] Robert Silverberg's 1970 novel Downward to the Earth uses themes and characters based on Heart of Darkness set on the alien world of Belzagor.[74] In Josef Škvorecký's 1984 novel The Engineer of Human Souls, Kurtz is seen as the epitome of exterminatory colonialism and, there and elsewhere, Škvorecký emphasises the importance of Conrad's concern with Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe.[75] Timothy Findley's 1993 novel Headhunter is an extensive adaptation that reimagines Kurtz and Marlow as psychiatrists in Toronto. The novel begins: "On a winter's day, while a blizzard raged through the streets of Toronto, Lilah Kemp inadvertently set Kurtz free from page 92 of Heart of Darkness."[76][77] Ann Patchett's 2011 novel State of Wonder reimagines the story with the central figures as female scientists in contemporary Brazil.[78][79] |

翻案と影響 ラジオと舞台 オーソン・ウェルズは、1938年11月6日にCBSラジオで放送された『マーキュリー・シアター・オン・ザ・エア』のシリーズで『闇の奥』を脚色し、主 演した。1939年、ウェルズはこの物語をRKO映画のために初めて映画化し、ジョン・ハウスマンと脚本を書いた[42]。ウェルズはマーロウとカーツを 演じるつもりであり[42]、全編マーロウの目からのPOVとして撮影される予定だった。ウェルズはその意図を説明する短いプレゼンテーション・フィルム も撮影した。それは失われたと伝えられている。ウェルズが読み上げる映画のプロローグには「あなたはこの映画を見るつもりはない。ウェルズは、CBSのラ ジオシリーズ『This Is My Best』のプロデューサースターとしての最初のプログラムとして、この物語の別のラジオ映画化を発表したときには、まだこの映画の製作を希望していた。 ウェルズの研究者であるブレット・ウッドは、1945年3月13日の放送を「ウェルズが作ったかもしれない映画の最も近い表現であるが、もちろん、物語の 視覚的要素(それは非常に綿密にデザインされていた)がないことと、放送が30分という長さであったために不自由であった」と呼んでいる[43]。 1991年、オーストラリアの作家/劇作家であるラリー・バットローズは、シドニーのクロスロード・シアター・カンパニーで『Kurtz』というタイトル の舞台化作品を書き、上演した[44]。この作品は、2011年8月にオーストラリアのラジオ局Vision Australia Radio Networkでラジオ劇として放送されることが発表され[45]、オーストラリア全土のRPH - Radio Print Handicapped Networkでも放送された。2011年、作曲家のタリク・オレガンと台本作家のトム・フィリップスが同名のオペラを脚色し、ロンドンのロイヤル・オペ ラ・ハウスのリンベリーシアターで初演された[46]。2015年、ジェイミー・ロイドとローレンス・ボーエンによるウェルズの脚本の翻案がBBCラジオ 4で放送された[48]。2021年に初放送されたBBCラジオ4の別の脚色では、アクションが21世紀に置き換えられている[49]。 映画とテレビ 1958年、CBSテレビのアンソロジー番組『Playhouse 90』(S3E7)で、90分のテレビ劇が放映された。スチュワート・スターンによって書かれたこのバージョンは、マーロウ(ロディ・マクドウォール)と カーツ(ボリス・カーロフ)の出会いを最終幕として使用し、マーロウがカーツの養子であったという裏設定を追加した。キャストにはインガ・スウェンソンと アースラ・キットがいる[50]。 おそらく最もよく知られた脚色は、ジョン・ミリアスによる脚本を基にしたフランシス・フォード・コッポラの1979年の映画『アポカリプス・ナウ』であ り、物語をコンゴからベトナム戦争中のベトナムとカンボジアに移している[51]。アポカリプス・ナウ』では、マーティン・シーンがマーロン・ブランド演 じるウォルター・E・カーツ大佐の「指揮を打ち切る」ことを命じられたアメリカ陸軍大尉ベンジャミン・L・ウィラード役で出演している。ハート・オブ・ ダークネス』というタイトルの製作記録映画がある: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse』と題された製作記録映画が1991年に公開された。この映画では、コッポラ監督が映画製作中に遭遇した一連の困難と挑戦が記録され ており、そのうちのいくつかは、この小説のテーマのいくつかを反映している。 TNTは、ニコラス・ローグが監督し、ティム・ロスがマーロウ役、ジョン・マルコヴィッチがカーツ役を演じた物語のバージョン(1993年)を放映した [52] ジェームズ・グレイ監督の2019年のSF映画『Ad Astra』は、小説の出来事にゆるやかにインスパイアされている。ブラッド・ピットが宇宙飛行士として太陽系の果てを旅し、暴走した父親(トミー・ リー・ジョーンズ)と対決し、殺す可能性がある。 2020年、ロブ・レムキンが監督・製作し、フェミ・ナイランダーが出演するドキュメンタリー映画『African Apocalypse』は、ポール・ヴーレ大尉と呼ばれる植民地殺人犯を追ってイギリスのオックスフォードからニジェールへ向かう旅を描く。ヴーレの蛮行 への転落は、コンラッドの『闇の奥』に登場するカーツのそれと重なる。ナイランダーは、ヴーレの虐殺が1899年にコンラッドが本を書いたのとまったく同 じ時期に起こったことを発見する。この作品は2021年5月にBBCによってドキュメンタリーシリーズ『Arena』のエピソードとして放送された [54]。 ジェラルド・コン監督により、この小説の英国アニメ映画化が計画されている。脚本はマーク・ジェンキンスとメアリー・ケイト・オー・フラナガン、製作はグ リッティ・リアリズムとマイケル・シーン。カーツの声をシーンが、ハーレクインの声をアンドリュー・スコットが担当する[55]。監督はロジェリオ・ヌネ スとアロイス・ディ・レオで、物語は近未来のリオデジャネイロに移る[57][58][59]。 ビデオゲーム 2008年10月21日に発売されたビデオゲーム『ファークライ2』は、『闇の奥』を緩やかに現代化したものである。プレイヤーはアフリカで活動する傭兵 の役割を担い、その任務は武器商人であるとらえどころのない「ジャッカル」を殺すことである。ゲームの最後のエリアは「闇の心臓」と呼ばれている[60] [61][62]。 2012年6月26日にリリースされたSpec Ops: The Lineは、Heart of Darknessを直接現代化したものである。プレイヤーはデルタフォースのオペレーターであるマーティン・ウォーカー大尉に扮し、彼と彼のチームはドバ イの生存者を捜索する。カーツに代わって登場するジョン・コンラッドというキャラクターは、ジョセフ・コンラッドへの言及である[63]。 文学 T. S.エリオットの1925年の詩『The Hollow Men』は、その最初のエピグラフとして『闇の奥』の一節を引用している: エリオットはこの物語のクライマックスからの引用を『荒地』のエピグラフとして使用することを計画していたが、エズラ・パウンドがそれに反対するよう助言 した[65]。エリオットはこの引用について「私が見つけることができる中で最も適切であり、いくらか解明的である」と述べている[66]。伝記作家の ピーター・アクロイドは、この一節が詩の中心的なテーマにインスピレーションを与えたか、少なくともそれを予期していたと示唆した[67]。 チヌア・アチェベの1958年の小説『Things Fall Apart』は、コンラッドがアフリカとアフリカ人を「ヨーロッパとそれゆえの文明のアンチテーゼ」という象徴として描いたことに対するアチェベの反応で ある。Things Fall Apart』では、植民地主義とキリスト教布教が西アフリカのイボ族のコミュニティに与えた影響を、そのコミュニティの西アフリカ人の主人公の目を通して 描いている。 また、『闇の奥』への恩義が認められる文学作品として、ウィルソン・ハリスの1960年のポストコロニアル小説『孔雀宮』がある[69][70] [71]。J・G・バラードの1962年の気候小説『溺れた世界』には、コンラッドの小説と多くの類似点がある。しかし、バラードはこの小説を書く前にコ ンラッドの作品は何も読んでいないと語っており、文芸評論家のロバート・S・リーマンは「この小説のコンラッドへの暗示は、実際にはコンラッドへの暗示で はないとしても、うまく機能している」と述べている[72][73]。 ロバート・シルバーバーグ(Robert Silverberg)の1970年の小説『Downward to the Earth』では、異世界ベルザゴールを舞台に『闇の奥』に基づくテーマとキャラクターが使用されている[74]。 ヨゼフ・シュクヴォレッキー(Josef Škvorecký)の1984年の小説『The Engineer of Human Souls』では、カーツは絶滅的植民地主義の典型とみなされており、シュクヴォレッキーはそこでも他の場所でも、東ヨーロッパにおけるロシア帝国主義に 対するコンラッドの懸念の重要性を強調している[75]。 ティモシー・フィンドリーの1993年の小説『ヘッドハンター』は、カーツとマーロウをトロントの精神科医として再構築した大規模な翻案である。小説はこ う始まる: ある冬の日、吹雪がトロントの街を吹き荒れる中、リラ・ケンプはうっかり『闇の奥』の92ページからカーツを自由にしてしまった」[76][77] アン・パチェットの2011年の小説『ステート・オブ・ワンダー』は、中心人物を現代ブラジルの女性科学者として物語を再構築している[78][79]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart_of_Darkness |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆