ヒトゲノム・プロジェクト

Human Genome Project

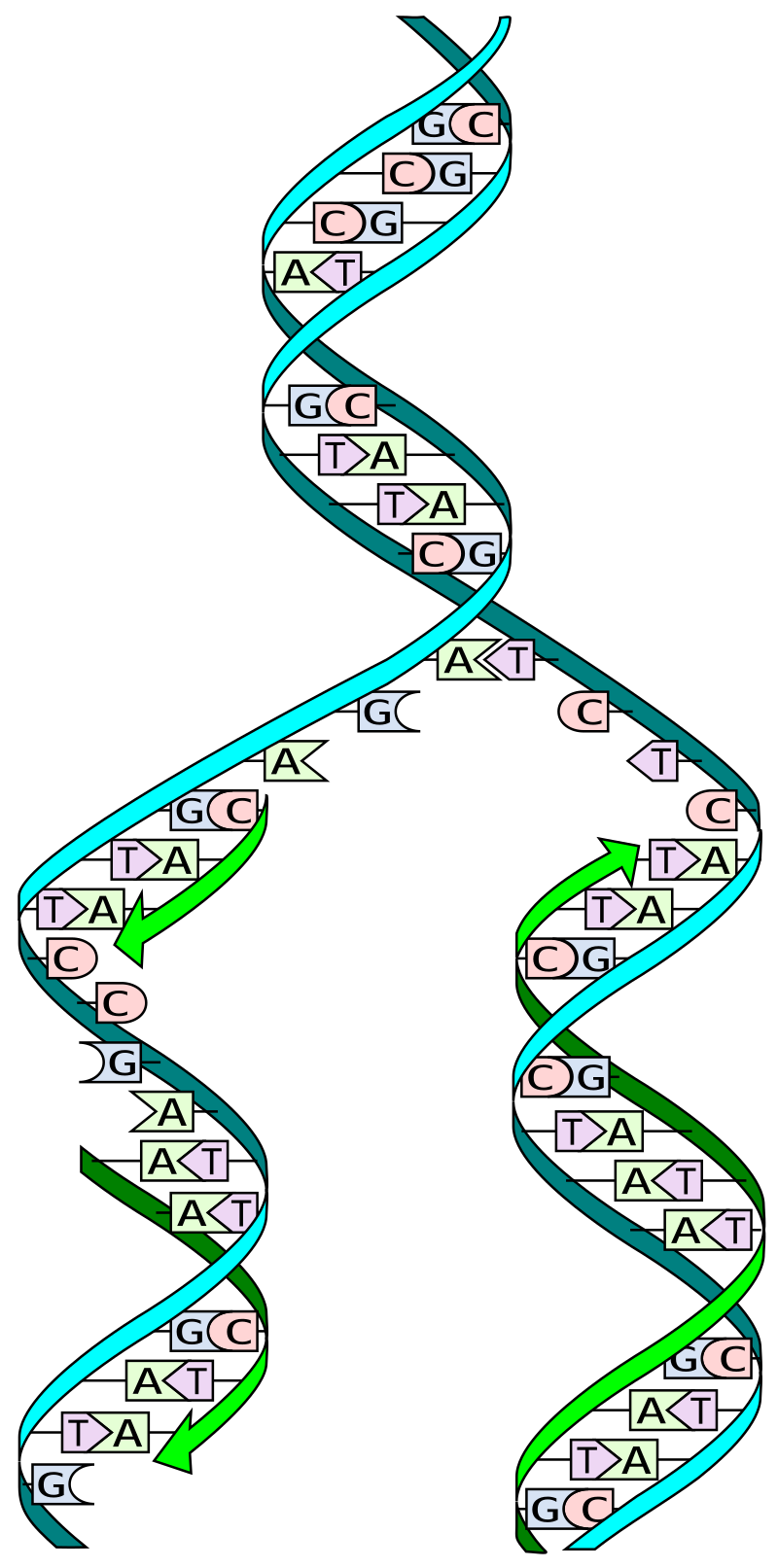

☆ ヒトゲノム計画(HGP)は、ヒトのDNAを構成する塩基対を決定し、ヒトゲノムの全遺伝子を物理的および機能的観点から同定し、マッピングし、塩基配列 を決定することを目的とした国際的な科学研究プロジェクトである[1]。1990年に開始され、2003年に完了した[1]。世界最大の生物学共同プロ ジェクトである[2]。1984年にアメリカ政府によって採択された後、プロジェクトの計画が開始され、1990年に正式に開始された。2003年4月 14日、ゲノムの約92%を含むゲノムの完成が宣言された[3]。2021年5月には、潜在的な問題に覆われた塩基はわずか0.3%であったが、「完全な ゲノム」レベルが達成された[4][5]。 資金提供は、米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)を通じての国民政府からのもので、その他にも世界中の数多くのグループから提供された。並行して、1998年に 正式に発足したセレラ・コーポレーション(セレラ・ジェノミクス)により、政府外でプロジェクトが実施された。政府が後援したシーケンシングのほとんど は、国際ヒトゲノムシーケンシングコンソーシアム(IHGSC)で活動する米国、英国、日本、フランス、ドイツ、中国の20の大学や研究センターで行われ た[7]。 ヒトゲノム計画はもともと、30億以上あるヒトのハプロイド参照ゲノムに含まれるヌクレオチドの完全なセットをマッピングすることを目的としていた。ヒト ゲノムのマッピングには、少数の個体から採取したサンプルの塩基配列を決定し、塩基配列を決定した断片を組み立てて、ヒトの染色体23対(常染色体22対 とアロソームと呼ばれる性染色体1対)それぞれの完全な塩基配列を得ることが必要である。したがって、完成したヒトゲノムはモザイク状であり、特定の個人 を表すものではない。このプロジェクトの有用性の多くは、ヒトゲノムの大部分がすべてのヒトで同じであるという事実に由来する。

| The Human Genome

Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the

goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of

identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human

genome from both a physical and a functional standpoint. It started in

1990 and was completed in 2003.[1] It remains the world's largest

collaborative biological project.[2] Planning for the project started

after it was adopted in 1984 by the US government, and it officially

launched in 1990. It was declared complete on April 14, 2003, and

included about 92% of the genome.[3] Level "complete genome" was

achieved in May 2021, with only 0.3% of the bases covered by potential

issues.[4][5] The final gapless assembly was finished in January

2022.[6] Funding came from the United States government through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as well as numerous other groups from around the world. A parallel project was conducted outside the government by the Celera Corporation, or Celera Genomics, which was formally launched in 1998. Most of the government-sponsored sequencing was performed in twenty universities and research centres in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany, and China,[7] working in the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC). The Human Genome Project originally aimed to map the complete set of nucleotides contained in a human haploid reference genome, of which there are more than three billion. The genome of any given individual is unique; mapping the human genome involved sequencing samples collected from a small number of individuals and then assembling the sequenced fragments to get a complete sequence for each of the 23 human chromosome pairs (22 pairs of autosomes and a pair of sex chromosomes, known as allosomes). Therefore, the finished human genome is a mosaic, not representing any one individual. Much of the project's utility comes from the fact that the vast majority of the human genome is the same in all humans. |

ヒトゲノム計画(HGP)は、ヒトのDNAを構成する塩基対を決定し、

ヒトゲノムの全遺伝子を物理的および機能的観点から同定し、マッピングし、塩基配列を決定することを目的とした国際的な科学研究プロジェクトである

[1]。1990年に開始され、2003年に完了した[1]。世界最大の生物学共同プロジェクトである[2]。1984年にアメリカ政府によって採択され

た後、プロジェクトの計画が開始され、1990年に正式に開始された。2003年4月14日、ゲノムの約92%を含むゲノムの完成が宣言された[3]。

2021年5月には、潜在的な問題に覆われた塩基はわずか0.3%であったが、「完全なゲノム」レベルが達成された[4][5]。 資金提供は、米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)を通じての国民政府からのもので、その他にも世界中の数多くのグループから提供された。並行して、1998年に 正式に発足したセレラ・コーポレーション(セレラ・ジェノミクス)により、政府外でプロジェクトが実施された。政府が後援したシーケンシングのほとんど は、国際ヒトゲノムシーケンシングコンソーシアム(IHGSC)で活動する米国、英国、日本、フランス、ドイツ、中国の20の大学や研究センターで行われ た[7]。 ヒトゲノム計画はもともと、30億以上あるヒトのハプロイド参照ゲノムに含まれるヌクレオチドの完全なセットをマッピングすることを目的としていた。ヒト ゲノムのマッピングには、少数の個体から採取したサンプルの塩基配列を決定し、塩基配列を決定した断片を組み立てて、ヒトの染色体23対(常染色体22対 とアロソームと呼ばれる性染色体1対)それぞれの完全な塩基配列を得ることが必要である。したがって、完成したヒトゲノムはモザイク状であり、特定の個人 を表すものではない。このプロジェクトの有用性の多くは、ヒトゲノムの大部分がすべてのヒトで同じであるという事実に由来する。 |

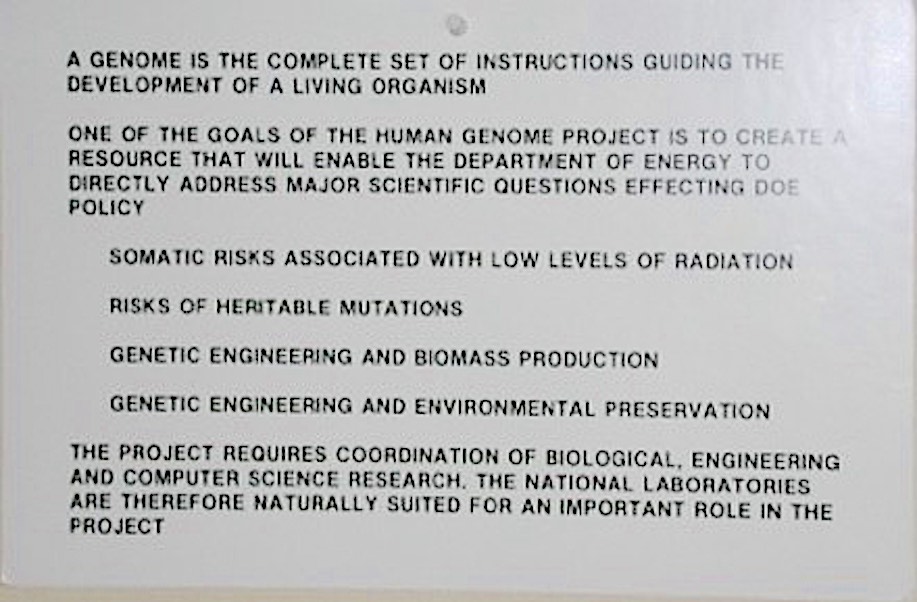

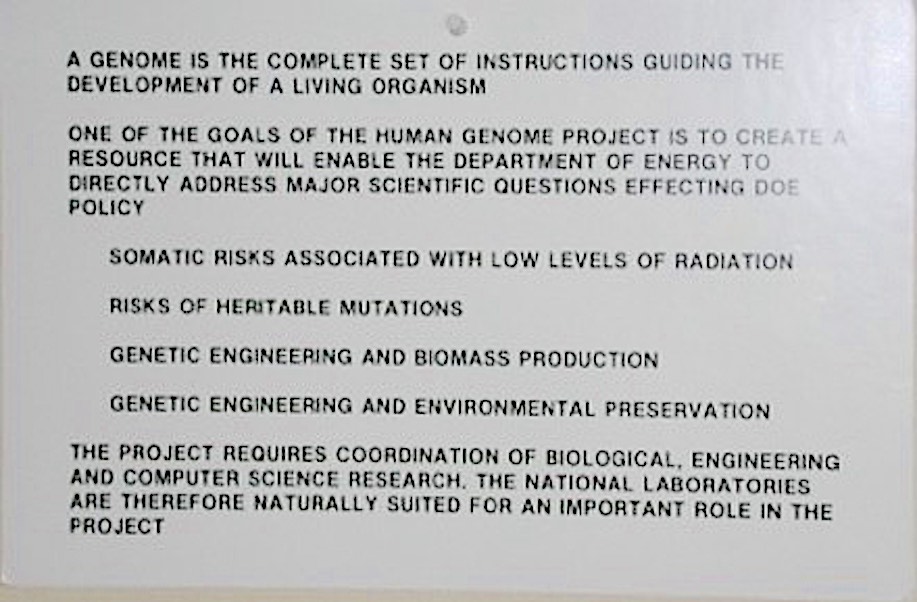

History The Human Genome Project was a 13 year-long publicly funded project initiated in 1990 with the objective of determining the DNA sequence of the entire euchromatic human genome within 13 years.[8][9] The idea of such a project originated in the work of Ronald A. Fisher, whose work is also credited with later initiating the project.[10] In May 1985, Robert Sinsheimer organized a workshop at the University of California, Santa Cruz, to discuss the feasibility of building a systematic reference genome using gene sequencing technologies.[11] In March 1986, the Santa Fe Workshop was organized by Charles DeLisi and David Smith of the Department of Energy's Office of Health and Environmental Research (OHER).[12] At the same time Renato Dulbecco, President of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, first proposed the concept of whole genome sequencing in an essay in Science.[13] The published work, titled "A Turning Point in Cancer Research: Sequencing the Human Genome", was shortened from the original proposal of using the sequence to understand the genetic basis of breast cancer.[14] James Watson, one of the discoverers of the double helix shape of DNA in the 1950s, followed two months later with a workshop held at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Thus the idea for obtaining a reference sequence had three independent origins: Sinsheimer, Dulbecco and DeLisi. Ultimately it was the actions by DeLisi that launched the project.[15][16][17][18] The fact that the Santa Fe Workshop was motivated and supported by a federal agency opened a path, albeit a difficult and tortuous one,[19] for converting the idea into public policy in the United States. In a memo to the Assistant Secretary for Energy Research Alvin Trivelpiece, then-Director of the OHER Charles DeLisi outlined a broad plan for the project.[20] This started a long and complex chain of events which led to approved reprogramming of funds that enabled the OHER to launch the project in 1986, and to recommend the first line item for the HGP, which was in President Reagan's 1988 budget submission,[19] and ultimately approved by Congress. Of particular importance in congressional approval was the advocacy of New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici, whom DeLisi had befriended.[21] Domenici chaired the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, as well as the Budget Committee, both of which were key in the DOE budget process. Congress added a comparable amount to the NIH budget, thereby beginning official funding by both agencies.[citation needed] Trivelpiece sought and obtained the approval of DeLisi's proposal from Deputy Secretary William Flynn Martin. This chart[22] was used by Trivelpiece in the spring of 1986 to brief Martin and Under Secretary Joseph Salgado regarding his intention to reprogram $4 million to initiate the project with the approval of John S. Herrington.[citation needed] This reprogramming was followed by a line item budget of $13 million in the Reagan administration's 1987 budget submission to Congress.[12] It subsequently passed both Houses. The project was planned to be completed within 15 years.[23]  Proposal to William F. Martin launching the Human Genome Project In 1990, the two major funding agencies, DOE and the National Institutes of Health, developed a memorandum of understanding in order to coordinate plans and set the clock for the initiation of the Project to 1990.[24] At that time, David J. Galas was Director of the renamed "Office of Biological and Environmental Research" in the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science and James Watson headed the NIH Genome Program. In 1993, Aristides Patrinos succeeded Galas and Francis Collins succeeded Watson, assuming the role of overall Project Head as Director of the NIH National Center for Human Genome Research (which would later become the National Human Genome Research Institute). A working draft of the genome was announced in 2000 and the papers describing it were published in February 2001. A more complete draft was published in 2003, and genome "finishing" work continued for more than a decade after that.[citation needed] The $3 billion project was formally founded in 1990 by the US Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, and was expected to take 15 years.[25] In addition to the United States, the international consortium comprised geneticists in the United Kingdom, France, Australia, China, and myriad other spontaneous relationships.[26] The project ended up costing less than expected, at about $2.7 billion (equivalent to about $5 billion in 2021).[7][27][28] Two technologies enabled the project: gene mapping and DNA sequencing. The gene mapping technique of restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) arose from the search for the location of the breast cancer gene by Mark Skolnick of the University of Utah,[29] which began in 1974.[30] Seeing a linkage marker for the gene, in collaboration with David Botstein, Ray White and Ron Davies conceived of a way to construct a genetic linkage map of the human genome. This enabled scientists to launch the larger human genome effort.[31] Because of widespread international cooperation and advances in the field of genomics (especially in sequence analysis), as well as parallel advances in computing technology, a 'rough draft' of the genome was finished in 2000 (announced jointly by U.S. President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair on June 26, 2000).[32][33] This first available rough draft assembly of the genome was completed by the Genome Bioinformatics Group at the University of California, Santa Cruz, primarily led by then-graduate student Jim Kent and his advisor David Haussler.[34] Ongoing sequencing led to the announcement of the essentially complete genome on April 14, 2003, two years earlier than planned.[35][36] In May 2006, another milestone was passed on the way to completion of the project when the sequence of the very last chromosome was published in Nature.[37] The various institutions, companies, and laboratories which participated in the Human Genome Project are listed below, according to the NIH:[7]  |

歴史 ヒトゲノムプロジェクトは、13年以内に全ユークロマティックヒトゲノムのDNA配列を決定することを目的として、1990年に開始された13年間の公的 資金によるプロジェクトであった[8][9]。このようなプロジェクトのアイデアは、後にプロジェクトを開始したロナルド・A・フィッシャー (Ronald A. Fisher)の研究に端を発している[10]。 1985年5月、ロバート・シンシハイマーはカリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校でワークショップを開催し、遺伝子配列決定技術を用いた体系的な参照ゲノ ム構築の実現可能性について議論した[11]。1986年3月、サンタフェ・ワークショップがエネルギー省保健環境研究局(OHER)のチャールズ・デ リージとデビッド・スミスによって開催された[12]。 [12] 同じ頃、ソーク生物学研究所(Salk Institute for Biological Studies)のレナート・ダルベッコ(Renato Dulbecco)所長は、『サイエンス(Science)』誌のエッセイで全ゲノム配列決定の概念を初めて提唱した[13]: 1950年代にDNAの二重らせん形状を発見した一人であるジェームズ・ワトソンは、その2ヵ月後にコールド・スプリング・ハーバー研究所でワークショッ プを開いた。このように、参照配列を得るというアイデアは、3つの独立した起源を持っていた: シンスハイマー、ダルベッコ、そしてデリージである。最終的にプロジェクトを立ち上げたのはデリージの行動であった[15][16][17][18]。 サンタフェ・ワークショップが連邦政府機関によって動機づけられ、支援されたという事実は、困難で紆余曲折はあったにせよ、このアイデアを米国の公共政策 に転換する道を開いた[19]。OHERのチャールズ・デリージ(Charles DeLisi)所長(当時)は、アルビン・トリベルピース(Alvin Trivelpiece)エネルギー研究次官補に宛てたメモの中で、このプロジェクトの大まかな計画を概説した[20]。このことから、長く複雑な出来事 の連鎖が始まり、OHERが1986年にプロジェクトを開始し、レーガン大統領が1988年に提出した予算[19]の中で、HGPの最初の行程項目を推薦 することを可能にする資金の再プログラムが承認された。議会承認で特に重要だったのは、デリージが懇意にしていたニューメキシコ州 上院議員ピート・ドメニシの擁護であった[21]。ドメニシは、DOE 予算プロセスで重要な役割を果たす上院エネルギー天然資源委員 会と予算委員会の委員長を務めていた。議会はNIH予算に同額を追加し、これにより両機関による正式な資金提供が始まった[要出典]。 トリベルピースは、ウィリアム・フリ ン・マーティン副長官にデリージの提案を求め、承認を得た。この図表[22]は、1986年春にTrivelpieceがマーティンとジョセフ・サルガド 次官に、ジョン・S・ヘリントンの承認を得て400万ドルを再計画してプロジェクトを開始する意向を説明するために使用された。プロジェクトは15年以内 に完了する予定だった[23]。  ウィリアム・F・マーティンへのヒトゲノム計画開始の提案 1990年、2つの主要な資金提供機関であるDOEと国立衛生研究所は、計画を調整するために覚書を作成し、プロジェクト開始の時期を1990年に設定し た[24]。当時、デビッド・J・ガラスは、米国エネルギー省科学局の「生物・環境研究室」と改称された局長であり、ジェームズ・ワトソンはNIHゲノ ム・プログラムの責任者であった。1993年、アリスティデス・パトリノスがガラスの後を継ぎ、フランシス・コリンズがワトソンの後を継いで、NIH国立 ヒトゲノム研究センター(後に国立ヒトゲノム研究所となる)の所長としてプロジェクト全体の責任者の役割を引き受けた。2000年にゲノムの作業草案が発 表され、2001年2月にそれを説明する論文が発表された。より完全な草稿は2003年に発表され、ゲノムの「仕上げ」作業はその後10年以上続いた[要 出典]。 この30億ドルのプロジェクトは、1990年に米国エネルギー省と国立衛生研究所によって正式に設立され、15年かかると予想されていた[25]。国際コ ンソーシアムは、米国に加えて、英国、フランス、オーストラリア、中国、その他無数の自然発生的関係の遺伝学者で構成されていた[26]。このプロジェク トは、最終的に約27億ドル(2021年の約50億ドルに相当)という予想よりも少ない費用で終了した[7][27][28]。 このプロジェクトを可能にしたのは、遺伝子マッピングとDNAシーケンシングという2つの技術であった。制限断片長多型(RFLP)という遺伝子マッピン グ技術は、1974年に始まったユタ大学のマーク・スコルニックによる乳がん遺伝子の位置の探索[29]から生まれた[30]。遺伝子の連鎖マーカーを見 て、デイヴィッド・ボットスタインと共同で、レイ・ホワイトとロン・デイヴィスはヒトゲノムの遺伝子連鎖地図を構築する方法を考案した。これによって科学 者たちは、より大規模なヒトゲノム研究を開始することができた[31]。 国際的な協力が広まり、ゲノムの分野(特に配列解析)が進歩し、コンピュータ技術も並行して進歩したため、2000年にはゲノムの「草稿」が完成した (2000年6月26日、ビル・クリントン米大統領とトニー・ブレア英首相が共同で発表)[32][33]。 [32][33]この最初に利用可能なゲノムのラフドラフトは、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校のゲノムバイオインフォマティクスグループによって完 成された。 NIHによると、ヒトゲノム計画に参加した様々な機関、企業、研究所は以下の通りである[7]。  |

| State of completion Notably, the project was not able to sequence all of the DNA found in human cells; rather, the aim was to sequence only euchromatic regions of the nuclear genome, which make up 92.1% of the human genome. The remaining 7.9% exists in scattered heterochromatic regions such as those found in centromeres and telomeres. These regions by their nature are generally more difficult to sequence and so were not included as part of the project's original plans.[38] The Human Genome Project (HGP) was declared complete in April 2003. An initial rough draft of the human genome was available in June 2000 and by February 2001 a working draft had been completed and published followed by the final sequencing mapping of the human genome on April 14, 2003. Although this was reported to cover 99% of the euchromatic human genome with 99.99% accuracy, a major quality assessment of the human genome sequence was published on May 27, 2004, indicating over 92% of sampling exceeded 99.99% accuracy which was within the intended goal.[39] In March 2009, the Genome Reference Consortium (GRC) released a more accurate version of the human genome, but that still left more than 300 gaps,[40] while 160 such gaps remained in 2015.[41] Though in May 2020, the GRC reported 79 "unresolved" gaps,[42] accounting for as much as 5% of the human genome,[43] months later, the application of new long-range sequencing techniques and a hydatidiform mole-derived cell line in which both copies of each chromosome are identical led to the first telomere-to-telomere, truly complete sequence of a human chromosome, the X chromosome.[44] Similarly, an end-to-end complete sequence of human autosomal chromosome 8 followed several months later.[45] In 2021, it was reported that the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium had filled in all of the gaps except five in repetitive regions of ribosomal DNA.[46] Months later, those gaps had also been closed. The full sequence did not contain the Y chromosome, which causes the embryo to become male, being absent in the cell line that served as the source for the DNA analyzed. About 0.3% of the full sequence proved difficult to check for quality, and thus might have contained errors,[47] which were being targeted for confirmation.[48] In April 2022, the complete non-Y chromosome sequence was formally published, providing a view of much of the 8% of the genome left out by the HGP.[49] In December, 2022, a preprint article claimed that the sequencing of the remaining missing regions of Y chromosome had been performed, thus completing the sequencing of all 24 human chromosomes.[50] In August 2023 this preprint was finally published.[51][52] |

完成状況 このプロジェクトの目的は、核ゲノムのユークロマティック領域(ヒトゲノムの92.1%を占める)の配列を決定することであった。残りの7.9%は、セン トロメアやテロメアに見られるような、散在するヘテロクロマティック領域に存在する。これらの領域はその性質上、一般的に配列決定が困難であるため、プロ ジェクトの当初の計画には含まれていなかった[38]。 ヒトゲノム計画(HGP)は2003年4月に完了宣言された。2000年6月にヒトゲノムの最初の草稿が公開され、2001年2月までに作業草稿が完成・ 公開され、2003年4月14日にヒトゲノムの最終的な塩基配列マッピングが行われた。これは、99.99%の精度で真性ヒトゲノムの99%をカバーする と報告されたが、2004年5月27日にヒトゲノム配列の主要な品質評価が発表され、92%以上のサンプリングが99.99%の精度を超え、意図した目標 の範囲内であることが示された[39]。 2009年3月、ゲノムリファレンスコンソーシアム(GRC)はより正確なヒトゲノムのバージョンを発表したが、それでも300以上のギャップが残っており[40]、2015年には160のギャップが残っている[41]。 2020年5月、GRCはヒトゲノムの5%を占める79の「未解決」ギャップ[42]を報告したが[43]、その数ヵ月後、新しい長距離シークエンシング 技術と、各染色体のコピーが両方とも同一である胞状奇胎由来の細胞株の応用により、ヒト染色体のX染色体の、テロメアからテロメアまでの、真に完全な配列 が初めて得られた[44]。 [44]。同様に、ヒト常染色体8番染色体の末端から末端までの完全な塩基配列が、数ヶ月後に続いた[45]。 2021年、Telomere-to-Telomere(T2T)コンソーシアムが、リボソームDNAの反復領域における5つのギャップを除くすべての ギャップを埋めたことが報告された[46]。全塩基配列には、胚が男性になる原因となるY染色体は含まれていなかった。全塩基配列の約0.3%は品質 チェックが難しく、エラーが含まれている可能性があることが判明した[47]。 [49]2022年12月、Y染色体の残りの欠落領域の塩基配列決定が行われ、ヒトの全24本の染色体の塩基配列決定が完了したとするプレプリント論文が 発表された[50]。2023年8月、このプレプリントが最終的に出版された[51][52]。 |

| Applications and proposed benefits The sequencing of the human genome holds benefits for many fields, from molecular medicine to human evolution. The Human Genome Project, through its sequencing of the DNA, can help researchers understand diseases including: genotyping of specific viruses to direct appropriate treatment; identification of mutations linked to different forms of cancer; the design of medication and more accurate prediction of their effects; advancement in forensic applied sciences; biofuels and other energy applications; agriculture, animal husbandry, bioprocessing; risk assessment; bioarcheology, anthropology and evolution. The sequence of the DNA is stored in databases available to anyone on the Internet. The U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (and sister organizations in Europe and Japan) house the gene sequence in a database known as GenBank, along with sequences of known and hypothetical genes and proteins. Other organizations, such as the UCSC Genome Browser at the University of California, Santa Cruz,[53] and Ensembl[54] present additional data and annotation and powerful tools for visualizing and searching it. Computer programs have been developed to analyze the data because the data itself is difficult to interpret without such programs. Generally speaking, advances in genome sequencing technology have followed Moore's Law, a concept from computer science which states that integrated circuits can increase in complexity at an exponential rate.[55] This means that the speeds at which whole genomes can be sequenced can increase at a similar rate, as was seen during the development of the Human Genome Project. |

アプリケーションと提案されている利点 ヒトゲノムの解読は、分子医学から人類の進化に至るまで、多くの分野に恩恵をもたらす。例えば、適切な治療を行うための特定ウイルスの遺伝子型決定、様々 な癌に関連する変異の特定、投薬の設計とその効果のより正確な予測、法医学応用科学の進歩、バイオ燃料やその他のエネルギー応用、農業、畜産業、バイオ加 工、リスク評価、生物考古学、人類学、進化学などである。DNAの塩基配列は、インターネット上で誰でも利用できるデータベースに保存されている。米国国 立生物工学情報センター(およびヨーロッパと日本の姉妹機関)は、既知および仮説の遺伝子やタンパク質の配列とともに、GenBankとして知られるデー タベースに遺伝子配列を格納している。カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校のUCSC Genome Browser[53]やEnsembl[54]などの他の組織では、さらなるデータとアノテーション、それを可視化し検索するための強力なツールが提供 されている。このようなプログラムなしではデータ自体の解釈が難しいため、データを解析するためのコンピュータープログラムが開発されてきた。一般的に 言って、ゲノム配列決定技術の進歩は、ムーアの法則(集積回路が指数関数的な速度で複雑さを増すというコンピュータ科学の概念)に従っている[55]。こ れは、ヒトゲノム計画の開発中に見られたように、全ゲノムを配列決定する速度も同様の速度で増加しうることを意味する。 |

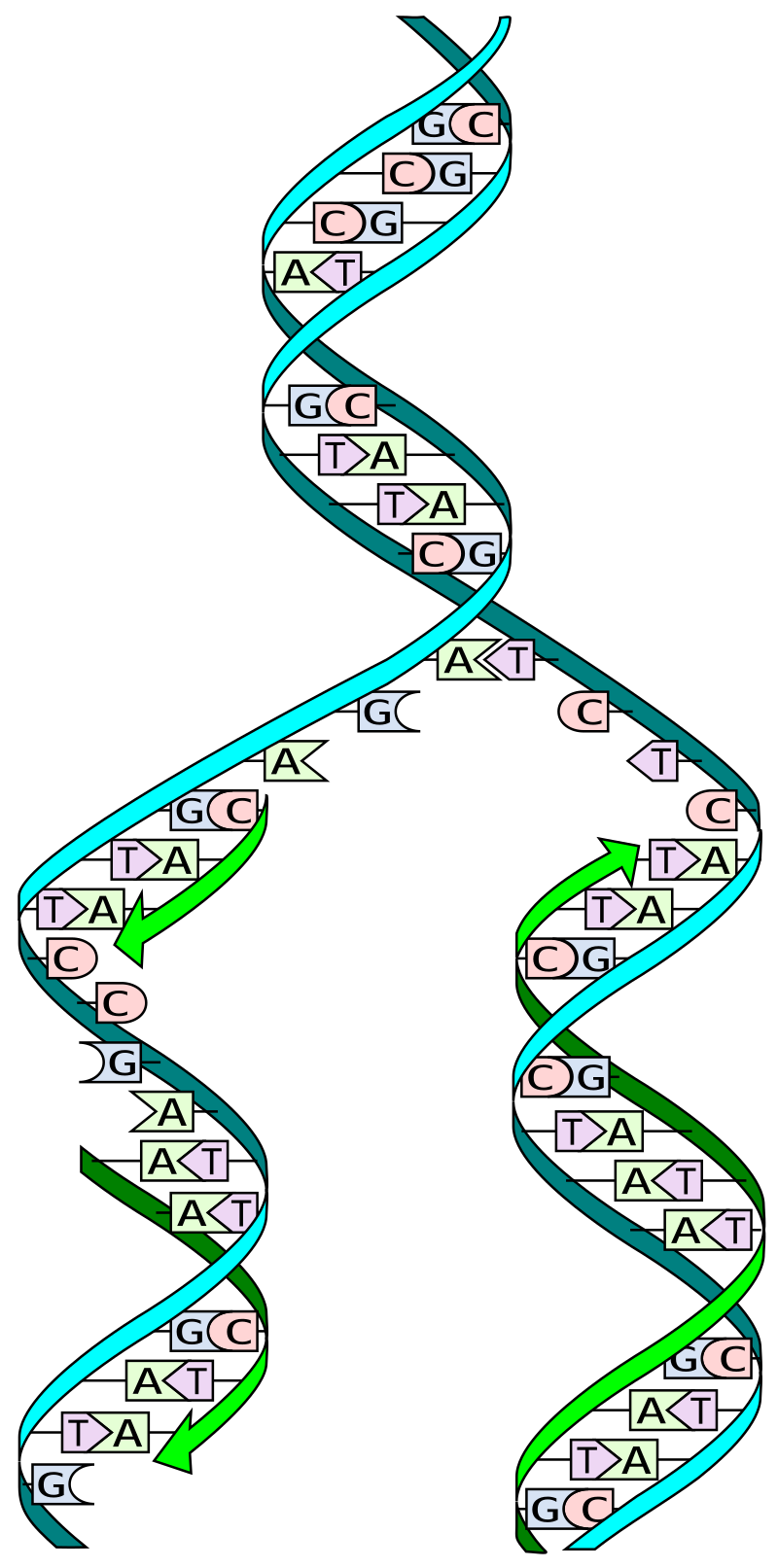

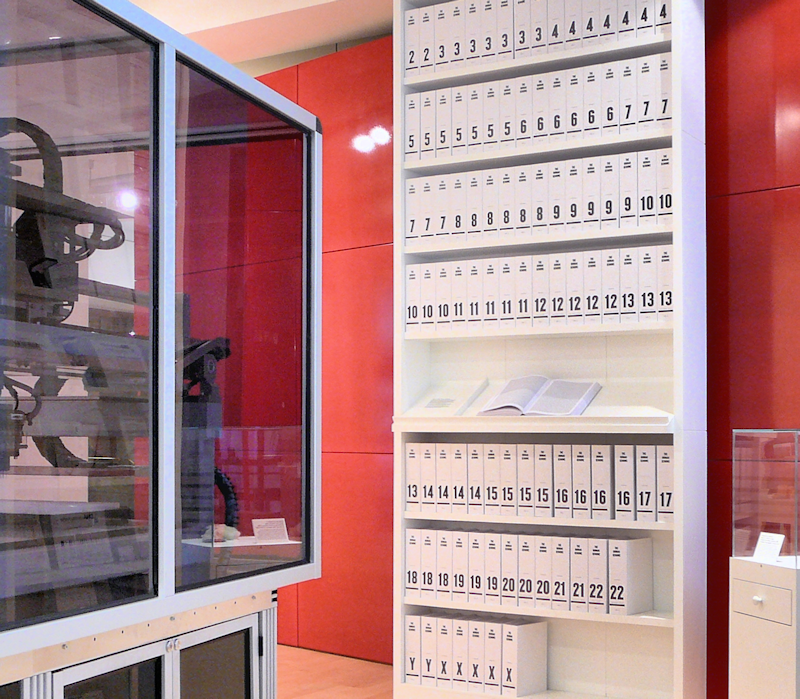

| Techniques and analysis The process of identifying the boundaries between genes and other features in a raw DNA sequence is called genome annotation and is in the domain of bioinformatics. While expert biologists make the best annotators, their work proceeds slowly, and computer programs are increasingly used to meet the high-throughput demands of genome sequencing projects. Beginning in 2008, a new technology known as RNA-seq was introduced that allowed scientists to directly sequence the messenger RNA in cells. This replaced previous methods of annotation, which relied on the inherent properties of the DNA sequence, with direct measurement, which was much more accurate. Today, annotation of the human genome and other genomes relies primarily on deep sequencing of the transcripts in every human tissue using RNA-seq. These experiments have revealed that over 90% of genes contain at least one and usually several alternative splice variants, in which the exons are combined in different ways to produce 2 or more gene products from the same locus.[56] The genome published by the HGP does not represent the sequence of every individual's genome. It is the combined mosaic of a small number of anonymous donors, of African, European and east Asian ancestry. The HGP genome is a scaffold for future work in identifying differences among individuals.[citation needed] Subsequent projects sequenced the genomes of multiple distinct ethnic groups, though as of 2019 there is still only one "reference genome".[57] Findings Key findings of the draft (2001) and complete (2004) genome sequences include: There are approximately 22,300[58] protein-coding genes in human beings, the same range as in other mammals. The human genome has significantly more segmental duplications (nearly identical, repeated sections of DNA) than had been previously suspected.[59][60][61] At the time when the draft sequence was published, fewer than 7% of protein families appeared to be vertebrate specific.[62] Accomplishments  The first printout of the human genome to be presented as a series of books, displayed at the Wellcome Collection, London The human genome has approximately 3.1 billion base pairs.[63] The Human Genome Project was started in 1990 with the goal of sequencing and identifying all base pairs in the human genetic instruction set, finding the genetic roots of disease and then developing treatments. It is considered a megaproject. The genome was broken into smaller pieces; approximately 150,000 base pairs in length.[64] These pieces were then ligated into a type of vector known as "bacterial artificial chromosomes", or BACs, which are derived from bacterial chromosomes which have been genetically engineered. The vectors containing the genes can be inserted into bacteria where they are copied by the bacterial DNA replication machinery. Each of these pieces was then sequenced separately as a small "shotgun" project and then assembled. The larger, 150,000 base pairs go together to create chromosomes. This is known as the "hierarchical shotgun" approach, because the genome is first broken into relatively large chunks, which are then mapped to chromosomes before being selected for sequencing.[65][66] Funding came from the US government through the National Institutes of Health in the United States, and a UK charity organization, the Wellcome Trust, as well as numerous other groups from around the world. The funding supported a number of large sequencing centers including those at Whitehead Institute, the Wellcome Sanger Institute (then called The Sanger Centre) based at the Wellcome Genome Campus, Washington University in St. Louis, and Baylor College of Medicine.[25][67] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) served as an important channel for the involvement of developing countries in the Human Genome Project.[68] |

技術と解析 未加工のDNA配列中の遺伝子とその他の特徴との境界を特定するプロセスは、ゲノムアノテーションと呼ばれ、バイオインフォマティクスの領域である。専門 家である生物学者が最良のアノテーターを務める一方で、彼らの作業は遅々として進まず、ゲノム配列決定プロジェクトの高スループット要求に応えるために、 コンピュータープログラムがますます使用されるようになっている。2008年から、RNA-seqとして知られる新技術が導入され、科学者たちは細胞内の メッセンジャーRNAを直接配列決定できるようになった。これにより、DNA配列の固有の性質に頼っていたこれまでのアノテーション方法が、より正確な直 接測定に取って代わられた。今日、ヒトゲノムやその他のゲノムのアノテーションは、主にRNA-seqを用いたヒトの全組織における転写産物のディープ シーケンスに依存している。これらの実験により、遺伝子の90%以上が、少なくとも1つ、通常は数個の代替スプライスバリアントを含んでいることが明らか になった[56]。 HGPによって公表されたゲノムは、すべての個人のゲノムの配列を表しているわけではない。アフリカ、ヨーロッパ、東アジアに祖先を持つ少数の匿名ドナー のモザイクを組み合わせたものである。HGPゲノムは、個人間の差異を特定する今後の研究の足場となるものである[要出典]。その後のプロジェクトでは、 複数の異なる民族グループのゲノムの配列が決定されたが、2019年現在、「参照ゲノム」はまだ1つしかない[57]。 所見 ドラフト(2001年)と完全(2004年)のゲノム配列の主な発見は以下の通りである: ヒトには約22,300[58]のタンパク質をコードする遺伝子があり、これは他の哺乳類と同じ範囲である。 ヒトゲノムには、これまで疑われていたよりもかなり多くのセグメント重複(DNAのほぼ同一の繰り返し部分)がある[59][60][61]。 ドラフト配列が発表された時点では、脊椎動物に特異的と思われるタンパク質ファミリーは7%以下であった[62]。 成果  ヒトゲノムのプリントアウトが初めて一連の書籍として出版された。 ヒトゲノムには約31億の塩基対がある。[63] ヒトゲノム計画は、ヒトの遺伝子の命令セットの全塩基対の配列決定と同定、病気の遺伝的ルーツの発見、そして治療法の開発を目的として1990年に開始された。これは巨大プロジェクトと考えられている。 ゲノムは、長さ約15万塩基対の小さな断片に分割された[64]。これらの断片は次に、遺伝子操作された細菌染色体から派生した「細菌人工染色体」 (BAC)として知られる一種のベクターにライゲーションされた。遺伝子を含むベクターはバクテリアに挿入され、バクテリアのDNA複製装置によってコ ピーされる。これらの断片はそれぞれ、小さな 「ショットガン 」プロジェクトとして別々に配列決定され、その後組み立てられた。より大きな15万塩基対が組み合わされ、染色体が作られる。これは「階層的ショットガ ン」と呼ばれる手法で、ゲノムをまず比較的大きな塊に分割し、それを染色体にマッピングしてから塩基配列を決定するというものである[65][66]。 資金提供は、米国の国立衛生研究所を通じた米国政府、英国の慈善団体であるウェルカム・トラスト、その他世界中の数多くのグループからであった。この資金 は、ホワイトヘッド研究所、ウェルカム・ゲノム・キャンパスを拠点とするウェルカム・サンガー研究所(当時はサンガー・センターと呼ばれていた)、セント ルイスのワシントン大学、ベイラー医科大学など、多くの大規模シークエンシングセンターを支えた[25][67]。 国連教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ)は、ヒトゲノム計画に発展途上国が参加するための重要なチャネルとして機能した[68]。 |

| Public versus private approaches In 1998, a similar, privately funded quest was launched by the American researcher Craig Venter, and his firm Celera Genomics. Venter was a scientist at the NIH during the early 1990s when the project was initiated. The $300 million Celera effort was intended to proceed at a faster pace and at a fraction of the cost of the roughly $3 billion publicly funded project. While the Celera project focused its efforts on production sequencing and assembly of the human genome, the public HGP also funded mapping and sequencing of the worm, fly, and yeast genomes, funding of databases, development of new technologies, supporting bioinformatics and ethics programs, as well as polishing and assessment of the genome assembly.[69] Both the Celera and public approaches spent roughly $250 million on the production sequencing effort.[70] For sequence assembly, Celera made use of publicly available maps at GenBank, which Celera was capable of generating, but the availability of which was "beneficial" to the privately-funded project.[59] Celera used a technique called whole genome shotgun sequencing, employing pairwise end sequencing,[71] which had been used to sequence bacterial genomes of up to six million base pairs in length, but not for anything nearly as large as the three billion base pair human genome. Celera initially announced that it would seek patent protection on "only 200–300" genes, but later amended this to seeking "intellectual property protection" on "fully-characterized important structures" amounting to 100–300 targets. The firm eventually filed preliminary ("place-holder") patent applications on 6,500 whole or partial genes. Celera also promised to publish their findings in accordance with the terms of the 1996 "Bermuda Statement", by releasing new data annually (the HGP released its new data daily), although, unlike the publicly funded project, they would not permit free redistribution or scientific use of the data. The publicly funded competitors were compelled to release the first draft of the human genome before Celera for this reason. On July 7, 2000, the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Group released a first working draft on the web. The scientific community downloaded about 500 GB of information from the UCSC genome server in the first 24 hours of free and unrestricted access.[72] In March 2000, President Clinton, along with Prime Minister Tony Blair in a dual statement, urged that all researchers who wished to research the sequence should have "unencumbered access" to the genome sequence.[73] The statement sent Celera's stock plummeting and dragged down the biotechnology-heavy Nasdaq. The biotechnology sector lost about $50 billion in market capitalization in two days.[citation needed] Although the working draft was announced in June 2000, it was not until February 2001 that Celera and the HGP scientists published details of their drafts. Special issues of Nature (which published the publicly funded project's scientific paper)[59] described the methods used to produce the draft sequence and offered analysis of the sequence. These drafts covered about 83% of the genome (90% of the euchromatic regions with 150,000 gaps and the order and orientation of many segments not yet established). In February 2001, at the time of the joint publications, press releases announced that the project had been completed by both groups. Improved drafts were announced in 2003 and 2005, filling in to approximately 92% of the sequence currently.[citation needed] |

公的アプローチと民間アプローチ 1998年、アメリカの研究者クレイグ・ヴェンターと彼の会社セレラ・ジェノミクスによって、同様の民間資金による探求が開始された。ヴェンターは、この プロジェクトが開始された1990年代初頭、NIHの科学者であった。セレラ社の3億ドルのプロジェクトは、30億ドルの公的資金を投入したプロジェクト に比べ、より速いペースとわずかなコストで進めることを意図したものであった。セレラプロジェクトがヒトゲノムの生産配列決定とアセンブルに力を注いだの に対し、公的なHGPは、ミミズ、ハエ、酵母ゲノムのマッピングと配列決定、データベースの資金援助、新技術の開発、バイオインフォマティクスと倫理プロ グラムの支援、さらにゲノムアセンブリの研磨と評価にも資金を提供した[69]。 [69]。配列のアセンブリーについては、セレラ社はGenBankで公開されているマップを利用した[70]。 Celeraは、ペアワイズエンドシーケンスを採用した全ゲノムショットガンシーケンスと呼ばれる技術[71]を使用した。この技術は、長さ600万塩基 対までの細菌ゲノムのシーケンスには使用されていたが、30億塩基対のヒトゲノムほど大規模なものには使用されていなかった。 セレラは当初、「わずか200~300」の遺伝子について特許保護を求めると発表したが、後にこれを修正し、100~300のターゲットに相当する「完全 に特性化された重要な構造」についての「知的財産権保護」を求めるとした。同社は最終的に、6,500の遺伝子全体または部分的な遺伝子について予備的 (「プレースホルダー」)特許出願を行った。セレラはまた、1996年の 「バミューダ声明 」の条件に従って、毎年新しいデータを発表し(HGPは毎日新しいデータを発表している)、研究成果を公表することを約束した。ただし、公的資金によるプ ロジェクトとは異なり、データの自由な再配布や科学的利用は認めなかった。公的資金で運営されている競合他社は、このような理由でセレラ社よりも先にヒト ゲノムの最初の草稿を公開せざるを得なかったのである。2000年7月7日、UCSCゲノム・バイオインフォマティクス・グループは最初のワーキングドラ フトをウェブ上で公開した。科学者コミュニティは、UCSCゲノムサーバーから最初の24時間で約500GBの情報をダウンロードした[72]。 2000年3月、クリントン大統領はトニー・ブレア首相とともに二重の声明を発表し、ゲノム配列の研究を希望するすべての研究者がゲノム配列に「無制限に アクセス」できるようにすべきであると促した[73]。この声明によってセレラの株価は急落し、バイオテクノロジー大国のナスダックの足を引っ張った。バ イオテクノロジー・セクターは2日間で約500億ドルの時価総額を失った[要出典]。 作業草案は2000年6月に発表されたが、セレラとHGPの科学者が草案の詳細を発表したのは2001年2月のことだった。Nature』誌の特別号(公 的資金が投入されたプロジェクトの科学論文を掲載)[59]には、ドラフト配列の作成に使用された方法が記載され、配列の分析が提供された。これらの草稿 はゲノムの約83%をカバーしている(15万個のギャップがある真性領域の90%で、多くのセグメントの順序と方向はまだ確立されていない)。2001年 2月、共同発表の際、プレスリリースで両グループによるプロジェクト完了が発表された。2003年と2005年には改良されたドラフトが発表され、現在の ところ配列の約92%まで埋まっている[citation needed]。 |

| Genome donors In the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC) public-sector HGP, researchers collected blood (female) or sperm (male) samples from a large number of donors. Only a few of many collected samples were processed as DNA resources. Thus the donor identities were protected so neither donors nor scientists could know whose DNA was sequenced. DNA clones taken from many different libraries were used in the overall project, with most of those libraries being created by Pieter J. de Jong. Much of the sequence (>70%) of the reference genome produced by the public HGP came from a single anonymous male donor from Buffalo, New York, (code name RP11; the "RP" refers to Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center).[74][75]  Schematic karyogram of a human, showing an overview of the human genome, with 22 homologous chromosomes, both the female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the sex chromosome (bottom right), as well as the mitochondrial genome (to scale at bottom left). The blue scale to the left of each chromosome pair (and the mitochondrial genome) shows its length in terms of millions of DNA base pairs. Further information: Karyotype HGP scientists used white blood cells from the blood of two male and two female donors (randomly selected from 20 of each) – each donor yielding a separate DNA library. One of these libraries (RP11) was used considerably more than others, because of quality considerations. One minor technical issue is that male samples contain just over half as much DNA from the sex chromosomes (one X chromosome and one Y chromosome) compared to female samples (which contain two X chromosomes). The other 22 chromosomes (the autosomes) are the same for both sexes. Although the main sequencing phase of the HGP has been completed, studies of DNA variation continued in the International HapMap Project, whose goal was to identify patterns of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) groups (called haplotypes, or "haps"). The DNA samples for the HapMap came from a total of 270 individuals; Yoruba people in Ibadan, Nigeria; Japanese people in Tokyo; Han Chinese in Beijing; and the French Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) resource, which consisted of residents of the United States having ancestry from Western and Northern Europe. In the Celera Genomics private-sector project, DNA from five different individuals were used for sequencing. The lead scientist of Celera Genomics at that time, Craig Venter, later acknowledged (in a public letter to the journal Science) that his DNA was one of 21 samples in the pool, five of which were selected for use.[76][77] |

ゲノム提供者 国際ヒトゲノムシークエンシングコンソーシアム(IHGSC)の公共部門HGPでは、研究者は多数のドナーから血液(女性)または精子(男性)サンプルを 収集した。収集された多くのサンプルのうち、DNAリソースとして処理されたのはごく一部である。したがって、ドナーの身元は保護され、ドナーも科学者も 誰のDNAが塩基配列決定されたかを知ることはできなかった。プロジェクト全体では、多くの異なるライブラリーから採取されたDNAクローンが使用された が、それらのライブラリーのほとんどはPieter J. de Jongによって作成された。公開HGPで作成された参照ゲノムの塩基配列の大部分(70%以上)は、ニューヨーク州バッファローの匿名の男性ドナー (コードネームRP11、「RP」はロズウェル・パーク総合がんセンターを指す)から得られたものである[74][75]。  22本の相同染色体、女性版(XX)と男性版(XY)の性染色体(右下)、ミトコンドリアゲノム(左下の縮尺)。各染色体(およびミトコンドリアゲノム)の左側にある青いスケールは、その長さを数百万DNA塩基対で示している。 さらに詳しい情報はこちら: 核型 HGPの科学者たちは、男性2人、女性2人のドナーの血液から白血球を採取し(それぞれ20人から無作為に選択)、それぞれのドナーから別々のDNAライ ブラリーを得た。これらのライブラリーのうち1つ(RP11)は、品質への配慮から、他のものよりかなり多く使用された。技術的な小さな問題として、男性 サンプルには性染色体(X染色体1本とY染色体1本)のDNAが、女性サンプル(X染色体2本)に比べて半分強含まれている。他の22本の染色体(常染色 体)は男女とも同じである。 HGPの主要なシークエンシング段階は終了したが、DNA変異の研究は、一塩基多型(SNP)グループのパターン(ハプロタイプまたは「ハップ」と呼ばれ る)を特定することを目的とした国際ハップマップ・プロジェクトで継続された。ハップマップ用のDNAサンプルは、ナイジェリアのイバダンに住むヨルバ 人、東京に住む日本人、北京に住む漢民族、そして西ヨーロッパと北ヨーロッパの祖先を持つ米国住民からなるフランスのCentre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain(CEPH)リソース、合計270人から採取された。 セレラ・ジェノミクス社の民間プロジェクトでは、5人のDNAが配列決定に使われた。当時、セレラ・ジェノミクスの主任科学者であったクレイグ・ヴェン ターは、後に(『サイエンス』誌への公開書簡の中で)自分のDNAがプールの21サンプルのうちの1つであり、そのうちの5つが使用されるために選ばれた ことを認めた[76][77]。 |

| Developments With the sequence in hand, the next step was to identify the genetic variants that increase the risk for common diseases like cancer and diabetes.[24][64] It is anticipated that detailed knowledge of the human genome will provide new avenues for advances in medicine and biotechnology. Clear practical results of the project emerged even before the work was finished. For example, a number of companies, such as Myriad Genetics, started offering easy ways to administer genetic tests that can show predisposition to a variety of illnesses, including breast cancer, hemostasis disorders, cystic fibrosis, liver diseases and many others. Also, the etiologies for cancers, Alzheimer's disease and other areas of clinical interest are considered likely to benefit from genome information and possibly may lead in the long term to significant advances in their management.[78][79] There are also many tangible benefits for biologists. For example, a researcher investigating a certain form of cancer may have narrowed down their search to a particular gene. By visiting the human genome database on the World Wide Web, this researcher can examine what other scientists have written about this gene, including (potentially) the three-dimensional structure of its product, its functions, its evolutionary relationships to other human genes, or to genes in mice, yeast, or fruit flies, possible detrimental mutations, interactions with other genes, body tissues in which this gene is activated, and diseases associated with this gene or other datatypes. Further, a deeper understanding of the disease processes at the level of molecular biology may determine new therapeutic procedures. Given the established importance of DNA in molecular biology and its central role in determining the fundamental operation of cellular processes, it is likely that expanded knowledge in this area will facilitate medical advances in numerous areas of clinical interest that may not have been possible without them.[80] The analysis of similarities between DNA sequences from different organisms is also opening new avenues in the study of evolution. In many cases, evolutionary questions can now be framed in terms of molecular biology; indeed, many major evolutionary milestones (the emergence of the ribosome and organelles, the development of embryos with body plans, the vertebrate immune system) can be related to the molecular level. Many questions about the similarities and differences between humans and their closest relatives (the primates, and indeed the other mammals) are expected to be illuminated by the data in this project.[78][81] The project inspired and paved the way for genomic work in other fields, such as agriculture. For example, by studying the genetic composition of Tritium aestivum, the world's most commonly used bread wheat, great insight has been gained into the ways that domestication has impacted the evolution of the plant.[82] It is being investigated which loci are most susceptible to manipulation, and how this plays out in evolutionary terms. Genetic sequencing has allowed these questions to be addressed for the first time, as specific loci can be compared in wild and domesticated strains of the plant. This will allow for advances in the genetic modification in the future which could yield healthier and disease-resistant wheat crops, among other things. |

開発 ヒトゲノムの塩基配列を手にした次のステップは、癌や糖尿病といった一般的な疾患のリスクを高める遺伝子変異を特定することであった[24][64]。 ヒトゲノムの詳細な知識は、医学とバイオテクノロジーの進歩に新たな道をもたらすと期待されている。このプロジェクトの明確な実用的成果は、作業が終了す る前から現れていた。例えば、乳がん、止血障害、嚢胞性線維症、肝臓病など、さまざまな病気の素因を示すことができる遺伝子検査を、ミリアド・ジェネ ティックスのような多くの企業が簡単に実施する方法を提供し始めた。また、がん、アルツハイマー病、その他の臨床的に関心の高い分野の病因も、ゲノム情報 から恩恵を受ける可能性が高いと考えられており、長期的には、その管理の大幅な進歩につながる可能性がある[78][79]。 生物学者にとっても、多くの目に見える利益がある。例えば、ある種の癌を研究している研究者は、特定の遺伝子に絞り込んで研究しているかもしれない。ワー ルド・ワイド・ウェブ上のヒトゲノムデータベースにアクセスすることで、この研究者はこの遺伝子について他の科学者が書いていることを調べることができ る。(潜在的に)その産物の立体構造、その機能、他のヒト遺伝子やマウス、酵母、ミバエの遺伝子との進化的関係、起こりうる有害な突然変異、他の遺伝子と の相互作用、この遺伝子が活性化される身体組織、この遺伝子や他のデータ型に関連する疾患などである。さらに、分子生物学レベルで病気のプロセスを深く理 解することで、新たな治療法が決定されるかもしれない。分子生物学におけるDNAの重要性が確立され、細胞プロセスの基本的な作動を決定する上で中心的な 役割を担っていることを考えると、この分野における知識の拡大は、それなしでは不可能であったかもしれない多くの臨床的関心分野における医学の進歩を促進 すると思われる[80]。 異なる生物のDNA配列間の類似性の解析は、進化の研究にも新たな道を開いている。実際、多くの主要な進化の節目(リボソームとオルガネラの出現、ボディ プランを持つ胚の発生、脊椎動物の免疫系)は、分子レベルに関連づけることができる。ヒトとその近縁種(霊長類、そして実際に他の哺乳類)との類似点と相 違点に関する多くの疑問が、このプロジェクトのデータによって解明されることが期待される[78][81]。 このプロジェクトは、農業など他の分野でのゲノム研究に刺激を与え、道を開いた。例えば、世界で最も一般的に使用されているパンコムギである Tritium aestivumの遺伝子組成を研究することにより、家畜化がこの植物の進化にどのような影響を与えたかについて大きな洞察が得られた[82]。遺伝子配 列決定によって、植物の野生株と家畜化された株で特定の遺伝子座を比較することができるようになったため、このような疑問に初めて取り組むことができるよ うになった。これにより、将来的には遺伝子組み換えが進み、より健康で病気に強い小麦作物などが得られるようになるだろう。 |

| Ethical, legal, and social issues At the onset of the Human Genome Project, several ethical, legal, and social concerns were raised in regard to how increased knowledge of the human genome could be used to discriminate against people. One of the main concerns of most individuals was the fear that both employers and health insurance companies would refuse to hire individuals or refuse to provide insurance to people because of a health concern indicated by someone's genes.[83] In 1996, the United States passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which protects against the unauthorized and non-consensual release of individually identifiable health information to any entity not actively engaged in the provision of healthcare services to a patient.[84] Along with identifying all of the approximately 20,000–25,000 genes in the human genome (estimated at between 80,000 and 140,000 at the start of the project), the Human Genome Project also sought to address the ethical, legal, and social issues that were created by the onset of the project.[85] For that, the Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) program was founded in 1990. Five percent of the annual budget was allocated to address the ELSI arising from the project.[25][86] This budget started at approximately $1.57 million in the year 1990, but increased to approximately $18 million in the year 2014.[87] Whilst the project may offer significant benefits to medicine and scientific research, some authors have emphasized the need to address the potential social consequences of mapping the human genome. Historian of science Hans-Jörg Rheinberger wrote that "the prospect of 'molecularizing' diseases and their possible cure will have a profound impact on what patients expect from medical help, and on a new generation of doctors' perception of illness."[88] In July, 2024, an investigation by Undark Magazine[89] and co-published with STAT News[90] revealed for the first time several ethical lapses by the scientists spearheading the Human Genome Project. Chief among these was the use of roughly 75– percent of a single donor's DNA in the construction of the reference genome, despite informed consent forms, provided to each of the 20 anonymous donors participating, that indicated no more than 10 percent of any one donor's DNA would be used. About 10 percent of the reference genome belonged to one of the project's lead scientists, Pieter De Jong.[89] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Genome_Project |

倫理的、法的、社会的問題 ヒトゲノム計画が開始された当初、ヒトゲノムに関する知識の増大が人々を差別するためにどのように利用されるかに関して、いくつかの倫理的、法的、社会的 懸念が提起された。1996年、米国は医療保険の相互運用性と説明責任に関する法律(HIPAA)を制定し、患者に対する医療サービスの提供に積極的に関 与していないいかなる団体に対しても、個人を特定できる健康情報が無許可かつ同意なしに開示されることを防止した[84]。 ヒトゲノム計画では、ヒトゲノムに含まれる約20,000~25,000個の遺伝子(プロジェクト開始時点では80,000~140,000個と推定)を すべて同定するとともに、プロジェクトの開始によって生じた倫理的、法的、社会的問題に対処することも目指した[85]。この予算は、1990年には約 157万ドルであったが、2014年には約1800万ドルに増加した[87]。 このプロジェクトは医学と科学研究に大きな利益をもたらすかもしれないが、ヒトゲノムのマッピングがもたらす潜在的な社会的影響に対処する必要性を強調す る著者もいる。科学史家のハンス=ヨルグ・ラインベルガーは、「病気とその治療法の可能性が『分子化』されるという見通しは、患者が医療に何を期待する か、そして新世代の医師たちの病気に対する認識に大きな影響を与えるだろう」と書いている[88]。 2024年7月、『Undark』誌[89]がSTAT News[90]と共同発表した調査によって、ヒトゲノム計画を率いる科学者たちの倫理的な過ちが初めて明らかになった。その最たるものが、参加する20 人の匿名ドナーそれぞれにインフォームド・コンセントの文書が提出され、1人のドナーのDNAの10パーセント以上は使用しないことが示されていたにもか かわらず、参照ゲノムの構築に1人のドナーのDNAの約75パーセントを使用したことである。参照ゲノムの約10パーセントは、このプロジェクトの主任研 究者の一人であるピーテル・デ・ヨングのものであった[89]。 |

| 1000 Genomes Project – International research effort on genetic variation 100,000 Genomes Project – UK Government project that is sequencing whole genomes from National Health Service patients Chimpanzee genome project – Effort to determine the DNA sequence of the chimpanzee genome ENCODE – Research consortium investigating functional elements in human and model organism DNA Physiome HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee – Committee for human gene name standards Human Brain Project – Scientific research project Human Connectome Project – Research project Human Cytome Project – Single-cell biology and biochemistry Human Epigenome Project Human Microbiome Project – Former research initiative Human proteome project – Scientific project coordinated by the Human Proteome Organization Human Variome Project List of biological databases Neanderthal genome project – Effort to sequence the Neanderthal genome Wellcome Sanger Institute – British genomics research institute Genographic Project – Citizen science project https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Genome_Project |

1000ゲノムプロジェクト - 遺伝子変異に関する国際的な研究活動 100,000人ゲノムプロジェクト - 国民健康保険サービスの患者から全ゲノムの塩基配列を決定する英国政府のプロジェクト チンパンジーゲノムプロジェクト - チンパンジーゲノムのDNA配列を決定する取り組み ENCODE - ヒトおよびモデル生物DNAの機能要素を調査する研究コンソーシアム フィジオーム HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee - ヒト遺伝子命名基準委員会 Human Brain Project - 科学研究プロジェクト Human Connectome Project - 研究プロジェクト ヒトサイトームプロジェクト - 単一細胞生物学と生化学 ヒトエピゲノムプロジェクト ヒトマイクロバイオームプロジェクト - かつての研究イニシアティブ ヒトプロテオームプロジェクト - ヒトプロテオーム機構によって調整されている科学プロジェクト ヒトバリオームプロジェクト 生物学データベース一覧 ネアンデルタール人ゲノムプロジェクト - ネアンデルタール人ゲノムの配列決定に取り組む ウェルカム・サンガー研究所 - イギリスのゲノム研究機関 Genographic Project - 市民科学プロジェクト |

| The 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP),

taken place from January 2008 to 2015, was an international research

effort to establish the most detailed catalogue of human genetic

variation at the time. Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at

least one thousand anonymous healthy participants from a number of

different ethnic groups within the following three years, using

advancements in newly developed technologies. In 2010, the project

finished its pilot phase, which was described in detail in a

publication in the journal Nature.[1] In 2012, the sequencing of 1092

genomes was announced in a Nature publication.[2] In 2015, two papers

in Nature reported results and the completion of the project and

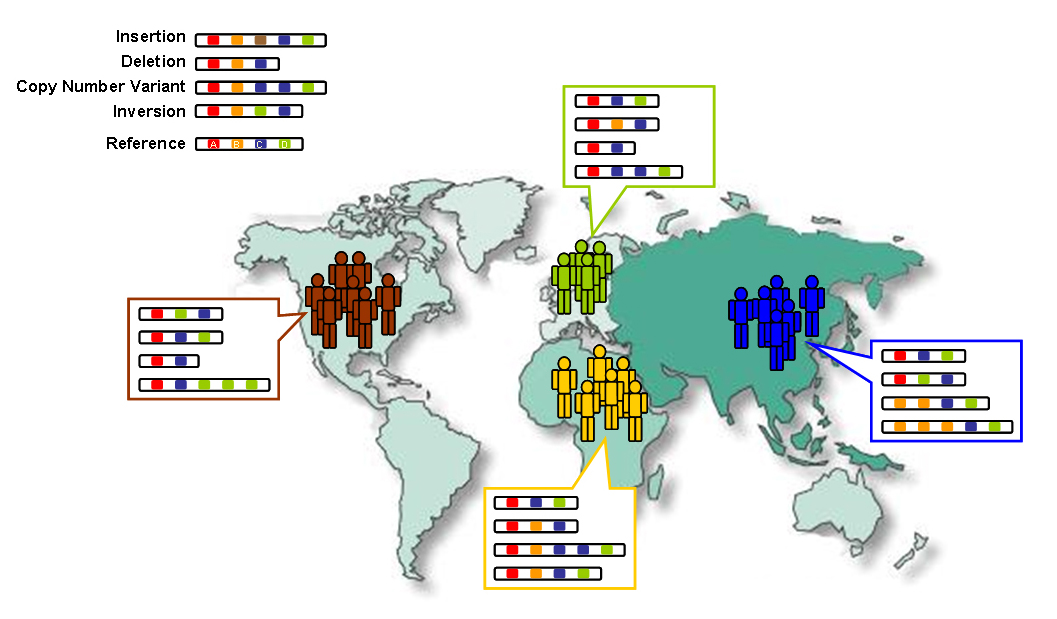

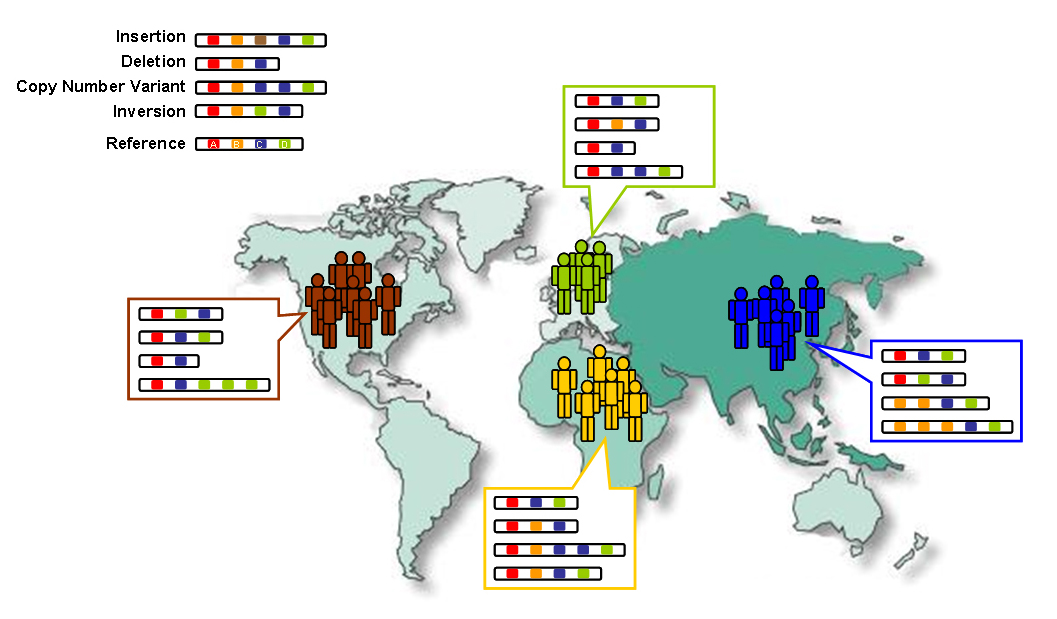

opportunities for future research.[3][4] Many rare variations, restricted to closely related groups, were identified, and eight structural-variation classes were analyzed.[5] The project united multidisciplinary research teams from institutes around the world, including China, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Nigeria, Peru, the United Kingdom, and the United States contributing to the sequence dataset and to a refined human genome map freely accessible through public databases to the scientific community and the general public alike.[2] The International Genome Sample Resource was created to host and expand on the data set after the project's end.[6]  Changes in the number and order of genes (A-D) create genetic diversity within and between populations |

2008

年1月から2015年まで行われた1000人ゲノムプロジェクト(1KGP)は、当時最も詳細なヒトの遺伝的変異のカタログを確立するための国際的な研究

活動であった。科学者たちは、新しく開発された技術の進歩を利用し、その後3年以内に、多くの異なる民族から少なくとも1000人の匿名の健康な参加者の

ゲノムの配列を決定することを計画した。2010年、このプロジェクトは試験段階を終了し、その詳細は学術誌『Nature』に掲載された[1]。

2012年、1092人のゲノムの塩基配列決定が『Nature』誌で発表された[2]。2015年、『Nature』誌に掲載された2つの論文で、プロ

ジェクトの結果と終了、そして今後の研究の可能性が報告された[3][4]。 近縁のグループに限定された多くの稀な変異が同定され、8つの構造変異クラスが解析された[5]。 このプロジェクトは、中国、イタリア、日本、ケニア、ナイジェリア、ペルー、英国、米国など、世界中の研究機関の学際的研究チームを結集し、配列データセットと、公開データベースを通じて科学界と一般市民が自由にアクセスできる精緻なヒトゲノムマップに貢献した[2]。 国際ゲノム・サンプル・リソース(International Genome Sample Resource)は、プロジェクト終了後にデータセットをホストし、拡張するために設立された[6]。  遺伝子の数と順序の変化(A-D)は、集団内および集団間の遺伝的多様性を生み出す。 |

| Background Since the completion of the Human Genome Project advances in human population genetics and comparative genomics enabled further insight into genetic diversity.[7] The understanding about structural variations (insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNV), retroelements), single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and natural selection were being solidified.[8][9][10][11] The diversity of Human genetic variation such as that Indels were being uncovered and investigating human genomic variations[citation needed] Natural selection It also aimed to provide evidence that can be used to explore the impact of Natural selection on population differences. Patterns of DNA polymorphisms can be used to reliably detect signatures of selection and may help to identify genes that might underlie variation in disease resistance or drug metabolism.[12][13] Such insights could improve understanding of phenotypic variations, genetic disorders and Mendelian inheritance and their effects on survival and/or reproduction of different human populations. Project description This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2021) Goals The 1000 Genomes Project was designed to bridge the gap of knowledge between rare genetic variants that have a severe effect predominantly on simple traits (e.g. cystic fibrosis, Huntington disease) and common genetic variants have a mild effect and are implicated in complex traits (e.g. cognition, diabetes, heart disease).[14] The primary goal of this project was to create a complete and detailed catalogue of human genetic variations, which can be used for association studies relating genetic variation to disease. The consortium aimed to discover >95 % of the variants (e.g. SNPs, CNVs, indels) with minor allele frequencies as low as 1% across the genome and 0.1-0.5% in gene regions, as well as to estimate the population frequencies, haplotype backgrounds and linkage disequilibrium patterns of variant alleles.[15] Secondary goals included the support of better SNP and probe selection for genotyping platforms in future studies and the improvement of the human reference sequence. The completed database was expected be a useful tool for studying regions under selection, variation in multiple populations and understanding the underlying processes of mutation and recombination.[15] Outline The human genome consists of approximately 3 billion DNA base pairs and is estimated to carry around 20,000 protein coding genes. In designing the study the consortium needed to address several critical issues regarding the project metrics such as technology challenges, data quality standards and sequence coverage.[15] Over the course of the next three years,[clarification needed] scientists at the Sanger Institute, BGI Shenzhen and the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Large-Scale Sequencing Network planned to sequence a minimum of 1,000 human genomes. Due to the large amount of sequence data that was required, recruiting additional participants was maintained.[14] Almost 10 billion bases were to be sequenced per day over a period of the two year production phase, equating to more than two human genomes every 24 hours. The intended sequence dataset was to comprise 6 trillion DNA bases, 60-fold more sequence data than what has been published in DNA databases at the time.[14] To determine the final design of the full project three pilot studies were to be carried out within the first year of the project. The first pilot intends to genotype 180 people of 3 major geographic groups at low coverage (2×). For the second pilot study, the genomes of two nuclear families (both parents and an adult child) are going to be sequenced with deep coverage (20× per genome). The third pilot study involves sequencing the coding regions (exons) of 1,000 genes in 1,000 people with deep coverage (20×).[14][15] It was estimated that the project would likely cost more than $500 million if standard DNA sequencing technologies were used. Several newer technologies (e.g. Solexa, 454, SOLiD) were to be applied, lowering the expected costs to between $30 million and $50 million. The major support will be provided by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, England; the Beijing Genomics Institute, Shenzhen (BGI Shenzhen), China; and the NHGRI, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).[14] In keeping with Fort Lauderdale principles Archived 2013-12-28 at the Wayback Machine, all genome sequence data (including variant calls) is freely available as the project progresses and can be downloaded via ftp from the 1000 genomes project webpage. Human genome samples  Locations of population samples of 1000 Genomes Project.[16] Each circle represents the number of sequences in the final release. Based on the overall goals for the project, the samples will be chosen to provide power in populations where association studies for common diseases are being carried out. Furthermore, the samples do not need to have medical or phenotype information since the proposed catalogue will be a basic resource on human variation.[15] For the pilot studies human genome samples from the HapMap collection will be sequenced. It will be useful to focus on samples that have additional data available (such as ENCODE sequence, genome-wide genotypes, fosmid-end sequence, structural variation assays, and gene expression) to be able to compare the results with those from other projects.[15] Complying with extensive ethical procedures, the 1000 Genomes Project will then use samples from volunteer donors. The following populations will be included in the study: Yoruba in Ibadan (YRI), Nigeria; Japanese in Tokyo (JPT); Chinese in Beijing (CHB); Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe (CEU); Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK); Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (MKK); Toscani in Italy (TSI); Peruvians in Lima, Peru (PEL); Gujarati Indians in Houston (GIH); Chinese in metropolitan Denver (CHD); people of Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles (MXL); and people of African ancestry in the southwestern United States (ASW).[14]  Community meeting Data generated by the 1000 Genomes Project is widely used by the genetics community, making the first 1000 Genomes Project one of the most cited papers in biology.[17] To support this user community, the project held a community analysis meeting in July 2012 that included talks highlighting key project discoveries, their impact on population genetics and human disease studies, and summaries of other large-scale sequencing studies.[18] Project findings Pilot phase The pilot phase consisted of three projects: low-coverage whole-genome sequencing of 179 individuals from 4 populations high-coverage sequencing of 2 trios (mother-father-child) exon-targeted sequencing of 697 individuals from 7 populations It was found that on average, each person carries around 250–300 loss-of-function variants in annotated genes and 50-100 variants previously implicated in inherited disorders. Based on the two trios, it is estimated that the rate of de novo germline mutation is approximately 10−8 per base per generation.[1] |

背景 ヒトゲノムプロジェクトが完了して以来、ヒト集団遺伝学と比較ゲノム学の進歩により、遺伝的多様性についてのさらなる洞察が可能になった[7]。構造変異 (挿入/欠失(インデル)、コピー数変異(CNV)、レトロエレメント)、一塩基多型(SNP)、自然淘汰についての理解が固まりつつあった[8][9] [10][11]。 インデルのようなヒトの遺伝的変異の多様性が明らかにされ、ヒトゲノムの変異が調査されていた[要出典]。 自然淘汰 また、集団の違いに対する自然淘汰の影響を探るために使用できる証拠を提供することも目的としていた。DNA多型のパターンは、淘汰のサインを確実に検出 するために使用することができ、疾患耐性や薬物代謝における変異の根底にある遺伝子を同定するのに役立つ可能性がある[12][13]。このような洞察 は、表現型の変異、遺伝性疾患、メンデル遺伝、およびそれらが異なるヒト集団の生存や繁殖に及ぼす影響についての理解を向上させる可能性がある。 プロジェクトの説明 このセクションは更新が必要である。最近の出来事や新たに入手した情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力いただきたい。(2021年4月) 目標 1000人ゲノムプロジェクトは、主に単純な形質(嚢胞性線維症、ハンチントン病など)に深刻な影響を及ぼすまれな遺伝的変異と、複雑な形質(認知、糖尿 病、心臓病など)に関与する軽度の影響を及ぼす一般的な遺伝的変異との間の知識のギャップを埋めるために設計された[14]。 このプロジェクトの主な目標は、ヒトの遺伝的変異の完全かつ詳細なカタログを作成し、遺伝的変異と疾患との関連研究に利用できるようにすることであった。 コンソーシアムは、マイナーアレル頻度がゲノム全体で1%、遺伝子領域で0.1-0.5%と低い変異体(SNPs、CNVs、indelなど)の95%以 上を発見し、変異対立遺伝子の集団頻度、ハプロタイプの背景、連鎖不平衡パターンを推定することを目指した[15]。 二次的な目標としては、将来の研究におけるジェノタイピングプラットフォームのためのより良いSNPとプローブの選択のサポート、およびヒトの参照配列の 改良が含まれた[15]。完成したデータベースは、選択下にある領域の研究、複数の集団における変異の研究、変異と組換えの基礎過程の理解に有用なツール となることが期待された[15]。 概要 ヒトゲノムは約30億のDNA塩基対からなり、約20,000のタンパク質コード遺伝子を持つと推定されている。この研究を設計するにあたり、コンソーシ アムは、技術的課題、データ品質基準、配列カバレッジなど、プロジェクトの指標に関するいくつかの重要な問題に取り組む必要があった[15]。 サンガー研究所、BGI深圳、そして国民ゲノム研究所のLarge-Scale Sequencing Networkの科学者たちは、今後3年間で、最低でも1,000のヒトゲノムの配列を決定することを計画した。大量の配列データが必要なため、参加者の 追加募集は維持された[14]。 2年間の製作期間中、1日あたりほぼ100億塩基の塩基配列が決定される予定であり、これは24時間ごとに2人以上のヒトゲノムの塩基配列が決定されるこ とに相当する。意図された塩基配列データセットは、6兆個のDNA塩基で構成される予定であり、当時のDNAデータベースで公開されていた塩基配列データ の60倍であった[14]。 プロジェクト全体の最終的な設計を決定するために、プロジェクトの最初の1年間に3つのパイロット研究が実施されることになっていた。最初のパイロット研 究では、3つの主要な地理的グループの180人を低カバレッジ(2×)で遺伝子型解析する予定である。2つ目のパイロット研究では、2つの核家族(両親と 成人した子供)のゲノムをディープカバレッジ(ゲノムあたり20倍)で配列決定する。3番目のパイロット研究では、1,000人の1,000遺伝子のコー ド領域(エクソン)をディープカバレッジ(20倍)で配列決定する[14][15]。 標準的なDNA配列決定技術を使用した場合、このプロジェクトには5億ドル以上の費用がかかると見積もられている。いくつかの新しい技術(Solexa、 454、SOLiDなど)が適用され、予想されるコストは3,000万ドルから5,000万ドルの間に引き下げられる予定であった。主な支援は、英国ヒン クストンのウェルカム・トラスト・サンガー研究所、中国深センの北京ゲノム研究所(BGI Shenzhen)、および国民衛生研究所(NIH)の一部であるNHGRIが行う予定である[14]。 フォートローダーデールの原則に則り、プロジェクトの進行に伴い、すべてのゲノム配列データ(バリアントコールを含む)が自由に利用できるようになり、1000ゲノムプロジェクトのウェブページからftp経由でダウンロードできるようになった。 ヒトゲノムサンプル  1000ゲノムプロジェクトの集団サンプルの位置[16]。各円は最終リリースに含まれる配列数を表す。 プロジェクトの全体的な目標に基づき、サンプルは一般的な疾患の関連研究が行われている集団で力を発揮するように選ばれる。さらに、提案されているカタロ グはヒトの変異に関する基本的なリソースとなるため、サンプルは医学的情報や表現型情報を持っている必要はない[15]。 パイロット研究では、HapMapコレクションからのヒトゲノムサンプルが配列決定される。他のプロジェクトからの結果と比較できるように、追加データ (ENCODE配列、ゲノムワイド遺伝子型、ホスミド末端配列、構造変異アッセイ、遺伝子発現など)が利用可能なサンプルに焦点を当てることは有用であろ う[15]。 広範な倫理的手続きを遵守し、1000人ゲノムプロジェクトはボランティアドナーからのサンプルを使用する。以下の集団が研究の対象となる: ナイジェリアのイバダンに住むヨルバ人(YRI)、東京に住む日本人(JPT)、北京に住む中国人(CHB)、ヨーロッパ北部および西部の祖先を持つユタ 州の住民(CEU)、ケニアのウェブイエに住むルヒヤ人(LWK)、ケニアのキニヤワに住むマサイ人(MKK)、イタリアのトスカーニ人(TSI); ペルーのリマに住むペルー人(PEL)、ヒューストンに住むグジャラティ・インディアン(GIH)、デンバー大都市圏に住む中国人(CHD)、ロサンゼル スに住むメキシコ系祖先を持つ人々(MXL)、アメリカ南西部に住むアフリカ系祖先を持つ人々(ASW)である。 [14]  コミュニティミーティング 1000ゲノムプロジェクトによって生成されたデータは、遺伝学のコミュニティで広く利用されており、最初の1000ゲノムプロジェクトは生物学で最も引 用された論文の1つとなっている[17]。このユーザーコミュニティを支援するため、プロジェクトは2012年7月にコミュニティ分析会議を開催し、プロ ジェクトの主要な発見、集団遺伝学やヒト疾患研究への影響、他の大規模シーケンス研究の概要について講演を行った[18]。 プロジェクトの成果 パイロット段階 パイロットフェーズは3つのプロジェクトで構成されていた: 4つの集団から179人の低カバレッジ全ゲノムシーケンス 2つのトリオ(母-父-子)のハイカバレッジシークエンシング 7個体群から697個体のエクソンターゲットシークエンシング その結果、注釈付き遺伝子の機能喪失バリアントは平均して一人当たり約250~300個、遺伝性疾患に以前から関与していたバリアントは50~100個保 有していることが判明した。この2つのトリオに基づくと、de novo生殖細胞突然変異の割合は、1世代あたり1塩基あたり約10-8であると推定される[1]。 |

| Human Genome Project HapMap Project Personal genomics Population groups in biomedicine 1000 Plant Genomes Project List of biological databases |

ヒトゲノムプロジェクト ハップマッププロジェクト 個人ゲノム 生物医学における集団 1000植物ゲノムプロジェクト 生物学データベースのリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1000_Genomes_Project |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆