インフォームド・コンセント

Informed consent

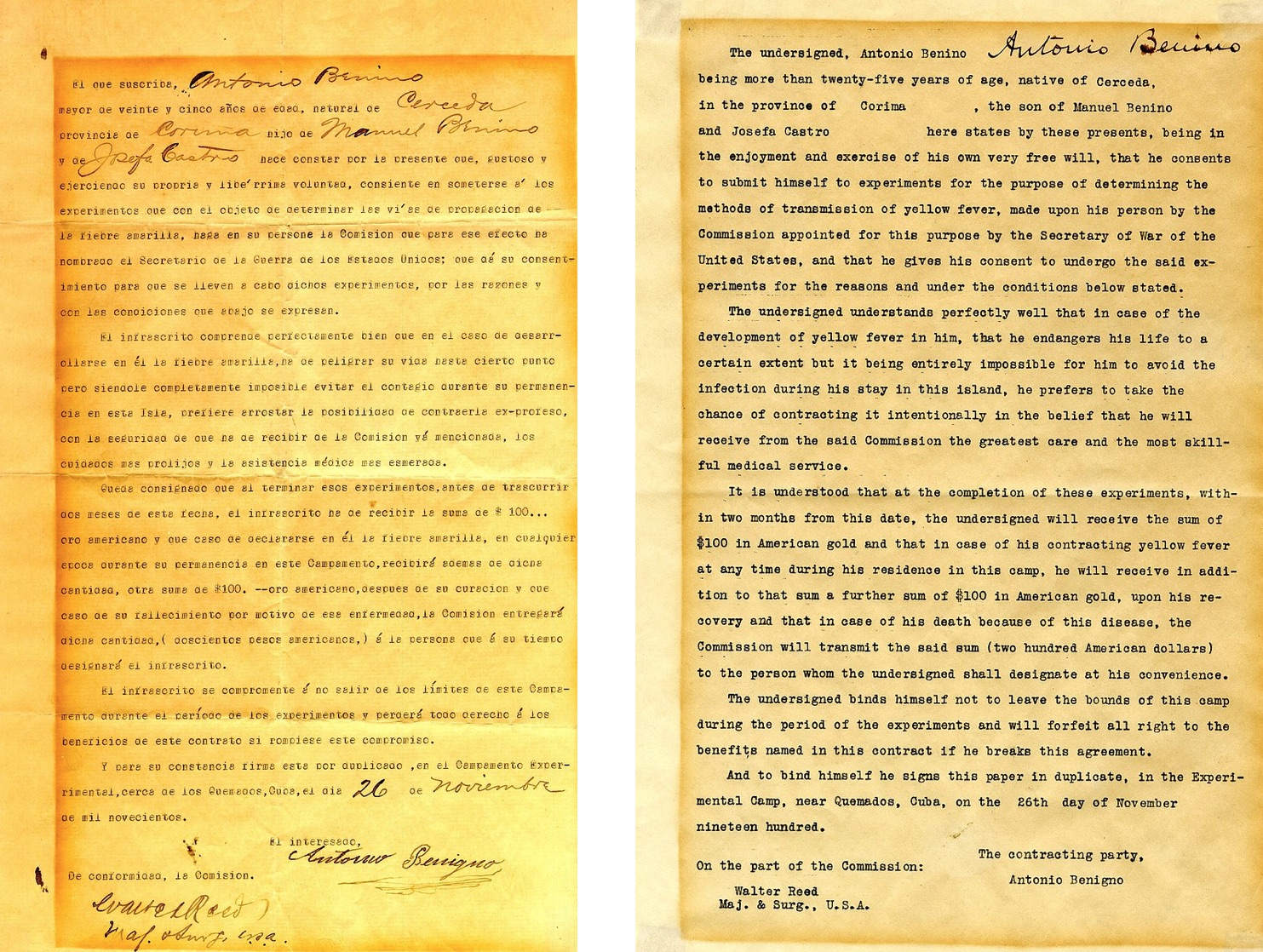

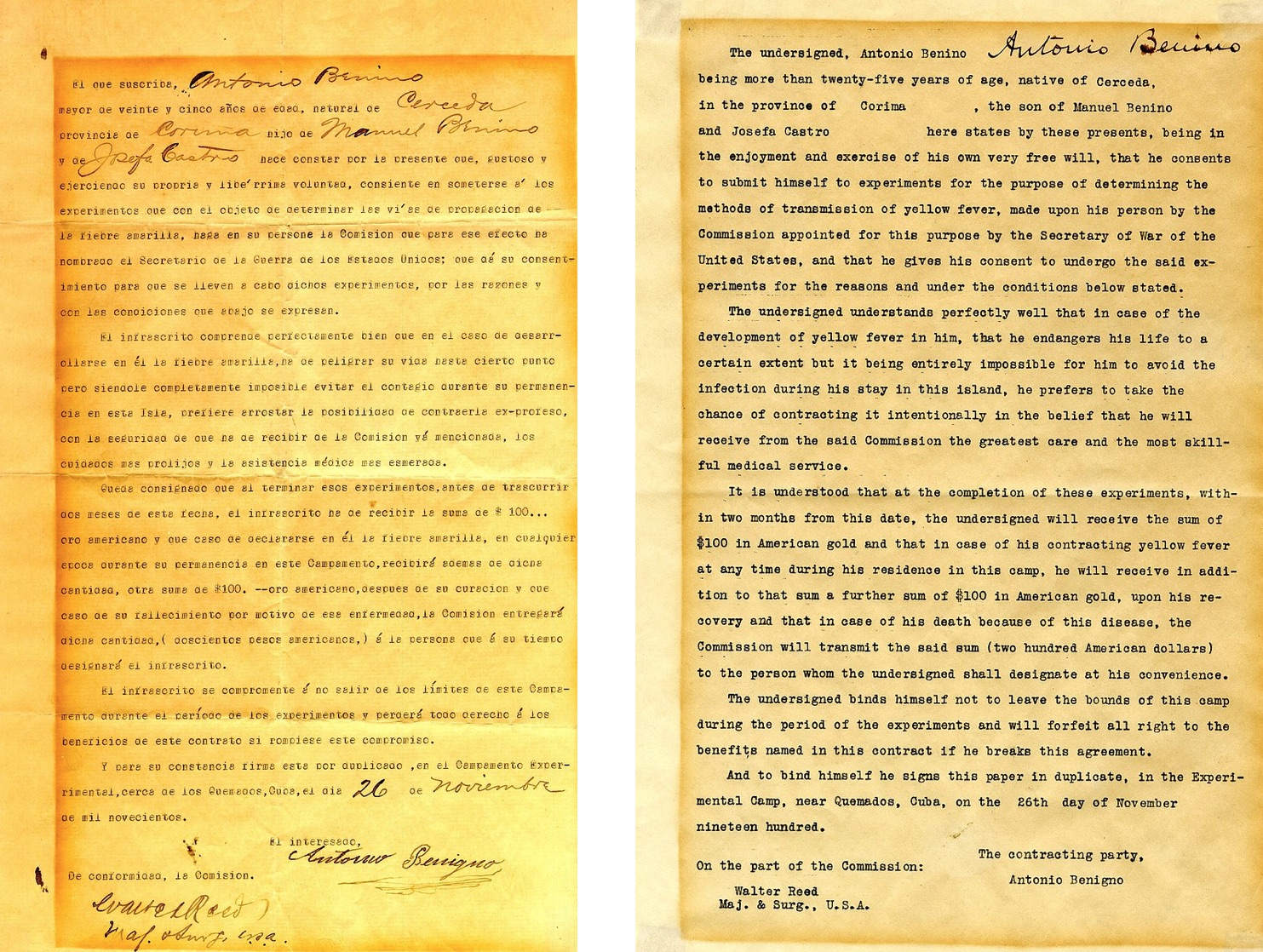

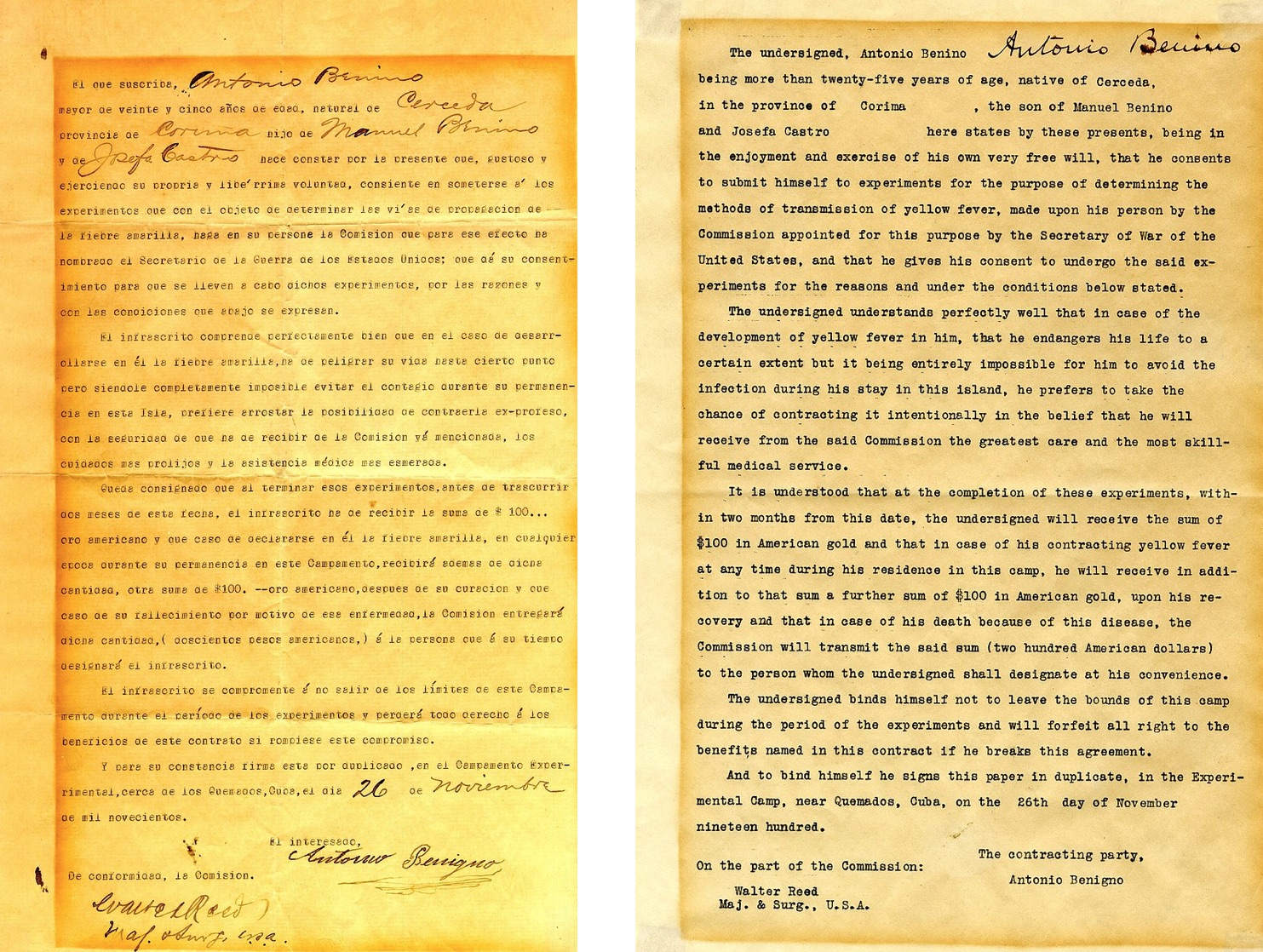

Informed consent document in which research participant Antonio Benigno agrees to researcher Walter Reed's clinical trial examining the transmission of yellow fever.

☆ インフォームド・コンセント(Informed consent, IC)とは、ある契約において、文字通り、契約する者が包み隠されることのない「情報を提供された状態(informed)」をもってはじめて、契約者が 合意/不同意を決定することができると考える契約のタイプのことを言い、また、そのような「情報を包み隠さず提供された上で合意した状態」のことをさす。

☆さて、インフォームド・コンセントには現在2つの顔がある;ひとつは(1)我々の日常生活のなかで定着しつつある説明を聞いた上での同意(不同意を含む)概念や慣行、であり、もうひとつは(2)合理的な2者のあいだで締結する理想的契約関係あるいは擬制のことである。

★「ヘルシンキ宣言」にはICが、医学研究者と被験者の間の契約が必須ということを示唆している。日本における医療者と患者の間のインフォームドコン セントも、この宣言に準拠するものとして取り扱われている。

★ヘルシンキ宣言においてICがあるのは、24項、26項、29項である。

★ 「24. 判断能力のある人間を対象とする医学研究において、それぞれの被験者候補 は、目的、方法、資金源、起こりうる利益相反、研究者の関連組織との関わり、 研究によって期待される利益と起こりうるリスク、ならびに研究に伴いうる不 快な状態、その他研究に関するすべての側面について、十分に説明されなけれ ばならない。被験者候補は、いつでも不利益を受けることなしに、研究参加を 拒否するか、または参加の同意を撤回する権利のあることを知らされなければ ならない。被験者候補ごとにどのような情報を必要としているかとその情報の 伝達方法についても特別な配慮が必要である。被験者候補がその情報を理解し たことを確認したうえで、医師または他の適切な有資格者は、被験者候補の自由意思に よるインフォームド・コンセントを、望ましくは文書で求めなければ ならない。同意が書面で表明されない場合、その文書によらない同意 は、正式 な文書に記録され、証人によって証明されるべきである。」

"24.

In medical research involving competent human subjects, each potential

subject must be adequately informed of the aims, methods, sources of

funding, any possible conflicts of interest, institutional affiliations

of the researcher, the anticipated benefits and potential risks of the

study and the discomfort it may entail, and any other relevant aspects

of the study. The potential subject must be informed of the right to

refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw consent to

participate at any time without reprisal. Special attention should be

given to the specific information needs of individual potential

subjects as well as to the methods used to deliver the information.

After ensuring that the potential subject has understood the

information, the physician or another appropriately qualified

individual must then seek the potential subject’s freely-given informed

consent, preferably in writing. If the consent cannot be expressed in

writing, the non-written consent must be formally documented and

witnessed."

★

「26. 研究参加へのインフォームド・コンセントを求 める場合、医師は、被験者候補

が医師に依存した関係にあるか否か、または強制の下に同意するおそれがあるか否かについて、特別に注意すべきである。このような状況下では、インフォ

ームド・コンセントは、そのような関係とは完全に独立した、適切な有資格者 によって求められるべきである。」

"26.

When seeking informed consent for participation in a research study the

physician should be particularly cautious if the potential subject is

in a dependent relationship with the physician or may consent under

duress. In such situations the informed consent should be sought by an

appropriately qualified individual who is completely independent of

this relationship."

★29項は、ICがとれない場合の必要条件や代替的方法に書いてあるが、これはかなり問題含みの内容である。

★「29. 例えば、意識不明の患者のように、肉体的、精神的に同意を与えることができ ない被験者を対象とした研究は、インフォームド・コンセントを与えることを 妨げる肉体的・精神的状態が、その対象集団の必要な特徴である場合に限って 行うことができる。このような状況では、医師は法律上の権限を有する代理人 からのインフォームド・コンセントを求めるべきである。そのような代理人が 存在せず、かつ研究を延期することができない場合には、インフォームド・コ ンセントを与えることができない状態にある被験者を対象とする特別な理由を 研究計画書の中で述べ、かつ研究倫理委員会で承認されることを条件として、 この研究はインフォームド・コンセントなしに開始することができる。 研究に 引き続き参加することに対する同意を、できるだけ早く被験者または法律上の 代理人から取得するべきである。」

"29.

Research involving subjects who are physically or mentally incapable of

giving consent, for example, unconscious patients, may be done only if

the physical or mental condition that prevents giving informed consent

is a necessary characteristic of the research population. In such

circumstances the physician should seek informed consent from the

legally authorized representative. If no such representative is

available and if the research cannot be delayed, the study may proceed

without informed consent provided that the specific reasons for

involving subjects with a condition that renders them unable to give

informed consent have been stated in the research protocol and the

study has been approved by a research ethics committee. Consent to

remain in the research should be obtained as soon as possible from the

subject or a legally authorized representative."

★イ ンフォームド・コンセントとは、医療倫理、医療法、メディア研究における原則であり、患者が医療ケアに関する決定を行う前に、十分な情報と理解を得ていな ければならないというものである。適切な情報には、治療のリスクと利益、代替治療、治療における患者の役割、治療を拒否する権利などが含まれる。ほとんど の制度では、医療従事者は患者の同意が十分な情報に基づいたものであることを保証する法的および倫理的な責任を負っている。この原則は、医療介入よりも広 範に適用され、例えば研究の実施や個人の医療情報の開示などにも適用される。

Example of informed consent document from the PARAMOUNT trial

★小児に対する同意をとる方法は、インフォームド・アセント(Informed assent)といわれる(このページの下で説明)

| Informed consent

is a principle in medical ethics, medical law and media studies, that a

patient must have sufficient information and understanding before

making decisions about their medical care. Pertinent information may

include risks and benefits of treatments, alternative treatments, the

patient's role in treatment, and their right to refuse treatment. In

most systems, healthcare providers have a legal and ethical

responsibility to ensure that a patient's consent is informed. This

principle applies more broadly than healthcare intervention, for

example to conduct research and to disclose a person's medical

information. Within the US, definitions of informed consent vary, and the standard required is generally determined by the state.[1] These standards in medical contexts are formalized in the requirement for decision-making capacity and professional determinations in these contexts have legal authority.[2] This requirement can be summarized in brief to presently include the following conditions, all of which must be met in order for one to qualify as possessing decision-making capacity: 1. Choice, the ability to provide or evidence a decision. 2. Understanding, the capacity to apprehend the relevant facts pertaining to the decision at issue. 3. Appreciation, the ability of the patient to give informed consent with concern for, and belief in, the impact the relevant facts will have upon oneself. 4. Reasoning, the mental acuity to make the relevant inferences from, and mental manipulations of, the information appreciated and understood to apply to the decision at hand.[3] Impairments to reasoning and judgment that may preclude informed consent include intellectual or emotional immaturity, high levels of stress such as post-traumatic stress disorder or a severe intellectual disability, severe mental disorder, intoxication, severe sleep deprivation, dementia, or coma. Obtaining informed consent is not always required. If an individual is considered unable to give informed consent, another person is generally authorized to give consent on the individual's behalf—for example, the parents or legal guardians of a child (though in this circumstance the child may be required to provide informed assent) and conservators for the mentally disordered. Alternatively, the doctrine of implied consent permits treatment in limited cases, for example when an unconscious person will die without immediate intervention. Cases in which an individual is provided insufficient information to form a reasoned decision raise serious ethical issues. When these issues occur, or are anticipated to occur, in a clinical trial, they are subject to review by an ethics committee or institutional review board. Informed consent is codified in both national and international law. 'Free consent' is a cognate term in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted in 1966 by the United Nations, and intended to be in force by 23 March 1976. Article 7 of the covenant prohibits experiments conducted without the "free consent to medical or scientific experimentation" of the subject.[4] As of September 2019, the covenant has 173 parties and six more signatories without ratification.[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Informed_consent |

イ

ンフォームド・コンセントとは、医療倫理、医療法、メディア研究における原則であり、患者が医療ケアに関する決定を行う前に、十分な情報と理解を得ていな

ければならないというものである。適切な情報には、治療のリスクと利益、代替治療、治療における患者の役割、治療を拒否する権利などが含まれる。ほとんど

の制度では、医療従事者は患者の同意が十分な情報に基づいたものであることを保証する法的および倫理的な責任を負っている。この原則は、医療介入よりも広

範に適用され、例えば研究の実施や個人の医療情報の開示などにも適用される。 米国ではインフォームドコンセントの定義は様々であり、一般的に必要とされる基準は州によって決定される。[1] 医療の文脈におけるこれらの基準は意思決定能力の要件として正式化されており、医療の専門家の判断には法的権限がある。[2] この要件は簡単にまとめると、現在、以下の条件を含み、意思決定能力があると認められるためには、これらの条件をすべて満たさなければならない。 1. 選択:意思決定を行う能力、または意思決定の証拠を提示する能力。 2. 理解:問題となっている意思決定に関連する事実を把握する能力。 3. 評価:患者が、関連する事実が自身に与える影響を考慮し、それを信じる意思をもってインフォームド・コンセントを行う能力。 4. 推論:理解し理解した情報を基に、関連する推論を行う精神的な鋭敏さ、および精神的な操作。 インフォームド・コンセントを妨げる可能性がある推論および判断の障害には、知的または情緒的な未熟さ、心的外傷後ストレス障害などの高レベルのストレス、重度の知的障害、重度の精神障害、酩酊、重度の睡眠不足、認知症、または昏睡状態などが含まれる。 インフォームド・コンセントの取得は、常に必要とされるわけではない。インフォームド・コンセントを与える能力がないとみなされた場合、通常は、その個人 の代理として、別の人物が同意を与える権限を持つ。例えば、未成年者の両親または法定後見人(ただし、この状況では、未成年者はインフォームド・アセント を提供する必要がある場合がある)、および精神障害者の後見人などである。また、黙示の同意の原則により、例えば、即時の介入を行わないと意識不明の患者 が死亡するような場合など、限られた状況下での治療が許可される。個人が合理的な判断を下すのに十分な情報を提供されない場合、深刻な倫理上の問題が生じ る。臨床試験においてこのような問題が発生した場合、または発生が予想される場合、倫理委員会または治験審査委員会による審査の対象となる。 インフォームド・コンセントは、国内法および国際法の両方で規定されている。「自由意思による同意」は、1966年に国連で採択され、1976年3月23 日までに発効することが意図された「市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約」における同族語である。この協定の第7条では、対象者の「自由な同意」なしに 実施される医学的または科学的実験を禁止している。[4] 2019年9月現在、この協定には173の締約国があり、さらに6つの署名国があるが、批准はされていない。[5] |

| Assessment Informed consent can be complex to evaluate, because neither expressions of consent, nor expressions of understanding of implications, necessarily mean that full adult consent was in fact given, nor that full comprehension of relevant issues is internally digested.[6] Consent may be implied within the usual subtleties of human communication, rather than explicitly negotiated verbally or in writing. For example, if a doctor asks a patient to take their blood pressure, a patient may demonstrate consent by offering their arm for a blood pressure cuff. In some cases consent cannot legally be possible, even if the person protests he does indeed understand and wish. There are also structured instruments for evaluating capacity to give informed consent, although no ideal instrument presently exists.[7] Thus, there is always a degree to which informed consent must be assumed or inferred based upon observation, or knowledge, or legal reliance. This especially is the case in sexual or relational issues. In medical or formal circumstances, explicit agreement by means of signature—normally relied on legally—regardless of actual consent, is the norm. This is the case with certain procedures, such as a "do not resuscitate" directive that a patient signed before onset of their illness.[8] Brief examples of each of the above: 1. A person may verbally agree to something from fear, perceived social pressure, or psychological difficulty in asserting true feelings. The person requesting the action may honestly be unaware of this and believe the consent is genuine, and rely on it. Consent is expressed, but not internally given. 2. A person may claim to understand the implications of some action, as part of consent, but in fact has failed to appreciate the possible consequences fully and may later deny the validity of the consent for this reason. Understanding needed for informed consent is present but is, in fact (through ignorance), not present. 3. A person signs a legal release form for a medical procedure, and later feels he did not really consent. Unless he can show actual misinformation, the release is usually persuasive or conclusive in law, in that the clinician may rely legally upon it for consent. In formal circumstances, a written consent usually legally overrides later denial of informed consent (unless obtained by misrepresentation). 4. Informed consent in the U.S. can be overridden in emergency medical situations pursuant to 21CFR50.24, which was first brought to the general public's attention via the controversy surrounding the study of Polyheme. |

評価(アセスメント) インフォームド・コンセントの評価は複雑になりうる。なぜなら、同意の表明も、影響の理解の表明も、必ずしも成人による完全な同意が実際に与えられたこと を意味するわけではなく、関連する問題の完全な理解が内面的に消化されたことを意味するわけでもないからである。[6] 同意は、口頭または書面で明示的に交渉されるよりも、むしろ通常の人間同士のコミュニケーションの微妙なニュアンスの中で暗示される場合がある。例えば、 医師が患者に血圧を測るように頼んだ場合、患者は腕を血圧計のカフに当てることで同意を示すかもしれない。 本人が理解し、希望していると抗議しても、法的に同意が不可能な場合もある。 インフォームドコンセントを与える能力を評価するための構造化された手段もあるが、現時点では理想的な手段は存在しない。 したがって、インフォームドコンセントは、観察や知識、または法的信頼に基づいて想定または推測される程度が常に存在する。これは特に、性的または人間関 係に関する問題において顕著である。医療または正式な状況においては、実際の同意の有無に関わらず、通常は法的根拠として信頼される署名による明示的な合 意が一般的である。これは、患者が発症前に署名した「蘇生処置を行わない」指示書のような特定の手続きの場合である。 上記各項目の簡単な例: 1. ある人は、恐怖心や、知覚された社会的圧力、あるいは本音を主張することの心理的な困難さから、口頭で何かに同意することがある。その行為を要求する人 は、このことを正直に認識しておらず、同意が本物であると信じており、それに依存している。同意は表明されているが、内心では与えられていない。 2. ある行為の意味するところを理解していると主張するが、実際には起こりうる結果を十分に理解しておらず、後にこの理由で同意の正当性を否定する可能性がある。インフォームドコンセントに必要な理解は存在するが、実際には(無知により)存在していない。 3. ある人が医療処置に関する法的免責同意書に署名し、後に本当に同意したわけではないと感じた場合。 誤った情報が実際に提供されたことを証明できない限り、通常、免責同意書は説得力があり、法的に決定的なものであり、臨床医は同意に関して法的に免責同意 書に依拠することができる。 正式な状況では、書面による同意は通常、インフォームドコンセントの後の拒否を法的に無効にする(虚偽の陳述によって得られた同意を除く)。 4. 米国では、21CFR50.24に従い、緊急の医療状況下ではインフォームド・コンセントが優先される。ポリヘムの研究を巡る論争により、この規定が初めて一般の人々の注目を集めることとなった。 |

| Valid elements For an individual to give valid informed consent, three components must be present: disclosure, capacity and voluntariness.[9][10] 1. Disclosure requires the researcher to supply each prospective subject with the information necessary to make an autonomous decision and also to ensure that the subject adequately understands the information provided. This latter requirement implies that a written consent form be written in lay language suited for the comprehension skills of subject population, as well as assessing the level of understanding through conversation (to be informed). 2. Capacity pertains to the ability of the subject to both understand the information provided and form a reasonable judgment based on the potential consequences of his/her decision. 3. Voluntariness refers to the subject's right to freely exercise his/her decision making without being subjected to external pressure such as coercion, manipulation, or undue influence. |

有効な要素 個人が有効なインフォームドコンセントを与えるためには、次の3つの要素が必要である。開示、能力、自発性である。[9][10] 1. 開示(disclosure)とは、研究者が各被験者候補に、自律的な意思決定を行うために必要な情報を提供し、また、被験者が提供された情報を十分に理 解していることを確認することを意味する。この後者の要件は、会話による理解度を評価(通知)するとともに、被験者集団の理解力に適した平易な言葉で書面 による同意書を作成することを意味する。 2. 能力とは、被験者が提供された情報を理解し、自身の決定がもたらす可能性のある結果に基づいて合理的な判断を下す能力を指す。 3. 自発性とは、被験者が強制、操作、不当な影響力といった外部からの圧力を受けずに、自らの意思決定を自由に下す権利を指す。 |

| From children Main article: Informed assent See also: Pediatric medicine § Pediatric autonomy in healthcare As children often lack the decision-making ability or legal power (competence) to provide true informed consent for medical decisions, it often falls on parents or legal guardians to provide informed permission for medical decisions. This "consent by proxy" usually works reasonably well, but can lead to ethical dilemmas when the judgment of the parents or guardians and the medical professional differ with regard to what constitutes appropriate decisions "in the best interest of the child". Children who are legally emancipated, and certain situations such as decisions regarding sexually transmitted diseases or pregnancy, or for unemancipated minors who are deemed to have medical decision making capacity, may be able to provide consent without the need for parental permission depending on the laws of the jurisdiction the child lives in. The American Academy of Pediatrics encourages medical professionals also to seek the assent of older children and adolescents by providing age appropriate information to these children to help empower them in the decision-making process.[11] Research on children has benefited society in many ways. The only effective way to establish normal patterns of growth and metabolism is to do research on infants and young children. When addressing the issue of informed consent with children, the primary response is parental consent. This is valid, although only legal guardians are able to consent for a child, not adult siblings.[12] Additionally, parents may not order the termination of a treatment that is required to keep a child alive, even if they feel it is in the best interest.[12] Guardians are typically involved in the consent of children, however a number of doctrines have developed that allow children to receive health treatments without parental consent. For example, emancipated minors may consent to medical treatment, and minors can also consent in an emergency.[12] |

子供の場合 詳細は「インフォームド・アセント」を参照 小児医学 § 医療における小児の自律性」も参照 子供はしばしば、医療上の決定について真のインフォームドコンセントを与えるための意思決定能力や法的権限(能力)を欠いているため、医療上の決定につい てインフォームドコンセントを与えるのは、親や法的後見人の役割となることが多い。この「代理人による同意」は通常、妥当に機能するが、「子供の最善の利 益」となる適切な決定とは何かについて、親や後見人と医療従事者の判断が異なると、倫理的なジレンマにつながる可能性がある。法的に成人とみなされる子 供、および性感染症や妊娠に関する決定など特定の状況、あるいは医療上の決定能力があるとみなされる未成年者については、その子供が居住する管轄区域の法 律によっては、親の許可がなくても同意を与えることができる場合がある。米国小児科学会は、医療従事者に対して、意思決定プロセスにおけるこれらの子供た ちの能力向上を支援するために、年齢に適した情報を提供し、年長の子供や青少年の同意を得ることも推奨している。[11] 子供を対象とした研究は、さまざまな形で社会に貢献している。正常な成長と代謝のパターンを確立する唯一の有効な方法は、乳児と幼児を対象とした研究を行 うことである。子供を対象としたインフォームドコンセントの問題を扱う場合、第一の対応は親の同意である。これは有効であるが、未成年者の同意は法的後見 人にのみ認められており、成人した兄弟姉妹には認められていない。[12] さらに、たとえそれが最善の利益であると両親が感じていたとしても、子供を生かしておくために必要な治療の中止を両親が命じることはできない。[12] 通常、未成年者の同意には後見人が関与するが、両親の同意なしに子供が医療治療を受けられるようにする多くの原則が発展している。例えば、法的成人に達し た未成年者は医療処置に同意することができ、未成年者も緊急時には同意することができる。[12] |

| Waiver of requirement The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (December 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Waiver of the consent requirement may be applied in certain circumstances where no foreseeable harm is expected to result from the study or when permitted by law, federal regulations, or if an ethical review committee has approved the non-disclosure of certain information.[13] Besides studies with minimal risk, waivers of consent may be obtained in a military setting. According to 10 USC 980, the United States Code for the Armed Forces, Limitations on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, a waiver of advanced informed consent may be granted by the Secretary of Defense if a research project would:[14] 1. directly benefit subjects 2. advance the development of a medical product necessary to the military and 3. be carried out under all laws and regulations (i.e., Emergency Research Consent Waiver) including those pertinent to the FDA. While informed consent is a basic right and should be carried out effectively, if a patient is incapacitated due to injury or illness, it is still important that patients benefit from emergency experimentation.[15][better source needed] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) joined[when?] to create federal guidelines to permit emergency research, without informed consent.[15] However, they[who?] can only proceed with the research if they obtain a waiver of informed consent (WIC) or an emergency exception from informed consent (EFIC).[15] 21st Century Cures Act The 21st Century Cures Act enacted by the 114th United States Congress in December 2016 allows researchers to waive the requirement for informed consent when clinical testing "poses no more than minimal risk" and "includes appropriate safeguards to protect the rights, safety, and welfare of the human subject."[16] |

要件の免除 このセクションの例や見解は主にアメリカ合衆国に関するものであり、この主題に関する世界的な見解を表しているわけではない。必要に応じて、このセクショ ンを改善したり、トークページで問題について議論したり、新しいセクションを作成したりすることができる。 (December 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 同意要件の免除は、研究から予見可能な害が生じることが予想されない特定の状況下で適用される場合、または法律や連邦規則で許可されている場合、あるいは倫理審査委員会が特定の情報の非開示を承認している場合に適用される場合がある。[13] 最小限のリスクを伴う研究以外にも、軍事環境下ではインフォームド・コンセントの免除が認められる場合がある。合衆国軍隊法典第10編第980条「実験対 象としての人間の使用に関する制限」によると、研究プロジェクトが以下の条件を満たす場合、国防長官は高度なインフォームド・コンセントの免除を認めるこ とができる。 1. 被験者に直接的な利益をもたらす 2. 軍事上必要な医療製品の開発を促進する 3 FDAに関連するものも含むすべての法律および規制(すなわち、緊急研究同意免除)に従って実施される場合。 インフォームド・コンセントは基本的な権利であり、効果的に実施されるべきであるが、患者が負傷または疾病により意思決定能力を喪失している場合でも、緊 急実験から患者が利益を得ることは依然として重要である。[15][より適切な出典が必要] 食品医薬品局(FDA)と保健社会福祉省(DHHS)は、 は、インフォームド・コンセントなしで緊急研究を許可する連邦ガイドラインを作成するために、いつ結成されたのか?[15] しかし、彼ら[誰?]は、インフォームド・コンセントの免除(WIC)またはインフォームド・コンセントの緊急例外(EFIC)を取得した場合にのみ、研 究を進めることができる。[15] 21世紀治療法 2016年12月に第114回米国議会で可決された21世紀治療法では、臨床試験が「最小限のリスクしか伴わない」場合、また「被験者の権利、安全、福祉 を保護するための適切な保護措置が含まれている」場合、研究者はインフォームド・コンセントの要件を免除できると定めている[16]。 |

| Medical sociology Medical sociologists have studied informed consent as well bioethics more generally. Oonagh Corrigan, looking at informed consent for research in patients, argues that much of the conceptualization of informed consent comes from research ethics and bioethics with a focus on patient autonomy, and notes that this aligns with a neoliberal worldview.[17]: 770 Corrigan argues that a model based solely around individual decision making does not accurately describe the reality of consent because of social processes: a view that has started to be acknowledged in bioethics.[17]: 771 She feels that the liberal principles of informed consent are often in opposition with autocratic medical practices such that norms values and systems of expertise often shape and individuals ability to apply choice.[17]: 789 Patients who agree to participate in trials often do so because they feel that the trial was suggested by a doctor as the best intervention.[17]: 782 Patients may find being asked to consent within a limited time frame a burdensome intrusion on their care when it arises because a patient has to deal with a new condition.[17]: 783 Patients involved in trials may not be fully aware of the alternative treatments, and an awareness that there is uncertainty in the best treatment can help make patients more aware of this.[17]: 784 Corrigan notes that patients generally expect that doctors are acting exclusively in their interest in interactions and that this combined with "clinical equipose" where a healthcare practitioner does not know which treatment is better in a randomized control trial can be harmful to the doctor-patient relationship.[17]: 780–781 |

医療社会学 医療社会学者は、インフォームドコンセントだけでなく、より一般的な生命倫理についても研究している。患者を対象とした研究におけるインフォームドコンセ ントについて考察したオナ・コリガンは、インフォームドコンセントの概念化の多くは、患者の自主性に焦点を当てた研究倫理や生命倫理から来ていると主張 し、これが新自由主義的世界観と一致していると指摘している。[17]: 770 コリガンは、個人の意思決定のみに基づくモデルでは、 社会的プロセスがあるため、個人の意思決定のみに基づくモデルでは同意の現実を正確に描写できないという見解である。この見解は、生命倫理の分野でも認め られ始めている。[17]: 771 彼女は、インフォームドコンセントの自由主義的な原則は、しばしば専制的な医療行為と対立し、規範、価値観、専門知識の体系が個人の選択能力を形作ること が多いと感じている。[17]: 789 臨床試験への参加に同意する患者は、その臨床試験が最善の介入策として医師から勧められたと感じていることが多い。[17]: 782 患者は、新たな疾患と向き合わなければならない状況で、限られた時間枠内で同意を求められることを、ケアへの負担となる侵入と感じる場合がある。 [17]: 783 臨床試験に参加する患者は、代替治療について十分に理解していない場合があり、 最善の治療法に不確実性があることを認識することは、患者がこのことをより深く理解するのに役立つ可能性がある。[17]: 784 Corriganは、患者は一般的に、医師は患者の利益のみを考えて行動していると期待しており、このことが、医療従事者がランダム化比較試験においてど ちらの治療法が優れているかを知らない「臨床的等位」と組み合わさると、医師と患者の関係に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があると指摘している。[17]: 780–781 |

| Medical procedures The doctrine of informed consent relates to professional negligence and establishes a breach of the duty of care owed to the patient (see duty of care, breach of the duty, and respect for persons). The doctrine of informed consent also has significant implications for medical trials of medications, devices, or procedures. Requirements of the professional Until 2015 in the United Kingdom and in countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, informed consent in medical procedures requires proof as to the standard of care to expect as a recognised standard of acceptable professional practice (the Bolam Test), that is, what risks would a medical professional usually disclose in the circumstances (see Loss of right in English law). Arguably, this is "sufficient consent" rather than "informed consent." The UK has since departed from the Bolam test for judging standards of informed consent, due to the landmark ruling in Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board. This moves away from the concept of a reasonable physician and instead uses the standard of a reasonable patient, and what risks an individual would attach significance to.[18] Medicine in the United States, Australia, and Canada takes this patient-centric approach to "informed consent." Informed consent in these jurisdictions requires healthcare providers to disclose significant risks, as well as risks of particular importance to that patient. This approach combines an objective (a hypothetical reasonable patient) and subjective (this particular patient) approach.[citation needed] The doctrine of informed consent should be contrasted[according to whom?] with the general doctrine of medical consent, which applies to assault or battery. The consent standard here is only that the person understands, in general terms, the nature of and purpose of the intended intervention. As the higher standard of informed consent applies to negligence, not battery, the other elements of negligence must be made out. Significantly, causation must be shown: That had the individual been made aware of the risk he would not have proceeded with the operation (or perhaps with that surgeon).[original research?] Optimal establishment of an informed consent requires adaptation to cultural or other individual factors of the patient. As of 2011, for example, people from Mediterranean and Arab appeared to rely more on the context of the delivery of the information, with the information being carried more by who is saying it and where, when, and how it is being said, rather than what is said, which is of relatively more importance in typical "Western" countries.[19][better source needed] The informed consent doctrine is generally implemented through good healthcare practice: pre-operation discussions with patients and the use of medical consent forms in hospitals. However, reliance on a signed form should not undermine the basis of the doctrine in giving the patient an opportunity to weigh and respond to the risk. In one British case, a doctor performing routine surgery on a woman noticed that she had cancerous tissue in her womb. He took the initiative to remove the woman's womb; however, as she had not given informed consent for this operation, the doctor was judged by the General Medical Council to have acted negligently. The council stated that the woman should have been informed of her condition, and allowed to make her own decision.[citation needed] Obtaining informed consents To document that informed consent has been given for a procedure, healthcare organisations have traditionally used paper-based consent forms on which the procedure and its risks and benefits are noted, and is signed by both patient and clinician. In a number of healthcare organisations consent forms are scanned and maintained in an electronic document store. The paper consent process has been demonstrated to be associated with significant errors of omission,[20][21] and therefore increasing numbers of organisations are using digital consent applications where the risk of errors can be minimised, a patient's decision making and comprehension can be supported by additional lay-friendly and accessible information, consent can be completed remotely, and the process can become paperless. One form of digital consent is dynamic consent, which invites participants to provide consent in a granular way, and makes it easier for them to withdraw consent if they wish. Electronic consent methods have been used to support indexing and retrieval of consent data, thus enhancing the ability to honor to patient intent and identify willing research participants.[22][23][24][25] More recently, Health Sciences South Carolina, a statewide research collaborative focused on transforming healthcare quality, health information systems and patient outcomes, developed an open-source system called Research Permissions Management System (RPMS).[26][27] Competency of the patient This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The ability to give informed consent is governed by a general requirement of competency. In common law jurisdictions, adults are presumed competent to consent. This presumption can be rebutted, for instance, in circumstances of mental illness or other incompetence. This may be prescribed in legislation or based on a common-law standard of inability to understand the nature of the procedure. In cases of incompetent adults, a health care proxy makes medical decisions. In the absence of a proxy, the medical practitioner is expected to act in the patient's best interests until a proxy can be found. By contrast, 'minors' (which may be defined differently in different jurisdictions) are generally presumed incompetent to consent, but depending on their age and other factors may be required to provide Informed assent. In some jurisdictions (e.g. much of the U.S.), this is a strict standard. In other jurisdictions (e.g. England, Australia, Canada), this presumption may be rebutted through proof that the minor is 'mature' (the 'Gillick standard'). In cases of incompetent minors, informed consent is usually required from the parent (rather than the 'best interests standard') although a parens patriae order may apply, allowing the court to dispense with parental consent in cases of refusal. Deception Research involving deception is controversial given the requirement for informed consent. Deception typically arises in social psychology, when researching a particular psychological process requires that investigators deceive subjects. For example, in the Milgram experiment, researchers wanted to determine the willingness of participants to obey authority figures despite their personal conscientious objections. They had authority figures demand that participants deliver what they thought was an electric shock to another research participant. For the study to succeed, it was necessary to deceive the participants so they believed that the subject was a peer and that their electric shocks caused the peer actual pain. Nonetheless, research involving deception prevents subjects from exercising their basic right of autonomous informed decision-making and conflicts with the ethical principle of respect for persons. The Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct set by the American Psychological Association says that psychologists may conduct research that includes a deceptive compartment only if they can both justify the act by the value and importance of the study's results and show they could not obtain the results by some other way. Moreover, the research should bear no potential harm to the subject as an outcome of deception, either physical pain or emotional distress. Finally, the code requires a debriefing session in which the experimenter both tells the subject about the deception and gives subject the option of withdrawing the data.[28] Abortion In some U.S. states, informed consent laws (sometimes called "right to know" laws) require that a woman seeking an elective abortion receive information from the abortion provider about her legal rights, alternatives to abortion (such as adoption), available public and private assistance, and other information specified in the law, before the abortion is performed. Other countries with such laws (e.g. Germany) require that the information giver be properly certified to make sure that no abortion is carried out for the financial gain of the abortion provider and to ensure that the decision to have an abortion is not swayed by any form of incentive.[29][30] Some informed consent laws have been criticized for allegedly using "loaded language in an apparently deliberate attempt to 'personify' the fetus,"[31] but those critics acknowledge that "most of the information in the [legally mandated] materials about abortion comports with recent scientific findings and the principles of informed consent", although "some content is either misleading or altogether incorrect."[32] |

医療行為 インフォームド・コンセントの原則は、専門家の過失に関連し、患者に対する注意義務の違反を定めている(「注意義務」、「義務違反」、「人格の尊重」を参照)。 インフォームド・コンセントの原則は、薬、医療機器、または医療行為の臨床試験にも重大な影響を及ぼす。 専門家の要件 2015年まで、英国およびマレーシアやシンガポールなどの国々では、医療行為におけるインフォームド・コンセントには、容認される専門的業務の標準とし て期待されるケアの水準を証明することが必要であった(ボラムテスト)。つまり、医療専門家が通常、その状況で開示するであろうリスクは何か、ということ である(英国法における権利の喪失を参照)。 議論の余地はあるが、これは「インフォームド・コンセント」というよりも「十分な同意」である。英国では、Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board における画期的な判決により、インフォームドコンセントの基準を判断するボルアムテストから離脱した。これにより、合理的な医師という概念から離れ、代わ りに合理的な患者という基準が用いられることになり、個人が重大視するリスクが何であるかが問われるようになった。 米国、オーストラリア、カナダの医療では、この「インフォームド・コンセント」の患者中心のアプローチが採用されている。これらの管轄区域におけるイン フォームド・コンセントでは、医療提供者は重大なリスクだけでなく、その患者にとって特に重要なリスクも開示することが求められる。このアプローチは、客 観的(仮想的な合理的な患者)アプローチと主観的(この特定の患者)アプローチを組み合わせたものである。 インフォームド・コンセントの原則は、暴行または傷害に適用される一般的な医療同意の原則と対比されるべきである。この同意基準は、その人が一般用語で、 意図された介入の性質と目的を理解しているかどうかだけである。インフォームドコンセントのより高い基準は過失に適用されるのであって、暴行には適用され ないため、過失の他の要素を立証しなければならない。重要なのは、因果関係が示されなければならないということである。もしその個人がリスクを認識してい たならば、その手術(あるいはその外科医)は行われなかったであろう。 インフォームドコンセントを最適に確立するには、患者の文化的またはその他の個人的要因に適応させる必要がある。2011年現在、例えば、地中海沿岸地域 やアラブ地域の人々は、情報の伝達状況に依存する傾向が強いようである。情報は、誰がどこで、いつ、どのように伝えるかによって伝達されることが多く、伝 えられる内容よりも重要視される傾向にある。これは、典型的な「西洋」諸国では比較的より重要視される傾向にある。[19][より適切な出典が必要] インフォームドコンセントの原則は、一般的に、患者との手術前の話し合いや、病院での医療同意書の使用といった、適切な医療行為を通じて実施されている。 しかし、署名済みの書類に頼ることで、患者がリスクを考慮し、それに対応する機会を与えるという原則の根幹が損なわれるべきではない。英国のある事例で は、ある医師が女性に対して通常の外科手術を行ったところ、子宮に癌組織があることが判明した。 その医師は率先して女性の子宮を摘出したが、この手術についてインフォームドコンセントが得られていなかったため、医師は英国医師会(General Medical Council)から過失があったと判断された。 英国医師会は、女性には自身の状態について説明がなされるべきであり、自身の判断で決定を下す権利がある、と述べた。[要出典] インフォームドコンセントの取得 医療行為についてインフォームドコンセントが得られたことを文書化するために、医療機関では従来、医療行為とそのリスクおよび利益が記載され、患者と医療 従事者の双方が署名する紙ベースの同意書が使用されてきた。多くの医療機関では、同意書はスキャンされ、電子文書保管庫に保存されている。紙による同意プ ロセスには重大な記載漏れが発生する可能性があることが実証されており[20][21]、そのため、エラーのリスクを最小限に抑え、患者の意思決定と理解 を支援する追加の平易でアクセスしやすい情報を提供し、遠隔地から同意を完了でき、プロセスをペーパーレス化できるデジタル同意アプリケーションを採用す る医療機関が増えている。デジタル同意の1つの形態は動的同意であり、参加者にきめ細かく同意を提供してもらい、希望すれば同意を撤回しやすくするもので ある。 電子同意の方法は、同意データの索引付けと検索をサポートするために使用されており、それによって患者の意思を尊重し、研究への参加に前向きな被験者を特 定する能力が強化されている。[22][23][24][25] さらに最近では、医療の質、医療情報システム、患者の転帰の改善に焦点を当てた州全体の研究協力組織であるサウスカロライナ健康科学センターが、 Research Permissions Management System (RPMS) と呼ばれるオープンソースシステムを開発した。[26][27] 患者の能力 このセクションでは出典を全く示していない。出典を追加してこのセクションの改善にご協力ください。出典の明記されていない内容は、削除される場合があります。 (2023年1月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください) インフォームド・コンセントを与える能力は、一般的な能力要件によって規定されている。コモン・ローの管轄区域では、成人は同意する能力があると推定され る。この推定は、例えば精神疾患やその他の無能力状態にある状況では覆すことができる。これは法律で規定されている場合もあるし、手続きの性質を理解でき ないというコモンローの基準に基づく場合もある。無能力な成人の場合、医療代理人が医療上の決定を行う。代理人がいない場合、代理人が見つかるまでは医療 従事者が患者の最善の利益のために行動することが期待される。 これに対し、「未成年者」(管轄区域によって定義が異なる場合がある)は一般的に同意能力がないと推定されるが、年齢やその他の要因によってはインフォー ムド・アセント(十分な説明に基づく同意)が求められる場合がある。一部の管轄区域(米国の大部分など)では、この基準が厳格である。他の管轄区域(英 国、オーストラリア、カナダなど)では、未成年者が「成熟している」という証明によって、この推定を覆すことができる(「ギリック基準」)。未成年者が同 意能力を有しない場合、通常は親のインフォームド・コンセントが必要となる(「最善の利益基準」ではなく)。ただし、parens patriae(ラテン語で「父権」の意)命令が適用される場合、親の同意を拒否する場合には裁判所が親の同意を不要とすることができる。 欺瞞・だまし インフォームド・コンセントの要件を考慮すると、欺瞞(だまし)を伴う研究は議論の的となる。欺瞞(だまし)は通常、社会心理学において、特定の心理的プロセスを研究するため に、研究者が被験者を欺く必要がある場合に生じる。例えば、ミルグラムの実験では、研究者は、被験者が個人的に良心的な反対意見を持っていたとしても、権 威者に従う意思があるかどうかを判断しようとした。彼らは権威者に、被験者が別の研究参加者に電気ショックを与えたと思われるものを渡すよう要求させた。 この研究を成功させるには、被験者を欺いて、被験者が同僚であり、彼らの電気ショックが同僚に実際に痛みを与えていると信じさせる必要があった。 しかし、欺瞞を伴う研究は、被験者が基本的な権利である自主的な情報に基づく意思決定を行うことを妨げ、また、人格の尊重という倫理原則にも反する。 米国心理学会が定めた『心理学者の倫理原則および行動規範』では、心理学者が欺瞞的な要素を含む研究を行う場合、その行為が研究結果の価値と重要性を正当 化できること、また、他の方法では結果が得られないことを示すことができる場合にのみ、その行為が許されるとしている。さらに、欺瞞の結果として被験者に 身体的苦痛や精神的苦痛などの潜在的な危害が及ぶ可能性がないことも条件である。最後に、この規定では、実験者が被験者に欺瞞について説明し、被験者が データの使用を拒否できる機会を与える報告セッションの実施を義務付けている。[28] 中絶 米国の一部の州では、インフォームド・コンセント法(「知る権利」法と呼ばれることもある)により、中絶を希望する女性は、中絶実施前に、中絶を行う医療 従事者から、法的権利、中絶以外の選択肢(養子縁組など)、利用可能な公的および私的支援、および法律で規定されたその他の情報について説明を受けること が義務付けられている。同様の法律を持つ他の国々(例えばドイツ)では、中絶を行う医療提供者が金銭的利益のために中絶を行うことがないよう、また、中絶 の決定が何らかのインセンティブによって左右されることがないよう、情報を提供する側が適切に認定されることを求めている。[29][30] インフォームドコンセントに関する法律の一部は、「胎児を擬人化しようとする意図的な試みとして、意図的に選ばれた表現が用いられている」として批判され ているが[31]、これらの批判者は、「(法律で義務付けられている)中絶に関する資料のほとんどの情報は、最近の科学的知見とインフォームドコンセント の原則に適合している」と認めている。ただし、「一部の内容は誤解を招くか、まったく正しくない」[32]。 |

| Within research Medicine Informed consent is part of ethical clinical research as well, in which a human subject voluntarily confirms his or her willingness to participate in a particular clinical trial, after having been informed of all aspects of the trial that are relevant to the subject's decision to participate. Informed consent is documented by means of a written, signed, and dated informed consent form.[33] In medical research, the Nuremberg Code set a base international standard in 1947, in response to the ethical violation in the Holocaust. Standards continued to develop. Nowadays, medical research is overseen by an ethics committee that also oversees the informed consent process. Social sciences As the medical guidelines established in the Nuremberg Code were imported into the ethical guidelines for the social sciences, informed consent became a common part of the research procedure.[34] However, while informed consent is the default in medical settings, it is not always required in the social sciences. Here, firstly, research often involves low or no risk for participants, unlike in many medical experiments. Secondly, the mere knowledge that they participate in a study can cause people to alter their behavior, as in the Hawthorne Effect: "In the typical lab experiment, subjects enter an environment in which they are keenly aware that their behavior is being monitored, recorded, and subsequently scrutinized."[35]: 168 In such cases, seeking informed consent directly interferes with the ability to conduct the research, because the very act of revealing that a study is being conducted is likely to alter the behavior studied. Author J.A. List explains the potential dilemma that can result: "if one were interested in exploring whether, and to what extent, race or gender influences the prices that buyers pay for used cars, it would be difficult to measure accurately the degree of discrimination among used car dealers who know that they are taking part in an experiment."[36] In a case where such interference is likely, and after careful consideration, a researcher may forgo the informed consent process. This may be done after the researcher(s) and an Ethics Committee and/or Institutional Review Board (IRB) weigh the risk to study participants against the benefits to society and whether participants participate voluntarily and are to be treated fairly.[37] The birth of new online media, such as social media, has complicated the idea of informed consent. In an online environment people pay little attention to Terms of Use agreements and can subject themselves to research without thorough knowledge. This issue came to the public light following a study conducted by Facebook in 2014, and published by that company and Cornell University.[38] Facebook conducted a study without consulting an Ethics Committee or IRB where they altered the Facebook News Feeds of roughly 700,000 users to reduce either the amount of positive or negative posts they saw for a week. The study then analyzed if the users' status updates changed during the different conditions. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The lack of informed consent led to outrage among many researchers and users.[39] Many believed that by potentially altering the mood of users by altering what posts they see, Facebook put at-risk individuals at higher dangers for depression and suicide. However, supporters of Facebook claim that Facebook details that they have the right to use information for research in their terms of use.[40] Others say the experiment is just a part of Facebook's current work, which alters News Feeds algorithms continually to keep people interested and coming back to the site. Others pointed out that this specific study is not unique but rather news organizations constantly try out different headlines using algorithms to elicit emotions and garner clicks or Facebook shares.[41] They say this Facebook study is no different from things people already accept. Still, others say that Facebook broke the law when conducting the experiment on users that did not give informed consent.[42] The Facebook study controversy raises numerous questions about informed consent and the differences in the ethical review process between publicly and privately funded research. Some say Facebook was within its limits and others see the need for more informed consent and/or the establishment of in-house private review boards.[43] Duty to share findings See also: Return of results Some researchers and ethicists advocate for researchers to share experimental results with their subjects in a way they can understand, both as an ethical obligation and as a way to encourage more participation.[44] In 2023, the government of the United Kingdom proposed making this a requirement.[45] The Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications research program of the National Human Genome Research Institute in the United States has provided some funding for researchers to do this.[44] |

研究の範囲内では 医学 インフォームド・コンセントは倫理的な臨床研究の一部でもあり、被験者は、参加の意思決定に関連する臨床試験のあらゆる側面について説明を受けた上で、特 定の臨床試験に参加する意思を自主的に確認する。インフォームド・コンセントは、署名と日付が記入された書面によるインフォームド・コンセントの書式に よって文書化される。[33] 医学研究においては、ホロコーストにおける倫理違反を受けて、1947年にニュルンベルク綱領が国際的な基本基準を定めた。その後も基準は発展を続けてい る。現在では、医学研究は倫理委員会によって監督されており、同委員会はインフォームド・コンセントのプロセスも監督している。 社会科学 ニュルンベルク綱領で確立された医療ガイドラインが社会科学の倫理ガイドラインにも取り入れられたため、インフォームド・コンセントは研究手順の一般的な 一部となった。[34] しかし、医療現場ではインフォームド・コンセントがデフォルトであるのに対し、社会科学では必ずしも必要とされるわけではない。まず、多くの医学実験とは 異なり、研究に参加する人々にとってリスクが低い、あるいはリスクがまったくない場合が多い。次に、研究に参加しているという事実を知るだけで、人々は行 動を変える可能性がある。これは「ホーソン効果」として知られている。「典型的な実験室での実験では、被験者は、自分の行動が監視され、記録され、 [35]: 168 このような場合、インフォームド・コンセントを求めることは、研究を行う能力に直接的に干渉することになる。なぜなら、研究が行われていることを明らかに する行為そのものが、研究対象の行動に変化をもたらす可能性が高いからだ。著者のJ.A.リストは、その結果起こりうるジレンマについて次のように説明し ている。「人種や性別が中古車購入者の支払う価格にどの程度影響するかを調査したい場合、実験に参加していることを知っている中古車販売業者間の差別を正 確に測定することは難しいだろう」[36] このような干渉が起こりうる場合、慎重に検討した上で、研究者はインフォームド・コンセントの手続きを省略することができる。これは、研究参加者に対する リスクと社会に対する利益、および参加者が自発的に参加し、公平に扱われるかどうかを、研究者および倫理委員会および/またはIRB (Institutional Review Board)が検討した上で実施される場合がある。 ソーシャルメディアなどの新しいオンラインメディアの誕生により、インフォームドコンセントの概念は複雑化している。オンライン環境では、利用規約にほと んど注意を払わず、十分な知識を持たずに研究に参加してしまう可能性がある。この問題は、2014年にFacebookが実施し、同社とコーネル大学が発 表した研究により、広く知られるようになった。[38] Facebookは倫理委員会やIRBに相談することなく研究を実施し、約70万人のユーザーのFacebookニュースフィードを変更し、1週間の間に ユーザーが目にするポジティブまたはネガティブな投稿の量を減らした。その後、この研究では、異なる条件下でユーザーのステータス更新が変化したかどうか を分析した。この研究は『Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences』誌に掲載された。インフォームドコンセントが欠如していたことで、多くの研究者やユーザーから非難が寄せられた。[39] 多くの人々は、ユーザーが目にする投稿を変更することでユーザーの気分を変化させる可能性があることで、Facebookがうつ病や自殺の危険性が高い個 人をより危険な状態に置いていると信じていた。しかし、Facebookの支持者たちは、Facebookの利用規約には、研究目的で情報を使用する権利 を保有していることが明記されていると主張している。[40] また、この実験は、人々の関心を維持し、サイトへの再訪問を促すためにニュースフィードのアルゴリズムを絶えず変更しているFacebookの現在の取り 組みの一部に過ぎないという意見もある。また、この特定の研究は目新しいものではなく、ニュース機関は常にアルゴリズムを使用して異なる見出しを試し、感 情を刺激してクリックやFacebookのシェアを獲得しようとしていると指摘する声もある。[41] 彼らは、このFacebookの研究はすでに人々が受け入れていることと何ら変わりはないと主張している。それでもなお、インフォームド・コンセントを得 ていないユーザーを対象に実験を行ったことは、Facebookが法律に違反したという意見もある。[42] Facebookの研究をめぐる論争は、インフォームド・コンセントや、公的資金による研究と私的資金による研究における倫理審査プロセスの違いについ て、多くの疑問を投げかけている。Facebookの行為は妥当な範囲内だったという意見もあれば、よりインフォームド・コンセントを徹底する必要があ る、あるいは社内での非公開審査委員会の設置が必要だという意見もある。[43] 研究結果の共有義務 参照:結果のフィードバック 一部の研究者や倫理学者は、倫理上の義務として、またより多くの参加を促す方法として、研究者が被験者に対して理解できる形で実験結果を共有することを提 唱している。[44] 2023年には、英国政府がこれを義務化することを提案した。[45] 米国立ヒトゲノム研究所の倫理的、法的、社会的影響に関する研究プログラムでは、研究者がこれを行うための資金援助を行っている。[44] |

| Conflicts of interest Other, long-standing controversies underscore the role for conflicts of interest among medical school faculty and researchers. For example, in 2014 coverage of University of California (UC) medical school faculty members has included news of ongoing corporate payments to researchers and practitioners from companies that market and produce the very devices and treatments they recommend to patients.[46] Robert Pedowitz, the former chairman of UCLA's orthopedic surgery department, reported concern that his colleague's financial conflicts of interest could negatively affect patient care or research into new treatments.[47] In a subsequent lawsuit about whistleblower retaliation, the university provided a $10 million settlement to Pedowitz while acknowledging no wrongdoing.[47] Consumer Watchdog, an oversight group, observed that University of California policies were "either inadequate or unenforced...Patients in UC hospitals deserve the most reliable surgical devices and medication…and they shouldn't be treated as subjects in expensive experiments."[46] Other UC incidents include taking the eggs of women for implantation into other women without consent[48] and injecting live bacteria into human brains, resulting in potentially premature deaths.[49] |

利益相反 その他の長年にわたる論争は、医学部の教員や研究者の利益相反の役割を強調している。例えば、2014年のカリフォルニア大学(UC)医学部の教員に関す る報道には、彼らが患者に推奨する医療機器や治療法を販売・製造する企業から、研究者や実務家への企業からの支払いが行われているというニュースが含まれ ていた。[46] ロバート・ペドウィッツは、UCLA整形外科の元学部長であり、 同僚の金銭的利益相反が患者のケアや新しい治療法の研究に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があるという懸念を報告した。[47] 内部告発者に対する報復に関するその後の訴訟では、大学は不正行為を認めないまま、ペドウィッツ氏に1000万ドルの和解金を支払った。[47] 監視団体であるコンシューマー・ウォッチドッグは、カリフォルニア大学のポリシーは「不十分であるか、あるいは実施されていない」と指摘し、 。カリフォルニア大学病院の患者は、最も信頼性の高い手術器具や薬剤を必要としている。高額な実験の被験者として扱われるべきではない」[46] カリフォルニア大学では、この他にも、女性の卵子を本人の同意なしに他の女性の子宮に移植する[48] ことや、人間の脳に生きた細菌を注入し、早死にさせる可能性がある[49] といった事件が起きている。 |

History Informed consent document in which research participant Antonio Benigno agrees to researcher Walter Reed's clinical trial examining the transmission of yellow fever. Walter Reed authored these informed consent documents in 1900 for his research on yellow fever Informed consent is a technical term first used by attorney, Paul G. Gebhard, in a medical malpractice United States court case in 1957.[50] In tracing its history, some scholars have suggested tracing the history of checking for any of these practices:[51]: 54 A patient agrees to a health intervention based on an understanding of it. The patient has multiple choices and is not compelled to choose a particular one. The consent includes giving permission. These practices are part of what constitutes informed consent, and their history is the history of informed consent.[51]: 60 They combine to form the modern concept of informed consent—which rose in response to particular incidents in modern research.[51]: 60 Whereas various cultures in various places practiced informed consent, the modern concept of informed consent was developed by people who drew influence from Western tradition.[51]: 60 Medical history  In this Ottoman Empire document from 1539 a father promises to not sue a surgeon in case of death following the removal of his son's urinary stones.[52] Historians cite a series of medical guidelines to trace the history of informed consent in medical practice. The Hippocratic Oath, a Greek text dating to 500 B.C.E., was the first set of Western writings giving guidelines for the conduct of medical professionals. Consent by patients as well as several other, now considered fundamental issues, is not mentioned. The Hippocratic Corpus advises that physicians conceal most information from patients to give the patients the best care.[51]: 61 The rationale is a beneficence model for care—the doctor knows better than the patient, and therefore should direct the patient's care, because the patient is not likely to have better ideas than the doctor.[51]: 61 Henri de Mondeville, a French surgeon who in the 14th century, wrote about medical practice. He traced his ideas to the Hippocratic Oath.[51]: 63 [53][54] Among his recommendations were that doctors "promise a cure to every patient" in hopes that the good prognosis would inspire a good outcome to treatment.[51]: 63 Mondeville never mentioned getting consent, but did emphasize the need for the patient to have confidence in the doctor.[51]: 63 He also advised that when deciding therapeutically unimportant details the doctor should meet the patients' requests "so far as they do not interfere with treatment".[55] In Ottoman Empire records there exists an agreement from 1539 in which negotiates details of a surgery, including fee and a commitment not to sue in case of death.[52] This is the oldest identified written document in which a patient acknowledges risk of medical treatment and writes to express their willingness to proceed.[52] Benjamin Rush was an 18th-century United States physician who was influenced by the Age of Enlightenment cultural movement.[51]: 65 Because of this, he advised that doctors ought to share as much information as possible with patients. He recommended that doctors educate the public and respect a patient's informed decision to accept therapy.[51]: 65 There is no evidence that he supported seeking a consent from patients.[51]: 65 In a lecture titled "On the duties of patients to their physicians", he stated that patients should be strictly obedient to the physician's orders; this was representative of much of his writings.[51]: 65 John Gregory, Rush's teacher, wrote similar views that a doctor could best practice beneficence by making decisions for the patients without their consent.[51]: 66 [56] Thomas Percival was a British physician who published a book called Medical Ethics in 1803.[51]: 68 Percival was a student of the works of Gregory and various earlier Hippocratic physicians.[51]: 68 Like all previous works, Percival's Medical Ethics makes no mention of soliciting for the consent of patients or respecting their decisions.[51]: 68 Percival said that patients have a right to truth, but when the physician could provide better treatment by lying or withholding information, he advised that the physician do as he thought best.[51]: 68 When the American Medical Association was founded they in 1847 produced a work called the first edition of the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics.[51]: 69 Many sections of this book are verbatim copies of passages from Percival's Medical Ethics.[51]: 69 A new concept in this book was the idea that physicians should fully disclose all patient details truthfully when talking to other physicians, but the text does not also apply this idea to disclosing information to patients.[51]: 70 Through this text, Percival's ideas became pervasive guidelines throughout the United States as other texts were derived from them.[51]: 70 Worthington Hooker was an American physician who in 1849 published Physician and Patient.[51]: 70 This medical ethics book was radical demonstrating understanding of the AMA's guidelines and Percival's philosophy and soundly rejecting all directives that a doctor should lie to patients.[51]: 70 In Hooker's view, benevolent deception is not fair to the patient, and he lectured widely on this topic.[51]: 70 Hooker's ideas were not broadly influential.[51]: 70 The US Canterbury v. Spence case established the principle of informed consent in US law. Earlier legal cases had created the underpinnings for informed consent, but his judgment gave a detailed and thought through discourse on the matter.[57] The judgment cites cases going back to 1914 as precedent for informed consent.[58]: 56 Research history Historians cite a series of human subject research experiments to trace the history of informed consent in research. The U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission "is considered the first research group in history to use consent forms."[59] In 1900, Major Walter Reed was appointed head of the four man U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission in Cuba that determined mosquitoes were the vector for yellow fever transmission. His earliest experiments were probably done without formal documentation of informed consent. In later experiments he obtained support from appropriate military and administrative authorities. He then drafted what is now "one of the oldest series of extant informed consent documents."[60] The three surviving examples are in Spanish with English translations; two have an individual's signature and one is marked with an X.[60] Tearoom Trade is the name of a book by American psychologist Laud Humphreys. In it he describes his research into male homosexual acts.[61] In conducting this research he never sought consent from his research subjects and other researchers raised concerns that he violated the right to privacy for research participants.[61] Henrietta Lacks on January 29, 1951, shortly after the birth of her son Joseph, Lacks entered Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore with profuse bleeding. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer and was treated with inserts of radium tubes. During her radiation treatments for the tumor, two samples—one of healthy cells, the other of malignant cells—were removed from her cervix without her permission. Later that year, 31-year-old Henrietta Lacks died from the cancer. Her cells were cultured creating Hela cells, but the family was not informed until 1973, the family learned the truth when scientists asked for DNA samples after finding that HeLa had contaminated other samples. In 2013 researchers published the genome without the Lacks family consent. The Milgram experiment is the name of a 1961 experiment conducted by American psychologist Stanley Milgram. In the experiment Milgram had an authority figure order research participants to commit a disturbing act of harming another person.[62] After the experiment he would reveal that he had deceived the participants and that they had not hurt anyone, but the research participants were upset at the experience of having participated in the research.[62] The experiment raised broad discussion on the ethics of recruiting participants for research without giving them full information about the nature of the research.[62] Chester M. Southam used HeLa cells to inject into cancer patients and Ohio State Penitentiary inmates without informed consent to determine if people could become immune to cancer and if cancer could be transmitted.[63] |

歴史 研究参加者アントニオ・ベニーニョが、黄熱病の感染を調べるウォルター・リード研究者の臨床試験に同意するインフォームドコンセント文書。 ウォルター・リードは1900年に黄熱病の研究のためにこれらのインフォームドコンセント文書を執筆した インフォームドコンセントは、1957年の医療過誤に関する米国の裁判で弁護士ポール・G・ゲブハートが初めて使用した専門用語である。[50] その歴史をたどる中で、一部の学者は、これらの慣行のチェックの歴史をたどることを提案している。[51]:54 患者が医療介入について理解した上で同意する。 患者には複数の選択肢があり、特定の選択を強制されない。 同意には許可を与えることも含まれる。 これらの慣行はインフォームドコンセントを構成する要素の一部であり、その歴史はインフォームドコンセントの歴史でもある。[51]:60 これらが組み合わさって、現代のインフォームドコンセントの概念が形成された。この概念は、現代の研究における特定の出来事に対応して生まれたものであ る。[51]:60 さまざまな文化圏でインフォームドコンセントが実践されていた一方で、現代のインフォームドコンセントの概念は、西洋の伝統から影響を受けた人々によって 発展した。[51]:60 医療の歴史  1539年のオスマン帝国の文書では、父親が息子の尿路結石除去手術後に死亡した場合、外科医を訴えないことを約束している。[52] 歴史家は、医療行為におけるインフォームドコンセントの歴史をたどるために、一連の医療ガイドラインを引用している。 紀元前500年頃のギリシャ語で書かれたヒポクラテスの誓いは、医療従事者の行動指針を定めた西洋の最初の文書である。患者の同意、および現在では基本的 な問題とみなされているその他のいくつかの問題については言及されていない。ヒポクラテスの著作群は、患者に最善の治療を行うために、医師は患者にほとん どの情報を隠しておくべきであると助言している。[51]: 61 その根拠は、患者よりも医師の方がよく知っているため、患者よりも医師の方が患者の治療を指示すべきであるという、ケアにおける恩恵モデルである。 [51]: 61 アンリ・ド・モンデヴィルは、14世紀のフランスの外科医で、医療行為について著述した。彼は、その考えをヒポクラテスの誓いにさかのぼっている。 [51]: 63 [53][54] 彼が推奨したことのひとつに、医師が「すべての患者に治癒を約束する」というものがあった。良好な予後が治療の良好な結果につながることを期待してのこと である。[51]: 63 モン 同意を得るという概念については言及していないが、患者が医師を信頼する必要性を強調していた。[51]: 63 また、治療上重要でない詳細事項を決定する際には、「治療に支障をきたさない限りにおいて」、患者の要望に応えるべきであるとも助言していた。[55] オスマン帝国の記録には、1539年の合意文書が存在し、手術の詳細について交渉しており、料金や死亡した場合でも訴訟を起こさないという約束が含まれて いる。[52] これは、患者が医療行為のリスクを認識し、治療を受ける意思を表明するために手紙を書いた、確認されている最古の文書である。[52] ベンジャミン・ラッシュは、啓蒙時代という文化運動の影響を受けた18世紀の米国の医師であった。[51]: 65 このため、彼は医師は患者と可能な限り多くの情報を共有すべきだと助言した。彼は、医師は一般市民を教育し、患者が治療を受けるという十分な情報を得た上 での決定を尊重すべきであると提言した。[51]: 65 彼が患者の同意を求めることを支持していたという証拠はない。[51]: 65 「患者の医師に対する義務について」と題された講演で、彼は患者は 医師の指示には厳格に従うべきであると述べた。これは彼の著作の多くを代表するものであった。[51]: 65 ジョン・グレゴリーはラッシュの師であり、患者の同意なしに医師が患者のために決定を下すことが最善の慈悲であるという同様の見解を述べた。[51]: 66 [56] トーマス・パーシバルは1803年に『医療倫理』という本を出版したイギリスの医師である。[51]: 68 パーシバルはグレゴリーの著作や、それ以前のヒポクラテスの医師たちの著作を研究していた。[51]: 68 それまでの著作と同様に、パーシバルの『医療倫理』には 患者の同意を求めることや、患者の決定を尊重することについては一切言及していない。[51]: 68 パーシヴァルは、患者には真実を知る権利があるが、医師が嘘をついたり情報を隠したりすることでより良い治療ができる場合には、医師は最善と思われる方法 をとるべきだと述べた。[51]: 68 米国医師会が設立された1847年、彼らは『米国医師会医療倫理規定』初版と呼ばれる著作を出版した。[51]: 69 この本の多くのセクションは、パーシバルの『医療倫理』からの文章をそのままコピーしたものである。[51]: 69 この本における新しい概念は、 医師は他の医師と話す際には、患者に関するあらゆる詳細を正直に完全に開示すべきであるという考え方であったが、この文章では、この考え方を患者への情報 開示に適用していない。[51]: 70 この文章を通じて、パーシバルの考え方は、他の文章がそこから派生したように、米国全土に広まった指針となった。[51]: 70 ワシントン・フッカーは、1849年に『医師と患者』を出版したアメリカの医師である。この医療倫理に関する本は、AMAのガイドラインとパーシヴァルの 哲学を理解した上で、医師が患者に嘘をつくべきだというあらゆる指針を明確に否定するという、急進的な内容であった。。フッカーの見解では、患者に対する 思いやりから行う欺瞞は患者に対して公平ではないとし、このテーマについて広く講義を行った。 米国のカンタベリー対スペンス訴訟は、米国法におけるインフォームド・コンセントの原則を確立した。それ以前の訴訟ではインフォームド・コンセントの基礎 が築かれていたが、この判決ではこの問題について詳細かつ熟考された議論が展開された。[57] この判決では、1914年までさかのぼる判例がインフォームド・コンセントの先例として引用されている。[58]: 56 研究の歴史 歴史家は、一連の人体実験を引用して、研究におけるインフォームド・コンセントの歴史をたどっている。 米国陸軍黄熱病委員会は「同意書を使用した史上初の研究グループと考えられている」[59]。1900年、ウォルター・リード少佐は、蚊が黄熱病の媒介で あることを突き止めたキューバの米国陸軍黄熱病委員会(4名で構成)の委員長に任命された。おそらく、彼の初期の実験ではインフォームド・コンセントの正 式な文書は作成されていなかった。その後の実験では、彼は軍および行政当局から支援を得た。そして、現在「現存するインフォームド・コンセント文書の中で 最も古いもののひとつ」[60]となる草案を作成した。現存する3つの例はスペイン語で書かれており、英語訳が付されている。2つには個人の署名があり、 1つには×印が付けられている。 『ティールーム・トレード』は、アメリカの心理学者ラウド・ハンフリーズによる著書である。この本の中で、彼は男性同性愛行為に関する研究について述べて いる。[61] この研究を行うにあたり、彼は研究対象者から同意を得ることはなかった。他の研究者からは、研究参加者のプライバシーの権利を侵害しているのではないかと いう懸念が寄せられた。[61] ヘンリエッタ・ラックスは1951年1月29日、息子のジョセフを出産した直後に、大量出血のためボルチモアのジョンズ・ホプキンス病院に入院した。子宮 頸がんと診断された彼女はラジウム管を挿入する治療を受けた。腫瘍の放射線治療中、2つのサンプル(1つは健康な細胞、もう1つは悪性細胞)が彼女の承諾 なしに子宮頸部から採取された。その年、31歳のヘンリエッタ・ラックスは癌により死亡した。彼女の細胞は培養され、ヘラ細胞が作られたが、その事実が家 族に知らされたのは1973年になってからだった。ヘラ細胞が他のサンプルを汚染していることが判明し、科学者たちがDNAサンプルを求めたことで、家族 はその事実を知った。2013年には、ラックス家の同意なしにゲノムが研究者によって発表された。 ミルグラム実験とは、1961年にアメリカの心理学者スタンレー・ミルグラムが行った実験の名称である。この実験でミルグラムは、権威ある人物に研究参加 者に他人を傷つける不快な行為を命じさせた。[62] 実験後、ミルグラムは参加者を欺き、誰も傷つけていないことを明らかにしたが、研究参加者は研究に参加した経験に動揺した。[62] この実験は、研究の性質について十分な情報を与えずに研究参加者を募ることの倫理について、幅広い議論を引き起こした。[62] チェスター・M・サウザムは、ヒトパピローマウイルス(HPV)に感染した子宮頸がん細胞株であるヘラ細胞(HeLa細胞)を、インフォームドコンセント なしにがん患者とオハイオ州立刑務所の受刑者に注射し、人々ががんに対する免疫を得られるか、またがんが伝染するかを確かめる実験を行った。[63] |

| New areas With the growth of bioethics in the 21st century to include environmental sustainability,[64] some authors, such as Cristina Richie have proposed a "green consent". This would include information and education about the climate impact of pharmaceuticals (carbon cost of medications) and climate change health hazards.[65] |

新たな分野 21世紀における生命倫理の成長には、環境の持続可能性も含まれるようになり[64]、クリスティーナ・リッチーなどの一部の著者は「グリーン・コンセン ト」を提案している。これには、医薬品が気候に与える影響(医薬品の炭素コスト)や気候変動による健康被害に関する情報や教育が含まれることになる。 [65] |

| Anti-psychiatry Belmont Report Consent (BDSM) Consent (criminal law) Consensual crime Declaration of Geneva Declaration of Helsinki Deliberative democracy Dynamic consent Free, prior and informed consent Human experimentation Informed assent Informed refusal International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Involuntary treatment Minors and abortion Parental consent Patient safety Safe, sane and consensual World Medical Association |

反精神医学 ベルモントレポート 合意(BDSM) 合意(刑法) 合意に基づく犯罪 ジュネーブ宣言 ヘルシンキ宣言 熟議民主主義 動的同意 自由意思による事前の十分な説明を受けた上での同意 人体実験 インフォームド・アセント インフォームド・リフュージ 医薬品の承認申請のための技術的基準の調和に関する国際会議 非自発的治療 未成年者と中絶 親の同意 患者の安全 安全、正気、合意に基づく 世界医師会 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Informed_consent |

出 典:Bernard A Fischer, IV A Summary of Important Documents in the Field of Research Ethics, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 32, Issue 1, 1 January 2006, Pages 69–80, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj005

★小児に対する同意をとる方法は、インフォームド・アセント(Informed assent)といわれる。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆