イノベーション経済学

Innovation economics

REMEDIOS

VARO, Coincidencia, 1959, Oleo s/ masonite

☆

イノベーション経済学(Innovation

economics)は、イノベーションと起業家精神に重点を置く、経済理論と応用/実験経済学の新しい成長分野である。イノベーション経済学は、あらゆ

るタイプのイノベーション、特に技術的なイノベーションの経済的利用への応用の両方を含むが、それだけではない。古典派経済学では、これは顧客の新技術を

経済的に利用することであるが、革新的と考えられる新しい経済科学の発展を指すイノベーションと実験経済学の分野を指すこともある。経済学者ヨーゼフ・

シュンペーターは、1942年の著書『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』の中で、イノベーション経済という概念を紹介した。彼は、進化する制度、起業家、技

術的変化が経済成長の核心であると主張した。しかし、シュンペーターの考えに基づく「イノベーション経済」が主流の概念となったのは、近年になってからで

ある[1]。

| Innovation

economics is new, and growing field of economic theory and

applied/experimental economics that emphasizes innovation and

entrepreneurship. It comprises both the application of any type of

innovations, especially technological, but not only, into economic use.

In classical economics this is the application of customer new

technology into economic use; but also it could refer to the field of

innovation and experimental economics that refers the new economic

science developments that may be considered innovative. In his 1942

book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, economist Joseph Schumpeter

introduced the notion of an innovation economy. He argued that evolving

institutions, entrepreneurs and technological changes were at the heart

of economic growth. However, it is only in recent years[when?] that

"innovation economy," grounded in Schumpeter's ideas, has become a

mainstream concept".[1] |

イノベーション経済学は、イノベーションと起業家精神に重点を置く、経

済理論と応用/実験経済学の新しい成長分野である。イノベーション経済学は、あらゆるタイプのイノベーション、特に技術的なイノベーションの経済的利用へ

の応用の両方を含むが、それだけではない。古典派経済学では、これは顧客の新技術を経済的に利用することであるが、革新的と考えられる新しい経済科学の発

展を指すイノベーションと実験経済学の分野を指すこともある。経済学者ヨーゼフ・シュンペーターは、1942年の著書『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』の

中で、イノベーション経済という概念を紹介した。彼は、進化する制度、起業家、技術的変化が経済成長の核心であると主張した。しかし、シュンペーターの考

えに基づく「イノベーション経済」が主流の概念となったのは、近年になってからである[1]。 |

| Historical origins Joseph Schumpeter was one of the first and most important scholars who extensively tackled the question of innovation in economics.[2] In contrast to his contemporary John Maynard Keynes, Schumpeter contended that evolving institutions, entrepreneurs and technological change were at the heart of economic growth, not independent forces that are largely unaffected by policy. He argued that "capitalism can only be understood as an evolutionary process of continuous innovation and 'creative destruction'".[3][4] It is only in the 21st century that a theory and narrative of economic growth focused on innovation that was grounded in Schumpeter's ideas has emerged. Innovation economics attempted to answer the fundamental problem in the puzzle of total factor productivity growth. Continual growth of output could no longer be explained only in increase of inputs used in the production process as understood in industrialization. Hence, innovation economics focused on a theory of economic creativity that would impact the theory of the firm and organization decision-making. Hovering between heterodox economics that emphasized the fragility of conventional assumptions and orthodox economics that ignored the fragility of such assumptions, innovation economics aims for joint didactics between the two. As such, it enlarges the Schumpeterian analyses of new technological system by incorporating new ideas of information and communication technology in the global economy.[5] Innovation economics emerges from other schools of thought in economics, including new institutional economics, new growth theory, endogenous growth theory, evolutionary economics and neo-Schumpeterian economics. It provides an economic framework that explains and helps support growth in today's knowledge economy. Leading theorists of innovation economics include both formal economists as well as management theorists, technology policy experts and others. These include Paul Romer, Elhanan Helpman, Bronwyn Hall, W. Brian Arthur, Robert Axtell, Richard R. Nelson, Richard Lipsey, Michael Porter, Keun Lee and Christopher Freeman. |

歴史的起源 ヨーゼフ・シュンペーターは、経済学におけるイノベーションの問題に幅広く取り組んだ最初の、そして最も重要な学者の一人であった[2]。同時代のジョ ン・メイナード・ケインズとは対照的に、シュンペーターは、進化する制度、企業家、技術革新が経済成長の中心にあり、政策にほとんど影響されない独立した 力ではないと主張した。彼は「資本主義は継続的な革新と『創造的破壊』の進化的プロセスとしてのみ理解することができる」と主張した[3][4]。 シュンペーターの考えに基づいた、イノベーションに焦点を当てた経済成長の理論と物語が登場したのは、21世紀に入ってからである。イノベーション経済学 は、全要素生産性成長のパズルにおける根本的な問題に答えようとした。生産高の継続的な成長は、もはや工業化で理解されているように、生産プロセスで使用 される投入量の増加だけでは説明できなくなった。そこでイノベーション経済学は、企業や組織の意思決定の理論に影響を与える経済的創造性の理論に焦点を当 てた。従来の前提の脆弱性を強調するヘテロドックス経済学と、そのような前提の脆弱性を無視するオーソドックス経済学の間を行き来しながら、イノベーショ ン経済学は両者の共同教学を目指している。そのため、グローバル経済における情報通信技術の新しい考え方を取り入れることによって、新しい技術システムの シュンペーター的分析を拡大するものである[5]。 イノベーション経済学は、新制度経済学、新成長理論、内生的成長理論、進化経済学、新シュンペーター経済学など、経済学の他の学派から生まれたものである。今日の知識経済における成長を説明し、支える経済的枠組みを提供している。 イノベーション経済学の主要な理論家には、形式的な経済学者だけでなく、経営理論家や技術政策の専門家なども含まれる。ポール・ローマー、エルハナン・ヘ ルプマン、ブロンウィンホール、W.ブライアン・アーサー、ロバート・アクステル、リチャード・R.ネルソン、リチャード・リプシー、マイケル・ポー ター、キウン・リー、クリストファー・フリーマンなどである。 |

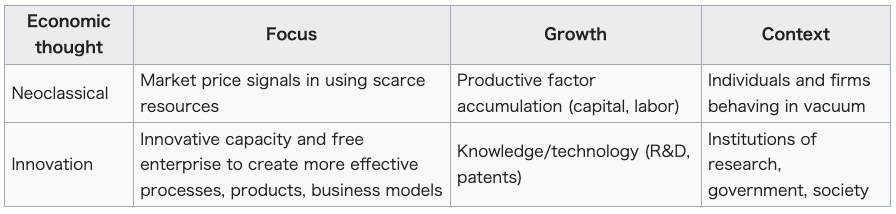

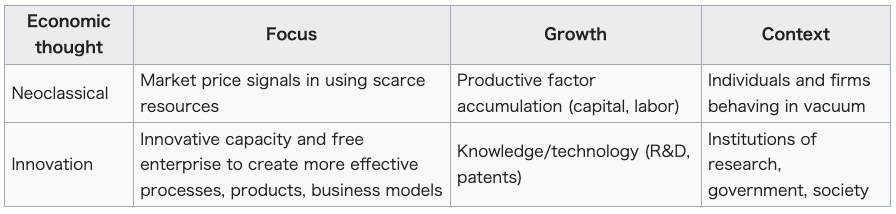

| Theory Innovation economists believe that what primarily drives economic growth in today's knowledge-based economy is not capital accumulation as neoclassical economics asserts, but innovative capacity spurred by appropriable knowledge and technological externalities. Economic growth in innovation economics is the end-product of:[5][6] knowledge (tacit vs. codified); regimes and policies allowing for entrepreneurship and innovation (i.e. R&D expenditures, permits and licenses); technological spillovers and externalities between collaborative firms; systems of innovation that create innovative environments (i.e. clusters, agglomerations and metropolitan areas). In 1970, economist Milton Friedman said in the New York Times that a business's sole purpose is to generate profits for their shareholders, and companies that pursued other missions would be less competitive, resulting in fewer benefits to owners, employees and society.[7] Yet, data over the past several decades shows that while profits matter, good firms supply far more, particularly in bringing innovation to the market. This fosters economic growth, employment gains and other society-wide benefits. Business school professor David Ahlstrom asserts that "the main goal of business is to develop new and innovative goods and services that generate economic growth while delivering benefits to society".[8] In contrast to neoclassical economics, innovation economics offer differing perspectives on main focus, reasons for economic growth and the assumptions of context between economic actors:  Despite the differences in economic thought, both perspectives are based on the same core premise, namely the foundation of all economic growth is the optimization of the utilization of factors and the measure of success is how well the factor utilization is optimized. Whatever the factors, it nonetheless leads to the same situation of special endowments, varying relative prices and production processes. Thus, while the two differ in theoretical concepts, innovation economics can find fertile ground in mainstream economics, rather than remain in diametric contention.[5] |

理論 イノベーション経済学者は、今日の知識集約型経済における経済成長の主な原動力は、新古典派経済学が主張するような資本蓄積ではなく、充当可能な知識と技 術的外部性によって促進される革新的能力であると考えている。イノベーション経済学における経済成長は、以下の最終成果である[5][6]。 知識(暗黙知対コード化された知識); 起業家精神とイノベーションを可能にする体制と政策(研究開発費、許認可など); 協力企業間の技術スピルオーバーと外部性; 革新的環境を生み出すイノベーションのシステム(クラスター、集積地、大都市圏など)。 1970年、経済学者のミルトン・フリードマンはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で、企業の唯一の目的は株主のために利益を生み出すことであり、それ以外の使命 を追求する企業は競争力を失い、その結果、経営者、従業員、そして社会への恩恵は少なくなると述べた[7]。しかし、過去数十年間のデータによれば、利益 は重要であるが、優れた企業は、特にイノベーションを市場にもたらすことで、はるかに多くのものを供給している。これは、経済成長、雇用の増加、その他の 社会全体の利益を促進する。ビジネススクールのデービッド・アールストローム教授は、「ビジネスの主な目標は、社会に利益をもたらしながら経済成長をもた らす、新しく革新的な商品やサービスを開発することである」と主張している[8]。 新古典派経済学とは対照的に、イノベーション経済学は、主な焦点、経済成長の理由、経済主体間の文脈の前提について異なる視点を提供している:  すなわち、すべての経済成長の基礎は、要因の利用の最適化であり、成功の尺度は、要因の利用がどれだけ最適化されているかということである。要因が何であ れ、それは特別な供給、相対価格の変動、生産プロセスという同じ状況をもたらす。したがって、両者は理論的な概念において異なるが、イノベーション経済学 は、正反対の対立にとどまるのではなく、主流派経済学の中に肥沃な土壌を見出すことができる。 |

| Evidence Empirical evidence worldwide points to a positive link between technological innovation and economic performance. For instance: The drive of innovation in Germany was due to the R&D subsidies to joint projects, network partners and close cognitive distance of collaborative partners within a cluster.[9] These factors increased patent performance in various industries such as biotech.[10] Innovation capacity explains much of the GDP growth in India and China between 1981 and 2004, but especially in the 1990s. Their development of a National Innovation System through heavy investment of R&D expenditures and personnel, patents and high-tech/service exports strengthened their innovation capacity. By linking the science sector with the business sector, establishing incentives for innovative activities and balancing the import of technology and indigenous R&D effort, both countries experienced rapid economic growth in recent decades.[11] The Council of Foreign Relations also asserted that since the end of the 1970s the U.S. has gained a disproportionate share of the world's wealth through their aggressive pursuit of technological change, demonstrating that technological innovation is a central catalyst of steady economic performance.[12] Concisely, evidence shows that innovation contributes to steady economic growth and rise in per capita income.[8] However, some empirical studies investigating the innovation-performance-link lead to rather mixed results and indicate that the relationship is more subtle and complex than commonly assumed.[13] In particular, the relationship between innovativeness and performance seems to differ in intensity and significance across empirical contexts, environmental circumstances and conceptual dimensions. All of the above has taken place in an era of data constraint as identified by Zvi Griliches in the 1990s.[14] Because the primary domain of innovation is commerce, the key data resides there, continually out of campus reach in reports hidden within factories, corporate offices and technical centers. This recusal still stymies progress today. Recent attempts at data transference have led not least to the positive link (above) being upgraded to exact algebra between R&D productivity and GDP, allowing prediction from one to the other. This is pending further disclosure from commercial sources, but several pertinent documents are already available.[15] |

エビデンス 技術革新と経済パフォーマンスの間に正の関係があることを示す実証的証拠は世界中にある。例えば、ドイツのイノベーションの原動力は、共同プロジェクトに 対する研究開発補助金、ネットワーク・パートナー、クラスター内の協働パートナーの認知的距離の近さによるものであった: ドイツにおけるイノベーションの原動力は、共同プロジェク トへの研究開発補助金、ネットワーク・パートナー、クラスター内の協 力パートナーの認知的距離の近さによるものであった[9]。 イノベーション能力は、インドと中国における1981年から2004年までのGDP成長の大部分を説明するが、特に1990年代において顕著である。研究 開発費と人材への多額の投資、特許、ハイテク・サービス輸出を通じた国民イノベーション・システムの発展が、イノベーション能力を強化した。科学部門をビ ジネス部門と結びつけ、革新的活動へのインセンティブを確立し、技術の輸入と自国の研究開発努力のバランスをとることによって、両国はここ数十年で急速な 経済成長を遂げた[11]。 外交問題評議会はまた、1970年代末以来、米国は技術革新の積極的な追求を通じて世界の富の不均衡なシェアを獲得しており、技術革新が安定した経済パフォーマンスの中心的触媒であることを示している、と主張している[12]。 簡潔に言えば、イノベーションが着実な経済成長と一人当たり所得の上昇に寄与していることを示す証拠である[8]。 しかし、イノベーションとパフォーマティビティとの関連性を調査したいくつかの実証研究では、かなり複雑な結果が得られており、その関係は一般に想定され ているよりも微妙で複雑であることが示されている[13]。特に、革新性とパフォーマン スとの関係は、実証的な文脈、環境的状況、概念的次元によって、その強度と重要性が異なるようである。 以上のことはすべて、1990年代にZvi Grilichesが指摘したようなデータ制約の時代に起こったことである[14]。イノベーションの主要領域は商業であるため、重要なデータはそこに存 在し、工場、企業オフィス、技術センターの中に隠された報告書の中で、絶えずキャンパスの手の届かないところに置かれている。この拒否反応は、今日でも進 歩を妨げている。最近のデータ移転の試みは、少なくとも、研究開発生産性とGDPの間の正のリンク(上記)を厳密な代数に格上げし、一方から他方への予測 を可能にすることにつながっている。これは商用ソースからのさらなる開示が待たれるところだが、いくつかの関連文書はすでに入手可能である[15]。 |

| Geography While innovation is important, it is not a happenstance occurrence as a natural harbor or natural resources are, but a deliberate, concerted effort of markets, institutions, policymakers and effective use of geographic space. In global economic restructuring, location has become a key element in establishing competitive advantage as regions focus on their unique assets to spur innovation (i.e. information technology in Silicon Valley, or digital media in Seoul). Even more, thriving metropolitan economies that carry multiple clusters (i.e. Tokyo, Chicago and London) essentially fuel national economies through their pools of human capital, innovation, quality places and infrastructure.[16] Cities become "innovative spaces" and "cradles of creativity" as drivers of innovation. They become essential to the system of innovation through the supply side as ready, available, abundant capital and labor, good infrastructure for productive activities and diversified production structures that spawn synergies and hence innovation. In addition, they grow due to the demand side as diverse population of varying occupations, ideas and skills, high and differentiated level of consumer demand and constant recreation of urban order especially infrastructure of streets, water systems, energy and transportation.[6] |

地理 イノベーションは重要であるが、それは天然の港や天然資源のように偶然に起こるものではなく、市場、制度、政策立案者、そして地理的空間の効果的な利用に よる意図的で協調的な取り組みである。世界的な経済再編の中で、立地は競争優位性を確立する上で重要な要素となっている。地域がイノベーションを促進する ために、その地域独自の資産(シリコンバレーの情報技術やソウルのデジタルメディアなど)に焦点を当てているからである。さらに、複数のクラスターを抱え る繁栄する大都市経済(東京、シカゴ、ロンドンなど)は、本質的に、人的資本、イノベーション、質の高い場所、インフラのプールを通じて国民経済に燃料を 供給している[16]。都市は、すぐに利用可能で豊富な資本と労働力、生産活動のための優れたインフラ、相乗効果を生み出し、それゆえにイノベーションを 生み出す多様な生産構造といった供給面を通じて、イノベーションのシステムにとって不可欠な存在となる。さらに、さまざまな職業、アイデア、スキルを持つ 多様な人口、高度で差別化された消費者需要、都市秩序の絶え間ない再整備、特に道路、水道、エネルギー、交通などのインフラといった需要面によっても成長 する[6]。 |

| Worldwide examples Semiconductors and information technology in Silicon Valley in California Fintechs and Cyber Security in Belfast in Northern Ireland Start-up Nation, Israel High-technology and life sciences in Research Triangle Park in North Carolina Energy companies in Energy Corridor in Houston, Texas Financial products and services in New York City Biotechnology in Genome Valley in Hyderabad, India and Boston, Massachusetts Nanotechnology in Tech Valley, New York (College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering) Precision engineering in South Yorkshire, United Kingdom Petrochemical complexes in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Train locomotive and rolling stock manufacturing in Beijing, China Automotive engineering in Baden-Württemberg, Germany Digital media technologies in Digital Media City in Seoul, South Korea |

世界の例 カリフォルニア州シリコンバレーにおける半導体と情報技術 北アイルランドのベルファストにおけるフィンテックとサイバーセキュリティ イスラエルのスタートアップ国民 ノースカロライナ州のリサーチ・トライアングル・パークにおけるハイテクとライフサイエンス テキサス州ヒューストンのエネルギー回廊のエネルギー企業 ニューヨークの金融商品・サービス インドのハイデラバードとマサチューセッツ州ボストンのゲノムバレーにあるバイオテクノロジー企業 ニューヨーク州テックバレーにあるナノテクノロジー(ナノスケール科学工学大学) 英国サウス・ヨークシャー州の精密工学 ブラジル、リオデジャネイロの石油化学コンビナート 中国・北京の鉄道機関車および車両製造 ドイツ、バーデン・ヴュルテンベルク州の自動車工学 韓国・ソウルのデジタルメディアシティにおけるデジタルメディア技術 |

| Business cluster Economic development Keynesian economics Knowledge economy Innovation International Innovation Index Metropolitan economy Neoclassical economics |

ビジネス・クラスター 経済発展 ケインズ経済学 知識経済 イノベーション 国際イノベーション指数 大都市経済 新古典派経済学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Innovation_economics |

|

Illustrates the intersection of supply and demand curves as the free market equilibrium

☆付録:経済的イノベーションについて考える

★ミルトン・フリードマンの宿敵の経済学者は誰ですか?

| 推論プロセス まず、ミルトン・フリードマンは新自由主義やマネタリズムの提唱者として知られています。彼の経済理論は政府の市場介入を最小限に抑えることを主張していました。宿敵となる経済学者を考える際には、フリードマンの主張と対立する立場の人物を探す必要があります。 ケインジアンの経済学者たちは、政府の積極的な財政政策を支持する点でフリードマンと対立していました。特にジョン・メイナード・ケインズの思想を継承す るポスト・ケインジアンの経済学者が挙げられます。例えば、ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイスは市場の不完全性を指摘し、政府の規制や介入を支持したため、フ リードマンと激しく論争しました。 また、マルクス主義の経済学者もフリードマンとは根本的に異なる立場です。例えば、ポール・スウィージーやポール・A・サミュエルソンは、資本主義の批判や混合経済の支持を主張し、フリードマンの市場原理主義と対立しました。 特に注目すべきは、フリードマンが1976年にノーベル経済学賞を受賞した際、同じ年にノーベル賞を受賞した経済学者との関係です。しかし、具体的な宿敵 としては、経済政策を巡って激しく対立した人物が適切でしょう。ガルブレイスとの論争は特に有名で、公共の場で何度も議論を交わしています。 さらに、フリードマンのマネタリズムに対抗して、ケインジアン経済学者のフランコ・モディリアーニも金融政策の効果について異なる見解を持っていました。彼らの理論的な対立は、経済学界で長く議論されました。 結論として、フリードマンの主な宿敵は、ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイスやポール・サミュエルソンといったケインジアンや混合経済を支持する経済学者たちと言えます。特にガルブレイスとは個人的にも思想的にも強い対立関係にありました。 ミルトン・フリードマンの主な宿敵とされる経済学者は、ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイス(John Kenneth Galbraith) です。両者は経済思想や政策をめぐり激しく対立しました。 |

☆

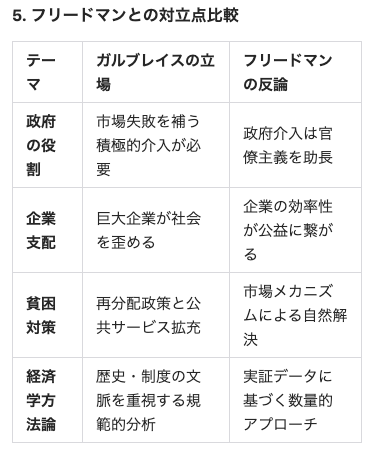

| ミルトン・フリードマンの主な宿敵とされる経済学者は、ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイス(John Kenneth Galbraith) です。両者は経済思想や政策をめぐり激しく対立しました。 対立の背景 思想的な対立 フリードマン:市場の自由を重視し、政府介入を最小限に抑える「新自由主義」や「マネタリズム」を提唱。 ガルブレイス:市場の不完全性を指摘し、政府の規制や公共投資を支持する「制度派経済学」の立場から批判。 政策への影響 ガルブレイスは1960年代のケネディ政権で経済顧問を務め、福祉政策や規制強化を推進。一方、フリードマンはレーガン政権の経済政策に影響を与え、規制緩和を主張しました。 公開討論 両者はテレビ番組や講演で直接議論を交わし、特に「資本主義のあり方」や「貧困対策」をめぐり激しい論争を繰り広げました。 その他の対立関係のある経済学者 ポール・サミュエルソン(Paul Samuelson) ケインジアン経済学の重鎮で、混合経済モデルを支持。フリードマンの市場原理主義を「現実離れ」と批判。 ジョーン・ロビンソン(Joan Robinson) ポスト・ケインジアン派の代表格。フリードマンの実証手法を「イデオロギー的」と断じた。 補足 フリードマンは「小さな政府」を掲げ、税制や教育バウチャー制度などで独自の改革案を提唱しましたが、これらはガルブレイスらから「格差拡大の要因」と批判されました。 |

★この脈絡のなかで、ミルトン・フリードマンに敵対するジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイスの業績をもっと詳しく教えてください。

☆

| ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイス(John Kenneth Galbraith)の主要な業績と思想 1. 「依存効果(Dependence Effect)」理論 市場経済における消費者の「ニーズ」が企業の広告によって人工的に創出される現象を指摘。 核心: 「消費は生産の従属物であり、企業が需要を操作する」 批判対象: 伝統的な経済学が想定する「消費者主権」の神話を解体し、大企業の市場支配力を問題化。 2. 「企業支配社会」の分析 1967年の著書『新しい産業国家(The New Industrial State)』で提唱: テクノストラクチャー(Technostructure): 巨大企業内の専門家集団が意思決定を掌握し、政府さえも影響下に置く構造を指摘。 計画システム: 市場メカニズムではなく、企業の長期計画が経済を支配すると主張。 3. 公共投資の重要性 『豊かな社会(The Affluent Society)』(1958年)で展開した思想: 私的豊かさ vs 公的貧困: 自動車や家電が溢れる一方で、教育・医療・インフラが軽視される矛盾を批判。 社会的バランス論: 民間部門の過剰投資と公共部門の投資不足を是正する政策を提唱。 4. 政策実践での影響力 ケネディ政権の経済顧問(1961-1963): 最低賃金引き上げや失業保険拡充を推進。ベトナム戦費増大に反対し辞任。 消費者保護運動の理論的支柱: 自動車安全性法(1966年)や消費者製品安全委員会(1972年)設立に思想的影響。 5. フリードマンとの対立点比較  テーマ ガルブレイスの立場 フリードマンの反論 政府の役割 市場失敗を補う積極的介入が必要 政府介入は官僚主義を助長 企業支配 巨大企業が社会を歪める 企業の効率性が公益に繋がる 貧困対策 再分配政策と公共サービス拡充 市場メカニズムによる自然解決 経済学方法論 歴史・制度の文脈を重視する規範的分析 実証データに基づく数量的アプローチ 6. 知られざるエピソード 文学的な筆力:経済書ながらベストセラー連発し、ピューリッツァー賞候補3回。 外交官としての経歴:第二次大戦後、ドイツ・日本の非軍事化政策に関与。 風刺の名手: 「経済予測の唯一の機能は、占星術をより尊敬できるものにすることだ」との警句を残す。 主要著作リスト(日本語訳版) 『豊かな社会』(1958)→ 公共投資の必要性を痛烈に主張 『新しい産業国家』(1967)→ 企業支配の構造分析 『不確実性の時代』(1977)→ 経済思想史の異端児的解説 『マネー』(1975)→ 金融システムの虚構性を暴露 ※生成AI Monica による |

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆