Guns,

Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies

(subtitled A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years in

Britain) is a 1997 transdisciplinary non-fiction book by Jared Diamond.

In 1998, it won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction and the

Aventis Prize for Best Science Book. A documentary based on the book,

and produced by the National Geographic Society, was broadcast on PBS

in July 2005.[1]

The book attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African

civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against

the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian

intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues

that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate

primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various

positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have

favored Eurasians (for example, written language or the development

among Eurasians of resistance to endemic diseases), he asserts that

these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on

societies and cultures (for example, by facilitating commerce and trade

between different cultures) and were not inherent in the Eurasian

genomes.

|

銃・病原菌・鉄。The Fates of Human

Societies(副題:A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years in

Britain)は、1997年に出版されたジャレド・ダイアモンドの学際的ノンフィクションである。1998年、ピューリッツァー賞(一般ノンフィク

ション部門)、アベンティス賞(最優秀科学書部門)を受賞した。この本を基にナショナルジオグラフィック協会が制作したドキュメンタリーは2005年7月

にPBSで放送された[1]。

本書は、ユーラシアと北アフリカの文明がなぜ生き残り、他を征服してきたかを説明しようとするもので、ユーラシアの覇権がいかなる形のユーラシアの知的、

道徳的、あるいは固有の遺伝的優位性に起因するという考えには反論している。ダイヤモンドは、人類社会間のパワーとテクノロジーの格差は、主に環境の違い

に起因し、それが様々な正のフィードバック・ループによって増幅されると論じている。文化的・遺伝的な差異がユーラシア人に有利に働いた場合(例えば、文

字言語や風土病に対する抵抗力の発達など)、それは地理が社会・文化に与えた影響であり(例えば、異文化間の商業・貿易の促進)、ユーラシア人のゲノムに

固有のものではないと彼は断言しているのである。

★ダイアモンド批判はこちら「『銃・病原菌・鉄』を再考する」を参照して

ください。

|

Synopsis

The prologue opens with an account of Diamond's conversation with Yali,

a New Guinean politician. The conversation turned to the obvious

differences in power and technology between Yali's people and the

Europeans who dominated the land for 200 years, differences that

neither of them considered due to any genetic superiority of Europeans.

Yali asked, using the local term "cargo" for inventions and

manufactured goods, "Why is it that you white people developed so much

cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little

cargo of our own?"[2]: 14

Diamond realized the same question seemed to apply elsewhere: "People

of Eurasian origin ... dominate ... the world in wealth and power."

Other peoples, after having thrown off colonial domination, still lag

in wealth and power. Still others, he says, "have been decimated,

subjugated, and in some cases even exterminated by European

colonialists."[2]: 15

The peoples of other continents (sub-Saharan Africans, Indigenous

people of the Americas, Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, and the

original inhabitants of tropical Southeast Asia) have been largely

conquered, displaced and in some extreme cases – referring to Native

Americans, Aboriginal Australians, and South Africa's indigenous

Khoisan peoples – largely exterminated by farm-based societies such as

Eurasians and Bantu. He believes this is due to these societies'

technological and immunological advantages, stemming from the early

rise of agriculture after the last ice age.

|

あらすじ

プロローグは、ダイアモンドとニューギニアの政治家ヤリとの会話から始まる。その会話は、200年にわたりこの地を支配してきたヨーロッパ人とヤリの人々

の間にある、権力と技術の明らかな差に及んだ。両者とも、ヨーロッパ人の遺伝的優位性によるものとは考えていなかった。ヤリは、発明や製造物を現地の言葉

で「カーゴ」と呼びながら、「なぜ、あなたたち白人はカーゴをたくさん開発してニューギニアに持ち込んだのに、私たち黒人はほとんどカーゴを持っていない

のですか」と尋ねた[2]。 14

ダイヤモンドは、同じ疑問が他の場所でも当てはまるようだと気づいた。「ユーラシア大陸出身の人々は......富と権力の面で世界を支配している」

[2]。他の民族は、植民地支配を脱した後でも、富と力の面で遅れをとっている。さらに他の民族は、「ヨーロッパの植民地主義者によって、衰退し、征服さ

れ、場合によっては絶滅さえしている」と彼は言う[2]。 15

他の大陸の人々(サハラ以南のアフリカ人、アメリカ大陸の先住民、オーストラリアのアボリジニ、ニューギニア人、熱帯東南アジアの原住民)は、ユーラシア

人やバンツーなどの農耕型社会によって大部分が征服され、追いやられ、極端な場合には-アメリカ先住民、オーストラリアのアボリジニ、南アフリカの先住民

コイサン族について-大部分が絶滅させられたのである。これは、氷河期以降に農耕が早くから発達したため、これらの社会が技術的、免疫的に優位に立ったた

めであると、彼は考えている。

|

Title

The book's title is a reference to the means by which farm-based

societies conquered populations and maintained dominance though

sometimes being vastly outnumbered, so that imperialism was enabled by

guns, germs, and steel.

Diamond argues geographic, climatic and environmental characteristics

which favored early development of stable agricultural societies

ultimately led to immunity to diseases endemic in agricultural animals

and the development of powerful, organized states capable of dominating

others.

|

タイトル

本書のタイトルは、農耕社会を基盤とする社会が、時には圧倒的に劣勢に立たされながらも集団を征服し、支配を維持する手段、すなわち帝国主義が銃、病原

菌、鉄によって可能になったことに由来している。

ダイヤモンドは、初期の安定した農耕社会の発展を支えた地理的、気候的、環境的特性が、最終的に農耕動物に特有の病気に対する免疫力を高め、他者を支配で

きる強力で組織的な国家を発展させたと論じている。

|

Outline

Diamond argues that Eurasian civilization is not so much a product of

ingenuity, but of opportunity and necessity. That is, civilization is

not created out of superior intelligence, but is the result of a chain

of developments, each made possible by certain preconditions.

The first step towards civilization is the move from nomadic

hunter-gatherer to rooted agrarian society. Several conditions are

necessary for this transition to occur: access to high-carbohydrate

vegetation that endures storage; a climate dry enough to allow storage;

and access to animals docile enough for domestication and versatile

enough to survive captivity. Control of crops and livestock leads to

food surpluses. Surpluses free people to specialize in activities other

than sustenance and support population growth. The combination of

specialization and population growth leads to the accumulation of

social and technological innovations which build on each other. Large

societies develop ruling classes and supporting bureaucracies, which in

turn lead to the organization of nation-states and empires.[2]

Although agriculture arose in several parts of the world, Eurasia

gained an early advantage due to the greater availability of suitable

plant and animal species for domestication. In particular, Eurasia has

barley, two varieties of wheat, and three protein-rich pulses for food;

flax for textiles; and goats, sheep, and cattle. Eurasian grains were

richer in protein, easier to sow, and easier to store than American

maize or tropical bananas.

As early Western Asian civilizations developed trading relationships,

they found additional useful animals in adjacent territories, such as

horses and donkeys for use in transport. Diamond identifies 13 species

of large animals over 100 pounds (45 kg) domesticated in Eurasia,

compared with just one in South America (counting the llama and alpaca

as breeds within the same species) and none at all in the rest of the

world. Australia and North America suffered from a lack of useful

animals due to extinction, probably by human hunting, shortly after the

end of the Pleistocene, and the only domesticated animals in New Guinea

came from the East Asian mainland during the Austronesian settlement

around 4,000–5,000 years ago. Biological relatives of the horse,

including zebras and onagers, proved untameable; and although African

elephants can be tamed, it is very difficult to breed them in

captivity.[2][3] Diamond describes the small number of domesticated

species (14 out of 148 "candidates") as an instance of the Anna

Karenina principle: many promising species have just one of several

significant difficulties that prevent domestication. He argues that all

large mammals that could be domesticated, have been.[2]: 168–174

Eurasians domesticated goats and sheep for hides, clothing, and cheese;

cows for milk; bullocks for tillage of fields and transport; and benign

animals such as pigs and chickens. Large domestic animals such as

horses and camels offered the considerable military and economic

advantages of mobile transport.

|

概要

ダイヤモンドは、ユーラシア文明が創意工夫の産物ではなく、機会と必然の産物であると主張する。つまり、文明は優れた知性から生み出されたものではなく、

それぞれがある前提条件によって可能となった一連の発展の結果である。

文明への第一歩は、遊牧民である狩猟採集民から、根付いた農耕社会への移行である。この移行にはいくつかの条件が必要である。貯蔵に耐える高炭水化物植物

へのアクセス、貯蔵が可能なほど乾燥した気候、家畜化できるほど従順で飼育に耐えるほど多才な動物へのアクセスなどである。作物と家畜の管理は、食糧の余

剰をもたらす。余剰食糧は、人々を栄養補給以外の活動に特化させ、人口増加を支える。専門化と人口増加が組み合わさると、社会的・技術的イノベーションが

蓄積され、それが相互に積み重なっていく。大規模な社会では支配階級とそれを支える官僚機構が発達し、それが国民国家や帝国の組織化につながっていく

[2]。

農業は世界のいくつかの地域で発生したが、ユーラシアは家畜化に適した植物や動物の種がより多く利用可能であったため、早くから優位に立つことができた。

特にユーラシア大陸には、食料となる大麦、2種類の小麦、タンパク質に富む3種類の豆類、織物用の亜麻、ヤギ、羊、牛が存在した。ユーラシア大陸の穀物

は、アメリカのトウモロコシや熱帯のバナナよりもタンパク質が豊富で、種まきも容易で、貯蔵もしやすかった。

西アジア初期の文明は交易関係を発展させながら、隣接する領土に輸送用の馬やロバなどの有用な動物を見出した。ダイヤモンド社は、ユーラシア大陸で家畜化

された45kg以上の大型動物は13種であるのに対し、南米ではわずか1種(ラマとアルパカは同じ種としてカウント)、その他の地域では全く存在しないこ

とを明らかにしている。オーストラリアや北アメリカでは更新世が終わった直後に、おそらく人間の狩猟によって絶滅し、有用動物の不足に悩まされた。ニュー

ギニアで唯一家畜化された動物は、約4000〜5000年前のオーストロネシア人の入植時に東アジア大陸からもたらされたものである。シマウマやオナガザ

ルを含むウマの近縁種は飼いならせないことが判明し、アフリカゾウは飼いならせるが、飼育下での繁殖は非常に難しい[2][3]

ダイヤモンドは、飼養種の少なさ(148の「候補」のうち14)を、「アナ・カレーニの原理」の例と表現する:有望種の多くが、飼養を妨げるいくつかの重

大な困難のうちの一つを持っているだけなのである。彼は、家畜化できる大型哺乳類はすべて家畜化されてきたと主張している[2]。 168-174

ユーラシア大陸では、皮革、衣服、チーズのためにヤギや羊を、牛乳のために牛を、畑の耕作や運搬のために雄牛を、そして豚や鶏のような温和な動物を家畜化

した。馬やラクダなどの大型家畜は、軍事的・経済的に大きな利点を持つ移動手段であった。

|

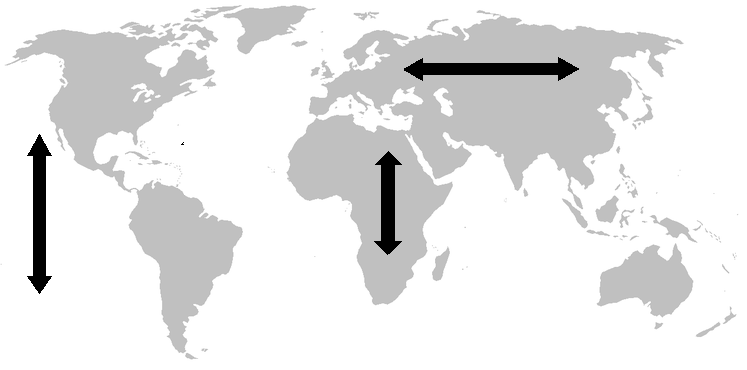

Eurasia's large landmass and

long east–west distance increased these advantages. Its large area

provided more plant and animal species suitable for domestication.

Equally important, its east–west orientation has allowed groups of

people to wander and empires to conquer from one end of the continent

to the other while staying at the same latitude. This was important

because similar climate and cycle of seasons let them keep the same

"food production system" – they could keep growing the same crops and

raising the same animals all the way from Scotland to Siberia. Doing

this throughout history, they spread innovations, languages and

diseases everywhere.

By contrast, the north-south orientation of the Americas and Africa

created countless difficulties adapting crops domesticated at one

latitude for use at other latitudes (and, in North America, adapting

crops from one side of the Rocky Mountains to the other). Similarly,

Africa was fragmented by its extreme variations in climate from north

to south: crops and animals that flourished in one area never reached

other areas where they could have flourished, because they could not

survive the intervening environment. Europe was the ultimate

beneficiary of Eurasia's east–west orientation: in the first millennium

BCE, the Mediterranean areas of Europe adopted Southwestern Asia's

animals, plants, and agricultural techniques; in the first millennium

CE, the rest of Europe followed suit.[2][3]

The plentiful supply of food and the dense populations that it

supported made division of labor possible. The rise of non-farming

specialists such as craftsmen and scribes accelerated economic growth

and technological progress. These economic and technological advantages

eventually enabled Europeans to conquer the peoples of the other

continents in recent centuries by using guns and steel, particularly

after the devastation of native populations by the epidemic diseases

from germs.

Eurasia's dense populations, high levels of trade, and living in close

proximity to livestock resulted in widespread transmission of diseases,

including from animals to humans. Smallpox, measles, and influenza were

the result of close proximity between dense populations of animals and

humans. Natural selection endowed most Eurasians with genetic

variations making them less susceptible to some diseases, and constant

circulation of diseases meant adult individuals had developed immunity

to a wide range of pathogens. When Europeans made contact with the

Americas, European diseases (to which Americans had no immunity)

ravaged the indigenous American population, rather than the other way

around. The "trade" in diseases was a little more balanced in Africa

and southern Asia, where endemic malaria and yellow fever made these

regions notorious as the "white man's grave".[4] Some researchers say

syphilis may have originated in the Americas,[citation needed] some say

it was known to Hippocrates,[5] and others think it was brought from

the Americas by Columbus and his successors.[6] The European diseases

from germs obliterated indigenous populations so that relatively small

numbers of Europeans could maintain dominance.[2][3]

Diamond proposes geographical explanations for why western European

societies, rather than other Eurasian powers such as China, have been

the dominant colonizers.[2][7] He said Europe's geography favored

balkanization into smaller, closer nation-states, bordered by natural

barriers of mountains, rivers, and coastline. Advanced civilization

developed first in areas whose geography lacked these barriers, such as

China, India and Mesopotamia. There, the ease of conquest meant they

were dominated by large empires in which manufacturing, trade and

knowledge flourished for millennia, while balkanized Europe remained

more primitive.

However, at a later stage of development, western Europe's fragmented

governmental structure actually became an advantage. Monolithic,

isolated empires without serious competition could continue mistaken

policies – such as China squandering its naval mastery by banning the

building of ocean-going ships – for long periods without immediate

consequences. In Western Europe, by contrast, competition from

immediate neighbors meant that governments could not afford to suppress

economic and technological progress for long; if they did not correct

their mistakes, they were out-competed and/or conquered relatively

quickly. While the leading powers alternated, the constant was rapid

development of knowledge which could not be suppressed. For instance,

the Chinese Emperor could ban shipbuilding and be obeyed, ending

China's Age of Discovery, but the Pope could not keep Galileo's

Dialogue from being republished in Protestant countries, or Kepler and

Newton from continuing his progress; this ultimately enabled European

merchant ships and navies to navigate around the globe. Western Europe

also benefited from a more temperate climate than Southwestern Asia

where intense agriculture ultimately damaged the environment,

encouraged desertification, and hurt soil fertility.

|

ユーラシア大陸は広大な国土と東西に長い距離を持ち、その優位性はます

ます高まっている。その広大な面積は、家畜化に適した植物や動物の種をより多く提供した。同様に重要なのは、東西に長いため、同じ緯度にいながら、大陸の

端から端まで人々の集団が放浪し、帝国が征服することができたことである。これは、気候や季節のサイクルが似ているため、スコットランドからシベリアま

で、同じ作物を育て、同じ動物を飼うという「食料生産システム」を維持できたことが重要である。スコットランドからシベリアまで、同じ作物を作り、同じ動

物を飼い続けることができたのです。そして、歴史を通じて、技術革新、言語、病気などを広めていきました。

一方、南北に長いアメリカ大陸とアフリカでは、ある緯度で栽培された作物を他の緯度で使用することは困難であった(北米では、ロッキー山脈の反対側で栽培

された作物を他の緯度に適応させることができた)。同様に、アフリカは南北で気候が極端に異なるため、ある地域で栄えた作物や動物が他の地域で栄えること

ができず、その間の環境に耐えることができないため、分断されてしまったのである。紀元前1千年紀にヨーロッパの地中海沿岸地域は西南アジアの動物、植

物、農業技術を取り入れ、紀元前1千年紀にはヨーロッパの他の地域もそれに続いた[2][3]。

豊富な食糧供給とそれを支える人口の密集は分業を可能にした。職人や書記など農耕以外の専門職が台頭し、経済成長と技術進歩が加速した。こうした経済的・

技術的な優位性により、特に細菌による伝染病で先住民が壊滅的な打撃を受けた後、ヨーロッパ人は銃と鉄を駆使して、ここ数世紀で他の大陸の人々を征服する

ことができるようになった。

ユーラシア大陸は人口が密集し、交易が盛んで、家畜が近くに住んでいたため、動物から人間への感染など、病気の伝播が広く行われた。天然痘、麻疹、インフ

ルエンザなどは、密集した動物集団と人間が接近した結果、発生したものである。自然淘汰により、ユーラシア大陸のほとんどの人は、病気にかかりにくい遺伝

的変異を持ち、また、常に病気の感染が繰り返されていたため、成人はさまざまな病原菌に対する免疫を獲得していた。ヨーロッパ人がアメリカ大陸と接触した

とき、アメリカ人が免疫を持っていなかったヨーロッパの病気は、アメリカ先住民を苦しめ、むしろその逆を行ったのである。アフリカや南アジアでは、病気の

「取引」はもう少しバランスが取れていた。マラリアや黄熱病が蔓延し、これらの地域は「白人の墓場」として悪名高い。

[4]梅毒はアメリカ大陸で発生した可能性があると言う研究者もいれば[citation

needed]、ヒポクラテスが知っていたと言う者もおり[5]、コロンブスとその後継者によってアメリカ大陸からもたらされたと考える者もいる。[6]

細菌によるヨーロッパの病気は比較的少数のヨーロッパ人が支配を維持できるように先住民を抹消した。[2][3]このように、ヨーロッパ人の病気は地理的

に説明することが可能である。

ダイヤモンドは、中国のような他のユーラシア勢力ではなく、西ヨーロッパ社会が支配的な植民地化者であった理由について地理的な説明を提案している[2]

[7]。

彼はヨーロッパの地理が、山、川、海岸線などの自然の障壁によって縁取られた、より小さく、より近い国民国家へとバルカン化を好んだと述べている。高度な

文明は、中国、インド、メソポタミアなど、これらの障壁を持たない地理的条件を持つ地域で最初に発展した。征服が容易であったため、大帝国が支配し、製

造、貿易、知識が数千年にわたり繁栄した。一方、バルカン半島のヨーロッパはより原始的なままであった。

しかし、その後の発展段階において、西ヨーロッパの断片的な政府機構は、かえって有利に働いた。一枚岩で孤立した帝国は、深刻な競争もなく、誤った政策

(例えば、中国は外航船の建造を禁止して海軍の支配力を浪費した)を長期にわたって続けても、すぐに影響が出ることはなかったのである。これとは対照的

に、西ヨーロッパでは、近隣諸国との競争があったため、政府は経済や技術の進歩を長期間にわたって抑制することができず、誤りを正さなければ、比較的早く

競争相手や征服者に打ち負かされることになった。もし失敗を正さなければ、比較的早く競争相手となり、あるいは征服されることになる。有力国が入れ替わる

一方で、抑制することができない知識の急速な発展が常にあった。例えば、中国の皇帝は造船を禁止し、それに従うことで中国の大航海時代を終わらせることが

できたが、ローマ教皇はガリレオの『対話篇』がプロテスタントの国で再出版されることや、ケプラーやニュートンがその進歩を続けることを阻止することがで

きなかった。また、西ヨーロッパは、激しい農業が環境を破壊し、砂漠化を促進し、土壌の肥沃度を損なった南西アジアに比べ、より温暖な気候の恩恵を受けて

いる。

|

Agriculture

Guns, Germs, and Steel argues that cities require an ample supply of

food, and thus are dependent on agriculture. As farmers do the work of

providing food, division of labor allows others freedom to pursue other

functions, such as mining and literacy.

The crucial trap for the development of agriculture is the availability

of wild edible plant species suitable for domestication. Farming arose

early in the Fertile Crescent since the area had an abundance of wild

wheat and pulse species that were nutritious and easy to domesticate.

In contrast, American farmers had to struggle to develop corn as a

useful food from its probable wild ancestor, teosinte.

Also important to the transition from hunter-gatherer to city-dwelling

agrarian societies was the presence of "large" domesticable animals,

raised for meat, work, and long-distance communication. Diamond

identifies a mere 14 domesticated large mammal species worldwide. The

five most useful (cow, horse, sheep, goat, and pig) are all descendants

of species endemic to Eurasia. Of the remaining nine, only two (the

llama and alpaca both of South America) are indigenous to a land

outside the temperate region of Eurasia.

Due to the Anna Karenina principle, surprisingly few animals are

suitable for domestication. Diamond identifies six criteria including

the animal being sufficiently docile, gregarious, willing to breed in

captivity and having a social dominance hierarchy. Therefore, none of

the many African mammals such as the zebra, antelope, cape buffalo, and

African elephant were ever domesticated (although some can be tamed,

they are not easily bred in captivity). The Holocene extinction event

eliminated many of the megafauna that, had they survived, might have

become candidate species, and Diamond argues that the pattern of

extinction is more severe on continents where animals that had no prior

experience of humans were exposed to humans who already possessed

advanced hunting techniques (such as the Americas and Australia).

Smaller domesticable animals such as dogs, cats, chickens, and guinea

pigs may be valuable in various ways to an agricultural society, but

will not be adequate in themselves to sustain a large-scale agrarian

society. An important example is the use of larger animals such as

cattle and horses in plowing land, allowing for much greater crop

productivity and the ability to farm a much wider variety of land and

soil types than would be possible solely by human muscle power. Large

domestic animals also have an important role in the transportation of

goods and people over long distances, giving the societies that possess

them considerable military and economic advantages..

|

農業

銃・病原菌・鉄』は、都市には十分な食料が必要であり、そのために農業に依存していると論じている。農民が食料を供給する仕事をすることで、分業が進み、

他の人々は鉱業や識字といった他の仕事に従事する自由を得ることができる。

農業が発展した決定的な要因は、家畜化に適した野生の食用植物種が利用可能であったことである。肥沃な三日月地帯では、栄養価が高く家畜化しやすい野生の

小麦や豆類が豊富にあったため、早くから農耕が行われていた。一方、アメリカの農民は、野生の祖先と思われるテオシンテから、有用な食料としてのトウモロ

コシを開発するのに苦労した。

狩猟採集社会から都市に住む農耕社会への移行には、食肉、労働、長距離コミュニケーションのために飼育される「大型」家畜の存在も重要であった。ダイヤモ

ンド社は、家畜化された大型哺乳類は世界でわずか14種であることを明らかにしている。最も有用な5種(牛、馬、羊、山羊、豚)は、いずれもユーラシア大

陸に生息する固有種の子孫である。残りの9種のうち、ユーラシア大陸の温帯域以外の土地に生息するのは2種(南米のラマとアルパカ)だけである。

アンナ・カレーニナの原理で、家畜化に適した動物は意外に少ない。ダイヤモンド社は、動物が十分に従順であること、群生していること、飼育下で繁殖する意

思があること、社会的な支配階層があることなど、6つの基準を挙げている。したがって、シマウマ、カモシカ、ケープバッファロー、アフリカゾウなど、アフ

リカの多くの哺乳類は家畜化されなかった(飼いならすことはできるが、飼育下で繁殖させることは容易でない)。完新世の絶滅は、生存していれば候補種に

なったかもしれない多くのメガファウナを絶滅させた。ダイヤモンドは、人類と接触したことのない動物が、すでに高度な狩猟技術を持つ人類にさらされた大陸

(アメリカ大陸やオーストラリアなど)で、絶滅のパターンがより深刻であると論じている。

犬、猫、鶏、モルモットなどの家畜化可能な小動物は、農耕社会にとって様々な意味で価値があるかもしれないが、大規模農耕社会を維持するためにはそれだけ

で十分とは言えないだろう。例えば、牛や馬のような大型の家畜が土地を耕すことで、作物の生産性が高まり、人間の筋力だけでは不可能な多様な土地や土壌を

耕すことができるようになる。また、大型の家畜は、長距離の物資や人の輸送に重要な役割を果たし、それを保有する社会は軍事的・経済的に大きな利点を得る

ことができる。

|

Geography

Diamond argues that geography shaped human migration, not simply by

making travel difficult (particularly by latitude), but by how climates

affect where domesticable animals can easily travel and where crops can

ideally grow easily due to the sun.

The dominant Out of Africa theory holds that modern humans developed

east of the Great Rift Valley of the African continent at one time or

another. The Sahara kept people from migrating north to the Fertile

Crescent, until later when the Nile River valley became accommodating.

Diamond continues to describe the story of human development up to the

modern era, through the rapid development of technology, and its dire

consequences on hunter-gathering cultures around the world.

Diamond touches on why the dominant powers of the last 500 years have

been West European rather than East Asian, especially Chinese. The

Asian areas in which big civilizations arose had geographical features

conducive to the formation of large, stable, isolated empires which

faced no external pressure to change which led to stagnation. Europe's

many natural barriers allowed the development of competing nation

states. Such competition forced the European nations to encourage

innovation and avoid technological stagnation.

|

地理学

ダイヤモンドは、人類の移動は、単に移動を困難にする(特に緯度によって)だけでなく、気候が家畜の移動しやすい場所や、太陽の影響で作物が理想的に育ち

やすい場所に影響を与えることによって形成されたと論じている。

主流となっている「アウト・オブ・アフリカ」説では、現代人はアフリカ大陸の大地溝帯の東側で、ある時期から発展してきたと考えられている。サハラ砂漠の

ために人々は北の肥沃な三日月地帯に移住できず、後にナイル川流域が受け入れられるようになるまで、サハラ砂漠は人々の移住を妨げた。

さらにダイヤモンドは、科学技術の急速な発展と、それが世界中の狩猟採集文化にもたらした悲惨な結果を通して、近代に至るまでの人類の発展の物語を描いて

いる。

ダイヤモンドは、過去500年の支配的な大国が、東アジア、特に中国ではなく、なぜ西ヨーロッパであったのかに触れている。大きな文明が生まれたアジア地

域は、大規模で安定した孤立した帝国の形成に資する地理的特徴があり、停滞をもたらす変化の外圧に直面することがなかった。一方、ヨーロッパは、自然の障

壁が多いため、国民国家が競い合って発展した。このような競争により、ヨーロッパ諸国は技術革新を促し、技術の停滞を回避することを余儀なくされた。

|

Germs

In the later context of the European colonization of the Americas, 95%

of the indigenous populations are believed to have been killed off by

diseases brought by the Europeans. Many were killed by infectious

diseases such as smallpox and measles. Similar circumstances were

observed in Australia and South Africa. Aboriginal Australians and the

Khoikhoi population were devastated by smallpox, measles, influenza,

and other diseases.[8][9]

Diamond questions how diseases native to the American continents did

not kill off Europeans, and posits that most of these diseases were

developed and sustained only in large dense populations in villages and

cities. He also states most epidemic diseases evolve from similar

diseases of domestic animals. The combined effect of the increased

population densities supported by agriculture, and of close human

proximity to domesticated animals leading to animal diseases infecting

humans, resulted in European societies acquiring a much richer

collection of dangerous pathogens to which European people had acquired

immunity through natural selection (such as the Black Death and other

epidemics) during a longer time than was the case for Native American

hunter-gatherers and farmers.

He mentions the tropical diseases (mainly malaria) that limited

European penetration into Africa as an exception. Endemic infectious

diseases were also barriers to European colonisation of Southeast Asia

and New Guinea.

Success and failure

Guns, Germs, and Steel focuses on why some populations succeeded. His

later book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, focuses

on environmental and other factors that have caused some populations to

fail.

|

病原菌

ヨーロッパ人がアメリカ大陸を植民地化した後、先住民の95%がヨーロッパ人が持ち込んだ病気によって殺されたと言われている。その多くが天然痘や麻疹な

どの感染症で命を落とした。同じような状況は、オーストラリアや南アフリカでも見られた。オーストラリアのアボリジニやコイコイの人々は、天然痘、はし

か、インフルエンザなどの病気によって壊滅的な打撃を受けた[8][9]。

ダイヤモンドは、アメリカ大陸固有の病気がなぜヨーロッパ人を絶滅させなかったのかに疑問を呈し、これらの病気のほとんどは、村や都市に密集した大規模な

集団においてのみ発生し維持されたものであると仮定している。また、ほとんどの伝染病は、家畜の同様の病気から発展したものであると述べている。農業に支

えられた人口密度の上昇と、人間が家畜に接近して動物の病気を人間に感染させるという複合的な効果によって、ヨーロッパ社会は、アメリカ先住民の狩猟採集

民や農民の場合よりも長い期間に、ヨーロッパ人が自然選択によって免疫を獲得した危険な病原体のコレクション(例えば黒死病やその他の疫病)をはるかに豊

富に獲得することになったのである。

彼は例外として、ヨーロッパ人のアフリカへの侵入を制限した熱帯病(主にマラリア)を挙げている。また、風土病は東南アジアやニューギニアへのヨーロッパ

人の植民地化の障壁となった。

成功と失敗

銃・病原菌・鉄』は、ある集団がなぜ成功したかに焦点を当てている。後に出版された「崩壊」(Collapse:

は、ある集団が失敗する原因となった環境要因やその他の要因に焦点を当てたものである。

|

Intellectual background

In the 1930s, the Annales School in France undertook the study of

long-term historical structures by using a synthesis of geography,

history, and sociology. Scholars examined the impact of geography,

climate, and land use. Although geography had been nearly eliminated as

an academic discipline in the United States after the 1960s, several

geography-based historical theories were published in the 1990s.[10]

In 1991, Jared Diamond already considered the question of "why is it

that the Eurasians came to dominate other cultures?" in The Third

Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal (part four).

Reception

The reception of Guns, Germs, and Steel by academics was generally

positive.

Praise

Many noted that the large scope of the work makes some

oversimplification inevitable while still praising the book as a very

erudite and generally effective synthesis of multiple different

subjects. Paul R. Ehrlich and E. O. Wilson both praised the book.[11]

Northwestern University economic historian Joel Mokyr interpreted

Diamond as a geographical determinist but added that the thinker could

never be described as "crude" like many determinists. For Mokyr,

Diamond's view that Eurasia succeeded largely because of a uniquely

large stock of domesticable plants is flawed because of the possibility

of crop manipulation and selection in the plants of other regions: the

drawbacks of an indigenous plant such as sumpweed could have been bred

out, Mokyr wrote, since "all domesticated plants had originally

undesirable characteristics" eliminated via "deliberate and lucky

selection mechanisms". Mokyr dismissed as unpersuasive Diamond's theory

that breeding specimens failing to fix characteristics controlled by

multiple genes "lay at the heart of the geographically challenged

societies". Mokyr also states that in seeing economic history as

centered on successful manipulation of environments, Diamond downplays

the role of "the option to move to a more generous and flexible area",

and speculated that non-generous environments were the source of much

human ingenuity and technology. However, Mokyr still argued that Guns,

Germs, and Steel is "one of the more important contributions to

long-term economic history and is simply mandatory to anyone who

purports to engage Big Questions in the area of long-term global

history". He lauded the book as full of "clever arguments about

writing, language, path dependence and so on. It is brimming with

wisdom and knowledge, and it is the kind of knowledge economic

historians have always loved and admired."[12]

Berkeley economic historian Brad DeLong described the book as a "work

of complete and total genius".[13] Harvard International Relations (IR)

scholar Stephen Walt in a Foreign Policy article called the book "an

exhilarating read" and put it on a list of the ten books every IR

student should read.[14] Tufts University IR scholar Daniel W. Drezner

listed the book on his top ten list of must-read books about

international economic history.[15]

International Relations scholars Iver B. Neumann (of the London School

of Economics and Political Science) and Einar Wigen (of University of

Oslo) use Guns, Germs, and Steel as a foil for their own

inter-disciplinary work. They write that "while empirical details

should, of course, be correct, the primary yardstick for this kind of

work cannot be attention to detail." According to the two writers,

"Diamond stated clearly that any problematique of this magnitude had to

be radically multi-causal and then set to work on one complex of

factors, namely ecological ones", and note that Diamond "immediately

came in for heavy criticism from specialists working in the disparate

fields on which he drew". But Neumann and Wigen also stated, "Until

somebody can come up with a better way of interpreting and adding to

Diamond’s material with a view to understanding the same overarching

problematique, his is the best treatment available of the ecological

preconditions for why one part of the world, and not another, came to

dominate."[16] Historian Tonio Andrade writes that Diamond's book "may

not satisfy professional historians on all counts" but that it "does

make a bold and compelling case for the different developments that

occurred in the Old World versus the New (he is less convincing in his

attempts to separate Africa from Eurasia)."[17]

Historian Tom Tomlinson wrote that the magnitude of the task makes it

inevitable that Professor Diamond would "[use] very broad brush-strokes

to fill in his argument", but ultimately commended the book. Taking the

account of prehistory "on trust" because it was not his area of

expertise, Tomlinson stated that the existence of stronger weapons,

diseases, and means of transport is convincing as an "immediate cause"

of Old World societies and technologies being dominant, but questioned

Diamond's view that the way this has transpired has been through

certain environments causing greater inventiveness which then caused

more sophisticated technology. Tomlinson noted that technology spreads

and allows for military conquests and the spread of economic changes,

but that in Diamond's book this aspect of human history "is dismissed

as largely a question of historical accident". Writing that Diamond

gives meager coverage to the history of political thought, the

historian suggested that capitalism (which Diamond classes as one of 10

plausible but incomplete explanations) has perhaps played a bigger role

in prosperity than Diamond argues.[18]

Tomlinson speculated that Diamond underemphasizes cultural

idiosyncrasies as an explanation, and argues (with regards to the

"germs" part of Diamond's triad of reasons) that the Black Death of the

14th century, as well as smallpox and cholera in 19th century Africa,

rival the Eurasian devastation of indigenous populations as overall

"events of human diffusion and coalescence". Tomlinson also found

contentious Diamond's view that humanity's future can one day be

foreseen with scientific rigor since this would involve a search for

general laws that new theoretical approaches deny the possibility of

establishing: "The history of humans cannot properly be equated with

the history of dinosaurs, glaciers or nebulas, because these natural

phenomena do not consciously create the evidence on which we try to

understand them". Tomlinson still described these flaws as "minor",

however, and wrote that Guns, Germs, and Steel "remains a very

impressive achievement of imagination and exposition".[18][19]

Another historian, professor J. R. McNeill, complimented the book for

"its improbable success in making students of international relations

believe that prehistory is worth their attention", but likewise thought

Diamond oversold geography as an explanation for history and

under-emphasized cultural autonomy.[3][20] McNeill wrote that the

book's success "is well-deserved for the first nineteen

chapters–excepting a few passages–but that the twentieth chapter

carries the argument beyond the breaking point, and excepting a few

paragraphs, is not an intellectual success." But McNeill concluded,

"While I have sung its praises only in passing and dwelt on its faults,

[...] overall I admire the book for its scope, for its clarity, for its

erudition across several disciplines, for the stimulus it provides, for

its improbable success in making students of international relations

believe that prehistory is worth their attention, and, not least, for

its compelling illustration that human history is embedded in the

larger web of life on earth." Tonio Andrade described McNeill's review

as "perhaps the fairest and most succinct summary of professional world

historians' perspectives on Guns, Germs, and Steel".[17]

In 2010, Tim Radford of The Guardian called the book "exhilarating" and

lauded the passages about plants and animals as "beautifully

constructed".[21]

|

知的背景

1930年代、フランスのアナール学派は、地理学、歴史学、社会学を総合して、長期的な歴史構造を研究していた。地理、気候、土地利用が及ぼす影響につい

て研究された。アメリカでは1960年代以降、地理学は学問としてほぼ消滅していたが、1990年代には地理学に基づく歴史理論がいくつか発表されている

[10]。

1991年には、ジャレド・ダイアモンドが『第三のチンパンジー:人類という動物の進化と未来(第4部)』で、「なぜユーラシア人が他の文化を支配するよ

うになったのか」という問いをすでに考察している。

受容と評価

銃・病原菌・鋼鉄』の学術的な評価は概して肯定的であった。

称賛の声

多くの人が、本書の範囲が広いため、ある程度の単純化は避けられないと指摘する一方で、本書が非常に博識で、複数の異なるテーマを概して効果的に統合した

ものであると賞賛している。ポール・R・エーリックとE・O・ウィルソンは共にこの本を賞賛している[11]。

ノースウェスタン大学の経済史家であるジョエル・モキールはダイアモンドを地理的決定論者と解釈しているが、この思想家は多くの決定論者のように「粗野」

と表現されることはないと付け加えている。モキールにとって、ユーラシア大陸が成功したのは家畜化できる植物が大量にあったからだとするダイヤモンドの見

解は、他の地域の植物に作物操作や淘汰が可能であることから、欠陥がある。モキールは、スッポンのような土着の植物の欠点は、「すべての家畜化植物にはも

ともと望ましくない性質」が「故意と幸運による選択メカニズム」によって除去されているので、品種改良された可能性があると書いている。モキールは、複数

の遺伝子によって制御される特性を固定化することに失敗した繁殖標本が「地理的に困難な社会の中心にあった」というダイヤモンドの説を説得力のないものと

して退けている。また、ダイヤモンドは、経済史を環境操作の成功が中心であると見なし、「より寛大で柔軟な地域に移動する選択肢」の役割を軽視していると

し、寛大でない環境が人間の多くの創意工夫や技術の源であったと推測している。しかし、モキール氏はそれでも、『銃・病原菌・鉄』は「長期経済史へのより

重要な貢献の一つであり、長期世界史の領域でビッグ・クエスチョンを扱うと主張する人には単に必須である」と論じた。彼はこの本を「文章、言語、経路依存

性などに関する巧妙な議論」に満ちていると賞賛している。知恵と知識にあふれており、経済史家が常に愛し、賞賛してきた知識である」[12]。

バークレー校の経済史家であるブラッド・デロングはこの本を「完全で完全な天才の作品」と評している[13]。

ハーバード大学の国際関係(IR)学者であるスティーブン・ウォルトはフォーリン・ポリシーの記事でこの本を「爽快な読書」と呼び、IRの学生が読むべき

10冊に挙げている[14]。 タフツ大学のIR学者であるダニエルWドレズナー

は国際経済史に関する必読書のトップ10リストに同書が挙げられている[15]。

国際関係学研究者のアイヴァー・B・ノイマン(ロンドン大学経済政治学院)とアイナー・ウィゲン(オスロ大学)は、「銃・病原菌・鉄」を自分たちの学際的

研究の箔付けとして使用している。彼らは、「経験的な詳細はもちろん正しいべきであるが、この種の仕事の第一の基準は細部へのこだわりではありえない」と

書いている。二人の著者によれば、「ダイアモンドは、このような大規模な問題提起は根本的に多因子でなければならないと明言した上で、生態学的要因という

一つの複合要因に着手」し、「彼が引き合いに出した異分野で働く専門家からすぐに激しい批判にさらされた」ことを指摘している。しかし、ノイマンとヴィー

ゲンは、「誰かが、同じ包括的な問題を理解するために、ダイヤモンドの資料を解釈し、それに加えるより良い方法を考え出すまでは、世界のある部分と別の部

分が支配するようになった理由についての生態学的前提条件について、彼のものが利用できる最善の治療法である」とも述べている[16]。 「16]

歴史家のトニオ・アンドラデは、ダイヤモンドの本は「すべてのカウントでプロの歴史家を満足させないかもしれない」が、「旧世界と新世界で起こった異なる

発展についての大胆で説得力のあるケースを作る(彼はアフリカとユーラシアを分ける試みにおいて説得力がない)」[17] と書いている。

歴史家トム・トムリンソン(Tom

Tomlinson)は、その課題の大きさからダイアモンド教授が「自分の議論を埋めるために非常に広い筆を使う」ことは避けられないと書いているが、最

終的にはこの本を賞賛している。トムリンソンは、先史時代に関する記述は自分の専門分野ではないので「信頼して」読んでいるが、より強力な武器、病気、輸

送手段の存在は、旧世界の社会と技術が支配的になった「直接的な原因」として説得力があると述べ、それが特定の環境によって大きな発明が生まれ、それがよ

り高度な技術をもたらしたというダイヤモンドの見解に疑問を呈している。トムリンソン氏は、技術が広まることで軍事的征服や経済的変化が起こるが、ダイヤ

モンドの著書では、人類の歴史のこの側面が「歴史的偶然の問題として片付けられている」と指摘した。ダイアモンドが政治思想の歴史にほとんどカバーしてい

ないと書きながら、歴史家は資本主義(ダイアモンドはもっともらしいが不完全な10の説明の1つに分類している)がおそらくダイアモンドが主張するよりも

繁栄に大きな役割を果たしてきたと示唆している[18]。

トムリンソンは、ダイヤモンドが文化的特異性を説明として過小評価していると推測し、(ダイヤモンドの3つの理由のうち「病原菌」の部分に関して)14世

紀の黒死病や19世紀のアフリカにおける天然痘やコレラは、ユーラシア大陸における先住民の荒廃と並ぶ、全体としての「人類の拡散と合体による出来事」だ

と論じている。またトムリンソンは、人類の未来はいつか科学的厳密さで予見できるというダイアモンドの見解も、新しい理論的アプローチが確立の可能性を否

定している一般法則の探索を伴うため、議論の余地があるとした。しかし、トムリンソンはこれらの欠点を「些細なもの」とし、『銃・病原菌・鉄』は「想像力

と説明力において非常に印象的な業績であり続ける」と書いている[18][19]。

もう一人の歴史家であるJ.R.マクニール教授は、「国際関係の学生に先史時代が彼らの注意を引く価値があると信じさせるという、ありえない成功」に対し

てこの本を賞賛したが、同様にダイヤモンドは歴史の説明として地理を売りすぎ、文化の自律性をあまり強調しなかったと考えている[3]。

[マクニールは、この本の成功について、「最初の19章は、いくつかの箇所を除いて、十分に値するが、20章は、議論を限界点以上に進めており、いくつか

の段落を除いて、知的成功とは言えない」と書いている。しかし、マクニールは、"私はこの本の賞賛をほんの少し歌い、欠点をくどくどと書いたが、

[...]全体として、私はこの本の範囲、明確さ、いくつかの分野にわたる博識、刺激を与えること、国際関係の学生に先史時代が彼らの注意を引く価値があ

ると信じさせるというありえない成功、そして特に、人類の歴史が地球上の生命の大きな網に組み込まれているという説得力ある説明のために賞賛している。"

と結論づけた。Tonio

AndradeはMcNeillのレビューを「おそらく『銃・病原菌・鉄』に対するプロの世界史家の視点を最も公平かつ簡潔にまとめたもの」だと評してい

る[17]。

2010年、ガーディアン紙のティム・ラドフォードはこの本を「爽快」と呼び、植物や動物に関する箇所を「美しく構成されている」と賞賛している

[21]。

|

Criticism

The anthropologist Jason Antrosio described Guns, Germs, and Steel as a

form of "academic porn", writing, "Diamond's account makes all the

factors of European domination a product of a distant and accidental

history" and "has almost no role for human agency—the ability people

have to make decisions and influence outcomes. Europeans become

inadvertent, accidental conquerors. Natives succumb passively to their

fate." He added, "Jared Diamond has done a huge disservice to the

telling of human history. He has tremendously distorted the role of

domestication and agriculture in that history. Unfortunately his

story-telling abilities are so compelling that he has seduced a

generation of college-educated readers."[22]

In his last book, published in 2000, the anthropologist and geographer

James Morris Blaut criticized Guns, Germs, and Steel, among other

reasons, for reviving the theory of environmental determinism, and

described Diamond as an example of a modern Eurocentric historian.[23]

Blaut criticizes Diamond's loose use of the terms "Eurasia" and

"innovative", which he believes misleads the reader into presuming that

Western Europe is responsible for technological inventions that arose

in the Middle East and Asia.[24]

Other critiques have been made over the author's position on the

agricultural revolution.[25][26] The transition from hunting and

gathering to agriculture is not necessarily a one-way process. It has

been argued[according to whom?] that hunting and gathering represents

an adaptive strategy, which may still be exploited, if necessary, when

environmental change causes extreme food stress for

agriculturalists.[27] In fact, it is sometimes difficult to draw a

clear line between agricultural and hunter–gatherer societies,

especially since the widespread adoption of agriculture and resulting

cultural diffusion that has occurred in the last 10,000 years.[28]

Kathleen Lowrey argued that Guns, Germs, and Steel "lets the West off

the hook" and "poisonously whispers: mope about colonialism, slavery,

capitalism, racism, and predatory neo-imperialism all you want, but

these were/are nobody's fault. This is a wicked cop-out. [...] It

basically says [non-Western cultures/societies] are sorta pathetic, but

that bless their hearts, they couldn't/can't help it."[11]

Economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson have

written extensively about the effect of political institutions on the

economic well-being of former European colonies. Their writing finds

evidence that, when controlling for the effect of institutions, the

income disparity between nations located at various distances from the

equator disappears through the use of a two-stage least squares

regression quasi-experiment using settler mortality as an instrumental

variable. Their writing in a 2001 academic paper explicitly mentions

and challenges the work of Diamond,[29] and this critique is brought up

again in Acemoglu and Robinson's 2012 book Why Nations Fail.[30] |

批判

人類学者のジェイソン・アントロシオは、『銃・病原菌・鉄』を「学術的ポルノ」

と評し、「ダイヤモンドの説明は、ヨーロッパ支配のすべての要因を、遠く偶然の歴史の産物としている」、「人間の行為能力-人々が意思決定し結果に影響を

与える能力-の役割をほとんど果たしていない」と書いている。ヨーロッパ人は不注意な、偶然の征服者である。原住民はその運命に受動的に屈するのだ。さら

に、「ジャレド・ダイアモンドは、人類の歴史を語る上で大きな侮辱を与えた。家畜化と農耕が人類史の中で果たした役割を著しく歪曲している。残念ながら、

彼のストーリーテリングの能力は非常に説得力があり、大学教育を受けた読者の世代を誘惑してしまった」[22]。

2000年に出版された最後の本で、人類学者であり地理学者であるジェームズ・モリス・ブラウトは、とりわけ環境決定論の復活を理由に『銃・病原菌・鉄』

を批判し、ダイヤモンドを現代ヨーロッパ中心主義の歴史家の例として説明している[23]。

ブラウトはダイヤモンドの「ユーラシア」と「革新的」という言葉の緩い使い方を批判し、読者が西欧が中東とアジアで発生した技術革新に責任があると誤解し

てしまうと考えていた[24]。

その他にも農業革命に対する著者の立場をめぐって批判がなされている[25][26]

狩猟採集から農耕への移行は必ずしも一方向のプロセスではないのである。実際、農耕社会と狩猟採集社会の間に明確な線引きをすることは、特に過去1万年の

間に起こった農耕の広範な導入とその結果として起こった文化の拡散以来、困難である場合がある[28]。

キャスリーン・ローリーは、『銃・病原菌・鉄』は「西洋を野放しにして」、「植民地

主義、奴隷制度、資本主義、人種差別、略奪的新帝国主義について好きなだけ嘆きなさい、しかしこれらは誰のせいでもなかった/そうである、と毒々しくささ

やく」と論じている。これはひどい言い逃れです。[中略)それは基本的に[非西洋の文化/社会]はある種哀れであり、しかし彼らの心には祝福があり、彼ら

はそれを助けることができなかった/できないと言っているのです」[11][11]。

経済学者のDaron Acemoglu、Simon Johnson、James A.

Robinsonは、旧ヨーロッパ植民地の経済的福利に対する政治制度の効果について広範囲に渡って書いている。彼らの著作は、制度の効果をコントロール

するとき、入植者の死亡率を道具変数として用いた2段階最小二乗回帰の擬似実験によって、赤道から様々な距離に位置する国々の間の所得格差が消えるという

証拠を発見している。2001年の学術論文における彼らの文章はDiamondの研究に明確に言及し、挑戦しており[29]、この批判はAcemoglu

and Robinsonの2012年の著書Why Nations Failにおいて再び持ち出されている[30]。(→「自由をめぐる「狭い回廊」仮説」)

|

Awards and honors

Guns, Germs, and Steel won the 1997 Phi Beta Kappa Award in

Science.[31] In 1998, it won the Pulitzer Prize for General

Non-Fiction, in recognition of its powerful synthesis of many

disciplines, and the Royal Society's Rhône-Poulenc Prize for Science

Books.[32][33]

Publication

Guns, Germs, and Steel was first published by W. W. Norton in March

1997. It was published in Great Britain with the title Guns, Germs, and

Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years by

Vintage in 1998.[34] It was a selection of Book of the Month Club,

History Book Club, Quality Paperback Book Club, and Newbridge Book

Club.[35]

In 2003 and 2007, updated English-language editions were released

without changing any conclusions.[36]

The National Geographic Society produced a documentary, starring Jared

Diamond, based on the book and of the same title, that was broadcast on

PBS in July 2005.[1][37]

|

受賞と栄誉

1997年にファイベータカッパ科学賞を受賞[31]。

1998年には、多くの学問分野を強力に統合したことが評価され、一般ノンフィクション部門でピューリッツァー賞を、科学書部門で王立協会のローヌ=プー

ラン賞を受賞[32][33]。

出版物

『銃・病原菌・鉄』は1997年3月にW.W.ノートンから初めて出版された。イギリスでは『銃・病原菌・鉄』というタイトルで出版された。1998年に

ヴィンテージから『A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000

Years』として出版された[34]。これはブックオブザマンスクラブ、ヒストリーブッククラブ、クオリティペーパーバックブッククラブ、ニューブリッ

ジブッククラブのセレクションであった[35]。

2003年と2007年には、結論を変えないまま、英語版の更新版が発売された[36]。

ナショナルジオグラフィック協会は、この本と同じタイトルのジャレド・ダイアモンド主演のドキュメンタリーを制作し、2005年7月にPBSで放映された

[1][37]。

|

Bantu expansion

James Burke (science historian)

Alfred W. Crosby

Yuval Harari

Marvin Harris

Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

Scramble for Africa

States and Power in Africa

Plough, Sword and Book

|

バントゥの拡大

ジェームズ・バーク(科学史家)

アルフレッド・W・クロスビー

ユヴァル・ハラリ

マーヴィン・ハリス

アメリカ大陸の先住民の人口史

アフリカのためのスクランブル

アフリカの国家と権力

耕し、剣、書

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guns,_Germs,_and_Steel

|

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator

|

|

Continental axes according to

the book

|

![tiocaima7n[at]me.com](gifadres.gif) あるいは、rosaldo[at]

cscd.osaka-u.ac.jp

あるいは、rosaldo[at]

cscd.osaka-u.ac.jp