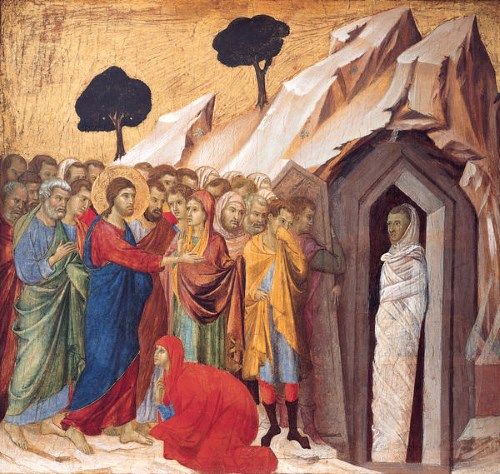

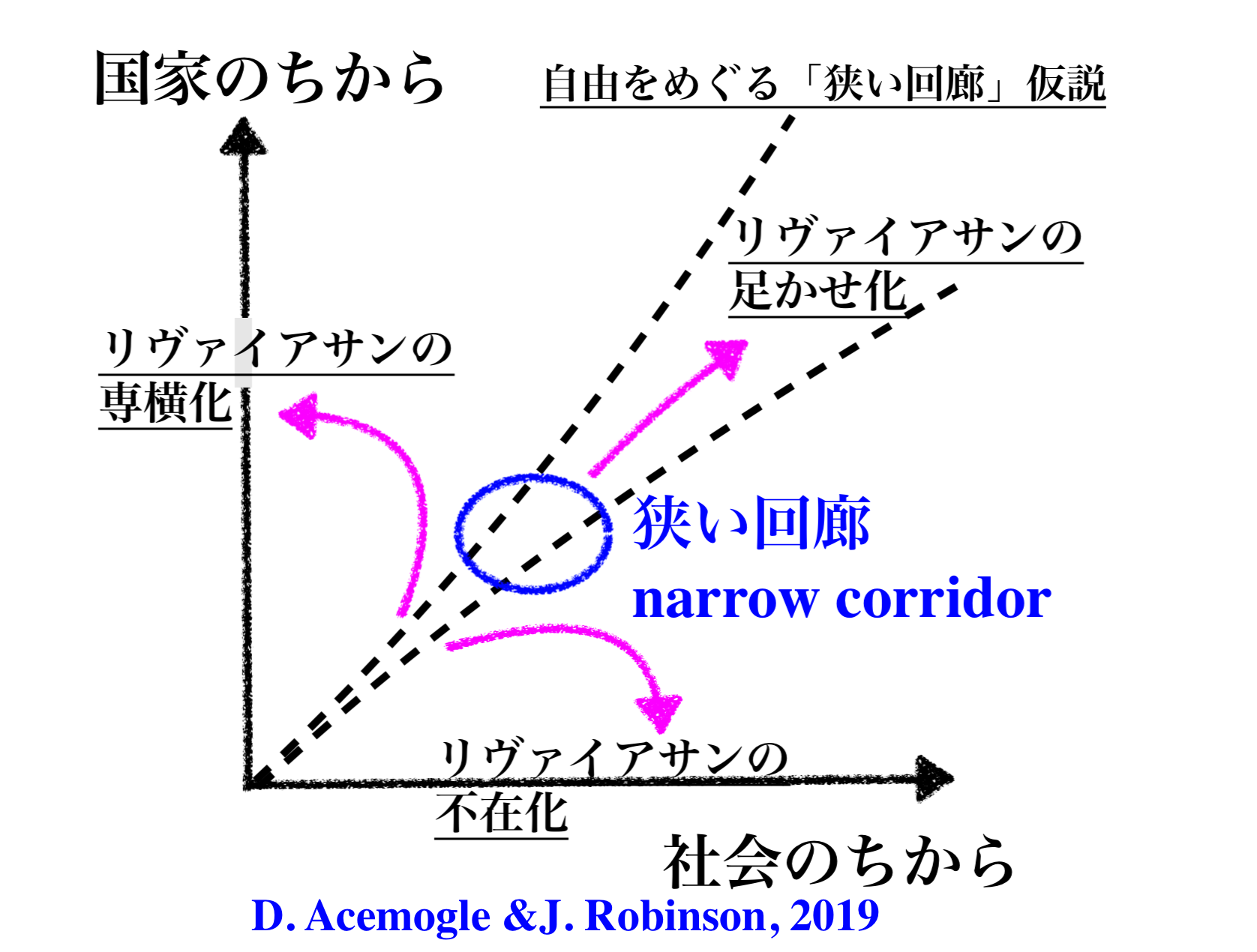

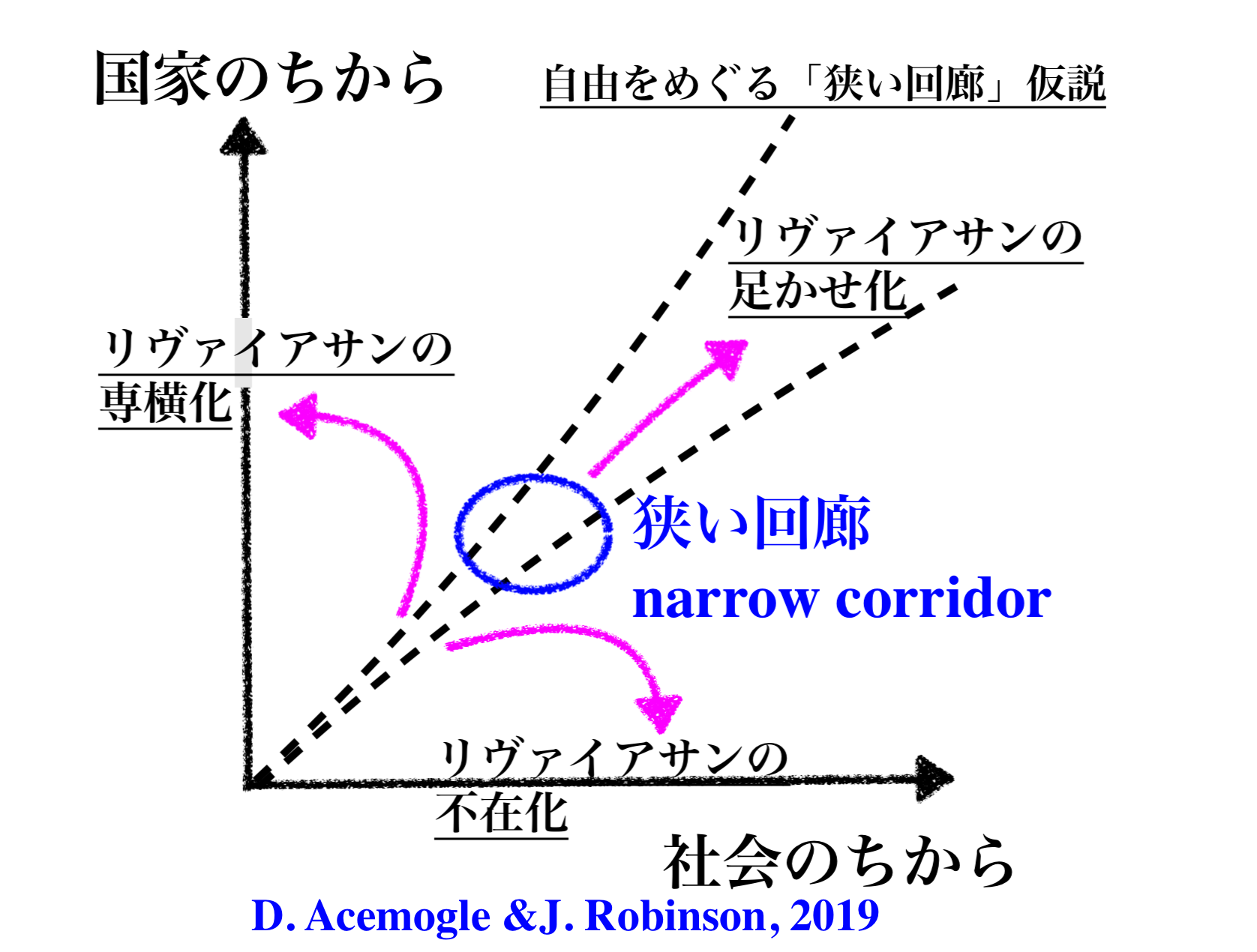

自由をめぐる「狭い回廊」仮説

On

The narrow-narrow corridor, how

states do not struggle for liberty 'cause they get jelous nation's love

自由をめぐる「狭い回廊」仮説

On

The narrow-narrow corridor, how

states do not struggle for liberty 'cause they get jelous nation's love

「あらゆるものが、かりそめである時代に陥ってしまった。新しい技術は、日に日に私たちの暮

らしを変えていく。過去の伝統はもう取り戻せない。同時に、未来が何をもたらしてくれるのかは、ほとんど見当もつかない。私たちは自由であるかのように生

きることを強いられている」——ジョン・グレイ『わらの犬 : 地球に君臨する人間』(John Gray, Straw Dog)

アセモグル(Daron Acemogle) とロビンソンの前提は、自由とは支配なき 状態であり、自由が成就するためには「選択の自由」と「自由を行使できる能力」が人々にあるべきだという考え方から出発する。

「選択の自由なんかいらねぇ、お国が決めて俺たちは 従 うことで十分だぜ」という考え方の持ち主に、アセモグルとロビンソンの主張は「馬の耳に念仏」あるいは「釈迦(=愚か者としての聖者)に説法」かもしれな い、というところが、この ご両人たちの痛いところ(=限界)である。

西洋の政治学者たちは、地球社会の区分する国家体制 の未来に、ひとつの楽観論と2つの悲観論をもって見ている。《楽観論》まず、フランシス・フクヤマ先生の、ヘーゲルの弁証法の議論から着想を得た「歴史の 終わり」論。これは、政治経済のリベラリズムが、双六(スゴロク)の上がりで、国家の権威を国民が信頼すると同時に監視し、民主主義を通してそれを維持し ていくことがベストな体制だと考えるものである。すなわち(米国の共和党や英国の保守党のような)共和主義的なデモクラシーこそが最適解とするものであ る。次に《悲観論:01》は、ジャーナリストのロバート・カプラン『地政学の逆襲』などに代表されるような、ポスト冷戦の時代には、東西の政治的バランス の均衡が崩壊して、徐々にアナーキー化が進んでいると見る。その悲惨な例が、イスラム原理主義の中東やユーラシアの国家レジームや武装集団(イラン、ハ マース、ヒズボラ、ムスリム同胞団、ターリバーン、アル・カーイダ、ISIL)あるいは、その分派集団(イスラム集団、武装イスラム集団、イスラム聖戦、 ラシュカレトイバ、ジェマ・イスラミア)などによる「侵食」であると考える。そして、最後に《悲観論: 02》の代表格ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ(Yuval Noah Harari, 1976- ; יובל נח הררי)『ホモ・デウス:テクノロジーとサピエンスの未来(Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow)』 にみられる「デジタル専制」体制の到来である。整理しよう

| 《楽観論》まず、フランシス・フクヤマ先生の、ヘーゲ ルの弁証法の議論から着想を得た「歴史の 終わり」論。これは、政治経済のリベラリズムが、双六(スゴロク)の上がりで、国家の権威を国民が信頼すると同時に監視し、民主主義を通してそれを維持し ていくことがベストな体制だと考えるものである。すなわち(米国の共和党や英国の保守党のような)共和主義的なデモクラシーこそが最適解とするものであ る。 |

| 《悲観論:01》は、ジャーナリストのロバート・カプ ラン『地政学の逆襲』などに代表されるような、ポスト冷戦の時代には、東西の政治的バランス の均衡が崩壊して、徐々にアナーキー化が進んでいると見る。その悲惨な例が、イスラム原理主義の中東やユーラシアの国家レジームや武装集団(イラン、ハ マース、ヒズボラ、ムスリム同胞団、ターリバーン、アル・カーイダ、ISIL)あるいは、その分派集団(イスラム集団、武装イスラム集団、イスラム聖戦、 ラシュカレトイバ、ジェマ・イスラミア)などによる「侵食」であると考える。 |

| 《悲観論: 02》の代表格ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ(Yuval Noah Harari, 1976- ; יובל נח הררי)『ホモ・デウス:テクノロジーとサピエンスの未来(Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow)』 にみられる「デジタル専制」体制の到来である。 |

●Why Nations Fail, 2012

☆章立て

序文

第1章 こんなに近いのに、こんなに違う

第2章 役に立たない理論

第3章 繁栄と貧困の形成過程

第4章 小さな相違と決定的な岐路—歴史の重み

第5章 「私は未来を見た。うまくいっている未来 を」—収奪的制度のもとでの成長

第6章 乖離

第7章 転換点

第8章 縄張りを守れ—発展の障壁

第9章 後退する発展

第10章 繁栄の広がり

第11章 好循環

第12章 悪循環

第13章 こんにち国家はなぜ衰退するのか

第14章 旧弊を打破する

第15章 繁栄と貧困を理解する

付録 著者と解説者の質疑応答

★内容

| Why Nations

Fail:

The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, first published in

2012,

is a book by economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. The book

applies insights from institutional economics, development economics

and economic history to understand why nations develop differently,

with some succeeding in the accumulation of power and prosperity and

others failing, via a wide range of historical case studies. The authors also maintain a website (with a blog inactive since 2014) about the ongoing discussion of the book.[1] |

なぜ国家は失敗するのか。2012年に初版が発行された、経済学者ダロ

ン・アセモグルとジェームズ・A・ロビンソンによる書籍である。本書は、制度経済学、開発経済学、経済史の知見を応用し、なぜ国家が異なる発展を遂げ、権

力と繁栄の蓄積に成功する国と失敗する国があるのかを、幅広い歴史的事例を通じて理解することを目的としている。 著者らは、本書の進行中の議論に関するウェブサイト(2014年以降はブログも休止中)も運営していた[1]。 |

| Context The book is the result of a synthesis of many years of research by Daron Acemoglu on the theory of economic growth and James Robinson on the economies of Africa and Latin America, as well as research by many other authors. It contains an interpretation of the history of various countries, both extinct and modern, from the standpoint of a new institutional school. The central idea of many of the authors' works is the defining role of institutions in the achievement of a high level of welfare by countries. An earlier book by the authors, "The Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy," is devoted to the same, but it did not contain a large number of various historical examples.[2][3][4] The authors enter into an indirect polemical dispute with the authors of other theories explaining global inequality: the authors of the interpretations of the geographical theory Jeffrey Sachs[5] and Jared Diamond,[6] representatives of the theory of ignorance of the elites Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo,[7] Martin Lipset and his modernization theory,[8] as well as with various types of cultural theories: the theory of David Landes about the special cultural structure of the inhabitants of Northern Europe,[9] the theory of David Fischer about the positive influence of British culture,[10] with the theory of Max Weber about the influence of Protestant ethic on economic development.[11][12] They most harshly criticized geographical theory as "unable to explain not only global inequality in general", but also the fact that many countries have been in stagnation for a long time, and then at a certain point in time began a rapid economic growth, although their geographical position did not change.[13] Simon Johnson co-authored many of Acemoglu and Robinson's works, but did not participate in the work on the book.[13] For example, in a 2002 article, they showed through statistical analysis that institutional factors dominate culture and geography in determining the GDP per capita of different countries.[14] And in the 2001 article they showed how mortality among European settlers in the colonies influenced the establishment of institutions and the future development of these territories.[15] |

内容紹介 本書は、Daron Acemogluによる経済成長理論、James Robinsonによるアフリカとラテンアメリカの経済に関する長年の研究、および他の多くの著者による研究の総合的な成果である。新しい制度学派の立場 から、滅亡した国や現代の様々な国の歴史を解釈したものが含まれている。著者の多くの著作の中心的な考え方は、国が高いレベルの福祉を達成する上で、制度 が決定的な役割を果たすというものである。著者らによる以前の著書『独裁と民主主義の経済的起源』も同じことに費やされているが、さまざまな歴史的事例を 数多く含んでいるわけではなかった[2][3][4]。 地理的理論の解釈の著者であるJeffrey Sachs[5]とJared Diamond[6]、エリートの無知理論の代表者であるAbhijit BanerjeeとEsther Duflo[7]、Martin Lipsetと彼の近代化理論[8]、さらに様々な文化理論のように世界の格差を説明している他の理論の著者に間接的に論争を持ち込んでいるのである。北 欧の住民の特別な文化構造に関するデイヴィッド・ランデスの理論[9]、イギリス文化のポジティブな影響に関するデイヴィッド・フィッシャーの理論 [10]、経済発展におけるプロテスタント倫理観の影響に関するマックス・ウェーバーの理論[11]などです。 [11][12] 彼らは地理的理論を「世界的な不平等全般だけでなく、多くの国が長い間停滞し、ある時期から地理的位置は変わらないのに急激な経済成長を始めるという事実 を説明できない」と最も厳しく批判している[13]。 サイモン・ジョンソンはアセモグルとロビンソンの多くの著作の共著者であるが、この本の作業には参加していない[13]。 例えば、2002年の論文において、彼らは統計分析を通じて、異なる国の一人当たり GDPを決定する際に制度要因が文化や地理に勝ることを示した[14]。 また2001年の論文において、植民地のヨーロッパ入植者の死亡率が制度の確立やこれらの領土の将来の発展にいかに影響したか を示した[15]。 |

Content Conditions for sustainable development Beginning with a description of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, the authors question the reasons for the dramatic difference in living standards on either side of the wall separating the two cities.[16] The book focuses on how some countries have managed to achieve high levels of prosperity, while others have consistently failed. Countries that have managed to achieve a high level of well-being have demonstrated stable high rates of economic growth for a long time: this state of the economy is called sustainable development. It is accompanied by a constant change and improvement of technologies — a process called scientific and technological progress. In search of the reasons why in some countries we observe this phenomenon, while others seem to have frozen in time, the authors come to the conclusion that for scientific and technological progress it is necessary to protect the property rights of wide strata of society and the ability to receive income from their enterprises and innovations (including from patents for inventions).[17] But as soon as a citizen receives a patent, he immediately becomes interested in that no one else patented a more perfect version of his invention, so that he can receive income from his patent forever. Therefore, for sustainable development, a mechanism is needed that does not allow him to do this, because together with the patent he receives a substantial wealth. The authors come to the conclusion that such a mechanism is pluralistic political institutions that allow wide sections of society to participate in governing the country.[18] In this example, the inventor of the previous patent loses, but everyone else wins. With pluralistic political institutions, a decision is made that is beneficial to the majority, which means that the inventor of the previous one will not be able to prevent a patent for a new invention and, thus, there will be a continuous improvement of technologies.[19][20] The interpretation of economic growth as a constant change of goods and technologies was first proposed by Joseph Schumpeter, who called this process creative destruction.[12][21][22] In the form of an economic model, this concept was implemented by Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt in the Aghion–Howitt model, where the incentive for the development of new products is the monopoly profit from their production, which ends after the invention of a better product.[23] Since only pluralistic political institutions can guarantee that the owners of existing monopolies, using their economic power, will not be able to block the introduction of new technologies, they, according to the authors, are a necessary condition for the country's transition to sustainable development. Another prerequisite is a sufficient level of centralization of power in the country, because in the absence of this, political pluralism can turn into chaos. The theoretical basis of the authors' work is presented in a joint article with Simon Johnson,[24] and the authors also note the great influence of Douglass North's[25][26][27] work on their views.[12] The authors support their position by analyzing the economic development of many modern and already disappeared countries and societies: the USA; medieval England and the British Empire; France; the Venetian Republic; the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire; Austria-Hungary; Russian Empire, USSR and modern Russia; Spain and its many former colonies: Argentina, Venezuela, Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico and Peru; Brazil; colonial period of the Caribbean region; Maya civilization; Natufian culture; the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey; Japan; North Korea and South Korea; the Ming and Qing empires, and modern China; the sultanates of Tidore, Ternate and Bakan, the island state of Ambon and other communities on the territory of modern Indonesia, and the consequences of the impact of the Dutch East India Company on them; Australia; Somalia and Afghanistan; the kingdoms of Aksum and modern Ethiopia; South Africa, Zimbabwe and Botswana; the kingdoms of the Congo and Cuba, and the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo; the states of Oyo, Dahomey and Ashanti, and modern Ghana; Sierra Leone; modern Egypt and Uzbekistan. Reviewers unanimously note the wealth of historical examples in the book.[3][28][29][30] |

内容 持続可能な発展の条件 アリゾナ州ノガレスとソノラ州ノガレスの描写から始まる著者は、両市を隔てる壁の両側で生活水準が劇的に異なる理由を問う[16]。本書は、高いレベルの 繁栄を達成できた国がある一方で、常に失敗し続けている国があることに着目している。高いレベルの幸福を達成することができた国は、長期にわたって安定し た高い経済成長率を示している。このような経済の状態は、持続可能な開発と呼ばれている。このような経済状態を「持続可能な発展」と呼びますが、この発展 には、絶え間ない技術の変化と向上、すなわち「科学技術の進歩」が伴います。このような現象がある国では見られるが、ある国では時間が止まったように見え るのはなぜか、その理由を探っていくと、科学技術の進歩のためには、社会の幅広い層の財産権と、その企業や技術革新から収入を得る能力(発明の特許権を含 む)を守る必要があるという結論に達する[17]。しかし市民は特許を取得するとすぐに、誰も自分の発明をより完璧にした特許を取っていないので、自分の 特許から永遠に収入を得られることに興味を持つようになる。したがって、持続可能な開発のためには、特許とともに相当な富を得るために、このようなことを 許さないメカニズムが必要である。そのようなメカニズムとは、社会の幅広い層が国の統治に参加できる多元的な政治制度であるというのが著者らの結論である [18]。この例では、先の特許の発明者は負けるが、他の誰もが勝つことになる。多元的な政治制度があれば、多数派にとって有益な決定がなされる。つま り、前の発明者は新しい発明の特許を阻止することができなくなり、その結果、技術の継続的な向上が起こる[19][20] 経済成長を財と技術の継続的な変化として解釈することはJoseph Schumpeterによって最初に提案され、この過程を創造的破壊と呼んだ。 [この概念は経済モデルの形で、フィリップ・アギョンとピーター・ハウィットによってアギョン-ハウィットモデルで実装され、新製品の開発のインセンティ ブはそれらの生産からの独占的利益であり、それはより良い製品の発明の後に終了する[23]。 [23] 既存の独占企業の所有者が、その経済力を利用して、新しい技術の導入を阻止することができないことを保証できるのは、多元的な政治制度だけなので、著者ら によれば、それらは、国が持続可能な開発へ移行するための必要条件である。もう一つの前提条件は、国内の中央集権化のレベルが十分であることで、これがな いと政治的多元主義がカオスに変わることができるからである。著者らの理論的基盤はサイモン・ジョンソンとの共同論文で提示されており[24]、著者らは またダグラス・ノース[25][26][27]の仕事が彼らの見解に大きな影響を与えたことに言及している[12]。 著者は、多くの近代およびすでに消滅した国や社会の経済発展を分析することでその立場を支持している:アメリカ、中世イングランドと大英帝国、フランス、 ヴェネツィア共和国、ローマ共和国とローマ帝国、オーストリア=ハンガリー、ロシア帝国、ソ連、現代ロシア、スペインとその多くの旧植民地。アルゼンチ ン、ベネズエラ、グアテマラ、コロンビア、メキシコ、ペルー、ブラジル、カリブ海地域の植民地時代、マヤ文明、ナチュフィア文化、オスマン帝国と現代トル コ、日本、北朝鮮と韓国、明・清帝国と現代中国、現代インドネシア領のティドール、テルナテ、バカン、アンボン島などのサルタンと、オランダ東インド会社 の影響が及んだ共同体を紹介。オーストラリア、ソマリアとアフガニスタン、アクスム王国と現代エチオピア、南アフリカ、ジンバブエ、ボツワナ、コンゴ王国 とキューバ、現代コンゴ民主共和国、オヨ、ダホメー、アシャンティ州と現代ガーナ、シエラレオネ、現代エジプトとウズベキスタンです。レビュアーは異口同 音に、本書における歴史的事例の豊富さを指摘している[3][28][29][30]。 |

| Contrasting two types of

institutions The decisive role for the development of countries, according to the authors, is played by institutions — a set of formal and informal rules and mechanisms for coercing individuals to comply with these rules that exist in society.[31] Acemoglu and Robinson divide institutions into two large groups: political [ru] and economic. The first regulate the distribution of powers between the various authorities in the country and the procedure for the formation of these bodies, and the second regulate the property relations of citizens. The concept of Acemoglu and Robinson consists in opposing two archetypes: the so-called. “extractive” (“extracting”, “squeezing”[32]) and “inclusive” (“including”, “uniting”[33]) economic and political institutions, which in both cases reinforce and support each other.[28][34][35][36] Inclusive economic institutions protect the property rights of wide sections of society (not just the elite), they do not allow unjustified alienation of property, and they allow all citizens to participate in economic relations in order to make a profit. Under the conditions of such institutions, workers are interested in increasing labour productivity. The first examples of such institutions are, for example, the commenda in the Venetian Republic and patents for inventions. The long-term existence of such economic institutions, according to the authors, is impossible without inclusive political institutions that allow wide sections of society to participate in governing the country and make decisions that are beneficial to the majority.[36] These institutions that are the foundation of all modern liberal democracies. In the absence of such institutions, when political power is usurped by a small stratum of society, sooner or later it will use this power to gain economic power to attack the property rights of others, and, therefore, to destroy inclusive economic institutions.[28][34][35] Extractive economic institutions exclude large segments of the population from the distribution of income from their own activities. They prevent everyone except the elite from benefiting from participation in economic relations, who, on the contrary, are allowed to even alienate the property of those who do not belong to the elite.[37] Examples include slavery, serfdom, and encomienda. In the context of such institutions, workers have no incentive to increase labour productivity, since all or almost all of the additional income will be withdrawn by the elite.[36] Such economic institutions are accompanied by extractive political institutions that exclude large sections of the population from governing the country and concentrate all political power in the hands of a narrow stratum of society (for example, the nobility). Examples are absolute monarchies and various types of dictatorial and totalitarian regimes, as well as authoritarian regimes with external elements of democracy (constitution and elections), which are so widespread in the modern world, where power is supported by power structures: the army, the police, and dependent courts. The very fact that there are elections in a country does not mean that its institutions cannot be classified as extractive: competition can be dishonest, candidates' opportunities and their access to the media are unequal, and voting is conducted with numerous violations, and in this case the elections are just a spectacle, the ending of which is known in advance.[9][34][35] |

2種類の制度を対比させる 著者らによれば、国の発展にとって決定的な役割を果たすのは制度、すなわち社会に存在する公式・非公式のルールとそのルールに従うよう個人に強制するため のメカニズムの集合である[31]。AcemogluとRobinsonは制度を大きく2つのグループ、政治(ru)と経済に分けている。前者は国の様々 な当局間の権力配分やこれらの機関の成立手続きを規制し、後者は市民の財産関係を規制する。AcemogluとRobinsonのコンセプトは、いわゆる 2つの原型を対立させることで成り立っている。"extractive"(「抽出する」、「搾り取る」[32])と "inclusive"(「含む」、「一体化」[33])の経済・政治制度は、どちらの場合も互いに強化し支え合っている[28][34][35] [36]。 包括的な経済制度は(エリートだけでなく)社会の幅広い層の財産権を保護し、財産の不当な疎外を許さず、すべての市民が利益を得るために経済関係に参加す ることを認めてる。このような制度のもとでは、労働者は労働生産性を高めることに関心を持つ。このような制度の最初の例は、たとえばヴェネツィア共和国の コンメンダや発明の特許である。著者によれば、このような経済制度の長期的な存続は、社会の幅広い層が国の統治に参加し、大多数にとって有益な決定を下す ことを可能にする包括的な政治制度なしには不可能である[36]。こうした制度がない場合、社会の小さな層によって政治的権力が簒奪されると、遅かれ早か れその権力を使って他者の財産権を攻撃する経済力を獲得し、それゆえ包括的な経済制度を破壊することになる[28][34][35]。 搾取的な経済制度は、自分たちの活動から得られる所得の分配から人口の大部分を排除している。彼らはエリートを除くすべての人が経済関係への参加から利益 を得ることを妨げ、逆にエリートに属さない人たちの財産を疎外することさえ許されている[37] 例として、奴隷制、農奴制、エンコミエンダが挙げられる。このような制度の文脈において、労働者は労働生産性を高めるインセンティブを持たない。なぜな ら、追加的な収入のすべて、あるいはほとんどすべてがエリートによって引き出されるからである[36]。このような経済制度は、国民の大部分を国の統治か ら排除し、社会の狭い層(例えば、貴族)の手にすべての政治力を集約する抽出的政治制度と結びついている。その例として、絶対君主制やさまざまなタイプの 独裁・全体主義体制、また現代世界に広く存在する民主主義の外形的要素(憲法や選挙)を備えた権威主義体制があり、軍隊、警察、従属裁判所といった権力機 構によって権力が支えられているのである。ある国に選挙があるという事実そのものが、その制度が抽出的であると分類できないことを意味しない。競争が不正 であったり、候補者の機会やメディアへのアクセスが不平等であったり、投票が多数の違反行為とともに行われたり、この場合選挙は単なる見世物であり、その 終わりは事前に知られている[9][34][35]。 |

| Analysis of the economic

development of different countries In fifteen chapters, Acemoglu and Robinson try to examine which factors are responsible for the political and economic success or failure of states. They argue that the existing explanations about the emergence of prosperity and poverty, e.g. geography, climate, culture, religion, race, or the ignorance of political leaders are either insufficient or defective in explaining it. Acemoglu and Robinson support their thesis by comparing country case studies. They identify countries that are similar in many of the above-mentioned factors, but because of different political and institutional choices become more or less prosperous. The most incisive example is Korea, which was divided into North Korea and South Korea in 1953. Both countries’ economies have diverged completely, with South Korea becoming one of the richest countries in Asia while North Korea remains among the poorest. Further examples include the border cities Nogales (Sonora, Mexico) and Nogales (Arizona, USA). By referencing border cities, the authors analyze the impact of the institutional environment on the prosperity of people from the same geographical area and same culture. Acemoglu and Robinson's major thesis is that economic prosperity depends above all on the inclusiveness of economic and political institutions. Institutions are "inclusive" when many people have a say in political decision-making, as opposed to cases where a small group of people control political institutions and are unwilling to change. They argue that a functioning democratic and pluralistic state guarantees the rule of law. The authors also argue that inclusive institutions promote economic prosperity because they provide an incentive structure that allows talents and creative ideas to be rewarded. In contrast, the authors describe "extractive" institutions as ones that permit the elite to rule over and exploit others, extracting wealth from those who are not in the elite. Nations with a history of extractive institutions have not prospered, they argue, because entrepreneurs and citizens have less incentive to invest and innovate. One reason is that ruling elites are afraid of creative destruction—a term coined by Joseph Schumpeter—the ongoing process of annihilating old and bad institutions while generating new and good ones. Creative destruction would fabricate new groups which compete for power against ruling elites, who would lose their exclusive access to a country's economic and financial resources. The authors use the example of the emergence of democratic pluralism, in which Parliament's authority over the Crown was established in Great Britain after the Glorious Revolution in 1688, as being critical for the Industrial Revolution. The book also tries to explain the recent economic boom in China using its framework. China's recent past does not contradict the book's argument: despite China's authoritarian regime, the economic growth in China is due to the increasingly inclusive economic policy by Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China's Opening up policy after the Cultural Revolution. According to Acemoglu and Robinson's framework, economic growth will change the economic resource distribution and thus affect political institutions. Therefore, despite the current rapid growth, if China does not improve political balance, China is expected to collapse like the Soviet Union did in the early 1990s. |

各国の経済発展の分析 アセモグルとロビンソンは、15章にわたって、国家の政治的・経済的な成功や失敗がどのような要因によるものかを検証しようと試みている。彼らは、繁栄と 貧困の出現に関する既存の説明、例えば、地理、気候、文化、宗教、人種、あるいは政治指導者の無知などは、それを説明するには不十分か欠陥があると主張し ている。 AcemogluとRobinsonは、各国のケーススタディを比較することによって、彼らのテーゼを裏付けている。彼らは、上記の要因の多くにおいて類 似しているが、異なる政治的・制度的選択のために、多かれ少なかれ繁栄した国々を特定している。最も鋭い例は、1953年に北朝鮮と韓国に分割された韓国 である。両国の経済は完全に乖離し、韓国はアジアで最も豊かな国の一つとなり、北朝鮮は依然として最貧国の一つである。さらに、国境都市であるノガレス (メキシコ・ソノラ州)とノガレス(米国・アリゾナ州)の例もある。著者らは、国境都市を参照することで、同じ地域、同じ文化圏の人々の繁栄に制度的環境 が与える影響を分析している。 AcemogluとRobinsonの主要なテーゼは、経済的繁栄は何よりも経済・政治制度の包摂性に依存するというものである。一部の人々が政治制度を 支配し、変えようとしない場合とは対照的に、多くの人々が政治的意思決定に発言権を持つ場合、制度は「包括的」である。彼らは、民主的で多元的な国家が機 能することで、法の支配が保証されると主張している。また、包括的な制度は、才能や創造的なアイデアが報われるようなインセンティブ構造を提供するため、 経済的な繁栄を促進すると主張している。 これに対し、著者らは「搾取的」制度とは、エリートが他者を支配・搾取し、エリートに属さない人々から富を引き出すことを可能にする制度であると述べてい る。その理由は、起業家や市民が投資やイノベーションを行うインセンティブが低いからである、と著者らは主張する。その理由の一つは、支配的なエリートが 創造的破壊を恐れているからである。創造的破壊とは、Joseph Schumpeterによって作られた用語で、古くて悪い制度を消滅させ、新しく良い制度を生み出す継続的なプロセスである。創造的破壊は、支配的エリー トに対抗して権力を争う新しい集団を作り出し、彼らは一国の経済・金融資源への排他的アクセスを失うことになるのだ。 著者は、1688年の栄光革命後、英国で議会の王室に対する権威が確立し、民主的多元主義が出現したことを例に、産業革命に不可欠であったことを指摘す る。本書はまた、その枠組みを使って、最近の中国の経済ブームを説明しようとしている。中国の最近の過去は、本書の主張と矛盾しない。中国の権威主義的な 体制にもかかわらず、中国の経済成長は、文化大革命後の中国の開放政策の立役者である鄧小平による包括的な経済政策の増大によるものである。 AcemogluとRobinsonのフレームワークによれば、経済成長は経済資源の配分を変え、その結果、政治制度に影響を与える。したがって、現在の 急成長にもかかわらず、中国が政治的バランスを改善しなければ、1990年代前半のソ連のように崩壊することが予想される。 |

| Drivers of democracy Acemoglu and Robinson's theory on what drives democracy is rooted in their prior game theoretic work.[38] This paper models mathematical reasons for oscillations between non-democracy and democracy based on the history of democratization of Western Europe and Latin America. The paper emphasizes the roles of the threat of revolution and social unrest in leading to democratization and of the desires of the elites to limit economic redistribution in causing switches to nondemocratic regimes. A number of assumptions underlie their game theoretic model, and allow for the authors' simplified model of society. First, Acemoglu and Robinson assume that society is simply divided between a small rich class and a large poor class. Second, they assume that regimes must be either democratic or nondemocratic; there is nothing in between. Third, people's preferences in society are defined only by monetary redistribution from the rich ruling class. The more monetary benefits they get, the more they prefer the ruling class. Fourth, people care not only about redistribution today but also redistribution in the future. Therefore, people would not only want more redistribution today but also they want to see a guarantee for more or stable redistribution in the future. Fifth, the economic output of a country fluctuates year by year, which means revolution is less costly for the ruling class during economic downturn. Finally and most importantly, each individual in the society tries to maximize their own utility. In their model, a country starts as a nondemocratic society in which a small rich group controls most of the wealth and rules the poor majority. As the ruling class, the rich receive taxation from the economy's output and they decide on the taxation rate as the only means of extraction. The poor majority can either take what is offered to them by the rich after they tax the output (the economy's output after tax divided by the population size), or they can choose to revolutionize against the ruling class, which comes with a certain cost. In a revolution, the poor's ultimate payoff is the benefit of the revolution minus the cost of the revolution. Under that circumstance, the payoff of the rich ruling class is split between, when the poor revolutionizes, the punishment for the ruling class and when the poor acquiesces, the taxation income. That is, the authors describe a two-stage sequential game (diagrammed below) in which the rich first decide on the taxation rate and the level of redistribution and then the poor decide whether revolution is the optimal choice. Because of the potential loss of economic benefits by revolution, knowing what the poor majority would prefer, the rich have an incentive to propose a taxation rate that does not provoke revolution, while at the same time not costing the rich too many benefits. Thus, democratization refers to the situation where the rich willingly increase monetary redistribution and thus franchise to the poor in order to avoid revolution. Based on the analysis above, it is not hard to conclude that the threat of revolution constantly incentivizes the rich to democratize. The theory also resonates with a paper by Clark, Golder and Golder in which the government decides between predate and not to predate citizens based on the payoff while the citizen has the option to exit (migrate to other countries), remain loyal and voice their concerns at a cost (protest).[39][unreliable source?] Similarly, this game also provides insights into how variables like exit payoff, cost of voicing and value of loyalty change state's behavior as to whether or not to predate. |

民主主義の原動力 AcemogluとRobinsonの民主主義の原動力に関する理論は、彼らの以前のゲーム理論的研究に根ざしている[38]。この論文は、西ヨーロッパ とラテンアメリカの民主化の歴史に基づき、非民主主義と民主主義の間で振動する数学的理由をモデル化したものである。この論文は、革命の脅威と社会不安が 民主化をもたらし、経済的再分配を制限したいというエリートの願望が非民主主義体制への転換を引き起こす役割を強調している。 彼らのゲーム理論モデルの根底には、いくつかの前提条件があり、それが著者らの簡略化された社会モデルを可能にしている。まず、Acemogluと Robinsonは、社会が少数の富裕層と多数の貧困層に単純に分割されていると仮定している。第二に、政権は民主的か非民主的かのどちらかであり、その 中間は存在しないと仮定している。第三に、社会における人々の選好は、富裕な支配層からの金銭的再分配によってのみ規定される。金銭的な利益を得れば得る ほど、支配階級を好むようになる。第四に、人々は現在の再分配だけでなく、将来の再分配も気にする。したがって、人々は今日のより多くの再分配を望むだけ でなく、将来、より多くの、あるいは安定した再分配が保証されることを望むだろう。第五に、一国の経済生産高は年ごとに変動する。つまり、革命は不況時に 支配階級にとってコストが低いということである。最後に、最も重要なことは、社会の各個人が自分自身の効用を最大化しようとすることである。 彼らのモデルでは、ある国は非民主的な社会としてスタートし、少数の富裕層が富の大半を支配し、大多数の貧困層を支配する。支配階級である金持ちは、経済 の生産物から税金を受け取り、彼らは唯一の搾取手段である課税率を決定する。貧しい多数派は、生産物(税引き後の経済生産高を人口規模で割ったもの)に課 税した後、金持ちから提供されるものを受け取るか、あるいは、一定のコストを伴う支配階級に対する革命を選択することができます。革命において、貧困層の 最終的なペイオフは、革命の利益から革命のコストを差し引いたものである。その場合、富裕な支配層のペイオフは、貧困層が革命を起こした場合の支配層への 罰と、貧困層が黙認した場合の課税所得とに分割される。 つまり、著者らは、まず金持ちが課税率と再分配の水準を決め、次に貧乏人が革命が最適かどうかを決めるという2段階の順次ゲーム(下図)を記述しているの である。革命によって経済的利益が失われる可能性があるため、大多数の貧しい人々が何を望むかを知ることで、金持ちは革命を引き起こさないような税率を提 案し、同時に金持ちの利益をあまり損なわないようにするインセンティブを持つ。 したがって、民主化とは、革命を回避するために、金持ちが進んで貧乏人への金銭的再分配、つまりフランチャイズを増やす状況を指すのである。 以上の分析から、革命の脅威が金持ちに民主化を促すインセンティブを常に与えていると結論づけることは難しくない。この理論はClark、Golder、 Golderによる論文とも共振しており、政府はペイオフに基づいて市民を捕食するかしないかを決定し、市民は退出(他国への移住)、忠誠心の維持、コス トをかけて懸念を表明(抗議)する選択肢を持っている[39] [unreliable source?] 同様に、このゲームも退出のペイオフ、表明のコスト、忠誠の価値といった変数が捕食するかどうかという国家行動をどう変更するのかという洞察を与えてくれ る。 |

| How democracy affects economic

performance Given that the factors leading to democratic vs. dictatorial regimes, the second part of the story in Why Nations Fail explains why inclusive political institutions give rise to economic growth. This argument was previously and more formally presented in another paper by Acemoglu and Robinson, Institutions as the Fundamental Cause for Long-Run Growth.[40] With this theory, Acemoglu and Robinson try to explain the different level of economic development of all countries with one single framework. Political institutions (such as a constitution) determine the de jure (or written) distribution of political power, while the distribution of economic resources determines the de facto (or actual) distribution of political power. Both de jure and de facto political power distribution affect the economic institutions in how production is carried out, as well as how the political institutions will be shaped in the next period. Economic institutions also determine the distribution of resources for the next period. This framework is thus time dependent—institutions today determine economic growth tomorrow and institutions tomorrow. For example, in the case of democratization of Europe, especially in England before the Glorious Revolution, political institutions were dominated by the monarch. However, profits from increasing international trade extended de facto political power beyond the monarch to commercially engaged nobles and a new rising merchant class. Because these nobles and the merchant class contributed to a significant portion of the economic output as well as the tax income for the monarch, the interaction of the two political powers gave rise to political institutions that increasingly favored the merchant class, plus economic institutions that protected the interests of the merchant class. This cycle gradually empowered the merchant class until it was powerful enough to take down the monarchy system in England and guarantee efficient economic institutions. In another paper with Simon Johnson at Massachusetts Institute of Technology called The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,[41] the authors use a natural experiment in history to show that different institutions result in different levels of economic growth. The paper examines institutional choices during the colonial period of several nations in relation to the same nations' economic development today. It found that in countries where the disease environment meant that it was hard for colonizers to survive (high mortality rate), they tended to set up extractive regimes, which resulted in poor economic growth today. In places where it was easier for colonizers to survive (low mortality rates), however, they tended to settle down and duplicate institutions from their country of origin, as we have seen in the colonial success of Australia and United States. Thus, the mortality rate among colonial settlers several hundred years ago has determined the economic growth of today's post-colonial nations by setting institutions on very different paths. The theory of interaction between political and economic institutions is further reinforced by Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson in The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth,[24] which covers the economic rise of Europe after 1500. The paper finds that the Transatlantic trade after the year 1500 increased profits from trade and thus created a merchant class that was in a position to challenge monarchical power. By conducting regression analysis on the interaction variable between institution type and the Atlantic trade, the paper also demonstrates a significant interaction between the Atlantic Trade and the political institution: the presence of an absolutist monarch power hampers the effect of the Atlantic Trade on economic rise. It explains why Spain, despite the same access to the Atlantic Trade fell behind England in economic development. Acemoglu and Robinson have explained that their theory is largely inspired by the work of Douglass North, an American economist, and Barry R. Weingast, an American political scientist.[citation needed] In North and Weingast's paper in 1989, Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England,[42] they conclude that historical winners shape institutions to protect their own interests. In the case of the Glorious Revolution, the winning merchant class established property rights laws and limited the power of the monarch, which essentially promoted economic growth. Later on, North, Wallis and Weingast call this law and order open access, in their 2009 paper Violence and the Rise of Open-Access Orders.[43] With open access, equality and diversity in thought—societies are more able to flourish and prosper. |

民主主義が経済パフォーマンスに与える影響 民主的な政権と独裁的な政権を生み出す要因を考えると、「なぜ国家は破綻するのか」のストーリーの第2部では、なぜ包括的な政治制度が経済成長をもたらす のかを説明します。この議論はAcemogluとRobinsonによる別の論文、Institutions as the Fundamental Cause for Long-Run Growthで以前より正式に提示されている[40]。この理論によってAcemogluとRobinsonは、すべての国の異なる経済発展のレベルを一 つのフレームワークで説明しようとしている。 政治制度(憲法など)は政治権力のデジュール(または文書による)分配を決定し、経済資源の分配は政治権力のデファクト(または実際の)分配を決定する。 デジュールとデファクトの両方の政治権力分布は、生産がどのように行われるかという経済制度に影響を与え、また次の時代に政治制度がどのように形成される かということにも影響を与える。また、経済制度は、次の期間の資源分配を決定する。このように、この枠組みは時間依存的であり、今日の制度が明日の経済成 長を決定し、明日の制度が決定される。 例えば、ヨーロッパの民主化の場合、特に栄光革命前のイギリスでは、政治制度は君主に支配されていた。しかし、国際貿易の拡大による利益は、事実上の政治 権力を君主の外に、商業に従事する貴族や新たに台頭してきた商人階級に拡大した。この貴族と商人層は、経済生産と君主の税収のかなりの部分を占めていたた め、2つの政治権力の相互作用によって、商人層に有利な政治制度と、商人層の利益を保護する経済制度が生み出された。この循環によって、商人階級は次第に 力をつけ、イングランドの君主制を崩壊させ、効率的な経済制度を保証するほどの力を持つに至ったのである。 マサチューセッツ工科大学のサイモン・ジョンソンとの別の論文では、The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development.と呼ばれている。An Empirical Investigation[41]では、著者らは歴史上の自然実験を用いて、異なる制度が異なるレベルの経済成長をもたらすことを明らかにしている。こ の論文では、いくつかの国の植民地時代における制度的選択を、同じ国の今日の経済発展との関連で検証している。その結果、疾病環境のために植民者が生き残 りにくい(死亡率が高い)国では、搾取的な体制をとる傾向があり、その結果、今日の経済成長が乏しいことがわかった。一方、植民者が生き残りやすい(死亡 率が低い)場所では、オーストラリアやアメリカの植民地支配の成功に見られるように、定住して出身国の制度を複製する傾向があった。このように、数百年前 の植民地移住者の死亡率が、今日のポスト植民地主義国の経済成長を決定づけ、制度を全く異なる方向に設定した。 政治的制度と経済的制度の相互作用の理論は、Acemoglu、Johnson、Robinsonの『The Rise of Europe』によってさらに補強されている。The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth』[24]は、1500年以降のヨーロッパの経済的台頭を扱っている。この論文では、1500年以降の大西洋貿易が貿易による利益を増加さ せ、その結果、君主権力に挑戦する立場にある商人階級を生み出したことを見出している。また、制度の種類と大西洋貿易の交互作用変数について回帰分析を行 うことで、大西洋貿易と政治制度の間に有意な交互作用があること、すなわち絶対主義君主権力の存在が大西洋貿易の経済的上昇への効果を阻害していることを 示す。同じように大西洋貿易にアクセスしたにもかかわらず、スペインが経済発展でイングランドに遅れをとった理由も説明されている。 アセモグルとロビンソンは、自分たちの理論がアメリカの経済学者であるダグラス・ノースとアメリカの政治学者であるバリー・R・ワインガストの研究に大き く影響を受けていると説明している[citation needed] ノースとワインガストの1989年の論文『Constitutions and Commitment』において、スペインは、そのような政治的・経済的・制度的な制約のもとで発展してきたと述べている。彼らは歴史的な勝者が自らの利 益を守るために制度を形成すると結論付けている[42]。栄光革命の場合、勝利した商人階級は財産権法を制定し、君主の権力を制限し、それによって本質的 に経済成長を促進させた。その後、ノース、ウォリス、ワインガストは2009年の論文「暴力とオープンアクセス秩序の台頭」において、この法と秩序をオー プンアクセスと呼んでいる[43]。オープンアクセスによって、思想における平等と多様性は社会がより繁栄し、栄えることができる。 |

| Critical reviews The critical reviews below are notable responses either directly or indirectly addressed towards the book, the authors, or the arguments made by the book. The section below is arranged in alphabetical order of the respondent's first name. Arvind Subramanian Indian economist Arvind Subramanian points out the potential problem of reverse causality in Acemoglu and Robinson's theory in his publication in The American Interest.[44] Why Nations Fail takes political institutions as causes and economic performance as results for granted. However, according to Modernization theory, causation can also go the other way around—improvement of political institutions can also be a result of economic modernization. The book thus fails to explain why this alternative perspective does not work; however, a 2001 paper by Acemoglu and Johnson with frequent collaborator Simon Johnson introduced a two-stage regression test using colonial settler disease mortality as an instrument attempted to answer this question and is included in the book's works cited. Subramanian also points out the limitation of the book to explain the recent economic development in China and India. Under an authoritarian regime (theoretically extractive political institution), China has achieved rapid economic development while democratic India (theoretically inclusive political institution) has lagged much behind. According to Surbramanian, one can say that China and India are outliers or that it is still too early to decide (that is, China might collapse and India might catch up according to the book's prediction). However, it is still unsatisfying that the theory is unable to explain the situation of 1/3 of the world's population, and it is unlikely that China or India will change drastically in the near future, according to the prediction. Acemoglu and Robinson counter[45] that their theory distinguishes between political and economic institutions and that it is not political institutions that contribute to growth directly but economic institutions shaped by the political institutions. In the case of China, even though the political institutions on a higher level are far from inclusive, the incentive to reform Chinese economy does come from political institutions; in 1978 from Deng Xiaoping's opening up policy at the end of the internal political feud during the Cultural Revolution. This exactly fits into the theory that the change in political institutions has shaped economic institutions and thus has influenced economic performance. This economic growth is further expected to shape the political institutions in China in the future. One can only say that China is an outlier to the theory when in the future China becomes as wealthy as U.S. or Germany but still remains an authoritarian regime. Regarding the case of India, the authors deny an equivalence between inclusive political institutions and electoral democracy. Electoral democracy is the de jure system adopted by a country while political institutions refer to the de facto structure and quality of the political system of a certain country. For example, India's political system has long been dominated by the Congress Party; the provision of public goods is preyed upon by political patrimonialism; various members of Lok Sabha (the Indian legislature) face criminal charges, and caste-based inequality still exists. The quality of democracy is very poor and thus the political institutions are flawed in India, which explains why economic institutions are equally poor and economic growth is stymied. David R. Henderson David R. Henderson wrote a generally positive review in Regulation[28] but criticized the authors for inconsistency when talking about a central government's role in promoting development. In some parts of the book, the authors attribute the failure of the states like Afghanistan, Haiti and Nepal to the lack of a strong central government that imposes rule and order. However, in other parts of the book, the authors seem to embrace weak government for growth, as in the example of Somalia after losing its central government. In addition, Henderson asserts the authors have made two errors in the book about the United States. First, the authors falsely accuse "monopolists" like Rockefeller of being the extractive power. But in fact Rockefeller did not raise the price of oil but lowered the price to gain market share rather than to extract from the economy. Second, he says the authors are oblivious of the mainstream scholarship on American economic history between the American Civil War and civil rights movements in America. Rather than diverging from the rich North, the South was actually converging.[28] |

批判的レビュー 以下の批評は、本書や著者、あるいは本書の主張に対して直接的、間接的に向けられた注目すべき反応です。以下のセクションは、回答者の名前のアルファベッ ト順に並んでいます。 アルビンド・スブラマニアン インドの経済学者であるArvind Subramanianは、The American Interestに発表した論文の中で、AcemogluとRobinsonの理論における逆因果の潜在的問題を指摘している[44] Why Nations Failは原因としての政治制度と結果としての経済パフォーマンスを当然のこととしている。しかし、近代化理論によれば、因果関係は逆にもなりうる-政治 制度の改善は経済の近代化の結果でもありうる-のである。しかし、AcemogluとJohnsonが2001年に発表した論文では、植民地時代の入植者 の疾病死亡率を指標とした二段階回帰検定が紹介されており、本書の引用文献の中に含まれている。 また、Subramanianは、中国とインドの最近の経済発展を説明するための本書の限界を指摘している。権威主義的な体制(理論的には抽出的な政治制 度)の下で、中国は急速な経済発展を遂げたが、民主主義のインド(理論的には包摂的な政治制度)は大きく立ち遅れているのである。 Surbramanianによれば、中国とインドが異常であるとか、まだ判断するのは早いということができる(つまり、この本の予測によれば、中国は崩壊 するかもしれないし、インドは追いつくかもしれない)。しかし、世界人口の1/3の状況をこの理論で説明できないのはやはり不満であり、近い将来、中国や インドが予測通りに大きく変化する可能性は低いと思われる。 AcemogluとRobinsonは、彼らの理論は政治的制度と経済的制度を区別しており、成長に直接寄与するのは政治的制度ではなく、政治的制度に よって形成される経済的制度であると反論している[45]。中国の場合、より高いレベルの政治制度は包括的とは言い難いものの、中国経済改革のインセン ティブは政治制度に由来しており、1978年には文化大革命の内紛の果てに鄧小平が開放政策を打ち出したことが挙げられる。これはまさに、政治制度の変化 が経済制度を形成し、その結果、経済パフォーマンスに影響を与えたという理論に合致している。この経済成長はさらに、将来の中国の政治制度を形成すること が期待される。将来、中国が米国やドイツのように豊かになっても、依然として権威主義的な体制が続いている場合、中国はこの理論の異常値であると言うこと ができる。 インドのケースについて、著者は包括的な政治制度と選挙制民主主義の等価性を否定している。選挙制民主主義はその国が採用しているデジュールな制度であ り、政治制度はその国の政治システムのデファクトな構造や質を指している。例えば、インドの政治体制は長く会議派に支配され、公共財の提供は政治的パトリ モニアリズムに食い物にされ、Lok Sabha(インドの立法府)の様々なメンバーが刑事告発され、カーストによる不平等が未だに存在している。民主主義の質が非常に低いため、インドでは政 治制度に欠陥があり、そのため経済制度も同様に貧弱で、経済成長が阻害されていることが説明できる。 デイヴィッド・R・ヘンダーソン David R. HendersonはRegulation[28]で概ね肯定的なレビューを書いているが、開発を促進する上での中央政府の役割について語るとき、著者は 矛盾していると批判している。この本のある部分では、著者はアフガニスタン、ハイチ、ネパールといった国家の失敗を、支配と秩序を押し付ける強力な中央政 府の欠如に起因すると考えている。しかし、本書の他の部分では、中央政府を失ったソマリアの例のように、著者は成長のために弱い政府を受け入れているよう である。さらにヘンダーソンは、著者が本書の中で米国について2つの誤りを犯していると主張する。第一に、著者はロックフェラーのような「独占者」が抽出 力であると誤って非難している。しかし、実際にはロックフェラーは石油の価格を上げたのではなく、経済から抜き取るためではなく、市場シェアを獲得するた めに価格を下げたのである。第二に、著者はアメリカの南北戦争から公民権運動にかけてのアメリカ経済史の主流の学問に気づかない、という。南部は豊かな北 部から乖離するのではなく、実際には収斂していたのである[28]。 |

| Francis Fukuyama In his article in The American Interest,[46] Francis Fukuyama criticized Acemoglu and Robinson's approach and argument for being very similar to a book by North, Wallis and Weingast in 2009, Violence and Social Orders.[47] Fukuyama approves of the books' central conclusion, which is that the failure of economies are often due to institutions beneficial to elites to the detriment of others, instead of the leaders' ignorance on policy matters. However, Fukuyama contended that the bifurcation of states into being "inclusive" or "extractive" oversimplifies the problem. This approach, he argues, lumps different institutions such as property rights, courts, electoral democracy, an impersonal state, and access to education, thereby failing to unpack their individual effect and makes flawed comparisons between societies across centuries. A modern state and the rule of law, Fukuyama writes, are demonstrably beneficial to economic growth, but popular democracy in poor countries can foster clientelism, corruption and hinder development. Fukuyama also points out that historical facts (on Rome and the Glorious Revolution) used to support the argument was flawed. Finally, Fukuyama specifically pointed out that the argument by Acemoglu and Robinson does not apply to the case of modern China, as China has "extractive" institutions but still flourishes economically. In response to Fukuyama's comments, Acemoglu and Robinson replied on their blog.[48] First, they agreed that their work is inspired by North et al.'s work but explained that they build on and complement each other's work. Second, with reference to the criticism of oversimplification, they countered by describing the oversimplification as an approach to decompose complex political institutions; it is necessary avoid focusing too narrowly on a single aspect of institutions. Last, on China, they attribute the rapid economic growth in China to the some (but yet limited) level of inclusiveness, as was also seen in the example of fast growth in the Soviet Union until the 1970s, but predicted that China will not reach per capita income comparable to those of Spain or Portugal with its current extractive institutions. |

フランシス・フクヤマ フランシス・フクヤマはThe American Interest誌の記事において、アセモグルとロビンソンのアプローチと議論が2009年のノース、ウォリス、ワインガストの著書『暴力と社会秩序』と 非常に似ていると批判している[47]。フクヤマは、経済の失敗はしばしば、政策問題に対する指導者の無知ではなく、エリートにとって有益で他者に不利益 を与える制度のせいだというこの本の中心結論を容認している。しかし、フクヤマは、国家を「包摂的」か「抽出的」かに二分することは、問題を単純化しすぎ ると主張する。このアプローチは、財産権、裁判所、選挙による民主主義、非人格的な国家、教育へのアクセスなど、異なる制度をひとまとめにし、その個別の 効果を解き明かすことができず、世紀を超えた社会間の比較には欠陥があると彼は主張している。近代国家と法の支配は経済成長にとって明らかに有益である が、貧困国における大衆民主主義は、顧客主義や汚職を助長し、発展を阻害することがあるとフクヤマは書いている。また、フクヤマは、この議論を支えるため に使われた歴史的事実(ローマや名誉革命に関するもの)に欠陥があることを指摘している。最後に福フクヤマは、アセモグルとロビンソンの議論は、中国が 「抽出的」な制度を持ちながらも経済的に繁栄している現代中国のケースには当てはまらないことを特に指摘している。 これに対して、アセモグルとロビンソンはブログで反論している[48]。第一に、彼らは自分たちの研究がノースらの研究に触発されていることに同意しつ つ、互いの研究を基礎とし補完していると説明している。第二に、単純化しすぎという批判について、彼らは、単純化しすぎは、複雑な政治制度を分解するため のアプローチであり、制度の一面に焦点を絞りすぎることを避ける必要があると述べて反論している。最後に、中国について、1970年代までのソ連の急成長 の例に見られるように、中国の急速な経済成長は、ある程度の(まだ限定的ではあるが)包括的なレベルであるとしながらも、現在の抽出的制度では、中国はス ペインやポルトガルのような一人当たりの所得に達することはないと予測している。 |

| Jared Diamond In Jared Diamond's book review on The New York Review of Books,[37] he points out the narrow focus of the book's theory only on institutions, ignoring other factors like geography. One major issue of the authors' argument is endogeneity: if good political institutions explain economic growth, then what explains good political institutions in the first place? That is why Diamond lands on his own theory of geographical causes for developmental differences. He looks at tropical (central Africa and South America) vs. temperate areas (North and South Africa and North America) and believes that the differences of wealth of nations are caused by the weather conditions: for example, in tropical areas, diseases are more likely to develop and agricultural productivity is lower. Diamond's second criticism is that Acemoglu and Robinson seem to only focus on small events in history like the Glorious Revolution in Britain as the critical juncture for political inclusion, while ignoring the prosperity in Western Europe. In response to Diamond's criticism,[49] the authors reply that the arguments in the book do take geographical factors into account but that geography does not explain the different level of development. Acemoglu and Robinson simply take geography as an original factor a country is endowed with; how it affects a country's development still depends on institutions. They mention their theory of Reversal of Fortune: that once-poor countries (like the U.S., Australia, and Canada) have become rich despite poor natural endowments. They refute the theory of "resource curse"; what matters is the institutions that shape how a country uses its natural resources in historical processes. Diamond rebutted[49] Acemoglu and Robinson's response, reinforcing his claim of the book's errors. Diamond insists geographical factors dominate why countries are rich and poor today. For example, he mentions that the tropical diseases in Zambia keep male workers sick for a large portion of their lifetime, thus reducing their labor productivity significantly. He reinforces his point that geography determines local plantations and gave rise to ancient agrarian practices. Agricultural practice further shapes a sedentary lifestyle as well as social interaction, both of which shape social institutions that result in different economic performances across countries. Diamond's review was excerpted by economist Tyler Cowen on Marginal Revolution.[50] |

ジャレド・ダイアモンド Jared DiamondのThe New York Review of Booksでの書評[37]では、本書の理論が制度のみに焦点を当て、地理など他の要素を無視している狭量さを指摘している。著者の主張の大きな問題の一 つは内生性である。もし優れた政治制度が経済成長を説明するならば、そもそも優れた政治制度は何によって説明されるのか。そこでDiamondは、発展差 の地理的原因に関する独自の理論に着地する。彼は、熱帯地域(アフリカ中部、南米)と温帯地域(アフリカ北部、南部、北米)に注目し、例えば熱帯地域では 病気が発生しやすく、農業生産性が低いなど、気象条件によって国家の豊かさが異なるという説をとっている。Diamondの第二の批判は、 AcemogluとRobinsonが、政治的包摂の臨界点としてイギリスの栄光革命のような歴史の中の小さな出来事だけに注目し、西ヨーロッパの繁栄を 無視しているように見えるということである。 ダイヤモンドの批判に対して、著者らは、本書における議論は地理的要因を考慮しているが、地理的要因は発展のレベルの違いを説明するものではないと答えて いる[49]。アセモグルとロビンソンは、地理を国がもともと持っている要素として捉えているだけであり、それがどのように国の発展に影響を与えるかは、 やはり制度に依存するのである。彼らは、かつて貧しかった国(米国、オーストラリア、カナダなど)が、貧弱な自然資源にもかかわらず豊かになったという 「運命の逆転」の理論に触れている。彼らは「資源の呪い」の理論に反論し、重要なのは歴史的過程においてその国が天然資源をどのように利用するかを形成す る制度であるとしている。 ダイアモンドはアセモグルとロビンソンの反論[49]に反論し、本書の誤りという主張を補強している。ダイヤモンドは、なぜ今日各国が豊かであり、貧しい のか、地理的要因が支配的であると主張している。例えば、彼はザンビアの熱帯病が男性労働者の生涯の大部分を病気にさせ、その結果、彼らの労働生産性を著 しく低下させることに言及している。さらに、地理的な条件からプランテーションが生まれ、古代の農耕習慣が生まれたと指摘する。農耕の習慣はさらに、定住 生活や社会的相互作用を形成し、その両方が社会制度を形成して、国によって異なる経済的パフォーマンスをもたらすのである。 Diamondのレビューは経済学者のTyler CowenによってMarginal Revolutionで抜粋された[50]。 |

| Jeffrey Sachs According to Jeffrey Sachs,[51] an American economist, the major problem of Why Nations Fail is that it focuses too narrowly on domestic political institutions and ignores other factors, such as technological progress and geopolitics. For example, geography plays an important role in shaping institutions, and weak governments in West Africa may be seen as a consequence of the unnavigable rivers in the region. Sachs also questions Acemoglu and Robinson's assumption that authoritarian regimes cannot motivate economic growth. Several examples in Asia, including Singapore and South Korea, easily refute Acemoglu and Robinson's arguments that democratic political institutions are prerequisites for economic growth. Moreover, Acemoglu and Robinson overlook macroeconomic factors like technological progress (e.g. industrialization and information technology). In response to Sachs' critique, Acemoglu and Robinson replied on their book blog with twelve specific points. First, on the role of geography, Acemoglu and Robinson agree that geography is crucial in shaping institutions but do not recognize a deterministic role of geography in economic performance. Second, on the positive role authoritarian governments can play in economic growth, especially in the case of China, the fast economic growth could be part of the catch-up effect. However, it does not mean that authoritarian governments are better than democratic governments in promoting economic growth. It is still way too early, according to Acemoglu and Robinson, to draw a definite conclusion solely based on the example of China. Last, on industrialization, they argue that industrialization is contingent upon institutions. Based on Acemoglu and Robinson's response, Sachs wrote a rebuttal on his personal website.[52] |

ジェフリー・サックス アメリカの経済学者であるJeffrey Sachs[51]によれば、『Why Nations Fail』の大きな問題は、国内の政治制度に焦点を絞りすぎて、技術進歩や地政学など他の要因を無視していることであるとしている。例えば、地理は制度の 形成に重要な役割を果たしており、西アフリカの弱い政府は、この地域の航行不可能な河川の結果と見なすことができるかもしれない。Sachsはまた、権威 主義的な体制は経済成長の動機になりえないというAcemogluとRobinsonの仮定に疑問を投げかけている。シンガポールや韓国などアジアにおけ るいくつかの例は、民主的な政治制度が経済成長の前提であるというAcemogluとRobinsonの議論に容易に反証を与えるものである。さらに、 AcemogluとRobinsonは、技術進歩(工業化や情報技術など)のようなマクロ経済的な要因を見落としている。 Sachsの批判に対し、AcemogluとRobinsonは自身の著書ブログで12項目の具体的な指摘をした上で反論している。第一に、地理的な役割 について、AcemogluとRobinsonは、地理が制度を形成する上で重要であることには同意するが、経済パフォーマンスにおいて地理が決定論的な 役割を果たすとは認めていない。第二に、権威主義的な政府が経済成長において果たしうる積極的な役割について、特に中国の場合、急速な経済成長はキャッチ アップ効果の一部である可能性がある。しかし、権威主義的な政府が民主主義的な政府よりも経済成長を促進する上で優れていることを意味するものではない。 AcemogluとRobinsonによれば、中国の例だけから明確な結論を出すのは、まだ早すぎるのである。最後に、工業化について、彼らは、工業化は 制度に依存していると主張している。アセモグルとロビンソンの回答に基づいて、サックスは個人的なウェブサイトに反論を書いた[52]。 |

| Paul Collier Development economist Paul Collier from the University of Oxford reviewed the book for The Guardian.[53] Collier's review summarizes two essential elements for growth from the book: first, a centralized state and second, inclusive political and economic institutions. Based on the case of China, a centralized state can draw a country out from poverty but without inclusive institutions, such growth is not sustainable, as argued by Acemoglu and Robinson. Such process is not natural, but only happens when the elites are willing to cede power to the majority under certain circumstances. Peter Forbes Peter Forbes reviewed the book for The Independent: "This book, by two U.S. economists, comes garlanded with praise by its obvious forebears – Jared Diamond, Ian Morris, Niall Ferguson, Charles C. Mann – and succeeds in making great sense of the history of the modern era, from the voyages of discovery to the present day."[54] Besides singing high praises for the book, Forbes links the message of the book and contemporary politics in developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. Though the two countries are by far some of the most inclusive economies in the world, various parts of them are, by nature, extractive—for instance, the existence of a shadow banking system, of conglomerate manufacturers, and so on. He warns against extractive practices under the guise of an inclusive economy. Warren Bass Warren Bass reviewed the book for the Washington Post, writing: "It's bracing, garrulous, wildly ambitious and ultimately hopeful. It may, in fact, be a bit of a masterpiece."[34] Despite his applause, Bass also points out several imperfections of the book. First of all, the definition of extractive and inclusive institution is vague in a way that cannot be utilized in policymaking. Second, though Acemoglu and Robinson are ambitious in covering cases of all nations across history, this attempt is subjected to scrutiny of regional experts and historians. For example, their accusation of Ottoman Empire as "highly absolutist" might not be correct, given the level of tolerance and diversity inside the Empire as compared to its European counterparts. William Easterly In a mixed review of the book in the Wall Street Journal, William Easterly was generally supportive of the plausibility of the book's thesis but critiqued the book's failure to cite extant statistics-based evidence to support the validity of the historical case studies.[55] For example, in the book's example about Congo, the stated reason Congo is impoverished is that Congo is close to slave trade shipping points. The approach of this historical case study only offers one data point. Moreover, Easterly also points out the danger of ex-post rationalization that the book only attributes different levels of development to institutions in a way a bit too neat. For example, to explain the fall of Venice, it could be the extractive regime during the time or it could also be the shift from Mediterranean trade to Atlantic trade. The historical case studies approach might be biased. |

ポール・コリアー オックスフォード大学の開発経済学者であるPaul Collierは、The Guardianのために本書のレビューを行った[53]。Collierのレビューは、本書から成長にとって不可欠な2つの要素、第1に中央集権国家、 第2に包括的政治・経済制度を要約したものである。中国の事例をもとに、中央集権的な国家は貧困から国を引き出すことができるが、包括的な制度がなけれ ば、アセモグルとロビンソンが主張するように、そうした成長は持続的なものにはならない。このようなプロセスは自然なものではなく、ある状況下でエリート が多数派に権力を譲ろうとする場合にのみ起こるものである。 ピーター・フォーブス Peter ForbesがThe Independent誌に書評を寄せている。「2人のアメリカの経済学者による本書は、ジャレド・ダイアモンド、イアン・モリス、ニール・ファーガソ ン、チャールズ・C・マンといった明らかな先達による賞賛に包まれ、大航海時代から現代までの近代史に大きな意味を与えることに成功している」[54]と 本書を高く評価するとともに、フォーブスは本書のメッセージとアメリカやイギリスといった先進国における現代政治を結びつけている。この2つの国は世界で 最も包括的な経済であるが、シャドーバンキングシステムやコングロマリットメーカーの存在など、その様々な部分が本質的に採鉱的である。彼は、包括的な経 済を装った搾取的な行為に警告を発している。 ウォーレン・バス ウォーレン・バスは、ワシントン・ポスト紙に本書の書評を寄稿し、次のように書いている。「勇ましく、雄弁で、野心的で、最終的には希望に満ちている。実 際、ちょっとした傑作かもしれない」[34]と称賛しているが、バスは本書のいくつかの欠点も指摘している。まず、抽出的制度と包括的制度の定義が曖昧で あり、政策立案に活用することができない点である。第二に、AcemogluとRobinsonは歴史上のあらゆる国の事例を網羅することに意欲的である が、この試みは地域の専門家や歴史家の批判にさらされていることである。例えば、オスマン帝国を「絶対主義が強い」とする彼らの指摘は、ヨーロッパと比較 した場合の帝国内の寛容性や多様性を考えると、正しくないかもしれない。 ウィリアム・イースタリー ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル』における本書の混成レビューにおいて、ウィリアム・イースタリーは本書の論文の妥当性を概ね支持していたが、歴史的事 例研究の妥当性を支持する現存する統計に基づく証拠を引用していないことを批判していた[55]。 例えば、本書のコンゴに関する事例では、コンゴが貧しい理由はコンゴが奴隷貿易船の出荷地点と近いからだと述べられている。この歴史的事例研究のアプロー チは、一つのデータポイントしか提供していない。さらに、Easterlyは、本書が発展のレベルの違いを、少しきれいごとで制度に帰着させるだけとい う、事後的な合理化の危険性も指摘している。例えば、ヴェニスの没落を説明するには、当時の採掘体制であったり、地中海貿易から大西洋貿易への移行であっ たりする。歴史的事例研究というアプローチには、偏りがあるかもしれない。 |

| Critical

juncture theory Environmental determinism Extractivism Modernization theory Resource curse States and Power in Africa World-systems theory |

クリティカルジャンクション理論 環境決定論 抽出主義 近代化論 資源の呪い アフリカの国家と権力 世界システム論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Why_Nations_Fail |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★Daron Acemoglu, b.1967

| Kamer Daron

Acemoğlu[a] (born September 3, 1967) is a Turkish-American economist of

Armenian descent who has taught at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology since 1993, where he is currently the Elizabeth and James

Killian Professor of Economics, and was named an Institute Professor at

MIT in 2019.[2] His primary research fields include political economy,

development economics, and labor economics. He received the John Bates

Clark Medal in 2005, and the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024.[2][3] Acemoglu ranked third, behind Paul Krugman and Greg Mankiw, in the list of "Favorite Living Economists Under Age 60" in a 2011 survey among American economists. In 2015, he was named the most cited economist of the past 10 years per Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) data. According to the Open Syllabus Project, Acemoglu is the third most frequently cited author on college syllabi for economics courses after Mankiw and Krugman.[4] In 2024, Acemoglu, James A. Robinson, and Simon Johnson were awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for their comparative studies in prosperity between states and empires.[5] He is regarded as a centrist with a focus on institutions, poverty and econometrics. |

カメル・ダロン・アセモグル[a](1967年9月3日生まれ)は、ア

ルメニア系のトルコ系アメリカ人経済学者である。1993年からマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭を執り、現在はエリザベス&ジェームズ・キリア

ン経済学教授を務めている。2019年にはMITの研究所教授に任命された。[2]

主な研究分野は、政治経済学、開発経済学、労働経済学である。2005年にジョン・ベイツ・クラーク賞、2024年にノーベル経済学賞を受賞した。[2]

[3] アセモグルは、2011年にアメリカの経済学者たちを対象に行った「60歳未満の最も好きな現役経済学者」の調査で、ポール・クルーグマン、グレッグ・マ ンキューに次ぐ3位に選ばれた。2015年には、Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) のデータによると、過去10年間で最も多く引用された経済学者として選ばれた。Open Syllabus Projectによると、アセモグルは、マンキューとクルーグマンに次いで、大学の経済学コースのシラバスで3番目に頻繁に引用されている著者である。 [4] 2024年、アセモグル、ジェームズ・A・ロビンソン、サイモン・ジョンソンは、国家と帝国の繁栄に関する比較研究により、ノーベル経済学賞を受賞した。彼は、制度、貧困、計量経済学に焦点を当てた中道派と見なされている。 |

| Early and personal life Kamer Daron Acemoğlu[6][7][b] was born in Istanbul to Armenian parents on September 3, 1967.[10][11][12] His father, Kevork Acemoglu (1938–1988), was a commercial lawyer and lecturer at Istanbul University. His mother, Irma Acemoglu (d. 1991), was a poet and the principal of Aramyan Uncuyan (tr; hy), an Armenian elementary school in Kadıköy,[13][14][15] which he attended, before graduating from Galatasaray High School in 1986.[16][17][18] He became interested in politics and economics as a teenager.[15] He was educated at the University of York, where he received a BA in economics in 1989, and at the London School of Economics (LSE), where he received an MSc in econometrics and mathematical economics in 1990, and a PhD in economics in 1992.[19] His doctoral thesis was titled Essays in Microfoundations of Macroeconomics: Contracts and Economic Performance.[10][7] His doctoral advisor was Kevin W. S. Roberts.[20] James Malcomson, one of his doctoral examiners at the LSE, said that even the weakest three of the seven chapters of his thesis were "more than sufficient for the award of a PhD."[21] Arnold Kling called him a wunderkind due to the fact that he received his PhD by the time he was 25.[22] Acemoglu is a naturalized US citizen.[23] He is fluent in English and Turkish,[24] and speaks some Armenian.[25] He is married to Asuman "Asu" Ozdağlar, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT,[15][26] who is the daughter of İsmail Özdağlar, a former Turkish government minister. Together, they have authored several articles.[27][28] As of 2015, they live in Newton, Massachusetts, with their two sons, Arda and Aras.[29] |

幼少期と私生活 カメル・ダロン・アセモグル[6][7][b]は、1967年9月3日にイスタンブールでアルメニア人の両親の間に生まれた[10][11][12]。父 親のケヴォーク・アセモグル(1938年~1988年)は、商事弁護士であり、イスタンブール大学の講師であった。母親のイルマ・アセモグル(1991年 没)は詩人であり、カドゥキョイにあるアルメニア人小学校「アラムヤン・ウンキュヤン(tr; hy)」の校長であった[13][14][15]。彼はこの学校に通い、1986年にガラタサライ高校を卒業した。[16][17][18] 10代の頃から政治と経済に興味を持つようになった。[15] ヨーク大学で学び、1989年に経済学の学士号を取得。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス(LSE)では、1990年に計量経済学および数理経済学 の修士号、1992年に経済学の博士号を取得した[19]。博士論文のタイトルは『マクロ経済学のミクロ的基礎に関するエッセイ:契約と経済パフォーマン ス』であった[10]。[7] 博士課程の指導教官はケビン・W・S・ロバーツであった。[20] LSEで彼の博士論文の審査員を務めたジェームズ・マルコムソンは、7章からなる博士論文の中で最も弱い3章でさえ「博士号取得には十分すぎる内容」であ ると述べた。[21] アーノルド・クリングは、彼が25歳で博士号を取得した事実から、彼を「天才児」と呼んだ。[22] アセモグルは米国籍を取得している。[23] 英語とトルコ語に堪能で[24]、アルメニア語も多少話す。[25] 妻は、MITの電気工学・コンピュータサイエンス教授であるアスマン・「アス」・オズダグラル[15][26]で、元トルコ政府大臣イスメール・オズダグ ラルの娘である。夫妻は共同でいくつかの論文を執筆している。[27][28] 2015年現在、夫妻は2人の息子、アルダとアラスとともにマサチューセッツ州ニュートンに住んでいる。[29] |

| Academic career Acemoglu in 2009 Acemoglu in his office, January 2020 Acemoglu was a lecturer in economics at the London School of Economics from 1992 to 1993.[2] He was appointed an assistant professor at MIT in 1993, where he became the Pentti Kouri Associate Professor of Economics in 1997, and was tenured in 1998.[2][30] He became a full professor at MIT in 2000, and served as the Charles P. Kindleberger Professor of Applied Economics there from 2004 to 2010.[2][31] In 2010, Acemoglu was appointed the Elizabeth and James Killian Professor of Economics at MIT.[10] In July 2019, he was named an Institute Professor, the highest faculty honor at MIT.[32] As of 2019, he has mentored over 60 PhD students.[32] Among his doctoral students are Ufuk Akçiġit, Robert Shimer, Mark Aguiar, Pol Antràs, and Gabriel Carroll.[20] In 2014, he made $841,380, making him one of the top earners at MIT.[33] Acemoglu is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society in 2005.[19][2][34] He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2006, and to the National Academy of Sciences in 2014.[35][36] He is also a Senior Fellow at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, and a member of several other learned societies.[19][37][38] He edited Econometrica, an academic journal published by the Econometric Society, from 2011 to 2015.[39] Acemoglu has authored hundreds of academic papers.[40] He noted that most of his research has been "motivated by trying to understand the sources of poverty."[23] His research includes a wide range of topics, including political economy, human capital theory, growth theory, economic development, innovation, labor economics,[19][41] income and wage inequality, and network economics, among others.[42] He noted in 2011 that most his research of the past 15 years concerned with what can be broadly called political economy.[43] He has made contribution to the labor economics field.[23] Acemoglu has extensively collaborated with James A. Robinson, a British political scientist and his peer at the London School of Economics.[30] Acemoglu has described it as a "very productive relationship." They have worked together on many articles and books, most of which are on the subject of growth and economic development.[23] The two have also extensively collaborated with economist Simon Johnson.[44] |

学術経歴 2009年のアセモグル 2020年1月、オフィスでのアセモグル アセモグルは1992年から1993年までロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで経済学の講師を務めた。[2] 1993年にMITの助教授に任命され、1997年にペンティ・クーリ経済学准教授となり、1998年に終身在職権を得た。[2][30] 2000年にMITの正教授となり、2004年から2010年までチャールズ・P・キンデルバーガー応用経済学教授を務めた。[2][31] 2010年、アセモグルはMITのエリザベス&ジェームズ・キリアン経済学教授に任命された。[10] 2019年7月、MITの最高位の教員栄誉である研究所教授に指名された。[32] 2019年現在、彼は60人以上の博士課程の学生を指導している。[32] 彼の博士課程の学生には、ウフク・アクチギット、ロバート・シマー、マーク・アグイア、ポル・アントラス、ガブリエル・キャロルなどがいる。[20] 2014年、彼の収入は841,380ドルで、MITで最も高収入の教員の一人となった。[33] アセモグルは全米経済研究所(NBER)の研究員であり、2005年に計量経済学会のフェローに選出された。[19][2][34] 2006年には米国芸術科学アカデミー、2014年には米国科学アカデミーの会員に選出された。[35][36] また、カナダ高等研究所の上級研究員であり、その他いくつかの学術団体の会員でもある。[19][37][38] 2011年から2015年まで、計量経済学会が発行する学術誌「Econometrica」の編集を担当した。[39] アセモグルは数百本の学術論文を執筆している。[40] 彼は、自身の研究の大半は「貧困の原因を理解しようとする動機から生まれた」と述べている。[23] 彼の研究は、政治経済学、人的資本理論、成長理論、経済開発、イノベーション、労働経済学、[19][41] 所得・賃金格差、ネットワーク経済学など、幅広い分野に及んでいる。[42] 彼は2011年、過去15年間の自身の研究のほとんどは、広く政治経済学と呼ばれる分野に関するものであると述べた。[43] 彼は労働経済学の分野にも貢献している。[23] アセモグルは、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの同僚である英国の政治学者、ジェームズ・A・ロビンソンと幅広く協力してきた。[30] アセモグルは、この関係を「非常に生産的な関係」と表現している。彼らは多くの論文や書籍を共同で執筆しており、そのほとんどは成長と経済開発に関するも のである。[23] また、2人は経済学者サイモン・ジョンソンとも幅広く協力してきた。[44] |

| Research and publications Acemoglu is considered a follower of new institutional economics.[45][46][47] His influences include Joel Mokyr, Kenneth Sokoloff,[48] Douglass North,[49] Seymour Martin Lipset,[50] and Barrington Moore.[50] Books Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy Published by Cambridge University Press in 2006, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy by Acemoglu and Robinson analyzes the creation and consolidation of democratic societies. They argue that "democracy consolidates when elites do not have a strong incentive to overthrow it. These processes depend on (1) the strength of civil society, (2) the structure of political institutions, (3) the nature of political and economic crises, (4) the level of economic inequality, (5) the structure of the economy, and (6) the form and extent of globalization."[51] The book's title is derived from Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, a 1966 book by Barrington Moore Jr.[52] Romain Wacziarg praised the book and argued that its substantive contribution is the theoretical fusion of the Marxist dialectical materialism ("institutional change results from distributional struggles between two distinct social groups, a rich ruling class and a poor majority, each of whose interests are shaped primarily by economic forces") and the ideas of Barry Weingast and Douglass North, who argued that "institutional reform can be a way for the elite to credibly commit to future policies by delegating their enactment to interests that will not wish to reverse them."[53] William Easterly called it "one of the most important contributions to the literature on the economics of democracy in a long time." Edward Glaeser described it as "enormously significant" work and a "great contribution to the field."[54] |

研究と出版物 アセモグルは新制度経済学の追随者と見なされている。[45][46][47] 彼に影響を与えた人物には、ジョエル・モキー、ケネス・ソコロフ、[48] ダグラス・ノース、[49] シーモア・マーティン・リップセット、[50] バリントン・ムーアなどがいる。[50] 著書 『独裁と民主主義の経済的起源』 2006年にケンブリッジ大学出版局から出版された、アセモグルとロビンソンによる『独裁と民主主義の経済的起源』は、民主主義社会の形成と定着を分析し ている。彼らは、「エリート層が民主主義を打倒する強い動機を持たない場合、民主主義は定着する。このプロセスは、(1)市民社会の力、(2)政治制度の 構造、(3)政治・経済危機の性質、(4)経済的不平等の程度、(5)経済の構造、(6)グローバル化の形態と程度、に依存する」と主張している。 [51] この本のタイトルは、バリントン・ムーア・ジュニアが1966年に出版した『独裁と民主主義の社会的起源』に由来している[52]。 ロマン・ワツィアルグはこの本を称賛し、その実質的な貢献は、マルクス主義の弁証法的唯物論(「制度的変化は、2つの異なる社会集団、すなわち豊かな支配 階級と貧しい多数派の間での分配をめぐる争いから生じる。それぞれの利益は主に経済的要因によって形作られる」)と、バリー・ワインガストおよびダグラ ス・ノースの考え、すなわち 「制度改革は、エリート層が、その実施を、それを覆そうとはしない利益団体に委任することで、将来の政策を信頼性をもって約束する手段となり得る」と主張 した[53]。ウィリアム・イースタリーは、この本を「民主主義の経済学に関する文献の中で、長い間最も重要な貢献の一つ」と評した。エドワード・グレイ ザーは、この本を「非常に重要な」著作であり、「この分野への大きな貢献」であると評した[54]。 |

| Why Nations Fail Why Nations Fail was included in the Shortlist of the 2012 Financial Times Business Book of the Year Award. In their 2012 book, Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson argue that economic growth at the forefront of technology requires political stability, which the Mayan civilization (to name only one) did not have,[55] and creative destruction. The latter cannot occur without institutional restraints on the granting of monopoly and oligopoly rights. They say that the Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain, because the English Bill of Rights 1689 created such restraints. Acemoglu and Robinson insist that "development differences across countries are exclusively due to differences in political and economic institutions, and reject other theories that attribute some of the differences to culture, weather, geography or lack of knowledge about the best policies and practices."[56] For example, "Soviet Russia generated rapid growth as it caught up rapidly with some of the advanced technologies in the world [but] was running out of steam by the 1970s" because of a lack of creative destruction.[57] The book was written for the general audience.[56] It was widely discussed by political analysts and commentators.[58][59][60][61] Warren Bass wrote of it in The Washington Post: "bracing, garrulous, wildly ambitious and ultimately hopeful. It may, in fact, be a bit of a masterpiece."[62] Clive Crook wrote in Bloomberg News that the book deserves most of the "lavish praise" it received.[63] In his review in Foreign Affairs Jeffrey Sachs criticized Acemoglu and Robinson for systematically ignoring factors such as domestic politics, geopolitics, technological discoveries, and natural resources. He also argued that the book's appeal was based on readers' desire to hear that "Western democracy pays off not only politically but also economically."[64] Bill Gates called the book a "major disappointment" and characterized the authors' analysis as "vague and simplistic."[65] Ryan Avent, an editor at The Economist, responded that "Acemoglu and Robinson might not be entirely right about why nations succeed or fail. But at least they're engaged with the right problem."[66] |

国民はなぜ失敗するのか 『国民はなぜ失敗するのか』は、2012年フィナンシャル・タイムズビジネス書大賞の最終候補に選ばれた。 アセモグルとロビンソンは2012年の著書『国民はなぜ失敗するのか』で、技術の最先端における経済成長には政治的安定が必要だと主張している。マヤ文明 (一例に過ぎない)にはそれが欠けていた[55]。また創造的破壊も必要だ。後者は、独占権や寡占権の付与に対する制度的制約なしには起こりえない。彼ら は、産業革命がイギリスで始まったのは、1689年の英国権利章典がそうした制約を生み出したからだと述べている。 アセモグルとロビンソンは「国家間の発展格差は、政治・経済制度の違いにのみ起因する」と主張し、格差の一部を文化・気候・地理・最良の政策・実践に関す る知識不足に帰する他の理論を退けている。[56] 例えば「ソビエトロシアは世界の先進技術に急速に追いついたことで急成長したが、創造的破壊の欠如により1970年代には勢いを失った」と指摘する。 [57] 本書は一般読者を対象に書かれたものである。[56] 政治アナリストや評論家によって広く議論された。[58][59][60][61] ウォーレン・バスはワシントン・ポスト紙でこう評した:「爽快で饒舌、途方もなく野心的であり、最終的には希望に満ちている。実際、これは傑作と呼べるか もしれない。」[62] クライヴ・クルックはブルームバーグ・ニュースで、本書が受けた「過剰な称賛」の大半は正当だと記した。[63] ジェフリー・サックスはフォーリン・アフェアーズ誌の書評で、アセモグルとロビンソンが国内政治、地政学、技術的発見、天然資源といった要素を体系的に無 視していると批判した。また、本書の魅力は「西洋の民主主義が政治的だけでなく経済的にも報われる」という読者の願望に基づいていると主張した。[64] ビル・ゲイツはこの本を「大きな失望」と呼び、著者の分析を「曖昧で単純化されすぎている」と評した。[65] 『エコノミスト』誌の編集者ライアン・エイヴェントは「アセモグルとロビンソンが国民の成功や失敗の理由について完全に正しいとは限らない。だが少なくと も彼らは正しい問題に取り組んでいる」と応じた。[66] |

| The Narrow Corridor In The Narrow Corridor. States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (2019), Acemoglu and Robinson argue that a free society is attained when the power of the state and of society evolved in rough balance.[67] The book introduces the concept of the "red queen effect," which suggests that liberty is maintained only when both the state and society continually evolve to keep each other in check. Power and Progress Published in 2023, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity is a book by Acemoglu and Simon Johnson on the historical development of technology and the social and political consequences of technology.[68] The book addresses three questions, on the relationship between new machines and production techniques and wages, on the way in which technology could be harnessed for social goods, and on the reason for the enthusiasm around artificial intelligence. Power and Progress argues that technologies do not automatically yield social goods, their benefits going to a narrow elite. It offers a rather critical view of artificial intelligence (AI), stressing its largely negative impact on jobs and wages and on democracy. Acemoglu and Johnson also provide a vision of how new technologies could be harnessed for social good. They see the Progressive Era as offering a model. They also discuss a list of policy proposals for the redirection of technology that includes: (1) market incentives, (2) the break up of big tech, (3) tax reform, (4) investing in workers, (5) privacy protection and data ownership, and (6) a digital advertising tax.[69] |

狭い回廊 『狭い回廊。国家、社会、そして自由の運命』(2019年)において、アセモグルとロビンソンは、国家と社会の力がほぼ均衡を保って進化した時に自由な社 会が達成されると論じている[67]。本書は「赤の女王効果」という概念を導入し、国家と社会が互いを牽制し続けるために絶えず進化する時のみ、自由が維 持されると示唆している。 権力と進歩 2023年に出版された『権力と進歩:技術と繁栄をめぐる千年の闘い』は、アセモグルとサイモン・ジョンソンによる技術の歴史的発展と、技術がもたらす社 会的・政治的帰結に関する著作である[68]。本書は三つの問いに取り組む。新たな機械と生産技術が賃金に与える影響、技術が社会公益のために活用される 方法、そして人工知能への熱狂の理由についてである。 『パワーと進歩』は、技術が自動的に社会的利益をもたらすわけではなく、その恩恵は限られたエリート層に集中すると論じる。人工知能(AI)に対してはかなり批判的な見解を示し、雇用や賃金、民主主義への悪影響を強調している。 アセモグルとジョンソンは、新技術を社会公益に活用する方法についてのビジョンも提示している。彼らは進歩主義時代をモデルとして提示する。さらに技術の 方向転換に向けた政策提案リストを議論しており、その内容は以下の通りである:(1)市場インセンティブ、(2)巨大テック企業の分割、(3)税制改革、 (4)労働者への投資、(5)プライバシー保護とデータ所有権、(6)デジタル広告税である。[69] |

| Papers Social programs and policies In a 2001 article, Acemoglu argued that the minimum wage and unemployment benefits "shift the composition of employment toward high-wage jobs. Because the composition of jobs in the laissez-faire equilibrium is inefficiently biased toward low-wage jobs, these labor market regulations increase average labor productivity and may improve welfare."[70] Furthermore, he has argued that "minimum wages can increase training of affected workers, by inducing firms to train their unskilled employees."[71] Democracy and economy Acemoglu et al. found that "democracy has a significant and robust positive effect on GDP" and suggested that "democratizations increase GDP per capita by about 20% in the long run."[72] In another paper, Acemoglu et al. found that "there is a significant and robust effect of democracy on tax revenues as a fraction of GDP, but no robust impact on inequality.".[73] The authors argue that democratic institutions contribute to economic growth by expanding education, improving public capacity, and encouraging investment. Social democracy and unions Acemoglu and Philippe Aghion argued in 2001 that although deunionization in the US and UK since the 1980s is not the "underlying cause of the increase in inequality", it "amplifies the direct effect of skill-biased technical change by removing the wage compression imposed by unions."[74] According to Acemoglu and Robinson, unions historically had a significant role in creating democracy, especially in western Europe, and in maintaining a balance of political power between established business interests and political elites.[75] Nordic model In a 2012 paper titled "Can't We All Be More Like Scandinavians?", co-written with Robinson and Verdier, he suggests that "it may be precisely the more 'cutthroat' American society that makes possible the more 'cuddly' Scandinavian societies based on a comprehensive social safety net, the welfare state and more limited inequality." They concluded that "all countries may want to be like the 'Scandinavians' with a more extensive safety net and a more egalitarian structure," however, if the United States shifted from being a "cutthroat [capitalism] leader", the economic growth of the entire world would be reduced.[76] He argued against the US adopting the Nordic model in a 2015 op-ed for The New York Times. He again argued: "If the US increased taxation to Denmark levels, it would reduce rewards for entrepreneurship, with negative consequences for growth and prosperity." He praised the Scandinavian experience in poverty reduction, creation of a level playing field for its citizens, and higher social mobility.[77] This was critiqued by Lane Kenworthy, who argues that, empirically, the US's economic growth preceded the divergence in 'cutthroat' and 'cuddly' policies, and there is no relationship between inequality and innovation for developed countries.[78] Colonialism "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development", co-written by Acemoglu, Robinson, and Simon Johnson in 2001, is by far his most cited work.[40] Graham Mallard described it as an "excellent example of his work: an influential paper that has led to much debate."[31] They argue that Europeans set up extractive institutions in colonies where they did not settle, unlike in places where they did settle and that these institutions have persisted. They estimated that "differences in institutions explain approximately three-quarters of the income per capita differences across former colonies."[79][80] Historical experience dominated by extractive institutions in these countries has created a vicious circle, which was exacerbated by the European colonization.[81] A critique of modernization theory Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, in their article "Income and Democracy" (2008) show that even though there is a strong cross-country correlation between income and democracy, once one controls for country fixed effects and removes the association between income per capita and various measures of democracy, there is "no causal effect of income on democracy."[82] In "Non-Modernization" (2022), they further argue that modernization theory cannot account for various paths of political development "because it posits a link between economics and politics that is not conditional on institutions and culture and that presumes a definite endpoint—for example, an 'end of history'."[83] Automation and Labor Markets Beginning in the late 2010s, Acemoglu expanded his research to focus on the economic effects of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets. In collaboration with Pascual Restrepo, he examined how industrial robots affected employment and wages in the United States. Their study “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from U.S. Labor Markets” (2020) found that regions with greater exposure to industrial robots experienced larger declines in employment and modest reductions in wages, suggesting that the economic benefits of automation were not evenly distributed.[84] Acemoglu and Restrepo extended this analysis in “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality” (2022), arguing that automation has contributed to rising wage inequality in the United States by replacing many middle-skill tasks while increasing demand for higher-skill labor.[85] This body of research has influenced broader discussions on the future of work, emphasizing that technological change does not automatically benefit workers and can lead to unequal outcomes if incentives favor labor-replacing technologies. Acemoglu has argued that policy and institutional frameworks play an important role in determining whether new technologies complement human labor or substitute for it. |

論文 社会プログラムと政策 2001年の論文でアセモグルは、最低賃金と失業手当が「雇用の構成を高賃金職へとシフトさせる」と主張した。自由放任均衡における職種の構成は低賃金職 に非効率的に偏っているため、こうした労働市場規制は平均労働生産性を高め、福祉を改善しうるという。[70] さらに彼は「最低賃金は、企業が未熟練従業員を訓練するよう促すことで、影響を受ける労働者の訓練を増加させ得る」とも論じている。[71] 民主主義と経済 アセモグルらは「民主主義はGDPに有意かつ頑健な正の効果をもたらす」と発見し、「民主化は長期的には一人当たりGDPを約20%増加させる」と示唆し た。[72] 別の論文でアセモグルらは「民主主義はGDPに占める税収比率に有意かつ頑健な影響を与えるが、不平等には頑健な影響を与えない」と結論付けた。[73] 著者らは、民主的制度が教育の拡大、公共能力の向上、投資の促進を通じて経済成長に寄与すると論じている。 社会民主主義と労働組合 アセモグルとフィリップ・アギオンは2001年、1980年代以降の米国と英国における脱組合化は「不平等拡大の根本原因ではない」としながらも、「組合が課していた賃金圧縮を解除することで、技能偏重の技術革新の直接的影響を増幅させる」と論じた[74]。 アセモグルとロビンソンによれば、労働組合は歴史的に、特に西ヨーロッパにおいて民主主義の創出に重要な役割を果たし、既存の企業利益と政治エリート間の政治力学の均衡を維持してきた。[75] 北欧モデル 2012年の論文「我々は皆、スカンジナビア人のように振る舞えないのか?」(ロビンソン、ヴェルディエとの共著)において、彼は「包括的な社会保障網、 福祉国家、より限定的な不平等に基づく『温かみのある』スカンジナビア社会を可能にしているのは、むしろ『熾烈な競争社会』であるアメリカ社会そのものか もしれない」と示唆している。彼らは「全ての国がより広範な安全網と平等主義的構造を持つ『スカンジナビア諸国』のような存在を望むかもしれない」と結論 づけた。しかし、米国が「熾烈な競争を特徴とする資本主義のリーダー」から転換すれば、世界全体の経済成長は減速すると述べた。[76] 彼は2015年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙への寄稿で、米国が北欧モデルを採用することに対して反対論を展開した。彼は再びこう主張した。「米国がデン マーク並みの課税水準に引き上げれば、起業家精神への報いが減少し、成長と繁栄に悪影響を及ぼすだろう」 彼は貧困削減、国民間の公平な競争環境の構築、高い社会流動性においてスカンジナビアの成果を称賛した[77]。これに対しレーン・ケンワージーは、実証 的に米国の経済成長は「過酷な」政策と「温和な」政策の分岐に先行しており、先進国において不平等とイノベーションの間に相関関係は存在しないと反論し た。[78] 植民地主義 「比較発展の植民地的起源」は、アセモグル、ロビンソン、サイモン・ジョンソンが2001年に共著したもので、彼の最も引用された著作である。[40] グラハム・マラードはこれを「彼の研究の優れた例:多くの議論を呼んだ影響力のある論文」と評した。[31] 彼らは、ヨーロッパ人が定住しなかった植民地では、定住地とは異なり搾取的な制度を構築し、それが持続してきたと主張する。彼らは「制度の差異が旧植民地 間の1人当たり所得格差の約4分の3を説明している」と推定した。[79][80] これらの国々における搾取的制度が支配的な歴史的経験は悪循環を生み、それはヨーロッパの植民地化によってさらに悪化した。[81] 近代化理論への批判 ダロン・アセモグルとジェームズ・A・ロビンソンは論文「所得と民主主義」(2008年)において、所得と民主主義の間に強い国際相関が存在するものの、 国固有の固定効果を制御し、一人当たり所得と様々な民主主義指標の関連性を除去すると、「所得が民主主義に因果的影響を与えない」ことを示した。[82] 彼らは『非近代化』(2022年)においてさらに、近代化理論が政治発展の多様な経路を説明できないと論じている。「なぜなら、同理論は制度や文化に依存 しない経済と政治の関連性を仮定し、例えば『歴史の終わり』のような明確な終着点を前提としているからだ」[83] 自動化と労働市場 2010年代後半から、アセモグルは研究対象を拡大し、自動化と人工知能が労働市場に及ぼす経済的影響に焦点を当てた。パスカル・レストレポとの共同研究 では、産業用ロボットが米国の雇用と賃金に与える影響を検証した。彼らの論文「ロボットと雇用:米国労働市場からの証拠」(2020年)は、産業用ロボッ トの影響を強く受けた地域ほど雇用減少幅が大きく、賃金も小幅ながら低下したことを明らかにし、自動化の経済的利益が均等に分配されていないことを示唆し た。[84] アセモグルとレストレポは『タスク、自動化、そして米国賃金格差の拡大』(2022年)でこの分析を深化させ、自動化が中技能タスクを代替しつつ高技能労 働の需要を増加させることで、米国の賃金格差拡大に寄与したと論じた。[85] この一連の研究は、仕事の未来に関する広範な議論に影響を与え、技術革新が自動的に労働者に利益をもたらすわけではなく、労働代替技術を優遇するインセン ティブが存在すれば不平等な結果を招きうると強調している。アセモグルは、新技術が人的労働を補完するか代替するかは、政策と制度的枠組みによって大きく 左右されると主張している。 |