自由

Liberty

★狼にとっての自由は、往々にして羊にとっての死を意味する——アイザイア・バーリン(「自由論」)

☆自由(Liberty)

とは、社会の中で、自分の生き方や行動、政治的見解に対して権力から課される抑圧的な制限から自由である状態のことである。自由の概念は、考え方や文脈に

よって異なることがある。米国の憲法では、秩序ある自由とは、個人が不必要な干渉を受けることなく行動する自由(消極的自由)と、目標を追求するための機

会や資源へのアクセス(積極的自由)を公平な法制度の中で持つ、バランスの取れた社会を作ることを意味する。

自由とは、専らではないにせよ、主として「自由」という言葉を、自分の意志のままに行動できること、また、自分にその力があることを意味し、「自由」とい

う言葉を、関係者全員の権利を考慮した上で、恣意的な拘束がないことを意味するものとして使うことによって、自由と区別されることがある。この意味におい

て、自由の行使は、能力に従い、他者の権利によって制限される。したがって自由とは、法の支配のもとで、他の誰からも自由を奪うことなく、責任をもって自

由を行使することを意味する。自由は刑罰として取り上げられることもある。多くの国では、犯罪行為で有罪判決を受けた場合、人々は自由を奪われることがあ

る。

自由はラテン語のliberに由来し、原語のイタリック語*louðeros、原語のインド・ヨーロッパ語*h₁léwdʰeros、*h₁lewdʰ-

(「人々」)に由来する。 [2] 「liberty 」という単語は、「Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of

Happiness」[3]や 「Liberté, égalité, fraternité」[4]などのスローガンや引用句でよく使われる。

| Liberty is the state

of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by

authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views.[1] The

concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In

the Constitutional law of the United States, Ordered liberty means

creating a balanced society where individuals have the freedom to act

without unnecessary interference (negative liberty) and access to

opportunities and resources to pursue their goals (positive liberty),

all within a fair legal system. Sometimes liberty is differentiated from freedom by using the word "freedom" primarily, if not exclusively, to mean the ability to do as one wills and what one has the power to do; and using the word "liberty" to mean the absence of arbitrary restraints, taking into account the rights of all involved. In this sense, the exercise of liberty is subject to capability and limited by the rights of others. Thus liberty entails the responsible use of freedom under the rule of law without depriving anyone else of their freedom. Liberty can be taken away as a form of punishment. In many countries, people can be deprived of their liberty if they are convicted of criminal acts. Liberty originates from the Latin word liber, from Proto-Italic *louðeros, from Proto-Indo-European *h₁léwdʰeros, from *h₁lewdʰ- ("people").[2] The word "liberty" is commonly used in slogans or quotes, such as in "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness"[3] and "Liberté, égalité, fraternité".[4] |

自由とは、社会の中で、自分の生き方や行動、政治的見解に対して権力か

ら課される抑圧的な制限から自由である状態のことである[1]。自由の概念は、考え方や文脈によって異なることがある。米国の憲法では、秩序ある自由と

は、個人が不必要な干渉を受けることなく行動する自由(消極的自由)と、目標を追求するための機会や資源へのアクセス(積極的自由)を公平な法制度の中で

持つ、バランスの取れた社会を作ることを意味する。 自由とは、専らではないにせよ、主として「自由」という言葉を、自分の意志のままに行動できること、また、自分にその力があることを意味し、「自由」とい う言葉を、関係者全員の権利を考慮した上で、恣意的な拘束がないことを意味するものとして使うことによって、自由と区別されることがある。この意味におい て、自由の行使は、能力に従い、他者の権利によって制限される。したがって自由とは、法の支配のもとで、他の誰からも自由を奪うことなく、責任をもって自 由を行使することを意味する。自由は刑罰として取り上げられることもある。多くの国では、犯罪行為で有罪判決を受けた場合、人々は自由を奪われることがあ る。 自由はラテン語のliberに由来し、原語のイタリック語*louðeros、原語のインド・ヨーロッパ語*h₁léwdʰeros、*h₁lewdʰ- (「人々」)に由来する。 [2] 「liberty 」という単語は、「Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness」[3]や 「Liberté, égalité, fraternité」[4]などのスローガンや引用句でよく使われる。 |

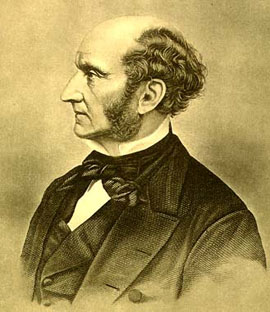

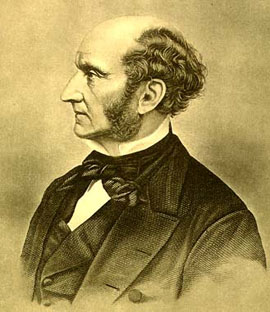

Philosophy John Stuart Mill Philosophers from the earliest times have considered the question of liberty. Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 AD) wrote: a polity in which there is the same law for all, a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed.[5] According to compatibilist Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): a free man is he that in those things which by his strength and wit he is able to do is not hindered to do what he hath the will to do. — Leviathan, Part 2, Ch. XXI. John Locke (1632–1704) rejected that definition of liberty. While not specifically mentioning Hobbes, he attacks Sir Robert Filmer who had the same definition. According to Locke: In the state of nature, liberty consists of being free from any superior power on Earth. People are not under the will or lawmaking authority of others but have only the law of nature for their rule. In political society, liberty consists of being under no other lawmaking power except that established by consent in the commonwealth. People are free from the dominion of any will or legal restraint apart from that enacted by their own constituted lawmaking power according to the trust put in it. Thus, freedom is not as Sir Robert Filmer defines it: 'A liberty for everyone to do what he likes, to live as he pleases, and not to be tied by any laws.' Freedom is constrained by laws in both the state of nature and political society. Freedom of nature is to be under no other restraint but the law of nature. Freedom of people under government is to be under no restraint apart from standing rules to live by that are common to everyone in the society and made by the lawmaking power established in it. Persons have a right or liberty to (1) follow their own will in all things that the law has not prohibited and (2) not be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, and arbitrary wills of others.[6] John Stuart Mill, in his 1859 work, On Liberty, was the first to recognize the difference between liberty as the freedom to act and liberty as the absence of coercion.[7] In his 1958 lecture "Two Concepts of Liberty", Isaiah Berlin formally framed the differences between two perspectives as the distinction between two opposite concepts of liberty: positive liberty and negative liberty. The latter designates a negative condition in which an individual is protected from tyranny and the arbitrary exercise of authority, while the former refers to the liberty that comes from self-mastery, the freedom from inner compulsions such as weakness and fear.[8] |

哲学 ジョン・スチュアート・ミル 古くから哲学者たちは自由の問題を考えてきた。ローマ皇帝マルクス・アウレリウス(西暦121-180年)はこう書いている: すべての人に同じ法が適用される政治、平等な権利と平等な言論の自由を尊重して運営される政治、そして被治者の自由を最も尊重する王権政治の思想である[5]。 相利共生論者のトマス・ホッブズ(1588-1679)によれば、次のようになる: 自由人とは、自分の力と知恵によってできることであって、自分の意志ですることを妨げられない人のことである。 - リヴァイアサン』第二部第二十一章。 ジョン・ロック(1632-1704)は自由の定義を否定した。ホッブズには特に触れていないが、同じ定義を持っていたロバート・フィルマー卿を攻撃している。ロックによれば 自然状態において、自由とは地上のいかなる優越的権力からも自由であることである。人々は他人の意思や法制定権の下にあるのではなく、自然の法則だけを支 配の拠り所としている。政治社会では、自由とは、連邦における同意によって確立された法制定権以外のいかなる法制定権の下にも置かれないことである。人々 は、自分たちの構成する法制定権力が、その信頼に従って制定した以外のいかなる意志や法的拘束の支配からも自由である。したがって、自由とは、ロバート・ フィルマー卿が定義するようなものではない: 誰もが好きなことをし、好きなように生き、いかなる法律にも縛られない自由」である。自然状態でも政治社会でも、自由は法律によって制約される。自然の自 由とは、自然の法則以外の拘束を受けないことである。政府のもとでの人々の自由とは、その社会に属するすべての人に共通し、その社会に設置された法制定権 によって作られた、生活するための常設の規則を別にすれば、いかなる拘束も受けないことである。人は、(1)法律が禁止していないすべての事柄において自 らの意志に従う権利または自由を有し、(2)他者の不変の、不確実な、未知の、恣意的な意志に従わない権利を有する[6]。 ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは1859年の著作『自由について』において、行動する自由としての自由と強制がないこととしての自由の違いを初めて認識した[7]。 アイザイア・バーリンは1958年の講義「自由の2つの概念」において、2つの観点の違いを、正反対の自由概念である「積極的自由」と「消極的自由」の区 別として正式に枠付けした。後者は、専制政治や権力の恣意的な行使から個人が保護されている否定的な状態を意味し、前者は、弱さや恐怖といった内面的な強 制からの解放、自己の支配から生じる自由を意味する[8]。 |

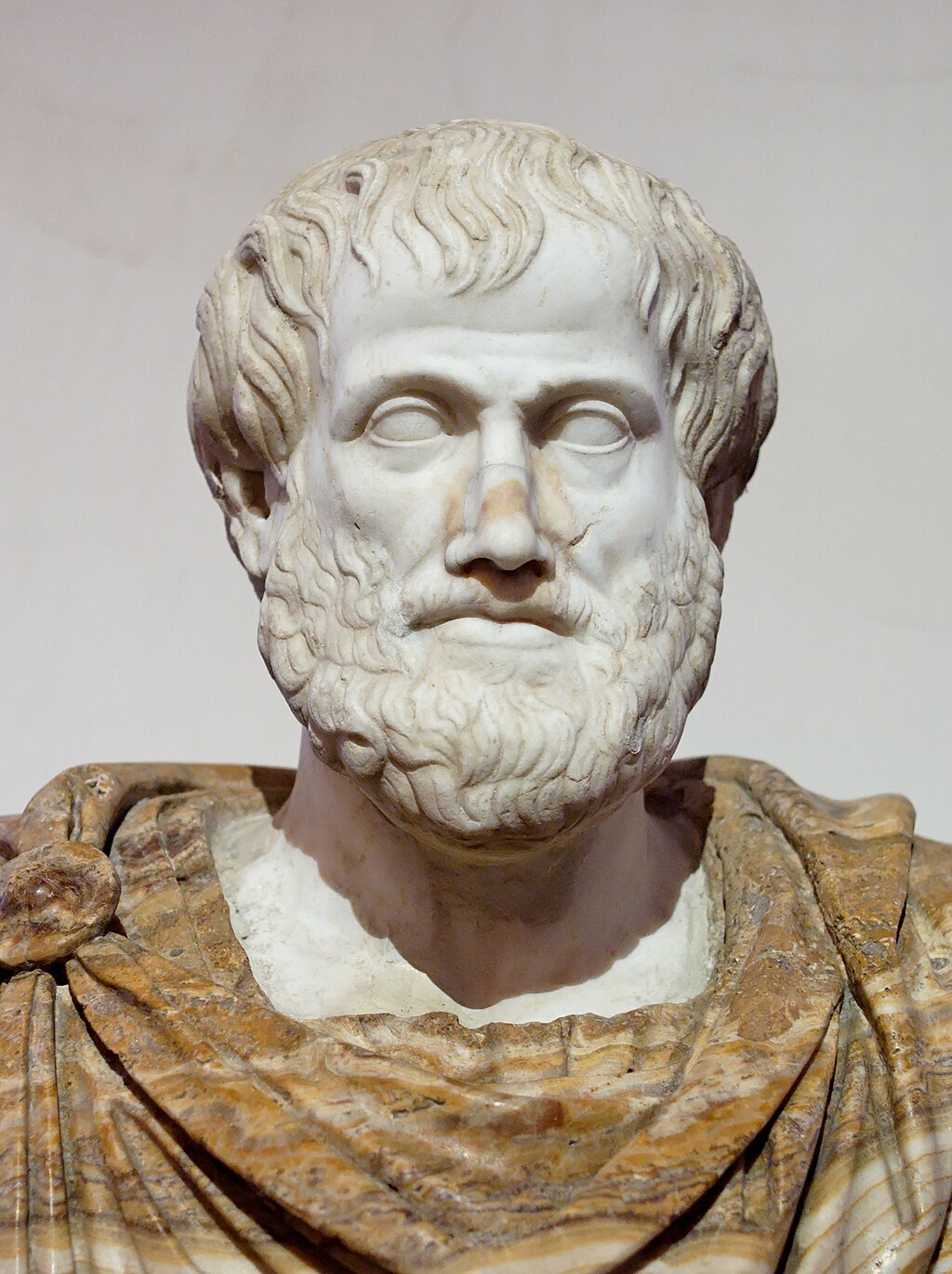

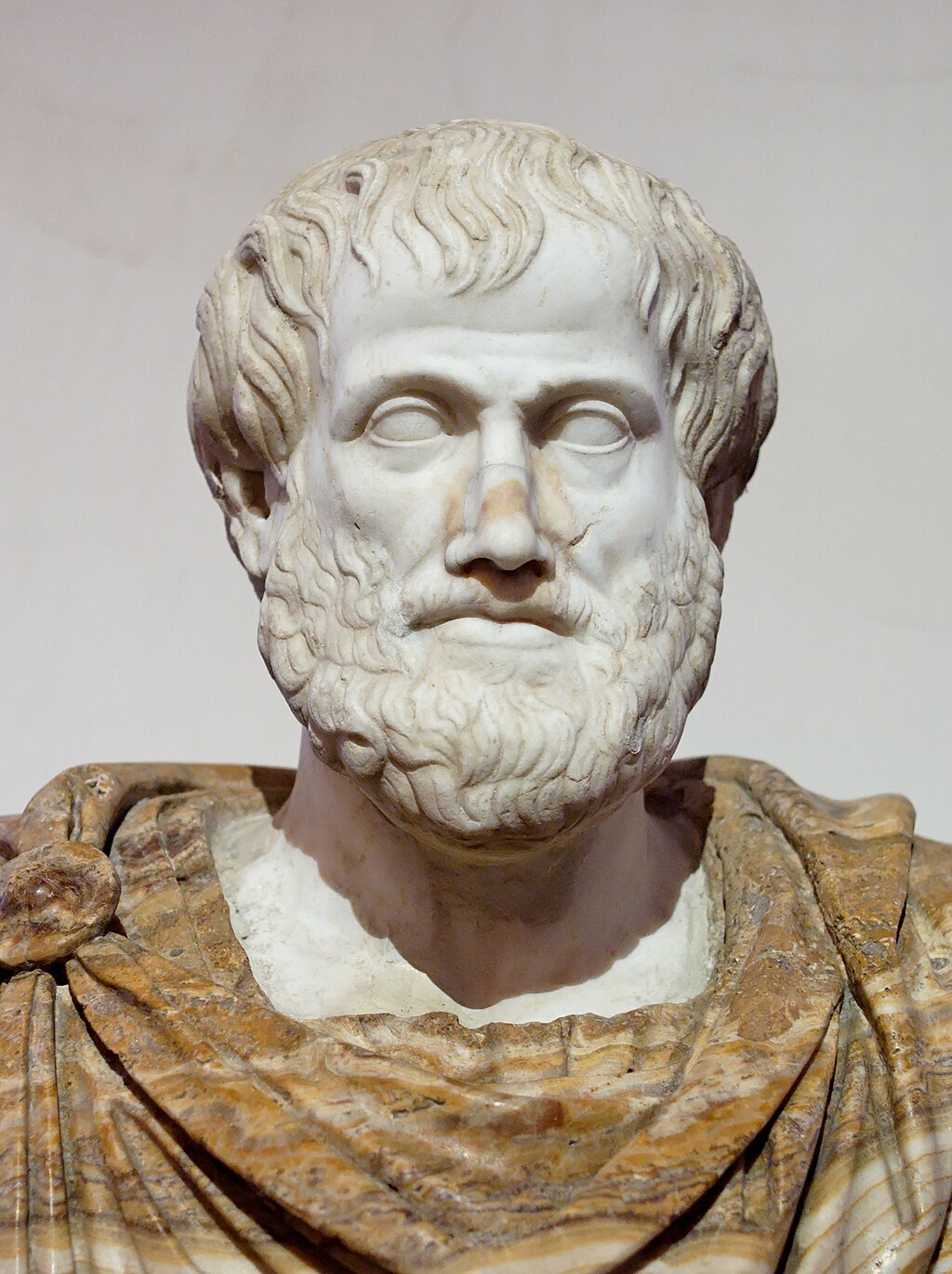

| Politics Main article: Political freedom History  Bust of Aristotle The modern day concept of political liberty has its origins in the Greek concepts of freedom and slavery.[9] To be free, to the Greeks, was not to have a master, to be independent from a master (to live as one likes).[10][11] That was the original Greek concept of freedom. It is closely linked with the concept of democracy, as Aristotle put it: "This, then, is one note of liberty which all democrats affirm to be the principle of their state. Another is that a man should live as he likes. This, they say, is the privilege of a freeman, since, on the other hand, not to live as a man likes is the mark of a slave. This is the second characteristic of democracy, whence has arisen the claim of men to be ruled by none, if possible, or, if this is impossible, to rule and be ruled in turns; and so it contributes to the freedom based upon equality."[12] This applied only to free men. In Athens, for instance, women could not vote or hold office and were legally and socially dependent on a male relative.[13] The populations of the Persian Empire enjoyed some degree of freedom. Citizens of all religions and ethnic groups were given the same rights and had the same freedom of religion, women had the same rights as men, and slavery was abolished (550 BC). All the palaces of the kings of Persia were built by paid workers in an era when slaves typically did such work.[14] In the Maurya Empire of ancient India, citizens of all religions and ethnic groups had some rights to freedom, tolerance, and equality. The need for tolerance on an egalitarian basis can be found in the Edicts of Ashoka the Great, which emphasize the importance of tolerance in public policy by the government. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war also appears to have been condemned by Ashoka.[15] Slavery also appears to have been non-existent in the Maurya Empire.[16] However, according to Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, "Ashoka's orders seem to have been resisted right from the beginning."[17] Roman law also embraced certain limited forms of liberty, even under the rule of the Roman Emperors. However, these liberties were accorded only to Roman citizens. Many of the liberties enjoyed under Roman law endured through the Middle Ages, but were enjoyed solely by the nobility, rarely by the common man.[citation needed] The idea of inalienable and universal liberties had to wait until the Age of Enlightenment. Social contract  In French Liberty. British Slavery (1792), James Gillray caricatured French "liberty" as the opportunity to starve and British "slavery" as bloated complaints about taxation. The social contract theory, most influentially formulated by Hobbes, John Locke and Rousseau (though first suggested by Plato in The Republic), was among the first to provide a political classification of rights, in particular through the notion of sovereignty and of natural rights. The thinkers of the Enlightenment reasoned that law governed both heavenly and human affairs, and that law gave the king his power, rather than the king's power giving force to law. This conception of law would find its culmination in the ideas of Montesquieu. The conception of law as a relationship between individuals, rather than families, came to the fore, and with it the increasing focus on individual liberty as a fundamental reality, given by "Nature and Nature's God," which, in the ideal state, would be as universal as possible. In On Liberty, John Stuart Mill sought to define the "...nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual," and as such, he describes an inherent and continuous antagonism between liberty and authority and thus, the prevailing question becomes "how to make the fitting adjustment between individual independence and social control".[18] |

政治 主な記事 政治的自由 歴史  アリストテレスの胸像 現代の政治的自由の概念は、ギリシアの自由と奴隷の概念に起源を持つ[9]。ギリシア人にとって自由とは、主人を持たず、主人から独立すること(好きなよ うに生きること)であった[10][11]。アリストテレスが言ったように、それは民主主義の概念と密接に結びついている: 「これは、すべての民主主義者がその国家の原理であると断言する自由の一つの注意点である。もうひとつは、人は好きなように生きるべきだということであ る。これは自由人の特権であり、他方、好きなように生きないことは奴隷の証であるという。これが民主主義の第二の特徴であり、可能であれば誰にも支配され ず、それが不可能であれば、支配と被支配を交互に行うという人間の主張が生まれてきたのである。 これは自由な男性にのみ適用された。たとえばアテネでは、女性は選挙権も役職に就くこともできず、法的にも社会的にも親族の男性に依存していた[13]。 ペルシャ帝国の人々はある程度の自由を享受していた。あらゆる宗教と民族の市民が同じ権利を与えられ、同じ信仰の自由を持ち、女性は男性と同じ権利を持 ち、奴隷制度は廃止された(紀元前550年)。ペルシアの王の宮殿は、通常奴隷がそのような仕事をしていた時代に、すべて有給労働者によって建てられた [14]。 古代インドのマウリヤ帝国では、あらゆる宗教と民族の市民が自由、寛容、平等の権利を有していた。平等主義に基づく寛容の必要性は、政府による公共政策に おける寛容の重要性を強調したアショーカ大王の勅令に見出すことができる。捕虜の虐殺や捕獲もアショーカによって非難されたようである[15]。奴隷制度 もマウリヤ帝国には存在しなかったようである[16]。しかし、ヘルマン・クルケとディートマー・ロータームントによれば、「アショーカの命令は最初から 抵抗されていたようである」[17]。 ローマ法もまた、ローマ皇帝の支配下においてさえ、一定の限定された形の自由を受け入れていた。しかし、これらの自由はローマ市民にのみ与えられていた。 ローマ法の下で享受された自由の多くは中世まで存続したが、貴族のみが享受し、庶民が享受することはほとんどなかった[要出典]。譲ることのできない普遍 的な自由という考え方は、啓蒙の時代まで待たなければならなかった。 社会契約  フランスの自由 イギリスの奴隷制』(1792年)の中で、ジェームズ・ギルレイはフランスの「自由」を飢餓の機会として、イギリスの「奴隷制」を課税に対する肥大した不満として風刺した。 社会契約説は、ホッブズ、ジョン・ロック、ルソーによって最も影響力を持って定式化され(プラトンが『共和国』で最初に提案したが)、特に主権と自然権の 概念を通じて、権利の政治的分類を提供した最初のもののひとつである。啓蒙思想家たちは、法は天と人の両面を支配し、王の権力が法に力を与えるのではな く、法が王に権力を与えると考えた。このような法の概念は、モンテスキューの思想にその頂点がある。家族ではなく個人間の関係としての法という概念が前面 に押し出されるようになり、それとともに、「自然と自然の神」によって与えられる基本的な現実としての個人の自由が重視されるようになり、それは理想国家 においては可能な限り普遍的なものとなった。 ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは『自由について』の中で、「社会が個人に対して合法的に行使することのできる権力の性質と限界」を定義しようとし、自由と権 威の間には本質的かつ継続的な拮抗関係があり、そのため「個人の自立と社会的統制の間の適切な調整をいかに行うか」が有力な問題となると述べている [18]。 |

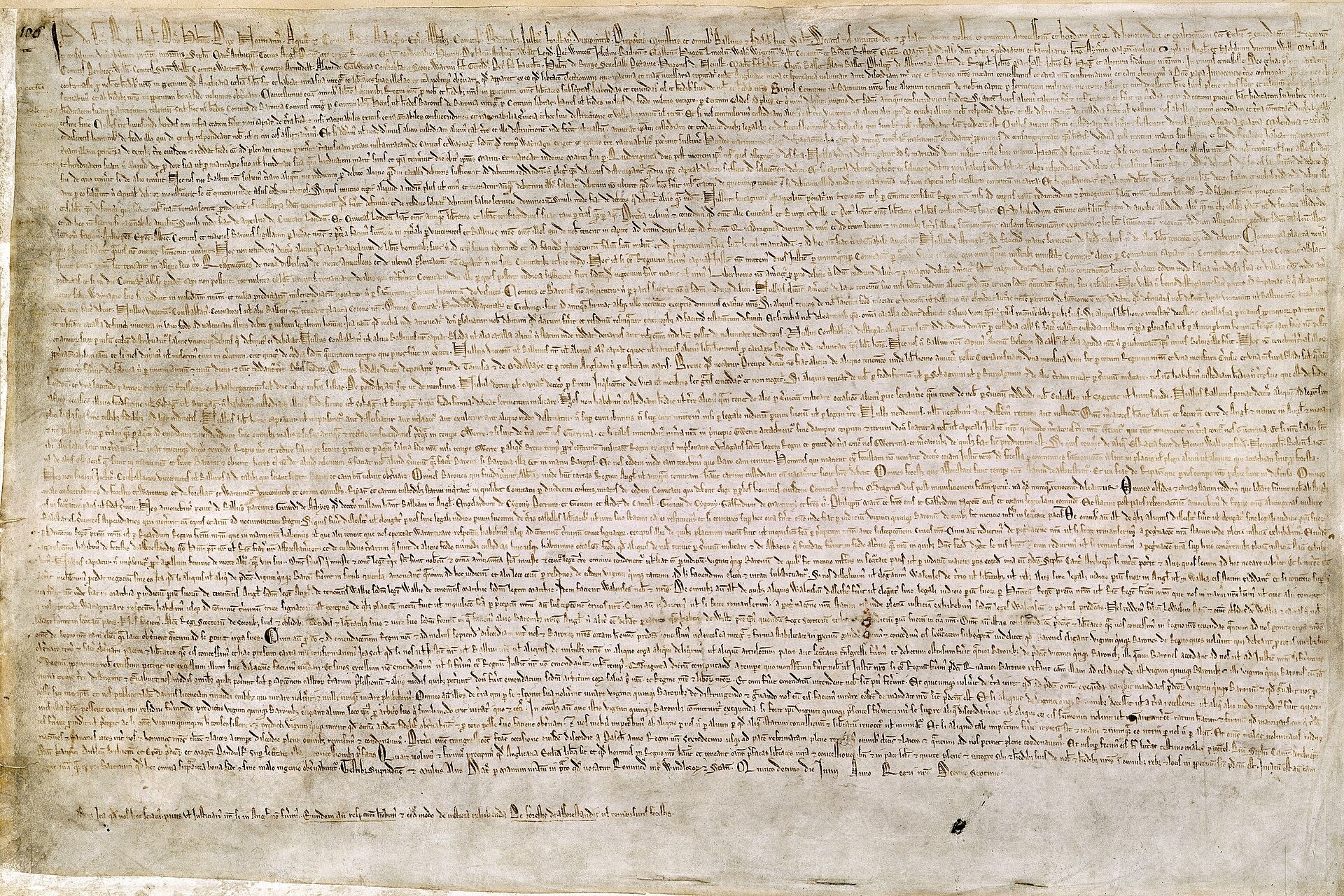

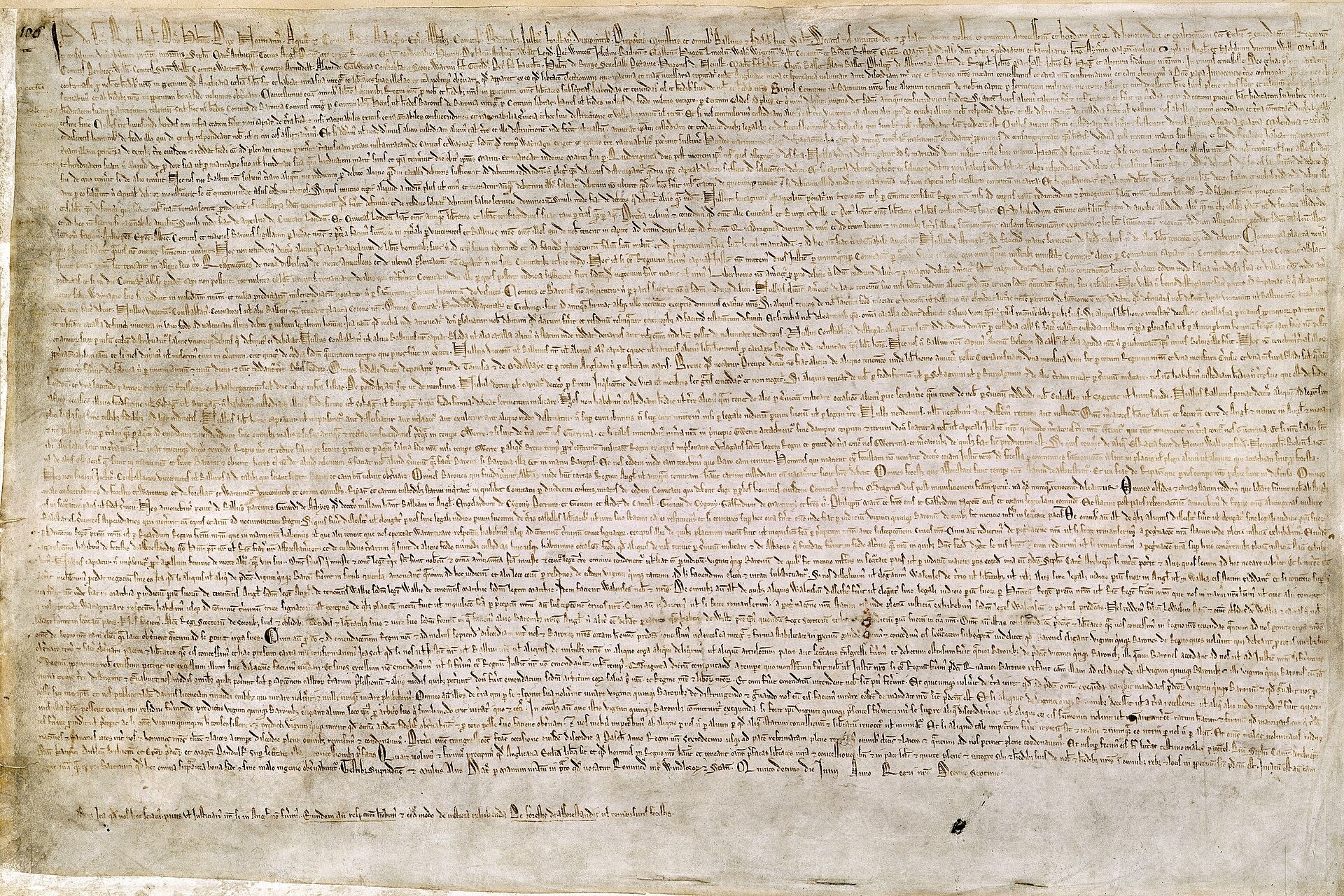

| Origins of political freedom England and Great Britain This section is in list format but may read better as prose. You can help by converting this section, if appropriate. Editing help is available. (October 2022)  Magna Carta (originally known as the Charter of Liberties) of 1215, written in iron gall ink on parchment in medieval Latin, using standard abbreviations of the period. This document is held at the British Library and is identified as "British Library Cotton MS Augustus II.106". Timeline: 1066 – as a condition of his coronation William the Conqueror assented to the London Charter of Liberties which guaranteed the "Saxon" liberties of the City of London. 1100 – the Charter of Liberties is passed which sets out certain liberties of nobles, church officials and individuals. 1166 – Henry II of England transformed English law by passing the Assize of Clarendon. The act, a forerunner to trial by jury, started the abolition of trial by combat and trial by ordeal.[19] 1187-1189 – publication of Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglie which contains authoritative definitions of freedom and servitude. 1215 – Magna Carta was enacted, becoming the cornerstone of liberty in first England, then Great Britain, and later the world.[20][21] 1628 – the English Parliament passed the Petition of Right which set out specific liberties of English citizens. 1679 – the English Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act which outlawed unlawful or arbitrary imprisonment. 1689 – the Bill of Rights granted "freedom of speech in Parliament", and reinforced many existing civil rights in England. The Scots law equivalent the Claim of Right is also passed.[22] 1772 – the Somerset v Stewart judgement found that slavery was unsupported by common law in England and Wales. 1859 – an essay by the philosopher John Stuart Mill, entitled On Liberty, argued for toleration and individuality. "If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility."[23][24] 1948 – British representatives attempted to but were prevented from adding a legal framework to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (It was not until 1976 that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights came into force, giving a legal status to most of the Declaration.)[25] 1958 – Two Concepts of Liberty, by Isaiah Berlin, identified "negative liberty" as an obstacle, as distinct from "positive liberty" which promotes self-mastery and the concepts of freedom.[26] United States  The Liberty Bell is a popular icon of liberty in the US. According to the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, all people have a natural right to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness". This declaration of liberty was troubled for 90 years by the continued institutionalization of legalized Black slavery, as slave owners argued that their liberty was paramount since it involved property, their slaves, and that Blacks had no rights that any White man was obliged to recognize. The Supreme Court, in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, upheld this principle. In 1866, after the American Civil War, the US Constitution was amended to extend rights to persons of color, and in 1920 voting rights were extended to women.[27] By the later half of the 20th century, liberty was expanded further to prohibit government interference with personal choices. In the 1965 United States Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut, Justice William O. Douglas argued that liberties relating to personal relationships, such as marriage, have a unique primacy of place in the hierarchy of freedoms.[28] Jacob M. Appel has summarized this principle: I am grateful that I have rights in the proverbial public square – but, as a practical matter, my most cherished rights are those that I possess in my bedroom and hospital room and death chamber. Most people are far more concerned that they can control their own bodies than they are about petitioning Congress.[29] In modern America, various competing ideologies have divergent views about how best to promote liberty. Liberals in the original sense of the word see equality as a necessary component of freedom. Progressives stress freedom from business monopoly as essential. Libertarians disagree, and see economic and individual freedom as best. The Tea Party movement sees "big government" as an enemy of freedom.[30][31] Other major participants in the modern American libertarian movement include the Libertarian Party,[32] the Free State Project,[33][34] and the Mises Institute.[35] France  Eugène Delacroix – Liberty Leading the People (La Liberté guidant le peuple) (1830) France supported the Americans in their revolt against English rule and, in 1789, overthrew their own monarchy, with the cry of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité". The bloodbath that followed, known as the reign of terror, soured many people on the idea of liberty. Edmund Burke, considered one of the fathers of conservatism, wrote "The French had shewn themselves the ablest architects of ruin that had hitherto existed in the world."[36] |

政治的自由の起源 イングランドとグレートブリテン このセクションはリスト形式であるが、散文として読んだ方がよいかもしれない。適切であれば、このセクションを変換することで手助けすることができる。編集のヘルプもある。(2022年10月)  1215年のマグナ・カルタ(当初は自由憲章として知られていた)は、中世ラテン語で羊皮紙に鉄胆インクで書かれ、当時の標準的な略語が使われている。こ の文書は大英図書館に所蔵されており、「British Library Cotton MS Augustus II.106 」と特定されている。 年表 1066年 - 征服王ウィリアムが戴冠の条件として、ロンドン市の「サクソン人」の自由を保証するロンドン自由憲章に同意する。 1100年 - 自由憲章が成立し、貴族、教会関係者、個人の自由が規定される。 1166年 - イングランド王ヘンリー2世がクラレンドン裁判を可決し、イギリス法に変革をもたらす。この法律は陪審裁判の先駆けであり、戦闘による裁判と試練による裁判の廃止が始まった[19]。 1187-1189 - Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglieが出版され、自由と隷属に関する権威ある定義が記載される。 1215年 - マグナ・カルタが制定され、イングランド、グレートブリテン、そして世界における自由の礎となる[20][21]。 1628年 - イギリス議会がイギリス市民の具体的な自由を定めた「権利の請願」を可決。 1679年 - イングランド議会が人身保護法を可決し、不法または恣意的な投獄を違法とした。 1689年 - 権利章典が「議会における言論の自由」を認め、イングランドにおける既存の市民権の多くを強化した。権利の主張に相当するスコットランド法も成立する[22]。 1772年 - サマセット対スチュワートの判決で、イングランドとウェールズのコモンローでは奴隷制は支持されないとされる。 1859年 - 哲学者ジョン・スチュアート・ミルが「自由について」と題したエッセイで寛容と個性を主張。「どのような意見であれ、沈黙を強いられるとすれば、その意見 が真実であるかもしれない。これを否定することは、われわれ自身の無謬性を前提とすることである」[23][24]。 1948年 - イギリスの代表が世界人権宣言に法的枠組みを加えようとしたが阻止される。(市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約が発効したのは1976年であり、宣言の大部分に法的地位が与えられた)[25]。 1958年 - アイザイア・バーリンによる『自由の2つの概念』では、「消極的自由」が障害であるとされ、自己修練と自由の概念を促進する「積極的自由」とは区別された[26]。 アメリカ合衆国  自由の鐘は、アメリカでは自由の象徴として人気がある。 1776年のアメリカ合衆国独立宣言によれば、すべての人は「生命、自由および幸福の追求」に対する自然権を有する。この自由宣言は、合法化された黒人奴 隷制度の継続的な制度化によって90年間悩まされ続けた。奴隷所有者たちは、自分たちの自由は奴隷という財産に関わるものであるため最優先されるべきであ り、黒人にはいかなる白人も認める義務のある権利はないと主張したからである。最高裁は1857年のドレッド・スコット判決で、この原則を支持した。南北 戦争後の1866年には、有色人種にも権利を拡大するために合衆国憲法が改正され、1920年には選挙権が女性にも拡大された[27]。 20世紀後半には、個人の選択に対する政府の干渉を禁止するために、自由はさらに拡大された。1965年の合衆国最高裁判決「グリスウォルド対コネチカッ ト州戦」において、ウィリアム・O・ダグラス判事は、結婚のような個人的関係に関する自由は、自由の階層において独自の優先的地位を有すると主張した [28]。 ジェイコブ・M・アペルはこの原則を要約している: しかし実際問題として、私が最も大切にしている権利は、寝室や病室や死の部屋で所有している権利である。ほとんどの人は、議会に請願することよりも、自分自身の身体をコントロールできることのほうをはるかに重視している[29]。 現代のアメリカでは、自由を促進する最善の方法について、様々な競合するイデオロギーが異なる見解を持っている。本来の意味でのリベラル派は、平等を自由 の必要な要素だと考えている。進歩主義者は、企業の独占からの自由が不可欠であると強調する。リバタリアンはこれに反対で、経済的自由と個人の自由を最良 と考える。ティーパーティー運動は「大きな政府」を自由の敵とみなしている[30][31]。現代アメリカのリバタリアン運動におけるその他の主な参加者 には、リバタリアン党、[32]フリー・ステート・プロジェクト、[33][34]、ミーゼス研究所などがある[35]。 フランス  ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ - 人民を導く自由(La Liberté guidant le peuple) (1830) フランスは、イギリスの支配に対するアメリカ人の反乱を支援し、1789年には「自由、平等、友愛」を叫びながら、自国の王政を打倒した。その後、恐怖政 治と呼ばれる大虐殺が続き、多くの人々が自由という考えに嫌気がさした。保守主義の父の一人とされるエドモンド・バークは、「フランス人は、これまで世界 に存在した中で最も優れた破滅の設計者であることを自ら証明してみせた」と書いている[36]。 |

| Ideologies Liberalism Main article: Liberalism According to the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, liberalism is "the belief that it is the aim of politics to preserve individual rights and to maximize freedom of choice". But they point out that there is considerable discussion about how to achieve those goals. Every discussion of freedom depends on three key components: who is free, what they are free to do, and what forces restrict their freedom.[37] John Gray argues that the core belief of liberalism is toleration. Liberals allow others freedom to do what they want, in exchange for having the same freedom in return. This idea of freedom is personal rather than political.[38] William Safire points out that liberalism is attacked by both the Right and the Left: by the Right for defending such practices as abortion, homosexuality, and atheism, and by the Left for defending free enterprise and the rights of the individual over the collective.[39] Libertarianism Main articles: Libertarianism, Minarchism, Austrian School, and Anarcho-capitalism According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, libertarians hold liberty as their primary political value.[40] Their approach to implementing liberty involves opposing any governmental coercion, aside from that which is necessary to prevent individuals from coercing each other.[41] Libertarianism is guided by the principle commonly known as the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP). The Non-Aggression Principle asserts that aggression against an individual or an individual's property is always an immoral violation of one's life, liberty, and property rights.[42][43] Utilizing deceit instead of consent to achieve ends is also a violation of the Non-Aggression principle. Therefore, under the framework of the Non-Aggression principle, rape, murder, deception, involuntary taxation, government regulation, and other behaviors that initiate aggression against otherwise peaceful individuals are considered violations of this principle.[44] This principle is most commonly adhered to by libertarians. A common elevator pitch for this principle is, "Good ideas don't require force."[45] Republican liberty According to republican theorists of freedom, like the historian Quentin Skinner[46][47] or the philosopher Philip Pettit,[48] one's liberty should not be viewed as the absence of interference in one's actions, but as non-domination. According to this view, which originates in the Roman Digest, to be a liber homo, a free man, means not being subject to another's arbitrary will, that is to say, dominated by another. They also cite Machiavelli who asserted that you must be a member of a free self-governing civil association, a republic, if you are to enjoy individual liberty.[49] The predominance of this view of liberty among parliamentarians during the English Civil War resulted in the creation of the liberal concept of freedom as non-interference in Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan.[citation needed] Socialism Main article: Socialism Socialists view freedom as a concrete situation as opposed to a purely abstract ideal. Freedom is a state of being where individuals have agency to pursue their creative interests unhindered by coercive social relationships, specifically those they are forced to engage in as a requisite for survival under a given social system. Freedom thus requires both the material economic conditions that make freedom possible alongside social relationships and institutions conducive to freedom.[50] The socialist conception of freedom is closely related to the socialist view of creativity and individuality. Influenced by Karl Marx's concept of alienated labor, socialists understand freedom to be the ability for an individual to engage in creative work in the absence of alienation, where "alienated labor" refers to work people are forced to perform and un-alienated work refers to individuals pursuing their own creative interests.[51] Marxism Main article: Marxism For Karl Marx, meaningful freedom is only attainable in a communist society characterized by superabundance and free access. Such a social arrangement would eliminate the need for alienated labor and enable individuals to pursue their own creative interests, leaving them to develop and maximize their full potentialities. This goes alongside Marx's emphasis on the ability of socialism and communism progressively reducing the average length of the workday to expand the "realm of freedom", or discretionary free time, for each person.[52][53] Marx's notion of communist society and human freedom is thus radically individualistic.[54] Anarchism Main article: Anarchism While many anarchists see freedom slightly differently, all oppose authority, including the authority of the state, of capitalism, and of nationalism.[55] For the Russian revolutionary anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, liberty did not mean an abstract ideal but a concrete reality based on the equal liberty of others. In a positive sense, liberty consists of "the fullest development of all the faculties and powers of every human being, by education, by scientific training, and by material prosperity." Such a conception of liberty is "eminently social, because it can only be realized in society," not in isolation. In a negative sense, liberty is "the revolt of the individual against all divine, collective, and individual authority."[56] |

イデオロギー 自由主義 主な記事 自由主義 コンサイス・オックスフォード政治辞典』によれば、自由主義とは「個人の権利を守り、選択の自由を最大化することが政治の目的であるという信念」である。 しかし、その目標を達成する方法についてはかなりの議論があると指摘している。自由に関するあらゆる議論は、誰が自由なのか、何をする自由があるのか、ど のような力が自由を制限するのか、という3つの重要な要素に依存している。リベラル派は、同じ自由を得ることと引き換えに、他者が自分のしたいことをする 自由を認める。ウィリアム・サファイアは、リベラリズムは右派と左派の両方から攻撃されていると指摘する。右派は中絶、同性愛、無神論などの慣習を擁護 し、左派は自由企業や集団に対する個人の権利を擁護している[39]。 リバタリアニズム 主な記事 リバタリアニズム、マイナキズム、オーストリア学派、アナルコ資本主義 ブリタニカ百科事典によれば、リバタリアンは自由を主要な政治的価値としている[40]。 自由を実現するための彼らのアプローチには、個人が互いに強制し合うことを防ぐために必要なことを除けば、政府による強制に反対することが含まれる[41]。 リバタリアニズムは、一般的に非侵略原則(NAP)として知られる原則に導かれている。非侵略原則は、個人や個人の財産に対する攻撃は常に生命、自由、財 産権の不道徳な侵害であると主張する[42][43]。目的を達成するために同意の代わりに欺瞞を利用することも非侵略原則の違反である。したがって、非 侵害原則の枠組みの下では、レイプ、殺人、欺瞞、非自発的な課税、政府による規制、その他平和的な個人に対する侵略を開始する行動は、この原則の違反とみ なされる[44]。この原則は、リバタリアンによって最も一般的に遵守されている。この原則の一般的なエレベーターピッチは、「良いアイデアには武力は必 要ない」である[45]。 共和主義者の自由 歴史家クエンティン・スキナー[46][47]や哲学者フィリップ・ペティット[48]のような自由の共和主義理論家によれば、人の自由は、人の行動に対 する干渉がないこととしてではなく、非支配として捉えられるべきである。ローマ時代のダイジェストに端を発するこの見解によれば、リベル・ホモ、すなわち 自由人であるということは、他者の恣意的な意思に従わないこと、つまり他者に支配されないことを意味する。彼らはまた、個人の自由を享受するためには、自 由な自治の市民団体である共和国の一員でなければならないと主張したマキアヴェッリも引用している[49]。 イギリス内戦中に議会主義者の間でこのような自由観が優勢となった結果、トマス・ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』において不干渉としての自由という自由主義的概念が生み出された[要出典]。 社会主義 主な記事 社会主義 社会主義者は、純粋に抽象的な理想とは対照的に、自由を具体的な状況として捉えている。自由とは、個人が強制的な社会的関係、特に与えられた社会体制の下 で生存するための必要条件として強制される関係に妨げられることなく、創造的な利益を追求する主体性を持つ状態である。したがって自由は、自由を可能にす る物質的な経済的条件と、自由を助長する社会的関係や制度の両方を必要とする[50]。 自由についての社会主義的概念は、創造性と個性についての社会主義的見解と密接に関連している。カール・マルクスの疎外された労働の概念に影響を受け、社 会主義者は自由とは個人が疎外のない状態で創造的な仕事に従事する能力であると理解しており、「疎外された労働」とは人々が強制される仕事を指し、「疎外 されていない仕事」とは個人が自身の創造的な利益を追求することを指す[51]。 マルクス主義 主な記事 マルクス主義 カール・マルクスにとって、意味のある自由は、超豊富と自由なアクセスを特徴とする共産主義社会においてのみ達成可能である。そのような社会的配置は、疎 外された労働の必要性を排除し、個人が自らの創造的な利益を追求することを可能にし、彼らの潜在的な可能性を発展させ、最大限に発揮させることを可能にす る。これはマルクスが社会主義や共産主義が労働時間の平均的な長さを漸進的に短縮することによって、各人の「自由の領域」、すなわち自由裁量時間を拡大す る能力を強調したことと並んでいる[52][53]。マルクスの共産主義社会と人間の自由に関する概念は、このように根本的に個人主義的である[54]。 アナキズム 主な記事 アナキズム 多くのアナーキストは自由を若干異なったものとして見ているが、国家、資本主義、国民主義の権威を含む権威にはすべて反対している。積極的な意味におい て、自由とは「教育、科学的訓練、物質的繁栄によって、すべての人間のすべての能力と力を最大限に発達させること」である。このような自由の概念は「極め て社会的なものであり、それは社会の中でしか実現できないからである。否定的な意味で、自由とは「あらゆる神的、集団的、個人的権威に対する個人の反乱」 である[56]。 |

| Historical writings on liberty John Locke (1689). Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, the False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. the Latter Is an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government. London: Awnsham Churchill. Frédéric Bastiat (1850). The Law. Paris: Guillaumin & Co. John Stuart Mill (1859). On Liberty. London: John W Parker and Son. James Fitzjames Stephen (1874). Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. London: Smith, Elder, & Co. |

自由に関する歴史的著作 ジョン・ロック(1689年) 二つの政府論: 前者では、ロバート・フィルマー卿とその追随者たちの誤った原理と基盤が見破られ、打倒される。後者では、市民政府の真の起源、範囲、および目的に関する試論である。ロンドン: アウンシャム・チャーチル フレデリック・バスティア (1850). The Law. パリ: Guillaumin & Co. ジョン・スチュアート・ミル (1859). 自由について. ロンドン: John W Parker and Son. James Fitzjames Stephen (1874). 自由、平等、友愛。London: Smith, Elder, & Co. |

| Autonomy Civil liberties Cognitive liberty Free will Gratis versus Libre Harm principle Independence Intentional living Liberté, égalité, fraternité Liberty (personification) List of freedom indices Political freedom Real freedom Refusal of work Rule according to higher law |

自治 市民の自由 認知の自由 自由意志/自由意思 無償と自由 害悪主義 自立 意図的な生活 自由、平等、友愛 自由(擬人化) 自由指標の一覧 政治的自由 実質的自由 労働の拒否 高次の法に基づく支配 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty |

|

★スティグリッツ資本主義と自由 / ジョセフ・E.スティグリッツ

| 第1章 序──自由の危機 第2章 経済学者は自由をどう考えているのか? 第1部 解放と自由──基本原則 第3章 ある人の自由はほかの人の不自由 第4章 強制により自由に──公共財とフリーライダー問題 第5章 一般の契約と社会契約と自由 第6章 自由と競争経済と社会正義 第7章 搾取する自由 第2部 自由と信念と選好、および公正な社会の創設 第8章 社会的強制と社会的結束 第9章 計画的に形づくられる個人や信念 第10章 寛容と社会的連帯と自由 第3部 公正で自由な優れた社会を推進するのはどのような経済なのか? 第11章 新自由主義的資本主義はなぜ失敗したのか? 第12章 自由と主権と国家間の強制 第13章 進歩的資本主義と社会民主主義と学習する社会 第14章 民主主義と自由と社会正義と公正な社会 |

|

| https://str.toyokeizai.net/books/9784492315644/ |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099