Remedios Varo, 1908-1963

Remedios Varo, 1908-1963

マリア・デ・ロス・レメディ オス・アリシア・ロドリガ・ヴァロ・イ・ウランガ(María de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga、通称レメディオス・ヴァ ロ(バロとも)、1908年12月16日 - 1963年10月8日)は、スペイン[1][2][3]のシュルレアリスムの画家で、スペイン、フランス、メキシコで活動した。(レメディオス・バロとも 表記可能)。レオノーラ・キャリントン(Leonora Carrington, 1917-2011)とは友人で同じシュールレアリスの盟友であった。

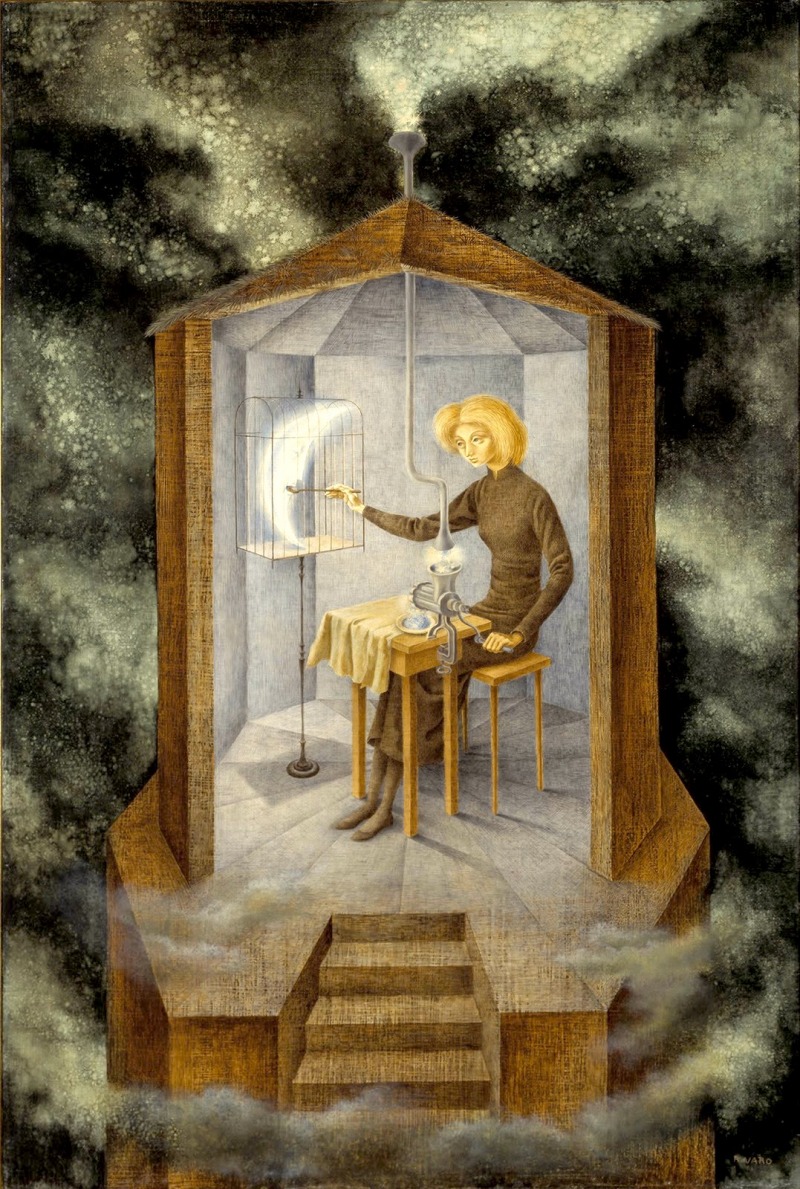

Remedios Varo

(En.); Remedios

Varo (Sp.), Creación de las aves - Creation of the Birds, 1957./

1955 La revelación o El relojero

| María de los

Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga

(known as Remedios Varo, 16 December 1908 – 8 October 1963) was a

Spanish [1][2][3] surrealist painter working in Spain, France, and

Mexico. Varo had a difficult life, struggling against poverty and fleeing from war in Spain and then France. In the last thirteen years of her life she found financial stability in Mexico, painting productively until her sudden death in 1963.[4] +++++++++++++ María de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y Uranga (Anglés, Gerona, España, 16 de diciembre de 1908-Ciudad de México, 8 de octubre de 1963), conocida como Remedios Varo, fue una pintora surrealista, escritora y artista gráfica española.2 La obra de Varo evoca un mundo surgido de su imaginación donde se mezcla lo científico, lo místico, lo esotérico y lo mágico. Fue una de las primeras mujeres que estudió en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando de Madrid. En 1932 se estableció en Barcelona, donde trabajó como diseñadora publicitaria, sumándose al grupo surrealista catalán Logicofobista. En 1937 viajó a París junto al poeta surrealista francés Benjamin Péret y en 1941, con la llegada de los nazis a la capital francesa, se exilió a México. Nunca regresó a España. Contrariamente a lo que se cree y da por sentado, Remedios Varo nunca adquirió la nacionalidad mexicana, conservando su nacionalidad española, aunque jamás quiso regresar a su tierra natal, a diferencia de su amiga Leonora Carrington quien sí se nacionalizó en el país americano.345 ++++++++++++++++ El Grupo Logicofobista fue un grupo de la vanguardia artística catalana nacido en enero de 1936 que perseguía la síntesis del espiritualismo y el surrealismo. Estaba formado por Magí Albert Cassanyes, el joven poeta José Viola Gamón, Ramon Marinel·lo, Jaume Sans, Leandre Cristòfol, Antoni Garcia Lamolla, Àngel Planells, Joan Massanet, Artur Carbonell, Remedios Varo, Esteban Francès, Andreu Gamboa González-Rothwoss, y Nadia Sokolova. También participaban artistas de la escena madrileña, como Ángel Ferrant y Maruja Mallo, y de la escena canaria como Juan Ismael. La voluntad del grupo era representar una nueva generación de surrealistas, más allá de Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí y Óscar Domínguez, y proyectar una implicación social del surrealismo. El 4 de mayo de 1936 el grupo realizó su primera y única muestra: Exposició Logicofobista en Barcelona. Tenían la intención de trasladarla a Madrid y otras ciudades españolas pero la guerra civil interrumpió el proyecto. El crítico Magí Albert Cassanyes principal promotor del proyecto adoptó el apelativo de logicofobistas como una “marca propia”, para remarcar la identidad rupturista del colectivo, la fobia a la lógica como una variante catalana del surrealismo.1 Orígenes  Paul Éluard en 1911 El grupo nació con motivo de la visita de Paul Éluard a Barcelona en enero de 1936. Viajó para dar unas conferencias en el marco de la exposición de Picasso en Barcelona patrocinada por el grupo ADLAN (Amics de l’art nou).1 El 19 de marzo de 1936 el pintor Antoni G. Lamolla escribía una carta al crítico Eduardo Westerdahl, del grupo canario de la revista Gaceta de Arte, donde le explicaba: “No sé si estará enterado de que, a raíz de la visita de Paul Éluard a Barcelona, hemos formado un grupo surrealista. Nos presentaremos al público con una exposición en Barcelona, Madrid y Bilbao. Figurarán en dicha exposición obras de Miró, Dalí, Fernández, Remedios, Francès…”.1 Los promotores del proyecto fueron Magí Albert Cassanyes, miembro activo de ADLAN y el entonces joven poeta José Viola Gamón, más tarde conocido por su pintura con el seudónimo de Manuel Viola.2 Ambos redactaron el manifiesto de la exposición que se inauguró el 4 de mayor de 1936 y, especialmente Viola, optaron por un surrealismo al servicio de la revolución.3 Entre los artistas que formaron el grupo estaban Ramon Marinel·lo y Jaume Sans –discípulos de Àngel Ferrant-, el escultor Leandre Cristòfol y el pintor Antoni Garcia Lamolla del núcleo vanguardista leridano, pintores surrealistas de la órbita daliniana ampurdanesa, como Àngel Planells y Joan Massanet, el pintor Artur Carbonell, de Sitges, amigo de Cassanyes. También dos íntimos colegas de Viola Gamón: Remedios Varo y Esteve Francès, y dos artistas poco conocidos, como Andreu Gamboa González-Rothwoss de Sabadell y Nadia Sokolova. También participaban artistas de la escena madrileña, como Ángel Ferrant y Maruja Mallo, y de la escena canaria como Juan Ismael. Exposición logicofobista La Exposición Logicofobista se inauguró el 4 de mayo de 1936 en las Galeries d’Art Catalònia de Barcelona. El principal promotor de la muestra, fue el crítico Magí Albert Cassanyes, en colaboración con el sombrerero y promotor de arte de vanguardia Joan Prats y otros miembros de ADLAN (Amics de l’art nou) grupo que a principios de año había organizado también una exposición de Picasso en la sala Esteva. Entre los artistas previstos inicialmente fallaron Joan Miró y Salvador Dalí, los más conocidos, y también Eudald Serra, que se encontraba de viaje en Japón. El objetivo era ofrecer una visión panorámica de la situación del surrealismo en España que incluyera a Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró y otros artistas más jóvenes. En el manifiesto-programa de la exposición, Cassanyes definía el término logicofobista desde un punto de vista filológico y filosófico, y se basaba en la dialéctica hegeliana para explicar que la consecuencia del temor a la lógica sería la adhesión a la metafísica. Por su parte, Viola relacionaba la exposición con el surrealismo, y señalaba que este movimiento era una especie de subconjunto del logicofobismo. A su juicio, la poesía era el portal que conduciría a los artistas a una nueva forma de conocimiento.4 Participaron en la exposición Artur Carbonell (con 3 obras), Leandre Cristòfol (con 4), Àngel Ferrant (2), Esteve Francès (3), Gamboa-Rothwoss (3), A.G. Lamolla (6), Ramon Marinel·lo (4), Joan Massanet (1), Maruja Mallo (2), Àngel Planells (3), Jaume Sans (1), Nadia Sokolova (1), Remedios Varo (3) y Juan Ismael (3). De las 39 obras que entonces se presentaron, se calcula que prácticamente la mitad se han perdido o fueron destruidas durante la guerra. En 2016 la fundación Apel·les Fenosa inauguró una exposición itinerante reconstruyendo la que se celebró 80 años atrás en las galerías Catalonia.1 |

マリア・デ・ロス・レメディオス・アリシア・ロドリガ・ヴァロ・イ・ウ

ランガ(María de los Remedios Alicia Rodriga Varo y

Uranga、通称レメディオス・ヴァロ、1908年12月16日 -

1963年10月8日)は、スペイン[1][2][3]のシュルレアリスムの画家で、スペイン、フランス、メキシコで活動した。 スペイン、そしてフランスでの戦争から逃れ、貧困と闘う厳しい人生を送った。晩年の13年間はメキシコで経済的な安定を得、1963年に急逝するまで生産 的に絵を描いていた[4]。 ++++++++++++++ レメディオス・バロとして知られるマリア・デ・ロス・レメディオス・アリシア・ロドリガ・バロ・イ・ウランガ1(1908年12月16日スペイン、ジェ ローナのアングレス-1963年10月8日メキシコ・シティ)は、スペインのシュルレアリスムの画家、作家、グラフィック・アーティストである2。 彼女は、マドリッドのサン・フェルナンド美術アカデミーで学んだ最初の女性の一人である。1932年にバルセロナに定住し、広告デザイナーとして働きなが ら、カタルーニャのシュルレアリスム・グループ、ロジコフォビスタ(下 記)に加わる。1937年、フランスのシュルレアリスム詩人ベンジャミン・ペレとパリに渡 り、1941年、フランスの首都にナチスが到着したため、メキシコに亡命。スペインに戻ることはなかった。 一般的な通念や推測に反して、レメディオス・ヴァロはメキシコ国籍を取得することはなく、スペイン国籍を保持したままであった。彼女は、アメリカへ帰化し た友人のレオノーラ・キャリントン(1917-2011)とは異なり、母国へ帰ろうとはしなかった。 ++++++++++++++++ ロジコフォビスタ・グループは、1936年1月に生まれたカタルーニャの前衛芸術グループで、精神主義とシュルレアリスムの統合を追求した。マギ・アル ベール・カサニェス、若き詩人ホセ・ビオラ・ガモン、ラモン・マリネルロ、ジャウマ・サンス、レアンドレ・クリストフォル、アントニ・ガルシア・ラモッ ラ、アンヘル・プラネルス、ジョアン・マサネ、アルトゥール・カルボネル、レメディオス・ヴァロ、エステバン・フランセス、アンドルー・ガンボア・ゴンサ レス=ロスウォス、ナディア・ソコロワで構成された。また、アンヘル・フェラントやマルハ・マヨといったマドリードのアーティストや、フアン・イスマエル といったカナリア諸島のアーティストも参加した。このグループの目的は、ジョアン・ミロ、サルバドール・ダリ、オスカル・ドミンゲスを超える新世代のシュ ルレアリストを代表し、シュルレアリスムの社会的含意を示すことだった。1936年5月4日、グループはバルセロナで最初で唯一の展覧会、 Exposició Logicofobistaを開催。マドリードや他のスペインの都市に会場を移す予定だったが、内戦により中断。批評家のマギ・アルベール・カサニェス は、このプロジェクトの主な推進者であったが、グループの破裂主義的アイデンティティ、シュルレアリスムのカタルーニャ的変種としての論理恐怖症を強調す るために、ロジコフォビスタという呼称を「トレードマーク」として採用した1。 起源  1911年のポール・エリュアール このグループは、1936年1月にポール・エリュアールがバルセロナを訪れた際に生まれた。エリュアールは、ADLAN(Amics de l'art nou)というグループが主催するバルセロナのピカソ展の一環として、講演を行うためにバルセロナを訪れた1。 1936年3月19日、画家のアントニ・G・ラモッラは、雑誌『ガセタ・デ・アルテ』のカナリア諸島グループの批評家エドゥアルド・ウェステルダールに手 紙を書き、その中で次のように説明している。私たちはバルセロナ、マドリッド、ビルバオで展覧会を開催する予定です。展覧会には、ミロ、ダリ、フェルナン デス、レメディオス、フランセの作品が含まれる予定である」1。 このプロジェクトの発起人は、ADLANの活動的なメンバーであったマギ・アルベール・カサニェスと、後にマヌエル・ヴィオラのペンネームで知られる、当 時まだ若かった詩人ホセ・ヴィオラ・ガモンであった2。両者とも、1936年5月4日に開幕した展覧会のマニフェストを書き、特にヴィオラは、革命に奉仕 するシュルレアリスムを選んだ3。 グループを形成した芸術家の中には、ラモン・マリネルロとジャウマ・サンス(アンヘル・フェラントの弟子)、彫刻家レアンドレ・クリストフォルと画家アン トニ・ガルシア・ラモッラ(リェイダ・アヴァンギャルドの核)、エンポルダにいたダリ周辺のシュルレアリスムの画家たち、例えばアンヘル・プラネルスや ジョアン・マサネ、カサニエスの友人であったシッチェスの画家アルトゥール・カルボネルなどがいた。また、ヴィオラ・ガモンと親交のあったレメディオス・ ヴァロとエステベ・フランセス、サバデルのアンドルー・ガンボア・ゴンサレス=ロスウォスとナディア・ソコロワというあまり知られていないアーティストも いる。また、アンヘル・フェラントやマルハ・マヨといったマドリードのアーティストや、フアン・イスマエルといったカナリア諸島のアーティストも参加し た。 ロジコフォビスタ展 ロジコフォビスタ展は1936年5月4日、バルセロナのカタルーニャ美術館で開催された。批評家のマギ・アルベール・カサニェスが中心となり、前衛芸術の プロモーターであるジョアン・プラッツやADLAN(Amics de l'art nou)のメンバーらと協力した。 当初は、ジョアン・ミロ、サルバドール・ダリ、そして日本を旅行中だったオイダルド・セラといったアーティストが予定されていた。 その目的は、サルバドール・ダリ、ジョアン・ミロ、その他の若手作家を含め、スペインにおけるシュルレアリスムの状況を俯瞰することであった。 展覧会のマニフェスト・プログラムの中で、カサニエスは言語学的・哲学的観点からロジックフォビストという言葉を定義し、ヘーゲル弁証法を引き合いに出し て、論理を恐れることの帰結は形而上学への固執であると説明した。 ヴィオラ側は、この展覧会をシュルレアリスムと結びつけ、この運動が論理恐怖症の一種のサブセットであると指摘した。彼の考えでは、詩は芸術家たちを新し い知の形へと導く入り口だった4。 この展覧会に参加したのは、アルトゥール・カルボネル(3点)、レアンドレ・クリストフォル(4点)、アンヘル・フェラン(2点)、エステベ・フランセス (3点)、ガンボア=ロスウォス(3点)、A.G.ラモッラ(6点)、A.G. Lamolla(6人)、Ramon Marinel-lo(4人)、Joan Massanet(1人)、Maruja Mallo(2人)、Àngel Planells(3人)、Jaume Sans(1人)、Nadia Sokolova(1人)、Remedios Varo(3人)、Juan Ismael(3人)。 当時応募された39作品のうち、半数近くが戦争中に紛失または破壊されたと推定されている。 2016年、アペル・レ・フェノサ財団は、カタルーニャのギャラリーで80年前に開催された展覧会を再現する巡回展を開催した1。 |

| Early life and education

(1908-1930) Remedios Varo Uranga was born in 1908 in Anglès, a small town in the province of Girona (Catalonia), in northeastern Spain.[5] Varo's mother, Ignacia Uranga Bergareche, had been born to Basque parents in Argentina; she was a devout Roman Catholic. Her mother named her newborn in honor of the patron saint of Anglès, Virgen de los Remedios (the "Virgin of Remedies"), after a recently deceased older sister.[6][5][7] Varo would have two surviving siblings: an older brother Rodrigo, and another brother Luis.[6] She was the only girl, and the youngest of the three siblings.[8]: 13 Varo's father, Rodrigo Varo y Zajalvo (Cejalvo),[9] was a hydraulic engineer. Because of his work, the family moved to different locations across Spain and North Africa.[10] Varo's father recognized her artistic talents early on and would have her copy the technical drawings of his work with their straight lines, radii, and perspectives, which she reproduced meticulously.[8]: 14 He encouraged independent thought and supplemented her education with science and adventure books, notably the novels of Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe. As she grew older, he provided her with texts on mysticism and philosophy. Those first few years of her life left an impression on Varo that would later show up as motifs in her work such as machinery, furnishings, and artifacts. Romanesque and Gothic architecture, unique to Anglès, also showed up in her later artistic production. Varo was given the basic education at a convent school that was typical for young ladies of a good upbringing at the time – but this experience fostered her rebellious tendencies. Varo took a critical view of religion, rejecting the religious ideology of her childhood education, and instead hewed to the liberal and universalist ideas that her father instilled in her.[5] Varo drew throughout her childhood and painted her first painting at age twelve.[11] The very first works of Varo's - a self-portrait and several portraits of family members - date to 1923, when she was studying for a baccalaureate at the School of Arts and Crafts. In 1924, aged 15, she enrolled at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Madrid, under the tutelage of Manuel Benedito.[11] This school emphasized traditional academic study, including painstaking development of technical artistic skills. Many renowned artists were alumni, including Salvador Dalí (though he was expelled for insubordination).[8]: 13–38 Varo was awarded her diploma as a drawing teacher in 1930.[5] Varo also exhibited in a collective exhibition organized by the Unión de Dibujantes de Madrid. Surrealistic elements were already apparent in her work at school, at the same time that French surrealism was having an early influence on Spanish surrealism; she also took an early interest in French surrealism.[7] While in Madrid, Varo had her initial introduction to surrealism through lectures, exhibitions, films, and theater. She was a regular visitor to the Prado Museum and took particular interest in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, most notably The Garden of Earthly Delights, as well as other artists, such as Francisco de Goya. The work that Varo created from 1926 to 1935 solidified her career as an artist, but was not seen by the public.[9]: 15–53 |

生い立ちと教育(1908年-1930年) レメディオス・ヴァロ・ウランガは1908年、スペイン北東部のジローナ県(カタルーニャ州)の小さな町アングレスに生まれた[5]。 ヴァロの母イグナシア・ウランガ・ベルガレチェは、アルゼンチンのバスク人の両親のもとに生まれた。母親は、最近亡くなった姉にちなんで、アングレスの守 護聖人であるレメディオスの聖母にちなんで、新生児に「レメディオスの聖母」と名付けた[6][5][7]。ヴァロには、兄のロドリゴと弟のルイスがい る: 13 バロの父ロドリゴ・バロ・イ・ザハルボ(セハルボ)は水力技師であった[9]。ヴァロの父は早くから彼女の芸術的才能を認め、直線、半径、遠近法などの技 術的な図面を模写させ、彼女はそれを丹念に再現した[8]: 14 自立した考えを奨励し、科学や冒険の本、特にアレクサンドル・デュマ、ジュール・ヴェルヌ、エドガー・アラン・ポーの小説で彼女の教育を補った。彼女が成 長するにつれ、彼は神秘主義や哲学のテキストを与えた。彼女の人生の最初の数年間は、後に機械、調度品、工芸品などのモチーフとして彼女の作品に現れるこ とになる印象をヴァロに残した。また、アングレ特有のロマネスクやゴシック建築も、後の彼女の作品に現れている。 ヴァロは、修道院付属の学校で、当時は良家のお嬢様として一般的だった基本的な教育を受けたが、この経験が彼女の反抗的な傾向を育んだ。ヴァロは宗教に対 して批判的な考えを持ち、幼少期の教育で宗教的なイデオロギーを否定し、代わりに父親から植え付けられた自由主義的で普遍主義的な考えに傾倒した[5]。 ヴァロの最初の作品である自画像と家族の肖像画は、美術工芸学校でバカロレア取得のために学んでいた1923年のものである。 1924年、15歳の彼女は、マヌエル・ベネディトの指導の下、マドリードのベラス・アルテス美術学校に入学した[11]。この学校は、伝統的な学問を重 視し、芸術的な技術も丹念に身につけることを目的としていた。サルバドール・ダリ(反抗的な態度で退学処分となったが)をはじめ、多くの著名な芸術家が同 窓生であった[8]: 13-38 ヴァロは1930年にデッサン教師としての免状を授与された[5]。 ヴァロはまた、マドリッドのデッサン家組合が主催する集団展にも出品した。マドリード滞在中、ヴァロは講義、展覧会、映画、演劇を通してシュルレアリスム に出会う。プラド美術館の常連客であった彼女は、特にヒエロニムス・ボスの絵画に興味を持ち、特に『歓楽の園』やフランシスコ・デ・ゴヤなどの他の画家に も興味を持った。 1926年から1935年にかけてヴァロが制作した作品は、彼女の芸術家としてのキャリアを確固たるものにしたが、一般に公開されることはなかった [9]: 15-53 |

| Spain and France (1930-1941) Varo met her first husband Gerardo Lizárraga at the Escuela de Bellas Artes, and married him in San Sebastián in 1930.[11] This marriage allowed her to flee her hometown and exercise her independence.[9]: 15–53 The couple left Spain for Paris to be nearer to where much of Europe's art scene was.[5][7] After a year, Lizárraga got a job in Spain and the couple moved to Barcelona, at that time a European center of the artistic avant-garde. Both Lizárraga and Varo worked for the J. Walter Thompson advertising company.[9] In 1935, Varo participated in a drawing exhibition in Madrid, which displayed her Composición (Composition).[9] As a young woman Varo had no doubts that she was meant to be an artist. After spending a year in Paris, Varo moved to Barcelona and formed her first artistic circle of friends, which included Josep-Lluis Florit, Óscar Domínguez, and Esteban Francés.[7] Varo soon separated from her husband and shared a studio with Francés in a neighborhood filled with young avant-garde artists. The summer of 1935 marked Varo's formal invitation into Surrealism when French surrealist Marcel Jean arrived in Barcelona. That same year, along with Jean and his artist friends, Dominguez and Francés, Varo took part in various surrealist games such as cadavres exquis ("exquisite corpses") that were meant to explore the subconscious association of participants by pairing different images at random. These cadavres exquis perfectly illustrated the principles André Breton wrote of in his Surrealist manifestos. Varo soon joined a collective of artists and writers, called the Grupo Logicofobista, who had an interest in Surrealism and wanted to unite art together with metaphysics, while resisting logic and reason. Varo exhibited with this group in 1936 at the Galería Catalonia although she recognized they were not pure Surrealists.[5] It was through the poet Benjamin Péret that Remedios Varo met André Breton and the Surrealist circle, which included Leonora Carrington, Dora Maar, Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen, and Max Ernst among others. Shortly after arriving in France, Varo took part in the International Surrealist exhibitions in Paris and in Amsterdam in 1938. She drew vignettes for the Dictionnaire abregé du surrealisme; the magazines Trajectoire du Rêve, Visage du Monde, and Minotaure featured her work. In late 1938, she participated in a collaborative series, Jeu de dessin communiqué (Game of Communicated Drawing), of works with Breton and Péret. The series was much like a game, which began with an initial drawing, which was shown to someone for 3 seconds, after which that person tried to recreate what they had been shown. The cycle continued with the showing of their drawing to the next person, and so on. Apparently, this led to very interesting psychological implications that Varo later used in her paintings many times. Compared to her later time in Mexico, she produced very little work while working in Paris. This may have been due to her status as a femme enfant and the way women were never taken seriously as surrealist artists. She said, reflecting on her time in Paris, "Yes, I attended those meetings where they talked a lot and one learned various things; sometimes I participated with works in their exhibitions; I was not old enough nor did I have the aplomb to face up to them, to a Paul Éluard, a Benjamin Péret, or an André Breton. I was with an open mouth within this group of brilliant and gifted people. I was together with them because I felt a certain affinity. Today I do not belong to any group; I paint what occurs to me and that is all."[8]: 17 In 1937, Varo met political activist and artist Esteban Francés, and left her first husband behind to flee the Spanish Civil War. She moved back to Paris with both Francés and the poet Benjamin Péret in order to escape from the political unrest and fighting, and shared a studio with them there. Varo never divorced Lizárraga and had different partners/lovers throughout her life; but she also remained friends with all of them, in particular with her husband Lizárraga and Péret. By 1939, victorious Francisco Franco forces had banned leftist exiles from returning to Spain. In Paris, Varo lived in poverty, working odd jobs and having to copy and even to forge paintings in order to get by.[7] After World War II began, Péret was imprisoned in 1940 by the French government for his political beliefs; Varo was also imprisoned as his romantic partner. A few days after Varo was freed, the Germans seized Paris, and she was forced to join other refugees leaving the city. Péret was freed soon after, and the two escaped south to Marseilles.[12][13][7] On 20 November 1941 Varo, along with Péret and Rubinstein, boarded the Serpa Pinto in Marseilles to flee Nazi-dominated Europe. The terror she experienced at this time remained as a significant psychological scar. |

スペインとフランス(1930-1941年) ヴァロは最初の夫ジェラルド・リザラガとベラス・アルテス学院で出会い、1930年にサン・セバスティアンで結婚した[11]: 15-53年、夫婦はス ペインを離れ、ヨーロッパのアートシーンの多くに近いパリへ向かう[5][7]。 1年後、リザラガはスペインで職を得、夫妻は当時ヨーロッパの前衛芸術の中心地であったバルセロナに移り住む。1935年、ヴァロはマドリードで開催され たデッサン展に参加し、「コンポジション」(Composición)を展示した[9]。 若い女性だったヴァロは、自分が芸術家になる運命にあると信じて疑わなかった。パリで1年を過ごした後、バルセロナに移り住んだヴァロは、ジョセップ=ル イス・フロリット、オスカル・ドミンゲス、エステバン・フランセスらと最初の芸術サークルを作る。1935年の夏、フランスのシュルレアリスト、マルセ ル・ジャンがバルセロナに到着し、ヴァロはシュルレアリスムに正式に誘われる。同年、ヴァロは、ジャンや彼の友人の画家ドミンゲス、フランセスとともに、 さまざまなシュルレアリスムゲームに参加した。これらのゲームは、アンドレ・ブルトンがシュルレアリスムのマニフェストに記した原則を見事に体現してい た。ヴァロはやがて、シュルレアリスムに関心を持ち、論理や理性に抵抗しながらも芸術を形而上学と結びつけようとする、ロジコフォビスタ・グループと呼ば れる芸術家や作家の集団に加わった。ヴァロは、彼らが純粋なシュルレアリスムではないと認識しながらも、1936年にカタロニア・ギャラリーでこのグルー プと展示を行った[5]。 レメディオス・ヴァロがアンドレ・ブルトンや、レオノーラ・キャリントン、ドラ・マール、ロベルト・マッタ、ヴォルフガング・パーレン、マックス・エルン ストらを含むシュルレアリスムのサークルと出会ったのは、詩人のベンジャミン・ペレを通してだった。フランスに到着して間もなく、ヴァロは1938年にパ リとアムステルダムで開催された国際シュルレアリスム展に参加。Dictionnaire abregé du surrealisme』誌にヴィネットを描き、雑誌『Trajectoire du Rêve』、『Visage du Monde』、『Minotaure』に作品を掲載。1938年後半には、ブルトンやペレとの共同シリーズ『Jeu de dessin communiqué(伝達されたドローイングゲーム)』に参加。このシリーズはゲームのようなもので、最初にドローイングを描き、それを誰かに3秒間見 せ、見せられたものを再現するというものだった。次の人にその絵を見せるというサイクルが続く。どうやらこれは、ヴァロが後に何度も絵に用いた、非常に興 味深い心理学的な意味合いにつながったようだ。 後にメキシコで活動するのに比べ、パリで活動していた時の彼女の作品は非常に少なかった。これは、彼女がファム・アンファンであったことと、女性がシュル レアリスムのアーティストとして真剣に取り上げられることがなかったことに起因しているのかもしれない。私はまだ年端もいかず、ポール・エリュアールやベ ンジャミン・ペレ、アンドレ・ブルトンに向かっていくような気概もなかった。私は、才気煥発で才能豊かな人々のグループの中で、口を開けていた。彼らと一 緒にいたのは、ある種の親近感を感じていたからだ。今日、私はどのグループにも属していない。私は思いついたものを描く、それだけだ」[8]: 17 1937年、ヴァロは政治活動家で画家のエステバン・フランセスと出会い、最初の夫を残してスペイン内戦から逃れる。政情不安と戦闘から逃れるため、フラ ンセスと詩人のベンジャミン・ペレとともにパリに戻り、アトリエを共にした。ヴァロはリザラガと離婚することなく、生涯を通じてさまざまなパートナーや恋 人を持ったが、特に夫のリザラガやペレとは友人であり続けた。1939年、勝利したフランシスコ・フランコは、左翼亡命者のスペインへの帰国を禁止した。 第二次世界大戦が始まると、ペレは政治的信条を理由に1940年にフランス政府によって投獄され、ヴァロもまた彼の恋愛相手として投獄された。ヴァロが釈 放された数日後、ドイツ軍がパリを占領し、彼女はパリを離れる他の難民と一緒になることを余儀なくされた。1941年11月20日、ヴァロはペレとルービ ンシュタインとともに、ナチスが支配するヨーロッパから逃れるため、マルセイユでセルパ・ピント号に乗り込んだ。この時に体験した恐怖は、大きな心の傷と して残った。 |

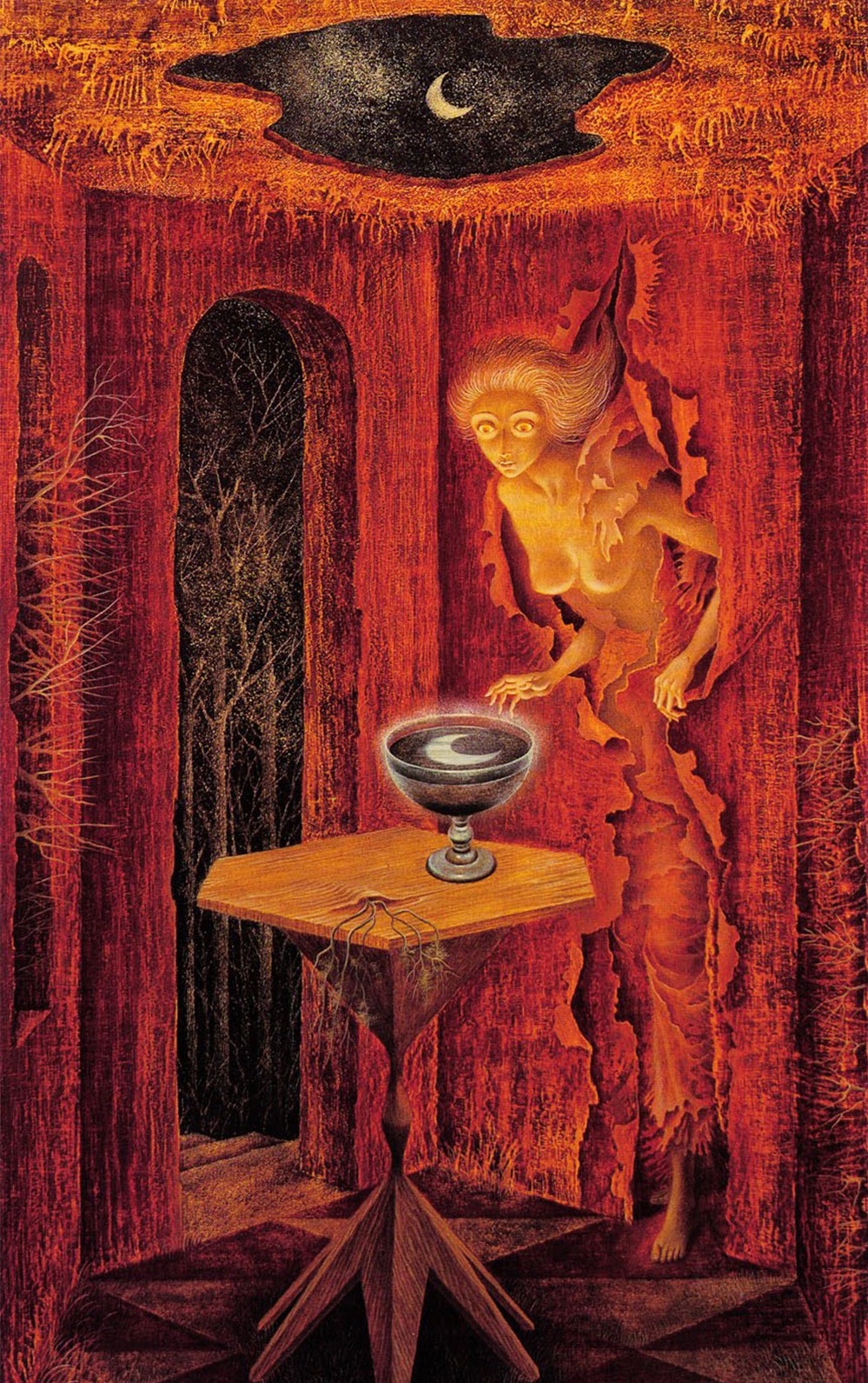

Mexico (1942-1963) Roulotte, 1956/55? La huida, detail, 1961 Varo initially considered her time in Mexico to be temporary. However, except for a year spent in Venezuela, she would reside in Mexico for the rest of her life,[14] producing around 110 paintings during her last decade.[8]: 18 She said about working in Mexico, "[In Europe] for me it was impossible to paint among such anxiety. In this country I have found the tranquility that I have always searched for".[8]: 17 In Mexico, she met regularly with other European artists such as Gunther Gerzso, Kati Horna, José Horna, and Wolfgang Paalen. In Mexico, she met native artists such as Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, but her strongest ties were to other exiles and expatriates, notably the Mexican painter of English origin Leonora Carrington and the French pilot and adventurer, Jean Nicolle. However, because Mexican muralism still dominated the country's art scene, surrealism was not generally well received. She worked as an assistant to Marc Chagall with the design of the costumes for the production of the ballet Aleko, which premiered in Mexico City in 1942.[5] Varo discovered an interest in the esoteric doctrine of G.I. Gurdjieff in 1943, and officially joined the group in 1944.[9] She worked at other jobs, including in publicity for the pharmaceutical company Bayer, and decorating for Clar Decor. In 1947, Péret returned to Paris, and Varo traveled to Venezuela.[5] The trip to Venezuela was part of a French scientific expedition which she joined in Paris during a visit there from Mexico.[9] Varo returned to Mexico in 1949 and began her third and last important relationship, with Austrian political refugee Walter Gruen, who had endured concentration camps before escaping from Europe. Gruen believed fiercely in Varo, and he gave her the economic and emotional support that allowed her to fully concentrate on her painting.[7] In 1952, Varo married Gruen.[15] His financial stability allowed Varo to stop working as a commercial illustrator, with more time to devote to her painting.[8]: 17 [16] The bulk of Varo's significant artwork was produced during 1953–1963.[8]: 18 In 1955, Varo opened her first solo exhibition at the Galería Diana in Mexico City, which was well received.[9] One reason for this was that Mexico had opened up to other artistic trends. Buyers were put on waiting lists for her work.[8]: 13 Even the established Mexican artist Diego Rivera was supportive. Her second showing was at the Salón de la Arte de Mujer in 1958. In 1960, her representative, Juan Martín, opened his own gallery and showed her work there, and he opened a second in 1962, at the height of her career. In 1963, Varo suddenly died of a heart attack;[5][7] she had been a heavy smoker.[4][8] André Breton commented that the death made her "the sorceress who left too soon".[5] |

メキシコ(1942-1963) ルロット、1956年 ラ・フイダ、詳細、1961年 ヴァロは当初、メキシコでの滞在を一時的なものと考えていた。しかし、ベネズエラで過ごした1年を除いて、彼女は生涯メキシコに住み続け、晩年の10年間 で約110点の絵画を制作した[14]: 18 彼女はメキシコでの制作について、「(ヨーロッパでは)私にとって、このような不安の中で絵を描くことは不可能でした。この国で、私はいつも探し求めてい た静けさを見つけた」と語っている[8]: 17 メキシコでは、グンター・ゲルツォ、カティ・ホルナ、ホセ・ホルナ、ヴォルフガング・パーレンといったヨーロッパの画家たちと定期的に会っていた。メキシ コではフリーダ・カーロやディエゴ・リベラのような先住民の芸術家たちとも出会ったが、彼女が最も強い絆で結ばれていたのは他の亡命者や国外追放者たちで あり、特にイギリス出身のメキシコ人画家レオノーラ・キャリントンやフランス人パイロットで冒険家のジャン・ニコルとの交流であった。しかし、メキシコの 壁画はまだ同国のアートシーンを支配していたため、シュルレアリスムは一般にはあまり受け入れられなかった。1942年にメキシコシティで初演されたバレ エ作品『アレコ』の衣装デザインでは、マルク・シャガールのアシスタントを務めた[5]。 1943年、ヴァロはG.I.グルジェフの秘教的教義に興味を持ち、1944年に正式にグルジェフ・グループに加わる[9]。 製薬会社バイエルの宣伝やクラール・デコールの装飾など、他の仕事も経験した。1947年、ペレはパリに戻り、ヴァロはベネズエラを訪れた[5]。ベネズ エラへの旅はフランスの科学探検の一環で、彼女はメキシコからパリを訪れた際に参加した[9]。 1949年にメキシコに戻ったヴァロは、ヨーロッパから逃れる前に強制収容所にいたオーストリアの政治難民ウォルター・グルエンとの、3度目で最後の重要 な交際を始めた。1952年、ヴァロはグリュエンと結婚[15]。彼の経済的な安定により、ヴァロは商業イラストレーターとしての仕事をやめ、より多くの 時間を絵に費やすことができるようになった[8]: 17 [16] ヴァロの重要な作品の大部分は1953年から1963年にかけて制作された[8]: 18 1955年、ヴァロはメキシコシティのディアナ画廊で初めての個展を開き、好評を博した[9]。彼女の作品を買い求めるバイヤーは、ウェイティングリスト に載せられていた[8]: 13 確立したメキシコの芸術家ディエゴ・リベラでさえ支持した。彼女の2回目の展示は、1958年のサロン・デ・ラ・アルテ・デ・ムジェールであった。 1960年、彼女の代理人フアン・マルティンは自身のギャラリーを開き、そこで彼女の作品を展示した。 1963年、ヴァロは心臓発作で急逝[5][7]。彼女はヘビースモーカーであった[4][8]。アンドレ・ブルトンは、この死が彼女を「あまりにも早く 去った魔術師」と評した[5]。 |

| Artistic influences Renaissance art inspired harmony, tonal nuances, and narrative structure in Varo's paintings. The allegorical nature of much of Varo's work especially recalls the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, and some critics, such as Dean Swinford, have described her art as "postmodern allegory", much in the tradition of Irrealism. Varo was influenced by styles as diverse as those of Francisco Goya, El Greco, Picasso, and Braque. While André Breton was a formative influence in her understanding of Surrealism, some of her paintings bear an uncanny resemblance to the Surrealist creations of her contemporary, the Greek-born Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. Her paintings reflected the painstaking precision drawing skills which she had learned early in life. While there is little overt influence of Mexican art on her work, Varo and the other surrealists were captivated by the seemingly porous borders between the marvelous and the real in Mexico.[8] Philosophical influences Varo considered surrealism as an "expressive resting place within the limits of Cubism, and as a way of communicating the incommunicable".[7] Even though Varo was critical of her childhood religion, Catholicism, her work was influenced by religion. She differed from other Surrealists because of her constant use of religion in her work.[10] She also turned to a wide range of mystic and hermetic traditions, both Western and non-Western, for influence. She was influenced by her belief in magic and animistic faiths. She was very connected to nature and believed that there was strong relation between the plant, human, animal, and mechanical world. Her belief in mystical forces greatly influenced her paintings.[8]: 13–38 Varo was aware of the importance of biology, chemistry, physics, and botany, and thought it should blend together with other aspects of life.[8]: 13–38 Her fascination with science, including Einstein's theory of relativity and Darwinian evolution, has been noted by admirers of her art.[17] She turned with equal interest to the ideas of Carl Jung as to the theories of George Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, Helena Blavatsky, Meister Eckhart, and the Sufis, and was as fascinated with the legend of the Holy Grail as with sacred geometry, witchcraft,[18] alchemy, and the I Ching. Varo described her beliefs about her own powers of witchcraft in a letter to English author Gerald Gardner, "Personally, I don’t believe I’m endowed with any special powers, but instead with an ability to see relationships of cause and effect quickly, and this beyond the ordinary limits of common logic."[19] In 1938 and 1939, Varo joined her closest companions Frances, Roberto Matta, and Gordon Onslow Ford in exploring the fourth dimension, basing much of their studies off of Ouspensky's book Tertium Organum. The books Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy by Grillot de Givry and The History of Magic and the Occult by Kurt Seligmann were highly valued in Breton's Surrealist circle. She saw in each of these an avenue to self-knowledge and the transformation of consciousness. She was also greatly influenced by her childhood journeys. She often depicted out-of-the-ordinary vehicles in mystifying lands. These works echo her family travels in her childhood.[10] Surrealist influences One critic states, "Remedios seems to never limit herself to one mode of expression. For her tools of the painter and the writer are unified in breaking down our visual and intellectual customs".[20] Even so, most classify her as a surrealist artist in that her work displays many trappings of the surrealist practice. Her work displays a liberating self-image and evokes a sense of otherworldliness which is so characteristic of the surrealist movement. One scholar notes that Varo's practice of automatic writing directly correlates to that of the Surrealists. The father of Surrealism, André Breton, excluded women as fundamental to the movement of Surrealism, but after Varo's death in 1963, he connected her “forever to the ranks of international surrealism". [9]: 15–53 The Surrealist movement tended to devalue women. Some of Varo's art elevated women, while still falling under the category of Surrealism. But it was not necessarily her intention for her work to address problems in gender inequality. But her art and actions challenged the traditional patriarchy, and it was mainly Wolfgang Paalen who encouraged her in this with his theories about the origins of civilization in matriarchal cultures, and the analogies between pre-classic Europe and pre-Mayan Mexico.[10][21] |

芸術的影響 ルネサンス芸術は、ヴァロの絵画における調和、調性のニュアンス、物語構造にインスピレーションを与えた。ヴァロの作品の多くは、特にヒエロニムス・ボス の絵画を想起させる寓意的な性質を持ち、ディーン・スウィンフォードのような一部の批評家は、彼女の芸術を「ポストモダンの寓意」と評し、イレアリスムの 伝統に大いに影響を受けている。 ヴァロは、フランシスコ・ゴヤ、エル・グレコ、ピカソ、ブラックなど多様なスタイルから影響を受けた。アンドレ・ブルトンは、彼女のシュルレアリスム理解 において形成的な影響を与えたが、彼女の絵画のいくつかは、同時代のギリシャ生まれのイタリア人画家ジョルジョ・デ・キリコのシュルレアリスム作品と不気 味なほど類似している。彼女の絵は、早い時期に身につけた丹念で精密なデッサン力を反映している。 彼女の作品にメキシコ美術のあからさまな影響はほとんど見られないが、ヴァロと他のシュルレアリストたちは、メキシコの驚異と現実の間にある、一見ポーラ スな境界線に魅了されていた[8]。 哲学的影響 ヴァロはシュルレアリスムを「キュビスムの限界の中にある表現的な休息場所であり、伝達不可能なものを伝達する方法」と考えていた[7]。 ヴァロは幼少期に信仰していたカトリックに批判的であったが、彼女の作品は宗教の影響を受けていた。また、西洋、非西洋を問わず、さまざまな神秘主義や秘 教的な伝統にも影響を受けた。彼女は魔術やアニミズム的な信仰に影響を受けた。彼女は自然との結びつきが強く、植物、人間、動物、機械の世界には強い関係 があると信じていた。彼女の神秘的な力への信仰は、彼女の絵画に大きな影響を与えた[8]: 13-38 ヴァロは生物学、化学、物理学、植物学の重要性を認識しており、それは生活の他の側面と融合するべきだと考えていた[8]: 13-38 アインシュタインの相対性理論やダーウィンの進化論など、彼女の科学に対する興味は、彼女の芸術を賞賛する人々によって指摘されている[17]。 ジョージ・グルジェフ、P.D.ウスペンスキー、ヘレナ・ブラヴァツキー、マイスター・エックハルト、スーフィズムの理論と同様にカール・ユングの思想に も興味を示し、神聖幾何学、魔術、錬金術、易経と同様に聖杯伝説にも魅了された[18]。個人的には、自分には特別な力が備わっているとは思っていません が、その代わりに、原因と結果の関係を素早く見る能力があり、これは一般的な論理の通常の限界を超えています」[19] 1938年と1939年、ヴァロは親しい仲間であるフランシス、ロベルト・マッタ、ゴードン・オンスロー・フォードとともに、ウスペンスキーの著書 『Tertium Organum』に基づいて4次元の探求を行った。グリロ・ド・ジブリの『Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy』やクルト・セリグマンの『History of Magic and the Occult』は、ブルトンのシュルレアリスム界で高く評価されていた。ブルトンは、これらの作品に自己認識と意識の変容への道を見出したのである。 彼女はまた、幼少期の旅からも大きな影響を受けていた。彼女はしばしば、神秘的な土地での常軌を逸した乗り物を描いた。これらの作品は、幼少期の家族旅行 と呼応している[10]。 シュルレアリスムからの影響 ある批評家は、「レメディオスは自分を一つの表現様式に限定することはないようだ。彼女の画家と作家のツールは、私たちの視覚的・知的慣習を打ち破ること で統一されているからだ」[20]。それでも、彼女の作品にはシュルレアリスムの実践の特徴が多く見られるという点で、ほとんどの人は彼女をシュルレアリ スムのアーティストとして分類している。彼女の作品は解放的な自己イメージを示し、シュルレアリスム運動の特徴である異世界感を呼び起こす。ある学者は、 ヴァロの自動筆記の実践は、シュルレアリスムのそれと直接的に関連していると指摘する。シュルレアリスムの父であるアンドレ・ブルトンは、シュルレアリス ム運動の根幹をなすものとして女性を排除していたが、ヴァロの死後(1963年)、彼は彼女を「国際的なシュルレアリスムの仲間に永遠に」つなげた。 [9]: 15-53 シュルレアリスム運動は女性を軽んじる傾向があった。ヴァロの芸術の中には、シュルレアリスムの範疇にありながら、女性を高く評価するものもあった。しか し、彼女の作品が必ずしも男女不平等の問題に取り組むことを意図していたわけではない。しかし、彼女の芸術と行動は伝統的な家父長制に挑戦しており、主に ヴォルフガング・パーレンが、母系制文化における文明の起源についての理論や、古典以前のヨーロッパとマヤ以前のメキシコの類似性によって、彼女を勇気づ けた[10][21]。 |

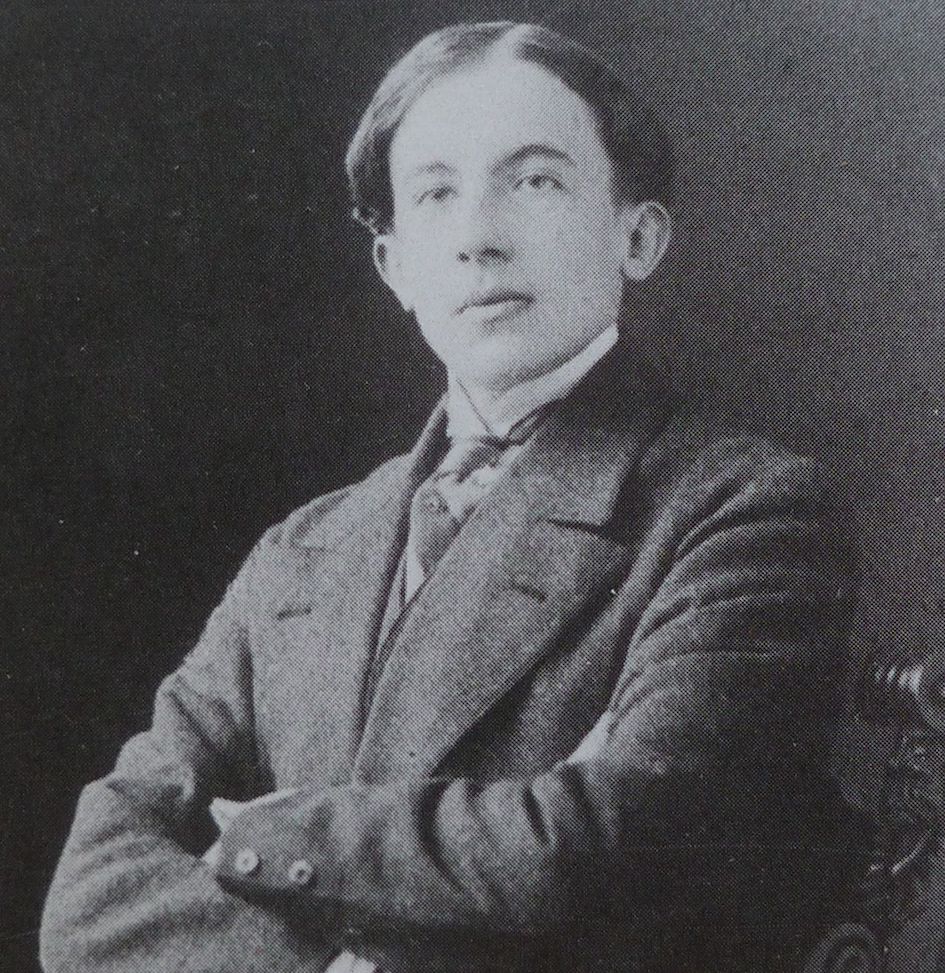

| Relationship with Leonora

Carrington and Kati Horna Among all the refugees that were forced to flee from Europe to Mexico City during and after World War II, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Kati Horna formed a bond that would immensely affect their lives and work. They all lived in proximity to each other in the Colonia Roma district of Mexico City. Varo and Carrington had previously met through André Breton while living in Paris. Although Horna did not meet the other two until they were all in Mexico City, she was already familiar with the work of Varo and Carrington after being given a few of their paintings by Edward James, a British poet and patron of the surrealist movement. All three attended the meetings of followers of the Russian mystics Peter Ouspensky and George Gurdjieff.[22] They were inspired by Gurdjieff's study of the evolution of consciousness and Ouspensky's idea of the possibility of four-dimensional painting. Though deeply influenced by the ideas of the Russian mystics, the women often ridiculed the practices and behavior of those in the circle.[citation needed] The trio were sometimes referred to as "the three witches", because of their interest in the occult and spiritual practices.[4] After becoming friends, Varo and Carrington began writing collaboratively and wrote two unpublished plays together: El santo cuerpo grasoso and Lady Milagra - the latter unfinished. Using a technique similar to that of the game called Cadavre Exquis, they took turns writing small segments of text and put them together. Even when not writing together, they were often working collaboratively, often drawing from the same sources of inspiration and using the same themes in their paintings. Despite the fact that their work was extremely similar, there was one major difference: Varo's painting was about line and form, while Carrington's work was about tone and color.[23] Varo and Carrington would remain extremely close friends for 20 years, until Varo's death in 1963.[24] Interpretations of Varo's artwork Varo often painted images of women in confined spaces, achieving a sense of isolation. While Varo did not deem her own work feminist, "her work stretches the limits of and directly challenges confabulated, patriarchal ideals of femininity".[20] Also, Varo's work redacts male interpretation of the female body. Her works focus on female empowerment and agency. The androgynous figures characteristic of her later work also challenge gender in that the figures do not fall neatly into gender normative categories, and often could be of either sex, creating a sense of the "middle area" between the two sexes and of the gender norms placed on them. One critic states, "Because the female body, a sacred erotic artistic space for men, is transformed by [Varo] into nongendered shapes and forms, namely animals and insects, the space becomes freed from monolithic sexual interpretation".[20] Later in her career, her characters developed into her emblematic androgynous figures with heart-shaped faces, large almond eyes, and the aquiline noses that represent her own features. Varo often depicted herself through these key features in her paintings, regardless of the figure's gender.[8]: 13–38 "Varo tends to not play out personal strife on the canvas but rather portrays herself in various roles in surreal dreamscapes".[20] "It is Varo herself who is the alchemist or explorer. In creating these characters, she is defining her identity".[25] Varo's work also focuses on psychoanalysis and its role in society and female agency. In speaking on Woman leaving the Psychoanalyst (1961), one of Varo's biographers states, "Not only does Varo debunk the idea of a correct process of mental healing, but also she trivializes the very nature of that process by representing the impossible: a physical and literal dismissal of the father, Order, and in Lacanian terms the official entrance into culture: verbal Language".[20] ++++++++++++++++++++ Obra Remedios Varo está considerada una artista de la alquimia dedicada a hacer revivir mundos que en su pintura surgen de los cuentos de hadas del insconsciente. Destaca en la recuperación de su memoria la periodista cultural e investigadora española Mercè Ibartz.21 La obra de la pintora es vasta y compleja con un estilo característico y fácilmente reconocible. En su obra aparecen con frecuencia figuras humanas estilizadas realizando tareas simbólicas, en las cuales se tienen a la vez elementos oníricos y arquetípicos. De su obra, Ascensión al monte análogo de 1960 la artista comenta: Como veis, ese personaje está remontando la corriente, solo, sobre un fragilísimo trocito de madera y sus propios vestidos le sirven de vela. Es el esfuerzo de aquellos que tratan de subir a otro nivel espiritual. R. V.21 Su obra completa está teñida de una atmósfera de misticismo, plasmado en las figuras representativas del mundo secular moderno. Su pintura está puntualizada por un marcado interés por la iconografía científica, por ello años después las obras de la pintora han sido retomadas cada vez con más frecuencia en la literatura de divulgación. Sus lienzos están realizados con la minuciosidad de un orfebre y reflejan la unidad cósmica y las interconexiones entre diferentes planos de la realidad: la materia y el espíritu, el mundo animal, el humano y el vegetal. Otro de sus grandes temas, que fascinó a los surrealistas, es el de la mujer maga, más ligada al inconsciente que los hombres y dotada de poderes superiores. Su originalidad reside en que la emplaza en el en ocasiones tan denostado ámbito doméstico.6 Remedios Varo es de las primeras mujeres artistas en introducir y popularizar su trabajo en México, gracias a sus relaciones personales con otras artistas que radicaban allí, como la pintora británica Leonora Carrington, con quien conservó una buena amistad, y otros miembros de la élite artística e intelectual mexicana de mediados del siglo xx.25 Sus cuadros, muchos de los cuales están conservados en el Museo de Arte Moderno de la Ciudad de México, han sido expuestos en numerosas ocasiones como exposiciones temporales. Junto con la obra de otras mujeres surrealistas se presentaron cuadros populares de Varo en In Wonderland, llevada a cabo en el Museo de Arte Moderno a finales del 2012 y principios del 2013. Su obra ha tenido un gran impacto en el mundo del arte especialmente en México, el país que la acogió y donde la imagen de Remedios Varo se ha popularizado. En España a pesar de algunos homenajes en Barcelona en el 2008 su obra es todavía poco conocida.21 En mayo de 2020 fueron dispuestas en línea por Malba Literatura ocho cartas que la pintora envió a su amiga Kati Horna, entre 1947 y 1958.262728 |

レオノーラ・キャリントン、カティ・ホルナとの関係 第二次世界大戦中と戦後、ヨーロッパからメキシコ・シティに逃れることを余儀なくされた難民の中で、レメディオス・バロ、レオノーラ・キャリントン、カ ティ・ホルナは、彼らの人生と仕事に多大な影響を与える絆を結んだ。彼らは皆、メキシコシティのコロニア・ローマ地区で互いに近接して暮らしていた。 ヴァロとキャリントンは以前、パリに住んでいたときにアンドレ・ブルトンを通じて知り合った。ヴァロとキャリントンの作品は、イギリスの詩人でシュルレア リスム運動のパトロンであったエドワード・ジェイムズから数点の絵を贈られ、すでに知っていた。 3人とも、ロシアの神秘主義者ピーター・ウスペンスキーとジョージ・グルジェフの信者の集会に参加していた[22]。彼らは、グルジェフの意識の進化に関 する研究と、ウスペンスキーの四次元絵画の可能性に関する考えに触発された。ロシアの神秘主義者の思想に深く影響を受けながらも、彼女たちはしばしばサー クルの人々の実践や行動を嘲笑していた[要出典]。オカルトや精神修養への関心から、3人組は「3人の魔女」と呼ばれることもあった[4]。 友人となった後、ヴァロとキャリントンは共同で執筆を始め、未発表の戯曲を2本一緒に書いた: El santo cuerpo grasoso』と『Lady Milagra』である。El santo cuerpo grasoso』と『Lady Milagra』である。一緒に書いていない時でも、彼らはしばしば共同作業をしており、同じインスピレーション源から絵を描いたり、同じテーマを使った りしていた。彼らの作品は非常によく似ていたにもかかわらず、ひとつだけ大きな違いがあった: ヴァロの絵画は線と形に重点を置いていたのに対し、キャリントンの作品は色調と色彩に重点を置いていたのである[23]。ヴァロとキャリントンは、 1963年にヴァロが亡くなるまでの20年間、非常に親しい友人であり続けた[24]。 ヴァロの作品の解釈 ヴァロはしばしば、閉ざされた空間にいる女性のイメージを描き、孤独感を表現した。ヴァロは自身の作品をフェミニストだとは考えていなかったが、「彼女の 作品は、女性らしさについての家父長制的な理想の限界を広げ、直接的にそれに挑戦している」[20]。彼女の作品は、女性のエンパワーメントと主体性に焦 点を当てている。彼女の後期の作品に特徴的なアンドロジナス的な人物像も、ジェンダー規範のカテゴリーにきちんと当てはまらないという点で、ジェンダーに 挑戦している。ある批評家は、「男性にとって神聖なエロティックな芸術空間である女性の身体が、[ヴァロによって]性別にとらわれない形や姿、すなわち動 物や昆虫に変容されることで、空間は一枚岩の性的解釈から解放される」と述べている[20]。 キャリアの後半になると、彼女のキャラクターは、ハート型の顔、大きなアーモンドの目、彼女自身の特徴を表す水晶形の鼻を持つ、彼女を象徴するアンドロジ ナスな人物へと発展した。ヴァロは、人物の性別に関係なく、絵画の中でこれらの重要な特徴を通して自分自身を描くことが多かった[8]: 13-38 「ヴァロはキャンバスの上で個人的な争いを演じるのではなく、むしろ超現実的な夢物語の中で様々な役割を演じる自分自身を描く傾向がある」[20]「錬金 術師や探検家であるのはヴァロ自身である。これらのキャラクターを創造することで、彼女は自分のアイデンティティを定義している」[25]。 ヴァロの作品は、精神分析と社会における役割、そして女性の主体性にも焦点を当てている。ヴァロの伝記作家の一人は、『精神分析医を去る女』(1961 年)について、「ヴァロは精神的治癒の正しいプロセスという考えを否定しているだけでなく、不可能なことを表現することによって、そのプロセスの本質を矮 小化している。 ++++++++++++++++++++ 作品 レメディオス・ヴァロは、無意識のおとぎ話から生まれた世界に命を吹き込む錬金術のアーティストである。スペインの文化ジャーナリストで研究者のメルセ ス・イバルツは、彼女の記憶の回復において際立っている21。 彼女の作品には、象徴的な作業を行う様式化された人物が頻繁に登場し、そこには夢のような要素と原型的な要素の両方がある。1960年の作品 『Ascent of the Analogue Mountain』について、作家はこう語っている: ご覧のように、この人物は非常に壊れやすい木片の上を、たった一人で沢を上っている。これは、別の精神的なレベルに登ろうとする人々の努力なのだ。 R. V.21 彼の全作品は、現代の世俗世界を代表する人物に具現化された神秘主義の雰囲気を帯びている。彼女の絵画は、科学的図像への顕著な関心によって区切られてお り、そのため、数年後、この画家の作品は、一般的な文献に掲載されることが多くなった。 彼女のキャンバスは金細工職人のような緻密さで描かれ、物質と精神、動物界、人間界、植物界といった異なる現実の平面の間の宇宙的な統一と相互関係を反映 している。シュルレアリスムたちを魅了した彼のもうひとつの大きなテーマは、男性よりも無意識と密接につながり、優れた力を持つ女性の魔術師である。彼女 の独創性は、時に悪者扱いされる家庭内に彼女を置いている点にある6。 レメディオス・ヴァロは、親交のあったイギリスの画家レオノーラ・キャリントンや、20世紀半ばのメキシコの芸術的・知識的エリートのメンバーなど、メキ シコ在住の他の芸術家たちとの個人的な関係によって、メキシコで自分の作品を紹介し、普及させた最初の女性芸術家の一人である25。 彼女の絵画の多くは、メキシコ・シティの近代美術館に収蔵されているが、企画展として何度も展示されている。2012年末から2013年初めにかけて近代 美術館で開催された『イン・ワンダーランド』では、他のシュルレアリスムの女性たちの作品とともに、ヴァロの人気絵画が紹介された。 彼女の作品は美術界に大きな影響を与え、特に彼女を迎え入れ、レメディオス・ヴァロのイメージが広まったメキシコでは大きな反響を呼んだ。スペインでは、 2008年にバルセロナで追悼式が行われたものの、彼女の作品はまだほとんど知られていない21。 2020年5月、マルバ・リテラトゥーラは、画家が1947年から1958年の間に友人カティ・ホルナに送った8通の手紙をオンラインで公開した 262728。 |

| Legacy but possibly contains

original research. Varo's artwork is well known in Mexico, but is not as well known throughout the rest of the world.[26] Her mature paintings, fraught with arguably feminist meaning, are predominantly from the last few years of her life. Varo's partner for the last 15 years of her life, Walter Gruen, dedicated his life to cataloguing her work and ensuring her legacy. The paintings of androgynous characters that share Varo's facial features, mythical creatures, the misty swirls, and eerie distortions of perspective are characteristic of Varo's unique strain of surrealism. Varo has painted images of isolated, androgynous, auto-biographical figures to highlight the captivity of the true woman. While her paintings have been interpreted as more surrealist canvases that are the product of her passion for mysticism and alchemy, or as auto-biographical narratives, her work carries implications far more significant.[26] In 1971 the posthumous retrospective exhibition organised by the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City, drew the largest audiences in its history — larger than those for Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco.[26] More than fifty of her works were displayed in a retrospective exhibition in 2000 at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.[27] The Crying of Lot 49, a novella by Thomas Pynchon, features a scene in which the main character recalls crying in front of a painting by Varo titled Bordando el Manto Terrestre ("Embroidering the Earth's Mantle").[28] Varo's painting The Lovers served as inspiration for some of the images used by Madonna in the music video for her 1995 single "Bedtime Story".[20] On 22 May 2019 Varo's 1955 painting Simpatía (La rabia del gato) ("Sympathy: the madness of the cat") sold for $3.1 million at an auction at Christie's, New York City.[29] |

レガシー(要改善) ヴァロの作品はメキシコではよく知られているが、世界的にはあまり知られていない[26]。 彼女の成熟した絵画は、間違いなくフェミニズム的な意味を孕んでおり、主に彼女の人生の最後の数年間に描かれたものである。ヴァロの最後の15年間のパー トナーであったウォルター・グルーエンは、彼女の作品のカタログ化と遺産の確保に生涯を捧げた。ヴァロの顔の特徴を共有するアンドロイドのキャラクター、 神話的な生き物、霧のような渦巻き、不気味な遠近法の歪みなどの絵は、ヴァロ独特のシュルレアリスムの系統を特徴づけている。ヴァロは、真の女性の囚われ を浮き彫りにするために、孤立したアンドロジナスな自伝的人物のイメージを描いてきた。 彼女の絵画は、神秘主義と錬金術への情熱の産物である、よりシュールレアリスム的なキャンバスとして、あるいは自己伝記的な物語として解釈されてきたが、 彼女の作品にははるかに重要な意味合いが含まれている[26]。 1971年、メキシコ・シティの近代美術館が主催した死後の回顧展は、ディエゴ・リベラやホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコの回顧展を上回る史上最大の観客を集 めた[26]。 2000年にはワシントンDCの国立女性芸術博物館で回顧展が開催され、50点以上の作品が展示された[27]。 トマス・ピンチョンによる小説『The Crying of Lot 49』では、主人公が「Bordando el Manto Terrestre」(「地球のマントを刺繍する」)と題されたヴァロの絵画の前で泣いていることを思い出すシーンが登場する[28]。 ヴァロの絵画『恋人たち』は、マドンナが1995年に発表したシングル「ベッドタイムストーリー」のミュージックビデオで使用された映像の一部のインスピ レーションとなった[20]。 2019年5月22日、ヴァロの1955年の絵画『Simpatía (La rabia del gato)』(「シンパシー:猫の狂気」)は、ニューヨークのクリスティーズのオークションで310万ドルで落札された[29]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remedios_Varo https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remedios_Varo |

|

| Lista de trabajos representativos Exposición de Varo en México, 2017-18. 1935 El tejido de los sueños 1938 Como un sueño 1938 Las almas de los montes o Los espíritus de la montaña 1942 Gruta mágica 1943 Paisaje Torre Centauro 1944 Ruedas metafísicas 1944 Invierno 1945 A mi amigo Agustín Lázaro 1947 Paludismo (Libélula) 1947 Laboratorio 1947 El hombre de la guadaña (Muerte en el mercado) 1947 La batalla 1947 Tiforal 1947 Insomnio I 1947 Gitana y Arlequín 1947 Amibiasis o Los vegetales 1948 Dolor 1948 Títeres vegetales 1948 Mujer en rojo 1948 Dolor reumático I 1948 Dolor reumático II 1948 Alegoría del Invierno 1950 Valle de la luna 1950 Mujer sedente 1951 Personajes Libélulas 1951 El jardín del amor 1953 Premonición 1954 Espacio tiempo 1955 Simpatía o La rabia del gato 1955 Ciencia inútil o El alquimista 1955 Ermitaño meditando 1955 La revelación o El relojero 1955 Trasmundo 1955 Ruptura 1955 El flautista 1955 El paraíso de los gatos 1955 Creación con rayos astrales 1956 A la felicidad de las damas 1956 La calle de las presencias ocultas 1956 Tres destinos 1956 Vuelo mágico 1956 Cazadora de astros 1956 Energía cósmica 1956 Hallazgo 1956 Los ancestros o Poema 1956 El malabarista o El juglar 1956 Tejedora 1956 La tejedora roja 1956 La tejedora de Verona 1957 Creación de las aves 1957 Modista 1957 Caminos tortuosos 1957 Mujer con esfera 1957 Bruja que va al Sabbat 1957 Reflejo lunar 1957 El gato helecho 1957 Retrato de Pilar y Clara Arnús 1957 Vagabundo 1957 Elixir 1957 El otro reloj 1958 Papilla estelar 1958 Visita inesperada 1958 La discreción 1958 Creación del mundo o Microcosmos 1958 La despedida 1959 Exploración de las fuentes del río Orinoco 1959 Catedral vegetal 1959 El visitante 1959 Encuentro (La cita) 1959 Trovador 1959 Locomoción capilar 1959 El Minotauro 1959 Ritos extraños 1960 Mimetismo 1960 Esquiador (Viajero) 1960 Mujer saliendo del psicoanalista 1960 Visita al cirujano plástico 1960 Hacia la torre 1960 Tránsito en espiral 1960 Nacer de nuevo 1961 Vampiro 1961 Planta insumisa 1961 Tejiendo el manto terrestre 1961 Monja en bicicleta 1961 Personaje 1962 Vampiros vegetarianos 1962 Fenómeno de ingravidez 1962 Tránsito espiral 1962 Taxi acuático 1962 Arquitectura vegetal 1962 Caballero encantado 1962 Emigrantes 1963 Naturaleza muerta resucitando 1963 Los amantes |

代表作品リスト 2017年から18年にかけてメキシコで開催されたヴァロ展 1935 夢を織る 1938 夢のように 1938 『山の魂』または『山の精霊』(The Souls of the Mountains or The Spirits of the Mountains 1942 魔法の洞窟 1943 ケンタウロスの塔の風景 1944年 形而上学の車輪 1944年 冬 1945年 友人アグスティン・ラサロへ 1947年 マラリア(トンボ) 1947年 実験室 1947年 大鎌を持った男(市場での死) 1947年 戦い 1947年 ティフォラル 1947年 不眠症 1947 ジプシーとハーレクイン 1947年 アミビア症あるいは野菜たち 1948年 痛み 1948年 野菜人形 1948年 赤い服の女 1948年 リウマチの痛み I 1948年 リウマチの痛みII 1948年 冬の寓意 1950年 月の谷 1950年 座った女 1951年 トンボのキャラクター 1951年 愛の庭 1953年 予感 1954年 宇宙の時間 1955 共感あるいは猫の狂犬病 1955 無用の科学/錬金術師 1955年 瞑想する隠者 1955 黙示録あるいは時計職人 1955年 トランスワールド 1955年 破裂 1955年 パイパー 1955年 猫の楽園 1955年 アストラル光線による創造 1956年 淑女たちの幸福のために 1956年 隠された存在の通り 1956年 3つの運命 1956年 魔法の飛行 1956 スター・ハンター 1956 宇宙エネルギー 1956 ファインディング 1956 ザ・アンセスターズ/ポエム 1956 曲芸師/吟遊詩人 1956 ザ・ウィーバー 1956 赤い織女 1956年 ヴェローナの織女 1957 鳥の創造 1957 ドレスメーカー 1957年 ワインディング・パス 1957年 球体を持つ女 1957年 安息日に行く魔女 1957年 月の反射 1957年 シダの猫 1957年 ピラールとクララ・アルヌスの肖像 1957年 さすらい人 1957年 エリクサー 1957 もうひとつの時計 1958年 ステラ・パピラ 1958年 予期せぬ訪問 1958年 裁量 1958年 世界の創造、あるいは小宇宙 1958年 別れ 1959年 オリノコ川の源流探検 1959年 野菜の大聖堂 1959年 訪問者 1959年 出会い(約束) 1959年 トラブル・ドール 1959年 毛管運動 1959年 ミノタウロス 1959年 奇妙な儀式 1960年 ミミクリー 1960年 スキーヤー(旅人) 1960年 精神分析医を去る女 1960年 形成外科医を訪ねる 1960年 塔に向かって 1960年 スパイラル・トランジット 1960年 生まれ変わる 1961年 吸血鬼 1961年 服従しない植物 1961年 大地のマントを編む 1961年 自転車に乗った修道女 1961年 キャラクター 1962 ベジタリアン吸血鬼 1962年 無重量現象 1962年 スパイラル・トランジット 1962 水上タクシー 1962 野菜建築 1962 魅惑の騎士 1962 移民 1963 復活する静物 1963 恋人たち |

|

Remedios_Varo_Ruptura_1955.jpg |

|

Remedios_Varo_renacer_1960.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Remedios Varo, Exploration of

the Source of the Orinoco River, 1959. |

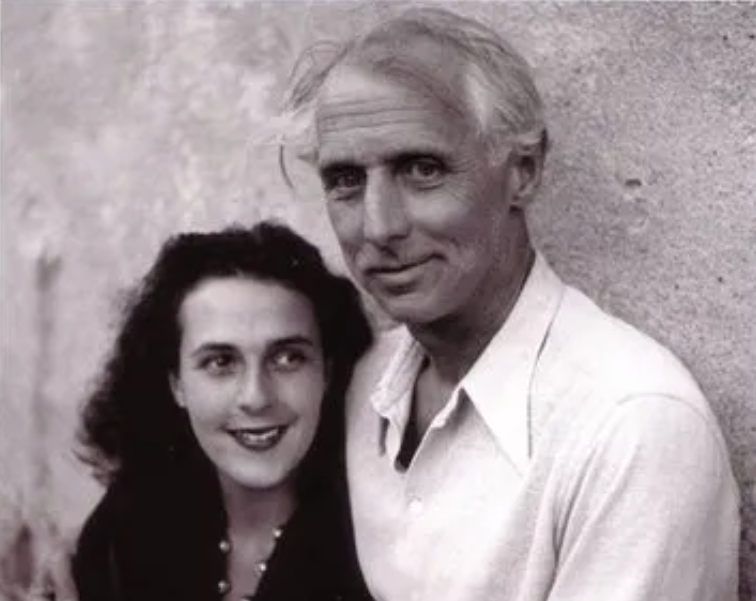

Leonora

Carrington キャンリントンとマックス・エルンスト |

レオノーラ・キャリントン 2011年のレオノーラ・キャリントン(The New Yorker) |

| Mary Leonora Carrington OBE (6

April 1917 – 25 May 2011[1]) was a British-born surrealist painter and

novelist. She lived most of her adult life in Mexico City and was one

of the last surviving participants in the surrealist movement of the

1930s.[2] Carrington was also a founding member of the women's

liberation movement in Mexico during the 1970s.[3][4] |

メ

アリー・レオノーラ・キャリントン(Mary

Leonora Carrington OBE、1917年4月6日 -

2011年5月25日[1])は、イギリス生まれのシュルレアリスムの画家、小説家。キャリントンはまた、1970年代のメキシコにおける女性解放運動の

創設メンバーでもあった[3][4]。 |

| Early life Mary Leonora Carrington was born at Westwood House in Clayton Green,[5][6][7] England, into a Roman Catholic family.[8] Her father, Harold Wylde Carrington, was a wealthy textile manufacturer,[6][9] and her mother, Marie (née Moorhead), was from Ireland.[10][6] She had three brothers: Patrick, Gerald, and Arthur.[11][12] From 1920 until 1927 she lived at Crookhey Hall, a Gothic Revival mansion in Cockerham, which exerted a great influence on her imagination.[11] Educated by governesses, tutors, and nuns, she was expelled from two schools, including New Hall School in Chelmsford[13] for her rebellious behaviour, until her family sent her to Florence, where she attended Mrs Penrose's Academy of Art. She also, briefly, attended St Mary's convent school in Ascot.[14] In 1927, at the age of ten, she saw her first Surrealist painting in a Left Bank gallery in Paris and later met many Surrealists, including Paul Éluard.[15] Her father opposed her career as an artist, but her mother encouraged her. She returned to England and was presented at Court, but according to her, she brought a copy of Aldous Huxley's Eyeless in Gaza (1936) to read instead. In 1935, she attended the Chelsea School of Art in London for one year, and with the help of her father's friend Serge Chermayeff, she was able to transfer to the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts established by the French modernist Amédée Ozenfant in London (1936–38).[11][16] She became familiar with Surrealism from a copy of Herbert Read's book, Surrealism (1936), given to her by her mother,[12] but she received little encouragement from her family to forge an artistic career. The Surrealist poet and patron Edward James was the champion of her work in Britain; James bought many of her paintings and arranged a show in 1947 for her work at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. Some works are still hanging at James' former family home, currently West Dean College in West Dean, West Sussex.[17] |

生い立ち メアリー・レオノーラ・キャリントンは、イギリスのクレイトン・グリーン[5][6][7]にあるウェストウッド・ハウスで、ローマ・カトリックの家庭に 生まれた[8]。 父のハロルド・ウィルド・キャリントンは裕福な織物製造業者[6][9]で、母のマリー(旧姓ムーアヘッド)はアイルランド出身だった[10][6]: 1920年から1927年までコッカハムにあるゴシック・リバイバル様式の邸宅クルックヘイ・ホールで暮らし、彼女の想像力に大きな影響を与えた [11]。 家庭教師、家庭教師、修道女による教育を受けた彼女は、反抗的な言動が原因でチェルムスフォードのニュー・ホール・スクール[13]を含む2つの学校から 追放された。1927年、10歳のとき、パリの左岸の画廊で初めてシュルレアリスムの絵画を目にし、後にポール・エリュアールなど多くのシュルレアリスト と出会う[15]。イギリスに戻り、宮廷に献上されたが、本人によると、代わりにオルダス・ハクスリーの『ガザの目なし』(1936年)を持参して読んだ という。1935年、ロンドンのチェルシー美術学校に1年間通い、父の友人セルジュ・シェルマエフの援助で、フランスのモダニスト、アメデ・オゼンファン がロンドンに設立したオゼンファン美術アカデミーに編入することができた(1936-38年)[11][16]。 母親から贈られたハーバート・リードの著書『シュルレアリスム』(1936年)からシュルレアリスムに親しむようになるが[12]、芸術家としてのキャリ アを築くために家族から励まされることはほとんどなかった。シュルレアリスムの詩人でありパトロンであったエドワード・ジェームズは、イギリスにおける彼 女の作品の擁護者であった。ジェームズは彼女の絵画の多くを購入し、1947年にはニューヨークのピエール・マティス・ギャラリーで彼女の作品展を開催し た。いくつかの作品は、ジェームズのかつての実家、現在はウェスト・サセックス州ウェスト・ディーンにあるウェスト・ディーン・カレッジに飾られている [17]。 |

| Association with Max Ernst In 1936 Carrington saw the work of the German surrealist Max Ernst at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London and was attracted to the Surrealist artist before she even met him. In 1937 Carrington met Ernst at a party held in London.[18]: 44 The artists bonded and returned together to Paris, where Ernst promptly separated from his wife. In 1938 they left Paris and settled in Saint Martin d'Ardèche in southern France. The new couple collaborated and supported each other's artistic development. The two artists created sculptures of guardian animals (Carrington created a plaster horse head, while Ernst created his birds) to decorate their home in Saint Martin d'Ardèche. In 1939 Carrington and Ernst painted portraits of each other. Both capture the ambivalence in their relationship, but whereas Ernst's The Triumph of Love features both artists in the composition,[19] Carrington's Portrait of Max Ernst focused solely on Ernst and is laced with heavy symbolisms.[11] The portrait was not her first Surrealist work; between 1937 and 1938 Carrington painted Self-Portrait, also called The Inn of the Dawn Horse, now exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sporting white jodhpurs and a wild mane of hair, Carrington is perched on the edge of a chair in this curious, dreamlike scene, her hand outstretched toward a prancing hyena and her back to a tailless rocking horse flying behind her. With the outbreak of World War II Ernst, who was German, was arrested by the French authorities for being a "hostile alien". With the intercession of Paul Éluard, and other friends, including the American journalist Varian Fry, he was discharged a few weeks later. Soon after the Nazis invaded France, Ernst was arrested again, this time by the Gestapo, because his art was considered by the Nazis to be "degenerate". He managed to escape and flee to the United States with the help of Peggy Guggenheim, who was a sponsor of the arts.[20] After Ernst's arrest Carrington was devastated and agreed to go to Spain with a friend, Catherine Yarrow.[21] She stayed with family friends in Madrid until her paralyzing anxiety and delusions led to a psychotic break and she was admitted into an asylum. She was given electroconvulsive therapy and was treated with the drugs Cardiazol (a powerful convulsant), and Luminal (a barbiturate).[22][23] She was released from the asylum into the care of a keeper, and was told that her parents had decided to send her to a sanatorium in South Africa. En route to South Africa, she stopped in Portugal, where she made her escape. She went to the Mexican Embassy to find Renato Leduc, a poet and Mexican Ambassador. Leduc was a friend of Pablo Picasso (they knew each other from bull fights) and agreed to a marriage of convenience with Carrington so that she would be accorded the immunity given to a diplomat's wife.[24] The pair divorced in 1943.[24] Meanwhile, Ernst had married Peggy Guggenheim in New York in 1941. That marriage ended a few years later. Ernst and Carrington never resumed their relationship. |

マックス・エルンストとの交流 1936年、キャリントンはロンドンで開催された国際シュルレアリスム展でドイツのシュルレアリスト、マックス・エルンストの作品を目にし、彼と出会う前 からシュルレアリスムの芸術家に惹かれていた。1937年、キャリントンはロンドンで開かれたパーティーでエルンストに出会う[18]: 44 二人は結ばれ、一緒にパリに戻ったが、エルンストはすぐに妻と別居。1938年、ふたりはパリを離れ、南フランスのサン・マルタン・ダルデシュに居を構え た。新しい夫婦は協力し合い、互いの芸術的成長を支え合った。ふたりの芸術家は、サン・マルタン・ダルデッシュの自宅を飾るために、守護動物の彫刻(キャ リントンは石膏の馬の頭部を、エルンストは鳥を制作)を制作した。1939年、キャリントンとエルンストは互いの肖像画を描いた。この肖像画は彼女の最初 のシュルレアリスム作品ではなく、1937年から1938年にかけてキャリントンは『自画像』を描いており、現在メトロポリタン美術館に展示されている 『夜明けの馬の宿』とも呼ばれている。白いジョッパーズパンツを履き、ワイルドなたてがみの髪を結ったキャリントンは、この不思議な夢のような場面で椅子 の縁に腰掛け、跳ね回るハイエナに向かって手を広げ、背後を飛ぶ無尾のロッキング・ホースに背を向けている。 第二次世界大戦が勃発すると、ドイツ人であったエルンストは「敵性外国人」としてフランス当局に逮捕された。ポール・エリュアールや、アメリカ人ジャーナ リストのヴァリアン・フライをはじめとする友人たちの取りなしで、彼は数週間後に除隊した。ナチスがフランスに侵攻した直後、エルンストは再びゲシュタポ に逮捕された。エルンストは、芸術のスポンサーであったペギー・グッゲンハイムの助けを借りて、なんとか脱出し、アメリカに逃れた[20]。 エルンストが逮捕された後、キャリントンは打ちのめされ、友人のキャサリン・ヤローとスペインに行くことに同意した[21]。麻痺した不安と妄想が精神病 の発作を引き起こし、精神病院に収容されるまで、彼女はマドリードの家族の友人の家に滞在した。彼女は電気けいれん療法を受け、カルディアゾール(強力な けいれん薬)、ルミナル(バルビツール酸薬)の治療を受けた。南アフリカに向かう途中、彼女はポルトガルに立ち寄り、そこで逃亡を図る。彼女はメキシコ大 使館に行き、詩人でメキシコ大使のレナト・レドゥックを探した。ルドゥックはパブロ・ピカソの友人であり(彼らは闘牛で知り合った)、外交官の妻に与えら れる免責特権が与えられるよう、キャリントンとの便宜的な結婚に同意した[24]。その結婚は数年後に終わった。エルンストとキャリントンが関係を再開す ることはなかった。 |

Mexico How Doth the Little Crocodile on Paseo de la Reforma. The statue was donated to Mexico City by Carrington in 2000 and was moved to its current location in 2006.[25] After spending a year in New York, Leduc and Carrington went to Mexico, where many European artists fled in search of asylum, in 1942, which she grew to love and where she lived, on and off, for the rest of her life.[24] When Carrington first came to Mexico she was preceded by the success of surrealist exhibitions which allowed her to create many connections within the surrealist movement. Her connections within these surrealist circles were influential in opening artistic doors that had long been closed to Mexican artists. After living in Mexico for seven years, Leonora Carrington held her first solo exhibition at the Galeria Clardecor. Much of the initial response from the public was very encouraging, and for months afterwards the press published positive and approving critic reviews.[26] After spending part of the 1960s in New York City, Carrington lived and worked in Mexico once again.[7] While in Mexico she was asked, in 1963, to create a mural which she named El Mundo Magico de los Mayas,[27] and which was influenced by folk stories from the region.[28] The mural is now located in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City. In 1973 Carrington designed Mujeres conciencia, a poster for the Women's Liberation movement in Mexico, depicting a 'new Eve'.[29] In the 1970s women artists of previous waves and generations responded to the more liberal climate and movement of the array of feminist waves. Many pushed the issues of women's liberation and consciousness within their work while others spoke out on issues instead of making art.[30] She frequently spoke about women's "legendary powers" and the need for women to take back "the rights that belonged to them." Many artists involved in the Surrealism regarded women to be useful as muses but not seen as artists in their own right. Carrington was adopted as a femme-enfant by the Surrealists because of her rebelliousness against her upper-class upbringing.[31] Carrington primarily focused on psychic freedom in the belief that such freedom cannot be achieved until political freedom is also accomplished.[3] Through these beliefs Carrington understood that "greater cooperation and sharing of knowledge between politically active women in Mexico and North America" was important for emancipation.[3] Carrington's political commitment led to her winning the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Women's Caucus for Art convention in New York in 1986.[3] Throughout the decade women identified and defined an array of relationships to feminist and mainstream concepts and concerns. Continuing through the decade women continued to question the meaning of existence through form and material.[30] I didn't have time to be anyone's muse... I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist. — Leonora Carrington[32] Second marriage and children She later married Emerico Weisz (nicknamed "Chiki"), born in Hungary in 1911, a photographer and the darkroom manager for Robert Capa during the Spanish Civil War. Together they had two sons: Gabriel, an intellectual and poet, and Pablo, a doctor and Surrealist artist. Chiki Weisz died 17 January 2007, at home. He was 97 years old. Death Leonora Carrington died on 25 May 2011, aged 94, in a hospital in Mexico City as a result of complications arising from pneumonia.[33][34] Her remains were buried at Panteón Inglés (English Cemetery) in Mexico City.[35] |

メキシコ パセオ・デ・ラ・レフォルマにある小さなワニの像。この像は2000年にキャリントンによってメキシコシティに寄贈され、2006年に現在の場所に移され た[25]。 ニューヨークで1年を過ごした後、ルドゥックとキャリントンは1942年、多くのヨーロッパ人芸術家が亡命を求めて逃亡したメキシコに行き、そこで彼女は メキシコを愛するようになり、残りの生涯をここで過ごしたり暮らしたりした[24]。 キャリントンが初めてメキシコに来たとき、彼女はシュルレアリスムの展覧会の成功に先行していた。こうしたシュルレアリスム界における彼女のつながりは、 長い間メキシコのアーティストに閉ざされていた芸術の扉を開く上で大きな影響力を持った。メキシコに7年間住んだ後、レオノーラ・キャリントンはガレリ ア・クラルデコールで初めての個展を開いた。一般の人々からの最初の反応の多くは非常に励みになるもので、その後数ヶ月間、マスコミは肯定的で承認的な批 評家の批評を掲載した[26]。 1960年代の一部をニューヨークで過ごした後、キャリントンは再びメキシコに住み、仕事をした[7]。メキシコ滞在中の1963年、彼女は壁画の制作を 依頼され、「エル・ムンド・マジコ・デ・ロス・マヤ」と名付けた[27]。 1973年、キャリントンはメキシコの女性解放運動のためのポスター「Mujeres conciencia」をデザイン。女性の解放と意識の問題を作品の中で押し進める者が多かった一方で、芸術を作る代わりに問題について発言する者もいた [30]。シュルレアリスムに関わる多くの芸術家たちは、女性をミューズとして重宝していたが、本来の芸術家としては見ていなかった。キャリントンは、上 流階級で育ったことに対する反抗心から、シュルレアリストたちにファム・アンファントとして採用された[31]。 キャリントンは、政治的自由も達成されない限り、そのような自由は達成されないという信念のもと、主に精神的自由に焦点を当てた[3]。このような信念を 通して、キャリントンは「メキシコと北米の政治的に活動的な女性たちの間で、より大きな協力と知識の共有」が解放のために重要であると理解していた。 [3]キャリントンの政治的コミットメントは、1986年にニューヨークで開催されたWomen's Caucus for Artの大会で生涯功労賞を受賞することにつながった。この10年間、女性たちは形や素材を通して存在の意味を問い続けた[30]。 誰かのミューズになる時間はなかった...。家族に反抗し、アーティストになることを学ぶので精一杯だった」。 - レオノーラ・キャリントン[32] 再婚と子供 彼女はその後、1911年にハンガリーで生まれた写真家で、スペイン内戦中にロバート・キャパの暗室マネージャーを務めたエメリコ・ヴァイシュ(愛称「チ キ」)と結婚。二人の間には二人の息子がいた: ガブリエルは知識人で詩人、パブロは医者でシュルレアリスムの芸術家。チキ・ワイズは2007年1月17日、自宅で死去。享年97歳。 死去 レオノーラ・キャリントンは2011年5月25日、肺炎による合併症のためメキシコシティの病院で94歳で死去した[33][34]。 遺骨はメキシコシティのパンテオン・イングレス(イギリス人墓地)に埋葬された[35]。 |

| Themes and major works Leonora Carrington, The Magical World of the Mayans (1963-1964), National Anthropology Museum Carrington stated that: "I painted for myself...I never believed anyone would exhibit or buy my work."[3] She was not interested in the writings of Sigmund Freud, as were other Surrealists in the movement. She instead focused on magical realism and alchemy and used autobiographical detail and symbolism as the subjects of her paintings. Carrington was interested in presenting female sexuality as she experienced it, rather than as that of male surrealists' characterization of female sexuality.[36] Carrington's work of the 1940s is focused on the underlying theme of women's role in the creative process.[3] Carrington's work is identified and compared with the surrealist movement. Within the surrealist movement, there was a strong exploration of the woman's body combined with the mysterious forces of nature. During this time women artists correlated the feminine figure with creative nature while using ironic stances.[37] When painting, she used small brushstroke techniques building up layers in a meticulous manner, creating rich imagery.  In Self-Portrait (1937-1938) Carrington offers her own interpretation of female sexuality by looking toward her own sexual reality rather than theorizing on the subject, as was custom by other Surrealists in the movement. Carrington's move away from the characterization of female sexuality subverted the traditional male role of the Surrealist movement. Self-Portrait (1937–38) also offers insight into Carrington's interest in the "alchemical transformation of matter and her response to the Surrealist cult of desire as a source of creative inspiration."[3] Self Portrait further explores the duality that comes with being a woman. This concept of duality is explored by Carrington using a mirror to assert duality of the self and the self being an observer with being observed.[38] The hyena depicted in Self-Portrait (1937–38) joins both male and female into a whole, metaphoric of the worlds of the night and the dream.[3] The symbol of the hyena is present in many of Carrington's later works, including "La Debutante" in her book of short stories The Oval Lady.[39] Three years after being released from the asylum and with the encouragement of André Breton,[40] Carrington wrote about her psychotic experience in her memoir Down Below.[41] In this, she explained how she had a nervous breakdown, didn't want to eat, and left Spain. This is where she was imprisoned in an asylum. She illustrates all that was done to her: ruthless institutional therapies, sexual assault, hallucinatory drugs, and unsanitary conditions. It has been suggested that the events of the book should not be taken literally, given Carrington's state at the time of her institutionalization; however, recent authors have sought to examine the details of her institution in order to discredit this theory.[42][43] She also created art to depict her experience, such as her Portrait of Dr. Morales and Map of Down Below.[44] Her book The Hearing Trumpet deals with aging and the female body. It follows the story of older women who, in the words of Madeleine Cottenet-Hage in her essay "The Body Subversive: Corporeal Imagery in Carrington, Prassinos and Mansour", seek to destroy the institutions of their imaginative society to usher in a "spirit of sisterhood."[45][46]: 86–87 The Hearing Trumpet also criticizes the shaming of the nude female body, and it is believed to be one of the first books to tackle the notion of gender identity in the twentieth century.[46] Carrington's views situated motherhood as a key experience to femininity. Carrington stated, "We, women, are animals conditioned by maternity.... For female animals love-making, which is followed by the great drama of the birth of a new animal, pushes us into the depths of the biological cave." While this may seem to differ from certain modern feminist perspectives, the cave, of which Carrington offers many versions, is the setting for a symbolic coming to life, not an actual birth-giving ("and this can mean aquatic or maternal, this can be double, in my opinion"; mère and mer, following Simone de Beauvoir).[47] Carrington had an interest in animals, myth, and symbolism. This interest became stronger after she moved to Mexico and started a relationship with the émigré Spanish artist Remedios Varo. The two studied alchemy, the kabbalah, and the post-classic Mayan mystical writings, Popol Vuh.[48][49] The first important exhibition of her work appeared in 1947 at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York City. Carrington was invited to show her work in an international exhibition of Surrealism, where she was the only female English professional painter. She became a celebrity almost overnight. In Mexico, she authored and successfully published several books.[50] Sculpture by Carrington on display near the University of Guanajuato during the 2015 Festival Internacional Cervantino The first major exhibition of her work in UK for twenty years took place at Chichester's Pallant House Gallery, West Sussex, from 17 June to 12 September 2010, and subsequently in Norwich at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, as part of a season of major international exhibitions called Surreal Friends that celebrated women's role in the Surrealist movement. Her work was exhibited alongside pieces by her close friends, the Spanish painter Remedios Varo (1908–1963) and the Hungarian photographer Kati Horna (1912–2000).[51]: 131 In 2013 Carrington was the subject of a major retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin. Titled The Celtic Surrealist, it was curated by Sean Kissane and examined Carrington's Irish background to illuminate many cultural, political and mythological themes present in her work.[52] Carrington's art often depicts horses, as in her Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) and the painting The Horses of Lord Candlestick.[11] Her fascination with drawing horses began in her childhood.[11] Horses also appear in her writings. In her first published short story, "The House of Fear", Carrington portrays a horse in the role of a psychic guide to a young heroine.[53] In 1935, Carrington's first essay, "Jezzamathatics or Introduction to the Wonderful Process of Painting", was published before her story "The Seventh Horse".[11] Carrington often used codes of words to dictate interpretation in her artwork. "Candlestick" is a code that she commonly used to represent her family, and the word "lord" for her father.[11] Carrington contributed to the 1973 Mexican horror film The Mansion of Madness directed by Juan López Moctezuma, loosely based on the Edgar Allan Poe short story The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether. She supervised the artistic design for the sets and costumes, with one of her sons, Gabriel Weisz. The repeated appearance of a white horse, Carrington's alter ego, and the elaborate surreal feasts and costumes show her influence and vision. In 2005 Christie's auctioned Carrington's Juggler (El Juglar),[54] and the realised price was US$713,000, setting a new record for the highest price paid at auction for a living surrealist painter. Carrington painted portraits of the telenovela actor Enrique Álvarez Félix,[55][56] son of actress María Félix, a friend of Carrington's first husband. In 2015, Carrington was honoured through a Google Doodle commemorating her 98th birthday. The Doodle was based on her painting, How Doth the Little Crocodile, drawn in surrealist style.[57] The painting was inspired by a poem in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, and this painting was eventually turned into Cocodrilo located on Paseo de la Reforma.[58] |

テーマと主な作品 レオノーラ・キャリントン『マヤ人の魔法の世界』(1963-1964年、国立人類学博物館蔵 キャリントンは次のように述べている: 「私は自分のために描いたのであって、誰かが私の作品を展示したり買ったりするとは思っていなかった」[3] 。その代わりに、魔術的リアリズムと錬金術に焦点を当て、自伝的なディテールと象徴主義を絵画の主題として用いた。1940年代のキャリントンの作品は、 創造的プロセスにおける女性の役割という根本的なテーマに焦点を当てている[3]。 キャリントンの作品はシュルレアリスム運動と特定され、比較される。シュルレアリスム運動の中では、自然の神秘的な力と組み合わされた女性の身体の強い探 求があった。この時期、女性芸術家たちは、アイロニカルなスタンスを用いながら、女性的な姿を創造的な自然と関連付けていた[37]。 絵画を描くとき、彼女は小さな筆致の技法を用い、綿密な方法で層を積み重ね、豊かなイメージを生み出した。  キャリントンは『自画像』(1938年)の中で、この運動における他のシュルレアリストたちの習慣のように、主題について理論化するのではなく、彼女自身 の性的現実を見つめることによって、女性のセクシュアリティについて独自の解釈を提示している。女性のセクシュアリティの特徴付けから離れたキャリントン の動きは、シュルレアリスム運動の伝統的な男性の役割を覆した。自画像』(1937-38年)はまた、キャリントンの「物質の錬金術的変容への関心と、創 造的インスピレーションの源としての欲望を崇拝するシュルレアリスムへの反応」[3]を洞察している。自画像』(1937-38)に描かれたハイエナは、 男性と女性の両者を一体化させ、夜と夢の世界を隠喩している[3]。ハイエナのシンボルは、彼女の短編集『オーバル・レディ』の「ラ・デビュタント」な ど、キャリントンのその後の作品の多くに登場する[39]。 精神病院から釈放された3年後、アンドレ・ブルトンの勧めもあり、キャリントンは回想録『Down Below』[41]の中で精神病の体験について書いている。そこで彼女は精神病院に収監された。冷酷な施設での治療、性的暴行、幻覚作用のある薬物、不 衛生な環境など、彼女に行われたすべてのことが描かれている。キャリントンが施設に収容された当時の状態を考えると、この本の出来事は文字通りに捉えるべ きではないと示唆されてきたが、最近の著者はこの説を否定するために、彼女の施設の詳細を検証しようとしている[42][43]。彼女はまた、『モラレス 博士の肖像』や『下界の地図』のような、自分の経験を描いた芸術作品を制作した[44]。 彼女の著書『The Hearing Trumpet』は、老化と女性の身体を扱っている。この本は、マドレーヌ・コッテネ=ヘイジのエッセイ「破壊的な身体」の言葉を借りれば、年老いた女性 たちの物語を追っている: キャリントン、プラシノス、マンスールにおける身体的イメージ」[45][46]: 86-87 『耳をすませば』はまた、裸体の女性の身体を辱めることを批判しており、20世紀におけるジェンダー・アイデンティティの概念に取り組んだ最初の本のひと つであると考えられている。キャリントンは「われわれ女性は母性によって条件づけられた動物である。メスの動物にとって、新しい動物の誕生という大いなる ドラマに続く愛の営みは、私たちを生物学的洞窟の深みへと押しやる。" これはある種の現代的なフェミニズムの視点とは異なるように思われるかもしれないが、キャリントンが多くのヴァージョンを提示する洞窟は、象徴的な生命の 誕生のための舞台であって、実際の出産を意味するものではない(「そしてこれは水生的な意味にも母性的な意味にもなり、私の考えではこれは二重の意味にな りうる」;シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールに倣ってmèreとmer)[47]。 キャリントンは動物、神話、象徴主義に興味を持っていた。彼女がメキシコに移り住み、移住してきたスペイン人アーティストのレメディオス・ヴァロと交際を 始めてから、この関心はより強くなった。二人は錬金術、カバラ、そして古典以降のマヤの神秘的な書物であるポポル・ヴフを研究した[48][49]。 彼女の作品の最初の重要な展覧会は、1947年にニューヨークのピエール・マティス・ギャラリーで開催された。キャリントンは、シュルレアリスムの国際展 に招待され、そこで唯一のイギリス人女性プロ画家として作品を発表した。彼女は一夜にして有名人となった。メキシコでは数冊の本を出版し、成功を収めた [50]。 2015年のFestival Internacional Cervantinoの期間中、グアナファト大学近くに展示されたキャリントンの彫刻作品 2010年6月17日から9月12日までウェスト・サセックス州のチチェスターのパラント・ハウス・ギャラリーで、その後ノリッチのセインズベリー・セン ター・フォー・ヴィジュアル・アーツで、シュルレアリスム運動における女性の役割を称える「シュルリアル・フレンズ」と呼ばれる大規模な国際展の一環とし て、20年ぶりに英国で彼女の作品の大規模な展覧会が開催された。彼女の作品は、親しい友人であったスペインの画家レメディオス・ヴァロ(1908- 1963)とハンガリーの写真家カティ・ホルナ(1912-2000)の作品とともに展示された[51]: 131 2013年、キャリントンはダブリンのアイルランド近代美術館で大規模な回顧展の対象となった。The Celtic Surrealist(ケルトのシュルレアリスト)」と題されたこの回顧展は、ショーン・キセインによってキュレーションされ、キャリントンの作品に存在 する多くの文化的、政治的、神話的なテーマを照らし出すために、キャリントンのアイルランドの背景を検証した[52]。 キャリントンの芸術は、彼女の自画像(夜明けの馬の宿)や絵画『The Horses of Lord Candlestick(キャンドルスティック卿の馬)』のように、しばしば馬を描いている[11]。馬を描くことへの彼女の魅力は、幼少期に始まった。 1935年、キャリントンの最初のエッセイ "Jezzamathatics or Introduction to the Wonderful Process of Painting "が "The Seventh Horse "の前に出版された。「燭台」は彼女が家族を表すためによく使った暗号であり、「主君」という言葉は彼女の父親を表している[11]。 キャリントンは、エドガー・アラン・ポーの短編小説『タル博士とフェザー教授のシステム』を大まかに基にした、フアン・ロペス・モクテスマ監督の1973 年のメキシコのホラー映画『狂気の館』に貢献。彼女は息子の一人、ガブリエル・ワイズとともにセットと衣装の美術デザインを監修した。キャリントンの分身 である白馬が繰り返し登場し、手の込んだ超現実的な祝宴や衣装は、彼女の影響とビジョンを示している。 2005年、クリスティーズはキャリントンの《手品師(El Juglar)》をオークションに出品し[54]、実現価格は71万3,000米ドルで、存命のシュルレアリスム画家のオークションでの最高落札価格の新 記録を樹立した。キャリントンは、キャリントンの最初の夫の友人であった女優マリア・フェリックスの息子で、テレノベラ俳優のエンリケ・アルバレス・フェ リックスの肖像画を描いた[55][56]。 2015年、キャリントンは98歳の誕生日を記念してGoogle Doodleで表彰された。このDoodleは、シュルレアリスム様式で描かれた彼女の絵画『How Doth the Little Crocodile』に基づいていた[57]。この絵画はルイス・キャロルの『不思議の国のアリス』の詩からインスピレーションを得ており、この絵画は最 終的にパセオ・デ・ラ・レフォルマにあるココドリロになった[58]。 |

| Legacy and influence Carrington is credited with feminising surrealism. Her paintings and writing brought a woman's perspective to what had otherwise been a largely male-dominated artistic movement. Carrington demonstrated that women should be seen as artists in their own right and not to be used as muses by male artists.[59][60] In 2022, the 59th International Art Exhibition was titled The Milk of Dreams. This name is borrowed from a book by Carrington, in which, as Cecilia Alemani says she, "describes a magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination, and where everyone can change, be transformed, become something and someone else."[61] Carrington's life inspired Out of This World: The Surreal Art of Leonora Carrington, a children's nonfiction book written by Michelle Markell and illustrated by Amanda Hall and which tells the story of Carrington's life and art as she pursues her creative talents and breaks with 20-century conventions about the ways in which an upper-class women and debutants should behave.[62] Carrington and her son were the subject of the experimental short film Leonora and Gabriel: An Instant. The film was made by Lizet Benrey at Carrington's residence in Mexico City. Carrington discussed the art in her home and life as a surrealist. The film premiered in 2012 at the San Diego Latino Film Festival.[63] |

遺産と影響 キャリントンはシュルレアリスムを女性化したと言われている。彼女の絵画や文章は、それまで男性優位の芸術運動であったシュルレアリスムに女性の視点をも たらした。キャリントンは、女性が男性芸術家のミューズとして利用されるのではなく、自分自身の権利において芸術家として見られるべきであることを示した [59][60]。 2022年、第59回国際美術展のタイトルは「夢のミルク」となった。この名前はキャリントンの著書から拝借したもので、その中でセシリア・アレマーニが 言うように、「想像力のプリズムを通して人生が常に再認識され、誰もが変化し、変容し、何か、そして誰かになることができる魔法のような世界が描かれてい る」[61]。 キャリントンの人生は、『Out of This World: ミシェル・マーケルが書き、アマンダ・ホールが挿絵を担当した児童向けノンフィクション『The Surreal Art of Leonora Carrington』は、上流階級の女性やデビューしたての女性がどう振る舞うべきかという20世紀の慣習を破り、創造的な才能を追求するキャリントン の人生と芸術を描いた物語である[62]。 キャリントンと彼女の息子は、実験的な短編映画『Leonora and Gabriel: An Instant』の題材となった。この映画はリゼット・ベンレイによってメキシコシティのキャリントン邸で制作された。キャリントンは自宅のアートとシュ ルレアリストとしての人生について語った。この映画は2012年にサンディエゴ・ラティーノ映画祭でプレミア上映された[63]。 |

| Women

surrealists |

|

+++

Detalle de La huida, 1961.

Alegoria del invierno, 1948

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

本研究は「中米・カリブにお

ける感覚のエスノグラフィーに関する実証研究」研究代表者:滝奈々子の研究成果に負っている

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆