直観

Intuition

☆ 直感(intuition)とは、意識的な推論に頼ることなく、また説明を必要とすることなく、知識を獲得する能力のことである。無意識の知識への直接アクセス、無意識の認識、 直感、内なる感覚、無意識のパターン認識への内なる洞察、意識的な推論を必要とせずに本能的に何かを理解する能力など、さまざまな分野で「直感」という言 葉が非常に異なる意味で使われているが、これらに限定されるものではない。

★直観主義(Intuitionism)についての説明はこちらよりタグジャンプします。数理哲学において、直観主義、または新直観主義(前直観主義とは対照的)とは、数学が客観的現実に存在すると主張される基本原理の発見ではなく、純粋に人 間の建設的な精神活動の結果であると考えられるアプローチである。すなわち、論理学と数学は、客観的現実の深い特性が明らかにされ、適用される分析 的活動とはみなされず、その代わりに、客観的現実に独立した存在である可能性にかかわらず、より複雑な精神的構成を実現するために使用される内部的に一貫 性のある方法の適用とみなされる(→「直観主義」)。

| Intuition

is the ability to acquire knowledge, without recourse to conscious

reasoning or needing an explanation.[2][3] Different fields use the

word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to:

direct access to unconscious knowledge; unconscious cognition; gut

feelings; inner sensing; inner insight to unconscious

pattern-recognition; and the ability to understand something

instinctively, without any need for conscious reasoning.[4][5]

Intuitive knowledge tends to be approximate.[6] The word intuition comes from the Latin verb intueri translated as "consider" or from the late middle English word intuit, "to contemplate".[2][7] Use of intuition is sometimes referred to as responding to a "gut feeling" or "trusting your gut".[8] |

直

感とは、意識的な推論に頼ることなく、また説明を必要とすることなく、知識を獲得する能力のことである。無意識の知識への直接アクセス、無意識の認識、直

感、内なる感覚、無意識のパターン認識への内なる洞察、意識的な推論を必要とせずに本能的に何かを理解する能力など、さまざまな分野で「直感」という言葉

が非常に異なる意味で使われているが、これらに限定されるものではない。直感的な知識はおおよそのものになりがちである。 直観という言葉は、ラテン語で「考える」と訳される動詞intueri、または中世後期の英語intuit「熟考する」に由来する。直感を使うことは、「直感」に反応すること、あるいは「直感を信じること」と呼ばれることもある。 |

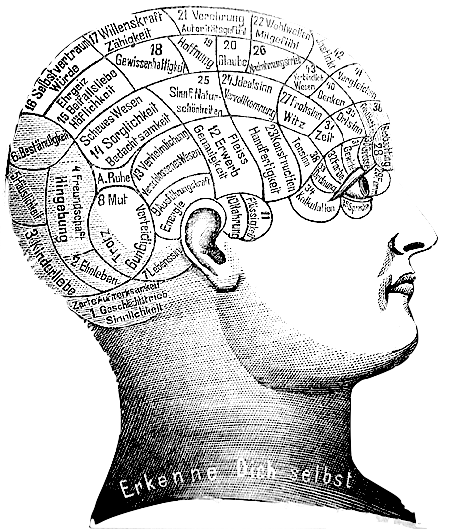

A

phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first

attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain. A

phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first

attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain. |

脳の骨相マッピング[1]-骨相学は、精神機能を脳の特定の部位と関連付ける最初の試みのひとつであった。 脳の骨相マッピング[1]-骨相学は、精神機能を脳の特定の部位と関連付ける最初の試みのひとつであった。 |

| Philosophy Both Eastern and Western philosophers have studied intuition. The discipline of epistemology deals with the concept. Eastern philosophy In the East intuition is mostly intertwined with religion and spirituality, and various meanings exist in different religious texts.[18] Hinduism In Hinduism, various attempts have been made to interpret how the Vedic and other esoteric texts regard intuition. For Sri Aurobindo, intuition comes under the realm of knowledge by identity. He describes the human psychological plane (often referred to as mana in Sanskrit) as having two natures: The first being its role in interpreting the external world (parsing sensory information), and the second being its role in generating consciousness. He terms this second nature "knowledge by identity."[19]: 68 Aurobindo finds that, as the result of evolution, the mind has accustomed itself to using certain physiological functions as its means of entering into relations with the material world; when people seek to know about the external world, they default to arriving at truths via their senses. Knowledge by identity, which currently only explains self-awareness, may extend beyond the mind and explain intuitive knowledge.[19]: 69–71 He says this intuitive knowledge was common to older humans (Vedic) and later was superseded by reason which currently organises our perception, thoughts, and actions and which resulted in a transition from Vedic thought to metaphysical philosophy and later to experimental science. He finds that this process, which seems to be decent,[clarification needed] is actually a circle of progress, as a lower faculty is being pushed to take up as much from a higher way of working.[clarification needed][19]: 75 He says that when self-awareness in the mind is applied to one's self and to the outer (other) self, this results in luminous self-manifesting identity;[jargon] and the reason also converts itself into the form of the self-luminous[jargon] intuitional knowledge.[19]: 72 [20][19]: 7 Osho believed human consciousness is in a hierarchy from basic animal instincts to intelligence and intuition, and humans being constantly living in that[ambiguous] conscious state often moving between these states depending on their affinity. He suggests that living in the state of intuition is one of the ultimate aims of humanity.[21] Advaita vedanta (a school of thought) takes intuition to be an experience through which one can come in contact with and experience Brahman.[22] Buddhism Buddhism finds intuition to be a faculty in the mind of immediate knowledge. Buddhism puts the term intuition beyond the mental process[clarification needed] of conscious thinking, as conscious thought cannot necessarily access subconscious information, or render such information into a communicable form.[23] In Zen Buddhism various techniques have been developed to help develop one's intuitive capability, such as koans – the resolving of which leads to states of minor enlightenment (satori). In parts of Zen Buddhism intuition is deemed a mental state between the Universal mind and one's individual, discriminating mind.[24] Western philosophy In the West, intuition does not appear as a separate field of study, but the topic features prominently in the works of many philosophers. Ancient philosophy Early mentions and definitions of intuition can be traced back to Plato. In his Republic he tries to define intuition as a fundamental capacity of human reason to comprehend the true nature of reality.[25] In his works Meno and Phaedo, he describes intuition as a pre-existing knowledge residing in the "soul of eternity", and as a phenomenon by which one becomes conscious of pre-existing knowledge. He provides an example of mathematical truths, and posits that they are not arrived at by reason. He argues that these truths are accessed using a knowledge already present in a dormant form and accessible to our intuitive capacity. This concept by Plato is also sometimes referred to as anamnesis. The study was later continued by his intellectual successors, the Neoplatonists.[26] Islam In Islam various scholars have varied interpretations of intuition (often termed as hadas, Arabic: حدس, "hitting correctly on a mark"), sometimes relating the ability to have intuitive knowledge to prophethood. Siháb al Din-al Suhrawadi, in his book Philosophy Of Illumination (ishraq), from following influences of Plato, finds that intuition is knowledge acquired through illumination and is mystical in nature; he also suggests mystical contemplation (mushahada) to bring about correct judgment.[27] Also influenced by Platonic ideas, Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) finds the ability to have intuition is a "prophetic capacity" and he describes intuition as knowledge obtained without intentionally acquiring it. He finds that regular knowledge is based on imitation while intuitive knowledge is based on intellectual certitude.[28] Early modern philosophy In his book Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes refers to an "intuition" (from the Latin verb intueor, which means "to see") as a pre-existing knowledge gained through rational reasoning or discovering truth through contemplation. This definition states that "whatever I clearly and distinctly perceive to be true is true";[29] this is commonly referred to as rational intuition[30] It is a component of a potential logical mistake called the Cartesian circle. Intuition and deduction, says Descartes, are the unique possible sources of knowledge of the human intellect;[31] the latter is a "connected sequence of intuitions",[32] each of which is a priori a self-evident, clear and distinct idea, before it is connected with the other ideas within a logical demonstration. Hume has a more ambiguous interpretation of intuition. Hume claims intuition is a recognition of relationships (relation of time, place, and causation). He states that "the resemblance" (recognition of relations) "will strike the eye" (which would not require further examination) but goes on to state, "or rather in mind"—attributing intuition to power of mind, contradicting the theory of empiricism.[33] Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant’s notion of "intuition" differs considerably from the Cartesian notion. It consists of the basic sensory information provided by the cognitive faculty of sensibility (equivalent to what might loosely be called perception). Kant held that our mind casts all of our external intuitions in the form of space, and all of our internal intuitions (memory, thought) in the form of time.[34] Contemporary philosophy Intuitions are customarily appealed to[clarification needed] independently of any particular theory of how intuitions provide evidence for claims. There are divergent accounts of what sort of mental state intuitions are, ranging from mere spontaneous judgment to a special presentation of a necessary truth.[35] Philosophers such as George Bealer have tried to defend appeals to intuition against Quinean doubts about conceptual analysis.[36] A different challenge to appeals to intuition comes from experimental philosophers, who argue that appeals to intuition must be informed by the methods of social science.[citation needed] The metaphilosophical assumption that philosophy ought to depend on intuitions has been challenged by experimental philosophers (e.g., Stephen Stich).[37] One of the main problems adduced by experimental philosophers is that intuitions differ, for instance, from one culture to another, and so it seems problematic to cite them as evidence for a philosophical claim.[38] Timothy Williamson responded to such objections against philosophical methodology by arguing that intuition plays no special role in philosophy practice, and that skepticism about intuition cannot be meaningfully separated from a general skepticism about judgment. On this view, there are no qualitative differences between the methods of philosophy and common sense, the sciences, or mathematics.[39] Others like Ernest Sosa seek to support intuition by arguing that the objections against intuition merely highlight a verbal disagreement[clarification needed].[40] Philosophy of mathematics and logic Intuitionism is a position advanced by L. E. J. Brouwer in philosophy of mathematics derived from Kant's claim that all mathematical knowledge is knowledge of the pure forms of the intuition—that is, intuition that is not empirical. Intuitionistic logic was devised by Arend Heyting to accommodate this position (it has also been adopted by other forms of constructivism). It is characterized by rejecting the law of excluded middle: as a consequence it does not in general accept rules such as double negation elimination and the use of reductio ad absurdum to prove the existence of something.[citation needed] |

哲学 東洋と西洋の哲学者はともに直観を研究してきた。認識論という学問分野は概念を扱う。 東洋哲学 東洋では直観はほとんどの場合、宗教やスピリチュアリティと絡み合っており、様々な宗教的テキストに様々な意味が存在する[18]。 ヒンドゥー教 ヒンドゥー教では、ヴェーダやその他の秘教的なテキストが直観をどのように捉えているかを解釈するために様々な試みがなされてきた。 スリ・オーロビンドにとって、直観は同一性による知識の領域に属する。彼は人間の心理面(サンスクリット語ではしばしばマナと呼ばれる)には2つの性質が あると説明する: ひとつは外界を解釈する役割(感覚情報の解析)であり、もうひとつは意識を生成する役割である。彼はこの第二の性質を「同一性による知識」と呼んでいる [19]:68オーロビンドは、進化の結果、心は物質世界との関係を結ぶ手段として特定の生理的機能を使うことに慣れた。現在のところ自己認識のみを説明 する同一性による知識は、心を超えて広がり、直観的知識を説明するかもしれない[19]: 69-71 彼は、この直観的知識は古い人類(ヴェーダ)に共通するものであり、その後、現在我々の知覚、思考、行動を組織している理性に取って代わられ、その結果、 ヴェーダ思想から形而上学的哲学、そして後に実験科学へと移行したと言う。彼は、一見まともなように見える[clarification needed]この過程が、実は進歩の輪であり、低次の能力が高次の働き方から多くを取り入れるように押し出されていることに気づく。 [明確にする必要がある][19]: 75 彼は、心の中の自己認識が自己と外側の(他の)自己に適用されるとき、これは光り輝く自己顕示的な同一性;[専門用語]をもたらし、理性もまた自己光り輝 く[専門用語]直観的知識の形にそれ自身を変換すると言う[19]: 72 [20][19]: 7 オショーは、人間の意識は基本的な動物的本能から知性と直観に至る階層にあり、人間は常にその[曖昧な]意識状態の中で生きており、親和性に応じてこれら の状態の間をしばしば移動すると考えた。彼は直観の状態で生きることが人類の究極の目的のひとつであると示唆している[21]。 アドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタ(思想の一派)は、直観を、人がブラフマンと接触し経験することができる経験であるとする[22]。 仏教 仏教では、直観は即物的な知識を持つ心の能力であるとする。仏教では直観という言葉を、意識的思考の精神的プロセス[要解釈]を超えたものとしている。意 識的思考は必ずしも潜在意識の情報にアクセスすることができないし、そのような情報を伝達可能な形にすることもできないからである[23]。禅宗の一部で は、直観は普遍的な心と個人的な差別的な心の間にある精神状態とみなされている[24]。 西洋哲学 西洋では、直観は独立した研究分野として登場することはないが、多くの哲学者の著作の中でこのトピックが大きく取り上げられている。 古代哲学 直観に関する初期の言及や定義はプラトンにまで遡ることができる。プラトンは『共和国』において、直観を現実の本質を理解する人間の理性の基本的能力とし て定義しようとしている[25]。彼は数学的真理を例に挙げ、それらは理性によって到達するものではないとする。これらの真理は、すでに眠っている形で存 在し、私たちの直感的な能力によってアクセス可能な知識を用いてアクセスされるのだと主張する。プラトンのこの概念は、アナムネシスとも呼ばれる。この研 究は後に彼の知的後継者である新プラトン主義者たちによって続けられた[26]。 イスラム教 イスラム教では、様々な学者が直観(アラビア語では「ハダス」、حدس、「的中」と呼ばれる)を様々に解釈しており、直観的な知識を持つ能力を予言者と関 連付けることもある。シハーブ・アル・ディーン=アル・スフラワーディーは、プラトンの影響を受けて著した『照明の哲学』(ishraq)の中で、直観は 照明によって得られる知識であり、その性質は神秘的であるとし、正しい判断をもたらすために神秘的な観想(mushahada)を行うことを提案している [27]。彼は、通常の知識が模倣に基づくのに対し、直観的知識は知的確信に基づくと見なしている[28]。 近世哲学 デカルトは著書『第一哲学の瞑想』の中で、「直観」(ラテン語で「見る」を意味する動詞intueorに由来する)を理性的な推論や思索による真理の発見 によって得られる既存の知識としている。この定義では、「私が真であるとはっきりと認識するものはすべて真である」[29]とされており、これは一般的に 合理的直観と呼ばれている[30]。デカルトによれば、直観と演繹は人間の知性の唯一可能な知識源であり[31]、後者は「直観の連続」[32]であり、 それぞれの直観は、論理的実証の中で他の直観と接続される前に、先験的に自明で明確かつ明瞭な考えである。 ヒュームは直観をより曖昧に解釈している。ヒュームは直観とは関係(時間、場所、因果の関係)の認識であると主張する。彼は「類似性」(関係の認識)は 「眼を打つ」(それ以上の検証は必要ないだろう)と述べているが、続けて「いやむしろ心の中で」と述べており、直観を心の力に帰属させ、経験主義の理論と 矛盾させている[33]。 イマヌエル・カント イマヌエル・カントの「直観」の概念はデカルトの概念とはかなり異なっている。それは感性という認知能力(緩やかに知覚と呼ばれるものに相当する)によっ て提供される基本的な感覚情報から構成される。カントは、私たちの心は外的直観のすべてを空間という形で、内的直観(記憶、思考)のすべてを時間という形 で投げかけるとした[34]。 現代哲学 直観は、直観がどのように主張の証拠を提供するかについての特定の理論とは無関係に、慣習的に訴えられる[clarification needed]。直観がどのような精神状態であるかについては、単なる自発的な判断から必要な真理の特別な提示に至るまで、様々な説明がある[35]。 ジョージ・ビーラーなどの哲学者は、概念分析に関するクィーン派の疑念に対して直観への訴えを擁護しようとしている[36]。 直観への訴えに対する別の挑戦は実験哲学者からもたらされ、彼らは直観への訴えは社会科学の方法によって知らされなければならないと主張している[要出典]。 哲学は直観に依存すべきであるという形而上学的な仮定は、実験哲学者(例えば、スティーヴン・スティッチ)によって挑戦されてきた[37]、 ティモシー・ウィリアムソンは、哲学の方法論に対するこのような反論に対して、直観は哲学の実践において特別な役割を果たしておらず、直観に対する懐疑論 は判断に対する一般的な懐疑論から意味のある形で切り離すことはできないと主張している。この見解によれば、哲学の方法と常識、科学、数学の方法との間に は質的な違いはない[39]。アーネスト・ソーサのような他の者は、直観に対する反論は単に言葉による意見の相違を強調しているに過ぎないと主張すること によって直観を支持しようとしている[要解釈][40]。 数学と論理学の哲学 直観主義は数学哲学においてL. E. J. Brouwerによって提唱された立場であり、すべての数学的知識は直観の純粋形態の知識であるというカントの主張から派生したものである。 直観主義論理学は、この立場に対応するためにアレント・ヘイティングによって考案された(他の形の構成主義にも採用されている)。この論理学の特徴は排中 律を否定することである。その結果、二重否定の排除や、何かの存在を証明するための不条理帰納法の使用といった規則を一般的に認めない[要出典]。 |

| Psychology Freud According to Sigmund Freud, knowledge could only be attained through the intellectual manipulation of carefully made observations. He rejected any other means of acquiring knowledge such as intuition. His findings could have been an analytic turn of his mind towards the subject.[9] Jung In Carl Jung's theory of the ego, described in 1916 in Psychological Types, intuition is an "irrational function", opposed most directly by sensation, and opposed less strongly by the "rational functions" of thinking and feeling. Jung defined intuition as "perception via the unconscious": using sense-perception only as a starting point, to bring forth ideas, images, possibilities, or ways out of a blocked situation, by a process that is mostly unconscious.[10] Jung said that a person in whom intuition is dominant—an "intuitive type"—acts not on the basis of rational judgment but on sheer intensity of perception. An extroverted intuitive type, "the natural champion of all minorities with a future", orients to new and promising but unproven possibilities, often leaving to chase after a new possibility before old ventures have borne fruit, oblivious to his or her own welfare in the constant pursuit of change. An introverted intuitive type orients by images from the unconscious, ever exploring the psychic world of the archetypes, seeking to perceive the meaning of events, but often having no interest in playing a role in those events and not seeing any connection between the contents of the psychic world and him- or herself. Jung thought that extroverted intuitive types were likely entrepreneurs, speculators, cultural revolutionaries, often undone by a desire to escape every situation before it becomes settled and constraining—even repeatedly leaving lovers for the sake of new romantic possibilities. His introverted intuitive types were likely mystics, prophets, or cranks, struggling with a tension between protecting their visions from influence by others and making their ideas comprehensible and reasonably persuasive to others—a necessity for those visions to bear real fruit.[10] Modern psychology In modern psychology, intuition can encompass the ability to know valid solutions to problems and the making of decisions. For example, the recognition-primed decision (RPD) model explains how people can make relatively fast decisions without having to compare options. Gary Klein found that under time pressure, high stakes, and changing parameters, experts used their base of experience to identify similar situations and intuitively choose feasible solutions. The RPD model is a blend of intuition and analysis. The intuition is the pattern-matching process that quickly suggests feasible courses of action. The analysis is the mental simulation, a conscious and deliberate review of the courses of action.[11] Instinct is often misinterpreted as intuition. Its reliability is dependent on past knowledge and occurrences in a specific area.[dubious – discuss] For example, someone who has had more experience with children will tend to have better instincts about what they should do in certain situations with them. This is not to say that one with a great amount of experience is always going to have an accurate intuition.[12] Intuitive abilities were quantitatively tested at Yale University in the 1970s. While studying nonverbal communication, researchers noted that some subjects were able to read nonverbal facial cues before reinforcement occurred.[13] In employing a similar design[clarification needed], they noted that highly intuitive subjects made decisions quickly but could not identify their rationale. Their level of accuracy, however, did not differ from that of non-intuitive subjects.[14] According to the works of Daniel Kahneman, intuition is the ability to automatically generate solutions without long logical arguments or evidence.[15] He mentions two different systems that we use when making decisions and judgements: the first is in charge of automatic or unconscious thoughts, the second in charge of more intentional thoughts.[16][page needed] The first system is an example of intuition, and Kahneman believes people overestimate this system, using it as a source of confidence for knowledge they may not truly possess. These systems are connected with two versions of ourselves he calls the remembering self and experiencing self, relating to the creation of memories in "System 1"[jargon]. Its[ambiguous] automatic nature occasionally leads people to experience cognitive illusions, assumptions that our intuition gives us and are usually trusted without a second thought.[16][page needed] Gerd Gigerenzer described intuition as processes and thoughts that are devoid of typical logic. He described two primary characteristics to intuition: basic rules of thumb (that are heuristic in nature) and "evolved capacities of the brain".[5][page needed] The two work in tandem to give people thoughts and abilities that they do not actively think about as they are performed, and of which they cannot explain their formation or effectiveness. He does not believe that intuitions actively correlate to[clarification needed] knowledge; he believes that having too much information makes individuals overthink, and that some intuitions will actively defy known information.[5][page needed] Intuition is also seen as a figurative launch pad for logical thinking. Intuition's automatic nature tends to precede more thoughtful logic.[17][page needed] Even when based on moral or subjective standpoints, intuition provides a base—one that people will usually start to back up with logical thinking as a defense or justification rather than starting with a less biased viewpoint. The confidence in whether it is an intuition or not comes from how quickly they happen, because they[clarification needed] are instantaneous feelings or judgments that we have surprising confidence in.[17][page needed] |

心理学 フロイト ジークムント・フロイトによれば、知識は注意深くなされた観察の知的操作によってのみ得られる。彼は直感のような知識を得るための他の手段を否定した。彼の発見は、対象に対する彼の心の分析的転回であったかもしれない[9]。 ユング カール・ユングが1916年に『心理学的類型』の中で述べた自我の理論では、直観は「非合理的機能」であり、感覚と最も直接的に対立し、思考や感情といっ た「合理的機能」とはそれほど強く対立しない。ユングは直観を「無意識を介した知覚」と定義しており、感覚知覚を出発点としてのみ使用し、ほとんど無意識 的なプロセスによって、アイデア、イメージ、可能性、あるいは閉塞した状況から抜け出す方法を生み出すと述べている[10]。 ユングは、直感が支配的な人-「直感型」-は合理的な判断に基づいて行動するのではなく、知覚の強さに基づいて行動すると述べている。外向的な直観的タイ プは、「未来を持つすべての少数派の自然なチャンピオン」であり、新しい有望な、しかしまだ証明されていない可能性を志向し、しばしば古い事業が実を結ぶ 前に新しい可能性を追い求めるために出発し、絶え間ない変化の追求の中で自分自身の幸福に気づかない。内向的な直観的タイプは、無意識からのイメージに よって方向づけを行い、常に原型の心霊世界を探求し、出来事の意味を認識しようとするが、しばしばその出来事に関与することに関心がなく、心霊世界の内容 と自分自身との間につながりがあるとは考えない。ユングは、外向的な直観的タイプは起業家、投機家、文化革命家である可能性が高く、あらゆる状況が落ち着 き、束縛される前に逃げ出したいという願望にとらわれることが多いと考えた。内向的な直観的タイプは、神秘主義者、預言者、変人である可能性が高く、他者 からの影響からヴィジョンを守ることと、ヴィジョンが本当の実を結ぶために必要な、自分の考えを他者に理解させ、合理的な説得力を持たせることの間の緊張 に苦しんでいた[10]。 現代心理学 現代心理学では、直観は問題に対する有効な解決策を知る能力と意思決定を行う能力を包含する。例えば、認識主導型意思決定(RPD)モデルは、人々が選択 肢を比較することなく、比較的迅速に意思決定ができることを説明している。ゲイリー・クラインは、時間的なプレッシャーがかかり、利害関係が大きく、パラ メータが変化する状況下でも、専門家は経験に基づいて類似の状況を特定し、実現可能な解決策を直感的に選択することを発見した。RPDモデルは直感と分析 の融合である。直感は、実現可能な行動方針を素早く提案するパターンマッチングプロセスである。分析とは、精神的なシミュレーションであり、意識的かつ計 画的に行動方針を検討することである[11]。 直感はしばしば直観と誤解される。直感の信頼性は、過去の知識や特定の領域で起きた出来事に左右される。これは、経験が豊富な人が常に正確な直観を持つということを意味するものではない[12]。 直観的能力は1970年代にイェール大学で定量的にテストされた。同様のデザイン[clarification needed]を採用し たところ、直観力の高い被験者は素早く意思決定を行ったが、その 根拠を特定することはできなかった。しかし、その正確さのレベルは非直観的な被験者と変わらなかった[14]。 ダニエル・カーネマンの著作によると、直観とは、長い論理的な議論や証拠なしに自動的に解決策を生み出す能力である[15]。彼は、意思決定や判断を行う 際に使用する2つの異なるシステムについて言及している。1つ目は自動的または無意識的な思考を担当し、2つ目はより意図的な思考を担当する。これらのシ ステムは、カーネマンが「システム1」[専門用語]における記憶の創造に関連して「記憶する自己」と「経験する自己」と呼ぶ2つのバージョンの自分自身と つながっている。その[曖昧な]自動的な性質は、時折人々に認知的錯覚、つまり直感が私たちに与える思い込みを経験させ、通常は二の次に考えることなく信 頼される[16][要ページ]。 ゲルト・ギゲレンツァーは直観を典型的な論理を欠いたプロセスや思考であると説明した。彼は直観には2つの主要な特徴があると説明した:基本的な経験則 (それは本質的に発見的である)と「脳の進化した能力」である。彼は直観が積極的に知識[要出典]と相関するとは考えておらず、情報が多すぎると個人が考 えすぎてしまい、いくつかの直観は積極的に既知の情報に逆らうようになると考えている[5][要出典]。 直観はまた、論理的思考のための比喩的な発射台と見なされている。直観の自動的な性質は、より思慮深い論理に先行する傾向がある[17][page needed]。道徳的または主観的な視点に基づく場合でも、直観はベースとなるものを提供し、人々は通常、あまり偏りのない視点から始めるのではなく、 防御や正当化として論理的思考でバックアップし始める。直観であるかどうかの確信は、直観がいかに早く起こるかに由来する。なぜなら、直観[要出典]は瞬 間的な感情や判断であり、私たちは驚くほどの自信を持っているからである[17][要出典]。 |

| Artificial intelligence [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2021) Main article: Artificial intuition Researchers in artificial intelligence are trying to add intuition to algorithms, as the "fourth generation of AI"; this can be applied to many industries, especially finance.[41][unreliable source?] One example of artificial intuition is AlphaGo Zero, which used neural networks and was trained with reinforcement learning from a blank slate.[42][unreliable source?] In another example, ThetaRay partnered with Google Cloud to use artificial intuition for anti-money laundering purposes.[43][unreliable source?] Business decision-making In a 2022 Harvard Business Review article, Melody Wilding explored "how to stop overthinking and start trusting your gut", noting that "intuition... is frequently dismissed as mystical or unreliable". She suggested that there is a scientific basis for using intuition and refers to "surveys of top executives [which] show that a majority of leaders leverage feelings and experience when handling crises".[8] However, an earlier Harvard Business Review article ("Don't Trust Your Gut") advises that, although "trust in intuition is understandable... anyone who thinks that intuition is a substitute for reason is indulging in a risky delusion".[44] Intuition was assessed by a sample of 11 Australian business leaders as a gut feeling based on experience, which they considered useful for making judgments about people, culture, and strategy.[45] Such an example likens intuition to "gut feelings", which — when viable[clarification needed] — illustrate preconscious activity.[46] |

人工知能 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで貢献できます。(2021年6月) 主な記事 人工直観 人工知能の研究者は、「AIの第4世代」として、アルゴリズムに直感を加えようとしている。[41][信頼できない情報源?] 人工直感の一例として、ニューラルネットワークを使用し、白紙の状態から強化学習で訓練されたAlphaGo Zeroがある[42][信頼できない情報源?] 別の例では、ThetaRayがGoogle Cloudと提携し、マネーロンダリング防止の目的で人工直感を使用している[43][信頼できない情報源?] ビジネスの意思決定 2022年のハーバード・ビジネス・レビューの記事で、メロディ・ワイルディングは「直感は...しばしば神秘的で信頼できないものとして否定される」と 指摘し、「考えすぎるのをやめ、直感を信頼し始める方法」を探った。彼女は、直感を使うことには科学的根拠があることを示唆し、「トップエグゼクティブを 対象とした調査(危機に対処する際に、リーダーの大半が感情や経験を活用していることを示している)」に言及している[8]。しかし、ハーバード・ビジネ ス・レビューの以前の記事(「直感を信じるな」)では、「直感を信頼することは理解できるが、直感が理性の代わりだと考える人は、危険な妄想に耽ってい る」と忠告している[44]。 直感は、オーストラリアのビジネスリーダー11人のサンプルによって、経験に基づく直感であり、人、文化、戦略に関する判断を下すのに有用であると評価さ れている[45]。このような例は、直感を「直感」になぞらえており、直感が実行可能である場合[要解明]、それは無意識的な活動を示している[46]。 |

| Artistic inspiration Brainstorming Common sense Cognition Clairvoyance Cryptesthesia Déjà vu Dual process theory Extra-sensory perception Focusing (psychotherapy) Foresight Inner Relationship Focusing Grok Insight Intuition and decision-making Intuition pump Intelligence analysis#Trained intuition List of psychic abilities List of thought processes Luck Medical intuitive Morphic resonance Nous Phenomenology (philosophy) Precognition Psychic Rapport Religious experience Remote viewing Serendipity Social intuitionism Subconscious Synchronicity Tacit knowledge Truthiness Unconscious mind |

芸術的インスピレーション ブレインストーミング 常識 認知 千里眼 幻覚 デジャヴ 二重過程理論 超感覚的知覚 フォーカシング(心理療法) 先見の明 内的関係フォーカシング グロック 洞察 直観と意思決定 直感ポンプ 知能分析#訓練された直観 サイキック能力一覧 思考プロセス一覧 運 医療直感 モルフィック共鳴 ヌース 現象学(哲学) 予知能力 サイキック ラポール 宗教的体験 リモートビューイング セレンディピティ 社会的直観主義 潜在意識 シンクロニシティ 暗黙知 真実性 無意識 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intuition |

|

| Intuitionism In the philosophy of mathematics, intuitionism, or neointuitionism (opposed to preintuitionism), is an approach where mathematics is considered to be purely the result of the constructive mental activity of humans rather than the discovery of fundamental principles claimed to exist in an objective reality.[1] That is, logic and mathematics are not considered analytic activities wherein deep properties of objective reality are revealed and applied, but are instead considered the application of internally consistent methods used to realize more complex mental constructs, regardless of their possible independent existence in an objective reality. |

直観主義→「直観主義」 数学哲学(数理哲学)において、直観主義、または新直観主義(前直観主義とは対照的)とは、数学が客観的現実に存在すると主張される基本原理の発見ではな く、純粋に人間の建設的な精神活動の結果であると考えられるアプローチである[1]。すなわち、論理学と数学は、客観的現実の深い特性が明らかにされ、適 用される分析的活動とはみなされず、その代わりに、客観的現実に独立した存在である可能性にかかわらず、より複雑な精神的構成を実現するために使用される 内部的に一貫性のある方法の適用とみなされる。 |

| Truth and proof The fundamental distinguishing characteristic of intuitionism is its interpretation of what it means for a mathematical statement to be true. In Brouwer's original intuitionism, the truth of a mathematical statement is a subjective claim: a mathematical statement corresponds to a mental construction, and a mathematician can assert the truth of a statement only by verifying the validity of that construction by intuition. The vagueness of the intuitionistic notion of truth often leads to misinterpretations about its meaning. Kleene formally defined intuitionistic truth from a realist position, yet Brouwer would likely reject this formalization as meaningless, given his rejection of the realist/Platonist position. Intuitionistic truth therefore remains somewhat ill-defined. However, because the intuitionistic notion of truth is more restrictive than that of classical mathematics, the intuitionist must reject some assumptions of classical logic to ensure that everything they prove is in fact intuitionistically true. This gives rise to intuitionistic logic. To an intuitionist, the claim that an object with certain properties exists is a claim that an object with those properties can be constructed. Any mathematical object is considered to be a product of a construction of a mind, and therefore, the existence of an object is equivalent to the possibility of its construction. This contrasts with the classical approach, which states that the existence of an entity can be proved by refuting its non-existence. For the intuitionist, this is not valid; the refutation of the non-existence does not mean that it is possible to find a construction for the putative object, as is required in order to assert its existence. As such, intuitionism is a variety of mathematical constructivism; but it is not the only kind. The interpretation of negation is different in intuitionist logic than in classical logic. In classical logic, the negation of a statement asserts that the statement is false; to an intuitionist, it means the statement is refutable.[2] There is thus an asymmetry between a positive and negative statement in intuitionism. If a statement P is provable, then P certainly cannot be refutable. But even if it can be shown that P cannot be refuted, this does not constitute a proof of P. Thus P is a stronger statement than not-not-P. Similarly, to assert that A or B holds, to an intuitionist, is to claim that either A or B can be proved. In particular, the law of excluded middle, "A or not A", is not accepted as a valid principle. For example, if A is some mathematical statement that an intuitionist has not yet proved or disproved, then that intuitionist will not assert the truth of "A or not A". However, the intuitionist will accept that "A and not A" cannot be true. Thus the connectives "and" and "or" of intuitionistic logic do not satisfy de Morgan's laws as they do in classical logic. Intuitionistic logic substitutes constructability for abstract truth and is associated with a transition from the proof of model theory to abstract truth in modern mathematics. The logical calculus preserves justification, rather than truth, across transformations yielding derived propositions. It has been taken as giving philosophical support to several schools of philosophy, most notably the Anti-realism of Michael Dummett. Thus, contrary to the first impression its name might convey, and as realized in specific approaches and disciplines (e.g. Fuzzy Sets and Systems), intuitionist mathematics is more rigorous than conventionally founded mathematics, where, ironically, the foundational elements which Intuitionism attempts to construct/refute/refound are taken as intuitively given. |

真理と証明 直観主義の基本的な特徴は、数学的声明が真であることの意味についての解釈である。Brouwerの直観主義では、数学的記述の真理は主観的な主張であ る。数学的記述は心的構成に対応し、数学者は直観によってその構成の妥当性を検証することによってのみ、記述の真理を主張することができる。直観主義的な 真理概念の曖昧さは、しばしばその意味についての誤解を招く。Kleeneは実在論の立場から直観主義的真理を形式的に定義したが、Brouwerは実在 論/プラトン主義の立場を否定しているため、この形式化を無意味なものとして拒絶するだろう。したがって、直観主義的真理はやや定義しにくいままである。 しかし、直観主義的な真理概念は古典数学の真理概念よりも限定的であるため、直観主義者は、証明するものすべてが実際に直観主義的に真であることを保証す るために、古典論理学のいくつかの仮定を否定しなければならない。これが直観主義論理を生み出す。 直観主義者にとって、ある性質を持つ物体が存在するという主張は、その性質を持つ物体を構成できるという主張である。あらゆる数学的対象は心の構築の産物 であると考えられ、したがって対象の存在はその構築の可能性と等価である。これは、実体の存在はその非存在を反証することで証明できるとする古典的アプ ローチとは対照的である。直観主義者にとっては、これは妥当ではない。非存在の反証は、その存在を主張するために必要な、想定される対象の構成を見つける ことが可能であることを意味しない。このように、直観主義は数学的構成主義の一種であるが、それだけではない。 直観主義論理学では否定の解釈が古典論理学とは異なる。古典論理学では、文の否定はその文が偽であることを主張するが、直観主義者にとっては、それはその 文が反証可能であることを意味する。文Pが証明可能であるならば、Pは確かに反証不可能である。しかし、Pが反論できないことを示すことができたとして も、それはPの証明にはならない。 同様に、直観主義者にとって、AまたはBが成り立つと主張することは、AまたはBのどちらかが証明できると主張することである。特に、「AかAでないか」 という排中律は、有効な原理として認められていない。例えば、ある直観主義者がまだ証明も反証もしていない数学的言明をAとする場合、その直観主義者は 「AかAでないか」の真偽を主張しない。しかし、直観主義者は「AであってAでない」ことが真であるはずがないことを受け入れる。このように、直観主義論 理の接続詞 "and "と "or "は、古典論理のようにド・モルガンの法則を満たしていない。 直観主義論理は構成可能性を抽象的真理に置き換え、現代数学におけるモデル理論の証明から抽象的真理への移行と関連している。論理的微積分は、派生命題を もたらす変換を越えて、真理ではなく正当性を保持する。論理微積分は、哲学のいくつかの学派、特にマイケル・ダンメットの反現実主義に哲学的な支持を与え ていると考えられている。このように、直観主義の数学は、その名前が伝えるかもしれない第一印象に反して、また、特定のアプローチや分野(例えば、ファ ジィ集合とシステム)で実現されているように、従来の数学よりも厳密であり、皮肉なことに、直観主義が構築/反証/発見しようとする基礎的な要素は、直観 的に与えられたものとして取られる。 |

| Infinity Among the different formulations of intuitionism, there are several different positions on the meaning and reality of infinity. The term potential infinity refers to a mathematical procedure in which there is an unending series of steps. After each step has been completed, there is always another step to be performed. For example, consider the process of counting: 1, 2, 3, ... The term actual infinity refers to a completed mathematical object which contains an infinite number of elements. An example is the set of natural numbers, N = {1, 2, ...}. In Cantor's formulation of set theory, there are many different infinite sets, some of which are larger than others. For example, the set of all real numbers R is larger than N, because any procedure that you attempt to use to put the natural numbers into one-to-one correspondence with the real numbers will always fail: there will always be an infinite number of real numbers "left over". Any infinite set that can be placed in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers is said to be "countable" or "denumerable". Infinite sets larger than this are said to be "uncountable".[3] Cantor's set theory led to the axiomatic system of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZFC), now the most common foundation of modern mathematics. Intuitionism was created, in part, as a reaction to Cantor's set theory. Modern constructive set theory includes the axiom of infinity from ZFC (or a revised version of this axiom) and the set N of natural numbers. Most modern constructive mathematicians accept the reality of countably infinite sets (however, see Alexander Esenin-Volpin for a counter-example). Brouwer rejected the concept of actual infinity, but admitted the idea of potential infinity. According to Weyl 1946, 'Brouwer made it clear, as I think beyond any doubt, that there is no evidence supporting the belief in the existential character of the totality of all natural numbers ... the sequence of numbers which grows beyond any stage already reached by passing to the next number, is a manifold of possibilities open towards infinity; it remains forever in the status of creation, but is not a closed realm of things existing in themselves. That we blindly converted one into the other is the true source of our difficulties, including the antinomies – a source of more fundamental nature than Russell's vicious circle principle indicated. Brouwer opened our eyes and made us see how far classical mathematics, nourished by a belief in the 'absolute' that transcends all human possibilities of realization, goes beyond such statements as can claim real meaning and truth founded on evidence. — Kleene 1991, pp. 48–49 |

無限 直観主義のさまざまな定式化の中で、無限の意味と現実についていくつかの異なる立場がある。 潜在的無限という用語は、終わりのない一連のステップがある数学的手順を指す。各ステップが完了した後、常に別のステップが実行される。例えば、数を数える過程を考えてみよう: 1, 2, 3, ... 実際の無限という用語は、無限の要素を含む完成された数学的対象を指す。例えば、自然数の集合N = {1、2、...}である。 カントールの集合論の定式化では、多くの異なる無限集合があり、そのうちのいくつかは他のものよりも大きい。例えば、すべての実数の集合RはNより大き い。なぜなら、自然数を実数と一対一対応にしようとする手続きは常に失敗するからである。自然数と一対一対応に置くことができる無限集合は、「可算」また は「可算」と呼ばれる。これより大きい無限集合は「数えられない」と言われる[3]。 カントールの集合論は、現在現代数学の最も一般的な基礎となっているツェルメロ-フレンケル集合論(ZFC)の公理系につながった。直観主義は、カントールの集合論に対する反動として生まれた。 現代の構成的集合論には、ZFCの無限大の公理(またはこの公理の改訂版)と自然数の集合Nが含まれる。現代の構成的数学者の多くは、可算無限集合の実在を認めている(ただし、反例としてアレクサンダー・エセーニン=ヴォルピンを参照)。 Brouwerは実際の無限という概念を否定したが、潜在的無限という考えは認めた。 ウェイル1946によれば、「ブルワーは、すべての自然数の総体の実在的な性格を信じることを支持する証拠は何もないことを、私は疑いの余地なく明言し た...次の数に移ることによって、すでに到達した段階を超えて成長する数の列は、無限に向かって開かれた可能性の多様体である。私たちが一方を他方に盲 目的に変換していたことが、アンチノミーを含む私たちの困難の真の原因であり、ラッセルの悪循環原理が示すよりももっと根本的な性質の原因なのである。ブ ルワーは私たちの目を開かせ、人間のあらゆる実現の可能性を超越した「絶対」に対する信念に養われた古典数学が、証拠に基づいた真の意味と真理を主張でき るような記述をどこまで超えているのかを私たちに分からせてくれた。 - クリーネ1991、48-49頁 |

| History Intuitionism's history can be traced to two controversies in nineteenth century mathematics. The first of these was the invention of transfinite arithmetic by Georg Cantor and its subsequent rejection by a number of prominent mathematicians including most famously his teacher Leopold Kronecker—a confirmed finitist. The second of these was Gottlob Frege's effort to reduce all of mathematics to a logical formulation via set theory and its derailing by a youthful Bertrand Russell, the discoverer of Russell's paradox. Frege had planned a three volume definitive work, but just as the second volume was going to press, Russell sent Frege a letter outlining his paradox, which demonstrated that one of Frege's rules of self-reference was self-contradictory. In an appendix to the second volume, Frege acknowledged that one of the axioms of his system did in fact lead to Russell's paradox.[4] Frege, the story goes, plunged into depression and did not publish the third volume of his work as he had planned. For more see Davis (2000) Chapters 3 and 4: Frege: From Breakthrough to Despair and Cantor: Detour through Infinity. See van Heijenoort for the original works and van Heijenoort's commentary. These controversies are strongly linked as the logical methods used by Cantor in proving his results in transfinite arithmetic are essentially the same as those used by Russell in constructing his paradox. Hence how one chooses to resolve Russell's paradox has direct implications on the status accorded to Cantor's transfinite arithmetic. In the early twentieth century L. E. J. Brouwer represented the intuitionist position and David Hilbert the formalist position—see van Heijenoort. Kurt Gödel offered opinions referred to as Platonist (see various sources re Gödel). Alan Turing considers: "non-constructive systems of logic with which not all the steps in a proof are mechanical, some being intuitive".[5]. Later, Stephen Cole Kleene brought forth a more rational consideration of intuitionism in his Introduction to metamathematics (1952).[6] Nicolas Gisin is adopting intuitionist mathematics to reinterpret quantum indeterminacy, information theory and the physics of time.[7] |

歴史 直観主義の歴史は、19世紀の数学における2つの論争に遡ることができる。 その1つは、ゲオルク・カントールによる超限算術の発明であり、その後、彼の師であるレオポルド・クロネッカーを含む多くの著名な数学者によって否定された。 もうひとつは、ゴットローブ・フレーゲが数学のすべてを集合論による論理的定式化に還元しようとしたことで、ラッセルのパラドックスの発見者である若き バートランド・ラッセルによって頓挫させられた。フレーゲは3巻からなる決定的な著作を計画していたが、第2巻が出版されようとした矢先、ラッセルはフ レーゲにパラドックスの概要を記した手紙を送り、フレーゲの自己言及の規則のひとつが自己矛盾であることを証明した。第2巻の付録で、フレーゲは自分の体 系の公理のひとつが実際にラッセルのパラドックスにつながることを認めた[4]。 フレーゲはうつ病に陥り、予定していた第3巻を出版しなかったという話である。詳しくはDavis (2000) Chapter 3 and 4: Fregeを参照: 突破口から絶望へ』と『カントル: を参照。原著とvan Heijenoortの解説はvan Heijenoortを参照。 カントールが超限算術の結果を証明する際に用いた論理的手法は、ラッセルがパラドックスを構築する際に用いたものと本質的に同じであるため、これらの論争 は強く結びついている。従って、ラッセルのパラドックスをどのように解決するかは、カントールの超限算術にどのような地位を与えるかに直結する。 20世紀初頭、L. E. J. Brouwerは直観主義の立場を代表し、David Hilbertは形式主義の立場を代表した。クルト・ゲーデルはプラトン主義者と呼ばれる意見を述べた(ゲーデルに関する様々な資料を参照)。アラン・ チューリングは次のように考えている: 「非構成論的論理体系では、証明のすべての段階が機械的ではなく、一部は直感的である」[5]。その後、スティーヴン・コール・クリーンは『メタ数学入 門』(1952年)の中で直観主義をより合理的に考察している[6]。 ニコラ・ジザンは量子不確定性、情報理論、時間の物理学を再解釈するために直観主義数学を採用している[7]。 |

| Henri Poincaré (preintuitionism/conventionalism) L. E. J. Brouwer Michael Dummett Arend Heyting Stephen Kleene |

Henri Poincaré (preintuitionism/conventionalism) L. E. J. Brouwer Michael Dummett Arend Heyting Stephen Kleene |

| Intuitionistic logic Intuitionistic arithmetic Intuitionistic type theory Intuitionistic set theory Intuitionistic analysis |

直観主義論理 直観主義算術 直観主義型理論 直観主義集合論 直観主義的解析 |

| Anti-realism BHK interpretation Brouwer–Hilbert controversy Computability logic Constructive logic Curry–Howard isomorphism Foundations of mathematics Fuzzy logic Game semantics Intuition (knowledge) Model theory Topos theory Ultraintuitionism |

反リアリズム BHK解釈 ブルワー・ヒルベルト論争 計算可能性論理 構成的論理 カリー-ハワード同型論 数学の基礎 ファジィ論理 ゲーム意味論 直観(知識) モデル理論 トポス理論 超直観主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intuitionism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆