ジャン=リュック・マリオン

Jean-Luc Marion, b.1946

Jean-Luc Marion at the Élysée Palace after his meeting with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing on Thursday 7 September 1978.

☆ ジャン=リュック・マリオン(1946年7月3日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者、ローマ・カトリック神学者。マリオンはジャック・デリダの元教え子であり、 その研究は教父神学や神秘主義神学、現象学、現代哲学に影響を受けている。彼の学問的研究の多くはデカルトやマルティン・ハイデガーやエドムント・フッ サールのような現象学者だけでなく、宗教も扱っている。例えば、『存在することのない神』は偶像崇拝の分析に主眼を置いており、このテーマはマリオンの仕 事において愛や贈与と強く結びついている。

| Jean-Luc Marion

(born 3 July 1946) is a French philosopher and Roman Catholic

theologian. Marion is a former student of Jacques Derrida whose work is

informed by patristic and mystical theology, phenomenology, and modern

philosophy.[1] Much of his academic work has dealt with Descartes and

phenomenologists like Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl, but also

religion. God Without Being, for example, is concerned predominantly

with an analysis of idolatry, a theme strongly linked in Marion's work

with love and the gift, which is a concept also explored at length by

Derrida. |

ジャン=リュッ

ク・マリオン(1946年7月3日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者、ローマ・カトリック神学者。マリオンはジャック・デリダの元教え子であり、その研究は教父

神学や神秘主義神学、現象学、現代哲学に影響を受けている[1]。彼の学問的研究の多くはデカルトやマルティン・ハイデガーやエドムント・フッサールのよ

うな現象学者だけでなく、宗教も扱っている。例えば、『存在することのない神』は偶像崇拝の分析に主眼を置いており、このテーマはマリオンの仕事において

愛や贈与と強く結びついている。 |

| Biography Early years  Jean-Luc Marion at the Élysée Palace after his meeting with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing on Thursday 7 September 1978. Marion was born in Meudon, Hauts-de-Seine, on 3 July 1946. He studied at the University of Nanterre (now the University Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense) and the Sorbonne and then did graduate work in philosophy from the École normale supérieure in Paris from 1967 to 1971, where he was taught by Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser and Gilles Deleuze.[2] At the same time, Marion's deep interest in theology was privately cultivated under the personal influence of theologians such as Louis Bouyer, Jean Daniélou, Henri de Lubac, and Hans Urs von Balthasar. From 1972 to 1980 he studied for his doctorate and worked as an assistant lecturer at the Sorbonne. After receiving his doctorate in 1980, he began teaching at the University of Poitiers.[2] Career From there he moved to become the Director of Philosophy at the University Paris X – Nanterre, and in 1991 also took up the role of professeur invité at the Institut Catholique de Paris.[3] In 1996 he became Director of Philosophy at the University of Paris IV (Sorbonne), where he still teaches. Marion became a visiting professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School in 1994. He was then appointed the John Nuveen Professor of the Philosophy of Religion and Theology there in 2004, a position he held until 2010.[4] That year, he was appointed the Andrew Thomas Greeley and Grace McNichols Greeley Professor of Catholic Studies at the Divinity School, a position that had been vacated by the retirement of theologian David Tracy.[5] He retired from Chicago in 2022. On 6 November 2008, Marion was elected as an immortel by the Académie Française. Marion now occupies seat 4, an office previously held by Cardinal Lustiger.[6][7][8] |

バイオグラフィー 初期  1978年9月7日(木)、ヴァレリー・ジスカール・デスタン大統領との会談後、エリゼ宮にて。 1946年7月3日、オー・ド・セーヌ県ムードンに生まれる。ナンテール大学(現パリ・ウエスト・ナンテール・ラ・デファンス大学)とソルボンヌ大学で学 び、1967年から1971年までパリの高等師範学校で哲学を専攻。 [2] 同時に、ルイ・ブイエ、ジャン・ダニエルー、アンリ・ド・ルバック、ハンス・ウルス・フォン・バルタザールといった神学者たちから個人的な影響を受け、神 学への深い関心を育む。1972年から1980年までソルボンヌ大学で博士号取得のために学び、助教授を務めた。1980年に博士号を取得後、ポワチエ大 学で教鞭をとる[2]。 経歴 1996年にパリ第4大学(ソルボンヌ大学)の哲学部長となり、現在も教鞭をとっている[3]。 1994年、シカゴ大学神学部の客員教授に就任。同年、神学者デイヴィッド・トレイシーの退任により空席となっていた同校のカトリック研究教授に任命された[4]。2022年にシカゴを退職。 2008年11月6日、マリオンはアカデミー・フランセーズからイモーテルに選出された。マリオンは現在、以前ルスティガー枢機卿が務めていた第4席を占めている[6][7][8]。 |

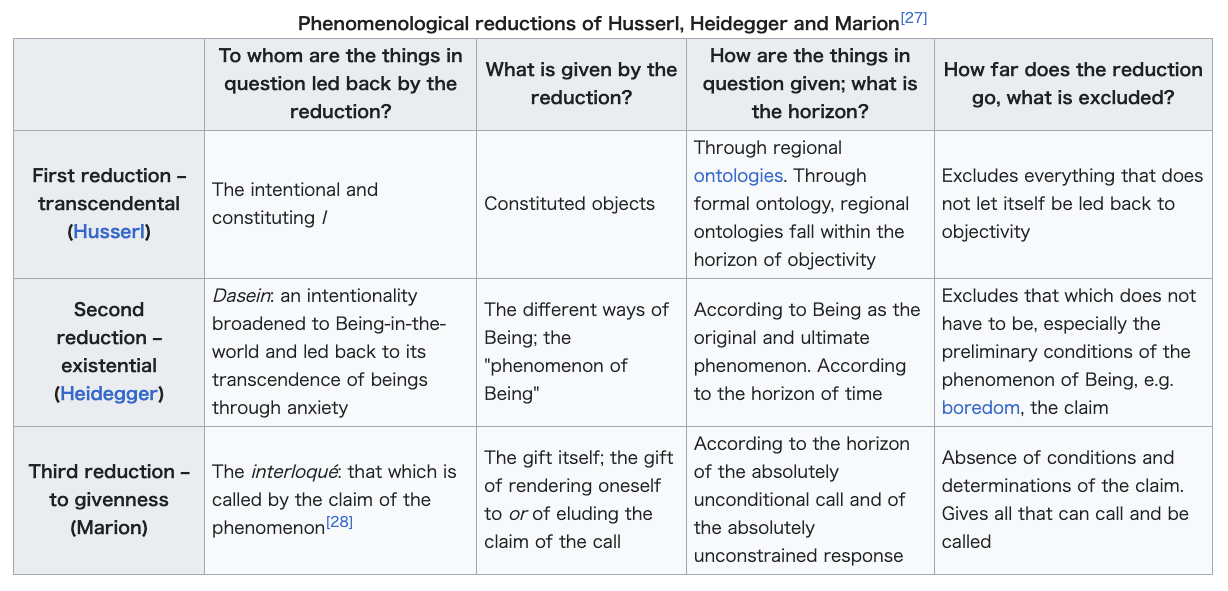

| Pholosophy Marion's phenomenological work is set out in three volumes which together form a triptych[11] or trilogy.[12] Réduction et donation: Etudes sur Husserl, Heidegger et la phénoménologie (1989) is an historical study of the phenomenological method followed by Husserl and Heidegger, with a view towards suggesting future directions for phenomenological research. The unexpected reaction that Réduction et donation provoked called for clarification and full development. This was addressed in Étant donné: Essai d'une phénoménologie de la donation (1997), a more conceptual work investigating phenomenological givenness, the saturated phenomenon and the gifted—a rethinking of the subject. Du surcroît (2001) provides an in-depth description of saturated phenomena.[13] Givenness Marion claims that he has attempted to "radically reduce the whole phenomenological project beginning with the primacy in it of givenness".[14] What he describes as his one and only theme is the givenness that is required before phenomena can show themselves in consciousness—"what shows itself first gives itself.[15] This is based on the argument that any and all attempts to lead phenomena back to immanence in consciousness, that is, to exercise the phenomenological reduction, necessarily results in showing that givenness is the "sole horizon of phenomena"[16] Marion radicalizes this argument in the formulation, "As much reduction, as much givenness",[17] and offers this as a new first principle of phenomenology, building on and challenging prior formulae of Husserl and Heidegger.[18] The formulation common to both, Marion argues, "So much appearance, so much Being", adopted from Johann Friedrich Herbart,[19] erroneously elevates appearing to the status of the "sole face of Being". In doing so, it leaves appearing itself undetermined, not subject to the reduction, and thus in a "typically metaphysical situation".[20] The Husserlian formulation, "To the things themselves!", is criticized on the basis that the things in question would remain what they are even without appearing to a subject—again circumventing the reduction or even without becoming phenomena. Appearing becomes merely a mode of access to objects, rendering the formulation inadequate as a first principle of phenomenology.[21] A third formulation, Husserl's "Principle of all Principles", states "that every primordial dator Intuition is a source of authority (Rechtsquelle) for knowledge, that whatever presents itself in 'intuition'...is simply to be accepted as it gives itself out to be, though only within the limits in which it then presents itself."[22] Marion argues that while the Principle of all Principles places givenness as phenomenality's criterion and achievement, givenness still remains uninterrogated.[23] Whereas it admits limits to intuition ("as it gives itself..., though only within the limits in which it presents itself"), "givenness alone is absolute, free and without condition"[24] Givenness then is not reducible except to itself, and so is freed from the limits of any other authority, including intuition; a reduced given is either given or not given. "As much reduction, as much givenness" states that givenness is what the reduction accomplishes, and any reduced given is reduced to givenness.[25] The more a phenomenon is reduced, the more it is given. Marion calls the formulation the last principle, equal to the first, that of the appearing itself.[26] |

その哲学 マリオンの現象学的研究は3巻からなり、3部作[11]となっている[12]: Etudes sur Husserl, Heidegger et la phénoménologie』(1989年)は、フッサールとハイデガーが辿った現象学的方法の歴史的研究であり、現象学的研究の将来の方向性を示唆す ることを視野に入れている。Réduction et donationが引き起こした予想外の反応は、その解明と全面的な発展を求めた。これは『Étant donné: Essai d'une phénoménologie de la donation (1997)は、現象学的な贈与、飽和現象、贈与された者の再考を研究した、より概念的な作品である。Du surcroît (2001)は飽和現象についての詳細な記述を提供している[13]。 所与性 マリオンは「現象学的プロジェクト全体を、所与性の優位性から出発して根本的に還元する」ことを試みてきたと主張している[14]。 彼の唯一無二のテーマとして説明するのは、現象が意識においてそれ自身を示すことができるようになる前に必要とされる所与性であり、「それ自身を示すもの は、まずそれ自身を与える」[15]。 これは、現象を意識における内在性へと導こうとするあらゆる試み、すなわち現象学的還元を行使しようとするあらゆる試みが、必然的に所与性が「現象の唯一 の地平」であることを示す結果になるという議論に基づいている[16]。 マリオンはこの議論を「還元と同じだけの所与性」[17]という定式において急進化し、これを現象学の新たな第一原理として提示し、フッサールとハイデ ガーの先行する定式を基礎とし、それに挑戦している[18]。 両者に共通する定式としてマリオンが主張するのは、ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ヘルバート[19]から採用された「出現と同じだけの存在」であり、出現を「存 在の唯一の面」の地位にまで誤って高めている。そうすることで、それは出現それ自体を未決定のままにしておき、還元に従わず、したがって「典型的な形而上 学的状況」に置くことになる[20]。 フッサール的な定式化である「事物それ自体に!」は、問題となっている事物は、主体に対して現われることなくとも、また還元を回避することなく、あるいは 現象になることなくとも、それが何であるかにとどまるであろうという理由で批判される。第三の定式化であるフッサールの「すべての原理の原理」は、「すべ ての根源的な直観は知識にとっての権威の源泉(Rechtsquelle)であり、『直観』においてそれ自身を提示するものは何でも、それがそれ自身を提 示する限界の範囲内においてのみではあるが、それがそれ自身を提示するものとして単純に受け入れられるべきである」と述べている[21]。 マリオンは、「すべての原理の原理」が所与性を現象性の基準であり達成であるとしながらも、所与性は依然として尋問されないままであると論じている [23]。直観に限界を認める(「それ自身を与えるように...、それ自身を提示する限界の中だけではあるが」)のに対して、「所与性だけは絶対的であ り、自由であり、条件なしである」[24]。 そのとき「与えられたもの」は、それ自体に還元されることはなく、したがって直観を含む他のいかなる権威の限界からも解放される。「ある現象が還元されれ ばされるほど、それはより多く与えられることになる。マリオンはこの定式化を最後の原理と呼んでいるが、それは最初の原理、つまり現れること自体の原理と 等しい[26]。 |

|

『存在なき神』内容説明 存在しない神、神であることなき神—。ハイデガーやレヴィナス以降、“存在”やその“外部”をめぐる思索は、抹消線を付された神についてどのように語る ことができるのか?西洋キリスト教学の伝統にたち、ポストモダン期における「現象学の神学的転回」を代表する哲学者マリオンが、偶像、愛、贈与、メランコ リー、御言などの独自の分析を通じて存在の神秘に迫る主著。 目次 ・存在なき神(偶像とイコン;二重の偶像崇拝;“存在”の十字;空しさの裏面;神学の聖体拝領的な場から/について) ・テキストの外(現在と贈与;究極の厳格さ) |

| By

describing the structures of phenomena from the basis of givenness,

Marion claims to have succeeded in describing certain phenomena that

previous metaphysical and phenomenological approaches either ignore or

exclude—givens that show themselves but which a thinking that does not

go back to the given is powerless to receive.[29] In all, three types

of phenomena can be shown, according to the proportionality between

what is given in intuition and what is intended: Phenomena where little or nothing is given in intuition.[30] Examples include the Nothing and death,[31] mathematics and logic.[32] Marion claims that metaphysics, in particular Kant (but also Husserl), privileges this type of phenomenon.[33] Phenomena where there is adequation between what is given in intuition and what is intended. This includes any objective phenomena.[34] Phenomena where what is given in intuition fills or surpasses intentionality. These are named saturated phenomena.[35] The saturated phenomenon Marion defines "saturated phenomena," which contradicts the Kantian claim that phenomena can only occur if they are congruent with the a priori knowledge upon which an observer's cognitive function is founded. For example, Kant would claim that the phenomenon "three years is a longer period of time than four years" cannot occur.[36] According to Marion, "saturated phenomena" (such as divine revelation) overwhelm the observer with their complete and perfect givenness, such that they are not shaped by the particulars of the observer's cognition at all. These phenomena may be conventionally impossible, and still occur because their givenness saturates the cognitive architecture innate to the observer.[37][38] "The Intentionality of Love" The fourth section of Marion's work Prolegomena to Charity is entitled "The Intentionality of Love" and primarily concerns intentionality and phenomenology. Influenced by (and dedicated to) the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, Marion explores the human idea of love and its lack of definition: "We live with love as if we knew what it was about. But as soon as we try to define it, or at least approach it with concepts, it draws away from us."[39] He begins by explaining the essence of consciousness and its "lived experiences." Paradoxically, the consciousness concerns itself with objects transcendent and exterior to itself, objects irreducible to consciousness, but can only comprehend its 'interpretation' of the object; the reality of the object arises from consciousness alone. Thus the problem with love is that to love another is to love one's own idea of another, or the "lived experiences" that arise in the consciousness from the "chance cause" of another: "I must, then, name this love my love, since it would not fascinate me as my idol if, first, it did not render to me, like an unseen mirror, the image of myself. Love, loved for itself, inevitably ends as self-love, in the phenomenological figure of self-idolatry."[39] Marion believes intentionality is the solution to this problem, and explores the difference between the I who intentionally sees objects and the me who is intentionally seen by a counter-consciousness, another, whether the me likes it or not. Marion defines another by its invisibility; one can see objects through intentionality, but in the invisibility of the other, one is seen. Marion explains this invisibility using the pupil: "Even for a gaze aiming objectively, the pupil remains a living refutation of objectivity, an irremediable denial of the object; here for the first time, in the very midst of the visible, there is nothing to see, except an invisible and untargetable void...my gaze, for the first time, sees an invisible gaze that sees it."[39] Love, then, when freed from intentionality, is the weight of this other's invisible gaze upon one's own, the cross of one's own gaze and the other's and the "unsubstitutability" of the other. Love is to "render oneself there in an unconditional surrender...no other gaze must respond to the ecstasy of this particular other exposed in his gaze." Perhaps in allusion to a theological argument, Marion concludes that this type of surrender "requires faith."[39] |

所与性に基づいて現象の構造を記述することによって、マリオンは、これまでの形而上学的・現象学的アプローチが無視するか排除するかのどちらかであった、ある種の現象を記述することに成功したと主張している: 直観においてほとんど何も与えられない現象[30]。例としては、無と死[31]、数学と論理学[32]が挙げられる。マリオンは形而上学、特にカント(フッサールも)がこのタイプの現象を特権化していると主張している[33]。 直観において与えられるものと意図されるものとの間に妥当性がある現象。これにはあらゆる客観的現象が含まれる[34]。 直観において与えられるものが意図性を満たすか超える現象。これらは飽和現象と名付けられる[35]。 飽和現象 マリオンは「飽和現象」を定義しているが、これは、現象は観察者の認識機能が基づいている先験的知識と一致する場合にのみ起こりうるというカント的主張と矛盾する。例えば、カントは「3年は4年より長い期間である」という現象は起こりえないと主張することになる[36]。 マリオンによれば、(神の啓示のような)「飽和現象」は、観察者の認識の特殊性によって形づくられることがまったくないような、完全で完璧な所与性によっ て観察者を圧倒する。このような現象は従来不可能であったかもしれないが、それでも起こるのは、その所与性が観察者に生得的に備わっている認識アーキテク チャを飽和させるからである[37][38]。 "愛の意図性" マリオンの著作『慈愛へのプロレゴメナ』の第4章は「愛の意図性」と題され、主に意図性と現象学に関するものである。フランスの哲学者エマニュエル・レ ヴィナスの影響を受け(そしてレヴィナスに捧げられ)、マリオンは人間の愛に対する考え方とその定義の欠如を探求している: 「私たちは愛が何であるかを知っているかのように生きている。しかし、私たちがそれを定義しようとするやいなや、あるいは少なくとも概念でそれに近づこう とするやいなや、愛は私たちから遠ざかってしまう」[39]。彼はまず、意識の本質とその「生きた経験」について説明する。逆説的だが、意識は自分自身を 超越し、自分自身の外部にある対象、つまり意識にとって還元不可能な対象に関心を持つが、その対象の「解釈」を理解することしかできない。したがって、愛 の問題とは、他者を愛するということは、他者に対する自分の考え、あるいは他者という「偶然の原因」から意識に生じる「生きた経験」を愛することなのであ る: 「この愛は、私の偶像として私を魅了することはないだろう、もし最初に、目に見えない鏡のように、私自身の姿を私に見せないならば。それ自身のために愛さ れる愛は、必然的に自己愛として、自己偶像化という現象学的な姿で終わる」[39]。マリオンは、意図性がこの問題の解決策であると考え、意図的に対象を 見る私と、その私が好むと好まざるとにかかわらず、反意識である他者によって意図的に見られる私との違いを探求する。マリオンは他者をその不可視性によっ て定義する。人は意図性によって対象を見ることができるが、他者が不可視であることで、人は見られるのである。マリオンはこの不可視性を、瞳孔を使って説 明する。「客観的な視線を向ける視線にとってさえ、瞳孔は客観性に対する生きた反駁、対象に対する救いようのない否定であり続ける。 私のまなざしは、初めて、それを見る見えないまなざしを見るのである」[39]。そして愛とは、意図性から解放されたとき、この他者の見えないまなざしが 自分のまなざしに重くのしかかることであり、自分のまなざしと他者のまなざしの十字架であり、他者の「代替不可能性」である。愛とは、"無条件降伏のうち にそこに身を委ねること......彼のまなざしの中にさらけ出されたこの特別な他者のエクスタシーに、他のいかなるまなざしも応えてはならない "ことである。おそらく神学的な議論を暗示しているのだろうが、マリオンはこの種の降伏には「信仰が必要だ」と結論づけている[39]。 |

| Publications God Without Being, University of Chicago Press, 1991. [Dieu sans l'être; Hors-texte, Paris: Librarie Arthème Fayard, (1982)] Reduction and Givenness: Investigations of Husserl, Heidegger and Phenomenology, Northwestern University Press, 1998. [Réduction et donation: recherches sue Husserl, Heidegger et la phénoménologie, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1989)] Cartesian Questions: Method and Metaphysics, University of Chicago Press, 1999. [Questions cartésiennes I: Méthode et métaphysique, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1991)] 'In the Name: How to Avoid Speaking of 'Negative Theology', in JD Caputo and MJ Scanlon, eds, God, the Gift and Postmodernism, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999) On Descartes' Metaphysical Prism: The Constitution and the Limits of Onto-theo-logy in Cartesian Thought, University of Chicago Press, 1999. [Sur le prisme métaphysique de Descartes. (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1986)] The Idol and Distance: Five Studies, Fordham University Press, 2001. [L'idole et la distance: cinq études, (Paris: B Grasset, 1977)] Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness, Stanford University Press, 2002. [Étant donné. Essai d'une phénoménologie de la donation, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1997)] In Excess: Studies of Saturated Phenomena, Fordham University Press, 2002. [De surcroit: études sur les phénomenes saturés, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2001)] Prolegomena to Charity, Fordham University Press, 2002. [Prolégomènes á la charité, (Paris: E.L.A. La Différence, 1986] The Crossing of the Visible, Stanford University Press, 2004. [La Croisée du visible, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996)] The Erotic Phenomenon: Six Meditations, University of Chicago Press, 2007. [Le phénomene érotique: Six méditations, (Paris: Grasset, 2003)] On the Ego and on God, Fordham University Press, 2007. [Questions cartésiennes II: Sur l'ego et sur Dieu, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996)] The Visible and the Revealed, Fordham University Press, 2008. [Le visible et le révélé. (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2005)] The Reason of the Gift (Richard Lectures), University of Virginia Press, 2011. In the Self's Place: The Approach of St. Augustine, Stanford University Press, 2012. [Au lieu de soi, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2008)] Givenness & Hermeneutics (Pere Marquette Lectures in Theology), Marquette University Press, 2013. Negative Certainties, University of Chicago Press, 2015. [Certitudes négatives. (Paris: Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2009)] Givenness and Revelation (Gifford Lectures), Oxford University Press, 2016. Believing in Order to See: On the Rationality of Revelation and the Irrationality of Some Believers, Fordham University Press, 2017. A Brief Apology for a Catholic Moment, University of Chicago Press, 2017. [Brève apologie pour un moment catholique, (Paris: Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2017)] On Descartes' Passive Thought: The Myth of Cartesian Dualism, University of Chicago Press, 2018. [Sur la pensée de Descartes, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2013)] Descartes' Grey Ontology: Cartesian Science and Aristotelian Thought in the Regulae, St. Augustine's Press, Forthcoming – May 2022. Descartes' White Theology, Saint Augustine's Press, Translation in process. Revelation Comes from Elsewhere. Stanford University Press. Translation in process. [D'ailleurs, la révélation, Paris: Grasset, 2020)] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Luc_Marion |

出版物 『存在なき神』シカゴ大学出版局、1991年。[Dieu sans l'être; Hors-texte、パリ:Librarie Arthème Fayard、1982年] 『還元と与えられ:フッサール、ハイデガー、現象学の研究』ノースウェスタン大学出版局、1998年。[還元と与えられ:フッサール、ハイデガー、現象学に関する研究、(パリ:プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、1989年)] デカルト的疑問:方法と形而上学、シカゴ大学出版局、1999年。[デカルト的疑問 I:方法と形而上学、(パリ:プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、1991年)] 『In the Name: How to Avoid Speaking of 』Negative Theology『, in JD Caputo and MJ Scanlon, eds, God, the Gift and Postmodernism, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999) On Descartes』 Metaphysical Prism: The Constitution and the Limits of Onto-theo-logy in Cartesian Thought, University of Chicago Press, 1999. [デカルトの形而上学的プリズムについて。(パリ:プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、1986年)] 偶像と距離:五つの研究、フォードハム大学出版、2001年。[偶像と距離:五つの研究、(パリ:B Grasset、1977年)] 与えられしもの:与えられしものの現象学に向けて、スタンフォード大学出版、 2002年。[与えられたもの。贈与の現象学への試み、(パリ: プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、1997年)] 過剰:飽和現象の研究、フォードハム大学出版、2002年。[過剰:飽和現象の研究、(パリ: プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、2001年)] 『慈善への序説』フォードハム大学出版、2002年。[『慈善への序説』パリ:E.L.A. La Différence、1986年] 『可視の交差』スタンフォード大学出版、2004年。[『可視の交差』パリ:Presses Universitaires de France、1996年] The Erotic Phenomenon: Six Meditations, University of Chicago Press, 2007. [エロティックな現象:六つの瞑想、(パリ:Grasset、2003)] On the Ego and on God, Fordham University Press, 2007. [自我と神について、(パリ:Presses Universitaires de France、1996)] 自我と神について、(パリ: プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、1996)] The Visible and the Revealed, Fordham University Press, 2008. [見えるものと見えるもの。(パリ: レ・エディシオン・デュ・セルフ、2005)] The Reason of the Gift (Richard Lectures), University of Virginia Press, 2011. 『自己の代わりに:聖アウグスティヌスのアプローチ』(スタンフォード大学出版、2012年)。 『与えられと解釈学(ペレ・マルケット神学講義)』(マルケット大学出版、2013年)。 Negative Certainties(否定的な確実性)、シカゴ大学出版局、2015年。[Certitudes négatives(否定的な確実性)。(パリ:Editions Grasset & Fasquelle、2009年)] Givenness and Revelation(与えられしものと啓示)(ギフォード・レクチャー)、オックスフォード大学出版局、2016年。 『見ることのために信じる:啓示の合理性と一部の信者の非合理性について』フォードハム大学出版、2017年。 『カトリックの瞬間に対する短い弁明』シカゴ大学出版、2017年。[『カトリックの瞬間に対する短い弁明』 (パリ:エディション・グラッセット&ファスケール、2017年)] デカルトの受動的思考について:デカルト的二元論の神話、シカゴ大学出版局、2018年。[デカルトの思考について、(パリ:プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、2013年)] デカルトの灰色のオントロジー:Regulaeにおけるデカルト的科学とアリストテレス的思考、セント・オーガスティンズ・プレス、2022年5月刊行予定。 『デカルトの白き神学』Saint Augustine's Press、翻訳中。 『啓示は別の場所から来る』スタンフォード大学出版局、翻訳中。[『啓示は別の場所から来る』パリ:グラセット、2020年) 『https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Luc_Marion』 |

| Christian existentialism Postmodern Christianity Rational mysticism |

キリスト教実存主義 ポストモダン・キリスト教 合理的神秘主義 |

| Christian existentialism

is a theo-philosophical movement which takes an existentialist approach

to Christian theology. The school of thought is often traced back to

the work of the Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard

(1813–1855) who is widely regarded as the father of existentialism.[1] Kierkegaardian themes  Søren Kierkegaard Christian existentialism relies on Kierkegaard's understanding of Christianity. Kierkegaard addressed themes such as authenticity, anxiety, love, and the irrationality and subjectivity of faith, rejecting efforts to contain God in an objective, logical system. To Kierkegaard, the focus of theology was on the individual grappling with subjective truth rather than a set of objective claims – a point he demonstrated by often writing under pseudonyms that had different points of view. He contended that each person must make independent choices, which then constitute his or her existence. Each person suffers from the anguish of indecision (whether knowingly or unknowingly) until committing to a way to live. Kierkegaard posited three stages of human existence: the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious, the latter coming after what is often called the leap of faith.[citation needed] Kierkegaard argued that the universe is fundamentally paradoxical, and that its greatest paradox is the transcendent union of God and humans in the person of Jesus Christ. He also posited having a personal relationship with God that supersedes all prescribed moralities, social structures and communal norms,[2] since he asserted that following social conventions is essentially a personal aesthetic choice made by individuals.[citation needed] Major premises One of the major premises of Kierkegaardian Christian existentialism entails calling the masses back to a more genuine form of Christianity. This form is often identified with some notion of Early Christianity, which mostly existed during the first three centuries after Christ's crucifixion. Beginning with the Edict of Milan, which was issued by Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 313, Christianity enjoyed a level of popularity among Romans and later among other Europeans. And yet Kierkegaard asserted that by the 19th century, the ultimate meaning of New Testament Christianity (love, cf. agape, mercy and loving-kindness) had become perverted, and Christianity had deviated considerably from its original threefold message of grace, humility, and love. Another major premise of Kierkegaardian Christian existentialism involves Kierkegaard's conception of God and Love. For the most part, Kierkegaard equates God with Love.[3] Thus, when a person engages in the act of loving, he is in effect achieving an aspect of the divine. Kierkegaard also viewed the individual as a necessary synthesis of both finite and infinite elements. Therefore, when an individual does not come to a full realization of his infinite side, he is said to be in despair. For many contemporary Christian theologians, the notion of despair can be viewed as sin. However, to Kierkegaard, a man sinned when he was exposed to this idea of despair and chose a path other than one in accordance with God's will. A final major premise of Kierkegaardian Christian existentialism entails the systematic undoing of evil acts. Kierkegaard asserted that once an action had been completed, it should be evaluated in the face of God, for holding oneself up to divine scrutiny was the only way to judge one's actions. Because actions constitute the manner in which something is deemed good or bad, one must be constantly conscious of the potential consequences of his actions. Kierkegaard believed that the choice for goodness ultimately came down to each individual. Yet Kierkegaard also foresaw the potential limiting of choices for individuals who fell into despair.[4] The Bible Christian Existentialism often refers to what it calls the indirect style of Christ's teachings, which it considers to be a distinctive and important aspect of his ministry. Christ's point, it says, is often left unsaid in any particular parable or saying, to permit each individual to confront the truth on his own.[5] This is particularly evident in (but is certainly not limited to) his parables; for example in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 18:21–35). A good example of indirect communication in the Old Testament is the story of David and Nathan in 2 Samuel 12:1–14.[citation needed] An existential reading of the Bible demands that the reader recognize that he is an existing subject, studying the words that God communicates to him personally. This is in contrast to looking at a collection of truths which are outside and unrelated to the reader.[6] Such a reader is not obligated to follow the commandments as if an external agent is forcing them upon him, but as though they are inside him and guiding him internally. This is the task Kierkegaard takes up when he asks: "Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor's distance from everyday life, or the learner who should put it to use?"[7] Existentially speaking, the Bible doesn't become an authority in a person's life until they permit the Bible to be their personal authority.[citation needed] Notable Christian existentialists Christian existentialists include German Protestant theologians Paul Tillich and Rudolf Bultmann, American existential psychologist Rollo May (who introduced much of Tillich's thought to a general American readership), British Anglican theologian John Macquarrie, American philosopher Clifford Williams, French Catholic philosophers Gabriel Marcel, Louis Lavelle, Emmanuel Mounier and Pierre Boutang and French Protestant Paul Ricœur, German philosopher Karl Jaspers, Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, and Russian philosophers Nikolai Berdyaev and Lev Shestov. Karl Barth added to Kierkegaard's ideas the notion that existential despair leads an individual to an awareness of God's infinite nature. Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky could be placed within the tradition of Christian existentialism.[citation needed] The roots of existentialism have been traced back as far as Augustine of Hippo.[8][9][10] Some of the most striking passages in Pascal's Pensées, including the famous section on the Wager, deal with existentialist themes.[11][12][13][14] Jacques Maritain, in Existence and the Existent: An Essay on Christian Existentialism,[15] finds the core of true existentialism in the thought of Thomas Aquinas.[citation needed] Existential Theology In the monograph, Existential Theology: An Introduction (2020), Hue Woodson provides a constructive primer to the field and, he argues, thinkers that can be considered more broadly as engaging with existential theology, defining a French school including Gabriel Marcel, Jacques Maritain, and Jean-Luc Marion,[16] a German school including Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer,[17] and a Russian school including Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Nikolai Berdyaev.[18] Radical Existential Christianity It has been claimed that Radical Existential Christians’ faith is based in their sensible and immediate and direct experience of God indwelling in human terms.[19] It is suggested that individuals do not make or create their Christian existence; it does not come as a result of a decision one personally makes. The radical Protestants of the 17th century, for example Quakers may have been in some ways theo-philosophically aligned with radical existential Christianity.[citation needed] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_existentialism |

キ

リスト教実存主義は、キリスト教神学に実存主義的なアプローチをとる神哲学運動である。この学派の思想はしばしば、実存主義の父と広くみなされているデン

マークの哲学者であり神学者であるセーレン・キルケゴール(1813-1855)の研究にまで遡ることができる[1]。 キルケゴール的テーマ  キルケゴール キリスト教実存主義は、キルケゴールのキリスト教理解に依拠している。キルケゴールは、真正性、不安、愛、信仰の非合理性と主観性といったテーマを取り上 げ、神を客観的で論理的な体系に封じ込めようとする努力を否定した。キルケゴールにとって神学の焦点は、客観的な主張の集合ではなく、主観的な真理に取り 組む個人にあった。彼は、人はそれぞれ独立した選択をしなければならず、それがその人の存在を構成すると主張した。人はそれぞれ、生きる道を決めるまで、 (知ってか知らずか)優柔不断の苦悩に苦しむ。キルケゴールは人間存在の3つの段階を仮定した:美的、倫理的、宗教的。彼はまた、社会的慣習に従うことは 本質的に個人による美的選択であると主張したため、すべての規定された道徳、社会構造、共同体規範に優先する神との個人的関係を持つことを提起した [2]。 主要な前提 キルケゴール的キリスト教実存主義の大前提のひとつは、大衆をより純粋なキリスト教へと呼び戻すことである。この形態は、キリストが十字架につけられてか ら最初の3世紀に存在した初期キリスト教の概念と同一視されることが多い。AD313年にローマ皇帝コンスタンティヌス1世が発布したミラノ勅令を皮切り に、キリスト教はローマ人の間で、そして後には他のヨーロッパ人の間でも人気を博した。しかし、キルケゴールは、19世紀までに新約聖書のキリスト教の究 極的な意味(愛、アガペー、慈悲、慈愛)が変質し、キリスト教が本来持っていた恵み、謙遜、愛という3つのメッセージから大きく逸脱してしまったと主張し た。 キルケゴール的キリスト教実存主義のもう一つの大前提は、キルケゴールの神と愛についての概念に関わる。キルケゴールはほとんどの場合、神と愛を同一視し ている[3]。したがって、人が愛するという行為に従事するとき、その人は事実上、神の一面を達成することになる。キルケゴールはまた、個人を有限と無限 の両方の要素の必要な統合とみなしていた。それゆえ、個人が自分の無限の側面を完全に実現できないとき、その人は絶望の中にいると言われる。現代のキリス ト教神学者の多くにとって、絶望という概念は罪とみなすことができる。しかし、キルケゴールにとって人は、この絶望という観念にさらされ、神の意志に従っ た道以外の道を選んだときに罪を犯したのである。 キルケゴール的キリスト教実存主義の最後の大前提は、悪行を体系的に取り消すことである。キルケゴールは、ある行為が完了したら、それは神の面前で評価さ れるべきであると主張した。行動とは、善悪を決定するものであるから、人は自分の行動がもたらす潜在的な結果を常に意識していなければならない。キルケ ゴールは、善を選択するのは最終的には各個人であると考えていた。しかしキルケゴールはまた、絶望に陥った個人の選択が制限される可能性も予見していた [4]。 聖書 キリスト教実存主義は、キリストの教えの間接的なスタイルと呼ばれるものにしばしば言及する。キリストの主張は、たとえ話や格言の中でしばしば語られるこ となく、各個人が自分自身で真理に立ち向かえるようにしている[5] 。旧約聖書における間接的なコミュニケーションの好例は、サムエル記下12章1~14節のダビデとナタンの物語である[要出典]。 聖書の実存的な読解は、読者が、神が個人的に彼に伝えている言葉を研究している、現存する主体であることを認識することを要求する。そのような読者は、あ たかも外部の存在が戒律を強制しているかのように戒律に従う義務を負うのではなく、あたかも戒律が読者の内部にあり、読者を内的に導いているかのように戒 律に従うのである。これが、キルケゴールが問いかける課題である: 「日常生活から流星のような距離を置いて真面目に講義する教師と、それを活用すべき学習者、どちらがより困難な課題を持っているだろうか」[7] 実存的に言えば、聖書がその人の人生における権威となるのは、聖書がその人の個人的な権威となることを認めるまでである[要出典]。 著名なキリスト教実存主義者 キリスト教実存主義者には、ドイツのプロテスタント神学者パウル・ティリッヒとルドルフ・ブルートマン、アメリカの実存心理学者ロロ・メイ(ティリッヒの 思想の多くをアメリカの一般読者に紹介した)、イギリス聖公会の神学者ジョン・マッカリー、 アメリカの哲学者クリフォード・ウィリアムズ、フランスのカトリック哲学者ガブリエル・マルセル、ルイ・ラヴェル、エマニュエル・ムニエ、ピエール・ブー タン、フランスのプロテスタント哲学者ポール・リクール、ドイツの哲学者カール・ヤスパース、スペインの哲学者ミゲル・デ・ウナムーノ、ロシアの哲学者ニ コライ・ベルジャエフとレフ・シェストフ。カール・バルトはキルケゴールの考えに、実存的絶望が神の無限の本質を認識させるという概念を加えた。ロシアの 作家フョードル・ドストエフスキーはキリスト教的実存主義の伝統の中に位置づけられる[要出典]。 実存主義のルーツはヒッポのアウグスティヌスまで遡ることができる[8][9][10]。 パスカルの『ペンシーズ』(Pensées)の中で最も印象的な箇所は、有名な『賭博』の章を含め、実存主義のテーマを扱っている[11][12] [13][14]: An Essay on Christian Existentialism』[15]では、真の実存主義の核心をトマス・アクィナスの思想に見出している[要出典]。 実存神学 単行本『実存神学入門』(2020年)の中で、フエは実存神学の核心をトマス・アクィナスに見出している: フエ・ウッドソンは『実存神学入門』(2020年)において、この分野への建設的な入門書を提供し、より広く実存神学に関わる思想家を論じ、ガブリエル・ マルセル、ジャック・マリタン、ジャン=リュック・マリオンを含むフランス学派[16]、イマヌエル・カント、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテ、フリード リヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨーゼフ・シェリング、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、ディートリヒ・ボンヘッファーを含むドイツ学派[17]、 フョードル・ドストエフスキー、レオ・トルストイ、ニコライ・ベルジャエフを含むロシア学派を定義している。 [18] 急進的実存主義キリスト教 急進的実存主義キリスト教徒たちの信仰は、人間的に内在する神の感覚的で直接的な体験に基づいていると主張されている。17世紀の急進的なプロテスタント、例えばクエーカー教徒は、ある意味で急進的な実存的キリスト教と神哲学的に一致していたかもしれない[要出典]。 |

| Postmodern theology[citation

needed], also known as the continental philosophy of religion,[citation

needed] is a philosophical and theological movement that interprets

theology in light of post-Heideggerian continental philosophy,

including phenomenology, post-structuralism, and deconstruction.[1] History Postmodern theology emerged in the 1980s and 1990s when a handful of philosophers who took philosopher Martin Heidegger as a common point of departure began publishing influential books on theology.[2] Some of the more notable works of the era include Jean-Luc Marion's 1982 book God Without Being,[3] Mark C. Taylor's 1984 book Erring,[4] Charles Winquist's 1994 book Desiring Theology,[5] John D. Caputo's 1997 book The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida,[6] and Carl Raschke's 2000 book The End of Theology.[7] There are at least two branches of postmodern theology, each of which has evolved around the ideas of particular post-Heideggerian continental philosophers. Those branches are radical orthodoxy and weak theology. Radical orthodoxy Main article: Radical orthodoxy Radical orthodoxy is a branch of postmodern theology that has been influenced by the phenomenology of Jean-Luc Marion, Paul Ricœur, and Michel Henry, among others.[8] Although radical orthodoxy is informally organized, its proponents often agree on a handful of propositions. First, there is no sharp distinction between reason on the one hand and faith or revelation on the other. In addition, the world is best understood through interactions with God, even though a full understanding of God is never possible. Those interactions include culture, language, history, technology, and theology. Further, God directs people toward truth, which is never fully available to them. In fact, a full appreciation of the physical world is only possible through a belief in transcendence. Finally, salvation is found through interactions with God and others.[9] Prominent advocates of radical orthodoxy include John Milbank, Catherine Pickstock, and Graham Ward. Weak theology Weak theology is a branch of postmodern theology that has been influenced by the deconstructive thought of Jacques Derrida,[10] including Derrida's description of a moral experience he calls "the weak force."[11] Weak theology rejects the idea that God is an overwhelming physical or metaphysical force. Instead, God is an unconditional claim without any force whatsoever. As a claim without force, the God of weak theology does not intervene in nature. As a result, weak theology emphasizes the responsibility of humans to act in this world here and now.[12] John D. Caputo is a prominent advocate of the movement. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_theology John D. Caputo Richard Kearney Mario Kopić Jean-Luc Marion Françoise Meltzer John Milbank James Olthuis Catherine Pickstock Carl Raschke Peter Rollins Mary-Jane Rubenstein James K.A. Smith Mark C. Taylor Gabriel Vahanian Gianni Vattimo Charles Winquist Catherine Keller Mikhail Epstein |

ポストモダンの神学[要出典]は、大陸宗教哲学としても知られ[要出典]、現象学、ポスト構造主義、脱構築を含むハイデガー以後の大陸哲学に照らして神学を解釈する哲学的・神学的運動である[1]。 歴史 ポストモダンの神学は、哲学者マルティン・ハイデガーを共通の出発点とする一握りの哲学者が神学に関する影響力のある本を出版し始めた1980年代から 1990年代にかけて出現した。テイラーの1984年の著書『Erring』[4]、チャールズ・ウィンクイストの1994年の著書『Desiring Theology』[5]、ジョン・D・カプートの1997年の著書『The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida』[6]、カール・ラシュケの2000年の著書『The End of Theology』[7]などがある。 ポストモダン神学には少なくとも2つの分派があり、それぞれが特定のハイデガー以後の大陸哲学者の思想を中心に発展してきた。それらの枝分かれとは、急進的正統主義と弱い神学である。 急進的正統主義 主な記事 急進的正統主義 急進的正統主義はポストモダン神学の一分野であり、ジャン=リュック・マリオン、ポール・リクール、ミシェル・アンリなどの現象学の影響を受けている[8]。 急進的正統主義は非公式に組織されているが、その支持者たちはしばしば一握りの命題に同意している。第一に、一方では理性、他方では信仰や啓示を峻別しな い。さらに、神の完全な理解は決して不可能であるにもかかわらず、世界は神との相互作用を通して最もよく理解される。そうした相互作用には、文化、言語、 歴史、技術、神学が含まれる。さらに、神は人々を真理へと導くが、それは決して完全には手に入らない。実際、物理的世界を完全に理解することは、超越を信 じることによってのみ可能となる。最後に、救いは神や他者との相互作用を通して見出される[9]。 急進的正統主義の著名な提唱者には、ジョン・ミルバンク、キャサリン・ピックストック、グレアム・ウォードなどがいる。 弱者の神学 弱者の神学とは、ジャック・デリダの脱構築的思想に影響を受けたポストモダン神学の一派であり[10]、彼が「弱い力」と呼ぶ道徳的経験についてのデリダ の記述も含まれる[11]。その代わり、神とはいかなる力も持たない無条件の主張である。力のない主張として、弱い神学の神は自然に介入しない。その結 果、弱い神学は、今ここでこの世界で行動する人間の責任を強調する[12]。ジョン・D・カプートはこの運動の著名な提唱者である。 |

| Rational mysticism,

which encompasses both rationalism and mysticism, is a term used by

scholars, researchers, and other intellectuals, some of whom engage in

studies of how altered states of consciousness or transcendence such as

trance, visions, and prayer occur. Lines of investigation include

historical and philosophical inquiry as well as scientific inquiry

within such fields as neurophysiology and psychology. Overview The term "rational mysticism" was in use at least as early as 1911 when it was the subject of an article by Henry W. Clark in the Harvard Theological Review.[1] In a 1924 book, Rational Mysticism, theosophist William Kingsland correlated rational mysticism with scientific idealism.[2][3] South African philosopher J. N. Findlay frequently used the term, developing the theme in Ascent to the Absolute and other works in the 1960s and 1970s.[4] Columbia University pragmatist John Herman Randall, Jr. characterized both Plotinus and Baruch Spinoza as “rationalists with overtones of rational mysticism” in his 1970 book Hellenistic Ways of Deliverance and the Making of Christian Synthesis.[5] Rice University professor of religious studies Jeffrey J. Kripal, in his 2001 book Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom, defined rational mysticism as “not a contradiction in terms” but “a mysticism whose limits are set by reason.”[6] In response to criticism of his book The End of Faith, author Sam Harris used the term rational mysticism for the title of his rebuttal.[7][8][9][10] University of Pennsylvania neurotheologist Andrew Newberg has been using nuclear medicine brain imaging in similar research since the early 1990s.[11][12] Executive editor of Discover magazine Corey S. Powell, in his 2002 book, God in the Equation, attributed the term to Albert Einstein: “In creating his radical cosmology, Einstein stitched together a rational mysticism, drawing on—but distinct from—the views that came before.”[13] Science writer John Horgan interviewed and profiled James Austin, Terence McKenna, Michael Persinger, Christian Rätsch, Huston Smith, Ken Wilber, Alexander Shulgin and others for Rational Mysticism: Dispatches from the Border Between Science and Spirituality,[14] his 2003 study of “the scientific quest to explain the transcendent.”[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_mysticism Analytic philosophy Henosis Philosophy of Baruch Spinoza Relationship between religion and science Sociology of scientific knowledge |

合理主義と神秘主義の両方を包含す

る合理的神秘主義とは、学者、研究者、その他の知識人によって使用される用語であり、トランス状態、ビジョン、祈りなどの意識の変容状態や超越がどのよう

に起こるかについての研究に従事する人もいる。その研究対象には、歴史的・哲学的な探求や、神経生理学や心理学などの分野における科学的な探求が含まれ

る。 概要 理性的神秘主義」という用語は、少なくとも1911年のハーバード大学神学論集(Harvard Theological Review)に掲載されたヘンリー・W・クラーク(Henry W. Clark)の論文の主題として早くから使用されていた[1]。 1924年の著書『理性的神秘主義(Rational Mysticism)』において、神智学者であるウィリアム・キングスランド(William Kingsland)は理性的神秘主義と科学的観念論を関連付けている[2][3]。 南アフリカの哲学者であるJ・N・フィンドレー(J. N. Findlay)はこの用語を頻繁に使用し、1960年代から1970年代にかけて『絶対への上昇(Ascent to the Absolute)』やその他の著作においてこのテーマを展開している[4]。 コロンビア大学のプラグマティストであるジョン・ハーマン・ランドール・ジュニアは、1970年に出版した著書『Hellenistic Ways of Deliverance and the Making of Christian Synthesis』において、プロティノスとバルーク・スピノザを「合理的神秘主義の含みを持つ合理主義者」と特徴づけている[5]。ライス大学の宗教 学教授であるジェフリー・J・クリパルは、2001年に出版した著書『Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom』において、合理的神秘主義を「言葉の矛盾」ではなく「理性によってその限界が設定される神秘主義」と定義している[6]。 著者のサム・ハリスは、自身の著書『The End of Faith(信仰の終焉)』に対する批判に対して、反論のタイトルに合理的神秘主義という言葉を使用した[7][8][9][10]。 ペンシルバニア大学の神経神学者アンドリュー・ニューバーグは、1990年代初頭から同様の研究に核医学による脳イメージングを使用している[11] [12]。 ディスカヴァー』誌のエグゼクティブ・エディターであるコリー・S・パウエルは、2002年の著書『God in the Equation』の中で、この言葉をアルベルト・アインシュタインに帰するとしている: 「彼の急進的な宇宙論を創造する際に、アインシュタインは合理的な神秘主義をつなぎ合わせた。 科学ライターのジョン・ホーガンは、『理性的神秘主義』のために、ジェームズ・オースティン、テレンス・マッケンナ、マイケル・パーシンガー、クリスチャ ン・レッチュ、ヒューストン・スミス、ケン・ウィルバー、アレクサンダー・シュルギンらにインタビューし、プロフィールを紹介している: Dispatches from the Border Between Science and Spirituality』[14]は、「超越的なものを説明しようとする科学的探求」[15]に関する彼の2003年の研究である。 |

| 否定神学(ひていしんがく、ギリシア語 apophatike theologia)とは、キリスト教神学において、神を論ずる際に使われた方法論の一つ。ラテン語では via negativa 否定の道、否定道 とも呼ぶ。 概要 神の本質は人間が思惟しうるいかなる概念にも当てはまらない、すなわち一切の述語を超えたものであるとして、「神は~でない」と否定表現でのみ神を語ろう と試みる。肯定神学とともに、キリスト教神学における二潮流を形作る。神秘主義との関連が強く、またドイツ語圏を中心に哲学へも影響を与えた。 また、視野を広げて見るとインドや中国においても、ウパニシャッドの思索者やインド仏教の龍樹(ナーガールジュナ)の中論、中国仏教の三論宗においても彼等は、その哲理を「無」や「不」などの否定に托して語っている[1]。 具体例 万物の原因であって万物を超えているものは、非存在ではなく、生命なきものでもなく、理性なきものでもなく、知性なきものでもない。 万物の原因であって万物を超えているものは、身体をもたず、姿ももたず、形ももたず、質ももたず、量ももたない。 万物の原因であって万物を超えているものは、いかなる場所にも存在せず、見られもせず、感覚で触れることもできず、感覚もせず、感覚されることもできない。 万物の原因であって万物を超えているものは、光を欠くこともなく、変化もなく、消滅もなく、分割もなく、欠如もなく、流転もなく、そのほか感覚で捉えられるどんなものでもない。(『神秘神学』より[2]) 得も無く亦至も無く、断ならず亦常ならず、生ぜず亦滅せず、是を説いて涅槃と名づく。(『中論』「涅槃品第二十五」より[1]) されば名号(みょうごう)は青(しょう)黄(おう)赤(しゃく)白(びゃく)の色にもあらず。長短方円の形にもあらず、有(う)にもあらず無(む)にもあ らず、五味(ごみ)をもはなれたる故に。口にとなふれどもいかなる法味(ほうみ)ともおぼへず。すべていかなるものとも思い量(はかる)べき法(ほう)に あらず。これを無疑(むぎ)無慮(むりょ)といひ、十方の諸佛はこれを不可思議とは讃(さん)じたまへり。唯(ただ)声にまかせてとなふれば、無窮(むぐ う)の生死(しょうじ)をはなるる言語道断の法なり。(一遍上人語録『門人伝説』より[3]) 否定神学の目的と思想 この神学は「いかなる仕方で神に様々な属性を述語づけることが可能か」を目的とするものではなく、「いかにして神と合一し、神を賛美するべきか」を問題とし、探求することを目的としている [4]。 そして、否定神学は人間が神と合一する最終局面において、人間が神の臨在のなかで言語にも思惟にも窮してしまい、ただ沈黙するしかできなくなったときの神理解を問題とするのである[5]。 理性によって神を知る方法は二つの方法があり、その一つは肯定的に知る方法で、もう一つは否定的に知る方法である。我々は、神の創造に触れれば認めないわ けにはいかないその無上の完全さのために、神は聖であり、賢明であり、慈悲に満ち、神こそ光であり、生命であるという言葉で肯定的に表現することができ る。しかし、神はすべての被造物を超えていることから、否定的方法も存在する。つまり、神は賢明であられるが、神の所有される英知は人間の持つ知恵とは質 が違っており、神の真、善、美は人間の知っている真、善、美とは異なっているのである。それ故に、神は人間の知っているどんなものとも似ていない、つま り、神について人間が持っている概念では、神を認識するにはまったく不十分であるということを心に留めておかなければならないのである。[6] 歴史 否定神学は偽ディオニュシオス・アレオパギテスの書、『神名論』『神秘神学』(6世紀ごろ)で展開されたが、イエス・キリストと同時代のユダヤ人哲学者で 中期プラトン学派のフィロンの著作『カインの子孫』[7]、3世紀新プラトン学派のプロティノスの著作『エネアデス』(「善なるもの一なるもの」) [8]、4世紀の神学者ニュッサのグレゴリウスの『モーセの生涯』にその原型を見出すことが出来る[9]。偽ディオニュシオスは肯定神学と否定神学の二つ の道を示す。肯定神学により人が認識する神についての知識は有意義ではあるが神についての一面的な知識に過ぎない。神についての知識は肯定神学と否定神学 を併用することによってより深く探求できる、あるいは浄化、照明、合一の道を実践できるというものである。 『神秘神学』に代表される「ディオニュシオス文書」は、7世紀の告白者マクシモスや8世紀のダマスコのヨアンネスなどに受容され、正教会神学における静寂 主義(ヘシュカズム)の成立にも影響を与えた。さらに偽ディオニュシオスの著作は9世紀のヨハネス・スコトゥス・エリウゲナによりラテン語訳されるととも に、『天上位階論』に対する註解書『天上位階論註解』も著されて、以後「ディオニュシオス文書」は西方神学にも東方神学同様に絶大な権威を持って受容され ていった[10]。 トマス・アクイナス、マイスター・エックハルト、ニコラウス・クザーヌスやドイツ神秘主義にその受容と影響をみることができる。また、14世紀イギリスの 『不可知の雲(英語版)』の匿名の著者によって英語に翻訳されて、17-18世紀のイギリス神秘主義の黄金期にも影響を与えている[11]。 |

Palamism

or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas (c.

1296 – 1359), whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox practice of

Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are

sometimes referred to as Palamites. Palamism

or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas (c.

1296 – 1359), whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox practice of

Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are

sometimes referred to as Palamites.Seeking to defend the assertion that humans can become like God through deification without compromising God's transcendence, Palamas distinguished between God's inaccessible essence and the energies through which he becomes known and enables others to share his divine life.[1] The central idea of the Palamite theology is a distinction between the divine essence and the divine energies[2] that is not a merely conceptual distinction.[3] Palamism is a central element of Eastern Orthodox theology, being made into dogma in the Eastern Orthodox Church by the Hesychast councils.[4] Palamism has been described as representing "the deepest assimilation of the monastic and dogmatic traditions, combined with a repudiation of the philosophical notion of the exterior wisdom".[5] Historically, Western Christianity has tended to reject Palamism, especially the essence–energies distinction, sometimes characterizing it as a heretical introduction of an unacceptable division in the Trinity.[6][7] Further, the practices used by the later hesychasts used to achieve theosis were characterized as "magic" by the Western Christians.[4] More recently, some Roman Catholic thinkers have taken a positive view of Palamas's teachings, including the essence–energies distinction, arguing that it does not represent an insurmountable theological division between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[8] The rejection of Palamism by the West and by those in the East who favoured union with the West (the "Latinophrones"), actually contributed to its acceptance in the East, according to Martin Jugie, who adds: "Very soon Latinism and Antipalamism, in the minds of many, would come to be seen as one and the same thing".[9] パラミズムまたはパラミテ神学は、グレゴリウス・パラマ(1296年頃-1359年)の教えから成り、彼の著作は東方正教会のヘシシャズムの実践をバーラムの攻撃から擁護した。パラマスの信奉者はパラマス派と呼ばれることもある。 パラマスは、人間は神の超越性を損なうことなく、神化によって神のようになることができるという主張を擁護するために、神の近づきがたい本質と、神が知ら れるようになり、他者が神の生命を共有することを可能にするエネルギーとを区別した[1]。パラマスの神学の中心的な考え方は、神の本質と神のエネルギー [2]との区別であり、それは単に概念的な区別にとどまらない[3]。 パラミズムは東方正教会の神学の中心的な要素であり、ヘシキスタ公会議によって東方正教会の教義とされた[4]。パラミズムは「修道院と教義の伝統の最も深い同化であり、外的な知恵という哲学的な概念の否定と結びついたもの」[5]と説明されている。 歴史的に、西方キリスト教はパラミズム、特に本質とエネルギーの区別を拒絶する傾向があり、時にはそれを三位一体における受け入れがたい分割の異端的な導 入として特徴づけることもあった[6][7]。さらに、テオーシスを達成するために使用された後世のヘーシカストによって使用された実践は、西方キリスト 教徒によって「魔術」として特徴づけられた。 [4]最近では、一部のローマ・カトリックの思想家が、本質とエネルギーの区別を含むパラマスの教えを肯定的に捉えており、それはローマ・カトリックと東 方正教会の間の乗り越えられない神学的分裂を示すものではないと主張している[8]。 マーティン・ジュギーによれば、西洋と西洋との統合を支持する東洋の人々(「ラテン主義者」)によるパラム主義の拒絶は、東洋におけるパラム主義の受容に 実際に貢献した: 「やがてラテン主義と反パラミズムは、多くの人々の心の中で、同じものとみなされるようになった」[9]。 |

| Apophatic

theology, also known as negative theology,[1] is a form of theological

thinking and religious practice which attempts to approach God, the

Divine, by negation, to speak only in terms of what may not be said

about the perfect goodness that is God.[web 1] It forms a pair together

with cataphatic theology, which approaches God or the Divine by

affirmations or positive statements about what God is.[web 2] The apophatic tradition is often, though not always, allied with the approach of mysticism, which aims at the vision of God, the perception of the divine reality beyond the realm of ordinary perception.[2] Etymology and definition "Apophatic", Ancient Greek: ἀπόφασις (noun); from ἀπόφημι apophēmi, meaning 'to deny'. From Online Etymology Dictionary: apophatic (adj.) "involving a mention of something one feigns to deny; involving knowledge obtained by negation", 1850, from Latinized form of Greek apophatikos, from apophasis "denial, negation", from apophanai "to speak off," from apo "off, away from" (see apo-) + phanai "to speak," related to pheme "voice," from PIE root *bha- (2) "to speak, tell, say."[web 3] Via negativa or via negationis (Latin), 'negative way' or 'by way of denial'.[1] The negative way forms a pair together with the kataphatic or positive way. According to Deirdre Carabine, Pseudo Dionysius describes the kataphatic or affirmative way to the divine as the "way of speech": that we can come to some understanding of the Transcendent by attributing all the perfections of the created order to God as its source. In this sense, we can say "God is Love", "God is Beauty", "God is Good". The apophatic or negative way stresses God's absolute transcendence and unknowability in such a way that we cannot say anything about the divine essence because God is so totally beyond being. The dual concept of the immanence and transcendence of God can help us to understand the simultaneous truth of both "ways" to God: at the same time as God is immanent, God is also transcendent. At the same time as God is knowable, God is also unknowable. God cannot be thought of as one or the other only.[web 2] Origins and development According to Fagenblat, "negative theology is as old as philosophy itself;" elements of it can be found in Plato's unwritten doctrines, while it is also present in Neo-Platonic, Gnostic and early Christian writers. A tendency to apophatic thought can also be found in Philo of Alexandria.[3] According to Carabine, "apophasis proper" in Greek thought starts with Neo-Platonism, with its speculations about the nature of the One, culminating in the works of Proclus.[4] Carabine writes that there are two major points in the development of apophatic theology, namely the fusion of the Jewish tradition with Platonic philosophy in the writings of Philo, and the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who infused Christian thought with Neo-Platonic ideas.[4] The Early Church Fathers were influenced by Philo,[4] and Meredith even states that Philo "is the real founder of the apophatic tradition."[5] Yet, it was with Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Maximus the Confessor,[6] whose writings shaped both Hesychasm, the contemplative tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Churches, and the mystical traditions of western Europe, that apophatic theology became a central element of Christian theology and contemplative practice.[4] Elijah's hearing of a "still, small voice" at I Kings 19:11-13 has been proposed as a Biblical example of apophatic prayer. |

否

定神学としても知られるアポファティック神学[1]は、否定によって神である神に近づこうとする神学的思考と宗教的実践の一形態であり、神である完全な善

について語ることができないことについてのみ語ろうとするものである[web

1]。神が何であるかについての肯定や肯定的な記述によって神や神に近づくカタファティック神学と対をなす[web 2]。 アポファティズムの伝統は、常にではないが、神の幻視、すなわち通常の知覚の領域を超えた神の実在の知覚を目指す神秘主義のアプローチとしばしば結びついている[2]。 語源と定義 Apophatic", 古代ギリシャ語: ἀπόφασις (名詞); 「否定する」を意味する ἀπόφημι apophēmi から。オンライン語源辞典より: apophatic (adj.)「否定するように見せかける言及を含む;否定によって得られる知識を含む」、1850年、ギリシャ語のapophatikosのラテン語化し た形から、apophasis「否定、否定」から、apophanai「離れて話す」から、apo「離れて、離れて」(apo-を参照)+phanai 「話す」、pheme「声」に関連、PIE語源*bha- (2)「話す、伝える、言う」から[web 3]。 Via negativaまたはvia negationis(ラテン語)、「否定的な方法」または「否定によって」[1] 否定的な方法は、kataphaticまたは肯定的な方法とともにペアを形成する。ディアドレ・カラビーンによれば ディオニュシウス偽書は、神へのカタファティックな、あるいは肯定的な道を「言葉の道」と表現している。この意味で、私たちは「神は愛である」、「神は美 である」、「神は善である」と言うことができる。アポファティックな、あるいは否定的な方法は、神の絶対的な超越性と不可知性を強調するものである。神の 内在性と超越性という二重の概念は、神に対する両方の "道 "の同時真理を理解するのに役立つ:神が内在的であると同時に、神は超越的でもある。神が内在的であると同時に、神は超越的でもある。神はどちらか一方だ けと考えることはできない。 起源と発展 ファゲンブラットによれば、「否定神学は哲学そのものと同じくらい古いもの」であり、その要素はプラトンの書かれなかった教義に見出すことができ、また新 プラトン主義、グノーシス主義、初期キリスト教の作家にも存在する。アポファティック思想の傾向はアレクサンドリアのフィロにも見られる[3]。 カラビネによれば、ギリシア思想における「アポファシスの正体」は、唯一者の本質についての思索を伴う新プラトン主義から始まり、プロクロスの著作で頂点 に達する[4]。カラビネは、アポファシス神学の発展には2つの主要なポイントがあると書いている。すなわち、フィロの著作におけるユダヤ教の伝統とプラ トン哲学の融合と、キリスト教思想に新プラトン主義の思想を吹き込んだアレオパギテ人偽ディオニュシオスの著作である[4]。 初期教父たちはフィロの影響を受けており[4]、メレディスはフィロが「アポファティックな伝統の真の創始者である」とさえ述べている[5]。しかし、ア ポファティックな神学がキリスト教神学と観想的実践の中心的な要素となったのは、アレオパギテウス偽ディオニシウスと告解者マクシムス[6]の著作が、東 方正教会の観想的伝統であるヘシシャズムと西ヨーロッパの神秘主義的伝統の両方を形成したからである[4]。 エリヤがⅠ列王記19:11-13で「静まれ、小さな声」を聞いたことは、アポファティックな祈りの聖書の例として提唱されている。 |

| Greek Philosophy Pre-Socratic For the ancient Greeks, knowledge of the gods was essential for proper worship.[7] Poets had an important responsibility in this regard, and a central question was how knowledge of the Divine forms can be attained.[7] Epiphany played an essential role in attaining this knowledge.[7] Xenophanes (c. 570 – c. 475 BC) noted that the knowledge of the Divine forms is restrained by the human imagination, and Greek philosophers realized that this knowledge can only be mediated through myth and visual representations, which are culture-dependent.[7] According to Herodotus (484–425 BC), Homer and Hesiod (between 750 and 650 BC) taught the Greek the knowledge of the Divine bodies of the Gods.[8] The ancient Greek poet Hesiod (between 750 and 650 BC) describes in his Theogony the birth of the gods and creation of the world,[web 4] which became an "ur-text for programmatic, first-person epiphanic narratives in Greek literature,"[7][note 1] but also "explores the necessary limitations placed on human access to the divine."[7] According to Platt, the statement of the Muses who grant Hesiod knowledge of the Gods "actually accords better with the logic of apophatic religious thought."[10][note 2] Parmenides (fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC), in his poem On Nature, gives an account of a revelation on two ways of inquiry. "The way of conviction" explores Being, true reality ("what-is"), which is "What is ungenerated and deathless,/whole and uniform, and still and perfect."[12] "The way of opinion" is the world of appearances, in which one's sensory faculties lead to conceptions which are false and deceitful. His distinction between unchanging Truth and shifting opinion is reflected in Plato's allegory of the Cave. Together with the Biblical story of Moses's ascent of Mount Sinai, it is used by Gregory of Nyssa and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite to give a Christian account of the ascent of the soul toward God.[13] Cook notes that Parmenides poem is a religious account of a mystical journey, akin to the mystery cults,[14] giving a philosophical form to a religious outlook.[15] Cook further notes that the philosopher's task is to "attempt through 'negative' thinking to tear themselves loose from all that frustrates their pursuit of wisdom."[15] Plato Plato Silanion Musei Capitolini MC1377. Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC), "deciding for Parmenides against Heraclitus" and his theory of eternal change,[16] had a strong influence on the development of apophatic thought.[16] Plato further explored Parmenides's idea of timeless truth in his dialogue Parmenides, which is a treatment of the eternal forms, Truth, Beauty and Goodness, which are the real aims for knowledge.[16] The Theory of Forms is Plato's answer to the problem how one fundamental reality or unchanging essence can admit of many changing phenomena, other than by dismissing them as being mere illusion.[16] In The Republic, Plato argues that the "real objects of knowledge are not the changing objects of the senses, but the immutable Forms,"[web 5] stating that the Form of the Good[note 3] is the highest object of knowledge.[17][18][web 5][note 4] His argument culminates in the Allegory of the Cave, in which he argues that humans are like prisoners in a cave, who can only see shadows of the Real, the Form of the Good.[18][web 5] Humans are to be educated to search for knowledge, by turning away from their bodily desires toward higher contemplation, culminating in an intellectual[note 5] understanding or apprehension of the Forms, c.q. the "first principles of all knowledge."[18] According to Cook, the Theory of Forms has a theological flavour, and had a strong influence on the ideas of his Neo-Platonist interpreters Proclus and Plotinus.[16] The pursuit of Truth, Beauty and Goodness became a central element in the apophatic tradition,[16] but nevertheless, according to Carabine "Plato himself cannot be regarded as the founder of the negative way."[19] Carabine warns not to read later Neo-Platonic and Christian understandings into Plato, and notes that Plato did not identify his Forms with "one transcendent source," an identification which his later interpreters made.[20] Middle Platonism Main article: Middle Platonism Middle Platonism (1st century BC–3rd century AD)[web 6] further investigated Plato's "Unwritten Doctrines," which drew on Pythagoras' first principles of the Monad and the Dyad (matter).[web 6] Middle Platonism proposed a hierarchy of being, with God as its first principle at its top, identifying it with Plato's Form of the Good.[21] An influential proponent of Middle Platonism was Philo (c. 25 BC–c. 50 AD), who employed Middle Platonic philosophy in his interpretation of the Hebrew scriptures, and asserted a strong influence on early Christianity.[web 6] According to Craig D. Allert, "Philo made a monumental contribution to the creation of a vocabulary for use in negative statements about God."[22] For Philo, God is undescribable, and he uses terms which emphasize God's transcendence.[22] Neo-Platonism Main article: Neo-Platonism Neo-Platonism was a mystical or contemplative form of Platonism, which "developed outside the mainstream of Academic Platonism."[web 7] It started with the writings of Plotinus (204/5–270 AD), and ended with the closing of the Platonic Academy by Emperor Justinian in 529 AD, when the pagan traditions were ousted.[web 8] It is a product of Hellenistic syncretism, which developed due to the crossover between Greek thought and the Jewish scriptures, and also gave birth to Gnosticism.[web 7] Proclus of Athens (*412–485 C.E.) played a crucial role in the transmission of Platonic philosophy from antiquity to the Middle Ages., serving as head or ‘successor’ (diadochos, sc. of Plato) of the Platonic ‘Academy’ for over 50 years.[23] His student Pseudo-Dionysius had a far-stretching Neo-Platonic influence on Christianity and Christian mysticism.[web 7] Plotinus Plotinus, 204/5–270 AD. Plotinus (204/5–270 AD) was the founder of Neo-Platonism.[24] In the Neo-Platonic philosophy of Plotinus and Proclus, the first principle became even more elevated as a radical unity, which was presented as an unknowable Absolute.[21] For Plotinus, the One is the first principle, from which everything else emanates.[24] He took it from Plato's writings, identifying the Good of the Republic, as the cause of the other Forms, with the One of the first hypothesis of the second part of the Parmenides.[24] For Plotinus, the One precedes the Forms,[24] and "is beyond Mind and indeed beyond Being."[21] From the One comes the Intellect, which contains all the Forms.[24] The One is the principle of Being, while the Forms are the principle of the essence of beings, and the intelligibility which can recognize them as such.[24] Plotinus's third principle is Soul, the desire for objects external to itself. The highest satisfaction of desire is the contemplation of the One,[24] which unites all existents "as a single, all-pervasive reality."[web 8] The One is radically simple, and does not even have self-knowledge, since self-knowledge would imply multiplicity.[21] Nevertheless, Plotinus does urge for a search for the Absolute, turning inward and becoming aware of the "presence of the intellect in the human soul,"[note 6] initiating an ascent of the soul by abstraction or "taking away," culminating in a sudden appearance of the One.[25] In the Enneads Plotinus writes: Our thought cannot grasp the One as long as any other image remains active in the soul [...] To this end, you must set free your soul from all outward things and turn wholly within yourself, with no more leaning to what lies outside, and lay your mind bare of ideal forms, as before of the objects of sense, and forget even yourself, and so come within sight of that One. Carabine notes that Plotinus' apophasis is not just a mental exercise, an acknowledgement of the unknowability of the One, but a means to ecstasis and an ascent to "the unapproachable light that is God."[web 10] Pao-Shen Ho, investigating what are Plotinus' methods for reaching henosis,[note 7] concludes that "Plotinus' mystical teaching is made up of two practices only, namely philosophy and negative theology."[28] According to Moore, Plotinus appeals to the "non-discursive, intuitive faculty of the soul," by "calling for a sort of prayer, an invocation of the deity, that will permit the soul to lift itself up to the unmediated, direct, and intimate contemplation of that which exceeds it (V.1.6)."[web 8] Pao-Shen Ho further notes that "for Plotinus, mystical experience is irreducible to philosophical arguments."[28] The argumentation about henosis is preceded by the actual experience of it, and can only be understood when henosis has been attained.[28] Ho further notes that Plotinus's writings have a didactic flavour, aiming to "bring his own soul and the souls of others by way of Intellect to union with the One."[28] As such, the Enneads as a spiritual or ascetic teaching device, akin to The Cloud of Unknowing,[29] demonstrating the methods of philosophical and apophatic inquiry.[30] Ultimately, this leads to silence and the abandonment of all intellectual inquiry, leaving contemplation and unity.[31] Proclus Proclus (412-485) introduced the terminology used in apophatic and cataphatic theology.[32] He did this in the second book of his Platonic Theology, arguing that Plato states that the One can be revealed "through analogy," and that "through negations [dia ton apophaseon] its transcendence over everything can be shown."[32] For Proclus, apophatic and cataphatic theology form a contemplatory pair, with the apophatic approach corresponding to the manifestation of the world from the One, and cataphatic theology corresponding to the return to the One.[33] The analogies are affirmations which direct us toward the One, while the negations underlie the confirmations, being closer to the One.[33] According to Luz, Proclus also attracted students from other faiths, including the Samaritan Marinus. Luz notes that "Marinus' Samaritan origins with its Abrahamic notion of a single ineffable Name of God (יהוה) should also have been in many ways compatible with the school's ineffable and apophatic divine principle."[34] |

ギリシア哲学 ソクラテス以前 古代ギリシア人にとって、神々に関する知識は適切な礼拝のために不可欠なものであった[7]。詩人たちはこの点において重要な責任を負っており、中心的な問題は、神々の姿に関する知識をどのようにして得ることができるのかということであった[7]。 ヘロドトス(BC484-425)によれば、ホメロスとヘシオドス(BC750-650)は神々の神体についての知識をギリシア人に教えた。 8]古代ギリシャの詩人ヘシオドス(前750年~前650年)は『神統記』の中で神々の誕生と世界の創造を描写しており[web 4]、これは「ギリシャ文学におけるプログラム的で一人称的なエピファニックな物語の原典」[7][注 1]となったが、同時に「神への人間のアクセスに課せられた必要な制限を探求している」[7][注 2]。 「7] プラットによれば、ヘシオドスに神々の知識を与えるミューズたちの記述は、「実際にはアポファティックな宗教思想の論理によりよく合致している」[10] [注釈 2]。 パルメニデス(紀元前6世紀後半から5世紀初頭)は、その詩『自然について』の中で、2つの探求の道に関する啓示の説明を与えている。「確信の道」は存 在、真の実在(「在るもの」)を探求するものであり、それは「生成せず、死なず、/全体であり、一様であり、静止しており、完全であるもの」である [12]。不変の真理と移り変わる意見との間の彼の区別は、プラトンの洞窟の寓話に反映されている。洞窟の寓話は、聖書のモーゼのシナイ山登頂の物語とと もに、ニッサのグレゴリウスやアレオパギテの偽ディオニュシオスによって、キリスト教における神への魂の登頂の説明として用いられている。 [13]クックは、パルメニデスの詩は神秘カルトに似た神秘的な旅の宗教的な説明であり[14]、宗教的な見通しに哲学的な形式を与えるものであると指摘 している[15]。クックはさらに、哲学者の仕事は「『否定的な』思考を通じて、知恵の追求を挫くものすべてから自らを引き離そうと試みること」であると 指摘している[15]。 プラトン プラトン シラニオン カピトリーニ美術館 MC1377. プラトン(前428/427年または前424/423年 - 前348/347年)は、「ヘラクレイトスに対するパルメニデスの決起」と彼の永遠変化論[16]によって、アポファティック思想の発展に強い影響を与えた[16]。 プラトンは対話篇『パルメニデス』において、パルメニデスの時間を超越した真理という考えをさらに探求しており、この対話篇『パルメニデス』では、知の真 の目的である永遠の形相、真理、美、善について論じている[16]。形相論は、プラトンが、一つの根本的な実在や不変の本質が、単なる幻想であると見なす 以外に、どのようにして多くの変化する現象を認めることができるのかという問題に対する答えである[16]。 プラトンは『共和国』において、「知識の真の対象は感覚の変化する対象ではなく、不変の形相である」[web 5]と主張し、善の形相[注釈 3]が知識の最高の対象であると述べている[17][18][web 5][注釈 4]。プラトンの議論は洞窟の寓話において頂点に達し、人間は洞窟の囚人のようなものであり、善の形相である実在の影しか見ることができないと論じてい る。 [18][web5]人間は、身体的な欲望からより高次の観照へと向かうことによって、知識を探求するように教育されるべきであり、最終的には「あらゆる 知識の第一原理」である形相の知的な[注釈 5]理解や把握に至るのである[18]。 クックによれば、『形相論』は神学的な趣があり、彼の新プラトン主義的解釈者であるプロクロスとプロティノスの思想に強い影響を与えた[16]。 「19]カラビネは、後の新プラトン主義やキリスト教的理解をプラトンに読み込まないように警告しており、プラトンは自らの形相を「一つの超越的源泉」と 同一視していなかったが、後の解釈者たちはこの同一視を行ったと指摘している[20]。 中期プラトン主義 主な記事 中期プラトン主義 中期プラトン主義(紀元前1世紀~紀元後3世紀)[web 6]は、ピュタゴラスのモナドとダイアド(物質)の第一原理を利用したプラトンの「書かれざる教義」をさらに研究した[web 6]。 [21] 中プラトン主義の有力な提唱者はフィロ(紀元前25年頃-紀元後50年頃)であり、彼はヘブライ聖典の解釈に中プラトン哲学を用い、初期キリスト教に強い 影響を与えたと主張している。アッラートによれば、「フィロは神についての否定的な記述に用いられる語彙の創造に記念碑的な貢献をした」[22]。フィロ にとって神は記述不可能な存在であり、彼は神の超越性を強調する用語を用いている[22]。 新プラトン主義 主な記事 新プラトン主義 ネオ・プラトニズムはプラトニズムの神秘主義的または観想的な形態であり、「アカデミック・プラトニズムの主流の外側で発展した」[web 7] プロティノス(西暦204/5-270年)の著作に始まり、異教の伝統が追放された西暦529年にユスティニアヌス帝によってプラトン・アカデミーが閉鎖 されたことで終わった。 [ギリシア思想とユダヤ教聖典のクロスオーバーによって発展したヘレニズム的シンクレティズムの産物であり、グノーシス主義も生み出した[web 7] アテネのプロクロス(*412-485 C.E.)は、古代から中世へのプラトン哲学の伝達において重要な役割を果たした、 彼の弟子であるシュード=ディオニュシオスは、キリスト教とキリスト教神秘主義に新プラトン主義的な影響を及ぼした[web 7]。 プロティノス プロティノス(西暦204/5-270年 プロティノス(AD204/5-270)は新プラトン主義の創始者である[24]。プロティノスとプロクロスの新プラトン哲学において、第一原理は根本的 な統一体としてさらに高められた。 [21]プロティノスにとって、唯一なるものは第一原理であり、他のすべてのものはそこから発している。 [プロティノスにとって、唯一なるものは諸形態に先立つものであり[24]、「精神を超え、実に存在を超えるもの」である[21]。欲望の最高の充足は 「唯一なるもの」[24]を観想することであり、「唯一なるもの」はすべての存在者を「単一の、すべてに遍満する実在として」統合している[web 8]。 というのも、自己認識は多義性を意味するからである[21]。それにもかかわらず、プロティノスは絶対者の探求を促し、内側に向き直り、「人間の魂におけ る知性の存在」[注釈 6]を認識するようになり、抽象化あるいは「奪う」ことによって魂の上昇を開始し、突然の「唯一者」の出現において頂点に達するのである[25]。プロ ティノスは『エネアデス』の中でこう書いている: この目的のためには、魂を外界のものから解き放ち、外界のものに傾倒することなく、完全に自分の内側に向かわなければならない。 カラビネは、プロティノスのアポファシスは単なる精神的な訓練であり、「唯一なるもの」の不可知性を認めることではなく、エクスタシスへの手段であり、 「神である近づきがたい光」[web 10]への上昇であると指摘している。 パオシェン・ホーは、ヘノーシスに到達するためのプロティノスの方法が何であるかを調査し[注釈 7]、「プロティノスの神秘的な教えは、哲学と否定神学という二つの実践のみから成っている」と結論付けている。 「28] ムーアによれば、プロティノスは「魂の非回帰的で直観的な能力」に訴えかけており、「一種の祈り、神への呼びかけを求めることによって、魂がそれを超える ものの無媒介的で直接的で親密な観想へと自らを高めることを可能にする(V.1 .6)」[web 8] パオシェン・ホーはさらに、「プロティノスにとって、神秘体験は哲学的議論には還元できないものである」[28]と指摘している。 ヘノーシスについての議論は、ヘノーシスの実際の体験に先行するものであり、ヘノーシスに到達して初めて理解できるものである」[28]。 ホーはさらに、プロティノスの著作には教訓的な趣があり、「知性によって彼自身の魂と他者の魂を唯一なるものと合一させる」ことを目指していると指摘して いる。 28]このように、『無明の雲』に似た精神的あるいは禁欲的な教育装置としての『エネアデス』[29]は、哲学的かつアポファティックな探求の方法を示し ている。 30]最終的に、これは沈黙とすべての知的探求の放棄につながり、観想と統一を残す。 プロクロス プロクロス(412-485)は、アポファティック神学とカタファティック神学で使用される用語を紹介した[32]。 「プロクロスによれば、アポファティック神学とカタファティック神学は観想的なペアを形成しており、アポファティックなアプローチは唯一なるものからの世 界の顕現に対応し、カタファティック神学は唯一なるものへの回帰に対応している[33]。類比は唯一なるものへと私たちを導く肯定であり、否定は確証の根 底にあるもので、唯一なるものにより近いものである。ルズは、「マリヌスのサマリア人の起源は、アブラハム的な単一の不可知なる神の御名(יהוה)の概 念と、この学派の不可知でアポファティックな神の原理と多くの点で適合していたはずである」と指摘している[34]。 |

| Christianity Apostolic Age The Book of Revelation 8:1 mentions "the silence of the perpetual choir in heaven." According to Dan Merkur, The silence of the perpetual choir in heaven had mystical connotations, because silence attends the disappearance of plurality during experiences of mystical oneness. The term "silence" also alludes to the "still small voice" (1 Kings 19:12) whose revelation to Elijah on Mount Horeb rejected visionary imagery by affirming a negative theology.[35][note 8] Early Church Fathers The Early Church Fathers were influenced by Philo[4] (c. 25 BC – c. 50 AD), who saw Moses as "the model of human virtue and Sinai as the archetype of man's ascent into the "luminous darkness" of God."[36] His interpretation of Moses was followed by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, the Cappadocian Fathers, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Maximus the Confessor.[37][38][5][39] God's appearance to Moses in the burning bush was often elaborated on by the Early Church Fathers,[37] especially Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 395),[38][5][39] realizing the fundamental unknowability of God;[37][40] an exegesis which continued in the medieval mystical tradition.[41] Their response is that, although God is unknowable, Jesus as person can be followed, since "following Christ is the human way of seeing God."[42] Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215) was an early proponent of apophatic theology.[43][5] Clement holds that God is unknowable, although God's unknowability, concerns only his essence, not his energies, or powers.[43] According to R.A. Baker, in Clement's writings the term theoria develops further from a mere intellectual "seeing" toward a spiritual form of contemplation.[44] Clement's apophatic theology or philosophy is closely related to this kind of theoria and the "mystic vision of the soul."[44] For Clement, God is transcendent and immanent.[45] According to Baker, Clement's apophaticism is mainly driven not by Biblical texts, but by the Platonic tradition.[46] His conception of an ineffable God is a synthesis of Plato and Philo, as seen from a Biblical perspective.[47] According to Osborne, it is a synthesis in a Biblical framework; according to Baker, while the Platonic tradition accounts for the negative approach, the Biblical tradition accounts for the positive approach.[48] Theoria and abstraction is the means to conceive of this ineffable God; it is preceded by dispassion.[49] According to Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240), [t]hat which is infinite is known only to itself. This it is which gives some notion of God, while yet beyond all our conceptions – our very incapacity of fully grasping Him affords us the idea of what He really is. He is presented to our minds in His transcendent greatness, as at once known and unknown.[50] Saint Cyril of Jerusalem (313-386), in his Catechetical Homilies, states: For we explain not what God is but candidly confess that we have not exact knowledge concerning Him. For in what concerns God to confess our ignorance is the best knowledge.[51]  Filippo Lippi, Vision of St. Augustine, c. 1465, tempera, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) defined God aliud, aliud valde, meaning "other, completely other", in Confessions 7.10.16,[52] wrote Si [enim] comprehendis, non est Deus,[53] meaning "if you understand [something], it is not God", in Sermo 117.3.5[54] (PL 38, 663),[55][56] and a famous legend tells that, while walking along the Mediterranean shoreline meditating on the mystery of the Trinity, he met a child who with a seashell (or a little pail) was trying to pour the whole sea into a small hole dug in the sand. Augustine told him that it was impossible to enclose the immensity of the sea in such a small opening, and the child replied that it was equally impossible to try to understand the infinity of God within the limited confines of the human mind.[57][58][59] The Chalcedonian Christological dogma See also: Kenosis and eternal super-kenosis The Christological dogma, formulated by the Fourth Ecumenical Council held in Chalcedon in 451, is based on dyophysitism and hypostatic union, concepts used to describe the union of humanity and divinity in a single hypostasis, or individual existence, that of Jesus Christ. This remains transcendent to our rational categories, a mystery which has to be guarded by apophatic language, as it is a personal union of a singularly unique kind.[60] Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite Apophatic theology found its most influential expression in the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 5th to early 6th century), a student of Proclus (412-485) who combined a Christian worldview with Neo-Platonic ideas.[61] He is a constant factor in the contemplative tradition of the eastern Orthodox Churches, and from the 9th century onwards his writings also had a strong impact on western mysticism.[62] Dionysius the Areopagite was a pseudonym, taken from Acts of the Apostles chapter 17, in which Paul gives a missionary speech to the court of the Areopagus in Athens.[63] In verse 23 Paul makes a reference to an altar-inscription, dedicated to the Unknown God, "a safety measure honoring foreign gods still unknown to the Hellenistic world."[63] For Paul, Jesus Christ is this unknown God, and as a result of Paul's speech Dionysius the Areopagite converts to Christianity.[64] Yet, according to Stang, for Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite Athens is also the place of Neo-Platonic wisdom, and the term "unknown God" is a reversal of Paul's preaching toward an integration of Christianity with Neo-Platonism, and the union with the "unknown God."[64] According to Corrigan and Harrington, "Dionysius' central concern is how a triune God, ... who is utterly unknowable, unrestricted being, beyond individual substances, beyond even goodness, can become manifest to, in, and through the whole of creation in order to bring back all things to the hidden darkness of their source."[65] Drawing on Neo-Platonism, Pseudo-Dionysius described human ascent to divinity as a process of purgation, illumination and union.[62] Another Neo-Platonic influence was his description of the cosmos as a series of hierarchies, which overcome the distance between God and humans.[62] Eastern Orthodox Christianity Main article: Eastern Orthodox Church In Orthodox Christianity apophatic theology is taught as superior to cataphatic theology. The fourth-century Cappadocian Fathers[note 9] stated a belief in the existence of God, but an existence unlike that of everything else: everything else that exists was created, but the Creator transcends this existence, is uncreated. The essence of God is completely unknowable; mankind can acquire an incomplete knowledge of God in His attributes (propria), positive and negative, by reflecting upon and participating in His self-revelatory operations (energeiai).[67] Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 395), John Chrysostom (c. 349 – 407), and Basil the Great (329–379) emphasized the importance of negative theology to an orthodox understanding of God. John of Damascus (c.675/676–749) employed negative theology when he wrote that positive statements about God reveal "not the nature, but the things around the nature." Maximus the Confessor (580–622) took over Pseudo-Dionysius' ideas, and had a strong influence on the theology and contemplative practices of the Eastern Orthodox Churches.[61] Gregory Palamas (1296–1359) formulated the definite theology of Hesychasm, the Eastern Orthodox practices of contemplative prayer and theosis, "deification." Influential 20th-century Orthodox theologians include the Neo-Palamist writers Vladimir Lossky, John Meyendorff, John S. Romanides, and Georges Florovsky. Lossky argues, based on his reading of Dionysius and Maximus Confessor, that positive theology is always inferior to negative theology, which is a step along the way to the superior knowledge attained by negation.[68] This is expressed in the idea that mysticism is the expression of dogmatic theology par excellence.[69] According to Lossky, outside of directly revealed knowledge through Scripture and Sacred Tradition, such as the Trinitarian nature of God, God in His essence is beyond the limits of what human beings (or even angels) can understand. He is transcendent in essence (ousia). Further knowledge must be sought in a direct experience of God or His indestructible energies through theoria (vision of God).[70][71] According to Aristotle Papanikolaou, in Eastern Christianity, God is immanent in his hypostasis or existences.[72] Western Christianity  In The Creation of Adam painted by Michelangelo (c. 1508–1512), the two index fingers are separated by a small gap [3⁄4 inch (1.9 cm)]:[73] some scholars think that it represents the unattainability of divine perfection by man.[74] Negative theology has a place in the Western Christian tradition as well. The 9th-century theologian John Scotus Erigena wrote: We do not know what God is. God Himself does not know what He is because He is not anything [i.e., "not any created thing"]. Literally God is not, because He transcends being.[75] When he says "He is not anything" and "God is not", Scotus does not mean that there is no God, but that God cannot be said to exist in the way that creation exists, i.e. that God is uncreated. He is using apophatic language to emphasise that God is "other".[76] Theologians like Meister Eckhart and John of the Cross (San Juan de la Cruz) exemplify some aspects of or tendencies towards the apophatic tradition in the West. The medieval work, The Cloud of Unknowing and Saint John's Dark Night of the Soul are particularly well known. In 1215 apophatism became the official position of the Catholic Church, which, on the basis of Scripture and church tradition, during the Fourth Lateran Council formulated the following dogma: Between Creator and creature no similitude can be expressed without implying an even greater dissimilitude.[77][note 10] The via eminentiae See also: Credo ut intelligam and Fides et ratio Thomas Aquinas was born ten years later (1225-1274) and, although in his Summa Theologiae he quotes Pseudo-Dionysius 1,760 times,[80] stating that "Now, because we cannot know what God is, but rather what He is not, we have no means for considering how God is, but rather how He is not"[81][82] and leaving the work unfinished because it was like "straw" compared to what had been revealed to him,[83] his reading in a neo-Aristotelian key[84] of the conciliar declaration overthrew its meaning inaugurating the "analogical way" as tertium between via negativa and via positiva: the via eminentiae (see also analogia entis). In this way, the believers see what attributes are common between them and God, as well as the unique, not human, properly divine and not understandable way in respect of which God possesses that attributes.[85] According to Adrian Langdon, The distinction between univocal, equivocal, and analogous language and relations corresponds to the distinction between the via positiva, via negativa, and via eminentiae. In Thomas Aquinas, for example, the via positiva undergirds the discussion of univocity, the via negativa the equivocal, and the via eminentiae the final defense of analogy.[86] According to Catholic Encyclopedia, the Doctor Angelicus and the scholastici declare [that] God is not absolutely unknowable, and yet it is true that we cannot define Him adequately. But we can conceive and name Him in an "analogical way". The perfections manifested by creatures are in God, not merely nominally (equivoce) but really and positively, since He is their source. Yet, they are not in Him as they are in the creature, with a mere difference of degree, nor even with a mere specific or generic difference (univoce), for there is no common concept including the finite and the Infinite. They are really in Him in a supereminent manner (eminenter) which is wholly incommensurable with their mode of being in creatures. We can conceive and express these perfections only by an analogy; not by an analogy of proportion, for this analogy rests on a participation in a common concept, and, as already said, there is no element common to the finite and the Infinite; but by an analogy of proportionality.[87] Since then Thomism has played a decisive role in resizing the negative or apophatic tradition of the magisterium.[88][89] |