Politische Theologie by Carl Schmitt, 1888-1985

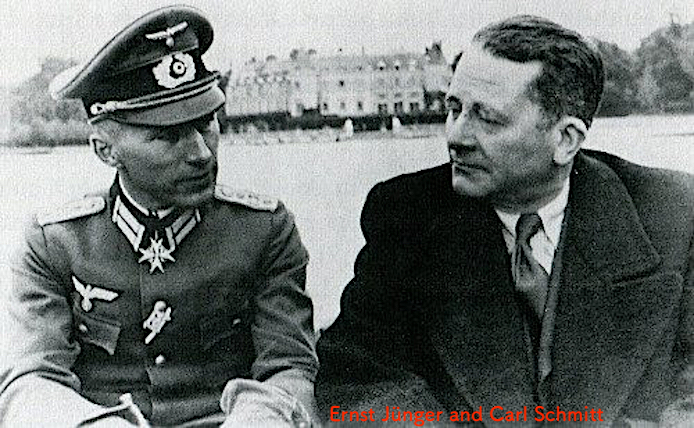

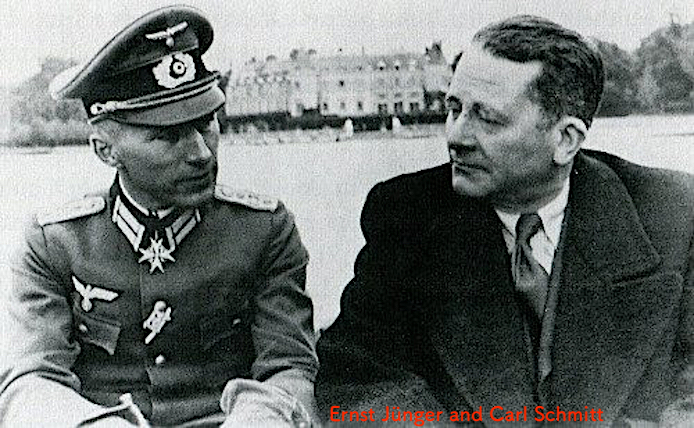

エルンスト・ユンガーとカール・シュミット(Ernst Jünger and Carl Schmitt)

カール・シュミット

Politische Theologie by Carl Schmitt, 1888-1985

エルンスト・ユンガーとカール・シュミット(Ernst Jünger and Carl Schmitt)

カール・シュミット(Carl Schmitt-Dorotić)(1888年7月11日プレッテンベルク生まれ、1985年4月7日死亡)は、ドイツの憲法学者で、政治哲学者としても 知られる人物である。20世紀のドイツの憲法および国際法における最も有名な法律家の一人であり、同時に最も議論の多い法律家でもある。シュミットは 1933年以降、ナチス政権にコミットし、1933年5月1日にNSDAP [Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei]に加入し、ナチスの支配が終わるまでメンバーであった。シュミットは、1934 年のいわゆるレーム事件防止のための殺人を、「総統命令」の法理によって正当化した。彼は、1935年の反ユダヤ主義のニュルンベルク法を「自由の憲法」 と呼んだ。1936年には、NSDAPからも日和見主義として非難された。党の役職は失ったが、NSDAPの党員であることに変わりはない。ヘルマン・ ゲーリングの保護により、シュミットはプロイセン国家評議員に留まり、ベルリンの教授職も維持した。

シュミットの思想は、権力、暴力、法の実現という問 題を中心に展開された。憲法学だけでなく、政治学、社会学、神学、ドイツ学、哲学など、さまざまな分野の著作がある。法律や政治に関する著作だけでなく、 風刺、旅行記、思想史研究、ドイツ語テキストの解釈など、幅広いジャンルのテキストを執筆している。法学者として、「憲法の現実」、「政治神学」、「敵味 方の区別」、「希薄な定型的妥協」など、科学的、政治的、一般的に使われるようになった多くの用語や概念を作り出した。彼の弟子や保守的な崇拝者たちを通 じて、第二次世界大戦後も西ドイツに影響を及ぼした。シュミットは、国家社会主義を国法的に擁護したことから、議会制民主主義や自由主義に反対し、「自分 の出世のためならどんな政府にも仕える良心的な科学者の原型」として、今日では広く敬遠されている。しかし、初期の連邦共和国における憲法や法学に間接的 に影響を与えたことから、「政治思想の古典」と呼ばれることもある(→「シュミットの思想」)。

シュミットは、トマス・ホッブズ、ニコロ・マキアヴェリ、アリストテレス、ジャン・ジャッ ク・ルソー、フアン・ドノソ・コルテス(Juan Donoso Cortés, 1809-1853)などの政治哲学者や国家論者、あるいはジョルジュ・ソレルやヴィルフレド・パレートなどの同時代の学者から形成的な影響を受けてい る。

| Carl Schmitt

(zeitweise auch Carl Schmitt-Dorotić;[1] * 11. Juli 1888 in

Plettenberg; † 7. April 1985 ebenda) war ein deutscher Jurist, der auch

als politischer Philosoph rezipiert wird. Er gilt als einer der

bekanntesten, wirkmächtigsten und zugleich umstrittensten deutschen

Staats- und Völkerrechtler des 20. Jahrhunderts. Schmitts Denken kreiste um Fragen der Macht, der Gewalt und der Rechtsverwirklichung. Neben dem Staats- und Verfassungsrecht streifen seine Veröffentlichungen zahlreiche weitere Disziplinen wie Politikwissenschaft, Soziologie, Theologie, Germanistik und Philosophie. Sein breitgespanntes Œuvre umfasst außer juristischen und politischen Arbeiten weitere Textgattungen wie Satiren, Reisenotizen, ideengeschichtliche Untersuchungen oder germanistische Textinterpretationen. Als Jurist prägte er eine Reihe von Begriffen und Konzepten, die in den wissenschaftlichen, politischen und allgemeinen Sprachgebrauch eingegangen sind, etwa „Politische Theologie“ (1922), „Freund-Feind-Unterscheidung“ (1927), „Verfassungswirklichkeit“ (1928), oder „dilatorischer Formelkompromiss“ (1931).[2] Schmitt trat ab 1933 für den Nationalsozialismus ein und wurde am 1. Mai 1933 Mitglied der NSDAP. Die Morde zur vorgeblichen Prävention des sogenannten Röhm-Putsches von 1934 rechtfertigte Schmitt durch sein juristisches Prinzip der „Führer-Ordnung“. Die antisemitischen Nürnberger Gesetze von 1935 nannte er eine „Verfassung der Freiheit“. Er war Protegé von Hermann Göring und Hans Frank.[3] 1936 wurde ihm aus Kreisen der SS Opportunismus vorgeworfen; er verlor zwar daraufhin seine Parteiämter, blieb aber Mitglied der NSDAP. Dank der Protektion durch Göring und Frank blieb er Preußischer Staatsrat und behielt auch seine Professur an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin. Nach dem Ende des Nationalsozialismus verweigerte er sich einer Entnazifizierung und wirkte fortan als Privatgelehrter ohne Professur. Über seine Schüler und Bewunderer verfügte er über einen gewissen Einfluss in der westdeutschen Rechtswissenschaft. Schmitt wird aufgrund seiner wissenschaftlichen Positionen und insbesondere wegen seines staatsrechtlichen Einsatzes für den Nationalsozialismus als Gegner der parlamentarischen Demokratie und des Liberalismus sowie als „Prototyp des gewissenlosen Wissenschaftlers, der jeder Regierung dient, wenn es der eigenen Karriere nutzt“[4] angesehen. Allerdings wird er aufgrund seiner indirekten Wirkung auf das Staatsrecht und die Rechtswissenschaft der frühen Bundesrepublik sowie der breiten internationalen Rezeption seiner Gedanken mitunter auch als „Klassiker des politischen Denkens“ eingeordnet.[5] Prägende Einflüsse für sein Denken bezog Schmitt von politischen Philosophen und Staatsdenkern wie Thomas Hobbes,[6] Niccolò Machiavelli, Aristoteles,[7] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Juan Donoso Cortés oder Zeitgenossen wie Georges Sorel[8] und Vilfredo Pareto.[9] Sein antisemitisches Weltbild war von den Thesen Bruno Bauers geprägt.[10] |

カール・シュミット(Carl

Schmitt、一時カール・シュミット=ドロティッチ(Carl

Schmitt-Dorotić)とも呼ばれる[1]、1888年7月11日、プレッテンベルク生まれ、1985年4月7日、同地死去)は、ドイツの法学

者であり、政治哲学者としても知られている。彼は、20世紀のドイツで最も著名で影響力があり、同時に最も論争の的となった国家法および国際法学者の一人

とされている。 シュミットの思想は、権力、暴力、法の実現といった問題を中心に展開していた。彼の著作は、国家法や憲法だけでなく、政治学、社会学、神学、ドイツ文学、 哲学など、数多くの分野に及んでいる。彼の幅広い著作は、法学や政治学に関する著作のほか、風刺、旅行記、思想史の研究、ドイツ文学のテキスト解釈など、 さまざまなジャンルに及んでいる。法学者として、彼は「政治神学」(1922年)、「友敵の区別」(1927年)、「憲法現実」(1928年)、あるいは 「遅延的公式妥協」 (1931年)などです。[2] シュミットは1933年からナチズムを支持し、1933年5月1日にNSDAP(国家社会主義ドイツ労働者党)に入党しました。1934年に、いわゆる レーームの反乱を未然に防ぐために行われた殺人は、シュミットは「指導者の秩序」という法的な原則によって正当化しました。1935年の反ユダヤ主義的な ニュルンベルク法については、「自由の憲法」と表現した。彼はヘルマン・ゲーリングとハンス・フランクの弟子だった。[3] 1936年、SS内部から機会主義者であると非難され、党の役職を剥奪されたが、NSDAPの党員は引き続き維持した。ゲーリングとフランクの保護のおか げで、彼はプロイセン国務顧問の地位を維持し、ベルリンのフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学での教授職も維持した。ナチズムの終焉後、彼は非ナチ化に反対 し、教授職のない私的学者として活動した。彼の弟子や崇拝者たちを通じて、彼は西ドイツの法学界に一定の影響力を持っていた。 シュミットは、その学術的立場、特に国家法におけるナチズムへの貢献から、議会制民主主義と自由主義の敵、そして「自分のキャリアに有利であれば、あらゆ る政府に仕える良心の欠落した学者の典型」[4] と見なされている。しかし、連邦共和国初期における憲法および法学に与えた間接的な影響、そして彼の思想が国際的に広く受容されたことから、彼は「政治思 想の古典」と評価されることもある[5]。 シュミットの思想に大きな影響を与えたのは、トマス・ホッブズ[6]、ニッコロ・マキャヴェッリ、アリストテレス[7]、ジャン・ジャック・ルソー、フア ン・ドノソ・コルテスなどの政治哲学者や国家思想家、そしてジョルジュ・ソレル[8]やヴィルフレド・パレート[9]などの同時代人だった。彼の反ユダヤ 主義的世界観は、ブルーノ・バウアーの説に影響を受けていた[10]。 |

| Leben Kindheit, Jugend, Ehe Carl Schmitt (Mitte) mit Mitschülern vor dem Attendorner Konvikt im Winter 1902/03 Carl Schmitt als Schüler im Jahre 1904 Schmitt entstammte einer katholisch-kleinbürgerlichen Familie im Sauerland. Er war das zweite von fünf Kindern des Krankenkassenverwalters Johann Schmitt (1853–1945) und dessen Frau Louise, geb. Steinlein (1863–1943). Der Junge wohnte im katholischen Konvikt in Attendorn und besuchte dort das staatliche Gymnasium. Nach dem Abitur wollte Schmitt zunächst Philologie studieren; auf dringendes Anraten eines Onkels hin studierte er dann aber Jura. Sein Studium begann Schmitt zum Sommersemester 1907 an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin. In der Weltstadt traf er als „obskurer junger Mann bescheidener Herkunft“ aus dem Sauerland auf ein Milieu, von dem für ihn eine „starke Repulsion“ ausging.[11] Zum Sommersemester 1908 wechselte er an die Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Ab dem Wintersemester 1908/09 setzte Schmitt sein Studium an der Universität Straßburg fort, wurde dort 1910 mit der von Fritz van Calker betreuten strafrechtlichen Arbeit Über Schuld und Schuldarten promoviert und absolvierte im Frühjahr 1915 das Assessor-Examen. Im Februar 1915 trat Schmitt als Kriegsfreiwilliger in das Bayerische Infanterie-Leibregiment in München ein, kam jedoch nicht zum Fronteinsatz, da er bereits Ende März 1915 zur Dienstleistung beim Stellvertretenden Generalkommando des I. bayerischen Armee-Korps kommandiert wurde.[12] Im selben Jahr heiratete Schmitt Pawla Dorotić, eine angebliche kroatische Adelstochter, die Schmitt zunächst für eine spanische Tänzerin hielt und die sich später – im Zuge eines für Schmitt peinlichen Skandals – als Hochstaplerin herausstellte.[13] 1924 wurde die Ehe vom Landgericht Bonn annulliert. 1926 heiratete er eine frühere Studentin, die Serbin Duška Todorović (1903–1950).[14] Da seine vorige Ehe nicht kirchenrechtlich annulliert wurde, blieb er als Katholik allerdings bis zum Tode seiner zweiten Frau im Jahre 1950 exkommuniziert. Aus der zweiten Ehe ging sein einziges Kind hervor, die Tochter Anima (1931–1983). |

生涯 幼少期、青年期、結婚 1902年から1903年の冬、アッテンドルフのコンヴィクトの前で同級生たちと一緒に写るカール・シュミット(中央 1904年の学生時代のカール・シュミット シュミットは、ザウアーラント地方のカトリックの小さな中産階級の家庭に生まれた。彼は、健康保険事務員ヨハン・シュミット(1853-1945)と、そ の妻ルイーズ(旧姓シュタインライン、1863-1943)の5人の子供のうちの2番目だった。少年はアッテンドルンのカトリック寄宿学校に住み、そこで 公立のギムナジウムに通った。高校卒業後は、最初は文学を勉強したいと思ったが、 叔父の強い勧めで法学を勉強することになった。 シュミットは1907年の夏学期、ベルリンのフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学で勉強を始めた。この国際都市で、ザウアーラント出身の「謙虚な出身で無名な 青年」は、彼にとって「強い嫌悪感」を抱かせるような環境に出合った。[11] 1908年の夏学期、彼はミュンヘン・ルートヴィヒ・マクシミリアン大学に移った。 1908/09年の冬学期から、シュミットはストラスブール大学で学業を続け、1910年にフリッツ・ファン・カルカーの指導を受けた刑法に関する論文 「罪と罪の種類」で博士号を取得し、1915年の春に司法官試験に合格した。1915年2月、シュミットは戦争志願兵としてミュンヘンのバイエルン歩兵親 衛連隊に入隊したが、1915年3月末にバイエルン第1軍団副司令官府に配属されたため、前線には出なかった。[12] 同年、シュミットは、クロアチアの貴族の娘とされるパウラ・ドロティッチと結婚したが、シュミットは当初、彼女をスペインのダンサーだと思っていた。しか し、後にシュミットにとって恥ずかしいスキャンダルが巻き起こり、彼女は詐欺師であることが判明した。[13] 1924年、ボン地方裁判所は、この結婚を無効とした。1926年、シュミットは、元学生であるセルビア人のドゥシュカ・トドロヴィッチ(1903年 ~1950年)と結婚した。[14] しかし、前の結婚は教会法上無効と認められなかったため、彼は1950年に2番目の妻が亡くなるまでカトリック教徒として破門されたままであった。2番目 の結婚から、彼の唯一の子供である娘アニマ(1931年~1983年)が生まれた。 |

| Kunst und Bohème, Beginn der akademischen Karriere, erste Veröffentlichungen Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität, 1922 Carl Schmitt, München 1917 Bereits früh zeigte sich bei Schmitt eine künstlerische Ader. So trat er mit eigenen literarischen Versuchen hervor (Der Spiegel, Die Buribunken, Schattenrisse; er soll sich sogar mit dem Gedanken an einen Gedichtzyklus mit dem Titel Die große Schlacht um Mitternacht getragen haben) und verfasste eine Studie über den bekannten zeitgenössischen Dichter Theodor Däubler (Theodor Däublers ‚Nordlicht‘). Er kann zu dieser Zeit als Teil der „Schwabinger Bohème“ betrachtet werden.[15] Seine literarischen Arbeiten bezeichnete der Staatsrechtler später als „Dada avant la lettre“. Mit einem der Gründerväter des Dadaismus, Hugo Ball, war er befreundet, ebenso mit dem Dichter und Herausgeber Franz Blei, einem Förderer Robert Musils und Franz Kafkas. Der ästhetisierende Jurist und die politisierenden Belletristen tauschten sich regelmäßig aus, und es sind wechselseitige Beeinflussungen feststellbar. Mit Lyrikern pflegte Schmitt zu dieser Zeit besonders enge Kontakte, etwa mit dem mittlerweile vergessenen Dichter des politischen Katholizismus, Konrad Weiß. Gemeinsam mit Hugo Ball besuchte Schmitt den Literaten Hermann Hesse – ein Kontakt, der sich jedoch nicht aufrechterhalten ließ. Später freundete sich Schmitt mit Ernst Jünger sowie mit dem Maler und Schriftsteller Richard Seewald an. Schmitt habilitierte sich 1914 mit der Arbeit Der Wert des Staates und die Bedeutung des Einzelnen für Staats- und Verwaltungsrecht, Völkerrecht und Staatstheorie. Nach einer Lehrtätigkeit an der Handelshochschule München (1920) folgte Schmitt in kurzen Abständen Rufen nach Greifswald (1921), Bonn (1921), an die Handelshochschule Berlin (1928), Köln (1933) und wieder Berlin (Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität 1933–1945). Der Habilitationsschrift folgten kurz nacheinander weitere Veröffentlichungen, etwa Politische Romantik (1919) oder Die Diktatur (1921) im Verlag Duncker & Humblot unter dem Lektorat von Ludwig Feuchtwanger. Seine erste akademische Anstellung in München sowie später den Ruf an die Handelshochschule Berlin verdankte Schmitt dem jüdischen Nationalökonomen Moritz Julius Bonn.[16] Auch unter Nichtjuristen wurde Schmitt durch seine sprachmächtigen und schillernden Formulierungen schnell bekannt. Sein Stil war neu und galt in weit über das wissenschaftliche Milieu hinausgehenden Kreisen als spektakulär. Er schrieb nicht wie ein Jurist, sondern inszenierte seine Texte poetisch-dramatisch und versah sie mit mythischen Bildern und Anspielungen.[17] Seine Schriften waren überwiegend kleine Broschüren, die in ihrer thesenhaften Zuspitzung zur Auseinandersetzung zwangen. Schmitt war überzeugt, dass „oft schon der erste Satz über das Schicksal einer Veröffentlichung entscheidet“.[18] Viele Eröffnungssätze seiner Veröffentlichungen – etwa: „Es gibt einen antirömischen Affekt“, „Der Begriff des Staates setzt den Begriff des Politischen voraus“ oder „Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet“ – wurden schnell berühmt.[19] Von der Breite und Vielfältigkeit der Reaktionen, die Schmitt auslöste, zeugt insbesondere die umfangreiche Korrespondenz, die heute in seinem Nachlass – einem der größten in deutschen Archiven aufbewahrten Nachlässe überhaupt – einsehbar ist und sukzessive publiziert wird.[20] In Bonn pflegte der Staatsrechtler Kontakte zum Jungkatholizismus (er schrieb u. a. für Carl Muths Zeitschrift Hochland) und zeigte ein verstärktes Interesse an kirchenrechtlichen Themen. Dies führte ihn 1924 mit dem evangelischen Theologen und späteren Konvertiten Erik Peterson zusammen, mit dem er bis 1933 eng befreundet war.[21] Die Beschäftigung mit dem Kirchenrecht schlug sich in Schriften wie Politische Theologie (1922) und Römischer Katholizismus und politische Form (1923, in zweiter Auflage mit kirchlichem Imprimatur) nieder.[22] Freundschaftlich verbunden war Schmitt in dieser Zeit auch mit einigen katholischen Theologen, allen voran Karl Eschweiler (1886–1936), den er als Privatdozenten für Fundamentaltheologie in Bonn Mitte der 1920er Jahre kennengelernt hatte und mit dem er bis zu dessen Tod 1936 wissenschaftlich und persönlich in engem Kontakt blieb.[23] Bis 1933 pflegte Schmitt „teilweise freundschaftliche Beziehungen“ zu jüdischen Kollegen wie Hermann Heller, Erich Kaufmann und Hans Kelsen und aus anderen Bereichen, wie dem Schriftsteller Franz Blei und dem Nationalökonomen Moritz Julius Bonn.[24] Seine Verfassungslehre (1928) widmete er seinem 1914 gefallenen jüdischen Freund, Fritz Eisler.[25] „Mit Eisler zusammen hatte Schmitt seine pseudonyme satirische Schrift Schattenrisse publiziert, freundschaftliche Kontakte zum expressionistischen Dichter Theodor Däubler gepflegt und ein Buch über Däubler geplant.“[26] |

芸術とボヘミアン生活、学業の開始、最初の出版 政治神学。主権に関する四つの章、1922年 カール・シュミット、ミュンヘン、1917年 シュミットは早くから芸術的才能を発揮した。彼は独自の文学作品(『Der Spiegel』、『Die Buribunken』、『Schattenrisse』など。彼は『Die große Schlacht um Mitternacht』という題の詩集を執筆しようとしたとも伝えられている)を発表し、当時の著名な詩人テオドール・ダウブラーに関する研究 (『Theodor Däublers ‚Nordlicht‘』)も執筆した。)。この頃は、「シュヴァービンガー・ボヘーム」の一員と見なすことができるでしょう[15]。 憲法学者は後に、自身の文学作品を「ダダ・アヴァン・ラ・レター」と表現しています。彼は、ダダイズムの創始者の一人であるヒューゴ・ボール、そして詩人 であり編集者のフランツ・ブライ(ロベルト・ムジルやフランツ・カフカを支援した人物)とも親交がありました。美意識の高い法学者と政治的な小説家たち は、定期的に意見交換を行い、相互に影響を与え合っていたことがわかる。当時、シュミットは詩人たちと特に親しい交流があり、今では忘れ去られた政治カト リックの詩人、コンラート・ヴァイスとも親交があった。シュミットは、ヒューゴ・ボールとともに、文学者ヘルマン・ヘッセを訪ねたが、この交流は長くは続 かなかった。その後、シュミットはエルンスト・ユンガー、そして画家であり作家でもあるリヒャルト・ゼーヴァルトと親交を結んだ。 シュミットは、1914年に『国家の価値と個人と国家法および行政法、国際法、国家論におけるその意義』という論文で教授資格を取得した。ミュンヘン商業 大学(1920年)で教鞭をとった後、シュミットは、グライフスヴァルト(1921年)、ボン(1921年)、ベルリン商業大学(1928年)、ケルン (1933年)、そして再びベルリン(フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学、1933年~1945年)と、短期間で転職を繰り返した。ハビリテーション論文に 続き、1919年に『政治的ロマン主義』、1921年に『独裁』などの著作が、ルートヴィヒ・フォイクトヴァンガーの編集により、ダンカー&フンブロット 社から相次いで出版された。ミュンヘンでの最初の学職、そして後にベルリン商業大学への招聘は、ユダヤ人経済学者モーリッツ・ユリウス・ボンのおかげだっ た[16]。 シュミットは、その雄弁で華麗な表現力により、法学者以外の人々の間でもすぐに有名になった。彼のスタイルは斬新で、学術界をはるかに超えた界隈で「驚異 的」と評された。彼は法学者らしい文章ではなく、詩的かつ劇的な表現で文章を構成し、神話的なイメージや暗示をちりばめた。[17] 彼の著作は、そのほとんどが小さなパンフレットで、その主張の鋭さから議論を迫るものだった。シュミットは、「多くの場合、最初の1文が著作の運命を決め る」と確信していた。[18] 彼の著作の冒頭の文、例えば「反ローマ感情がある」、「国家という概念は政治という概念を前提としている」、「例外状態を決定する者が主権者である」など は、すぐに有名になった[19]。 シュミットが引き起こした反応の広範さと多様性は、彼の遺品(ドイツ国内で保存されている遺品の中で最大規模のものの一つ)に保存され、順次公開されている膨大な書簡集に特に顕著に表れている。[20] ボンでは、憲法学者は若いカトリック教徒たちとの付き合いがあり(カール・ムートの雑誌『Hochland』などに寄稿)、教会法に関するテーマに強い関 心を示していた。これにより、1924年に、プロテスタントの神学者で後に改宗したエリック・ペーターソンと知り合い、1933年まで親しい友人関係に あった。[21] 教会法への関心は、『政治神学』(1922年)や『ローマカトリックと政治形態』(1923年、教会による認可を受けて第2版が発行)などの著作にも反映 されている。[22] この頃、シュミットは、カトリック神学者たちとも親交があった。その代表は、1920年代半ばにボンで基礎神学の私講師として知り合ったカール・エシュ ヴァイラー(1886-1936)で、1936年にエシュヴァイラーが亡くなるまで、学術的、個人的にも親しい関係が続いた。[23] 1933年まで、シュミットは、ヘルマン・ヘラー、エーリッヒ・カウフマン、ハンス・ケルセンなどのユダヤ人の同僚や、作家フランツ・ブライ、経済学者 モーリッツ・ユリウス・ボンなど、他の分野の人たちとも「一部友好的な関係」を維持していた。[24] 彼は、1914年に戦死したユダヤ人の友人、フリッツ・アイスラーに『憲法学』(1928年)を捧げた。[25] 「シュミットはアイスラーとともに、偽名による風刺作品『影絵』を出版し、表現主義の詩人テオドール・ダウブラーと親しい交流を持ち、ダウブラーに関する 著書を企画していた。」[26] |

| Politische Publizistik und Beratertätigkeit in der Weimarer Republik Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus, 2. Auflage, 1926 1924 erschien Schmitts erste explizit politische Schrift mit dem Titel Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus. Im Jahre 1928 legte er sein bedeutendstes wissenschaftliches Werk vor, die Verfassungslehre, in der er die Weimarer Verfassung einer systematischen juristischen Analyse unterzog und eine neue wissenschaftliche Literaturgattung begründete: neben der klassischen Staatslehre etablierte sich seitdem die Verfassungslehre als eigenständige Disziplin des Öffentlichen Rechts. Im Jahr des Erscheinens der Verfassungslehre wechselte er an die Handelshochschule in Berlin, auch wenn das in Bezug auf seinen Status als Wissenschaftler einen Rückschritt bedeutete. Dafür konnte er im politischen Berlin zahlreiche Kontakte knüpfen, die bis in Regierungskreise hinein reichten. Hier entwickelte er gegen die herrschenden Ansichten die Theorie vom „unantastbaren Wesenskern“ der Verfassung („Verfassungslehre“). Ordnungspolitisch trat der ökonomisch informierte Jurist für einen starken Staat ein, der auf einer „freien Wirtschaft“ basieren sollte. Hier traf sich Schmitts Vorstellung in vielen Punkten mit dem Ordoliberalismus oder späteren Neoliberalismus, zu deren Ideengebern er in dieser Zeit enge Kontakte unterhielt, insbesondere zu Alexander Rüstow. In einem Vortrag vor Industriellen im November 1932 mit dem Titel Starker Staat und gesunde Wirtschaft forderte er eine aktive „Entpolitisierung“ des Staates und einen Rückzug aus „nichtstaatlichen Sphären“: „Immer wieder zeigt sich dasselbe: nur ein starker Staat kann entpolitisieren, nur ein starker Staat kann offen und wirksam anordnen, daß gewisse Angelegenheiten, wie Verkehr oder Rundfunk, sein Regal sind und von ihm als solche verwaltet werden, daß andere Angelegenheiten der […] wirtschaftlichen Selbstverwaltung zugehören, und alles übrige der freien Wirtschaft überlassen wird.“[27] Bei diesen Ausführungen spielte Schmitt auf einen Vortrag Rüstows an, den dieser zwei Monate zuvor unter dem Titel Freie Wirtschaft, starker Staat gehalten hatte.[28] Rüstow hatte sich darin seinerseits auf Carl Schmitt bezogen: „Die Erscheinung, die Carl Schmitt im Anschluß an Ernst Jünger den ‚totalen Staat‘ genannt hat […], ist in Wahrheit das genaue Gegenteil davon: nicht Staatsallmacht, sondern Staatsohnmacht. Es ist ein Zeichen jämmerlichster Schwäche des Staates, einer Schwäche, die sich des vereinten Ansturms der Interessentenhaufen nicht mehr erwehren kann. Der Staat wird von den gierigen Interessenten auseinandergerissen. […] Was sich hier abspielt, staatspolitisch noch unerträglicher als wirtschaftspolitisch, steht unter dem Motto: ‚Der Staat als Beute‘.“[29] Den so aufgefassten Egoismus gesellschaftlicher Interessensgruppen bezeichnete Schmitt (in negativer Auslegung des gleichnamigen Konzeptes von Harold Laski) als Pluralismus. Dem Pluralismus partikularer Interessen setzte er die Einheit des Staates entgegen, die für ihn durch den vom Volk gewählten Reichspräsidenten repräsentiert wurde. In Berlin erschienen Der Begriff des Politischen (1927 zunächst als Aufsatz), Der Hüter der Verfassung (1931) und Legalität und Legitimität (1932). Mit Hans Kelsen lieferte sich Schmitt eine vielbeachtete Kontroverse über die Frage, ob der „Hüter der Verfassung“ der Verfassungsgerichtshof oder der Reichspräsident sei.[30] Zugleich näherte er sich reaktionären Strömungen an, indem er Stellung gegen den Parlamentarismus bezog. Als Hochschullehrer war Schmitt wegen seiner Kritik an der Weimarer Verfassung zunehmend umstritten. So wurde er etwa von den der Sozialdemokratie nahestehenden Staatsrechtlern Hans Kelsen und Hermann Heller scharf kritisiert. Die Weimarer Verfassung, so meinte er, schwäche den Staat durch einen „neutralisierenden“ Liberalismus und sei somit nicht fähig, die Probleme der aufkeimenden „Massendemokratie“ zu lösen. Liberalismus war für Schmitt im Anschluss an Cortés nichts anderes als organisierte Unentschiedenheit: „Sein Wesen ist Verhandeln, abwartende Halbheit, mit der Hoffnung, die definitive Auseinandersetzung, die blutige Entscheidungsschlacht könnte in eine parlamentarische Debatte verwandelt werden und ließe sich durch ewige Diskussion ewig suspendieren“.[31] Das Parlament ist in dieser Perspektive der Hort der romantischen Idee eines „ewigen Gesprächs“. Daraus folge: „Jener Liberalismus mit seinen Inkonsequenzen und Kompromissen lebt […] nur in dem kurzen Interim, in dem es möglich ist, auf die Frage: Christus oder Barrabas, mit einem Vertagungsantrag oder der Einsetzung einer Untersuchungskommission zu antworten“.[32] Die Garantien der Oppositionsrechte in den Geschäftsordnungen wirkten, so Schmitt, „wie eine überflüssige Dekoration, unnütz und sogar peinlich, als hätte jemand die Heizkörper einer modernen Zentralheizung mit roten Flammen angemalt, um die Illusion eines lodernden Feuers hervorzurufen.“[33] Die parlamentarische Demokratie hielt Schmitt für eine veraltete „bürgerliche“ Regierungsmethode, die gegenüber den aufkommenden „vitalen Bewegungen“ ihre Evidenz verloren habe. Der „relativen“ Rationalität des Parlamentarismus trete der Irrationalismus mit einer neuartigen Mobilisierung der Massen gegenüber. Der Irrationalismus versuche gegenüber der ideologischen Abstraktheit und den „Scheinformen der liberal-bürgerlichen Regierungsmethoden“ zum „konkret Existenziellen“ zu gelangen. Dabei stütze er sich auf einen „Mythus vom vitalen Leben“. Daher proklamierte Schmitt: „Diktatur ist der Gegensatz zu Diskussion“.[34] Als Vertreter des Irrationalismus identifizierte Schmitt zwei miteinander verfeindete Bewegungen: den revolutionären Syndikalismus der Arbeiterbewegung und den Nationalismus des italienischen Faschismus. „Der stärkere Mythus“ liegt ihm zufolge aber „im Nationalen“.[35] Als Beleg führte er Mussolinis Marsch auf Rom an. Den italienischen Faschismus verwendete Schmitt als eine Folie, vor deren Hintergrund er die Herrschaftsformen des „alten Liberalismus“ kritisierte. Dabei hatte er sich nie mit den realen Erscheinungsformen des Faschismus auseinandergesetzt. Sein Biograph Paul Noack urteilt: „[Der] Faschismus wird von [Schmitt] als Beispiel eines autoritären Staates (im Gegensatz zu einem totalitären) interpretiert. Dabei macht er sich kaum die Mühe, die Realität dieses Staates hinter dessen Rhetorik aufzuspüren. Hier wie in anderen Fällen genügt ihm die Konstruktionszeichnung, um sich das Haus vorzustellen. Zweifellos ist es der Anspruch von Größe und Geschichtlichkeit, der ihn in bewundernde Kommentare über Mussolinis neapolitanische Rede vor dem Marsch auf Rom ausbrechen läßt.“[36] Laut Schmitt bringt der Faschismus einen totalen Staat aus Stärke hervor, keinen totalen Staat aus Schwäche. Er ist kein „neutraler“ Mittler zwischen den Interessensgruppen, kein „kapitalistischer Diener des Privateigentums“, sondern ein „höherer Dritter zwischen den wirtschaftlichen Gegensätzen und Interessen“. Dabei verzichte der Faschismus auf die „überlieferten Verfassungsklischees des 19. Jahrhunderts“ und versuche eine Antwort auf die Anforderungen der modernen Massendemokratie zu geben. „Daß der Faschismus auf Wahlen verzichtet und den ganzen ‚elezionismo‘ haßt und verachtet, ist nicht etwa undemokratisch, sondern antiliberal und entspringt der richtigen Erkenntnis, daß die heutigen Methoden geheimer Einzelwahl alles Staatliche und Politische durch eine völlige Privatisierung gefährden, das Volk als Einheit ganz aus der Öffentlichkeit verdrängen (der Souverän verschwindet in der Wahlzelle) und die staatliche Willensbildung zu einer Summierung geheimer und privater Einzelwillen, das heißt in Wahrheit unkontrollierbarer Massenwünsche und -ressentiments herabwürdigen.“ Gegen ihre desintegrierende Wirkung kann man sich Schmitt zufolge nur schützen, wenn man im Sinne von Rudolf Smends Integrationslehre eine Rechtspflicht des einzelnen Staatsbürgers konstruiert, bei der geheimen Stimmabgabe nicht sein privates Interesse, sondern das Wohl des Ganzen im Auge zu haben – angesichts der Wirklichkeit des sozialen und politischen Lebens sei dies aber ein schwacher und sehr problematischer Schutz. Schmitts Folgerung lautet: „Jene Gleichsetzung von Demokratie und geheimer Einzelwahl ist Liberalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts und nicht Demokratie.“[37] Nur zwei Staaten, das bolschewistische Russland und das faschistische Italien, hätten den Versuch gemacht, mit den überkommenen Verfassungsprinzipien des 19. Jahrhunderts zu brechen, um die großen Veränderungen in der wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Struktur auch in der staatlichen Organisation und in einer geschriebenen Verfassung zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Gerade nicht intensiv industrialisierte Länder wie Russland und Italien könnten sich eine moderne Wirtschaftsverfassung geben. In hochentwickelten Industriestaaten ist die innenpolitische Lage nach Schmitts Auffassung vom „Phänomen der ‚sozialen Gleichgewichtsstruktur‘ zwischen Kapital und Arbeit“ beherrscht: Arbeitgeber und Arbeitnehmer stehen sich mit gleicher sozialer Macht gegenüber und keine Seite kann der anderen eine radikale Entscheidung aufdrängen, ohne einen furchtbaren Bürgerkrieg auszulösen. Dieses Phänomen sei vor allem von Otto Kirchheimer staats- und verfassungstheoretisch behandelt worden. Aufgrund der Machtgleichheit seien in den industrialisierten Staaten „auf legalem Wege soziale Entscheidungen und fundamentale Verfassungsänderungen nicht mehr möglich, und alles, was es an Staat und Regierung gibt, ist dann mehr oder weniger eben nur der neutrale (und nicht der höhere, aus eigener Kraft und Autorität entscheidende) Dritte“.[38] Der italienische Faschismus versuche demnach, mit Hilfe einer geschlossenen Organisation diese Suprematie des Staates gegenüber der Wirtschaft herzustellen. Daher komme das faschistische Regime auf Dauer den Arbeitnehmern zugute, weil diese heute das Volk seien und der Staat nun einmal die politische Einheit des Volkes. Die Kritik bürgerlicher Institutionen war es, die Schmitt in dieser Phase für junge sozialistische Juristen wie Ernst Fraenkel, Otto Kirchheimer und Franz Neumann interessant machte.[39] Umgekehrt profitierte Schmitt von den unorthodoxen Denkansätzen dieser linken Systemkritiker. So hatte Schmitt den Titel einer seiner bekanntesten Abhandlungen (Legalität und Legitimität) von Otto Kirchheimer entliehen.[40] Ernst Fraenkel besuchte Schmitts staatsrechtliche Arbeitsgemeinschaften[41] und bezog sich positiv auf dessen Kritik des destruktiven Misstrauensvotums (Fraenkel, Verfassungsreform und Sozialdemokratie, Die Gesellschaft, 1932). Franz Neumann wiederum verfasste am 7. September 1932 einen euphorisch zustimmenden Brief anlässlich der Veröffentlichung des Buches Legalität und Legitimität.[42] Kirchheimer urteilte über die Schrift im Jahre 1932: „Wenn eine spätere Zeit den geistigen Bestand dieser Epoche sichtet, so wird sich ihr das Buch von Carl Schmitt über Legalität und Legitimität als eine Schrift darbieten, die sich aus diesem Kreis sowohl durch ihr Zurückgehen auf die Grundlagen der Staatstheorie als auch durch ihre Zurückhaltung in den Schlussfolgerungen auszeichnet.“[43] In einem Aufsatz von Anfang 1933 mit dem Titel Verfassungsreform und Sozialdemokratie[44], in dem Kirchheimer verschiedene Vorschläge zur Reform der Weimarer Verfassung im Sinne einer Stärkung des Reichspräsidenten zu Lasten des Reichstags diskutierte, wies der SPD-Jurist auch auf Anfeindungen hin, der die Zeitschrift Die Gesellschaft aufgrund der positiven Anknüpfung an Carl Schmitt von kommunistischer Seite ausgesetzt war: „In Nr. 24 des Roten Aufbaus wird von ‚theoretischen Querverbindungen‘ zwischen dem ‚faschistischen Staatstheoretiker‘ Carl Schmitt und dem offiziellen theoretischen Organ der SPD, der Gesellschaft gesprochen, die besonders anschaulich im Fraenkelschen Aufsatz zutage treten sollen.“ Aus den fraenkelschen Ausführungen, in denen dieser sich mehrfach auf Schmitt bezogen hatte, ergebe sich in der logischen Konsequenz die Aufforderung zum Staatsstreich, die Fraenkel nur nicht offen auszusprechen wage. In der Tat hatte Fraenkel in der vorherigen Ausgabe der „Gesellschaft“ unter ausdrücklicher Anknüpfung an Carl Schmitt geschrieben: „Es hieße, der Sache der Verfassung den schlechtesten Dienst zu erweisen, wenn man die Erweiterung der Macht des Reichspräsidenten bis hin zum Zustande der faktischen Diktatur auf den Machtwillen des Präsidenten und der hinter ihm stehenden Kräfte zurückführen will. Wenn der Reichstag zur Bewältigung der ihm gesetzten Aufgaben unfähig wird, so muß vielmehr ein anderes Staatsorgan die Funktion übernehmen, die erforderlich ist, um in gefährdeten Zeiten den Staatsapparat weiterzuführen. Solange eine Mehrheit grundsätzlich staatsfeindlicher, in sich uneiniger Parteien im Parlament, kann ein Präsident, wie immer er auch heißen mag, gar nichts anderes tun, als den destruktiven Beschlüssen dieses Parlaments auszuweichen. Carl Schmitt hat unzweifelhaft recht, wenn er bereits vor zwei Jahren ausgeführt hat, daß die geltende Reichsverfassung einem mehrheits- und handlungsfähigen Reichstag alle Rechte und Möglichkeiten gibt, um sich als den maßgebenden Faktor staatlicher Willensbildung durchzusetzen. Ist das Parlament dazu nicht im Stande, so hat es auch nicht das Recht, zu verlangen, daß alle anderen verantwortlichen Stellen handlungsunfähig werden.“[45] Schmitt war ab 1930 für eine autoritäre Präsidialdiktatur eingetreten und pflegte Bekanntschaften zu politischen Kreisen, etwa dem späteren preußischen Finanzminister Johannes Popitz.[46] Auch zur Reichsregierung selbst gewann er Kontakt, indem er enge Beziehungen zu Mittelsmännern des Generals, Ministers und späteren Kanzlers Kurt von Schleicher unterhielt. Schmitt stimmte sogar Publikationen und öffentliche Vorträge im Vorfeld mit den Mittelsmännern des Generals ab.[47] Für die Regierungskreise waren einige seiner politisch-verfassungsrechtlichen Arbeiten, etwa die erweiterten Ausgaben von „Der Hüter der Verfassung“ (1931) oder „Der Begriff des Politischen“ (1932), von Interesse.[48] Trotz seiner Kritik an Pluralismus und parlamentarischer Demokratie stand Schmitt vor der Machtergreifung 1933 den Umsturzbestrebungen von KPD und NSDAP gleichermaßen ablehnend gegenüber.[49] Er unterstützte die Politik Schleichers, die darauf abzielte, das „Abenteuer Nationalsozialismus“ zu verhindern.[50] In seiner im Juli 1932 abgeschlossenen Abhandlung Legalität und Legitimität forderte der Staatsrechtler eine Entscheidung für die Substanz der Verfassung und gegen ihre Feinde.[51] Er fasste dies in eine Kritik am neukantianischen Rechtspositivismus, wie ihn der führende Verfassungskommentator Gerhard Anschütz vertrat. Gegen diesen Positivismus, der nicht nach den Zielen politischer Gruppierungen fragte, sondern nur nach formaler Legalität, brachte Schmitt – hierin mit seinem Antipoden Heller einig – eine Legitimität in Stellung, die gegenüber dem Relativismus auf die Unverfügbarkeit politischer Grundentscheidungen verwies. Die politischen Feinde der bestehenden Ordnung sollten klar als solche benannt werden, andernfalls führe die Indifferenz gegenüber verfassungsfeindlichen Bestrebungen in den politischen Selbstmord.[52] Zwar hatte Schmitt sich hier klar für eine Bekämpfung verfassungsfeindlicher Parteien ausgesprochen, was er jedoch mit einer „folgerichtigen Weiterentwicklung der Verfassung“ meinte, die an gleicher Stelle gefordert wurde, blieb unklar. Hier wurde vielfach vermutet, es handele sich um einen konservativ-revolutionären „Neuen Staat“ Papen’scher Prägung, wie ihn etwa Heinz Otto Ziegler beschrieben hatte (Autoritärer oder totaler Staat, 1932).[53] Verschiedene neuere Untersuchungen argumentieren dagegen, Schmitt habe im Sinne Schleichers eine Stabilisierung der politischen Situation erstrebt und Verfassungsänderungen als etwas Sekundäres betrachtet.[54] In dieser Perspektive war die geforderte Weiterentwicklung eine faktische Veränderung der Machtverhältnisse, keine Etablierung neuer Verfassungsprinzipien. 1932 war Schmitt auf einem vorläufigen Höhepunkt seiner politischen Ambitionen angelangt: Er vertrat die Reichsregierung unter Franz von Papen zusammen mit Carl Bilfinger und Erwin Jacobi im Prozess um den sogenannten Preußenschlag gegen die staatsstreichartig abgesetzte preußische Regierung Otto Braun vor dem Staatsgerichtshof.[55] Als enger Berater im Hintergrund wurde Schmitt in geheime Planungen eingeweiht, die auf die Ausrufung eines Staatsnotstands hinausliefen. Schmitt und Personen aus Schleichers Umfeld wollten durch einen intrakonstitutionellen „Verfassungswandel“ die Gewichte in Richtung einer konstitutionellen Demokratie mit präsidialer Ausprägung verschieben. Dabei sollten verfassungspolitisch diejenigen Spielräume genutzt werden, die in der Verfassung angelegt waren oder zumindest von ihr nicht ausgeschlossen wurden. Konkret schlug Schmitt vor, der Präsident solle gestützt auf Artikel 48 regieren, destruktive Misstrauensvoten oder Aufhebungsbeschlüsse des Parlaments sollten mit Verweis auf ihre fehlende konstruktive Basis ignoriert werden. In einem Positionspapier für Schleicher mit dem Titel: „Wie bewahrt man eine arbeitsfähige Präsidialregierung vor der Obstruktion eines arbeitsunwilligen Reichstages mit dem Ziel, ’die Verfassung zu wahren'“ wurde der „mildere Weg, der ein Minimum an Verfassungsverletzung darstellt“, empfohlen, nämlich: „die authentische Auslegung des Art. 54 [der das Misstrauensvotum regelt] in der Richtung der naturgegebenen Entwicklung (Mißtrauensvotum gilt nur seitens einer Mehrheit, die in der Lage ist, eine positive Vertrauensgrundlage herzustellen)“. Das Papier betonte: „Will man von der Verfassung abweichen, so kann es nur in der Richtung geschehen, auf die sich die Verfassung unter dem Zwang der Umstände und in Übereinstimmung mit der öffentlichen Meinung hin entwickelt. Man muß das Ziel der Verfassungswandlung im Auge behalten und darf nicht davon abweichen. Dieses Ziel ist aber nicht die Auslieferung der Volksvertretung an die Exekutive (der Reichspräsident beruft und vertagt den Reichstag), sondern es ist Stärkung der Exekutive durch Abschaffung oder Entkräftung von Art. 54 bezw. durch Begrenzung des Reichstages auf Gesetzgebung und Kontrolle. Dieses Ziel ist aber durch die authentische Interpretation der Zuständigkeit eines Mißtrauensvotums geradezu erreicht. Man würde durch einen erfolgreichen Präzedenzfall die Verfassung gewandelt haben.“[56] Wie stark Schmitt bis Ende Januar 1933 seine politischen Aktivitäten mit Kurt v. Schleicher verbunden hatte, illustriert sein Tagebucheintrag vom 27. Januar 1933: „Es ist etwas unglaubliches Geschehen. Der Hindenburg-Mythos ist zu Ende. Der Alte war schließlich auch nur ein Mac Mahon. Scheußlicher Zustand. Schleicher tritt zurück; Papen oder Hitler kommen. Der alte Herr ist verrückt geworden.“[57] Auch war Schmitt, wie Schleicher, zunächst ein Gegner der Kanzlerschafts Hitlers. Am 30. Januar verzeichnet sein Tagebuch den Eintrag: „Dann zum Cafe Kutscher, wo ich hörte, daß Hitler Reichskanzler und Papen Vizekanzler geworden ist. Zu Hause gleich zu Bett. Schrecklicher Zustand.“ Einen Tag später hieß es: „War noch erkältet. Telefonierte Handelshochschule und sagte meine Vorlesung ab. Wurde allmählich munterer, konnte nichts arbeiten, lächerlicher Zustand, las Zeitungen, aufgeregt. Wut über den dummen, lächerlichen Hitler.“[58] |

ワイマール共和国における政治ジャーナリズムと顧問活動 今日の議会制の精神史的状況、第2版、1926年 1924年、シュミットは、最初の明確な政治論文「今日の議会制の精神史的状況」を発表しました。1928 年、彼は最も重要な学術著作『憲法学』を発表し、ワイマール憲法を体系的な法的分析にかけ、新しい学術文学のジャンルを確立した。それ以来、古典的な国家 学と並んで、憲法学は公法の一分野として独立した学問として確立された。 憲法論』が出版された年、彼はベルリンの商科大学に移った。これは、学者としての地位にとっては後退だった。しかし、その代わりに、彼は政治の舞台である ベルリンで、政府関係者にまで及ぶ数多くの人脈を築くことができた。ここで彼は、当時の主流意見に反して、憲法の「不可侵の本質」に関する理論(「憲法 論」)を展開した。 経済に精通した法学者である彼は、秩序政策に関しては、「自由経済」に基づく強力な国家を主張した。この点では、シュミットの考えは、当時彼が密接な交流 を持っていた、オーダリー・リベラリズムやその後の新自由主義の思想と多くの点で一致していた。特に、アレクサンダー・リュストウとは親しい間柄だった。 1932年11月に産業関係者に向けて行った講演「強力な国家と健全な経済」では、国家の積極的な「脱政治化」と「非国家領域」からの撤退を求めた。 「同じことが何度も繰り返されている。政治から脱却できるのは強力な国家だけであり、強力な国家だけが、交通や放送などの特定の事項は国家の権限であり、 国家が管理すべきであると、また、その他の事項は経済自治に属し、残りは自由経済に委ねるべきであると、率直かつ効果的に命じることができる」[27] この発言で、シュミットは、2 か月前にリュストウが「自由経済、強力な国家」というタイトルで発表した講演をほのめかしていた。[28] リストウは、その講演の中で、カール・シュミットに言及していた。「カール・シュミットがエルンスト・ユンガーに倣って『総体国家』と呼んだ現象は、実際 にはその正反対である。それは国家の絶対的権力ではなく、国家の無力さである。それは、国家の最も哀れな弱さの表れであり、利害関係者の団結した攻撃にも はや抵抗できない弱さだ。国家は、貪欲な利害関係者に引き裂かれる。[…] ここで起こっていることは、経済政策よりも国家政策の観点からさらに耐え難いものであり、「国家は略奪の対象」というモットーの下で行われている。」 [29] このように解釈された社会的利益団体の利己主義を、シュミットは(ハロルド・ラスキの同名の概念を否定的に解釈して)多元主義と呼んだ。彼は、特定の利益の多元主義に対抗するものとして、国民によって選出された帝国大統領によって代表される国家の統一を掲げた。 ベルリンでは、『政治の概念』(1927年、当初は論文として発表)、『憲法の守護者』(1931年)、『合法性と正当性』(1932年)が刊行された。 シュミットは、ハンス・ケルセンと、「憲法の守護者」は憲法裁判所か帝国大統領かについて、大きな論争を繰り広げた[30]。同時に、議会制に反対の立場 を取り、反動的な潮流に近づいた。 大学教授として、シュミットはワイマール憲法に対する批判から、ますます論争の的となった。そのため、社会民主党に近い憲法学者ハンス・ケルセンやヘルマ ン・ヘラーから厳しい批判を受けた。ワイマール憲法は、「中立化」する自由主義によって国家を弱体化させ、台頭する「大衆民主主義」の問題を解決すること はできない、と彼は考えていた。 コルテスに倣って、シュミットにとって自由主義とは、組織化された優柔不断さに他ならないものでした。「その本質は、最終的な対決、血なまぐさい決戦が議 会での議論に変わり、永遠の議論によって永遠に延期されるという希望を抱いた、交渉と様子見の半端さにある」。[31] この観点では、議会は「永遠の対話」というロマンチックな思想の砦だ。その結果、「その不首尾と妥協に満ちた自由主義は、キリストかバラバか、という質問 に対して、審議延期や調査委員会の設置で答えることができる、短い暫定期間にのみ存続する」と結論づけられる。[32] 議事規則における反対権の保証は、シュミットによれば、「現代の中央暖房のラジエーターに赤い炎を描いて、燃え盛る火の幻想を演出するような、不必要で、 さらには恥ずかしい装飾のように見える」[33] シュミットは、議会制民主主義を、台頭する「活力ある運動」に対してその有効性を失った、時代遅れの「市民的」な統治方法だと考えていた。議会制の「相対 的な」合理性に対抗するのは、大衆の新たな動員を伴う非合理主義だ。非合理主義は、イデオロギー的な抽象性や「自由主義的市民的統治手法の虚像」に対抗し て、「具体的な実存」に到達しようとしている。その際、非合理主義は「活力ある生命の神話」に支えられている。そのため、シュミットは「独裁は議論の対極 にある」と宣言した。[34] シュミットは、非合理主義の代表として、2つの敵対する運動、すなわち労働者運動の革命的シンジカリズムとイタリアのファシズムのナショナリズムを挙げ た。しかし、彼によれば、「より強力な神話」は「国民性」にある[35]。その証拠として、彼はムッソリーニのローマ進軍を挙げた。 シュミットは、イタリアのファシズムを背景として、「旧来の自由主義」の支配形態を批判した。しかし、彼はファシズムの実際の現象について深く考察したこ とはなかった。彼の伝記作家ポール・ノアックは、「シュミットは、ファシズムを(全体主義とは対照的な)権威主義国家の例として解釈している。その際、彼 は、その国家のレトリックの背後にある現実を掘り下げる努力をほとんどしていない。このケースも他のケースと同様、彼はその構造図だけでその家屋を想像す るのに十分だと考えている。ムッソリーニがローマ進軍前のナポリでの演説について、彼が賞賛に満ちたコメントを口にしたのは、間違いなく、偉大さと歴史性 を求める気持ちからだった」[36]。 シュミットによれば、ファシズムは弱さからではなく、強さから総力国家を生み出す。ファシズムは、利益団体の間の「中立的な」仲介者でも、「私有財産の資 本主義的僕」でもなく、「経済的対立と利益の間の、より高次の第三者」だ。その過程で、ファシズムは「19世紀の伝統的な憲法上の決まり文句」を放棄し、 現代の大衆民主主義の要求に対する答えを試みている。 「ファシズムが選挙を放棄し、すべての『エレツィオニズモ』を憎悪し、軽蔑するのは、非民主的だからではなく、反自由主義的であり、今日の秘密の個別選挙 という手法が、国家と政治を完全な民営化によって危険にさらし、 国民を一体として公の場から完全に排除し(主権者は投票所で姿を消す)、国家の意思形成を、秘密の個人的な意思の合計、つまり実際には制御不可能な大衆の 願望や感情の合計に貶める」と述べています。 シュミットによれば、その解体的な影響から身を守るには、ルドルフ・スメンドの統合論の趣旨に沿って、秘密投票において個人の私的利益ではなく、全体の福 祉を念頭に置くという、個々の市民に対する法的義務を構築するしかない。しかし、社会的・政治的生活の現実を考えると、これは弱く、非常に問題のある保護 手段だ。シュミットの結論は次のとおりだ。 「民主主義と秘密の個人投票を同一視することは、19世紀の自由主義であり、民主主義ではない」。[37] 19世紀の伝統的な憲法原則を打ち破り、経済・社会構造の大変化を国家組織や成文憲法にも反映させようとした試みは、ボルシェビキ革命後のロシアとファシ スト政権下のイタリアの2カ国だけだった。ロシアやイタリアのような工業化が進んでいない国こそ、近代的な経済憲法を制定できるのだ。 高度に発展した工業国では、シュミットの見解によれば、国内政治は「資本と労働の『社会的均衡構造』という現象」によって支配されている。雇用者と被雇用 者は同等の社会的権力を持って対立しており、どちらの側も、恐ろしい内戦を引き起こさない限り、相手に過激な決定を押し付けることはできない。この現象 は、オットー・キルヒハイマーによって、国家論および憲法論の観点から主に論じられてきた。権力の均衡により、工業化国では「合法的な手段による社会的決 定や根本的な憲法改正はもはや不可能であり、国家や政府の存在は、多かれ少なかれ、中立的な(自らの力と権威によって決定する、より高次の)第三者に過ぎ ない」とキルヒハイマーは指摘している。[38] したがって、イタリアのファシズムは、閉鎖的な組織を駆使して、経済に対する国家の優位性を確立しようとしている。そのため、ファシスト政権は、今日、労 働者が国民であり、国家が国民の政治的統一体であることから、長期的には労働者に利益をもたらすことになる。 この段階において、シュミットをエルンスト・フレーンケル、オットー・キルヒハイマー、フランツ・ノイマンなどの若い社会主義法学者たちにとって興味深い 人物にしたのは、市民的機関に対する批判だった[39]。その一方で、シュミットは、これらの左派体制批判者たちの非正統的な考えから恩恵を受けた。例え ば、シュミットは、最も有名な論文のひとつ(『合法性と正当性』)のタイトルをオットー・キルヒハイマーから借用している。[40] エルンスト・フレーネルは、シュミットの憲法研究会の会合に出席し[41]、破壊的な不信任決議に対するシュミットの批判を肯定的に評価した(フレーネル 『憲法改革と社会民主主義』、Die Gesellschaft、1932年)。一方、フランツ・ノイマンは、1932年9月7日に、『合法性と正当性』の出版に際し、熱狂的に賛同する手紙を 書いた。[42] キルヒハイマーは1932年にこの著作について、「後世がこの時代の知的遺産を検証するとき、カール・シュミットの『合法性と正当性』は、国家理論の基礎 に立ち返り、結論を控えめに表現している点で、このサークルの中で際立った著作として評価されるだろう」と評している。[43] 1933年初頭の論文「憲法改革と社会民主主義[44] で、キルヒハイマーは、帝国議会を犠牲にして帝国大統領の権限を強化するという、ワイマール憲法改正に関するさまざまな提案について論じ、SPD の法律家であるキルヒハイマーは、カール・シュミットと親しい関係にあることを理由に、雑誌『Die Gesellschaft』が共産主義者たちから敵対されていることを指摘している。「『Roter Aufbau』誌第24号では、『ファシストの国家理論家』カール・シュミットと、SPDの公式理論機関誌である『Die Gesellschaft』との「理論的な横のつながり」について述べられており、それはフレネルクの論文で特に顕著に表れている」と。フラエンケルが シュミットに何度も言及した記述からは、論理的な帰結として、フラエンケルが公然と口に出さないだけで、国家転覆を煽っていることがわかる。実際、フレネ ルクは『ゲゼルシャフト』の前号で、カール・シュミットに明確に言及して、次のように書いていた。「帝国大統領の権力を事実上の独裁状態にまで拡大するこ とを、大統領とその背後に立つ勢力の権力意志に起因すると考えることは、憲法に最悪の害を及ぼすことになる。帝国議会が、その任務を遂行できなくなった場 合、むしろ、別の国家機関が、危機的な状況において国家機構を継続するために必要な機能を引き継ぐ必要がある。議会において、国家に敵対的で、内部で意見 が分かれた政党が過半数を占めている限り、大統領は、その名称がどうであれ、この議会の破壊的な決定を回避する以外には何もできない。カール・シュミット は、2年前に、現行の帝国憲法は、多数決能力と行動能力を備えた帝国議会に、国家の意思形成の決定的な要因としてその地位を確立するためのあらゆる権利と 可能性を与えている、と述べたが、その見解は間違いなく正しい。議会がそれを行う能力がない場合、議会は、他のすべての責任機関に行動不能になることを要 求する権利も持たない。[45] シュミットは 1930 年から権威主義的な大統領独裁制を支持し、後のプロイセン財務大臣ヨハネス・ポピッツなどの政治界の人々と親交があった。[46] また、将軍、大臣、そして後の首相となるクルト・フォン・シュライヒャーの仲介者たちと親密な関係を持つことで、帝国政府とも接触を深めた。シュミット は、将軍の中間者たちと事前に出版物や公開講演の内容も調整していた[47]。政府関係者は、彼の政治・憲法に関する著作、例えば『憲法の守護者』 (1931年)の増補版や『政治の概念』(1932年)などに興味を持っていた。[48] 多様主義や議会制民主主義を批判していたにもかかわらず、シュミットは1933年の政権奪取以前、KPDとNSDAPの革命運動を同様に拒否していた。 [49] 彼は、「ナチズムの冒険」を阻止することを目指したシュライヒャーの政策を支持していた。[50] 1932年7月に完成した論文『合法性と正当性』の中で、憲法学者は、憲法の本質と、その敵対者たちに対して決断を下すことを要求した。[51] 彼はこれを、憲法解説者の第一人者ゲルハルト・アンシュッツが提唱した新カント派の法実証主義に対する批判としてまとめた。政治団体の目標を問うことな く、形式的な合法性のみを求めるこの実証主義に対して、シュミットは、その対極にあるヘラーと一致して、相対主義に対して、政治的基本決定の不可侵性を指 摘する正当性を主張した。 既存の秩序の政治的敵は、そのように明確に指名されるべきであり、そうしないと、憲法に敵対する動きに対する無関心は政治的自殺につながる、とシュミット は主張した[52]。シュミットはここでは、憲法に敵対する政党との闘争を明確に支持したが、同所で要求した「憲法の論理的な発展」とは何を意味するのか は不明確だった。ここでは、パペンが提唱したような保守革命的な「新国家」のことだと推測されることが多かった(ハインツ・オットー・ツィーグラー『権威 主義的国家または全体主義国家』(1932年)など)。[53] しかし、最近のさまざまな研究では、シュミットはシュライヒャーの考えに沿って政治情勢の安定化を目指しており、憲法改正は二次的な問題だと考えていたと 反論している[54]。この見解によれば、要求された発展とは、事実上の権力関係の変化であり、新しい憲法原則の確立ではなかった。 1932年、シュミットは政治的野心の暫定的な頂点に達していた。彼は、カール・ビルフィンガー、エルヴィン・ヤコビとともに、フランツ・フォン・パペン の率いる帝国政府を代表して、クーデターによって追放されたオットー・ブラウン率いるプロイセン政府に対する、いわゆる「プロイセン打倒」事件に関する国 家裁判所での裁判に出廷した。[55] シュミットは、裏で緊密な顧問として、国家非常事態の宣言につながる秘密の計画に関与していた。シュミットとシュライヒャーの周辺人物たちは、憲法内の 「憲法変更」によって、大統領制の憲法民主主義へと権力のバランスをシフトさせようとしていた。その際、憲法に規定されている、あるいは少なくとも憲法で 排除されていない憲法上の余地を活用することだった。具体的には、シュミットは、大統領は憲法第48条に基づいて統治し、破壊的な不信任決議や議会の廃止 決議は、建設的な根拠がないことを理由に無視すべきだと提案した。シュライヒャーのために作成された「『憲法を守る』ことを目標とする、仕事をする気のな い帝国議会による妨害から、機能する大統領制政府を守るには」と題された意見書では、「憲法違反を最小限に抑える穏やかな方法」が推奨されている。すなわ ち、「第54条 (不信任決議を規定する)を、自然の発展の方向(不信任決議は、肯定的な信頼の基盤を築くことができる過半数の支持によってのみ有効となる)に沿って解釈 すること」とされている。この文書は、「憲法から逸脱しようとする場合、それは、状況の強制と世論の合意の下で憲法が発展する方向においてのみ行うことが できる」と強調している。憲法改正の目標を見失ってはならない。しかし、この目標は、国民代表を行政機関(帝国大統領が帝国議会を召集・休会する)に委ね ることでなく、第 54 条を廃止または無効化し、帝国議会を立法と監督に限定することで行政機関を強化することだ。しかし、この目標は、不信任決議の権限の真正な解釈によって、 まさに達成されている。この先例が成功すれば、憲法が改正されたことになるだろう」[56] 1933年1月末まで、シュミットがクルト・フォン・シュライヒャーとどの程度政治活動を連携していたかは、1933年1月27日の日記の記述からわか る。「信じられないようなことが起こった。ヒンデンブルク神話は終わった。結局、老人はマックマホンにすぎなかった。ひどい状況だ。シュライヒャーは辞任 し、パペンかヒトラーが台頭するだろう。老人は狂った」[57]。シュライヒャーと同様、シュミットも当初はヒトラーの首相就任に反対していた。1月30 日の日記には、「それからカフェ・クッチャーに行き、ヒトラーが帝国首相、パペンが副首相になったことを聞いた。帰宅後、すぐに就寝。ひどい状況だ」と記 されている。その翌日には、「まだ風邪が治ってなかった。商科大学に電話して講義をキャンセルした。徐々に元気になってきたが、何も仕事ができず、ばかば かしい状況だった。新聞を読んで興奮した。愚かでばかばかしいヒトラーに怒りを感じた」[58] と記されている。 |

| Deutungsproblem 1933: Zäsur oder Kontinuität? Das Ermächtigungsgesetz – für Schmitt Quelle neuer Legalität Nach dem Ermächtigungsgesetz vom 24. März 1933 präsentierte sich Schmitt als überzeugter Anhänger der neuen Machthaber. Ob er dies aus Opportunismus oder aus innerer Überzeugung tat, ist umstritten. Fakt ist, dass Schmitt sich als „einer der ersten früheren Nationalsozialisten unter den Rechtslehrern“ sehr bald an die neuen Machtverhältnisse anpasst.[59] Er entwickelt „einen außerordentlichen literarischen Eifer, der, wie sein Schriftenverzeichnis ausweist, bis Ende 1936 unvermindert andauerte“.[60] Von April 1933, dem Zeitraum seines Eintritts in die NSDAP bis zum Verlust seiner relevanten Ämter im Dezember 1936, verfasste Schmitt mehr als vierzig Beiträge, viele davon erschienen außerhalb der Fachpresse.[61] „Man muß für diese Phase wohl eher von rastloser Propaganda für den NS-Staat sprechen, die er zu seinem Arbeitsprogramm erhob.“[62] Im Berliner Verlag Duncker & Humblot erschienen seine meisten Werke. Schmitts am stärksten nationalsozialistisch gefärbte Veröffentlichungen erschienen jedoch in der Hanseatischen Verlagsanstalt Wandsbek.[26] Während einige Beobachter bei Schmitt einen „unbändigen Geltungsdrang“ sehen, der ihn dazu bewog, sich allen Regierungen seit Hermann Müller im Jahre 1930 als Berater anzudienen (nach 1945 habe er sogar versucht, sich Sowjets[63] und US-Amerikanern zur Verfügung zu stellen), sehen andere in Schmitt einen radikalen Kritiker des Liberalismus, dessen Denken im Kern eine „allen rationalen Deduktionen vorausliegende, politische Option“ für den Nationalsozialismus aufgewiesen habe.[64] Kurz, die Frage lautet, ob Schmitts Engagement für den Nationalsozialismus ein Problem der Theorie oder ein Problem des Charakters ist. Dieses ungelöste Forschungsproblem wird heute vorwiegend an der Frage diskutiert, ob das Jahr 1933 in der Theorie Schmitts einen Bruch darstelle oder eine Kontinuität. Dass diese sich widersprechenden Thesen bis heute vertreten werden, ist dem Umstand geschuldet, dass Schmitt in seinen Schriften mehrdeutig formulierte und sich als „Virtuose der retrospektiven, jeweils wechselnden Rechtfertigungsbedürfnissen angepaßten Selbstauslegung“ (Wilfried Nippel) erwies.[65] Daher können sich auch Vertreter beider Extrempositionen (Bruch versus Kontinuität) zur Stützung ihrer These auf Selbstauskünfte Schmitts berufen. Henning Ottmann bezeichnet die Antithese: „occasionelles Denken oder Kontinuität“ als die Grundfrage aller Schmitt-Deutung. Offen ist also, ob Schmitts Denken einer inneren Logik folgte (Kontinuität), oder ob es rein von äußeren Anlässen (Occasionen) getrieben war, denen innere Konsistenz und Folgerichtigkeit geopfert wurden. Eine Antwort auf diese Frage ist laut Ottmann nicht leicht zu finden: Wer bloße Occasionalität behaupte, müsse die Leitmotive schmittschen Denkens bis zu einem Dezisionismus verflüchtigen, der sich für alles und jedes entscheiden kann; wer dagegen reine Kontinuität erkennen wolle, müsse einen kurzen Weg konstruieren, der vom Antiliberalismus oder Antimarxismus zum nationalsozialistischen Unrechtsstaat führt. Ottmann spricht daher von „Kontinuität und Wandlung“ bzw. auch von teilweise „mehr Wandel als Kontinuität“.[66] Mit Blick auf Schmitts Unterstützung des Regierungskurses Kurt von Schleichers sprechen einige Historiker in Bezug auf das Jahr 1933 von einer Zäsur. Andere erkennen aber auch verborgene Kontinuitätslinien, etwa in der sozialen Funktion seiner Theorie oder in seinem Katholizismus. Hält man sich die Abruptheit des Seitenwechsels im Februar 1933 vor Augen, so scheint die Annahme einer opportunistischen Grundhaltung naheliegend. Gleichwohl gab es durchaus auch inhaltliche Anknüpfungspunkte, etwa den Antiliberalismus oder die Bewunderung des Faschismus, so dass Schmitts Wechsel zum Nationalsozialismus nicht nur als Problem des Charakters, sondern auch als „Problem der Theorie“ zu begreifen ist, wie Karl Graf Ballestrem betont.[67] |

1933年の解釈の問題:断絶か、継続か? 授権法 – シュミットにとって新たな合法性の源泉 1933年3月24日の授権法の後、シュミットは新しい権力者の熱烈な支持者として姿を現した。彼がそれを機会主義から行ったのか、あるいは内なる確信か ら行ったのかは議論の分かれるところだ。事実、シュミットは「法学者の間で最初のナチス支持者の一人」として、新しい権力構造に非常に早く適応した [59]。彼は「並外れた文学的熱意」を発揮し、その著作リストからもわかるように、1936年末までその熱意は衰えることがなかった。[60] 1933年4月のナチス党入党から1936年12月に重要な役職を失うまでの間に、シュミットは40件以上の論文を執筆し、その多くは専門誌以外で発表さ れました。[61] 「この段階では、彼は自分の仕事プログラムとして、ナチス国家のための執拗な宣伝活動を行っていたと表現すべきだろう」[62] 彼の著作の多くは、ベルリンの出版社 Duncker & Humblot から出版された。しかし、シュミットの最もナチス色の強い著作は、ハンザ同盟の出版社 Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt Wandsbek から出版された。[26] 一部の観察者は、シュミットに「抑えきれない名誉欲」があり、それが1930年のヘルマン・ミュラー以来、すべての政府に顧問として仕えるようになった (1945年以降は、ソ連[63] や米国にも仕えようとした)と見る一方、 一方、シュミットを、その思想の核心にナチズムに対する「あらゆる合理的な推論に先立つ政治的選択肢」を見出した、自由主義の過激な批判者だと見る者もい る。[64] 要するに、シュミットのナチズムへの関与は、理論の問題なのか、性格の問題なのか、という疑問がある。この未解決の研究課題は、今日、シュミットの理論に おいて1933年が断絶であるのか、連続性であるのかという疑問を中心に議論されている。これらの相反する説が今日まで主張され続けているのは、シュミッ トが著作の中で曖昧な表現を用い、「回顧的かつ状況に応じて変化する自己解釈の達人」であったためだ(ヴィルフリート・ニッペル)。[65] そのため、両極端の立場(断絶対継続)の支持者たちは、それぞれの説を裏付けるためにシュミット自身の発言を引用することができる。 ヘニング・オットマンは、この対極にある「偶発的な思考か、連続性か」という問題を、シュミット解釈の根本的な問題だと指摘している。つまり、シュミット の思考は、内的な論理(連続性)に従っていたのか、それとも、内的な一貫性や論理性を犠牲にして、純粋に外的な出来事(偶発性)に駆り立てられていたの か、という疑問が残る。オットマンによれば、この疑問に対する答えは簡単には見出せない。単なる偶発性を主張する者は、シュミットの思考のモチーフを、あ らゆる事柄について決定できる決定主義にまで蒸発させてしまうことになる。一方、純粋な連続性を認識しようとする者は、反自由主義や反マルクス主義からナ チスの不正義国家へと至る短い道筋を構築しなければならない。そのため、オットマンは「連続性と変化」、あるいは「連続性よりも変化の方が大きい」と表現 している[66]。シュミットがクルト・フォン・シュライヒャーの政権方針を支持したことを踏まえ、一部の歴史家は 1933 年を「断絶」と表現している。しかし、彼の理論の社会的機能やカトリック信仰など、隠れた連続性を見出す学者もいる。1933年2月の突然の転向を念頭に 置くと、彼の態度は機会主義的だったと推測するのは当然のことのように思える。しかし、反自由主義やファシズムへの賞賛など、内容面での共通点も確かに存 在したため、シュミットのナチズムへの転向は、性格の問題だけでなく、「理論の問題」としても理解すべきだとカール・グラフ・バレストレムは強調している [67]。 |

| Zeit des Nationalsozialismus Nach Angaben Schmitts spielte Popitz bei seiner Kontaktaufnahme zu nationalsozialistischen Regierungsstellen eine entscheidende Rolle. Der Politiker war Minister ohne Geschäftsbereich im Kabinett Schleicher und war im April 1933 preußischer Finanzminister geworden. Popitz vermittelte Schmitt erste Kontakte zu nationalsozialistischen Funktionären während der Arbeiten für das Reichsstatthaltergesetz, an denen Schmitt ebenso wie sein Kollege aus der Prozessvertretung im Preußenprozess, Carl Bilfinger, beteiligt wurde. „Der wahre Führer ist immer auch Richter“ – Carl Schmitts Apotheose des Nationalsozialismus gilt als besondere Perversion des Rechtsdenkens Auch wenn die Gründe nicht abschließend geklärt werden können, so gilt als unzweifelhaft, dass Schmitt voll auf die neue Linie umschwenkte.[68] Er bezeichnete das Ermächtigungsgesetz als „Vorläufiges Verfassungsgesetz des neuen Deutschland“[69] und trat am 1. Mai 1933 als sogenannter „Märzgefallener“ in die NSDAP (Mitgliedsnummer 2.098.860) ein.[70] Am 31. Mai 1933 verfluchte er im Westdeutschen Beobachter „die deutschen Intellektuellen“, die vor dem beginnenden Naziterror geflohen waren: „Aus Deutschland sind sie ausgespien für alle Zeiten.“[71] Zum Sommersemester 1933 kam er einer Berufung aus dem Jahr 1932 nach und wechselte als Nachfolger für Fritz Stier-Somlo an die Universität zu Köln,[72] wo er binnen weniger Wochen die Wandlung in die Rolle eines Staatsrechtlers im Sinne der neuen nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft vollzog. Hatte er zuvor zahlreiche persönliche Kontakte zu jüdischen Kollegen unterhalten, die auch großen Anteil an seiner raschen akademischen Karriere hatten, so begann er nach 1933 seine jüdischen Professorenkollegen zu denunzieren und antisemitische Kampfschriften zu veröffentlichen.[73] Zum Beispiel versagte Schmitt Hans Kelsen, der sich zuvor dafür eingesetzt hatte, Schmitt an die Universität zu Köln zu berufen, jede Unterstützung, als Kollegen eine Resolution gegen dessen Amtsenthebung verfassten.[74] Diese Haltung zeigte Schmitt jedoch nicht allen jüdischen Kollegen gegenüber. So verwendete er sich etwa in einem persönlichen Gutachten für Erwin Jacobi. Gegenüber Kelsen formulierte Schmitt noch nach 1945 antisemitische Invektiven.[75] In der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus bezeichnete er ihn stets als den „Juden Kelsen“. Am 11. Juli 1933 berief ihn sein „Gönner und Förderer“[76], der preußische Ministerpräsident Hermann Göring, in den Preußischen Staatsrat[77] – ein Titel, auf den er zeitlebens besonders stolz war. Noch 1972 soll er gesagt haben, er sei dankbar, Preußischer Staatsrat geworden zu sein und nicht Nobelpreisträger.[78] Als „Vertrauter“ des Reichsrechtsführers Hans Frank wurde Schmitt Herausgeber der Deutschen Juristenzeitung (DJZ), Mitglied der Akademie für Deutsches Recht und Reichsgruppenwalter der Reichsgruppe Hochschullehrer im NS-Rechtswahrerbund.[79] Im Juli 1934 wurde Schmitt zum Mitglied der Hochschulkommission der NSDAP ernannt.[80] In seiner Schrift Staat, Bewegung, Volk: Die Dreigliederung der politischen Einheit (1933) betonte Schmitt die Legalität der „deutschen Revolution“: Die Machtübernahme Hitlers bewege sich „formal korrekt in Übereinstimmung mit der früheren Verfassung“, sie entstamme „Disziplin und deutschem Ordnungssinn“. Der Zentralbegriff des nationalsozialistischen Staatsrechts sei „Führertum“, unerlässliche Voraussetzung dafür „rassische“ Gleichheit von Führer und Gefolge. Indem Schmitt die Rechtmäßigkeit der „nationalsozialistischen Revolution“ betonte, verschaffte er der Führung der NSDAP eine juristische Legitimation. Aufgrund seines juristischen und verbalen Einsatzes für den Staat der NSDAP wurde er von Zeitgenossen, insbesondere von politischen Emigranten (darunter Schüler und Bekannte), als „Kronjurist des Dritten Reiches“ bezeichnet. Den Begriff prägte der „Interpret des politischen Katholizismus“ und frühere Schmitt-Intimus Waldemar Gurian im Jahr 1934 als Reaktion auf dessen Rechtfertigung der Röhm-Morde.[81] Im Herbst 1933 wurde Schmitt aus „staatspolitischen Gründen“ an die Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin berufen und entwickelte dort die Lehre vom konkreten Ordnungsdenken, der zufolge jede Ordnung ihre institutionelle Repräsentanz im Entscheidungsmonopol eines Amtes mit Unfehlbarkeitsanspruch findet. Diese amtscharismatische Souveränitätslehre mündete in einer Propagierung des Führerprinzips und der These einer Identität von Wille und Gesetz („Der Wille des Führers ist Gesetz“).[82] Damit konnte Schmitt seinen Ruf bei den neuen Machthabern weiter festigen. Zudem diente der Jurist als Stichwortgeber, dessen Wendungen wie totaler Staat – totaler Krieg oder geostrategischer Großraum mit Interventionsverbot für raumfremde Mächte enormen Erfolg hatten, wenngleich sie nicht mit seinem Namen verbunden wurden. Von 1934 bis 1935 war Bernhard Ludwig von Mutius Schmitts wissenschaftlicher Assistent. Schmitts Einsatz für das neue Regime war bedingungslos. Als Beispiel kann seine Instrumentalisierung der Verfassungsgeschichte zur Legitimation des NS-Regimes dienen.[83] Viele seiner Stellungnahmen gingen weit über das hinaus, was von einem linientreuen Juristen erwartet wurde. Schmitt wollte sich offensichtlich durch besonders schneidige Formulierungen profilieren. In Reaktion auf die Morde des NS-Regimes vom 30. Juni 1934 während der Röhm-Affäre – unter den Getöteten war auch der ihm politisch nahestehende ehemalige Reichskanzler Kurt von Schleicher – rechtfertigte er die Selbstermächtigung Hitlers mit den Worten: „Der Führer schützt das Recht vor dem schlimmsten Missbrauch, wenn er im Augenblick der Gefahr kraft seines Führertums als oberster Gerichtsherr unmittelbar Recht schafft.“ Der wahre Führer sei immer auch Richter, aus dem Führertum fließe das Richtertum.[84] Wer beide Ämter trenne, so Schmitt, mache den Richter „zum Gegenführer“ und wolle „den Staat mit Hilfe der Justiz aus den Angeln heben“. Verfechtern der Gewaltenteilung warf Schmitt „Rechtsblindheit“ vor.[85] Diese behauptete Übereinstimmung von „Führertum“ und „Richtertum“ gilt als Zeugnis einer besonderen Perversion des Rechtsdenkens. Schmitt schloss den Artikel mit dem politischen Aufruf: „Wer den gewaltigen Hintergrund unserer politischen Gesamtlage sieht, wird die Mahnungen und Warnungen des Führers verstehen und sich zu dem großen geistigen Kampfe rüsten, in dem wir unser gutes Recht zu wahren haben.“ Die Nürnberger Rassengesetze im Reichsgesetzblatt Nr. 100, 16. September 1935 – für Schmitt die „Verfassung der Freiheit“ Öffentlich trat Schmitt wiederum als Rassist und Antisemit[86] hervor, als er die Nürnberger Rassengesetze von 1935 in selbst für nationalsozialistische Verhältnisse grotesker Stilisierung als Verfassung der Freiheit bezeichnete (so der Titel eines Aufsatzes in der Deutschen Juristenzeitung).[87] Mit dem sogenannten Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre, das Beziehungen zwischen Juden (in der Definition der Nationalsozialisten) und „Deutschblütigen“ unter Strafe stellte, trat für Schmitt „ein neues weltanschauliches Prinzip in der Gesetzgebung“ auf. Diese „von dem Gedanken der Rasse getragene Gesetzgebung“ stößt, so Schmitt, auf die Gesetze anderer Länder, die ebenso grundsätzlich rassische Unterscheidungen nicht kennen oder sogar ablehnen.[88] Dieses Aufeinandertreffen unterschiedlicher weltanschaulicher Prinzipien war für Schmitt Regelungsgegenstand des Völkerrechts. Höhepunkt der Schmittschen Parteipropaganda war die im Oktober 1936 unter seiner Leitung durchgeführte Tagung Das Judentum in der Rechtswissenschaft.[89] Hier bekannte er sich ausdrücklich zum nationalsozialistischen Antisemitismus und forderte, jüdische Autoren in der juristischen Literatur nicht mehr zu zitieren oder jedenfalls als Juden zu kennzeichnen. „Was der Führer über die jüdische Dialektik gesagt hat, müssen wir uns selbst und unseren Studenten immer wieder einprägen, um der großen Gefahr immer neuer Tarnungen und Zerredungen zu entgehen. Mit einem nur gefühlsmäßigen Antisemitismus ist es nicht getan; es bedarf einer erkenntnismäßig begründeten Sicherheit. […] Wir müssen den deutschen Geist von allen Fälschungen befreien, Fälschungen des Begriffes Geist, die es ermöglicht haben, dass jüdische Emigranten den großartigen Kampf des Gauleiters Julius Streicher als etwas ‚Ungeistiges‘ bezeichnen konnten.“[90] Etwa zur selben Zeit gab es eine nationalsozialistische Kampagne gegen Schmitt, die zu seiner weitgehenden Entmachtung führte und in deren Mittelpunkt das „Intrigantentrio“ Otto Koellreutter, Karl August Eckhardt und Reinhard Höhn stand.[91] Reinhard Mehring schreibt dazu: „Da diese Tagung aber Ende 1936 zeitlich eng mit einer nationalsozialistischen Kampagne gegen Schmitt und seiner weitgehenden Entmachtung als Funktionsträger zusammenfiel, wurde sie – schon in nationalsozialistischen Kreisen – oft als opportunistisches Lippenbekenntnis abgetan und nicht hinreichend beachtet, bis Schmitt 1991 durch die Veröffentlichung des „Glossariums“, tagebuchartiger Aufzeichnungen aus den Jahren 1947 bis 1951, auch nach 1945 noch als glühender Antisemit dastand, der kein Wort des Bedauerns über Entrechtung, Verfolgung und Vernichtung fand. Seitdem ist sein Antisemitismus ein zentrales Thema. War er katholisch-christlich oder rassistisch-biologistisch begründet? … Die Diskussion ist noch lange nicht abgeschlossen.“[92] In dem der SS nahestehenden Parteiblatt Schwarzes Korps wurde Schmitt „Opportunismus“ und eine fehlende „nationalsozialistische Gesinnung“ vorgeworfen. Hinzu kamen Vorhaltungen wegen seiner früheren Unterstützung der Regierung Schleichers sowie Bekanntschaften zu Juden: „An der Seite des Juden Jacobi focht Carl Schmitt im Prozess Preußen-Reich für die reaktionäre Zwischenregierung Schleicher [sic! recte: Papen].“ In den Mitteilungen zur weltanschaulichen Lage des Amtes Rosenberg hieß es, Schmitt habe „mit dem Halbjuden Jacobi gegen die herrschende Lehre die Behauptung aufgestellt, es sei nicht möglich, dass etwa eine nationalsozialistische Mehrheit im Reichstag auf Grund eines Beschlusses mit Zweidrittelmehrheit nach dem Art. 76 durch verfassungsänderndes Gesetz grundlegende politische Entscheidungen der Verfassung, etwa das Prinzip der parlamentarischen Demokratie, ändern könne, denn eine solche Verfassungsänderung sei dann Verfassungswechsel, nicht Verfassungsrevision.“ Ab 1936 bemühten sich demnach nationalsozialistische Organe, Schmitt seiner Machtposition zu berauben, ihm eine nationalsozialistische Gesinnung abzusprechen und ihm Opportunismus nachzuweisen.[93] Durch die Publikationen im Schwarzen Korps entstand ein Skandal, in dessen Folge das NSDAP-Mitglied Schmitt 1936 alle Ämter in den Parteiorganisationen verlor, aber im Preußischen Staatsrat blieb, den Göring im selben Jahr zum letzten Mal einberufen sollte. Schmitt wird daher in der wissenschaftlichen Literatur ähnlich wie Martin Heidegger oder Hans Freyer zu den "gescheiterten Vordenkern" des Nationalsozialismus gezählt.[94] Bis zum Ende des Nationalsozialismus arbeitete Schmitt als Professor an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin hauptsächlich auf dem Gebiet des Völkerrechts, versuchte aber auch hier, zum Stichwortgeber des Regimes zu avancieren. Das zeigt etwa sein 1939 zu Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs entwickelter Begriff der „völkerrechtlichen Großraumordnung“, den er als deutsche Monroe-Doktrin verstand. Dies wurde später zumeist als Versuch gewertet, die Expansionspolitik Hitlers völkerrechtlich zu fundieren. So war Schmitt etwa an der sogenannten Aktion Ritterbusch beteiligt, mit der zahlreiche Wissenschaftler die nationalsozialistische Raum- und Bevölkerungspolitik beratend begleiteten.[95] |

ナチス政権時代 シュミットによると、ポピッツは、ナチス政権の政府機関との接触において重要な役割を果たした。この政治家は、シュライヒャー内閣の無任所大臣であり、 1933年4月にプロイセン財務大臣に就任した。ポピッツは、シュミットがプロイセン裁判の弁護団の一員として関わった帝国総督法 (Reichsstatthaltergesetz)の制定作業中に、シュミットにナチス幹部の最初の連絡先を紹介した。 「真の指導者は常に裁判官でもある」―カール・シュミットのナチズムの絶賛は、法思想の特別な歪曲とみなされている。 その理由は完全には解明されていないが、シュミットが新しい方針に全面的に転換したことは疑いの余地がない。[68] 彼は、授権法を「新しいドイツの暫定憲法」[69] と表現し、1933年5月1日に、いわゆる「3月落選者」としてナチス党に入党した(党員番号 2.098.860)。[70] 1933年5月31日、彼は『西ドイツ観察者』誌で、ナチスの恐怖政治の開始前にドイツから逃亡した「ドイツの知識人」たちを「ドイツから永遠に追放され た者たち」と罵った[71]。 1933年の夏学期、彼は1932年に受けた招聘に応じて、フリッツ・スティール・ソムロの後任としてケルン大学に移った[72]。そこでは、わずか数週 間のうちに、新しいナチス政権の国家法学者としての役割へと転向した。それまでは、彼の急速な学業上の成功に大きく貢献したユダヤ人の同僚たちと多くの個 人的な交流があったが、1933年以降、彼はユダヤ人の同僚教授たちを告発し、反ユダヤ主義の闘争文書を発表し始めた。[73] 例えば、シュミットをケルン大学に招へいするために尽力していたハンス・ケルセンが、同僚たちがシュミットの解任を求める決議案を作成したとき、シュミッ トはケルセンへの支援を一切拒否した。[74] しかし、シュミットはすべてのユダヤ人同僚に対してこのような態度をとったわけではない。例えば、彼はエルヴィン・ヤコビの個人鑑定書で彼を支援してい る。1945年以降も、シュミットはケルセンに対して反ユダヤ主義的な中傷を繰り返し、ナチス政権時代には、彼を常に「ユダヤ人ケルセン」と呼んでいた。 1933年7月11日、彼の「後援者」[76]であるプロイセン首相ヘルマン・ゲーリングは、彼をプロイセン国務顧問[77]に任命した。これは、彼が一 生、特に誇りに思っていた称号だった。1972年にも、彼は、ノーベル賞受賞者ではなく、プロイセン国務顧問になったことを感謝していると述べたと伝えら れている[78]。帝国法務長官ハンス・フランクの「腹心」として、シュミットはドイツ法学雑誌(DJZ)の編集者、ドイツ法アカデミー会員、ナチス法保 護連盟の帝国大学教員グループ代表に就任した[79]。1934年7月、シュミットはナチス党の大学委員会委員に任命された[80]。 シュミットは、著書『国家、運動、国民:政治の三分立』(1933年)の中で、「ドイツ革命」の合法性を強調した。ヒトラーの権力掌握は「以前の憲法に形 式的に適合しており」、それは「規律とドイツの秩序意識」から生じている、と述べた。ナチス国家法の中心概念は「指導者主義」であり、その不可欠な前提は 指導者と追随者の「人種的」平等だ。 シュミットは「ナチス革命」の合法性を強調することで、NSDAPの指導部に法的正当性を与えた。NSDAP国家のために法的・言語的に尽力したことか ら、同時代の人々、特に政治亡命者(その中には弟子や知人もいた)から「第三帝国の最高法学者」と呼ばれた。この用語は、「政治カトリックの解釈者」であ り、かつてシュミットの親しい友人であったヴァルデマー・グリアンが、1934年に、シュミットがレーム殺害を正当化したことに対して反応して作ったもの だよ[81]。 1933年秋、シュミットは「国家政治上の理由」により、フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学ベルリンに招かれ、そこでは、あらゆる秩序は、その決定権を独占 し、誤りを犯さないことを主張する機関によって制度的に代表されるという、具体的な秩序思想の教義を展開した。この官職のカリスマ性による主権説は、総統 主義の宣伝と、「総統の意志は法である」という意志と法の同一性説へと発展した[82]。これにより、シュミットは新しい権力者たちからの評判をさらに固 めることができた。さらに、この法学者は、総体国家・総力戦、あるいは他国による介入を禁じる地政学的大圏圏といった、彼の造語が大成功を収めたものの、 彼の名前とは結びつけられなかったキーワードの提供者としても活躍した。1934年から1935年まで、ベルンハルト・ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ムティウス はシュミットの学術助手だった。 シュミットは、新政権に無条件に献身した。その一例として、ナチス政権の正当化のために憲法史を利用したことが挙げられる[83]。彼の意見の多くは、党 の路線に忠実な法学者として期待される範囲をはるかに超えていた。シュミットは、特に鋭い表現で自己を際立たせたいと願っていたようだ。1934年6月 30日にナチス政権がレーム事件で殺害した人々(その中には、彼と政治的に親しい元帝国首相クルト・フォン・シュライヒャーも含まれていた)に対して、彼 はヒトラーの独裁権を次のように正当化した。 「指導者は、危険の瞬間に、最高裁判官としての権威をもって直接正義を行うことによって、権利を最悪の乱用から保護する」 真の指導者は常に裁判官でもあり、指導者の地位から裁判官の地位が派生する[84]。シュミットによれば、この2つの職務を分離する者は、裁判官を「対立 する指導者」とし、「司法の力を借りて国家の基盤を覆そうとする」のだ。シュミットは、三権分立の支持者を「法盲」と非難した[85]。「指導力」と「裁 判官の権力」の一致を主張したこの見解は、法思想の特別な歪曲を示す証拠とみなされている。シュミットは、この記事を次のような政治的呼びかけで締めく くっている。 「私たちの政治情勢の背後にある巨大な背景を見抜く者は、総統の警告と注意を理解し、私たちの正当な権利を守るために必要な大きな精神的闘争に備えるだろう」。 帝国法報第 100 号に掲載されたニュルンベルク人種法、 1935年9月16日 – シュミットにとっては「自由の憲法」 シュミットは、1935年のニュルンベルク人種法を、ナチス政権の基準でもグロテスクな表現で「自由の憲法」と表現した論文(ドイツ法曹新聞に掲載)を発 表し、人種差別主義者および反ユダヤ主義者として再び公に台頭した。[87] ユダヤ人(ナチスの定義による)と「ドイツ人」との交際を罰する、いわゆる「ドイツ人の血と名誉の保護に関する法律」が制定され、シュミットにとっては 「立法における新しい世界観の原則」が登場した。シュミットによれば、この「人種思想に基づく立法」は、人種差別を根本的に認めない、あるいは人種差別を 否定する他の国の法律と衝突する。この異なる世界観の原則の衝突は、シュミットにとって国際法の規制対象だった。シュミットによる政党宣伝の頂点は、 1936年10月に彼の指揮の下で開催された会議「法学におけるユダヤ教」だった[89]。ここで彼は、ナチスの反ユダヤ主義を明確に支持し、法学文献に おいてユダヤ人著者の引用を禁止、あるいは少なくともその著者をユダヤ人であると明記することを要求した。 「総統がユダヤ人の弁証法について述べたことは、新たな偽装や分裂という大きな危険を回避するために、私たち自身と学生たちに繰り返し教え込まなければな らない。感情的な反ユダヤ主義だけでは不十分だ。認識的に根拠のある確信が必要だ。[…] 私たちは、ドイツの精神をあらゆる偽造から解放しなければならない。ユダヤ人移民たちが、ガウライター・ユリウス・シュトライヒャーの偉大な闘争を「非精 神的なもの」と表現することを可能にした、精神という概念の偽造から解放しなければならない」[90] ほぼ同時期に、シュミットに対するナチスによるキャンペーンが行われ、彼は事実上権力を失いました。このキャンペーンの中心人物は、オットー・ケルレウッ ター、カール・アウグスト・エックハルト、ラインハルト・ヘーンという「陰謀のトリオ」でした[91]。ラインハルト・メーリングは、このことについて次 のように書いています。「しかし、この会議は1936年末、シュミットに対するナチスによるキャンペーンと、彼の公職からのほぼ完全な失脚と時期が重なっ たため、ナチス界では、しばしば機会主義的な口先だけの宣言として一蹴され、あまり注目されなかった。1991年に、シュミットが1947年から1951 年までの日記風の記録をまとめた『用語集』を出版するまで、彼は1945年以降も、熱烈な反ユダヤ主義者として、権利を剥奪されたことについて一言の反省 の言葉も発しなかった人物として知られていた。」 1947年から1951年までの日記のような記録を出版して、1945年以降も熱烈な反ユダヤ主義者であり、権利の剥奪、迫害、絶滅について一言の反省の 言葉もなかったことが明らかになった。それ以来、彼の反ユダヤ主義は中心的なテーマとなっている。それはカトリック・キリスト教に基づくものなのか、それ とも人種差別主義・生物学主義に基づくものなのか?…この議論は、まだ決着にはほど遠い。[92] SS に近い党機関紙「シュヴァルツェス・コルプス」は、シュミットを「機会主義者」であり、「国家社会主義の思想」を欠いていると非難した。さらに、シュライ ヒャー政権をかつて支持したことや、ユダヤ人との関係も非難の対象となった。「ユダヤ人ヤコビの側に立ち、カール・シュミットは、プロイセン帝国裁判で、 反動的な暫定政権であるシュライヒャー(原文のまま!正しくはパペン)のために戦った」。ローゼンバーグ局の世界観に関する報告では、シュミットは「半ユ ダヤ人であるヤコビとともに、支配的な教義に反して、次のような主張を行った」と記載されています。「帝国議会におけるナチス党の過半数が、憲法第 76 条に基づく 3 分の 2 の多数決により、憲法改正法によって、憲法の基本的な政治決定、例えば議会制民主主義の原則を変更することは不可能である。なぜなら、そのような憲法改正 は、憲法改正ではなく、憲法の変更にあたるから」と主張した。1936年以降、ナチス機関は、シュミットを権力の座から追放し、彼のナチス思想を否定し、 彼に機会主義を立証しようと努めた。[93] シュヴァルツェン・コルプス誌に掲載された記事によりスキャンダルが発生し、その結果、ナチ党員であったシュミットは1936年に党組織内のすべての役職 を剥奪されたが、プロイセン州議会議員は留任し、同年にゲーリングが最後に招集した州議会に出席した。そのため、シュミットは、マーティン・ハイデガーや ハンス・フライヤーと同様に、ナチズムの「失敗した先駆者」として学術文献で取り上げられている。[94] ナチズムの終焉まで、シュミットはベルリンのフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学で教授として主に国際法の分野で活躍したが、ここでも政権の代弁者となること を目指していた。その一例として、第二次世界大戦開始時の1939年に彼が考案した「国際法上の大圏秩序」という概念がある。これは、ドイツ版モンロー主 義と解釈された。これは後に、ヒトラーの拡張政策を国際法的に正当化するための試みであると評価されるようになった。例えば、シュミットは、多くの学者た ちがナチスの領土政策と人口政策に助言を行った「リッターブッシュ作戦」に関与していた。[95] |

| Nach 1945 Das Kriegsende erlebte Schmitt in Berlin. Am 30. April 1945 wurde er von sowjetischen Truppen verhaftet, nach kurzem Verhör aber wieder auf freien Fuß gesetzt. Am 26. September 1945 verhafteten ihn die Amerikaner und internierten ihn bis zum 10. Oktober 1946 in verschiedenen Berliner Lagern. Ein halbes Jahr später wurde er erneut verhaftet, nach Nürnberg verbracht und dort anlässlich der Nürnberger Prozesse vom 29. März bis zum 13. Mai 1947 in Einzelhaft arretiert. Während dieser Zeit wurde er vom stellvertretenden Hauptankläger Robert Kempner als possible defendant (potentieller Angeklagter) bezüglich seiner „Mitwirkung direkt und indirekt an der Planung von Angriffskriegen, von Kriegsverbrechen und Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit“ verhört. Zu einer Anklage kam es jedoch nicht, weil eine Straftat im juristischen Sinne nicht festgestellt werden konnte: „Wegen was hätte ich den Mann anklagen können?“, begründete Kempner diesen Schritt später. „Er hat keine Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit begangen, keine Kriegsgefangenen getötet und keine Angriffskriege vorbereitet.“[96] Schmitt selbst hatte sich in einer schriftlichen Stellungnahme als reinen Wissenschaftler beschrieben, der allerdings ein „intellektueller Abenteurer“ gewesen sei und für seine Erkenntnisse einige Risiken auf sich genommen habe. Kempner entgegnete: „Wenn aber das, was Sie Erkenntnissuchen nennen, in der Ermordung von Millionen von Menschen endet?“ Schmitts Antwort relativiert die Verbrechen des Holocaust, indem er darauf hinweist, dass auch das Christentum „in der Ermordung von Millionen von Menschen geendet“ habe.[97] Während seiner circa siebenwöchigen Einzelhaft im Nürnberger Kriegsverbrechergefängnis schrieb Schmitt verschiedene kürzere Texte, u. a. das Kapitel Weisheit der Zelle seines 1950 erschienenen Bandes Ex Captivitate Salus. Darin erinnerte er sich der geistigen Zuflucht, die ihm während seines Berliner Semesters die Werke Max Stirners geboten hatten. So auch jetzt wieder: „Max ist der Einzige, der mich in meiner Zelle besucht.“ Ihm verdanke er, „dass ich auf manches vorbereitet war, was mir bis heute begegnete, und was mich sonst vielleicht überrascht hätte.“[98] Daneben erstellte er auf Wunsch Kempners verschiedene Gutachten, etwa über die Stellung der Reichsminister und des Chefs der Reichskanzlei sowie über die Frage, warum das Beamtentum Adolf Hitler gefolgt war. Ende 1945 war Schmitt ohne jegliche Versorgungsbezüge aus dem Staatsdienst entlassen worden. Um eine Professur bewarb er sich nicht mehr; dies wäre wohl auch aussichtslos gewesen. Stattdessen zog er sich in seine Heimatstadt Plettenberg zurück, wo er weitere Veröffentlichungen – zunächst unter einem Pseudonym – vorbereitete, etwa eine Rezension des Bonner Grundgesetzes als „Walter Haustein“, die in der Eisenbahnerzeitung erschien.[99] Am 19. Juli 1954 erschien in der Wochenzeitung Die Zeit ein Artikel Schmitts mit dem Titel: „Im Vorraum der Macht“.[100] Verantwortlich dafür war der Zeit-Mitbegründer und Chefredakteur Richard Tüngel. Dies führte zu einer Redaktionskrise mit dem Ergebnis, dass die damalige Leiterin des Politikressorts Marion Gräfin Dönhoff aus Protest die Zeitung verließ. Dönhoff war schon längere Zeit darüber verärgert, dass Tüngel „seit einigen Jahren bei Schmitt ein- und ausgeht“, und machte früh klar: „Wenn der Kerl jemals in der ZEIT schreiben sollte, bin ich am nächsten Tag weg“.[101] Auch durch unter Pseudonym veröffentlichte Leserbriefe nahm Schmitt gelegentlich Stellung zu politischen oder rechtlichen Themen. Es ist beispielsweise dokumentiert, dass Schmitt 1961 im Zusammenhang mit dem Fernsehurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts mehrere teilweise stark polemisch gefärbte kritische Stellungnahmen verfasste. Diese wurden unter Verwendung verschiedener Pseudonyme als Kommentare oder getarnt als Leserbriefe in der Deutschen Zeitung veröffentlicht. Zu deren Chefredakteur Hans Hellwig und zu Johannes Gross, der als Bonner Korrespondent der Zeitung fungierte, pflegte Schmitt engen Kontakt.[102] Schmitt veröffentlichte nach 1945 noch eine Reihe von Werken, u. a. Der Nomos der Erde,[103] Theorie des Partisanen[104] und Politische Theologie II. 1952 konnte er sich eine Rente erstreiten, aus dem akademischen Leben blieb er aber ausgeschlossen. Eine Mitgliedschaft in der Vereinigung der Deutschen Staatsrechtslehrer wurde ihm verwehrt. Einen Wirkungskreis fand Schmitt ab 1957 in den von Ernst Forsthoff organisierten Ebracher Ferienseminaren, in deren Rahmen Schmitts Gedanken zur „Tyrannei der Werte“ entstanden. Plettenberg, Brockhauser Weg 10: Wohnhaus Carl Schmitts bis zu seinem Umzug nach Pasel im Jahr 1971 Obwohl Schmitt unter seiner Isolation litt, verzichtete er auf eine Rehabilitation, die möglich gewesen wäre, wenn er – wie zum Beispiel die NS-Rechtstheoretiker Theodor Maunz oder Otto Koellreutter – sich von seinem Wirken im Dritten Reich distanziert und sich um Entnazifizierung bemüht hätte. In seinem Tagebuch notierte er am 1. Oktober 1949: „Warum lassen Sie sich nicht entnazifizieren? Erstens: weil ich mich nicht gern vereinnahmen lasse und zweitens, weil Widerstand durch Mitarbeit eine Nazi-Methode aber nicht nach meinem Geschmack ist.“[105] Das einzige öffentlich überlieferte Bekenntnis seiner Scham stammt aus den Verhörprotokollen von Kempner, die später veröffentlicht wurden. Kempner: „Schämen Sie sich, daß Sie damals [1933/34] derartige Dinge [wie „Der Führer schützt das Recht“] geschrieben haben?“ Schmitt: „Heute selbstverständlich. Ich finde es nicht richtig, in dieser Blamage, die wir da erlitten haben, noch herumzuwühlen.“ Kempner: „Ich will nicht herumwühlen.“ Schmitt: „Es ist schauerlich, sicherlich. Es gibt kein Wort darüber zu reden.“[106] Zentraler Gegenstand der öffentlichen Vorwürfe gegen Schmitt in der Nachkriegszeit war seine Verteidigung der Röhm-Morde („Der Führer schützt das Recht…“) zusammen mit den antisemitischen Texten der von ihm geleiteten „Judentagung“ 1936 in Berlin.[107] Beispielsweise griff der Tübinger Jurist Adolf Schüle Schmitt 1959 deswegen heftig an.[108] Zum Holocaust hat Schmitt auch nach dem Ende des nationalsozialistischen Regimes nie ein bedauerndes Wort gefunden, wie die posthum publizierten Tagebuchaufzeichnungen (Glossarium) zeigen. Stattdessen relativierte er auch hier das Verbrechen: „Genozide, Völkermorde, rührender Begriff.“[109] Der einzige Eintrag, der sich explizit mit der Shoa befasst, lautet: „Wer ist der wahre Verbrecher, der wahre Urheber des Hitlerismus? Wer hat diese Figur erfunden? Wer hat die Greuelepisode in die Welt gesetzt? Wem verdanken wir die 12 Mio. [sic!] toten Juden? Ich kann es euch sehr genau sagen: Hitler hat sich nicht selbst erfunden. Wir verdanken ihn dem echt demokratischen Gehirn, das die mythische Figur des unbekannten Soldaten des Ersten Weltkriegs ausgeheckt hat.“[110] Kai nomon egnō („und er erkannte den Nomos“)[111] – Grabstein Carl Schmitts auf dem katholischen Friedhof Plettenberg-Eiringhausen Auch nach 1945 wich Schmitt nicht von seinem Antisemitismus ab. Als Beleg hierfür gilt ein Eintrag in sein Glossarium vom 25. September 1947,[112] in dem er den „assimilierten Juden“ als den „wahren Feind“ bezeichnete: „Denn Juden bleiben immer Juden. Während der Kommunist sich bessern und ändern kann. Das hat nichts mit nordischer Rasse usw. zu tun. Gerade der assimilierte Jude ist der wahre Feind. Es hat keinen Zweck, die Parole der Weisen von Zion als falsch zu beweisen.“[113] „San Casciano“, Wohnhaus Carl Schmitts in Plettenberg-Pasel, Am Steimel 7, von 1971 bis 1985 Schmitt flüchtete sich in Selbstrechtfertigungen und stilisierte sich als „christlicher Epimetheus“.[114] Die Selbststilisierung wurde zu seinem Lebenselixier. Er erfand verschiedene, immer anspielungs- und kenntnisreiche Vergleiche, die seine Unschuld illustrieren sollten. So behauptete er etwa, er habe in Bezug auf den Nationalsozialismus wie der Chemiker und Hygieniker Max von Pettenkofer gehandelt, der vor Studenten eine Kultur von Cholera-Bakterien zu sich nahm, um seine Resistenz zu beweisen. So habe auch er, Schmitt, das Virus des Nationalsozialismus freiwillig geschluckt und sei nicht infiziert worden. In seiner Rückschau auf seinen Weg durch das Dritte Reich sah sich Schmitt als den „letzten bewußten Vertreter des jus publicum Europaeum“.[115] An anderer Stelle verglich Schmitt sich mit Benito Cereno,[116] einer Figur Herman Melvilles aus der gleichnamigen Erzählung von 1856, in der ein Kapitän auf dem eigenen Schiff von Meuterern gefangen gehalten wird. Bei der Begegnung mit anderen Schiffen zwingen die aufständischen Sklaven den Kapitän, Normalität vorzuspielen, was diesen verwirrt und gefährlich erscheinen lässt. Auf dem Schiff steht der Spruch: „Folgt eurem Führer“ („Seguid vuestro jefe“). Seine Faszination für diese Novelle brachte Schmitt auch in einem Briefwechsel mit Ernst Jünger zum Ausdruck: „Ich bin von dem ganz ungewollten, hintergründigen Symbolismus der Situation als solcher ganz überwältigt.“[117] Jünger bezeugte in seinem Tagebuch ein Treffen mit Schmitt in Paris 1941: „Carl Schmitt verglich seine Lage mit der des weißen, von schwarzen Sklaven beherrschten Kapitäns in Melvilles Benito Cereno, und zitierte dazu den Spruch: ‚Non possum scribere contra eum, qui potest proscribere‘“ [Ich kann nicht gegen den schreiben, der in der Lage ist zu ächten].[118] Sein Haus in Plettenberg titulierte Schmitt als „San Casciano“, in Anlehnung an den Rückzugsort Machiavellis.[119] Schmitt wurde fast 97 Jahre alt. Seine Krankheit, Zerebralsklerose, brachte in Schüben immer länger andauernde Wahnvorstellungen mit sich. Schmitt, der auch schon früher durchaus paranoide Anwandlungen gezeigt hatte, fühlte sich nun von Schallwellen und Stimmen regelrecht verfolgt. Wellen wurden seine letzte Obsession. Einem Bekannten soll er gesagt haben: „Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg habe ich gesagt: ‚Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet‘. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, angesichts meines Todes, sage ich jetzt: ‚Souverän ist, wer über die Wellen des Raumes verfügt.‘“[120] Seine geistige Umnachtung ließ ihn überall elektronische Wanzen und unsichtbare Verfolger befürchten. Am 7. April 1985, einem Ostersonntag, starb Schmitt im Evangelischen Krankenhaus in Plettenberg. Den in der Friedhofskapelle befindlichen Sarg ließ Niklas Frank, der Sohn Hans Franks, kurz vor der Beisetzung öffnen, da er in Schmitt seinen leiblichen Vater vermutete und diesen sehen wollte.[121] Schmitts Grab befindet sich auf dem katholischen Friedhof in Plettenberg-Eiringhausen. Sein erster Testamentsvollstrecker war sein Schüler Joseph Heinrich Kaiser, heutiger Verwalter seines wissenschaftlichen Nachlasses ist der Staatsrechtler Florian Meinel. |