Geopolitics

(from Greek γῆ gê "earth, land" and πολιτική politikḗ "politics") is

the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on

politics and international relations.[1][2] While geopolitics usually

refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on

two other kinds of states: de facto independent states with limited

international recognition and relations between sub-national

geopolitical entities, such as the federated states that make up a

federation, confederation or a quasi-federal system.

At the level of international relations, geopolitics is a method of

studying foreign policy to understand, explain, and predict

international political behavior through geographical variables. These

include area studies, climate, topography, demography, natural

resources, and applied science of the region being evaluated.[3]

Geopolitics focuses on political power linked to geographic space. In

particular, territorial waters and land territory in correlation with

diplomatic history. Topics of geopolitics include relations between the

interests of international political actors focused within an area, a

space, or a geographical element, relations which create a geopolitical

system.[4] Critical geopolitics deconstructs classical geopolitical

theories, by showing their political/ideological functions for great

powers.[5] There are some works that discuss the geopolitics of

renewable energy.[6][7]

According to Christopher Gogwilt and other researchers, the term is

currently being used to describe a broad spectrum of concepts, in a

general sense used as "a synonym for international political

relations", but more specifically "to imply the global structure of

such relations"; this usage builds on an "early-twentieth-century term

for a pseudoscience of political geography" and other pseudoscientific

theories of historical and geographic determinism.[8][9][10][2]

|

地政学(ちせいがく、ギリシャ語:γῆ

gê「地球、土地」とπολιτική politik_117

「政治」から)は、政治や国際関係における地球の地理(人間および物理)の影響の研究である[1][2]。

[地政学は通常、国と国同士の関係を指すが、他の2種類の国家にも焦点を当てることがある:限定的な国際的承認を受けた事実上の独立国家と、連邦、連邦ま

たは準連邦システムを構成する連邦国家のようなサブナショナルな地政学的実体間の関係である。

国際関係のレベルでは、地政学は地理的変数を通して国際政治行動を理解、説明、予測するための外交政策の研究方法である。これらは評価される地域の地域研

究、気候、地形、人口統計学、天然資源、応用科学などを含む[3]。

地政学は、地理的空間と結びついた政治力に焦点を当てている。特に、外交史との関連で領海や陸域に注目する。地政学のトピックとしては、ある地域、空間、

地理的要素に焦点を当てた国際政治主体の利害関係、地政学的システムを構築する関係などがある[4]。批判的地政学では、大国に対する政治・思想的機能を

示すことによって古典的地政学理論を脱構築する[5]。

クリストファー・ゴグウィルトや他の研究者によれば、現在この用語は広範な概念を表すために使用されており、一般的な意味では「国際政治関係の同義語」と

して使用されるが、より具体的には「そのような関係のグローバルな構造を意味する」。この使用法は「20世紀初めの政治地理学の疑似科学に対する用語」や

歴史・地理的決定論の他の疑似科学的理論に基づいて構築されている[8][9][10][2]。

|

Alfred Thayer Mahan and sea power

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914) was a frequent commentator on world

naval strategic and diplomatic affairs. Mahan believed that national

greatness was inextricably associated with the sea—and particularly

with its commercial use in peace and its control in war. Mahan's

theoretical framework came from Antoine-Henri Jomini, and emphasized

that strategic locations (such as choke points, canals, and coaling

stations), as well as quantifiable levels of fighting power in a fleet,

were conducive to control over the sea. He proposed six conditions

required for a nation to have sea power:

Advantageous geographical position;

Serviceable coastlines, abundant natural resources, and favorable

climate;

Extent of territory

Population large enough to defend its territory;

Society with an aptitude for the sea and commercial enterprise; and

Government with the influence and inclination to dominate the sea.[11]

Mahan distinguished a key region of the world in the Eurasian context,

namely, the Central Zone of Asia lying between 30° and 40° north and

stretching from Asia Minor to Japan.[12] In this zone independent

countries still survived – Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, China, and

Japan. Mahan regarded those countries, located between Britain and

Russia, as if between "Scylla and Charybdis". Of the two monsters –

Britain and Russia – it was the latter that Mahan considered more

threatening to the fate of Central Asia. Mahan was impressed by

Russia's transcontinental size and strategically favorable position for

southward expansion. Therefore, he found it necessary for the

Anglo-Saxon "sea power" to resist Russia.[13]

|

アルフレッド・セイヤー・メーハンとシーパワー

アルフレッド・セイヤー・メーハン(1840-1914)は、世界の海軍の戦略や外交問題について頻繁に論評していた。マハンは、国家の偉大さは海と密接

に関係しており、特に平時の商業利用や戦時の統制と密接に関係していると考えていた。マハンの理論的枠組みはアントワーヌ=アンリ・ジョミニに由来し、戦

略的位置(チョークポイント、運河、コーリングステーションなど)と艦隊の戦闘力を定量化することが海の支配につながると強調した。彼は、国家がシーパ

ワーを持つために必要な6つの条件を提案した。

有利な地理的位置。

有利な地理的位置、整備された海岸線、豊富な天然資源、良好な気候。

領土の広さ

領土を守れるだけの人口がいること

海や商業に適した社会。

海を支配する影響力と傾斜を持つ政府[11]。

マハンはユーラシアの文脈で世界の重要な地域、すなわち北緯30度から40度の間に横たわり、小アジアから日本まで伸びるアジアの中央地帯を区別した

[12]。

この地帯にはトルコ、ペルシャ、アフガニスタン、中国、日本という独立国がまだ存続していた。マハンはイギリスとロシアの間に位置するこれらの国々を「ス

キュラとカリブディス」の間にあるようなものだと考えた。マハンは、イギリスとロシアという2つの怪物のうち、中央アジアの命運を握っているのは後者であ

ると考えた。マハンは、ロシアの大陸横断的な大きさと、南下するための戦略的に有利な位置に感心していた。それゆえ、彼はアングロサクソンの「海の力」が

ロシアに対抗することが必要であると考えた[13]。

|

Homer Lea

Homer Lea, in The Day of the Saxon (1912), asserted that the entire

Anglo-Saxon race faced a threat from German (Teuton), Russian (Slav),

and Japanese expansionism: The "fatal" relationship of Russia, Japan,

and Germany "has now assumed through the urgency of natural forces a

coalition directed against the survival of Saxon supremacy." It is "a

dreadful Dreibund".[14] Lea believed that while Japan moved against Far

East and Russia against India, the Germans would strike at England, the

center of the British Empire. He thought the Anglo-Saxons faced certain

disaster from their militant opponents.

|

ホーマー・リー

ホーマー・リーは、『サクソンの日』(1912年)の中で、アングロサクソン民族全体が、ドイツ(チュートン)、ロシア(スラブ)、日本の拡張主義の脅威

に直面していると主張した。ロシア、日本、ドイツの「宿命的」関係は、「今や自然の力の緊急性によって、サクソンの優位の存続に向けられた連合体として想

定されるようになった」。それは「恐ろしいドライヴント」である[14]。リーは、日本が極東に、ロシアがインドに向かう一方で、ドイツは大英帝国の中心

であるイングランドに襲いかかると考えたのである。彼は、アングロサクソンは過激な相手から確実に災難を受けると考えていた。

|

Kissinger, Brzezinski and the

Grand Chessboard

Two famous security advisors from the Cold War period, Henry Kissinger

and Zbigniew Brzezinski, argued to continue the United States

geopolitical focus on Eurasia and, particularly on Russia, despite the

dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War. Both continued

their influence on geopolitics after the end of the Cold War,[5]

writing books on the subject in the 1990s—Diplomacy and The Grand

Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives.[15] The

Anglo-American classical geopolitical theories were revived.

Kissinger argued against the belief that with the dissolution of the

USSR, hostile intentions had come to an end and traditional foreign

policy considerations no longer applied. "They would argue … that

Russia, regardless of who governs it, sits astride the territory which

Halford Mackinder called the geopolitical heartland, and it is the heir

to one of the most potent imperial traditions." Therefore, the United

States must "maintain the global balance of power vis-à-vis the country

with a long history of expansionism."[16]

After Russia, the second geopolitical threat which remained was Germany

and, as Mackinder had feared ninety years ago, its partnership with

Russia. During the Cold War, Kissinger argues, both sides of the

Atlantic recognized that, "unless America is organically involved in

Europe, it would later be obliged to involve itself under circumstances

which would be far less favorable to both sides of the Atlantic. That

is even more true today. Germany has become so strong that existing

European institutions cannot strike a balance between Germany and its

European partners all by themselves. Nor can Europe, even with the

assistance of Germany, manage […] Russia" all by itself. Thus Kissinger

believed that no country's interests would ever be served if Germany

and Russia were to ever form a partnership in which each country would

consider itself the principal partner. They would raise fears of

condominium.[clarification needed] Without America, Britain and France

cannot cope with Germany and Russia; and "without Europe, America could

turn … into an island off the shores of Eurasia."[17]

Nicholas J. Spykman's vision of Eurasia was strongly confirmed:

"Geopolitically, America is an island off the shores of the large

landmass of Eurasia, whose resources and population far exceed those of

the United States. The domination by a single power of either of

Eurasia's two principal spheres—Europe and Asia—remains a good

definition of strategic danger for America. Cold War or no Cold War.

For such a grouping would have the capacity to outstrip America

economically and, in the end, militarily. That danger would have to be

resisted even if the dominant power was apparently benevolent, for if

its intentions ever changed, America would find itself with a grossly

diminished capacity for effective resistance and a growing inability to

shape events."[18] The main interest of the American leaders is

maintaining the balance of power in Eurasia.[19]

Having converted from an ideologist into a geopolitician, Kissinger

retrospectively interpreted the Cold War in geopolitical terms—an

approach which was not characteristic of his works during the Cold War.

Now, however, he focused on the beginning of the Cold War: "The

objective of moral opposition to Communism had merged with the

geopolitical task of containing Soviet expansion."[20] Nixon, he added,

was a geopolitical rather than an ideological cold warrior.[21]

Three years after Kissinger's Diplomacy, Zbigniew Brzezinski followed

suit, launching The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its

Geostrategic Imperatives and, after three more years, The Geostrategic

Triad: Living with China, Europe, and Russia. The Grand Chessboard

described the American triumph in the Cold War in terms of control over

Eurasia: for the first time ever, a "non-Eurasian" power had emerged as

a key arbiter of "Eurasian" power relations.[15] The book states its

purpose: "The formulation of a comprehensive and integrated Eurasian

geostrategy is therefore the purpose of this book."[15] Although the

power configuration underwent a revolutionary change, Brzezinski

confirmed three years later, Eurasia was still a mega-continent.[22]

Like Spykman, Brzezinski acknowledges that: "Cumulatively, Eurasia's

power vastly overshadows America's."[15]

In classical Spykman terms, Brzezinski formulated his geostrategic

"chessboard" doctrine of Eurasia, which aims to prevent the unification

of this mega-continent.

"Europe and Asia are politically and economically powerful…. It follows

that… American foreign policy must…employ its influence in Eurasia in a

manner that creates a stable continental equilibrium, with the United

States as the political arbiter.… Eurasia is thus the chessboard on

which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played, and that

struggle involves geo- strategy – the strategic management of

geopolitical interests…. But in the meantime it is imperative that no

Eurasian challenger emerges, capable of dominating Eurasia and thus

also of challenging America… For America the chief geopolitical prize

is Eurasia…and America's global primacy is directly dependent on how

long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is

sustained."[15]

|

キッシンジャー、ブレジンスキーとグランドチェス盤

冷戦時代の二人の有名な安全保障顧問、ヘンリー・キッシンジャーとズビグニュー・ブレジンスキーは、ソビエト連邦の解体や冷戦の終結にもかかわらず、米国

の地政学的なユーラシアへの注目、特にロシアへの注目を継続させることを主張した。両者は冷戦終結後も地政学に影響を与え続け[5]、1990年代には

『外交』と『グランド・チェスボード』というテーマで著作を残した。英米の古典的な地政学的理論が復活した[15]。

キッシンジャーは、ソ連の解体によって敵対的な意図は終焉を迎え、伝統的な外交政策の考慮はもはや適用されないという信念に反論していた。「ロシアは、誰

が統治しようとも、ハルフォード・マッキンダーが地政学的中心地と呼んだ領土にまたがっており、最も強力な帝国の伝統の一つを受け継いでいる」と主張する

のだ。したがって、米国は「拡張主義の長い歴史を持つ国に対して、世界の力の均衡を維持しなければならない」[16]。

ロシアに続く第二の地政学的脅威はドイツであり、90年前にマッキンダーが懸念したように、そのロシアとの連携であった。冷戦期には、「アメリカがヨー

ロッパに有機的に関与しない限り、後に大西洋の両側にとってはるかに不利な状況下で関与せざるを得なくなる」という認識が大西洋の両側にはあった、とキッ

シンジャーは主張する。このことは、今日、さらに顕著である。ドイツがあまりにも強くなりすぎて、既存の欧州の制度だけではドイツと欧州のパートナーとの

バランスをとることができなくなっている。また、ヨーロッパは、たとえドイツの援助があったとしても、「...ロシア」を単独で管理することはできない。

このように、キッシンジャーは、ドイツとロシアが、それぞれが主要なパートナーであると考えるようなパートナーシップを結ぶことは、どの国の利益にもつな

がらないと考えていたのである。アメリカ抜きではイギリスとフランスはドイツとロシアに対処できず、「ヨーロッパ抜きではアメリカは...ユーラシアの沖

の島になりかねない」[17]のである。

ニコラス・J・スパイクマンのユーラシア大陸のビジョンは強く確認された。「地政学的には、アメリカはユーラシア大陸の沖に浮かぶ島であり、その資源と人

口はアメリカのそれをはるかに超えている。ユーラシアの二つの主要圏、すなわちヨーロッパとアジアのいずれかが単一の勢力によって支配されることは、アメ

リカにとって戦略的な危険の定義として有効である。冷戦であろうとなかろうと、である。そのような集団は、経済的にも、最終的には軍事的にも、アメリカを

凌駕する能力を持つからである。その危険は、支配的なパワーが一見慈悲深いものであっても抵抗しなければならない。もしその意図が変わることがあれば、ア

メリカは効果的な抵抗のための能力を著しく低下させ、出来事を形作ることがますますできなくなることに気づくだろう」[18]

アメリカの指導者の主たる関心は、ユーラシアにおける力の均衡を維持することである[19]。

イデオロギー論者から地政学者に転じたキッシンジャーは、冷戦を地政学的な観点から回顧し、冷戦期の彼の著作にはないアプローチをとっている。しかし現在

では、冷戦の始まりに焦点を当て、「共産主義に対する道徳的な反対という目的は、ソ連の拡張を封じ込めるという地政学的な任務と融合していた」[20]と

し、ニクソンはイデオロギー的というよりも地政学的な冷戦者であったと付け加えている[21]。

キッシンジャーの『外交』から3年後、ズビグニュー・ブレジンスキーがそれに続き、『グランド・チェスボード』を発表している。そして、さらに3年後、

『地政学的三国志』(The Geostrategic

Triad)を発表した。中国、ヨーロッパ、ロシアとの共存」を発表した。グランド・チェスボード』は、冷戦におけるアメリカの勝利をユーラシア大陸の支

配という観点から説明した。史上初めて、「非ユーラシア」の大国が「ユーラシア」の力関係の重要な決定者として出現したのである[15]。

[このように、ユーラシア大陸の勢力図は革命的な変化を遂げたが、ブレジンスキーは3年後に、ユーラシア大陸は依然としてメガコンチネンタルであることを

確認している[22]。「累積的にユーラシアのパワーはアメリカのパワーを大きく上回っている」[15]と認めている。

古典的なスパイクマンの用語では、ブレジンスキーは、このメガ大陸の統一を防ぐことを目的としたユーラシアの地政学的「チェス盤」ドクトリンを策定してい

る。

「ヨーロッパとアジアは政治的、経済的に強力である......。ユーラシア大陸は、世界の優位をめぐる戦いが続くチェス盤であり、その戦いには地政学的

利益を戦略的に管理する地政学的戦略が含まれる。しかし、その一方で、ユーラシアを支配し、したがってアメリカに挑戦することのできるユーラシアの挑戦者

が出現しないことが不可欠である。アメリカにとっての地政学的な賞はユーラシアであり、アメリカの世界的優位はユーラシア大陸での優位がどれだけの期間、

どれだけの効果で維持されるかに直接かかっている」[15]。

|

United Kingdom

Emil Reich

The Austro-Hungarian historian Emil Reich (1854–1910) is considered to

be the first having coined the term in English[23][8] as early as 1902

and later published in England in 1904 in his book Foundations of

Modern Europe.[24]

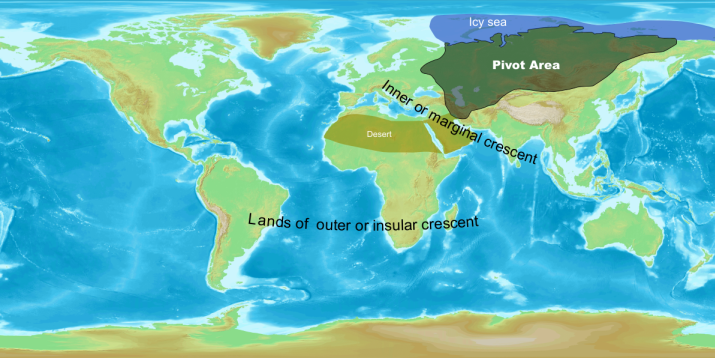

Mackinder and the Heartland theory

Sir Halford Mackinder's Heartland Theory initially received little

attention outside the world of geography, but some thinkers would claim

that it subsequently influenced the foreign policies of world

powers.[25] Those scholars who look to MacKinder through critical

lenses accept him as an organic strategist who tried to build a foreign

policy vision for Britain with his Eurocentric analysis of historical

geography.[5] His formulation of the Heartland Theory was set out in

his article entitled "The Geographical Pivot of History", published in

England in 1904. Mackinder's doctrine of geopolitics involved concepts

diametrically opposed to the notion of Alfred Thayer Mahan about the

significance of navies (he coined the term sea power) in world

conflict. He saw navy as a basis of Colombian era empire (roughly from

1492 to the 19th century), and predicted the 20th century to be domain

of land power. The Heartland theory hypothesized a huge empire being

brought into existence in the Heartland—which wouldn't need to use

coastal or transoceanic transport to remain coherent. The basic notions

of Mackinder's doctrine involve considering the geography of the Earth

as being divided into two sections: the World Island or Core,

comprising Eurasia and Africa; and the Peripheral "islands", including

the Americas, Australia, Japan, the British Isles, and Oceania. Not

only was the Periphery noticeably smaller than the World Island, it

necessarily required much sea transport to function at the

technological level of the World Island—which contained sufficient

natural resources for a developed economy.

Mackinder posited that the industrial centers of the Periphery were

necessarily located in widely separated locations. The World Island

could send its navy to destroy each one of them in turn, and could

locate its own industries in a region further inland than the Periphery

(so they would have a longer struggle reaching them, and would face a

well-stocked industrial bastion). Mackinder called this region the

Heartland. It essentially comprised Central and Eastern Europe:

Ukraine, Western Russia, and Mitteleuropa.[26] The Heartland contained

the grain reserves of Ukraine, and many other natural resources.

Mackinder's notion of geopolitics was summed up when he said:

Who rules Central and Eastern Europe commands the Heartland. Who rules

the Heartland commands the World-Island. Who rules the World-Island

commands the World.

Nicholas J. Spykman was both a follower and critic of geostrategists

Alfred Mahan, and Halford Mackinder. His work was based on assumptions

similar to Mackinder's,[5] including the unity of world politics and

the world sea. He extends this to include the unity of the air. Spykman

adopts Mackinder's divisions of the world, renaming some:

1. The Heartland;

2. The Rimland (analogous to Mackinder's "inner or marginal crescent"

also an intermediate region, lying between the Heartland and the

marginal sea powers); and

3. The Offshore Islands & Continents (Mackinder's "outer or insular

crescent").[27]

Under Spykman's theory, a Rimland separates the Heartland from ports

that are usable throughout the year (that is, not frozen up during

winter). Spykman suggested this required that attempts by Heartland

nations (particularly Russia) to conquer ports in the Rimland must be

prevented. Spykman modified Mackinder's formula on the relationship

between the Heartland and the Rimland (or the inner crescent), claiming

that "Who controls the rimland rules Eurasia. Who rules Eurasia

controls the destinies of the world." This theory can be traced in the

origins of containment, a U.S. policy on preventing the spread of

Soviet influence after World War II (see also Truman Doctrine).

Another famous follower of Mackinder was Karl Haushofer who called

Mackinder's Geographical Pivot of History a "genius' scientific

tractate."[28] He commented on it: "Never have I seen anything greater

than those few pages of geopolitical masterwork."[29] Mackinder located

his Pivot, in the words of Haushofer, on "one of the first solid,

geopolitically and geographically irreproachable maps, presented to one

of the earliest scientific forums of the planet – the Royal Geographic

Society in London"[28] Haushofer adopted both Mackinder's Heartland

thesis and his view of the Russian-German alliance – powers that

Mackinder saw as the major contenders for control of Eurasia in the

twentieth century. Following Mackinder he suggested an alliance with

the Soviet Union and, advancing a step beyond Mackinder, added Japan to

his design of the Eurasian Bloc.[30]

In 2004, at the centenary of The Geographical Pivot of History, famous

Historian Paul Kennedy wrote: "Right now with hundreds of thousands of

US troops in the Eurasian rimlands and with administration constantly

explaining why it has to stay the course, it looks as if Washington is

taking seriously Mackinder's injunction to ensure control of the

geographical pivot of history."[31]

|

イギリス

エミール・ライヒ

オーストリア・ハンガリーの歴史家エミール・ライヒ(1854-1910)が、1902年に早くも英語でこの言葉を作り[23][8]、その後1904年

にイギリスで『近代ヨーロッパの基礎』の中で発表したのが最初とされている[24]。

マッキンダーとハートランド理論

マッキンダー(Sir Halford

Mackinder)のハートランド理論は、当初、地理学の世界以外ではほとんど注目されていなかったが、一部の思想家は、それがその後、世界の大国の外

交政策に影響を与えたと主張している[25]。マッキンダーを批判的なレンズを通して見る学者は、歴史地理学のヨーロッパ中心の分析によってイギリスの外

交政策ビジョンを構築しようとした有機的な戦略家として彼を受け入れる[5] 彼のハートランド理論の定式化は、「The Geographical

Pivot of History」という論文によって定められており、1904年にイギリスで出版されている[4].

マッキンダーの地政学の教義は、世界紛争における海軍(彼はシーパワーという言葉を作った)の重要性についてのアルフレッド・セイヤー・メイハンの概念と

正反対の概念に関わるものであった。彼は海軍をコロンビア時代(およそ1492年から19世紀まで)の帝国の基礎と見なし、20世紀はランドパワーの領域

であると予測したのである。ハートランド説は、ハートランドに巨大な帝国が誕生し、その帝国は沿岸輸送や大洋横断輸送を必要とせず、一貫性を保つことがで

きると仮定している。マッキンダーの学説の基本的な考え方は、地球の地理をユーラシアとアフリカからなる「世界の島(コア)」と、アメリカ、オーストラリ

ア、日本、イギリス諸島、オセアニアなどの「周辺部の島」に分けて考えるというものであった。周縁部は世界島より明らかに小さいだけでなく、世界島の技術

水準で機能するには多くの海上輸送を必要とし、先進国経済にとって十分な天然資源を有していた。

マッキンダーは、「世界島」と「周辺部」の産業集積地は、必然的に離れた場所にあると考えた。世界島は海軍を派遣してそれらの一つ一つを順番に破壊するこ

とができ、自国の産業を周辺部よりさらに内陸に位置させることができました(そのため、彼らは到達するのに長い間苦労し、十分に蓄積された産業の砦に直面

することになります)。マッキンダーはこの地域を「ハートランド」と呼んだ。この地域は基本的に中欧と東欧で構成されていた。ハートランドはウクライナの

穀物資源と他の多くの天然資源を含んでいた[26]。マッキンダーの地政学の考え方は、次のように要約される。

中・東欧を支配するものはハートランドを支配する。ハートランドを支配する者は、世界島を支配する。ハートランドを支配するものが世界を支配し、世界島を

支配するものが世界を支配する」。

ニコラス・J・スパイクマンは、地政学者アルフレッド・マハンやハルフォード・マッキンダーの信奉者であると同時に批判者であった。彼の研究はマッキン

ダーと同様の仮定に基づいており[5]、世界政治と世界の海の統一を含むものであった。彼はこれを拡張して空域の統一を含むようにした。スパイクマンは

マッキンダーの世界の区分を採用し、一部を改名した。

1. ハートランド

2. リムランド(マッキンダーの "inner or marginal crescent

"に相当し、ハートランドと限界海域の間に横たわる中間領域)、および

3. オフショア諸島と大陸(マッキンダーの「外側または島国の三日月」)[27]。

スパイクマンの理論では、リムランドはハートランドと年間を通じて使用可能な(つまり冬に凍結しない)港を隔てている。このため、ハートランド諸国(特に

ロシア)がリムランドの港を征服しようとするのを防がなければならないとスパイクマンは提案した。スパイクマ

ンはマッキンダーのハートランドとリムランド(または三日月地帯)の関係式を修正し、「リムランドを支配する者がユーラシアを支配する。ユーラシアを支配

する者が世界の運命を支配する"。この理論は、第二次世界大戦後のアメリカのソ連の影響力拡大防止政策である封じ込め政策(トルーマン・ドクトリンも参

照)の原点にたどり着くことができる。

マッキンダーのもう一人の有名な信奉者はカール・ハウスホーファーで、彼はマッキンダーの『歴史の地理的軸』を「天才的科学書」と呼んでいる[28]。こ

の数ページの地政学的な名著に勝るものはない」[29] と評している。

マッキンダーは、ハウスホーファーの言葉を借りれば、その「軸」を「この惑星の最も初期の科学的フォーラムの一つであるロンドンの王立地理学会に提出され

た、地政学的にも地理学的にも問題のない、最初の強固な地図の一つ」の上に置いた[28]。ハウスホーファーはマッキンダーのハートランド論文とロシア・

ドイツ同盟についての彼の見解-マッキンダーが20世紀にユーラシアの支配を争った主要国として見ていた-の両方を採択した。マッキンダーに続いて、彼は

ソ連との同盟を提案し、マッキンダーから一歩進んで、ユーラシアブロックの設計に日本を加えている[30]。

2004年、『歴史の地理的枢軸』の100周年において、有名な歴史家であるポール・ケネディは次のように書いている。「今まさにユーラシアの縁辺部に数

十万のアメリカ軍がおり、政権はなぜこの方針を維持しなければならないかを絶えず説明しているが、それはまるで、歴史の地理的軸を確実に制御するという

マッキンダーの命題にワシントンが真剣に取り組んでいるように見える」[31]と。

|

Germany

Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904), influenced by thinkers such as Darwin and

zoologist Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, contributed to 'Geopolitik' by the

expansion on the biological conception of geography, without a static

conception of borders. Positing that states are organic and growing,

with borders representing only a temporary stop in their movement, he

held that the expanse of a state's borders is a reflection of the

health of the nation—meaning that static countries are in decline.

Ratzel published several papers, among which was the essay "Lebensraum"

(1901) concerning biogeography. Ratzel created a foundation for the

German variant of geopolitics, geopolitik. Influenced by the American

geostrategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, Ratzel wrote of aspirations for

German naval reach, agreeing that sea power was self-sustaining, as the

profit from trade would pay for the merchant marine, unlike land power.

The geopolitical theory of Ratzel has been criticized as being too

sweeping, and his interpretation of human history and geography being

too simple and mechanistic. Critically, he also underestimated the

importance of social organization in the development of power.[32]

The association of German Geopolitik with Nazism

After World War I, the thoughts of Rudolf Kjellén and Ratzel were

picked up and extended by a number of German authors such as Karl

Haushofer (1869–1946), Erich Obst, Hermann Lautensach and Otto Maull.

In 1923, Karl Haushofer founded the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (Journal

for Geopolitics), which was later used in the propaganda of Nazi

Germany. The key concepts of Haushofer's Geopolitik were Lebensraum,

autarky, pan-regions, and organic borders. States have, Haushofer

argued, an undeniable right to seek natural borders which would

guarantee autarky.

Haushofer's influence within the Nazi Party has been challenged, given

that Haushofer failed to incorporate the Nazis' racial ideology into

his work.[32] Popular views of the role of geopolitics in the Nazi

Third Reich suggest a fundamental significance on the part of the

geo-politicians in the ideological orientation of the Nazi state.

Bassin (1987) reveals that these popular views are in important ways

misleading and incorrect.

Despite the numerous similarities and affinities between the two

doctrines, geopolitics was always held suspect by the National

Socialist ideologists. This was understandable, for the underlying

philosophical orientation of geopolitics did not comply with that of

National Socialism. Geopolitics shared Ratzel's scientific materialism

and geographic determinism, and held that human society was determined

by external influences—in the face of which qualities held innately by

individuals or groups were of reduced or no significance. National

Socialism rejected in principle both materialism and determinism and

also elevated innate human qualities, in the form of a hypothesized

'racial character,' to the factor of greatest significance in the

constitution of human society. These differences led after 1933 to

friction and ultimately to open denunciation of geopolitics by Nazi

ideologues.[33] Nevertheless, German Geopolitik was discredited by its

(mis)use in Nazi expansionist policy of World War II and has never

achieved standing comparable to the pre-war period.

The resultant negative association, particularly in U.S. academic

circles, between classical geopolitics and Nazi or imperialist

ideology, is based on loose justifications. This has been observed in

particular by critics of contemporary academic geography, and

proponents of a "neo"-classical geopolitics in particular. These

include Haverluk et al., who argue that the stigmatization of

geopolitics in academia is unhelpful as geopolitics as a field of

positivist inquiry maintains potential in researching and resolving

topical, often politicized issues such as conflict resolution and

prevention, and mitigating climate change.[34]

Disciplinary differences in perspectives

Negative associations with the term "geopolitics" and its practical

application stemming from its association with World War II and

pre-World War II German scholars and students of Geopolitics are

largely specific to the field of academic Geography, and especially

sub-disciplines of human geography such as political geography.

However, this negative association is not as strong in disciplines such

as history or political science, which make use of geopolitical

concepts. Classical Geopolitics forms an important element of analysis

for military history as well as for sub-disciplines of political

science such as international relations and security studies. This

difference in disciplinary perspectives is addressed by Bert Chapman in

Geopolitics: A Guide To the Issues, in which Chapman makes note that

academic and professional International Relations journals are more

amenable to the study and analysis of Geopolitics, and in particular

Classical Geopolitics, than contemporary academic journals in the field

of political geography.[35]

In disciplines outside Geography, Geopolitics is not negatively viewed

(as it often is among academic geographers such as Carolyn Gallaher or

Klaus Dodds) as a tool of imperialism or associated with Nazism, but

rather viewed as a valid and consistent manner of assessing major

international geopolitical circumstances and events, not necessarily

related to armed conflict or military operations.

|

ドイツ

フリードリヒ・ラッツェル

フリードリヒ・ラッツェル(1844-1904)は、ダーウィンや動物学者エルンスト・ハインリッヒ・ヘッケルなどの思想家の影響を受け、国境という静的

な概念を排除し、地理学の生物学的概念を拡張することで「地政学」に貢献した人物である。国家は有機的に成長し、国境はその動きを一時的に止めるものに過

ぎないと代表することができ、国家の国境の広がりは国家の健全性を反映している、つまり静的な国は衰退していくのだとした。ラッツェルは、生物地理学に関

する論文「Lebensraum」(1901)を発表した。ラッツェルは、ドイツにおける地政学の変種である地政学(geopolitik)の基礎を築い

た。アメリカの地政学者アルフレッド・セイヤー・マハンの影響を受け、ラッツェルは、陸上権力とは異なり、貿易による利益が商船に支払われるため、海上権

力は自立的であるとし、ドイツの海軍力の向上への希望を記した。

ラッツェルの地政学的理論は、あまりにも広範囲に及び、人類の歴史と地理に対する解釈が単純で機械的であるとの批判がある。また、権力の発展における社会

組織の重要性を過小評価していると批判されている[32]。

ドイツ地政学とナチズムの関連性

第一次世界大戦後、Rudolf Kjellén と Ratzel の思想は、Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), Erich

Obst, Hermann Lautensach, Otto Maull など多くのドイツの作家によって取り上げられ拡張されていった。1923

年、カール・ハウスホーファーは Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (Journal for Geopolitics)

を創刊したが、これは後にナチスドイツのプロパガンダに利用されることになった。ハウスホーファーの地政学の主要な概念は、リーベンスラウム、独立国、パ

ン・リージョン、有機的国境であった。国家には、独立を保証する自然な国境を求める否定しがたい権利があると、ハウスホーファーは主張した。

ナチス第三帝国における地政学の役割に関する一般的な見解は、ナチス国家のイデオロギー的方向づけにおいて地政学者の側に基本的な意義があったことを示唆

している[32]。バシン(1987)は、こうした一般的な見解が重要な点で誤解を招き、間違っていることを明らかにしている。

2 つの教義の間には数多くの類似点と親和性があるにもかかわらず、地政学は国家社会主義者

のイデオロギー担当者によって常に疑われていたのである。これは理解できることで、地政学の根本的な哲学的方向性は、国家社会主義のそれとは一致しないも

のであったからだ。地政学は、ラッツェルの科学的唯物論と地理的決定論を共有し、人間社会は外部の影響によって決定され、その中で個人や集団が生来的に

持っている資質は、ほとんど意味を持たないとしたのである。国家社会主義は、唯物論も決定論も原理的に否定し、「人種的性格」という仮説の形で、人間の生

来の資質を人間社会の構成における最も重要な要素に押し上げた。これらの相違は1933年以降、摩擦を引き起こし、最終的にはナチスのイデオローグによっ

て地政学が公然と非難されるに至った[33]

にもかかわらず、ドイツの地政学は第二次世界大戦のナチスの拡張主義政策における(誤った)使用によって信用を失い、戦前と同等の地位を得ることはなかっ

た。

その結果、特にアメリカの学界では、古典的な地政学とナチスや帝国主義のイデオロギーとの間に否定的な関連性が生じ、緩やかな正当化に基づいている。この

ことは、特に現代の学術的な地理学に対する批判、特に「新」古典的な地政学の支持者によって観察されてきた。これらの中にはHaverlukらが含まれて

おり、実証主義的な探求のフィールドとしての地政学が、紛争の解決や予防、気候変動の緩和といったトピック的でしばしば政治化された問題を研究し解決する

可能性を維持しているので、学術界における地政学のスティグマ化は助けにならないと主張している[34]。

専門分野による見解の相違

「地政学」という言葉に対する否定的なイメージと、第二次世界大戦や第二次世界大戦前のドイツの学者や学生との関連からくるその実用化は、学術的な地理学の

分野、特に政治地理学などの人文地理学の下位学問に特有なものであることが大きい。しかし、歴史学や政治学など、地政学的な概念を利用する分野では、この

否定的な関連性はそれほど強くはない。古典的な地政学は、戦史学や、国際関係論や安全保障研究などの政治学の下位学問分野にとって、重要な分析要素を形成

している。このような学問的視点の違いは、Bert Chapmanが書いたGeopolitics, A Guide To

Issueの中で述べられている。その中でチャップマンは、学術的かつ専門的な国際関係学の学術雑誌は、政治地理学の分野における現代の学術雑誌よりも地

政学、特に古典的な地政学の研究と分析に従順であることを指摘している[35]。

地理学以外の分野では、地政学は(キャロリン・ギャラハーやクラウス・ドッズのような学術的な地理学者の間でしばしば見られるように)帝国主義の道具とし

て、またはナチズムと関連して否定的に見られるのではなく、必ずしも武力紛争や軍事作戦に関連していない主要な国際地政学的状況や出来事を評価する有効か

つ一貫した方法として見られているのである。

|

France

French geopolitical doctrines broadly opposed to German Geopolitik and

reject the idea of a fixed geography. French geography is focused on

the evolution of polymorphic territories being the result of mankind's

actions. It also relies on the consideration of long time periods

through a refusal to take specific events into account. This method has

been theorized by Professor Lacoste according to three principles:

Representation; Diachronie; and Diatopie.

In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu outlined the view that man and

societies are influenced by climate. He believed that hotter climates

create hot-tempered people and colder climates aloof people, whereas

the mild climate of France is ideal for political systems. Considered

one of the founders of French geopolitics, Élisée Reclus, is the author

of a book considered a reference in modern geography (Nouvelle

Géographie universelle). Alike Ratzel, he considers geography through a

global vision. However, in complete opposition to Ratzel's vision,

Reclus considers geography not to be unchanging; it is supposed to

evolve commensurately to the development of human society. His marginal

political views resulted in his rejection by academia.

French geographer and geopolitician Jacques Ancel (1879-1936) is

considered to be the first theoretician of geopolitics in France, and

gave a notable series of lectures at the European Center of the

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Paris and published

Géopolitique in 1936. Like Reclus, Ancel rejects German determinist

views on geopolitics (including Haushofer's doctrines).

Braudel's broad view used insights from other social sciences, employed

the concept of the longue durée, and downplayed the importance of

specific events. This method was inspired by the French geographer Paul

Vidal de la Blache (who in turn was influenced by German thought,

particularly that of Friedrich Ratzel whom he had met in Germany).

Braudel's method was to analyse the interdependence between individuals

and their environment.[36] Vidalian geopolitics is based on varied

forms of cartography and on possibilism (founded on a societal approach

of geography—i.e. on the principle of spaces polymorphic faces

depending from many factors among them mankind, culture, and ideas) as

opposed to determinism.

Due to the influence of German Geopolitik on French geopolitics, the

latter were for a long time banished from academic works. In the

mid-1970s, Yves Lacoste—a French geographer who was directly inspired

by Ancel, Braudel and Vidal de la Blache—wrote La géographie, ça sert

d'abord à faire la guerre (Geography first use is war) in 1976. This

book—which is very famous in France—symbolizes the birth of this new

school of geopolitics (if not so far the first French school of

geopolitics as Ancel was very isolated in the 1930s–40s). Initially

linked with communist party evolved to a less liberal approach. At the

end of the 1980s he founded the Institut Français de Géopolitique

(French Institute for Geopolitics) that publishes the Hérodote revue.

While rejecting the generalizations and broad abstractions employed by

the German and Anglo-American traditions (and the new geographers),

this school does focus on spatial dimension of geopolitics affairs on

different levels of analysis. This approach emphasizes the importance

of multi-level (or multi-scales) analysis and maps at the opposite of

critical geopolitics which avoid such tools. Lacoste proposed that

every conflict (both local or global) can be considered from a

perspective grounded in three assumptions:

1. Representation: Each group or individuals is the product of an

education and is characterized by specific representations of the world

or others groups or individuals. Thus, basic societal beliefs are

grounded in their ethnicity or specific location. The study of

representation is a common point with the more contemporary critical

geopolitics. Both are connected with the work of Henri Lefebvre (La

production de l'espace, first published in 1974)

2. Diachronie. Conducting an historical analysis confronting "long

periods" and short periods as the prominent French historian Fernand

Braudel suggested.

3. Diatopie: Conducting a cartographic survey through a multi-scale

mapping.

Connected with this stream, and former member of Hérodote editorial

board, the French geographer Michel Foucher developed a long term

analysis of international borders. He coined various neologism among

them: Horogenesis: Neologism that describes the concept of studying the

birth of borders, Dyade: border shared by two neighbouring states (for

instance US territory has two terrestrial dyades : one with Canada and

one with Mexico). The main book of this searcher "Fronts et frontières"

(Fronts and borders) first published in 1991, without equivalent

remains untranslated in English. Michel Foucher is an expert of the

African Union for borders affairs.

More or less connected with this school, Stéphane Rosière can be quoted

as the editor in Chief of the online journal L'Espace politique, this

journal created in 2007 became the most prominent French journal of

political geography and Geopolitics with Hérodote.[37]

A much more conservative stream is personified by François Thual. Thual

was a French expert in geopolitics, and a former official of the

Ministry of Civil Defence. Thual taught geopolitics of the religions at

the French War College, and has written thirty books devoted mainly to

geopolitical method and its application to various parts of the world.

He is particularly interested in the Orthodox, Shiite, and Buddhist

religions, and in troubled regions like the Caucasus. Connected with F.

Thual, Aymeric Chauprade, former professor of geopolitics at the French

War College and now member of the extreme-right party "Front national",

subscribes to a supposed "new" French school of geopolitics which

advocates above all a return to realpolitik and "clash of civilization"

(Huntington). The thought of this school is expressed through the

French Review of Geopolitics (headed by Chauprade) and the

International Academy of Geopolitics. Chauprade is a supporter of a

Europe of nations, he advocates a European Union excluding Turkey, and

a policy of compromise with Russia (in the frame of a Eurasian alliance

which is en vogue among European extreme-right populists) and supports

the idea of a multi-polar world—including a balanced relationship

between China and the U.S.

French philosopher Michel Foucault's dispositif introduced for the

purpose of biopolitical research was also adopted in the field of

geopolitical thought where it now plays a role.[38]

|

フランス

フランスの地政学は、ドイツの地政学と大きく対立し、固定的な地理学の考え方を否定している。フランスの地理学は、人類の行動の結果である多形的な領土の

進化に焦点を当てるものである。また、特定の事象を考慮せず、長い時間軸で考察することに重点を置いている。この方法は、ラコスト教授によって、3つの原

則に従って理論化されている。表象」「通時性」「ディアトピエ」である。

モンテスキューは『法の精神』の中で、人間や社会は気候の影響を受けるという見解を示した。暑い気候は短気な人間を生み、寒い気候は飄々とした人間を生む

が、フランスの温暖な気候は政治体制に理想的であると考えたのである。フランスの地政学の創始者の一人とされるエリゼ・ルクルスは、現代地理学の参考書と

される本(Nouvelle Géographie

universelle)を著した人物である。ラッツェルと同様、地理をグローバルな視野で捉えている。しかし、ラッツェルとは全く異なり、地理は不変の

ものではなく、人間社会の発展に応じて進化していくものだと考えている。このような政治的な観点から、彼はアカデミアから拒絶されることになった。

フランスの地理学者で地政学者のジャック・アンセル(1879-1936)は、フランスで最初の地政学理論家といわれ、パリのカーネギー国際平和財団ヨー

ロッパセンターで連続講演を行い、1936年に『Géopolitique』を出版して注目された。アンセルはレクリュス同様、ドイツ決定論的な地政学

(ハウスホーファーの教義を含む)を否定している。

ブローデルの広義の見解は、他の社会科学からの洞察を用い、longue

duréeの概念を採用し、特定の事象の重要性を軽視するものであった。この方法は、フランスの地理学者ポール・ヴィダル・ド・ラ・ブラッシュ(彼はドイ

ツ思想、特にドイツで出会ったフリードリヒ・ラッツェルの思想に影響を受けている)の影響を受けている。ヴィダリアン地政学は様々な形態の地図製作と、決

定論とは対照的にポッシビリズム(地理学の社会的アプローチ、すなわち人間、文化、思想などの多くの要因によって多形性を持つ空間の原則に基づく)に基づ

いている[36]。

ドイツの地政学がフランスの地政学に影響を及ぼしたため,長い間,ドイツの地政学は学術的な研究からは排除されていた。1970年代半ば、アンセル、ブ

ローデル、ヴィダル・ド・ラ・ブラッシュの影響を直接受けたフランスの地理学者イヴ・ラコストが、1976年に『地理学、その最初の使用は戦争である

(La géographie, ça sert d'abord à faire la

guerre)』という本を著した。この本はフランスでは非常に有名で、この新しい地政学派の誕生を象徴している(アンセルは1930年代から40年代に

かけて非常に孤立していたので、フランス初の地政学派とまでは言えないかもしれない)。当初は共産党と結びついていたが、よりリベラルなアプローチへと発

展していった。1980年代末、彼は Institut Français de Géopolitique (French Institute

for Geopolitics) を設立し、Hérodote revue

を発行している。この学派は、ドイツや英米の伝統(および新地理学者)が採用した一般化や幅広い抽象化を否定しながらも、さまざまなレベルの分析で地政学

の問題の空間的次元に焦点を当てる。このアプローチは、マルチレベル(またはマルチスケール)分析と地図の重要性を強調し、そのようなツールを避ける批判

的地政学とは正反対である。ラコステは、あらゆる紛争(ローカルなものもグローバルなものも)は、3つの前提に基づいた視点から考察することができると提

唱している。

1.

表象。各グループや個人は教育の産物であり、世界や他のグループや個人に対する特定の表象によって特徴付けられる。したがって、社会の基本的な信念は、そ

の民族性や特定の場所に根ざしている。表象の研究は、より現代的な批判的地政学と共通点がある。どちらもアンリ・ルフェーヴル(La

production de l'espace、1974年初版)の仕事と関連している。

2.

ジアクロニー(Diachronie)。フランスの著名な歴史家フェルナン・ブローデルが示唆したように、「長い時代」と「短い時代」とを対峙させる歴史

分析を行うこと。

3. Diatopie(ディアトピー)。マルチスケールマッピングによる地図製作のこと。

この流れに連なる、フランスの地理学者ミシェル・フーシェ(Hérodote編集委員)は、国際国境の長期的な分析を展開した。彼は様々な新語を生み出し

ました。Horogenesis(ホロジェネシス)。国境誕生を研究する概念を表す新造語、「ダイアード」:隣接する二つの国家が共有する国境(例えば、

米国領土はカナダとメキシコとの間に二つの陸上ダイアードがある)。この研究者の主著『Fronts et

frontières』(前線と国境)は1991年に出版されたが、同等のものはなく、英語では未翻訳のままである。Michel

Foucherは、アフリカ連合の国境問題の専門家である。

この学派と多かれ少なかれ関係があるのは、オンラインジャーナルであるL'Espace politiqueの編集長であるStéphane

Rosièreであり、2007年に作成されたこの雑誌はHérodoteとともに政治地理・地政学のフランスの最も著名な雑誌となった[37]。

より保守的な流れはフランソワ・トゥアルに象徴される。トゥアルは地政学のフランスの専門家であり、民間防衛省の元職員であった。トゥアルはフランスの戦

争大学で宗教の地政学を教えており、主に地政学的方法とその世界各地への適用に捧げられた30冊の本を書いている。特に正教会、シーア派、仏教の宗教と

コーカサスなどの紛争地域に関心を持っている。元フランス陸軍大学校地政学教授で、現在は極右政党「国民戦線」のメンバーであるアイメリック・ショープ

ラードは、F.

トゥアルと関連して、現実政治への回帰と「文明の衝突」(ハンティントン)を何よりも主張するフランスの「新しい」地政学派とされているものを支持し

ている。この学派の思想は、ショープラードが主宰する「フランス地政学評論」と「国際地政学アカデミー」を通じて表現されている。ショープラードは、国家

によるヨーロッパを支持し、トルコを除くEU、ロシアとの妥協政策(ヨーロッパの極右ポピュリストの間で流行しているユーラシア同盟の枠組み)を主張し、

中国とアメリカの均衡関係を含む多極化した世界という考えを支持している。

フランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーが生政治的な研究のために導入したディスポジティブは、地政学的な思想の分野でも採用され、現在その役割を担っている

[38]。

|

Russia

The geopolitical stance adopted by Russia has traditionally been

informed by a Eurasian perspective, and Russia's location provides a

degree of continuity between the Tsarist and Soviet geostrategic stance

and the position of Russia in the international order.[39] In the

1990s, a senior researcher at the Institute of Philosophy, Russian

Academy of Sciences of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Vadim

Tsymbursky [ru] (1957–2009), coined the term "island-Russia" and

developed the "Great Limitrophe" concept.

Colonel-General Leonid Ivashov (retired), a Russian geopolitics

specialist of the early 21st century, headed the Academy of

Geopolitical Problems (Russian: Академия геополитических проблем),

which analyzes the international and domestic situations and develops

geopolitical doctrine. Earlier, he headed the Main Directorate for

International Military Cooperation of the Ministry of Defence of the

Russian Federation.

Vladimir Karyakin, leading researcher at the Russian Institute for

Strategic Studies, has proposed the term "geopolitics of the third

wave".[40][clarification needed]

Aleksandr Dugin, a Russian political analyst who has developed a close

relationship with Russia's Academy of the General Staff wrote "The

Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia" in 1997,

which has had a large influence within the Russian military, police,

and foreign policy elites [41] and it has been used as a textbook in

the Academy of the General Staff of the Russian military.[42][41] Its

publication in 1997 was well received in Russia and powerful Russian

political figures subsequently took an interest in Dugin.[43]

|

ロシア

ロシアが採用する地政学的スタンスは伝統的にユーラシアの視点に基づくものであり、ロシアの位置はツァーリズムとソ連の地政学的スタンスと国際秩序におけ

るロシアの位置の間にある程度の連続性をもたらしている[39]。

1990年代、ロシア科学アカデミー哲学研究所の上級研究員ヴァディム・ツィムブルスキー[ru](1957-2009)は「島-ロシア」という用語を作

り、「大限界」概念を発展させている。

21世紀初頭のロシアの地政学専門家であるレオニード・イワショフ大佐(引退)は、国際情勢と国内情勢を分析し、地政学的ドクトリンを開発する地政学問題

アカデミー(ロシア語:Академия геополитических

проблем)を率いている。それ以前は、ロシア連邦国防省の国際軍事協力主管局を統括していた。

ロシア戦略研究所の主要研究者であるウラジーミル・カリャキンは、「第3の波の地政学」という言葉を提唱している[40][要解説]。

ロシアの参謀本部アカデミーと密接な関係を築いているロシアの政治アナリストであるアレクサンドル・ドゥーギンは、「地政学の基礎」を執筆した。1997

年に出版された『地政学的なロシアの未来』は、ロシアの軍、警察、外交政策のエリートの中で大きな影響力を持ち[41]、ロシア軍の参謀アカデミーで教科

書として使われている[42][41]。1997年の出版はロシアで評判となり、その後ロシアの有力な政治家がドゥーギンに関心を持つようになった

[43]。

|

China

According to Li Lingqun, a major feature of the People's Republic of

China's geopolitics is attempting to change the laws of the sea to

advance claims in the South China Sea.[44] Another geopolitical issue

is China's claims over Taiwan, amounting to a geopolitical rivalry

between the two independent states.[45]

Various analysts state that China created the Belt and Road Initiative

as a geostrategic effort to take a larger role in global affairs, and

undermine what the Communist Party perceives as a hegemony of

liberalism.[46][47][48] It has also been argued that China co-founded

the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank to

compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in

development finance.[49][50] According to Bobo Lo, the Shanghai

Cooperation Organization has been advertised as a "political

organization of a new type" claimed to transcend geopolitics.[51]

Political scientist Pak Nung Wong says that a major form of geopolitics

between the US and China includes cybersecurity competition, policy

regulations regarding technology standards and social media platforms,

and traditional and non-traditional forms of espionage.[52]

One view of the New Great Game is a shift to geoeconomic compared to

geopolitical competition. The interest in oil and gas includes

pipelines that transmit energy to China's east coast. Xiangming Chen

believes that China's role is more like Britain's than Russia's in the

New Great Game, where Russia plays the role that the Russian Empire

originally did. Chen stated, "Regardless of the prospect, China through

the BRI is deep in playing a 'New Great Game' in Central Asia that

differs considerably from its historical precedent about 150 years ago

when Britain and Russia jostled with each other on the Eurasian

steppes."[53] In the Carnegie Endowment, Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng

wrote in 2018 that China has not fundamentally challenged any Russian

interests in Central Asia.[54]

|

中国

李玲群によれば、中華人民共和国の地政学の大きな特徴は、南シナ海での主張を進めるために海洋法を変更しようとしていることである[44]。もう一つの地

政学的問題は台湾に対する中国の主張であり、二つの独立国家の間の地政学的対抗に等しいものである[45]。

また、中国が開発金融において世界銀行と国際通貨基金に対抗するためにアジアインフラ投資銀行と新開発銀行を共同設立したことも議論されている[46]

[47][48]。 [49][50] Bobo

Loによれば、上海協力機構は地政学を超越すると主張される「新しいタイプの政治組織」として宣伝されている[51] 政治学者のPak Nung

Wongは、米国と中国の間の地政学の主要形態にはサイバーセキュリティ競争、技術標準やソーシャルメディアのプラットフォームに関する政策規制、伝統

的・非伝統的形態のスパイが含まれると述べている[52]。

ニュー・グレート・ゲームの一つの見方は、地政学的競争と比較して地理経済的なものへの移行である。石油とガスに対する関心は、中国の東海岸にエネルギー

を送るパイプラインを含んでいる。陳祥明は、新グレートゲームにおいて、中国の役割はロシアよりもイギリスに近く、ロシアは元々ロシア帝国が担っていた役

割を担っていると考えている。陳は「見通しがどうであれ、BRIを通じて中国は、イギリスとロシアがユーラシアの草原で互いに争った約150年前の歴史的

先例とはかなり異なる中央アジアにおける『新グレートゲーム』を深く演じている」と述べていた[53]。

カーネギー財団では、ポール・ストロンスキーとニコール・ンが2018年に、中国は中央アジアにおけるロシアのいかなる利益にも根本的に挑戦していないこ

とを書いている[54]。

|

Charles University, Prague

Sciences Po Paris

Balsillie School of International Affairs

King's College London

Hertie School

Harvard Kennedy School of Government

London School of Economics

Munk School of Global Affairs

Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies

School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University

Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs

University of Cambridge

University of Oxford

Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Geneva

SOAS, University of London

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

|

プラハ・カレル大学

パリ政治学院

バルシリ国際問題研究所

キングス・カレッジ・ロンドン

ヘルティ・スクール

ハーバード・ケネディ行政大学院

ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス

ムンク国際問題大学院

ポール・H・ニッツェ高等国際問題研究大学院

コロンビア大学国際公共政策大学院

ウッドロウ・ウィルソン公共国際問題大学院

ケンブリッジ大学

オックスフォード大学

ジュネーブ国際開発研究大学院

ロンドン大学 SOAS

リー・クアンユー公共政策大学院

|

Balkanization

Critical geopolitics

Choke point

Geopolitics (journal)

Eurasianism

Geoeconomics

Geopolitik

Biopolitics

Geojurisprudence

Geopolitical ontology

Geostrategy

Guns, Germs, and Steel

Intermediate Region

Lebensraum

Natural gas and list of natural gas fields and Category:Natural gas

pipelines

Petroleum politics

Political geography

Realpolitik

Space geostrategy

Sphere of influence

Strategic depth

The Great Game

Theopolitics

Water politics

The Cold War

|

バルカニゼーション

批判的地政学(以下で説明)

チョークポイント

地政学 (雑誌)

ユーラシア主義

地質経済学

地政学

生政治

地政学

地政学オントロジー

地政学

銃・病原菌・鉄

中間領域

リーベンスラウム

天然ガスと天然ガス田のリストとCategory:天然ガスパイプライン

石油政治

政治的地理

現実政治

宇宙地球戦略

影響圏

戦略的深度

グレートゲーム

地政学

水の政治

冷戦

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geopolitics

|

|

☆

☆