カール・マルクス「ブルーノ・バウアー『ユダヤ人問題』によせて」

Karl Marx criticize

Bruno Bauer on "Jewish Question"

カール・マルクス「ブルーノ・バウアー『ユダヤ人問題』によせて」

Karl Marx criticize

Bruno Bauer on "Jewish Question"

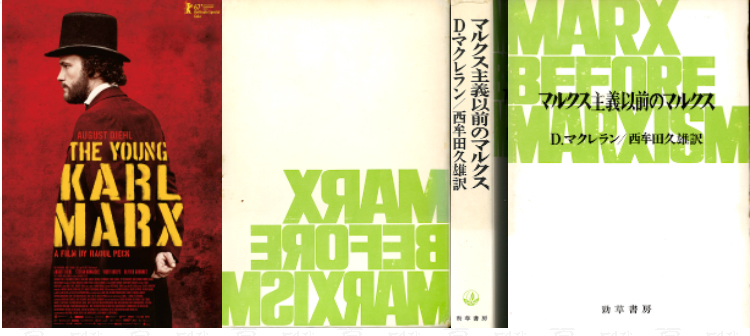

左:バウアー、右:マルクス

1843年「ユダヤ人問題に寄せて」のな かでマルクスは、ユダヤ人がキリスト教国家と調停するために[国家制度によるユダヤ 人の保証と見返り に]ユダヤ教の棄教を考慮すべきであるという考えを展開するヘーゲル左派であったB・バウアー(Bruno Bauer, 1809-1882)を批判して、国家が人間の解放を保証するあり方を〈政 治的〉 とするならば、ユダヤ人性を保証しつつ国家と交渉するユダヤ人は政治のカテゴリーで自らを考えているとした。ロバート・マイスター [1990] (Robert Meister, 1947- )によると、ヨーロッパにおける政治的アイ デンティティの議論はここにまで遡れるとした[太田 2009:251-252]。たしかに。マルクスの学位論文『デモクリトスの自然哲学とエピクロスの自然哲学の差異』を、ヘーゲルのエピクロスの低評価の 読み直しをおこない、その際に、(ヘーゲルがみるように)エピクロスをデモクリトスの亜流として描くのではなく、西洋哲学の没落を示す、エピクロスを「主 観的な形式」——主観的な「自己意識の哲学」——を体現する哲学者と描く。マルクスのみるエピクロスは、自己意識の哲学者であり、それは、ヘーゲルの(真 理の哲学よりもなお)自己意識の理論のそれであり、ヘーゲルを引き継いだヘーゲル左派(Linkshegelianer, 青年ヘーゲル派= Junghegelianer)の、ブルノー・バウアーに「自己意識の概念」をみることができる[中 山 2014:267-269]。

先に、「ブルーノ・バウアー『ユダヤ人問 題』によせ て」を読んでから、本文の後で、この原稿が書かれた事情や、青年期のマルクスがどのようなものであったか、ブルーノ・バウアーがどんな青年であったのか、 を解説する。本文をスキップしたい方は、ここを、 クリックしてください(サイト内ジャンプ)。

●カール・マルクス「ブルーノ・バウアー『ユダヤ人問題』によせて」の翻訳:ドイツ語からの英訳と英語から日本語への重訳です。| I Bruno Bauer, The Jewish Question, Braunschweig, 1843 The German Jews desire emancipation. What kind of emancipation do they desire? Civic, political emancipation. Bruno Bauer replies to them: No one in Germany is politically emancipated. We ourselves are not free. How are we to free you? You Jews are egoists if you demand a special emancipation for yourselves as Jews. As Germans, you ought to work for the political emancipation of Germany, and as human beings, for the emancipation of mankind, and you should feel the particular kind of your oppression and your shame not as an exception to the rule, but on the contrary as a confirmation of the rule. Or do the Jews demand the same status as Christian subjects of the state? In that case, they recognize that the Christian state is justified and they recognize, too, the regime of general oppression. Why should they disapprove of their special yoke if they approve of the general yoke? Why should the German be interested in the liberation of the Jew, if the Jew is not interested in the liberation of the German? The Christian state knows only privileges. In this state, the Jew has the privilege of being a Jew. As a Jew, he has rights which the Christians do not have. Why should he want rights which he does not have, but which the Christians enjoy? In wanting to be emancipated from the Christian state, the Jew is demanding that the Christian state should give up its religious prejudice. Does he, the Jew, give up his religious prejudice? Has he, then, the right to demand that someone else should renounce his religion? By its very nature, the Christian state is incapable of emancipating the Jew; but, adds Bauer, by his very nature the Jew cannot be emancipated. So long as the state is Christian and the Jew is Jewish, the one is as incapable of granting emancipation as the other is of receiving it. The Christian state can behave towards the Jew only in the way characteristic of the Christian state – that is, by granting privileges, by permitting the separation of the Jew from the other subjects, but making him feel the pressure of all the other separate spheres of society, and feel it all the more intensely because he is in religious opposition to the dominant religion. But the Jew, too, can behave towards the state only in a Jewish way – that is, by treating it as something alien to him, by counterposing his imaginary nationality to the real nationality, by counterposing his illusory law to the real law, by deeming himself justified in separating himself from mankind, by abstaining on principle from taking part in the historical movement, by putting his trust in a future which has nothing in common with the future of mankind in general, and by seeing himself as a member of the Jewish people, and the Jewish people as the chosen people. On what grounds, then, do you Jews want emancipation? On account of your religion? It is the mortal enemy of the state religion. As citizens? In Germany, there are no citizens. As human beings? But you are no more human beings than those to whom you appeal. Bauer has posed the question of Jewish emancipation in a new form, after giving a critical analysis of the previous formulations and solutions of the question. What, he asks, is the nature of the Jew who is to be emancipated and of the Christian state that is to emancipate him? He replies by a critique of the Jewish religion, he analyzes the religious opposition between Judaism and Christianity, he elucidates the essence of the Christian state – and he does all this audaciously, trenchantly, wittily, and with profundity, in a style of writing that is as precise as it is pithy and vigorous. How, then, does Bauer solve the Jewish question? What is the result? The formulation of a question is its solution. The critique of the Jewish question is the answer to the Jewish question. The summary, therefore, is as follows: We must emancipate ourselves before we can emancipate others. The most rigid form of the opposition between the Jew and the Christian is the religious opposition. How is an opposition resolved? By making it impossible. How is religious opposition made impossible? By abolishing religion. As soon as Jew and Christian recognize that their respective religions are no more than different stages in the development of the human mind, different snake skins cast off by history, and that man is the snake who sloughed them, the relation of Jew and Christian is no longer religious but is only a critical, scientific, and human relation. Science, then, constitutes their unity. But, contradictions in science are resolved by science itself. The German Jew, in particular, is confronted by the general absence of political emancipation and the strongly marked Christian character of the state. In Bauer’s conception, however, the Jewish question has a universal significance, independent of specifically German conditions. It is the question of the relation of religion to the state, of the contradiction between religious constraint and political emancipation. Emancipation from religion is laid down as a condition, both to the Jew who wants to be emancipated politically, and to the state which is to effect emancipation and is itself to be emancipated. “Very well,” it is said, and the Jew himself says it, “the Jew is to become emancipated not as a Jew, not because he is a Jew, not because he possesses such an excellent, universally human principle of morality; on the contrary, the Jew will retreat behind the citizen and be a citizen, although he is a Jew and is to remain a Jew. That is to say, he is and remains a Jew, although he is a citizen and lives in universally human conditions: his Jewish and restricted nature triumphs always in the end over his human and political obligations. The prejudice remains in spite of being outstripped by general principles. But if it remains, then, on the contrary, it outstrips everything else.” “Only sophistically, only apparently, would the Jew be able to remain a Jew in the life of the state. Hence, if he wanted to remain a Jew, the mere appearance would become the essential and would triumph; that is to say, his life in the state would be only a semblance or only a temporary exception to the essential and the rule.” (“The Capacity of Present-Day Jews and Christians to Become Free,” Einundzwanzig Bogen, pp. 57) Let us hear, on the other hand, how Bauer presents the task of the state. “France,” he says, “has recently shown us” (Proceedings of the Chamber of Deputies, December 26, 1840) “in the connection with the Jewish question – just as it has continually done in all other political questions – the spectacle of a life which is free, but which revokes its freedom by law, hence declaring it to be an appearance, and on the other hand contradicting its free laws by its action.” (The Jewish Question, p. 64) “In France, universal freedom is not yet the law, the Jewish question too has not yet been solved, because legal freedom – the fact that all citizens are equal – is restricted in actual life, which is still dominated and divided by religious privileges, and this lack of freedom in actual life reacts on law and compels the latter to sanction the division of the citizens, who as such are free, into oppressed and oppressors.” (p. 65) When, therefore, would the Jewish question be solved for France? “The Jew, for example, would have ceased to be a Jew if he did not allow himself to be prevented by his laws from fulfilling his duty to the state and his fellow citizens, that is, for example, if on the Sabbath he attended the Chamber of Deputies and took part in the official proceedings. Every religious privilege, and therefore also the monopoly of a privileged church, would have been abolished altogether, and if some or many persons, or even the overwhelming majority, still believed themselves bound to fulfil religious duties, this fulfilment ought to be left to them as a purely private matter.” (p. 65) “There is no longer any religion when there is no longer any privileged religion. Take from religion its exclusive power and it will no longer exist.” (p. 66) “Just as M. Martin du Nord saw the proposal to omit mention of Sunday in the law as a motion to declare that Christianity has ceased to exist, with equal reason (and this reason is very well founded) the declaration that the law of the Sabbath is no longer binding on the Jew would be a proclamation abolishing Judaism.” (p. 71) Bauer, therefore, demands, on the one hand, that the Jew should renounce Judaism, and that mankind in general should renounce religion, in order to achieve civic emancipation. On the other hand, he quite consistently regards the political abolition of religion as the abolition of religion as such. The state which presupposes religion is not yet a true, real state. “Of course, the religious notion affords security to the state. But to what state? To what kind of state?” (p. 97) At this point, the one-sided formulation of the Jewish question becomes evident. It was by no means sufficient to investigate: Who is to emancipate? Who is to be emancipated? Criticism had to investigate a third point. It had to inquire: What kind of emancipation is in question? What conditions follow from the very nature of the emancipation that is demanded? Only the criticism of political emancipation itself would have been the conclusive criticism of the Jewish question and its real merging in the “general question of time.” Because Bauer does not raise the question to this level, he becomes entangled in contradictions. He puts forward conditions which are not based on the nature of political emancipation itself. He raises questions which are not part of his problem, and he solves problems which leave this question unanswered. When Bauer says of the opponents of Jewish emancipation: “Their error was only that they assumed the Christian state to be the only true one and did not subject it to the same criticism that they applied to Judaism” (op. cit., p. 3), we find that his error lies in the fact that he subjects to criticism only the “Christian state,” not the “state as such,” that he does not investigate the relation of political emancipation to human emancipation and, therefore, puts forward conditions which can be explained only by uncritical confusion of political emancipation with general human emancipation. If Bauer asks the Jews: Have you, from your standpoint, the right to want political emancipation? We ask the converse question: Does the standpoint of political emancipation give the right to demand from the Jew the abolition of Judaism and from man the abolition of religion? The Jewish question acquires a different form depending on the state in which the Jew lives. In Germany, where there is no political state, no state as such, the Jewish question is a purely theological one. The Jew finds himself in religious opposition to the state, which recognizes Christianity as its basis. This state is a theologian ex professo. Criticism here is criticism of theology, a double-edged criticism – criticism of Christian theology and of Jewish theology. Hence, we continue to operate in the sphere of theology, however much we may operate critically within it. In France, a constitutional state, the Jewish question is a question of constitutionalism, the question of the incompleteness of political emancipation. Since the semblance of a state religion is retained here, although in a meaningless and self-contradictory formula, that of a religion of the majority, the relation of the Jew to the state retains the semblance of a religious, theological opposition. Only in the North American states – at least, in some of them – does the Jewish question lose its theological significance and become a really secular question. Only where the political state exists in its completely developed form can the relation of the Jew, and of the religious man in general, to the political state, and therefore the relation of religion to the state, show itself in its specific character, in its purity. The criticism of this relation ceases to be theological criticism as soon as the state ceases to adopt a theological attitude toward religion, as soon as it behaves towards religion as a state – i.e., politically. Criticism, then, becomes criticism of the political state. At this point, where the question ceases to be theological, Bauer’s criticism ceases to be critical. “In the United States there is neither a state religion nor a religion declared to be that of the majority, nor the predominance of one cult over another. The state stands aloof from all cults.” (Marie ou l’esclavage aux Etats-Unis, etc., by G. de Beaumont, Paris, 1835, p. 214) Indeed, there are some North American states where “the constitution does not impose any religious belief or religious practice as a condition of political rights.” (op. cit., p. 225) Nevertheless, “in the United States people do not believe that a man without religion could be an honest man.” (op. cit., p. 224) Nevertheless, North America is pre-eminently the country of religiosity, as Beaumont, Tocqueville, and the Englishman Hamilton unanimously assure us. The North American states, however, serve us only as an example. The question is: What is the relation of complete political emancipation to religion? If we find that even in the country of complete political emancipation, religion not only exists, but displays a fresh and vigorous vitality, that is proof that the existence of religion is not in contradiction to the perfection of the state. Since, however, the existence of religion is the existence of defect, the source of this defect can only be sought in the nature of the state itself. We no longer regard religion as the cause, but only as the manifestation of secular narrowness. Therefore, we explain the religious limitations of the free citizen by their secular limitations. We do not assert that they must overcome their religious narrowness in order to get rid of their secular restrictions, we assert that they will overcome their religious narrowness once they get rid of their secular restrictions. We do not turn secular questions into theological ones. History has long enough been merged in superstition, we now merge superstition in history. The question of the relation of political emancipation to religion becomes for us the question of the relation of political emancipation to human emancipation. We criticize the religious weakness of the political state by criticizing the political state in its secular form, apart from its weaknesses as regards religion. The contradiction between the state and a particular religion, for instance Judaism, is given by us a human form as the contradiction between the state and particular secular elements; the contradiction between the state and religion in general as the contradiction between the state and its presuppositions in general. The political emancipation of the Jew, the Christian, and, in general, of religious man, is the emancipation of the state from Judaism, from Christianity, from religion in general. In its own form, in the manner characteristic of its nature, the state as a state emancipates itself from religion by emancipating itself from the state religion – that is to say, by the state as a state not professing any religion, but, on the contrary, asserting itself as a state. The political emancipation from religion is not a religious emancipation that has been carried through to completion and is free from contradiction, because political emancipation is not a form of human emancipation which has been carried through to completion and is free from contradiction. The limits of political emancipation are evident at once from the fact that the state can free itself from a restriction without man being really free from this restriction, that the state can be a free state [pun on word Freistaat, which also means republic] without man being a free man. Bauer himself tacitly admits this when he lays down the following condition for political emancipation: “Every religious privilege, and therefore also the monopoly of a privileged church, would have been abolished altogether, and if some or many persons, or even the overwhelming majority, still believed themselves bound to fulfil religious duties, this fulfilment ought to be left to them as a purely private matter.” [The Jewish Question, p. 65] It is possible, therefore, for the state to have emancipated itself from religion even if the overwhelming majority is still religious. And the overwhelming majority does not cease to be religious through being religious in private. But, the attitude of the state, and of the republic [free state] in particular, to religion is, after all, only the attitude to religion of the men who compose the state. It follows from this that man frees himself through the medium of the state, that he frees himself politically from a limitation when, in contradiction with himself, he raises himself above this limitation in an abstract, limited, and partial way. It follows further that, by freeing himself politically, man frees himself in a roundabout way, through an intermediary, although an essential intermediary. It follows, finally, that man, even if he proclaims himself an atheist through the medium of the state – that is, if he proclaims the state to be atheist – still remains in the grip of religion, precisely because he acknowledges himself only by a roundabout route, only through an intermediary. Religion is precisely the recognition of man in a roundabout way, through an intermediary. The state is the intermediary between man and man’s freedom. Just as Christ is the intermediary to whom man transfers the burden of all his divinity, all his religious constraint, so the state is the intermediary to whom man transfers all his non-divinity and all his human unconstraint. The political elevation of man above religion shares all the defects and all the advantages of political elevation in general. The state as a state annuls, for instance, private property, man declares by political means that private property is abolished as soon as the property qualification for the right to elect or be elected is abolished, as has occurred in many states of North America. Hamilton quite correctly interprets this fact from a political point of view as meaning: “the masses have won a victory over the property owners and financial wealth.” [Thomas Hamilton, Men and Manners in America, 2 vols, Edinburgh, 1833, p. 146] Is not private property abolished in idea if the non-property owner has become the legislator for the property owner? The property qualification for the suffrage is the last political form of giving recognition to private property. Nevertheless, the political annulment of private property not only fails to abolish private property but even presupposes it. The state abolishes, in its own way, distinctions of birth, social rank, education, occupation, when it declares that birth, social rank, education, occupation, are non-political distinctions, when it proclaims, without regard to these distinction, that every member of the nation is an equal participant in national sovereignty, when it treats all elements of the real life of the nation from the standpoint of the state. Nevertheless, the state allows private property, education, occupation, to act in their way – i.e., as private property, as education, as occupation, and to exert the influence of their special nature. Far from abolishing these real distinctions, the state only exists on the presupposition of their existence; it feels itself to be a political state and asserts its universality only in opposition to these elements of its being. Hegel, therefore, defines the relation of the political state to religion quite correctly when he says: “In order [...] that the state should come into existence as the self-knowing, moral reality of the mind, its distinction from the form of authority and faith is essential. But this distinction emerges only insofar as the ecclesiastical aspect arrives at a separation within itself. It is only in this way that the state, above the particular churches, has achieved and brought into existence universality of thought, which is the principle of its form” (Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, 1st edition, p. 346). Of course! Only in this way, above the particular elements, does the state constitute itself as universality. The perfect political state is, by its nature, man’s species-life, as opposed to his material life. All the preconditions of this egoistic life continue to exist in civil society outside the sphere of the state, but as qualities of civil society. Where the political state has attained its true development, man – not only in thought, in consciousness, but in reality, in life – leads a twofold life, a heavenly and an earthly life: life in the political community, in which he considers himself a communal being, and life in civil society, in which he acts as a private individual, regards other men as a means, degrades himself into a means, and becomes the plaything of alien powers. The relation of the political state to civil society is just as spiritual as the relations of heaven to earth. The political state stands in the same opposition to civil society, and it prevails over the latter in the same way as religion prevails over the narrowness of the secular world – i.e., by likewise having always to acknowledge it, to restore it, and allow itself to be dominated by it. In his most immediate reality, in civil society, man is a secular being. Here, where he regards himself as a real individual, and is so regarded by others, he is a fictitious phenomenon. In the state, on the other hand, where man is regarded as a species-being, he is the imaginary member of an illusory sovereignty, is deprived of his real individual life and endowed with an unreal universality. Man, as the adherent of a particular religion, finds himself in conflict with his citizenship and with other men as members of the community. This conflict reduces itself to the secular division between the political state and civil society. For man as a bourgeois [i.e., as a member of civil society, “bourgeois society” in German], “life in the state” is “only a semblance or a temporary exception to the essential and the rule.” Of course, the bourgeois, like the Jew, remains only sophistically in the sphere of political life, just as the citoyen [‘citizen’ in French, i.e., the participant in political life] only sophistically remains a Jew or a bourgeois. But, this sophistry is not personal. It is the sophistry of the political state itself. The difference between the merchant and the citizen [Staatsbürger], between the day-laborer and the citizen, between the landowner and the citizen, between the merchant and the citizen, between the living individual and the citizen. The contradiction in which the religious man finds himself with the political man is the same contradiction in which the bourgeois finds himself with the citoyen, and the member of civil society with his political lion’s skin. This secular conflict, to which the Jewish question ultimately reduces itself, the relation between the political state and its preconditions, whether these are material elements, such as private property, etc., or spiritual elements, such as culture or religion, the conflict between the general interest and private interest, the schism between the political state and civil society – these secular antitheses Bauer allows to persist, whereas he conducts a polemic against their religious expression. “It is precisely the basis of civil society, the need that ensures the continuance of this society and guarantees its necessity, which exposes its existence to continual dangers, maintains in it an element of uncertainty, and produces that continually changing mixture of poverty and riches, of distress and prosperity, and brings about change in general.” (p. 8) Compare the whole section: “Civil Society” (pp. 8-9), which has been drawn up along the basic lines of Hegel’s philosophy of law. Civil society, in its opposition to the political state, is recognized as necessary, because the political state is recognized as necessary. Political emancipation is, of course, a big step forward. True, it is not the final form of human emancipation in general, but it is the final form of human emancipation within the hitherto existing world order. It goes without saying that we are speaking here of real, practical emancipation. Man emancipates himself politically from religion by banishing it from the sphere of public law to that of private law. Religion is no longer the spirit of the state, in which man behaves – although in a limited way, in a particular form, and in a particular sphere – as a species-being, in community with other men. Religion has become the spirit of civil society, of the sphere of egoism, of bellum omnium contra omnes. It is no longer the essence of community, but the essence of difference. It has become the expression of man’s separation from his community, from himself and from other men – as it was originally. It is only the abstract avowal of specific perversity, private whimsy, and arbitrariness. The endless fragmentation of religion in North America, for example, gives it even externally the form of a purely individual affair. It has been thrust among the multitude of private interests and ejected from the community as such. But one should be under no illusion about the limits of political emancipation. The division of the human being into a public man and a private man, the displacement of religion from the state into civil society, this is not a stage of political emancipation but its completion; this emancipation, therefore, neither abolished the real religiousness of man, nor strives to do so. The decomposition of man into Jew and citizen, Protestant and citizen, religious man and citizen, is neither a deception directed against citizenhood, nor is it a circumvention of political emancipation, it is political emancipation itself, the political method of emancipating oneself from religion. Of course, in periods when the political state as such is born violently out of civil society, when political liberation is the form in which men strive to achieve their liberation, the state can and must go as far as the abolition of religion, the destruction of religion. But it can do so only in the same way that it proceeds to the abolition of private property, to the maximum, to confiscation, to progressive taxation, just as it goes as far as the abolition of life, the guillotine. At times of special self-confidence, political life seeks to suppress its prerequisite, civil society and the elements composing this society, and to constitute itself as the real species-life of man, devoid of contradictions. But, it can achieve this only by coming into violent contradiction with its own conditions of life, only by declaring the revolution to be permanent, and, therefore, the political drama necessarily ends with the re-establishment of religion, private property, and all elements of civil society, just as war ends with peace. Indeed, the perfect Christian state is not the so-called Christian state – which acknowledges Christianity as its basis, as the state religion, and, therefore, adopts an exclusive attitude towards other religions. On the contrary, the perfect Christian state is the atheistic state, the democratic state, the state which relegates religion to a place among the other elements of civil society. The state which is still theological, which still officially professes Christianity as its creed, which still does not dare to proclaim itself as a state, has, in its reality as a state, not yet succeeded in expressing the human basis – of which Christianity is the high-flown expression – in a secular, human form. The so-called Christian state is simply nothing more than a non-state, since it is not Christianity as a religion, but only the human background of the Christian religion, which can find its expression in actual human creations. The so-called Christian state is the Christian negation of the state, but by no means the political realization of Christianity. The state which still professes Christianity in the form of religion, does not yet profess it in the form appropriate to the state, for it still has a religious attitude towards religion – that is to say, it is not the true implementation of the human basis of religion, because it still relies on the unreal, imaginary form of this human core. The so-called Christian state is the imperfect state, and the Christian religion is regarded by it as the supplementation and sanctification of its imperfection. For the Christian state, therefore, religion necessarily becomes a means; hence, it is a hypocritical state. It makes a great difference whether the complete state, because of the defect inherent in the general nature of the state, counts religion among its presuppositions, or whether the incomplete state, because of the defect inherent in its particular existence as a defective state, declares that religion is its basis. In the latter case, religion becomes imperfect politics. In the former case, the imperfection even of consummate politics becomes evident in religion. The so-called Christian state needs the Christian religion in order to complete itself as a state. The democratic state, the real state, does not need religion for its political completion. On the contrary, it can disregard religion because in it the human basis of religion is realized in a secular manner. The so-called Christian state, on the other hand, has a political attitude to religion and a religious attitude to politics. By degrading the forms of the state to mere semblance, it equally degrades religion to mere semblance. In order to make this contradiction clearer, let us consider Bauer’s projection of the Christian state, a projection based on his observation of the Christian-German state. “Recently,” says Bauer, “in order to prove the impossibility or non-existence of a Christian state, reference has frequently been made to those sayings in the Gospel with which the [present-day] state not only does not comply, but cannot possibly comply, if it does not want to dissolve itself completely [as a state].” “But the matter cannot be disposed of so easily. What do these Gospel sayings demand? Supernatural renunciation of self, submission to the authority of revelation, a turning-away from the state, the abolition of secular conditions. Well, the Christian state demands and accomplishes all that. It has assimilated the spirit of the Gospel, and if it does not reproduce this spirit in the same terms as the Gospel, that occurs only because it expresses this spirit in political forms, i.e., in forms which, it is true, are taken from the political system in this world, but which in the religious rebirth that they have to undergo become degraded to a mere semblance. This is a turning-away from the state while making use of political forms for its realization.” (p. 55) Bauer then explains that the people of a Christian state is only a non-people, no longer having a will of its own, but whose true existence lies in the leader to whom it is subjected, although this leader by his origin and nature is alien to it – i.e., given by God and imposed on the people without any co-operation on its part. Bauer declares that the laws of such a people are not its own creation, but are actual revelations, that its supreme chief needs privileged intermediaries with the people in the strict sense, with the masses, and that the masses themselves are divided into a multitude of particular groupings which are formed and determined by chance, which are differentiated by their interests, their particular passions and prejudices, and obtain permission as a privilege, to isolate themselves from one another, etc. (p. 56) However, Bauer himself says: “Politics, if it is to be nothing but religion, ought not to be politics, just as the cleaning of saucepans, if it is to be accepted as a religious matter, ought not to be regarded as a matter of domestic economy.” (p. 108) In the Christian-German state, however, religion is an “economic matter” just as “economic matters” belong to the sphere of religion. The domination of religion in the Christian-German state is the religion of domination. The separation of the “spirit of the Gospel” from the “letter of the Gospel” is an irreligious act. A state which makes the Gospel speak in the language of politics – that is, in another language than that of the Holy Ghost – commits sacrilege, if not in human eyes, then in the eyes of its own religion. The state which acknowledges Christianity as its supreme criterion, and the Bible as its Charter, must be confronted with the words of Holy Scripture, for every word of Scripture is holy. This state, as well as the human rubbish on which it is based, is caught in a painful contradiction that is insoluble from the standpoint of religious consciousness when it is referred to those sayings of the Gospel with which it “not only does not comply, but cannot possibly comply, if it does not want to dissolve itself completely as a state.” And why does it not want to dissolve itself completely? The state itself cannot give an answer either to itself or to others. In its own consciousness, the official Christian state is an imperative, the realization of which is unattainable, the state can assert the reality of its existence only by lying to itself, and therefore always remains in its own eyes an object of doubt, an unreliable, problematic object. Criticism is, therefore, fully justified in forcing the state that relies on the Bible into a mental derangement in which it no longer knows whether it is an illusion or a reality, and in which the infamy of its secular aims, for which religion serves as a cloak, comes into insoluble conflict with the sincerity of its religious consciousness, for which religion appears as the aim of the world. This state can only save itself from its inner torment if it becomes the police agent of the Catholic Church. In relation to the church, which declares the secular power to be its servant, the state is powerless, the secular power which claims to be the rule of the religious spirit is powerless. It is, indeed, estrangement which matters in the so-called Christian state, but not man. The only man who counts, the king, is a being specifically different from other men, and is, moreover, a religious being, directly linked with heaven, with God. The relationships which prevail here are still relationships dependent of faith. The religious spirit, therefore, is still not really secularized. But, furthermore, the religious spirit cannot be really secularized, for what is it in itself but the non-secular form of a stage in the development of the human mind? The religious spirit can only be secularized insofar as the stage of development of the human mind of which it is the religious expression makes its appearance and becomes constituted in its secular form. This takes place in the democratic state. Not Christianity, but the human basis of Christianity is the basis of this state. Religion remains the ideal, non-secular consciousness of its members, because religion is the ideal form of the stage of human development achieved in this state. The members of the political state are religious owing to the dualism between individual life and species-life, between the life of civil society and political life. They are religious because men treat the political life of the state, an area beyond their real individuality, as if it were their true life. They are religious insofar as religion here is the spirit of civil society, expressing the separation and remoteness of man from man. Political democracy is Christian since in it man, not merely one man but everyman, ranks as sovereign, as the highest being, but it is man in his uncivilized, unsocial form, man in his fortuitous existence, man just as he is, man as he has been corrupted by the whole organization of our society, who has lost himself, been alienated, and handed over to the rule of inhuman conditions and elements – in short, man who is not yet a real species-being. That which is a creation of fantasy, a dream, a postulate of Christianity, i.e., the sovereignty of man – but man as an alien being different from the real man – becomes, in democracy, tangible reality, present existence, and secular principle. In the perfect democracy, the religious and theological consciousness itself is in its own eyes the more religious and the more theological because it is apparently without political significance, without worldly aims, the concern of a disposition that shuns the world, the expression of intellectual narrow-mindedness, the product of arbitrariness and fantasy, and because it is a life that is really of the other world. Christianity attains, here, the practical expression of its universal-religious significance in that the most diverse world outlooks are grouped alongside one another in the form of Christianity and still more because it does not require other people to profess Christianity, but only religion in general, any kind of religion (cf. Beaumont’s work quoted above). The religious consciousness revels in the wealth of religious contradictions and religious diversity. We have, thus, shown that political emancipation from religion leaves religion in existence, although not a privileged religion. The contradiction in which the adherent of a particular religion finds himself involved in relation to his citizenship is only one aspect of the universal secular contradiction between the political state and civil society. The consummation of the Christian state is the state which acknowledges itself as a state and disregards the religion of its members. The emancipation of the state from religion is not the emancipation of the real man from religion. Therefore, we do not say to the Jews, as Bauer does: You cannot be emancipated politically without emancipating yourselves radically from Judaism. On the contrary, we tell them: Because you can be emancipated politically without renouncing Judaism completely and incontrovertibly, political emancipation itself is not human emancipation. If you Jews want to be emancipated politically, without emancipating yourselves humanly, the half-hearted approach and contradiction is not in you alone, it is inherent in the nature and category of political emancipation. If you find yourself within the confines of this category, you share in a general confinement. Just as the state evangelizes when, although it is a state, it adopts a Christian attitude towards the Jews, so the Jew acts politically when, although a Jew, he demands civic rights. [ * ] But, if a man, although a Jew, can be emancipated politically and receive civic rights, can he lay claim to the so-called rights of man and receive them? Bauer denies it. “The question is whether the Jew as such, that is, the Jew who himself admits that he is compelled by his true nature to live permanently in separation from other men, is capable of receiving the universal rights of man and of conceding them to others.” “For the Christian world, the idea of the rights of man was only discovered in the last century. It is not innate in men; on the contrary, it is gained only in a struggle against the historical traditions in which hitherto man was brought up. Thus the rights of man are not a gift of nature, not a legacy from past history, but the reward of the struggle against the accident of birth and against the privileges which up to now have been handed down by history from generation to generation. These rights are the result of culture, and only one who has earned and deserved them can possess them.” “Can the Jew really take possession of them? As long as he is a Jew, the restricted nature which makes him a Jew is bound to triumph over the human nature which should link him as a man with other men, and will separate him from non-Jews. He declares by this separation that the particular nature which makes him a Jew is his true, highest nature, before which human nature has to give way.” “Similarly, the Christian as a Christian cannot grant the rights of man.” (p. 19-20) According to Bauer, man has to sacrifice the “privilege of faith” to be able to receive the universal rights of man. Let us examine, for a moment, the so-called rights of man – to be precise, the rights of man in their authentic form, in the form which they have among those who discovered them, the North Americans and the French. These rights of man are, in part, political rights, rights which can only be exercised in community with others. Their content is participation in the community, and specifically in the political community, in the life of the state. They come within the category of political freedom, the category of civic rights, which, as we have seen, in no way presuppose the incontrovertible and positive abolition of religion – nor, therefore, of Judaism. There remains to be examined the other part of the rights of man – the droits de l’homme, insofar as these differ from the droits du citoyen. Included among them is freedom of conscience, the right to practice any religion one chooses. The privilege of faith is expressly recognized either as a right of man or as the consequence of a right of man, that of liberty. Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, 1791, Article 10: “No one is to be subjected to annoyance because of his opinions, even religious opinions.” “The freedom of every man to practice the religion of which he is an adherent.” Declaration of the Rights of Man, etc., 1793, includes among the rights of man, Article 7: “The free exercise of religion.” Indeed, in regard to man’s right to express his thoughts and opinions, to hold meetings, and to exercise his religion, it is even stated: “The necessity of proclaiming these rights presupposes either the existence or the recent memory of despotism.” Compare the Constitution of 1795, Section XIV, Article 354. Constitution of Pennsylvania, Article 9, § 3: “All men have received from nature the imprescriptible right to worship the Almighty according to the dictates of their conscience, and no one can be legally compelled to follow, establish, or support against his will any religion or religious ministry. No human authority can, in any circumstances, intervene in a matter of conscience or control the forces of the soul.” Constitution of New Hampshire, Article 5 and 6: “Among these natural rights some are by nature inalienable since nothing can replace them. The rights of conscience are among them.” (Beaumont, op. cit., pp. 213,214) Incompatibility between religion and the rights of man is to such a degree absent from the concept of the rights of man that, on the contrary, a man’s right to be religious, in any way he chooses, to practise his own particular religion, is expressly included among the rights of man. The privilege of faith is a universal right of man. The droits de l’homme, the rights of man, are, as such, distinct from the droits du citoyen, the rights of the citizen. Who is homme as distinct from citoyen? None other than the member of civil society. Why is the member of civil society called “man,” simply man; why are his rights called the rights of man? How is this fact to be explained? From the relationship between the political state and civil society, from the nature of political emancipation. Above all, we note the fact that the so-called rights of man, the droits de l’homme as distinct from the droits du citoyen, are nothing but the rights of a member of civil society – i.e., the rights of egoistic man, of man separated from other men and from the community. Let us hear what the most radical Constitution, the Constitution of 1793, has to say: Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Article 2. “These rights, etc., (the natural and imprescriptible rights) are: equality, liberty, security, property.” What constitutes liberty? Article 6. “Liberty is the power which man has to do everything that does not harm the rights of others,” or, according to the Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1791: “Liberty consists in being able to do everything which does not harm others.” Liberty, therefore, is the right to do everything that harms no one else. The limits within which anyone can act without harming someone else are defined by law, just as the boundary between two fields is determined by a boundary post. It is a question of the liberty of man as an isolated monad, withdrawn into himself. Why is the Jew, according to Bauer, incapable of acquiring the rights of man? “As long as he is a Jew, the restricted nature which makes him a Jew is bound to triumph over the human nature which should link him as a man with other men, and will separate him from non-Jews.” But, the right of man to liberty is based not on the association of man with man, but on the separation of man from man. It is the right of this separation, the right of the restricted individual, withdrawn into himself. The practical application of man’s right to liberty is man’s right to private property. What constitutes man’s right to private property? Article 16. (Constitution of 1793): “The right of property is that which every citizen has of enjoying and of disposing at his discretion of his goods and income, of the fruits of his labor and industry.” The right of man to private property is, therefore, the right to enjoy one’s property and to dispose of it at one’s discretion (à son gré), without regard to other men, independently of society, the right of self-interest. This individual liberty and its application form the basis of civil society. It makes every man see in other men not the realization of his own freedom, but the barrier to it. But, above all, it proclaims the right of man “of enjoying and of disposing at his discretion of his goods and income, of the fruits of his labor and industry.” There remain the other rights of man: égalité and sûreté. Equality, used here in its non-political sense, is nothing but the equality of the liberté described above – namely: each man is to the same extent regarded as such a self-sufficient monad. The Constitution of 1795 defines the concept of this equality, in accordance with this significance, as follows: Article 3 (Constitution of 1795): “Equality consists in the law being the same for all, whether it protects or punishes.” And security? Article 8 (Constitution of 1793): “Security consists in the protection afforded by society to each of its members for the preservation of his person, his rights, and his property.” Security is the highest social concept of civil society, the concept of police, expressing the fact that the whole of society exists only in order to guarantee to each of its members the preservation of his person, his rights, and his property. It is in this sense that Hegel calls civil society “the state of need and reason.” The concept of security does not raise civil society above its egoism. On the contrary, security is the insurance of egoism. None of the so-called rights of man, therefore, go beyond egoistic man, beyond man as a member of civil society – that is, an individual withdrawn into himself, into the confines of his private interests and private caprice, and separated from the community. In the rights of man, he is far from being conceived as a species-being; on the contrary, species-life itself, society, appears as a framework external to the individuals, as a restriction of their original independence. The sole bond holding them together is natural necessity, need and private interest, the preservation of their property and their egoistic selves. It is puzzling enough that a people which is just beginning to liberate itself, to tear down all the barriers between its various sections, and to establish a political community, that such a people solemnly proclaims (Declaration of 1791) the rights of egoistic man separated from his fellow men and from the community, and that indeed it repeats this proclamation at a moment when only the most heroic devotion can save the nation, and is therefore imperatively called for, at a moment when the sacrifice of all the interest of civil society must be the order of the day, and egoism must be punished as a crime. (Declaration of the Rights of Man, etc., of 1793) This fact becomes still more puzzling when we see that the political emancipators go so far as to reduce citizenship, and the political community, to a mere means for maintaining these so-called rights of man, that, therefore, the citoyen is declared to be the servant of egotistic homme, that the sphere in which man acts as a communal being is degraded to a level below the sphere in which he acts as a partial being, and that, finally, it is not man as citoyen, but man as private individual [bourgeois] who is considered to be the essential and true man. “The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man.” (Declaration of the Rights, etc., of 1791, Article 2) “Government is instituted in order to guarantee man the enjoyment of his natural and imprescriptible rights.” (Declaration, etc., of 1793, Article 1) Hence, even in moments when its enthusiasm still has the freshness of youth and is intensified to an extreme degree by the force of circumstances, political life declares itself to be a mere means, whose purpose is the life of civil society. It is true that its revolutionary practice is in flagrant contradiction with its theory. Whereas, for example, security is declared one of the rights of man, violation of the privacy of correspondence is openly declared to be the order of the day. Whereas “unlimited freedom of the press” (Constitution of 1793, Article 122) is guaranteed as a consequence of the right of man to individual liberty, freedom of the press is totally destroyed, because “freedom of the press should not be permitted when it endangers public liberty.” (“Robespierre jeune,” Historie parlementaire de la Révolution française by Buchez and Roux, vol.28, p. 159) That is to say, therefore: The right of man to liberty ceases to be a right as soon as it comes into conflict with political life, whereas in theory political life is only the guarantee of human rights, the rights of the individual, and therefore must be abandoned as soon as it comes into contradiction with its aim, with these rights of man. But, practice is merely the exception, theory is the rule. But even if one were to regard revolutionary practice as the correct presentation of the relationship, there would still remain the puzzle of why the relationship is turned upside-down in the minds of the political emancipators and the aim appears as the means, while the means appears as the aim. This optical illusion of their consciousness would still remain a puzzle, although now a psychological, a theoretical puzzle. The puzzle is easily solved. Political emancipation is, at the same time, the dissolution of the old society on which the state alienated from the people, the sovereign power, is based. What was the character of the old society? It can be described in one word – feudalism. The character of the old civil society was directly political – that is to say, the elements of civil life, for example, property, or the family, or the mode of labor, were raised to the level of elements of political life in the form of seigniory, estates, and corporations. In this form, they determined the relation of the individual to the state as a whole – i.e., his political relation, that is, his relation of separation and exclusion from the other components of society. For that organization of national life did not raise property or labor to the level of social elements; on the contrary, it completed their separation from the state as a whole and constituted them as discrete societies within society. Thus, the vital functions and conditions of life of civil society remained, nevertheless, political, although political in the feudal sense – that is to say, they secluded the individual from the state as a whole and they converted the particular relation of his corporation to the state as a whole into his general relation to the life of the nation, just as they converted his particular civil activity and situation into his general activity and situation. As a result of this organization, the unity of the state, and also the consciousness, will, and activity of this unity, the general power of the state, are likewise bound to appear as the particular affair of a ruler and of his servants, isolated from the people. The political revolution which overthrew this sovereign power and raised state affairs to become affairs of the people, which constituted the political state as a matter of general concern, that is, as a real state, necessarily smashed all estates, corporations, guilds, and privileges, since they were all manifestations of the separation of the people from the community. The political revolution thereby abolished the political character of civil society. It broke up civil society into its simple component parts; on the one hand, the individuals; on the other hand, the material and spiritual elements constituting the content of the life and social position of these individuals. It set free the political spirit, which had been, as it were, split up, partitioned, and dispersed in the various blind alleys of feudal society. It gathered the dispersed parts of the political spirit, freed it from its intermixture with civil life, and established it as the sphere of the community, the general concern of the nation, ideally independent of those particular elements of civil life. A person’s distinct activity and distinct situation in life were reduced to a merely individual significance. They no longer constituted the general relation of the individual to the state as a whole. Public affairs as such, on the other hand, became the general affair of each individual, and the political function became the individual’s general function. But, the completion of the idealism of the state was at the same time the completion of the materialism of civil society. Throwing off the political yoke meant at the same time throwing off the bonds which restrained the egoistic spirit of civil society. Political emancipation was, at the same time, the emancipation of civil society from politics, from having even the semblance of a universal content. Feudal society was resolved into its basic element – man, but man as he really formed its basis – egoistic man. This man, the member of civil society, is thus the basis, the precondition, of the political state. He is recognized as such by this state in the rights of man. The liberty of egoistic man and the recognition of this liberty, however, is rather the recognition of the unrestrained movement of the spiritual and material elements which form the content of his life. Hence, man was not freed from religion, he received religious freedom. He was not freed from property, he received freedom to own property. He was not freed from the egoism of business, he received freedom to engage in business. The establishment of the political state and the dissolution of civil society into independent individuals – whose relation with one another epend on law, just as the relations of men in the system of estates and guilds depended on privilege – is accomplished by one and the same act. Man as a member of civil society, unpolitical man, inevitably appears, however, as the natural man. The “rights of man” appears as “natural rights,” because conscious activity is concentrated on the political act. Egoistic man is the passive result of the dissolved society, a result that is simply found in existence, an object of immediate certainty, therefore a natural object. The political revolution resolves civil life into its component parts, without revolutionizing these components themselves or subjecting them to criticism. It regards civil society, the world of needs, labor, private interests, civil law, as the basis of its existence, as a precondition not requiring further substantiation and therefore as its natural basis. Finally, man as a member of civil society is held to be man in the proper sense, homme as distinct from citoyen, because he is man in his sensuous, individual, immediate existence, whereas political man is only abstract, artificial man, man as an allegorical, juridical person. The real man is recognized only in the shape of the egoistic individual, the true man is recognized only in the shape of the abstract citizen. Therefore, Rousseau correctly described the abstract idea of political man as follows: “Whoever dares undertake to establish a people’s institutions must feel himself capable of changing, as it were, human nature, of transforming each individual, who by himself is a complete and solitary whole, into a part of a larger whole, from which, in a sense, the individual receives his life and his being, of substituting a limited and mental existence for the physical and independent existence. He has to take from man his own powers, and give him in exchange alien powers which he cannot employ without the help of other men.” All emancipation is a reduction of the human world and relationships to man himself. Political emancipation is the reduction of man, on the one hand, to a member of civil society, to an egoistic, independent individual, and, on the other hand, to a citizen, a juridical person. Only when the real, individual man re-absorbs in himself the abstract citizen, and as an individual human being has become a species-being in his everyday life, in his particular work, and in his particular situation, only when man has recognized and organized his “own powers” as social powers, and, consequently, no longer separates social power from himself in the shape of political power, only then will human emancipation have been accomplished. |