ジョン・ロックの哲学

John Locke's Philosophy

☆ジョン・ロック(John Locke、1632 年8月29日 - 1704年10月28日)は、イギリスの哲学者。哲学者としては、イギリス経験論の父と呼ばれ、主著『人間悟性論』(『人間知性論』)において経験論的認 識論を体系化した。また、「自由主義の父」とも呼ばれ[2][3][4]、政治哲学者としての側面も非常に有名である。『統治二論』などにおける彼の政治 思想は名誉革命を理論的に正当化するものとなり、その中で示された社会契約や抵抗権についての考えはアメリカ独立宣言、フランス人権宣言に大きな影響を与 えた(→政治については「ジョン・ロックの政治哲学」を参照)。

| Slavery and child labour Locke's views on slavery were multifaceted and complex. Although he wrote against slavery in general, Locke was an investor and beneficiary of the slave trading Royal Africa Company. In addition, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy and gave Carolinian planters absolute power over their enslaved chattel property; the constitutions pledged that "every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves". Philosopher Martin Cohen notes that Locke, as secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations and a member of the Board of Trade, was "one of just half a dozen men who created and supervised both the colonies and their iniquitous systems of servitude".[42][43] According to American historian James Farr, Locke never expressed any thoughts concerning his contradictory opinions regarding slavery, which Farr ascribes to his personal involvement in the slave trade.[44] Locke's positions on slavery have been described as hypocritical, and laying the foundation for the Founding Fathers to hold similarly contradictory thoughts regarding freedom and slavery.[45] Locke also drafted implementing instructions for the Carolina colonists designed to ensure that settlement and development was consistent with the Fundamental Constitutions. Collectively, these documents are known as the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina.[citation needed] Historian Holly Brewer has argued, however, that Locke's role in the Constitution of Carolina has been exaggerated and that he was merely paid to revise and make copies of a document that had already been partially written before he became involved; she compares Locke's role to a lawyer writing a will.[46] She further notes that Locke was paid in Royal African Company stock in lieu of money for his work as a secretary for a governmental sub-committee and that he sold the stock after only a few years.[47] Brewer likewise argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Trade created by William of Orange following the Glorious Revolution. He specifically attacked colonial policy granting land to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian education of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slavery—that they were heathens that possessed no rights.[48] Locke also supported child labour. In his "Essay on the Poor Law", he turns to the education of the poor; he laments that "the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old".[49]: 190 He suggests, therefore, that "working schools" be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be "from infancy [three years old] inured to work".[49]: 190 He goes on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they will be profitable for the parish, but also that they will instill a good work ethic in the children.[49]: 191 |

奴隷制と児童労働 ロックの奴隷制度に対する考え方は多面的で複雑であった。ロックは奴隷制度に反対していたが、奴隷貿易会社であるロイヤル・アフリカ会社の出資者であり、 その恩恵を受けていた。この憲法では、「カロライナのすべての自由民は、その黒人奴隷に対して絶対的な権力と権威を持つ」ことがうたわれている。哲学者の マーティン・コーエンは、ロックが貿易・農園評議会の秘書として、また貿易委員会のメンバーとして、「植民地とその不義な隷属制度の両方を作り、監督した わずか6人のうちの1人」であると指摘している[42][43]。アメリカの歴史家ジェームズ・ファーによれば、ロックは奴隷制に関する彼の矛盾した意見 について考えを示すことはなく、ファーが奴隷貿易への彼の個人的関与によるものとしている[44]。 [ロックはまた、カロライナ植民者のために、入植と開発が基本憲法と一致することを保証するための実施要領を起草した[45]。これらの文書はまとめて、 カロライナ州のグランドモデルとして知られている[citation needed]。 しかし、歴史家のホリー・ブリューワーは、カロライナ憲法におけるロックの役割は誇張されており、ロックが関与する前にすでに部分的に書かれていた文書の 改訂とコピーを作るために支払われただけだと主張し、ロックの役割を遺言書を書く弁護士に例えている[46]。 [さらに、ロックは政府の小委員会の秘書としての仕事に対して、お金の代わりにロイヤル・アフリカ会社の株で支払われ、その株は数年後に売却したと述べて いる[47]。ブリュワーは同様に、ロックが栄光革命後にオレンジ公ウィリアムが設立した貿易委員会を率いながらバージニア州の奴隷制度を弱めるために活 発に働いたと主張している。彼は特に奴隷所有者に土地を与える植民地政策を攻撃し、奴隷にされたアフリカ人の子供たちに洗礼とキリスト教教育を奨励し、彼 らが権利を持たない異教徒であるという奴隷制の主要な正当性を弱体化させた[48]。 ロックはまた児童労働を支持していた。彼は「貧民法に関するエッセイ」において、貧民の教育に目を向け、「労働者の子どもは教区にとって普通の負担であ り、通常怠惰に維持されているため、彼らの労働も一般的には12歳か14歳になるまで失われる」ことを嘆いている[49]。 したがって、彼は、貧しい子 供たちのために、イングランドの各教区に「労働学校」を設立し、彼らが「乳児(3歳)から労働に慣れるようにする」ことを提案する[49]。 190 彼はさらにこれらの学校の経済的な概要を述べ、教区にとって有益であるばかりでなく、子供たちに優れた労働倫理を身につけさせることができると主張する [49]。 191 |

| Accumulation of wealth According to Locke, unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature,[54] but, with the introduction of "durable" goods, men could exchange their excessive perishable goods for those which would last longer and thus not offend the natural law. In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage.[55] He also includes gold or silver as money because they may be "hoarded up without injury to anyone",[56] as they do not spoil or decay in the hands of the possessor. In his view, the introduction of money eliminates limits to accumulation. Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating property. Locke is aware of a problem posed by unlimited accumulation, but does not consider it his task. He just implies that government would function to moderate the conflict between the unlimited accumulation of property and a more nearly equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem. However, not all elements of his thought form a consistent whole. For example, the labour theory of value in the Two Treatises of Government stands side by side with the demand-and-supply theory of value developed in a letter he wrote titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money. Moreover, Locke anchors property in labour but, in the end, upholds unlimited accumulation of wealth.[57] |

富の蓄積 ロックによれば、未使用の財産は浪費であり、自然に対する違反であるが[54]、「耐久財」の導入によって、人間は過剰な腐敗する財をより長持ちする財と 交換することができ、したがって自然法則に違反することがない。彼の見解では、貨幣の導入はこのプロセスの頂点であり、腐敗による浪費を引き起こすことな く財産の無制限の蓄積を可能にした[55]。また彼は金や銀を貨幣として含んでいるが、それはそれらが所有者の手の中で腐敗したり腐ったりしないので「誰 にも害を与えずにため込む」ことができる[56]からであった。彼の見解では、貨幣の導入は蓄積に対する制限をなくすものである。ロックは、不平等が市民 社会を確立する社会契約や財産を規制する土地法によってではなく、貨幣の使用に関する暗黙の合意によってもたらされたことを強調している。ロックは、無制 限の蓄積がもたらす問題を認識しているが、それを自分の課題とは考えていない。彼は、無制限の財産の蓄積とより平等な富の分配との間の対立を緩和するため に政府が機能することを示唆するだけで、この問題を解決するために政府が適用すべき原則を特定することはしていない。しかし、彼の思想のすべての要素が一 貫して全体を形成しているわけではない。例えば、『政体論』における労働価値説は、『利子の低下と貨幣価値の上昇の結果に関する若干の考察』と題する書簡 で展開された需要供給価値説と並存しているのである。さらに、ロックは財産を労働に固定するが、最終的には富の無制限な蓄積を支持する[57]。 |

| Economics On price theory Locke's general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory, set out in a letter to a member of parliament in 1691, titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money.[58] In it, he refers to supply as quantity and demand as rent: "The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers" and "that which regulates the price…[of goods] is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent." The quantity theory of money forms a special case of this general theory. His idea is based on "money answers all things" (Ecclesiastes) or "rent of money is always sufficient, or more than enough" and "varies very little". Locke concludes that, as far as money is concerned, the demand for it is exclusively regulated by its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains demand for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation, such as of land, which has value because "by its constant production of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income". He considers the demand for money as almost the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether money is wanted as medium of exchange. As a medium of exchange, he states, "money is capable by exchange to procure us the necessaries or conveniences of life" and, for loanable funds, "it comes to be of the same nature with land by yielding a certain yearly income…or interest". |

経済学 価格理論について ロックは、1691年に国会議員に宛てた書簡「利子の低下と貨幣価値の上昇の結果に関する若干の考察」の中で、供給を量、需要を家賃とし、「あらゆる商品 の価格は、買い手と売り手の数の割合によって上昇または下落する」、「価格・・・(商品)を調節するものは、その家賃に比例した量に他ならない」と言って いる[58] 。 貨幣数量説は、この一般理論の特殊なケースを形成している。彼の考えは、「貨幣は万物に答える」(『伝道者の書』)、あるいは「貨幣の賃借料は常に十分 か、あるいは十二分にある」、「ほとんど変化しない」ことに基づくものである。ロックは、貨幣に関する限り、その需要が無制限であるか一定であるかにかか わらず、その量によって排他的に規制されると結論付けている。彼はまた、需要と供給の決定要因についても調査している。供給については、財の価値は、その 希少性と交換・消費される能力に基づいていると説明する。また、財の需要については、財が所得の流れを生み出す能力に基づいて説明する。ロックは、「販売 可能な商品を絶えず生産することによって、一定の年間所得をもたらす」ために価値を持つ土地などの資本化に関する初期の理論を展開している。彼は、貨幣の 需要は、財や土地の需要とほとんど同じであり、貨幣が交換媒体として必要とされるかどうかにかかっていると考えている。交換媒体としては、「貨幣は交換に よって生活必需品や便益を調達することができる」とし、貸付可能な資金としては、「一定の年収...あるいは利子をもたらすことによって、土地と同じ性質 を持つようになる」と述べている。 |

| Monetary thoughts Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a counter to measure value, and as a pledge to lay claim to goods. He believes that silver and gold, as opposed to paper money, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which issues it. Locke argues that a country should seek a favourable balance of trade, lest it fall behind other countries and suffer a loss in its trade. Since the world money stock grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its own stock. Locke develops his theory of foreign exchanges, in addition to commodity movements, there are also movements in country stock of money, and movements of capital determine exchange rates. He considers the latter less significant and less volatile than commodity movements. As for a country's money stock, if it is large relative to that of other countries, he says it will cause the country's exchange to rise above par, as an export balance would do. He also prepares estimates of the cash requirements for different economic groups (landholders, labourers, and brokers). In each group he posits that the cash requirements are closely related to the length of the pay period. He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, have a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.[citation needed] |

貨幣思想 ロックは、貨幣の機能を、価値を計るためのカウンターとしての機能と、財を要求するための質料としての機能の二つに分類している。彼は、国際的な取引には 紙幣ではなく、銀と金が適切な通貨であると考える。銀と金は人類が等しく価値を持つものとして扱われるため、誰にでも質草として扱うことができるが、紙幣 の価値はそれを発行する政府の下でのみ有効である、と彼は言っている。 ロックは、一国は他国に遅れをとって貿易で損をしないように、有利な貿易収支を追求すべきだと主張する。世界の貨幣在庫は絶えず増加するので、一国は常に 自国の貨幣在庫を増加させようとしなければならない。ロックは外国為替に関する理論を展開し、商品の動きだけでなく、国の貨幣ストックの動きもあり、資本 の動きが為替レートを決定するとした。彼は、後者については、商品の動きよりも重要性が低く、変動も少ないと考えている。マネーストックについては、他国 のマネーストックと比較して大きい場合、輸出収支のように為替が額面以上に上昇する原因になるという。 また、経済グループ別(土地所有者、労働者、仲介業者)の現金必要量の試算も行っている。それぞれのグループにおいて、現金必要額は給与期間の長さと密接 な関係があると仮定している。彼は、仲介者-その活動が貨幣回路を拡大し、その利益が労働者や土地所有者の収入を食い潰すため、個人と彼らが貢献している はずの公共経済の両方に悪影響を及ぼすと主張している[citation needed]。 |

| Theory of value and property Locke uses the concept of property in both broad and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to material goods. He argues that property is a natural right that is derived from labour. In Chapter V of his Second Treatise, Locke argues that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce such goods—"at least where there is enough [land], and as good, left in common for others" (para. 27)—or to use property to produce goods beneficial to human society.[59] Locke states in his Second Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a labour theory of value,[59] Locke developed a labour theory of property, whereby ownership of property is created by the application of labour. In addition, he believed that property precedes government and government cannot "dispose of the estates of the subjects arbitrarily". Karl Marx later critiqued Locke's theory of property in his own social theory.[citation needed] |

価値と財産の理論 ロックは、財産という概念を広義にも狭義にも用いている。広義には、人間の利益や願望を幅広くカバーし、より狭義には、物質的な財を指している。彼は、財 産は労働に由来する自然権であると主張する。第二論文集の第五章において、ロックは財と財産の個人の所有は、そのような財を生産するために発揮される労働 -「少なくとも、十分な(土地)、そして善として、他人のために共有で残される場合」(パラグラフ27)、または人間社会に有益な財を生産するために財産 を使用するために発揮される労働によって正当化されると論じている[59]。 ロックは『第二論』において、自然はそれ自体では社会に対してほとんど価値を提供しないと述べており、財の創造に費やされる労働がその価値を与えることを 暗示している。この前提から、ロックは価値の労働理論として理解し[59]、財産の所有は労働の適用によって生み出されるという財産の労働理論を展開し た。さらに彼は、財産は政府に先行し、政府は「臣民の財産を恣意的に処分する」ことができないと考えた。カール・マルクスは後に、自身の社会理論において ロックの財産論を批判した[citation needed]。 |

| The self Locke defines the self as "that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, made up of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends".[60] He does not, however, wholly ignore "substance", writing that "the body too goes to the making the man".[61] In his Essay, Locke explains the gradual unfolding of this conscious mind. Arguing against both the Augustinian view of man as originally sinful and the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows basic logical propositions, Locke posits an 'empty mind', a tabula rasa, which is shaped by experience; sensations and reflections being the two sources of all of our ideas.[62] He states in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding: This source of ideas every man has wholly within himself; and though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called 'internal sense.'[63] Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education is an outline on how to educate this mind. Drawing on thoughts expressed in letters written to Mary Clarke and her husband about their son,[64] he expresses the belief that education makes the man—or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty cabinet":[65] I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education. Locke also wrote that "the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences".[65] He argues that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other".[66] This theory came to be called associationism, going on to strongly influence 18th-century thought, particularly educational theory, as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749). Dream argument Locke was critical of Descartes's version of the dream argument, with Locke making the counter-argument that people cannot have physical pain in dreams as they do in waking life.[67] |

自己 ロックは自己を「意識的に考えるもの、(精神的であろうと物質的であろうと、単純であろうと複合的であろうと、どんな物質で構成されていようと関係ない) 感覚を持ち、喜びと痛みを意識し、幸福と不幸を可能にし、その意識が及ぶ限り、自分自身に関心を持つ」と定義している[60]。 しかし彼は「肉体も人間を作るために行く」、と書いていて完全に「物質」を無視はしていない[61]。 ロックは『エッセイ』の中で、この意識的な心が徐々に展開されることを説明している。ロックは『人間の理解に関するエッセイ』の中で、人間をもともと罪深 いものとするアウグスティヌス派の見解と、人間が基本的な論理命題を生得的に知っているとするデカルト派の立場の両方に反論して、経験によって形作られる 「空の心」、タブラ・ラサ、感覚と反射が人間のすべての考えの二つの源であると仮定している[62]。 この発想の源はすべての人が完全に自分の中に持っており、それは外部の対象とは何の関係もないので感覚ではないが、しかしそれに非常に似ており、適切に十 分に「内的感覚」と呼ばれるかもしれない[63]」。 ロックの『教育に関するいくつかの考え』は、この心をどのように教育するかについての概要である。メアリー・クラークとその夫に息子について書かれた手紙 に表現された考えを引き合いに出して、彼は教育が人間を作るという信念、より根本的には心が「空のキャビネット」であるという信念を表明している [64]:[65]。 私たちが出会うすべての人間のうち、10人のうち9人は教育によって、善であれ悪であれ、有用であれそうでないものであると言うことができると思う」。 ロックはまた、「幼少期の小さな、ほとんど気づかないような印象が非常に重要で永続的な結果をもたらす」と書いており[65]、幼少期に作る「考えの連 想」が後に作るものよりも重要であると論じている、それはそれが自己の基盤であり、別の言葉で言えば、それが最初にタブラ・ラサをマークするものだからで ある。この両方の概念が導入された『エッセイ』において、ロックは例えば「愚かな女中」が子供に「妖怪や精霊」が夜と関連していると信じ込ませることに対 して警告しており、「暗闇はその後、それらの恐ろしい考えをもたらすであろうし、それらはとても結合されて、彼は他よりも一方に耐えられなくなるだろうか ら」と述べている[66]。 この理論は連合主義と呼ばれるようになり、18世紀の思想、特に教育論に強い影響を与えるようになり、ほぼすべての教育作家が子供に負の連想を持たせない ように親に警告していた。また、デイヴィッド・ハートリーが『人間観察』(1749年)で連合論の生物学的メカニズムを発見しようとしたことで、心理学な どの新しい学問の発展にもつながった。 夢の議論 ロックはデカルト版の夢論に批判的であり、ロックは夢の中で人は起きている時のような肉体的苦痛を持つことはできないという反論を行った[67]。 |

| Religion Religious beliefs Some scholars have seen Locke's political convictions as being based from his religious beliefs.[68][69][70] Locke's religious trajectory began in Calvinist trinitarianism, but by the time of the Reflections (1695) Locke was advocating not just Socinian views on tolerance but also Socinian Christology.[71] However Wainwright (1987) notes that in the posthumously published Paraphrase (1707) Locke's interpretation of one verse, Ephesians 1:10, is markedly different from that of Socinians like Biddle, and may indicate that near the end of his life Locke returned nearer to an Arian position, thereby accepting Christ's pre-existence.[72][71] Locke was at times not sure about the subject of original sin, so he was accused of Socinianism, Arianism, or Deism.[73] Locke argued that the idea that "all Adam's Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Infinite Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam" was "little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Great and Infinite God", leading Eric Nelson to associate him with Pelagian ideas.[74] However, he did not deny the reality of evil. Man was capable of waging unjust wars and committing crimes. Criminals had to be punished, even with the death penalty.[75] With regard to the Bible, Locke was very conservative. He retained the doctrine of the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures.[36] The miracles were proof of the divine nature of the biblical message. Locke was convinced that the entire content of the Bible was in agreement with human reason (The Reasonableness of Christianity, 1695).[76][36] Although Locke was an advocate of tolerance, he urged the authorities not to tolerate atheism, because he thought the denial of God's existence would undermine the social order and lead to chaos.[77] That excluded all atheistic varieties of philosophy and all attempts to deduce ethics and natural law from purely secular premises.[78] In Locke's opinion the cosmological argument was valid and proved God's existence. His political thought was based on Protestant Christian views.[78][79] Additionally, Locke advocated a sense of piety out of gratitude to God for giving reason to men.[80] Philosophy from religion Locke's concept of man started with the belief in creation.[81] Like philosophers Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf, Locke equated natural law with the biblical revelation.[82][83][84] Locke derived the fundamental concepts of his political theory from biblical texts, in particular from Genesis 1 and 2 (creation), the Decalogue, the Golden Rule, the teachings of Jesus, and the letters of Paul the Apostle.[85] The Decalogue puts a person's life, reputation and property under God's protection. Locke's philosophy on freedom is also derived from the Bible. Locke derived from the Bible basic human equality (including equality of the sexes), the starting point of the theological doctrine of Imago Dei.[86] To Locke, one of the consequences of the principle of equality was that all humans were created equally free and therefore governments needed the consent of the governed.[87] Locke compared the English monarchy's rule over the British people to Adam's rule over Eve in Genesis, which was appointed by God.[88] Following Locke's philosophy, the American Declaration of Independence founded human rights partially on the biblical belief in creation. Locke's doctrine that governments need the consent of the governed is also central to the Declaration of Independence.[89 |

宗教 宗教的信念 ある学者はロックの政治的信念が彼の宗教的信念に基づいていると見ている[68][69][70]。ロックの宗教的軌道はカルビン主義の三位一体論で始 まったが、『反省』(1695年)の時点でロックは寛容に関するソシン派の見解だけでなくソシン派のキリスト論も提唱していた[71]。 しかし、ウェインライト(1987)は、死後に出版された『パラフレーズ』(1707)において、エフェソ1:10という一節に対するロックの解釈がビド ルなどのソシン派の解釈と著しく異なっており、ロックが晩年近くにアリウス派の立場に戻り、キリストの前世を受け入れたことを示していると指摘している [71][82]。 [ロックは、「すべてのアダムの子孫は、アダムの違反のために、永遠の無限の刑罰を受ける運命にある」という考えは、「偉大で無限の神の正義や善意とほと んど一致しない」と主張し、エリック・ネルソンにペラギウス思想と関連づけさせた[74]。 しかし彼は悪の実在を否定していなかった。人間は不当な戦争を行い、犯罪を犯すことができた。犯罪者は死刑であっても罰せられなければならなかった [75]。 聖書に関して、ロックは非常に保守的であった。彼は聖書の言語的霊感の教義を保持していた[36]。奇跡は聖書のメッセージの神性を証明するものであっ た。ロックは聖書の内容全体が人間の理性と一致していると確信していた(The Reasonableness of Christianity, 1695)[76][36]ロックは寛容を提唱していたが、彼は神の存在の否定が社会秩序を損ない混沌に導くと考えて、無神論を許容しないよう当局に強く 求めていた。 [それは哲学のすべての無神論的な種類と純粋に世俗的な前提から倫理と自然法を演繹するすべての試みを除外した[78]。ロックの意見では、宇宙論的議論 は有効であり、神の存在を証明するものであった。彼の政治思想はプロテスタントのキリスト教の見解に基づいていた[78][79]。 さらにロックは人間に理性を与えてくれた神への感謝から敬虔な感覚を提唱していた[80]。 宗教からの哲学 哲学者フーゴ・グロティウスやサミュエル・プフェンドルフと同様に、ロックは自然法を聖書の啓示と同一視していた[82][83][84]。ロックは彼の 政治理論の基本概念を聖書のテキストから、特に創世記1および2(創造)、デカログ、黄金律、イエスの教え、使徒パウロの書状から導き出した[85]。デ カログは人の生命、評判、財産を神の保護下に置いていた。 自由に関するロックの哲学もまた聖書に由来している。ロックは神学的教義であるイマゴ・デイの出発点である基本的な人間の平等(男女の平等を含む)を聖書 から導き出した[86]。ロックにとって、平等原則の結果の1つは、すべての人間が平等に自由に創造されており、それゆえ政府は被治者の同意を必要とする ということだった[87]。 ロックはイギリス王政がイギリス国民に対して行った支配を、創世記における神が定めたアダムのイヴに対する支配と比較した[88]。 ロックの哲学に続いて、アメリカの独立宣言は創造における聖書の信仰に部分的に人権を創設した。政府が被治者の同意を必要とするというロックの教義はまた 独立宣言の中心である[89]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke. |

|

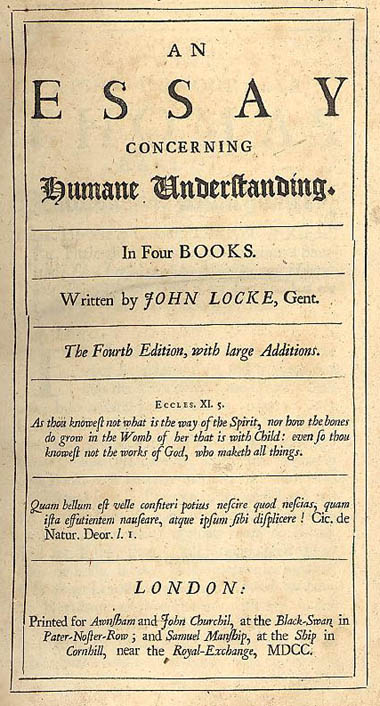

| 『人間知性論』(にんげんちせいろん、(英: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding)は、1689年に出版された、イギリスの哲学者ジョン・ロックの哲学書。ロックは20年かけてこの著作を書き上げ、近代イギリス経験論の確立に寄与した。旧訳は『人間悟性論』。 |

|

| 構成 本書の構成は、以下の通り。 導入部 : 読者への手紙、序論 第1篇: 原理(principles)や観念(ideas)は、いずれも生得的(innate)ではない 第1章 生得の理論的(推論的)原理(speculatvie principles)は無い 第2章 生得の実践的原理(practical principles)は無い 第3章 理論的(推論的)・実践的な生得原理に関する余論 第2篇: 観念(ideas)について 第1章 観念一般、及びその起源について 第2章 単純観念(simple ideas)について 第3章 単感覚(sense)の単純観念について 第4章 固性(solidity)の観念 第5章 多感覚(divers senses)の単純観念について 第6章 内省(reflection)の単純観念について 第7章 感覚・内省双方の単純観念について 第8章 感覚の単純観念に関する補論 第9章 知覚(perception)について 第10章 保持(retention)について 第11章 識別(discerning)、及びその他の心的作用について 第12章 複雑観念(complex ideas)について 第13章 単純様相(simple modes)の複雑観念 --- まず空間(space)観念の単純様相について 第14章 持続(duration)観念と、その単純様相 第15章 持続と拡張(expansion)の観念を合わせた考察 第16章 数(number)の観念 第17章 無限(infinity)について 第18章 他の単純様相 第19章 思考(thinking)の様相について 第20章 快(pleasure)と苦(pain)の様相について 第21章 力(power)について 第22章 混合様相(mixed modes)について 第23章 実体(substances)の複雑観念について 第24章 実体(substances)の集合観念(collective ideas)について 第25章 関係(relation)について 第26章 原因(cause)と効果(effect)、他の関係について 第27章 同一性(identity)と多様性(diversity)について 第28章 他の関係について 第29章 明瞭(clear)・不明瞭(obscure)、明確(distinct)・混乱(confused)的な観念について 第30章 実在的(real)・空想的(fantastical)な観念について 第31章 十分(adequate)・不十分(inadequate)な観念について 第32章 真(true)・偽(false)的な観念について 第33章 観念の連合(association)について 第3篇: 言葉(words)について 第1章 言葉と言語(language)一般について 第2章 言葉の意味表示(signification)について 第3章 一般名辞(general terms)について 第4章 単純観念の名前(names)について 第5章 混合様相と関係の名前について 第6章 実体の名前について 第7章 不変化詞(particles)について 第8章 抽象的(abstract)・具体的(concrete)な名辞について 第9章 言葉の不完全性(imperfection)について 第10章 言葉の誤用(abuse)について 第11章 前途の不完全性(foregoing imperfection)と誤用の救済(remedies)について 第4篇: 知識(knowledge)と蓋然性(probability)について 第1章 知識一般について 第2章 我々の知識の程度(degrees)について 第3章 人知の範囲(extent)について 第4章 知識の真実性(reality)について 第5章 真理(truth)一般について 第6章 普遍的命題(universal propositions)、その真理と確実性(certainty)について 第7章 公準(maxims)について 第8章 無価値な命題(trifling propositions)について 第9章 存在(exstense)に関する我々の3様(threefold )の知識について 第10章 神(God)の存在に関する我々の知識について 第11章 他の事物の存在に関する我々の知識について 第12章 我々の知識の改善(improvement)について 第13章 我々の知識についての補論 第14章 判断(judgement)について 第15章 蓋然性について 第16章 同意(assent)の程度について 第17章 理性(reason)について 第18章 信仰(faith)と理性、及びそれらと区別される領域(provinces)について 第19章 狂信(enthusiasm)について 第20章 間違った同意(wrong assent)もしくは錯誤(error)について 第21章 学(sciences)の区分(division)について |

|

| 主題 本書の中心的な主題は人間の知識である。人間の知識がどれほどの範囲内において確実性を持ちうるのかを明らかにすることが重要な問題であり、ロックは内省 的方法によってこの問題の研究を行っている。このことによって、ロックは人間の理解がどのような対象を扱うのに適しており、またどのような対象には適して いないのかを明らかにすることを試みる。 つまり本書『人間悟性論』はあらゆる事柄を明らかにすることではなく、人間の行為に関連するものを知ることを研究の目標としている。ロックは基本的な視座 として知識の限界を識別することで悟性を観察対象とする。そして観念が発生する起源、悟性が観念により得る知識の性質と範囲、そして信仰や見解の根源につ いて順に検討する。 ロックは生得論を批判し、観念が発生する以前の心の状態が白紙(タブラ・ラーサ)であると考えた。あらかじめ感性のうちに存しなかったものは、知性のうち に存しないのである。観念はそれ自体が複雑なものであっても、すべて経験に由来するものであると捉えられる。つまり、外界から得られた感覚現象とそれへの 心理的作用により観念は発生しており、それが悟性に材料を提供している。観念には「単純観念」とそれを組み合わせた「複合観念」があり、その内容には物体 の客体的性質と物体に対する主観的内容が含まれる。 ロックは客体的性質について「第一性質」と呼んで個体性、延長、形状、運動、数量などの単純観念を生み出すが、後者は第一性質が人間にもたらす作用に過ぎ ない。観念の記憶として言語があり、ロックは言語を観念の典型的または抽象的な形態として使用させる手段として把握する。知識は観念よりもさらに限定的な ものであり、観念と一致または不一致の知覚である。このようなロックの議論は経験論の立場から知識の源泉である観念の発生とその形式や内容について明らか にし、言語や知識との関係性について説明を試みている。 |

|

| 仏語翻訳の影響 フランスのピエール・コスト(フランス語版) (1668-1747) による『人間悟性論』のフランス語訳は1700年に出版された。この翻訳本によってジョン・ロックの経験論はヨーロッパ大陸へ普及した。『人間知性新論』 を書いたドイツ人ライプニッツや、ジョン・ロックの経験論をフランスに根付かせたコンディヤックもオリジナルの英語本ではなく、コストのフランス語翻訳本 で学んだ。イギリスに滞在してロックと交流のあったコストは、フランス語訳を刊行するにあたりジョン・ロック自身の校閲を受けた(ロックは4年間フランス で過ごしていてフランス語ができた)。ただこの書にはロック独自の用語やmindとsoulの微妙な使い分けなど、フランス語で正確に対応する語彙のない 箇所もあったがコストは版を重ねながら改善を続けた。ボイルやニュートンなどイギリスの自然科学はすでにヨーロッパ大陸に伝わって多大な影響を及ぼしてい たが、このコストのフランス語訳があってはじめてイギリスの経験論も大陸で幅広く認識されたといっていい。[1] |

|

| 日本語訳 『悟性論』八太舟三訳、春秋社 1930年 『人間悟性論』岩波文庫復刻版 加藤卯一郎訳、一穂社 2005年 『人間悟性論』上下巻 加藤卯一郎訳、岩波書店 1940年 『世界の名著 32 ロック ヒューム』(『人間知性論』) 大槻春彦訳、中央公論新社《中公バックス》 1999年 『世界の名著 27 ロック ヒューム』(『人間知性論』) 大槻春彦訳、中央公論新社 1968年 『人間知性論』1巻〜4巻 大槻春彦訳、岩波書店 1974年 |

|

| 参考文献 福島清紀「ライプニッツ 人間知性新論 再考─仏語版 人間知性論 の介在」『人文社会学部紀要』第3巻、富山国際大学、2002年3月、83-92頁、NAID 40005391407、2015年8月24日閲覧。 |

|

| https://x.gd/e7FNA |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099