On Hurbinek Primo Levi's "La Tregua," 1963.

On Hurbinek Primo Levi's "La Tregua," 1963.

プリーモ・レーヴィ『休 戦』竹山博英訳、岩波文庫、岩波書店、2010年

この小説は、アウシュビッツを体験したイタリア出身の化学者が、解放されて9か月を難民として放浪して自分の生まれ故郷であるトリノに帰還する ロード小説とも言えるものだ。この彼の 苦渋の物語——でもなぜか各所にユーモアと諧謔感がないまぜになって奇妙な明るさというものがある——のなかに「愛」はあるだろうか? 僕がこの小説で忘 れない箇所が一つある、アウシュビッツで生まれたが、腕に入れ墨だけがあり、通称はあったが、おそらく先に処刑された家族からは名前も与えられず、ソビエ ト軍が収容所を解放する直前に死んだ3歳の男の子の話である。レーヴィは書く「彼の存在を証明するのは私のこの文章だけである」。僕はこれが作者の無名の 犠牲者への愛であり、この本は、そのために存在するのではないかと思うほどなのだ。(→オリジナル出典:「愛の技法、または愛するという技」)

フルビネクとYに

フルビネクは三歳で、おそらくアウシュビッツで生まれ、木を見たことがなかった。彼は息を引き取るまで、人間の世界への入場を果たそうと、大人 のように戦った。彼は野蛮な力によってそこから放逐されていたのだ。フルビネクには名前がなかったが、その細い腕にはやはりアウシュビッツの入れ墨が刻印 されていた。フルビネクは1945年3月初旬に死んだ。彼は解放されたが、救済はされなかった。彼に関しては何も残っていない。彼の存在を証明するのは私 のこの文章だけである。——プリーモ・レーヴィ『休戦』竹山博英 訳

スペイン語訳

Hurbinek, que tenía tres años y probablemente había nacido en

Auschwitz, y nunca había visto un árbol; Hurbinek, que había luchado

como un hombre, hasta el último suspiro, por conquistar su entrada en

el mundo de los hombres, del cual un poder bestial lo había exiliado;

Hurbinek, el sinnombre, cuyo minúsculo antebrazo había sido firmado con

el tatuaje de Auschwitz; Hurbinek murió en los primeros días de marzo

de 1945, libre pero no redimido. Nada queda de él: el testimonio de su

existencia son estas palabras mías. Primo Levi, La tregua

Per aspera ad astra. (困難を超えて星へ)[→看 護人類学入門]

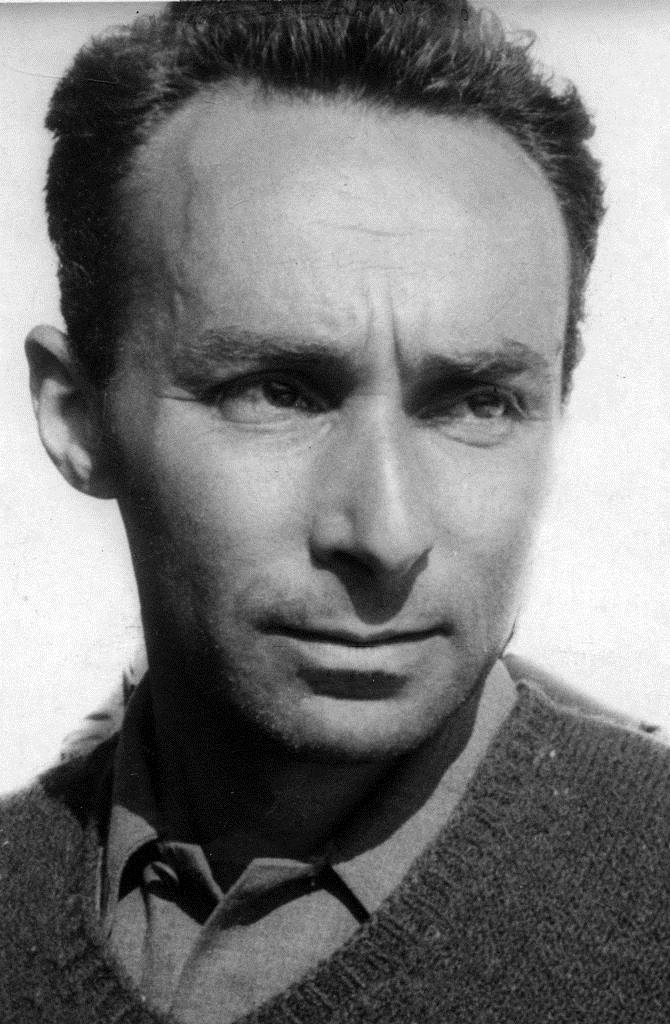

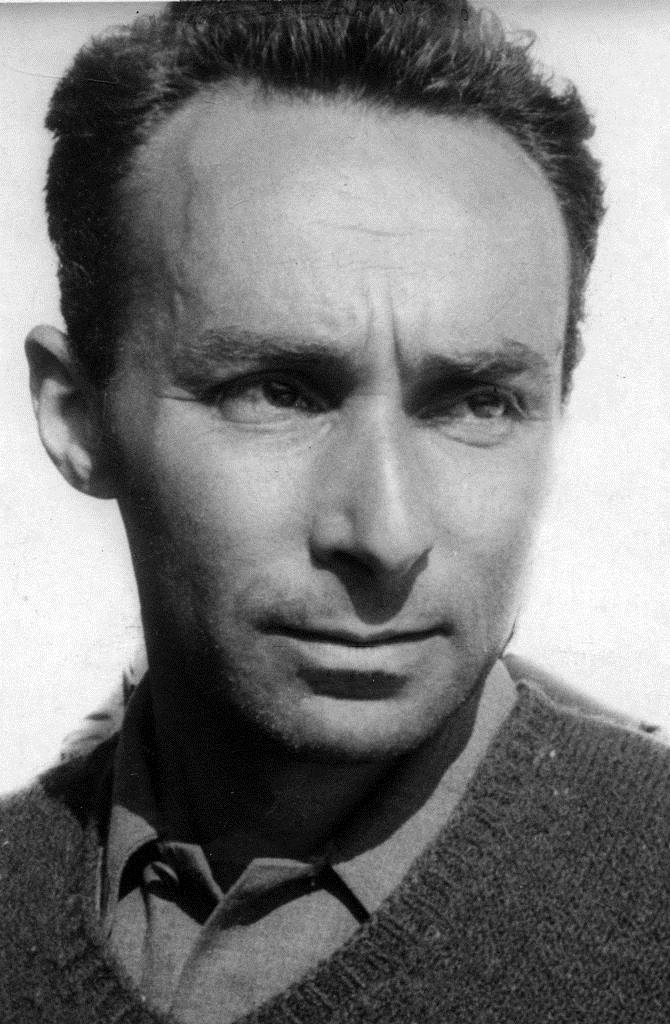

Primo Levi, 1919-1987 (picture taken in ca. 1950s)

【設問】※まだ考えていません(これはかつて授業用資料でしたので)

1.

2.

★

| Primo Michele

Levi[1][2] (Italian: [ˈpriːmo ˈlɛːvi]; 31 July 1919 – 11 April 1987)

was an Italian chemist, partisan, writer, and Jewish Holocaust

survivor. He was the author of several books, collections of short

stories, essays, poems and one novel. His best-known works include If

This Is a Man (1947, published as Survival in Auschwitz in the United

States), his account of the year he spent as a prisoner in the

Auschwitz concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland; and The Periodic

Table (1975), a collection of mostly autobiographical short stories

each named after a chemical element as it played a role in each story,

which the Royal Institution named the best science book ever written.[3] Levi died in 1987 from injuries sustained in a fall from a third-story apartment landing. His death was officially ruled a suicide, but some, after careful consideration, have suggested that the fall was accidental because he left no suicide note, there were no witnesses, and he was on medication that could have affected his blood pressure and caused him to fall accidentally.[4][5] |

プリモ・ミケーレ・リーヴァイ[1][2](イタリア語: [ˈ ˈ

ɛːvi]; 1919年7月31日 -

1987年4月11日)は、イタリアの化学者、パルチザン、作家、ユダヤ人ホロコースト生存者。数冊の著書、短編小説集、エッセイ集、詩集、1冊の小説が

ある。代表作に、ナチス占領下のポーランドのアウシュヴィッツ強制収容所で囚人として過ごした1年間を綴った『If This Is a

Man』(1947年、アメリカでは『Survival in Auschwitz』として出版)、主に自伝的な短編を集めた『The

Periodic Table』(1975年)などがある。 リヴァイは1987年、アパートの3階から転落して負傷し、死去。彼の死は公式には自殺と断定されたが、慎重に検討した結果、遺書が残されていないこと、 目撃者がいないこと、血圧に影響を与える可能性のある薬を服用していたため誤って転落した可能性があることから、転落は偶発的なものであったとする説もあ る[4][5]。 |

| Biography Early life Levi was born in 1919 in Turin, Italy, at Corso Re Umberto 75, into a liberal Jewish family.[6] His father, Cesare, worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi's mother, Ester, known to everyone as Rina, was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. She too was an avid reader, played the piano, and spoke fluent French.[7][8] The marriage between Rina and Cesare had been arranged by Rina's father.[7] On their wedding day, Rina's father, Cesare Luzzati, gave Rina the apartment at Corso Re Umberto, where Primo Levi lived for almost his entire life. Levi, c.1950s In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister, was born; he remained close to her all her life. In 1925 he entered the Felice Rignon primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and considered himself ugly; he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which he was tutored at home, at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini.[9] The children spent summers with their mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin, where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in the city, partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.[10] In September 1930 Levi entered the Massimo d'Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements.[11] In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest, as well as being the only Jew. Only two boys there bullied him for being Jewish, but their animosity was traumatic.[12] In August 1932, following two years attendance also at the Talmud Torah school in Turin to pick up the elements of doctrine and culture, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah.[13][6] In 1933, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists. He avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin.[14] As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens, Levi and a few friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.[8] In July 1934 at the age of 14, he sat the exams for the Liceo Classico D'Azeglio, a Lyceum (sixth form or senior high school) specializing in the classics, and was admitted that year. The school was noted for its well-known anti-Fascist teachers, among them the philosopher Norberto Bobbio, and Cesare Pavese, who later became one of Italy's best-known novelists.[15] Levi continued to be bullied during his time at the Lyceum, although six other Jews were in his class.[16] Upon reading Concerning the Nature of Things by Australian scientist Sir William Bragg, Levi decided that he wanted to be a chemist.[17] In 1937, he was summoned before the War Ministry and accused of ignoring a draft notice from the Italian Royal Navy—one day before he was to write a final examination on Italy's participation in the Spanish Civil War, based on a quote from Thucydides: "We have the singular merit of being brave to the utmost degree." Distracted and terrified by the draft accusation, he failed the exam—the first poor grade of his life—and was devastated. His father was able to keep him out of the Navy by enrolling him in the Fascist militia (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale). He remained a member through his first year of university, until passage of the Italian Racial Laws of 1938 forced his expulsion. Levi later recounted this series of events in the short story "Fra Diavolo on the Po".[18] He retook and passed his final examinations, and in October enrolled at the University of Turin to study chemistry. As one of 80 candidates, he spent three months taking lectures, and in February, after passing his colloquio (oral examination), he was selected as one of 20 to move on to the full-time chemistry curriculum. In the liberal period as well as in the first decade of the Fascist regime, Jews held many public positions, and were prominent in literature, science and politics.[19] In 1929 Mussolini signed an agreement with the Catholic Church, the Lateran Treaty, which established Catholicism as the State religion, allowed the Church to influence many sectors of education and public life, and relegated other religions to the status of "tolerated cults". In 1936 Italy's conquest of Ethiopia and the expansion of what the regime regarded as the Italian "colonial empire" brought the question of "race" to the forefront. In the context set by these events, and the 1940 alliance with Hitler's Germany, the situation of the Jews of Italy changed radically. In July 1938 a group of prominent Italian scientists and intellectuals published the "Manifesto of Race," a mixture of racial and ideological antisemitic theories from ancient and modern sources. This treatise formed the basis for the Italian Racial Laws of October 1938. After its enactment Italian Jews lost their basic civil rights, positions in public offices, and their assets. Their books were prohibited: Jewish writers could no longer publish in magazines owned by Aryans. Jewish students who had begun their course of study were permitted to continue, but new Jewish students were barred from entering university. Levi had matriculated a year earlier than scheduled enabling him to take a degree.[8] In 1939, Levi discovered his passion for mountain hiking.[20] A friend, Sandro Delmastro, taught him how to hike, and they spent many weekends in the mountains above Turin. Physical exertion, the risk, and the battle with the elements while following Sandro's example enabled him to put out of his mind the nightmare situation precipitating all over Europe as, communing with the sky and earth, he managed to satisfy his desire for liberty, realize fully his own strength, and the reasons behind his ardent need to grasp the nature of things that had led him to study chemistry,[clarification needed] as he later wrote in the chapter "Iron" of The Periodic Table (1975).[21] In June 1940 Italy declared war as an ally of Germany against Britain and France, and the first Allied air raids on Turin began two days later. Levi's studies continued during the bombardments. The family suffered additional strain as his father became bedridden with bowel cancer. Chemistry Because of the new racial laws and the increasing intensity of prevalent fascism, Levi had difficulty finding a supervisor for his graduation thesis, which was on the subject of Walden inversion, a study of the asymmetry of the carbon atom. Eventually taken on by Dr. Nicolò Dallaporta, he graduated in mid-1941 with full marks and merit, having submitted additional theses on x-rays and electrostatic energy. His degree certificate bore the remark, "of Jewish race". The racial laws prevented Levi from finding a suitable permanent job after graduation.[8] In December 1941 Levi received an informal job offer from an Italian officer to work as a chemist, under a clandestine identity, at an asbestos mine in San Vittore. The project was to extract nickel from the mine spoil, a challenge he accepted with pleasure. Levi later understood that, if successful, he would be aiding the German war effort, which was suffering nickel shortages in the production of armaments.[22] The job required Levi to work under a false name with false papers. Three months later, in March 1942, his father died. Levi left the mine in June to work in Milan. Recruited through a fellow student at Turin University, working for the Swiss firm of A Wander Ltd on a project to extract an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter, he took the job in a Swiss company to escape the race laws. It soon became clear that the project had no chance of succeeding, but it was in no one's interest to say so.[23] In July 1943, King Victor Emmanuel III deposed Mussolini and appointed a new government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio, prepared to sign the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies. When the armistice was made public on 8 September, the Germans occupied northern and central Italy, liberated Mussolini from imprisonment and appointed him as head of the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state in German-occupied northern Italy. Levi returned to Turin to find his mother and sister in refuge in their holiday home 'La Saccarello' in the hills outside the city. The three embarked to Saint-Vincent in the Aosta Valley, where they could be hidden. Being pursued as Jews, many of whom had already been interned by the authorities, they moved up the hillside to Amay in the Col de Joux [it], a rebellious area highly suitable for guerilla activities.[24] The Italian resistance movement became increasingly active in the German-occupied zone. Levi and some comrades took to the foothills of the Alps, and in October formed a partisan group in the hope of being affiliated to the liberal Giustizia e Libertà. Untrained for such a venture, he and his companions were arrested by the Fascist militia on 13 December 1943. When told he would be shot as an Italian partisan, Levi confessed to being Jewish. He was sent to the internment camp at Fossoli near Modena. He recalled that as long as Fossoli was under the control of the Italian Social Republic, rather than Nazi Germany, he was not harmed. We were given, on a regular basis, a food ration destined for the soldiers", Levi's testimony stated, "and at the end of January 1944, we were taken to Fossoli on a passenger train. Our conditions in the camp were quite good. There was no talk of executions and the atmosphere was quite calm. We were allowed to keep the money we had brought with us and to receive money from the outside. We worked in the kitchen in turn and performed other services in the camp. We even prepared a dining room, a rather sparse one, I must admit.[25] |

略歴 生い立ち レヴィは1919年、イタリアのトリノ、コルソ・レ・ウンベルト75番地で、リベラルなユダヤ人家庭に生まれた[6]。 父のチェーザレは、製造会社ガンツに勤め、ガンツの拠点であったハンガリーで海外勤務に明け暮れていた。チェーザレは熱心な読書家で、独学者でもあった。 リヴァイの母、エステルはリナとして知られ、マリア・レティツィア学院に通っていた。リナとチェーザレの結婚は、リナの父親が取り持ったものであった [7][8]。結婚式の日、リナの父親チェーザレ・ルッツァーティは、プリモ・レヴィがほぼ生涯を過ごしたコルソ・レ・ウンベルトのアパートをリナに与え た。 1950年代頃のレヴィ 1921年、レヴィの妹アンナ・マリアが生まれた。1925年、トリノのフェリーチェ・リニョン小学校に入学。やせっぽちで繊細な彼は、内気で自分を醜い と思っていた。学業成績は優秀であったが、長期欠席を余儀なくされ、その間、エミリア・グラウダや哲学者ジーノ・ジーニの娘マリサ・ジーニに家庭教師を受 けた[9]。父親は田舎暮らしを嫌って都会に残ったが、不倫のせいでもあった[10]。 1930年9月、レヴィは通常の入学資格より1年早くマッシモ・ダゼリオ王立ギムナジウムに入学した[11]。クラスでは最年少で、背が低く、頭がよく、 唯一のユダヤ人であった。1932年8月、教義と文化の要素を学ぶためにトリノのタルムード・トーラーの学校にも2年間通った後、地元のシナゴーグでバ ル・ミツヴァーのために歌った[13][6]。1933年、イタリアの若い男子学生全員に期待されたように、彼は若いファシストのためのアヴァンギャル ディスティ運動に参加した。少年時代、レヴィは病気、特に胸の感染症に悩まされたが、体を動かすことには熱心だった。10代の頃、レヴィは数人の友人と一 緒に、使われなくなったスポーツ競技場に忍び込み、運動競技を行っていた[8]。 1934年7月、14歳の彼は、古典を専門とするリセウム(6年生または高等学校)であるリセオ・クラシコ・ダゼリオの試験を受け、その年に入学を許可さ れた。同校は、哲学者のノルベルト・ボッビオや、後にイタリアで最も有名な小説家の一人となるチェーザレ・パヴェーゼなど、反ファシストの有名な教師がい ることで知られていた[15]。オーストラリアの科学者ウィリアム・ブラッグ卿の『物事の本質について』を読んだレヴィは、化学者になりたいと決心した [17]。 1937年、彼は陸軍省に呼び出され、スペイン内戦へのイタリアの参加について、トゥキュディデスからの引用に基づいて最終試験を書く前日に、イタリア王 立海軍からの徴兵通知を無視したことを非難された: 「われわれは最大限の勇気をもっているという特異な長所を持っている」。徴兵制の非難に気を取られ、恐怖に駆られた彼は、人生で初めて不合格となり、打ち のめされた。父親は、彼をファシストの民兵組織(Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale)に入隊させることで、海軍に入隊させないようにした。1938年にイタリア人種法が成立し、追放されるまで、彼は大学1年まで在籍し た。レヴィは後に、この一連の出来事を短編小説『ポー河畔のフラ・ディアヴォロ』の中で語っている[18]。 最終試験を受け直し合格したレヴィは、10月に化学を学ぶためにトリノ大学に入学した。80人の候補者の一人として3カ月間講義を受け、2月にコロキオ(口頭試問)に合格すると、全日制の化学課程に進む20人の一人に選ばれた。 1929年、ムッソリーニはカトリック教会との間でラテラノ条約を締結し、カトリックを国教とし、教会が教育や公共生活の多くの分野に影響を及ぼすことを 認め、他の宗教を「寛容なカルト」の地位に追いやった。1936年、イタリアはエチオピアを征服し、イタリアの「植民地帝国」とみなす体制を拡大した。こ れらの出来事と1940年のヒトラー率いるドイツとの同盟がもたらした背景の中で、イタリアのユダヤ人の状況は激変した。 1938年7月、イタリアの著名な科学者や知識人のグループが、古今東西の人種論とイデオロギー的な反ユダヤ主義理論を混ぜ合わせた「人種宣言」を発表し た。この論文は、1938年10月のイタリア人種法の基礎となった。この法律が制定された後、イタリアのユダヤ人は基本的市民権、公職における地位、資産 を失った。彼らの著書は禁止された: ユダヤ人作家は、アーリア人が所有する雑誌で出版することができなくなった。ユダヤ人作家は、アーリア人が所有する雑誌を出版することができなくなった。 すでに勉強を始めていたユダヤ人学生には勉強を続けることが許可されたが、新たに大学に入学するユダヤ人学生は禁止された。リヴァイは予定より1年早く入 学し、学位を取得することができた[8]。 1939年、レヴィは山歩きに情熱を燃やすようになる[20]。友人のサンドロ・デルマストロから山歩きの仕方を教わり、週末は何度もトリノ上空の山で過 ごした。サンドロの手本に従いながら、肉体的な努力、危険、そして元素との戦いを経験することで、彼はヨーロッパ全土で勃発した悪夢のような状況を頭から 消し去り、空や大地と交わりながら、自由への欲求を満たし、自分自身の強さを十分に実感し、後に『周期表』(1975年)の「鉄」の章に書いたように、化 学を学ぶようになった物事の本質を把握したいという熱烈な欲求の背後にある理由を理解することができた[clarification needed]。 [21] 1940年6月、イタリアはドイツの同盟国としてイギリスとフランスに対して宣戦布告し、その2日後には連合国による最初のトリノ空襲が始まった。レヴィ は空襲の間も勉強を続けた。父親が腸がんで寝たきりになり、家族はさらに大きな負担を強いられた。 化学 人種差別撤廃法が施行され、ファシズムがますます強まったため、レヴィは卒業論文の指導教官を見つけるのに苦労した。結局、ニコロ・ダラポルタ博士の指導 を受け、レヴィは1941年半ば、X線と静電エネルギーに関する追加の論文を提出し、満点と優秀な成績で卒業した。学位記には「ユダヤ人」と記されてい た。人種法によって、レヴィは卒業後に適当な定職に就くことができなかった[8]。 1941年12月、レヴィはイタリア人将校から、サン・ヴィットーレのアスベスト鉱山で秘密裏に化学者として働く内定を得る。鉱山からニッケルを抽出する というもので、レヴィは喜んで引き受けた。後にレヴィは、成功すれば、軍需品の生産でニッケル不足に苦しんでいたドイツの戦争に貢献することになると理解 した[22]。3ヵ月後の1942年3月、父親が亡くなった。リヴァイは6月に鉱山を去り、ミラノで働くことになった。トリノ大学の学生仲間の紹介で、植 物性物質から抗糖尿病薬を抽出するプロジェクトでスイスのア・ワンダー社に就職した。プロジェクトが成功する見込みがないことはすぐに明らかになったが、 それを口にすることは誰にも得策ではなかった[23]。 1943年7月、国王ヴィクトル・エマニュエル3世はムッソリーニを退位させ、ピエトロ・バドリオ元帥率いる新政府を任命し、連合国とのカッシビレ休戦協 定に調印する準備を整えた。9月8日に休戦協定が公表されると、ドイツ軍はイタリア北部と中部を占領し、ムッソリーニを投獄から解放して、ドイツ占領下の 北イタリアの傀儡国家であるイタリア社会共和国の元首に任命した。レヴィはトリノに戻り、郊外の丘にある別荘「ラ・サカレッロ」に避難している母と妹を見 つけた。3人はアオスタ渓谷のサン・ヴァンサンへ向かった。ユダヤ人として追われる身となった彼らは、その多くがすでに当局によって収容されていたため、 ゲリラ活動に非常に適した反乱地域であるジュウ渓谷のアマイまで丘陵地帯を移動した[24]。 イタリアのレジスタンス運動はドイツ占領地域でますます活発になっていった。レヴィと何人かの同志はアルプスの麓に行き、10月にパルチザンのグループを 結成し、自由主義的なGiustizia e Libertàに加盟することを目指した。そのような事業を行うための訓練を受けていなかった彼と仲間たちは、1943年12月13日にファシストの民兵 に逮捕された。イタリアのパルチザンとして銃殺されると告げられ、レヴィはユダヤ人であることを告白した。彼はモデナ近郊のフォッソーリの収容所に送られ た。フォッソーリがナチス・ドイツではなく、イタリア社会共和国の支配下にある限り、危害を加えられることはなかったと彼は回想している。 レヴィの証言によれば、「私たちは定期的に兵士用の食糧配給を受け、1944年1月末に旅客列車でフォッソーリに連れて行かれた。収容所での私たちの条件 はかなりよかった。処刑の話もなく、雰囲気はとても穏やかでした。持ってきたお金を持ち続けることも、外からお金を受け取ることも許されていました。私た ちは順番に厨房で働き、収容所内で他の奉仕活動も行った。食堂も用意しましたが、正直言って、かなり粗末なものでした[25]。 |

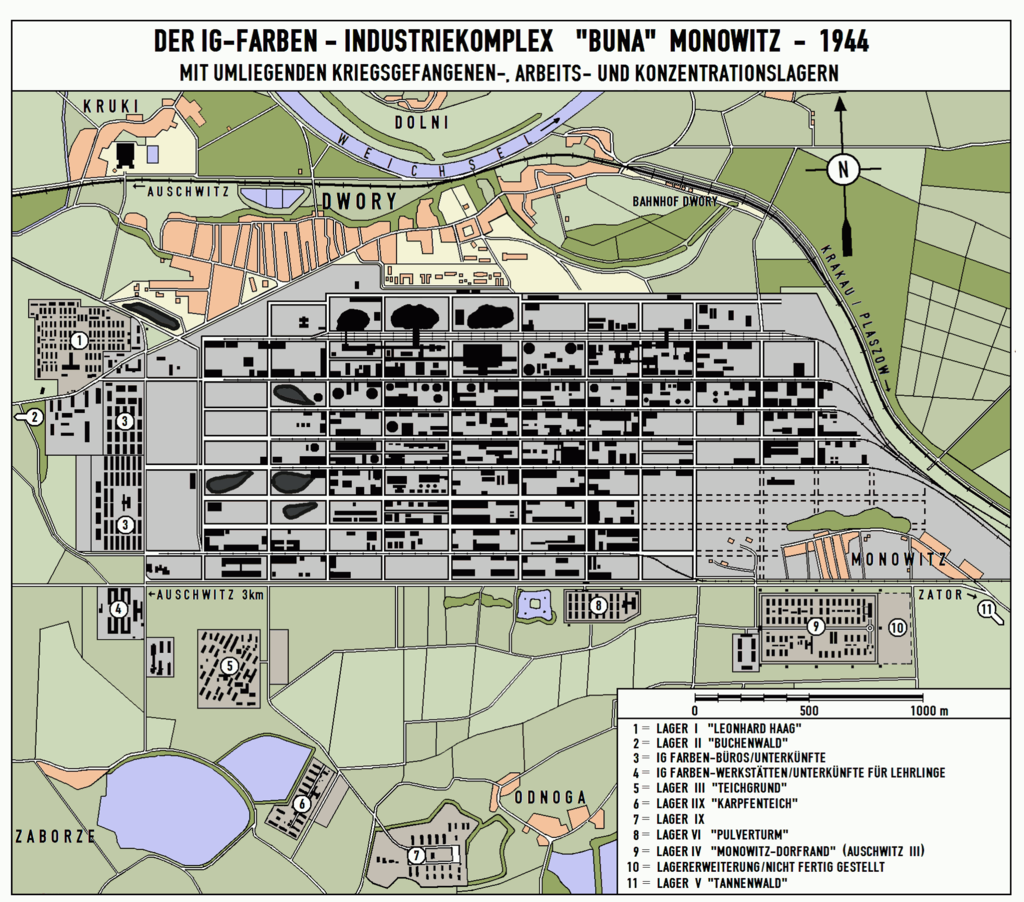

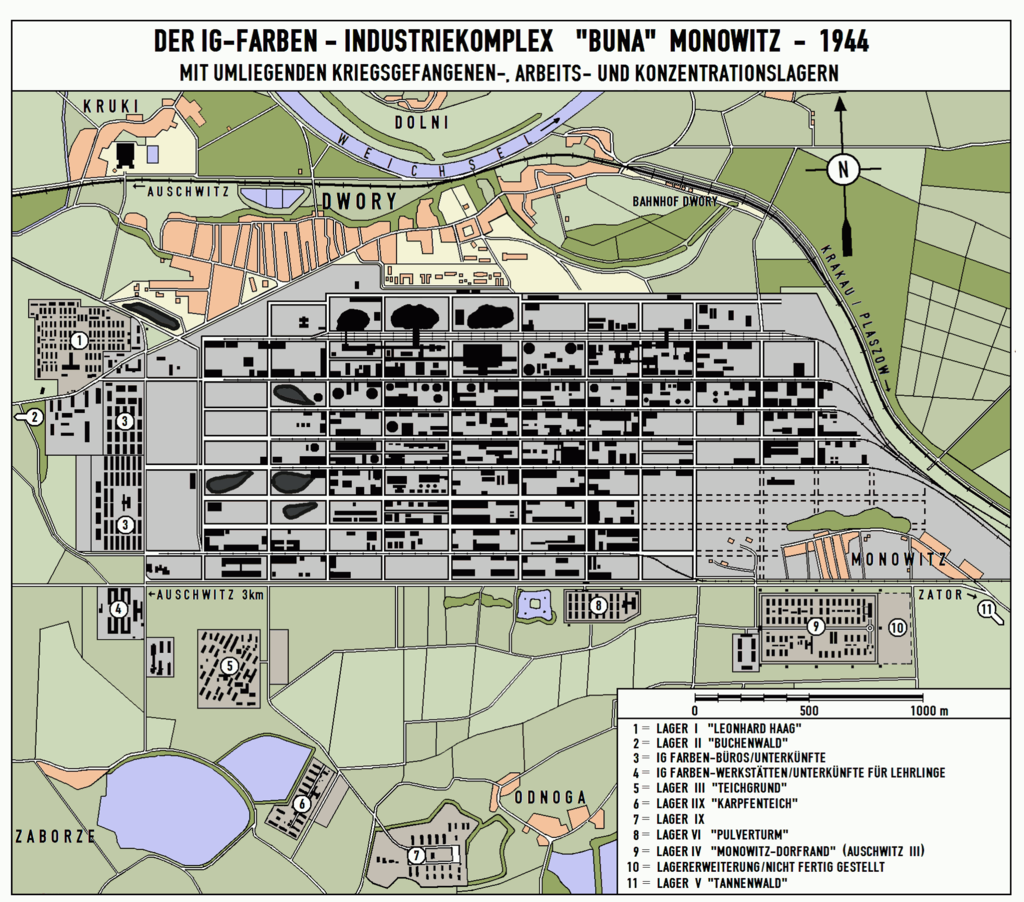

Auschwitz IG Farben factory in Monowitz (near Auschwitz) 1941 50.036094°N 19.275534°E  Buna Werke, Monowitz and subcamps Fossoli was then taken over by the Nazis, who started arranging the deportations of the Jews to eastern concentration and death camps. On the second of these transports, on 21 February 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to Monowitz, one of the three main camps in the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. Levi (record number 174517) spent eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army on 27 January 1945. Before their arrival, people were sorted according to whether they could work or not. An acquaintance said that it would make no difference, in the end, and declared he was unable to work and was killed immediately. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his transport, Levi was one of twenty who left the camps alive. The average life expectancy of a new entrant at the camp was three to four months. Levi knew some German from reading German publications on chemistry; he worked to orient quickly to life in the camp without attracting the attention of the privileged inmates. He used bread to pay a more experienced Italian prisoner for German lessons and orientation in Auschwitz. He was given a smuggled soup ration each day by Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian bricklayer working there as a forced labourer. Levi's professional qualifications were useful: in mid-November 1944, he secured a position as an assistant in IG Farben's Buna Werke laboratory that was intended to produce synthetic rubber. By avoiding hard labour in freezing outdoor temperatures he was able to survive; also, by stealing materials from the laboratory and trading them for extra food.[26] Shortly before the camp was liberated by the Red Army, he fell ill with scarlet fever and was placed in the camp's sanatorium (camp hospital). On 18 January 1945, the SS hurriedly evacuated the camp as the Red Army approached, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march to a site further from the front, which resulted in the deaths of the vast majority of the remaining prisoners on the march. Levi's illness spared him this fate. Although liberated on 27 January 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until 19 October 1945. After spending some time in a Soviet camp for former concentration camp inmates, he embarked on an arduous journey home in the company of former Italian prisoners of war who had been part of the Italian Army in Russia. His long railway journey home to Turin took him on a circuitous route from Poland, through Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Germany – an arduous journey described especially in his 1963 work The Truce – noting the millions of displaced people on the roads and trains throughout Europe in that period. |

アウシュヴィッツ モノヴィッツのIGファルベン工場(アウシュヴィッツ近郊) 1941年 北緯50.036094度 東経19.275534度  ブナ・ヴェルケ、モノヴィッツとサブキャンプ その後、フォッソーリはナチスに占領され、ナチスはユダヤ人を東部の強制収容所や死の収容所に強制送還する手配を始めた。1944年2月21日、リヴァイ と他の収容者たちは、12台の狭い家畜トラックで、アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所群の3つの主要収容所の一つであるモノヴィッツに移送された。リヴァイ(記 録番号174517)は、1945年1月27日に赤軍によって収容所が解放されるまで、そこで11ヶ月を過ごした。到着する前に、人々は働けるか働けない かで選別された。ある知人は、結局は違いはないだろうと言い、自分は働けないと宣言し、すぐに殺された。彼の移送車に乗っていた650人のイタリア系ユダ ヤ人のうち、レヴィは生きて収容所を出た20人のうちの1人だった。収容所での新入者の平均余命は3~4ヵ月だった。 レヴィは、化学に関するドイツの出版物を読んで、ドイツ語を少し知っていた。彼は、特権階級の収容者の注意を引くことなく、収容所での生活に早く慣れるよ うに努力した。彼は、アウシュヴィッツでのドイツ語レッスンとオリエンテーションのために、経験豊富なイタリア人囚人にパンを払っていた。彼は、強制労働 者として収容所で働いていたイタリア人の民間人レンガ職人ロレンツォ・ペローネから、毎日密輸されたスープの配給を受けた。1944年11月中旬、レヴィ はIGファルベンのブナ・ヴェルケ研究所で合成ゴムの製造助手の職を得た。赤軍によって収容所が解放される直前、彼は猩紅熱にかかり、収容所の療養所(収 容所病院)に収容された。1945年1月18日、赤軍の接近に伴い、親衛隊は収容所を急遽退去させ、重病人を除く全員を戦線から離れた場所への長い死の行 軍に追いやった。リヴァイは病気であったため、この運命を免れた。 1945年1月27日に解放されたものの、レヴィがトリノに到着したのは1945年10月19日のことであった。元強制収容所収容者のためのソビエト収容 所でしばらく過ごした後、ロシアでイタリア軍に属していた元イタリア兵捕虜たちと一緒に、困難な帰国の旅に出た。トリノへの長い鉄道の旅は、ポーランドか らベラルーシ、ウクライナ、ルーマニア、ハンガリー、オーストリア、ドイツを経由する迂回路を辿った。この苦難の旅は、特に1963年の著作『The Truce』に描かれており、当時のヨーロッパ中の道路や列車に何百万人もの避難民がいたことを記している。 |

| Writing career 1946–1960 Levi was almost unrecognisable on his return to Turin. Malnutrition edema had bloated his face. Sporting a scrawny beard and wearing an old Red Army uniform, he returned to Corso Re Umberto. The next few months gave him an opportunity to recover physically, re-establish contact with surviving friends and family, and start looking for work. Levi suffered from the psychological trauma of his experiences. Having been unable to find work in Turin, he started to look for work in Milan. On his train journeys, he began to tell people he met stories about his time at Auschwitz. At a Jewish New Year party in 1946, he met Lucia Morpurgo, who offered to teach him to dance. Levi fell in love with Lucia. At about this time, he started writing poetry about his experiences in Auschwitz. On 21 January 1946 he started work at DUCO, a Du Pont Company paint factory outside Turin. Because of the extremely limited train service, Levi stayed in the factory dormitory during the week. This gave him the opportunity to write undisturbed. He started to write the first draft of If This Is a Man.[27] Every day he scribbled notes on train tickets and scraps of paper as memories came to him. At the end of February, he had ten pages detailing the last ten days between the German evacuation and the arrival of the Red Army. For the next ten months, the book took shape in his dormitory as he typed up his recollections each night. On 22 December 1946, the manuscript was complete. Lucia, who now reciprocated Levi's love, helped him to edit it, to make the narrative flow more naturally.[28] In January 1947, Levi was taking the finished manuscript around to publishers. It was rejected by Einaudi on the advice of Natalia Ginzburg, and in the United States was turned down by Little, Brown and Company on the advice of rabbi Joshua Liebman, an opinion which contributed to the neglect of his work in that country for four decades.[29][30] The social wounds of the war years were still too fresh, and he had no literary experience to give him a reputation as an author. Eventually Levi found a publisher, Franco Antonicelli, through a friend of his sister's.[31] Antonicelli was an amateur publisher, but as an active anti-Fascist, he supported the idea of the book. At the end of June 1947, Levi suddenly left DUCO and teamed up with an old friend Alberto Salmoni to run a chemical consultancy from the top floor of Salmoni's parents' house. Many of Levi's experiences of this time found their way into his later writing. They made most of their money from making and supplying stannous chloride for mirror makers,[32] delivering the unstable chemical by bicycle across the city. The attempts to make lipsticks from reptile excreta and a coloured enamel to coat teeth were turned into short stories. Accidents in their laboratory filled the Salmoni house with unpleasant smells and corrosive gases. In September 1947, Levi married Lucia and a month later, on 11 October, If This Is a Man was published with a print run of 2,000 copies. In April 1948, with Lucia pregnant with their first child, Levi decided that the life of an independent chemist was too precarious. He agreed to work for Accatti in the family paint business which traded under the name SIVA. In October 1948, his daughter Lisa was born. During this period, his friend Lorenzo Perrone's physical and psychological health declined. Lorenzo had been a civilian forced worker in Auschwitz, who for six months had given part of his ration and a piece of bread to Levi without asking for anything in return.[33] The gesture saved Levi's life. In his memoir, Levi contrasted Lorenzo with everyone else in the camp, prisoners and guards alike, as someone who managed to preserve his humanity. After the war, Lorenzo could not cope with the memories of what he had seen, and descended into alcoholism. Levi made several trips to rescue his old friend from the streets, but in 1952 Lorenzo died.[31] In gratitude for his kindness in Auschwitz, Levi named both of his children, Lisa Lorenza and Renzo, after him. In 1950, having demonstrated his chemical talents to Accatti, Levi was promoted to Technical Director at SIVA.[34] As SIVA's principal chemist and trouble shooter, Levi travelled abroad. He made several trips to Germany and carefully engineered his contacts with senior German businessmen and scientists. Wearing short-sleeved shirts, he made sure they saw his prison camp number tattooed on his arm. He became involved in organisations pledged to remembering and recording the horror of the camps. In 1954 he visited Buchenwald to mark the ninth anniversary of the camp's liberation from the Nazis. Levi dutifully attended many such anniversary events over the years and recounted his own experiences. In July 1957, his son Renzo was born. Despite a positive review by Italo Calvino in L'Unità, only 1,500 copies of If This Is a Man were sold. In 1958 Einaudi, a major publisher, published it in a revised form and promoted it. In 1958 Stuart Woolf, in close collaboration with Levi, translated If This Is a Man into English, and it was published in the UK in 1959 by Orion Press. Also in 1959 Heinz Riedt, also under close supervision by Levi,[35] translated it into German. As one of Levi's primary reasons for writing the book was to get the German people to realise what had been done in their name, and to accept at least partial responsibility, this translation was perhaps the most significant to him. 1961–1974 Levi began writing The Truce early in 1961; it was published in 1963, almost 16 years after his first book. That year it won the first annual Premio Campiello literary award. It is often published in one volume with If This Is a Man, as it covers his long return through eastern Europe from Auschwitz. Levi's reputation was growing. He regularly contributed articles to La Stampa, the Turin newspaper. He worked to gain a reputation as a writer about subjects other than surviving Auschwitz. In 1963, he suffered his first major bout of depression. At the time he had two young children, and a responsible job at a factory where accidents could and did have terrible consequences. He travelled and became a public figure. But the memory of what happened less than twenty years earlier still burned in his mind. Today the link between such trauma and depression is better understood. Doctors prescribed several different drugs over the years, but these had variable efficacy and side effects. In 1964 Levi collaborated on a radio play based upon If This Is a Man with the state broadcaster RAI, and in 1966 with a theatre production. He published two volumes of science fiction short stories under the pen name of Damiano Malabaila, which explored ethical and philosophical questions. These imagined the effects on society of inventions which many would consider beneficial, but which, he saw, would have serious implications. Many of the stories from the two books Storie naturali (Natural Histories, 1966) and Vizio di forma (Structural Defect, 1971) were later collected and published in English as The Sixth Day and Other Tales. In 1974 Levi arranged to go into semi-retirement from SIVA in order to have more time to write. He also wanted to escape the burden of responsibility for managing the paint plant.[36] 1975–1987 In 1975 a collection of Levi's poetry was published under the title L'osteria di Brema (The Bremen Beer Hall). It was published in English as Shema: Collected Poems. He wrote two other highly praised memoirs, Lilit e altri racconti (Moments of Reprieve, 1978) and Il sistema periodico (The Periodic Table, 1975). Moments of Reprieve deals with characters he observed during imprisonment. The Periodic Table is a collection of mostly autobiographical short stories and also includes two fictional stories that he wrote while being employed in 1941 at the asbestos mine in San Vittore. Each story is named after a chemical element and the story matter is related to that element. At London's Royal Institution on 19 October 2006, The Periodic Table was as the best science book ever written.[37] In 1977 at the age of 58, Levi retired as a part-time consultant at the SIVA paint factory to devote himself full-time to writing. Like all his books, La chiave a stella (1978), published in the US in 1986 as The Monkey Wrench and in the UK in 1987 as The Wrench, is difficult to categorize. Some reviews describe it as a collection of stories about work and workers told by a narrator who resembles Levi. Others have called it a novel, created by the linked stories and characters. Set in the Fiat-run Russian company town of Togliattigrad, it portrays the engineer as a hero on whom others depend. The Piedmontese engineer Faussone has travelled the world as an expert in erecting cranes and bridges. Most of the stories involve the solution of industrial problems by the use of troubleshooting skills; many stories come from the author's personal experience. The underlying philosophy is that pride in one's work is necessary for fulfillment. The Wrench won the Strega Prize in 1979 and brought Levi a wider audience in Italy, though left-wing critics regretted that he did not describe the harsh working conditions on the assembly lines at Fiat.[38] In 1984 Levi published his only novel, If Not Now, When?— or his second novel, if The Monkey Wrench is counted. It traces the fortunes of a group of Jewish partisans behind German lines during World War II as they seek to survive and continue their fight against the occupier. With the ultimate goal of reaching Palestine to take part in the development of a Jewish national home, the partisan band reaches Poland and then German territory. There the surviving members are officially received as displaced persons in territory held by the Western allies. Finally, they succeed in reaching Italy, on their way to Palestine. The novel won both the Premio Campiello and the Premio Viareggio. The book was inspired by events during Levi's train journey home after release from the camp, narrated in The Truce. At one point in the journey, a band of Zionists hitched their wagon to the refugee train. Levi was impressed by their strength, resolve, organisation, and sense of purpose. Levi became a major literary figure in Italy, and his books were translated into many other languages. The Truce became a standard text in Italian schools. In 1985, he flew to the United States for a 20-day speaking tour. Although he was accompanied by Lucia, the trip was very draining for him. In the Soviet Union his early works were not accepted by censors as he had portrayed Soviet soldiers as slovenly and disorderly rather than heroic. In Israel, a country formed partly by Jewish survivors who lived through horrors similar to those Levi described, many of his works were not translated and published until after his death.[6] Rudolf Höss immediately before being hanged In March 1985 he wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography[39] of Rudolf Höss, who was commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp from 1940 to 1943. In it he writes, "It's filled with evil . . . and reading it is agony." Also in 1985 a volume of his essays, previously published in La Stampa, was published under the title L'altrui mestiere (Other People's Trades). Levi used to write these stories and hoard them, releasing them to La Stampa at the rate of about one a week. The essays ranged from book reviews and ponderings about strange things in nature, to fictional short stories.[6] In 1986 his book I sommersi e i salvati (The Drowned and the Saved), was published. In it he tried to analyse why people behaved the way they did at Auschwitz, and why some survived whilst others perished. In his typical style, he makes no judgments but presents the evidence and asks the questions. For example, one essay examines what he calls "The grey zone", those Jews who did the Germans' dirty work for them and kept the rest of the prisoners in line.[40] He questioned, what made a concert violinist behave as a callous taskmaster? Also in 1986 another collection of short stories, previously published in La Stampa, was assembled and published as Racconti e saggi (some of which were published in the English volume The Mirror Maker). At the time of his death in April 1987, Levi was working on another selection of essays called The Double Bond, which took the form of letters to "La Signorina".[41] These essays are very personal in nature. Approximately five or six chapters of this manuscript exist. Carole Angier, in her biography of Levi, describes how she tracked some of these essays down. She wrote that others were being kept from public view by Levi's close friends, to whom he gave them, and they may have been destroyed. In March 2007 Harper's Magazine published an English translation of Levi's story "Knall", about a fictitious weapon that is fatal at close range but harmless more than a meter away. It originally appeared in his 1971 book Vizio di forma, but was published in English for the first time by Harper's. A Tranquil Star, a collection of seventeen stories translated into English by Ann Goldstein and Alessandra Bastagli[42][43] was published in April 2007. In 2015, Penguin published The Complete Works of Primo Levi, ed. Ann Goldstein. This is the first time that Levi's entire oeuvre has been translated into English. |

執筆活動 1946-1960 トリノに戻ったレヴィは、ほとんど見分けがつかなくなっていた。栄養失調による浮腫で顔が肥大していた。やせ細ったあごひげを生やし、古い赤軍の軍服を着 て、コルソ・レ・ウンベルトに戻った。それから数カ月、彼は肉体的に回復し、生き残った友人や家族と再び連絡を取り合い、仕事を探し始める機会を得た。レ ヴィは、自分の体験による心理的トラウマに苦しんでいた。トリノで仕事を見つけることができなかった彼は、ミラノで仕事を探し始めた。列車での移動中、彼 は出会う人々にアウシュビッツでの体験談を語り始めた。 1946年、ユダヤ人の新年パーティーでルチア・モルプルゴに出会い、ダンスを教えてもらう。リヴァイはルシアと恋に落ちた。この頃、アウシュビッツでの体験を詩にして書き始める。 1946年1月21日、彼はトリノ郊外にあるデュポン社の塗料工場DUCOで働き始めた。列車の便が非常に限られていたため、レヴィは平日は工場の寮に滞 在した。そのため、誰にも邪魔されずに執筆することができた。毎日、彼は列車の切符や紙切れにメモを走り書きした。2月末には、ドイツ軍の撤退から赤軍の 到着までの10日間を詳細に記した10ページが出来上がった。それから10ヵ月間、彼は寮で毎晩、回想録をタイプしながら、この本は形になっていった。 1946年12月22日、原稿は完成した。1947年1月、レヴィは完成した原稿を出版社に持ち込んだ。ナタリア・ギンズブルグの助言でエイナウディに断られ、アメリカではラビのジョシュア・リーブマンの助言でリトル・ブラウン・アンド・カンパニーに断られた。 やがてレヴィは姉の友人を通じてフランコ・アントニチェッリという出版社を見つける[31]。アントニチェッリはアマチュアの出版社だったが、積極的な反ファシストとして本の構想を支持した。 1947年6月末、レヴィは突然DUCOを去り、旧友のアルベルト・サルモニと組んで、サルモニの実家の最上階で化学コンサルタント会社を経営した。サル モニの実家の最上階で化学コンサルタントを始めたのである。彼らは、鏡製造業者向けに塩化第二錫を製造・供給することで収入の大半を稼ぎ、不安定な化学薬 品を自転車で街中に配達していた[32]。爬虫類の排泄物から口紅を作ったり、歯に塗る着色エナメルを作ろうとした試みは短編小説になった。実験室での事 故は、サルモニの家に不快な匂いと腐食性のガスを充満させた。 1947年9月、レヴィはルチアと結婚し、1ヵ月後の10月11日、『これが男なら』を2000部で出版した。1948年4月、ルシアが第一子を妊娠した ため、レヴィは独立した化学者の生活は不安定すぎると判断した。レヴィはアカッティのもとで、SIVA(シヴァ)という社名で商売をしていた塗料会社で働 くことにした。1948年10月、娘のリサが生まれた。 この時期、友人のロレンツォ・ペローネの心身の健康は悪化していた。ロレンツォはアウシュヴィッツの民間人強制労働者で、6ヶ月間、見返りを求めずに配給 の一部とパン一切れをリヴァイに与えていた[33]。レヴィは回顧録の中で、ロレンツォを収容所の囚人も看守も含めた他のすべての人々と対比させ、人間性 を保つことができた人物としている。戦後、ロレンツォは見たものの記憶に対処できず、アルコール中毒に陥った。アウシュヴィッツでの彼の優しさに感謝し、 レヴィは自分の子供たちにリサ・ロレンツァとレンツォという名前をつけた。 1950年、アカッティに化学の才能を見せつけたレヴィは、SIVAのテクニカルディレクターに昇進した[34]。彼は何度もドイツを訪れ、ドイツの上級 ビジネスマンや科学者との接触を慎重に図った。半袖のシャツを着て、腕に入れた収容所番号の入れ墨が彼らに見えるようにした。 収容所の恐怖を記憶し、記録することを誓約する団体に参加するようになった。1954年には、ナチスからの解放9周年を記念してブッヘンヴァルトを訪れ た。レヴィは何年にもわたってこのような記念行事に出席し、自らの体験を語った。1957年7月、息子のレンゾが生まれた。 イタロ・カルヴィーノが『L'Unità』誌で好意的な批評をしたにもかかわらず、『これが男なら』はわずか1,500部しか売れなかった。1958年、大手出版社のエイナウディが改訂版を出版し、宣伝。 1958年、スチュアート・ウルフがレヴィと緊密に協力して『これが男なら』を英訳し、1959年にオリオン出版社からイギリスで出版された。同じく 1959年、ハインツ・リードは、レヴィの緊密な監修のもと、この作品をドイツ語に翻訳した[35]。レヴィがこの本を書いた主な理由の一つは、ドイツ国 民に自分たちの名において何が行われたかを認識させ、少なくとも部分的な責任を引き受けさせることであったため、この翻訳は彼にとっておそらく最も重要な ものであった。 1961-1974 レヴィが『休戦』の執筆を始めたのは1961年のことで、最初の著作から16年近く経った1963年に出版された。その年、この作品は第1回カンピエッロ 賞文学賞を受賞した。アウシュヴィッツから東欧への長い帰還を描いた作品であるため、『これが人間なら』と一冊にまとめられて出版されることが多い。レ ヴィの名声は高まっていた。トリノの新聞『ラ・スタンパ』に定期的に記事を寄稿。アウシュビッツからの生還以外のテーマについても、作家としての評判を得 ようと努力した。 1963年、彼は初めて大きなうつ病にかかった。当時、彼には2人の幼い子供がおり、事故が恐ろしい結果をもたらす可能性のある工場で責任ある仕事をして いた。彼は旅をし、公人になった。しかし、20年も前に起こったことの記憶は、まだ彼の心に焼き付いていた。今日では、このようなトラウマとうつ病の関連 性はよりよく理解されている。医師は何年もの間、何種類もの薬を処方したが、効き目や副作用にばらつきがあった。 1964年、レヴィは国営放送RAIと『もしこの人が男なら』を題材にしたラジオ劇を共同制作し、1966年には劇場で上演した。 ダミアーノ・マラバイラというペンネームで、倫理的、哲学的な問題を扱ったSF短編集を2冊出版。これらの短編は、多くの人が有益だと考える発明が社会に 及ぼす影響を想像したものだが、彼はそれが深刻な影響を及ぼすと考えた。Storie naturali』(自然史、1966年)と『Vizio di forma』(構造的欠陥、1971年)の2冊に収録された物語の多くは、後に『The Sixth Day and Other Tales』として英語版で出版された。 1974年、レヴィは執筆の時間を確保するため、SIVAを半引退する。また、塗装工場の経営責任という重荷からも逃れたいと考えていた[36]。 1975-1987 1975年、レヴィの詩集が『L'osteria di Brema(ブレーメンのビアホール)』というタイトルで出版された。英語では『Shema』として出版された: 詩集『シェマ』として英語版も出版された。 また、『Lilit e altri racconti』(Moments of Reprieve、1978年)と『Il sistema periodico』(The Periodic Table、1975年)という2冊の回顧録が高く評価されている。釈放の瞬間』は投獄中に彼が観察した人物を扱っている。周期表』は主に自伝的な短編を 集めたもので、1941年にサン・ヴィットーレのアスベスト鉱山で働いていたときに書いたフィクションも2編含まれている。それぞれの物語には化学元素の 名前が付けられており、物語の内容はその元素に関連している。2006年10月19日、ロンドンの王立研究所で、『周期表』はこれまで書かれた中で最も優 れた科学書として表彰された[37]。 1977年、58歳のとき、レヴィは執筆活動に専念するため、SIVA塗料工場の非常勤コンサルタントを退職した。1978年に出版された『La chiave a stella』(アメリカでは1986年に『The Monkey Wrench』として、イギリスでは1987年に『The Wrench』として出版)は、彼の他の著書と同様、分類が難しい。ある書評は、リヴァイに似た語り手によって語られる仕事と労働者に関する物語集と評し ている。また、連鎖する物語と登場人物によって生み出された小説と呼ぶ評者もいる。フィアットが経営するロシアの企業都市トリアッティグラードを舞台に、 エンジニアを他の人々が頼るヒーローとして描いている。ピエモンテ出身の技術者ファウッソーネは、クレーンや橋の架設のエキスパートとして世界中を飛び 回っている。ストーリーの大半は、トラブルシューティングの技術を駆使して産業上の問題を解決するもので、著者の個人的な体験に基づくものが多い。根底に あるのは、自分の仕事に誇りを持つことが充実感を得るために必要だという哲学である。レンチ』は1979年にストレガ賞を受賞し、レヴィはイタリアでより 多くの読者を獲得したが、左派の批評家たちは、フィアットの組み立てラインでの過酷な労働条件を描写していないことを残念がった[38]。 1984年、レヴィは唯一の小説『今でなければ、いつ』(『モンキー・レンチ』を含めると2作目)を発表。この小説は、第二次世界大戦中、ドイツ軍の戦線 裏にいたユダヤ人パルチザンの一団が、占領軍に対抗して生き延び、戦いを続けようとする運命を描いたものである。最終目標はパレスチナに到達し、ユダヤ人 の民族的故郷の建設に参加することだが、パルチザンの一団はポーランド、そしてドイツ領に到達する。そこで生き残ったメンバーは、西側同盟国の領土で避難 民として公式に受け入れられる。そしてついに、彼らはパレスチナに向かう途中のイタリアにたどり着く。この小説はカンピエッロ賞とヴィアレッジョ賞を受賞 した。 本書は、『休戦』の中で語られる、収容所から釈放されたレヴィが列車で帰郷する途中の出来事から着想を得ている。旅の途中、難民列車にシオニストの一団が乗り合わせた。レヴィは彼らの強さ、決意、組織、目的意識に感銘を受けた。 レヴィはイタリアで主要な文学者となり、著書は多くの言語に翻訳された。休戦』はイタリアの学校で標準テキストとなった。1985年、レヴィは20日間の講演ツアーのためアメリカに飛んだ。ルチアも同行したが、この旅は彼にとって非常に疲れるものだった。 ソビエト連邦では、ソ連兵を英雄的というより、だらしなく無秩序に描いていたため、彼の初期の作品は検閲に受け入れられなかった。イスラエルは、レヴィが 描写したのと同じような恐怖を生き抜いたユダヤ人生存者によって形成された国であり、彼の作品の多くは、彼の死後まで翻訳・出版されなかった[6]。 絞首刑直前のルドルフ・ヘス 1985年3月、彼は、1940年から1943年までアウシュヴィッツ強制収容所の所長であったルドルフ・ヘスの自伝[39]の再出版の序文を書いた。その中で彼はこう書いている。"それは悪に満ちている......そしてそれを読むことは苦悩である"。 また、1985年には、『La Stampa』誌に掲載されていた彼のエッセイ集が、『L'altrui mestiere(他人の商売)』というタイトルで出版された。レヴィはこれらのエッセイを書き溜め、1週間に1本のペースでラ・スタンパ紙に発表してい た。そのエッセイは、書評や自然界の奇妙なものについての考察から、フィクションの短編まで多岐にわたった[6]。 1986年、彼の著書『I sommersi e i salvati(溺れる者と救われる者)』が出版された。その中で彼は、なぜアウシュヴィッツで人々があのような行動をとったのか、なぜ生き残った者もい れば、滅びた者もいるのかを分析しようとした。彼の典型的なスタイルとして、彼は判断を下さず、証拠を提示し、疑問を投げかけている。例えば、あるエッセ イでは、彼が「グレーゾーン」と呼ぶ、ドイツ軍のために汚れ仕事をし、他の囚人たちの秩序を保ったユダヤ人たちについて考察している[40]。 また、1986年には、『La Stampa』に掲載された短編小説をまとめ、『Racconti e saggi』として出版。 1987年4月に死去したとき、レヴィは『二重の絆』という別のエッセイ集に取り組んでいた。この原稿はおよそ5、6章が現存する。キャロル・アンジェは リヴァイの伝記の中で、これらのエッセイのいくつかをどのように探し出したかを述べている。キャロル・アンジェはリヴァイの伝記の中で、どのようにしてこ れらのエッセイのいくつかを探し出したかを記している。 2007年3月、『ハーパーズ』誌は、近距離では致命的だが1メートル以上離れると無害になる架空の武器についてのレヴィの物語「クノール」の英訳を掲載 した。この作品は1971年に出版された『Vizio di forma』に収録されていたが、ハーパーズ誌によって初めて英語で出版された。 2007年4月には、アン・ゴールドスタインとアレッサンドラ・バスターリ[42][43]によって英訳された17の物語を集めた『A Tranquil Star』が出版された。 2015年、ペンギンは『プリモ・レヴィ全集』(アン・ゴールドスタイン編)を刊行。アン・ゴールドスタイン。レヴィの全作品が英訳されたのはこれが初めてである。 |

Death DeathLevi died on 11 April 1987 after a fall from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below. The coroner ruled his death a suicide. Three of his biographers (Angier, Thomson and Anissimov) agreed, but other writers (including at least one who knew him personally) questioned that determination.[44][45] In his later life, Levi indicated that he was suffering from depression; factors likely included responsibility for his elderly mother and mother-in-law, with whom he was living, and lingering traumatic memories of his experiences.[46] According to the chief rabbi of Rome Elio Toaff, Levi telephoned him for the first time ten minutes before the incident. Levi said he found it impossible to look at his mother, who was ill with cancer, without recalling the faces of people stretched out on benches in Auschwitz.[47] The Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel said, at the time, "Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later."[48] However, several of Levi's friends and associates have argued otherwise. The Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta noted that Levi left no suicide note, nor any other indication that he was considering suicide. Documents and testimony suggested that he had plans for both the short- and longer-term at the time. In the days before his death, he had complained to his physician of dizziness due to an operation he had undergone some three weeks earlier. After visiting the apartment complex, Gambetta suggested that Levi lost his balance and fell accidentally.[49] The Nobel laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini, a close friend of Levi, agreed. "As a chemical engineer," she said, "he might have chosen a better way [of exiting the world] than jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed."[50] Views on Nazism, Soviet Union and antisemitism Levi wrote If This Is a Man to bear witness to the horrors of the Nazis' attempt to exterminate the Jewish people and others. In turn, he read many accounts by witnesses and survivors, and attended meetings of survivors, becoming a prominent symbolic figure for anti-fascists in Italy.[6] Levi visited over 130 schools to talk about his experiences in Auschwitz. He vigorously repudiated historical revisionist attitudes in German historiography that emerged in the Historikerstreit led by the works of people like Andreas Hillgruber and Ernst Nolte, who drew parallels between Nazism and Stalinism.[51] Levi rejected the idea that the labor camp system depicted in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago and that of the Nazi Lager (German: konzentrationslager; see Nazi concentration camps) were comparable. The death rate in Stalin's gulags was 30% at worst, he wrote, while in the extermination camps he estimated it to be 90–98%.[52][53][54] His view was that the Nazi death camps and the attempted annihilation of the Jews was a horror unique in history because the goal was the complete destruction of a race by one that saw itself as superior. He noted that it was highly organized and mechanized; it entailed the degradation of Jews to the point of using their ashes as materials for paths.[55] Distinct purpose of extermination camps The purpose of the Nazi camps was not the same as that of Stalin's gulags, Levi wrote in an appendix to If This Is a Man, though it is a "lugubrious comparison between two models of hell."[56] The goal of the Lager was the extermination of the Jewish race in Europe, and no one could renounce Judaism; the Nazis treated Jews as a racial group rather than as a religious one. Levi, along with most of Turin's Jewish intellectuals, had not been religiously observant before World War II, but the Italian racial laws and the Nazi camps impressed on him his identity as a Jew. Of the many children deported to the camps, almost all were murdered.[57] Levi wrote in clear, dispassionate style about his experiences in Auschwitz, with an embrace of whatever humanity he found, showing no lasting hatred of the Germans, although he made it clear that he did not forgive any of the culprits.[58] |

死 死1987年4月11日、トリノの自宅アパート3階の踊り場から地下1階へ転落死。検視官は自殺と断定した。彼の伝記作家の3人(アンジェ、トムソン、アニ シモフ)はこれに同意したが、他の作家(彼を個人的に知っていた少なくとも1人を含む)はその判断に疑問を呈した[44][45]。 後年、レヴィはうつ病を患っていたことを示唆しており、その要因としては、同居していた年老いた母親と義母に対する責任感や、自分の体験のトラウマ的な記 憶が残っていたことが考えられる[46]。 ローマのチーフ・ラビであるエリオ・トアフによると、レヴィは事件の10分前に初めて彼に電話をかけた。ノーベル賞受賞者でホロコーストを生き延びたエ リー・ヴィーゼルは当時、「プリモ・レヴィは40年後にアウシュヴィッツで死んだ」と語った[48]。 しかし、レヴィの友人や仲間の何人かはそうではないと主張している。オックスフォード大学の社会学者ディエゴ・ガンベッタは、レヴィが遺書も残しておら ず、自殺を考えていた形跡もないと指摘した。文書や証言によれば、リヴァイは当時、短期的な計画も長期的な計画も立てていた。死の数日前、彼は3週間ほど 前に受けた手術によるめまいを主治医に訴えていた。アパートを訪ねたガンベッタは、リヴァイがバランスを崩して誤って転落したのではないかと示唆した [49]。リヴァイの親友でノーベル賞受賞者のリタ・レヴィ=モンタルチーニも同意した。「化学技術者であった彼女は、「彼は、半身不随になる危険を冒し て狭い階段の吹き抜けに飛び込むよりも、より良い方法(この世から去る方法)を選んだかもしれない」と語った[50]。 ナチズム、ソ連、反ユダヤ主義に対する見解 レヴィは、ナチスがユダヤ人などを絶滅させようとした恐怖を目撃するために『これが人間なら』を書いた。その一方で、目撃者や生存者による多くの証言を読み、生存者の会合に出席し、イタリアにおける反ファシストの象徴的存在となった[6]。 アウシュヴィッツでの体験を語るために130以上の学校を訪問。レヴィは、ナチズムとスターリン主義を並列に描くアンドレアス・ヒルグルーバーやエルンス ト・ノルテのような人々の著作に代表されるヒストリカーシュトライトに登場したドイツの歴史学における歴史修正主義的な態度を激しく否定した[51]。ア レクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィンの『収容所群島』に描かれた労働収容所システムとナチスのラーゲル(ドイツ語: konzentrationslager、ナチスの強制収容所を参照)のそれが比較可能であるという考えを否定した。スターリンの収容所での死亡率は最悪 でも30%であったと彼は書いているが、絶滅収容所では90~98%であったと彼は推定している[52][53][54]。 彼の見解では、ナチスの死の収容所とユダヤ人の絶滅の試みは歴史上類を見ない恐怖であった。彼は、それが高度に組織化され機械化されていたこと、ユダヤ人の灰をパスの材料として使用するまでにユダヤ人を堕落させることを含んでいたことを指摘している[55]。 絶滅収容所の明確な目的 ナチスの収容所の目的はスターリンの収容所のそれと同じではなかったとレヴィは『これが人間であるなら』の付録で書いているが、それは「地獄の二つのモデ ルの間の気の遠くなるような比較」である[56]。ナチスはユダヤ人を宗教的な集団ではなく、人種的な集団として扱った。レヴィは、トリノのユダヤ人知識 人の多くと同様、第二次世界大戦前は宗教的な信仰を持っていなかったが、イタリアの人種法とナチスの収容所によって、ユダヤ人としてのアイデンティティを 植え付けられた。収容所に送られた多くの子どもたちのうち、ほとんど全員が殺害された[57]。 レヴィはアウシュヴィッツでの体験について、明晰で冷静な文体で書いており、彼が見出した人間性は何であれ受け入れ、ドイツ人に対する憎悪を永続的に示すことはなかったが、加害者の誰一人として許すことはなかったと明言している[58]。 |

|

|

| Five of Levi's poems (Shema, 25

Febbraio 1944, Il canto del corvo, Cantare and Congedo) have been set

to music by Simon Sargon in the song cycle Shema: 5 Poems of Primo Levi

in 1987.[59] In 2021 the work was performed by Megan Marie Hart during

the opening event of the festival year 1700 Jahre jüdisches Leben in

Deutschland [de] commemorating the first documented mention of Jewish

communities in the territory of present-day Germany.[60] The 1997 film La Tregua (The Truce), starring John Turturro, was adapted from his 1963 memoir of the same title and recounts Levi's long journey home with other displaced people after his liberation from Auschwitz. If This Is a Man was adapted by Antony Sher into a one-man stage production Primo in 2004. A version of this production was broadcast on BBC Four in the UK on 20 September 2007.[61] |

|

| In popular culture Till My Tale is Told: Women's Memoirs of the Gulag (1999), uses a part of the quatrain by Coleridge quoted by Levi in The Drowned and the Saved as its title. Christopher Hitchens' book The Portable Atheist, a collection of extracts of atheist texts, is dedicated to the memory of Levi, "who had the moral fortitude to refuse false consolation even while enduring the 'selection' process in Auschwitz". The dedication quotes Levi in The Drowned and the Saved, asserting, "I too entered the Lager as a nonbeliever, and as a nonbeliever I was liberated and have lived to this day."[62][63] The Primo Levi Center, a non-profit organisation dedicated to studying the history and culture of Italian Jewry, was named after the author and established in New York City in 2003.[64] A quotation from Levi appears on the sleeve of the second album by the Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers, titled Gold Against the Soul. The quote is from Levi's poem "Song of Those Who Died in Vain".[65][66] David Blaine has Primo Levi's Auschwitz camp number, 174517, tattooed on his left forearm.[67] In Lavie Tidhar's 2014 novel A Man Lies Dreaming, the protagonist Shomer (a Yiddish pulp writer) encounters Levi in Auschwitz, and is witness to a conversation between Levi and the author Ka-Tzetnik on the subject of writing the Holocaust.[68] In the pilot episode of Black Earth Rising, Rwandan genocide survivor and self-described "major depressive" Kate Ashby tells her therapist, in her final session addressing her survivors' guilt and having overmedicated herself with antidepressants, that she has read the Primo Levi book he'd assigned her, and if she chooses to attempt suicide, she'll jump straight out of a third story window. The last track on The Noise by Peter Hammill is entitled "Primo on the Parapet".[69] |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primo_Levi |

リンク

文献

Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!