愛の技法

The Art of Loving: An Essay

Syriac Lectionary Mosul (Iraq), 1216-1220 The Holy Women at the Empty Tomb - The Resurrection, British Library

愛の技法

The Art of Loving: An Essay

Syriac Lectionary Mosul (Iraq), 1216-1220 The Holy Women at the Empty Tomb - The Resurrection, British Library

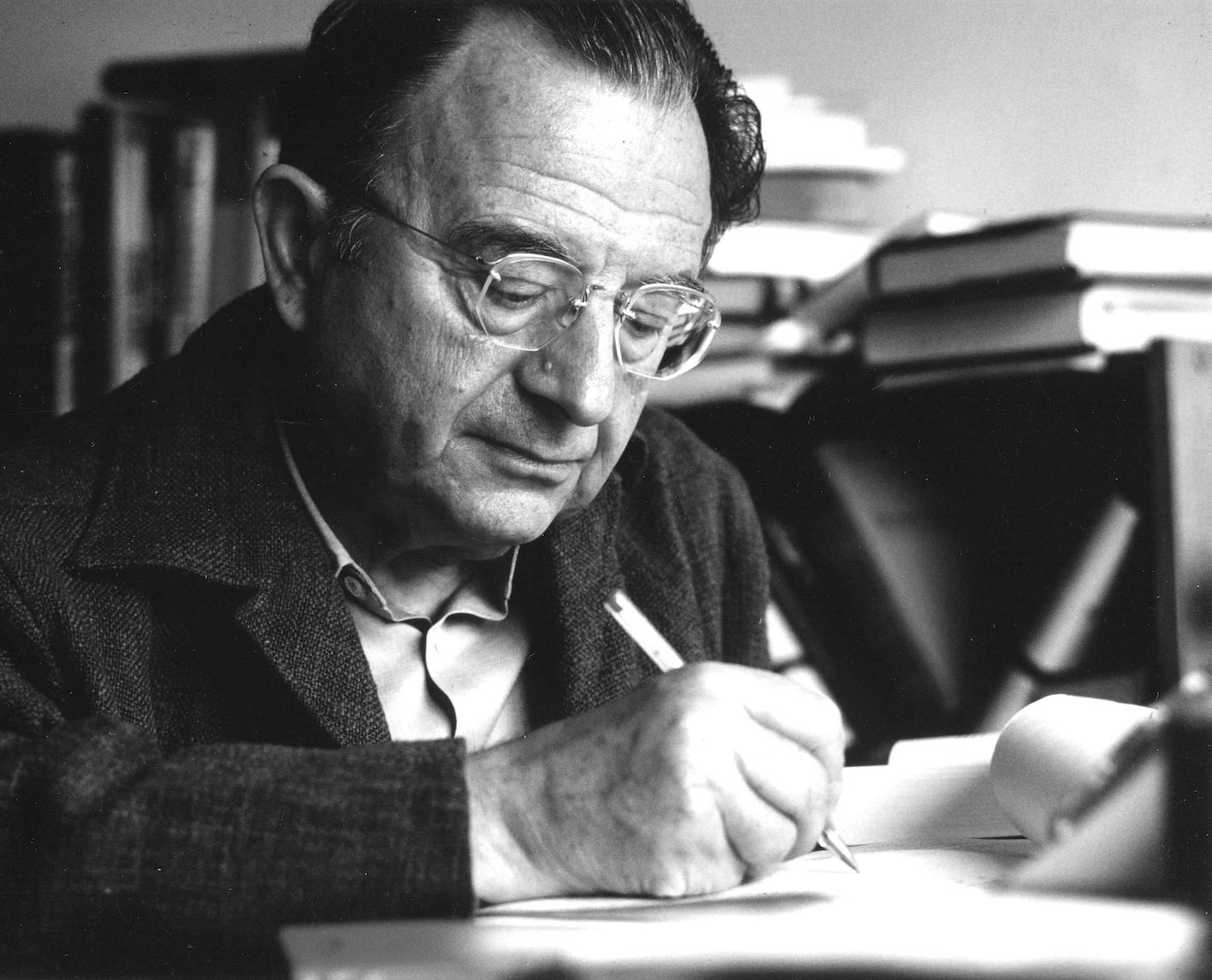

このページは、エーリッヒ・フロム(Erich

Seligmann Fromm)『愛するということ』

鈴木晶訳、紀伊國屋書店、1991年という書物にまつわる、愛に関するエッセーです。

このページは、エーリッヒ・フロム(Erich

Seligmann Fromm)『愛するということ』

鈴木晶訳、紀伊國屋書店、1991年という書物にまつわる、愛に関するエッセーです。

フロム『愛するということ』

エーリッヒ・フロム『愛するということ(The Art of Loving)』は、実は今回初めて読んだのだ。だが僕にとってはすでに読んだことのあるような気にさせてくれる既視感のある「なつかしい本」である。フ ロイト左派とか実存主義思想のグル(精神的指導者)と言われた彼は、僕たちにとっては、商業主義に薄汚れた「資本主義社会」においてもなお正しく 生きるた めの数多くの著作を発表している。大学紛争や学生革命が沈静化した1970年代に青春を迎えた僕たちは、過激な抵抗や革命の試みが図らずも失敗した時代の 中で、もっと酷い第二次大戦のホロコーストがあったことを知り、これらの著作は、理不尽な虚無的状況を克服してより正しく生きることを教えてくれた。恋愛 やセックスについて悩んでいた僕たちに、それまでの誤解を解き、時代や社会的背景による変化——つまりそれらは万古不易な普遍ではなく相対的なものだと教 える——や、新たなる文化創造の可能性の道を示してくれたからなのだ。

「フロムの世界観の中心は、タルムードとハシディズムの解釈であった。彼

は、若い頃からラビ・J・ホロヴィッツに師事し、後にチャバド・ハシドのラビ・サルマン・バルフ・ラビンコウに師事してタルムードを学び始めた。

ハイデルベルク大学で社会学の博士号取得を目指す傍ら[11]、チャ

バドの創始者であるリアディのラビ・シュヌール・ザルマンの『ターニャ』を研究した。また、フランクフルト留学中にネヘミア・ノーベルとルードヴィヒ・ク

ラウゼに師事している。父方の祖父と曾祖父はラビで、母方の大叔父は著名なタルムード学者であった。しかし、1926年に正統派ユダヤ教から離れ、聖典の

理想を世俗的に解釈するようになる。フロムの人文主義思想の根幹は、アダムとイブがエデンの園を追放されたという聖書の物語に対する解釈で

ある。フロムは、タルムードの知識をもとに、善悪の

区別がつくことは一般に美徳とされているが、聖書学者たちは、アダムとイブが神に背き、知識の木から食べることによって罪を犯したと考えるのが一般的であ

ると指摘した。しかし、フロムはこの点について、従来の宗教的正統性から離れ、権威主義的な道徳観に固執するのではなく、人間が自主的に行動し、理性を

使って道徳的価値を確立することを美徳としている。権威主義的な価値観を非難するだけでなく、アダムとイブの物語を、人間の生物学的進化と実存的苦悩の寓

話的説明として使われ、アダムとイブが「知識の木」

を食べたとき、自分たちが自然の一部でありながら自然から分離されていると認識したと主張している。アダムとイブが「知識の木」を食べたとき、自分たちは

自然の一部でありながら、自然から切り離されていることを自覚し、「裸」であり「恥ずかしい」と感じたという。フロムは、このような人間存在の分裂を自覚

することが罪悪感と羞恥心の源泉であり、この実存的二律背反の解決は、愛と理性という人間特有の力を開発することに見いだされるとした。し

かし、フロムは

自分の愛という概念を、無反省な通俗的概念やフロイトの逆説的愛と区別している。フ

ロムは、愛を感情ではなく、対人的な創造的能力であると考え、この創造的能力を、一般に「真の愛」の証明として持ち出される(ものとし)、

自己愛的神経症やサド・マゾヒスティック傾向の諸形態と区別していた。フロムは、

「恋に落ちる」という体験は、愛の本質を理解していない証拠だと考えている。

愛の本質とは、配慮、責任、尊敬、知識という共通の要素を常に持っていると考えていた。また、ヨナはニネベの住民をその罪の結果から救おうとはしなかった

が、これは、ほとんどの人間関係において、配慮と責任というものが欠如しているという考えを示すものである(→「ヨナ書」)。また、現代

社会では、相手の自律性を尊重する

人は少なく、ましてや相手が何を望んでいるのか、何を必要としているのかを客観的に知ることはできないと主張した」出典:「批判理論とその実践」)

| The Art of

Loving

is a 1956 book by psychoanalyst and social philosopher Erich Fromm. It

was originally published as part of the World Perspectives series

edited by Ruth Nanda Anshen.[1] In this work, Fromm develops his

perspective on human nature from his earlier works, Escape from Freedom

and Man for Himself – principles which he revisits in many of his other

major works. |

精神分析医であり社会哲学者でもあるエーリッヒ・フロムが1956年に

出版した『愛することの技法』(原題:The Art of

Loving)。この本でフロムは、彼の初期の作品である『自由からの逃走』と『自分のための人間』から人間の本質についての視点を発展させ、その原則は

彼の他の多くの主要作品でも再確認されている[1]。 |

| Background In 1930, Fromm was recruited to the Frankfurt School by Max Horkheimer.[2] Fromm played a central role in the early development of the school.[3] He left the school in the late 1930's, following a "bitter and contentious" deterioration in his relationship with Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno.[3] In 1956, the year The Art of Loving was released, Fromm's relationship with Herbert Marcuse, also a member of the Frankfurt School, also deteriorated. Dissent published a debate between the two, and though later scholars would come to view Marcuse's arguments as being weaker than Fromm's, Marcuse's were better received within their lifetimes, and Fromm's reputation in leftist circles was permanently damaged.[4][5] |

背景 1930年、マックス・ホルクハイマーによってフランクフルト学派に勧誘されたフロムは、学派の初期の発展において中心的な役割を果たした[2]。 1930年代後半、ホルクハイマーやテオドール・アドルノとの関係が「苦く論争的」に悪化し、学派を去った[3]。『愛することの芸術』が発表された 1956年には、同じフランクフルト学派のヘルベルト・マルクーゼと の関係が悪くなる。『ディセント』は二人の討論を掲載し、後の学者はマルクーゼの主張がフロムより弱いと見るようになるが、二人の存命中にはマルクーゼの 方が評判が良く、左翼界におけるフロムの評判は永久に損なわれることになった[4][5]。 |

| Summary The Art of Loving is divided across four chapters and a preface; the chapter headings are I. Is Love an Art?, II. The Theory of Love, III. Love and Its Disintegration in Contemporary Western Society, and IV. The Practice of Love.[6] An epigraph consisting of a quote from Paracelsus concerning the relationship between love and knowledge is included in the front matter.[7] Preface In the preface, Fromm states that the book does not provide instruction in what he terms the "art of loving", but rather it argues that love, rather than a sentiment, is an artistic practice. Any attempt to love another is bound to fail if one does commit their total personality to learning and practicing loving. He states that "individual love cannot be attained without the capacity to love one's neighbour, without true humility, courage, faith and discipline." He also expresses that the ideas he expresses in The Art of Loving are similar to those he has already written about in Escape from Freedom, Man for Himself, and The Sane Society.[8] |

概要 愛することの芸術」は、4つの章と序文に分かれており、章の見出しは、I.愛は芸術か、II.愛の理論、III. 現代西洋社会における愛とその崩壊、そしてIV. 愛の実践について、である。パラケルススの引用からなる碑文が巻頭に掲載されている[7]。 序文 序文でフロムは、本書は彼が「愛の技法」と呼ぶものの指南書ではなく、むしろ愛は感 情ではなく、アーティステックな実践であると論じている、と述べている。愛する ことを学び、実践することに全人格を捧げなければ、他者を愛そうとする試みは失敗するに違いない。彼は、「個人の愛は、隣人を愛する能力、真の謙虚さ、勇 気、信仰、規律なしには達成できない」と述べている。また、『愛する技術』で表現している考え方は、彼がすでに『自由からの逃走』『自分のための人間』 『正気な社会』で書いていることと似ている[8]と表現している。 |

| I. Is Love an Art? Fromm opens the first chapter by critiquing the place of love in Western society. He says that though people think that love is important, they think that there is nothing for them to learn about love, an attitude which Fromm believes is misguided. For Fromm, a major factor in the development of this attitude is that the majority of people "see the problem of love primarily as that of being loved, rather than that of loving, of one's capacity to love."[9] As a result, people become focused on being attractive rather than on loving others, and as a result, what is meant in Western society by "being lovable is essentially a mixture between being popular and having sex appeal".[9] The second problem Fromm identifies in people's attitudes towards love is that they think of the "problem of love" as that of an "object", rather than a skill.[10] In other words, they believe that to love is simple, but to find the right person to love or be loved by is difficult.[10] He believes that this results in a culture in which human relations of love resemble a labour market, whereby people seek a "bargain" of a romantic partner: one of high social value, who desires them in return, in consideration of the "limitations of their own exchange values." [11] Fromm also identifies a confusion between the initial experience of 'falling in love', and what he terms 'standing' in love, or the "permanent state of being in love".[11] He says that falling in love is by its very nature not lasting, and so if people have not put in the work in order to stand in love together, as they get "well acquainted, their intimacy loses more and more of its miraculous character, until their antagonism, their disappointments, their mutual boredom kill whatever is left of their initial excitement."[11] Furthermore, people consider the intensity of feeling upon falling in love with someone to be proof of the intensity of their love for each other, when for Fromm, this "may only prove the degree of their preceding loneliness".[11] Fromm concludes the chapter by stating that there "is hardly any activity, any enterprise, which is started with such tremendous hope and expectations, and yet, which fails so regularly as love."[12] Fromm contends that this is because of the above attitudes to love, and the neglect of love as an art form, which he states means that it consists of both theory and practice. To master love, however, requires more than learning the theory and implementing the practice, but that "the mastery of the art must be a matter of ultimate concern; there must be nothing else in the world more important than the art".[12] He briefly states that though most people crave love, their desire for success, prestige, money, and power, as desired in capitalist society, relegate love to being of lesser importance to them, and that this is why most people fail to truly love others.[13] |

I. 愛はアートか? フロムは第一章の冒頭で、西洋社会における愛の位置づけを批判している。人々は愛が重要だと考えているにもかかわらず、愛について学ぶべきことは何もない と考えている、と彼は言うのだが、この態度は間違っているとフロムは考えている。フロムにとって、このような態度を発展させた大きな要因は、大多数の人々 が「愛の問題を、愛すること、愛する能力の問題ではなく、主に愛されることの問題として捉えている」[9]ことであり、その結果、人々は人を愛することよ りも魅力的であることに焦点を当て、西洋社会で「愛されること」が意味するものは本質的に、人気者とセックスアピールとの間の混合である[9]と述べてい る。 フロムは、人々の愛に対する態度の2つ目の問題として、「愛の問題」をスキルではなく「対象」の問題として考えていることを挙げている[10]。言い換え れば、愛することは簡単だが、愛する、または愛されるために適切な人を見つけることは難しいと考えているのである[10]。 その結果、恋愛の人間関係が労働市場のようになり、人々は「交換価値の限界」を考慮して、見返りとして自分を欲する社会的価値の高い相手という恋愛相手の 「掘り出し物」を求める文化になっていると考えている[10]。[11] またフロムは、「恋に落ちる」という最初の体験と、彼が「恋に立つ」あるいは「恋をしている永続的な状態」と呼ぶものとの間に混乱があることを指摘する [11]。彼は、恋に落ちることは本質的に永続しないため、人々が共に恋に立つために仕事をしなかった場合、「よく知り合うと彼らの親密さはますますその 奇跡的特性を失い、彼らの反目、失望、お互いの退屈が最初の興奮を殺していくまで」と述べている[12][13]。 「さらに、人は誰かと恋に落ちたときの感情の激しさを、互いへの愛の激しさの証拠と考えるが、フロムにとってはそれは「先行する孤独の度合いを証明するだ けかもしれない」のである[11]。 フロムはこの章の最後に、「愛ほど大きな希望と期待を持って始められ、しかも定期的に失敗する活動や事業はほとんどない」[12]と述べている。これは愛 に対する上記の態度と、愛をアートの形式として軽視しているからだとフロムは主張し、愛は理論と実践からなることを意味していると述べている。しかし、愛 を習得するためには、理論を学び、実践すること以上に、「アートの習得は究極の関心事でなければならず、世界にはアートよりも重要なものは他にないはず だ」と述べている[12]。 また、ほとんどの人は愛を切望しているが、資本主義社会で望まれる成功、名声、金銭、権力への欲求が愛を重要視しないものに追いやったため、ほとんどの人 は真に人を愛することができなくなったと短く述べている[13]。 |

| II. The Theory of Love 1. Love, the Answer to the Problem of Human Existence Fromm opens this chapter by stating that "Any theory of love must begin with a theory of man, of human existence."[14] From Fromm, a person's key trait is their ability to reason. Prior to humans developing the ability to reason, we were part of the animal kingdom and in a state of harmony. To recover this state of harmony it is impossible for us to regress to the idyll of the animal kingdom, but rather humanity must progress to a new harmony by developing their ability to reason.[14] This ability to reason makes humanity "life being aware of itself", and separates us from all other creatures.[14] This separation is, for Fromm, "the source of all anxiety".[15] He says that by understanding the story of Adam and Eve, people can understand the barriers to loving connection. For Fromm, when man and woman develop awareness of their difference from each other, they remain strangers, and this is the source of shame, guilt, and anxiety, and it is reunion through love which allows people to overcome this feeling of difference.[15] For Fromm the fundamental question facing mankind is "the question of how to overcome separateness, how to achieve union, how to transcend one's own individual life and find at-onement".[16] In other words, that people are fundamentally isolated, and seek union with others to overcome this feeling of isolation. He develops this idea, stating that different cultures and religions have had different techniques to achieve this, and gives five examples of how these unions are achieved. He describes "orgiastic states", in which "separateness" is abated by taking drugs, participating in sexual orgies, or both.[17] For Fromm, the problem with this approach is that the feeling of unity is temporary and fleeting.[17] He proceeds to state that in modern capitalist society, people find union in conformity.[18] The meaning of equality, for Fromm, has been changed from meaning "oneness" to meaning "sameness". The result of pursuing the Enlightenment concept of l'âme ne pas de sexe (literally, "the soul has no sex"), has resulted is the disappearance of the polarity of the sexes, and with it, erotic love.[19] He criticises the effect that union by conformity has on people, turning them into "nine to fiver[s]", who sacrifice their fulfillment outside of work by their commitment to filling a labour role.[20] A third way that Fromm suggests people seek union is through what he terms "Symbiotic union", which he divides into sadism and masochism.[21] In this paradigm, both the masochist and the sadist are dependent on the other, which he believes reduces the integrity of each.[22] Fromm proposes that the most harmful way people may find union is through domination, which is an extreme form of sadism. He provides the example of a child tearing apart a butterfly to understand how it functions.[23] Fromm contrasts symbiotic union with mature love, the final way people may seek union, as union in which both partners respect the integrity of the other.[22] Fromm states that "Love is an active power in a man",[24] and that in the general sense, the active character of love is primarily that of "giving".[25] He further delineates what he views as the four core tenets of love: care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge.[26] He defines love as care by stating that "Love is the active concern for the life and the growth of that which we love", and gives an example of a mother and a baby, saying that nobody would believe the mother loved the baby, no matter what she said, if she neglected to feed it, bathe it, or comfort it.[26] He further says that "One loves that for which one labours, and one labours for that which one loves."[27] The second principle of love, to Fromm, is responsibility. He contrasts his definition of responsibility with that of duty, stating that responsibility is the voluntary desire to respond to the needs of one's partner. Without his third principle of love, respect, Fromm warns that responsibility can devolve into exploitation. Fromm says that in a loving relationship, people have a responsibility not to exploit their partners.[27] He explains that L'amour est l'enfant de la liberté (literally, "love is the child of liberty"), and that love must desire the growth of the partner as they are, not how one may want them to grow. As such, for Fromm, "respect is possible only if I have achieved independence".[27] According to Fromm, in order to respect someone we must know them, and so knowledge is his fourth principle of love.[27] For Fromm, attainment of these four attitudes are only possible in the mature person, one "who only wants to have that which he has worked for, who has given up narcissistic dreams of omniscience and omnipotence, who has acquired humility based on the inner strength which only genuine productive activity can give."[28] He concludes the chapter by criticising Freud for not understanding sex well enough.[29] |

II. 愛の理論 1. 人間の存在問題への解答としての愛 フロムはこの章の冒頭で、「いかなる愛の理論も、人間に関する理論、人間の存在に関する理論から始めなければならない」[14]と述べている。フロムは、 人間の重要な特性は理性的能力であるとする。人間が理性的な能力を身につける以前、人間は動物界の一部であり、調和のとれた状態にあった。この調和の状態 を回復するためには、動物界の牧歌的な状態に逆戻りすることは不可能であり、むしろ人類は理性の能力を発達させることによって新しい調和へと進歩しなけれ ばならない[14]。この理性の能力によって人類は「生命が自分自身を認識する」ようになり、他のすべての生物から分離される[14]。 この分離がフロムにとって「すべての不安の原因」である。 アダムとイブの話を理解すれば、愛のつながりを阻むものが理解できると言うのである[15]。フロムにとって、男と女が互いの違いを意識するとき、彼らは 他人のままであり、これが恥、罪悪感、不安の源であり、この違いという感覚を克服できるのは、愛による再会である[15]。 つまり、人は根本的に孤立しており、その孤立感を克服するために他者との結合を求めるというのである[16]。彼はこの考えを発展させ、異なる文化や宗教 がこれを達成するために異なる技術を持っていたと述べ、これらの結合がどのように達成されるかについて5つの例を挙げている。彼は、「分離性」が薬物を摂 取すること、性的乱交に参加すること、あるいはその両方によって緩和される「オルギアス状態」について述べている[17]。フロムにとってこのアプローチ の問題は、一体感の感覚が一時的ではかないということである[17]。 そして、現代の資本主義社会では、人々は適合性の中に一体感を見つけると述べる[18]。フロムにとって平等の意味は、「一体感」から「同一性」の意味へ と変化しているのである。魂には性別がない」という啓蒙的な概念を追求した結果、男女の極性が消滅し、それに伴ってエロティックな愛も消滅してしまったの である[19]。 彼は、適合による組合が人々に与える影響を批判し、労働者の役割を満たすことにコミットすることによって仕事以外の充実感を犠牲にする「9時から5時ま で」の人たちに変えてしまう[20]と述べている。 フロムは人々が結合を求める第三の方法として、彼が「共生的結合」と 呼ぶ、サディズムとマゾヒズムに分けることを提案している[21]。このパラダイムでは、マゾヒストとサディストはどちらも相手に依存し、それがそれぞれ の完全性を低下させると彼は信じている[22]。 フロムは人々が結合を見つけることができる最も有害な方法は支配であり、それはサディズムの極端な形態であると提案する。彼は子供が蝶の機能を理解するた めに蝶を引き裂くという例を提示している[23]。 フロムは共生的な結合を、両パートナーが相手の完全性を尊重する結合として、人が結合を求める最後の方法である成熟した愛と対比している[22]。 フロムは「愛は人間の中の能動的な力である」と述べており[24]、一般的な意味において、愛の能動性は主に「与えること」である[25]。さらに彼は愛 の4つの核と考えられる考え方、ケア、責任、尊敬、知識を明確にしている[26]。 26]彼は「愛とは、愛するものの生命と成長に対する積極的な関心である」と述べ、母親と赤ん坊の例を挙げ、母親が赤ん坊に食べ物を与えず、風呂に入れ ず、慰めることを怠れば、彼女が何を言っても誰もその赤ん坊を愛しているとは信じないだろうと言う[26]。さらに彼は「人はそのために労働するものを愛 し、そのために愛するものを労働する」[27]と言う[27]。 フロムにとっての愛の第二の原理は、責任である。彼は責任の定義を義務の定義と対比させ、責任とは相手の必要に応えようとする自発的な欲求であると述べて いる[27]。フロムは、愛の第三の原則である「尊敬」がなければ、「責任」は「搾取」に堕してしまうと警告しています。フロムは、愛の関係において、人 は相手を搾取しない責任があるという。「愛は自由の子」(L'amour est l'enfant de la liberté)と説明し、愛は相手にどう成長してほしいかではなく、相手のあるがままの成長を望まなければならないという。そのため、フロムにとって、 「尊敬は、私が自立を達成した場合にのみ可能である」[27] という。 [フロムにとってこれらの4つの態度の達成は成熟した人間においてのみ可能であり、「自分のために働いたものだけを持ちたいと願い、全知全能というナルシ スティックな夢をあきらめ、本物の生産活動のみが与えることのできる内なる強さに基づいた謙虚さを獲得した人間」である[28]と彼は本章を締めくくり、 フロイトは性について十分に理解していないと批判している[29]。 |

| 2. Love Between Parents and Child Fromm opens this section by hypothesizing on love through the eyes of a baby in relation to its mother. In this dynamic, the child intuits that "I am loved for what I am", or rather "I am loved because I am". This love is unconditional: "it need not be acquired, it need not be deserved."[30] The unconditional aspect of motherly love, a blessing if present, produces a problem of its own: if this love is absent, there is nothing the child can do to create it.[30] Before growing to the age from eight and a half to ten, Fromm considers that children experience being loved, but do not themselves begin to love. At this point a child begins to practice love by giving a gift to one of their parents.[30] Fromm states that it takes many years for this form of love to develop into mature love.[31] He contrasts the difference, the primary one being that someone who loves maturely believes that loving is more pleasurable than receiving love. Through practicing love, and thus producing love, the individual overcomes the dependence on being loved, having to be "good" to deserve love. He contrasts the immature phrases "I love because I am loved" and "I love you because I need you" with mature expressions of love, "I am loved because I love", and "I need you because I love you."[31] He contrasts motherly love with fatherly love. Fromm contends that mothers and fathers represent opposite poles of human existence: the mother represent the natural world, while the father embodies the world of thought, man-made thing, and adventure.[32] Unlike motherly love, fatherly love is conditional for Fromm, it can be earned.[33] Fromm contends that in infancy, people care more about motherly love, while in later childhood they crave fatherly love.[32] Upon reaching maturity, a well-adjusted individual reaches a synthesis of motherly and fatherly love within their own being; they become their own source for both.[34] Fromm believes that receiving an inadequate balance of both motherly and fatherly love results in various forms of neurosis in adults.[35] |

2. 親と子の間の愛 フロムはこの章の冒頭で、母親に対する赤ん坊の目を通して、愛について仮説を立てている。このとき、子どもは「私は私であるがゆえに愛されている」、い や、「私であるがゆえに愛されている」と直感する。この愛は無条件であり、「獲得する必要もなく、当然である必要もない」[30]。母性愛の無条件性は、 それがあれば幸せであるが、もしその愛がなければ、子どもはそれを作り出すために何もできない、という問題を生む[30]。この時点で子どもは両親のどち らかに贈り物をすることで愛を実践し始める[30]。 フロムはこの愛の形が成熟した愛に発展するには何年もかかると述べている[31]。彼はその違いについて、成熟した愛を持つ人は、愛することは愛を受ける よりも楽しいと考えるということを第一に対比している。愛を実践し、愛を生み出すことで、愛されることへの依存、愛に値する「良い人」でなければならない という依存を克服していく。愛されているから愛する」「あなたが必要だから愛する」という未熟な表現と、「愛しているから愛されている」「愛しているから あなたが必要だ」という成熟した愛の表現を対比させる[31]。 彼は母性愛と父性愛を対比させる。フロムは母親と父親が人間存在の対極を表していると主張し、母親は自然界を代表し、父親は思考、人工物、冒険の世界を体 現している[32] 母性愛と異なり、父親愛はフロムにとって条件付きであり、獲得できる[33] 幼児期に人はより母性愛を気にし、晩年期に人は父親的愛を渇望するとフロムは主張している。 [フロムは母性愛と父性愛のバランスが不十分な場合、大人になってから様々な形で神経症になると考えている[34]。 |

| 3. The Objects of Love Fromm subdivides opens this section by stating that it is a fallacy to believe that loving one person and no others is a testament to the intensity of that love. He proposes that one can only truly love an individual if one is capable of loving anyone.[36] (a) Brotherly Love Brotherly love, for Fromm, is not love between siblings but rather the love one feels for their fellow man, originating in their common experiences of humanity. This is a love between equals, though "even as equals we are not always 'equal'; inasmuch as we are human, we are all in need of help. Today I, Tomorrow you."[37] The beginning of brotherly love is described as love for the helpless, the poor, and the stranger. He compares brotherly love to Exodus 22:21, "You know the heart of the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt", adding "therefore love the stranger!"[38] (b) Motherly Love In this section Fromm expands his previous description of motherly love to include an element beyond the minimum care and responsibility required to support the child's life and growth.[38] He says that a mother has a responsibility to instill a love for life in her children, and compares these two forms of responsibility to milk and honey. Here milk symbolises the first of the two, the responsibility of care and affirmation.[39] Honey symbolizes the sweetness of life, a love and joy for the experience of living, which only a truly happy mother can instill in her children. Unlike brotherly love (and later, erotic love), motherly love is by its very nature not shared between equals.[39] Fromm states that most mother succeed as showing motherly love when their children are infants, but the true test of motherly love, for Fromm, is to continue to love as the child grows, matures, and eventually detaches themselves from their reliance on the mother.[40] (c) Erotic Love This section is concerned with romantic love shared between one man and one woman treating each other as equals. Erotic love, for Fromm, is the craving of complete fusion with one other person, and considers sexual union to be a vital part of this fusion.[41] Sex, says Fromm, can be blend and be stimulated by any strong emotion, not only love. When two people who truly love each other have sex, however, the act is devoid of greediness, and is defined by tenderness. Because the notion of sexual desire is often conflated with love in western society, such desire is often mistakenly considered a sign of loving someone. Though having sex with someone can give the illusion of unity, absent of love this act will leave the participants just as much strangers to each other as before, and can induce feelings of shame or hatred for the other. Fromm criticizes the misinterpretation of the exclusive nature of erotic love as possessive attachment. He states that is common to find two people who consider themselves to be in love with each other but have no love for anyone else. Fromm considers this an "egotism á deux", as one should love all of mankind through the love of their romantic partner.[42] Fromm concludes the section by criticizing views that love is either exclusively a feeling or exclusively an act of will, stating that is somewhere between the two.[43] (d) Self-Love Fromm says that modern humans are alienated from each other and from nature, and we seek refuge from our lonesomeness in romantic love and marriage. One of the book's concepts is self-love. According to Fromm, loving oneself is quite different from arrogance, conceit or egocentrism. Loving oneself means caring about oneself, taking responsibility for oneself, respecting oneself, and knowing oneself (e.g. being realistic and honest about one's strengths and weaknesses). In order to be able to truly love another person, one needs first to love oneself in this way. The book includes explorations of the theories of brotherly love, motherly and fatherly love, erotic love, self-love, and the love of God, and an examination into love's disintegration in contemporary Western culture. Fromm explains what he calls "paradoxical logic"—the ability to reconcile opposing principles in one same instance. He highlights paradoxical logic in the chapters dedicated to the love of God and erotic love. |

3. 愛の対象 フロムはこのセクションの冒頭で、一人の人を愛して他の人を愛さないことがその愛の強さの証であると信じるのは誤りであると述べている[36]。彼は、人 は誰でも愛することができる場合にのみ、個人を真に愛することができると提案する[36]。 (a)同胞愛 フロムにとっての兄弟愛とは、兄弟間の愛ではなく、人類という共通の体験に由来する、同胞に対する愛である。これは対等な者同士の愛であるが、「対等で あっても、私たちは常に『対等』ではない。今日は私、明日はあなた」[37] 兄弟愛の始まりは、無力な者、貧しい者、見知らぬ者に対する愛として描かれる。出エジプト記22章21節「あなたがたは、エジプトの地でよそ者であったか ら、よそ者の心を知っている」と兄弟愛をたとえ、「だから、よそ者を愛しなさい!」と付け加えている[38]。 (b)母性愛 この節でフロムは、これまでの母性愛の記述を発展させて、子どもの生命と成長を支えるために必要な最低限の世話と責任以上の要素を含んでいる[38]と し、母親には子どもに生命に対する愛を植え付ける責任があるとし、この二つの責任を乳と蜜にたとえている[39]。ここで牛乳は2つのうちの最初のもの、 つまり世話と肯定の責任を象徴している[39]。蜂蜜は人生の甘さ、生きる経験に対する愛と喜びを象徴しており、本当に幸せな母親だけが子供に植え付ける ことができる。フロムは、ほとんどの母親は子どもが乳児のときに母性愛を示すことに成功するが、フロムにとって母性愛の真のテストは、子どもが成長して成 熟し、最終的に母親への依存から自らを切り離すときに愛し続けることであると述べている[39]。 (c) エロティックな愛 このセクションは、一人の男性と一人の女性が互いに対等に接する恋愛に関わるものである。フロムにとってエロティックな愛とは、一人の他者との完全な融合 を渇望することであり、その融合のために性的結合が不可欠であると考える[41]。 フロムは、セックスは愛だけでなく、どんな強い感情によってもブレンドされ、刺激されることがあると言う。しかし、本当に愛し合う二人がセックスすると き、その行為には欲がなく、優しさによって定義される。欧米では性欲と愛が混同されているため、性欲は愛している証と誤解されがちである。セックスをする ことで一体感を得ることはできても、愛がなければ、その行為はお互いを他人扱いし、相手を恥ずかしく思ったり、憎んだりすることになる。フロムは、エロ ティックな愛の排他性を独占的な愛着と誤解していることを批判している。そして、自分では愛し合っていると思っていても、他の誰にも愛情を抱いていない二 人がいることはよくあることだと述べている。フロムはこれを「2人のエゴイズム(egotism á deux)」と考え、人は恋愛相手の愛を通して全人類を愛するべきであるとしている[42]。フロムは、愛は感情だけであるか意志の行為だけであるという 見方を批判し、この二つの間のどこかにあると述べてこのセクションを締めくくっている[43]。 (d) 自己愛 フロムは、現代人は互いに、また自然から疎外されており、その孤独感から恋愛や結婚に逃げ場を求めているという。 この本のコンセプトのひとつに「自己愛」がある。フロムによれば、自分を愛するということは、傲慢、うぬぼれ、自己中心主義とは全く違うものである。自分 を愛するとは、自分を大切にすること、自分に責任を持つこと、自分を尊重すること、自分を知ること(例えば、自分の長所と短所を現実的に、正直に知るこ と)である。他者を真に愛することができるようになるためには、まずこのように自分自身を愛することが必要である。 本書では、兄弟愛、母性愛、父性愛、エロティックな愛、自己愛、神への愛などの理論が探求され、現代の西洋文化における愛の崩壊についての考察がなされて いる。 また、フロムは「逆説の論理」と呼ばれる、相反する原理を同じ事例で調和させる能力について説明する。神への愛とエロティックな愛についての章では、逆説 的な論理が強調されている。 |

| III. Love and its Disintegration

in Contemporary Western Society Fromm calls the general idea of love in contemporary Western society égoïsme à deux – a relationship in which each person is entirely focused on the other, to the detriment of other people around them. The current belief is that a couple should be a well-assorted team, sexually and functionally, working towards a common aim. This is in contrast with Fromm's description of true erotic love and intimacy, which involves willful commitment directed toward a single unique individual. One cannot truly love another person if one does not love all of mankind including oneself. IV. The Practice of Love Fromm begins the last chapter, "The Practice of Love", by saying: "[...] many readers of this book, expect to be given prescriptions of 'how to do it to yourself' [...]. I am afraid that anyone who approaches this last chapter in this spirit will be gravely disappointed". He says that in order to master the art of loving, one must practice discipline, concentration, and patience in every facet of one's life. |

III. 現代西洋社会における愛とその崩壊 フロムは、現代西洋社会における一般的な恋愛観を「エゴイズム・ア・ドゥー」(égoïsme à deux)と呼んでいる。現在のカップルは、性的に、また機能的に、共通の目的に向かって働く、よくまとまったチームであるべきだという考えである。これ は、フロムの言う「真のエロティックな愛と親密さ」とは対照的で、一人のユニークな人間に対する意志あるコミットメントを伴う。自分を含む全人類を愛さな い限り、他者を真に愛することはできないのである。 IV. 愛の実践 フロムは最終章「愛の実践」の冒頭で、次のように語っている。この本の多くの読者は、「自分自身にどうすればいいか」という処方箋が与えられることを期待 している。このような精神でこの最終章に臨む人は、ひどく失望することになると思う」。彼は、愛するという技術を習得するためには、人生のあらゆる面で規 律、集中、忍耐を実践しなければならないと述べています。 |

| Reception The Art of Loving is Fromm's best-selling work, having sold millions of copies.[44] The book enhanced the perception of Fromm as a populariser, a writer who over simplifies their work to appeal to a broader audience.[44] At the time of its release, it initiated criticism within leftist circles as not being emancipatory in nature.[45] |

レセプション The Art of Loving』はフロムのベストセラーであり、何百万部も売れた[44]。この本は、より多くの読者にアピールするために自分の仕事を過度に単純化する作 家である大衆作家としてのフロムの認識を高めた。 発売当時、左翼界では本質的に 解放的ではないとして批判が始まった[44]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Art_of_Loving |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

以下、関連書の紹介:7点8冊です。

(1)順不同

ヘーゲル『精 神現象学』 長谷川宏訳、作品社、5800円 ISBN:9784878932946

この作品全体がというよりも、主と奴(あるいは主人と奴隷)という関係の議論に僕は焦点を当てたい。つまり愛する者と愛される者との弁証法的

な関係を考

えるのに重要なものであるという示唆を大いに与えてくれた。詳しいことは僕のウェブページ「ジェンダー・バトル、あるいは〈愛の操作術〉について」

(http://bit.ly/18M3des)をご覧ください。

(2)

デーヴィッド・マーゴリック『ビリー・ホリデイと『奇妙な

果実』:20世

紀最高の歌の物語』小村公次訳、大月書店、2100円 ISBN: 9784272612109

「奇妙な果実」——アメリカの南部の過酷な黒人差別の結果、木に吊るされた死体——これが、どうして「愛」に関係するのかといぶかしげに思われるかもしれ

ない。愛に飢えた孤高の天才的ジャズシンガーであるビリー・ホリディの人生を通して、彼女の愛への渇望とそのグロテスクな歌が人々の心を揺さぶり、やがて

普遍的な人類愛の探究ゆえの社会運動としての公民権運動と繋がる。これらの結びつきの奇妙なもつれを描く〈もうひとつの愛の物語〉のドキュメントなのだ。

(3)

原田正純『水

俣病』

岩波新書、岩波書店、840円、ISBN: 9784004111139

一昨年の6月11日に物故された水俣病患者運動の象徴的存在であった医師・原田正純の代表作。水俣病が原因企業側の研究者であった細川医師よりネコ400

号実験でその原因が、工場廃液から出る物質であることをつきとめた。この1959年に、原田は熊本大学医学部を卒業する。生涯をかけて水俣病患者運動に関

わってゆく理由を彼は「患者さんの状況をそこで見てしまったからだ」と説明する。フロムが言うように、愛はたんなる感情ではなく、人と人の間の関係性であ

る。原田の水俣病救済にかける情熱も、また公害による環境汚染に苛まれる人と関わることのなかで育まれたという点で、本物の愛であったと言っても過言では

ない。

(4)

シャルル・フーリエ『四

運動の理論(上)(下)』巌谷国士訳、現代思潮社、2940円、ISBN:9784329004192、およびISBN:

9784329004208

フランスの空想主義的社会主義者シャルル・フーリエ(1772-1837)のこの著作は、そのタイトルとは想像もつかないほどの奇書と言っても

よいだろ

う。健全なる社会労働をおこなえば、四つの月が現れて地球を煌々と照らし、北極と南極の氷は溶け、それにより海の水は甘くなり(淡水化し)、猛獣が人間の

言うことを聞くようになるというのだ。彼には『愛の新世界』という

死後130年後に発見されたノートがあるが、これも詳細な註釈が付された翻訳があり日本

語で読むことができる。

(5)

池田光穂『看 護人類学入 門』文化書房博文社、2520円、ISBN: 9784830111648

フロムは、愛は感情ではなく、人間の関係性から生まれるものだと喝破したが、そうだとすれば、愛とは社会性をもって人が生きることと実は同義な のだ。現 代社会において、人間が生きることに直接関わり、側面から多くの人間観察をおこなっている分野は何かと言われれば、それは医学の専門家ではなく、看護の専 門家なのである。だが現在では医学の過度の生物科学主義化によって看護の領域にも、人間全体を見ずして、病気だけを見ようとする誤った専門分化が生まれて いることを危惧する声がある。看護学は人間学であるという主張に立った、この書物は、愛が生まれる人間の関係性について幅広く論じている。【看護人 類学への関連リンク】

(6)

プリーモ・レーヴィ『休 戦』竹山博英訳、岩波文庫、岩波書店、987円、ISBN: 9784003271711

アウシュビッツを体験したイタリア出身の化学者が、解放されて9か月を難民として放浪して自分の生まれ故郷であるトリノに帰還するロード小説。 この彼の 苦渋の物語——でもなぜか各所にユーモアと諧謔感がないまぜになって奇妙な明るさというものがある——のなかに「愛」はあるだろうか? 僕がこの小説で忘 れない箇所が一つある、アウシュビッツで生まれたが、腕に入れ墨だけがあり、通称はあったが、おそらく先に処刑された家族からは名前も与えられず、ソビエ ト軍が収容所を解放する直前に死んだ3歳の男の子の話である。レーヴィは書く「彼の存在を証明するのは私のこの文章だけである」。僕はこれが作者の無名の 犠牲者への愛であり、この本は、そのために存在するのではないかと思うほどなのだ。

(7)

ハンナ・アーレント『ア ウグスティヌスの愛の概念』千葉真訳、みすず書房、3150円、ISBN:9784622083498

生前は特異な思想家とみなされていたが、死後20年ぐらいたってから20世紀最大の思想家と持て囃されるようになったアーレント。そのような神 格化を彼 女自身は「ばかばかしく愚かしいことだ」と墓の中で呟いていることだろう——そのような確信は彼女の伝記であるヤングブルーエル『ハンナ・アーレント伝』 晶文社(現在は品切)を読めばわかる。その彼女の学位論文が本書だが、難解と呼ばれる彼女の著作のなかでも、かなり難しい。古代哲学とキリスト教の融合的 調和をなしとげた大神学者のアウグスチヌスに取り組んだ彼女の22歳の作品だと考えると、それも故無しとは言えない。アウグスチヌス哲学の彼女の著作への 影響は極めて大きく主著の『全体主義の起源』や『人間の条件』にも、 そして晩年の『精神の生活』の中にも随所にみられる。隣人愛や、神への愛と自己への愛 の共存の可能性など、フロムの愛の概念の考察と交錯する部分が多く、驚かされる。

Syriac Lectionary Mosul (Iraq), 1216-1220 The Holy Women at the Empty Tomb - The Resurrection, British Library

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate

students!!!