ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン

Lewis Henry Morgan, 1818-1881

ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン(1818年11月21日 - 1881年12月17日)は、鉄道会社の弁護士として活躍したアメリカの人類学者、社会理論家のパイオニア的存在である。親族関係や社会構造に関する研 究、社会進化論、イロコイ族の民族誌でよく知られている。社会を結びつけているものに関心を持ち、人類最古の家庭制度は家父長的な家族ではなく母系的な氏 族であるという概念を提唱した。

| Lewis Henry Morgan

(November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American

anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He

is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his

theories of social evolution, and his ethnography of the Iroquois.

Interested in what holds societies together, he proposed the concept

that the earliest human domestic institution was the matrilineal clan,

not the patriarchal family. Also interested in what leads to social change, he was a contemporary of the European social theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who were influenced by reading his work on social structure and material culture, the influence of technology on progress. Morgan is the only American social theorist to be cited by such diverse scholars as Marx, Charles Darwin, and Sigmund Freud. Elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences, Morgan served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1880.[1] Morgan was a Republican member of the New York State Assembly (Monroe Co., 2nd D.) in 1861, and of the New York State Senate in 1868 and 1869. |

ル

イス・ヘンリー・モーガン(1818年11月21日 -

1881年12月17日)は、鉄道会社の弁護士として活躍したアメリカの人類学者、社会理論家のパイオニア的存在である。親族関係や社会構造に関する研

究、社会進化論、イロコイ族の民族誌でよく知られている。社会を結びつけているものに関心を持ち、人類最古の家庭制度は家父長的な家族ではなく母系的な氏

族であるという概念を提唱した。 また、社会の変化をもたらすものに関心を持ち、ヨーロッパの社会理論家であるカール・マルクスやフリードリヒ・エンゲルスと同時代に、社会構造と物質文 化、進歩に対するテクノロジーの影響に関する彼の著作を読んで影響を受けた。マルクス、ダーウィン、フロイトなど多様な学者から引用された唯一のアメリカ 人社会理論家である。全米科学アカデミーの会員に選ばれたモーガンは、1880年にアメリカ科学振興協会の会長を務めた[1]。 1861年にはニューヨーク州議会(モンロー郡、第2区)の共和党議員、1868年と1869年にはニューヨーク州上院議員に就任した。 |

| The American Morgans According to Herbert Marshall Lloyd, an attorney and editor of Morgan's works, Lewis was descended from James Morgan, a Welsh pioneer.[2] Various sources record that James and his brothers, Miles and John, the three sons of William Morgan of Llandaff, Glamorganshire, left Wales for Boston in 1636. From there John Morgan went to Virginia, Miles to Springfield, Massachusetts, and James to New London, Connecticut.[3] Lloyd writes, "From these two brothers [James and Miles] all the Morgans prominent in the annals of New York and New England are believed to be descended." It is these Morgans who played a critical part in the foundation of the colonies. During the American Revolutionary War, they were Continentals. Immediately after the war, James’s line, along with many other land-hungry Yankees, migrated into New York State. Following the United States' victory against the British, the new government forced the latter's Iroquois allies to cede most of their traditional lands in New York and Pennsylvania to the US. New York made 5 million acres available for public sale. In addition, the US government granted some plots in western New York to Revolutionary War veterans as compensation for their military service. |

アメリカのモルガン家 弁護士でモーガン著作の編集者であるハーバート・マーシャル・ロイドによれば、ルイスはウェールズの開拓者ジェームズ・モーガンの子孫である[2]。 グラモーガンシャー州ランダフのウィリアム・モーガンの三男ジェームズとその兄弟マイルズ、ジョンが1636年にウェールズからボストンへ向かったことが 各種資料で確認されています。Lloydは、"この二人の兄弟(JamesとMiles)から、ニューヨークとニューイングランドの歴史に登場するすべて のMorgansが生まれたと考えられている "と書いている[3]。植民地の建設に重要な役割を果たしたのは、このモルガン家の人々である。アメリカ独立戦争では、彼らはコンチネンタル派であった。 戦争直後、ジェームズの一族は、土地を求める多くのヤンキーたちとともに、ニューヨーク州に移住した。米国が英国に勝利した後、新政府は後者の同盟者であ るイロコイ族のニューヨークとペンシルベニアの伝統的な土地のほとんどを米国に割譲するよう強要した。ニューヨークは500万エーカーを公売に付した。さ らに、アメリカ政府は独立戦争の退役軍人の軍務に対する補償として、ニューヨーク西部のいくつかの区画を許可した。 |

| Early life and education Lewis' grandfather, Thomas Morgan of Connecticut, had been a Continental soldier in the Revolutionary War. Afterward he and his family migrated west to New York's Finger Lakes region, where he bought land from the Cayuga people and planted a farm on the shores of Lake Cayuga near Aurora. He and his wife already had three sons, including Jedediah, the future father of Lewis; and a daughter. In 1797, Jedediah Morgan (1774–1826) married Amanda Stanton, settling on a 100-acre gift of land from his father. After she had five children and died, Jedediah married Harriet Steele of Hartford, Connecticut. They had eight more children, including Lewis. As an adult, he adopted the middle initial "H."[4] Morgan later decided that this H, if anything, stood for "Henry".[5] A multi-skilled Yankee, Jedediah Morgan invented a plow and formed a business partnership to manufacture parts for it; he built a blast furnace for the factory. He moved to Aurora, leaving the farm to a son. After joining the Masons, he helped to form the first Masonic lodge in Aurora. Elected a state senator, Morgan supported the construction of the Erie Canal, which opened in 1825. At his death in 1826, Jedediah left 500 acres with herds and flocks in trust for the support of his family. This provided for education as well. Morgan studied classical subjects at Cayuga Academy: Latin, Greek, rhetoric and mathematics.[6] His father had bequeathed money specifically for his college education, after giving land to the other children for their occupations. Morgan chose Union College in Schenectady. Due to his work at Cayuga Academy, Morgan finished college in two years, 1838–1840, graduating at age 22. The curriculum continued study of classics combined with science, especially mechanics and optics.[7] Morgan was strongly interested in the works of the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. Eliphalet Nott, the president of Union College, was an inventor of stoves and a boiler; he held 31 patents. A Presbyterian minister, he kept the young men under a tight discipline, forbidding alcoholic beverages and requiring students to get permission to go to town. He held up the Bible as the one practical standard for all behavior. His career ended with some notoriety when he was investigated by the state for attempting to raise funds for the college through a lottery. The students evaded his strict regime by founding secret (and forbidden) fraternities, such as the Kappa Alpha Society. Lewis Morgan joined in 1839.[8] |

幼少期の生活と教育 ルイスの祖父は、独立戦争で大陸軍の兵士として活躍したコネティカット出身のトーマス・モーガンである。その後、一家で西に移動し、ニューヨークのフィン ガーレイクス地方でカユーガ族から土地を買い、オーロラ近くのカユーガ湖畔に畑を作った。彼とその妻には、後にルイスの父となるジェデダイアを含む3人の 息子と、1人の娘がすでにいた。 1797年、Jedediah Morgan(1774-1826)はAmanda Stantonと結婚し、父親から贈られた100エーカーの土地に定住した。彼女が5人の子供を産んで死んだ後、ジェデダイアはコネチカット州ハート フォードのハリエット・スチールと結婚した。二人はさらにルイスを含む8人の子供をもうけた。成人後、彼はミドルイニシャル「H」を採用した[4]。後に モーガンは、このHはどちらかといえば「ヘンリー」の略であると判断した[5]。 多芸多才なヤンキーだったジェデダイア・モーガンは、鋤を発明し、その部品を製造する事業提携を結び、工場のための溶鉱炉を建設した。オーロラに移り住 み、農場を息子に託す。メイソンに入会し、オーロラで最初のメイソンロッジの設立に貢献。州議会議員に選ばれたモーガンは、1825年に開通したエリー運 河の建設を支持した。 1826年に亡くなるとき、ジェデダイアは家族の扶養のために500エーカーの土地と牛や羊の群れを信託として残した。これは教育にも役立った。モーガン は、カユーガ・アカデミーで古典的な科目を学んだ。父親は、他の子供たちに職業用の土地を与えた後、彼の大学教育のために特別にお金を遺贈していた [6]。モーガンは、シェネクタディのユニオン・カレッジを選んだ。カユーガ・アカデミーでの仕事の関係で、モーガンは1838年から1840年までの2 年間で大学を卒業し、22歳で卒業した。カリキュラムは、古典と科学、特に力学と光学を組み合わせた勉強を続けた[7]。モーガンは、フランスの博物学者 ジョルジュ・キュヴィエの著作に強い関心を抱いていた。 ユニオン・カレッジの学長であったエリファレット・ノットは、ストーブやボイラーを発明し、31の特許を取得していた。長老派の牧師であった彼は、若者た ちに厳しい規律を与え、アルコール飲料を禁じ、街に出るには許可を得なければならなかった。聖書は、すべての行動の基準となるものである。しかし、宝くじ で大学の資金を集めようとしたため、州から調査を受け、その結果、彼の人生は悪評のうちに終わった。学生たちは、カッパ・アルファ協会のような秘密の(そ して禁じられた)友愛団体を設立することで、彼の厳しい体制から逃れた。ルイス・モーガンは1839年に加入している[8]。 |

| The New Confederacy of the

Iroquois After graduating in 1840, Morgan returned to Aurora to read the law with an established firm.[9] In 1842 he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, where he went into partnership with a Union classmate, George F. Danforth, a future judge. They could find no clients, as the nation was in an economic depression, which had started with the Panic of 1837. Morgan wrote essays, which he had begun to do while studying law, and published some in The Knickerbocker under the pen name Aquarius.[10] On January 1, 1841, Morgan and some friends from Cayuga Academy formed a secret fraternal society which they called the Gordian Knot.[11] As Morgan's earliest essays from that time had classical themes, the club may have been a kind of literary society, as was common then. In 1841 or 1842 the young men redefined the society, renaming it the Order of the Iroquois. Morgan referred to this event as cutting the knot. In 1843 they named it the Grand Order of the Iroquois, followed by the New Confederacy of the Iroquois.[12] They made the group a research organization to collect information on the Iroquois, whose historical territory for centuries had included central and upstate New York west of the Hudson and the Finger Lakes region. The men intended to resurrect the spirit of the Iroquois. They tried to learn the languages, assumed Iroquois names, and organized the group by the historic pattern of Iroquois tribes. In 1844 they received permission from the former Freemasons of Aurora to use the upper floor of the Masonic temple as a meeting hall. New members underwent a secret rite called inindianation in which they were transformed spiritually into Iroquois.[13] They met in the summer around campfires and paraded yearly through the town in costume.[14] Morgan seemed infused with the spirit of the Iroquois. He said, "We are now upon the very soil over which they exercised dominion ... Poetry still lingers around the scenery. ... "[15] These new Iroquois retained a literary frame of mind, but they intended to focus on "the writing of a native American epic that would define national identity".[16]  Masonic temple, constructed 1819 in Aurora. After "the Morgan Affair", the building was not used for freemasonry from 1827 to 1846. The Gordian Knot met on the second floor in the early 1840s. In 1847 the Scipio Lodge #110 started Masonic activities again. |

イロコイ族の新連合体 1842年、ロチェスターで弁護士として認められ、ユニオン組の同級生で後に判事となるジョージ・F・ダンフォースとパートナーシップを組むことになる。 1837年のパニックに始まった経済不況の中、二人は顧客を見つけることができなかった。モーガンは法律を勉強している間に始めていたエッセイを書き、 『ニッカーボッカー』誌にアクエリアスというペンネームでいくつか発表した[10]。 1841年1月1日、モーガンとカユーガ・アカデミーの友人たちは、ゴルディアス・ノットと呼ばれる秘密の友愛団体を結成した[11]。当時のモーガンの 初期のエッセイは古典をテーマにしていたので、クラブは当時よくあったように一種の文学会だったのかもしれない。1841年か1842年、青年たちはクラ ブを再定義し、「イロコイ騎士団」と改名する。モーガンはこの出来事を「結び目を切る」と表現している。1843年にはグランド・オーダー・オブ・ザ・イ ロコイ、次いでニュー・コンフェデラシー・オブ・ザ・イロコイと名付けた[12]。彼らはグループを研究組織とし、数世紀にわたってハドソン川の西の ニューヨーク中央部と北部、フィンガーレイクス地方を歴史的領土としてきたイロコイに関する情報を収集した。 彼らは、イロコイの精神を復活させることを意図していた。彼らは言語を学び、イロコイ族の名前を名乗り、イロコイ族の歴史的なパターンに基づいてグループ を編成しました。1844年、彼らはオーロラの旧フリーメイソンから、メイソン寺院の上階を集会場として使用する許可を得た。新メンバーはイノディアネー ションと呼ばれる秘密の儀式を受け、精神的にイロコイ族に変身した[13]。 夏にはキャンプファイヤーの周りで会合を持ち、毎年仮装して町を練り歩いた[14]。私たちは今、彼らが支配していたまさにその土地の上にいるの だ......」と彼は言った。詩はまだ風景の周りに残っている。... 「と述べている[15]。これらの新しいイロコイ族は文学的な心構えを保持していたが、彼らは「国家のアイデンティティを定義するようなアメリカ先住民の 叙事詩を書く」ことに集中するつもりであった[16]。  1819年にオーロラに建てられたフリーメイソン寺院。 「モルガン事件」の後、1827年から1846年まではフリーメイソンとしての使用はされなかった。 1840年代初頭、ゴードンノットは2階で会合を開いていた。 1847年、スキピオ・ロッジ第110支部が再びフリーメイソンとしての活動を始めた。 |

| Encounter with the Iroquois On an 1844 business trip to New York’s capital, Albany, Morgan started research on old Cayuga treaties in the state archives. The Seneca people were also studying old US-Native American treaties to support their land claims. After the Revolutionary War, the United States had forced the four Iroquois tribes allied with the British to cede their lands and migrate to Canada. By specific treaties, the US set aside small reservations in New York for their own allies, the Onondaga and Seneca. In the 1840s, long after the war, the Ogden Land Company, a real estate venture, laid claim to the Seneca Tonawanda Reservation on the basis of a fraudulent treaty. The Seneca sued and had representatives at the state capital pressing their case when Morgan was there. The delegation, led by Jimmy Johnson, its chief officer (and son of chief Red Jacket), were essentially former officers of what was left of the Iroquois Confederacy. Johnson's 16-year-old grandson Ha-sa-ne-an-da (Ely Parker) accompanied them as their interpreter, as he had attended a mission school and was bilingual. By chance Morgan and the young Parker encountered each other in an Albany book store. Soon intrigued by Morgan's talk of the New Confederacy, Parker invited the older man to interview Johnson and meet the delegation. Morgan took pages of organizational notes, which he used to remodel the New Confederacy. Beyond such details of scholarship, Morgan and the Seneca men formed deep attachments of friendship.[17] Morgan and his colleagues invited Parker to join the New Confederacy. They (chiefly Morgan) paid for the rest of Parker's education at the Cayuga Academy, along with his sister and a friend of hers. Later the Confederacy paid for Parker's studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, where he graduated in civil engineering. After military service in the American Civil War, from which Parker retired at the rank of brigadier general, he entered the upper ranks of civil service in the presidency of his former commander, Ulysses S. Grant.  Finger Lakes, upstate New York. |

イロコイ族との出会い 1844年、ニューヨークの首都オールバニに出張したモーガンは、州の公文書館でカユーガ族の古い条約について調査を始めた。セネカ族もまた、自分たちの 土地の主張を裏付けるために、アメリカとネイティブ・アメリカンの古い条約を研究していたのである。 独立戦争後、アメリカはイギリスと同盟を結んでいたイロコイ4部族に土地を譲り、カナダに移住することを強要していました。そのため、アメリカは同盟関係 にあったオノンダガ族とセネカ族のために、ニューヨーク州に小さな保留地を確保した。戦後間もない1840年代、不動産業を営むオグデン・ランド・カンパ ニーが、不正な条約に基づいてセネカ族のトナワンダ保留地の領有権を主張した。セネカ族は訴訟を起こし、モーガンがいた州都に代表者を集めて訴えた。 代表団は、その最高責任者であるジミー・ジョンソン(レッド・ジャケット酋長の息子)に率いられ、実質的にはイロコイ族連合に残っていた元将校たちでし た。ジョンソンの16歳の孫Ha-sa-ne-an-da(Ely Parker)は、ミッションスクールに通っていてバイリンガルだったため、彼らの通訳として同行しました。モーガンと若きパーカーは、オルバニーの書店 で偶然にも再会した。モーガンが語る新連邦の話に興味を持ったパーカーは、ジョンソンにインタビューし、代表団に会うよう年上の男を誘った。モーガンは、 何ページにもわたる組織的なメモを取り、それをもとに「新連合王国」の改造を行った。モーガンとセネカの男たちは、そのような学問の細部にとどまらず、深 い友情の絆を結んだ[17]。 モーガンたちはパーカーを新連合に参加させるよう誘った。彼らは(主にモーガンは)パーカーの姉とその友人とともに、カユーガ・アカデミーでの残りの教育 費を負担した。その後、盟約者団はニューヨーク州トロイにあるレンセラー工科大学でのパーカーの学費を負担し、彼は土木工学を専攻して卒業した。南北戦争 で軍務に就き、准将の地位で退役した後、元司令官ユリシーズ・S・グラントの大統領府で上層部の文官になった。  ニューヨーク州北部にあるフィンガー湖群。 |

| The Ogden Land Company affair Meanwhile, the organization had had activist goals from the beginning. In his initial New Gordius address Morgan had said:[18] ... when the last tribe shall slumber in the grass, it is to be feared that the stain of blood will be found on the escutcheon of the American republic. This nation must shield their declining day ... In 1838 the Ogden Land Company began a campaign to defraud the remaining Iroquois in New York of their lands. By Iroquois law, only a unanimous vote of all the chiefs sitting in council could effect binding decisions relating to the tribe. The OLC set about to purchase the votes of as many chiefs as it could, plying some with alcohol. The chiefs in many cases complied, believing any resolutions to sell the land would be defeated in council. Obtaining a majority vote for sale at one council called for the purpose, the OLC took their treaty to the Congress of the United States, which knew nothing of Iroquois law. President Martin Van Buren advised Congress that the treaty was fraudulent but on June 11, 1838, Congress adopted it as a resolution. After being compensated for their land by $1.67 per acre (Morgan said it was worth $16 per acre), the Seneca were to be evicted forthwith.[19] The great majority of the tribe were against the sale of the land. When they discovered they had been defrauded, they were galvanized to action. The New Confederacy stepped into the case on the side of the Seneca, conducting a major publicity campaign. They held mass meetings, circulated a general petition, and spoke to congressmen in Washington. The US Indian agent and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft and other influential men became honorary members. In 1846 a general convention of the population of Genesee County, New York sent Morgan to Congress with a counter-offer. The Seneca were allowed to buy back some land at $20 per acre, at which time the Tonawanda Reservation was created. The previous treaty was thrown out. Returning home, Morgan was adopted into the Hawk Clan, Seneca Tribe, as the son of Jimmy Johnson on October 31, 1847,[20] in part to honor his work with the Seneca on the reservation issues. They named him Tayadaowuhkuh, meaning "bridging the gap" (between the Iroquois and the European Americans).[21] After Morgan was admitted to the tribe, he lost interest in the New Confederacy. The group retained its secrecy and initiation requirements, but they were being hotly disputed.[22] When internal dissent began to impede the group's efficacy in 1847, Morgan stopped attending. For practical purposes it ceased to exist, but Morgan and Parker continued with a series of "Iroquois Letters" to the American Whig Review, edited by George Colton.[23] The Seneca case dragged on. Finally in 1857 the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed that only the federal government could evict the Seneca from their land. As it declined to do that, the case was over.[24] The Ogden Land Company collapsed.  Grant's staff. Ely Parker sits on the left. |

オグデン・ランド・カンパニー事件 一方、この組織は当初から活動家としての目標を持っていた。モーガンは最初の『新ゴルディウス』演説で次のように述べていた[18]。 最後の部族が草の中でまどろむとき、アメリカ共和国の徽章に血の染みを 見出すことが懸念される。この国は、彼らの衰退の日を遮らなければならない......」。 1838年、オグデン・ランド・カンパニーが、ニューヨークに残るイロコイ族から土地を詐取する作戦を開始した。イロコイ族の法律では、部族に関する決定 は、会議に出席しているすべての族長の一致した投票によってのみ行えることになっていた。OLCは、酋長の何人かに酒を飲ませ、できるだけ多くの酋長の票 を獲得しようとした。酋長たちは、土地売却の決議が議会で否決されることを信じて、多くの場合それに従った。この目的のために招集されたある協議会で、売 却に賛成する多数決を獲得したOLCは、イロコイ族の法律を知らないアメリカ連邦議会にその条約を持ち込んだ。マーティン・ヴァン・ビューレン大統領は、 この条約は詐欺であると議会に忠告したが、1838年6月11日、議会はこの条約を決議として採択した。1エーカーあたり1.67ドルの土地の補償を受け た後(モーガンは1エーカーあたり16ドルの価値があると言った)、セネカ族は直ちに立ち退くことになった[19]。 部族の大多数は、土地の売却に反対していた。しかし、セネカ族の大多数は土地の売却に反対していた。新連邦は、セネカ族の味方としてこの訴訟に乗り出し、 大規模な宣伝活動を展開した。集会や嘆願書の配布、ワシントンでの議員への演説など、大々的な宣伝活動を行った。アメリカのインディアン捜査官で民族学者 のヘンリー・ロウ・スクラフトやその他の有力者が名誉会員となった。1846年、ニューヨーク州ジェネシー郡の住民による一般大会が、モーガンを議会に送 り、反対提案をした。セネカ族は、1エーカーあたり20ドルで土地の買い戻しを許され、その時にトナワンダ保留地が作られた。前の条約は破棄された。帰国 したモーガンは、居留地問題でセネカ族と協力した功績もあり、1847年10月31日にセネカ族のホーク・クランにジミー・ジョンソンの息子として養子に 出される[20]。彼らは彼を「(イロコイ族とヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の間の)ギャップを埋める」という意味のTayadaowuhkuhと名づけた [21]。 モーガンが部族に認められた後、彼は新連邦への関心を失った。1847年に内部の反対意見がグループの効力を阻害し始めると、モーガンは出席をやめた [22]。実質的には消滅したが、モーガンとパーカーはジョージ・コルトンが編集する『アメリカン・ホイッグ・レビュー』誌に「イロコイ・レターズ」の連 載を続けていた[23]。1857年、ついに連邦最高裁判所は、連邦政府のみがセネカを土地から立ち退かせることができることを認めた。オグデン・ラン ド・カンパニーは崩壊した[24]。  グラントのスタッフ。左側に座っているのはエリ・パーカー。 |

| Marriage and family In 1851 Morgan summarized his investigation of Iroquois customs in his first book of note, League of the Iroquois, one of the founding works of ethnology. In it he compares systems of kinship. In that year also he married his cross-cousin, Mary Elizabeth Steele, his companion and partner for the rest of his life. She had intended to become a Presbyterian missionary. On their wedding day he presented to her an ornate copy of his new book. It was dedicated to his collaborator, Ely Parker.[25] In 1853 Mary's father died, leaving her a large inheritance. The Morgans bought a brownstone in a wealthy suburb of Rochester. In that year they had a son, Lemuel, who "turned out to be mentally handicapped".[26] Morgan's rising fame had brought him public attention, and Lemuel's condition (on no specific evidence) was universally attributed to the first-cousin marriage. The Morgans had to endure perpetual criticism, which they accepted as true, Lewis going so far as to take a stand against cousin marriage in his book Ancient Society.[27] The Morgan marriage nevertheless remained a close and affectionate one.[28] In 1856, Mary Elisabeth was born and in 1860 Helen King. Morgan and his wife were active in the First Presbyterian Church of Rochester, although it was mainly of interest to Mary. Lewis refused to make "the public profession of Christ that was necessary for full membership".[29] They both sponsored and contributed to charitable works. |

結婚と家族 1851年、モーガンはイロコイの風習を調査し、最初の著書『イロコイ同盟』としてまとめました。この本で彼は親族制度を比較している。この年、彼は従兄 弟のメアリー・エリザベス・スティールと結婚し、生涯の伴侶となった。彼女は長老派の宣教師になるつもりであった。結婚式の日、彼は彼女に自分の新著の豪 華な本を贈った。それは彼の協力者であるエリイ・パーカーに捧げられたものであった[25]。 1853年、メアリーの父親が亡くなり、彼女に多額の遺産が残された。モーガン夫妻はロチェスターの裕福な郊外にブラウンストーンを購入した。その年、 「精神障害者であることが判明した」息子レミュエルが生まれる[26]。モーガンの名声が高まり、世間の注目を集め、レミュエルの症状は(特に根拠はない が)一般的にいとこ同士の結婚が原因であるとされるようになった。モルガン夫妻は絶え間ない批判に耐えなければならなかったが、彼らはそれを真実として受 け入れ、ルイスは著書『Ancient Society』の中でいとこ婚に反対する立場をとった[27]。 それでもモルガンの結婚は親密で愛情のあるものであり続けた。 1856年にはMary Elisabethが生まれ、1860年にはHelen Kingが生まれた[28]。 モーガン夫妻はロチェスターの第一長老教会で活発に活動していたが、それは主にメアリーへの関心事であった。ルイスは「完全な会員になるために必要なキリ ストの公言」を拒否した[29]。 二人は慈善事業を後援し、貢献した。 |

| Supporting education For several years "his ethnical interests lay dormant",[29] but not his scholarship and writing. In 1852 Morgan and eight other "Rochester intellectuals" instituted The Pundit Club, shortened later to just The Club, a scientific and literary society before which the members read papers they had researched for the occasion. Morgan read papers to The Club every year for the rest of his life. He also joined the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Morgan and other leading men of Rochester decided to found a university, the University of Rochester. It did not support the matriculation of women. The group resolved to found a college for women, the Barleywood Female University, which was advertised but apparently never started. In the same year of its foundation, 1852, the donor of the land on which it was to be located gave it to the University of Rochester instead. Morgan was gravely disappointed. He believed that equality of the sexes is a mark of advanced civilization. For the present, he lacked the wealth and connections to prevent the collapse of Barleywood. Later he would serve as a founding trustee of the board of Wells College in Aurora. In addition, he and Mary would leave their estate to the University of Rochester for the foundation of a women's college.[30] |

教育支援 数年間、「彼の民族的興味は眠っていた」[29]が、学問と執筆はそうではなかった。1852年、モーガンと他の8人の「ロチェスターの知識人」は、後に 「ザ・クラブ」と略称される科学・文学協会を設立し、会員たちはこの日のために研究してきた論文を読み上げるようになった。モーガンは、生涯にわたって毎 年クラブで論文を読み続けた。また、アメリカ科学振興協会にも入会した。 モーガンをはじめとするロチェスターの有力者たちは、大学「ロチェスター大学」の設立を決定した。しかし、この大学は女子の入学を認めていなかった。そこ で、女子大学「バーレイウッド女子大学」を設立することを決め、募集をかけたが、結局設立されなかった。創立と同じ1852年、大学の敷地を提供した人 が、代わりにその敷地をロチェスター大学に寄贈したのである。モーガンはひどく落胆した。彼は、男女平等が進んだ文明の証であると信じていた。バーレイ ウッドの崩壊を食い止めるだけの財力も人脈もなかったのだ。その後、彼はオーロラにあるウェルズ大学の創立理事を務めることになる。さらに、彼とメアリー は、女子大学の設立のために、ロチェスター大学に遺産を残すことになる[30]。 |

| Success at last In 1855 Morgan and other Rochester businessmen invested in the expanding metals industry of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. After a brief sojourn on the 5-man board of the Iron Mountain Railroad, Morgan joined them in creating the Bay de Noquet and Marquette Railroad Company, connecting the entire Upper Peninsula by a single, ore-bearing line.[21] He became its attorney and director. At that time the U.S. government was selling lands previously confiscated from the natives in cases where the sale benefited the public good. Although the Upper Peninsula was known for its great natural beauty, the discovery of iron persuaded Morgan and others to develop wide-scale mining and industrialization of the peninsula. He spent the next few years between Washington, lobbying for the sale of the land to his company, and in large cities such as Detroit and Chicago, where he fought lawsuits to prevent competitors from taking it.[31] Morgan vigorously defended American capitalism to protect his own interests. After the stockholders refused to pay him for some of his legal work, he all but withdrew from business in favor of field work in anthropology. In 1861 in the middle of his field work, Morgan was elected as Member of the New York State Assembly on the Republican ticket. The Morgans traditionally had belonged to the Whigs, which dissolved in 1856; most Whigs joined the Republicans, created in 1854. Morgan did not run with any agenda except his own as it pertained to the Iroquois. He was seeking appointment by the President of the United States as Commissioner of the new Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Morgan anticipated that William H. Seward would be elected president, and outlined to him plans to employ the natives in the manufacture and sale of Indian goods.[32] At the last moment Abraham Lincoln displaced Seward as the Republican candidate. The new president was deluged by letters from Morgan's associates asking that Morgan be appointed commissioner. Lincoln explained that the post had already been exchanged by his campaign manager for political support. With the chance for appointment lost, Morgan, who had made no pretense of interest in New York state's government, returned to field study of the natives. |

ついに成功 1855年、モーガンとロチェスターの他の実業家たちは、ミシガン州アッパー半島で拡大する金属産業に投資した。アイアン・マウンテン鉄道の5人の役員と して短期間滞在した後、モーガンは彼らと共に、アッパー半島全体を鉱脈で結ぶベイ・デ・ノケ・アンド・マーケット鉄道会社を設立した[21]。 彼はその弁護士と取締役になった。当時、アメリカ政府は、先住民から没収した土地を、公共の利益のために売却することを認めていた。アッパー半島は素晴ら しい自然の美しさで知られていたが、鉄の発見により、モーガンらは半島の大規模な採掘と工業化の開発を説得された。彼は、その後数年間、ワシントンでのロ ビー活動や、デトロイトやシカゴなどの大都市で、競合他社に土地を奪われないよう訴訟を起こしながら過ごした[31]。モルガンは、自らの利益を守るた め、精力的にアメリカの資本主義を擁護した。しかし、株主から法的な報酬を拒否されると、人類学のフィールドワークに専念するために、ビジネスから撤退す る。 1861年、モルガンはその仕事のさなかに、ニューヨーク州議会議員に共和党から選出された。モーガン家は伝統的にウィッグ党に属していたが、1856年 に解散し、ほとんどのウィッグ党は1854年に創設された共和党に入党した。モーガンは、イロコイ族に関連する自分の課題以外を掲げて立候補することはな かった。彼は、合衆国大統領による新しいインディアン問題局(BIA)の長官への就任を希望していました。モーガンはウィリアム・H・スワードが大統領に 選出されることを予期しており、彼にインディアン製品の製造と販売で先住民を雇用する計画の概要を説明した[32]。 最後の瞬間、エイブラハム・リンカーンは共和党の候補者としてスワードを追いやった。新大統領のもとには、モーガンの仲間からモーガンを総監に任命するよ う求める手紙が殺到した。リンカーンは、このポストは既に選挙責任者が政治的支援と引き換えに手に入れたものだと説明した。任命の機会を失ったモーガン は、ニューヨーク州政に関心があるような素振りは見せず、原住民の現地調査に戻った。 |

| Field anthropologist After attending the 1856 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Morgan decided on an ethnology study to compare kinship systems. He conducted a field research program funded by himself and the Smithsonian Institution, 1859–1862. He made four expeditions, two to the Plains tribes of Kansas and Nebraska, and two more up the Missouri River past Yellowstone. This was before the development of any inland transportation system. Passengers on riverboats could shoot Bison and other game for food along the upper Missouri River. He collected data on 51 kinship systems. Tribes included the Winnebago, Crow, Yankton, Kaw, Blackfeet, Omaha and others.[33] At the height of Morgan's anthropological field work, death struck his family. In May and June, 1862, their two daughters, ages 6 and 2, died as a result of scarlet fever while Morgan was traveling in the West. In Sioux City, Iowa, Morgan received the news from his wife. He wrote in his journal:[34] Two of three of my children are taken. Our family is destroyed. The intelligence has simply petrified me. I have not shed a tear. It is too profound for tears. Thus ends my last expedition. I go home to my stricken and mourning wife, a miserable and destroyed man. |

フィールド人類学者 1856年、アメリカ科学振興協会の会合に出席したモーガンは、親族制度を比較する民族学研究を決意した。彼は、1859年から1862年にかけて、自身 とスミソニアン協会の資金で野外調査を実施した。カンザス州とネブラスカ州の平原部族に2回、ミズーリ川を遡ってイエローストーンを過ぎたところに2回の 探検を行いました。これは、内陸部の交通機関が発達する前のことである。川船の乗客は、ミズーリ川上流でバイソンや他の狩猟動物を撃って食料にすることが できた。彼は51の親族制度に関するデータを収集した。部族にはウィネベーゴ、クロウ、ヤンクトン、カウ、ブラックフィート、オマハなどが含まれていた [33]。 モーガンの人類学的なフィールドワークの絶頂期に、彼の家族を死が襲った。1862年5月と6月、モーガンが西部を旅している間に、6歳と2歳の娘が猩紅 熱で死亡したのである。アイオワ州のスーシティで、モーガンは妻からその知らせを受けた。彼は日記にこう書いている[34]。 3人の子供のうち2人が連れ去られた。私たちの家族は破壊された。この 情報には、ただただ茫然自失とさせられた。私は涙を流していない。涙を流すにはあまりに深遠である。こうして私の最後の遠征は終わった。私は打ちひしが れ、嘆き悲しむ妻のもとに帰り、惨めで破滅的な男となってしまった。 |

| The Civil War During this time, neither Morgan nor Mary showed any interest in abolitionism, nor did they participate in the American Civil War. They differed markedly from their friend Ely Parker. The latter attempted to raise an Iroquois regiment but was denied, on the grounds that he was not a US citizen, and denied service on the same ground. He entered the army finally by the intervention of his friend, Ulysses S. Grant, serving on Grant's staff. Parker was present at the surrender of General Lee; to Lee's remark that Parker was the "true American" (as an American Indian), he responded, "We are all Americans here, sir." Morgan held no consistent views on the war. He could easily have joined the anti-slavery cause if he had wished to do so. Rochester, as the last station before Canada on the Underground Railroad, was a center of abolitionism. Frederick Douglass published the North Star in Rochester. Like Morgan, Douglass supported the equality of women, yet they never made connection. Morgan was anti-slavery but opposed abolitionism on the grounds that slavery was protected by law. Before the war he assented to the possible division of the nation on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences", that is, slavery, between regions. Morgan began to change his mind when some of his friends who had gone out to watch the First Battle of Bull Run were captured and imprisoned by the Confederates for the duration. By the end of the war, he was insisting along with most others that Jefferson Davis be hanged as a traitor. In 1866 he formed the Rochester Committee for the Relief of Southern Starvation.[35] Morgan did participate indirectly in the war through his company. Recovering from the deaths of his daughters and having resolved to end the expeditions that had taken him away from home, he gave his life totally over to business. In 1863 he and Samuel Ely formed a partnership creating the Morgan Iron Company in northern Michigan. The war had created such a high demand for metals that within the first year of business, the company paid off its founding debt and offered 100% dividends on its stock. The demand went on until 1868, enabling the company to construct a blast furnace. Morgan became independently wealthy and could retire from the practice of law.[36] |

南北戦争 この時期、モーガンもメアリーも奴隷制度には関心を示さず、南北戦争にも参加しなかった。友人のエリイ・パーカーとは対照的であった。パーカーはイロコイ 連隊を結成しようとしたが、アメリカ市民でないことを理由に拒否され、さらに同じ理由で兵役にも就けなかった。友人であるユリシーズ・S・グラントの仲介 でようやく入隊し、グラントの幕僚を務めた。パーカーはリー将軍の降伏に立ち会ったが、リーがパーカーこそ「真のアメリカ人」(アメリカン・インディアン として)と発言したのに対し、"We are all Americans here, sir. "と答えた。 モーガンは、戦争について一貫した見解を持っていなかった。彼が望めば、反奴隷運動に参加することも簡単にできただろう。ロチェスターは、地下鉄道 (Underground Railroad)のカナダに至る最後の駅であり、奴隷廃止運動の中心地であった。フレデリック・ダグラスはロチェスターで「北極星」を出版した。ダグラ スはモーガンと同様、女性の平等を支持したが、二人の間に接点はなかった。 モーガンは反奴隷だったが、奴隷制は法律で保護されているという理由で、廃止論に反対した。戦前、彼は地域間の「和解しがたい相違」、すなわち奴隷制を理 由とする国家の分裂の可能性に同意していた。しかし、第一次ブルランの戦いの観戦に出かけた友人たちが捕らえられ、その間、南軍に幽閉されたことから、 モーガンは考えを改めるようになる。戦争が終わる頃には、他の多くの人々と共に、ジェファーソン・デイヴィスを裏切り者として絞首刑にすることを主張する ようになった。1866年、彼は南部の飢餓救済のためのロチェスター委員会を結成した[35]。 モーガンは自分の会社を通して間接的に戦争に参加した。娘たちの死から立ち直り、故郷を離れての遠征を終わらせることを決意し、人生を完全にビジネスに捧 げることにした。1863年、サミュエル・エリイと共同で、ミシガン州北部に「モーガン・アイアン・カンパニー」を設立した。戦争がもたらした金属への高 い需要は、創業1年目にして創業時の負債を返済し、株式には100%の配当がつくようになった。この需要は1868年まで続き、会社は溶鉱炉を建設するこ とができた。モルガンは独立して裕福になり、弁護士業から引退することができた[36]。 |

| The Erie Railroad affair Morgan took up trout fishing during his Michigan period. He fished in the wilds of Michigan during the summers, sometimes with Ojibwe guides. During this recreational activity, he became interested in beavers, which had greatly modified the lowlands. After several summers of tracking and observing beavers in the field, in 1868 he published a work describing in detail the biology and habits of this animal, which shaped the environment through its construction of dams.[37] In that year also, his wealth secure and free of business, Morgan entered the state government again as a senator, 1868–1869, still seeking appointment as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He was ridiculed by the Union Advertiser as being a "hobby candidate".[38] The Republicans that year were running on a platform of moral probity. They argued that as a superior class, they could and should serve as guardians of the public morals. Morgan passed muster on the heredity because of his descent and Mary's descent from William Bradford, of Mayflower note. Morgan soon was immersed in such issues as whether beer drinking on Sunday should be allowed (a veiled hit at the new German immigrants). As member of the Standing Committee on Railroads, Morgan became embroiled in a major issue of the day and one closer to his interests: monopoly. The New York Central Railroad, under Cornelius Vanderbilt, had attempted a hostile takeover of the Erie Railroad under Jay Gould by buying up its stock. The two railroads competed for the Rochester market. Daniel Drew, Erie's treasurer, defended successfully by creating new stock, which he had his friends sold short, dropping the value of the stock. Vanderbilt dumped the stock, barely covering the losses. Ordinarily such stock manipulations were illegal. The Railroad Act of 1850, however, allowed railroads to borrow money in exchange for bonds convertible to stocks. Given essentially free stocks, friends of the Erie Railroad grew rich; that is, Drew had found a way to transfer Vanderbilt's wealth to his own friends. Vanderbilt just escaped ruin. He immediately appealed to the state government.[39] The Railroad Committee investigated the affair. Gould purchased inaction among the senators, a practice Morgan had seen in the Ogden Land Company Affair. This time he worked to protect his friends from investigation. No action was taken. The Erie Railroad affair tapped Morgan's deepest ideological beliefs. To him the role of capitalism in creating mobile wealth was essential to the advancement of civilization. A monopoly such as Vanderbilt had been trying to build would choke off the downward flow of wealth. His report of the Railroad Committee attacked both Vanderbilt and Gould. It argued that the system in its "tendency to combination" was broken. He asserted that the people had to use government action to rein in the power of large corporations. For the time being the Erie Railroad was supported, but Morgan noted that its victory was just as dangerous to society as its defeat would have been. |

エリー鉄道事件 モーガンはミシガン時代、マス釣りを始めた。夏にはミシガンの原野で釣りをし、時に はオジブエ族のガイドをつけたこともあったらしい。このレクリエーション活動の中で、彼は低地を大きく改変していたビーバーに興味を持つようになった。数 年の夏、ビーバーを追跡し、野外で観察した後、1868年に、ダムを建設することによって環境を形成するこの動物の生態と習性を詳細に記述した著作を出版 した[37]。 その年も、富が確保され、ビジネスから解放されたモーガンは、1868年から1869年にかけて上院議員として再び州政府に入り、やはりインディアン問題 局の局長への就任を目指した。彼は、ユニオン・アドバタイザー紙に「趣味の候補者」と揶揄された[38]。この年の共和党は、道徳的高潔さを綱領として掲 げていた。彼らは、上流階級として、風俗の番人としての役割を果たすことができ、またそうあるべきだと主張した。モーガンは、自分とメアリーがメイフラ ワー号のウィリアム・ブラッドフォードの子孫であることから、遺伝の問題で合格した。モーガンはやがて、日曜日にビールを飲むことを認めるべきかどうか (ドイツからの新移民への当てつけ)、といった問題に没頭するようになった。 鉄道常任委員会のメンバーとして、モーガンは当時の重要な問題、そして彼の関心に近い独占問題に巻き込まれることになった。ヴァンダービルト率いるニュー ヨーク・セントラル鉄道は、ジェイ・グールド率いるエリー鉄道の株式を買い占め、敵対的買収を試みていた。この2つの鉄道は、ロチェスターの市場を争って いた。エリー鉄道の財務担当者ダニエル・ドリューは、新しい株を作り、それを仲間に空売りさせて株の価値を下げ、うまく防衛した。ヴァンダービルトはその 株を捨て、かろうじて損失をカバーした。通常、このような株式操作は違法であった。しかし、1850年に制定された鉄道法では、鉄道会社は株式に転換でき る債券と引き換えに資金を借りることができるようになった。つまり、ドリューは、ヴァンダービルトの富を自分の仲間に移す方法を見つけたのである。ヴァン ダービルトは破滅を免れた。彼はすぐに州政府に訴えた[39]。 鉄道委員会はこの事件を調査した。グールドは、オグデン・ランド・カンパニー事件でモーガンが経験したように、議員たちの不作為を買った。このとき彼は、 自分の友人を調査から守るために動いた。そして、何も行動を起こさなかった。エリー鉄道事件は、モルガンの思想的深層心理を突いたものであった。彼にとっ て、移動可能な富を生み出す資本主義の役割は、文明の進歩に不可欠なものであった。ヴァンダービルトのような独占企業は、富の下降線を遮断することにな る。鉄道委員会の報告書は、ヴァンダービルトとグールドの両者を攻撃するものであった。この報告書は、「結合の傾向」にあるシステムは崩壊していると主張 した。そして、大企業の力を抑制するためには、国民が政府の力を借りなければならないと主張した。エリー鉄道は当面支持されたが、モーガンは、その勝利は 社会にとって敗北と同じくらい危険であると指摘した。 |

| The Grant-Parker policy on

Native Americans Despite his new interest in government, which was to come to be expressed in his subsequent works on social systems, Morgan persisted in his major goal in running for office, to be appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The choice was now up to President Grant. Together in The League, Parker and Morgan had determined the policy Grant was to adopt. They thought that, much as Parker had assimilated, American Indians should assimilate into American society; they were not yet considered US citizens. Of the two men responsible for his policy, Grant chose his former adjutant. Terribly disappointed, Morgan never applied for the post again. The two collaborators did not speak to each other during Parker's tenure, but Morgan stayed on intimate terms with Parker's family. The implementation of assimilation policy was more difficult than either man had anticipated. Parker controlled none of the variables. The American Indians were to be moved into reservations, assisted with supplies and food so they could start subsistence farming, and educated at mission schools to be converted to Christianity and American values, until they adopted European-American ways. In theory they would then be able to enter American society at large. The system of appointed Indian agents and traders had long been corrupt; in addition, unscrupulous land agents took the best land and moved American Indians into the desert lands, which did not support small-scale household farms and did not have sufficient game for hunting. Thieves among the agents replaced food and goods intended for the Indians with inedible or no foodstuffs. Faced with these realities, the American Indians refused the reservations or abandoned them, and attempted to return to ancestral lands, now occupied by white settlers. In other cases, they raided white settlements for food or attacked them seeking to repel the invaders. Grant resorted to military solutions and used U.S. soldiers to repress the tribes. This warfare exacerbated the failure of the army to protect the American Indians against depredations and encroachment by white settlers. In 1871 Congress took action to halt the suppression of the Natives. It created a Board of Indian Commissioners and relieved Parker of his main responsibilities. Parker resigned in protest.[40] After suffering years of poverty and attempt to suppress their cultures, American Indians were admitted to citizenship in 1924. The government continued to send their children to Indian boarding schools, started in the late 1870s, where Indian languages and cultures were prohibited. Policies of diversity and limited sovereignty were adopted. The Grant administration is universally regarded as inept in Indian affairs as well as have been rife with corruption. Although Morgan contributed to the ideology of assimilation, he escaped accountability for the results. |

ネイティブアメリカンに対するグラント・パーカー政策 モーガンは、その後の社会制度に関する著作に表れているように、政府への新たな関心を持ちながらも、出馬の大きな目標であるインディアン問題担当長官に任 命されることに固執していた。その選択は、グラント大統領に委ねられていた。パーカーとモーガンは、『同盟』の中で、グラントが採用すべき政策を決定して いた。彼らは、パーカーが同化したように、アメリカン・インディアンもアメリカ社会に同化すべきであり、彼らはまだアメリカ市民とは見なされていないと考 えた。グラント大統領は、自分の政策に責任を持つ二人の人物のうち、元副官を選んだ。ひどく失望したモーガンは、二度とそのポストに就くことはなかった。 パーカーの在任中、二人の協力者は互いに言葉を交わすことはなかったが、モーガンはパーカーの家族と親密な関係を保った。 同化政策の実行は、両者の予想以上に困難なものであった。パーカーはどの変数もコントロールできなかったのである。アメリカン・インディアンは保留地に移 され、自給自足の農業を始められるように物資と食料を援助され、キリスト教とアメリカの価値観に改宗するためにミッションスクールで教育を受け、ヨーロッ パ・アメリカ人のやり方を身につけるまでとされる。そして、キリスト教とアメリカ的価値観に改めさせ、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の習慣を身につけさせるとい うものであった。インディアンの代理人や貿易商を任命する制度は長い間腐敗していた。さらに、悪徳土地エージェントが最良の土地を手に入れ、アメリカン・ インディアンを、小規模な家庭農場を支えられない、狩猟に十分な獲物がいない砂漠の土地に移動させた。また、斡旋業者の中には泥棒もいて、インディアンに 渡すはずの食糧や物資を食べられないものにすり替えたり、全く食べられないものに変えたりしていた。このような現実を前に、アメリカ・インディアンは居留 地を拒否し、あるいは放棄し、白人の入植者が住む先祖代々の土地に戻ろうとした。また、白人の居住地を襲って食料を得たり、侵略者を撃退するために襲撃す ることもあった。グラント大統領は、アメリカ兵を使って部族を弾圧し、軍事的な解決策を講じた。この戦争は、白人の入植者による略奪や侵入からアメリカ ン・インディアンを守るための軍隊の失敗をさらに悪化させた。 1871年、アメリカ議会は先住民の弾圧を食い止めるために行動を起こした。インディアン委員会(Board of Indian Commissioners)を設立し、パーカー(Parker)の主要な職責を解いた。パーカーは抗議して辞任した[40]。長年にわたる貧困と彼らの文化の抑圧の試みに苦しんだ後、1924年にアメリカン・インディア ンは市民権を得た。しかし、1870 年代後半に始まったインディアンの寄宿学校では、インディアンの言語や文化が禁止され、政府は彼らの子供たちを送り続けた。インディアンの言語と文化は禁 止され、多様性と限定的な主権の政策が採用された。グラント政権は、インディアン問題において無能であり、また汚職が蔓延していたとされている。モーガン は同化のイデオロギーに貢献したが、その結果に対する説明責任からは逃れられた。 |

| Later career Having failed to become Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Morgan applied for various ambassadorships under the Grant administration, including to China and Peru. Grant's administration rejected all the applications, after which Morgan resolved to visit Europe on his own with a professional as well as a personal agenda. For one year, 1870–71, the three Morgans went on a grand tour of Europe. During his European travels, Morgan met Charles Darwin and the great British anthropologists of the age. He visited Sir John Lubbock,[41] who had coined the words "Paleolithic" and "Neolithic", and used the terms "barbarians" and "savages" in his own studies of the three-age system. Morgan adopted these terms, but with an altered sense, in Ancient Society. Lubbock was using modern ethnology as he knew it to reconstruct the ways of human ancestors. Lubbock's main works had already been published by the time of Morgan's visit. Morgan recorded his European travel and contacts in a journal of several volumes. Extracts were published in 1937 by Leslie White. He continued with his independent scholarship, never becoming affiliated with any university, although he associated with university presidents and the leading ethnologists looked up to him as a founder of the field. He was an intellectual mentor to those who followed, including John Wesley Powell, who became head of the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879 at the Smithsonian Institution. Morgan was consulted by the highest levels of government on appointments and other ethnological matters. In 1878 he conducted one final field trip, leading a small party in search of native ruins in the American Southwest. They were the first to describe the Aztec ruins on the Animas River but missed discovering Mesa Verde.[42] |

その後の経歴 インディアン問題担当長官になれなかったモーガンは、グラント政権下で中国やペルーなど様々な大使に応募した。しかし、グラント政権では大使就任を拒否さ れたため、モーガンは個人的な目的だけでなく、仕事上の目的も兼ねて単独でヨーロッパを訪問することを決意する。 1870年から71年の1年間、モーガン家の3人はヨーロッパを大旅行 した。このヨーロッパ旅行で、モーガンはチャールズ・ダーウィンや当時のイギリスの偉大な人類学者たちに会っている。彼は、「旧石器時代」と「新石器時 代」という言葉を作り、「野蛮人」と「未開人」という言葉を彼自身の三世代システムの研究において使用したジョン・ラボック卿[41]を訪問している。 モーガンは『古代社会』でこれらの用語を、意味を変えながら採用している。ラボックは、近代民族学を駆使して、人類の祖先の生き方を再構築していたのであ る。ラボックの主要な著作は、モーガンの訪問時にはすでに出版されていた。モーガンは、ヨーロッパでの旅と接触を数巻の日記に記録している。その抜粋は、 1937年にレスリー・ホワイトによって出版された。 彼は独立した学問を続け、どの大学にも所属しなかったが、大学の学長たちとも関わり、主要な民族学者たちは彼をこの分野の創始者として尊敬していた。1879年にスミソニアン博物館の民族学局長に就任したジョン・ウェスリー・パウエルなど、後 進の知的指導者であった。 モーガンは、政府の最高幹部から、人事やその他の民族学的な事柄について相談を受けていました。1878年には、アメリカ南西部で先住民の遺跡を探す小隊 を率いて、最後の現地調査を行いました。彼らはアニマス川のアステカ遺跡を最初に記述したが、メサベルデの発見は逃した[42]。 |

| Death and legacy In 1879 Morgan completed two construction projects. One was his library, an addition to the house he had purchased with Mary many years before and where he died in December 1881.[citation needed] He combined the opening of the library with a celebration of the 25th anniversary of The Club. It included a dinner for 40 persons, who were by that time the leading lights of Rochester. The library acquired some fame as a local monument. Pictures were taken and published. The Club only met there one other time, however, at Morgan's funeral in 1881. The second building project was a mausoleum for his daughters in Mount Hope Cemetery. It became the resting place of the entire remainder of the family, starting with Lewis.[41] His wife survived him by two years. They both left wills. A nephew of Lewis moved to Rochester with his family and took up residence in the house to care for Lewis' and Mary's son. On the son's death 20 years later, the entire estate reverted to the University of Rochester, which by the terms of the wills was to use the funds for the endowment of a college for women, dedicated as a memorial to the Morgan daughters.[43] The nephew attempted to break the wills on his behalf but lost the case in the state supreme court. The house with the library survived into mid-20th-century, when it was demolished to make way for a highway bypass system. Materials relating to Morgan's writings are held in a special collection at the University of Rochester library. |

死と遺産 1879年、モーガンは2つの建設プロジェクトを完了させた。ひとつは図書館で、何年も前にメアリーとともに購入し、1881年12月に亡くなった家の増 築である[citation needed]。彼は図書館の開館を、クラブの25周年のお祝いと組み合わせた。その際、当時ロチェスターの有力者であった40人を招いて夕食会が開かれ た。図書館は地元の記念碑として有名になった。写真も撮られ、出版された。しかし、クラブがそこに集まったのは、1881年のモーガンの葬儀のときの1回 きりである。2つ目の建築プロジェクトは、マウント・ホープ墓地にある彼の娘たちのための霊廟であった。そこは、ルイスを始めとする残りの家族全員の安息 の地となった[41]。 妻は彼に2年先立たれた。二人とも遺書を残している。ルイスの甥は家族と共にロチェスターに移り住み、ルイスとメアリーの息子の世話をするためにこの家に 住み着いた。その20年後に息子が亡くなると、遺産はすべてロチェスター大学に戻り、その資金はモーガン家の娘たちを記念する女子大学の基金として使われ ることになった[43]。甥は自分に代わって遺言を破棄しようとしたが、州の最高裁判所において敗訴している。図書館のある家は20世紀半ばまで存続した が、高速道路のバイパス工事に伴い取り壊された。モーガンの著作に関する資料は、ロチェスター大学図書館の特別コレクションに所蔵されている。 |

| Lewis Henry Morgan Lecture The Lewis Henry Morgan Lecture is a distinguished lecture held annually by the Department of Anthropology at the University of Rochester. Begun in 1963, the lectures honor the career and seminal research of American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan.[45][46] Many of the lectures have been published,[47] including the inaugural one by South African anthropologist Meyer Fortes. Professional associations Morgan was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1865.[44] He was elected president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1879. Morgan was also a member of the National Academy of Sciences. |

ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン講演 ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン・レクチャーは、ロチェスター大学人類学部が毎年開催する著名な講演会である。1963年に始まったこの講演会は、アメリカ人 人類学者ルイス・H・モーガンの業績と画期的な研究を称えるものである[45][46]。講演会の多くは出版されており[47]、南アフリカ人人類学者マ イヤー・フォーテスの記念すべき第1回講演も含まれている。 専門家集団 1865年、アメリカ古代協会の会員に選ばれる[44]。1879年、アメリカ科学振興協会の会長に選ばれる[44]。また、全米科学アカデミーのメン バーでもあった。 |

| Work in ethnology In the 1840s, Morgan had befriended the young Ely S. Parker of the Seneca tribe and the Tonawanda Reservation. With a classical missionary education, Parker went on to study law. With his help, Morgan studied the culture and the structure of Iroquois society. Morgan had noticed they used different terms than Europeans to designate individuals by their relationships within the extended family. He had the creative insight to recognize this was meaningful in terms of their social organization. He defined European terms as "descriptive" and Iroquois (and Native American) terms as "classificatory", terms that continue to be used as major divisions by anthropologists and ethnographers. Based on his research enabled by Parker, Morgan and Parker wrote and published The League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee or Iroquois (1851). Morgan dedicated the book to Parker (who was then 23) and "our joint researches".[45] In subsequent publications of the book Parker's name was omitted. This work presented the complexity of Iroquois society in a path-breaking ethnography that was a model for future anthropologists, as Morgan presented the kinship system of the Iroquois with unprecedented nuance. Morgan expanded his research far beyond the Iroquois. Although Benjamin Barton had posited Asian origins for Native Americans as early as 1797, in the mid-nineteenth century, other American and European scholars still supported widely varying ideas, including a theory they were one of the lost tribes of Israel, because of the strong influence of biblical and classical conceptions of history.[46] Morgan had begun to theorize the Native Americans originated in Asia. He thought he could prove it by a broad study of kinship terms used by people in Asia as well as tribes in North America. He wanted to provide evidence for monogenesis, the theory that all human beings descend from a common source (as opposed to polygenism). In the late 1850s and 1860s, Morgan collected kinship data from a variety of Native American tribes. In his quest to do comparative kinship studies, Morgan also corresponded with scholars, missionaries, US Indian agents, colonial agents, and military officers around the world. He created a questionnaire which others could complete so he could collect data in a standardized way. Over several years, he made months-long trips to what was then the Wild West to further his research. With the help of local contacts and, after intensive correspondence over the course of years, Morgan analyzed his data and wrote his seminal Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871),[47] which was printed by the Smithsonian Press. It "created at a stroke what without exaggeration might be called the seminal concern of contemporary anthropology, the study of kinship ..."[48] In this work, Morgan set forth his argument for the unity of humankind. At the same time, he presented a sophisticated schema of social evolution based upon the relationship terms, the categories of kinship, used by peoples around the world. Through his analysis of kinship terms, Morgan discerned that the structure of the family and social institutions develop and change according to a specific sequence. |

民族学への取り組み 1840年代、モーガンは、セネカ族とトナワンダ保留地の若きイーリー S. パーカーと親交を深めた。パーカーは古典的な宣教師としての教育を受け、法律を学ぶために進学した。モーガンは彼の助けを借りて、イロコイ社会の文化や構 造を研究した。モーガンは、彼らがヨーロッパ人とは異なる用語を使って、大家族の中での関係で個人を指定していることに気づいていた。彼は、このことが彼 らの社会組織において意味があることを認識する創造的な洞察力を持っていた。彼は、ヨーロッパ人の用語を「記述的」、イロコイ(およびネイティブ・アメリ カン)の用語を「分類的」と定義し、この用語は現在も人類学者や民族学者の主要な区分として使用されている。 パーカーによって可能になった彼の研究をもとに、モーガンとパーカーは『ホ・デ・ノ・ソ・ネまたはイロコイの同盟』(1851年)を執筆・出版した。モー ガンはこの本をパーカー(当時23歳)と「我々の共同研究」に捧げた[45]。その後の出版ではパーカーの名前は省かれている。この作品は、イロコイ社会 の複雑さを画期的な民族誌として提示したもので、モーガンはイロコイの親族制度を前例のないニュアンスで提示し、後の人類学者の模範となるものであった。 モーガンは、研究をイロコイ族にとどまらず、はるかに拡大した。ベンジャミン・バートンは、1797年には早くもアメリカ先住民のアジア起源を仮定してい たが、19世紀半ばには、他のアメリカやヨーロッパの学者たちは、聖書や古典的歴史概念の強い影響により、彼らがイスラエルの失われた部族の一つであると いう説を含め、まだ大きく異なる考えを支持していた[46] 。 モーガンは、アメリカ先住民がアジアで発生したという理論を始めたのである。彼は、北米の部族と同様にアジアの人々が使う親族関係の用語を広く研究するこ とによって、それを証明できると考えた。 彼は、すべての人類は共通の源から派生しているという理論である単生成(多生成とは対照的)の証拠を提供したかったのである。 1850年代後半から1860年代にかけて、モーガンはアメリカ先住民の様々な部族から血縁関係のデータを収集した。また、モーガンは、比較血縁研究を行 うために、世界中の学者、宣教師、アメリカのインディアンエージェント、植民地エージェント、軍人と連絡を取りあった。彼は、標準化された方法でデータを 集めることができるように、他の人が記入できる質問表を作った。また、数年にわたり、当時の西部開拓時代へ数カ月の旅をし、調査を進めた。 現地の人脈の助けを借り、何年にもわたる集中的な手紙のやりとりを経て、モーガンはデータを分析し、『ヒト科の血縁と相性システム』(1871年)を執筆 し、スミソニアン出版社から印刷されることになる[47]。この著作でモーガンは、「誇張なしに現代人類学の主要な関心事と呼ばれる親族関係の研究を一挙 に生み出した」[48]。同時に、彼は世界中の民族が使用している関係用語、親族のカテゴリーに基づいて、社会進化の洗練されたスキーマを提示した。モー ガンは、親族関係の用語の分析を通じて、家族の構造や社会制度が特定の順序に従って発展し、変化することを見いだした。 |

| Theory of social evolution This original theory became less relevant because of the Darwinian revolution, which demonstrated how change happens over time. In addition, Morgan became increasingly interested in the comparative study of kinship (family) relations as a window into understanding larger social dynamics. He saw kinship relations as a basic part of society. Morgan viewed society as a living system that changes over time.[citation needed] In the years that followed, Morgan developed his theories. Combined with an exhaustive study of classic Greek and Roman sources, he crowned his work with his magnum opus Ancient Society (1877). Morgan elaborated upon his theory of social evolution. He introduced a critical link between social progress and technological progress. He emphasized the centrality of family and property relations. He traced the interplay between the evolution of technology, of family relations, of property relations, of the larger social structures and systems of governance, and intellectual development. Looking across an expanded span of human existence, Morgan presented three major stages: savagery, barbarism, and civilization. He divided and defined the stages by technological inventions, such as use of fire, bow, pottery in the savage era; domestication of animals, agriculture, and metalworking in the barbarian era; and development of the alphabet and writing in the civilization era. In part, this was an effort to create a structure for North American history that was comparable to the three-age system of European pre-history, which had been developed as an evidence-based system by the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen in the 1830s; his work Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed (Guideline to Scandinavian Antiquity) was published in English in 1848. The concept of evidence-based chronological dating received wider notice in English-speaking nations as developed by J. J. A. Worsaae, whose The Primeval Antiquities of Denmark was published in English in 1849.[49] Initially Morgan's work was accepted as integral to American history, but later it was treated as a separate category of anthropology. Henry Adams wrote of Ancient Society that it "must become the foundation of all future work in American historical science." The historian Francis Parkman also was a fan, but later nineteenth-century historians pushed Native American history to the side of the American story.[50] Morgan's final work, Houses and House-life of the American Aborigines (1881), was an elaboration on what he had originally planned as an additional part of Ancient Society. In it, Morgan presented evidence, mostly from North and South America, that the development of house architecture and house culture reflected the development of kinship and property relations. Although many specific aspects of Morgan's evolutionary position have been rejected by later anthropologists, his real achievements remain impressive. He founded the sub-discipline of kinship studies. Anthropologists remain interested in the connections which Morgan outlined between material culture and social structure. His impact has been felt far beyond the Ivory Tower. Morgan was not quite the social reformer some would believe him to be. Outraged at the manipulations of the Ogden Land Company to get possession of the Tonawanda Seneca Reservation, Morgan exerted some effort in behalf of the Indians, but not nearly as much or to such effect as is generally supposed.[51] Most of his effort seems to have been limited to a few months in 1846, and the issue was not settled until 1857, more than ten years later. The Indians' principal legal counsel in these years was not Morgan, but John Martindale. Morgan's role, such as it was, was that of citizen activist. Then, too, although a champion of the Indian, Morgan was not an advocate of cultural pluralism nor did he work for "cultural survival." The Indian, Morgan exhorted his fellow citizens, ought to be rescued "from his impending destiny," "reclaimed and civilized, and thus saved eventually from the fate which has already befallen so many of our aboriginal races" by education and Christianity.[52] |

社会進化論 この当初の理論は、時間の経過とともにどのように変化が起こるかを示したダーウィン革命のために、あまり意味をなさなくなった。さらにモーガンは、より大 きな社会力学を理解するための窓として、親族(家族)関係の比較研究にますます興味を抱くようになった。彼は親族関係を社会の基本的な部分として捉えてい た。モーガンは、社会を時間とともに変化する生きたシステムとして捉えていた[citation needed]。 その後の数年間で、モーガンは自分の理論を発展させた。古典的なギリシャやローマの資料の徹底的な研究と組み合わせて、彼は彼の偉大な作品古代社会 (1877)で彼の仕事の王冠を飾った。モーガンは、社会進化論を発展させた。社会的な進歩と技術的な進歩の間に重要な関係があることを紹介した。また、 家族関係や財産関係の重要性を強調した。そして、技術の進化、家族関係の進化、財産関係の進化、より大きな社会構造と統治システムの進化、そして知的発展 の間の相互作用を追跡した。 モーガンは、人類生存の拡大したスパンを見渡して、3つの主要な段階、すなわち、野蛮化、野蛮化、そして文明化を提示した。未開の時代には火の使用、弓、 陶器の使用、蛮族の時代には動物の家畜化、農業、金属加工、文明の時代にはアルファベットと文字の発達といった技術的発明によって段階を分け、定義してい る。これは、1830年代にデンマークの古美術商クリスチャン・ユルゲンセン・トムセンが証拠に基づく年代測定法として開発したヨーロッパ先史時代の3時 代制に匹敵する北米史の構造を作ろうとしたもので、1848年に英語で出版された『Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed (Guideline to Scandinavian Antiquity)』はその一例である。証拠に基づく年代測定の概念は、J. J. A. Worsaaeによって発展し、1849年に『The Primeval Antiquities of Denmark』が英語で出版され、英語圏の国々で広く知られるようになった[49]。 当初、モーガンの仕事はアメリカの歴史に不可欠なものとして受け入れられていたが、後に人類学の別のカテゴリーとして扱われるようになった。ヘンリー・ア ダムスは『古代社会』について、"アメリカの歴史科学における将来のすべての仕事の基礎とならなければならない "と書いている。歴史家のフランシス・パークマンもファンであったが、後の19世紀の歴史家たちはアメリカ先住民の歴史をアメリカの物語の側に押しやった [50]。 モーガンの最後の著作であるHouses and House-life of the American Aborigines (1881)は、彼がもともとAncient Societyの追加部分として計画していたものをさらに発展させたものであった。その中でモーガンは、家屋建築や家屋文化の発展が親族関係や財産関係の 発展を反映しているという証拠を、主に北南米から集めて提示した。 モーガンの進化論的立場は、後の人類学者によって否定された部分も多いが、彼の実質的な業績は依然として印象的である。彼は親族研究というサブディシプリ ンを確立した。人類学者は、モーガンが示した物質文化と社会構造との関連に関心を持ち続けている。彼の影響は、象牙の塔をはるかに超えて感じられます。 モルガンは、一部の人が信じているような社会改革者ではなかった。オグデン・ランド・カンパニーがトナワンダ・セネカ居留地を手に入れるために行った工作 に憤慨したモーガンは、インディアンのためにいくらかの努力をしたが、一般に考えられているほどには、また大きな効果を上げることはなかった[51]。こ の時期のインディアンの主要な法律顧問はモーガンではなく、ジョン・マーティンデールであった。モーガンの役割は、あくまでも市民運動家であった。そし て、インディアンの擁護者でありながら、文化的多元主義の擁護者でもなければ、「文化的生存」のために活動したわけでもない。インディアンは、教育とキリ スト教によって「差し迫った運命から」「再生され、文明化され、その結果、我々の原住民族の多くにすでに降りかかっている運命から」救われるべきである と、モーガンは同胞の市民に呼びかけていた[52]。 |

| Influence on Marxism In 1881, Karl Marx started reading Morgan's Ancient Society, thus beginning Morgan's posthumous influence among European thinkers. Friedrich Engels also read his work after Morgan's death. Although Marx never finished his own book based on Morgan's work, Engels continued his analysis. Morgan's work on the social structure and material culture strongly influenced Engels' sociological theory of dialectical materialism (expressed in his work The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, 1884). Scholars of the Communist bloc considered Morgan as the preeminent anthropologist.[53][54] Morgan's work has led to some believing that early communist-like societies existed in Native American society. Though the belief of primitive communism as based on Morgan's work is flawed due to Morgan's misunderstandings of Haudenosaunee society and his, since proven wrong, theory of social evolution.[55][56][57][58][59] This, and subsequent more accurate research, has led to the society of the Haudenosaunee to be of interest in communist and anarchist analysis.[60] Particularly aspects where land was not treated as a commodity,[61] communal ownership[62][63] and near non-existent rates of crime.[62][63][64] |

マルクス主義への影響 1881年、カール・マルクスがモルガンの『古代社会』を読み始め、モルガンの死後、ヨーロッパの思想家たちに影響を与えることになる。フリードリヒ・エ ンゲルスもモルガンの死後、彼の著作を読んだ。マルクスはモルガンの著作をもとにした自著を完成させることはなかったが、エンゲルスはその分析を継続し た。社会構造と物質文化に関するモルガンの研究は、エンゲルスの弁証法的唯物論(『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』1884年に表現)の社会学理論に強い影 響を与えた。共産圏の学者たちはモーガンを傑出した人類学者とみなしていた[53][54]。モーガンの研究は、初期の共産主義的な社会がアメリカ先住民 社会に存在したと信じる者たちにつながっている。しかし、モーガンの研究に基づく原始共産主義の信念は、ホーデノーサニー社会に対するモーガンの誤解と彼 の社会進化論(その後、間違っていることが証明された)のために、欠陥がある。 [55][56][57][58][59] これとその後のより正確な研究により、ハウデノサウニーの社会は共産主義者や無政府主義者の分析において関心を持たれるようになった[60] 特に土地が商品として扱われなかった側面、共同所有[61]、犯罪のほぼ存在しない率など[62][63][64]がある。 |

| Eponymous honors Annual lecture in Morgan's name at the Anthropology Department of the University of Rochester. Rochester Public School #37 in the 19th Ward named "Lewis H. Morgan #37 School" Lewis Henry Morgan Institute (a research organization), SUNYIT, Utica, New York Lewis H. Morgan Rochester Regional Chapter of the New York State Archeological Association |

同名の栄誉 ロチェスター大学人類学部でモーガンの名を冠した講演会が毎年開催される。 19区にあるロチェスター公立学校37番を "Lewis H. Morgan #37 School "と命名 ニューヨーク州ユーティカのSUNYITにルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン研究所(研究機関)を設立 ニューヨーク州考古学協会ルイス・H・モーガン・ロチェスター地域支部 |

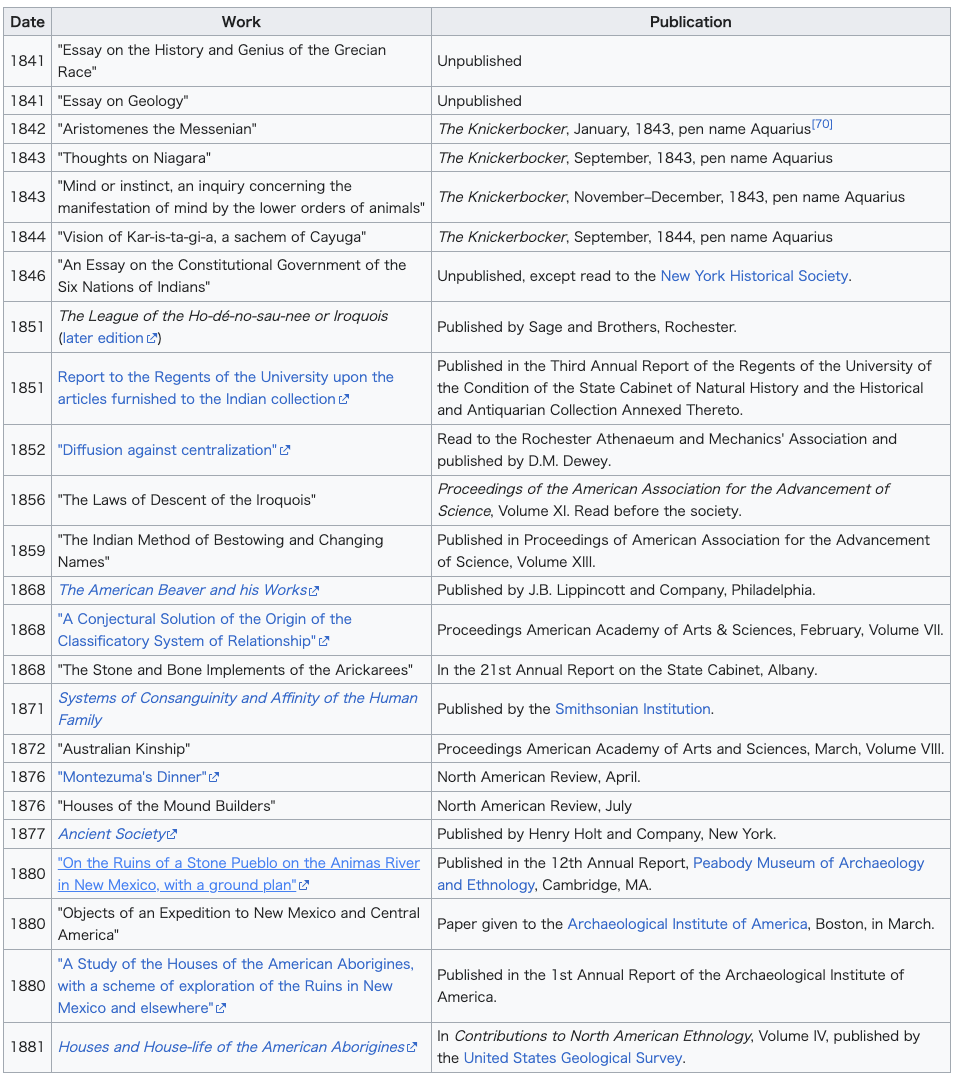

| List of Morgan's writings Lewis Morgan wrote continuously, whether letters, papers to be read, or published articles and books. A list of his major works follows. Some of the letters and papers have been omitted. A complete list, as far as was known, is given by Lloyd in the 1922 revised edition (posthumous) of The League ... .[65] Specifically omitted are 14 "Letters on the Iroquois" read before the New Confederacy, 1844–1846, and published in The American Review in 1847 under another pen name, Skenandoah; 31 papers read before The Club, 1854–1880; and various book reviews published in The Nation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_H._Morgan#cite_note-Stites-63 |

モーガンの著作一覧 ルイス・モーガンは絶え間なく執筆した。書簡であれ、発表論文であれ、出版された記事や書籍であれ。以下に彼の主要著作を列挙する。一部の書簡や論文は省 略されている。完全な一覧は、ロイドが1922年に改訂版(死後刊行)として出版した『ザ・リーグ...』に記載されている。[65] 具体的には、1844年から1846年にかけてニュー・コンフェデラシーで発表され、1847年に別筆名のスケナンドア名義で『アメリカン・レビュー』誌 に掲載された「イロコイ族に関する書簡」14通、1854年から1880年にかけてザ・クラブで発表された論文31編、および『ネイション』誌に掲載され た各種書評が省略されている。 |

| Bibliography Conn, Steven (2004). History's Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Deloria, Philip Joseph (1998) [1994]. Playing Indian. Yale Historical Publications. New Haven: Department of History of Yale University. Feeley-Harnik, Gillian (2001). "'The Mystery of Life in All Its Forms': Religious Dimensions in the Culture of Early American Anthropology". In Mizruchi, Susan Laura (ed.). Religion and Cultural Studies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 140–191.. Lloyd, Herbert M. (1922). "Appendix B, Notes". In Lloyd, Herbert Marshall (ed.). League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois. Vol. II (New ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 145–310.. Morgan, Lewis Henry (1993). White, Leslie A. (ed.). The Indian Journals, 1859-62. New York: Dover Publications. Moses, Daniel Noah (2009). The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. Porter, Charles T. (1922). "Personal Reminiscences". In Lloyd, Herbert Marshall (ed.). League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois. Vol. II (New ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 153–161. Stern, Bernhard J. "Lewis Henry Morgan Today; An Appraisal of His Scientific Contributions," Science & Society, vol. 10, no. 2 (Spring 1946), pp. 172–176. In JSTOR. Trautman, Thomas R.; Kabelac, Karl Sanford (1994). The Library of Lewis Henry Morgan and Mary Elizabeth Morgan. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, volume 84, Parts 6-7. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. White, Leslie A. (1951). "Lewis H. Morgan's Western Field Trips" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 53: 11–18. doi:10.1525/aa.1951.53.1.02a00030. |

参考文献 コン、スティーブン(2004)。『歴史の影:19世紀におけるネイティブアメリカンと歴史意識』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。 デロリア、フィリップ・ジョセフ(1998)[1994]。『インディアンを演じる』。イェール歴史出版物。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学歴史学部。 フィーリー=ハーニック、ジリアン(2001)。「あらゆる形態における生命の神秘」:初期アメリカ人類学文化における宗教的側面。ミズルチ、スーザン・ローラ(編)。『宗教と文化研究』。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。pp. 140–191.. ロイド、ハーバート・M.(1922)。「付録B、注記」。ロイド、ハーバート・マーシャル(編)。ホーデノソーニー族、すなわちイロコイ族連盟。第II巻(新編)。ニューヨーク:ドッド・ミード社。pp. 145–310。 モーガン、ルイス・ヘンリー(1993)。ホワイト、レスリー・A.(編)。『インディアン日記、1859-62年』。ニューヨーク:ドーバー出版。 モーゼス、ダニエル・ノア(2009)。『進歩の約束:ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンの生涯と業績』。コロンビア:ミズーリ大学出版局。 ポーター、チャールズ・T.(1922)。「個人的回想」。ロイド、ハーバート・マーシャル(編)。『ホーデノソーニー族、すなわちイロコイ族の同盟』。第II巻(新編)。ニューヨーク:ドッド・ミード社。pp. 153–161。 スターン、バーナード・J. 「現代におけるルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン:その科学的貢献の評価」、『科学と社会』第10巻第2号(1946年春)、pp. 172–176。JSTOR収録。 トラウトマン、トーマス・R.;カベラック、カール・サンフォード(1994)。『ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンとメアリー・エリザベス・モーガンの図書館』。アメリカ哲学会紀要、第84巻、第6-7部。フィラデルフィア:アメリカ哲学会。 ホワイト、レスリー・A.(1951)。「ルイス・H・モーガンの西部フィールドトリップ」(PDF)。『アメリカ人類学者』。53: 11–18。doi:10.1525/aa.1951.53.1.02a00030。 |

| External links Works by Lewis H. Morgan at Project Gutenberg Works by or about Lewis H. Morgan at Internet Archive Morgan, Lewis H. (2004). "Ancient Society". Marxist Internet Archive Reference Archive. 1963 reissue of Ancient Society with introductions by Eleanor Leacock Lewis Henry Morgan at Find a Grave "Morgan, Lewis Henry". River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester. McKelvey, Blake (Winter 1965). "The Pundit Club and the City of Rochester". University of Rochester Library Bulletin. XX (2). Knight, C. 2008. Early Human Kinship was Matrilineal. In N. J. Allen, H. Callan, R. Dunbar and W. James (eds), Early Human Kinship. London: Royal Anthropological Institute, pp. 61–82. "Morgan, Lewis Henry" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905. Lewis H. Morgan — Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences |

外部リンク プロジェクト・グーテンベルクにおけるルイス・H・モーガンの著作 インターネットアーカイブにおけるルイス・H・モーガンの著作、あるいはモーガンに関する著作 モーガン、ルイス・H. (2004). 「古代社会」. マルクス主義インターネットアーカイブ参考資料アーカイブ. 1963年再版『古代社会』エレノア・リーコックによる序文付き ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン、Find a Grave 「モーガン、ルイス・ヘンリー」。リバーキャンパス図書館、ロチェスター大学。 マッケルベイ、ブレイク(1965年冬)。「パンディット・クラブとロチェスター市」。ロチェスター大学図書館紀要。XX (2)。 ナイト、C. 2008年。初期の人間の親族関係は母系であった。N. J. アレン、H. キャラン、R. ダンバー、W. ジェームズ(編)『初期の人間の親族関係』所収。ロンドン:王立人類学協会、61-82 ページ。 「モーガン、ルイス・ヘンリー」 『新国際百科事典』 1905 年。 ルイス・H・モーガン — 国立科学アカデミー伝記回顧録 |

| Cultural

evolution Sociocultural evolution Ethnology Unilineal evolution Origins of society List of important publications in anthropology |

文化進化 社会文化的進化(Sociocultural evolution) 民族学 単線的進化 社会の起源 人類学における重要な出版物のリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_H._Morgan | https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆