社会文化的進化

Sociocultural evolution

☆ 社会文化進化論(しゃかいぶんかしんかろん)、社会文化進化論(しゃかいぶんかしんかろん)、社会進化論(しゃかいしんかろん)とは、社会や文化が時間と ともにどのように変化するかを説明する社会生物学と文化進化の理論である。社会文化的発展が社会や文化の複雑性を増大させる傾向のあるプロセスを追跡する のに対し、社会文化的進化は複雑性の減少(退化)につながる可能性のあるプロセスや、複雑性に一見大きな変化がなくても変異や増殖を生み出す可能性のある プロセス(クラドジェネシス)も考慮する[1]。社会文化的進化とは「構造的再編成が時間を通じて影響を受け、最終的に祖先の形態とは質的に異なる形態や 構造を生み出すプロセス」である[2]。 19世紀と20世紀の社会文化へのアプローチのほとんどは、人類全体としての進化のモデルを提供することを目的としており、異なる社会は社会的発展の異な る段階に達していると主張していた。タルコット・パーソンズ(1902-1979)の研究は、社会文化システムの発展を中心とした社会進化の一般理論を展 開する最も包括的な試みであり、世界史の理論を含む規模で行われた。もうひとつの試みは、イマニュエル・ウォーラーステイン(1930-2019)とその 追随者たちによる世界システム論的アプローチで、1970年代から始まった。 より最近のアプローチでは、個々の社会に特有の変化に焦点を当て、それぞれの文化が推定される社会進歩の直線的な尺度に沿ってどこまで進んだかによって文 化が異なるという考え方を否定している。現代の考古学者や文化人類学者の多くは、新進化論、社会生物学、近代化論の枠組みの中で研究を行っている。

★︎社会生物学▶︎文化進化▶︎︎エルマン・サービス▶バンド・部族・首長制・国家︎▶︎︎生態人類学▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| Sociocultural

evolution, sociocultural evolutionism or social evolution

are theories

of sociobiology

and cultural evolution that describe how societies and

culture change over time. Whereas sociocultural development traces

processes that tend to increase the complexity of a society or culture,

sociocultural evolution also considers process that can lead to

decreases in complexity (degeneration) or that can produce variation or

proliferation without any seemingly significant changes in complexity

(cladogenesis).[1] Sociocultural evolution is "the process by which

structural reorganization is affected through time, eventually

producing a form or structure that is qualitatively different from the

ancestral form".[2] Most of the 19th-century and some 20th-century approaches to socioculture aimed to provide models for the evolution of humankind as a whole, arguing that different societies have reached different stages of social development. The most comprehensive attempt to develop a general theory of social evolution centering on the development of sociocultural systems, the work of Talcott Parsons (1902–1979), operated on a scale which included a theory of world history. Another attempt, on a less systematic scale, originated from the 1970s with the world-systems approach of Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019) and his followers. More recent approaches focus on changes specific to individual societies and reject the idea that cultures differ primarily according to how far each one has moved along some presumed linear scale of social progress. Most[quantify] modern archaeologists and cultural anthropologists work within the frameworks of neoevolutionism, sociobiology, and modernization theory. |

社会文化進化論(しゃかいぶんかしんかろん)、社会文化進化論(しゃか

いぶんかしんかろん)、社会進化論(しゃかいしんかろん)とは、社会や文化が時間とともにどのように変化するかを説明する社会生物学と文化進化の

理論であ

る。社会文化的発展が社会や文化の複雑性を増大させる傾向のあるプロセスを追跡するのに対し、社会文化的進化は複雑性の減少(退化)につながる可能性のあ

るプロセスや、複雑性に一見大きな変化がなくても変異や増殖を生み出す可能性のあるプロセス(クラドジェネシス)も考慮する[1]。社会文化的進化とは

「構造的再編成が時間を通じて影響を受け、最終的に祖先の形態とは質的に異なる形態や構造を生み出すプロセス」である[2]。 19世紀と20世紀の社会文化へのアプローチのほとんどは、人類全体としての進化のモデルを提供することを目的としており、異なる社会は社会的発展の異な る段階に達していると主張していた。タルコット・パーソンズ(1902-1979)の研究は、社会文化システムの発展を中心とした社会進化の一般理論を展 開する最も包括的な試みであり、世界史の理論を含む規模で行われた。もうひとつの試みは、イマニュエル・ウォーラーステイン(1930-2019)とその 追随者たちによる世界システム論的アプローチで、1970年代から始まった。 より最近のアプローチでは、個々の社会に特有の変化に焦点を当て、それぞれの文化が推定される社会進歩の直線的な尺度に沿ってどこまで進んだかによって文 化が異なるという考え方を否定している。現代の考古学者や文化人類学者の多くは、新進化論、社会生物学、近代化論の枠組みの中で研究を行っている。 |

| Introduction Anthropologists and sociologists often assume that human beings have natural social tendencies but that particular human social behaviours have non-genetic causes and dynamics (i.e. people learn them in a social environment and through social interaction).[citation needed] Societies exist in complex social environments (for example: with differing natural resources and constraints) and adapt themselves to these environments. It is thus inevitable that all societies change. Specific theories of social or cultural evolution often attempt to explain differences between coeval societies by positing that different societies have reached different stages of development. Although such theories typically provide models for understanding the relationship between technologies, social structure or the values of a society, they vary as to the extent to which they describe specific mechanisms of variation and change. While the history of evolutionary thinking with regard to humans can be traced back at least to Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, early sociocultural-evolution theories – the ideas of Auguste Comte (1798–1857), Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881) – developed simultaneously with, but independently of, the work of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and were popular from late in the 19th century to the end of World War I. The 19th-century unilineal evolution theories claimed that societies start out in a primitive state and gradually become more civilized over time; they equated the culture and technology of Western civilization with progress. Some forms of early sociocultural-evolution theories (mainly unilineal ones) have led to much-criticised theories like social Darwinism and scientific racism, sometimes used in the past by European imperial powers to justify existing policies of colonialism and slavery and to justify new policies such as eugenics.[3] Most 19th-century and some 20th-century approaches aimed to provide models for the evolution of humankind as a single entity. However, most 20th-century approaches, such as multilineal evolution, focused on changes specific to individual societies. Moreover, they rejected directional change (i.e. orthogenetic, teleological or progressive change). Most archaeologists work within the framework of multilineal evolution.[citation needed] Other contemporary approaches to social change include neoevolutionism, sociobiology, dual inheritance theory, modernisation theory and postindustrial theory.[citation needed] In his seminal 1976 book The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins wrote that "there are some examples of cultural evolution in birds and monkeys, but ... it is our own species that really shows what cultural evolution can do".[4] |

はじめに 人類学者や社会学者はしばしば、人間には自然な社会的傾向があるが、特定の人間の社会的行動には遺伝的ではない原因や力学がある(つまり、人は社会的環境 の中で、社会的相互作用を通じてそれを学ぶ)と仮定する[要出典]。 社会は複雑な社会環境(例えば、天然資源や制約が異なる)の中に存在し、これらの環境に適応する。したがって、すべての社会が変化することは避けられな い。 社会的または文化的進化に関する特定の理論では、異なる社会が異なる発展段階に達したと仮定することで、同時代の社会間の違いを説明しようとすることが多 い。このような理論は通常、技術、社会構造、社会の価値観の関係を理解するためのモデルを提供するが、変動と変化の具体的なメカニズムをどの程度説明する かについては様々である。 人間に関する進化論の歴史は、少なくともアリストテレスやその他のギリシャ哲学者にまで遡ることができるが、初期の社会文化進化論、すなわちオーギュス ト・コント(1798-1857)、ハーバート・スペンサー(1820-1903)、ルイス・ヘンリー・モルガン(1818-1881)の考え方は、 チャールズ・ダーウィン(1809-1882)の研究と同時に、しかしそれとは独立して発展し、19世紀後半から第一次世界大戦の終わり頃まで人気を博し た。19世紀の一元的進化論は、社会は原始的な状態から出発し、時間の経過とともに徐々に文明化していくと主張した。初期の社会文化進化論(主に単線的な もの)のいくつかの形態は、社会ダーウィニズムや科学的人種差別主義のような多くの批判を浴びる理論につながり、過去には植民地主義や奴隷制の既存の政策 を正当化するために、また優生学のような新しい政策を正当化するためにヨーロッパの帝国権力によって使用されたこともあった[3]。 19世紀のほとんどのアプローチと20世紀のいくつかのアプローチは、単一の存在としての人類の進化のモデルを提供することを目的としていた。しかし、多 系統進化のような20世紀のアプローチのほとんどは、個々の社会に特有の変化に焦点を当てたものであった。さらに、彼らは方向性のある変化(すなわち正統 的変化、目的論的変化、漸進的変化)を否定した。ほとんどの考古学者は多系統進化の枠組みの中で研究している。[要出典] 社会変化に対する他の現代的なアプローチには、新進化論、社会生物学、二重継承理論、近代化理論、ポスト産業化理論などがある[要出典]。 1976年の代表的な著書『利己的な遺伝子』の中で、リチャード・ドーキンスは「鳥やサルには文化的進化の例がいくつかあるが、......文化的進化に 何ができるかを本当に示しているのは、私たち自身の種である」と書いている[4]。 |

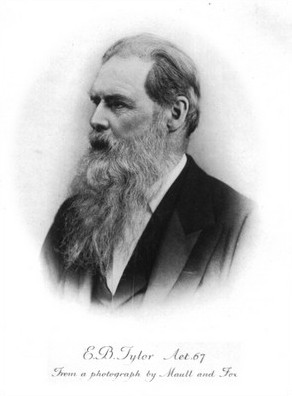

| Stadial theory Enlightenment and later thinkers often speculated that societies progressed through stages: in other words, they saw history as stadial. While expecting humankind to show increasing development, theorists looked for what determined the course of human history. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), for example, saw social development as an inevitable process.[citation needed] It was assumed that societies start out primitive, perhaps in a state of nature, and could progress toward something resembling industrial Europe. While earlier authors such as Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) had discussed how societies change through time, the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century proved key in the development of the idea of sociocultural evolution.[citation needed] In relation to Scotland's union with England in 1707, several Scottish thinkers pondered the relationship between progress and the affluence brought about by increased trade with England. They understood the changes Scotland was undergoing as involving transition from an agricultural to a mercantile society. In "conjectural histories", authors such as Adam Ferguson (1723–1816), John Millar (1735–1801) and Adam Smith (1723–1790) argued that societies all pass through a series of four stages: hunting and gathering, pastoralism and nomadism, agriculture, and finally a stage of commerce.  Auguste Comte (1798–1857) Philosophical concepts of progress, such as that of Hegel, developed as well during this period. In France, authors such as Claude Adrien Helvétius (1715–1771) and other philosophes were influenced by the Scottish tradition. Later thinkers such as Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) developed these ideas.[citation needed] Auguste Comte (1798–1857) in particular presented a coherent view of social progress and a new discipline to study it: sociology. These developments took place in a context of wider processes. The first process was colonialism. Although imperial powers settled most differences of opinion with their colonial subjects through force, increased awareness of non-Western peoples raised new questions for European scholars about the nature of society and of culture. Similarly, effective colonial administration required some degree of understanding of other cultures. Emerging theories of sociocultural evolution allowed Europeans to organise their new knowledge in a way that reflected and justified their increasing political and economic domination of others: such systems saw colonised people as less evolved, and colonising people as more evolved. Modern civilization (understood as the Western civilization), appeared the result of steady progress from a state of barbarism, and such a notion was common to many thinkers of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire (1694–1778). The second process was the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism, which together allowed and promoted continual revolutions in the means of production. Emerging theories of sociocultural evolution reflected a belief that the changes in Europe brought by the Industrial Revolution and capitalism were improvements. Industrialisation, combined with the intense political change brought about by the French Revolution of 1789 and the U.S. Constitution, which paved the way for the dominance of democracy, forced European thinkers to reconsider some of their assumptions about how society was organised. Eventually, in the 19th century three major classical theories of social and historical change emerged: sociocultural evolutionism the social cycle theory the Marxist theory of historical materialism. These theories had a common factor: they all agreed that the history of humanity is pursuing a certain fixed path, most likely that of social progress. Thus, each past event is not only chronologically, but causally tied to present and future events. The theories postulated that by recreating the sequence of those events, sociology could discover the "laws" of history.[5] Sociocultural evolutionism and the idea of progress Main article: Unilineal evolution While sociocultural evolutionists agree that an evolution-like process leads to social progress, classical social evolutionists have developed many different theories, known as theories of unilineal evolution. Sociocultural evolutionism became the prevailing theory of early sociocultural anthropology and social commentary, and is associated with scholars like Auguste Comte, Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, Benjamin Kidd, L. T. Hobhouse and Herbert Spencer. Such stage models and ideas of linear models of progress had a great influence not only on future evolutionary approaches in the social sciences and humanities,[6] but also shaped public, scholarly, and scientific discourse surrounding the rising individualism and population thinking.[7] Sociocultural evolutionism attempted to formalise social thinking along scientific lines, with the added influence from the biological theory of evolution. If organisms could develop over time according to discernible, deterministic laws, then it seemed reasonable that societies could as well. Human society was compared to a biological organism, and social science equivalents of concepts like variation, natural selection, and inheritance were introduced as factors resulting in the progress of societies. The idea of progress led to that of a fixed "stages" through which human societies progress, usually numbering three – savagery, barbarism, and civilization – but sometimes many more. At that time, anthropology was rising as a new scientific discipline, separating from the traditional views of "primitive" cultures that was usually based on religious views.[8] Already in the 18th century, some authors began to theorize on the evolution of humans. Montesquieu (1689–1755) wrote about the relationship laws have with climate in particular and the environment in general, specifically how different climatic conditions cause certain characteristics to be common among different people.[9] He likens the development of laws, the presence or absence of civil liberty, differences in morality, and the whole development of different cultures to the climate of the respective people,[10] concluding that the environment determines whether and how a people farms the land, which determines the way their society is built and their culture is constituted, or, in Montesquieu's words, the "general spirit of a nation".[11] Also Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) presents a conjectural stage-model of human sociocultural evolution:[12] first, humans lived solitarily and only grouped when mating or raising children. Later, men and women lived together and shared childcare, thus building families, followed by tribes as the result of inter-family interactions, which lived in "the happiest and the most lasting epoch" of human history, before the corruption of civil society degenerated the species again in a developmental stage-process.[13] In the late 18th century, the Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794) listed ten stages, or "epochs", each advancing the rights of man and perfecting the human race. Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Charles Darwin's grandfather, was an enormously influential natural philosopher, physiologist and poet whose remarkably insightful ideas included a statement of transformism and the interconnectedness of all forms of life. His works, which are enormously wide-ranging, also advance a theory of cultural transformation: his famous The Temple of Nature is subtitled 'the Origin of Society'.[14] This work, rather than proposing in detail a strict transformation of humanity between different stages, instead dwells on Erasmus Darwin's evolutionary mechanism: Erasmus Darwin does not explain each stage one-by-one, trusting his theory of universal organic development, as articulated in the Zoonomia, to illustrate cultural development as well.[15] Erasmus Darwin therefore flits with abandon through his chronology: Priestman notes that it jumps from the emergence of life onto land, the development of opposable thumbs, and the origin of sexual reproduction directly to modern historical events.[14] Another more complex theorist was Richard Payne Knight (1751-1824), an influential amateur archeologist and universal theologian. Knight's The Progress of Civil Society: A Didactic Poem in Six Books (1796) fits precisely into the tradition of triumphant historical stages, beginning with Lucretius and reaching Adam Smith––but just for the first four books.[16] In his final books, Knight then grapples with the French revolution and wealthy decadence. Confronted with these twin issues, Knight's theory ascribes progress to conflict: 'partial discord lends its aid, to tie the complex knots of general harmony'.[16] Competition in Knight's mechanism spurs development from any one stage to the next: the dialectic of class, land and gender creates growth.[17] Thus, Knight conceptualised a theory of history founded in inevitable racial conflict, with Greece representing 'freedom' and Egypt 'cold inactive stupor'.[18] Buffon, Linnaeus, Camper and Monboddo variously forward diverse arguments about racial hierarchy, grounded in early theories of species change––though many thought that environmental changes could create dramatic changes in form without permanently altering the species or causing species transformation. However, their arguments still bear on race: Rousseau, Buffon and Monboddo cite orangutans as evidence of an earlier prelinguistic human type, and Monboddo even insisted Orangutans and certain African and South Asian races were identical. Other than Erasmus Darwin, the other pre-eminent scientific text with a theory of cultural transformation was advanced by Robert Chambers (1802-1871). Chambers was a Scottish evolutionary thinker and philosopher who, though he was then and now perceived as scientifically inadequate and criticized by prominent contemporaries, is important because he was so widely read. There are records of everyone from Queen Victoria to individual dockworkers enjoying his Robert Chambers' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), including future generations of scientists. That The Vestiges did not establish itself as the scientific cutting edge is precisely the point, since the Vestiges's influence means it was both the concept of evolution the Victorian public was most likely to experience, and the scientific presupposition laid earliest in the minds of bright young scholars.[19] Chambers propounded a 'principle of development' whereby everything evolved by the same mechanism and towards higher order structure or meaning. In his theory, life advanced through different 'classes', and within each class animals began at the lowest form and then advanced to more complex forms in the same class.[20] In short, the progress of animals was like the development of a foetus. More than just an indistinct analogy, this parallel between embryology and species development had the status of a genuine causal mechanism in Chambers' theory: more advanced species developed longer as embryos into all their complexity.[21] Motivated by this comparison, Chambers ascribed development to the 'laws of creation', though he also supposed that the whole development of species was in some way preordained: it was just that the preordination of the creator acted through establishing those laws.[21] This, as discussed above, is similar to Spencer's later concept of development. Thus Chambers believed in a sophisticated theory of progress driven by a developmental analogy.  Herbert Spencer In the mid-19th century, a "revolution in ideas about the antiquity of the human species" took place "which paralleled, but was to some extent independent of, the Darwinian revolution in biology."[22] Especially in geology, archaeology, and anthropology, scholars began to compare "primitive" cultures to past societies and "saw their level of technology as parallel with that of Stone Age cultures, and thus used these peoples as models for the early stages of human evolution." A developmental model of the evolution of the mind, culture, and society was the result, paralleling the evolution of the human species:[23] "Modern savages [sic] became, in effect, living fossils left behind by the march of progress, relics of the Paleolithic still lingering on into the present."[24] Classical social evolutionism is most closely associated with the 19th-century writings of Auguste Comte and of Herbert Spencer (coiner of the phrase "survival of the fittest").[25] In many ways, Spencer's theory of "cosmic evolution" has much more in common with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Auguste Comte than with contemporary works of Charles Darwin. Spencer also developed and published his theories several years earlier than Darwin. In regard to social institutions, however, there is a good case that Spencer's writings might be classified as social evolutionism. Although he wrote that societies over time progressed – and that progress was accomplished through competition – he stressed that the individual rather than the collectivity is the unit of analysis that evolves; that, in other words, evolution takes place through natural selection and that it affects social as well as biological phenomenon. Nonetheless, the publication of Darwin's works[which?] proved a boon to the proponents of sociocultural evolution, who saw the ideas of biological evolution as an attractive explanation for many questions about the development of society.[26] Both Spencer and Comte view society as a kind of organism subject to the process of growth—from simplicity to complexity, from chaos to order, from generalisation to specialisation, from flexibility to organisation. They agree that the process of societal growth can be divided into certain stages, have[clarification needed] their beginning and eventual end, and that this growth is in fact social progress: each newer, more-evolved society is "better". Thus progressivism became one of the basic ideas underlying the theory of sociocultural evolutionism.[25] However, Spencer's theories were more complex than just a romp up the great chain of being. Spencer based his arguments on an analogy between the evolution of societies and the ontogeny of an animal. Accordingly, he searched for "general principles of development and structure" or "fundamental principles of organization", rather than being content simply ascribing progress between social stages to the direct intervention of some beneficent deity.[27] Moreover, he accepted that these conditions are "far less specific, far more modifiable, far more dependent on conditions that are variable": in short, that they are a messy biological process.[28] Though Spencer's theories transcended the label of 'stagism' and appreciate biological complexity, they still accepted a strongly fixed direction and morality to natural development.[29] For Spencer, interference with the natural process of evolution was dangerous and had to be avoided at all costs. Such views were naturally coupled to the pressing political and economic questions of the time. Spencer clearly thought society's evolution brought about a racial hierarchy with Caucasians at the top and Africans at the bottom.[29] This notion is deeply linked to the colonial projects European powers were pursuing at the time, and the idea of European superiority used paternalistically to justify those projects. The influential German zoologist Ernst Haeckel even wrote that 'natural men are closer to the higher vertebrates than highly civilized Europeans', including not just a racial hierarchy but a civilizational one.[30] Likewise, Spencer's evolutionary argument advanced a theory of statehood: "until spontaneously fulfilled a public want should not be fulfilled at all" sums up Spencer's notion about limited government and the free operation of market forces.[31] This is not to suggest that stagism was useless or entirely motivated by colonialism and racism. Stagist theories were first proposed in contexts where competing epistemologies were largely static views of the world. Hence "progress" had in some sense to be invented, conceptually: the idea that human society would move through stages was a triumphant invention. Moreover, stages were not always static entities. In Buffon's theories, for example, it was possible to regress between stages, and physiological changes were species' reversibly adapting to their environment rather than irreversibly transforming.[32] In addition to progressivism, economic analyses influenced classical social evolutionism. Adam Smith (1723–1790), who held a deeply evolutionary view of human society,[33] identified the growth of freedom as the driving force in a process of stadial societal development.[34] According to him, all societies pass successively through four stages: the earliest humans lived as hunter-gatherers, followed by pastoralists and nomads, after which society evolved to agriculturalists and ultimately reached the stage of commerce.[35] With the strong emphasis on specialisation and the increased profits stemming from a division of labour, Smith's thinking also exerted some direct influence on Darwin himself.[36] Both in Darwin's theory of the evolution of species and in Smith's accounts of political economy, competition between selfishly functioning units plays an important and even dominating rôle.[37] Similarly occupied with economic concerns as Smith, Thomas R. Malthus (1766–1834) warned that given the strength of the sex drive inherent in all animals, Malthus argued, populations tend to grow geometrically, and population growth is only checked by the limitations of economic growth, which, if there would be growth at all, would quickly be outstripped by population growth, causing hunger, poverty, and misery.[38] Far from being the consequences of economic structures or social orders, this "struggle for existence" is an inevitable natural law, so Malthus.[39] Auguste Comte, known as "the father of sociology", formulated the law of three stages: human development progresses from the theological stage, in which nature was mythically conceived and man sought the explanation of natural phenomena from supernatural beings; through a metaphysical stage in which nature was conceived of as a result of obscure forces and man sought the explanation of natural phenomena from them; until the final positive stage in which all abstract and obscure forces are discarded, and natural phenomena are explained by their constant relationship.[40] This progress is forced through the development of human mind, and through increasing application of thought, reasoning and logic to the understanding of the world.[41] Comte saw the science-valuing society as the highest, most developed type of human organization.[40] Herbert Spencer, who argued against government intervention as he believed that society should evolve toward more individual freedom,[42] followed Lamarck in his evolutionary thinking,[43] in that he believed that humans do over time adapt to their surroundings.[44] He differentiated between two phases of development as regards societies' internal regulation:[40] the "military" and "industrial" societies.[40] The earlier (and more primitive) military society has the goal of conquest and defense, is centralised, economically self-sufficient, collectivistic, puts the good of a group over the good of an individual, uses compulsion, force and repression, and rewards loyalty, obedience and discipline.[40] The industrial society, in contrast, has a goal of production and trade, is decentralised, interconnected with other societies via economic relations, works through voluntary cooperation and individual self-restraint, treats the good of individual as of the highest value, regulates the social life via voluntary relations; and values initiative, independence and innovation.[40][45] The transition process from the military to industrial society is the outcome of steady evolutionary processes within the society.[40] Spencer "imagined a kind of feedback loop between mental and social evolution: the higher the mental powers the greater the complexity of the society that the individuals could create; the more complex the society, the greater the stimulus it provided for further mental development. Everything cohered to make progress inevitable or to weed out those who did not keep up."[46] Regardless of how scholars of Spencer interpret his relation to Darwin, Spencer became an incredibly popular figure in the 1870s, particularly in the United States. Authors such as Edward L. Youmans, William Graham Sumner, John Fiske, John W. Burgess, Lester Frank Ward, Lewis H. Morgan (1818–1881) and other thinkers of the gilded age all developed theories of social evolutionism as a result of their exposure to Spencer as well as to Darwin.  Lewis H. Morgan In his 1877 classic Ancient Societies, Lewis H. Morgan, an anthropologist whose ideas have had much impact on sociology, differentiated between three eras:[47] savagery, barbarism and civilization, which are divided by technological inventions, like fire, bow, pottery in the savage era, domestication of animals, agriculture, metalworking in the barbarian era and alphabet and writing in the civilization era.[48] Thus Morgan drew a link between social progress and technological progress. Morgan viewed technological progress as a force behind social progress, and held that any social change—in social institutions, organizations or ideologies—has its beginnings in technological change.[48][49] Morgan's theories were popularized by Friedrich Engels, who based his famous work The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State on them.[48] For Engels and other Marxists this theory was important, as it supported their conviction that materialistic factors—economic and technological—are decisive in shaping the fate of humanity.[48] Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), a pioneer of anthropology, focused on the evolution of culture worldwide, noting that culture is an important part of every society and that it is also subject to a process of evolution. He believed that societies were at different stages of cultural development and that the purpose of anthropology was to reconstruct the evolution of culture, from primitive beginnings to the modern state.  Edward Burnett Tylor Anthropologists Sir E.B. Tylor in England and Lewis Henry Morgan in the United States worked with data from indigenous people, who (they claimed) represented earlier stages of cultural evolution that gave insight into the process and progression of evolution of culture. Morgan had a significant influence on Karl Marx and on Friedrich Engels, who developed a theory of sociocultural evolution in which the internal contradictions in society generated a series of escalating stages that ended in a socialist society (see Marxism). Tylor and Morgan elaborated the theory of unilinear evolution, specifying criteria for categorising cultures according to their standing within a fixed system of growth of humanity as a whole and examining the modes and mechanisms of this growth. Theirs was often a concern with culture in general, not with individual cultures. Their analysis of cross-cultural data was based on three assumptions: contemporary societies may be classified and ranked as more "primitive" or more "civilized" there are a determinate number of stages between "primitive" and "civilized" (e.g. band, tribe, chiefdom, and state) all societies progress through these stages in the same sequence, but at different rates Theorists usually measured progression (that is, the difference between one stage and the next) in terms of increasing social complexity (including class differentiation and a complex division of labour), or an increase in intellectual, theological, and aesthetic sophistication. These 19th-century ethnologists used these principles primarily to explain differences in religious beliefs and kinship terminologies among various societies.  Lester Frank Ward Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), sometimes referred to[by whom?] as the "father" of American sociology, rejected many of Spencer's theories regarding the evolution of societies. Ward, who was also a botanist and a paleontologist, believed that the law of evolution functioned much differently in human societies than it did in the plant and animal kingdoms, and theorized that the "law of nature" had been superseded by the "law of the mind".[50] He stressed that humans, driven by emotions, create goals for themselves and strive to realize them (most effectively with the modern scientific method) whereas there is no such intelligence and awareness guiding the non-human world.[51] Plants and animals adapt to nature; man shapes nature. While Spencer believed that competition and "survival of the fittest" benefited human society and sociocultural evolution, Ward regarded competition as a destructive force, pointing out that all human institutions, traditions and laws were tools invented by the mind of man and that that mind designed them, like all tools, to "meet and checkmate" the unrestrained competition of natural forces.[50] Ward agreed with Spencer that authoritarian governments repress the talents of the individual, but he believed that modern democratic societies, which minimized the role of religion and maximized that of science, could effectively support the individual in his or her attempt to fully utilize their talents and achieve happiness. He believed that the evolutionary processes have four stages: First comes cosmogenesis, creation and evolution of the world. Then, when life arises, there is biogenesis.[51] Development of humanity leads to anthropogenesis, which is influenced by the human mind.[51] Finally there arrives sociogenesis, which is the science of shaping the evolutionary process itself to optimize progress, human happiness and individual self-actualization.[51] Ward regarded modern societies as superior to "primitive" societies (one need only look to the impact of medical science on health and lifespan[citation needed]) and shared theories of white supremacy. Though he supported the Out-of-Africa theory of human evolution, he did not believe that all races and social classes were equal in talent. When a Negro rapes a white woman, Ward declared, he is impelled not only by lust but also by the instinctive drive to improve his own race.[52][53] Ward did not think that evolutionary progress was inevitable and he feared the degeneration of societies and cultures, which he saw as very evident in the historical record.[54] Ward also did not favor the radical reshaping of society as proposed by the supporters of the eugenics movement or by the followers of Karl Marx; like Comte, Ward believed that sociology was the most complex of the sciences and that true sociogenesis was impossible without considerable research and experimentation.[52]  Émile Durkheim Émile Durkheim, another of the "fathers" of sociology, developed a dichotomal view of social progress.[55] His key concept was social solidarity, as he defined social evolution in terms of progressing from mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity.[55] In mechanical solidarity, people are self-sufficient, there is little integration and thus there is the need for the use of force and repression to keep society together.[55] In organic solidarity, people are much more integrated and interdependent and specialisation and cooperation are extensive.[55] Progress from mechanical to organic solidarity is based firstly on population growth and increasing population density, secondly on increasing "morality density" (development of more complex social interactions) and thirdly on increasing specialisation in the workplace.[55] To Durkheim, the most important factor in social progress is the division of labour.[55] This[clarification needed] was later used in the mid-1900s by the economist Ester Boserup (1910–1999) to attempt to discount some aspects of Malthusian theory. Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936) describes evolution as the development from informal society, where people have many liberties and there are few laws and obligations, to modern, formal rational society, dominated by traditions and laws, where people are restricted from acting as they wish.[56] He also notes that there is a tendency to standardisation and unification, when all smaller societies are absorbed into a single, large, modern society.[56] Thus Tönnies can be said to describe part of the process known today as globalization. Tönnies was also one of the first sociologists to claim that the evolution of society is not necessarily going in the right direction, that social progress is not perfect, and it can even be called a regression as the newer, more evolved societies are obtained only after paying a high cost, resulting in decreasing satisfaction of the individuals making up that society.[56] Tönnies' work became the foundation of neoevolutionism.[56] Although Max Weber is not usually counted[by whom?] as a sociocultural evolutionist, his theory of tripartite classification of authority can be viewed[by whom?] as an evolutionary theory as well. Weber distinguishes three ideal types of political leadership, domination and authority: charismatic domination traditional domination (patriarchs, patrimonialism, feudalism) legal (rational) domination (modern law and state, bureaucracy) Weber also notes that legal domination is the most advanced, and that societies evolve from having mostly traditional and charismatic authorities to mostly rational and legal ones. Critique and impact on modern theories The early 20th-century inaugurated a period of systematic critical examination, and rejection of the sweeping generalisations of the unilineal theories of sociocultural evolution. Cultural anthropologists such as Franz Boas (1858–1942), along with his students, including Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, are regarded[by whom?] as the leaders of anthropology's rejection of classical social evolutionism. However, the school of Boas ignore some of the complexity in evolutionary theories that emerged outside Herbert Spencer's influence. Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species gave a mechanistic account of the origins and development of animals, quite apart from Spencer's theories that emphasized the inevitable human development through stages. Consequently, many scholars developed more sophisticated understandings of how cultures evolve, relying on deep cultural analogies, than the theories in Herbert Spencer's tradition.[57] Walter Bagehot (1872) applied selection and inheritance to the development of human political institutions. Samuel Alexander (1892) discusses the natural selection of moral principles in society.[58] William James (1880) considered the 'natural selection' of ideas in learning and scientific development. In fact, he identified a 'remarkable parallel […] between the facts of social evolution on the one hand, and of zoological evolution as expounded by Mr Darwin on the other'.[58] Charles Sanders Peirce (1898) even proposed that the current laws of nature we have exist because they have evolved over time.[58] Darwin himself, in Chapter 5 of the Descent of Man, proposed that human moral sentiments were subject to group selection: "A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection."[59] Through the mechanism of imitation, cultures as well as individuals could be subject to natural selection. While these theories involved evolution applied to social questions, except for Darwin's group selection the theories reviewed above did not advance a precise understanding of how Darwin's mechanism extended and applied to cultures beyond a vague appeal to competition.[60] Ritchie's Darwinism and Politics (1889) breaks this trend, holding that "language and social institutions make it possible to transmit experience quite independently of the continuity of race."[61] Hence Ritchie saw cultural evolution as a process that could operate independently of and on different scales to the evolution of species, and gave it precise underpinnings: he was 'extending its range', in his own words, to ideas, cultures and institutions.[62] Thorstein Veblen, around the same time, came to a similar insight: that humans evolve to their social environment, but their social environment in turn also evolves.[63] Veblen's mechanism for human progress was the evolution of human intentionality: Veblen labelled men 'a creature of habit' and thought that habits were 'mentally digested' from those who influenced him.[57] In short, as Hodgson and Knudsen point out, Veblen thinks: "the changing institutions in their turn make for a further selection of individuals endowed with the fittest temperament, and a further adaptation of individual temperament and habits to the changing environment through the formation of new institutions." Thus, Veblen represented an extension of Ritchie's theories, where evolution operates at multiple levels, to a sophisticated appreciation of how each level interacts with the other.[64] This complexity notwithstanding, Boas and Benedict used sophisticated ethnography and more rigorous empirical methods to argue that Spencer, Tylor, and Morgan's theories were speculative and systematically misrepresented ethnographic data. Theories regarding "stages" of evolution were especially criticised as illusions. Additionally, they rejected the distinction between "primitive" and "civilized" (or "modern"), pointing out that so-called primitive contemporary societies have just as much history, and were just as evolved, as so-called civilized societies. They therefore argued that any attempt to use this theory to reconstruct the histories of non-literate (i.e. leaving no historical documents) peoples is entirely speculative and unscientific. They observed that the postulated progression, which typically ended with a stage of civilization identical to that of modern Europe, is ethnocentric. They also pointed out that the theory assumes that societies are clearly bounded and distinct, when in fact cultural traits and forms often cross social boundaries and diffuse among many different societies (and are thus an important mechanism of change). Boas in his culture-history approach focused on anthropological fieldwork in an attempt to identify factual processes instead of what he criticized as speculative stages of growth. His approach greatly influenced American anthropology in the first half of the 20th century, and marked a retreat from high-level generalization and from "systems building". Later critics observed that the assumption of firmly bounded societies was proposed precisely at the time when European powers were colonising non-Western societies, and was thus self-serving. Many anthropologists and social theorists now consider unilineal cultural and social evolution a Western myth seldom based on solid empirical grounds. Critical theorists argue that notions of social evolution are simply justifications for power by the élites of society. Finally, the devastating World Wars that occurred between 1914 and 1945 crippled Europe's self-confidence. After millions of deaths, genocide, and the destruction of Europe's industrial infrastructure, the idea of progress seemed dubious at best. Thus modern sociocultural evolutionism rejects most of classical social evolutionism due to various theoretical problems: The theory was deeply ethnocentric—it makes heavy value judgments about different societies, with Western civilization seen as the most valuable. It assumed all cultures follow the same path or progression and have the same goals. It equated civilization with material culture (technology, cities, etc.) Because social evolution was posited as a scientific theory, it was often used to support unjust and often racist social practices – particularly colonialism, slavery, and the unequal economic conditions present within industrialized Europe. Social Darwinism is especially criticised, as it purportedly led to some philosophies used by the Nazis. Max Weber, disenchantment, and critical theory  Max Weber in 1917 Main articles: Max Weber and Critical theory Weber's major works in economic sociology and the sociology of religion dealt with the rationalization, secularisation, and so called "disenchantment" which he associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity.[65] In sociology, rationalization is the process whereby an increasing number of social actions become based on considerations of teleological efficiency or calculation rather than on motivations derived from morality, emotion, custom, or tradition. Rather than referring to what is genuinely "rational" or "logical", rationalization refers to a relentless quest for goals that might actually function to the detriment of a society. Rationalization is an ambivalent aspect of modernity, manifested especially in Western society – as a behaviour of the capitalist market, of rational administration in the state and bureaucracy, of the extension of modern science, and of the expansion of modern technology.[citation needed] Weber's thought regarding the rationalizing and secularizing tendencies of modern Western society (sometimes described as the "Weber Thesis") would blend with Marxism to facilitate critical theory, particularly in the work of thinkers such as Jürgen Habermas (born 1929). Critical theorists, as antipositivists, are critical of the idea of a hierarchy of sciences or societies, particularly with respect to the sociological positivism originally set forth by Comte. Jürgen Habermas has critiqued the concept of pure instrumental rationality as meaning that scientific-thinking becomes something akin to ideology itself. For theorists such as Zygmunt Bauman (1925–2017), rationalization as a manifestation of modernity may be most closely and regrettably associated with the events of the Holocaust. |

段階説 啓蒙思想以降の思想家たちは、社会は段階を経て進歩すると考えることが多かった。つまり、彼らは歴史を段階的なものだと考えたのである。人類がますます発 展していくことを期待する一方で、理論家たちは何が人類の歴史の流れを決定するのかを探った。例えば、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル (1770-1831)は、社会の発展は必然的なプロセスであると考えた。 ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ(Michel de Montaigne, 1533-1592)のような以前の著者は、社会が時間によってどのように変化するかを論じていたが、18世紀のスコットランドの啓蒙思想は、社会文化的 進化という考えを発展させる上で重要な役割を果たした[要出典]。 スコットランドが1707年にイングランドと統合したことに関連して、スコットランドの数人の思想家は、イングランドとの貿易の増加によってもたらされた 豊かさと進歩との関係について考えた。彼らはスコットランドが経験している変化を、農業社会から商業社会への移行が関わっていると理解していた。アダム・ ファーガソン(1723-1816)、ジョン・ミラー(1735-1801)、アダム・スミス(1723-1790)といった著者は、「推測史」の中で、 社会はすべて狩猟採集、牧畜・遊牧、農業、そして最終的に商業という4つの段階を経るものだと主張した。  オーギュスト・コント(1798-1857) この時期には、ヘーゲルのような進歩に関する哲学的概念も発展した。フランスでは、クロード・アドリアン・ヘルヴェティウス(1715-1771)をはじ めとする哲学者たちがスコットランドの伝統に影響を受けた。特にオーギュスト・コント(1798-1857)は、社会進歩に関する首尾一貫した見解と、そ れを研究するための新しい学問分野、すなわち社会学を提示した。 これらの発展は、より広範なプロセスの中で起こった。最初の過程は植民地主義であった。帝国権力は植民地臣民との意見の相違のほとんどを武力によって解決 したが、非西洋人に対する認識の高まりは、社会と文化の本質についてヨーロッパの学者に新たな問題を提起した。同様に、効果的な植民地行政を行うには、他 国の文化をある程度理解する必要があった。社会文化進化論が台頭したことで、ヨーロッパ人は自分たちの新しい知識を、他者に対する政治的・経済的支配の拡 大を反映・正当化する形で整理することができるようになった。このような理論体系では、植民地化された人々はより進化しておらず、植民地化した人々はより 進化していると見なされた。近代文明(西洋文明として理解される)は、野蛮な状態からの着実な進歩の結果として現れ、このような考え方は、ヴォルテール (1694-1778)を含む啓蒙思想家の多くに共通するものだった。 第二の過程は、産業革命と資本主義の台頭であり、これらはともに生産手段の絶え間ない革命を可能にし、促進した。新興の社会文化進化論は、産業革命と資本 主義がもたらしたヨーロッパの変化は改善であるという信念を反映していた。産業化は、1789年のフランス革命と民主主義の支配への道を開いた合衆国憲法 によってもたらされた激しい政治的変化と相まって、ヨーロッパの思想家たちに、社会がどのように組織されるかについてのいくつかの前提を再考することを余 儀なくさせた。 やがて19世紀には、社会と歴史の変化に関する3つの主要な古典的理論が登場した: 社会文化進化論 社会文化進化論 マルクス主義の史的唯物論である。 これらの理論には共通点があった。それは、人類の歴史はある一定の道筋をたどっており、おそらくは社会進歩の道筋をたどっているという点である。したがっ て、過去の出来事は時系列的であるだけでなく、現在および未来の出来事と因果的に結びついている。これらの理論は、それらの出来事の順序を再現することに よって、社会学は歴史の「法則」を発見できると仮定していた[5]。 社会文化進化論と進歩の思想 主な記事 単線的進化 社会文化進化論者は、進化のようなプロセスが社会の進歩につながるという点で同意しているが、古典的な社会進化論者は、単線的進化論として知られるさまざ まな異なる理論を展開してきた。社会文化進化論は、初期の社会文化人類学や社会評論の主流となった理論であり、オーギュスト・コント、エドワード・バー ネット・タイラー、ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン、ベンジャミン・キッド、L.T.ホブハウス、ハーバート・スペンサーといった学者に関連している。このよ うな段階モデルや直線的な進歩モデルの考え方は、社会科学や人文科学における将来の進化論的アプローチに大きな影響を与えただけでなく[6]、個人主義や 集団思考の台頭をめぐる一般大衆、学者、科学者の言説を形成した[7]。 社会文化進化論は、生物学的進化論からの影響を加えながら、社会的思考を科学的な線に沿って形式化しようとした。もし生物が識別可能で決定論的な法則に 従って時間をかけて発展しうるのであれば、社会も同様に発展しうると考えられたのである。人間社会は生物になぞらえられ、社会の進歩をもたらす要因とし て、変動、自然淘汰、遺伝といった社会科学に相当する概念が導入された。進歩の概念は、人間社会が進歩する一定の「段階」を示すものへと発展し、通常は野 蛮、野蛮、文明の3つであったが、もっと多くの段階を経ることもあった。当時、人類学は新しい科学分野として台頭しており、宗教的見解に基づく伝統的な 「原始」文化観から切り離されつつあった[8]。 18世紀にはすでに、何人かの著者が人類の進化について理論化し始めた。モンテスキュー(1689-1755)は、法律が特に気候や環境一般とどのような 関係にあるか、特に気候条件の違いによって特定の特徴が異なる人々の間でどのように共通するようになるかについて書いた。 [モンテスキューは、法律の発展、市民的自由の有無、道徳の違い、異なる文化の発展全体をそれぞれの民族の風土になぞらえており[10]、環境は民族が土 地を耕作するかどうか、どのように耕作するかを決定し、それによって社会が構築され、文化が構成される方法、モンテスキューの言葉を借りれば「民族の一般 精神」が決定されると結論付けている。 [11] また、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー(1712-1778)は、人類の社会文化的進化に関する推測的な段階モデルを提示している。その後、男女が同居し、育児 を分担することで家族が形成され、家族間の相互作用の結果として部族が誕生し、人類史上「最も幸福で最も永続的な時代」を過ごしたが、市民社会の腐敗に よって再び種が退化し、発展段階的な過程を経るようになった[13]。 18世紀後半、コンドルセ侯爵(1743-1794)は10の段階(エポック)を挙げ、それぞれが人間の権利を向上させ、人類を完成させた。 チャールズ・ダーウィンの祖父であるエラスマス・ダーウィン(1731-1802)は、非常に影響力のある自然哲学者、生理学者、詩人であった。彼の有名 な『自然の神殿』には、「社会の起源」という副題がついている[14]。この著作は、異なる段階間での人類の厳密な変容を詳細に提案するのではなく、エラ スムス・ダーウィンの進化のメカニズムに言及している: エラスムス・ダーウィンは各段階をひとつひとつ説明するのではなく、『動物誌』で明らかにされた普遍的な有機的発達の理論を信頼して、文化的発達をも説明 するのである[15]。それゆえ、エラスムス・ダーウィンは年表を自由に飛び回る: プリーストマンは、ダーウィンは陸上への生命の出現、逆指し可能な親指の発達、有性生殖の起源から現代の歴史的出来事に直接ジャンプしていると指摘してい る[14]。 もう一人のより複雑な理論家は、影響力のあるアマチュア考古学者であり普遍神学者であったリチャード・ペイン・ナイト(1751-1824)であった。ナ イトの『市民社会の進歩』(The Progress of Civil Society)である: 1796年)は、ルクレティウスに始まりアダム・スミスに至る歴史の勝利の段階という伝統に正確に適合している。これらの双子の問題に直面したナイトの理 論は、進歩を対立に帰着させる。「部分的な不和は、一般的な調和の複雑な結び目を結ぶために、その助けを貸す」[16]。ナイトのメカニズムにおける競争 は、ある段階から次の段階への発展を促す。階級、土地、ジェンダーの弁証法が成長を生み出すのである[17]。こうしてナイトは、必然的な人種間の対立を 基礎とする歴史理論を概念化し、ギリシャは「自由」を、エジプトは「冷徹な不活発な茫然自失」を表している。 [18]ビュフォン、リンネ、カンペール、モンボドは、種変化に関する初期の理論に基づき、人種階層に関する様々な議論を展開している。しかし、彼らの主 張は依然として人種に関わるものである: ルソー、ビュフォン、モンボドは、オランウータンを言語以前の人間のタイプの証拠として挙げ、モンボドはオランウータンとアフリカや南アジアのある種族が 同一であるとさえ主張した。 エラスマス・ダーウィンの他に、文化的変容の理論で卓越した科学的文章を書いたのは、ロバート・チェンバーズ(1802-1871)である。チェンバーズ はスコットランドの進化思想家であり哲学者であったが、当時も現在も科学的に不十分であると認識され、同時代の著名人たちから批判されているが、彼が重要 なのは、非常に広く読まれていたからである。ビクトリア女王から港湾労働者まで、後世の科学者を含め、誰もがロバート・チェンバーズの『天地創造の自然 史』(1844年)を楽しんだという記録が残っている。ヴェスティゲス』が科学の最先端としての地位を確立しなかったことこそが重要なのだが、『ヴェス ティゲス』の影響力は、ヴィクトリア朝の一般大衆が最も経験しやすい進化の概念であると同時に、聡明な若い学者たちの心に最も早く刻まれた科学的前提で あったことを意味している[19]。 チェンバーズは、すべてのものが同じメカニズムによって、より高次の構造や意味に向かって進化するという「発展の原理」を提唱した。彼の理論では、生命は さまざまな「階級」を経て進化し、それぞれの階級の中で動物は最も低い形態から始まり、同じ階級の中でより複雑な形態へと進化していった。この比較に突き 動かされ、チェンバーズは発生を「創造の法則」に帰属させたが、彼は種の発生全体が何らかの形で予め定められていたとも考えていた。このようにチェンバー ズは、発達のアナロジーによって推進される洗練された進歩の理論を信じていた。  ハーバート・スペンサー 19世紀半ば、「生物学におけるダーウィン的革命と並行して、しかしある程度は独立して、人類という種の古代性に関する考え方の革命」が起こった [22]。その結果、精神、文化、社会の進化の発展モデルが生まれ、人類という種の進化と並行することになった。 「24] 古典的な社会進化論は、19世紀のオーギュスト・コントやハーバート・スペンサー(「適者生存」という言葉の生みの親)の著作と最も密接に関連している [25]。多くの点で、スペンサーの「宇宙進化論」の理論は、チャールズ・ダーウィンの同時代の著作よりも、ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクやオーギュス ト・コントの著作と共通点が多い。また、スペンサーはダーウィンよりも数年早く理論を展開し、発表している。しかし、社会制度に関しては、スペンサーの著 作が社会進化論に分類される可能性は十分にある。彼は、社会は時とともに進歩し、その進歩は競争によって達成されると書いたが、彼は、進化する分析単位は 集団ではなく個人であること、言い換えれば、進化は自然淘汰によって起こり、それは生物学的現象だけでなく社会的現象にも影響することを強調した。にもか かわらず、ダーウィンの著作の出版は社会文化進化論の支持者たちにとって好都合であり、彼らは生物学的進化の考え方を、社会の発展に関する多くの疑問に対 する魅力的な説明と見なした[26]。 スペンサーもコントも、社会を、単純化から複雑化へ、混沌から秩序へ、一般化から特殊化へ、柔軟性から組織化へと成長する過程を経た一種の有機体として捉 えている。彼らは、社会の成長過程は一定の段階に分けることができ、その始まりと最終的な終わりがあり[要解説]、この成長は実際には社会の進歩であり、 より新しく、より進化した社会はそれぞれ「より良い」ものであるという点で一致している。こうして進歩主義は、社会文化進化論の基礎となる基本的な考え方 のひとつとなった[25]。 しかし、スペンサーの理論は、単に存在の偉大な連鎖を駆け上がるだけでなく、より複雑なものであった。スペンサーは、社会の進化と動物の個体発生とのアナ ロジーに基づいて議論を展開した。したがって彼は、社会的段階間の進歩が何らかの慈悲深い神の直接的な介入によるものであると単純に考えて満足するのでは なく、「発達と構造の一般的な原理」や「組織の基本的な原理」を探求した[27]。さらに彼は、これらの条件は「はるかに具体的ではなく、はるかに変更可 能であり、はるかに可変的な条件に依存している」、要するに、それらは厄介な生物学的プロセスであることを受け入れた[28]。 スペンサーの理論は「段階主義」のレッテルを超越し、生物学的な複雑性を認めてはいたが、それでもなお、自然な発達に強く固定された方向性と道徳性を認め ていた[29]。 スペンサーにとって、進化の自然な過程への干渉は危険であり、何としても避けなければならなかった。このような見解は、当然ながら当時の差し迫った政治 的・経済的問題と結びついていた。スペンサーは明らかに、社会の進化が白人を頂点としアフリカ人を底辺とする人種階層をもたらすと考えていた[29]。こ の考え方は、当時ヨーロッパ列強が進めていた植民地事業と深く結びついており、それらの事業を正当化するためにパターナリスティックに用いられたヨーロッ パ人の優越性の考え方である。ドイツの有力な動物学者エルンスト・ヘッケルは、「自然人は高度に文明化されたヨーロッパ人よりも高等脊椎動物に近い」とま で書いており、これには人種的なヒエラルキーだけでなく文明的なヒエラルキーも含まれていた[30]。同様に、スペンサーの進化論は国家論を推進した。 「公共の欲求が自発的に満たされるまでは、まったく満たされるべきではない」というのが、制限された政府と市場原理の自由な運用に関するスペンサーの考え 方を要約したものである[31]。 これは、スタジズムが無用のものであったとか、植民地主義や人種差別によって完全に動機づけられたものであったということを示唆するものではない。スタジ ズムの理論が最初に提唱されたのは、競合する認識論が主として静的な世界観であった文脈においてであった。それゆえ、「進歩」はある意味で概念的に発明さ れなければならなかった。人間社会が段階を経て移動するという考えは、勝利のための発明だったのである。さらに、段階は必ずしも静的なものではなかった。 例えばビュフォンの理論では、段階間を逆行することは可能であり、生理学的な変化とは、不可逆的に変化するのではなく、種が可逆的に環境に適応することで あった[32]。 進歩主義に加えて、経済分析も古典的な社会進化論に影響を与えた。アダム・スミス(1723-1790)は人間社会を深く進化論的に捉えており[33]、 自由の成長を段階的な社会発展の過程における原動力と見なしていた。 [初期人類は狩猟採集民として生活し、牧畜民と遊牧民がそれに続いた。 [ダーウィンの種の進化論においても、スミスの政治経済学の説明においても、利己的に機能する単位間の競争が重要な、さらには支配的な役割を果たしている [37]。マルサス(1766-1834)は、すべての動物に内在する性欲の強さを考えると、個体数は幾何級数的に増加する傾向があり、人口増加は経済成 長の限界によってのみ抑制されるのであり、経済成長がまったくないとしても、人口増加はすぐにそれを上回り、飢餓、貧困、悲惨を引き起こすと警告した [38]。経済構造や社会秩序の結果であるどころか、この「生存のための闘争」は不可避の自然法則であるとマルサスは主張した[39]。 社会学の父」として知られるオーギュスト・コントは、人間の発達は、自然が神話的に観念され、人間が自然現象の説明を超自然的存在に求めた神話的段階か ら、自然が曖昧な力の結果として観念され、人間が自然現象の説明をそれらに求めた形而上学的段階を経て、すべての抽象的で曖昧な力が捨て去られ、自然現象 がそれらの一定の関係によって説明される最終的な積極的段階に至るという3段階の法則を定式化した。 [この進歩は、人間の精神の発達を通じて、そして世界の理解への思考、推論、論理の適用の増大を通じて強制される[41]。 ハーバート・スペンサーは、社会はより個人の自由に向かって進化すべきであると考え、政府の介入に反対を主張していたが[42]、人間は時間の経過ととも に周囲の環境に適応していくと考えるという点で、進化論的思考においてラマルクを踏襲していた[43]。 [初期の(そしてより原始的な)軍事社会は征服と防衛を目標とし、中央集権的で、経済的に自給自足的で、集団主義的で、個人の利益よりも集団の利益を優先 し、強制、力、抑圧を用い、忠誠、服従、規律に報いる。 [対照的に産業社会は、生産と貿易を目標とし、分散化され、経済関係を通じて他の社会と相互に結びつき、自発的な協力と個人の自制によって機能し、個人の 善を最高の価値として扱い、自発的な関係を通じて社会生活を規制し、自発性、独立性、革新性を重んじる。 [40][45]軍事社会から産業社会への移行過程は、社会内の着実な進化過程の結果である。 スペンサーは「精神的進化と社会的進化の間に一種のフィードバック・ループを想像していた:精神力が高ければ高いほど、個人が創造できる社会の複雑さが増 し、社会が複雑であればあるほど、さらなる精神的発達のための刺激が増す。社会が複雑であればあるほど、さらなる精神発達のための刺激も大きくなるのであ る」[46]。 スペンサーの研究者がダーウィンとの関係をどのように解釈しているかにかかわらず、スペンサーは1870年代、特にアメリカで絶大な人気を誇る人物となっ た。エドワード・L・ユーマンス、ウィリアム・グラハム・サムナー、ジョン・フィスク、ジョン・W・バージェス、レスター・フランク・ウォード、ルイス・ H・モルガン(1818-1881)といった金ぴか時代の思想家たちは、ダーウィンだけでなくスペンサーにも接した結果、社会進化論の理論を展開した。  ルイス・H・モーガン 人類学者であり、その思想は社会学に多くの影響を与えたルイス・H・モーガンは、その1877年の古典『古代社会』において、3つの時代、すなわち未開、 野蛮、文明を区別した[47]。未開の時代には火、弓、陶器、野蛮の時代には動物の家畜化、農業、金属加工、文明の時代にはアルファベットと文字のような 技術的発明によって分けられる[48]。モルガンは技術的進歩を社会的進歩の背後にある力とみなし、社会制度、組織、イデオロギーにおけるあらゆる社会的 変化は技術的変化から始まると考えていた[48][49]。 モルガンの理論はフリードリヒ・エンゲルスによって普及され、彼は有名な著作『家族、私有財産、国家の起源』に基づいていた[48]。 人類学の先駆者であるエドワード・バーネット・タイラー(1832-1917)は、文化があらゆる社会の重要な部分であり、またそれは進化の過程にも従う ものであると指摘し、世界的な文化の進化に焦点を当てた。彼は、社会は文化的発展のさまざまな段階にあり、人類学の目的は、原始的な始まりから近代国家ま での文化の進化を再構築することであると考えた。  エドワード・バーネット・タイラー イギリスの人類学者E.B.タイラー卿とアメリカの人類学者ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンは、文化進化の過程と進行を洞察するために、文化進化の初期段階を 代表する(と彼らが主張する)先住民のデータを用いて研究を行った。モルガンはカール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスに大きな影響を与え、彼らは社 会の内部矛盾が一連のエスカレートした段階を生み出し、社会主義社会で終わるという社会文化進化論を展開した(マルクス主義を参照)。タイラーとモーガン は単線的進化論を精緻化し、人類全体の成長という固定されたシステムの中での位置づけに従って文化を分類する基準を明示し、この成長の様式とメカニズムを 検討した。彼らの関心は多くの場合、個々の文化ではなく、文化全般に向けられていた。 彼らの異文化データの分析は、次の3つの仮定に基づいていた: 現代社会は、より "原始的 "か、より "文明的 "かに分類され、ランク付けされる。 原始的 "と "文明的 "の間には、決まった数の段階がある(例:バンド、部族、首長国、国家)。 すべての社会はこれらの段階を同じ順序で進むが、その速度は異なる 理論家たちは通常、社会的複雑さ(階級分化や複雑な分業を含む)の増大、あるいは知的、神学的、美的洗練の増大という観点から、進歩(つまりある段階と次 の段階との差)を測定した。19世紀の民族学者たちは主に、さまざまな社会間の宗教的信仰や親族関係の用語の違いを説明するために、こうした原則を用い た。  レスター・フランク・ウォード レスター・フランク・ウォード(1841-1913)は、アメリカ社会学の「父」と呼ばれることもあるが、社会の進化に関するスペンサーの理論の多くを否 定した。植物学者であり古生物学者でもあったウォードは、進化の法則は人間社会では動植物界とは大きく異なる機能を果たすと考え、「自然の法則」は「心の 法則」に取って代わられたと理論化した[50]。ウォードは、人間は感情に突き動かされて自ら目標を作り出し、(近代的な科学的方法によって最も効果的 に)それを実現しようと努力するのに対し、人間以外の世界にはそのような知性や意識は存在しないと強調した[51]。スペンサーが競争と「適者生存」が人 間社会と社会文化的進化に利益をもたらすと考えていたのに対して、ウォードは競争を破壊的な力とみなし、人間のあらゆる制度、伝統、法律は人間の心によっ て発明された道具であり、その心はすべての道具と同様に、自然の力の無制限な競争に「出会い、牽制する」ためにそれらを設計したのだと指摘した[50]。 [50] ウォードは、権威主義的な政府が個人の才能を抑圧するという点ではスペンサーに同意したが、宗教の役割を最小化し、科学の役割を最大化した近代民主主義社 会は、才能を十分に活用し、幸福を達成しようとする個人を効果的に支援することができると信じていた。彼は、進化の過程には4つの段階があると考えた: まず宇宙発生、世界の創造と進化が起こる。 まず宇宙発生、世界の創造と進化があり、次に生命が生まれると生物発生がある[51]。 人類の発展は人間発生につながり、人間発生は人間の心に影響される[51]。 最後に社会発生があり、それは進歩、人間の幸福、個人の自己実現を最適化するために、進化のプロセスそのものを形成する科学である[51]。 ウォードは現代社会を「原始的」社会よりも優れているとみなし(健康や寿命に対する医学の影響を見ればわかる[要出典])、白人至上主義の理論を共有して いた。彼は人類の進化に関するOut-of-Africa理論を支持していたが、すべての人種や社会階級が才能において平等だとは信じていなかった。 ウォードは、黒人が白人女性をレイプするとき、彼は欲望に駆られるだけでなく、自分の種族を向上させようとする本能的な衝動に駆られると宣言した[52] [53]。 [54]ウォードはまた、優生学運動の支持者やカール・マルクスの信奉者によって提案されたような社会の急進的な再構築を支持しなかった。コントと同様 に、ウォードは社会学が科学の中で最も複雑であり、真の社会形成はかなりの研究と実験なしには不可能であると考えていた[52]。  エミール・デュルケム 社会学のもう一人の「父」であるエミール・デュルケームは、社会的進歩の二項対立的な見方を発展させた[55]。彼の重要な概念は社会的連帯であり、彼は 社会的進化を機械的連帯から有機的連帯への進歩という観点から定義した[55]。機械的連帯においては、人々は自給自足的であり、統合はほとんどなく、し たがって社会を維持するために力と抑圧を使用する必要がある[55]。 [機械的連帯から有機的連帯への進歩は、第一に人口増加と人口密度の増加、第二に「道徳密度」の増加(より複雑な社会的相互作用の発展)、第三に職場にお ける専門性の増加に基づく[55]。 フェルディナント・テニエス(1855-1936)は、進化とは、人々が多くの自由を持ち、法律や義務がほとんどないインフォーマルな社会から、伝統と法 律に支配され、人々が思い通りに行動することが制限される近代的でフォーマルな合理的社会へと発展することであると述べている。トニースはまた、社会の進 化は必ずしも正しい方向に進んでいるわけではなく、社会の進歩は完全なものではなく、より新しく進化した社会は高いコストを支払って初めて得られるもので あり、その社会を構成する個人の満足度を低下させる結果となるため、それは退行と呼ぶことさえできると主張した最初の社会学者の一人でもあった[56]。 マックス・ウェーバーは通常[誰が?]社会文化進化論者として数えられてはいないが、彼の権威の三者分類の理論は[誰が?]進化論としても見ることができ る。ヴェーバーは政治的リーダーシップ、支配、権威の3つの理想的なタイプを区別している: カリスマ的支配 伝統的支配(家父長制、家父長制、封建制) 法的(合理的)支配(近代法と国家、官僚制) ヴェーバーはまた、法的支配が最も進んでおり、社会は伝統的でカリスマ的な権威を持つものから、合理的で法的な権威を持つものへと進化していくことを指摘 している。 批判と現代理論への影響 20世紀初頭には、体系的な批判的検討の時期が始まり、社会文化進化に関する一元的理論の大雑把な一般化が否定された。フランツ・ボアス (1858~1942)のような文化人類学者は、ルース・ベネディクトやマーガレット・ミードを含む彼の弟子たちとともに、人類学が古典的な社会進化論を 否定した指導者とみなされている。 しかし、ボアスの学派は、ハーバート・スペンサーの影響外で生まれた進化論の複雑さを無視している。チャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』は、動物の起源 と発達について機械論的な説明をしており、必然的な人間の段階的発達を強調したスペンサーの理論とはまったく異なっていた。その結果、多くの学者が、文化 がどのように進化するかについて、ハーバート・スペンサーの伝統に基づく理論よりも、深い文化的類推に依拠した、より洗練された理解を発展させた [57]。サミュエル・アレクサンダー(1892年)は、社会における道徳原理の自然淘汰について論じている[58]。ウィリアム・ジェームズ(1880 年)は、学習と科学の発展における観念の「自然淘汰」について考察した。事実、彼は「一方における社会的進化の事実と、他方におけるダーウィン氏によって 説かれた動物学的進化の事実との間に、驚くべき並行性[...]」を見出した[58]。チャールズ・サンダース・ピアース(1898年)は、私たちが現在 持っている自然法則が存在するのは、それが時間をかけて進化してきたからだとさえ提唱した[58]。 ダーウィン自身、『人間の下降』の第5章において、人間の道徳的感情は集団淘汰の対象であると提唱した: 「愛国心、忠実さ、従順さ、勇気、同情といった精神を高度に持ち、互いに助け合い、共通の利益のために自らを犠牲にする用意が常にある部族を多く含む部族 は、他のほとんどの部族に勝利するだろう。 これらの理論は社会的な問題に適用される進化論に関わるものであったが、ダーウィンの集団淘汰を除けば、上で検討した理論は、競争に対する漠然とした訴え を超えて、ダーウィンのメカニズムが文化にどのように拡張され適用されるのかについて正確な理解を進めるものではなかった。 [60]リッチーの『ダーウィニズムと政治』(1889年)はこの傾向を打破するものであり、「言語と社会制度は人種の連続性とはまったく無関係に経験を 伝達することを可能にしている」と主張している[61]。それゆえリッチーは文化的進化を種の進化とは無関係に、またそれとは異なるスケールで作用しうる プロセスとして捉え、それに正確な裏付けを与えた。 トースタイン・ヴェブレンは同じ頃、同じような洞察に到達していた。つまり、人間はその社会的環境に応じて進化するが、その社会的環境もまた進化するとい うことであった[63]: ヴェブレンは人間を「習慣の生き物」と呼び、習慣は彼に影響を与えた人々から「精神的に消化された」ものだと考えていた[57]。 つまり、ホジソンとクヌッセンが指摘するように、ヴェブレンはこう考えている: 「変化する制度は、それにつれて、最も適性な気質に恵まれた個人をさらに選別し、新しい制度の形成を通じて、変化する環境に個人の気質と習慣をさらに適応 させる」。このように、ヴェブレンは、進化が複数のレベルで作用するというリッチーの理論を拡張し、各レベルが他のレベルとどのように相互作用するかにつ いて洗練された理解を示すものであった[64]。 このような複雑さにもかかわらず、ボアスとベネディクトは洗練された民族誌とより厳密な実証的方法を用いて、スペンサー、タイラー、モーガンの理論は思弁 的であり、民族誌のデータを組織的に誤って表現していると主張していた。特に進化の「段階」に関する理論は幻想であると批判した。さらに、彼らは「原始」 と「文明」(あるいは「近代」)の区別を否定し、いわゆる原始的な現代社会は、いわゆる文明社会と同じだけの歴史があり、同じように進化してきたと指摘し た。したがって、この理論を使って文字を持たない(つまり史料を残さない)民族の歴史を再構築しようとする試みは、まったく推測の域を出ず、非科学的であ ると主張した。 彼らは、一般的に近代ヨーロッパと同じ文明の段階で終わると仮定される進歩は、民族中心主義的であると指摘した。彼らはまた、この理論では社会が明確に境 界を持ち、区別されていると仮定しているが、実際には文化的特徴や形態はしばしば社会の境界を越え、多くの異なる社会の間で拡散している(したがって、変 化の重要なメカニズムとなっている)ことを指摘した。ボースは文化史的アプローチにおいて、人類学的フィールドワークを重視し、思弁的な成長段階と批判す る代わりに事実のプロセスを明らかにしようとした。彼のアプローチは20世紀前半のアメリカ人類学に大きな影響を与え、高度な一般化や「システム構築」か らの後退を示した。 後の批評家たちは、強固に境界づけられた社会という仮定は、まさにヨーロッパ列強が非西洋社会を植民地化していた時期に提唱されたものであり、したがって 利己的なものであったと指摘している。現在、多くの人類学者や社会理論家は、一元的な文化的・社会的進化は西洋の神話であり、確かな経験的根拠に基づくこ とはほとんどないと考えている。批判的理論家たちは、社会進化という概念は、社会のエリートたちによる権力の正当化に過ぎないと主張している。最後に、 1914年から1945年にかけて起こった壊滅的な世界大戦は、ヨーロッパの自信を失わせた。何百万人もの死者、大量虐殺、ヨーロッパの産業基盤の破壊の 後では、進歩という考えはせいぜい疑わしいものにしか思えなかった。 このように、現代の社会文化進化論は、さまざまな理論的問題のために、古典的な社会進化論のほとんどを否定している: この理論には深い民族中心主義があり、西洋文明を最も価値あるものとみなして、さまざまな社会について重い価値判断を下していた。 すべての文化が同じ道筋をたどり、同じ目標を持つと仮定していた。 文明を物質文化(技術、都市など)と同一視した。 社会進化論は科学理論として提唱されたため、不公正でしばしば人種差別的な社会慣行、特に植民地主義、奴隷制度、工業化ヨーロッパに存在する不平等な経済 状況を支持するためにしばしば利用された。社会ダーウィニズムは、ナチスが用いたいくつかの哲学につながったとされ、特に批判されている。 マックス・ウェーバー、幻滅、批判理論  1917年のマックス・ウェーバー 主な記事 マックス・ウェーバーと批判理論 ヴェーバーの経済社会学と宗教社会学の主要な著作は、資本主義と近代の台頭と結びついた合理化、世俗化、そしていわゆる「幻滅」を扱っていた[65]。社 会学において合理化とは、社会的行動の数が増えるにつれて、道徳、感情、慣習、伝統に由来する動機ではなく、むしろ目的論的な効率や計算の考慮に基づいて 行われるようになる過程を指す。合理化とは、純粋に「合理的」であったり「論理的」であったりするものを指すのではなく、社会の不利益になるような目標を 執拗に追い求めることを指す。合理化は近代の両義的な側面であり、特に西洋社会において、資本主義市場の行動、国家や官僚制における合理的な管理、近代科 学の拡張、近代技術の拡大として現れている[要出典]。 近代西洋社会の合理化と世俗化の傾向に関するウェーバーの思想(「ウェーバー・テーゼ」と表現されることもある)は、マルクス主義と融合し、特にユルゲ ン・ハーバーマス(1929年生まれ)のような思想家の仕事において批判理論を促進することになる。批判的理論家は、反実証主義者として、科学や社会のヒ エラルキーという考え方に批判的であり、特にコントが最初に提唱した社会学的実証主義に批判的である。ユルゲン・ハーバーマスは、純粋な道具的合理性とい う概念は、科学的思考がイデオロギーそのものに近いものになることを意味すると批判している。ジグムント・バウマン(1925-2017)のような理論家 にとって、近代性の現れとしての合理化は、ホロコーストの出来事と最も密接に、そして遺憾なことに結びついているかもしれない。 |