社会生物学

Sociobiology

debate for Medical

Anthropologists

社会生物学(しゃかいせいぶつがく; sociobiology)あるいは 行動生物学(こうどうせいぶつがく)とは、現代生物学の成果をもとに動物の「社会的行 動」の進化を研究する分野である。社会生物学者は、ほとんどの生物種の集団的な振舞い、その集団の組織化(=生態学者たちはこれを「社会」と呼ぶ)などを 長大な進化論の枠組みに位置づける。この分野はもともと、生態学の一分野と して出発したが、現在では動物社会学の研究領域の主流を形成している。

動物の本能行動の比較研究(ethnology)、 蟻や蜂などの群れをつくる社会性昆虫の研究、高等哺乳動物の社会構造の解明などによって、 それらを総括的に論じる機運が高まった。そのなかで、利他的行動についての説明はひとつの難問であった。利他的行動とは、ちょうど「働き蜂」が自らは子を 作らず自分の親や兄弟などの子育てを行なうような、<自己の個体の遺伝子の保持することを犠牲にして他者に利するような行為>をいう。現代進化論では、行 動は遺伝子に支配されると考えるが、この場合、利他個体は子孫を作らないので、その行動を発現させる遺伝子は子孫に伝わらず、利他行動の進化は不可能とな る。この問題は1964年にW・ハミルトンが、自分の遺伝子を直接子孫に残さなくても、その血縁者を助け血縁者が多数の子を作るならば、利他行動は進化す る、という数学的理論(包括適応度)を提示して「解決」をみた。これ が刺激となって、社会生物学における理論的研究が飛躍的に発展した。

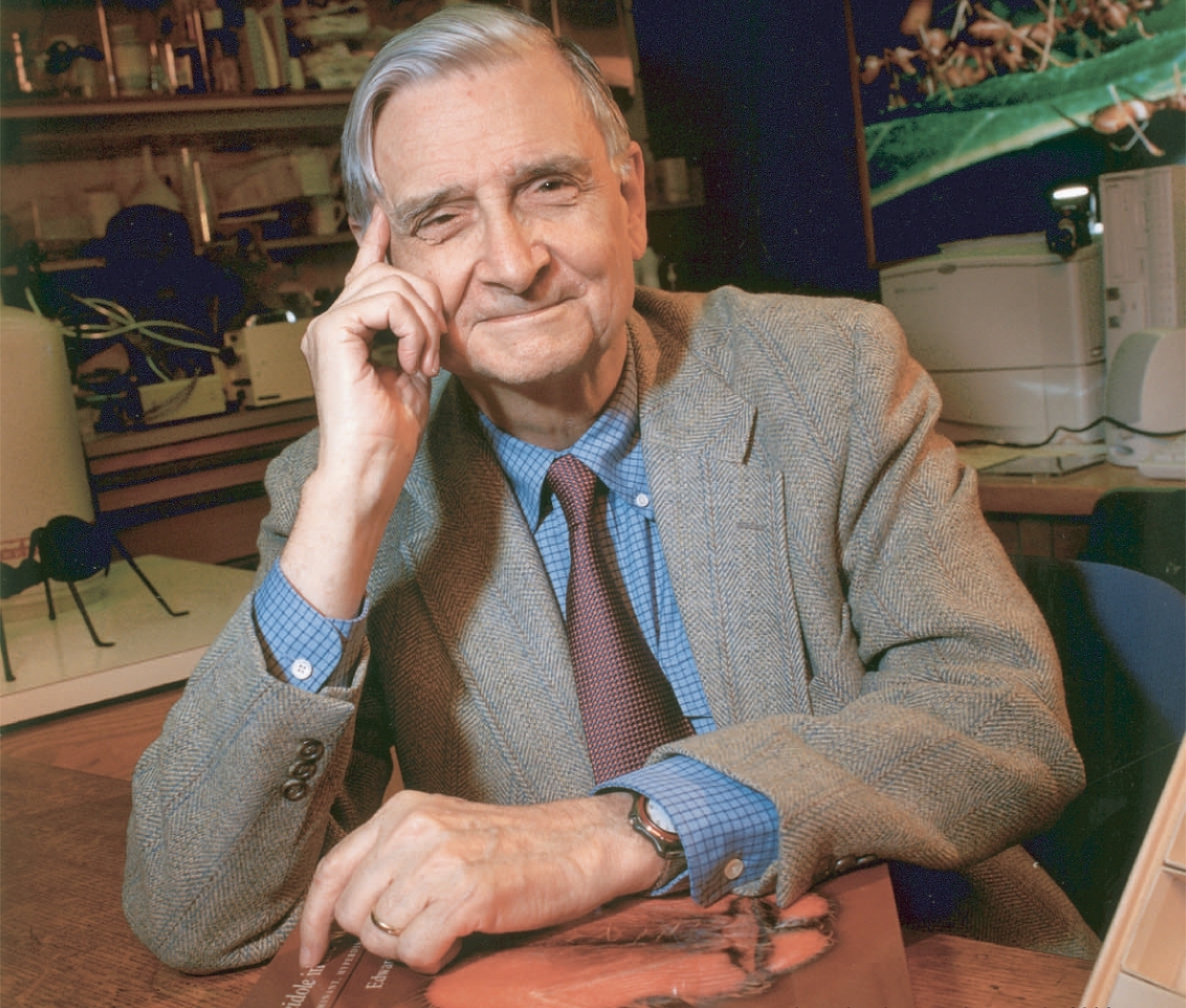

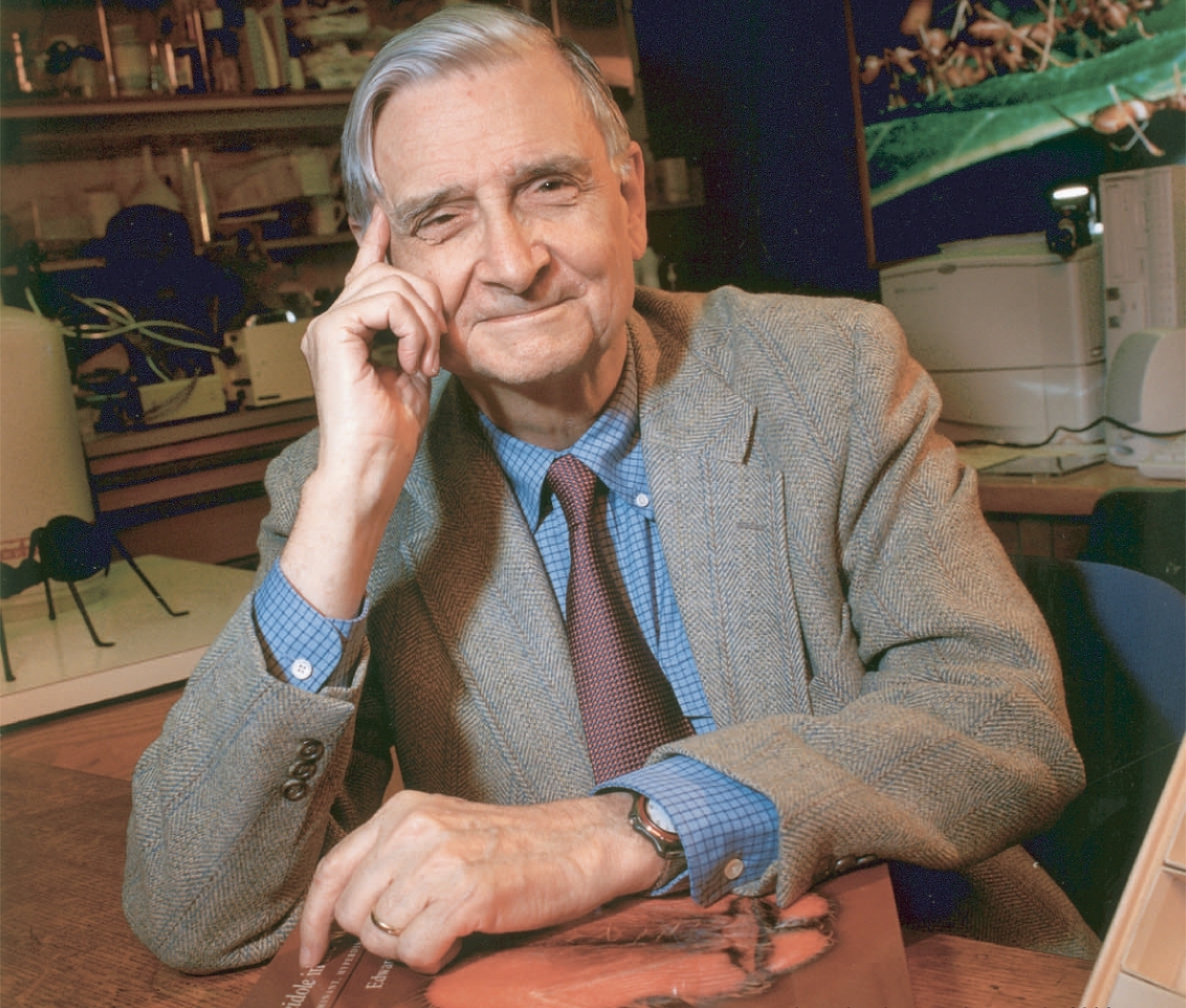

人間は他の動物に比べてかなり特殊な形態 と生活様式を有しているにもかかわらず、生物種である以上、それらの一般的諸法則からは逃れ られないとするのが生物学的な観点である。そして、一九七〇年代中葉に米国で活発に論戦がなされたのが「社会生物学論争」である。「論争」の震源であり、 そのことによって社会生物学の名を一般に知らしめたのは、一九七五年に出版された昆虫生態学者E・O・ウィルソン(E. O. Wilson, 1929- )の著書『社会生物学−新総合学説』である。こ れは、それまでの膨大な野外および実験研究の生態学を中心とする文献を網羅し、この分野の方向性を決定づけた。論争の火種となったのは、その著書の最終章 や別の著作『人間の本性について』(一九七八)において、この考えを人間にまで敷衍したことである。彼によれば、人間の倫理性とは遺伝子の保持しようとす ることに由来し、人格は哺乳動物のなかに既にみられるものであるという。また宗教や芸術は脳の進化の産物であるので、系統的に分析すら可能という。さらに *同性愛者は、それが家族を持たないにもかかわらず、近親者の育児を援助する機能を持つゆえに、同性愛の遺伝的素因(遺伝子)が人間集団に保存されるとい うのだ。

また、リチャード・ドーキンスは『利己的 な遺伝子』(1976)において、先のハミルトンを援用しながら、人間の利他行動を一般の人に もわかりやすく説明し、〈文化〉という名の自己複製子であるミームの産物こそが人間であるというビジョンを提示した。

これらの主張に対して米国ボストンの社会 科学者や遺伝学者を中心にした研究者たち、「人民のための科学」グループからは激しい反論が 続出した。ウィルソン一派にたいする批判は、科学的妥当性−遺伝学モデルの理論は完成したものではなく、内部でも様々な議論が起っている−と、人間の集団 の理解にたいする生物学主義的な決定論−あらゆる行動の源泉を生物学的原理、ここでは遺伝子に還元しようとすること−に向けられた。特に後者の決定論にた いする反発は強く、社会生物学を「疑似科学」、ウィルソンを「ファシスト」呼ばわりするまでにエスカレートした。戦争やファシズムが動物の本性に由来する と主張する生物学者はウィルソン以前にもいたし、現在の我々の周囲にもいる。しかし、彼はそれを生物学的説明で「理論化」することを試みた。人間は行為の 自己決定権を持つと信じ、それを主張する近代合理主義者としての「人民のための科学」者たちにとって、社会生物学は戦争やファシズムという事実を合法化す るように見えたのは当り前である。

社会生物学側のメイナード=スミス (1920-2004, 進化ゲーム理論の創設者のひとりで、進化的安定戦略(Evolutionary Stable Strategy, ESS)をジョージ・プライスとともに提唱した)も主張するように、ウィルソンたちが使う「生物学的に自然で本性的であること」は、人間社会にお ける「倫 理的な正しさや正当性」とは全くの別物である。また「社会」や「利他行為」などの日常用語とそれを借用した専門語との間に概念の混乱があることも事実であ る。しかし、仮にそのようなことを認め、理論的枠組みをより整備し、未熟なことを改善することで社会生物学の主張は「擁護されるべきもの」となり得るだろ うか。

■氏か育ちか論争としての社会生物学論争

社会生物学論争は、自然か文化か、環境か 遺伝か、氏か育ちか(Nature/Nurture)等の二元的な論争のひとつの「到達点」 である。そして、論争は生物学者のみならず人間を研究するあらゆる学問に潜んでいる生物学的決定論がどのような末路をたどるのかを明らかにした。「科学を 倫理的に中立」であると信じる科学者のユートピアが現実の社会との齟齬を起こすことは明かであり、「ウィルソンは学問的良心から自説を述べた」と弁護して も説得力を持たない。

氏か育ちかの議論の系譜は古く、Charles Cooley,

1896. Nature versus Nurture' in the Making of Social Careers,

Proceedings of the 23rd Conference of Charities and Corrections:

399-405, というものがある。

この論争は、とどのつまりは、過去に幾た びか繰り返されてきた、<自然か文化か><環境か遺伝か><氏か育ちか (Nature/Nurture)>などの一連の論争と共通する部分がある。それは「生物学主義」と「文化決定論」の対立図式に当てはめるものである。

生物学主義とは、文化や社会をこえた人間 の行動様式を生物学的な特性に求める主張である。これに対して文化決定論は、人間の行動様式 は、その人びとが属している社会や文化によって決まることを強調する。例えば、人間が戦争をおこなう理由を、動物そのものが持つ「攻撃性」から説明し、そ の結果引き起こされる人口の減少を、人口増加を抑えるために予めそのような行動パータンが遺伝子にプログラムされている、という見方をとる。

文化決定論は、さまざまな社会や文化に よって、人間の行動がいかに多様であるかを、正反対の事例を挙げて説明する。例えばM・ミード は南太平洋の諸民族を比較して、私たちが「自然」だと感じる<男性>の<たくましさ>と<女性>の<やさしさ>という性のありかたが逆転した社会があるこ とを示唆した。すなわち、性のあり方は、社会の数ほど多様であり、それが社会的・文化的に決定されていると考えるほかはない。

この二つの立場の論争を見てみると、生物 学主義は人間の集団の「共通点」を強調するために用いられ、文化決定論はそれらの「多様性」 を説明するために使われていることが明らかになろう。

生

物決定論について、つねに疑問符をつきつけたリチャード・

レウォンティン[またはルーウォンティン]について

生

物決定論について、つねに疑問符をつきつけたリチャード・

レウォンティン[またはルーウォンティン]について

"In this powerful lecture from 2003 given at Berkeley, you can see Richard Lewontin start by acknowledging emphatically that race is a social reality, and then systematically, using an overwhelming amount of quantitative genetic data, dismantle notions of there being any genetic basis to race that goes deeper than skin deep:...Lewontin was also the rare scientist who recognized the influence of society and ideology on science and the academy. He showed not only the importance of understanding the historical and sociocultural contexts in which any particular science is conducted but also, for the field of biology, how one can enhance our understanding of nature by being explicit about these sociological and ideological influences in our work. His books Not In Our Genes (coauthored with psychologist Leon J. Kamin and neurobiologist Steven Rose), The Dialectical Biologist, and Biology Under The Influence (both coauthored with Richard Levins), and the short classic Biology as Ideology (a lecture published as a book), are ones I rank highly among those that have played a deeply formative role in my own growth as an evolutionary biologist and as a public scientist pushing for decoloniality in science." -Remembering Richard Lewontin: A Tribute From a Student Who Never Got to Meet Him.

「2003年にバークレー校で行われたこ

の力強い講義では、リチャード・ルーウォンティンが、人種が社会的現実であることを力強く認めることか

ら始まり、圧倒的な量の定量的遺伝学的データを用い

て、人種に肌感覚以上の遺伝的根拠があるという概念を体系的に解体していく様子を見ることができる。彼は、特定の科学が行われている歴史的・社会文化的背

景を理解することの重要性を示しただけでなく、生物学の分野においては、私たちの研究においてこのような社会学的・イデオロギー的影響を明示することに

よって、いかに自然に対する理解を深めることができるかを示したのである。彼の著書『Not In Our

Genes』(心理学者レオン・J・カミン、神経生物学者スティーブン・ローズとの共著)、『The Dialectical

Biologist』、『Biology Under The

Influence』(いずれもリチャード・レヴィンスとの共著)、そして短編の名著『Biology as

Ideology』(書籍として出版された講演)は、進化生物学者として、また科学における脱植民地主義を推進するパブリック・サイエンティストとして、

私自身の成長に深く形成的な役割を果たしたものの中で、私が高く評価しているものである。」

The Concept of Race with Richard Lewontin

★社会生物学についてのウィキペディアの 記事より

| Sociobiology is a

field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of

evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology,

anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics.

Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely allied to

evolutionary anthropology, human behavioral ecology, evolutionary

psychology,[1] and sociology.[2][3] Sociobiology investigates social behaviors such as mating patterns, territorial fights, pack hunting, and the hive society of social insects. It argues that just as selection pressure led to animals evolving useful ways of interacting with the natural environment, so also it led to the genetic evolution of advantageous social behavior.[4] While the term "sociobiology" originated at least as early as the 1940s; the concept did not gain major recognition until the publication of E. O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1975. The new field quickly became the subject of controversy. Critics, led by Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, argued that genes played a role in human behavior, but that traits such as aggressiveness could be explained by social environment rather than by biology. Sociobiologists responded by pointing to the complex relationship between nature and nurture. Among sociobiologists, the controversy between laying weight to different levels of selection was settled between D.S. Wilson and E.O. Wilson in 2007.[5] |

社会生物学は生物学の一分野であり、社会行動を進化の観点から説明する

ことを目的としている。心理学、倫理学、人類学、進化学、動物学、考古学、集団遺伝学などの学問分野からなる。人間社会の研究において、社会生物学は進化

人類学、人間行動生態学、進化心理学[1]、社会学と密接に関連している[2][3]。 社会生物学は、交尾パターン、縄張り争い、群れ狩り、社会性昆虫の巣社会などの社会行動を調査する。社会生物学は、淘汰圧によって動物が自然環境と相互作 用する有用な方法を進化させたように、有利な社会的行動の遺伝的進化もまた淘汰圧によってもたらされたと主張する[4]。 社会生物学」という言葉は少なくとも1940年代には生まれていたが、この概念が大きく認知されるようになったのは、E・O・ウィルソンの著書『社会生物 学』が出版されてからである: 1975年にE. この新分野はすぐに論争の的となった。リチャード・レウォンチンやスティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドに代表される批評家たちは、人間の行動には遺伝子が関与 しているが、攻撃性などの形質は生物学ではなく社会環境によって説明できると主張した。社会生物学者はこれに対し、自然と育ちとの間の複雑な関係を指摘し た。社会生物学者の間では、2007年にD.S.ウィルソンとE.O.ウィルソンの間で、異なるレベルの選択に重きを置くかどうかの論争に決着がついた [5]。 |

| Definition E. O. Wilson defined sociobiology as "the extension of population biology and evolutionary theory to social organization".[6] Sociobiology is based on the premise that some behaviors (social and individual) are at least partly inherited and can be affected by natural selection.[7] It begins with the idea that behaviors have evolved over time, similar to the way that physical traits are thought to have evolved. It predicts that animals will act in ways that have proven to be evolutionarily successful over time. This can, among other things, result in the formation of complex social processes conducive to evolutionary fitness. The discipline seeks to explain behavior as a product of natural selection. Behavior is therefore seen as an effort to preserve one's genes in the population. Inherent in sociobiological reasoning is the idea that certain genes or gene combinations that influence particular behavioral traits can be inherited from generation to generation.[5] For example, newly dominant male lions often kill cubs in the pride that they did not sire. This behavior is adaptive because killing the cubs eliminates competition for their own offspring and causes the nursing females to come into heat faster, thus allowing more of his genes to enter into the population. Sociobiologists would view this instinctual cub-killing behavior as being inherited through the genes of successfully reproducing male lions, whereas non-killing behavior may have died out as those lions were less successful in reproducing.[8] |

定義 E. O.ウィルソンは社会生物学を「集団生物学と進化理論を社会組織に拡張したもの」と定義した[6]。 社会生物学は、いくつかの行動(社会的行動と個体行動)は少なくとも部分的には遺伝し、自然淘汰の影響を受けうるという前提に基づいている。動物が進化的 に成功したと証明された方法で行動するようになることを予測する。これはとりわけ、進化的適性を助長する複雑な社会的プロセスの形成をもたらす可能性があ る。 この学問分野では、行動を自然淘汰の産物として説明しようとする。したがって行動は、集団の中で自分の遺伝子を残すための努力とみなされる。社会生物学的 推論に内在するのは、特定の行動特性に影響を与える特定の遺伝子や遺伝子の組み合わせは、世代から世代へと受け継がれるという考え方である[5]。 例えば、新しく支配者となった雄ライオンは、自分が産んだのではないプライド内の子ライオンを殺すことが多い。子ライオンを殺すことで自分の子孫をめぐる 競争がなくなり、授乳中のメスが早く発情するようになるため、この行動は適応的である。社会生物学者は、この本能的な子ライオンを殺す行動は、繁殖に成功 したオスライオンの遺伝子を通して受け継がれたものであり、一方、殺さない行動は、それらのライオンが繁殖に成功しなくなるにつれて絶滅した可能性がある と見ている[8]。 |

History E. O. Wilson, a central figure in the history of sociobiology, from the publication in 1975 of his book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis The philosopher of biology Daniel Dennett suggested that the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes was the first proto-sociobiologist, arguing that in his 1651 book Leviathan Hobbes had explained the origins of morals in human society from an amoral sociobiological perspective.[9] The geneticist of animal behavior John Paul Scott coined the word sociobiology at a 1948 conference on genetics and social behavior, which called for a conjoint development of field and laboratory studies in animal behavior research.[10] With John Paul Scott's organizational efforts, a "Section of Animal Behavior and Sociobiology" of the Ecological Society of America was created in 1956, which became a Division of Animal Behavior of the American Society of Zoology in 1958. In 1956, E. O. Wilson came in contact with this emerging sociobiology through his PhD student Stuart A. Altmann, who had been in close relation with the participants to the 1948 conference. Altmann developed his own brand of sociobiology to study the social behavior of rhesus macaques, using statistics, and was hired as a "sociobiologist" at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center in 1965. Wilson's sociobiology is different from John Paul Scott's or Altmann's, insofar as he drew on mathematical models of social behavior centered on the maximization of the genetic fitness by W. D. Hamilton, Robert Trivers, John Maynard Smith, and George R. Price. The three sociobiologies by Scott, Altmann and Wilson have in common to place naturalist studies at the core of the research on animal social behavior and by drawing alliances with emerging research methodologies, at a time when "biology in the field" was threatened to be made old-fashioned by "modern" practices of science (laboratory studies, mathematical biology, molecular biology).[11] Once a specialist term, "sociobiology" became widely known in 1975 when Wilson published his book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, which sparked an intense controversy. Since then "sociobiology" has largely been equated with Wilson's vision. The book pioneered and popularized the attempt to explain the evolutionary mechanics behind social behaviors such as altruism, aggression, and nurturance, primarily in ants (Wilson's own research specialty) and other Hymenoptera, but also in other animals. However, the influence of evolution on behavior has been of interest to biologists and philosophers since soon after the discovery of evolution itself. Peter Kropotkin's Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, written in the early 1890s, is a popular example. The final chapter of the book is devoted to sociobiological explanations of human behavior, and Wilson later wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book, On Human Nature, that addressed human behavior specifically.[12] Edward H. Hagen writes in The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology that sociobiology is, despite the public controversy regarding the applications to humans, "one of the scientific triumphs of the twentieth century." "Sociobiology is now part of the core research and curriculum of virtually all biology departments, and it is a foundation of the work of almost all field biologists. " Sociobiological research on nonhuman organisms has increased dramatically and continuously in the world's top scientific journals such as Nature and Science. The more general term behavioral ecology is commonly substituted for the term sociobiology in order to avoid the public controversy.[13] |

歴史 E. O.ウィルソンは、1975年に『社会生物学』を出版して以来、社会生物学の歴史の中心人物である: 新しい総合 生物学の哲学者ダニエル・デネットは、政治哲学者トマス・ホッブズが最初の社会生物学者であると示唆し、1651年の著書『リヴァイアサン』において、 ホッブズは人間社会におけるモラルの起源を非道徳的な社会生物学的観点から説明したと主張した[9]。 動物行動学の遺伝学者であるジョン・ポール・スコットは、1948年に開催された遺伝学と社会行動学に関する会議で社会生物学という言葉を作り、動物行動 学研究における野外研究と実験室研究の共同発展を呼びかけた[10]。 ジョン・ポール・スコットの組織的努力により、1956年にアメリカ生態学会の「動物行動学・社会生物学部門」が創設され、1958年にはアメリカ動物学 会の動物行動学部門となった。1956年、E.O.ウィルソンは、1948年の会議参加者と親しい関係にあった博士課程の学生スチュアート・A.アルトマ ンを通じて、この新興社会生物学に接触した。アルトマンは統計学を用いてアカゲザルの社会行動を研究するため、彼独自の社会生物学を開発し、1965年に ヤーキース地域霊長類研究センターに「社会生物学者」として雇われた。ウィルソンの社会生物学は、W.D.ハミルトン、ロバート・トリバース、ジョン・メ イナード・スミス、ジョージ・R.プライスによる遺伝的適合度の最大化を中心とした社会行動の数理モデルを参考にした点で、ジョン・ポール・スコットやア ルトマンの社会生物学とは異なっている。スコット、アルトマン、ウィルソンによる3つの社会生物学は、「野外での生物学」が科学の「近代的」実践(実験室 研究、数理生物学、分子生物学)によって古臭くなる恐れがあった時代に、自然主義研究を動物の社会行動研究の中核に据え、新たな研究方法論との連携を図っ た点で共通している[11]。 かつては専門用語であった「社会生物学」が広く知られるようになったのは、1975年にウィルソンが『社会生物学』を出版してからである: この本は激しい論争を巻き起こした。それ以来、「社会生物学」はウィルソンのビジョンとほぼ同一視されるようになった。この本は、利他主義、攻撃性、養育 などの社会的行動の背後にある進化的メカニズムを説明する試みの先駆者であり、一般化した。しかし、進化が行動に及ぼす影響については、進化そのものが発 見された直後から、生物学者や哲学者の関心を集めてきた。ピーター・クロポトキンの『相互扶助』である: 1890年代初頭に書かれたピーター・クロポトキンの『相互扶助:進化の要因』は、その代表的な例である。この本の最終章は、人間の行動に関する社会生物 学的な説明に費やされており、ウィルソンは後にピューリッツァー賞を受賞した『人間の本性について』を執筆し、人間の行動を具体的に取り上げている [12]。 エドワード・H・ヘイゲンは、『進化心理学ハンドブック』の中で、社会生物学は、人間への応用に関する世論の論争にもかかわらず、「20世紀の科学的勝利 の一つ」であると書いている。「社会生物学は今や、事実上すべての生物学部の中核的研究とカリキュラムの一部であり、ほとんどすべてのフィールド生物学者 の研究の基礎となっている。人間以外の生物に関する社会生物学的研究は、『ネイチャー』や『サイエンス』といった世界トップクラスの科学雑誌において、飛 躍的かつ継続的に増加している。世間での論争を避けるため、より一般的な用語である行動生態学が社会生物学という用語に一般的に置き換えられている [13]。 |

| Theory Sociobiologists maintain that human behavior, as well as nonhuman animal behavior, can be partly explained as the outcome of natural selection. They contend that in order to fully understand behavior, it must be analyzed in terms of evolutionary considerations. Natural selection is fundamental to evolutionary theory. Variants of hereditary traits which increase an organism's ability to survive and reproduce will be more greatly represented in subsequent generations, i.e., they will be "selected for". Thus, inherited behavioral mechanisms that allowed an organism a greater chance of surviving and/or reproducing in the past are more likely to survive in present organisms. That inherited adaptive behaviors are present in nonhuman animal species has been multiply demonstrated by biologists, and it has become a foundation of evolutionary biology. However, there is continued resistance by some researchers over the application of evolutionary models to humans, particularly from within the social sciences, where culture has long been assumed to be the predominant driver of behavior.  Nikolaas Tinbergen, whose work influenced sociobiology Sociobiology is based upon two fundamental premises: Certain behavioral traits are inherited, Inherited behavioral traits have been honed by natural selection. Therefore, these traits were probably "adaptive" in the environment in which the species evolved. Sociobiology uses Nikolaas Tinbergen's four categories of questions and explanations of animal behavior. Two categories are at the species level; two, at the individual level. The species-level categories (often called "ultimate explanations") are the function (i.e., adaptation) that a behavior serves and the evolutionary process (i.e., phylogeny) that resulted in this functionality. The individual-level categories (often called "proximate explanations") are the development of the individual (i.e., ontogeny) and the proximate mechanism (e.g., brain anatomy and hormones). Sociobiologists are interested in how behavior can be explained logically as a result of selective pressures in the history of a species. Thus, they are often interested in instinctive, or intuitive behavior, and in explaining the similarities, rather than the differences, between cultures. For example, mothers within many species of mammals – including humans – are very protective of their offspring. Sociobiologists reason that this protective behavior likely evolved over time because it helped the offspring of the individuals which had the characteristic to survive. This parental protection would increase in frequency in the population. The social behavior is believed to have evolved in a fashion similar to other types of nonbehavioral adaptations, such as a coat of fur, or the sense of smell. Individual genetic advantage fails to explain certain social behaviors as a result of gene-centred selection. E.O. Wilson argued that evolution may also act upon groups.[14] The mechanisms responsible for group selection employ paradigms and population statistics borrowed from evolutionary game theory. Altruism is defined as "a concern for the welfare of others". If altruism is genetically determined, then altruistic individuals must reproduce their own altruistic genetic traits for altruism to survive, but when altruists lavish their resources on non-altruists at the expense of their own kind, the altruists tend to die out and the others tend to increase. An extreme example is a soldier losing his life trying to help a fellow soldier. This example raises the question of how altruistic genes can be passed on if this soldier dies without having any children.[15] Within sociobiology, a social behavior is first explained as a sociobiological hypothesis by finding an evolutionarily stable strategy that matches the observed behavior. Stability of a strategy can be difficult to prove, but usually, it will predict gene frequencies. The hypothesis can be supported by establishing a correlation between the gene frequencies predicted by the strategy, and those expressed in a population. Altruism between social insects and littermates has been explained in such a way. Altruistic behavior, behavior that increases the reproductive fitness of others at the apparent expense of the altruist, in some animals has been correlated to the degree of genome shared between altruistic individuals. A quantitative description of infanticide by male harem-mating animals when the alpha male is displaced as well as rodent female infanticide and fetal resorption are active areas of study. In general, females with more bearing opportunities may value offspring less, and may also arrange bearing opportunities to maximize the food and protection from mates. An important concept in sociobiology is that temperament traits exist in an ecological balance. Just as an expansion of a sheep population might encourage the expansion of a wolf population, an expansion of altruistic traits within a gene pool may also encourage increasing numbers of individuals with dependent traits. Studies of human behavior genetics have generally found behavioral traits such as creativity, extroversion, aggressiveness, and IQ have high heritability. The researchers who carry out those studies are careful to point out that heritability does not constrain the influence that environmental or cultural factors may have on those traits.[16][17] Various theorists have argued that in some environments criminal behavior might be adaptive.[18] The evolutionary neuroandrogenic (ENA) theory, by sociologist/criminologist Lee Ellis, posits that female sexual selection has led to increased competitive behavior among men, sometimes resulting in criminality. In another theory, Mark van Vugt argues that a history of intergroup conflict for resources between men have led to differences in violence and aggression between men and women.[19] The novelist Elias Canetti also has noted applications of sociobiological theory to cultural practices such as slavery and autocracy.[20] |

理論 社会生物学者は、人間の行動も人間以外の動物の行動も、一部は自然淘汰の結果として説明できると主張している。彼らは、行動を完全に理解するためには、進 化論的な観点から分析しなければならないと主張する。 自然選択は進化論の基本である。生物の生存・繁殖能力を高める遺伝形質の変異型は、その後の世代でより多く発現する、つまり「淘汰」される。従って、過去 に生物が生存・繁殖する可能性を高めた遺伝的行動メカニズムは、現在の生物にも生き残る可能性が高い。人間以外の動物種にも遺伝的適応行動が存在すること は、生物学者によって何度も実証されており、進化生物学の基礎となっている。しかし、進化モデルをヒトに適用することについては、一部の研究者の間で抵抗 が続いている。特に社会科学の分野では、文化が行動の支配的な原動力であると長い間考えられてきた。  社会生物学に影響を与えたニコラス・ティンバーゲン 社会生物学は2つの基本的前提に基づいている: ある種の行動特性は遺伝する、 遺伝した行動特性は自然淘汰によって磨かれたものである。したがって、これらの形質はおそらく、種が進化した環境において「適応的」であった。 社会生物学では、ニコラウス・ティンバーゲンが提唱した4つのカテゴリーを用いて、動物の行動に関する疑問や説明を行う。つのカテゴリーは種レベルで、2 つは個体レベルである。種レベルのカテゴリー(しばしば「究極の説明」と呼ばれる)は以下の通りである。 行動が果たす機能(すなわち適応)と その機能をもたらした進化の過程(系統)である。 個体レベルのカテゴリー(しばしば「近接説明」と呼ばれる)とは、以下のようなものである。 個体の発達(すなわち個体発生学)と 近接メカニズム(脳解剖学やホルモンなど)である。 社会生物学者は、ある種の歴史における選択圧力の結果として、行動がどのように論理的に説明できるかに関心を持つ。そのため、本能的な行動や、文化間の違 いではなく類似性を説明することに興味を持つことが多い。例えば、ヒトを含む多くの哺乳類の母親は、子孫を非常に大切にする。社会生物学者は、この保護行 動は、その特徴を持つ個体の子孫が生き残るのに役立つため、長い時間をかけて進化した可能性が高いと推論している。このような親の保護行動は、集団の中で 頻度を増していく。社会的行動は、毛皮や嗅覚のような他の非行動適応と同じような方法で進化したと考えられている。 遺伝子を中心とした淘汰の結果、個体の遺伝的優位性はある種の社会的行動を説明できない。E.O.ウィルソンは、進化は集団にも作用する可能性があると主 張した[14]。集団選択を引き起こすメカニズムには、進化ゲーム理論から借用したパラダイムと集団統計が用いられている。利他主義は「他者の福祉に対す る関心」と定義される。利他主義が遺伝的に決定されるのであれば、利他主義者が生き残るためには、利他主義者自身の遺伝形質を再生産しなければならない が、利他主義者が同族を犠牲にして非利他主義者に資源を惜しむと、利他主義者は死に絶え、他者が増加する傾向がある。極端な例は、仲間の兵士を助けようと して命を落とす兵士である。この例では、この兵士が子供を作らずに死んだ場合、利他的な遺伝子がどのように受け継がれるのかという疑問が生じる。 社会生物学では、観察された行動に合致する進化的に安定した戦略を見つけることによって、社会的行動が社会生物学的仮説としてまず説明される。戦略の安定 性を証明するのは難しいが、通常は遺伝子頻度を予測することができる。その仮説は、その戦略によって予測される遺伝子頻度と、集団で発現する遺伝子頻度と の間に相関関係を確立することによって裏付けられる。 社会性昆虫と同腹子の間の利他行動は、このような方法で説明されてきた。いくつかの動物における利他的行動、つまり利他的な個体の見かけ上の犠牲の上に他 の個体の繁殖適性を高める行動は、利他的な個体間で共有されるゲノムの程度と相関している。雄のハーレム交配動物による、アルファ雄がいなくなったときの 嬰児殺しや、げっ歯類の雌の嬰児殺しと胎児吸収の定量的記述は、活発な研究分野である。一般に、出産機会の多いメスは子孫を残すことにあまり価値を見出さ ず、また出産機会を調整して交尾相手からの保護と餌を最大化することもある。 社会生物学における重要な概念は、気質形質は生態学的バランスの中に存在するということである。羊の個体数の増加がオオカミの個体数の増加を促すように、 遺伝子プール内の利他的形質の増加が依存的形質を持つ個体数の増加を促すこともある。 人間の行動遺伝学に関する研究では、創造性、外向性、攻撃性、IQなどの行動特性は遺伝率が高いことが一般的に分かっている。これらの研究を実施する研究 者は、遺伝率は環境や文化的要因がそれらの特質に及ぼす影響を抑制するものではないことを注意深く指摘している[16][17]。 社会学者/犯罪学者であるリー・エリスによる進化的神経アンドロゲン(ENA)理論は、女性の性淘汰が男性間の競争行動を増加させ、時には犯罪につながる と仮定している。別の理論では、マーク・ヴァン・ヴクトが、男性間の資源をめぐる集団間の争いの歴史が、男女間の暴力や攻撃性の違いにつながったと論じて いる[19]。 小説家のエリアス・カネッティも、奴隷制や独裁制といった文化的慣習への社会生物学的理論の応用を指摘している[20]。 |

| Support for premise Genetic mouse mutants illustrate the power that genes exert on behavior. For example, the transcription factor FEV (aka Pet1), through its role in maintaining the serotonergic system in the brain, is required for normal aggressive and anxiety-like behavior.[21] Thus, when FEV is genetically deleted from the mouse genome, male mice will instantly attack other males, whereas their wild-type counterparts take significantly longer to initiate violent behavior. In addition, FEV has been shown to be required for correct maternal behavior in mice, such that offspring of mothers without the FEV factor do not survive unless cross-fostered to other wild-type female mice.[22] A genetic basis for instinctive behavioral traits among non-human species, such as in the above example, is commonly accepted among many biologists; however, attempting to use a genetic basis to explain complex behaviors in human societies has remained extremely controversial.[23][24] |

前提の裏付け 遺伝的マウス変異体は、遺伝子が行動に及ぼす力を示している。例えば、転写因子FEV(別名Pet1)は、脳内のセロトニン作動系を維持する役割を通じ て、正常な攻撃的行動や不安様行動に必要である。さらに、FEVはマウスの正しい母性行動に必要であることが示されており、FEV因子を持たない母親の子 どもは、他の野生型メスマウスと交配飼育しない限り生存できない[22]。 上記の例のような、ヒト以外の種における本能的な行動特性に対する遺伝的基盤は、多くの生物学者の間で一般的に受け入れられている。しかし、ヒト社会にお ける複雑な行動を説明するために遺伝的基盤を用いようとする試みは、依然として極めて議論の多いところである[23][24]。 |

| Reception Steven Pinker argues that critics have been overly swayed by politics and a fear of biological determinism,[a] accusing among others Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin of being "radical scientists", whose stance on human nature is influenced by politics rather than science,[26] while Lewontin, Steven Rose and Leon Kamin, who drew a distinction between the politics and history of an idea and its scientific validity,[27] argue that sociobiology fails on scientific grounds. Gould grouped sociobiology with eugenics, criticizing both in his book The Mismeasure of Man.[28] Noam Chomsky has expressed views on sociobiology on several occasions. During a 1976 meeting of the Sociobiology Study Group, as reported by Ullica Segerstråle, Chomsky argued for the importance of a sociobiologically informed notion of human nature.[29] Chomsky argued that human beings are biological organisms and ought to be studied as such, with his criticism of the "blank slate" doctrine in the social sciences (which would inspire a great deal of Steven Pinker's and others' work in evolutionary psychology), in his 1975 Reflections on Language.[30] Chomsky further hinted at the possible reconciliation of his anarchist political views and sociobiology in a discussion of Peter Kropotkin's Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which focused more on altruism than aggression, suggesting that anarchist societies were feasible because of an innate human tendency to cooperate.[31] Wilson has claimed that he had never meant to imply what ought to be, only what is the case. However, some critics have argued that the language of sociobiology readily slips from "is" to "ought",[27] an instance of the naturalistic fallacy. Pinker has argued that opposition to stances considered anti-social, such as ethnic nepotism, is based on moral assumptions, meaning that such opposition is not falsifiable by scientific advances.[32] The history of this debate, and others related to it, are covered in detail by Cronin (1993), Segerstråle (2000), and Alcock (2001). |

レセプション(受容) スティーヴン・ピンカーは、批評家たちが政治と生物学的決定論への恐怖に過度に左右されていると主張し[a]、とりわけスティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドと リチャード・ルウォンティンを、人間の本性に関するスタンスが科学よりもむしろ政治に影響されている「急進的科学者」であると非難している[26]。グー ルドは社会生物学を優生学とグループ化し、著書『The Mismeasure of Man』の中で両者を批判している[28]。 ノーム・チョムスキーは何度か社会生物学についての見解を述べている。Ullica Segerstråleによって報告されているように、1976年の社会生物学研究グループの会議において、チョムスキーは社会生物学的な情報に基づいた 人間性の概念の重要性を主張した。 [29]チョムスキーは1975年のReflections on Language(言語についての考察)の中で、社会科学における「白紙委任状(blank slate)」の教義(これは進化心理学におけるスティーヴン・ピンカーや他の研究者たちに多くのインスピレーションを与えることになる)への批判ととも に、人間は生物学的な有機体であり、そのようなものとして研究されるべきであると主張していた[30]: 同書は攻撃性よりも利他性に重点を置いており、人間が生来持っている協力傾向のために無政府主義社会が実現可能であることを示唆していた[31]。 ウィルソンは、自分はあるべき姿を示唆するつもりはなく、あるべき姿だけを示唆したのだと主張している。しかし、一部の批評家は、社会生物学の言葉は「あ る(is)」から「あるべき(ought)」へと容易に抜け落ち、自然主義的誤謬の一例であると論じている[27]。ピンカーは、民族的(エスニック)ネポティズムのよ うな反社会的とみなされるスタンスへの反対は道徳的仮定に基づいており、そのような反対は科学の進歩によって反証可能ではないということを意味していると 主張している[32]。この議論の歴史やそれに関連する他の議論については、Cronin(1993)、Segerstråle(2000)、 Alcock(2001)が詳しく取り上げている。 |

| Biocultural

anthropology Biosemiotics Cultural evolution Cultural selection theory Darwinian anthropology Dual inheritance theory Evolutionary anthropology Evolutionary developmental psychology Evolutionary ethics Evolutionary neuroscience Evolutionary psychology Genopolitics Human behavioral ecology Kin selection Memetics Phytosemiotics Social evolution Social neuroscience Sociophysiology Zoosemiotics |

生物文化人類学 生物記号論 文化進化論 文化淘汰論 ダーウィン人類学 二重継承説 進化人類学 進化発達心理学 進化倫理学 進化論的神経科学 進化心理学 ジェノポリティクス 人間行動生態学 キン・セレクション 記憶論 植物記号論 社会進化論 社会神経科学 社会生理学 動物記号学 |

| Sources Alcock, John (2001). The triumph of sociobiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514383-6. Barkow, Jerome, ed. (2006). Missing the Revolution: Darwinism for Social Scientists. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513002-7. Cronin, Helena (1993). The ant and the peacock: Altruism and sexual selection from Darwin to today. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45765-1. Segerstråle, Ullica (2000). Defenders of the truth: The sociobiology debate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286215-0. Further reading Etcoff, Nancy (1999). Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-47942-4. Kaplan, Gisela; Rogers, Lesley J. (2003). Gene Worship: Moving Beyond the Nature/Nurture Debate over Genes, Brain, and Gender. Other Press. ISBN 978-1-59051-034-6. Lerner, Richard M. (1992). Final Solutions: Biology, Prejudice, and Genocide. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00793-9. Ovcharov, Dmitry (2023). "The problem of biological and social in Russian philosophy of the second half of the XX — beginning of the XXI century: historical and philosophical analytical review". Bulletin of the Chelyabinsk State University. 477 (7): 61–67. doi:10.47475/1994-2796-2023-477-7-61-67. Richards, Janet Radcliffe (2000). Human Nature After Darwin: A Philosophical Introduction. London: Routledge. |

情報源 Alcock, John (2001). 社会生物学の勝利 Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514383-6. Barkow, Jerome, ed. (2006). Missing the Revolution: 社会科学者のためのダーウィニズム. オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-513002-7. Cronin, Helena (1993). アリとクジャク: ダーウィンから今日までの利他主義と性淘汰. ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-45765-1. Segerstråle, Ullica (2000). 真実の擁護者:社会生物学論争. オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-286215-0. さらに読む Etcoff, Nancy (1999). Survival of the Prettiest: 美の科学. アンカー・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-385-47942-4. Kaplan, Gisela; Rogers, Lesley J. (2003). 遺伝子崇拝: Gene Worship: Moving Beyond the Nature/Nurture Debate over the Genes, Brain, and Gender. Other Press. ISBN 978-1-59051-034-6. Lerner, Richard M. (1992). 最終的な解決策: Biology, Prejudice, and Genocide. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00793-9. Ovcharov, Dmitry (2023). 「20世紀後半から21世紀初頭のロシア哲学における生物学的・社会学的問題:歴史的・哲学的分析レビュー」. チェリャビンスク国立大学紀要. 477 (7): 61–67. doi:10.47475/1994-2796-2023-477-7-61-67. Richards, Janet Radcliffe (2000). ダーウィン以後の人間本性: A Philosophical Introduction. London: Routledge. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociobiology |

リンク

リンク(医療人類学関連)

文献

***

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆