マックス・シェーラーのルサンチマン

Max Scheler's Ressentiment

☆

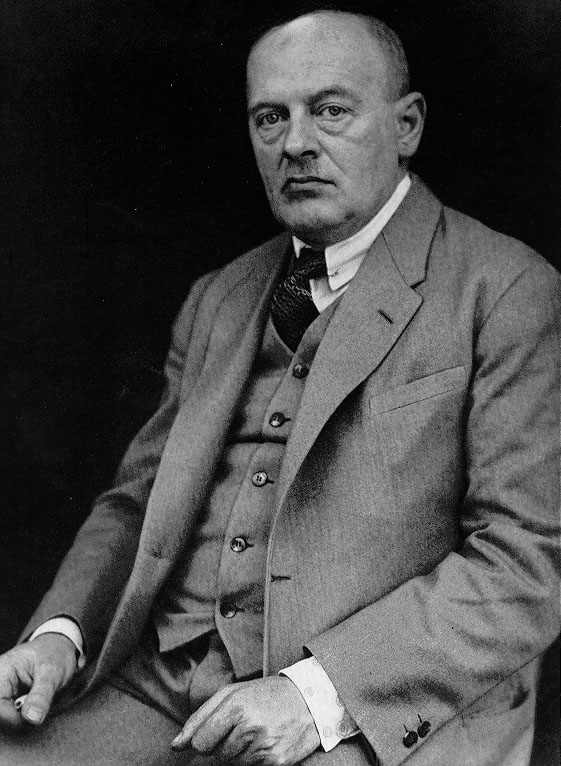

『ルサンチマン』(ドイツ語の正式タイトルは『ルサンチマンと道徳的価値判断について』)は、1912年にマックス・シェーラー(1874

年-1928年)によって書かれた本である。シェーラーは、現象学の伝統における20世紀初頭の主要なドイツの大陸哲学者の中で、最も尊敬され、かつ顧み

られない人物であったと考えられている。[1] シェーラーは、「人間特有の憎悪」[2] および関連する社会現象や心理現象に関する観察と洞察から、

[2] および関連する社会心理学的現象に関する彼の観察と洞察は、「ルサンチマン」という彼の哲学概念の記述的基礎となった。[3]

広く認められた慣例として、この用語のフランス語のスペルは、哲学界では、幅広い意味と適用を維持するためにそのまま使用されている。[4]

シェーラーは1928年に心臓発作で急死し、膨大な未完成の作品を残した。それ以来、彼の思想の推論は常にさまざまなトピックに関する関心と議論を刺激し

てきた。[5] 彼の著作はナチスによる焚書リストに載っていた。

倫理研究に属する概念として、ルサンチマンはシェーラーの情動に裏打ちされた非形式的価値倫理の対極にあるプロセスを表している。[6]

しかし、ルサンチマンは同時に、シェーラーの最も心理学的かつ社会学的であり、かつ最も暗いテーマであるともいえる。それは、それらの特定の社会科学にお

ける多くの後年の発見を予見している。

民衆の知恵は、ルサンチマンを非生産的で、究極的には時間とエネルギーの浪費となる自己破滅的な心の動きとして認識することで、シェーラーの意図に最も近

いものとなる。成熟した人間であれば、持続的な憎悪は憎悪の対象よりも憎悪する当人自身をはるかに傷つけることを知っている。憎悪を長引かせると、感情の

成長が妨げられ、憎悪の対象(すなわち、他人、グループ、または人種)によって何らかの形で引き起こされた苦痛以上の成長が妨げられることで、奴隷状態に

陥る。[7]

★ 哲学において、ルサンチマン(/rəˌsɒ̃.tiˈmɒ̃/、フランス語発音: [ʁə.sɑ̃.ti.mɑ̃] ⓘ)は、憤りや敵意の形のひとつである。この概念は、19世紀の思想家たち、特にフリードリヒ・ニーチェに特に興味を持たれた。彼らの用法によると、ルサ ンチマンとは、自分の欲求不満の原因であると特定した対象に向けられた敵意であり、すなわち、自分の欲求不満の原因を他者に帰属させることである。[1] 原因」に対する弱さや劣等感、あるいは嫉妬の感覚は、拒絶や正当化の価値体系、すなわち、自分の欲求不満の原因と認識されるものを攻撃したり否定したりす る道徳観を生み出す。この価値観は、羨望の対象を客観的に劣っていると見なすことで、自身の弱点を正当化する手段として用いられる。これは防衛機制のひと つであり、不満を抱く個人が不安や欠点を認識し、克服することを妨げる。エゴは、罪悪感から自らを守るために敵を作り出す(→「ルサンチマン(一般)」)。

| Ressentiment Ressentiment (full German title: Über Ressentiment und moralisches Werturteil) is a 1912 book by Max Scheler (1874–1928), who is sometimes considered to have been both the most respected and neglected of the major early 20th century German Continental philosophers in the phenomenological tradition.[1] His observations and insights concerning "a special form of human hate" [2] and related social and psychological phenomenon furnished a descriptive basis for his philosophical concept of "Ressentiment".[3] As a widely recognized convention, the French spelling of this term has been retained in philosophical circles so as to preserve a broad sense of discursive meaning and application.[4] Scheler died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1928 leaving a vast body of unfinished works. Extrapolations from his thoughts have always since piqued interest and discussion on a variety of topics.[5] His works were on the Nazi book burn list. As a concept belonging to the study of ethics, Ressentiment represents the antithetical process of Scheler's emotively informed non-formal ethics of values.[6] But Ressentiment can also be said to be, at once, Scheler's darkest as well as his most psychological and sociological of topics, foreshadowing many later findings in those particular social sciences. Folk wisdom comes closest to Scheler's meaning by recognizing Ressentiment as a self-defeating turn of mind which is non-productive and ultimately a waste of time and energy. Maturity informs most of us that sustained hatred hurts the hater far more than the object of our hate. Sustained hatred enslaves by preventing emotional growth from progressing beyond the sense of pain having been precipitated, in some way, by whom or what is hated (i.e., another person, group or class of persons).[7] |

『ルサンチマン』 『ルサンチマン』(ドイツ語の正式タイトルは『ルサンチマンと道徳的価 値 判断について』)は、1912年にマックス・シェーラー(1874年-1928年)によって書かれた本である。シェーラーは、現象学の伝統における20世 紀初頭の主要なドイツの大陸哲学者の中で、最も尊敬され、かつ顧みられない人物であったと考えられている。[1] シェーラーは、「人間特有の憎悪」[2] および関連する社会現象や心理現象に関する観察と洞察から、 [2] および関連する社会心理学的現象に関する彼の観察と洞察は、「ルサンチマン」という彼の哲学概念の記述的基礎となった。[3] 広く認められた慣例として、この用語のフランス語のスペルは、哲学界では、幅広い意味と適用を維持するためにそのまま使用されている。[4] シェーラーは1928年に心臓発作で急死し、膨大な未完成の作品を残した。それ以来、彼の思想の推論は常にさまざまなトピックに関する関心と議論を刺激し てきた。[5] 彼の著作はナチスによる焚書リストに載っていた。 倫理研究に属する概念として、ルサンチマンはシェーラーの情動に裏打ちされた非形式的価値倫理の対極にあるプロセスを表している。[6] しかし、ルサンチマンは同時に、シェーラーの最も心理学的かつ社会学的であり、かつ最も暗いテーマであるともいえる。それは、それらの特定の社会科学にお ける多くの後年の発見を予見している。 民衆の知恵は、ルサンチマンを非生産的で、究極的には時間とエネルギーの浪費となる自己破滅的な心の動きとして認識することで、シェーラーの意図に 最も近いものとなる。成熟した人間であれば、持続的な憎悪は憎悪の対象よりも憎悪する当人自身をはるかに傷つけることを知っている。憎悪を長引かせると、 感情の成長が妨げられ、憎悪の対象(すなわち、他人、グループ、または人種)によって何らかの形で引き起こされた苦痛以上の成長が妨げられることで、奴隷 状態に陥る。[7] |

| Background It is difficult to imagine the intellectual concern of the late 19th and early 20th century over the collective drift in Western civilization away from old-guard monarchical and hierarchical societal structures (i.e., one's station in life being determined primarily by birth), toward the relative uncertainty and instability embodied in such Enlightenment Era ideals such as democracy, nationhood, class struggle (Karl Marx), human equality, humanism, egalitarianism, utilitarianism and the like. As such, Ressentiment, as a phenomenon, was first viewed as a pseudo-ethically based political force enabling the lower classes of society to rise in their situation in life at the (perceived) expense of the higher, or more inherently "noble" classes. Hence, Ressentiment first emerged as, what some might view, a reactionary and elitist concept by today's democratic standards; while others of a more conservative mind-set might view Ressentiment as liberalism disguised as a socialist attempt at usurping the role of individual responsibility and self-determination. In any event Scheler's contributions regarding this topic can not be fully appreciated without some cursory reference to the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). Friedrich Nietzsche used the term Ressentiment to explain this emerging degenerative morality issuing from an underlying existential distinction between what he saw as the two basic character options available to the individual: the Strong (the "Master") or the Weak (the "Slave"). The Master-type fully accepts the burdens of freedom and decides a path of self-determination. The Slave, rather than deciding to be the authentic author of his own destiny, chooses a repressed unsatisfying mode of life, blaming (by projection) his submissiveness, loss of self-esteem and pitiful lot in life upon the dominant Master figure (and his entire social class) who by contrast seems to flourish at every moment. A true enough assessment, given that economic exploitation always seems to lie at the heart of any intrinsic Master / Slave social arrangement, along with the Master class "washing their hands" (so to speak) of the burdens of social responsibility. This underlying Ressentiment forms the underlying rationale for a code of conduct (e.g., passive acceptance of abuse, fear of reprisal for asserting personal rights due to implied intimidation, or inability to enjoy life) belonging to the Slave-type or class ("Slave Morality").[8] Nietzsche was an atheist and harbored a particular disdain for Christianity, which he viewed as playing a key role in supporting Slave Morality. In supporting the Weak and disadvantaged of humanity, Christianity undermined the authority, social position and cultural progress of the Strong.[9] Nietzsche viewed the progress of such Slave Morality as a sort of violation of the natural order and a thwarting of the authentic advancements of civilization available only through the Strong. This view of a "natural order", so typical of 19th Century Europe (e.g., Darwin's Theory of Evolution) is expressed in Nietzsche's metaphysical principal – Will to Power.[10] Scheler, by comparison, ultimately viewed the universal salvic nature of Christian love as contradicting Nietzsche's assessments,[11] and in later life developed an alternate metaphysical dualism of Vital Urge[Note 1] and Spirit:[Note 2] Vital Urge as closely allied to Will to Power, and Spirit as dependent yet truly distinct in character. Contrary to Nietzsche's ultimate intent, much of his legacy ultimately led to an implosion of objectivity in which (i) truth became relative to individual perspective, (ii) "might ultimately made right" ("Social Darwinism"), and (iii) ethics would become subjective and solipsistic. By contrast, Scheler, who also was skeptical over the historically emerging unchecked power of mass culture and the prevalence and leveling power of mediocrity upon ethical standards and upon the individual human person (as a unique sacred value), was nonetheless a theistic ethical objectivist.[14][15] For Scheler, the phenomenon of Ressentiment principally involved Spirit (as opposed to Will to Power, Drives or Vital Urge), which entailed deeper personal issues involving distortion of the objective realm of values, the self-poisoning of moral character, and personality disorder.[16] |

背景 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、西欧文明が旧態依然とした君主制や階級社会(すなわち、生まれによって人生の地位がほぼ決定される)から、民主主 義、国民国家、階級闘争(カール・マルクス)、人間の平等、ヒューマニズム、平等主義、功利主義などの啓蒙主義時代の理想に体現される相対的な不確実性や 不安定さに向かって集団的に流れていくことに対する知的関心は、想像するのが難しい。このように、ルサンチマンは、社会の下層階級が、より上位の階級、あ るいはより本質的に「高貴な」階級を(認識されている)犠牲にして生活状況を向上させることを可能にする、偽りの倫理に基づく政治的勢力として、まず最初 に捉えられた。したがって、レッセティマンは、今日の民主主義の基準から見ると、反動的でエリート主義的な概念として最初に登場した。一方、より保守的な 考え方を持つ人々は、レッセティマンを、個人責任と自己決定の役割を奪おうとする社会主義的な試みを装った自由主義と見なすかもしれない。いずれにして も、このテーマに関するシェーラーの貢献は、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ(1844~1900)の思想を概観的に参照することなしには十分に理解することはで きない。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、この台頭しつつある退化的な道徳を説明するために「ルサンチマン」という用語を使用した。それは、彼が個人が持つ2つの基本的 な性格オプションと見なしたもの、すなわち「強い者(「主人」)」または「弱い者(「奴隷」)」という根本的な実存的区別から生じるものだった。マスター 型は、自由の重荷を完全に引き受け、自己決定の道を選ぶ。一方、スレイブは、自らの運命の真の作者となることを決意するのではなく、抑圧された満足のいか ない生き方を選び、服従心、自尊心の喪失、そして哀れな境遇を、あらゆる場面で成功しているように見える支配的なマスター像(およびその社会階級全体)に 投影し、その責任をなすりつける。経済的搾取が、本質的なマスター/スレーブの社会的取り決めの中核に常に存在していることを考えると、この評価は的を射 ている。マスター階級は、社会的責任の重荷から「手を洗う」(いわば)のである。この根底にあるルサンチマンは、奴隷的なタイプや階級に属する人々の行動 規範(例えば、虐待を黙って受け入れること、暗黙の威嚇により自己の権利を主張することに対する報復を恐れること、人生を楽しむことができないことなど) の根底にある論理的根拠となっている。[8] ニーチェは無神論者であり、キリスト教に対して特に嫌悪感を抱いていた。キリスト教は奴隷道徳を支える重要な役割を果たしていると彼は考えていた。キリス ト教は、人間社会の弱者や恵まれない人々を支援することで、強者の権威、社会的地位、文化的な進歩を損なっていたのである。[9] ニーチェは、このような奴隷道徳の進歩を、自然の秩序に対する一種の侵害であり、強者だけが利用できる真の文明の進歩を妨げるものだと考えていた。この 「自然の秩序」という見解は、19世紀のヨーロッパ(例えば、ダーウィンの進化論)に典型的なものであり、ニーチェの形而上学の原則である「力への意志」 に表現されている。[10] これに対しシェーラーは、キリスト教の普遍的な救済的な愛の本質は、 愛はニーチェの評価とは矛盾するものであると見ていた[11]。晩年には、生命衝動[注1]と精神[注2]という代替的な形而上学的な二元論を展開した。 生命衝動は「力への意志」と密接に関連し、精神は依存的でありながらも本質的に異なる性格を持つ。 ニーチェの最終的な意図とは逆に、彼の遺産の多くは最終的に客観性の崩壊につながった。すなわち、(i) 真実は個人の視点によって相対的なものとなり、(ii) 「強者が最終的に正義となる」(「社会ダーウィニズム」)、そして(iii) 倫理は主観的で自己中心的になる、というものである。 これに対し、シェーラーは、歴史的に台頭してきた大衆文化の抑制されない力や、倫理基準や人間個人(唯一無二の神聖な価値)に対する平凡さの蔓延と平準化 の力に対して懐疑的であったが、それでもなお有神論的倫理的客観論者であった。[14][1 シェーラーにとって、ルサンチマンの現象は、本質的には精神(「力への意志」、「衝動」、「生命衝動」とは対照的)に関わるものであり、それは価値の客観 的領域の歪曲、道徳的特質の自己中毒、人格障害といったより深い個人的問題を伴うものであった。[16] |

| Basic features of Ressentiment Scheler's described Ressentiment in his 1913 book by the same title as follows: "…Ressentiment is a self-poisoning of the mind which has quite definite causes and consequences. It is a lasting mental attitude, caused by the systematic repression of certain emotions and affects which, as such are normal components of human nature. Their repression leads to the constant tendency to indulge in certain kinds of value delusions and corresponding value judgments. The emotions and affects primarily concerned are revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite."[17] Although scholars do not agree on a fixed number or attributes materially defining Ressentiment, they have nonetheless collectively articulated about ten authoritative and insightful points (many times combining them) which stake-out the boundaries of this concept: 1) Ressentiment must first and foremost be understood in relation to, what Scheler termed the apriori hierarchy of value modalities. While the direction of personal transcendence and ethical action is one toward positive and higher values, the direction of Ressentiment and unethical action is one toward negative and lower values. Scheler viewed values as emotively experienced with reference to the aforementioned universal, objective, constant and unchanging hierarchy. From lowest to highest, these modalities (with their respective positive and corresponding negative dis-value forms) are as follows: sensual values of the agreeable and the disagreeable; vital values of the noble and vulgar; mental (psychic) values of the beautiful and ugly, right and wrong and truth and falsehood; and finally values of the Holy and Unholy of the Divine and Idols.[18] Ressentiment represents the dark underside, or inversion, of Scheler's vision of a personal and transformational non-formal ethics of values. 2) Ressentiment, as a personal disposition, has its genesis in negative psychic feelings and feeling states which most people experience as normal reactive responses to the demands of social life:[19] i.e., envy, jealousy, anger, hatred, spite, malice, joy over another's misfortune, mean spirited competition, etc. The objective sources of such feeling states responses might be occasioned by almost anything: e.g., personal criticism, ridicule, mockery, rejection, abandonment, etc. For the individual person, the ethical and psychological issue becomes how the energy from these feeling states will be channeled so as to better benefit the individual person and society. 3) Ressentiment is highly situational in character in that it always involves "mental comparisons" (value-judgments) with other people who allegedly have no such Ressentiment feelings,[20][21] and who likewise exhibit genuinely positive values. Hence, although Ressentiment might begin with something like admiration and respect, but surely ends in a sort of coveting of those personal qualities and goods of another: i.e., advantages afforded by their beauty, intelligence, charm, wit, personality, education, talent, skills, possessions, wealth, work achievement, family affiliation and the like. This early stage of Ressentiment resembles what we might refer to today as an inferiority complex. However, one can easily extend this notion of "comparing" to externally acquired qualifiers having the potential for negative valuations which also tend to a support consumer based economics: i.e., status symbol possessions (a lavish house, or car), expensive fashion accessories, special privileges, club memberships, plastic surgery and the like.[22] This principal is expressed in our common colloquialism of "Keeping-up with the Jones'". The subliminal result of all of these "comparisons" tend to lend credence the idea that one's self-concept, self-image, self-esteem, worth or social desirability is linked to our social inclusion or exclusion in a favored superior class having the means to insulate themselves from the rest of society. 4) Ressentiment, as situational, also typically extends to inherent social roles. Many social roles involve relationships frequently occasioning some level of inter-personal value-judgment with accompanying negative psychic feelings and feeling states which suggest dominant and submissive roles, not unlike Nietzsche's Master-Slave dichotomy. For example: The subordinate and/or submissive gender roles assigned to woman in terms of sexuality, child rearing and nurturing tasks.[23] Generational Divides ("Generation Gaps"): The rejection of a younger generation by members of an older generation, due to the latter's inability to accept their own changes and to move beyond the value pursuits proper to those preceding stages of life. Also, the reverse is true. The rejection of an older generation by members of a younger generation due to latter's inability to accept the fact that the older generation understands and sympathizes with the challenges they face.[24] Progressive forms of inter-family and blended-family relations: i.e., younger siblings toward the elder sense of entitlement; the hyper-critical mother-in-law toward the daughter-in-law;,[24] or even the more contemporarily abandonment of an ex-spouse in favor of "trophy wife" or "trophy husband" as a status symbol signaling a raise in social status; the relational neglect toward children from a previous marriage over ones of the current; the reactions of peer friends and family to a romantic relationship involving partners of vastly different ages; the pathetic efforts of a mediocre ne’er-do-well child to live up to the standards of a successful high achieving parent, etc. The classic employee / employer adversarial relationships. 5) Ressentiment triggers a tendency in people which Scheler termed "Man's Inherent Fundamental Moral Weakness":[25][26] a sense of hopelessness which pre-disposes a person to regress and seek surrogates of lower value as a source of solace. When personal progress becomes stagnant or frustrated in moving from a negative to a more positive plateau given a relatively high vital or psychic level of value attainment, there is an inherent tendency toward regression in terms of indulgence in traditional vices and a host of other physical and psychological addictions and self-destructive modes of behavior (e.g., the use of narcotics).[27] This tendency to seek surrogates to compensate for a frustration with higher value attainment inserts itself into the scenario of consumerist materialism as an insatiable self-defeating need "to have more" in order to fill the void of our own philosophical bankruptcy and spiritual poverty. |

ルサンチマンの基本的特徴 シェーラーは1913年に出版した同名の著書の中で、ルサンチマンを次のように説明している。 「ルサンチマンとは、明確な原因と結果を持つ精神の自己中毒である。それは、人間の本質的な要素である特定の感情や情動が体系的に抑圧されることによって 生じる永続的な心理的傾向である。抑圧された感情は、特定の種類の価値観の妄想や、それに対応する価値判断にふけるという傾向を常に生み出す。 主に問題となる感情や情動は、復讐、憎悪、悪意、妬み、中傷したいという衝動、悪意である。」[17] 学者たちは、レッサンタンを物質的に定義する固定された数や属性について意見が一致していないが、この概念の境界を明確にする10の権威ある洞察力に富ん だポイント(多くの場合、それらを組み合わせている)を総体的に明確にしている。 1) まず第一に、レッセマンティは、シェーラーが「価値様式のアプリオリな階層」と呼んだものとの関連で理解されなければならない。個人の超越と倫理的行動の 方向性は、肯定的な価値、より高い価値に向かうものであるが、レッセマンティと非倫理的行動の方向性は、否定的な価値、より低い価値に向かうものである。 シェーラーは、価値を前述の普遍的、客観的、不変かつ恒常的な階層を参照しながら情動的に経験されるものとして捉えていた。 最も低いものから最も高いものへと、これらの様態(それぞれの肯定的なものと、それに対応する否定的な価値の否定形)は以下の通りである。快と不快の感覚 的価値、高貴と低俗の生命価値、美と醜、善と悪、真実と虚偽の精神(心理)価値 、そして最後に神聖と不浄、偶像崇拝の価値である。[18] ルサンチマンは、シェーラーの価値観における個人的かつ変容的な非形式倫理の暗い裏側、あるいは逆転を表している。 2) 個人的な性向としてのルサンチマンは、社会生活の要求に対する正常な反応としてほとんどの人が経験する否定的な心理的感覚や感情状態にその起源がある。す なわち、羨望、嫉妬、怒り、憎悪、悪意、他人の不幸に対する喜び、卑劣な競争などである。このような感情状態の反応の客観的な原因は、ほとんど何であれ引 き起こされる可能性がある。例えば、個人的な批判、嘲笑、あざけり、拒絶、見捨てられることなどである。 個人にとって、倫理的・心理的な問題は、これらの感情状態から生じるエネルギーを、個人や社会にとってより有益な方向にどう導くかということになる。 3)ルサンチマンは、常にルサンチマン感情を持たない(とされる)他の人々との「精神的な比較」(価値判断)を伴うという点で、極めて状況的な性格を持 つ。[20][21] また、同様に純粋にポジティブな価値観を示す人々もいる。したがって、ルサンチマンは、尊敬や賞賛といった感情から始まるかもしれないが、最終的には、他 者の個人的な資質や所有物に対する羨望へと発展する。すなわち、他者の美しさ、知性、魅力、機知、人格、教育、才能、技能、所有物、富、仕事の業績、家族 関係などから得られる優位性である。ルサンチマンの初期段階は、今日でいうところの劣等感に似ている。 しかし、この「比較」という概念は、消費経済を支える傾向にある、否定的な評価を受ける可能性のある外見的な要素にも容易に拡大することができる。すなわ ち、ステータスシンボルとなる所有物(豪邸や高級車)、高価なファッションアクセサリー、特別な特権、クラブの会員権、美容整形などである。[22] この原則は、私たちが日常的に使う「ジョーンズ家(Jones)に遅れを取らないようにする」という表現に表れている。こうした「比較」の潜在的な結果 は、自己概念、自己イメージ、自尊心、価値、あるいは社会的望ましさが、社会から隔絶された手段を持つ、好まれる上流階級への社会的包含あるいは排除と結 びついているという考えを信憑性のあるものにする傾向がある。 4) 状況依存的なルサンチマンは、典型的に、本来的な社会的役割にも及ぶ。多くの社会的役割は、支配的・従属的な役割を示唆する否定的な精神的な感情や心理状 態を伴う、ある程度の対人価値判断を頻繁に引き起こす関係を含む。例えば、 女性に割り当てられた性的役割、子育てや育児の役割といった従属的・従順的な性別役割などである。 ジェネレーションギャップ(ジェネレーションギャップ):年長世代が自身の変化を受け入れられず、それまでの人生の段階で追求してきた価値観から脱却でき ないために、若い世代を拒絶すること。また、その逆もある。若い世代が直面する困難を年長世代が理解し共感しているという事実を受け入れられないために、 若い世代が年長世代を拒絶すること。 家族内および混合家族間の関係における進歩的な形態:例えば、年下の兄弟姉妹が年長者に対して権利意識を持つこと、批判的な義母が義理の娘に対して批判的 になること、[24] あるいは、社会的地位の向上を示すステータスシンボルとして「トロフィーワイフ」や「トロフィーハズバンド」を好むあまり、元配偶者を捨ててしまうことさ えある 社会的地位の向上を示すステータスシンボルとして、前の結婚で生まれた子供に対する現在の結婚で生まれた子供への関係的な無視、年齢が大きく異なるパート ナーとの恋愛関係に対する友人や家族の反応、平凡でろくでなしの子供が成功を収めた高学歴の親の基準に合わせようとする哀れな努力などである。 古典的な従業員と雇用主の敵対的な関係。 5) ルサンチマンは、シェーラーが「人間の生来の根本的な道徳的弱さ」と呼んだ傾向を人々に引き起こす。[25][26] 絶望感は、人を後退させ、安らぎの源として価値の低い代替品を求める傾向を生み出す。 比較的価値の高い生命や精神レベルを達成しているにもかかわらず、個人的な進歩が停滞したり、否定的な状態からより肯定的な状態へと移行するのに挫折した りした場合、伝統的な悪徳や、その他の身体的・心理的依存症、自己破壊的な行動様式(例えば 。[27] 価値達成の欲求不満を補うための代替品を求めるこの傾向は、消費主義的唯物論のシナリオに、自己破滅的な「もっと欲しい」という飽くことのない欲求として 入り込む。それは、私たちの哲学的な破綻と精神的な貧困の空虚感を埋めるためのものである。 |

| Essential structures of

Ressentiment proper: "Pathological Ressentiment" Further refining Ressentiment, Scheler wrote: "Through its very origin, ressentiment is therefore chiefly confined to those who serve and are dominated at the moment, who fruitlessly resent the sting of authority. When it occurs elsewhere, it is either due to psychological contagion—and the spiritual venom of ressentiment is extremely contagious – or to the violent suppression of an impulse which subsequently revolts by "embittering" and "poisoning" the personality."[16] Hence, certain advanced characteristics of Ressentiment link this phenomenon to what we might refer to today as personality disorders. As such, Ressentiment Proper [20] ("Pathological Ressentiment’) is not materially linked exclusively to issues of socio-economic status, but rather cuts across all socio-economic strata of society to include even the most powerful. 6) In Pathological Ressentiment a Sense of Impotency develops on the part of those experiencing ressentiment-feelings, especially if situational and social factors weigh so heavily so as render a person unable to release or resolve negative psychic feelings and feeling states in a positive and constructive manner:[28] what we refer to today in psychological terms as repression. Originally understood, Ressentiment is defused whenever one has the power and ability to physically retaliate, or act out, against an oppressor. For example, an ancient Roman citizen, as Master, could be expected to take revenge straight away upon his Slave while the reverse would be unthinkable. "When [negative psychic feelings and feeling states] can be acted out, no ressentiment results. But when a person is unable to release these feelings against the persons or groups evoking them, thus developing a sense of impotence, and when these feelings are continuously re-experienced over time, then ressentiment arises."[29] But for Scheler, the essence of Impotency as characteristic of Pathological Ressentiment has less to do with the actual presence of an external oppressor, and more to do with a self-inflicted personal sense of inadequacy over limitations in the face of positive value attainment itself.[30] Hence, Ressentiment-feelings tend to be continuously re-experienced over time in a self-perpetuating manner, primarily fueled by a sense of inadequacy felt within the self which the "other" really only occasions.[31] For example, one can have every advantage in life given them, yet prove to lack the talent for achieving the goals set for him or her self. These re-experienced feelings of impotency become rationalized on a subconscious level as knee-jerk attitudinal projections: i.e., prejudices, bias, racism, bigotry, cynicism, and closed mindedness. Noteworthy is the "abstract" focus of Ressentiment: the fact that specific individuals (i.e., the "Master figure" or their counterpart "Slave figure") are no longer even required for Ressentiment feelings and their rationalized forms of expression to continue and drive forward. One only needs a representative member of the class of one's focus of resentment to be represented in some way. "Members of a group can become random targets of hate, borne out of impotence that seeks to level the group."[32] Such a random formal treatment of "otherness" offers a plausible explanation for hate crimes, serial killings (in part), genocide, the general framing of an enemy in faceless non-human terms, as well as any top-down or bottom-up form of class warfare agenda, etc. Hence, there must be a psychic distancing of de-personalization between Master and Slave perceptions of "the other" in order for Ressentiment to operate effectively. 7) Pathological Ressentiment entails "Value-Delusion". Value Delusion is "a tendency to belittle, degrade, dismiss or to ‘reduce’ genuine values as well as their bearers."[29] However, this is done in a distinctively non-productive manner because "ressentiment does not lead to affirmation of counter-values since ressentiment-imbued persons secretly crave the values they publicly denounce."[29] This aspect of Value Delusions represents a horizontal shift of value judgment concerning things and the world from a positive to a more negative orientation. What was once loved or thought of as good becomes devalued as "sour grapes" [33][34] or "damaged goods" in the mind of the Ressentiment-imbued person, and what was previously lacking in value is now elevated to the status of acceptable. In spite of this decidedly negative direction, "the ressentiment-subject is continuously 'plagued' by those distractions of unattainable values in that he emotionally replaces them with disvalues issuing forth from his impotence. In the background of such an illusory and self-deceiving over-turning of positive values with illusory negative valuations there still remains transparency of the true objective order of values and their ranks."[20] Hence, the demands of Value-Delusion manifest in what we commonly refer to as a superiority complex, i.e., arrogance, hubris, hypocrisy, employment of double standards, denial, revenge, and self-projection of one's own negative qualities onto the opposition. Correspondingly, negative feeling states suggest the absence, repudiation or flight from positive values. But nonetheless, negative values do not stand on their own intrinsic merit: they always refer back in some way to correspondingly positive values.[35] Emotionally, Value Delusion turns happiness to sadness, compassion to hate, hope to despair, self-respect to shame, love and acceptance to rejection (or worse, competition), resolve to dread, and so on down throughout the human emotional strata. Delusion is essential for the Ressentiment-imbued person in order to maintain any semblance of mental homeostasis. 8) Pathological Ressentiment ultimately manifests as "Metaphysical Confusion". Metaphysical Confusion is a form of Value Delusion in which the value shift is more vertical in character,[36] in relation to the apriori hierarchy of value modalities. In this dimension, Value Delusion occurs a sort of twisting, or false inversion, of the value hierarchy wherein higher value-contents and bearers are viewed as lower, and lower as higher. Today we commonly refer to this phenomenon as "Having One's Priorities Out of Order." Scheler illustrated such an inversion in his analysis of Western civilizations humanistic, materialistic and capitalistic propensities to elevate utility values above those of vital values.[37][38] Carried to the logical extreme, "Ressentiment brings its most important achievement when it determines a whole "morality," perverting the rules of preference until what was "evil" appears "good".[39] 9) Pathological Ressentiment ultimately results in a deadening (psychological numbing) of normal sympathetic feeling states, as well as all higher forms of psychic and spiritual feelings and feeling states. As opposed to a pure well ordered emotive life (Ordo Amoris) appropriate to the ethical person as created in God's image through love (ens amans), Pathological Ressentiment emotively results in a disordered heart (de’ordre du coeurs),[36] or what we might commonly refer to as a "hardened heart." For Scheler, morality finds expression in response to "the call of the hour",[40] or exercise of personal conscience, which is based the heart's proper order of love (Ordo Amoris) in relation to positive and higher values. By contrast, Ressentiment with its corresponding Value-Delusions willfully favors varying degrees of a disordered heart (de’ordre du coeurs) and twisted emotions consistent with personality disorders. For example, it is precisely the failure to feel for and identify with their victims (even to the extent of deriving sadistic pleasure) which characterizes the sociopath, the psychopath, the serial killer, the dictator, the rapist, the bully, the corrupt CEO and the ruthless drug dealer—all share this same common denominator.[41] Common Law would refer to this quality as "cold blooded". Author Erick Larson in his book Devil in the White City renders with great precision a literary description of this deadening of higher feeling states in reference to America's first serial killer, Herman Webster Mudgett, alias Dr. H.H. Holmes "…Holmes was charming and gracious, but something about him made Belkamp [the antagonist] uneasy. He could not have defined it. Indeed for the next several decades alienists [early psychologists] and their successors would find themselves hard-pressed with any precision what it was about men like Holmes that caused them to seem warm and integrating but also telegraph the vague sense that some important element of humanness was missing. At first alienists described this condition as "moral insanity" and those who exhibited the disorder as "moral imbeciles." They later adopted the term "psychopath"…as a "new malady" and stated, "Besides his own person and his own interests, nothing is sacred to the psychopath."[42] The Ressentiment-Imbued person exercises such a pronounced psychic distance from his victims so as to never fully achieve the desired lasting satisfaction produced though his own unethical actions. "Retaliation" of this sort no longer yields any good, and "expression" of this sort lacks all possibility of positive results. "In true ressentiment there is no emotive satisfaction but only a life-long anger and anguish in feelings that are compared with others."[19] Unfortunately in general, our particular era suffers from a pronounced inability to feel higher levels of vital psychic (intellectual and sympathetic) and spiritual feeling states.[43] For example, the process of our legal system tends to convert the absolute character of moral sentiments to a "blameless" game of negotiation of cost vs. benefits.[44] Can we even imagine the moral education furnished by such archaic practices as the stockade or tar and feathering so as to invoke real public humiliation for crimes? In addition, we as a culture have become so desensitized to feelings of outrage over public persons of power and stature lacking in all feelings of shame over their wrongdoings that our greatest moral problem becomes one of complacency. |

ルサンチマンの本質的な構造:「病的なルサンチマン」 ルサンチマンをさらに詳しく説明するために、シェーラーは次のように書いている。 「ルサンチマンの起源からして、それは主に、その時々に仕え、支配されている人々、権威の痛みをむなしく憤慨する人々に限定される。それが他の場所で発生 する場合は、心理的な伝染によるものであり、ルサンチマンの精神的な毒は極めて伝染性が高い。あるいは、人格を「苦々しく」し「毒する」ことで後に反乱を 起こす衝動の暴力的な抑制によるものである。」[16] したがって、ルサンチマンの特定の先進的な特徴は、この現象を今日「パーソナリティ障害」と呼ぶものに関連付けている。このように、正統派のルサンチマン (「病的ルサンチマン」)[20]は、社会経済的地位の問題に排他的に結びついているわけではなく、むしろ社会のあらゆる社会経済階層にまたがっており、 最も権力のある人々も含んでいる。 6) 「病的なルサンチマン」においては、ルサンチマン感情を抱く人々の側で無力感が生じる。特に、状況や社会的な要因が重くのしかかり、否定的な精神状態や感 情を肯定的な建設的な方法で解放したり解決したりできない場合である。[28] これを今日、心理学用語で「抑圧」と呼ぶ。 本来の理解では、抑圧者に物理的な報復や行動を起こす力や能力がある限り、ルサンチマンは解消される。例えば古代ローマの市民は、主人として奴隷に対して すぐに復讐することが期待されていたが、その逆は考えられなかった。「否定的な精神感情や感情状態」が表出できる場合には、ルサンチマンは生じない。しか し、それらを引き起こす個人や集団に対してその感情を解放できない場合、無力感が生じ、その感情が長期間にわたって再体験され続けると、ルサンチマンが生 じる。 しかし、シェーラーにとって、病的なルサンチマンの特徴である無力感の本質は、実際の外部からの抑圧者の存在とはあまり関係がなく、むしろ、積極的な価値 の達成そのものに対する限界に対する自己による個人的な不適格感と関係がある。[30] したがって、ルサンチマン感情は、 自己永続的な形で、継続的に再体験される傾向がある。主に、他者によって引き起こされたと感じられる自己の不適格感によって煽られる。[31] たとえば、人は与えられた人生のあらゆる利点を得ているにもかかわらず、自らに課された目標を達成する才能に欠けていることが証明されることがある。 こうした無力感の再体験は、潜在意識レベルで即座に態度として投影されるものとして合理化される。すなわち、偏見、先入観、人種主義、偏狭、皮肉、偏狭な どである。 注目すべきは、レッセティメントの「抽象的」な焦点である。すなわち、レッセティメントの感情や、その合理化された表現形態が継続し、推進されるために は、特定の個人(すなわち、「支配者像」またはその対極にある「被支配者像」)はもはや必要とされないという事実である。憤りの対象となる階級の代表的な メンバーが、何らかの形で表現されていればよいのである。「集団のメンバーは、その集団を平らにしようとする無力感から生じる憎悪の無作為な標的となる可 能性がある」[32] このような「他者性」の無作為な形式的な扱い方は、憎悪犯罪、連続殺人(一部)、大量虐殺、敵対者を顔のない非人間的な用語で一般的に表現すること、さら には、トップダウンまたはボトムアップの階級闘争の議題など、あらゆるものに対して説得力のある説明を提供している。したがって、レサンテマンが効果的に 作用するためには、「他者」に対するマスターとスレーブの認識の間に、脱人格化による心理的な距離が必要となる。 7) 病的なルサンチマンは「価値妄想」を伴う。価値妄想とは、「真の価値やそれを体現するものを軽視、貶め、否定したり、あるいは『減じたり』する傾向」であ る。[29] しかし、これは明らかに非生産的な方法で行われる。なぜなら、「ルサンチマンは ルサンチマンに染まった人物は、公に非難している価値を内心では密かに欲しているため、対抗する価値を肯定することにはつながらない」[29] という理由からである。価値幻想のこの側面は、物事や世界に対する価値判断が、肯定的な方向からより否定的な方向へと水平移動するものである。かつて愛さ れていたものや良いものと思われていたものが、ルサンチマンに侵された人の心の中では「負け惜しみ」[33][34]や「傷物」として価値が下がる。そし て、以前は価値が欠けていたものが、今では受け入れられる状態にまで高められる。 このような明らかに否定的な方向性にもかかわらず、「ルサンチマンを抱える者は、達成不可能な価値観に気を取られ続け、無力感から生じる価値の低いものに 感情的に置き換えてしまう。このような幻想的で自己欺瞞的な、幻想的な否定的評価による肯定的な価値の転覆の背景には、依然として価値の真の客観的秩序と その序列の透明性が残っている」[20]。したがって、 価値の幻想の要求は、一般的に優越複合、すなわち傲慢、思い上がり、偽善、二重基準の使用、否定、復讐、そして反対派に対する自己の否定的な性質の投影と して現れる。 それに対応して、否定的な感情状態は、肯定的な価値の不在、否定、逃避を示唆する。しかし、それでもなお、否定的な価値はそれ自体の本質的な価値に立脚し ているわけではない。否定的な価値は、常に何らかの形で対応する肯定的な価値に言及している。[35] 感情的には、価値妄想は幸福を悲しみに変え、思いやりを憎悪に変え、希望を絶望に変え、自尊心を恥に変え、愛と受容を拒絶(あるいはさらに悪いことには競 争)に変え、決意を恐怖に変える。 妄想は、精神の恒常性を保つために、ルサンチマンに染まった人にとって不可欠なものである。 8) 病理的なルサンチマンは、最終的には「形而上学的混乱」として現れる。形而上学的混乱とは、価値転換がより垂直的な性格を持つ価値妄想の一形態である。 [36] 価値様態の事前階層との関係においてである。この次元では、価値妄想は価値階層をねじ曲げるか、あるいは偽りの転倒を起こす。より高い価値内容や担い手が より低いものと見なされ、より低いものがより高いものと見なされるのである。今日、私たちはこの現象を「優先順位の混乱」と呼ぶのが一般的である。シェー ラーは、実用価値を本質的価値よりも上位に置く傾向を持つ、ヒューマニズム、唯物主義、資本主義といった西洋文明を分析する中で、このような倒錯を説明し ている。[37][38] 論理の極限まで推し進めると、「ルサンチマンは、全体的な『道徳性』を決定づける際に、最も重要な成果をもたらす。優先順位のルールを歪め、それまで 『悪』とされていたものが『善』に見えるようになるまでである。[39] 9) 病的なルサンチマンは、最終的には、通常の共感的な感情状態だけでなく、精神的な高次な感情や感情状態をも麻痺させる。愛(ens amans)を通じて神の姿に創造された道徳的人間にふさわしい、純粋で秩序正しい情動生活(Ordo Amoris)とは対照的に、病的なルサンチマンは情動的に無秩序な心(de’ordre du coeurs)[36]、すなわち一般的に「かたくなな心」と呼ばれるものをもたらす。 シェーラーにとって、道徳性は「時代の要請」に応えること、すなわち、愛の正しい秩序(オルド・アモリス)を肯定的な価値やより高い価値と関連づける個人 的な良心の実践に表現される。それに対して、価値幻想と結びついたルサンチマンは、人格障害と一致するさまざまな程度の心の乱れ(デ・オルドル・デュ・ クール)や歪んだ感情を故意に好む。例えば、犠牲者に同情したり、共感したりできないこと(サディスティックな快楽を享受する程度にまで至る)こそが、反 社会的人間、精神病質者、連続殺人犯、独裁者、強姦犯、いじめっ子、腐敗した最高経営責任者、冷酷な麻薬の売人といった人物の特徴であり、これらすべてに 共通する要素である。[41] 慣習法では、この性質を「冷血」と呼ぶだろう。 作家エリック・ラーソンは著書『ホワイト・シティの悪魔』の中で、アメリカ初の連続殺人犯であるハーマン・ウェブスター・マッドジェット(別名ドクター・ H・H・ホームズ)について、この高潔な感情の喪失を非常に正確に文学的に描写している。 「...ホームズは魅力的で礼儀正しかったが、彼には何か不安を覚えるところがあった。 それを明確に定義することはできなかった。 実際、その後数十年にわたって、精神医学者(初期の心理学者)とその後継者たちは、ホームズのような人物が温厚で協調的に見える一方で、人間性の重要な要 素が欠けているという漠然とした感覚を伝える原因となったのは、一体何なのかを正確に突き止めるのに苦労することになる。当初、精神医学者はこの状態を 「道徳的狂気」と表現し、その障害を示す人々を「道徳的白痴者」と呼んだ。その後、「新しい病気」として「精神病質者」という用語を採用し、「精神病質者 にとって、自分自身や自分の利益以外に神聖なものなど何もない」と述べた。[42] ルサンチマンに満ちた人物は、自らの非倫理的な行動によってもたらされる望ましい永続的な満足感を完全に達成することがないよう、犠牲者に対して際立った 心理的距離を置く。この種の「報復」はもはや何の利益ももたらさず、この種の「表現」は肯定的な結果を生み出す可能性を一切欠いている。「真のルサンチマ ンには感情的な満足感はなく、他者と比較される感情における生涯にわたる怒りと苦悩だけがある」[19] 残念ながら一般的に、私たちの時代は、より高度な精神的な(知的および共感的)感覚や精神的な感覚状態を感じることが著しくできないという問題を抱えてい る。[43] たとえば、私たちの法制度のプロセスは、道徳的な感情の絶対的な性格を コスト対利益の「非難の余地のない」交渉ゲームに変えてしまう傾向がある。[44] 犯罪に対する真の社会的屈辱を呼び起こすために、柵やタールと羽毛を付けるといった時代遅れの慣習によって行われる道徳教育を想像することさえできるだろ うか? さらに、私たちは文化として、権力や地位を持つ公人が自らの悪事に対して恥の感情を一切持たないことに対する憤りの感情に麻痺してしまい、私たちの最大の 道徳的問題は自己満足の問題となっている。 |

| Ressentiment and wider societal

impact 10) Finally, Pathological Ressentiment bears a particular relation to the Socio-Political Realm by virtue of, what Scheler describes as, man's lowest form of social togetherness, "Psychic Contagion".[45][46] Psychic Contagion is the phenomenon of uncritically "following the crowd", or mob mentality, liken to lemmings charging over a cliff. Positive examples, are good natured crowds in a pub or at sporting events; a negative example, violent rioting. As a concept, Psychic Contagion bears an affinity to Nietzsche's assessment of Slave-type mentality. To the extent that the politically powerful (i.e., the "Master" faction or "Slave" faction of society, as the case might be) are able to rally collective cultural animosities through the use of Psychic Contagion, they increase their ability to achieve their underlying socio-political objectives. Such methods usually take the forms of incendiary rhetoric, scapegoat tactics (e.g., anti-Semitism, homophobia, hatred toward welfare recipients and the disadvantaged, etc.), class warfare, partisan politics, propaganda, excessive secrecy / non-transparency, closed minded political ideology, jingoism, misguided nationalism, violence, and waging unjust war. The use of such methods of negative Psychic Contagion can be viewed as having propelled such historical figures or movements as Nero (burning of Rome), the French Revolution (Ressentiment in the original concept), Hitler (genocide of the Jews and the Aryan Master Race agenda), the 1975-1979 Cambodian Khmer Rouge (genocidal social engineering), the 1994 Rwanda (tribal based genocide) or fundamentalist Islamism. |

ルサンチマンとより広範な社会への影響 10) 最後に、病理的ルサンチマンは、シェーラーが「精神の伝染」と呼ぶ人間の最も低俗な社会的一体性の形態によって、社会政治的領域と特別な関係を持つ。 [45][46] 精神の伝染とは、無批判に「群集に追随する」現象、すなわち、崖に向かって突進するレミングのような暴徒心理である。肯定的な例としては、パブやスポーツ イベントでの善良な観衆が挙げられる。否定的な例としては、暴動が挙げられる。概念としては、サイキック・コンタギョンは、奴隷型の精神性を評したニー チェの評価と類似している。 政治的に力を持つ者(すなわち、社会における「主人」派または「奴隷」派)がサイキック・コンタギョンを利用して集団の文化的反感を煽ることで、彼らはそ の根底にある社会政治的目標を達成する能力を高める。このような手法は、扇動的な暴言、スケープゴート戦術(反ユダヤ主義、同性愛嫌悪、生活保護受給者や 社会的弱者に対する憎悪など)、階級闘争、党派政治、プロパガンダ、過剰な秘密主義/透明性の欠如、偏狭な政治思想、軍国主義、誤ったナショナリズム、暴 力、そして不当な戦争の遂行といった形を取ることが多い。 このような否定的な精神感染の手法の使用は、ネロ(ローマの焼失)、フランス革命(原初の概念におけるルサンチマン)、ヒトラー(ユダヤ人の大量虐殺と アーリア人至上主義の政策)、1975年から1979年のカンボジアのクメール・ルージュ(大量虐殺的社会工学)、1994年のルワンダ(部族を基盤とし た大量虐殺)、あるいは原理主義的イスラム主義といった歴史上の人物や運動を推進したと見なすことができる。 |

| Conclusions It is a mistake to assess Scheler's concept of Ressentiment as chiefly a theory of psychological pathology, though surely it is that in part. In addition, Ressentiment is a philosophical and ethical concept from which to assess the spiritual and cultural health both of individual persons and society as a whole: a task which seems all the more urgent given economic globalization (i.e., a tendency toward carte blanche predatory capitalism).[47] For example, it is entirely acceptable to view human ethical transcendence as complementary and commensurate with a bottom-up psychology of needs and drives so long as the arch of that qualitative direction is positive in nature. However the reverse is false. Negative parallel aspects are irreducible to Scheler's top-down metaphysical principal of good as emanating from our personal development as spiritual beings. This distinction is illustrated by the many cases in which negative role models can, and do, emerge as highly self-actualized economically powerful individuals from a psychological standpoint (clearly "Superman" type persons), but who are entirely lacking from an ethical, social and spiritual standpoint: e.g., the drug king-pin or pimp as a person young boys admire and look up to, or the corrupt CEO who absconds with obscene bonuses while his company goes bankrupt and the employee pension fund disintegrates. These negative manifestations of values and value inversions demonstrate how the philosophical conception of Ressentiment rests upon qualitatively different grounds transcending science and pure economics. For Scheler, Ressentiment is essentially a matter of self in relation to values, and only proximately an issue of social conflict over resources, power and the like (Master / Slave, or dominant / submissive relationships). For Scheler, what we call "having class", for instance, is not something as one-dimensional as power, money, or goods and services readily sold or purchased. Rather, liken to the array of apriori hierarchy of value modalities, "class" has to do with who you make of yourself as a person,[48] which involves a whole range of factors including moral character, integrity, talents, aptitudes, achievements, education, virtues (i.e., generosity), reciprocal respect among diverse individuals (active citizenship) and the like. Since society must be guided by the rule of law above power, we must promote government which relies upon fairness (See John Rawls) and egalitarian principal [49] in terms of channeling our national economic forces. Self-interest (as in Adam Smith's "invisible hand") is man's (and nature's) most highly efficient means of positively converting Vital Urge into human economic benefits-—the point at which "the rubber hits the road"—but it is also a force highly susceptible to greed. Therefore, government must insure that such raw pursuit of utility value is not purely an end in itself, but must serve primarily to form an economic base upon which genuine value strata and culture can take root and flourish for the common good as well as everyone's respective individual needs. We should realize that living with less materially does not diminish in any way our access to greater emotional, intellectual, artistic and spiritual fulfillment. Only in such ways can virtue truly become its own reward. |

結論 シェーラーの「ルサンチマン」概念を主に心理病理学の理論として評価するのは誤りである。確かに、その側面もあるが。さらに、「ルサンチマン」は、個人と 社会全体の精神と文化の健全性を評価するための哲学的・倫理的概念である。経済のグローバル化(すなわち、白紙委任状を伴う略奪資本主義の傾向)を踏まえ ると、この課題は一層緊急であるように思われる。略奪資本主義)がますます急務となっている。[47] たとえば、人間の倫理的超越を、ニーズや欲求というボトムアップの心理と補完的で釣り合いの取れたものとして捉えることは、その質的な方向性が本質的にポ ジティブである限り、まったく問題ない。しかし、その逆は誤りである。否定的な並列的な側面は、精神的存在としての私たちの個人的な成長から発する善とい うシェーラーのトップダウンの形而上学的原理に還元することはできない。この区別は、否定的なロールモデルが、心理学的観点から非常に自己実現した経済的 に強力な個人として現れる可能性があり、実際に現れるという多くの事例によって示されている(明らかに「スーパーマン」タイプの人物)。しかし、倫理的、 社会的、 例えば、少年たちが憧れ、見習うべき人物として麻薬の元締や売春斡旋業者が挙げられる。また、会社が倒産し、従業員年金基金が崩壊する一方で、法外なボー ナスを持ち逃げする腐敗した最高経営責任者(CEO)も挙げられる。こうした価値観の負の表出や価値の転倒は、科学や純粋経済学を超越した質的に異なる根 拠に立脚するルサンチマンの哲学的概念を如実に示している。 シェーラーにとって、ルサンチマンとは本質的には価値との関係における自己の問題であり、間接的には資源や権力などをめぐる社会的な対立の問題(主従関 係、支配/服従関係)である。シェーラーにとって、例えば私たちが「階級」と呼ぶものは、権力や金銭、あるいは容易に売買される商品やサービスといったよ うな単純なものではない。むしろ、価値の様態のあらかじめ備わった階層に似たものであり、「階級」とは、人として自分がどうあるかを意味するものであり、 [48] それは道徳的資質、誠実さ、才能、適性、業績、教育、美徳(すなわち寛大さ)、多様な個人間の相互尊重(積極的な市民権)など、さまざまな要因を含む。 社会は権力よりも法の支配によって導かれなければならないため、国民経済力を活用するにあたっては、公平性(ジョン・ロールズを参照)と平等主義の原則 [49]に依拠する政府を推進しなければならない。利己心(アダム・スミスのいう「見えざる手」のような)は、人間(および自然)が「生存本能」を人間の 経済的利益に積極的に転換させるための最も効率的な手段である。しかし、それはまた、強欲に非常に影響されやすい力でもある。したがって、政府は、そうし た純粋な効用価値の追求が、それ自体が目的化することのないよう保証しなければならない。そうではなく、真の価値の層や文化が根付き、繁栄するための経済 基盤を形成することが第一の目的でなければならない。物質的に少ないもので暮らすことが、感情面、知性面、芸術面、精神面での充実を妨げることは決してな いのだということを、私たちは理解すべきである。そうしてこそ、美徳は真にそれ自体が報酬となるのである。 |

| Max Scheler Scheler's Stratification of Emotional Life Ressentiment Master-slave morality A Theory of Justice (John Rawls) |

マックス・シェーラー シェーラーの感情生活の階層化 ルサンチマン 主人-奴隷道徳 正義論(ジョン・ロールズ) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ressentiment_(book) |

***

| Max Ferdinand Scheler

(German: [ˈʃeːlɐ]; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German

philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and

philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most

prominent German philosophers,[1] Scheler developed the philosophical

method of Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology. After Scheler's death in 1928, Martin Heidegger affirmed, with Ortega y Gasset, that all philosophers of the century were indebted to Scheler and praised him as "the strongest philosophical force in modern Germany, nay, in contemporary Europe and in contemporary philosophy as such."[2] |

マックス・フェルディナント・シェーラー(Max

Ferdinand Scheler、ドイツ語: [(↪Llɐ]; 1874年8月22日 -

1928年5月19日)は、現象学、倫理学、哲学的人間学の研究で知られるドイツの哲学者である。生前はドイツで最も著名な哲学者の一人とされ[1]、現

象学の創始者であるエドムント・フッサールの哲学的方法を発展させた。 1928年にシェーラーが亡くなった後、マルティン・ハイデガーはオルテガ・イ・ガセットとともに、今世紀のすべての哲学者はシェーラーに恩義を感じていると断言し、「近代ドイツ、いや、現代ヨーロッパ、そして現代哲学において最強の哲学的力」[2]と称えた。 |

| Life and career Childhood Max Scheler was born in Munich, Germany, on 22 August 1874, to a well-respected orthodox Jewish family.[1] He had "a rather typical late nineteenth century upbringing in a Jewish household bent on assimilation and agnosticism."[3] Student years Scheler began his university studies as a medical student at the University of Munich; he then transferred to the University of Berlin where he abandoned medicine in favor of philosophy and sociology, studying under Wilhelm Dilthey, Carl Stumpf and Georg Simmel. He moved to the University of Jena in 1896 where he studied under Rudolf Eucken, at that time a very popular philosopher who went on to win the Nobel Prize for literature in 1908. (Eucken corresponded with William James, a noted proponent of philosophical pragmatism, and throughout his life, Scheler entertained a strong interest in pragmatism.) It was at Jena that Scheler completed his doctorate and his habilitation and began his professional life as a teacher. His doctoral thesis, completed in 1897, was entitled Beiträge zur Feststellung der Beziehungen zwischen den logischen und ethischen Prinzipien (Contribution to establishing the relationships between logical and ethical principles). In 1898 he made a trip to Heidelberg and met Max Weber, who also had a significant impact on his thought. He earned his habilitation in 1899 with a thesis entitled Die transzendentale und die psychologische Methode (The transcendental and the psychological method) directed by Eucken. He became a lecturer (Privatdozent) at the University of Jena in 1901.[1] First period (Jena, Munich, Gottingen and World War I) When his first marriage, to Amalie von Dewitz,[4][5] ended in divorce, Scheler married Märit Furtwängler in 1912, who was the sister of the noted conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. Scheler's son by his first wife, Wolf Scheler, became troublesome after the divorce, often stealing from his father, and in 1923, after Wolf had tried to force him to pay for a prostitute, Scheler sent him to his former student Kurt Schneider, a psychiatrist, for diagnosis. Schneider diagnosed Wolf as not being mentally ill, but a psychopath, using two diagnostic categories (Gemütlos and Haltlos) essentially equivalent to today's "antisocial personality disorder".[6] Second period (Cologne) After 1921 he disassociated himself in public from Catholic teaching and even from the Judeo-Christian-Islamic God,[7][8] committing himself to pantheism and philosophical anthropology.[9] Scheler had developed the habit of smoking between sixty and eighty cigarettes a day which contributed to a series of heart attacks throughout 1928, forcing him to cancel any travel plans. On May 19, 1928, he died in a Frankfurt hospital due to complications from a severe heart attack.[10] |

生涯とキャリア 幼少時代 マックス・シェラーは1874年8月22日、ドイツのミュンヘンで、正統派ユダヤ人の家系に生まれた[1]。 同化と不可知論に傾倒したユダヤ人の家庭で、19世紀末の典型的な少年時代を過ごした」[3]。 学生時代 その後、ベルリン大学に移り、医学を捨てて哲学と社会学を学び、ヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ、カール・シュトゥンプ、ゲオルク・ジンメルに師事した。 1896年にイエナ大学に移り、当時大人気の哲学者で1908年にノーベル文学賞を受賞したルドルフ・オイッケンに師事した。(オイケンは哲学的プラグマ ティズムの提唱者として知られるウィリアム・ジェームズと交流があり、シェラーは生涯を通じてプラグマティズムに強い関心を抱いていた)。イエナでシェ ラーは博士号とハビリテーションを取得し、教師としての職業生活を始めた。1897年に完成した博士論文のタイトルは『論理的原理と倫理的原理との関係を 確立するための貢献』(Beiträge zur Feststellung der Beziehung zwischen logischen und ethischen Prinzipien)であった。1898年にはハイデルベルクを訪れ、マックス・ウェーバーと出会い、彼の思想にも大きな影響を与えた。1899年、 『超越論的方法と心理学的方法』(Die transzendentale und die psychologische Methode)というタイトルの論文を執筆し、ユーケンの指導のもとでハビリテーションを取得した。1901年にイエナ大学の講師となる[1]。 第一期(イエナ、ミュンヘン、ゴッティンゲン、第一次世界大戦) 最初の結婚相手であるアマリー・フォン・デヴィッツ[4][5]が離婚に終わると、シェラーは1912年に著名な指揮者ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー の妹であるメーリット・フルトヴェングラーと結婚した。最初の妻との間にもうけた息子のヴォルフ・シェラーは、離婚後、しばしば父親のものを盗むなど厄介 な存在となり、1923年、ヴォルフが娼婦に金を払わせようとしたため、シェラーはヴォルフをかつての教え子で精神科医のクルト・シュナイダーに診断に出 した。シュナイダーは、ヴォルフを精神疾患ではなく精神病質者と診断し、今日の「反社会性人格障害」に本質的に相当する2つの診断カテゴリー(ゲミュトロ スとハルトロス)を用いた[6]。 第二期(ケルン) 1921年以降、彼は公の場でカトリックの教えから、さらにはユダヤ教・キリスト教・イスラム教の神からも距離を置き、汎神論と哲学的人間学に身を投じた[7][8]。 シェラーは1日に60本から80本のタバコを吸う習慣を身につけ、1928年を通じて心臓発作を繰り返し、旅行の計画をキャンセルせざるを得なくなった。1928年5月19日、重度の心臓発作の合併症によりフランクフルトの病院で死去した[10]。 |

| Philosophical contributions Love and the "phenomenological attitude" When the editors of Geisteswissenschaften invited Scheler (about 1913/14) to write on the then developing philosophical method of phenomenology, Scheler indicated that the phenomenological movement was not defined by universally accepted theses but by a "common bearing and attitude toward philosophical problems."[11] Scheler disagrees with Husserl that phenomenology is a method of strict phenomenological reduction, but rather "an attitude of spiritual seeing...something which otherwise remains hidden...."[11] Calling phenomenology a method fails to take seriously the phenomenological domain of original experience: the givenness of phenomenological facts (essences or values as a priori) "before they have been fixed by logic,"[11] and prior to assuming a set of criteria or symbols, as is the case in the natural and human sciences as well as other (modern) philosophies which tailor their methods to those of the sciences. Rather, that which is given in phenomenology "is given only in the seeing and experiencing act itself." The essences are never given to an 'outside' observer without direct contact with a specific domain of experience. Phenomenology is an engagement of phenomena, while simultaneously a waiting for its self-givenness; it is not a methodical procedure of observation as if its object is stationary. Thus, the particular attitude (Geisteshaltung, lit. "disposition of the spirit" or "spiritual posture") of the philosopher is crucial for the disclosure, or seeing, of phenomenological facts. This attitude is fundamentally a moral one, where the strength of philosophical inquiry rests upon the basis of love. Scheler describes the essence of philosophical thinking as "a love-determined movement of the inmost personal self of a finite being toward participation in the essential reality of all possibles."[12] The movement and act of love is important for philosophy for two reasons: (1) If philosophy, as Scheler describes it, hearkening back to the Platonic tradition, is a participation in a "primal essence of all essences" (Urwesen), it follows that for this participation to be achieved one must incorporate within oneself the content or essential characteristic of the primal essence.[13] For Scheler, such a primal essence is most characterized according to love, thus the way to achieve the most direct and intimate participation is precisely to share in the movement of love. It is important to mention, however, that this primal essence is not an objectifiable entity whose possible correlate is knowledge; thus, even if philosophy is always concerned with knowing, as Scheler would concur, nevertheless, reason itself is not the proper participative faculty by which the greatest level of knowing is achieved. Only when reason and logic have behind them the movement of love and the proper moral preconditions can one achieve philosophical knowledge.[14] (2) Love is likewise important insofar as its essence is the condition for the possibility of the givenness of value-objects and especially the givenness of an object in terms of its highest possible value. Love is the movement which "brings about the continuous emergence of ever-higher value in the object--just as if it was streaming out from the object of its own accord, without any sort of exertion...on the part of the lover. ...true love opens our spiritual eyes to ever-higher values in the object loved."[15] Hatred, on the other hand, is the closing off of oneself or closing one's eyes to the world of values. It is in the latter context that value-inversions or devaluations become prevalent, and are sometimes solidified as proper in societies. Furthermore, by calling love a movement, Scheler hopes to dispel the interpretation that love and hate are only reactions to felt values rather than the very ground for the possibility of value-givenness (or value-concealment). Scheler writes, "Love and hate are acts in which the value-realm accessible to the feelings of a being...is either extended or narrowed."[16] |

哲学的貢献 「愛と "現象学的態度」 Geisteswissenschaften』誌の編集者が当時発展しつつあった現象学の哲学的方法について執筆するようシェーラーを招いたとき (1913/14年頃)、シェーラーは現象学運動が普遍的に受け入れられたテーゼによって定義されたのではなく、「哲学的問題に対する共通の姿勢と態度」 [11]によって定義されたものであることを示した。 現象学を方法と呼ぶことは、自然科学や人間科学、また科学の方法に方法を合わせる他の(近代的な)哲学の場合のように、「論理によって固定される前の」 [11]、そして一連の基準や象徴を仮定する前の現象学的事実(先験的な本質や価値)の所与性という、原体験の現象学的領域を真剣に受け止めることに失敗 している。 そうではなく、現象学で与えられるものは、「見たり体験したりする行為そのものにのみ与えられる 」のである。エッセンスは、特定の経験領域との直接的な接触なしに、「外部」の観察者に与えられることはない。現象学とは、現象に関わることであると同時 に、現象が自ずから与えられることを待つことであり、対象が静止しているかのような方法論的な観察手続きではない。したがって、哲学者の特定の態度 (Geisteshaltung、「精神の態度」または「精神的な姿勢」)は、現象学的事実の開示、すなわち「見る」ために極めて重要である。この態度は 基本的に道徳的なものであり、哲学的探求の強さは愛に基づいている。シェラーは哲学的思考の本質を、「すべての可能性の本質的実在への参加に向けた、有限 な存在の内なる個人的自己の、愛によって決定された運動」[12]と表現している。 愛の運動と行為が哲学にとって重要なのは、次の2つの理由による。(1)シェラーがプラトン的伝統に立ち返りつつ述べているように、哲学が「すべての本質 の原初的本質」(ウルヴェーセン)への参加であるとすれば、この参加が達成されるためには、原初的本質の内容や本質的な特徴を自分の中に取り込まなければ ならないことになる。したがって、シェラーが同意するように、哲学が常に知ることに関係しているとしても、理性そのものは、知ることの最大のレベルを達成 するための適切な参加能力ではない。理性と論理の背後に愛の運動と適切な道徳的前提条件があってはじめて、人は哲学的知識を達成することができるのであ る。愛とは、「あたかも、恋人の側で何らかの努力をすることなく、その対象から自ずから流れ出るかのように、対象においてより高い価値が絶えず出現する」 運動なのである。......真の愛は、愛される対象の中にあるこれまで以上に高い価値に対して、私たちの精神的な目を開かせる」[15]。一方、憎しみ とは、自分自身を閉ざすこと、あるいは価値の世界に対して目を閉ざすことである。後者の文脈では、価値観の逆転や切り捨てが蔓延し、社会における適切なも のとして固められることもある。さらにシェラーは、愛を運動と呼ぶことで、愛と憎しみが価値付与(あるいは価値隠蔽)の可能性の根拠そのものではなく、感 じられた価値に対する反応に過ぎないという解釈を払拭したいと考えている。シェラーは「愛と憎しみは、ある存在の感情にアクセス可能な価値領域が拡張され るか狭められるかのいずれかの行為である」と書いている[16]。 |

| Material value-ethics Values and their corresponding disvalues are ranked according to their essential interconnections as follows: 1. Religiously relevant values (holy/unholy) 2. Spiritual values (beauty/ugliness, knowledge/ignorance, right/wrong) 3. Vital values (health/unhealthiness, strength/weakness) 4. Sensible values (agreeable/disagreeable, comfort/discomfort)[17] Further essential interconnections apply with respect to a value's (disvalue's) existence or non-existence: The existence of a positive value is itself a positive value. The existence of a negative value (disvalue) is itself a negative value. The non-existence of a positive value is itself a negative value. The non-existence of a negative value is itself a positive value.[18] And with respect to values of good and evil: Good is the value that is attached to the realization of a positive value in the sphere of willing. Evil is the value that is attached to the realization of a negative value in the sphere of willing. Good is the value that is attached to the realization of a higher value in the sphere of willing. Evil is the value that is attached to the realization of a lower value [at the expense of a higher one] in the sphere of willing.[18] Goodness, however, is not simply "attached" to an act of willing, but originates ultimately within the disposition (Gesinnung) or "basic moral tenor" of the acting person. Accordingly: The criterion of 'good' consists in the agreement of a value intended, in the realization, with the value preferred, or in its disagreement with the value rejected. The criterion of 'evil' consists in the disagreement of a value intended, in the realization, with the value preferred, or in its agreement with the value rejected.[18] |

物質的価値倫理 価値とそれに対応する不価値は、その本質的な相互関係に従って以下のようにランク付けされる: 1. 宗教的に関連する価値(聖なるもの/神聖でないもの) 2. 精神的価値(美/醜、知識/無知、善/悪) 3. バイタルな価値観(健康/不健康、強さ/弱さ) 4. 感性的価値(賛成/反対、快適/不快)[17]。 価値(不価値)の存否に関しては、さらに本質的な相互関係が適用される: 正の価値が存在すること自体が正の価値である。 負の価値(不価値)の存在は、それ自体が負の価値である。 正の値の非存在は、それ自体が負の値である。 否定的価値の非存在は、それ自体が肯定的価値である[18]。 また、善と悪の価値に関してもそうである: 善とは、意志の領域における正の価値の実現に付随する価値である。 悪とは、意志の領域における負の価値の実現に付随する価値である。 善とは、意志の領域において、より高い価値を実現することに付随する価 値である。 悪とは、意志の領域において、[より高い価値を犠牲にして]より低い価 値を実現することに付随する価値である[18]。 しかし、善は、単に意志の行為に「付随」しているのではなく、最終的には行為者の気質(Gesinnung)すなわち「基本的な道徳的傾向」のうちに由来するのである。従って 善」の基準は、意図された価値が、その実現において、好ましい価値と一致する こと、あるいは拒絶された価値と一致しないことにある。 悪」の基準は、意図された価値が、実現において、好ましい価値と一致しないこと、あるいは拒絶された価値と一致することにある[18]。 |

| Man and History (1924) Scheler planned to publish his major work in anthropology in 1929, but the completion of such a project was curtailed by his premature death in 1928. Some fragments of such work have been published in Nachlass.[19] In 1924, Man and History (Mensch und Geschichte), Scheler gave some preliminary statements on the range and goal of philosophical anthropology.[20] In this book, Scheler argues for a tabula rasa of all the inherited prejudices from the three main traditions that have formulated an idea of man: religion, philosophy and science.[21][22] Scheler argues that it is not enough just to reject such traditions, as did Nietzsche with the Judeo-Christian religion by saying that "God is dead"; these traditions have impregnated all parts of our culture, and therefore still determine a great deal of the way of thinking even of those that don't believe in the Christian God.[23] |

人間と歴史(1924年) シェーラーは1929年に人類学の大著を出版する予定であったが、1928年に早逝したため、その完成は頓挫した。1924年に出版された『人間と歴史』 (Mensch und Geschichte)において、シェーラーは哲学的人間学の範囲と目標についていくつかの予備的な見解を述べている[20]。 この本の中でシェーラーは、宗教、哲学、科学という人間についての考え方を形成してきた3つの主要な伝統から受け継いだすべての偏見をタブラ・ラサにする ことを主張している[21][22]。シェーラーは、ニーチェが「神は死んだ」と言うことによってユダヤ・キリスト教を否定したように、このような伝統を 否定するだけでは不十分であり、これらの伝統は私たちの文化のあらゆる部分に浸透しており、それゆえキリスト教の神を信じない人々でさえもいまだに考え方 の大部分を決定していると主張している[23]。 |

Works Max Scheler Zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Sympathiegefühle und von Liebe und Hass, 1913 Der Genius des Kriegs und der Deutsche Krieg, 1915 Der Formalismus in der Ethik und die materiale Wertethik, 1913–1916 Krieg und Aufbau, 1916 Die Ursachen des Deutschenhasses, 1917 Vom Umsturz der Werte, 1919 Neuer Versuch der Grundlegung eines ethischen Personalismus, 1921 Vom Ewigen im Menschen, 1921 Probleme der Religion. Zur religiösen Erneuerung, 1921 Wesen und Formen der Sympathie, 1923 (newly edited as: Zur Phänomenologie ... 1913) Schriften zur Soziologie und Weltanschauungslehre, 3 Bände, 1923/1924 Die Wissensformen und die Gesellschaft, 1926 Der Mensch im Zeitalter des Ausgleichs, 1927 Die Stellung des Menschen im Kosmos, 1928 Philosophische Weltanschauung, 1929 Logik I. (Fragment, Korrekturbögen). Amsterdam 1975 |

作品 マックス・シェラー 共感と愛憎の感情の現象学と理論について』1913年 戦争の天才とドイツ戦争, 1915 倫理学における形式主義と価値観の物質倫理学, 1913-1916 戦争と復興 (1916) ドイツ人の憎悪の原因 1917年 価値観の転覆 1919年 倫理的個人主義の基礎を築く新たな試み (1921) 人間における永遠性について, 1921 宗教の問題 宗教的刷新について、1921年 シンパシーの本質と形式、1923年(現象学について...1913年として新たに編集された) 社会学・世界観研究』全3巻 1923/1924 知の形態と社会』1926年 平等化の時代における人間』 1927年 宇宙における人間の位置, 1928 哲学的世界観, 1929 論理学 I. (断片、訂正シート)。アムステルダム 1975 |

| English translations The Nature of Sympathy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954. Philosophical Perspectives. translated by Oscar Haac. Boston: Beacon Press. 1958. 144 pages. (German title: Philosophische Weltanschauung.) On the Eternal in Man. translated by Bernard Noble. London: SCM Press. 1960. 480 pages. Ressentiment. edited by Lewis A. Coser, translated by William W. Holdheim. New York: Schocken. 1972. 201 pages. ISBN 0-8052-0370-2. Selected Philosophical Essays. translated by David R. Lachterman. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. 1973. ISBN 9780810103795. 359 pages. ISBN 0-8101-0379-6. Formalism in Ethics and Non-Formal Ethics of Values: A New Attempt toward the Foundation of an Ethical Personalism. Translated by Manfred S. Frings and Roger L. Funk. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. 1973. 620 pages. ISBN 0-8101-0415-6. (Original German edition: Der Formalismus in der Ethik und die materiale Wertethik, 1913–16.) Problems of a Sociology of Knowledge. translated by Manfred S. Frings. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1980. 239 pages. ISBN 0-7100-0302-1. Person and Self-value: Three Essays. edited and partially translated by Manfred S. Frings. Boston: Nijhoff. 1987. 201 pages. ISBN 90-247-3380-4. On Feeling, Knowing, and Valuing. Selected Writings. edited and partially translated by Harold J. Bershady. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1992. 267 pages. ISBN 0-226-73671-7. The Human Place in the Cosmos. translated by Manfred Frings. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. 2009. 79 pages. ISBN 978-0-8101-2529-2. |

英訳 The Nature of Sympathy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954. オスカー・ハーク訳『哲学的展望』ボストン: 1954年。ボストン: ビーコン・プレス 1958. 144ページ。(ドイツ語タイトル:Philosophische Weltanschauung.) バーナード・ノーブル訳。London: SCM Press. 1960. 480ページ。 ルサンチマン』 ルイス・A・コーサー編 ウィリアム・W・ホールドハイム訳 ニューヨーク: ショッケン。1972. 201ページ。ISBN 0-8052-0370-2. 哲学エッセイ選集』 デイヴィッド・R・ラクターマン訳。イリノイ州エバンストン: ノースウェスタン大学出版局。1973. ISBN 9780810103795。359ページ。ISBN 0-8101-0379-6. 倫理学における形式主義と非形式的価値倫理: 倫理的個人主義の基礎に向けた新たな試み。マンフレッド・S・フリングス、ロジャー・L・ファンク訳。イリノイ州エバンストン: ノースウェスタン大学出版局。1973. 620ページ。ISBN 0-8101-0415-6. (原著はドイツ語版: ドイツ語原書:Der Formalismus in der Ethik und die materiale Wertethik, 1913-16.) 知識社会学の問題点』マンフレッド・S・フリングス訳。ロンドン: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1980. 239ページ。ISBN 0-7100-0302-1. 人と自己価値: マンフレッド・S・フリングス編・部分訳。ボストン: Nijhoff. 1987. 201ページ。ISBN 90-247-3380-4. 感じること、知ること、価値について。ハロルド・J・バーシャディ編・部分訳。シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局。1992. 267ページ。ISBN 0-226-73671-7. マンフレッド・フリングス著『コスモスにおける人間の位置』(エバンストン、1992年)。エバンストン: ノースウェスタン大学出版局. 2009. 79ページ。ISBN 978-0-8101-2529-2. |

| Axiological ethics Ressentiment (Scheler) Mimpathy Stratification of emotional life (Scheler) |

公理論的倫理 ルサンチマン(シェーラー) ミンパシー 感情生活の階層化(シェーラー) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Scheler |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆