マヤ人

Maya peoples

左:ヤシュチラン遺跡の石彫(Detail of Lintel 26 from Yaxchilan):右:メキシコ・チアパス州のシナカンタンの若者(George E. Stuart and National Geographic

★マヤ(Maya)は、メソアメリカの先住民の民族言語グループで ある。古代マヤ文明はこのグループのメンバーによって形成され、今日のマヤは一般的にその歴史的地域に住んでいた人々の子孫である。現在、彼らはメキシコ 南部、グアテマラ、ベリーズ、エルサルバドル最西部、ホンジュラスに居住していほか、グローバルな移民の結果、北米ならびにヨーロッパを中心に世界各地に居住している。

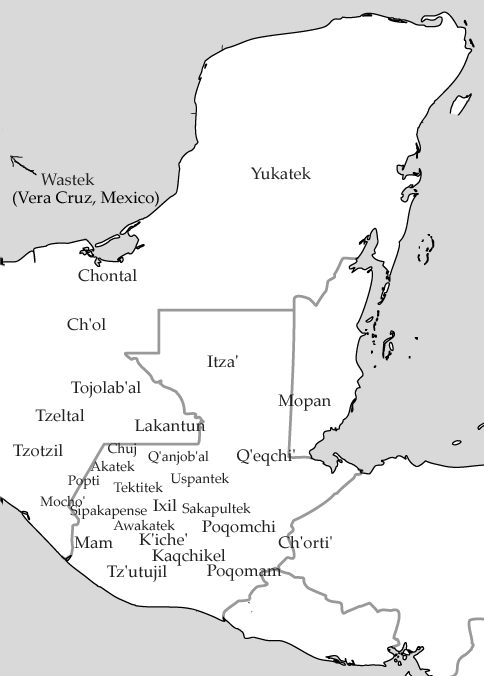

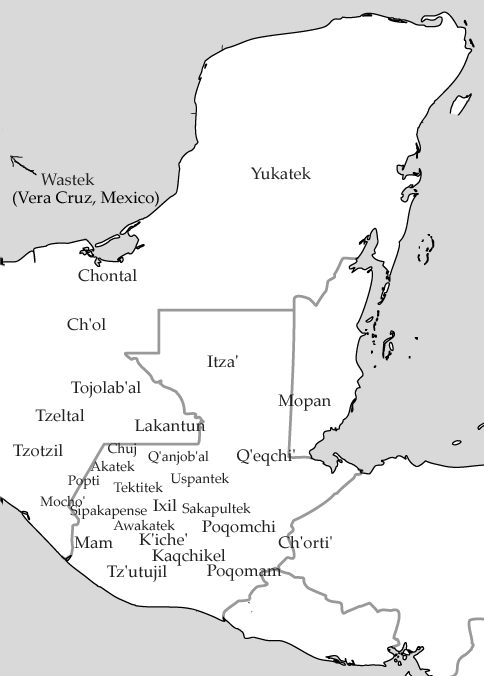

☆ Map showing the extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to all other Mesoamerica cultures (black). Within Central America and southern North America (Mexico). This map also shows the cities and cultural mainsteads of the Maya, who did not have an empire but rather a group of loosely associated city-states.

★古代マヤ文明(赤)の範囲を他のメソアメリカ文化(黒)と比較した地図。中 央アメリカと北アメリカ南部(メキシコ)の範囲。この地図はまた、帝国を持たず、緩やかに関連した都市国家のグループであったマヤの都市と文化的な主要拠 点を示している。

| The Maya (/ˈmaɪə/)

are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The

ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and

today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that

historical region. Today they inhabit southern Mexico, Guatemala,

Belize, and westernmost El Salvador and Honduras. "Maya" is a modern collective term for the peoples of the region; however, the term was not historically used by the indigenous populations themselves. There was no common sense of identity or political unity among the distinct populations, societies and ethnic groups because they each had their own particular traditions, cultures and historical identity.[10] It is estimated that seven million Maya were living in this area at the start of the 21st century.[1][2] Guatemala, southern Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, El Salvador, and western Honduras have managed to maintain numerous remnants of their ancient cultural heritage. Some are quite integrated into the majority hispanicized mestizo cultures of the nations in which they reside, while others continue a more traditional, culturally distinct life, often speaking one of the Mayan languages as a primary language.  |

マヤ(/ˈmaɪə/)は、メソアメリカの先住民の民族言語グループで

ある。古代マヤ文明はこのグループのメンバーによって形成され、今日のマヤは一般的にその歴史的地域に住んでいた人々の子孫である。現在、彼らはメキシコ

南部、グアテマラ、ベリーズ、エルサルバドル最西部、ホンジュラスに居住している。 「マヤ 」は、この地域の人々の現代的な総称である。しかし、この言葉は歴史的に先住民族自身によって使われていたわけではない。それぞれ独自の伝統、文化、歴史 的アイデンティティを持っていたため、異なる集団、社会、民族の間に共通のアイデンティティや政治的統一感はなかった[10]。 グアテマラ、メキシコ南部とユカタン半島、ベリーズ、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラス西部は、古代の文化遺産の数々を維持することに成功している。また、伝 統的で文化的に独特な生活を続けている人々もおり、多くの場合、マヤ語のいずれかを主要言語として話している。  |

Yucatan Peninsula One of the largest groups of Maya live in the Yucatan Peninsula, which includes the Mexican states of Yucatán State, Campeche, and Quintana Roo as well as the nation of Belize. These people identify themselves as "Maya" with no further ethnic subdivision (unlike in the Highlands of Western Guatemala). They speak the language which anthropologists term "Yucatec Maya", but is identified by speakers and Yucatecos simply as "Maya". Among Maya speakers, Spanish is commonly spoken as a second or first language.[citation needed] There is a significant amount of confusion as to the correct terminology to use—Maya or Mayan—and the meaning of these words with reference to contemporary or pre-Columbian peoples, to Maya peoples in different parts of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and to languages or peoples. oxlahun ahau u katunil u 13 he›cob cah mayapan: maya uinic u kabaob: uaxac ahau paxci u cabobi: ca uecchahi ti peten tulacal: uac katuni paxciob ca haui u maya-bulub ahau u kaba u katunil hauci u maya kabaob maya uinicob: christiano u kabaob "Ahau was the katun when they founded the cah of Mayapan; they were [thus] called Maya men. In 8 Ahau their lands were destroyed and they were scattered throughout the peninsula. Six katun after they were destroyed they ceased to be called Maya; 11 Ahau was the name of the katun when the Maya men ceased to be called Maya [and] were called Christians." Chilam Balam Chumayel[11] Linguists refer to the Maya language as Yucatec or Yucatec Maya to distinguish it from other Mayan languages. This norm has often been misinterpreted to mean that the people are also called Yucatec Maya; that term refers only to the language, and the correct name for the people is simply Maya (not Mayans). (Yucatec) Maya is one language in the Mayan language family.[12] Confusion of the term Maya/Mayan as an ethnic label occurs because Maya women who use traditional dress identify by the ethnic term mestiza and not Maya.[13] Persons use a strategy of ethnic identification that Juan Castillo Cocom refers to as "ethnoexodus"—meaning that ethnic self-identification as Maya is quite variable, situational, and articulated not to processes of producing group identity, but of escaping from discriminatory processes of sociocultural marginalization.[14][15] The Yucatán's indigenous population was first exposed to Europeans after a party of Spanish shipwreck survivors came ashore in 1511. One of the sailors, Gonzalo Guerrero, is reported to have taken up with a local woman and started a family; he became a war captain in the Postclassic Mayan state of Chetumal. Later Spanish expeditions to the region were led by Córdoba in 1517, Grijalva in 1518, and Cortés in 1519. From 1528 to 1540, several attempts by Francisco Montejo to conquer the Yucatán failed. His son, Francisco de Montejo the Younger, fared almost as badly when he first took over: while invading Chichen Itza, he lost 150 men in a single day.[16] European diseases, massive recruitment of native warriors from Campeche and Champoton, and internal hatred between the Xiu Maya and the lords of Cocom eventually turned the tide for Montejo the Younger. Chichen Itza was conquered by 1570.[16] In 1542, the western Yucatán Peninsula also surrendered to him. Historically, the population in the eastern half of the peninsula was less affected by and less integrated with Hispanic culture than the western half. In the 21st century in the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexican states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo), between 750,000 and 1,200,000 people speak Mayan. However, three times more than that are of Maya origins, hold ancient Maya surnames, and do not speak Mayan languages as their first language. Matthew Restall, in his book The Maya Conquistador,[17] mentions a series of letters sent to the King of Spain in the 16th and 17th centuries. The noble Maya families at that time signed documents to the Spanish royal family; surnames mentioned in those letters are Pech, Camal, Xiu, Ucan, Canul, Cocom, and Tun, among others.  Yucateken A large 19th-century revolt by the native Maya people of Yucatán (Mexico), known as the Caste War of Yucatán, was one of the most successful modern Native American revolts.[18] For a period the Maya state of Chan Santa Cruz was recognized as an independent nation by the British Empire, particularly in terms of trading with British Honduras.  Former governor of Yucatán, Francisco Luna Kan, is a Maya with the very common surname "Kan" Francisco Luna-Kan was elected governor of the state of Yucatán from 1976 to 1982. Luna-Kan was born in Mérida, Yucatán, and he was a doctor of medicine, then a professor of medicine before his political offices. He was first appointed as overseer of the state's rural medical system. He was the first governor of the modern Yucatán Peninsula to be of full Maya ancestry. In the early 21st century, dozens of politicians, including deputies, mayors and senators, are of full or mixed Maya heritage from the Yucatán Peninsula. According to the National Institute of Geography and Informatics (Mexico's INEGI), in Yucatán State there were 1.2 million Mayan speakers in 2009, representing just under 60% of the inhabitants.[19] Due to this, the cultural section of the government of Yucatán began on-line classes for grammar and proper pronunciation of Maya.[20] Maya people from Yucatán Peninsula living in the United States of America have been organizing Maya language lessons and Maya cooking classes since 2003 in California and other states: clubs of Yucatec Maya[21] are registered in Dallas and Irving, Texas; Salt Lake City in Utah; Las Vegas, Nevada; and California, with groups in San Francisco, San Rafael, Chino, Pasadena, Santa Ana, Garden Grove, Inglewood, Los Angeles, Thousand Oaks, Oxnard, San Fernando Valley and Whittier.[21] Maya language is taught at the college and graduate level; beginning, intermediate, and advanced courses in Maya have been taught at Indiana University since 2010. The Open School of Ethnography and Anthropology offers immersion Maya courses in a six week intensive summer program |

ユカタン半島 メキシコのユカタン州、カンペチェ州、キンタナ・ロー州とベリーズを含むユカタン半島には、マヤの最大グループのひとつが住んでいる。グアテマラ西部の高 地とは異なり)これらの人々は、それ以上の民族区分はなく、自らを「マヤ」と称している。彼らは人類学者が「ユカテク・マヤ」と呼ぶ言語を話すが、話者や ユカテコ人は単に「マヤ」と呼ぶ。マヤ語を話す人々の間では、スペイン語が第二言語または第一言語として話されているのが一般的である[要出典]。マヤ語 またはマヤ語のどちらを使用するのが正しいのか、また、現代または先コロンビア時代の民族、メキシコ、グアテマラ、ベリーズのさまざまな地域のマヤ民族、 言語または民族に関連するこれらの単語の意味については、かなりの混乱がある。 oxlahunアハウ・ウ・カトゥニル・ウ13・ヘコブ・カ・マヤパン:マヤ・ウイニック・ウ・カバオブ:ウアクサク・アハウ・パクシ・ウ・カボビ:カ・ ウエチャヒ・ティ・ペテン・トゥラカル:ウアクサク・カトゥニ・パクシオブ・カ・ハウイ・ウ・マヤ・ブルブ アハウ・ウ・カバ・ウ・カトゥニル・ウ・シ・ウ・マヤ・カバオブ マヤ・ウイニック・ウ・カバオブ:クリスティアーノ・ウ・カバオブ 「アハウは、マヤパンのカを築いたときのカトゥンであり、彼らはマヤ人と呼ばれた。アハウ8年、彼らの土地は破壊され、彼らは半島中に散らばった。マヤ人 がマヤと呼ばれなくなり、クリスチャンと呼ばれるようになったのは、11アハウがそのカトゥンの名前である。" チラム・バラム・チュマイエル[11]。 言語学者たちは、マヤ語を他のマヤ語から区別するために、ユカテク語またはユカテク・マヤ語と呼んでいる。この呼称は言語のみを指すものであり、民族の正 しい呼称は単にマヤ(マヤ人ではない)である。(ユカテク)マヤはマヤ語族の1つの言語である[12]。民族的なラベルとしてのマヤ/マヤという用語の混 乱は、伝統的なドレスを使用するマヤの女性がマヤではなくメスチサという民族的な用語で識別するために起こる[13]。 フアン・カスティーリョ・ココムが「エスノエクソダス(ethnoexodus)」と呼ぶ民族的アイデンティフィケーションの戦略をマヤの人々は用いてお り、マヤとしての民族的自認は非常に多様であり、状況的であり、集団のアイデンティティを生み出すプロセスではなく、社会文化的疎外という差別的プロセス から逃れるためのものであることを意味している[14][15]。 ユカタン先住民が初めてヨーロッパ人と接触したのは、1511年に難破船から生還したスペイン人の一団が上陸した後のことである。船員の一人であったゴン サロ・ゲレロは、地元の女性と結婚して家庭を築き、後古典期マヤのチェトゥマル州で戦争隊長となったと伝えられている。その後、スペインは1517年にコ ルドバ、1518年にグリハルバ、1519年にコルテスを率いてこの地を探検した。1528年から1540年まで、フランシスコ・モンテホによるユカタン 征服の試みは何度も失敗した。彼の息子であるフランシスコ・デ・モンテホは、チチェン・イッツァを侵略した際、1日で150人の兵士を失った[16]。 ヨーロッパの疫病、カンペチェとチャンポトンからの原住民戦士の大量徴集、シュー・マヤとココム領主の間の内紛が、最終的にモンテホに流れを変えた。 1570年にはチチェン・イッツァが征服され、1542年にはユカタン半島西部もモンテホに降伏した[16]。 歴史的に、半島の東半分の人口は、西半分に比べてヒスパニック文化の影響を受けにくく、ヒスパニック文化との融合も少なかった。21世紀のユカタン半島 (メキシコのカンペチェ州、ユカタン州、キンタナ・ロー州)では、75万人から120万人がマヤ語を話す。しかし、その3倍以上の人々がマヤに起源を持 ち、古代マヤの姓を持ち、マヤ語を母語としていない。 マシュー・レスタルは著書『マヤのコンキスタドール』[17]の中で、16世紀から17世紀にかけてスペイン国王に送られた一連の手紙について触れてい る。当時のマヤの高貴な一族がスペイン王家に宛てた文書に署名している。それらの書簡に記載されている姓は、ペチ、カマル、シュー、ウカン、カヌル、ココ ム、トゥンなどである。  ユカテケン ユカタン(メキシコ)の先住民マヤ族による19世紀の大規模な反乱は、ユカタンのカースト戦争として知られ、最も成功した近代アメリカ先住民の反乱のひと つであった[18]。 一時期、マヤのチャン・サンタ・クルス州は大英帝国から独立国として認められ、特にイギリス領ホンジュラスとの交易の面で認められた。  元ユカタン州知事のフランシスコ・ルナ=カンは、「カン 」という非常に一般的な姓を持つマヤ人である。 フランシスコ・ルナ=カンは1976年から1982年までユカタン州知事に選出された。ルナ=カンはユカタン州メリダで生まれ、医学博士、医学教授を経て 政治家になった。最初に任命されたのは州の農村医療システムの監督官だった。近代ユカタン半島でマヤの血を引く最初の知事である。21世紀初頭、代議士、 市長、上院議員を含む数十人の政治家が、ユカタン半島出身のマヤの完全な、あるいは混血である。 国立地理情報研究所(メキシコのINEGI)によると、ユカタン州では2009年に120万人のマヤ語話者がおり、住民の60%弱を占めている[19]。 このため、ユカタン州政府の文化部門は、マヤ語の文法と正しい発音のためのオンラインクラスを開始した[20]。 テキサス州ダラスとアービング、ユタ州ソルトレイクシティ、ネバダ州ラスベガス、そしてカリフォルニア州では、サンフランシスコ、サンラファエル、チノ、 パサデナ、サンタアナ、ガーデングローブ、イングルウッド、ロサンゼルス、サウザンドオークス、オックスナード、サンフェルナンドバレー、ウィッティアに グループがある。 [21]マヤ語は大学や大学院レベルでも教えられており、インディアナ大学では2010年からマヤ語の初級、中級、上級コースが開講されている。民族学・ 人類学のオープンスクールでは、6週間の集中サマープログラムでマヤ語イマージョン・コースを提供している。 |

Chiapas Maya populations in Chiapas. The area officially assigned to the Lacandon Community is the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, which partly overlaps with the Tzeltal, Tojolabal and Chʼol areas. Note. The Zoque are not Maya. Chiapas was for many years one of the regions of Mexico that was least touched by the reforms of the Mexican Revolution. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation, launched a rebellion against the Mexican state, Chiapas in January 1994, declared itself to be an indigenous movement and drew its strongest and earliest support from Chiapan Maya. Today its number of supporters is relevant. (see also the EZLN and the Chiapas conflict) Maya groups in Chiapas include the Tzotzil and Tzeltal, in the highlands of the state, the Tojolabalis concentrated in the lowlands around Las Margaritas, the Chʼol in the jungle, and in the south eastern uplands, the endangered Mochó and the Kaqchikel, also widely spoken in the Guatemalan highlands. (See map. Note. The Zoque are not Maya.) The most traditional of Maya groups are the Lacandon, a small population avoiding contact with outsiders until the late 20th century by living in small groups in the Lacandon Jungle. These Lacandon Maya came from the Campeche/Petén area (north-east of Chiapas) and moved into the Lacandon rain-forest at the end of the 18th century. In the course of the 20th century, and increasingly in the 1950s and 1960s, other people (mainly the Maya and subsistence peasants from the highlands), also entered into the Lacandon region; initially encouraged by the government. This immigration led to land-related conflicts and an increasing pressure on the rainforest. To halt the migration, the government decided in 1971 to declare a large part of the forest (614,000 hectares, or 6140 km2) a protected area: the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. They appointed only one small population group (the 66 Lacandon families) as tenants (thus creating the Lacandon Community), thereby displacing 2000 Tzeltal and Chʼol families from 26 communities, and leaving non-Lacandon communities dependent on the government for granting their rights to land. In the decades that followed the government carried out numerous programs to keep the problems in the region under control, using land distribution as a political tool; as a way of ensuring loyalty from different campesino groups. This strategy of divide and rule led to great disaffection and tensions among population groups in the region. (see also the Chiapas conflict and the Lacandon Jungle). |

チアパス チアパス州のマヤの集団である。ラカンドン共同体に公式に割り当てられた地域はモンテス・アズレス生物圏保護区で、ツェルタル、トジョラバル、チオール地 域と一部重なっている。注。ゾケ族はマヤ族ではない。 チアパスは長年、メキシコ革命の改革に最も触れられなかった地域のひとつであった。1994年1月にメキシコのチアパス州に対して反乱を起こしたサパティ スタ民族解放軍は、自らを先住民運動であると宣言し、チアパン・マヤから最も強力かつ初期の支持を得た。今日、その支持者の数は関連している。(EZLN とチアパス紛争も参照)。 チアパス州のマヤグループには、州の高地に住むツォツィル族とツェルタル族、ラス・マルガリータス周辺の低地に集中するトジョラバリス族、ジャングルに住 むチロル族、南東部の高地に住む絶滅危惧種のモチョ族と、グアテマラ高地でも広く話されているカクチケル族がいる。(地図参照。注:ゾケ族はマヤ族ではな い)。 最も伝統的なマヤ・グループはラカンドン族で、20世紀後半までラカンドン・ジャングルの小さな集団で生活し、部外者との接触を避けていた。このラカンド ン・マヤはカンペチェ/ペテン地域(チアパス州北東部)からやってきて、18世紀末にラカンドンの熱帯雨林に移り住んだ。 20世紀に入り、1950年代と1960年代には、他の人々(主にマヤ族と高地からの自給自足農民)もラカンドン地方に移住してきた。この移住は土地にま つわる紛争を引き起こし、熱帯雨林への圧力を増大させた。移住を食い止めるため、政府は1971年、森林の大部分(614,000ヘクタール、 6140km2)を保護区(モンテス・アズレス生物圏保護区)に指定することを決定した。その結果、26のコミュニティから2000人のツェルタル族とチ ロル族が追放され、ラカンドン族以外のコミュニティは土地の権利を政府に依存することになった。その後数十年間、政府はこの地域の問題をコントロールし続 けるために数々のプログラムを実施し、土地の分配を政治的手段として、異なるカンペシーノ・グループからの忠誠心を確保する手段として利用した。この分割 統治戦略は、この地域の住民グループ間に大きな不満と緊張をもたらした。 (チアパス紛争とラカンドン・ジャングルも参照)。 |

| Belize [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2012) The Maya population in Belize is concentrated in the Corozal, Cayo, Toledo and Orange Walk districts, but they are scattered throughout the country. The Maya are thought to have been in Belize and the Yucatán region since the second millennium BC. Much of Belize's original Maya population died as a result of new infectious diseases and conflicts between tribes and with Europeans. They are divided into the Yucatec, Kekchi, and Mopan. These three Maya groups now inhabit the country. The Yucatec Maya (many of whom came from Yucatán, Mexico to escape the Caste War of the 1840s) there have been evidence of several Yucatec Maya groups living by the Yalbac area of Belize and in the Orange Walk district near the present day Lamanai at the time the British reach. The Mopan (indigenous to Belize but were forced out by the British; they returned from Guatemala to evade slavery in the 19th century), and Kekchi (also fled from slavery in Guatemala in the 19th century). The later groups are chiefly found in the Toledo District.[22] |

ベリーズ [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要だ。あなたはそれを追加することによって助けることができる。(2012年1月) ベリーズのマヤ人口は、コロサル、カヨ、トレドとオレンジウォーク地区に集中しているが、彼らは全国に散らばっている。マヤは、紀元前2千年以来、ベリー ズとユカタン地域にあると考えられている。ベリーズの元のマヤの人口の多くは、新しい感染症や部族間の紛争やヨーロッパ人との結果として死亡した。彼らは ユカテク、ケクチ、そしてMopanに分かれている。現在、これら3つのマヤ・グループがこの国に居住している。 ユカテクマヤ(その多くは1840年代のカースト戦争を逃れるためにユカタン州、メキシコから来た)英国の到達時にベリーズのYalbac領域によって、 現在のLamanaiの近くにオレンジウォーク地区に住んでいるいくつかのユカテクマヤグループの証拠があった。Mopan(ベリーズの先住民族が、英国 によって追い出された。彼らは19世紀に奴隷制度を回避するためにグアテマラから戻った)、およびKekchi(また、19世紀にグアテマラの奴隷制度か ら逃れた)。後者のグループは主にトレド地区で見られる[22]。 |

| Tabasco [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2012) The Mexican state of Tabasco is home to the Chontal Maya. Tabasco is a Mexican state with a northern coastline fringing the Gulf of Mexico. In its capital, Villahermosa, Parque Museo la Venta is known for its zoo and colossal stone sculptures dating to the Olmec civilization. The grand Museo de Historia de Tabasco chronicles the area from prehistoric times, while the Museo Regional de Antropología has exhibits on native Maya and Olmec civilizations. |

タバスコ [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要だ。追加することで手助けができる。(2012年1月) メキシコのタバスコ州は、チョンタール・マヤの故郷である。タバスコ州はメキシコ湾に面した北部の海岸線を持つメキシコの州である。州都ビジャエルモサに は、動物園とオルメカ文明に遡る巨大な石の彫刻で知られるラ・ベンタ公園(Parque Museo la Venta)がある。タバスコ歴史博物館(Museo de Historia de Tabasco)には先史時代からこの地域の歴史が展示され、地域人類学博物館(Museo Regional de Antropología)には先住民のマヤ文明とオルメカ文明に関する展示がある。 |

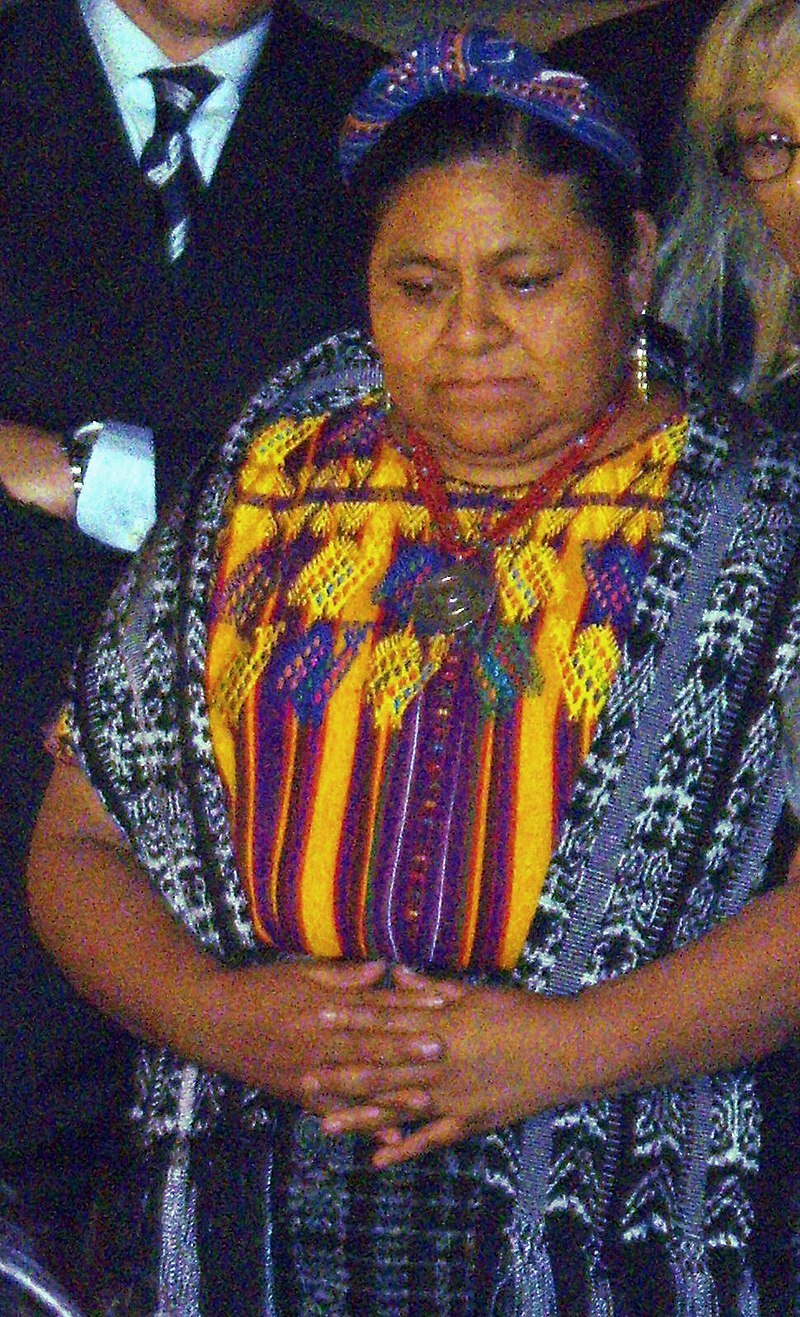

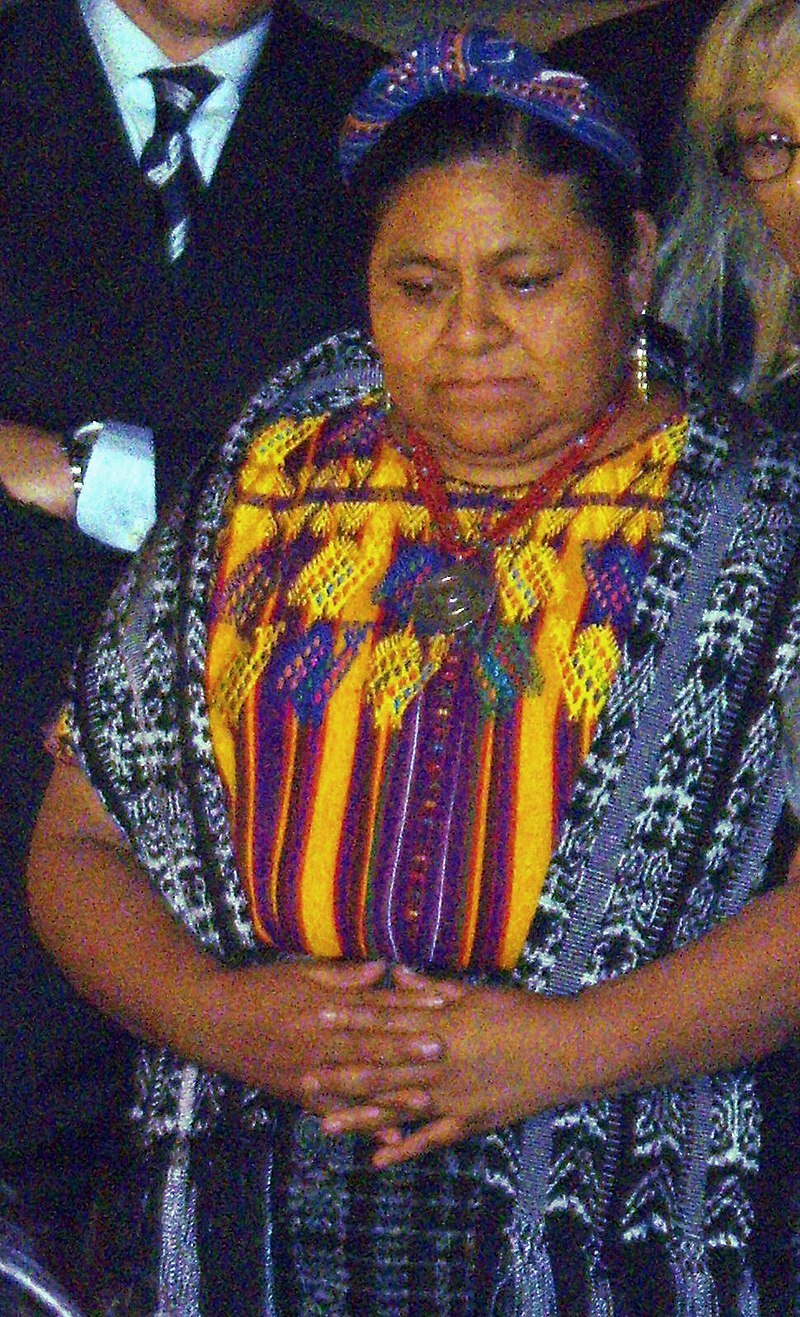

| Guatemala In Guatemala, indigenous people of Maya descent comprise around 42% of the population.[3][23] Despite the population size, it is reported that many still experience discrimination and oppression. The largest and most traditional Maya populations are in the western highlands in the departments of Baja Verapaz, Quiché, Totonicapán, Huehuetenango, Quetzaltenango, and San Marcos; their inhabitants are mostly Maya.[24] The Maya people of the Guatemala highlands include the Achi, Akatek, Chuj, Ixil, Jakaltek, Kaqchikel, Kʼicheʼ, Mam, Poqomam, Poqomchiʼ, Qʼanjobʼal, Qʼeqchiʼ, Tzʼutujil and Uspantek. The Qʼeqchiʼ live in lowland areas of Alta Vera Paz, Peten, and Western Belize. Over the course of the succeeding centuries a series of land displacements, re-settlements, persecutions and migrations resulted in a wider dispersal of Qʼeqchiʼ communities, into other regions of Guatemala (Izabal, Petén, El Quiché). They are the 2nd largest ethnic Maya group in Guatemala (after the Kʼicheʼ) and one of the largest and most widespread throughout Central America. In Guatemala, the Spanish colonial pattern of keeping the native population legally separate and subservient continued well into the 20th century.[citation needed] This resulted in many traditional customs being retained, as the only other option than traditional Maya life open to most Maya was entering the Hispanic culture at the very bottom rung. Because of this many Guatemalan Maya, especially women, continue to wear traditional clothing, that varies according to their specific local identity. The southeastern region of Guatemala (bordering with Honduras) includes groups such as the Chʼortiʼ. The northern lowland Petén region includes the Itza, whose language is near extinction but whose agroforestry practices, including use of dietary and medicinal plants may still tell us much about pre-colonial management of the Maya lowlands.[25] Genocide Main article: Guatemalan genocide  Human rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Rigoberta Menchú Tum in Acaya, Province of Lecce (Italy), at the opening press conference of the International Forum of Peace. The 36 year long Guatemalan Civil War from 1960 to 1996 left more than 200,000 people dead, half a million driven from their homes, and at least 100,000 women raped; most of the victims were Maya.[26][27] The genocide against Mayan people took place throughout the whole civil war because indigenous people were seen as supporting the leftist guerillas, but most acts against humanity occurred during Efraín Ríos Montt's presidency (1982–1983). Ríos Montt instituted a campaign of state terror intended to destroy the Mayas in the name of countering "communist subversion" and ridding the country of its indigenous culture. This was also known as Operation Sofia. Within Operation Sofia, the military followed through with "scorched earth policies" which allowed them to destroy whole villages, including killing livestock, destroying cultural symbols, destroying crops, and murdering civilians.[28] In some areas, government forces killed about 40% of the total population; the campaign destroyed at least 626 Mayan villages.[29] On January 26, 2012, former president Ríos Montt was formally indicted in Guatemala for overseeing the massacre of 1,771 civilians of the Ixil Maya group and appeared in court for genocide and crimes against humanity[30] for which he was then sentenced to 80 years in prison on May 10, 2013.[31] This ruling was overturned by the constitutional court on May 20, 2013, over alleged irregularities in the handling of the case.[32][33] The ex-president appeared in court again on January 5, 2015, amongst protest from his lawyers regarding his health conditions[34] and on August 25, 2015, it was deliberated that a re-trial of the 2013 proceedings could find Ríos Montt guilty or not, but that the sentence would be suspended.[35][36] Ríos Montt died on April 1, 2018, of a heart attack.[37] Maya heritage This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Guatemalan girls in their traditional clothing from the town of Santa Catarina Palopó on Lake Atitlán The Maya people are known for their brightly colored, yarn-based, textiles that are woven into capes, shirts, blouses, huipiles and dresses. Each village has its own distinctive pattern, making it possible to distinguish a person's home town. Women's clothing consists of a shirt and a long skirt. The Maya religion is Roman Catholicism combined with the indigenous Maya religion to form the unique syncretic religion which prevailed throughout the country and still does in the rural regions. Beginning from negligible roots prior to 1960, however, Protestant Pentecostalism has grown to become the predominant religion of Guatemala City and other urban centers, and mid-sized towns. The unique religion is reflected in the local saint, Maximón, who is associated with the subterranean force of masculine fertility and prostitution. Always depicted in black, he wears a black hat and sits on a chair, often with a cigar placed in his mouth and a gun in his hand, with offerings of tobacco, alcohol, and Coca-Cola at his feet. The locals know him as San Simon of Guatemala.  Maximón, a Maya deity The Popol Vuh is the most significant work of Guatemalan literature in the Kʼicheʼ language, and one of the most important works of Pre-Columbian American literature. It is a compendium of Maya stories and legends, aimed to preserve Maya traditions. The first known version of this text dates from the 16th century and is written in Quiché transcribed in Latin characters. It was translated into Spanish by the Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez in the beginning of the 18th century. Due to its combination of historical, mythical, and religious elements, it has been called the Maya Bible. It is a vital document for understanding the culture of Pre-Columbian America. The Rabinal Achí is a dramatic work consisting of dance and text that is preserved as it was originally represented. It is thought to date from the 15th century and narrates the mythical and dynastic origins of the Toj Kʼicheʼ rulers of Rabinal, and their relationships with neighboring Kʼicheʼ of Qʼumarkaj.[38] The Rabinal Achí is performed during the Rabinal festival of January 25, the day of Saint Paul. It was declared a masterpiece of oral tradition of humanity by UNESCO in 2005. The 16th century saw the first native-born Guatemalan writers that wrote in Spanish. |

グアテマラ グアテマラでは、マヤ系の先住民が人口の約42%を占めている[3][23]。人口が多いにもかかわらず、いまだに差別や抑圧を経験している人が多いと報 告されている。最大かつ最も伝統的なマヤ人口は、バハ・ベラパス県、キチェ県、トトニカパン県、フエウエテナンゴ県、ケツァルテナンゴ県、サンマルコス県 の西部高地に存在し、その住民のほとんどがマヤ族である[24]。 グアテマラ高地のマヤ族には、Achi、Akatek、Chuj、Ixil、Jakaltek、Kaqchikel、Kʼicheʼ、Mam、 Poqomam、Poqomchiʼ、Qʼanjobʼal、Qʼeqchiʼ、Tzʼutujil、Uspantekが含まれる。 QʼeqchiʼはAlta Vera Paz、Peten、西ベリーズの低地に住んでいる。その後何世紀にもわたって、土地の移動、再定住、迫害、移住が繰り返され、Qʼeqchiʼのコミュ ニティはグアテマラの他の地域(Izabal、Petén、El Quiché)へと広く分散した。彼らはグアテマラでKʼicheʼ族に次いで2番目に大きなマヤ民族グループであり、中央アメリカ全体で最も大きく、最 も広く分布しているグループのひとつである。 グアテマラでは、先住民を法的に分離し従属させるというスペイン植民地時代のパターンが20世紀まで続いた[要出典]。その結果、多くの伝統的な習慣が保 持されることになり、ほとんどのマヤにとって伝統的なマヤの生活以外の選択肢は、最底辺のヒスパニック文化に入ることしかなかった。このため、グアテマ ラ・マヤの多く、特に女性は、それぞれの地域のアイデンティティによって異なる伝統的な衣服を着続けている。 グアテマラ南東部(ホンジュラスとの国境)にはChʼortiʼのようなグループがある。ペテン北部の低地にはイツァ族がおり、その言語はほぼ消滅してい るが、食用植物や薬用植物の使用を含むアグロフォレストリーの実践は、植民地時代以前のマヤ低地の管理について多くのことを物語っている[25]。 ジェノサイド 主な記事 グアテマラ虐殺  人権活動家でノーベル平和賞受賞者のリゴベルタ・メンチューは、イタリアのレッチェ県アカヤで開催された国際平和フォーラムの記者会見に出席した。 1960年から1996年までの36年間に及ぶグアテマラ内戦では、20万人以上が死亡し、50万人が家を追われ、少なくとも10万人の女性がレイプされ た。 マヤ族に対する大量虐殺は、先住民が左翼ゲリラを支持しているとみなされたため、内戦全体を通して行われたが、人道に対する行為のほとんどは、エフライ ン・リオス・モントの大統領時代(1982年~1983年)に起こった。リオス・モントは、「共産主義者の破壊活動」に対抗し、国内から先住民族文化を排 除するという名目で、マヤ族を滅ぼすことを目的とした国家テロキャンペーンを実施した。これはソフィア作戦とも呼ばれた。ソフィア作戦の中で軍は、家畜の 殺処分、文化的シンボルの破壊、農作物の破壊、民間人の殺害を含む村全体の破壊を可能にする「焦土作戦」を貫いた[28]。いくつかの地域では、政府軍は 全人口の約40%を殺害し、この作戦は少なくとも626のマヤの村を破壊した[29]。 2012年1月26日、リオス・モント元大統領はグアテマラでイクシルマヤの1,771人の民間人の虐殺を監督したとして正式に起訴され、ジェノサイドと 人道に対する罪で出廷した[30]。 [32][33]元大統領は2015年1月5日、彼の健康状態に関する弁護士からの抗議の中、再び裁判所に出廷し[34]、2015年8月25日、 2013年の手続きの再審理でリオス・モントが有罪となるかどうかは審議されたが、判決は保留された[35][36]。 リオス・モントは2018年4月1日、心臓発作のため死去した[37]。 マヤの遺産 このセクションは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異議 申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性がある。(2012年8月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  アティトラン湖畔の町、サンタ・カタリーナ・パロポの民族衣装を着たグアテマラの少女たち マヤの人々は、色鮮やかな糸を使った織物で知られ、ケープ、シャツ、ブラウス、ホイピレ、ドレスなどに織られる。村ごとに独特の模様があるため、その人の 出身地を見分けることができる。女性の服装はシャツとロングスカートである。 マヤの宗教は、ローマ・カトリックとマヤの土着宗教が融合した独特の神仏習合宗教である。しかし、1960年以前はごくわずかだったプロテスタントのペン テコステ派が、グアテマラ・シティをはじめとする都市部や中規模の町で優勢な宗教に成長した。この独特の宗教は、地元の聖人マキシモンに反映されている。 マキシモンは、男性的な豊穣と売春の地下的な力に関連している。常に黒い姿で描かれ、黒い帽子をかぶり、椅子に座り、しばしば葉巻を口にくわえ、手には銃 を持ち、足元にはタバコ、アルコール、コカ・コーラなどの供物を置いている。地元ではグアテマラのサン・シモンと呼ばれている。  マヤの神、マシモン ポポル・ヴフは、Kʼicheʼ言語によるグアテマラ文学の最も重要な作品であり、先コロンブス期のアメリカ文学の最も重要な作品のひとつである。マヤの 伝統の保存を目的とした、マヤの物語と伝説の大要である。この文書の最初の版は16世紀に書かれたもので、ラテン文字で転写されたキチェ語で書かれてい る。18世紀初頭にドミニコ会の司祭フランシスコ・ヒメネスによってスペイン語に翻訳された。その歴史的、神話的、宗教的要素の組み合わせから、マヤの聖 書と呼ばれている。先コロンビア・アメリカの文化を理解する上で欠かせない文献である。ラビナル・アチは舞踊とテキストで構成される劇作品であり、当初の 表現そのままに保存されている。15世紀に作られたと考えられており、ラビナルの支配者Toj Kʼicheʼの神話と王朝の起源、そして隣国QʼmarkajのKʼicheʼとの関係が語られている[38]。Rabinal Achíは、1月25日の聖パウロの日に行われるラビナルの祭りで上演される。2005年にユネスコによって人類の口承伝統の傑作とされた。16世紀に は、スペイン語で書かれたグアテマラ初の生粋の作家が誕生した。 |

Maya cultural heritage tourism Maya family from Yucatán A boy playing Maya trumpet opposite of Palacio Nacional, Mexico City, Mexico. There is often a relationship between cultural heritage, tourism, and a national identity. In the case of the Maya, the many national identities have been constructed because of the growing demands placed on them by cultural tourism. By focusing on lifeways through costumes, rituals, diet, handicrafts, language, housing, or other features, the identity of the economy shifts from the sale of labor to that of the sale of culture.[39] Global tourism is now considered one of the largest scale movement of goods, services, and people in history and a significant catalyst for economic development and sociopolitical change.[40] Estimated that between 35 and 40 per cent of tourism today is represented by cultural tourism or heritage tourism, this alternative to mass tourism offers opportunities for place-based engagement that frames context for interaction by the lived space and everyday life of other peoples, as well as sites and objects of global historical significance.[41] In this production of tourism the use of historic symbols, signs, and topics form a new side that characterizes a nation and can play an active role in nation building.[42] With this type of tourism, people argue that ethno-commerce may open unprecedented opportunities for creating value of various kinds. Tourists travel with cultural expectations, which has created a touristic experience sometimes faced with the need to invent traditions of artificial and contrived attractions, often developed at the expense of local tradition and meanings.[43] An example of this can be seen in "Mayanizing Tourism on Roatan Island, Honduras: Archaeological Perspectives on Heritage, Development, and Indignity." Alejandro J. Figueroa et al., combine archaeological data and ethnographic insights to explore a highly contested tourism economy in their discussion of how places on Roatan Island, Honduras, have become increasingly "Mayanized" over the past decade. As tour operators and developers continue to invent an idealized Maya past for the island, non-Maya archaeological remains and cultural patrimony are constantly being threatened and destroyed. While heritage tourism provides economic opportunities for some, it can devalue contributions made by less familiar groups.[44] |

マヤ文化遺産観光 ユカタン州のマヤ一家 メキシコシティ、パラシオ・ ナシオナルの向かいでマヤのトランペットを吹く少年。 文化遺産と観光、そしてナショナル・アイデンティティの間にはしばしば関係がある。マヤの場合、文化観光による需要の高まりによって、多くのナショナル・ アイデンティティが構築されてきた。衣装、儀式、食事、手工芸品、言語、住居、あるいはその他の特徴を通じて生活様式に焦点を当てることによって、経済の アイデンティティは労働力の販売から文化の販売へと移行する[39]。 グローバル・ツーリズムは現在、歴史上最大規模のモノ、サービス、人の移動であり、経済発展と社会政治的変化の重要な触媒であると考えられている。 [40]今日の観光の35~40%は文化観光または遺産観光に代表されると推定されており、マスツーリズムに代わるこのタイプの観光は、世界的に歴史的意 義のある場所や物だけでなく、他民族の生活空間や日常生活によって相互作用の文脈を枠組みづける、場所に根ざした関与の機会を提供している[41]。 このような観光の生産において、歴史的なシンボル、標識、トピックの使用は、国家を特徴づける新たな側面を形成し、国家建設において積極的な役割を果たす ことができる[42]。 この種の観光では、エスノ・コマースによって、さまざまな種類の価値を創造する前例のない機会が開かれる可能性があると人々は主張する。観光客は文化的な 期待を抱いて旅行するため、観光体験は時に、地元の伝統や意味を犠牲にして開発されることが多い、人為的で作為的なアトラクションの伝統を発明する必要性 に直面する。 ホンジュラス、ロアタン島におけるマヤ化する観光」にその例を見ることができる: Archaeological Perspectives on Heritage, Development, and Indignity"(ホンジュラス、ロアタン島におけるマヤ化する観光:遺産、開発、侮辱に関する考古学的視点)に見ることができる。アレハンドロ・ J・フィゲロア(Alejandro J. Figueroa)らは、考古学的データと民俗学的洞察を組み合わせて、ホンジュラスのロアタン島の場所が過去10年の間にどのように「マヤ化」していっ たかについて論じ、非常に論争的な観光経済を探求している。ツアーオペレーターや開発業者がこの島に理想化されたマヤの過去を創作し続ける一方で、マヤ以 外の遺跡や文化遺産は絶えず脅かされ、破壊されている。ヘリテージ・ツーリズムは一部の人々に経済的機会を提供する一方で、あまり馴染みのないグループに よる貢献を軽んじることにもなりかねない[44]。 |

| Notable Maya people See also: Category:Maya people Ah Ahaual, a 7th-century captive of noble lineage recorded in pre-Columbian Maya inscriptions Hunac Ceel (fl. c. 1300), Maya general and founder of the Cocom dynasty at Chichen Itzá Apoxpalon (fl. 1525), Maya merchant and regional ruler of Itzamkanac Tecun Uman (died c. 1524), legendary Kʼicheʼ Mayan leader who refused to give way to the conquistadors in Guatemala and was slain by Pedro de Alvarado Napuc Chi or Ah Kin Chi (died c. 1541), general-in-chief of the army and king of Tutul-Xiu, i. e. Maní Gaspar Antonio Chi (c. 1531–1610), Maya noble from Maní, son of Napuc Chi Jacinto Canek (c. 1731–1761), Maya revolutionary Crescencio Poot (1820–1885), general in the Caste War of Yucatán Felipe Carrillo Puerto (1874–1924), Mexican journalist and politician, governor of the Mexican state of Yucatán (1922–1924) Paula Nicho Cumez (born 1955), is a Mayan-Guatemalan artist. Cumez is inspired by Mayan tradition and culture and focuses on expressing the context of native women’s experience in her artwork; additionally, Cumez is inspired by the Popol Vuh Andrés Curruchich (1891–1969), Guatemalan painter of the Kaqchikel people Carlos Mérida (1891–1985), Spanish-Kʼicheʼ artist from Guatemala Francisco Luna Kan (1925–2023), Mexican politician, governor of Yucatán (1976–1982) Armando Manzanero Canché (1935-2020), Mexican musician, singer, and composer Luis Rolando Ixquiac Xicara (born 1947), indigenous artist born in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala Marcial Mes (c. 1949–2014), Belizean politician Rosalina Tuyuc (born 1956), Guatemalan human rights activist Rigoberta Menchú (born 1959), Kʼicheʼ political activist from Guatemala Comandanta Ramona (1959–2006), 'officer' of the autonomist Zapatista Army of National Liberation Juan Jose Pacho (born 1963), Mexican former baseball player and manager Aníbal López (1964–2014), Guatemalan artist Jesús Tecú Osorio (born 1971), Guatemalan social activist Hilario Chi Canul (born 1981), Mexican linguist Oscar Santis (born 1999), Footballer |

マヤの著名人 こちらも参照のこと: カテゴリー:マヤの人々 Ah Ahaual、7世紀の捕虜で、先コロンブス期のマヤの碑文に記録されている高貴な血筋の人物。 Hunac Ceel(1300年頃)、マヤの将軍でチチェン・イッツァのココム王朝の創始者。 アポクスパロン(1525年生)、マヤの商人、イツァムカナックの地域統治者 Tecun Uman(1524年頃没)、伝説的なKʼicheʼマヤの指導者で、グアテマラでコンキスタドールに道を譲ることを拒否し、Pedro de Alvaradoによって殺害された。 Napuc ChiまたはAh Kin Chi(1541年頃没)、軍の総司令官でTutul-Xiu、すなわちManiの王。 ガスパール・アントニオ・チ(1531年頃~1610年)、マニのマヤ貴族、ナプック・チの息子 ハシント・カネック(1731年頃-1761年)、マヤの革命家 クレセンシオ・プート(1820~1885)、ユカタンカースト戦争の将軍 フェリペ・カリージョ・プエルト(1874~1924)、メキシコのジャーナリスト、政治家、メキシコ・ユカタン州知事(1922~1924) パウラ・ニコ・クメス(1955年生まれ)は、マヤ・グアテマラのアーティストである。マヤの伝統と文化にインスパイアされ、先住民の女性の経験を作品に 表現することに重点を置いている。 アンドレス・クルチッチ(1891-1969)、カクチケル族のグアテマラ人画家 カルロス・メリダ(1891-1985)、グアテマラのスペイン系カチケル人画家 フランシスコ・ルナ・カン(1925-2023)メキシコの政治家、ユカタン州知事(1976-1982) アルマンド・マンサネロ・カンチェ(1935-2020)メキシコのミュージシャン、歌手、作曲家 ルイス・ロランド・イクスキアック・キシカラ(1947年生まれ)、グアテマラ、ケツァルテナンゴ生まれの先住民アーティスト マルシャル・メス(1949年~2014年)、ベリーズの政治家 ロザリーナ・トゥユック(1956年生)、グアテマラ人権活動家 リゴベルタ・メンチュー(1959年生まれ)、グアテマラのKʼicheʼ政治活動家 コマンダンタ・ラモーナ(1959年~2006年)、サパティスタ民族解放軍の「将校」。 フアン・ホセ・パチョ(1963年生)、メキシコの元野球選手、監督 アニバル・ロペス(1964-2014)、グアテマラ人アーティスト ヘスス・テクー・オソリオ(1971年生まれ)、グアテマラ人社会活動家 ヒラリオ・チ・カヌル(1981年生まれ)メキシコの言語学者 オスカル・サンティス(1999年生) サッカー選手 |

| Acala Chʼol Chinamita Genetic history of indigenous peoples of the Americas Indigenous peoples of the Americas Kejache Lakandon Chʼol List of Mayan languages Manche Chʼol |

アカラ・チョル チナミタ アメリカ大陸先住民の遺伝史 アメリカ大陸の先住民 ケジャケ Lakandon Chʼol マヤ語リスト マンチェ語 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_peoples |

|

"The

Guatemalan genocide, also referred to as the Maya genocide,[2] or

the Silent Holocaust[3] (Spanish: Genocidio guatemalteco, Genocidio

maya, o Holocausto silencioso), was the massacre of Maya civilians

during the Guatemalan military government's counterinsurgency

operations. Massacres, forced disappearances, torture and summary

executions of guerrillas and especially civilian collaborators at the

hands of US-backed security forces had been widespread since 1965 and

was a longstanding policy of the military regime, which US officials

were aware of.[4][5][6] A report from 1984 discussed "the murder of

thousands by a military government that maintains its authority by

terror".[7] Human Rights Watch has described "extraordinarily cruel"

actions by the armed forces, mostly against unarmed civilians.[8]

The repression reached genocidal levels in the predominantly indigenous

northern provinces where the EGP guerrillas operated. There, the

Guatemalan military viewed the Maya – traditionally seen as subhumans –

as siding with the insurgency and began a campaign of wholesale

killings and disappearances of Mayan peasants. While massacres of

indigenous peasants had occurred earlier in the war, the systematic use

of terror against the indigenous population began around 1975 and

peaked during the first half of the 1980s.[9] The military had carried

out 626 massacres against the Maya during the conflict.[10] The

Guatemalan army itself acknowledged destroying 440 Mayan villages

between 1981 and 1983, during the most intense phase of the repression.

In some municipalities such as Rabinal and Nebaj, at least one-third of

the villages were evacuated or destroyed. A study by the Juvenile

Division of the Supreme Court sanctioned in March 1985 revealed that

over 200,000 children had lost at least one parent in the killings, of

whom 25% had lost both since 1980, meaning that between 45,000 and

60,000 adult Guatemalans were killed during the period from 1980 and

1985.[11] This does not account for the fact that children often became

targets of mass killings by the army in events such as the Río Negro

massacres.[12] Former military dictator General Efrain Ríos Montt

(1982–1983) was indicted for his role in the most intense stage of the

genocide.

An estimated 200,000 Guatemalans were killed during the Guatemalan

Civil War including at least 40,000 persons who "disappeared". 93% of

civilian executions were carried out by government forces. Of the

42,275 individual cases of killing and "disappearances" documented by

the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), 83% of the victims

were Maya and 17% Ladino.[1] A UN-sponsored Commission for Historical

Clarification in 1999 concluded that a genocide had taken place at the

hands of the US-backed Armed Forces of Guatemala, and that US training

of the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques "had a significant

bearing on human rights violations during the armed

confrontation".[9][13][5][14]" Guatemalan

Genocide. |

「グアテマラ大虐殺は、マヤ大虐殺または沈黙のホロコースト(スペイン

語:Genocidio guatemalteco, Genocidio maya, o Holocausto

silencioso)とも呼ばれ、グアテマラ軍政の対反乱作戦中に行われたマヤ系市民の虐殺である。アメリカの支援を受けた治安部隊の手によるゲリラや

特に民間人協力者の虐殺、強制失踪、拷問、即決処刑は1965年以来広まっており、アメリカ政府高官も認識していた軍事政権の長年の政策であった。

1984年の報告書は、「恐怖によって権威を維持する軍事政権による数千人の殺害」について論じている。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは、武装勢力による

「非常に残酷な」行為について、そのほとんどが非武装の市民に対するものであったと述べている。EGPゲリラが活動していた先住民族が多い北部州では、弾

圧は虐殺レベルに達した。そこでグアテマラ軍は、伝統的に亜人とみなされてきたマヤ族を反乱軍に味方するとみなし、マヤ族の農民の大規模な殺害と失踪の

キャンペーンを開始した。先住民農民の虐殺は戦争の初期にもあったが、先住民に対する組織的な恐怖の行使は1975年頃から始まり、1980年代前半に

ピークを迎えた。軍は紛争中、マヤ族に対して626件の虐殺を行った。グアテマラ軍自身も、弾圧が最も激しかった1981年から1983年の間に、440

のマヤ族の村を破壊したことを認めている。ラビナルやネバジなどいくつかの自治体では、少なくとも村の3分の1が避難または破壊された。1985年3月に

認可された最高裁判所少年部の調査によると、20万人以上の子どもが殺害によって少なくとも片親を失い、そのうち25%は1980年以降に両親を失ってい

た。これは、リオ・ネグロの大虐殺のような事件で、子どもたちがしばしば軍隊による大量殺戮の標的になったという事実を考慮に入れていない。元軍事独裁者

エフレイン・リオス・モント将軍(1982~1983年)は、ジェノサイドの最も激しい段階での役割で起訴された。グアテマラ内戦では、少なくとも4万人

の「失踪者」を含め、推定20万人のグアテマラ人が殺害された。民間人処刑の93%は政府軍によって行われた。歴史解明委員会(CEH)が記録した

42,275件の殺害と「失踪」のうち、犠牲者の83%がマヤ人、17%がラディーノ人であった。1999年に国連が主催した歴史解明委員会は、米国が支

援したグアテマラ軍の手によって大量虐殺が行われ、米国が将校隊に対反乱戦技術を訓練したことが「武力衝突中の人権侵害に大きく関係していた」と結論づけ

た。グアテマラのジェノサイド |

| Migrants

pass through Ixtepec, Mexico, atop a train known as “la bestia.”

(Photo by John Moore/Getty Images.) "First wave of migration:Due to the war in Guatemala, many Maya people were killed. The two parties in the war were both hurting the basic living circumstances of Maya people by destroying infrastructure, such as railroads, farmlands, factories, they also burned most of the Mayan books. The destruction of these basic tools created a very difficult environment for Maya people to make a living. Without a way to sustain themselves, many Maya people decided to move somewhere that they were able to live. Many people moved to Mexico and some moved to the United States, which was also their first encounter with the US. Many Mayans who moved to the US mainly moved to areas like Florida, Houston, and Los Angeles:Second wave of migration: After the peace agreement among both parties in Guatemala after a 36-year war, the two parties built a new government. But the new government is also not protecting the benefit of people, especially the native people like Maya people. The new government was trying to unite all the culture together which in another word, is trying to assimilate all the culture within Maya people. In addition, the new government was not only trying to eliminate the culture but also was keeping the lands to itself rather than gave them back to the Maya people. Without a way to grow crops and food, Maya people were in extreme poverty. They have to find a way to make a living which they started the second migration movement to the United States"  |

メキシコのイクステペックを通過する移民たち。「ラ・ベスティア

」と呼ばれる列車の上から。(写真:John Moore/Getty

Images)「移住の第一波:グアテマラでの戦争により、多くのマヤの人々が殺された。戦争の両当事者は、鉄道、農地、工場などのインフラを破壊するこ

とによって、マヤの人々の基本的な生活環境を傷つけた。これらの基本的な道具の破壊は、マヤの人々が生計を立てるのに非常に困難な環境を作り出した。自活

する術を失ったマヤの人々の多くは、自分たちが生活できる場所に移住することを決めた。多くの人々はメキシコに移り住み、ある人々はアメリカに移り住ん

だ。アメリカに移住した多くのマヤ人は、主にフロリダ、ヒューストン、ロサンゼルスといった地域に移り住んだ:

グアテマラでは36年にわたる戦争の後、両当事者による和平合意がなされ、両当事者は新政府を樹立した。しかし、新政府もまた人々の利益、特にマヤ族のよ

うな先住民の利益を守っていない。新政府はすべての文化を一つにまとめようとしており、別の言葉で言えば、マヤ民族の中のすべての文化を同化させようとし

ている。さらに、新政府は文化を排除しようとしただけでなく、土地をマヤの人々に返すのではなく、自分たちのものにしようとしていた。農作物や食料を栽培

する方法がなければ、マヤの人々は極度の貧困に陥っていた。彼らは生計を立てる方法を見つけなければならず、それがアメリカへの第二次移住運動の始まり

だった。 |

Gentes de Indígena de Nebaj, Guatemala. ca.1915

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆