Niche theories

ニッチ理論

Niche theories

ニッチ(niche)あるいは生態学的ニッチ/地位 (ecological niche)とは、ある特定の生物の種が、生態的環境のなかで占める位置づけである。この位置とはただ単に空間的なもの(例えば、深海の砂の低地に住ま う、3000メートル以上の高地の上空や山壁を生活の場所にする)のみならず、食物連鎖の位置づけ(例えば、どのような種を捕食するか/被食されるか) や、共生関係(動物間のみならず植物やバクテリアなどの関係)の位置づけなどでも、表現されるものである。ちなみに、ニッチとは、共同墓地における墓場の 位置や納棺のための棚(セル)のことを表現するのに使われるので、空間的占有という比喩表現に 由来するものである。

これを踏まえて、ニッチ構築(niche contruction)とは、生物種が同一種ないしは関連する生物種と共同して、固有の環境をつくりだして、生存の可能性を広げることを意味す る。端的 にいうと、ビーバー(Castoridae, Castor sp.)のダム構築は、典型的なニッチ構築といえる。

出典は:http: //www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/beaver/ およびhttp: //biblicalisraeltours.com/2013/03/the-arcasolium-tomb/

Beaver dam in Hesse, Germany. By exploiting the resource of available wood, beavers are affecting biotic conditions for other species that live within their habitat.

| In ecology, a

niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.[1][2]

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution

of resources and competitors (for example, by growing when resources

are abundant, and when predators, parasites and pathogens are scarce)

and how it in turn alters those same factors (for example, limiting

access to resources by other organisms, acting as a food source for

predators and a consumer of prey). "The type and number of variables

comprising the dimensions of an environmental niche vary from one

species to another [and] the relative importance of particular

environmental variables for a species may vary according to the

geographic and biotic contexts".[3] A Grinnellian niche is determined by the habitat in which a species lives and its accompanying behavioral adaptations. An Eltonian niche emphasizes that a species not only grows in and responds to an environment, it may also change the environment and its behavior as it grows. The Hutchinsonian niche uses mathematics and statistics to try to explain how species coexist within a given community. The concept of ecological niche is central to ecological biogeography, which focuses on spatial patterns of ecological communities.[4] "Species distributions and their dynamics over time result from properties of the species, environmental variation..., and interactions between the two—in particular the abilities of some species, especially our own, to modify their environments and alter the range dynamics of many other species."[5] Alteration of an ecological niche by its inhabitants is the topic of niche construction.[6] The majority of species exist in a standard ecological niche, sharing behaviors, adaptations, and functional traits similar to the other closely related species within the same broad taxonomic class, but there are exceptions. A premier example of a non-standard niche filling species is the flightless, ground-dwelling kiwi bird of New Zealand, which feeds on worms and other ground creatures, and lives its life in a mammal-like niche. Island biogeography can help explain island species and associated unfilled niches. |

生態学においてニッチとは、ある種が特定の環境条件に適合することであ

る[1][2]。

それは、ある生物または集団が資源と競合の分布にどのように対応し(例えば、資源が豊富なときに成長し、捕食者や寄生虫、病原菌が少ないときに)、次にそ

れらの同じ要因をどのように変えるか(例えば、他の生物による資源へのアクセスを制限し、捕食者の食料源と餌の消費者として機能するなど)説明するもので

ある。「環境ニッチの次元を構成する変数の種類と数は、種によって異なり、(中略)ある種にとっての特定の環境変数の相対的重要性は、地理的・生物学的状

況に応じて変化する可能性がある」[3]。 グリネル型ニッチは、種が生活する生息地とそれに伴う行動適応によって決定される。エルトン型ニッチは、種が環境の中で成長し、環境に対応するだけでな く、成長とともに環境とその行動を変化させる可能性があることを強調する。ハッチンソン型ニッチは、数学と統計学を用いて、ある地域社会の中で種がどのよ うに共存しているかを説明しようとするものである。 生態学的ニッチの概念は、生態学的コミュニティの空間パターンに焦点を当てた生態生物地理学の中心である[4]。「種の分布とその時間的ダイナミクスは、 種の特性、環境の変動・・・、および2つの間の相互作用、特にいくつかの種、特に私たちの種の環境を変更する能力と他の多くの種の範囲ダイナミクスから生 じる」[5]。 大多数の種は標準的な生態学的ニッチに存在し、同じ広範な分類学上のクラス内の他の近縁種と同様の行動、適応、機能特性を共有しますが、例外も存在しま す。標準的なニッチを満たさない種の代表的な例として、ニュージーランドに生息する飛べない地上棲のキーウィ鳥がある。この鳥はミミズやその他の地上生物 を食べ、哺乳類に似たニッチで一生を送る。島嶼生物地理学は、島嶼種とそれに関連する未充填のニッチを説明するのに役立つことができる。 |

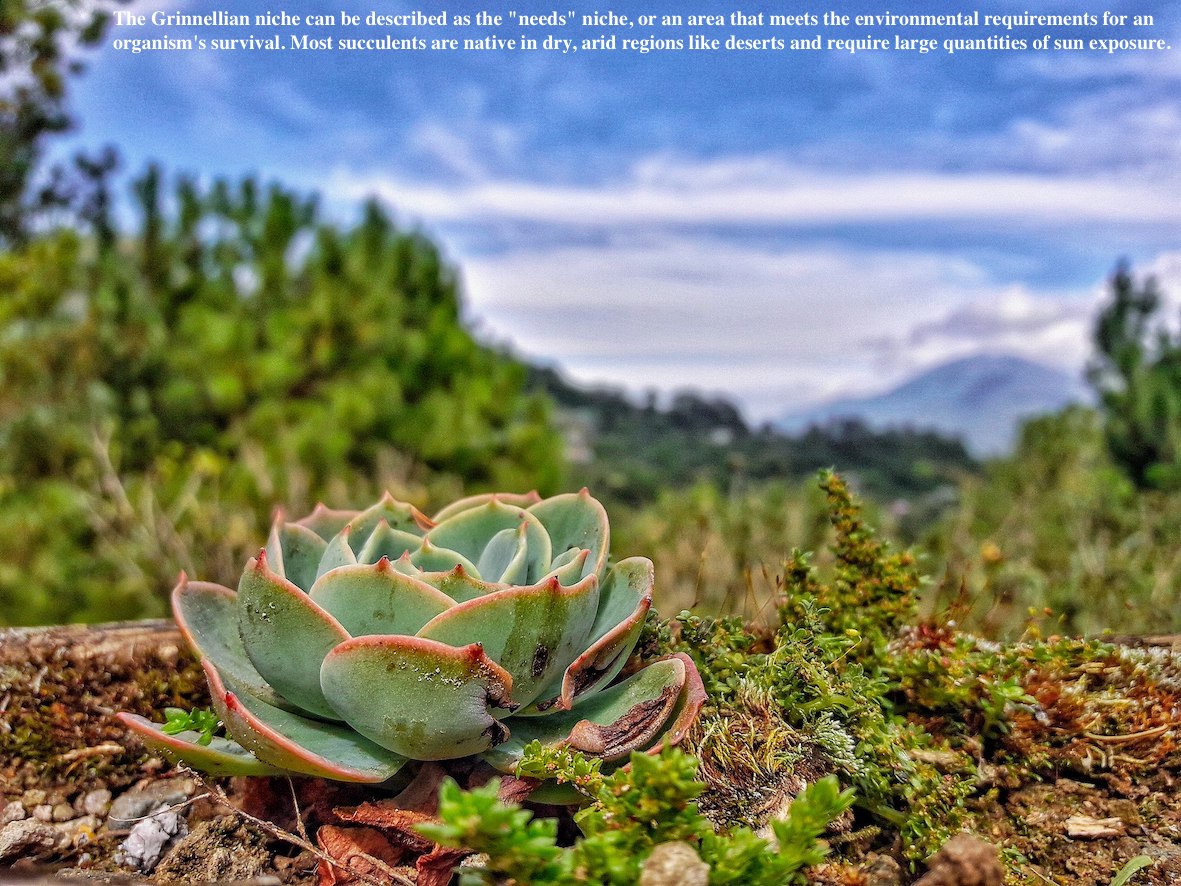

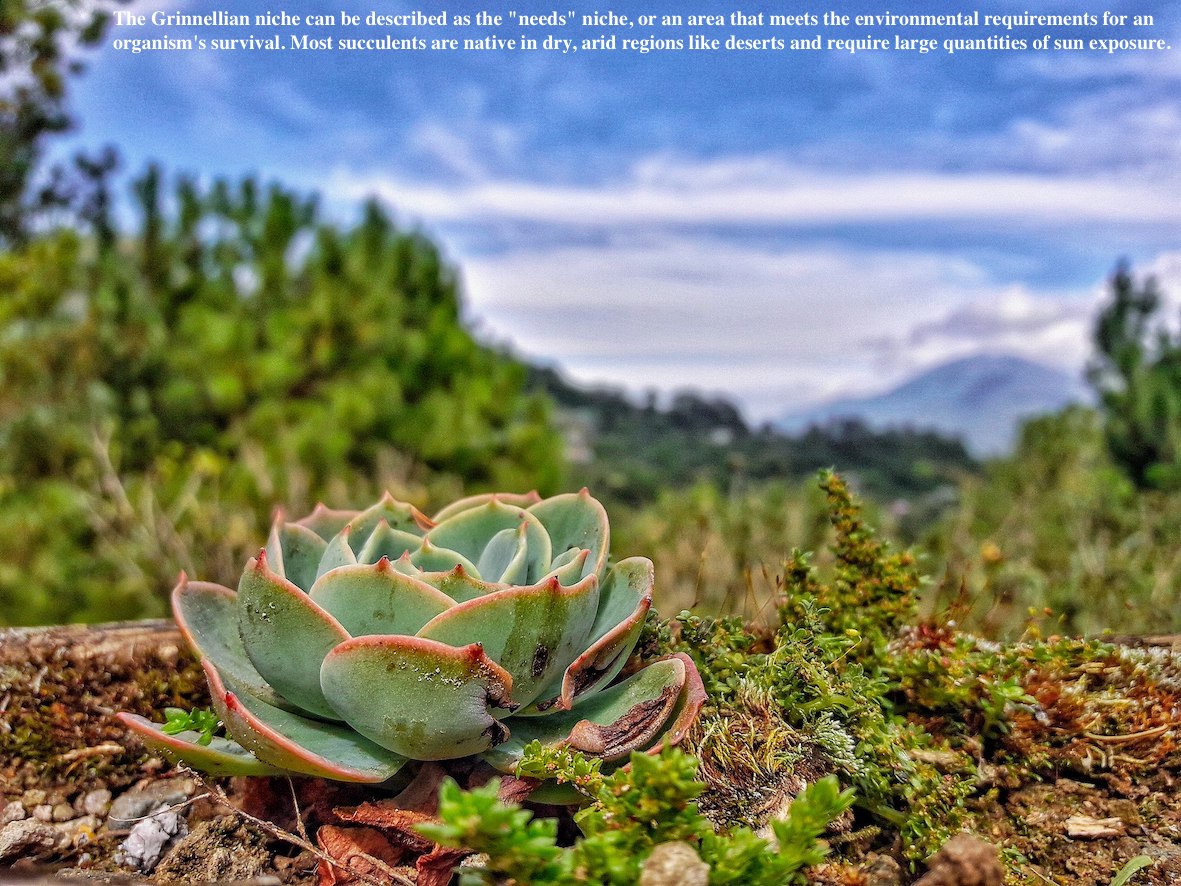

| Grinnellian niche The ecological meaning of niche comes from the meaning of niche as a recess in a wall for a statue,[7] which itself is probably derived from the Middle French word nicher, meaning to nest.[8][7] The term was coined by the naturalist Roswell Hill Johnson[9] but Joseph Grinnell was probably the first to use it in a research program in 1917, in his paper "The niche relationships of the California Thrasher".[10][1] The Grinnellian niche concept embodies the idea that the niche of a species is determined by the habitat in which it lives and its accompanying behavioral adaptations. In other words, the niche is the sum of the habitat requirements and behaviors that allow a species to persist and produce offspring. For example, the behavior of the California thrasher is consistent with the chaparral habitat it lives in—it breeds and feeds in the underbrush and escapes from its predators by shuffling from underbrush to underbrush. Its 'niche' is defined by the felicitous complementing of the thrasher's behavior and physical traits (camouflaging color, short wings, strong legs) with this habitat.[10] Grinnellian niches can be defined by non-interactive (abiotic) variables and environmental conditions on broad scales.[11] Variables of interest in this niche class include average temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and terrain aspect which have become increasingly accessible across spatial scales. Most literature has focused on Ginnellian niche constructs, often from a climatic perspective, to explain distribution and abundance. Current predictions on species responses to climate change strongly rely on projecting altered environmental conditions on species distributions.[12] However, it is increasingly acknowledged that climate change also influences species interactions and an Eltonian perspective may be advantageous in explaining these processes. This perspective of niche allows for the existence of both ecological equivalents and empty niches. An ecological equivalent to an organism is an organism from a different taxonomic group exhibiting similar adaptations in a similar habitat, an example being the different succulents found in American and African deserts, cactus and euphorbia, respectively.[13] As another example, the anole lizards of the Greater Antilles are a rare example of convergent evolution, adaptive radiation, and the existence of ecological equivalents: the anole lizards evolved in similar microhabitats independently of each other and resulted in the same ecomorphs across all four islands. |

グリネリアンニッチ ニッチの生態学的な意味は、像のための壁の凹みというニッチの意味からきており[7]、それ自体は巣を意味する中フランス語のnicherからきていると 思われる[8][7]。 この用語は博物学者のロスウェルヒル・ジョンソンによって作られたが[9]、研究プログラムにおいて最初に使ったのはおそらく1917年にジョセフ・グリ ンネルの論文「The niche relationships of the California Thrasher」[10][1] でであろう。 グリネル式ニッチ概念は、ある種のニッチは、その種が生息する生息環境とそれに伴う行動適応によって決定されるという考えを具現化したものである。言い換 えれば、ニッチとは、ある種が存続し子孫を残すための生息地の要件と行動の総和である。例えば、カリフォルニア・スラッシャーは、下草の中で繁殖し、餌を 食べ、下草から下草へと移動することで捕食者から逃れるという、生息するチャパラルと一致した行動をとる。ツチノコの行動と身体的特徴(カモフラージュ 色、短い翼、強い脚)がこの生息地でうまく補完されることによって、その「ニッチ」が定義される[10]。 グリネリアンニッチは、非相互作用的な(非生物的)変数と広いスケールでの環境条件によって定義することができる。11] このニッチクラスで関心のある変数には、平均気温、降水量、太陽放射、地形の側面などがあり、空間スケールでますますアクセスしやすくなっている。ほとん どの文献は、分布と個体数を説明するために、しばしば気候学的な観点からジネリアンニッチの構成に焦点を当ててきた。気候変動に対する種の反応に関する現 在の予測は、環境条件の変化を種の分布に予測することに強く依存している[12]。しかし、気候変動が種の相互作用にも影響を与えることが次第に認識され るようになり、エルトン的な視点がこれらのプロセスを説明するのに有利になる可能性がある。 このニッチの視点は、生態学的同等物と空のニッチの両方を存在させることができる。ある生物の生態学的同等物とは、異なる分類群の生物が同じような生息環 境で同じような適応を示すことで、例えば、アメリカとアフリカの砂漠で見られる多肉植物は、それぞれサボテンとユーフォルビアである[13]。別の例とし て、大アンティル諸島のアノールトカゲは収束進化、適応放射、生態学的同等物の存在の珍しい例で、アノールトカゲは互いに独立して似た微小生息環境で進化 し、4島全てで同じ異形をもたらした。 |

| Eltonian niche In 1927 Charles Sutherland Elton, a British ecologist, defined a niche as follows: "The 'niche' of an animal means its place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies."[14] Elton classified niches according to foraging activities ("food habits"):[15] For instance there is the niche that is filled by birds of prey which eat small animals such as shrews and mice. In an oak wood this niche is filled by tawny owls, while in the open grassland it is occupied by kestrels. The existence of this carnivore niche is dependent on the further fact that mice form a definite herbivore niche in many different associations, although the actual species of mice may be quite different.[14] Conceptually, the Eltonian niche introduces the idea of a species' response to and effect on the environment. Unlike other niche concepts, it emphasizes that a species not only grows in and responds to an environment based on available resources, predators, and climatic conditions, but also changes the availability and behavior of those factors as it grows.[16] In an extreme example, beavers require certain resources in order to survive and reproduce, but also construct dams that alter water flow in the river where the beaver lives. Thus, the beaver affects the biotic and abiotic conditions of other species that live in and near the watershed.[17] In a more subtle case, competitors that consume resources at different rates can lead to cycles in resource density that differ between species.[18] Not only do species grow differently with respect to resource density, but their own population growth can affect resource density over time. Eltonian niches focus on biotic interactions and consumer–resource dynamics (biotic variables) on local scales.[11] Because of the narrow extent of focus, data sets characterizing Eltonian niches typically are in the form of detailed field studies of specific individual phenomena, as the dynamics of this class of niche are difficult to measure at a broad geographic scale. However, the Eltonian niche may be useful in the explanation of a species' endurance of global change.[16] Because adjustments in biotic interactions inevitably change abiotic factors, Eltonian niches can be useful in describing the overall response of a species to new environments. |

エルトン・ニッチ 1927年、イギリスの生態学者チャールズ・サザランド・エルトンはニッチを次のように定義した。ある動物の「ニッチ」とは、生物環境におけるその場所、 食物や敵との関係を意味する」[14]。 エルトンは採食活動(「食性」)に応じてニッチを分類している[15]。 例えば、トガリネズミやネズミなどの小動物を食べる猛禽類がいるニッチがある。例えば、カシワ林ではオオコノハズクが、開けた草地ではチョウゲンボウがこ のニッチを占める。この肉食動物のニッチの存在は、さらに、実際のネズミの種は全く異なるかもしれないが、ネズミが多くの異なる仲間において明確な草食動 物のニッチを形成しているという事実によって成り立っている[14]。 概念的には、エルトン型ニッチは、環境に対する種の反応と影響という考えを導入している。他のニッチ概念とは異なり、種が利用可能な資源、捕食者、気候条 件に基づいて環境の中で成長し対応するだけでなく、成長とともにそれらの要因の利用可能性や行動を変化させることを強調している[16] 極端な例として、ビーバーは生存と繁殖のために特定の資源を必要とするが、ビーバーが生息する川の水の流れを変えるダム建設も行っている。より繊細な例で は、異なる速度で資源を消費する競争相手が、種間で異なる資源密度のサイクルを引き起こす可能性があります。 エルトン・ニッチは、局所的なスケールでの生物学的相互作用と消費者-資源動態(生物学的変数)に焦点を当てています[11]。このクラスのニッチの動態 を広い地理的スケールで測定することは難しいため、焦点の範囲が狭く、エルトン・ニッチを特徴付けるデータセットは通常、特定の個々の現象の詳細なフィー ルド調査の形式をとっています。しかし、エルトン・ニッチは、地球規模の変化に耐える種の説明には有用かもしれない[16]。生物学的相互作用の調整は必 然的に生物学的要因を変えるので、エルトン・ニッチは新しい環境に対する種の全体的な反応を説明するのに有用であろう。 |

| Hutchinsonian niche The Hutchinsonian niche is an "n-dimensional hypervolume", where the dimensions are environmental conditions and resources, that define the requirements of an individual or a species to practice its way of life, more particularly, for its population to persist.[2] The "hypervolume" defines the multi-dimensional space of resources (e.g., light, nutrients, structure, etc.) available to (and specifically used by) organisms, and "all species other than those under consideration are regarded as part of the coordinate system."[19] The niche concept was popularized by the zoologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson in 1957.[19] Hutchinson inquired into the question of why there are so many types of organisms in any one habitat. His work inspired many others to develop models to explain how many and how similar coexisting species could be within a given community, and led to the concepts of 'niche breadth' (the variety of resources or habitats used by a given species), 'niche partitioning' (resource differentiation by coexisting species), and 'niche overlap' (overlap of resource use by different species).[20] Statistics were introduced into the Hutchinson niche by Robert MacArthur and Richard Levins using the 'resource-utilization' niche employing histograms to describe the 'frequency of occurrence' as a function of a Hutchinson coordinate.[2][21] So, for instance, a Gaussian might describe the frequency with which a species ate prey of a certain size, giving a more detailed niche description than simply specifying some median or average prey size. For such a bell-shaped distribution, the position, width and form of the niche correspond to the mean, standard deviation and the actual distribution itself.[22] One advantage in using statistics is illustrated in the figure, where it is clear that for the narrower distributions (top) there is no competition for prey between the extreme left and extreme right species, while for the broader distribution (bottom), niche overlap indicates competition can occur between all species. The resource-utilization approach consists in postulating that not only competition can occur, but also that it does occur, and that overlap in resource utilization directly enables the estimation of the competition coefficients.[23] This postulate, however, can be misguided, as it ignores the impacts that the resources of each category have on the organism and the impacts that the organism has on the resources of each category. For instance, the resource in the overlap region can be non-limiting, in which case there is no competition for this resource despite niche overlap.[1][20][23] |

ハッチンソン式ニッチ ハッチンソン式ニッチは、次元が環境条件と資源である「n次元の超体積」であり、個体または種がその生き方を実践するための、より詳細にはその集団が存続 するための要件を定義する[2]。 超体積」は、生物が利用できる(そして特に利用する)資源(例えば、光、栄養素、構造など)の多次元空間を定義し、「検討対象以外のすべての種は座標シス テムの一部と見なされる」[19]。 ニッチの概念は、1957年に動物学者のG.Evelyn Hutchinsonによって広められた[19]。Hutchinsonは、なぜ一つの生息地に非常に多くの種類の生物が存在するのかという問題を探求し ていた。彼の研究は、多くの他の研究者に刺激を与え、与えられたコミュニティ内で共存する種の数と類似性を説明するモデルを開発し、「ニッチの広がり」 (与えられた種が利用する資源や生息地の多様性)、「ニッチ分割」(共存する種による資源の分化)、「ニッチの重複」(異なる種による資源利用の重複)と いう概念につながった[20]。 統計学は、ロバート・マッカーサーとリチャード・レビンスによって、ハッチンソン座標の関数として「出現頻度」を記述するヒストグラムを用いた「資源利 用」ニッチに導入されました[2][21]。したがって例えば、ガウシアンはある種のサイズがある餌を食べる頻度を記述し、単に中央値または平均の餌のサ イズを特定するよりも詳細なニッチ記述を与えることができます。このようなベル型分布の場合、ニッチの位置、幅、形態は、平均、標準偏差、実際の分布その ものに対応します。しかし,この仮定は,各カテゴリーの資源が生物に与える影響と,生物が各カテゴリーの資源に与える影響を無視するため,誤った仮定とな る可能性があります.例えば、重複領域の資源は非限定的であることができ、その場合、ニッチの重複にもかかわらず、この資源に対する競争はない[1] [20][23]。 |

| An organism free of interference

from other species could use the full range of conditions (biotic and

abiotic) and resources in which it could survive and reproduce which is

called its fundamental niche.[24] However, as a result of pressure

from, and interactions with, other organisms (i.e. inter-specific

competition) species are usually forced to occupy a niche that is

narrower than this, and to which they are mostly highly adapted; this

is termed the realized niche.[24] Hutchinson used the idea of

competition for resources as the primary mechanism driving ecology, but

overemphasis upon this focus has proved to be a handicap for the niche

concept.[20] In particular, overemphasis upon a species' dependence

upon resources has led to too little emphasis upon the effects of

organisms on their environment, for instance, colonization and

invasions.[20] The term "adaptive zone" was coined by the paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson to explain how a population could jump from one niche to another that suited it, jump to an 'adaptive zone', made available by virtue of some modification, or possibly a change in the food chain, that made the adaptive zone available to it without a discontinuity in its way of life because the group was 'pre-adapted' to the new ecological opportunity.[25] Hutchinson's "niche" (a description of the ecological space occupied by a species) is subtly different from the "niche" as defined by Grinnell (an ecological role, that may or may not be actually filled by a species—see vacant niches). A niche is a very specific segment of ecospace occupied by a single species. On the presumption that no two species are identical in all respects (called Hardin's 'axiom of inequality'[26]) and the competitive exclusion principle, some resource or adaptive dimension will provide a niche specific to each species.[24] Species can however share a 'mode of life' or 'autecological strategy' which are broader definitions of ecospace.[27] For example, Australian grasslands species, though different from those of the Great Plains grasslands, exhibit similar modes of life.[28] Once a niche is left vacant, other organisms can fill that position. For example, the niche that was left vacant by the extinction of the tarpan has been filled by other animals (in particular a small horse breed, the konik). Also, when plants and animals are introduced into a new environment, they have the potential to occupy or invade the niche or niches of native organisms, often outcompeting the indigenous species. Introduction of non-indigenous species to non-native habitats by humans often results in biological pollution by the exotic or invasive species. The mathematical representation of a species' fundamental niche in ecological space, and its subsequent projection back into geographic space, is the domain of niche modelling.[29] |

しかし、他の生物からの圧力や他の生物との相互作用(すなわち種間競

争)の結果、種は通常これよりも狭いニッチを占めることを余儀なくされ、そのほとんどが高度に適応しており、これを実現ニッチと呼んでいる[24]。

[ハッチンソンは、生態学を駆動する主要なメカニズムとして資源に対する競争という考えを用いていたが、この焦点に過度に重点を置くことは、ニッチ概念に

とってハンディキャップであることが判明した[20]。

特に、種の資源への依存に過度に重点を置くことは、生物が環境に与える影響、例えば、植民や侵略に過度に重点を置かないことにつながった[20]。 適応領域」という用語は、古生物学者のジョージ・ゲイロード・シンプソンによって作られたもので、集団があるニッチからそれに適した別のニッチへとジャン プできること、何らかの改変、あるいはおそらく食物連鎖の変化によって利用可能になった「適応領域」にジャンプできること、集団が新しい生態的機会に「あ らかじめ適応」していたためにその生活様式の中断なく適応領域が利用可能であったことを説明するためのものである[25]。 ハッチンソンの「ニッチ」(種が占める生態学的空間の記述)は、グリネルが定義した「ニッチ」(生態学的役割で、種によって実際に埋められるかどうかは不 明-空白のニッチ参照)とは微妙に異なっています。 ニッチとは、一つの種が占有する生態空間の非常に特殊な区分のことである。2つの種はすべての点で同一ではない(ハーディンの「不平等の公理」[26]) という仮定と競争排除の原則に基づき、何らかの資源または適応的側面がそれぞれの種に特有のニッチを提供する[24]。しかし種は、生態空間のより広い定 義である「生活様式」または「自生生態戦略」を共有することはできる。例えばオーストラリアの草原の種は、大平原の草原と異なるが同様の生活様式を見せる [28]。 いったんニッチが空くと、他の生物はその位置を埋めることができる。例えば、ターパンが絶滅して空いたニッチは、他の動物(特に小型馬の一種であるコニ ク)によって埋められている。また、動植物が新しい環境に導入された場合、在来生物のニッチまたはニッチを占拠または侵入する可能性があり、しばしば在来 種を駆逐してしまうことがある。人間によって非在来種が非在来種の生息地に導入されると、しばしば外来種または侵入種による生物学的汚染を引き起こす。 生態学的空間における種の基本的なニッチの数学的表現と、それに続く地理的空間への投影は、ニッチモデリングの領域である[29]。 |

| Contemporary niche theory Contemporary niche theory (also called "classic niche theory" in some contexts) is a framework that was originally designed to reconcile different definitions of niches (see Grinnellian, Eltonian, and Hutchinsonian definitions above), and to help explain the underlying processes that affect Lotka-Volterra relationships within an ecosystem. The framework centers around "consumer-resource models" which largely split a given ecosystem into resources (e.g. sunlight or available water in soil) and consumers (e.g. any living thing, including plants and animals), and attempts to define the scope of possible relationships that could exist between the two groups.[30] In contemporary niche theory, the "impact niche" is defined as the combination of effects that a given consumer has on both a). the resources that it uses, and b). the other consumers in the ecosystem. Therefore, the impact niche is equivalent to the Eltonian niche since both concepts are defined by the impact of a given species on its environment.[30] The range of environmental conditions where a species can successfully survive and reproduce (i.e. the Hutchinsonian definition of a realized niche) is also encompassed under contemporary niche theory, termed the "requirement niche". The requirement niche is bounded by both the availability of resources as well as the effects of coexisting consumers (e.g. competitors and predators).[30] |

現代のニッチ理論 現代のニッチ理論(文脈によっては「古典的ニッチ理論」とも呼ばれる)は、もともとニッチの異なる定義(上記のグリネル型、エルトン型、ハッチンソン型の 定義を参照)を調整し、生態系内のロトカ=ウォルテラ関係に影響を与える基礎的なプロセスを説明するために考案された枠組みである。このフレームワーク は、与えられた生態系を資源(例えば、太陽光や土壌中の利用可能な水)と消費者(例えば、植物や動物を含むあらゆる生物)に大きく分け、2つのグループの 間に存在し得る関係の範囲を定義しようとする「消費者-資源モデル」を中心に据えたものである[30]。 現代のニッチ理論では、「影響ニッチ」は、ある消費者がa)その消費者が利用する資源と b)生態系内の他の消費者の両方に与える影響の組み合わせとして定義されています。したがって、影響ニッチはエルトンニッチと等価であり、両概念は与えら れた種がその環境に与える影響によって定義されるからである[30]。 ある種がうまく生存して繁殖できる環境条件の範囲(すなわち、ハッチンソン流の実現ニッチの定義)は、現代のニッチ理論の下でも包含され、「要件ニッチ」 と呼ばれています。要求ニッチは、資源の利用可能性と共存する消費者(競争相手や捕食者等)の影響の両方によって境界が定められる[30]。 |

| Coexistence under contemporary

niche theory Contemporary niche theory provides three requirements that must be met in order for two species (consumers) to coexist:[30] 1. The requirement niches of both consumers must overlap. 2. Each consumer must outcompete the other for the resource that it needs most. For example, if two plants (P1 and P2) are competing for nitrogen and phosphorus in a given ecosystem, they will only coexist if they are limited by different resources (P1 is limited by nitrogen and P2 is limited by phosphorus, perhaps) and each species must outcompete the other species to get that resource (P1 needs to be better at obtaining nitrogen and P2 needs to be better at obtaining phosphorus). Intuitively, this makes sense from an inverse perspective: If both consumers are limited by the same resource, one of the species will ultimately be the better competitor, and only that species will survive. Furthermore, if P1 was outcompeted for the nitrogen (the resource it needed most) it would not survive. Likewise, if P2 was outcompeted for phosphorus, it would not survive. 3.The availability of the limiting resources (nitrogen and phosphorus in the above example) in the environment are equivalent. These requirements are interesting and controversial because they require any two species to share a certain environment (have overlapping requirement niches) but fundamentally differ the ways that they use (or "impact") that environment. These requirements have repeatedly been violated by nonnative (i.e. introduced and invasive) species, which often coexist with new species in their nonnative ranges, but do not appear to be constricted these requirements. In other words, contemporary niche theory predicts that species will be unable to invade new environments outside of their requirement (i.e. realized) niche, yet many examples of this are well-documented.[31][32] Additionally, contemporary niche theory predicts that species will be unable to establish in environments where other species already consume resources in the same ways as the incoming species, however examples of this are also numerous.[33][32] |

現代のニッチ理論における共存 現代のニッチ理論は、2つの種(消費者)が共存するために満たさなければならない3つの要件を提示している[30]。 1. 両方の消費者の要求ニッチが重なっていなければならない。 2. それぞれの消費者が最も必要とする資源をめぐって、もう一方の消費者と競争しなければならない。例えば、ある生態系で2つの植物(P1とP2)が窒素とリ ンをめぐって競合している場合、それらが異なる資源によって制限され(P1は窒素によって、P2はリンによって、おそらく制限される)、それぞれの種がそ の資源を得るために他の種に勝たなければ共存できない(P1は窒素を得るのが得意である必要があり、P2はリンを得るのが得意である必要がある)。直感的 には、これは逆の観点から理にかなっている。もし両方の消費者が同じ資源で制限されている場合、最終的にはどちらかの種がより良い競争相手となり、その種 だけが生き残ることになります。さらに、もしP1が窒素(最も必要とする資源)をめぐって競争していたら、生き残ることはできないだろう。同様に、P2が リンをめぐって競合した場合にも、生き残ることはできない。 3.環境中の制限資源(上記の例では窒素とリン)の利用可能性が同等であること。 この要件は、2つの種がある環境を共有しながら(要件ニッチが重複している)、その環境の利用方法(または「影響」)が根本的に異なることを要求するもの で、興味深い論争を呼んでいる。これらの要件は、外来種(すなわち導入種や侵入種)によって繰り返し破られてきた。外来種は、しばしばその非外来域で新し い種と共存するが、これらの要件が制約されているようには見えない。言い換えれば、現代のニッチ理論は、種がその要求(=実現)ニッチ以外の新しい環境に 侵入することはできないと予測するが、その例は数多く記録されている[31][32]。さらに、現代のニッチ理論は、他の種がすでに流入する種と同じ方法 で資源を消費している環境では種が定着できないと予測するが、その例もまた数多く記録されている[33][32]。 |

| Niche and Geographic Range The geographic range of a species can be viewed as a spatial reflection of its niche, along with characteristics of the geographic template and the species that influence its potential to colonize. The fundamental geographic range of a species is the area it occupies in which environmental conditions are favorable, without restriction from barriers to disperse or colonize.[4] A species will be confined to its realized geographic range when confronting biotic interactions or abiotic barriers that limit dispersal, a more narrow subset of its larger fundamental geographic range. An early study on ecological niches conducted by Joseph H. Connell analyzed the environmental factors that limit the range of a barnacle (Chthamalus stellatus) on Scotland's Isle of Cumbrae.[34] In his experiments, Connell described the dominant features of C. stellatus niches and provided explanation for their distribution on intertidal zone of the rocky coast of the Isle. Connell described the upper portion of C. stellatus's range is limited by the barnacle's ability to resist dehydration during periods of low tide. The lower portion of the range was limited by interspecific interactions, namely competition with a cohabiting barnacle species and predation by a snail.[34] By removing the competing B. balanoides, Connell showed that C. stellatus was able to extend the lower edge of its realized niche in the absence of competitive exclusion. These experiments demonstrate how biotic and abiotic factors limit the distribution of an organism. |

ニッチと地理的範囲 種の地理的範囲は、その種のニッチを空間的に反映したものと見ることができ、さらにその種が 植民地化する可能性に影響を与える地理的テンプレートと種の特性も合わせて見ることができ る。種の基本的な地理的範囲は、環境条件が良好で、分散またはコロニー形成の障壁による制限のない、その種が占める領域である[4]。生物的相互作用また は分散を制限する生物的障壁に直面したとき、その種は実現した地理的範囲に閉じ込められるが、その大きな基本的地理的範囲のより狭い部分集合である。 ジョセフ・H・コネルによる生態的ニッチに関する初期の研究では、スコットランドのカンブレー島におけるフジツボ(Chthamalus stellatus)の範囲を制限する環境要因を分析しました[34]。コネルは実験の中で、C. stellatusのニッチの主要な特徴を説明し、島の岩場海岸の潮間帯における分布について説明しました。また,C. stellatusの生息域の上部は,干潮時の脱水に対するフジツボの抵抗力によって制限されると説明した.また,同居するフジツボ類との競合やカタツム リによる捕食といった種間相互作用によって,生息域の下限が制限されていた[34]。競合するB. balanoidesを取り除くことで,競合排除がなくてもC. stellatusが実現したニッチの下端を拡張できることをConnellは示している。これらの実験は、生物学的・非生物学的な要因がいかに生物の分 布を制限しているかを示している。 |

| Parameters The different dimensions, or plot axes, of a niche represent different biotic and abiotic variables. These factors may include descriptions of the organism's life history, habitat, trophic position (place in the food chain), and geographic range. According to the competitive exclusion principle, no two species can occupy the same niche in the same environment for a long time. The parameters of a realized niche are described by the realized niche width of that species.[26] Some plants and animals, called specialists, need specific habitats and surroundings to survive, such as the spotted owl, which lives specifically in old growth forests. Other plants and animals, called generalists, are not as particular and can survive in a range of conditions, for example the dandelion.[35] |

パラメータ ニッチの異なる次元、またはプロット軸は、異なる生物学的および非生物学的変数を代表することができる。これらの要因には、生物の生活史、生息地、栄養的 位置(食物連鎖における位置)、地理的範囲などの記述が含まれる場合がある。競争排除の原則によれば、2つの種が同じ環境下で長期間にわたって同じニッチ を占有することはできない。実現されたニッチのパラメータは、その種の実現されたニッチ幅によって記述される[26]。スペシャリストと呼ばれる一部の動 植物は、原生林に特異的に生息するシマフクロウのように、生存のために特定の生息地や環境を必要とする。一方、ジェネラリストと呼ばれる植物や動物は、そ れほど特殊ではなく、例えばタンポポのように様々な条件で生存することができる[35]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecological_niche. |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator. |

Where three species eat

some of the same prey, a statistical picture of each niche shows

overlap in resource usage between three species, indicating where

competition is strongest.

リンク

文献

For all undergraduate students! - Do not paste our message to your homework reports, You SHOULD [re]think the message in this page!!