Nomads are

communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from

areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning

livestock), tinkers and trader nomads.[1][2] In the twentieth century,

the population of nomadic pastoral tribes slowly decreased, reaching an

estimated 30–40 million nomads in the world as of 1995.[3]

Nomadic hunting and gathering—following seasonally available wild

plants and game—is by far the oldest human subsistence method.[4]

Pastoralists raise herds of domesticated livestock, driving or

accompanying them in patterns that normally avoid depleting pastures

beyond their ability to recover.[5] Nomadism is also a lifestyle

adapted to infertile regions such as steppe, tundra, or ice and sand,

where mobility is the most efficient strategy for exploiting scarce

resources. For example, many groups living in the tundra are reindeer

herders and are semi-nomadic, following forage for their animals.

Sometimes also described as "nomadic" are various itinerant populations

who move among densely populated areas to offer specialized services

(crafts or trades) to their residents—external consultants, for

example. These groups are known as "peripatetic nomads".[6][7]

|

遊牧民とは、定住地を持たず、定期的に地域を行き来する共同体のことで

ある。このような集団には、狩猟採集民、牧畜遊牧民(家畜を所有)、ティンカー、商人遊動民などが含まれる[1][2]。20世紀には、牧畜遊牧民の人口

は徐々に減少し、1995年現在、世界で推定3,000万~4,000万人の遊牧民が存在する[3]。

遊牧民は家畜の群れを飼育し、通常、牧草地が回復能力を超えて枯渇するのを避けるパターンで、家畜を駆る、または同行する[5]。遊牧はまた、草原、ツン

ドラ、または氷と砂のような不毛の地域に適応したライフスタイルであり、移動は希少資源を開発するための最も効率的な戦略である。例えば、ツンドラ地帯に

住む多くの集団はトナカイの牧畜民であり、家畜の飼料を追って半遊牧生活を送っている。

また、

遊牧民を意味した「ノマド」と表現されることもあるが、人口密度の高い地域を移動し、住民に専門的なサービス(工芸品や商売)を提供するさまざまな旅人集団すなわち遊動民(ノマド)もいる

(外部のコンサルタントなど)。こうした集団は「周遊民・遊動民」として知られている[6][7]。

|

Etymology

The English word nomad comes from the Middle French nomade, from Latin

nomas ("wandering shepherd"), from Ancient Greek νομᾰ́ς (nomás,

“roaming, wandering, esp. to find pasture”), which is derived from the

Ancient Greek νομός (nomós, “pasture”).[8][dubious – discuss]

|

語源

英語の nomad は、古代ギリシア語の νομός(nomós、「牧草地」)に由来するラテン語 nomas(「放浪する羊飼い」)に由来する中フランス語 nomade に由来する[8][dubious - discuss]。

|

Common characteristics

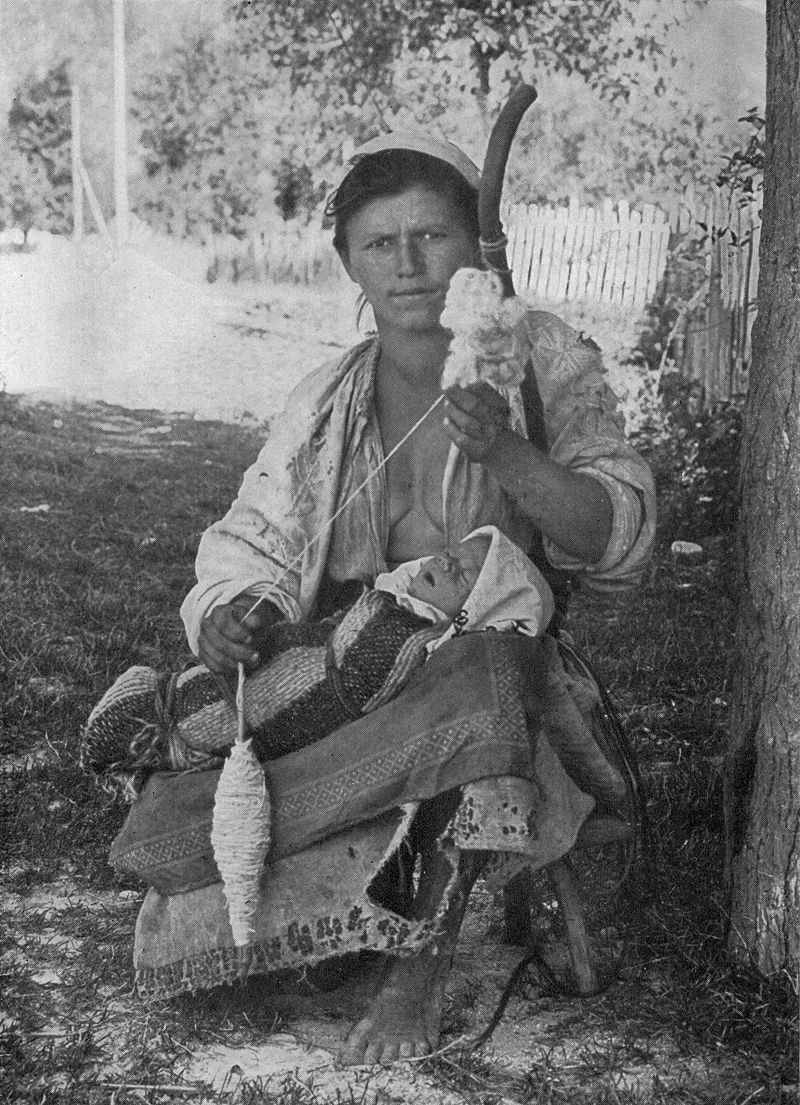

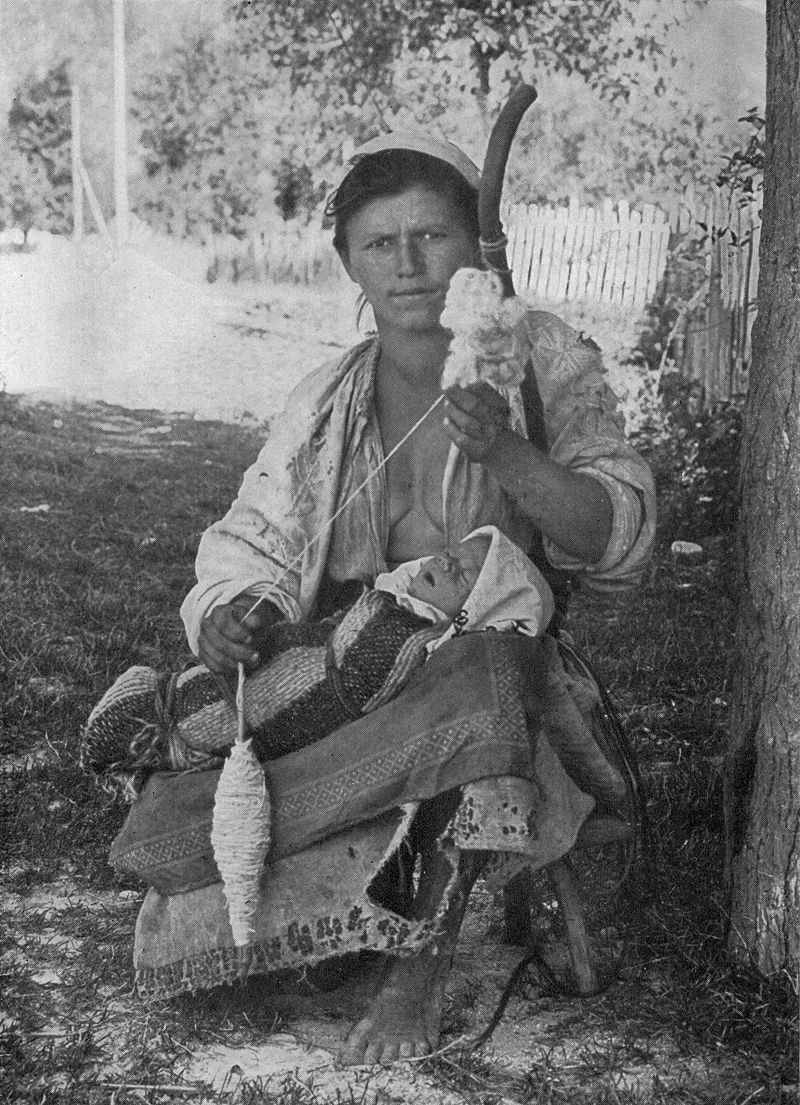

Roma mother and child

Nomads on the Changtang, Ladakh

Rider in Mongolia, 2012. While nomadic life is less common in modern times, the horse remains a national symbol in Mongolia.

Beja nomads from Northeast Africa

Nomads are communities who move from place to place as a way of

obtaining food, finding pasture for livestock, or otherwise making a

living. Most nomadic groups follow a fixed annual or seasonal pattern

of movements and settlements. Nomadic people traditionally travel by

animal, canoe or on foot. Animals include camels, horses and alpaca.

Today, some nomads travel by motor vehicle. Some nomads may live in

homes or homeless shelters, though this would necessarily be on a

temporary or itinerant basis.[citation needed]

Nomads keep moving for different reasons. Nomadic foragers move in

search of game, edible plants, and water. Aboriginal Australians,

Negritos of Southeast Asia, and San of Africa, for example,

traditionally move from camp to camp to hunt and gather wild plants.

Some tribes of the Americas followed this way of life. Pastoral nomads,

on the other hand, make their living raising livestock such as camels,

cattle, goats, horses, sheep, or yaks; these nomads usually travel in

search of pastures for their flocks. The Fulani and their cattle travel

through the grasslands of Niger in western Africa. Some nomadic

peoples, especially herders, may also move to raid settled communities

or to avoid enemies. Nomadic craftworkers and merchants travel to find

and serve customers. They include the Gadia Lohar blacksmiths of India,

the Roma traders, Scottish travellers and Irish travellers.[citation

needed]

Many nomadic and pastorally nomadic peoples are associated with

semi-arid and desert climates; examples include the Mongolic and Turkic

peoples of Central Asia, the Plains Indians of the Great Plains, and

the Amazigh and other peoples of the Sahara Desert. Pastoral nomads who

are residents of arid climates include the Fulani of the Sahel, the

Khoikhoi of South Africa and Namibia, groups of Northeast Africa such

as Somalis and Oromo, and the Bedouin of the Middle East.

Most nomads travel in groups of families, bands, or tribes. These

groups are based on kinship and marriage ties or on formal agreements

of cooperation. A council of adult males makes most of the decisions,

though some tribes have chiefs.[citation needed]

In the case of Mongolian nomads, a family moves twice a year. These two

movements generally occur during the summer and winter. The winter

destination is usually located near the mountains in a valley and most

families already have fixed winter locations. Their winter locations

have shelter for animals and are not used by other families while they

are out. In the summer they move to a more open area in which the

animals can graze. Most nomads usually move within the same region and

do not travel very far. Since they usually circle around a large area,

communities form and families generally know where the other ones are.

Often, families do not have the resources to move from one province to

another unless they are moving out of the area permanently. A family

can move on its own or with others; if it moves alone, they are usually

no more than a couple of kilometres from each other. The geographical

closeness of families is usually for mutual support. Pastoral nomad

societies usually do not have large populations.

One nomadic society, the Mongols, gave rise to the largest land empire

in history. The Mongols originally consisted of loosely organized

nomadic tribes in Mongolia, Manchuria, and Siberia. In the late 12th

century, Genghis Khan united them and other nomadic tribes to found the

Mongol Empire, which eventually stretched the length of Asia.[9]

The nomadic way of life has become increasingly rare. Many countries

have converted pastures into cropland and forced nomadic peoples into

permanent settlements.[10]

Modern forms of nomadic peoples are variously referred to as

"shiftless", "gypsies", "rootless cosmopolitans", hunter-gatherers,

refugees and urban homeless or street-people, depending on their

individual circumstances. These terms may be used in a derogatory sense.

According to Gérard Chaliand, terrorism originated in nomad-warrior

cultures. He points to Machiavelli's classification of war into two

types, which Chaliand interprets as describing a difference between

warfare in sedentary and nomadic societies:[11]

There are two different kinds of war. The one springs from the ambition

of princes or republics that seek to extend their empire; such were the

wars of Alexander the Great, and those of the Romans, and those which

two hostile powers carry on against each other. These wars are

dangerous but never go so far as to drive all its inhabitants out of a

province, because the conqueror is satisfied with the submission of the

people... The other kind of war is when an entire people, constrained

by famine or war, leave their country with their families for the

purpose of seeking a new home in a new country, not for the purpose of

subjecting it to their dominion as in the first case, but with the

intention of taking absolute possession of it themselves and driving

out or killing its original inhabitants.

Primary historical sources for nomadic steppe-style warfare are found

in many languages: Chinese, Persian, Polish, Russian, Classical Greek,

Armenian, Latin and Arabic. These sources concern both the true steppe

nomads (Mongols, Huns, Magyars and Scythians) and also the semi-settled

people like Turks, Crimean Tatars and Russians, who retained or, in

some cases, adopted the nomadic form of warfare.[12]

|

共通の特徴

ロマの母子

ラダック、チャンタンの遊牧民たち

2012年、モンゴルの騎手。現代では遊牧民の生活は少なくなったが、モンゴルでは馬は依然として国のシンボルである。

アフリカ北東部のベジャ族遊牧民

遊牧民とは、食料を得るため、家畜の放牧地を探すため、あるいは生計を立てるために各地を移動する共同体のことである。遊牧民の多くは、年間または季節ご

とに決まったパターンで移動し、定住する。遊牧民は伝統的に動物、カヌー、徒歩で移動する。動物にはラクダ、馬、アルパカなどがいる。今日では、自動車で

移動する遊牧民もいる。遊牧民の中には、家やホームレスシェルターに住む者もいるが、これは必然的に一時的または遍歴的なものである[要出典]。

遊牧民が移動を続ける理由はさまざまである。遊牧民は獲物や食用植物、水を求めて移動する。例えば、オーストラリアの原住民、東南アジアのネグリト族、ア

フリカのサン族は、伝統的にキャンプからキャンプへと移動し、狩猟や野草採集を行う。アメリカ大陸の一部の部族も、このような生活様式を踏襲している。一

方、牧畜遊牧民はラクダ、ウシ、ヤギ、ウマ、ヒツジ、ヤクなどの家畜を飼育して生計を立てている。これらの遊牧民は通常、群れのための牧草地を求めて旅を

する。フラニ族とその牛は、アフリカ西部のニジェールの草原を旅している。遊牧民、特に牧畜民の中には、定住社会を襲撃するため、あるいは敵を避けるため

に移動することもある。遊牧民の工芸品職人や商人は、顧客を見つけて仕えるために移動する。インドのガディア・ロハール鍛冶屋、ロマの商人、スコットラン

ドの旅行者、アイルランドの旅行者などがこれにあたる[要出典]。

遊牧民や牧畜遊牧民の多くは、半乾燥気候や砂漠気候に関連している。中央アジアのモンゴル族やテュルク族、大平原の平原インディアン、サハラ砂漠のアマジ

族などがその例である。乾燥気候の住民である牧畜遊牧民には、サヘルのフラニ族、南アフリカとナミビアのコイコイ族、ソマリアやオロモなどのアフリカ北東

部のグループ、中東のベドウィンなどがいる。

遊牧民の多くは、家族、バンド、部族などのグループで移動する。これらのグループは、親族関係や婚姻関係、または正式な協力協定に基づいている。部族によっては首長がいる場合もあるが、ほとんどの意思決定は成人男性からなる評議会が行う[要出典]。

モンゴルの遊牧民の場合、一家は年に2回移動する。この2回の移動は一般的に夏と冬に行われる。冬の移動先はたいてい山の近くの谷間であり、ほとんどの家

族はすでに決まった冬の場所を持っている。冬の場所は動物用のシェルターがあり、留守中は他の家族に使われることはない。夏には、動物が草を食むことがで

きる、より開けた場所に移動する。遊牧民の多くは同じ地域内を移動し、あまり遠くへは行かない。彼らは通常、広い地域を周遊するため、共同体が形成され、

家族はたいてい他の家族の居場所を知っている。多くの場合、家族はその地域から永久に引っ越すのでない限り、ある地方から別の地方へ移動する資源を持って

いない。家族が単独で移動することもあれば、他の家族と一緒に移動することもある。単独で移動する場合、互いの距離は通常2、3キロメートル以内である。

家族が地理的に近いのは、通常、相互扶助のためである。牧畜遊牧民社会は通常、人口が多くない。

遊牧民社会のひとつであるモンゴル人は、歴史上最大の陸上帝国を生み出した。モンゴル人はもともと、モンゴル、満州、シベリアのゆるやかに組織された遊牧

民族から成っていた。12世紀後半、チンギス・ハーンは彼らと他の遊牧民族を統合してモンゴル帝国を創設し、最終的にはアジア全土に広がった[9]。

遊牧民の生活様式はますます珍しくなっている。多くの国が牧草地を農地に変え、遊牧民を定住地に押し込めている[10]。

遊牧民の現代的な形態は、個々の状況に応じて、「シフトレス」、「ジプシー」、「根無し草のコスモポリタン」、狩猟採集民、難民、都市のホームレスや路上生活者などと様々に呼ばれている。これらの言葉は蔑称の意味で使われることもある。

ジェラール・シャリアンによれば、テロリズムの起源は遊牧戦士文化にあるという。彼はマキアヴェッリが戦争を2つのタイプに分類していることを指摘し、シャリアンはこれを定住社会と遊牧社会における戦争の違いを表していると解釈している[11]。

戦争には二つの種類がある。一つは、帝国を拡大しようとする君主や共和国の野心から生じるもので、アレクサンダー大王の戦争やローマ帝国の戦争がそうであ

り、敵対する二つの大国が互いに争う戦争がそうである。これらの戦争は危険ではあるが、すべての住民をその地方から追い出すまでには至らない。もう一つの

戦争は、飢饉や戦争で窮地に追い込まれた民族全体が、新しい国に新居を求める目的で、家族とともに国を離れる場合である。

遊牧民の草原型戦争に関する一次史料は、多くの言語に見られる:

中国語、ペルシア語、ポーランド語、ロシア語、古典ギリシア語、アルメニア語、ラテン語、アラビア語などである。これらの史料は、真の草原遊牧民(モンゴ

ル人、フン族、マジャール人、スキタイ人)と、トルコ人、クリミア・タタール人、ロシア人のような半定住民の両方に関するものであり、遊牧民の戦争形態を

維持したり、場合によっては取り入れたりしている[12]。

|

Hunter-gatherers

Main article: Hunter-gatherer

Starting fire by hand. San people in Botswana.

Hunter-gatherers (also known as foragers) move from campsite to

campsite, following game and wild fruits and vegetables. Hunting and

gathering describes early peoples' subsistence living style. Following

the development of agriculture, most hunter-gatherers were eventually

either displaced or converted to farming or pastoralist groups. Only a

few contemporary societies, such as the Pygmies, the Hadza people, and

some uncontacted tribes in the Amazon rainforest, are classified as

hunter-gatherers; some of these societies supplement, sometimes

extensively, their foraging activity with farming or animal husbandry.

|

狩猟採集民

主な記事 狩猟採集民

手で火をおこす。ボツワナのサン族。

狩猟採集民(フォリジャーとも呼ばれる)は、キャンプ場からキャンプ場へと移動し、獲物や野生の果物や野菜を追いかける。狩猟採集は、初期の人々の自給自

足の生活スタイルを表している。農耕が発達すると、ほとんどの狩猟採集民はやがて土地を追われるか、農耕民や牧畜民に転換した。現代の社会で狩猟採集民に

分類されるのは、ピグミー族やハザ族、アマゾンの熱帯雨林に住む未接触の部族などごく少数である。

|

Pastoralism

Main articles: Pastoralism, Transhumance, and nomadic pastoralism

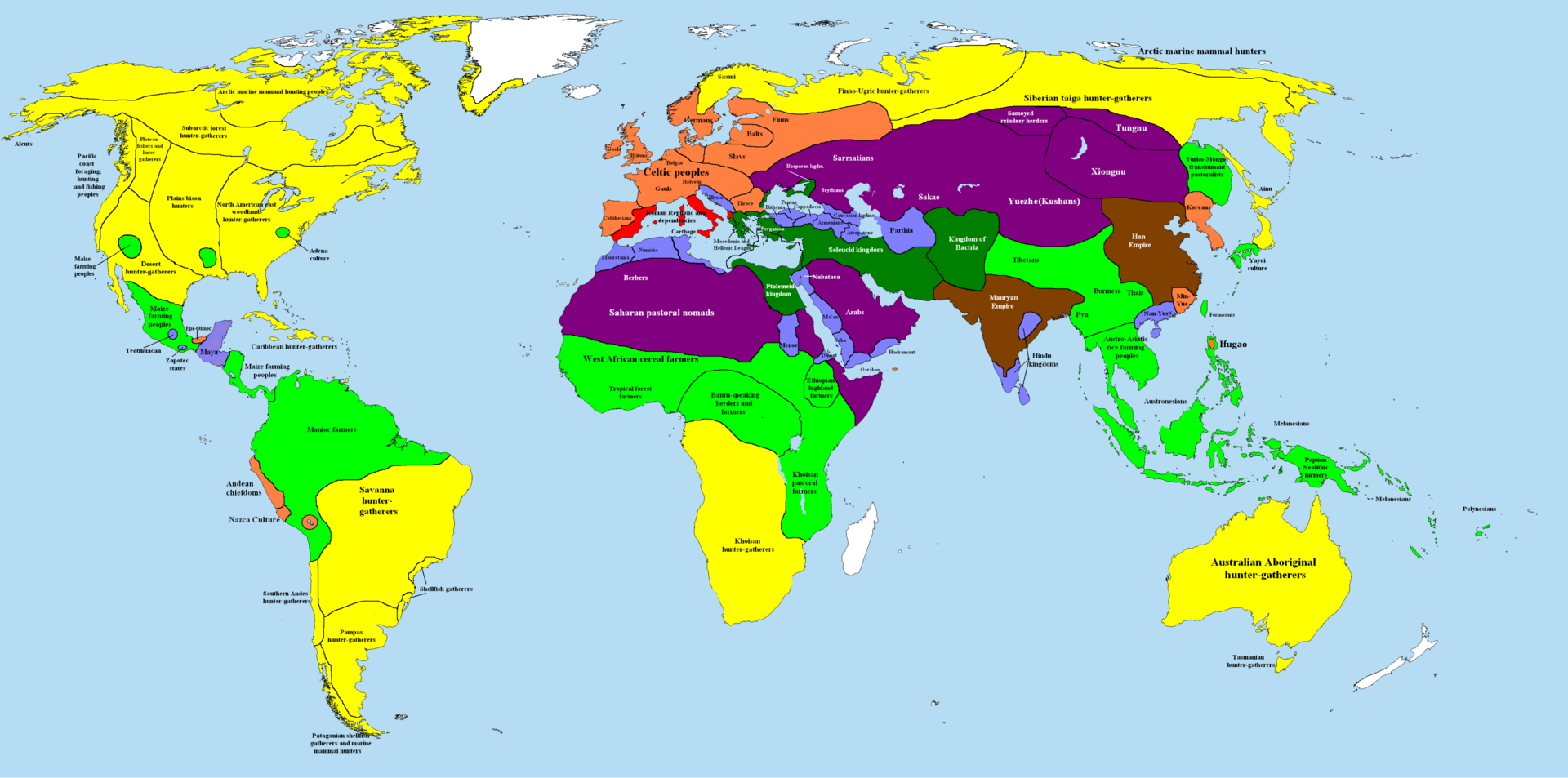

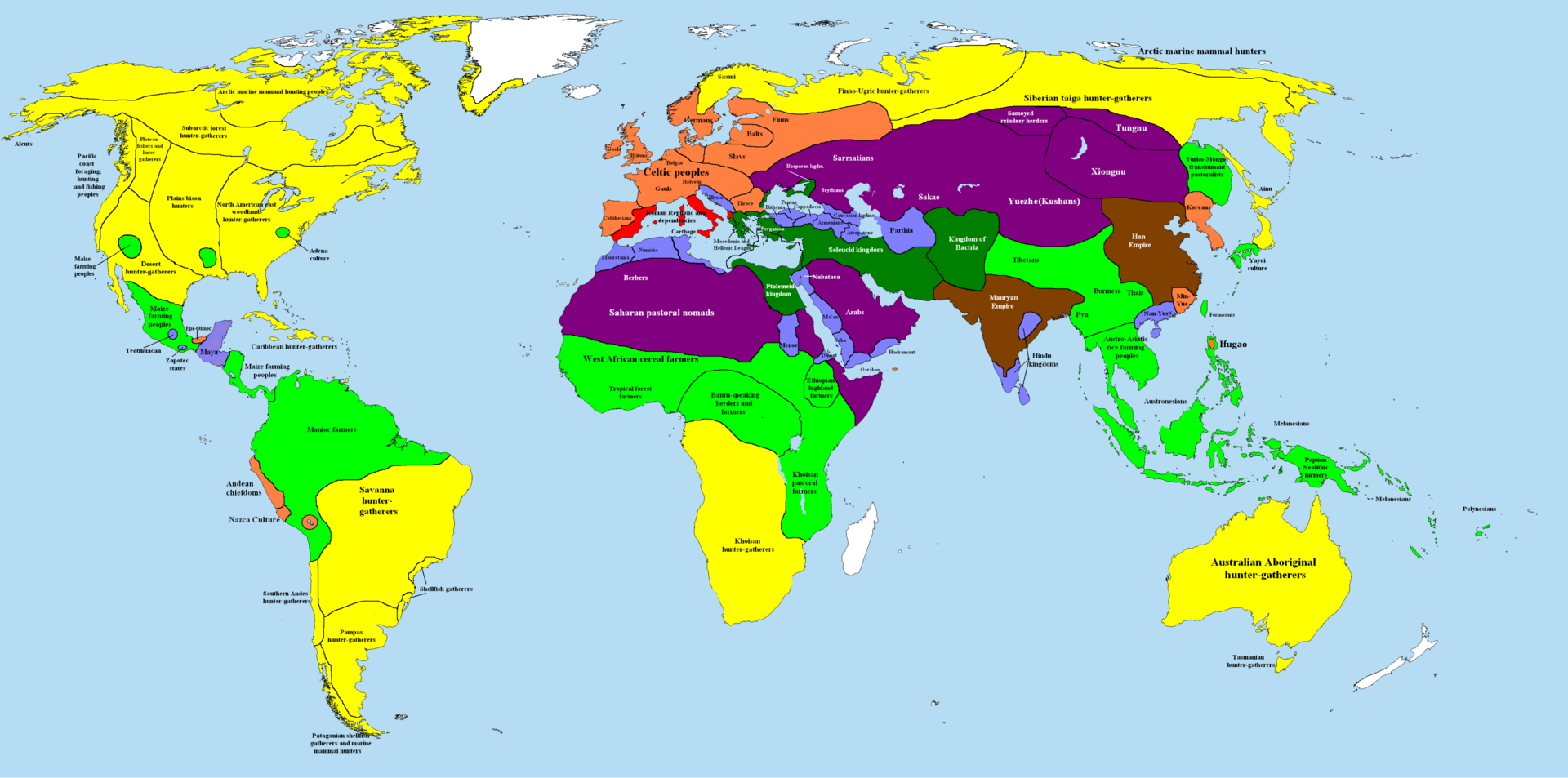

Overview map of the world in 200 BC:

Sarmatians, Saka, Yuezhi, Xiongnu and other nomadic pastoralists

Cuman nomads, Radziwiłł Chronicle, 13th century.

A yurt in front of the Gurvan Saikhan Mountains. Approximately 30% of Mongolia's 3 million people are nomadic or semi-nomadic.

A Sámi family in Norway around 1900. Reindeer have been herded for

centuries by several Arctic and Subarctic people including the Sámi and

the Nenets.[13]

Pastoral nomads are nomads moving between pastures. Nomadic pastoralism

is thought to have developed in three stages that accompanied

population growth and an increase in the complexity of social

organization. Karim Sadr has proposed the following stages:[14]

Pastoralism: This is a mixed economy with a symbiosis within the family.

Agropastoralism: This is when symbiosis is between segments or clans within an ethnic group.

True Nomadism: This is when symbiosis is at the regional level,

generally between specialised nomadic and agricultural populations.

The pastoralists are sedentary to a certain area, as they move between

the permanent spring, summer, autumn and winter (or dry and wet season)

pastures for their livestock. The nomads moved depending on the

availability of resources.[15]

History

Origins

Nomadic pastoralism seems to have developed first as a part of the

secondary-products revolution proposed by Andrew Sherratt, in which

early pre-pottery Neolithic cultures that had used animals as live meat

("on the hoof") also began using animals for their secondary products,

for example: milk and its associated dairy products, wool and other

animal hair, hides (and consequently leather), manure (for fuel and

fertilizer), and traction.[citation needed]

The first nomadic pastoral society developed in the period from 8,500

to 6,500 BCE in the area of the southern Levant.[16] There, during a

period of increasing aridity, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) cultures

in the Sinai were replaced by a nomadic, pastoral pottery-using

culture, which seems to have been a cultural fusion between them and a

newly-arrived Mesolithic people from Egypt (the Harifian culture),

adopting their nomadic hunting lifestyle to the raising of stock.[17]

This lifestyle quickly developed into what Jaris Yurins has called the

circum-Arabian nomadic pastoral techno-complex and is possibly

associated with the appearance of Semitic languages in the region of

the Ancient Near East. The rapid spread of such nomadic pastoralism was

typical of such later developments as of the Yamnaya culture of the

horse and cattle nomads of the Eurasian steppe (c. 3300–2600 BCE), and

of the Mongol spread in the later Middle Ages.[17]

Yamnaya steppe pastoralists from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, who were

among the first to master horseback riding, played a key role in

Indo-European migrations and in the spread of Indo-European languages

across Eurasia.[18][19]

Trekboers in southern Africa adopted nomadism from the 17th

century.[20] Some elements of gaucho culture in colonial South America

also re-invented nomadic lifestyles.[21]

Increase in post-Soviet Central Asia

One of the results of the break-up of the Soviet Union and the

subsequent political independence and economic collapse of its Central

Asian republics has been the resurgence of pastoral nomadism.[22]

Taking the Kyrgyz people as a representative example, nomadism was the

centre of their economy before Russian colonization at the turn of the

20th century, when they were settled into agricultural villages. The

population became increasingly urbanized after World War II, but some

people still take their herds of horses and cows to high pastures

(jailoo) every summer, continuing a pattern of transhumance.[citation

needed]

Since the 1990s, as the cash economy shrank, unemployed relatives were

reabsorbed into family farms, and the importance of this form of

nomadism has increased.[citation needed] The symbols of nomadism,

specifically the crown of the grey felt tent known as the yurt, appears

on the national flag, emphasizing the central importance of nomadism in

the genesis of the modern nation of Kyrgyzstan.[23]

Sedentarization

See also: Sedentism

From 1920 to 2008, the population of nomadic pastoral tribes slowly

decreased from over a quarter of Iran's population.[24] Tribal pastures

were nationalized during the 1960s. The National Commission of UNESCO

registered the population of Iran at 21 million in 1963, of whom two

million (9.5%) were nomads.[25] Although the nomadic population of Iran

has dramatically decreased in the 20th century, Iran still has one of

the largest nomadic populations in the world, an estimated 1.5 million

in a country of about 70 million.[26]

In Kazakhstan where the major agricultural activity was nomadic

herding,[27] forced collectivization under Joseph Stalin's rule met

with massive resistance and major losses and confiscation of

livestock.[28] Livestock in Kazakhstan fell from 7 million cattle to

1.6 million and from 22 million sheep to 1.7 million. The resulting

famine of 1931–1934 caused some 1.5 million deaths: this represents

more than 40% of the total Kazakh population at that time.[29]

Fulani herdsman in Togo. Spread throughout West Africa, the Fulani are the largest nomadic group in the world.

In the 1950s as well as the 1960s, large numbers of Bedouin throughout

the Middle East started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to

settle in the cities of the Middle East, especially as home ranges have

shrunk and population levels have grown. Government policies in Egypt

and Israel, oil production in Libya and the Persian Gulf, as well as a

desire for improved standards of living, effectively led most Bedouin

to become settled citizens of various nations, rather than stateless

nomadic herders. A century ago, nomadic Bedouin still made up some 10%

of the total Arab population. Today, they account for some 1% of the

total.[30]

At independence in 1960, Mauritania was essentially a nomadic society.

The great Sahel droughts of the early 1970s caused massive problems in

a country where 85% of its inhabitants were nomadic herders. Today only

15% remain nomads.[31]

As many as 2 million nomadic Kuchis wandered over Afghanistan in the

years before the Soviet invasion, and most experts agreed that by 2000

the number had fallen dramatically, perhaps by half. A severe drought

had destroyed 80% of the livestock in some areas.[32]

Niger experienced a serious food crisis in 2005 following erratic

rainfall and desert locust invasions. Nomads such as the Tuareg and

Fulani, who make up about 20% of Niger's 12.9 million population, had

been so badly hit by the Niger food crisis that their already fragile

way of life is at risk.[33] Nomads in Mali were also affected.[34] The

Fulani of West Africa are the world's largest nomadic group.[35]

Lifestyle

Tents of Pashtun nomads in Badghis Province, Afghanistan. They migrate from region to region depending on the season.

Pala nomads living in Western Tibet have a diet that is unusual in that

they consume very few vegetables and no fruit. The main staple of their

diet is tsampa and they drink Tibetan style butter tea. Pala will eat

heartier foods in the winter months to help keep warm. Some of the

customary restrictions they explain as cultural saying only that drokha

do not eat certain foods, even some that may be naturally abundant.

Though they live near sources of fish and fowl these do not play a

significant role in their diet, and they do not eat carnivorous

animals, rabbits or the wild asses that are abundant in the environs,

classifying the latter as horse due to their cloven hooves. Some

families do not eat until after the morning milking, while others may

have a light meal with butter tea and tsampa. In the afternoon, after

the morning milking, the families gather and share a communal meal of

tea, tsampa and sometimes yogurt. During winter months the meal is more

substantial and includes meat. Herders will eat before leaving the camp

and most do not eat again until they return to camp for the evening

meal. The typical evening meal may include thin stew with tsampa,

animal fat and dried radish. Winter stew would include a lot of meat

with either tsampa or boiled flour dumplings.[36]

Nomadic diets in Kazakhstan have not changed much over centuries. The

Kazakh nomad cuisine is simple and includes meat, salads, marinated

vegetables and fried and baked breads. Tea is served in bowls, possibly

with sugar or milk. Milk and other dairy products, like cheese and

yogurt, are especially important. Kumiss is a drink of fermented milk.

Wrestling is a popular sport, but the nomadic people do not have much

time for leisure. Horse riding is a valued skill in their culture.[37]

Movement of nomads in Chad

Perception

Ann Marie Kroll Lerner states that the pastoral nomads were viewed as

"invading, destructive, and altogether antithetical to civilizing,

sedentary societies" during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

According to Lerner, they are rarely accredited as "a civilizing

force".[38]

Allan Hill and Sara Randall observe that western authors have looked

for "romance and mystery, as well as the repository of laudable

characteristics believed lost in the West, such as independence,

stoicism in the face of physical adversity, and a strong sense of

loyalty to family and to tribe" in nomadic pastoralist societies. Hill

and Randall observe that nomadic pastoralists are stereotypically seen

by the settled populace in Africa and Middle East as "aimless

wanderers, immoral, promiscuous and disease-ridden" peoples. According

to Hill and Randall, both of these perceptions "misrepresent the

reality".[39]

|

牧畜業

主な記事 牧畜、牧畜転換、遊牧

紀元前200年の世界地図:

サルマティア人、サカ人、越中国、匈奴、その他の遊牧民。

クマン族の遊牧民、ラジヴィウ年代記、13世紀。

グルヴァン・サイハン山脈の前にあるユルト。モンゴルの人口300万人のうち約30%が遊牧民または準遊牧民である。

1900年頃のノルウェーのサーミ人家族。トナカイは、サーメ人やネネツ人などの北極圏や亜寒帯の人々によって何世紀にもわたって飼われてきた[13]。

牧畜遊牧民とは、牧草地間を移動する遊牧民のことである。遊牧民は、人口増加と社会組織の複雑化に伴い、3つの段階を経て発展したと考えられている。カリム・サドルは以下の段階を提唱している[14]。

牧畜: 家族内共生の混合経済。

農耕牧畜主義: これは、民族グループ内の区分や氏族間の共生である。

真の遊牧: これは地域レベルでの共生であり、一般的には専門化した遊牧民と農耕民の間の共生である。

牧畜民は一定の地域に定住し、家畜のために春、夏、秋、冬(または乾季と雨季)の牧草地を移動する。遊牧民は資源の有無によって移動する。

歴史

起源

遊牧社会は、アンドリュー・シェラットによって提唱された二次産品革命の一環として最初に発展したようである。この革命では、土器以前の新石器時代初期に

動物を生きた肉として(「蹄の上で」)利用していた文化が、二次産品、例えば、牛乳とそれに関連する乳製品、羊毛やその他の動物の毛、皮革(ひいては皮

革)、堆肥(燃料や肥料)、牽引力などにも動物を利用するようになった[要出典]。

最初の遊牧社会は、レバント南部の地域で前8,500年から前6,500年の期間に発展した[16]。そこでは、乾燥化が進む時期に、シナイ半島の前陶器

新石器時代B(PPNB)文化が、遊牧民の牧畜陶器使用文化に取って代わられた。これは、エジプトから新たに到来した中石器時代の人々(ハリフィア文化)

との間の文化的融合であったようで、彼らの遊牧狩猟生活様式を家畜の飼育に取り入れたものであった[17]。

このライフスタイルは、ヤリス・ユリンスが周アラビア遊牧テクノコンプレックスと呼ぶものへと急速に発展し、おそらく古代近東地域におけるセム系言語の出

現と関連している。このような遊牧の急速な広がりは、ユーラシア草原の馬と牛の遊牧民によるヤムナヤ文化(前3300年頃~前2600年頃)や、後期中世

におけるモンゴルの伝播のような、後の展開の典型であった[17]。

ポンティック-カスピ海ステップのヤムナヤ草原の牧畜民は、乗馬を最初に習得した一人であり、インド・ヨーロッパ語族の移動とユーラシア大陸におけるインド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語の普及において重要な役割を果たした[18][19]。

南部アフリカのトレックボアは17世紀から遊牧を取り入れた[20]。 植民地時代の南米におけるガウチョ文化のいくつかの要素も遊牧のライフスタイルを再発明した[21]。

ソビエト連邦崩壊後の中央アジアにおける増加

ソビエト連邦の崩壊とそれに続く中央アジア諸国の政治的独立と経済的崩壊の結果のひとつが、牧畜遊牧の復活である[22]。キルギス人を代表例として挙げ

ると、20世紀初頭のロシアによる植民地化以前は遊牧が経済の中心であり、農村に定住していた。第二次世界大戦後は都市化が進んだが、一部の人々は毎年夏

になると馬や牛の群れを高地の牧草地(ジェイルー)に連れて行き、放牧のパターンを続けている[要出典]。

1990年代以降、現金経済が縮小するにつれて、失業した親族が家族経営の農場に再吸収され、この形態の遊牧の重要性が増している[要出典]。遊牧のシン

ボル、特にユルトとして知られる灰色のフェルト製テントの王冠が国旗に描かれており、近代国家キルギスの起源における遊牧の中心的重要性を強調している

[23]。

定住化

以下も参照: 定住化

1920年から2008年にかけて、遊牧民族の人口はイランの人口の4分の1以上から徐々に減少した[24]。ユネスコ国内委員会は1963年にイランの

人口を2,100万人と登録したが、そのうち200万人(9.5%)が遊牧民であった[25]。20世紀に入ってイランの遊牧民人口は劇的に減少したが、

イランは依然として世界最大級の遊牧民人口を擁しており、約7,000万人の国土のうち150万人が遊牧民であると推定されている[26]。

主要な農業活動が遊牧であったカザフスタン[27]では、ヨシフ・スターリンの支配下で強制的な集団化が行われ、大規模な抵抗と家畜の大規模な損失と没収に見舞われた[28]。その結果、1931年から1934年にかけての飢饉によって約150万人が死亡した。

トーゴのフラニ族の牧畜民。西アフリカに広がるフラニは、世界最大の遊牧民グループである。

1950年代だけでなく1960年代にも、中東全域で多数のベドウィンが伝統的な遊牧生活を離れ、中東の都市に定住し始めた。エジプトやイスラエルにおけ

る政府の政策、リビアやペルシャ湾での石油生産、そして生活水準の向上への願望によって、ほとんどのベドウィンは無国籍の遊牧民ではなく、さまざまな国の

定住市民となった。100年前、遊牧民ベドウィンはまだアラブ全人口の10%ほどを占めていた。現在では全体の1%程度である[30]。

1960年の独立時、モーリタニアは基本的に遊牧民社会であった。1970年代初頭のサヘル大干ばつは、住民の85%が遊牧民であったモーリタニアに大問題を引き起こした。現在、遊牧民はわずか15%にすぎない[31]。

ソビエト侵攻前の数年間、アフガニスタンには200万人ものクチ族の遊牧民が放浪していたが、2000年までにはその数は激減し、おそらく半減していたというのが大方の専門家の見解であった。深刻な干ばつで家畜の80%が壊滅した地域もあった[32]。

ニジェールは2005年、不規則な降雨と砂漠のイナゴの侵入により、深刻な食糧危機を経験した。ニジェールの人口1,290万人の約20%を占めるトゥア

レグ族やフラニ族などの遊牧民は、ニジェールの食糧危機によって大きな打撃を受け、すでに脆弱な彼らの生活様式が危機に瀕している[33]。

マリの遊牧民もまた影響を受けた[34]。

ライフスタイル

アフガニスタンのバドギス州にあるパシュトゥーン遊牧民のテント。季節によって地域を移動する。

西チベットに住むパラ族の遊牧民は、野菜や果物をほとんど摂らないという珍しい食生活を送っている。主食はツァンパで、チベット式のバター茶を飲む。パラ

族は冬の間、体を温めるためによりボリュームのある食べ物を食べる。習慣的な制限のいくつかは、文化的なものとして説明され、ドローカは自然に豊富である

可能性があるものでさえ、特定の食物を食べないということだけである。また、肉食の動物やウサギ、周辺に多く生息する野生の驢馬も食べないが、後者は蹄が

あることから馬に分類される。朝の搾乳が終わるまで食事をとらない家庭もあれば、バター茶とツァンパで軽食をとる家庭もある。午後になると、午前中の搾乳

の後、家族が集まり、お茶、ツァンパ、時にはヨーグルトを一緒に食べる。冬の間は、肉類を含むより豪華な食事となる。牧童たちはキャンプを出発する前に食

事をとり、ほとんどの場合、夜食のためにキャンプに戻るまで食事をとらない。典型的な夜食は、ツァンパ、動物性脂肪、切り干し大根を使った薄いシチューで

ある。冬のシチューには、ツァンパかゆでた小麦粉の団子と一緒にたくさんの肉が入る[36]。

カザフスタンの遊牧民の食事は何世紀にもわたってあまり変わっていない。カザフスタンの遊牧民の料理はシンプルで、肉、サラダ、野菜のマリネ、揚げパン、

焼きパンなどがある。お茶はお茶碗で出され、砂糖やミルクが添えられることもある。牛乳やチーズ、ヨーグルトなどの乳製品は特に重要である。クミスは牛乳

を発酵させた飲み物である。レスリングは人気のあるスポーツだが、遊牧民には余暇を過ごす時間があまりない。乗馬は彼らの文化では重要な技能である

[37]。

チャドにおける遊牧民の動き

認識

アン・マリー・クロール・ラーナーによれば、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、牧畜遊牧民は「侵略的、破壊的、文明化した定住社会とは全く相反する存在」とみなされていた。ラーナーによれば、彼らが「文明化する力」として認められることはほとんどない[38]。

アラン・ヒルとサラ・ランドールは、西洋の作家が遊牧民社会に「ロマンスと神秘性、そして西洋で失われたと考えられている、独立心、肉体的逆境に直面した

ときのストイックさ、家族や部族に対する強い忠誠心といった称賛に値する特性の宝庫」を求めてきたと観察している。HillとRandallは、遊牧民は

アフリカや中東の定住民から「無目的な放浪者、不道徳、乱婚、病気に罹患した」民族としてステレオタイプに見られていると指摘する。ヒルとランドールによ

れば、こうした認識はいずれも「現実を誤って伝えている」[39]。

|

Contemporary peripatetic minorities in Eurasia

This section may contain

material not related to the topic of the article. Please help improve

this section or discuss this issue on the talk page. (July 2013) (Learn

how and when to remove this message)

Further information: Herder and Vagrancy (people)

See also: List of nomadic peoples, Eurasian nomads, Eurasian Steppe, and Nomadic empire

A tent of Romani nomads in Hungary, 19th century.

Peripatetic minorities are mobile populations moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.[40]

Each existing community is primarily endogamous, and subsists

traditionally on a variety of commercial or service activities.

Formerly, all or a majority of their members were itinerant, and this

largely holds true today. Migration generally takes place within the

political boundaries of a single state these days.

Each of the peripatetic communities is multilingual, it speaks one or

more of the languages spoken by the local sedentary populations, and,

additionally, within each group, a separate dialect or language is

spoken. They are speaking languages of Indic origin and many are

structured somewhat like an argot or secret language, with vocabularies

drawn from various languages. There are indications that in northern

Iran at least one community speaks Romani language, and some groups in

Turkey also speak Romani.

Asia

Afghanistan

Main article: Peripatetic groups of Afghanistan

India

Main article: Nomads of India

See also: Denotified Tribes

Camel grazers in the Thar Desert

Dom people

Main article: Dom people

In Afghanistan, the Nausar worked as tinkers and animal dealers.

Ghorbat men mainly made sieves, drums, and bird cages, and the women

peddled these as well as other items of household and personal use;

they also worked as moneylenders to rural women. Peddling and the sale

of various goods was also practiced by men and women of various groups,

such as the Jalali, the Pikraj, the Shadibaz, the Noristani, and the

Vangawala. The latter and the Pikraj also worked as animal dealers.

Some men among the Shadibaz and the Vangawala entertained as monkey or

bear handlers and snake charmers; men and women among the Baluch were

musicians and dancers. The Baluch men were warriors that were feared by

neighboring tribes and often were used as mercenaries. Jogi men and

women had diverse subsistence activities, such as dealing in horses,

harvesting, fortune-telling, bloodletting, and begging.[citation needed]

In Iran, the Asheq of Azerbaijan, the Challi of Baluchistan, the Luti

of Kurdistan, Kermānshāh, Īlām, and Lorestān, the Mehtar in the

Mamasani district, the Sazandeh of Band-i Amir and Marv-dasht, and the

Toshmal among the Bakhtyari pastoral groups worked as professional

musicians. The men among the Kowli worked as tinkers, smiths,

musicians, and monkey and bear handlers; they also made baskets,

sieves, and brooms and dealt in donkeys. Their women made a living from

peddling, begging, and fortune-telling.

The Ghorbat among the Basseri were smiths and tinkers, traded in pack

animals, and made sieves, reed mats, and small wooden implements. In

the Fārs region, the Qarbalband, the Kuli, and Luli were reported to

work as smiths and to make baskets and sieves; they also dealt in pack

animals, and their women peddled various goods among pastoral nomads.

In the same region, the Changi and Luti were musicians and balladeers,

and their children learned these professions from the age of 7 or 8

years.[citation needed]

The nomadic groups in Turkey make and sell cradles, deal in animals,

and play music. The men of the sedentary groups work in towns as

scavengers and hangmen; elsewhere they are fishermen, smiths, basket

makers, and singers; their women dance at feasts and tell fortunes.

Abdal men played music and made sieves, brooms, and wooden spoons for a

living. The Tahtacı traditionally worked as lumberers; with increased

sedentarization, however, they have taken to agriculture and

horticulture.[citation needed]

Little is known for certain about the past of these communities; the

history of each is almost entirely contained in their oral traditions.

Although some groups—such as the Vangawala—are of Indian origin,

some—like the Noristani—are most probably of local origin; still others

probably migrated from adjoining areas. The Ghorbat and the Shadibaz

claim to have originally come from Iran and Multan, respectively, and

Tahtacı traditional accounts mention either Baghdad or Khorāsān as

their original home. The Baluch say they[clarification needed] were

attached as a service community to the Jamshedi, after they fled

Baluchistan because of feuds.[41][42]

Kochi people

Main article: Kochi people

Yörüks

Main article: Yörük

Still some groups such as Sarıkeçililer continues nomadic lifestyle

between coastal towns Mediterranean and Taurus Mountains even though

most of them were settled by both late Ottoman and Turkish republic.

Bukat People of Borneo

The Bukat people of Borneo in Malaysia live within the region of the

river Mendalam, which the natives call Buköt. Bukat is an ethnonym that

encapsulates all the tribes in the region. These natives are

historically self-sufficient but were also known to trade various

goods. This is especially true for the clans who lived on the periphery

of the territory. The products of their trade were varied and

fascinating, including: "...resins (damar, Agathis dammara; jelutong

bukit, Dyera costulata, gutta-percha, Palaquium spp.); wild honey and

beeswax (important in trade but often unreported); aromatic resin from

insence wood (gaharu, Aquilaria microcarpa); camphor (found in the

fissures of Dryobalanops aromaticus); several types of rotan of cane

(Calamus rotan and other species); poison for blowpipe darts (one

source is ipoh or ipu: see Nieuwenhuis 1900a:137); the antlers of deer

(the sambar, Cervus unicolor); rhinoceros horn (see Tillema 1939:142);

pharmacologically valuable bezoar stones (concretions formed in the

intestines and gallbladder of the gibbon, Seminopithecus, and in the

wounds of porcupines, Hestrix crassispinus); birds' nests, the edible

nests of swifts (Collocalia spp.); the heads and feathers of two

species of hornbills (Buceros rhinoceros, Rhinoplax vigil); and various

hides (clouded leopards, bears, and other animals)."[43] These nomadic

tribes also commonly hunted boar with poison blow darts for their own

needs.

Europe

Main article: Itinerant groups in Europe

Roma

Main article: Romani people

|

ユーラシアにおける現代の周辺少数民族

このセクションには、記事のトピックとは関係のない内容が含まれている可能性があります。このセクションの改善にご協力いただくか、トークページでこの問題について議論してください。(2013年7月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

さらなる情報 ヘルダーと浮浪者 (人々)

こちらも参照: 遊牧民のリスト, ユーラシア遊牧民, ユーラシア草原, 遊牧帝国

19世紀、ハンガリーのロマニ遊牧民のテント。

周遊少数民族とは、定住人口の間を移動しながら工芸品や交易を提供する移動人口である[40]。

既存の各コミュニティは主に内婚的であり、伝統的に様々な商業活動やサービス活動で生計を立てている。かつては、その構成員の全員または過半数が遍歴しており、現在もほぼ同様である。移住は一般に、最近では一つの州の政治的境界線内で行われる。

各移住コミュニティは多言語であり、その地域の定住人口が話す言語の1つ以上を話し、さらに各グループ内では別の方言や言語が話されている。また、各集団

内では、それぞれ別の方言や言語が話されている。これらの言語はインド系言語を起源とし、その多くは、さまざまな言語から語彙を集めた、アルゴットや秘密

言語のような構造をしている。イラン北部では、少なくとも1つのコミュニティがロマニ語を話していることが示唆されており、トルコにもロマニ語を話すグ

ループがある。

アジア

アフガニスタン

主な記事 アフガニスタンの周縁民族

インド

主な記事 インドの遊牧民

以下も参照: 否定された部族

タール砂漠のラクダ放牧民。

ドム族

主な記事 ドム族

アフガニスタンでは、ナウサルは鋳掛屋や動物商として働いていた。ゴルバトの男性は主にふるい、ドラム缶、鳥かごを作り、女性は家庭用品や個人用品を行商

していました。行商や様々な商品の販売も、ジャラリ族、ピクラジ族、シャディバズ族、ノリスタニ族、ヴァンガワラ族など、様々な集団の男女によって行われ

ていた。後者やピクラジは動物商人としても働いていた。シャディバズとヴァンガワラの中には、猿や熊の使い手や蛇使いとして娯楽を楽しむ男もいた。バルー

チ族の男性は近隣部族から恐れられる戦士であり、しばしば傭兵として使われた。ジョギ族の男女は馬の売買、収穫、占い、血抜き、物乞いなど多様な生計活動

をしていた[要出典]。

イランでは、アゼルバイジャンのアシェク族、バルチスタンのチャリ族、クルディスタン、ケルマーンシャー、ウスラーム、ロレスターンのルティ族、ママサニ

地方のメタル族、バンド・イ・アミールとマルヴ・ダシュトのサザンデ族、バクティアリ地方の牧畜民のトシュマル族が職業音楽家として働いていた。カウリ族

の男たちは、鋳掛職人、鍛冶職人、音楽家、猿や熊を扱う職人として働き、籠、ふるい、ほうきを作ったり、ロバを扱ったりもした。女性たちは行商、物乞い、

占いで生計を立てていた。

バセリ族のゴルバト族は鍛冶職人や鋳掛職人であり、荷役動物の売買を行い、ふるいや葦のマット、小さな木製の道具を作った。ファールス地方では、カルバル

バンド族、クリ族、ルリ族が鍛冶職人として働き、籠やふるいを作ったと報告されている。同じ地域のチャンギ族とルティ族は音楽家とバラード奏者であり、彼

らの子供たちは7、8歳からこれらの職業を学んだ[要出典]。

トルコの遊牧民グループは、ゆりかごを作ったり売ったり、動物を扱ったり、音楽を演奏したりする。定住集団の男性は、町では廃品回収業者や吊り手として働

き、それ以外の場所では漁師、鍛冶屋、かご職人、歌い手として働き、女性は宴会で踊ったり、占いをしたりする。アブダル族の男性は音楽を演奏し、ふるい、

ほうき、木のスプーンなどを作って生活していた。タフタク族は伝統的に窯焚き職人として働いていたが、定住化が進むにつれて農業や園芸を行うようになっ

た。

これらの共同体の過去については、ほとんど確かなことは分かっていない。ヴァンガワラ族のようにインド起源のグループもあれば、ノリスタニ族のように地元

起源のグループもある。ゴルバト族とシャディバズ族はそれぞれイランとムルターンから来たと主張し、タフタクの伝統的な記述ではバグダードかホラーサーン

が原産地とされている。バルーチ族は、彼らが確執のためにバルチスターンを逃れた後、ジャムシェディ族に奉仕する共同体として付けられたと言う[41]

[42]。

高知県人

主な記事 コチ族

ヨリュクス人

主な記事: 高知県人 ヨリュク人

オスマン帝国末期とトルコ共和国の両方によって定住されたにもかかわらず、サルケチリルのようないくつかの集団は地中海沿岸の町とタウルス山脈の間で遊牧生活を続けている。

ボルネオのブカット族

マレーシアのボルネオ島のブカット族は、原住民がブコートと呼ぶメンダラム川流域に住んでいる。ブカットとは、この地域のすべての部族を包括する民族名で

ある。これらの原住民は歴史的に自給自足をしているが、様々な商品を交易していたことでも知られている。特に領土の周辺部に住んでいた氏族はそうだった。

彼らの交易品は多種多様で、次のような魅力的なものだった:

「...樹脂(ダマール、アガチス・ダムマラ、ジェルトン・ブキット、ダイラ・コスチュラータ、グッタペルカ、パラキウム属)、野生のハチミツ、蜜蝋など

である。 )、野生の蜂蜜と蜜蝋(貿易上重要だが、報告されていないことが多い)、インセンスウッド(gaharu, Aquilaria

microcarpa)の芳香樹脂、樟脳(Dryobalanops

aromaticusの裂け目に含まれる)、数種類のサトウキビのロータン(Calamus

rotanやその他の種)、吹き矢の毒(ipohまたはipuが出典のひとつ。Nieuwenhuis 1900a.を参照): 137

参照);シカの角(Sambar, Cervus unicolor);サイの角(Tillema 1939:142

参照);薬理学的に貴重なベゾアール石(テナガザル Seminopithecus の腸や胆嚢、ヤマアラシ Hestrix

crassispinus の傷口に形成されるコンクリート);鳥の巣、ツバメの食用巣(Collocalia spp.

これらの遊牧民族はまた、自分たちの必要に応じて、毒吹き矢でイノシシを狩ることも一般的であった。

ヨーロッパ

主な記事 ヨーロッパの遊牧民

ロマ

主な記事 ロマ人

|

Image gallery

|

イメージ・ギャラリー(省略)

|

Nomadic peoples of Europe

Seasonal human migration

Nomadic conflict

Sea Gypsies

Pastoral society

Pastoralism

Transhumance

Figurative use of the term:

Global nomad

Digital nomad

Snowbird (people)

Military brat

The Nomadic Project

Perpetual traveler

RV lifestyle

Third culture kid

Overlanding

|

ヨーロッパの遊牧民

季節的な人間の移動

遊牧民の紛争

海ジプシー

牧畜社会

牧畜

横断牧畜

比喩的な用法

グローバル・ノマド

デジタル・ノマド

スノーバード

ミリタリーブラット

ノマド・プロジェクト

永久旅行者

RVライフスタイル

サードカルチャーキッド

オーバーランディング

|

|

|

|

|

☆

☆