核軍縮

Nuclear disarmament

Little

boy(mock-up model) and The peace symbol ( was designed by Gerald Holtom

in 1958, displaying the letters N and D in flag semaphore, and is the

official symbol of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

☆核軍縮(Nuclear disarmament)とは、核兵器を削減または廃絶する行為である。最終的な状態は、核兵器が完全に廃絶された核兵器のない世界となる。完全な核軍縮に至るプロセスを指して非核化という用語も用いられる。

軍縮条約および核不拡散条約は、核戦争および核兵器保有に内在する極度の危険性ゆえに合意されたものである。

核軍縮の推進派は、特に誤報による事故や報復攻撃を考慮すると、核軍縮により核戦争の発生確率が低下するだろうと主張している。 核軍縮の批判派は、核軍縮は抑止力を損ない、通常戦争をより一般的になるだろうと主張している。

| Nuclear disarmament

is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state

can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are

completely eliminated. The term denuclearization is also used to

describe the process leading to complete nuclear disarmament.[2][3] Disarmament and non-proliferation treaties have been agreed upon because of the extreme danger intrinsic to nuclear war and the possession of nuclear weapons. Proponents of nuclear disarmament say that it would lessen the probability of nuclear war occurring, especially considering accidents or retaliatory strikes from false alarms.[4] Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine deterrence and make conventional wars more common. |

核軍縮とは、核兵器を削減または廃絶する行為である。最終的な状態は、

核兵器が完全に廃絶された核兵器のない世界となる。完全な核軍縮に至るプロセスを指して非核化という用語も用いられる。[2][3] 軍縮条約および核不拡散条約は、核戦争および核兵器保有に内在する極度の危険性ゆえに合意されたものである。 核軍縮の推進派は、特に誤報による事故や報復攻撃を考慮すると、核軍縮により核戦争の発生確率が低下するだろうと主張している。[4] 核軍縮の批判派は、核軍縮は抑止力を損ない、通常戦争をより一般的になるだろうと主張している。 |

| Organizations Nuclear disarmament groups include the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Peace Action, Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, Greenpeace, Soka Gakkai International, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Mayors for Peace, Global Zero, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, and the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. There have been many large anti-nuclear demonstrations and protests. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the Cold War arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.[5][6] In recent years, some U.S. elder statesmen have also advocated nuclear disarmament. Sam Nunn, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and George Shultz have called upon governments to embrace the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and in various op-ed columns have proposed an ambitious program of urgent steps to that end. The four have created the Nuclear Security Project to advance this agenda. Organisations such as Global Zero, an international non-partisan group of 300 world leaders dedicated to eliminating all nuclear weapons, have also been established. |

団体 核軍縮を推進する団体には、核軍縮キャンペーン、ピース・アクション、パグウォッシュ会議、グリーンピース、創価学会インタナショナル、核戦争防止国際医 師会議、平和市長会議、グローバルゼロ、核兵器廃絶国際キャンペーン、核時代平和財団などがある。大規模な反核デモや抗議活動も数多く行われている。 1982年6月12日には、ニューヨーク市のセントラルパークで100万人が核兵器と冷戦の軍拡競争に反対するデモを行った。これは、アメリカ史上最大の 反核抗議活動であり、最大の政治的デモであった。[5][6] 近年では、一部のアメリカの元政府高官も核軍縮を提唱している。サム・ナン、ウィリアム・ペリー、ヘンリー・キッシンジャー、ジョージ・シュルツの4人 は、核兵器のない世界というビジョンを各国政府に受け入れるよう呼びかけ、さまざまな論説欄でその目的を達成するための緊急のステップとなる野心的なプロ グラムを提案している。この4人は、この議題を推進するために核安全保障プロジェクトを立ち上げた。また、すべての核兵器の廃絶を目的とする国際的な超党 派グループであるグローバルゼロのような組織も設立されている。 |

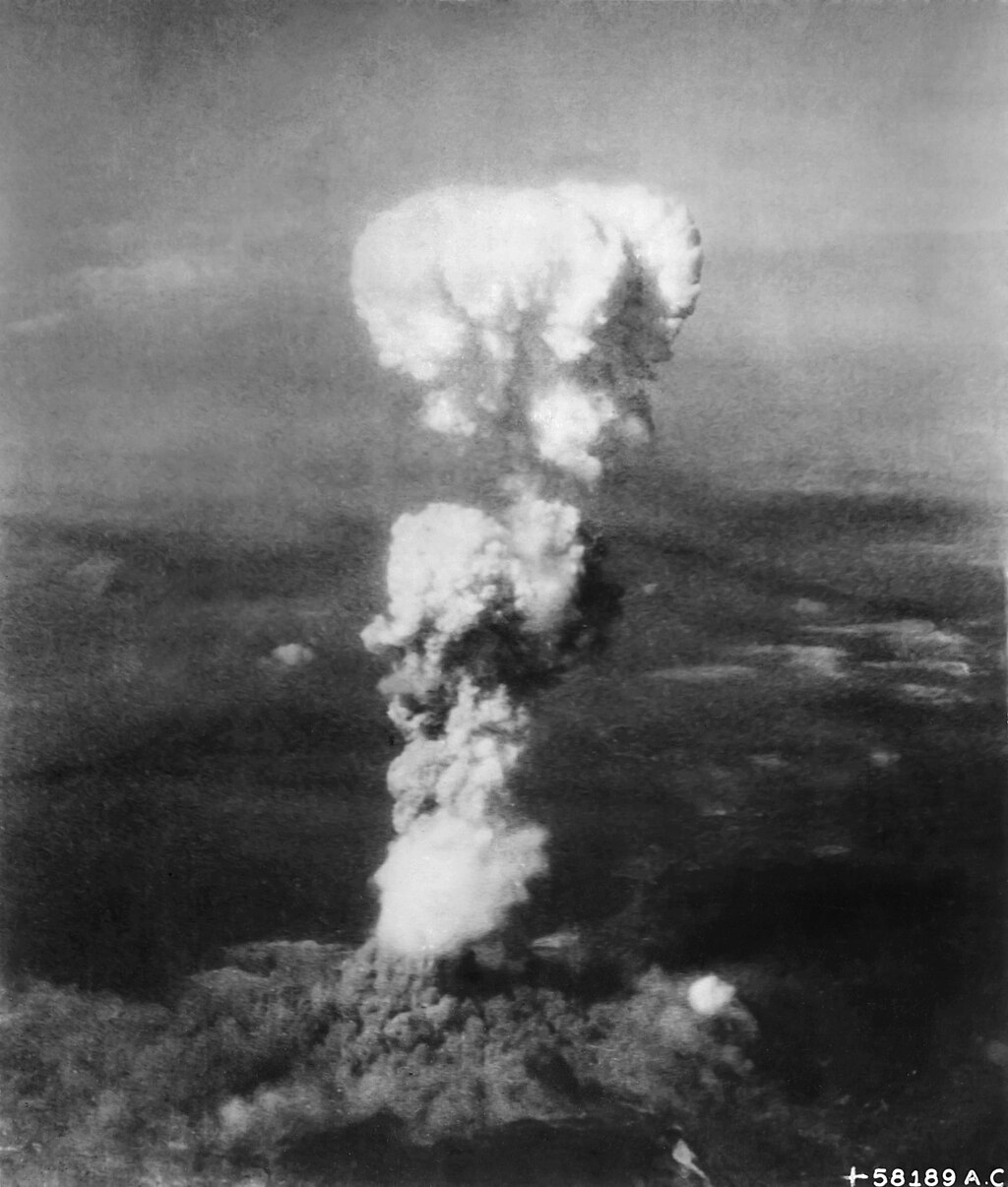

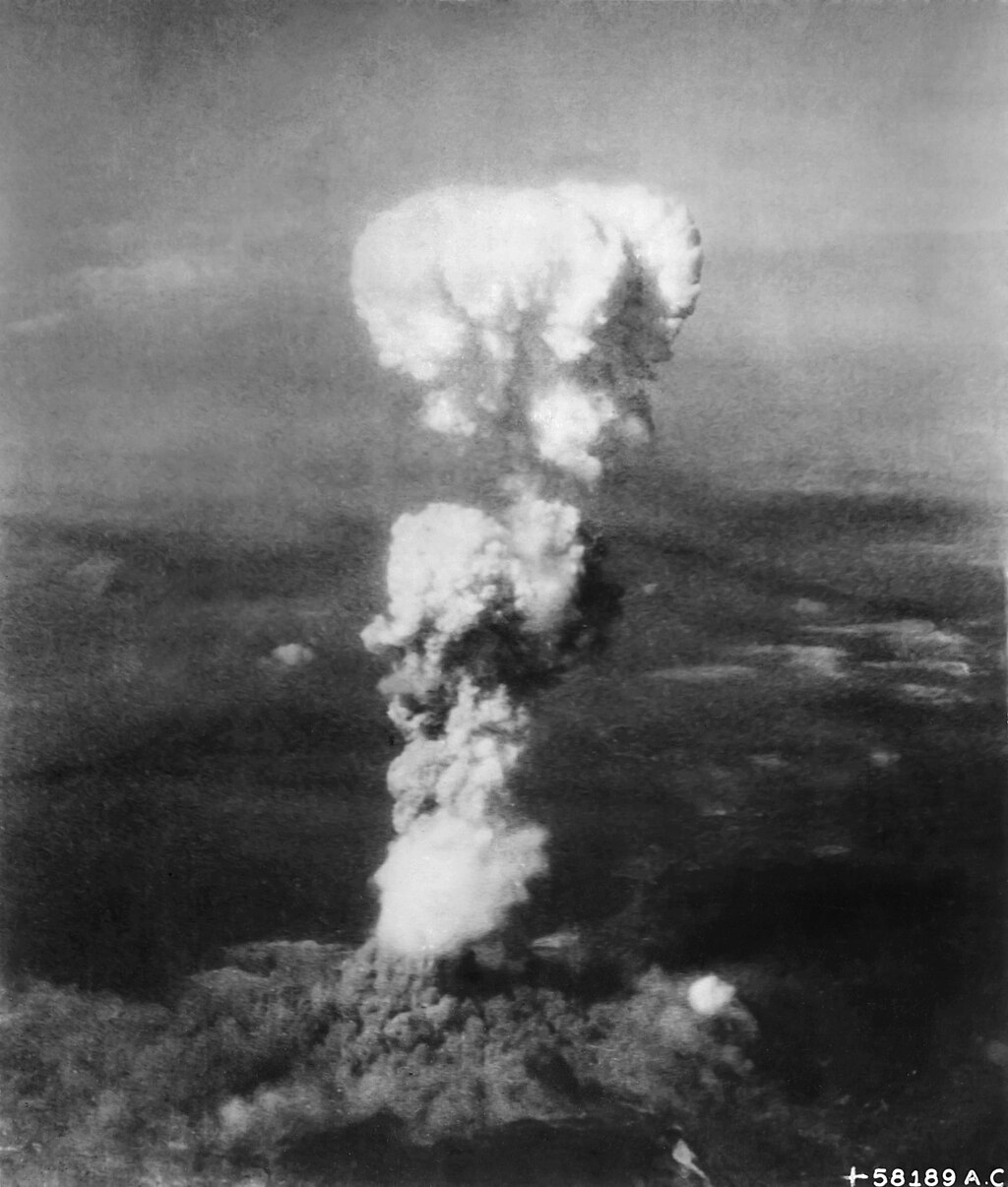

History The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima after the dropping of the atomic bomb nicknamed 'Little Boy' (Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945).  Mushroom-shaped cloud and water column from the underwater nuclear explosion of July 25, 1946, which was part of Operation Crossroads.  November 1951 nuclear test at the Nevada Test Site, from Operation Buster, with a yield of 21 kilotons. It was the first U.S. nuclear field exercise conducted on land; troops shown are 6 mi (9.7 km) from the blast. In 1945 in the New Mexico desert, American scientists conducted "Trinity", the first nuclear weapons test, marking the beginning of the atomic age.[7] Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.[8] On August 6, 1945, towards the end of World War II, the "Little Boy" device was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division) and killed 70,000–80,000 people outright, with total deaths being around 90,000–146,000.[9] Detonation of the "Fat Man" device exploded over the Japanese city of Nagasaki three days later on August 9, 1945, destroying 60% of the city and killing 35,000–40,000 people outright, though up to 40,000 additional deaths may have occurred over some time after that.[10][11] Subsequently, the world's nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.[7] In 1946 the Truman administration commissioned the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed the international control of the nuclear fuel cycle, revealing atomic energy technology to the USSR, and the decommissioning of all existing nuclear weapons through the new United Nations (UN) system, via the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC). With key modifications, the report became US policy in the form of the Baruch Plan, which was presented to the UNAEC during its first meeting in June 1946. As Cold War tensions emerged, it became clear that Stalin wanted to develop his own atomic bomb and that the United States insisted on an enforcement regime that would have overridden the UN Security Council veto. This soon led to deadlock in the UNAEC.[12][13] Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads came from scientists and diplomats. Manhattan Project scientists argued that further nuclear testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous. A Los Alamos study warned "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a 'witch's brew' of radioactivity". To prepare the atoll for the nuclear tests, Bikini's native residents were evicted from their homes and resettled on smaller, uninhabited islands where they were unable to sustain themselves.[14] Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[15] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[15] The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".[16] |

歴史 「リトルボーイ」の愛称で呼ばれた原子爆弾が広島に投下された後のきのこ雲(1945年の広島と長崎への原爆投下)。  クロスロード作戦の一部として1946年7月25日に実施された水中核実験によるきのこ雲と水柱。  1951年11月、ネバダ核実験場でのバスター作戦による核実験。爆発規模は21キロトン。これは、米国が陸上で実施した初の核野外演習であり、爆心地から6マイル(9.7キロ)の地点に軍隊が配置されている。 1945年、ニューメキシコ州の砂漠で、アメリカの科学者たちは「トリニティ」と呼ばれる史上初の核実験を実施し、原子力の時代が始まった。[7] トリニティ実験以前から、各国の指導者たちは核兵器が国内および外交政策に与える影響について議論していた。 核兵器政策に関する議論には、科学者コミュニティも関与していた。 科学者コミュニティは、原子力科学者連盟や科学と世界情勢に関するパグウォッシュ会議などの専門家団体を通じて議論に参加していた。[8] 1945年8月6日、第二次世界大戦末期に、広島市上空で「リトルボーイ」が爆発した。TNT火薬12,500トンに相当する威力で爆発したこの原爆の爆 風と熱線により、約5万棟の建物(第2総軍および第5師団司令部を含む)が破壊され、7万~8万人が即死し、死者は合計で9万~14万6000人に上った とされる。「ファットマン」が1945年8月9日に日本の長崎市上空で爆発し、市街地の60%が破壊され、3万5000人から4万人が即死した。ただし、 その後しばらくしてさらに4万人が死亡した可能性もある。[10][11] その後、世界の核兵器備蓄は増加した。[7] 1946年、トルーマン政権は「アチソン・リリエンタール報告書」を委託した。この報告書は、核燃料サイクルの国際管理、原子力技術のソビエト連邦への開 示、国際連合(国連)の新しいシステムを通じた国連原子力委員会(UNAEC)による既存の核兵器の全廃を提案した。この報告書は、重要な修正を加えら れ、1946年6月の第1回会合でUNAECに提示されたバルーク・プランという形で米国の政策となった。 冷戦の緊張が高まる中、スターリンが独自の原爆開発を望んでいることが明らかになり、米国は国連安全保障理事会の拒否権を無効にする強制体制を主張した。 これにより、UNAECはすぐに機能不全に陥った。[12][13] クロスロード作戦(Operation Crossroads)は、1946年夏にアメリカが太平洋のビキニ環礁で行った一連の核実験である。その目的は、核兵器が艦船に与える影響をテストする ことだった。クロスロード作戦の中止を求める圧力は、科学者や外交官から寄せられた。マンハッタン計画の科学者たちは、さらなる核実験は不必要であり、環 境に危険であると主張した。ロスアラモス研究所の研究では、「最近の表面爆発の近くの水は、放射能の『魔女の薬』となるだろう」と警告した。環礁を核実験 の準備のために、ビキニの原住民は自宅から立ち退きを命じられ、より小さく、無人島に移住させられたが、そこでは生活を維持することができなかった。 [14] 核実験による放射性降下物は、1954年に太平洋で行われた水爆実験により、日本の漁船「第五福竜丸」の乗組員が被曝したことで初めて世間の注目を集め た。[15] 漁師の1人は7か月後に日本で死亡した。この事件は世界中で大きな懸念を引き起こし、「多くの国々で反核兵器運動が勃興する決定的なきっかけとなった」 [15]。反核兵器運動は急速に拡大した。なぜなら、多くの人々にとって原爆は「社会が向かっている最悪の方向性を象徴するもの」だったからだ。[16] |

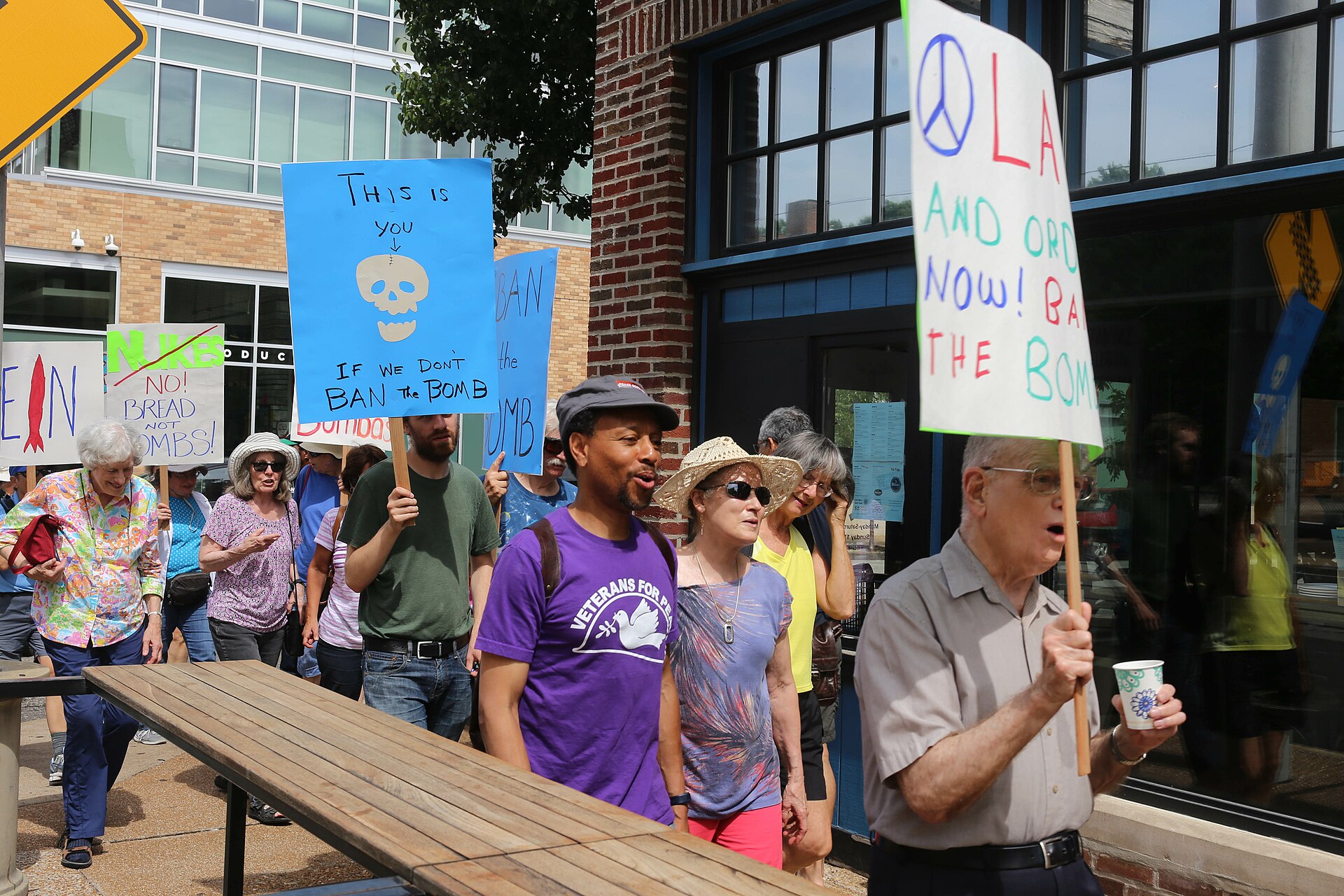

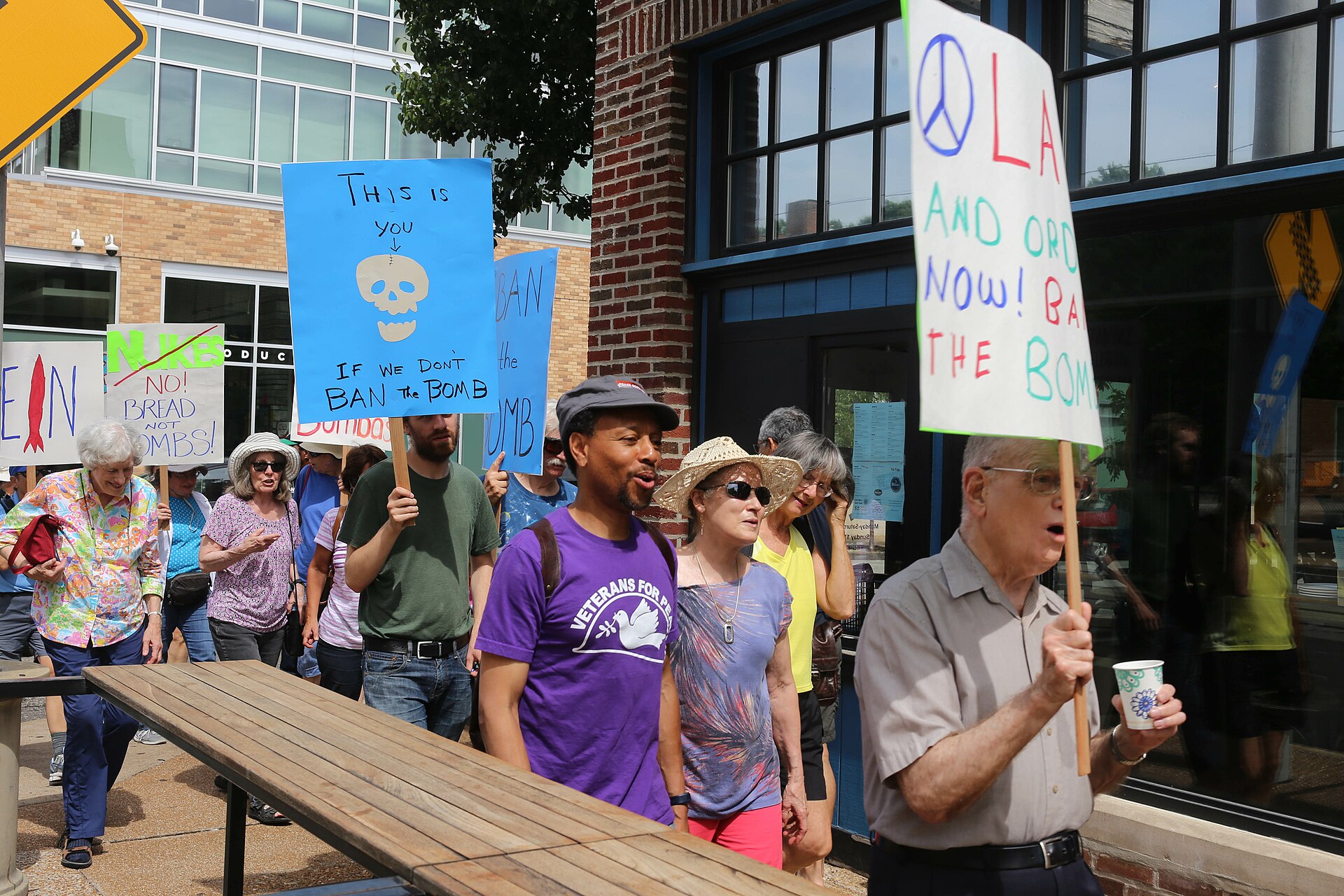

Nuclear disarmament movement 1952 World Peace Council congress in East Berlin showing Picasso peace dove above the stage  Women Strike for Peace during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962  Demonstration in Lyon, France, in the 1980s against nuclear weapons tests  On December 12, 1982, 30,000 women held hands around the 6-mile (9.7 km) perimeter of the RAF Greenham Common base to protest the decision to site American cruise missiles there. See also: History of the anti-nuclear movement and List of peace activists Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[16] In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Direct Action Committee and supported by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place on Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[17][18] CND organised Aldermaston marches into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day events.[16] On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.[19][20] In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear-weapon testing. The "Baby Tooth Survey", headed by Louise Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass.[21][22][23] Public pressure and the research results subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev.[24] On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize, describing him as "Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts."[8][25] Pauling started the International League of Humanists in 1974. He was president of the scientific advisory board of the World Union for Protection of Life and also one of the signatories of the Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement. In the 1980s, a movement for nuclear disarmament again gained strength in the light of the weapons build-up and statements of US President Ronald Reagan. Reagan had "a world free of nuclear weapons" as his personal mission,[26][27][28] and was largely scorned for this in Europe.[28] Reagan was able to start discussions on nuclear disarmament with Soviet Union.[28] He changed the name "SALT" (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) to "START" (Strategic Arms Reduction Talks).[27] On June 3, 1981, William Thomas launched the White House Peace Vigil in Washington, D.C.[29] He was later joined on the vigil by anti-nuclear activists Concepcion Picciotto and Ellen Benjamin.[30] On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.[5][6] International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983, at 50 sites across the United States.[31][32] Large demonstrations and the disruption of US naval visits led the New Zealand government to ban nuclear-armed and powered ships from entering the country's territorial waters in 1984.[33] Hundreds of thousands of people took part in Palm Sunday and other demonstrations for peace and nuclear disarmament in Australia during the mid-1980s.[34] In 1986, hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament.[35] There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.[36][37] On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[38][39][40] In 2008, 2009, and 2010, there have been protests about, and campaigns against, several new nuclear reactor proposals in the United States.[41][42][43] There is an annual protest against U.S. nuclear weapons research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California and in the 2007 protest, 64 people were arrested.[44] There have been a series of protests at the Nevada Test Site and in the April 2007 Nevada Desert Experience protest, 39 people were cited by police.[45] There have been anti-nuclear protests at Naval Base Kitsap for many years, and several in 2008.[46][47][48] In 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize "for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons".[49] World Peace Council One of the earliest peace organisations to emerge after the Second World War was the World Peace Council,[50][51][52] which was directed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union through the Soviet Peace Committee. Its origins lay in the Communist Information Bureau's (Cominform) doctrine, put forward 1947, that the world was divided between peace-loving progressive forces led by the Soviet Union and warmongering capitalist countries led by the United States. In 1949, Cominform directed that peace "should now become the pivot of the entire activity of the Communist Parties", and most western Communist parties followed this policy.[53] Lawrence Wittner, a historian of the post-war peace movement, argues that the Soviet Union devoted great efforts to the promotion of the WPC in the early post-war years because it feared an American attack and American superiority of arms[54] at a time when the USA possessed the atom bomb but the Soviet Union had not yet developed it.[55] In 1950, the WPC launched its Stockholm Appeal[56] calling for the absolute prohibition of nuclear weapons. The campaign won support, collecting, it is said, 560 million signatures in Europe, most from socialist countries, including 10 million in France (including that of the young Jacques Chirac), and 155 million signatures in the Soviet Union – the entire adult population.[57] Several non-aligned peace groups who had distanced themselves from the WPC advised their supporters not to sign the Appeal.[55] The WPC had uneasy relations with the non-aligned peace movement and has been described as being caught in contradictions as "it sought to become a broad world movement while being instrumentalized increasingly to serve foreign policy in the Soviet Union and nominally socialist countries."[58] From the 1950s until the late 1980s it tried to use non-aligned peace organizations to spread the Soviet point of view. At first there was limited co-operation between such groups and the WPC, but western delegates who tried to criticize the Soviet Union or the WPC's silence about Russian armaments were often shouted down at WPC conferences[54] and by the early 1960s they had dissociated themselves from the WPC. |

核軍縮運動 1952年、東ベルリンで開催された世界平和評議会会議のステージ上のピカソの平和の鳩  1962年のキューバ危機における平和のための女性ストライキ  1980年代のフランス・リヨンにおける核兵器実験反対デモ  1982年12月12日、3万人の女性たちが、アメリカ軍の巡航ミサイルがイギリス空軍グリーンハム・コモン基地に配備される決定に抗議して、同基地の周囲6マイル(9.7km)を囲むように手をつないでデモ行進を行った。 参照:反核運動の歴史、平和活動家の一覧 日本では1954年に平和運動が勃興し、統一された「原水爆禁止日本協議会」が結成された。太平洋核実験に対する日本の反対運動は広範囲に及び、「核兵器 禁止を求める嘆願書に推定3500万の署名が集められた」[16]。イギリスでは、直接行動委員会が組織し、核軍縮キャンペーンが支援した最初のオルダー マストン行進が1958年の復活祭に行われた。ロンドンのトラファルガー広場からイングランドのバークシャー州オルダーマストン近郊にある原子兵器研究施 設まで4日間行進し、核兵器への反対を表明した。[17][18] CNDは1960年代後半までオルダーマストン行進を組織し、4日間のイベントには数万人が参加した。[16] 冷戦の真っ只中の1961年11月1日、平和のための女性ストライキによって集まった約5万人の女性たちが、核兵器に反対するデモ行進を米国の60都市で行った。これは20世紀における国内最大の女性平和抗議活動であった。 1958年には、ライナス・ポーリングと彼の妻が、核兵器実験の停止を求める11,000人以上の科学者の署名入りの嘆願書を国連に提出した。ルイーズ・ ライスが主導した「乳歯調査」は、1961年に、地上核実験が、汚染された草を食んだ牛の乳から主に広がる放射性降下物という形で、公衆衛生に重大なリス クをもたらすことを決定的に証明した。[21][22][23] 世論の圧力と研究結果により、 それに続いて、1963年にジョン・F・ケネディとニキータ・フルシチョフによって調印された部分的核実験禁止条約が締結された。[24] 条約が発効したその日、ノーベル賞委員会はポーリングにノーベル平和賞を授与し、彼を「 1946年以来、核兵器実験、核拡散、核兵器の使用だけでなく、国際紛争解決の手段としての戦争そのものにも反対し、たゆまぬキャンペーンを展開してき た」と評した。[8][25] ポーリングは1974年に国際ヒューマニスト連盟を設立した。生命保護世界連合の科学諮問委員会の会長であり、また「ドゥブロヴニク・フィラデルフィア声 明」の署名者の一人でもあった。 1980年代、核兵器の増強とレーガン大統領の声明を背景に、核軍縮運動が再び活発化した。レーガンは「核兵器のない世界」を個人的な使命としており [26][27][28]、この点についてヨーロッパでは概ね軽蔑されていた[28]。レーガンはソビエト連邦との核軍縮交渉を開始することができた。彼 は「SALT」(戦略兵器制限条約)の名称を「START」(戦略兵器削減条約)に変更した。 1981年6月3日、ウィリアム・トマスはワシントンD.C.でホワイトハウス平和祈念行進を開始した。[29] 後に、反核活動家のコンセプシオン・ピッチオットとエレン・ベンジャミンがこの祈念行進に参加した。[30] 1982年6月12日、ニューヨーク市のセントラルパークで100万人が核兵器に反対し、冷戦の軍拡競争に終止符を打つことを求めてデモを行った。これ は、反核運動としては最大規模であり、またアメリカ史上最大の政治的デモであった。[5][6] 1983年6月20日には、核軍縮国際デーの抗議活動がアメリカ国内50か所で行われた。[31][32] 大規模なデモとアメリカ海軍の訪問の妨害により、 ニュージーランド政府は1984年に、核兵器を搭載した艦船および原子力艦船の領海への入港を禁止した。[33] 1980年代半ばには、オーストラリアで数十万人が棕櫚の主日やその他の平和と核軍縮を求めるデモに参加した。[34] 19 1986年には、世界的な核軍縮を求める大規模な平和行進が行われ、数百人がロサンゼルスからワシントンD.C.までを歩いた。[35] 1980年代から1990年代にかけて、ネバダ核実験場では、ネバダ砂漠体験の抗議活動や平和キャンプが数多く行われた。[36][37] 2005年5月1日、広島と長崎への原爆投下から60年後、4万人の反核・反戦デモ参加者がニューヨークの国連本部前を行進した。[38][ 39][40] 2008年、2009年、2010年には、アメリカ国内で提案された複数の新型原子炉計画に対して抗議や反対運動が行われた。 カリフォルニア州にあるローレンス・リバモア国立研究所での米国の核兵器研究に対する抗議は毎年行われており、2007年の抗議では64人が逮捕された。 2007年4月のネバダ砂漠体験抗議では、39人が警察に拘束された。[45] キトサップ海軍基地では長年にわたり反核抗議が行われており、2008年にも数回行われた。[46][47][48] 2017年には、「核兵器の使用がもたらす壊滅的な人道的結末に注目を集めるための活動と、条約に基づく核兵器禁止を実現するための画期的な取り組み」が評価され、核兵器廃絶国際キャンペーンがノーベル平和賞を受賞した。[49] 世界平和評議会 第二次世界大戦後に登場した最も初期の平和団体の一つが世界平和評議会(World Peace Council)である。[50][51][52] ソビエト平和委員会を通じてソビエト連邦共産党が指導していた。その起源は、1947年に打ち出された共産主義情報局(Cominform)の教義にあ り、世界はソビエト連邦が主導する平和を愛する進歩勢力と、アメリカ合衆国が主導する好戦的な資本主義国とに分かれているというものだった。1949年、 コミンフォルムは平和を「共産党の活動全体の中心に据えるべきである」と指示し、ほとんどの西側共産党がこの政策に従った。[53] 戦後の平和運動の歴史家ローレンス・ウィトナーは、 ソ連は、アメリカが原爆を保有していたがソ連はまだ開発していなかった当時、アメリカの攻撃と軍事的優位を恐れて、戦後初期に世界平和評議会の推進に多大 な努力を傾けたと論じている。 1950年、世界平和評議会は核兵器の絶対禁止を呼びかけるストックホルム・アピールを開始した。このキャンペーンは支持を集め、ヨーロッパでは5億 6000万の署名を集めたと言われている。その大半は社会主義国のもので、フランスでは1000万(若き日のジャック・シラクのものを含む)に上り、ソビ エト連邦では1億5500万の署名が集まった。これは全成人人口に相当する。[57] WPCから距離を置いていた非同盟平和団体は、支持者にアピールへの署名を控えるよう勧めた。[55] WPCは非同盟平和運動との関係に不安を抱えており、「広範な世界運動となることを目指しながら、ソ連や名目上社会主義諸国の外交政策にますます利用され るようになった」という矛盾に陥っていると評されている。[58] 1950年代から1980年代後半まで、WPCは非同盟平和組織を利用してソ連の見解を広めようとしていた。当初は、このようなグループとWPCとの協力 関係は限定的であったが、ソ連を批判しようとしたり、ロシアの軍備増強について沈黙を続けるWPCを批判しようとした西側の代表団は、WPCの会議でしば しば大声で非難された[54]。そして1960年代初頭までに、彼らはWPCから距離を置くようになった。 |

Arms reduction treaties United States and USSR/Russian nuclear weapons stockpiles, 1945–2014. These numbers include warheads not actively deployed, including those on reserve status or scheduled for dismantlement. Stockpile totals do not necessarily reflect nuclear capabilities since they ignore size, range, type, and delivery mode. After the 1986 Reykjavík Summit between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and the new Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, the United States and the Soviet Union concluded two important nuclear arms reduction treaties: the INF Treaty (1987) and START I (1991). After the end of the Cold War, the United States and the Russian Federation concluded the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (2003) and the New START Treaty (2010). The US withdrew from the INF Treaty in 2019 under president Donald Trump,[59] and launched the United States–Russia Strategic Stability Dialogue (SSD) in 2021 under president Joe Biden.[60][61] When the extreme danger intrinsic to nuclear war and the possession of nuclear weapons became apparent to all sides during the Cold War, a series of disarmament and nonproliferation treaties were agreed upon between the United States, the Soviet Union, and several other states throughout the world. Many of these treaties involved years of negotiations, and seemed to result in important steps in arms reductions and reducing the risk of nuclear war. Key treaties Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) 1963: Prohibited all testing of nuclear weapons except underground. Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—signed 1968, came into force 1970: An international treaty (currently with 189 member states) to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. The treaty has three main pillars: nonproliferation, disarmament, and the right to peacefully use nuclear technology. Interim Agreement on Offensive Arms (SALT I) 1972: The Soviet Union and the United States agreed to a freeze in the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) that they would deploy. Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) 1972: The United States and Soviet Union could deploy ABM interceptors at two sites, each with up to 100 ground-based launchers for ABM interceptor missiles. In a 1974 Protocol, the US and Soviet Union agreed to only deploy an ABM system to one site. Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) 1979: Replacing SALT I, SALT II limited both the Soviet Union and the United States to an equal number of ICBM launchers, SLBM launchers, and heavy bombers. Also placed limits on Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles (MIRVS). Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) 1987: Banned US and Soviet Union land-based ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and missile launchers with ranges of 500–1,000 kilometers (310–620 mi) (short medium-range) and 1,000–5,500 km (620–3,420 mi) (intermediate-range). Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I)—signed 1991, ratified 1994: Limited long-range nuclear forces in the United States and the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union to 6,000 attributed warheads on 1,600 ballistic missiles and bombers. Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II (START II)—signed 1993, never put into force: START II was a bilateral agreement between the US and Russia which attempted to commit each side to deploy no more than 3,000 to 3,500 warheads by December 2007 and also included a prohibition against deploying multiple independent reentry vehicles (MIRVs) on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT or Moscow Treaty)—signed 2002, into force 2003: A very loose treaty that is often criticized by arms control advocates for its ambiguity and lack of depth, Russia and the United States agreed to reduce their "strategic nuclear warheads" (a term that remained undefined in the treaty) to between 1,700 and 2,200 by 2012. Was superseded by New Start Treaty in 2010. Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)—signed 1996, not yet in force: The CTBT is an international treaty (currently with 181 state signatures and 148 state ratifications) that bans all nuclear explosions in all environments. While the treaty is not in force, Russia has not tested a nuclear weapon since 1990 and the United States has not since 1992.[62] New START Treaty—signed 2010, into force in 2011: replaces SORT treaty, reduces deployed nuclear warheads by about half, will remain into force until 2026. Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons—signed 2017, entered into force on January 22, 2021: prohibits possession, manufacture, development, and testing of nuclear weapons, or assistance in such activities, by its parties. Only one country (South Africa) has been known to ever dismantle an indigenously developed nuclear arsenal completely. The apartheid government of South Africa produced half a dozen crude fission weapons during the 1980s, but they were dismantled in the early 1990s.[63] |

軍縮条約 米国とソ連/ロシアの核兵器備蓄、1945年~2014年。これらの数字には、予備状態にあるものや解体予定のものなど、実際に配備されていない弾頭も含 まれる。備蓄総数は、規模、射程距離、種類、および配備形態を無視しているため、必ずしも核戦力を反映しているわけではない。 1986年のレイキャビク・サミットで、当時の米国大統領ロナルド・レーガンとソ連の新書記ミハイル・ゴルバチョフが会談した後、米国とソ連は2つの重要 な核兵器削減条約、すなわちINF条約(1987年)と第一次戦略兵器削減条約(START I)(1991年)を締結した。冷戦終結後、米国とロシア連邦は戦略攻撃兵器削減条約(2003年)と新戦略兵器削減条約(2010年)を締結した。米国 はドナルド・トランプ大統領の下、2019年にINF条約から脱退し[59]、ジョー・バイデン大統領の下、2021年に米露戦略安定対話(SSD)を開 始した[60][61]。 冷戦中、核戦争と核兵器保有に内在する極度の危険性がすべての当事者に明らかになったため、米国、ソ連、および世界中のいくつかの国家間で一連の軍縮およ び核不拡散条約が合意された。これらの条約の多くは、何年もの交渉を経ており、兵器削減と核戦争のリスク低減における重要な一歩となった。 主な条約 部分的核実験禁止条約(PTBT)1963年:地下核実験を除くすべての核実験を禁止。 核拡散防止条約(NPT)1968年調印、1970年発効:核兵器の拡散を制限する国際条約(現在189カ国が加盟)。この条約の主な柱は、核拡散防止、核軍縮、核技術の平和利用の3つである。 第一次戦略兵器削減条約(SALT I)1972年:ソビエト連邦と米国は、配備する大陸間弾道ミサイル(ICBM)と潜水艦発射弾道ミサイル(SLBM)の数を凍結することで合意した。 1972年の弾道弾迎撃ミサイル条約(ABM):米国とソ連はABM迎撃ミサイルを2つの基地に配備することができ、各基地には最大100基のABM迎撃 ミサイル発射機を設置できる。1974年の議定書で、米国とソ連はABMシステムを1つの基地にのみ配備することで合意した。 戦略兵器制限条約(SALT II)1979年:SALT Iに代わるSALT IIは、ソ連と米国の両国が、ICBM発射機、SLBM発射機、重爆撃機の数を同数に制限するものだった。また、多弾頭独立再突入車両(MIRVS)にも制限を設けた。 中距離核戦力全廃条約(INF)1987年:米国とソ連の陸上配備型弾道ミサイル、巡航ミサイル、射程距離500~1,000キロメートル (310~620マイル)(短距離中距離)および1,000~5,500キロメートル(620~3,420マイル)(中距離)のミサイル発射機を禁止し た。 戦略兵器削減条約(START I)—1991年調印、1994年批准:米国と旧ソ連の新生独立国家における長距離核戦力を、弾道ミサイルと爆撃機に搭載された6,000個の核弾頭に限定した。 第二次戦略兵器削減条約(START II)—1993年に調印されたが発効せず:START IIは、米国とロシア間の二国間協定であり、2007年12月までに双方が3,000から3,500個の弾頭を超えないように配備することを義務付けるこ とを試みた。また、大陸間弾道ミサイル(ICBM)に多弾頭再突入体(MIRV)を配備することを禁止することも盛り込まれていた 戦略攻撃兵器削減条約(SORTまたはモスクワ条約)—2002年調印、2003年発効:この条約は非常に緩やかなもので、しばしばその曖昧さや深みのな さを理由に軍備管理の擁護者たちから批判されているが、ロシアと米国は「戦略核弾頭」(条約では定義されていない用語)を2012年までに1,700から 2,200の間まで削減することで合意した。2010年に新戦略兵器削減条約(New Start Treaty)に取って代わられた。 包括的核実験禁止条約(CTBT)—1996年に調印、未発効:CTBTは、あらゆる環境におけるすべての核爆発を禁止する国際条約(現在、181カ国が 署名、148カ国が批准)である。この条約が発効していない間、ロシアは1990年以降、米国は1992年以降、核兵器実験を行っていない。[62] 新戦略兵器削減条約(New START Treaty)—2010年署名、2011年発効:SORT条約に代わるもので、配備核弾頭数を約半分に削減する。2026年まで有効。 核兵器禁止条約—2017年に署名、2021年1月22日に発効:締約国による核兵器の保有、製造、開発、実験、またはそれらの活動への支援を禁止する。 自国で開発した核兵器を完全に解体した国は、南アフリカ共和国ただ一国である。アパルトヘイト政権下の南アフリカは1980年代に6発の粗雑な核分裂兵器を製造したが、それらは1990年代初頭に解体された。[63] |

United Nations UN Representative for Disarmament Affairs, Angela Kane, at a 2012 ceremony marking the anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings Main article: United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs In its landmark resolution 1653 of 1961, "Declaration on the prohibition of the use of nuclear and thermo-nuclear weapons," the UN General Assembly stated that use of nuclear weaponry "would exceed even the scope of war and cause indiscriminate suffering and destruction to mankind and civilization and, as such, is contrary to the rules of international law and to the laws of humanity".[64] The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) is a department of the United Nations Secretariat established in January 1998 as part of the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan's plan to reform the UN as presented in his report to the General Assembly in July 1997.[65] Its goal is to promote nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation and the strengthening of the disarmament regimes in respect to other weapons of mass destruction, chemical and biological weapons. It also promotes disarmament efforts in the area of conventional weapons, especially land mines and small arms, which are often the weapons of choice in contemporary conflicts. Following the retirement of Sergio Duarte in February 2012, Angela Kane was appointed as the new High Representative for Disarmament Affairs. On July 7, 2017, a UN conference adopted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons with the backing of 122 states. It opened for signature on September 20, 2017. The 2022 United Nations Disarmament Yearbook described highlights and challenges in the previous year. As reported by the UN Press, "On the one hand, we saw record levels of military spending and division within important arms-control frameworks, including the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. On the other hand, we also saw the first-ever Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons"[66] |

国際連合 国連軍縮担当代表アンゲラ・ケインは、2012年の広島・長崎原爆投下記念式典で 詳細は「国際連合軍縮部」を参照 1961年の画期的な決議1653「核兵器および熱核兵器の使用禁止に関する宣言」において、国連総会は核兵器の使用は「戦争の域をこえて人類と文明に無差別な苦痛と破壊をもたらすものであり、それゆえ国際法の規則と人道の法に反する」と述べた。[64] 国連軍縮部(UNODA)は、1997年7月に国連総会に提出されたコフィ・アナン国連事務総長の国連改革案の一部として、1998年1月に設立された国連事務局の一部門である。 その目標は、核軍縮と核不拡散、および化学兵器や生物兵器といった他の大量破壊兵器に関する軍縮体制の強化を推進することである。また、通常兵器、特に現代の紛争でしばしば使用される地雷や小型武器の分野における軍縮努力も推進している。 2012年2月にセルジオ・ドゥアルテが退任した後、アンジェラ・ケインが新たな軍縮問題担当上級代表に任命された。 2017年7月7日、国連会議は122カ国の賛成多数で核兵器禁止条約を採択した。2017年9月20日に署名が開始された。 2022年の国連軍縮年鑑は、前年のハイライトと課題について述べている。国連プレスが報じたところによると、「一方では、核兵器不拡散条約(NPT)を 含む重要な軍備管理枠組み内での軍事費の記録的な水準と分裂が見られた。他方では、核兵器禁止条約の締約国会議が初めて開催されたこともあった」 [66]。 |

U.S. nuclear policy Protest against the nuclear arms race between the U.S./NATO and the Soviet Union, in Bonn, West Germany, 1981  Protest against the deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe, Hague, Netherlands, 1983 Despite a general trend toward disarmament in the early 2000s, the George W. Bush administration repeatedly pushed to fund policies that would allegedly make nuclear weapons more usable in the post–Cold War environment.[67][68] To date the U.S. Congress has refused to fund many of these policies. However, some [69] feel that even considering such programs harms the credibility of the United States as a proponent of nonproliferation. Controversial U.S. nuclear policies Reliable Replacement Warhead Program (RRW): This program seeks to replace existing warheads with a smaller number of warhead types designed to be easier to maintain without testing. Critics charge that this would lead to a new generation of nuclear weapons and would increase pressures to test.[70] Congress has not funded this program. Complex Transformation: Complex transformation, formerly known as Complex 2030, is an effort to shrink the U.S. nuclear weapons complex and restore the ability to produce "pits", the fissile cores of the primaries of U.S. thermonuclear weapons. Critics see it as an upgrade to the entire nuclear weapons complex to support the production and maintenance of the new generation of nuclear weapons. Congress has not funded this program. Nuclear bunker buster: Formally known as the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP), this program aimed to modify an existing gravity bomb to penetrate into soil and rock in order to destroy underground targets. Critics argue that this would lower the threshold for use of nuclear weapons. Congress did not fund this proposal, which was later withdrawn. Missile Defense: Formerly known as National Missile Defense, this program seeks to build a network of interceptor missiles to protect the United States and its allies from incoming missiles, including nuclear-armed missiles. Critics have argued that this would impede nuclear disarmament and possibly stimulate a nuclear arms race. Elements of missile defense are being deployed in Poland and the Czech Republic, despite Russian opposition. Former U.S. officials Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Bill Perry, and Sam Nunn (aka 'The Gang of Four' on nuclear deterrence)[71] proposed in January 2007 that the United States rededicate itself to the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons, concluding: "We endorse setting the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons and working energetically on the actions required to achieve that goal." Arguing a year later that "with nuclear weapons more widely available, deterrence is decreasingly effective and increasingly hazardous," the authors concluded that although "it is tempting and easy to say we can't get there from here, [...] we must chart a course toward that goal."[72] During his presidential campaign, former U.S. President Barack Obama pledged to "set a goal of a world without nuclear weapons, and pursue it."[73] U.S. programs to reduce risk of nuclear terrorism The United States has taken the lead in ensuring that nuclear materials globally are properly safeguarded. A popular program that has received bipartisan domestic support for over a decade is the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (CTR). While this program has been deemed a success, many [who?] believe that its funding levels need to be increased so as to ensure that all dangerous nuclear materials are secured in the most expeditious manner possible.[citation needed] The CTR program has led to several other innovative and important nonproliferation programs that need to continue to be a budget priority in order to ensure that nuclear weapons do not spread to actors hostile to the United States.[citation needed] Key programs: Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR): The CTR program provides funding to help Russia secure materials that might be used in nuclear or chemical weapons as well as to dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in Russia. Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI): Expanding on the success of the CTR, the GTRI will expand nuclear weapons and material securing and dismantlement activities to states outside of the former Soviet Union. |

米国の核政策 1981年、西ドイツのボンにおける、米・NATOとソ連間の核軍拡競争に対する抗議  1983年、オランダのハーグにおける、ヨーロッパへのパーシングIIミサイル配備に対する抗議 2000年代初頭には軍縮の傾向が一般的であったにもかかわらず、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ政権は、冷戦後の環境下で核兵器をより使用しやすくする政策への 資金提供を繰り返し推進した。[67][68] 現在まで、米国議会はこれらの政策の多くへの資金提供を拒否している。しかし、一部の人々は[69]、そのようなプログラムを検討することさえ、核不拡散 の推進者としての米国の信頼性を損なうと考える。 物議を醸した米国の核政策 信頼性代替弾頭プログラム(RRW):このプログラムは、既存の弾頭を、試験を必要とせず維持管理が容易なように設計された少数の弾頭タイプに置き換える ことを目指している。批判派は、このプログラムが次世代の核兵器につながり、核実験への圧力を高めることになる、と主張している。[70] 議会は、このプログラムへの資金提供を行っていない。 複雑な変革:複雑な変革(以前は「複雑な2030」として知られていた)は、米国の核兵器複合体を縮小し、米国の熱核兵器のプライマリ(一次核分裂装置) の核分裂性コアである「ピット」の生産能力を回復させる取り組みである。 批判派は、この取り組みを、次世代の核兵器の生産と維持を支援するための核兵器複合体の全体的なアップグレードと見なしている。 議会は、このプログラムに資金を提供していない。 核バンカーバスター:正式名称は強固な核地球貫通兵器(RNEP)で、この計画は既存の重力爆弾を改良し、土壌や岩盤を貫通して地下の標的を破壊すること を目的としている。 批判派は、この計画は核兵器使用の敷居を下げることになる、と主張している。 議会はこの提案に資金提供せず、後にこの計画は撤回された。 ミサイル防衛:以前は国家ミサイル防衛として知られていたこの計画は、核ミサイルを含む飛来ミサイルから米国とその同盟国を守るための迎撃ミサイルのネッ トワーク構築を目指している。 批判派は、この計画は核軍縮を妨げ、核軍拡競争を刺激する可能性があると主張している。 ミサイル防衛の一部は、ロシアの反対にもかかわらず、ポーランドとチェコ共和国に配備されている。 元米国政府高官のヘンリー・キッシンジャー、ジョージ・シュルツ、ビル・ペリー、サム・ナン(核抑止力に関する「4人組」とも呼ばれる)[71]は、 2007年1月、米国が核兵器廃絶の目標に再び専心することを提案し、「核兵器のない世界という目標を掲げ、その目標を達成するために必要な行動に精力的 に取り組むことを支持する」と結論づけた。1年後、「核兵器がより広く入手可能になっているため、抑止力はますます効果を失い、危険性が増している」と主 張し、著者は「ここからそこへ到達することはできないと主張するのは魅力的で容易であるが、[...] その目標に向かって進路を定めなければならない」と結論付けた。[72] 大統領選挙キャンペーン中、前米国大統領のバラク・オバマ氏は、「核兵器のない世界という目標を設定し、それを追求する」と誓った。[73] 核テロのリスクを低減するための米国のプログラム 米国は、世界中の核物質が適切に保護されることを確保する取り組みを主導してきた。10年以上にわたって超党派で国内の支持を得ている人気の高いプログラ ムは、脅威削減協力プログラム(CTR)である。このプログラムは成功を収めているとみなされているが、多くの人々は、すべての危険な核物質が可能な限り 迅速に確保されるよう、その資金レベルを増加させる必要があると信じている。CTRプログラムは、米国に敵対する勢力に核兵器が拡散しないよう確保するた めに、予算の優先事項として継続する必要がある、いくつかの革新的で重要な核不拡散プログラムにつながっている。 主なプログラム: 協調的脅威削減(CTR):CTRプログラムは、ロシアが核兵器や化学兵器に使用される可能性のある物質を確保し、ロシア国内の大量破壊兵器および関連インフラを解体するための資金援助を行っている。 グローバル脅威削減イニシアティブ(GTRI):CTRの成功を基に、GTRIは核兵器および核物質の確保と解体活動を旧ソ連圏以外の国々にも拡大する。 |

| Other states Main article: List of states with nuclear weapons List of countries' nuclear weapons development status represented by color. Five "nuclear weapons states" from the NPT Other states known to possess nuclear weapons (India, Pakistan and North Korea) Other presumed nuclear powers (Israel) States formerly possessing nuclear weapons (Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Africa and Ukraine) States suspected of being in the process of developing nuclear weapons and/or nuclear programs States which at one point had nuclear weapons and/or nuclear weapons research programs While the vast majority of states have adhered to the stipulations of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, a few states have either refused to sign the treaty or have pursued nuclear weapons programs while not being members of the treaty. Many view the pursuit of nuclear weapons by these states as a threat to nonproliferation and world peace.[74] Declared nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT:[75] Indian nuclear weapons: 80–100 active warheads Pakistani nuclear weapons: 90–110 active warheads North Korean nuclear weapons: <30 active warheads Undeclared nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT: Israeli nuclear weapons: 75–200 active warheads[76] Nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT that disarmed and joined the NPT as non-nuclear weapons states: South African nuclear weapons: disarmed from 1989–1993 Former Soviet states that disarmed and joined the NPT as non-nuclear weapons states: Belarus Kazakhstan Ukraine Non-nuclear weapon states party to the NPT currently accused of seeking nuclear weapons: Iran Non-nuclear weapon states party to the NPT who acknowledged and eliminated past nuclear weapons programs: Libya[77] |

その他の国家 詳細は「核兵器を保有する国家の一覧」を参照 各国の核兵器開発状況を色で表した一覧。 NPTの「核兵器国」5カ国 核兵器を保有していることが知られているその他の国(インド、パキスタン、北朝鮮 その他の推定核保有国(イスラエル かつて核兵器を保有していた国(ベラルーシ、カザフスタン、南アフリカ、ウクライナ 核兵器および/または核兵器開発計画の進行中であると疑われている国 かつて核兵器および/または核兵器開発計画を持っていた国 大多数の国家は核拡散防止条約の規定を順守しているが、少数の国家は条約への署名を拒否しているか、条約に加盟していないにもかかわらず核兵器開発を進めている。 これらの国家による核兵器開発は、核拡散防止と世界平和に対する脅威であると考える者も多い。[74] NPT非加盟の核兵器保有国:[75] インドの核兵器:80~100発の稼働可能な弾頭 パキスタンの核兵器:90~110発の稼働可能な弾頭 北朝鮮の核兵器:30発未満の稼働可能な弾頭 NPT未加盟の非申告核兵器国: イスラエルの核兵器:75~200発の稼働可能な弾頭[76] NPT未加盟の核兵器国で、核兵器を廃棄し非核兵器国としてNPTに加盟した国: 南アフリカの核兵器:1989年から1993年にかけて武装解除 武装解除し非核兵器国としてNPTに加盟した旧ソ連諸国: ベラルーシ カザフスタン ウクライナ 現在、核兵器開発疑惑をかけられている非核兵器国としてNPTに加盟している国: イラン 過去に核兵器開発計画を認め、廃棄した非核兵器国としてNPTに加盟している国: リビア[77] |

| Semiotics The precise use of terminology in the context of disarmament may have important implications for political Signaling theory.[78] In the case of North Korea, "denuclearization" has historically been interpreted as different from "disarmament" by including withdrawal of American nuclear capabilities from the region.[79] More recently, this term has become provocative due to its comparisons to the collapse of the Gaddafi regime after disarmament.[80] The Biden administration has been criticized for its reaffirming of a strategy of denuclearization with Korea and Japan, as opposed to a "freeze" or "pause" on new nuclear developments.[81][82][83][84] Similarly, the term "irreversible" has been argued to set an impossible standard for states to disarm.[85] |

記号論 軍縮の文脈における用語の正確な使用は、政治的なシグナリング理論にとって重要な意味を持つ可能性がある。[78] 北朝鮮の場合、「非核化」は歴史的に、この地域からのアメリカの核戦力の撤退を含めることで、「軍縮」とは異なるものとして解釈されてきた。[79] さらに最近では、この用語は、 カダフィ政権崩壊後の武装解除との比較から、挑発的な意味合いを持つようになった。[80] バイデン政権は、新たな核開発の「凍結」や「一時停止」ではなく、韓国と日本との非核化戦略を再確認したとして批判されている。[81][82][83] [84] 同様に、「不可逆的」という用語は、国家による武装解除に不可能な基準を設定していると主張されている。[85] |

| Recent developments UN vote on adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons on July 7, 2017 Yes No Did not vote Eliminating nuclear weapons has long been an aim of the pacifist left. But now many mainstream politicians, academic analysts, and retired military leaders also advocate nuclear disarmament. Sam Nunn, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and George Shultz have called upon governments to embrace the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and in three op-eds in The Wall Street Journal proposed an ambitious program of urgent steps to that end. The four have created the Nuclear Security Project to advance this agenda. Nunn reinforced that agenda during a speech at the Harvard Kennedy School on October 21, 2008, saying, "I'm much more concerned about a terrorist without a return address that cannot be deterred than I am about deliberate war between nuclear powers. You can't deter a group who is willing to commit suicide. We are in a different era. You have to understand the world has changed."[86] In 2010, the four were featured in a documentary film entitled Nuclear Tipping Point. The film is a visual and historical depiction of the ideas laid forth in The Wall Street Journal op-eds and reinforces their commitment to a world without nuclear weapons and the steps that can be taken to reach that goal.[87] Global Zero is an international non-partisan group of 300 world leaders dedicated to achieving nuclear disarmament.[88] The initiative, launched in December 2008, promotes a phased withdrawal and verification for the destruction of all devices held by official and unofficial members of the nuclear club. The Global Zero campaign works toward building an international consensus and a sustained global movement of leaders and citizens for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Goals include the initiation of United States-Russia bilateral negotiations for reductions to 1,000 total warheads each and commitments from the other key nuclear weapons countries to participate in multilateral negotiations for phased reductions of nuclear arsenals. Global Zero works to expand the diplomatic dialogue with key governments and continue to develop policy proposals on the critical issues related to the elimination of nuclear weapons. The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament took place in Oslo in February 2008, and was organized by The Government of Norway, the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Hoover Institute. The Conference was entitled Achieving the Vision of a World Free of Nuclear Weapons and had the purpose of building consensus between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states in relation to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty.[89]  Anti-nuclear weapons protest march in St. Louis, United States, June 17, 2017 The Tehran International Conference on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation took place in Tehran in April 2010. The conference was held shortly after the signing of the New START, and resulted in a call of action toward eliminating all nuclear weapons. Representatives from 60 countries were invited to the conference. Non-governmental organizations were also present. Among the prominent figures who have called for the abolition of nuclear weapons are "the philosopher Bertrand Russell, the entertainer Steve Allen, CNN's Ted Turner, former Senator Claiborne Pell, Notre Dame president Theodore Hesburgh, South African Bishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama".[90] Others have argued that nuclear weapons have made the world relatively safer, with peace through deterrence and through the stability–instability paradox, including in south Asia.[91][92] Kenneth Waltz has argued that nuclear weapons have created a nuclear peace, and further nuclear weapon proliferation might even help avoid the large scale conventional wars that were so common prior to their invention at the end of World War II.[93] In the July 2012 issue of Foreign Affairs Waltz took issue with the view of most U.S., European, and Israeli, commentators and policymakers that a nuclear-armed Iran would be unacceptable. Instead Waltz argues that it would probably be the best possible outcome, as it would restore stability to the Middle East by balancing Israel's regional monopoly on nuclear weapons.[94] Professor John Mueller of Ohio State University, the author of Atomic Obsession,[95] has also dismissed the need to interfere with Iran's nuclear program and expressed that arms control measures are counterproductive.[96] During a 2010 lecture at the University of Missouri, which was broadcast by C-SPAN, Mueller has also argued that the threat from nuclear weapons, especially nuclear terrorism, has been exaggerated, both in the popular media and by officials.[97]  Jeremy Corbyn speaking at the#StopTrident rally at Trafalgar Square on February 27, 2016 Former Secretary Kissinger says there is a new danger, which cannot be addressed by deterrence: "The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn't operate in any comparable way".[98] George Shultz has said, "If you think of the people who are doing suicide attacks, and people like that get a nuclear weapon, they are almost by definition not deterrable".[99] Andrew Bacevich wrote that there is no feasible scenario under which the US could sensibly use nuclear weapons: For the United States, they are becoming unnecessary, even as a deterrent. Certainly, they are unlikely to dissuade the adversaries most likely to employ such weapons against us -- Islamic extremists intent on acquiring their own nuclear capability. If anything, the opposite is true. By retaining a strategic arsenal in readiness (and by insisting without qualification that the dropping of atomic bombs on two Japanese cities in 1945 was justified), the United States continues tacitly to sustain the view that nuclear weapons play a legitimate role in international politics ... .[100] In The Limits of Safety, Scott Sagan documented numerous incidents in US military history that could have produced a nuclear war by accident. He concluded: while the military organizations controlling U.S. nuclear forces during the Cold War performed this task with less success than we know, they performed with more success than we should have reasonably predicted. The problems identified in this book were not the product of incompetent organizations. They reflect the inherent limits of organizational safety. Recognizing that simple truth is the first and most important step toward a safer future.[101] On January 3, 2022, the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, China, France, Russia, Britain, and the United States issued a statement on prevention of nuclear war, affirming that "a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought."[102] On February 21, 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin suspended Russia's participation in the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty with the United States.[103] |

最近の動向 2017年7月7日、核兵器禁止条約の採択に関する国連投票 【青】 はい 【赤】いいえ(オランダか?) 【灰色】投票せず 核兵器廃絶は、平和主義的な左派が長年掲げてきた目標である。しかし今では、多くの主流派政治家、学識者、退役軍人指導者も核軍縮を提唱している。サム・ ナン、ウィリアム・ペリー、ヘンリー・キッシンジャー、ジョージ・シュルツの4人は、核兵器のない世界というビジョンを各国政府に受け入れるよう呼びか け、ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に3度にわたって寄稿し、その目的を達成するための緊急措置として野心的なプログラムを提案した。この4人は、こ の議題を推進するために「核安全保障プロジェクト」を立ち上げた。 ナン氏は2008年10月21日、ハーバード大学ケネディスクールでの講演でこの議題をさらに強化し、「私は、抑止できない宛先不明のテロリストについ て、核保有国間の意図的な戦争よりもはるかに懸念している。 自殺を望む集団を阻止することはできない。 私たちは異なる時代に生きている。世界は変わったということを理解しなければならない」[86] 2010年には、4人は『Nuclear Tipping Point』という題名のドキュメンタリー映画で取り上げられた。この映画は、ウォールストリート・ジャーナル紙の社説で提示されたアイデアを視覚的かつ 歴史的に描写したものであり、核兵器のない世界への彼らの献身と、その目標を達成するために取ることができる措置を強調している。 グローバルゼロは、核軍縮の実現を目的とする、300人の世界の指導者たちによる超党派の国際的グループである。[88] 2008年12月に発足したこのイニシアティブは、核保有国および非保有国の政府が保有するすべての核兵器の段階的な撤去と検証を推進している。グローバ ルゼロキャンペーンは、核兵器廃絶に向けた国際的な合意と、指導者および市民による持続的な世界的な運動の構築を目指している。その目標には、米国とロシ アがそれぞれ1,000発ずつの核弾頭削減に向けて二国間交渉を開始すること、そして他の主要核保有国が核兵器の段階的削減に向けた多国間交渉に参加する ことへの同意が含まれている。グローバルゼロは、主要各国政府との外交対話を拡大し、核兵器廃絶に関する重要な問題についての政策提言を継続的に開発して いる。 2008年2月には、ノルウェー政府、核脅威イニシアティブ、フーバー研究所の主催で、核軍縮に関する国際会議がオスロで開催された。この会議は「核兵器 のない世界というビジョンの実現」と題され、核兵器国と非核兵器国との間で核拡散防止条約(NPT)に関する合意を形成することを目的としていた。  2017年6月17日、米国セントルイスでの反核兵器デモ行進 2010年4月には、テヘランで「テヘラン軍縮・不拡散国際会議」が開催された。この会議は、新戦略兵器削減条約(新START)の調印直後に開催され、 すべての核兵器の廃絶に向けた行動の呼びかけを採択した。この会議には60カ国の代表が招待された。非政府組織も参加した。 核兵器廃絶を訴えた著名人には、「哲学者のバートランド・ラッセル、エンターテイナーのスティーブ・アレン、CNNのテッド・ターナー、元上院議員のクレ アボーン・ペル、ノートルダム大学学長のセオドア・ヘスブルック、南アフリカの司教デズモンド・ツツ、ダライ・ラマ」などがいる。[90] また、核兵器は世界を相対的に安全にしてきたという意見もある。抑止力や安定と不安定のパラドックスによって平和が保たれてきたという意見であり、南アジ アも含むものである。[91][92] ケネス・ウォルツは、核兵器が核の平和を作り出したと主張しており、さらに核兵器の拡散は、 第二次世界大戦の終結時に核兵器が発明される以前には頻繁に起こっていた大規模な通常戦争を回避するのに役立つ可能性さえあると主張している。[93] ウォルツは、2012年7月の『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』誌で、核兵器を保有するイランは容認できないという、米国、欧州、イスラエルの大半の論客や政 策立案者の見解に異議を唱えた。ウォルツは、むしろ、それはおそらく最善の結果をもたらすだろうと主張している。なぜなら、それはイスラエルの地域独占に よる核兵器のバランスを回復することで、中東に安定をもたらすからだ。[94] 『Atomic Obsession』の著者であるオハイオ州立大学のジョン・ミューラー教授も、イランの核開発プログラムに干渉する必要はないと主張し また、軍備管理措置は逆効果であると述べている。[96] ミューラーは、2010年にミズーリ大学で行った講演(C-SPANが放送)でも、核兵器、特に核テロによる脅威は、一般メディアでも政府高官の間でも誇 張されていると主張している。[97]  2016年2月27日、トラファルガー広場での#StopTrident集会で演説するジェレミー・コービン キッシンジャー元国務長官は、抑止では対処できない新たな危険性があると述べている。「抑止の古典的な概念は、侵略者や悪人が後ずさりするような結果が存 在するというものだった。自爆テロが横行する世界では、そのような計算はまったく通用しない」と述べている。[98] ジョージ・シュルツは、「自爆テロを行う人々について考えた場合、そのような人々が核兵器を入手すれば、ほぼ定義上、抑止は不可能だ」と述べている。 [99] アンドリュー・ベーセビッチは、米国が核兵器を賢明に利用できる現実的なシナリオは存在しないと書いている。 米国にとって、核兵器は抑止力としても不要になりつつある。確かに、核兵器を最も使用してくる可能性が高い敵対者、すなわち核保有能力の獲得に固執するイ スラム過激派を思いとどまらせることはできないだろう。むしろ、その反対が真実である。戦略核兵器を即時使用可能な状態で維持し続けていること(そして、 1945年に日本の2都市に原爆が投下されたことは正当であったと無条件に主張し続けていること)によって、米国は、核兵器が国際政治において正当な役割 を果たすという見解を暗黙のうちに支持し続けているのである。 スコット・セーガンは著書『The Limits of Safety』の中で、米国の軍事史上、偶発的に核戦争を引き起こしかねなかった数多くの事例を記録している。彼は次のように結論づけている。 冷戦時代に米国の核戦力を管理していた軍事組織は、その任務を私たちが認識しているよりも少ない成功度で遂行していたが、私たちが合理的に予測すべきで あったよりも高い成功度で遂行していた。この本で指摘された問題は、無能な組織が生み出したものではない。それは組織の安全性に内在する限界を反映したも のである。この単純な真実を認識することが、より安全な未来への第一歩であり、最も重要なステップである。[101] 2022年1月3日、国際連合安全保障理事会の常任理事国である中国、フランス、ロシア、イギリス、アメリカ合衆国は、核戦争防止に関する声明を発表し、「核戦争に勝者はないし、決して戦ってはならない」と断言した。 2023年2月21日、ロシアのウラジーミル・プーチン大統領は、米国との核兵器削減条約「新戦略兵器削減条約(New START)」へのロシアの参加を停止した。[103] |

| Anti-nuclear organizations Baruch Plan Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Countdown to Zero International Atomic Energy Agency List of anti-war organizations List of peace activists Megatons to Megawatts Program Nuclear-free zone Nuclear proliferation Nuclear warfare Nuclear weapons and the United States Nuclear weapons convention Nuclear-Weapon-Ban treaty Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Prevention of nuclear catastrophe Pacem in terris Seabed Arms Control Treaty Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) Tehran International Conference on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, 2010 Trust, but verify |

反核団体 バルーク計画 包括的核実験禁止条約 ゼロへのカウントダウン 国際原子力機関 反戦団体一覧 平和活動家一覧 メガトンからメガワットへプログラム 非核地帯 核拡散 核戦争 核兵器と米国 核兵器禁止条約 核兵器禁止条約 非核兵器地帯 核の大惨事の防止 平和のための地球 海底軍備管理条約 戦略攻撃削減条約(SORT) 2010年のテヘラン軍縮・不拡散国際会議 信頼は重要だが、検証も必要だ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_disarmament |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099