オホーツク文化とそれを担った人びと

Okhotsk culture and their people

☆ オホーツク文化は、第1千年紀の後半から第2千年紀の前半にかけて、サハリン、北海道北東部、千島列島を含むオホーツク海沿岸南部地域で発達した考古学的 な沿岸漁撈・狩猟採集文化である。オホーツク人はニヴフ人の祖先であるとされることが多いが、初期のアイヌ語話者であるとする説もある。北 ユーラシアの諸民族、アイヌ人、ニヴフ人に共通する習慣である熊信仰は、オホーツク文化の重要な要素であったが、縄文時代の日本では一般的ではなかったこ とが示唆されている。 考古学的証拠によれば、オホーツク文化は紀元後5世紀にサハリン南部と北海道北西部のススヤ文化に由来する。

Cultural changes in Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kurils

▶鈴谷文化▶続縄文(epi-Jomon)︎文化︎▶オホーツク文化(Okhotsk culture)※このページです︎▶擦文文化(Satsumon)︎︎▶︎トビニタイ文化(Tobinitai culture)▶

オホーツク文化の前段階とされる「鈴谷(すすや)文化」(→鈴谷式土器)

| The Okhotsk culture

is an archaeological coastal fishing and hunter-gatherer culture that

developed around the southern coastal regions of the Sea of Okhotsk,

including Sakhalin, northeastern Hokkaido, and the Kuril Islands during

the last half of the first millennium to the early part of the second.

The Okhotsk are often associated to be the ancestors of the Nivkhs,[3]

while others argue them to be identified with early Ainu-speakers.[4]

It is suggested that the bear cult, a practice shared by various

Northern Eurasian peoples, the Ainu and the Nivkhs, was an important

element of the Okhotsk culture but was uncommon in Jomon period

Japan.[5] Archaeological evidence indicates that the Okhotsk culture

proper originated in the 5th century AD from the Susuya culture of

southern Sakhalin and northwestern Hokkaido.[6] Etymology The Okhotsk culture is named after the eponymous Sea of Okhotsk, which is named after the Okhota river, which is in turn named after the Even word окат (okat) meaning "river".[7]  The Moyoro Shell Midden at Abashiri, Hokkaidō, the ruins of the Okhotsk culture |

オ

ホーツク文化は、第1千年紀の後半から第2千年紀の前半にかけて、サハリン、北海道北東部、千島列島を含むオホーツク海沿岸南部地域で発達した考古学的な

沿岸漁撈・狩猟採集文化である。オホーツク人はニヴフ人の祖先であるとされることが多いが[3]、初期のアイヌ語話者であるとする説もある[4]。北ユー

ラシアの諸民族、アイヌ人、ニヴフ人に共通する習慣である熊信仰は、オホーツク文化の重要な要素であったが、縄文時代の日本では一般的ではなかったことが

示唆されている。 [5]考古学的証拠によれば、オホーツク文化は紀元後5世紀にサハリン南部と北海道北西部のススヤ文化に由来する[6]。 語源 オホーツク文化はオホーツク海から名付けられ、オホタ川は「川」を意味するокат(okat)に由来する[7]。  オホーツク文化の遺跡、北海道網走市のモヨロ貝塚 |

| History The Okhotsk culture is inferred to have formed on Sakhalin by the admixture of Jōmon people of Japan with Ancient Paleo-Siberians (represented by Chukotko-Kamchatkans) and subsequent Ancient Northeast Asian geneflow from the Amur River region.[8] Kisao Ishizuki of the Sapporo University suggests that the people of the Okhotsk culture were recorded under the name Mishihase on the Japanese record Nihon Shoki,[9] while others suggest that the term Mishihase described a different group or one of the Nivkh tribes.[10] The Nihon Shoki (AD 720) includes the following entry for the year 544: At Cape Minabe, on the northern side of the Island of Sado, there arrived men of Su-shen in a boat and stayed there. During the spring and summer, they caught fish, which they used for food. The men of that island said they were not human beings. They also called them devils and did not dare to go near them. — Nihon Shoki, Book XIX The name is written with Chinese characters referring to a people from Manchuria who appear in Chinese records as early as the 6th century BC. The name Sushen is believed to denote a Tungusic people who were ancestral to the Mohe and Jurchen (Aston 1972, II, 58). The anachronistic use of ‘Sushen’ in Japanese records a thousand years after the name was first used in China was an attempt to give legitimacy to Japan’s early state. In the Japanese context, the term Sushen is probably best interpreted as a traditional label for a ‘northern people’ rather than a specific ethnic group from Manchuria. According to later entries in the Nihon Shoki, the Sushen also lived in Hokkaido.[11] During the reign of the empress Saimei (r. 655–661), Abe no Omi, Warden of the Province of Koshi (modern-day Hokuriku region), was sent on several military expeditions to the north by the Yamato state based in western Japan. During these expeditions, the main enemies of Abe no Omi were the Sushen, who were attacking the Emishi people. In the third month of 660: Abe no Omi was sent on an expedition with a fleet of 200 ships against the land of Su-shen. Abe no Omi made some Yemishi of Michinoku embark on board his own ship. They arrived close to a great river. Upon this over a thousand Yemishi of Watari-shima assembled … saying:- ‘The Su-shen fleet has arrived in great force and threatens to slay us.’ (Aston 1972, II, 263–264) — Nihon Shoki, Book XXVI There was rapid disappearance of Okhotsk sites and artifacts from the Kuril archipelago. As identified in the radiocarbon record of the Kuril Islands, a drastic decline in radiocarbon dates occurs around 800 BP with almost no radiocarbon samples providing a date between 600 and 400 BP. In Hokkaido, the absence of Okhotsk remains after 800 BP is largely considered to be a product of assimilation of Okhotsk culture into the neighboring and contemporaneous expanding Satsumon culture of southern and western Hokkaido. With the onset of yet another cold period, the Little Ice Age, it can be hypothesized that the exchange relationships the Kuril Okhotsk maintained with populations in Kamchatka did not provide the necessary access to materials or exchange partnerships to remain viable in the central and north central regions. With increasing long winters, more difficult travel conditions and potentially less demand or increased costs for marine products, the incentives for continued habitation in the remote Kurils may have declined. Given the concurrent combination of economic, social and environmental factors constraining habitation of this region, Okhotsk populations may simply have chosen to abandon their settlements in the Kuril Islands.[12] |

歴史 オホーツク文化は、日本の縄文人と古代古シベリア人(チュコトコ・カムチャッカ人に代表される)との混血、およびそれに続くアムール川流域からの古代北東アジアの遺伝子流入によってサハリンに形成されたと推測されている[8]。 札幌大学の石月喜佐央は、オホーツク文化の人々が『日本書紀』にミシハセという名前で記録されていることを示唆している[9]: 佐渡島の北側のみなべ岬に、蘇臣(そしん)の人たちが船に乗ってやってきて、そこに滞在した。春と夏の間、彼らは魚を獲って食用にした。その島の人々は、彼らは人間ではないと言った。また、彼らを悪魔と呼び、あえて近づこうとしなかった。 - 日本書紀』第十九書 この名前は漢字で書かれ、紀元前6世紀には中国の記録に登場している満州の人々を指している。スシェンという名は、靺鞨族や女真族の祖先であるツングース 系民族を指すと考えられている(Aston 1972, II, 58)。中国で「スシェン」という呼称が初めて使われてから1000年も経ってから、日本の記録で「スシェン」という時代錯誤的な呼称が使われるように なったのは、日本の初期国家に正当性を与えようとする試みであった。日本の文脈では、「スシェン」という言葉は、満州の特定の民族というよりは、「北方民 族」の伝統的な呼称として解釈するのが最も適切であろう。後の『日本書紀』の記述によれば、スシェンは北海道にも居住していた[11]。斉明天皇(在位 655~661年)の時代、越国(現在の北陸地方)の長官であった安倍能美は、西日本を拠点とするヤマト国から北方への軍事遠征に何度か派遣された。これ らの遠征の間、安倍能美の主な敵は蝦夷(えみし)人を攻撃していた須勢(すせ)人であった。660年3月: アベノオミは200隻の船でスシェンの国へ遠征した。アベノオミはミチノクのエミシ数人を自分の船に乗せた。一行は大河の近くに到着した。この時、亘理島 の千人以上のエミシが集まり、『蘇神の艦隊が大挙してやって来て、我々を殺そうとしている。(アストン1972、II、263-264)。 - 日本書紀』第二十六書 千島列島からオホーツクの遺跡や遺物が急速に消失した。千島列島の放射性炭素年代記録で確認されるように、放射性炭素年代は800BP前後で激減し、 600~400BPの年代を示す放射性炭素試料はほとんどない。北海道では、800BP以降にオホーツク文化が見られなくなるのは、オホーツク文化が近隣 の同時期に拡大した北海道南部・西部の薩摩文化に同化したためと考えられている。小氷期というもう一つの寒冷期が到来したことで、千島オホーツクがカム チャッカの集団と維持してきた交流関係は、中部・北中部地域で存続するために必要な資材の入手や交流提携を提供するものではなくなったという仮説が成り立 つ。冬が長くなり、移動がより困難な状況になり、海産物の需要が減少するかコストが上昇する可能性があったため、遠隔地のクリル諸島に居住し続けるインセ ンティブが低下した可能性がある。この地域の居住を制約する経済的、社会的、環境的要因が同時に重なったことから、オホーツクの人々は単にクリル諸島の居 住地を放棄することを選んだのかもしれない[12]。 |

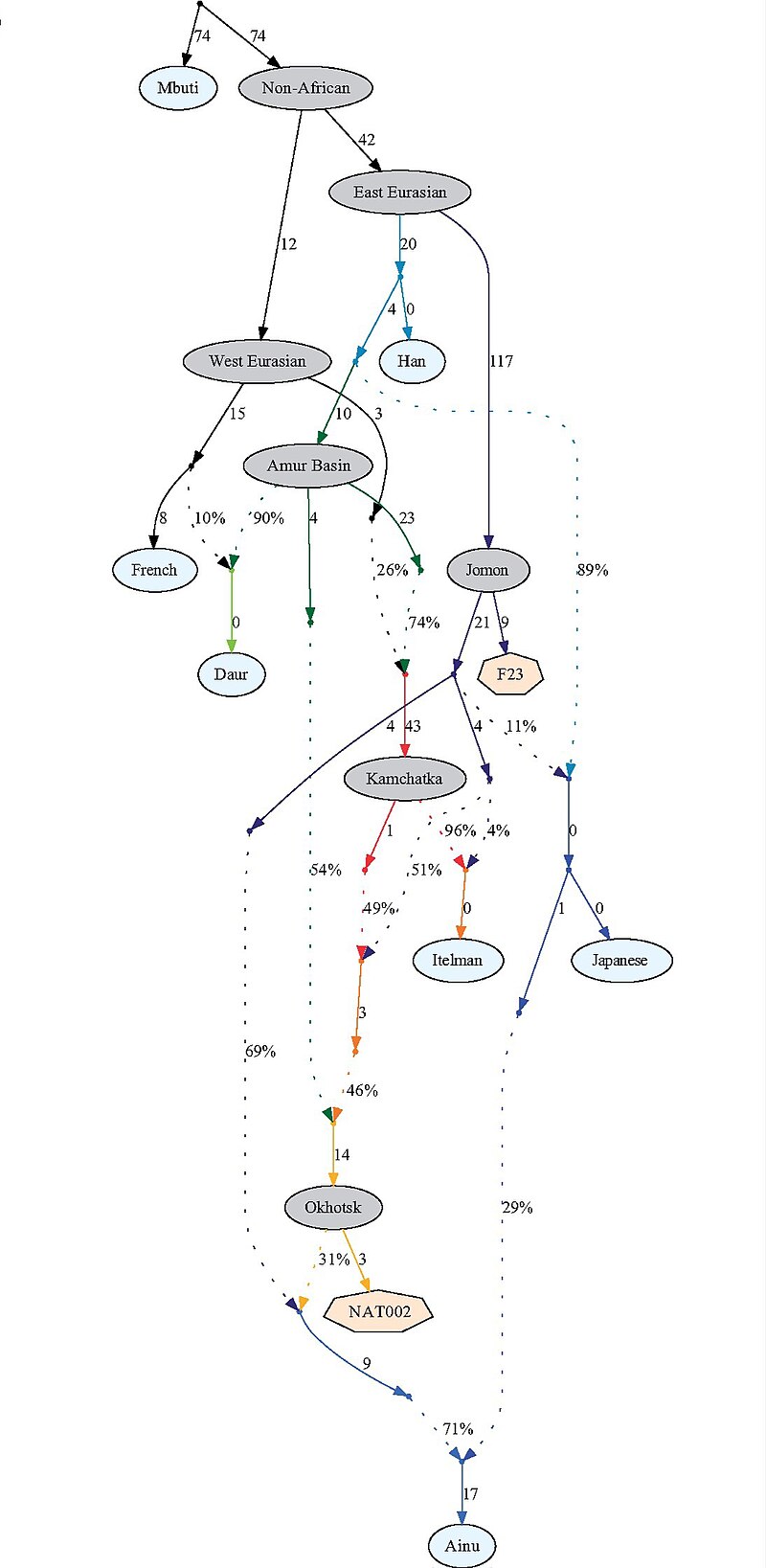

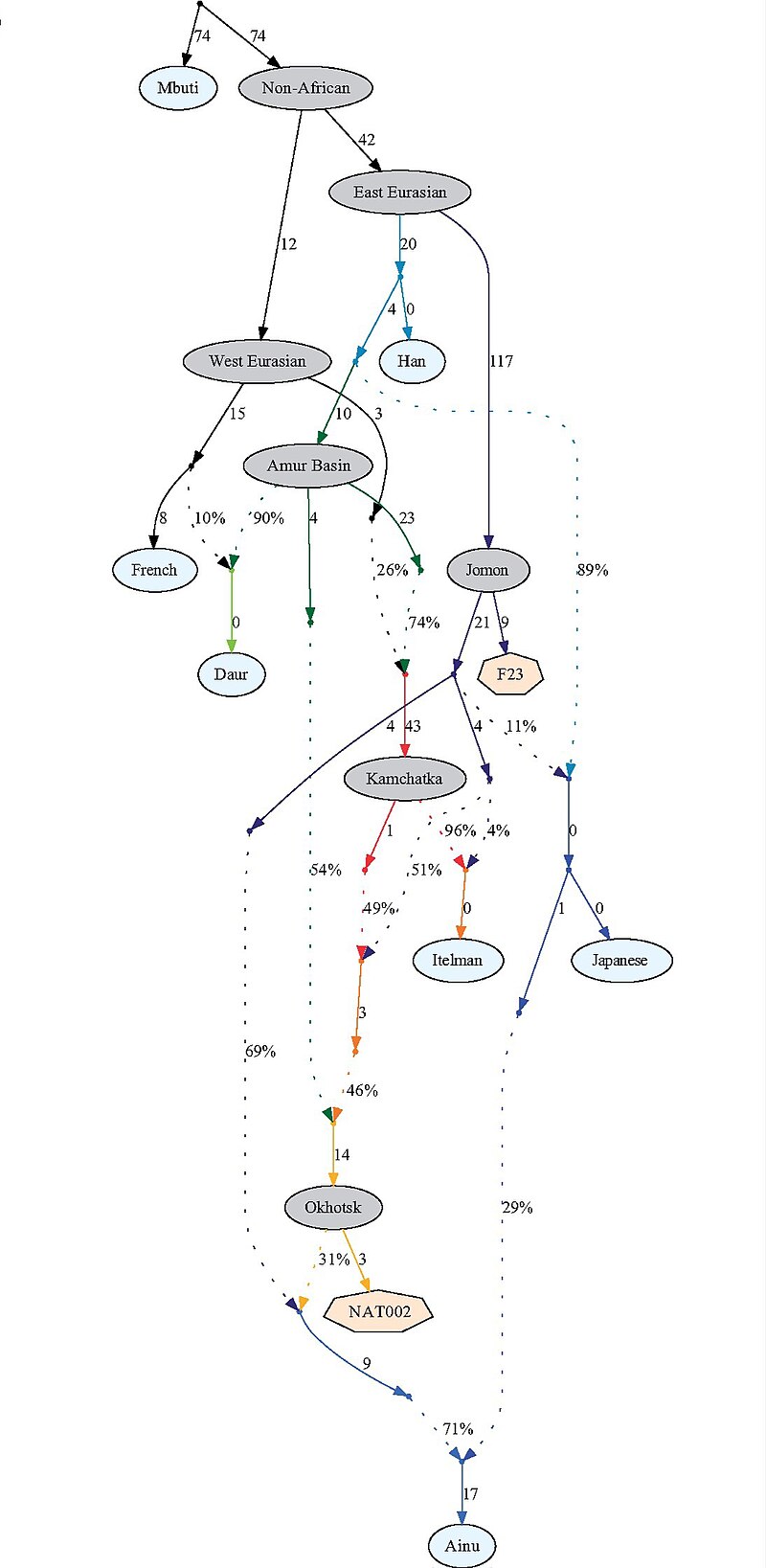

Archaeogenetics Admixture graph based on the genomic data of Okhotsk (NAT002), Jomon (F23), and modern populations Morphological studies of the skeletal remains of the Okhotsk people have suggested broad similarity to populations currently living around the Amur Basin and in northern Sakhalin, but also hinting to a more heterogenous makeup.[13] Full genome analyses of Okhotsk remains found them to be derived from three major sources, notably Ancient Northeast Asians, Ancient Paleo-Siberians, and Jōmon people of Japan. An admixture analysis revealed them to carry c. 54% Ancient Northeast Asian, c. 22% Ancient Paleo-Siberian, and c. 24% Jōmon ancestries respectively.[14] Haplogroups Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups Y1, G1b, and N9b, which were shared among the Lower Amur populations at high frequencies, were commonly detected among Okhotsk skeletal remains (Sato et al. 2009b), which suggests that the Okhotsk people originated in the Lower Amur region. The mitochondrial haplogroup frequencies in 37 Okhotsk skeletal remains from a 2009 study were as follows: A, 8.1%; B5, 2.7%; C3, 5.4%; G1, 24.3%; M7, 5.4%; N9, 10.8%; Y, 43.2%. Thus, in the mitochondrial gene pool of the Okhotsk people, haplogroup Y was major. This genetic feature is similar to those of populations currently living around the lower regions of the Amur River, such as the Ulchi, Nivkhi, and Negidals. The findings show that the Okhotsk people are genetically closer to populations currently living around the lower regions of the Amur River as well as to the Ainu people of Hokkaido. Moreover, the study indicates that the Okhotsk people were also affected by gene flow from the Kamchatka peninsula.[15] |

考古遺伝学 オホーツク人(NAT002)、縄文人(F23)、現代人のゲノムデータに基づく混血グラフ オホーツク人の骨格の形態学的研究は、現在アムール盆地周辺やサハリン北部に住んでいる集団との幅広い類似性を示唆しているが、より異質な構成も示唆して いる[13]。混血分析の結果、彼らはそれぞれ約54%の古代東北アジア人、約22%の古代古シベリア人、約24%の縄文人の祖先を持っていることが判明 した[14]。 ハプログループ ミトコンドリアDNAハプログループY1、G1b、N9bは、アムール下流域の集団の間で高い頻度で共有されており、オホーツク人の骨格標本からは共通し て検出された(Sato et al. 2009年の調査で得られた37体のオホーツク人骨格標本におけるミトコンドリア・ハプログループ頻度は以下の通りであった: A、8.1%;B5、2.7%;C3、5.4%;G1、24.3%;M7、5.4%;N9、10.8%;Y、43.2%。このように、オホーツク人のミト コンドリア遺伝子プールでは、ハプログループYが主要であった。この遺伝的特徴は、ウルチ族、ニブヒ族、ネギダル族など、現在アムール川下流域周辺に住ん でいる集団と類似している。この調査結果は、オホーツク人は現在アムール川下流域に住んでいる集団や北海道のアイヌ民族に遺伝的に近いことを示している。 さらに、オホーツク人はカムチャツカ半島からの遺伝子流の影響も受けていることが示された[15]。 |

| Subsistence A distinctive trait of the Okhotsk culture was its subsistence strategy, traditionally categorised as a specialised system of marine resource gathering.[16] This is in accord with the geographic distribution of archeological sites in coastal regions and confirmed by studies of animal remains and tools, that pointed to intensive marine hunting, fishing, and gathering activities.[17] Stable nitrogen isotope studies in human remains also point to a diet with rich protein intake derived from marine organisms.[18][19][20] Collagen analysis of human bones revealed a relative contribution of marine protein in a range of 60 to 94% for individuals from Rebun Island and from 80 to 90% for individuals from eastern Hokkaido. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that the Okhotsk people's diet was much more diverse than isotopic data suggests. Their diet was probably complemented with terrestrial mammals, such as deer, foxes, rabbits, and martens. Cut marks in domesticated dog bones suggest they were also part of the diet, and remains of domestic pigs are limited to the north of Hokkaido. There is also evidence of the use of cultivation of barley and foraging of wild plants, including Aralia, Polygonum, Actinidia, Vitis, Sambucus, crowberry, Rubus sp., Phellodendron amurense, and Juglans. Little is known about the role of these plants in the economy or if they had dietary or ritual roles.[21] Economy Kikuchi[22] has shown that many of the bronzes and other exotic artifacts found in Okhotsk sites originated in Manchuria and the Russian Far East. At the same time, it has long been suggested that trade in animal furs was a significant component of the Okhotsk economy.[23][24] However, there is little evidence to suggest the importance of long-distance trade or specialized production for exchange. Objects clearly obtained through trade with areas outside the Okhotsk culture are rare. Most such objects come from two sites, Menashi-domari and Moyoro, and few trade goods have been found at Okhotsk sites in the Soya Straits or on Sakhalin. The available archaeological and documentary evidence, therefore, lends little support to suggestions that the Okhotsk people were heavily involved in trading sea mammal products to Manchuria or Japan.[16] Compositional analysis of pottery[25] and obsidian[26] demonstrate that Okhotsk populations living in the remote Kuril Islands had broader and more dense exchange networks as compared to Epi-Jomon populations. In particular, obsidian sourcing demonstrates the extensive procurement and use of Kamchatka obsidian[27] by Okhotsk populations inhabiting the remote islands. |

自給自足 オホーツク文化の特徴的な特徴はその自給自足戦略であり、伝統的に海洋資源採集の特殊化されたシステムとして分類されている[16]。これは沿岸地域の考 古学的遺跡の地理的分布と一致しており、集中的な海洋での狩猟、漁撈、採集活動を示唆する動物遺体や道具の研究によって確認されている[17]。 [17] 人骨の安定窒素同位体比研究でも、海洋生物に由来する豊富なタンパク質を摂取した食生活が指摘されている[18][19][20]。人骨のコラーゲン分析 では、礼文島の個体では60~94%、北海道東部の個体では80~90%の範囲で、海洋タンパク質の相対的な寄与が明らかになった。しかし、オホーツク人 の食生活は同位体データが示唆するよりもはるかに多様であったことを示唆する十分な証拠がある。彼らの食事はおそらく、シカ、キツネ、ウサギ、テンなどの 陸生哺乳類で補完されていた。家畜化されたイヌの骨に刻まれた傷跡は、イヌも食事の一部であったことを示唆しており、家畜化されたブタの遺骨は北海道の北 部に限られている。また、大麦の栽培や、アラリア、ポリゴナム、アクチニジア、ヴィティス、サンブカス、カラスウリ、ルブス属、フェロデンドロン・アムレ ンセ、ユグランスなどの野生植物の採集が行われていた証拠もある。これらの植物が経済においてどのような役割を担っていたのか、あるいは食用や儀礼的な役 割を担っていたのかについてはほとんど知られていない[21]。 経済 菊池[22]は、オホーツクの遺跡で発見された青銅器やその他の異国情緒あふれる工芸品の多くが満州やロシア極東で生まれたものであることを示している。 同時に、動物の毛皮の交易がオホーツク経済の重要な構成要素であったことが長い間示唆されてきた[23][24]が、長距離交易や交換のための特殊生産の 重要性を示唆する証拠はほとんどない。オホーツク文化圏以外の地域との交易によって得られたことが明らかな遺物はまれである。そのような遺物のほとんど は、メナシ泊とモヨロという2つの遺跡から出土したもので、宗谷海峡やサハリンのオホーツク遺跡からは交易品はほとんど見つかっていない。したがって、入 手可能な考古学的・文書学的証拠は、オホーツク人が満州や日本との海棲哺乳類産物の交易に深く関与していたという指摘をほとんど裏付けるものではない。特 に黒曜石の調達は、離島に住むオホーツク系住民がカムチャツカ産黒曜石[27]を広範囲に調達し使用していたことを示している。 |

| Culture Pottery  Examples of the four most common primary decorative motifs for the Northern Hokkaido Okhotsk Culture pottery, present at the Hamanaka 2 site in layers V, IV, IIIa-e and IIb-c. Pottery produced by the Okhotsk is flat based and has a plain body. Decoration is concentrated around the exterior of the rim showing several types of easily distinguishable decorative motifs. The Okhotsk cultural sequence can be divided into four stages in northern Hokkaido, according to the four main styles of pottery. Given the challenges associated with the dating of Okhotsk culture assemblages – as most datable materials are heavily exposed to marine reservoir effects – most chronological work on the Okhotsk is based on comparative analyses of pottery and seriation.[28] The most distinctive and common external feature of Okhotsk ceramic containers is the thick residual organic residue inside and outside the orifice and on the upper part of the walls, and sometimes in the lower part as well. Phosphate chemical analysis of the residue reveals a high content of phosphorus, which indicates an animal origin of organic matter rich in fat. The main function of this pottery was cooking animal products.[29] Pottery assemblages from the late stage of the Okhotsk culture provide evidence of certain innovations. These include the somewhat diminishing role of large cooking vessels and the appearance of a series of small, wide-mouthed pots. This phenomenon may be explained by social, ecological, and technological changes that occurred in the late stage of the Okhotsk culture, spanning the 10th to 13th centuries. During this period a growth in the use of imported metal items took place. Some sites contain evidence of iron cauldrons obviously used for cooking. Such containers are much more effective and long-Iasting than non-hermetic and fragile ceramic vessels. Considering the harsh climatic conditions of Sakhalin, which is problematic for pottery making, the gradual decline of this craft with the arrival of metal pots is likely.[29] Some sites attributed to the Okhotsk reveal the remains of thermal structures used for heating and cooking. These structures were built of clay or stone slabs and located inside pit houses. Thermal structures for heating and cooking are known in archaeological sites on Hokkaido dated to the 6th or 7th to the 12th or 13th centuries. These data may be interpreted as probable evidence that the Okhotsk people were acquainted with the principles of thermal processes and built special thermal structures not only for heating and cooking but also for primitive metalworking and pottery firing.[29] Religion The Okhotsk from Rebun Island transported adult bears and bear cubs (Ursus arctos) from the Hokkaido mainland for ceremonial activities, while also practicing small-scale pig (Sus scrofa inoi) and dog (Canis domesticus) rearing.[30][31][32] Ten ivory figurines depicting females with elaborate clothing are known from Okhotsk sites in both northern and eastern Hokkaido. A baby quadruped on a figurine from the Hamanaka 2 site on Rebun has been interpreted as a bear cub by Maeda.[33] If correct, this may link women with the raising of bears for rituals. This is important because bears probably became ‘‘socially valued goods’’ in Okhotsk society and a DNA analysis of brown bear remains from Kafukai has shown that juvenile bears were brought by boat from southwest Hokkaido to Rebun Island. Bear rituals were important in Okhotsk households but there is no evidence (from burials for example) that female status increased because of their involvement in shamanistic activities related to bear ceremonies.[16] Like the Ainu, the Okhotsk also appear to have engaged in the rearing of live bear cubs, and these earlier traditions appear to be the origins of later Ainu practices. Many interpretations of the significance of Okhotsk human-animal interactions draw on direct historical analogies with the Ainu. The parallels are often striking – for example, in almost all households of the Okhotsk Culture, bear crania are gathered in the sacred rear part of the house and placed on a special raised platform shrine – this may have formed a sacred area where likely only certain members of the group are given access. Many Okhotsk Culture sites also contain abundant evidence for a much wider repertoire of elaborate and deeply respectful animal-related mythology, including animal burials, clusters of animal bones subjected to ritualised treatments, with some clusters found in association with elaborate carved objects, that together may have been utilised as part of specific rituals.[28] Another dimension to human-animal cosmological relations is the sanctity of shell middens. Again, there appears to be deep continuity between traditions of the Okhotsk and Ainu cultures. In the Ainu culture, shell middens comprise a wide range of marine fauna, such as abalone shells, which are not viewed as discarded food or refuse, but rather sacred areas belonging to the spirits and ancestors. In and around these shell middens, animals, plants, tools, and other objects important to the Ainu are deposited – and sent back to the deities – through the celebration of sending rites. This tradition aligns well with the material culture and settlement patterning witnessed at numerous Okhotsk sites, where shell middens accumulate around the habitats and other social spaces. Plenty of material evidence suggests that rituals were performed around these areas, and for instance at the Hamanaka 2 site several human and dog burials were documented in shell midden contexts. The Okhotsk may therefore have regarded shell middens similarly, or even passed on this tradition to the Ainu in the early 2nd millennium.[28] |

文化 土器  浜中2遺跡のV層、IV層、IIIa-e層、IIb-c層に見られる、北海道北部オホーツク文化土器で最も一般的な4つの主要装飾モチーフの例。 オホーツクで生産された土器は平板で、素地は無地である。装飾は縁の外側に集中しており、容易に区別できる数種類の装飾モチーフが見られます。オホーツク の一連の文化は、4つの主要な土器様式によって、北海道北部で4つの段階に分けることができる。オホーツク文化の年代測定には困難が伴うため(ほとんどの 年代測定可能な土器は海洋貯水池の影響を強く受けているため)、オホーツクに関するほとんどの年代測定は、土器の比較分析と年代測定に基づいている [28]。オホーツク陶器の最も特徴的で共通した外見的特徴は、開口部の内側と外側、壁の上部、時には下部にも厚く残留する有機物である。残渣のリン酸塩 化学分析から、リンの含有量が高いことが明らかになり、これは脂肪分を多く含む有機物が動物由来であることを示している。この土器の主な機能は動物性食品 の調理であった[29]。 オホーツク文化後期の土器群からは、ある種の革新の証拠が得られる。これには、大型の調理用土器の役割がやや減少し、口の広い小型の土器が次々と出現した ことが含まれる。この現象は、10世紀から13世紀にかけてのオホーツク文化後期に起こった社会的、生態学的、技術的変化によって説明できるかもしれな い。この時期、輸入された金属製品の使用が増加した。いくつかの遺跡には、明らかに調理に使われた鉄製大釜の証拠が残されている。このような容器は、非密 閉性で壊れやすい陶器の容器よりもはるかに効果的で長持ちする。サハリンの厳しい気候条件を考慮すると、陶器作りには問題があり、金属製の鍋の到来ととも にこの工芸品が徐々に衰退していった可能性が高い[29]。 オホーツク人とされるいくつかの遺跡からは、暖房や調理に使用された熱構造物の遺跡が発見されている。これらの構造物は粘土板や石板で造られ、竪穴住居の 中にあった。暖房や調理のための熱構造物は、6~7世紀から12~13世紀にかけての北海道の遺跡で確認されている。これらのデータは、オホーツク人が熱 プロセスの原理を知っており、暖房や調理のためだけでなく、原始的な金属加工や陶器焼成のためにも特別な熱構造物を建設していた可能性が高い証拠と解釈す ることができる[29]。 宗教 礼文島のオホーツク人は、儀式活動のために北海道本土から成熊と子熊(Ursus arctos)を輸送し、また小規模な豚(Sus scrofa inoi)と犬(Canis domesticus)の飼育も行っていた[30][31][32]。 道北・道東のオホーツク遺跡からは、精巧な衣服をまとった女性を描いた象牙の置物10点が知られている。礼文島浜中2遺跡出土の置物に描かれた四足動物の 赤ちゃんは、前田によって熊の子供と解釈されている[33]。これは重要なことである。というのも、熊はおそらくオホーツク社会で''社会的に価値のある 品物''になっており、香風海から出土したヒグマの遺骨のDNA分析によって、幼熊が北海道南西部から礼文島まで船で運ばれていたことが明らかになってい るからである。熊の儀式はオホーツクの家庭で重要であったが、熊の儀式に関連するシャーマニズム的活動に関与したために女性の地位が上昇したという証拠 (埋葬などから)はない[16]。 アイヌと同様に、オホーツク人も生きた子熊の飼育に従事していたようであり、これらの初期の伝統は後のアイヌの慣習の起源であると思われる。オホーツクの 人間と動物の交流の重要性についての多くの解釈は、アイヌとの直接的な歴史的類似を引き合いに出している。例えば、オホーツク文化のほとんどすべての家庭 で、熊の頭蓋は家の後部の神聖な場所に集められ、特別に高くされた壇上の祠の上に置かれる。オホーツク文化の遺跡の多くには、動物の埋葬、儀式的な処理が 施された動物の骨のクラスター、精巧な彫刻が施されたオブジェと一緒に発見されたクラスターなど、動物にまつわる精巧で深い敬意を表した神話のレパート リーを示す証拠も豊富に含まれており、それらは特定の儀式の一部として利用された可能性がある[28]。 人間と動物の宇宙論的関係のもう一つの側面は、貝塚の神聖さである。ここでも、オホーツク文化とアイヌ文化の伝統には深い連続性があるようだ。アイヌ文化 では、貝塚はアワビの貝殻をはじめとするさまざまな海洋生物から構成されており、それらは廃棄された食物やゴミとしてではなく、精霊や祖先のものである神 聖な場所とみなされている。これらの貝塚とその周辺には、アイヌにとって重要な動物、植物、道具、その他のものが堆積され、送りの儀式を祝って神々に送り 返される。この伝統は、オホーツクの多くの遺跡で見られる物質文化や集落のパターンとよく一致しており、貝塚は住居やその他の社会的空間の周囲に蓄積され ている。例えば、浜中2遺跡では、貝塚の文脈の中で人や犬の埋葬がいくつか記録されている。したがって、オホーツク人も貝塚を同じように考えていたかもし れないし、2千年紀初頭にこの伝統をアイヌ人に伝えたかもしれない[28]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okhotsk_culture |

|

| オ

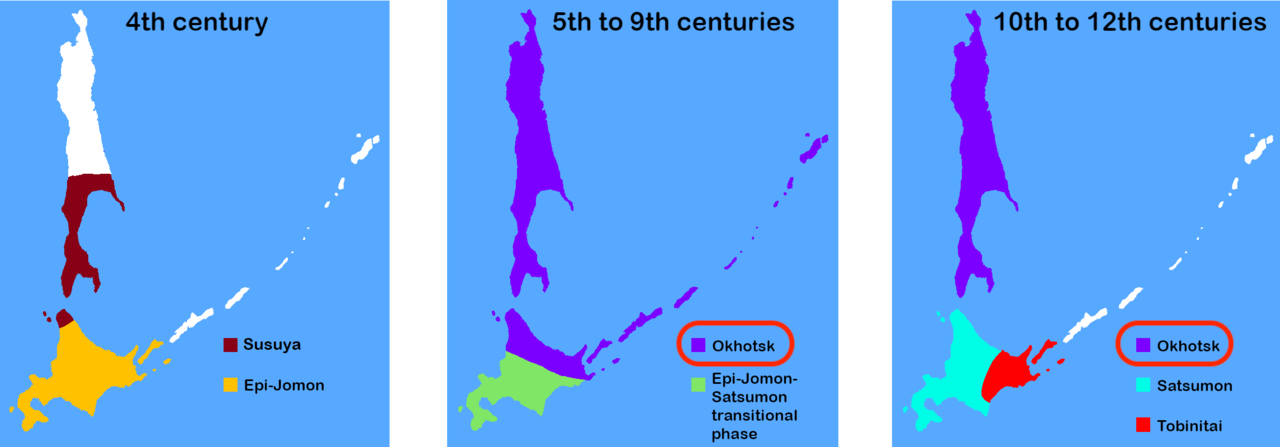

ホーツク文化(オホーツクぶんか)は、3世紀から13世紀までオホーツク海沿岸を中心とする北海道北海岸、樺太、南千島の沿海部に栄えた海洋漁猟民族の文

化である[1]。この文化の遺跡が主としてオホーツク海の沿岸に分布していることから名付けられた。このうち、北海道に分布している遺跡の年代は5世紀か

ら9世紀までと推定されている。 同時期の日本の北海道にあった、続縄文文化や擦文文化とは異質の文化である。 概要 海獣狩猟や漁労を中心とする生活を送っていたオホーツク文化の担い手を、オホーツク文化人、また単にオホーツク人とも呼ぶ。『日本書紀』に現れる粛慎と考 える説がある。この説では、658年から660年で阿倍比羅夫が行ったとされる粛慎の討伐地を北海道のいくつかの地域であると仮定し、それら地域ではオ ホーツク文化の遺跡が発掘されている事から、オホーツク人=粛慎としている。粛慎 (日本)参照。 トビニタイ文化をオホーツク文化に含めるかどうかについては、現在のところ意見が分かれている。トビニタイ文化は9世紀から13世紀まで北海道東部にあ り、擦文文化の影響を受け、海岸から離れた内陸部にも展開した。オホーツク文化が擦文文化と融合し両者の中間的なトビニタイ文化へ変化し、最終的に擦文文 化に吸収されたという説もあるが[1]、両者の継続性を認めてオホーツク文化の一部にする考えと、生活の違いを重視してオホーツク文化に含めない考えとが ある。本項では煩を避けるためトビニタイ文化を含めずに説明する。 時代と分布  北海道、樺太の時代による文化変遷の図。4世紀は北海道全域が続縄文文化、樺太はオホーツク文化の前段階とされる「鈴谷(すすや)文化」。5世紀は北海道 の大半が続縄文から擦文への転換期。オホーツク海沿岸に樺太、千島列島はオホーツク文化。10世紀から12世紀は北海道の大半が擦文文化でオホーツク文化 人は樺太に撤退、根室、釧路地方にはトビニタイ文化が成立 オホーツク文化は土器の特徴にもとづいて、初期、前期、中期、後期、終末期の5期に区分される。オホーツク文化の発生地は樺太南西端と北海道北端で、初期 は3世紀から4世紀までで、土器の形式からは先行する鈴谷文化(英語版)を継承している。そこから拡大して北海道ではオホーツク海沿岸を覆い、樺太の南半 分を占めた。この5世紀から6世紀を時期を十和田式土器に代表される前期とする。中期は7世紀から8世紀で、活動領域はさらに広く、オホーツク文化の痕跡 は東は国後島、南は奥尻島、北は樺太全域に及んでいる。9世紀から10世紀の後期には、土器の様相が各地で異なる。終末期の11世紀から13世紀には土器 の地域的な差違がさらに明確化する。 9世紀に北海道北部では擦文文化の影響が強まり、オホーツク文化は消滅した[1]。同じ頃、北海道東部ではオホーツク文化を継承しながら擦文文化の影響を 受けたトビニタイ文化が成立した[1]。樺太ではオホーツク文化がなお続き、アイヌ文化の進出によって消えたと考えられるが、その様相ははっきりしていな い。 生活 オホーツク文化期の骨製針入れ(北海道根室市弁天島出土)。表面には捕鯨の模様が描かれている この地域での稲作は当時は技術的に不可能であり、北海道北部と樺太では漁業に、北海道東部では海獣を対象とした狩猟におくなど海に依存して暮らしていた [1]。流氷の影響を受ける道東が冬の漁業に適していなかったためと考えられている。秋にホッケ、冬にタラ、春にはニシンなどの海水魚類を対象とした網漁 が行われた。アザラシ、オットセイ、トド、アシカなどの海獣も冬に得られた。夏にはカサゴ・ソイなど様々な魚を獲ったが、その量は冬より少なかった。遺物 に描かれた絵[注釈 1]から捕鯨を行っていたこともわかっている。 また、弥生時代以降の本州と同様に家畜である豚と犬を飼い、どちらも食用にしていた。道東では豚飼育は低調だった。また、熊(ヒグマ)をはじめとして様々な狩猟獣を狩った[1]。そこでは毛皮獣の比重が高く、交易用の毛皮を入手するための狩りと考えられている。 集落は海岸のそばに置かれた。住居は竪穴建物であるが、木材や土で補強し床には粘土を敷くなどの工夫が見られた[1]。大規模住居は中心集落では複数の家族が生活できる大型の住居と[1]、一つの核家族で暮らしたと思われる小型の住居があった。 オホーツク人は、秋から春までは中心集落に住んで共同で大規模な漁を営み、漁が低調になる夏には各地の海岸に分散したと考えられている。住居の奥に動物の 骨を並べる風習があった。並べられた動物は様々だが、特に熊が重要視されていた[1]。熊の重視は、道具類の意匠にも見られる特徴である[1]。 道具としては、オホーツク式土器、石器、骨角器、木器がみられる。製鉄技術が無かったため金属製品は少なく、本州との交易で入手した蕨手刀が副葬品として 少数見つかった程度である[2]。実用品の装飾に動物の意匠を用いたほか、牙や骨で作った動物や女性の像が作られた。船の土製の模型から、オホーツク人が 丸木舟ではなく構造船を建造していたことが分かっている[1]。 衣服は不明であるが、アイヌやニヴフなどこの地域に住む民族は魚皮衣を使っている。 死者は基本的に屈葬された。しかし、目梨泊遺跡の人々は伸展葬の伝統を持ち続けた。 起源と末裔 オホーツク文化には大陸系文化の影響が明確に認められ、同文化のアムール流域靺鞨族の直接移住説をはじめ多くの大陸起源説、影響説が提出されている[3]。 オホーツク人の系統については、文献と考古学的証拠が少ないことから論議があった。現在のところ、大陸からの直接的な移住者が形成したものではなく、鈴谷 式土器の時代(紀元前1世紀から紀元6世紀)から樺太に住んでいた人々の中から生まれた文化で、下って現在のニヴフにつながるとする説が有力である(外部 リンク参照)。他に、靺鞨同仁文化のような大陸の文化や、古コリャーク文化、トカレフ文化のようなオホーツク海北岸の文化との類似性が指摘される[4]。 オホーツク文化は、後期に擦文文化の要素を取り入れるようになった。トビニタイ文化の時代に擦文文化の要素はさらに強くなり、両方の文化要素の混在が見ら れるようになった。また、後のアイヌ文化の中には、熊の崇拝のようなオホーツク文化にあって擦文文化にない要素がある。そのため、この方面のオホーツク人 は、擦文文化の担い手とともにアイヌ文化を形成したと考えられている[5][6]。アイヌは和船のような構造船(イタオマチㇷ゚)を使っていたと推察され るが、これもオホーツク文化の影響ともされる。 最近の研究には、アイヌの起源とアイヌ語の拡散に、オホーツク文化が大きな影響を与えたとするものもあるが、東北地方のアイヌ語地名や記紀に現れるアイヌ語の単語がオホーツク文化よりも古いことを説明できないため、限定的な影響と考えられる。 オホーツク人の遺伝子 2009年、北海道のオホーツク文化遺跡で発見された人骨が、現在では樺太北部やシベリアのアムール川河口一帯に住むニブフ族に最も近く、またアムール川 下流域に住むウリチ、さらに現在カムチャツカ半島に暮らすイテリメン族、コリヤーク族とも祖先を共有することがDNA調査でわかった[7][8]。 近年の研究で、オホーツク人がアイヌ民族と共通性があるとの研究結果も出ている。オホーツク人のなかには縄文人には無いがアイヌが持つ遺伝子のタイプであ るmtDNAハプログループY遺伝子が確認され、アイヌ民族とオホーツク人との遺伝的共通性も判明した [9]。アイヌ民族は縄文人や和人にはないハプログループY遺伝子を20%の比率で持っていることが過去の調査で判明していたが、これまで関連が不明だっ た。 文献史料 詳細は「流鬼国」を参照 日本書紀には、7世紀に阿倍比羅夫が遠征の航海の途上、大河の河口で蝦夷と粛慎の交戦を知り、幣賄弁島(へろべのしま、樺太[10]や奥尻島ではないかと 言う説がある)で粛慎と戦ったと記されている。その大河を石狩川とし、粛慎をオホーツク人とする説はあるが、確証はない。 『通典』 『唐会要』、『資治通鑑』、『新唐書』など中国唐時代の記録には、2代皇帝・太宗の貞観14年(640年)、北方の流鬼国より朝貢使節団が来朝したとの記述がある。この流鬼国は、オホーツク文化人を指すのではないかという説がある。 主な遺跡 モヨロ貝塚(網走市) 目梨泊遺跡(枝幸町) オムサロ遺跡 (紋別市) 常呂遺跡(ところ遺跡の森)(北見市旧常呂町) 標津遺跡群(標津町) チャシコツ岬上遺跡(斜里町) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆