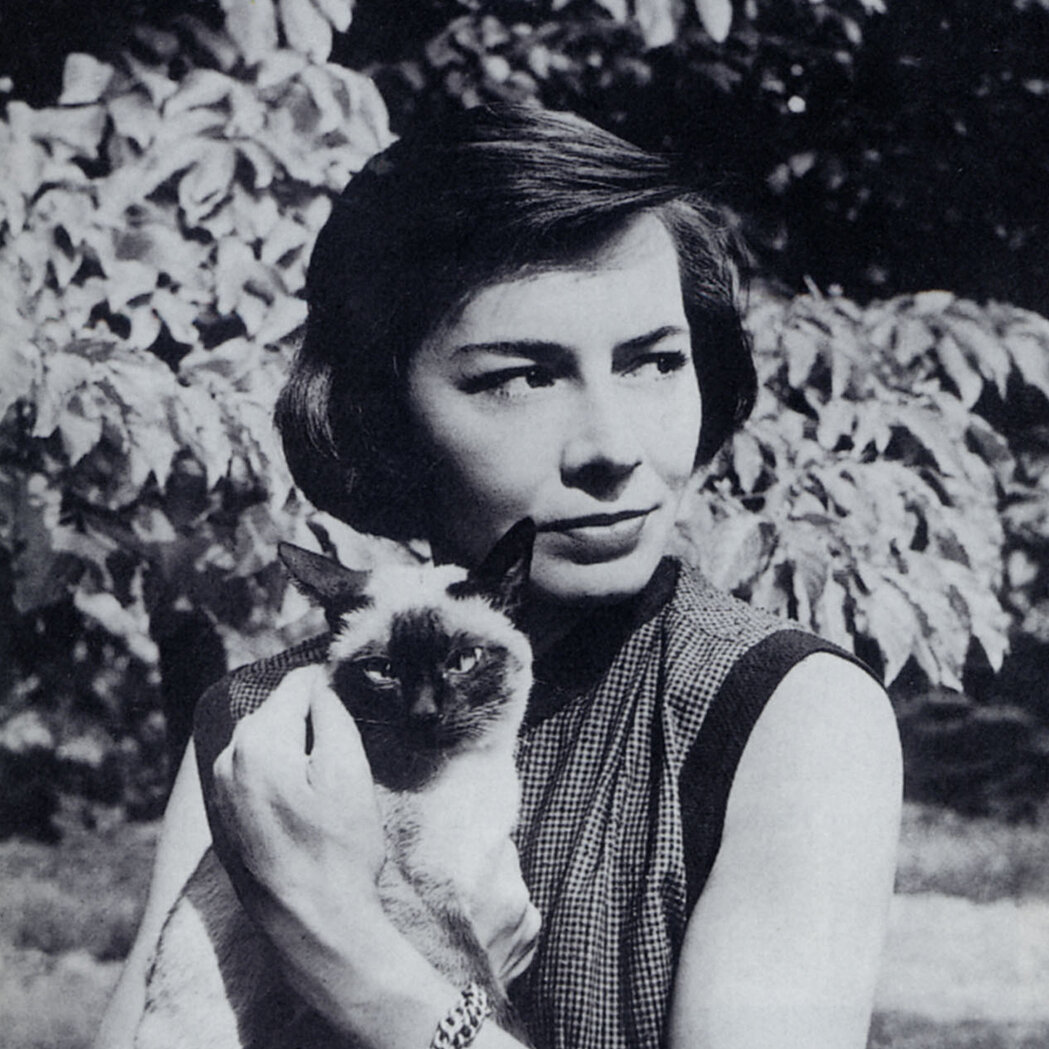

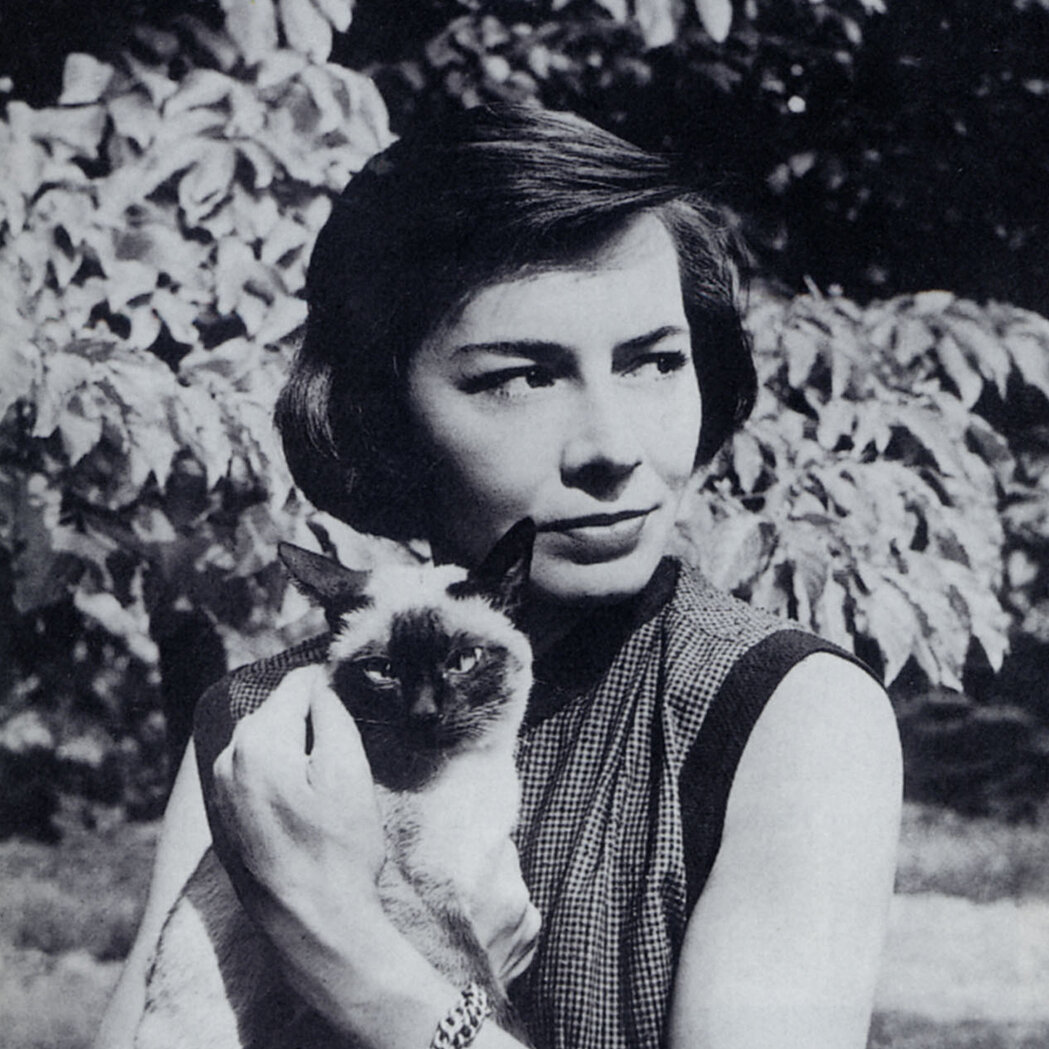

パトリシア・ハイスミス

Mary Patricia Plangman

as Patricia Highsmith, 1921-1995

☆ 書誌の説明:「「私が猫と遊んでいるとき、私が猫を相手に暇つぶしをしているのか、猫が私を相手に暇つぶしをしているのか、私にはわからない。」これはモ ンテーニュの言葉。政治哲学者ジョン・グレイ(John Gray, b.1948)は本書で、何世紀にもわたる哲学や、コレット、ハイスミス、谷崎らの小説を渉猟し、人が猫にどう反応し行動す るかを定めてきた複雑で親密なつながりを探究している。その核心にあるのは猫への感謝の念だ。なぜなら、どんな動物にもまして猫は、人間という孤独な存在 にもそなわっている動物本性を感じさせてくれるからである。」https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC10852537

Patricia

Highsmith

(born Mary Patricia Plangman; January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995)[1]

was an American novelist and short story writer widely known for her

psychological thrillers, including her series of five novels featuring

the character Tom Ripley. She wrote 22 novels and numerous short

stories throughout her career spanning nearly five decades, and her

work has led to more than two dozen film adaptations. Her writing

derived influence from existentialist literature,[2] and questioned

notions of identity and popular morality.[3] She was dubbed "the poet

of apprehension" by novelist Graham Greene.[4] Patricia

Highsmith

(born Mary Patricia Plangman; January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995)[1]

was an American novelist and short story writer widely known for her

psychological thrillers, including her series of five novels featuring

the character Tom Ripley. She wrote 22 novels and numerous short

stories throughout her career spanning nearly five decades, and her

work has led to more than two dozen film adaptations. Her writing

derived influence from existentialist literature,[2] and questioned

notions of identity and popular morality.[3] She was dubbed "the poet

of apprehension" by novelist Graham Greene.[4]Her first novel, Strangers on a Train (1950), has been adapted for stage and screen, the best known being the 1951 film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley has been adapted for film multiple times. Writing under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, Highsmith published The Price of Salt in 1952, the first lesbian novel with a "happy ending";[5] it was republished 38 years later as Carol under her own name and later adapted into a 2015 film. |

パ

トリシア・ハイスミス(Mary Patricia Plangman、1921年1月19日 -

1995年2月4日)[1]は、トム・リプリーを主人公にした5つの小説シリーズを含むサイコ・スリラーで広く知られるアメリカの小説家、短編作家であ

る。50年近いキャリアを通じて22冊の小説と多数の短編小説を執筆し、その作品は20本以上の映画化につながった。彼女の作品は実存主義文学の影響を受

けており[2]、アイデンティティや大衆道徳の概念に疑問を投げかけている[3]。小説家のグレアム・グリーンからは「不安の詩人」と呼ばれている

[4]。 パ

トリシア・ハイスミス(Mary Patricia Plangman、1921年1月19日 -

1995年2月4日)[1]は、トム・リプリーを主人公にした5つの小説シリーズを含むサイコ・スリラーで広く知られるアメリカの小説家、短編作家であ

る。50年近いキャリアを通じて22冊の小説と多数の短編小説を執筆し、その作品は20本以上の映画化につながった。彼女の作品は実存主義文学の影響を受

けており[2]、アイデンティティや大衆道徳の概念に疑問を投げかけている[3]。小説家のグレアム・グリーンからは「不安の詩人」と呼ばれている

[4]。彼女の処女作『見知らぬ乗客』(1950年)は舞台や映画化されており、最もよく知られているのはアルフレッド・ヒッチコック監督による1951年の映画 である。1955年の小説『The Talented Mr.Ripley』は何度も映画化されている。クレア・モーガンというペンネームで執筆していたハイスミスは、1952年に『塩の代償』を発表した。こ の小説は、「ハッピーエンド」のレズビアン小説としては初のものであり[5]、38年後に彼女自身の名前で『キャロル』として再出版され、後に2015年 に映画化された。 |

| Early life Highsmith was born Mary Patricia Plangman in Fort Worth, Texas. She was the only child of artists Jay Bernard Plangman (1889–1975), who was of German descent,[6] and Mary Plangman (née Coates; September 13, 1895 – March 12, 1991). The couple divorced ten days before their daughter's birth.[7] In 1927, Highsmith, her mother and her adoptive stepfather, artist Stanley Highsmith, whom her mother had married in 1924, moved to New York City.[7] When she was 12 years old, Highsmith was sent to Fort Worth and lived with her maternal grandmother for a year.[8] She called this the "saddest year" of her life and felt "abandoned" by her mother. She returned to New York to continue living with her mother and stepfather, primarily in Manhattan, but also in Astoria, Queens. According to Highsmith, her mother once told her that she had tried to abort her by drinking turpentine,[9] although a biography of Highsmith indicates Jay Plangman tried to persuade his wife to have the abortion but she refused.[7](p.65) Highsmith never resolved this love–hate relationship, which reportedly haunted her for the rest of her life, and which she fictionalized in "The Terrapin", her short story about a young boy who stabs his mother to death.[7] Highsmith's mother predeceased her by only four years, dying at the age of 95.[9] Highsmith's grandmother taught her to read at an early age, and she made good use of her grandmother's extensive library. At the age of nine, she found a resemblance to her own imaginative life in the case histories of The Human Mind by Karl Menninger, a popularizer of Freudian analysis.[7] Many of Highsmith's 22 novels were set in Greenwich Village.[10] In 1942, Highsmith graduated from Barnard College, where she studied English composition, playwriting, and short story prose.[7] After graduating from college, and despite endorsements from "highly placed professionals,"[11] she applied without success for a job at publications such as Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, Mademoiselle, Good Housekeeping, Time, Fortune, and The New Yorker.[12] Based on the recommendation from Truman Capote, Highsmith was accepted by the Yaddo artist's retreat during the summer of 1948, where she worked on her first novel, Strangers on a Train.[13][14] |

生い立ち ハイスミスはテキサス州フォートワースでメアリー・パトリシア・プラングマンとして生まれた。ドイツ系の芸術家ジェイ・バーナード・プラングマン (1889-1975)とメアリー・プラングマン(旧姓コーツ、1895年9月13日-1991年3月12日)の間の一人っ子だった[6]。夫妻は娘が生 まれる10日前に離婚した[7]。 1927年、ハイスミスは母親と、母親が1924年に結婚した養父で継父の画家スタンリー・ハイスミスとともにニューヨークへ移り住む[7]。ニューヨー クに戻り、母親と継父のもと、主にマンハッタンで、クイーンズのアストリアでも暮らし続けた。 ハイスミスの伝記によれば、ジェイ・プラングマンは中絶するよう妻を説得しようとしたが、妻は拒否したというが[7](p.65)。 ハイスミスはこの愛憎関係を解決することはなく、それは彼女の残りの人生を悩ませ、母親を刺し殺す少年を描いた短編『テラピン』でフィクション化したと言 われている[7]。ハイスミスの母親は彼女にわずか4年先立たれ、95歳で亡くなった[9]。 ハイスミスは幼い頃から祖母に読書を教わり、祖母の蔵書を活用した。9歳のとき、彼女はフロイト分析の普及者であるカール・メニンガーによる『人間の心』 のケースヒストリーの中に、彼女自身の想像力豊かな人生と似たものを見出した[7]。 1942年、ハイスミスはバーナード・カレッジを卒業し、そこで英作文、劇作、短編散文を学んだ[7]。大学卒業後、「非常に地位のある専門家」[11] からの推薦にもかかわらず、彼女は『ハーパーズ・バザー』、『ヴォーグ』、『マドモアゼル』、『グッド・ハウスキーピング』、『タイム』、『フォーチュ ン』、『ニューヨーカー』などの出版社に就職したが、成功しなかった[12]。 トルーマン・カポーティの推薦に基づき、ハイスミスは1948年の夏にヤドの芸術家保養所に受け入れられ、そこで処女作『見知らぬ乗客』の執筆に取り組ん だ[13][14]。 |

Personal life Highsmith endured cycles of depression, some of them deep, throughout her life. Despite literary success, she wrote in her diary of January 1970: "[I] am now cynical, fairly rich ... lonely, depressed, and totally pessimistic."[15] Over the years, Highsmith had female hormone deficiency (Hypoestrogenism), anorexia nervosa,[16] chronic anemia, Buerger's disease, and lung cancer.[17] To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envies, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace. – Patricia Highsmith, "My New Year's Toast", journal entry, 1947[18] According to her biographer, Andrew Wilson, Highsmith's personal life was a "troubled one". She was an alcoholic who, allegedly, never had an intimate relationship that lasted for more than a few years, and she was seen by some of her contemporaries and acquaintances as misanthropic and hostile.[19] Her chronic alcoholism intensified as she grew older.[20][21] She famously preferred the company of animals to that of people and stated in a 1991 interview, "I choose to live alone because my imagination functions better when I don't have to speak with people."[22] Otto Penzler, her U.S. publisher through his Penzler Books imprint,[23] had met Highsmith in 1983, and four years later witnessed some of her theatrics intended to create havoc at dinner tables and shipwreck an evening.[24] He said after her death that "[Highsmith] was a mean, cruel, hard, unlovable, unloving human being ... I could never penetrate how any human being could be that relentlessly ugly. ... But her books? Brilliant."[25] Other friends, publishers, and acquaintances held different views of Highsmith. Editor Gary Fisketjon, who published her later novels through Knopf, said that "She was very rough, very difficult ... But she was also plainspoken, dryly funny, and great fun to be around."[25] Composer David Diamond met Highsmith in 1943 and described her as being "quite a depressed person—and I think people explain her by pulling out traits like cold and reserved, when in fact it all came from depression."[26] J. G. Ballard said of Highsmith, "The author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley was every bit as deviant and quirky as her mischievous heroes, and didn't seem to mind if everyone knew it."[27] Screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, who adapted The Price of Salt into the 2015 film Carol, met Highsmith in 1987 and the two remained friends for the rest of Highsmith's life.[28] Nagy said that Highsmith was "very sweet" and "encouraging" to her as a young writer, as well as "wonderfully funny."[29][30] She was considered by some as "a lesbian with a misogynist streak."[31] Highsmith loved cats, and she bred about three hundred snails in her garden at home in Suffolk, England.[32] Highsmith once attended a London cocktail party with a "gigantic handbag" that "contained a head of lettuce and a hundred snails" which she said were her "companions for the evening."[32] She loved woodworking tools and made several pieces of furniture. Highsmith worked without stopping. In later life, she became stooped, with an osteoporotic hump.[7] Though the 22 novels and 8 books of short stories she wrote were highly acclaimed, especially outside of the United States, Highsmith preferred her personal life to remain private.[33] A lifelong diarist, Highsmith left behind eight thousand pages of handwritten notebooks and diaries.[34]  345 E. 57th Street, NYC – Residence of Patricia Highsmith Sexuality As an adult, Patricia Highsmith's sexual relationships were predominantly with women.[35][36] She occasionally engaged in sex with men without physical desire for them, and wrote in her diary: "The male face doesn't attract me, isn't beautiful to me."[37][a] She told writer Marijane Meaker in the late 1950s that she had "tried to like men. I like most men better than I like women, but not in bed."[38] In a 1970 letter to her stepfather Stanley, Highsmith described sexual encounters with men as "steel wool in the face, a sensation of being raped in the wrong place—leading to a sensation of having to have, pretty soon, a boewl [sic] movement," stressing, "If these words are unpleasant to read, I can assure you it is a little more unpleasant in bed."[35] Phyllis Nagy described Highsmith as "a lesbian who did not very much enjoy being around other women" and the few sexual dalliances she had had with men occurred just to "see if she could be into men in that way because she so much more preferred their company."[28] In 1943, Highsmith had an affair with artist Allela Cornell who, despondent over unrequited love from another woman, died by suicide in 1946 by drinking nitric acid.[13] During her stay at Yaddo, Highsmith met writer Marc Brandel, son of author J. D. Beresford.[35] Even though she told him about her homosexuality,[35] they soon entered into a short-lived relationship.[39] He convinced her to visit him in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he introduced her to Ann Smith, a painter and designer with a previous métier as a Vogue fashion model, and the two became involved.[35] After Smith left Provincetown, Highsmith felt she was "in prison" with Brandel and told him she was leaving. "[B]ecause of that I have to sleep with him, and only the fact that it is the last night strengthens me to bear it." Highsmith, who had never been sexually exclusive with Brandel, resented having sex with him.[40] Highsmith temporarily broke off the relationship with Brandel and continued to be involved with several women, reuniting with him after the well-received publication of his new novel. Beginning November 30, 1948, and continuing for the next six months, Highsmith underwent psychoanalysis in an effort "to regularize herself sexually" so she could marry Brandel. The analysis was brought to a stop by Highsmith, after which she ended her relationship with him.[40] After ending her engagement to Marc Brandel, she had an affair with psychoanalyst Kathryn Hamill Cohen, the wife of British publisher Dennis Cohen and founder of Cresset Press, which later published Strangers on a Train.[41][42] To help pay for the twice-a-week therapy sessions, Highsmith had taken a sales job during Christmas rush season in the toy section of Bloomingdale's department store.[40] Ironically, it was during this attempt to "cure" her homosexuality that Highsmith was inspired to write her semi-autobiographical novel The Price of Salt, in which two women meet in a department store and begin a passionate affair.[43][44][b] Believing that Brandel's disclosure that she was homosexual, along with the publication of The Price of Salt, would hurt her professionally, Highsmith had an unsuccessful affair with Arthur Koestler in 1950, designed to hide her homosexuality.[49][50] In early September 1951, she began an affair with sociologist Ellen Blumenthal Hill, traveling back and forth to Europe to meet with her.[7] When Highsmith and Hill came to New York in early May 1953, their affair ostensibly "in a fragile state", Highsmith began an "impossible" affair with the homosexual German photographer Rolf Tietgens, who had played a "sporadic, intense, and unconsummated role in her emotional life since 1943."[7] She was reportedly attracted to Tietgens on account of his homosexuality, confiding that she felt with him "as if he is another girl, or a singularly innocent man." Tietgens shot several nude photographs of Highsmith, but only one has survived, torn in half at the waist so that only her upper body is visible.[51][7] She dedicated The Two Faces of January (1964) to Tietgens. Between 1959 and 1961, Highsmith was in love with author Marijane Meaker.[52][53] Meaker wrote lesbian stories under the pseudonym "Ann Aldrich" and mystery/suspense fiction as "Vin Packer", and later wrote young adult fiction as "M. E. Kerr."[53] In the late 1980s, after 27 years of separation, Highsmith began corresponding with Meaker again, and one day showed up on Meaker's doorstep, slightly drunk and ranting bitterly. Meaker later said she was horrified at how Highsmith's personality had changed.[c] Highsmith was attracted to women of privilege who expected their lovers to treat them with veneration.[54] According to Phyllis Nagy, she belonged to a "very particular subset of lesbians" and described her conduct with many women she was interested in as being comparable to a movie "studio boss" who chased starlets. Many of these women, who to some extent belonged to the Carol Aird-type[d] and her social set, remained friendly with Highsmith and confirmed the stories of seduction.[28] An intensely private person, Highsmith was remarkably open and outspoken about her sexuality.[33][35] She told Meaker: "the only difference between us and heterosexuals is what we do in bed."[55] |

私生活 ハイスミスは生涯を通じてうつ病を繰り返し、その中には深いものもあった。文学的な成功にもかかわらず、彼女は1970年1月の日記にこう書いている: 「私は今、皮肉屋で、かなり裕福で......孤独で、憂鬱で、すっかり悲観的になっている」[15]。長年にわたり、ハイスミスは女性ホルモン欠乏症 (低エストロゲン症)、神経性食欲不振症[16]、慢性貧血、バージャー病、肺がんを患っていた[17]。 すべての悪魔、欲望、情熱、貪欲、嫉妬、愛、憎しみ、奇妙な欲望、幽霊のような敵、現実の敵、記憶の軍団、私が戦う相手、それらが決して私に安らぎを与え てくれませんように。 - パトリシア・ハイスミス、「私の新年の乾杯」、1947年の日記[18]。 彼女の伝記作家であるアンドリュー・ウィルソンによれば、ハイスミスの私生活は「問題の多いもの」だった。彼女はアルコール依存症で、数年以上続く親密な 関係を持ったことがなかったとされ、同時代の友人や知人からは人間嫌いで敵対的な人物と見られていた[19]。 彼女は人間よりも動物との付き合いを好んだことで有名で、1991年のインタビューでは「人と話さなくていいほうが想像力が働くから、私はひとりで生きる ことを選ぶの」と答えている[22]。 彼女の米国での出版社であるペンズラー・ブックスのオットー・ペンズラーは、1983年にハイスミスと出会い[23]、その4年後に、夕食のテーブルを大 混乱に陥れ、夜を難破させることを意図した彼女の芝居を目撃した[24]。あんなに容赦なく醜い人間がいるのか、私には理解できなかった。しかし彼女の本 は 素晴らしい」[25]。 他の友人、出版社、知人はハイスミスについて異なる見方をしていた。ノップフ社から彼女の後期の小説を出版した編集者のゲーリー・フィスケジョンは、「彼 女はとても荒々しく、とても気難しかった......。しかし、彼女はまた率直で、辛口で面白く、一緒にいてとても楽しかった」と述べている[25]。作 曲家のデイヴィッド・ダイアモンドは1943年にハイスミスに会い、彼女のことを「かなり鬱屈した人間で、人々は冷淡で控えめといった特徴を引っ張り出し て彼女を説明すると思うが、実際はすべて鬱屈からきている」と評した[26]。塩の代償』を2015年の映画『キャロル』に脚色した脚本家のフィリス・ナ ギーは、1987年にハイスミスと出会い、2人はハイスミスの生涯を通じて友人であり続けた[28] 。 彼女は「女性差別主義者の傾向を持つレズビアン」と見なされていた[31]。 ハイスミスは猫を愛し、イギリスのサフォークにある自宅の庭で約300匹のカタツムリを飼育していた[32]。ハイスミスは「巨大なハンドバッグ」を持っ てロンドンのカクテルパーティに出席したことがあるが、その中には「レタスの頭と100匹のカタツムリが入っていた」。 彼女は木工道具が大好きで、家具をいくつか作った。ハイスミスは休むことなく働き続けた。後年、彼女は猫背になり、骨粗鬆症のようなこぶを持つようになっ た[7]。彼女が書いた22冊の小説と8冊の短編集は、特にアメリカ国外では高く評価されたが、ハイスミスは私生活はプライベートのままであることを好ん だ[33]。 生涯日記を書き続けたハイスミスは、8000ページにも及ぶ手書きのノートと日記を残した[34]。  ニューヨーク市57丁目345番地-パトリシア・ハイスミス邸 セクシュアリティ 大人になってからのパトリシア・ハイスミスの性的関係は、主に女性とのものであった[35][36]。 肉体的な欲求がなくても、男性とセックスをすることもあり、日記にこう書いている: 「男性の顔には惹かれないし、美しくもない」[37][a] 彼女は1950年代後半に作家のマリジャン・ミーカーに「男性を好きになろうとした。1970年、継父のスタンリーに宛てた手紙の中で、ハイスミスは男性 との性的な出会いを「顔に鋼鉄の羊毛を当てられ、間違った場所でレイプされたような感覚に陥り、やがてブーヴル(中略)運動をしなければならないような感 覚に至る」と表現し、「これらの言葉が読むのに不快であるなら、ベッドの上ではもう少し不快であると断言できる」と強調した。 「フィリス・ナギーはハイスミスを「他の女性と一緒にいることをあまり喜ばないレズビアン」と評し、彼女が男性と交わした数少ない性的戯れは、「男性との 付き合いの方が好きなので、そのような形で男性に夢中になれるかどうか確かめる」ためだけに起こったと述べている[28]。 1943年、ハイスミスは画家のアレラ・コーネルと関係を持ったが、彼は他の女性からの片思いに落胆し、1946年に硝酸を飲んで自殺した[13]。 ヤドに滞在中、ハイスミスは作家J.D.ベレスフォードの息子で作家のマーク・ブランデルと出会った[35]。 [39]彼は彼女を説得してマサチューセッツ州プロヴィンスタウンに彼を訪ねさせ、そこでヴォーグ誌のファッションモデルとして活躍していた画家でデザイ ナーのアン・スミスを紹介し、2人は交際するようになった[35]。スミスがプロヴィンスタウンを去った後、ハイスミスはブランデルと「牢獄の中」にいる と感じ、彼に別れを告げた。「そのため、私は彼と寝なければならず、それが最後の夜だという事実だけが、それに耐える私を強くしてくれた」。ハイスミスは ブランデルとの関係を一時的に断ち切り、何人かの女性と関係を続けた。1948年11月30日からその後6ヶ月間、ハイスミスはブランデルと結婚するため に「自分を性的に正統化する」ために精神分析を受けた。分析はハイスミスによって中止され、その後彼女は彼との関係を終わらせた[40]。 マーク・ブランデルとの婚約を解消した後、彼女はイギリスの出版社デニス・コーエンの妻で、後に『見知らぬ乗客』を出版するクレセット出版社の創設者であ る精神分析家キャサリン・ハミル・コーエンと関係を持った[41][42]。 皮肉なことに、ハイスミスはこの同性愛を「治療」しようとする試みの中で、デパートで出会った二人の女性が情熱的な情事を始めるという半自伝的小説『塩の 値段』を書くことになった[43][44][b]。 ブランデルが同性愛者であることを公表したことは、『塩の値段』の出版とともに、彼女の仕事上のダメージになると考えたハイスミスは、1950年にアー サー・ケストラーと不倫関係を築き、同性愛者であることを隠すように画策したが失敗した[49][50]。 1951年9月初旬、彼女は社会学者エレン・ブルメンタール・ヒルと不倫関係を始め、彼女と会うためにヨーロッパを往復した[7]。1953年5月初旬に ハイスミスとヒルがニューヨークに来たとき、二人の関係は表向き「もろい状態」であったが、ハイスミスは同性愛者のドイツ人写真家ロルフ・ティートゲンス との「ありえない」不倫関係を始めた。 「彼女はティートゲンスが同性愛者であることに惹かれ、「まるで彼がもう一人の少女であるかのように、あるいは特異な純真な男性であるかのように 」感じたと告白している[7]。ティートゲンズはハイスミスのヌード写真を何枚か撮影したが、現存しているのは1枚だけで、上半身だけが見えるように腰の 部分で半分に破られている[51][7]。彼女は『1月の二つの顔』(1964年)をティートゲンズに捧げた。 1959年から1961年にかけて、ハイスミスは作家のマリジェーン・ミーカーと恋仲だった[52][53]。ミーカーは「アン・アルドリッチ」というペ ンネームでレズビアン小説を、「ヴィン・パッカー」というペンネームでミステリー/サスペンス小説を書き、後に「M・E・カー」としてヤングアダルト小説 を書いていた[53]。1980年代後半、27年の別離の後、ハイスミスは再びミーカーと文通を始め、ある日、少し酔ってミーカーの家の前に現れ、辛辣に わめき散らした。ミーカーは後に、ハイスミスの性格の変わりようにぞっとしたと語っている[c]。 フィリス・ナギーによれば、彼女は「レズビアンの非常に特殊なサブセット」に属しており、興味を持った多くの女性たちとの行為を、スター女優を追いかける 映画の「撮影所のボス」に匹敵すると表現した[54]。キャロル・エアードタイプ[d]と彼女の社会的セットにある程度属していたこれらの女性の多くは、 ハイスミスと友好的であり続け、誘惑の話を確認した[28]。 激しく私的な人間であったハイスミスは、自分のセクシュアリティについては驚くほどオープンで率直であった[33][35]: 「私たちと異性愛者の唯一の違いは、ベッドで何をするかということです」[55]。 |

| Death Highsmith died on February 4, 1995, at 74, from a combination of aplastic anemia and lung cancer at Carita Hospital in Locarno, Switzerland, near the village where she had lived since 1982. She was cremated at the cemetery in Bellinzona; a memorial service was conducted in the Chiesa di Tegna in Tegna, Ticino, Switzerland; and her ashes were interred in its columbarium.[56][57][58][59] She left her estate, worth an estimated $3 million, and the promise of any future royalties, to the Yaddo colony, where she spent two months in 1948 writing the draft of Strangers on a Train.[35][e] Highsmith bequeathed her literary estate to the Swiss Literary Archives at the Swiss National Library in Bern, Switzerland.[61] Her Swiss publisher, Diogenes Verlag, was appointed literary executor of the estate.[62] |

死去 ハイスミスは1995年2月4日、再生不良性貧血と肺がんを併発し、1982年から住んでいた村に近いスイス・ロカルノのカリタ病院で74歳で死去した。 彼女はベリンツォーナの墓地で火葬され、追悼式はスイスのティチーノ州テーニャにあるテーニャ教会で執り行われ、遺灰はその墓地に埋葬された[56] [57][58][59]。 彼女は推定300万ドル相当の遺産と将来の印税の約束をヤド・コロニー(Yaddo colony) に遺し、1948年に2ヶ月間『見知らぬ乗客』の草稿を執筆した[35][e]。ハイスミスは彼女の文学的遺産をスイスのベルンにあるスイス国立図書館の スイス文学史料館に遺贈した[61]。彼女のスイスの出版社であるディオゲネス出版が遺産の文学的遺言執行者に任命された[62]。 |

| Political views Highsmith described herself as a social democrat.[57] She believed in American democratic ideals and in "the promise" of U.S. history, but was also highly critical of the reality of the country's 20th-century culture and foreign policy.[citation needed] Beginning in 1963, she resided exclusively in Europe.[7] She retained her United States citizenship, despite the tax penalties, of which she complained bitterly while living for many years in France and Switzerland.[citation needed] Highsmith was a resolute atheist.[63] Although she considered herself a liberal, and in her school years had gotten along with black students,[64] in later years she believed that black people were responsible for the welfare crisis in America.[65]: 19 She disliked Koreans because "they ate dogs".[57] Highsmith supported Palestinian self-determination.[65] As a member of Amnesty International, she felt duty-bound to express publicly her opposition to the displacement of Palestinians.[65]: 429 Highsmith prohibited her books from being published in Israel after the election of Menachem Begin as prime minister in 1977.[65]: 431 She dedicated her 1983 novel People Who Knock on the Door to the Palestinian people: To the courage of the Palestinian people and their leaders in the struggle to regain a part of their homeland. This book has nothing to do with their problem. The inscription was dropped from the U.S. edition with permission from her agent but without consent from Highsmith.[65]: 418 Highsmith contributed financially to the Jewish Committee on the Middle East, an organization that represented American Jews who supported Palestinian self-determination.[65]: 430 She wrote in an August 1993 letter to Marijane Meaker: "USA could save 11 million per day if they would cut the dough to Israel. The Jewish vote is 1%."[66] Although Highsmith was an active supporter of Palestinian rights, according to Carol screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, her expression of this "often teetered into outright antisemitism."[67] Highsmith was an avowed antisemite; she described herself as a "Jew hater" and described The Holocaust as "the semicaust".[68] When she was living in Switzerland in the 1980s, she used nearly 40 aliases when writing to government bodies and newspapers deploring the state of Israel and the "influence" of the Jews.[69] |

政治的見解 ハイスミスは自らを社会民主主義者と称した[57]。彼女はアメリカの民主主義の理想と、アメリカの歴史の「約束」を信じていたが、同時にこの国の20世 紀の文化と外交政策の現実を強く批判していた。 ハイスミスは断固とした無神論者であった[63]。彼女は自分自身をリベラルだと考えており、学生時代には黒人の学生たちと仲良くしていたが[64]、後 年にはアメリカの福祉危機の責任は黒人にあると考えていた[65]: 19 韓国人が嫌いな理由は「犬を食べるから」であった[57]。 ハイスミスはパレスチナ人の自決を支持していた[65]。 アムネスティ・インターナショナルのメンバーとして、パレスチナ人の強制移住に反対することを公に表明する義務があると感じていた[65]: 429 1977年にメナケム・ベギンが首相に選出された後、ハイスミスはイスラエルで自分の本を出版することを禁じた[65]: 431 彼女は1983年の小説『扉をたたく人々』をパレスチナの人々に捧げた: 祖国の一部を取り戻すための闘いにおけるパレスチナの人々とその指導者たちの勇気に捧げる。この本は彼らの問題とは何の関係もない。 この碑文は彼女のエージェントの許可を得て、ハイスミスの同意なしにアメリカ版から削除された[65]: 418 ハイスミスはパレスチナの自決を支持するアメリカのユダヤ人を代表する組織である中東ユダヤ人委員会に資金援助をしていた[65]: 430 彼女は1993年8月、Marijane Meakerに宛てた手紙にこう書いている: 「アメリカはイスラエルへの援助を減らせば、1日あたり1,100万ドルを節約できる。ユダヤ人票は1%だ」[66]。 ハイスミスはパレスチナの権利を積極的に支持していたが、『キャロル』の脚本家フィリス・ナギーによれば、彼女の表現は「しばしば明白な反ユダヤ主義に傾 いた」[67]。ハイスミスは反ユダヤ主義者であることを公言しており、自らを「ユダヤ人嫌い」と表現し、ホロコーストを「セミカスト」と表現していた [68]。 1980年代にスイスに住んでいたとき、イスラエル国家とユダヤ人の「影響力」を非難する手紙を政府機関や新聞に出す際には、40近い偽名を使った [69]。 |

| Writing history Comic books After graduating from Barnard College, before her short stories started appearing in print, Highsmith wrote for comic book publishers from 1942 and 1948, while she lived in New York City and Mexico. Answering an ad for "reporter/rewrite", she landed a job working for comic book publisher Ned Pines in a "bullpen" with four artists and three other writers. Initially scripting two comic-book stories a day for $55-a-week paychecks, Highsmith soon realized she could make more money by freelance writing for comics, a situation which enabled her to find time to work on her own short stories and live for a period in Mexico. The comic book scriptwriter job was the only long-term job Highsmith ever held.[7] From 1942 to 1943, for the Sangor–Pines shop (Better/Cinema/Pines/Standard/Nedor), Highsmith wrote "Sergeant Bill King" stories, contributed to Black Terror and Fighting Yank comics, and wrote profiles such as Catherine the Great, Barney Ross, and Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker for the "Real Life Comics" series. From 1943 to 1946, under editor Vincent Fago at Timely Comics, she contributed to its U.S.A. Comics wartime series, writing scenarios for comics such as Jap Buster Johnson and The Destroyer. During these same years she wrote for Fawcett Publications, scripting for Fawcett Comics characters "Crisco and Jasper" and others.[70] Highsmith also wrote for True Comics, Captain Midnight, and Western Comics.[71] When Highsmith wrote the psychological thriller novel The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), one of the title character's first victims is a comic-book artist named Reddington: "Tom had a hunch about Reddington. He was a comic-book artist. He probably didn't know whether he was coming or going."[72] Early novels and short stories Highsmith's first novel, Strangers on a Train, proved modestly successful upon publication in 1950, and Alfred Hitchcock's 1951 film adaptation of the novel enhanced her reputation. How was it possible to be afraid and in love, Therese thought. The two things did not go together. How was it possible to be afraid, when the two of them grew stronger together every day? And every night. Every night was different, and every morning. Together they possessed a miracle. –The Price of Salt, chapter eighteen (Coward-McCann, 1952) Highsmith's second novel, The Price of Salt, was published in 1952 under the pen name Claire Morgan.[73] Highsmith mined her personal life for the novel's content.[46] Its groundbreaking happy ending[5][f] and departure from stereotypical conceptions about lesbians made it stand out in lesbian fiction.[74] In what BBC 2's The Late Show presenter Sarah Dunant described as a "literary coming out" after 38 years of disaffirmation,[75] Highsmith finally acknowledged authorship of the novel publicly when she agreed to the 1990 publication by Bloomsbury retitled Carol. Highsmith wrote in the "Afterword" to the new edition: If I were to write a novel about a lesbian relationship, would I then be labelled a lesbian-book writer? That was a possibility, even though I might never be inspired to write another such book in my life. So I decided to offer the book under another name. The appeal of The Price of Salt was that it had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together. Prior to this book, homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing – alone and miserable and shunned – into a depression equal to hell.[76] The paperback version of the novel sold nearly one million copies before its 1990 reissue as Carol.[77] The Price of Salt is distinct for also being the only one of Highsmith's novels in which no violent crime takes place,[48] and where her characters have "more explicit sexual existences" and are allowed "to find happiness in their relationship."[2] Her short stories appeared for the first time in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in the early 1950s. Her last novel, Small g: a Summer Idyll, was rejected by Knopf (her usual publisher by then) several months before her death,[78] leaving Highsmith without an American publisher.[62] It was published posthumously in the United Kingdom by Bloomsbury Publishing in March 1995,[79] and nine years later in the United States by W. W. Norton.[80] The "Ripliad" In 1955, Highsmith wrote The Talented Mr. Ripley, a novel about Tom Ripley, a charming criminal who murders a rich man and steals his identity. Highsmith wrote four sequels: Ripley Under Ground (1970), Ripley's Game (1974), The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980) and Ripley Under Water (1991), about Ripley's exploits as a con artist and serial killer who always gets away with his crimes. The series—collectively called "The Ripliad"—are some of Highsmith's most popular works. The "suave, agreeable and utterly amoral" Ripley is Highsmith's most famous character, and has been critically acclaimed for being "both a likable character and a cold-blooded killer."[81] He has typically been regarded as "cultivated", a "dapper sociopath", and an "agreeable and urbane psychopath."[82] Sam Jordison of The Guardian wrote, "It is near impossible, I would say, not to root for Tom Ripley. Not to like him. Not, on some level, to want him to win. Patricia Highsmith does a fine job of ensuring he wheedles his way into our sympathies."[83] Film critic Roger Ebert made a similar appraisal of the character in his review of Purple Noon, René Clément's 1960 film adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley: "Ripley is a criminal of intelligence and cunning who gets away with murder. He's charming and literate, and a monster. It's insidious, the way Highsmith seduces us into identifying with him and sharing his selfishness; Ripley believes that getting his own way is worth whatever price anyone else might have to pay. We all have a little of that in us."[84] Novelist Sarah Waters esteemed The Talented Mr. Ripley as the "one book I wish I'd written."[85] According to biographer Joan Schenkar, Highsmith only once gave a direct response to a question about the definition of a murderer. On the British late-night television discussion programme After Dark she said: "Frankly...I'd call them sick if they were murderers, mentally sick".[86] The first three books of the "Ripley" series have been adapted into films five times. In 2015, The Hollywood Reporter announced that a group of production companies were planning a television series based on the novels.[87][88] Ripley ultimately premiered on Netflix in 2024.[89][90] Honors 1979 : Grand Master, Swedish Crime Writers' Academy 1987 : Prix littéraire Lucien Barrière [fr], Festival du Cinéma Américain de Deauville[91] 1989 : Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, French Ministry of Culture 1993 : Best Foreign Literary Award, Finnish Crime Society[92] 2008 : Greatest Crime Writer, The Times[93] Awards and nominations 1946 : O. Henry Award, Best First Story, for The Heroine (in Harper's Bazaar) 1951 : Nominee, Edgar Allan Poe Award, Best First Novel, Mystery Writers of America, for Strangers on a Train[94] 1956 : Edgar Allan Poe Scroll (special award), Mystery Writers of America, for The Talented Mr. Ripley 1957 : Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, International, for The Talented Mr. Ripley 1963 : Nominee, Edgar Allan Poe Award, Best Short Story, Mystery Writers of America, for The Terrapin (in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine) 1963 : Special Award, Mystery Writers of America, for The Terrapin 1964 : Silver Dagger Award, Best Foreign Novel, Crime Writers' Association, for The Two Faces of January (pub. Heinemann)[95] 1975 : Prix de l'Humour noir Xavier Forneret [fr] for L'Amateur d'escargots (pub. Calmann-Lévy) (English title: Eleven) |

執筆の歴史 コミックブック バーナード・カレッジを卒業後、彼女の短編小説が活字になる前の1942年から1948年にかけて、ハイスミスはニューヨークとメキシコに住みながらコ ミック出版社で執筆活動を行った。レポーター/リライト」の広告に答えた彼女は、コミック出版社ネッド・パインズの「ブルペン」で、4人のアーティストと 3人のライターとともに働くことになった。当初は週給55ドルで1日2本のコミックの脚本を書いていたが、すぐにフリーランスでコミックの脚本を書けば もっと稼げることに気づいた。コミックの脚本家としての仕事は、ハイスミスがこれまでに経験した唯一の長期的な仕事であった[7]。 1942 年から 1943 年にかけて、サンゴー・パインズ社(Better/Cinema/Pines/Standard/Nedor)のために、ハイスミスは「ビル・キング軍 曹」の物語を書き、「ブラック・テラー(Black Terror)」と「ファイティング・ヤンク(Fighting Yank)」のコミックに寄稿し、「リアル・ライフ・コミック(Real Life Comics)」シリーズのために、キャサリン大帝、バーニー・ロス(Barney Ross)、エディ・リッケンバッカー少佐などのプロフィールを書いた。1943年から1946年まで、タイムリー・コミックスの編集者ヴィンセント・ ファゴのもとで、戦時中のU.S.A.コミックス・シリーズに貢献し、『ジャップ・バスター・ジョンソン』や『ザ・デストロイヤー』などのコミックスにシ ナリオを書いた。ハイスミスはまた、トゥルー・コミックス(True Comics)、キャプテン・ミッドナイト(Captain Midnight)、ウェスタン・コミックス(Western Comics)にも執筆していた[71]。 ハイスミスが心理スリラー小説『The Talented Mr. Ripley』(1955年)を書いたとき、タイトル・キャラクターの最初の犠牲者のひとりはレディントンという名のコミック・ブック・アーティストだっ た: 「トムはレディントンについて直感した。彼は漫画家だった。トムはレディントンについて直感した。彼は漫画家だった。 初期の小説と短編 ハイスミスの処女作『見知らぬ乗客』は1950年の出版と同時にそこそこの成功を収め、1951年にはアルフレッド・ヒッチコックがこの小説を映画化し、 彼女の名声を高めた。 恐怖を感じながら恋に落ちるなんてあり得るのだろうか、とテレーズは思った。この2つは両立しない。二人は日に日に絆を深めていったのに、どうして恐れる ことができたのだろう?そして毎晩だった。毎夜、毎朝、違っていた。ふたりは奇跡を起こしたのだ。 -塩の値段』第18章(カワード・マッカン、1952年) ハイスミスの2作目の小説である『塩の代償』は、1952年にクレア・モーガンというペンネームで出版された[73]。 [ハイスミスは1990年にブルームズベリー社から『キャロル』と改題して出版されることに同意した際、BBC 2の司会者サラ・デュナントが38年ぶりに「文学的カミングアウト」と表現したように[75]、この小説の著者であることをついに公に認めた。ハイスミス は新版の「あとがき」にこう書いている: もし私がレズビアンの関係についての小説を書いたら、レズビアン本の作家というレッテルを貼られるだろうか?もし私がレズビアンの関係について小説を書い たら、レズビアン本の作家というレッテルを貼られるだろうか?そこで私は、この本を別の名前で提供することにした。 塩の代償』の魅力は、二人の主人公がハッピーエンドを迎えること、少なくとも二人が将来を共にしようとすることだった。本書以前は、アメリカの小説に登場 する男女の同性愛者は、手首を切ったり、プールで溺れたり、異性愛に転向したり(そう書かれていた)、あるいは孤独で惨めで敬遠され、地獄に等しい憂鬱に 陥ることによって、逸脱の代償を払わなければならなかった[76]。 この小説のペーパーバック版は、1990年に『キャロル』として復刊されるまでに100万部近く売れた[77]。『塩の代償』は、ハイスミスの小説の中で 唯一暴力犯罪が起こらず[48]、登場人物が「より露骨な性的存在」を持ち、「二人の関係に幸福を見出す」ことが許されているという点でも特徴的である [2]。 彼女の短編小説は1950年代初頭にエラリー・クイーンズ・ミステリ・マガジンに初めて掲載された。 遺作となった『Small g: a Summer Idyll』は死の数カ月前にクノップフ社(それまで彼女がいつも使っていた出版社)に拒絶され[78]、ハイスミスはアメリカの出版社を失った [62]。 リプリアス 1955年、ハイスミスは富豪を殺害し、その身元を盗み出す魅力的な犯罪者トム・リプリーを描いた小説『The Talented Mr. ハイスミスは4つの続編を書いた: Ripley Under Ground』(1970年)、『Ripley's Game』(1974年)、『The Boy Who Followed Ripley』(1980年)、『Ripley Under Water』(1991年)である。リプリアッド」と総称されるこのシリーズは、ハイスミスの代表作のひとつである。 上品で好感が持て、まったく道徳的でない」リプリーはハイスミスの最も有名なキャラクターであり、「好感の持てるキャラクターであると同時に冷血な殺人 鬼」[81]であるとして批評家から高く評価されている。彼は一般的に「教養があり」、「洒落た社会病質者」、「好感の持てる都会的な精神病質者」とみな されている[82]。 ガーディアン』紙のサム・ジョーディソンは、「トム・リプリーを応援しないのは不可能に近い。彼を好きにならないことはない。あるレベルでは、彼に勝って ほしいと思わないこともない。パトリシア・ハイスミスは、彼がわれわれの同情心を確実にかき立てる見事な仕事をしている」[83]。映画評論家のロ ジャー・エバートも、ルネ・クレマンが1960年に映画化した『パープル・ヌーン』(原題:The Talented Mr. 彼は魅力的で識字率が高く、怪物だ。リプリーは、自分の道を切り開くことで、他の誰かがどんな代償を払わなくてはならないとしても、その価値があると信じ ている。リプリーは、自分の思い通りになることが、他の誰かがどんな代償を払うことになろうとも、その価値があると信じている。私たちは皆、少しはそうい うところがある」[84]。小説家のサラ・ウォーターズは、『才能あるミスター・リプリー』を「私が書きたかった一冊」として高く評価している[85]。 伝記作家のジョーン・シェンカーによれば、ハイスミスは一度だけ、殺人者の定義についての質問に直接答えたことがある。イギリスの深夜テレビ討論番組『ア フター・ダーク』で彼女はこう言った: 「率直に言って......もし彼らが殺人者であれば、私は彼らを病人、精神病者と呼ぶでしょう」[86]。 リプリー」シリーズの最初の3冊は5回映画化されている。2015年、The Hollywood Reporterは、制作会社グループが小説を基にしたテレビシリーズを計画していると発表した[87][88]。 リプリーは最終的に2024年にNetflixで初放送された[89][90]。 名誉 1979 : グランドマスター、スウェーデン犯罪作家アカデミー 1987 : Prix littéraire Lucien Barrière [fr], Festival du Cinéma Américain de Deauville[91]. 1989 : フランス文化省より芸術文化勲章シュヴァリエを授与される。 1993 : 最優秀外国文学賞、フィンランド犯罪協会[92]. 2008 : 最も偉大な犯罪作家、タイムズ紙[93]。 受賞とノミネート 1946 : 『ヒロイン』(ハーパーズ・バザー誌)でO・ヘンリー賞最優秀処女作賞 1951年:『見知らぬ乗客』でエドガー・アラン・ポー賞、最優秀処女作、アメリカ推理作家賞ノミネート[94]。 1956 : エドガー・アラン・ポー賞(特別賞)、アメリカ推理作家協会、『才能あるリプリー氏』で受賞。 1957 : 才能あるリプリー』で国際文学ポリティシエール賞グランプリ受賞 1963 : 『テラピン』(エラリー・クイーンズ・ミステリ・マガジン)でエドガー・アラン・ポー賞、最優秀短編賞、アメリカ推理作家賞ノミネート 1963 : 「テラピン」でアメリカ推理作家協会特別賞受賞 1964年:『1月の二つの顔』(ハイネマン社)で、犯罪作家協会、シルバー・ダガー賞、最優秀外国小説賞[95]。 1975年:『エスカルゴの素人』(カルマン=レヴィ社)でグザヴィエ・フォルネレ賞(フランス)を受賞。 |

| Bibliography Main article: Patricia Highsmith bibliography Novels Strangers on a Train (1950) The Price of Salt (1952) (as Claire Morgan) (republished as Carol in 1990 under Highsmith's name) The Blunderer (1954) Deep Water (1957) A Game for the Living (1958) This Sweet Sickness (1960) The Cry of the Owl (1962) The Two Faces of January (1964) The Glass Cell (1964) A Suspension of Mercy (1965) (published as The Story-Teller in the U.S.) Those Who Walk Away (1967) The Tremor of Forgery (1969) A Dog's Ransom (1972) Edith's Diary (1977) People Who Knock on the Door (1983) Found in the Street (1986) Small g: a Summer Idyll (1995) The "Ripliad" The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) Ripley Under Ground (1970) Ripley's Game (1974) The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980) Ripley Under Water (1991) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_Highsmith |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆