What is

Cultural Voyeurism?

出歯亀学

What is

Cultural Voyeurism?

解説:池田光穂

いささか不遜で

危険な(そして100%事実な)言い方であるが、文化人類学者ロバート・フランシ

ス・マーフィー(Robert

F. Murphy, 1924-1990)The Body Silent(1980)の著者は、文化人類学者

を、人間社会の「出歯亀=でばがめ(voyeur)」とまで定義しています。でばがめ(=窃視者, voyeur)するとは、相手の文

化(=異文化)に対する強烈な関心があり、また、それが妄想的な

思い込みであっても相手との関与——関係性の構築——を試みようとする企てにほかなりません。文化人類学は、人間社会の文化構築性を明らかにすると同時に、フィールドにおいて、対象社会の関係をなんらかの形で構築することであります。民族

誌(エスノグラフィー)は、人類学者と対象社会との関係性に関する再帰的な記録

であると言えましょう。

いささか不遜で

危険な(そして100%事実な)言い方であるが、文化人類学者ロバート・フランシ

ス・マーフィー(Robert

F. Murphy, 1924-1990)The Body Silent(1980)の著者は、文化人類学者

を、人間社会の「出歯亀=でばがめ(voyeur)」とまで定義しています。でばがめ(=窃視者, voyeur)するとは、相手の文

化(=異文化)に対する強烈な関心があり、また、それが妄想的な

思い込みであっても相手との関与——関係性の構築——を試みようとする企てにほかなりません。文化人類学は、人間社会の文化構築性を明らかにすると同時に、フィールドにおいて、対象社会の関係をなんらかの形で構築することであります。民族

誌(エスノグラフィー)は、人類学者と対象社会との関係性に関する再帰的な記録

であると言えましょう。

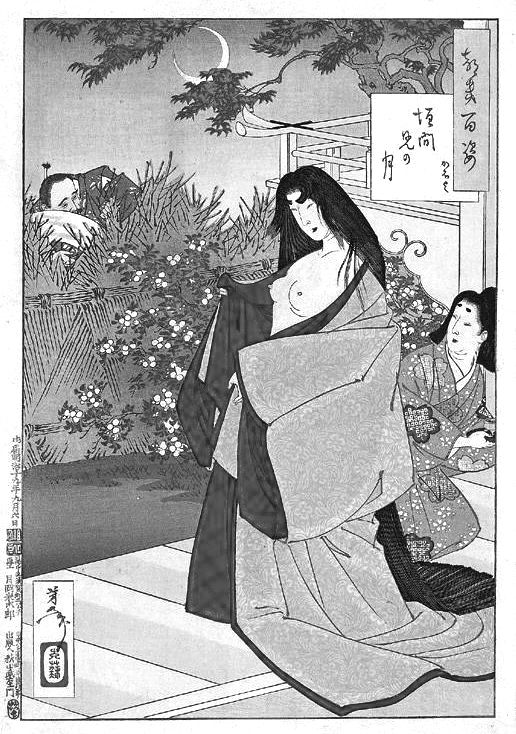

元祖出歯亀(a voyeur)創作の中の塩冶高貞(えんや・たかさだ)※左奥。覗かれているのは妻顔世御前(出典:月岡芳 年『月百姿』(19世紀末)37「垣間見の月 かほよ」。『仮名手本忠臣蔵』 で高貞(浅野長矩)の夫人とされた顔世御前の裸婦像。奥には高師直(吉良義 央)の姿)

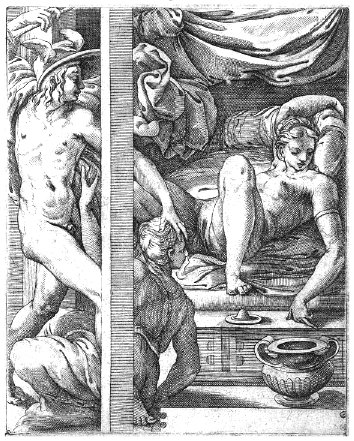

Voyeurism is the sexual interest in or practice of watching other people engaged in intimate behaviors, such as undressing, sexual activity, or other actions of a private nature.The term comes from the French voir which means "to see". A male voyeur is commonly labelled as "Peeping Tom" or a "Jags", a term which originates from the Lady Godiva legend. However, that term is usually applied to a male who observes somebody secretly and, generally, not in a public space.- "Mercury and Herse", scene from The Loves of the Gods by Gian Giacomo Caraglio, showing Mercury, Herse, and Aglaulos.

覗き見あるいは盗視症(Voyeurism)とは、他人が服を脱いだり、性行為をしたり、その他プライベートな行為をしているのを見ることに性的関心を持つこと、また はそれを実践することである。この言葉は、「見る」という意味のフランス語voirから来ている。男性の覗き魔は、一般に「Peeping Tom」または「Jags」と呼ばれ、この用語はレディ・ゴディバ伝説に由来するものである。しかし、この言葉は通常、誰かを密かに観察する男性に適用さ れ、一般的に公共の空間では適用されない。 - 「マーキュリーとヘルセ」、ジャン・ジャコモ・カラグリオ作『神々の恋』の一場面で、マーキュリー、ヘルセ、アグラウロスが登場する。

| The American

Psychiatric Association has classified certain voyeuristic fantasies,

urges and behaviour patterns as a paraphilia in the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) if the person has acted on these urges, or

the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal

difficulty.[3] It is described as a disorder of sexual preference in

the ICD-10.[4] The DSM-IV defines voyeurism as the act of looking at

"unsuspecting individuals, usually strangers, who are naked, in the

process of disrobing, or engaging in sexual activity".[5] The diagnosis

would not be given to people who experience typical sexual arousal

simply by seeing nudity or sexual activity. In order to be diagnosed

with voyeuristic disorder the symptoms must persist for over six months

and the person in question must be over the age of 18.[6] |

アメリカ精神医学会は、診断統計マニュアル(DSM-IV)において、

ある種の盗撮的な空想、衝動、行動パターンを、これらの衝動を行動に移した場合、あるいは性的衝動や空想が著しい苦痛や対人的困難を引き起こす場合に、パ

ラフィリアとして分類している[3]。 ICD-10の中では、性的選好の障害として記述される。 [4]

DSM-IVでは、覗き見を「裸、脱衣の過程、または性的活動に従事している無防備な個人、通常は他人」を見る行為と定義している[5]。

裸や性的活動を見るだけで典型的な性的興奮を経験する人にはこの診断は下されないだろう。盗撮障害と診断されるためには、症状が6ヶ月以上継続し、該当者

が18歳以上であることが必要である[6]。 |

| Historical perspectives There is relatively little academic research regarding voyeurism. When a review was published in 1976 there were only 15 available resources.[7] Voyeurs were well-paying hole-lookers in especially Parisian brothels, a commercial innovation described as far back as 1857 but not gaining much notoriety until the 1880s, and not attracting formal medical-forensic recognition until the early 1890s.[8] Society has accepted the use of the term voyeur as a description of anyone who views the intimate lives of others, even outside of a sexual context.[9] This term is specifically used regarding reality television and other media which allow people to view the personal lives of others. This is a reversal from the historical perspective, moving from a term which describes a specific population in detail, to one which describes the general population vaguely. One of the few historical theories on the causes of voyeurism comes from psychoanalytic theory. Psychoanalytic theory proposes that voyeurism results from a failure to accept castration anxiety and as a result of failure to identify with the father.[5] |

歴史的な視点 盗撮に関する学術的な研究は比較的少ない。7] 覗き魔は特にパリの売春宿で高給取りの覗き魔であり、1857年までさかのぼるが、1880年代まであまり有名にならず、1890年代初頭まで医学・法医 学的に正式に認識されなかった商業的革新であった[8]。 [8] 社会は、性的な文脈以外でも他人の親密な生活を見る人の説明として、覗き見という用語の使用を受け入れている[9] この用語は、人々が他人の私生活を見ることができるリアリティテレビと他のメディアに関して特に使用されている。これは歴史的な観点からの逆転であり、特 定の集団を詳細に記述する用語から、一般集団を漠然と記述する用語へと移行している。 盗撮の原因に関する数少ない歴史的学説は、精神分析理論に由来するものである。精神分析理論は、盗撮が去勢不安を受け入れられず、父親との同一化に失敗した結果として生じることを提唱している[5]。 |

| Prevalence Voyeurism has high prevalence rates in most studied populations. Voyeurism was initially believed to only be present in a small portion of the population. This perception changed when Alfred Kinsey discovered that 30% of men prefer coitus with the lights on.[5] This behaviour is not considered voyeurism by today's diagnostic standards, but there was little differentiation between normal and pathological behaviour at the time. Subsequent research showed that 65% of men had engaged in peeping, which suggests that this behaviour is widely spread throughout the population.[5] Congruent with this, research found voyeurism to be the most common sexual law-breaking behaviour in both clinical and general populations. [10] An earlier study, based on 60 college men from a rural area, indicates that 54% had voyeuristic fantasies, and that 42% had tried voyeurism, concluding that young men are more easily aroused by the idea.[11] In a national study of Sweden it was found that 7.7% of the population (16% of men and 4% of women) had engaged in voyeurism at some point.[12] It is also believed that voyeurism occurs up to 150 times more frequently than police reports indicate.[12] This same study also indicates that there are high levels of co-occurrence between voyeurism and exhibitionism, finding that 63% of voyeurs also report exhibitionist behaviour.[12] |

有病率 盗撮は、ほとんどの研究対象集団において高い有病率を示している。盗撮は当初、人口のごく一部にしか存在しないと信じられていた。この認識は、アルフレッ ド・キンゼイが30%の男性が明かりをつけたままの性交を好むことを発見したときに変わった[5]。この行動は、今日の診断基準では盗撮とはみなされない が、当時は正常な行動と病的な行動の区別はほとんどなかった。その後の研究では、男性の65%が覗きに従事したことがあることが示され、この行動が人口に 広く普及していることが示唆された[5]。 これと一致して、研究では、臨床および一般集団の両方で盗撮が最も共通の性的法律違反の行動であることが判明した[10]。[10] 地方都市の60人の大学生男性を対象とした以前の研究では、54%が盗撮の妄想を持っており、42%が盗撮を試したことがあることを示しており、若い男性 はその考えに興奮しやすいと結論づけている[11]。 スウェーデンの全国調査では、人口の7.7%(男性の16%、女性の4%)がある時点で盗撮に従事したことがあることがわかった[12]。 また、盗撮は警察の報告より最大150倍も頻繁に起こると考えられている[12]。 この同じ調査は、盗撮と展示主義の間に高いレベルの共起があることも示し、盗撮者の63%が展示主義的行動も報告していることが判明した[12]。 |

| Characteristics People engage in voyeuristic behaviours for diverse reasons, but statistics can indicate which groups are likelier to engage in the act. Early research indicated that voyeurs were more mentally healthy than other groups with paraphilias.[7] Compared to the other groups studied, it was found that voyeurs were unlikely to be alcoholics or drug users. More recent research shows that, compared to the general population, voyeurs were moderately more likely to have psychological problems, use alcohol and drugs, and have higher sexual interest generally.[12] This study also shows that voyeurs have a greater number of sexual partners per year, and are more likely to have had a same-sex partner than most of the populations.[12] Both older and newer research found that voyeurs typically have a later age of first sexual intercourse.[7][12] However, other research found no difference in sexual history between voyeurs and non-voyeurs.[11] Voyeurs who are not also exhibitionists tend to be from a higher socioeconomic status than those who do show exhibitionist behaviour.[12] |

特徴 人はさまざまな理由で盗撮行為に及ぶが、統計によってどのような集団がその行為に及ぶ可能性が高いかを示すことができる。 初期の研究では、盗撮者は他のパラフィリア群と比較して精神的に健康であることが示された[7]。また、研究対象となった他の群と比較して、盗撮者はアル コール中毒者や薬物使用者である可能性が低いことが判明した。より最近の研究では、一般集団と比較して、ボイラーは心理的問題を抱え、アルコールや薬物を 使用し、一般的に高い性的関心を持つ傾向が中程度に高いことが示されている[12]。この研究はまた、ボイラーはほとんどの集団よりも年間の性的パート ナーの数が多く、同性パートナーを持ったことがある傾向があることを示す[12]。 [12] 古い研究と新しい研究の両方が、ボイラーは一般的に最初の性交の年齢が遅いことを発見した[7][12]。 しかし、他の研究は、ボイラーと非ボイラーの間の性的履歴の違いを発見しなかった[11] ボイラーはまた露出狂ではない人は、露出狂行動を示す人よりも社会経済状態が高い傾向があります[12]。 |

| Gender differences Research shows that, like almost all paraphilias, voyeurism is more common in men than in women.[12] However, research has found that men and women both report roughly the same likelihood that they would hypothetically engage in voyeurism.[13] There appears to be a greater gender difference when actually presented with the opportunity to perform voyeurism. There is very little research done on voyeurism in women, so very little is known on the subject. One of the few studies deals with a case study of a woman who also had schizoid personality disorder, which limits the degree to which it can generalize to normal populations.[14] A 2021 study found that 36.4% of men and 63.8% of women were strongly repulsed by the idea of voyeurism. Men were more likely to be mildly or moderately aroused than women, but there was little gender difference among those who reported strong arousal. Men reported slightly higher willingness to commit voyeurism but, when risk is introduced, willingness diminishes in both sexes proportionally to the risk involved. Individual differences in sociosexuality and sexual compulsivity were found to contribute to the sex differences in voyeurism.[15] |

性差 ほぼすべてのパラフィリアと同様に、盗撮は女性よりも男性に多いという研究結果がある[12]。 しかし、研究によると、男性も女性も仮想的に盗撮を行う可能性はほぼ同じであると報告している。 13] 実際に盗撮を行う機会が与えられた場合には、より大きな性差があるようだ。女性の盗撮について行われた研究は非常に少ないので、このテーマについてはほと んど知られていません。数少ない研究の1つは、統合失調症性人格障害を併発した女性の事例を扱ったものであり、通常の集団に一般化できる度合いには限界が ある[14]。 2021年の研究では、男性の36.4%、女性の63.8%が盗撮というものに強く反発していることがわかった。男性は女性よりも軽度または中等度の興奮 を覚える傾向があったが、強い興奮を覚えたと報告した人々の間では性差はほとんどなかった。男性は盗撮行為に対する意欲がやや高いが、リスクが生じると、 男女ともその意欲はリスクに比例して減退する。社会性・性的強迫性における個人差が盗撮の性差に寄与していることが明らかになった[15]。 |

| Current perspectives Lovemap theory suggests that voyeurism exists because looking at naked others shifts from an ancillary sexual behaviour, to a primary sexual act.[13] This results in a displacement of sexual desire making the act of watching someone the primary means of sexual satisfaction. Voyeurism has also been linked with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). When treated by the same approach as OCD, voyeuristic behaviours significantly decrease.[16] |

現在の視点 ラブマップ理論では、他人の裸を見ることが付随的な性行動から主要な性行為に移行するために盗撮が存在することを示唆する[13]。この結果、性欲が変位し、誰かを見るという行為が性的満足の主要な手段となる。 また、覗き見は強迫性障害(OCD)とも関連がある。強迫性障害と同じアプローチで治療すると、覗き見の行動は有意に減少する[16]。 |

| Treatment Professional treatment Historically voyeurism has been treated in a variety of ways. Psychoanalytic, group psychotherapy and shock aversion approaches have all been attempted with limited success.[7] There is some evidence which shows that pornography can be used as a form of treatment for voyeurism. This is based on the idea that countries with pornography censorship have high amounts of voyeurism.[17] Additionally shifting voyeurs from voyeuristic behaviour, to looking at graphic pornography, to looking at the nudes in Playboy has been successfully used as a treatment.[18] These studies show that pornography can be used as a means of satisfying voyeuristic desires without breaking the law. Voyeurism has also been successfully treated with a mix of anti-psychotics and antidepressants. However the patient in this case study had a multitude of other mental health problems. Intense pharmaceutical treatment may not be required for most voyeurs.[19] There has also been success in treating voyeurism through using treatment methods for obsessive compulsive disorder. There have been multiple instances of successful treatment of voyeurism through putting patients on fluoxetine and treating their voyeuristic behaviour as a compulsion.[9][16] |

治療法 専門家による治療 歴史的に盗撮は、さまざまな方法で治療されてきた。精神分析、集団心理療法、ショック回避のアプローチはすべて試みられたが、その成功は限られたもので あった。これは、ポルノ検閲のある国は盗撮の量が多いという考えに基づいている[17]。さらに、盗撮者を盗撮行動から、グラフィックポルノを見ること、 プレイボーイのヌードを見ることにシフトすることが治療として成功した[18]。これらの研究は、ポルノが法律を破ることなく盗撮欲求を満たす手段として 使用することができることを示している[18]。 また、盗撮症は、抗精神病薬と抗うつ薬の混合薬による治療にも成功している。しかし、この事例の患者は、他の多くの精神衛生上の問題を抱えていた。ほとんどの盗撮犯にとって、強力な薬物治療は必要ないかもしれません[19]。 強迫性障害の治療法を用いて盗撮を治療することに成功した例もある。患者にフルオキセチンを投与し、強制として彼らの盗撮行動を治療することによって盗撮の治療に成功した複数の事例がある[9][16]。 |

| Techniques The increased miniaturisation of hidden cameras and recording devices since the 1950s has enabled those so minded to surreptitiously photograph or record others without their knowledge and consent. The vast majority of mobile phones, for example, are readily available to be used for their camera and recording ability. |

技術編 1950年代以降、隠しカメラや録画機器の小型化が進み、他人の知らないところでこっそり撮影・録画することができるようになりました。例えば、携帯電話の大半は、カメラや録音機能を備えており、簡単に利用することができる。 |

| Criminology Non-consensual voyeurism is considered to be a form of sexual abuse.[20] [21][irrelevant citation] [22][irrelevant citation] When the interest in a particular subject is obsessive, the behaviour may be described as stalking. The United States FBI assert that some individuals who engage in "nuisance" offences (such as voyeurism) may also have a propensity for violence based on behaviours of serious sex offenders.[23] An FBI researcher has suggested that voyeurs are likely to demonstrate some characteristics that are common, but not universal, among serious sexual offenders who invest considerable time and effort in the capturing of a victim (or image of a victim); careful, methodical planning devoted to the selection and preparation of equipment; and often meticulous attention to detail.[24] Little to no research has been done into the demographics of voyeurs. |

犯罪学 合意のない盗撮は性的虐待の一形態と考えられている[20] [21][関係ない引用] [22][関係ない引用] 特定の対象への関心が強迫的である場合、その行動はストーキングと表現される場合がある。 アメリカ合衆国のFBIは、(盗撮などの)「迷惑な」犯罪に従事する一部の個人は、深刻な性犯罪者の行動に基づく暴力傾向も持っているかもしれないと主張 している[23]。 FBIの研究者は、盗撮者は被害者(または被害者の画像)を捕らえるためにかなりの時間と労力を注ぎ、機器の選択と準備に慎重で計画的に専念し、しばしば 細部に細心の注意を払って、普遍ではないが、深刻な性犯罪者に共通するいくつかの特性を示すと思われると示唆している[24]。 覗き魔の人口統計学的な調査はほとんど行われていない。 |

| Legal status Voyeurism is not a crime at common law. In common law countries it is only a crime if made so by legislation. In Canada, for example, voyeurism was not a crime when the case Frey v. Fedoruk et al. arose in 1947. In that case, in 1950, the Supreme Court of Canada held that courts could not criminalise voyeurism by classifying it as a breach of the peace and that Parliament would have to specifically outlaw it. On November 1, 2005, this was done when section 162 was added to the Canadian Criminal Code, declaring voyeurism to be a sexual offence when it violates a reasonable expectation of privacy.[25] In the case of R v Jarvis, the Supreme Court of Canada held that for the purposes of that law, the expectation of privacy is not all-or-nothing; rather there are degrees of privacy, and although secondary-school pupils in the school building cannot reasonably expect as much privacy as in the bedroom, nonetheless they can expect enough privacy so that photographing them without their consent for the purpose of sexual gratification is forbidden.[26] In some countries voyeurism is considered to be a sex crime. In the United Kingdom, for example, non-consensual voyeurism became a criminal offence on May 1, 2004.[27] In the English case of R v Turner (2006),[28] the manager of a sports centre filmed four women taking showers. There was no indication that the footage had been shown to anyone else or distributed in any way. The defendant pleaded guilty. The Court of Appeal confirmed a sentence of nine months' imprisonment to reflect the seriousness of the abuse of trust and the traumatic effect on the victims. In another English case in 2009, R v Wilkins (2010),[29][30] a man who filmed his intercourse with five of his lovers for his own private viewing was sentenced to eight months in prison and ordered to sign onto the Sex Offender Register for ten years. In 2013, 40-year-old Mark Lancaster was found guilty of voyeurism and jailed for 16 months, after he tricked an 18-year-old student into traveling to a rented flat in Milton Keynes, where he filmed her with four secret cameras dressing up as a schoolgirl and posing for photographs before he had sex with her.[31] In a more recent English case in 2020, the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction of Tony Richards after Richards sought "to have two voyeurism charges under section 67 of the Sexual Offences Act dismissed on the grounds that he had committed no crime".[32][33] Richards "secretly videoed himself having sex with two women who had consented to sex in return for money but had not agreed to being captured on camera".[34] In an unusual step, the court allowed Emily Hunt, a person not involved in the case, to intervene on behalf of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). Hunt had an ongoing judicial review against the CPS since the CPS had argued that Hunt's alleged attacker had not violated the law when he "took a video lasting over one minute of her naked and unconscious" in a hotel room on the basis that there should be no expectation of privacy in the bedroom. However, in terms of what is considered a private act for the purposes of voyeurism, the CPS was arguing the opposite in the Richards appeal.[33][34] The Court of Appeal clarified that consenting to sex in a private place does not amount to consent to be filmed without that person's knowledge. Anyone who films or photographs another person naked, without their permission, is breaking the law under sections 67 and 68 of the Sexual Offences Act.[32][35] In the United States, video voyeurism is an offense in twelve states[36] and may require the convicted person to register as a sex offender.[37][failed verification] The original case that led to the criminalisation of voyeurism has been made into a television movie called Video Voyeur and documents the criminalisation of secret photography. Criminal voyeurism statutes are related to invasion of privacy laws[38] but are specific to unlawful surreptitious surveillance without consent and unlawful recordings including the broadcast, dissemination, publication, or selling of recordings involving places and times when a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy and a reasonable supposition they are not being photographed or filmed by "any mechanical, digital or electronic viewing device, camera or any other instrument capable of recording, storing or transmitting visual images that can be utilised to observe a person."[39] Saudi Arabia banned the sale of camera phones nationwide in April 2004, but reversed the ban in December 2004. Some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, require all camera phones sold in their country to make a clearly audible sound whenever a picture is being taken. In 2013, the Indian Parliament made amendments to the Indian Penal Code, introducing voyeurism as a criminal offence.[40] A man committing the offence of voyeurism would be liable for imprisonment not less than one year and which may extend up to three years for the first offence, and shall also be liable to fine and for any subsequent conviction would be liable for imprisonment for not less than three years and which may extend up to seven years and with fine. Voyeurism is generally deemed illegal in Singapore. It sentences technologically-enabled voyeurs to a maximum punishment of one year's jail and a fine under the context of insulting a woman's modesty.[41] Recent cases in 2016 include the sentencing of church facility manager Kenneth Yeo Jia Chuan who filmed women in toilets by planting pinhole cameras in a handicapped toilet at the Church of Singapore at Bukit Timah, and in the unisex toilet of the church's office at Bukit Timah Shopping Centre.[42][43] Secret photography by law enforcement authorities is called surveillance and is not considered to be voyeurism, though it may be unlawful or regulated in some countries. |

法的地位 盗撮はコモンローでは犯罪ではありません。コモンローの国々では、法律で定められた場合のみ犯罪となります。 例えば、カナダでは、1947年にフレイ対フェドルク裁判が起こったとき、盗撮は犯罪ではありませんでした。この事件では、1950年にカナダ最高裁判所 は、裁判所は盗撮を平和の侵害に分類して犯罪にすることはできず、議会が特に違法化しなければならないと判示しました。2005年11月1日に、セクショ ン162は、それがプライバシーの合理的な期待を侵害したときに性的犯罪であることが盗撮を宣言し、カナダの刑法に追加されたときに、これが行われまし た。 [25] R v Jarvisのケースで、カナダの最高裁判所は、その法律の目的のために、プライバシーの期待はオール・オア・ナッシングではなく、むしろプライバシーの 程度があり、校舎内の中学生の生徒たちは寝室でのプライバシーと同じくらい合理的に期待できないが、それでも彼らは性的満足のために同意なしに彼らを撮影 することが禁じられるように十分なプライバシーを期待できる、と判示した[26]。 いくつかの国では、盗撮は性犯罪であるとみなされている。例えばイギリスでは、2004年5月1日に合意のない盗撮が刑事犯罪となった[27]。 R v Turner(2006)のイギリスのケースでは、スポーツセンターの管理者がシャワーを浴びる4人の女性を撮影していた[28]。映像が他の誰かに見せ られたり、何らかの形で配布された形跡はなかった。被告人は有罪を主張しました。控訴裁判所は、信頼の乱用の深刻さと被害者に対する心的外傷の影響を反映 し、9ヶ月の禁固刑を確定させました。 2009年の別の英国の事例であるR v Wilkins (2010)[29][30]では、5人の恋人との性交を自分のプライベートな視聴のために撮影した男が、8か月の禁固刑と10年間の性犯罪者登録への署 名を命じられた。2013年には、40歳のマーク・ランカスターが、18歳の学生を騙してミルトン・ケインズの賃貸アパートに旅行させ、そこで女子学生の 格好をして写真撮影をするところを4台の秘密カメラで撮影してから彼女とセックスした後、盗撮の罪で有罪となり16ヶ月の懲役を課された[31]。 2020年のより最近のイギリスの事件では、控訴裁判所は、リチャーズが「性犯罪法第67条に基づく2つの盗撮容疑を、犯罪を犯していないという理由で棄 却させる」よう求めた後、トニー・リチャーズの有罪判決を支持した。 [32][33] リチャーズは「金銭と引き換えにセックスすることに同意していたが、カメラで撮影されることに同意していなかった2人の女性とセックスしているところを密 かにビデオ撮影した」[34] 異例のことに、裁判所は事件に関与していないエミリー・ハントに、クラウン検察局(CPS)を代表して介入することを許可しました。ハントは、CPSに対 して現在進行中の司法審査を受けていました。CPSは、ハントの加害者とされる人物がホテルの部屋で「彼女の裸と意識を失った姿を1分以上撮影した」と き、寝室にプライバシーは期待できないとして、法に違反しないと主張していたからです。しかし、盗撮の目的上、何が私的行為とみなされるかについて、 CPSはリチャーズの控訴審で反対のことを主張していた[33][34]。控訴裁判所は、私的な場所でのセックスに同意することは、その人が知らないうち に撮影されることに同意することにはならないことを明確にした。他人の裸をその人の許可なく撮影したり、写真に撮ったりする人は、性犯罪法の67条と68 条の下で法律を破っていることになります[32][35]。 米国では、ビデオの盗撮は12の州で犯罪であり[36]、有罪判決を受けた者は性犯罪者として登録する必要がある場合がある[37][検証失敗] 盗撮の犯罪化につながったオリジナルのケースは、Video Voyeurというテレビ映画になっており、盗撮の犯罪化を文書化したものであった。犯罪的な盗撮法はプライバシーの侵害に関する法律[38]に関連して いますが、人がプライバシーに対する合理的な期待を持ち、「人を観察するために利用することができる視覚画像を記録、保存、送信することができるあらゆる 機械、デジタル、電子視聴装置、カメラ、その他の機器」によって写真や映画撮影されていないと合理的に仮定する場所と時間に関わる記録の放送、普及、出 版、販売を含む同意なしの不法な盗撮に特化しています[39]。 サウジアラビアは2004年4月に全国でカメラ付き携帯電話の販売を禁止したが、2004年12月に禁止を撤回した。韓国や日本など一部の国では、国内で販売されるすべてのカメラ付き携帯電話に対して、写真を撮影する際にはっきりと聞こえる音を出すことを義務付けている。 2013年、インド議会はインド刑法を改正し、盗撮を刑事犯罪として導入した[40]。 盗撮の犯罪を犯した者は、初犯の場合、1年以上3年以下の懲役、また罰金の責任を負い、その後の有罪判決に対しては、3年以上7年以下の懲役、罰金の責任を負わなければならい。 シンガポールでは、盗撮は一般的に違法とされています。女性の慎み深さを侮辱するという文脈で、技術的に可能な盗撮者には最高で1年の懲役と罰金を科す [41]。 2016年の最近の事例では、ブキティマのシンガポール教会の障害者用トイレと、ブキティマのショッピングセンターの教会事務所の男女兼用トイレにピン ホールカメラを仕込んでトイレにいる女性を撮影した教会施設管理者のケネス・ヨウ・ジアチュアンへの判決[42][43]があった。 法執行機関による秘匿撮影は監視と呼ばれ、盗撮とはみなされないが、国によっては違法または規制されている場合がある[42]。 |

| Popular culture Films Voyeurism is a main theme in films such as The Secret Cinema (1968), Peepers (2010), and Sliver (1993), based on a book of the same name by Ira Levin. Voyeurism is a common plot device in both: Serious films, e.g., Rear Window (1954), Klute (1971), Blue Velvet (1986), Disturbia (2007), and X (2022) and Humorous films, e.g., Animal House (1978), Gregory's Girl (1981), Porky's (1981), American Pie (1999), and Semi-Pro (2008) Voyeuristic photography has been a central element of the mis-en-scene of films such as: Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960), and Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup (1966) Pedro Almodovar's Kika (1993) deals with both sexual and media voyeurism. In Malèna, a teenage boy constantly spies on the title character. The television movie Video Voyeur: The Susan Wilson Story (2002) is based on a true story about a woman who was secretly videotaped and subsequently helped to get laws against voyeurism passed in parts of the United States.[44] Voyeurism is a key plot device in the Japanese movie Love Exposure (Ai no Mukidashi). The main character Yu Honda takes upskirt photos to find his 'Maria' to become a man and get his first taste of sexual stimulation. Literature In the light novel series Baka to Test to Shōkanjū, Kōta Tsuchiya is subject to voyeurism, explaining why he is referred to as "Voyeur". Manga The manga Colourful, Nozo×Kimi and Nozoki Ana included elements of voyeurism in their plot. Music "Voyeur", the second track on blink-182's album Dude Ranch, written by Tom DeLonge, features explicit references to the practice of voyeurism. "Sirens", also written by DeLonge, from Angels & Airwaves' album I-Empire is also about voyeurism, albeit in a more subtle way. Photography Merry Alpern with her works, Dirty Windows, 1993–1994.[45] Kohei Yoshiyuki with his works called The Park.[46] |

|

| Courtship disorder Exhibitionism Frey v. Fedoruk et al. Gaze Male gaze Invasion of privacy Peep show Sex show Scopophilia Scopophobia, the fear of being stared at Sexual attraction Upskirt Johns Hopkins Hospital#Controversy - a male gynecologist at JHH took voyeuristic photographs of more than 8,000 patients. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyeurism |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Candaules, King of Lydia, Shews his Wife by Stealth to Gyges, One of his Ministers, as She Goes to Bed by William Etty. This image illustrates Herodotus's version of the tale of Gyges (see: candaulism).

リンク

文献

その他の情報

より詳しい説明は〈こちら〉を読みましょう!

次のページでのおさらいをしましょう!

〈リ ンク〉

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

「大序」 四代目坂東三津五郎の高師直、三代目岩井粂三郎のかほ世御前。嘉永2年(1849

年)7月、江戸中村座。三代目歌川豊国画。