論点先取

Begging the question, Petitio Principi

論点先取

Begging the question, Petitio Principi

論点先取とは議論のやり方において、証明 すべき命題 が、問題を論じる前提のひとつとして使われている(先に「問題を乞う=必要とする」という意味での"Begging the question") という誤った論法のこと。誤った論法を、誤謬(ごびゅう)ないしは誤謬論法ともいう。論点先取の典型例は、循環論法である。例えば、次のような三段論法を 考えてみよ。1)太郎は嘘を言うような奴ではない。2)太郎は何かを話している。3)だから、太郎の話は本当である。これは、3)太郎の話は本当であると 結論づけられる、前提に1)太郎は嘘を言うような奴ではない、が含まれているので、太郎は嘘をついているか/いないか(本当のことであるか/ないか)とい う議論が、このなかでは永遠に問題にされない。なぜならば、1)と3)は同じ意味内容を繰り返したにすぎない。だから、これを循環論法であり、1)は3) にとっての論点先取の前提であると指摘することができる。

コロナ禍での閉鎖された大学の授業をおこなうには「遠隔や対面授業がよ い!/やっぱり対面授業がいいに決まっている!」の大手メディアの主張は世論工作マシンである?!なるほど、コロナ禍で生じた「ネット授 業」の是非の中にもどのような循環論法があるのか考えてみよう。

1)コロナが流行る前からネット授業の有 効性は証明されている。

2)コロナ禍によりネット授業を導入せざ るをえなくなった。

3)だからコロナ禍 でのネット授業は有効である。

このような議論は、次のような前提を議論 の中に包含していない。つまり、「コロナが流行る前」 には、対面授業との補完的な機能としてネット授業が行われてきた。あるいは、遠隔地で授業登録した学生でも参加できるために100%ネットで、「対面授業 と変わらない」クオリティを維持できるようなカリキュラムや評価法が確立していた。そのような準備もなく、インターネットを経由するから、ネット授業が有 効であると主張するのは「一般論」としては、そうだが、個別の「授業の質」を保証することには繋がらない。対面授業でも、さまざまな評価者がお墨付きをつ けるような優秀な授業がある一方で、スーパーバイザーの判断で、次年度の継続が認められなくなる授業もあることを忘れている。ネットでの授業も、確立され たノウハウと、場数という経験が必要である。私の経験だと、数セメスターは同じ内容のものを、さまざまなネット授業のツールやソフトウェアを使ってみて行 うまで、ネット授業の是非を一般論で論じるのは、対面授業の是非を論じるのと同様ナンセンスである。というか、対面授業での授業の方法の改良について、我 が国でもアクティブラーニングなどの導入が声高に言われるようなったのは、この10年から10 数年であろう。

さらに、ネット授業を導入後に、産業界や 初等中等教育の現状に照らして、対面授業への回帰を文部科学大臣がアナウンス(2020年8月4日) し、その折衷案として「ネット授業と対面授業」のハイブッド/ブレンド授業を、各地の感染の状況をまったく議論せずに、さらに疫学や学校教育の専門家の熟 議ぬきに主張することは、上掲のような批判的議論が、文部科学省にすらできていないことの証拠である(→不正論理入門)。

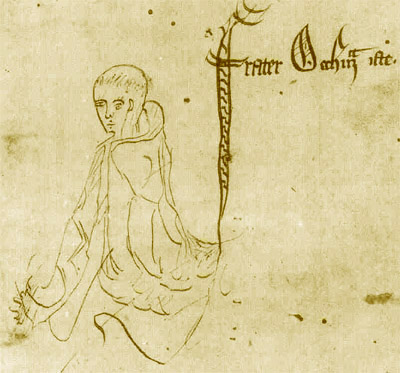

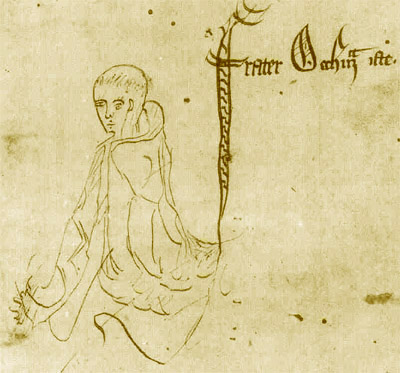

オッカム『大論理学』の論点先取の解説

Book III. On Syllogisms, Chapter 15 deals with begging the question (petitio principii).

| ラテン語 | 英語 |

日本語 |

| CAP. 15. DE FALLACIA PETITIONIS

PRINCIPII. |

||

| Post fallacias penes quas

peccant argumenta peccantia in forma dicendum est de fallaciis penes

quas non peccant argumenta sophistica, sed penes quas peccat opponens

in arguendo contra respondentem. Quarum prima est petitio principii,

quae tunc accidit quando opponens, quamvis inferat conclusionem quam

intendit, tamen non potest convincere respondentem, eo quod accipit

quod deberet probare. |

After the fallacies where the

arguments are erroneous in form, we must speak of fallacies where the

sophistical arguments are not erroneous, but where the opponent is in

error against the respondent. Of which the first is ‘begging the

question’, which happens when the opponent, although he infers the

conclusion which he intends, nevertheless cannot refute the respondent,

because he accepts what ought to be proved. |

論証の形式が誤っている場合の誤謬の次に、詭弁が誤っているのではな

く、相手が回答者に対して誤りを犯している場合の誤謬について述べなければならない。このうち、第一の誤りは「論点先取(begging the

question)」である。これは、相手が自分の意図する結論を推論しているにも

かかわらず、証明されるべきことを受け入れているために、回答者に反論できない場合である。 |

| Et dicitur `petitio principii'

non quia accipit illud idem quod deberet inferre, tunc enim nulla esset

apparentia, sed dicitur opponens petere principium quando accipit aeque

ignotum vel ignotius illo quod deberet inferre. |

And it is called ‘begging the

question’ not because he accepts that same thing which ought to be

inferred, for then nothing would be apparent, but rather the opponent

is said to beg the question when he accepts what is equally unknown, or

more unknown than that which ought to be inferred. |

そして、このようなことが「論点」と呼ばれるのは、彼が推論されるべき

同じものを受け入れているからではなく、それでは何も明らかでなくなるからであるが、むしろ、相手が、推論されるべきものと同等かそれ以上に未知のものを

受け入れるとき、質問をはぐらかすと言われるのだ。 |

| Et propter hoc semper potest

respondens petere probationem assumpti quousque accipiat aliquid notius. |

And because of this the

respondent can always seek a proof of what is assumed until he accepts

something more known. |

このため、回答者は、より既知のものを受け入れるまで、常に想定される

ことの証明を求めることができる。 |

| Fit autem ista fallacia multis

modis. Uno modo fit quando arguitur a nomine synonymo ad synonymum;

sicut sic arguendo `Marcus currit, igitur Tullius currit'. |

This fallacy can happen in many

ways. It happens in one way when it is argued from a synonymous name to

a synonym, for example in arguing ‘Mark runs therefore Tully runs’. |

この誤謬はいろいろな形で起こりうる。例えば、「マークが走るからタ

リーが走る」と主張するように、同義語の名前から同義語へ論証する場合に起こる。 |

| Statim enim accipitur aliquid

aeque ignotum cum conclusione inferenda. |

For immediately there is

accepted something as equally unknown as the conclusion to be inferred. |

なぜなら、推論される結論と同じくらい未知のものが即座に受け入れられ

るからである。 |

| Alius modus est quando arguitur

a definitione exprimente quid nominis ad definitum vel e converso. Et

hoc quia in omni disputatione debent praesupponi significata

vocabulorum. Unde patet quod hic est petitio principii `ignis est

productivus caloris, igitur ignis est calefactivus'. Alius modus est

quando arguitur ab una convertibili propositione ad aliam, quarum

neutra est prior vel notior alia; sicut hic `nullus musicus est

grammaticus, igitur nullus grammaticus est musicus'. Unde universaliter

quando assumitur aeque ignotum vel ignotius ipsi respondenti quam sit

conclusio inferenda, est petitio principii. Sciendum est tamen quod

quamvis respondens non possit convinci per rationem dum accipitur aeque

ignotum vel ignotius, potest tamen convinci per auctoritatem, si velit

auctoritatem recipere. Sicut si respondens nolens negare auctoritatem

aliquam, neget istam `Marcus currit', quamvis opponens sic arguat

`Tullius currit, igitur Marcus currit' non convincet eum; si tamen

ostendit istam `Tullius currit' in auctore quem non vult negare,

convincet eum sufficienter. |

Another way is when it is argued

from a nominal definition to what is defined, or conversely. And this

is because in every disputation the significates of the words

(vocabulorum) ought to be presupposed. Hence it is clear that 'fire is

productive of heat, therefore fire is calefactive' is begging the

question.[1] Another way is when it is argued from one convertible

proposition to another, of which neither is prior or better known than

the other, for example 'no musical thing is skilled in grammar,

therefore nothing skilled in grammar is a musical thing'. Hence

universally when it is assumed what is equally unknown, or more unknown

to that respondent than the conclusion to be inferred, there is begging

of the question. It should be known that although the respondent could

not be refuted by reasoning while he accepts what is equally unknown or

more unknown, yet he may be refuted by authority, if he wishes to

receive the authority. For example, if the respondent, not wishing to

deny some authority, denies 'Mark runs', although the opponent argues

'Tully runs, therefore Mark runs', the opponent does not refute him.

But if if he shows 'Tully runs' in some author which he does not wish

to deny, he refutes him sufficiently. |

もう一つの方法は、名目的な定義から定義されたものへと論じる場合、あ

るいはその逆の場合である。なぜなら、あらゆる論争において、言葉の意味(vocabulorum)は前提されるべきものだからである。したがって、「火

は熱を生産する、したがって火は熱量がある」というのは明らかに論点先取である[1]。もう一つの方法は、例えば「音楽的なものは文法に熟達していない、

したがって文法に熟達しているものは音楽的ではない」というように、どちらも他よりも先行したりよく知られていない、ある変換可能な命題から別の命題へ論

じる場合である。したがって、普遍的に、その回答者にとって推論される結論と同等かそれ以上に未知であるものを仮定する場合、そこには論点先取

(begging of the

question)が存在するのである。回答者が同様に未知のもの、あるいはより未知のものを受け入れている間は、推論によって反論することはできない

が、権威を受けようと思えば、権威によって反論することができる、ということは知っておくべきだろう。例えば、ある権威を否定したくない回答者が「マーク

は走る」を否定した場合、相手が「タリーは走る、だからマークは走る」と主張しても、相手は反論しない。しかし、否定したくない何らかの著者の中で『タ

リーが走る』を示せば、十分に反論することができる。 |

| Et ita est de aliis. |

And so it is in other

[cases]. |

そして、それは他の[ケース]でも同様であう。 |

| http://www.logicmuseum.com/wiki/Authors/Ockham/Summa_Logicae/Book_III-4/Chapter_15 |

[1] i.e. because 'productive of

heat' and 'calefactive' are synonyms |

[1]たとえば、「熱が生み出すもの」と「熱い状態」は同義だからであ

る。 |

リンク

文献

その他

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆