池田光穂

ピエール・ポール・ブローカ

Pierre

Paul Broca, 1824-1880

池田光穂

ピエール・ポール・ブローカ( Pierre Paul Broca、1824年6月28日 – 1880年7月9日)は、フランスの内科医、外科医、解剖学者、人類学者。ジロンド県サント=フォア=ラ=グランド出身。彼に因んで名づけられた前頭葉中 の一領域ブローカ野の研究で最も知られる。ブローカ野は発話能力を司る。失語症を患った患者が大脳皮質左前部の特定の領域に障害を有していたことが彼の研 究により明らかになった。これは脳機能が局在していることの最初の解剖学的証明である。ブローカの研究は形質人類学の発展にも資するところがあり、人体測 定学を発展させた[1]。

| Pierre Paul Broca

(/ˈbroʊkə/,[1][2][3] also UK: /ˈbrɒkə/, US: /ˈbroʊkɑː/,[4] French: [pɔl

bʁɔka]; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist

and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area,

a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is

involved with language. His work revealed that the brains of patients

with aphasia contained lesions in a particular part of the cortex, in

the left frontal region. This was the first anatomical proof of

localization of brain function. Broca's work also contributed to the

development of physical anthropology, advancing the science of

anthropometry.[5] |

ピエール・ポール・ブローカ(/ˈbrokə/,[1][2][3] また、イギリス: /ˈɒkə/, US: /ˈˈ,[4] フランス語: [pɔl bʁ]; 1824年6月28日 - 1880年7月9日)は、フランスの医師、解剖学者、人類学者である。ブロカ野の研究で最もよく知られており、前頭葉の一領域であるブロカ野は彼の名にち なんで命名された。ブロカ野は言語に関与する領域である。彼の研究により、失語症の患者の脳は、左前頭葉の大脳皮質の特定の部分に病変があることが明らか になった。これは、脳機能の局在を解剖学的に証明した最初の例である。また、ブローカの研究は、身体人類学の発展にも寄与し、人体測定の科学を発展させた [5]。 |

| Biography Paul Broca was born on 28 June 1824 in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, Bordeaux, France, the son of Jean Pierre "Benjamin" Broca, a medical practitioner and former surgeon in Napoleon's service, and Annette Thomas, a well-educated daughter of a Calvinist, Reformed Protestant, preacher.[6][7] Huguenot Broca received basic education in the school in his hometown, earning a bachelor's degree at the age of 16. He entered medical school in Paris when he was 17, and graduated at 20, when most of his contemporaries were just beginning as medical students.[8] After graduating, Broca undertook an extensive internship, first with the urologist and dermatologist Philippe Ricord (1800–1889) at the Hôpital du Midi, then in 1844 with the psychiatrist François Leuret (1797–1851) at the Bicêtre Hospital. In 1845, he became an intern with Pierre Nicolas Gerdy (1797–1856), a great anatomist and surgeon. After two years with Gerdy, Broca became his assistant.[8] In 1848, Broca became the Prosector, performing dissections for lectures of anatomy, at the University of Paris Medical School. In 1849, he was awarded a medical doctorate. In 1853, Broca became professor agrégé, and was appointed surgeon of the hospital. He was elected to the chair of external pathology at the Faculty of Medicine in 1867, and one year later professor of clinical surgery. In 1868, he was elected a member of the Académie de medicine, and appointed the Chair of clinical surgery. He served in this capacity until his death. He also worked for the Hôpital St. Antoine, the Pitié, the Hôtel des Clinques, and the Hôpital Necker.[8] As a researcher, Broca joined the Society Anatomique de Paris in 1847. During his first six years in the society, Broca was its most productive contributor.[9] Two months after joining, he was on the society's journal editorial committee. He became its secretary and then vice president by 1851.[10] Soon after its creation in 1848, Broca joined the Société de Biologie.[11] He also joined and in 1865 became the president of the Societe de Chirurgie (Surgery).[12][13] In parallel with his medical career, in 1848, Broca founded a society of free-thinkers, sympathetic to Charles Darwin's theories. He once remarked, "I would rather be a transformed ape than a degenerate son of Adam".[8][14] This brought him into conflict with the church, which regarded him as a subversive, materialist, and a corrupter of the youth. The church's animosity toward him continued throughout his lifetime, resulting in numerous confrontations between Broca and the ecclesiastical authorities.[8] In 1857, feeling pressured by others, and especially his mother, Broca married Adele Augustine Lugol. She came from a Protestant family and was the daughter of a prominent physician Jean Guillaume Auguste Lugol. The Brocas had three children: a daughter Jeanne Francoise Pauline (1858–1935), a son Benjamin Auguste (1859–1924), and a son Élie André (1863–1925). One year later, Broca's mother died and his father, Benjamin, came to Paris to live with the family until his death in 1877.[15] In 1858, Paul Broca was elected as member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.[16] In 1859, he founded the Society of Anthropology of Paris. In 1872, he founded the journal Revue d'anthropologie, and in 1876, the Institute of Anthropology. The French Church opposed the development of anthropology, and in 1876 organized a campaign to stop the teaching of the subject in the Anthropological Institute.[5][8] In 1872, Broca was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[17] Near the end of his life, Paul Broca was elected a senator for life, a permanent position in the French senate. He was also a member of the Académie française and held honorary degrees from many learned institutions, both in France and abroad.[8] He died of a brain hemorrhage on 9 July 1880, at the age of 56.[5] During his life he was an atheist and identified as a Liberal.[18] His wife died in 1914 when she was 79. Like their father, Auguste and Andre went on to study medicine. Auguste Broca became a professor of pediatric surgery, now known for his contribution to the Broca-Perthes-Blankart operation, while André became a professor of medical optics and is known for developing the Pellin-Broca prism.[8] |

略歴 1824年6月28日、フランス、ボルドーのサント・フォワ・ラ・グランに、ナポレオンに仕えた外科医ジャン・ピエール・"ベンジャミン"・ブロカと、カ ルヴァン派、改革派プロテスタントの牧師の娘で教養あるアネット・トマスの息子として生まれる[6][7]。ユグノー教徒のブロカは故郷の学校で基礎教育 を受け、16歳で学士号を取得した。17歳でパリの医学部に入学し、20歳で卒業したが、これは同時代のほとんどの者が医学生になりたての頃であった [8]。 卒業後、ミディ病院の泌尿器科医・皮膚科医フィリップ・リコール(1800-1889)のもとで研修し、1844年にはビセートル病院の精神科医フランソ ワ・ルレ(1797-1851)のもとで研修を受けた。1845年には、解剖学者で外科医のピエール・ニコラ・ジェルディ(1797-1856)のもとで 研修医として働くことになった。1848年、ブロカはパリ大学医学部で解剖学の講義のために解剖を行うプロッセクターとなった[8]。1849年、医学博 士号を授与される。1853年、特任教授となり、病院の外科医に任命された。1867年には医学部の外部病理学講座に、1年後には臨床外科の教授に選出さ れた。1868年、医学アカデミー会員に選出され、臨床外科の教授に就任した。死ぬまでこの職を務めた。また、サン・アントワーヌ病院、ピティエ病院、オ テル・デ・クリンクス、ネッケル病院でも働いた[8]。 研究者として、ブロカは1847年にパリ解剖学協会に入会した。入会から2ヶ月後には学会誌の編集委員となった[9]。1848年の設立後すぐに生物学協 会に参加し[11]、1865年には外科学会に参加し会長となった[12][13]。 医学的なキャリアと並行して、1848年にブロカはチャールズ・ダーウィンの理論に共鳴する自由思想家たちの協会を設立した。彼はかつて「私はアダムの堕 落した息子であるよりも、むしろ変質した猿でありたい」と発言した[8][14]。このため彼は教会と対立し、教会は彼を破壊者、物質主義者、若者の堕落 者と見なした。教会の彼に対する反感は彼の生涯を通じて続き、結果としてブロカと教会当局の間で何度も対立が起こった[8]。 1857年、周囲、特に母親からのプレッシャーを感じていたブロカは、アデーレ・オーギュスティーヌ・ルゴールと結婚した。彼女はプロテスタントの家系 で、著名な医師ジャン・ギヨーム・オーギュスト・ルゴールの娘であった。娘のジャンヌ・フランソワーズ(1858-1935)、息子のベンジャミン・オー ギュスト(1859-1924)、息子のエリー・アンドレ(1863-1925)である。1年後、ブロカの母親が亡くなり、父親のベンジャミンがパリに来 て、1877年に亡くなるまで一家で暮らした[15]。 1858年、ドイツ科学アカデミー・レオポルディナ会員に選出される[16]。1859年、パリ人類学協会を設立する。1872年には雑誌『Revue d'anthropologie』を創刊し、1876年には人類学研究所を設立した[16]。フランス教会は人類学の発展に反対し、1876年に人類学研 究所でこの科目の教育を停止するキャンペーンを組織した[5][8]。 1872年にブロカはアメリカ哲学協会の会員として選出された[17]。 人生の終わりに、ポール・ブローカはフランスの元老院の終身議員に選出された。1880年7月9日、脳出血のため56歳で死去した[5] 。父と同じく、オーギュストとアンドレは医学の勉強をすることになった。オーギュスト・ブロカは小児外科の教授となり、ブロカ・ペルテス・ブランカール手 術の貢献で知られ、アンドレは医用光学の教授となり、ペリン・ブロカプリズムの開発で知られるようになった[8]。 |

| Since the 1600s, the majority of

medical advancements emerged through interaction in independent and

sometimes secret societies.[19] The Society Anatomique de Paris met

every Friday and was chaired by anatomist Jean Cruveilhier, and

interned by "the Father of French neurology" Jean-Martin Charcot; both

of whom were instrumental in the later discovery of multiple

sclerosis.[20] At its meetings, members would make presentations

regarding their scientific findings, which would then be published in

the regular bulletin of the society's activities.[9] Like Cruveilhier and Charcot, Broca made regular Society Anatomique presentations on musculoskeletal disorders.[19] He demonstrated that rickets, a disorder that results in weak or soft bones in children, was caused by an interference with ossification due to disruption of nutrition.[21][22] In their work on osteoarthritis, a form of arthritis, Broca and Amédée Deville,[23] Broca showed that, like nails and teeth, cartilage is a tissue that requires absorption of nutrients from nearby blood vessels, and described in detail, the process that lead to degeneration of cartilage in joints.[24][25][n 1] Broca also made regular presentations on the clubfoot disorder, a birth defect where infants feet where rotated inwards at birth. At the time Broca saw degeneration of muscle tissue as an explanation for this condition,[26] and while the root cause of it is still undetermined, Broca's theory of the muscle degeneration would lead to understanding the pathology of muscular dystrophy.[27] As an anatomist, Broca can be considered as making 250 separate contributions to medical science.[28][n 2] As a surgeon, Broca wrote a detailed review on recently discovered use of chloroform as anesthesia, as well as on his own experiences of using novel pain managing methods during surgery, such as hypnosis and carbon dioxide as a local anesthetics.[29] Broca used hypnosis during surgical removal of an abscess and received mixed results, as the patient felt pain at the beginning which then went away, and she could not remember anything afterwards. Because, of inconsistent results reported by other doctors, Broca did not repeat in using hypnosis as an anesthetic.[n 3] Because of his patient's memory loss, he saw the most potential in using it as a psychological tool.[30][31] In 1856, Broca published On Aneurysms and their Treatment, a detailed, almost a thousand page long review of all accessible records on diagnosis and surgical and non treatment for these weakened blood vessels conditions. This book was one of the first published monograms on a specific subject. Before his later achievements, it was this work, that Broca was known for by other French doctors.[32][33] In 1857, Broca contributed to Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard's work on the nervous system, conducting vivisection experiments, where specific spinal nerves were cut to demonstrate the spinal pathways for sensory and motor systems. As a result of this work. Brown-Séquard became known for demonstrating the principle of decussation, where a vertebrate's neural fibers cross from one lateral side to another, resulting in phenomenon of the right side of that animals brain controlling the left side of the other.[34] As a scientist, Broca also developed theories and made hypotheses that would eventually be disproven. Based on reported findings, for example, he published work in support of viewing syphilis as a virus.[34] When western medicine discovered the qualities of the muscle relaxant curare, used by South American Indian hunters as poison, Broca thought there was strong support for the incorrect idea that, aside from being applied topically, curare could also be diluted and ingested to counter tetanus caused muscle spasms.[35][34] Broca also spent many of his earlier years researching cancer. His wife had a known family history of carcinoma, and it is possible that this piqued his interest in exploring possible hereditary causes of cancer. In his investigations, he accumulated evidence supporting the hereditary nature of some cancers while also discovering that cancer cells can run through the blood.[36] Many scientists were skeptical of Broca's hereditary hypothesis, with most believing that it is merely coincidental. He stated two hypotheses for the cause of cancer, diathesis and infection. He believed that the cause may lie somewhere between the two. He then hypothesized that (1) diathesis produces the first cancer (2) cancer produces infection, and (3) infection produces secondary multiple tumors, cachexia, and death."[37] |

1600年代以降、医学の進歩の大部分は独立した、時には秘密結社での

交流を通して生まれた[19]

パリ解剖学会は毎週金曜日に開かれ、解剖学者のジャン・クルヴェイエが会長を務め、「フランス神経学の父」ジャン=マルタン・シャルコがインターンを務め

た。 その会合で、メンバーは科学的発見に関する発表を行い、それは学会活動の定期刊行物に掲載される[9] 。 ブロカは、クルヴェイエやシャルコーのように、解剖学会で筋骨格系の障害について定期的に発表し、子どもの骨が弱くなったり柔らかくなったりする病気であ るくる病が、栄養障害による骨化の阻害によって引き起こされることを証明した[19][21][22]。 [21][22] ブロカとアメデ・ドゥヴィルは、関節炎の一種である変形性関節症に関する研究で、軟骨が爪や歯と同様に近くの血管からの栄養の吸収を必要とする組織である ことを示し、関節の軟骨が変性する過程を詳細に述べた[24][25][n 1] ブロカは、出生時に幼児が足を内側に回転させている内足症についても定期的に発表を行っている。当時、ブロカはこの症状の説明として筋肉組織の退化を見て おり[26]、その根本原因はまだ解明されていないが、筋肉の退化に関するブロカの理論は筋ジストロフィーの病理の理解につながる[27]。 解剖学者としてのブロカは、医学に対して250の別の貢献をしたと考えることができる[28][n2]。 外科医として、ブロカは最近発見された麻酔としてのクロロホルムの使用に関する詳細なレビューや、催眠や局所麻酔としての二酸化炭素など、手術中に新しい 疼痛管理方法を使用した自身の経験について書いている[29]。 ブロカは膿瘍の除去手術中に催眠を使用したが、患者が最初に痛みを感じ、その後消え、その後何も思い出せないという、さまざまな結果を得た。1856年、 ブロカは「動脈瘤とその治療法」を出版し、これらの弱った血管の状態に対する診断と外科的および非治療に関するすべてのアクセス可能な記録を詳細に、ほぼ 1000ページに渡って検討した。この本は、特定のテーマについて出版された最初のモノグラムの1つである。後の業績以前に、ブロカが他のフランス人医師 から知られていたのはこの作品であった[32][33]。 1857年、ブロカはシャルル=エドゥアール・ブラウン=セカールの神経系に関する研究に貢献し、生体解剖実験を行い、特定の脊髄神経を切断して感覚系と 運動系の脊髄経路を実証した。この研究の結果 ブラウン=セカールは、脊椎動物の神経線維が一方の側面から他方の側面へと交差し、その動物の右側の脳が他方の左側を制御する現象が生じるという、脱共役 の原理を実証したことで知られるようになった[34]。 科学者としてのブローカはまた、理論を展開し、やがて反証されるような仮説を立てた。例えば、報告された知見に基づいて、梅毒をウイルスとみなすことを支 持する研究を発表した[34]。西洋医学が南米のインディアンの狩猟者が毒として使用していた筋弛緩剤クラーレの性質を発見したとき、ブロカはクラーレが 局所的に適用する以外に、破傷風の引き起こす筋肉の痙攣に対抗するために希釈して摂取できるという間違った考えに対する強い支持があると考えた[35] [34]。 ブロカはまた、癌の研究にも若い頃を費やしていた。彼の妻は癌の既知の家族歴を持っており、これは癌の可能な遺伝的原因を探求する彼の興味を刺激したこと が可能である。多くの科学者はブロカの遺伝性仮説に懐疑的であり、単なる偶然に過ぎないという意見が大半であった[36]。彼は、がんの原因として、病因 論と感染論の2つの仮説を述べている。彼は、その2つの間のどこかに原因があるのではないかと考えた。そして、(1)発端が最初のがんを生じさせる(2) がんが感染を生じさせる(3)感染が二次的な多発性腫瘍、悪液質、死を生じさせる、という仮説を立てた[37]。 |

| Anthropology Broca spent much time at his Anthropological Institute studying skulls and bones. It has been argued that he was attempting to use the measurements obtained by these studies as his main criteria for ranking racial groups in order of superiority. In that sense, Broca was a pioneer in the study of physical anthropology a part of which has been called 'scientific racism.' He advanced the science of cranial anthropometry by developing many new types of measuring instruments (craniometers) and numerical indices.[38] He published around 223 papers on general anthropology, physical anthropology, ethnology, and other branches of this field. He founded the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris in 1859, the Revue d'Anthropologie in 1872, and the School of Anthropology in Paris in 1876. Broca first became acquainted with anthropology through the works of Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Antoine Étienne Reynaud Augustin Serres and Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, and by the late 1850s it became his lifetime interest. Broca defined Anthropology as "the study of the human group, considered as whole."[39] Like other scientists, he rejected relying on religious texts, and looked for a scientific explanation of human origins. In 1857, Broca was presented with a hybrid leporid, a result of a cross species reproduction between a rabbit and hare. The crossbreeding was done for commercial rather than scientific reasons, as the resulting hybrids became very popular pets. Specific circumstances had to be set up in order for differently behaving species to reproduce and for their hybrid descendants to be able to reproduce between themselves. To Broca, the fact that different animals are able to intermix and create fertile offspring did not prove that they were of the same species.[40] In 1858, Broca presented these findings on leporids to the Société de Biologie. He believed that the key element of his work was its implication that physical differences between human races could be explained by them being different species with different origins rather than the single moment of creation. While Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species did not come out until the following year, the topic of human origin was already widely discussed in science, but still capable of producing a negative response from the government. Because of that worry, Pierre Rayer the president of the Société, along with other members with which Broca was on good relations, asked Broca to stop further discussion of the topic. Broca agreed, but was adamant for the discussion to continue, so in 1859 he formed the Société d'Anthropologie.[41] |

人

類学 ブロカは人類学研究所で多くの時間をかけて頭蓋骨や骨の研究をしてい た。その結果得られた測定値をもとに、人種的な優劣をつけることを試みていたのだと言われている。その意味で、ブロカは「科学的人種主義」と呼ばれる部分 の自然人類学のパイオニアであった。彼は多くの新しいタイプの測定器(クラニオメーター)や数値指標を開発し、頭蓋人間測定の科学を発展させた[38]。 彼は一般人類学、身体人類学、民族学などこの分野の他の枝について約223の論文を発表している。1859年にはパリ人類学協会を、1872年には人類学 雑誌を、1876年にはパリ人類学大学院を設立した。 ブロカは、イジドール・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレール、アントワーヌ・エ チエンヌ・レイノー・オーギュスタン・セール、ジャン・ルイ・アルマン・ド・カトルファージュ・ド・ブレオの著作を通じて人類学に初めて触れ、1850年 代末には生涯を通じて関心を持つようになった。ブロカは人類学を「全体として捉えた人間集団の研究」と定義した[39]。他の科学者と同様、彼は宗教書に 頼ることを拒否し、人間の起源を科学的に説明することを模索した。 1857年、ブロカはウサギとノウサギの異種間繁殖の結果生まれたハイ ブリッドレポリードを提示された。この交配は、科学的な理由というより、商業的な理由で行われたもので、出来上がった交配種はペットとして大変人気があっ た。異なる行動をする種が繁殖し、その雑種の子孫同士が繁殖するためには、特殊な状況が必要だったのだ。ブロカにとって、異なる動物が混ざり合い、繁殖可 能な子孫を作ることができるという事実は、それらが同じ種であることを証明するものではなかった[40]。 1858年、ブロカはレポリートに関するこれらの知見を生物学会に発表 した。彼は、自分の研究の重要な要素は、人類の人種間の身体的な違いは、創造の瞬間ではなく、異なる起源を持つ異なる種であることによって説明できると示 唆したことであると信じていた。ダーウィンの『種の起源』が世に出たのは翌年であったが、人間の起源に関する話題は、すでに科学の世界で広く語られていた ものの、政府から否定的な反応を引き出すことが可能であった。そのため、ソシエテ会長のピエール・レイヤーは、ブロカと親交のあった他のメンバーととも に、これ以上このテーマを議論しないようブロカに要請した。ブロカはこれに同意したが、議論の継続に固執したため、1859年に人類学協会を設立した [41]。 |

| Racial groups and human species As a proponent of polygenism, Broca rejected the monogenistic approach that all humans have a common ancestor. Instead he viewed human racial groups as coming from different origins. Like most of the proponents on either side, he viewed each racial group as having a place on a 'barbarism' to 'civilization' progression. He saw European colonization of other territories as justified by its being an attempt to civilize the barbaric populations.[n 4] In his 1859 work On the Phenomenon of Hybridity in the Genus Homo, he argued that it was reasonable to view humanity as composed of independent racial groups – such as Australian, Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. He saw each racial group as its own species, connected to a geographic location. All together, these different species were part of the single genus homo.[42] Per the standard of the time, Broca would also refer to the Caucasian racial group as white, and to the Ethiopian racial group as Negro. In his writings, Broca's use of the word race was narrower than how it is used today. Broca considered Celts, Gauls, Greeks, Persians and Arabs to be distinct races that were part of the Caucasian racial group.[43][n 5] Races within each group had specific physical characteristics that distinguished them from other racial groups. Like his work in anatomy, Broca emphasized that his conclusions rested on empirical evidence, rather than a priori reasoning.[44] He thought that the distinct geographic location of each racial group was one of the main problems with the monogenists argument for common ancestry: There was even, no necessity to insist upon the difficulty, or greater geographical impossibility of the dispersion of so many races proceeding from a common origin, nor to remark that before the remote and the almost recent migrations of Europeans, each natural group of human races occupied upon our planet a region characterized by a special fauna; that no American animal was found either in Australia nor in the ancient continent, and where men of a new type were discovered, there were only found animals belonging to species, then to general, and sometimes to zoological orders, without analogues in other regions of the globe.[45] Broca also felt that there was not enough evidence for the theory that appearance of different races could be changed by the qualities of the environments that they lived in. Broca saw the physical characteristic of Jews being the same as those portrayed in the Egyptian paintings from the 2,500 b.c., even though, by 1850 A.D. that population had spread to different locations with vastly different environments. He pointed out that his opponents were unable to provide similar long-term comparisons.[46] |

人種集団と人類種 ブローカは多系統主義を提唱し、人類は共通の祖先を持つという一元論的な考え方を否定した。その代わりに、彼は人類の人種集団は異なる起源から生まれたと 考えた。ブロカは、人類が共通の祖先から生まれたとする一元論を否定し、人類の人種はそれぞれ異なる起源を持つものと考えた。1859年に発表した『ホモ 属における雑種性の現象について』では、人類をオーストラリア人、白人、モンゴル人、マレー人、エチオピア人、アメリカ人といった独立した人種集団から構 成されていると見るのが妥当であると主張した[n 4]。彼は、それぞれの人種グループを、地理的な場所に関連した独自の種としてとらえた。また当時の標準では、ブロカはコーカサス人種を白人と呼び、エチ オピア人種をニグロと呼んでいた[42]。彼の著作において、ブロカの人種という言葉の使用は、今日使用されている方法よりも狭義であった。ブロカはケル ト人、ガリア人、ギリシャ人、ペルシャ人、アラブ人をコーカサス人種集団の一部である個別の人種とみなしていた[43][n 5] 各集団の中の人種は、他の人種集団と区別する特定の物理特性を有していた。解剖学における彼の仕事と同様に、ブロカは彼の結論が先験的推論よりも経験的証 拠に基づいていることを強調していた[44]。 彼は各人種集団の異なる地理的位置が共通祖先を主張する単元主義者の主要な問題の1つであると考えていた。 オーストラリアでも古代大陸でもアメリカの動物は発見されておらず、新しいタイプの人間が発見されたところでは、地球の他の地域では類似していない種に属 する動物、次に一般に属する動物、そして時には動物学的目に属する動物が発見されるだけであった。 [45] ブロカはまた、異なる人種の外見が彼らが住んでいる環境の質によって変化しうるという理論に対して十分な証拠がないと感じていた。ブロカは、ユダヤ人の身 体的特徴は、紀元前2500年のエジプトの絵画に描かれたものと同じであると見ていたが、紀元1850年までにその人口は、環境が大きく異なる様々な場所 に広がっていたのである。彼は、彼の反対者たちが同様の長期的な比較を行うことができないことを指摘した[46]。 |

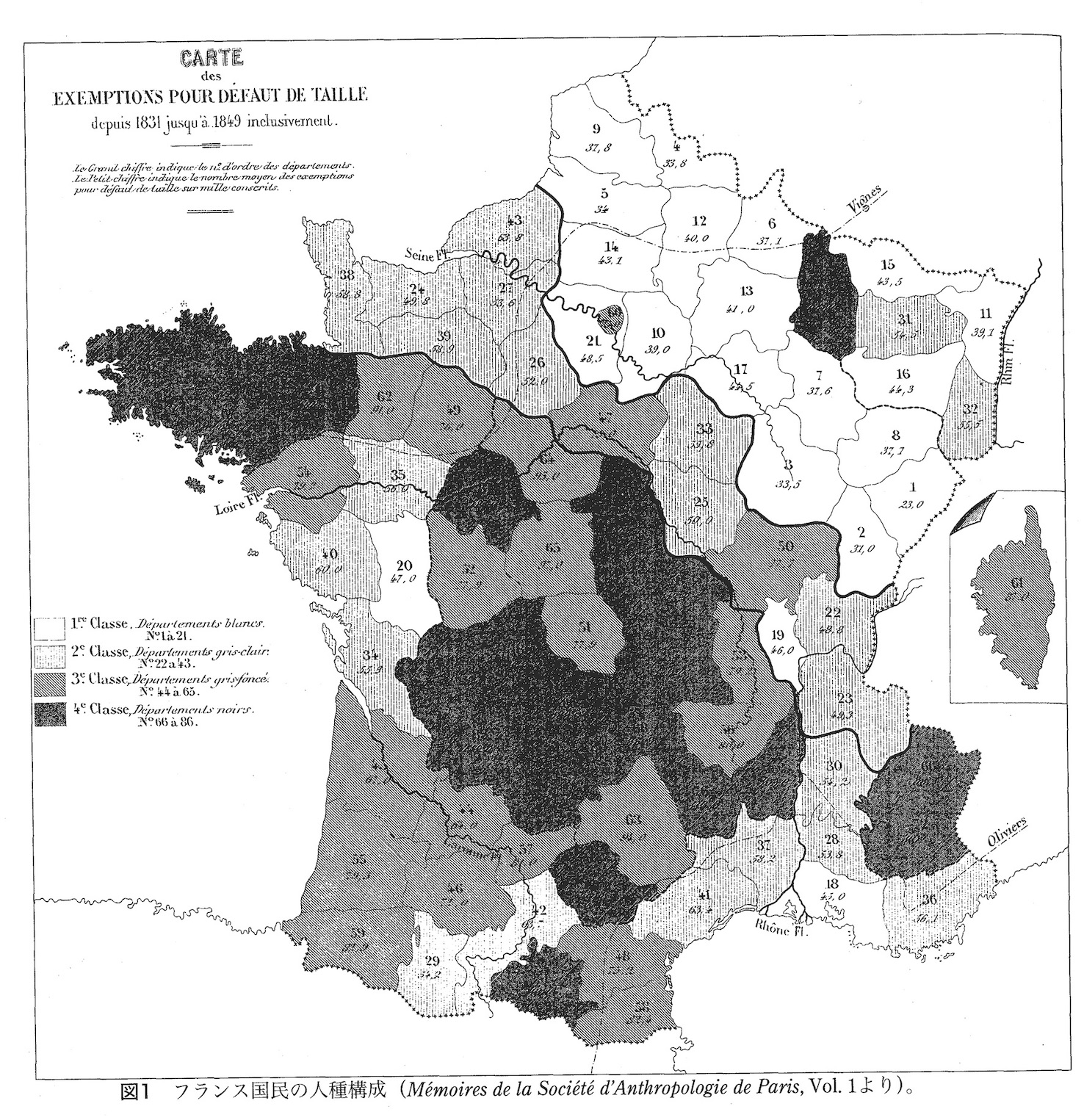

| Hybridity Broca, influenced by previous work of Samuel George Morton, used the concept of hybridity as his primary argument against monogenism, and that it was flawed to see all of humanity as a single species.[47] Different racial groups' ability to reproduce with each was not sufficient to prove that idea.[48] Under Broca's view on hybridity, the result of a reproduction between two different races could fall into four categories: 1) The resulting offspring are infertile; 2) Where the resulting offspring are infertile when they reproduce between themselves but are sometimes successful when they reproduce with the parent groups; 3) Known as paragenesic, where the offspring's descendants are able reproduce within themselves and with parents, but the success of the reproduction lowers with every generation until it ends; and 4) Known as eugenesic, where a successful reproduction can continue indefinitely, between the intermix descendants and with the parent group.[49] Looking at historical population figures, Broca concluded that the population of France was an example of a eugenesic mixed race, resulting from intermixing of Cimri, Celtic, Germanic and Northern races within the Caucasian group.[50] On the other hand, the thought that observations and population data from different regions of Africa, Southeast Asia, and North and South America, showed a significant decrease in physical and intellectual abilities of mixed groups when compared to the different races that they originated from. Concluding that intermixed descendants of different racial groups could only be Paragenesic. I am far from advancing these suppositions as demonstrated truths. I have studied and analysed all documents within my reach; but I cannot be responsible for facts not ascertained by myself, and which are too much in opposition to generally received opinions to be admitted without strict investigation... Until we obtain further particulars we can only reason upon the known facts; but these, it must be admitted, are so numerous and so authentic as to constitute if not a rigorous definitive demonstration, at least a strong presumption of the doctrines of polygenists.[51] On the Phenomenon of Hybridity was published the same year as Darwin's presentation of the theory of evolution in the On the Origin of Species. At that time, Broca thought of each racial group as independently created by nature. He was against slavery and disturbed by extinction of native populations caused by colonization.[52] Broca thought that monogenism was often used to justify such actions, when it was argued that, if all races were of a single origin then the lower status of non-Caucasians was caused by how their race acted following creation. He wrote: The difference of origin by no means implicates the subordination of races. It, on the contrary, implicates the idea that each race of men has originated in a determined region, as it were, as the crown of the fauna of that region; and if it were permitted to guess at the intention of nature, we might be led to suppose that she has assigned a distinct inheritance to each race, because, despite of all that has been said of the cosmopolitism of man, the inviolability of the domain of certain races is determined by their climate.[53] |

雑種性 ブロカはサミュエル・ジョージ・モートンの先行研究に影響され、一元論に対する主要な議論として混血の概念を用い、人類全体を単一の種として見ることは欠 陥があるとした[47]。 異なる人種のグループがそれぞれ繁殖する能力は、その考えを証明するには十分ではなかった[48] ブロカの混血に関する見解では、二つの異なる人種間の繁殖の結果は4つに分類することができた。1)結果として生じる子孫は不妊である、2)結果として生 じる子孫が自分たちの間で繁殖するときは不妊であるが、親グループと繁殖するときは成功することがある、3)パラジェネティックとして知られている、子孫 の子孫は自分たちの間と親と繁殖できるが、繁殖が終了するまで世代ごとに成功率が下がる、4)ユージェネティックとして知られている、繁殖成功者は混血子 孫と親グループの間で無限に続くことができる、であった[49]。 一方、アフリカ、東南アジア、南北アメリカの各地域の観測と人口データから、混血集団の身体的・知的能力は出身人種と比較して著しく低下していると考えた [50][50]。異なる人種の子孫が混在するのは、パラジェネティックなものでしかあり得ないと結論づけた。 私は、これらの推測を実証された真実として提唱しているわけではありません。私は手の届く範囲のあらゆる文献を研究し、分析した。しかし、私自身が確認し なかった事実や、一般に受け入れられている意見にあまりにも反しており、厳密な調査なしに認めることはできない...については責任を持てない。しかし、 これらの事実は、厳密な決定的証拠とは言えないまでも、少なくとも多元論者の教義に対する強い推定を構成するように、非常に多く、非常に確実であることが 認められなければならない[51]。 雑種性の現象について』はダーウィンが『種の起源』の中で進化論を提示したのと同じ年に出版された。当時、ブロカは各人種集団が自然によって独立して創造 されたものと考えていた。彼は奴隷制に反対し、植民地化による先住民の絶滅に心を痛めていた[52]。ブロカは、すべての人種が単一の起源であるならば、 非白人の地位の低さは、彼らの人種が創造後にどのように行動したかによって引き起こされると主張したとき、そのような行動を正当化するために一元論がしば しば使用されると考えていた。彼はこう書いている。 起源の違いは、決して人種間の従属を意味するものではない。もし自然の意図を推測することが許されるのであれば、自然は各人種に異なる遺産を割り当てたと 推測することになるかもしれない。 |

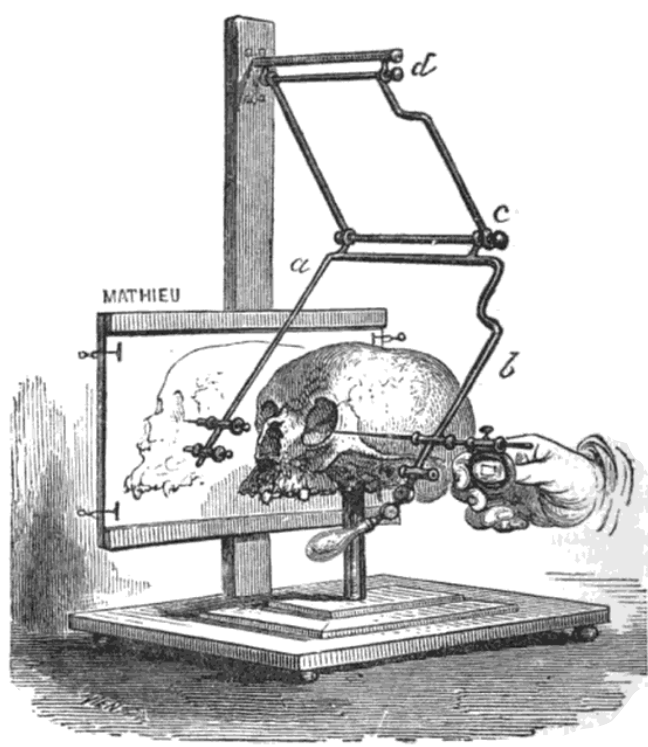

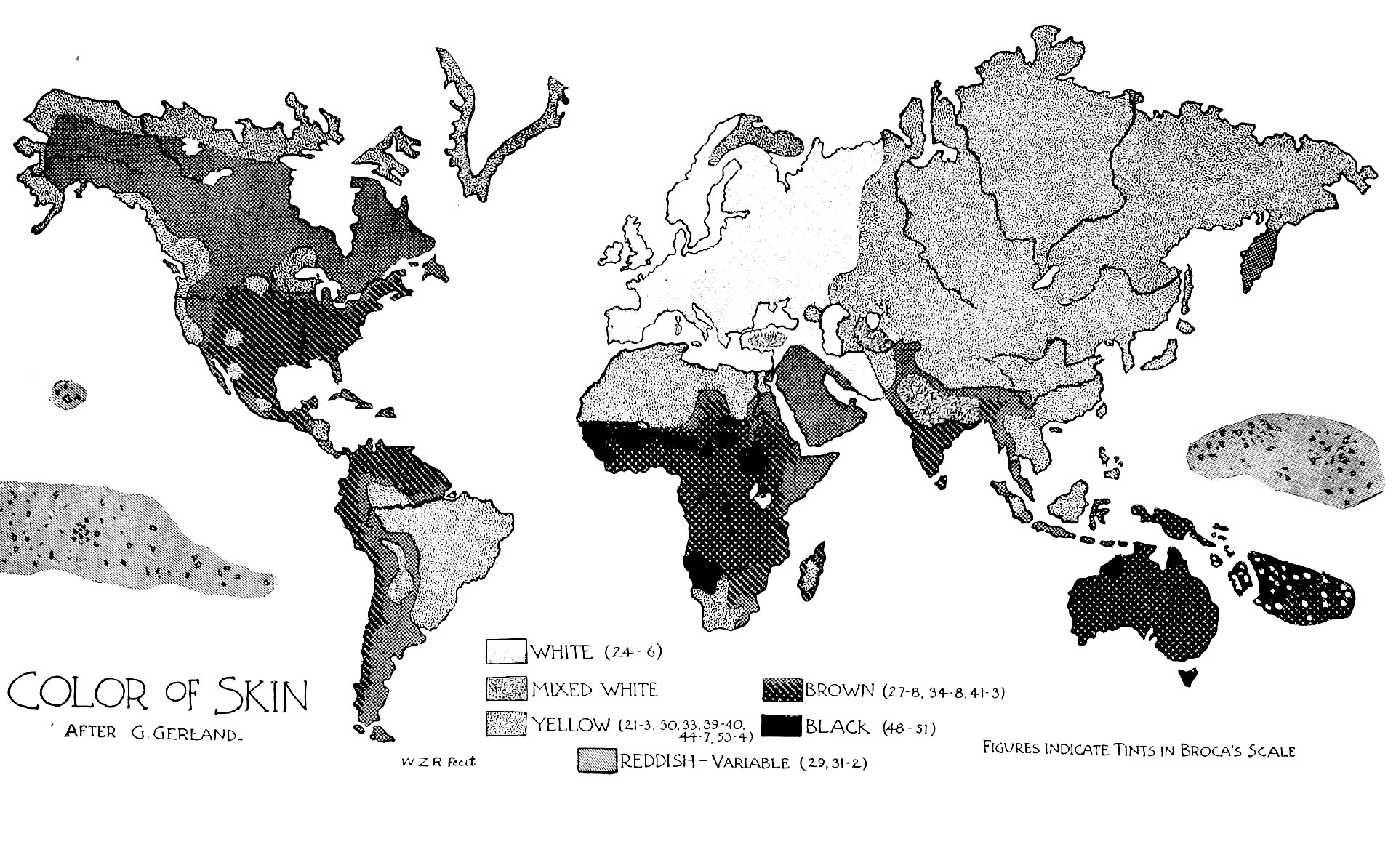

| Craniometry Broca is known for making contributions towards anthropometry—the scientific approach to measurements of human physical features. He developed numerous instruments and data points that were the basis of current methods of medical and archeological craniometry. Specifically, cranial points like glabella and inion and instruments like craniograph and stereograph.[54] Unlike Morton, who believed that a subject's brain size was the main indicator of intelligence, Broca thought that there were other factors that were more important. These included prognathic facial angles, with closer to right angles indicating higher intelligence, and the cephalic index relationship between the brain's length and width, that was directly proportional with intelligence, with the most intelligent European group being 'long headed', while the least intelligent Negro group being 'short headed'.[55] He thought that the most important aspect, was the relative size between the frontal and rear areas of the brain, with Caucasians having a larger frontal area than Negroes.[55] Broca eventually came to the conclusion that larger skulls were not associated with higher intelligence, but still believed brain size was important in some aspects such as social progress, material security, and education.[56][n 6] He compared cranial capacity of different types of Parisian skulls. In doing so he found that the average oldest Parisian skull was smaller than a modern, wealthier Parisian skull and that both were bigger than the average skull from a poor Parisian's grave.[n 7] Aside from his approaches to craniometry, Broca made other contributions to anthropometry, such as developing field work scales and measuring techniques for classifying eye, skin, and hair color, designed to resist water and sunlight damage.[60] |

クラニオメトリー ブロカは、人体計測学(人間の身体的特徴を科学的に測定する方法)に貢献したことで知られている。彼は、現在の医学や考古学の頭蓋測定の方法の基礎となる 数多くの機器やデータポイントを開発した。具体的には、グラベラやイニオンなどの頭蓋点、クラニオグラフやステレオグラフなどの器具である[54]。脳の 大きさが知能の主な指標であると考えたモートンとは異なり、ブロカはより重要な他の要因があると考えた。それらは、直角に近いほど知能が高いことを示す前 突顔の角度や、脳の長さと幅の関係である頭蓋指数は知能と正比例し、最も知能の高いヨーロッパ人は「長頭」であり、最も低い黒人グループは「短頭」である というものであった[55]。 [55] 彼は最も重要な側面は脳の前頭部と後頭部の間の相対的な大きさであり、白人は黒人よりも前頭部が大きいと考えた[55] ブロカは結局、大きな頭蓋骨は高い知能と関連しないという結論に達したが、それでも脳の大きさは社会進歩、物質的安全、教育などのいくつかの側面において 重要であると考えた[56][n 6] 彼は異なるタイプのパリの頭蓋骨の頭蓋骨の容量を比較した。そうすることで彼は、平均的な最古のパリの頭蓋骨は現代の裕福なパリの頭蓋骨よりも小さく、両 方とも貧しいパリの墓の平均的な頭蓋骨よりも大きいことを発見した[n 7] 頭蓋測定への彼のアプローチとは別に、ブロカは人体測定への他の貢献、例えば水や日光による損傷に耐えられるように設計された眼、皮膚、髪の色を分類する ための野外作業のスケールと測定技術を開発した[60]。 |

| Criticism Darwin In 1868 the English naturalist Charles Darwin criticized Broca for believing in the existence of a tailless mutant of the Ceylon junglefowl, described in 1807 by the Dutch aristocrat, zoologist and museum director Coenraad Jacob Temminck.[61] Stephen Jay Gould Broca was one of the first anthropologists engaged in comparative anatomy of primates and humans. Comparing then dominant craniometry-based measures of intelligence as well as other factors such as relative forearm-to-arm length, he proposed that Negroes were an intermediate form between apes and Europeans.[55] The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould criticized Broca and his contemporaries of being engaged in "scientific racism" when conducting their research. Basing their work on biological determinism, and "a priori expectations" that "social and economic differences between human groups—primarily races, classes, and sexes—arise from inherited, inborn distinctions and that society, in this sense, is an accurate reflection of biology."[62][63] Evolution Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, and two years later Broca published On the Phenomenon of Hybridity. Soon after Darwin's publication, Broca accepted evolution as one of the main elements of a broader explanation for diversification of species: "I am one of those who do not think that Charles Darwin has discovered the true agents of organic evolution; on the other hand I am not one of those who fail to recognize the greatness of his work ... Vital competition ... is a law; the resultant selection is a fact; individual variation, another fact."[64] He came to reject polygenism as applied to humans, conceding that all races were of single origin. In 1866, after the discovery of a chinless and protruded neanderthal jaw, he wrote: "I have already had occasion to state that I am not a Darwinist ... Yet I do not hesitate ... to call this the first link in the chain which, according to the Darwinists, extends from man to ape..."[65] He saw some differences between groups of animals as too distinct to be explained through evolution from a single source: There is no reason for limiting to a single spot and single moment the spontaneous evolution of matter ... To me it seems most likely that centers of organization appeared in very different places and at very different periods ... This polygenic transformism is what I would be inclined to accept ... My objection against Darwinism would be invalid if it conceded that organized beings have an undetermined but considerable number of distinct origins and if structural analogies were no longer considered sufficient proof for common parentage.[66] Even on a narrower level Broca saw evolution as insufficient explanation for the presence of some traits: Apply Darwin's thinking to the genus Orang (Satyrus) ... He alone, of all the primates, has no nail on his big toe. Why? ... The Darwinists will answer that one day a certain Pithecus was born without a big toe nail, and his descendants have perpetuated this variety ... Let us call this ape ... Prosatyrus I, as it behooves the founder of a dynasty ... While, according to the law of immediate heredity, some of his offspring were like their other ancestors in having a nail on every toe, one or more were deprived of the first nail like their father ... Thanks to natural selection, this character finally became constant ... But I do not see ... how this negative characteristic ... might give him advantage in the struggle for existence.[67] Ultimately, Broca believed that there had to be a process that ran parallel to evolution, to fully explain the origins of, and divergences, between different species.[68] |

批判 ダーウィン 1868年、イギリスの自然科学者チャールズ・ダーウィンは、オランダの貴族、動物学者、博物館館長のコエンラッド・ヤコブ・テンミンクが1807年に記 載したセイロンジャングルファウルの無尾変異体の存在を信じるブロカを批判している[61]。 スティーブン・ジェイ・グールド ブロカは、霊長類と人間の比較解剖学に携わった最初の人類学者の一人であった。進化生物学者のスティーブン・ジェイ・グールドは、ブロカと彼の同時代の研 究者が研究を行う際に「科学的人種主義」に従事していると批判した[55]。彼らの研究は生物学的決定論に基づいており、「人間集団の間の社会的・経済的 差異-主に人種、階級、性別-は遺伝的、先天的区別から生じ、この意味で社会は生物学を正確に反映している」という「先験的期待」[62][63]を有し ていた。 進化論 ダーウィンの『種の起源』は1859年に出版されたが、その2年後にブロカは『雑種性の現象について』を出版した。ダーウィンの『種の起源』が出版された 直後、ブロカは進化論を種の多様性を説明する主要な要素の1つとして認めた。私はダーウィンが有機的進化の真の担い手を発見したとは思わないが、一方で彼 の仕事の偉大さを認めない者でもない......」。生命的な競争は...法則であり、その結果としての淘汰は事実であり、個体の変異は別の事実である」 [64]。 彼は人間に適用される多系統主義を否定するようになり、すべての人種は単一起源であることを認めるようになった。1866年、顎のない突出したネアンデル タール人の顎が発見された後、彼はこう書いている:「私はすでにダーウィン主義者ではないことを述べる機会があった......。しかし、私はこれを、 ダーウィン主義者によれば、人間から猿に至る連鎖の最初のリンクと呼ぶことに躊躇しない...」[65] 彼は動物のグループ間のいくつかの違いは、単一のソースからの進化によって説明するにはあまりにも明確であると考えたのである。 物質の自然発生的な進化を一箇所、一瞬間に限定する理由は何もない。私には、組織の中心が非常に異なった場所、非常に異なった時期に出現した可能性が高い ように思われる・・・。この多遺伝子変換論は、私が受け入れたいと思うものである・・・。ダーウィニズムに対する私の反論は、組織化された存在が未確定で はあるが相当数の異なる起源を持つことを認め、構造的類似性が共通の親を持つことの十分な証拠とは考えられなくなれば、無効となるであろう[66]」。 より狭いレベルでさえも、ブローカは進化がいくつかの形質の存在に対して不十分な説明であると見なしていた。 ダーウィンの考え方をオランジュ(Satyrus)属に適用してみると...彼だけが、すべての霊長類の中で、外反母趾に爪がないのである。なぜか?ダー ウィン主義者は、ある日、あるピテクスが外反母趾の爪を持たずに生まれ、その子孫がこの品種を永続させたと答えるだろう ... この猿をこう呼ぼう プロサテュロス1世と呼ぶことにしよう.即席の遺伝の法則によれば、彼の子孫の中には、すべての足の指に爪があるという点で他の祖先と同じものがあった が、一人またはそれ以上のものは、父親のように最初の爪がない.自然淘汰のおかげで、この特性は最終的に一定になった.... しかし私はこの負の特性が......どのように生存のための闘争において彼に優位性を与えるかもしれないとは思わない[67]。 最終的にブロカは、異なる種の起源と分岐を完全に説明するために、進化と並行して進行するプロセスが存在しなければならないと考えていた[68]。 |

| Broca's area Broca is celebrated for his theory that the speech production center of the brain is located on the left side of the brain and for pinpointing the location to the ventroposterior region of the frontal lobes (now known as Broca's area). He arrived at this discovery by studying the brains of aphasic patients (persons with speech and language disorders resulting from brain injuries).[69] This area of study began for Broca with the dispute between the proponents of cerebral localization – whose views derived from the phrenology of Franz Joseph Gall – and their opponents led by Pierre Flourens. Phrenologists believed that the human mind has a set of various mental faculties, each one represented in a different area of the brain. With specific areas representing personality characteristics like one's aggressiveness or spirituality, but also memory and linguistic abilities. Their opponents claimed that, by careful ablation (specific way of removing material) of various brain regions, Flourens had disproved Gall's hypotheses. However, Gall's former student, Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud, kept the localization of function hypothesis alive (especially with regards to a "language center"), although he rejected much of the remaining phrenological thinking. In 1848, Bouillaud relied on his work with brain-damaged patients to challenge other professionals to disprove him by finding a case of frontal lobe damage unaccompanied by a disorder of speech.[70] His son-in-law, Ernest Aubertin (1825–1893), began seeking out cases to either support or disprove the theory, and he found several in support of it.[69] Broca's Society of Anthropology of Paris was where language was regularly discussed in the context of race and nationality, it also became a platform for addressing its physiological aspects. The localization of function controversy became a topic of regular debate when several experts of head and brain anatomy, including Aubertin, joined the society. Most of these experts still supported Flourens argument, but Aubertin was persistent in presenting new patients to counter their views. However, it was Broca, not Aubertin, who finally put the localization issue to rest. In 1861, Broca visited a patient in the Bicêtre Hospital named Louis Victor Leborgne, who had a 21-year progressive loss of speech and paralysis but not a loss of comprehension nor mental function. He was nicknamed "Tan" due to his inability to clearly speak any words other than "tan" (pronounced \tɑ̃\, as in the French word temps, "time").[71][72][69][73] Leborgne died several days later due to an uncontrolled infection and resultant gangrene, Broca performed an autopsy, hoping to find a physical explanation for Leborgne's disability.[74] He determined that, as predicted, Leborgne did in fact have a lesion in the frontal lobe in one of the cerebral hemispheres, which in this case turned out to be the left. From a comparative progression of Leborgne's loss of speech and motor movement, the area of the brain important for speech production was determined to lie within the third convolution of the left frontal lobe, next to the lateral sulcus.[75][76] One day after Tan's death Broca presented his findings to the anthropological society.[77] A second case after Leborgne is what solidified Broca's beliefs that human speech function was localized. Lazare Lelong was an 84-year-old grounds worker who was being treated at Bicêtre for dementia. He had also lost the ability to speak other than five simple, meaningful words – these included his own name, "yes", "no", "always" as well as the number "three".[78] After his death his brain was also autopsied. Broca found a lesion that encompassed much the same area as had been affected in Leborgne's brain. This finding concluded that a specific area controlled one's ability to produce meaningful sounds, and when it is affected, one can lose their capability to communicate.[72] For the next two years, Broca went on to find autopsy evidence from twelve more cases in support of the localization of articulated language.[69][73] Broca published his findings from the autopsies of the twelve patients in his paper "Localization of Speech in the Third Left Frontal Cultivation" in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, had made similar observations a generation earlier. Based on his work with approximately forty patients and subjects from other papers, Dax presented his findings at an 1836 conference of southern France physicians in Montpellier.[79][n 8] Dax died soon after this presentation and it was not reported or published until after Broca made his initial findings.[80] Accordingly, Dax's and Broca's conclusions that the left frontal lobe is essential for producing language are considered to be independent.[81][80] However, the brains of Leborgne and Lelong had been preserved whole; Broca had never sliced them to reveal the other damaged structures beneath. Over 100 years later Nina Dronkers, an American cognitive neuroscientist, obtained permission to re-examine these brains using modern MRI technology. This imaging resulted in virtual slices of the historic brains and revealed that theses patients had sustained much more damage to the brain than Broca could have known from just studying the outer surface. Their lesions extended to deeper layers beyond the left frontal lobe, including portions of insular cortex and critical white matter pathways below the cortex. This work was published in a peer-reviewed article, and has been cited.[82] The brains of many of Broca's aphasic patients are still preserved and available for viewing on a limited basis in the special collections of the Pierre-and-Marie-Curie University (UPMC) in Paris. The collection was formerly displayed in the Musée Dupuytren. His collection of casts is in the Musée d'Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière. Broca presented his study on Leborgne in 1861 in the Bulletin of the Société Anatomique.[69][73] Patients with damage to Broca's area or to neighboring regions of the left inferior frontal lobe are often categorized clinically as having Expressive aphasia (also known as Broca's aphasia). This type of aphasia, which often involves impairments in speech output, can be contrasted with receptive aphasia, (also known as Wernicke's aphasia), named for Karl Wernicke, which is characterized by damage to more posterior regions of the left temporal lobe, and is often characterized by impairments in language comprehension.[69][73] |

ブローカ野 ブロカは、脳の音声生成中枢が左脳にあるという説と、その位置を前頭葉の腹側後方領域(現在ブロカ野として知られている)に特定したことで有名である [69]。彼は失語症患者(脳の損傷に起因する言語障害を持つ人)の脳を研究することによってこの発見に至った[69]。 この分野の研究は、フランツ・ヨーゼフ・ガルの骨相学に由来する大脳定位論者と、ピエール・フルーランスを中心とする反対派との論争からブローカが始めた ものである。骨相学者は、人間の心には様々な精神能力があり、それぞれは脳の異なる領域に代表することができると考えていた。その領域は、攻撃性や精神性 といった性格的なものから、記憶力や言語能力などを代表するものである。このようなガルの仮説に対して、フルーレンスは、脳の様々な部位を注意深く切除す ることで、ガルの仮説を否定したと反論したのである。しかし、ガルのかつての教え子であるジャン・バティスト・ブイヨーは、残りの骨相学的思考の多くを否 定しながらも、機能の局在化という仮説(特に「言語中枢」に関して)を維持し続けた。1848年、ブイヨーは脳障害患者を対象とした研究に依拠し、言語障 害を伴わない前頭葉の損傷の事例を見つけることによって、他の専門家に彼を反証するよう挑んだ[70]。彼の義理の息子であるエルネスト・オーベタン (1825-1893)は理論を支持または反証する事例を探し始め、理論を支持するものをいくつか見つけることに成功した[69]。 ブロカのパリの人類学協会は、言語が人種や国籍の文脈で定期的に議論される場所であったが、それはまたその生理学的側面を扱うためのプラットフォームと なった。機能の局所化論争は、オーベルタンを含む頭部と脳の解剖学の数人の専門家が学会に参加したときに、定期的な議論のトピックとなった。これらの専門 家の多くは、依然としてフローレンの主張を支持していたが、オーベルタンは新しい患者を提示して彼らの意見に対抗することに執念を燃やしていた。しかし、 最終的に局在の問題を解決したのは、オーベルタンではなくブロカであった。 1861年、ブロカはビセートル病院にルイ・ヴィクトル・ルボルニュという患者を訪ねた。彼は、21年間進行性の失語と麻痺があったが、理解力や精神機能 の喪失はなかった。タン」(フランス語の temps 「時間」の意)以外の言葉をはっきりと話すことができないため、「タン」というあだ名がつけられていた[71][72][69][73] ルボルニュは制御不能な感染症とその結果生じた壊疽により数日後に死亡し、ブロカはルボルニュの障害について物理的説明を見出すべく解剖を行った [74]。 [その結果、予想通り、ルボーニュは大脳半球の片方の前頭葉に病変があることが判明した(この場合、左半球であることが判明した)。ルボルニュの言語と運 動の喪失の比較進行から、言語生成に重要な脳の領域は左前頭葉の第3凸部内、側溝の隣にあると判断された[75][76] タンの死の1日後にブロカは人類学協会にその発見を発表した[77]。 人間の音声機能は局所的なものであるというブロカの考えを確固たるものにしたのは、ルボーニュに続く2例目のケースである。ラザール・レロングは、84歳 のグランドワーカーで、認知症のためビセートルで治療を受けていた。彼は、自分の名前、「はい」、「いいえ」、「いつも」、数字の「3」など、簡単で意味 のある5つの単語以外を話すことができなくなっていた[78]。彼の死後、彼の脳も解剖された。ブロカは、ルボーニュの脳とほぼ同じ部位に病変を発見し た。この発見は、特定の領域が意味のある音を出す能力を制御しており、それが冒されたとき、人はコミュニケーションの能力を失うことができると結論付けた [72]。 その後2年間、ブロカはさらに12例の剖検証拠を見つけ、有声言語の局在を支持することになった[69][73]。 ブロカは1865年に彼の論文「左前頭部第三の培養における音声の局在」で12人の患者の剖検から得た知見を発表した。彼の研究は、より多くの脳領域を感 覚や運動機能に関連付けることを目的として、注意深く剖検を行うよう他の人々に刺激を与えた。この発見はブロカのものとされているが、その一世代前にフラ ンスの神経学者マルク・ダックスも同様の観察を行っていた。ダックスは約40人の患者と他の論文の被験者との研究に基づいて、1836年にモンペリエで開 かれた南フランスの医師の会議で彼の発見を発表した[79][n 8] ダックスはこの発表後すぐに死亡し、ブロカが最初の発見を行った後まで報告も発表もされなかった[80] 従って、左前頭葉が言語を生み出すのに不可欠であるというダックスの結論とブロカの結果は独立していると見なされる[81][80]。 しかし、ルボーニュとレロンの脳は丸ごと保存されており、ブロカはその下にある他の損傷した構造を明らかにするためにそれらをスライスすることはなかっ た。100年以上経って、アメリカの認知神経科学者であるニーナ・ドロンカースは、現代のMRI技術を使用してこれらの脳を再検査する許可を得た。この画 像処理によって、歴史的な脳の仮想スライスが作成され、これらの患者は、ブロカが外側の表面を調べただけではわからないほど、脳に大きなダメージを受けて いたことが明らかになった。彼らの病変は、左前頭葉を越えて、島皮質の一部や皮質の下にある重要な白質経路など、より深い層にまで及んでいたのだ。この研 究は、査読付きの論文に掲載され、引用されている[82]。 ブロカ失語症患者の多くの脳は、現在もパリのピエール・アンド・マリー・キュリー大学(UPMC)の特別コレクションに保存されており、限定的に閲覧する ことが可能である。このコレクションは、以前はデュピュイトレン美術館に展示されていた。彼の鋳型のコレクションはデルマス=オルフィラ=ルヴィエール解 剖学博物館にある。ブロカは1861年にルボーニュに関する研究を『Bulletin of the Société Anatomique』に発表した[69][73]。 ブローカ野または左下前頭葉の隣接領域に損傷を受けた患者は、しばしば臨床的に表現性失語症(ブローカ失語症としても知られる)に分類される。このタイプ の失語症は、しばしば言語出力における障害を伴い、左側頭葉のより後方の領域の損傷によって特徴づけられる、カール・ウェルニッケに因んで名付けられた受 容性失語症(ウェルニッケ失語症としても知られる)と対比することができ、言語理解における障害によってしばしば特徴づけられる[69][73]。 |

| The discovery of Broca's area

revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech

production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this

area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of

function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne

and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the

location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically Wernicke's

area.[citation needed] New research has found that dysfunction in the area may lead to other speech disorders such as stuttering and apraxia of speech. Recent anatomical neuroimaging studies have shown that the pars opercularis of Broca's area is anatomically smaller in individuals who stutter whereas the pars triangularis appears to be normal.[83] He also invented more than 20 measuring instruments for the use in craniology, and helped standardize measuring procedures.[8] His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower. |

ブローカ野の発見は、言語処理、音声生成、理解、そしてこの野の損傷が

どのような影響をもたらすかについての理解を一変させた。ブローカは、ルボーニュと彼の12症例によってこの問題を科学的に解決し、機能局在の議論に大き

な役割を果たした。彼の研究は他の研究者に、他の多種多様な機能、特にウェルニッケ野の位置を発見させることにつながった[要出典]。 新しい研究では、この領域の機能不全が吃音や失語症など他の言語障害につながる可能性があることが判明している。最近の解剖学的神経画像研究によると、ブ ローカ野のオペラ座は吃音者では解剖学的に小さく、一方、三角座は正常のようであることが示されている[83]。 彼はまた、頭蓋学で使用する20以上の測定器を発明し、測定手順の標準化に貢献した[8]。 彼の名前は、エッフェル塔に刻まれた72の名前のうちの1つである。 |

| Selected publications 1849. De la propagation de l'inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs dites cancéreuses. Doctoral dissertation. 1856. Des anévrysmes et de leur traitement. Paris: Labé & Asselin 1861. "Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales". Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 2: 190–204. 1861. "Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 2: 235–38. 1861. "Remarques sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé, suivies d'une observation d'aphémie (perte de la parole)." Bulletin de la Société Anatomique de Paris 6: 330–357 1861. "Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales." Bulletin de la Société Anatomique 36: 398–407. 1863. "Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 4: 200–208. 1864. On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo. London: Pub. for the Anthropological society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts 1865. "Sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 6: 377–393 1866. "Sur la faculté générale du langage, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie deuxième série 1: 377–82 1871–1878. Mémoires d'anthropologie, 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald (vol. 1 | vol. 2 | vol. 3) 1879. "Instructions relatives à l'étude anthropologique du système dentaire." In: Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, III° Série. Tome 2, 1879. pp. 128–163. |

主な出版物 1849年 『炎症の伝播について ― いわゆる癌性腫瘍に関するいくつかの提案』 博士論文 1856年 『動脈瘤とその治療について』 パリ:Labé & Asselin 1861年 「脳の位置決定の原理について」 『人類学協会報』 2:190-204 1861年。「言語障害、慢性的な軟化、および左前頭葉の部分的な破壊について」。人類学協会報 2: 235–38。 1861年。「明瞭な言語能力の座に関する考察、および失語症(言語障害)の観察結果」。パリ解剖学会報 6: 330–357 1861年。「第2および第3前頭回後部の損傷によって生じた失語症の新たな観察」。解剖学会報 36: 398–407。 1863年。「脳機能の局在。言語能力の座」『人類学協会報』4:200-208。 1864年。ヒト属における雑種現象について。ロンドン:人類学協会出版、ロングマン、グリーン、ロングマン、ロバーツ社 1865年。「言語能力の座について」 人類学協会報 6: 377–393 1866年。「言語能力全般と、言語能力との関係について」。人類学協会報 第二シリーズ 1: 377–82 1871–1878年。人類学に関する回顧録、全3巻。パリ:C. Reinwald (第 1 巻 | 第 2 巻 | 第 3 巻) 1879年。「歯系の人類学的研究に関する指示」。『パリ人類学協会報』第 III シリーズ第 2 巻、1879年、128–163 ページ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Broca |

+++++

| ピエール・ポール・ブローカ | ピエール・ポール・ブローカ( Pierre Paul

Broca、1824年6月28日 –

1880年7月9日)は、フランスの内科医、外科医、解剖学者、人類学者。ジロンド県サント=フォア=ラ=グランド出身。彼に因んで名づけられた前頭葉中

の一領域ブローカ野の研究で最も知られる。ブローカ野は発話能力を司る。失語症を患った患者が大脳皮質左前部の特定の領域に障害を有していたことが彼の研

究により明らかになった。これは脳機能が局在していることの最初の解剖学的証明である。ブローカの研究は形質人類学の発展にも資するところがあり、人体測

定学(英語版)を発展させた[1]。 |

| 生涯 |

ピエール・ポール・ブローカは、町医者で一時は外科医としてナポレオン

に仕えていたバンジャマン・ブローカの息子として、フランスジロンド県サント=フォア=ラ=グランドで1824年6月28日に生まれた。ブローカの母はプ

ロテスタントの説教師の娘であった。ブローカは故郷の町で初等教育を受け、16歳で学士号を授与された。彼はパリの医学校に17歳で入学して20歳で卒業

したが、当時医学を学ぶ人々は早くとも20歳ごろに医学を学び始めるのが通例であった[2]。 卒業後彼は、最初にHôpital du Midiで泌尿器科医・皮膚科医のフィリップ・リコール(1800年-1889年)、1843年にBicêtreでフランソワ・ルーレ(1797年- 1851年)というように豊富なインターンシップを経た。1844年には偉大な解剖学者・外科医ピエール・ニコラス・ジェルディ(1797年-1856 年)の下でインターンを受けることができた。ジェルディの下で過ごして2年後、ブローカは彼の助手となった[2]。 1848年には、ブローカはチャールズ・ダーウィンの理論に同調する自由思想家の協会を設立した。ブローカは非常に進化の思想全般に感化されており、「私 は堕落したアダムの子であるよりもむしろ変異した類人猿でありたい[2][3]」と、ある時宣言した。 このため彼と教会との間で摩擦が生じ、教会から若者を退廃させる破壊的な唯物論者とみなされた。彼は生涯を通じて教会から敵意を持たれ、教会の権威との間 に直接・間接に無数の対立が生じた[2]。 1848年には、ブローカはパリ大学医学部の解剖係となったが、これは史上最年少でのこの職務への就任であった。彼は解剖学会の書記にも就任した。 1849年には、彼は医学博士号を授与された。1859年に、エティエンヌ・ユジェーヌ・アザム、シャルル・ピエール・デノンヴィリエ、フランソワ・アン ティム・ユジェーヌ・フォラン、そしてアルフレー・アルマン・ルイ・マリー・ヴェルポーらとともに、ヨーロッパで初めて催眠術を外科的麻酔として用いた実 験を行った[2]。 1853年にはブローカはPRAGとなり、病院の外科医に就任した。1867年には医学部の外面病理学教室の座長となり、その2年後には臨床外科の教授と なった。1868年には国民医学アカデミーのメンバーとなり、臨床外科教室の座長にもなった。この後彼は死ぬまでこの地位にあった。彼はHôpital St. Antoine、Hôpital de la Salpêtrière、the Hôtel des Clinques、Hôpital Neckerといった病院に勤めた[2]。 医学的活動と並行して、ブローカは人類学に対する関心をも追求した。1859年、彼はパリ人類学会を創設した。彼は1862年以降この学会の書記の任に就 いた。さらに彼は、1872年には『Revue d'anthropologie』誌を創刊して1876年には人類学学校を創設した[4]。教会はフランスにおける人類学の発展に反対し、1876年には 人類学学校における教授をやめさせようというキャンペーンを行った[1][2]。 ポール・ブローカは晩年には元老院の終身議員に選ばれた。彼はアカデミー・フランセーズの会員にもなり、その他フランスおよび海外の多くの学術機関から名 誉学位を授与された[2]。 ブローカは1880年7月9日に脳出血により56歳で死んだ[1]。彼の2人の子供はいずれも医科学の教授として有名になった[2]。 |

| 研究 |

ブローカの初期の科学的研究は骨および軟骨の組織学を対象としていた

が、腫瘍病理、動脈瘤の療法、乳児死亡率なども研究していた。彼が最も関心を持っていたことの1つは脳の比較解剖学であった。彼は神経解剖学者として、大

脳辺縁系および嗅脳の理解に大きく貢献した。嗅覚は彼にとって動物性の現われであった。彼は当時のフランスで変異(仏:Transformisme)とし

て知られた生物の進化に関して広範に著述した(この語は当時英語でも用いられたが今日ではどの言語でもほとんど用いられない[2])。 その後半生において、ブローカは公衆衛生及び公教育に関する著述を行った。彼は貧困者の公衆衛生に関する議論に関わり、Assistance Publiqueにおける重要人物となった。彼は婦人教育や婦人教育の教会からの分離をも唱道した。婦人教育の管理を続けようとした有名なローマ・カト リックのオルレアン司教フェリックス・ドゥパンループ(1802年-1878年)に対して彼は反対したのである[2]。 ブローカが専門知識を有した主な領域の1つは脳の比較解剖学である。言語能力の局在に関する彼の研究によって、脳機能の左右分化という全く新しい研究が導 かれた[2]。 |

| 音声研究 |

ブローカは、脳の前頭葉腹後側に位置する発声を司る領域(今日ではブ

ローカ野として知られる)の発見で最も有名である。彼は失語症患者(脳に傷害を受けたことで発話・言語能力に障害を有する人)の研究によってこの発見にた

どり着いた[5]。 ブローカはこの研究を知性的攻撃とそれに続く挑戦から始めた。まず、フランツ・ヨゼフ・ガル(1758年-1828年)が非常に有名な骨相学の理論と脳機 能局在論を唱えたがピエール・フルーラン(1794年-1867年)に反論された。彼は脳の様々な領域を慎重に切除する実験を行い、ガルの仮説を反証した と主張した。それに対してガルのかつての弟子ジャン=バティスト・ブイヨー(1796年-1881年)が脳機能局在説(特に言語中枢に関して)を護持し続 けたが最終的には骨相学の学説の多くを放棄した。ブイヨーは当時の専門家に、言語障害だけが起こった前頭葉損傷の症例を見つけて自分を反駁してみろと挑ん だ。彼の義理の息子エルネスト・オーベルタン(1825年-1893年)がこの理論を証明あるいは反証できる患者を捜し、理論を支持する症例をいくつか発 見した[5]。 ブローカのパリ人類学会は、オーベルタンを含む何人かの脳解剖学の専門家が加入して、機能局在論争の新たな戦場となった。これら専門家のほとんどはフルー ランの主張を支持していたが、オーベルタンは彼らの主張を攻撃する新しい症例を提示し続けた。しかし、オーベルタンではなくブローカこそが最終的に脳機能 局在説を確立した[5]。 1861年に、Bicêtre Hospitalにいて21年間進行性の言語障害と麻痺を患っているが理解能力や心的機能には障害のないルボルニュという患者のことをブローカは聞きつけ た。彼は「タン」としかはっきり発音できなかったため「タン」とあだ名されていた[5][6]。 その後間もなくルボルニュが死んだため、ブローカは剖検を行った。予想通りルボルニュは大脳左半球の前頭葉に傷害を負っていたとブローカは確定した。ルボ ルニュの言語障害と自動症がかなり進行していたことから、言語活動に重要な領域は左前頭葉の外側溝に隣接する第三脳回にあると決定される。その後2年間 で、ブローカは12以上の症例から、発声能力の局在説を支持する剖検的証拠を発見し続けた[5][6]。 歴史はこの発見をブローカに帰しているが、別のフランスの神経学者マルク・ダックスが先行して同様の知見を得ていた。しかし彼はそれをさらに推し進める機 会を得ずにすぐに死んでしまった[要出典]。今日、ブローカの扱った失語症患者のうちの多くの脳がデュピュイトラン博物館に所蔵されており、彼の鋳型のコ レクションはデルマー・オルフィラ・ルヴィエール解剖学博物館に所蔵されている。ブローカは1861年にルボルニュのに関する研究を解剖学会の会報で発表 した[5][6]。 ブローカ野や、前頭葉の左下側に隣接する領域に傷害を負った患者は臨床的にはしばしば運動性失語(ブローカ失語としても知られる)と診断される。この種の 失語症はしばしば発話機能の減損を伴い、感覚性失語(カール・ヴェルニッケに因んでウェルニッケ失語としても知られる)と対比される。感覚性失語は左側頭 葉のより後位の傷害という特徴を持ち、しばしば言語理解能力の減損によって特徴づけられる[5][6]。 |

| 人類学的研究 |

ブローカは初めイシドール・ジョフロワ=サン・イレール(1805年-

1861年)、アントワーヌ・エティエンヌ・レイノー・オーギュスタン・セレ(1786年-1868年)、ジャン・ルイ・アルマン・ド・キャトルファ

ジェ・ド・ブロー(1810年-1892年)らの著作を通じて人類学に親しみ、すぐに人類学が彼の終生の関心事となった。彼は多くの時間を自身の設立した

人類学会ですごし、頭蓋骨や骨を研究した。この点で、ブローカは形質人類学の草分けと言える。彼は様々な種類の計測器具(頭骨計測器)や測定基準を新しく

作り出して頭骨人体測定学を発展させた[2]。 ブローカは霊長類の比較解剖学にも大きく貢献した。彼は脳の解剖学的特徴と、知性のような心的能力との関係に関心を抱いた。彼は多くの同時代人と同様に、 人間の知的性質は脳の大きさによって測定できると考えていた[要出典]。 ブローカは一般人類学、形質人類学、民族学、その他の関連分野に関しておよそ223の論文を著した。彼は1859年にパリ人類学会を設立し、1872年に 『Revue d'Anthropologie』を創刊し、1876年にパリ人類学校を創設した[要出典]。 |

| ブローカの影響 |

ブローカ野とブローカ野の傷害により起こることの発見により、言語処

理・発話・言語了解に関する理解に革命が起きた。ブローカはルボルニュおよび彼に続く12の症例によって科学的に問題を解決したことで、機能局在論争にお

いて主導的な役割を果たした。彼の研究により他の人々が他の様々な機能の局在を、特にウェルニッケ野を発見した[要出典]。 ブローカ野に障害が起きると吃音症や発話失行といった他の言語障害が併発することが新たな研究により示されている。ブローカ野弁蓋部は吃音症患者で健常者 より小さいが三角部は健常者と変わらないことが近年の解剖学の神経画像処理の研究によりわかっている[要出典]。 彼は頭蓋学で用いる計測器具を20以上発明してもおり、測定手続きの標準化を促進した[2]。 |

| 著作 |

Broca, Paul. 1849. De la

propagation de l’inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs

dites cancéreuses. Doctoral dissertation. Broca, Paul. 1856. Traité des anévrismes et leur traitement. Paris: Labé & Asselin Broca, Paul. 1861. Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 2: 190–204. Broca, Paul. 1861. Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 2: 235–38. Broca, Paul. 1861. Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales gauches. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique 36: 398–407. Broca, Paul. 1863. Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du langage articulé. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 4: 200–208. Broca, Paul. 1866. Sur la faculté générale du langage, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du langage articulé. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie deuxième série 1: 377–82. Broca, Paul. 1871–1878. Mémoires d'anthropologie, 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald, |

| 1849. De la

propagation de l'inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs

dites cancéreuses. Doctoral dissertation. 1856. Des anévrysmes et de leur traitement. Paris: Labé & Asselin 1861. "Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales". Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 2: 190–204. 1861. "Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 2: 235–38. 1861. "Remarques sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé, suivies d'une observation d'aphémie (perte de la parole)." Bulletin de la Société Anatomique de Paris 6: 330–357 1861. "Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales." Bulletin de la Société Anatomique 36: 398–407. 1863. "Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 4: 200–208. 1864. On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo. London: Pub. for the Anthropological society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts 1865. "Sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie 6: 377–393 1866. "Sur la faculté générale du langage, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du langage articulé." Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie deuxième série 1: 377–82 1871–1878. Mémoires d'anthropologie, 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald (vol. 1 | vol. 2 | vol. 3) 1879. "Instructions relatives à l'étude anthropologique du système dentaire." In: Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, III° Série. Tome 2, 1879. pp. 128–163 |

|

| 出典 | https://bit.ly/3INsPdZ. |

Stereograph designed by Paul Broca and manufactured by Mathieu, Map of Color of Skin: Figures indicate tint in Broca's scale

Louis Victor "Tan" Lebourgne's brain. By Pierre Marie.

ポール・ブローカによるフランス人種分布地図(パリ人類学会紀要, 1巻, 1861)

●司法的同一性の誕生 : 市民社会における個体識別と登録 / 渡辺公三著, 言叢社 , 2003

西欧における同一性の系譜

第1部 人類学と行刑学のあいだ

1,2,3. ベルティヨンと司法的同一性の誕生 (不肖の息子;公僕の務め;地下室からの眺め))

第2部 個体—市民社会の光学

4. 近代システムへの「インドからの道」—あるい は「指紋」の発見

5. 顔を照らす光・顔に差す影—写真と同一性

6. スフィンクスへの問い

第3部 群集・兵士・原住民—市民社会の暗闇の斜面

7. 帝国と人種—植民地支配のなかの人類学的知

8. 人種あるいは差異としての身体

9. 19世紀末フランスにおける市民=兵士の同一

性の変容

第4部 日本への刻印

10. 戸籍・鑑札・旅券—明治初期の同一性の制度 化と川路利良の「内国旅券規則」案

11. 「個人識別法の新紀元」—日本における指紋 法導入の文脈

12. 指紋と国家

13. 西欧的同一性は解体するか—技術とその限界

++++++++++++++++++++++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099