ポカホンタス

Pocahontas, ca.1956-1917

☆

ポカホンタス[Pocahontas](米国発音: /ˌpoʊkəˈhɒntəs/、英国発音:

/ˌpɒk-/、本名アモヌート[1]、別名マトーアカ、レベッカ・ロルフ。1596年頃 -

1617年3月)は、バージニア州ジェームズタウンの植民地入植地との関わりで知られる、ポウハタン族に属するネイティブアメリカンの女性である。彼女は

ワフンセナカウ(ワフンセナカウ)の娘であった。ワフンセナカウは、ツェナコマカ(英語名:ポウハタン連合)に属する複数の部族の首長であり、現在のアメ

リカ合衆国バージニア州のタイドウォーター地域を支配していた。

1613年の敵対行為の際、ポカホンタスはイギリス人入植者に捕らえられ身代金目的で拘束された。監禁中、キリスト教への改宗を勧められ、レベッカという

名で洗礼を受けた。1614年4月、17歳か18歳の時にタバコ栽培者ジョン・ロルフと結婚し、1615年1月に息子トマス・ロルフを出産した。

1616年、ロルフ夫妻はロンドンへ渡り、ポカホンタスは「文明化された野蛮人」の象徴として英国社会に紹介された。これはジェームズタウンへの投資促進

が目的であった。この渡英中、彼女はニューイングランドのパタウセット族出身者スクアントと出会った可能性がある[3]。ポカホンタスは有名人となり、優

雅な歓待を受け、ホワイトホール宮殿での仮面舞踏会にも出席した。1617年、ロルフ夫妻はバージニアへ渡航する予定だったが、ポカホンタスはイングラン

ド・ケント州グレイブゼンドで原因不明の死を遂げた。享年20歳か21歳。彼女はグレイブゼンドの聖ジョージ教会に埋葬されたが、火災で焼失した教会が再

建されたため、墓の正確な位置は不明である。[1]

アメリカ合衆国の多くの場所、ランドマーク、製品は、ポカホンタスの名前にちなんで名付けられている。彼女の物語は長年にわたりロマンチックに描かれ、そ

の多くは架空のものである。英国の探検家ジョン・スミスが彼女について語った物語の多くは、彼女の記録に残る子孫たちによって異議が唱えられている。

[4]

彼女は芸術、文学、映画の対象となっている。バージニアのファーストファミリー、エディス・ウィルソン元大統領夫人、アメリカの俳優グレン・ストレンジ、

天文学者パーシバル・ローウェルなど、多くの有名人が彼女の子孫であると主張している。

| Pocahontas (US:

/ˌpoʊkəˈhɒntəs/, UK: /ˌpɒk-/; born Amonute,[1] also known as Matoaka

and Rebecca Rolfe; c. 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman

belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the

colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of

Wahunsenacawh, the paramount chief[2] of a network of tributary tribes

in the Tsenacommacah (known in English as the Powhatan Confederacy),

encompassing the Tidewater region of what is today the U.S. state of

Virginia. Pocahontas was captured and held for ransom by English colonists during hostilities in 1613. During her captivity, she was encouraged to convert to Christianity and was baptized under the name Rebecca. She married the tobacco planter John Rolfe in April 1614 at the age of about 17 or 18, and she bore their son, Thomas Rolfe, in January 1615.[1] In 1616, the Rolfes travelled to London, where Pocahontas was presented to English society as an example of the "civilized savage" in hopes of stimulating investment in Jamestown. On this trip, she may have met Squanto, a Patuxet man from New England.[3] Pocahontas became a celebrity, was elegantly fêted, and attended a masque at Whitehall Palace. In 1617, the Rolfes intended to sail for Virginia, but Pocahontas died at Gravesend, Kent, England, of unknown causes, aged 20 or 21. She was buried in St George's Church, Gravesend; her grave's exact location is unknown because the church was rebuilt after being destroyed by a fire.[1] Numerous places, landmarks, and products in the United States have been named after Pocahontas. Her story has been romanticized over the years, many aspects of which are fictional. Many of the stories told about her by the English explorer John Smith have been contested by her documented descendants.[4] She is a subject of art, literature, and film. Many famous people have claimed to be among her descendants, including members of the First Families of Virginia, First Lady Edith Wilson, American actor Glenn Strange, and astronomer Percival Lowell.[5] |

ポカホンタス[Pocahontas](米国発音:

/ˌpoʊkəˈhɒntəs/、英国発音: /ˌpɒk-/、本名アモヌート[1]、別名マトーアカ、レベッカ・ロルフ。1596年頃 -

1617年3月)は、バージニア州ジェームズタウンの植民地入植地との関わりで知られる、ポウハタン族に属するネイティブアメリカンの女性である。彼女は

ワフンセナカウ(ワフンセナカウ)の娘であった。ワフンセナカウは、ツェナコマカ(英語名:ポウハタン連合)に属する複数の部族の首長であり、現在のアメ

リカ合衆国バージニア州のタイドウォーター地域を支配していた。 1613年の敵対行為の際、ポカホンタスはイギリス人入植者に捕らえられ身代金目的で拘束された。監禁中、キリスト教への改宗を勧められ、レベッカという 名で洗礼を受けた。1614年4月、17歳か18歳の時にタバコ栽培者ジョン・ロルフと結婚し、1615年1月に息子トマス・ロルフを出産した。 1616年、ロルフ夫妻はロンドンへ渡り、ポカホンタスは「文明化された野蛮人」の象徴として英国社会に紹介された。これはジェームズタウンへの投資促進 が目的であった。この渡英中、彼女はニューイングランドのパタウセット族出身者スクアントと出会った可能性がある[3]。ポカホンタスは有名人となり、優 雅な歓待を受け、ホワイトホール宮殿での仮面舞踏会にも出席した。1617年、ロルフ夫妻はバージニアへ渡航する予定だったが、ポカホンタスはイングラン ド・ケント州グレイブゼンドで原因不明の死を遂げた。享年20歳か21歳。彼女はグレイブゼンドの聖ジョージ教会に埋葬されたが、火災で焼失した教会が再 建されたため、墓の正確な位置は不明である。[1] アメリカ合衆国の多くの場所、ランドマーク、製品は、ポカホンタスの名前にちなんで名付けられている。彼女の物語は長年にわたりロマンチックに描かれ、そ の多くは架空のものである。英国の探検家ジョン・スミスが彼女について語った物語の多くは、彼女の記録に残る子孫たちによって異議が唱えられている。 [4] 彼女は芸術、文学、映画の対象となっている。バージニアのファーストファミリー、エディス・ウィルソン元大統領夫人、アメリカの俳優グレン・ストレンジ、 天文学者パーシバル・ローウェルなど、多くの有名人が彼女の子孫であると主張している。 |

| Early life Pocahontas's birth year is unknown, but some historians estimate it to have been around 1596.[1] In A True Relation of Virginia (1608), the English explorer John Smith described meeting Pocahontas in the spring of 1608 when she was "a child of ten years old".[6] In a 1616 letter, Smith again described her as she was in 1608, but this time as "a child of twelve or thirteen years of age".[7] Pocahontas was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, paramount chief of Tsenacommacah, an alliance of about thirty Algonquian-speaking groups and petty chiefdoms in the Tidewater region of the present-day U.S. state of Virginia.[8] Her mother's name and origin are unknown, but she was probably of lowly status. English adventurer Henry Spelman had lived among the Powhatan people as an interpreter, and he noted that, when one of the paramount chief's many wives gave birth, she was returned to her place of origin and supported there by the paramount chief until she found another husband.[9] However, little is known about Pocahontas's mother, and it has been theorized that she died in childbirth.[10] The Mattaponi Reservation people are descendants of the Powhatans, and their oral tradition claims that Pocahontas's mother was the first wife of Powhatan and that Pocahontas was named after her.[11] Names According to colonist William Strachey, "Pocahontas" was a childhood nickname meaning "little wanton".[12] Some interpret the meaning as "playful one".[13] In his account, Strachey describes Pocahontas as a child visiting the fort at Jamestown and playing with the young boys; she would "get the boys forth with her into the marketplace and make them wheel, falling on their hands, turning up their heels upwards, whom she would follow and wheel so herself, naked as she was, all the fort over".[14] Historian William Stith claimed that "her real name, it seems, was originally Matoax, which the Native Americans carefully concealed from the English and changed it to Pocahontas, out of a superstitious fear, lest they, by the knowledge of her true name, should be enabled to do her some hurt."[15] According to anthropologist Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas revealed her secret name to the colonists "only after she had taken another religious – baptismal – name" of Rebecca.[16] Title and status Pocahontas is frequently viewed as a princess in popular culture. In 1841, William Watson Waldron of Trinity College, Dublin, published Pocahontas, American Princess: and Other Poems, calling her "the beloved and only surviving daughter of the king".[17] She was her father's "delight and darling", according to colonist Captain Ralph Hamor,[18] but she was not in line to inherit a position as a weroance, sub-chief, or mamanatowick (paramount chief). Instead, Powhatan's brothers and sisters and his sisters' children all stood in line to succeed him.[19] In his A Map of Virginia, John Smith explained how matrilineal inheritance worked among the Powhatans: His kingdom descendeth not to his sonnes nor children: but first to his brethren, whereof he hath three namely Opitchapan, Opechanncanough, and Catataugh; and after their decease to his sisters. First to the eldest sister, then to the rest: and after them to the heires male and female of the eldest sister; but never to the heires of the males. |

幼少期 ポカホンタスの生年は不明だが、一部の歴史家は1596年頃と推定している。[1] イングランドの探検家ジョン・スミスは『バージニアの真実の記録』(1608年)の中で、1608年の春にポカホンタスと出会ったと記述している。その時 の彼女は「十歳の子供」であった[6]。1616年の手紙では、スミスは再び1608年当時の彼女について言及しているが、今度は「十二歳か十三歳の子 供」と記している。[7] ポカホンタスはパウハタン酋長の娘であった。パウハタンはツェナコマカ(現在のアメリカ合衆国バージニア州沿岸地域に存在した、約30のアルゴンキン語族 集団と小規模な首長国からなる連合体)の最高酋長であった。[8] 彼女の母親の名前と出身は不明だが、おそらく身分の低い者であった。イギリス人冒険家ヘンリー・スペルマンは通訳としてポウハタン族に滞在し、最高酋長の 複数の妻が出産する際には、出身地に戻され、新たな夫を見つけるまで最高酋長によって養われる慣習を記している。[9] しかしポカホンタスの母についてはほとんど知られておらず、出産時に死亡したとの説もある。[10] マッタポニ保留地の人々はポウハタン族の子孫であり、彼らの口承伝承によれば、ポカホンタスの母はポウハタン族の最初の妻であり、ポカホンタスはその母に 因んで名付けられたという。[11] 名前 入植者ウィリアム・ストラッチーによれば、「ポカホンタス」は幼い頃の愛称で「小さな奔放な子」を意味するという。[12] 一部では「遊び好きな者」と解釈される。[13] ストラッチーの記述によれば、ポカホンタスは幼い頃ジェームズタウンの砦を訪れ、少年たちと遊んでいた。彼女は「少年たちを市場に連れ出し、彼らに手をつ いて回転させ、かかとを上に反らせた。そして自らも裸のまま砦中を転がり回った」という。[14] 歴史家ウィリアム・スティスは「彼女の本名は元々マトアクスだったようだ。先住民はこれをイギリス人から慎重に隠し、ポカホンタスと改名した。本名を知ら れると害を及ぼされるという迷信的な恐れからだった」と主張している。[15] 人類学者ヘレン・C・ラウントリーによれば、ポカホンタスは入植者たちに秘密の名前を明かすのは「別の宗教的な名、つまり洗礼名であるレベッカを受け取っ た後」だったという。[16] 称号と地位 ポカホンタスはポピュラー・カルチャーにおいてしばしば王女と見なされる。1841年、ダブリンのトリニティ・カレッジのウィリアム・ワトソン・ウォルド ロンは『ポカホンタス、アメリカの王女:その他の詩』を出版し、彼女を「王の愛されし唯一の生き残った娘」と呼んだ。[17] 植民者のラルフ・ハモア船長によれば、彼女は父の「喜びと愛娘」であった[18]。しかし彼女は、ウェロアンス(副首長)やママナトウィック(最高首長) の地位を継承する立場にはなかった。代わりに、ポウハタンの兄弟姉妹、そして姉妹の子孫たちが彼の後継者となる資格を有していた。[19] ジョン・スミスは『バージニア地図』の中で、パウハタン族における母系相続の仕組みをこう説明している: 彼の王国は息子や子孫には継承されない。まず兄弟、すなわちオピチャパン、オペチャンカノー、カタタウの三人に継承される。彼らが亡くなれば姉妹に継承さ れる。まず最年長の姉へ、次に他の姉たちへ。その後、最年長の姉の男女の相続人へ。ただし男子の相続人には決して継承されない。 |

| Interactions with the colonists John Smith  Pocahontas saves the life of John Smith in this chromolithograph, credited to the New England Chromo. Lith. Company around 1870. The scene is idealized; there are no mountains in Tidewater, Virginia, for example, and the Powhatans lived in thatched houses rather than tipis. Pocahontas is most famously linked to colonist John Smith, who arrived in Virginia with 100 other settlers in April 1607. The colonists built a fort on a marshy peninsula on the James River, and had numerous encounters over the next several months with the people of Tsenacommacah – some of them friendly, some hostile. A hunting party led by Powhatan's close relative Opechancanough captured Smith in December 1607 while he was exploring on the Chickahominy River and brought him to Powhatan's capital at Werowocomoco. In his 1608 account, Smith describes a great feast followed by a long talk with Powhatan. He does not mention Pocahontas in relation to his capture, and claims that they first met some months later.[20][21] Margaret Huber suggests that Powhatan was attempting to bring Smith and the other colonists under his own authority. He offered Smith rule of the town of Capahosic, which was close to his capital at Werowocomoco, as he hoped to keep Smith and his men "nearby and better under control".[22] In 1616, Smith wrote a letter to Queen Anne of Denmark, the wife of King James, in anticipation of Pocahontas' visit to England. In this new account, his capture included the threat of his own death: "at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine; and not only that but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown."[7] He expanded on this in his 1624 Generall Historie, published seven years after the death of Pocahontas. He explained that he was captured and taken to the paramount chief where "two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could layd hands on him [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death."[23] Karen Ordahl Kupperman suggests that Smith used such details to embroider his first account, thus producing a more dramatic second account of his encounter with Pocahontas as a heroine worthy of Queen Anne's audience. She argues that its later revision and publication was Smith's attempt to raise his own stock and reputation, as he had fallen from favor with the London Company which had funded the Jamestown enterprise.[24] Anthropologist Frederic W. Gleach suggests that Smith's second account was substantially accurate but represents his misunderstanding of a three-stage ritual intended to adopt him into the confederacy,[25][26] but not all writers are convinced, some suggesting the absence of certain corroborating evidence.[4] Early histories did establish that Pocahontas befriended Smith and the colonists. She often went to the settlement and played games with the boys there.[14] When the colonists were starving, "every once in four or five days, Pocahontas with her attendants brought [Smith] so much provision that saved many of their lives that else for all this had starved with hunger."[27] As the colonists expanded their settlement, the Powhatans felt that their lands were threatened, and conflicts arose again. In late 1609, an injury from a gunpowder explosion forced Smith to return to England for medical care and the colonists told the Powhatans that he was dead. Pocahontas believed that account and stopped visiting Jamestown but learned that Smith was living in England when she traveled there with her husband John Rolfe.[28] |

入植者たちとの交流 ジョン・スミス  このクロモリトグラフでは、ポカホンタスがジョン・スミスの命を救っている。1870年頃、ニューイングランド・クロモ・リト・カンパニーによる作品とさ れる。この場面は理想化された描写だ。例えばバージニア州タイドウォーター地域には山はなく、ポウハタン族はティピーではなく藁葺きの家に住んでいた。 ポカホンタスは、1607年4月に100人の入植者と共にバージニアに到着したジョン・スミスと最も有名に結びついている。入植者たちはジェームズ川の湿 地帯の半島に砦を築き、その後数ヶ月にわたりツェナコマカ族の人々と数多くの接触を持った。友好的なものもあれば、敵対的なものもあった。 1607年12月、ポウハタンの近親者オペチャンカノーが率いる狩猟隊が、チカホミニー川を探検中のスミスを捕らえ、ポウハタンの首都ウェロウォコモコへ 連行した。スミスは1608年の記録で、盛大な宴とそれに続くポウハタンとの長談義について記述している。捕縛時のポカホンタスの言及はなく、二人が初め て会ったのは数か月後だと主張している。[20][21] マーガレット・フーバーは、パウハタンがスミスと他の入植者を自らの支配下に置こうとしていたと示唆している。彼はスミスに、首都ウェロコモコに近いカパ ホシックの町の統治権を提案した。スミスとその部下を「近くに置き、よりよく管理下に置きたい」と考えたからだ。[22] 1616年、スミスはポカホンタスの英国訪問を見据え、ジェームズ王の妻であるデンマークのアン王妃に書簡を送った。この新たな記述では、自身の捕縛に死 の脅威が伴っていたと記されている。「処刑の瞬間、彼女は自らの脳みそを叩き潰す危険を冒してまで私の命を救おうとした。それだけでなく、父を説得して私 をジェームズタウンへ無事に送り届けたのだ」 [7] 彼はこの話を、ポカホンタスの死から7年後に刊行された1624年の『ジェネラル・ヒストリーズ』でさらに詳述した。捕らえられた自分は最高首長の前に連 行され、「二つの大きな石がポウハタン王の前に運ばれた。すると彼(スミス)に手をかけられるだけの者が、彼を石まで引きずり、その上に彼の頭を載せた。 棍棒で脳みそを叩き潰そうと構えたその時、王の最も愛する娘ポカホンタスが、どんな懇願も通じない中、彼の頭を腕に抱え、自らの頭を彼の頭の上に載せて死 から救ったのだ。」[23] カレン・オーダール・クッパーマンは、スミスが最初の記録を脚色するためにこうした詳細を用い、ポカホンタスとの出会いをより劇的な第二の記録として作り 上げたとしている。彼女は、この記録が後に改訂・出版されたのは、スミスが自身の地位と評判を高めようとした試みだと主張する。当時スミスは、ジェームズ タウン事業に資金を提供していたロンドン会社からの支持を失っていたからだ。[24] 人類学者フレデリック・W・グリーチは、スミスの第二の記述は概ね正確だが、彼を部族連合に迎え入れるための三段階の儀礼を誤解した結果だと示唆している [25][26]。しかし全ての研究者がこれを支持しているわけではなく、裏付けとなる証拠が欠けていると指摘する者もいる。[4] 初期の歴史書は、ポカホンタスがスミスと入植者たちと親交を持ったことを確かに記している。彼女は頻繁に入植地を訪れ、そこで少年たちと遊んだ[14]。 入植者たちが飢餓状態にあった時、「4、5日に一度、ポカホンタスは従者を伴い、[スミス]に多くの食糧をもたらした。それにより多くの命が救われ、さも なければ皆飢え死にしていただろう」[27]。入植者たちが居住地を拡大するにつれ、ポウハタン族は自分たちの土地が脅かされていると感じ、再び衝突が起 きた。1609年後半、火薬爆発による負傷でスミスは治療のためイングランドへ帰国せざるを得なくなり、入植者たちはポウハタン族に彼が死亡したと伝え た。ポカホンタスはそれを信じ、ジェームズタウンを訪れるのをやめたが、夫ジョン・ロルフと共にイングランドへ渡った際、スミスが生きていることを知っ た。[28] |

Capture The abduction of Pocahontas (1624) by Johann Theodor de Bry, depicting a full narrative. Starting in the lower left, Pocahontas (center) is deceived by weroance Iopassus, who holds a copper kettle as bait, and his wife, who pretends to cry. At center right, Pocahontas is put on the boat and feasted. In the background, the action moves from the Potomac to the York River, where negotiations fail to trade a hostage and the colonists attack and burn a Native village.[29] Pocahontas' capture occurred in the context of the First Anglo-Powhatan War, a conflict between the Jamestown settlers and the Natives which began late in the summer of 1609.[30] In the first years of war, the colonists took control of the James River, both at its mouth and at the falls. In the meantime, Captain Samuel Argall pursued contacts with Native tribes in the northern portion of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom. The Patawomecks lived on the Potomac River and were not always loyal to Powhatan, and living with them was Henry Spelman, a young English interpreter. In March 1613, Argall learned that Pocahontas was visiting the Patawomeck village of Passapatanzy and living under the protection of the weroance Iopassus (also known as Japazaws).[31] With Spelman's help interpreting, Argall pressured Iopassus to assist in Pocahontas' capture by promising an alliance with the colonists against the Powhatans.[31] Iopassus, with the help of his wives, tricked Pocahontas into boarding Argall's ship, Treasurer, and held her for ransom, demanding the release of colonial prisoners held by her father and the return of various stolen weapons and tools.[32] During the year-long wait, Pocahontas was held at the English settlement of Henricus in present-day Chesterfield County, Virginia. Little is known about her life there, although colonist Ralph Hamor wrote that she received "extraordinary courteous usage" (meaning she was treated well).[33] Linwood "Little Bear" Custalow refers to an oral tradition which claims that Pocahontas was raped; Helen Rountree counters that "other historians have disputed that such oral tradition survived and instead argue that any mistreatment of Pocahontas would have gone against the interests of the English in their negotiations with Powhatan. A truce had been called, the Indians still far outnumbered the English, and the colonists feared retaliation."[34] At this time, Henricus minister Alexander Whitaker taught Pocahontas about Christianity and helped her improve her English. Upon her baptism, she took the Christian name "Rebecca".[35] In March 1614, the stand-off escalated to a violent confrontation between hundreds of colonists and Powhatan men on the Pamunkey River, and the colonists encountered a group of senior Native leaders at Powhatan's capital of Matchcot. The colonists allowed Pocahontas to talk to her tribe when Powhatan arrived, and she reportedly rebuked him for valuing her "less than old swords, pieces, or axes". She said that she preferred to live with the colonists "who loved her".[36] Possible first marriage Mattaponi tradition holds that Pocahontas' first husband was Kocoum, brother of the Patawomeck weroance Japazaws, and that Kocoum was killed by the colonists after his wife's capture in 1613.[37] Today's Patawomecks believe that Pocahontas and Kocoum had a daughter named Ka-Okee who was raised by the Patawomecks after her father's death and her mother's abduction.[38] Kocoum's identity, location, and very existence have been widely debated among scholars for centuries; the only mention of a "Kocoum" in any English document is a brief statement written about 1616 by William Strachey that Pocahontas had been living married to a "private captaine called Kocoum" for two years.[39] Pocahontas married John Rolfe in 1614, and no other records even hint at any previous husband, so some have suggested that Strachey was mistakenly referring to Rolfe himself, with the reference being later misunderstood as one of Powhatan's officers.[40] |

捕縛 ヨハン・テオドール・ド・ブリ作『ポカホンタスの誘拐』(1624年)。物語全体を描いた作品である。左下から始まる構図では、ポカホンタス(中央)が、 銅の釜を餌に差し出す首長イオパッスと、泣いているふりをするその妻に騙されている。右中央では、ポカホンタスが船に乗せられ、宴に招かれている。背景で は、ポトマック川からヨーク川へと舞台が移り、人質交換交渉が失敗すると入植者たちが先住民の村を襲撃し焼き払う。[29] ポカホンタスの捕縛は、1609年夏の終わりに始まったジェームズタウン入植者と先住民との紛争、第一次アングロ・ポウハタン戦争の文脈で発生した。 [30] 戦争初期、入植者たちはジェームズ川の河口と滝の両方を掌握した。その間、サミュエル・アーゴール大尉はパウハタン最高首長領の北部地域で先住民部族との 接触を続けた。ポタワメック族はポトマック川流域に住み、パウハタンに常に忠実とは限らなかった。彼らと共に暮らしていたのが、若い英国人通訳ヘンリー・ スペルマンである。1613年3月、アーゴールはポカホンタスがパタウォメック族の村パサパタンジーを訪れ、首長イオパスス(ジャパゾウスとも呼ばれる) の保護下で暮らしていることを知った。[31] スペルマンの通訳を得て、アーガールはイオパススに圧力をかけ、植民地側とパウハタン族に対する同盟を約束することで、ポカホンタスの捕獲への協力を迫っ た。[31] イオパススは妻たちの協力を得て、ポカホンタスを騙してアーガールの船「トレジャラー号」に乗船させ、身代金目的で彼女を拘束した。要求内容は、彼女の父 が拘束している植民地側の捕虜の解放と、盗まれた様々な武器や道具の返還であった。[32] 一年間に及ぶ身代金交渉の間、ポカホンタスは現在のバージニア州チェスターフィールド郡にあるヘンリカス英人入植地に拘束されていた。入植者のラルフ・ハ モアが「並外れた礼遇」(つまり良く扱われたという意味)を受けたと記しているものの、彼女の生活についてはほとんど知られていない。[33] リンウッド・「リトル・ベア」・カスタローは、ポカホンタスがレイプされたとする口承の伝承に言及している。ヘレン・ラウントリーは、「他の歴史家たち は、そのような口承の伝承が残っていることを争い、ポカホンタスに対する虐待は、ポウハタンとの交渉におけるイギリス側の利益に反するだろうと主張してい る」と反論している。休戦が宣言されていたが、インディアンは依然としてイギリス人よりも数で圧倒的に優勢であり、入植者たちは報復を恐れていた」と反論 している。この頃、ヘンリカスの牧師アレクサンダー・ウィテカーはポカホンタスにキリスト教を教え、彼女の英語力向上を支援した。洗礼を受けた彼女は、キ リスト教の名前「レベッカ」を名乗った。 1614年3月、パムンキー川で数百人の入植者とポウハタン族の男たちとの間で暴力的な対立が激化し、入植者たちはポウハタンの首都マッチコットで先住民 の長老たちの一団と遭遇した。ポウハタンが到着すると、入植者たちはポカホンタスに部族と話し合うことを許可し、彼女はポウハタンを「古い剣や銃、斧より も価値が低い」と叱責したと伝えられている。彼女は「自分を愛してくれる」入植者たちと共に生きることを選んだと語った。[36] 最初の結婚の可能性 マッタポニ族の伝承によれば、ポカホンタスの最初の夫はパタウォメック族の首長ジャパザウズの弟コクームであり、1613年に妻が捕らえられた後、コクー ムは入植者たちによって殺害されたとされる。[37] 現代のパタウォメック族は、ポカホンタスとコカムの間にカ・オキーという娘がおり、父の死と母の拉致後、パタウォメック族に育てられたと信じている。 [38] コクームの正体、所在、そして存在そのものは、何世紀にもわたり学者の間で広く議論されてきた。英語文書で「コクーム」に言及しているのは、ウィリアム・ ストラッチーが1616年頃に記した「ポカホンタスは『コクームという名の私兵隊長』と結婚して2年間暮らしていた」という短い記述だけである。[39] ポカホンタスは1614年にジョン・ロルフと結婚しており、それ以前の夫を示唆する記録は一切存在しない。このため、ストラッチーが誤ってロルフ自身を指 し、その記述が後にパウハタンの部下の一人と誤解されたのではないかと指摘する者もいる。[40] |

Marriage to John Rolfe Marriage of Pocahontas (1855) During her stay at Henricus, Pocahontas met John Rolfe. Rolfe's English-born wife Sarah Hacker and child Bermuda had died on the way to Virginia after the wreck of the ship Sea Venture on the Summer Isles, now known as Bermuda. He established the Virginia plantation Varina Farms, where he cultivated a new strain of tobacco. Rolfe was a pious man and agonized over the potential moral repercussions of marrying a heathen, though in fact Pocahontas had accepted the Christian faith and taken the baptismal name Rebecca. In a long letter to the governor requesting permission to wed her, he expressed his love for Pocahontas and his belief that he would be saving her soul. He wrote that he was: motivated not by the unbridled desire of carnal affection, but for the good of this plantation, for the honor of our country, for the Glory of God, for my own salvation... namely Pocahontas, to whom my hearty and best thoughts are, and have been a long time so entangled, and enthralled in so intricate a labyrinth that I was even a-wearied to unwind myself thereout.[41] The couple were married on April 5, 1614, by chaplain Richard Buck, probably at Jamestown. For two years they lived at Varina Farms, across the James River from Henricus. Their son, Thomas, was born in January 1615.[42] The marriage created a climate of peace between the Jamestown colonists and Powhatan's tribes; it endured for eight years as the "Peace of Pocahontas".[43] In 1615, Ralph Hamor wrote, "Since the wedding we have had friendly commerce and trade not only with Powhatan but also with his subjects round about us."[44] The marriage was controversial in the English court at the time because "a commoner" had "the audacity" to marry a "princess".[45][46] |

ジョン・ロルフとの結婚 ポカホンタスの結婚(1855年) ヘンリカスに滞在中、ポカホンタスはジョン・ロルフと出会った。ロルフのイギリス生まれの妻サラ・ハッカーと子供バーミューダは、バージニアへ向かう途 中、現在のバミューダ諸島であるサマー諸島で船シー・ベンチャー号が難破した際に死亡していた。彼はバージニアのプランテーション「ヴァリーナ農場」を設 立し、そこで新品種のタバコを栽培した。ロルフは敬虔な男で、異教徒との結婚がもたらす道徳的な影響に苦悩したが、実際にはポカホンタスはキリスト教を受 け入れ、洗礼名レベッカを名乗っていた。総督に結婚許可を求める長文の手紙の中で、彼はポカホンタスへの愛と、彼女を救うことになるという信念を表明し た。彼はこう記している: これは肉欲の奔放な欲望による動機ではなく、この植民地の利益のため、我が国の名誉のため、神の栄光のため、そして私自身の救いのためである... すなわちポカホンタスである。私の心は彼女に深く惹かれ、長い間複雑な迷路に絡め取られ、そこから抜け出すことすら疲れるほどであった。[41] 二人は1614年4月5日、おそらくジェームズタウンにて、牧師リチャード・バックによって結婚した。二人はその後二年、ヘンリカスの対岸にあるヴァリーナ農場に住んだ。息子トーマスは1615年1月に生まれた。[42] この結婚はジェームズタウン入植者とポウハタン部族の間に平和の雰囲気をもたらし、「ポカホンタスの平和」として八年間続いた。[43] 1615年、ラルフ・ハモアはこう記している。「結婚式以来、我々はパウハタンだけでなく、周囲の臣民たちとも友好的な交流と交易を続けている」 [44]。この結婚は当時のイングランド宮廷では物議を醸した。なぜなら「平民」が「王女」と結婚するとは「厚かましい」行為だったからだ。[45] [46] |

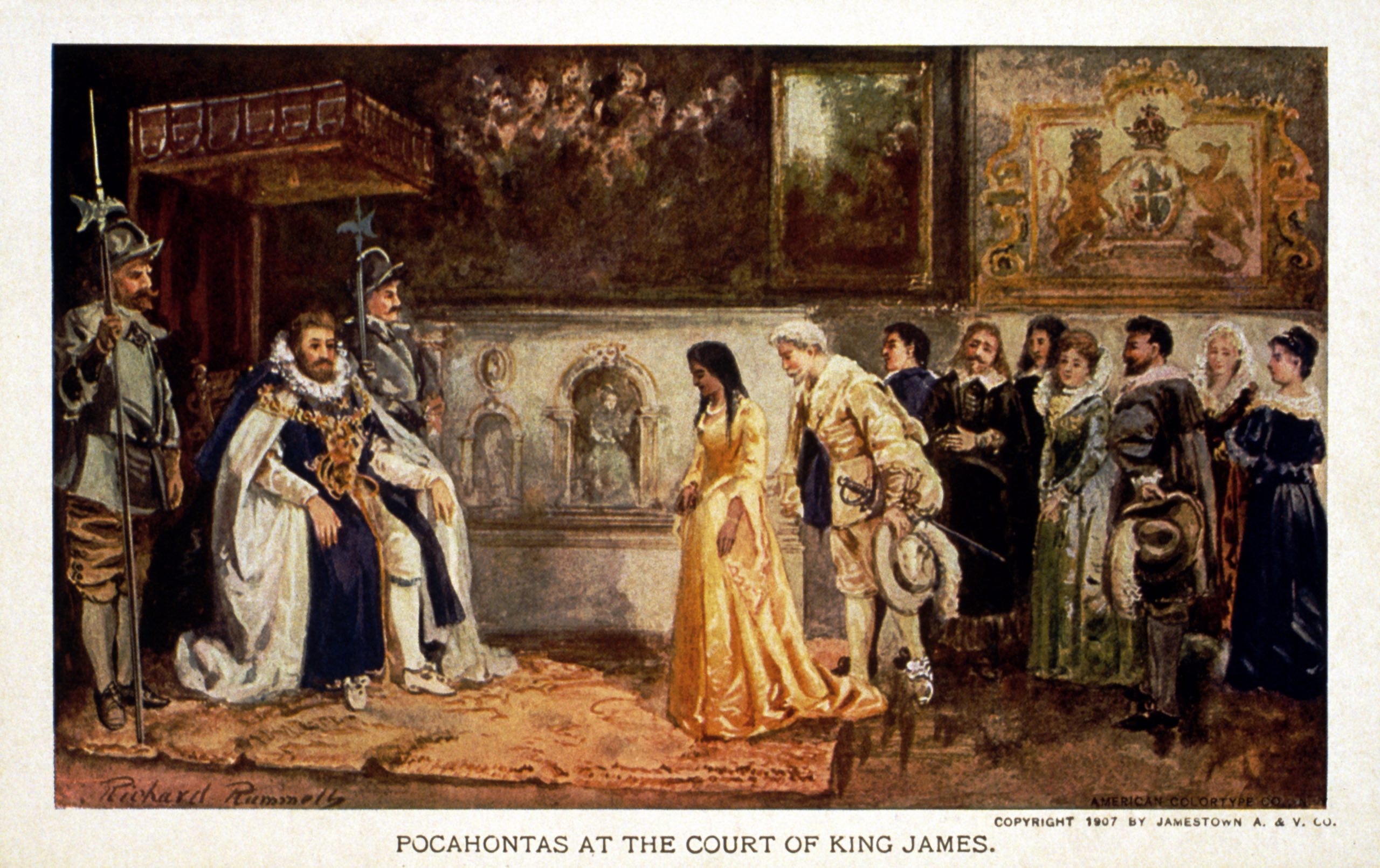

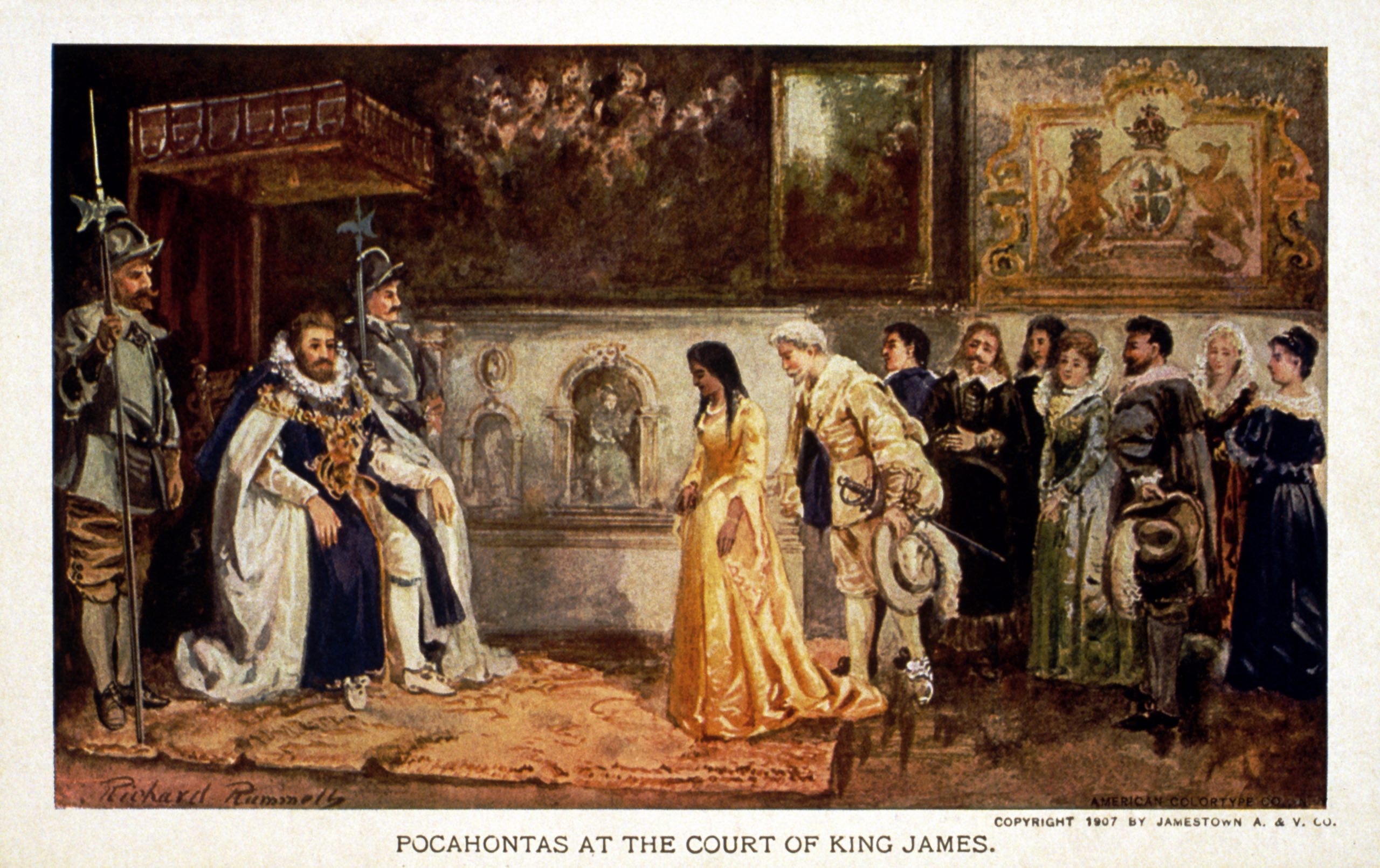

England Pocahontas at the court of King James of England One goal of the London Company was to convert Native Americans to Christianity, and they saw an opportunity to promote further investment with the conversion of Pocahontas and her marriage to Rolfe, all of which also helped end the First Anglo-Powhatan War. The company decided to bring Pocahontas to England as a symbol of the tamed New World "savage" and the success of the Virginia colony,[47] and the Rolfes arrived at the port of Plymouth on June 12, 1616.[48] The family journeyed to London by coach, accompanied by eleven other Powhatans including a holy man named Tomocomo.[49] John Smith was living in London at the time while Pocahontas was in Plymouth, and she learned that he was still alive.[50] Smith did not meet Pocahontas, but he wrote to Queen Anne urging that Pocahontas be treated with respect as a royal visitor. He suggested that, if she were treated badly, her "present love to us and Christianity might turn to... scorn and fury", and England might lose the chance to "rightly have a Kingdom by her means".[7] Pocahontas was entertained at various social gatherings. On January 5, 1617, she and Tomocomo were brought before King James at the old Banqueting House in the Palace of Whitehall at a performance of Ben Jonson's masque The Vision of Delight.[51] According to Smith, the king was so unprepossessing that neither Pocahontas nor Tomocomo realized whom they had met until it was explained to them afterward.[50] Pocahontas was not a princess in Powhatan culture, but the London Company presented her as one to the English public because she was the daughter of an important chief. The inscription on a 1616 engraving of Pocahontas reads "MATOAKA ALS REBECCA FILIA POTENTISS : PRINC : POWHATANI IMP:VIRGINIÆ", meaning "Matoaka, alias Rebecca, daughter of the most powerful prince of the Powhatan Empire of Virginia". Many English at this time recognized Powhatan as the ruler of an empire, and presumably accorded to his daughter what they considered appropriate status. Smith's letter to Queen Anne refers to "Powhatan their chief King".[7] Cleric and travel writer Samuel Purchas recalled meeting Pocahontas in London, noting that she impressed those whom she met because she "carried her selfe as the daughter of a king".[52] When he met her again in London, Smith referred to her deferentially as a "King's daughter".[53] Pocahontas was apparently treated well in London. At the masque, her seats were described as "well placed"[54] and, according to Purchas, London's Bishop John King "entertained her with festival state and pomp beyond what I have seen in his greate hospitalitie afforded to other ladies".[55] Not all the English were so impressed, however. Helen C. Rountree claims that there is no contemporaneous evidence to suggest that Pocahontas was regarded in England "as anything like royalty," despite the writings of John Smith. Rather, she was considered to be something of a curiosity, according to Rountree, who suggests that she was merely "the Virginian woman" to most Englishmen.[19] Pocahontas and Rolfe lived in the suburb of Brentford, Middlesex, for some time, as well as at Rolfe's family home at Heacham, Norfolk. In early 1617, Smith met the couple at a social gathering and wrote that, when Pocahontas saw him, "without any words, she turned about, obscured her face, as not seeming well contented," and was left alone for two or three hours. Later, they spoke more; Smith's record of what she said to him is fragmentary and enigmatic. She reminded him of the "courtesies she had done," saying, "you did promise Powhatan what was yours would be his, and he the like to you." She then discomfited him by calling him "father", explaining that Smith had called Powhatan "father" when he was a stranger in Virginia, "and by the same reason so must I do you". Smith did not accept this form of address because, he wrote, Pocahontas outranked him as "a King's daughter". Pocahontas then said, "with a well-set countenance": Were you not afraid to come into my father's country and caused fear in him and all his people (but me) and fear you here I should call you "father"? I tell you then I will, and you shall call me child, and so I will be for ever and ever your countryman.[50] Finally, Pocahontas told Smith that she and her tribe had thought him dead, but her father had told Tomocomo to seek him "because your countrymen will lie much".[50] |

イングランド イングランドのジェームズ王の宮廷におけるポカホンタス ロンドン会社の目的の一つは、ネイティブアメリカンをキリスト教に改宗させることであった。彼らはポカホンタスの改宗とロルフとの結婚を機に、さらなる投 資を促進する機会を見出した。これらはすべて、第一次アングロ・ポウハタン戦争の終結にも寄与した。会社はポカホンタスを「飼いならされた新世界の野蛮 人」とバージニア植民地の成功の象徴としてイングランドに連れて行くことを決めた[47]。そして1616年6月12日、ロルフ夫妻はプリマス港に到着し た[48]。一行は馬車でロンドンへ向かい、トモコモという名の聖職者を含む11人のパウハタン族が同行した。[49] ポカホンタスがプリマスにいる間、ジョン・スミスはロンドンに滞在しており、彼女はスミスが生存していることを知った。[50] スミスはポカホンタスと面会しなかったが、アン女王に書簡を送り、王室賓客として敬意をもって接するよう強く要請した。もし彼女を粗末に扱えば、「現在我 々やキリスト教への好意が…軽蔑と怒りに変わる」可能性があり、イングランドは「彼女を通じて正当に王国を得る機会」を失うかもしれないと述べた。[7] ポカホンタスは様々な社交行事で歓待を受けた。1617年1月5日、彼女と夫は王室賓客として王室を訪問し、アン女王と面会した。軽蔑と怒りに変わる」可 能性があり、イングランドは「彼女を通じて正当に王国を得る機会」を失うかもしれないと述べた。[7] ポカホンタスは様々な社交行事で歓待を受けた。1617年1月5日、彼女とトモコモはホワイトホール宮殿内の旧宴会場で、ベン・ジョンソンの仮面劇『歓喜 の幻影』の公演中にジェームズ王の前に連れて行かれた。[51] スミスによれば、国王はそれほど目立たない人物だったため、ポカホンタスもトモコモも、後で説明されるまで誰に会ったのか気づかなかったという。[50] ポカホンタスはパウハタン文化において王女ではなかったが、ロンドン会社は彼女を重要な酋長の娘であるとして、英国国民に王女として紹介した。1616年 のポカホンタス版画の銘文には「MATOAKA ALS REBECCA FILIA POTENTISS : PRINC : POWHATANI IMP:VIRGINIÆ」と記されている。これは「マトーアカ、別名レベッカ、バージニア州ポウハタン帝国の最強の王子の娘」を意味する。当時の多くの イギリス人はパウハタンを帝国の支配者と認識しており、おそらくその娘にも相応しい地位を与えたのだろう。スミスがアン女王に送った手紙には「彼らの首長 パウハタン王」と記されている[7]。聖職者で旅行記作家のサミュエル・パーチャスはロンドンでポカホンタスに会ったことを回想し、彼女が「王の娘らしく 振る舞っていた」ため出会った人々を感銘させたとしている。[52] ロンドンで再会した際、スミスは彼女を「王の娘」と敬意を込めて呼んだ。[53] ポカホンタスはロンドンで明らかに丁重に扱われた。仮面舞踏会では彼女の席は「良い位置」と評され[54]、パーチャスによれば、ロンドンのジョン・キン グ司教は「他の貴婦人たちに示した彼の偉大な歓待を超えた、祝祭的な格式と華やかさで彼女をもてなした」という。[55] しかし、全ての英国人がそれほど感銘を受けたわけではない。ヘレン・C・ラウントリーは、ジョン・スミスの記述にもかかわらず、ポカホンタスが英国で「王 族のような存在」と見なされていたことを示す同時代の証拠は存在しないと主張する。むしろラウントリーによれば、彼女は一種の珍品と見なされており、ほと んどの英国人にとって単なる「バージニアの女」に過ぎなかったという。[19] ポカホンタスとロルフは、ミドルセックス州ブレントフォードの郊外や、ノーフォーク州ヒーチャムにあるロルフの実家でしばらく暮らした。1617年初頭、 スミスは社交の場でこの夫婦と会い、ポカホンタスが彼を見た時「一言も発さず、顔を背け、不機嫌そうに顔を隠した」と記している。彼女はその後二、三時 間、一人にされた。後に二人はさらに会話を交わしたが、スミスが記録した彼女の言葉は断片的で謎めいている。彼女は「かつての礼儀」を思い出させ、「あな たはパウハタンに、自分のものは彼のものになると約束した。彼も同様にあなたに約束した」と言った。そして彼を当惑させるように「父」と呼び、「あなたが バージニアの異邦人だった時、パウハタンを『父』と呼んだ。同じ理由で私もあなたをそう呼ばねばならない」と説明した。スミスはこの呼び名を拒んだ。ポカ ホンタスが「王の娘」として自分より位が高いからだ。するとポカホンタスは「整った表情で」こう言った: お前は俺の父の領地に来て、父や民衆(俺を除く)を怖がらせたのに、ここで俺がお前を「父」と呼ぶのを恐れてるのか?ならばそう呼ぶと宣言する。お前は私を子と呼べ。そうすれば私は永遠に、お前たちの同胞となるのだ。[50] 最後にポカホンタスはスミスに、自分と部族はお前が死んだと思っていたが、父がトモコモにお前を探すよう命じたと伝えた。「お前たちの同胞はよく嘘をつくからな」と。[50] |

Death Statue of Pocahontas outside St George's Church, Gravesend, Kent, where she was buried in a grave now lost In March 1617, Rolfe and Pocahontas boarded a ship to return to Virginia, but they had sailed only as far as Gravesend on the River Thames when Pocahontas became gravely ill.[56] She was taken ashore, where she died from unknown causes, aged approximately 21 and "much lamented". According to Rolfe, she declared that "all must die"; for her, it was enough that her child lived.[57] Speculated causes of her death include pneumonia, smallpox, tuberculosis, hemorrhagic dysentery ("the Bloody flux") and poisoning.[58][59] Pocahontas's funeral took place on March 21, 1617, in the parish of St George's Church, Gravesend.[60] Her grave is thought to be underneath the church's chancel, though that church was destroyed in a fire in 1727 and its exact site is unknown.[61] Since 1958 she has been commemorated by a life-sized bronze statue in St. George's churchyard, a replica of the 1907 Jamestown sculpture by the American sculptor William Ordway Partridge.[62] |

死 ポカホンタスの像は、ケント州グレイブゼンドの聖ジョージ教会外にある。彼女はここに埋葬されたが、その墓は現在失われている 1617年3月、ロルフとポカホンタスはバージニアへ戻る船に乗り込んだ。しかしテムズ川のグレイブゼンドまでしか航行していないうちに、ポカホンタスは 重病に倒れた[56]。彼女は陸に運ばれ、原因不明の病で死去した。享年約21歳、「深く嘆かれた」という。ロルフによれば、彼女は「誰もが死ぬ」と宣言 し、自分の子供が生きていることだけで十分だと語ったという[57]。死因としては肺炎、天然痘、結核、出血性赤痢(「血の流れる病」)、毒殺などが推測 されている[58]。[59] ポカホンタスの葬儀は1617年3月21日、グレイブゼンドの聖ジョージ教会教区で行われた。[60] 彼女の墓は教会の聖壇の下にあると考えられているが、その教会は1727年の火災で焼失し、正確な場所は不明である。[61] 1958年以降、セント・ジョージ教会の墓地には等身大のブロンズ像が建立され、彼女が追悼されている。この像は、アメリカの彫刻家ウィリアム・オード ウェイ・パートリッジが1907年にジェームズタウンに制作した彫刻の複製である。[62] |

| Legacy Pocahontas and John Rolfe had a son, Thomas Rolfe, born in January 1615.[63] Thomas and his wife, Jane Poythress, had a daughter, Jane Rolfe,[64] who was born in Varina, in present-day Henrico County, Virginia, on October 10, 1650.[65] Jane married Robert Bolling of present-day Prince George County, Virginia. Their son, John Bolling, was born in 1676.[65] John Bolling married Mary Kennon[65] and had six surviving children, each of whom married and had surviving children.[66] In 1907, Pocahontas was the first Native American to be honored on a U.S. stamp.[67] She was a member of the inaugural class of Virginia Women in History in 2000.[68] In July 2015, the Pamunkey Native tribe became the first federally recognized tribe in the state of Virginia; they are descendants of the Powhatan chiefdom, of which Pocahontas was a member.[69] Pocahontas is the twelfth great-grandmother of the American actor Edward Norton.[70] |

遺産 ポカホンタスとジョン・ロルフの間には、1615年1月に生まれた息子トーマス・ロルフがいた。[63] トーマスとその妻ジェーン・ポイスレスの間には、1650年10月10日にバージニア州ヘンリコ郡のヴァリーナで生まれた娘ジェーン・ロルフがいた。 [64] [65] ジェーンは現在のバージニア州プリンスジョージ郡出身のロバート・ボリングと結婚した。彼らの息子ジョン・ボリングは1676年に生まれた。[65] ジョン・ボリングはメアリー・ケノンと結婚し[65]、6人の生存した子供をもうけた。それぞれの子供が結婚し、生存した子供をもうけた。[66] 1907年、ポカホンタスは米国切手に描かれた最初のネイティブアメリカンとなった[67]。彼女は2000年に創設された「バージニア州歴史上の女性た ち」の初代メンバーに選ばれた。[68] 2015年7月、パムンキー族はバージニア州で初めて連邦政府に認定された先住民族部族となった。彼らはポカホンタスが属したポウハタン首長国の末裔であ る。[69] ポカホンタスはアメリカ人俳優エドワード・ノートンの12代前の曾祖母にあたる。[70] |

| Image gallery |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pocahontas |

| Cultural representations A 19th-century depiction After her death, increasingly fanciful and romanticized representations were produced about Pocahontas, in which she and Smith are frequently portrayed as romantically involved. Contemporaneous sources substantiate claims of their friendship but not romance.[43] The first claim of their romantic involvement was in John Davis' Travels in the United States of America (1803).[72] Rayna Green has discussed the similar fetishization that Native and Asian women experience. Both groups are viewed as "exotic" and "submissive", which aids their dehumanization.[73] Also, Green touches on how Native women had to either "keep their exotic distance or die," which is associated with the widespread image of Pocahontas trying to sacrifice her life for John Smith.[73] Cornel Pewewardy writes, "In Pocahontas, Indian characters such as Grandmother Willow, Meeko, and Flit belong to the Disney tradition of familiar animals. In so doing, they are rendered as cartoons, certainly less realistic than Pocahontas and John Smith; In this way, Indians remain marginal and invisible, thereby ironically being 'strangers in their own lands' – the shadow Indians. They fight desperately on the silver screen in defense of their asserted rights, but die trying to kill the white hero or save the Indian woman."[74] |

文化的表現 19世紀の描写 彼女の死後、ポカホンタスについては、ますます空想的でロマンチックな表現が生まれ、彼女とスミスはしばしば恋愛関係にあると描かれるようになった。同時 代の資料は、彼らの友情は裏付けているが、恋愛関係については裏付けていない。[43] 彼らの恋愛関係について最初に主張したのは、ジョン・デイヴィスの『アメリカ合衆国旅行記』(1803年)である。[72] レイナ・グリーンは、ネイティブアメリカンとアジアの女性が経験する同様のフェティシズムについて論じている。どちらのグループも「エキゾチック」で「従 順」と見なされ、それが彼女たちの非人間化を助長している。[73] また、グリーンは、ネイティブアメリカンの女性が「エキゾチックな距離を保つか、死を選ぶか」を迫られたことに触れ、これは、ジョン・スミスのために自分 の命を犠牲にしようとしたポカホンタスの広く知られたイメージに関連している。[73] コーネル・ピューワーディはこう記している。「『ポカホンタス』において、ウィローおばあさん、ミーコ、フリットといったインディアンキャラクターは、 ディズニーの伝統的な『身近な動物』の範疇に属する。そうしたことで、彼らは漫画的な存在として描かれ、確かにポカホンタスやジョン・スミスよりも現実味 に欠ける。こうしてインディアンは境界的な存在であり続け、皮肉にも『自らの土地における異邦人』―影のインディアンとなる。彼らは銀幕上で自らの権利を 守るため必死に戦うが、白人ヒーローを殺そうとするか、インディアン女性を救おうとする過程で死ぬのである。」[74] |

| Stage Pocahontas: Schauspiel mit Gesang, in fünf Akten (A Play with Songs, in five Acts) by Johann Wilhelm Rose (1784) Captain Smith and the Princess Pocahontas (1806) James Nelson Barker's The Indian Princess; or, La Belle Sauvage (1808) George Washington Parke Custis, Pocahontas; or, The Settlers of Virginia (1830) John Brougham's production of the burlesque Po-ca-hon-tas, or The Gentle Savage (1855) Brougham's burlesque revised for London as La Belle Sauvage, opening at St James's Theatre, November 27, 1869[75] Sydney Grundy's Pocahontas, a comic opera, music by Edward Solomon, which opened at the Empire Theatre in London on December 26, 1884, and ran for just 24 performances with Lillian Russell in the title role and C. Hayden Coffin in his stage debut in the piece, taking the role of Captain Smith for the final six nights[76] Miss Pocahontas (Broadway musical), Lyric Theatre, New York City, October 28, 1907 Pocahontas ballet by Elliot Carter Jr., Martin Beck Theatre, New York City, May 24, 1939 Pocahontas musical by Kermit Goell, Lyric Theatre, West End, London, November 14, 1963 Stamps The Jamestown Exposition was held in Norfolk, Virginia from April 26 to December 1, 1907, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement, and three commemorative postage stamps were issued in conjunction with it. The five-cent stamp portrays Pocahontas, modeled from Simon van de Passe's 1616 engraving. About 8 million were issued.[77] Film Pocahontas had renewed popularity within the media after the release of the Pocahontas Disney film in 1995.[citation needed] Pocahontas is depicted as a "noble, romantic savage–an innocent, one with nature, and inherently good"[78] person, despite her being a Native woman only perpetuates the "single image mainstream society has of Natives as gentle, traditional, and stuck in the past."[78] Films about Pocahontas include: Pocahontas (1910), a Thanhouser Company silent short drama Pocahontas and John Smith (1924), a silent film directed by Bryan Foy Captain John Smith and Pocahontas (1953), directed by Lew Landers and starring Jody Lawrance as Pocahontas Pocahontas (1994), a Japanese animated production from Jetlag Productions directed by Toshiyuki Hiruma Takashi Pocahontas: The Legend (1995), a Canadian film based on her life Pocahontas (1995), a Walt Disney Company animated feature, one of the Disney Princess films, and the most well known adaptation of the Pocahontas story. The film presents a fictional romantic affair between Pocahontas and John Smith, in which Pocahontas teaches Smith respect for nature. Irene Bedard voiced and provided the physical model for the title character. Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World (1998), a direct-to-video Disney sequel depicting Pocahontas falling in love with John Rolfe and traveling to England The New World (2005), film directed by Terrence Malick and starring Q'orianka Kilcher as Pocahontas[79] Pocahontas: Dove of Peace (2016), a docudrama produced by Christian Broadcasting Network[80] Literature Davis, John (1803). Travels in the United States of America.[72] The first settlers of Virginia: an historical novel New York: Printed for I. Riley and Co. 1806 Lydia Sigourney's long poem Pocahontas relates her history and is the title work of her 1841 collection of poetry. Art Simon van de Passe's engraving of 1616 The abduction of Pocahontas (1619), a narrative engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry William Ordway Partridge's bronze statue (1922) of Pocahontas in Jamestown, Virginia; a replica (1958) stands in the grounds of St George's Church, Gravesend[81] Baptism of Pocahontas (1840), a painting by John Gadsby Chapman which hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building Others Lake Matoaka, an 18th-century mill pond on the campus of the College of William & Mary renamed for Pocahontas's Powhatan name in the 1920s The USS Princess Matoika, a Barbarossa-class ocean liner seized by the U.S. and used as a transport during the First World War[82] The SS Pocahontas, name of three vessels including one that Virginia Ferry Corporation completed in 1940 for Little Creek–Cape Charles Ferry, sold to Cape May–Lewes Ferry in 1963, and renamed as the SS Delaware, operating from 1964 to 1974 The USS Pocahontas (ID-3044) The Pocahontas – a passenger train of the Norfolk and Western Railway, running from Norfolk, Virginia to Cincinnati, Ohio The minor planet 4487 Pocahontas[83] |

舞台 ポカホンタス:歌付き劇、五幕(ヨハン・ヴィルヘルム・ローゼ作、1784年) スミス船長とポカホンタス姫(1806年) ジェームズ・ネルソン・バーカー作『インディアン姫、あるいは美しい野蛮人』(1808年) ジョージ・ワシントン・パーク・カスティス『ポカホンタス、あるいはバージニアの開拓者たち』(1830年) ジョン・ブロアム制作の滑稽劇『ポカホンタス、あるいは優しい野蛮人』(1855年) ブロアムの滑稽劇はロンドン向けに改訂され『ラ・ベル・サヴァージュ』として、1869年11月27日にセント・ジェームズ劇場で初演された [75] シドニー・グランディの喜劇オペラ『ポカホンタス』。音楽はエドワード・ソロモンが担当し、1884年12月26日にロンドンのエンパイア劇場で初演され た。リリアン・ラッセルがタイトルロールを演じ、C・ヘイデン・コフィンが舞台デビューを果たし、最後の6公演ではキャプテン・スミス役を演じたが、上演 回数はわずか24回だった[76] ミス・ポカホンタス(ブロードウェイミュージカル)、リリック劇場、ニューヨーク市、1907年10月28日 エリオット・カーター・ジュニアのポカホンタスバレエ、マーティン・ベック劇場、ニューヨーク市、1939年5月24日 カーミット・ゴエルのポカホンタスマジカル、リリック劇場、ウエストエンド、ロンドン、1963年11月14日 切手 1907年4月26日から12月1日まで、バージニア州ノーフォークでジェームズタウン入植300周年を記念してジェームズタウン博覧会が開催され、それ に合わせて3種類の記念切手が発行された。5セント切手には、サイモン・ヴァン・デ・パスによる1616年の彫刻をモデルにしたポカホンタスが描かれてい る。約800万枚が発行された。[77] 映画 1995年にディズニー映画『ポカホンタス』が公開された後、ポカホンタスはメディアで再び人気を博した。[出典必要] ポカホンタスは「高貴でロマンチックな野蛮人―無垢で自然と一体となり、本質的に善良な」[78]人格として描かれている。しかし彼女がネイティブの女性 であるという事実は、むしろ「主流社会がネイティブに対して抱く『穏やかで伝統的、過去に固執した存在』という単一のイメージ」[78]を永続させるだけ である。 ポカホンタスを題材とした映画には以下がある: 『ポカホンタス』(1910年)、タンハウザー・カンパニー製作の無声短編ドラマ 『ポカホンタスとジョン・スミス』(1924年)、ブライアン・フォイ監督による無声映画 『キャプテン・ジョン・スミスとポカホンタス』(1953年)、ルー・ランダーズ監督、ジョディ・ローレンス主演(ポカホンタス役) ポカホンタス(1994年)は、ジェットラグプロダクションズ制作の日本アニメ作品で、監督は平間敏之。 ポカホンタス:ザ・レジェンド(1995年)は、彼女の生涯を基にしたカナダ映画。 ポカホンタス(1995年)は、ウォルト・ディズニー・カンパニー制作のアニメ長編映画で、ディズニープリンセス作品の一つであり、ポカホンタス物語の最 も有名な映像化作品である。この映画はポカホンタスとジョン・スミスの架空の恋愛を描き、ポカホンタスがスミスに自然への敬意を教える。アイリーン・ベ ダードがタイトルキャラクターの声を担当し、実写モデルも務めた。 『ポカホンタスII 新たなる世界へ』(1998年)は、ポカホンタスがジョン・ロルフと恋に落ち、イングランドへ旅立つ様子を描いたディズニーのビデオ作品 『ニューワールド』(2005年)は、テレンス・マリック監督、コリアンカ・キルチャーがポカホンタス役を演じた映画である[79]。 『ポカホンタス:平和の鳩』(2016年)は、クリスチャン・ブロードキャスティング・ネットワークが制作したドキュメンタリードラマである[80]。 文献 デイヴィス、ジョン(1803)。『アメリカ合衆国旅行記』。[72] バージニアの最初の入植者たち:歴史小説 ニューヨーク:I. ライリー社印刷 1806年 リディア・シグニーの長い詩「ポカホンタス」は彼女の歴史を綴ったもので、1841年の詩集の表題作である。 芸術 サイモン・ヴァン・デ・パスによる1616年の彫刻 ポカホンタスの誘拐(1619年)、ヨハン・テオドール・ド・ブリによる物語的彫刻 ウィリアム・オードウェイ・パートリッジによる、バージニア州ジェームズタウンにあるポカホンタスの銅像(1922年)。その複製(1958年)は、グレイブゼンドのセント・ジョージ教会敷地内に立っている[81] ポカホンタスの洗礼(1840年)、ジョン・ガズビー・チャップマンの絵画で、アメリカ合衆国議会議事堂の円形ホールに飾られている。 その他 マトーカ湖、18世紀にウィリアム&メアリー大学のキャンパス内に造られた水車池で、1920年代にポカホンタスのパウハタン族の名前から改名された。 USSプリンセス・マトイカ号は、バルバロッサ級遠洋定期船で、第一次世界大戦中に米国が押収し、輸送船として使用した[82]。 SS ポカホンタス号は、3 隻の船舶の名称である。そのうちの 1 隻は、バージニア・フェリー社が 1940 年にリトルクリーク・ケープチャールズフェリーのために完成させ、1963 年にケープメイ・ルイスフェリーに売却され、SS デラウェア号と改名され、1964 年から 1974 年まで運航された。 USS ポカホンタス号 (ID-3044) ポカホンタス号 – ノーフォーク・アンド・ウェスタン鉄道の旅客列車。バージニア州ノーフォークからオハイオ州シンシナティまで運行した。 小惑星4487 ポカホンタス[83] |

La Malinche

– a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who played a major role in

the Spanish-Aztec War as an interpreter for the Spanish conquistador

Hernán Cortés List of kidnappings before 1900 Mary Kittamaquund – daughter of a Piscataway chief in colonial Maryland Sedgeford Hall Portrait – once thought to represent Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe but now believed to depict the wife (Pe-o-ka) and son of Seminole Chief Osceola  The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History |

ラ・マリンチェ – メキシコ湾岸出身のナワ族の女性。スペイン征服者エルナン・コルテスの通訳として、スペイン・アステカ戦争で重要な役割を果たした。 1900年以前の誘拐事件一覧 メアリー・キッタマクンド – 植民地時代のメリーランド州ピスカタウェイ族の酋長の娘 セッジフォード・ホール肖像画 – かつてはポカホンタスとトーマス・ロルフを描いたものとされたが、現在はセミノール族の酋長オセオラの妻(ペオカ)と息子を描いたものと信じられている  ポカホンタスの真実の物語:歴史の裏側 |

| References 1. Stebbins, Sarah J (August 2010). "Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 7, 2015. "A Guide to Writing about Virginia Indians and Virginia Indian History" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Virginia Council on Indians. January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012. Rose, E.M. (2020). "Did Squanto meet Pocahontas, and What Might they have Discussed?". The Junto. Retrieved September 24, 2020. Price, pp. 243–244 Shapiro, Laurie Gwen (June 22, 2014). "Pocahontas: Fantasy and Reality". Slate. The Slate Group. Retrieved April 7, 2015. Smith, True Relation Archived September 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p. 93. Smith."John Smith's 1616 Letter to Queen Anne of Great Britain". Digital History. Retrieved January 22, 2009. Huber, Margaret Williamson (January 12, 2011)."Powhatan (d. 1618)" Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Spelman, Relation. 1609. 10. Stebbins, Sarah J (August 2010). "Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend". National Park Service. Retrieved April 6, 2015. Linwood., Custalow (2007). The true story of Pocahontas : the other side of history. Daniel, Angela L. Golden, Colo.: Fulcrum Pub. ISBN 9781555916329. OCLC 560587311. Strachey, William (1849) [composed c. 1612]. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 111. Retrieved January 5, 2019. Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010). "Cooking in Early Virginia Indian Society". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 27, 2011. Strachey, Historie, p. 65 Stith, William (1865). "The History of the First Discovery and Settlement of Virginia". archive.org. p. 136. Retrieved April 8, 2014. Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010) "Uses of Personal Names by Early Virginia Indians". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Waldron, William Watson. Pocahontas, American Princess: and Other Poems (New York: Dean and Trevett, 1841), p. 8. Hamor, True Discourse. p. 802. Rountree, Helen C. (January 25, 2011). "Pocahontas (d. 1617)". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 24, 2011. 20. Lemay, J. A. Leo. Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith? Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992, p. 25. See also Birchfield, 'Did Pocahontas' Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. "Smith, A True Relation". Mith2.umd.edu. Retrieved August 10, 2013. Huber, Margaret Williamson (January 12, 2010). "Powhatan (d. 1618)". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 18, 2011. "Smith, Generall Historie, p. 49". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved August 10, 2013. Karen Ordahl Kupperman, The Jamestown Project, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007, 51–60, 125–126 Gleach, Powhatan's World, pp. 118–121. Karen Ordahl Kupperman, Indians and English, pp. 114, 174. Smith, General History, p. 152. Smith, Generall Historie, 261. Early Images of Virginia Indians: Invented Scenes for Narratives. Archived December 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Virginia Historical Society. Archived February 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved February 27, 2011. 30. Fausz, J. Frederick. "An 'Abundance of Blood Shed on Both Sides': England's First Indian War, 1609–1614". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 98:1 (January 1990), pp. 3ff. Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010). "Pocahontas (d. 1617)". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Argall, Letter to Nicholas Hawes. p. 754; Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010). "Pocahontas (d. 1617)". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Hamor, True Discourse, p. 804. Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010). "Pocahontas (d. 1617)". Encyclopedia Virginia Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 4, 2011. "Pocahontas", V28, Virginia Highway Historical Markers, accessed September 17, 2009 Dale, Letter to 'D.M.', pp. 843–844. Custalow, Dr. Linwood "Little Bear"; Daniel, Angela L. "Silver Star" (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing. pp. 43, 47, 51, 89. ISBN 9781555916329. Retrieved September 18, 2014. Deyo, William "Night Owl" (September 5, 2009). "Our Patawomeck Ancestors" (PDF). Patawomeck Tides. 12 (1): 2–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2015. Strachey, Historie, p. 54 40. Warner, Charles Dudley (2012) [first published 1881]. The Story of Pocahontas. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 18, 2014. Rolfe. Letter to Thomas Dale. p. 851. "John Rolfe". history.com. October 28, 2019. "Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend – Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". NPS. Retrieved November 28, 2015. Hamor. True Discourse. p. 809. Robert S. Tilton, Pocahontas: The Evolution of an American Narrative (Cambridge: CUP, 1994), p. 18 PBS, Race – The Power of an Illusion > Race Timeline Price, Love and Hate. p. 163. "Biography: Pocahontas—Born, 1594—Died, 1617". The Family Magazine. 4. New York: Redfield & Lindsay: 90. 1837. Retrieved August 10, 2013. Dale. Letter to Sir Ralph Winwood. p. 878. 50. Smith, General History. p. 261. Lauren Working, "James VI and I's Banqueting Houses: A Transatlantic Perspective", British Art Studies, 29 (December 2025). doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/lworking Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus. Vol. 19 p. 118. Smith, Generall Historie, p. 261. Qtd. in Herford and Simpson, eds. Ben Jonson, vol. 10, 568–569 Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus, Vol. 19, p. 118 Price, Love and Hate. p. 182. Rolfe. Letter to Edwin Sandys. p. 71. Rountree, Helen. "Pocahontas (d. 1617)" Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, (February 25, 2021). Web. September 6, 2021. Rountree considers hemorrhagic dysentery the most likely cause, as the ship's arrival in America was attended by an outbreak of the same. Dr. Linwood "Little Bear" Custalow and Angela L. Danieal "Silver Star", The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History 60. Anon. "Entry in the Gravesend St. George composite parish register recording the burial of Princess Pocahontas on 21 March 1616/1617". Medway: City Ark Document Gallery. Medway Council. Retrieved September 17, 2009. "Pocahontas". St. George's, Gravesend. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2012. "Virginia Indians Festival: reports and pictures". Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2006. "John Rolfe". History.com. December 16, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2019. "Thomas Rolfe – Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Yorktown. John Frederick Dorman, Adventurers of Purse and Person, 4th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 23–36. Henrico County Deeds & Wills 1697–1704, p. 96 "Postage Stamps – Postal Facts". "Virginia Women in History". Lva.virginia.gov. June 30, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016. Heim, Joe (July 2, 2015). "A renowned Virginia Indian tribe finally wins federal recognition". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 27, 2015. 70. Halpert, Madeline (January 5, 2023). "How actor Edward Norton is related to Pocahontas". BBC News. Retrieved January 7, 2023. "Pocahontas". npg.si.edu. Retrieved October 21, 2023. Tilton. Pocahontas. pp. 35, 41. Green, Rayna (1975). "The Pocahontas Perplex: The Image of Indian Women in American Culture". The Massachusetts Review. 16 (4). The Massachusetts Review, Inc.: 710. JSTOR 25088595. Pewewardy, Cornel (1997). "The Pocahontas Paradox: A Cautionary Tale for Educators". Journal of Navajo Education. Fall/Winter 1996/97. Clarence, Reginald (1909). "The Stage" Cyclopaedia: A Bibliography of Plays. New York: Burt Franklin. p. 42. Gänzl, Kurt (1986). The British musical theatre. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-39839-4. OCLC 59021270. Haimann, Alexander T. "Jamestown Exposition Issue". Arago: People, postage & the post. National Postal Museum online. Brown, Katrina (January 15, 2019). "Native American Stereotypes in Literature: The Noble Savage, the Utopian Man". Digital Literature Review. 6: 42–53. doi:10.33043/DLR.6.0.42-53. ISSN 2692-904X. "The New World". IMDb. January 20, 2005. Retrieved April 6, 2015. 80. Kevin Porter (November 2016). "Thanksgiving Day Film: 'Pocahontas: Dove of Peace' Reveals Christian Life of 'Emissary Between 2 Nations'". The Christian Post. "St. George's Church website (accessed 16 June 2017)". Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2017. Putnam, William Lowell (2001). The Kaiser's Merchant Ships in World War I. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0923-5. OCLC 46732396. 83. "(4487) Pocahontas". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. 2003. p. 386. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_4430. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7. |

参考文献 1. Stebbins, Sarah J (2010年8月). 「ポカホンタス:その生涯と伝説」. 国立公園局. 米国内務省. 2015年4月7日閲覧. 「バージニア州の先住民および先住民の歴史に関する執筆ガイド」 (PDF). バージニア州政府、バージニア州インディアン評議会。2012年1月。2012年2月24日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2012年7月19日に取得。 ローズ、E.M. (2020). 「スクアントはポカホンタスと会ったのか、そして彼らは何を話し合ったのか?」. ザ・ジュント. 2020年9月24日に取得。 プライス、243-244 ページ シャピロ、ローリー・グウェン (2014年6月22日)。「ポカホンタス:幻想と現実」。スレート。スレート・グループ。2015年4月7日取得。 スミス、真実の関係 2013年9月28日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、93 ページ。 スミス。「ジョン・スミスによる 1616 年の英国女王アンへの手紙」。デジタル・ヒストリー。2009 年 1 月 22 日取得。 フーバー、マーガレット・ウィリアムソン (2011 年 1 月 12 日)。「ポウハタン (1618 年没)」 エンサイクロペディア・バージニア 2017 年 5 月 3 日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2011 年 2 月 18 日取得。 スペルマン、関係。1609年。 10. ステビンズ、サラ・J(2010年8月)。「ポカホンタス:その生涯と伝説」。国立公園局。2015年4月6日取得。 リンウッド、カスタロー(2007)。ポカホンタスの真実:歴史のもう一つの側面。ダニエル、アンジェラ・L. ゴールデン、コロラド州:フルクラム出版。ISBN 9781555916329。OCLC 560587311。 ストラチェイ、ウィリアム(1849年)[1612年頃作成]。『バージニア・ブリタニアへの航海史』。ロンドン:ハクルート協会。111ページ。2019年1月5日取得。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年11月3日)。「初期バージニア・インディアン社会における調理」。『バージニア百科事典』2017年5月3日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2011年2月27日取得。 ストラッチー、『歴史』、65ページ スティス、ウィリアム(1865年)。「バージニアの最初の発見と入植の歴史」. archive.org. p. 136. 2014年4月8日取得. ラウントリー, ヘレン・C. (2010年11月3日) 「初期バージニア・インディアンによる個人的な名前の使用」. バージニア百科事典 2017年5月3日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ. 2011年2月18日取得. ウォルドロン、ウィリアム・ワトソン。『ポカホンタス、アメリカの王女:その他の詩』(ニューヨーク:ディーン・アンド・トレベット、1841年)、8ページ。 ハモール、『真実の言説』。802ページ。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2011年1月25日)。「ポカホンタス(没1617年)」。バージニア百科事典 2017年5月3日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2011年2月24日閲覧。 20. レメイ、J・A・レオ。『ポカホンタスはジョン・スミス船長を救ったのか?』ジョージア州アセンズ:ジョージア大学出版局、1992年、25頁。バーチフィールド、「ポカホンタスは」も参照。2012年6月26日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。 「スミス、真実の物語」。Mith2.umd.edu。2013年8月10日取得。 フーバー、マーガレット・ウィリアムソン(2010年1月12日)。「ポウハタン(1618年没)」。バージニア百科事典 2017年5月3日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2011年2月18日取得。 「スミス、ジェネラル・ヒストリー、49ページ」。Docsouth.unc.edu。2013年8月10日取得。 カレン・オーダール・クッパーマン、『ジェームズタウン・プロジェクト』、ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2007年、51-60、125-126 グリーチ、『ポウハタンの世界』、118-121ページ。 カレン・オーダール・クッパーマン、『インディアンとイギリス人』、114、174ページ。 スミス、『総合歴史』、152頁。 スミス、『総合歴史』、261頁。 バージニア先住民の初期イメージ:物語のための創作された場面。ウェイバックマシンに2010年12月22日アーカイブ。バージニア歴史協会。ウェイバックマシンに2012年2月25日アーカイブ。2011年2月27日取得。 30. フォーズ、J・フレデリック。「『双方に流された血の多さ』:イングランド初のインディアン戦争、1609–1614年」。『バージニア歴史伝記雑誌』98巻1号(1990年1月)、pp. 3ff。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C. (2010年12月8日). 「ポカホンタス (1617年没)」. バージニア百科事典 2017年5月3日時点のアーカイブ. 2011年2月18日閲覧. アーガル、ニコラス・ホーズ宛ての手紙。754ページ;ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年12月8日)。「ポカホンタス(没1617年)」。『バージニア百科事典』2017年5月3日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。2011年2月18日閲覧。 ハモール、『真実の言説』、804ページ。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年12月8日)。「ポカホンタス(1617年没)」。『バージニア百科事典』ウェイバックマシンに2017年5月3日アーカイブ。2011年3月4日閲覧。 「ポカホンタス」、V28、バージニア州道歴史標識、2009年9月17日閲覧 デール、『D.M.』宛ての手紙、843–844頁。 カスタロー、リンウッド・「リトル・ベア」博士;ダニエル、アンジェラ・L・「シルバー・スター」(2007年)。『ポカホンタスの真実の物語:歴史のも う一つの側面』。コロラド州ゴールデン:フルクラム出版。43、47、51、89頁。ISBN 9781555916329。2014年9月18日閲覧。 デヨ、ウィリアム「ナイト・オウル」(2009年9月5日)。「我らのパタウォメックの祖先たち」(PDF)。『パタウォメック・タイズ』12巻1号:2–7頁。2017年7月6日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブされた。2015年6月18日に取得。 ストラチェイ、『歴史』、54ページ 40. ワーナー、チャールズ・ダドリー(2012年)[初版1881年]。『ポカホンタスの物語』。プロジェクト・グーテンベルク。2014年9月18日に取得。 ロルフ. トーマス・デイルへの手紙. p. 851. 「ジョン・ロルフ」. history.com. 2019年10月28日. 「ポカホンタス:その生涯と伝説 – 植民地国立歴史公園の一部である歴史的ジェームズタウン(米国国立公園局)」. NPS. 2015年11月28日閲覧. ハモール。『真実の言説』。809ページ。 ロバート・S・ティルトン、『ポカホンタス:アメリカ物語の変遷』(ケンブリッジ:CUP、1994年)、18ページ PBS、『人種 – 幻想の力』>人種年表 プライス、『愛と憎しみ』。163ページ。 「伝記:ポカホンタス―生誕1594年―没1617年」。『ファミリー・マガジン』第4号。ニューヨーク:レッドフィールド&リンジー:90頁。1837年。2013年8月10日閲覧。 デール。ラルフ・ウィンウッド卿への書簡。878頁。 50. スミス、『一般史』。261頁。 ローレン・ワーキング「ジェームズ6世/1世の宴会場:大西洋を越えた視点」『ブリティッシュ・アート・スタディーズ』29号(2025年12月)。doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/lworking パーチャス『ハクリュートゥス・ポスチュマス』第19巻118頁。 スミス『総合歴史』261頁。 ハーフォード&シンプソン編『ベン・ジョンソン』第10巻568-569頁に引用。 パーチャス『ハクルートゥス・ポスツムス』第19巻118頁。 プライス『愛と憎しみ』182頁。 ロルフ。エドウィン・サンディス宛書簡。p. 71. ラウントリー、ヘレン。「ポカホンタス(1617年没)」『バージニア百科事典』。バージニア人文科学協会、(2021年2月25日)。ウェブ。2021 年9月6日。ラウントリーは、出血性赤痢が最も可能性の高い死因だと考えている。船がアメリカに到着した際、同じ病気の流行が確認されたからだ。 リンウッド・「リトル・ベア」・カスタロー博士とアンジェラ・L・ダニエル・「シルバー・スター」、『ポカホンタスの真実の物語:歴史の裏側』 60. 無記名。「1616年/1617年3月21日のポカホンタス王女の埋葬を記録したグレイブゼンド聖ジョージ合同教区登録簿の記載」。メドウェイ:シティ・アーク文書ギャラリー。メドウェイ評議会。2009年9月17日取得。 「ポカホンタス」。セント・ジョージ教会、グレイブゼンド。2012年2月13日オリジナルからアーカイブ。2012年5月31日取得。 「バージニア・インディアン祭:報告と写真」。2009年3月14日オリジナルからアーカイブ。2006年7月13日取得。 「ジョン・ロルフ」。History.com。2009年12月16日。2019年1月25日閲覧。 「トーマス・ロルフ – 植民地国立歴史公園の一部である歴史的ジェームズタウン(米国国立公園局)」。www.nps.gov。ヨークタウン。 ジョン・フレデリック・ドーマン、『財布と人格の冒険者たち』第4版、第3巻、23-36ページ。 ヘンリコ郡証書・遺言書 1697-1704年、96ページ 「切手 – 郵便の事実」。 「歴史上のバージニア女性」。Lva.virginia.gov。2016年6月30日。2016年12月13日閲覧。 ハイム、ジョー(2015年7月2日)。「著名なバージニア先住民部族がついに連邦政府の承認を得る」。ワシントン・ポスト。2015年10月27日閲覧。 70. Halpert, Madeline (2023年1月5日). 「俳優エドワード・ノートンとポカホンタスの関係」. BBCニュース. 2023年1月7日閲覧. 「ポカホンタス」. npg.si.edu. 2023年10月21日閲覧. ティルトン. 『ポカホンタス』. pp. 35, 41. グリーン, レイナ (1975). 「ポカホンタスの困惑:アメリカ文化におけるインディアン女性のイメージ」. 『マサチューセッツ・レビュー』. 16 (4). The Massachusetts Review, Inc.: 710. JSTOR 25088595. ペウェワーディ、コーネル(1997)。「ポカホンタスのパラドックス:教育者への警告」『ナバホ教育ジャーナル』1996/97年秋/冬号。 クラレンス、レジナルド(1909)。『舞台』サイクロペディア:戯曲書誌。ニューヨーク:バート・フランクリン。42ページ。 ガーンツル、クルト (1986)。英国のミュージカル劇場。ベージングストーク:マクミラン。ISBN 0-333-39839-4。OCLC 59021270。 ハイマン、アレクサンダー T. 「ジェームズタウン博覧会問題」。アラゴ:人々、郵便、そして郵便。国立郵便博物館オンライン。 ブラウン、カトリーナ(2019年1月15日)。「文学におけるネイティブアメリカンの固定観念:高貴な野蛮人、ユートピア的な人間」。デジタル文学レビュー。6:42–53。doi:10.33043/DLR.6.0.42-53。ISSN 2692-904X。 「新世界」。IMDb。2005年1月20日。2015年4月6日取得。 80. ケビン・ポーター(2016年11月)。「感謝祭の映画:『ポカホンタス:平和の鳩』が『二つの国の使者』のキリスト教的生活を明らかにする」。ザ・クリスチャン・ポスト。 「セント・ジョージ教会ウェブサイト(2017年6月16日アクセス)」。2015年5月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年6月16日に閲覧。 パットナム、ウィリアム・ローウェル(2001)。『第一次世界大戦におけるカイザーの商船』ノースカロライナ州ジェファーソン:マクファーランド。ISBN 978-0-7864-0923-5。OCLC 46732396。 83. 「(4487) ポカホンタス」. 小惑星名辞典. スプリンガー. 2003. p. 386. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_4430. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7. |

| Bibliography Argall, Samuel. Letter to Nicholas Hawes. June 1613. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Bulla, Clyde Robert. "Little Nantaquas." In Pocahontas and The Strangers, ed Scholastic Inc., New York. 1971. Custalow, Linwood "Little Bear" and Daniel, Angela L. "Silver Star." The True Story of Pocahontas, Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado 2007, ISBN 978-1-55591-632-9. Dale, Thomas. Letter to 'D.M.' 1614. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Dale, Thomas. Letter to Sir Ralph Winwood. June 3, 1616. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Fausz, J. Frederick. "An 'Abundance of Blood Shed on Both Sides': England's First Indian War, 1609–1614". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 98:1 (January 1990), pp. 3–56. Gleach, Frederic W. Powhatan's World and Colonial Virginia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. Hamor, Ralph. A True Discourse of the Present Estate of Virginia. 1615. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Herford, C.H. and Percy Simpson, eds. Ben Jonson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925–1952). Huber, Margaret Williamson (January 12, 2011). "Powhatan (d. 1618)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000. Lemay, J.A. Leo. Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith? Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992 Price, David A. Love and Hate in Jamestown. New York: Vintage, 2003. Purchas, Samuel. Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes. 1625. Repr. Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1905–1907. vol. 19 Rolfe, John. Letter to Thomas Dale. 1614. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998 Rolfe, John. Letter to Edwin Sandys. June 8, 1617. Repr. in The Records of the Virginia Company of London, ed. Susan Myra Kingsbuy. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1906–1935. Vol. 3 Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010). "Divorce in Early Virginia Indian Society". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010). "Early Virginia Indian Education". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved February 27, 2011. Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010). "Uses of Personal Names by Early Virginia Indians". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010). "Pocahontas (d. 1617)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved February 18, 2011. Smith, John. A True Relation of such Occurrences and Accidents of Noate as hath Hapned in Virginia, 1608. Repr. in The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631). Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 Smith, John. A Map of Virginia, 1612. Repr. in The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631), Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 Smith, John. Letter to Queen Anne. 1616. Repr. as 'John Smith's Letter to Queen Anne regarding Pocahontas'. Caleb Johnson's Mayflower Web Pages 1997, Accessed April 23, 2006. Smith, John. The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles. 1624. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Spelman, Henry. A Relation of Virginia. 1609. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. Strachey, William. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Brittania. c. 1612. Repr. London: Hakluyt Society, 1849. Symonds, William. The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia. 1612. Repr. in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith. Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986. Vol. 1 Tilton, Robert S. (1994). Pocahontas: The Evolution of an American Narrative. Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-46959-3. Waldron, William Watson. Pocahontas, American Princess: and Other Poems. New York: Dean and Trevett, 1841 Warner, Charles Dudley. Captain John Smith, 1881. Repr. in Captain John Smith Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 Woodward, Grace Steele. Pocahontas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. |

参考文献 アーガル、サミュエル。ニコラス・ホーズ宛ての手紙。1613年6月。エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編『ジェームズタウン物語集』に再録。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス、1998年。 ブラ、クライド・ロバート。「リトル・ナンタクアス」。スコラスティック社編『ポカホンタスと異邦人たち』所収。ニューヨーク、1971年。 カスタロウ、リンウッド「リトル・ベア」及びダニエル、アンジェラ・L.「シルバー・スター」共著『ポカホンタスの真実の物語』フルクラム出版、コロラド州ゴールデン、2007年、ISBN 978-1-55591-632-9。 デール、トーマス。『D.M.』宛ての手紙。1614年。『ジェームズタウン物語集』エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編に再録。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス社、1998年。 デール、トーマス。ラルフ・ウィンウッド卿への書簡。1616年6月3日。『ジェームズタウン物語集』エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編に再録。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス社、1998年。 フォーズ、J・フレデリック。「双方に流された大量の血:イングランド初のインディアン戦争、1609–1614年」。『バージニア歴史伝記雑誌』98巻1号(1990年1月)、3–56頁。 グリーチ、フレデリック・W. 『ポウハタンの世界と植民地バージニア』。リンカーン:ネブラスカ大学出版局、1997年。 ハモール、ラルフ。『バージニアの現状に関する真実の言説』。1615年。エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編『ジェームズタウン物語』に再掲載。バージニア州シャンプレーン:ラウンドハウス、1998年。 ハーフォード、C.H.、パーシー・シンプソン編。『ベン・ジョンソン』(オックスフォード:クレアンドン出版社、1925年~1952年)。 フーバー、マーガレット・ウィリアムソン(2011年1月12日)。「ポウハタン(1618年没)」。エンサイクロペディア・バージニア。2011年2月18日取得。 クッパーマン、カレン・オーダール。『インディアンとイギリス人:初期アメリカにおける対立』。ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版、2000年。 レメイ、J.A. レオ。ポカホンタスはジョン・スミス船長を救ったのか?ジョージア州アセンズ:ジョージア大学出版、1992年 プライス、デビッド・A。ジェームズタウンにおける愛と憎しみ。ニューヨーク:ヴィンテージ、2003年。 パーチャス、サミュエル。Hakluytus Posthumus または Purchas His Pilgrimes。1625年。再版。グラスゴー:ジェームズ・マクレホーズ、1905–1907年。第19巻 ロルフ、ジョン。『トマス・デイルへの手紙』。1614年。再版。『ジェームズタウン物語集』所収、編者エドワード・ライト・ヘイル。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス、1998年 ロルフ、ジョン。『エドウィン・サンディスへの手紙』。1617年6月8日。再版『ロンドン・バージニア会社記録集』スーザン・マイラ・キングスバイ編。ワシントン:米国政府印刷局、1906–1935年。第3巻 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C. (2010年11月3日). 「初期バージニア・インディアン社会における離婚」. バージニア百科事典. 2011年2月18日閲覧。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年11月3日)。「初期バージニアのインディアン教育」。『バージニア百科事典』。2011年2月27日閲覧。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年11月3日)。「初期バージニア・インディアンによる個人的な名前の用法」。『バージニア百科事典』。2011年2月18日閲覧。 ラウントリー、ヘレン・C.(2010年12月8日)。「ポカホンタス(1617年没)」。『バージニア百科事典』。2011年2月18日閲覧。 スミス、ジョン。『バージニアにおける諸事象と事故の真実の記録』(1608年)。ジョン・スミス全集(1580–1631)に再録。フィリップ・L・バーバー編。チャペルヒル:バージニア大学出版局、1983年。第1巻 スミス、ジョン。『バージニア地図』、1612年。ジョン・スミス全集(1580–1631)に再録、フィリップ・L・バーバー編。チャペルヒル:バージニア大学出版局、1983年。第1巻 スミス、ジョン。『アン女王への手紙』。1616年。『ポカホンタスに関するジョン・スミスのアン女王への手紙』として再版。カレブ・ジョンソンのメイフラワー号ウェブページ、1997年、2006年4月23日アクセス。 スミス、ジョン。『バージニア、ニューイングランド、サマー諸島の総合史』。1624年。エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編『ジェームズタウン物語集』に再録。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス、1998年。 スペルマン、ヘンリー。『バージニアに関する報告』。1609年。『ジェームズタウン物語集』に再録。エドワード・ライト・ヘイル編。バージニア州シャンプレイン:ラウンドハウス社、1998年。 ストラチェイ、ウィリアム。『バージニア・ブリタニアへの航海史』。1612年頃。再版。ロンドン:ハクルート協会、1849年。 サイモンズ、ウィリアム。『バージニアにおけるイングランド植民地の経緯』。1612年。再版『ジョン・スミス船長全集』フィリップ・L・バーバー編。チャペルヒル:ノースカロライナ大学出版局、1986年。第1巻 ティルトン、ロバート・S.(1994)。『ポカホンタス:アメリカ物語の変遷』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-46959-3。 ウォルドロン、ウィリアム・ワトソン。『ポカホンタス、アメリカの王女:その他の詩』 ニューヨーク:ディーン・アンド・トレベット、1841年 ワーナー、チャールズ・ダドリー。『キャプテン・ジョン・スミス』 1881年。キャプテン・ジョン・スミス・プロジェクト・グーテンベルク・テキストに再版、2006年7月4日アクセス ウッドワード、グレース・スティール。『ポカホンタス』 ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版、1969年。 |

| Further reading Elmer Boyd Smith, The story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1906. Neill, Rev. Edward D. Pocahontas and Her Companions. Albany: Joel Munsell, 1869. Price, David A. Love and Hate in Jamestown. Alfred A. Knopf, 2003 ISBN 0-375-41541-6 Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8061-2280-3 Strong, Pauline Turner. Animated Indians: Critique and Contradiction in Commodified Children's Culture. Cultural Anthology, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Aug. 1996), pp. 405–424 Sandall, Roger. 2001 The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays ISBN 0-8133-3863-8 Townsend, Camilla. Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004. ISBN 0-8090-7738-8 Warner, Charles Dudley, Captain John Smith, 1881. Repr. in Captain John Smith Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 Warner, Charles Dudley, The Story of Pocahontas, 1881. Repr. in The Story of Pocahontas Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 Woodward, Grace Steele. Pocahontas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. ISBN 0-8061-0835-5 or ISBN 0-8061-1642-0 Weidemeyer, John William (1900). "Powhatan" . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. Pocahontas, Alias Matoaka, and Her Descendants Through Her Marriage at Jamestown, Virginia, in April 1614, with John Rolfe, Gentleman, Wyndham Robertson, Printed by J. W. Randolph & English, Richmond, Va., 1887 |

追加文献(さらに読む) エルマー・ボイド・スミス『ポカホンタスとジョン・スミス船長の物語』ボストン:ホートン・ミフリン社、1906年。 ニール、エドワード・D・牧師『ポカホンタスとその仲間たち』オールバニ:ジョエル・マンセル社、1869年。 デイヴィッド・A・プライス著『ジェームズタウンにおける愛と憎しみ』。アルフレッド・A・クノップ社、2003年 ISBN 0-375-41541-6 ヘレン・C・ラウントリー著『ポカホンタスの民:4世紀にわたるバージニアのポウハタン族インディアン』。ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版、1990年 ISBN 0-8061-2280-3 ストロング、ポーリーン・ターナー。アニメ化されたインディアン:商品化された子供文化における批判と矛盾。文化アンソロジー、第 11 巻、第 3 号(1996 年 8 月)、405-424 ページ サンドール、ロジャー。2001年 『カルト文化:デザイナー部族主義とその他のエッセイ』 ISBN 0-8133-3863-8 タウンゼント、カミラ。ポカホンタスとポウハタン族のジレンマ。ニューヨーク:ヒル・アンド・ワン、2004年。ISBN 0-8090-7738-8 ワーナー、チャールズ・ダドリー、『キャプテン・ジョン・スミス』、1881年。キャプテン・ジョン・スミス・プロジェクト・グーテンベルク・テキストに再掲載、2006年7月4日アクセス ワーナー、チャールズ・ダドリー、『ポカホンタスの物語』、1881年。ポカホンタスの物語・プロジェクト・グーテンベルク・テキストに再掲載、2006年7月4日アクセス ウッドワード、グレース・スティール。ポカホンタス。ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版、1969年。ISBN 0-8061-0835-5 または ISBN 0-8061-1642-0 ワイデマイヤー、ジョン・ウィリアム (1900)。「ポウハタン」 『アップルトンズ・サイクロペディア・オブ・アメリカン・バイオグラフィー』 ポカホンタス、別名マトアカ、および 1614 年 4 月、バージニア州ジェームズタウンで紳士ジョン・ロルフと結婚した彼女の子孫たち、ウィンダム・ロバートソン、J. W. ランドルフ&イングリッシュ印刷、バージニア州リッチモンド、1887 年 |

| Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend – National Park Service – Historic Jamestowne "Contact and Conflict". The Story of Virginia: An American Experience. Virginia Historical Society. "The Anglo-Powhatan Wars". The Story of Virginia: An American Experience. Virginia Historical Society. Virtual Jamestown. Includes text of many original accounts "The Pocahontas Archive", a comprehensive bibliography of texts about Pocahontas On this day in history: Pocahontas marries John Rolfe, History.com Michals, Debra. "Pocahontas". National Women's History Museum. 2015. |

ポカホンタス:その生涯と伝説 – 国立公園局 – 歴史的ジェームズタウン 「接触と衝突」。バージニア物語:アメリカ体験。バージニア歴史協会。 「アングロ=ポウハタン戦争」。バージニア物語:アメリカ体験。バージニア歴史協会。 バーチャル・ジェームズタウン。多くの原典記録のテキストを含む 「ポカホンタス・アーカイブ」。ポカホンタスに関する文献の包括的な書誌 歴史上のこの日:ポカホンタスがジョン・ロルフと結婚、History.com ミカルズ、デブラ。「ポカホンタス」。国立女性歴史博物館。2015年。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099