人種と遺伝学

Race and genetics

☆研究者たちは、生物学が人間の人種分類にどのように寄与しているのか、あるいは寄与していない のかを理解する努力の一環として、人種と遺伝学(race and genetics)の関係を調査してきた。今日、科学者の間では、人種は社 会的構築物であり、集団間の遺伝的差異の代理として人種を用いることは誤解を招くというのがコンセンサスとなっている。 人種に関する多くの概念は、表現型形質や地理的祖先と関連しており、カール・リンネのような学者は、少なくとも18世紀以降、人種組織に関する科学的モデ ルを提唱してきた。メンデル遺伝学の発見とヒトゲノムのマッピングの後、人種の生物学に関する疑問はしばしば遺伝学の観点から組み立てられてきた。個々の 形質の研究、大規模集団と遺伝的クラスターの研究、疾病の遺伝的危険因子の研究など、ヒトの変異のパターンと祖先や人種集団との関係を調べるために幅広い 研究方法が採用されてきた。 また、人種と遺伝に関する研究は、科学的人種差別から生まれたもの、あるいは科学的 人種差別に加担するものとして批判されてきた。形質や集団に関する遺伝学的研究は、人種に関連する社会的不平等を正当化するために利用されてきた。ヒトの 変異のパターンはほとんどがクローナルであることが示されており、ヒトの遺伝暗号は個人間で約99.6%~99.9%同一であり、集団間の明確な境界がな いという事実にもかかわらず、である。 一部の研究者は、同じ人種カテゴリーに属する個人は共通の祖先を共有している可能性があるため、人種は遺伝的祖先の代理として機能することができると主張 しているが、この見解は専門家の間では次第に支持されなくなってきている。主流的な見解は、生物学と、人種に関する概念に寄与している社会的、政治的、文 化的、経済的要因を区別する必要があるというものである。 表現型はDNAと間接的な関係を持つかもしれないが、それでも他の様々な遺伝情報を省略した大まかな代理でしかない。今日、「ジェンダー」がより明確な「生物学的性別」と区別されるのと多少似たような方法で、科 学者たちは潜在的に「人種」/表現型はより明確な「祖先」と区別することができると述べている。しかし、このシステムもまた、同じ問題——遺伝的価値のほ とんどない、大きくて曖昧なグループ分け——に陥る可能性があるとして、依然として批判を受けている。

| Researchers have

investigated the relationship between race and genetics as part of

efforts to understand how biology may or may not contribute to human

racial categorization. Today, the consensus among scientists is that

race is a social construct, and that using it as a proxy for genetic

differences among populations is misleading.[1][2] Many constructions of race are associated with phenotypical traits and geographic ancestry, and scholars like Carl Linnaeus have proposed scientific models for the organization of race since at least the 18th century. Following the discovery of Mendelian genetics and the mapping of the human genome, questions about the biology of race have often been framed in terms of genetics.[3] A wide range of research methods have been employed to examine patterns of human variation and their relations to ancestry and racial groups, including studies of individual traits,[4] studies of large populations and genetic clusters,[5] and studies of genetic risk factors for disease.[6] Research into race and genetics has also been criticized as emerging from, or contributing to, scientific racism. Genetic studies of traits and populations have been used to justify social inequalities associated with race,[7] despite the fact that patterns of human variation have been shown to be mostly clinal,[8] with human genetic code being approximately 99.6%-99.9% identical between individuals and without clear boundaries between groups.[9] Some researchers have argued that race can act as a proxy for genetic ancestry because individuals of the same racial category may share a common ancestry, but this view has fallen increasingly out of favor among experts.[2][10] The mainstream view is that it is necessary to distinguish between biology and the social, political, cultural, and economic factors that contribute to conceptions of race.[11][12] Phenotype may have a tangential connection to DNA, but it is still only a rough proxy that would omit various other genetic information.[2][13][14] Today, in a somewhat similar way that "gender" is differentiated from the more clear "biological sex", scientists state that potentially "race" / phenotype can be differentiated from the more clear "ancestry".[15] However, this system has also still come under scrutiny as it may fall into the same problems – which would be large, vague groupings with little genetic value.[16] |

研究者たちは、生物学が人間の人種分類にどのように寄与しているのか、

あるいは寄与していないのかを理解する努力の一環として、人種と遺伝学の関係を調査してきた。今日、科学者の間では、人種は社会的構築物であり、集団間の

遺伝的差異の代理として人種を用いることは誤解を招くというのがコンセンサスとなっている[1][2]。 人種に関する多くの概念は、表現型形質や地理的祖先と関連しており、カール・リンネのような学者は、少なくとも18世紀以降、人種組織に関する科学的モデ ルを提唱してきた。メンデル遺伝学の発見とヒトゲノムのマッピングの後、人種の生物学に関する疑問はしばしば遺伝学の観点から組み立てられてきた[3]。 個々の形質の研究[4]、大規模集団と遺伝的クラスターの研究[5]、疾病の遺伝的危険因子の研究[6]など、ヒトの変異のパターンと祖先や人種集団との 関係を調べるために幅広い研究方法が採用されてきた。 また、人種と遺伝に関する研究は、科学的人種差別から生まれたもの、あるいは科学的人種差別に加担するものとして批判されてきた。形質や集団に関する遺伝 学的研究は、人種に関連する社会的不平等を正当化するために利用されてきた[7]。ヒトの変異のパターンはほとんどがクローナルであることが示されており [8]、ヒトの遺伝暗号は個人間で約99.6%~99.9%同一であり、集団間の明確な境界がないという事実にもかかわらず、である[9]。 一部の研究者は、同じ人種カテゴリーに属する個人は共通の祖先を共有している可能性があるため、人種は遺伝的祖先の代理として機能することができると主張 しているが、この見解は専門家の間では次第に支持されなくなってきている[2][10]。主流的な見解は、生物学と、人種に関する概念に寄与している社会 的、政治的、文化的、経済的要因を区別する必要があるというものである[11][12]。 表現型はDNAと間接的な関係を持つかもしれないが、それでも他の様々な遺伝情報を省略した大まかな代理でしかない[2][13][14]。今日、「ジェ ンダー」がより明確な「生物学的性別」と区別されるのと多少似たような方法で、科学者たちは潜在的に「人種」/表現型はより明確な「祖先」と区別すること ができると述べている[15]。しかし、このシステムもまた、同じ問題-遺伝的価値のほとんどない、大きくて曖昧なグループ分け-に陥る可能性があるとし て、依然として批判を受けている[16]。 |

| Overview The concept of race See also: Race (human categorization) The concept of "race" as a classification system of humans based on visible physical characteristics emerged over the last five centuries, influenced by European colonialism.[11][17] However, there is widespread evidence of what would be described in modern terms as racial consciousness throughout the entirety of recorded history. For example, in Ancient Egypt there were four broad racial divisions of human beings: Egyptians, Asiatics, Libyans, and Nubians.[18] There was also Aristotle of Ancient Greece, who once wrote: "The peoples of Asia... lack spirit, so that they are in continuous subjection and slavery."[19] The concept has manifested in different forms based on social conditions of a particular group, often used to justify unequal treatment. Early influential attempts to classify humans into discrete races include 4 races in Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae (Homo europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer)[20][21] and 5 races in Johann Friedrich Blumenbach's On the Natural Variety of Mankind.[22] Notably, over the next centuries, scholars argued for anywhere from 3 to more than 60 race categories.[23] Race concepts have changed within a society over time; for example, in the United States social and legal designations of "White" have been inconsistently applied to Native Americans, Arab Americans, and Asian Americans, among other groups (See main article: Definitions of whiteness in the United States). Race categories also vary worldwide; for example, the same person might be perceived as belonging to a different category in the United States versus Brazil.[24] Because of the arbitrariness inherent in the concept of race, it is difficult to relate it to biology in a straightforward way. Race and human genetic variation There is broad consensus across the biological and social sciences that race is a social construct, not an accurate representation of human genetic variation.[25][9] As more progress has been made on sequencing the human genome, it has been found that any two humans will share an average of 99.35% of their DNA based on the approximately 3.1 billion haploid base pairs.[26][27] However, this number should be understood as an average, any two specific individuals can have their genomes differ by more or less than 0.65%. Additionally, this average is an estimate, subject to change as additional sequences are discovered and populations sampled. In 2010, the genome of Craig Venter was found to differ by an estimated 1.59% from a reference genome created by the National Center for Biotechnology Information.[28] We nonetheless see wide individual variation in phenotype, which arises from both genetic differences and complex gene-environment interactions. The vast majority of this genetic variation occurs within groups; very little genetic variation differentiates between groups.[5] Crucially, the between-group genetic differences that do exist do not map onto socially recognized categories of race. Furthermore, although human populations show some genetic clustering across geographic space, human genetic variation is "clinal", or continuous.[11][9] This, in addition to the fact that different traits vary on different clines, makes it impossible to draw discrete genetic boundaries around human groups. Finally, insights from ancient DNA are revealing that no human population is "pure" – all populations represent a long history of migration and mixing.[29] |

概要 人種の概念 こちらも参照のこと: 人種(人間の分類) 目に見える身体的特徴に基づく人間の分類システムとしての「人種」という概念は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義の影響を受けて、過去5世紀にわたって出現した [11][17]。しかし、記録された歴史全体を通して、現代の言葉で人種意識と表現されるような証拠が広く存在する。例えば、古代エジプトでは、人間に は4つの大まかな人種区分があった: 古代ギリシアのアリストテレスもまた、「アジアの諸民族は......精神が欠如しているため、絶えず服従と奴隷の状態にある」[19]と書いている。人 間を個別の人種に分類する初期の影響力のある試みとしては、カール・リンネの『自然体系』における4つの人種(ホモ・ヨーロッパ人、アジア人、アメリカ 人、アファー人)[20][21]、ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ブルーメンバッハの『人類の自然的多様性について』における5つの人種が挙げられる[22]。 [例えば、アメリカでは「白人」という社会的・法的呼称は、他のグループの中でもネイティブ・アメリカン、アラブ系アメリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人に対し て一貫して適用されていない(主要記事:アメリカにおける白人の定義参照)。人種という概念には恣意性が内在しているため、それを生物学と単純に関連付け ることは難しい。 人種とヒトの遺伝的変異 ヒトゲノムの解読が進むにつれ、約31億のハプロイド塩基対に基づき、2人のヒトは平均99.35%のDNAを共有していることが判明している[26] [27]。しかし、この数字は平均値として理解されるべきであり、特定の2人のゲノムは0.65%以上異なることもあれば、0.65%以下異なることもあ る。さらに、この平均値は推定値であり、新たな配列が発見され、個体群がサンプリングされるにつれて変化する可能性がある。2010年、クレイグ・ヴェン ターのゲノムは、全米バイオテクノロジー情報センターが作成した参照ゲノムと推定1.59%の差があることが判明した[28]。 それにもかかわらず、私たちは、遺伝的差異と複雑な遺伝子-環境相互作用の両方から生じる、表現型の幅広い個人差を目の当たりにしている。この遺伝的変異 の大部分は集団内で生じており、集団間で分化する遺伝的変異はごくわずかである。さらに、ヒトの集団は地理的空間にわたってある程度の遺伝的クラスターを 示すものの、ヒトの遺伝的変異は「クリン」、つまり連続的である[11][9]。このことは、異なる形質が異なるクリン上で変化するという事実に加えて、 ヒトの集団の周囲に個別の遺伝的境界線を引くことを不可能にしている。最後に、古代DNAからの洞察は、どのようなヒト集団も 「純粋 」ではないことを明らかにしつつある。 |

| Sources of human genetic variation Main article: Human genetic variation Genetic variation arises from mutations, from natural selection, migration between populations (gene flow) and from the reshuffling of genes through sexual reproduction.[30] Mutations lead to a change in the DNA structure, as the order of the bases are rearranged. Resultantly, different polypeptide proteins are coded. Some mutations may be positive and can help the individual survive more effectively in their environment. Mutation is counteracted by natural selection and by genetic drift; note too the founder effect, when a small number of initial founders establish a population which hence starts with a correspondingly small degree of genetic variation.[31] Epigenetic inheritance involves heritable changes in phenotype (appearance) or gene expression caused by mechanisms other than changes in the DNA sequence.[32] Human phenotypes are highly polygenic (dependent on interaction by many genes) and are influenced by environment as well as by genetics. Nucleotide diversity is based on single mutations, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The nucleotide diversity between humans is about 0.1 percent (one difference per one thousand nucleotides between two humans chosen at random). This amounts to approximately three million SNPs (since the human genome has about three billion nucleotides). There are an estimated ten million SNPs in the human population.[33] Research has shown that non-SNP (structural) variation accounts for more human genetic variation than single nucleotide diversity. Structural variation includes copy-number variation and results from deletions, inversions, insertions and duplications. It is estimated that approximately 0.4 to 0.6 percent of the genomes of unrelated people differ.[9][34] |

ヒトの遺伝的変異の原因 主な記事 ヒトの遺伝的変異 遺伝的変異は、突然変異、自然淘汰、集団間の移動(遺伝子フロー)、有性生殖による遺伝子の入れ替えによって生じる[30]。突然変異は、塩基の順番が入 れ替わることでDNA構造に変化をもたらす。その結果、異なるポリペプチドタンパク質がコード化される。突然変異の中にはポジティブなものもあり、その個 体が環境でより効果的に生き残るのに役立つこともある。突然変異は、自然淘汰や遺伝的ドリフトによって打ち消される。創始者効果とは、少数の創始者が集団 を形成し、その集団がそれに応じて遺伝的変異の程度が小さくなることである[31]。エピジェネティック遺伝には、DNA配列の変化以外のメカニズムに よって引き起こされる、表現型(外見)や遺伝子発現における遺伝可能な変化が含まれる[32]。 ヒトの表現型は高度に多遺伝子性(多くの遺伝子による相互作用に依存する)であり、遺伝だけでなく環境の影響を受ける。 ヌクレオチドの多様性は、単一の変異、一塩基多型(SNP)に基づいている。ヒト間のヌクレオチド多様性は約0.1%(ランダムに選ばれた2人のヒトの間 で、1000ヌクレオチドあたり1つの違い)である。これは約300万個のSNPに相当する(ヒトゲノムのヌクレオチドは約30億個なので)。ヒト集団に は推定1000万個のSNPが存在する[33]。 SNP以外の(構造的)変異は、一塩基の多様性よりもヒトの遺伝的変異の多くを占めていることが研究で示されている。構造的変異にはコピー数の変異が含ま れ、欠失、逆位、挿入、重複に起因する。無関係な人々のゲノムの約0.4~0.6%が異なっていると推定されている[9][34]。 |

| Genetic basis for race Much scientific research has been organized around the question of whether or not there is genetic basis for race. In Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza's book (circa 1994) "The History and Geography of Human Genes"[35] he writes, "From a scientific point of view, the concept of race has failed to obtain any consensus; none is likely, given the gradual variation in existence. It may be objected that the racial stereotypes have a consistency that allows even the layman to classify individuals. However, the major stereotypes, all based on skin color, hair color and form, and facial traits, reflect superficial differences that are not confirmed by deeper analysis with more reliable genetic traits and whose origin dates from recent evolution mostly under the effect of climate and perhaps sexual selection". In 2018 geneticist David Reich reaffirmed the conclusion that the traditional views which assert a biological basis for race are wrong: Today, many people assume that humans can be grouped biologically into "primeval" groups, corresponding to our notion of "races"... But this long-held view about "race" has just in the last years been proven wrong. — David Reich, Who We Are and How We Got Here, (Introduction, pg. xxiv). In 1956, some scientists proposed that race may be similar to dog breeds within dogs. However, this theory has since been discarded, with one of the main reasons being that purebred dogs have been specifically bred artificially, whereas human races developed organically.[36] Furthermore, the genetic variation between purebred dog breeds is far greater than that of human populations. Dog-breed intervariation is roughly 27.5%, whereas human populations inter-variation is only at 10-15.6%.[37][38][39][40] Including non purebreds would substantially decrease the 27.5% genetic variance, however. Mammal taxonomy is rarely defined by genetic variance alone. |

人種の遺伝的基盤 多くの科学的研究は、人種に遺伝的基盤があるかどうかという問題を中心に整理されてきた。ルイジ・ルカ・カヴァッリ=スフォルツァの著書(1994年頃) 『人類遺伝子の歴史と地理』[35]の中で、彼はこう書いている。「科学的見地から見ると、人種という概念はコンセンサスを得ることができなかった。人種 的ステレオタイプには、素人でも個人を分類できる一貫性があると反論されるかもしれない。しかし、肌の色、髪の色と形、顔の特徴に基づく主要なステレオタ イプは、表面的な違いを反映したものであり、より信頼性の高い遺伝的特徴を用いた深い分析では確認できない。 2018年、遺伝学者のデイヴィッド・ライヒは、人種に生物学的根拠があるとする従来の見解は間違っているという結論を再確認した: 今日、多くの人々が、人間は生物学的に 「原始的な 」グループに分類できると考えている。しかし、この「人種」に関する長年の見解は、ここ数年で間違いであることが証明された。 - デイヴィッド・ライヒ『われわれは何者か、そしていかにしてここに来たか』(序章、xxiv頁)。 1956年、一部の科学者は、人種は犬の中の犬種に似ているのではないかと提唱した。しかしその後、この説は破棄された。その主な理由のひとつは、純血種 の犬は特別に人為的に繁殖されたのに対し、人間の人種は有機的に発展してきたからである[36]。さらに、純血種の犬種間の遺伝的変異は、人間の個体群よ りもはるかに大きい。犬種間の遺伝的変異はおよそ27.5%であるのに対し、人間集団の遺伝的変異は10~15.6%にすぎない[37][38][39] [40]。しかし、純血種以外を含めると、27.5%の遺伝的変異は大幅に減少することになる。哺乳類の分類学が遺伝的変異だけで定義されることはほとん どない。 |

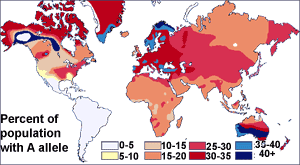

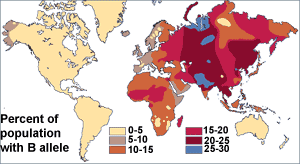

| Research methods Scientists investigating human variation have used a series of methods to characterize how different populations vary. Early studies of traits, proteins, and genes See also: Race (classification of human beings) Early racial classification attempts measured surface traits, particularly skin color, hair color and texture, eye color, and head size and shape. (Measurements of the latter through craniometry were repeatedly discredited in the late 19th and mid-20th centuries due to a lack of correlation of phenotypic traits with racial categorization.[41]) In actuality, biological adaptation plays the biggest role in these bodily features and skin type. A relative handful of genes accounts for the inherited factors shaping a person's appearance.[42][43] Humans have an estimated 19,000–20,000 human protein-coding genes.[44] Richard Sturm and David Duffy describe 11 genes that affect skin pigmentation and explain most variations in human skin color, the most significant of which are MC1R, ASIP, OCA2, and TYR.[45] There is evidence that as many as 16 different genes could be responsible for eye color in humans; however, the main two genes associated with eye color variation are OCA2 and HERC2, and both are localized in chromosome 15.[46] Analysis of blood proteins and between-group genetics Multicolored world map  Geographic distribution of blood group A Multicolored world map  Geographic distribution of blood group B Before the discovery of DNA, scientists used blood proteins (the human blood group systems) to study human genetic variation. Research by Ludwik and Hanka Herschfeld during World War I found that the incidence of blood groups A and B differed by region; for example, among Europeans 15 percent were group B and 40 percent group A. Eastern Europeans and Russians had a higher incidence of group B; people from India had the greatest incidence. The Herschfelds concluded that humans comprised two "biochemical races", originating separately. It was hypothesized that these two races later mixed, resulting in the patterns of groups A and B. This was one of the first theories of racial differences to include the idea that human variation did not correlate with genetic variation. It was expected that groups with similar proportions of blood groups would be more closely related, but instead it was often found that groups separated by great distances (such as those from Madagascar and Russia), had similar incidences.[47] It was later discovered that the ABO blood group system is not just common to humans, but shared with other primates,[48] and likely predates all human groups.[49] In 1972, Richard Lewontin performed a FST statistical analysis using 17 markers (including blood-group proteins). He found that the majority of genetic differences between humans (85.4 percent) were found within a population, 8.3 percent were found between populations within a race and 6.3 percent were found to differentiate races (Caucasian, African, Mongoloid, South Asian Aborigines, Amerinds, Oceanians, and Australian Aborigines in his study). Since then, other analyses have found FST values of 6–10 percent between continental human groups, 5–15 percent between different populations on the same continent and 75–85 percent within populations.[50][51][52][53][54] This view has been affirmed by the American Anthropological Association and the American Association of Physical Anthropologists since.[55] Critiques of blood protein analysis While acknowledging Lewontin's observation that humans are genetically homogeneous, A. W. F. Edwards in his 2003 paper "Human Genetic Diversity: Lewontin's Fallacy" argued that information distinguishing populations from each other is hidden in the correlation structure of allele frequencies, making it possible to classify individuals using mathematical techniques. Edwards argued that even if the probability of misclassifying an individual based on a single genetic marker is as high as 30 percent (as Lewontin reported in 1972), the misclassification probability nears zero if enough genetic markers are studied simultaneously. Edwards saw Lewontin's argument as based on a political stance, denying biological differences to argue for social equality.[56] Edwards' paper is reprinted, commented upon by experts such as Noah Rosenberg, and given further context in an interview with philosopher of science Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther in a recent anthology.[57] As referred to before, Edwards criticises Lewontin's paper as he took 17 different traits and analysed them independently, without looking at them in conjunction with any other protein. Thus, it would have been fairly convenient for Lewontin to come up with the conclusion that racial naturalism is not tenable, according to his argument.[58] Sesardic also strengthened Edwards' view, as he used an illustration referring to squares and triangles, and showed that if you look at one trait in isolation, then it will most likely be a bad predicator of which group the individual belongs to.[59] In contrast, in a 2014 paper, reprinted in the 2018 Edwards Cambridge University Press volume, Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther argues that "Lewontin's Fallacy" is effectively a misnomer, as there really are two different sets of methods and questions at play in studying the genomic population structure of our species: "variance partitioning" and "clustering analysis." According to Winther, they are "two sides of the same mathematics coin" and neither "necessarily implies anything about the reality of human groups."[60] |

研究方法 ヒトの変異を研究する科学者たちは、異なる集団がどのように異なるかを特徴付けるために、一連の方法を用いてきた。 形質、タンパク質、遺伝子の初期の研究 以下も参照のこと: 人種(人間の分類) 初期の人種分類の試みは、表面的な形質、特に皮膚の色、髪の色と質感、目の色、頭の大きさと形を測定した。(後者の頭蓋測定による測定は、19世紀後半か ら20世紀半ばにかけて、表現型形質と人種分類との相関が認められなかったため、繰り返し否定された[41])。実際には、これらの身体的特徴や肌のタイ プには、生物学的適応が最も大きな役割を果たしている。ヒトには推定19,000-20,000のヒトのタンパク質をコードする遺伝子がある[44]。リ チャード・スタームとデイヴィッド・ダフィーは、皮膚の色素沈着に影響し、ヒトの肌の色のほとんどのバリエーションを説明する11の遺伝子について述べて いる。 [45] ヒトの目の色については、16もの異なる遺伝子が関与している可能性があるという証拠がある;しかしながら、目の色の変化に関連する主な2つの遺伝子は OCA2とHERC2であり、どちらも第15染色体に局在している[46]。 血液タンパク質の分析とグループ間遺伝学 多色世界地図  血液型Aの地理的分布 多色世界地図  血液型Bの地理的分布 DNAが発見される以前、科学者は血液タンパク質(ヒト血液型)を使ってヒトの遺伝的変異を研究していた。第一次世界大戦中のルドウィク・ヘルシュフェル ドとハンカ・ヘルシュフェルドの研究によると、血液型A群とB群の発生率は地域によって異なっていた。例えば、ヨーロッパ人では15%がB群、40%がA 群であった。ハーシュフェルド夫妻は、人類は2つの 「生化学的人種 」から構成され、別々に生まれたと結論づけた。この2つの人種が後に混合し、A群とB群のパターンになったという仮説が立てられたのである。血液型の比率 が似ているグループはより近縁であると予想されたが、その代わりに、(マダガスカルとロシアのような)遠く離れたグループでも同じような発生率であること がしばしば発見された[47]。後に、ABO式血液型システムはヒトだけに共通するものではなく、他の霊長類とも共有されており[48]、おそらくすべて のヒトグループよりも古くから存在していたことが発見された[49]。 1972年、リチャード・ルウォンティンは17のマーカー(血液型タンパク質を含む)を用いてFST統計分析を行った。彼は、ヒトの遺伝的差異の大部分 (85.4%)が集団内で見られ、8.3%が人種内の集団間で見られ、6.3%が人種(彼の研究では、白人、アフリカ人、モンゴロイド、南アジアのアボリ ジニ、アメリカ人、オセアニア人、オーストラリアのアボリジニ)を区別するものであることを発見した。それ以来、他の分析では、大陸の人類集団間では 6~10パーセント、同じ大陸の異なる集団間では5~15パーセント、集団内では75~85パーセントのFST値が見つかっている[50][51] [52][53][54]。この見解は、その後、アメリカ人類学会とアメリカ身体人類学者協会によって肯定されている[55]。 血液タンパク質分析に対する批判 ヒトは遺伝的に均質であるというレウォンティンの観察を認めつつも、A. W. F. エドワーズは2003年の論文「ヒトの遺伝的多様性」の中で、「レウォンティンの誤謬」と論じている: Lewontin's Fallacy(レウォンティンの誤謬)」という2003年の論文で、集団同士を区別する情報は対立遺伝子頻度の相関構造に隠されており、数学的手法を 使って個体を分類することが可能であると主張した。エドワーズは、単一の遺伝マーカーに基づいて個体を誤分類する確率が(1972年にルウォンティンが報 告したように)30%と高くても、十分な遺伝マーカーを同時に研究すれば、誤分類の確率はゼロに近くなると主張した。エドワーズは、レウォンティンの議論 を、社会的平等を主張するために生物学的差異を否定するという政治的スタンスに基づくものと見ていた[56]。エドワーズの論文は再版され、ノア・ローゼ ンバーグなどの専門家によってコメントされ、最近のアンソロジーにおける科学哲学者ラスムス・グロンフェルト・ウィンターとのインタビューにおいてさらな る文脈が与えられている[57]。 前述したように、エドワーズはレウォンティンの論文を批判している。彼は17の異なる形質を取り上げて、他のタンパク質と組み合わせて見ることなく、単独 で分析したのである。セサルディックもまたエドワーズの見解を強化した。彼は正方形と三角形に言及した図解を用いて、ある形質を単独で見た場合、その形質 がその個体がどのグループに属するかを予測するのに不利になる可能性が高いことを示したからである[58]。 [59]これとは対照的に、ラスマス・グロンフェルト・ウィンターは2014年の論文で、2018年のEdwards Cambridge University Pressの本に再掲されている: 「分散分割」と「クラスタリング解析」である。ウィンターによれば、これらは「同じ数学のコインの裏表」であり、どちらも「人間集団の現実については必ず しも何も暗示しない」[60]。 |

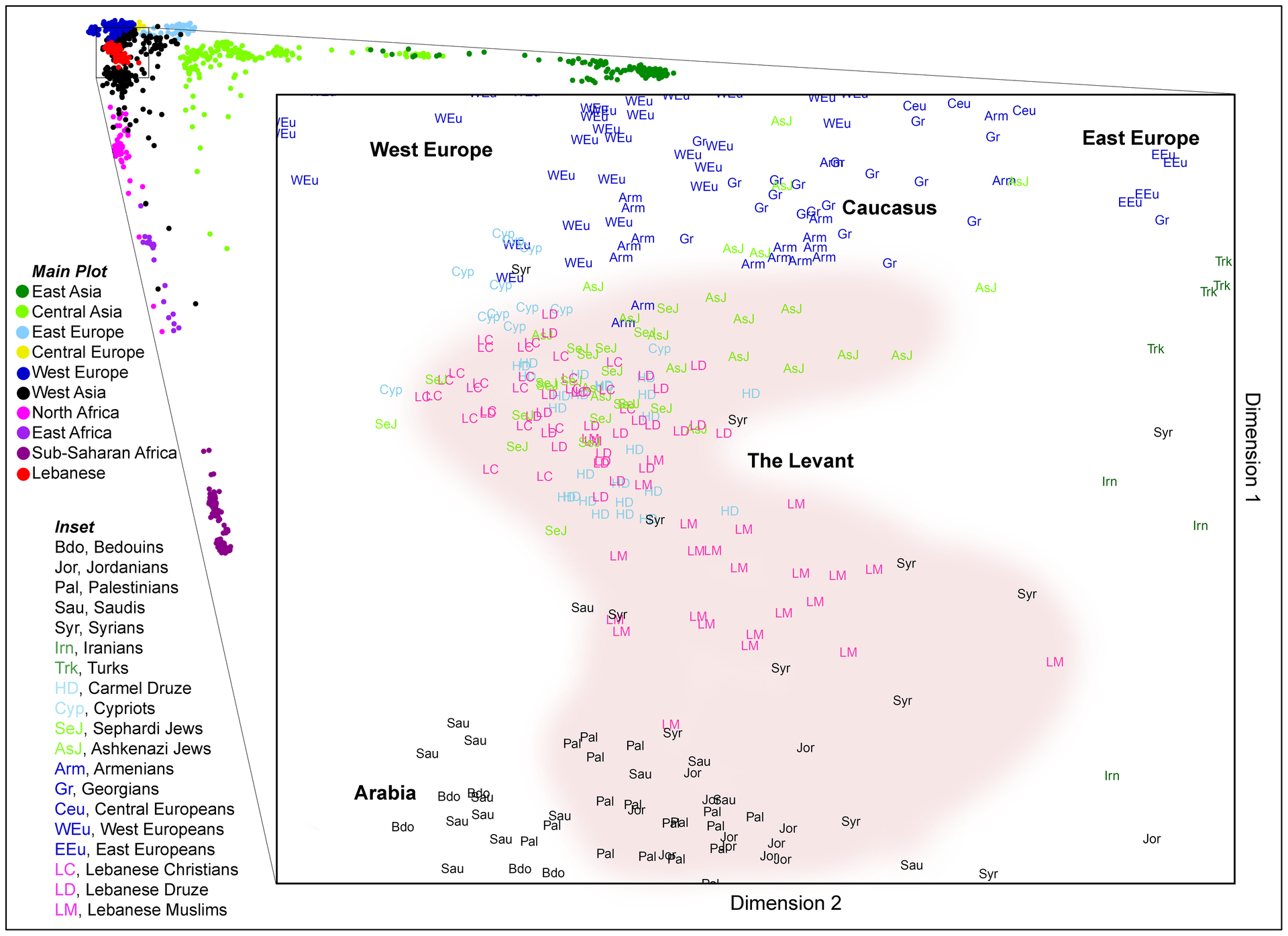

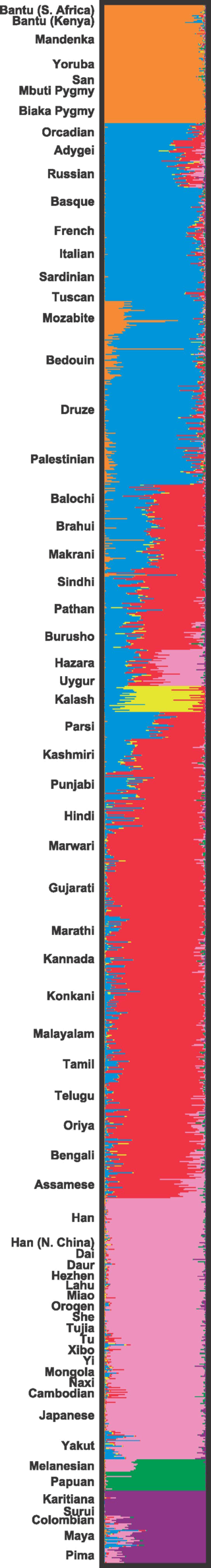

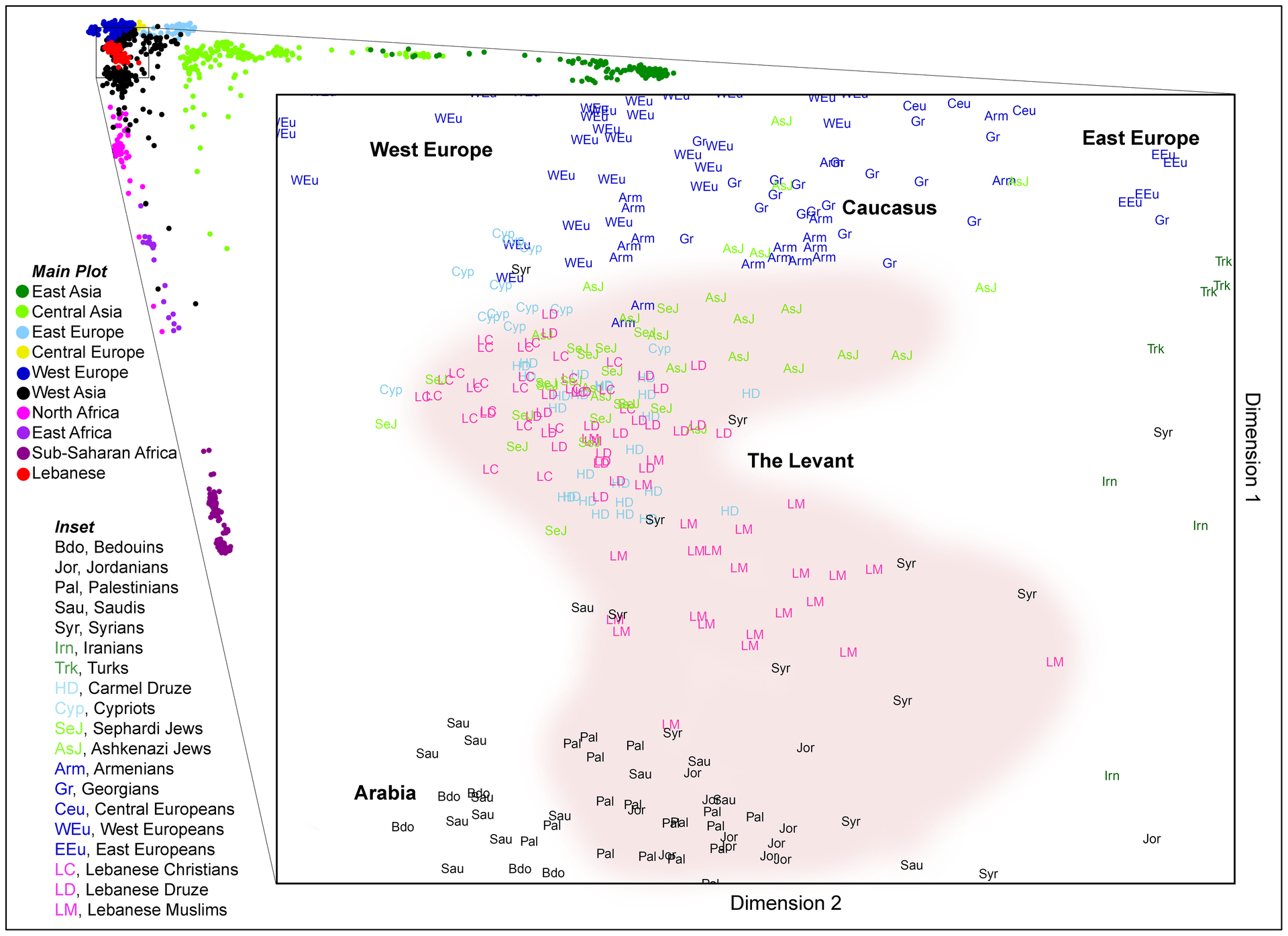

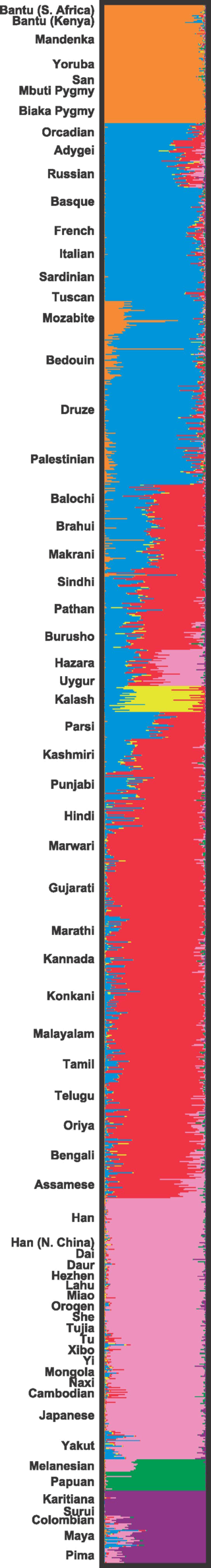

| Current studies of population genetics This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: All references are more than 13 years old. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (December 2022) Researchers currently use genetic testing, which may involve hundreds (or thousands) of genetic markers or the entire genome. Structure  Principal component analysis of fifty populations, color-coded by region, illustrates the differentiation and overlap of populations found using this method of analysis.  Individuals mostly have genetic variants which are found in multiple regions of the world. Based on data from "A unified genealogy of modern and ancient genomes".[61] Several methods to examine and quantify genetic subgroups exist, including cluster and principal components analysis. Genetic markers from individuals are examined to find a population's genetic structure. While subgroups overlap when examining variants of one marker only, when a number of markers are examined different subgroups have different average genetic structure. An individual may be described as belonging to several subgroups. These subgroups may be more or less distinct, depending on how much overlap there is with other subgroups.[62] In cluster analysis, the number of clusters to search for K is determined in advance; how distinct the clusters are varies. The results obtained from cluster analyses depend on several factors: A large number of genetic markers studied facilitates finding distinct clusters.[63] Some genetic markers vary more than others, so fewer are required to find distinct clusters.[5] Ancestry-informative markers exhibit substantially different frequencies between populations from different geographical regions. Using AIMs, scientists can determine a person's ancestral continent of origin based solely on their DNA. AIMs can also be used to determine someone's admixture proportions.[64] The more individuals studied, the easier it becomes to detect distinct clusters (statistical noise is reduced).[5] Low genetic variation makes it more difficult to find distinct clusters.[5] Greater geographic distance generally increases genetic variation, making identifying clusters easier.[65] A similar cluster structure is seen with different genetic markers when the number of genetic markers included is sufficiently large. The clustering structure obtained with different statistical techniques is similar. A similar cluster structure is found in the original sample with a subsample of the original sample.[66] Recent studies have been published using an increasing number of genetic markers.[5][66][67][68][69][70] Focus on study of structure has been criticized for giving the general public a misleading impression of human genetic variation, obscuring the general finding that genetic variants which are limited to one region tend to be rare within that region, variants that are common within a region tend to be shared across the globe, and most differences between individuals, whether they come from the same region or different regions, are due to global variants.[71] Distance Genetic distance is genetic divergence between species or populations of a species. It may compare the genetic similarity of related species, such as humans and chimpanzees. Within a species, genetic distance measures divergence between subgroups. Genetic distance significantly correlates to geographic distance between populations, a phenomenon sometimes known as "isolation by distance".[72] Genetic distance may be the result of physical boundaries restricting gene flow such as islands, deserts, mountains or forests. Genetic distance is measured by the fixation index (FST). FST is the correlation of randomly chosen alleles in a subgroup to a larger population. It is often expressed as a proportion of genetic diversity. This comparison of genetic variability within (and between) populations is used in population genetics. The values range from 0 to 1; zero indicates the two populations are freely interbreeding, and one would indicate that two populations are separate. Many studies place the average FST distance between human races at about 0.125. Henry Harpending argued that this value implies on a world scale a "kinship between two individuals of the same human population is equivalent to kinship between grandparent and grandchild or between half siblings". In fact, the formulas derived in Harpending's paper in the "Kinship in a subdivided population" section imply that two unrelated individuals of the same race have a higher coefficient of kinship (0.125) than an individual and their mixed race half-sibling (0.109).[73] Critiques of FST While acknowledging that FST remains useful, a number of scientists have written about other approaches to characterizing human genetic variation.[74][75][76] Long & Kittles (2009) stated that FST failed to identify important variation and that when the analysis includes only humans, FST = 0.119, but adding chimpanzees increases it only to FST = 0.183.[74] Mountain & Risch (2004) argued that an FST estimate of 0.10–0.15 does not rule out a genetic basis for phenotypic differences between groups and that a low FST estimate implies little about the degree to which genes contribute to between-group differences.[75] Pearse & Crandall 2004 wrote that FST figures cannot distinguish between a situation of high migration between populations with a long divergence time, and one of a relatively recent shared history but no ongoing gene flow.[76] In their 2015 article, Keith Hunley, Graciela Cabana, and Jeffrey Long (who had previously criticized Lewontin's statistical methodology with Rick Kittles[55]) recalculate the apportionment of human diversity using a more complex model than Lewontin and his successors. They conclude: "In sum, we concur with Lewontin's conclusion that Western-based racial classifications have no taxonomic significance, and we hope that this research, which takes into account our current understanding of the structure of human diversity, places his seminal finding on firmer evolutionary footing."[77] Anthropologists (such as C. Loring Brace),[78] philosopher Jonathan Kaplan and geneticist Joseph Graves[79] have argued that while it is possible to find biological and genetic variation roughly corresponding to race, this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations: the cluster structure of genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental; with other sampling patterns, the clusters would be different. Weiss and Fullerton note that if one sampled only Icelanders, Mayans and Maoris, three distinct clusters would form; all other populations would be composed of genetic admixtures of Maori, Icelandic and Mayan material.[80] Kaplan therefore concludes that, while differences in particular allele frequencies can be used to identify populations that loosely correspond to the racial categories common in Western social discourse, the differences are of no more biological significance than the differences found between any human populations (e.g., the Spanish and Portuguese).[81] Historical and geographical analyses Current-population genetic structure does not imply that differing clusters or components indicate only one ancestral home per group; for example, a genetic cluster in the US comprises Hispanics with European, Native American and African ancestry.[63] Geographic analyses attempt to identify places of origin, their relative importance and possible causes of genetic variation in an area. The results can be presented as maps showing genetic variation. Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues argue that if genetic variations are investigated, they often correspond to population migrations due to new sources of food, improved transportation or shifts in political power. For example, in Europe the most significant direction of genetic variation corresponds to the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago.[82] Such geographic analysis works best in the absence of recent large-scale, rapid migrations. Historic analyses use differences in genetic variation (measured by genetic distance) as a molecular clock indicating the evolutionary relation of species or groups, and can be used to create evolutionary trees reconstructing population separations.[82] Results of genetic-ancestry research are supported if they agree with research results from other fields, such as linguistics or archeology.[82] Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues have argued that there is a correspondence between language families found in linguistic research and the population tree they found in their 1994 study. There are generally shorter genetic distances between populations using languages from the same language family. Exceptions to this rule are also found, for example Sami, who are genetically associated with populations speaking languages from other language families. The Sami speak a Uralic language, but are genetically primarily European. This is argued to have resulted from migration (and interbreeding) with Europeans while retaining their original language. Agreement also exists between research dates in archeology and those calculated using genetic distance.[5][82] Self-identification studies Jorde and Wooding found that while clusters from genetic markers were correlated with some traditional concepts of race, the correlations were imperfect and imprecise due to the continuous and overlapping nature of genetic variation, noting that ancestry, which can be accurately determined, is not equivalent to the concept of race.[33] A 2005 study by Tang and colleagues used 326 genetic markers to determine genetic clusters. The 3,636 subjects, from the United States and Taiwan, self-identified as belonging to white, African American, East Asian or Hispanic ethnic groups. The study found "nearly perfect correspondence between genetic cluster and SIRE for major ethnic groups living in the United States, with a discrepancy rate of only 0.14 percent".[63] Paschou et al. found "essentially perfect" agreement between 51 self-identified populations of origin and the population's genetic structure, using 650,000 genetic markers. Selecting for informative genetic markers allowed a reduction to less than 650, while retaining near-total accuracy.[83] Correspondence between genetic clusters in a population (such as the current US population) and self-identified race or ethnic groups does not mean that such a cluster (or group) corresponds to only one ethnic group. African Americans have an estimated 20–25-percent European genetic admixture; Hispanics have European, Native American and African ancestry.[63] In Brazil there has been extensive admixture between Europeans, Amerindians and Africans. As a result, skin color differences within the population are not gradual, and there are relatively weak associations between self-reported race and African ancestry.[84][85] Ethnoracial self- classification in Brazilians is certainly not random with respect to genome individual ancestry, but the strength of the association between the phenotype and median proportion of African ancestry varies largely across population.[86] Critique of genetic-distance studies and clusters Colored circles, illustrating gene-pool changes  A change in a gene pool may be abrupt or clinal. Genetic distances generally increase continually with geographic distance, which makes a dividing line arbitrary. Any two neighboring settlements will exhibit some genetic difference from each other, which could be defined as a race. Therefore, attempts to classify races impose an artificial discontinuity on a naturally occurring phenomenon. This explains why studies on population genetic structure yield varying results, depending on methodology.[87] Rosenberg and colleagues (2005) have argued, based on cluster analysis of the 52 populations in the Human Genetic Diversity Panel, that populations do not always vary continuously and a population's genetic structure is consistent if enough genetic markers (and subjects) are included. Examination of the relationship between genetic and geographic distance supports a view in which the clusters arise not as an artifact of the sampling scheme, but from small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance for most population pairs on opposite sides of geographic barriers, in comparison with genetic distance for pairs on the same side. Thus, analysis of the 993-locus dataset corroborates our earlier results: if enough markers are used with a sufficiently large worldwide sample, individuals can be partitioned into genetic clusters that match major geographic subdivisions of the globe, with some individuals from intermediate geographic locations having mixed membership in the clusters that correspond to neighboring regions. They also wrote, regarding a model with five clusters corresponding to Africa, Eurasia (Europe, Middle East, and Central/South Asia), East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas: For population pairs from the same cluster, as geographic distance increases, genetic distance increases in a linear manner, consistent with a clinal population structure. However, for pairs from different clusters, genetic distance is generally larger than that between intracluster pairs that have the same geographic distance. For example, genetic distances for population pairs with one population in Eurasia and the other in East Asia are greater than those for pairs at equivalent geographic distance within Eurasia or within East Asia. Loosely speaking, it is these small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance—across oceans, the Himalayas, and the Sahara—that provide the basis for the ability of STRUCTURE to identify clusters that correspond to geographic regions.[66] This applies to populations in their ancestral homes when migrations and gene flow were slow; large, rapid migrations exhibit different characteristics. Tang and colleagues (2004) wrote, "we detected only modest genetic differentiation between different current geographic locales within each race/ethnicity group. Thus, ancient geographic ancestry, which is highly correlated with self-identified race/ethnicity—as opposed to current residence—is the major determinant of genetic structure in the U.S. population".[63]  Gene clusters from Rosenberg (2006) for K=7 clusters. (Cluster analysis divides a dataset into any prespecified number of clusters.) Individuals have genes from multiple clusters. The cluster prevalent only among the Kalash people (yellow) only splits off at K=7 and greater. Cluster analysis has been criticized because the number of clusters to search for is decided in advance, with different values possible (although with varying degrees of probability).[88] Principal component analysis does not decide in advance how many components for which to search.[89] The 2002 study by Rosenberg et al. exemplifies why meanings of these clusterings can be disputable, though the study shows that at the K=5 cluster analysis, genetic clusterings roughly map onto each of the five major geographical regions.[5] Similar results were gathered in further studies in 2005.[90] Critique of ancestry-informative markers Ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) are a genealogy tracing technology that has come under much criticism due to its reliance on reference populations. In a 2015 article, Troy Duster outlines how contemporary technology allows the tracing of ancestral lineage but along only the lines of one maternal and one paternal line. That is, of 64 total great-great-great-great-grandparents, only one from each parent is identified, implying the other 62 ancestors are ignored in tracing efforts.[91] Furthermore, the 'reference populations' used as markers for membership of a particular group are designated arbitrarily and contemporarily. In other words, using populations who currently reside in given places as references for certain races and ethnic groups is unreliable due to the demographic changes which have occurred over many centuries in those places. Furthermore, ancestry-informative markers being widely shared among the whole human population, it is their frequency which is tested, not their mere absence/presence. A threshold of relative frequency has, therefore, to be set. According to Duster, the criteria for setting such thresholds are a trade secret of the companies marketing the tests. Thus, we cannot say anything conclusive on whether they are appropriate. Results of AIMs are extremely sensitive to where this bar is set.[92] Given that many genetic traits are found to be very similar amid many different populations, the designated threshold frequencies are very important. This can also lead to mistakes, given that many populations may share the same patterns, if not exactly the same genes. "This means that someone from Bulgaria whose ancestors go back to the fifteenth century could (and sometime does) map as partly 'Native American'".[91] This happens because AIMs rely on a '100% purity' assumption of reference populations. That is, they assume that a pattern of traits would ideally be a necessary and sufficient condition for assigning an individual to an ancestral reference populations. |

集団遺伝学の最新の研究 このセクションは更新する必要がある。理由は、全ての文献が13年以上前のものだからである。最近の出来事や新たに入手可能な情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力いただきたい。(2022年12月) 研究者は現在、数百(あるいは数千)の遺伝子マーカー、あるいは全ゲノムに関わる遺伝子検査を用いている。 構造  地域別に色分けされた50の集団の主成分分析は、この分析法を用いて発見された集団の分化と重複を示している。  ほとんどの個体は、世界の複数の地域で見られる遺伝的変異体を持っている。A unified genealogy of modern and ancient genomes "のデータに基づく[61]。 クラスター分析や主成分分析など、遺伝的サブグループを調査し定量化する方法がいくつか存在する。個体から得られた遺伝子マーカーを調べ、集団の遺伝的構 造を見つける。1つのマーカーの変異のみを調べる場合はサブグループは重なり合うが、多数のマーカーを調べる場合は、異なるサブグループは異なる平均遺伝 構造を持つ。個体はいくつかのサブグループに属していると言えるかもしれない。これらのサブグループは、他のサブグループとの重なり具合によって、多かれ 少なかれ区別されることがある[62]。 クラスター分析では、Kを探索するクラスターの数が事前に決定される。 クラスター分析から得られる結果はいくつかの要因に依存する: 研究した遺伝マーカーの数が多いほど、明確なクラスターを見つけやすくなる[63]。 ある遺伝子マーカーは他の遺伝子マーカーよりも変異が大きいため、明確なクラスターを見つけるために必要な遺伝子マーカーの数は少なくなる[5]。祖先情 報マーカーは、異なる地理的地域の集団間で実質的に異なる頻度を示す。AIMを用いることで、科学者はDNAのみからその人の祖先の出身大陸を特定するこ とができる。AIMはまた、その人の混血比率を決定するためにも使用できる[64]。 研究対象が多ければ多いほど、明確なクラスターを検出することが容易になる(統計的ノイズが減少する)[5]。 遺伝的変異が少ないと、明確なクラスターを見つけることが難しくなる[5]。地理的距離が遠いと、一般的に遺伝的変異が大きくなり、クラスターの同定が容易になる[65]。 含まれる遺伝マーカーの数が十分に多い場合、異なる遺伝マーカーでも同様のクラスター構造が見られる。異なる統計的手法で得られたクラスター構造も同様である。元の標本のサブサンプルでも同様のクラスター構造が見られる[66]。 最近の研究では、遺伝子マーカーの数が増加している[5][66][67][68][69][70]。 ある地域に限定された遺伝的変異はその地域内では稀である傾向があり、ある地域内で一般的な変異は世界中で共有される傾向があり、同じ地域出身であろうと 異なる地域出身であろうと、個人間の差のほとんどは世界的な変異によるものであるという一般的な知見が不明瞭になり、一般大衆にヒトの遺伝的変異について 誤解を招くような印象を与えているという批判がある[71]。 距離 遺伝的距離とは、ある種の種間や個体群間の遺伝的分岐のことである。ヒトとチンパンジーのような近縁種の遺伝的類似性を比較することもある。種内では、遺 伝的距離はサブグループ間の分岐を測定する。遺伝的距離は個体群間の地理的距離と有意な相関があり、この現象は「距離による隔離」として知られることもあ る[72]。遺伝的距離は、島、砂漠、山、森林など、遺伝子の流れを制限する物理的境界の結果である場合もある。遺伝的距離は固定指数(FST)によって 測定される。FSTとは、ある部分集団で無作為に選ばれた対立遺伝子の、より大きな集団に対する相関のことである。遺伝的多様性の割合として表されること が多い。この集団内(および集団間)の遺伝的変異性の比較は集団遺伝学で用いられる。値の範囲は0から1までで、0は2つの集団が自由に交雑していること を示し、1は2つの集団が分離していることを示す。 多くの研究では、ヒトの人種間の平均FST距離は約0.125とされている。ヘンリー・ハーペンディングは、この値は世界規模では「同じ人類集団の2個体 間の親族関係は、祖父母と孫、あるいは異母兄弟間の親族関係に相当する」と主張している。実際、ハーペンディングの論文の「細分化された集団における親族 関係」の項で導き出された公式は、同じ人種の血縁関係のない2人の個人は、個人とその混血の異母兄弟姉妹(0.109)よりも高い親族係数(0.125) を持つことを意味している[73]。 FSTに対する批判 FSTが依然として有用であることを認めつつも、多くの科学者がヒトの遺伝的変異を特徴づける他のアプローチについて書いている[74][75] [76]。Long & Kittles (2009)は、FSTは重要な変異を同定できず、ヒトだけを分析に含めるとFST = 0. 74]。Mountain & Risch (2004)は、0.10-0.15のFST推定値は集団間の表現型の違いの遺伝的基礎を否定するものではなく、低いFST推定値は遺伝子が集団間の違い に寄与する度合いについてほとんど示唆しないと主張した。 [75] Pearse & Crandall 2004は、FSTの数値では、長い分岐時間を持つ集団間の移動が多い状況と、比較的最近に共有された歴史があるが遺伝子の流れが続いていない状況を区別 することはできないと書いている[76]。2015年の論文では、Keith Hunley、Graciela Cabana、Jeffrey Long(彼らは以前Rick Kittles[55]と共にLewontinの統計的手法を批判していた)が、Lewontinと彼の後継者たちよりも複雑なモデルを用いて人類の多様 性の配分を再計算している。彼らはこう結論づけている: 「まとめると、我々は西洋に基づく人種分類には分類学的な意義がないというルウォンティンの結論に同意し、人類の多様性の構造に関する我々の現在の理解を 考慮に入れたこの研究が、彼の重要な発見をより強固な進化論的な足場に置くことを望んでいる」[77]。 人類学者(C.ローリング・ブレイスなど)[78]、哲学者ジョナサン・カプラン、遺伝学者ジョセフ・グレイブス[79]は、人種にほぼ対応する生物学 的・遺伝学的変異を見出すことは可能であるが、これはほとんどすべての地理的に異なる集団に当てはまることであると主張している。遺伝データのクラスター 構造は、研究者の初期仮説とサンプリングされた集団に依存する。大陸の集団をサンプリングすると、クラスターは大陸的なものになり、他のサンプリングパ ターンではクラスターは異なるものになる。WeissとFullertonは、アイスランド人、マヤ人、マオリ人だけをサンプリングした場合、3つの異な るクラスターが形成され、それ以外の集団はすべてマオリ人、アイスランド人、マヤ人の遺伝的混血で構成されると指摘している[80]。したがって、 Kaplanは、特定の対立遺伝子頻度の違いは、西洋の社会的言説で一般的な人種カテゴリーに緩やかに対応する集団を識別するために使用することができる が、その違いは、あらゆる人間集団の間に見られる違い(例えば、スペイン人とポルトガル人)以上の生物学的意義はないと結論づけている[81]。 歴史的・地理的分析 例えば、アメリカにおける遺伝子クラスターは、ヨーロッパ系、ネイティブアメリカン系、アフリカ系の祖先を持つヒスパニック系で構成されている[63]。 地理的解析は、ある地域における出身地、その相対的重要性、遺伝的変異の可能性のある原因を特定しようとするものである。その結果は、遺伝的変異を示す地 図として提示することができる。Cavalli-Sforzaたちは、遺伝的変異が調査された場合、新しい食料源、交通手段の改善、政治的権力の移動など による集団移動に対応することが多いと論じている。例えばヨーロッパでは、遺伝的変異の最も顕著な方向は、10,000年から6,000年前の間に中東か らヨーロッパに農業が広まったことに対応している[82]。このような地理的分析は、最近の大規模で急速な移動がない場合に最も有効である。 歴史的分析では、(遺伝的距離によって測定される)遺伝的変異の違いを、種や集団の進化的関係を示す分子時計として使用し、集団の分離を再構築する進化系統樹を作成するために使用することができる[82]。 カヴァッリ-スフォルツァらは、言語学的研究で発見された言語族と1994年の研究で発見された集団樹との間には対応関係があると主張している[82]。 一般的に、同じ語族の言語を使用する集団間の遺伝的距離は短い。この法則には例外もあり、例えばサーミ人は遺伝的に他の語族の言語を話す集団と関連してい る。サーミ人はウラル語を話すが、遺伝的には主にヨーロッパ人である。これは、ヨーロッパ人との移動(および交雑)の結果であると主張されている。考古学 における調査年代と遺伝的距離を用いて算出された年代との間にも一致が見られる[5][82]。 自認研究 JordeとWoodingは、遺伝子マーカーからのクラスターは人種に関する伝統的な概念と相関しているが、遺伝的変異の連続的で重複した性質のために 相関は不完全で不正確であることを発見し、正確に決定することができる祖先は人種の概念と同等ではないことを指摘した[33]。 Tangらによる2005年の研究では、326の遺伝子マーカーを用いて遺伝的クラスターを決定した。米国と台湾の3,636人の被験者は、白人、アフリ カ系アメリカ人、東アジア系、ヒスパニック系のいずれかの民族に属すると自認していた。Paschouらは、65万個の遺伝子マーカーを用いて、51の自 称出身集団と集団の遺伝的構造との間に「基本的に完全な」一致を見出した。情報量の多い遺伝マーカーを選択することで、ほぼ完全な精度を保ちながら、 650個以下に減らすことができた[83]。 ある集団(現在の米国集団など)における遺伝的クラスターと、自認する人種や民族グループとの対応関係は、そのようなクラスター(またはグループ)が一つ の民族グループにのみ対応することを意味するものではない。アフリカ系アメリカ人は推定20-25パーセントのヨーロッパ人との混血を持っており、ヒスパ ニック系はヨーロッパ人、アメリカ先住民、アフリカ人の祖先を持っている[63]。ブラジルでは、ヨーロッパ人、アメリカ先住民、アフリカ人の間に広範な 混血があった。その結果、集団内の肌の色の差は緩やかではなく、自己申告の人種とアフリカ系祖先の間には比較的弱い関連がある[84][85]。ブラジル 人の民族的自己分類は、ゲノム個人の祖先に関しては確かにランダムではないが、表現型とアフリカ系祖先の割合の中央値との間の関連の強さは集団によって大 きく異なる[86]。 遺伝的距離研究とクラスターに対する批判 遺伝子プールの変化を示す色付きの円  遺伝子プールの変化は、急激な場合もあれば、集団的な場合もある。 遺伝的距離は一般に地理的距離とともに連続的に増加するため、境界線は恣意的なものとなる。隣接する2つの集落は、互いに何らかの遺伝的差異を示し、それ は人種として定義されうる。したがって、人種を分類しようとする試みは、自然に起こる現象に人為的な不連続性を押し付けることになる。このことは、集団の 遺伝的構造に関する研究が、方法論によってさまざまな結果をもたらす理由を説明している[87]。 Rosenbergら(2005年)は、ヒト遺伝的多様性パネルに含まれる52集団のクラスター分析に基づき、集団は常に連続的に変化しているわけではなく、十分な遺伝マーカー(および被験者)が含まれていれば、集団の遺伝的構造は一貫していると主張している。 遺伝学的距離と地理的距離の関係を調べると、クラスターはサンプリング方式のアーチファクトとしてではなく、地理的障壁の反対側にあるほとんどの個体群対 の遺伝学的距離が、同じ側にある対の遺伝学的距離と比較して小さく不連続にジャンプしていることから生じているという見解が支持される。このように、 993個の遺伝子座データセットの解析は、我々の以前の結果を裏付けるものであった。十分な数のマーカーを用い、十分な大きさの世界的サンプルを用いれ ば、個体は地球上の主要な地理的区分と一致する遺伝的クラスターに分割することができ、中間の地理的位置から来た個体の中には、隣接する地域に対応するク ラスターに混在するものもある。 彼らはまた、アフリカ、ユーラシア(ヨーロッパ、中東、中央/南アジア)、東アジア、オセアニア、アメリカ大陸に対応する5つのクラスターを持つモデルについても書いている: 同じクラスターに属する個体群ペアでは、地理的距離が長くなるにつれて遺伝的距離も直線的に長くなり、これはクリナル集団構造と一致する。しかし、異なる クラスターに属する個体群ペアでは、遺伝的距離は地理的距離が同じクラスター内ペア間のそれよりも一般的に大きい。例えば、一方の個体群がユーラシア大陸 にあり、もう一方の個体群が東アジアにある個体群ペアの遺伝的距離は、ユーラシア大陸内や東アジア内の同等の地理的距離にあるペアの遺伝的距離よりも大き い。大洋、ヒマラヤ、サハラ砂漠を越えた遺伝的距離の小さな不連続なジャンプが、STRUCTUREが地理的地域に対応するクラスターを同定できる根拠と なっている[66]。 これは、移動と遺伝子の流れが緩やかであった祖先の故郷にいた個体群に当てはまり、大規模で急速な移動は異なる特徴を示す。Tangら(2004)は、 「各人種・民族グループ内の異なる現在の地理的地域間の遺伝的差異はわずかであった。したがって、現在の居住地とは対照的に、自認する人種・民族性と高い 相関を示す古代の地理的祖先が、米国集団における遺伝的構造の主要な決定要因である」と書いている[63]。 Rosenberg(2006)のK=7クラスターの遺伝子クラスター。(クラスター分析は、データセットを任意の数のクラスターに分割する。) 個体は複数のクラスターの遺伝子を持つ。カラシュ族にのみ広く見られるクラスター(黄色)は、K=7以上で分岐している。 クラスター分析が批判されているのは、探索するクラスターの数が事前に決定され、(確率の程度は異なるが)異なる値が可能だからである[88]。主成分分析では、探索する成分の数は事前に決定されない[89]。  Rosenbergらによる2002年の研究は、K=5のクラスター分析において、遺伝的クラスターが5つの主要な地理的地域のそれぞれにほぼマッピングされることを示しているが、これらのクラスター分類の意味がなぜ議論の余地があるのかを例証している[5]。 先祖情報マーカーの批判 祖先情報マーカー(AIM)は、参照集団に依存しているために多くの批判にさらされている系図追跡技術である。2015年の論文でトロイ・ダスターは、現 代の技術では祖先の血統を追跡することができるが、母方と父方の血統に沿ったものしか追跡できないことを概説している。つまり、合計64人の曽曽曽祖父母 のうち、それぞれの親から1人ずつしか特定されず、他の62人の祖先は追跡作業において無視されることになる[91]。さらに、特定の集団に属するための マーカーとして使用される「参照集団」は、恣意的かつ同時代的に指定される。言い換えれば、特定の人種や民族集団の基準として、特定の場所に現在居住して いる集団を使用することは、その場所で何世紀にもわたって起こってきた人口動態の変化のために信頼できない。さらに、先祖を示すマーカーは全人類に広く共 有されているため、検査されるのはその頻度であり、単に存在しないかどうかではない。したがって、相対頻度の閾値を設定しなければならない。ダスター氏に よれば、このような閾値を設定する基準は、検査を販売する企業の企業秘密だという。したがって、それが適切かどうかについては、決定的なことは言えない。 AIMの結果は、この基準値がどこに設定されるかに非常に敏感である[92]。多くの遺伝形質が、多くの異なる集団の中で非常に類似していることが判明し ていることを考えると、指定された閾値頻度は非常に重要である。多くの集団が、全く同じ遺伝子ではないにせよ、同じパターンを共有している可能性があるこ とを考えると、これも間違いにつながる可能性がある。これは、ブルガリア出身で先祖が15世紀までさかのぼる人が、部分的に 「ネイティブアメリカン 」としてマッピングされる可能性がある(そして時にはそうなる)ことを意味する」[91]。これはAIMが参照集団の 「100%純粋性 」の仮定に依存しているために起こる。つまり、AIMは理想的にはある形質のパターンが、ある個体を祖先の参照集団に割り当てるための必要十分条件である と仮定しているのである。 |

| Race, genetics, and medicine Main article: Race and health There are certain statistical differences between racial groups in susceptibility to certain diseases.[93] Genes change in response to local diseases; for example, people who are Duffy-negative tend to have a higher resistance to malaria. The Duffy negative phenotype is highly frequent in central Africa and the frequency decreases with distance away from Central Africa, with higher frequencies in global populations with high degrees of recent African immigration. This suggests that the Duffy negative genotype evolved in Sub-Saharan Africa and was subsequently positively selected for in the Malaria endemic zone.[94] A number of genetic conditions prevalent in malaria-endemic areas may provide genetic resistance to malaria, including sickle cell disease, thalassaemias and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Cystic fibrosis is the most common life-limiting autosomal recessive disease among people of European ancestry; a hypothesized heterozygote advantage, providing resistance to diseases earlier common in Europe, has been challenged.[95] Scientists Michael Yudell, Dorothy Roberts, Rob DeSalle, and Sarah Tishkoff argue that using these associations in the practice of medicine has led doctors to overlook or misidentify disease: "For example, hemoglobinopathies can be misdiagnosed because of the identification of sickle-cell as a 'Black' disease and thalassemia as a 'Mediterranean' disease. Cystic fibrosis is underdiagnosed in populations of African ancestry, because it is thought of as a 'White' disease."[25] Information about a person's population of origin may aid in diagnosis, and adverse drug responses may vary by group.[5][dubious – discuss] Because of the correlation between self-identified race and genetic clusters, medical treatments influenced by genetics have varying rates of success between self-defined racial groups.[96] For this reason, some physicians[who?] consider a patient's race in choosing the most effective treatment,[97] and some drugs are marketed with race-specific instructions.[98] Jorde and Wooding (2004) have argued that because of genetic variation within racial groups, when "it finally becomes feasible and available, individual genetic assessment of relevant genes will probably prove more useful than race in medical decision making". However, race continues to be a factor when examining groups (such as epidemiologic research).[33] Some doctors and scientists such as geneticist Neil Risch argue that using self-identified race as a proxy for ancestry is necessary to be able to get a sufficiently broad sample of different ancestral populations, and in turn to be able to provide health care that is tailored to the needs of minority groups.[99] Usage in scientific journals Some scientific journals have addressed previous methodological errors by requiring more rigorous scrutiny of population variables. Since 2000, Nature Genetics requires its authors to "explain why they make use of particular ethnic groups or populations, and how classification was achieved". Editors of Nature Genetics say that "[they] hope that this will raise awareness and inspire more rigorous designs of genetic and epidemiological studies".[100] A 2021 study that examined over 11,000 papers from 1949 to 2018 in The American Journal of Human Genetics, found that "race" was used in only 5% of papers published in the last decade, down from 22% in the first. Together with an increase in use of the terms "ethnicity," "ancestry," and location-based terms, it suggests that human geneticists have mostly abandoned the term "race."[101] Gene-environment interactions Lorusso and Bacchini[6] argue that self-identified race is of greater use in medicine as it correlates strongly with risk-related exposomes that are potentially heritable when they become embodied in the epigenome. They summarise evidence of the link between racial discrimination and health outcomes due to poorer food quality, access to healthcare, housing conditions, education, access to information, exposure to infectious agents and toxic substances, and material scarcity. They also cite evidence that this process can work positively – for example, the psychological advantage of perceiving oneself at the top of a social hierarchy is linked to improved health. However they caution that the effects of discrimination do not offer a complete explanation for differential rates of disease and risk factors between racial groups, and the employment of self-identified race has the potential to reinforce racial inequalities. +++++++++++++++++++ Criticism of race-based medicine Troy Duster points out that genetics is often not the predominant determinant of disease susceptibilities, even though they might correlate with specific socially defined categories. This is because this research oftentimes lacks control for a multiplicity of socio-economic factors. He cites data collected by King and Rewers that indicates how dietary differences play a significant role in explaining variations of diabetes prevalence between populations. Duster elaborates by putting forward the example of the Pima of Arizona, a population suffering from disproportionately high rates of diabetes. The reason for such, he argues, was not necessarily a result of the prevalence of the FABP2 gene, which is associated with insulin resistance. Rather he argues that scientists often discount the lifestyle implications under specific socio-historical contexts. For instance, near the end of the 19th century, the Pima economy was predominantly agriculture-based. However, as the European American population settles into traditionally Pima territory, the Pima lifestyles became heavily Westernised. Within three decades, the incidence of diabetes increased multiple folds. Governmental provision of free relatively high-fat food to alleviate the prevalence of poverty in the population is noted as an explanation of this phenomenon.[102] Lorusso and Bacchini argue against the assumption that "self-identified race is a good proxy for a specific genetic ancestry"[6] on the basis that self-identified race is complex: it depends on a range of psychological, cultural and social factors, and is therefore "not a robust proxy for genetic ancestry".[103] Furthermore, they explain that an individual's self-identified race is made up of further, collectively arbitrary factors: personal opinions about what race is and the extent to which it should be taken into consideration in everyday life. Furthermore, individuals who share a genetic ancestry may differ in their racial self-identification across historical or socioeconomic contexts. From this, Lorusso and Bacchini conclude that the accuracy in the prediction of genetic ancestry on the basis of self-identification is low, specifically in racially admixed populations born out of complex ancestral histories. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_and_genetics |

人種、遺伝、医学 主な記事 人種と健康 特定の病気に対する感受性には、人種間で統計的に一定の差がある[93]。遺伝子はその地域の病気に対応して変化する。例えば、ダッフィー陰性の人はマラ リアに対する抵抗性が高い傾向がある。ダッフィー陰性表現型は中央アフリカで頻度が高く、その頻度は中央アフリカから離れるにつれて減少し、最近アフリカ からの移民が多い世界の集団で頻度が高くなる。このことは、ダッフィー陰性遺伝子型がサハラ以南のアフリカで進化し、その後マラリア流行地帯で積極的に選 択されたことを示唆している[94]。鎌状赤血球症、タラセミア、グルコース-6-リン酸デヒドロゲナーゼなど、マラリア流行地域で流行している多くの遺 伝的疾患がマラリアに対する遺伝的抵抗性をもたらす可能性がある。嚢胞性線維症は、ヨーロッパに先祖を持つ人々の間で最も一般的な、生命を制限する常染色 体劣性遺伝性疾患である。ヘテロ接合体の優位性が、ヨーロッパで以前から一般的であった疾患に対する耐性をもたらすという仮説は、疑問視されている: 例えば、ヘモグロビン異常症は、鎌状赤血球は 「黒人 」の病気であり、サラセミアは 「地中海性 」の病気であるため、誤診されることがある。嚢胞性線維症は『白人』の病気と考えられているため、アフリカ系血統の集団では過小診断されている」 [25]。 その人の出身集団に関する情報は診断に役立つ可能性があり、薬物有害反応は集団によって異なる可能性がある[5][dubious - discuss]。自認する人種と遺伝子クラスターには相関があるため、遺伝学の影響を受けた医学的治療は、自認する人種集団間で成功率が異なる [96]。 98]。JordeとWooding(2004年)は、人種集団内の遺伝的変異のために、「最終的に実現可能で利用できるようになれば、関連遺伝子の個々 の遺伝学的評価は、おそらく医学的意思決定において人種よりも有用であることが証明されるであろう」と主張している。しかし、集団の調査(疫学調査など) においては、人種は引き続き要因である[33]。遺伝学者のニール・リッシュのような一部の医師や科学者は、祖先の代理として自認する人種を使用すること は、異なる祖先集団の十分な広範なサンプルを得るために必要であり、ひいてはマイノリティ集団のニーズに合わせた医療を提供するために必要であると主張し ている[99]。 科学雑誌における使用 科学雑誌の中には、母集団変数のより厳密な精査を要求することで、以前の方法論の誤りに対処しているものもある。2000年以降、Nature Genetics誌は著者に「特定の民族グループや集団を用いた理由と、その分類がどのように達成されたかを説明する」ことを求めている。Nature Genetics誌の編集者は、「これによって意識が高まり、遺伝学的研究や疫学的研究がより厳密にデザインされることを期待している」と述べている [100]。 1949年から2018年までの『American Journal of Human Genetics』の11,000以上の論文を調査した2021年の研究によると、過去10年間に発表された論文のうち「人種」が使用されたのはわずか 5%で、最初の10年間の22%から減少していた。エスニシティ」、「祖先」、場所に基づく用語の使用が増加していることと合わせて、ヒト遺伝学者が「人 種」という用語をほとんど放棄していることを示唆している[101]。 遺伝子と環境の相互作用 LorussoとBacchini[6]は、自認された人種は、エピゲノムに具現化されたときに遺伝する可能性のあるリスクに関連したエクスポソームと強 く相関するため、医学においてより有用であると論じている。彼らは、食物の質の低下、医療へのアクセス、住居環境、教育、情報へのアクセス、感染症や有害 物質への暴露、物質的欠乏などによる人種差別と健康結果との関連についての証拠をまとめている。例えば、社会的ヒエラルキーの頂点に立つという心理的優位 性は、健康増進につながる。しかし、差別の影響は人種間の疾病率や危険因子の差を完全に説明するものではなく、自認する人種の雇用は人種間の不平等を強化 する可能性があるとしている。 +++++++++++++++++++ 人種に基づく医療への批判 トロイ・ダスターは、遺伝子が特定の社会的に定義されたカテゴリーと相関する可能性があっても、疾患感受性の主要な決定要因ではないことが多いと指摘す る。これは、こうした研究がしばしば複数の社会経済的要因に対する制御を欠いているためだ。彼はキングとレワーズが収集したデータを引用し、食事の違いが 集団間の糖尿病有病率の差異を説明する上で重要な役割を果たすことを示している。 ダスターは、糖尿病罹患率が異常に高い苦悩を抱えるアリゾナ州のピマ族を例に挙げて論を展開する。その原因は、インスリン抵抗性に関連するFABP2遺伝 子の存在に必ずしも起因しない。むしろ科学者たちは、特定の社会歴史的文脈における生活様式の要因を軽視しがちだと彼は主張する。例えば19世紀末、ピマ 族の経済基盤は主に農業であった。しかし欧州系アメリカ人が伝統的なピマ族の居住地に定住するにつれ、ピマ族の生活様式は急速に西洋化された。わずか30 年で糖尿病発症率は数倍に増加した。この現象の背景には、貧困層への支援として政府が提供した比較的脂肪分の多い無料食糧が指摘されている。[102] ロルッソとバッキーニは、「自己申告による人種が特定の遺伝的祖先の良い代用指標である」という仮定に異議を唱えている[6]。その根拠として、自己申告 による人種は複雑であり、心理的・文化的・社会的要因に依存するため、「遺伝的祖先の確固たる代用指標とはなり得ない」と論じている。[103] さらに彼らは、個人の自己申告による人種は、人種とは何かという個人的見解や日常生活で人種を考慮すべき範囲といった、集合的に恣意的な要素によって構成 されていると説明する。さらに、同じ遺伝的祖先を持つ個人でも、歴史的・社会経済的文脈によって人種的自己認識が異なる場合がある。このことから、ロルッ ソとバッキーニは、自己認識に基づく遺伝的祖先の予測精度は低いと結論づけている。特に、複雑な祖先史から生まれた人種的に混血した集団においてはそう だ。 |

| Objections to racial naturalism Racial naturalism is the view that racial classifications are grounded in objective patterns of genetic similarities and differences. Proponents of this view have justified it using the scientific evidence described above. However, this view is controversial and philosophers[102] of race have put forward four main objections to it. Semantic objections, such as the discreteness objection, argue that the human populations picked out in population-genetic research are not races and do not correspond to what "race" means in the United States. "The discreteness objection does not require there to be no genetic admixture in the human species in order for there to be US 'racial groups' ... rather ... what the objection claims is that membership in US racial groups is different from membership in continental populations. ... Thus, strictly speaking, Blacks are not identical to Africans, Whites are not identical to Eurasians, Asians are not identical to East Asians and so forth."[103] Therefore, it could be argued that scientific research is not really about race. The next two objections, are metaphysical objections which argue that even if the semantic objections fail, human genetic clustering results do not support the biological reality of race. The 'very important objection' stipulates that races in the US definition fail to be important to biology, in the sense that continental populations do not form biological subspecies. The 'objectively real objection' states that "US racial groups are not biologically real because they are not objectively real in the sense of existing independently of human interest, belief, or some other mental state of humans."[104] Racial naturalists, such as Quayshawn Spencer, have responded to each of these objections with counter-arguments. There are also methodological critics who reject racial naturalism because of concerns relating to the experimental design, execution, or interpretation of the relevant population-genetic research.[105] Another semantic objection is the visibility objection which refutes the claim that there are US racial groups in human population structures. Philosophers such as Joshua Glasgow and Naomi Zack believe that US racial groups cannot be defined by visible traits, such as skin colour and physical attributes: "The ancestral genetic tracking material has no effect on phenotypes, or biological traits of organisms, which would include the traits deemed racial, because the ancestral tracking genetic material plays no role in the production of proteins it is not the kind of material that 'codes' for protein production."[106][page needed] Spencer contends that certain racial discourses require visible groups, but disagrees that this is a requirement in all US racial discourse.[citation needed][undue weight? – discuss] A different objection states that US racial groups are not biologically real because they are not objectively real in the sense of existing independently of some mental state of humans. Proponents of this second metaphysical objection include Naomi Zack and Ron Sundstrom.[106][107] Spencer argues that an entity can be both biologically real and socially constructed. Spencer states that in order to accurately capture real biological entities, social factors must also be considered.[citation needed][undue weight? – discuss] It has been argued that knowledge of a person's race is limited in value, since people of the same race vary from one another.[33] David J. Witherspoon and colleagues have argued that when individuals are assigned to population groups, two randomly chosen individuals from different populations can resemble each other more than a randomly chosen member of their own group. They found that many thousands of genetic markers had to be used for the answer to "How often is a pair of individuals from one population genetically more dissimilar than two individuals chosen from two different populations?" to be "Never". This assumed three population groups, separated by large geographic distances (European, African and East Asian). The global human population is more complex, and studying a large number of groups would require an increased number of markers for the same answer. They conclude that "caution should be used when using geographic or genetic ancestry to make inferences about individual phenotypes",[108] and "The fact that, given enough genetic data, individuals can be correctly assigned to their populations of origin is compatible with the observation that most human genetic variation is found within populations, not between them. It is also compatible with our finding that, even when the most distinct populations are considered and hundreds of loci are used, individuals are frequently more similar to members of other populations than to members of their own population".[109] This is similar to the conclusion reached by anthropologist Norman Sauer in a 1992 article on the ability of forensic anthropologists to assign "race" to a skeleton, based on craniofacial features and limb morphology. Sauer said, "the successful assignment of race to a skeletal specimen is not a vindication of the race concept, but rather a prediction that an individual, while alive was assigned to a particular socially constructed 'racial' category. A specimen may display features that point to African ancestry. In this country that person is likely to have been labeled Black regardless of whether or not such a race actually exists in nature".[110] Criticism of race-based medicines Troy Duster points out that genetics is often not the predominant determinant of disease susceptibilities, even though they might correlate with specific socially defined categories. This is because this research oftentimes lacks control for a multiplicity of socio-economic factors. He cites data collected by King and Rewers that indicates how dietary differences play a significant role in explaining variations of diabetes prevalence between populations. Duster elaborates by putting forward the example of the Pima of Arizona, a population suffering from disproportionately high rates of diabetes. The reason for such, he argues, was not necessarily a result of the prevalence of the FABP2 gene, which is associated with insulin resistance. Rather he argues that scientists often discount the lifestyle implications under specific socio-historical contexts. For instance, near the end of the 19th century, the Pima economy was predominantly agriculture-based. However, as the European American population settles into traditionally Pima territory, the Pima lifestyles became heavily Westernised. Within three decades, the incidence of diabetes increased multiple folds. Governmental provision of free relatively high-fat food to alleviate the prevalence of poverty in the population is noted as an explanation of this phenomenon.[111] Lorusso and Bacchini argue against the assumption that "self-identified race is a good proxy for a specific genetic ancestry"[6] on the basis that self-identified race is complex: it depends on a range of psychological, cultural and social factors, and is therefore "not a robust proxy for genetic ancestry".[112] Furthermore, they explain that an individual's self-identified race is made up of further, collectively arbitrary factors: personal opinions about what race is and the extent to which it should be taken into consideration in everyday life. Furthermore, individuals who share a genetic ancestry may differ in their racial self-identification across historical or socioeconomic contexts. From this, Lorusso and Bacchini conclude that the accuracy in the prediction of genetic ancestry on the basis of self-identification is low, specifically in racially admixed populations born out of complex ancestral histories. |

人種自然主義への反論 人種自然主義とは、人種分類は遺伝的な類似点と相違点の客観的パターンに基づいているという見解である。この見解の支持者は、上述の科学的証拠を用いてそ れを正当化している。しかしながら、この見解には議論の余地があり、人種に関する哲学者[102]たちはそれに対して4つの主な異論を提唱している。 意味論的な異議、例えば離散性の異議は、集団遺伝学的研究で抽出された人間の集団は人種ではなく、米国で「人種」が意味するものとは一致しないと主張す る。「離散性異議は、アメリカの 「人種集団 」が存在するために、ヒトという種に遺伝的混血がないことを要求しているのではない......むしろ......この異議が主張しているのは、アメリカ の人種集団の構成員は大陸の集団の構成員とは異なるということである。... したがって、厳密に言えば、黒人はアフリカ人と同一ではなく、白人はユーラシア人と同一ではなく、アジア人は東アジア人と同一ではないのである。 次の2つの反論は形而上学的な反論であり、意味論的な反論が失敗したとしても、ヒトの遺伝的クラスター形成の結果は人種という生物学的現実を支持しないと 主張するものである。非常に重要な異論」は、大陸の集団は生物学的亜種を形成しないという意味で、米国の定義における人種は生物学にとって重要ではないと する。客観的に実在する異論」は、「アメリカの人種集団は、人間の関心や信念、あるいはその他の精神状態とは無関係に存在するという意味で、客観的に実在 するものではないから、生物学的に実在するものではない」と述べている[104]。クエイショーン・スペンサーなどの人種自然主義者は、これらの異論にそ れぞれ反論している。また、関連する集団遺伝学的研究の実験計画、実行、解釈に関連する懸念から人種的自然主義を否定する方法論的批判者もいる [105]。 もう一つの意味論的な反論は、人間の集団構造の中に米国の人種集団が存在するという主張を否定する可視性反論である。ジョシュア・グラスゴーやナオミ・ ザックなどの哲学者は、米国の人種集団は肌の色や身体的属性といった目に見える形質によって定義することはできないと信じている: 祖先の遺伝的追跡物質は、表現型、つまり人種的とみなされる形質を含むであろう生物の生物学的形質には何の影響も及ぼさない。なぜなら、祖先の追跡遺伝物 質はタンパク質の生産に何の役割も果たさないからであり、それはタンパク質の生産を「コード」するような物質ではないからである」[106][要ページ] スペンサーは、ある種の人種的言説は目に見える集団を必要とすると主張するが、これがすべてのアメリカの人種的言説における要件であるということには同意 しない。 別の反論では、アメリカの人種集団は生物学的に実在しておらず、それは人間の何らかの精神状態とは無関係に存在するという意味で客観的に実在していないか らだと述べている。この第二の形而上学的反論の支持者には、ナオミ・ザックやロン・サンドストロームがいる[106][107]。 スペンサーは、実体は生物学的に実在しうるし、社会的に構築されうるとも主張している。現実の生物学的実体を正確に捉えるためには、社会的要因も考慮され なければならないとスペンサーは述べている[citation needed][不当な重み付け? - 論じる]。 デイヴィッド・J・ウィザースプーン(David J. Witherspoon)らは、個体が集団グループに割り当てられた場合、異なる集団から無作為に選ばれた2人の個体は、同じ集団から無作為に選ばれたメ ンバーよりも互いに似ている可能性があると主張している。異なる2つの集団から選ばれた2人の個体よりも、1つの集団から選ばれた2人の個体の方が遺伝的 に似ていないことがどれだけあるか」という問いに対する答えが「ない」となるためには、何千もの遺伝マーカーを使わなければならないことがわかった。これ は、地理的に大きな距離を隔てた3つの集団(ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、東アジア)を想定したものである。世界のヒト集団はもっと複雑であり、多数の集団を研 究すれば、同じ答えを得るためにはより多くのマーカーが必要になる。彼らは、「個人の表現型に関する推論を行うために地理的または遺伝的祖先を使用する際 には注意が必要である」[108]と結論づけ、「十分な遺伝的データがあれば、個人をその出身集団に正しく割り当てることができるという事実は、ヒトの遺 伝的変異のほとんどが集団間ではなく集団内で見られるという観察結果と一致する。また、最も異なる集団を考慮し、数百の遺伝子座を使用した場合でも、個体 はしばしば自分の集団のメンバーよりも他の集団のメンバーに類似しているという我々の発見とも一致する」[109]。 これは、人類学者ノーマン・サウアーが1992年に発表した、法人類学者が頭蓋顔面の特徴と四肢の形態に基づき、骨格に「人種」を割り当てる能力に関する論文で達した結論と同様である。サウアーは、「骨格標本に人種を割り当てることに成功したことは、人種概念の正当性を証明するものではなく、その個人が生きている間に、社会的に構築された特定の『人種』カテゴリーに割り当てられたことを予測するものである」と述べている。ある骨格標本はアフリカ人の祖先を示す特徴を示すかもしれない。この国では、そのような人種が実際に自然界に存在するか否かにかかわらず、その人物は黒人のレッテルを貼られた可能性が高い」[110]。 人種に基づく医薬品への批判 トロイ・ダスターは、社会的に定義された特定のカテゴリーと相関することはあっても、遺伝学が疾患感受性の主要な決定要因ではないことが多いと指摘する。 なぜなら、このような研究では、社会経済的要因のコントロールが欠けていることが多いからである。ダスターは、KingとRewersが収集したデータを 引用し、集団間の糖尿病有病率のばらつきを説明する上で、食生活の違いがいかに重要な役割を果たしているかを示している。 ダスターは、アリゾナ州のピマ族という不釣り合いなほど高い糖尿病罹患率に苦しんでいる集団の例を出して詳しく説明する。その理由は、インスリン抵抗性に 関連するFABP2遺伝子の有病率によるものとは限らないと彼は主張する。むしろ彼は、科学者たちは特定の社会的歴史的文脈のもとで、ライフスタイルの意 味をしばしば割り引いて考えていると主張する。例えば、19世紀の終わり頃、ピマ族の経済は農業が中心であった。しかし、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人が伝統的 なピマの領土に定住するようになると、ピマのライフスタイルは大きく西洋化した。30年以内に糖尿病の発症率は何倍にも増加した。この現象の説明として、 人口の貧困の蔓延を緩和するために政府が比較的高脂肪の食品を無料で提供したことが指摘されている[111]。 LorussoとBacchiniは、「自認される人種は特定の遺伝的祖先の良い代理」[6]であるという仮定に対して、自認される人種は複雑であり、心 理的、文化的、社会的要因の範囲に依存するため、「遺伝的祖先の強固な代理ではない」[112]と反論している。さらに、遺伝的な先祖を共有する個人は、 歴史的あるいは社会経済的な文脈の違いによって、人種的自認が異なる場合がある。このことから、ロルッソとバッキーニは、特に複雑な祖先の歴史から生まれ た人種混血集団では、自認に基づく遺伝的祖先の予測精度は低いと結論付けている。 |

| List of Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world History of anthropometry – Historical uses of anthropometry, section; 4.2 Race, identity and cranio-facial description Human subspecies – Classification of the human species Human Genetic Diversity: Lewontin's Fallacy – 2003 paper by A. W. F. Edwards Zionism, race and genetics |

世界の集団におけるY染色体ハプログループのリスト 人体計測の歴史 - 人体計測の歴史的利用、セクション;4.2 人種、アイデンティティ、頭蓋顔面の記述 ヒトの亜種 - ヒトの種の分類 ヒトの遺伝的多様性: ルウォンティンの誤謬 - A. W. F. Edwardsによる2003年の論文 シオニズム、人種、遺伝学 |

| Glasgow J (2009). A Theory of Race. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415990721. Helms JE, Jernigan M, Mascher J (January 2005). "The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it: a methodological perspective" (PDF). The American Psychologist. 60 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.27. PMID 15641919. S2CID 1676488. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2019. Keita SO, Kittles RA, Royal CD, et al. (November 2004). "Conceptualizing human variation". Nature Genetics. 36 (11 Suppl): S17–20. doi:10.1038/ng1455. PMID 15507998. Koenig BA, Lee SS, Richardson SS, eds. (2008). Revisiting Race in a Genomic Age. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4324-6. This review of current research includes chapters by Jonathan Marks, John Dupré, Sally Haslanger, Deborah A. Bolnick, Marcus W. Feldman, Richard C. Lewontin, Sarah K. Tate, David B. Goldstein, Jonathan Kahn, Duana Fullwiley, Molly J. Dingel, Barbara A. Koenig, Mark D. Shriver, Rick A. Kittles, Henry T. Greely, Kimberly Tallbear, Alondra Nelson, Pamela Sankar, Sally Lehrman, Jenny Reardon, Jacqueline Stevens, and Sandra Soo-Jin Lee. Lieberman L, Kirk RC, Corcoran M (2003). "The Decline of Race in American Physical Anthropology" (PDF). Przegląd Antropologiczny – Anthropological Review. 66: 3–21. ISSN 0033-2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2010. Long JC, Kittles RA (August 2003). "Human genetic diversity and the nonexistence of biological races". Human Biology. 75 (4): 449–71. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0058. PMID 14655871. S2CID 26108602. Miththapala S, Seidensticker J, O'Brien SJ (1996). "Phylogeographic Subspecies Recognition in Leopards (Panthera pardus): Molecular Genetic Variation". Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 1115–1132. Bibcode:1996ConBi..10.1115M. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041115.x. Ossorio P, Duster T (January 2005). "Race and genetics: controversies in biomedical, behavioral, and forensic sciences". The American Psychologist. 60 (1): 115–28. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.115. PMID 15641926. Parra EJ, Kittles RA, Shriver MD (November 2004). "Implications of correlations between skin color and genetic ancestry for biomedical research". Nature Genetics. 36 (11 Suppl): S54–60. doi:10.1038/ng1440. PMID 15508005. Sawyer SL, Mukherjee N, Pakstis AJ, et al. (May 2005). "Linkage disequilibrium patterns vary substantially among populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (5): 677–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201368. PMID 15657612. Rohde DL, Olson S, Chang JT (September 2004). "Modelling the recent common ancestry of all living humans". Nature. 431 (7008): 562–6. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..562R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.78.8467. doi:10.1038/nature02842. PMID 15457259. S2CID 3563900. Serre D, Pääbo S (September 2004). "Evidence for Gradients of Human Genetic Diversity Within and Among Continents". Genome Research. 14 (9): 1679–85. doi:10.1101/gr.2529604. PMC 515312. PMID 15342553. Smedley A, Smedley BD (January 2005). "Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race". The American Psychologist. 60 (1): 16–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.568.4548. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16. PMID 15641918. |

グラスゴー J (2009). 『人種論』. ニューヨーク: ラウトレッジ. ISBN 9780415990721. ヘルムズ JE, ジャーニガン M, マッシャー J (2005年1月). 「心理学における人種の意味とその変革方法:方法論的視点」 (PDF). アメリカ心理学者. 60 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.27. PMID 15641919. S2CID 1676488. 2019年2月26日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブされた。 Keita SO, Kittles RA, Royal CD, et al. (2004年11月). 「ヒトの変異の概念化」. ネイチャー・ジェネティクス. 36 (11 Suppl): S17–20. doi:10.1038/ng1455. PMID 15507998. Koenig BA、Lee SS、Richardson SS編(2008)。『ゲノム時代における人種の再考』。ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック:ラトガース大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8135-4324-6。この最新研究のレビューには、ジョナサン・マークス、ジョン・デュプレ、サリー・ハスランガー、デボラ・A・ボル ニック、マーカス・W・フェルドマン、リチャード・C・レウォンティン、サラ・K・テイト、デイビッド・B・ゴールドスタイン、ジョナサン・カーン、デュ アナ・フルワイリー、モリー・J・ディンゲル、バーバラ・A・ケーニッヒ、マーク・D・シュライバー、リック・A・ キトルズ、ヘンリー・T・グリーリー、キンバリー・タルベア、アロンドラ・ネルソン、パメラ・サンカー、サリー・レールマン、ジェニー・リアードン、ジャ クリーン・スティーブンス、サンドラ・スー・ジン・リーによる章が掲載されている。 リーバーマン L、カーク RC、コーコラン M (2003)。「アメリカ自然人類学における人種の衰退」 (PDF). Przegląd Antropologiczny – Anthropological Review. 66: 3–21. ISSN 0033-2003. 2011年6月8日時点のオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2010年9月12日閲覧。 ロング JC、キトルズ RA (2003年8月). 「ヒトの遺伝的多様性と生物学的人種の非存在」. 『ヒューマン・バイオロジー』. 75 (4): 449–71. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0058. PMID 14655871. S2CID 26108602. Miththapala S, Seidensticker J, O'Brien SJ (1996). 「ヒョウ(Panthera pardus)における系統地理学的亜種認識:分子遺伝学的変異」. Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 1115–1132. Bibcode:1996ConBi..10.1115M. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041115.x. オソリオ P、ダスター T (2005年1月). 「人種と遺伝学:生物医学、行動科学、法科学における論争」. アメリカ心理学者. 60 (1): 115–28. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.115. PMID 15641926. Parra EJ, Kittles RA, Shriver MD (2004年11月). 「皮膚色と遺伝的祖先間の相関が生物医学研究に与える示唆」. ネイチャー・ジェネティクス. 36 (11 Suppl): S54–60. doi:10.1038/ng1440. PMID 15508005. ソーヤー SL、ムカジー N、パクスティス AJ 他 (2005年5月). 「連鎖不平衡パターンは集団間で大きく異なる」. European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (5): 677–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201368. PMID 15657612. Rohde DL, Olson S, Chang JT (2004年9月). 「全人類の最近の共通祖先をモデル化する」. Nature. 431 (7008): 562–6. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..562R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.78.8467. doi:10.1038/nature02842. PMID 15457259. S2CID 3563900. Serre D, Pääbo S (2004年9月). 「大陸内および大陸間におけるヒト遺伝的多様性の勾配に関する証拠」. Genome Research. 14 (9): 1679–85. doi:10.1101/gr.2529604. PMC 515312. PMID 15342553. Smedley A, Smedley BD (2005年1月). 「人種は生物学的には虚構であり、人種主義は社会問題として現実である:人種の社会的構築に関する人類学的・歴史的視点」. The American Psychologist. 60 (1): 16–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.568.4548. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16. PMID 15641918. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_and_genetics |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆