人種と知能

Race and intelligence

☆ 人種と知能に関する議論、特に人種による知能の違いに関する主張は、近代的な人種概念が初めて登場して以来、一般科学と学術研究の両方で取り上げられてき た。20世紀初頭にIQテストが導入されて以来、人種集団間の平均的なテスト成績の違いが観察されてきたが、これらの違いは変動しており、多くの場合、時 が経つにつれて着実に減少している。さらに問題を複雑にしているのは、現代科学では人種は生物学的な現実というよりも社会的に構築された現象であると結論 づけていること、そして知能についてもさまざまな相反する定義が存在していることである。特に、人間の知能を測る指標としてのIQテストの有効性について は異論がある。今日では、遺伝はグループ間のIQテストのパフォーマンスの差異を説明できないという点で科学的なコンセンサスが得られており、観察された 差異は環境に起因するものであると考えられている。 人種間の知能の生得的な違いを主張する疑似科学は、科学的な人種差別の歴史において中心的な役割を果たしてきた。米国の異なる集団間のIQスコアの差異を 示した最初のテストは、第一次世界大戦における米国陸軍の新兵テストであった。1920年代には、優生学ロビイストのグループが、これらの結果はアフリカ 系アメリカ人と特定の移民グループがアングロサクソン系白人と比べて知能が劣っていることを示しており、それは生来の生物学的な違いによるものであると主 張した。そして、彼らはこのような信念を人種隔離政策を正当化するために利用した。しかし、これらの結論に異議を唱え、陸軍テストでは、グループ間の社会 経済的および教育的不平等などの環境要因を十分に制御できていなかったと主張する研究が、すぐに発表された。 その後、フリン効果や出生前ケアへのアクセス格差などの現象の観察により、環境要因がグループのIQの違いに影響を与える方法が浮き彫りになった。ここ数 十年で、人間の遺伝学に対する理解が進むにつれ、人種間の知能に本質的な違いがあるという主張は、理論的および経験的な根拠から、科学者たちによって広く 否定されるようになった。

★︎人種と知性に関する論争の歴史▶︎リチャード・リンの研究▶︎︎科学人種主義の歴史▶︎形質人類学における人種理論▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| Discussions of race

and intelligence – specifically regarding claims of differences in

intelligence along racial lines – have appeared in both popular science

and academic research since the modern concept of race was first

introduced. With the inception of IQ testing in the early 20th century,

differences in average test performance between racial groups have been

observed, though these differences have fluctuated and in many cases

steadily decreased over time. Complicating the issue, modern science

has concluded that race is a socially constructed phenomenon rather

than a biological reality, and there exist various conflicting

definitions of intelligence. In particular, the validity of IQ testing

as a metric for human intelligence is disputed. Today, the scientific

consensus is that genetics does not explain differences in IQ test

performance between groups, and that observed differences are

environmental in origin. Pseudoscientific claims of inherent differences in intelligence between races have played a central role in the history of scientific racism. The first tests showing differences in IQ scores between different population groups in the United States were the tests of United States Army recruits in World War I. In the 1920s, groups of eugenics lobbyists argued that these results demonstrated that African Americans and certain immigrant groups were of inferior intellect to Anglo-Saxon white people, and that this was due to innate biological differences. In turn, they used such beliefs to justify policies of racial segregation. However, other studies soon appeared, contesting these conclusions and arguing that the Army tests had not adequately controlled for environmental factors, such as socioeconomic and educational inequality between the groups. Later observations of phenomena such as the Flynn effect and disparities in access to prenatal care highlighted ways in which environmental factors affect group IQ differences. In recent decades, as understanding of human genetics has advanced, claims of inherent differences in intelligence between races have been broadly rejected by scientists on both theoretical and empirical grounds. |

人種と知能に関する議論、特に人種による知能の違いに関する主張は、近

代的な人種概念が初めて登場して以来、一般科学と学術研究の両方で取り上げられてきた。20世紀初頭にIQテストが導入されて以来、人種集団間の平均的な

テスト成績の違いが観察されてきたが、これらの違いは変動しており、多くの場合、時が経つにつれて着実に減少している。さらに問題を複雑にしているのは、

現代科学では人種は生物学的な現実というよりも社会的に構築された現象であると結論づけていること、そして知能についてもさまざまな相反する定義が存在し

ていることである。特に、人間の知能を測る指標としてのIQテストの有効性については異論がある。今日では、遺伝はグループ間のIQテストのパフォーマン

スの差異を説明できないという点で科学的なコンセンサスが得られており、観察された差異は環境に起因するものであると考えられている。 人種間の知能の生得的な違いを主張する疑似科学は、科学的な人種差別の歴史において中心的な役割を果たしてきた。米国の異なる集団間のIQスコアの差異を 示した最初のテストは、第一次世界大戦における米国陸軍の新兵テストであった。1920年代には、優生学ロビイストのグループが、これらの結果はアフリカ 系アメリカ人と特定の移民グループがアングロサクソン系白人と比べて知能が劣っていることを示しており、それは生来の生物学的な違いによるものであると主 張した。そして、彼らはこのような信念を人種隔離政策を正当化するために利用した。しかし、これらの結論に異議を唱え、陸軍テストでは、グループ間の社会 経済的および教育的不平等などの環境要因を十分に制御できていなかったと主張する研究が、すぐに発表された。 その後、フリン効果や出生前ケアへのアクセス格差などの現象の観察により、環境要因がグループのIQの違いに影響を与える方法が浮き彫りになった。ここ数 十年で、人間の遺伝学に対する理解が進むにつれ、人種間の知能に本質的な違いがあるという主張は、理論的および経験的な根拠から、科学者たちによって広く 否定されるようになった。 |

| History of the controversy Main article: History of the race and intelligence controversy See also: Scientific racism  Autodidact and abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1817–1895) served as a high-profile counterexample to myths of black intellectual inferiority. Claims of differences in intelligence between races have been used to justify colonialism, slavery, racism, social Darwinism, and racial eugenics. Claims of intellectual inferiority were used to justify British wars and colonial campaigns in Asia.[1] Racial thinkers such as Arthur de Gobineau in France relied crucially on the assumption that black people were innately inferior to white people in developing their ideologies of white supremacy. Even Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson, a slave owner, believed black people to be innately inferior to white people in physique and intellect.[2] At the same time in the United States, prominent examples of African-American genius such the autodidact and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the pioneering sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, and the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar stood as high-profile counterexamples to widespread stereotypes of black intellectual inferiority.[3][4] In Britain, Japan's military victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War[1] began to reverse negative stereotypes of "oriental" inferiority.[5]  Alfred Binet (1857–1911), inventor of the first intelligence test Early IQ testing The first practical intelligence test, the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test, was developed between 1905 and 1908 by Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon in France for school placement of children. Binet warned that results from his test should not be assumed to measure innate intelligence or used to label individuals permanently.[6] Binet's test was translated into English and revised in 1916 by Lewis Terman (who introduced IQ scoring for the test results) and published under the name Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales. In 1916 Terman wrote that Mexican-Americans, African-Americans, and Native Americans have a mental "dullness [that] seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family stocks from which they come."[7] The US Army used a different set of tests developed by Robert Yerkes to evaluate draftees for World War I. Based on the Army's data, prominent psychologists and eugenicists such as Henry H. Goddard, Harry H. Laughlin, and Princeton professor Carl Brigham wrote that people from southern and eastern Europe were less intelligent than native-born Americans or immigrants from the Nordic countries, and that black Americans were less intelligent than white Americans.[8] The results were widely publicized by a lobby of anti-immigration activists, including the conservationist and theorist of scientific racism Madison Grant, who considered the so-called Nordic race to be superior, but under threat because of immigration by "inferior breeds." In his influential work, A Study of American Intelligence, psychologist Carl Brigham used the results of the Army tests to argue for a stricter immigration policy, limiting immigration to countries considered to belong to the "Nordic race".[9] In the 1920s, some US states enacted eugenic laws, such as Virginia's 1924 Racial Integrity Act, which established the one-drop rule (of 'racial purity') as law. Many scientists reacted negatively to eugenicist claims linking abilities and moral character to racial or genetic ancestry. They pointed to the contribution of environment (such as speaking English as a second language) to test results.[10] By the mid-1930s, many psychologists in the US had adopted the view that environmental and cultural factors played a dominant role in IQ test results. The psychologist Carl Brigham repudiated his own earlier arguments, explaining that he had come to realize that the tests were not a measure of innate intelligence.[11] Discussions of the issue in the United States, especially in the writings of Madison Grant, influenced German Nazi claims that the "Nordics" were a "master race."[12] As American public sentiment shifted against the Germans, claims of racial differences in intelligence increasingly came to be regarded as problematic.[13] Anthropologists such as Franz Boas, Ruth Benedict, and Gene Weltfish did much to demonstrate that claims about racial hierarchies of intelligence were unscientific.[14] Nonetheless, a powerful eugenics and segregation lobby funded largely by textile-magnate Wickliffe Draper continued to use intelligence studies as an argument for eugenics, segregation, and anti-immigration legislation.[15] The Pioneer Fund and The Bell Curve As the desegregation of the American South gained traction in the 1950s, debate about black intelligence resurfaced. Audrey Shuey, funded by Draper's Pioneer Fund, published a new analysis of Yerkes' tests, concluding that black people really were of inferior intellect to white people. This study was used by segregationists to argue that it was to the advantage of black children to be educated separately from the superior white children.[16] In the 1960s, the debate was revived when William Shockley publicly defended the view that black children were innately unable to learn as well as white children.[17] Arthur Jensen expressed similar opinions in his Harvard Educational Review article, "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?," which questioned the value of compensatory education for African-American children.[18] He suggested that poor educational performance in such cases reflected an underlying genetic cause rather than lack of stimulation at home or other environmental factors.[19][20] Another revival of public debate followed the appearance of The Bell Curve (1994), a book by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray that supported the general viewpoint of Jensen.[21] A statement in support of Herrnstein and Murray titled "Mainstream Science on Intelligence," was published in The Wall Street Journal with 52 signatures. The Bell Curve also led to critical responses in a statement titled "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" of the American Psychological Association and in several books, including The Bell Curve Debate (1995), Inequality by Design (1996) and a second edition of The Mismeasure of Man (1996) by Stephen Jay Gould.[22][23] Some of the authors proposing genetic explanations for group differences have received funding from the Pioneer Fund, which was headed by J. Philippe Rushton until his death in 2012.[15][22][24][25][26] Arthur Jensen, who jointly with Rushton published a 2005 review article arguing that the difference in average IQs between blacks and whites is partly due to genetics, received $1.1 million in grants from the Pioneer Fund.[27][28] According to Ashley Montagu, "The University of California's Arthur Jensen, cited twenty-three times in The Bell Curve's bibliography, is the book's principal authority on the intellectual inferiority of blacks."[29] The Southern Poverty Law Center lists the Pioneer Fund as a hate group, citing the fund's history, its funding of race and intelligence research, and its connections with racist individuals.[30] Other researchers have criticized the Pioneer Fund for promoting scientific racism, eugenics and white supremacy.[15][31][32][33] |

論争の歴史 詳細は「人種と知能の論争の歴史」を参照 関連項目:科学的人種主義  独学で学んだ奴隷制度廃止論者フレデリック・ダグラス(1817年 - 1895年)は、黒人の知的能力の低さという神話に対する著名な反証となった。 人種間の知能の差異に関する主張は、植民地主義、奴隷制、人種差別、社会ダーウィニズム、人種改良主義を正当化するために利用されてきた。知能の劣等性に 関する主張は、英国のアジアにおける戦争や植民地化を正当化するために利用されてきた。[1] フランスのアルチュール・ド・ゴビノーのような人種差別主義者は、白人優越主義のイデオロギーを展開する上で、黒人は生まれつき白人に劣っているという前 提を非常に重視していた。奴隷所有者であったトーマス・ジェファーソンなどの啓蒙思想家でさえ、黒人は体格や知性において白人に生まれつき劣っていると信 じていた。[2] その一方で、米国では、独学で学んだ奴隷制度廃止論者フレデリック・ダグラス、社会学者の先駆者W. E. B. デュボア、詩人のポール・ローレンス・ダンバーといった著名なアフリカ系アメリカ人の天才たちは、広く浸透していた黒人の知性の低さという固定観念に対す る注目度の高い反証となった。[3][4] 英国では、日露戦争における日本の軍事的勝利により[1]、「東洋人」の劣等性という否定的な固定観念が覆され始めた。[5]  アルフレッド・ビネ(1857年 - 1911年)は、最初の知能テストを考案した人物である 初期のIQテスト 最初の実践的な知能テストであるビネ・シモン知能検査は、1905年から1908年の間にアルフレッド・ビネとテオドール・シモンがフランスの学校で児童 のクラス分けのために開発した。ビネは、このテストの結果は先天的な知能を測定するものではないし、また個人のレッテルを貼るために永続的に使用されるべ きではないと警告した。[6] ビネのテストは英語に翻訳され、1916年にルイス・ターマンによって改訂された(ターマンはテスト結果にIQスコアを導入した)。このテストはスタン フォード・ビネ知能尺度という名称で出版された。ターマンは1916年に、メキシコ系アメリカ人、アフリカ系アメリカ人、ネイティブアメリカンには「人種 的、あるいは少なくとも彼らの家系に内在すると思われる精神的な鈍さ」がある、と記している。 米国陸軍は、ロバート・ヤーキスが開発した別のテストセットを使用して、第一次世界大戦の徴兵候補者を評価した。陸軍のデータに基づき、著名な心理学者や 優生学者であるヘンリー・H・ゴダード、ハリー・H・ラフリン、プリンストン大学のカール・ブリガム教授らは、南ヨーロッパや東ヨーロッパ出身者は、アメ リカ生まれのアメリカ人や北欧からの移民よりも知能が低い また、黒人アメリカ人は白人アメリカ人よりも知能が劣っていると結論づけた。[8] この結果は、いわゆる「北欧人種」が優れているが、「劣等人種」の移民によって脅威にさらされていると考える、自然保護論者であり科学人種論の理論家でも あるマディソン・グラントをはじめとする反移民活動家のロビー活動によって広く喧伝された。心理学者カール・ブリガムは、影響力のある著書『アメリカ人の 知能に関する研究』の中で、陸軍のテスト結果を引用し、移民を「北欧人種」に属する国々に限定するなど、移民政策の厳格化を主張した。[9] 1920年代には、バージニア州の1924年の人種純血法(1ドロップ・ルール)のような優生学に関する法律がいくつかの州で制定された。多くの科学者 は、能力や道徳的資質を人種や遺伝的背景に関連付ける優生学の主張に否定的な反応を示した。彼らは、テスト結果に環境(英語を第二言語として話すことな ど)が影響していることを指摘した。[10] 1930年代半ばまでに、米国の多くの心理学者は、IQテストの結果には環境や文化的な要因が支配的な役割を果たしているという見解を採用していた。心理 学者カール・ブリガムは、以前の自身の主張を否定し、テストは生来の知能を測る尺度ではないと気づいたと説明した。[11] 米国におけるこの問題に関する議論、特にマディソン・グラントの著作は、ドイツのナチスによる「北欧人」は「マスター・レース」であるという主張に影響を 与えた。[12] 米国の世論がドイツ人に対して敵対的になるにつれ、知能における人種差異の主張は次第に問題視されるようになった。[13] フランツ・ボアズ、ルース・ベネディクト、ジーン・ウェルチフィッシュなどの人類学者は、 ジェーン・ベンディクト、ジーン・ウェルチといった人類学者は、知能に関する人種的ヒエラルキーの主張が非科学的であることを証明するために多くのことを 行った。[14] しかし、繊維業界の大物ウィクリフ・ドレイパーが主に資金提供していた強力な優生学および人種隔離ロビーは、知能研究を優生学、人種隔離、反移民法の論拠 として使い続けた。[15] パイオニア基金と『ザ・ベルカーブ』 1950年代にアメリカ南部の分離政策が勢いを増すにつれ、黒人の知能に関する議論が再燃した。オードリー・シュイーは、ドレイパーのパイオニア基金から 資金提供を受け、ヤーキーズのテストに関する新たな分析を発表し、黒人の知能は白人よりも明らかに劣っていると結論付けた。この研究は、人種隔離論者たち が「優秀な白人の子供たちとは別に黒人の子供たちを教育することが黒人の子供たちのためになる」と主張するのに利用された。[16] 1960年代には、ウィリアム・ショックレーが黒人の子供たちは生まれつき白人の子供たちほどには学べないという見解を公に擁護したことで、この論争が再 燃した。[17] アーサー・ジェンセンは ハーバード教育評論誌に発表した論文「IQと学業成績をどれだけ伸ばせるか?」で同様の意見を述べ、アフリカ系アメリカ人の子供に対する補償教育の価値を 疑問視した。[18] 彼は、このような場合の教育成績の低さは、家庭での刺激不足やその他の環境要因よりも、むしろ根底にある遺伝的原因を反映していると示唆した。[19] [20] ジェンセンの一般的な見解を支持するリチャード・ヘルンスタインとチャールズ・マレーによる著書『The Bell Curve』(1994年)の出版により、再び世論の議論が再燃した。[21] ヘルンスタインとマレーを支持する声明「Mainstream Science on Intelligence」には52人の署名が添えられ、ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に掲載された。『The Bell Curve』はまた、アメリカ心理学会による「知能: アメリカ心理学会の「知能:既知と未知」と、スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドによる『The Bell Curve Debate』(1995年)、『Inequality by Design』(1996年)、『The Mismeasure of Man』(1996年)第2版を含む複数の書籍で批判的な反応を引き起こした。 集団間の差異を遺伝学的に説明しようとする著者の一部は、2012年に死去するまでJ.フィリップ・ラシュトンが代表を務めていたパイオニア・ファンドか ら資金援助を受けている。[15][22][24][25][26] アーサー・ジェンセンはラシュトンと共同で、黒人と白人の平均IQの差異は 遺伝が一部原因であると主張する2005年の総説をラシュトンと共同執筆したアーサー・ジェンセンは、パイオニア基金から110万ドルの助成金を受け取っ た。[27][28] アシュレイ・モンタギューによると、「カリフォルニア大学のアーサー・ジェンセンは、『ベルカーブ』の参考文献で23回言及されており、この本における黒 人の知能の低さに関する主要な権威である」[29] 南部貧困法律センターは、パイオニア基金の歴史、人種および知能研究への資金提供、人種差別主義者とのつながりを挙げ、同基金を憎悪集団としてリストアッ プしている。[30] 他の研究者も、パイオニア基金が科学的人種差別、優生学、白人至上主義を推進していると批判している。[15][31][32][33] |

| Conceptual issues Intelligence and IQ Main articles: Human intelligence, Intelligence quotient, and G factor (psychometrics) The concept of intelligence and the degree to which intelligence is measurable are matters of debate. There is no consensus about how to define intelligence; nor is it universally accepted that it is something that can be meaningfully measured by a single figure.[34] A recurring criticism is that different societies value and promote different kinds of skills and that the concept of intelligence is therefore culturally variable and cannot be measured by the same criteria in different societies.[34] Consequently, some critics argue that it makes no sense to propose relationships between intelligence and other variables.[35] Correlations between scores on various types of IQ tests led English psychologist Charles Spearman to propose in 1904 the existence of an underlying factor, which he referred to as "g" or "general intelligence", a trait which is supposed to be innate.[36] Another proponent of this view is Arthur Jensen.[37] This view, however, has been contradicted by a number of studies showing that education and changes in environment can significantly improve IQ test results.[38][39][40] Other psychometricians have argued that, whether or not there is such a thing as a general intelligence factor, performance on tests relies crucially on knowledge acquired through prior exposure to the types of tasks that such tests contain. This means that comparisons of test scores between persons with widely different life experiences and cognitive habits do not reveal their relative innate potentials.[41] Race Main articles: Race (human categorization) and Race and genetics The consensus view among geneticists, biologists and anthropologists is that race is a sociopolitical phenomenon rather than a biological one,[42][43][44] a view supported by considerable genetics research.[45][46] The current mainstream view is that race is a social construction based on folk ideologies that construct groups based on social disparities and superficial physical characteristics.[47] A 2023 consensus report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine stated: "In humans, race is a socially constructed designation, a misleading and harmful surrogate for population genetic differences, and has a long history of being incorrectly identified as the major genetic reason for phenotypic differences between groups."[42] The concept of human "races" as natural and separate divisions within the human species has also been rejected by the American Anthropological Association. The official position of the AAA, adopted in 1998, is that advances in scientific knowledge have made it "clear that human populations are not unambiguous, clearly demarcated, biologically distinct groups" and that "any attempt to establish lines of division among biological populations [is] both arbitrary and subjective."[48] A more recent statement from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (2019) declares that "Race does not provide an accurate representation of human biological variation. It was never accurate in the past, and it remains inaccurate when referencing contemporary human populations. Humans are not divided biologically into distinct continental types or racial genetic clusters."[49] Anthropologists such as C. Loring Brace,[50] the philosophers Jonathan Kaplan and Rasmus Winther,[51][52][53] and the geneticist Joseph Graves,[54] have argued that the cluster structure of genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the influence of these hypotheses on the choice of populations to sample. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental, but if one had chosen other sampling patterns, the clustering would be different. Weiss and Fullerton have noted that if one sampled only Icelanders, Mayans and Maoris, three distinct clusters would form and all other populations could be described as being clinally composed of admixtures of Maori, Icelandic and Mayan genetic materials.[55] Kaplan and Winther conclude that while racial groups are characterized by different allele frequencies, this does not mean that racial classification is a natural taxonomy of the human species, because multiple other genetic patterns can be found in human populations that crosscut racial distinctions. Moreover, the genomic data underdetermines whether one wishes to see subdivisions (i.e., splitters) or a continuum (i.e., lumpers). Under Kaplan and Winther's view, racial groupings are objective social constructions (see Mills 1998[56]) that have conventional biological reality only insofar as the categories are chosen and constructed for pragmatic scientific reasons. Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd (2005) argue that the social construction of race derives not from any valid scientific basis but rather "from people's desire to classify."[35] In studies of human intelligence, race is almost always determined using self-reports rather than analyses of genetic characteristics. According to psychologist David Rowe, self-report is the preferred method for racial classification in studies of racial differences because classification based on genetic markers alone ignore the "cultural, behavioral, sociological, psychological, and epidemiological variables" that distinguish racial groups.[57] Hunt and Carlson disagreed, writing that "Nevertheless, self-identification is a surprisingly reliable guide to genetic composition," citing a study by Tang et al. (2005).[58] Sternberg and Grigorenko disputed Hunt and Carlson's interpretation of Tang's results as supporting the view that racial divisions are biological; rather, "Tang et al.'s point was that ancient geographic ancestry rather than current residence is associated with self-identification and not that such self-identification provides evidence for the existence of biological race."[59] |

概念上の問題 知能とIQ 詳細は「人間の知能」、「知能指数」、および「G因子 (心理測定学)」を参照 知能の概念と、知能がどの程度まで測定可能であるかについては、議論の余地がある。知能を定義する方法についてコンセンサスは得られていない。また、知能 をひとつの数値で有意義に測定できると一般的に受け入れられているわけでもない。[34] 繰り返し指摘される批判として、異なる社会では異なる種類のスキルが評価され、促進されるため、知能の概念は文化によって異なり、異なる社会で同じ基準で 測定することはできないというものがある。[34] その結果、知能と他の変数との関係を提案することに意味がないと主張する批評家もいる。[35] さまざまなタイプのIQテストのスコア間の相関関係から、イギリスの心理学者チャールズ・スピアマンは1904年に、生得的な特性である「g」または「一 般知能」と呼ばれる基礎的要因の存在を提唱した。 36] この見解の支持者には、アーサー・ジェンセンもいる。[37] しかし、教育や環境の変化がIQテストの結果を大幅に改善できることを示す多くの研究結果により、この見解は否定されている。[38][39][40] 他の心理測定学者たちは、一般的な知能因子が存在するかどうかに関わらず、テストの成績は、そのテストに含まれるような種類の課題に事前に触れることで得 られる知識に大きく依存していると主張している。これは、人生経験や認知習慣が大きく異なる人々のテストの成績を比較しても、その相対的な先天的潜在能力 は明らかにならないことを意味する。 人種 詳細は「人種 (人間の分類)」および「人種と遺伝学」を参照 遺伝学者、生物学者、人類学者の間では、人種は生物学的なものではなく、社会政治的な現象であるという見解が一般的である。現在の主流の考え方は、人種と は社会的格差や表面的な身体的特徴に基づいて集団を構築する民衆のイデオロギーに基づく社会的構築物であるというものである。[47] 2023年の全米科学アカデミー、工学アカデミー、医学アカデミーによるコンセンサス報告書では、「ヒトにおいて、人種とは社会的に構築された呼称であ り、集団間の表現型の違いの主な遺伝的理由として誤って特定されてきた長い歴史を持つ、集団遺伝的差異の誤解を招き有害な代理である」と述べている。 [42] ヒトの「人種」という概念は、ヒトという種の中で自然かつ独立した区分であるという考え方も、アメリカ人類学会によって否定されている。1998年に採択 されたアメリカ人類学会の公式見解では、科学的知識の進歩により、「ヒト集団は明確で、はっきりと区別された、生物学的に異なる集団ではないことが明らか になった」とし、「 生物学的集団間に境界線を引く試みは、恣意的かつ主観的なものである」と述べている。[48] アメリカ自然人類学会(2019年)のより最近の声明では、「人種は、人間の生物学的多様性を正確に表現するものではない。過去において決して正確なもの ではなく、現代の人間集団を参照しても依然として不正確である。人間は、生物学的には異なる大陸型や人種的遺伝子クラスターに分けられるものではない」と 宣言している。[49] 人類学者のC. ローリング・ブレイス(C. Loring Brace)[50]、哲学者のジョナサン・カプラン(Jonathan Kaplan)とラスムス・ヴィンター(Rasmus Winther)[51][52][53]、遺伝学者のジョセフ・グレイブス(Joseph Graves)[54]らは、遺伝子データのクラスター構造は研究者の初期仮説に依存しており、その仮説が標本とする集団の選択に影響を与えると主張して いる。ある大陸グループをサンプリングすると、クラスターは大陸別になるが、他のサンプリングパターンを選択した場合、クラスタリングは異なるものにな る。WeissとFullertonは、アイスランド人、マヤ人、マオリ人のみをサンプリングした場合、3つの異なるクラスターが形成され、他のすべての 集団は、マオリ人、アイスランド人、マヤ人の遺伝物質の混血として構成されているとみなすことができると指摘している。 55] カプランとウィンターは、人種集団は異なる対立遺伝子頻度によって特徴づけられるが、人種分類が人類の自然分類であることを意味するわけではないと結論づ けている。なぜなら、人種的区別を横断する複数の他の遺伝的パターンが人類集団内で見られるからである。さらに、ゲノムデータは、細分化(すなわち分割 者)を望むか、連続性(すなわち一括者)を望むかによって、その解釈が異なる。カプランとウィンターの見解では、人種分類は客観的な社会的構築物(ミルズ 1998[56]を参照)であり、実用的な科学的理由からカテゴリーが選択され構築される限りにおいてのみ、従来の生物学的な現実性を持つ。 スターンバーグ、グリゴレンコ、キッド(2005)は、人種に関する社会的構築は有効な科学的根拠からではなく、「人々が分類したいという欲求から」生じ ていると主張している[35]。 人間の知能に関する研究では、人種は遺伝的特性の分析ではなく、ほぼ常に自己申告によって決定されている。心理学者のデビッド・ロウによると、人種間の違 いを研究する上で、自己申告は人種分類に好ましい方法である。なぜなら、遺伝子マーカーのみに基づく分類では、人種集団を区別する「文化的、行動的、社会 学的、心理学的、疫学的変数」が無視されるからだ。[57] ハントとカールソンはこれに反対し、「とはいえ、自己申告は遺伝的構成を驚くほど正確に示している」と述べ、タンらの研究(2005年)を引用している。 (2005年)を引用し、「それにもかかわらず、自己認識は遺伝的構成を明らかにする驚くほど信頼性の高い指針である」と述べている。[58] スターンバーグとグリゴレンコは、タンによる研究結果を人種的区分は生物学的なものであるという見解を裏付けるものとして解釈したハントとカールソンの見 解に異議を唱えた。むしろ、「タンらの主張は、現在の居住地ではなく古代の地理的祖先が自己認識と関連しているということであり、そのような自己認識が生 物学的な人種の存在を示す証拠となるというものではない」[59] |

| Group differences The study of human intelligence is one of the most controversial topics in psychology, in part because of difficulty reaching agreement about the meaning of intelligence and objections to the assumption that intelligence can be meaningfully measured by IQ tests. Claims that there are innate differences in intelligence between racial and ethnic groups—which go back at least to the 19th century—have been criticized for relying on specious assumptions and research methods and for serving as an ideological framework for discrimination and racism.[60][61] In a 2012 study of tests of different components of intelligence, Hampshire et al. expressed disagreement with the view of Jensen and Rushton that genetic factors must play a role in IQ differences between races, stating that "it remains unclear ... whether population differences in intelligence test scores are driven by heritable factors or by other correlated demographic variables such as socioeconomic status, education level, and motivation. More relevantly, it is questionable whether [population differences in intelligence test scores] relate to a unitary intelligence factor, as opposed to a bias in testing paradigms toward particular components of a more complex intelligence construct."[62] According to Jackson and Weidman, There are a number of reasons why the genetic argument for race differences in intelligence has not won many adherents in the scientific community. First, even taken on its own terms, the case made by Jensen and his followers did not hold up to scrutiny. Second, the rise of population genetics undercut the claims for a genetic cause of intelligence. Third, the new understanding of institutional racism offered a better explanation for the existence of differences in IQ scores between the races.[61] Test scores Main article: Achievement gap in the United States In the United States, Asians on average score the same as White people, who tend to score higher than Hispanics, who tend to score higher than African Americans.[60] Much greater variation in IQ scores exists within each ethnic group than between them.[clarification needed][63][64] A 2001 meta-analysis of the results of 6,246,729 participants tested for cognitive ability or aptitude found a difference in average scores between black people and white people of 1.1 standard deviations. Consistent results were found for college and university application tests such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (N = 2.4 million) and Graduate Record Examination (N = 2.3 million), as well as for tests of job applicants in corporate settings (N = 0.5 million) and in the military (N = 0.4 million).[65] In response to the controversial 1994 book The Bell Curve, the American Psychological Association (APA) formed a task-force of eleven experts, which issued a report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" in 1996.[60] Regarding group differences, the report reaffirmed the consensus that differences within groups are much wider than differences between groups, and that claims of ethnic differences in intelligence should be scrutinized carefully, as such claims had been used to justify racial discrimination. The report also acknowledged problems with the racial categories used, as these categories are neither consistently applied, nor homogeneous (see Race and ethnicity in the United States).[60] In the UK, some African groups have higher average educational attainment and standardized test scores than the overall population.[66] In 2010–2011, white British pupils were 2.3% less likely to have gained 5 A*–C grades at GCSE than the national average, whereas the likelihood was 21.8% above average for those of Nigerian origin, 5.5% above average for those of Ghanaian origin, and 1.4% above average for those of Sierra Leonian origin. For the two other African ethnic groups on which data was available, the likelihood was 23.7% below average for those of Somali origin and 35.3% below average for those of Congolese origin.[67] In 2014, Black-African pupils of 11 language groups were more likely to pass Key Stage 2 Maths 4+ in England than the national average. Overall, the average pass rate by ethnicity was 86.5% for white British (N = 395,787), whereas it was 85.6% for Black-Africans (N = 18,497). Nevertheless, several Black-African language groups, including Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Akan, Ga, Swahili, Edo, Ewe, Amharic speakers, and English-speaking Africans, each had an average pass rate above the white British average (total N = 9,314), with the Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba, and Amhara having averages above 90% (N = 2,071).[68] In 2017–2018, the percentage of pupils getting a strong pass (grade 5 or above) in the English and maths GCSE (in Key Stage 4) was 42.7% for whites (N = 396,680) and 44.3% for Black-Africans (N = 18,358).[69] Flynn effect and the closing gap Main article: Flynn effect The 'Flynn effect' — a term coined after researcher James R. Flynn — refers to the substantial rise in raw IQ test scores observed in many parts of the world during the 20th century. In the United States, the increase was continuous and approximately linear from the earliest years of testing to about 1998 when the gains stopped and some tests even showed decreasing test scores. For example, the average scores of black people on some IQ tests in 1995 were the same as the scores of white people in 1945.[70] As one pair of academics phrased it, "the typical African American today probably has a slightly higher IQ than the grandparents of today's average white American."[71] Flynn himself argued that the dramatic changes having taken place between one just generation and the next pointed strongly at an environmental explanation, and that it is highly unlikely that genetic factors could have accounted for the increasing scores. The Flynn effect, along with Flynn's analysis, continues to hold significance in the context of the black/white IQ gap debate, demonstrating the potential for environmental factors to influence IQ test scores by as much as 1 standard deviation, a scale of change that had previously been doubted.[72] A distinct but related observation has been the gradual narrowing of the American black-white IQ gap in the last decades of the 20th century, as black test-takers increased their average scores relative to white test-takers. For instance, Vincent reported in 1991 that the black–white IQ gap was decreasing among children, but that it was remaining constant among adults.[73] Similarly, a 2006 study by Dickens and Flynn estimated that the difference between mean scores of black people and white people closed by about 5 or 6 IQ points between 1972 and 2002,[39] a reduction of about one-third. In the same period, the educational achievement disparity also diminished.[74] Reviews by Flynn and Dickens,[39] Mackintosh,[75] and Nisbett et al. accept the gradual closing of the gap as a fact.[76] Flynn and Dickens summarize this trend, stating, "The constancy of the Black-White IQ gap is a myth and therefore cannot be cited as evidence that the racial IQ gap is genetic in origin."[39] |

グループ間の違い 人間の知能の研究は心理学において最も論争の多いトピックのひとつである。その理由のひとつは、知能の意味について合意に達することが難しいこと、また、 知能はIQテストによって有意義に測定できるという前提に対する異論があることである。少なくとも19世紀まで遡る、人種や民族集団の間には先天的な知能 の差異があるという主張は、根拠のない仮定や研究方法に依拠しており、差別や人種差別のイデオロギー的枠組みとなっているとして批判されてきた。[60] [61] 2012年の知能のさまざまな要素のテストに関する研究において、ハンプシャーらは、ジェンセンとラシュトンの「人種間のIQの違いには遺伝的要因が関 わっているに違いない」という見解に反対の意を示し、「知能テストのスコアにおける集団間の違いが遺伝的要因によるものなのか、あるいは社会経済的地位、 教育レベル、動機づけといった他の相関する人口統計学的変数によるものなのかは依然として不明である。さらに言えば、[知能テストのスコアにおける集団間 の差異]が、より複雑な知能構造の特定の要素に対するテストパラダイムの偏りではなく、単一の知能因子に関連しているかどうかは疑問である」[62]と述 べている。ジャクソンとワイドマンによると、 知能における人種差に関する遺伝的論拠が科学界で多くの支持者を獲得していないのには、いくつかの理由がある。第一に、ジェンセンとその追随者たちが主張 した内容は、その言葉通りに受け取ったとしても、精査に耐えるものではなかった。第二に、集団遺伝学の台頭により、知能の遺伝的原因に関する主張は弱まっ た。第三に、制度上の人種差別に対する新たな理解が、人種間のIQスコアの差異の存在について、より優れた説明を提供した。[61] テストの成績 詳細は「アメリカ合衆国の学力格差」を参照 アメリカ合衆国では、アジア系は平均して白人と同等であり、ヒスパニック系は平均してアフリカ系アメリカ人よりも高い傾向にある。 3][64] 2001年のメタ分析では、6,246,729人の参加者が認知能力や適性をテストした結果、黒人と白人の平均スコアに1.1標準偏差の差があることが分 かった。大学入学適性試験(N = 240万人)や大学院進学適性試験(N = 230万人)などの大学・カレッジの入学試験でも、また企業(N = 50万人)や軍隊(N = 40万人)の就職希望者の試験でも、同様の結果が得られた。[65] 1994年に出版され物議を醸した『The Bell Curve』を受けて、米国心理学会(APA)は11人の専門家によるタスクフォースを結成し、1996年に「知能:既知と未知」という報告書を提出し た。Knowns and Unknowns(知能:既知と未知)」を1996年に発表した。[60] 集団間の差異について、この報告書は集団内の差異の方が集団間の差異よりもはるかに大きいというコンセンサスを再確認し、知能における民族間の差異に関す る主張は、人種差別を正当化するために使われてきたものであるため、慎重に精査されるべきであると述べた。また、この報告書は、使用されている人種カテゴ リーに問題があることを認め、これらのカテゴリーは一貫して適用されているわけでも、均質でもないことを指摘した(「米国における人種と民族」を参照)。 [60] 英国では、アフリカ系住民の一部のグループは、平均的な教育達成度や標準テストの成績が、全体的な人口よりも高い。[66] 2010年から2011年にかけて、英国の白人の生徒が、 一方で、ナイジェリア出身者は平均を21.8%上回り、ガーナ出身者は平均を5.5%上回り、シエラレオネ出身者は平均を1.4%上回っていた。データが 入手できた他の2つのアフリカ系民族グループについては、ソマリア系は平均より23.7%低く、コンゴ系は平均より35.3%低かった。[67] 2014年には、11の言語グループに属する黒人アフリカ人の生徒は、イングランドにおいて全国平均よりもキー・ステージ2の数学4+に合格する可能性が 高かった。全体として、民族ごとの平均合格率は、白人系英国人(N = 395,787)では86.5%であったのに対し、黒人アフリカ人(N = 18,497)では85.6%であった。しかし、ヨルバ語、イボ語、ハウサ語、アカン語、ガー語、スワヒリ語、エド語、エウェ語、アムハラ語話者、英語話 者アフリカ人など、いくつかのアフリカの言語グループは、それぞれ白人の英国人平均(合計N = 9,314)を上回る平均合格率を達成しており、ハウサ語、イボ語、ヨルバ語、アムハラ語は90%以上の平均を達成している(N = 2,07 1)。[68] 2017年から2018年にかけて、英語と数学のGCSE(キー・ステージ4)で「グレード5以上」の成績(「強い合格」)を得た生徒の割合は、白人が 42.7%(N = 396,680)、黒人アフリカ人が44.3%(N = 18,358)であった。[69] フリン効果と縮小する格差 詳細は「フリン効果」を参照 「フリン効果」とは、研究者のジェームズ・R・フリンにちなんで名付けられた用語で、20世紀に世界中の多くの地域で観察された、IQテストの生得得点の 大幅な上昇を指す。米国では、テストの初期から1998年頃まで上昇が継続し、ほぼ直線的であったが、その後上昇は止まり、一部のテストでは得点の低下さ え見られた。例えば、1995年の一部のIQテストにおける黒人の平均スコアは、1945年の白人のスコアと同じであった。[70] 一組の学者が表現したように、「今日の典型的なアフリカ系アメリカ人のIQは、おそらく今日の平均的な白人の祖父母よりもわずかに高い」のである。 [71] フリン自身は、1世代から次の世代へと劇的な変化が起こっていることから、環境要因による説明が強く示唆されると主張し、遺伝的要因が得点上昇を説明でき る可能性は極めて低いと述べた。フリン効果とフリンの分析は、黒人と白人のIQギャップに関する議論の文脈において、依然として重要な意味を持ち続けてい る。環境要因がIQテストのスコアに1標準偏差もの影響を与える可能性を示しており、これは以前は疑われていた変化の規模である。 また、関連性はあるものの異なる観察結果として、20世紀の最後の数十年間において、黒人と白人のIQの差が徐々に縮まっていることが挙げられる。黒人の テスト受験者の平均スコアが、白人のテスト受験者と比較して上昇しているためである。例えば、ヴィンセントは1991年に、子どもの間では黒人と白人の IQの差が縮まっているが、成人では差は一定であると報告している。[73] 同様に、ディケンズとフリンによる2006年の研究では、1972年から2002年の間に黒人と白人の平均スコアの差はIQポイントで5~6ポイント縮ま り、約3分の1減少したと推定されている。同じ期間において、教育達成度の格差も縮小した。[74] フリンとディケンズによるレビュー[39]、マッキントッシュ[75]、ニスベットらによるレビュー[76]は、徐々に縮小する格差を事実として受け入れ ている。フリンとディケンズは、この傾向を次のようにまとめている。「黒人と白人のIQ格差が一定しているというのは神話であり、したがって、人種間の IQ格差が遺伝的起源によるものであるという証拠として引用することはできない」[39] |

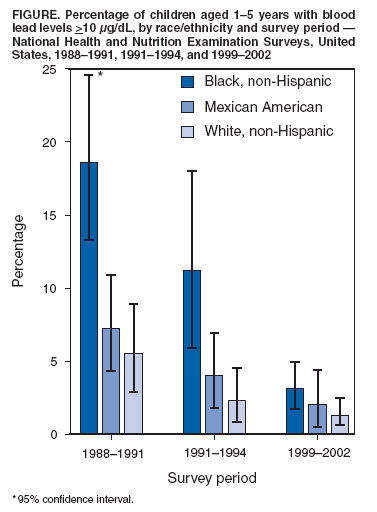

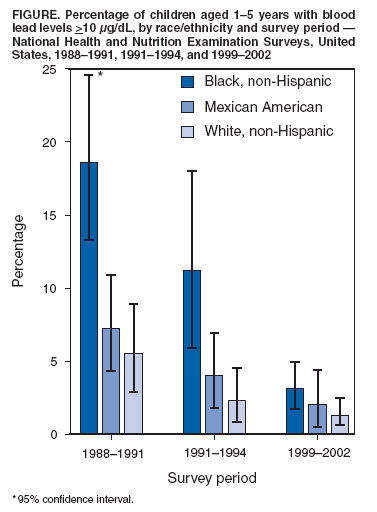

| Environmental factors Health and nutrition Main article: Impact of health on intelligence  Percentage of children aged 1–5 with blood lead levels at least 10 μg/dL. Black and Hispanic children have much higher levels than white children. A 10 μg/dL increase in blood lead at 24 months is associated with a 5.8-point decline in IQ.[77] Although the Geometric Mean Blood Lead Levels (GM BLL) are declining, a CDC report (2002) states that: "However, the GM BLL for non-Hispanic black children remains higher than that for Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white children, indicating that differences in risk for exposure still persist."[78] Environmental factors including childhood lead exposure,[77] low rates of breast feeding,[79] and poor nutrition[80][81] are significantly correlated with poor cognitive development and functioning. For example, childhood exposure to lead — associated with homes in poorer areas[82] — correlates with an average IQ drop of 7 points,[83] and iodine deficiency causes a decline, on average, of 12 IQ points.[84][85] Such impairments may sometimes be permanent, but in some cases they be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth. The first two years of life are critical for malnutrition, the consequences of which are often irreversible and include poor cognitive development, educability, and future economic productivity.[86] Mackintosh points out that, for American black people, infant mortality is about twice as high as for white people, and low birth weight is twice as prevalent. At the same time, white mothers are twice as likely to breastfeed their infants, and breastfeeding is directly correlated with IQ for low-birth-weight infants. In this way, a wide number of health-related factors which influence IQ are unequally distributed between the two groups.[87] The Copenhagen consensus in 2004 stated that lack of both iodine and iron has been implicated in impaired brain development, and this can affect enormous numbers of people: it is estimated that one-third of the total global population is affected by iodine deficiency. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged four and under have anaemia because of insufficient iron in their diets.[88] Other scholars have found that simply the standard of nutrition has a significant effect on population intelligence, and that the Flynn effect may be caused by increasing nutrition standards across the world.[89] James Flynn has himself argued against this view.[90] Some recent research has argued that the retardation caused in brain development by infectious diseases, many of which are more prevalent in non-white populations, may be an important factor in explaining the differences in IQ between different regions of the world. The findings of this research, showing the correlation between IQ, race and infectious diseases was also shown to apply to the IQ gap in the US, suggesting that this may be an important environmental factor.[91] A 2013 meta-analysis by the World Health Organization found that, after controlling for maternal IQ, breastfeeding was associated with IQ gains of 2.19 points. The authors suggest that this relationship is causal but state that the practical significance of this gain is debatable; however, they highlight one study suggesting an association between breastfeeding and academic performance in Brazil, where "breastfeeding duration does not present marked variability by socioeconomic position."[92] Colen and Ramey (2014) similarly find that controlling for sibling comparisons within families, rather than between families, reduces the correlation between breastfeeding status and WISC IQ scores by nearly a third, but further find the relationship between breastfeeding duration and WISC IQ scores to be insignificant. They suggest that "much of the beneficial long-term effects typically attributed to breastfeeding, per se, may primarily be due to selection pressures into infant feeding practices along key demographic characteristics such as race and socioeconomic status."[93] Reichman estimates that no more than 3 to 4% of the black–white IQ gap can be explained by black–white disparities in low birth weight.[94] Education Several studies have proposed that a large part of the gap in IQ test performance can be attributed to differences in quality of education.[95] Racial discrimination in education has been proposed as one possible cause of differences in educational quality between races.[96] According to a paper by Hala Elhoweris, Kagendo Mutua, Negmeldin Alsheikh and Pauline Holloway, teachers' referral decisions for students to participate in gifted and talented educational programs were influenced in part by the students' ethnicity.[97] The Abecedarian Early Intervention Project, an intensive early childhood education project, was also able to bring about an average IQ gain of 4.4 points at age 21 in the black children who participated in it compared to controls.[79] Arthur Jensen agreed that the Abecedarian project demonstrated that education can have a significant effect on IQ, but also declared his view that no educational program thus far had been able to reduce the black–white IQ gap by more than a third, and that differences in education are thus unlikely to be its only cause.[98] A series of studies by Joseph Fagan and Cynthia Holland measured the effect of prior exposure to the kind of cognitive tasks posed in IQ tests on test performance. Assuming that the IQ gap was the result of lower exposure to tasks using the cognitive functions usually found in IQ tests among African American test takers, they prepared a group of African Americans in this type of tasks before taking an IQ test. The researchers found that there was no subsequent difference in performance between the African-Americans and white test takers.[99][100] Daley and Onwuegbuzie conclude that Fagan and Holland demonstrate that "differences in knowledge between black people and white people for intelligence test items can be erased when equal opportunity is provided for exposure to the information to be tested".[101] A similar argument is made by David Marks who argues that IQ differences correlate well with differences in literacy suggesting that developing literacy skills through education causes an increase in IQ test performance.[102][103] A 2003 study found that two variables—stereotype threat and the degree of educational attainment of children's fathers—partially explained the black–white gap in cognitive ability test scores, undermining the hereditarian view that they stemmed from immutable genetic factors.[104] Socioeconomic environment Different aspects of the socioeconomic environment in which children are raised have been shown to correlate with part of the IQ gap, but they do not account for the entire gap.[105] According to a 2006 review, these factors account for slightly less than half of one standard deviation.[106] Other research has focused on different causes of variation within low socioeconomic status (SES) and high SES groups.[107][108][109] In the US, among low SES groups, genetic differences account for a smaller proportion of the variance in IQ than among high SES populations.[110] Such effects are predicted by the bioecological hypothesis—that genotypes are transformed into phenotypes through nonadditive synergistic effects of the environment.[111] Nisbett et al. (2012a) suggest that high SES individuals are more likely to be able to develop their full biological potential, whereas low SES individuals are likely to be hindered in their development by adverse environmental conditions. The same review also points out that adoption studies generally are biased towards including only high and high middle SES adoptive families, meaning that they will tend to overestimate average genetic effects. They also note that studies of adoption from lower-class homes to middle-class homes have shown that such children experience a 12 to 18 point gain in IQ relative to children who remain in low SES homes.[76] A 2015 study found that environmental factors (namely, family income, maternal education, maternal verbal ability/knowledge, learning materials in the home, parenting factors, child birth order, and child birth weight) accounted for the black–white gap in cognitive ability test scores.[112] Test bias A number of studies have reached the conclusion that IQ tests may be biased against certain groups.[113][114][115][116] The validity and reliability of IQ scores obtained from outside the United States and Europe have been questioned, in part because of the inherent difficulty of comparing IQ scores between cultures.[117][118] Several researchers have argued that cultural differences limit the appropriateness of standard IQ tests in non-industrialized communities.[119][120] A 1996 report by the American Psychological Association states that intelligence can be difficult to compare across cultures, and notes that differing familiarity with test materials can produce substantial differences in test results; it also says that tests are accurate predictors of future achievement for black and white Americans, and are in that sense unbiased.[60] The view that tests accurately predict future educational attainment is reinforced by Nicholas Mackintosh in his 1998 book IQ and Human Intelligence,[121] and by a 1999 literature review by Brown, Reynolds & Whitaker (1999). James R. Flynn, surveying studies on the topic, notes that the weight and presence of many test questions depends on what sorts of information and modes of thinking are culturally valued.[122] Stereotype threat and minority status Main article: Stereotype threat Stereotype threat is the fear that one's behavior will confirm an existing stereotype of a group with which one identifies or by which one is defined; this fear may in turn lead to an impairment of performance.[123] Testing situations that highlight the fact that intelligence is being measured tend to lower the scores of individuals from racial-ethnic groups who already score lower on average or are expected to score lower. Stereotype threat conditions cause larger than expected IQ differences among groups.[124] Psychometrician Nicholas Mackintosh considers that there is little doubt that the effects of stereotype threat contribute to the IQ gap between black people and white people.[125] A large number of studies have shown that systemically disadvantaged minorities, such as the African American minority of the United States, generally perform worse in the educational system and in intelligence tests than the majority groups or less disadvantaged minorities such as immigrant or "voluntary" minorities.[60] The explanation of these findings may be that children of caste-like minorities, due to the systemic limitations of their prospects of social advancement, do not have "effort optimism", i.e. they do not have the confidence that acquiring the skills valued by majority society, such as those skills measured by IQ tests, is worthwhile. They may even deliberately reject certain behaviors that are seen as "acting white."[60][126][127] Research published in 1997 indicates that part of the black–white gap in cognitive ability test scores is due to racial differences in test motivation.[128] Some researchers have suggested that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-life performance gaps, and have raised the possibility of publication bias.[129][130][131] Other critics have focused on correcting what they claim are misconceptions of early studies showing a large effect.[132] However, numerous meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown significant evidence for the effects of stereotype threat, though the phenomenon defies over-simplistic characterization.[133][134][135][136][137][138][139][excessive citations] For instance, one meta-analysis found that with female subjects "subtle threat-activating cues produced the largest effect, followed by blatant and moderately explicit cues" while with minorities "moderately explicit stereotype threat-activating cues produced the largest effect, followed by blatant and subtle cues".[134] Some researchers have argued that studies of stereotype threat may in fact systematically under-represent its effects, since such studies measure "only that portion of psychological threat that research has identified and remedied. To the extent that unidentified or unremedied psychological threats further undermine performance, the results underestimate the bias."[135] |

環境要因 健康と栄養 詳細は「健康が知能に与える影響」を参照  1~5歳の子供の血中鉛濃度が10μg/dL以上の割合。黒人とヒスパニック系の子供は、白人の子供よりもはるかに高い値を示している。24ヶ月時点での 血中鉛濃度が10μg/dL増加すると、IQは5.8ポイント低下する。[77] 幾何平均血中鉛濃度(GM BLL)は低下しているが、CDCの報告書(2002年)では次のように述べている。「しかし、非ヒスパニック系黒人の子どもの平均鉛血中濃度は、メキシ コ系アメリカ人と非ヒスパニック系白人の子どもよりも依然として高く、曝露リスクの差が依然として存在していることを示している」[78] 幼少期の鉛曝露[77]、母乳育児率の低さ[79]、栄養不良[80][81]などの環境要因は、認知能力の発達と機能の低下と著しく相関している。例え ば、貧困地域にある家庭に関連する幼少期の鉛への曝露は、平均IQを7ポイント低下させることが分かっている。[83] また、ヨード欠乏症は平均IQを12ポイント低下させる。[84][85] このような障害は時に永続的であるが、場合によってはその後の成長によって部分的に、あるいは完全に補われることもある。 栄養不良は、その影響が往々にして不可逆的であり、認知能力の発達や教育適応能力、将来の経済生産性などの低下を伴うため、人生最初の2年間が非常に重要 である。[86] マッキントッシュは、アメリカ黒人の乳児死亡率は白人の約2倍であり、低体重出生の割合も2倍であると指摘している。同時に、白人の母親が自分の乳児に母 乳を与える可能性は2倍であり、低体重出生児のIQは母乳育児と直接相関している。このように、IQに影響を与える健康関連の要因の多くが、2つのグルー プ間で不平等に分布している。[87] 2004年のコペンハーゲン・コンセンサスでは、ヨウ素と鉄分の不足がともに脳の発達障害に関与していると述べられており、これは膨大な数の人々に影響を 及ぼす可能性がある。ヨウ素欠乏症に罹患している人口は世界人口の3分の1に上ると推定されている。発展途上国では、4歳以下の子供の40%が食事中の鉄 分不足により貧血であると推定されている。 他の学者は、単に栄養水準が人口の知能に著しい影響を及ぼすこと、そしてフリン効果は世界中で栄養水準が向上したことによって引き起こされた可能性があることを発見している。[89] ジェームズ・フリン自身もこの見解に反対している。[90] 最近の研究では、非白人人口に多く見られる感染症による脳の発達遅延が、世界の地域間におけるIQの差異を説明する重要な要因である可能性を指摘してい る。この研究では、IQ、人種、感染症の間に相関関係があることが示されており、このことは米国におけるIQ格差にも当てはまることが示されている。この ことは、これが重要な環境要因である可能性を示唆している。 2013年の世界保健機関によるメタ分析では、母親のIQを統制した上で、母乳育児はIQの2.19ポイントの向上と関連していることが分かった。著者 は、この関係は因果関係があることを示唆しているが、この向上の実際的な意義については議論の余地があると述べている。しかし、彼らは、ブラジルにおける 母乳育児と学業成績の関連を示唆する研究を強調しており、そこでは「母乳育児の期間は社会経済的地位による著しい変動は見られない」と述べている [92]。また、ColenとRamey(2014年)も同様に、家族間ではなく家族内のきょうだい比較を制御することで、母乳育児の状況とWISC IQスコアの相関関係がほぼ3分の1に減少することを発見したが、さらに、母乳育児期間とWISC IQスコアの関係は有意ではないことも発見した。彼らは、「一般的に母乳育児に起因するとされる長期的な有益な効果の多くは、人種や社会経済的地位などの 主要な人口統計的特性に沿った乳児の栄養摂取方法への選択圧力が主な原因である可能性がある」と示唆している。[93] ライヒマンは、黒人と白人のIQの差の3~4%以下しか、低出生体重児における黒人と白人の格差によって説明できないと推定している。[94] 教育 IQテストの成績における格差の大部分は、教育の質の違いに起因するという見解が、複数の研究によって示されている。[95] 人種による教育差別が、人種間の教育の質の違いの原因のひとつである可能性が指摘されている。[96] Hala Elhoweris、Kagendo Mutua、Negmeldin Alsheikh、Pauline Hollowayによる論文によると、才能ある児童生徒を対象とした教育プログラムへの参加を教師が推薦する決定は、児童生徒の民族性に影響される部分が あるという。 また、幼児教育の集中プログラムである「アベセダリアン・アーリー・インターベンション・プロジェクト」に参加した黒人の子供たちは、対照群と比較して、 21歳時点での平均IQが4.4ポイント上昇したという結果も出ている。[79] アーサー・ジェンセンは、アベセダリアン・プロジェクトが この幼児教育プロジェクトは、教育がIQに大きな影響を与えることを示しているが、これまでの教育プログラムでは黒人と白人のIQの差を3分の1以上縮め ることはできず、教育の違いが唯一の原因である可能性は低いという見解を表明した。 ジョセフ・フェイガンとシンシア・ホランドによる一連の研究では、IQテストで出題されるような認知課題への事前の曝露がテストの成績に与える影響を測定 した。IQの差は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の被験者たちがIQテストで通常見られる認知機能を使用する課題への曝露が少ないことが原因であると仮定し、彼ら はIQテストを受ける前に、アフリカ系アメリカ人のグループにこの種の課題を準備した。研究者らは、アフリカ系アメリカ人と白人受験者のその後の成績に差 異は見られなかったと結論付けた。[99][100] デイリーとオンウェグブジーは、ファガンとホランドが「知能テストの問題に対する黒人と白人の知識の差異は、 テスト対象となる情報に平等に触れる機会が与えられれば、黒人と白人の知能テスト項目に関する知識の差は解消される」と結論づけている。[101] デビッド・マークスも同様の主張を展開しており、IQの差異は識字能力の差異とよく相関していると論じている。教育を通じて識字能力を向上させることが、 IQテストの成績向上につながることを示唆している。[102][103] 2003年の研究では、ステレオタイプ・スレットと子供の父親の学歴の2つの変数が、認知能力テストの黒人と白人の成績の差を部分的に説明しており、認知能力が不変の遺伝的要因に由来するという遺伝論的な見解を否定している。 社会経済環境 子供たちが育つ社会経済環境のさまざまな側面が、IQの差の一部と相関することが示されているが、その差のすべてを説明できるわけではない。[105] 2006年のレビューによると、これらの要因は標準偏差の半分弱を占める。[106] 他の研究では、低社会経済的地位(SES)グループと高SESグループにおける異なる原因に焦点を当てている。[107][108][109] 米国では、低SESグループでは、遺伝的差異がIQのばらつきの割合を占める割合は、高SES人口よりも少ない。[110] このような影響は、生物生態学的な仮説によって予測されている。 生態学的仮説、すなわち、遺伝子型は環境の非相加的相乗効果を通じて表現型へと変化するという仮説によって予測される。[111] ニスベットら(2012a)は、高 SES 個人は生物学的潜在能力を最大限に発揮できる可能性が高いが、低 SES 個人は不利な環境条件によってその発達が妨げられる可能性が高いと示唆している。また、同レビューでは、養子研究は一般的に、高・中上位の社会経済的地位 の養子家庭のみを対象とする傾向があり、平均的な遺伝的効果を過大評価する傾向があることも指摘している。また、低所得層から中流層への養子研究では、低 所得層の家庭にとどまる子供と比較して、IQが12~18ポイント上昇することが示されている。[76] 2015年の研究では 環境要因(すなわち、家族収入、母親の教育、母親の言語能力/知識、家庭内の学習教材、子育て要因、子供の出生順、子供の出生体重)が、黒人と白人の認知 能力テストのスコアの差を説明していることが分かった。 テストの偏り 多くの研究が、IQテストが特定のグループに対して偏見を持っている可能性があるという結論に達している。[113][114][115][116] 米国や欧州以外の地域で得られたIQスコアの妥当性と信頼性は疑問視されており、 その理由の一部は、文化間のIQスコア比較が本質的に困難であることによるものである。[117][118] 複数の研究者は、文化の違いが非工業化社会における標準的なIQテストの妥当性を制限していると主張している。[119][120] 米国心理学会の1996年の報告書では、知能は文化によって比較が難しい場合があるとし、テスト問題に対する慣れがテスト結果に大きな違いを生む可能性が あると指摘している。また、テストは黒人および白人のアメリカ人の将来の達成度を正確に予測できるものであり、その意味では 。テストが将来の教育達成を正確に予測するという見解は、ニコラス・マッキントッシュが1998年に出版した著書『IQと人間的知性』[121]や、 1999年のブラウン、レイノルズ、ウィテカーによる文献レビューによって裏付けられている。 このテーマに関する調査研究を行っているジェームズ・R・フリンは、多くのテスト問題の比重や出題内容は、文化的にどのような情報が重視され、どのような思考様式が評価されるかによって決まる、と指摘している。 ステレオタイプ・スレットとマイノリティの地位 詳細は「ステレオタイプ・スレット」を参照 ステレオタイプ・スレットとは、自分が属する、あるいは定義される集団に対する既存のステレオタイプを、自分の行動が裏付けるのではないかという不安であ る。この不安は、ひいてはパフォーマンスの低下につながる可能性がある。ステレオタイプ・スレットの状態は、グループ間で予想以上のIQの差を生じさせ る。[124] 心理測定学者のニコラス・マッキントッシュは、ステレオタイプ・スレットの影響が黒人と白人のIQの差に寄与していることは疑いがないと考えている。 [125] 多数の研究が、米国のアフリカ系アメリカ人などの組織的に不利な立場にあるマイノリティは、一般的に教育システムや知能テストにおいて、多数派グループや 移民や「自発的」マイノリティなどのより不利でないマイノリティよりも成績が悪いことを示している。[60] これらの調査結果の説明としては、 カーストのようなマイノリティの子供たちは、社会的な昇進の見込みが制度的に限られているため、「努力に対する楽観性」を持たない、つまり、IQテストで 測定されるような、多数派社会で評価されるスキルを習得することが価値のあることだという自信を持たない、ということがその理由であるかもしれない。彼ら は「白人らしく振る舞う」と見られる特定の行動を意図的に拒絶することさえある。[60][126][127] 1997年に発表された研究では、認知能力テストのスコアにおける黒人と白人の格差の一部は、テストに対する動機づけにおける人種間の違いによるものであ ることが示されている。[128] 一部の研究者は、ステレオタイプ・スレットを現実のパフォーマンス格差の要因として解釈すべきではないと主張し、出版バイアスの可能性を提起している。 [129][130][131] 他の批判者は、大きな影響を示した初期の研究における誤解を正すことに焦点を当てている。[132] しかしながら、 しかし、ステレオタイプ・スレットの効果を示す重要な証拠は、多数のメタ分析や系統的レビューによって示されている。ただし、この現象は単純化しすぎると 本質を見失うものである。[133][134][135][136][137][138][139][過剰引用] 例えば、あるメタ分析では、女性被験者では「微妙な脅威を活性化する手がかりが最も大きな効果を生み出し、露骨なものと中程度に明示的な手がかりがそれに 続いた」一方で、マイノリティでは「中程度に明示的なステレオタイプ脅威を活性化する手がかりが最も大きな効果を生み出し、露骨なものと微妙な手がかりが それに続いた」ことが分かった。[134] 一部の研究者は、ステレオタイプ・スレットの研究では、実際にはその効果を系統的に過小評価している可能性があると主張している。なぜなら、そのような研 究では「研究によって特定され、改善された心理的脅威の部分のみ」を測定しているからだ。特定されていない、または改善されていない心理的脅威がさらにパ フォーマンスを低下させる程度まで、結果はバイアスを過小評価している」[135]。 |

| Research into possible genetic factors See also: Heritability of IQ Although IQ differences between individuals have been shown to have a large hereditary component, it does not follow that mean group-level disparities (between-group differences) in IQ necessarily have a genetic basis.[140][141] The scientific consensus is that there is no evidence for a genetic component behind IQ differences between racial groups.[142][143][144][145][141][146][147][148][60] Growing evidence indicates that environmental factors, not genetic ones, explain the racial IQ gap.[39][141][149][146] Genetics of race and intelligence Main article: Race and genetics Geneticist Alan R. Templeton argued that the question about the possible genetic effects on the test score gap is muddled by the general focus on "race" rather than on populations defined by gene frequency or by geographical proximity, and by the general insistence on phrasing the question in terms of heritability.[150] Templeton pointed out that racial groups neither represent sub-species nor distinct evolutionary lineages, and that therefore there is no basis for making claims about the general intelligence of races.[150] He argued that, for these reasons, the search for possible genetic influences on the black–white test score gap is a priori flawed, because there is no genetic material shared by all Africans or by all Europeans. Mackintosh (2011), on the other hand, argued that by using genetic cluster analysis to correlate gene frequencies with continental populations it might be possible to show that African populations have a higher frequency of certain genetic variants that contribute to differences in average intelligence. Such a hypothetical situation could hold without all Africans carrying the same genes or belonging to a single evolutionary lineage. According to Mackintosh, a biological basis for the observed gap in IQ test performance thus cannot be ruled out on a priori grounds.[page needed] Hunt (2010, p. 447) noted that "no genes related to difference in cognitive skills have across the various racial and ethnic groups have ever been discovered. The argument for genetic differences has been carried forward largely by circumstantial evidence. Of course, tomorrow afternoon genetic mechanisms producing racial and ethnic differences in intelligence might be discovered, but there have been a lot of investigations, and tomorrow has not come for quite some time now." Mackintosh (2011, p. 344) concurred, noting that while several environmental factors have been shown to influence the IQ gap, the evidence for a genetic influence has been negligible. A 2012 review by Nisbett et al. (2012a) concluded that the entire IQ gap can be explained by known environmental factors, and Mackintosh found this view to be plausible. More recent research attempting to identify genetic loci associated with individual-level differences in IQ has yielded promising results, which led the editorial board of Nature to issue a statement differentiating this research from the "racist" pseudoscience which it acknowledged has dogged intelligence research since its inception.[151] It characterized the idea of genetically determined differences in intelligence between races as definitively false.[151] Heritability within and between groups  An environmental factor that varies between groups but not within groups can cause group differences in a trait that is otherwise 100 percent heritable. Twin studies of intelligence have reported high heritability values. However, these studies have been criticized for being based on questionable assumptions.[152][153][154] When used in the context of human behavior genetics, the term "heritability" can be misleading, as it does not necessarily convey information about the relative importance of genetic or environmental factors on the development of a given trait, nor does it convey the extent to which that trait is genetically determined.[155] Arguments in support of a genetic explanation of racial differences in IQ are sometimes fallacious. For instance, hereditarians have sometimes cited the failure of known environmental factors to account for such differences, or the high heritability of intelligence within races, as evidence that racial differences in IQ are genetic.[156] Psychometricians have found that intelligence is substantially heritable within populations, with 30–50% of variance in IQ scores in early childhood being attributable to genetic factors in analyzed US populations, increasing to 75–80% by late adolescence.[60][157] In biology heritability is defined as the ratio of variation attributable to genetic differences in an observable trait to the trait's total observable variation. The heritability of a trait describes the proportion of variation in the trait that is attributable to genetic factors within a particular population. A heritability of 1 indicates that variation correlates fully with genetic variation and a heritability of 0 indicates that there is no correlation between the trait and genes at all. In psychological testing, heritability tends to be understood as the degree of correlation between the results of a test taker and those of their biological parents. However, since high heritability is simply a correlation between child and parents, it does not describe the causes of heritability which in humans can be either genetic or environmental. Therefore, a high heritability measure does not imply that a trait is genetic or unchangeable. In addition, environmental factors that affect all group members equally will not be measured by heritability, and the heritability of a trait may also change over time in response to changes in the distribution of genetic and environmental factors.[60] High heritability does not imply that all of the heritability is genetically determined; rather, it can also be due to environmental differences that affect only a certain genetically defined group (indirect heritability).[158] The figure to the right demonstrates how heritability works. In each of the two gardens the difference between tall and short cornstalks is 100% heritable, as cornstalks that are genetically disposed for growing tall will become taller than those without this disposition. But the difference in height between the cornstalks to the left and those on the right is 100% environmental, as it is due to different nutrients being supplied to the two gardens. Hence, the causes of differences within a group and between groups may not be the same, even when looking at traits that are highly heritable.[158] Spearman's hypothesis Main article: Spearman's hypothesis Spearman's hypothesis states that the magnitude of the black–white difference in tests of cognitive ability depends entirely or mainly on the extent to which a test measures general mental ability, or g. The hypothesis was first formalized by Arthur Jensen, who devised the statistical "method of correlated vectors" to test it. If Spearman's hypothesis holds true, then the cognitive tasks that have the highest g-load are the tasks in which the gap between black and white test takers are greatest. Jensen and Rushton took this to show that the cause of g and the cause of the gap are the same—in their view, genetic differences.[159] Mackintosh (2011, pp. 338–39) acknowledges that Jensen and Rushton showed a modest correlation between g-loading, heritability, and the test score gap, but does not agree that this demonstrates a genetic origin of the gap. Mackintosh argues that it is exactly those tests that Rushton and Jensen consider to have the highest g-loading and heritability, such as the Wechsler test, that have seen the greatest increases in black performance due to the Flynn effect. This likely suggests that they are also the most sensitive to environmental changes, which undermines Jensen's argument that the black–white gap is most likely caused by genetic factors. Nisbett et al. (2012a, p. 146) make the same point, noting also that the increase in the IQ scores of black test takers necessarily indicates an increase in g. James Flynn argued that his findings undermine Spearman's hypothesis.[160] In a 2006 study, he and William Dickens found that between 1972 and 2002 "The standard measure of the g gap between Blacks and Whites declined virtually in tandem with the IQ gap."[39] Flynn also criticized Jensen's basic assumption that a correlation between g-loading and test score gap implies a genetic cause for the gap.[161] In a 2014 suite of meta-analyses, along with co-authors Jan te Nijenhuis and Daniel Metzen, he showed that the same negative correlation between IQ gains and g-loading obtains for cognitive deficits of known environmental cause: iodine deficiency, prenatal cocaine exposure, fetal alcohol syndrome, and traumatic brain injury.[162] Adoption studies A number of IQ studies have been done on the effect of similar rearing conditions on children from different races. The hypothesis is that this can be determined by investigating whether black children adopted into white families demonstrated gains in IQ test scores relative to black children reared in black families. Depending on whether their test scores are more similar to their biological or adoptive families, that could be interpreted as supporting either a genetic or an environmental hypothesis. Critiques of such studies question whether the environment of black children—even when raised in white families—is truly comparable to the environment of white children. Several reviews of the adoption study literature have suggested that it is probably impossible to avoid confounding biological and environmental factors in this type of study.[163] Another criticism by Nisbett et al. (2012a, pp. 134) is that adoption studies on the whole tend to be carried out in a restricted set of environments, mostly in the medium-high SES range, where heritability is higher than in the low-SES range. The Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study (1976) examined the IQ test scores of 122 adopted children and 143 nonadopted children reared by advantaged white families. The children were restudied ten years later.[164][165][166] The study found higher IQ for white people compared to black people, both at age 7 and age 17.[164] Acknowledging the existence of confounding factors, Scarr and Weinberg, the authors of the original study, did not consider that it provided support for either the hereditarian or environmentalist view.[167] Three other studies lend support to environmental explanations of group IQ differences: Eyferth (1961) studied the out-of-wedlock children of black and white soldiers stationed in Germany after World War II who were then raised by white German mothers in what has become known as the Eyferth study. He found no significant differences in average IQ between groups. Tizard et al. (1972) studied black (West Indian), white, and mixed-race children raised in British long-stay residential nurseries. Two out of three tests found no significant differences. One test found higher scores for non-white people. Moore (1986) compared black and mixed-race children adopted by either black or white middle-class families in the United States. Moore observed that 23 black and interracial children raised by white parents had a significantly higher mean score than 23 age-matched children raised by black parents (117 vs 104), and argued that differences in early socialization explained these differences. Frydman and Lynn (1989) showed a mean IQ of 119 for Korean infants adopted by Belgian families. After correcting for the Flynn effect, the IQ of the adopted Korean children was still 10 points higher than that of the Belgian children.[168][169] Reviewing the evidence from adoption studies, Mackintosh finds that environmental and genetic variables remain confounded and considers evidence from adoption studies inconclusive, and fully compatible with a 100% environmental explanation.[163] Similarly, Drew Thomas argues that race differences in IQ that appear in adoption studies are in fact an artifact of methodology, and that East Asian IQ advantages and black IQ disadvantages disappear when this is controlled for.[170] Racial admixture studies Most people have ancestry from different geographical regions. In particular, African Americans typically have ancestors from both Africa and Europe, with, on average, 20% of their genome inherited from European ancestors.[171] If racial IQ gaps have a partially genetic basis, one might expect black people with a higher degree of European ancestry to score higher on IQ tests than black people with less European ancestry, because the genes inherited from European ancestors would likely include some genes with a positive effect on IQ.[172] Geneticist Alan Templeton has argued that an experiment based on the Mendelian "common garden" design, where specimens with different hybrid compositions are subjected to the same environmental influences, are the only way to definitively show a causal relation between genes and group differences in IQ. Summarizing the findings of admixture studies, he concludes that they have shown no significant correlation between any cognitive ability and the degree of African or European ancestry.[173] Studies have employed different ways of measuring or approximating relative degrees of ancestry from Africa and Europe. Some studies have used skin color as a measure, and others have used blood groups. Loehlin (2000) surveys the literature and argues that the blood groups studies may be seen as providing some support to the genetic hypothesis, even though the correlation between ancestry and IQ was quite low. He finds that studies by Eyferth (1961), Willerman, Naylor & Myrianthopoulos (1970) did not find a correlation between degree of African/European ancestry and IQ. The latter study did find a difference based on the race of the mother, with children of white mothers with black fathers scoring higher than children of black mothers and white fathers. Loehlin considers that such a finding is compatible with either a genetic or an environmental cause. All in all Loehlin finds admixture studies inconclusive and recommends more research. Reviewing the evidence from admixture studies Hunt (2010) considers it to be inconclusive because of too many uncontrolled variables. Mackintosh (2011, p. 338) quotes a statement by Nisbett (2009) to the effect that admixture studies have not provided a shred of evidence in favor of a genetic basis for the IQ gap. Mental chronometry Main article: Mental chronometry Mental chronometry measures the elapsed time between the presentation of a sensory stimulus and the subsequent behavioral response by the participant. These studies have shown inconsistent results when comparing black and white populations groups, with some studies showing whites outperforming blacks, and others showing blacks outperforming whites.[174] Arthur Jensen argued that this reaction time (RT) is a measure of the speed and efficiency with which the brain processes information,[175] and that scores on most types of RT tasks tend to correlate with scores on standard IQ tests as well as with g.[175] Nisbett argues that some studies have found correlations closer to 0.2, and that a correlation is not always found.[176] Nisbett points to the Jensen & Whang (1993) study in which a group of Chinese Americans had longer reaction times than a group of European Americans, despite having higher IQs. Nisbett also mentions findings in Flynn (1991) and Deary (2001) suggesting that movement time (the measure of how long it takes a person to move a finger after making the decision to do so) correlates with IQ just as strongly as reaction time, and that average movement time is faster for black people than for white people.[177] Mackintosh (2011, p. 339) considers reaction time evidence unconvincing and comments that other cognitive tests that also correlate well with IQ show no disparity at all, for example the habituation/dishabituation test. He further comments that studies show that rhesus monkeys have shorter reaction times than American college students, suggesting that different reaction times may not tell us anything useful about intelligence. Brain size Main article: Brain size A number of studies have reported a moderate statistical correlation between differences in IQ and brain size between individuals in the same group.[178][179] Some scholars have reported differences in average brain sizes between racial groups,[180] although this is unlikely to be a good measure of IQ as brain size also differs between men and women, but without significant differences in IQ.[76] At the same time newborn black children have the same average brain size as white children, suggesting that the difference in average size could be accounted for by differences in environment.[76] Several environmental factors that reduce brain size have been demonstrated to disproportionately affect black children.[76] Archaeological data Archaeological evidence does not support claims by Rushton and others that black people's cognitive ability was inferior to white people's during prehistoric times.[181] |

遺伝的要因の可能性に関する研究 参照:IQの遺伝率 個人間のIQの差異には大きな遺伝的要素があることが示されているが、IQの集団レベルの平均値の差異(集団間の差異)には必ずしも遺伝的要素があるわけ ではない。[140][141] 科学的コンセンサスでは、人種集団間のIQの差異の背後にある遺伝的要素の証拠はないとされている。[ 142][143][144][145][141][146][147][148][60] 増えつつある証拠は、人種間のIQの差異は遺伝的要因ではなく環境要因によって説明できることを示している。 人種と知能の遺伝学 詳細は「人種と遺伝学」を参照 遺伝学者のアラン・R・テンプルトンは、テストのスコアの差に遺伝的影響があるかどうかという問題は、遺伝子頻度や地理的近接性によって定義された集団で はなく、「人種」に一般的に焦点が当てられていること、また、遺伝率という観点から問題を表現することに一般的に固執していることによって、混乱している と主張した。[150] テンプルトンは、人種集団は 亜種でもなければ、進化の系統をなすものでもないため、人種一般の知能について主張する根拠はないと指摘した。[150] これらの理由から、黒人と白人のテストスコアの差に遺伝的影響があるかどうかを調べることは、先験的に欠陥がある、と彼は主張した。なぜなら、すべてのア フリカ人やすべてのヨーロッパ人に共通する遺伝物質は存在しないからだ。一方、マッキントッシュ(2011)は、遺伝子クラスター分析を用いて遺伝子頻度 と大陸の人口を相関させることで、アフリカの人口は平均的な知能の差異に寄与する特定の遺伝子変異の頻度が高いことを示すことができるかもしれないと主張 している。このような仮説は、アフリカ人がすべて同じ遺伝子を持っている、あるいは単一の進化系統に属しているという前提なしでも成り立つ可能性がある。 マッキントッシュによると、IQテストの成績における観察された格差の生物学的な根拠は、先験的な理由で否定することはできない。 ハント(2010年、447ページ)は、「認知能力の差に関連する遺伝子は、さまざまな人種や民族集団全体にわたって発見されたことはない」と指摘してい る。遺伝的差異に関する議論は、状況証拠によって主に推し進められてきた。もちろん、人種や民族による知能の差異を生み出す遺伝的メカニズムが明日午後に 発見される可能性はあるが、これまでに多くの調査が行われており、明日が訪れることはもうしばらくないだろう。マッキントッシュ(2011年、344ペー ジ)も同意見であり、いくつかの環境要因がIQの格差に影響を及ぼすことが示されている一方で、遺伝的要因の影響を示す証拠はほとんどないことを指摘して いる。ニセベットら(2012年)による2012年のレビュー(2012a)では、IQの格差全体は既知の環境要因によって説明できると結論づけ、マッキ ントッシュもこの見解は妥当であると考えている。 IQの個人レベルの差異に関連する遺伝子座を特定しようとするより最近の研究は有望な結果を生み出し、Natureの編集委員会は、この研究を、知能研究 の開始以来、知能研究につきまとっていると認めている「人種差別主義的な」疑似科学と区別する声明を発表した。[151] その声明では、人種間の知能における遺伝的に決定される差異という考えは、明確に誤りであると特徴づけている。[151] グループ内およびグループ間の遺伝率  グループ間で変化するが、グループ内では変化しない環境要因が、それ以外では100パーセント遺伝する形質におけるグループ間の差異を引き起こす可能性がある。 知能に関する双生児研究では、高い遺伝率が報告されている。しかし、これらの研究は疑わしい仮定に基づいているとして批判されている。[152] [153][154] 「遺伝率」という用語は、人間の行動遺伝学の文脈で使用される場合、誤解を招く可能性がある。ある形質の発達における遺伝的要因と環境要因の相対的重要性 に関する情報を必ずしも伝えているわけではなく、また、その形質が遺伝的にどの程度決定されているかという情報を伝えているわけでもない。[155] IQにおける人種差を遺伝で説明することの支持論は、時に誤りである。例えば、遺伝学者は、そのような差異を説明できないことが知られている環境要因の失 敗、あるいは人種内での知能の遺伝率の高さを、IQにおける人種差が遺伝によるものであるという証拠として引用することがある。[156] 心理測定学者は、知能は集団内でかなり遺伝するものであることを発見しており、分析された米国の集団では、幼児期のIQスコアのばらつきの30~50%が 遺伝的要因に起因し、思春期後期には75~80%にまで増加する。生物学では、遺伝率は、観察可能な形質における遺伝的差異に起因するばらつきの、その形 質の観察可能な総ばらつきに対する比率として定義される。ある形質の遺伝率は、特定の集団における形質における遺伝的要因に起因する変化の割合を説明す る。遺伝率が1の場合、変化は遺伝的変化と完全に相関し、遺伝率が0の場合、形質と遺伝子との間には相関が全くないことを示す。心理テストでは、遺伝率は テスト受験者と実の親の結果の相関の度合いとして理解される傾向にある。しかし、高い遺伝率は単に子供と両親の相関関係に過ぎないため、遺伝率の原因を説 明しているわけではない。人間の場合、遺伝率の原因は遺伝的または環境的なものである。 したがって、高い遺伝率の測定値は、その形質が遺伝的であることや不変であることを意味するものではない。さらに、集団のメンバー全員に均等に影響する環 境要因は遺伝率では測定されず、遺伝率や環境要因の分布の変化に応じて、形質の遺伝率も時間とともに変化する可能性がある。[60] 遺伝率が高いからといって、その遺伝率がすべて遺伝的に決定されているわけではない。むしろ、遺伝的に定義された特定のグループにのみ影響する環境の違い による可能性もある(間接遺伝率)。[158] 右の図は、遺伝率の仕組みを示している。2つの庭のそれぞれにおいて、トウモロコシの茎の高さの違いは100%遺伝する。なぜなら、遺伝的に背が高くなる ようにできているトウモロコシの茎は、そうでないものよりも背が高くなるからだ。しかし、左のトウモロコシと右のトウモロコシの丈の違いは100%環境に よるものであり、それは2つの庭に供給される栄養素が異なることによる。したがって、遺伝率の高い形質を観察する場合でも、集団内および集団間の差異の原 因は同じではない可能性がある。[158] スピアマンの仮説 詳細は「スピアマンの仮説」を参照 スピアマンの仮説は、認知能力のテストにおける黒人と白人の差の大きさは、テストが一般的な精神能力(g)をどの程度測定しているかによって、完全にまた は主に左右されるというものである。この仮説は、それを検証するための統計的手法「相関ベクトル法」を考案したアーサー・ジェンセンによって初めて公式化 された。もしスピアマンの仮説が正しいとすると、g負荷が最も高い認知課題とは、黒人と白人の受験者の間の格差が最も大きい課題ということになる。ジェン センとラシュトンは、gの原因と格差の原因は同じであると主張した。彼らの見解では、その原因は遺伝的差異である。 マッキントッシュ(2011年、338-39ページ)は、ジェンセンとラシュトンがg負荷、遺伝率、テストスコアの格差の間にわずかな相関関係を示したこ とを認めているが、このことが格差の遺伝的起源を示すものだとは同意していない。マッキントッシュは、ルシュトンとジェンセンがg負荷と遺伝率が最も高い とみなしているウェクスラーテストなどのテストこそが、フリン効果により黒人の成績が最も伸びたテストであると主張している。これは、これらのテストが環 境の変化にもっとも敏感であることを示唆している可能性が高く、ジェンセンの「黒人と白人の格差は遺伝的要因によって引き起こされている可能性が高い」と いう主張を覆すものである。ニスベットら(2012a, p. 146)も同じ指摘を行っており、黒人のテスト受験者のIQスコアの増加は、必然的にgの増加を示していると指摘している。 ジェームズ・フリンは、彼の調査結果はスピアマンの仮説を覆すものであると主張した。[160] 2006年の研究で、フリンとウィリアム・ディキンズは、1972年から2002年の間に「黒人と白人のg格差の標準的な測定値は、IQ格差とほぼ同時に 低下した」ことを発見した。[39] フリンはまた、g負荷とテストスコアの格差の相関関係は、 遺伝がその差の原因であることを暗示しているというジェンセンの基本的な仮定を批判した。[161] 2014年の一連のメタ分析において、共同執筆者のJan te NijenhuisとDaniel Metzenとともに、彼は、IQの向上とg-loadingの間に同じ負の相関が、環境が原因であることが知られている認知障害、すなわち、ヨード欠乏 症、出生前のコカイン曝露、胎児性アルコール症候群、外傷性脳損傷にも当てはまることを示した。[162] 養子縁組に関する研究 異なる人種の子供たちに対する類似した養育条件の影響について、多くのIQ研究が行われている。仮説は、黒人の子供たちが白人家庭に養子として引き取られ た場合、黒人の家庭で育った子供たちと比較して、IQテストのスコアが向上するかどうかを調査することで、これを判断できるというものである。彼らのテス トスコアが実の家族と養子先の家族のどちらにより近いかによって、遺伝説または環境説のどちらかを裏付けるものとして解釈できる。このような研究に対する 批判では、黒人の子供たちが白人家庭で育てられたとしても、その環境が白人家庭で育つ子供たちの環境と本当に比較できるのかという疑問が呈されている。養 子研究の文献のいくつかのレビューでは、この種の研究では生物学的要因と環境要因の混同を避けるのはおそらく不可能であると示唆されている。[163] ニセベットら(2012a、134ページ)による別の批判は、養子研究は全体として、限られた環境、主に中~高の社会経済的地位の範囲で実施される傾向が あり、そこでは遺伝率が低~中程度の社会経済的地位の範囲よりも高いというものである。 ミネソタ人種間養子研究(1976年)では、恵まれた白人家庭で育てられた122人の養子と143人の非養子のIQテストスコアを調査した。10年後に、 これらの子供たちを再調査した。[164][165][166] この研究では、7歳と17歳の両方において、黒人と比較して白人のIQが高いことが分かった。[164] 混同要因の存在を認めた上で、この研究の著者であるScarrとWeinbergは、この研究が遺伝説または環境説のいずれかの見解を裏付けるものとは考 えていなかった。[167] 集団間のIQの差異に関する環境要因説を裏付ける研究は他にも3つある。 Eyferth(1961年)は、第二次世界大戦後にドイツに駐留していた黒人と白人の兵士の婚外子を研究し、その子供たちはドイツ人の母親に育てられ た。この研究はEyferth研究として知られるようになった。彼は、集団間の平均IQに有意な差異は見られないことを発見した。 Tizard ら(1972年)は、英国の長期間滞在型保育所で育った黒人(西インド諸島系)、白人、混血の子供たちを調査した。3つのテストのうち2つでは、有意な差は見られなかった。1つのテストでは、非白人のほうが高いスコアを示した。 ムーア(1986)は、米国の中流階級の黒人家庭または白人家庭に養子として引き取られた黒人と混血の子供たちを比較した。ムーアは、白人の親に育てられ た23人の黒人と異人種間の子供たちの平均得点が、同年齢の黒人の親に育てられた23人の子供たち(117対104)よりも有意に高いことを観察し、これ らの違いは幼少期の社会化の違いによって説明できると主張した。 フライドマンとリン(1989年)は、ベルギーの家庭に養子として迎えられた韓国人の乳児の平均IQは119であることを示した。フリン効果を補正した後でも、養子となった韓国人の子どものIQはベルギー人の子どもよりも10ポイント高かった。[168][169] 養子研究の証拠を再検討したマッキントッシュは、環境と遺伝の変数には依然として混同が残っていると結論づけ、養子研究の証拠は決定的ではないとし、 100%環境による説明と完全に一致すると考えている。[163] 同様に、ドリュー・トーマスは、養子研究で示されるIQにおける人種差は実際には方法論の産物であり、これを制御すると東アジアのIQの優位性と黒人の IQの不利性は消えると主張している。[170] 人種混血に関する研究 ほとんどの人は、異なる地理的地域にルーツを持っている。特に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の祖先は、平均するとゲノムの20%がヨーロッパの祖先から受け継が れているが、アフリカとヨーロッパの両方の祖先を持っているのが一般的である。[171] 人種間のIQの差が部分的には遺伝的な要因によるものであるとすれば、ヨーロッパの祖先の割合が高い黒人の方が、ヨーロッパの祖先の割合が低い黒人よりも IQテストで高いスコアを出すことが予想される。なぜなら、 ヨーロッパ人の祖先から受け継いだ遺伝子には、IQにプラスの影響を与える遺伝子が含まれている可能性が高いからである。[172] 遺伝学者のアラン・テンプルトンは、メンデルの「共通庭」デザインに基づく実験、すなわち異なるハイブリッド構成を持つ標本を同じ環境の影響にさらす実験 が、遺伝子とIQにおける集団差の因果関係を明確に示す唯一の方法であると主張している。混血研究の結果を要約し、彼は、認知能力とアフリカまたはヨー ロッパの遺伝的背景の度合いとの間に有意な相関関係は見られないと結論づけている。 研究では、アフリカとヨーロッパの遺伝的背景の度合いを測定または近似するさまざまな方法が用いられている。一部の研究では肌の色を測定基準としており、 また別の研究では血液型を用いている。Loehlin(2000)は文献を調査し、祖先とIQの相関関係はかなり低かったものの、血液型に関する研究は遺 伝的仮説を裏付けるものとして見なされる可能性があると論じている。Eyferth(1961)、Willerman、Naylor、 Myrianthopoulos(1970)の研究では、アフリカ系またはヨーロッパ系の祖先の度合いとIQとの相関関係は見られなかったと彼は結論づけ ている。後者の研究では、母親の民族に基づく違いが認められ、黒人の父親を持つ白人の母親の子供は、黒人の母親と白人の父親を持つ子供よりも高いスコアを 示した。 ローリンは、このような発見は遺伝的要因または環境的要因のいずれとも矛盾しないと考える。 ローリンは、混血研究は結論に至っていないと結論づけ、さらなる研究を推奨している。 混血研究の証拠を検討した Hunt (2010) は、制御されていない変数が多すぎるため、結論は出ていないと考える。Mackintosh (2011, p. 338) は、混血研究はIQ格差の遺伝的根拠を裏付ける証拠を一切提供していないというNisbett (2009) の主張を引用している。 メンタルクロノメトリー 詳細は「メンタルクロノメトリー」を参照 メンタルクロノメトリーは、感覚刺激の提示から被験者のその後の行動反応までの経過時間を測定する。これらの研究では、黒人と白人の集団を比較した際に一貫性のない結果が示されており、白人が黒人を上回るという研究結果もあれば、黒人が白人を上回るという研究結果もある。 アーサー・ジェンセンは、この反応時間(RT)は脳が情報を処理する速度と効率の指標であると主張し[175]、ほとんどの種類のRT課題のスコアは標準 的なIQテストのスコアおよびgとも相関する傾向にあると主張した[175]。ニスベットは、 0.2に近い相関関係が認められた研究もあるとし、相関関係が常に認められるわけではないと主張している。[176] ニスベットは、中国人系アメリカ人のグループが、IQは高いにもかかわらず、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人のグループよりも反応時間が長かったというジェンセン とウォング(1993年)の研究を指摘している。また、ニスベットはフリン(1991年)とディアリー(2001年)の研究結果にも言及しており、それら によると、反応時間と同様に移動時間(指を動かすという決定をしてから実際に指を動かすまでの時間)もIQと相関関係があり、平均的な移動時間は 黒人の方が白人よりも速いと指摘している。[177] マッキントッシュ(2011年、339ページ)は、反応時間の証拠は説得力に欠けるとし、IQと高い相関関係を示す他の認知テスト、例えば慣れ/慣れずし テストでは、まったく格差が見られないと指摘している。さらに、研究ではアカゲザルの方がアメリカの大学生よりも反応時間が短いことが示されており、反応 時間の違いは知能について何も有益なことを示さない可能性があると述べている。 脳の大きさ 詳細は「脳の大きさ」を参照 多くの研究が、同一グループ内の個人間のIQと脳の大きさの違いに、中程度の統計的相関があることを報告している。[178][179] 一部の学者は人種グループ間の平均的な脳の大きさの違いを報告しているが、[180] 脳の大きさは男女間でも異なるが、IQには有意な差がないため、これはIQの適切な尺度とはなり得ない可能性が高い。が、IQには有意な差異は見られな い。[76] 同時に、生まれたばかりの黒人の子どもの脳の平均サイズは白人の子どもと同じであり、平均サイズの差異は環境の違いによって説明できる可能性があることを 示唆している。[76] 脳のサイズを縮小させるいくつかの環境要因が、黒人の子どもに不均衡に影響することが実証されている。[76] 考古学的データ 考古学的証拠は、ラスストンや他の人々が主張するような、有史以前の時代において黒人の認知能力が白人よりも劣っていたという説を裏付けるものではない。[181] |

| Policy relevance and ethics Main article: Intelligence and public policy The ethics of research on race and intelligence has long been a subject of debate: in a 1996 report of the American Psychological Association;[60] in guidelines proposed by Gray and Thompson and by Hunt and Carlson;[58][182] and in two editorials in Nature in 2009 by Steven Rose and by Stephen J. Ceci and Wendy M. Williams.[183][184] Steven Rose maintains that the history of eugenics makes this field of research difficult to reconcile with current ethical standards for science.[184] On the other hand, James R. Flynn has argued that had there been a ban on research on possibly poorly conceived ideas, much valuable research on intelligence testing (including his own discovery of the Flynn effect) would not have occurred.[185] Many have argued for increased interventions in order to close the gaps.[186] Flynn writes that "America will have to address all the aspects of black experience that are disadvantageous, beginning with the regeneration of inner city neighborhoods and their schools."[187] Especially in developing nations, society has been urged to take on the prevention of cognitive impairment in children as a high priority. Possible preventable causes include malnutrition, infectious diseases such as meningitis, parasites, cerebral malaria, in utero drug and alcohol exposure, newborn asphyxia, low birth weight, head injuries, lead poisoning and endocrine disorders.[188] |

政策との関連性と倫理 詳細は「知能指数と公共政策」を参照 人種と知能に関する研究の倫理については、長い間議論の的となってきた。1996年の米国心理学会の報告書[60]、グレイとトンプソン、ハントとカール ソンが提案したガイドライン[58][182]、2009年の『ネイチャー』誌に掲載されたスティーブン・ローズとスティーブン・J・セシとウェンディ・ M・ウィリアムズによる2つの社説[183][184]などである。 スティーブン・ローズは、優生学の歴史がこの研究分野を現在の科学の倫理基準と調和させることを困難にしていると主張している。[184] 一方、ジェームズ・R・フリンは、おそらくは考えが甘いと思われるアイデアに関する研究が禁止されていたならば、知能テストに関する多くの貴重な研究(フ リン効果の発見を含む)は行われなかっただろうと主張している。[185] 格差を縮めるために介入を強化すべきであるという意見も多く出されている。[186] フリンは、「アメリカは、不利な立場にある黒人の経験のあらゆる側面に対処しなければならない。まずは、都市部の地域社会や学校の再生から始めなければな らない」と書いている。[187] 特に発展途上国では、社会が子どもの認知障害の予防を最優先課題として取り組むことが強く求められている。予防可能な原因としては、栄養不良、髄膜炎など の感染症、寄生虫、脳マラリア、胎児期の薬物やアルコールへの曝露、新生児仮死、低体重児出産、頭部外傷、鉛中毒、内分泌障害などが考えられる。 [188] |

| Behavioral epigenetics Melanin theory Model minority Nations and IQ Outline of human intelligence |

行動エピジェネティクス メラニン理論 モデルマイノリティ 国民とIQ 人間知性の概要 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_and_intelligence |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆