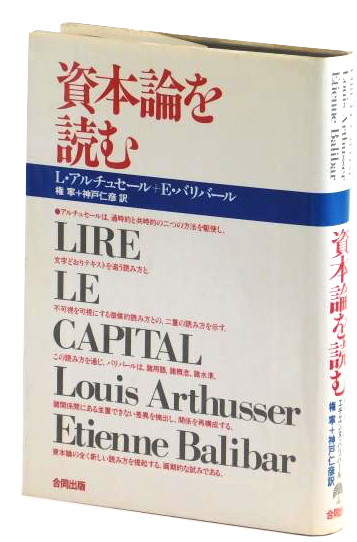

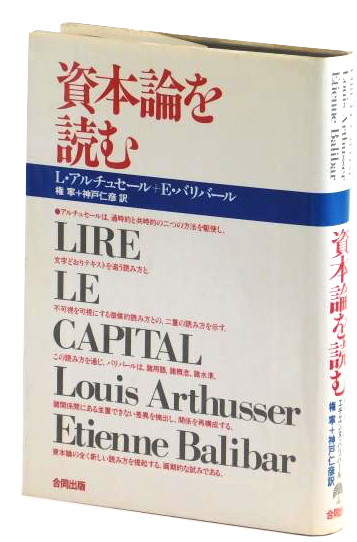

アルチュセール『資本論を読む』

Reading Capital (1965)

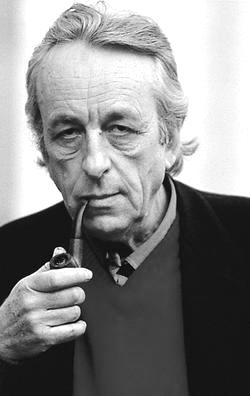

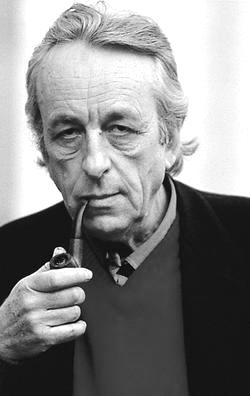

ルイ・アルチュセールの

初期の著作には、マルクスの『資本論』を集中的に哲学

的に読み直したアルチュセールとその弟子たちの仕事を集めた『資本論を読む』(1965年)という影響力のある一冊がある。この本は、「政治経済批判」と

してのマルクス主義理論の哲学的地位とその対象について考察している。アルチュセールは後に、このマルクス解釈における革新の多くが、バルーク・スピノザ に由来する概念をマルクス主義に同化させようとしていることを認める。全訳は2016年に出版された。

| Althusser's earlier

works include the influential volume Reading Capital (1965), which

collects the work of Althusser and his students in an intensive

philosophical rereading of Marx's Capital. The book reflects on the

philosophical status of Marxist theory as a "critique of political

economy", and on its object. Althusser would later acknowledge[165]

that many of the innovations in this interpretation of Marx attempt to

assimilate concepts derived from Baruch Spinoza into Marxism.[166] The

original English translation of this work includes only the essays of

Althusser and Étienne Balibar,[167] while the original French edition

contains additional contributions from Jacques Rancière, Pierre

Macherey, and Roger Establet. A full translation was published in 2016. Several of Althusser's theoretical positions have remained influential in Marxist philosophy. His essay "On the Materialist Dialectic" proposes a great "epistemological break" between Marx's early writings (1840–45) and his later, properly Marxist texts, borrowing a term from the philosopher of science Gaston Bachelard.[168] His essay "Marxism and Humanism" is a strong statement of anti-humanism in Marxist theory, condemning ideas like "human potential" and "species-being", which are often put forth by Marxists, as outgrowths of a bourgeois ideology of "humanity".[169] His essay "Contradiction and Overdetermination" borrows the concept of overdetermination from psychoanalysis, in order to replace the idea of "contradiction" with a more complex model of multiple causality in political situations[170] (an idea closely related to Antonio Gramsci's concept of cultural hegemony).[171] Althusser is also widely known as a theorist of ideology. His best-known essay, "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Toward an Investigation",[172] establishes the concept of ideology. Althusser's theory of ideology draws on Marx and Gramsci, but also on Freud's and Lacan's psychological concepts of the unconscious and mirror-phase respectively, and describes the structures and systems that enable the concept of self. For Althusser, these structures are both agents of repression and inevitable: it is impossible to escape ideology and avoid being subjected to it. On the other hand, the collection of essays from which "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses" is drawn[173] contains other essays which confirm that Althusser's concept of ideology is broadly consistent with the classic Marxist theory of class struggle. Althusser's thought evolved during his lifetime. It has been the subject of argument and debate, especially within Marxism and specifically concerning his theory of knowledge (epistemology). Epistemological break Althusser argues that Marx's thought has been fundamentally misunderstood and underestimated. He fiercely condemns various interpretations of Marx's works—historicism,[174] idealism and economism—on grounds that they fail to realize that with the "science of history", historical materialism, Marx has constructed a revolutionary view of social change. Althusser believes these errors result from the notion that Marx's entire body of work can be understood as a coherent whole. Rather, Marx's thought contains a radical "epistemological break". Although the works of the young Marx are bound by the categories of German philosophy and classical political economy, The German Ideology (written in 1845) makes a sudden and unprecedented departure.[175] This break represents a shift in Marx's work to a fundamentally different "problematic", i.e., a different set of central propositions and questions posed, a different theoretical framework.[176] Althusser believes that Marx himself did not fully comprehend the significance of his own work, and was able to express it only obliquely and tentatively. The shift can be revealed only by a careful and sensitive "symptomatic reading".[177] Thus, Althusser's project is to help readers fully grasp the originality and power of Marx's extraordinary theory, giving as much attention to what is not said as to the explicit. Althusser holds that Marx has discovered a "continent of knowledge", History, analogous to the contributions of Thales to mathematics or Galileo to physics,[178] in that the structure of his theory is unlike anything posited by his predecessors. Althusser believes that Marx's work is fundamentally incompatible with its antecedents because it is built on a groundbreaking epistemology (theory of knowledge) that rejects the distinction between subject and object. In opposition to empiricism, Althusser claims that Marx's philosophy, dialectical materialism, counters the theory of knowledge as vision with a theory of knowledge as production.[179][180] On the empiricist view, a knowing subject encounters a real object and uncovers its essence by means of abstraction.[181] On the assumption that thought has a direct engagement with reality, or an unmediated vision of a "real" object, the empiricist believes that the truth of knowledge lies in the correspondence of a subject's thought to an object that is external to thought itself.[182] By contrast, Althusser claims to find latent in Marx's work a view of knowledge as "theoretical practice". For Althusser, theoretical practice takes place entirely within the realm of thought, working upon theoretical objects and never coming into direct contact with the real object that it aims to know.[183] Knowledge is not discovered, but rather produced by way of three "Generalities": (I) the "raw material" of pre-scientific ideas, abstractions and facts; (II) a conceptual framework (or "problematic") brought to bear upon these; and (III) the finished product of a transformed theoretical entity, concrete knowledge.[184][185] In this view, the validity of knowledge does not lie in its correspondence to something external to itself. Marx's historical materialism is a science with its own internal methods of proof.[186] It is therefore not governed by interests of society, class, ideology, or politics, and is distinct from the superstructure. In addition to its unique epistemology, Marx's theory is built on concepts—such as forces and relations of production—that have no counterpart in classical political economy.[187] Even when existing terms are adopted—for example, the theory of surplus value, which combines David Ricardo's concepts of rent, profit, and interest—their meaning and relation to other concepts in the theory is significantly different.[188] However, more fundamental to Marx's "break" is a rejection of homo economicus, or the idea held by the classical economists that the needs of individuals can be treated as a fact or "given" independent of any economic organization. For the classical economists, individual needs can serve as a premise for a theory explaining the character of a mode of production and as an independent starting point for a theory about society.[189] Where classical political economy explains economic systems as a response to individual needs, Marx's analysis accounts for a wider range of social phenomena in terms of the parts they play in a structured whole. Consequently, Marx's Capital has greater explanatory power than does political economy because it provides both a model of the economy and a description of the structure and development of a whole society. In Althusser's view, Marx does not merely argue that human needs are largely created by their social environment and thus vary with time and place; rather, he abandons the very idea that there can be a theory about what people are like that is prior to any theory about how they come to be that way.[190] Although Althusser insists that there was an epistemological break,[191] he later states that its occurrence around 1845 is not clearly defined, as traces of humanism, historicism, and Hegelianism are found in Capital.[192] He states that only Marx's Critique of the Gotha Programme and some marginal notes on a book by Adolph Wagner are fully free from humanist ideology.[193] In line with this, Althusser replaces his earlier definition of Marx's philosophy as the "theory of theoretical practice" with a new belief in "politics in the field of history"[194] and "class struggle in theory".[195] Althusser considers the epistemological break to be a process instead of a clearly defined event — the product of incessant struggle against ideology. Thus, the distinction between ideology and science or philosophy is not assured once and for all by the epistemological break.[196] Practices Because of Marx's belief that the individual is a product of society, Althusser holds that it is pointless to try to build a social theory on a prior conception of the individual. The subject of observation is not individual human elements, but rather "structure". As he sees it, Marx does not explain society by appealing to the properties of individual persons—their beliefs, desires, preferences, and judgements. Rather, Marx defines society as a set of fixed "practices".[197] Individuals are not actors who make their own history, but are instead the "supports" (Träger) of these practices.[198] Althusser uses this analysis to defend Marx's historical materialism against the charge that it crudely posits a base (economic level) and superstructure (culture/politics) "rising upon it" and then attempts to explain all aspects of the superstructure by appealing to features of the (economic) base (the well known architectural metaphor). For Althusser, it is a mistake to attribute this economic determinist view to Marx. Just as Althusser criticises the idea that a social theory can be founded on an historical conception of human needs, so does he reject the idea that economic practice can be used in isolation to explain other aspects of society.[199] Althusser believes that the base and the superstructure are interdependent, although he keeps to the classic Marxist materialist understanding of the determination of the base "in the last instance" (albeit with some extension and revision). The advantage of practices over human individuals as a starting point is that although each practice is only a part of a complex whole of society, a practice is a whole in itself in that it consists of a number of different kinds of parts. Economic practice, for example, contains raw materials, tools, individual persons, etc., all united in a process of production.[200] Althusser conceives of society as an interconnected collection of these wholes: economic practice, ideological practice, and politico-legal practice. Although each practice has a degree of relative autonomy, together they make up one complex, structured whole (social formation).[201] In his view, all practices are dependent on each other. For example, among the relations of production of capitalist societies are the buying and selling of labour power by capitalists and workers respectively. These relations are part of economic practice, but can only exist within the context of a legal system which establishes individual agents as buyers and sellers. Furthermore, the arrangement must be maintained by political and ideological means.[202] From this it can be seen that aspects of economic practice depend on the superstructure and vice versa.[203] For him this was the moment of reproduction and constituted the important role of the superstructure. Contradiction and overdetermination An analysis understood in terms of interdependent practices helps us to conceive of how society is organized, but also permits us to comprehend social change and thus provides a theory of history. Althusser explains the reproduction of the relations of production by reference to aspects of ideological and political practice; conversely, the emergence of new production relations can be explained by the failure of these mechanisms. Marx's theory seems to posit a system in which an imbalance in two parts could lead to compensatory adjustments at other levels, or sometimes to a major reorganization of the whole. To develop this idea, Althusser relies on the concepts of contradiction and non-contradiction, which he claims are illuminated by their relation to a complex structured whole. Practices are contradictory when they "grate" on one another and non-contradictory when they support one another. Althusser elaborates on these concepts by reference to Lenin's analysis of the Russian Revolution of 1917.[204] Lenin posited that despite widespread discontent throughout Europe in the early 20th century, Russia was the country in which revolution occurred because it contained all the contradictions possible within a single state at the time.[205] In his words, it was the "weakest link in a chain of imperialist states".[206] He explained the revolution in relation to two groups of circumstances: firstly, the existence within Russia of large-scale exploitation in cities, mining districts, etc., a disparity between urban industrialization and medieval conditions in the countryside, and a lack of unity amongst the ruling class; secondly, a foreign policy which played into the hands of revolutionaries, such as the elites who had been exiled by the Tsar and had become sophisticated socialists.[207] For Althusser, this example reinforces his claim that Marx's explanation of social change is more complex than the result of a single contradiction between the forces and the relations of production.[208] The differences between events in Russia and Western Europe highlight that a contradiction between forces and relations of production may be necessary, but not sufficient, to bring about revolution.[209] The circumstances that produced revolution in Russia were heterogeneous, and cannot be seen to be aspects of one large contradiction.[210] Each was a contradiction within a particular social totality. From this, Althusser concludes that Marx's concept of contradiction is inseparable from the concept of a complex structured social whole. To emphasize that changes in social structures relate to numerous contradictions, Althusser describes these changes as "overdetermined", using a term taken from Sigmund Freud.[211] This interpretation allows us to account for the way in which many different circumstances may play a part in the course of events, and how these circumstances may combine to produce unexpected social changes or "ruptures".[210] However, Althusser does not mean to say that the events that determine social changes all have the same causal status. While a part of a complex whole, economic practice is a "structure in dominance": it plays a major part in determining the relations between other spheres, and has more effect on them than they have on it. The most prominent aspect of society (the religious aspect in feudal formations and the economic aspect in capitalist formations) is called the "dominant instance", and is in turn determined "in the last instance" by the economy.[212] For Althusser, the economic practice of a society determines which other formation of that society dominates the society as a whole. Althusser's understanding of contradiction in terms of the dialectic attempts to rid Marxism of the influence and vestiges of Hegelian (idealist) dialectics, and is a component part of his general anti-humanist position. In his reading, the Marxist understanding of social totality is not to be confused with the Hegelian. Where Hegel sees the different features of each historical epoch – its art, politics, religion, etc. – as expressions of a single essence, Althusser believes each social formation to be "decentred", i.e., that it cannot be reduced or simplified to a unique central point.[213] Ideological state apparatuses Main article: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses Because Althusser held that a person's desires, choices, intentions, preferences, judgements, and so forth are the effects of social practices, he believed it necessary to conceive of how society makes the individual in its own image. Within capitalist societies, the human individual is generally regarded as a subject—a self-conscious, "responsible" agent whose actions can be explained by their beliefs and thoughts. For Althusser, a person's capacity to perceive themselves in this way is not innate. Rather, it is acquired within the structure of established social practices, which impose on individuals the role (forme) of a subject.[214] Social practices both determine the characteristics of the individual and give them an idea of the range of properties they can have, and of the limits of each individual. Althusser argues that many of our roles and activities are given to us by social practice: for example, the production of steelworkers is a part of economic practice, while the production of lawyers is part of politico-legal practice. However, other characteristics of individuals, such as their beliefs about the good life or their metaphysical reflections on the nature of the self, do not easily fit into these categories. In Althusser's view, our values, desires, and preferences are inculcated in us by ideological practice, the sphere which has the defining property of constituting individuals as subjects.[215] Ideological practice consists of an assortment of institutions called "ideological state apparatuses" (ISAs), which include the family, the media, religious organizations, and most importantly in capitalist societies, the education system, as well as the received ideas that they propagate.[216] No single ISA produces in us the belief that we are self-conscious agents. Instead, we derive this belief in the course of learning what it is to be a daughter, a schoolchild, black, a steelworker, a councillor, and so forth. Despite its many institutional forms, the function and structure of ideology is unchanging and present throughout history;[217] as Althusser states, "ideology has no history".[218] All ideologies constitute a subject, even though he or she may differ according to each particular ideology. Memorably, Althusser illustrates this with the concept of "hailing" or "interpellation". He compares ideology to a policeman shouting "Hey you there!" toward a person walking on the street. Upon hearing this call, the person responds by turning around and in doing so, is transformed into a subject.[219] The person being hailed recognizes themselves as the subject of the hail, and knows to respond.[220] Althusser calls this recognition a "mis-recognition" (méconnaissance),[221] because it works retroactively: a material individual is always already an ideological subject, even before he or she is born.[222] The "transformation" of an individual into a subject has always already happened; Althusser here acknowledges a debt to Spinoza's theory of immanence.[222] To highlight this, Althusser offers the example of Christian religious ideology, embodied in the Voice of God, instructing a person on what their place in the world is and what he must do to be reconciled with Christ.[223] From this, Althusser draws the point that in order for that person to identify as a Christian, he must first already be a subject; that is, by responding to God's call and following His rules, he affirms himself as a free agent, the author of the acts for which he assumes responsibility.[224] We cannot recognize ourselves outside ideology, and in fact, our very actions reach out to this overarching structure. Althusser's theory draws heavily from Jacques Lacan and his concept of the Mirror Stage[225]—we acquire our identities by seeing ourselves mirrored in ideologies.[226] Aleatory materialism In various short papers drafted from 1982 to 1986 and published posthumously,[227][228] Althusser is critical of the relation of Marxist science to the philosophy of dialectical materialism and materialist philosophy in general. Althusser rejects dialectical materialism and introduces a new concept: the Philosophy of the Encounter, renamed Aleatory Materialism in 1986.[229] To develop this idea, Althusser holds that there exists an “underground” or barely recognized philosophical current of Aleatory Materialism,[230] articulated by Marx, Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius, Machiavelli, Spinoza, Hobbes, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Derrida.[231] He argues that it was an idealist and teleological mistake to think that there are general laws of history and that social relations are determined in the same manner as physical relations. Emphasising the role of contingency in history over laws of development he states that reconstructed historical materialism has as its object complex historical singularities or conjunctures,[232] The conjuncture is the pivotal point, where political practice may intervene,[233] and Aleatory Materialism is a materialist philosophy to understand this conjuncture. Reception and influence While Althusser's writings were born of an intervention against reformist and ecumenical tendencies within Marxist theory,[234] the eclecticism of his influences reflected a move away from the intellectual isolation of the Stalin era. He drew as much from pre-Marxist systems of thought and contemporary schools such as structuralism, philosophy of science and psychoanalysis as he did from thinkers in the Marxist tradition. Furthermore, his thought was symptomatic of Marxism's growing academic respectability and of a push towards emphasizing Marx's legacy as a philosopher rather than only as an economist or sociologist. Tony Judt saw this as a criticism of Althusser's work, saying he removed Marxism "altogether from the realm of history, politics and experience, and thereby ... render[ed] it invulnerable to any criticism of the empirical sort."[235] Althusser has had broad influence in the areas of Marxist philosophy and post-structuralism: interpellation has been popularized and adapted by the feminist philosopher and critic Judith Butler, and elaborated further by Göran Therborn; the concept of ideological state apparatuses has been of interest to Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek; the attempt to view history as a process without a subject garnered sympathy from Jacques Derrida; historical materialism was defended as a coherent doctrine from the standpoint of analytic philosophy by G. A. Cohen;[236] the interest in structure and agency sparked by Althusser was to play a role in sociologist Anthony Giddens's theory of structuration. Althusser's influence is also seen in the work of economists Richard D. Wolff and Stephen Resnick, who have interpreted that Marx's mature works hold a conception of class different from the normally understood ones. For them, in Marx class refers not to a group of people (for example, those that own the means of production versus those that do not), but to a process involving the production, appropriation, and distribution of surplus labour. Their emphasis on class as a process is consistent with their reading and use of Althusser's concept of overdetermination in terms of understanding agents and objects as the site of multiple determinations. Althusser's work has also been criticized from a number of angles. In a 1971 paper for Socialist Register, Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski[237] undertook a detailed critique of structural Marxism, arguing that the concept was seriously flawed on three main points: I will argue that the whole of Althusser's theory is made up of the following elements: 1. common sense banalities expressed with the help of unnecessarily complicated neologisms; 2. traditional Marxist concepts that are vague and ambiguous in Marx himself (or in Engels) and which remain, after Althusser's explanation, exactly as vague and ambiguous as they were before; 3. some striking historical inexactitudes. Kołakowski further argued that, despite Althusser's 'verbal claims to "scientificity"', is himself "building a gratuitous ideological project". In 1980, sociologist Axel van den Berg[238] described Kołakowski's critique as "devastating", proving that "Althusser retains the orthodox radical rhetoric by simply severing all connections with verifiable facts". G. A. Cohen, in his essay 'Complete Bullshit', has cited the 'Althusserian school' as an example of 'bullshit' and a factor in his co-founding the 'Non-Bullshit Marxism Group'.[239] He says that 'the ideas that the Althusserians generated, for example, of the interpellation of the subject, or of contradiction and overdetermination, possessed a surface allure, but it often seemed impossible to determine whether or not the theses in which those ideas figured were true, and, at other times, those theses seemed capable of just two interpretations: on one of them they were true but uninteresting, and, on the other, they were interesting, but quite obviously false'.[240] Althusser was vehemently attacked by British Marxist historian E. P. Thompson in his book The Poverty of Theory.[241][242] Thompson claimed that Althusserianism was Stalinism reduced to the paradigm of a theory.[243] Where the Soviet doctrines that existed during the lifetime of the dictator lacked systematisation, Althusser's theory gave Stalinism "its true, rigorous and totally coherent expression".[244] As such, Thompson called for "unrelenting intellectual war" against the Marxism of Althusser.[245] |

アルチュセールの初期の著作には、マルクスの『資本論』を集中的に哲学

的に読み直したアルチュセールとその弟子たちの仕事を集めた『資本論を読む』(1965年)という影響力のある一冊がある。この本は、「政治経済批判」と

してのマルクス主義理論の哲学的地位とその対象について考察している。アルチュセールは後に、このマルクス解釈における革新の多くが、バルーク・スピノザ

に由来する概念をマルクス主義に同化させようとしていることを認める[165]。全訳は2016年に出版された。 アルチュセールの理論的立場のいくつかは、マルクス主義哲学において影響力を持ち続けている。彼のエッセイ「唯物論的弁証法について」は、マルクスの初期 の著作(1840-45年)と、その後の、正しくマルクス主義的なテキストとの間の大きな「認識論的断絶」を提案しており、これは科学哲学者ガストン・バ シュラールの言葉を借用したものである。 [彼のエッセイ「マルクス主義とヒューマニズム」は、マルクス主義理論における反ヒューマニズムの強い主張であり、マルクス主義者によってしばしば打ち出 される「人間の可能性」や「種的存在」のような考えを、「人間性」のブルジョア・イデオロギーの産物として非難している。 [彼のエッセイ「矛盾と過剰決定」は、「矛盾」の概念を政治的状況における複数の因果関係のより複雑なモデルに置き換えるために、精神分析から過剰決定の 概念を借りている[170](アントニオ・グラムシの文化的ヘゲモニーの概念と密接に関連する考え方)[171]。 アルチュセールはイデオロギーの理論家としても広く知られている。彼の最も有名なエッセイ「イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家機構: Notes Toward an Investigation"[172]はイデオロギーの概念を確立している。アルチュセールのイデオロギー論は、マルクスとグラムシだけでなく、それぞ れフロイトとラカンの無意識と鏡相の心理学的概念にも依拠しており、自己の概念を可能にする構造とシステムについて述べている。アルチュセールにとって、 これらの構造は抑圧の主体であると同時に必然的なものでもある。イデオロギーから逃れることも、イデオロギーに服従することを避けることも不可能なのだ。 他方、『イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家機構』が引用されている小論集[173]には、アルチュセールのイデオロギー概念が古典的なマルクス主義の階級 闘争論と広範に一致していることを確認する他の小論が収められている。 アルチュセールの思想は彼の存命中に発展した。それは、特にマルクス主義内部で、特に彼の知識論(認識論)に関する議論と論争の対象となってきた。 認識論的断絶 アルチュセールは、マルクスの思想は根本的に誤解され、過小評価されてきたと主張する。彼は、マルクスの著作に対する様々な解釈-歴史主義、観念論 [174]、経済主義-を激しく非難しているが、その理由は、それらが「歴史の科学」である史的唯物論によって、マルクスが社会変化に関する革命的な見解 を構築したことを理解していないからである。アルチュセールは、こうした誤りは、マルクスの著作全体が首尾一貫した全体として理解できるという考え方に起 因すると考えている。むしろ、マルクスの思想には根本的な「認識論的断絶」がある。若きマルクスの著作はドイツ哲学と古典的政治経済学の範疇に縛られてい るが、『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1845年執筆)は突如として前例のない出発をする。したがって、アルチュセールのプロジェクトは、読者がマルクスの非 凡な理論の独創性と力を完全に把握できるようにすることであり、明示的なことと同様に、語られていないことにも注意を払うことである。アルチュセールは、 マルクスが数学におけるタレスや物理学におけるガリレオの貢献に類似した「知の大陸」である「歴史」を発見したと考えている[178]。 アルチュセールは、マルクスの著作は、主体と客体の区別を否定する画期的な認識論(知識論)の上に構築されているため、その先例とは根本的に相容れないと 考えている。経験主義に対抗して、アルチュセールは、マルクスの哲学である弁証法的唯物論は、視覚としての知識の理論に対抗して、生産としての知識の理論 を持っていると主張している[179][180]。 [181]思考が現実との直接的な関わりを持つ、あるいは「現実の」対象に対する媒介されないヴィジョンを持つという前提のもとで、経験主義者は知識の真 理が思考それ自体の外部にある対象に対する主体の思考の対応にあると信じている[182]。 対照的に、アルチュセールは「理論的実践」としての知識観をマルクスの著作に潜在的に見出すと主張している。アルチュセールにとって、理論的実践は完全に 思考の領域内で行われ、理論的対象に働きかけ、それが知ろうとする現実の対象に直接接触することはない。 [183]知識は発見されるのではなく、むしろ3つの「一般性」によって生み出される:(I)前科学的なアイデア、抽象、事実の「原料」、(II)これら に対してもたらされる概念的枠組み(あるいは「問題」)、そして(III)変換された理論的実体の完成品である具体的知識である。マルクスの史的唯物論 は、それ自身の内部的な証明方法をもつ科学であり、したがって、社会、階級、イデオロギー、政治の利害に支配されることはなく、上部構造とは区別される。 そのユニークな認識論に加えて、マルクスの理論は、諸力や生産関係といった、古典的な政治経済学には対応するものがない概念に基づいて構築されている。 [しかし、マルクスの「断絶」にとってより根本的なのは、ホモ・エコノミクス、すなわち、個人のニーズはいかなる経済組織からも独立した事実あるいは「所 与のもの」として扱うことができるという古典派経済学者が抱いていた考え方の否定である。古典派経済学者にとって、個人の欲求は、生産様式の性格を説明す る理論の前提としても、社会についての理論の独立した出発点としても機能することができる[189]。古典派政治経済学が経済システムを個人の欲求への応 答として説明するのに対して、マルクスの分析は、構造化された全体においてそれらが果たす役割という観点から、より広範な社会現象を説明する。その結果、 マルクスの『資本論』は、経済のモデルと社会全体の構造と発展の記述の両方を提供しているため、政治経済学よりも説明力が高い。アルチュセールの見解で は、マルクスは単に人間の欲求が社会環境によって生み出されるものであり、したがって時と場所によって変化するということを主張しているのではなく、むし ろ、人間がどのようにしてそのようになるのかという理論に先立つ、人間がどのようなものであるかについての理論が存在しうるという考えそのものを放棄して いる[190]。 アルチュセールは認識論的な断絶があったと主張しているが[191]、『資本論』には人文主義、歴史主義、ヘーゲル主義の痕跡が見られるため、1845年 頃にそのような断絶が起こったことは明確には定義されていないと後に述べている[192]。 彼はマルクスの『ゴータ綱領批判』とアドルフ・ワーグナーの本に関するいくつかの余白のメモだけが人文主義的なイデオロギーから完全に自由であると述べて いる。 [193]これに沿って、アルチュセールは「理論的実践の理論」としてのマルクスの哲学の彼の以前の定義を「歴史の場における政治」[194]と「理論に おける階級闘争」[195]に対する新しい信念に置き換えている。したがって、イデオロギーと科学や哲学の区別は、認識論的断絶によってきっぱりと保証さ れるわけではない[196]。 実践 個人は社会の産物であるというマルクスの信念のゆえに、アルチュセールは、個人についての先行概念の上に社会理論を構築しようとすることは無意味であると する。観察の対象は個々の人間の要素ではなく、むしろ「構造」である。彼の考えでは、マルクスは個々の人間の特性-信念、欲望、選好、判断-に訴えること によって社会を説明するのではない。むしろマルクスは社会を固定された「実践」の集合として定義している[197]。個人は彼ら自身の歴史を作る行為者で はなく、その代わりにこれらの実践の「支え」(Träger)なのである[198]。 アルチュセールはこの分析を用いて、マルクスの史的唯物論が粗雑に基盤(経済水準)と上部構造(文化/政治)を「その上にそびえ立つ」ものとして仮定し、 (経済的な)基盤の特徴に訴えることによって上部構造のあらゆる側面を説明しようとする(よく知られた建築の比喩)という非難からマルクスの史的唯物論を 擁護している。アルチュセールにとって、この経済決定論的な見方をマルクスに帰するのは間違いである。アルチュセールは、社会理論が人間の欲求の歴史的な 概念に基づいて基礎づけられるという考えを批判しているのと同様に、経済的実践が社会の他の側面を説明するために単独で使用できるという考えを否定してい る[199]。アルチュセールは、基層と上部構造は相互依存していると考えているが、基層の「最終的な事例における」決定という古典的なマルクス主義的唯 物論的理解を(若干の拡張と修正はあるにせよ)守っている。人間の個人を出発点とした実践の利点は、各実践は社会の複雑な全体の一部にすぎないが、実践は それ自体、多くの異なる種類の部分から構成されるという点で全体であるということである。例えば、経済的実践は、原材料、道具、個々の人間などを含んでお り、それらはすべて生産の過程において一体化されている[200]。 アルチュセールは、社会について、経済的実践、イデオロギー的実践、政治的・法的実践といったこれらの全体が相互に結びついた集合体として考えている。そ れぞれの実践はある程度の相対的な自律性を持っているが、それらが一緒になって一つの複雑な構造化された全体(社会形成)を構成している[201]。彼の 見解では、すべての実践は互いに依存している。たとえば、資本主義社会の生産関係のなかには、資本家と労働者それぞれによる労働力の売買がある。こうした 関係は経済慣行の一部であるが、個々の主体を買い手と売り手として定める法制度の文脈の中でしか存在しえない。さらに、この取り決めは政治的・イデオロ ギー的な手段によって維持されなければならない[202]。ここから、経済的実践の側面は上部構造に依存し、その逆もまた然りであることがわかる [203]。 矛盾と過剰決定 相互依存的な実践の観点から理解される分析は、社会がどのように組織化されているかを考えるのに役立つだけでなく、社会変動を理解することを可能にし、し たがって歴史理論を提供する。アルチュセールは、生産関係の再生産をイデオロギー的・政治的実践の側面に言及することによって説明し、逆に、新しい生産関 係の出現は、これらのメカニズムの失敗によって説明することができる。マルクスの理論は、2つの部分における不均衡が、他のレベルにおける代償的な調整、 あるいは時には全体の大規模な再編成につながるようなシステムを想定しているようである。この考えを発展させるために、アルチュセールは矛盾と非矛盾の概 念に依拠している。実践が互いに「耳障り」なものであれば矛盾し、互いに支え合うものであれば非矛盾である。アルチュセールは、1917年のロシア革命に 関するレーニンの分析を参照することで、これらの概念について詳しく説明している[204]。 レーニンは、20世紀初頭のヨーロッパ全体に不満が広がっていたにもかかわらず、ロシアが革命を起こした国であったのは、当時の単一の国家の中で可能で あったすべての矛盾を含んでいたからであると仮定していた[205]。彼の言葉を借りれば、それは「帝国主義国家の連鎖の中で最も弱い連鎖」であった [206]、 第二に、ツァーリによって追放され、洗練された社会主義者となったエリートたちのような革命主義者の手に乗る対外政策であった[207]。 アルチュセールにとって、この例は、社会変化に関するマルクスの説明は、諸力と生産諸関係の間の単一の矛盾の結果よりも複雑であるという彼の主張を補強す るものである[208]。ロシアと西ヨーロッパにおける出来事の違いは、諸力と生産諸関係の間の矛盾が革命をもたらすために必要であるかもしれないが、十 分ではないことを浮き彫りにしている[209]。ロシアにおいて革命をもたらした状況は異質であり、1つの大きな矛盾の側面であるとみなすことはできない [210]。このことから、アルチュセールは、マルクスの矛盾の概念は、複雑に構造化された社会全体の概念と不可分であると結論づけている。社会構造の変 化が多数の矛盾に関連していることを強調するために、アルチュセールは、ジークムント・フロイトから引用した用語を用いて、これらの変化を「過剰決定」 (overdetermined)と表現している[211]。この解釈は、多くの異なる状況が出来事の経過に関与することがあり、これらの状況がどのよう に組み合わさって予期せぬ社会的変化や「断裂」を生み出すことがあるのかを説明することを可能にしている[210]。 しかしながら、アルチュセールは、社会的変化を決定する出来事がすべて同じ因果的地位にあると言いたいわけではない。複雑な全体の一部ではあるが、経済的 実践は「支配的な構造」であり、他の諸領域間の関係を決定する上で主要な役割を果たし、他の諸領域がそれに及ぼす影響よりも大きな影響を及ぼす。社会の最 も顕著な側面(封建的形成における宗教的側面と資本主義的形成における経済的側面)は「支配的事例」と呼ばれ、経済によって「最終的に」決定される [212] 。 アルチュセールの弁証法の観点からの矛盾の理解は、マルクス主義からヘーゲル的(観念論的)弁証法の影響と名残を取り除こうとするものであり、彼の一般的 な反人間主義の立場の構成部分である。彼の読みでは、社会的全体性についてのマルクス主義的理解は、ヘーゲル的なものと混同されるべきではない。ヘーゲル が、各歴史的エポックのさまざまな特徴(芸術、政治、宗教など)を、単一の本質の表現と見なしているのに対し、アルルは、各歴史的エポックのさまざまな特 徴を、単一の本質の表現と見なしている。- ヘーゲルがそれぞれの歴史的時代におけるさまざまな特徴-その芸術、政治、宗教など-を単一の本質の表現とみなすのに対して、アルチュセールは、それぞれ の社会的形成は「差別化」されている、すなわち、固有の中心点に還元されたり単純化されたりすることはあり得ないと考えている[213]。 イデオロギー的国家装置 主な記事 イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家機構 アルチュセールは、人の欲望、選択、意図、嗜好、判断などは社会的実践の影響であるとしたため、社会がどのように個人を自らのイメージの中に作り上げるか を考える必要があると考えた。資本主義社会では、一般に個人は主体、つまり自己意識に基づく「責任ある」主体であり、その行動は信念や思考によって説明で きると考えられている。アルチュセールにとって、このように自らを認識する能力は生まれつきのものではない。むしろ、それは確立された社会的実践の構造の 中で獲得されるものであり、社会的実践は個人に主体の役割(forme)を課しているのである[214]。社会的実践は個人の特性を決定すると同時に、個 人が持ちうる特性の範囲と各個人の限界についての考えを与える。例えば、鉄鋼労働者の生産は経済的実践の一部であり、弁護士の生産は政治・法律的実践の一 部である。例えば、鉄鋼労働者の生産は経済的実践の一部であり、弁護士の生産は政治・法律的実践の一部である。しかし、善き人生についての信念や自己の本 質についての形而上学的考察など、個人の他の特徴は、これらのカテゴリーに容易に当てはまらない。 アルチュセールの見解では、われわれの価値観、欲望、嗜好は、イデオロギー的実践によってわれわれに植えつけられる。イデオロギー的実践は、「イデオロ ギー的国家装置」(ISA)と呼ばれる諸制度から構成されており、家族、メディア、宗教組織、そして資本主義社会において最も重要な教育制度、さらにはそ れらが伝播する受容された思想を含んでいる[216]。それどころか、娘であること、小学生であること、黒人であること、鉄鋼労働者であること、参議院議 員であることなどが何であるかを学ぶ過程で、私たちはこの信念を導き出すのである。 アルチュセールが述べるように、「イデオロギーには歴史がない」[218]。アルチュセールはこのことを「呼びかけ」や「インターペレーション」という概 念で説明している。彼はイデオロギーを、道を歩いている人に向かって「おい、そこのお前!」と叫ぶ警官に例えている。この呼びかけを聞いたとき、その人は 振り向くことによって応答し、そうすることによって主体へと変容する。 [アルチュセールはこの認識を「誤認」(méconnaissance)と呼んでいるが[221]、それはそれが遡及的に機能するからである。アルチュ セールはここでスピノザの内在性理論への恩義を認めている[222]。 このことを強調するために、アルチュセールは、キリスト教の宗教的イデオロギーの例を提示しており、それは神の声のなかに具現化され、世界における自分の 位置が何であるか、キリストと和解するために何をしなければならないかを人に指示している。 [つまり、神の呼びかけに応え、神の規則に従うことで、その人は自分自身を自由な行為者、つまり自分が責任を負う行為の作者として肯定するのである [224]。 私たちはイデオロギーの外側で自分自身を認識することはできないし、事実、私たちの行為そのものがこの包括的な構造に手を伸ばしているのである。アルチュ セールの理論は、ジャック・ラカンと彼の鏡像段階[225]の概念に大きく依拠しており、私たちはイデオロギーの中に映し出された自分自身を見ることに よってアイデンティティを獲得している[226]。 寓意的唯物論 1982年から1986年にかけて起草され、死後に出版された様々な短い論文の中で、アルチュセールはマルクス主義科学と弁証法的唯物論の哲学および唯物 論哲学全般との関係について批判的である[227][228]。アルチュセールは弁証法的唯物論を否定し、1986年にアレオリー・マテリアリズム (Aleatory Materialism)と改名された「出会いの哲学」という新しい概念を導入している。 彼は、歴史には一般的な法則があり、社会的関係は物理的関係と同じように決定されると考えるのは観念論的かつ目的論的な誤りであると主張する。彼は発展の 法則よりも歴史における偶発性の役割を強調し、再構築された史的唯物論はその対象として複雑な歴史的特異点や接続点を持つと述べており[232]、接続点 は政治的実践が介入しうる極めて重要な地点であり[233]、アレアトリー・マテリアリズムはこの接続点を理解するための唯物論的哲学である。 受容と影響 アルチュセールの著作は、マルクス主義理論内の改革主義的傾向やエキュメニカルな傾向に対する介入から生まれたものであったが[234]、彼の影響の折衷 主義はスターリン時代の知的孤立からの脱却を反映していた。彼はマルクス主義以前の思想体系や、構造主義、科学哲学、精神分析といった現代の学派からも、 マルクス主義の伝統にある思想家たちからも同様に多くの影響を受けていた。さらに、彼の思想は、マルクス主義が学問的に尊重されるようになり、経済学者や 社会学者としてだけでなく、哲学者としてのマルクスの遺産を強調しようとする動きを示すものであった。トニー・ジャットはこれをアルチュセールの研究に対 する批判とみなし、彼がマルクス主義を「歴史、政治、経験の領域から完全に排除し、それによって......経験的な種類のいかなる批判に対しても無防備 にした」と述べている[235]。 アルチュセールは、マルクス主義哲学とポスト構造主義の分野で幅広い影響力を持っている: インターペラシオンはフェミニストの哲学者であり批評家であるジュディス・バトラーによって一般化され、脚色され、ヨーラン・テルボーンによってさらに推 敲された。イデオロギー的国家装置の概念はスロヴェニアの哲学者スラヴォイ・ジジェクにとって興味深いものであった。社会学者アンソニー・ギデンズの構造 化理論では、アルチュセールが提起した構造と主体への関心が役割を果たすことになった。 アルチュセールの影響は経済学者のリチャード・D・ウルフとスティーヴン・レズニックの研究にも見られ、彼らはマルクスの成熟した著作が通常理解されてい るものとは異なる階級の概念を保持していると解釈している。彼らによれば、マルクスにおける階級とは、人々の集団(例えば、生産手段を所有する者とそうで ない者)を指すのではなく、剰余労働の生産、充当、分配を含む過程を指す。プロセスとしての階級を強調する彼らの姿勢は、複数の決定の場としての主体や対 象を理解するという点で、アルチュセールの過剰決定の概念を読み解き、利用していることと一致している。 アルチュセールの仕事もまた、さまざまな角度から批判されてきた。ポーランドの哲学者Leszek Kołakowski[237]は1971年に『Socialist Register』に寄稿した論文の中で、構造マルクス主義の詳細な批判を行い、この概念には3つの主要な点において重大な欠陥があると論じている: 私は、アルチュセールの理論全体が以下の要素で構成されていると主張する: 1.不必要に複雑な新語の助けを借りて表現された常識的な平凡さ、2.マルクス自身(あるいはエンゲルス)において曖昧で曖昧であり、アルチュセールの説 明の後でも、以前とまったく同じように曖昧で曖昧なままである伝統的なマルクス主義の概念、3.いくつかの顕著な歴史的非現実性。 Kołakowskiはさらに、アルチュセールが「科学性を口先では主張」しているにもかかわらず、彼自身は「無償のイデオロギー的プロジェクトを構築」 している、と論じた。1980年、社会学者アクセル・ヴァン・デン・ベルグ[238]は、コワコフスキーの批評を「壊滅的」と評し、「アルチュセールは、 検証可能な事実とのつながりをすべて断ち切るだけで、正統的なラディカル・レトリックを保持している」ことを証明している。 G.A.コーエンは、そのエッセイ「完全なでたらめ」の中で、「でたらめ」の例として「アルチュセール派」を挙げており、「でたらめでないマルクス主義グ ループ」を共同設立した要因となっている。 [アルチュセール派が生み出した思想、例えば、主体のインターペレーションや矛盾と過剰決定といった思想は、表面的には魅力的であったが、しばしば、それ らの思想が構成する論題が真実であるかどうかを判断することは不可能であるように思えた。 アルチュセールはイギリスのマルクス主義者の歴史家E・P・トンプソンによってその著書『理論の貧困』(The Poverty of Theory)の中で激しく攻撃されていた[241][242] 。 [243]独裁者の存命中に存在したソビエトの教義が体系化を欠いていたところ、アルチュセールの理論はスターリニズムに「その真の、厳密で完全に首尾一 貫した表現」を与えた[244]。 |

| Legacy Since his death, the reassessment of Althusser's work and influence has been ongoing. The first wave of retrospective critiques and interventions ("drawing up a balance sheet") began outside of Althusser's own country, France, because, as Étienne Balibar pointed out in 1988, "there is an absolute taboo now suppressing the name of this man and the meaning of his writings."[246] Balibar's remarks were made at the "Althusserian Legacy" Conference organized at Stony Brook University by Michael Sprinker. The proceedings of this conference were published in September 1992 as the Althusserian Legacy and included contributions from Balibar, Alex Callinicos, Michele Barrett, Alain Lipietz, Warren Montag, and Gregory Elliott, among others. It also included an obituary and an extensive interview with Derrida.[246] Eventually, a colloquium was organized in France at the University of Paris VIII by Sylvain Lazarus on May 27, 1992. The general title was Politique et philosophie dans l'oeuvre de Louis Althusser, the proceedings of which were published in 1993.[247] In retrospect, Althusser's continuing influence can be seen through his students.[14] A dramatic example of this points to the editors and contributors of the 1960s journal Cahiers pour l'Analyse: "In many ways, the 'Cahiers' can be read as the critical development of Althusser's own intellectual itinerary when it was at its most robust."[248] This influence continues to guide much philosophical work, as many of these same students became eminent intellectuals in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s: Alain Badiou, Étienne Balibar and Jacques Rancière in philosophy, Pierre Macherey in literary criticism and Nicos Poulantzas in sociology. The prominent Guevarist Régis Debray also studied under Althusser, as did the aforementioned Derrida (with whom he at one time shared an office at the ENS), noted philosopher Michel Foucault, and the pre-eminent Lacanian psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller.[14] Badiou has lectured and spoken on Althusser on several occasions in France, Brazil, and Austria since Althusser's death. Badiou has written many studies, including "Althusser: Subjectivity without a Subject", published in his book Metapolitics in 2005. Most recently, Althusser's work has been given prominence again through the interventions of Warren Montag and his circle; see for example the special issue of borderlands e-journal edited by David McInerney (Althusser & Us) and "Décalages: An Althusser Studies Journal", edited by Montag. (See "External links" below for access to both of these journals.) In 2011 Althusser continued to spark controversy and debate with the publication in August of that year of Jacques Rancière's first book, Althusser's Lesson (1974). It marked the first time this groundbreaking work was to appear in its entirety in an English translation. In 2014, On the Reproduction of Capitalism was published, which is an English translation of the full text of the work from which the ISAs text was drawn.[249] The publication of Althusser's posthumous memoir[citation needed] cast some doubt on his own scholarly practices. For example, although he owned thousands of books, Althusser revealed that he knew very little about Kant, Spinoza, and Hegel. While he was familiar with Marx's early works, he had not read Capital when he wrote his own most important Marxist texts. Additionally, Althusser had "contrived to impress his first teacher, the Catholic theologian Jean Guitton, with a paper whose guiding principles he had simply filched from Guitton's own corrections of a fellow student's essay," and "he concocted fake quotations in the thesis he wrote for another major contemporary philosopher, Gaston Bachelard."[250] |

遺産 彼の死後、アルチュセールの仕事と影響力の再評価が続いている。回顧的な批評や介入(「貸借対照表の作成」)の最初の波は、アルチュセールの母国であるフ ランス国外で始まった。1988年にエティエンヌ・バリバールが指摘したように、「この人物の名前と著作の意味を抑圧する絶対的なタブーが現在存在してい る」からである[246]。この会議の議事録は1992年9月に「アルチュセリアンの遺産」として出版され、バリバール、アレックス・カリニコス、ミシェ ル・バレット、アラン・リピエッツ、ウォーレン・モンターグ、グレゴリー・エリオットらの寄稿が含まれている。また、追悼文とデリダへの広範なインタ ビューも含まれていた[246]。 最終的には、1992年5月27日にシルヴァン・ラザルスによってフランスのパリ第8大学でコロキウムが開催された。一般的なタイトルは「ルイ・アルチュ セールの作品における政治と哲学」であり、その議事録は1993年に出版された[247]。 振り返ってみると、アルチュセールの継続的な影響力は彼の弟子たちを通して見ることができる: 多くの点で、『カイエ』はアルチュセール自身の知的遍歴が最も強固であったときの批評的展開として読むことができる」[248]。この影響は、1960年 代、1970年代、1980年代、1990年代に同じ教え子たちの多くが著名な知識人となったように、多くの哲学的仕事を導き続けている: 哲学ではアラン・バディウ、エティエンヌ・バリバール、ジャック・ランシエール、文芸批評ではピエール・マシェリー、社会学ではニコス・プーランザスなど である。著名なゲバリストのレジス・ドブレもアルチュセールに師事し、前述のデリダ(ENSでオフィスを共有していた時期もある)、著名な哲学者ミシェ ル・フーコー、卓越したラカン派の精神分析家ジャック=アラン・ミラーもアルチュセールに師事していた[14]。 バディウはアルチュセールの死後、フランス、ブラジル、オーストリアでアルチュセールに関する講演を行っている。アルチュセールの死後、フランス、ブラジ ル、オーストリアなどでアルチュセールに関する講演や講義を行っている: 2005年に著書『メタポリティクス』の中で発表した『アルチュセール:主体なき主体性』をはじめ、多くの研究を著している。最近では、ウォーレン・モン ターグとその関係者の介入によって、アルチュセールの仕事が再び脚光を浴びている。例えば、デイヴィッド・マキナニーが編集した電子ジャーナル 『borderlands』の特集号(Althusser & Us)や『Décalages: モンタグが編集した『アルチュセール研究ジャーナル』(An Althusser Studies Journal)を参照。(これら2誌へのアクセスについては、後述の「外部リンク」を参照)。 2011年、アルチュセールは、ジャック・ランシエールの最初の著書『アルチュセールの教訓』(1974年)を同年8月に出版し、論争と議論を巻き起こし 続けた。この画期的な著作の全文が英訳されたのはこれが初めてである。2014年には『資本主義の再生産について』が出版され、これはISAのテキストが 引用された作品の全文の英訳である[249]。 アルチュセールの死後の回想録[citation needed]の出版は、彼自身の学問的実践にいくつかの疑念を投げかけた。例えば、アルチュセールは何千冊もの本を所有していたにもかかわらず、カン ト、スピノザ、ヘーゲルについてはほとんど知らなかったことを明らかにしている。マルクスの初期の著作には親しんでいたものの、自身の最も重要なマルクス 主義のテキストを執筆したときには『資本論』を読んでいなかった。さらに、アルチュセールは「最初の教師であったカトリックの神学者ジャ ン・ギトンに、ギトンが仲間の学生の小論文を添削したものをそのまま引用した指導原理を論文にして印象づけようと画策」し、「もう一人の主要な現代哲学者 であるガストン・バシュラールのために書いた論文では、偽の引用をでっち上げた」[250]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Althusser |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099