シドニー・ミンツ

Sidney Wilfred Mintz (November 16, 1922 –

December 27, 2015)

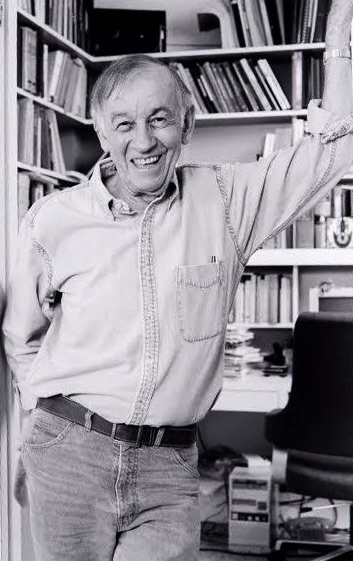

☆ シドニー・ウィルフレッド・ミンツ(1922年11月16日 - 2015年12月27日)は、カリブ海地域、クレオール化、食文化人類学の研究で知られるアメリカの人類学者である。ミンツは1951年にコロンビア大学 で博士号を取得し、プエルトリコのサトウキビ労働者を対象に主なフィールドワークを実施した。その後、ハイチとジャマイカにも民族誌学的研究を広げ、奴隷 制とグローバル資本主義、文化の混成性、カリブ海地域の農民、食料商品の政治経済に関する歴史的・民族誌学的研究を行った。ミンツは20年間イエール大学 で教鞭を執った後、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学人類学部創設に携わり、同大学で定年まで教壇に立った。ミンツの著書『甘さと権力』は、文化人類学および食文 化研究において最も影響力のある出版物の一つとみなされている。

| Sidney Wilfred Mintz

(November 16, 1922 – December 27, 2015) was an American anthropologist

best known for his studies of the Caribbean, creolization, and the

anthropology of food. Mintz received his PhD at Columbia University in

1951 and conducted his primary fieldwork among sugar-cane workers in

Puerto Rico. Later expanding his ethnographic research to Haiti and

Jamaica, he produced historical and ethnographic studies of slavery and

global capitalism, cultural hybridity, Caribbean peasants, and the

political economy of food commodities. He taught for two decades at

Yale University before helping to found the Anthropology Department at

Johns Hopkins University, where he remained for the duration of his

career. Mintz's history of sugar, Sweetness and Power, is considered

one of the most influential publications in cultural anthropology and

food studies.[2][full citation needed][3][full citation needed] |

シドニー・ウィルフレッド・ミンツ(1922年11月16日 -

2015年12月27日)は、カリブ海地域、クレオール化、食文化人類学の研究で知られるアメリカの人類学者である。ミンツは1951年にコロンビア大学

で博士号を取得し、プエルトリコのサトウキビ労働者を対象に主なフィールドワークを実施した。その後、ハイチとジャマイカにも民族誌学的研究を広げ、奴隷

制とグローバル資本主義、文化の混成性、カリブ海地域の農民、食料商品の政治経済に関する歴史的・民族誌学的研究を行った。ミンツは20年間イエール大学

で教鞭を執った後、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学人類学部創設に携わり、同大学で定年まで教壇に立った。ミンツの著書『甘さと権力』は、文化人類学および食文

化研究において最も影響力のある出版物の一つとみなされている。[2][要出典][3][要出典] |

| Early life and education Mintz was born in Dover, New Jersey,[4] to Fanny and Soloman Mintz. His father was a New York tradesman, and his mother was a garment-trade organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World.[5] Mintz studied at Brooklyn College, earning his B.A in psychology in 1943.[5] After enlisting in the US Army Air Corps for the remainder of World War II, he enrolled in the doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University and completed a dissertation on sugar-cane plantation workers in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico under the supervision of Julian Steward and Ruth Benedict.[2] While at Columbia, Mintz was one of a group of students who developed around Steward and Benedict known as the Mundial Upheaval Society.[2][5] Many prominent anthropologists such as Marvin Harris, Eric Wolf, Morton Fried, Stanley Diamond, Robert Manners, and Robert F. Murphy were among this group. |

生い立ちと教育 ミンツはニュージャージー州ドーバーでファニーとソロマン・ミンスの間に生まれた。父親はニューヨークの商人で、母親は世界産業労働組合の衣料品取引の組 織者であった。[5] ミンスはブルックリン大学で学び、1943年に心理学の学士号を取得した。[5] 第二次世界大戦の残りの期間をアメリカ陸軍航空隊で過ごした後、コロンビア大学の人類学博士課程に入学し、 ジュリアン・スチュワードとルース・ベネディクトの指導の下、プエルトリコのサンタ・イサベルにおけるサトウキビ農園労働者に関する論文を完成させた。 [2] コロンビア大学在学中、ミンツはスチュワードとベネディクトの周囲に集まった学生グループの1人であった。このグループは「ムンディアル・アップヘイバ ル・ソサエティ」として知られていた。[2][5] このグループには、マーヴィン・ハリス、エリック・ウォルフ、モートン・フリード、スタンレー・ダイヤモンド、ロバート・マナーズ、ロバート・F・マー フィーなど、著名な人類学者が多数参加していた。 |

| Career Mintz had a long academic career at Yale University (1951–74) before helping to found the Anthropology Department at Johns Hopkins University. He has been a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the École Pratique des Hautes Études and the Collège de France (Paris) and elsewhere. His work has been the subject of several studies.,[6][7][8][9] in addition to his reflections on his own ideas and fieldwork.[10][11] He was honored by the establishment of the annual Sidney W. Mintz Lecture in 1992.[12] Mintz was a member of the American Ethnological Society and was President of that body from 1968 to 1969, a fellow of the American Anthropological Association and the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Mintz taught as a lecturer at City College (now City College of the City University of New York), New York City, in 1950, at Columbia University, New York City, in 1951, and at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut between 1951 and 1974. At Yale, Mintz started as an instructor, but was Professor of Anthropology from 1963 to 1974. He also served as Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland since 1974. Mintz was also a Visiting Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1964–65 academic year, a Directeur d'Etudes at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris in 1970–1971. He was a Lewis Henry Morgan Lecturer at the University of Rochester in 1972, a Visiting Professor at Princeton University in 1975–1976, a Christian Gauss Lecturer, 1978-1979, Guggenheim Fellow in 1957, a Social Science Research Council faculty research fellow, 1958-59. He was awarded a master's degree from Yale University in 1963, a Fulbright senior research award in 1966–67 and in 1970–71, a William Clyde DeVane Medal from Yale University in 1972 and was a National Endowment for the Humanities fellow, 1978–79. He died on December 26, 2015, at the age of 93, following severe head trauma resulting from a fall.[13] |

キャリア ミンツは、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学人類学部創設に携わる以前、1951年から1974年までイエール大学で長きにわたって教鞭をとっていた。マサ チューセッツ工科大学、高等実践学院、コレージュ・ド・フランス(パリ)など、他の大学でも客員講師を務めた。彼の研究は、いくつかの研究の対象となって おり、[6][7][8][9] 自身のアイデアやフィールドワークに関する考察も発表している。[10][11] 1992年には、シドニー・W・ミンツレクチャーが毎年開催されるようになった。 。 ミンツはアメリカ民族学会の会員であり、1968年から1969年にかけては同会の会長を務めた。また、アメリカ人類学会および英国・アイルランド王立人 類学協会のフェローでもあった。ミンツは、1950年にニューヨーク市立大学シティカレッジ(現ニューヨーク市立大学シティカレッジ)、1951年に ニューヨークのコロンビア大学、1951年から1974年にかけてはコネチカット州ニューヘイブンのイェール大学で講師を務めた。イェール大学では講師と してスタートしたが、1963年から1974年にかけては人類学の教授を務めた。また、1974年よりメリーランド州ボルチモアのジョンズ・ホプキンス大 学でも人類学の教授を務めた。ミンツは、1964年から65年にかけてマサチューセッツ工科大学の客員教授、1970年から71年にかけてはパリの高等実 践学院の研究部長を務めた。1972年にはロチェスター大学のルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン講座教授、1975年から1976年にはプリンストン大学の客員 教授、1978年から1979年にはクリスチャン・ガウス講座教授、1957年にはグッゲンハイム研究員、1958年から1959年には社会科学研究評議 会研究員を務めた。1963年にイェール大学より修士号を、1966年から67年、および1970年から71年にはフルブライト上級研究賞を、1972年 にはイェール大学よりウィリアム・クライド・デヴァインメダルを授与され、1978年から79年には全米人文科学基金フェローを務めた。2015年12月 26日、転倒による重度の頭部外傷のため、93歳で死去した。[13] |

| Additional work and awards Mintz has served as a consultant to various institutions including the Overseas Development Program, he has conducted field work in several countries, and he has been recognized with many awards including: Social Science Research Council Faculty Research Fellow, 1958–59; M.A., Yale University, 1963; Ford Foundation, 1957-62, and United States-Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico, 1964–65; directeur d'etudes, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Paris), 1970-71. He received the Franz Boas Award at the 2012 American Anthropological Association. |

追加の業務と受賞歴 ミンツは、海外開発プログラムをはじめとするさまざまな機関のコンサルタントを務め、複数の国々で現地調査を実施し、また、以下を含む数々の賞を受賞し ている。1958年から59年にかけて社会科学研究評議会研究員、1963年にイェール大学で修士号取得、1957年から62年にかけてフォード財団、 1964年から65年にかけて米国・プエルトリコ委員会、1970年から71年にかけて高等実践学院(パリ)研究部長。2012年、アメリカ人類学会でフ ランツ・ボアス賞を受賞。 |

| Training and influences In his training Mintz was particularly influenced by Steward, Ruth Benedict (Mintz 1981a), and Alexander Lesser,[14] and by his classmate and co-author, Eric Wolf (1923-1999). Combining a Marxist and historical materialist approach with U.S. cultural anthropology, Mintz’s focus has been those large processes, starting in the fifteenth century, that marked the advent of capitalism and European expansion in the Caribbean, and the myriad institutional and political forms which buttressed that growth, on the one hand; and on the other, the local cultural responses to such processes. His ethnography centered on how these responses are manifested in the lives of Caribbean people. For Mintz, history did not erode differences to create homogeneity among regions, even while a capitalist world-system was emerging. Larger forces were always confronted by local responses that affected the cultural outcomes. Considering this relationship Mintz wrote: It must be stressed that the integration of varied forms of labor-extraction within any component region addresses the way that region, as a totality, fits within the so-called world-system. There was give-and-take between the demands and initiatives originating with the metropolitan centers of the world-system, and the ensemble of labor forms typical of the local zones with which they were enmeshed....The postulation of a world-system forces us frequently to lift our eyes from the particulars of local history, which I would consider salutary. But equally salutary is the constant revisiting of events “on the ground,” so that the architecture of the world-system can be laid bare."[15] This orientation found varied expressions in Mintz’s works, from his life history of “Taso” (Anastacio Zayas Alvarado), a Puerto Rican sugar worker,[16] to debating whether the Caribbean slave could be considered a proletarian.[17] He reasoned that, because slavery in the Caribbean was implicated in capitalism, slavery there was unlike Old World slavery; but also that because slave status meant unfree labor, Caribbean slavery was not a fully capitalistic labor-form for the extraction of surplus value. There were other contradictions: Caribbean slaves were legally defined as property, but often owned property; though slaves produced wealth for their owners, they also reproduced their labor through “proto-peasant” agriculture and market activities, reducing long-term supply costs for the owners. The slave was a capital good, hence not commoditized labor; but some skilled slaves hired out to others produced income for their masters and could keep a share for themselves. In his book Caribbean Transformations[18] and elsewhere, Mintz claimed that modernity originated in the Caribbean—Europe’s first factories were embodied in a plantation complex devoted to the cultivation of sugar cane and a few other agricultural commodities. The advent of this system certainly had profound effects on Caribbean “plantation society” (Mintz 1959a), but the commercialization of sugar’s products had lasting effects in Europe as well, from providing the wherewithal for the industrial revolution to transforming whole foodways and creating a revolution in European tastes and consumer behavior.[14][19] Mintz repeatedly insisted on the Caribbean region’s particularities[20][21] to contest pop notions of “globalization” and “diaspora,” that would make of the region a mere metaphor without acknowledging its historical distinctiveness. Mintz's commitment to proper representation of Caribbean society is illustrated by Haitian-American anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot's statement that Mintz possessed a "deep knowledge of Haitian society, a knowledge only matched by his deeper respect for Haitian culture."[22] |

トレーニングと影響 ミンツは、トレーニングにおいて、スチュワート、ルース・ベネディクト(Mintz 1981a)、アレクサンダー・レッサー、そして同級生であり共著者でもあるエリック・ウォルフ(1923-1999)から特に影響を受けた。ミンツは、 マルクス主義と唯物史観のアプローチを米国文化人類学と組み合わせ、15世紀に始まる資本主義の到来とカリブ海地域におけるヨーロッパの拡大を特徴づける 大きな流れ、そしてその成長を支えた無数の制度や政治形態に焦点を当ててきた。一方で、そのようなプロセスに対する地域文化の反応にも注目した。彼の民族 誌学は、これらの反応がカリブ海の人々の生活にどのように現れるかに焦点を当てている。ミンツにとって、資本主義的世界システムが台頭しつつあった時代 においても、歴史は地域間の差異を均質化するものではなかった。常に大きな力が地域的な反応と対峙し、それが文化的な成果に影響を与えた。この関係性を踏 まえて、ミントゥは次のように書いている。 あらゆる構成地域における多様な労働形態の統合は、その地域が全体としていわゆる世界システムに適合する方法を扱っていることを強調しなければならない。 世界システムの中心都市から生じる要求やイニシアティブと、それらが複雑に絡み合う地域特有の労働形態の集合体との間で、互いに影響を与え合っていた。世 界システムの仮定は、私たちに地域史の細部に目を向けることを頻繁に強いるが、私はそれは有益だと考える。しかし、同様に有益なのは、「現場」での出来事 を常に再検証することであり、それによって世界システムの構造が明らかになるのである。 この方向性は、プエルトリコの砂糖労働者「タソ」(アナスタシオ・ザヤス・アルバラード)の生涯を描いた作品[16]から、 16] カリブ海地域の奴隷をプロレタリアートと見なすことができるかどうかを論じている。彼は、カリブ海地域の奴隷制は資本主義と関連しているため、旧世界にお ける奴隷制とは異なると論じた。しかし、奴隷の地位は不自由労働を意味するため、カリブ海地域の奴隷制は、剰余価値を抽出するための完全な資本主義的労働 形態ではないとも論じた。他にも矛盾はあった。カリブ海の奴隷は法律上は財産と定義されていたが、しばしば財産を所有していた。奴隷は所有者のために富を 生み出すが、同時に「原始的農民」としての農業や市場活動を通じて労働力を再生産し、所有者の長期的な供給コストを削減していた。奴隷は資本財であり、商 品化された労働力ではなかった。しかし、一部の熟練した奴隷は他者に貸し出され、主人に収入をもたらし、自分自身のために一部を確保することもできた。ミ ンツは著書『カリブ海地域の変容』[18] やその他の著作で、近代はカリブ海地域で始まったと主張している。ヨーロッパ初の工場は、サトウキビやその他のいくつかの農作物の栽培に専念するプラン テーション複合体として具現化された。このシステムの登場は、カリブ海地域の「プランテーション社会」に確かに大きな影響を与えたが(Mintz 1959a)、砂糖製品の商業化はヨーロッパにも長期的な影響を与え、産業革命の原動力となったほか、食生活全体を変え、 。ミントは、カリブ海地域の特殊性について繰り返し主張し[20][21]、「グローバル化」や「ディアスポラ」といった一般的な概念に異議を唱えた。こ れらの概念は、この地域の歴史的な独自性を認めず、この地域を単なる隠喩として扱うことになる。ミントがカリブ社会を正しく表現することに尽力しているこ とは、ハイチ系アメリカ人である人類学者ミシェル=ロルフ・トゥルイヨの「ミントはハイチ社会について深い知識を持っており、その知識はハイチ文化に対す る彼の深い敬意に匹敵する」という発言によって示されている。[22] |

| Research Caribbean anthropology Mintz carried out his first fieldwork in the Caribbean in 1948 as part of Julian Steward’s application of anthropological methods to the study of a complex society. This fieldwork was eventually published as The People of Puerto Rico ?[23] Since then, Mintz has authored several books and nearly 300 scientific articles on varied themes, including slavery, labor, Caribbean peasantries, and the anthropology of food in the context of globalizing capitalism. In a field where insularity is common, and anthropologists usually chose one language area and one colonial power for study, Mintz has done fieldwork in three different Caribbean societies: Puerto Rico (1948–49, 1953, 1956), Jamaica (1952, 1954), and Haiti (1958–59, 1961), as well as later working in Iran (1966–67) and Hong Kong (1996, 1999). Mintz has always taken a historical approach and used historical materials in studying Caribbean cultures.[7][9] |

研究 カリブ海地域の人類学 ミンツは、ジュリアン・スチュワートが複雑な社会の研究に人類学的手法を応用した一環として、1948年にカリブ海地域で初めてのフィールドワークを実 施した。このフィールドワークは最終的に『プエルトリコの人々』として出版された。[23] それ以来、ミントは奴隷制度、労働、カリブ海地域の農民、グローバル化する資本主義の文脈における食文化人類学など、さまざまなテーマについて、数冊の著 書と300近い学術論文を執筆している。 島国根性が一般的で、人類学者が研究対象として通常、言語圏と植民地支配国を1つずつ選ぶことが多い分野において、ミントは3つの異なるカリブ海社会で フィールドワークを行っている。プエルトリコ(1948~49年、1953年、1956年)、ジャマイカ(1952年、1954年)、ハイチ (1958~59年、1961年)の3つの異なるカリブ社会でフィールドワークを行い、その後、イラン(1966~67年)と香港(1996年、1999 年)でも研究を行った。ミンツは常に歴史的なアプローチをとり、カリブ文化の研究に歴史的な資料を使用してきた。[7][9] |

Peasantry Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History One of Mintz’s main contributions to Caribbean anthropology[24] has been his analysis of the origins and establishment of the peasantry. Mintz argued that Caribbean peasantries emerged alongside of and after industrialization, probably like nowhere else in the world.[17][25] Defining these as “reconstituted” because they began as something other than peasants, Mintz offered a tentative group typology. Such groups varied from the “squatters” who settled on the land in the early days after the Columbian conquest, through the “early yeomen,” European indentured plantation workers who finished the terms of their contracts; to the “proto-peasantry,” honing farming and marketing skills while still enslaved; and the “runaway peasantries” or maroons, who formed communities outside colonial authority, based on subsistence farming in mountainous or interior forest regions. For Mintz, these adaptations were a “mode of response” to the plantation system and a “mode of resistance” to superior power.[26] Acknowledging the difficulties in defining “peasantry,” Mintz pointed to the Caribbean experience, stressing internal peasant diversity in any given Caribbean society, as well as their relationships to landless wage-earning agricultural workers or “rural proletarians,” and how the experience of any individual might span or combine these categories.[27][28] Mintz was also interested in gender relations and the domestic economy, and especially in women’s roles in marketing.[29][30][31] |

農民 サトウキビ畑の労働者: プエルトリコのライフヒストリー ミンツがカリブ海地域の人類学に大きく貢献したことのひとつに、農民の起源と確立に関する分析がある。ミンツは、カリブ海地域の農民は工業化と並行して、 おそらく世界でも他に類を見ないほど急速に台頭したと主張した。[17][25] 農民としてではなく、他の何者かとして始まったことから、ミンツはこれを「再構成された」と定義し、暫定的なグループの類型を提示した。こうしたグループ には、コロンブスによる征服後、初期にその土地に定住した「不法占拠者」から、契約期間を終えたヨーロッパ人契約農場労働者である「初期の自営農民」、奴 隷として農耕や販売の技術を磨き、後に「原始的農民」となった人々、そして、植民地当局の支配下から離れ、山岳地帯や内陸部の森林地域で自給自足の農耕を 基盤とした共同体を形成した「逃亡農民」またはマローンなどが含まれる。ミントにとって、こうした適応は、プランテーション制度に対する「反応様式」であ り、支配者層に対する「抵抗様式」であった。[26] 「農民」を定義することの難しさを認めた上で、ミントはカリブ海地域の経験に注目し、カリブ海社会における農民の内部の多様性、および土地を持たない賃金 労働者である農業労働者、つまり「農村のプロレタリアート」との関係を強調し、個人の経験がこれらのカテゴリーにまたがったり、組み合わさったりする可能 性について論じた。また、個人の経験がこれらのカテゴリーにまたがったり、組み合わさったりすることもあると強調した。[27][28] ミントはジェンダー関係や家庭経済にも関心を示し、特にマーケティングにおける女性の役割について研究した。[29][30][31] |

| Sociocultural analysis Anxious to illustrate complexity and diversity within the Caribbean, as well as the commonalities bridging cultural, linguistic, and political frontiers, Mintz argued in The Caribbean as a Socio-Cultural Area that The very diverse origins of Caribbean populations; the complicated history of European cultural impositions; and the absence in most such societies of any firm continuity of the culture of the colonial power have resulted in a very heterogeneous cultural picture” when considering the region as a whole historically. “And yet the societies of the Caribbean — taking the word ‘society’ to refer here to forms of social structure and social organization — exhibit similarities that cannot possibly be attributed to mere coincidence” so that any “pan-Caribbean uniformities turn out to consist largely of parallels of economic and social structure and organization, the consequence of lengthy and rather rigid colonial rule,” such that many Caribbean societies “also share similar or historically related cultures.[32] Mintz took a dialectical approach that highlighted contradictory forces. Thuss, Caribbean slaves were individualized through the process of slavery and the relationship with modernity, “but not dehumanized by it.” Once free, they exhibited “quite sophisticated ideas of collective activity or cooperative unity. The push in Guyana to purchase plantations collectively; the use of cooperative work groups for house building, harvesting, and planting; the growth of credit institutions; and the links between kinship and coordinated work all suggest the powerful individualism that slavery helped to create did not wholly obviate group activity.”[33] |

社会文化分析 カリブ海地域の複雑性と多様性を明らかにすること、また ミンツは著書『社会文化圏としてのカリブ海』で、カリブ海地域の複雑性と多様性、そして文化、言語、政治の境界を越えた共通点を説明しようと試みた。 カリブ海地域の人口の起源はきわめて多様であり、ヨーロッパ文化の押し付けという複雑な歴史があり、ほとんどの社会では植民地支配国の文化がしっかりと継 続していない。こうしたことが、歴史的に地域全体を考える場合、きわめて異質な文化の様相を生み出している。「しかし、カリブ海地域の社会(ここでいう 『社会』とは社会構造や社会組織の形態を指す)には、単なる偶然の一致ではありえない類似性が見られる」ため、いかなる「汎カリブ海的な均一性も、 経済的・社会的構造と組織の類似性、つまり長きにわたるかなり硬直的な植民地支配の結果が大部分を占めている」ことが明らかになり、多くのカリブ社会が 「同様の、あるいは歴史的に関連する文化を共有している」のである。 ミントは弁証法的なアプローチを採用し、矛盾する力を強調した。 つまり、カリブ海地域の奴隷たちは奴隷制と近代化の過程を通じて個人化されたが、「それによって人間性を奪われたわけではない」のである。 一度自由になると、彼らは「集団活動や協調的な団結に関する非常に洗練された考え」を示した。ガイアナでは、農園を共同で購入しようという動きがあった。 また、家屋の建築、収穫、植え付けには協同作業グループが用いられ、信用機関が発展し、親族関係と協調的な労働の結びつきが強かったことは、奴隷制が作り 出した強力な個人主義が集団活動を完全に排除しなかったことを示唆している。 [33] |

|

Slavery Mintz has compared slavery and forced labor across islands, time and colonial structures, as in Jamaica and Puerto Rico (Mintz 1959b); and addressed the question of differing colonial systems engendering differing degrees of cruelty, exploitation, and racism. The view of some historians and political leaders in the Caribbean and Latin America was that the Iberian colonies, with their tradition of Catholicism and sense of aesthetics, meant a more humane slavery; while north European colonies, with their individualizing Protestant religions, found it easier to exploit the slaves and to draw hard and fast social categories. But Mintz argued that the treatment of slaves had to do instead with the integration of the colony into the world economic system, the degree of control of the metropolis over the colony, and the intensity of exploitation of labor and land.'[34] In collaboration with anthropologist Richard Price, Mintz considered the question of creolization (a sort of blending of multiple cultural traditions to create a new one) in African American culture in the book The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Approach (Mintz and Price 1992, first published in 1976 and first delivered as a conference paper in 1973). There, the authors qualify anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits's view that Afro-American culture was mainly African cultural survivals. But they also oppose those who claimed African culture was stripped from the slaves through enslavement, such that nothing "African" remains in Afro-American cultures today. Combining Herskovits's cultural anthropological approach and the structuralism of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, Mintz and Price argued that Afro-Americana is characterized by deep-level "grammatical principles" of various African cultures, and that these principles extend to motor behaviors, kinship practices, gender relations, and religious cosmologies. This has been an influential model in the ongoing anthropology of the African diaspora.[24] |

奴隷制 Mintzは、ジャマイカやプエルトリコのように、島や時代、植民地構造の違いを超えて奴隷制と強制労働を比較し(Mintz 1959b)、異なる植民地制度が異なる程度の残酷さ、搾取、人種差別を生み出すという問題を取り上げた。カリブ海地域とラテンアメリカにおける一部の歴 史家や政治指導者の見解では、カトリックの伝統と美的感覚を持つイベリア半島の植民地では、より人道的な奴隷制度が敷かれていた。一方、個人主義的なプロ テスタントの宗教を持つ北ヨーロッパの植民地では、奴隷を搾取し、厳格な社会カテゴリーを画定することがより容易であった。しかし、ミントは、奴隷の扱い はむしろ、植民地が世界経済システムに統合されているか、植民地に対する宗主国の支配の度合い、労働力と土地の搾取の度合いに関係していると主張した。 [34] 人類学者のリチャード・プライスと共同で、ミントは『アフリカ系アメリカ文化の誕生: (Mintz and Price 1992、初版は1976年、1973年に学会論文として初発表)。 著者は、アフリカ系アメリカ文化は主にアフリカ文化の遺物であるという人類学者メルヴィル・J・ハーシュコビッツの見解を支持している。 しかし、奴隷制によってアフリカ文化が奴隷から奪われ、今日のアフリカ系アメリカ文化には「アフリカ的」なものは何も残っていないと主張する人々にも反対 している。ミンツとプライスは、ハーコビッツの文化人類学的アプローチと人類学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの構造主義を組み合わせ、アフロ・アメリカ ニカはさまざまなアフリカ文化の深いレベルの「文法原則」によって特徴づけられるとし、これらの原則は運動行動、親族慣習、ジェンダー関係、宗教的宇宙論 にまで及ぶと論じた。これは、現在も進行中のアフリカ系ディアスポラの人類学において影響力のあるモデルとなっている。[24] |

|

Recent work More recent work by Mintz has focused on the history and meaning of food (e.g., Mintz 1985b, 1996a; Mintz and Du Bois 2002), including ongoing work on the consumption of soy foods.[35] |

最近の研究 ミンツの最近の研究は、食品の歴史と意味に焦点を当てている(例えば、Mintz 1985b, 1996a; Mintz and Du Bois 2002)が、これには大豆食品の消費に関する継続中の研究も含まれている。[35] |

| References General Baca, George. 2016 "Sidney W. Mintz: from the Mundial Upheaval Society to a dialectical anthropology," Dialectical Anthropology, 40: 1–11. Brandel, Andrew and Sidney W. Mintz. 2013. "Preface: Levi-Strauss and the True Sciences." Special Issue of "Hau: A Journal of Ethnographic Theory" 3(1). Duncan, Ronald J., ed. 1978 "Antropología Social en Puerto Rico/Social Anthropology in Puerto Rico." Special Section of Revista/Review Interamericana 8(1). Ghani, Ashraf, 1998 "Routes to the Caribbean: An Interview with Sidney W. Mintz". Plantation Society in the Americas 5(1):103-134. Lauria-Perriceli, Antonio, 1989 A Study in Historical and Critical Anthropology: The Making of The People of Puerto Rico. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, New School for Social Research. Mintz, Sidney W. 1959a "The Plantation as a Socio-Cultural Type". In Plantation Systems of the New World. Vera Rubin, ed. Pp. 42–53. Washington, DC: Pan-American Union. Mintz, Sydney W. 1959b "Labor and Sugar in Puerto Rico and in Jamaica, 1800–1850". In Comparative Studies in Society and History 1(3): 273–281. Mintz, Sidney W. 1960 Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History. New Haven: Yale University Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1966 "The Caribbean as a Socio-Cultural Area". In Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale 9: 912–937. Mintz, Sidney W. 1971 "Men, Women and Trade". In Comparative Studies in Society and History 13(3): 247–269. Mintz, Sidney W. 1973 "A Note on the Definition of Peasantries". In Journal of Peasant Studies 1(1): 91–106. Mintz, Sidney W. 1974a Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine. Mintz, Sidney W. 1974b "The Rural Proletariat and the Problem of Rural Proletarian Consciousness". In Journal of Peasant Studies 1(3): 291–325. Mintz, Sidney W. 1977 "The So-Called World-System: Local Initiative and Local Response". In Dialectical Anthropology 2(2): 253–270. Mintz, Sidney W. 1978 "Was the Plantation Slave a Proletarian?" In Review 2(1):81-98. Mintz, Sidney W. 1981a "Ruth Benedict". In Totems and Teachers: Perspectives on the History of Anthropology. Sydel Silverman, ed. Pp. 141–168. New York: Columbia University Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1981b "Economic Role and Cultural Tradition". In The Black Woman Cross-Culturally. Filomina Chioma Steady, ed. Pp. 513–534. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman. Mintz, Sidney W. ed., 1985a History, Evolution, and the Concept of Culture: Selected Papers by Alexander Lesser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mintz, Sidney Wilfred (1985b). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-68702-2. Mintz, Sidney W. 1985c "From Plantations to Peasantries in the Caribbean". In Caribbean Contours. Sidney W. Mintz and Sally Price, eds. Pp. 127–153. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1989 "The Sensation of Moving While Standing Still". In American Ethnologist 17(4):786-796. Mintz, Sidney W. 1992 "Panglosses and Pollyannas; or Whose Reality Are We Talking About?" In The Meaning of Freedom: Economics, Politics, and Culture after Slavery. Frank McGlynn and Seymour Drescher, eds. Pp. 245–256. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1996a Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past. Boston: Beacon Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1996b "Enduring Substances, Trying Theories: The Caribbean Region as OikoumenL". In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 2(2): 289–311. Mintz, Sidney W. 1998 "The Localization of Anthropological Practice: From Area Studies to Transnationalism". In Critique of Anthropology 18(2): 117–133. Mintz, Sidney W. 2002 "People of Puerto Rico Half a Century Later: One Author’s Recollections". In Journal of Latin American Anthropology 6(2): 74–83. Mintz, Sidney W. and Christine M. Du Bois, 2002, "The Anthropology of Food and Eating". In Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 99–119. Mintz, Sidney W. and Chee Beng Tan 2001 "Bean-Curd Consumption in Hong Kong". Ethnology 40(2): 113–128. Mintz, Sidney W. and Richard Price 1992 The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Approach. Boston: Beacon Press. Scott, David 2004 "Modernity that Predated the Modern: Sidney Mintz’s Caribbean". In History Workshop Journal 58: 191–210. Steward, Julian H. Steward, Robert A. Manners, Eric R. Wolf, Elena Padilla Seda, Sidney W. Mintz, and Raymond L. Scheele 1956 The People of Puerto Rico: A Study in Social Anthropology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Yelvington, Kevin A. 1996 "Caribbean". In Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology. Alan Barnard and Jonathan Spencer, eds. Pp. 86–90. London: Routledge. Yelvington, Kevin A. 2001 "The Anthropology of Afro-Latin America and the Caribbean: Diasporic Dimensions". Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 227–260. |

参考文献 一般 Baca, George. 2016 「シドニー・W・ミンツ:世界動乱学会から弁証法的人類学へ」『弁証法的人類学』40: 1–11. Brandel, Andrew and Sidney W. Mintz. 2013. 「序文:レヴィ=ストロースと真の科学」『Hau: A Journal of Ethnographic Theory』3(1). ダンカン、ロナルド・J. 編、1978年「プエルトリコにおける社会人類学」『レヴィスタ:民族誌理論ジャーナル』特別号、3(1)。 ガニ、アシュラフ、1998年「カリブ海への航路:シドニー・W・ミンツとのインタビュー」『アメリカ大陸におけるプランテーション社会』5(1): 103-134。 Lauria-Perriceli, Antonio, 1989 A Study in Historical and Critical Anthropology: The Making of The People of Puerto Rico. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, New School for Social Research. Mintz, Sidney W. 1959a 「The Plantation as a Socio-Cultural Type」. In Plantation Systems of the New World. Vera Rubin, ed. Pp. 42–53ページ。ワシントンDC:パンアメリカン連合。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1959b 「プエルトリコとジャマイカにおける労働と砂糖、1800年~1850年」『社会と歴史の比較研究』1(3): 273–281。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1960 『サトウキビ畑の労働者:プエルトリコ人のライフヒストリー』 ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版 Mintz, Sidney W. 1966 「社会文化圏としてのカリブ海地域」。『世界史研究』第9号:912-937ページ Mintz, Sidney W. 1971 「男性、女性、そして貿易」。『社会と歴史の比較研究』第13号3:247-269ページ Mintz, Sidney W. 1973 「農民階級の定義に関する覚書」『農民研究ジャーナル』1(1): 91–106. Mintz, Sidney W. 1974a 『カリブ海地域の変容』シカゴ: Aldine. Mintz, Sidney W. 1974b 「農村プロレタリアートと農村プロレタリアートの意識の問題」『 『農民研究ジャーナル』1(3): 291–325. Mintz, Sidney W. 1977 「いわゆる世界システム:地域イニシアティブと地域対応」『弁証法的人類学』2(2): 253–270. Mintz, Sidney W. 1978 「プランテーションの奴隷はプロレタリアートだったのか?」『レビュー』2(1):81-98. Mintz, Sidney W. 1981a 「ルース・ベネディクト」 In Totems and Teachers: Perspectives on the History of Anthropology. Sydel Silverman, ed. Pp. 141–168. New York: Columbia University Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1981b 「経済的役割と文化的伝統」 In The Black Woman Cross-Culturally. Filomina Chioma Steady, ed. Pp. 513–534. ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:シェンクマン。 Mintz, Sidney W. 編、1985a 『歴史、進化、文化の概念:アレクサンダー・レッサーの論文集』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 Mintz, Sidney Wilfred (1985b). 『甘さと力:近代史における砂糖の役割』ニューヨーク:ヴァイキング。ISBN 0-670-68702-2。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1985c 「カリブ海地域におけるプランテーションから農場へ」。『カリブ海地域の輪郭』。Sidney W. Mintz and Sally Price, eds. Pp. 127–153. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Mintz, Sidney W. 1989 「立ち止まりながら動く感覚」。『アメリカ民族誌』17(4):786-796。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1992 「パンクロッサスとポリアンナ、あるいは我々が語っているのは誰の現実なのか?」『自由の意味:奴隷制後の経済、政治、文化』Frank McGlynn and Seymour Drescher 編、245-256ページ。ピッツバーグ:ピッツバーグ大学出版。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1996a 『食べ物を味わう、自由を味わう: 食文化、文化、そして過去への小旅行』。ボストン:ビーコン・プレス。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1996b 「不変の物質、試行錯誤の理論:カリブ海地域をオイコウメーとして」『王立人類学協会紀要(新シリーズ)』2(2): 289–311。 Mintz, Sidney W. 1998 「人類学の実践の地域化:地域研究からトランスナショナリズムへ」『人類学評論』18(2): 117–133. Mintz, Sidney W. 2002 「半世紀後のプエルトリコの人々:ある著者の回想」『ラテンアメリカ人類学ジャーナル』6(2): 74–83. Mintz, Sidney W. and Christine M. Du Bois, 2002, 「The Anthropology of Food and Eating」. In Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 99–119. Mintz, Sidney W. and Chee Beng Tan 2001 「Bean-Curd Consumption in Hong Kong」. Ethnology 40(2): 113–128. Mintz, Sidney W. and Richard Price 1992 The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Approach. Boston: Beacon Press. Scott, David 2004 「Modernity that Predated the Modern: Sidney Mintz's Caribbean」. 『History Workshop Journal』58: 191–210. スチュワート、ジュリアン・H. スチュワート、ロバート・A. マナーズ、エリック・R. ウォルフ、エレナ・パディージャ・セダ、シドニー・W. ミントツ、レイモンド・L. シェール 1956 『プエルトリコの人々:社会人類学的研究』。 アーバナ:イリノイ大学出版。 Yelvington, Kevin A. 1996 「カリブ海地域」『社会文化人類学事典』Alan Barnard and Jonathan Spencer編、86-90ページ。ロンドン:Routledge。 Yelvington, Kevin A. 2001 「アフリカ系ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域の文化人類学:ディアスポラの視点」『人類学年鑑』30:227-260。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Mintz |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆