Stress and Strress Theory

ストレスとストレス理論

Stress and Strress Theory

★ストレス(Stress) は、生理的、生物学的、心理的のいずれであっても、環境条件や生活環境の変化などのストレス要因に対する生物の反応である。[1][2] ストレス要因によって生物の環境が変化すると、体内の複数のシステムが反応する。[1] 人間とほとんどの哺乳類では、自律神経系と視床下部-下垂体-副腎(HPA)軸が、ストレスに反応する主要な2つのシステムである[3][4]。 ストレス状況下で人間が産生するよく知られたホルモンには、アドレナリンとコルチゾールがある。[3][4] 交感神経系と副腎髄質軸(SAM)は、交感神経系を通じて闘争・逃走反応を活性化し、ストレスへの急性適応のためにより関連性の高い身体システムにエネル ギーを集中させる一方、副交感神経系は身体を恒常性に戻す。[3][4] 第二の主要な生理的ストレス応答中枢であるHPA軸は、代謝、心理、免疫機能など多くの身体機能に影響を与えるコルチゾールの分泌を調節する。[4] SAM軸とHPA軸は、辺縁系、前頭前野、扁桃体、視床下部、終板など複数の脳領域によって調節されている。[3] これらのメカニズムを通じて、ストレスは記憶機能、報酬、免疫機能、代謝、および病気への感受性を変化させる可能性がある。[3][4] 病気のリスクは、精神疾患に特に関連しており、慢性または重度のストレスは、いくつかの精神疾患の一般的な危険因子となっている。[1][5]

| Stress, whether

physiological, biological or psychological, is an organism's response

to a stressor, such as an environmental condition or change in life

circumstances.[1][2] When stressed by stimuli that alter an organism's

environment, multiple systems respond across the body.[1] In humans and

most mammals, the autonomic nervous system and

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are the two major systems

that respond to stress.[3][4] Two well-known hormones that humans

produce during stressful situations are adrenaline and cortisol.[3][4] The sympathoadrenal medullary axis (SAM) may activate the fight-or-flight response through the sympathetic nervous system, which dedicates energy to more relevant bodily systems to acute adaptation to stress, while the parasympathetic nervous system returns the body to homeostasis.[3][4] The second major physiological stress-response center, the HPA axis, regulates the release of cortisol, which influences many bodily functions, such as metabolic, psychological and immunological functions.[4] The SAM and HPA axes are regulated by several brain regions, including the limbic system, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus, and stria terminalis.[3] Through these mechanisms, stress can alter memory functions, reward, immune function, metabolism, and susceptibility to diseases.[3][4] Disease risk is particularly pertinent to mental illnesses, whereby chronic or severe stress remains a common risk factor for several mental illnesses.[1][5] |

ストレスは、生理的、生物学的、心理的のいずれであっても、環境条件や

生活環境の変化などのストレス要因に対する生物の反応である。[1][2]

ストレス要因によって生物の環境が変化すると、体内の複数のシステムが反応する。[1]

人間とほとんどの哺乳類では、自律神経系と視床下部-下垂体-副腎(HPA)軸が、ストレスに反応する主要な2つのシステムである[3][4]。

ストレス状況下で人間が産生するよく知られたホルモンには、アドレナリンとコルチゾールがある。[3][4] 交感神経系と副腎髄質軸(SAM)は、交感神経系を通じて闘争・逃走反応を活性化し、ストレスへの急性適応のためにより関連性の高い身体システムにエネル ギーを集中させる一方、副交感神経系は身体を恒常性に戻す。[3][4] 第二の主要な生理的ストレス応答中枢であるHPA軸は、代謝、心理、免疫機能など多くの身体機能に影響を与えるコルチゾールの分泌を調節する。[4] SAM軸とHPA軸は、辺縁系、前頭前野、扁桃体、視床下部、終板など複数の脳領域によって調節されている。[3] これらのメカニズムを通じて、ストレスは記憶機能、報酬、免疫機能、代謝、および病気への感受性を変化させる可能性がある。[3][4] 病気のリスクは、精神疾患に特に関連しており、慢性または重度のストレスは、いくつかの精神疾患の一般的な危険因子となっている。[1][5] |

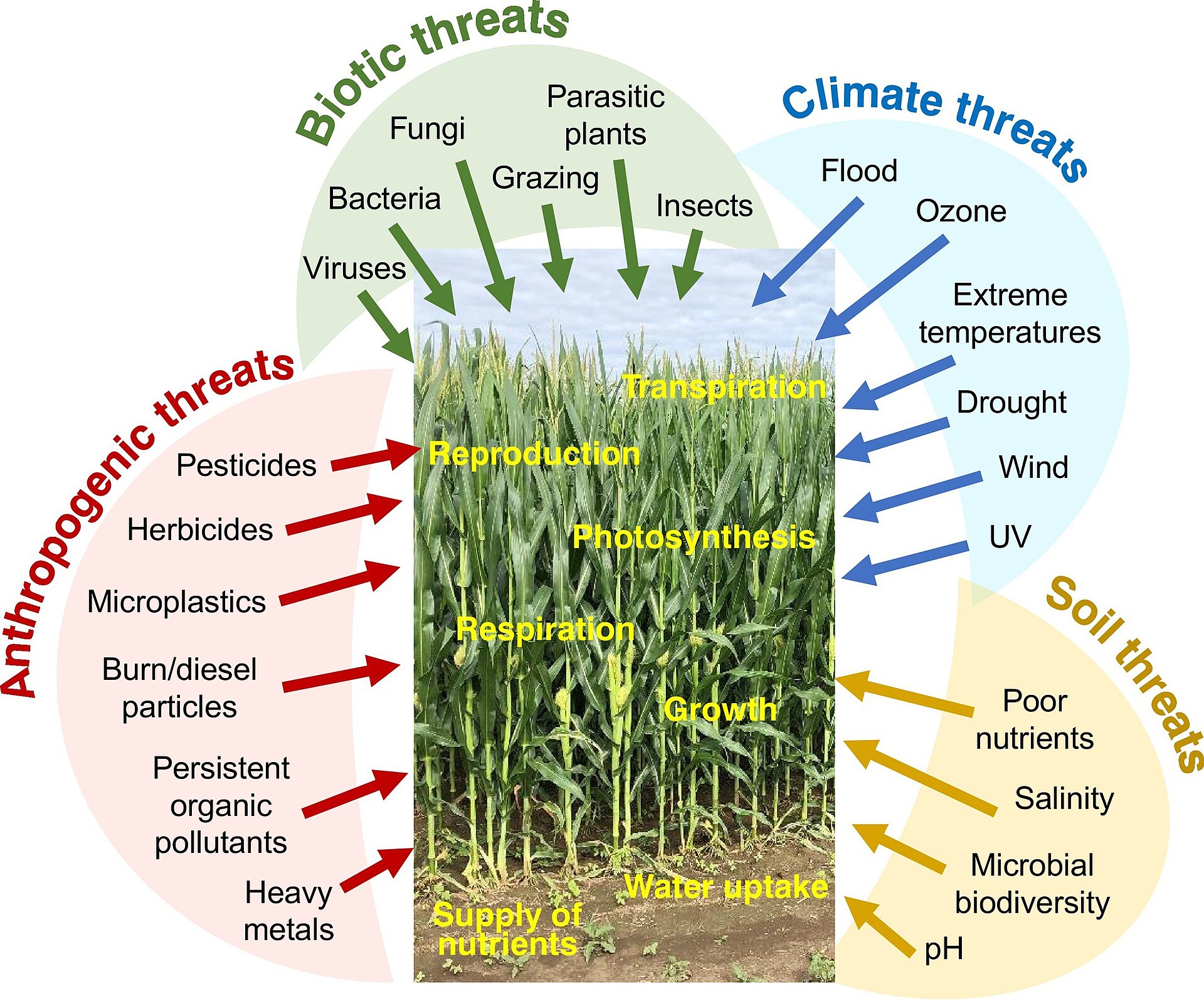

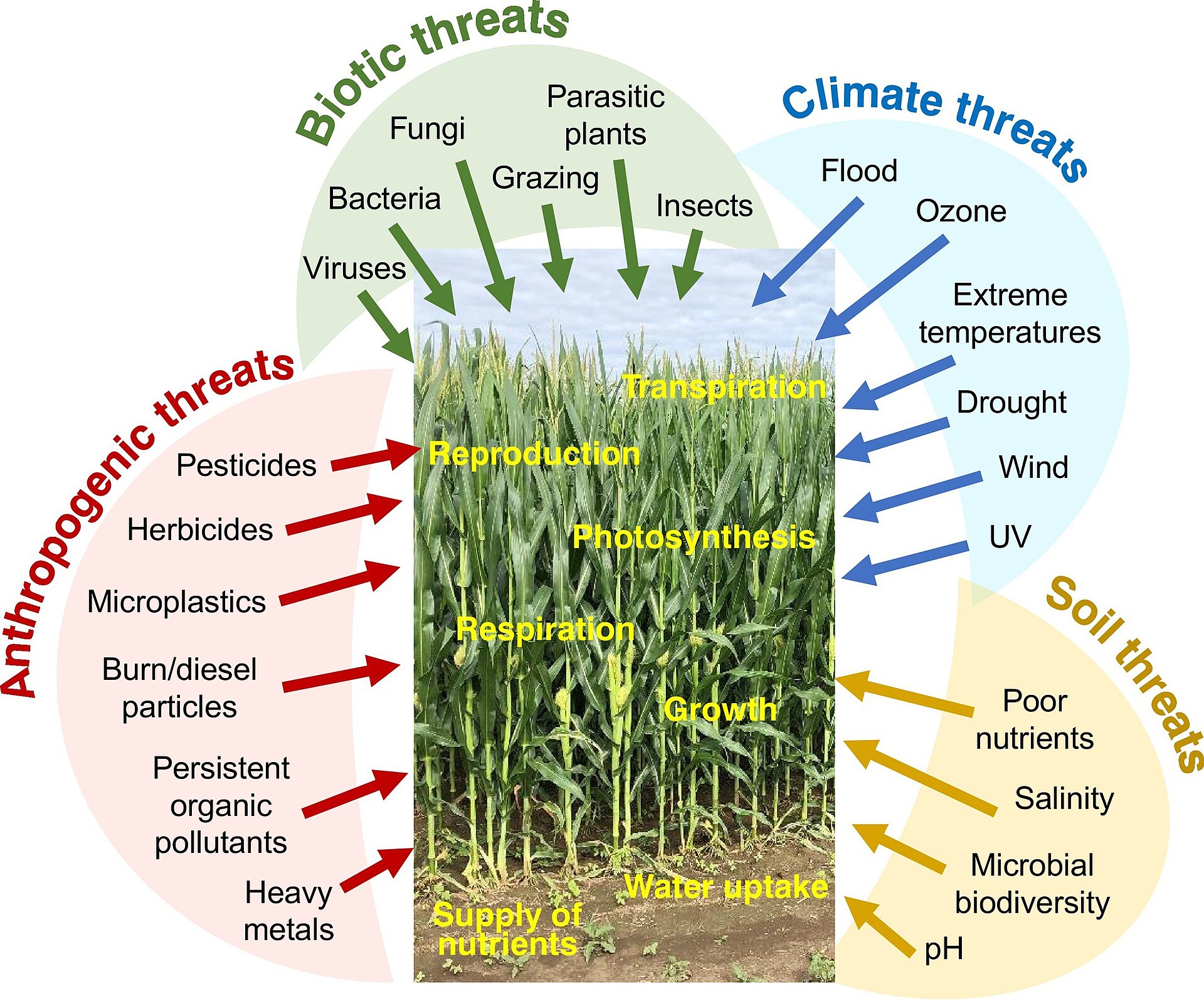

Schematic overview of the classes of stresses in plants |

植物におけるストレスの分類の概略図 |

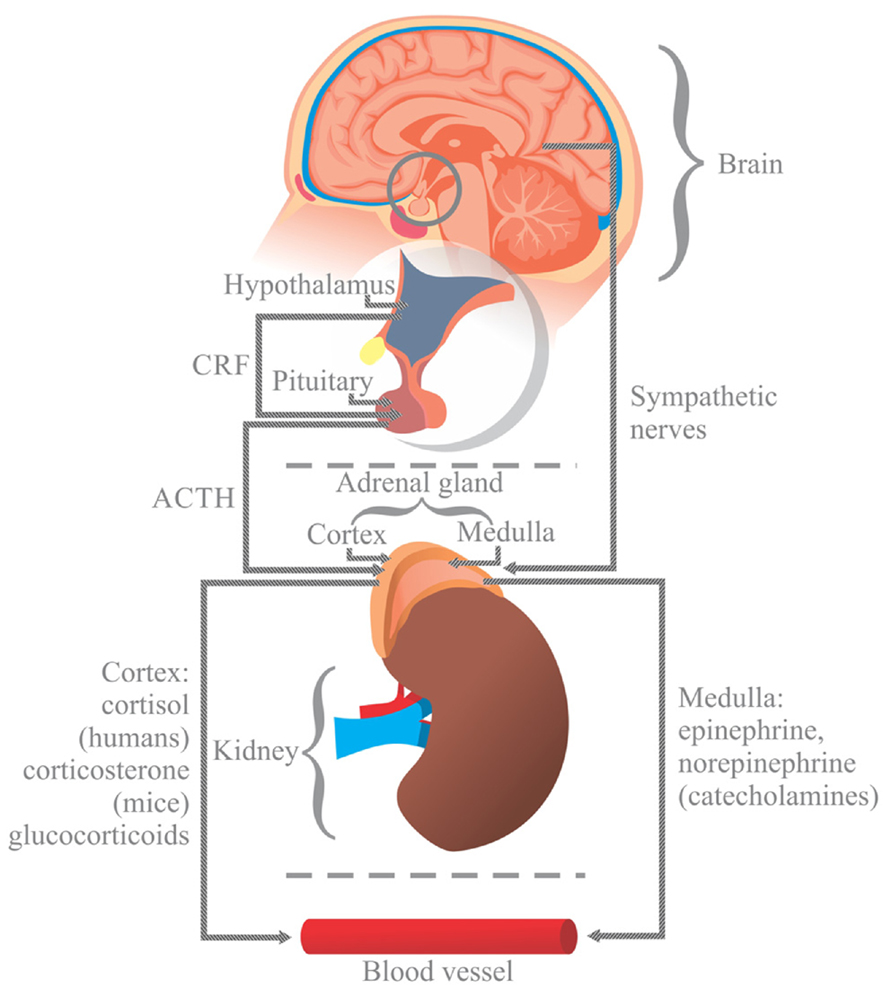

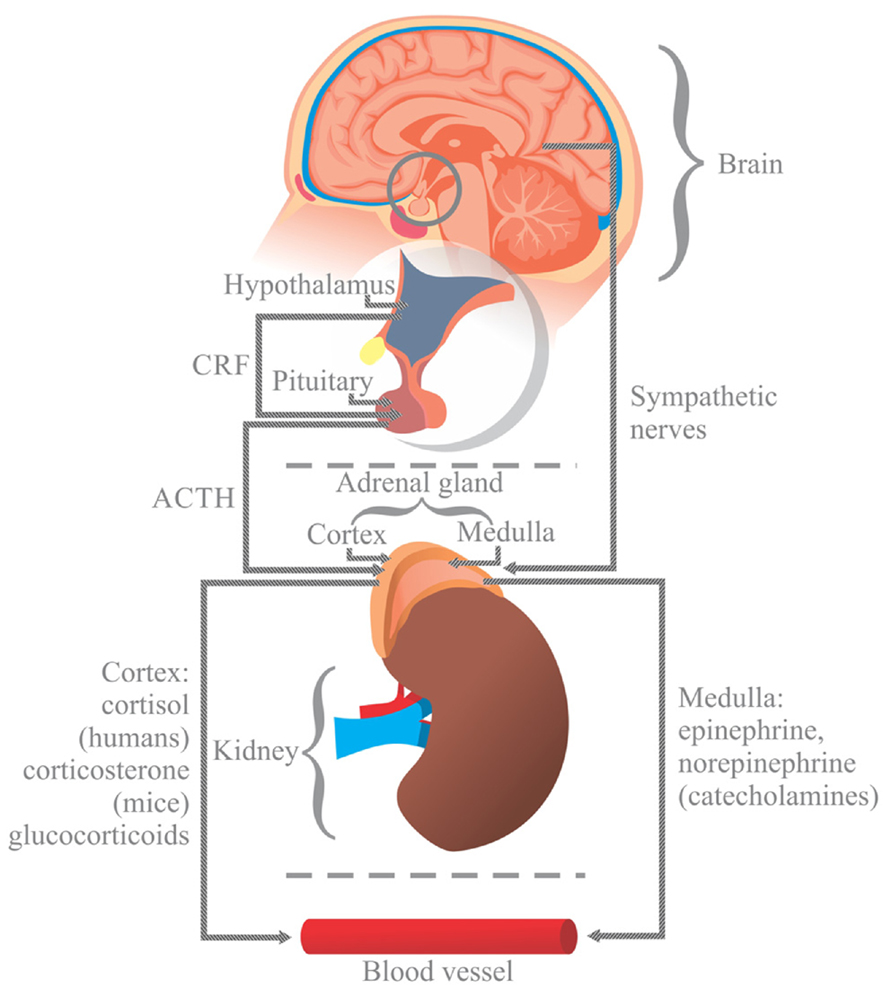

Neurohormonal response to stress |

ストレスに対する神経ホルモン反応 |

| Psychology Main article: Psychological stress Acute stressful situations where the stress experienced is severe is a cause of change psychologically to the detriment of the well-being of the individual, such that symptomatic derealization and depersonalization, and anxiety and hyperarousal, are experienced.[6] The International Classification of Diseases includes a group of mental and behavioral disorders which have their aetiology in reaction to severe stress and the consequent adaptive response.[7][8] Chronic stress, and a lack of coping resources available, or used by an individual, can often lead to the development of psychological issues such as delusions,[9] depression and anxiety.[4] Chronic stressors may not be as intense as acute stressors such as natural disaster or a major accident, but persist over longer periods of time and tend to have a more negative effect on health because they are sustained and thus require the body's physiological response to occur daily.[4] This depletes the body's energy more quickly and usually occurs over long periods of time, especially when these microstressors cannot be avoided.[4] When humans are under chronic stress, permanent changes in their physiological, emotional, and behavioral responses may occur.[10] Chronic stress can include events such as caring for a spouse with dementia, or may result from brief focal events that have long term effects, such as experiencing a sexual assault. Studies have also shown that psychological stress may directly contribute to the disproportionately high rates of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality and its etiologic risk factors. Specifically, acute and chronic stress have been shown to raise serum lipids and are associated with clinical coronary events.[11] However, it is possible for individuals to exhibit hardiness—a term referring to the ability to be both chronically stressed and healthy.[12] Even though psychological stress is often connected with illness or disease, most healthy individuals can still remain disease-free after being confronted with chronic stressful events. This suggests that there are individual differences in vulnerability to the potential pathogenic effects of stress; individual differences in vulnerability arise due to both genetic and psychological factors. In addition, the age at which the stress is experienced can dictate its effect on health. Research suggests chronic stress at a young age can have lifelong effects on the biological, psychological, and behavioral responses to stress later in life.[13] |

心理学 主な記事:心理的ストレス 経験するストレスが深刻な急性ストレス状況は、個人の幸福を損なう心理的変化の原因となり、症状としての現実感の喪失や自己の喪失、不安や過覚醒などが経 験される。[6] 国際疾病分類(ICD)には、重度のストレスへの反応とその後の適応反応を原因とする精神および行動障害のグループが含まれている。[7][8] 慢性的なストレスや、個人が利用可能な対処資源の不足、またはその利用不足は、妄想[9]、うつ病、不安障害などの心理的課題の発症につながる可能性があ る。[4] 慢性ストレス要因は、自然災害や重大な事故などの急性ストレス要因ほど強烈ではないかもしれませんが、長期間にわたって持続し、身体への悪影響が大きい傾 向があります。これは、これらの要因が持続的であり、毎日身体の生理的反応を必要とするためです。[4] これにより、身体のエネルギーがより早く消耗し、特にこれらの微小ストレス要因を避けられない場合、通常、長期間にわたって発生します。[4] 人間が慢性的なストレスにさらされると、生理的、感情的、行動的反応に永続的な変化が生じる場合があります。[10] 慢性的なストレスには、認知症の配偶者の介護などの出来事や、性的暴行などの短期間で集中的な出来事によって生じる、長期的な影響のあるストレスがありま す。また、心理的ストレスは、冠状動脈性心臓病の罹患率および死亡率の過度に高い割合、およびその病因的危険因子に直接寄与している可能性があることも研 究で明らかになっています。具体的には、急性および慢性ストレスは血清脂質値を上昇させ、臨床的な冠動脈イベントと関連があることが示されている [11]。 しかし、個人によって、慢性的なストレスにさらされても健康を維持できる「ハーディネス(頑健性)」という能力がある場合もある[12]。心理的ストレス は病気や疾患と関連することが多いが、ほとんどの健康な人は、慢性的なストレスの多い出来事に直面しても、病気にはならない。これは、ストレスの潜在的な 病原性に対する脆弱性には個人差があり、その脆弱性の個人差には遺伝的要因と心理的要因の両方が関わっていることを示唆している。さらに、ストレスを経験 した年齢も、健康への影響を左右する要因となる。研究によると、若い頃に受けた慢性的なストレスは、後年のストレスに対する生物学的、心理的、行動的反応 に生涯にわたる影響を与える可能性があることが示唆されている[13]。 |

| Etymology and historical usage The term "stress" had none of its contemporary connotations before the 1920s. It is a form of the Middle English destresse, derived via Old French from the Latin stringere, "to draw tight".[14] The word had long been in use in physics to refer to the internal distribution of a force exerted on a material body, resulting in strain. In the 1920s and '30s, biological and psychological circles occasionally used "stress" to refer to a physiological or environmental perturbation that could cause physiological and mental "strain". The amount of strain in reaction to stress depends on the resilience. Excessive strain would appear as illness.[15][16] Walter Cannon used it in 1926 to refer to external factors that disrupted what he called homeostasis.[17] But "...stress as an explanation of lived experience is absent from both lay and expert life narratives before the 1930s".[18] Physiological stress represents a wide range of physical responses that occur as a direct effect of a stressor causing an upset in the homeostasis of the body. Upon immediate disruption of either psychological or physical equilibrium the body responds by stimulating the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. The reaction of these systems causes a number of physical changes that have both short- and long-term effects on the body.[19] The Holmes and Rahe stress scale was developed as a method of assessing the risk of disease from life changes.[20] The scale lists both positive and negative changes that elicit stress. These include things such as a major holiday or marriage, or death of a spouse and firing from a job.[citation needed] |

語源と歴史的用法 「ストレス」という用語は、1920年代以前は現代的な意味合いをまったく持っていなかった。これは中英語 destresse の形であり、古フランス語を経て、ラテン語の stringere(「強く引っ張る」)から派生した。[14] この単語は、物質体に作用する力の内部分布を指す物理学用語として、長い間使用されてきた。1920年代から1930年代にかけて、生物学や心理学の分野 で「ストレス」が、生理的または環境的な擾乱を指す言葉として時々使われるようになった。ストレスに対する反応としてのひずみの量は、その対象の回復力に 依存する。過剰なひずみは病気として現れる。[15][16] ウォルター・キャノンは1926年に、彼が「ホメオスタシス」と呼ぶ状態を乱す外部要因を指す言葉としてこの用語を使用した。[17] しかし、「ストレスを経験の説明として用いることは、1930年代以前には一般人の生活叙述にも専門家の叙述にも存在しなかった」。[18] 生理的ストレスは、ストレス因子が身体のホメオスタシスを乱すことで直接的に引き起こされる、多様な物理的反応を指す。心理的または物理的な均衡が突然乱 れると、体は神経系、内分泌系、免疫系を刺激して反応する。これらの系の反応は、体に短期的な影響と長期的な影響の両を与える数多くの物理的変化を引き起 こす。[19] ホルムズとレイのストレス尺度(Holmes and Rahe stress scale)は、人生の変化による病気のリスクを評価する方法として開発された。[20] この尺度には、ストレスを引き起こすポジティブな変化とネガティブな変化がリストされている。これには、主要な休暇や結婚、配偶者の死亡、解雇などが含ま れる。[出典が必要] |

| Biological need for equilibrium Homeostasis is a concept central to the idea of stress.[21] In biology, most biochemical processes strive to maintain equilibrium (homeostasis), a steady state that exists more as an ideal and less as an achievable condition. Environmental factors, internal or external stimuli, continually disrupt homeostasis; an organism's present condition is a state of constant flux moving about a homeostatic point that is that organism's optimal condition for living.[22] Factors causing an organism's condition to diverge too far from homeostasis can be experienced as stress. A life-threatening situation such as a major physical trauma or prolonged starvation can greatly disrupt homeostasis. On the other hand, an organism's attempt at restoring conditions back to or near homeostasis, often consuming energy and natural resources, can also be interpreted as stress.[23] The ambiguity in defining this phenomenon was first recognized by Hans Selye (1907–1982) in 1926. In 1951 a commentator loosely summarized Selye's view of stress as something that "...in addition to being itself, was also the cause of itself, and the result of itself".[24][25] First to use the term in a biological context, Selye continued to define stress as "the non-specific response of the body to any demand placed upon it". Neuroscientists such as Bruce McEwen and Jaap Koolhaas believe that stress, based on years of empirical research, "should be restricted to conditions where an environmental demand exceeds the natural regulatory capacity of an organism".[26] Indeed, in 1995 Toates already defined stress as a "chronic state that arises only when defense mechanisms are either being chronically stretched or are actually failing,"[27] while according to Ursin (1988) stress results from an inconsistency between expected events ("set value") and perceived events ("actual value") that cannot be resolved satisfactorily,[28] which also puts stress into the broader context of cognitive-consistency theory.[29] |

生物の平衡の必要性 ホメオスタシス(恒常性)は、ストレスの概念の中心となる概念だ。[21] 生物学では、ほとんどの生化学的プロセスは、理想として存在し、達成可能な状態としてはあまり見られない、平衡(ホメオスタシス)を維持しようと努めてい る。環境要因や内部・外部からの刺激は、常にホメオスタシスを乱す。生物の現在の状態は、その生物の生存に最適な状態であるホメオスタシス点を中心に、常 に変動している状態だ。[22] 生物の状態がホメオスタシスから過度に逸脱する要因は、ストレスとして体験される。重大な物理的外傷や長期の飢餓のような生命を脅かす状況は、ホメオスタ シスを大きく乱す。一方、生物がホメオスタシスに戻すか、それに近い状態に戻そうとする試み(エネルギーや自然資源を消費することが多い)も、ストレスと 解釈されることがある。[23] この現象の定義の曖昧さは、1926年にハンス・セリエ(1907–1982)によって初めて認識された。1951年、ある評論家は、セリエのストレス観を「それ自体であるだけでなく、それ自体の原因であり、結果でもあるもの」と大まかに要約した。[24][25] 生物学的文脈でこの用語を初めて使用したセリエは、ストレスを「身体に課せられたあらゆる要求に対する非特異的な反応」と定義し続けた。ブルース・マク イーウェンやヤープ・クールハースのような神経科学者は、長年の実証的研究に基づき、ストレスは「環境からの要求が生物の自然な調節能力を超える条件に限 定されるべきだ」と主張している。[26] 実際、1995年にトーツはストレスを「防御メカニズムが慢性的に過度に伸張されているか、実際に機能不全に陥っている場合にのみ生じる慢性状態」と定義 した。[27] 一方、ウルシン(1988)によると、ストレスは、期待される出来事(「設定値」)と認識される出来事(「実際の値」)の矛盾が満足に解決できないことか ら生じる[28]とされ、これはストレスを認知的一致理論のより広い文脈に位置づけている[29]。 |

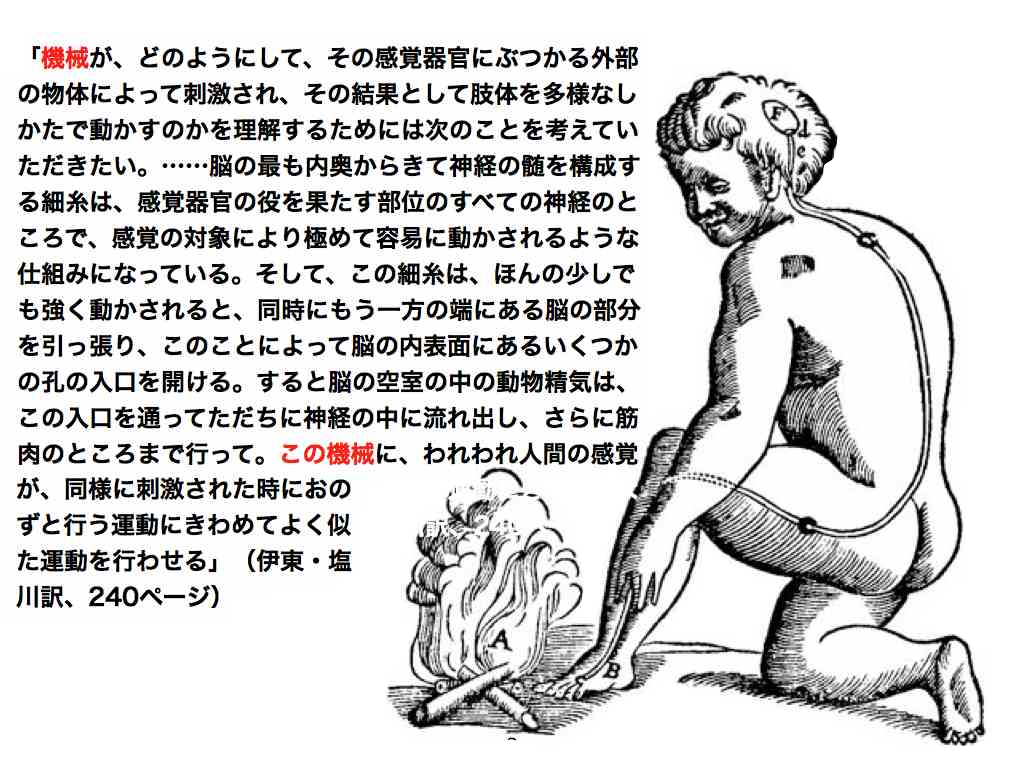

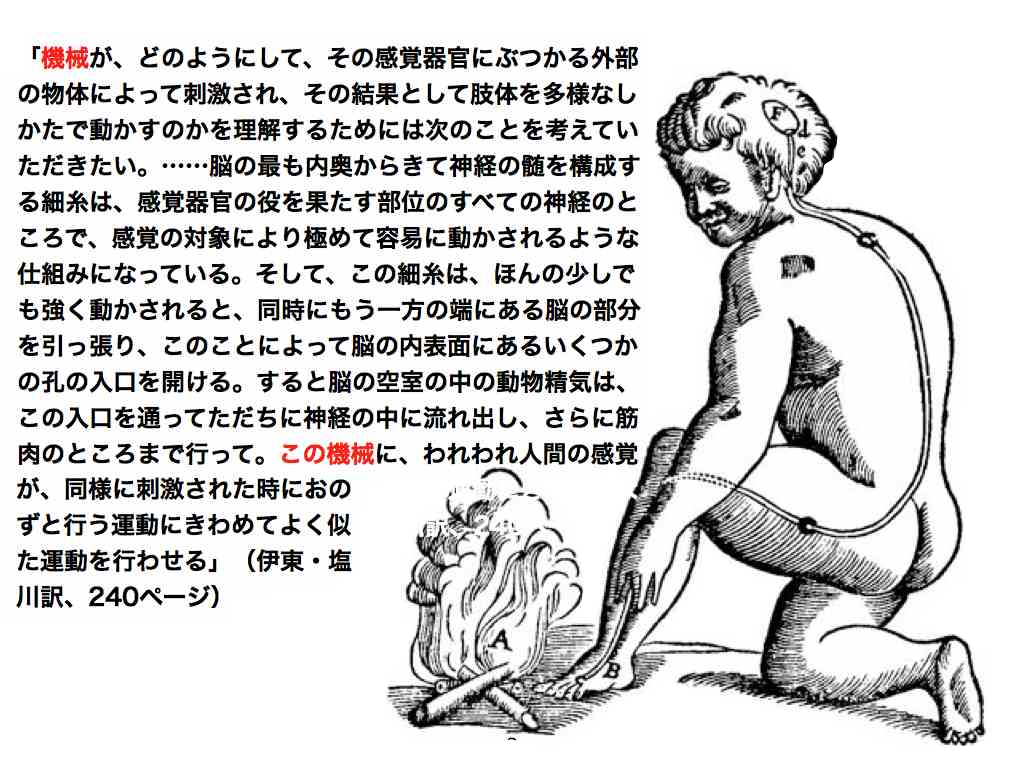

Biology of stress rotating human brain with various parts highlighted in different colors Human brain: hypothalamus = red amygdala = green hippocampus/fornix = blue pons= yellow pituitary gland= pink The brain endocrine interactions are relevant in the translation of stress into physiological and psychological changes.[4] The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays an important role by translating stress reflexively into a response both to physical stressors and higher level inputs by the brain.[30] The ANS is composed of the parasympathetic nervous system and sympathetic nervous system, two branches that are both tonically active with opposing activities.[30] The ANS directly innervates tissue through the postganglionic nerves, which is controlled by preganglionic neurons.[30] The ANS receives inputs from the medulla, hypothalamus, limbic system, prefrontal cortex, midbrain and monoamine nuclei.[4][31] The activity of the sympathetic nervous system drives what is called the "fight or flight" response.[4] The fight or flight response to emergency or stress involves increased heart rate and force contraction, vasoconstriction, bronchodilation, sweating, and secretion of the epinephrine and cortisol from the adrenal medulla, among numerous other physiological and hormonal responses.[30] The parasympathetic nervous response involves return to maintaining homeostasis, and involves miosis, bronchoconstriction, increased activity of the digestive system, and contraction of the bladder walls.[30] Complex relationships between protective and vulnerability factors on the effect of childhood home stress on psychological illness, cardiovascular illness and adaption have been observed.[4][32] ANS related mechanisms may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease after major stressful events.[4][33] The HPA axis is a neuroendocrine system that mediates a stress response.[4] Neurons in the hypothalamus, particularly the paraventricular nucleus, release vasopressin and corticotropin releasing hormone, which travel through the hypophysial portal vessel where they travel to and bind to the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor on the anterior pituitary gland.[4][30] Multiple CRH peptides have been identified, and their corresponding receptors exist in multiple brain regions, including the amygdala.[4] CRH is the main regulatory molecule of the release of ACTH.[4] The secretion of ACTH into the systemic circulation allows it to bind to and activate melanocortin receptors, where it stimulates the release of steroid hormones.[4] The immune system may be influenced by stress. The HPA axis ultimately results in the release of cortisol, which generally has immunosuppressive effects.[4] |

ストレスの生物学 さまざまな部分が異なる色で強調表示された回転する人間の脳 人間の脳: 視床下部 =赤 扁桃体 =緑 海馬/脳梁 =青 橋 =黄色 下垂体 =ピンク 脳の内分泌相互作用は、ストレスが生理的および心理的な変化に転換される過程で重要な役割を果たす。[4] 自律神経系(ANS)は、ストレスを反射的に物理的ストレス因子および脳からの高次入力に対する反応に転換する重要な役割を果たす。[30] ANSは、対立する活動を示す2つの枝からなる副交感神経系と交感神経系で構成されている。[30] ANSは、前神経節神経によって制御される後神経節神経を介して組織に直接神経支配している。[30] ANSは、延髄、視床下部、辺縁系、前頭前野、中脳、およびモノアミン核から入力を受けている。[4][31] 交感神経系の活動は「闘争・逃走反応」と呼ばれる反応を引き起こす。[4] 緊急時やストレスに対する闘争・逃走反応には、心拍数と心拍力の増加、血管収縮、気管支拡張、発汗、副腎髄質からのエピネフリンとコルチゾールの分泌な ど、数多くの生理的・ホルモン反応が含まれる。[30] 副交感神経系反応は、恒常性の維持に戻すプロセスであり、瞳孔縮小、気管支収縮、消化系活動の増加、膀胱壁の収縮などが含まれます。[30] 幼少期の家庭ストレスが心理的疾患、心血管疾患、適応に与える影響に関する保護要因と脆弱性要因の複雑な関係が観察されています。[4][32] ANSに関連するメカニズムは、重大なストレスイベント後に心血管疾患のリスクを高める可能性があります。[4][33] HPA 軸は、ストレス反応を媒介する神経内分泌系である。[4] 視床下部のニューロン、特に視床下部の傍室核は、バソプレシンおよびコルチコトロピン放出ホルモンを放出する。これらのホルモンは、下垂体門脈を通って前 葉下垂体にあるコルチコトロピン放出ホルモン受容体に到達し、そこに結合する。[4][30] 複数のCRHペプチドが同定されており、その対応する受容体は扁桃体を含む複数の脳領域に存在します。[4] CRHはACTHの放出を主に調節する分子です。[4] ACTHが全身循環に分泌されると、メラノコルチン受容体に結合し活性化し、ステロイドホルモンの放出を刺激します。[4] ストレスは免疫系に影響を与える可能性があります。HPA軸は最終的にコルチゾールの分泌を引き起こし、これは一般的に免疫抑制作用を有しています。 [4] |

| Effects of chronic stress Main article: Chronic stress Chronic stress is a term sometimes used to differentiate it from acute stress. Definitions differ, and may be along the lines of continual activation of the stress response,[34] stress that causes an allostatic shift in bodily functions,[3] or just as "prolonged stress".[35] While responses to acute stressors typically do not impose a health burden on young, healthy individuals, chronic stress in older or unhealthy individuals may have long-term effects that are detrimental to health.[36] Infectious Some studies have observed increased risk of upper respiratory tract infection during chronic life stress. In patients with HIV, increased life stress and cortisol was associated with poorer progression of HIV.[34] Also with an increased level of stress, studies have proven evidence that it can reactivate latent herpes viruses.[37] Development Chronic stress has also been shown to impair developmental growth in children by lowering the pituitary gland's production of growth hormone, as in children associated with a home environment involving serious marital discord, alcoholism, or child abuse.[38] More generally, prenatal life, infancy, childhood, and adolescence are critical periods in which the vulnerability to stressors is particularly high.[39][40] Psychopathology A 2024 review reported that the global estimated lifetime prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults is approximately 3.9%.[41] Stress may contribute to various disorders, such as fibromyalgia,[42] chronic fatigue syndrome,[43] depression,[44] as well as functional somatic syndromes.[45] |

慢性ストレスの影響 主な記事:慢性ストレス 慢性ストレスは、急性ストレスと区別するために使用されることがある用語です。その定義はさまざまで、ストレス反応の継続的な活性化[34]、身体機能の アルロスタティックシフトを引き起こすストレス[3]、あるいは単に「長期にわたるストレス」など[35] があります。急性ストレス要因に対する反応は、通常、若くて健康な個人には健康上の負担とはなりませんが、高齢者や不健康な個人における慢性ストレスは、 健康に悪影響を及ぼす長期的な影響をもたらす可能性があります[36]。 感染 いくつかの研究では、慢性的な生活ストレス中に上気道感染症のリスクが高まることが観察されています。HIV 患者では、生活ストレスとコルチゾールの増加は HIV の進行悪化と関連していました[34]。また、ストレスレベルの上昇に伴い、潜在的なヘルペスウイルスが再活性化される可能性があることが研究で証明され ています[37]。 発達 慢性的なストレスは、深刻な夫婦不和、アルコール依存症、児童虐待などの家庭環境にある子供たちのように、下垂体の成長ホルモン分泌を低下させることに よって、子供の発育を損なうことも示されている[38]。より一般的には、出生前の生活、乳児期、小児期、および青年期は、ストレス要因に対する脆弱性が 特に高い重要な時期である[39][40]。 精神病理 2024年のレビューでは、成人の生涯有病率の推定値は世界中で約3.9%と報告されています。[41] ストレスは、線維筋痛症[42]、慢性疲労症候群[43]、うつ病[44]、機能性身体症候群[45]など、さまざまな障害に寄与する可能性があります。 |

| Psychological concepts Main article: Stress (psychological) Eustress Main article: Eustress Stressors that are enjoyable or inspiring are termed eustress, which has generally positive effects on energy, cardiovascular health, and cognitive functions.[4] In 1975, Selye published a model dividing stress into eustress and distress.[46] Where stress enhances function (physical or mental, such as through strength training or challenging work), it may be considered eustress.[4] Persistent stress that is not resolved through coping or adaptation, deemed distress, may lead to anxiety or withdrawal (depression) behavior.[4][46] The difference between experiences that result in eustress and those that result in distress is determined by the disparity between an experience (real or imagined) and personal expectations, and resources to cope with the stress.[4][47] Cognitive appraisal Lazarus[48] argued that, in order for a psychosocial situation to be stressful, it must be appraised as such. He argued that cognitive processes of appraisal are central in determining whether a situation is potentially threatening, constitutes a harm/loss or a challenge, or is benign. Both personal and environmental factors influence this primary appraisal, which then triggers the selection of coping processes. Problem-focused coping is directed at managing the problem, whereas emotion-focused coping processes are directed at managing the negative emotions. Secondary appraisal refers to the evaluation of the resources available to cope with the problem, and may alter the primary appraisal. In other words, primary appraisal includes the perception of how stressful the problem is and the secondary appraisal of estimating whether one has more than or less than adequate resources to deal with the problem that affects the overall appraisal of stressfulness. Further, coping is flexible in that, in general, the individual examines the effectiveness of the coping on the situation; if it is not having the desired effect, they will, in general, try different strategies.[49] |

心理学的概念 主な記事:ストレス(心理学的 ユーストレス 主な記事:ユーストレス 楽しく、刺激的なストレス要因はユーストレスと呼ばれ、エネルギー、心臓血管の健康、認知機能に一般的に良い影響を与える。[4] 1975年、セリエはストレスをユーストレスとディストレスに分類するモデルを発表した。[46] ストレスが機能(身体的または精神的、例えば筋力トレーニングや挑戦的な仕事など)を向上させる場合、それはユーストレスとみなされる。[4] 対処や適応によって解決されない持続的なストレスはディストレスとされ、不安や引きこもり(うつ病)行動を引き起こす可能性がある。[4][46] ユーストレスをもたらす経験とディストレスをもたらす経験の違いは、経験(現実の、あるいは想像上の)と個人的な期待、およびストレスに対処するためのリソースとの格差によって決まる。[4][47] 認知的評価 ラザラス[48]は、心理社会的状況がストレスフルであるためには、そのように評価されなければならないと主張した。彼は、状況が潜在的に脅威であるか、 危害/損失を構成するか、挑戦であるか、または無害であるかを決定する中心的な役割を果たすのは、評価の認知プロセスであると主張した。 この一次評価には、個人的要因と環境的要因の両方が影響し、その評価に基づいて対処プロセスが選択される。問題重視の対処は問題の管理に向けられるのに対 し、感情重視の対処プロセスはネガティブな感情の管理に向けられる。二次評価とは、問題に対処するために利用できるリソースの評価を指し、一次評価を変え ることがある。 つまり、一次評価には、問題がどれほどストレスであるかの認識と、その問題に対処するのに十分なリソースがあるかどうかの二次評価が含まれ、これらがスト レスの全体的な評価に影響を与える。さらに、対処は柔軟性があり、一般的に、個人は状況に対する対処の有効性を検討し、望ましい効果が得られない場合は、 通常、異なる戦略を試す。[49] |

| Assessment Health risk factors Both negative and positive stressors can lead to stress. The intensity and duration of stress changes depending on the circumstances and emotional condition of the person with it (Arnold. E and Boggs. K. 2007). Some common categories and examples of stressors include: Sensory input such as pain, bright light, noise, temperatures, or environmental issues such as a lack of control over environmental circumstances, such as food, air and/or water quality, housing, health, freedom, or mobility. Social issues can also cause stress, such as struggles with conspecific or difficult individuals and social defeat, or relationship conflict, deception, or break ups, and major events such as birth and deaths, marriage, and divorce. Life experiences such as poverty, unemployment, clinical depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, heavy drinking,[50] or insufficient sleep can also cause stress. Students and workers may face performance pressure stress from exams and project deadlines. Adverse experiences during development (e.g. prenatal exposure to maternal stress,[51][52] poor attachment histories,[53] sexual abuse)[54] are thought to contribute to deficits in the maturity of an individual's stress response systems. One evaluation of the different stresses in people's lives is the Holmes and Rahe stress scale. |

評価 健康上のリスク要因 ストレスには、ネガティブなストレス要因とポジティブなストレス要因の両方があります。ストレスの強さや持続期間は、その状況やストレスを受ける人の感情 の状態によって異なります(Arnold. E and Boggs. K. 2007)。ストレス要因の一般的な分類と例としては、次のようなものがあります。 痛み、明るい光、騒音、温度などの感覚入力、あるいは、食物、空気や水の質、住居、健康、自由、移動の自由など、環境の状況に対するコントロールの欠如などの環境問題。 また、同種や難しい個人との葛藤、社会的敗北、人間関係の葛藤、欺瞞、別れ、出産や死、結婚、離婚などの大きな出来事もストレスの原因となる。 貧困、失業、臨床的うつ病、強迫性障害、過度の飲酒[50]、睡眠不足などの人生経験もストレスの原因となる。学生や労働者は、試験やプロジェクトの締め切りによるパフォーマンスのプレッシャーによるストレスに直面する場合がある。 発達過程における悪影響(例えば、母親のストレスへの胎児期の曝露[51][52]、愛着形成の失敗[53]、性的虐待[54])は、個人のストレス反応 システムの成熟の欠如の一因となることが考えられている。人々の生活におけるさまざまなストレスを評価する手法の一つに、ホームズ・レイストレススケール がある。 |

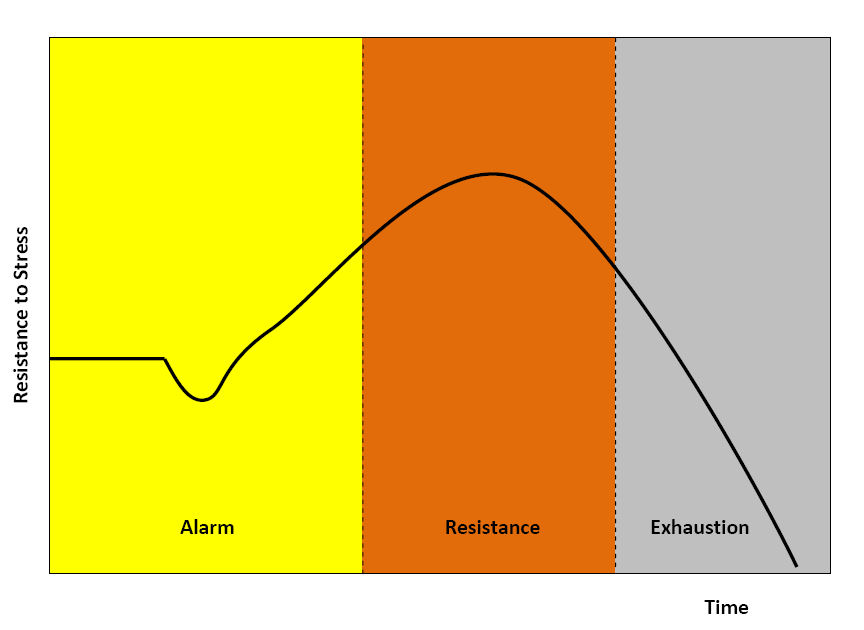

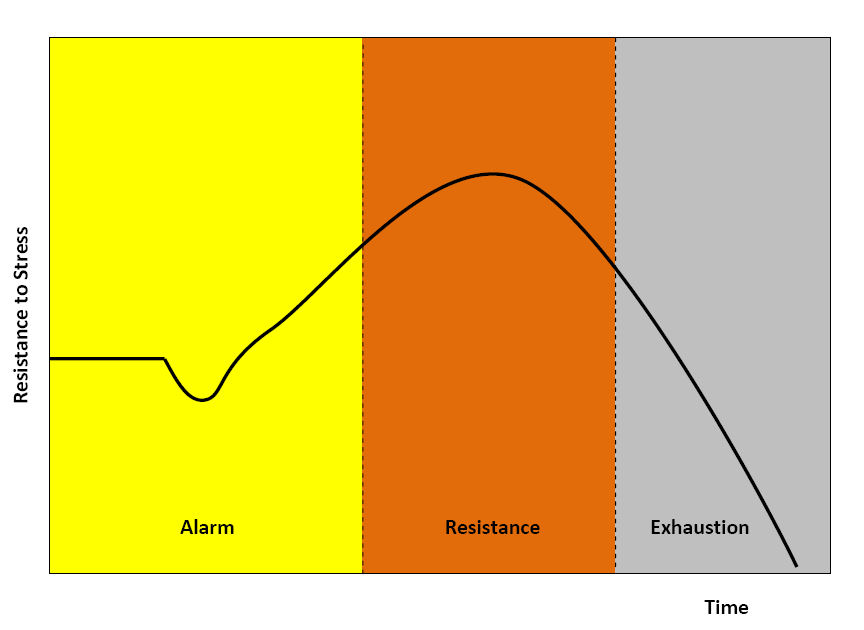

General adaptation syndrome A diagram of the general adaptation syndrome model This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. Please review the contents of the section and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Stress" biology – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2025) Physiologists define stress as how the body reacts to a stressor - a stimulus, real or imagined. Acute stressors affect an organism in the short term; chronic stressors over the longer term. The general adaptation syndrome (GAS), developed by Hans Selye, is a profile of how organisms respond to stress; GAS is characterized by three phases: a nonspecific alarm mobilization phase, which promotes sympathetic nervous system activity; a resistance phase, during which the organism makes efforts to cope with the threat; and an exhaustion phase, which occurs if the organism fails to overcome the threat and depletes its physiological resources.[55] Stage 1 Alarm is the first stage, which is divided into two phases: the shock phase and the antishock phase.[56] Shock phase: During this phase, the body can endure changes such as hypovolemia, hypoosmolarity, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hypoglycemia—the stressor effect. This phase resembles Addison's disease. The organism's resistance to the stressor drops temporarily below the normal range and some level of shock (e.g. circulatory shock) may be experienced. Antishock phase: When the threat or stressor is identified or realized, the body starts to respond and is in a state of alarm. During this stage, the locus coeruleus and sympathetic nervous system activate the production of catecholamines including adrenaline, engaging the popularly-known fight-or-flight response. Adrenaline temporarily provides increased muscular tonus, increased blood pressure due to peripheral vasoconstriction and tachycardia, and increased glucose in blood. There is also some activation of the HPA axis, producing glucocorticoids (cortisol, aka the S-hormone or stress-hormone). Stage 2 Resistance is the second stage. During this stage, increased secretion of glucocorticoids intensifies the body's systemic response. Glucocorticoids can increase the concentration of glucose, fat, and amino acid in blood. In high doses, one glucocorticoid, cortisol, begins to act similarly to a mineralocorticoid (aldosterone) and brings the body to a state similar to hyperaldosteronism. If the stressor persists, it becomes necessary to attempt some means of coping with the stress. The body attempts to respond to stressful stimuli, but after prolonged activation, the body's chemical resources will be gradually depleted, leading to the final stage. |

一般適応症候群 一般適応症候群モデルの図 このセクションは、検証のために信頼性の高い医学的参考文献が必要、または一次資料に過度に依存している。このセクションの内容を確認し、可能であれば適 切な参考文献を追加してください。出典が明記されていない、または出典が不明な内容は、削除される場合があります。出典を探す:「ストレス」生物学 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2025年3月) 生理学者は、ストレスを、現実のまたは想像上の刺激であるストレス要因に対する身体の反応と定義している。急性ストレス要因は、短期間に生物に影響を与え る。慢性ストレス要因は、長期間にわたって影響を与える。ハンス・セリエが提唱した一般適応症候群(GAS)は、生物がストレスに反応するパターンをモデ ル化したもので、3つの段階からなる:非特異的警報動員段階(交感神経系の活動を促進する)、抵抗段階(生物が脅威に対処する努力を行う)、および消耗段 階(生物が脅威を克服できず、生理的資源が消耗する)。[55] ステージ1 アラームは最初の段階であり、ショック期と抗ショック期の2つの段階に分けられる。[56] ショック期:この段階では、低血容量、低浸透圧、低ナトリウム血症、低クロール血症、低血糖症などの変化に身体が耐えることができる。この段階はアディソ ン病に類似している。生物のストレス要因に対する抵抗力が一時的に正常範囲を下回り、ある程度のショック(例:循環性ショック)を経験する可能性がある。 抗ショック期:脅威やストレス因子が認識または自覚されると、体は反応を開始し、警報状態になります。この段階では、青斑核と交感神経系がアドレナリンを 含むカテコールアミンの産生を活性化し、よく知られている「闘争・逃走反応」を引き起こします。アドレナリンは一時的に筋緊張の増加、末梢血管収縮による 血圧上昇、頻脈、および血液中のグルコース濃度の上昇を引き起こします。HPA軸も一部活性化し、グルココルチコイド(コルチゾール、別名Sホルモンまた はストレスホルモン)が分泌されます。 第2段階 抵抗は第2段階です。この段階では、グルココルチコイドの分泌が増加し、体の全身反応が強化されます。グルココルチコイドは、血液中のグルコース、脂肪、 アミノ酸の濃度を増加させます。高用量では、グルココルチコイドの一種であるコルチゾールがミネラルコルチコイド(アルドステロン)と同様の作用を示し、 身体をハイパーアルドステロニズムに似た状態に導きます。ストレス因子が持続する場合、ストレスに対処するための何らかの手段を講じる必要が生じます。身 体はストレス刺激に反応しようとしますが、長期にわたる活性化により、身体の化学的資源が徐々に消耗され、最終段階に至ります。 |

| History in research The current usage of the word stress arose out of Hans Selye's 1930s experiments. He started to use the term to refer not just to the agent but to the state of the organism as it responded and adapted to the environment. His theories of a universal non-specific stress response attracted great interest and contention in academic physiology and he undertook extensive research programs and publication efforts.[57] While the work attracted continued support from advocates of psychosomatic medicine, many in experimental physiology concluded that his concepts were too vague and unmeasurable. During the 1950s, Selye turned away from the laboratory to promote his concept through popular books and lecture tours. He wrote for both non-academic physicians and, in an international bestseller entitled Stress of Life, for the general public. A broad biopsychosocial concept of stress and adaptation offered the promise of helping everyone achieve health and happiness by successfully responding to changing global challenges and the problems of modern civilization. Selye coined the term "eustress" for positive stress, by contrast to distress. He argued that all people have a natural urge and need to work for their own benefit, a message that found favor with industrialists and governments.[57] He also coined the term stressor to refer to the causative event or stimulus, as opposed to the resulting state of stress. Selye was in contact with the tobacco industry from 1958 and they were undeclared allies in litigation and the promotion of the concept of stress, clouding the link between smoking and cancer, and portraying smoking as a "diversion", or in Selye's concept a "deviation", from environmental stress.[58] From the late 1960s, academic psychologists started to adopt Selye's concept; they sought to quantify "life stress" by scoring "significant life events", and a large amount of research was undertaken to examine links between stress and disease of all kinds. By the late 1970s, stress had become the medical area of greatest concern to the general population, and more basic research was called for to better address the issue. There was also renewed laboratory research into the neuroendocrine, molecular, and immunological bases of stress, conceived as a useful heuristic not necessarily tied to Selye's original hypotheses. The US military became a key center of stress research, attempting to understand and reduce combat neurosis and psychiatric casualties.[57] The psychiatric diagnosis post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was coined in the mid-1970s, in part through the efforts of anti-Vietnam War activists and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and Chaim F. Shatan. The condition was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as posttraumatic stress disorder in 1980.[59] PTSD was considered a severe and ongoing emotional reaction to an extreme psychological trauma, and as such often associated with soldiers, police officers, and other emergency personnel. The stressor may involve threat to life (or viewing the actual death of someone else), serious physical injury, or threat to physical or psychological integrity. In some cases, it can also be from profound psychological and emotional trauma, apart from any actual physical harm or threat. Often, however, the two are combined. By the 1990s, "stress" had become an integral part of modern scientific understanding in all areas of physiology and human functioning, and one of the great metaphors of Western life. Focus grew on stress in certain settings, such as workplace stress, and stress management techniques were developed. The term also became a euphemism, a way of referring to problems and eliciting sympathy without being explicitly confessional, just "stressed out". It came to cover a huge range of phenomena from mild irritation to the kind of severe problems that might result in a real breakdown of health. In popular usage, almost any event or situation between these extremes could be described as stressful. The American Psychological Association's 2015 Stress In America Study[60] found that nationwide stress is on the rise and that the three leading sources of stress were "money", "family responsibility", and "work". |

研究の歴史 ストレスという言葉の現在の使用法は、1930年代にハンス・セリエが行った実験から生まれた。彼は、この用語を、単にストレスの原因を指すだけでなく、 環境に対して反応し適応する生物の状態を指すものとして使い始めた。彼の普遍的な非特異的ストレス反応の理論は、生理学界で大きな関心と論争を呼び、彼は 広範な研究プログラムと出版活動を行った。[57] 彼の研究は心身医学の支持者から継続的な支援を受けたが、実験生理学の多くは、彼の概念が曖昧で測定不能すぎると結論付けた。1950年代、セリエは研究 室を離れ、一般向け書籍や講演ツアーを通じて自身の概念を普及させることに注力した。彼は非学術的な医師向けに執筆する一方、国際的なベストセラー『スト レスの生理学』では一般読者向けに執筆した。 ストレスと適応に関する幅広い生物心理社会的概念は、変化する世界的な課題や現代文明の問題にうまく対応することで、誰もが健康と幸福を実現できると期待 された。セリエは、ディストレスとは対照的なポジティブなストレスを「ユーストレス」と表現した。彼は、すべての人々は自分の利益のために働くという自然 な欲求と必要性を持っていると主張し、そのメッセージは産業家や政府に支持された[57]。また、ストレスの結果である状態とは対照的に、その原因となる 出来事や刺激を指す「ストレス要因」という用語も作った。 セリエは1958年からタバコ業界と接触しており、訴訟やストレス概念の普及において非公式な同盟関係にあった。これにより、喫煙とがんとの関連性が曖昧になり、喫煙は「環境ストレスからの逸脱」と表現された。[58] 1960年代後半から、学術心理学者たちはセリエの概念を採用し始め、重要な人生の出来事をスコア化して「人生のストレス」を定量化しようとした。ストレ スとあらゆる種類の病気の関連性を調べるための大規模な研究が実施された。1970年代後半には、ストレスは一般市民が最も懸念する医療分野となり、問題 に対処するためにより基礎的な研究が求められた。ストレスの神経内分泌、分子、免疫学的基盤に関する実験室研究も再興し、セリエの元の仮説に必ずしも縛ら れない有用な手法として考案された。米国軍はストレス研究の主要な拠点となり、戦闘神経症と精神科的被害の理解と軽減を試みた。[57] 心的外傷後ストレス障害(PTSD)という精神医学的診断名は、1970年代半ばに、ベトナム戦争反対活動家やベトナム戦争反対退役軍人団体、チャイム・ F・シャタンらの努力により提唱された。この状態は、1980年に『精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』に「外傷後ストレス障害」として追加された。 [59] PTSDは、極度の心理的トラウマに対する深刻で持続的な感情反応とされ、兵士、警察官、その他の緊急要員と関連付けられることが多かった。ストレス要因 には、生命の脅威(または他者の実際の死亡を目撃すること)、重大な身体的損傷、または身体的または心理的な完全性の脅威が含まれる。場合によっては、実 際の身体的危害や脅威とは関係なく、深刻な心理的・感情的なトラウマによって生じることもある。しかし、多くの場合、この 2 つが組み合わさっている。 1990年代までに、「ストレス」は、生理学や人間の機能に関するあらゆる分野における現代科学の理解に欠かせない要素となり、西洋の生活における偉大な 隠喩のひとつとなった。職場でのストレスなど、特定の状況におけるストレスが注目され、ストレス管理手法が開発された。また、この用語は、問題を暗に表現 し、明示的に告白することなく同情を引き出すための婉曲表現としても使われるようになった。ストレスという言葉は、軽度の苛立ちから、健康の著しい悪化に つながるような深刻な問題まで、幅広い現象を網羅するようになった。一般的な使用法では、この両極端の間にあるほぼすべての出来事や状況を「ストレス」と 表現することができる。 アメリカ心理学会(APA)の2015年「アメリカにおけるストレス調査」[60]では、全国的なストレスが増加傾向にあり、ストレスの主な原因として「お金」「家族責任」「仕事」の3つが挙げられた。 |

| Autonomic nervous system Defense physiology HPA axis Inflammation Plant stress measurement Trier social stress test Xenohormesis Stress in early childhood Weathering hypothesis Endorphins |

自律神経系 防御生理学 HPA 軸 炎症 植物ストレス測定 トリアー社会ストレステスト 異種ホルモン作用 幼児期のストレス 風化仮説 エンドルフィン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stress_(biology) |

ストレスのもっとも直接的な定義は「外部からもたらされる歪み、ないしは歪みの原因」ということ である。

ハンス・セリエのストレス理論のすばらしい点は、このような物理的な歪みに関する隠喩(メタ ファー)を、人間の生体にも起こることを医学的に証明したことである。他方(あるいは同時に)この理論の弱点は、このようなわかりやすい隠喩をすべて内分 泌理論で説明しようしたことである。とくに、後者の、内分泌での全理論体系の説明は破たんしているにもかかわらず、説明のメカニズムそのものはブラック ボックスとして表現される(=機械的イメージとしては理解できず全体的イメージとして表現される)ために「ストレスの原因(=ストレッサー)」と「その歪 み(=ストレスの病理)」は、なんでも使えるようになり、今日のような、ストレス理論万能説——言い方を変えるとストレス理論では何も説明*できない—— がはびこる世の中になってしまった。

*ストレス理論では何も説明できない、というのは、K・ポパー流の反証可能性という科学言説の構 造を有しない議論のタイプになったということで、ストレス理論そのものが、「科学的に」ナンセンスであるという意味ではない。

■ テクノストレス

ストレス資料集

セリエのストレス

【現象】

「警告反応と訳される医学、生物学用語。生体に有害刺激が加わると、脳の特定部位や下垂体前 葉の分泌細胞の活動が高まり、それによって副腎(ふくじん)皮質刺激ホルモン(ACTH)の分泌が増加し、その結果、血中の糖質コルチコイド濃度が上昇す る」。

【機能α】有害刺激から身を守る(概括的意義の付与)

「この下垂体前葉—副腎皮質系の機能上昇は、有害刺激から生命を守り、生命を維持するために は不可欠なものである。カナダの内分泌学者セリエH. Selyeは、ACTH分泌を増加させる有害刺激をストレッサーstressorと定義した(1936)」。

【用語法の由来】

「これは生体諸機能にひずみstrainを生ぜしめるものという意味であるが、現在このよう なひずみをおこすことを含めてストレスとよんでいる」〈川上正澄〉。

【ストレッサーの探究】

1936年以降・・・「カナダの内分泌学者フォーティアC. Fortierは、ストレッサーをその有害刺激の作用の仕方から、神経性(音、光、痛み、恐れ、悩み)、体液性(毒素、ヒスタミン、ホルマリンなど)、な らびにこれら両者の混合した型の3種に大別した。

【機能β】=生命の維持

「これらの異常刺激に生体が曝露(ばくろ)されると、生体は視床下部—下垂体前葉—副腎皮質 系の活動を高めて循環血液中に副腎皮質から糖質コルチコイド濃度を上昇させて自己を防衛する。その際、ストレッサーは、その種類によって生体にそれぞれ特 異的な反応を引き起こすとともに、非特異的な変化を惹起(じやつき)する。この非特異的変化は、生体がストレッサーに曝露されたときに生体に備わっている 防衛機構を刺激して、生体に適応させて生命を維持するものである」。

【破壊の予兆/破たんの“メカニズム”】

否定辞でつなげるところがポイントである。「しかし、有害刺激があまりにも強いと、適応機能 は破綻(はたん)し、ついに疲憊(ひはい)に陥って死に至る。これら一連の反応過程を総括して、セリエは汎(はん)適応症候群general adaptation syndrome(GASと略す)と名づけ、次の三つの時期に区分した」。

【第一期前期】=ショック・フェイズ?

「第一期には二つの時期がある。初めにストレスを受けると、生体は強いショック状態(血圧の 低下、心臓機能の低下、骨格筋の緊張や脊髄(せきずい)反射の減弱、体温の低下、意識の低下など)に陥る。これがショック期とよばれる時期である」。

【第一期後期】=警告反応期、原語は?emergency という用語が後述(される。

「ついでストレス刺激により、視床下部から副腎皮質刺激ホルモン放出ホルモン(CRH)が放 出され、これが下垂体前葉からACTHを一般体循環に放出する。このACTHが副腎皮質に作用して副腎皮質ホルモンの一つである糖質コルチコイドの分泌を 促進する。この時期を警告反応期といい、生体の防衛機序が働き始める時期である。

【第二期】抵抗期=症状の軽減?

「第二期は、第一期を経過して、ストレスに対する生体諸機能を有機的に再構成し、ストレスに 耐え、適応するようになる時期で、抵抗期ともいう」。

【第三期】疲憊(ひはい:こんな字読めんがな・・)

「第三期は、ストレスがさらに持続し、生体の適応機序に破綻を生じ、生体諸器官が協調的に機 能しなくなり、生体の恒常性が失われる時期である。この時期を疲憊期ともいう」。

【セリエの説明のおさらい】 ※セリエとそれ以外の人たちのセオリーの区分の説明がない。セリエの複数の業績の内的理論の変化への言及がない。(学説史的フォローができない)。

「ストレッサーによって刺激された視床下部—下垂体前葉—副腎皮質系の活動によって放出され た糖質コルチコイドは、〔1〕間葉組織の炎症反応に対して細胞のリソゾーム膜を安定化させる作用(抗炎症作用)、〔2〕筋その他の組織における糖新生作 用、ならびに肝臓に直接作用することによって糖新生に関与する一連の酵素の合成を賦活(ふかつ)する作用、〔3〕他のホルモン、たとえば甲状腺(せん)ホ ルモン、成長ホルモン、性ホルモン、インスリン、カテコールアミンなどの効果を増強する作用があるとされる。これらの作用によって、ストレスに曝露された 生体諸機能のひずみは正常状態に戻る、というのがセリエの考えである」。

【補遺】どういう意味で問題なのか? が説明されていない。古典になるということは、問題がある ということなのか? もしそうならストレス学説はナンセンスなのか?

「しかし、その後の研究から、セリエの学説には問題点のあることが明らかにされ、現代では古 典的なものになっている」。

■内部環境の恒常性■

「生体の生存している生体外部の環境がきわめて変化に富み、刺激も多いにもかかわらず、生体 の内部環境は恒常的に維持されている。 このことは、19世紀の後半にフランスの生理学者ベルナールC. Bernardによって発見された。この内部環境の不動性こそ、生命を維持するうえに必要なものである。この内部環境の特性を、アメリカの生理学者キャノ ンW. B. Cannonはホメオスタシス(恒常性)とよび、これを保つ仕組みには視床下部—交感神経—副腎髄質系が大きな役割を演じていることを明らかにした (1927)」

※つまり、キャノンはセリエの提唱の9年前に上記のようなことを理解していたのだ。

【システムの呈示】

「この系(視床下部—交感神経—副腎髄質系、引用者註)を刺激する生理的要因には、感情の激 動、痛み、寒さ、酸素欠乏、飢え、激しい筋作業など多くのものがある。このような因子がストレッサーとして生体に作用すると、視床下部—交感神経系が刺激 され、副腎髄質からアドレナリン、ノルアドレナリンが血中に放出される」。

「これらのホルモン(アドレナリン、ノルアドレナリン:引用者註)は、両者にわずかな差異は あっても、ともに心臓機能の亢進(こうしん)、血圧上昇、骨格筋への血流増加、血糖(血液のブドウ糖)の血中への増加をもたらし、筋活動に必要なエネル ギーの供給、脾臓(ひぞう)収縮による循環血流への赤血球放出増加、気管支の平滑筋の弛緩(しかん)による呼吸気量の増加、立毛(鳥肌)などをおこす」。

※ホルモンの用語が定義なしに登場。(血中で作用する生体由来の物質がホルモンということな のか?)

「これらの変化がおこることによって、生体は非常事態に遭遇した場合でも、生体を防衛するた めの可能な限りの努力が払えるわけである。キャノンはこれらの事実から、生体が非常事態に直面したときには、主として交感神経—副腎髄質系の活動によって 生体を危機から防衛することができると考え、緊急反応理論emergency theoryを展開した」。

【その後の展開:つまりセリエを批判する?あるいは補強する説なのか?】

「この副腎皮質の働きは、動物がストレス環境にない場合には生命維持に必須(ひつす)ではな いが、ストレスに曝露された場合には必要となる。一般にACTH分泌を増加させるような有害刺激は、交感神経—副腎髄質系の活動も高める。このACTHと アドレナリンやノルアドレナリンのようなカテコールアミンとの協同活動については不明な点が多いが、血中糖質コルチコイドがカテコールアミンに対する血管 の反応性を維持することはわかっている。また、カテコールアミンは遊離脂肪酸を血中に遊離させる作用を促進するほか、生体がストレス刺激を受けて緊急状態 に置かれた場合には、エネルギー源としても重要な働きをもつことが明らかにされている」。〈以上の説明はすべて『スーパーニッポニカ』による川上正澄先生 の説明〉

■動物とストレス■

この項目の作成者は? おお、我が鹿大時代の町田先生だ!

「ストレスとその適応症候群の考えは、動物の個体群生態学にも大きな影響を及ぼした。アメリ カのクリスチャンJ. J. Christianは、ノネズミなど哺乳(ほにゅう)類の個体数変動の機構を、セリエのストレス学説によって説明しようと試みた(1950)」。

※クリスチャン理論を抑えることが重要

「すなわち、大発生により食物の欠乏、すみかの不足、闘争など個体間の干渉の増大がおこる と、これらがストレッサーとなって作用し、生殖機能の低下、出生率の低下、死亡率の上昇がおこり、個体数の減少に至るというものである。セリエのストレス 学説と同様、クリスチャンのこの説明にも、その後さまざまな批判がなされ、修正が加えられてはいるが、現在でも個体群の動態を生理学的に解明しようとする もっとも有力な仮説とされている」。〈町田武生〉

※これは、人間界での説明に合致。動物群から人間社会へのメタファーの転換が起こったのか? あるいはこの頃は、同時に、〈行動〉というキータームで統一的に理解しようとしていたのか? 1950年という時期は、行動科学の発達期であるゆえに。

■現代のストレスチェック:50問以上の4〜5択の簡単な質問を答えて、その結果が出る。この データを出しておかなければ、職場の定期健康診断を受けられない(2017年5月の自験例より)。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆