頁

|

パラ

|

|

|

228

|

1

|

・人類学は宗教研究から離れてきている

Despite some recent attempts to renew them, it would seem that past

twenty years anthropology has more and more turned away from studies

field of religion. At the same time, and precisely because professional

anthropologists' interest has withdrawn from primitive religion, all

kinds of amateurs belong to other disciplines have seized this

opportunity to move in, thereby into their private playground what we

had left as a wasteland. Thus, the for the scientific study of religion

have been undermined in two ways.

|

近年、それらを刷新しようとする試みがいくつか見られるも

のの、過去20年間、人類学は宗教研究からますます遠ざかっているように思われる。同時に、そしてまさに専門の人類学者の関心が原始宗教から遠ざかったか

らこそ、他の分野に属するあらゆる種類の素人がこの機会を捉えて参入し、荒地として残されていたものを彼らの私的な遊び場へと変えた。こうして、宗教の科

学的研究は2つの方法で損なわれてしまった。

|

|

2

|

・宗教がなんであるかについて、宗教学はなにも応えていない

The explanation for that situation lies to some extent in the fact

anthropological study of religion was started by men like Tylor,

Frazer, heim who were psychologically oriented, although not in a

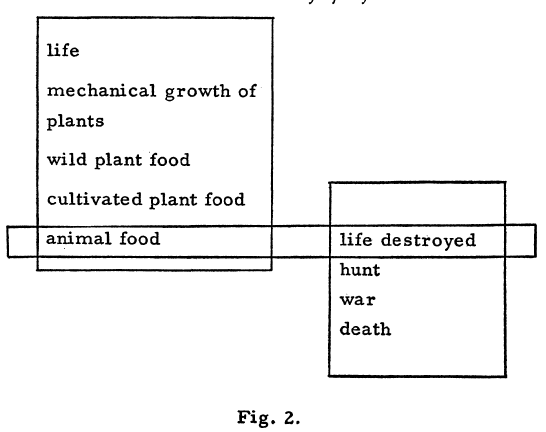

position to the progress of psychological research and theory.

Therefore, their interpretations soon became vitiated by the outmoded

psychological approach which their backing. Although they were

undoubtedly right in giving their intellectual processes, the way they

handled them remained so coarse as them altogether. This is much to be

regretted since, as Hocart so profoundly in his introduction to a

posthumous book recently published,' psychological pretations were

withdrawn from the intellectual field only to be introduced the field

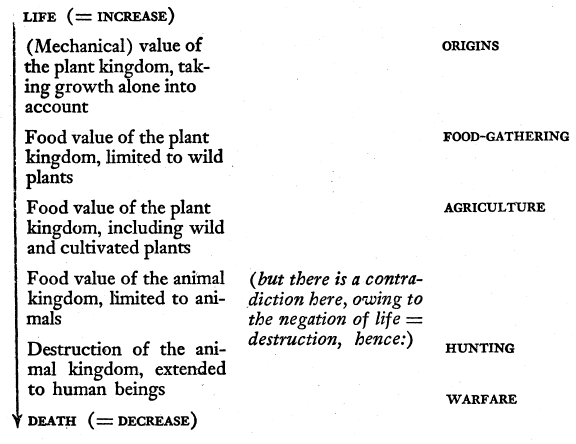

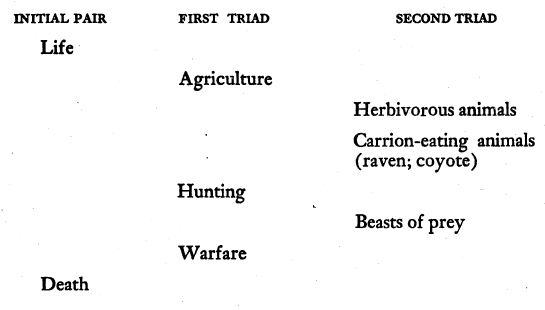

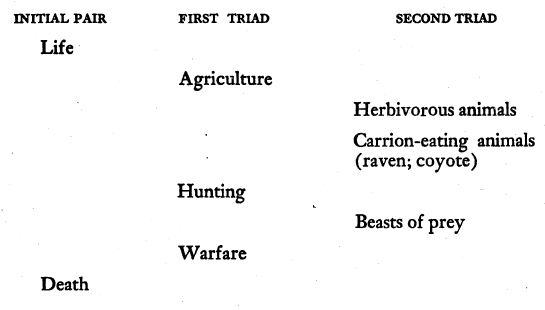

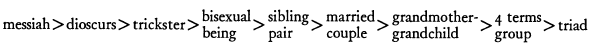

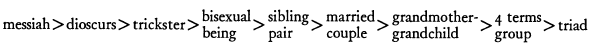

of affectivity, thus adding to "the inherent defects of the

psychological school . . . the mistake of deriving clear-cut ideas . .

. from vague emotions." of trying to enlarge the framework of our logic

to include processes which, their apparent differences, belong to the

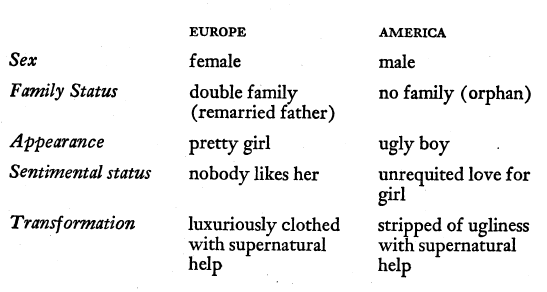

same kind of intellectual operations, attempt was made to reduce them

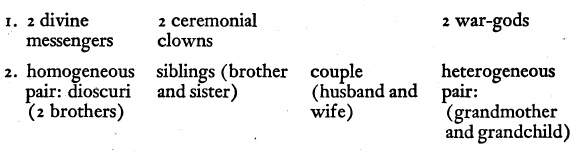

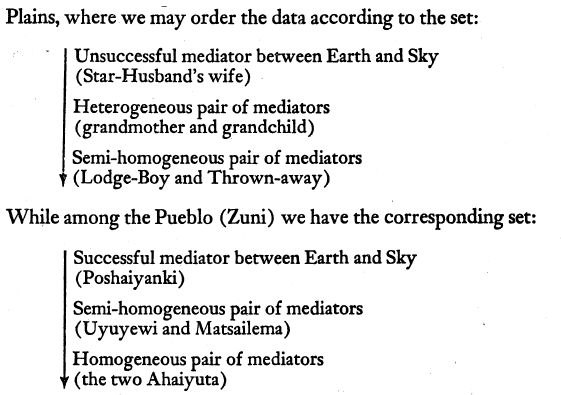

to inarticulate emotional drives which only in withering our studies.

|

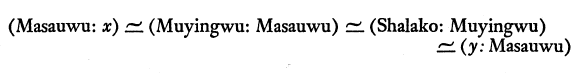

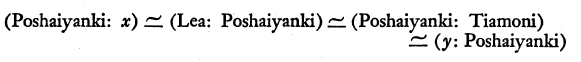

その状況の説明は、ある程度、宗教人類学が、心理学的研究や理論の進歩

には至っていないものの、心理学的志向のタイラー、フレイザー、デユルケームといった人物によって始められたという事実にある。そのため、彼らの解釈は、

彼らの基盤となった時代遅れの心理学的アプローチによってすぐに損なわれてしまった。彼らの知的プロセスを明らかにしたことは間違いなく正しいが、その処

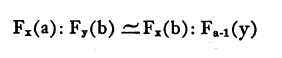

理方法は彼ら自身と同様に粗雑なものにとどまった。これは非常に遺憾なことであり、ホカートが最近出版された遺作の序文で深く述べているように、「心理学

的虚飾は、知的な分野から感情の分野に導入されただけであった。それにより、「心理学的学派の固有の欠陥に、...曖昧な感情から明確な概念を導き出すと

いう間違い...」が加わった。曖昧な感情から明確な概念を導き出すという過ちを犯すこと。一見異なるように見えるが、同じ種類の知的作業に属するプロセ

スを論理の枠組みに含めようとする試み。それらを不明瞭な感情的な衝動に還元しようとする試み。それは私たちの研究を衰退させるだけである。

|

229

|

3

|

・神話学も事情はおなじ

Of all the chapters of religious anthropology probably none has tarried

same extent as studies in the field of mythology. From a theoretical

point situation remains very much the same as it was fifty years ago,

namely, chaos. Myths are still widely interpreted in conflicting ways:

collective outcome of a kind of esthetic play, the foundation of

ritual.... Mythological are considered as personified abstractions,

divinized heroes or decayed gods. the hypothesis, the choice amounts to

reducing mythology either to an to a coarse kind of speculation.

|

宗教人類学のすべての章の中で、おそらく神話の研究ほど長らく同じ範囲

にとどまっているものはない。理論的な観点から見ると、状況は50年前とほとんど変わらず、つまり混沌としている。神話は、いまだに相反する解釈が広く行

われている。美的戯れの集合的な成果、儀式の基礎など…。神話は、抽象概念を擬人化したものと見なされ、英雄を神格化したり、神を退廃させたりしている。

この仮説や選択は、神話を大ざっぱな憶測に還元することに等しい。

|

|

4

|

・神話とはなにかに、応えられない

In order to understand what a myth really is, are we compelled between

platitude and sophism? Some claim that human societies through their

mythology, fundamental feelings common to the whole of mankind, such as

love, hate, revenge; or that they try to provide some kind of

explanations for phenomena which they cannot understand otherwise:

astronomical, meteorological, and the like. But why should these

societies do it in such elaborate and devious ways, since all of them

are also acquainted with positive explanations? On the other hand,

psychoanalysts and many anthropologists have shifted the problems to be

explained away from the natural or cosmological towards the

sociological and psychological fields. But then the interpretation

becomes too easy: if a given mythology confers prominence to a certain

character, let us say an evil grandmother, it will be claimed that in

such a society grandmothers are actually evil and that mythology

reflects the social structure and the social relations; but should the

actual data be conflicting, it would be readily claimed that the

purpose of mythology is to provide an outlet for repressed feelings.

Whatever the situation may be, a clever dialectic will always find a

way to pretend that a meaning has been unravelled.

|

神話が本当に何であるかを理解するためには、陳腐なものと詭弁の狭間で

決断を迫られるのだろうか?

人類社会は神話を通じて、愛や憎しみ、復讐といった人類全体に共通する根源的な感情を表現したり、天文学や気象学など、理解できない現象に対して何らかの

説明を与えようとしているという主張がある。しかし、これらの社会は、すべて肯定的な説明も知っているのだから、なぜこのような手の込んだ、曲解された方

法を取る必要があるのだろうか?一方、精神分析学者や多くの人類学者は、説明すべき問題を自然や宇宙論から社会学や心理学の分野へと移した。しかし、その

解釈はあまりにも安易である。ある神話が特定のキャラクター、例えば邪悪な祖母を際立たせている場合、そのような社会では祖母は実際に邪悪であり、神話は

社会構造や社会関係を反映していると主張されるだろう。しかし、実際のデータが矛盾する場合、神話の目的は抑圧された感情の出口を提供することであると簡

単に主張されるだろう。どのような状況であっても、巧妙な弁証法によって、意味が解き明かされたかのように見せかける方法を見つけることができる。

|

230

|

5

|

・神話は矛盾したもので「いい」のだ

Mythology confronts the student with a situation which at first sight

could be looked upon as contradictory. On the one hand, it would seem

that in the course of a myth anything is likely to happen. There is no

logic, no continuity. Any characteristic can be attributed to any

subject; every conceivable relation can be met. With myth, everything

becomes possible. But on the other hand, this apparent arbitrariness is

belied by the astounding similarity between myths collected in widely

different regions. Therefore the problem: if the content of a myth is

contingent, how are we going to explain that throughout the world myths

do resemble one another so much?

It is precisely this awareness of a basic antinomy pertaining to the

nature of myth that may lead us towards its solution. For the

contradiction which we face is very similar to that which in earlier

times brought considerable worry to the first philosophers concerned

with linguistic problems; linguistics could only begin to evolve as a

science after this contradiction had been overcome. Ancient

philosophers were reasoning about language the way we are about

mythology. On the one hand, they did notice that in a given language

certain sequences of sounds were associated with definite meanings, and

they earnestly aimed at discovering a reason for the linkage between

those sounds and that meaning. Their attempt, however, was thwarted

from the very beginning by the fact that the same sounds were equally

present in other languages though the meaning they conveyed was

entirely different. The contradiction was surmounted only by the

discovery that it is the combination of sounds, not the sounds in

themselves, which provides the significant data.

|

神話は、一見矛盾しているように見える状況と学生を対峙させる。

一方では、神話の過程では何でも起こりうるように思える。 論理も連続性も存在しない。

どんな特徴でもどんな主題にも当てはめることができ、考えられるあらゆる関係が存在し得る。 神話では、ありとあらゆることが起こりうる。

しかしその一方で、この一見したところでは恣意的な様相は、広範囲に収集された神話間の驚くべき類似性によって否定される。したがって、問題となるのは、

神話のコンテンツが偶然であるならば、なぜ世界中の神話がこれほど似ているのか、ということだ。

神話の性質に関する基本的な矛盾を認識することが、その解決につながる可能性がある。なぜなら、私たちが直面している矛盾は、言語の問題に関心を抱いてい

た初期の哲学者たちが非常に悩んだ矛盾と非常によく似ているからだ。この矛盾が克服されて初めて、言語学は科学として発展し始めることができた。古代の哲

学者たちは、私たちが神話について考えるのと同じように言語について考えていた。一方、彼らは特定の言語において、特定の音の並びが明確な意味と結びつい

ていることに気づき、その音と意味の結びつきの理由を発見することに真剣に取り組んだ。しかし、彼らの試みは、同じ音が他の言語にも同じように存在してい

るが、その意味は全く異なるという事実によって、最初から挫折させられていた。この矛盾は、重要なデータとなるのは音そのものではなく、音の組み合わせで

ある、という発見によってのみ克服された。

|

|

6-1

6-2

|

・神話に関するさまざまな「理論→議論」の跋扈

Now, it is easy to see that some of the more recent interpretations of

mytho- logical thought originated from the same kind of misconception

under which those early linguists were laboring. Let us consider, for

instance, Jung's idea that a given mythological pattern-the so-called

archetype-possesses a certain signification. This is comparable to the

long supported error that a sound may possess a certain affinity with a

meaning: for instance, the "liquid" semi-vowels with water, the open

vowels with things that are big, large, loud, or heavy, etc., a kind of

theory which still has its supporters.2 Whatever emendations the

original formulation may now call for, everybody will agree that the

Saussurean principle of the arbitrary character of the linguistic signs

was a prerequisite for the acceding of linguistics to the scientific

level.

|

現在では、神話的思考の最近の解釈のいくつかは、初期の言語学者たちが

苦労していたのと同じような誤解から生まれたものであることが容易に理解できる。例えば、ユングの考え方を考えてみよう。ユングは、神話上のパターン、い

わゆる元型には特定の意味があるとしている。これは、音と意味の間に一定の類似性があるとする、長い間支持されてきた誤りと比較できる。例えば、「リキッ

ド」と呼ばれる半母音と水、開音と大きくて重いもの、大きな音、などである。2

このような理論は今でも支持者がいる。元の定式化にどのような修正が必要であろうと、言語記号が恣意的なものであるというソシュールの原則は、言語学を科

学のレベルに引き上げるための前提条件であったという点では誰もが同意するだろう。

|

231

|

7

|

・神話は言語のなかにありながら、言語の外にある

To invite the mythologist to compare his precarious situation with that

of the linguist in the prescientific stage is not enough. As a matter

of fact we may thus be led only from one difficulty to another. There

is a very good reason why myth cannot simply be treated as language if

its specific problems are to be solved; myth is language: to be known,

myth has to be told; it is a part of human speech. In order to preserve

its specificity we should thus put ourselves in a position to show that

it is both the same thing as language, and also something different

from it. Here, too, the past experience of linguists may help us. For

language itself can be analyzed into things which are at the same time

similar and different. This is precisely what is expressed in

Saussure's distinction between langue and parole, one being the

structural side of language, the other the statistical aspect of it,

langue belonging to a revertible time, whereas parole is

non-revertible. If those two levels already exist in language, then a

third one can conceivably be isolated.

|

神話学者に、彼の不安定な状況を科学以前の段階における言語学者の状況

と比較するよう求めるだけでは不十分である。実際、そうすることで、私たちはただ一

つの困難から別の困難へと導かれるだけかもしれない。神話特有の諸問題を解決するためには、神話を単に言語として扱うわけにはいかないという非常に妥当な

理由がある。神話は言語である。神話を知ってもらうためには、神話を語らなければならない。神話は人間の言語の一部である。その特殊性を保持するために

は、神話が言語と同じものであると同時に、それと異なるものであることを示す立場に身を置くべきである。ここでも、言語学者の過去の経験が役立つかもしれ

ない。言語それ自体は、類似点と相違点の両方を持つものに分析できるからだ。これはまさに、ソシュールが言語(langue)と話し言葉(parole)

を区別したことに表れている。一方は言語の構造的側面であり、もう一方は言語の統計的側面である。langueは可逆的な時間の中に属し、一方、

paroleは不可逆的である。言語にすでにこの2つのレベルが存在しているなら、第3のレベルを抽出することは可能だろう。 |

|

8

|

We have just distinguished

langue and parole by the different time

referents which they use. Keeping this in mind, we may notice that myth

uses a third referent which combines the properties of the first two.

On the one hand, a myth always refers to events alleged to have taken

place in time: before the world was created, or during its first

stages-anyway, long ago. But what gives the myth an operative value is

that the specific pattern described is everlasting; it explains the

present and the past as well as the future. This can be made clear

through a comparison between myth and what appears to have largely

replaced it in modern societies, namely, politics. When the historian

refers to the French Revolution it is always as a sequence of past

happenings, a non-revertible series of events the remote consequences

of which may still be felt at present. But to the French politician, as

well as to his followers, the French Revolution is both a sequence

belonging to the pastas to the historian-and an everlasting pattern

which can be detected in the present French social structure and which

provides a clue for its interpretation, a lead from which to infer the

future developments. See, for instance, Michelet who was a

politically-minded historian. He describes the French Revolution thus:

"This day . . . everything was possible. . . . Future became present .

. . that is, no more time, a glimpse of eternity." It is that double

structure, altogether historical and anhistorical, which explains that

myth, while pertaining to the realm of the parole and calling for an

explanation as such, as well as to that of the langue in which it is

expressed, can also be an absolute object on a third level which,

though it remains linguistic by nature, is nevertheless distinct from

the other two. |

私たちは、言語と会話が使用する異なる時間参照によって、それらを区別

している。このことを念頭に置いてみると、神話は最初の2つの特性を組み合わせた第

3の参照を使用していることがわかる。一方、神話は常に、世界が創造される前、あるいはその初期段階、いずれにしてもはるか昔に起こったとされる出来事を

指している。しかし、神話に現実的な価値を与えるのは、そこに描かれている特定のパターンが永遠に続くことである。つまり、神話は現在と過去、そして未来

をも説明できるのだ。これは、神話と現代社会において神話をほぼ置き換えたと思われる政治を比較することで明らかになる。歴史家がフランス革命について言

及する場合、それは常に過去の出来事の連続として、取り返しのつかない一連の出来事であり、その遠い影響は現在でも感じられるかもしれない。しかし、フラ

ンスの政治家や支持者たちにとって、フランス革命は、歴史家にとって過去の出来事であると同時に、現在のフランスの社会構造に認められる永遠のパターンで

あり、その解釈の手がかりとなり、将来の展開を推測する糸口となる。例えば、政治的な関心を持つ歴史家ミシュレは、フランス革命について次のように述べて

いる。「この日、あらゆることが起こり得た。未来が現在となった。つまり、もはや時間はなく、永遠の片鱗が垣間見えたのだ。」この神話を説明するのは、歴

史的かつ非歴史的な二重構造である。それは、parole

の領域に関連し、それゆえの説明が必要とされると同時に、表現されている言語の領域にも関連するが、第 3

のレベルでは絶対的な対象となり得る。それは本質的には言語的であるが、他の 2 つとは区別される。 |

232

|

9

|

・翻訳は裏切りである(traduttore, traditore)

A remark can be introduced at this point which will help to show the

singularity of myth among other linguistic phenomena. Myth is the part

of language where the formula traduttore, tradittore reaches its lowest

truth-value. From that point of view it should be put in the whole

gamut of linguistic expressions at the end opposite to that of poetry,

in spite of all the claims which have been made to prove the contrary.

Poetry is a kind of speech which cannot be translated except at the

cost of serious distortions; whereas the mythical value of the myth

remains preserved, even through the worst translation. Whatever our

ignorance of the language and the culture of the people where it

originated, a myth is still felt as a myth by any reader through-out

the world. Its substance does not lie in its style, its original music,

or its syntax, but in the story which it tells. It is language,

functioning on an especially high level where meaning succeeds

practically at "taking off" from the linguistic ground on which it

keeps on rolling.

|

ここで、神話が他の言語現象の中でも特異な存在であることを示すため

に、ある指摘を紹介しよう。神話は、言語の分野において、翻訳者、伝達者の公式がもっとも真実味を失う部分である。その観点からすれば、神話は、詩歌とは

正反対の言語表現の全体像の中に位置づけられるはずである。詩は、深刻な歪みを引き起こすことなく翻訳することのできない一種の言語表現である。一方、神

話の神話的価値は、最悪の翻訳を経てもなお保たれる。その言語や文化について私たちがどれだけ無知であろうと、神話は世界中のあらゆる読者にとって神話と

して感じられる。その本質は、文体や独特の音楽性、構文にあるのではなく、物語にある。それは、言語が特に高いレベルで機能し、意味が言語の基盤から「飛

び立つ」ように、絶え間なく転がり続けるところにある。

|

233

|

10

|

To sum up the discussion at this

point, we have so far made the following claims: 1. If there is a

meaning to be found in mythology, this cannot reside in the isolated

elements which enter into the composition of a myth, but only in the

way those elements are combined. 2. Although myth belongs to the same

category as language, being, as a matter of fact, only part of it,

language in myth unveils specific properties. 3. Those properties are

only to be found above the ordinary linguistic level; that is, they

exhibit more complex features beside those which are to be found in any

kind of linguistic expression.

|

ここで議論をまとめると、我々はこれまで以下の主張をしてきた。1.神

話に意味があるとするなら、それは神話の要素となる個々の言葉ではなく、それらの要素が組み合わさったときにのみ存在する。2.神話は言語と同じカテゴ

リーに属するが、実際には言語の一部である。3.

これらの特性は、通常の言語レベルの上に見出されるものであり、つまり、あらゆる種類の言語表現に見られるものに加えて、より複雑な特徴を示すものであ

る。

|

|

11

|

・神話素の設定(音素概念からの導入)

How shall we proceed in order to identify and isolate these gross

constituent units? We know that they cannot be found among phonemes,

morphemes, or semantemes, but only on a higher level; otherwise myth

would become confused with any other kind of speech. Therefore, we

should look for them on the sentence level. The only method we can

suggest at this stage is to proceed tentatively, by trial and error,

using as a check the principles which serve as a basis for any kind of

structural analysis: economy of explanation; unity of solution; and

ability to reconstruct the whole from a fragment, as well as further

stages from previous ones.

|

これらの粗構成単位を特定し、切り離すにはどうすればよいだろうか。音

素、形態素、意味素の中には見つけることができないが、より高いレベルでは見つけることができる。さもなければ、神話は他の種類の言語と混同されてしまう

だろう。したがって、文レベルでそれらを探す必要がある。現段階で提案できる唯一の方法は、あらゆる種類の構造分析の基礎となる原則を検証しながら、試行

錯誤で進めていくことである。すなわち、説明の簡潔さ、解決の一致性、断片から全体、さらに前の段階から次の段階を再構築する能力である。

|

|

12

|

|

|

234

|

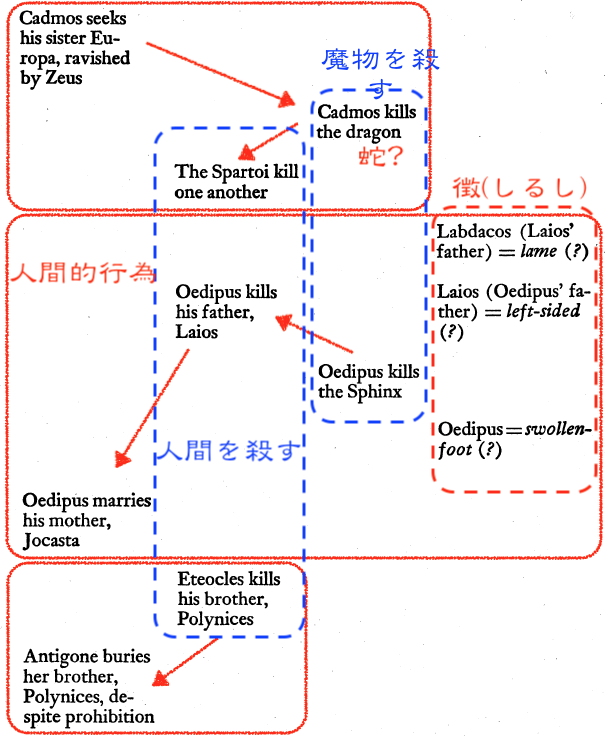

13

|

The technique which has been

applied so far by this writer consists in

analyzing each myth individually, breaking down its story into the

shortest possible sentences, and writing each such sentence on an index

card bearing a number corresponding to the unfolding of the story.

Practically each card will thus show that a certain function is, at a

given time, predicated to a given subject. Or, to put it otherwise,

each gross constituent unit will consist in a relation.

|

筆者がこれまで用いてきた手法は、神話を一つ一つ分析し、その物語をで

きるだけ短い文章に分解し、物語の展開に対応する番号が書かれたインデックスカードにそれぞれの文章を記入するというものである。

したがって、実際には、各カードは、特定の機能が、特定の時点で、特定の対象に関連付けられていることを示すことになる。あるいは、別の言い方をすれば、

各総体的な構成単位は、関係によって構成されることになる。

|

|

14

|

However, the above definition

remains highly unsatisfactory for two different reasons. In the first

place, it is well known to structural linguists that constituent units

on all levels are made up of relations and the true difference between

our gross units and the others stays unexplained; moreover, we still

find ourselves in the realm of a non-revertible time since the numbers

of the cards correspond to the unfolding of the informant's speech.

Thus, the specific character of mythological time, which as we have

seen is both revertible and non-revertible, synchronic and diachronic,

remains unaccounted for. Therefrom comes a new hypothesis which

constitutes the very core of our argument: the true constituent units

of a myth are not the isolated relations but bundles of such relations

and it is only as bundles that these relations can be put to use and

combined so as to produce a meaning. Relations pertaining to the same

bundle may appear diachronically at remote intervals, but when we have

succeeded in grouping them together, we have reorganized our myth

according to a time referent of a new nature corresponding to the

prerequisite of the initial hypothesis, namely, a two-dimensional time

referent which is simultaneously diachronic synchronic and which

accordingly integrates the characteristics of the langue hand, and

those of the parole on the other. To put it in even more linguistic is

as though a phoneme were always made up of all explain what we have in

mind.

Two comparisons may help to explain what we have in mind.

|

しかし、上記の定義は2つの理由から、依然として非常に不十分である。

第一に、構造言語学者には、あらゆるレベルの構成単位は関係によって構成されていることがよく知られているが、私たちの粗い単位と他の単位の真の違いは説

明されていない。さらに、カードの数は情報提供者の発話の展開に対応しているため、私たちは依然として非可逆的な時間の領域にいる。このように、神話的時

間の特異な性質、すなわち可逆性と非可逆性、共時性と通時性については、いまだ説明されていない。そこから、我々の議論の核心をなす新たな仮説が生まれ

た。すなわち、神話の真の構成要素は孤立した関係ではなく、そのような関係の束であり、これらの関係は束としてのみ意味を生み出すために利用され、組み合

わせることができる。同じ束に関連する関係は、時間的に離れた間隔で通時的に現れるかもしれないが、それらをグループ化することに成功したとき、私たち

は、最初の仮説の前提条件、すなわち、同時に通時的・共時的であり、それゆえ言語的手と言語的口述の特性を統合する2次元の時間参照体という、新しい性質

の時間参照体に従って神話を再編成した。さらに言語学的に表現すると、音素は常に、私たちが考えていることをすべて説明するように構成されているようなも

のである。

2つの比較が、私たちが何を考えているかを説明するのに役立つだろう。

|

|

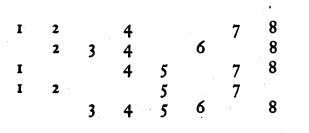

15

|

|

|

235

|

16

|

・ジプシーのトランプ占い

|

|

|

17

|

・オーケストラの一連のメロディ

|

|

|

18

|

|

|

237

|

19

|

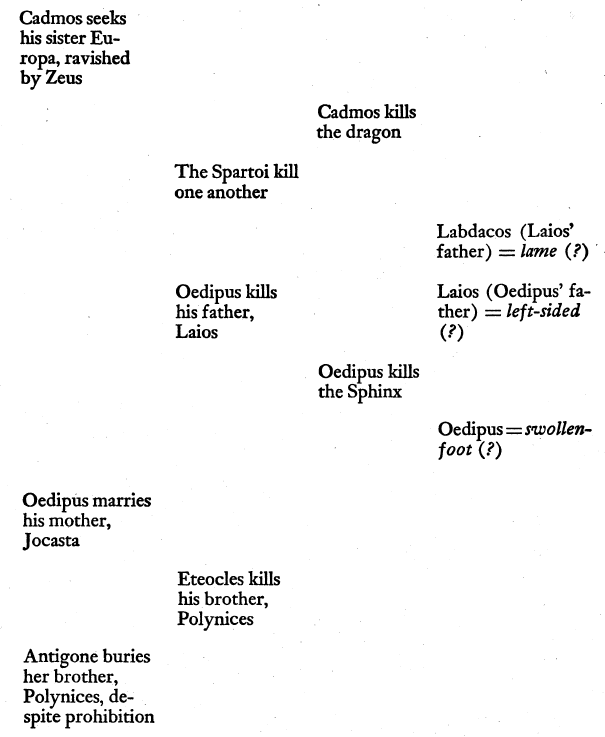

・縦のラインは4列ある

|

|

|

20

|

・(左第一欄)近親さが度を越してるケースを表している

・(第二欄)過大評価された(価値を下げられた)親族関係を示す

・(第三欄)怪物退治

・(第四欄)固有名が共通性をもつ

|

|

238

|

21

|

|

|

|

22

|

(第四欄)固有名が共通性をもつ→足の不自由。最初に生まれた人間は、

あしがよちよちで、おぼつかない |

|

|

23

|

・アメリカ先住民風に解釈されたオイディプス神話

|

|

240

|

24

|

・これまでの説明では、イオカステーの自殺やオイディプスの失明が説明

できない。

・イオカステの自己破壊は、(第三欄)に関係し、オイディプスの失明は(第四欄)=不具になる、を説明する。 |

|

|

25

|

・フロイトもオイディプス神話の分析の資料のひとつだ

|

|

241

|

26

|

・神話はヴァリアントの総体からなるので、それぞれの要素は全体分析の

資料になる

・ヴァリアントのパターンが重層的に読まれる

|

・L=Sは、上掲の図で、恣意的に要素を抽出したことの「過失」を忘却

している。

|

242

|

27

|

|

|

|

28

|

・中心的な「真の」神話は存在しない。あらゆる話型(toutes)は

神話に属している

|

|

|

29

|

|

|

243

|

30

|

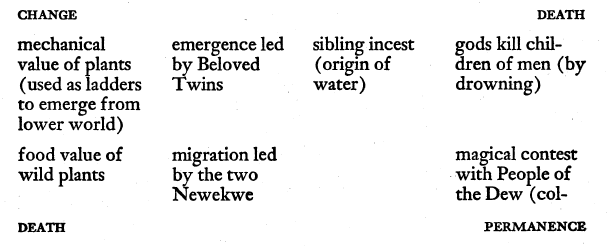

・ズニの神話を分析した

|

|

|

31

|

|

|

244

|

32

|

・この表は、生と死の媒介をなす、論理的道具だ。

|

|

245

|

33

|

|

|

|

34

|

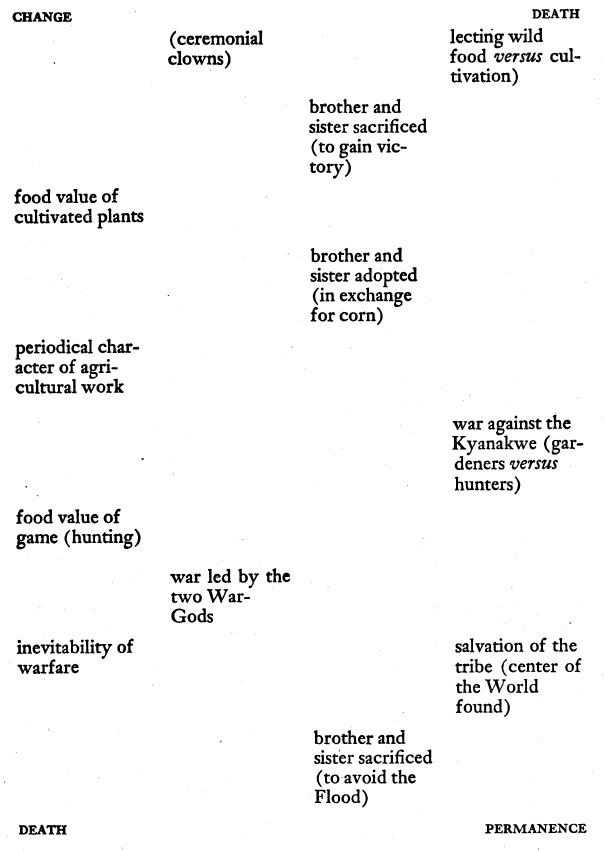

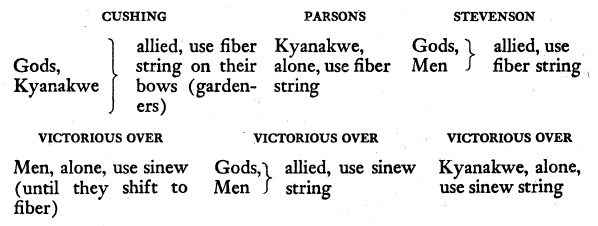

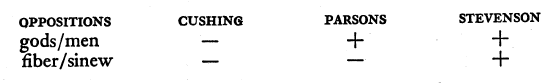

・パーソンズ、カッシング、スティーブンソンの異動

|

|

|

35

|

|

|

246

|

36

|

|

|

|

37

|

|

|

247

|

38

|

Some Central and Eastern Pueblos proceed the other way around. They begin

by stating the identity of hunting and cultivation (first corn obtained by Game-

Father sowing deer-dewclaws), and they try to derive both life and death from that

central notion. Then, instead of extreme terms being simple and intermediary ones

duplicated as among the Western groups, the extreme terms become duplicated (i.e.,

the two sisters of the Eastern Pueblo) while a simple mediating term comes to the

foreground (for instance, the Poshaiyanne of the Zia), but endowed with equivocal

attributes. Hence the attributes of this "messiah" can be deduced from the place it

occupies in the time sequence: good when at the beginning (Zuni, Cushing), equivocal

in the middle (Central Pueblo), bad at

the end (Zia), except in Bunzel where

the sequence is reversed as has been shown.

|

中

央および東部のプエブロ族の一部は、逆の順序で進めている。彼らは狩猟と耕作のアイデンティティ(最初にゲームファーザーがシカの手足を播種して得たトウ

モロコシ)を最初に述べ、その中心概念から生と死の両方を導き出そうとする。そして、極端な用語が単純で、西洋のグループのように中間的な用語が複製され

る代わりに、極端な用語が複製され(すなわち、東部プエブロの2人の姉妹)、単純で中間的な用語が前景に出てくる(例えば、ジアのポシャヤンネ)が、曖昧

な属性を持つ。したがって、この「救世主」の属性は、時間軸上の位置づけから推測できる。すなわち、始まり(ズニ、カッシング)では善良、中間(セントラ

ル・プエブロ)では曖昧、終わり(ジア)では悪である。ただし、ブンツェルでは、前述のように、この順序が逆転している。

|

|

39

|

By using systematically this

kind of structural analysis it becomes possible to

organize all the known variants of a myth as a series forming a kind of

permutation

group, the two variants placed at the far-ends being in a symmetrical,

though inverted,

relationship to each other.

Our method not only has the advantage of bringing some kind of order to

what was previously chaos; it also enables us to perceive some basic

logical processes which are at the root of mythical thought. Three main

processes should be distinguished.

|

このような構造的分析を体系的に行うことで、神話の既知のすべてのバリ

エーションを並べ替えグループのような一連のパターンとして整理することが可能になる。両端のバリエーションは、対称的な関係にあるが、反転している。

我々の方法は、混沌としていたものに何らかの秩序をもたらすという利点

があるだけでなく、神話的思考の根底にある基本的な論理的プロセスを認識することも可能にする。3つの主要なプロセスを区別すべきである。

|

248

|

40

|

The trickster of American

mythology has remained so far a problematic

figure. Why is it that throughout North America his part is assigned

practically everywhere

to either coyote or raven? If we keep in mind that mythical thought

always

works from the awareness of oppositions towards their progressive

mediation, the

reason for those choices becomes clearer. We need only to assume that

two opposite

terms with no intermediary always tend to be replaced by two equivalent

terms which

allow a third one as a mediator; then one of the polar terms and the

mediator becomes

replaced by a new triad and so on. Thus we have:

With the unformulated argument: carrion-eating animals are like prey

animals (they

eat animal food), but they are also like food-plant producers (they do

not kill what

they eat). Or, to put it otherwise, Pueblo style: ravens are to gardens

as prey animals

are to herbivorous ones. But it is also clear that herbivorous animals

may be called

first to act as mediators on the assumption that they are like

collectors and gatherers

(vegetal-food eaters) while they can be used as animal food though not

themselves

hunters. Thus we may have mediators of the first order, of the second

order, and so

on, where each term gives birth to the next by a double process of

opposition and correlation.

|

アメリカ神話のいたずら好き(トリックスター)は、これまでずっと問題

のある人物であり続けてきた。なぜ北米では、彼の役割はいたるところでコヨーテかカラスに割り当てられているのだろうか?神話的思考は、対立する概念の認

識から、それらの概念の進歩的な調停へと向かうということを念頭に置くと、これらの選択の理由が明らかになる。中間項を持たない2つの相反する概念は、常

に2つの同等の概念に置き換えられ、その概念の間に第3の概念が仲介者として入るようになる、と仮定するだけです。そして、極概念と仲介概念の1つが新た

な3項に置き換えられ、以下同様となる。したがって、次のようなことが言える。

未解決の議論として、腐肉食動物は獲物食動物(動物性食品を食べる)のようなものであるが、同時に食料植物生産者(食べるものを殺さない)のようなもので

ある、ということがある。あるいは、プエブロ族風に言えば、カラスは庭園にとって、獲物食動物は草食動物にとって、それぞれ同じようなものである。しか

し、草食動物は、狩猟はしないが動物性食糧として利用できるという前提で、収集・採集者(植物食)のような存在であるとみなされ、仲介者として真っ先に呼

び出される可能性があることも明らかである。したがって、第一次の仲介者、第二次の仲介者などがあり、それぞれの用語は、対立と相関の二重プロセスによっ

て次の用語を生み出す。

|

|

41

|

|

|

|

42

|

|

|

249

|

43

|

|

|

|

44

|

On the other hand, correlations

may appear on a transversal axis; true even on the linguistic level;

see the manifold connotation of the root Tewa according to Parsons:

coyote, mist, scalp, etc.). Coyote is intermediary between

herbivorous and carnivorous in the same way as mist between sky and

earth; between war and hunt (scalp is war-crop); corn smut between wild

plants and plants; garments between "nature" and "culture"; refuse

between village outside; ashes between roof and hearth (chimney). This

string of mediators, may call them so, not only throws light on whole

pieces of North American why the Dew-God may be at the same time the

Game-Master and the of raiments and be personified as an "Ash-Boy"; or

why the scalps are mist or why the Game-Mother is associated with corn

smut; etc.-but it also probably

corresponds to a universal way of organizing daily experience. See, for

instance, French for vegetal smut; nielle, from Latin nebula; the

luck-bringing power attributed

to refuse (old shoe) and ashes (kissing chimney-sweepers); and compare

the American

Ash-Boy cycle with the Indo-European Cinderella: both phallic figures

(mediator

between male and female); master of the dew and of the game; owners of

raiments; and social bridges (low class marrying into high class);

though impossible

to interpret through recent diffusion as has been sometimes contended

since Ash-and Cinderella are symmetrical but inverted in every detail

(while the borrowed

Cinderella tale in America-Zuni Turkey-Girl-is parallel to the

prototype):

|

一方、相関関係は横軸上に現れることがある。これは言語レベルでも当て

はまり、パーソンズによるテワ語根の多様な意味合い(コヨーテ、霧、頭皮など)を参照のこと。コヨーテは草食動物と肉食動物の仲介者であり、霧は空と大地

の仲介者である。戦争と狩猟(頭皮は戦利品)の間にも霧がある。トウモロコシの黒穂病は野生植物と植物の間にある。衣服は「自然」と「文化」の間にある。

ゴミは村の外部にある。灰は屋根と暖炉(煙突)の間にある。この一連の仲介者、そう呼ぶこともできるが、北米全体について、なぜ露の神が同時に狩猟の達人

であり、衣服の守護神であり、「灰の少年」として擬人化されているのか、あるいはなぜ頭皮が霧なのか、あるいはなぜ狩猟の女神がトウモロコシのすす病と関

連づけられているのか、などを明らかにするだけでなく、おそらくは日常的な経験を整理する普遍的な方法にも一致している。例えば、植物性のカビを意味する

フランス語の「nielle」や、ラテン語の「nebula」に由来する「nielle」、古靴や灰に幸運をもたらす力があると信じられていること(古い

靴や灰にキスをする煙突掃除夫)、そしてアメリカの灰小僧の物語とインド・ヨーロッパ語族のシンデレラを比較してみよう。どちらも男性と女性の仲介役であ

り、

露と狩猟の主人であり、衣服の所有者であり、社会的橋渡し役(下層階級が上流階級に嫁ぐ)でもある。ただし、アッシュとシンデレラは左右対称だが細部がす

べて逆になっているため(アメリカ・ズニ族の「七面鳥の少女」に借用されたシンデレラ物語は原型と並行している)、最近の普及を通して解釈することは不可

能である。

|

250

|

45

|

Thus, the mediating function of

the trickster explains that since its position

is halfway between two polar terms he must retain something of that

duality, namely

an ambiguous and equivocal character. But the trickster figure is not

the only conceivable

form of mediation; some myths seem to devote themselves to the

exhausting all the possible solutions to the problem of bridging the

gap between two

and one. For instance, a comparison between all the variants of the

Zuni emergence

myth provides us with a series of mediating devices, each of which

creates the next

one by a process of opposition and correlation:

|

このように、トリックスターの仲介機能は、その立場が2つの極間の半ば

にあるため、その二面性、すなわち曖昧で矛盾した性格をある程度は保持しなければならないことを説明している。しかし、トリックスターは仲介の唯一考えら

れる形態ではない。2つの間のギャップを埋める問題の解決法をすべて考えつくすことに専念している神話もある。例えば、ズニ族の出現神話のすべてのバリ

エーションを比較すると、一連の仲介装置が見えてくる。それぞれの装置は、対立と相関のプロセスによって次の装置を生み出す。

|

|

46

|

In Cushing's version, this dialectic is accompanied by a change from

the space dimension

(mediating between sky and earth) to the time dimension (mediating

between

summer and winter, i.e., between birth and death). But while the shift

is being made

from space to time, the final solution (triad) re-introduces space,

since a triad consists

in a dioscur pair plus a messiah simultaneously present; and while the

point of

departure was ostensibly formulated in terms of a space referent (sky

and earth) this

was nevertheless implicitly conceived in terms of a time referent

(first the messiah

calls; then the dioscurs descend). Therefore the logic of myth

confronts us with a

double, reciprocal exchange of functions to which we shall return

shortly.

|

クッシングのバージョンでは、この弁証法は空間次元(空と大地の間を仲介する)から時間次元(夏と冬の間、すなわち生と死の間を仲介する)への変化を伴

う。しかし、空間から時間への移行が行われている間、最終的な解決策(三位一体)は再び空間を導入する。なぜなら、三位一体は、同時に存在する二神と救世

主から構成されるからである。出発点は、一見、空間的な参照(空と大地)の観点から策定されたが、それにもかかわらず、暗黙のうちに時間的な参照(最初に

救世主が呼びかけ、次に二神が降臨する)の観点から構想されていた。したがって、神話の論理は、私たちに二重の相互交換機能をもたらし、これについては後

ほど再び触れることにする。

|

251

|

47

|

Not only can we account for the

ambiguous character of the trickster, but we

may also understand another property of mythical figures the world

over, namely,

that the same god may be endowed with contradictory attributes; for

instance, he

may be good and bad at the same time. If we compare the variants of the

Hopi myth

of the origin of Shalako, we may order them so that the following

structure becomes

apparent:

|

この神話の登場人物の曖昧な性格を説明できるだけでなく、世界中の神話

に登場する人物に共通するもう一つの性質、すなわち、同じ神に相反する属性が備わっている場合があること、例えば、同時に善と悪の両方の性質を持っている

場合があることについても理解できるかもしれない。ホピ族のシャラコ誕生神話のバリエーションを比較すると、次のような構造が明らかになる。

|

|

48

|

where x and y represent arbitrary values corresponding to the fact that

in the two

"extreme" variants the god Masauwu, while appearing alone instead of

associated

with another god, as in variant two, or being absent, as in three,

still retains intrinsically

a relative value. In variant one, Masauwu (alone) is depicted as

helpful to mankind

(though not as helpful as he could be), and in version four, harmful to

mankind

(though not as harmful as he could be); whereas in two, Muyingwu is

relatively

more helpful than Masauwu, and in three, Shalako more helpful than

Muyingwu.

We find an identical series when ordering the Keresan variants:

|

ここで、x と y

は、2つの「極端な」バリエーションにおいて、神マサウウは、バリエーション2のように他の神と関連付けられておらず単独で登場する場合、あるいはバリ

エーション3のように存在しない場合、本質的には相対的な価値を維持しているという事実に相当する任意の値を表す。バリエーション1では、マサウウ(単

独)は人類にとって有益(ただし、本来であれば有益であるほどではない)であると描かれており、バージョン4では人類にとって有害(ただし、本来であれば

有害であるほどではない)であると描かれている。一方、バリエーション2ではムインウがマサウウよりも相対的に有益であり、バリエーション3ではシャラコ

がムインウよりも有益である。ケレサンバリエーションを並べた場合、同じ系列を見つけることができる。

|

252

|

49

|

This logical framework is

particularly interesting since sociologists are

already acquainted with it on two other levels: first, with the problem

of the pecking

order among hens; and second, it also corresponds to what this writer

has called

general exchange in the field of kinship. By recognizing it also on the

level of mythical

thought, we may find ourselves in a better position to appraise its

basic importance

in sociological studies and to give it a more inclusive theoretical

interpretation.

|

この論理的枠組みは、社会学者にとって特に興味深いものである。なぜな

ら、社会学者たちはすでに2つの異なるレベルでこの枠組みを知っているからだ。まず、雌鶏の序列(ペッキングオーダ:つつきの順位)問題。次に、筆者が親

族の分野における「一般的な交換」と呼んでいるものにも対応する。この枠組みを神話的思考のレベルでも認識することで、社会学研究におけるその基本的重要

性をより適切に評価し、より包括的な理論的解釈を与えることができるだろう。

|

|

50

|

Finally, when we have succeeded

in organizing a whole series of variants in

a kind of permutation group, we are in a position to formulate the law

of that group.

Although it is not possible at the present stage to come closer than an

approximate

formulation which will certainly need to be made more accurate in the

future, it seems

that every myth (considered as the collection of all its variants)

corresponds to a

formula of the following type:

where, two terms being given as well as two functions of these terms,

it is stated that

a relation of equivalence still exists between two situations when

terms and relations

are inverted, under two conditions: I. that one term be replaced by its

contrary;

2. that an inversion be made between the function and the term value of

two elements.

|

最後に、一連の変化形を並べ替えグループにうまく整理できた場合、その

グループの法則を定式化できる。現段階では、より正確な定式化が必要であることは確かだが、近似的な定式化以上のことは不可能である。しかし、すべての神

話(その変化形の集合として考えられる)は、以下のタイプの公式に対応しているようだ。

ここで、2つの用語とそれらの用語の2つの機能が与えられ、2つの条件、すなわち、1.ある用語をその反対語に置き換えること、2.2つの要素の機能と用

語値の間で反転を行うこと、の下では、用語と関係が反転しても、2つの状況の間に等価関係が依然として存在することが述べられている。

|

|

51

|

This formula becomes highly

significant when we recall that Freud considered

that two traumas (and not one as it is so commonly said) are necessary

in

order to give birth to this individual myth in which a neurosis

consists. By trying to

apply the formula to the analysis of those traumatisms (and assuming

that they

correspond to conditions I. and 2. respectively) we should not only be

able to improve

it, but would find ourselves in the much desired position of developing

side by side

the sociological and the psychological aspects of the theory; we may

also take it to the

laboratory and subject it to experimental verification.

|

フロイトは、神経症を構成するこの個人の神話を生み出すためには、2つ

のトラウマ(一般的に言われているように1つではない)が必要だと考えていたことを思い出すと、この公式が非常に重要な意味を持つことがわかる。この公式

をそれらのトラウマ(それぞれ条件 I. と条件 2.

に相当すると仮定する)の分析に適用しようとすることで、この公式を改善できるだけでなく、理論の社会学的側面と心理学的側面を並行して発展させるとい

う、非常に望ましい立場に立つことができるだろう。また、この公式を実験室に持ち込んで、実験的に検証することもできるだろう。

|

253

|

52

|

At this point it seems

unfortunate that, with the limited means at the disposal

of French anthropological research, no further advance can be made. It

should be

emphasized that the task of analyzing mythological literature, which is

extremely

bulky, and of breaking it down into its constituent units, requires

team work and

secretarial help. A variant of average length needs several hundred

cards to be

properly analyzed. To discover a suitable pattern of rows and columns

for those

cards, special devices are needed, consisting of vertical boards about

two meters long

and one and one-half meters high, where cards can be pigeon-holed and

moved at will;

in order to build up three-dimensional models enabling one to compare

the variants,

several such boards are necessary, and this in turn requires a spacious

workshop, a

kind of commodity particularly unavailable in Western Europe nowadays.

Furthermore,

as soon as the frame of reference becomes multi-dimensional (which

occurs at

an early stage, as has been shown in 5.3.) the board-system has to be

replaced by

perforated cards which in turn require I.B.M. equipment, etc. Since

there is little

hope that such facilities will become available in France in the near

future, it is

much desired that some American group, better equipped than we are here

in Paris,

will be induced by this paper to start a project of its own in

structural mythology. Three final remarks may serve as conclusion.

|

この時点で、フランスの人類学研究が利用できる手段が限られているた

め、これ以上の進展が見込めないのは残念である。非常に膨大な神話文学を分析し、それを構成要素に分解するという作業は、チームワークと秘書的な支援を必

要とするものであることを強調しておきたい。平均的な長さのバリエーションを適切に分析するには、数百枚のカードが必要である。それらのカードに適切な行

と列のパターンを発見するには、縦2メートル、横1.5メートルの板からなる特別な装置が必要である。この板にはカードを自由に分類したり移動させたりで

きる。バリエーションを比較できる三次元モデルを構築するには、このような板がいくつか必要であり、そのためには広々とした作業場が必要となる。さらに、

参照の枠組みが多次元になると(5.3で述べたように、これは早い段階で起こる)、ボードシステムは穴あきカードに置き換えられ、そのカードにはIBMの

機器などが必要になる。このような設備がフランスで近い将来利用可能になる見込みはほとんどないため、パリの私たちよりも設備が整ったアメリカのグループ

が、この論文をきっかけに独自の構造神話プロジェクトに着手してくれることを強く望む。最後に3つのコメントを述べ、結論としたい。

|

|

53

|

First, the question has often

been raised why myths, and more generally oral

literature, are so much addicted to duplication, triplication or

quadruplication of the

same sequence. If our hypotheses are accepted, the answer is obvious:

repetition has

as its function to make the structure of the myth apparent. For we have

seen that the

synchro-diachronical structure of the myth permits us to organize it

into diachronical

sequences (the rows in our tables) which should be read synchronically

(the columns).

Thus, a myth exhibits a "slated" structure which seeps to the surface,

if one

may say so, through the repetition process

|

まず、神話や、より一般的に口承文学が、なぜ同じシーケンスの複製、三

重化、四重化にこれほどまでに執着するのかという疑問がしばしば提起されてきた。我々の仮説が受け入れられるのであれば、答えは明白である。繰り返しの機

能は、神話の構造を明らかにすることにある。なぜなら、神話の共時的・通時的構造によって、神話を通時的順序(表の行)に整理し、それを通時的に読む(表

の列)ことができることがわかったからだ。このように、神話は、いわば反復プロセスを通じて表面に現れる「予定調和」の構造を示している。

|

254

|

54

|

However, the slates are not

absolutely identical to each other. And since the

purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a

contradiction

(an impossible achievement if, as it happens, the contradiction is

real), a theoretically

infinite number of slates will be generated, each one slightly

different from the others.

Thus, myth grows spiral-wise until the intellectual impulse which has

originated it is

exhausted. Its growth is a continuous process whereas its structure

remains discontinuous.

If this is the case we should consider that it closely corresponds, in

the realm

of the spoken word, to the kind of being a crystal is in the realm of

physical matter. This analogy may help us understand better the

relationship of myth on one hand

to both langue and parole on the other.

|

しかし、それぞれのスレートは完全に同一ではない。神話の役割は矛盾を

克服できる論理的モデルを提供することにあるため(矛盾が現実のものだった場合、それは不可能な達成である)、理論的には無限に多くのスレートが生み出さ

れ、それぞれが少しずつ異なるものとなる。こうして、神話はそれを生み出した知的な衝動が尽きるまで螺旋状に成長していく。その成長は連続的なプロセスで

ある一方、その構造は不連続のままである。もしそうであるなら、口頭言語の領域における「結晶」の存在は、物理的物質における「結晶」の存在と密接に対応

していると考えられる。この類推は、神話と、言語と、言葉の両方との関係について、より深く理解する助けとなるかもしれない。

|

|

55

|

Prevalent attempts to explain

alleged differences between the so-called

"primitive" mind and scientific thought have resorted to qualitative

differences

between the working processes of the mind in both cases while assuming

that the

objects to which they were applying themselves remained very much the

same. If our

interpretation is correct, we are led toward a completely different

view, namely, that

the kind of logic which is used by mythical thought is as rigorous as

that of

modern science, and that the difference lies not in the quality of the

intellectual

process, but in the nature of the things to which it is applied. This

is well in agreement

with the situation known to prevail in the field of technology: what

makes a

steel ax superior to a stone one is not that the first one is better

made than the second.

They are equally well made, but steel is a different thing than stone.

In the same way

we may be able to show that the same logical processes are put to use

in myth as in

science, and that man has always been thinking equally well; the

improvement lies,

not in an alleged progress of man's conscience, but in the discovery of

new things to

which it may apply its unchangeable abilities.

|

いわゆる「原始的」な心と科学的な思考の相違点とされるものを説明しよ

うとする試みは、両者の心の働き方の質的な違いに言及する一方で、対象としているものはほとんど同じであると仮定している。もし我々の解釈が正しいのであ

れば、全く異なる見解、すなわち神話的思考で使用される論理は現代科学の論理と同じくらい厳密であり、その違いは知的プロセスの質ではなく、それが適用さ

れるものの性質にあるという見解に導かれる。これは、技術分野に広く知られている状況とよく一致している。鋼鉄の斧が石斧よりも優れているのは、前者が後

者よりもよくできているからではない。両者は同じようによくできているが、鋼鉄は石とは別物なのだ。同様に、神話においても科学においても同じ論理的プロ

セスが用いられ、人間は常に同じように思考してきたことを示すことができるかもしれない。進歩は、人間の良心の進歩という主張ではなく、その不変の能力を

適用できる新しいものの発見にある。

|

|

56

|

|

|

|

57

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

☆

☆