Claude Levi-Strauss, 1908-2009

クロード・レヴィ=ストロース

Claude Levi-Strauss, 1908-2009

解説:池田光穂

クロード・レヴィ=

ストロース(Claude Lévi-Strauss、1908年11月28日 -

2009年10月30日)は、フランスの社会人類学者、民族学者。ベルギーのブリュッセルで生まれ、フランスのパリで育った。コレージュ・ド・フランスの

社会人類学講座を1984年まで担当し、アメリカ先住民の神話研究を中心に研究を行った。ユダヤ人家庭に生まれたが、ユダヤあるいはヘブライ的伝統に関す

る発言はほとんどない。アカデミー・フランセーズ会員。専門分野は人類学、神話学。構造主義ないしは構造主義人類学(後者は同名の自著がある)の提唱者で

ある。彼の影響を受けた思想家たちには、ジャック・ラカン、ミシェル・フーコー、ロラン・バルト、ルイ・アルチュセールなどがいる。

| Claude

Lévi-Strauss

(/klɔːd ˈleɪvi ˈstraʊs/ klawd LAY-vee STROWSS,[2] French: [klod levi

stʁos]; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009)[3][4][5] was a French

anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of

the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology.[6] He held

the chair of Social Anthropology at the Collège de France between 1959

and 1982, was elected a member of the Académie française in 1973 and

was a member of the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences

in Paris. He received numerous honors from universities and

institutions throughout the world. Lévi-Strauss argued that the "savage" mind had the same structures as the "civilized" mind and that human characteristics are the same everywhere.[7][8] These observations culminated in his famous book Tristes Tropiques (1955) that established his position as one of the central figures in the structuralist school of thought. As well as sociology, his ideas reached into many fields in the humanities, including philosophy. Structuralism has been defined as "the search for the underlying patterns of thought in all forms of human activity."[4] He won the 1986 International Nonino Prize in Italy. |

クロード・レヴィ=ストロース(/klɔːd ↪Lm_2As/

klawd LAY-vee STROWSS, [2] French: [klod levi stʁos]; 1908年11月28日 -

2009年10月30日)[3][4][5]はフランスの人類学者、民族学者。

[1959年から1982年までコレージュ・ド・フランスで社会人類学の講座を受け持ち、1973年にはアカデミー・フランセーズ会員に選出された。世界

中の大学や機関から数々の栄誉を受けた。 レヴィ=ストロースは、「未開人」の心は「文明人」の心と同じ構造を持っており、人間の特性はどこでも同じであると主張した。社会学だけでなく、彼の思想 は哲学を含む人文科学の多くの分野に及んだ。構造主義とは、"あらゆる人間活動の根底にある思考パターンの探求 "と定義されている。1986年イタリアでノニーノ国際賞を受賞。 |

| Biography Early life and education Gustave Claude Lévi-Strauss was born in 1908 to French-Jewish (turned agnostic) parents who were living in Brussels at the time, where his father was working as a portrait painter.[9][10][11] He grew up in Paris, living on a street of the upscale 16th arrondissement named after the artist Claude Lorrain, whose work he admired and later wrote about.[12] During the First World War, from age 6 to 10, he lived with his maternal grandfather, who was the Rabbi of Versailles.[9][13][14] Despite his religious environment early on, Claude Lévi-Strauss was an atheist or agnostic, at least in his adult life.[15][16] From 1918 to 1925 he studied at Lycée Janson de Sailly high school, receiving a baccalaureate in June 1925 (age of 16).[9] In his last year (1924), he was introduced to philosophy, including the works of Marx[citation needed] and Kant,[citation needed] and began shifting to the political left (however, unlike many other socialists, he never became communist). From 1925, he spent the next two years at the prestigious Lycée Condorcet preparing for the entrance exam to the highly selective École normale supérieure. However, for reasons that are not entirely clear, he decided not to take the exam. In 1926, he went to Sorbonne in Paris, studying law and philosophy, as well as engaging in socialist politics and activism. In 1929, he opted for philosophy over law (which he found boring), and from 1930 to 1931, put politics aside to focus on preparing for the agrégation in philosophy, in order to qualify as a professor. In 1931, he passed the agrégation, coming in 3rd place, and youngest in his class at age 22. By this time, the Great Depression had hit France, and Lévi-Strauss found himself needing to provide not only for himself, but his parents as well.[17] Early career In 1935, after a few years of secondary-school teaching, he took up a last-minute offer to be part of a French cultural mission to Brazil in which he would serve as a visiting professor of sociology at the University of São Paulo while his then wife, Dina, served as a visiting professor of ethnology. The couple lived and did their anthropological work in Brazil from 1935 to 1939. During this time, while he was a visiting professor of sociology, Claude undertook his only ethnographic fieldwork. He accompanied Dina, a trained ethnographer in her own right, who was also a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo, where they conducted research forays into the Mato Grosso and the Amazon Rainforest. They first studied the Guaycuru and Bororó Indian tribes, staying among them for a few days. In 1938, they returned for a second, more than half-year-long expedition to study the Nambikwara and Tupi-Kawahib societies. At this time, his wife had an eye infection that prevented her from completing the study, which he concluded. This experience cemented Lévi-Strauss's professional identity as an anthropologist. Edmund Leach suggests, from Lévi-Strauss's own accounts in Tristes Tropiques, that he could not have spent more than a few weeks in any one place and was never able to converse easily with any of his native informants in their native language, which is uncharacteristic of anthropological research methods of participatory interaction with subjects to gain a full understanding of a culture. In the 1980s, he discussed why he became vegetarian in pieces published in Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica and other publications anthologized in the posthumous book Nous sommes tous des cannibales (2013): A day will come when the thought that to feed themselves, men of the past raised and massacred living beings and complacently exposed their shredded flesh in displays shall no doubt inspire the same repulsion as that of the travelers of the 16th and 17th century facing cannibal meals of savage American primitives in America, Oceania, Asia or Africa. Expatriation Lévi-Strauss returned to France in 1939 to take part in the war effort and was assigned as a liaison agent to the Maginot Line. After the French capitulation in 1940, he was employed at a lycée in Montpellier, but then was dismissed under the Vichy racial laws (Lévi-Strauss's family, originally from Alsace, was of Jewish ancestry). By the same laws, he was denaturalized, of his French citizenship and forced to escape persecution.[18] Around that time, he and his first wife separated. She stayed behind and worked in the French resistance, while he managed to escape Vichy France by boat to Martinique,[19] from where he was finally able to continue traveling. (Victor Serge describes conversations with Lévi-Strauss aboard the freighter Capitaine Paul-Lemerle from Marseilles to Martinique in his Notebooks.).[20] In 1941, he was offered a position at the New School for Social Research in New York City and granted admission to the United States. A series of voyages brought him, via South America, to Puerto Rico, where he was investigated by the FBI after German letters in his luggage aroused the suspicions of customs agents. Lévi-Strauss spent most of the war in New York City. Along with Jacques Maritain, Henri Focillon, and Roman Jakobson, he was a founding member of the École Libre des Hautes Études, a sort of university-in-exile for French academics. The war years in New York were formative for Lévi-Strauss in several ways. His relationship with Jakobson helped shape his theoretical outlook (Jakobson and Lévi-Strauss are considered to be two of the central figures on which structuralist thought is based).[21] In addition, Lévi-Strauss was also exposed to the American anthropology espoused by Franz Boas, who taught at Columbia University. In 1942, while having dinner at the Faculty House at Columbia, Boas died in Lévi-Strauss's arms.[22] This intimate association with Boas gave his early work a distinctive American inclination that helped facilitate its acceptance in the U.S. After a brief stint from 1946 to 1947 as a cultural attaché to the French embassy in Washington, DC, Lévi-Strauss returned to Paris in 1948. At this time, he received his state doctorate from the Sorbonne by submitting, in the French tradition, both a "major" and a "minor" doctoral thesis. These were La vie familiale et sociale des indiens Nambikwara (The Family and Social Life of the Nambikwara Indians) and Les structures élémentaires de la parenté (The Elementary Structures of Kinship).[23]: 234 Later life and death Wikinews has related news: French structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss dies at age 100 In 2008, he became the first member of the Académie française to reach the age of 100 and one of the few living authors to have his works published in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. On the death of Maurice Druon on 14 April 2009, he became the Dean of the Académie, its longest-serving member. He died on 30 October 2009, a few weeks before his 101st birthday.[3] The death was announced four days later.[3] French President Nicolas Sarkozy described him as "one of the greatest ethnologists of all time".[24] Bernard Kouchner, the French Foreign Minister, said Lévi-Strauss "broke with an ethnocentric vision of history and humanity ... At a time when we are trying to give meaning to globalization, to build a fairer and more humane world, I would like Claude Lévi-Strauss's universal echo to resonate more strongly".[25] In a similar vein, a statement by Lévi-Strauss was broadcast on National Public Radio in the remembrance produced by All Things Considered on 3 November 2009: "There is today a frightful disappearance of living species, be they plants or animals. And it's clear that the density of human beings has become so great, if I can say so, that they have begun to poison themselves. And the world which I am finishing my existence is no longer a world that I like."[citation needed] The Daily Telegraph said in its obituary that Lévi-Strauss was "one of the dominating postwar influences in French intellectual life and the leading exponent of Structuralism in the social sciences".[26] Permanent secretary of the Académie française Hélène Carrère d'Encausse said: "He was a thinker, a philosopher.... We will not find another like him".[27] |

生涯 生い立ちと教育 ギュスターヴ・クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは1908年、当時ブリュッセルに住んでいたフランス系ユダヤ人(不可知論者に転向)の両親のもとに生まれ る。 [12]第一次世界大戦中、6歳から10歳まで、彼はヴェルサイユのラビであった母方の祖父と一緒に住んでいた[9][13][14]彼の宗教的な環境に もかかわらず、クロード-レヴィ-ストロースは、少なくとも彼の成人期には、無神論者または不可知論者であった[15][16]。 1918年から1925年まで、彼はリセ・ジャンソン・ド・セイリー高等学校で学び、1925年6月(16歳)にバカロレアを取得した[9]。最後の年 (1924年)に、彼はマルクス[要出典]やカント[要出典]の著作を含む哲学に触れ、政治的左派にシフトし始めた(しかし、他の多くの社会主義者とは異 なり、彼は共産主義者になることはなかった)。1925年から2年間、名門リセ・コンドルセで、超難関の高等師範学校(École normale supérieure)の入学試験に備える。しかし、理由は定かではないが、受験を断念。1926年、パリのソルボンヌ大学に進学し、法学と哲学を学ぶと 同時に、社会主義政治や活動にも参加した。1929年、彼は法学よりも哲学を選択し(退屈に感じた)、1930年から1931年まで、政治はさておき、教 授の資格を得るため、哲学のアグレガシオン試験の準備に専念した。1931年、彼はアグレガシオン試験に3位で合格し、22歳でクラス最年少となった。こ の頃、フランスは世界恐慌に見舞われ、レヴィ=ストロースは自分だけでなく両親も養う必要があることに気づく[17]。 初期のキャリア 1935年、中等教育で数年間教鞭をとった後、フランスからブラジルへの文化使節団の一員として、サンパウロ大学で社会学の客員教授を務めることになっ た。 夫妻は1935年から1939年までブラジルに住み、人類学的研究を行った。この間、社会学の客員教授であったクロードは、唯一の民族学的フィールドワー クを行った。彼は、サンパウロ大学の客員教授でもあり、自らも民族誌学者としての訓練を受けたディナを伴って、マトグロッソとアマゾンの熱帯雨林に調査に 出かけた。彼らはまずグアイクル族とボロロ族を調査し、数日間滞在した。1938年、彼らは再び半年以上にわたる2度目の探検に戻り、ナンビクワラとトゥ ピ・カワヒブの社会を調査した。この時、妻は目の感染症にかかり、研究を終えることができなかった。この経験は、人類学者としてのレヴィ=ストロースの職 業的アイデンティティを確固たるものにした。エドマンド・リーチは、『Tristes Tropiques』におけるレヴィ=ストロース自身の証言から、彼が1つの場所に滞在したのは数週間にも満たなかったこと、そしてどの原住民のイン フォーマントとも彼らの母国語で簡単に会話することができなかったことを示唆している。 1980年代、彼はイタリアの日刊紙『ラ・レプッブリカ』などに掲載された遺稿集『Nous sommes tous des cannibales』(2013年)で、ベジタリアンになった理由を語っている: 自分たちを養うために、昔の人たちは生き物を飼育し、虐殺し、その細切れの肉を満足げに陳列していたのだと思うと、16~17世紀の旅行者がアメリカ、オ セアニア、アジア、アフリカで野蛮なアメリカ原住民の人肉食に直面したときと同じような反感を抱く日が来るに違いない。 海外移住 レヴィ=ストロースは1939年、戦争に参加するためフランスに戻り、マジノ線の連絡係に任命された。1940年のフランス降伏後、彼はモンペリエのリセ に就職したが、ヴィシーの人種法によって解雇された(レヴィ=ストロースの家族はアルザス出身で、先祖はユダヤ人)。同法により、彼はフランス国籍を剥奪 され、迫害から逃れることを余儀なくされた[18]。 その頃、最初の妻とは別居。彼女は残り、フランスのレジスタンスで働き、一方、彼は船でヴィシー・フランスからマルティニークに逃れ、そこからようやく旅 を続けることができた[19]。(ヴィクトール・セルジュは、『ノート』の中で、マルセイユからマルティニークに向かう貨物船キャプテーヌ・ポール・ル メール号でのレヴィ=ストロースとの会話を記している)[20]。 1941年、レヴィ=ストロースはニューヨークのニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチで職を得、アメリカへの入学を許可される。一連の航海で 南米を経由してプエルトリコに到着したレヴィ=ストロースは、荷物の中にあったドイツ語の手紙に税関職員が疑念を抱き、FBIの調査を受ける。レヴィ=ス トロースは戦争のほとんどをニューヨークで過ごした。ジャック・マリタン、アンリ・フォシヨン、ロマン・ヤコブソンらとともに、フランスの学者たちの亡命 大学のようなものである高等研究学院の創立メンバーであった。 ニューヨークでの戦時中は、レヴィ=ストロースにとっていくつかの点で形成的な時期であった。ヤコブソンとの関係は、彼の理論的展望を形成するのに役立っ た(ヤコブソンとレヴィ=ストロースは、構造主義思想の基盤となっている中心人物の2人と考えられている)[21]。さらに、レヴィ=ストロースは、コロ ンビア大学で教鞭を執っていたフランツ・ボースが信奉するアメリカの人類学にも触れた。1942年、コロンビア大学のファカルティハウスで夕食をとってい たボースは、レヴィ=ストロースの腕の中で息を引き取った。 1946年から1947年まで、ワシントンDCのフランス大使館文化担当官として短期間滞在した後、レヴィ=ストロースは1948年にパリに戻った。ソル ボンヌ大学で博士号を取得するため、フランスの伝統に従って「主論文」と「副論文」の両方を提出した。それらは、La vie familiale et sociale des indiens Nambikwara(南ビクワラ・インディアンの家族と社会生活)とLes structures élémentaires de la parenté(親族関係の初歩的構造)であった[23]: 234。 その後の人生と死 ウィキニュースに関連ニュースが掲載されています: フランスの構造学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、100歳で死去 2008年、レヴィ=ストロースはアカデミー・フランセーズ会員として初めて100歳を迎え、現存する数少ない作家の一人としてプレヤード図書館に作品が 収められた。2009年4月14日、モーリス・ドルオンの死去に伴い、アカデミー長に就任。 訃報はその4日後に発表された[3]。 フランスのニコラ・サルコジ大統領は、レヴィ=ストロースを「史上最も偉大な民族学者の一人」と評した[24]。フランスのベルナール・クシュネル外相 は、レヴィ=ストロースについて「歴史と人類に対する民族中心主義的なヴィジョンを打ち破った。グローバリゼーションに意味を与え、より公平で人道的な世 界を築こうとしている今、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの普遍的な響きをより強く響かせたい」[25] 同様の意味で、レヴィ=ストロースの声明は、2009年11月3日にAll Things Consideredが制作した追悼番組でNational Public Radioで放送された: 「今日、植物であれ動物であれ、生物の種が恐ろしいほど消滅している。そして、人間の密度が非常に高くなったことは明らかです。デイリー・テレグラフ紙は 追悼記事で、レヴィ=ストロースは「戦後フランスの知的生活に大きな影響を与えた人物の一人であり、社会科学における構造主義の代表的な提唱者であった」 と述べている[26]。 エレーヌ・カレール・ダンカッセ・アカデミーフランセ常任秘書は次のように述べている: 「彼は思想家であり、哲学者であった。彼のような人物は他にいないでしょう」[27]。 |

| Career and development of

structural anthropology This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) The Elementary Structures of Kinship was published in 1949 and quickly came to be regarded as one of the most important anthropological works on kinship. It was even reviewed favorably by Simone de Beauvoir, who saw it as an important statement of the position of women in non-Western cultures. A play on the title of Durkheim's famous Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, Lévi-Strauss' Elementary Structures re-examined how people organized their families by examining the logical structures that underlay relationships rather than their contents. While British anthropologists such as Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown argued that kinship was based on descent from a common ancestor, Lévi-Strauss argued that kinship was based on the alliance between two families that formed when women from one group married men from another.[28] Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Lévi-Strauss continued to publish and experienced considerable professional success. On his return to France, he became involved with the administration of the CNRS and the Musée de l'Homme before finally becoming professor (directeur d'études) of the fifth section of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, the 'Religious Sciences' section where Marcel Mauss was previously professor, the title of which chair he renamed "Comparative Religion of Non-Literate Peoples". While Lévi-Strauss was well known in academic circles, in 1955 he became one of France's best-known intellectuals by publishing Tristes Tropiques in Paris that year by Plon (best-known translated into English in 1973, published by Penguin). Essentially, this book was a memoir detailing his time as a French expatriate throughout the 1930s, and his travels. Lévi-Strauss combined exquisitely beautiful prose, dazzling philosophical meditation, and ethnographic analysis of the Amazonian peoples to produce a masterpiece. The organizers of the Prix Goncourt, for instance, lamented that they were not able to award Lévi-Strauss the prize because Tristes Tropiques was nonfiction.[citation needed] Lévi-Strauss was named to a chair in social anthropology at the Collège de France in 1959. At roughly the same time he published Structural Anthropology, a collection of his essays that provided both examples and programmatic statements about structuralism. At the same time as he was laying the groundwork for an intellectual program, he began a series of institutions to establish anthropology as a discipline in France, including the Laboratory for Social Anthropology where new students could be trained, and a new journal, l'Homme, for publishing the results of their research. |

構造人類学のキャリアと発展 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性があります。(2016年1月) (このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) The Elementary Structures of Kinship(親族関係の初歩的構造)』は1949年に出版され、すぐに親族関係に関する人類学的著作の中で最も重要なものの1つとみなされるように なった。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールも、非西洋文化圏における女性の立場を示す重要な書物であると評価した。デュルケムの有名な『宗教生活の初歩的形 態』のタイトルをもじったレヴィ=ストロースの『初歩的構造』は、人間関係の内容ではなく、人間関係の根底にある論理的構造を検討することによって、人々 がどのように家族を組織しているかを再検討した。アルフレッド・レジナルド・ラドクリフ=ブラウンのようなイギリスの人類学者が親族関係は共通の祖先から の子孫に基づいていると主張したのに対して、レヴィ=ストロースは親族関係はある集団の女性が別の集団の男性と結婚したときに形成される2つの家族の間の 同盟に基づいていると主張した[28]。 1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、レヴィ=ストロースは出版活動を続け、仕事上でもかなりの成功を収めた。フランスに戻ると、CNRSと人 間博物館の運営に携わるようになり、最終的に高等師範学校第5部「宗教科学」の教授(directeur d'études)となった。 レヴィ=ストロースは学界ではよく知られていたが、1955年、パリで『Tristes Tropiques』をプロン社から出版し、フランスで最もよく知られた知識人の一人となった(英語への翻訳は1973年にペンギン社から出版されたもの が最もよく知られている)。本書は基本的に、1930年代を通じてフランスに駐在していた彼の時代と旅の詳細を記した回想録である。レヴィ=ストロース は、絶妙に美しい散文、めくるめく哲学的瞑想、アマゾン民族の民族誌的分析を組み合わせ、傑作を生み出した。例えば、ゴンクール賞の主催者は、 『Tristes Tropiques』がノンフィクションであったため、レヴィ=ストロースに賞を与えることができなかったと嘆いた[要出典]。 レヴィ=ストロースは1959年にコレージュ・ド・フランスの社会人類学の講座に任命された。ほぼ同時期に、彼は構造主義についての実例と綱領的な声明を 提供したエッセイ集『構造人類学』を出版した。知的プログラムの基礎を固めると同時に、彼はフランスで人類学を学問として確立するための一連の制度を開始 した。その中には、新入生を訓練するための社会人類学研究室や、研究成果を発表するための新しい雑誌『l'Homme』などがあった。 |

| The Savage Mind In 1962, Lévi-Strauss published what is for many people his most important work, La Pensée Sauvage, translated into English as The Savage Mind. The French title is an untranslatable pun, as the word pensée means both 'thought' and 'pansy', while sauvage has a range of meanings different from English 'savage'. Lévi-Strauss supposedly suggested that the English title be Pansies for Thought, borrowing from a speech by Ophelia in Shakespeare's Hamlet (Act IV, Scene V). French editions of La Pensée Sauvage are often printed with an image of wild pansies on the cover. The Savage Mind discusses not just "primitive" thought, a category defined by previous anthropologists, but also forms of thought common to all human beings. The first half of the book lays out Lévi-Strauss's theory of culture and mind, while the second half expands this account into a theory of history and social change. This latter part of the book engaged Lévi-Strauss in a heated debate with Jean-Paul Sartre over the nature of human freedom. On the one hand, Sartre's existentialist philosophy committed him to a position that human beings fundamentally were free to act as they pleased. On the other hand, Sartre also was a leftist who was committed to ideas such as that individuals were constrained by the ideologies imposed on them by the powerful. Lévi-Strauss presented his structuralist notion of agency in opposition to Sartre. Echoes of this debate between structuralism and existentialism eventually inspired the work of younger authors such as Pierre Bourdieu. |

野蛮な精神(『野生の思考』) 1962年、レヴィ=ストロースは彼の最も重要な著作である『La Pensée Sauvage』(英語では『The Savage Mind』)を出版した。フランス語のタイトルは翻訳不可能なダジャレで、penséeは「思考」と「パンジー」の両方の意味を持ち、sauvageは英 語の「野蛮人」とは異なるさまざまな意味を持つ。レヴィ=ストロースは、シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』(第4幕第5場)に登場するオフィーリアの演説を 引用して、英語のタイトルを『Pansies for Thought(思考のためのパンジー)』にすることを提案したと言われている。フランス語版『La Pensée Sauvage』の表紙には、しばしば野生のパンジーの花が描かれている。 野蛮な心』は、これまでの人類学者が定義してきた「原始的な」思考だけでなく、すべての人間に共通する思考形態についても論じている。本書の前半はレヴィ =ストロースの文化と心に関する理論を展開し、後半はこの理論を歴史と社会の変化に関する理論へと発展させている。本書の後半部では、人間の自由の本質を めぐって、レヴィ=ストロースはジャン=ポール・サルトルと激しい論争を繰り広げた。一方では、サルトルの実存主義哲学は、人間は基本的に好きなように行 動する自由があるとする立場をとっていた。他方で、サルトルは左翼主義者でもあり、権力者によって押しつけられたイデオロギーによって個人が束縛されると いった考え方に傾倒していた。レヴィ=ストロースは、サルトルに対抗して、構造主義的な主体性の概念を提示した。この構造主義と実存主義の論争の反響は、 やがてピエール・ブルデューのような若い作家たちの仕事に影響を与えた。 |

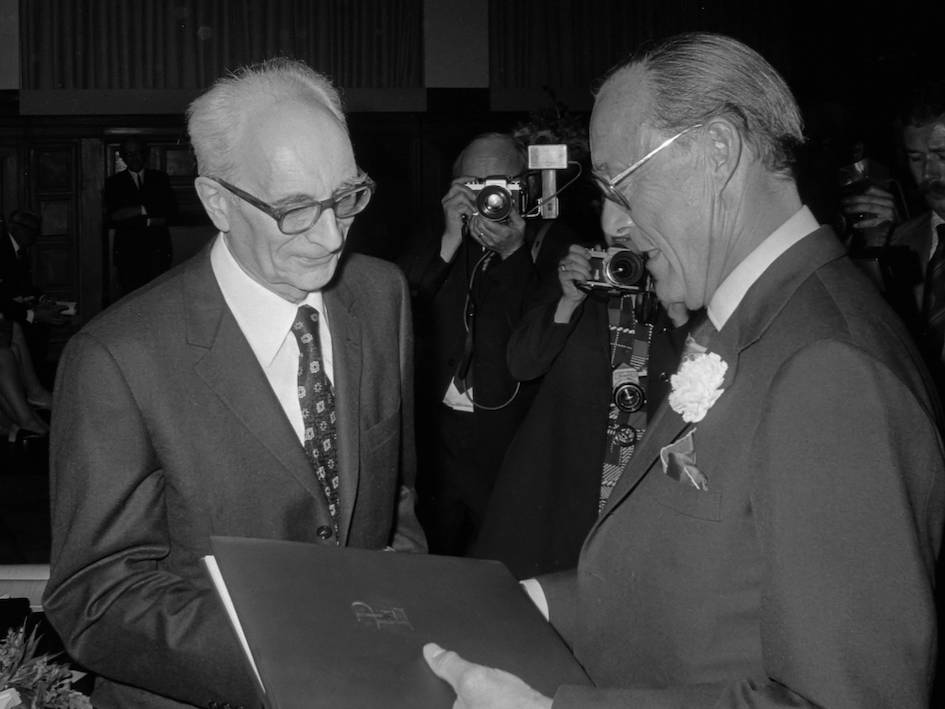

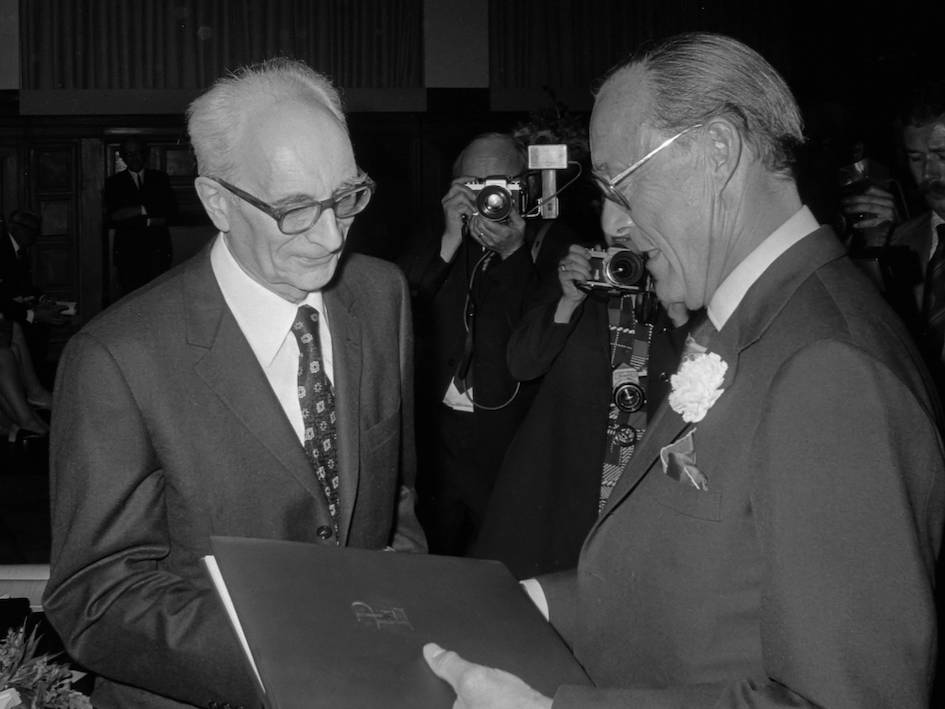

| Mythologiques Now a worldwide celebrity, Lévi-Strauss spent the second half of the 1960s working on his master project, a four-volume study called Mythologiques. In it, he followed a single myth from the tip of South America and all of its variations from group to group north through Central America and eventually into the Arctic Circle, thus tracing the myth's cultural evolution from one end of the Western Hemisphere to the other. He accomplished this in a typically structuralist way, examining the underlying structure of relationships among the elements of the story rather than focusing on the content of the story itself. While Pensée Sauvage was a statement of Lévi-Strauss's big-picture theory, Mythologiques was an extended, four-volume example of analysis. Richly detailed and extremely long, it is less widely read than the much shorter and more accessible Pensée Sauvage, despite its position as Lévi-Strauss's masterwork.  Claude Lévi-Strauss, receiving the Erasmus Prize (1973) Lévi-Strauss completed the final volume of Mythologiques in 1971. On 14 May 1973, he was elected to the Académie française, France's highest honour for a writer.[29] He was a member of other notable academies worldwide, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1956, he became foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[30] He then became a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1960 and the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1967.[31] He received the Erasmus Prize in 1973, the Meister-Eckhart-Prize for philosophy in 2003, and several honorary doctorates from universities such as Oxford, Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. He also was the recipient of the Grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur, was a Commandeur de l'ordre national du Mérite, and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. In 2005, he received the XVII Premi Internacional Catalunya (Generalitat of Catalonia). After his retirement, he continued to publish occasional meditations on art, music, philosophy, and poetry. |

神話学 今や世界的な有名人となったレヴィ=ストロースは、1960年代後半、『Mythologiques(神話学)』と呼ばれる4巻からなる研究書の執筆に没 頭した。その中でレヴィ=ストロースは、ひとつの神話を南米の先端から、そのすべての変種を集団から集団へと追いかけ、中米を北上し、最終的には北極圏に 至るまで、西半球の端から端まで神話の文化的進化をたどった。彼は典型的な構造主義的手法でこれを成し遂げ、物語の内容そのものに焦点を当てるのではな く、物語の要素間の関係の根底にある構造を考察した。Pensée Sauvage』がレヴィ=ストロースの大局的な理論の表明であったのに対し、『Mythologiques』は4巻からなる拡大された分析例であった。 レヴィ=ストロースの代表作であるにもかかわらず、『Mythologiques』は『Pensée Sauvage』よりもはるかに短く、親しみやすい。  エラスムス賞を受賞したクロード・レヴィ=ストロース(1973年) レヴィ=ストロースは1971年に『神話学』の最終巻を完成させた。1973年5月14日、作家としてフランス最高の栄誉であるアカデミー・フランセーズ に選出される[29]。1973年にエラスムス賞、2003年にマイスター・エックハート賞(哲学部門)、オックスフォード大学、ハーバード大学、イェー ル大学、コロンビア大学などから名誉博士号を授与。また、レジオンドヌール勲章を受章し、国家勲章コマンドゥール、芸術文化勲章コマンドゥールも受章して いる。2005年には第17回カタルーニャ国際賞を受賞。引退後も、芸術、音楽、哲学、詩についての思索を折に触れて発表している。 |

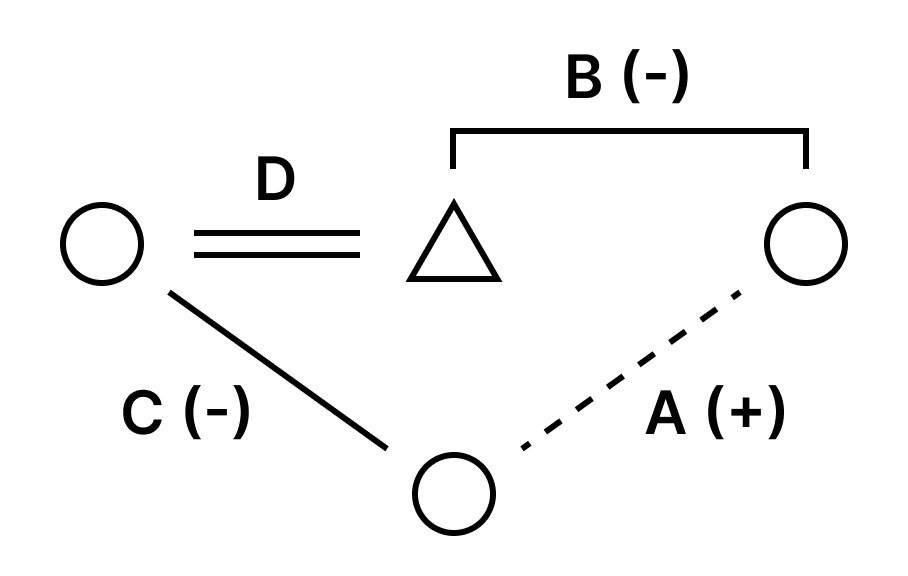

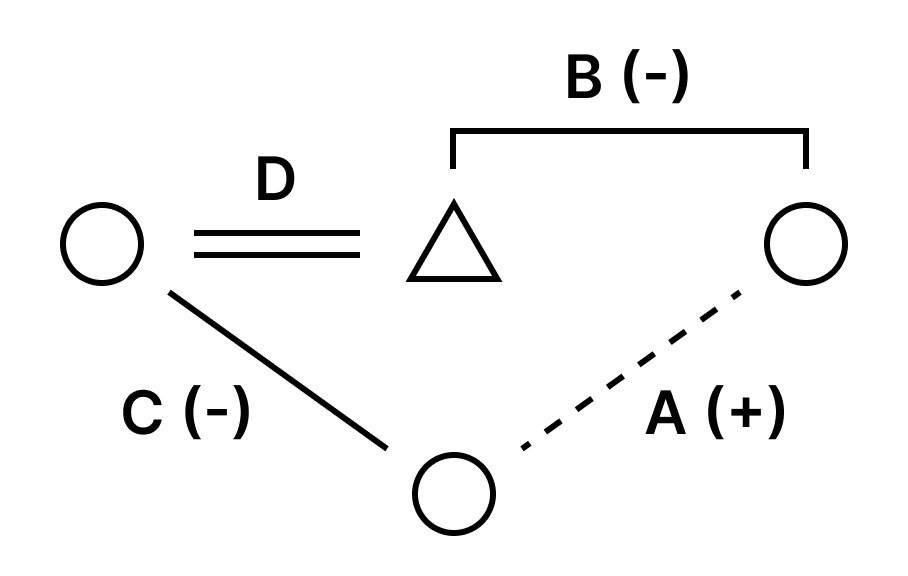

| Anthropological theories This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) This section possibly contains original research. (May 2013) Lévi-Strauss sought to apply the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure to anthropology.[32] At the time, the family was traditionally considered the fundamental object of analysis but was seen primarily as a self-contained unit consisting of a husband, a wife, and their children. Nephews, cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents all were treated as secondary. Lévi-Strauss argued that akin to Saussure's notion of linguistic value, families acquire determinate identities only through relations with one another. Thus, he inverted the classical view of anthropology, putting the secondary family members first and insisting on analyzing the relations between units instead of the units themselves.[33]  A diagram illustrating Lévi-Strauss's theory of kinship. In such a case, one can infer that D is positive. In his own analysis of the formation of the identities that arise through marriages between tribes, Lévi-Strauss noted that the relation between the uncle and the nephew was to the relation between brother and sister, as the relation between father and son is to that between husband and wife, that is, A is to B as C is to D. Therefore, if we know A, B, and C, we can predict D. An example of this law is illustrated in the diagram. The four relation units are marked with A to D. Lévi-Strauss noted that if A is positive, B is negative, and C is negative, then it can inferred that D is positive, thereby satisfying the constraint 'A is to B as C is to D'; in this case, the relations are contrasting. The goal of Lévi-Strauss's structural anthropology, then, was to simplify the masses of empirical data into generalized, comprehensible relations between units, which allow for predictive laws to be identified, such as A is to B as C is to D.[33] Lévi-Strauss's theory is set forth in Structural Anthropology (1958). Briefly, he considers culture a system of symbolic communication, to be investigated with methods that others have used more narrowly in the discussion of novels, political speeches, sports, and movies. His reasoning makes best sense when contrasted against the background of an earlier generation's social theory. He wrote about this relationship for decades. A preference for "functionalist" explanations dominated the social sciences from the turn of the 20th century through the 1950s, which is to say that anthropologists and sociologists tried to state the purpose of a social act or institution. The existence of a thing was explained, if it fulfilled a function. The only strong alternative to that kind of analysis was historical explanation, accounting for the existence of a social fact by stating how it came to be. The idea of social function developed in two different ways, however. The English anthropologist Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, who had read and admired the work of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, argued that the goal of anthropological research was to find the collective function, such as what a religious creed or a set of rules about marriage did for the social order as a whole. Behind this approach was an old idea, the view that civilization developed through a series of phases from the primitive to the modern, everywhere in the same manner. All of the activities in a given kind of society would partake of the same character; some sort of internal logic would cause one level of culture to evolve into the next. On this view, a society can easily be thought of as an organism, the parts functioning together as do the parts of a body. In contrast, the more influential functionalism of Bronisław Malinowski described the satisfaction of individual needs, what a person derived by participating in a custom. In the United States, where the shape of anthropology was set by the German-educated Franz Boas, the preference was for historical accounts. This approach had obvious problems, which Lévi-Strauss praises Boas for facing squarely. Historical information seldom is available for non-literate cultures. The anthropologist fills in with comparisons to other cultures and is forced to rely on theories that have no evidential basis, the old notion of universal stages of development or the claim that cultural resemblances are based on some unrecognized past contact between groups. Boas came to believe that no overall pattern in social development could be proven; for him, there was no single history, only histories. There are three broad choices involved in the divergence of these schools; each had to decide: what kind of evidence to use; whether to emphasize the particulars of a single culture or look for patterns underlying all societies; and what the source of any underlying patterns might be, the definition of a common humanity. Social scientists in all traditions relied on cross-cultural studies,[citation needed] as it was always necessary to supplement information about a society with information about others. Thus, some idea of a common human nature was implicit in each approach. The critical distinction, then, remained twofold: Does a social fact exist because it is functional for the social order, or because it is functional for the person? Do uniformities across cultures occur because of organizational needs that must be met everywhere, or because of the uniform needs of human personality? For Lévi-Strauss, the choice was for the demands of the social order. He had no difficulty bringing out the inconsistencies and triviality of individualistic accounts. Malinowski said, for example, that magic beliefs come into being when people need to feel a sense of control over events when the outcome was uncertain. In the Trobriand Islands, he found the proof of this claim in the rites surrounding abortions and weaving skirts. But in the same tribes, there is no magic attached to making clay pots even though it is no more certain a business than weaving. So, the explanation is not consistent. Furthermore, these explanations tend to be used in an ad hoc, superficial way – one postulates a trait of personality when needed. However, the accepted way of discussing organizational function did not work either. Different societies might have institutions that were similar in many obvious ways and yet, served different functions. Many tribal cultures divide the tribe into two groups and have elaborate rules about how the two groups may interact. However, exactly what they may do—trade, intermarry—is different in different tribes; for that matter, so are the criteria for distinguishing the groups. Nor will it do to say that dividing-in-two is a universal need of organizations, because there are a lot of tribes that thrive without it. For Lévi-Strauss, the methods of linguistics became a model for all his earlier examinations of society. His analogies usually are from phonology (though also later from music, mathematics, chaos theory, cybernetics, and so on). "A really scientific analysis must be real, simplifying, and explanatory," he writes.[34] Phonemic analysis reveals features that are real, in the sense that users of the language can recognize and respond to them. At the same time, a phoneme is an abstraction from language – not a sound, but a category of sound defined by the way it is distinguished from other categories through rules unique to the language. The entire sound-structure of a language may be generated from a relatively small number of rules. In the study of the kinship systems that first concerned him, this ideal of explanation allowed a comprehensive organization of data that partly had been ordered by other researchers. The overall goal was to find out why family relations differed among various South American cultures. The father might have great authority over the son in one group, for example, with the relationship rigidly restricted by taboos. In another group, the mother's brother would have that kind of relationship with the son, while the father's relationship was relaxed and playful. A number of partial patterns had been noted. Relations between the mother and father, for example, had some sort of reciprocity with those of father and son–if the mother had a dominant social status and was formal with the father, for example, then the father usually had close relations with the son. But these smaller patterns joined in inconsistent ways. One possible way of finding a master order was to rate all the positions in a kinship system along several dimensions. For example, the father was older than the son, the father produced the son, the father had the same sex as the son, and so on; the matrilineal uncle was older and of the same sex, but did not produce the son, and so on. An exhaustive collection of such observations might cause an overall pattern to emerge. However, for Lévi-Strauss, this kind of work was considered "analytical in appearance only". It results in a chart that is far more difficult to understand than the original data and is based on arbitrary abstractions (empirically, fathers are older than sons, but it is only the researcher who declares that this feature explains their relations). Furthermore, it does not explain anything. The explanation it offers is tautological—if age is crucial, then age explains a relationship. And it does not offer the possibility of inferring the origins of the structure. A proper solution to the puzzle is to find a basic unit of kinship which can explain all the variations. It is a cluster of four roles – brother, sister, father, son. These are the roles that must be involved in any society that has an incest taboo requiring a man to obtain a wife from some man outside his own hereditary line.[clarification needed] A brother may give away his sister, for example, whose son might reciprocate in the next generation by allowing his own sister to marry exogamously. The underlying demand is a continued circulation of women to keep various clans peacefully related. Right or wrong, this solution displays the qualities of structural thinking. Even though Lévi-Strauss frequently speaks of treating culture as the product of the axioms and corollaries that underlie it, or the phonemic differences that constitute it, he is concerned with the objective data of field research. He notes that it is logically possible for a different atom of kinship structure to exist–sister, sister's brother, brother's wife, daughter – but there are no real-world examples of relationships that can be derived from that grouping. The trouble with this view has been shown by Australian anthropologist Augustus Elkin, who insisted on the point that in a four class marriage system, the preferred marriage was with a classificatory mother's brother's daughter and never with the true one. Lévi-Strauss's atom of kinship structure deals only with consanguineal kin. There is a big difference between the two situations, in that the kinship structure involving the classificatory kin relations allows for the building of a system which can bring together thousands of people. Lévi-Strauss's atom of kinship stops working once the true MoBrDa is missing.[clarification needed] Lévi-Strauss also developed the concept of the house society to describe those societies where the domestic unit is more central for social organization than the descent group or lineage. The purpose of structuralist explanation is to organize real data in the simplest effective way. All science, he says, is either structuralist or reductionist.[35] In confronting such matters as the incest taboo, one is facing an objective limit of what the human mind has accepted so far. One could hypothesize some biological imperative underlying it, but so far as social order is concerned, the taboo has the effect of an irreducible fact. The social scientist can only work with the structures of human thought that arise from it. And structural explanations can be tested and refuted. A mere analytic scheme that wishes causal relations into existence is not structuralist in this sense. Lévi-Strauss's later works are more controversial, in part because they impinge on the subject matter of other scholars. He believed that modern life and all history was founded on the same categories and transformations that he had discovered in the Brazilian backcountry—The Raw and the Cooked, From Honey to Ashes, The Naked Man (to borrow some titles from the Mythologiques). For instance, he compares anthropology to musical serialism and defends his "philosophical" approach. He also pointed out that the modern view of primitive cultures was simplistic in denying them a history. The categories of myth did not persist among them because nothing had happened–it was easy to find the evidence of defeat, migration, exile, repeated displacements of all the kinds known to recorded history. Instead, the mythic categories had encompassed these changes. He argued for a view of human life as existing in two timelines simultaneously, the eventful one of history and the long cycles in which one set of fundamental mythic patterns dominates and then perhaps another. In this respect, his work resembles that of Fernand Braudel, the historian of the Mediterranean and 'la longue durée,' the cultural outlook and forms of social organization that persisted for centuries around that sea. He is right in that history is difficult to build up in non-literate society, nevertheless, Jean Guiart's anthropological and José Garanger's archeological work in central Vanuatu, bringing to the fore the skeletons of former chiefs described in local myths, who had thus been living persons, shows that there can be some means of ascertaining the history of some groups which otherwise would be deemed a historical. Another issue is the experience that the same person can tell one a myth highly charged in symbols, and some years later a sort of chronological history claiming to be the chronic of a descent line (e.g., in the Loyalty islands and New Zealand), the two texts having in common that they each deal in topographical detail with the land-tenure claims of the said descent line (see Douglas Oliver on the Siwai in Bougainville). Lévi-Strauss would agree to these aspects be explained inside his seminar but would never touch them on his own. The anthropological data content of the myths was not his problem. He was only interested with the formal aspects of each story, considered by him as the result of the workings of the collective unconscious of each group, which idea was taken from the linguists, but cannot be proved in any way although he was adamant about its existence and would never accept any discussion on this point. |

人類学の理論 このセクションには複数の問題があります。改善にご協力いただくか、トークページでこれらの問題について議論してください。(これらのテンプレートメッ セージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) このセクションは検証のために追加の引用が必要です。(2013年5月) このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。(2013年5月) レヴィ=ストロースは、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの構造言語学を人類学に適用しようとした[32]。当時、家族は伝統的に分析の基本的な対象とみな されていたが、主に夫、妻、そしてその子どもたちからなる自己完結的な単位とみなされていた。甥、いとこ、叔父、叔母、祖父母はすべて二次的なものとして 扱われていた。レヴィ=ストロースは、ソシュールの言語的価値の概念と同様に、家族は互いの関係を通じてのみ確定的なアイデンティティを獲得すると主張し た。したがって、彼は古典的な人類学の見方を逆転させ、二次的な家族構成員を第一に考え、単位そのものではなく、単位間の関係を分析することを主張した [33]。  レヴィ=ストロースの親族関係を示す図。このような場合、Dは肯定的であると推測できる。 レヴィ=ストロースは、部族間の結婚によって生じるアイデンティティの形成に関する彼自身の分析において、叔父と甥の関係は、父と息子の関係が夫と妻の関 係にあるように、兄と妹の関係にあると指摘した。レヴィ=ストロースは、Aが正、Bが負、Cが負であれば、Dが正であると推論でき、それによって「CがD であるように、AはBである」という制約を満たすと指摘した。レヴィ=ストロースの構造人類学の目標は、大量の経験的データを一般化された理解可能な単位 間の関係へと単純化することであった。 レヴィ=ストロースの理論は『構造人類学』(1958年)に示されている。簡単に言えば、彼は文化を象徴的なコミュニケーションのシステムであると考え、 小説、政治的演説、スポーツ、映画などの議論において、他の人々がより狭い範囲で用いてきた方法で調査する。彼の推論は、それ以前の世代の社会理論を背景 として対比させたときに、最も理にかなっている。彼はこの関係について何十年も書き続けた。 つまり、人類学者や社会学者は、社会的行為や制度の目的を述べようとしたのである。つまり、人類学者や社会学者は、社会的行為や制度の目的を明らかにしよ うとしたのである。この種の分析に代わる唯一の有力な方法は歴史的説明であり、ある社会的事実がどのようにして存在するようになったかを述べることによっ て、その存在を説明することであった。 しかし、社会的機能という考え方は、2つの異なる方法で発展した。イギリスの人類学者アルフレッド・レジナルド・ラドクリフ=ブラウンは、フランスの社会 学者エミール・デュルケムの著作を読んで尊敬し、人類学的研究の目標は、宗教的信条や結婚に関する一連の規則が社会秩序全体に対してどのような役割を果た しているかといった集団的機能を見出すことだと主張した。このアプローチの背後には、文明は原始から近代までの一連の段階を経て発展し、どこでも同じよう に発展するという古い考え方があった。ある種の社会における活動はすべて同じ性格を帯びており、ある種の内的論理が、あるレベルの文化を次のレベルへと進 化させるのである。この考え方では、社会は有機体として考えることができ、身体の各部分のように、各部分が互いに機能し合う。これとは対照的に、より影響 力のあったブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーの機能主義は、個人の欲求の充足、つまり人が習慣に参加することで得られるものについて述べている。 ドイツで教育を受けたフランツ・ボースによって人類学の形が定められたアメリカでは、歴史的な説明が好まれた。このアプローチには明らかな問題があった が、レヴィ=ストロースはボアスが正面から向き合ったことを称賛している。文字を持たない文化では、歴史的な情報が得られることはめったにない。人類学者 は他文化との比較で埋め合わせをし、何の証拠もない理論、つまり普遍的な発達段階という古い概念や、文化的類似性はグループ間の過去の未認識の接触に基づ くという主張に頼らざるを得ない。ボースは、社会発展の全体的なパターンは証明できないと考えるようになった。彼にとって、単一の歴史は存在せず、歴史だ けが存在するのである。 これらの学派の乖離には3つの大まかな選択肢がある: どのような証拠を使うか; ひとつの文化の特殊性を強調するか、それともすべての社会の根底にあるパターンを探すか。 その根底にあるパターンの源は何か、共通の人間性の定義とは何か。 ある社会についての情報を他の社会についての情報で補うことが常に必要であったため、あらゆる伝統の社会科学者は異文化研究に依存していた[要出典]。し たがって、共通の人間性についての考え方は、それぞれのアプローチに暗黙のうちに含まれていた。そして、決定的な違いは2つあった: ある社会的事実が存在するのは、それが社会秩序にとって機能的だからなのか、それともその人にとって機能的だからなのか。 社会的事実が存在するのは、社会秩序にとって機能的だからなのか、それとも人間にとって機能的だからなのか? レヴィ=ストロースにとって、その選択は社会秩序の要請によるものだった。レヴィ=ストロースは、個人主義的な説明の矛盾やつまらなさを指摘するのに苦労 はしなかった。例えば、マリノフスキーは、魔術的な信仰は、結果が不確かな出来事に対して、人々が支配しているという感覚を感じる必要があるときに生まれ るのだと言った。彼はトロブリアンド諸島で、中絶とスカートを編む儀式にこの主張の証拠を見つけた。しかし、同じ部族では、土鍋を作ることは機織りほど確 実な仕事ではないにもかかわらず、魔法は存在しない。つまり、説明に一貫性がないのだ。さらに、このような説明はその場しのぎの表面的な方法で使われる傾 向がある。しかし、組織機能を論じる方法として受け入れられているものも、うまく機能しなかった。異なる社会には、多くの明白な点で類似していながら、異 なる機能を果たす制度があるかもしれない。多くの部族文化では、部族を2つのグループに分け、2つのグループがどのように相互作用するかについて入念な ルールを定めている。しかし、部族によって貿易や婚姻など、具体的に何をするのかは異なる。また、2つに分けることが組織の普遍的な必要性だと言うことも できない。 レヴィ=ストロースにとって、言語学の方法は、それ以前に彼が行っていた社会に関するすべての研究の手本となった。レヴィ=ストロースにとって、言語学の 手法は、それ以前に彼が行っていた社会に関する考察のすべての手本となった。彼の類推は通常、音韻論からなされている(後に音楽、数学、カオス理論、サイ バネティクスなどからもなされている)。「本当に科学的な分析は、現実的で、単純化され、説明的でなければならない」と彼は書いている。同時に、音素は言 語から抽象化されたものであり、音ではなく、言語に特有の規則によって他のカテゴリーと区別される方法によって定義された音のカテゴリーである。言語の音 構造全体は、比較的少数の規則から生成される。 彼が最初に関心を抱いた親族システムの研究では、この理想的な説明によって、他の研究者によって部分的に秩序づけられていたデータを包括的に整理すること ができた。全体的な目標は、南米のさまざまな文化圏で家族関係が異なる理由を突き止めることだった。たとえば、あるグループでは父親が息子に対して大きな 権限を持ち、その関係はタブーによって厳しく制限されている。別のグループでは、母親の兄弟が息子とそのような関係を持ち、父親の関係はリラックスして遊 び心に満ちている。 いくつかの部分的なパターンが指摘されている。例えば、母親と父親の関係は、父親と息子の関係とある種の相互性を持っていた。例えば、母親が支配的な社会 的地位にあり、父親と形式的な関係を持っていた場合、父親は息子と親密な関係を持つのが普通であった。しかし、これらの小さなパターンは一貫性のない形で 結合していた。マスター・オーダーを見つける一つの可能な方法は、親族制度におけるすべての立場をいくつかの次元に沿って評価することであった。例えば、 父親は息子より年上である、父親は息子を産んだ、父親は息子と同性である、など。母系血統の叔父は年上で同性であるが、息子を産んでいない、など。このよ うな観察を網羅的に集めれば、全体的なパターンが浮かび上がってくるかもしれない。 しかし、レヴィ=ストロースにとって、このような作業は「外見だけの分析的なもの」であった。その結果、元のデータよりもはるかに理解しにくく、恣意的な 抽象論に基づいた図ができあがる(経験的には、父親は息子よりも年上だが、この特徴で二人の関係が説明できると宣言するのは研究者だけである)。しかも、 何も説明していない。もし年齢が重要なら、年齢が関係を説明することになる。また、その構造の起源を推論する可能性もない。 パズルの適切な解決策は、すべてのバリエーションを説明できる親族関係の基本単位を見つけることである。それは、兄弟、姉妹、父親、息子という4つの役割 の集まりである。これらは、近親相姦のタブーによって男性が自分の世襲以外の男性から妻を得ることが義務づけられている社会では、必ず関わってくる役割で ある。根底にあるのは、さまざまな氏族が平和的な関係を保つための女性の継続的な流通である。 善し悪しは別として、この解決策には構造的思考の特質が表れている。レヴィ=ストロースは、文化をその根底にある公理や定理の産物として、あるいは文化を 構成する音素の差異として扱うことを頻繁に口にするにもかかわらず、フィールド調査という客観的データに関心を寄せている。彼は、姉、姉の弟、弟の妻、娘 という異なる原子の親族構造が存在することは論理的に可能だが、そのグループ分けから導き出される関係の実例は現実には存在しないと指摘する。この見解の 問題点は、オーストラリアの人類学者オーガスタス・エルキンによって示されている。彼は、4分類の結婚システムでは、分類上の母親の兄弟の娘との結婚が好 まれ、決して本当の母親とは結婚しないという点を主張した。レヴィ=ストロースの親族構造のアトムは、血縁関係にある親族のみを扱っている。この2つの状 況には大きな違いがある。分類的親族関係を含む親族関係構造は、何千人もの人々をまとめることができるシステムの構築を可能にするという点である。レヴィ =ストロースの親族関係の原子は、真のMoBrDaが欠落すると機能しなくなる。[clarification needed] レヴィ=ストロースはまた、家単位が子孫集団や血統よりも社会組織の中心である社会を説明するために、家社会という概念を開発した。 構造主義的説明の目的は、現実のデータを最も単純で効果的な方法で整理することである。近親相姦のタブーのような問題に直面することは、人間の心がこれま で受け入れてきたことの客観的限界に直面することである。その根底にある生物学的な要請を仮定することはできるが、社会秩序に関する限り、タブーは還元不 可能な事実の効果を持つ。社会科学者が扱うことができるのは、そこから生じる人間の思考構造だけである。そして、構造的な説明は検証され、反論されうる。 因果関係の存在を願うような単なる分析スキームは、この意味で構造主義的ではない。 レヴィ=ストロースの後期の著作は、他の研究者の主題に影響を及ぼしていることもあり、より論争的である。レヴィ=ストロースは、ブラジルの奥地で発見し た「生と調理」、「蜜から灰へ」、「裸の人間」(『神話学』のタイトルをいくつか引用する)と同じカテゴリーと変容の上に、現代の生活とすべての歴史が成 り立っていると考えた。例えば、彼は人類学を音楽的直列主義と比較し、自らの「哲学的」アプローチを擁護している。彼はまた、原始文化に対する近代的な見 方が、彼らの歴史を否定する単純なものであることを指摘した。敗戦、移住、追放、記録された歴史に知られるあらゆる種類の移住の繰り返しの証拠を見つける のは簡単だった。その代わりに、神話の範疇はこれらの変化を包含していたのである。 彼は人間の生を、歴史という波乱万丈のタイムラインと、ある基本的な神話的パターンが支配し、また別のパターンが支配するという長いサイクルの、2つのタ イムラインの中に同時に存在するという見方を主張した。この点で、彼の仕事は、地中海と「la longue durée」、つまり地中海周辺で何世紀にもわたって存続した文化的展望と社会組織の形態を研究した歴史家、フェルナン・ブローデルの仕事に似ている。と はいえ、バヌアツ中央部におけるジャン・ギアートの人類学的、ホセ・ガランジェの考古学的研究は、現地の神話に描かれている元酋長の骸骨を浮かび上がらせ た。もうひとつの問題は、同一人物が、ある神話を象徴的に語り、その数年後に、ある系譜の年代史のようなものを語ることがあるという経験である(ロイヤリ ティ諸島やニュージーランドなど)。レヴィ=ストロースは、ゼミ内でこうした側面が説明されることには同意したが、自分では決して触れようとはしなかっ た。神話の人類学的データ内容は彼の問題ではなかった。レヴィ=ストロースが関心を持ったのは、それぞれの物語の形式的な側面だけであり、それは各集団の 集合的無意識の働きの結果であると彼は考えた。 |

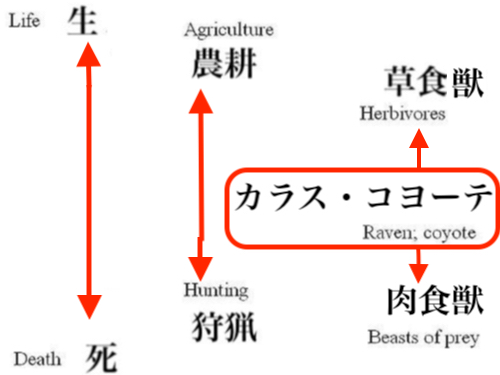

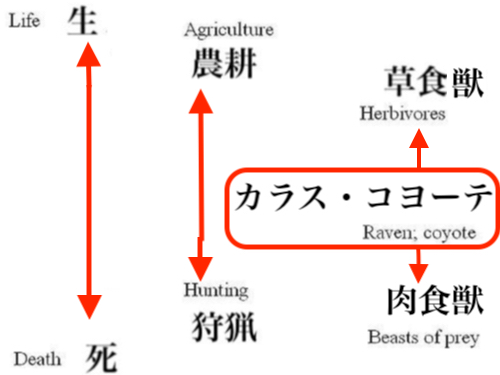

| Structuralist approach to myth Main article: Structuralist theory of mythology Similar to his anthropological theories, Lévi-Strauss identified myths as a type of speech through which a language could be discovered. His work is a structuralist theory of mythology which attempted to explain how seemingly fantastical and arbitrary tales could be so similar across cultures. Because he believed there was no one "authentic" version of a myth, rather that they were all manifestations of the same language, he sought to find the fundamental units of myth, namely, the mytheme. Lévi-Strauss broke each of the versions of a myth down into a series of sentences, consisting of a relation between a function and a subject. Sentences with the same function were given the same number and bundled together. These are mythemes.[36] What Lévi-Strauss believed he had discovered when he examined the relations between mythemes was that a myth consists of juxtaposed binary oppositions. Oedipus, for example, consists of the overrating of blood relations and the underrating of blood relations, the autochthonous origin of humans, and the denial of their autochthonous origin. Influenced by Hegel, Lévi-Strauss believed that the human mind thinks fundamentally in these binary oppositions and their unification (the thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad), and that these are what makes meaning possible.[37] Furthermore, he considered the job of myth to be a sleight of hand, an association of an irreconcilable binary opposition with a reconcilable binary opposition, creating the illusion, or belief, that the former had been resolved.[36] Lévi-Strauss sees a basic paradox in the study of myth. On one hand, mythical stories are fantastic and unpredictable: the content of myth seems completely arbitrary. On the other hand, the myths of different cultures are surprisingly similar:[34]: 208 On the one hand it would seem that in the course of a myth anything is likely to happen. ... But on the other hand, this apparent arbitrariness is belied by the astounding similarity between myths collected in widely different regions. Therefore the problem: If the content of myth is contingent [i.e., arbitrary], how are we to explain the fact that myths throughout the world are so similar? Lévi-Strauss proposed that universal laws must govern mythical thought and resolve this seeming paradox, producing similar myths in different cultures. Each myth may seem unique, but he proposed it is just one particular instance of a universal law of human thought. In studying myth, Lévi-Strauss tries "to reduce apparently arbitrary data to some kind of order, and to attain a level at which a kind of necessity becomes apparent, underlying the illusions of liberty."[38] Laurie suggests that for Levi-Strauss, "operations embedded within animal myths provide opportunities to resolve collective problems of classification and hierarchy, marking lines between the inside and the outside, the Law and its exceptions, those who belong and those who do not."[39] According to Lévi-Strauss, "mythical thought always progresses from the awareness of oppositions toward their resolution."[34]: 224 In other words, myths consist of: 1. elements that oppose or contradict each other and 2. other elements that "mediate", or resolve, those oppositions. For example, Lévi-Strauss thinks the trickster of many Native American mythologies acts as a "mediator". Lévi-Strauss's argument hinges on two facts about the Native American trickster: 1. the trickster has a contradictory and unpredictable personality; 2. the trickster is almost always a raven or a coyote. Lévi-Strauss argues that the raven and coyote "mediate" the opposition between life and death. The relationship between agriculture and hunting is analogous to the opposition between life and death: agriculture is solely concerned with producing life (at least up until harvest time); hunting is concerned with producing death. Furthermore, the relationship between herbivores and beasts of prey is analogous to the relationship between agriculture and hunting: like agriculture, herbivores are concerned with plants; like hunting, beasts of prey are concerned with catching meat. Lévi-Strauss points out that the raven and coyote eat carrion and are therefore halfway between herbivores and beasts of prey: like beasts of prey, they eat meat; like herbivores, they do not catch their food. Thus, he argues, "we have a mediating structure of the following type":[34]: 224  By uniting herbivore traits with traits of beasts of prey, the raven and coyote somewhat reconcile herbivores and beasts of prey: in other words, they mediate the opposition between herbivores and beasts of prey. As we have seen, this opposition ultimately is analogous to the opposition between life and death. Therefore, the raven and coyote ultimately mediate the opposition between life and death. This, Lévi-Strauss believes, explains why the coyote and raven have a contradictory personality when they appear as the mythical trickster: The trickster is a mediator. Since his mediating function occupies a position halfway between two polar terms, he must retain something of that duality—namely an ambiguous and equivocal character.[34]: 226 Because the raven and coyote reconcile profoundly opposed concepts (i.e., life and death), their own mythical personalities must reflect this duality or contradiction: in other words, they must have a contradictory, "tricky" personality. This theory about the structure of myth helps support Lévi-Strauss's more basic theory about human thought. According to this more basic theory, universal laws govern all areas of human thought: If it were possible to prove in this instance, too, that the apparent arbitrariness of the mind, its supposedly spontaneous flow of inspiration, and its seemingly uncontrolled inventiveness [are ruled by] laws operating at a deeper level...if the human mind appears determined even in the realm of mythology, a fortiori it must also be determined in all its spheres of activity.[38] Out of all the products of culture, myths seem the most fantastic and unpredictable. Therefore, Lévi-Strauss claims, if even mythical thought obeys universal laws, then all human thought must obey universal laws |

神話への構造主義的アプローチ 主な記事 神話の構造主義理論 レヴィ=ストロースは、人類学的理論と同様に、神話を言語を発見するための一種の音声としてとらえた。彼の研究は神話の構造主義理論であり、一見空想的で 恣意的な物語が文化圏を越えてなぜこれほど類似しているのかを説明しようとした。レヴィ=ストロースは、神話にはひとつの「真正な」バージョンは存在せ ず、むしろそれらはすべて同じ言語の現れであると考え、神話の基本的な単位、すなわち神話(mytheme)を見出そうとした。レヴィ=ストロースは神話 の各バージョンを、機能と主語の関係からなる一連の文に分解した。同じ機能を持つ文には同じ番号が与えられ、ひとまとめにされた。これが神話主題である [36]。 レヴィ=ストロースが神話主題間の関係を検討したときに発見したと考えたのは、神話は並置された二項対立から構成されているということであった。例えばオ イディプスは、血縁関係の過大評価と過小評価、人間の自生的起源とその自生的起源の否定から構成されている。ヘーゲルの影響を受けたレヴィ=ストロース は、人間の心は基本的にこのような二項対立とその統一(テーゼ、アンチテーゼ、シンセシスの三項対立)において思考しており、これらが意味を可能にしてい ると考えていた[37]。さらに彼は神話の仕事を手品のようなもの、つまり和解不可能な二項対立と和解可能な二項対立の関連付けであり、前者が解決された かのような錯覚、あるいは信念を生み出すものだと考えていた[36]。 レヴィ=ストロースは神話の研究に基本的なパラドックスを見出している。一方では、神話的な物語は幻想的で予測不可能であり、神話の内容は完全に恣意的で あるように思われる。他方で、異なる文化の神話は驚くほど類似している。 一方では、神話の過程では何でも起こりそうだと思われる。... しかし他方では、この見かけの恣意性は、広く異なる地域で収集された神話の間の驚くほどの類似性によって裏切られる。神話の内容が偶発的[=恣意的]であ るならば、世界中の神話がこれほど似ているという事実をどう説明すればいいのだろうか? レヴィ=ストロースは、普遍的な法則が神話的思考を支配し、この一見パラドックスを解決して、異なる文化圏に類似した神話を生み出すに違いないと提唱し た。それぞれの神話はユニークに見えるかもしれないが、それは人間の思考における普遍的法則の特殊な一例に過ぎないと彼は提唱したのである。神話を研究す る際、レヴィ=ストロースは「明らかに恣意的なデータをある種の秩序に還元し、自由の幻想の根底にある一種の必然性が明らかになる水準に到達しようとす る」[38]。 レヴィ=ストロースによれば、「神話的思考は常に対立の認識からその解決に向かって進歩する」[34]: 1. 互いに対立したり矛盾したりする要素と 2. それらの対立を「媒介」する、つまり解決する他の要素である。 例えば、レヴィ=ストロースは、多くのアメリカ先住民の神話に登場するトリックスターが「媒介者」として機能すると考えている。レヴィ=ストロースの議論 は、アメリカ先住民のトリックスターに関する2つの事実に基づいている: 1. トリックスターは矛盾した予測不可能な性格である; 2. トリックスターはほとんどの場合、カラスかコヨーテである。 レヴィ=ストロースは、カラスとコヨーテが生と死の対立を「媒介」していると主張する。農業と狩猟の関係は、生と死の対立に類似している。農業は(少なく とも収穫期までは)生命を生み出すことだけに関心があり、狩猟は死を生み出すことに関心がある。さらに、草食動物と猛獣の関係は、農業と狩猟の関係に類似 している。農業のように草食動物は植物に関係し、狩猟のように猛獣は肉を捕らえることに関係する。レヴィ=ストロースは、カラスやコヨーテが腐肉を食べる ことから、草食動物と猛獣の中間的な存在であると指摘する。したがって、彼は「次のような仲介構造がある」と主張する[34]: 224。  草食動物の形質を猛獣の形質と一体化させることで、カラスとコヨーテは草食動物と猛獣をいくらか和解させている。これまで見てきたように、この対立は究極 的には生と死の対立に類似している。したがって、カラスとコヨーテは究極的には生と死の対立を媒介する。レヴィ=ストロースは、コヨーテとカラスが神話の トリックスターとして登場するとき、なぜ矛盾した人格を持つのか、このことが説明できると考えている: トリックスターは調停者である。トリックスターは媒介者であり、その媒介機能は二つの極論の中間的な位置を占めているため、その二元性のようなもの、つま り曖昧で偶発的な性格を保持しなければならない。 カラスとコヨーテは深く対立する概念(すなわち生と死)を和解させるので、彼ら自身の神話的人格はこの二重性や矛盾を反映したものでなければならない。 神話の構造に関するこの理論は、人間の思考に関するレヴィ=ストロースのより基本的な理論を支持するのに役立つ。このより基本的な理論によれば、普遍的な 法則が人間の思考のあらゆる領域を支配している: もしこの例においても、心の見かけの恣意性、その自然発生的と思われるひらめきの流れ、そしてその一見制御不能な独創性が、[より深いレベルで作用する] 法則によって支配されていることを証明することが可能であれば......人間の心が神話の領域においてさえ決定されているように見えるのであれば、必然 的にそれはまた、その活動のすべての領域においても決定されているに違いない[38]。 文化のあらゆる産物の中で、神話は最も幻想的で予測不可能なものに見える。したがってレヴィ=ストロースは、神話的思考でさえ普遍的法則に従うのであれ ば、人間の思考はすべて普遍的法則に従わなければならないと主張する。 |

| The Savage Mind: bricoleur and

engineer Lévi-Strauss developed the comparison of the Bricoleur and Engineer in The Savage Mind. Bricoleur has its origin in the old French verb bricoler, which originally referred to extraneous movements in ball games, billiards, hunting, shooting and riding, but which today means do-it-yourself building or repairing things with the tools and materials on hand, puttering or tinkering as it were. In comparison to the true craftsman, whom Lévi-Strauss calls the Engineer, the Bricoleur is adept at many tasks and at putting preexisting things together in new ways, adapting his project to a finite stock of materials and tools. The Engineer deals with projects in their entirety, conceiving and procuring all the necessary materials and tools to suit his project. The Bricoleur approximates "the savage mind" and the Engineer approximates the scientific mind. Lévi-Strauss says that the universe of the Bricoleur is closed, and he often is forced to make do with whatever is at hand, whereas the universe of the Engineer is open in that he is able to create new tools and materials. However, both live within a restrictive reality, and so the Engineer is forced to consider the preexisting set of theoretical and practical knowledge, of technical means, in a similar way to the Bricoleur. Criticism Lévi-Strauss's theory on the origin of the Trickster has been criticized on a number of points by anthropologists. Stanley Diamond notes that while the secular civilized often consider the concepts of life and death to be polar, primitive cultures often see them "as aspects of a single condition, the condition of existence."[40]: 308 Diamond remarks that Lévi-Strauss did not reach such a conclusion by inductive reasoning, but simply by working backwards from the evidence to the "a priori mediated concepts"[40]: 310 of "life" and "death", which he reached by assumption of a necessary progression from "life" to "agriculture" to "herbivorous animals", and from "death" to "warfare" to "beasts of prey". For that matter, the coyote is well known to hunt in addition to scavenging and the raven also has been known to act as a bird of prey, in contrast to Lévi-Strauss's conception. Nor does that conception explain why a scavenger such as a bear would never appear as the Trickster. Diamond further remarks that "the Trickster names 'raven' and 'coyote' which Lévi-Strauss explains can be arrived at with greater economy on the basis of, let us say, the cleverness of the animals involved, their ubiquity, elusiveness, capacity to make mischief, their undomesticated reflection of certain human traits."[40]: 311 Finally, Lévi-Strauss's analysis does not appear to be capable of explaining why representations of the Trickster in other areas of the world make use of such animals as the spider and mantis. Edmund Leach wrote that "The outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or English, is that it is difficult to understand; his sociological theories combine baffling complexity with overwhelming erudition. Some readers even suspect that they are being treated to a confidence trick."[41] Sociologist Stanislav Andreski criticized Lévi-Strauss's work generally, arguing that his scholarship was often sloppy and moreover that much of his mystique and reputation stemmed from his "threatening people with mathematics", a reference to Lévi-Strauss's use of quasi-algebraic equations to explain his ideas.[42] Drawing on postcolonial approaches to anthropology, Timothy Laurie has suggested that "Lévi-Strauss speaks from the vantage point of a State intent on securing knowledge for the purposes of, as he himself would often claim, salvaging local cultures...but the salvation workers also ascribe to themselves legitimacy and authority in the process."[43] |

野蛮な心:ブリコルールとエンジニア レヴィ=ストロースは『野蛮な心』 の中で、ブリコルールとエンジニアの比較を展開した。 ブリコルールの語源は古いフランス語のbricolerという動詞で、もともとは球技、ビリヤード、狩猟、射撃、乗馬などでの余分な動きを指していたが、 今日では手持ちの道具や材料を使って自分で何かを作ったり修理したりすること、いわばパタリングやいじくり回すことを意味する。レヴィ=ストロースが「エ ンジニア」と呼ぶ真の職人に比べ、「ブリコルール」は多くの作業に精通し、既存のものを新しい方法で組み合わせることに長けている。 エンジニアはプロジェクト全体を扱い、自分のプロジェクトに必要な材料や道具をすべて考え、調達する。ブリコルールは「野蛮人の心」に近く、エンジニアは 「科学者の心」に近い。レヴィ=ストロースは、ブリコルールの宇宙は閉鎖的であり、手近にあるものでやりくりせざるを得ないことが多いのに対し、エンジニ アの宇宙は新しい道具や材料を生み出すことができるという点で開放的であると言う。しかし、両者とも制限された現実の中で生きているため、技術者はブリコ ルールと同様に、既存の理論的・実践的知識、技術的手段を考慮せざるを得ないのである。 批判と批評 トリックスターの起源に関するレヴィ=ストロースの理論は、人類学者から多くの点で批判されている。 スタンリー・ダイアモンドは、世俗的な文明人はしばしば生と死の概念を両極のものと考えるが、原始文化はしばしばそれらを「存在の条件という単一の条件の 側面として」見ていると指摘している[40]: 308 ダイアモンドは、レヴィ=ストロースは帰納的推論によってそのような結論に達したのではなく、単に証拠から「アプリオリに媒介された概念」[40]へと逆 算することによってそのような結論に達したのだと述べている: 生」から「農耕」、「草食動物」へ、そして「死」から「戦争」、「猛獣」へと必然的に進む と仮定することによって到達したのである。その点、コヨーテは清掃に加えて狩りをすることでもよく知られているし、カラスもまた、レヴィ=ストロースの観 念とは対照的に、猛禽類として行動することが知られている。また、熊のようなスカベンジャーがトリックスターとして登場しない理由も、この概念では説明で きない。ダイヤモンドはさらに、「レヴィ=ストロースが説明するトリックスターの名前『ワタリガラス』や『コヨーテ』は、関係する動物の賢さ、どこにでも いること、逃げやすいこと、いたずらをする能力、ある種の人間の特質をそのまま反映していることなどを根拠として、より経済的に導き出すことができる」と 述べている[40]: 311 最後に、レヴィ=ストロースの分析は、世界の他の地域におけるトリックスターの表象が、なぜクモやカマキリのような動物を用いるのかを説明することはでき ないようである。 エドマンド・リーチは、「フランス語であれ英語であれ、彼の文章の際立った特徴は、難解であるということである。社会学者スタニスラフ・アンドレスキは、 レヴィ=ストロースの研究を一般的に批判し、彼の学問はしばしば杜撰であり、さらに彼の神秘性と評判の多くは、レヴィ=ストロースが自分の考えを説明する ために準代数方程式を用いたことにちなんで、「数学で人々を脅かす」ことから生じていると論じている[42]。 [人類学へのポストコロニアル・アプローチに基づき、ティモシー・ローリーは「レヴィ=ストロースは、彼自身がしばしば主張するように、現地の文化を救済 するという目的のために知識を確保しようとする国家の立場から語っている。 |

| Personal life He married Dina Dreyfus in 1932. They later divorced. He was then to married Rose Marie Ullmo from 1946 to 1954. They had one son, Laurent. His third and last wife was Monique Roman; they were married in 1954. They had one son, Matthieu.[44] |

私生活 1932年にディナ・ドレフュスと結婚。後に離婚。その後、1946年から1954年までローズ・マリー・ウルモと結婚。二人の間には息子ローランがい る。3人目、そして最後の妻はモニク・ローマンで、1954年に結婚。二人の間には息子マチューが一人いる[44]。 |

| Works 1926. Gracchus Babeuf et le communisme. L'églantine. 1948. La Vie familiale et sociale des Indiens Nambikwara. Paris: Société des Américanistes. 1949. Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté The Elementary Structures of Kinship, translated by J. H. Bell, J. R. von Sturmer, and R. Needham. 1969.[45] 1952. Race et histoire, (as part of the series The Race Question in Modern Science). UNESCO.[46] 1955. "The Structural Study of Myth." Journal of American Folklore 68(270):428–44.[36] 1955. Tristes Tropiques ['Sad Tropics'], A World on the Wane, translated by J. Weightman and D. Weightman. 1973. 1958. Anthropologie structurale Structural Anthropology, translated by C. Jacobson and B. G. Schoepf. 1963. 1962. Le Totemisme aujourdhui Totemism, translated by R. Needham. 1963. 1962. La Pensée sauvage The Savage Mind. 1966. 1964–1971. Mythologiques I–IV, translated by J. Weightman and D. Weightman. 1964. Le Cru et le cuit (The Raw and the Cooked, 1969) 1966. Du miel aux cendres (From Honey to Ashes, 1973) 1968. L'Origine des manières de table (The Origin of Table Manners, 1978) 1971. L'Homme nu (The Naked Man, 1981) 1973. Anthropologie structurale deux Structural Anthropology, Vol. II, translated by M. Layton. 1976 1972. La Voie des masques The Way of the Masks, translated by S. Modelski, 1982. Lévi-Strauss, Claude (2005), Myth and Meaning, First published 1978 by Routledge & Kegan Paul, U.K, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 0-415-25548-1, retrieved 5 November 2010 1978. Myth and Meaning. UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.[47] 1983. Le Regard éloigné The View from Afar, translated by J. Neugroschel and P. Hoss. 1985. 1984. Paroles donnés Anthropology and Myth: Lectures, 1951–1982, translated by R. Willis. 1987. 1985. La Potière jalouse The Jealous Potter, translated by B. Chorier. 1988. 1991. Histoire de Lynx The Story of Lynx, translated by C. Tihanyi. 1996.[48] 1993. Regarder, écouter, lire Look, Listen, Read, translated by B. Singer. 1997. 1994. Saudades do Brasil. Paris: Plon. 1994. Le Père Noël supplicié. Pin-Balma: Sables Éditions. 2011. L'Anthropologie face aux problèmes du monde moderne. Paris: Seuil. 2011. L'Autre face de la lune, Paris: Seuil. Interviews 1978. "Comment travaillent les écrivains," interviewed by Jean-Louis de Rambures. Paris. 1988. "De près et de loin," interviewed by Didier Eribon (Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss, trans. Paula Wissing, 1991) 2005. "Loin du Brésil," interviewed by Véronique Mortaigne, Paris, Chandeigne. |

著作 1926年。グラッス・バベーフと共産主義。エグランティーヌ。 1948年。ナンビクワラ族の家族生活と社会生活。パリ:アメリカ学会。 1949年。親族の基礎的構造 『親族の基礎構造』、J. H. ベル、J. R. フォン・シュトルマー、R. ニーダム訳。1969年。[45] 1952年。『人種と歴史』(『人種問題』シリーズの一部)。ユネスコ。[46] 1955年 「神話の構造的研究」『アメリカン・フォークロージャー』68(270):428–44. 1955年 『悲しみの熱帯』『 衰亡する世界』、J. ウェイトマンとD. ウェイトマン訳。1973年 1958. 『構造的人類学 Structural Anthropology』、C. ジェイコブソンとB. G. シェップによる翻訳。1963年。 1962. 『今日のトーテミズム Totemism』、R. ニーダムによる翻訳。1963年。 1962. 『野生の思考 The Savage Mind』。1966年。 1964年~1971年。『神話学』I~IV、J. ウェイトマンとD. ウェイトマン訳。 1964年。『生と調理』(『生と調理』1969年) 1966年。『蜂蜜から灰へ』(『蜂蜜から灰へ』1973年) 1968年 『テーブルマナーの起源』(The Origin of Table Manners, 1978) 1971年 『裸の男』(The Naked Man, 1981) 1973年 『構造人類学第2巻 Structural Anthropology, Vol. II』、M. Layton 訳。1976年 1972年 『仮面の道 『仮面の道』、S. Modelski 訳、1982年。 レヴィ=ストロース、クロード(2005年)、『神話と意味』、初版1978年、英国Routledge & Kegan Paul、Taylor & Francis Group、ISBN 0-415-25548-1、2010年11月5日取得 1978年。神話と意味。英国:Routledge & Kegan Paul。[47] 1983年。Le Regard éloigné 遠くからの眺め、J. NeugroschelとP. Hossによる翻訳。1985年。 1984年。Paroles donnés 人類学と神話:講義、1951年~1982年、R. Willisによる翻訳。1987年。 1985. La Potière jalouse 嫉妬深い陶芸家、B. Chorier 訳。1988. 1991. Histoire de Lynx リンクスの物語、C. Tihanyi 訳。1996.[48] 1993. Regarder, écouter, lire 見る、聞く、読む、B. Singer 訳。1997. 1994. Saudades do Brasil. Paris: Plon. 1994. Le Père Noël supplicié. Pin-Balma: Sables Éditions. 2011. L'Anthropologie face aux problèmes du monde moderne. Paris: Seuil. 2011. L'Autre face de la lune, Paris: Seuil. インタビュー 1978年 「作家の仕事」ジャン=ルイ・ド・ランビュールによるインタビュー。パリ。 1988年 「近くから、そして遠くから」ディディエ・エリボンによるインタビュー(『クロード・レヴィ=ストロースとの対話』ポーラ・ウィッシング著、1991年) 2005年 「ブラジルから遠く離れて」ヴェロニク・モルテーニュによるインタビュー、パリ、シャンドンヌ社。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss |

★

草

食動物の形質を猛獣の形質と一体化させることで、カラスとコヨーテは草食動物と猛獣をいくらか和解させている。これまで見てきたように、この対立は究極的

には生と死の対立に類似している。したがって、カラスとコヨーテは究極的には生と死の対立を媒介する。レヴィ=ストロースは、コヨーテとカラスが神話のト

リックスターとして登場するとき、なぜ矛盾した人格を持つのか、このことが説明できると考えている:

トリックスターは調停者である。トリックスターは媒介者であり、その媒介機能は二つの極論の中間的な位置を占めているため、その二元性のようなもの、つま

り曖昧で偶発的な性格を保持しなければならない。

カラスとコヨーテは深く対立する概念(すなわち生と死)を和解させるので、彼ら自身の神話的人格はこの二重性や矛盾を反映したものでなければならない。

年譜

1908 11月28日ベルギーのブリュッセルで生まれる(Nov.18)。

祖父は音楽家のイサーク・ストロース、父は肖像画家のレーモン、母エンマ(旧姓レヴィ)

1914 父は招集され、母方の祖父(ユダヤ教会の首長)のベルサイユ家に転居。

1918 パリに戻り、16区ジャンソン・ド・サイ高校に学ぶ

1924-1925 マルクスに熱中。社会主義学生連盟で活躍

1927 パ リ 大学法学部に入学、同時に哲学を学ぶ(ca.1928)。セレスタン・ブーグレの指導で「史的唯物論の哲学的諸前提」で学士論文

1928 哲学教授資格試験の受験勉強

1929 パリ大学法学士

1931 アグレガシオン(哲学教授資格)に合格。同期に、ボーヴォワール、メルロ=ポンティ。 この年エメ・セゼールは、成績優秀であったため奨学金留学生としてマルチニークからフランス本土へ渡航した。

1932 パリとストラスブールで兵役。ディナ・ドレイフュスと結婚。

1932-33 フランスの中学校(リセ)で教鞭をとる。

1933 ロバート・ ローウィ(Robert Lowie, 1883-1957)『未開社会』を読む

1934 高校時代の恩師ブーグレ から、サンパウロ大学の社会学講師の招聘をうけて、承諾、翌年渡伯。

1935 サンパウロ大学(社会学)教授(〜1938)カドゥヴェオとボロロの調査。(→Tristes Tropiques,1955)Lévi-Strauss’

photographs: an anthropology of the sensible body.

Ruth Landes

(1908-1991) with Claude Lévi-Strauss and other researchers at the Museu Nacional

in Rio de Janeiro, 1930s

1936 「ボロロ・インディアンの社会組織研究への寄与」論文

Lévi-Strauss’ Bororo informant who met the

Pope (Lévi-Strauss 1936) ※ボロロのインフォーマント(調

査協力者)※中公クラシックス版(II巻37ページにある).

1937

1938 クイアバからマデイラ河への踏査旅行(〜1939)

1939 フランスに一時帰国した後、1940年まで招集、その後フランスの敗北、反ユダヤ政策 のためアメリカに亡命(1941)する。

1940 兵役を解かれ、高校の教師となるが、ユダヤ人のため失職する。

1941 ダーシー・トムソン(Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth, 1860-1948)『生物のかたち(On Growth and Form, 1915)』を読む。エメ・セゼールはマルチニークでtropiquesを創刊。

1941 (ロックフェラー財団学者救済計画)アメリカ亡命(アンドレ・ブルドンらも乗船)/自

由フランスの科学派遣団として在米。北西海岸の仮面を買い漁る

1942 ニュースクール・フォ・ソーシャル・リサーチ(New School for Social Research)教授(〜1945)。

親族の基本構造の内容に関する授業をおこなう。ローマン・ヤコブソンと知り合う。のちに『音 と意味についての6章』の序文を書く

1945

在米フランス大使館文 化顧問/あるいは参事官。ディナと離婚、ローズ=マリー・ユルモと結婚

1946 在米フランス大使館文化顧問(cultural attach)

1948

「親族の基本構造」主論文「ナンビクワラの家族と社会生活」副論文で文学博士(→フランス人 類学博物館:Musée de l'Homme)。ジャック・ラカン宅で、モニク・ローマンと出会う。

1949 『親 族の基本構造』[→「自然と文化」の読解]

1950 パリ大学高等研究院教授(Director of Studies at the Ecole Practique des Hautes Etudes):無文字民族比較宗教学講座

1952

「民族学におけるアルカイスムの概念」[関 連内容]。

1954 ローズ=マリーと離婚。モニク・ローマンと結婚。「悲しき熱帯」の原稿執筆。

1955 『悲しき熱帯()』絶賛を浴びる。

1958 『構造人類学』(邦訳 1972)

「レヴィ=ストロースは構造主義人類学の創始者と言われ、文化現象を普遍的モデルの中に還元

し

て論じる傾向の強い研究者です。しかしながら「呪術師とその呪術」は、呪術が使われる社会的文脈と呪術の社会的機能の役割、そして、呪術的な説明のやり

方、失敗の取り繕い方、そして、呪術になる過程における知識と技術の探求の過程などが紹介され、普段のレヴィ=ストロースのような難解ではない、リラック

スした説明が試みられています。他方「象徴的効果」はスウェーデンの民族誌学者がパナマのカリブ海沿岸に住むクナの産婆が難産の時に唱える呪文の分析で

す。呪文の分析の古典としてはマリノフスキーのトロブリアンドの呪文の分析や、トロブリアンドとザンデの呪文の比較の中にそれぞれの社会構造を見いだそう

としたエヴァンズ=プリチャードの論文などが有名ですが、この論文もそれに劣らず有名です。そして、その3つの論文とも日本語で読めるのが大変嬉しいです

ね。」〈病む〉ことの文化人類学より)

1959 メルロ=ポンティの尽力で、コレージュ・ド・フランス教授(社会人類学、〜1982)

1961 雑誌『ロム』の創刊に関わる

1962 『野生の思考』(→J-P.サルトル批判)

1964 『神話学(第1巻)』(〜1971)

1971 『神話学(第4巻)』

1975 『仮面の道』(1975, 1979)

1979 アカデミーフランセーズ会員

1982 コレージュ・ド・フランス定年退職

1983 『はるかなる視線』

1985 『やきもち焼きの土器作り』

1990 Mauro W. Barbosa de Almeida,

Symmetry and Entropy: Mathematical Metaphors in the Work of

Levi-Strauss.

CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY Volume 3I, Number 4, August-October I990

ABSTRACT;

"Levi-Strauss's structuralism is here considered as part of an

intellectual trend that gained currency during the first half of this

century a trend towards greater concern in the mathematical, physical,

and biological sciences for invariance and structure that is

characterized by the importance of the concept of the transformaion

group. Levi-Strauss has introduced the essence of this trend, more at a

stylistic level than by means of definite demonstrations into the human

sciences. Basic mathematical structures, the principal one being that

of the algebraic structure of the transformation group, underlie all

the models he has examined. It can be argued that his anthropology

leads to the conclusion that the human mind operates in different

cultures according to these basic structures that they are universals.

But Levi-Strauss is also concerned with processes of change, decay, and

evolution in structures. The effort to combine the structural approach

with an inter est in disorder and change is a neglected but essential

aspect of his theory."

1991 『オオヤマネコの話』

1992 『見る、聞く、笑う』

1994 『ブラジルへの郷愁』

2009年10月30日 死亡

テキスト

リンク

文献

「リーヴァイ・ストラウス(Levi Strauss, 1929-1902)は「ストラウス」が姓、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは「レヴィ=ストロース」が姓に当たり、全く別の姓である」(ウィキペ ディア「リーヴァイ・ストラウス」)

レヴィ=ストロースに関係する人物や理論

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆