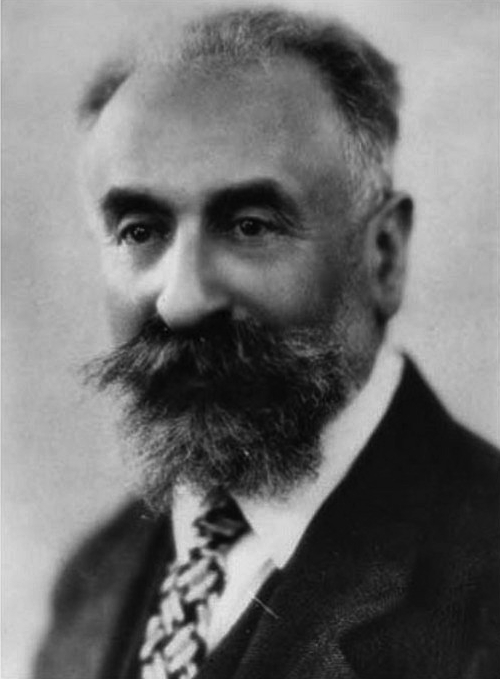

マルセル・モース

Marcel

Mauss, 1872-1950

マルセル・モース

Marcel

Mauss, 1872-1950

解説:池田光穂

マルセル・モース(Marcel Mauss, 1872-1950)ユダヤ系フランスの社会学者・民族学者。エミール・デュル ケーム(David Émile Durkheim, 1858-1917)の甥である。「フランス民族学の父」として知られるフランスの社会学 者・人類学者である。エミール・デュル ケームの甥であるモースは、その学問的研究において、社 会学と人類学の境界を越えた。今日、彼は後者の学問分野、特に世界中の異なる文化における魔法、生け贄、贈与交換といったトピックの分析に影響を与えたこ とでよく知られている。モースは、構造人類学の創始者であるクロード・レヴィ=ストロースに大きな影響を与えた。 彼の最も有名な著作は『贈与論』(1925年)である。

| Marcel Mauss

(French: [mos]; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French

sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French

ethnology".[1] The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic

work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today,

he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter

discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as

magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the

world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the

founder of structural anthropology.[2] His most famous work is The Gift

(1925). |

マルセル・モース(フランス語: [mos];

1872年5月10日 -

1950年2月10日)は、「フランス民族学の父」として知られるフランスの社会学者・人類学者である[1]。エミール・デュルケムの甥であるモースは、

その学問的研究において、社会学と人類学の境界を越えた。今日、彼は後者の学問分野、特に世界中の異なる文化における魔法、生け贄、贈与交換といったト

ピックの分析に影響を与えたことでよく知られている。モースは、構造人類学の創始者であるクロード・レヴィ=ストロースに大きな影響を与えた[2]。

彼の最も有名な著作は『贈与』(1925年)である。 |

| Background Mauss was born in Épinal, Vosges, to a Jewish family, his father a merchant and his mother an embroidery shop owner. Unlike his younger brother, Mauss did not join the family business and instead he joined the socialist and cooperative movement in the Vosges. Following the death of his grandfather, the Mauss and Durkheim families grew close and at this time Mauss began to feel concerned about his education and took initiatives in order to learn. Mauss obtained a religious education and was bar mitzvahed, yet by the age of eighteen he stopped practicing his religion.[3] Mauss studied philosophy at Bordeaux, where his maternal uncle Émile Durkheim was teaching at the time. In the 1890s, Mauss began his lifelong study of linguistics, Indology, Sanskrit, Hebrew, and the 'history of religions and uncivilized peoples' at the École pratique des hautes études[4]. He passed the agrégation in 1893. He was also the first cousin of the much younger Claudette (née Raphael) Bloch, a marine biologist and mother of Maurice Bloch, who became a noted anthropologist. Instead of taking the usual route of teaching at a lycée following college, Mauss moved to Paris and took up the study of comparative religion and Sanskrit. His first publication in 1896 marked the beginning of a prolific career that would produce several landmarks in sociological literature. Like many members of the Année Sociologique group, Mauss was attracted to socialism, especially that espoused by Jean Jaurès. He was particularly engaged around the anti-semitic political events of the Dreyfus affair. Towards the end of the century, he helped edit such left-wing papers as Le Populaire, L'Humanité and Le Mouvement socialiste, the last in collaboration with Georges Sorel. In 1901, Mauss began drawing more on ethnography, and his work began to develop characteristics now associated with formal anthropology. Mauss served in the French army during World War I from 1914 to 1919 as an interpreter.[5] The military service was liberating from Mauss's intense academics, as he stated, "I'm doing wonderfully. I just wasn't made for the intellectual life and I am enjoying the life war is giving me" (Fournier 2006: 175). While liberating, he also dealt with the devastation and violence of the war as many of his friends and colleagues died in the war, and his uncle Durkheim died shortly before its end. Mauss began to write a book "On Politics" that remained unfinished, but the early 1920s emphasized his energy for politics through criticism of the Bolshevik's coercive resort to violence and their destruction of the market economy.[6] Like many other followers of Durkheim, Mauss took refuge in administration. He secured Durkheim's legacy by founding institutions to carry out research, such as l'Institut Français de Sociologie (1924) and l'Institut d'Ethnologie in 1926. These institutions stimulated the development of fieldwork-based anthropology by young academics. Among the students he influenced were George Devereux, Jeanne Cuisinier, Alfred Metraux, Marcel Griaule, Georges Dumezil, Denise Paulme, Michel Leiris, Germaine Dieterlen, Louis Dumont, Andre-Georges Haudricourt, Jacques Soustelle, and Germaine Tillion.[5] In 1901, Mauss was appointed to the Chair of the History of Religions of Non-Civilized Peoples at the École pratique des hautes études.[7] [7] Two years later in 1931 Mauss was elected as the first holder of the Chair of Sociology in the Collège de France, and soon after he married his secretary in 1934 who soon was bedridden after a poisonous gas incident. Later, in 1940, Mauss was forced out of his job as the Chair of Sociology and out of Paris due to the German occupation and anti-Semitic legislation passed. Mauss remained socially isolated following the war and died in 1950.[6] |

生い立ちの背景 父は商人、母は刺繍店の店主だった。弟とは異なり、家業には入らず、ヴォージュ地方の社会主義運動や協同組合運動に参加した。祖父の死後、モース家とデュ ルケム家は親密になり、この頃からモースは自分の教育に不安を感じ始め、学ぼうと積極的に行動するようになった。モースは宗教教育を受け、バル・ミツワの 儀式を受けたが、18歳までに宗教をやめた[3]。 当時、母方の叔父であるエミール・デュルケムが教鞭をとっていたボルドーで哲学を学ぶ。1890年代には、École pratique des hautes études[4]で言語学、インド学、サンスクリット語、ヘブライ語、「宗教と未開の民族の歴史」を生涯にわたって学び始める。1893年、アグレガシ オン試験に合格。彼はまた、海洋生物学者で、著名な人類学者となったモーリス・ブロックの母であるクローデット(旧姓ラファエル)・ブロックのいとこでも あった。大学卒業後、リセで教鞭をとるという通常の道を歩む代わりに、モースはパリに移り住み、比較宗教学とサンスクリット語の研究を始めた。 1896年の最初の出版は、社会学文献にいくつかの画期的な出来事をもたらす多作なキャリアの始まりとなった。Année Sociologiqueグループの多くのメンバーと同様、モースは社会主義、特にジャン・ジョレスによって支持された社会主義に惹かれていた。特にドレ フュス事件という反ユダヤ主義的な政治的出来事の周辺に、彼は関わっていた。世紀末には、『ル・ポピュレール』、『ル・ヒューマニテ』、『ル・ムーヴメン ト・ソーシャリスト』といった左翼紙の編集に携わり、最後の『ル・ムーヴメント・ソーシャリスト』はジョルジュ・ソレルと共同で編集した。 1901年、モースは民俗学に重点を置くようになり、彼の研究は、現在では正式な人類学と結びついた特徴を持ち始めた。 1914年から1919年までの第一次世界大戦中、モースは通訳としてフランス軍に従軍した[5]。私は知的生活には向いていなかったので、戦争が与えて くれる生活を楽しんでいます」(Fournier 2006: 175)。多くの友人や同僚が戦争で亡くなり、叔父のデュルケームも戦争が終わる直前に亡くなったからだ。モースは『政治について』という本を書き始めた が未完のままであった。しかし1920年代初頭には、ボリシェヴィキの強権的な暴力への手段と市場経済の破壊に対する批判を通じて、彼の政治へのエネル ギーが強調された[6]。 デュルケムの他の多くの信奉者と同様に、モースは行政に避難した。彼は、1924年のフランス社会学研究所や1926年の民族学研究所など、研究を行うた めの機関を設立することで、デュルケムの遺産を確保した。これらの機関は、若い学者たちによるフィールドワークに基づく人類学の発展を促した。彼が影響を 与えた学生の中には、ジョージ・デヴリュー、ジャンヌ・キュイジニエ、アルフレッド・メトロー、マルセル・グリオール、ジョルジュ・デュメジル、ドゥニー ズ・ポールム、ミシェル・レイリス、ジェルメーヌ・ディーターレン、ルイ・デュモン、アンドレ=ジョルジュ・オードリクール、ジャック・スステル、ジェル メーヌ・ティリオンなどがいた[5]。 1901年、モースは高等師範学校(École pratique des hautes études)の非文明人の宗教史の講座に任命された[7] [7] 2年後の1931年、モースはコレージュ・ド・フランスの社会学の講座の最初の保持者に選出され、すぐに彼はすぐに毒ガス事件の後に寝たきりになった 1934年に彼の秘書と結婚した。その後、1940年、ドイツ軍の占領と反ユダヤ主義法案の成立により、モースは社会学講座の職を追われ、パリを離れる。 戦争後もモースは社会的に孤立し、1950年に亡くなった[6]。 |

Theoretical views Theoretical viewsMarcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim Marcel Mauss's studies under his uncle Durkheim at Bordeaux led to their doing work together on Primitive Classification which was published in the Année Sociologique. In this work, Mauss and Durkheim attempted to create a French version of the sociology of knowledge, illustrating the various paths of human thought taken by different cultures, in particular how space and time are connected back to societal patterns. They focused their study on tribal societies in order to achieve depth. While Mauss called himself a Durkheimian, he interpreted the school of Durkheim as his own. His early works reflect the dependence on Durkheim's school, yet as more works, including unpublished texts were read, Mauss preferred to start many projects and often not finish them. Mauss concerned himself more with politics than his uncle, as a member of the Collectivistes, French workers party, and Revolutionary socialist workers party. His political involvement led up to and after World War I.[8] The Gift Mauss has been credited for his analytic framework which has been characterized as more supple, more appropriate for the application of empirical studies, and more fruitful than his earlier studies with Durkheim. His work fell into two categories, one being major ethnological works on exchange as a symbolic system, body techniques and the category of the person, and the second being social science methodology.[9] In his classic work The Gift [see external links for PDF], Mauss argued that gifts are never truly free, rather, human history is full of examples of gifts bringing about reciprocal exchange. The famous question that drove his inquiry into the anthropology of the gift was: "What power resides in the object given that causes its recipient to pay it back?".[10] The answer is simple: the gift is a "total prestation" (see law of obligations), imbued with "spiritual mechanisms", engaging the honour of both giver and receiver (the term "total prestation" or "total social fact" (fait social total) was coined by his student Maurice Leenhardt after Durkheim's social fact). Such transactions transcend the divisions between the spiritual and the material in a way that, according to Mauss, is almost "magical". The giver does not merely give an object but also part of himself, for the object is indissolubly tied to the giver: "the objects are never completely separated from the men who exchange them" (1990:31). Because of this bond between giver and gift, the act of giving creates a social bond with an obligation to reciprocate on the part of the recipient. Not to reciprocate means to lose honour and status, but the spiritual implications can be even worse: in Polynesia, failure to reciprocate means to lose mana, one's spiritual source of authority and wealth. To cite Goldman-Ida's summary, "Mauss distinguished between three obligations: giving, the necessary initial step for the creation and maintenance of social relationships; receiving, for to refuse to receive is to reject the social bond; and reciprocating in order to demonstrate one's own liberality, honour, and wealth" (2018:341). Mauss describes how society is blinded by ideology, and therefore a system of prestations survives in societies when regarding the economy. Institutions are founded on the unity of individuals and society, and capitalism rests on an unsustainable influence on an individual's wants. Rather than focusing on money, Mauss describes the need to focus on faits sociaux totaux, total social facts, which are legal, economic, religious, and aesthetic facts which challenge the sociological method.[6] An important notion in Mauss's conceptualization of gift exchange is what Gregory (1982, 1997) refers to as "inalienability". In a commodity economy, there is a strong distinction between objects and persons through the notion of private property. Objects are sold, meaning that the ownership rights are fully transferred to the new owner. The object has thereby become "alienated" from its original owner. In a gift economy, however, the objects that are given are unalienated from the givers; they are "loaned rather than sold and ceded". It is the fact that the identity of the giver is invariably bound up with the object given that causes the gift to have a power which compels the recipient to reciprocate. Because gifts are unalienable they must be returned; the act of giving creates a gift-debt that has to be repaid. Because of this, the notion of an expected return of the gift creates a relationship over time between two individuals. In other words, through gift-giving, a social bond evolves that is assumed to continue through space and time until the future moment of exchange. Gift exchange therefore leads to a mutual interdependence between giver and receiver. According to Mauss, the "free" gift that is not returned is a contradiction because it cannot create social ties. Following the Durkheimian quest for understanding social cohesion through the concept of solidarity, Mauss's argument is that solidarity is achieved through the social bonds created by gift exchange. Mauss emphasizes that exchanging gifts resulted from the will of attaching other people – 'to put people under obligations', because "in theory such gifts are voluntary, but in fact they are given and repaid under obligation".[11] Mauss and Hubert Mauss also focused on the topic of sacrifice. The book Sacrifice and its Function which he wrote with Henri Hubert in 1899 argued that sacrifice is a process involving sacralising and desacralising. This was when the "former directed the holy towards the person or object, and the latter away from a person or object."[12] Mauss and Hubert proposed that the body is better understood not as a natural given. Instead, it should be seen as the product of specific training in attributes, deportments, and habits. Furthermore, the body techniques are biological, sociological, and psychological and in doing an analysis of the body, one must apprehend these elements simultaneously. They defined the person as a category of thought, the articulation of particular embodiment of law and morality. Mauss and Hubert believed that a person was constituted by personages (a set of roles) which were executed through the behaviors and exercise of specific body techniques and attributes. Mauss and Hubert wrote another book titled A General Theory of Magic in 1902 [see external links for PDF]. They studied magic in 'primitive' societies and how it has manifested into our thoughts and social actions. They argue that social facts are subjective and therefore should be considered magic, but society is not open to accepting this. In the book, Mauss and Hubert state: In magic, we have officers, actions, and representations: we call a person who accomplishes magical actions a magician, even if he is not professional; magical representations are those ideas and beliefs which correspond to magical actions; as for these actions, with regard to which we have defined the other elements of magic, we shall call them magical rites. At this stage it is important to distinguish between these activities and other social practices with which they might be confused.[13] They go on to say that only social occurrences can be considered magical. Individual actions are not magic because if the whole community does not believe in efficacy of a group of actions, it is not social and therefore, cannot be magical. |

理論的見解 理論的見解マルセル・モースとエミール・デュル ケーム マルセル・モースは、ボルドーで叔父のデュルケムに師事し、『社会学年鑑』に掲載された『原始分類』を共同で執筆した。この著作の中で、モースとデュル ケームはフランス版の知識社会学を構築しようと試み、異なる文化が歩んだ人間の思考のさまざまな道筋、特に空間と時間がどのように社会的パターンに結びつ いているかを説明した。彼らは深化を達成するために、部族社会に焦点を当てて研究を行った。 モースは自らをデュルケーム派と称しながら、デュルケーム学派を自分の学派として解釈した。彼の初期の作品は、デュルケームの学派への依存を反映している が、未発表のテキストを含むより多くの作品を読むにつれて、モースは多くのプロジェクトを開始し、しばしばそれを完了しないことを好んだ。モースは、集団 主義者、フランス労働者党、革命的社会主義労働者党のメンバーとして、彼の叔父よりも政治に自分自身を懸念した。彼の政治的関与は、第一次世界大戦までと 大戦後につながった[8]。 贈与 モースの分析的枠組みは、デュルケムとの初期の研究よりもしなやかで、経験的研究の応用に適しており、実り多いものであったと評価されている。彼の研究は 2つのカテゴリーに分類され、1つは象徴体系としての交換、身体技法、人のカテゴリーに関する主要な民族学的著作であり、もう1つは社会科学の方法論であ る。贈与の人類学への彼の探究を促した有名な問いは次のようなものであった: 「その答えは簡単である。贈与は「精神的メカニズム」を帯びた「総プレストレーション」(義務の法則を参照)であり、贈る側と贈られる側の両方の名誉に関 わるものである(「総プレストレーション」または「総社会的事実」(fait social total)という用語は、デュルケムの社会的事実にちなんで、彼の弟子であるモーリス・リーンハルトによって作られた)。このような取引は、モースによ れば、精神的なものと物質的なものとの区分を超越した、ほとんど「魔術的」なものである。与える者は単に物を与えるだけでなく、自分自身の一部をも与える のである: 「モノは交換する人間から完全に切り離されることはない」(1990:31)。贈り手と贈り物の間にこのような結びつきがあるため、贈与という行為は、受 け取る側にお返しをする義務を伴う社会的な結びつきを生み出す。お返しをしないということは、名誉と地位を失うことを意味するが、精神的な意味合いはさら に悪い。ポリネシアでは、お返しをしないということは、権威と富の精神的源泉であるマナを失うことを意味する。ゴールドマン=アイダの要約を引用すると、 「モースは3つの義務を区別した:与えること、それは社会的関係の創造と維持に必要な最初のステップである;受け取ること、それは受け取ることを拒否する ことは社会的絆を拒絶することである;そしてお返しをすることは、自分自身の寛大さ、名誉、富を示すためである」(2018:341)。モースは、社会が いかにイデオロギーによって盲目化されているかを説明し、それゆえ、経済に関して言えば、社会には威信のシステムが存続している。制度は個人と社会の一体 性の上に成り立っており、資本主義は個人の欲求に対する持続不可能な影響力の上に成り立っている。モースは、貨幣に焦点を当てるのではなく、社会学的手法 に挑戦する法的、経済的、宗教的、美的事実であるfaits sociaux totaux(総合的社会的事実)に焦点を当てる必要性を述べている[6]。 モースの贈与交換の概念化における重要な概念は、グレゴリー(1982、1997)が「不可侵性」と呼ぶものである。商品経済では、私有財産の概念を通じ て、モノと人との間に強い区別がある。モノが売られるということは、所有権が新しい所有者に完全に移転するということである。それによって、モノは元の所 有者から「疎外」される。しかし贈与経済では、贈与されたモノは贈与者から疎外されることはない。贈与者のアイデンティティが必ず贈与された物と結びつい ているという事実が、贈与に受領者にお返しを迫る力を持たせているのである。贈与は不可侵であるため、贈与は返されなければならない。贈与行為は、返済さ れなければならない贈与負債を生むのである。このため、贈与の返礼が期待されるという概念は、2人の個人の間に長期的な関係を生み出す。言い換えれば、贈 与を通じて社会的な絆が生まれ、それは時空を超えて、将来交換される瞬間まで続くと想定される。したがって、贈り物の交換は、贈り手と受け手の相互依存に つながる。モースによれば、返されない「無償の」贈り物は、社会的絆を生み出すことができないので矛盾である。連帯の概念を通じて社会的結束を理解しよう とするデュルケム流の探求に倣い、モースの主張は、贈与交換によって生まれる社会的絆を通じて連帯が達成されるというものである。モースは「理論的にはそ のような贈与は自発的なものであるが、実際には義務の下で贈与され、返済される」ので、贈与の交換は他の人々をくっつけようとする意志、すなわち「人々を 義務の下に置くこと」から生じたものであることを強調している[11]。 モースとユベール モースは犠牲というテーマにも着目していた。1899年にアンリ・ユベールとともに著した『犠牲とその機能』(Sacrifice and its Function)では、犠牲とは聖化することと脱聖化することを含むプロセスであると論じている。前者は聖なるものを人や物に向け、後者は人や物から遠 ざける」[12]。その代わりに、それは属性、デポーション、習慣における特定の訓練の産物として見られるべきである。さらに、身体技法は生物学的、社会 学的、心理学的なものであり、身体を分析する際には、これらの要素を同時に理解しなければならない。彼らは個人を思考の範疇として定義し、法と道徳の特定 の具体化を明確にした。モースとユベールは、人はペルソナージュ(一連の役割)によって構成され、それは特定の身体技法や属性の行動や行使を通じて実行さ れると考えた。 モースとユベールは1902年に『魔術の一般理論』(A General Theory of Magic)という別の本を書いた[PDFは外部リンクを参照]。彼らは「原始的な」社会における魔術を研究し、それが私たちの思考や社会的行動にどのよ うに現れているかを研究した。彼らは、社会的事実は主観的なものであり、それゆえ魔法とみなされるべきであると主張しているが、社会はこれを受け入れるこ とを受け入れていない。この本の中で、モースとユベールはこう述べている: 魔術には、役員、行為、表象がある。われわれは、たとえ専門家でなくても、魔術的行為を行う人を魔術師と呼ぶ。魔術的表象とは、魔術的行為に対応する考え や信念のことである。この段階では、これらの活動と混同されるかもしれない他の社会的実践とを区別することが重要である[13]。 彼らはさらに、社会的な出来事のみが魔術的であるとみなすことができると言う。なぜなら、コミュニティ全体がある集団の行為の効能を信じなければ、それは 社会的なものではなく、したがって魔術的なものにはなりえないからである。 |

| Legacy While Mauss is known for several of his own works – most notably his masterpiece Essai sur le Don ('The Gift') – much of his best work was done in collaboration with members of the Année Sociologique, including Durkheim (Primitive Classification), Henri Hubert (Outline of a General Theory of Magic and Essay on the Nature and Function of Sacrifice), Paul Fauconnet (Sociology) and others. Mauss influenced French anthropology and social science. He did not have a great number of students like many other Sociologists did, however, he taught ethnographic method to first generation French anthropology students. In addition to this, Mauss's ideas have had a significant impact on Anglophile post-structuralist perspectives in anthropology, cultural studies, and cultural history. He modified post-structuralist and post-Foucauldian intellectuals because he combines an ethnographic approach with contextualization that is historical, sociological, and psychological. Mauss served as an important link between the sociology of Durkheim and contemporary French sociologists. Some of these sociologists include: Claude Levi Strauss, Pierre Bourdieu, Marcel Granet, and Louis Dumont. The essay on The Gift is the origin for anthropological studies of reciprocity. His analysis of the Potlatch has inspired Georges Bataille (The Accursed Share), then the situationists (the name of the first situationist journal was Potlatch). This term has been used by many interested in gift economies and open-source software, although this latter use sometimes differs from Mauss's original formulation. See also Lewis Hyde's revolutionary critique of Mauss in "Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property". He also impacted the Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Sciences Sociales and David Graeber.[14] |

レガシー マルセル・モースは、自身の著作(特に代表作『エッサイ・シュル・ル・ドン(贈与)』)で知られているが、彼の代表作の多くは、デュルケーム(『原始分 類』)、アンリ・ユベール(『魔術一般理論概論』『生贄の本質と機能に関する試論』)、ポール・フォコネ(『社会学』)ら、社会学会のメンバーとの共同研 究によるものである。 モースはフランスの人類学と社会科学に影響を与えた。彼は他の多くの社会学者のように多くの学生を抱えてはいなかったが、フランスの人類学の第一世代の学 生たちに民族誌的方法を教えた。これに加えて、モースの思想は、人類学、文化研究、文化史における英国びいきのポスト構造主義の視点にも大きな影響を与え た。彼がポスト構造主義者やポスト・フーコー派の知識人に影響を与えたのは、民族誌的アプローチと歴史学的、社会学的、心理学的な文脈づけを組み合わせた からである。 モースはデュルケムの社会学と現代のフランスの社会学者をつなぐ重要な役割を果たした。このような社会学者には、以下のような人々がいる: クロード・レヴィ・ストロース、ピエール・ブルデュー、マルセル・グラネ、ルイ・デュモンなどである。贈与』に関するエッセイは、人類学における互酬性研 究の原点である。ポトラッチに関する彼の分析は、ジョルジュ・バタイユ(『呪われた共有』)、そして状況主義者たち(最初の状況主義雑誌の名前はポトラッ チ)に影響を与えた。この用語は、贈与経済やオープンソースソフトウェアに関心を持つ多くの人々によって使われているが、後者の使われ方はモースのオリジ ナルの定式化とは異なることがある。ルイス・ハイドの革命的なモース批判『想像力と財産のエロティックな生活』も参照。彼はまた社会科学反ユニタリスト運 動(Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Sciences Sociales)やデイヴィッド・グレーバー(David Graeber)にも影響を与えた[14]。 |

| Critiques Mauss's views on the nature of gift exchange have had critics. Main critiques against Mauss stem from beliefs that Mauss's essay is analyzing all primitive and archaic societies, but rather his essay is used to apply to one society and relationships within.[15] French anthropologist Alain Testart (1998), for example, argues that there are "free" gifts, such as passers-by giving money to beggars, e.g. in a large Western city. Donor and receiver do not know each other and are unlikely ever to meet again. In this context, the donation certainly creates no obligation on the side of the beggar to reciprocate; neither the donor nor the beggar have such an expectation. Testart argues that only the latter can actually be enforced. He feels that Mauss overstated the magnitude of the obligation created by social pressures, particularly in his description of the potlatch amongst North American Indians. Gift Economy theorist Genevieve Vaughan (1997) criticizes the French school of thought based on Mauss, exemplified by Jacques Godbout and Serge Latouche and the Mouvement Anti-utilittarisse des Sciences Sociales, for defining gift-giving as consisting of "three moments: giving, receiving, and giving back. The insistence upon reciprocity hides the communicative character of simple giving and receiving without reciprocity and does not allow this group to make a clear distinction between gift-giving and exchange as two opposing paradigms."[16] In subsequent works, for example, The Gift in the Heart of Language: The Maternal Source of Meaning (2015)[17] Vaughan elaborated on gift-giving as a relation between giver and receiver that takes its form from the primal human experience of mothering and being mothered. Another example of a non-reciprocal "free" gift is provided by British anthropologist James Laidlaw (2000). He describes the social context of Indian Jain renouncers, a group of itinerant celibate renouncers living an ascetic life of spiritual purification and salvation. The Jainist interpretation of the doctrine of ahimsa (an extremely rigorous application of principles of nonviolence) influences the diet of Jain renouncers and compels them to avoid preparing food, as this could potentially involve violence against microscopic organisms. Since Jain renouncers do not work, they rely on food donations from lay families within the Jain community. However, the former must not appear to be having any wants or desires, and only very hesitantly and apologetically receives the food prepared by the latter. "Free" gifts therefore challenge the aspects of the Maussian notion of the gift unless the moral and non-material qualities of gifting are considered. These aspects are, of course, at the heart of the gift, as demonstrated in books such as Annette Weiner's (1992) Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping While Giving. Mauss's view on sacrifice was also controversial at the time. This was because it conflicted with the psychologisation of individuals and social behavior. In addition to this, Mauss's terms like persona and habitus have been used among some sociological approaches. French philosopher Georges Bataille used The Gift to draw new conclusions based on economic anthropology, in this case, an interpretation of how money is increasingly being wasted in society.[15] They have also been included in recent sociological and cultural studies by Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu used Mauss's concept habitus through sociological concepts of socialization the embodiment of consciousness, an example being muscle memory. |

批判 贈与交換の本質に関するモースの見解には批判もある。モースに対する主な批判は、モースのエッセイがすべての原始社会や古風な社会を分析しているのではな く、むしろ彼のエッセイがある社会やその中の人間関係に適用するために使用されているという信念から生じている[15] フランスの人類学者アラン・テスタール(1998年)は、例えば西洋の大都市では、通行人が物乞いにお金を渡すような「無償の」贈り物が存在すると主張し ている。寄付をする側とされる側は、お互いに面識がなく、二度と会うことはないだろう。この文脈では、確かに寄付は乞食の側にお返しをする義務を生じさせ ない。寄付をする側にも乞食の側にも、そのような期待はない。テスタートは、実際に強制できるのは後者だけだと主張する。彼は、特に北米インディアンのポ トラッチに関する記述において、モースが社会的圧力によって生じる義務の大きさを誇張しすぎていると感じている。 贈与経済理論家のジュヌヴィエーヴ・ヴォーン(Genevieve Vaughan)(1997)は、ジャック・ゴドブー(Jacques Godbout)やセルジュ・ラトゥーシュ(Serge Latouche)、社会科学反利用運動(Mouvement Anti-utilittarisse des Sciences Sociales)に代表される、モースに基づくフランスの学派が、贈与を「与える、受け取る、お返しする」という3つの瞬間からなると定義していること を批判している。互酬性へのこだわりは、互酬性のない単純な授受のコミュニケーション的性格を隠し、このグループが贈与と交換を2つの対立するパラダイム として明確に区別することを許さない」[16]: The Maternal Source of Meaning』(2015年)[17]でヴォーンは、贈与を、母になること、母にされることという人間の原初的な経験からその形をとる、贈り手と受け手 の関係として詳しく述べている。 非互恵的な「無償」贈与のもう一つの例は、イギリスの人類学者ジェイムズ・レイドロー(James Laidlaw)(2000)によって提供されている。彼は、インドのジャイナ教の出家者の社会的背景について述べている。出家者は、精神的な浄化と救済 のために禁欲的な生活を送りながら、独身で遍歴するグループである。ジャイナ教のアヒムサ(非暴力の原則を極めて厳格に適用すること)の教義の解釈は、 ジャイナ教の出家者たちの食生活に影響を与え、微小な生物に対する暴力を伴う可能性があるため、食べ物を調理することを避けさせる。ジャイナ教の出家者は 働かないので、ジャイナ教のコミュニティ内の一般家庭からの食料の寄付に頼っている。しかし、出家者は欲望や欲望があるように見せてはならず、出家者が用 意した食べ物を申し訳なさそうに、ためらいがちに受け取るだけである。したがって、「無償 」の贈与は、贈与の道徳的・非物質的特質が考慮されない限り、マウシアンの贈与概念の側面に挑戦することになる。アネット・ワイナー(1992)の 『Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping While Giving(与えながら所有し続けることのパラドックス)』などである。 犠牲に関するモースの見解も当時は物議を醸した。個人や社会行動の心理学化と対立していたからだ。これに加えて、ペルソナやハビトゥスといったモースの用 語は、いくつかの社会学的アプローチの間で使われてきた。フランスの哲学者ジョルジュ・バタイユは、経済人類学に基づく新たな結論を導き出すために『贈 与』を使用した。ブルデューはモースのハビトゥスという概念を、社会化の社会学的概念、意識の具現化、例えば筋肉の記憶などを通して用いている。 |

| Essai sur la nature et la

fonction du sacrifice, (with Henri Hubert) 1898. La sociologie: objet et méthode, (with Paul Fauconnet) 1901. De quelques formes primitives de classification, (with Durkheim) 1902. Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie, (with Henri Hubert) 1902. Essai sur le don, 1925. Les techniques du corps, 1934. Marcel Mauss, "Les techniques du corps" (1934) Journal de Psychologie 32 (3–4). Reprinted in Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF. Sociologie et anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950. Manuel d'ethnographie. 1967. Editions Payot & Rivages. (Manual of Ethnography 2009. Translated by N. J. Allen. Berghan Books.) |

犠牲の性質と機能に関する試論』(アンリ・ユベールと共著)1898年。 社会学:目的と方法』(ポール・フォコネと共著)1901年。 分類のいくつかの原形』(デュルケムとの共著)1902年 魔術の一般理論の概要』(アンリ・ユベールと共著)1902年 贈与論、1925年 1934年、『身体の技法』。Marcel Mauss, 「Les techniques du corps」 (1934) Journal de Psychologie 32 (3-4). Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF. Sociologie et anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950. Manuel d'ethnographie. 1967. Editions Payot & Rivages. (民族誌マニュアル2009。N.J.アレン訳。ベルガン・ブックス) |

| Archaeology of trade Bronisław Malinowski De Beneficiis Kula ring Ernest Becker Emile Durkheim |

交易の考古学 ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキ デ・ベネフィシス クラ・リング アーネスト・ベッカー エミール・デュル ケーム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcel_Mauss |

"Marcel Mauss

(French: [mos]; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French

sociologist. The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work,

crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is

perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline,

particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic,

sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world.

Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder

of structural anthropology.[1] His most famous work is The Gift

(1925)."-Marcel

Mauss.

1872 5月10日Épinal, Vosges(ヴォージュ県の県庁所在地エピナル)で生まれる。

1893 アグレガシオン合格(Agrégation in France; 高等師範学校教授資格に相当)

1898[9?] Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice, (with Henri Hubert) 1899. Melanges_2_sacrifice.docx with password (c_S_c_d wtih four small captal letters)

1901 La sociologie: objet et méthode, (with Paul Fauconnet) 1901.

1902 École pratique des

hautes études にて「非文明民族の宗教史」講座(〜1930)

1902 De quelques formes primitives de classification, (with Durkheim) 1902.

1902 Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie, (with Henri Hubert) 1902.

1925 Essai sur le don, 1925.

1926 Lucien Lévy-Bruhl はパリ大学に民族学研究所 (l'Institut d'Ethnologie)を創設(ポール・フィヴィエとマ ルセル・モースは常任理事)。

1931 Collège de France

社会学講座(〜1939)

1934 Les techniques du corps, 1934. [1] Journal de Psychologie 32 (3-4). Reprinted in Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF.techniques_corps.pdf

1950 Sociologie et anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950.

1967(死後出版):Manuel d'ethnographie. 1967. Editions Payot & Rivages. (Manual of Ethnography 2009. Translated by N. J. Allen. Berghan Books.) manuel_ethnographie.pdf

| 1. - REMARQUES PRÉLIMINAIRES Difficultés de l'enquête

ethnographique. - Principes d'observation

2. - MÉTHODES D'OBSERVATION.Plan d'étude d'une société

3. - MORPHOLOGIE SOCIALEMéthodes d’observation 1) L’habitat; 2) La langue

4. - TECHNOLOGIETechniques du corps

5. - ESTHÉTIQUETechniques générales à usages généraux Techniques mécaniques Le feu Techniques spéciales à usages généraux ou industries générales à usages spéciaux : Industries spécialisées à usages spéciaux Les jeux :

6. - PHÉNOMÈNES ÉCONOMIQUESLes arts 7. - PHÉNOMÈNES JURIDIQUES Méthodes d'observation

8. - PHÉNOMÈNES MORAUXOrganisation sociale et politique ;Formes primaires de l’organisation sociale, et Formes secondaires de l’organisation sociale Organisation domestique La propriété Droit contractuel Droit pénal Organisation judiciaire et procédure 9. - PHÉNOMÈNES RELIGIEUX Phénomènes religieux stricto sensu

Cultes Publics: le totémisme; grands cultes tribaux Cultes privés : Cultes domestiques; Cultes privés individuels; Les rites Représentations religieuses Phénomènes religieux lato sensu : La magie; La divination; Superstitions populaires |

1968 Sociologie et anthropologie. Paris : Les Presses universitaires de France, 1968, Quatrième édition, 482 pages.

« Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie » (1902-1903)

« Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques » (1923-1924)

« Rapports réels et pratiques de la psychologie et de la sociologie » (1924)

« Une catégorie de l'esprit humain: la notion de personne, celle de "moi" » (1938)

« Les techniques du corps » (1934)

« Morphologie

sociale. Essai sur les variations saisonnières des sociétés Eskimos.

Étude de morphologie sociale. » (1904-1905)

| Marcel Mauss,

né le 10 mai 1872 à Épinal et mort le 11 février 1950 (à 77 ans) à

Paris[2], est un sociologue et anthropologue généralement considéré

comme le « père de l'anthropologie française[3] ». |

マルセル・モースは、1872年5月10日にエピナルで生まれ、1950年2月11日にパリで77歳で亡くなった[2]。社会学者、人類学者であり、一般に「フランス人類学の父[3]」とみなされている。 |

| Biographie Marcel Mauss naît en 1872 dans la ville d’Épinal au sein d'une famille de confession juive. Son père Gerson, originaire du Bas-Rhin, a épousé quelques années auparavant Rosine Durkheim, la sœur aînée d’Émile Durkheim, qu’il a rejointe dans la ville lorraine pour y reprendre l’atelier textile de sa mère, qui devient sous la houlette du jeune couple la Fabrique de Broderie à Main, Mauss-Durkheim[4]. Outre Marcel, ils ont un fils, Henri, né en 1876[5]. Son oncle, Émile Durkheim, de quatorze ans son aîné, joue un rôle majeur dans sa vocation, puis sa carrière[6]. En 1895, Marcel Mauss obtient l’agrégation de philosophie, qu’il a préparée à Bordeaux, où il a rejoint en 1890 Durkheim, qui y enseigne cette discipline. À l’issue du concours, il ne prend pas de poste dans l’enseignement secondaire, et à l’automne 1895 il s’installe à Paris pour suivre les cours de l'École pratique des hautes études[6]. Il étudie les langues (et notamment le sanskrit) à la 4e section (section des sciences historiques et philologiques) et les sciences religieuses (5e section), avec l’objectif de réunir le matériau nécessaire à une thèse de doctorat sur la prière[7], qu'il entreprend à partir de 1909[8]. Ses professeurs se nomment Léon Marillier, Antoine Meillet, Louis Finot, Israël Lévi ou Sylvain Levi[9]. Il rencontre également à l’EPHE quelques-uns des futurs membres du cercle durkheimien, avec lesquels il nouera de véritables liens d’amitié (Henri Hubert avec qui il écrit « Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice », un des textes fondateurs de l'anthropologie des religions, Robert Hertz…). Il devient en 1901 titulaire de la chaire d’« histoire des religions des peuples non civilisés » à la 5e section de l’EPHE[6]. En 1901, il rejoint l'équipe de L'Année sociologique, revue biennale créée par Émile Durkheim. Celui-ci décédera en 1917 et Mauss se verra échoir du travail de publication posthume de son oncle. Enfin en 1925, il fonde, avec Lucien Lévy-Bruhl et Paul Rivet l'Institut d'ethnologie de Paris. Il participe en 1928 au premier cours universitaire de Davos, avec de nombreux autres intellectuels français et allemands. En 1931, il obtient après trois campagnes de candidature une chaire au Collège de France ; créée pour l’occasion en remplacement de la chaire de « Philosophie sociale » de Jean Izoulet, cette chaire de « Sociologie » marque l’entrée de cette discipline dans la prestigieuse institution[10]. Il a connu deux Guerres mondiales et a été un militant socialiste fidèle à ses convictions, ayant pris position en faveur du capitaine dans l'Affaire Dreyfus, se rapprochant à cette occasion de Jean Jaurès. En septembre 1940, il donne sa démission de professeur, avant que le statut des Juifs soit décrété ; les années d'Occupation sont douloureuses : lois antisémites, pension de retraite non payée, déménagement à la suite de la réquisition de son appartement (1942), maladie de son épouse Marthe, perte de certains élèves (Boris Vildé, Anatole Lewitsky, Yvonne Oddon, Germaine Tillion, Deborah Lifchitz)[11]. Plusieurs auteurs dont David Graeber[12], Alain Guyard ou Bruno Viard[13], le classifient comme socialiste révolutionnaire. |

伝記 マルセル・モースは1872年、エピナルでユダヤ教徒の家庭に生まれた。父親のジェルソンは、バ=ラン県出身で、数年前にエミール・デュルケームの長姉で あるロジーヌ・デュルケームと結婚した。彼はロレーヌ地方のこの街に移住し、母親の繊維工房を引き継いだ。この工房は、若い夫婦の手によって「マウズ= デュルケーム手刺繍工場」となった。マルセルの他に、1876年に生まれた息子アンリがいた。14歳年上の叔父エミール・デュルケームは、マルセルの天 職、そしてその後のキャリアにおいて重要な役割を果たした。 1895年、マルセル・モースは哲学の教員資格を取得した。彼は1890年に、この分野を教えているデュルケームが在籍していたボルドーで、その資格取得 の準備をしていた。試験終了後、彼は中等教育の職には就かず、1895年の秋、高等実践学校(École pratique des hautes études)の授業を受けるためにパリに移住した。[6]で講義を受けるために移った。彼は第4部門(歴史学・文献学部門)で言語(特にサンスクリット 語)を、第5部門で宗教学を学び、1909年から着手した祈りをテーマとする博士論文[7]に必要な資料を集めることを目標としていた[8]。彼の教授 は、レオン・マリリエ、アントワーヌ・メイエ、ルイ・フィノ、イスラエル・レヴィ、シルヴァン・レヴィだった[9]。また、EPHEでは、後にデュルケー ム学派のメンバーとなる数人の人物と出会い、彼らと真の友情を育んだ(アンリ・ユベールとは、宗教人類学の基礎となるテキストの一つである『犠牲の性質と 機能に関する試論』を共同執筆、ロベール・ヘルツなど)。1901年には、EPHEの第5部門で「未開民族の宗教史」の教授職に就いた[6]。 1901年、エミール・デュルケームが創刊した隔年刊行誌『L'Année sociologique』の編集チームに加わった。デュルケームは1917年に死去し、モースは叔父の死後出版の仕事を引き継ぐことになった。そして 1925年、ルシアン・レヴィ=ブリュール、ポール・リヴェとともにパリ民族学研究所を設立した。1928年には、他の多くのフランス人およびドイツ人知 識人と共に、ダボスで開催された最初の大学講座に参加した。1931年、3回の立候補を経て、コレージュ・ド・フランスで教授職を獲得した。この「社会 学」の教授職は、ジャン・イズーレの「社会哲学」の教授職に代わるものとして創設されたもので、この分野が同名門機関に参入したことを示すものだった。 彼は2つの世界大戦を経験し、ドレフュス事件では軍隊の立場を支持し、ジャン・ジョレスと親交を深めるなど、自らの信念に忠実な社会主義活動家であった。 1940年9月、ユダヤ人に関する法令が公布される前に、教授職を辞任した。占領下の数年は苦難に満ちていた。反ユダヤ主義法、年金支給停止、アパートの 接収に伴う引越し(1942年)、妻マルテの病気、一部の教え子(ボリス・ヴィルデ、アナトール・ルウィツキー、イヴォンヌ・オドン、ジェルメーヌ・ティ リオン、デボラ・リフチッツ)の死などである。 デヴィッド・グレーバー[12]、アラン・ギヤール、ブルーノ・ヴィアール[13]など、多くの著者が彼を革命的社会主義者と分類している。 |

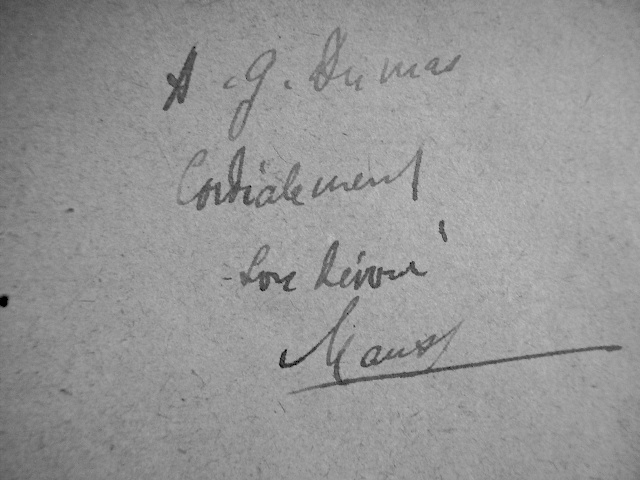

Travaux Envoi autographe de Marcel Mauss à Georges Dumas conservé à la Bibliothèque de sciences humaines et sociales Paris Descartes-CNRS. Considéré comme l'un des pères de l'anthropologie, Mauss n'a jamais publié d’ouvrage de synthèse de sa pensée mais un grand nombre d'articles dans différentes revues (dont L'Année sociologique), d'esquisses, de comptes-rendus et d'essais. Sa thèse sur la prière reste inachevée. De ses rares monographies, on retient surtout l’Essai sur le don. Il est surtout connu pour quelques grandes théories, notamment celle du don et du contre-don (liée à l'étude du potlatch (anthropologie), et de la dépense pure), et il a abordé une grande variété de sujets comme en témoignent ses études sur les techniques du corps, la religion ou la magie. Il veut saisir les réalités dans leur totalité et pour cela élabore le concept novateur de « fait social total », qui connaîtra un vif succès d'intérêt et d'usage en sciences sociales. Pour lui un fait social est intrinsèquement pluridimensionnel ; il comporte toujours des dimensions économiques, culturelles, religieuses, symboliques ou encore juridiques et ne peut être réduit à un seul de ces aspects. Marcel Mauss veut aussi appréhender l'être humain dans sa réalité concrète : physiologique, psychologique et sociologique. Il esquissera ainsi le concept « d'homme total » qui nourrira notamment Pierre Bourdieu dans ses analyses en termes « d'habitus ». Il s'intéresse à la signification sociale du don dans les sociétés tribales, ainsi qu'au phénomène religieux : la magie est considérée comme un phénomène social qui peut notamment s'expliquer par la notion de mana. Tout en créant du lien social, le don est agoniste (il « oblige » celui qui reçoit, qui ne peut se libérer que par un « contre-don »). Pour Marcel Mauss, le don est essentiel dans la société humaine et comporte trois phases : l'obligation de donner, l'obligation de recevoir et l'obligation de rendre[N 1]. S'il prend les sociétés « primitives » comme terrain d'étude, c'est moins parce que le primitif serait toujours aussi le simple et l'originel, que parce qu'il est difficile de rencontrer ailleurs une pratique du don et du contre-don « plus nette, plus complète, plus consciente » c'est-à-dire comme un « fait social total »[3]. Méthode : il est partisan d’une division du travail entre celui qui collecte les faits — tâche qu’il assigne à l’ethnographe — et celui qui les interprète pour les rendre intelligibles. « Il faut des sociologues et des ethnographes. Les uns expliquent et les autres renseignent »[14]. Marcel Mauss a très peu pratiqué les études de terrain, à une période où cette méthode qui s’impose progressivement dans le monde anglo-saxon, notamment sous l’influence de Malinowski, restait marginale, en particulier en France. Ses quelques observations directes figurent par exemple dans ses travaux sur « les techniques du corps », elles sont issues de son expérience dans l'armée ou de son enfance en Touraine. Cependant, signe d’une évolution de la discipline, il a incité ses élèves à se rendre sur place pour les observations et a rédigé un Manuel d’ethnographie qui répertorie l’ensemble des dispositions à prendre lors d’une étude de terrain[15]. |

著作 マルセル・モースからジョルジュ・デュマへの直筆の書簡は、パリ・デカルト大学・CNRS人文社会科学図書館に所蔵されている。 人類学の父の一人として知られるモースは、自身の思想をまとめた著作は出版しなかったが、さまざまな雑誌(『L'Année sociologique』など)に数多くの記事、草稿、報告、エッセイを寄稿した。祈りに関する論文は未完のままである。彼の数少ないモノグラフの中 で、特に注目されるのは『贈与に関するエッセイ』だ。 彼は、贈与と対価(ポトラッチ(人類学)の研究に関連)や純粋な支出に関する理論など、いくつかの重要な理論で特に知られており、身体の技術、宗教、魔術に関する研究からもわかるように、非常に幅広いテーマに取り組んだ。 彼は現実をその全体として把握したいと考え、そのために「社会的総体」という革新的な概念を打ち出した。この概念は社会科学の分野で大きな関心と利用を得 た。彼にとって、社会的総体は本質的に多次元的であり、常に経済的、文化的、宗教的、象徴的、あるいは法的側面を含み、これらの側面のいずれか一つに還元 することはできない。 マルセル・モースはまた、人間をその具体的な現実、すなわち生理学的、心理学的、社会学的側面から理解しようとした。こうして彼は「総合的な人間」という概念を提唱し、これは特にピエール・ブルデューの「ハビトゥス」という概念の分析に影響を与えた。 彼は、部族社会における贈与の社会的意味、そして宗教的現象、すなわち、特にマナという概念によって説明できる社会的現象としての魔法に関心を持った。贈 与は社会的絆を創り出すと同時に、アゴニスト的である(受け取った者は「義務」を負い、その義務は「対価の贈与」によってのみ解放される)。マルセル・ モースにとって、贈与は人間社会において不可欠であり、3つの段階(与える義務、受け取る義務、返す義務)から成っている。彼が「原始」社会を研究対象と したのは、原始社会が常に単純で原始的であるからというよりも、他の社会では「より明確で、より完全で、より意識的な」、つまり「総合的な社会的事実」と しての贈与と返礼の慣習を見出すことが困難であるからだった。 方法:彼は、事実を収集する者(この任務は民族誌学者に割り当てられる)と、それを解釈して理解可能にする者との分業を支持している。「社会学者と民族誌学者の両方が必要だ。前者は説明し、後者は情報を提供する」[14]。 マルセル・モースは、この方法が、特にマリンノフスキーの影響により、アングロサクソン圏で徐々に普及していた時期に、特にフランスではまだごく一部に留 まっていたため、フィールドワークをほとんど行わなかった。彼の数少ない直接観察は、例えば「身体の技術」に関する研究に見られ、軍隊での経験やトゥレー ヌでの子供時代の経験から得られたものである。しかし、この分野の発展の兆しとして、彼は学生たちに現地で観察を行うよう促し、フィールドワークの際に取 るべき措置をすべてまとめた『民族誌学マニュアル』を執筆した[15]。 |

| Archives de Marcel Mauss Celles de ses archives qui ont survécu à deux guerres mondiales sont conservées à l'Institut Mémoires de l'édition contemporaine (IMEC). Elles concernent son travail de sociologue, mais aussi son exploration de l'ethnographie et de l'histoire des religions, de l'Économie et de l'innovation sociale. Ce fonds d'archives est commun avec celui de Henri Hubert qui fut le frère de travail de Mauss à partir de 1896 lors de leur rencontre à l'École pratique des hautes études (c'est par exemple avec lui qu'il va construire et co-écrire « l'Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice » ou « l'Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie » comme le montrent des correspondances et des manuscrits souvent inédits conservés dans ce fond[16]. |

マルセル・モースのアーカイブ 二度の世界大戦を生き延びた彼のアーカイブは、現代出版記憶研究所(IMEC)に保管されている。それらは彼の社会学者としての仕事だけでなく、民族誌学 や宗教史、経済学、社会革新に関する研究も扱っている。このアーカイブは、1896年に高等実践学校で出会い、モーの共同研究者となったアンリ・ユベール のアーカイブと共有されている。例えば、モーはユベールとともに『犠牲の性質と機能に関する試論 」や「魔術の一般理論の概説」を共同執筆した。この資料には、そのことを示す、多くの未公開の手紙や原稿が保存されている[16]。 |

| Prix et distinctions 1938 : Huxley Memorial Medal |

受賞歴 1938年:ハクスリー記念メダル |

| Bibliographie Écrits de Marcel Mauss par année de publication (liste non exhaustive) « La religion et les origines du droit pénal d'après un livre récent », la Revue de l'histoire des religions, no 34, 1896, pp. 269 à 295, (lire en ligne) [archive] Sur le livre de M. R. Steinmetz, Ethnologische Studien zur ersten Entwickelung der Strafe. « L'école anthropologique anglaise et la théorie de la religion selon Jevons. » l'Année sociologique 1, 1898, pp. 169 à 170, (lire en ligne) [archive]. « Religions populaires et folklore de l’Inde septentrionale. », l'Année sociologique, n°1, 1897, pp. 210 à 218.[1] [archive] (lire en ligne)] Compte-rendu du livre de William Crooke, The Popular Religions and Folklore of Northern India, Westminster, 1896, « Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice », l'Année sociologique, no 2, 1899, pages 29 à 138. (avec Henri Hubert), (lire en ligne) [archive] « Rites funéraires en Chine. », l'Année sociologique, II, 1899, pages 221-226, (lire en ligne) [archive] Compte-rendu des trois premiers volumes du monumental ouvrage de J.-M. de Groot : The Religious System of China. Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect. Manners, Customs and Social institutions Connected therewith. Leyde, Vol. I. 1892. Vol. II. 1894, Vol. III. 1897. « Les tribus de l’Australie centrale. » l'Année sociologique, 3, 1900, pp. 205 à 215, (lire en ligne) [archive] « Sociologie » , la Grande Encyclopédie, vol. 30, Société anonyme de la Grande Encyclopédie, Paris, 1901. (avec Paul Fauconnet), lire en ligne [archive]. « Magie malaise. » L'Année sociologique, 4, 1901, pp. 169 à 174, (lire en ligne) [archive]. « Métier d’ethnographe, méthode sociologique. », “ Leçon d’ouverture à l’enseignement de l’histoire des religions des peuples non civilisés ”. Revue de l’histoire des religions, 45, 1902, pp. 42 à 54. (lire en ligne) [archive]. « Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie », l'Année sociologique, 1902-1903. (avec Henri Hubert), (lire en ligne) [archive]. « De quelques formes de classification - contribution à l'étude des représentations collectives », l'Année sociologique, 6, (1901-1902), pp. 1-72. (avec Émile Durkheim) (lire en ligne) [archive] « Mythologie et symbolisme indiens. », l'Année sociologique, no 6, 1903, pp. 247 à 253 (lire en ligne) [archive] « L’origine des pouvoirs magiques dans les sociétés australiennes. Étude analytique et critique de documents ethnographiques », l’École pratique des hautes études, section des sciences religieuses. Paris : 1904, pp. 1 à 55. (avec Henri Hubert) (lire en ligne) [archive]. « Les Esquimo », l'Année sociologique, no 7, 1904, pp. 225 à 230, lire en ligne [archive] «Essai sur les variations saisonnières des sociétés eskimos. Étude de morphologie sociale» (1904-1905), l'Année sociologique, tome IX, 1904-1905, avec la collaboration d'Henri Beuchat. (lire en ligne) [archive] « Étude sommaire de la représentation du temps dans la religion et la magie », l’École pratique des hautes études, section des sciences religieuses. Paris, 1905, pp. 1 à 39, lire en ligne [archive]. « Les tribus de l’Australie centrale et septentrionale », in L'Année sociologique, 8, 1905, pp. 243 à 251, lire en ligne [archive]. Les tribus de l’Australie du Sud-Est. » Extrait de L'Année sociologique, 9, 1906, pp. 177 à 183. (lire en ligne) [archive] « Les Euahlayi. », L'Année sociologique, 10, 1907, pp. 230 à 233, lire en ligne [archive] « L’art et le mythe d’après M. Wundt», Revue philosophique de la France et de l’étranger, 66, juillet à décembre 1908, pp. 48 à 78, lire en ligne [archive] Sur la Völkerpsychologie de Wilhelm Wundt «Introduction à l'analyse de quelques phénomènes religieux », la Revue d’histoire des religions, 58, 1908, pages 163-203. (lire en ligne [archive]) La prière, Paris: Félix Alcan, Éditeur, 1909, pp. 3 à 175. la première partie inachevée de sa thèse. L’auteur retira ce livre de l’imprimerie de la maison d’édition en 1909. Mélanges d'histoire des religions, Paris, Alcan, 1909, 1929 (avec Hubert Henri) reprend trois articles antérieurs : « Introduction à l'analyse de quelques phénomènes religieux. » (1906), « Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice. » (1899) et « L'origine des pouvoirs magiques dans les sociétés australiennes. Étude analytique et critique de documents ethnographiques. » (1904) « Mythologie et organisations des Indiens Pueblo », l'Année sociologique, 11, 1910, pp. 119 à 133, lire en ligne [archive] « Les Aranda et Loritja d’Australie centrale I », l'Année sociologique, 11, 1910 pp 76-81, lire en ligne [archive] « La religion des habitants de Torrès », L'Année sociologique, 11, 1910, pp. 86 à 93 (lire en ligne) [archive] « Les Haida et les Tlingit », L'Année sociologique, 11, 1910, pp. 111 à 119, lire en ligne [archive] « Cultes des tribus du Bas-Niger », l'Année sociologique, no 11, 1910, pages 136 à 148, lire en ligne [archive] compte-rendu d'ouvrages « La démonologie et la magie en Chine », l'Année sociologique, no 11, 1910, pp. 227 à 233, lire en ligne [archive]. « Anna-Viraj » in Mélanges d'indianisme offerts par ses élèves à Sylvain Lévy, pp.333-341, Ernest-Leroux, Paris. « Note sur la notion de civilisation. », L'Année sociologique, 12, 1913, pp. 46 à 50. (avec Émile Durkheim) (lire en ligne [archive]) « Les Aranda et Loritja d’Australie centrale. II. », l'Année sociologique, 12, 1913, pp. 101 à 104, (lire en ligne) [archive] « L’ethnographie en France et à l’étranger. » Extrait de la Revue de Paris, 20, 1913, pp. 537 à 560 et 815 à 837. lire en ligne [archive] « Les origines de la notion de monnaie. » Communication faite à l’Institut français d’anthropologie. « Comptes-rendus des séances », II, tome I, supplément à l’Anthropologie, 1914, 25, pp. 14 à 19 (lire en ligne) [archive] « La nation et l'internationalisme ») Communication en français à un colloque : « The Problem of Nationality », Proceedings of the Aristotelien Society, Londres, 20, 1920, pp. 242 à 251 lire en ligne [archive]) « L'expression obligatoire des sentiments (rituels oraux funéraires australiens) », Journal de psychologie, 18, 1921 (lire en ligne) [archive]. « Une forme ancienne de contrat chez les Thraces. » Revue des études grecques, 34, 1921, pp. 388 à 397, (lire en ligne) [archive] « Rapports réels et pratiques de la psychologie et de la sociologie», Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique, 1924. (lire en ligne) [archive] Communication présentée le 10 janvier 1924 à la Société de Psychologie. « Appréciation sociologique du Bolchevisme », Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 31e année, n°1, janvier-mars, pp. 103-132. « In memoriam. L'œuvre inédite de Durkheim et de ses collaborateurs. », l'Année sociologique, Nouvelle série, I, 1925, pp. 8 à 29, (lire en ligne) [archive] « Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques », l'Année sociologique, seconde série, 1923-1924, tome I. (lire en ligne) [archive] « Sur un texte de Posidonius : le suiciden contre-prestation suprême », Revue Celtique, XLII nos 3-4, pp 324-329. « Connexions et convergences. Le point de vue comparatif. Critique interne de la “ légende d’Abraham ”. », Mélanges offerts à M. Israël Lévi, par ses élèves et ses amis à l’occasion de son 70e anniversaire, Revue des études juives, 82, 1926, pp. 35 à 44. Paris, (lire en ligne) [archive] «Effets physiques chez l'individu de l'idée de mort suggérée par la collectivité (Australie, Nouvelle-Zélande)», Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique, 1926 (lire en ligne) [archive] Communication présentée à la Société de Psychologie. « Note de méthode sur l’extension de la sociologie. Énoncé de quelques principes à propos d’un livre récent », l'Année sociologique, Nouvelle série, no 2, 1927, pp. 178 à 192. lire en ligne [archive] « Divisions et proportions des divisions de la sociologie », l'Année sociologique, nouvelle série, 2 (lire en ligne) [archive] « Parentés à plaisanteries. », l’Annuaire de l’École pratique des Hautes études, section des sciences religieuses, Paris, 1928, pp. 3 à 21. (lire en ligne) [archive] Texte d’une communication présentée à l’Institut français d’anthropologie en 1926. « L'identité des touaregs et des libyens », L'Anthropologie, tome XXXIX, nos 1-3, p.130. « L'œuvre sociologique et anthropologique de Frazer », Europe, 17, 1928, pp. 716 à 724. (lire en ligne) [archive] Sur l'anthropologue écossais James George Frazer « Les civilisations : Éléments et formes », Exposé présenté à la Première Semaine Internationale de Synthèse, Civilisation. Le mot et l’idée, La Renaissance du livre, Paris, 1930, pp. 81 à 106 (lire en ligne) [archive] « La cohésion sociale dans les sociétés polysegmentaires. », Bulletin de l’Institut français de sociologie, I, 1931, pp. 49 à 68 (lire en ligne) [archive] « Débat sur les rapports entre la sociologie et la psychologie », extrait d’un débat (1931)faisant suite aux communications de Pierre Janet et de Jean Piaget à la Troisième semaine internationale de synthèse. L’individualité. Paris : Félix Alcan, 1933 (pp. 51 à 53 et 118 à 121), (lire en ligne) [archive] « La sociologie en France depuis 1914. » la Science française, tome I, Larousse, Paris: 1933, pp. 36 à 46 (lire en ligne) [archive] « Les techniques du corps », Journal de Psychologie, XXXII, n° 3-4, 15 mars - 15 avril 1936. (communication présentée à la Société de Psychologie le 17 mai 1934) lire en ligne [archive] « Fragment d’un plan de sociologie générale descriptive. Classification et méthode d’observation des phénomènes généraux de la vie sociale dans les sociétés de types archaïques (phénomènes généraux spécifiques de la vie intérieure de la société. », Années sociologiques, série A, fascicule 1, 1934, pp. 1 à 56, (lire en ligne)* «Une catégorie de l'esprit humain: la notion de personne celle de "moi"» [archive], Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. LXVIII, 1938, Londres (Huxley Memorial Lecture, 1938). (lire en ligne) [archive]Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. LXVIII, 1938, Londres (Huxley Memorial Lecture, 1938). (lire en ligne)* « Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1857-1939). », Annales de l'Université de Paris, no 14, 1939, pages 408 à 411 [archive] (lire en ligne) [archive] Manuel d'ethnographie, Payot 1947 manuel établi par Denise Paulme à partir de notes de cours (lire en ligne) [archive]. « La nation. » l'Année sociologique, Troisième série, 1953-1954, pp. 7 à 68. lire en ligne [archive] des fragments publiés par Henri Levy-Bruhl d'une grande œuvre commencée vers 1920, mais jamais terminée “Fait social et formation du caractère”, Sociologie et sociétés, vol. 36, no 2, automne 2004. Notes préparatoires pour une communication qu'il devait présenter au Congrès international des sciences anthropologiques et Ethnologiques qui se tint à Copenhague dans le courant de l'été 1938 publié par Marcel Fournier |

参考文献 マルセル・モースの著作(出版年順) (不完全なリスト) 「最近の書籍に基づく宗教と刑法の起源」、『宗教史レビュー』第34号、1896年、269~295ページ(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] M. R. シュタインメッツ著『刑罰の初期の発展に関する民族学的研究』について。 「英国の人類学派とジェヴォンズによる宗教理論」『社会学年報』1、1898年、169~170ページ、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]。 「北インドの民間信仰と民俗学」、『社会学年報』第1号、1897年、210~218ページ。[1] [アーカイブ] (オンラインで読む)] ウィリアム・クルック著『北インドの民間信仰と民俗学』の書評、ウェストミンスター、1896年、 「 犠牲の性質と機能に関する試論」、『社会学年報』第2号、1899年、29~138ページ。(アンリ・ユベールと共著)、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「中国の葬送の儀式」、『社会学年報』II、1899年、221~226ページ、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] J.-M. de Groot の大著『The Religious System of China. Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect. Manners, Customs and Social institutions Connected therewith.』の最初の 3 巻の書評。ライデン、第 I 巻、1892 年。第 II 巻、1894 年、第 III 巻、1897 年。 「オーストラリア中央部の部族」『社会学年報』3、1900年、205~215ページ、(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「社会学」『大百科事典』第30巻、大百科事典株式会社、パリ、1901年。(ポール・フォコンネと共著)、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]。 「マレーの魔術」『社会学年報』4、1901年、169~174ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ]。 「民族誌学者という職業、社会学的方法」『未開民族の宗教史教育に関する開講講義』 『宗教史レビュー』45、1902年、42~54ページ。(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]。 「魔術の一般理論の概説」、『社会学年報』、1902-1903年。(アンリ・ユベールと共著)、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]。 「いくつかの分類形態について ― 集団的表象の研究への貢献」、『社会学年報』6、(1901-1902)、1-72 ページ。(エミール・デュルケームとの共著) (オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「インドの神話と象徴主義」、『社会学年報』第6号、1903年、247-253ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「オーストラリア社会における魔法の力の起源。民族誌的資料の分析的・批判的研究」、『高等実践学校』、宗教学部門。パリ:1904年、1~55ページ。(アンリ・ユベールと共著)(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ]。 「エスキモー」、『社会学年報』第7号、1904年、225~230ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「エスキモー社会の季節的変化に関する考察。社会形態の研究」(1904-1905年)、『社会学年報』第9巻、1904-1905年、アンリ・ブシャとの共著。(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「宗教と魔術における時間の表現に関する概要研究」、高等実践学校、宗教学部門。パリ、1905年、1~39ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]。 「オーストラリア中部および北部の部族」、『社会学年報』第8巻、1905年、243~251ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]。 南東オーストラリアの部族」『社会学年報』9、1906年、177~183ページ。(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「エウアライ族」『社会学年報』10、1907年、230~233ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「ヴント氏による芸術と神話」、『フランスおよび外国の哲学雑誌』66、1908年7月から12月、48~78ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの民族心理学について 「いくつかの宗教現象の分析入門」、『宗教史雑誌』58、1908年、163-203ページ。(オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]) 祈り、パリ:フェリックス・アルカン出版社、1909年、3~175ページ。 彼の論文の未完成の第一部。著者は1909年にこの本を出版社から回収した。 宗教史の雑録、パリ、アルカン、1909年、1929年 (ユベール・アンリとの共著) は、3つの以前の論文を収録している。「いくつかの宗教現象の分析入門」(1906年)、「犠牲の性質と機能に関する試論」(1899年)、「オーストラリア社会における魔法の力の起源。民族誌的資料の分析的・批判的研究」。(1904) 「プエブロ族のインド人の神話と組織」、『社会学年報』、11、1910年、119~133ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「中央オーストラリアのアランダ族とロリチャ族 I」、『社会学年報』、11、1910年、76~81ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「トレス諸島住民の宗教」、『社会学年報』11、1910年、86~93ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「ハイダ族とトリンギット族」、『社会学年報』11、1910年、111~119ページ、オンラインで読む[アーカイブ] 「下ナイジェリア部族の信仰」、L'Année sociologique、11、1910年、136~148ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 書籍のレビュー 「中国の悪魔学と魔術」、『社会学年報』第11号、1910年、227~233ページ、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]。 「アンナ・ヴィラジ」、『シルヴァン・レヴィの弟子たちによるインド学論文集』、333~341ページ、アーネスト・ルルー、パリ。 「文明の概念に関する注記」、『社会学年報』12号、1913年、46~50ページ(エミール・デュルケームと共著)(オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]) 「オーストラリア中部アランダ族とロリチャ族。II」、『社会学年報』12号、1913年、 pp. 101 à 104, (オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「フランスおよび海外における民族誌学」『パリ評論』20、1913年、pp. 537 à 560 et 815 à 837。オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「貨幣の概念の起源」フランス人類学研究所における発表。「会議録」、II、第 I 巻、人類学補遺、1914年、25、14~19 ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「国家と国際主義」フランス語によるシンポジウムでの発表: 「国籍の問題」『アリストテレス協会会議録』ロンドン、20、1920年、242~251ページ オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]) 「感情の強制的な表現(オーストラリアの葬式の口頭儀式)」『心理学雑誌』18、1921年(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]。 「トラキア人の古代の契約形態」『ギリシャ研究誌』34、1921年、388~397ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「心理学と社会学の現実的かつ実践的な関係」『正常および病理心理学雑誌』1924年(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 1924年1月10日に心理学協会で発表された論文。 「ボルシェヴィズムの社会学的評価」『形而上学と道徳のレビュー』第31年、第1号、1月~3月、103~132ページ。 「追悼。デュルケームとその協力者たちの未発表作品」『社会学年報』新シリーズ、第1巻、1925年、8~29ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ]。」『社会学年報』新シリーズ、I、1925年、8-29ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「贈与に関する試論。古代社会における交換の形態と理由」『社会学年報』第2シリーズ、1923-1924年、第I巻(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「ポシドニウスの文章について:自殺という究極の対価」、『ケルト誌』、XLII 3-4号、324-329ページ。 「関連性と収斂性。比較の観点。『アブラハムの伝説』に対する内部批判。」、イスラエル・レヴィ氏への献辞、その70歳の誕生日を記念して、その弟子たち および友人たちによる、ユダヤ研究誌、82、1926年、35~44ページ。パリ、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「集団によって示唆される死の概念が個人に及ぼす身体的影響 (オーストラリア、ニュージーランド)」、Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique、1926年(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 心理学会で発表された論文。 「社会学の拡張に関する方法論的注記。最近の書籍に関するいくつかの原則の表明」、l'Année sociologique、新シリーズ、第2号、1927年、 178~192 ページ。オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「社会学の区分と区分比率」『社会学年報』新シリーズ、2 (オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「冗談の親族関係」『高等実践学校年鑑』宗教学部門、パリ、1928 年、 3~21ページ。(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 1926年にフランス人類学研究所で発表された論文。 「トゥアレグ族とリビア人のアイデンティティ」、『人類学』第39巻、第1~3号、130ページ。 「フレイザーの社会学および人類学上の業績」、『ヨーロッパ』誌、17、1928年、716~724ページ。(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] スコットランドの人類学者、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザーについて 「文明:要素と形態」、第1回国際総合週間、文明で発表された講演。言葉と概念、La Renaissance du livre、パリ、1930年、81~106ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「多層社会における社会的結束」、Bulletin de l’Institut français de sociologie、I、1931年、49~68ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「社会学と心理学の関係に関する討論」、ピエール・ジャネとジャン・ピアジェによる第3回国際総合週間での発表を受けて行われた討論(1931年)からの 抜粋。個性の問題。パリ:フェリックス・アルカン、1933年(51~53ページおよび118~121ページ)、(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 「1914年以降のフランスにおける社会学」『フランス科学』第I巻、ラルース、パリ:1933年、36~46ページ(オンラインで読む)[アーカイブ] 「身体の技術」『心理学雑誌』XXXII、第3-4号、1936年3月15日~4月15日。(1934年5月17日に心理学協会で発表された論文) オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] 「記述的一般社会学計画の一部。古風な社会における社会生活の一般的な現象の分類と観察方法(社会内部生活の一般的な現象)」、 Années sociologiques、シリーズ A、第 1 冊、1934 年、1~56 ページ、(オンラインで読む)* 「人間の精神の一カテゴリー:人格の概念、すなわち「私」の概念」[アーカイブ]、Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute、第 LXVIII 巻、1938 年、ロンドン(Huxley Memorial Lecture、1938 年)。(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute、vol. LXVIII、1938年、ロンドン(Huxley Memorial Lecture、1938年)。(オンラインで読む)* 「ルシアン・レヴィ=ブリュール(1857-1939)。」、パリ大学年報、第 14 号、1939 年、408 ページから 411 ページ [アーカイブ] (オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 民族誌学ハンドブック、Payot 1947 デニス・ポールムが講義ノートをもとに作成したハンドブック (オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ]。 「国家」。『社会学年報』、第3シリーズ、1953-1954年、7~68ページ。オンラインで読む [アーカイブ] アンリ・レヴィ=ブリュールが1920年頃に着手したが、完成には至らなかった大作の一部。 「社会的事実と性格形成」『Sociologie et sociétés』第36巻第2号、2004年秋。 1938年夏にコペンハーゲンで開催された国際人類学・民族学会議で発表予定だった講演の準備ノート。マルセル・フルニエにより出版された。 |

| Recueils présentés et rééditions Sociologie et anthropologie, recueil de textes, préface de Claude Lévi-Strauss, Presses universitaires de France, 1950. Recueil d'articles comprenant l' Essai sur le don. (lire en ligne) [archive] Œuvres, présentation par Victor Karady, comprenant trois volumes : I. - La fonction sociale du sacré, 1968, Paris, Minuit, 633 p. II. - Représentations collectives et diversité des civilisations, 739 p. III. - Cohésion sociale et division de la sociologie, 734 p. 1968, 1969, Paris, Minuit, collection Sens commun, dirigée par Pierre Bourdieu. Écrits politiques, Fayard, textes réunis et présentés par Marcel Fournier. Paris : Fayard, Éditeur, 1997, 814 pages. Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques (1925), Introduction de Florence Weber, Quadrige/Presses universitaires de France, 2007. La nation, édition et présentation de Marcel Fournier et Jean Terrier, Paris, Puf (Quadrige), 2013. Études sur Marcel Mauss Georges Balandier (1996) « Marcel Mauss, un itinéraire scientifique paradoxal », Revue européenne des sciences sociales, 34(105), 21-25 (résumé [archive]). Jean-François Bert (2010) Les archives de Marcel Mauss ont-elles une spécificité ? – le cas de la collaboration de Marcel Mauss et Henri Hubert. Durkheimian Studies, 16(1), 94-108 (résumé [archive]) Jean-François Bert L'atelier de Marcel Mauss CNRS éditions Paris 22/11/2012 Série:Socio/Athropo (ISBN 978-2-271-07589-5) Jean-François Bert, Marcel Mauss ou la confusion géniale. Introduction à son oeuvre, Le croquant édition, 2025. Philippe Chanial (dir) La société vue du don. Manuel de sociologie anti-utilitariste appliquée Paris, La Découverte, 2008 o (ISBN 9782707154569) Erwan Dianteill, ed., Marcel Mauss, en théorie et en pratique - Anthropologie, sociologie, philosophie, Paris, Archives Kareline, 397 p. Erwan Dianteill, ed., Marcel Mauss – L’anthropologie de l’un et du multiple, Paris, PUF, collection « Débats philosophiques », 2013, 208 p. Pascal Michon, Marcel Mauss retrouvé. Origines de l'anthropologie du rythme, Paris, Rhuthmos, 2010. Accessible ici [archive] Sylvain Dzimira, Marcel Mauss, savant et politique [archive], La Découverte, 2007 (lire en ligne la préface de Marcel Fournier, le sommaire et l'intro. [archive]). Marcel Fournier, Marcel Mauss, Fayard, 1994 - biographie avec une bibliographie exhaustive Bruno Karsenti, L'Homme total. Sociologie, anthropologie et philosophie chez Marcel Mauss, PUF, 1997. Camille Tarot, Sociologie et anthropologie de Marcel Mauss, collection Repères, La Découverte, 2003. Camille Tarot, De Durkheim à Mauss, l'invention du symbolique, collection recherches, Bibliothèque du MAUSS, MAUSS/La Découverte, 1999. Daniel Lidenberg. Marcel Mauss et le "judaïsme". Revue européenne des sciences sociales, T. 34. No. 105, 1966, pp. 45-50[17]. (de) Stephan Moebius, Marcel Mauss, Konstanz: UVK, 2006, 156 p. (ISBN 3-89669-546-0) (de) Stephan Moebius/Christian Papilloud (Ed.), Gift – Marcel Mauss' Kulturtheorie der Gabe, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden: VS, 2006, 359 p. (ISBN 3-531-14731-5, lire en ligne [archive]) Présences de Marcel Mauss, numéro spécial de la revue Sociologie et sociétés (lire en ligne [archive]). Autres Revue du MAUSS. Cette revue n'est pas à proprement parler consacrée à Marcel Mauss, mais s'inspire notamment de ses œuvres, en particulier de l'Essai sur le don. |

紹介された論文集および再版 Sociologie et anthropologie(社会学と人類学)、論文集、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースによる序文、Presses universitaires de France、1950年。『贈与に関する試論』を含む論文集。(オンラインで読む) [アーカイブ] 作品集、ヴィクトル・カラディによる紹介、全3巻: I. - 神聖の社会的機能、1968年、パリ、ミニュイ社、633ページ。 II. - 集団的表象と文明の多様性、739ページ。 III. - 社会的結束と社会学の分裂、734 ページ。1968年、1969年、パリ、ミニュイ、ピエール・ブルデュー監修、センス・コミューン・コレクション。 政治に関する著作、ファヤール、マルセル・フルニエによる編集・紹介。パリ:ファヤール出版社、1997年、814 ページ。 『贈与に関する試論。古代社会における交換の形態と理由』(1925年)、フローレンス・ウェーバーによる序文、クアドリージュ/プレス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、2007年。 『国家』、マルセル・フルニエとジャン・テリエによる編集・紹介、パリ、Puf(クアドリージュ)、2013年。 マルセル・モースに関する研究 ジョルジュ・バランディエ(1996)『マルセル・モース、逆説的な科学的軌跡』Revue européenne des sciences sociales、34(105)、21-25(要約[アーカイブ])。 ジャン=フランソワ・ベルト(2010)『マルセル・モースのアーカイブには特異性があるか?-マルセル・モースとアンリ・ユベールの共同研究の場合』 Durkheimian Studies、16(1)、94-108(要約 [アーカイブ]) ジャン=フランソワ・ベルト 『マルセル・モースのアトリエ』 CNRS éditions パリ 2012年11月22日 シリーズ:Socio/Athropo (ISBN 978-2-271-07589-5) ジャン=フランソワ・ベルト、『マルセル・モース、あるいは天才的な混乱。その作品への序論』、ル・クロカン版、2025年。 フィリップ・シャニアル(編)、『贈与から見た社会。応用反功利主義社会学マニュアル』、パリ、ラ・デクーヴェルト、2008年 o (ISBN 9782707154569) エルワン・ディアンテール編、マルセル・モース、理論と実践 - 人類学、社会学、哲学、パリ、アルシュヴ・カレリン、397 ページ。 エルワン・ディアンテール編、マルセル・モース - 単数と複数の人類学、パリ、PUF、コレクション「哲学的討論」、2013年、208 ページ。 パスカル・ミション、『再発見されたマルセル・モース。リズムの人類学の起源』、パリ、ルースモス、2010年。こちらで閲覧可能 [アーカイブ] シルヴァン・ジミラ、『学者であり政治家であったマルセル・モース』 [アーカイブ]、ラ・デクーヴェルト、2007年(マルセル・フルニエによる序文、目次、序論をオンラインで読むことができる [アーカイブ])。 マルセル・フルニエ、『マルセル・モース』、Fayard、1994年 - 完全な書誌付き伝記 ブルーノ・カルセンティ、『全人的人間。マルセル・モースの社会学、人類学、哲学』、PUF、1997年。 カミーユ・タロット、『マルセル・モースの社会学と人類学』、コレクション・レペール、ラ・デクーヴェルト、2003年。 カミーユ・タロット『デュルケームからモースへ、象徴の発明』、コレクション・レシェルシュ、MAUSS図書館、MAUSS/ラ・デクーヴェルト、1999年。 ダニエル・リデンバーグ『マルセル・モースと「ユダヤ教」』。ヨーロッパ社会科学雑誌、T. 34. No. 105、1966年、45-50ページ[17]。 (de) ステファン・メビウス、マルセル・モース、コンスタンツ:UVK、2006年、156ページ。(ISBN 3-89669-546-0) (de) ステファン・メビウス/クリスチャン・パピルー (編)、『贈り物 ― マルセル・モースの贈与の文化理論』、ヴィースバーデン、ヴィースバーデン:VS、2006年、359ページ。(ISBN 3-531-14731-5、オンラインで読む [アーカイブ]) マルセル・モースの臨在、雑誌『Sociologie et sociétés』の特別号(オンラインで読む [アーカイブ])。 その他 MAUSS 誌。この雑誌は、厳密に言えばマルセル・モースに捧げられたものではないが、彼の作品、特に『贈与に関するエッセイ』から特に影響を受けている。 |

| Références 1. « リンク切れ [archive] » (consulté le 7 avril 2019) 2. Acte de décès (avec date et lieu de naissance) à Paris 14e, n° 651, vue 6/31. [archive] 3. Sociologie-Ethnologie. Auteurs et textes fondateurs. (ss dir) d'Alain Gras. Publications de la Sorbonne, 2003 4. Marcel Fournier, Marcel Mauss : a biography, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 10. 5. Marcel Fournier (2006), p. 9. 6. Jean-François Bert, émission Idées sur RFI, 3 février 2013 7. Marcel Fournier (2006), p. 43 8. König R.(2014) Marcel Mauss [archive] (1872-1950). Trivium. Revue franco-allemande de sciences humaines et sociales-Deutsch-französische Zeitschrift für Geistes-und Sozialwissenschaften, (17). 9. Marcel Fournier (2006), p. 43-44 10. Marcel Fournier (2006), p. 273. 11. Christophe Labaune, "Biographie de Marcel Mauss - présentation pour le fonds d'archives", pp. 9-10, in Fonds Marcel Mauss (cote 57 CDF 1-170), Collège de France - La Salamandre, en ligne: https://salamandre.college-de-france.fr/archives-en-ligne/functions/ead/detached//57CDF/mauss-biographie.pdf [archive] (consulté le 2 juin 2025). 12. Pour une anthropologie anarchiste, éditions Lux, 2006, page 31 13. "À 22 ans, en 1894, Mauss adhéra au Parti ouvrier socialiste révolutionnaire de Jean Allemane, organisation anti-guédiste" Les trois neveux, ou, l'altruisme et l'égoïsme réconciliés: Pierre Leroux, 1797-1871, Marcel Mauss, 1872-1950, Paul Diel, 1893-1972. Bruno Viard, Presses universitaires de France, 2002, pages 64-66 14. Mauss, « Le manuel d'anthropologie de Kroeber », in Œuvres, Éditions de Minuit, Paris, vol. 3, p. 389. Cité dans Victor Karady, « Durkheim et les débuts de l'ethnologie universitaire ». In Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. Vol. 74, septembre 1988. Recherches sur la recherche, p. 30 15. Robert Deliège, Une histoire de l’anthropologie. Écoles, auteurs, théories, Éditions du Seuil, 2006, p. 69. 16. Jean-François Bert (2010) Les archives de Marcel Mauss ont-elles une spécificité ? – le cas de la collaboration de Marcel Mauss et Henri Hubert. Durkheimian Studies, 16(1), 94-108 (résumé [archive]) 17. Daniel Lidenberg. Marcel Mauss et le "judaïsme", 1966, pp. 45-5-. [archive] |

参考文献 1. 「リンク切れ [アーカイブ]」 (2019年4月7日アクセス) 2. 死亡証明書 (生年月日および出生地記載) パリ14区、No. 651、6/31ページ。[アーカイブ] 3. 社会学・民族学。著者および基礎文献。(編) アラン・グラ。ソルボンヌ出版、2003年 4. マルセル・フルニエ、マルセル・モース:伝記、プリンストン大学出版、2006年、10ページ。 5. マルセル・フルニエ(2006年)、9ページ。 6. ジャン=フランソワ・ベルト、RFIの番組「Idées」、2013年2月3日 7. マルセル・フルニエ(2006)、43ページ 8. ケーニッヒ R.(2014)マルセル・モース [アーカイブ](1872-1950)。トリヴィウム。フランス・ドイツ人文社会科学雑誌-Deutsch-französische Zeitschrift für Geistes-und Sozialwissenschaften、(17)。 9. マルセル・フルニエ (2006)、43-44ページ 10. マルセル・フルニエ(2006)、273ページ。 11. クリストフ・ラボーヌ、「マルセル・モースの伝記 - アーカイブ資料の紹介」、9-10ページ、Fonds Marcel Mauss(コード 57 CDF 1-170)、 コレージュ・ド・フランス - ラ・サラマンドル、オンライン:https://salamandre.college-de-france.fr/archives-en- ligne/functions/ead/detached//57CDF/mauss-biographie.pdf [アーカイブ] (2025年6月2日アクセス)。 12. Pour une anthropologie anarchiste(アナキスト人類学のために)、Lux 出版社、2006年、31ページ 13. 「1894年、22歳のとき、モースはジャン・アレマンの革命社会主義労働者党、反ゲディスト組織に加入した」 Les trois neveux, ou, l『altruisme et l』égoïsme réconciliés(3人の甥たち、あるいは、利他主義と利己主義の和解): ピエール・ルルー、1797-1871、マルセル・モース、1872-1950、ポール・ディエル、1893-1972。ブルーノ・ヴィアール、プレス・ ユニヴェルシテール・ド・フランス、2002年、64-66ページ 14. モース、「クロエバーの人類学ハンドブック」、作品集、ミニュイ出版社、パリ、第3巻、389ページ。ヴィクトル・カラディ、「デュルケームと大学における民族学の始まり」で引用。社会科学研究論文集。第74巻、1988年9月。研究に関する研究、30ページ 15. ロベール・デリエージュ、『人類学の歴史。学校、著者、理論』、エディション・デュ・セイル、2006年、69ページ。 16. ジャン=フランソワ・ベルト(2010)『マルセル・モースのアーカイブは特異性を持つか?-マルセル・モースとアンリ・ユベールの共同研究の場合』。Durkheimian Studies、16(1)、94-108(要約 [アーカイブ]) 17. ダニエル・リデンバーグ。マルセル・モースと「ユダヤ教」、1966年、45-5ページ。[アーカイブ] |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcel_Mauss |

リンク

文献

その他の情報:哲学 者は宴の後で(post festum)でやってくる ——カール・マルクス

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆