共感覚

Synesthesia

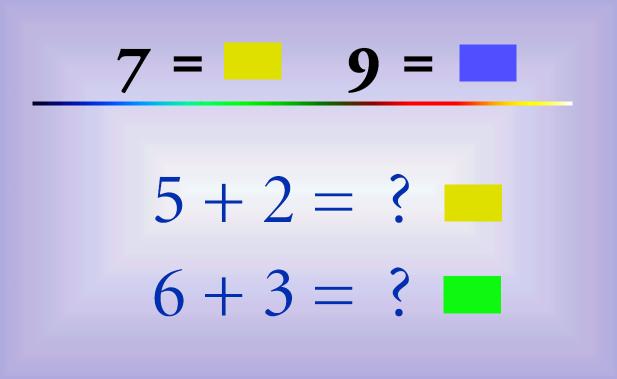

A person with synesthesia may associate certain letters and numbers with certain colors. Most synesthetes see characters just as others do (in whichever color actually displayed) but they may simultaneously perceive colors as associated with or evoked by each one.

共感覚を持つ人は、特定の文字や数字を特定の色に関連付けることがある。ほとんどの共感覚者は、他の人と同じように(実際に表示されているどの色でも)文字を見るが、同時にそれぞれの文字に関連する、あるいはそれによって喚起される色を知覚することがある。

☆共感覚(synesthesia; アメリカ英語)または共感覚(synaesthesia; イギリス英語)とは、ある感覚または認知経路を刺激すると、第二の感覚または認知経路で不随意的な体験が起こる知覚 現象である[1][2][3][4]。例えば、共感覚を持つ人は、音楽を聴くと色を体験したり、特定の香りを嗅ぐと形が見えたり、言葉を見ると味を感じた りする。このような体験が生涯続く人は、共感覚者として知られている。共感覚の知覚は、個人によって異なり、その人独自の人生経験や共感覚の種類によって 異なる。 書記素-色彩型共感覚または色彩-書記素型共感覚として知られる一般的な共感覚では、文字や数字が固有の色として知覚される。空 間-系列型、または数字型共感覚では、数字、年の月、または曜日が空間における正確な位置を示す(例えば、1980年は、1980年より「遠い」かもしれ ない、 1980年は1990年よりも「遠い」かもしれない)、あるいは三次元の地図(時計回りまたは反時計回り)として現れるかもしれない。共感 覚的連想はどのような組み合わせでも、またどのような数の感覚や認知経路でも起こりうる(→「クロスモーダル・イディアステシア」)。

| Synesthesia (American English) or synaesthesia (British English)

is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or

cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory

or cognitive pathway.[1][2][3][4] For instance, people with synesthesia

may experience colors when listening to music, see shapes when smelling

certain scents, or perceive tastes when looking at words. People who

report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as synesthetes.

Awareness of synesthetic perceptions varies from person to person with

the perception of synesthesia differing based on an individual's unique

life experiences and the specific type of synesthesia that they

have.[5][6] In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme–color

synesthesia or color–graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are

perceived as inherently colored.[7][8] In spatial-sequence, or number

form synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week

elicit precise locations in space (e.g., 1980 may be "farther away"

than 1990), or may appear as a three-dimensional map (clockwise or

counterclockwise).[9][10] Synesthetic associations can occur in any

combination and any number of senses or cognitive pathways.[11] Little is known about how synesthesia develops. It has been suggested that synesthesia develops during childhood when children are intensively engaged with abstract concepts for the first time.[12] This hypothesis—referred to as semantic vacuum hypothesis—could explain why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme-color, spatial sequence, and number form. These are usually the first abstract concepts that educational systems require children to learn. The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet.[13] However, there is disagreement as to whether Locke described an actual instance of synesthesia or was using a metaphor.[14] The first medical account came from German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812.[14][15][16] The term is from Ancient Greek σύν syn 'together' and αἴσθησις aisthēsis 'sensation'.[13] |

共

感覚(synesthesia; アメリカ英語)または共感覚(synaesthesia;

イギリス英語)とは、ある感覚または認知経路を刺激すると、第二の感覚または認知経路で不随意的な体験が起こる知覚現象である[1][2][3][4]。

例えば、共感覚を持つ人は、音楽を聴くと色を体験したり、特定の香りを嗅ぐと形が見えたり、言葉を見ると味を感じたりする。このような体験が生涯続く人

は、共感覚者として知られている。共感覚の知覚は、個人によって異なり、その人独自の人生経験や共感覚の種類によって異なる。

[5][6]書記素-色彩型共感覚または色彩-書記素型共感覚として知られる一般的な共感覚では、文字や数字が固有の色として知覚される[7][8]。空

間-系列型、または数字型共感覚では、数字、年の月、または曜日が空間における正確な位置を示す(例えば、1980年は、1980年より「遠い」かもしれ

ない、

1980年は1990年よりも「遠い」かもしれない)、あるいは三次元の地図(時計回りまたは反時計回り)として現れるかもしれない[9][10]。共感

覚的連想はどのような組み合わせでも、またどのような数の感覚や認知経路でも起こりうる[11]。 共感覚がどのように発達するかについてはほとんど知られていない。この仮説(意味的真空仮説と呼ばれる)は、共感覚の最も一般的な形態が、書記素-色彩、 空間系列、および数形態である理由を説明しうる。これらは通常、教育システムが子どもたちに最初に学ばせる抽象概念である。 共感覚の最も古い記録は、オックスフォード大学の学者で哲学者のジョン・ロックによるもので、彼は1690年に、トランペットの音を聞くと緋色を感じると いう盲目の男について報告した。 [13]しかし、ロックが共感覚の実際の例を述べたのか、比喩を用いたのかについては意見が分かれている[14]。医学的な最初の記述は1812年にドイ ツの医師ゲオルク・トビアス・ルートヴィヒ・ザックスによってなされた[14][15][16]。この用語は古代ギリシャ語のσύν syn「一緒に」とαἴσθησις aisthēsis「感覚」に由来する[13]。 |

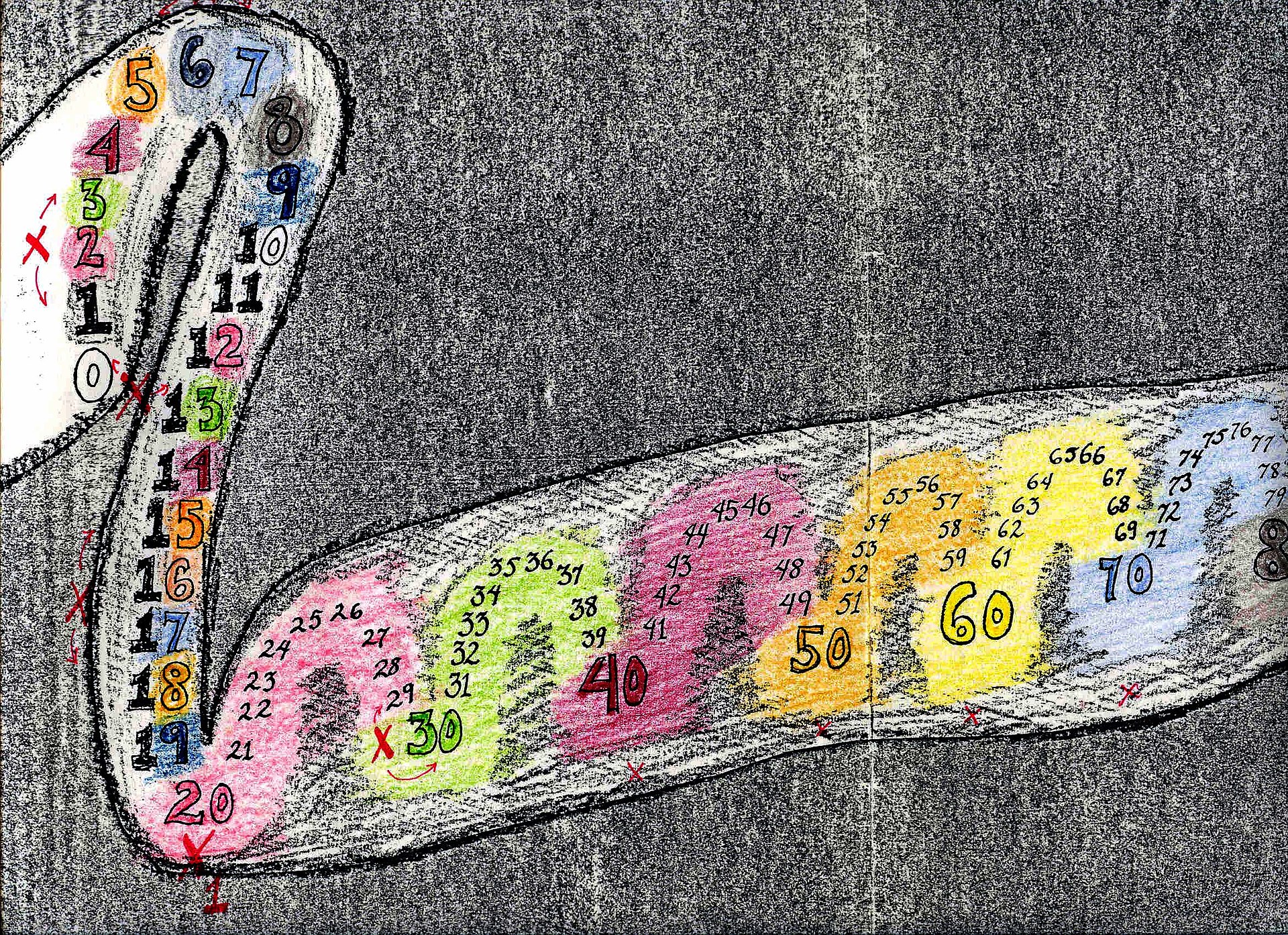

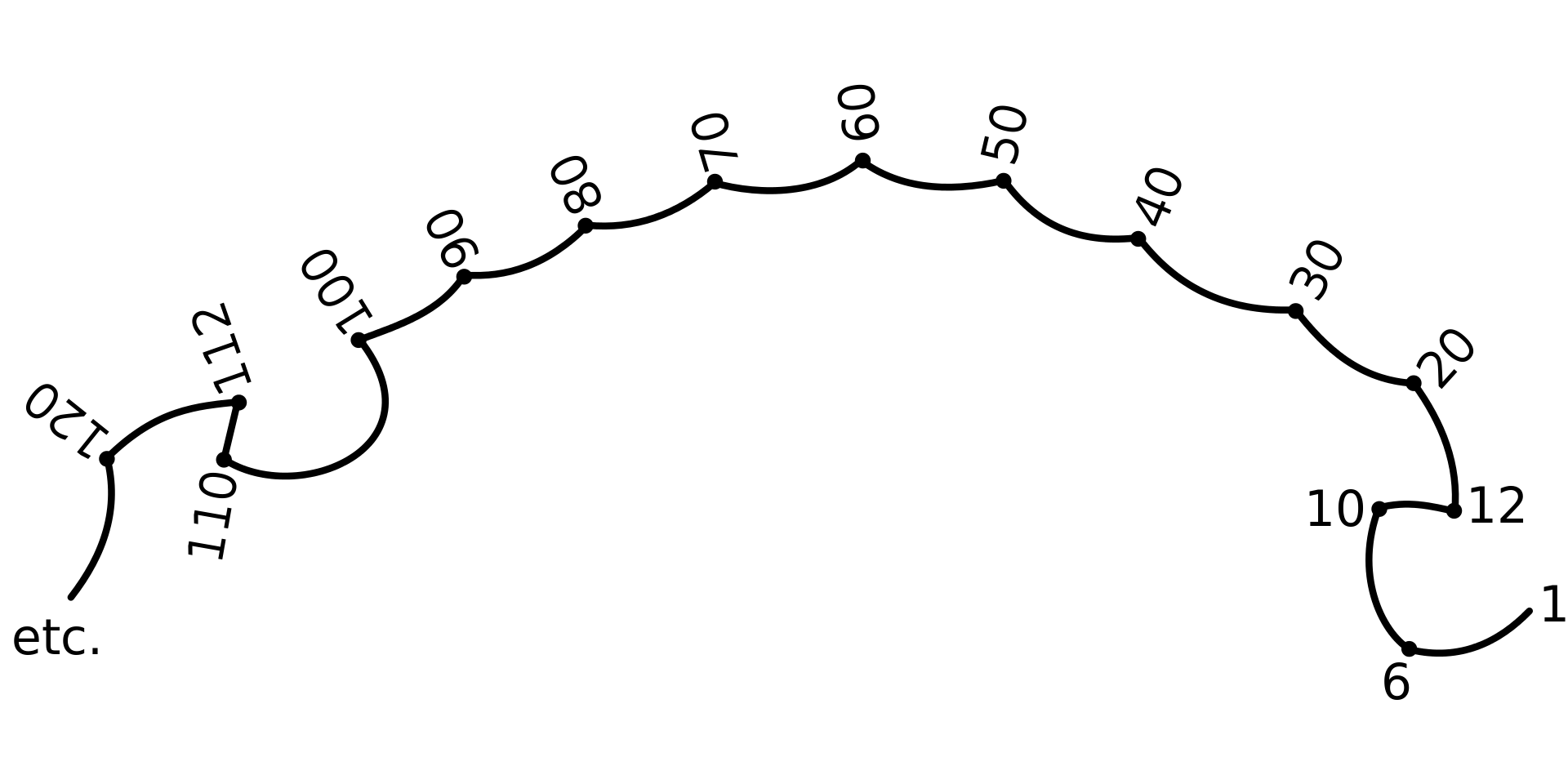

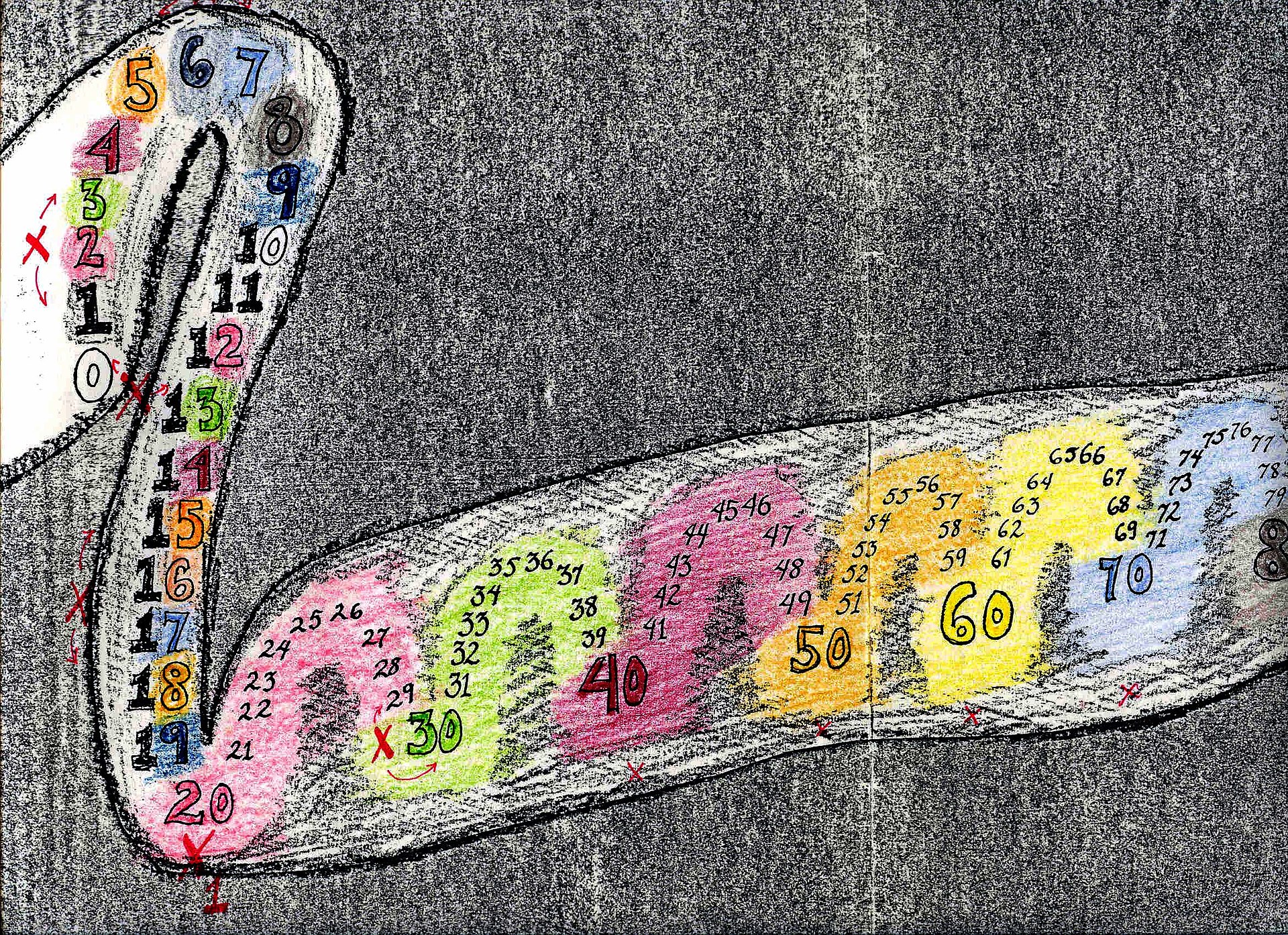

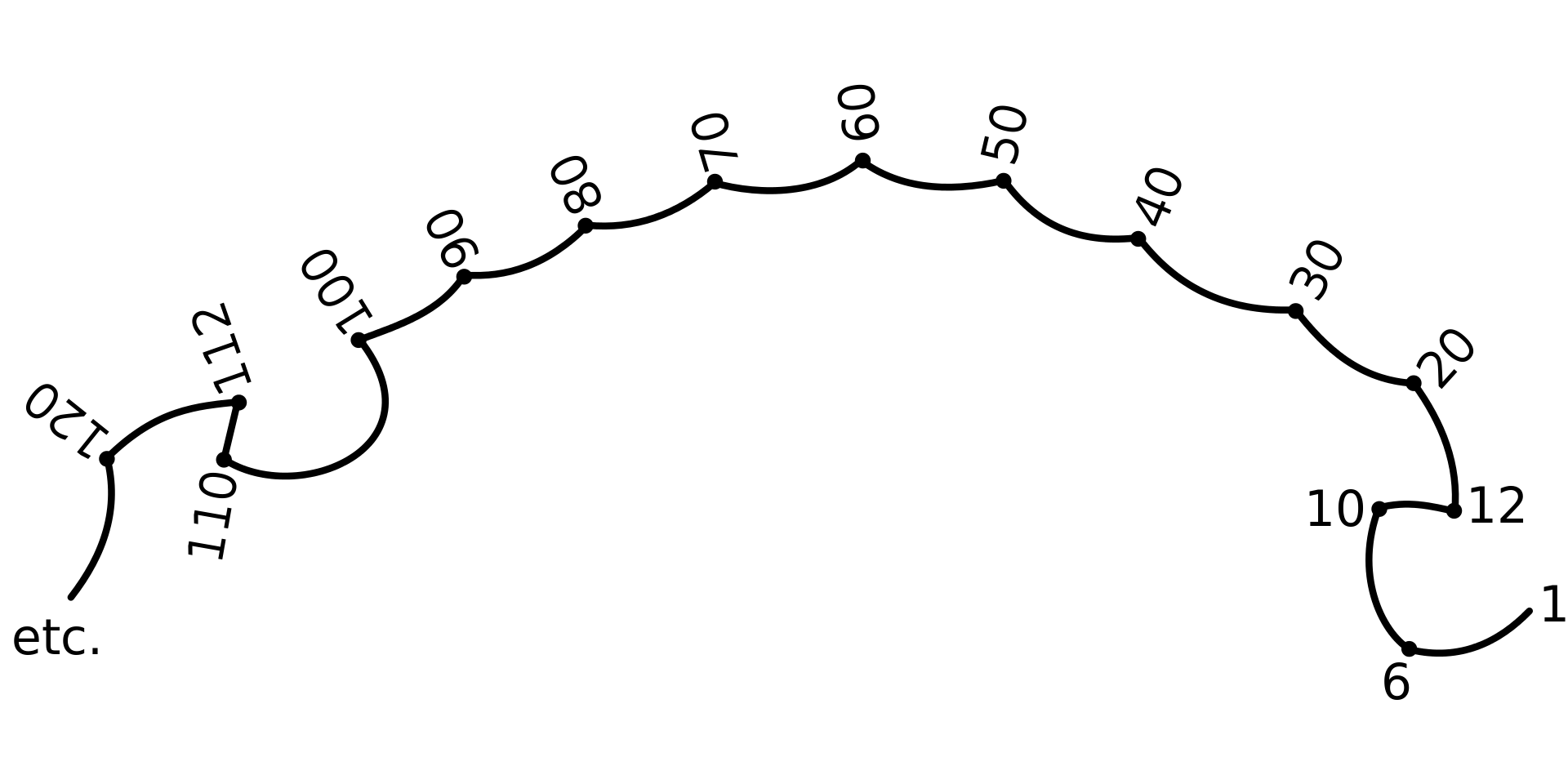

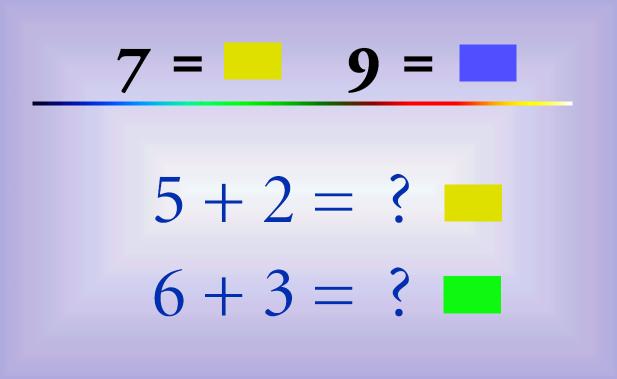

| Types There are two overall forms of synesthesia: projective synesthesia: seeing colors, forms, or shapes when stimulated (the widely understood version of synesthesia) associative synesthesia: feeling a very strong and involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers For example, in chromesthesia (sound to color), a projector may hear a trumpet, and see an orange triangle in space, while an associator might hear a trumpet, and think very strongly that it sounds "orange".[citation needed] Synesthesia can occur between nearly any two senses or perceptual modes, and at least one synesthete, Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia that linked all five senses.[17] Types of synesthesia are indicated by using the notation x → y, where x is the "inducer" or trigger experience, and y is the "concurrent" or additional experience. For example, perceiving letters and numbers (collectively called graphemes) as colored would be indicated as grapheme-color synesthesia. Similarly, when synesthetes see colors and movement as a result of hearing musical tones, it would be indicated as tone → (color, movement) synesthesia. While nearly every logically possible combination of experiences can occur, several types are more common than others. Grapheme–color synesthesia Main article: Grapheme–color synesthesia  From the 2009 non-fiction book Wednesday Is Indigo Blue In one of the most common forms of synesthesia, individual letters of the alphabet and numbers (collectively referred to as "graphemes") are "shaded" or "tinged" with a color. While different individuals usually do not report the same colors for all letters and numbers, studies with large numbers of synesthetes find some commonalities across letters (e.g., A is likely to be red).[18] Some authors had argued that the term synaesthesia may not be correct when applied to the so-called grapheme-colour synesthesia and similar phenomena in which the inducer is conceptual (e.g. a letter or number) rather than sensory (e.g. sound or color). They have postulated that the term ideasthesia is a more accurate description.[19][20] Chromesthesia Main article: Chromesthesia Another common form of synesthesia is the association of sounds with colors. For some, everyday sounds can trigger seeing colors. For others, colors are triggered when musical notes or keys are being played. People with synesthesia related to music may also have perfect pitch because their ability to see and hear colors aids them in identifying notes or keys.[21] The colors triggered by certain sounds, and any other synesthetic visual experiences, are referred to as photisms. According to Richard Cytowic,[3] chromesthesia is "something like fireworks": voice, music, and assorted environmental sounds such as clattering dishes or dog barks trigger color and firework shapes that arise, move around, and then fade when the sound ends. Sound often changes the perceived hue, brightness, scintillation, and directional movement. Some individuals see music on a "screen" in front of their faces. For Deni Simon, music produces waving lines "like oscilloscope configurations – lines moving in color, often metallic with height, width, and, most importantly, depth. My favorite music has lines that extend horizontally beyond the 'screen' area." Individuals rarely agree on what color a given sound is. Composers Franz Liszt and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov famously disagreed on the colors of musical keys. Spatial sequence synesthesia Those with spatial sequence synesthesia (SSS) tend to see ordinal sequences as points in space. People with SSS may have superior memories; in one study, they were able to recall past events and memories far better and in far greater detail than those without the condition. They can also see months or dates in the space around them, but most synesthetes "see" these sequences in their mind's eye. Some people see time like a clock above and around them.[22][23][24] Number form Main article: Number form  A number form from one of Francis Galton's subjects (1881).[9] Note how the first 4 digits roughly correspond to their positions on a clock face. A number form is a mental map of numbers that automatically and involuntarily appear whenever someone who experiences number-forms synesthesia thinks of numbers. These numbers might appear in different locations and the mapping changes and varies between individuals. Number forms were first documented and named in 1881 by Francis Galton in "The Visions of Sane Persons".[25] Auditory–tactile synesthesia In auditory–tactile synesthesia, certain sounds can induce sensations in parts of the body. For example, someone with auditory–tactile synesthesia may experience that hearing a specific word or sound feels like touch in one specific part of the body or may experience that certain sounds can create a sensation in the skin without being touched (not to be confused with the milder general reaction known as frisson, which affects approximately 50% of the population). It is one of the least common forms of synesthesia.[26] Ordinal linguistic personification Main article: Ordinal linguistic personification Ordinal-linguistic personification (OLP, or personification) is a form of synesthesia in which ordered sequences, such as ordinal numbers, week-day names, months, and alphabetical letters are associated with personalities or genders (Simner & Hubbard 2006). Although this form of synesthesia was documented as early as the 1890s,[27][28] researchers have, until recently, paid little attention to it (see History of synesthesia research). This form of synesthesia was named "OLP" in the contemporary literature by Julia Simner and colleagues[29] although it is now also widely recognised by the term "sequence-personality" synesthesia. Ordinal linguistic personification normally co-occurs with other forms of synesthesia such as grapheme–color synesthesia. Misophonia Main article: Misophonia Misophonia is a neurological disorder in which negative experiences (anger, fright, hatred, disgust) are triggered by specific sounds. Cytowic suggests that misophonia is related to, or perhaps a variety of, synesthesia.[1] Edelstein and her colleagues have compared misophonia to synesthesia in terms of connectivity between different brain regions as well as specific symptoms.[1] They hypothesize that "a pathological distortion of connections between the auditory cortex and limbic structures could cause a form of sound-emotion synesthesia."[30] Studies suggest that individuals with misophonia have a normal hearing sensitivity level, but their limbic system and autonomic nervous system are constantly in a "heightened state of arousal" in which abnormal reactions to sounds will be more prevalent.[31] Newer studies suggest that, depending on its severity, misophonia could be associated with lower cognitive control when individuals are exposed to certain associations and triggers.[32] It is unclear what causes misophonia. Some scientists believe the condition could be genetic, while others believe it to be present with additional conditions.[33] There are no current treatments for the condition, but management of symptoms involves numerous coping strategies.[33] These strategies include avoidance of situations that could trigger the reaction, mimicking the sounds, and cancelling out the sounds by using earplugs or music. Most misophoniacs use these to "overwrite" these sounds produced by others.[34] Mirror-touch synesthesia Main article: Mirror-touch synesthesia This is a form of synesthesia where individuals feel the same/similar sensation as another person (such as touch). For instance, when such a synesthete observes someone being tapped on their shoulder, the synesthete involuntarily feels a tap on their own shoulder as well. People with this type of synesthesia have been shown to have higher empathy levels compared to the general population. This may be related to the so-called mirror neurons present in the motor areas of the brain, which have also been linked to empathy.[35] Lexical–gustatory synesthesia Main article: Lexical–gustatory synesthesia This is another form of synesthesia where certain tastes are experienced when hearing words. For example, the word basketball might taste like waffles. The documentary 'Derek Tastes of Earwax' gets its name from this phenomenon, in references to pub owner James Wannerton who experiences this particular sensation whenever he hears the name spoken.[36][37] It is estimated that 0.2% of the synesthesia population has this form of synesthesia, making it one of the rarest forms.[38] Kinesthetic synesthesia Kinesthetic synesthesia is one of the rarest documented forms of synesthesia in the world.[39] This form of synesthesia is a combination of various different types of synesthesia. Features appear similar to auditory–tactile synesthesia but sensations are not isolated to individual numbers or letters but complex systems of relationships. The result is the ability to memorize and model complex relationships between numerous variables by feeling physical sensations around the kinesthetic movement of related variables. Reports include feeling sensations in the hands or feet, coupled with visualizations of shapes or objects when analyzing mathematical equations, physical systems, or music. In another case, a person described seeing interactions between physical shapes causing sensations in the feet when solving a math problem. Generally, those with this type of synesthesia can memorize and visualize complicated systems, and with a high degree of accuracy, predict the results of changes to the system. Examples include predicting the results of computer simulations in subjects such as quantum mechanics or fluid dynamics when results are not naturally intuitive.[18][40] Other forms Other forms of synesthesia have been reported, but little has been done to analyze them scientifically. There are at least 80 types of synesthesia.[39] In August 2017 a research article in the journal Social Neuroscience reviewed studies with fMRI to determine if persons who experience autonomous sensory meridian response are experiencing a form of synesthesia. While a determination has not yet been made, there is anecdotal evidence that this may be the case, based on significant and consistent differences from the control group, in terms of functional connectivity within neural pathways. It is unclear whether this will lead to ASMR being included as a form of existing synesthesia, or if a new type will be considered.[41] |

種類 共感覚には2つのタイプがある: 投射型共感覚:刺激を受けると色や形が見える(広く理解されている共感覚のバージョン)。 連想性共感覚:刺激とそれが引き起こす感覚との間に、非常に強い不随意的なつながりを感じる。 例えば、色彩感覚(音と色)では、投射者はトランペットを聞いて、空間にオレンジ色の三角形を見るかもしれないが、連想者はトランペットを聞いて、それが「オレンジ色」に聞こえると非常に強く思うかもしれない[要出典]。 共感覚は、ほぼすべての2つの感覚または知覚モードの間で起こる可能性があり、少なくとも1人の共感覚者であるソロモン・シェレシェフスキーは、すべての 五感を結びつける共感覚を経験している[17]。例えば、文字や数字(総称して書記素と呼ばれる)を色として知覚することは、書記素-色共感覚として示さ れる。同様に、共感覚者が楽音を聞いた結果として色や動きを見る場合、それは音色→(色、動き)共感覚と示される。 論理的に可能なほぼすべての経験の組み合わせが起こりうるが、いくつかのタイプは他のタイプよりも一般的である。 書記素-色彩感覚 主な記事 書記素-色彩感覚  2009年のノンフィクション『水曜日はインディゴブルー』より 最も一般的な共感覚のひとつでは、アルファベットや数字の個々の文字(総称して「書記素」と呼ばれる)が、ある色で「陰影」または「色調」を帯びる。異な る個人は通常、すべての文字や数字について同じ色を報告するわけではないが、多数の共感覚者を対象とした研究では、文字間でいくつかの共通点が見出されて いる(例えば、Aは赤である可能性が高い)[18]。 共感覚という用語は、いわゆる書記素-色の共感覚や、誘発因子が感覚的(音や色など)ではなく概念的(文字や数字など)である類似の現象に適用する場合に は正しくないかもしれないと主張する著者もいた。彼らは、観念感覚という用語がより正確な表現であると仮定している[19][20]。 色覚 主な記事 色彩感覚 共感覚のもう一つの一般的な形態は、音と色の関連付けである。日常的な音によって色が見えるようになる人もいる。また、音符や鍵盤が奏でられると色が浮か び上がる人もいる。音楽に関する共感覚を持つ人は、色を見たり聞いたりする能力が音符や鍵盤を識別するのに役立つため、完全な音程を持つこともある [21]。 特定の音によって引き起こされる色や、その他の共感覚的な視覚体験は、フォティズムと呼ばれる。 リチャード・サイトウイックによると[3]、色彩感覚は「花火のようなもの」であり、声、音楽、食器がぶつかる音や犬の鳴き声など、さまざまな環境音が引 き金となって色や花火の形が浮かび上がり、動き回り、音が終わると消えてしまう。音はしばしば、知覚される色相、明るさ、シンチレーション、方向の動きを 変化させる。顔の前にある 「スクリーン 」に音楽が見える人もいる。デニ・サイモンにとって、音楽は「オシロスコープを構成するような」波打つ線を作り出す。私の好きな音楽には、「スクリーン 」の領域を超えて水平に伸びる線がある」。 ある音が何色であるかについて、個人の意見が一致することはめったにない。作曲家のフランツ・リストとニコライ・リムスキー=コルサコフが、鍵盤の色について意見が対立したのは有名な話だ。 空間系列共感覚 空間列共感覚(SSS)を持つ人は、順序列を空間の点として見る傾向がある。ある研究では、SSSの人はそうでない人に比べて、過去の出来事や記憶をはる かに詳細に思い出すことができた。また、周囲の空間に月や日付を見ることもできるが、ほとんどの共感覚者は、心の目でこれらの配列を「見る」のである。上 や周囲に時計のような時間が見える人もいる[22][23][24]。 数形 主な記事 数形  フランシス・ゴルトンの被験者の一人による数形(1881年)[9]。最初の4桁が時計の文字盤上の位置にほぼ対応していることに注意。 数形とは、数形共感覚を経験した人が数字を思い浮かべたときに、自動的に、無意識のうちに現れる数字の心的地図である。これらの数字はさまざまな場所に現 れることがあり、そのマッピングは変化し、個人差がある。数形は、1881年にフランシス・ガルトンが『The Visions of Sane Persons』の中で初めて記録し、命名した[25]。 聴覚触覚の共感覚 聴覚触覚の共感覚では、特定の音が身体の一部の感覚を誘発することがある。例えば、聴覚触覚の共感覚を持つ人は、特定の単語や音を聞くと、身体の特定の部 位が触られるように感じたり、特定の音が触れられることなく皮膚に感覚を生じさせることを経験したりする(人口の約50%が罹患するフリッソンとして知ら れる、より穏やかな一般的反応と混同してはならない)。これは最も一般的でない共感覚の一つである[26]。 序列言語擬人化 主な記事 序列言語擬人化 序数-言語的擬人化(OLP、personification)は、序数、曜日名、月、アルファベット文字などの順序列が人格や性別と関連づけられる共感 覚の一形態である(Simner & Hubbard 2006)。この形態の共感覚は1890年代にはすでに記録されていたが[27][28]、研究者は最近までほとんど注目していなかった(共感覚研究の歴 史を参照)。この形態の共感覚は、ジュリア・シムナー(Julia Simner)らによって現代の文献で「OLP」と名付けられたが[29]、現在では「配列-人格」共感覚という用語でも広く認識されている。序列的言語 人格化は通常、書記素-色彩感覚などの他の形態の共感覚と共起する。 失声症 主な記事 失声症 失声症は、特定の音によって否定的な体験(怒り、恐怖、憎悪、嫌悪)が引き起こされる神経疾患である。Cytowicは、ミソフォニアが共感覚と関連して いるか、あるいはおそらく共感覚の一種であることを示唆している[1]。Edelsteinと彼女の同僚は、異なる脳領域間の結合や特異的な症状という点 で、ミソフォニアを共感覚と比較している[1]。彼らは、「聴覚野と大脳辺縁系構造間の結合の病的な歪みが、一種の音情動共感覚を引き起こす可能性があ る」という仮説を立てている。 「30] 研究によると、ミソフォニアの患者は聴覚の感度レベルは正常であるが、大脳辺縁系と自律神経系は常に「高まった覚醒状態」にあり、音に対する異常な反応が より強くなることが示唆されている[31]。 新しい研究によると、ミソフォニアは、その重症度にもよるが、特定の連想や誘因にさらされた場合、認知コントロールの低下と関連する可能性があることが示唆されている[32]。 失声症の原因は不明である。この病態は遺伝的なものであると考える科学者もいれば、他の病態に伴って発症すると考える科学者もいる[33]。ほとんどの失声症患者は、他者が発するこれらの音を「上書き」するためにこれらを使用している[34]。 ミラータッチ共感覚 主な記事 ミラータッチ共感覚 これは共感覚の一形態で、個人が他の人と同じ/似た感覚(触覚など)を感じるものである。例えば、このような共感覚者は、誰かが肩を叩かれているのを観察 すると、無意識のうちに自分の肩も叩かれているように感じる。この種の共感覚を持つ人は、一般の人と比べて共感レベルが高いことが示されている。これは、 脳の運動野に存在する、いわゆるミラーニューロンと関連している可能性があり、ミラーニューロンも共感と関連している[35]。 語彙性-味覚性共感覚 主な記事 語彙-味覚的共感覚 これも共感覚の一種で、言葉を聞いたときに特定の味を感じる。例えば、バスケットボールという単語はワッフルの味がするかもしれない。ドキュメンタリー映 画『耳垢のデレク味』は、パブのオーナーであるジェームズ・ワナートンが、その名前を聞くたびにこの特別な感覚を体験することにちなんで、この現象からそ の名前が付けられた[36][37]。このような形態の共感覚を持つ人は、共感覚人口の0.2%と推定されており、最も稀な形態の一つである[38]。 運動感覚性共感覚 運動感覚性共感覚は、世界で記録されている共感覚の中で最もまれな形態のひとつである[39]。この形態の共感覚は、さまざまな異なるタイプの共感覚が組 み合わされたものである。特徴は聴覚-触覚の共感覚に似ているが、感覚は個々の数字や文字に孤立しているのではなく、複雑な関係のシステムである。その結 果、関連する変数の運動感覚にまつわる身体感覚を感じることで、多数の変数間の複雑な関係を記憶し、モデル化することができる。数学の方程式や物理システ ム、音楽を分析するときに、手や足に感覚を感じ、図形や物体を視覚化するという報告もある。別の例では、数学の問題を解くときに、物理的な形状の相互作用 が足の感覚を引き起こすのを見たという人がいる。一般的に、このタイプの共感覚を持つ人は、複雑なシステムを記憶し、視覚化することができ、高い精度でシ ステムに変更を加えた結果を予測することができる。例としては、量子力学や流体力学のような科目において、結果が自然には直感的に理解できない場合に、コ ンピュータシミュレーションの結果を予測することが挙げられる[18][40]。 その他の形態 他の形態の共感覚も報告されているが、それらを科学的に分析することはほとんど行われていない。共感覚には少なくとも80のタイプがある[39]。 2017年8月にSocial Neuroscience誌に掲載された研究論文では、自律感覚経絡反応を経験する人が共感覚の一形態を経験しているかどうかを判断するためにfMRIを 用いた研究がレビューされている。断定はまだなされていないが、神経経路内の機能的結合性という点で、対照群との有意かつ一貫した差異に基づき、そうかも しれないという逸話的証拠がある。これにより、ASMRが既存の共感覚の一形態として含まれるようになるのか、それとも新しいタイプが検討されるようにな るのかは不明である[41]。 |

| Signs and symptoms Some synesthetes often report that they were unaware their experiences were unusual until they realized other people did not have them, while others report feeling as if they had been keeping a secret their entire lives.[42] The automatic and ineffable nature of a synesthetic experience means that the pairing may not seem out of the ordinary. This involuntary and consistent nature helps define synesthesia as a real experience. Most synesthetes report that their experiences are pleasant or neutral, although, in rare cases, synesthetes report that their experiences can lead to a degree of sensory overload.[18] Though often stereotyped in the popular media as a medical condition or neurological aberration,[citation needed] many synesthetes themselves do not perceive their synesthetic experiences as a handicap. On the contrary, some report it as a gift – an additional "hidden" sense – something they would not want to miss. Most synesthetes become aware of their distinctive mode of perception in their childhood. Some have learned how to apply their ability in daily life and work. Synesthetes have used their abilities in memorization of names and telephone numbers, mental arithmetic, and more complex creative activities like producing visual art, music, and theater.[42] Despite the commonalities which permit the definition of the broad phenomenon of synesthesia, individual experiences vary in numerous ways. This variability was first noticed early in synesthesia research.[43] Some synesthetes report that vowels are more strongly colored, while for others consonants are more strongly colored.[18] Self-reports, interviews, and autobiographical notes by synesthetes demonstrate a great degree of variety in types of synesthesia, the intensity of synesthetic perceptions, awareness of the perceptual discrepancies between synesthetes and non-synesthetes, and the ways synesthesia is used in work, creative processes, and daily life.[42][44] Synesthetes are very likely to participate in creative activities.[40] It has been suggested that individual development of perceptual and cognitive skills, in addition to one's cultural environment, produces the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic phenomena.[6][44] Synesthesia may also give a memory advantage. In one study, conducted by Julia Simner of the University of Edinburgh, it was found that spatial sequence synesthetes have a built-in and automatic mnemonic reference. Whereas a non-synesthete will need to create a mnemonic device to remember a sequence (like dates in a diary), a synesthete can simply reference their spatial visualizations.[45] |

兆候と症状 共感覚を持つ人の中には、他の人が共感覚を持っていないことに気づくまで、自分の体験が異常なものであることに気づかなかったとしばしば報告する人もいれ ば、生涯秘密を守り続けてきたかのように感じたと報告する人もいる[42]。この不随意的で一貫した性質は、共感覚を現実の体験として定義するのに役立 つ。ほとんどの共感覚者は、その体験は快いものであるか、あるいはニュートラルなものであると報告しているが、まれに、その体験が感覚過敏になることがあ ると報告している[18]。 一般的なメディアではしばしば医学的な症状や神経学的な異常としてステレオタイプ化されるが[要出典]、多くの共感覚者自身は自分の共感覚体験をハンディ キャップとして認識していない。それどころか、それを贈り物、つまり「隠された」付加的な感覚、見逃したくないものとして報告する人もいる。ほとんどの共 感覚者は、幼少期に自分の独特な知覚様式に気づく。日常生活や仕事において、その能力をどのように応用するかを学んだ人もいる。共感覚者はその能力を、名 前や電話番号の暗記、暗算、視覚芸術や音楽、演劇の制作などのより複雑な創造的活動に用いてきた[42]。 共感覚という広範な現象の定義を可能にする共通点にもかかわらず、個々の体験は多くの点で異なっている。この多様性は、共感覚研究の初期に初めて注目され た[43]。ある共感覚者は母音がより強く着色されると報告し、他の共感覚者は子音がより強く着色されると報告する。 [18] 共感覚者による自己報告、インタビュー、自伝的ノートは、共感覚のタイプ、共感覚的知覚の強さ、共感覚者と非共感覚者の知覚の不一致の認識、仕事、創造的 プロセス、日常生活における共感覚の使用方法において、非常に多様であることを示している[42][44]。 共感覚者は創造的な活動に参加する可能性が非常に高い[40]。文化的環境に加え、知覚や認知能力の個人的な発達が、共感覚現象の多様な認識や実用的な使 用を生み出していることが示唆されている[6][44]。エジンバラ大学のジュリア・シムナー(Julia Simner)により行われたある研究では、空間配列の共感覚者は、内蔵された自動的なニモニック参照を持っていることがわかった。非共感覚者は、(日記 の日付のように)順序を記憶するためにニモニックデバイスを作成する必要があるが、共感覚者は単に空間的視覚化を参照することができる[45]。 |

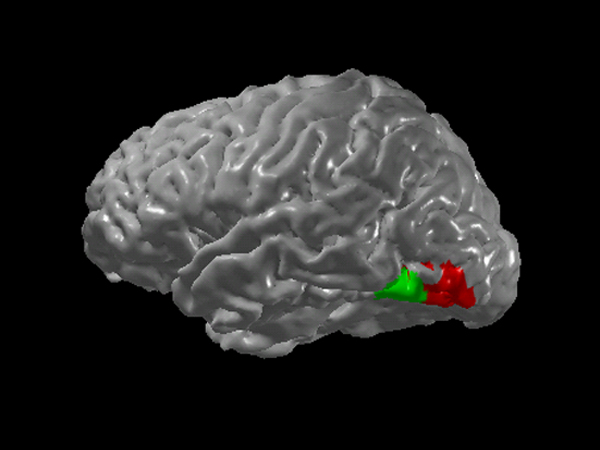

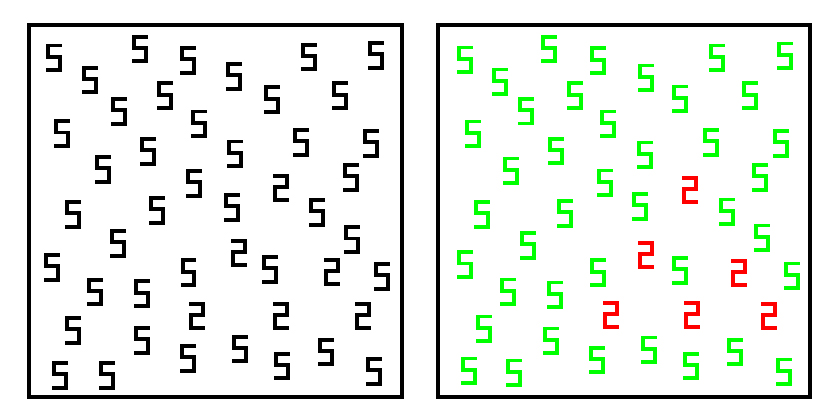

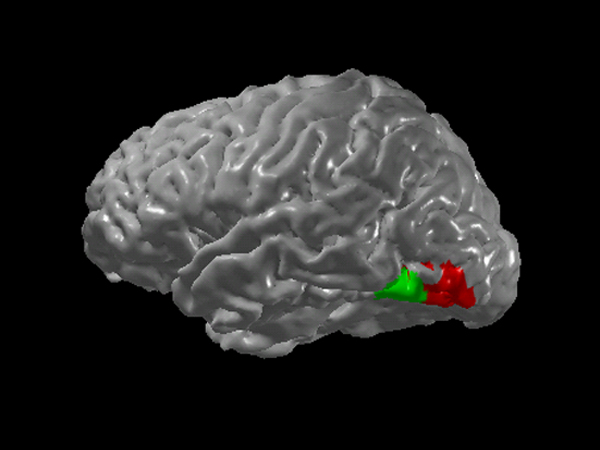

| Mechanism Main article: Neural basis of synesthesia  Regions thought to be cross-activated in grapheme–color synesthesia (green=grapheme recognition area, red=V4 color area)[46] As of 2015, the neurological correlates of synesthesia had not been established.[47] Dedicated regions of the brain are specialized for given functions. Increased cross-talk between regions specialized for different functions may account for the many types of synesthesia. For example, the additive experience of seeing color when looking at graphemes might be due to cross-activation of the grapheme-recognition area and the color area called V4 (see figure).[46] This is supported by the fact that grapheme–color synesthetes can identify the color of a grapheme in their peripheral vision even when they cannot consciously identify the shape of the grapheme.[46] An alternative possibility is disinhibited feedback, or a reduction in the amount of inhibition along normally existing feedback pathways.[48] Normally, excitation and inhibition are balanced. However, if normal feedback were not inhibited as usual, then signals feeding back from late stages of multi-sensory processing might influence earlier stages such that tones could activate vision. Cytowic and Eagleman find support for the disinhibition idea in the so-called acquired forms[3] of synesthesia that occur in non-synesthetes under certain conditions: temporal lobe epilepsy,[49] head trauma, stroke, and brain tumors. They also note that it can likewise occur during stages of meditation, deep concentration, sensory deprivation, or with use of psychedelics such as LSD or mescaline, and even, in some cases, marijuana.[3] However, synesthetes report that common stimulants, like caffeine and cigarettes do not affect the strength of their synesthesia, nor does alcohol.[3]: 137–40 A very different theoretical approach to synesthesia is that based on ideasthesia. According to this account, synesthesia is a phenomenon mediated by the extraction of the meaning of the inducing stimulus. Thus, synesthesia may be fundamentally a semantic phenomenon. Therefore, to understand neural mechanisms of synesthesia the mechanisms of semantics and the extraction of meaning need to be understood better. This is a non-trivial issue because it is not only a question of a location in the brain at which meaning is "processed" but pertains also to the question of understanding – epitomized in e.g., the Chinese room problem. Thus, the question of the neural basis of synesthesia is deeply entrenched into the general mind–body problem and the problem of the explanatory gap.[50] Genetics Main article: Genetics of synesthesia Due to the prevalence of synesthesia among the first-degree relatives of people affected,[51] there may be a genetic basis, as indicated by the monozygotic twins studies showing an epigenetic component.[medical citation needed] Synesthesia might also be an oligogenic condition, with locus heterogeneity, multiple forms of inheritance, and continuous variation in gene expression.[medical citation needed] While the exact genetic loci for this trait haven't been identified, research indicates that the genetic constructs underlying synesthesia are most likely more complex than the simple X-linked mode of inheritance that early researchers believed it to be.[8] Further, it remains uncertain as to whether synesthesia perseveres in the genetic pool because it provides a selective advantage, or because it has become a byproduct of some other useful selected trait.[52] Women have a higher chance of developing synesthesia, as demonstrated in population studies conducted in the city of Cambridge, England where females were 6 times more likely to have it.[51] As technological equipment continues to advance, the search for clearer answers regarding the genetics behind synesthesia will become more promising. Although often termed a "neurological condition," synesthesia is not listed in either the DSM-IV or the ICD since it usually does not interfere with normal daily functioning.[53] Indeed, most synesthetes report that their experiences are neutral or even pleasant.[18] Like perfect pitch, synesthesia is simply a difference in perceptual experience.  Reaction times for answers that are congruent with a synesthete's automatic colors are shorter than those whose answers are incongruent.[3] The simplest approach is test-retest reliability over long periods of time, using stimuli of color names, color chips, or a computer-screen color picker providing 16.7 million choices. Synesthetes consistently score around 90% on the reliability of associations, even with years between tests.[1] In contrast, non-synesthetes score just 30–40%, even with only a few weeks between tests and a warning that they would be retested.[1] Many tests exist for synesthesia. Each common type has a specific test. When testing for grapheme–color synesthesia, a visual test is given. The person is shown a picture that includes black letters and numbers. A synesthete will associate the letters and numbers with a specific color. An auditory test is another way to test for synesthesia. A sound is turned on and one will either identify it with a taste or envision shapes. The audio test correlates with chromesthesia (sounds with colors). Since people question whether or not synesthesia is tied to memory, the "retest" is given. One is given a set of objects and is asked to assign colors, tastes, personalities, or more. After a period of time, the same objects are presented and the person is asked again to do the same task. The synesthete can assign the same characteristics because that person has permanent neural associations in the brain, rather than memories of a certain object.[medical citation needed]  The automaticity of synesthetic experience. A synesthete might perceive the left panel like the panel on the right.[46] Grapheme–color synesthetes, as a group, share significant preferences for the color of each letter (e.g., A tends to be red; O tends to be white or black; S tends to be yellow, etc.)[18] Nonetheless, there is a great variety in types of synesthesia, and within each type, individuals report differing triggers for their sensations and differing intensities of experiences. This variety means that defining synesthesia in an individual is difficult, and the majority of synesthetes are completely unaware that their experiences have a name.[18] Neurologist Richard Cytowic identifies the following diagnostic criteria for synesthesia in his first edition book. However, the criteria are different in the second book:[1][2][3] Synesthesia is involuntary and automatic Synesthetic perceptions are spatially extended, meaning they often have a sense of "location." For example, synesthetes speak of "looking at" or "going to" a particular place to attend to the experience Synesthetic percepts are consistent and generic (i.e., simple rather than pictorial) Synesthesia is highly memorable Synesthesia is laden with affect Cytowic's early cases mainly included individuals whose synesthesia was frankly projected outside the body (e.g., on a "screen" in front of one's face). Later research showed that such stark externalization occurs in a minority of synesthetes. Refining this concept, Cytowic and Eagleman differentiated between "localizers" and "non-localizers" to distinguish those synesthetes whose perceptions have a definite sense of spatial quality from those whose perceptions do not.[3] Prevalence Estimates of prevalence of synesthesia have ranged widely, from 1 in 4 to 1 in 25,000–100,000. However, most studies have relied on synesthetes reporting themselves, introducing self-referral bias.[54] In what is cited as the most accurate prevalence study so far,[54] self-referral bias was avoided by studying 500 people recruited from the communities of Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities; it showed a prevalence of 4.4%, with 9 different variations of synesthesia.[55] This study also concluded that one common form of synesthesia – grapheme–color synesthesia (colored letters and numbers) – is found in more than one percent of the population, and this latter prevalence of graphemes–color synesthesia has since been independently verified in a sample of nearly 3,000 people in the University of Edinburgh.[56] The most common forms of synesthesia are those that trigger colors, and the most prevalent of all is day–color.[55] Also relatively common is grapheme–color synesthesia. We can think of "prevalence" both in terms of how common is synesthesia (or different forms of synesthesia) within the population, or how common are different forms of synesthesia within synesthetes. So within synesthetes, forms of synesthesia that trigger color also appear to be the most common forms of synesthesia with a prevalence rate of 86% within synesthetes.[55] In another study, music–color is also prevalent at 18–41%.[citation needed] Some of the rarest are reported to be auditory–tactile, mirror-touch, and lexical–gustatory.[57] There is research to suggest that the likelihood of having synesthesia is greater in people with autism spectrum condition.[58] |

メカニズム 主な記事 共感覚の神経基盤  書記素-色彩の共感覚において交差活性化されると考えられる領域(緑=書記素認識領域、赤=V4色彩領域)[46]。 2015年現在、共感覚の神経学的相関は確立されていない[47]。 脳の専用領域は特定の機能に特化している。異なる機能に特化した領域間のクロストークが増加することで、多くの種類の共感覚が説明できるかもしれない。例 えば、書記素を見たときに色が見えるという加法的な経験は、書記素認識野とV4と呼ばれる色彩野の交差活性化によるものかもしれない(図参照)[46]。 このことは、書記素-色彩共感覚者が、書記素の形状を意識的に識別できない場合でも、周辺視野で書記素の色を識別できるという事実によって裏付けられてい る[46]。 別の可能性として、抑制されないフィードバック、つまり通常存在するフィードバック経路に沿った抑制の量が減少していることが考えられる[48]。通常、 興奮と抑制は釣り合っている。しかし、もし正常なフィードバックが通常通り抑制されな かったとすると、多感覚処理の後期段階からフィードバックされる信号 が前期段階に影響を及ぼし、音によって視覚が活性化される可能性 がある。CytowicとEaglemanは、側頭葉てんかん、[49]頭部外傷、脳卒中、脳腫瘍など、特定の条件下で非共感覚者に生じる、いわゆる後天 的な共感覚の形態[3]に、抑制解除の考えを支持するものを見出している。また、瞑想、深い集中、感覚遮断、あるいはLSDやメスカリンなどのサイケデ リックの使用、さらに場合によってはマリファナの使用でも同様に起こりうることも指摘している[3]。しかしながら、共感覚者は、カフェインやタバコなど の一般的な刺激物は共感覚の強さに影響せず、アルコールも影響しないと報告している[3]: 137-40 共感覚に対する非常に異なった理論的アプローチは、イデア感覚に基づくものである。この説明によれば、共感覚は誘発刺激の意味の抽出によって媒介される現 象である。したがって、共感覚は基本的に意味現象であると考えられる。したがって、共感覚の神経メカニズムを理解するためには、意味論と意味の抽出のメカ ニズムをよりよく理解する必要がある。この問題は、意味が「処理」される脳の位置の問題であるだけでなく、例えば中国語の部屋問題に象徴されるように、理 解の問題にも関わるからである。このように、共感覚の神経基盤の問題は、一般的な心身問題と説明ギャップの問題に深く入り込んでいる[50]。 遺伝学 主な記事 共感覚の遺伝学 一卵性双生児の研究がエピジェネティックな要素を示していることからわかるように、共感覚には遺伝的基盤があるかもしれない[51]。 [この特性の正確な遺伝子座は特定されていないが、研究によると、共感覚の根底にある遺伝的構成は、初期の研究者が信じていた単純なX連鎖遺伝様式よりも 複雑である可能性が高い。 [8]さらに、共感覚が遺伝子の中に残っているのは、それが選択的な利点をもたらすからなのか、それとも他の有用な選択形質の副産物になったからなのかに ついては、依然として不明である[52]。イギリス・ケンブリッジ市で行われた集団調査では、女性の方が共感覚を持つ確率が6倍も高いことが実証されてい るように、女性の方が共感覚を発症する確率が高い[51]。 しばしば「神経学的状態」と呼ばれるが、共感覚は通常、通常の日常生活に支障をきたさないため、DSM-IVにもICDにも記載されていない[53]。実 際、ほとんどの共感覚者は、その体験が中立的であるか、あるいは快いものであると報告している[18]。完全音感と同様に、共感覚は単に知覚経験の差であ る。  共感覚者の自動的な色と一致する答えの反応時間は、不一致の答えの反応時間よりも短い[3]。 最も単純なアプローチは、色名、カラーチップ、または1,670万 の選択肢を提供するコンピュータ画面のカラーピッカーの刺激を 用いた、長期間にわたるテスト・リテスト信頼性である。共感覚者は、テストとテストの間に何年もの間隔があいたとしても、連想の信頼性において常に90% 前後のスコアを獲得する[1]。対照的に、非共感覚者は、テストとテストの間に数週間しか空けず、再テストを行うと警告した場合でも、わずか30~40% のスコアしか獲得できない[1]。 共感覚については多くの検査が存在する。一般的なタイプにはそれぞれ特有の検査がある。書記素-色彩の共感覚を検査する場合、視覚検査が行われる。黒い文 字と数字を含む絵を見せる。共感覚者は、文字や数字から特定の色を連想する。聴覚テストも共感覚をテストする方法のひとつである。音を鳴らし、その音から 味を感じたり、形を思い浮かべたりする。音声テストは色彩感覚(音と色)と相関がある。共感覚が記憶と結びついているかどうかが疑問視されているため、 「再テスト」が行われる。一組の物体を渡され、色、味、個性、あるいはそれ以上のものを割り当てられる。一定時間後、同じものが提示され、再び同じ作業を 求められる。共感覚を持つ人は、特定の物体に関する記憶ではなく、脳内の永続的な神経連合を持つため、同じ特徴を割り当てることができる[要医学的引 用]。  共感覚体験の自動性 共感覚者は左のパネルを右のパネルのように知覚するかもしれない[46]。 書記素色の共感覚者は、グループとして、各文字の色に対する重要な嗜好を共有している(例えば、Aは赤、Oは白または黒、Sは黄色などの傾向がある) [18]。それにもかかわらず、共感覚のタイプには非常に多様性があり、各タイプの中でも、個人によって感覚のきっかけや経験の強さが異なると報告されて いる。このような多様性は、個人の共感覚を定義することが困難であることを意味し、大多数の共感覚者は自分の経験に名前があることに全く気づいていない [18]。 神経学者であるリチャード・サイトウィックは、その初版の本の中で、共感覚の診断基準として以下のものを挙げている。しかし、第2版では基準が異なっている。 共感覚は不随意的かつ自動的である。 共感覚的知覚は空間的に拡張され、しばしば 「位置 」の感覚を持つ。例えば、共感覚を持つ人は、その体験に参加するために特定の場所を「見る」あるいは「行く」と話す。 共感覚的知覚は一貫しており、一般的である(すなわち、絵画的というよりは単純である)。 共感覚は非常に記憶に残りやすい。 共感覚は情動を伴う サイトウイックの初期の症例は、共感覚が率直に身体の外(例えば、顔の前にある「スクリーン」)に映し出される人たちが中心であった。その後の研究で、こ のような鮮明な外在化が起こるのは共感覚者の少数派であることが示された。この概念を改良して、サイトウィックとイーグルマンは、知覚に明確な空間的質感 がある共感覚者とそうでない共感覚者を区別するために、「ローカライザー」と「ノン・ローカライザー」を区別した[3]。 有病率 共感覚の有病率の推定値は、4人に1人から25,000~100,000人に1人までと幅が広い。しかし、ほとんどの研究は、共感覚者の自己申告に頼って おり、自己紹介バイアスが生じている[54]。これまでで最も正確な有病率研究として挙げられている[54]研究では、エジンバラ大学とグラスゴー大学の コミュニティから募集した500人を調査することで、自己紹介バイアスを回避した。 [55] この研究ではまた、共感覚の一般的な形態の1つである書記素-色彩共感覚(色付きの文字と数字)が人口の1%以上に見られると結論づけられ、その後、この 書記素-色彩共感覚の後者の有病率は、エジンバラ大学の約3,000人のサンプルで独自に検証されている[56]。 共感覚の最も一般的な形態は色を引き金とするものであり、その中で最も有病率が高いのは昼色である[55]。また、書記素-色彩の共感覚も比較的一般的で ある。有病率」は、人口の中で共感覚(または異なる形態の共感覚)がどの程度一般的であるか、あるいは共感覚者の中で異なる形態の共感覚がどの程度一般的 であるか、という両方の観点から考えることができる。そのため、共感覚者の中では、色を引き金とする共感覚の形態が最も一般的であり、その有病率は86% である[55]。別の研究では、音楽-色彩も18~41%と一般的である[要出典]。最も稀なものとして、聴覚-触覚、鏡-触覚、語彙-味覚が報告されて いる[57]。 自閉症スペクトラムの患者では共感覚を持つ可能性が高いことを示唆する研究がある[58]。 |

| History Main article: History of synesthesia research The interest in colored hearing dates back to Greek antiquity when some theorists wondered whether the color (chroia, what we now call timbre) of music was a quantifiable quality of sound, together with pitch and duration. Additionally, one kind of musical scale (genos) introduced by Plato's friend Archytas of Tarentum in the fourth century BC was named chromatic. The late sixth century BC kitharist Lysander of Sicyon was said to have introduced a more 'colorful' style, even before the development of the chromatic scale itself. In Plato's time, the description of melody as 'colored' had become part of professional jargon, while the musical terms 'tone' and 'harmony' soon became integrated into the vocabulary of color in visual art.[59] Isaac Newton proposed that musical tones and color tones shared common frequencies, as did Goethe in his book Theory of Colours.[60] There is a long history of building color organs such as the clavier à lumières on which to perform colored music in concert halls.[61][62] The first medical description of "colored hearing" is in an 1812 thesis by the German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs.[63][14][15] The "father of psychophysics," Gustav Fechner, reported the first empirical survey of colored letter photisms among 73 synesthetes in 1876,[64][65] followed in the 1880s by Francis Galton.[9][66][67] Carl Jung refers to "color hearing" in his Symbols of Transformation in 1912.[68] In the early 1920s, the Bauhaus teacher and musician Gertrud Grunow researched the relationships between sound, color, and movement and developed a 'twelve-tone circle of colour' which was analogous with the twelve-tone music of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951).[69] She was a participant in at least one of the Congresses for Colour-Sound Research (German:Kongreß für Farbe-Ton-Forschung) held in Hamburg in the late 1920s and early 1930s.[70] Research into synesthesia proceeded briskly in several countries, but due to the difficulties in measuring subjective experiences and the rise of behaviorism, which made the study of any subjective experience taboo, synesthesia faded into scientific oblivion between 1930 and 1980.[citation needed] As the 1980s cognitive revolution made inquiry into internal subjective states respectable again, scientists returned to synesthesia. Led in the United States by Larry Marks and Richard Cytowic, and later in England by Simon Baron-Cohen and Jeffrey Gray, researchers explored the reality, consistency, and frequency of synesthetic experiences. In the late 1990s, the focus settled on grapheme → color synesthesia, one of the most common[18] and easily studied types. Psychologists and neuroscientists study synesthesia not only for its inherent appeal but also for the insights it may give into cognitive and perceptual processes that occur in synesthetes and non-synesthetes alike. Synesthesia is now the topic of scientific books and papers, Ph.D. theses, documentary films, and even novels.[citation needed] Since the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, synesthetes began contacting one another and creating websites devoted to the condition. These rapidly grew into international organizations such as the American Synesthesia Association, the UK Synaesthesia Association, the Belgian Synesthesia Association, the Canadian Synesthesia Association, the German Synesthesia Association, and the Netherlands Synesthesia Web Community.[citation needed] |

歴史 主な記事 共感覚研究の歴史 色彩聴覚への関心は、音楽の色彩(クロイア、現在では音色と呼ばれる)が音程や持続時間と共に定量化可能な音の質ではないか、と考えた理論家たちがいたギ リシャ古代にまで遡る。さらに、紀元前4世紀にプラトンの友人であったタレントゥムのアルキタスによって導入された音階の一種(ジェノス)は、半音階と名 付けられた。紀元前6世紀末のキタリスト、シシオンのリサンダーは、半音階そのものが開発される以前から、より「カラフル」なスタイルを導入していたと言 われている。プラトンの時代には、旋律を「色彩的」と表現することが専門用語の一部となっており、音楽用語の「音色」や「ハーモニー」はすぐに視覚芸術に おける色彩の語彙に統合された[59]。 色彩聴覚」に関する最初の医学的記述は、ドイツの医師ゲオルク・トビアス・ルートヴィヒ・ザックスによる1812年の論文にある[63][14] [15]。 精神物理学の父」であるグスタフ・フェヒナーは、1876年に73人の共感覚者の間で色文字の光覚に関する最初の実証的調査を報告し[64][65]、 1880年代にはフランシス・ガルトンがそれに続いている[9][66][67]。カール・ユングは1912年に『変容の象徴』の中で「色彩聴覚」に言及 している[68]。 1920年代初頭、バウハウスの教師であり音楽家であったゲルトルート・グリューノフは音、色彩、運動の関係を研究し、オーストリアの作曲家アーノルド・ シェーンベルク(1874-1951)の十二音音楽に類似した「色彩の十二音圏」を開発した[69]。彼女は1920年代後半から1930年代初頭にかけ てハンブルクで開催された色彩音響研究会議(ドイツ語:Kongreß für Farbe-Ton-Forschung)の少なくとも1つに参加していた[70]。 共感覚の研究はいくつかの国で活発に進められたが、主観的な経験を測定することの難しさと、あらゆる主観的な経験の研究をタブー視する行動主義の台頭により、共感覚は1930年から1980年の間に科学的な忘却の彼方へと消えていった[要出典]。 1980年代の認知革命によって、内的主観的状態に対する探究が再び尊重されるようになると、科学者たちは共感覚に戻ってきた。アメリカではラリー・マー クスとリチャード・サイトウィックが、イギリスではサイモン・バロン=コーエンとジェフリー・グレイが主導し、研究者たちは共感覚体験の現実性、一貫性、 頻度について探求した。1990年代後半には、最も一般的[18]で研究しやすいタイプの一つである、書記素→色の共感覚に焦点が当てられるようになっ た。心理学者や神経科学者が共感覚を研究するのは、その本質的な魅力のためだけでなく、共感覚者と非共感者に共通して生じる認知や知覚のプロセスについて 洞察するためでもある。共感覚は現在、科学書や論文、博士論文、ドキュメンタリー映画、さらには小説のテーマにもなっている[要出典]。 1990年代にインターネットが台頭して以来、共感覚者は互いに連絡を取り合い、この症状に特化したウェブサイトを作り始めた。これらは急速に発展し、ア メリカ共感覚協会、イギリス共感覚協会、ベルギー共感覚協会、カナダ共感覚協会、ドイツ共感覚協会、オランダ共感覚ウェブコミュニティなどの国際的な組織 となった[要出典]。 |

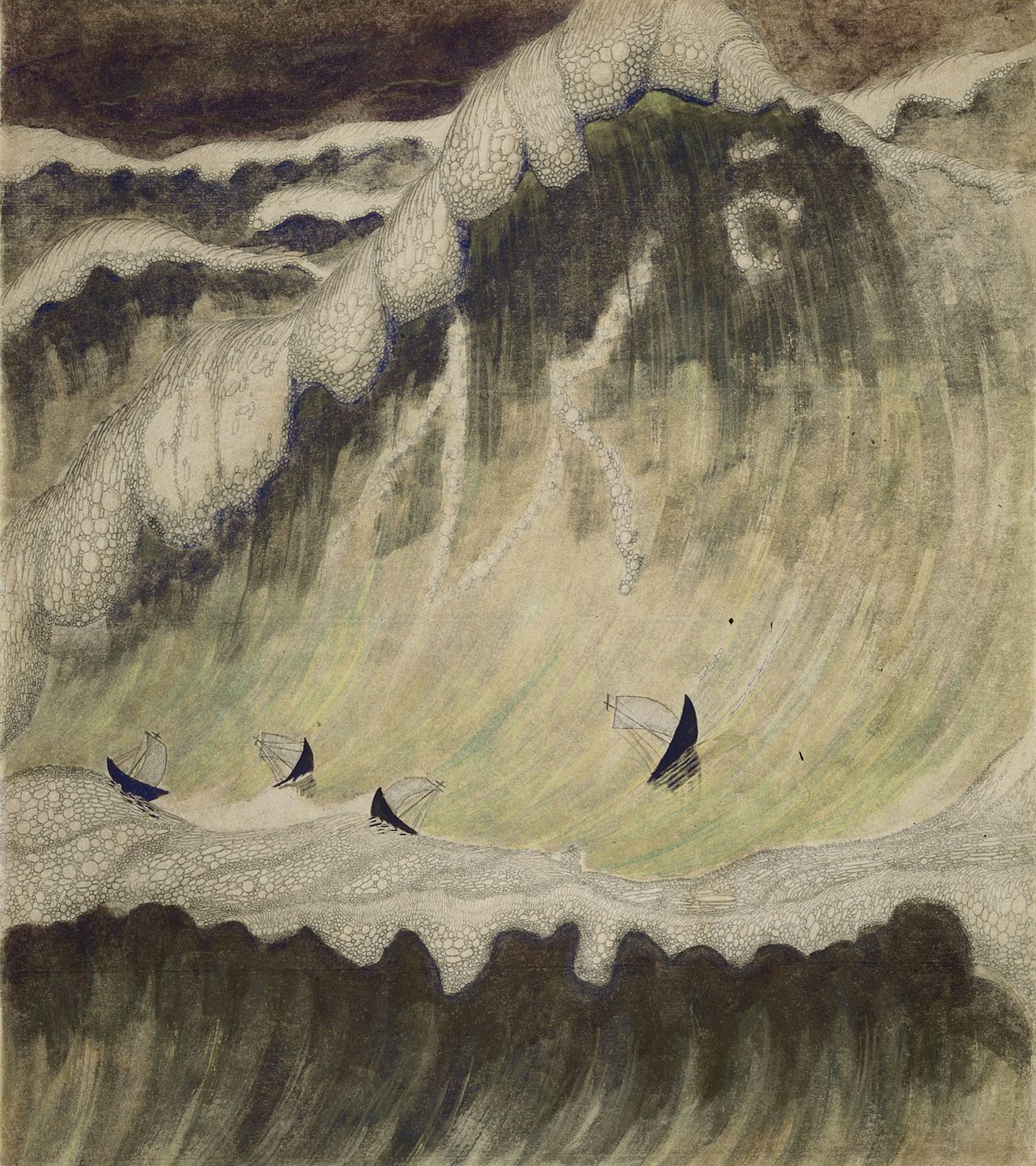

| Society and culture Notable cases Main article: List of people with synesthesia Solomon Shereshevsky, a newspaper reporter turned mnemonist, was discovered by Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria to have a rare fivefold form of synesthesia,[17] of which he is the only known case. Words and text were not only associated with highly vivid visuospatial imagery but also sound, taste, color, and sensation.[17] Shereshevsky could recount endless details of many things without form, from lists of names to decades-old conversations, but he had great difficulty grasping abstract concepts. The automatic, and nearly permanent, retention of every detail due to synesthesia greatly inhibited Shereshevsky's ability to understand what he read or heard.[17] Neuroscientist and author V.S. Ramachandran studied the case of a grapheme–color synesthete who was also color blind. While he couldn't see certain colors with his eyes, he could still "see" those colors when looking at certain letters. Because he didn't have a name for those colors, he called them "Martian colors."[71] Art Main article: Synesthesia in art Other notable synesthetes come particularly from artistic professions and backgrounds. Synesthetic art historically refers to multi-sensory experiments in the genres of visual music, music visualization, audiovisual art, abstract film, and intermedia.[42][72][73][74][75][76] Distinct from neuroscience, the concept of synesthesia in the arts is regarded as the simultaneous perception of multiple stimuli in one gestalt experience.[77] Neurological synesthesia has been a source of inspiration for artists, composers, poets, novelists, and digital artists. Writers Vladimir Nabokov wrote explicitly about synesthesia in several novels. Nabokov described his grapheme–color synesthesia at length in his autobiography, Speak, Memory:[78] I present a fine case of colored hearing. Perhaps "hearing" is not quite accurate, since the color sensations seem to be produced by the very act of my orally forming a given letter while I imagine its outline. The long a of the English alphabet (and it is this alphabet I have in mind farther on unless otherwise stated) has for me the tint of weathered wood, but the French a evokes polished ebony. This black group also includes hard g (vulcanized rubber) and r (a sooty rag being ripped). Oatmeal n, noodle-limp l, and the ivory-backed hand mirror of o take care of the whites. I am puzzled by my French on which I see as the brimming tension-surface of alcohol in a small glass. Passing on to the blue group, there is steely x, thundercloud z, and huckleberry k. Since a subtle interaction exists between sound and shape, I see q as browner than k, while s is not the light blue of c, but a curious mixture of azure and mother-of-pearl. Daniel Tammet wrote a book on his experiences with synesthesia called Born on a Blue Day.[79] Joanne Harris, author of Chocolat, is a synesthete who says she experiences colors as scents.[80] Her novel Blueeyedboy features various aspects of synesthesia. Painters and photographers Wassily Kandinsky (a synesthete) and Piet Mondrian (not a synesthete) both experimented with image–music congruence in their paintings. Contemporary artists with synesthesia, such as Carol Steen[81] and Marcia Smilack[82] (a photographer who waits until she gets a synesthetic response from what she sees and then takes the picture), use their synesthesia to create their artwork. Linda Anderson, according to NPR considered "one of the foremost living memory painters", creates with oil crayons on fine-grain sandpaper representations of the auditory-visual synaesthesia she experiences during severe migraine attacks.[83][84] Brandy Gale, a Canadian visual artist, experiences an involuntary joining or crossing of any of her senses – hearing, vision, taste, touch, smell and movement. Gale paints from life rather than from photographs and by exploring the sensory panorama of each locale attempts to capture, select, and transmit these personal experiences.[85][86][87] David Hockney perceives music as color, shape, and configuration and uses these perceptions when painting opera stage sets (though not while creating his other artworks). Kandinsky combined four senses: color, hearing, touch, and smell.[1][3] American painter and visual artist Perry Hall attributes synaesthesia— both chromesthesia and the experience of visual sensations creating sounds— as an inspiration and guide for his creative work, including his Sound Drawing series.[88] Composers  "Symphonic Poem "The Sea" and the matching painting "Sonata of the Sea. "Finale" (1908) by synesthete Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. Multiple composers had experienced synesthesia. Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, a Lithuanian painter, composer and writer, perceived colors and music simultaneously. Many of his paintings bear the names of matching musical pieces: sonatas, fugues, and preludes. Alexander Scriabin composed colored music that was deliberately contrived and based on the circle of fifths, whereas Olivier Messiaen invented a new method of composition (the modes of limited transposition) specifically to render his bi-directional sound–color synesthesia.[3][89] For example, the red rocks of Bryce Canyon are depicted in his symphony Des canyons aux étoiles... ("From the Canyons to the Stars"). New art movements such as literary symbolism, non-figurative art, and visual music have profited from experiments with synesthetic perception and contributed to the public awareness of synesthetic and multi-sensory ways of perceiving.[42] Other composers who reported synesthesia include Duke Ellington,[90] Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov,[91] and Jean Sibelius.[73] Several contemporary composers with a synesthesia are Michael Torke,[73] and Ramin Djawadi, best known for his work on composing the theme songs and scores for such TV series as Game of Thrones, Westworld and for the Iron Man movie. He says he tends to "associate colors with music, or music with colors."[92] British composer Daniel Liam Glyn created the classical-contemporary music project Changing Stations using Grapheme Colour Synaesthesia. Based on the 11 main lines of the London Underground, the eleven tracks featured on the album represent the eleven main tube line colours.[93] Each track focuses heavily on the different speeds, sounds, and mood of each line, and are composed in the key signature synaesthetically assigned by Glyn with reference to the colour of the tube line on the map.[94] Musicians The producer, rapper, and fashion designer Kanye West is a prominent interdisciplinary case. In an impromptu speech he gave during an Ellen interview, he described his condition, saying that he sees sounds, and that everything he sonically makes is a painting.[95] Other notable synesthetes include musicians Billy Joel,[96]: 89, 91 Andy Partridge,[97] Itzhak Perlman,[96]: 53 Lorde,[98] Billie Eilish,[99] Brendon Urie,[100][101] Ida Maria,[102] Brian Chase,[103][104] and classical pianist Hélène Grimaud. Musician Kristin Hersh sees music in colors.[105] Drummer Mickey Hart of The Grateful Dead wrote about his experiences with synaesthesia in his autobiography Drumming at the Edge of Magic.[106] John Frusciante, guitarist of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, talks about his experiences with synesthesia in a podcast with Rick Rubin.[107] Pharrell Williams, of the groups The Neptunes and N.E.R.D., also experiences synesthesia[108][109] and used it as the basis of the album Seeing Sounds. Singer/songwriter Marina and the Diamonds experiences music → color synesthesia and reports colored days of the week.[110] Awsten Knight from Waterparks has chromesthesia, which influences many of the band's artistic choices.[111] Artists without synesthesia Some artists frequently mentioned as synesthetes did not, in fact, have the neurological condition. Scriabin's 1911 Prometheus, for example, is a deliberate contrivance whose color choices are based on the circle of fifths and appear to have been taken from Madame Blavatsky.[3][112] The musical score has a separate staff marked luce whose "notes" are played on a color organ. Technical reviews appear in period volumes of Scientific American.[3] On the other hand, his older colleague Rimsky-Korsakov (who was perceived as a fairly conservative composer) was, in fact, a synesthete.[113] French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire wrote of synesthetic experiences, but there is no evidence they were synesthetes themselves. Baudelaire's 1857 Correspondances introduced the notion that the senses can and should intermingle. Baudelaire participated in a hashish experiment by psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau and became interested in how the senses might affect each other.[42] Rimbaud later wrote Voyelles (1871), which was perhaps more important than Correspondances in popularizing synesthesia. He later boasted "J'inventais la couleur des voyelles!" (I invented the colors of the vowels!).[114] Science Some technologists, like inventor Nikola Tesla,[115] and scientists also reported being synesthetic. Physicist Richard Feynman describes his colored equations in his autobiography, What Do You Care What Other People Think?:[116] "When I see equations, I see the letters in colors. I don't know why. I see vague pictures of Bessel functions with light-tan j's, slightly violet-bluish n's, and dark brown x's flying around."[117] Literature Main articles: Synesthesia in literature and Synesthesia in fiction Synesthesia is sometimes used as a plot device or way of developing a character's inner life. Author and synesthete Pat Duffy describes four ways in which synesthetic characters have been used in modern fiction.[118][119] Synesthesia as Romantic ideal: in which the condition illustrates the Romantic ideal of transcending one's experience of the world. Books in this category include The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov. Synesthesia as pathology: in which the trait is pathological. Books in this category include The Whole World Over by Julia Glass. Synesthesia as Romantic pathology: in which synesthesia is pathological but also provides an avenue to the Romantic ideal of transcending quotidian experience. Books in this category include Holly Payne's The Sound of Blue and Anna Ferrara's The Woman Who Tried To Be Normal. Synesthesia as psychological health and balance: Painting Ruby Tuesday by Jane Yardley, and A Mango-Shaped Space by Wendy Mass. Literary depictions of synesthesia are criticized as often being more of a reflection of an author's interpretation of synesthesia than of the phenomenon itself.[citation needed] |

社会と文化 注目すべき事例 主な記事 共感覚を持つ人々のリスト 新聞記者から記憶術家に転身したソロモン・シェレシェフスキーは、ロシアの神経心理学者アレクサンドル・ルリアによって、珍しい五重の共感覚を持つことが 発見された[17]。シェレシェフスキーは、名前のリストから数十年前の会話に至るまで、多くの事柄の詳細を形容することなく無限に語ることができたが、 抽象的な概念を把握することは非常に困難であった。共感覚によって細部まで自動的に、そしてほぼ永久的に保持されることは、シェレシェフスキーが読んだり 聞いたりしたものを理解する能力を大きく阻害した[17]。 神経科学者で作家のV.S.ラマチャンドランは、色盲でもある書記素と色の共感覚者のケースを研究した。彼は特定の色を目で見ることはできなかったが、特 定の文字を見るとその色を「見る」ことができた。彼はそれらの色の名前を持っていなかったので、それを「火星人の色」と呼んだ[71]。 芸術 主な記事 芸術における共感覚 他の著名な共感覚者は、特に芸術的な職業や背景を持っている。神経科学とは異なり、芸術における共感覚の概念は、1つのゲシュタルト体験の中で複数の刺激を同時に知覚することと考えられている[77]。 作家 ウラジーミル・ナボコフはいくつかの小説で共感覚について明確に書いている。ナボコフは自伝『Speak, Memory』の中で、書記素-色彩の共感覚について詳しく述べている[78]。 私は色聴の立派な症例である。おそらく「聴覚」というのは正確ではないだろう。色彩感覚は、私が与えられた文字の輪郭を想像しながら、その文字を口頭で形 成するという行為そのものによって生み出されるように思われるからだ。英語のアルファベットの長いa(特に断りのない限り、このアルファベットを念頭に置 いている)は、私にとって風化した木の色合いを帯びているが、フランス語のaは磨き上げられた黒檀を連想させる。この黒いグループには、硬いg(加硫ゴ ム)やr(煤けた雑巾を裂いたもの)も含まれる。オートミールn、ヌードルリンプl、そしてoの象牙の背の手鏡が白を担当する。私は、小さなグラスに注が れたアルコールのなみなみとしたテンションの表面に見えるフランス語に戸惑っている。音と形の間には微妙な相互作用が存在するため、私はqをkよりも茶色 く見ている。 ダニエル・タメットは『Born on a Blue Day(青い日に生まれて)』という共感覚の経験を綴った本を書いている[79]。『Chocolat(ショコラ)』の著者ジョアン・ハリスは共感覚者で、色を香りとして体験していると語っている[80]。 画家と写真家 ワシリー・カンディンスキー(共感覚者)とピエト・モンドリアン(共感覚者ではない)は、絵画においてイメージと音楽の一致を試みた。キャロル・スティー ン[81]やマーシャ・スミラック[82](見たものから共感覚的反応を得るまで待ち、それから写真を撮る写真家)のような共感覚を持つ現代のアーティス トたちは、共感覚を使って作品を制作している。NPRによれば、リンダ・アンダーソンは、「生きている記憶の画家の第一人者」の一人であり、激しい片頭痛 発作の際に経験する聴覚-視覚の共感覚を、目の細かいサンドペーパーに油絵の具でクレヨンで表現している[83][84]。 カナダのビジュアル・アーティスト、ブランディ・ゲイルは、聴覚、視覚、味覚、触覚、嗅覚、運動など、あらゆる感覚が不随意に結合したり交差したりする経 験をする。ゲイルは写真からではなく生活から絵を描き、それぞれの場所の感覚のパノラマを探求することで、これらの個人的な経験を捉え、選択し、伝達しよ うと試みている[85][86][87]。 デイヴィッド・ホックニーは音楽を色、形、構成として知覚し、オペラの舞台装置を描くときにこれらの知覚を用いる(他の作品を制作するときには用いない が)。カンディンスキーは色彩、聴覚、触覚、嗅覚の4つの感覚を組み合わせている[1][3]。アメリカの画家でありビジュアル・アーティストであるペ リー・ホールは、共感覚-色彩感覚と視覚的感覚が音を生み出すという経験の両方-を、彼のサウンド・ドローイング・シリーズを含む創作活動のインスピレー ションと指針としている[88]。 作曲家  「交響詩《海》と、それに合わせた絵画《海のソナタ》。「共感覚者Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionisによる《フィナーレ》(1908年)。 複数の作曲家が共感覚を体験している。 リトアニアの画家、作曲家、作家であるミカロユス・コンスタンティナス・チュルリオーニスは、色彩と音楽を同時に知覚した。彼の絵画の多くには、ソナタ、フーガ、前奏曲など、一致する音楽曲の名前が付けられている。 一方、オリヴィエ・メシアンは、音と色の双方向の共感覚を表現するために、新しい作曲法(限定的移調のモード)を考案した[3][89]。文学的象徴主 義、非具象的芸術、視覚音楽などの新しい芸術運動は、共感覚的知覚の実験から利益を得ており、共感覚的知覚や多感覚的知覚の方法を一般に認知させることに 貢献している[42]。共感覚を報告した他の作曲家には、デューク・エリントン[90]、ニコライ・リムスキー=コルサコフ[91]、ジャン・シベリウス などがいる[73]。 共感覚を持つ現代の作曲家としては、マイケル・トーケ[73]や、『ゲーム・オブ・スローンズ』や『ウエストワールド』などのテレビシリーズ、映画『アイ アンマン』の主題歌や音楽を作曲したことで知られるラミン・ジャワディがいる。彼は「色と音楽、あるいは音楽と色を結びつける」傾向があると言う [92]。 イギリスの作曲家Daniel Liam Glynは、Grapheme Colour Synaesthesiaを使って、クラシックとコンテンポラリーの音楽プロジェクト「Changing Stations」を制作した。ロンドンの地下鉄の11の主要路線に基づき、アルバムに収録された11のトラックは11の主要路線の色を表している [93]。各トラックは、各路線の異なるスピード、サウンド、ムードに重点を置いており、地図上の地下鉄路線の色を参考にグリンによって共感覚的に割り当 てられたキーシグネチャーで作曲されている[94]。 ミュージシャン プロデューサー、ラッパー、ファッションデザイナーのカニエ・ウェストは、学際的なケースとして著名である。エレンのインタビュー中に行った即興のスピー チで、彼は自分の状態を説明し、自分は音を見ており、音で作るものはすべて絵画であると語った[95]。 その他の著名な共感覚者には、ミュージシャンのビリー・ジョエル[96]、[89]、[91] アンディ・パートリッジ、[97] イツァーク・パールマン、[96]: 53 Lorde、[98] Billie Eilish、[99] Brendon Urie、[100][101] Ida Maria、[102] Brian Chase、[103][104] そしてクラシックピアニストのHélène Grimaudがいる。ミュージシャンのクリスティン・ハーシュは音楽を色で見ている[105]。グレイトフル・デッドのドラマー、ミッキー・ハートは自 伝『Drumming at the Edge of Magic』で共感覚の経験について書いている[106]。レッド・ホット・チリ・ペッパーズのギタリスト、ジョン・フルシアンテはリック・ルービンとの ポッドキャストで共感覚の経験について語っている[107]、 も共感覚を体験しており[108][109]、アルバム『Seeing Sounds』のベースとして使用している。シンガーソングライターのマリーナ・アンド・ザ・ダイアモンズは、音楽→色の共感覚を体験しており、曜日を色 分けして報告している[110]。 ウォーターパークスのアウステン・ナイトは色彩感覚を持っており、バンドの芸術的選択の多くに影響を与えている[111]。 共感覚を持たないアーティスト 共感覚者として頻繁に言及されるアーティストの中には、実際にはその神経症状を持っていなかった者もいる。例えば、スクリャービンの1911年の「プロメ テウス」は意図的な仕掛けで、その色の選択は5分の円に基づいており、マダム・ブラヴァツキーから引用されたと思われる[3][112]。一方、彼の先輩 であるリムスキー=コルサコフ(かなり保守的な作曲家として認識されていた)は、実際には共感覚者であった[113]。 フランスの詩人アルチュール・ランボーとシャルル・ボードレールは共感覚的体験について書いているが、彼ら自身が共感覚者であったという証拠はない。ボー ドレールの1857年の『Correspondances』は、感覚は混ざり合うことができ、また混ざり合うべきであるという概念を紹介した。ボードレー ルは精神科医ジャック=ジョゼフ・モローによるハシッシ ュの実験に参加し、感覚が互いにどのような影響を与え合うのかに興味を持つようになった[42]。ランボーは後に『Voyelles』(1871年)を書 いたが、この作品は共感覚を一般に広める上で、おそらく『Correspondances』よりも重要であった。彼は後に "J'inventais la couleur des voyelles! (私は母音の色を発明した!)」と自慢している[114]。 科学 発明家ニコラ・テスラのような技術者[115]や科学者も共感覚者であると報告している。物理学者のリチャード・ファインマンは、彼の自伝『他人の目を気 にすることなかれ』の中で、色付きの方程式について次のように述べている[116]。なぜかはわからない。薄茶色のj、少し紫がかった青みがかったn、こ げ茶色のxが飛び交うベッセル関数の漠然とした絵が見える」[117]。 文学 主な記事 文学における共感覚と小説における共感覚 共感覚は、筋書きの仕掛けや登場人物の内面を描写する方法として使われることがある。作家であり共感覚者でもあるパット・ダフィーは、現代のフィクションにおいて共感覚を持つキャラクターが使われてきた4つの方法を説明している[118][119]。 ロマン主義的理想としての共感覚:その状態は、自分の世界経験を超越するというロマン主義的理想を説明している。このカテゴリーの本には、ウラジーミル・ナボコフの『ギフト』が含まれる。 病理としての共感覚:その特徴が病理的である。このカテゴリーの本には、ジュリア・グラスの『The Whole World Over』などがある。 ロマン主義的病理学としての共感覚:共感覚が病理学的であると同時に、ありふれた経験を超越するというロマン主義の理想への道を提供する。このカテゴリー の本には、ホリー・ペインの『The Sound of Blue』やアンナ・フェラーラの『The Woman Who Tried To Be Normal』などがある。 心理的健康とバランスとしての共感覚: ジェーン・ヤードリー著『ルビー・チューズデーを描く』、ウェンディ・マス著『マンゴー型の空間』などである。 文学的な共感覚の描写は、しばしば現象そのものよりも、共感覚に対する作者の解釈を反映していると批判される[要出典]。 |

Research Tests like this demonstrate that people do not attach sounds to visual shapes arbitrarily. When people are given a choice between the words "Bouba" and "Kiki", the left shape is almost always called "Kiki" while the right is called "Bouba" Research on synesthesia raises questions about how the brain combines information from different sensory modalities, referred to as crossmodal perception or multisensory integration.[citation needed] An example of this is the bouba/kiki effect. In an experiment first designed by Wolfgang Köhler, people are asked to choose which of two shapes is named bouba and which kiki. The angular shape, kiki, is chosen by 95–98% and bouba for the rounded one. Individuals on the island of Tenerife showed a similar preference between shapes called takete and maluma. Even 2.5-year-old children (too young to read) show this effect.[120] Research indicated that in the background of this effect may operate a form of ideasthesia.[121] Researchers hope that the study of synesthesia will provide better understanding of consciousness and its neural correlates. In particular, synesthesia might be relevant to the philosophical problem of qualia,[4][122] given that synesthetes experience extra qualia (e.g., colored sound). An important insight for qualia research may come from the findings that synesthesia has the properties of ideasthesia,[19] which then suggest a crucial role of conceptualization processes in generating qualia.[12] Technological applications Synesthesia also has a number of practical applications, including 'intentional synesthesia' in technology,[123] and sensory prosthetics.[124] The Voice (vOICe) Peter Meijer developed a sensory substitution device for the visually impaired called The vOICe (the capital letters "O," "I," and "C" in "vOICe" are intended to evoke the expression "Oh I see"). The vOICe is a privately owned research project, running without venture capital, that was first implemented using low-cost hardware in 1991.[125] The vOICe is a visual-to-auditory sensory substitution device (SSD) preserving visual detail at high resolution (up to 25,344 pixels).[126] The device consists of a laptop, head-mounted camera or computer camera, and headphones. The vOICe converts visual stimuli of the surroundings captured by the camera into corresponding aural representations (soundscapes) delivered to the user through headphones at a default rate of one soundscape per second. Each soundscape is a left-to-right scan, with height represented by pitch, and brightness by loudness.[127] The vOICe compensates for the loss of vision by converting information from the lost sensory modality into stimuli in a remaining modality.[128] Sonified Artists Perry Hall and Jonathan Jones-Morris created Sonified in 2011, software which translates visual information from a video camera into music in real-time, as a means of creating a synaesthetic experience for the user.[129] |

研究 このようなテストは、人が視覚的形状に音を恣意的に付けるわけではないことを実証している。人が 「Bouba 」と 「Kiki 」のどちらかを選ぶと、ほとんどの場合、左の図形は 「Kiki 」と呼ばれ、右の図形は 「Bouba 」と呼ばれる。 共感覚に関する研究は、クロスモーダル知覚または多感覚統合と呼ばれる、異なる感覚モダリティからの情報を脳がどのように組み合わせるのかという疑問を提起している[要出典]。 その一例が、ボバ/キキ効果である。ヴォルフガング・ケーラーが最初に考案した実験では、人々は2つの形状のうち、どちらが「ブーバ」、どちらが「キキ」 と名付けられるかを選ぶよう求められる。角ばった形のキキは95~98%に選ばれ、丸みを帯びた形はブーバに選ばれる。テネリフェ島の人々も、タケテとマ ルマと呼ばれる形に対して同様の嗜好を示した。2歳半の子ども(字を読むには幼すぎる)でさえ、この効果を示す[120]。この効果の背景には、一種のイ デア感覚(ideasthesia)が働いている可能性があるという研究結果が示された[121]。 研究者たちは、共感覚の研究によって、意識とその神経相関についてよりよく理解できるようになることを期待している。特に、共感覚者が余分なクオリア(例 えば色つきの音)を経験することから、共感覚はクオリアの哲学的問題に関連するかもしれない[4][122]。クオリア研究にとって重要な洞察は、共感覚 がイデア感覚[19]の特性を持っているという発見から得られるかもしれない。 技術的応用 共感覚はまた、テクノロジーにおける「意図的な共感覚」[123]や感覚補綴[124]など、多くの実用的な応用もある。 声(vOICe) ピーター・マイヤーは、vOICeと呼ばれる視覚障害者用の感覚代替装置を開発した(vOICeの大文字の「O」、「I」、「C」は、「なるほど」という 表現を想起させることを意図している)。vOICeは、高解像度(最大25,344ピクセル)で視覚の細部を保存する視覚-聴覚感覚代替装置(SSD)で ある[126]。この装置は、ラップトップ、ヘッドマウントカメラまたはコンピュータカメラ、ヘッドフォンから構成される。vOICeは、カメラで撮影さ れた周囲の視覚的刺激を、対応する聴覚的表現(サウンドスケープ)に変換し、デフォルトでは1秒間に1つのサウンドスケープの割合で、ヘッドフォンを通じ てユーザーに届ける。vOICeは、失われた感覚モダリティからの情報を残りのモダリティの刺激に変換することで、視覚の喪失を補う[128]。 音波化 アーティストのペリー・ホールとジョナサン・ジョーンズ=モリスは、2011年にSonifiedを創作した。Sonifiedは、ビデオカメラからの視 覚情報をリアルタイムで音楽に変換するソフトウェアであり、ユーザーに共感覚的体験をもたらす手段として使用される[129]。 |

| Allochiria Apophenia Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response Fantasy prone personality Hallucination Ideasthesia Ideophone Vibration theory of olfaction Parosmia Psychedelic drug Sensory substitution Thought-Forms Visual music The Yellow Sound McCollough effect Richard Cytowic |

アロキリア アポフェニア 自律感覚経絡反応 空想癖 幻覚 イデア感覚 イデオフォン 嗅覚の振動理論 パロスミア サイケデリックドラッグ 感覚代替 思考形態 視覚音楽 イエロー・サウンド マッコロー効果 リチャード・サイトウイック |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synesthesia |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆