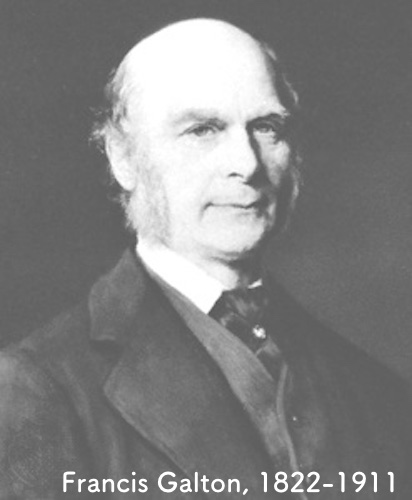

フランシス・ゴルトン

Francis Galton, 1822-1911

フランシス・ゴルトン

Francis Galton, 1822-1911

フランシス・ゴルトン(Francis Galton, FRS FRAI, /ˈɡɔ January 17 1911)は、統計学者、社会学者、心理学者、人類学者、熱帯探索者、地理学者、発明家、気象学者、原始遺伝学者、心理測定学者、社会ダーウィニズム、優生学、科学的人種主義の 提唱者である、イギリスのヴィクトリアン時代の多才な人であった。1909年にナイトの称号を授与された(関連記事→「人種主義と戦う科学雑誌『ネイチャー』」)。

”Although UCL geneticist Adam Rutherford, author of the 2020 book How to Argue With a Racist, was a signatory of that letter, he supported and participated in the reconsideration of the legacies of geneticists Francis Galton and Ronald A. Fisher and statistician Karl Pearson at UCL. The university elected to remove their names from the Galton Lecture Theatre, Pearson Building and R. A. Fisher Centre for Computational Biology in June 2020. The buildings, which UCL will consider renaming in the future, are now known as Lecture Theatre 115, the North-West Wing and the Centre for Computational Biology, respectively. Galton more or less created the field of eugenics — the supposed betterment of humanity by suppressing reproduction in people considered of ‘inferior stock’. All three men, says Rutherford, held virulently racist views, even by the standards of their time in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

Souce: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03253-y

翻訳「2020年に出版される『How to Argue With a Racist(人種差別主義者と議論する方法)』の著者であるUCLの遺伝学者アダム・ラザフォードは、その書簡の署名者であったが、UCLにおける遺伝 学者フランシス・ゴルトンとロナルド・A・フィッシャー、統計学者カール・ピアソンの遺産の再考を支持し、参加した。大学は、2020年6月にガルトン講 義室、ピアソンビルディング、R.A.フィッシャー計算生物学センターから彼らの名前を削除することを選択した。これらの建物は、UCLが将来的に改名を 検討するもので、現在はそれぞれレクチャーシアター115、ノースウエストウィング、計算生物学センターとして知られている。ガルトンは多かれ少なかれ、 優生学という学問を創始した。ラザフォードによれば、3人とも、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけての当時の基準から見ても、人種差別的な考えを持ってい た。」

| Sir

Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (/ˈɡɔːltən/; 16 February 1822

– 17 January

1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician,

sociologist, psychologist,[1] anthropologist, tropical explorer,

geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician

and a proponent of social Darwinism, eugenics, and scientific racism.

He was knighted in 1909. Galton produced over 340 papers and books. He also created the statistical concept of correlation and widely promoted regression toward the mean. He was the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human differences and inheritance of intelligence, and introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys for collecting data on human communities, which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for his anthropometric studies. He was a pioneer of eugenics, coining the term itself in 1883, and also coined the phrase "nature versus nurture".[2] His book Hereditary Genius (1869) was the first social scientific attempt to study genius and greatness.[3] As an investigator of the human mind, he founded psychometrics (the science of measuring mental faculties) and differential psychology, as well as the lexical hypothesis of personality. He devised a method for classifying fingerprints that proved useful in forensic science. He also conducted research on the power of prayer, concluding it had none due to its null effects on the longevity of those prayed for.[4] His quest for the scientific principles of diverse phenomena extended even to the optimal method for making tea.[5] As the initiator of scientific meteorology, he devised the first weather map, proposed a theory of anticyclones, and was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale.[6] He also invented the Galton Whistle for testing differential hearing ability.[7] He was Charles Darwin's half-cousin.[8] |

フ

ランシス・ゴルトン(Francis Galton, FRS FRAI, /ˈɡɔ January 17

1911)は、統計学者、社会学者、心理学者、人類学者、熱帯探索者、地理学者、発明家、気象学者、原始遺伝学者、心理測定学者、社会ダーウィニズム、優

生学、科学的人種主義の提唱者である、イギリスのヴィクトリアン時代の多才な人である。1909年にナイトの称号を授与された。 フ

ランシス・ゴルトン(Francis Galton, FRS FRAI, /ˈɡɔ January 17

1911)は、統計学者、社会学者、心理学者、人類学者、熱帯探索者、地理学者、発明家、気象学者、原始遺伝学者、心理測定学者、社会ダーウィニズム、優

生学、科学的人種主義の提唱者である、イギリスのヴィクトリアン時代の多才な人である。1909年にナイトの称号を授与された。ゴルトンは340以上の論文や著書を発表した。また、相関関係という統計的概念を生み出し、平均への回帰を広く提唱した。また、統計的手法を人為差や知能 の遺伝の研究に初めて適用し、家系図や伝記、身体測定の研究に必要な人間集団のデータ収集にアンケート調査を導入した。彼は優生学の先駆者であり、 1883年にこの言葉自体を生み出し、「自然対育成」という言葉も生み出した[2]。彼の著書『天才の遺伝』(1869)は天才と偉大さを研究する最 初の社会科学的試みとなった[3]。 人間の心の研究者として、彼は心理測定学(精神的能力を測定する科学)と微分心理学、そして人格の語彙仮説を確立した。また、指紋の分類法を考案し、法医 学に役立てた。また、祈りの力の研究を行い、祈られた人の寿命に効果がないことから、祈りの力はないと結論づけた[4]。さまざまな現象の科学的原理を追 求し、最適なお茶の入れ方にまで及んだ[5]。 科 学的気象学の創始者として、最初の天気図を考案し、高気圧の理論を提案し、ヨーロッパ規模で短期の気候現象の完全な記録を初めて確立した[6]。 また、聴力差を調べるためのゴルトンホイッスルを発明した[7]。 チャールズ・ダーウィンの母方の祖父の又従兄弟(またいとこ)であった[8]。

|

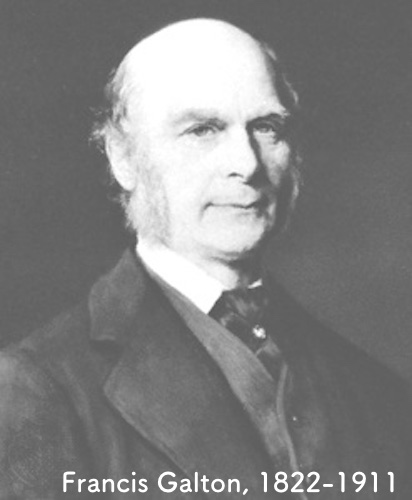

| Early life Galton was born at "The Larches", a large house in the Sparkbrook area of Birmingham, England, built on the site of "Fair Hill", the former home of Joseph Priestley, which the botanist William Withering had renamed. He was Charles Darwin's half-cousin, sharing the common grandparent Erasmus Darwin. His father was Samuel Tertius Galton, son of Samuel Galton, Jr. He was also a cousin of Douglas Strutt Galton. The Galtons were Quaker gun-manufacturers and bankers, while the Darwins were involved in medicine and science. Both the Galton and Darwin families included Fellows of the Royal Society and members who loved to invent in their spare time. Both Erasmus Darwin and Samuel Galton were founding members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which included Matthew Boulton, James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley and Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Both families were known for their literary talent. Erasmus Darwin composed lengthy technical treatises in verse. Galton's aunt Mary Anne Galton wrote on aesthetics and religion, and her autobiography detailed the environment of her childhood populated by Lunar Society members. Galton was a child prodigy – he was reading by the age of two; at age five he knew some Greek, Latin and long division, and by the age of six he had moved on to adult books, including Shakespeare for pleasure, and poetry, which he quoted at length.[9] Galton attended King Edward's School, Birmingham, but chafed at the narrow classical curriculum and left at 16.[10] His parents pressed him to enter the medical profession, and he studied for two years at Birmingham General Hospital and King's College London Medical School. He followed this up with mathematical studies at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1840 to early 1844.[11] According to the records of the United Grand Lodge of England, it was in February 1844 that Galton became a freemason at the Scientific lodge, held at the Red Lion Inn in Cambridge, progressing through the three masonic degrees: Apprentice, 5 February 1844; Fellow Craft, 11 March 1844; Master Mason, 13 May 1844. A note in the record states: "Francis Galton Trinity College student, gained his certificate 13 March 1845".[12] One of Galton's masonic certificates from Scientific lodge can be found among his papers at University College, London.[13] A nervous breakdown prevented Galton's intent to try for honours. He elected instead to take a "poll" (pass) B.A. degree, like his half-cousin Charles Darwin.[14] (Following the Cambridge custom, he was awarded an M.A. without further study, in 1847.) He briefly resumed his medical studies but the death of his father in 1844 left him emotionally destitute, though financially independent,[citation needed] and he terminated his medical studies entirely, turning to foreign travel, sport and technical invention. In his early years Galton was an enthusiastic traveller, and made a notable solo trip through Eastern Europe to Constantinople, before going up to Cambridge. In 1845 and 1846, he went to Egypt and travelled up the Nile to Khartoum in the Sudan, and from there to Beirut, Damascus and down to Jordan. In 1850 he joined the Royal Geographical Society, and over the next two years mounted a long and difficult expedition into then little-known South West Africa (now Namibia). He wrote a book on his experience, "Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa".[15] He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's Founder's Gold Medal in 1853 and the Silver Medal of the French Geographical Society for his pioneering cartographic survey of the region.[16] This established his reputation as a geographer and explorer. He proceeded to write the best-selling The Art of Travel, a handbook of practical advice for the Victorian on the move, which went through many editions and is still in print. |

生い立ち ゴルトンは、イギリス・バーミンガムのスパークブルック地区にある「ラルヒズ」という大きな家で生まれた。この家は、ジョセフ・プリーストリーの旧宅 「フェアヒル」を植物学者のウィザリングが改名したものである。ウィザリングは、チャールズ・ダーウィンの異母兄妹であり、祖父母にはエラスムス・ダー ウィンがいる。父親はサミュエル・ゴルトンJr.の息子サミュエル・テルティウス・ゴルトンで、ダグラス・ストラット・ゴルトンのいとこでもある。ガルト ン家はクエーカー教徒の銃製造業と銀行家であり、ダーウィン家は医学と科学に携わっていた。 ゴルトンとダーウィンの両家には王立協会の会員がおり、余暇に発明をするのが好きなメンバーもいた。エラスマス・ダーウィンもサミュエル・ゴルトンも、マ シュー・バルトン、ジェームズ・ワット、ジョサイア・ウェッジウッド、ジョセフ・プリーストリー、リチャード・ラヴェル・エッジワースらが所属するバーミ ンガムのルナー協会の創設メンバーであった。両家とも文才があることで知られていた。エラスマス・ダーウィンは、長大な技術論を詩で書いていた。ゴルトン の叔母メアリー・アン・ゴルトンは美学と宗教について執筆し、自伝にはルナー・ソサエティ会員に囲まれた幼少期の環境が詳細に記されている。 ゴルトンは神童で、2歳までに本を読み、5歳でギリシャ語、ラテン語、長割を知り、6歳までに大人の本へと進み、趣味でシェークスピアを読んだり、詩を長 く引用したりした。 [ゴルトンはバーミンガムのキング・エドワード・スクールに通ったが、狭い古典的なカリキュラムに嫌気がさし、16歳で退学した[10]。その後、 1840年から1844年初頭までケンブリッジのトリニティ・カレッジで数学の勉強をした[11]。 United Grand Lodge of Englandの記録によると、1844年2月にケンブリッジのRed Lion Innで開催されたScientific lodgeで、ゴルトンはフリーメイソンとなり、3つのメーソン階程を経た後、フリーメイソンとなった。1844年2月5日にアプレンティス、1844年 3月11日にフェロー・クラフト、1844年5月13日にマスター・メイソンとなった。記録には次のように記されている。「ゴルトンのサイエンティフィッ ク・ロッジからの証明書は、ロンドンのユニバーシティ・カレッジにある彼の書類の中に見つけることができる[12]。 神経衰弱のため、ゴルトンは優等生になろうとすることができなかった。その代わりに、異母兄のチャールズ・ダーウィンと同じように「ポール」(合格)の学 士号を取ることを選んだ[14](ケンブリッジの慣習に従って、彼は1847年にそれ以上の研究をせずに修士号を授与されている)。医学の勉強を一時的に 再開したが、1844年に父親が亡くなり、経済的には独立したものの精神的には貧しくなり[citation needed]、医学の勉強を完全に打ち切り、外国旅行、スポーツ、技術発明に転じた。 若い頃のゴルトンは熱心な旅行家で、ケンブリッジに上がる前に東ヨーロッパを通り、コンスタンチノープルまで一人旅をしたことが有名である。1845年と 1846年にはエジプトに行き、ナイル川を遡ってスーダンのハルツームに行き、そこからベイルート、ダマスカス、ヨルダンへと下った。 1850年、王立地理学会に入会し、その後2年間にわたり、当時はあま り知られていなかった南西アフリカ(現在のナミビア)への長く困難な探検を行った。 1853年には王立地理学会の創設者金メダル、フランス地理学会の銀メダルを受賞し、地理学者、探検家としての名声を確立した[16]。その後、移動する ビクトリア人のための実用的なアドバイスのハンドブックであるベストセラー『旅の技術』を執筆し、多くの版を重ね、現在も印刷されている。 |

| Middle years Galton was a polymath who made important contributions in many fields, including meteorology (the anticyclone and the first popular weather maps), statistics (regression and correlation), psychology (synaesthesia), biology (the nature and mechanism of heredity), and criminology (fingerprints). Much of this was influenced by his penchant for counting and measuring. Galton prepared the first weather map published in The Times (1 April 1875, showing the weather from the previous day, 31 March), now a standard feature in newspapers worldwide.[17] He became very active in the British Association for the Advancement of Science, presenting many papers on a wide variety of topics at its meetings from 1858 to 1899.[18] He was the general secretary from 1863 to 1867, president of the Geographical section in 1867 and 1872, and president of the Anthropological Section in 1877 and 1885. He was active on the council of the Royal Geographical Society for over forty years, in various committees of the Royal Society, and on the Meteorological Council. James McKeen Cattell, a student of Wilhelm Wundt who had been reading Galton's articles, decided he wanted to study under him. He eventually built a professional relationship with Galton, measuring subjects and working together on research.[19] In 1888, Galton established a lab in the science galleries of the South Kensington Museum. In Galton's lab, participants could be measured to gain knowledge of their strengths and weaknesses. Galton also used these data for his own research. He would typically charge people a small fee for his services.[20] In 1873, Galton wrote a controversial letter to The Times titled 'Africa for the Chinese', where he argued that the Chinese, as a race capable of high civilization and only temporarily stunted by the recent failures of Chinese dynasties, should be encouraged to immigrate to Africa and displace the supposedly inferior aboriginal blacks.[21] |

中年期 気象学(高気圧と最初の天気図)、統計学(回帰と相関)、心理学(共感覚)、生物学(遺伝の性質とメカニズム)、犯罪学(指紋)など、多くの分野で重要な 貢献をした多才な人物であった。その多くは、彼の数え上げや計測の趣味に影響されたものである。ゴルトンは、タイムズ紙に掲載された最初の天気図 (1875年4月1日、前日3月31日の天気を示す)を作成し、今では世界中の新聞で定番の特集となっている[17]。 1863年から1867年まで事務局長、1867年と1872年には地理学部門の会長、1877年と1885年には人類学部門の会長を務めた[18]。 40年以上にわたって王立地理学会の評議員、王立協会のさまざまな委員会、気象学評議会で活躍した。 ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの教え子で、ゴルトンの論文を読んでいたジェームズ・マッキン・キャッテルは、彼のもとで学びたいと考えた。彼は最終的にゴルトンと 専門的な関係を築き、被験者を測定し、研究を共にするようになった[19]。 1888年、ゴルトンはサウス・ケンジントン博物館の科学ギャラリーに研究室を設立した。ゴルトンの研究室では、被験者を測定して、彼らの長所と短所に関 する知識を得ることができた。ゴルトンはこれらのデータを自身の研究にも利用した。彼は通常、自分のサービスのために人々に少額の手数料を請求していた [20]。 1873年、ゴルトンはタイムズ紙に「中国人のためのアフリカ」と題す る物議を醸す手紙を書き、そこで彼は、中国人は高度な文明を持つことができる人種で あり、最近の中国王朝の失敗によって一時的に阻害されているだけなので、アフリカへの移民を奨励し、劣るとされる原住民の黒人を駆逐すべきであると主張し た[21]。 |

| Heredity and eugenics The publication by his cousin Charles Darwin of The Origin of Species in 1859 was an event that changed Galton's life.[22] He came to be gripped by the work, especially the first chapter on "Variation under Domestication", concerning animal breeding. Galton devoted much of the rest of his life to exploring variation in human populations and its implications, at which Darwin had only hinted in The Origin of Species, although he returned to it in his 1871 book The Descent of Man, drawing on his cousin's work in the intervening period. Galton established a research program which embraced multiple aspects of human variation, from mental characteristics to height; from facial images to fingerprint patterns. This required inventing novel measures of traits, devising large-scale collection of data using those measures, and in the end, the discovery of new statistical techniques for describing and understanding the data. Galton was interested at first in the question of whether human ability was hereditary, and proposed to count the number of the relatives of various degrees of eminent men. If the qualities were hereditary, he reasoned, there should be more eminent men among the relatives than among the general population. To test this, he invented the methods of historiometry. Galton obtained extensive data from a broad range of biographical sources which he tabulated and compared in various ways. This pioneering work was described in detail in his book Hereditary Genius in 1869.[3] Here he showed, among other things, that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when going from the first degree to the second degree relatives, and from the second degree to the third. He took this as evidence of the inheritance of abilities. Galton recognized the limitations of his methods in these two works, and believed the question could be better studied by comparisons of twins. His method envisaged testing to see if twins who were similar at birth diverged in dissimilar environments, and whether twins dissimilar at birth converged when reared in similar environments. He again used the method of questionnaires to gather various sorts of data, which were tabulated and described in a paper The history of twins in 1875. In so doing he anticipated the modern field of behaviour genetics, which relies heavily on twin studies. He concluded that the evidence favored nature rather than nurture. He also proposed adoption studies, including trans-racial adoption studies, to separate the effects of heredity and environment. Galton recognized that cultural circumstances influenced the capability of a civilization's citizens, and their reproductive success. In Hereditary Genius, he envisaged a situation conducive to resilient and enduring civilization as follows: The best form of civilization in respect to the improvement of the race, would be one in which society was not costly; where incomes were chiefly derived from professional sources, and not much through inheritance; where every lad had a chance of showing his abilities, and, if highly gifted, was enabled to achieve a first-class education and entrance into professional life, by the liberal help of the exhibitions and scholarships which he had gained in his early youth; where marriage was held in as high honor as in ancient Jewish times; where the pride of race was encouraged (of course I do not refer to the nonsensical sentiment of the present day, that goes under that name); where the weak could find a welcome and a refuge in celibate monasteries or sisterhoods, and lastly, where the better sort of emigrants and refugees from other lands were invited and welcomed, and their descendants naturalized. — Galton 1869, p. 362 |

遺伝と優生学(この項目には、より確証のあるデータと記述が要求されて

いる) 1859年に従兄弟のダーウィンが『種の起源』を出版したことは、ゴルトン の人生を変えた出来事であった[22]。彼はこの著作、特に動物の品種改良に関する「家畜化のもとでの変異」の第1章に心を奪われるようになった。 ダーウィンが『種の起源』の中でほのめかしただけで、1871年に出版した『人間の進化』の中で再び取り上げ、その間に従兄弟が行った研究を参考にしてい る。ゴルトンは、精神的特徴から身長まで、顔画像から指紋パターンまで、人間の多様な側面を網羅する研究プログラムを確立した。そのためには、特徴を表 す新しい尺度の考案、その尺度を用いた大規模なデータ収集の工夫、そして最終的にはデータを記述し理解するための新しい統計的手法の発見が必要であった。 ゴルトンは当初、人間の能力は遺伝するのかという問題に関心を持ち、様々な程度の高 い人物の親族の数を数えることを提案した。もし、人間の能力が遺伝的な ものであるなら、その親族には一般人よりも多くの優秀な人物がいるはずだと考えたのである。これを検証するために、彼はヒストリオメトリ(後述)の方法を考案した。ゴルトンは 幅広い伝記資料から膨大なデータを入手し、それを様々な方法で集計し、比較した。この先駆的な研究は、1869年に出版された『Hereditary Genius』[3]に詳しく述べられている。ここで彼は、特に、1親等から2親等に、また2親等から3親等になると、著名な親族の数が少なくなることを 示した。彼はこれを能力の遺伝の証拠としたのである。 ゴルトンは、この2つの著作で自分の方法の限界を認識し、この問題は双子の比較でよりよく研究できると考えた。彼の方法は、生まれつき似ている双子が異な る環境で分岐するかどうか、生まれつき似ていない双子が似た環境で育てられると収束するかどうかを調べることを想定している。彼はまた、アンケートという 手法でさまざまなデータを集め、それを集計して1875年に論文「The history of twins」にまとめた。このように、彼は双子研究に大きく依存する現代の行動遺伝学の分野を先取りしていたのである。そして、その証拠は「育ち」よりも 「自然」を支持すると結論づけた。また、遺伝と環境の影響を分けるために、人種を超えた養子縁組の研究などを提案しました。 ゴルトンは、文化的環境が市民の能力や生殖の成功に影響を与えることを認識していた。 彼は『天才の遺伝』の中で、弾力的で永続的な文明に資する状況を次のように想定している。 民族の向上に関して最良の文明は、社会が高価でなく、収入が主として職 業に由来し、相続によるものがあまりなく、すべての若者が自分の能力を発揮する機会 を持ち、もし高い才能があれば、若い頃に得た展覧会や奨学金の寛大な援助によって、一流の教育を受け、職業生活に入ることができるようなものであろう」。 結婚が古代ユダヤ時代と同じように尊重され、民族の誇りが奨励され(もちろん、このような名称のもとに行われる現代の無意味な感情には言及しない)、弱者 は独身修道院や姉妹会に歓迎と避難所を見つけることができ、最後に、他国からの優れた移民や難民が招かれ歓迎されて、その子孫が帰化した。- ゴルトン 1869, p.362 |

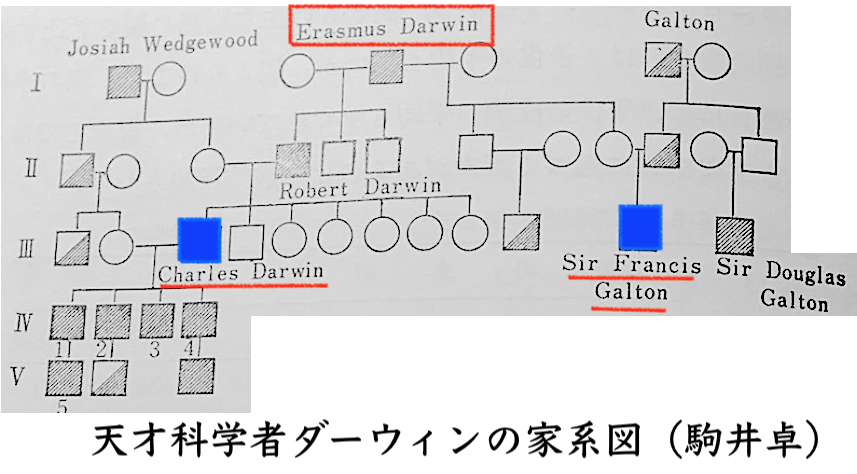

| Galton

invented the term eugenics in 1883 and set down many of his

observations and conclusions in a book, Inquiries into Human Faculty

and Its Development. In the book's introduction, he wrote: [This book's] intention is to touch on various topics more or less connected with that of the cultivation of race, or, as we might call it, with "eugenic" questions, and to present the results of several of my own separate investigations. This is, with questions bearing on what is termed in Greek, eugenes, namely, good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, eugeneia, etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalized one than viriculture, which I once ventured to use. — Galton 1883, pp. 24–25 He believed that a scheme of 'marks' for family merit should be defined, and early marriage between families of high rank be encouraged via provision of monetary incentives. He pointed out some of the tendencies in British society, such as the late marriages of eminent people, and the paucity of their children, which he thought were dysgenic. He advocated encouraging eugenic marriages by supplying able couples with incentives to have children. On 29 October 1901, Galton chose to address eugenic issues when he delivered the second Huxley lecture at the Royal Anthropological Institute.[19] The Eugenics Review, the journal of the Eugenics Education Society, commenced publication in 1909. Galton, the Honorary President of the society, wrote the foreword for the first volume.[19] The First International Congress of Eugenics was held in July 1912. Winston Churchill and Carls Elliot were among the attendees.[19] According to the Encyclopedia of Genocide, Galton bordered on the justification of genocide when he stated: "There exists a sentiment, for the most part quite unreasonable, against the gradual extinction of an inferior race."[23] In June 2020, UCL announced the renaming of a lecture theatre named after Galton because of his connection with eugenics.[24] |

ゴル

トンは1883年に優生学という言葉を生み出し、その観察と結論の多くを『人間の能力とその発達に関する研究』という書物にまとめた。この本の冒頭で、彼

はこう書いている。 ゴル

トンは1883年に優生学という言葉を生み出し、その観察と結論の多くを『人間の能力とその発達に関する研究』という書物にまとめた。この本の冒頭で、彼

はこう書いている。[この本の]意図は、多かれ少なかれ、人種の育成、あるいは「優生学」 とでも呼ぶべき問題に関連するさまざまな話題に触れ、私自身のいくつかの個別の調査 の結果を提示することである。つまり、ギリシャ語で「オイゲネス(eugenes)」と呼ばれるもの、すなわち、遺伝的に高貴な資質を備えた優れた家系に 関係する問題である。この言葉や、関連する言葉であるオイゲニアなどは、人間、哺乳類、植物に等しく適用される。家畜を改良する科学は、決して賢明な交配 の問題にとどまらず、特に人間の場合、より適した人種や血統が、そうでないものに比べてより早く優勢になる機会を与える傾向が、どんなに遠くとも、あらゆ る影響を考慮に入れていることを表す簡潔な言葉が非常に必要である。優生学という言葉は、この考えを十分に表現している。少なくとも、かつて私があえて 使ったことのあるウイルス培養学よりは、すっきりした言葉で、より一般的なものであろう。- ゴルトン 1883、24-25頁(https://gutenberg.org/files/11562/11562-h/11562-h.htm) 彼は、家柄の良さを示す「点数」の制度を定め、金銭的なインセンティブを与えることによって、身分の高い家族間の早婚を奨励すべきであると考えていた。彼 は、イギリス社会における傾向として、著名人の晩婚化やその子供の少なさなどを指摘し、それは異質なものであると考えた。そして、優秀な夫婦に子供をつく るインセンティブを与えることで、優生的な結婚を奨励することを提唱した。1901年10月29日、ゴルトンは王立人類学研究所で2回目のハクスリー講義 を行った際に優生学の問題を取り上げることを選択した[19]。 優生学教育協会の機関誌である『優生学評論』は1909年に創刊された。1912年7月には、第1回国際優生学会議が開催された[19]。ウィンストン・ チャーチルやカールス・エリオットが出席していた[19]。 Encyclopedia of Genocideによると、ゴルトンは大量虐殺を正当化するような発言をしている。「劣等人種を徐々に絶滅させることに反対する感情は、ほとんどの場合、非常に不合理なものであ る。」"There exists a sentiment, for the most part quite unreasonable, against the gradual extinction of an inferior race."[23] と述べている。--Stigler, Stephen M. (1 July 2010). "Darwin, Galton and the Statistical Enlightenment". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 173 (3): 469–482. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2010.00643.x 2020年6月、UCLは優生学との関係から、ゴルトンにちなんで名付けられた講義室の名称を変更することを発表した[24]。 |

| Model for population stability Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability. Although Galton's first attempt to study Darwinian questions, Hereditary Genius, generated little enthusiasm at the time, the text led to his further studies in the 1870s concerning the inheritance of physical traits.[25] This text contains some crude notions of the concept of regression, described in a qualitative matter. For example, he wrote of dogs: "If a man breeds from strong, well-shaped dogs, but of mixed pedigree, the puppies will be sometimes, but rarely, the equals of their parents. They will commonly be of a mongrel, nondescript type, because ancestral peculiarities are apt to crop out in the offspring."[26] This notion created a problem for Galton, as he could not reconcile the tendency of a population to maintain a normal distribution of traits from generation to generation with the notion of inheritance. It seemed that a large number of factors operated independently on offspring, leading to the normal distribution of a trait in each generation. However, this provided no explanation as to how a parent can have a significant impact on his offspring, which was the basis of inheritance.[27] Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, as he was serving at the time as President of Section H: Anthropology.[28] The address was published in Nature, and Galton further developed the theory in "Regression toward mediocrity in hereditary stature" and "Hereditary Stature."[29][30] An elaboration of this theory was published in 1889 in Natural Inheritance. There were three key developments that helped Galton develop this theory: the development of the law of error in 1874–1875, the formulation of an empirical law of reversion in 1877, and the development of a mathematical framework encompassing regression using human population data during 1885.[27] Galton's development of the law of regression to the mean, or reversion, was due to insights from the Galton board ('bean machine') and his studies of sweet peas. While Galton had previously invented the quincunx prior to February 1874, the 1877 version of the quincunx had a new feature that helped Galton demonstrate that a normal mixture of normal distributions is also normal.[31] Galton demonstrated this using a new version of quincunx, adding chutes to the apparatus to represent reversion. When the pellets passed through the curved chutes (representing reversion) and then the pins (representing family variability), the result was a stable population. On Friday 19 February 1877 Galton gave a lecture entitled Typical Laws of Heredity at the Royal Institution in London.[31] In this lecture, he posited that there must be a counteracting force to maintain population stability. However, this model required a much larger degree of intergenerational natural selection than was plausible.[25] In 1875, Galton started growing sweet peas, and addressed the Royal Institution on his findings on 9 February 1877.[31] He found that each group of progeny seeds followed a normal curve, and the curves were equally disperse. Each group was not centered about the parent's weight, but rather at a weight closer to the population average. Galton called this reversion, as every progeny group was distributed at a value that was closer to the population average than the parent. The deviation from the population average was in the same direction, but the magnitude of the deviation was only one-third as large. In doing so, Galton demonstrated that there was variability among each of the families, yet the families combined to produce a stable, normally distributed population. When Galton addressed the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1885, he said of his investigation of sweet peas, "I was then blind to what I now perceive to be the simple explanation of the phenomenon."[28] Galton was able to further his notion of regression by collecting and analyzing data on human stature. Galton asked for help of mathematician J. Hamilton Dickson in investigating the geometric relationship of the data. He determined that the regression coefficient did not ensure population stability by chance, but rather that the regression coefficient, conditional variance, and population were interdependent quantities related by a simple equation.[27] Thus Galton identified that the linearity of regression was not coincidental but rather was a necessary consequence of population stability. The model for population stability resulted in Galton's formulation of the Law of Ancestral Heredity. This law, which was published in Natural Inheritance, states that the two parents of an offspring jointly contribute one half of an offspring's heritage, while the other, more-removed ancestors constitute a smaller proportion of the offspring's heritage.[32] Galton viewed reversion as a spring, that when stretched, would return the distribution of traits back to the normal distribution. He concluded that evolution would have to occur via discontinuous steps, as reversion would neutralize any incremental steps.[33] When Mendel's principles were rediscovered in 1900, this resulted in a fierce battle between the followers of Galton's Law of Ancestral Heredity, the biometricians, and those who advocated Mendel's principles.[34] |

母集団の安定性に関するモデル ゴルトンが回帰を定式化し、二変量正規分布と結びつけたのは、母集団の安定性に関する数学的モデルを開発しようとしたことに端を発している。ダーウィンの 問題を研究するゴルトンの最初の試みであるHereditary Geniusは、当時はほとんど熱狂的な支持を受けなかったが、このテキストは1870年代の身体的形質の継承に関する彼のさらなる研究につながった [25]。このテキストには、質的な事柄で記述された回帰の概念のいくつかの粗い概念が含まれている。例えば、彼は犬についてこう書いている。「もしある 人が、丈夫で形の良い、しかし血統の混じった犬から繁殖させると、その子犬は、時には、しかしまれに、親と同等になるであろう。先祖の特異性が子孫に現れ やすいため、一般的には雑種的で、何の変哲もないタイプになる」[26]。 この考え方はゴルトンに問題を引き起こし、集団が世代から世代へと形質 の正常な分布を維持する傾向と遺伝の概念とを調和させることができなかった。多くの要因が独立して子孫に作用し、各世代で形質が正規分布するように思われ たのである。しかし、これでは、遺伝の基本である親が子に大きな影響を与えることができるのか、説明がつかない[27]。 この問題に対するゴルトンの解決策は、当時セクションH:人類学の会長を務めていたため、1885年9月の英国科学振興協会の会合での会長講演で発表され た[28]。この講演は『ネイチャー』に掲載され、ゴルトンはさらに「Regression towards mediocrity in hereditary stature」及び「Hereitary Stature」で理論を展開した[29][30] この理論の詳細が1889年に『ナチュラルインヘリシング』に掲載されていた。1874年から1875年にかけての誤差の法則の開発、1877年の経験的 な復帰の法則の定式化、1885年の間に人間の人口データを用いた回帰を包含する数学的枠組みの開発であった[27]。 ゴルトンが平均への回帰、または回帰の法則を開発したのは、ゴルトンボード(「豆マシン」)とスイートピーに関する研究からの洞察によるものであった。ガ ルトンは1874年2月以前に五分儀を発明していたが、1877年版の五分儀には、ゴルトンが正規分布の正規混合物も正規であることを示すのに役立つ新し い機能があった[31]。ゴルトンは新しいバージョンの五分儀を使ってこれを示し、器具にシュートを追加して、回帰を代表することができた。ペレットが湾 曲したシュート(回帰を表す)を通過し、次にピン(家族のばらつきを表す)を通過すると、結果は安定した集団となった。1877年2月19日、ゴルトンは ロンドンの王立研究所で『遺伝の典型的な法則』と題した講演を行った[31]が、この講演で彼は、集団の安定を維持するためには、それに対抗する力が必要 であると仮定した。しかし、このモデルは世代間自然淘汰の程度をもっともらしくよりもはるかに大きくする必要があった[25]。 1875年、ゴルトンはスイートピーを栽培し始め、1877年2月9日に王立研究所でその結果について講演を行った[31]。彼は、子孫の種の各グループ が正規曲線に沿い、その曲線は均等に散らばっていることを発見した。各グループは親の体重を中心としたものではなく、集団平均に近い体重であった。すべて の子孫グループが親よりも母集団平均に近い値で分布していることから、ゴルトンはこれを復帰と呼んだ。母集団平均からの偏差は同じ方向であるが、その大き さは3分の1になった。このように、ゴルトンは、家族それぞれにばらつきがありながら、家族が組み合わさって、安定した正規分布の集団を作り出しているこ とを示したのである。1885年に英国科学振興協会で講演した際、ゴルトンはスイートピーに関する調査について、「私は当時、この現象の単純な説明である と今私が認識していることに対して盲目であった」[28]と述べている。 ゴルトンは人間の身長に関するデータを収集し分析することで、回帰の概念をさらに深めることができた。ゴルトンは数学者のJ. ハミルトン・ディクソンに協力を求め、データの幾何学的関係を調査していた。そして、回帰係数が偶然に人口の安定性を保証しているのではなく、回帰係数、 条件分散、人口が簡単な方程式で関係する相互依存的な量であることを突き止めた[27]。 こうして、回帰の線形性は偶然ではなく、人口の安定性に必要な結果であることをゴルトンは確認した。 集団の安定性のモデルは、ゴルトンが定式化した「先祖伝来の法則」に結実した。この法則は『Natural Inheritance』で発表され、子孫の2人の親は共同で子孫の遺産の半分を提供し、他のもっと離れた祖先は子孫の遺産のより少ない割合を構成すると 述べている[32]。ゴルトンは回帰をバネのように捉え、それが伸ばされると形質の分布を正規分布に戻そうとするものだった。1900年にメンデルの原理 が再発見されると、ゴルトンの先祖遺伝の法則の信奉者である生物測定学者とメンデルの原理を主張する人々との間で激しい戦いが起こった[34]。 |

| Empirical test of pangenesis and

Lamarckism Galton conducted wide-ranging inquiries into heredity which led him to challenge Charles Darwin's hypothesis of pangenesis. Darwin had proposed as part of this model that certain particles, which he called "gemmules" moved throughout the body and were also responsible for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Galton, in consultation with Darwin, set out to see if they were transported in the blood. In a long series of experiments in 1869 to 1871, he transfused the blood between dissimilar breeds of rabbits, and examined the features of their offspring.[35] He found no evidence of characters transmitted in the transfused blood.[36] Darwin challenged the validity of Galton's experiment, giving his reasons in an article published in Nature where he wrote: Now, in the chapter on Pangenesis in my Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication I have not said one word about the blood, or about any fluid proper to any circulating system. It is, indeed, obvious that the presence of gemmules in the blood can form no necessary part of my hypothesis; for I refer in illustration of it to the lowest animals, such as the Protozoa, which do not possess blood or any vessels; and I refer to plants in which the fluid, when present in the vessels, cannot be considered as true blood. The fundamental laws of growth, reproduction, inheritance, &c., are so closely similar throughout the whole organic kingdom, that the means by which the gemmules (assuming for the moment their existence) are diffused through the body, would probably be the same in all beings; therefore the means can hardly be diffusion through the blood. Nevertheless, when I first heard of Mr. Galton's experiments, I did not sufficiently reflect on the subject, and saw not the difficulty of believing in the presence of gemmules in the blood. — Darwin 1871, pp. 502–503 Galton explicitly rejected the idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (Lamarckism), and was an early proponent of "hard heredity"[37] through selection alone. He came close to rediscovering Mendel's particulate theory of inheritance, but was prevented from making the final breakthrough in this regard because of his focus on continuous, rather than discrete, traits (now regarded as polygenic traits). He went on to found the biometric approach to the study of heredity, distinguished by its use of statistical techniques to study continuous traits and population-scale aspects of heredity. This approach was later taken up enthusiastically by Karl Pearson and W. F. R. Weldon; together, they founded the highly influential journal Biometrika in 1901. (R. A. Fisher would later show how the biometrical approach could be reconciled with the Mendelian approach.[38]) The statistical techniques that Galton invented (correlation and regression—see below) and phenomena he established (regression to the mean) formed the basis of the biometric approach and are now essential tools in all social sciences. |

パンゲネシスとラマルク説の実証的検証 ゴルトンは、遺伝について幅広く研究し、ダーウィンのパンゲネシス(遺伝)仮説に異議を唱えるようになった。ダーウィンは、「ジェムル」と呼ばれる粒子が 体内を移動し、後天的な特徴を遺伝させるという説を提唱していた。ゴルトンは、ダーウィンと相談しながら、この粒子が血液中を移動しているかどうかを確か めることにした。1869年から1871年にかけての長い一連の実験で、彼は異品種のウサギの間で輸血を行い、その子孫の特徴を調べた[35]。 彼は輸血された血液の中で文字が伝達された証拠を見いだせなかった[36]。 ダーウィンはゴルトンの実験の正当性に異議を唱え、その理由を『ネイ チャー』誌に掲載された論文でこう書いている。 さて、『家畜化された動植物の変異』の「パンゲネシス」の章では、血液 や循環系に適した液体について一言も述べていない。なぜなら、私はこの仮説につい て、血液も血管も持たない原生動物のような最下層の動物に言及し、また、血管内に液体が存在しても真の血液とは見なされない植物に言及しているからでであ る。 成長、生殖、遺伝などの基本的な法則は、生物界全体で非常によく似ているので、宝石が体内を拡散する手段(仮に宝石が存在するとして)は、おそらくすべて の生物で同じであろうと思われる。とはいえ、私が最初にゴルトン氏の実験を聞いたとき、この問題について十分に考察していなかったので、血液中にゲ ミュールが存在することを信じることの難しさを感じなかったのである。- ダーウィン1871年、502-503頁 ゴルトンは、後天的な特性の遺伝という考え方(ラマルク主義)を明確に否定し、選択のみによる「ハード・ヘレディティ」[37]の初期の提唱者であった。 彼はメンデルの微粒子遺伝説の再発見に迫ったが、離散形質ではなく連続形質(現在では多遺伝子形質とみなされている)に注目したため、この点での最後のブ レークスルーが阻まれた。その後、彼は、連続形質や集団規模の遺伝を研究するために統計的手法を用いることで、遺伝の研究に対する生物測定学的アプローチ を確立したのである。 この方法は、後にカール・ピアソンとW・F・R・ウェルドンによって積極的に取り入れ られ、彼らは1901年に非常に影響力のある雑誌『バイオメトリカ』 を創刊しました。(ゴルトンが発明した統計手法(相関と回帰-後述)と彼が確立した現象(平均への回帰)は、バイオメトリクス・アプローチの基礎となり、 現在ではすべての社会科学において不可欠なツールとなっている[38]。 |

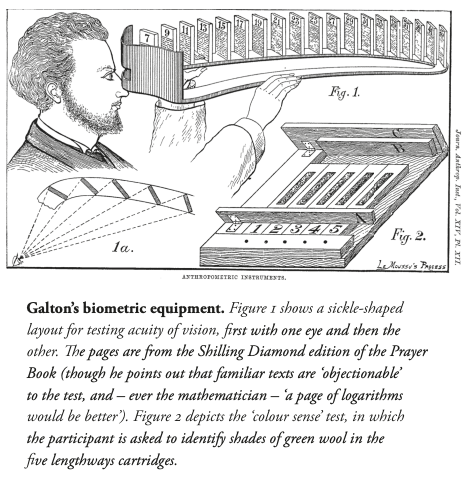

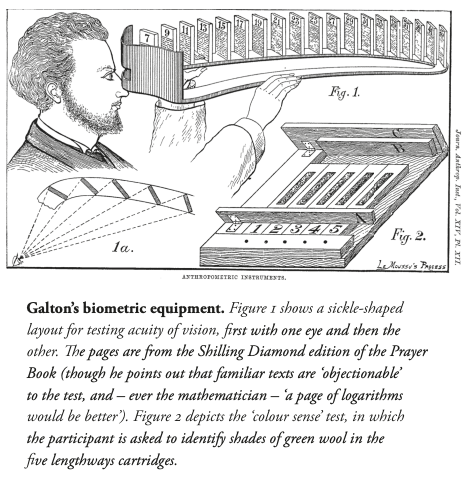

| Anthropometric Laboratory at the

1884 International Health Exhibition In 1884, London hosted the International Health Exhibition. This exhibition placed much emphasis on highlighting Victorian developments in sanitation and public health, and allowed the nation to display its advanced public health outreach, compared to other countries at the time. Francis Galton took advantage of this opportunity to set up his anthropometric laboratory. He stated that the purpose of this laboratory was to "show the public the simplicity of the instruments and methods by which the chief physical characteristics of man may be measured and recorded."[39] The laboratory was an interactive walk-through in which physical characteristics such as height, weight, and eyesight, would be measured for each subject after payment of an admission fee. Upon entering the laboratory, a subject would visit the following stations in order. First, they would fill out a form with personal and family history (age, birthplace, marital status, residence, and occupation), then visit stations that recorded hair and eye color, followed by the keenness, color-sense, and depth perception of sight. Next, they would examine the keenness, or relative acuteness, of hearing and highest audible note of their hearing followed by an examination of their sense of touch. However, because the surrounding area was noisy, the apparatus intended to measure hearing was rendered ineffective by the noise and echoes in the building. Their breathing capacity would also be measured, as well as their ability to throw a punch. The next stations would examine strength of both pulling and squeezing with both hands. Lastly, subjects' heights in various positions (sitting, standing, etc.) as well as arm span and weight would be measured.[39] One excluded characteristic of interest was the size of the head. Galton notes in his analysis that this omission was mostly for practical reasons. For instance, it would not be very accurate and additionally it would require much time for women to disassemble and reassemble their hair and bonnets.[40] The patrons would then be given a souvenir containing all their biological data, while Galton would also keep a copy for future statistical research. Although the laboratory did not employ any revolutionary measurement techniques, it was unique because of the simple logistics of constructing such a demonstration within a limited space, and because of the speed and efficiency with which all the necessary data were gathered. The laboratory itself was a see-through (lattice-walled) fenced off gallery measuring 36 feet long by 6 feet long. To collect data efficiently, Galton had to make the process as simple as possible for people to understand. As a result, subjects were taken through the laboratory in pairs so that explanations could be given to two at a time, also in the hope that one of the two would confidently take the initiative to go through all the tests first, encouraging the other. With this design, the total time spent in the exhibit was fourteen minutes for each pair.[39] Galton states that the measurements of human characteristics are useful for two reasons. First, he states that measuring physical characteristics is useful in order to ensure, on a more domestic level, that children are developing properly. A useful example he gives for the practicality of these domestic measurements is regularly checking a child's eyesight, in order to correct any deficiencies early on. The second use for the data from his anthropometric laboratory is for statistical studies. He comments on the usefulness of the collected data to compare attributes across occupations, residences, races, etc.[39] The exhibit at the health exhibition allowed Galton to collect a large amount of raw data from which to conduct further comparative studies. He had 9,337 respondents, each measured in 17 categories, creating a rather comprehensive statistical database.[40] After the conclusion of the International Health Exhibition, Galton used these data to confirm in humans his theory of linear regression, posed after studying sweet peas. The accumulation of this human data allowed him to observe the correlation between forearm length and height, head width and head breadth, and head length and height. With these observations he was able to write Co-relations and their Measurements, chiefly from Anthropometric Data.[41] In this publication, Galton defined what co-relation as a phenomenon that occurs when "the variation of the one [variable] is accompanied on the average by more or less variation of the other, and in the same direction."[42]  |

1884年国際衛生博覧会の人体測定室 1884年、ロンドンで「国際衛生博覧会」が開催された。この博覧会では、ヴィクトリア朝の衛生と公衆衛生の発展を強調し、当時の他国と比較して先進的な 公衆衛生の普及活動をアピールすることができた。ゴルトンはこの機会を利用して、人体計測研究所を設立した。彼はこの研究所の目的を「人間の主要な身体的 特徴を測定し記録するための器具と方法の簡便さを一般大衆に示すこと」と述べている[39]。この研究所は、入場料を支払うと被験者ごとに身長、体重、視 力などの身体的特徴が測定される、対話型のウォークスルーであった。実験室に入ると、被験者は以下のステーションを順番に訪れる。 まず、年齢、出生地、配偶者の有無、居住地、職業などの個人情報および家族情報を記入し、次に髪と目の色を記録するステーション、そして視力の鋭さ、色 感、奥行き感を記録するステーションを訪れる。次に聴覚の鋭敏さ、最高音感、触覚の検査が行われる。しかし、周囲が騒々しいので、聴覚を測定するための装 置が、建物内の騒音や反響で役に立たなかった。続いて、呼吸の状態、パンチの強さを測定する。次に両手で引っ張ったり、握ったりする力を測定する。最後 に、被験者の様々な姿勢(座る、立つなど)での身長、腕の長さと体重が測定される[39]。 除外された特徴で興味深かったのは、頭の大きさである。ゴルトンは分析の中で、この省略はほとんど実用的な理由によるものだと述べている。例えば、それは あまり正確ではなく、さらに女性が髪とボンネットを分解して組み立てるのに多くの時間を必要とする[40]。その後、顧客は彼らのすべての生物学的データ を含む記念品を与えられ、一方でゴルトンは将来の統計研究のためにコピーを取っておくことになる。 この実験室は画期的な測定技術を採用したわけではないが、限られたスペースでこのような実演を行うという単純なロジスティクスと、必要なすべてのデータを 収集する速度と効率という点でユニークなものであった。実験室は、縦36フィート、横6フィートのフェンスで囲まれたシースルー(格子状の壁)のギャラ リーであった。効率よくデータを集めるために、ゴルトンはそのプロセスをできるだけシンプルにし、人々に理解させる必要があった。その結果、被験者を二人 一組にして、一度に二人に説明できるようにし、また、二人のうちの一人が自信を持って、最初にすべてのテストを行い、もう一人を励ますようにしたのであ る。この設計では、展示室で過ごす時間は1組あたり14分であった[39]。 ゴルトンは、人間の特性を測定することは、二つの理由で有用であると述べている。第一に、身体的特徴の測定は、より家庭的なレベルで、子供が適切に成長し ていることを確認するために有用であるとしている。例えば、子供の視力を定期的に測定することで、早期に視力不足を改善することができる。2つ目の用途 は、統計学的な研究です。彼は、収集したデータが職業、住居、人種などの属性を比較するのに有用であるとコメントしている[39]。健康博覧会への出展に より、ゴルトンはさらに比較研究を行うための大量の生データを収集することができた。彼は9,337人の回答者を持ち、それぞれが17のカテゴリーで測定 され、かなり包括的な統計データベースを作成した[40]。 国際健康博覧会の終了後、ゴルトンはこれらのデータを使って、スイートピーを研究した後に提起した線形回帰の理論を人間で確認した。この人間のデータの蓄 積によって、彼は前腕の長さと身長、頭の幅と頭の幅、頭の長さと身長の相関を観察することができた。この出版物の中で、ゴルトンは「一方の(変数)の変動 が、他方の(変数)の多かれ少なかれ、同じ方向への変動を平均的に伴う」ときに起こる現象としての共相関とは何かを定義した[42]。  |

| Innovations

in statistics and psychological theory Historiometry The method used in Hereditary Genius has been described as the first example of historiometry. To bolster these results, and to attempt to make a distinction between 'nature' and 'nurture' (he was the first to apply this phrase to the topic), he devised a questionnaire that he sent out to 190 Fellows of the Royal Society. He tabulated characteristics of their families, such as birth order and the occupation and race of their parents. He attempted to discover whether their interest in science was 'innate' or due to the encouragements of others. The studies were published as a book, English men of science: their nature and nurture, in 1874. In the end, it promoted the nature versus nurture question, though it did not settle it, and provided some fascinating data on the sociology of scientists of the time.[citation needed] The lexical hypothesis Sir Francis was the first scientist to recognise what is now known as the lexical hypothesis.[43] This is the idea that the most salient and socially relevant personality differences in people's lives will eventually become encoded into language. The hypothesis further suggests that by sampling language, it is possible to derive a comprehensive taxonomy of human personality traits. The questionnaire Galton's inquiries into the mind involved detailed recording of people's subjective accounts of whether and how their minds dealt with phenomena such as mental imagery. To better elicit this information, he pioneered the use of the questionnaire. In one study, he asked his fellow members of the Royal Society of London to describe mental images that they experienced. In another, he collected in-depth surveys from eminent scientists for a work examining the effects of nature and nurture on the propensity toward scientific thinking.[44] Variance and standard deviation Core to any statistical analysis is the concept that measurements vary: they have both a central tendency, or mean, and a spread around this central value, or variance. In the late 1860s, Galton conceived of a measure to quantify normal variation: the standard deviation.[45] Galton was a keen observer. In 1906, visiting a livestock fair, he stumbled upon an intriguing contest. An ox was on display, and the villagers were invited to guess the animal's weight after it was slaughtered and dressed. Nearly 800 participated, and Galton was able to study their individual entries after the event. Galton stated that "the middlemost estimate expresses the vox populi, every other estimate being condemned as too low or too high by a majority of the voters",[46] and reported this value (the median, in terminology he himself had introduced, but chose not to use on this occasion) as 1,207 pounds. To his surprise, this was within 0.8% of the weight measured by the judges. Soon afterwards, in response to an enquiry, he reported[47] the mean of the guesses as 1,197 pounds, but did not comment on its improved accuracy. Recent archival research[48] has found some slips in transmitting Galton's calculations to the original article in Nature: the median was actually 1,208 pounds, and the dressed weight of the ox 1,197 pounds, so the mean estimate had zero error. James Surowiecki[49] uses this weight-judging competition as his opening example: had he known the true result, his conclusion on the wisdom of the crowd would no doubt have been more strongly expressed. The same year, Galton suggested in a letter to the journal Nature a better method of cutting a round cake by avoiding making radial incisions.[50] Experimental derivation of the normal distribution Studying variation, Galton invented the Galton board, a pachinko-like device also known as the bean machine, as a tool for demonstrating the law of error and the normal distribution.[9] Bivariate normal distribution He also discovered the properties of the bivariate normal distribution and its relationship to correlation and regression analysis. Correlation and regression In 1846, the French physicist Auguste Bravais (1811–1863) first developed what would become the correlation coefficient.[52] After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of correlation in 1888[53][54] and demonstrated its application in the study of heredity, anthropology, and psychology.[44] Galton's later statistical study of the probability of extinction of surnames led to the concept of Galton–Watson stochastic processes.[55] Galton invented the use of the regression line[56] and for the choice of r (for reversion or regression) to represent the correlation coefficient.[44] In the 1870s and 1880s he was a pioneer in the use of normal theory to fit histograms and ogives to actual tabulated data, much of which he collected himself: for instance large samples of sibling and parental height. Consideration of the results from these empirical studies led to his further insights into evolution, natural selection, and regression to the mean. Regression toward the mean Galton was the first to describe and explain the common phenomenon of regression toward the mean, which he first observed in his experiments on the size of the seeds of successive generations of sweet peas. The conditions under which regression toward the mean occurs depend on the way the term is mathematically defined. Galton first observed the phenomenon in the context of simple linear regression of data points. Galton[57] developed the following model: pellets fall through a quincunx or "bean machine" forming a normal distribution centered directly under their entrance point. These pellets could then be released down into a second gallery (corresponding to a second measurement occasion). Galton then asked the reverse question "from where did these pellets come?" The answer was not "on average directly above". Rather it was "on average, more towards the middle", for the simple reason that there were more pellets above it towards the middle that could wander left than there were in the left extreme that could wander to the right, inwards. — Stigler 2010, p. 477 Theories of perception Galton went beyond measurement and summary to attempt to explain the phenomena he observed. Among such developments, he proposed an early theory of ranges of sound and hearing, and collected large quantities of anthropometric data from the public through his popular and long-running Anthropometric Laboratory, which he established in 1884, and where he studied over 9,000 people.[19] It was not until 1985 that these data were analysed in their entirety. He made a beauty map of Britain, based on a secret grading of the local women on a scale from attractive to repulsive. The lowest point was in Aberdeen.[58] Differential psychology Main article: Differential psychology Galton's study of human abilities ultimately led to the foundation of differential psychology and the formulation of the first mental tests. He was interested in measuring humans in every way possible. This included measuring their ability to make sensory discrimination which he assumed was linked to intellectual prowess. Galton suggested that individual differences in general ability are reflected in performance on relatively simple sensory capacities and in speed of reaction to a stimulus, variables that could be objectively measured by tests of sensory discrimination and reaction time.[59] He also measured how quickly people reacted which he later linked to internal wiring which ultimately limited intelligence ability. Throughout his research Galton assumed that people who reacted faster were more intelligent than others. Composite photography Galton also devised a technique called "composite portraiture" (produced by superimposing multiple photographic portraits of individuals' faces registered on their eyes) to create an average face (see averageness). In the 1990s, a hundred years after his discovery, much psychological research has examined the attractiveness of these faces, an aspect that Galton had remarked on in his original lecture. Others, including Sigmund Freud in his work on dreams, picked up Galton's suggestion that these composites might represent a useful metaphor for an Ideal type or a concept of a "natural kind" (see Eleanor Rosch)—such as Jewish men, criminals, patients with tuberculosis, etc.—onto the same photographic plate, thereby yielding a blended whole, or "composite", that he hoped could generalise the facial appearance of his subject into an "average" or "central type".[7][60] (See also entry Modern physiognomy under Physiognomy). This work began in the 1880s while the Jewish scholar Joseph Jacobs studied anthropology and statistics with Francis Galton. Jacobs asked Galton to create a composite photograph of a Jewish type.[61] One of Jacobs' first publications that used Galton's composite imagery was "The Jewish Type, and Galton's Composite Photographs," Photographic News, 29, (24 April 1885): 268–269. Galton hoped his technique would aid medical diagnosis, and even criminology through the identification of typical criminal faces. However, his technique did not prove useful and fell into disuse, although after much work on it including by photographers Lewis Hine and John L. Lovell and Arthur Batut. |

【ゴルトンが考案したアイディア】 ヒストリオメトリー 『天才の遺伝』で用いられた方法は、ヒストリオメトリーの最初の例と言われている。この結果を補強し、「生まれつき」と「育ち」を区別するために(この言 葉をこのテーマに適用したのは彼が初めて)、彼はアンケートを考案し、王立協会の190人のフェローに送付した。彼は、190人の英国王立協会会員にアン ケートを送り、彼らの家族の特徴、例えば出生順、両親の職業や人種を集計した。そして、彼らの科学への関心が「生来のもの」なのか、それとも「周囲の勧め によるもの」なのかを探ろうとした。この研究は、1874年に「English men of science: their nature and nurture」という本として出版された。結局、この本は、自然対育成の問題に決着をつけることはなかったが、それを促進し、当時の科学者の社会学につ いて興味深いデータを提供した[citation needed]。 語彙論的仮説 フランシス卿は、現在語彙仮説として知られているものを認識した最初の科学者であった[43]。これは、人々の生活の中で最も顕著で社会的に関連する性格 の違いは、最終的に言語に符号化されるという考えである。この仮説はさらに、言語をサンプリングすることによって、人間の性格特性の包括的な分類法を導き 出すことが可能であることを示唆している。 質問紙 ゴルトンが行った心の研究は、心的イメージのような現象をどのように扱うかについて、人々の主観的な説明を詳細に記録することであった。このような情報を よりよく引き出すために、彼は質問紙を使った研究を行った。ある研究では、ロンドン王立協会の会員に、自分が体験した心的イメージを記述するように求め た。また、科学的思考傾向に対する生まれと育ちの影響を検証する研究のために、著名な科学者から詳細なアンケートを集めた[44]。 分散と標準偏差 あらゆる統計分析の核心は、測定値が変化するという概念である:それらは中心傾向、または平均、およびこの中心値の周りの広がり、または分散の両方を持っ ている。1860年代後半、ゴルトンは通常のばらつきを定量化するための指標、すなわち標準偏差を考え出した[45]。 ゴルトンは鋭い観察者であった。1906年、家畜の品評会を訪れたとき、彼は興味深いコンテストに出くわした。牛が展示され、村人たちは屠殺され、服を着 せられた後の牛の体重を当てるよう招待された。800人近くが参加し、ゴルトンはイベント終了後、彼らの個々の応募作品を研究することができた。ゴルトン は、「一番真ん中の推定値は、有権者の意見を表しており、他のすべての推定値は、有権者の大多数によって低すぎる、または高すぎると非難される」と述べ [46]、この値(中央値、彼自身が導入した用語で、この機会には使用しないことを選んだ)を1207ポンドと報告した。驚いたことに、これは審査員に よって測定された体重の0.8%以内であった。その後すぐに、問い合わせに応えて、彼は推測の平均値を1,197ポンドと報告[47]したが、その精度が 向上したことについてはコメントしなかった。最近のアーカイブ研究[48]では、ゴルトンの計算を『ネイチャー』誌のオリジナル論文に転記する際にいくつ かのミスがあったことが判明している。中央値は実際には1,208ポンド、牛のドレス重量は1,197ポンドであり、平均推定値は誤差ゼロだった。ジェー ムズ・スロヴィッキ(James Surowiecki)[49]は、この体重測定競争を冒頭の例として挙げている。もし彼が本当の結果を知っていたならば、群衆の知恵に関する彼の結論は より強く表明されたに違いない。 同年、ゴルトンは雑誌ネイチャーに宛てた手紙の中で、丸いケーキを切る際に放射状の切り込みを入れないようにすることで、より良い方法を提案している [50]。 正規分布の実験的導出 バラツキを研究していたゴルトンは、誤差の法則と正規分布を実証するための道具として、豆マシンとしても知られるパチンコのような装置、ゴルトンボードを 発明した[9]。 二変量正規分布 また、二変量正規分布の性質や相関・回帰分析との関係も発見した。 相関と回帰 1846年にフランスの物理学者オーギュスト・ブラヴェ(1811-1863)が相関係数となるものを初めて開発した[52]。前腕と身長の測定値を調べ た後、1888年にゴルトンが独立して相関の概念を再発見[53][54]、遺伝、人類学、心理学の研究においてその応用を実証した[44]。ゴルトンの 後の名字消滅の確立の統計的研究はゴルトン-ワトソン確率過程という概念につながった[55]。 ゴルトンは回帰線の使用[56]と相関係数を代表することができるようにr(復帰または回帰の意味)の選択について発明している[44]。 1870年代と1880年代には、彼はヒストグラムやオガーブを実際の表データに適合させるために正規理論の使用におけるパイオニアであり、その多くは彼 自身が収集したもので、例えば兄弟や親の身長の大きなサンプルなどでした。これらの経験的研究から得られた結果を考察することで、進化、自然選択、平均へ の回帰に関する彼のさらなる洞察を導き出しました。 平均への回帰 ゴルトンは、スイートエンドウの種子の大きさに関する実験で初めて観察された「平均への回帰」という一般的な現象を説明した。 平均への回帰が起こる条件は、数学的な定義の仕方によって異なる。ゴルトンは、データ点の単純な線形回帰の文脈でこの現象を初めて観察した。Galton [57]は次のモデルを開発した:ペレットは、その入口点の真下を中心とする正規分布を形成する五分儀または「豆機」を通って落下する。これらのペレット は,次に第2の回廊(第2の測定機会に相当)に向かって放出することができる.そして、ゴルトンは「このペレットはどこから来たのか」という逆質問をし た。 その答えは、「平均して真上」ではなかった。というのも、真ん中より上にあるペレットの方が、右の内側にあるペレットよりも、左側にあるペレットの方が、 より多く存在するからである。 - スティグラー 2010, p. 477 知覚の理論 ゴルトンは、測定や要約にとどまらず、観察した現象を説明しようと試みた。そのような開発の中で、彼は音と聴覚の範囲に関する初期の理論を提案し、 1884年に設立され、9000人以上を調査した人気のある長期間の人間測定研究所を通じて一般市民から大量の人間測定データを収集した[19]。 これらのデータが全体的に分析されたのは1985年になってからであった。 彼は、地元の女性を魅力的なものから嫌悪感を抱くものまでのスケールで秘密裏に採点し、イギリスの美人マップを作成した。最も低い地点はアバディーンに あった[58]。 差異心理学 主な記事 差異心理学 人間の能力に関するゴルトンの研究は、最終的に差延心理学の基礎となり、最初の心理テストの定式化につながった。彼は、人間をあらゆる方法で測定すること に関心を持った。その中には、感覚的な識別能力を測定することも含まれており、彼はそれが知的能力に関連していると仮定した。ゴルトンは一般的な能力の個 人差は比較的単純な感覚能力のパフォーマンスや刺激に対する反応の速さに反映されると示唆し、感覚識別や反応時間のテストによって客観的に測定できる変数 であった[59]。 彼はまた人々がどれだけ素早く反応するかを測定し、後に知能能力を最終的に制限する内部配線と関連づけた。ゴルトンは研究を通して、反応が早い人は他の人 よりも知的であると仮定していた。 合成写真 ゴルトンはまた、平均的な顔を作るために「合成写真」と呼ばれる技法を考案した。1990年代には、ゴルトンが講演で指摘した「顔の魅力」についての心理 学的研究が盛んに行われるようになった。また、ジークムント・フロイトの夢に関する研究をはじめ、ゴルトンは、ユダヤ人、犯罪者、結核患者などの「理想 型」や「自然型」(エレノア・ロッシュ参照)のメタファーとしてこれらの合成写真が有用であることを指摘した。 -その結果、彼は被写体の顔の外観を「平均的」または「中心型」に一般化できると期待した[7][60](人相学の項目の近代人相学も参照)。 この研究は、1880年代にユダヤ人学者のジョセフ・ジェイコブスが人類学と統計学をゴルトンに師事している間に始まった。ジェイコブスはゴルトンにユダ ヤ人のタイプの合成写真を作るよう依頼した[61]。 ゴルトンの合成画像を用いたジェイコブスの最初の出版物の1つが「ユダヤ人のタイプ、およびゴルトンの合成写真」『写真ニュース』29、(1885年4月 24日): 268-269. ゴルトンは、この技術が医学的診断や、犯罪者の典型的な顔を識別することによって犯罪学に役立つことを期待していた。しかし、写真家のルイス・ハイン、 ジョン・L・ラヴェル、アーサー・バトゥットらによる研究が行われたものの、彼の技術は役に立たず、廃れることになった。 |

| Fingerprints The method of identifying criminals by their fingerprints had been introduced in the 1860s by Sir William James Herschel in India, and their potential use in forensic work was first proposed by Dr Henry Faulds in 1880. Galton was introduced to the field by his half-cousin Charles Darwin, who was a friend of Faulds's, and he went on to create the first scientific footing for the study (which assisted its acceptance by the courts[62]) although Galton did not ever give credit that the original idea was not his.[63] In a Royal Institution paper in 1888 and three books (Finger Prints, 1892; Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints, 1893; and Fingerprint Directories, 1895),[64] Galton estimated the probability of two persons having the same fingerprint and studied the heritability and racial differences in fingerprints. He wrote about the technique (inadvertently sparking a controversy between Herschel and Faulds that was to last until 1917), identifying common pattern in fingerprints and devising a classification system that survives to this day. He described and classified them into eight broad categories: 1: plain arch, 2: tented arch, 3: simple loop, 4: central pocket loop, 5: double loop, 6: lateral pocket loop, 7: plain whorl, and 8: accidental.[65] |

指紋 指紋で犯罪者を識別する方法は、1860年代にインドのサー・ウィリアム・ジェームズ・ハーシェルによって紹介され、1880年にヘンリー・フォールズ博 士によって初めて法医学への応用が提案された。ゴルトンはフォールズの友人であった従兄弟のチャールズ・ダーウィンによってこの分野に紹介され、この研究 のための最初の科学的基盤を作ることになったが、ゴルトンは元のアイデアが彼のものではないことを決して認めなかった[63]。 1888年の王立研究所の論文と3冊の本(Finger Prints, 1892; Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints, 1893; and Fingerprint Directories, 1895)の中で、ゴルトンは2人が同じ指紋を持つ確率を推定し、指紋の遺伝性と人種差を研究した[64]。彼は、その技術について執筆し(不注意にも、 ハーシェルとフォールズの間で1917年まで続く論争を巻き起こした)、指紋の共通パターンを特定し、今日まで残っている分類体系を考案した。彼は、指紋 を8つのカテゴリーに大別し、説明しました。1:プレーンアーチ、2:テントアーチ、3:単純ループ、4:中央ポケットループ、5:ダブルループ、6:側 面ポケットループ、7:プレーンホワール、8:アクシデンタル[65]である。 |

| Final years In an effort to reach a wider audience, Galton worked on a novel entitled Kantsaywhere from May until December 1910. The novel described a utopia organized by a eugenic religion, designed to breed fitter and smarter humans. His unpublished notebooks show that this was an expansion of material he had been composing since at least 1901. He offered it to Methuen for publication, but they showed little enthusiasm. Galton wrote to his niece that it should be either "smothered or superseded". His niece appears to have burnt most of the novel, offended by the love scenes, but large fragments survived,[66] and it was published online by University College, London.[67] Galton is buried in the family tomb in the churchyard of St Michael and All Angels, in the village of Claverdon, Warwickshire.[68] |

晩年 より多くの読者を獲得するために、ゴルトンは1910年5月から12月まで『カン ツァイウェア』という小説の執筆に取り組んだ。この小説は、優生学的な宗教によって組織されたユートピアを描いたもので、健康で賢い人間を繁殖させること を目的としていた。未 発表のノートによると、この小説は、少なくとも1901年以来、彼が執筆していたものを発展させたものであった。メチュエン社に出版を申し入れたが、メ チュエン社はあまり乗り気ではなかった。ゴルトンは姪に、この本は「窒息させるか、取って代わらせる」べきだと書き送った。姪はラブシーンに腹を立てて小 説の大部分を焼却したようだが、大きな断片は残り[66]、ロンドンのユニバーシティ・カレッジからオンラインで出版された[67]。 ゴルトンはウォリックシャー州クラバードンの村にあるSt Michael and All Angelsの教会堂にある家族の墓に埋葬されている[68]。 |

| Personal life and character In January 1853, Galton met Louisa Jane Butler (1822–1897) at his neighbour's home and they were married on 1 August 1853. The union of 43 years proved childless.[69][70] It has been written of Galton that "On his own estimation he was a supremely intelligent man."[71] Later in life, Galton proposed a connection between genius and insanity based on his own experience: Men who leave their mark on the world are very often those who, being gifted and full of nervous power, are at the same time haunted and driven by a dominant idea, and are therefore within a measurable distance of insanity. — Pearson & 1914, 1924, 1930 |

私生活と性格 1853年1月、ゴルトンは近所の家でルイザ・ジェーン・バトラー(1822-1897)と出会い、1853年8月1日に結婚した。43年間の結婚生活に は子供がいないことが証明された[69][70]。 後年、ゴルトンは自身の経験に基づいて天才と狂気の間の接続を提案した[71]。 世界に足跡を残す人は、才能があり、神経に満ちあふれていて、同時に支配的な考えに取りつかれ、駆り立てられる人が非常に多く、したがって、狂気の測定可 能な距離内にいるのである。 - ピアソンと1914年、1924年、1930年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Galton |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Historiometry

is the historical study of human progress or individual personal

characteristics, using statistics to analyze references to geniuses,[1]

their statements, behavior and discoveries in relatively neutral texts.

Historiometry combines techniques from cliometrics, which studies

economic history and from psychometrics, the psychological study of an

individual's personality and abilities. |

ヒストリオメトリーとは、人間の進歩や個人の特性を歴史的に研究するも

ので、比較的中立的な文章に登場する天才たちの発言や行動、発見などを統計学を用いて分析する。ヒストリオメトリーは、経済史を研究するクリオメトリック

スと、個人の性格や能力を心理学的に研究するサイコメトリックスの技術を融合させたものである。 |

| Origins Historiometry started in the early 19th century with studies on the relationship between age and achievement by Belgian mathematician Adolphe Quetelet in the careers of prominent French and English playwrights [2][3] but it was Sir Francis Galton, an English polymath who popularized historiometry in his 1869 work, Hereditary Genius.[4] It was further developed by Frederick Adams Woods (who coined the term historiometry[5][6]) in the beginning of the 20th century.[7] Also psychologist Paul E. Meehl published several papers on historiometry later in his career, mainly in the area of medical history, although it is usually referred to as cliometric metatheory by him.[8][9] Historiometry was the first field studying genius by using scientific methods.[1] |

起源 ヒストリオメトリーは19世紀初頭にベルギーの数学者アドルフ・ケテレがフランスとイギリスの著名な劇作家の経歴から年齢と業績の関係を研究したことから 始まったが[2][3]、1869年の著作『Hereditary Genius』でヒストリオメトリーを広めたのはイギリスの多才な学者であるフランシス・ゴルトン卿であった[4]。 [また心理学者のポール・E・ミールは後年、主に医学史の分野でヒストリオメトリーに関する論文をいくつか発表しているが、ゴルトン自身は通常、クリオメ トリック・メタセオリーと呼んでいる[8][9]。 ヒストリオメトリーは科学的な手法で天才を研究する最初の分野であった[1]。 |

| Current research Prominent current historiometry researchers include Dean Keith Simonton and Charles Murray.[10] Historiometry is defined by Dean Keith Simonton as: a quantitative method of statistical analysis for retrospective data. In Simonton's work the raw data comes from psychometric assessment of famous personalities, often already deceased, in an attempt to assess creativity, genius and talent development.[11] Charles Murray's Human Accomplishment is one example of this approach to quantify the impact of individuals on technology, science and the arts. This work tracks many famous innovators in these areas, and quantifies how much attention to them has been paid by past historians, in terms of the number of references and the number of pages of reference material devoted to each subject. However, this work has been criticized for manipulating its data to derive conclusions that would not follow from unmanipulated data.[12] |

現在の研究 現在のヒストリオメトリーの著名な研究者には、Dean Keith SimontonとCharles Murrayがいる[10]。 ヒストリオメトリーとは、Dean Keith Simontonによって「回顧的データの定量的統計分析法」と定義されている。サイモントンの研究では、生データは創造性、天才、才能開発を評価する試 みで、しばしば既に亡くなった有名な人物の心理学的評価から得られる[11]。 Charles MurrayのHuman Accomplishmentは、個人の技術、科学、芸術への影響を定量化するこのアプローチの一例である。この著作は、これらの分野における多くの有名 なイノベーターを追跡し、過去の歴史家が彼らにどれだけ注目したかを、それぞれのテーマに割かれた参考文献の数やページ数で数値化したものである。しか し、この作品は、データを操作して、操作していないデータからは導かれないような結論を導き出しているという批判がある[12]。 |

| Examples of research Since historiometry deals with subjective personal traits as creativity, charisma or openness most studies deal with the comparison of scientists, artists or politicians. The study (Human Accomplishment) by Charles Murray classifies, for example, Einstein and Newton as the most important physicists and Michelangelo as the top ranking western artist.[10] As another example, several studies have compared charisma and even the IQ of presidents and presidential candidates of the United States of America.[13][14] The latter study classifies John Quincy Adams as the most clever US president, with an estimated IQ between 165 and 175.[15] A historiometric analysis has also been applied successfully in the field of musicology. In one groundbreaking study,[16] researchers analyzed statistically a collection of over 1,300 printed program leaflets (playbills) of concerts given by Clara Schumann (1819-1896) throughout her lifetime. The resulting analysis revealed Clara Schumann's influential role in the canonization of classical piano music repertoire. Her strategy of repertoire selection was guided by extremely traditionalistic tendencies. |

研究例 歴史学は創造性、カリスマ性、開放性などの主観的な個人特性を扱うため、ほとんどの研究は科学者、芸術家、政治家の比較を扱っている。チャールズ・マーレ イによる研究(Human Accomplishment)は、例えば、アインシュタインとニュートンを最も重要な物理学者として、ミケランジェロをトップランクの西洋芸術家として 分類する[10] 別の例として、いくつかの研究は、カリスマ性と、アメリカ合衆国の大統領と大統領候補のIQを比較しました。後者の研究は、推定IQ 165から175の間でジョン クインシー アダムズを最も賢いアメリカ大統領として分類します[14] 歴史測定分析も音楽学分野でうまく適用されてきました[15]。ある画期的な研究では[16]、クララ・シューマン(1819-1896)が生涯を通じて 行ったコンサートのプログラムチラシ(プレイビル)1,300枚以上の印刷物を統計的に分析しました。その結果、クララ・シューマンがクラシック・ピアノ 音楽のレパートリーの正典化に大きな影響を及ぼしたことが明らかになった。彼女のレパートリー選択の戦略は、極めて伝統的な傾向に導かれたものであった。 |

| Critique Since historiometry is based on indirect information like historic documents and relies heavily on statistics, the results of these studies are questioned by some researchers, mainly because of concerns about over-interpretation of the estimated results.[17][18] The previously mentioned study of the intellectual capacity of US presidents, a study by Dean Keith Simonton, attracted a lot of media attention and critique mainly because it classified the former US president, George W. Bush, as second to last of all US presidents since 1900.[15][19] The IQ of G.W. Bush was estimated as between 111.1 and 138.5, with an average of 125,[14] exceeding only that of president Warren Harding, who is regarded as a failed president,[15] with an average IQ of 124. Although controversial and imprecise (due to gaps in available data), the approach used by Simonton to generate his results was regarded "reasonable" by fellow researchers.[20] In the media, the study was sometimes compared with the U.S. Presidents IQ hoax, a hoax that circulated via email in mid-2001, which suggested that G.W. Bush had the lowest IQ of all US presidents.[21] |

批判 ヒストリオメトリは史料などの間接的な情報に基づき、統計に大きく依存しているため、主に推定結果の過大解釈の懸念から、一部の研究者からは疑問視されて いる[17][18]。 先に述べたアメリカ大統領の知的能力に関する研究、ディーン・キース・サイモントンによる研究は、主に前アメリカ大統領のジョージ・W・ブッシュを 1900年以降の全てのアメリカ大統領の中で最後から2番目に分類したことから多くのメディアの注目と批判を集めた[15][19]。 G・W・ブッシュのIQは平均125の111.1〜138.5と推定され、失敗大統領とされるウォレン・ハーディング大統領の平均124だけを上回った [15]。メディアでは、2001年半ばに電子メールで流布された、G.W.ブッシュが歴代大統領の中で最もIQが低いというデマ「U.S. Presidents IQ hoax」と比較されることもあった[21]。 |

| Catharine Cox Cliometrics Psychometrics Quantitative history Quantitative psychology |

キャサリン・コックス クリオメトリクス サイコメトリクス 計量歴史学 計量心理学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historiometry |

+++

出典は、アダム・ラザフォード

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報