タイノへの虐殺

Taíno genocide

Statue of Agüeybaná II, El Bravo, at the Monument to Agüeybaná II, El Bravo, Park, at the intersection of the Ponce Bypass and the Ave. Hostos, Playa neighborhood, Ponce, Puerto Rico

ア

グエイバナ2世の像、エル・ブラボ、アグエイバナ2世の記念碑、公園、ホストス通りとポンセバイパス通りの交差点、プエルトリコ、ポンセ、プラヤ地区

☆ タイノ族への大虐殺は、16世紀にスペインがカリブ海地域を植民地化して いた時代に、スペイン人によってタイノ族先住民に対して行われた。 [3] クリストファー・コロンブスがイスパニョーラ島と命名したクィスクェヤ(Ayití)島に1492年にスペイン帝国が到達する以前のタイノ族の人口は、1 万から100万の間と推定されている。 [3][5] 1504年に最後のタイノ族の首長が退位させられた後、スペイン人は彼らを奴隷として扱い、虐殺やそ の他の暴力的な扱いを行った。1514年までに人口は わずか3万2000人にまで減少したと伝えられている[3]。1565年には200人にまで減少したと報告され、1802年にはスペイン植民地当局によっ て絶滅したと宣言された。しかし、タイノ族の子孫は今も生存しており、記録から姿を消したことは、スペイン帝国が彼らを歴史から抹消する意図で作り出した 架空の物語の一部であった。[6]

★ タイノ(タイーノ)への虐殺行為(The Taíno genocide)

[Plate p.10. Conquistadors attacking a village of Indians. Scene of hangings and stake.] [Call number: BNF C43324]. / / A 16th-century illustration by Flemish Protestant Theodor de Bry for Las Casas' Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, depicting Spanish atrocities during the conquest of Hispaniola. Bartolome wrote: "They erected certain Gibbets, large, but low made, so that their feet almost reached the ground, every one of which was so ordered as to bear Thirteen Persons in Honour and Reverence (as they said blasphemously) of our Redeemer and his Twelve Apostles, under which they made a Fire to burn them to Ashes whilst hanging on them"

[プ

レート p.10. インディアンの村を襲うコンキスタドールたち。絞首刑と火あぶりの場面。] [請求記号:BNF C43324] / /

ラス・カサス著『インディアスの破壊についての簡潔な報告』のためにフランドル人のプロテスタント、テオドール・デ・ブリが描いた16世紀の挿絵。イスパ

ニョーラ征服時のスペイン人の残虐行為を描いている。バルトロメは次のように書いている。「彼らは、背の低い大きな絞首台を建て、その足が地面にほぼ届く

ようにした。その絞首台には、救い主と12使徒の(彼らが冒涜的に呼ぶところの)13の尊い人格を象徴するものを掲げ、その下で火を燃やし、吊るしたまま

灰にするよう命じた」

| The Taíno genocide

was committed against the Taíno Indigenous people by the Spanish during

their colonization of the Caribbean during the 16th century.[3] The

population of the Taíno before the arrival of the Spanish Empire on the

island of Quisqueya or Ayití in 1492,[4]which Christopher Columbus

baptized as Hispaniola, is estimated at between 10,000 and

1,000,000.[3][5] The Spanish subjected them to slavery, massacres and

other violent treatment after the last Taíno chief was deposed in 1504.

By 1514, the population had reportedly been reduced to just 32,000

Taíno,[3] by 1565, the number was reported at 200, and by 1802, they

were declared extinct by the Spanish colonial authorities. However,

descendants of the Taíno continue to live and their disappearance from

records was part of a fictional story created by the Spanish Empire

with the intention of erasing them from history.[6] |

タイノ族の大虐殺は、16世紀にスペインがカリブ海地域を植民地化して

いた時代に、スペイン人によってタイノ族先住民に対して行われた。 [3]

クリストファー・コロンブスがイスパニョーラ島と命名したクィスクェヤ(Ayití)島に1492年にスペイン帝国が到達する以前のタイノ族の人口は、1

万から100万の間と推定されている。 [3][5]

1504年に最後のタイノ族の首長が退位させられた後、スペイン人は彼らを奴隷として扱い、虐殺やその他の暴力的な扱いを行った。1514年までに人口は

わずか3万2000人にまで減少したと伝えられている[3]。1565年には200人にまで減少したと報告され、1802年にはスペイン植民地当局によっ

て絶滅したと宣言された。しかし、タイノ族の子孫は今も生存しており、記録から姿を消したことは、スペイン帝国が彼らを歴史から抹消する意図で作り出した

架空の物語の一部であった。[6] |

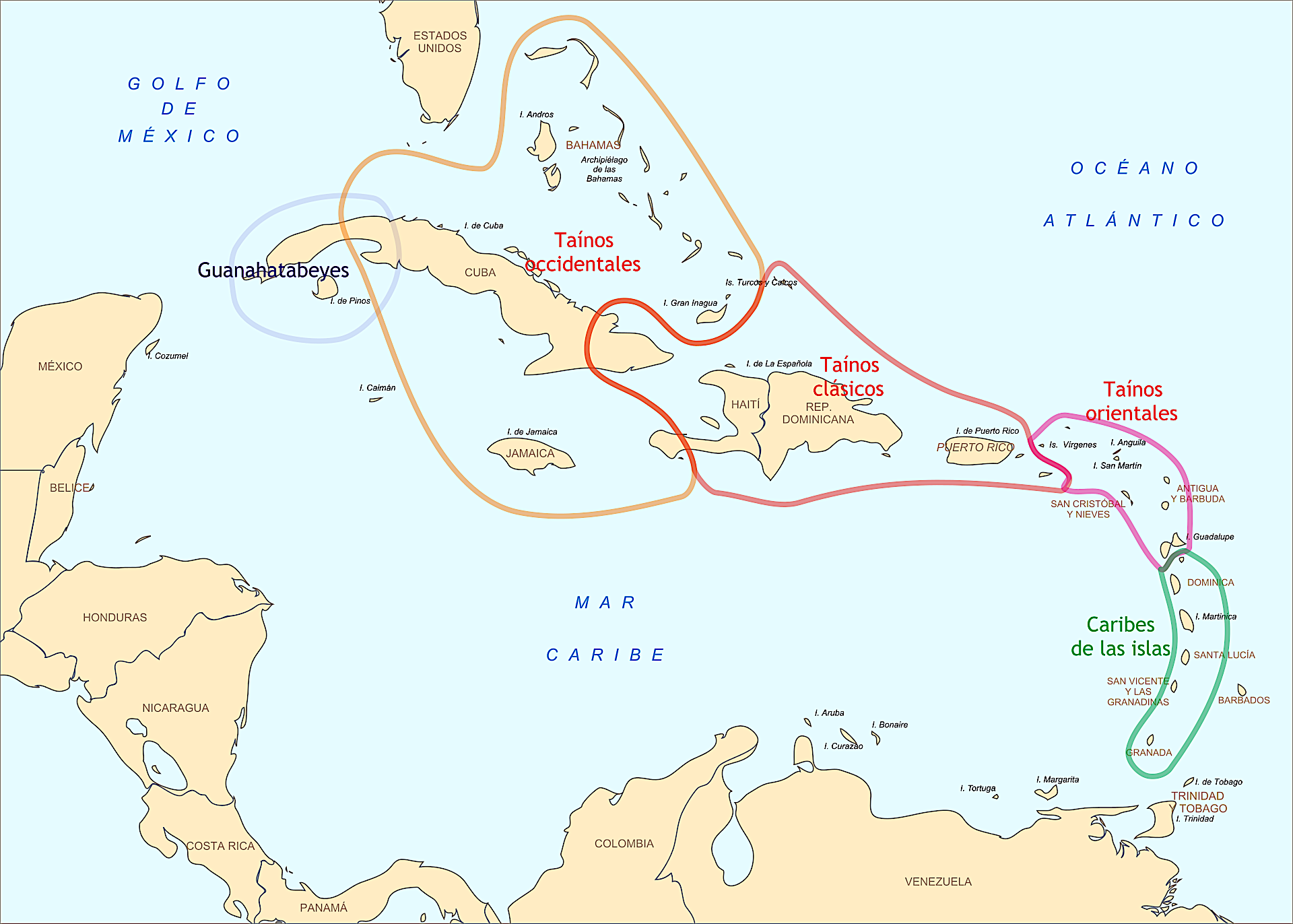

| History The Taíno people were the descendants of the Arawak people who arrived in the Caribbean approximately 4000 years before the conquest, [6] and they lived in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles and the Lesser Antilles.[7] Christopher Columbus was looking for gold. However, when he did not find it, he focused on the slavery. Upon arriving on the island, a confrontation occurred between the crew of the Santa María and the Taíno after the crew sexually abused Taíno women.[4] In 1503 most of the caciques were captured and burned alive in the Jaragua massacre.[4] Fray Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that in that massacre the Spanish also attacked the other inhabitants, cutting off the children's legs as they ran.[4] For several months after the massacre, Nicolás de Ovando continued a campaign of persecution against the Taíno until their numbers became very small, [4] according to historian Samuel M. Wilson in his book Hispaniola. Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. The Taíno suffered physical abuse in the gold mines and sugar cane fields, as well as religious persecution during the Spanish Inquisition, along with the exposure to diseases that arrived with the colonizers.[6] Others were captured and taken to Spain to be traded as slaves, which resulted in numerous deaths due to poor human conditions during the journey.[8] In thirty years, between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died.[1][2] Because of the increased number of people (Spanish) on the island, there was a higher demand for food. Taíno cultivation was converted to Spanish methods. In hopes of frustrating the Spanish, some Taínos refused to plant or harvest their crops. The supply of food became so low in 1495 and 1496 that some 50,000 died from famine.[9] Some historians have determined that the massive decline was due more to infectious disease outbreaks than any warfare or direct attacks.[10][11] By 1507, their numbers had shrunk to 60,000. Scholars believe that epidemic disease (smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus) was an overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous people,[12] and also attributed a "large number of Taíno deaths...to the continuing bondage systems" that existed.[13][14] |

歴史 タイノ族は、征服の約4000年前にカリブ海に到着したアラワク族の子孫であり、バハマ諸島、大アンティル諸島、小アンティル諸島に居住していた。[7] クリストファー・コロンブスは金を探していた。しかし、金を見つけられなかったため、奴隷制度に目を向けた。島に到着すると、サンタ・マリア号の乗組員と タイノ族の間で対立が生じ、乗組員がタイノ族の女性を性的虐待した後に衝突が起こった。[4] 1503年には、ほとんどの首長が捕らえられ、ジャラグア虐殺で生きたまま焼かれた。[4] バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス修道士は、スペイン人がこの虐殺で他の住民も攻撃し、逃げ惑う子供たちの足を切断したと記している。[4] 歴史学者サミュエル・M・ウィルソンは著書『イスパニョーラ。コロンブスの時代のカリブ海首長国』の中で、この虐殺の後数ヶ月間、ニコラス・デ・オバンド はタイノ族に対する迫害を続け、タイノ族の人口は激減したと述べている。タイノ族は金鉱やサトウキビ畑での肉体労働を強いられ、スペイン異端審問による宗 教的迫害を受け、入植者とともに持ち込まれた病気にさらされた。[6] また、捕らえられてスペインに連れて行かれ、奴隷として売買された者もおり、その過酷な旅の途中で多数の死者が出た。[8] 30年間で、タイノ族の人口の80%から90%が死亡した。[1][2] 島にスペイン人が増えたため、食糧の需要が高まった。タイノ族の農耕はスペイン式に転換された。スペイン人を困らせることを期待して、一部のタイノ族は作 物の植え付けや収穫を拒否した。1495年と1496年には食糧供給が極度に不足し、5万人が飢餓で死亡した。[9] 一部の歴史家は、この大幅な人口減少は、戦争や直接攻撃よりも感染症の流行によるものだと結論づけている。[10][11] 1507年までに、人口は6万人にまで減少した。学者たちは、先住民の人口減少の圧倒的な原因は伝染病(天然痘、インフルエンザ、麻疹、チフス)であった と考えている。また、存在していた「継続的な奴隷制度」が「多数のタイノ族の死」の原因であったとも考えられている。[13][14] |

| Academic discourse Academics, such as historian Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis, assert that disease alone does not explain the destruction of Indigenous populations of Hispaniola. While the populations of Europe rebounded following the devastating population decline associated with the Black Death, there was no such rebound for the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean. He concludes that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, meaning perhaps they did not spread as fast as initially believed, and that, unlike Europeans, the Indigenous populations were subjected to enslavement, exploitation, and forced labor in gold and silver mines on an enormous scale.[15] Reséndez says that "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous people of the Caribbean.[16] Anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that the lethal forced labor in these mines killed a third of the Indigenous people there every six months.[17] Subsequently, in the United States, Yale University classified the atrocities which the Spanish Empire committed against the Taíno as a "genocide" and it also included the Taíno genocide in its Genocide Studies Program.[3] Raphael Lemkin considered Spain's abuses of the native population of the Americas to constitute cultural and even outright genocide including the abuses of the encomienda system.[18] University of Hawaii historian David Stannard describes the encomienda as a genocidal system which "had driven many millions of native peoples in Central and South America to early and agonizing deaths."[19] Scholars Bridget Conley and Alex de Waal highlight the weaponisation of starvation employed by conquistadors against the Taíno as being a contributing factor to the genocide,[20] and historian Harald E. Braun highlight Jaragua massacre in 1503 as a case of genocidal massacre.[21] |

学術的な議論 カリフォルニア大学デービス校の歴史学者アンドレス・レセンデス氏などの学者は、疾病だけではイスパニョーラ島の先住民の人口減少を説明できないと主張し ている。ヨーロッパでは、ペストによる壊滅的な人口減少の後、人口が回復した一方で、カリブ海地域では先住民の人口が回復することはなかった。彼は、スペ イン人が天然痘などの致死性の高い病気を認識していたにもかかわらず、1519年まで新大陸での言及が一切ないことから、当初考えられていたほど急速に広 まらなかった可能性があると結論づけている。また、ヨーロッパ人と異なり、先住民は奴隷化、搾取、金銀鉱山での強制労働に大規模にさらされたと述べてい る。 [15] レゼンデスは、「奴隷制がカリブ海の先住民の主要な死因となっている」と述べている。[16] 人類学者ジェイソン・ヒッケルは、これらの鉱山での致死的な強制労働により、先住民の3分の1が半年ごとに死亡したと推定している。[17] その後、米国ではイェール大学がスペイン帝国がタイノ族に対して行った残虐行為を「ジェノサイド」と分類し、ジェノサイド研究プログラムにもタイノ族の ジェノサイドを含めた。 ラファエル・レムキンは、スペインによるアメリカ大陸先住民に対する虐待は、エンコミエンダ制度の虐待を含め、文化的なものであり、さらには明白なジェノ サイドであるとみなした。[18] ハワイ大学の歴史学者デビッド・スタナードは、エンコミエンダを「何百万人もの中米および南米の先住民を早すぎる苦悩に満ちた死へと追い込んだ」ジェノサ イドのシステムであると表現している。 [19] 学者のブリジット・コンリーとアレックス・デ・ウォールは、征服者たちがタイノ族に対して行った飢餓の武器化が大量虐殺の要因のひとつであると強調してい る。[20] また、歴史家のハラルド・E・ブラウンは、1503年のジャラグア虐殺を大量虐殺の事例として挙げている。[21] |

| Jaragua massacre Colonialism and genocide Genocide of indigenous peoples Genocides in history Indigenous response to colonialism List of ethnic cleansing campaigns List of genocides |

ジャラグア虐殺 植民地主義と大量虐殺 先住民の大量虐殺 歴史上の大量虐殺 先住民の植民地主義への対応 民族浄化作戦の一覧 大量虐殺の一覧 |

| Works cited Braun, Harald E. (2023). "Genocidal Massacres in the Spanish Conquest of the Americas: Xaragua, Cholula and Toxcatl, 1503–1519". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 622–647. doi:10.1017/9781108655989. ISBN 978-1-108-65598-9. Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex (2023). "Genocide, Starvation and Famine". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, Tracy Maria; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 127–149. doi:10.1017/9781108493536. ISBN 978-1-108-49353-6. D'Anghiera, Pietro Martire (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010. Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0547640983. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019. Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0. ... estimated population for the year 1769 ... Nationwide by this time only about one-third of one percent of America's population—250,000 out of 76,000,000 people—were natives. The worst human holocaust the world had ever witnessed ... finally had leveled off. There was, at last, almost no one left to kill. |

引用文献 Braun, Harald E. (2023). 「スペインのアメリカ大陸征服における大量虐殺: Xaragua, Cholula and Toxcatl, 1503-1519". Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-108-65598-9. Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex (2023). 「Genocide, Starvation and Famine". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, Tracy Maria; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. 第1巻:古代・中世・前近代世界におけるジェノサイド。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-108-49353-6. D'Anghiera, Pietro Martire (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781113147608. 2010年7月21日取得。 Reséndez, Andrés (2016). もうひとつの奴隷: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. ホートン・ミフリン・ハーコート。ISBN 978-0547640983. 2019年10月14日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2019年6月21日取得。 Stannard, David E. (1993). アメリカン・ホロコースト: The Conquest of the New World. オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0. ... 1769年の推定人口...この時点でアメリカ全土の人口の1/3、7600万人のうち25万人だけが原住民であった。世界が目撃した最悪の人類大虐殺 は、ついに横ばいになった。ついに、殺すべき人間がほとんどいなくなったのだ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ta%C3%ADno_genocide |

脚 注

1.

"La tragédie des Taïnos" [The Tragedy of the Tainos]. L'Histoire (in

French) (322): 16. July–August 2007.

2. Diaz Soler, Luis Manuel (1950). Historia De La Esclavitud Negra en

Puerto Rico (Thesis). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses.

Retrieved January 12, 2021.

3. "Hispaniola". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. Archived

from the original on May 22, 2024.

4. Pichardo, Carolina (October 12, 2022). "Anacaona, the Aboriginal

chieftain who defied Christopher Columbus and was sentenced to a tragic

death". BBC News.

5. Fernandes, Daniel M.; Sirak, Kendra A.; Ringbauer, Harald; Sedig,

Jakob; Rohland, Nadin; Cheronet, Olivia; Mah, Matthew; Mallick, Swapan;

Olalde, Iñigo; Culleton, Brendan J.; Adamski, Nicole (February 2021).

"A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844):

103–110. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..103F. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2.

ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

6. Baracutei Estevez, Jorge (October 15, 2019). "Conoce a los

supervivientes de un «genocidio sobre el papel»" [Meet the survivors of

a "genocide on paper"]. National Geographic (in Spanish). Archived from

the original on June 28, 2024.

7. Méndez, Luis (October 12, 2022). "Los taínos: los indígenas que se

extinguieron en el Caribe tras la conquista española" [The Taínos: the

indigenous people who became extinct in the Caribbean after the Spanish

conquest]. La Noticia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May

31, 2024.

8. Haczek, Ángela Reyes (October 11, 2022). "Cómo la Conquista de

América se cobró la vida de más de 50 millones de personas" [How the

Conquest of America claimed the lives of more than 50 million people].

CNN in Spanish (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 28,

2022.

9. D'Anghiera 2009, p. 108.

10. D'Anghiera 2009, p. 160.

11. Aufderheide, Arthur C.; Rodríguez-Martín, Conrado; Langsjoen, Odin

(1998). The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge

University Press. pp. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5. Archived from the

original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

12. Watts, Sheldon (2003). Disease and medicine in world history.

Routledge. pp. 86, 91. ISBN 978-0-415-27816-4. Archived from the

original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

13. Schimmer, Russell. "Puerto Rico". Genocide Studies Program. Yale

University. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved

December 4, 2011.

14. Raudzens, George (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial

Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. Brill. p. 41. ISBN

978-0-391-04206-3. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016.

Retrieved January 5, 2016.

15. Treuer, David (May 13, 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery'

will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times.

Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

16. Reséndez 2016, p. 17.

17. Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global

Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN

978-1786090034.

18. "Raphael Lemkin's History of Genocide and Colonialism". United

States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[permanent dead link]

19. Stannard 1993, p. 139.

20. Conley & de Waal 2023, pp. 128–129.

21. Braun 2023, pp. 626–628.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099